BEST PRACTICES IN SCHOOL COUNSELING

Prepared for Utah Leading through Effective, Actionable, and Dynamic Education

January 2019

In the following report, Hanover Research and ULEAD provide an overview of school counseling

models and roles of school counselors across school levels. More specifically, the report

highlights the American School Counselor Association’s National School Counseling Model. The

report also includes a discussion of school counselors’ roles in providing mental health and

social-emotional services, grade-level specific roles, and strategies for time and caseload

management. Findings from this report can assist Utah’s districts and schools in evaluating and

improving their school counseling programs.

Hanover Research | January 2019

ULEAD…Utah Leading through Effective, Actionable, and Dynamic Education

Utah State Board of Education 250 East 500 South P.O. Box 144200 Salt Lake City, Utah 84114-4200

https://www.schools.utah.gov/ulead/practicereports

© 2019 Hanover Research

2

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Executive Summary .......................................................................................................... 3

INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 3

RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................................................................................... 3

KEY FINDINGS ............................................................................................................................. 4

Section I: School Counseling Models ................................................................................ 7

ASCA NATIONAL MODEL FOR SCHOOL COUNSELING .......................................................................... 7

Foundation ......................................................................................................................... 8

Delivery ............................................................................................................................ 10

Management ................................................................................................................... 11

Accountability .................................................................................................................. 12

STATE SCHOOL COUNSELING MODELS ........................................................................................... 12

INTERNATIONAL MODEL FOR SCHOOL COUNSELING PROGRAMS .......................................................... 21

Section II: Roles of School Counselors ............................................................................ 23

GENERAL ROLES OF SCHOOL COUNSELORS ..................................................................................... 23

College and Career Readiness ......................................................................................... 25

Mental Health and Social-Emotional Services ................................................................. 26

GRADE-LEVEL SPECIFIC ROLES OF SCHOOL COUNSELORS ................................................................... 32

Elementary School ........................................................................................................... 32

Middle School .................................................................................................................. 32

High School ...................................................................................................................... 33

CASELOAD MANAGEMENT FOR SCHOOL COUNSELORS ...................................................................... 35

Student-to-Counselor Ratios ........................................................................................... 35

Strategies for Managing Counselor Caseloads ................................................................ 37

Hanover Research | January 2019

ULEAD…Utah Leading through Effective, Actionable, and Dynamic Education

Utah State Board of Education 250 East 500 South P.O. Box 144200 Salt Lake City, Utah 84114-4200

https://www.schools.utah.gov/ulead/practicereports

© 2019 Hanover Research

3

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

INTRODUCTION

To provide high-quality support and services to its districts and constituents, Utah Leading

through Effective, Actionable, and Dynamic Education (ULEAD) is interested in understanding

best practices in school counseling in K-12 schools. To support this effort, Hanover Research

(Hanover) reviewed literature and best practice guidelines related to school counseling

models, roles of school counselors across school levels, and strategies for managing

caseloads. This report includes two sections:

Section I: School Counseling Models presents school counseling models including the

American School Counselor Association’s (ASCA) National Model, the International

Model for School Counseling Programs, and several state- specific school counseling

models.

Section II: Roles of School Counselors reviews the general and grade-level specific

roles of school counselors. Specifically, Hanover discusses counselors’ roles in

providing college and career readiness support, mental health care, social-emotional

support, suicide prevention, and trauma-informed care. Hanover also presents best

practices for time and caseload management.

RECOMMENDATIONS

District leaders could consider:

Aligning their school counseling practices and services to the American School

Counselor Association’s (ASCA) National Model.

Providing professional development to help school counselors support students’

social-emotional development and mental health.

Releasing school counselors from administrative and other non-counseling duties so

they have more time to dedicate to serving students.

Hanover Research | January 2019

ULEAD…Utah Leading through Effective, Actionable, and Dynamic Education

Utah State Board of Education 250 East 500 South P.O. Box 144200 Salt Lake City, Utah 84114-4200

https://www.schools.utah.gov/ulead/practicereports

© 2019 Hanover Research

4

KEY FINDINGS

The American School Counselor Association’s (ASCA) National Model is a common

and effective model for school counseling programs. Several state counseling models

are based on the ASCA National Model. The states profiled in this report typically

adopt the entirety of the ASCA National Model and may incorporate additional

components (e.g., Oregon added an equity lens). Additionally, the International

Model for School Counseling Programs adds a Global Perspective domain to the ASCA

National Model and modifies the language and standards to reflect the unique needs

of students outside the United States.

The ASCA National Model consists of four components: a foundation, delivery

system, management system, and accountability system.

o The foundation of the model defines the program’s focus through mission

statements and a set of value principles. This component also outlines student

learning standards in the domains of academic, career, and social/emotional

development. Finally, the ASCA outlines professional competencies and ethical

standards for school counselors in this component.

o The delivery system includes direct and indirect services. Direct services are the

school counseling curriculum, individual student planning, and responsive

services. Indirect services include consultation and collaboration with other

stakeholders (e.g., parents, teachers, and community organizations).

o The management system outlines assessments and tools that districts can use to

evaluate the organizational efficacy of the school counseling program. Examples

of these assessments and tools include use-of-time assessments; curriculum,

small-group, and closing-the-gap action plans; and school counselor competency

and school counseling program assessments.

o The accountability system involves collecting data and information to measure

and evaluate the impact of the school counseling program. As an example, Utah’s

accountability system for school counseling programs includes an analysis of

results reports, a review of the school counseling program’s alignment with state

standards, and a review of school counselors’ performance.

SCHOOL COUNSELING MODELS

Hanover Research | January 2019

ULEAD…Utah Leading through Effective, Actionable, and Dynamic Education

Utah State Board of Education 250 East 500 South P.O. Box 144200 Salt Lake City, Utah 84114-4200

https://www.schools.utah.gov/ulead/practicereports

© 2019 Hanover Research

5

School counselors’ primary roles increasingly involve meeting students’ social-

emotional and mental health needs using proactive rather than reactive

approaches. Research finds that promoting social-emotional development and

mental health among students at all grade levels reduces school violence and

prevents student suicide.

o School counselors can support students’ social-emotional development by

providing direct instruction of the school counseling core curriculum; facilitating

targeted, individual interventions; and evaluating social-emotional programming.

o To provide suicide prevention and intervention services, school counselors

typically provide services in a tiered framework of student supports. School

counselors are also part of crisis response teams that coordinate school-based

services for students at risk of suicide.

o School counselors also play a critical role in fostering trauma-informed school

environments. That is, school counselors are equipped to identify students

impacted by traumatic events and provide trauma-informed practices through

the school counseling curriculum.

School counselors work within a continuum of mental health services. This service

model also includes school-employed mental health professionals, such as school

psychologists, and community service providers. Within the continuum, school

counselors are typically responsible for providing school-based, universal mental

health supports.

Additionally, school counselors are often tasked with guiding students to college

and career readiness. Research suggests that students of all grade levels benefit from

college and career readiness counseling. Experts suggest that school counselors cover

college and career readiness topics that are developmentally appropriate for a given

grade level. For example, the college admissions process and the transition from high

school to college or career are topics most appropriate for the high school level.

o The Utah State Board of Education recommends that school counselors support

students’ college and career planning through transitions planning, individual and

small group planning sessions, and parent-student meetings.

Experts recommend that school counselors differentiate services by grade level.

o Elementary school counseling programs should be developmentally-appropriate

and focus on basic academic learning skills and social-emotional competencies.

Further, experts encourage school counselors to dedicate most of their time to

administering the school counseling curriculum and individual student planning.

o At the middle school level, school counselors play a key role in encouraging

students to explore their self-identity and maximize their personal and academic

potential. Like elementary school counselors, experts recommend that middle

school counselors spend most of their time on the school counseling curriculum

and individual student planning.

ROLES OF SCHOOL COUNSELORS

Hanover Research | January 2019

ULEAD…Utah Leading through Effective, Actionable, and Dynamic Education

Utah State Board of Education 250 East 500 South P.O. Box 144200 Salt Lake City, Utah 84114-4200

https://www.schools.utah.gov/ulead/practicereports

© 2019 Hanover Research

6

o Experts recommend that high school counselors support students in creating

college and career goals while also meeting their academic potential. Additionally,

experts suggest that high school counselors dedicate slightly more time to

individual student planning and responsive services than other tasks.

The ASCA recommends a maximum student-to-counselor ratio of 250:1. However,

across the country, the average ratio across all school levels is 482 students to one

counselor (as of the 2014-2015 school year). In Utah, the average student-to-

counselor ratio is 684:1. Research finds that lower student-to-counselor ratios

improve college and career outcomes for students; for example, one study found that

hiring an additional counselor increased the percentage of students who enrolled in

a four-year college by ten percentage points.

The ASCA also recommends that school counselors spend at least 80 percent of their

time providing direct and indirect services to students. This recommendation

corresponds with empirical research that suggests that postsecondary outcomes

improve when school counselors spend more time on college counseling activities.

However, research finds that school counselors are often tasked with activities

unrelated to counseling (e.g., academic testing) and may be unable to meet ASCA’s

standard due to an unsuitable assignment of responsibilities.

Hanover Research | January 2019

ULEAD…Utah Leading through Effective, Actionable, and Dynamic Education

Utah State Board of Education 250 East 500 South P.O. Box 144200 Salt Lake City, Utah 84114-4200

https://www.schools.utah.gov/ulead/practicereports

© 2019 Hanover Research

7

SECTION I: SCHOOL COUNSELING MODELS

In this section, Hanover presents school counseling models including the American School

Counselor Association’s (ASCA) National Model, the International Model for School

Counseling Programs, and several state-specific school counseling models.

ASCA NATIONAL MODEL FOR SCHOOL COUNSELING

The American School Counselor Association (ASCA) developed the ASCA National Model to

help districts develop a comprehensive, data-driven, and effective school counseling

program.

1

Several research studies find that implementation of the model increases

“academic achievement, career development, parent satisfaction, school climate, and

attendance.”

2

The ASCA National Model:

3

Ensures equitable access to a rigorous education for all students;

Identifies the knowledge and skills all students will acquire as a result of the K-12

comprehensive school counseling program;

Is delivered to all students in a systematic fashion;

Is based on data-driven decision making; and

Is provided by a state-credentialed school counselor.

Schools implementing the ASCA National Model can apply to be designated as a Recognized

ASCA Model Program (RAMP).

4

The ASCA uses a Scoring Rubric to determine if schools meet

the criteria for a RAMP designation. The rubric is organized into 12 sections: vision statement,

mission statement, school counseling program goals, ASCA Mindsets & Behaviors for Student

Success, annual agreement, advisory council, calendars, school counseling core curriculum

action plan and lesson plans, school counseling core curriculum results report, small-group

responsive services, closing-the-gap results report, and the program evaluation reflection.

Schools are assigned points in each section depending on the degree to which they meet the

criteria outlined for each.

5

1

[1] “ASCA National Model.” American School Counselor Association. https://www.schoolcounselor.org/school-

counselors-members/asca-national-model [2] “The ASCA National Model.” Deer Park Independent School District.

p. 1. https://www.dpisd.org/cms/lib4/TX01001079/Centricity/Domain/152/asca_national_model.pdf

2

“The ASCA National Model,” Op. cit., p. 1.

3

Bullet points were taken verbatim with minor modification from “ASCA National Model: A Framework for School

Counseling Programs.” American School Counselor Association. p. 1.

https://schoolcounselor.org/ascanationalmodel/media/anm-templates/anmexecsumm.pdf

4

Wilkerson, K., R. Perusse, and A. Hughes. “Comprehensive School Counseling Programs and Student Achievement

Outcomes: A Comparative Analysis of RAMP versus Non-RAMP Schools.” Professional School Counseling, 16:3. pp.

173–174. https://www.schoolcounselor.org/asca/media/asca/RAMP/Wilkenson-RAMP-article.pdf

5

“Recognized ASCA Model Program (RAMP) Scoring Rubric.” American School Counselor Association, July 2017.

https://www.schoolcounselor.org/asca/media/asca/RAMP/Rubric.pdf

Hanover Research | January 2019

ULEAD…Utah Leading through Effective, Actionable, and Dynamic Education

Utah State Board of Education 250 East 500 South P.O. Box 144200 Salt Lake City, Utah 84114-4200

https://www.schools.utah.gov/ulead/practicereports

© 2019 Hanover Research

8

The ASCA National Model includes four components: foundation, delivery, management,

and accountability. The remainder of this subsection discusses each of these components in

detail.

FOUNDATION

As the foundation of the ASCA National Model, school counselors must clarify the

program’s focus, set student standards, and meet professional competencies. Figure 1.1

describes each of these components.

Figure 1.1: Components of the ASCA National Model Foundation

PROGRAM

FOCUS

To establish program focus, school counselors identify personal beliefs that address

how all students benefit from the school counseling program. Building on these

beliefs, school counselors create a vision statement defining what the future will look

like in terms of student outcomes. In addition, school counselors create a mission

statement aligned with their school’s mission and develop program goals defining

how the vision and mission will be measured.

STUDENT

STANDARDS

Enhancing the learning process for all students, the “ASCA Mindsets & Behaviors for

Student Success: College- and Career-Readiness Standards for Every Student” guide

the development of effective school counseling programs around three domains:

academic, career and social/emotional development. View the ASCA Mindsets &

Behaviors Planning Tool. School counselors also consider how other student

standards important to state and district initiatives complement and inform their

school counseling program.

PROFESSIONAL

COMPETENCIES

The ASCA School Counselor Competencies outline the knowledge, attitudes and

skills that ensure school counselors are equipped to meet the rigorous demands of

the profession. The ASCA Ethical Standards for School Counselors specify the

principles of ethical behavior necessary to maintain the highest standard of integrity,

leadership and professionalism. They guide school counselors’ decision-making and

help to standardize professional practice to protect both students and school

counselors.

Source: American School Counselor Association

6

The ASCA Mindsets and Behaviors for Student Success contains 35 standards that describe

the “knowledge, skills, and attitudes students need to achieve academic success, college and

career readiness, and social-emotional development.”

7

The standards, all of which apply to

academic, career, or social-emotional development, are organized into two domains: mindset

and behavior (see Figure 1.2 on the following page).

8

The ASCA provides a Planning Tool to

help school counselors develop a school counseling curriculum that will support students in

meeting the mindset and behavior standards.

6

Figure contents were taken verbatim from “ASCA National Model Foundation.” American School Counselor

Association. https://www.schoolcounselor.org/school-counselors/asca-national-model/foundation

7

“ASCA Mindsets & Behaviors for Student Success: K-12 College- and Career-Readiness Standards for Every Student.”

American School Counselor Association, September 2014. p. 1.

https://www.schoolcounselor.org/asca/media/asca/home/MindsetsBehaviors.pdf

8

Ibid., pp. 1–2.

Hanover Research | January 2019

ULEAD…Utah Leading through Effective, Actionable, and Dynamic Education

Utah State Board of Education 250 East 500 South P.O. Box 144200 Salt Lake City, Utah 84114-4200

https://www.schools.utah.gov/ulead/practicereports

© 2019 Hanover Research

9

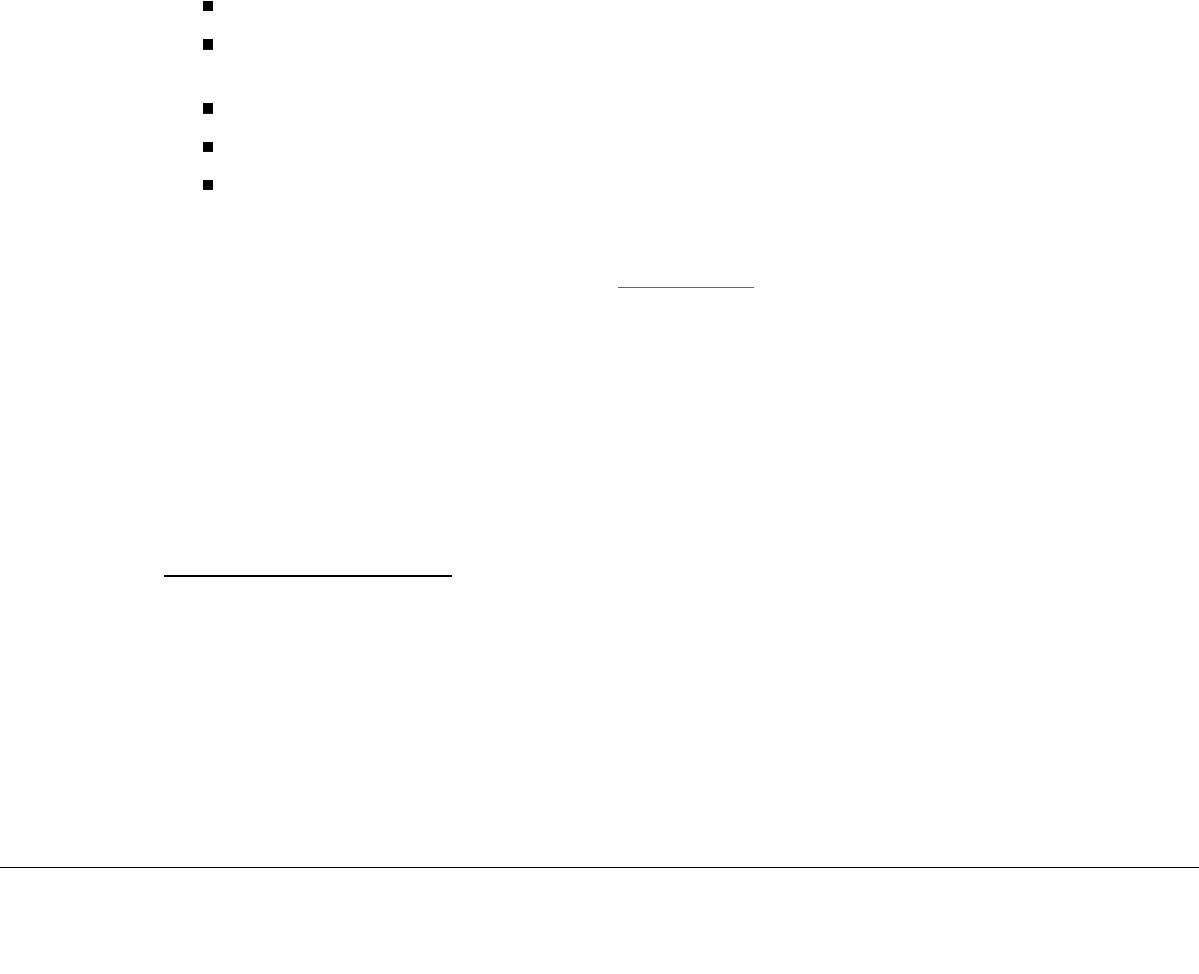

Figure 1.2: ASCA Mindset and Behavior Standards for Students

MINDSET STANDARDS

Includes standards related to the psycho-social attitudes or beliefs students have about themselves

in relation to academic work. These make up the students’ belief system as exhibited in behaviors.

BEHAVIOR STANDARDS

These standards include behaviors commonly associated with being a successful student. These

behaviors are visible, outward signs that a student is engaged and putting forth effort to learn. The

behaviors are grouped into three subcategories:

▪ Learning Strategies: Processes and tactics students employ to aid in the cognitive work of

thinking, remembering, or learning.

▪ Self-Management Skills: Continued focus on a goal despite obstacles (grit or persistence) and

avoidance of distractions or temptations to prioritize higher pursuits over lower pleasures

(delayed gratification, self-discipline, self-control).

▪ Social Skills: Acceptable behaviors that improve social interactions, such as those between peers

or between students and adults.

Source: American School Counselor Association

9

The ASCA School Counselor Competencies outline the knowledge, abilities and skills, and

attitudes school counselors should possess to facilitate an effective school counseling

program. The competencies are organized into a checklist and separated into the following

areas: school counseling programs, foundations, delivery, management, and accountability.

10

Figure 1.3 presents the competencies and provides an example of a checklist item associated

with each competency.

Figure 1.3: Examples of ASCA School Counselor Competencies

CATEGORY

COMPETENCY

SAMPLE CHECKLIST ITEM

School Counseling

Programs

Knowledge

Barriers to student learning and use of advocacy and data-driven

school counseling practices to close the achievement/opportunity

gap

Abilities and Skills

Plans, organizes, implements and evaluates a school counseling

program aligning with the ASCA National Model

Attitudes

Every student can learn, and every student can succeed

Foundations

Knowledge

Human development theories and developmental issues affecting

student success

Abilities and Skills

Demonstrates knowledge of a school’s particular educational vision

and mission

Attitudes

Has an impact on every student rather than a series of services

provided only to students in need

Delivery

Knowledge

The concept of a school counseling core curriculum

9

Bullet points were taken verbatim from Ibid.

10

“ASCA School Counselor Competencies.” American School Counselor Association, 2012.

https://www.schoolcounselor.org/asca/media/asca/home/SCCompetencies.pdf

Hanover Research | January 2019

ULEAD…Utah Leading through Effective, Actionable, and Dynamic Education

Utah State Board of Education 250 East 500 South P.O. Box 144200 Salt Lake City, Utah 84114-4200

https://www.schools.utah.gov/ulead/practicereports

© 2019 Hanover Research

10

CATEGORY

COMPETENCY

SAMPLE CHECKLIST ITEM

Abilities and Skills

Facilitates individual student planning

Attitudes

School counselors engage in developmental counseling and short-

term responsive counseling

Management

Knowledge

Data-driven decision making

Abilities and Skills

Conducts a school counseling program assessment

Attitudes

A school counseling program/department must be managed like

other programs and departments in a school

Accountability

Knowledge

Use of data to evaluate program effectiveness and to determine

program needs

Abilities and Skills

Analyzes and interprets process, perception and outcome data

Attitudes

School counseling programs should achieve demonstrable results

Source: American School Counselor Competencies

11

Additionally, the ASCA provides Ethical Standards for School Counselors to guide counselors

in understanding the profession’s expectations around the ethical treatment of various

stakeholder groups. The ethical standards help counselors self-assess their ethical behavior,

as well as make stakeholders aware of the ethical practices they should expect from school

counselors.

12

DELIVERY

The ASCA recommends that counselors deliver three types of direct and three types of

indirect services to students, as shown in Figure 1.4. The three direct services are the

counseling core curriculum, individual planning for students, and responsive services. Indirect

services, on the other hand, are consultation with school personnel, parents, and the

community; collaboration with school personnel, parents, and the community; and referrals

to outside services.

13

Figure 1.4: ASCA’s Recommended Student Services

DIRECT SERVICES

THE SCHOOL

COUNSELING CORE

CURRICULUM

▪ Structured activities designed to support desired learning outcomes

▪ Integrated into the school’s core curriculum and delivered by counselors

in collaboration with other school staff

INDIVIDUAL STUDENT

PLANNING

▪ Activities to help students develop personal goals and postsecondary

plans

RESPONSIVE SERVICES

▪ Activities in response to specific student needs

▪ May include individual counseling, group activities, or referral to other

resources

11

Figure contents were taken verbatim from Ibid.

12

“ASCA Ethical Standards for School Counselors.” American School Counselor Association, 2016. p. 1.

https://www.schoolcounselor.org/asca/media/asca/Ethics/EthicalStandards2016.pdf

13

“ASCA National Model: Delivery.” American School Counselor Association.

https://www.schoolcounselor.org/school-counselors/asca-national-model/delivery

Hanover Research | January 2019

ULEAD…Utah Leading through Effective, Actionable, and Dynamic Education

Utah State Board of Education 250 East 500 South P.O. Box 144200 Salt Lake City, Utah 84114-4200

https://www.schools.utah.gov/ulead/practicereports

© 2019 Hanover Research

11

INDIRECT SERVICES

CONSULTATION

▪ Share strategies supporting student achievement with parents, teachers,

other educators and community organizations

COLLABORATION

▪ Work with other educators, parents and the community to support

student achievement

REFERRALS

▪ Support for students and families to school or community resources for

additional assistance and information

Source: American School Counselor Association

14

MANAGEMENT

As part of the ASCA National Model, school counselors are encouraged to use assessments

and other tools to evaluate the organizational efficacy of the school counseling program.

Specifically, the ASCA recommends that school counselors use assessments that are

“concrete, clearly delineated, and reflective of the school’s needs.”

15

Examples of such

assessments and tools include:

16

School counselor competency and school counseling program assessments to self-

evaluate areas of strength and improvement for individual skills and program

activities;

Use-of-time assessments to determine the amount of time spent toward the

recommended 80 percent or more of the school counselor’s time to direct and

indirect services with students;

Annual agreements developed with and approved by administrators at the

beginning of the school year addressing how the school counseling program is

organized and what goals will be accomplished;

Advisory councils made up of students, parents, teachers, school counselors,

administrators and community members to review and make recommendations

about school counseling program activities and results;

Use of data to measure the results of the program as well as to promote systemic

change within the school system so every student graduates college- and career-

ready;

Curriculum, small-group, and closing-the-gap action plans including

developmental, prevention and intervention activities and services that measure

the desired student competencies and the impact on achievement, behavior and

attendance; and

14

Figure contents were taken verbatim from [1] “The Role of the School Counselor.” American School Counselor

Association. p. 2. https://www.schoolcounselor.org/asca/media/asca/Careers-Roles/RoleStatement.pdf [2] “The

Essential Role of High School Counselors.” American School Counselor Association, 2017. p. 2.

https://www.schoolcounselor.org/asca/media/asca/Careers-Roles/WhyHighSchool.pdf

15

“ASCA National Model: Management.” American School Counselor Association.

https://www.schoolcounselor.org/school-counselors/asca-national-model/management

16

Bullet points were taken verbatim from Ibid.

Hanover Research | January 2019

ULEAD…Utah Leading through Effective, Actionable, and Dynamic Education

Utah State Board of Education 250 East 500 South P.O. Box 144200 Salt Lake City, Utah 84114-4200

https://www.schools.utah.gov/ulead/practicereports

© 2019 Hanover Research

12

Annual and weekly calendars to keep students, parents, teachers and

administrators informed and to encourage active participation in the school

counseling program.

ACCOUNTABILITY

The ASCA encourages school counselors to collect data to measure and evaluate the impact

of the school counseling program. That is, the ASCA recommends that school counselors

should be continuously “analyzing school and school counseling program data to determine

how students are different as a result of the school counseling program.”

17

Using these data,

school counselors can demonstrate the impact of the program. Additionally, school

counselors can identify areas in which modifications can be made to further improve

students’ outcomes in the areas of academic achievement, attendance, and behavior.

18

STATE SCHOOL COUNSELING MODELS

Many state’s school counseling models are largely based on the ASCA National Model. In the

remainder of this section, Hanover summarizes how five states have adapted the ASCA

National Model.

CONNECTICUT MODEL

The Connecticut Comprehensive School Counseling Program is based on the ASCA National

Model.

19

The Connecticut Model, like the ASCA National Model, consists of a program

foundation, delivery system, program management system, and program accountability

system. Further, the Connecticut Model focuses on three domains that are intended to

promote “achievement and success for all students:” academic, career, and personal/social.

20

These three domains, described in Figure 1.5 on the following page, are the core of the

Connecticut Model.

17

“ASCA National Model: Accountability.” American School Counselor Association.

https://www.schoolcounselor.org/school-counselors/asca-national-model/accountability

18

Ibid.

19

McQuillan, M.K. et al. “Comprehensive School Counseling.” Connecticut State Board of Education, 2008. p. v.

https://portal.ct.gov/-/media/SDE/Special-Education/counseling.pdf

20

Ibid., p. viii.

Hanover Research | January 2019

ULEAD…Utah Leading through Effective, Actionable, and Dynamic Education

Utah State Board of Education 250 East 500 South P.O. Box 144200 Salt Lake City, Utah 84114-4200

https://www.schools.utah.gov/ulead/practicereports

© 2019 Hanover Research

13

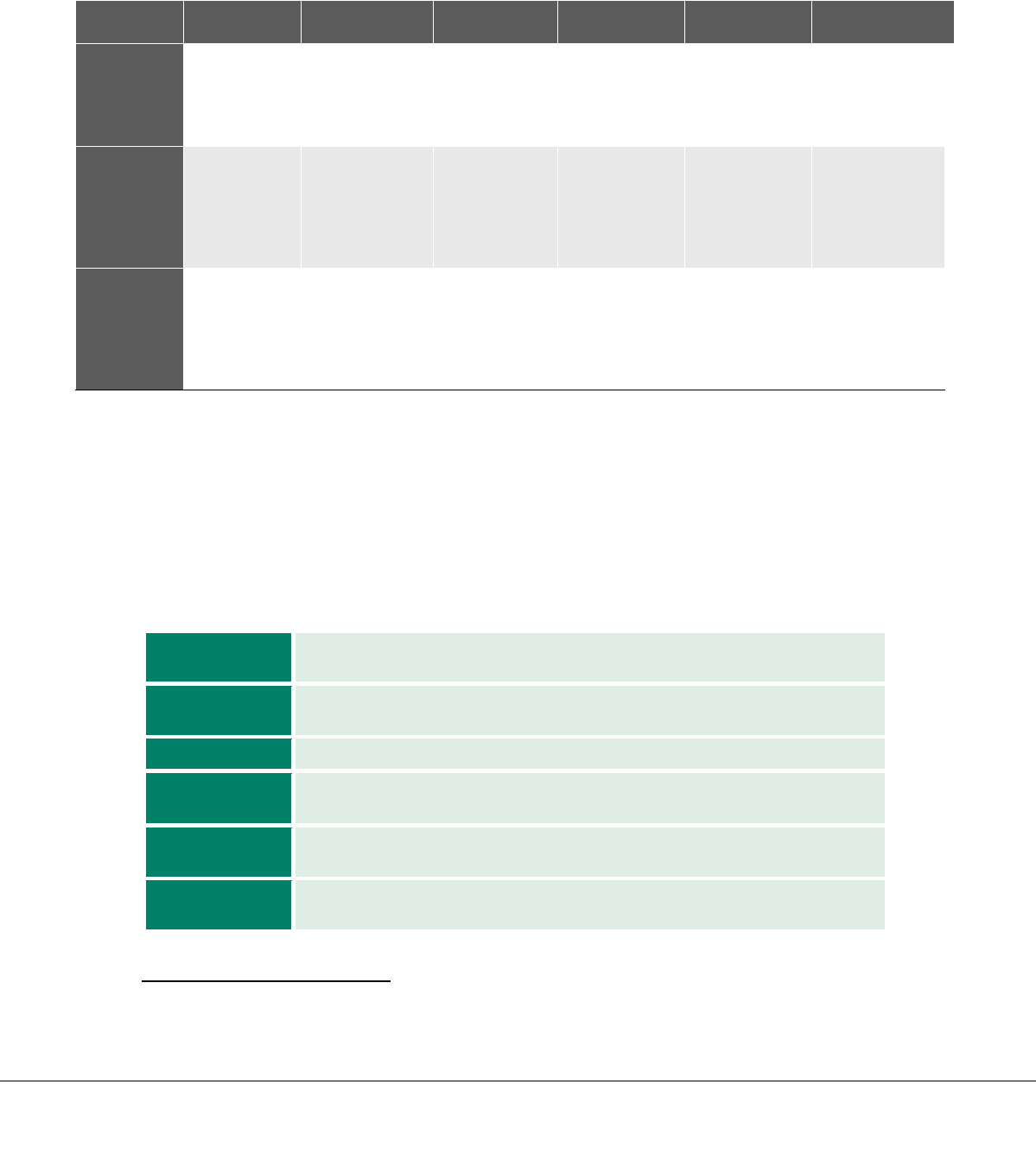

Figure 1.5: Core Domains of the Connecticut School Counseling Model

ACADEMIC

DEVELOPMENT

Includes acquiring skills, attitudes and knowledge that contribute

to effective learning in school; employing strategies to achieve

success in school; and understanding the relationship of academics

to the world of work, and to life at home and in the community.

Academic goals support the premise that all students should meet

or exceed the local, state and national goals.

CAREER

DEVELOPMENT

These goals guide the school counseling program to provide the

foundation for the acquisition of skills, attitudes and knowledge

that enable students to make a successful transition from school

to the world of work and from job to job across the life span.

Career development goals and competencies ensure that students

develop career goals as a result of their participation in a

comprehensive plan of career awareness, exploration and

preparation activities.

PERSONAL/SOCIAL

DEVELOPMENT

These goals guide the school counseling program to provide the

foundation for personal and social growth as students progress

through school and into adulthood. Personal/social development

contributes to academic and career success by helping students

understand and respect themselves and others, acquire effective

interpersonal skills, understand safety and survival skills and

develop into contributing members of society.

Source: Connecticut State Board of Education

21

School counselors in Connecticut deliver services related to the three domains described

above in Figure 1.5 through the program delivery system. Like the ASCA National Model, the

school counseling program consists of the counseling curriculum, individual student planning,

responsive services, and collaboration within and outside the school community.

22

The

Connecticut State Board of Education recommends that high school counselors dedicate

slightly more time to individual student planning and responsive services than the other two

components. At the elementary and middle school levels, school counselors are encouraged

to dedicated most of their time to providing responsive services and administering the school

counseling curriculum.

23

The Connecticut State Board of Education provides a Monthly

Report template for school counselors to track the time they have dedicated to the four

program components as well as non-guidance activities.

24

To guide implementation of the school counseling curriculum, the Connecticut State Board

of Education provides learning standards for Grades 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12. The learning

standards are organized under nine overarching standards that cover the academic, career,

and personal/social domains.

25

Figure 1.6 presents a sample of these learning standards.

21

Figure contents were taken verbatim from Ibid., p. 2.

22

Ibid., p. 3.

23

Ibid., p. 4.

24

Ibid., p. 43.

25

Ibid., pp. 14–15, 21–29.

Hanover Research | January 2019

ULEAD…Utah Leading through Effective, Actionable, and Dynamic Education

Utah State Board of Education 250 East 500 South P.O. Box 144200 Salt Lake City, Utah 84114-4200

https://www.schools.utah.gov/ulead/practicereports

© 2019 Hanover Research

14

Figure 1.6: Sample Standards of the Connecticut School Counseling Model

BY GRADE 2,

STUDENTS WILL:

BY GRADE 4,

STUDENTS WILL:

BY GRADE 6

STUDENTS WILL:

BY GRADE 8,

STUDENTS WILL:

BY GRADE 10,

STUDENTS WILL:

BY GRADE 12,

STUDENTS WILL:

ACADEMIC

State reasons

for learning

Describe the

rights and

responsibilities of

self and others

Demonstrate

competence

and confidence

as a learner

Implement

effective

organizational

study and test-

taking skills

Demonstrate

organizational

and study skills

needed for high

school success

Demonstrate

responsibility for

academic

achievement

CAREER

Identify

personal likes

and dislikes

Recognize that

people differ in

likes, interests,

and talents

Explore the

concept of

career clusters

and learn about

jobs in those

clusters

Take a career

interest

inventory

Develop skills to

locate, evaluate,

and interpret

career

information

Assess strengths

and weaknesses

based on high

school

performance

PERSONAL/

SOCIAL

Identify and

express

feelings

Demonstrate

skills for getting

along with others

Learn what

actions and

words

communicate

about them

Summarize the

factors

influencing

positive

friendships

Recognize the

impact of

change and

transition on

their personal

development

Recognize that

everyone has

rights and

responsibilities

Source: Connecticut State Board of Education

26

Under the Connecticut Model, school counseling programs use the MEASURE process for

accountability purposes. The process “moves school counselors from a ‘counting tasks’

system to aligning the school counseling program with standards-based reform.”

27

MEASURE

relies on data such as “retention rates, test scores, and postsecondary going rates” to

evaluate and improve school counseling programs.

28

Figure 1.7 describes each step of the

process.

Figure 1.7: Accountability System of the Connecticut School Counseling Model

MISSION

Connect the comprehensive K-12 school-counseling program to the mission of the

school and to the goals of the annual school improvement plan

ELEMENTS

Identify the critical data elements that are important to the internal and external

stakeholders

ANALYZE

Discuss carefully which elements need to be aggregated or disaggregated and why

STAKEHOLDERS –

UNITE

Determine which stakeholders need to be involved in addressing these school-

improvement issues and unite to develop strategies

RESULTS

Assess your results to see if you met your goal and compare it to your baseline

data

EDUCATE

Show the positive impact the school-counseling program has had on student

achievement and on the goals of the school improvement plan

Source: Connecticut State Board of Education

29

26

Figure contents were taken verbatim from Ibid., pp. 21–29.

27

Ibid., p. 35.

28

Ibid.

29

Figure contents were taken verbatim from Ibid.

Hanover Research | January 2019

ULEAD…Utah Leading through Effective, Actionable, and Dynamic Education

Utah State Board of Education 250 East 500 South P.O. Box 144200 Salt Lake City, Utah 84114-4200

https://www.schools.utah.gov/ulead/practicereports

© 2019 Hanover Research

15

OREGON MODEL

Oregon’s Framework for Comprehensive School Counseling Programs, like the ASCA

National Model, includes a program foundation, management system, delivery system, and

accountability system.

30

The features of each of these components are the same as those of

the ASCA National Model. For example, the delivery system in the Oregon Model consists of

direct and indirect student services. Direct services are the counseling core curriculum,

individual student planning, and responsive services. Indirect services, on the other hand, are

those that involve “consultation and collaboration with parents, teachers, other educators,

and community organizations.”

31

In terms of program management, the Oregon Department of Education recommends that

districts use all the assessments and tools outlined in the ASCA National Model to “develop,

implement, and evaluate their school counseling program.”

32

Regarding the accountability

system, the Oregon Model calls for districts to analyze school data profiles and conduct use-

of-time assessment analyses to determine how school counselors allocate their time.

33

The

Oregon Department of Education also encourages districts to evaluate program results

through an examination of curriculum, small-group, and closing-the-gap results reports.

34

Further, districts in Oregon should use these data to evaluate the efficacy of the school

counseling program and school counselors’ performance, as well as make improvements

where necessary.

35

Oregon adds an equity lens to its counseling model. Under the Oregon Model, “educational

leaders, including school counselors, actively initiate and lead conversations about equity,

collecting and analyzing data, continually learning and sharing data with stakeholders to

identify disparities.”

36

School counselors in Oregon may also work with “culturally-specific

and linguistically-diverse groups” in the community to promote student outcomes.

37

To assist districts in implementing school counseling models according to Oregon’s

framework, the Oregon Department of Education provides an Implementation Checklist. The

checklist is divided into several categories: district policy, professional staff, staff

development, instructional materials, facilities, and management systems. Figure 1.8

presents a sampling of checklist items for each category.

30

“Oregon’s Framework for Comprehensive School Counseling Programs.” Oregon Department of Education. pp. 4, 9–

10. https://www.oregon.gov/ode/educator-

resources/standards/guidance_counseling/Documents/2018%20Framework%20for%20CSC%20Programs.pdf

31

Ibid., pp. 9–10.

32

Ibid., p. 34.

33

Ibid., pp. 53–54.

34

Ibid., pp. 55–57.

35

Ibid., p. 58.

36

Ibid., p. 13.

37

Ibid.

Hanover Research | January 2019

ULEAD…Utah Leading through Effective, Actionable, and Dynamic Education

Utah State Board of Education 250 East 500 South P.O. Box 144200 Salt Lake City, Utah 84114-4200

https://www.schools.utah.gov/ulead/practicereports

© 2019 Hanover Research

16

Figure 1.8: Excerpt of Oregon Department of Education’s Implementation Checklist for

School Counseling Programs

DISTRICT POLICY INDICATORS

The school district’s board has recognized the comprehensive counseling program and the student

standards as an essential and integral part of the entire educational program as reflected in

appropriate policy documents and directives.

PROFESSIONAL STAFF INDICATORS

Licensed school counselors are part of the team that plans and coordinates the district and building

comprehensive school counseling program, based upon student outcome data utilizing continuous

improvement processes.

Student to counselor ratios are reasonable and reflect state and national professional standards.

STAFF DEVELOPMENT INDICATORS

The school district’s position descriptions reflect comprehensive counseling program duties for all

staff members, particularly those who have specific, assigned program roles and responsibilities.

Performance standards for each position reflect relevant professional standards.

INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS INDICATORS

All curriculum materials and tools used in the comprehensive counseling program meet district and

state standards for quality.

FACILITIES INDICATORS

Confidential space for individual and group counseling activities is available in each building when

needed.

Adequate and protected storage space is provided for program materials and student work, such

as career portfolios.

MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS INDICATORS

The school district has developed a counseling program budget that covers the cost of delivering

the content described in its comprehensive program plan.

Source: Oregon Department of Education

38

SOUTH DAKOTA MODEL

Like other state models, the South Dakota Comprehensive School Counseling Program

Model is also based on the ASCA National Model.

39

According to the South Dakota School

Counselor Association, the model allows districts to:

40

Develop a vision of what students should know and be able to do as a result of

participating in a standards-based counseling program.

Use results of data and program analysis to develop and implement activities,

strategies, and services.

Demonstrate the impact of school counseling programs on student achievement and

success.

38

Figure contents were taken verbatim from Ibid., p. 25.

39

“South Dakota Comprehensive School Counseling Model.” South Dakota School Counselor Association.

http://www.sdschoolcounselors.com/comprehensive-school-counseling-model.html

40

Bullet points were taken verbatim from Ibid.

Hanover Research | January 2019

ULEAD…Utah Leading through Effective, Actionable, and Dynamic Education

Utah State Board of Education 250 East 500 South P.O. Box 144200 Salt Lake City, Utah 84114-4200

https://www.schools.utah.gov/ulead/practicereports

© 2019 Hanover Research

17

The South Dakota Model is also organized around a foundation, management system,

delivery system, and accountability system. Like the ASCA National Model, the South Dakota

Model also covers the domains of academic, career, and social-emotional development.

41

As

part of the program focus element of the foundation component, the South Dakota

Department of Education encourages districts to set SMART goals (see Figure 1.9). That is,

goals for school counseling programs should be specific, measurable, attainable, results-

oriented, and time-bound.

42

Figure 1.9: School Counseling Program SMART Goals, South Dakota Model

SPECIFIC ISSUE

What is the specific issue based on our school’s data?

MEASURABLE

How will we measure the effectiveness of our interventions?

ATTAINABLE

What outcome would stretch us but it still attainable?

RESULTS-ORIENTED

Is the goal reported in results-oriented data (process, perception, and

outcome)?

TIME-BOUND

When will our goal be accomplished?

Source: South Dakota Department of Education

43

The South Dakota Model incorporates a variety of assessments, tool, and strategies into the

management system component. The assessments and tools included in the model are those

that the ASCA recommends as part of the National Model.

44

The delivery system of the South

Dakota Model includes a school counseling curriculum, individual planning, and responsive

services, like the ASCA National Model.

45

The South Dakota Model’s school counseling

curriculum consists of classroom activities, group activities, and individual activities.

46

Individual planning services include individual appraisal and advisement. Responsive services

include individual and small group counseling as well as crisis response.

47

The South Dakota

Model also includes indirect services, which are the same as those included in the ASCA

National Model.

48

Finally, the South Dakota Model accountability system includes an analysis of the school data

profile and use-of-time assessments. The South Dakota Department of Education

recommends that districts share program evaluation results and use school counselor

competencies assessments and school counseling program assessments to evaluate and

improve school counseling programs.

49

41

Bardhoshi, G. “South Dakota Comprehensive School Counseling Program Model: Fourth Edition.” South Dakota

Department of Education, 2016. pp. 9–10. http://www.sdschoolcounselors.com/uploads/1/2/0/0/12000575/16-

schoolcounselorsmodel.pdf

42

Ibid., p. 13.

43

Figure contents were taken verbatim from Ibid.

44

Ibid., pp. 15–20.

45

Ibid., p. 25.

46

Ibid., p. 26.

47

Ibid., pp. 27–28.

48

Ibid., p. 30.

49

Ibid., pp. 31–34.

Hanover Research | January 2019

ULEAD…Utah Leading through Effective, Actionable, and Dynamic Education

Utah State Board of Education 250 East 500 South P.O. Box 144200 Salt Lake City, Utah 84114-4200

https://www.schools.utah.gov/ulead/practicereports

© 2019 Hanover Research

18

UTAH MODEL

The Utah Model for Comprehensive Counseling and Guidance: K-12 Programs is organized

into a foundation, delivery system, management system, and accountability system.

50

The

Utah Model, like the ASCA National Model, is designed to be preventative rather than

responsive and to fit students’ developmental needs.

51

Further, the Utah Model is built upon

the same themes as the ASCA National Model: leadership, advocacy, collaboration, and

systemic change.

52

The four components of the Utah Model contain largely the same features as the ASCA

National Model. For example, the foundation of the Utah Model consists of a set of beliefs, a

mission statement, student outcomes, and the domains of academic, career, and

personal/social development. The Utah Model’s delivery system includes a curriculum

component, individual student planning, responsive services, and systems support. Systems

support encompasses the indirect services of the ASCA National Model (e.g., consultation and

collaboration).

53

The school counseling curriculum includes classroom instruction, group

activities, and parent workshops. The model emphasizes the school guidance curriculum as a

vehicle to drive the delivery of activities with students in a way that reflects the core

counseling goals in a school. Moreover, individual student planning consists of individual or

small-group appraisal and advisement. Responsive services include individual and small-

group counseling, crisis counseling, and peer facilitation.

54

As part of the Utah Model’s management system, the Utah State Board of Education

encourages districts to use a management agreement tool, advisory council, and to analyze

data related to student progress and closing the gap. Districts can also develop guidance

curriculum and closing-the-gap action plans, conduct use-of-time assessments, and develop

weekly and monthly calendars to ensure that all stakeholders know what activities are

scheduled.

55

The Utah State Board of Education provides a sample guidance curriculum action

plan, as shown in Figure 1.10 on the following page.

The accountability system of the Utah Model encompasses an analysis of results reports, a

review of the school counseling program’s alignment with state standards, and a review of

school counselors’ performance.

56

50

“Utah Model for Comprehensive Counseling and Guidance: K-12 Programs.” Utah State Board of Education. pp. 32–

34. http://www.suusuccesscounseling.org/docs/Utah_Model_for_Comprehensive_Counseling_and_Guidance.pdf

51

Ibid., pp. 21–22.

52

Ibid., pp. 35–36.

53

Ibid., pp. 32–33.

54

Ibid., pp. 48–51.

55

Ibid., pp. 33–34.

56

Ibid., p. 34.

Hanover Research | January 2019

ULEAD…Utah Leading through Effective, Actionable, and Dynamic Education

Utah State Board of Education 250 East 500 South P.O. Box 144200 Salt Lake City, Utah 84114-4200

https://www.schools.utah.gov/ulead/practicereports

© 2019 Hanover Research

19

Figure 1.10: Utah Sample Guidance Curriculum Action Plan

GRADE

LEVEL

GUIDANCE

LESSON

CONTENT

UTAH STUDENT

COMPETENCY

DOMAIN/STANDARD

CURRICULUM

AND

MATERIALS

PROJECT

DATES

PROJECTED

NUMBER OF

STUDENTS

AFFECTED

LESSON WILL BE

PRESENTED IN WHICH

CLASS/SUBJECT?

EVALUATION

METHODS

Grade 6

Violence

Prevention

Personal/Social C

XYZ Violence

Lesson

11/18 to

2/19

450

Social Studies

Pre-post tests;

number of

violent

incidents

Promotion and

Retention

Criteria

Academic/Learning

ABC

PowerPoint

District Policy

2/18 to

4/18

450

Language Arts

Pre-post tests;

number of

students

retained

Organizational

Study and Test-

Taking Skills

Academic/Learning

ABC

XYZ Study

Skills

Curriculum

9/18 to

11/18

450

Language Arts

Pre-post tests;

scores on

tests

Source: Utah State Board of Education

57

The Utah State Board of Education recommends a five-step process for districts beginning

to adopt the Utah Model for school counseling programs. Figure 1.11 presents a summary

of the process which includes the steps of planning, building the foundation, designing the

delivery system, implementing the program, and making the program accountable.

58

See the

document describing the Utah Model for the full list of implementation steps.

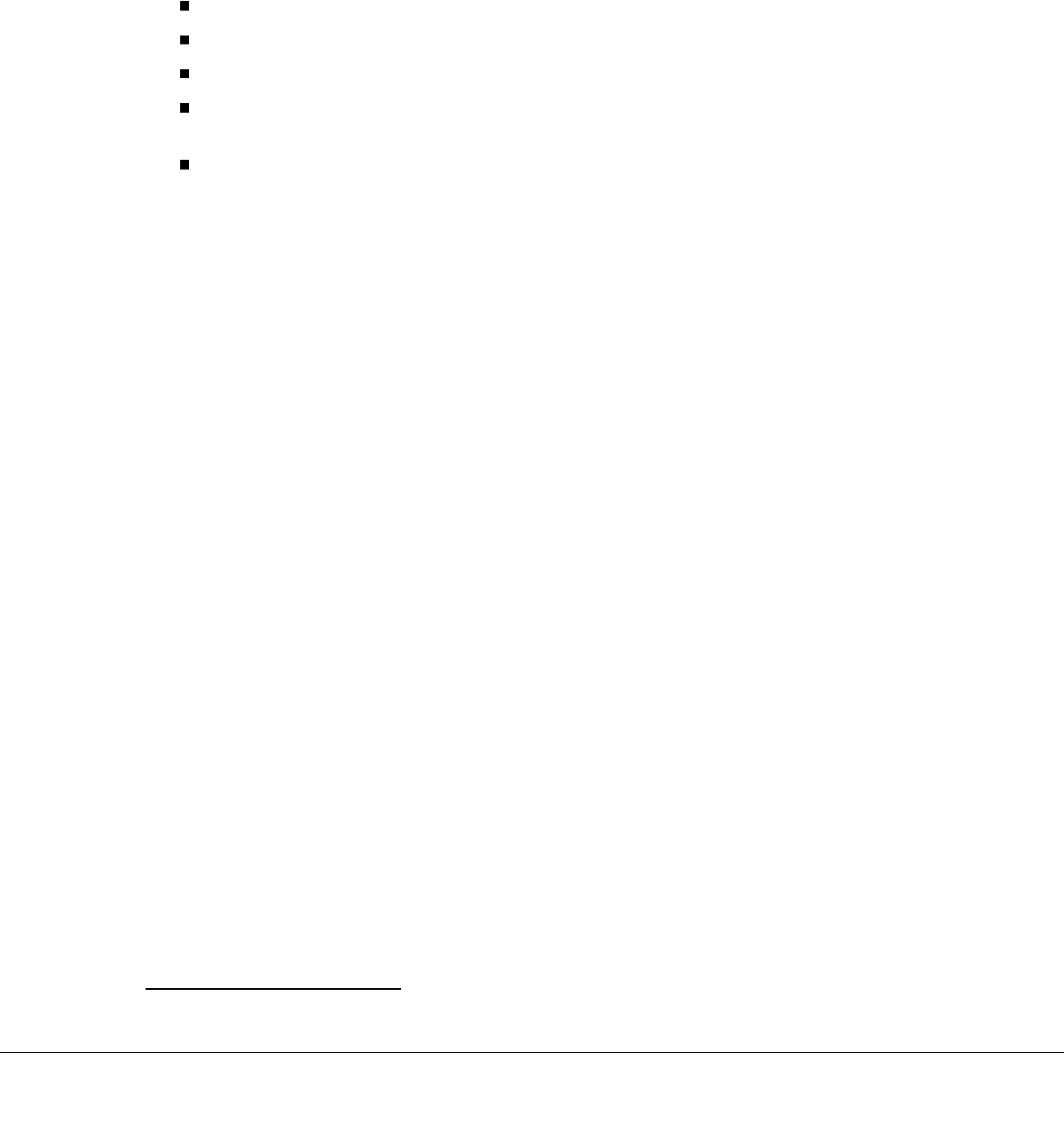

Figure 1.11: Selected Steps to Implement the Utah Model

PLAN THE PROGRAM

▪ Secure commitment from stakeholders

▪ Create a program development team

▪ Create a timeline for program development

▪ Assess the current program

BUILD THE FOUNDATION

▪ Assess the needs of the school and district

▪ Commit to the program by writing the program philosophy and program mission statement

DESIGN THE DELIVERY SYSTEM

▪ Identify specific counseling elements for each

program components

▪ Develop action plans

▪ Identify the curriculum to be used

▪ Determine data to collect when implementing

the program

57

Figure was reproduced with minor modifications from Ibid., p. 63.

58

Ibid., pp. 83–86.

Hanover Research | January 2019

ULEAD…Utah Leading through Effective, Actionable, and Dynamic Education

Utah State Board of Education 250 East 500 South P.O. Box 144200 Salt Lake City, Utah 84114-4200

https://www.schools.utah.gov/ulead/practicereports

© 2019 Hanover Research

20

IMPLEMENT THE PROGRAM

▪ Establish a budget for the program

▪ Complete the management agreement forms

▪ Develop a master planning calendar

▪ Determine school counselor target time

allocations

▪ Conduct professional development activities

▪ Promote the school counseling program

through brochures and websites

MAKE THE PROGRAM ACCOUNTABLE

▪ Monitor program results

▪ Monitor counselors’ growth and performance

▪ Monitor students’ progress

Source: Utah State Board of Education

59

WISCONSIN MODEL

The Wisconsin Comprehensive School Counseling Model incorporates elements from the

ASCA National Model, an earlier version of the Wisconsin Model, the National Framework for

State Programs of Guidance and Counseling, the Education Trust School Counseling Initiative,

and Wisconsin’s Quality Educator Initiative. The Wisconsin Model, like the ASCA National

Model, encompasses a school counseling curriculum, individual student planning, responsive

services, and system support services. Further, the Wisconsin Model is based on nine learning

standards which cover the domains of academic, career, and personal/social development.

Figure 1.12 presents these standards, which mirror those that are part of the ASCA National

Model.

60

Figure 1.12: Wisconsin Model School Counseling Student Standards

ACADEMIC DOMAIN

PERSONAL/SOCIAL DOMAIN

CAREER DOMAIN

▪ Students will acquire the attitudes,

knowledge, and skills that

contribute to successful learning in

school and across the life span.

▪ Students will develop the academic

skills and attitudes necessary to

make effective transitions from

elementary to middle school, from

middle school to high school, and

from high school to a wide range of

postsecondary options.

▪ Students will understand how their

academic experiences prepare

them to be successful in the world

▪ Students will acquire the

knowledge, attitudes, and

interpersonal skills to understand

themselves and appreciate the

diverse backgrounds and

experiences of others.

▪ Students will demonstrate effective

decision-making, problem-solving,

and goal-setting skills.

▪ Students will understand and use

safety and wellness skills.

▪ Students will acquire the self-

knowledge necessary to make

informed career decisions.

▪ Students will understand the

relationship between educational

achievement and career

development.

▪ Students will employ career

management strategies to achieve

future career success and

satisfaction.

59

Figure contents were taken verbatim with modifications from Ibid.

60

“Wisconsin Comprehensive School Counseling Model (WCSCM).” Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction.

https://dpi.wi.gov/sspw/pupil-services/school-counseling/models/state

Hanover Research | January 2019

ULEAD…Utah Leading through Effective, Actionable, and Dynamic Education

Utah State Board of Education 250 East 500 South P.O. Box 144200 Salt Lake City, Utah 84114-4200

https://www.schools.utah.gov/ulead/practicereports

© 2019 Hanover Research

21

ACADEMIC DOMAIN

PERSONAL/SOCIAL DOMAIN

CAREER DOMAIN

of work, in their interpersonal

relationships, and in the

community.

Source: Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction

61

INTERNATIONAL MODEL FOR SCHOOL COUNSELING PROGRAMS

Two school counseling experts developed the International Model for School Counseling

Programs, a model that is endorsed by the Association of American Schools in South America

and the U.S. Department of State – Office of Overseas Schools. Notably, “over 300

international school counselors, organizations, and interested parties have participated in the

development of the International Model.”

62

The model is largely based on the ASCA National

Model with adaptations that make the model meet the needs of students outside the United

States. More specifically, the International Model accounts for the “unique needs of

international school students [including]…frequent transitions and distinctive challenges with

identity formation.”

63

The four adaptations are:

64

Language used in the Model reflects the international context in which overseas

counselors work.

The Model includes information about the elements of a counseling program that

accurately represents the environment and factors of school counseling in a foreign

country. Often, these responsibilities exceed the expectations placed upon

counselors who work in public and state schools in the United Kingdom, Australia,

New Zealand, the United States, and Western Europe.

The new fourth domain—Global Perspective—offers content standards that focus on

encouraging mindful cross-cultural interaction and intercultural communication for

school counselors and students.

Academic, Career, Personal/Social and Global Perspective content standards reflect

the needs of third culture kids (and host country nationals) in international schools.

Like the ASCA National Model, the International Model consists of a foundation, delivery

system, management system, and accountability system. Generally, the features of these

components are the same as those in the ASCA National Model.

65

The most substantial

addition to the International Model is the Global Perspective domain. As such, the

International Model seeks to develop students’ global view in addition to their academic,

61

Figure contents were taken verbatim from Ibid.

62

“The Model.” International School Counselor Association. https://iscainfo.com/The-Model

63

Fezler, W.B. and C. Brown. “The International Model for School Counseling Programs.” Association of American

Schools in South America and the U.S. Department of State, Office of Overseas Schools, July 2011. p. 9.

https://iscainfo.com/resources/Documents/International-Model-for-School-Counseling-Programs-Aug-2011-First-

Edition.pdf

64

Bullet points were taken verbatim from Ibid., p. 7.

65

Ibid., pp. 17–20.

Hanover Research | January 2019

ULEAD…Utah Leading through Effective, Actionable, and Dynamic Education

Utah State Board of Education 250 East 500 South P.O. Box 144200 Salt Lake City, Utah 84114-4200

https://www.schools.utah.gov/ulead/practicereports

© 2019 Hanover Research

22

career, social-emotional skills.

66

Under the Global Perspective domain, students are expected

to:

67

Develop an understanding of culture as a social construct;

Acquire an awareness of their family culture and own cultural identity;

Understand their host country and home(s) country’s cultures;

Develop a personal practice for applying intercultural competence and bridging

successfully across cultural difference; and

Acquire knowledge and attitudes to manage transition effectively.

66

Ibid., pp. 12–13.

67

Bullet points were taken verbatim from Ibid., p. 13.

Hanover Research | January 2019

ULEAD…Utah Leading through Effective, Actionable, and Dynamic Education

Utah State Board of Education 250 East 500 South P.O. Box 144200 Salt Lake City, Utah 84114-4200

https://www.schools.utah.gov/ulead/practicereports

© 2019 Hanover Research

23

SECTION II: ROLES OF SCHOOL COUNSELORS

In this section, Hanover reviews the general and grade-level specific roles of school

counselors. Specifically, Hanover discusses counselors’ roles in providing college and career

readiness support, mental health care, social-emotional support, suicide prevention, and

trauma-informed care. Hanover also presents best practices for time and caseload

management.

GENERAL ROLES OF SCHOOL COUNSELORS

An increasingly important aspect of school counselors’ roles in schools is meeting students’

social-emotional and mental health needs using proactive rather than reactive

approaches.

68

Integrating social-emotional supports into schools at all grade levels is

important for reducing school violence and preventing student suicide.

69

As a result, school

counselors no longer only play a role in course selection and the college admissions process.

Rather, they are now also involved in school-based mental health care, social-emotional

learning curricula, suicide prevention, and trauma-informed care.

A 2012 book titled Professional School Counseling provides a summary of a school counselor’s

role. The author describes counselors’ responsibilities as falling into four categories of a

counseling program: guidance curriculum, individual planning, responsive services, and

system support (see Figure 2.1).

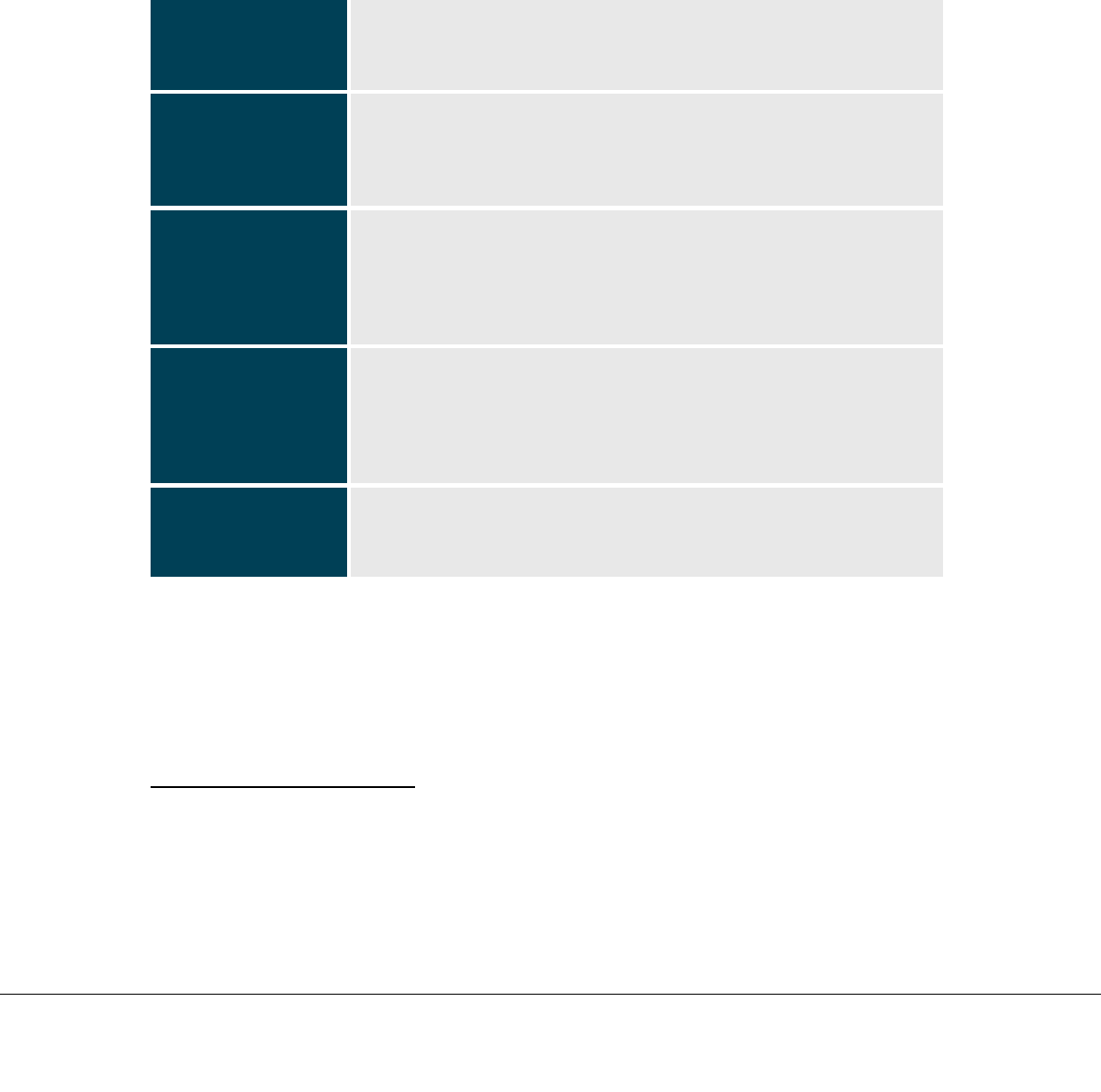

Figure 2.1: Summary of School Counselors’ Roles

COMPONENT

DESCRIPTION

TOPICS/ACTIVITIES

COUNSELOR’S ROLE

GUIDANCE

CURRICULUM

Provides guidance

content in a systematic

way to all students K–12

▪ Career awareness

▪ Conflict resolution

▪ Decision-making skills

▪ Substance abuse prevention

▪ Study skills

▪ Job preparation

▪ Structured groups

▪ Classroom presentations

▪ Schoolwide workshops for

teachers, students, and

families

68

[1] Levesque, K. “A School Counselor Puts Social-Emotional Learning First.” Social-Emotional Learning in Action,

14:4, October 4, 2018. http://www.ascd.org/ascd-express/vol14/num04/A-School-Counselor-Puts-Social-

Emotional-Learning-First.aspx [2] Paolini, A. “School Shootings and Student Mental Health: Role of the School

Counselor in Mitigating Violence.” American Counseling Association Knowledge Center, 2015.

https://www.counseling.org/docs/default-source/vistas/school-shootings-and-student-mental-health.p

69

[1] Buchesky, S. “The Answer to School Violence Is Social-Emotional Learning.” Real Clear Education, June 12, 2018.

https://www.realcleareducation.com/articles/2018/06/12/the_answer_to_school_violence_is_social-

emotional_learning_110283.html [2] Vollandt, L. “Social-Emotional Learning & Upstream Approaches to Suicide

Prevention in Schools.” GoGuardian Blog, September 20, 2018. https://blog.goguardian.com/social-emotional-

learning-in-schools [3] Paolini, Op. cit., p. 7.

Hanover Research | January 2019

ULEAD…Utah Leading through Effective, Actionable, and Dynamic Education

Utah State Board of Education 250 East 500 South P.O. Box 144200 Salt Lake City, Utah 84114-4200

https://www.schools.utah.gov/ulead/practicereports

© 2019 Hanover Research

24

COMPONENT

DESCRIPTION

TOPICS/ACTIVITIES

COUNSELOR’S ROLE

INDIVIDUAL

PLANNING

Assists students in

planning, monitoring, and

managing their academic,

personal/social, and

career development

▪ Course selection

▪ Transitioning

▪ Career shadowing

▪ Setting personal goals

▪ Appraisal

▪ Career planning

▪ Transitions

▪ Schoolwide workshops for

teachers, students, and

families

RESPONSIVE

SERVICES

Addresses the immediate

needs and concerns of

students

▪ Academic concerns

▪ Relationship concerns

▪ Substance abuse

▪ Family issues

▪ Sexuality issues

▪ Physical/sexual/emotional

abuse

▪ Suicide prevention

▪ Individual and small-group

counseling

▪ Consultation

▪ Referral

▪ Crisis intervention and

management

▪ Schoolwide workshops for

teachers, students, and

families

SYSTEM SUPPORT

Includes program, staff,

and school support

activities and services

▪ Comprehensive guidance

counseling program

▪ School counselor

professional development

▪ Advisory committee

▪ Program planning and

development

▪ Documentation

▪ Data analysis

▪ Community outreach

▪ Public relations

▪ Parent/guardian

involvement

▪ Program management

▪ Professional development

▪ Staff and community

relations

▪ Consultation

▪ Committee participation

▪ Community outreach

▪ Evaluation

▪ Self-care

Source: Professional School Counseling

70

In the remainder of this section, Hanover discusses more specific roles of school counselors

related to college and career readiness as well as mental health care services.

70

Figure contents were taken verbatim from Thompson, R.A. “Professional School Counseling: Best Practices for

Working in the Schools - Third Edition.” Professional School Counseling, 2012. pp. 52–53.

http://tandfbis.s3.amazonaws.com/rt-media/pp/common/sample-chapters/9780415998499.pdf

Hanover Research | January 2019

ULEAD…Utah Leading through Effective, Actionable, and Dynamic Education

Utah State Board of Education 250 East 500 South P.O. Box 144200 Salt Lake City, Utah 84114-4200

https://www.schools.utah.gov/ulead/practicereports

© 2019 Hanover Research

25

COLLEGE AND CAREER READINESS

Research suggests that all students benefit from

access to college and career readiness counseling.

71

The College Board National Office for School

Counselor Advocacy (NOSCA) identifies the core

elements of college and career counseling, shown in

Figure 2.2 below. Counselors can consider covering

these components in the school counseling

curriculum. At the elementary and middle school

levels, the NOSCA recommends that counselors cover

all the topics listed in Figure 2.2, except the college

and career admission process and the transition from high school to college enrollment.

These two topics are more appropriate for counselors to review at the high school level than

at the elementary or middle school levels.

72

Later in this section, Hanover describes grade-

level specific practices for promoting college and career readiness in greater detail.

Figure 2.2: Components of College and Career Readiness Counseling

COLLEGE

ASPIRATIONS

K-12

Build a college-going culture based on early college awareness by

nurturing in students the confidence to aspire to college and the resilience

to overcome challenges along the way. Maintain high expectations by

providing adequate supports, building social capital and conveying the

conviction that all students can succeed in college.

ACADEMIC

PLANNING FOR

COLLEGE AND

CAREER READINESS

K-12

Advance students’ planning, preparation, participation and performance

in a rigorous academic program that connects to their college and career

aspirations and goals.

ENRICHMENT AND

EXTRACURRICULAR

ENGAGEMENT

K-12

Ensure equitable exposure to a wide range of extracurricular and

enrichment opportunities that build leadership, nurture talents and

interests, and increase engagement with school.

COLLEGE AND

CAREER

EXPLORATION AND

SELECTION PROCESS

K-12

Provide early and ongoing exposure to experiences and information

necessary to make informed decisions when selecting a college or career

that connects to academic preparation and future aspirations.

COLLEGE AND

CAREER

ASSESSMENTS

K-12

Promote preparation, participation and performance in college and career

assessments by all students.

71

Curry, J. and A. Milsom. Career and College Readiness Counseling in P-12 Schools: Second Edition. Springer

publishing company, 2017. p. 56. http://lghttp.48653.nexcesscdn.net/80223CF/springer-

static/media/samplechapters/9780826136145/9780826136145_chapter.pdf

72

“Eight Components of College and Career Readiness Counseling.” The College Board National Office for School

Counselor Advocacy. p. 4. https://secure-

media.collegeboard.org/digitalServices/pdf/nosca/11b_4416_8_Components_WEB_111107.pdf

Click the link below to access

resources provided by the Utah

State Board of Education that

school counselors can use to

support students in college and

career readiness.

School Counselor Toolkit: College

and Career Readiness

Hanover Research | January 2019

ULEAD…Utah Leading through Effective, Actionable, and Dynamic Education

Utah State Board of Education 250 East 500 South P.O. Box 144200 Salt Lake City, Utah 84114-4200

https://www.schools.utah.gov/ulead/practicereports

© 2019 Hanover Research

26

COLLEGE

AFFORDABILITY

PLANNING

K-12

Provide students and families with comprehensive information about

college costs, options for paying for college, and the financial aid and

scholarship processes and eligibility requirements, so they are able to plan

for and afford a college education.

COLLEGE AND

CAREER ADMISSIONS

PROCESSES

9-12

Ensure that students and families have an early and ongoing

understanding of the college and career application and admission

processes so they can find the postsecondary options that are the best fit

with their aspirations and interests.

TRANSITION FROM

HIGH SCHOOL

GRADUATION TO

COLLEGE

ENROLLMENT

9-12

Connect students to school and community resources to help the students

overcome barriers and ensure the successful transition from high school

to college.

Source: College Board National Office for School Counselor Advocacy

73

The Utah State Board of Education recommends that school counselors support students’

college and career planning through transitions planning, individual and small group planning

sessions, and parent-student meetings.

74

The Utah State Board of Education provides two

rubrics that districts can use to evaluate their new and existing college and career readiness

school counseling programs. The evaluation criteria were developed to ensure the college

and career readiness of all students and to be consistent with the modern needs of students

related to changes in technology usage, college admissions and curriculum, and the needs of

the workforce.

75

MENTAL HEALTH AND SOCIAL-EMOTIONAL SERVICES

In addition to college and career counseling, school counselors are responsible for

contributing to the positive development of students’ mental health and social-emotional

competencies. According to the National Association of School Psychologists (NASP), school

counselors typically work within a continuum of mental health services that also includes

school psychologists, social workers, and community service providers. Within the

continuum, school counselors typically provide school-based, universal mental supports to all

students. School counselors can also refer students requiring more intense interventions to

school-employed mental health professionals such as school psychologists or community

providers.

76

73

Figure contents were taken verbatim from Ibid., p. 3.

74

“College and Career Readiness School Counseling Program Model: Second Edition.” Utah State Board of Education,

2016. p. 26. https://www.uen.org/ccr/counselor-toolkit/documents/CCRpmBOOK5_10_ADA_version.pdf

75

“Utah College and Career Readiness School Counseling Program: On-Site Review Performance Self-Evaluation for

Existing Programs.” Utah State Board of Education. p. 2.

https://resources.finalsite.net/images/v1524846386/davisk12utus/a9wh4a1wcplxcb8jvfr7/UtahCCRSchoolCouns

eling-ReviewBooklet.pdf

76

Cowan, K.C. et al. “A Framework for Safe and Successful Schools.” National Association of School Psychologists,

2013. pp. 7, 10–11.

https://www.naesp.org/sites/default/files/Framework%20for%20Safe%20and%20Successful%20School%20Enviro

nments_FINAL_0.pdf

Hanover Research | January 2019

ULEAD…Utah Leading through Effective, Actionable, and Dynamic Education

Utah State Board of Education 250 East 500 South P.O. Box 144200 Salt Lake City, Utah 84114-4200

https://www.schools.utah.gov/ulead/practicereports

© 2019 Hanover Research

27

According to the ASCA, school counselors are in a unique position to provide social-

emotional and mental health services to students. School counselors have training in

meeting students’ social-emotional needs and are often the first person to identify and

provide services to students in need of social-emotional or mental health supports given that

they provide universal services. School counselors support students’ social-emotional and

mental health needs through the counseling core curriculum, small-group counseling, and

individual counseling.

77

Figure 2.3 presents a list of other ways school counselors play a role

in developing students social-emotional skills.

Figure 2.3: School Counselors’ Roles in Social-Emotional Development

❖ Provide direct instruction, team-teach or assist in teaching the school counseling core curriculum,