The Silent Epidemic

Perspectives of High School Dropouts

A report by Civic Enterprises in association with

Peter D. Hart Research Associates

for the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

By: John M. Bridgeland

John J. DiIulio, Jr.

Karen Burke Morison

March 2006

Table of Contents

Open Letter to the American People.............................................................................i

Executive Summary ...................................................................................................iii

The Silent Epidemic....................................................................................................1

Consequences of our Nation’s Low Graduation Rates .........................................2

Who is Dropping Out?........................................................................................2

Why Students Drop Out of High School ..............................................................3

Their Regrets ..................................................................................................10

What Might Help Students Stay in School........................................................11

Policy Pathways ..............................................................................................14

A National Conversation and Response ............................................................19

Conclusion ......................................................................................................20

Acknowledgements and Note....................................................................................21

Appendix I — Poll Methodology ................................................................................22

Appendix II — Compulsory School Attendance Laws by State ...................................23

Notes.......................................................................................................................25

Bibliography .............................................................................................................31

i

T

here is a high school dropout epidemic in America. Each year, almost one

third of all public high school students – and nearly one half of all blacks,

Hispanics and Native Americans – fail to graduate from public high school

with their class. Many of these students abandon school with less than two years

to complete their high school education.

This tragic cycle has not substantially improved during the past few decades

when education reform has been high on the public agenda. During this time, the

public has been almost entirely unaware of the severity of the dropout problem

due to inaccurate data. The consequences remain tragic.

The decision to drop out is a dangerous one for the student. Dropouts are

much more likely than their peers who graduate to be unemployed, living in

poverty, receiving public assistance, in prison, on death row, unhealthy, divorced,

and single parents with children who drop out from high school themselves.

Our communities and nation also suffer from the dropout epidemic due to

the loss of productive workers and the higher costs associated with increased

incarceration, health care and social services.

Given the clear detrimental economic and personal costs to them, why do

young people drop out of high school in such large numbers? Almost every

elementary and middle school student reports ambitions that include high

school graduation and at least some college. Why are so many dreams cut

short? And what steps should be taken to turn the tide?

In an effort to better understand the lives and circumstances of students

who drop out of high school and to help ground the research in the stories and

reflections of the former students themselves, a series of focus groups and a

survey were conducted of young people aged 16-25 who identified themselves

as high school dropouts in 25 different locations throughout the United States.

These interviews took place in large cities, suburbs and small towns with high

dr

opout rates.

A primar

y purpose of this report is to approach the dropout problem from a

perspective that has not been much considered in past studies – that of the stu-

dents themselves. These efforts were designed to paint a more in-depth picture of

who these young people ar

e, why they dr

opped out of high school, and what might

have helped them complete their high school education. We wanted to give their

stories and insights a voice, and to of

fer our own views on next steps, in the hope

that this report could be a further wake-up call to educators, policymakers, other

leaders, and the public to summon the national will to address the high school

dropout epidemic.

An Open Letter to the American People

The central message of this report is that while

some students drop out because of significant

academic challenges, most dropouts are students

who could have, and believe they could have,

succeeded in school. This survey of young people

who left high school without graduating suggests

that, despite career aspirations that require

education beyond high school and a majority

having grades of a C or better, circumstances in

students’ lives and an inadequate response to

those cir

cumstances from the schools led to

dropping out. While reasons vary, the general

categories remain the same, whether in inner

city Los Angeles or suburban Nebraska.

Why Students Drop Out

There is no single reason why students drop out

of high school. Respondents report different

reasons: a lack of connection to the school

environment; a perception that school is boring;

feeling unmotivated; academic challenges; and

the weight of real world events. But indications

are strong that these barriers to graduation are

not insurmountable.

n Nearly half (47 percent) said a major reason for

dropping out was that classes were not inter-

esting. These young people r

epor

ted being

bor

ed and disengaged fr

om high school. Almost

as many (42 percent) spent time with people

who wer

e not interested in school. These were

among the top r

easons selected by those with

high GPAs and by those who said they were

motivated to work hard.

n Nearly 7 in 10 r

espondents (69 per

cent) said

they were not motivated or inspired to work

hard, 80 percent did one hour or less of home-

work each day in high school, two-thir

ds would

have worked harder if more was demanded of

them (higher academic standards and more

studying and homework), and 70 per

cent wer

e

confident they could have graduated if they had

tried.

Even a majority of those with low GPAs

thought they could have graduated.

n Many students gave personal reasons for

leaving school. A third (32 percent) said they

had to get a job and make money; 26 percent

said they became a parent; and 22 percent

said they had to care for a family member.

Many

of these young people reported doing

reasonably well in school and had a strong

belief that they could have graduated if they

had stayed in school. These students also were

the most likely to say they would have worked

harder if their schools had demanded more of

them and provided the necessary support.

It is clear that some dropouts, but not the

majority, leave school because of significant

academic challenges.

n Thirty-five percent said that “failing in school”

was a major factor for dropping out; three out of

ten said they could not keep up with school-

work; and 43 percent said they missed too

many days of school and could not catch up.

n Forty-five percent said they started high school

poorly prepared by their earlier schooling. Many

of these students likely fell behind in elemen-

tary and middle school and could not make up

the necessary ground. They reported that addi-

tional supports in high school that would have

made a difference (such as tutoring or after

school help) were not there.

n Thirty-two percent were required to repeat a

grade before dropping out and twenty-nine

percent expressed significant doubts that they

could have met their high school’

s r

equir

ements

for graduation even if they had put in

the necessary effort. The most academically

challenged students wer

e the most likely to

report that their schools were not doing enough

to help students when they had tr

ouble lear

ning

and to expr

ess doubt about whether they would

have worked harder if more had been expected

of them.

iii

Executive Summary

Executive Summary

As complex as these individual circumstances

may be, for almost all young people, dropping out

of high school is not a sudden act, but a gradual

process of disengagement; attendance patterns

are a clear early sign.

n Fifty-nine to 65 percent of respondents missed

class often the year before dropping out.

Students described a pattern of refusing to

wake up, skipping class, and taking three hour

lunches; each absence made them less willing

to go back. These students had long periods

of absences and were sometimes referred to

the truant officer, only to be brought back to

the same environment that led them to

become disengaged.

n Thirty-eight percent believed they had “too

much freedom” and not enough rules. As

students grew older, they had more freedom and

more options, which led some away from class

or the school building. It was often too easy to

skip class or engage in activities

outside of school.

For those students who dropped out, the level of

proactive parental involvement in their education

was low.

n Fifty-nine percent of parents or guardians of

respondents were involved in their child’s

schooling,

with only one-fifth (21 percent)

“ver

y” involved. Mor

e than half of those

parents or guardians who were involved at all

were involved mainly for discipline reasons.

n Sixty-eight percent of respondents said their

parents became more involved only when they

wer

e aware that their child was on the verge of

dr

opping out. The majority of par

ents wer

e “not

aware” or “just somewhat aware” of their

child’s grades or that they were about to

leave school.

In hindsight, young people who dropped out of

school almost universally expr

essed gr

eat

remorse for having left high school and expressed

strong interest in re-entering school with students

their age.

n As adults, the overwhelming majority of poll par-

ticipants (81 percent) said that graduating from

high school was important to success

in life.

n Three-fourths (74 percent) said that if they

were able to relive the experience, they would

have stayed in school and 76 percent said they

would definitely or pr

obably re-enroll in a high

school for people their age if they could.

n Forty-seven percent would say that not having a

diploma makes it hard to find a good job. They

wished they had listened to those who warned

them of problems associated with

dropping out, or that such voices had been

more persistent.

What Might Help Students

Stay in School

While there are no simple solutions to the

dropout crisis, there are clearly “supports” that

can be provided within the academic environment

and at home that would improve students’

chances of staying in school. While most dropouts

blame themselves for failing to graduate, there are

things they say schools can do to help them finish.

n

Improve teaching and curricula to make school

more relevant and engaging and enhance the

connection between school and work: Four out

of five (81 percent) said there should be more

opportunities for real-world learning and some in

the focus groups called for more experiential

lear

ning. They said students need to see the

connection between school and getting a

good job.

n Improve instruction, and access to supports, for

struggling students:

Four out of five (81

per

cent) wanted better teachers and thr

ee-

four

ths wanted smaller classes with mor

e

iv

Executive Summary

individualized instruction. More than half (55

percent) felt that more needed to be done

to help students who had problems learning,

and 70 percent believed more tutoring, summer

school and extra time with teachers would have

improved their chances of graduating.

n Build a school climate that fosters academics:

Seven in ten favored increasing supervision in

school and more than three in five (62 percent)

felt more classroom discipline was necessary.

More than half (57 percent) felt their schools

did not do enough to help students feel safe

from violence. Seven in ten (71 percent) said

their schools did not do enough to make

school interesting.

n Ensure that students have a strong relationship

with at least one adult in the school: While

two-thirds (65 percent) said there was a staff

member or teacher who cared about their

success, only 56 percent said they could go

to a staff person for school problems and just

two-fifths (41 percent) had someone in school

to talk to about personal problems. More than

three out of five (62 percent) said their school

needed to do more to help students with prob-

lems outside of class. Seven in ten favored

mor

e par

ental involvement.

n Impr

ove the communication between par

ents

and schools:

Seventy-one percent of young

people surveyed felt that one of the keys to

keeping students in school was to have better

communication between the parents and the

school, and increasing parental involvement in

their child’s education. Less than half said their

school contacted their parents or themselves

when they were absent (47 percent) or when

they dropped out (48 percent).

Policy Pathways

The stories, insights and reflections from this

student survey and the focus groups reveal the

importance of the student voice in the discussion

about what must be done to improve high school

graduation rates and to prepare struggling stu-

dents for successful futures. The students have

spoken. It is time for us to respond. To help these

students succeed, we need:

In Schools and Communities

n Different schools for different students. Instead

of the usual “one-size fits all” school, districts

should develop options for students, including a

curriculum that connects what they are learning

in the classroom with real life experiences and

with work, smaller learning communities with

more individualized instruction, and alternative

schools that offer specialized programs to stu-

dents at-risk of dropping out. Teachers should

have high expectations for their students and

try different approaches to motivate them to

learn.

n Parent engagement strategies and individual-

ized graduation plans. Schools and teachers

should strengthen their communication with par-

ents and work with them to ensure students

show up and complete their work and develop

graduation plans that are shared with parents.

n Early war

ning systems.

Schools need to develop

district-wide (or even state-wide) early warning

systems to help them identify students at risk

of failing in school and to develop mechanisms

that trigger

, and ensure there is follow through

on, the appropriate support for the students.

One clear step r

elates to absenteeism. Every

day

, schools should have a r

eliable list of the

students who failed to attend school and should

notify parents or guardians immediately and

take appr

opriate action to ensur

e students

attend school and have the support they need

to remain in school.

n Additional suppor

ts and adult advocates.

Schools need to provide a wide range of

supplemental services or intensive assistance

v

strategies for struggling students in schools –

literacy programs, attendance monitoring,

school and peer counseling, mentoring, tutoring,

double class periods, internships, service-learn-

ing, summer school programs,

and more – and provide adult advocates in the

school who can help students find the support

they need. Schools also need to provide appro-

priate supports to students with special needs,

such as pregnant women and students with

disabilities, and enhance their coordination

with community-based institutions and

government agencies.

In States

n A re-examination of the compulsory school

age requirements.

Students identified “too

much freedom” as a key factor that enabled

them to drop out of school, and attendance is

a strong predictor of dropping out. States

should consider raising the age at which

students can legally leave school from 16 or

17 to 18. Together with well-trained staffs,

more manageable caseloads, working partner-

ships with government agencies, and efforts to

address the underlying conditions that caused

students to leave school in the first place, we

believe this action could have a significant

effect on reducing dropout rates.

n More accurate data from states and school

districts. Schools and communities cannot

adequately address the dropout problem without

an accurate account of it. There are too many

ways to calculate graduation and dropout rates

that disguise the problem. The National

Gover

nors Association has made good progress

in getting all 50 states to agree to a common

definition for calculating graduation rates.

Mor

e work needs to be done to build the data

systems that will allow states to collect and

publish information on graduation and dropout

rates and to monitor pr

ogr

ess state by state

over time.

In the Nation

n More accurate national data from federal

departments and agencies.

Just as all 50 states

are working to obtain more accurate data to

help schools and communities understand the

extent of the dropout problem, the federal gov-

ernment should review the Current Population

Survey and other data it collects to ensure that

national data also paints an accurate picture of

the problem.

n Better incentives under federal law. Low-per-

forming students need more support in school.

Schools should have incentives under the No

Child Left Behind law to raise both test scores

and graduation rates and to ensure there is a

balance between the two so that proper atten-

tion is given to low-performing students. If

schools are only rewarded for raising test

scores, the law could have the unintended

effect of giving schools an incentive to “push

out” low-performing students whose test

scores would bring down school averages.

n Research on what works and dissemination

of best practices.

While states and school

districts have instituted many dr

opout prevention

programs, there remains a need for federal evalu-

ations of these programs and the sharing

of the most innovative and successful pr

ograms

that can be brought to scale.

Next Steps

n A national conversation and response.

Educators, policymakers and leaders from vari-

ous sectors should make addressing the high

school dr

opout epidemic a top national priority

.

All avenues to invest leaders in a better under-

standing of the problem and common solutions

should be under

taken – including congr

essional

hearings, White House conferences, summits of

state and local of

ficials, and public forums in

schools and communities. In all cases, the

voices of young people who dropped out of

high school should be heard.

vi

Executive Summary

High dropout rates are a silent epidemic

afflicting our nation’s high schools. The dropout

epidemic in the United States disproportionately

affects young people who are low-income, minori-

ty, urban, single-parent children attending large,

public high schools in the inner city. But the prob-

lem is not unique to young people in such

circumstances. Nationally, research puts the

graduation rate between 68 and 71 percent,

which means that almost one-third of all public

high school students in America fail to graduate.

1

For minority students (black, Hispanic or Native

American), the rate at which they finish public

high school with a regular diploma declines to

approximately 50 percent.

2

Graduation rates for

whites and Asians hover around 75 to 77 percent,

respectively, with about one-quarter of these

students failing to graduate.

3

On average, female

students graduate at slightly higher rates.

4

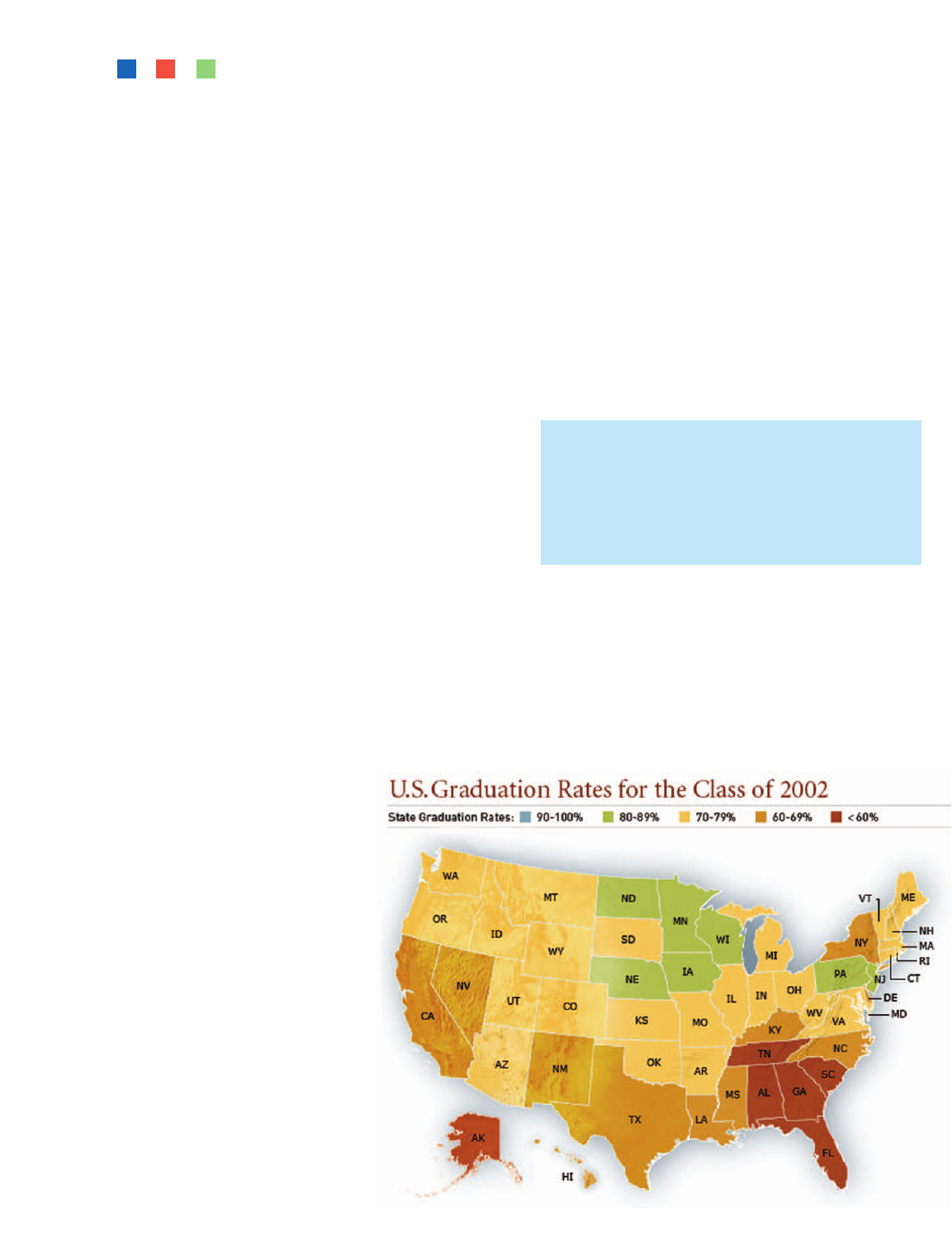

Graduation and dropout rates vary considerably by

state and region of the country, sometimes by as

much as 30 percentage points.

5

And the dropout

problem radiates beyond cities to suburbs, towns

and rural areas.

6

In 2003, 3.5 million youth

ages 16 to 25 did not have a

high school diploma and were

not enr

olled in school.

7

Ther

e

are nearly 2,000 high schools

in the countr

y with low gradua

-

tion rates, concentrated in

about 50 large cities, and in 15

primarily southern and south-

western states.

8

In more than

20 of these cities, 75 percent

or more of the students attend

public high schools where grad-

uating is less than a 60 percent

pr

oposition.

9

This tragic cycle

has not substantially improved

during the past few decades

when education r

efor

m has

been high on the public agenda.

Some exper

ts expect the

dropout problem to increase

substantially through 2020 unless significant

improvements are made.

10

Tragically, the public is almost entirely

unaware of the severity of the problem due to

inaccurate data – both the underestimation of

dropout rates and the overestimation of gradua-

tion rates. As a former Deputy Secretary of the

U.S. Department of Education has observed,

“Many schools in America can’t tell us on

any given day who’s in school and who’s not,

nor in any given year how many students

have successfully made it through their four

years of schooling to graduate and how

many have dropped out.”

11

This report is written from the perspective of

high school dropouts in the context of what we

know from decades of studies about the problem.

It paints a picture of who drops out from high

school, shares their insights and reflections about

why they dropped out and what schools could

have done to help them stay in school, and offers

ways forward to inform a national conversation on

the dropout epidemic in America.

Based on data from Greene, Jay and Marcus Winters (2005). Public High School

Graduation and College-Readiness Rates: 1991–2002.

Education W

orking Paper No. 8.

New Y

ork: Center for Civic Innovation at the Manhattan Institute.

The Silent Epidemic

1

Consequences of our Nation’s

Low Graduation Rates

The decision to dr

op out is a dangerous one

for the student, particularly in a post-Industrial

and technological age in which workers need at

least a high school diploma to compete in the

workforce. Dropouts are much more likely than

their peers who graduate to be unemployed, living

in poverty, receiving public assistance, in prison,

on death row, unhealthy, divorced, and ultimately

single parents with children who drop out from

high school themselves.

12

High school dropouts, on average, earn

$9,200 less per year than high school graduates,

and about $1 million less over a lifetime than col-

lege graduates.

13

Students who drop out of high

school are often unable to support themselves;

high school dropouts were over three times more

likely than college graduates to be unemployed in

2004.

14

They are twice as likely as high school

graduates to slip into poverty from one year to

the next.

15

And there even seems to be a correla-

tion with education and good health: at every age

range, the more education, the healthier the indi-

vidual. Among Americans over 45, college

graduates are twice as likely as dropouts to

report being in excellent or very good health.

16

The prevalence of high dropout rates not

only imperils individual futures but also profoundly

impacts our communities and nation due to the

loss of productive workers, the earnings and

revenues they would have generated, and the

higher costs associated with increased incarcera-

tion, health care and social services. Four out of

every 10 young adults (ages 16 – 24) lacking a

high school diploma received some type of govern-

ment assistance in 2001, and a dropout is more

than eight times as likely to be in jail or prison as

a person with at least a high school diploma.

17

Studies show that the lifetime cost to the nation

for each youth who drops out of school and later

moves into a life of crime and drugs ranges from

$1.7 to $2.3 million.

18

Given the clear costs to them and to the

country, why do young people drop out of high

school in such large numbers? Almost every

elementary and middle school student reports

ambitions that include high school graduation and

at least some college. A poll released by MTV and

the National Governors Association in the Spring

of 2005 found that 87 percent of all young people

want to go onto college.

19

And yet, young people

continue to drop out of high school in stunningly

large numbers. This report seeks to answer the

question of why so many dreams are cut short,

and to foster a national conversation about what

might be done about it.

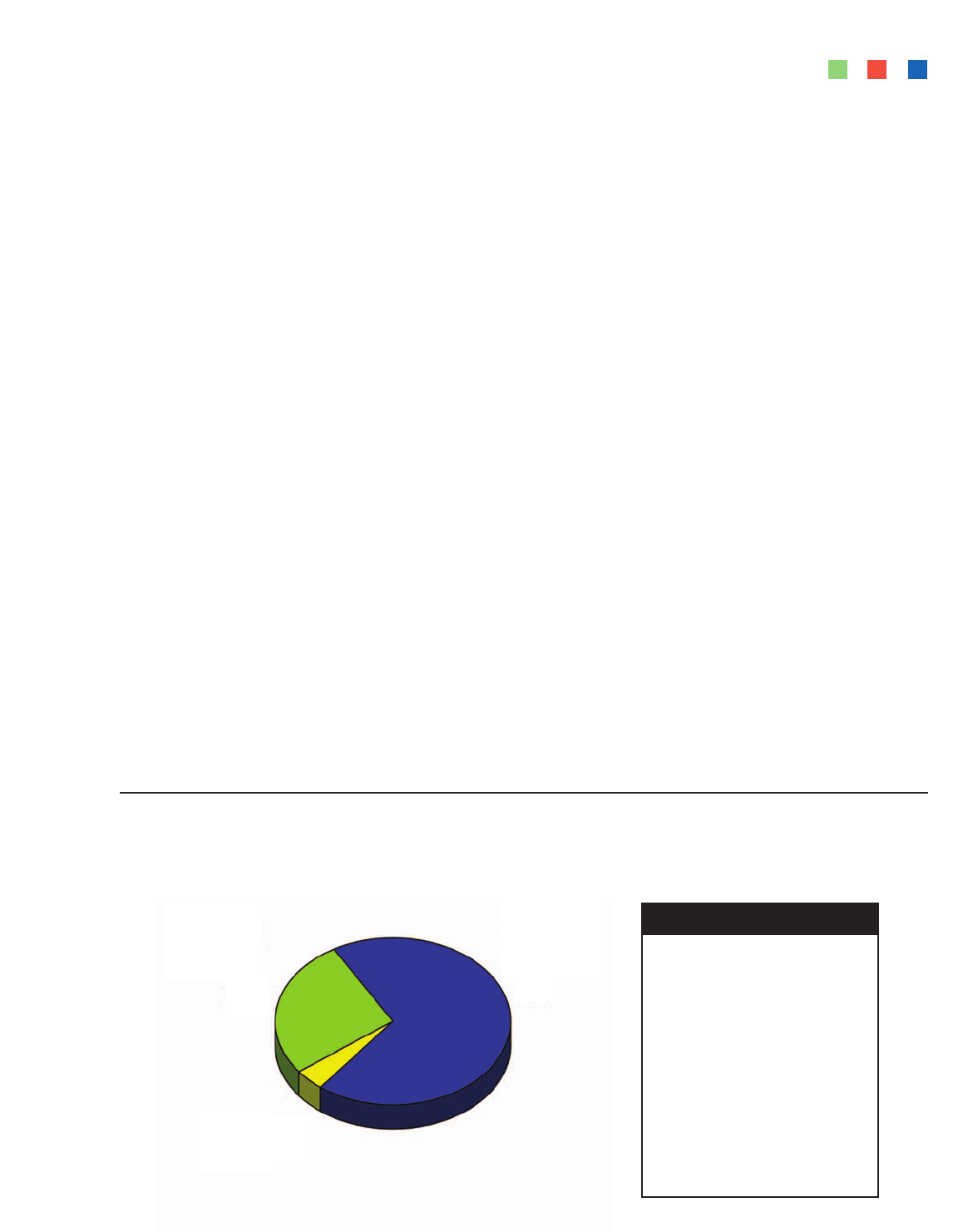

Who is Dropping Out?

To answer this question, we went right to

the source—dropouts themselves. This report

is based on four focus gr

oups of ethnically and

racially diverse 16 to 24-year-olds who did not

complete high school and on interviews, primarily

face to face, with 467 ethnically and racially

diverse students aged 16 through 25 who had

dropped out of public high schools in 25 different

locations—including lar

ge cities, suburbs and

small towns—with high dr

opout rates. W

e did not

attempt to obtain a sample of students that

r

epr

esented the same demographics as the

nation as a whole.

20

The methodology we used

for sur

veying students is set for

th in mor

e detail

in Appendix I.

The Silent Epidemic

2

High school dropouts, on average,

earn $9,200 less per year than

high school graduates, and about

$1 million less over a lifetime than

college graduates. Students who

drop out of high school are often

unable to support themselves; high

school dropouts were over three

times more likely than college

graduates to be unemployed in

2004. They are twice as likely as

high school graduates to slip into

poverty from one year to the next.

Our survey, which again we emphasize may

not in all cases mirror national statistics, paints a

picture of the American high school dropout that

may surprise people:

n 88 percent had passing grades, with 62 per-

cent having “C’s and above”;

n 58 percent dropped out with just two years

or less to complete high school;

n 66 percent would have worked harder if

expectations were higher;

n 70 percent were confident they could have

graduated from high school;

n 81 percent recognized that graduating from

high school was vital to their success;

n 74 percent would have stayed in school if

they had to do it over again;

n 51 percent accepted personal responsibility

for not graduating and an additional 26

percent shared the responsibility between

themselves and their school, leaving very

few who blamed the schools alone; and

n Nearly all of the students had thoughtful

ideas about what their schools could have

done to keep them from dropping out and

would counsel students who are thinking of

dropping out not to do so.

The young people surveyed appeared thought-

ful and honest about their school experiences and

their current (and prior) life circumstances and

how the two intersected. They talked about their

expectations and dreams for themselves, which

were generally high; the regrets they had about

dropping out of school; how they would counsel

others not to make the same mistake; and

how they accepted personal responsibility for

their decisions.

Why Students Drop Out of

High School

Considering that many of these for

mer

students understood the importance of education

in fulfilling their goals and many had passing

grades and only a couple of years to go, why

did they drop out? There is no single reason why

students drop out of high school. The decision

to drop out is complex and relates to the individ-

ual student – and their family, school and

community.

21

The decision is personal, reflects

their unique life circumstances, and is part of a

slow process of disengagement from school.

There appear to be, however, clusters of

reasons or common responses that emerge

relating to the academic environment, real life

events, and a lack of personal motivation and

external sour

ces of motivation and guidance.

The Silent Epidemic

3

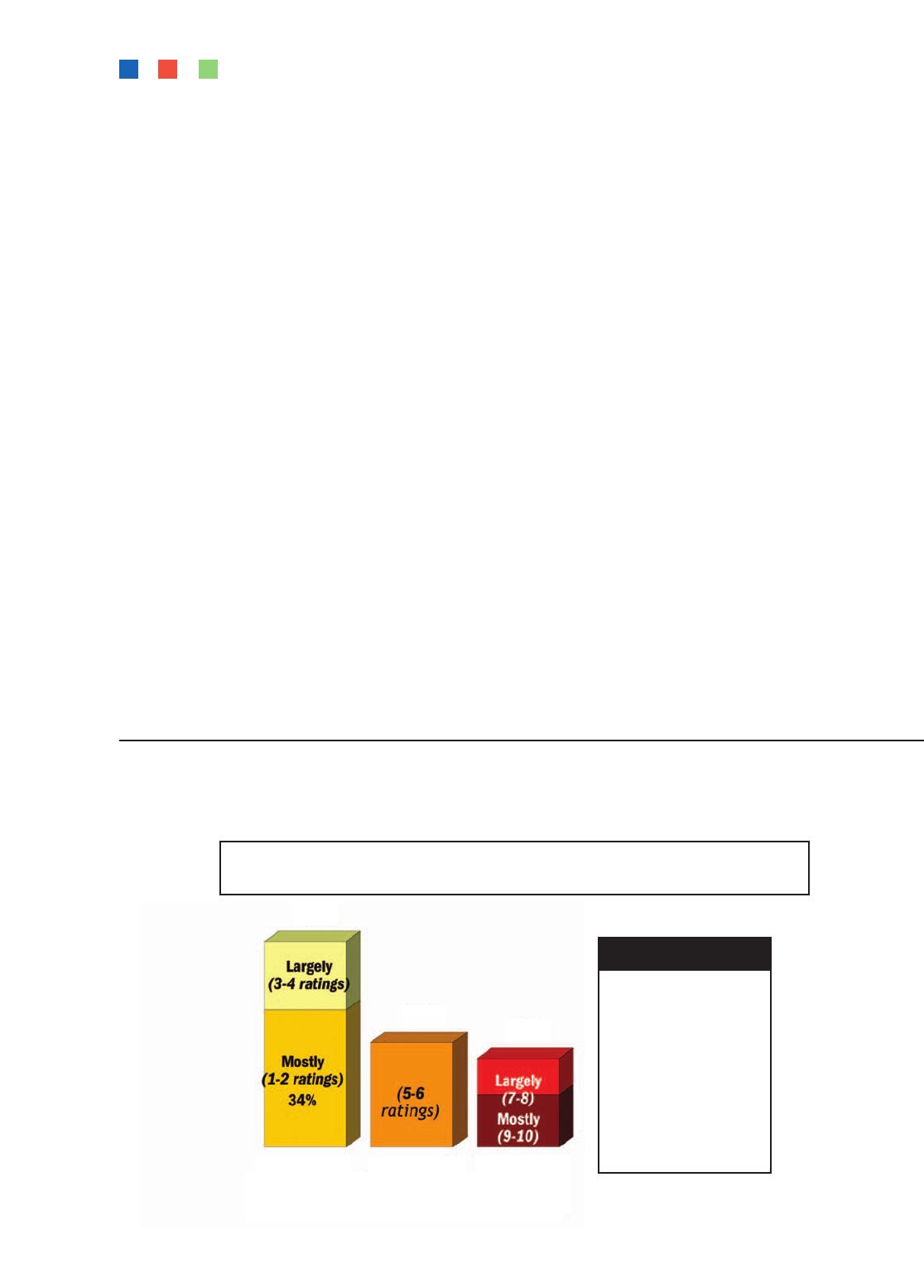

Top Five Reasons Dropouts Identify as Major

Factors For Leaving School

Classes were

not interesting

Missed too many days

and could not catch up

Spent time with people

who were not interested

in school

Had too much freedom

and not enough rules in my life

Was failing

in school

47%

43%

42%

38%

35%

There is no single reason why students drop

out of high school. Respondents report different

reasons: a lack of connection to the school

environment; a perception that school is boring;

feeling unmotivated; academic challenges; and

the weight of real world events. But indications

are strong that these barriers to graduation are

not insurmountable.

School is Boring

47 Percent Said Classes Were Not Interesting

Nearly half (47 percent) of former students

surveyed said a major factor in their decision to

drop out was that classes were not interesting.

Spending time with people who wer

e not interest-

ed in school was another major factor in the

decision to drop out for 42 percent of our

respondents. These were among the top reasons

selected by those with high GPAs and by those

who said they were motivated to work hard. Still,

even this group will need more supports to meet

higher standards and to connect what they are

learning in the classroom to the skills they will

need in the workforce.

When the participants in our focus groups

were asked in what areas their high school did

not do enough, their highest level of response

related to “not making school interesting.” Again

and again, participants recounted how high

school was “boring, nothing I was interested in,”

or “it was boring, …the teacher just stood in

front of the room and just talked and didn’t really

like involve you.” A female from Baltimore said,

“There wasn’t any learning going on,” and another

complained, “they make you take classes in

school that you’re never going to use in life.”

Many felt even their teachers were not engaged

in the classes and teachers “only care about

getting through their day too.”

Uninspired Teaching, Unmotivated

Students

Low Expectations Held by Adults for the Students

Contrast to the High Expectations Students Have

for Themselves

Sixty-nine percent of respondents to our

survey also cited not feeling motivated or inspired

to work hard, and many indicated they would

have liked to have been so inspired. In our focus

groups, young adults consistently said that their

classes were boring and that their school did not

do enough to make them work hard. Students

said they went to school because they had to,

not because they learned anything. School did

The Silent Epidemic

4

Dropouts Did Not Feel Motivated Or Inspired To Work Hard

Was not motivated/inspired

Year dropped out:

9th-10th g

rade

75%

11th grade 69%

12th g

rade

59%

High GPA 56%

Medium GPA 74%

Low GPA 79%

Whites 76%

African Americans 63%

Hispanics 71%

Parents involved 63%

Parents not involved 78%

Was

motivated/

inspired

Was not

motivated/

inspired

Not

sure

27%

4%

69%

The Silent Epidemic

5

Teachers Are Doing Well, But Could Be Doing More

not seem relevant and some complained teachers

just told them what to do without involving them

in the lesson.

In our focus groups, one young man from

Philadelphia reflected, “The work wasn’t even

hard… once I figured I wasn’t going to get any

learning done in there, there wasn’t any need to

go.” Many high schools use a system of tracking

that shunt low-performing students to low level

classes with unchallenging work.

22

Participants in

our focus groups expressed sadness that they

were not challenged more and that the classes

and teachers were not inspiring. Studies show

that the expectations that teachers have for their

students has an effect both on student perform-

ance and whether they drop out of school.

23

Interestingly, our sample indicated that 26

percent did no homework, and, including them, 80

percent of those surveyed did one hour or less of

homework each day. Part of this may have been

the result of a lack of student motivation and

some of it may have been attributable to low

expectations their teachers or schools had for

them. In our focus groups, participants shared

stories that would indicate both. There have been

studies showing that students who do little or no

homework each week increase their risk of

dropping out.

24

These low expectations for the students were

in stark contrast to the high expectations they

had for themselves. Seventy percent of our

respondents surveyed were confident that they

would have been able to graduate if they had put

forth the necessary effort. While a majority said

that their school’s requirements for graduating

were difficult, two-thirds (66 percent) said they

would have worked harder if more had been

demanded of them – higher academic standards

and more studying and homework – to earn a

diploma. In the focus groups, students sounded

disappointed at the lack of challenge. Even a

majority of those with a low grade point average

thought they could have graduated. While many of

These low expectations for the

students were in stark contrast to

the high expectations they had for

themselves. Seventy percent of

our respondents were confident

that they would have been able

to graduate.

There was at least one teacher or

staff member w

ho personally

cared about my success

There was at least one teacher or

staff member to w

hom I could

talk about my school problems

There was at least one teacher or

staff member to whom I could

talk about my personal problems

This applied to my high school experience.

This did not apply to my high school experience.

65%

33%

56%

43%

41%

57%

these students indicated they would have worked

harder if they had been challenged, they also

would have needed much more support to meet

those higher expectations.

This lack of challenge contributed to stu-

dents’ boredom and problems with attendance.

They felt it acceptable to skip class since they

could do make-up work and, in the words of one

focus group participant, “They just let you pass,

anything you got.”

For Some, Real Life Events Got in the

Way of School

32 Percent Left to Get a Job; 26 Percent

Became a Parent; and 22 Percent Had to

Help Their Family

It may seem natural to assume that high

school dropouts are those who are already failing,

who leave school so they do not have to admit

they cannot do the work. While certainly true of

some, the decision to drop out of high school was

sometimes affected by a student’s personal

circumstances, unrelated to school.

Many students suggested a reason other than

school prevented them from graduating. For

instance, one-third (32 percent) said they had to

get a job and make money (36 percent of the

young men and 28 percent of the young women

we surveyed); 26 percent said they became a

parent; and 22 percent said they had to care for

a family member.

Twenty-six percent of all respondents and

one-third of all young women we surveyed said

that becoming a parent was a major factor in

their decision to leave school. Many young

women who became pregnant were unable to

juggle the pressures of young motherhood and

school, so they dropped out. Others identified

personal circumstances in the home – needing to

be there to care for siblings or take care of other

tasks at home because parents were out working

or other

wise unavailable – that had a strong influ-

ence on their ability to attend or focus on school.

Many of these young people reported doing

reasonably well in school and had a strong belief

that they could have graduated if they had stayed

in school. Of all of the students we surveyed,

these students were the most likely to say they

would have worked harder if their schools had

demanded more of them and provided the

necessary support.

We did not probe in any considerable depth

how the schools offered these participants with

special needs additional assistance, but it was

clear from the data in the survey and the focus

groups that students were not aware of such

assistance, even if it was present.

The Silent Epidemic

6

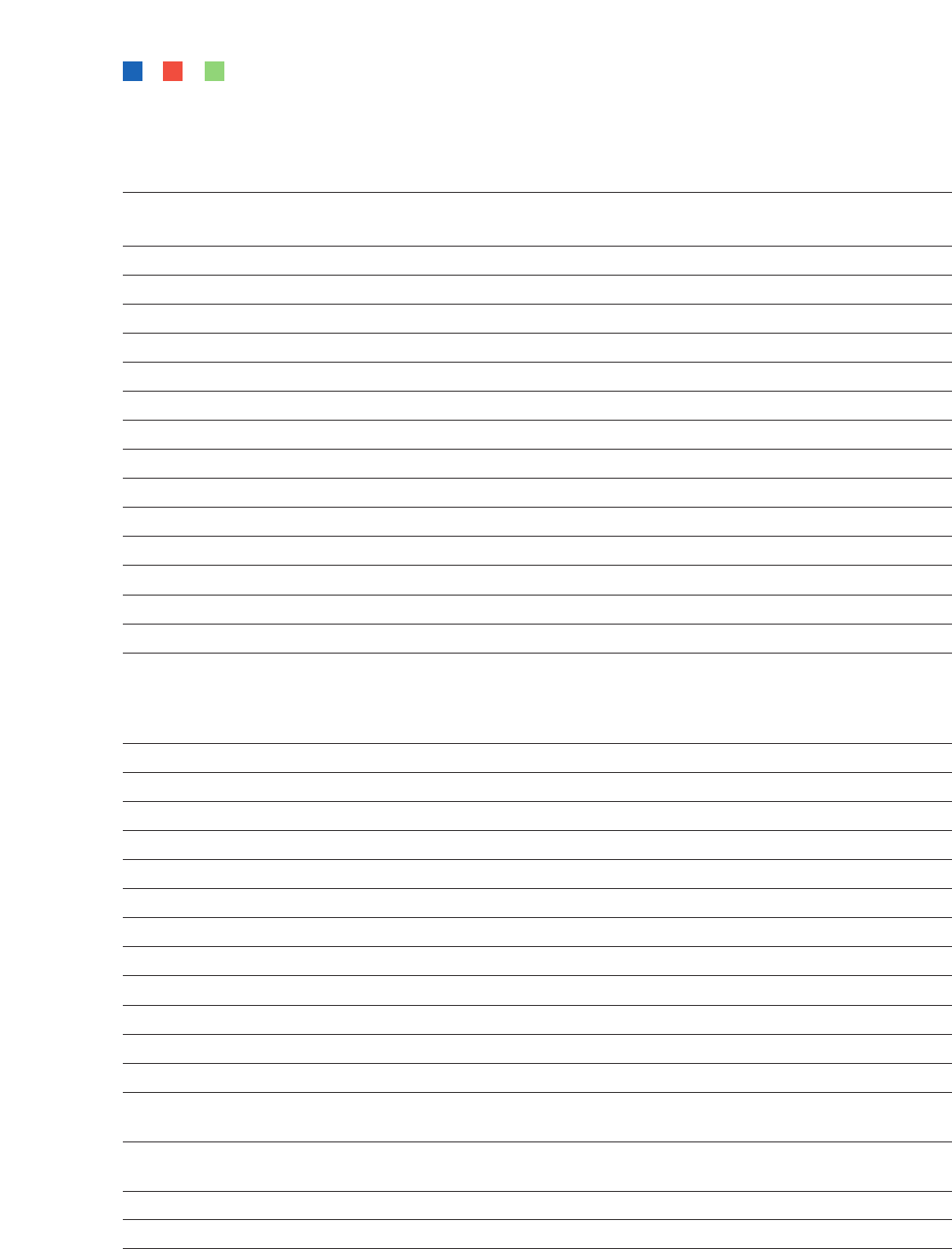

Majority Are Confident That They Could Have Graduated

How confident are you that you would have been able to meet your school’s

requirements for graduation if you had put in the necessary effort?

Very/somewhat confident

High GPA 80%

Medium GPA 72%

Low GPA 58%

66% of dropouts say they

would have worked harder

if their high school had

demanded more.

Not at all

confident

Not

sure

Very

confident

Not that

confident

Somewhat confident

70%

confident

7%

1%

30%

40%

22%

It is clear that some who do not graduate,

but not the majority, leave school because of

significant academic challenges.

Struggling in School and Needing

More Help

A Third (35 percent) Said They Were Failing

In School

“Failing in school” was one of the top five

reasons survey respondents identified for leaving

school, chosen by 35 percent of poll respondents.

This r

eason is often more highly ranked by stu-

dents in national surveys.

25

Three in ten said that

they could not keep up with their schoolwork and

43 per

cent said they missed too many days of

school and could not catch up. Many of these

students likely fell behind in elementary and

middle school and were not able to make up the

necessary ground; almost half of dropouts polled

(45 percent) said their previous schooling had

not prepared them for high school.

The majority of survey respondents (57

percent) reported that it was difficult to pass

from one grade to the next and that the high

school requirements for graduating were too

difficult. When asked how the high school made

it too difficult to pass from one grade to the next,

participants indicated that in addition to the tests

being too difficult, teachers were not available to

give them extra help, classes were uninteresting,

and many of them simply missed too many days

to catch up with their schoolwork. In our focus

groups, two former students summed up these

views – “They [the teachers] don’t put forth that

effort to give us the help that we need” and “You

see like when I was in 11th grade, everybody in

my school, by 11th grade was getting out by...

1:00 p.m. because you didn’t need that many

credits. So they [the teachers] were throwing

more at us and faster, so we had like a pile of

homework that would just stack up…”

Thir

ty-two percent of respondents were

required to repeat a grade before dropping out

and 29 percent expressed significant doubts that

they could have met their high school’s require-

ment for graduation, even if they had put forth

the necessary effort. The most academically

challenged students were the most likely to

report that their schools did not do enough to

help students when they had trouble learning or

understanding the material they were being

taught. These students were also the most

likely to express doubt about whether they

would have worked harder if more had been

expected of them.

As complex as these individual circumstances

may be, for almost all young people, dropping out

The Silent Epidemic

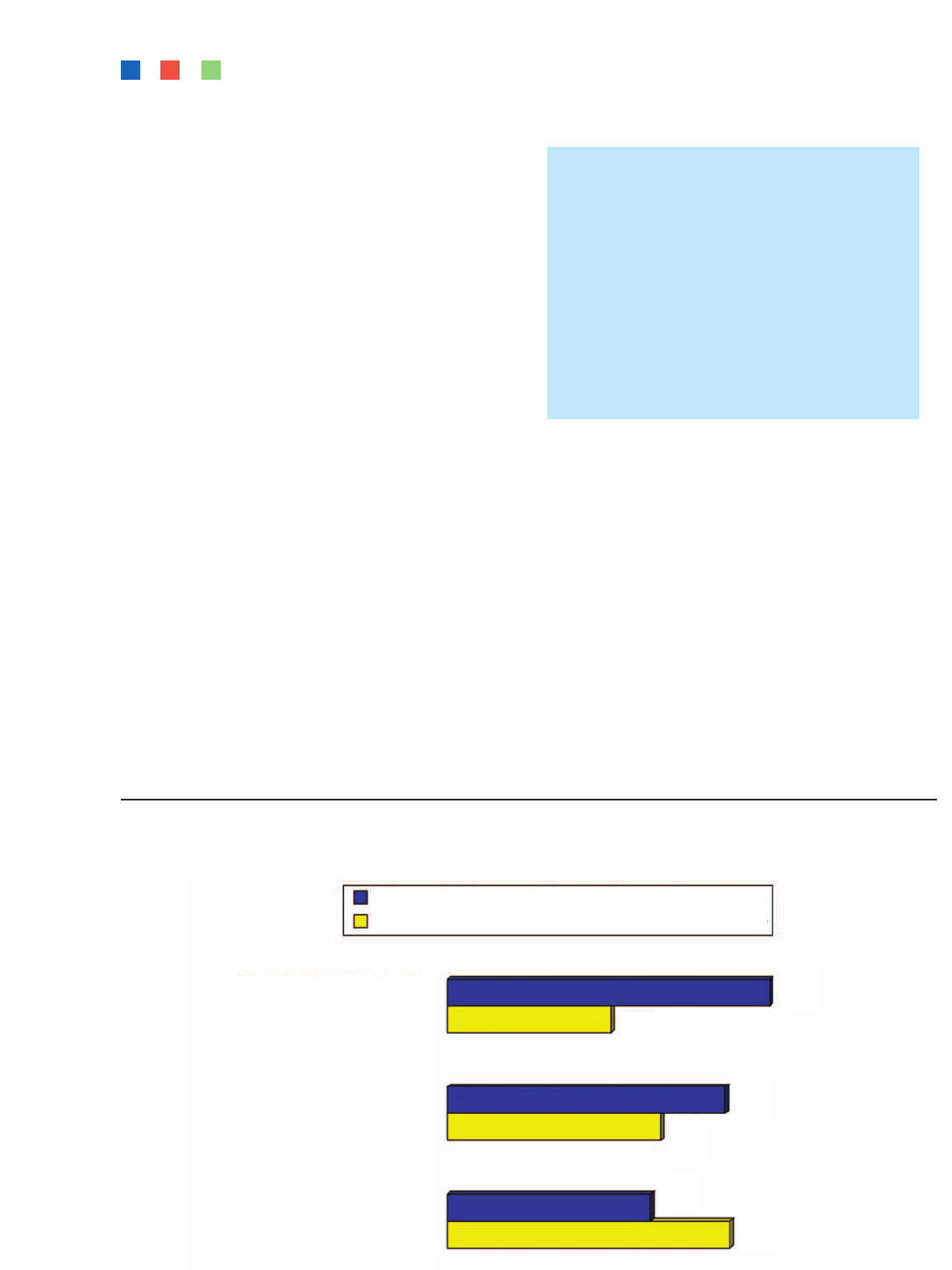

Attendance Is Strong Predictor of Dropping Out

Missed class often year before dropping out

Missed class often y

ear dropped out

9

th

grade

dropouts

10

th

grade

dropouts

11

th

grade

dropouts

12

th

grade

dropouts

7

65%

36%

61%

33%

59%

45%

63%

of high school is not a sudden act, but a gradual

process of disengagement; attendance patterns

are a clear early sign.

Slow Process of Disengagement

Attendance Patterns are a Key

Warning Sign

As complex as these individual circumstances

may be, what is clear is that dropping out of high

school is not a sudden act, but a slow process of

disengagement, often both academically and

socially, and is often influenced by a student’s

perception of the high school’s expectations of

him or her and his or her early school experi-

ences.

26

Dropping out is not a decision that is

made on a single morning. The survey probed

students’ experiences before dropping out of high

school and found that there are clear warning

signs for at least one to three years before they

drop out that these students are losing interest in

school. National studies show that such warning

signs appear and can be predictive of dropping

out as early as elementary school.

27

Students described a pattern of refusing to

wake up, missing school, skipping class, and

taking three hour lunches – and each absence

made them less willing to go back. These stu-

dents had long periods of absences and were

sometimes referred to the truant officer, only to

be brought back to the same environment that led

them to become disengaged. In our survey, 59 to

65 percent of respondents missed class often the

year they dropped out and 33 to 45 percent

missed class often the year before they dropped

out. Consistent with national data, absenteeism

is the most common indicator of overall student

engagement and a significant pr

edictor of

dropping out.

28

Other warning signs include: low grades,

discipline and behavioral problems, lack of

involvement in class and in school activities,

pregnancy, being held back a grade or more,

students who transfer from another school, and

those who experience dif

ficulty with the transition

year of 9th grade itself.

Respondents r

epor

t that they star

ted to lose

interest in school well before dropping out, with

71 per

cent saying they lost inter

est in school in

the 9th and 10th grades. Fifty-eight percent of our

survey respondents indicated that they dropped

out in the 11th and 12th grades. Nationally, much

of the dropping out of school has shifted from the

last two years of high school (typical three

decades ago) to between 9th and 10th grades

today.

29

Still, a plurality of students drop out

with less than two years to go in their high

school education.

30

Too Much Freedom

38 Percent Say Too Much Freedom and Not

Enough Rules

As young adults grew older, they had more

freedom and more options, which led some away

from class or the school building. It was too easy

to skip class or join in activities outside of

school. Nearly two-fifths (38 percent) of respon-

dents to the survey cited this as a factor in their

decision to drop out of high school. In our focus

groups, a young man from Philadelphia told us,

“Once you get in high school, it’s more like you

have more freedom. In middle school, you have to

go to your next class or they are going to get you.

In high school, if you don’t go to class, there isn’t

anybody who is going to get you. You just do your

own thing.”

“Too much freedom” seemed to relate to the

most basic conditions in the school – lack of

order, discipline and rules, making sure students

attended class, and even limiting chaos that

made students feel unsafe. Many participants in

our focus groups felt that there were many things

in their lives that pulled them away from school

and the new found freedom of high school made

it more compelling to leave than to stay.

In our Philadelphia focus groups, one boy who

had just told us that his best days in school were

when he worked hard and could talk about what

he learned at home, lamented the fact that he

only went to school once a week, and highlighted

the consequences of too much freedom in the

school environment. He said, in response to a

question about why he only came to school once

a week, the “streets would call you. Being there

listening to somebody talking to you all day, writ-

ing on the board, and then you start looking

outside at the streets…..We got to leave for

The Silent Epidemic

8

lunch in my school. And then once we got out

there, smelled that fresh air…..”

In our focus groups, participants talked again

and again about waking up late for school, skip-

ping classes, hanging out in the hallways with no

consequences, and the lack of order and rules for

them. For a young man in Baltimore, school

became an afterthought and the school let it be

so, “Like in the middle of the year, I just started

going out with my friends, and I never went to

school. It’s like I forgot about it.”

When asked what their high schools could

have done to help more students stay in school,

three out of the six leading answers related to too

much freedom and not enough order and safety –

68 percent cited “keeping students from skipping

classes,” 62 percent “maintaining classroom

discipline,” and 57 percent “helping students

feel safe from violence.”

Some respondents even noted their ability,

under state law, to drop out of school either

because they reached an age to do so or their

parents signed them out. One young man from our

Baltimore focus groups told us how he felt right

before he turned 16 – “I can’t wait until my 16th

birthday so I didn’t have to come back here no

more. I mean, I can’t wait to drop out kind of

thing.” A female from Baltimore said, when asked

about her decision to drop out, “you couldn’t drop

out until like, my parents had to sign me out

because it was before I was the age of 16. And

there was like a day when we went up to the

school and they just signed me out.” We note

that in the majority of states, students are only

required to stay in school until they are 16 or 17

and many states permit multiple exemptions.

For those students who dropped out, the level

of pr

oactive parental involvement in their educa-

tion was low.

Parents Engaged Too Late

Often the Impetus for Parental Involvement is

Related to Discipline

Former students describe differing levels of

parental involvement, different reasons for their

involvement, and different levels of awareness

that their child was about to drop out of school.

Fifty-nine percent of parents or guardians were

The Silent Epidemic

9

Parental Awareness

My parents’ awareness of my school

attendance and grades

My parents’ awareness that I was on the

verge of leaving school

47% say their parents’

work schedules kept

them from k

eeping

up with what was

happening at school.

Very aware

Not at all aware

Fairly aware

Just somewhat aware

48%

51%

48%

50%

68% sa

y their parents

g

ot more in

v

olv

ed

when they became

a

ware their child

was on the v

erg

e

of leaving school

involved in their children’s schooling, with only

one-fifth “very” involved. More than half of those

who were involved at all were involved “mainly for

discipline reasons.”

The majority of parents were “not aware” or

just “somewhat aware” of their child’s grades or

that they were about to leave school. Nearly half

of the respondents said their parents’ work sched-

ules kept them from knowing more about what

was happening at school and 68 percent said

their parents got more involved when they

became aware their child was on the verge of

dropping out.

Respondents who said that their parents were

not involved in school were more likely to drop

out in the first two years of high school than

those who said their parents were involved even

when they were not in trouble. Students said their

parents were much more involved in middle

school but gave them more responsibility and

freedom in high school.

Students also needed more supervision at

home and in school; only 47 percent of the former

students we surveyed said they or their parents

would even be contacted by the school if they

were absent. This pattern continues after partici-

pants drop out, with 48 percent of dropouts

saying their school contacted them or their

parents to find out why they left school or to

encourage them to return. But this means that

in the majority of cases, such contact may not

even occur.

In hindsight, young people who dropped out

of school almost universally expressed great

remorse for having left school and expressed

strong interest in re-entering school with students

their age.

Their Regrets

One 17-year-old male in our focus groups put

it simply

, “It’s important to get an education to

do well in life.” A 19-year-old female said of drop-

ping out, “I wouldn’t make the same decision. I

would stay in school.” A female fr

om Baltimor

e

put it succinctly, “I think it’s one of the worst

r

egr

ets of my life.”

They said they did not think of their future

when deciding to drop out but wanted freedom

or money right then, or gave up on their dreams

because graduation seemed far away. This con-

forms to models of adolescent psychology that

have found adolescents have difficulty with

long-term planning and delayed gratification.

31

But as adults, four out of five poll participants

said that graduating from high school is very (60

percent) or fairly (21 percent) important to suc-

cess in life. Seventy-four percent of our survey

respondents said they would have stayed in

school, knowing what they know today about the

expectations of the world, and 76 percent said

they would definitely or probably re-enroll in a

high school for people their age if they could. At

the time of their decision to leave high school,

fifty-thr

ee per

cent had planned to go back and

graduate. Since that time, however, only 11

per

cent have actually gone back and graduated.

In the survey, 47 percent said that not having

a diploma makes it har

d to find a good job.

Participants in our focus groups counseled others

to stay in school for this reason. For instance, a

male fr

om Philadelphia said, “… I would tell him

like, I haven’t finished high school. I don’t have a

diploma. I don’t have a job. I am broke …. You

can’t make it without that. You can’t go any-

wher

e, for real, on the legal side…. If you go to

school, get your diploma, you can do more things

the right way

. Y

ou might succeed.”

Participants in the focus groups wished they

had listened to those who war

ned them of the

The Silent Epidemic

10

“… I would tell him like, I haven't

finished high school. I don't have a

diploma. I don't have a job. I am

broke …. You can't make it without

that. You can't go anywhere, for real,

on the legal side…. If you go to

school, get your diploma, you can

do more things the right way. You

might succeed.”

problems associated with dropping out or that

such voices had been more persistent.

While there are no simple solutions to

the dropout crisis, there are clearly “supports”

that could be provided to improve students’

chances of staying in school. While most dropouts

blame themselves for failing to graduate, there

are things they say schools can do to help

them finish.

What Might Help Students

Stay in School

In order to look more closely at what might

be done to address the dropout epidemic, one

natural question is “who or what is responsible

for their dropping out and how can we fix it?”

While there are no simple solutions to the dropout

crisis, there are clearly “supports” that could be

provided within the school and the home that

would improve students’ chances of graduating.

While most of the dropouts in our survey blamed

themselves for failing to graduate and some focus

group participants said there was nothing their

school could have done to convince them to stay,

others pointed out things schools could have done

to help them finish.

Students who are at risk of dropping out can

and must be reached, and in order to effectively

reach at risk students, we first need to listen to

the views, experiences, concerns, life circum-

stances and ideas for reform of these young

people so we can help others in the future. The

following recommendations are based on what

dropouts themselves told us in focus groups and

the survey.

Improve Teaching and Curricula to Make

School More Relevant and Engaging and

Enhance the Connection between School

and Work

Our respondents had many thoughtful ideas

about the specific actions schools could take to

improve the chances that a student would stay in

high school. Their most common answers related

to classroom instruction – making what is learned

in classes more relevant to their lives, having bet-

ter teachers who keep classes interesting, and

having smaller classes with more one-on-one

instruction, involvement and feedback.

The Silent Epidemic

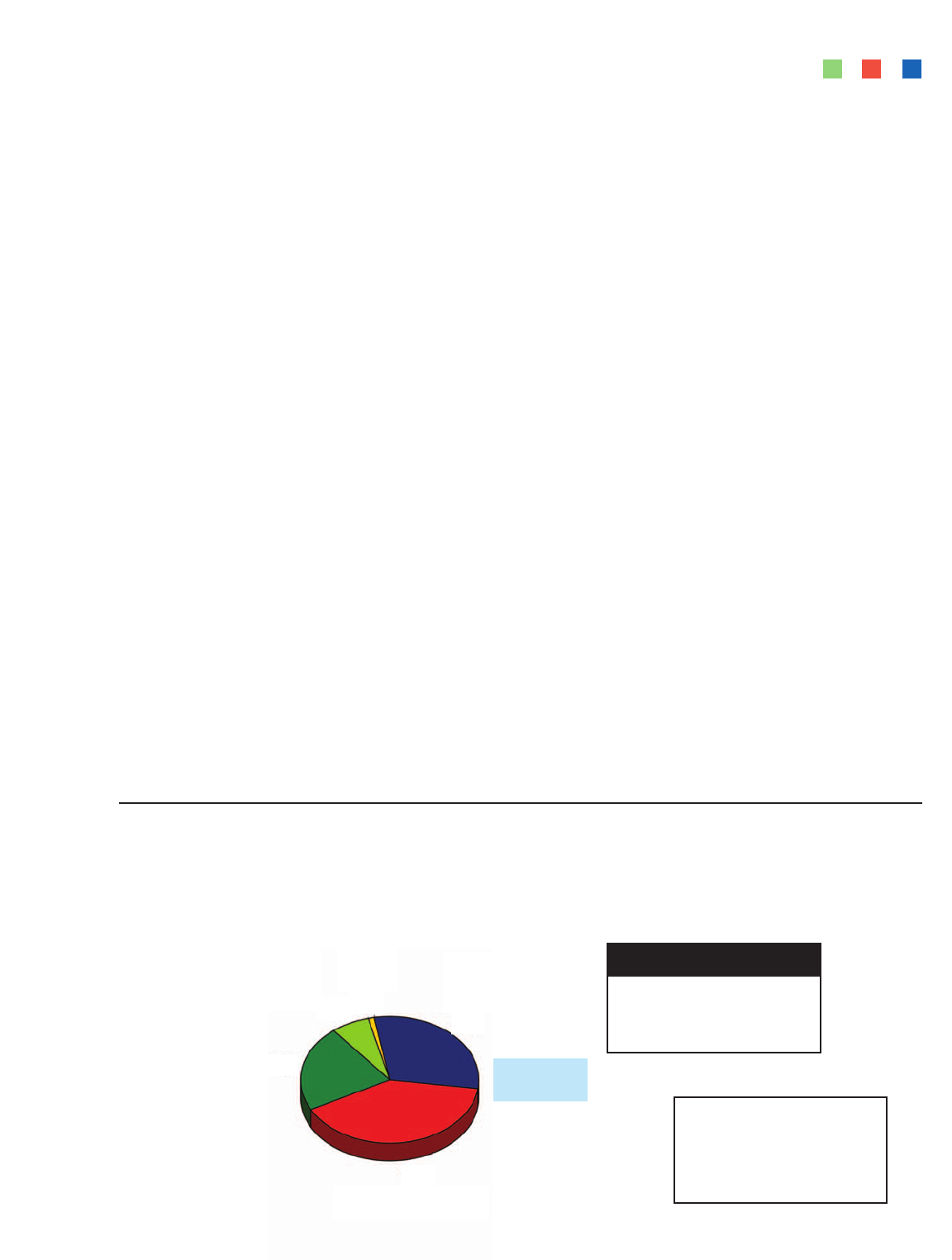

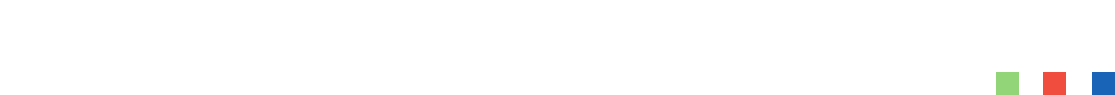

Young People Accept Responsibility For Not Graduating

Who was responsible for your leaving school: mostly the school, mostly you, or both?*

* Ratings on ten-point scale: 10 = I did everything I could to stay in school/the school

failed me; 1 = I alone was responsible/school did everything it could to keep me there

Mean Ratings

All dropouts 4.4

Afr. Americans 4.9

Whites 4.0

Hispanics 4.0

City 4.3

Suburbs 4.9

Small town/ 4.1

rural

11

I was

responsible

Both equally

responsible

School was

responsible

51%

26%

22%

The class work in high school needs to make

some connection to students’ interests and what

they find relevant, especially as seven in ten said

their school did not do enough to make learning

interesting. One bright young woman who was a

leader in her focus group said: “If they related to

me more and understand that at that point in

time, my life was…what I was going through,

where I lived, where I came from. Who knows?

That book might have been in my book bag. I

might have bought a book bag and done

some work.”

Eighty-one percent of survey respondents

said that if schools pr

ovided opportunities for

real-world learning (internships, service learning

projects, and other opportunities), it would have

improved the students’ chances of graduating

from high school. Outside studies have noted

that clarifying the links between school and get-

ting a job may convince more students to stay

in school.

32

Improve Instruction and Access to

Supports for Struggling Students

Four out of five participating dropouts (81

percent) wanted better teachers and three-fourths

wanted smaller classes with more individualized

instruction. Over half (55 percent) felt that more

needed to be done to help students with problems

learning. Seventy percent of survey participants

believed that more after-school tutoring, Saturday

school, summer school and extra help from teach-

ers would have enhanced their chances of staying

in school.

While some of the students’ best days in

school were when teachers paid attention to

them, many others had classes that wer

e so big

that teachers did not know their names. In our

focus gr

oups, par

ticipants r

epeated again and

again that they believed smaller class sizes would

have helped ensure that teachers maintained

or

der in the classr

oom and would have pr

ovided

more individual attention. The problem of large

schools and the need for smaller class sizes and

more personal instruction emerged more than

12 separate times from the participants in our

four focus groups in Philadelphia and Baltimore.

Seventy-five per

cent of sur

vey participants

agreed that smaller classes with more one on

one teaching would have improved students’

chances of graduating.

There are studies suggesting that small

schools are more likely to promote the engage-

ment of both students and staff that is so critical

to reducing the number of dropouts, and that the

largest direct effect appears to be in low socioe-

conomic status schools,

33

although there is

debate about the appropriate size of such smaller

schools.

34

There is also a body of literature that

reveals that small learning communities and

interdisciplinary teaming are associated with

lower dropout rates.

35

And there is some evidence

that alternative schools serving students at risk

of dropping out can also reduce dropout rates.

36

Build a School Climate that

Fosters Academics

Seven in ten surveyed favored increasing

super

vision in school and mor

e than thr

ee in five

(62 percent) felt more classroom discipline was

necessary. More than half (57 percent) believed

their high schools did not do enough to help

students feel safe from violence. Students in

the focus groups talked about how they could

not do homework or pay attention in class

because of the many disruptions, including

the fear of violence. Seven in ten (71 per

cent)

said their schools did not do enough to make

school interesting.

The Silent Epidemic

12

“If they related to me more and

understand that at that point in time,

my life was…what I was going

through, where I lived, where I came

from. Who knows? That book might

have been in my book bag. I might

have bought a book bag and done

some work.”

Ensure Strong Adult-Student

Relationships within the School

While two-thir

ds (65 percent) said there was

a staff member or teacher who cared about their

success, only 56 percent said they could go to a

staff person for school problems and just two-

fifths (41 percent) had someone in school with

whom to talk about personal problems. More than

three out of five (62 percent) said their school

needed to do more to help students with prob-

lems outside of class. Seven out of ten favored

more parental involvement.

These young people craved one-on-one atten-

tion from their teachers, and when they received

it, they remembered it making a difference.

Participants in the focus groups recounted that

some of their best days were when their teachers

noticed them, got them involved in class, and told

them they were doing well. Studies have shown

that if students perceive their teachers to be of a

higher quality, there is a lower likelihood that the

students will drop out.

37

In our survey, four out of

five agreed that better, more qualified teachers

who could keep class interesting would improve

students’ chances for graduating.

Improve the Communication between

Parents and Schools

Seventy-one per

cent of young people surveyed

felt that one of the keys to keeping students in

school was to have better communication

between the parents and the school, and increas-

ing parental or guardian involvement in their

child’s education. Less than half said their school

contacted their parents or themselves when

they were absent (47 percent) or when they

dropped out (48 percent). Respondents suggest-

ed that increased parental involvement could

influence very basic things – such as ensuring

students came to school every day and attended

their classes.

Studies have shown that students with

parents who are engaged in their lives – by moni-

toring and regulating their activities, talking with

them about their problems, encouraging individual

decision-making and being more involved in the

school – are less likely to drop out of school.

38

The communication links between parents and

schools are critical if such involvement is to work

effectively to monitor such activities, exchange

information about school performance and prob-

lems, and ensure that such problems are

addressed early and quickly.

The Silent Epidemic

13

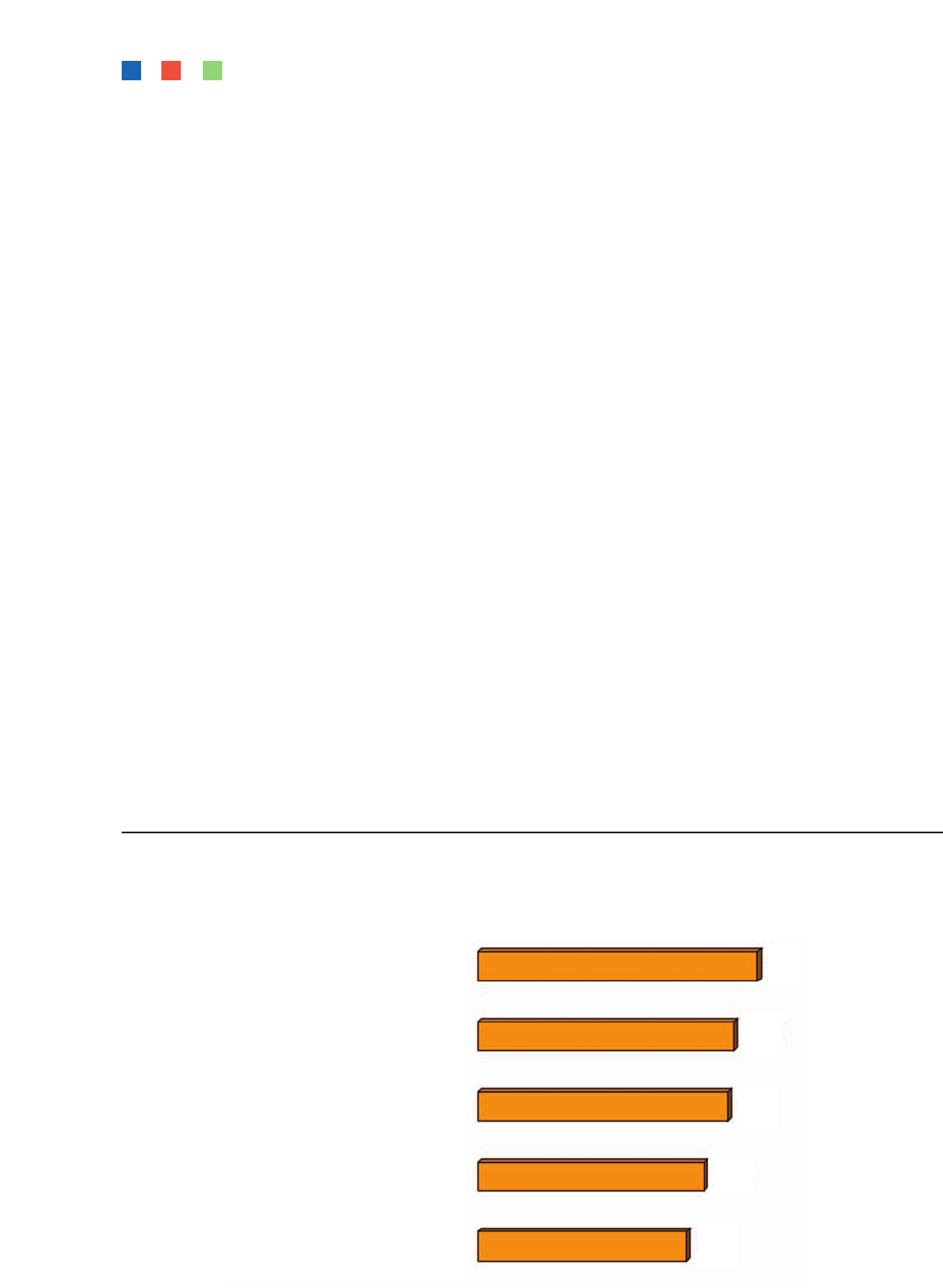

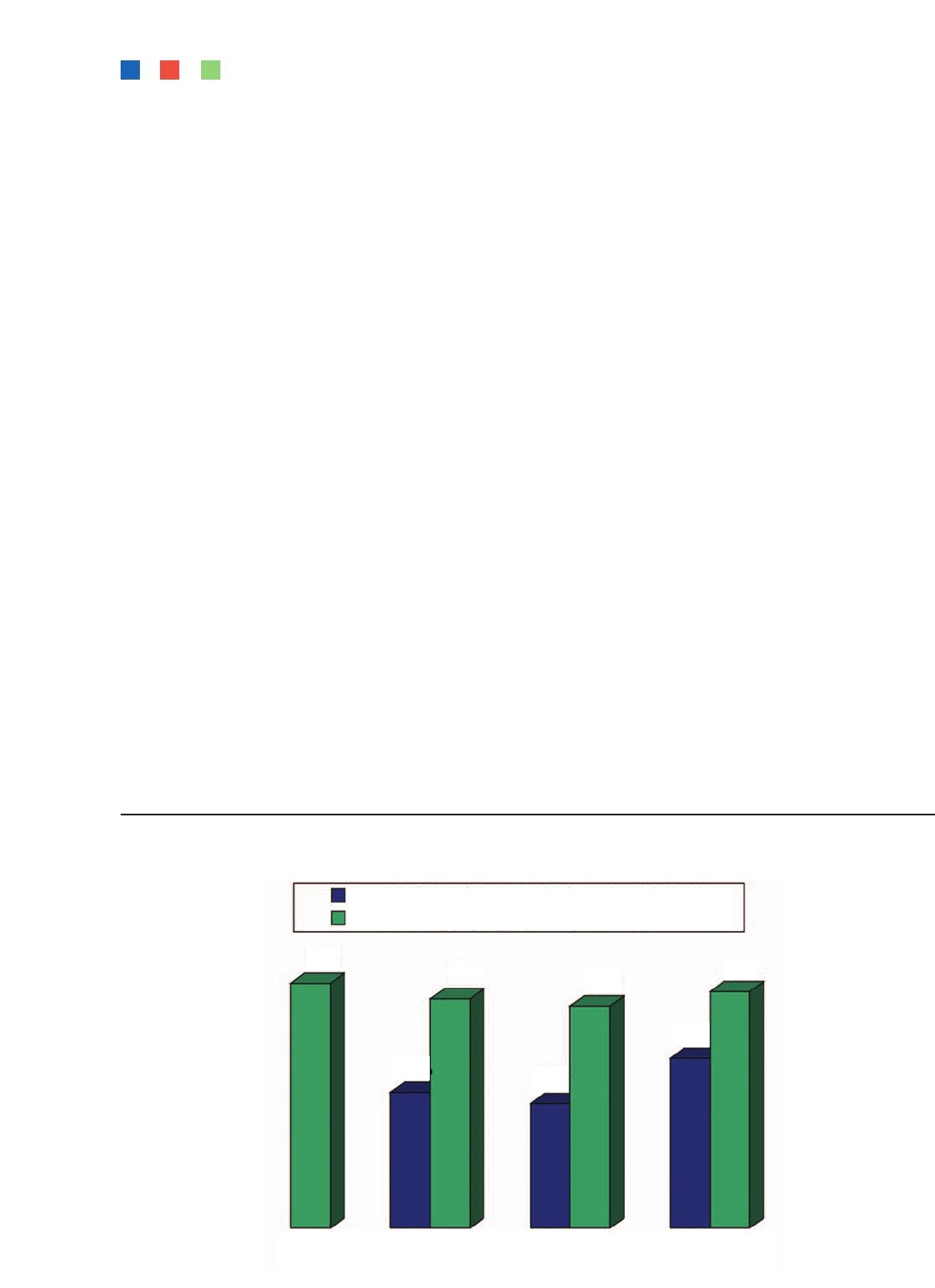

What Dropouts Believe Would Improve Students’ Chances

Opportunities for real-world learning

(internships, service learning, etc.) to

make classroom more relevant

Better teachers who keep

classes interesting

Smaller classes with more

individual instruction

Better communication between parents

& school, get parents more involved

P

arents mak

e sure their

kids go to school every day

Increase supervision at school:

ensure students attend classes

This would improve students’ chances of staying in school

81%

75%

71%

71%

70%

81%

Policy Pathways

We believe the stories, insights and reflec-

tions from our student survey and focus groups

can add a new, personal, and urgently needed

dimension to a discussion of the dropout epidem-

ic. We offer ideas for reform that relate to what

students believe would have helped them. We

also offer observations, particularly in the sec-

tions “In States” and “In the Nation” below, about

various policies, laws and additional work that

might be done. We hope that this report will fur-

ther inform a national conversation on the dropout

epidemic in America, and that it will help galva-

nize policymakers, educators, local and national

media, non-profit and foundation leaders, business

executives, and concerned citizens to take com-

prehensive action to address this national crisis.

In Schools and Communities

Different Schools for Different Students

Students in our survey wanted classes to be

more relevant to their interests and lives and

longed for smaller learning communities with

more individualized attention. Great schools learn

to treat each student differently, rather than

demanding that all students fit into the “one size

fits all” format of schooling that is widely used

today. In light of the fact that our current educa-

tional system produces about one-third of kids

who do not graduate, and another one-third who

are not sufficiently prepared by the education

they have received to be college ready, it is

crystal clear that some structural reforms

are necessary.

39

Options offered to students, and supported by

the r

esear

ch, can include alter

native high schools

that offer individualized plans for each student.

40

This model can be an ef

fective way to addr

ess

the varied needs of potential dropouts. Options

can include schools with traditional structures,

but with a commitment to providing all students

with a rigorous curriculum which prepares them

for college or a family-wage job. Theme-based

schools, such as ones that focus on science and

technology or the ar

ts, ar

e another way to pr

e-

pare students for their future.

Small learning communities with one-on-one

instruction that engage students in their studies

and relate the material to their lives and goals,

and interdisciplinary teaming of teachers and

students have each shown promise in lowering

school-wide dropout rates.

41

What seems clear is that a multitude of

choices must be made available, particularly

in those school districts that have the highest

dropout rates, in an effort to make school more

relevant to the lives and goals of the students, to

give them the individual attention they need, to

have high expectations for them, and to address

pr

omptly their special needs and circumstances

to keep them on track for graduating.

Parent Engagement Strategies & Individualized

Graduation Plans

The young people we surveyed believe the

communication between schools and parents

needs to be greatly strengthened – that schools

need to do more to invite parents in and be part

of the solutions, and that parents need to do

more themselves to be involved. One of the ways

this deficit of parent involvement shows up is in

truancy, where parents can be more involved by

simply making sure their child shows up each day

at school. When we asked focus group partici-

pants about their school’s follow-up policy for

truancy and other acts of student disengagement,

more often than not the respondents perceived

that the schools did too little, or perhaps were

over

whelmed with the numbers of such cases.

42

Simple things such as teacher feedback to

par

ents about class par

ticipation, missed assign-

ments, grades and other issues can be critical to

helping keep students on track. Although schools

cannot be expected to address and solve weak-

nesses in the family structure, which our survey

shows is a common factor for students who dr

op

out, they need to recognize and develop ways to

address different types of family circumstances.

This includes ways to bridge other school-family

dif

ferences, such as in language, culture, educa-

tional attainment or reaching a single working

par

ent. When additional educational choices ar

e

of

fer

ed to students, which can include the

restructuring of existing schools or the creation

of new ones, these schools can incorporate into

The Silent Epidemic

14

their new structure ways to improve parent

involvement and school-home communication.

Another way to further strengthen the linkage

between school and home is for the schools to

develop individualized graduation plans for each

student, particularly for those at risk of dropping

out. This additional step would help the parents

become more aware of the specific requirements

for their high school student so they can take the

steps necessary to help ensure they are carried

out to completion. This knowledge would also

help empower the parent further to advocate for

their child.

Research from the U.S. Department of

Education and others shows that the involvement

of family members can have a positive influence

on their child’s school achievement.

43

It can help

improve their student’s grades and test scores,

as well as help make sure they actually attend

school, complete their homework, and have a bet-

ter attitude overall.

Early Warning Systems

Our student survey and national studies show

that dropping out is a slow process of disengage-

ment and that problems predictive of dropping out

often emerge early in a student’s life. Many of

these problems appear to go unnoticed.

Schools need to develop district-wide (or even

state-wide) early warning systems to help them

identify students who they anticipate are less

likely to succeed in the school where they are.

This will not only serve those who stay in one

school, but will help those students who transfer

fr

om school to school to make sure they do not

get lost in the various systems in which they are

enr

olled. Mechanisms need to be developed to

ensur

e such war

ning systems trigger the appr

opri

-

ate support and provide follow through until the

student is back on track. One clear step r

elates

to absenteeism. Every day, schools should have a

reliable list of the students who failed to attend

school and should notify parents or guardians

immediately and take appropriate action to

ensur

e students attend school and have the

suppor

t they need to r

emain in school. It is

critical that schools addr

ess the cir

cumstances

that drove students away from the school in the

first place.

Additional Supports and Adult Advocates

There are a wide range of supplemental

services or intensive assistance strategies for

struggling students in schools – attendance

monitoring, school and peer counseling, mentor-

ing, tutoring, double class periods, internships,

service-learning, summer school programs, and

more – that have their strong advocates (and

usually some research to back it up) that can

make a difference in the lives of students who are

at risk of dropping out. Such services, together

with intensive, best-practices literacy programs,

should be made accessible to low-performing stu-

dents to ensure they learn to read at grade level

and stay on the graduation track. Schools need to

enhance their coordination with community-based

institutions and government agencies to ensure

that students receive the proper support. Schools

also need to consider the importance of supports

for students with special needs, such as pregnant

women and students with disabilities.

The range of programs and supports can be

overwhelming and finding the right supports a

challenge. Since research shows the value of

having an adult at the school who is involved

with and familiar with the student, we believe

more schools should consider developing adult

advocacy programs within the school environ-

ment.

44

This could involve teachers or other

school staff, including administrative and support

staff, coaches, and counselors. Ensuring that

there is an adult advocate is particularly impor-

tant in large schools in districts in which the

dropout epidemic is most severe. The National

Middle School Association supports such an idea,

stating that the system works when “the concept

of advocacy is fundamental to the school’s cul-

ture, embedded in its every aspect. Advocacy is

not a singular event or a r

egularly scheduled time;

it is an attitude of caring that translates into

action when adults are responsive to the needs of

each and ever

y young adolescent in their

charge.”

45

The National Association of Secondary

School Principals recommends that every high

school student have a mentor, or “Personal Adult

Advocate,” to help personalize the education

experience.

46

This would help identify academic

and personal crises earlier

, and to head off those

things that this survey shows might lead to the

student being inclined to dr

op out.

The Silent Epidemic

15

In States

Compulsory School Age Requirements under

State Laws

Respondents in the survey and focus groups

identified “too much freedom” as a key factor

that enabled them to drop out of school. Even

some recommended that schools and parents do