Forschungsinstitut

zur Zukunft der Arbeit

Institute for the Study

of Labor

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES

On the Interpretation of World Values Survey Trust

Question: Global Expectations vs. Local Beliefs

IZA DP No. 9872

April 2016

Ritwik Banerjee

On the Interpretation of

World Values Survey Trust Question:

Global Expectations vs. Local Beliefs

Ritwik Banerjee

Aarhus University

and IZA

Discussion Paper No. 9872

April 2016

IZA

P.O. Box 7240

53072 Bonn

Germany

Phone: +49-228-3894-0

Fax: +49-228-3894-180

E-mail: [email protected]

Any opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in

this series may include views on policy, but the institute itself takes no institutional policy positions.

The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity.

The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) in Bonn is a local and virtual international research center

and a place of communication between science, politics and business. IZA is an independent nonprofit

organization supported by Deutsche Post Foundation. The center is associated with the University of

Bonn and offers a stimulating research environment through its international network, workshops and

conferences, data service, project support, research visits and doctoral program. IZA engages in (i)

original and internationally competitive research in all fields of labor economics, (ii) development of

policy concepts, and (iii) dissemination of research results and concepts to the interested public.

IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion.

Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be

available directly from the author.

IZA Discussion Paper No. 9872

April 2016

ABSTRACT

On the Interpretation of World Values Survey Trust Question:

Global Expectations vs. Local Beliefs

*

How should we interpret the World Values Survey (WVS) trust question? We conduct an

experiment in India, a low trust country, to correlate the WVS trust question with trust

decisions in an incentivized Trust Game. Evidence supports findings from one strand of the

fractured literature – the WVS trust question captures expectations about others’

trustworthiness, though not always. We show that WVS trust question correlates with globally

determined stable expectations but does not correlate with short term locally determined

fluctuations in beliefs about trustworthiness. One implication of our study is that survey based

methods may not be used to measure contextualized beliefs.

JEL Classification: corruption, social capital, belief, trust games

Keywords: C91, C92, D03

Corresponding author:

Ritwik Banerjee

Department of Economics and Business

Aarhus University

Fuglesangs Allé 4

8210 Århus V

Denmark

E-mail: [email protected]

*

I thank Alexander Koch, Nabanita Datta Gupta, Marco Piovesan, Klaus Abbink, Luigi Zingales, Marie

Claire Villeval, Emma von Essen, seminar/conference participants at Aarhus University, IIM Calcutta,

IIT Gandhinagar, IIM Ahmedabad, Winter School at DSE 2014 for their comments and suggestions. I

also thank Sujoy Chakrabarty and Bibek Banerjee for making it possible for me to run the experiment

and Manas Pathak for his research assistance. The experiment was funded with grants from

Department of Economics and Business, Aarhus University.

1 Introduction

Trust has been found to play an important role in determining economic activity. Higher levels

of trust have been associated with higher levels of economic growth (Knack and Keefer, 1997),

higher levels of financial development (Guiso et al., 2004, 2008), and greater international trade and

investment (Guiso et al., 2009). Most of these cross country studies have relied on the response to

the generalized trust question asked in the World Values Survey (WVS) or General Social Survey

(GSS). The generalized trust question is the following: “Generally speaking, would you say that

most people can be trusted or that you need to be very careful in dealing with people?” On the

other hand the experimental literature, following Berg et al. (1995), has evolved in a different

direction - this literature has focused on measuring trust and trustworthiness through incentivized

experimental games. The classic experimental Trust Game mimics a situation where a sender

decides whether or not to cooperate with the receiver. Cooperation makes sense for the sender only

if her perceived chance that the receiver will reciprocate is high enough. Of course the receiver

may or may not decide to reciprocate the sender. Interestingly, this mechanism elicits trust and

trustworthiness behavior in a direct definitional sense while the WVS trust question relies more on

respondent’s interpretation of the question and her frame of reference.

Since nationally representative scale incentivized Trust Games are expensive, WVS trust question

is a widely used trust measure. As both incentivized elicitation and survey based measure claim to

measure trust, it has been a long standing project of economists to examine how the two measures

correlate and even if they do, whether they measure the same behavioral primitive. However, past

studies have been unable to find an unambiguous or even nearly conclusive evidence in this regard.

(Fehr et al., 2003; Bellemare and Kroger, 2007) found that the response to WVS trust question is

correlated with the sender’s trust behavior in lab based experimental Trust Games but not with

receiver’s trustworthiness behavior. (Glaeser et al., 2000; Lazzarini et al., 2004), on the other hand,

found that the WVS trust measure is correlated, not with trust, but with trustworthiness instead.

In an important study, Thöni et al. (2012) report that WVS-trust question is a proxy for

cooperative preferences rather than beliefs about how cooperative people are. This is contradicted

soon after by Sapienza et al. (2013), who make a significant contribution to this literature by

showing that the survey response actually relates to neither trust nor trustworthiness but relates to

a subject’s belief about how trustworthy others are. They argue that the measure, that is most

consistent with the definition of trust, is the belief component of the sender’s behavior in the Trust

Game and not the preference based component. According to them, it is this belief or expectation

about how others behave which is well captured by the WVS trust question.

With this background of multifarious results in the literature, we aim to revisit this issue

and understand what is it that the WVS trust question measures. If it does measure the belief

about others’ trustworthiness, then under which circumstance(s) does the claim that the WVS

trust captures the belief based component of trust hold true and when does the relation fail? In

2

particular, we ask, are the reference frame in which the WVS trust question is answered same as

that under which incentivized trust decisions in laboratory Trust Games made? Does the WVS

trust question capture the short term fluctuations in our beliefs?

A second aim of this study is to analyze this issue in a cultural context very different from all

previous studies on this subject. Why is that important? Remember that World Values Survey

is a global research project which aims to track “...Political and Sociocultural Change” through

nationally representative survey in more than 100 countries over time. In other words, World

Values Survey aims to be globally representative. In order to ensure global representativeness WVS

does employ the necessary instrument, namely, a common questionnaire across the world. However,

this is far from being sufficient. In order for the survey results to be consistent, comparable and

globally representative, it is critical that the questions in WVS are interpreted in the same way

by people everywhere. And this is far from obvious given the nature of the inquiry - that it is

engaged with subjective opinions, values and beliefs. As an example, consider someone being ill.

Queries about her illness may be considered invasion of privacy in some parts of the world while it

may be interpreted as coming from genuine concern in some other. Social desirability bias may

systematically vary across cultures as well, rendering responses across countries incomparable.

We design an experiment where we can measure trust, trustworthiness and also separately

identify long term stable expectations and short term fluctuations in beliefs about how trustworthy

others are. Then we elicit response to the WVS trust question to see if the latter is correlated which

type of beliefs the WVS trust question correlates with. The way we induce a negative fluctuation in

beliefs is by letting subjects go through a negative experience before they play a Trust Game - more

specifically they go through an experience of having to give bribe in order to have what is rightfully

theirs in a corruption game. Corruption have been studied through lab based experimental games

in the past (see for example Cameron et al. (2009); Alatas et al. (2009)). In our between subject

design, “Citizens” and “Public Officials” play a real effort harassment bribery game

1

. A Citizen

performs a task and earns a prize, if successful. However, a Public Official, may demand a bribe

before the Citizen can have her prize which she may accept or reject. The negative experience of

having to pay a bribe may lead people to believe that people are less trustworthy in a Trust Game

that follows, relative to a standalone baseline Trust Game. Thus, a difference in beliefs between

the baseline Trust Game and Trust Game preceded by a bribery game may be attributed to the

negative experience of having to pay a bribe. The observed treatment effect in beliefs could be

attributed to either bribe or the pure income effect of the bribe amount. In order to precisely pin

down the source of the negative belief shock, we probe even further.

We construct a strategically identical but differently framed counterfactual where Participant A

(analogous to the Citizen), upon successfully completing the task, earns the right to go to the second

1

In a harassment bribery game a Citizen is entitled to a prize but a Public Official demands a bribe from the

Citizen before he lets her have the prize. It mimics a situation where ordinary Citizens are entitled to government

services such as passport or driver’s license but have to either pay a bribe in order to obtain them or suffer inordinate

procedural delays. Abbink et al. (2014) and ? study different aspects of harassment bribery game.

3

stage of the game. At the second stage, Participant B (analogous to the Public Official) plays

an Ultimatum Game with the same stake size as the prize in the bribery game, and decides how

much to share with Participant A, which the latter can accept or reject. After subjects have gone

through the experience of either the Bribery Game or the Ultimatum Game and have known the

outcomes, we measure their trust behavior in a standard Trust Game. Thus, in all our experiment

comprises of three treatments, to which subjects are randomly assigned - Bribery Game treatment,

Ultimatum Game treatment and the baseline Trust Game. Each treatment is followed by a short

survey where subjects are asked to respond to the WVS trust question, among other things. The

logic of the design wrests on a finding by

?

, who show that the difference in behavior between the

Bribery Game and its strategically identical counterpart - the Ultimatum Game can be partly

attributed to the difference in social norm governing the two frames. Specifically, a bribe demand

is considered inappropriate from a moral standpoint but the same amount when retained in an

ultimatum game may be considered appropriate. As a result a bribe demand in the Bribery Game

may induce a negative shock in the belief about how trustworthy people are whereas the same

amount, when retained in the Ultimatum Game, may not.

Our findings suggest that WVS trust response is not correlated with the sending decisions

in the Trust Game. Instead, it is correlated with the expectation about how trustworthy others

are. Deeper probe reveals that in fact beliefs about trustworthiness do suffer a negative shock in

the Bribery Game treatment relative to the Ultimatum Game and the baseline trust treatment.

The centerpiece of our results is a consequence of that - the correlation between WVS trust and

expectation about trustworthiness holds for Participant As and baseline subjects, but not for the

Citizens. Since the expectation of the Citizens about the trustworthiness of the matched partners

is lower than that of the Participant As and baseline subjects, our main result suggests that WVS

trust response does well in capturing stable expectations about how others in general behave,

however, it is a bad proxy for locally determined short term fluctuations in beliefs. Our preferred

interpretation of this result is that while the reference frame of beliefs, elicited through Trust

Games, is more immediate, subjects view the WVS trust question in a longer term pan-societal

context.

So should we rely on survey based measures as a proxy for beliefs? Our results show that

the answer to this question is yes only if we are interested in measuring long run stable beliefs

and not its short run fluctuations. Thus, laboratory experiments, which are more geared towards

generating psycho-emotional triggers, may not use survey based methods such as in WVS to

measure beliefs. This is the main contribution of our paper. Second, we demonstrate the need to

see stable beliefs as different from its short run fluctuations. The stable beliefs are conceptually

closer to the sense in which beliefs are understood in a rational expectation framework. They are

formed by aggregation of our experiences in multiple domains of our life and hence may as well

be called “global expectations.” To the contrary, the short run fluctuations in beliefs are shaped

by local environments and immediate experiences. These fluctuations are more likely to converge

4

to the stable steady state over time and hence may be called “local beliefs”. While differentiating

between global expectations and local beliefs, we show that measuring these two concepts require

different set of instruments. An interesting implication of our result is people do not seem to

generalize negative experiences to population at large immediately.

Third, the literature on framing shows that framing has an important effect on how people

behave. Our paper contributes to that literature by demonstrating that not only does framing affects

behavior, but it also has a spillover effect on beliefs in an unrelated domain. Finally, our study is

directionally consistent with results from Sapienza et al. (2013) in a socio-cultural environment

very different from theirs, indicating that respondents interpret the WVS trust question in a similar

way across the two cultures. We believe this is only a beginning of a series of study which needs

to be conducted to understand how questions about values, opinions and beliefs are interpreted

across cultural regions. Only then will we be able to ensure that responses to such queries are truly

globally representative.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 lays out the experimental design

and briefly sketches the important survey questions. Section 3 presents the broad results and

the mechanisms behind the results and Section 4 discusses the results and offers the concluding

remarks.

2 Experimental Design

One way to induce a negative shock to the beliefs of subjects is by letting them go through a

negative experience. We simulate such a situation by letting subjects play a harassment bribery

game (BG) before playing a Trust Game. Beliefs about trustworthiness following BG may then

be contrasted to beliefs about trustworthiness in a baseline Trust Game (i.e. a Trust Game not

preceded by a bribery game) and the difference may be interpreted as a shock to expectations

about others’ trustworthiness. However, source of such a shock can be interpreted as either a result

of bribe extraction or simply the negative income effect. In order to tease apart the origin of the

shock, we design a counterfactual of the bribery game treatment, which is strategically identical

to the bribery game but is differently framed. It turns out that this strategically identical but

differently framed game is a variant of what is standardly known as an Ultimatum Game (UG). The

Bribery Game and the Ultimatum Game differ from each other on two aspects - one, the former

uses a loaded language (e.g. Citizen, Public Official, bribe etc.) while the latter uses a neutral

language (e.g. Participant A, Participant B and transfer); two, in terms of the difference in the

sense of entitlement among the subjects induced by a difference in the endowment (see Banerjee

(2016) for a detailed analysis of the difference in two frames). Thus, the three treatments in our

experiment are - Trust Game preceded by BG, Trust Game preceded by UG and baseline Trust

Game. Each subject then answers a survey questionnaire which includes the World Values Survey

trust question, among others.

5

The premise of the experimental design is that a bribe demand may be considered unfair in BG

but the same amount in UG may be considered fair. Thus, the two frames are expected to trigger

different psychological responses despite being identical in strategic terms. In particular, we expect

that immorality of bribe demand will lead to a negative shock to beliefs about how trustworthy a

matched partner is, relative to the ultimatum game and the baseline Trust Game. This approach

of examining the behavioral response by inducing psychological triggers has been adopted in the

past; for example Burnham et al. (2000) study how framing the matched partner as friend or foe

affects behavior, Rosaz and Villeval (2012) andMaggian and Villeval (2015) use it in the context of

lying, Buser and Dreber (2013) study the effect of competition on cooperation and Drouvelis et al.

(2010) study prime cooperation in social dilemma games.

2.1 Bribery Game and Ultimatum Game

The Bribery Game is illustrated in Figure 1(a). A Citizen (C) is given ten minutes, within which

she has to complete a real effort task

2

. This gets her a prize winning code which entitles her to

a prize of 400 Mohars

3

(

M

400). If she is unable to reach the code within the stipulated time

then she only earns the participation fee of

M

200. However, even if the Citizen does get the prize

winning code a matched Public Official (PO) may demand a bribe of amount

b

before he lets her

have the entitled prize. Notice that any bribe that the PO demands is an extract from the Citizen’s

entitlement, which in this case is

M

400. We let the bribe amount take the following values - 0, 100,

200, 300, 400 Mohars. Upon being asked to pay a bribe, a Citizen may either accept it or reject it.

She earns

M

(200 + 400

− b

) if she accepts the bribe demand and only

M

200 if she rejects it. The

PO on the other hand earns the participation fee of

M

200 and a salary of

M

400 for approving the

Citizen’s entitlement. Additionally, he gets the bribe amount demanded if he does demand a bribe

and it is accepted i.e. his total earning in this case is

M

(200 + 400 +

b

). If the Citizen rejects the

bribe demand then of he earns only the M600.

This is a one shot game and the real effort task is calibrated in a way such that a Citizen is more

likely to complete the task and get the prize winning code. However, making the Citizens perform

the real effort task was crucial to induce a sense of harassment among them. This version of the

Bribery Game closely mimics the often encountered situations in developing countries where a

Citizen is entitled to a passport or a driving license but still has to pay a bribe to get it. Such bribe

extractions are typically considered unfair since it means being forced to give up resources which

2

We employ a computer based task - Citizens have to count the number of occurrences of the letter “A” in five

different panels, each with a random sequence of letters A, B, C, D, E. The panels appear one after the other and a

subject is not be able to proceed unless she correctly counts the number of As in the incumbent sequence. The prize

winning code is mentioned at the end of the fifth panel. The task ensures that a Public Official does not need to

grade the Citizen’s answers, but is still able to figure out, whether she has been able to complete the task or not by

looking at the prize winning code in her response sheet.

3

Mohar or gold coins were used as currency in medieval India. It was used as a currency in our experimental set

up.

6

are rightfully one’s own. A design feature which is used to exacerbate the sense of unfairness is that

the lower bound of PO’s earning is also the upper bound of C’s earnings. The bribe amount only

increases PO’s already high earnings. Furthermore, this ensures that no demand can be interpreted

as being motivated by inequality aversion. We expect that a consequence of such bribe extraction

will be to reduce people’s expectations about how fair others are. Hence, our decision to implement

this design.

Figure 1(b) lays out the Ultimatum Game and it is isomorphic to the Bribery Game. There

are, however, two main differences: First, UG uses a neutral language frame (e.g. Participant A,

Participant B and transfer) while BG uses a loaded language frame (Citizens, Public Officials and

bribe); second, while a Citizens in BG is entitled to a prize once she completes the task, Participant

A in UG only qualifies to the next round of the game in which Participant B play an ultimatum

game with her with the same stake size as the prize in BG. Suppose P-B retains

x

with him then

P-A receives

M

400

− x.

The payoffs in the UG are the following: If P-A accepts (rejects) the offer

then she gets

M

200 + 400

− x (M

200

)

and P-B earns

M

200 + 400+

x (M

600

).

Clearly, the UG is

a strategically identical but differently framed counterfactual to BG with markedly different sense

of entitlements. As a result, we expect UG to trigger different psychological response than BG.

Figure 1: Bribery Game (BG) and Ultimatum Game (UG)

(a) BG

Citizen performs a task,

needs to complete it in 10 minutes

Successfully completes

the task, C wins a prize of 400

PO decides whether

to ask for a bribe

and if yes how much.

Unable to complete

the task

b={0,100,200,300,400}

Reject

C: 200+400-b

PO: 600+b

C: 200

PO: 600

C decides whether to

accept or reject the demand

for bribe

C: 200

PO: 600

Accept

(b) UG

Participant A performs a task,

needs to complete it in 10 minutes

Successfully completes

the task

P-A quali

es for the next

part of the game where P-B

decides how much

to share with P-A

Unable to complete

the task

x={0,100,200,300,400}

Reject

P-A: 200+400-x

P-B: 600+x

P-A: 200

P-B: 600

P-A decides whether to

accept or reject the offer

P-A: 200

P-B: 600

Accept

7

2.2 Trust Game

The Trust Game, which follows the BG and UG treatments, is a close variant of the Trust Game

proposed by Berg et al. (1995). A sender has

M

400 and is matched to a receiver. The sender sends

an amount

s

to the receiver where

s

can take values from the set {0, 50, 100, ... 400}. The amount

is multiplied by 3 before reaching the receiver. The receiver then sends back an amount to the

sender. Thus, the amount the receiver sends back (say

r

) takes a value from the set {0, 50, ...

3s}. The final payoff of the sender is

M

400

− s

+

r

whereas that of the receiver is

M

3

s − r.

The

literature interprets s as a measure of trust and r as a measure of trustworthiness.

Subjects make their decisions both as a sender and a receiver through a strategy elicitation

method and role uncertainty is enforced. First, subjects make their decision as senders and decide

how much to transfer to the receivers. Second, they reveal how much they believe the receiver will

return for each possible amount sent. This helps us obtain off the equilibrium path responses too.

They are rewarded

M

100, if their belief in a randomly chosen trust category matches the actual

outcome. Third, subjects make their decisions as receivers, where they indicate how much they will

have sent back for every possible amount, which they could have possibly received.

.

2.3 Survey Data

At the end, the subjects write an exit survey, which is designed to acquire demographic data and

measure various personality traits. Our main survey measure of trust came from the standard

trust question of the World Values Survey : “Generally speaking, would you say that most people

can be trusted or that you need to be very careful in dealing with people?” Sapienza et al. (2013)

had administered this question, as a part of the survey, one week before the actual experiment

was conducted. In our case, it was important that this question was asked after the experiment

was conducted in order to allow for the possibility that experimental behavior could influence its

response. Table A2 in the Appendix gives the summary statistics of the responses to this question.

In our sample, 32% of the students said that most people can be trusted. The corresponding figure

in the nationally representative data from all the waves of the World Values Survey in India is 35%.

The survey included two additional measures of trust. The first one, also taken from WVS, was:

“Do you think most people would try to take advantage of you if they got the chance, or would

they try to be fair?” The second question was, “Suppose you left your wallet with Rs. 500 in the

Metro. On a scale of 1 to 10, how much do you think are the chances that you will get it back?”

The response to these questions have not been included in the analysis below, but the pairwise

correlations and summary statistics have been reported in Table A2 in the Appendix.

Besides the trust questions, we also obtain risk preference by asking survey based questions.

These questions have been used to measure risk in large scale behavioral surveys such as the

German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP). For example, one question directly asks subjects to make

8

an assessment about their general willingness to take risks on a scale of 1 to 10: “How willing are

you to take risks, in general?” Though the survey also includes other questions about risk attitudes

in specific dimensions such as financial matters, car driving, health and career, the analysis below

relies on the general measure of risk, since Dohmen et al. (2011) found that the general measure is

the best predictor of risky behavior elicited through an experiment. The descriptive statistics of

the variables used in the analysis are presented in Table A1 in the Appendix.

2.4 Experiment Procedure

The experiment was conducted in Delhi in January 2014. Subjects were recruited from a private

management training institute. 218 students participated with 45 pairs in the UG treatment, 46

pairs in the BG treatment and another 36 pairs in the baseline treatment. Subjects were randomly

assigned in the UG and BG treatment and then were randomly assigned roles. Different roles in

each treatment were allocated different rooms. Citizens/P-As first completed the computer based

task and mentioned the prize winning code in the response sheet which was then transferred to

the POs/P-Bs. They put down their demand decision on the response sheets, and these were

then transferred back to the Citizens/P-As for their acceptance decisions. Citizens/P-A were then

informed of their final earnings. It was important that we informed them how much less they were

being paid than what they deserved, in order to reinforce in them the sense of unfairness.

The Trust Game followed the BG/UG games. Subjects played both the roles of sender and

receiver but their earnings from this part was determined by randomly picking one of the roles.

The final earning from the experiment was determined by randomly picking one of the two parts.

The sessions lasted for one and a half hour. The instructions were read out in English. All payoffs

for this experiment were stated in terms of a fictitious currency called Mohar. At the end of the

experiment, participants exchanged their earnings for Rupees at the rate of 100 Mohars = Rs. 50.

The earnings ranged from Rs. 100 to Rs. 700 with an average of Rs. 252 (~ 10 PPP USD ).

3 Results

3.1 Behavior in BG, UG and Trust Game

Since the focus of this paper is to examine how WVS trust question correlates with trust, trustwor-

thiness and expectations about trustworthiness, we will only briefly state the results of the bribery

game, ultimatum game and the Trust Game. A detailed exposition of the mechanisms behind the

framing effects between BG and UG and their differential effects on the Trust Game may be found

in Banerjee (2015).

Despite being strategically identical, subjects behaved very differently in the BG and UG games.

19% of the subjects demanded no bribe in BG whereas everyone in the UG demanded a positive

9

amount (

χ

2

test, p-value=0.00). The full sample mean amount demanded in BG is

M

182.6 while

that in UG is

M

268.9 (

t

-test,

p

-value<0.001). If we restrict our attention to the non-zero sample

then the average amount demanded in BG and UG are

M

245.9 and

M

268.8 (

t

-test,

p

-value=0.02).

Clearly, BG and UG have triggered different behavioral responses in PO/P-B. C/P-A too have

perceived the two frames very differently - for a given amount, a greater proportion of Cs in BG

choose reject than P-As in UG, indicating that a demand in the former is considered more unfair

than in the latter. Table 1 provides a summary of the differences and shows that the difference is

statistically significant for the amounts 200 and 300 (χ

2

test, p-value<0.001 ).

It turns out that not only have the two frames triggered different reactions from the subjects,

but they have induced different behavioral spillovers on the the Trust Game too. The full sample

mean amount sent by Citizens in the role of the sender is

M

205.4 while that for P-A is

M

261.1

(

t

-test, p-value=0.04). The corresponding figures for the restricted (i.e. non-zero) sample are

M

230.5 and

M

273.3 (

t

-test, p-value=0.08). These results indicate that Citizens in BG tend to

trust less than Participant As in UG. It is clear from 1 that the baseline trust, which in some sense

captures the native distribution of trust, appears to be statistically indistinguishable from the trust

behavior in the UG treatment but not that in the BG treatment. Thus, we could as well have used

the baseline trust measure as the counterfactual to the BG.

To study trustworthiness, we convert the amount returned by a receiver to a Return Ratio

(RR) where

RR

=

AmountReturned/AmountReceived

. RRs averaged over all the possible trust

categories give our trustworthiness measure for a given person. We do not find any difference in

this measure of trustworthiness between C and P-A. The average RR for all the subjects are plotted

for each trust category in 2(b). The close co-movement of the RRs and the fact that they are

statistically insignificant between BG, UG and baseline treatments for all the trust categories show

that trustworthiness has remained stable across the treatments.

10

Table 1: Treatment Effects in Bribery Game, Ultimatum Game and Trust Game

Variable Names

a

BG UG Diff(1)

b

Percent who asked for bribe/ultim 81 100 19 (<0.01)

Full Sample Bribe/ultim amount 182.6 268.8 71.1 (<0.01)

Restricted Sample Bribe/ultim amount 245.9 268.8 22.9 (0.02)

Percent accepted when amount=100 93.5 97.8 4.3 (0.31)

Percent accepted when amount=200 80.4 97.8 17.4 (<0.01)

Percent accepted when amount=300 73.3 41.3 32.0 (<0.01)

Percent accepted when amount=400 17.8 10.8 7 (0.34)

BG UG Baseline Diff(1) Diff(2)

c

Diff(3)

d

Percent decided to trust 89.1 95.6 94.4 6.5 (0.25) 5.31 (0.39) 1.2 (0.82)

Full Sample Trust Amount 205.4 261.1 256.9 55.7 (0.04) 51.5 (0.06) 26.8 (0.88)

Restricted Sample Trust Amount 230.5 273.3 272.1 42.8 (0.08) 88.8 (0.08) 1.2 (0.96)

a

The restricted sample comprises of only those who demanded a non-zero amount in the BG, UG or the Trust

Game.

b

Diff(1) denotes the difference between UG and BG. The numbers in the brackets represent

p−

values. For

comparing proportions in the table,

p

-values from

χ

2

test of equality of proportions are reported. For comparison of

sample mean, p-values from t-test are reported.

c

Diff(2) denotes the difference between BG and Baseline.

d

Diff(3) denotes the difference between UG and Baseline.

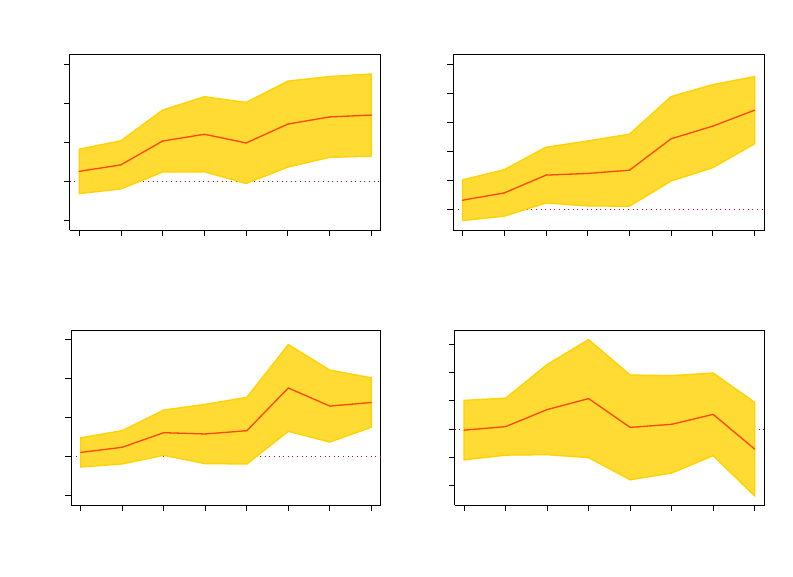

To examine whether the treatments had differential effects on beliefs, we now focus our attention

on beliefs about others’ trustworthiness. Remember that we had collected this data in a strategy

method as well - hence, we have belief about trustworthiness for each trust category as reported

by each person. To arrive at a sensible measure we normalize the beliefs to Expected Return

on Trust (ERoT) where

ERoT

= (

ExpectedReturnfor atrustlevel − T rustlevel

)

/T rustlevel

. In

2(a) we plot mean ERoT for Citizens, P-As and baseline subjects for all trust categories using the

full strategy vector. The data reveals that the expected return is significantly less for Citizens

than for P-As and the baseline subjects, particularly for lower levels of trust. This indicates

that Citizens have suffered a negative shock in their beliefs about how trustworthy their matched

partners are. This belief is significantly lower than beliefs of Participant A or baseline subjects.

The data also reveals that subjects have largely negative expectations about their matched partners’

trustworthiness when the full strategy vector is considered. Of course the expectations corresponding

to actual response is greater than zero and thus consistent (not reported).

11

Figure 2: Expected Return on Trust

6(a)

−.6 −.4 −.2 0 .2

Expected Return on Trust

50 100 150 200 250 300 350 400

Hypothetical Amount Sent

BG UG

Baseline

Note: The panel plots the average Expected Return on Trust for full strategy vector data of subjects in baseline and

those playing Citizen and Participant A in BG and UG, respectively.

6(b)

.2 .3 .4 .5

Return Ratio

50 100 150 200 250 300 350 400

Amount Sent by the Sender

BG UG

Baseline

Note: The above figure plots the average return ratio (i.e. trustworthiness), for all possible bribe amounts, of

subjects in baseline and those playing Citizen and Participant A in BG and UG, respectively.

3.2 Analysis of actual behavior, beliefs and WVS-trust

Panel 2(A) in Table 2 reports the probit regression of the WVS trust on trustworthiness. Col (1)

- (8), which report the marginal effects, indicate that trustworthiness do predict WVS trust for

higher amounts of trust. The marginal effects are economically significant for higher amounts of

trust, though statistical significance remains weak. A 10% increase in trustworthiness increases

the conditional probability that WVS trust takes value one by 4.3 to 4.8 ppts for 300 or higher

amount sent. This seemingly supports results found in past studies such as by Lazzarini et al.

(2004) and Glaeser et al. (2000), who interpret WVS trust as measuring trustworthiness. However,

this interpretation is incorrect. Col (1) - (8) in Panel 2(B) report the marginal effects of probit

estimation of EVS-trust on trustworthiness for each trust category after controlling for the expected

12

return on trust. Once ERoT is included, we notice that WVS trust is actually predicted by ERoT

and not the trustworthiness - a 10% increase in ERoT increases the probability that WVS trust

takes a value 1 by 2.1 to 2.8 percentage points (ppts). The relation only holds for trust levels

of 150 and higher. This implies that subjects’ responses to WVS trust are not independently

associated with their trustworthiness. Instead, they are associated with the expectations that

subjects form about their matched receivers’ responses. In other words, WVS trust captures the

subjects’ expectations about how trustworthy a matched partner is, when the stakes are high

enough. Panel 2(C) estimates a probit model of WVS trust on ERoT and risk preference as

measured by the generalized risk question. Clearly, the WVS trust response is predicted not only

by the ERoT, response to the risk question too turns out to be a consistent and economically and

statistically significant predictor of WVS-trust. Why do trustworthiness correlate with expectations

about how others will behave? Our view is that this is a homogenous subject pool and

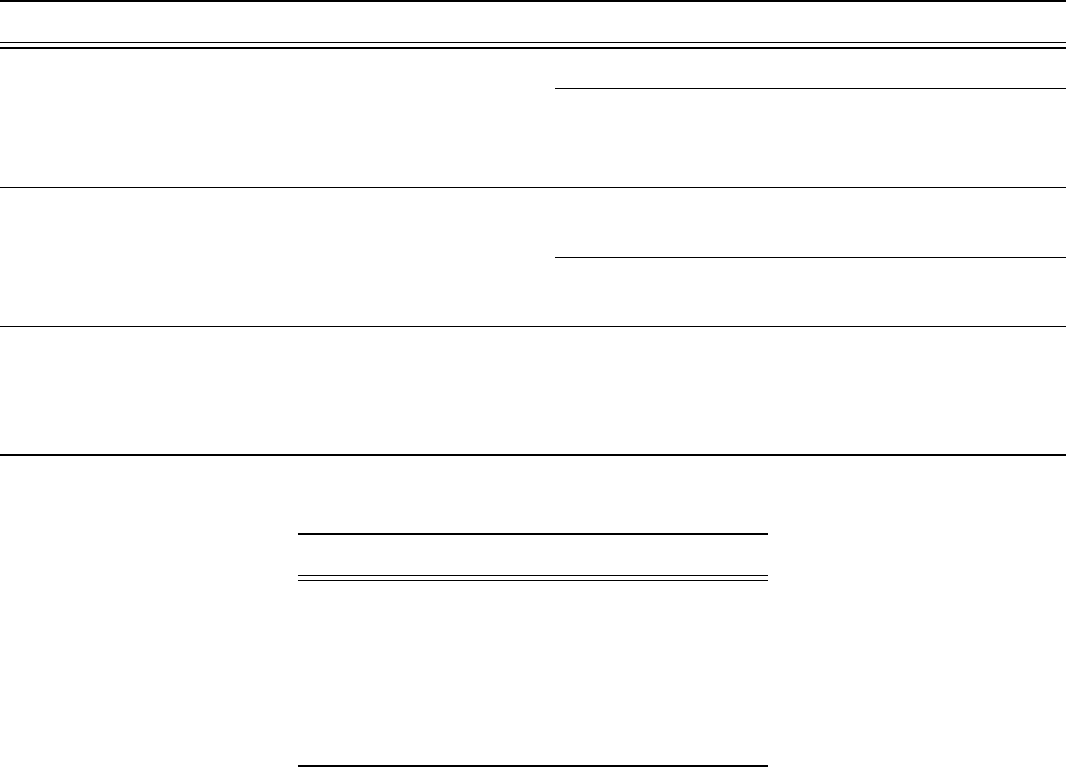

We now take a closer look at how WVS trust captures the belief component of the senders

belonging to different treatment groups. In particular, remember that C had a very different belief

profile than P-A and baseline subjects. Our main focus now is to understand to what extent the

WVS trust question captures the beliefs of each of the treatment subgroups. Hence, we restrict our

attention to the responses from Citizens, Participant As and baseline subjects in the analysis that

follows. In Table 3, where we adopt the same empirical specification as in Panel 2(C) of Table 2,

we report the probit regression results of WVS trust on Expected Return on Trust for all possible

amounts sent and the risk preference. Panel 3(A) reports the results for Citizens, Participant As

and baseline subjects, panel 3(B) for P-A and baseline, panel 3(C) for P-A only and panel 3(D) for

Citizens only. It turns out that the coefficient of ERoT is statistically significant in Panel 3(A),

3(B) and 3(C). Besides, the coefficients are economically significant too - a 10% increase in ERoT

leads to a 2.0 ppts to 3.4 ppts increase in the odds that a subject responds by saying that most

people can be trusted, as reported in in Panel 3(A). The corresponding figures in Panel 3(B) are

2.4 ppts to 6.8 ppts and in Panel 3(C) are 3.1 ppts to 8.8 ppts. As the trust level increases, the

strength of the association between expectations about others’ trustworthiness and WVS trust

increase, so do the statistical significance. Also, it increasingly better explains the variation in WVS

trust as is indicated by the increase in Pseudo-R2

4

as the hypothetical amount sent increases. Also

note that in all the panels the risk preference measure consistently predicts WVS-trust. However,

this pattern does not hold in Panel 3(D) which restricts the sample to the Citizens from BG. While

the risk measure continues to predict WVS trust response, ERoT does not. The magnitude of

the marginal effects remain small even for higher levels of trust and the standard errors are large.

Clearly, WVS trust has failed to capture beliefs about others’ trustworthiness in so far as the

Citizens are concerned. A snapshot of these findings can be found in Figure 3.

4

It is well known that Pseudo-R2 cannot be interpreted as a R2, but the Pseudo-R2 still has a consistent

meaning when compared to another Pseudo-R2 predicting the same outcome in the same data. In such a situation,

a comparison of Pseudo-R2 indicates which model better predicts the outcome.

13

The same pattern is revealed when the data is analyzed through another angle. Now we

restrict the data to BG and UG and report the probit regression estimates of WVS trust on ERoT,

treatment dummy and their interaction in Table 4 in Appendix 1. ERoT is a significant predictor

of WVS trust - a 10% increase in ERoT increases the odds that WVS trust will take value 1 by

2.8 to 10 ppts. However, the negative coefficients for interaction term, specially corresponding to

higher amounts of trust, reflect that the marginal effect of ERoT on WVS trust is significantly

higher for UG than for BG. In other words, response from ERoT to the odds that WVS trust takes

a value 1 is significantly higher for P-As in UG than for Cs in BG, for sufficiently high trust levels.

Why is it that the response to WVS trust question is predicted by ERoT for the P-As and

the baseline subjects but not for the Cs? Recall from Figure 2 that ERoT is lower for Citizens

than for P-As and baseline subjects. Table in the Appendix uses belief data for each trust category

separately and Table pools the data together to essentially arrive at the same conclusion - beliefs

systematically differ across treatments. In particular, beliefs about how trustworthy someone is

suffers a negative shock in BG relative to UG and baseline treatments. If we believe that the

baseline treatment captures the native belief distribution then beliefs in UG closely follow that

native distribution whereas those in BG does not. Clearly, the negative belief shock in BG can be

attributed to the negative experience of having to pay a bribe in BG. The fact that WVS trust

correlates with the beliefs in UG and baseline treatment but not in BG treatment indicates that

conceptually there is a need to separate stable expectations from short term fluctuations in beliefs.

The former is globally determined from the aggregation of experiences whereas the latter is a result

of immediate experiences and is inherently unstable. The WVS trust does well in capturing long

run stable expectations but not in measuring its short term fluctuations.

4 Discussion and Conclusion

World Values Survey is a unique data source in the sense that it aims to measure a gamut of

otherwise unobservable characteristics through globally comparable and nationally representative

surveys in over 100 countries. The operative phrase here is “unobservable characteristics”, implying

that the focus is one measuring subjective perceptions, opinions and values. For cross country

comparability to be valid it is critical that respondents interpret and react to the questions used

in the World Values Survey in the same way across different socio-cultural regions across the

world. This is particularly of first order importance given the nature of the inquiry and its aim at

measuring subjective perceptions, opinions and values. However, there is surprisingly little in the

literature with regard to establishing a correspondence between WVS responses and incentivized

elicitation of behavior beyond Western subject pools. In fact to the best of our knowledge ours is

the first study in this direction.

This study was inspired in part by Sapienza et al. (2013) - they found that WVS trust question

measured expectation about others’ trustworthiness. Our study was designed with two important

14

Figure 3: Regression Coefficients from Table 3

−.2 0 .2 .4 .6

Coefficient of ERoT

50 100 150 200 250 300 350 400

Hypothetical Trust Level

Citizens, P−As, Baseline

0 .2 .4 .6 .8 1

Coefficient of ERoT

50 100 150 200 250 300 350 400

Hypothetical Trust Level

Participant As, Baseline

−.5 0 .5 1 1.5

Coefficient of ERoT

50 100 150 200 250 300 350 400

Hypothetical Trust Level

Participant As

−.4 −.2 0 .2 .4 .6

Coefficient of ERoT

50 100 150 200 250 300 350 400

Hypothetical Trust Level

Citizens

Each panel plots the regression coefficients for each subgroup. The coefficient is significantly different from

zero when it comes to the baseline subjects and P-As. However, it is not different from zero for the

Citizens i.e. WVS trust question does not predict Citizens’ belief about how trustworthy others are.

15

aims: one, to investigate if people interpreted the WVS trust question in the same way in India - a

socio-cultural environment very different from the West, where the literature is currently located;

two, to understand under what conditions, if any, the correspondence between WVS trust and

behavior in lab based Trust Games held and under what condition it did not. So far as the second

objective is concerned, our hypothesis was the following. If at all, the WVS trust question would

be much better at capturing stable expectations about generalized behavior in a population than

capturing short term variations in beliefs. We tested this hypothesis using a experimental design

where subjects where induced a negative shock to their beliefs about how others would behave by

making them go through a negative experience. In our case the negative experience was driven

by extraction of a bribe from a subject’s entitlement - an earned prize, in a simulated corruption

game. The comparison group comprised of subjects who either did not go through the bribery

game experience or went through an experience in a strategically identical but differently framed

ultimatum game.

At one level our findings corroborate findings from Sapienza et al. (2013) as we find that WVS

trust does capture expectations about others’ trustworthiness. However, there is an important

difference. WVS trust question does well in capturing long term, globally determined, stable

expectations about others’ behavior - such expectations are determined over the long run through

cumulative life experiences (e.g. Malmendier and Nagel (2011) show how long run risk attitudes are

shaped by personal experiences in times of macroeconomic instability). However, it is ill-suited to

capture the locally affected fluctuations in beliefs about how others will behave. That is precisely the

reason why we found a correspondence between subjects’ native expectations about others’ behavior

and response to the WVS trust question but not for the set of subjects who went through the bribe

demand induced negative belief shock. This negative belief shock was most likely temporary in

nature and perhaps would have had little bearing on decisions outside the immediate context. This

is only an hypothesis - our experiment is not designed to identify whether or how these short term

changes dissipate and the long run steady state beliefs are arrived at. Despite that, it is important

to conceptually distinguish between the two and the fact that survey based elicitations are only

well poised to identify stable expectations and not short term changes in beliefs.

An interesting aspect of our finding is people do not seem to generalize local experiences

to the population at large. In our setting of course subjects were familiar with the population.

It will be interesting to see whether subjects generalize local behavior to a wider pan societal

contexts immediately in a setting where they are not familiar with the population. The process of

generalization has important implications for how stereotypes are formed. This is an angle which

needs further investigation.

The implication of our finding is the following. After the important work of Dohmen et al.

(2011), who find a robust correspondence between elicited risk in experiments and a survey question

on attitude to risk in general, a number of studies, including ours, have come to rely on the survey

based question about generalized risk to measure risk preference. The convenience of replacing a

16

treatment by a question is hard to overstate. If other survey based questions were to be found to

robustly measure other behavioral correlates, then we could, at least in principle, replace costly

experiments with such survey based measures. Our study shows that in the context of measuring

beliefs about others’ trustworthiness, we cannot make a blanket use of the WVS trust question

since it cannot capture the short term changes in locally formed beliefs. The reference group, which

dictates behavior in Trust Games, especially in a homogenous subject pool like in our case, is

typically different from the reference group people have in mind when they answer the WVS trust

question. As a result, Trust Games and the WVS trust question remain relevant in their respective

domains of inquiry, namely, behavioral analysis in the short run and generalized expectations about

trustworthiness in the long run, respectively.

Throughout this paper, as perhaps elsewhere in the literature, we used the words “expectation”

and “belief” interchangeably. Perhaps we should develop a consistent typological distinction between

the different notions of beliefs - global expectations and local beliefs. Global expectations may be

thought of as a steady state belief, it is stable and is formed through our aggregate experiences or

a series of local experiences. Conceptually, this is the relevant notion of belief we have when we

talk about rational expectations. On the other hand, local beliefs are short term perturbations

caused by psychological triggers from immediate experiences. These perturbations are inherently

unstable and likely to converge to the global expectations soon after.

References

Abbink, Klaus, Utteeyo Dasgupta, Lata Gangadharan, and Tarun Jain

, “Letting the

briber go free: An experiment on mitigating harassment bribes,” Journal of Public Economics,

2014, 111 (C), 17–28.

Alatas, Vivi, Lisa Cameron, Ananish Chaudhuri, Nisvan Erkal, and Lata Gangadha-

ran

, “Subject pool effects in a corruption experiment: A comparison of Indonesian public servants

and Indonesian students,” Experimental Economics, March 2009, 12 (1), 113–132.

Banerjee, Ritwik

, “Corruption, Norm Violation and Decay in Social Capital,” Economics Working

Papers 2015-05, School of Economics and Management, University of Aarhus November 2015.

, “On the interpretation of bribery in a laboratory corruption game: moral frames and social

norms,” Experimental Economics, 2016, 19 (1), 240–267.

Bellemare, Charles and Sabine Kroger

, “On representative social capital,” European Economic

Review, January 2007, 51 (1), 183–202.

Berg, Joyce, John Dickhaut, and Kevin McCabe

, “Trust, Reciprocity, and Social History,”

Games and Economic Behavior, July 1995, 10 (1), 122–142.

17

Burnham, Terence, Kevin McCabe, and Vernon L. Smith

, “Friend-or-foe intentionality

priming in an extensive form trust game,” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization,

September 2000, 43 (1), 57–73.

Buser, Thomas and Anna Dreber

, “The Flipside of Comparative Payment Schemes,” Tinburgen

Institute Discussion Paper TI 2013-190/1, Tinburgen Institute 2013.

Cameron, Lisa, Ananish Chaudhuri, Nisvan Erkal, and Lata Gangadharan

, “Propensities

to engage in and punish corrupt behavior: Experimental evidence from Australia, India, Indonesia

and Singapore,” Journal of Public Economics, August 2009, 93 (7-8), 843–851.

Dohmen, Thomas, Armin Falk, David Huffman, Uwe Sunde, Jurgen Schupp, and

Gert G. Wagner

, “Individual Risk Attitudes: Measurement, Determinants, And Behavioral

Consequences,” Journal of the European Economic Association, 06 2011, 9 (3), 522–550.

Drouvelis, Michalis, Robert Metcalfe, and Nattavudh Powdthavee

, “Priming Cooperation

in Social Dilemma Games,” IZA Discussion Papers 4963, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA)

May 2010.

Fehr, Ernst, Urs Fischbacher, Jurgen Schupp, Bernhard von Rosenbladt, and

Gert Georg Wagner

, “A Nationwide Laboratory Examining Trust and Trustworthiness by

Integrating Behavioural Experiments into Representative Surveys,” CEPR Discussion Papers

3858, C.E.P.R. Discussion Papers April 2003.

Glaeser, Edward L., David I. Laibson, Jose A. Scheinkman, and Christine L. Soutter

,

“Measuring Trust,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 2000, 115 (3), 811–846.

Guiso, Luigi, Paola Sapienza, and Luigi Zingales

, “The Role of Social Capital in Financial

Development,” American Economic Review, June 2004, 94 (3), 526–556.

, , and

, “Trusting the Stock Market,” Journal of Finance, December 2008, 63 (6), 2557–2600.

, , and

, “Cultural Biases in Economic Exchange?,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics,

August 2009, 124 (3), 1095–1131.

Knack, Stephen and Philip Keefer

, “Does Social Capital Have an Economic Payoff? A

Cross-Country Investigation,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 1997, 112 (4), 1251–1288.

Lazzarini, S. G., R. C Madalozzo, R. Artes, and J. O. Siqueira

, “Measuring trust: An

experiment in Brazil,” Insper Working Papers 42, Insper Working Paper, Insper Instituto de

Ensino e Pesquisa October 2004.

Maggian, Valeria and MarieClaire Villeval

, “Social preferences and lying aversion in children,”

Experimental Economics, 2015, pp. 1–23.

18

Malmendier, Ulrike and Stefan Nagel

, “Depression Babies: Do Macroeconomic Experiences

Affect Risk Taking?*,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 2011, 126 (1), 373–416.

Rosaz, Julie and Marie Claire Villeval

, “Lies and biased evaluation: A real-effort experiment,”

Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 2012, 84 (2), 537 – 549.

Sapienza, Paola, Anna Toldra-Simats, and Luigi Zingales

, “Understanding Trust,” The

Economic Journal, 2013, 123 (573), 1313–1332.

Thöni, Christian, Jean-Robert Tyran, and Erik Wengström

, “Microfounrations of Social

Capital,” Journal of Public Economics, 2012, 96 (78), 635–643.

19

Table 2: Marginal Effects from Probit Regression of WVS trust on trust, trustworthiness and ERoT

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8)

VARIABLES if sent 50 if sent 100 if sent 150 if sent 200 if sent 250 if sent 300 if sent 350 if sent 400

Panel 2(A)

trustworthiness -0.08 -0.00 0.07 0.13 0.26 0.43* 0.45* 0.48*

(0.12) (0.14) (0.18) (0.20) (0.23) (0.24) (0.25) (0.25)

Observations 218 218 218 218 218 218 218 218

Pseudo R-sq 0.00187 2.10e-06 0.000518 0.00155 0.00477 0.0112 0.0121 0.0132

Panel 2(B)

trustworthiness -0.11 -0.10 -0.16 -0.17 -0.03 0.06 0.05 0.04

(0.12) (0.15) (0.19) (0.23) (0.25) (0.27) (0.28) (0.29)

ERoT 0.06 0.10* 0.21*** 0.26*** 0.24*** 0.28*** 0.28*** 0.27***

(0.05) (0.05) (0.07) (0.08) (0.09) (0.10) (0.09) (0.09)

Observations 218 218 218 218 218 218 218 218

Pseudo R-sq 0.00746 0.0110 0.0309 0.0353 0.0325 0.0406 0.0445 0.0433

Panel 2( C)

ERoT 0.04 0.08 0.17*** 0.20*** 0.22*** 0.26*** 0.26*** 0.24***

(0.04) (0.05) (0.06) (0.07) (0.07) (0.08) (0.08) (0.07)

risk 0.08*** 0.08*** 0.07*** 0.07*** 0.07*** 0.07*** 0.07*** 0.07***

(0.01) (0.01) (0.01) (0.01) (0.01) (0.01) (0.01) (0.01)

Observations 218 218 218 218 218 218 218 218

Pseudo R-sq 0.0938 0.0996 0.117 0.119 0.120 0.128 0.130 0.126

†

Note: Numbers in the parentheses represent the Standard errors. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1. The dependent variable is WVS-trust.

The dependent variable in col (1) is trust while that in col (2) - (9) is trustworthiness measured in terms of Return Ratio for each

possible amount sent by the sender.

20

Table 3: Marginal Effects from Probit Regression of WVS trust on ERoT and Risk

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8)

Panel (A) if sent 50 if sent 100 if sent 150 if sent 200 if sent 250 if sent 300 if sent 350 if sent 400

ERoT 0.05 0.09 0.21** 0.24** 0.20* 0.29*** 0.33*** 0.34***

(0.06) (0.06) (0.08) (0.10) (0.11) (0.11) (0.11) (0.11)

risk 0.08*** 0.08*** 0.08*** 0.07*** 0.08*** 0.07*** 0.08*** 0.07***

(0.02) (0.02) (0.02) (0.02) (0.02) (0.02) (0.02) (0.02)

Observations 127 127 127 127 127 127 127 127

Pseudo R-sq 0.0868 0.0930 0.119 0.117 0.102 0.122 0.137 0.137

Panel (B)

ERoT 0.06 0.11 0.24** 0.25** 0.27** 0.49*** 0.57*** 0.68***

(0.07) (0.08) (0.10) (0.11) (0.13) (0.15) (0.15) (0.12)

risk 0.08*** 0.07*** 0.07*** 0.07*** 0.07*** 0.07*** 0.07*** 0.07***

(0.02) (0.02) (0.02) (0.02) (0.02) (0.02) (0.02) (0.02)

Observations 81 81 81 81 81 81 81 81

Pseudo R-sq 0.094 0.104 0.134 0.128 0.125 0.165 0.184 0.242

Panel (C )

ERoT 0.06 0.12 0.31** 0.29 0.33 0.88*** 0.65*** 0.69***

(0.10) (0.11) (0.15) (0.19) (0.22) (0.28) (0.23) (0.16)

risk 0.08** 0.08** 0.08*** 0.07** 0.06** 0.05** 0.06** 0.06**

(0.03) (0.03) (0.03) (0.03) (0.03) (0.03) (0.03) (0.03)

Observations 45 45 45 45 45 45 45 45

Pseudo R-sq 0.0713 0.0848 0.125 0.102 0.105 0.216 0.187 0.265

Panel (D)

ERoT -0.01 0.02 0.14 0.22 0.01 0.03 0.10 -0.14

(0.11) (0.10) (0.16) (0.21) (0.19) (0.17) (0.15) (0.17)

risk 0.09*** 0.09*** 0.09*** 0.09*** 0.09*** 0.09*** 0.09*** 0.09***

(0.03) (0.03) (0.03) (0.03) (0.03) (0.03) (0.03) (0.03)

Observations 46 46 46 46 46 46 46 46

Pseudo R-sq 0.110 0.111 0.123 0.128 0.110 0.111 0.119 0.122

†

Note: Numbers in the parentheses represent the Standard errors. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1. The dependent

variable is WVS-trust. The independent variables are Expected Return on Trust (ERoT) and risk preference. Panel

A includes Citizens(C), Participant As(P-A) and baseline subjects (BS), Panel B includes P-A and BS, Panel C

includes P-A only and Panel D includes C only. The number of observations differs in the panels due to inclusion of

different set of subjects in each panel.

Appendix 1

21

Table A1: Summary Statistics

BG/UG Variables Description Mean Std. Dev

BG =1 if Treatment is BG 0.51 0.50

amount bribe/ultim demanded from C/P-A 232.97 109.60

Observations 91

Trust and Demographic Variables

Full Sample C+P-A+Baseline

Mean Std. Dev. Mean Std. Dev.

trust Amount sent as a sender in Trust Game 245.41 122.29 232.97 127.20

trustworthiness Return Ratio, averaged over all trust

categories.

0.39 0.14 0.39 0.14

ERoT Expected Return on Trust -0.02 0.41 -0.02 0.35

female =1 if subject is Female 0.26 0.44 0.25 0.44

age Age 24.37 1.81 24.35 1.86

score CAT/GMAT score in percentile 100.32 55.98 95.06 3.51

family_income Family Income

a

3.56 0.78 3.57 0.79

altruism Suppose you win a lottery of Rs.1000. How

much of it will you be willing to share with a

charity of your choice?

294.27 142.32 283.52 141.43

risk How do you see yourself: are you generally a

person who is fully prepared to take risks or

do you try to avoid taking risks?

5.76 2.00 5.90 1.86

Cronbach’s alpha for Return Ratio

b

0.86 0.86

Cronbach’s alpha for ERoT

b

0.92 0.90

Observations 218 91

Demographic Balance across Treatments

Variables BG UG Baseline

female 0.28 0.25 0.25

age 24 24.5 24.4

score 101.2 95.1 111.4

family_income 3.7 3.4 3.7

a

Categorical variable where category 1: <Rs. 20,000, 2: between Rs. 20,001 and Rs. 50,000, 3: between Rs. 50,001 and Rs. 1,00,000 and 4: >Rs. 1,00,001.

b

A measure of internal consistency, i.e. how closely related the set of items are as a group.

22

Table A2: Alternative measures of trust and the mutual correlations

(a) Definitions of different measures of trust used in the survey

Variable

Description/Question Values

Percentage/Mean

trust_wvs

Generally speaking, would you say that

most people can be trusted or that you

need to be very careful in dealing with

people?

Most people can be trusted

68%

Need to be very careful

32%

advantage

Do you think most people would try to

take advantage of you if they got the

chance, or would they try to be fair?

Most of the time they

would try to be fair

63%

Most of the time they

would try to take advantage

37%

wallet

Suppose you left your wallet in the

Metro. On a scale of 1 to 10, how

much do you think are the chances

that you will get it back?

1(almost no chance) to

10(very high chance)

3.04

(b) Raw Correlations among Survey Trust Questions. The numbers in the brackets represent p-values.

trust_wvs advantage wallet

trust_wvs 1

-

advantage 0.21 1

(0.002)

wallet 0.10 0.10 1

(0.13) (0.14)

23

Table 3: (a) Variation of Expected Return on Trust on different treatments

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8)

Variables if sent 50 if sent 100 if sent 150 if sent 200 if sent 250 if sent 300 if sent 350 if sent 400

UG 0.30** 0.34*** 0.21** 0.11 0.05 0.09 0.02 0.03

(0.14) (0.13) (0.09) (0.08) (0.08) (0.08) (0.08) (0.08)

Base 0.32** 0.44*** 0.40*** 0.27*** 0.17** 0.13 0.02 -0.02

(0.14) (0.13) (0.10) (0.08) (0.08) (0.08) (0.08) (0.08)

female -0.21 -0.03 0.03 0.05 0.09 0.06 0.04 -0.03

(0.14) (0.13) (0.09) (0.08) (0.08) (0.08) (0.08) (0.08)

age 0.01 0.02 0.02 0.03* 0.02 0.02 0.01 -0.01

(0.03) (0.03) (0.02) (0.02) (0.02) (0.02) (0.02) (0.02)

income -0.03 -0.01 -0.02 -0.00 -0.01 -0.03 -0.02 -0.03

(0.08) (0.07) (0.05) (0.05) (0.05) (0.04) (0.05) (0.05)

score -0.00 -0.00 -0.00** -0.00*** -0.00* -0.00 -0.00 -0.00

(0.00) (0.00) (0.00) (0.00) (0.00) (0.00) (0.00) (0.00)

Constant -0.51 -0.81 -0.55 -0.68 -0.42 -0.05 0.14 0.65

(0.95) (0.87) (0.64) (0.56) (0.54) (0.53) (0.56) (0.54)

Obs 127 127 127 127 127 127 127 127

R-squared 0.089 0.116 0.162 0.148 0.080 0.056 0.014 0.016

†

Note: Numbers in the parentheses represent the Standard errors. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1. The independent

variables are Expected Return on Trust (ERoT) for each hypothetical amount sent. The difference in ERoT across

treatments is obtained from the two treatment dummies: UG - dummy variable for the UG treatment and Base - dummy

variable for the baseline treatment.

24

Table A3: (b) Variation of Expected Return on

Trust on different treatments from pooled data

(1) (2)

Variables ERoT ERoT

UG 0.15*** 0.14***

(0.04) (0.04)

Base 0.19*** 0.21***

(0.04) (0.04)

female -0.00

(0.04)

age 0.02*

(0.01)

income -0.02

(0.02)

score -0.00***

(0.00)

Constant -0.08*** -0.28

(0.03) (0.26)

Observations 1,016 1,016

R-squared 0.028 0.050

†

Note: Numbers in the parentheses represent the Stan-

dard errors. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1. The inde-

pendent variable is Expected Return on Trust (ERoT)

pooled together for all possible amount sent. The differ-

ence in pooled ERoT across treatments is obtained from

the two treatment dummies: UG - dummy variable for

the UG treatment and Base - dummy variable for the

baseline treatment.

25

Table A4: Marginal Effects from Probit Regression of WVS trust on ERoT with treatment interaction terms

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8)

if sent 50 if sent 100 if sent 150 if sent 200 if sent 250 if sent 300 if sent 350 if sent 400

BG -0.06 -0.05 -0.03 -0.03 -0.03 0.29* 0.15 0.27**

(0.09) (0.09) (0.08) (0.08) (0.08) (0.17) (0.15) (0.13)

ERoT 0.02 0.10 0.28** 0.31* 0.37** 1.08*** 0.72*** 0.81***

(0.08) (0.10) (0.14) (0.17) (0.18) (0.40) (0.28) (0.23)

BG × ERoT 0.00 -0.04 -0.09 -0.04 -0.36 -1.04** -0.64** -0.88***

(0.13) (0.14) (0.21) (0.27) (0.26) (0.43) (0.32) (0.27)

Observations 91 91 91 91 91 91 91 91

Pseudo R-sq 0.00520 0.0134 0.0385 0.0379 0.0310 0.0849 0.0745 0.102

Standard errors in parentheses

** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

†

Note: Numbers in the parentheses represent the Standard errors. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1. The dependent variable is WVS-trust. The independent

variables are Expected Return on Trust (ERoT).

26

Appendix 2

1 Instructions for the Bribery and Ultimatum Game fol-

lowed by Baseline Trust Game

Welcome.

You are now taking part in an economic experiment. If you read the following instructions

carefully, you can, depending on your decisions and the decisions of other participants, earn a

considerable amount of money. It is prohibited to communicate with the other participants during

the experiment. Should you have any questions please raise your hand and we will come to you.

This is an anonymous experiment and you will not know either the identity or the choices that

others know. We will give each one of you an identity number which will facilitate your payments.

Overview

The experiment consists of 2 parts and a survey. Please start by reading the instructions for

the first part carefully. You will receive the instructions for the second part after the first part is

finished. And so on.

Earnings

During the experiment you can earn money by receiving a fictitious currency called “mohar”. All

mohars that you earn in the experiment will be exchanged into Rupees at the end of the experiment,

The exchange rate is: 1 mohar = Rs 0.50 (M denotes mohar henceforth). We will pay you 200

mohars for participating but you can earn additional money depending on the decisions you and

the others make. The experiment consists of two parts but remember you will be randomly paid

for only one of the two parts which will be determined by a toss. Since you donot know which one

you will be paid for, make your decisions for both the parts carefully.

1.1 Part 1 : Subject given either 1.1.1 or 1.1.2

1.1.1 Bribery Game

You may be paired with another participant in this experiment. The matching of two participants

will be randomly done. You will not be informed of the identity of the participant with whom you

have been matched.

Each participant today will receive a base participation fee of 200 M. We have divided the total

number of participants in this experiment session randomly into two equal groups: Citizens (C)

and Public Officials (PO).

A Citizen performs a task in ten minutes. Her task is to count the number of occurrences of

the letter "A" from a random sequence of letters. She has to perform this task for five different

sequences of letters. If she is unable to complete the task in ten minutes then she leaves the game

with her participation fee of 200 M and the Public Official gets 600 M. If she successfully does

complete the task she is entitled to a payment of 400 M (in addition to participation fee of 200

M). However before the experimenter hands over the entitlement to the Citizen, she needs the

approval of the Public Official who receives a salary of 400 M for his job of approval (in addition to

participation fee of 200 M). A Public Official, however, can ask for a bribe before approving the

entitlement for the corresponding Citizen. He may ask for a bribe of 100, 200, 300, 400 M. He may

choose not to ask for a bribe as well i.e. ask for 0 bribe. The information for demand for bribe

then is forwarded to the Citizen who can then decide whether to Accept or Reject the demand for

27

bribe. The final earnings will depend on the final choices each one makes i.e. PO’s choices about

demand for bribe, C’s choices about Acceptance or Rejection. Suppose PO demands a bribe

b

. If C

accepts the demand then PO gets (600 +

b

)M and C gets (200 +

b

)M. If she rejects the earnings

then C and PO get only 600M and 200M, respectively.

Take a look at the figure below to further clarify the rules of the game and the earnings.

Please go through the two examples given below.

Example. Citizen completes the task. She is entitled to a payment of 600 M . Public Official de-

mands a bribe of 100 M for himself. Citizen accepts it. Public Official’s earning is 200+400+100=700

M. Citizen’s earning is 200+400-100=500 M.

Example. Citizen completes the task. She is entitled to a payment of 600 M . Public Official

demands for a bribe of 400 M for himself. Citizen rejects it. Public Official’s earning is 600+0=600

M. Citizen’s earning is 200+0=200 M.

Instruction for Citizens

In this room all of you are Citizens. Note that you are matched anonymously with a participant

sitting in the other room. He is your corresponding Public Official who is in charge of approving

your entitlement if you do earn it.

In order to earn the entitlement of 400 M, you have to perform a simple task in 10 minutes

following which you will earn the key to your entitlement. What you will see is five sequences of

some random letters. Your task is to count the exact number of ’A’s for each of the sequences.

Only when you have correctly counted the number of As for a sequence will you be able to go to

the next sequence. When you count successfully for all the sequence you will receive the key for

your entitlement and you can use the key to make your choices subsequently.

In order to complete the task, click here to count the number of As for the five sequences of

random letters.

1. Input your Identity number. Enter the correct the number of ’A’s for each of the five

sequences.

2. If you have completed counting the number of As, please write down the Key to your

entitlement on a piece of paper and proceed. If you have not been able to complete the task in ten

minutes then you can collect your participation fee and leave.

Right click here and open the link in a new tab to input your choices

3. Please indicate on the response sheet and on the website whether you accept or reject the

demand for bribe for all possible bribe amount. We will match your response with the actual bribe

amount demanded and determine your earnings.

4. We will now collect your responses and match them with the response of your corresponding

Public Official.

5. You will now receive the response sheet, which mentions the bribe demanded, your accep-

tance/rejection decision and the final earning from this part.

Instruction for Public Officials

In this room all of you are Public Officials. You are responsible for the approving the entitlement

for the Citizens. Before approving you can ask for a bribe from the Citizen. You may also choose

not to ask for a bribe.

1. Now make your decision whether to ask for a bribe before you approve the entitlement for

the Citizen and if yes how much to ask for. Click here to input your choice.

2. We now collect your decision and match them with Citizen’s acceptance/rejection decision.

28

1.1.2 Ultimatum Game

Common for Participant A and Participant B

You may be paired with another participant in this experiment. The matching of two participants

will be randomly done. You will not be informed of the identity of the participant with whom you

have been matched.

Each participant today will receive a base participation fee of 200 M. We have divided the total

number of participants in this experiment session randomly into two equal groups: Participant A

(P-A) and Participant B (P-B).

Participant A performs a task in ten minutes. Her task is to count the number of occurrences

of the letter "A" from a random sequence of letters. She has to perform this task for five different

sequences of letters. If she cannot perform the task in ten minutes then she leaves the game with

her participation fee 200 M and P-B gets 600 M. If she successfully completes the task, then she

is entitled to playing the next stage of the game i.e. she earns the right to play the second stage

game. P-B’s earning is 400M in addition to the participation fee of 200 M (i.e. 600 M) for her

role, which is the following. In the second stage P-B decides to divide 400 M between himself and

P-A. For example if P-B keeps x with himself then P-A gets 400 – x M. The amount which P-B

transfers can only be in multiple of 100s i.e. either 0, 100, 200, 300, 400 in which cases he gets 400,

300, 200, 100, 0, respectively, for himself. P-A can then decide whether or not to Accept or Reject

the amount which is offered. If P-A accepts the offer then P-B gets (600 + x) M and P-A gets (200

+x) M. If she rejects the earnings then P-A and P-B get only 600 M and 200 M respectively.

Take a look at the figure below to further clarify the rules of the game and the earnings.

Please go through the two examples given below.

Example. P-A completes the task and proceeds to the next round. P-B divides 400 M into 100

M for himself and 300 M for himself. P-A accepts it. P-B’s earning is 200+400+100=700 M. P-A’s

earning is 200+400-100=500 M.

Example. P-A completes the task and proceeds to the next round. P-B divides 400 M into

400 M for himself and 0 for P-A. P-A rejects it. P-B’s earning is 600+0=600 M. P-A’s earning is

200+0=200 M.

Instruction for Participant A

In this room all of you are Participant As. Note that you are matched anonymously with a

participant sitting in the other room, he is your corresponding Participant B whom you will play in

second round.

In order to proceed to second round, you will have to perform a simple task in 10 minutes

following which you will earn the key to the second round. What you will see is five sequences of

some random letters. Your task is to count the exact number of ’A’s for each of the sequences.

Only when you have correctly counted the number of As for a sequence will you be able to go to

the next sequence. When you count successfully for all the sequence you will receive the key and

you can use the key to proceed.

1. Right click here and open the link in a new tab. Enter the correct the number of ’A’s for

each of the five sequences.

2. If you have completed counting the number of As, please write down the Key to your

entitlement on a piece of paper and proceed. If you have not been able to complete the task in ten

minutes then you can collect your participation fee and leave.

3. Please right click here and open a new tab and indicate on the response sheet whether

you accept or reject the amount demanded for all possible transfer amount. We will match your

response with the actual transfer amount and determine your earnings.

29

4. We will now collect your responses and match them with the response of your corresponding

P-B.

5. You will now receive the response sheet, which mentions the division proposed by P-B, your

acceptance/rejection decision and the final earnings from this part.

Instruction for Participant B

In this room all of you are Participant B.

1. Now make your decision about how to divide 400 M between yourself and Participant A i.e.

whether to share anything with him, if yes how much. Please right click here to open a new link

and input your decision. Your sharing amount should be in multiples of 100.

2. We now collect your decision.