568

Writing Like a Lawyer: How Law

Student Involvement Affects Self-

Reported Gains in Writing Skills in

Law School

Kirsten M. Winek

I. Introduction

Complaints that new lawyers struggle with legal writing skills are not new.

Nearly thirty years ago, in 1992, the American Bar Association’s MacCrate

Report suggested law schools improve the writing curriculum because there

was “the widely held perception that new lawyers today are deficient in

writing skills.”

1

Later, in a 2003 article, the surveyed judges, attorneys, and

legal writing faculty agreed in large numbers (57.3%) that new lawyers have

difficulty with writing in practice.

2

In particular, respondents noted that new

lawyer writing was wordy, unfocused, incomplete, unclear, and disorganized.

3

It also suffered from a misunderstanding of the issues at hand and problems

with grammar and writing fundamentals.

4

Some of these observations were

echoed in a 2009 article whose authors surveyed lawyers, judges, and judicial

law clerks and found that they, too, noticed lawyers struggling to be organized

1. LegaL education and ProfessionaL deveLoPment—an educationaL continuum,

rePort of the task force on Law schooLs and the Profession: narrowing the gaP

332 (Am. Bar Ass’n Section of Legal Educ. & Admissions to the Bar ed., 1992) [hereinafter

MacCrate Report]. This was not the first time an ABA task force complained about legal

writing skills. In 1979, an ABA task force opined that “too few students receive rigorous

training and experience in legal writing during their three years of law study.” rePort and

recommendations of the task force on Lawyer comPetency: the roLe of the Law

schooLs 15 (Am. Bar Ass’n Section of Legal Educ. & Admissions to the Bar ed., 1979).

2. Susan Hanley Kosse & David T. ButleRitchie, How Judges, Practitioners, and Legal Writing Teachers

Assess the Writing Skills of New Law Graduates: A Comparative Study, 53 J. LegaL educ. 80, 86 (2003).

3. Id. at 87.

4. Id. at 87.

Kirsten Winek, J.D., Ph.D., is Accreditation Counsel at the American Bar Association (ABA)

Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar. This article is based on dissertation

research for her Ph.D. in higher education. All views expressed are her own and not those of the

ABA. She wishes to thank Professors Eric Chaffee and Pamela Lysaght for their helpful comments

and feedback on this article.

Writing Like a Lawyer 569

and concise in their writing.

5

Focus groups with legal employers revealed that

they wanted new lawyers to advocate for a position and explain the strengths

and weaknesses of a client’s case in written work instead of merely reviewing

the law.

6

More recently, 47% of the litigation attorneys surveyed in a 2015 study

cited writing and drafting as the most deficient skills in new lawyers.

7

This

is especially notable given that 66% of these litigation attorneys considered

these skills crucial for new attorneys.

8

In particular, certain types of litigation

documents—trial briefs, motions, and pleadings—were cited as important

documents new lawyers write but lacked the skills to do so.

9

Even while in law school, some students perceive that their writing skills

may not be at the level needed for legal practice. In the Law School Survey

of Student Engagement’s (LSSSE) 2008 Annual Survey Results, nearly 40%

of the students surveyed wanted more writing opportunities that reflected the

work they would do in law practice.

10

An even higher percentage of students

(45%) opined that “their legal education does not contribute substantially

to their ability to apply legal writing skills in real-world situations.”

11

Furthermore, some law students working as summer associates in larger firms

surveyed in 2016 struggled with writing in the law firm setting, with 35%

feeling unprepared for at least one writing project.

12

Additionally, a number of

these summer associates thought more training in creating contracts (29.7%),

memos (28.8%), pleadings and motions (22.7%), and briefs (21.5%) would

have been helpful.

13

These complaints by legal professionals and student concerns are alarming,

as writing is especially critical at the start of a new lawyer’s career. Passing the

state bar exam is the first step to law practice, and, in most states, the written

5. Amy Vorenberg & Margaret Sova McCabe, Practice Writing: Responding to the Needs of the Bench

and Bar in First-Year Writing Programs, 2 Phoenix L. rev. 1, 9 (2009).

6. Susan C. Wawrose, What Do Legal Employers Want to See in New Graduates?: Using Focus Groups to

Find Out, 39 ohio n.u. L. rev. 505, 539–40 (2013).

7. White Paper: Hiring Partners Reveal New Attorney Readiness for Real World Practice, LexisNexis 7 (2015),

https://www.lexisnexis.com/documents/pdf/20150325064926_large.pdf [hereinafter

LexisNexis 2015].

8. Id. at 5.

9. Id. at 4.

10. 2008 Annual Survey Results: Student Engagement in Law School: Preparing 21st Century Lawyers, Law

School Survey of Student Engagement 10 (2008), https://lssse.indiana.edu/wp-content/

uploads/2016/01/LSSSE_Annual_Report_2008.pdf [hereinafter LSSSE 2008 Annual

Survey Results].

11. Id. at 10.

12. Summer Associates Identify Writing and Legal Research Skills Required on the Job,

LexisNexis 3 (2016), http://www.lexisnexis.com/documents/pdf/20161109032544_large.pdf

[hereinafter LexisNexis 2016].

13. Id.

570 Journal of Legal Education

portion of the exam usually comprises essay questions and/or performance

tests.

14

These written portions of the state bar exam are usually weighted at

half the total score or more.

15

This makes writing an important skill for success

on the bar exam. Furthermore, writing skills are important in obtaining a job

and working as a new attorney. Legal employers have expressed that good

writing and communication are highly relevant skills in new lawyers being

evaluated for jobs.

16

Once on the job, new lawyers learn that writing is essential

to their chosen profession. In a 2013 job analysis focusing on the work of new

lawyers, all respondents indicated they used written communication.

17

The

same respondents also thought written communication was important to their

work, rating it the highest on a list of thirty-six skills and abilities needed for

law practice.

18

In 2019, another job analysis revealed that writing continued to

be a critical skill for new attorneys, ranking third on a list of thirty-six skills

and abilities.

19

Because writing is essential to new lawyer success, this article recommends

law schools maintain their current first-year legal writing programs and

increase upper-level curricular opportunities to practice writing and

writing-related skills such as speaking, critical and analytical thinking, and

legal research. These recommendations are based on the author’s doctoral

dissertation research study, which sought to determine whether any law school

involvement activities affected student self-reported gains in writing skills in

full-time, third-year law students, using responses to the 2018 administration

of LSSSE.

20

LSSSE queries law students about their cocurricular activities,

interactions with peers and professors, class participation and coursework,

activities outside law school such as holding a job, satisfaction with various

aspects of law school, and perceptions of skills gains.

21

Specifically, this

14. Comprehensive Guide to Bar Admission Requirements 2020, National Conference of Bar Examiners

36–38 (Judith A. Gundersen & Claire J. Guback, eds., 2020), http://www.ncbex.org/

assets/BarAdmissionGuide/CompGuide2020_021820_Online_Final.pdf [hereinafter Bar

Admission Requirements 2020].

15. Id.

16. Neil W. Hamilton, Changing Markets Create Opportunities: Emphasizing the Competencies Legal Employers

Use in Hiring New Lawyers (Including Professional Formation/Professionalism), 65 s.c. L. rev. 547, 551–

58 (2014).

17. Susan M. Case, The NCBE Job Analysis: A Study of the Newly Licensed Lawyer, the Bar

examiner 52–53, 55, (Mar. 2013), https://thebarexaminer.org/wp-content/uploads/

PDFs/820113testingcolumn.pdf.

18. Id.

19. National Conference of Bar Examiners, Testing Task Force Phase 2 Report: 2019 Practice

Analysis, 25, 62 (Mar. 2020), https://testingtaskforce.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/

TestingTaskForce_Phase_2_Report_031020.pdf.

20. See discussion infra Part II.

21. E-mail from Chad Christensen, LSSSE Project Manager, Center for Postsecondary

Research, Indiana University, to author (Jan. 24, 2019, 10:10 CST) (on file with author).

This e-mail contained a copy of the questions for the 2018 administration of LSSSE. See also

Writing Like a Lawyer 571

study used blocked stepwise multiple regression to determine if any of these

activities, behaviors, or perceptions (collectively referred to in this study as

involvement activities) affected the scores on a LSSSE question asking law

student respondents to rate how much their law school experience “contributed

to your knowledge, skills, and personal development”

22

in writing. Alexander

Astin’s Involvement Theory

23

and I-E-O Model

24

served as the theoretical

and conceptual frameworks for this study, which created a basis for the study

and guided the data analysis process.

25

After analyzing the responses of

3803 full-time third-year law students who participated in the 2018 LSSSE

administration, the three items that had the strongest positive impacts on law

student self-reported gains in writing skills were three areas related to writing:

speaking skills, critical and analytical thinking skills, and legal research skills.

26

This essentially means legal writing is developed in conjunction with other

related skills. As such, law schools should use current first-year legal writing

programs and expand opportunities in the upper-level curriculum so students

can practice writing alongside speaking, critical and analytical thinking, and

legal research.

27

While this approach has some drawbacks, including law school

institutional inertia and the financial costs of curricular implementation,

28

helping students develop the writing skills needed for success on the bar exam

and the start of legal practice outweigh these concerns.

Furthermore, this study and its implications contribute to the existing legal

education literature. As this study formed the basis of a doctoral dissertation,

an in-depth review of the legal education literature on law student perceptions

of their writing skills and activities affecting law student self-reported gains in

writing skills during law school revealed few articles on these topics. The few

that surfaced included both quantitative and qualitative studies. For example,

one quantitative study examined first-year law students’ confidence in learning

legal writing before starting their legal writing course and their confidence

in their legal writing skills several weeks after starting the course.

29

Another

quantitative study used LSSSE data to determine which law school activities

LSSSE Survey, Law School Survey of Student engagement, https://lssse.indiana.edu/about-

lssse-surveys (last visited May 25, 2020).

22. Id.

23. Alexander W. Astin, Student Involvement: A Developmental Theory for Higher Education, 25 J. coLLege

student PersonneL 297 (1984), reprinted in 40 J. coLLege student dev. 518, 528–29 (1999).

24. aLexander w. astin, what matters in coLLege? four criticaL years revisited 7

(1993).

25. See discussion infra Part II.

26. See discussion infra Part II.

27. See discussion infra Part III.

28. See discussion infra Part IV.

29. Miriam E. Felsenburg & Laura P. Graham, Beginning Legal Writers in Their Own Words: Why the

First Weeks of Legal Writing are So Tough and What We Can Do about It, 16 LegaL writing 223, 239–

40, 279–80 (2010).

572 Journal of Legal Education

affected student self-reported gains in academic skills (writing was included

in academic skills) in third- and fourth-year law students.

30

LSSSE staff have

also looked at the relationships between certain law school activities covered

by LSSSE questions and student self-reported gains in writing skills as part

of their annual publications in 2006

31

and 2008.

32

Additionally, a qualitative

study examined the habits of students who had varying degrees of academic

success in a legal writing course.

33

Finally, only one prior doctoral dissertation

applied Astin’s Involvement Theory or I-E-O Model to law students

34

as this

article’s study has done. Thus, this study makes a new contribution to the

current legal education literature on law student perceptions of their writing

skills and activities affecting law student self-reported writing gains during law

school.

This article consists of four additional parts. Part II provides an overview

of the author’s dissertation study, including the theoretical and conceptual

frameworks, LSSSE data used, methodology for data analysis, and key

findings. Part III recommends maintaining current first-year legal writing

programs and expanding the upper-level curriculum to integrate more writing

and skills that may improve student self-reported gains in writing. Part IV

examines why law schools may struggle to adopt these recommendations, and

Part V provides concluding remarks.

II. Overview of Dissertation Study

This study was developed as a way to help address the issue of new lawyer

struggles with writing early in legal practice by examining whether any law

school involvement activities improve student self-reported gains in writing.

The following sections delve into the dissertation study’s research question

and frameworks, LSSSE dataset, study limitations, data analysis, and research

findings.

A. Research Question and Frameworks

This study’s research question asked whether any law school involvement

activities affected student self-reported gains in writing skills in full-time

third-year law students. Self-reported gains in writing were measured by

30. Carole Silver et al., Gaining from the System: Lessons from the Law School Survey of Student Engagement

About Student Development in Law School, 10 u. st. thomas L.J. 286, 287, 298–99 (2012).

31. 2006 Annual Survey Results: Engaging Legal Education: Moving Beyond the Status Quo, Law School

Survey of Student Engagement 11, 13, 15–16 (2006), http://lssse.indiana.edu/wp-content/

uploads/2016/01/LSSSE_2006_Annual_Report.pdf [hereinafter LSSSE 2006 Annual

Survey Results].

32. LSSSE 2008 Annual Survey Results, supra note 10, at 10–11.

33. Anne M. Enquist, Unlocking the Secrets of Highly Successful Legal Writing Students, 82 st. John’s L.

rev. 609, 610–11 (2008).

34. roBert r. detwiLer, assessing factors infLuencing student academic success

in Law schooL 41–43 (2011), https://etd.ohiolink.edu/apexprod/rws_etd/send_file/

send?accession=toledo1318730664&disposition=inline.

Writing Like a Lawyer 573

student responses to the LSSSE question that asked: “To what extent has

your experience at your law school contributed to your knowledge, skills,

and personal development in the following areas? . . . Writing clearly and

effectively.”

35

Student respondents were given the following answer choices:

“Very much, Quite a bit, Some, Very little.”

36

Examples of law school

involvement activities covered by LSSSE questions included cocurricular

activities, interacting with peers and professors, participating in classes,

undertaking various types of coursework, holding a job, and perceptions of the

law school experience.

37

To assist with data analysis, the research question was

broken into seven parts, with law school involvement activities divided among

parts three to seven: (1) Inputs (student characteristics), (2) Between-College

Characteristics (law school characteristics), (3) Academic Involvement,

(4) Student-Faculty Involvement, (5) Student-Student Involvement, (6)

Nonacademic Involvement, and (7) Intermediate Educational Outcomes.

Similar setups have been used by other researchers.

38

After the research question was determined, the study needed theoretical

and conceptual frameworks to provide both a theory underpinning the research

and a guide for the data analysis. Serving as the theoretical and conceptual

frameworks were Alexander Astin’s Involvement Theory

39

and I-E-O (Input-

Environment-Outcome) Model,

40

respectively.

Astin succinctly summarized his Involvement Theory as follows: “[T]he

greater the student’s involvement in college, the greater will be the amount of

student learning and personal development.”

41

To accomplish this, a school’s

curriculum “must elicit sufficient student effort and investment of energy

to bring about the desired learning and development.”

42

In other words,

students who engage themselves in school-related activities will likely learn

more from those experiences than students who choose to be less engaged

or unengaged. Astin focused on undergraduate students in developing his

Involvement Theory,

43

and only one researcher is currently known to have

applied Involvement Theory to a law student population.

44

Thus, using

35. E-mail from Chad Christensen, supra note 21.

36. Id.

37. Id.

38. See detwiLer, supra note 34, at 5–6; see also astin, supra note 24, at 13–15, 33–34, 70–77, 80–81.

39. Astin, supra note 23, at 528–29.

40. astin, supra note 24, at 7.

41. Astin, supra note 23, at 528–29.

42. Id. at 522.

43. Id. at 523.

44. See detwiLer, supra note 34, at 41–42.

574 Journal of Legal Education

Involvement Theory in the author’s dissertation study helps further expand

its use in studies of law students and enriches the literature in this area.

What does Involvement Theory mean for law schools? It may mean that

the more involved law students are with coursework, student organizations,

faculty members and peers, and cocurricular activities, the more knowledge

and skills gains (including those in writing) they may self-report as a result

of their legal education. The use of LSSSE data works well with this theory,

since LSSSE itself “is centered on the concept of student engagement—which

is based on the simple, yet powerful observation that the more engrossing the

educational experience, the more students will gain from it.”

45

In Astin’s I-E-O model, used here as the study’s conceptual framework,

researchers examine three types of data—inputs, environment, and outcomes.

46

Inputs (I) are the characteristics students possess when they first enter higher

education.

47

Environment (E) encompasses all the facets of the educational

experience—“the various programs, policies, faculty, peers, and educational

experiences to which the student is exposed.”

48

Outcomes (O) are the

characteristics students possess after spending time in higher education.

49

Researchers then review how student characteristics change over time (such

as between starting and finishing higher education) by comparing inputs to

outcomes and determining what impact an environment has on students’

outcomes.

50

However, in this dissertation’s study, legal education was

substituted for higher education in the I-E-O model, following the conceptual

framework of a similar dissertation study.

51

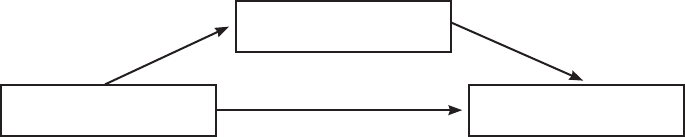

Figure 1 visually demonstrates the I-E-O model and the relationships among

inputs, environment, and outcomes. This study used inputs such as student

demographic characteristics, Law School Admission Test (LSAT) scores, and

undergraduate GPA. Activities students participate in during law school and

their perceptions of the law school experience served as environmental factors.

45. LSSSE Survey, Law School Survey of Student engagement, https://lssse.indiana.edu/about-

lssse-surveys (last visited May 25, 2020).

46. astin, supra note 24, at 7.

47. Id.

48. Id.

49. Id.

50. Id.

51. detwiLer, supra note 34, at 42.

Writing Like a Lawyer 575

The outcome of interest was student self-reported gains in writing skills by

full-time third-year law students. All of the data used in the I-E-O model came

from student responses to the 2018 LSSSE administration.

Figure 1. Astin’s I-E-O model

52

B. LSSSE Dataset

To determine whether any law school involvement activities affected student

self-reported gains in writing skills, this study used a dataset comprised of

all full-time, third-year law students who responded to LSSSE when it was

administered at their law schools in the spring semester of 2018. The goal of

limiting the dataset to solely full-time third-year law students was to obtain

a set of similarly situated survey respondents. Part-time students may not be

present at their law schools as often as full-time law students, and thus may

have different involvement levels or patterns from full-time students. This

approach was similar to how Astin limited one of his wide-ranging studies to

students who started college as full-time students because he recognized that a

full-time student population was very different from a part-time one.

53

Second,

because most full-time law students complete their studies in three years, these

third-year students would have taken LSSSE shortly before they graduated

from law school. This timing is important because some writing-focused law

school activities take place during the latter part of a student’s time in law

school, such as serving on a law review or journal, participating on moot court,

or working in a law school’s legal clinic.

54

Furthermore, these students have

already completed the first-year writing experience and have finished or are

nearly finished with upper-level writing experience required by the American

Bar Association (ABA).

55

Before examining the dataset used in the study, an overview of the law

school and law student participation in the 2018 administration of LSSSE

52. Figure adapted from aLexander w. astin & anthony Lising antonio, assessment for

exceLLence: the PhiLosoPhy and Practice of assessment and evaLuation in higher

education 19-20 (2d ed. 2012); astin, supra note 24, at 7.

53. astin, supra note 24, at xxv–xxvi.

54. ruta k. stroPus & charLotte d. tayLor, Bridging the gaP Between coLLege and Law

schooL: strategies for success 157 (2d ed. 2009).

55. ABA Standards and Rules of Procedure for Approval of Law Schools 2019-2020, Am. Bar Ass’n Section

of Legal Educ. & Admissions to the Bar, at 16 (2019) [hereinafter ABA Standards].

Environmental

Factors

OutcomesInputs

576 Journal of Legal Education

is instructive. In the 2018 spring semester, seventy-four U.S. law schools

administered LSSSE.

56

Only one of these law schools was not approved by

or seeking approval from the ABA.

57

With 203 ABA-approved law schools

nationwide,

58

this means approximately 36% of ABA-approved law schools

participated in the 2018 LSSSE administration. At these participating schools,

17,928 students from all years of law school participated in the survey, for an

overall response rate of 49%.

59

Because law schools must pay to administer LSSSE

60

and students

decide whether to participate in the survey,

61

LSSSE respondents are not a

random sample of all U.S. law students. This is a significant limitation of

the dissertation’s study. Because of this, Tables 1 and 2 are included to show

how U.S. law schools administering the 2018 LSSSE compared with all ABA-

approved law schools. LSSSE-administering schools tended to skew private

and slightly smaller (fewer than 500 students) than most ABA-approved law

schools, but otherwise they were fairly comparable.

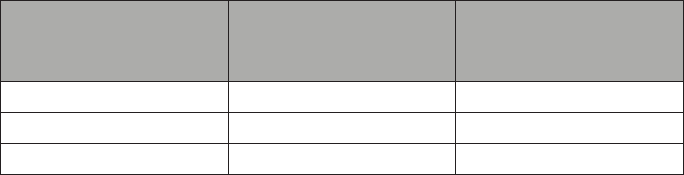

Table 1

62

Comparison of Law School Size

Law School Size

(in Students)

2018

LSSSE-Administering

Law Schools

All ABA-Approved

Law Schools

Fewer than 500 61% 53%

500–900 31% 35%

More than 900 8% 12%

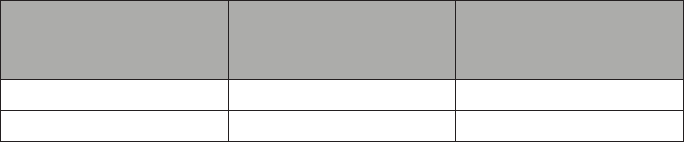

Table 2

63

56. E-mail from Jacquelyn Petzold, Research Analyst, Law School Survey of Student

Engagement, Center for Postsecondary Research, Indiana University, to author (Oct. 22,

2018, 15:17 CST) (on file with author).

57. E-mail from Jacquelyn Petzold, Research Analyst, Law School Survey of Student

Engagement, Center for Postsecondary Research, Indiana University, to author (Oct. 23,

2018, 14:14 CST) (on file with author).

58. ABA-Approved Law Schools, Am. Bar Ass’n Section of Legal Educ. & Admissions to the Bar,

https://www.americanbar.org/groups/legal_education/resources/aba_approved_law_

schools/ (last visited May 25, 2020).

59. E-mail from Jacquelyn Petzold, supra note 56.

60. Timeline and Fees, Law School Survey of Student Engagement, http://lssse.indiana.edu/

timeline-and-fees/ (last visited May 25, 2020).

61. Administering LSSSE, Law School Survey of Student Engagement, http://lssse.indiana.edu/

administering/ (last visited May 25, 2020).

62. E-mail from Chad Christensen, LSSSE Project Manager, Center for Postsecondary

Research, Indiana University, to author (Oct. 10, 2018, 13:15 CST) (on file with author).

63. Id.

Writing Like a Lawyer 577

Comparison of Law School Type

Type of Law School

2018

LSSSE-Administering

Law Schools

All ABA-Approved

Law Schools

Public 34% 42%

Private 66% 58%

This dissertation’s study sought to analyze survey responses of just one

group of LSSSE participants—full-time third-year students at U.S. law schools

who participated in the LSSSE when it was administered at their law schools

during the 2018 spring semester. This group equated to 4330 full-time third-year

law students. LSSSE staff were unable to provide a response rate specifically

for full-time third-year law students but recorded a response rate of 47.4% for

all third-year law students.

64

However, the actual number of full-time third-

year students whose survey responses were analyzed in this study was slightly

smaller, since certain student participants were excluded. Student respondents

were excluded if they did not answer the question about self-reported gains

in writing skills, which was the study’s outcome measure. Students were also

excluded if they did not answer both the LSAT score and undergraduate GPA

questions, as these served as proxy pretests for self-reported gains in writing,

since LSSSE does not have a pretest for writing skills. After removing these

students, this study analyzed the responses of 3803 full-time third-year law

students. This represented a loss of 527 students, or approximately 12.2%, of

the original group of all full-time third year students who participated in the

2018 LSSSE administration.

In terms of the student demographics for the dataset used in the regression,

52.9% of the students identified as female and 43.5% identified as male. The rest

(3.6%) either did not answer the question, did not wish to respond, or selected

“another gender identity.” The majority of students identified as white (63.2%),

while 26.8% identified as minority and 10% did not answer the minority status

question, declined to respond, or chose “other.” Regarding sexual orientation,

86.1% of the students in the dataset identified as heterosexual; 7.5% identified

as either gay, lesbian, bisexual, or questioning/unsure; and 6.4% did not

respond, preferred not to respond, or chose “another sexual orientation.” As

such, the average student in the dataset was a white heterosexual female.

Generally speaking, the student demographics of the dataset compared

favorably with those collected on all third-year law students by the ABA. As

of fall 2017 (the semester before the students in the dataset took LSSSE) there

were 33,726 total full- and part-time law students enrolled in ABA-approved law

schools.

65

Of this total, approximately 49.9% were female and 50.1% were male

64. E-mail from Jacqueline Petzold, supra note 56.

65. Section of Legal Education—ABA Required Disclosures, Am. Bar Ass’n Section of Legal Educ. &

Admissions to the Bar, http://abarequireddisclosures.org/Disclosure509.aspx (under

“Compilation—All Schools Data” select “2017” and “JD Enrollment and Ethnicity”) (last

visited May 25, 2020). This information is collected by the ABA each fall from all ABA-

578 Journal of Legal Education

(“other” gender consisted of a fraction of a percent).

66

In terms of minority

status, approximately 61.1% of all third-year law students were white, 30.7%

were minority, 3.5% were nonresidents, and 4.8% had an unknown minority

status.

67

While the ABA did not report information on sexual orientation and

the demographic data was not limited to full-time students, it did demonstrate

that the dataset’s gender and minority status reflected well the overall

population of all third-year law students at ABA-approved law schools. The

students in the dataset did skew slightly white and female, though.

A brief note about minority status and sexual orientation is in order. LSSSE

allows survey takers to choose from a large number of minority categories.

68

In the dissertation’s study, several of these categories did not have students

represented in the dataset, so it was decided to have two broad categories—

minority and nonminority. As for sexual orientation, even though the majority

of the students in the dataset were heterosexual, a decision was made not to

use two broad categories—heterosexual and nonheterosexual. The difference in

approach simply reflected the dataset’s inclusion of student respondents from

each of the sexual orientation categories, unlike the minority status categories.

For the academic profile, students in the dataset reported a mean LSAT

measure of 3.31 (the median was 3.00), with 3 representing an LSAT score in

the range of 151–155 and 4 representing an LSAT score in the range of 156–160.

As for undergraduate GPA measures, students in the sample reported a mean

of 4.14 (the median was 4.00), with 4 representing a GPA range of 3.00-3.49

and 5 representing a GPA range of 3.50 and higher. Last, for the question

“What have most of your grades been up to now at this law school?”

69

the

mean response was 5.85 (the median was 6.00), with a 5 being a “B” grade and

6 being a “B+” grade.

The students in the dataset came from law schools that were fairly evenly

spread out among all four 2018 U.S. News tiers, which are basically quartiles.

The tier breakdown was as follows: Tier 1: 26.3%, Tier 2: 20.4%, Tier 3: 21.4%,

and Tier 4: 31.9%. (LSSSE staff provided a school’s U.S. News tier for each

survey respondent in the dataset after a request from the author; it is not a

question on the survey.) The majority of the students in the dataset came from

private law schools (64.1%) vs. public law schools (35.9%). Additionally, law

schools attended by the students in the dataset generally enrolled 900 or fewer

students. LSSSE divides law schools into three categories by size: fewer than

500 students (47.9% of the students in the dataset), 500–900 students (39.4%

of the students in the dataset), and more than 900 students (12.6% of the

approved law schools as part of its annual questionnaire.

66. Id.

67. Id.

68. E-mail from Chad Christensen, supra note 21.

69. E-mail from Chad Christensen, supra note 21.

Writing Like a Lawyer 579

students in the dataset).

70

Thus, the average student in the dataset came from

a private law school with a relatively small student body.

D. Study Limitations

Before discussing the data analysis process, it should be noted that this

study contained several notable limitations. The most significant limitation

was that LSSSE relied on students to accurately and honestly self-report the

information requested by the survey. Law students participating in LSSSE

could have overestimated their involvement in law school or the gains in skills

they achieved, either because they did not know how to gauge their level of

involvement or progress, or they wanted to portray themselves in the most

favorable light. For example, one study found that first-year law students

were very optimistic in assessing their writing skills and predicting their legal

writing aptitude before taking a legal writing course.

71

Another important limitation was that this study had no pretest measure

for self-reported writing skills. LSSSE asked students to self-report their gains

in writing skills at the time they took the survey

72

(a post-test), but there was

nothing that measured students’ self-reported level of writing skills when they

entered law school (a pretest). Thus, there was no objective way to measure

these self-reported gains. To partially compensate for this lack of a pretest, this

dissertation’s study used students’ undergraduate GPAs and LSAT scores—as

measured by the corresponding LSSSE questions

73

—as proxy measures for the

level of writing skills students had when starting law school. Furthermore,

student self-reported writing skills gains are not an objective measure of

these skills like a graded writing assignment or exam. However, student self-

reported measures have merit because “[t]hese gains are based on students’

reflections on their own development stemming from law school . . . . [T]hey

are a useful complement to provide a more comprehensive understanding of

student learning and development.”

74

Last, there were no available data on the full-time third-year law students

who did not participate in LSSSE, either those students declining to participate

when LSSSE was offered at their law schools or those students whose schools

did not choose to participate in the 2018 administration of LSSSE. Thus,

it must be assumed that responding students’ answers to the survey were

representative of all law students nationwide, including those who did not

participate in the survey.

70. E-mail from Chad Christensen, supra note 62.

71. Felsenburg & Graham, supra note 29, at 239–40.

72. E-mail from Chad Christensen, supra note 21.

73. Id.

74. Silver et al., supra note 30, at 292.

580 Journal of Legal Education

C. Data Analysis

To start the data analysis process, student response data from the 112 LSSSE

questions used in this dissertation’s study were divided into seven blocks:

(1) Inputs, (2) Between-College Characteristics, (3) Academic Involvement,

(4) Student-Faculty Involvement, (5) Student-Student Involvement, (6)

Nonacademic Involvement, and (7) Intermediate Educational Outcomes.

These blocks corresponded to the seven parts of this study’s research question.

This setup also follows Astin’s I-E-O model,

75

as it has blocks representing

inputs as well as the different types of involvement activities in which students

can participate (environmental factors) so the researcher can determine

whether any of these activities affect the outcome of student self-reported

writing skills.

Block One (Inputs) contained demographic information including LSAT

score, undergraduate GPA, gender identity, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation,

age, and years between college graduation and starting law school, among

others. These were controlled to prevent bias in the outcomes.

76

Block Two

(Between-College Characteristics) comprised three law school characteristics—

size, status as public or private, and 2018 U.S. News ranking tier, as these were

the only law school characteristics provided in the dataset by LSSSE staff.

Block Three (Academic Involvement) grouped together educationally related

activities students may participate in during their time in law school, such as

class preparation; number of pages written; or participation in cocurricular

activities such as moot court, law review or journal, or law clinics. These

activities were of particular interest because a prior study with LSSSE data

found activities such as class preparation, class participation, and law review

or moot court participation had positive impacts on a measure of student self-

reported skills called academic gains (which included writing).

77

Block Four (Student-Faculty Involvement) included student activities

such as having conversations with faculty members, receiving feedback from

faculty, and working on projects or committees unrelated to coursework with

faculty members. One study using LSSSE data found a positive relationship

between frequent faculty feedback and student self-reported gains in writing;

78

another found a positive relationship between faculty interactions and student

self-reported academic gains.

79

Block Five (Student-Student Involvement)

included variables describing collaboration with other students, as well as

conversations with other students, including those of diverse backgrounds.

Block Six (Nonacademic Involvement) included student activities unrelated

to law school such as having a job and commuting.

75. astin, supra note 24, at 7.

76. Id. at 90.

77. Silver et al., supra note 30, at 298, 307–08.

78. LSSSE 2006 Annual Survey Results, supra note 31, at 11.

79. Silver et al., supra note 30, at 307.

Writing Like a Lawyer 581

Block Seven (Intermediate Educational Outcomes) comprised mainly

student satisfaction measures for different aspects of the law school experience,

student self-reported gains in various skills, and the likelihood that a student

would choose this law school or do a law degree once again. As such, this block

deserves some explanation. Astin’s I-E-O model is based on the assumption that

“the environmental variables occur prior in time to the outcome variables.”

80

While inputs describe students at entry into college, environmental variables

describe students’ activities during their time in college, which takes place

over the course of several years.

81

A student’s choice of activity early in college

may affect or influence the choice of activities later in college, and these later-

in-college activity choices (intermediate outcomes) could then influence the

outcomes (the O in the I-E-O model).

82

Interestingly, these intermediate

outcomes can even be regular outcome measures themselves, depending on

how the research is structured.

83

Because the influence and timing of these

intermediate educational outcomes is uncertain, this block is entered last in a

regression.

84

If there are multiple intermediate outcome blocks, they are added

“according to their known or expected temporal sequencing, with the most

ambiguous variables, such as student satisfaction with the college, consigned

to the last block.”

85

The SPSS software program analyzed the seven blocks of student response

data. Within SPSS, blocked stepwise multiple regression was used to

statistically determine whether any law school involvement activities affected

student self-reported gains in writing. In other words, this statistical analysis

revealed whether any law school involvement activity “adds anything to the

prediction of” student self-reported gains in writing beyond what might be

predicted by a student’s demographics, undergraduate GPA, LSAT score, and

other input measures.

86

The regression analysis controlled the input variables, because if there were

any existing relationships between certain inputs and environments, “the

possibility remains that any observed correlation between an environment and

an outcome measure may reflect the effect of some input characteristic rather

than the effect of the college environment.”

87

The actual blocked stepwise

multiple regression followed a process similar to that laid out by other

researchers.

88

The first block contained all the student responses to the various

80. astin, supra note 24, at 80.

81. Id.

82. Id.

83. Id.

84. Id. at 327.

85. Id. at 330.

86. Id. at 301.

87. astin, supra note 24, at 13–14.

88. astin & antonio, supra note 52, at 305–07; detwiLer, supra note 34, at 54–56, 64–65.

582 Journal of Legal Education

input questions and SPSS added each of these input questions (or variables)

individually into the regression “until no additional variable in that block is

capable of adding significantly to the prediction of”

89

law student self-reported

gains in writing. If an input question did not help predict student self-reported

gains in writing, it was not added to the regression equation. This process

was repeated for each of the six remaining blocks. When SPSS finished all

the blocks, the independent variables that remained in the final step helped

to predict student self-reported gains in writing. However, any variables in

the final step having beta weights that were not significant at the p<0.05 level

were removed from the regression, and another regression was run in order to

obtain a set of variables in the final step that were all significant at the p<0.05

level. These final variables were the law school involvement activities that had

statistically significant relationships to student self-reported writing gains.

D. Research Findings

While this study yielded fifteen law school involvement activities having a

statistically significant impact on student self-reported gains in writing skills,

this article will discuss only the three strongest ones. Interestingly, the three

involvement activities with the strongest impacts on student self-reported gains

in writing were not student involvement activities in the traditional sense—they

were other skills gains reported by students in the dataset. Speaking, critical

and analytical thinking, and legal research skills had the strongest impacts on

student self-reported gains in writing, respectively. The impact of each one

was positive, which means students who self-reported higher skills gains in

speaking, critical and analytical thinking, or legal research were more likely

to self-report higher skills gains in writing. Table 3 provides the numerical

strength of these impacts.

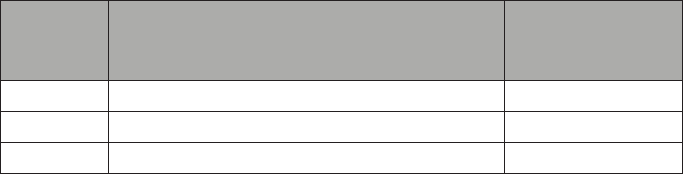

Table 3

Variables Affecting Student Self-Reported Gains in Writing Skills by Impact Strength

Ranking

Law School Involvement Activity

Final Step β

(Standardized

Coefficient β)

1 Speaking Clearly and Effectively 0.29***

2 Thinking Critically and Analytically 0.22***

3 Developing Legal Research Skills 0.21***

N = 3,803 R

2

= 0.571 Adjusted R

2

= 0.569

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

89. astin & antonio, supra note 52, at 305–07.

Writing Like a Lawyer 583

The main implication of these research findings is that writing skills in law

school are not developed in a vacuum—they are developed alongside speaking,

critical and analytical thinking, and legal research skills. This is unsurprising,

given that good speaking, thinking, and research go into effective legal

writing. For example, a description of a first-year writing course summarizes

how several of these skills are related:

[The course] does not just involve researching and writing.

Legal research itself is a complex task that may require

reading, evaluating, and filtering large amounts of material

just to enable the student to identify the issues to analyze.

Then, reading, reasoning, understanding, analyzing, and

even rereading must occur between the research process and

the writing process. Moreover, the writing process itself

should typically encompass outlining, multiple efforts at

drafting, revising, editing, formatting, and proofreading.

90

Additionally, a qualitative study of students in an introductory brief-writing

course reflected how these three skills were intertwined with legal writing.

91

In terms of speaking skills, more than half of the studied group of students

reported that their work in preparing for oral arguments helped them write

the first of two briefs for the course.

92

As for critical thinking skills in the

academically successful students, there was “an obvious connection between

their critical reading and critical thinking skills” as their notes reflected how

the cases they found would support their position (or their opponent’s

position) and how different cases might work together in their briefs.

93

Finally,

the academically successful students excelled at legal research—“[t]hey had the

ability to find the key cases, zero in on what was important in those cases, and

then know when to stop researching and start writing.”

94

III. Recommendation: Maintaining or Adding More Writing and

Writing-Related Activities to the Law School Curriculum

Based on the findings of this study, this section recommends maintaining the

first-year legal writing program and adding more curricular opportunities for

upper-level students to write and practice the skills shown to further students’

self-reported writing skills gains. Allowing students to practice writing as

well as speaking, critical and analytical thinking, and legal research will help

90. Felsenburg & Graham, supra note 29, at 293–94.

91. Enquist, supra note 33, at 657–58, 670.

92. Id. at 657–58.

93. Id. at 670.

94. Id. at 670.

584 Journal of Legal Education

prepare them for the writing they will encounter in legal practice and on the

state bar exam. As previously discussed, some students have reported feeling

unready for some law firm writing projects

95

and generally seem to want more

opportunities to work on writing they will use in legal practice.

96

Employers

seek to hire new lawyers with developed writing skills

97

and have lamented

that these writing skills have been lacking for decades.

98

However, students

will encounter difficulties in obtaining employment if they cannot pass the bar

exam, which includes writing sections comprising half or more of their score.

99

The next sections explore two recommendations. The first section will

discuss maintaining the current first-year legal writing curriculum, since

it generally incorporates writing and the three skills whose gains improved

students’ self-reported writing skills gains in the author’s dissertation study.

The second section discusses ways to integrate more opportunities to practice

writing and the three aforementioned skills in the upper-level curriculum.

A. Maintaining the First-Year Legal Writing Curriculum

The first-year legal writing course has long served as an introduction for law

students to the world of legal writing and should remain in its current form

as a key part of the law school curriculum. As the ABA mandates a first-year

writing experience,

100

the vast majority of law schools require students to take

two first-year legal writing courses.

101

Generally, the first course covers objective

and predictive writing and the second course covers persuasive writing.

102

Many legal writing faculty require students to complete office memorandums

and appellate or trial briefs as part of these courses.

103

Office memorandums

95. LexisNexis 2016, supra note 12, at 3.

96. LSSSE 2008 Annual Survey Results, supra note 1-0, at 10; LexisNexis, supra note 12, at 3.

97. Hamilton, supra note 16, at 551–58.

98. MacCrate report, supra note 1 at 332; Kosse & ButleRitchie, supra note 2, at 80, 86; LexisNexis

2015, supra note 7, at 7.

99. Bar Admission Requirements 2020, supra note 14, at 36–38.

100. ABA Standards, supra note 55, at 16.

101. ALWD/LWI Annual Legal Writing Survey: Report of the 2017-2018 Institutional Survey, Ass’n of Legal

Writing Directors & Legal Writing Institute at 25-26 (2017–2018), https://www.lwionline.org/

sites/default/files/Final%20ALWD%20LWI%202017-18%20Institutional%20Survey%20

Report.pdf [hereinafter ALWD/LWI 2017–2018 Survey].

102. Id.

103. am. Bar ass’n section of LegaL educ. & admissions to the Bar, sourceBook on LegaL

writing Programs 17, 21 (Eric B. Easton, ed., 2d ed. 2006) [hereinafter sourceBook];

see also Report of the Annual Legal Writing Survey 2015, Ass’n of Legal Writing Directors & Legal

Writing Institute at 13 (2015), https://www.alwd.org/images/resources/2015%20Survey%20

Report%20(AY%202014-2015).pdf [hereinafter ALWD/LWI 2015 Survey]. ALWD/LWI’s

Annual Legal Writing Survey was overhauled after the 2015 survey. As such, some footnotes

reference this version (2015) or the most recent version of the survey (2017–2018) depending

on the data sought simply because many of the questions have changed and thus the data is

not directly comparable.

Writing Like a Lawyer 585

are usually written by students to a fictional law firm partner predicting the

outcome of a client matter.

104

The goal of this assignment is objective legal

analysis that is written in a clear, organized way and includes correct legal

citations.

105

Mock briefs are written by students to persuade a trial or appellate

court to rule in favor of the students’ clients; the goal of the assignment is to

explore more challenging legal issues and analysis.

106

The emphasis on legal

analysis in both assignments is critical because “[l]egal writing is, after all, the

written expression of legal analysis.”

107

Two studies support the use of office memorandums and briefs as writing

assignments. Both assignments are created by legal writing faculty to mimic

documents students will see or use in legal practice. First, LSSSE found that

“practice-oriented writing assignments are more highly related to [student self-

reported] gains in . . . clear and effective writing” than academic papers.

108

Importantly, LSSSE included both memorandums and appellate briefs as types

of practice-oriented writing assignments.

109

Second, some summer associates

at larger firms thought additional training on how to write certain types of

documents would be helpful.

110

Almost 29% and 22% of the summer associates

surveyed specifically mentioned memorandums and briefs, respectively, as

areas where more training would be helpful.

111

Since students may work as

law firm summer associates after their first or second year of law school, this

means the first-year legal writing courses should continue or increase their use

of memorandums and briefs to prepare students for this work. However, if

students do not work as law firm summer associates until after their second

year of law school, their skills in memorandum and brief writing may become

rusty from lack of use.

Briefly reviewing how legal research is incorporated into the first-year legal

writing course is in order. It is usually taught by the course professor, a law

librarian, or both.

112

The amount of legal research practice law students get in

the first-year legal writing course varies with the writing assignments. Some

assignments require law students to do their own legal research, while others

require no research (a closed-universe assignment).

113

In most closed-universe

assignments, students are provided with the research materials needed to

complete the assignment. When students do their own research, that research

104. sourceBook, supra note 103, at 17.

105. Id. at 21.

106. Id.

107. Id. at 14.

108. LSSSE 2008 Annual Survey Results, supra note 10, at 11.

109. Id.

110. LexisNexis 2016, supra note 12, at 3.

111. Id.

112. ALWD/LWI 2015 Survey, supra note 103, at x, 11.

113. Id. at 12.

586 Journal of Legal Education

is closely intertwined with analysis and writing. Basically, “research, analysis,

and writing are not independent steps[;] [r]ather, students are taught to

begin their analysis and writing as they go through the research process.”

114

This process accords with the findings of this article’s dissertation study, as

it is reasonable to imagine that gains in self-reported critical and analytical

thinking or legal research skills would lead to self-reported gains in writing

skills.

Students in first-year legal writing courses typically receive feedback from

their professors as they prepare written drafts. Specific written feedback is

usually contained in margin notes, with general suggestions written at the end

of the draft.

115

Verbal feedback is usually provided in individual conferences

with the student and professor.

116

The professor may use the written comments

as a starting point for discussion, and students have the benefit of asking

the professor questions and learning more about the strengths and weakness

of their work.

117

Students are then able to incorporate this feedback into

subsequent drafts, strengthening their writing.

118

Discussions between students

and their professors about their writing are key to integrating speaking skills

into the first-year legal writing course, as there are fewer opportunities to

develop speaking skills compared with the legal research and thinking skills

that are integral to this course. However, for faculty to provide personalized

feedback and individual student conferences, these courses must have small

section enrollments. As such, the average course section has only twenty-one

to twenty-two students.

119

This feedback is important to students’ development as legal writers and

as professionals who will meet high expectations. For example, LSSSE data

showed that 87% of surveyed law students who reported receiving timely faculty

feedback “very often” realized substantial gains in self-reported writing skills;

this percentage dropped slightly to 80% for students reporting they received

this feedback “often.”

120

Additionally, LSSSE found statistically significant

and positive correlations for two survey questions related to receiving timely

faculty feedback and working to achieve the high expectations of faculty

members with student self-reported gains in writing skills.

121

A final component of the first-year legal writing course is oral advocacy.

Approximately 73% of surveyed law schools indicated they teach appellate

114. sourceBook, supra note 103, at 65.

115. Id. at 55.

116. Id. at 60.

117. Id. at 60–61.

118. Id.

119. ALWD/LWI 2017–2018 Survey supra note 101, at 27–28.

120. LSSSE 2006 Annual Survey Results, supra note 31, at 11.

121. Id. at 15.

Writing Like a Lawyer 587

argument skills in this course.

122

This allows students to argue the brief

they have written or are in the process of writing.

123

If students present oral

arguments while still writing the brief, they may “gain insights from the oral

argument that enhance their legal analysis, resulting in a much better written

brief.”

124

Students may similarly benefit if they argue a completed brief and

then revise it afterward.

125

The first-year legal writing course allows law students to practice their

writing skills and the three skills this article’s dissertation study found to

enhance student self-reported gains in writing skills. Students use speaking

skills when they meet with their professor to discuss feedback on their writing

or when they present mock oral arguments. Critical and analytical thinking

skills are woven throughout the first-year writing course, as are legal research

skills. As such, the first-year legal writing course in its present iteration must

be maintained.

B. Adding More Writing and Writing-Related Skills to the Upper-Level Curriculum

Currently, the ABA requires only one faculty-supervised writing experience

after a student’s first year of law school.

126

In the past, law students fulfilled

similar requirements “only by doing some sort of scholarly writing, such as a

journal article or seminar paper,” but there has been a trend toward allowing

students to take a practically oriented writing course instead.

127

As such, this

section discusses the primary types of courses law schools offer for students to

meet this ABA requirement or gain additional practice in legal writing after

their first year. It also examines how these courses incorporate opportunities to

practice the speaking, critical and analytical thinking, and legal research skills

found by this article’s dissertation study to boost student self-reported gains

in writing skills. Finally, this section recommends ways to integrate these skills

into traditional doctrinal courses in addition to legal writing courses.

While first-year legal writing courses are similar among law schools, the

same cannot be said of upper-level writing courses. For example, they can

cover topics as diverse as drafting for a specific area of law, more generalized

drafting for contracts or litigation, and scholarly writing.

128

Also, scholarly

writing is a major component of most seminar courses, as students usually

write a well-researched paper similar to the ones submitted to law reviews and

122. ALWD/LWI 2015 Survey, supra note 112, at xi, 13.

123. sourceBook, supra note 103, at 31.

124. Id.

125. Id.

126. ABA Standards, supra note 56, at 16.

127. ALWD/LWI 2015 Survey, supra note 103, at x.

128. ALWD/LWI 2017-2018 Survey, supra note 101, at 38.

588 Journal of Legal Education

journals.

129

Despite the variety of upper-level writing courses, they tend to fall

into two categories: scholarly writing and practical writing.

Both types of writing—scholarly and practical—help students practice

their writing skills, deepen their knowledge of the law, and prepare for their

work as attorneys. For instance, scholarly writing forces students to learn

and write about a topic in the way that practicing attorneys do—they must

identify the issue at hand and find a solution while teaching themselves about

the subject matter.

130

In doing so, students learn that writing is not linear—it

is very much recursive—and learn to balance this time-intensive process with

other competing responsibilities.

131

Similarly, practically focused writing helps

students prepare for legal practice through its emphasis on technical writing

and “the knowledge, skills, and professional judgments that are required for

successful writing.”

132

Scholarly writing is commonly taught in a seminar course.

133

A key part

of this course is student production of a paper of scholarly quality with

feedback and supervision from a faculty member, making it a popular way for

law schools to comply with the ABA Standards mandating another writing

experience after a student’s first year of legal education.

134

In a scholarly paper,

students write about a particular issue and propose a resolution “that builds

upon a basis of knowledge in multiple subject areas.”

135

Doing so requires

students to synthesize doctrinal legal knowledge and writing skills into the

same project when these skills may otherwise be taught separately in different

classes.

136

Ideally, the goals of a scholarly writing course can be summarized

as follows: “[T]he student will work with complex materials, receive advanced

research experience, and engage in a type of critical legal thinking that is unlike

the types of analyses required for other forms of legal writing.”

137

Despite its

scholarly nature, this writing can hone certain skills students need for law

practice, such as spotting issues and explaining how best to resolve them.

138

129. sourceBook, supra note 103, at 183, 193.

130. Kristina V. Foehrkolb & Marc A. DeSimone, Jr., Debunking the Myths Surrounding Student Scholarly

Writing, 74 md. L. rev. 169, 173–74, 177–78 (2014).

131. Id. at 175, 178.

132. Sherri Lee Keene, One Small Step for Legal Writing, One Giant Leap for Legal Education: Making the Case

for More Writing Opportunities in the “Practice-Ready” Law School Curriculum, 65 mercer L. rev. 467,

493 (2013).

133. sourceBook, supra note 103, at 193.

134. Id.

135. Foehrkolb & DeSimone, Jr., supra note 130, at 170.

136. Id. at 170, 177.

137. sourceBook, supra note 103, at 193.

138. Foehrkolb & DeSimone, Jr., supra note 130, at 170, 173–74.

Writing Like a Lawyer 589

From these descriptions, it is clear that scholarly writing courses allow

students to practice legal research and critical and analytical thinking skills.

However, one area in which these courses may be improved is in the area of

speaking skills. While there are likely some student speaking skills already

involved in the course—such as exploring paper topics and strategies and

discussing feedback with their professor—more can be added. For instance, the

professor can require students to make a formal presentation on their paper

topic or the final version of their paper to their course peers. Explaining their

work to peers helps students think about their writing in a different way and

allows them to answer questions and obtain feedback from another source.

Students can use the information gained from their presentation to revise and

strengthen their written work.

Recommending that students discuss or present their written work and

obtain feedback is not without precedent. Law faculty do this with their

own scholarly work when they “expand their knowledge and learn from the

expertise of their peers by discussing scholarly drafts before working groups

and providing feedback to one another on written drafts.”

139

Also providing

support for this recommendation is a quantitative study using LSSSE data

to identify aspects of legal education that promote third- and fourth-year

law students’ self-reported academic gains.

140

In the study, “academic gains”

comprised student self-reported gains in seven related areas: writing, speaking,

thinking, legal research, independent learning, job skills, and broad-based

education in law.

141

All seven skills are arguably used in a scholarly writing

course, so the results of this study are particularly pertinent. The aspects

of legal education that aided this cluster of skills called academic gains

were student interactions with professors and peers, the use of higher-order

learning in educational activities, preparation for and participation in courses,

and moot court or law review service.

142

The finding that interactions with

professors and peers stimulate academic gains gives additional credence to

the recommendation that students be given opportunities to discuss and get

feedback on their work in scholarly writing courses. However, to facilitate this

feedback and interaction with both the professor and peers, scholarly writing

courses must have a low student-faculty ratio. These courses may enroll only

about a dozen students per section.

143

The other type of law school writing course is practical writing. Courses on

practical writing center around the types of writing and documents used in law

practice. These courses can be more of an overview; a number of law schools

139. Keene, supra note 132, at 491.

140. Silver et al., supra note 30, at 287, 291–92.

141. Id. at 298.

142. Id. at 307–08.

143. ALWD/LWI 2017–2018 Survey, supra note 101, at 45.

590 Journal of Legal Education

offer courses in general drafting or creating contracts.

144

A general course on

drafting may include “draft[ing] a contract, a will or trust, a statute, and a set

of jury instructions to give students the broadest range of experience.”

145

Other

drafting courses focus on the documents needed for general or appellate

litigation.

146

Finally, other courses may focus on a particular legal practice area

(such as real estate), which allows students to write and familiarize themselves

with documents pertinent to that practice area.

147

Practical writing is important to students’ development as legal writers. As

part of a study using LSSSE data, researchers found that practical legal writing

had a stronger positive relationship to student self-reported gains in writing,

legal research, and job skills than more academic or scholarly writing.

148

Furthermore, this stronger positive relationship with practical writing also

extended to students’ self-reported gains in “[a]pplying . . . legal writing skills

to real-world situations.”

149

Practical writing courses offer several benefits to law students. Like other

legal writing courses, they “aid the students’ understanding of theory and

doctrine, sharpen their analytical skills, improve their understanding of the

legal profession, and in some instances cultivate their practical wisdom.”

150

Students receive faculty feedback on their work, since “[t]he best way to learn

this important skill [legal drafting] is by drafting documents and getting

timely, quality, individualized feedback.”

151

While the feedback helps students

improve their current writing, it also prepares them for the collaborative

nature of law practice. New attorneys must view written work as an ongoing

work-in-progress involving multiple drafts and feedback from colleagues or

supervisors.

152

As with other legal writing courses, enrollments must be kept

small. This generally limits course sections to about ten to fifteen students.

153

Practical writing courses integrate well the critical and analytical thinking

skills this article’s dissertation study found to advance students’ self-reported

gains in writing skills. Speaking skills are used in the course when students

discuss feedback or work with the professor to improve their draft documents.

144. Id. at 38.

145. sourceBook, supra note 103, at 178.

146. ALWD/LWI 2017–2018 Survey, supra note 101, at 38.

147. sourceBook, supra note 103, at 179–80.

148. LSSSE 2008 Annual Survey Results, supra note 10, at 11.

149. Id.

150. roy stuckey et aL., Best Practices for LegaL education: a vision and a roadmaP 148–

49 (2007) [hereinafter Best Practices for LegaL education].

151. sourceBook, supra note 103, at 182.

152. wiLLiam m. suLLivan et aL., educating Lawyers: PreParation for the Profession of

Law 98–99 (2007) [hereinafter Carnegie Report].

153. ALWD/LWI 2017–2018 Survey, supra note 101, at 42–45.

Writing Like a Lawyer 591

These speaking opportunities may be significant, since practical writing

courses optimally include “at least three and as many as six or seven graded

and critiqued drafts and assignments.”

154

However, legal research needs to be

incorporated into practical writing courses whenever possible. While the focus

of the course is document drafting, faculty can require students to do some

related independent legal research. For example, students can explore common

practitioner materials or form books for a particular type of document or area

of law. Not only does this exercise help students with their coursework, but it

also exposes them to resources used by practicing attorneys.

Both scholarly and practical writing courses provide students an avenue

to practice different types of legal writing. These courses also allow (or can

be modified to allow) students to use the three skills this article’s dissertation

study found to promote students’ self-reported gains in writing skills.

However, while law schools should continue offering some scholarly writing

courses, they must expand their practical writing course offerings, since these

are directly applicable to the work students will do shortly after graduation.

C. Writing in Doctrinal Courses

Most doctrinal courses involve minimal, if any, writing practice for

students.

155

This tradition, coupled with the ABA requirement of a first-year

and upper-level writing experience,

156

means students may take only two or

three courses focused on legal writing. Unless students seek out additional

elective writing courses, they may graduate with only limited curricular writing

experience. Limited opportunities for writing are worrisome, because the

more practice students have in writing, the more they improve.

157

Accordingly,

“[w]ith so little required writing, it is hardly surprising that new graduates do

not write as well as more senior members of the [legal] profession. After all,

repetition and practice are essential to improving writing skills.”

158

Some scholars suggest that legal writing should be a requisite part of

all six semesters of law school.

159

Having a legal writing-focused course or

legal writing experience in every semester of law school may not be easy or

practical to implement for most law schools without significant planning

154. sourceBook, supra note 103, at 182.

155. Keene, supra note 132, at 468.

156. ABA Standards, supra note 52, at 16.

157. Patrick T. O’Day & George D. Kuh, Assessing What Matters in Law School: The Law School Survey of

Student Engagement, 81 ind. L. J. 401, 406 (2006).

158. Kosse & ButleRitchie, supra note 2, at 87.

159. Adam Lamparello & Charles E. MacLean, Integrating Legal Writing and Experiential Learning

into a Required Six-Semester Curriculum that Trains Students in Core Competencies, “Soft” Skills, and Real-

World Judgement, 43 caP. u. L. rev. 59, 63 (2015); see also Kristen Konrad Tiscione, A Writing

Revolution: Using Legal Writing’s “Hobble” to Solve Legal Education’s Problem, 42 caP. u. L. rev. 143,

159–60 (2014).

592 Journal of Legal Education

and resources. Thus, as an intermediate step, one way to ensure all students

continue to practice legal writing is to incorporate writing assignments into

existing doctrinal courses, focusing on legal documents relevant to that

particular doctrinal area.

160

Also, in doctrinal courses whose subject matter is

tested on the bar exam, faculty can assign bar exam-style essay questions. This

type of assignment supports both writing practice and bar exam preparation.

However, the type of writing assigned to students is not as important as simply

having students engage in the act of writing.

161

Furthermore, LSSSE data

indicated a positive relationship between pages of writing completed during

the school year and student self-reported writing skills gains.

162

Students

seem to be interested in adding writing to their doctrinal courses as well.

163

Finally, and not insignificantly, adding writing to doctrinal courses spreads

the responsibility for teaching writing skills to the law faculty as a whole.

164

This may increase the amount of support for legal writing and emphasize its

importance to students.

Adding writing as a component of a doctrinal course must include drafting

assignments relevant to the topic of the course, as this allows students to

combine their subject-matter knowledge and writing skills to create a practice-

oriented document.

165

(The same idea applies to assigning bar exam essay

questions related to bar-tested course topics.) Doing so is part of the “writing

across the curriculum” pedagogical strategy and is specifically known as

“writing in the discipline.”

166

There are numerous examples of implementation.

“Students taking a Business Associations course could be required to draft

a partnership agreement or corporate bylaws. Students taking a course in

Intellectual Property could draft a licensing agreement . . . . Students taking

Evidence could draft a motion in limine and a supporting memorandum

of law.”

167

Subject-specific writing assignments should be used primarily in

upper-level doctrinal courses because students already have a foundation to

build upon from their first-year legal writing course.

168

As with other courses

involving writing, it is important that students receive feedback and credit

160. Pamela Lysaght & Cristina D. Lockwood, Writing-across-the-Law-School-Curriculum: Theoretical

Justifications, Curricular Implications, 2 J. ass’n LegaL writing directors 73, 100 (2004).

161. Tiscione, supra note 159, at 145.

162. LSSSE 2008 Annual Survey Results, supra note 10, at 10–11.

163. Carnegie Report, supra note 153, at 104.

164. Lysaght & Lockwood, supra note 160, at 73–74.

165. Id. at 100.

166. Id. at 75.

167. Kenneth D. Chestek, MacCrate (In)Action: The Case for Enhancing the Upper-Level Writing Requirement

in Law Schools, 78 u. coLo. L. rev. 115, 144 (2007).

168. Lysaght & Lockwood, supra note 160, at 76, 101–02.

Writing Like a Lawyer 593

for their written work product from their professor.

169

Feedback in doctrinal

courses can be beneficial to both students and the professor—students learn

whether their work would be acceptable in law practice (or on the bar exam),

and the professor can determine whether students understand and can apply

the concepts discussed in the course.

170

However, since doctrinal courses are

usually much larger than writing courses, feedback may be less in-depth and

individualized simply because of the higher student-faculty ratio.

Aside from giving students additional opportunities to practice writing,

adding subject-specific writing assignments to doctrinal courses has a

number of other benefits. First, students work like practicing attorneys by

using doctrinal knowledge and practical skills simultaneously. As one scholar

explained, “[M]ost legal skills cannot be easily segregated from legal theory

and doctrine, but instead require attorneys to apply their knowledge of the law