Report to the

U. S. Election Assistance Commission

On

Best Practices to Improve Provisional Voting

Pursuant to the

HELP AMERICA VOTE ACT OF 2002

Public Law 107-252

June 28, 2006

Submitted by

The Eagleton Institute of Politics, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey

The Moritz College of Law, The Ohio State University

2

Report to the

U. S. Election Assistance Commission

Best Practices to Improve Provisional Voting

CONTENTS

The Research Team 3

Executive Summary 5

Key Findings 6

Recommendations 9

Provisional Voting in 2004 12

Recommendations 19

Attachment 1: Data Sources 27

Appendix A: National Survey of Local Election Officials’ Experiences with

Provisional Voting

Appendix B: Relationship Between Time Allotted to Verify Provisional Ballots

and the Level of Ballots that are Verified

Appendix C: Provisional Ballot Litigation by Issue

Appendix D: Provisional Ballot Litigation by State

Appendix E: State Summaries

Appendix F: Provisional Voting Statutes by State

(Included in electronic form only)

3

The Research Team

This research report on Provisional Voting in the 2004 election is part of a broader

analysis that also includes a study of Voter Identification Requirements, a report

on which is forthcoming. Conducting the work was a consortium of The Eagleton

Institute of Politics of Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, and The Moritz

College of Law of The Ohio State University.

The Eagleton Institute explores state and national politics through research, education, and public

service, linking the study of politics with its day-to-day practice. It focuses attention on how contemporary

political systems work, how they change, and how they might work better. Eagleton regularly undertakes

projects to enhance political understanding and involvement, often in collaboration with government

agencies, the media, non-profit groups, and other academic institutions.

The Moritz College of Law has served the citizens of Ohio and the nation since its establishment in

1891.It has played a leading role in the legal profession through countless contributions made by

graduates and faculty. Its contributions to election law have become well known through its Election Law

@ Moritz website. Election Law @ Moritz illuminates public understanding of election law and its role in

our nation's democracy.

Project Management Team

Dr. Ruth B. Mandel

Director

The Eagleton Institute of Politics

Board of Governors Professor of Politics

Principal Investigator

Chair of the Project Management Team

Edward B. Foley

Robert M. Duncan/Jones Day Designated

Professor of Law

The Moritz College of Law

Director of Election Law @ Moritz

Ingrid Reed

Director of the New Jersey Project

The Eagleton Institute of Politics

Daniel P. Tokaji

Assistant Professor of Law

The Moritz College of Law

John Weingart

Associate Director

The Eagleton Institute of Politics

Thomas M. O’Neill

Consultant

The Eagleton Institute of Politics

Project Director

Dave Andersen

Graduate Assistant

The Eagleton Institute of Politics

John Harris

Graduate Assistant

The Eagleton Institute of Politics

Donald Linky

Senior Policy Fellow

The Eagleton Institute of Politics

April Rapp

Project Coordinator

Center for Public Interest Polling

The Eagleton Institute of Politics

Sara A. Sampson

Reference Librarian,

The Moritz College of Law

Tim Vercellotti

Assistant Research Professor

Assistant Director, Center for Public Interest

Polling

The Eagleton Institute

Laura Williams

The Moritz College of Law

4

Peer Review Group

R. Michael Alvarez

Professor of Political Science

California Institute of Technology

John C. Harrison

Massee Professor of Law

University of Virginia School of Law

Martha E. Kropf

Assistant Professor Political Science

University of Missouri-Kansas City

Daniel H. Lowenstein

Professor of Law, School of Law

University of California at Los Angeles

Timothy G. O’Rourke

Dean, Fulton School of Liberal Arts

Salisbury University

Bradley Smith

Professor of Law

Capital University Law School

Tim Storey

Program Principal

National Conference of State Legislatures

Peter G. Verniero

former Attorney General, State of New Jersey

Counsel, Sills, Cummis, Epstein and Gross, PC

The Peer Review Group improved the quality of our work by critiquing drafts of our analysis, conclusions

and recommendations. While the Group as a whole and the comments of its members individually

contributed generously to the research effort, any errors of fact or weaknesses in inference are the

responsibility of the Eagleton-Moritz research team. The members of the Peer Review Group do not

necessarily share the views reflected in the policy recommendations of the report.

5

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Background and Methodology

This report to the United States Election Assistance Commission (EAC) presents

recommendations for best practices to improve the process of provisional voting. It is based

on research conducted by the Eagleton Institute of Politics at Rutgers, the State University of

New Jersey, and the Moritz College of Law at Ohio State University under contract to the

EAC, dated May 24, 2005.

The Help America Vote Act of 2002 (HAVA, (Public Law 107-252) authorizes the EAC (SEC.

241, 42 USC 15381) to conduct periodic studies of election administration issues. The purpose

of these studies is to promote methods for voting and administering elections, including

provisional voting, that are convenient, accessible and easy to use; that yield accurate, secure

and expeditious voting systems; that afford each registered and eligible voter an equal

opportunity to vote and to have that vote counted; and that are efficient. Section 302(a) of HAVA

required states to establish provisional balloting procedures by January 2004.

1

The process

HAVA outlined left considerable room for variation among the states, arguably including such

critical questions as who qualifies as a registered voter eligible to cast a provisional ballot that

will be counted and in what jurisdiction (precinct or larger unit) the ballot must be cast in order to

be counted.

2

The general requirement for provisional voting is that, if a registered voter appears at a polling

place to vote in an election for Federal office, but either the potential voter’s name does not

appear on the official list of eligible voters for the polling place, or an election official asserts that

the individual is not eligible to vote, that potential voter must be permitted to cast a provisional

ballot. In some states, those who should receive a provisional ballot include, in the words of the

EAC’s Election Day Survey, “first-time voters who registered by mail without identification and

cannot provide identification, as required under HAVA. . .”

3

HAVA also provides that those who

vote pursuant to a court order keeping the polls open after the established closing hour shall vote

by provisional ballot. Election administrators are required by HAVA to notify individuals of their

opportunity to cast a provisional ballot.

1

The Election Center’s National Task Force Report on Election Reform in July 2001 had described provisional ballots

as providing “voters whose registration status cannot be determined at the polls or verified at the election office the

opportunity to vote. The validity of these ballots is determined later, thus ensuring that no eligible voter is turned

away and those truly ineligible will not have their ballots counted.” It recommended “in the absence of election day

registration or other solutions to address registration questions, provisional ballots must be adopted by all

jurisdictions. “ See www.electioncenter.org

.

2

The 2004 election saw at least a dozen suits filed on the issue of whether votes cast in the wrong precinct but the

correct county should be counted. One federal circuit court decided the issue in Sandusky County Democratic Party

v. Blackwell, 387 F.3d565 (6

th

Cir. 2004), which held that votes cast outside the correct precinct did not have to be

counted. The court relied on the presumption that Congress must be clear in order to alter the state-federal balance;

thus Congress, the court concluded would have been clearer had it intended to eliminate state control over polling

location (387 F.3d at 578). An alternative argument, that HAVA’s definition of “jurisdiction” incorporates the broader

definition in the National Voting Rights Act, however, has not been settled by a higher court. But for now states do

seem to have

discretion in how they define “jurisdiction” for the purpose of counting a provisional ballot.

3

The definition of who was entitled to a provisional ballot could differ significantly among the states. In California, for

example, the Secretary of State directed counties to provide voters with the option of voting on a provisional paper

ballot if they felt uncomfortable casting votes on the paperless e-voting machines. "I don't want a voter to not vote on

Election Day because the only option before them is a touch-screen voting machine. I want that voter to have the

confidence that he or she can vote on paper and have the confidence that their vote was cast as marked," Secretary

Shelley said. See http://wired.com/news/evote/0,2645,63298,00.html

. (Our analysis revealed no differences in the

use of provisional ballots in the counties with these paperless e-voting machines.) In Ohio, long lines at some polling

places resulted in legal action directing that voters waiting in line be given provisional ballots to enable them to vote

before the polls closed. (Columbus Dispatch, November 3, 2004 .)

6

Our research began in late May 2005. It focused on six key questions raised by the EAC.

1. How did the states prepare for the onset of the HAVA provisional ballot requirement?

2. How did this vary between states that had previously had some form of provisional ballot

and those that did not?

3. How did litigation affect implementation?

4. How effective was provisional voting in enfranchising qualified voters?

5. Did state and local processes provide for consistent counting of provisional ballots?

6. Did local election officials have a clear understanding of how to implement provisional

voting?

To answer those questions, we:

1. Surveyed 400 local (mostly county) election officials to learn their views about the

administration of provisional voting and to gain insights into their experience in the 2004

election.

2. Reviewed the EAC’s Election Day Survey, news and other published reports in all 50

states to understand the local background of provisional voting and develop leads for

detailed analysis.

4

3. Analyzed statistically provisional voting data from the 2004 election to determine

associations between the use of provisional voting and such variables as states’

experience with provisional voting, use of statewide registration databases, counting out-

of-precinct ballots, and use of different approaches to voter identification.

4. Collected and reviewed the provisional voting statutes and regulations in all 50 states.

5. Analyzed litigation affecting provisional voting or growing out of disputes over provisional

voting in all states.

Our research is intended to provide EAC with a strategy to engage the states in a continuing

effort to strengthen the provisional voting process and increase the consistency with which

provisional voting is administered, particularly within a state. As EAC and the states move

forward to assess and adopt the recommendations made here, provisional voting merits

continuing observation and research. The situation is fluid. As states, particularly those states

that did not offer a provisional ballot before 2004, gain greater experience with the process and

as statewide voter databases are adopted, the provisional voting process will demand further,

research-based refinement.

KEY FINDINGS

Variation among the states

In the 2004 election, nationwide about 1.9 million votes, or 1.6% of turnout, were cast as

provisional ballots. More than 1.2 million, or just over 63%, were counted. Provisional ballots

accounted for a little more than 1% of the final vote tally. These totals obscure the wide variation

in provisional voting among the states.

5

4

Attachment 1 provides detailed information on how this study classifies the states according to the characteristics of

their provisional voting procedures. It also describes how the data used in the statistical analysis may differ from the

data in the Election Day Survey, which became available as our research was concluding.

5

HAVA allows the states considerable latitude in how to implement provisional voting, including deciding who beyond

the required categories of voters should receive provisional ballots and how to determine which provisional ballots

should be counted.

7

• Six states accounted for two-thirds of all the provisional ballots cast.

6

• The percentage of provisional ballots in the total vote varied by a factor of 1,000 -- from

a high of 7% in Alaska to Vermont’s 0.006%.

• The portion of provisional ballots cast that were counted ranged from 96% in Alaska to

6% in Delaware.

• States with voter registration databases counted, on average, 20% of the provisional

ballots cast.

• States without databases counted ballots at more than twice that rate: 44%.

7

• States that provided more time to evaluate provisional ballots counted a greater

proportion of those ballots. Those that provided less than one week counted an average

of 35.4% of their ballots, while states that permitted more than 2 weeks, counted 60.8%.

An important source of variation among states was a state’s previous experience with

provisional voting and with the fail-safe voting provision of the National Voting Rights Act.

The share of provisional ballots in the total vote was six times greater in states that had

used provisional ballots before than in states where the provisional ballot was new. In the

25 states that had some experience with provisional voting before HAVA, a higher portion

of the total vote was cast as provisional ballots and a greater percentage of the

provisional ballots cast were counted than in the 18 new to provisional balloting.

8

Part of

that difference was due to how states had implemented the National Voting Rights Act,

particularly in regard to voters who changed address within weeks of the election. Voters

in California, for example, who moved within their county must cast a provisional ballot,

the information from which is used to update the voter’s address. Other states,

Tennessee for example, found that some fail-safe voters were reluctant to vote by

provisional ballot. As a result, Tennessee abandoned provisional voting for those who

moved within counties and allows failsafe voters cast a regular ballot. Relatively fewer

provisional ballots would tend to be cast in such states.

Variation within states

Within states, too, there was little consistency among different jurisdictions. Of the 20 states for

which we have county-level provisional ballot data, the rate of counting provisional ballots varied

by as much as 90% to 100% among counties in the same state. This variation suggests that

additional factors (including the training of election judges or poll workers) beyond statewide

factors, such as experience or the existence of voter registration databases, also influence the

use of provisional ballots.

• In Ohio some counties counted provisional ballots not cast in the assigned precinct even

though the state’s policy was to count only those ballots cast in the correct precinct.

• Some counties in Washington tracked down voters who would otherwise have had their

provisional ballots rejected because they had failed to complete part of their registration

form, gave them the chance to correct those omissions, and then counted the

provisional ballot.

6

California, New York, Ohio, Arizona, Washington, and North Carolina. The appearance of Arizona, Washington and

North Carolina on this list shows that the number of provisional ballots cast depends on factors other than the size of

the population.

7

As the Carter-Baker Commission report put it, “provisional ballots were needed half as often in states with unified

databases as in states without.” Report on the Commission on Federal Election Reform, “Building Confidence in U. S.

Elections,” September 2005, p. 16.

8

See the appendix for our classification of “old” and “new” states and explanation of why the total is less than 50.

8

Resources available to administer provisional voting varied considerably among and within

states. Differences in demographics and resources result in different experiences with

provisional voting. For example, the Election Day Survey found that staffing problems appeared

to be particularly acute for jurisdictions in the lowest income and education categories. Small,

rural jurisdictions and large, urban jurisdictions tended to report higher rates of an inadequate

number of poll workers within polling places or precincts.

• Jurisdictions with lower education and income tend to report more inactive voter

registrations, lower turnout, and more provisional ballots cast.

• Jurisdictions with higher levels of income and education reported higher average

numbers of poll workers per polling place or precinct and reported lower rates of staffing

problems per precinct.

In precincts located in districts where many voters live in poverty and have low levels of income

and education, the voting process, in general, may be managed poorly. Provisional ballots

cannot be expected to work much better. In these areas, the focus should be on broader

measures to improve the overall functionality of struggling voting districts, although improving

the management of provisional balloting may help at the margin.

The lessons of litigation

Successful legal challenges highlight areas where provisional voting procedures were wanting.

A flurry of litigation occurred around the country in October 2004 concerning the so-called

“wrong precinct issue” – whether provisional ballots cast by voters in a precinct other than their

designated one would be counted for statewide races. Most courts, including the U.S. Court of

Appeals for the Sixth Circuit (the only federal appeals court to rule on the issue), rejected the

contention that HAVA requires the counting of these wrong-precinct provisional ballots. This

litigation was significant nonetheless.

• First, the Sixth Circuit decision established the precedent that voters have the right to sue

in federal court to remedy violations of HAVA.

• Second --and significantly-- the litigation clarified the right of voters to receive provisional

ballots, even though the election officials were certain they would not be counted. The

decision also defined an ancillary right – the right to be directed to the correct precinct.

There voters could cast a regular ballot that would be counted. If they insisted on casting

a provisional ballot in the wrong precinct, they would be on notice that it would be a

symbolic gesture only.

• Third, these lawsuits prompted election officials to take better care in instructing precinct

officials on how to notify voters about the need to go to the correct precinct in order to

cast a countable ballot.

States move to improve their processes

Shortly after the 2004 election, several states came to the conclusion that the administration of

their provisional voting procedures needed to be improved, and they amended their statutes.

The new legislation highlights areas of particular concern to states about their provisional voting

process.

• Florida, Indiana, Virginia, and Washington have clarified or extended the timeline to

evaluate the ballots.

9

• Colorado, New Mexico, North Carolina, and Washington have passed legislation

focused on improving the efficacy and consistency of the voting and counting process.

• Colorado, Arkansas, and North Dakota took up the issue of counting provisional ballots

cast in the wrong precinct.

The wide variation in the implementation of provisional voting among and within states suggests

that EAC can help states strengthen their processes. Research-based recommendations for

best, or at least better, practices that draw on the experience gained in the 2004 election can be

useful in states’ efforts to achieve greater consistency in the administration of provisional voting.

The important effect of experience on the administration of the provisional ballot process

indicates that the states have much they can learn from each other.

SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS FOR BEST PRACTICES

State efforts to improve the provisional voting process have been underway since the 2004

election. By recommending best practices, the EAC will offer informed advice while respecting

diversity among the states.

Take a quality-improvement approach

Defining what constitutes a successful provisional voting system is difficult. Defining quality

requires a broad perspective about how well the system works, how open it is to error

recognition and correction, and how well provisional voting processes are connected to the

registration and voter identification regimes. A first step is for states to recognize that improving

quality begins with seeing the provisional voting process as a system and taking a systems

approach to regular evaluation through standardized metrics with explicit goals for performance.

EAC can facilitate action by the states by recommending as a best practice that:

• Each state collect data systematically on the provisional voting process to permit

evaluation of its voting system and assess changes from one election to the next. The

data collected should include: provisional votes cast and counted by county; reasons

why provisional ballots were not counted, measures of variance among jurisdictions, and

time required to evaluate ballots by jurisdiction

Emphasize the importance of clarity

Above all else, the EAC should emphasize the importance of clarity in the rules by which each

state governs provisional voting. As state legislators and election officials prepare for the 2006

election, answers to the questions listed in the recommendations section of this report could be

helpful. Among those questions are:

• Does the provisional voting system distribute, collect, record, and tally provisional ballots

with sufficient accuracy to be seen as procedurally legitimate by both supporters and

opponents of the winning candidate?

• Do the procedural requirements of the system permit cost-efficient operation?

• How great is the variation in the use of provisional voting in counties or equivalent levels

of voting jurisdiction within the state? Is the variation great enough to cause concern that

the system may not be administered uniformly across the state?

Court decisions suggest areas for action

10

The court decisions following the 2004 election also suggest procedures for states to

incorporate into their procedures for provisional voting. EAC should recommend to the states

that they:

• Promulgate clear standards for evaluating provisional ballots, and provide training for the

officials who will apply those standards.

• Provide effective materials to be used by local jurisdictions in training poll workers on

such procedures as how to locate polling places for potential voters who show up at the

wrong place.

• Make clear that the only permissible requirement to obtain a provisional ballot is an

affirmation that the voter is registered in the jurisdiction and eligible to vote in an election

for federal office. Poll workers need appropriate training to understand their duty to give

such voters a provisional ballot.

Assess each stage of the provisional voting process

Beyond the procedures suggested by court decisions, states should assess each stage of the

provisional voting process. They can begin by assessing the utility and clarity of the information

for voters on their websites and by considering what information might be added to sample

ballots mailed to voters before elections. The better voters understand their rights and

obligations, the easier the system will be to manage, and the more legitimate the appearance of

the process.

Avoiding error at the polling place will allow more voters to cast a regular ballot and all others

who request it to cast a provisional ballot. Our recommendations for best practices to avoid error

at the polling place include:

• The layout and staffing of the multi-precinct polling place is important. States should

ensure that training materials distributed to every jurisdiction make poll workers familiar

with the options available to voters.

• The provisional ballot should be of a design or color sufficiently different from a regular

ballot to avoid confusion over counting and include take-away information for the voter

on the steps in the ballot evaluation process.

• Because provisional ballots offer a fail-safe, supplies of the ballots at each polling place

should be sufficient for all the potential voters likely to need them. Best practice for

states should provide guidelines (as do Connecticut and Delaware) to estimate the

supply of provisional ballots needed at each polling place.

The clarity of criteria for evaluating voter eligibility is critical to a sound process for deciding

which of the cast provisional ballots should be counted.

• State statutes or regulations should define a reasonable period for voters who lack the

HAVA-specified ID or other information bearing on their eligibility to provide it in order to

facilitate the state’s ability to verify that the person casting the provisional ballot is the

same one who registered. At least 11 states allow voters to provide ID or other

information one to 13 days after voting. Kansas allows voters to proffer their ID by

electronic means or by mail, as well as in person.

• More provisional voters have their ballots counted in those states that count ballots cast

outside the correct precinct. While HAVA arguably leaves this decision up to the states,

pointing out the effect of the narrower definition on the portion of ballots counted could

be useful to the states in deciding this question. States should be aware, however, of the

additional burden placed on the ballot-evaluation process when out-of-precinct ballots

11

are considered. And tradeoffs are involved if out-of-precinct voters are unable to vote for

the local offices that might appear on the ballot in their district of residence.

• If a state does require voters to appear at their assigned precinct, where the same

polling site serves more than one precinct, a voter’s provisional ballot should count so

long as the voter cast that ballot at the correct polling site even if at the wrong precinct

within that location. While the best practice might be for poll workers to direct the voter to

correct precinct poll workers’ advice is not always correct, and the voter should be

protect against ministerial error.

• Officials should follow a written procedure, and perhaps a checklist, to identify the reason

why a provisional ballot is rejected. Colorado’s election rules offer particularly clear

guidance to the official evaluating a provisional ballot.

In verifying provisional ballots, the time by which election officials must make their eligibility

determinations is particularly important in presidential elections because of the need to certify

electors to the Electoral College. Our research did not identify an optimum division of the five

weeks available.

• The best practice here is for states to consider the issue and make a careful decision

about how to complete all steps in the evaluation of ballots and challenges to those

determinations within the five weeks available.

After the election, timely information to voters about the disposition of their provisional ballot can

enable voters to determine if they are registered for future elections and, if not, what they need

to do to become registered.

• Best practice for the states is to establish mechanisms to ensure that voters casting

provisional ballots are informed whether they are now registered for future elections and,

if not, what they need to do to become registered.

Final observation

The detailed examination of each stage in the provisional voting process can lay the foundation

each state needs to improve its system. Efforts to improve provisional voting may be most

effective as part of a broader effort by state and local election officials to strengthen their

systems. Collecting and analyzing data about those systems will enable states to identify which

aspects of the registration and electoral system are most important in shunting voters into the

provisional ballot process. Responsible officials can then look to their registration system,

identification requirements or poll worker training as ways to reduce the need for voters to cast

their ballots provisionally.

12

Provisional Voting in 2004

In the 2004 election, nationwide about 1.9 million votes, or 1.6% of turnout, were cast as

provisional ballots. More than 1.2 million or just over 63% were counted. Provisional ballots

accounted for a little more than 1% of the final vote tally.

These totals obscure the wide variation in provisional voting among the states.

9

Six states

accounted for two-thirds of all the provisional ballots cast.

10

State by state, the percentage of

provisional ballots in the total vote varied by a factor of 1,000 -- from a high of 7% in Alaska to

Vermont’s 0.006%. The portion of provisional ballots cast that were actually counted also

displayed wide variation, ranging from 96% in Alaska to 6% in Delaware. States with voter

registration databases counted, on average, 20% of the provisional ballots cast. Those without

databases counted provisional ballots at more than twice that rate, 44%.

An important source of variation was a state’s previous experience with provisional voting. The

share of provisional ballots in the total vote was six times greater in states that had used

provisional ballots before than in states where the provisional ballot was new. In the 25 states

that had some experience with provisional voting before HAVA, a higher portion of the total vote

was cast as provisional ballots and a greater percentage of the provisional ballots cast were

counted than in the 18 new to provisional balloting.

11

• The percentage of the total vote cast as provisional ballots averaged more than 2% in

the 25 experienced states. This was 4 times the rate in states new to provisional voting,

which averaged 0.47%.

12

• The experienced states counted an average of 58% of the provisional ballots cast,

nearly double the proportion in the new states, which counted just 33% of cast

provisional ballots.

• The combined effect of these two differences was significant. In experienced states

1.53% of the total vote came from counted provisional ballots. In new states, provisional

ballots accounted for only 0.23% of the total vote.

Those voting with provisional ballots in experienced states had their ballots counted more

frequently than those in the new states. This experience effect is evidence that there is room for

improvement in provisional balloting procedures, especially in those states new to the process.

13

That conclusion gains support from the perspectives of the local election officials revealed in the

survey conducted as a part of this research. Local (mostly county level) election officials from

“experienced” states were more likely to:

9

HAVA allows the states considerable latitude in how to implement provisional voting, including deciding who beyond

the required categories of voters should receive provisional ballots and how to determine which provisional ballots

should be counted.

10

California, New York, Ohio, Arizona, Washington, and North Carolina. The appearance of Arizona, Washington and

North Carolina on this list shows that the number of provisional ballots cast depends on factors other than the size of

the population.

11

See the appendix for our classification of “old” and “new” states and explanation of why the total is less than 50.

12

To compensate for the wide differences in vote turnout among the 50 states the average figures here are

calculated as the mean of the percent cast or counted rather than from the raw numbers of ballots cast or counted.

13

Managing the provisional voting process can strain the capacity election administrators. For example, Detroit,

counted 123 of the 1,350 provisional ballots cast there in 2004. A recent study concluded that Detroit’s “ 6-day time

limit to process provisional ballots was very challenging and unrealistic. To overcome this challenge, the entire

department’s employees were mobilized to process provisional ballots.” (emphasis added.) GAO Report-05-997,

“Views of Selected Local Officials on Managing Voter Registration and Ensuring Citizens Can Vote,” September

2005.

13

• Be prepared to direct voters to their correct precincts with maps;

• Regard provisional voting as easy to implement;

• Report that provisional voting sped up and improved polling place operations

• Conclude that the provisional voting process helped officials maintain accurate

registration databases.

Officials from “new” states, on the other hand, were more likely to agree with the statement that

provisional voting created unnecessary problems for election officials and poll workers.

If experience with provisional voting does turn out to be a key variable in performance, that is

good news. As states gain experience with provisional ballots their management of the process

could become more consistent and more effective over subsequent elections. Further

information from the EAC on best practices and the need for more consistent management of

the election process could sharpen the lessons learned by experience. The EAC can facilitate

the exchange of experience among the states and can offer all states information on more

effective administration of provisional voting.

Concluding optimistically that experience will make all the difference, however, may be

unwarranted. Only if the performance of the “new” states was the result of administrative

problems stemming from inexperience will improvement be automatic as election officials move

along the learning curve. Two other possibilities exist. Our current understanding of how

provisional voting worked in 2004 is not sufficient to determine unambiguously which view is

correct.

1. “New” states may have a political culture different from “old” states. That is, underlying

features of the “new” states political system may be the reason they had not adopted

some form of provisional voting before HAVA. The “new” states may strike a different

balance among the competing objectives of ballot access, ballot security and practical

administration. They may ascribe more responsibility to the individual voter to take such

actions as registering early, finding out where the right precinct is, or re-registering after

changing address. They may value keeping control at the local level, rather than ceding

authority to state or federal directives. The training they offer poll workers about

provisional ballots may not be as frequent or effective as in other states. If the

inconsistent performance in the “new” states arises out of this kind of political culture,

improving effectiveness in the use of the provisional ballots -- as measured by intrastate

consistency in administration--- will be harder and take longer to achieve.

14

2. “Old” states may devote fewer resources to updating their registration files or databases

because they consider provisional ballots as a reasonable fail safe way for voters with

registration problems a way to cast a ballot. The adoption of statewide voter registration

databases in compliance with HAVA therefore may reduce the variation in the use of

provisional ballots among the states.

Other influences decreasing consistency among the states include:

14

Despite differing political cultures among states and the latitude HAVA provides states, the statute does, indeed

impose some degree of uniformity on issues that Congress thought essential. For example, before HAVA, took effect,

“no state gave the voter the right to find out the status of their ballot after the election. “ Now all offer that opportunity.

See Bali and Silver, “The Impact of Politics, Race and Fiscal Strains on State Electoral Reforms after Election 2000,”

manuscript, Department of Political Science, Michigan State University. Resisting HAVA’s mandates through foot-

dragging lacks any legitimate foundation in law or policy.

14

• The more rigorous the verification requirements, the smaller the percentage of

provisional ballots that were counted. Some states verified provisional ballots by

comparing the voter’s signature to a sample, some matched such identifying data as

address, birth date, or social security number, others required voters who lacked ID at

the polling place to return later with the ID to evaluate the provisional ballot, and some

required provisional voters to execute an affidavit.

15

- In the 4 states that simply matched signatures, nearly 3.5% of the total turnout

consisted of provisional ballots, and just under three-fourths of those ballots

(73%) were counted.

- In the 14 states that required voters to provide such additional information as

address or date of birth just over 1.5% of the total turnout consisted of provisional

ballots, and 55% of those ballots were counted.

- In the 14 states that required an affidavit (attesting, for example, that the voter

was legally registered and eligible to vote in the jurisdiction) just over one-half of

a percent (0.6%) of turnout came from provisional ballots, and less than one-third

of those (30%) were counted. (But note that HAVA requires all voters to certify

that they are eligible and registered in order to cast a provisional ballot, which is

functionally an affidavit. The 14 states described here used an explicit affidavit

form.)

- In the 10 states that required voters to return later with identifying documents just

under 1.5% of the total turnout came from provisional ballots, and more than half

(52%) of these were counted. Voters apparently found this requirement less

onerous than the affidavit, even though it required a separate trip to a

government office

• Voter registration databases provided information that reduced the number of provisional

ballots counted.

16

In states using provisional voting for the first time, states with

registered-voter databases counted only 20% of the ballots that were cast. States

without such databases counted more than double that rate (44%). As HAVA’s

requirement for adoption of statewide databases spreads across the country, this

variation among states is likely to narrow. Real-time access to a continually updated,

statewide list of registered voters should reduce the number of provisional ballots used

and reduce the percentage counted since most of those who receive them will be less

likely to be actually registered in the state.

• States that counted out-of-precinct ballots counted 56% of the provisional ballots cast.

States that counted only ballots cast in the proper precinct counted an average of 42%

of provisional ballots.

17

- In experienced states, the disparity was even more pronounced: just over half of

provisional ballots cast were counted in states requiring in-district ballots, while

more than two-thirds were counted in those allowing out-of-precinct ballots.

- If all states had counted out-of-precinct ballots, perhaps 290,000 more

provisional ballots would have been counted across the country.

18

15

See Table 2 in Appendix 2 for information on the verification method used in each state.

16

The Election Day Survey found that states using statewide voter registration databases reported a lower incidence

of casting provisional ballots than states without voter registration databases, suggesting that better administration of

voter registration rolls might be associated with fewer instances where voters would be required to cast a provisional

ballot due to a problem with their voter registration.

17

The Election Day Survey concluded that : “Jurisdictions with jurisdiction-wide provisional ballot acceptance

reported higher rates of provisional ballots cast, 2.09 percent of registration or 4.67 percent of ballots cast in polling

places, than those with in-precinct-only acceptance, 0.72 and 1.18 percent, respectively. Predictably, those

jurisdictions with more permissive jurisdiction-wide acceptance reported higher rates of counting provisional ballots,

71.50 percent, than other jurisdictions, 52.50 percent.”

15

• States that provide a longer the time to evaluate provisional ballots counted a higher

proportion of those ballots.

19

- Fourteen states permitted less than one week to evaluate provisional ballots, 15

states permitted between one and two weeks, and 14 states permitted greater

than two weeks

20

.

- Those states that permitted less than one week counted an average of 35.4% of

their ballots.

- States that permitted between one and two weeks counted 47.1%.

- States that permitted more than 2 weeks, counted 60.8% of the provisional

ballots cast

21

.

- The effect of allowing more time for evaluation is felt most strongly in states

where more than 1% of the overall turnout was of provisional ballots. In states

where provisional ballots were used most heavily, those that permitted less than

one week to evaluate ballots counted 58.6% while those that permitted one to

two weeks counted 65.0% of ballots, and those states that permitted greater than

three weeks verified the highest proportion of provisional ballots, at 73.8%.

Variation Within States

Not only was there little consistency among states in the use of provisional ballots, there was

also little consistency within states. This was true in both new and old states. Of the 20 states

for which we have county-level provisional ballot data, the rate of counting provisional ballots

varied by as much as 90% to 100% among counties in the same state. This suggests that

additional factors beyond statewide factors, such as verification requirements or the time

provided for ballot evaluation, also influence the provisional voting process. Reacting to the lack

of consistency within states, the Carter-Baker Commission recommended that “states, not

counties or municipalities, should establish uniform procedures for the verification and counting

of provisional ballots, and that procedure should be applied uniformly throughout the state.”

22

Electionline reported that:

• In Ohio some counties counted provisional ballots not cast in the assigned precinct even

though the state’s policy was to count only those ballots cast in the correct precinct.

• Some counties in Washington tracked down voters who would otherwise have had their

provisional ballots rejected because they had failed to complete part of their registration

form, gave them the chance to correct those omissions, and then counted the

18

This estimate is a rough approximation. States that recognize out-of-precinct ballots counted, on average, 56% of

the provisional votes cast. Applying that ratio to the 1.9 million provisional ballots cast nationwide would result in 1.1

million provisional ballots that would have been counted if all states accepted out-of-precinct votes. States that did not

recognize out-of-precinct ballots counted 42% of the provisional ballots cast, or about 813,000 ballots, for a difference

of about 290,000 votes.

19

See Appendix, Relationship Between Time Allotted to Verify Provisional Ballots and the Level of Ballots that are

Verified, David Andersen, The Eagleton Institute of Politics

20

Many thanks to Ben Shepler, of the Moritz College of Law, for assembling complete data on the time requirements

states permitted for the counting of provisional ballots.

21

43 states are included in this analysis, including Washington D.C. The 7 election-day registration states are

omitted, as is Mississippi, which never provided data on provisional ballots. North Carolina is also omitted from the

regressions, as it does not have a statewide policy on how it verifies provisional ballots.

22

Recommendation 2.3.2 of the Report of the Commission on Federal Election Reform, “Building Confidence in U.S.

Elections,” September 2005, p.16. The report also observed that, “. . .different procedures for counting provisional

ballots within and between states led to legal challenges and political protests. Had the margin of victory for the

presidential contest been narrower, the lengthy dispute that followed the 2000 election could have been repeated.”

16

provisional ballot. This would probably not have come to light except for the sharp

examination caused by the very close election for governor.

Resources available to administer provisional voting varied considerably among and within

states. The result is that differences in demographics and resources result in different

experiences with provisional voting. For example, the Election Day Survey found that:

• Jurisdictions with lower education and income tend to report more inactive voter

registrations, lower turnout, and more provisional ballots cast.

• Jurisdictions with higher levels of income and education reported higher average

numbers of poll workers per polling place or precinct and reported lower rates of staffing

problems per precinct.

• Staffing problems appeared to be particularly acute for jurisdictions in the lowest income

and education categories. Small, rural jurisdictions and large, urban jurisdictions tended

to report higher rates of an inadequate number of poll workers within polling places or

precincts.

• Predominantly non-Hispanic, Black jurisdictions reported a greater percentage of polling

places or precincts with an inadequate number of poll workers. Predominantly non-

Hispanic, Native American jurisdictions reported the second highest percentage of

staffing problems.

The conclusions to be drawn from these findings are clear. In voting districts with lower

education levels, poverty, and inadequately staffed polling places, the voting process is unlikely

to function well. More people will end up casting provisional ballots. That makes the provisional

voting process especially important in such districts. But if jurisdictions struggle with regular

voting, how well are they likely to do with the more complicated provisional balloting process? In

precincts where the voting process, in general, is managed poorly, provisional ballots cannot be

expected to work much better. In these areas, the focus should be on broader measures to

improve the overall functionality of struggling voting districts, although improving the

management of provisional balloting may help at the margin.

Effectiveness of Provisional Voting

The certainty of our conclusions about the effectiveness of provisional voting is limited because

of the complexity of the problem and a lack of important information. An ideal assessment of

how well provisional ballots worked in 2004 would require knowing the decisions of local officials

in 200,000 precincts on how to inform voters about provisional voting; their performance in

providing a provisional ballot to those qualified to receive one, and their decisions whether to

count a provisional ballot. Information needed about the eligibility or registration status of

provisional voters is also not available.

We see no automatic correlation between the quality of a state’s voting system and either the

number of provisional ballots cast or counted. Low numbers could reflect accurate statewide

voting data and good voter education. Or they could suggest that provisional ballots were not

made easily available. High numbers could be seen as signifying an effective provisional voting

system or a weak registration process. But we do know that in 2004 provisional ballots allowed

1.2 million citizens to vote, citizens who would otherwise have been turned away from the polls.

Since we do not know how many registered voters who might have voted but could not, we

cannot estimate with any precision how effective provisional voting was in 2004. The Cal Tech –

MIT Voting Technology Project, however, estimated that 4 – 6 million votes were lost in the

17

2000 presidential election for the reasons shown in Table 1 below. The estimate is an

approximation, but it may provide data good enough for a general assessment of the size of the

pool of potential voters who might have been helped by the provisional ballot process.

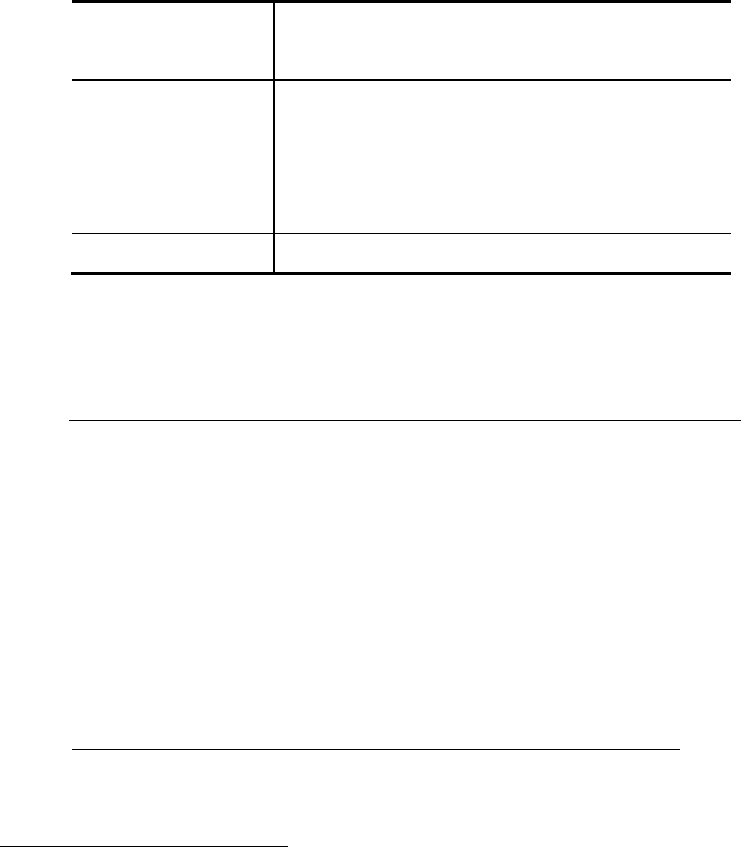

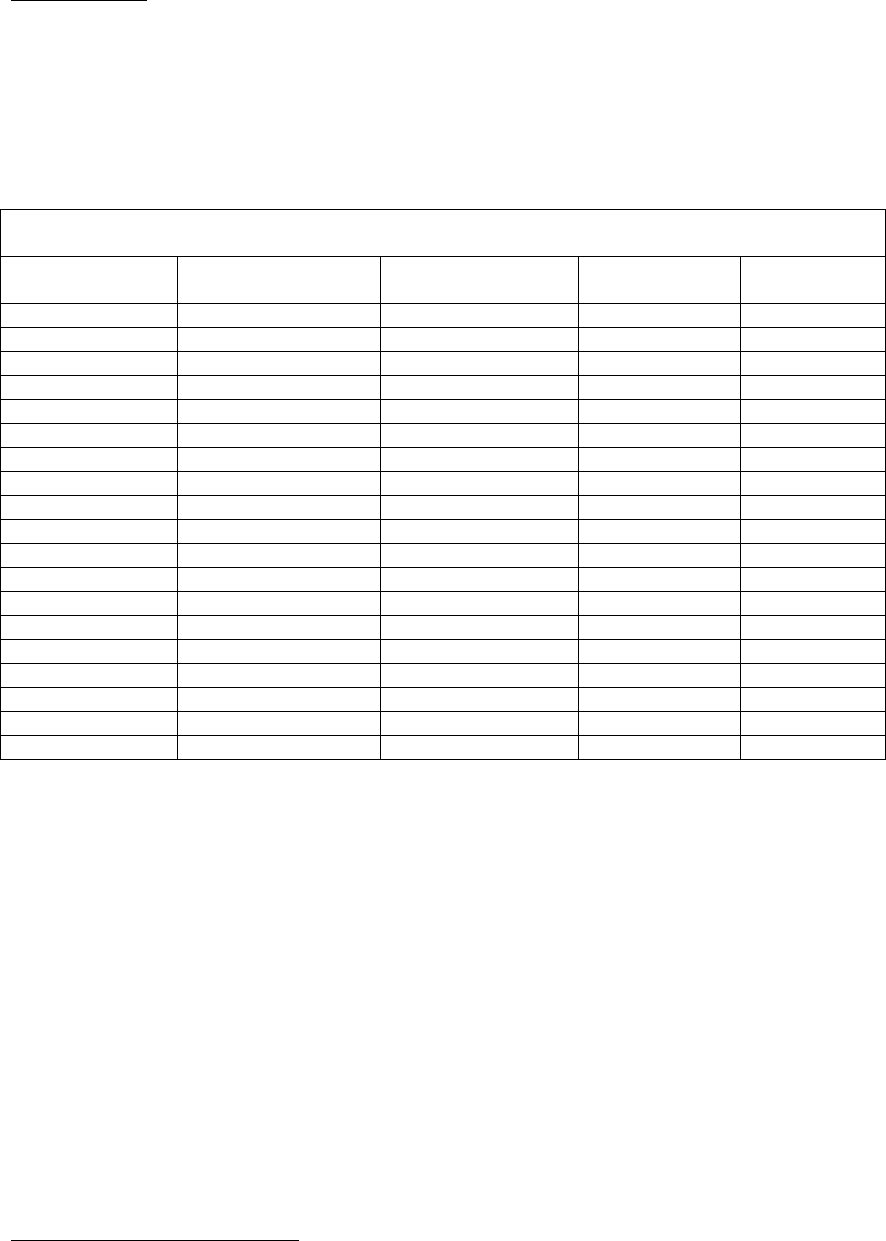

Estimates of Votes Lost In 2000 Presidential Election

Votes

Lost

(Millions)

Cause

1.5 – 2 Faulty equipment and confusing

ballots

1.5 – 3 Registration mix-ups

<1 Polling place operations

?

Absentee ballot administration

Table 1 Cal Tech – MIT Voting Technology Project Estimates

4 – 6 million votes are lost in presidential elections due to the causes

shown in the table. Registration mix-ups (e.g., name not on list) and polling

place operations (e.g., directed to wrong precinct) are the causes most

likely to be remedied by provisional voting.

The table shows that the universe of voters who could be helped by provisional voting might be

2.5 – 3 million voters. In 2004, about 1.2 million provisional voters were counted. A rough

estimate of the effectiveness of provisional voting in 2004, then, might be 40% to 50% (ballots

counted/votes lost)

23

. Whatever the precise figure, it seems reasonable to conclude that there

is considerable room for improvement in the administration of provisional voting.

Legislative Response

Indeed, several states

24

came to the conclusion that the administration of their provisional voting

procedures needed to be improved and amended their statutes after the 2004 election. State

legislation adopted since the election points to particular areas of concern.

• Not enough time to examine and count the provisional ballots.

Florida, Indiana, Virginia,

and Washington all have clarified or extended the timeline to evaluate the ballots. But

taking more time can prove a problem, particularly in presidential elections with the

looming deadline to certify the vote for the Electoral College.

25

23

Another interpretation of the data should be considered. The Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey (CPS)

developed the category of ”registration mix-ups” to assess the states’ registration systems. After each election the

CPS asks people if they were registered and if they voted. The CPS gives breakdowns of reasons why people did

not vote. Survey responders tend to deflect blame when answering questions about voting. In the narrow context of

provisional ballots, 'registration problems' would cover only voters who went to the polls where the determination that

they were not registered was wrong or they were registered, but in the wrong precinct. If they were in the wrong

precinct, provisional voting can help them in only 17 states. In 2004, only 6.8% of those not voting and registered

blamed registration problems, while 6.9% reported so in 2000.

24

Twelve states made statutory or regulatory changes: Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Indiana,

Louisiana, Montana, New Mexico, North Carolina, Virginia and Wyoming. See Table 4 in Appendix 2.

25

The resources available to evaluate and count provisional ballots within a tight schedule may not be easily

available. The General Accounting Office reports that Detroit, where 1,350 provisional ballots were cast and 123

counted, found the 6-day time frame for processing provisional ballots “very challenging and unrealistic. To overcome

this challenge, the entire department’s employees were mobilized to process provisional ballots.” The report also

found that in Los Angeles County, “staff had to prepare duplicate ballots to remove ineligible or invalid contests when

18

• Lack of uniform rules for counting ballots and effective training

of the election officials in

interpreting and applying those rules to determine the validity of ballots. Colorado, New

Mexico, North Carolina, and Washington have all passed legislation focused on

improving the efficacy and consistency of the voting and counting process.

Litigation

Successful legal challenges to the process highlight areas where provisional voting procedures

were wanting. A flurry of litigation occurred around the country in October 2004 concerning the

so-called “wrong precinct issue” – whether provisional ballots cast by voters in a precinct other

than their designated one would be counted for statewide races. These lawsuits were largely

unsuccessful in their stated goal: most courts, including the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth

Circuit (the only federal appeals court to rule on the issue), rejected the contention that HAVA

requires the counting of these wrong-precinct provisional ballots.

This litigation was significant nonetheless.

• First, the Sixth Circuit decision established the precedent that voters have the right to sue

in federal court to remedy violations of HAVA.

• Second --and significantly-- the litigation clarified the right of voters to receive provisional

ballots, even though the election officials were certain they would not be counted. The

decision also defined an ancillary right –the right to be directed to the correct precinct.

There voters could cast a regular ballot that would be counted. If they insisted on casting

a provisional ballot in the wrong precinct, they would be on notice that it would be a

symbolic gesture only.

• Third, these lawsuits prompted election officials to take better care in instructing precinct

officials on how to notify voters about the need to go to the correct precinct in order to

cast a countable ballot – although the litigation regrettably came too late to be truly

effective in this regard. In many states, on Election Day 2004, the procedures in place

for notifying voters about where to go were less than ideal, reflecting less-than-ideal

procedures for training poll workers on this point.

There was also pre-election litigation over the question whether voters who had requested an

absentee ballot were entitled to cast a provisional ballot. In both cases (one in Colorado and

one, decided on Election Day, in Ohio), the federal courts ruled that HAVA requires that these

voters receive a provisional ballot. Afterwards, it is for state officials under state law to

determine whether these provisional ballots will be counted, in part by determining if these

provisional voters already had voted by absentee ballot (in which case one ballot should be

ruled ineligible, in order to avoid double voting). These decisions confirm the basic premise that

provisional ballots should be available whenever voters believe they are entitled to them, so that

their preferences can be recorded, with a subsequent determination whether these preferences

count as valid votes.

voters cast their ballots at the wrong precinct. To overcome this challenge, staffing was increased to prepare the

duplicate ballots.” In a close, contested election, “duplicate” ballots would doubtless receive long and careful

scrutiny.” See Appendix 7, GAO, “Views of Selected Local Election Officials on Managing Voter Registration and

Ensuring Eligible Citizens Can Vote,” September 2005. (GAO Report-05-997)

19

RECOMMENDATIONS

Because every provisional ballot counted represents a voter who, if the system had worked

perfectly, should have voted by regular ballot, the advent of statewide registration databases is

likely to reduce the use provisional ballots. The one area in which such databases may not

make a difference is for those who voted by provisional ballot because they did not bring

required identification documents to the polling place. The statewide voter registration database

will facilitate verifying that ballot, but the voter will still have to vote provisionally. Beyond that

exception, even with statewide registries in every state, provisional voting will remain an

important failsafe, and voters should have confidence that the failsafe will operate correctly.

The wide variation in the implementation of provisional voting among and particularly within

states suggests that EAC can help states strengthen their processes. Research-based

recommendations for best, or at least better, practices based on the experience gained in the

2004 election can be useful in states’ efforts to achieve greater consistency in the administration

of provisional voting.

Recommendations for Best Practices

Recent legislative activity shows that state efforts to improve the provisional voting process are

underway. Those states, as well as others that have not yet begun to correct shortcomings that

became apparent in 2004, can benefit from considering the best practices described here. By

recommending best practices, the EAC will offer informed advice while respecting diversity

among the states. One way to strengthen the recommendations and build a constituency for

them would be for EAC to ask its advisory committee members to recommend as best practices

procedures that have worked in their states.

Self-evaluation of Provisional Voting –4 Key Questions

The first step to achieving greater consistency within each state is to think about provisional

voting systematically. As legislators, election officials, and citizens in the states prepare for the

2006 election, they should ask themselves these questions about their provisional voting

systems.

1. Does the provisional voting system distribute, collect, record, and tally provisional ballots

with sufficient accuracy to be seen as procedurally legitimate by both supporters and

opponents of the winning candidate? Does the tally include all votes cast by properly

registered voters who correctly completed the steps required?

2. Is the provisional voting system sufficiently robust to perform well under the pressure of

a close election when ballot evaluation will be under scrutiny and litigation looms?

3. Do the procedural requirements of the system permit cost-efficient operation? Are the

administrative demands of the system reasonably related to the staff and other resource

requirements available?

4. How great is the variation in the use of provisional voting in counties or equivalent levels

of voting jurisdiction within the state? Is the variation great enough to cause concern that

the system may not be administered uniformly across the state?

If the answers to these questions leave room for doubt about the effectiveness of the system or

some of its parts, the EAC’s recommendation of best practices should provide the starting point

for a state’s effort to improve its provisional voting system.

20

Best Practices For Each Step In The Process

We examined each step of the provisional voting process to identify specific areas where the

states should focus their attention to reduce the inconsistencies noted in our analysis. We offer

recommendations in each area appropriate to the responsibilities that HAVA assigns the EAC

for the proper functioning of the provisional voting process.

The Importance of Clarity

The EAC should emphasize above all else the importance of clarity in the rules governing every

stage of provisional voting. As the Century Foundation’s recent report observed, “Close

elections increasingly may be settled in part by the evaluating and counting of provisional

ballots. . . To avoid post election disputes over provisional ballots—disputes that will diminish

public confidence in the accuracy and legitimacy of the result-- well in advance of the election,

states should establish, announce, and publicize clear statewide standards for every aspect of

the provisional ballot process, from who is entitled to receive a provisional ballot to which ones

are counted.”

26

Litigation surrounding the 2004 election resulted in decisions that, if reflected in state statutes or

regulations and disseminated in effective training for poll workers, can increase the clarity of

provisional ballot procedures, increase predictability, and bolster confidence in the system. By

taking the following steps, states can incorporate those court rulings into their procedures.

• Promulgate, ideally by legislation, clear standards for evaluating provisional ballots, and

provide training for the officials who will apply those standards. For example, in

Washington State, the court determined that an election official’s failure in evaluating

ballots to do a complete check against all signature records is an error serious enough to

warrant re-canvassing.

27

Clear direction by regulation or statute on what records to use

in evaluating ballots could have saved precious time and effort and increased the

reliability of the provisional voting system.

• States should provide standard information resources for the training of poll workers by

local jurisdictions. Training materials might include, for example, maps or databases with

instruction on how to locate polling places for potential voters who show up at the wrong

place. Usable and useful information in the hands of poll workers can protect voters from

being penalized by ministerial errors at the polling place.

28

• State training materials provided to local jurisdictions should make clear that the only

permissible requirement to obtain a provisional ballot is an affirmation that the voter is

registered in the jurisdiction and eligible to vote in an election for federal office.

29

Recent

legislation in Arizona indicates that recommendations should emphasize HAVA’s

requirement that persons appearing at the polling place claiming to be registered voters

cannot be denied a ballot because they do not have identification with them. Poll

26

The Century Foundation, Balancing Access and Integrity, Report of the Working Group on State Implementation of

Election Reforms, July 2005.

27

See Washington State Republican Party v. King County Division of Records, 103 P3d 725, 727-728 (Wash. 2004)

28

See Panio v. Sunderland 824 N.E.2d 488, 490 (NY, 2005) See also Order, Hawkins v. Blunt, No.04-4177-CV-C-

RED (W.D. Mo. October 12, 2004). While rejecting the notion that all ballots cast in the wrong precinct should be

counted, the court ruled that provisional votes cast in the wrong precinct should be thrown out provided that the voter

had been directed to the correct precinct. This meant that provisional votes cast in the wrong precinct (and even the

wrong polling place) would count if there were no evidence that the voter had been directed to a different polling

place. The court placed a duty upon election officials to make sure the voters were in the correct locations. Note that

this question would not arise in a state that counted ballots cast in the wrong polling place but within the correct

county.

29

Sandusky County Democratic Party v. Blackwell, 387 F.3d 565, 774 (6

th

Cir. 2004)

21

workers may need appropriate training to understand their duty to give such voters a

provisional ballot.

30

A. Registration and Pre-Election Information for Voters

Providing crisp, clear information to voters before the election is important to the success of the

provisional voting process. The better voters understand their rights and obligations, the easier

the system will be to manage, and the more legitimate the appearance of the process. States

can begin by assessing the utility and clarity of the information for voters on their websites and

by considering what information might be added to sample ballots mailed to voters before

elections. Best practices in this area would include:

1. If states require identification at the time of registration, the kind of IDs required should

be stated precisely and clearly and be publicly and widely available in a form that all

voters can understand. For example, “You must bring your driver’s license. If you don’t

have a driver’s license, then you must bring an ID card with your photograph on it and

this ID card must be issued by a government agency. ”

31

2. The process to re-enfranchise felons should be clear and straightforward. To avoid

litigation over the registration status of felons, best practice should be defined as making

re-enfranchisement automatic, or no more burdensome than the process required for

any new registrant.

32

3. State or county websites for voters should offer full, clear information on boundaries of

precincts, location of polling places, requirements for identification, and other necessary

guidance that will facilitate registration and the casting of a regular ballot. An 800

number should also be provided. Models are available: the statewide databases in

Florida and Michigan provide voters with provisional voting information, registration

verification and precinct location information.

B. At the Polling Place

Avoiding error at the polling place will allow more voters to cast a regular ballot and all others

who request it to cast a provisional ballot.

1. The layout and staffing of the polling place, particularly the multi-precinct polling place is

important. Greeters, maps, and prominently posted voter information about provisional

ballots, ID requirements, and related topics can help the potential voters cast their ballot

in the right place. States should require poll workers to be familiar with the options and

provide the resources needed for them to achieve the knowledge needed to be helpful

and effective. Colorado has clear regulations on polling place requirements, including

HAVA information and voting demonstration display.

33

Many states require training of

poll workers. In some states that requirement is recent: after the 2004 election, New

Mexico adopted a requirement for poll workers to attend an “election school.”

34

A state

30

The Florida Democratic Party v. Hood, 342 F. Supp. 2d 1073, 1075-76 (N.D. Fla. 2004). The court explained that

provisional voting is designed to correct the situation that occurs when election officials do not have perfect

knowledge and when they make incorrect determinations about eligibility (the “fail-safe” notion). Denying voters

provisional ballots because of on-the-spot determinations directly contradicts this idea. Even before the cited

decision, the Florida Secretary of State’s office had determined that any voter who makes the declaration required by

federal law is entitled to vote a provisional ballot, even if the voter is in the wrong precinct.

31

Websites in 29 states describe, with varying degrees of specificity, the identification voters may need. In 18 states

voters can learn something about the precinct in which they should vote. And in 6 states (California, District of

Columbia, Kentucky, Michigan, North Carolina, and South Carolina) they can verify their registration on the website.

32

The Century Foundation, op. cit.

33

8 Colo. Code Regs. § 1505-1, Rule 7.1.

34

2005 N.M. Laws 270 page no. 4-5.

22

statutory requirement for training could facilitate uniform instruction of poll workers in

those states that do not already provide it.

2. The provisional ballot should be of a design or color sufficiently different from a regular

ballot to avoid confusion over counting, as occurred in Washington State. The ballot

might include a tear-off leaflet with information for voters such as: “Reasons Why Your

Provisional Ballot Might Not Be Counted” on one side and “What to Do if My Provisional

Ballot Is Not Counted” on the other.

3. Because provisional ballots offer a fail-safe, supplies of the ballots at each polling place

should be sufficient for all the potential voters likely to need them. In 2004, some polling

places ran out of ballots, with unknown effects on the opportunity to vote. In Middlesex

County, New Jersey, for example, on Election Day the Superior Court ordered the

county clerk to assure that sufficient provisional ballots were available at several heavily

used polling places, and it authorized the clerk “in the event additional provisional ballots

are required . . .to photocopy official provisional ballots.”

35

At least two states,

Connecticut and Delaware, provide guidelines to local election officials on how to

estimate the demand for provisional ballots. Connecticut sets the number at 1% of the

voters in the district, Delaware at 6%.

36

States that do not offer a practical method to

guide the supply of provisional ballots at polling places should consider doing so. The

guideline should take into account both the number of voters in the district and the

number of provisional ballots actually cast in recent elections.

4. To achieve the procedural clarity needed to forestall disputes, states should establish a

clear chain of custody for the handling of provisional ballots from production through

distribution, collection and, finally, evaluation. A number of states have clear procedures

for at least parts of this chain of custody. All states should examine their chain-of-

custody requirements for clarity. Illinois includes the potentially beneficial requirement

that ballots be transported by bi-partisan teams, which offers the potential to avoid some

charges of election fraud.

C. Evaluating Voter Eligibility and Counting Provisional Ballots

The clarity of criteria for evaluating voter eligibility is critical to a sound process for deciding

which of the cast provisional ballots should be counted. Public recognition of the validity of those

criteria is important to establishing the legitimacy of the system as a whole. The experience in

2004 in North Carolina, Washington, and Ohio underlines the importance of clear criteria. As the

Century Foundation report put it, “Whatever procedures the states choose [to determine if a

provisional ballot should be counted], the paramount consideration—as with all others

concerning provisional voting—is that they be clear and thus not susceptible to post-election

manipulation and litigation.”

37

Nonetheless, the Panio v. Sutherland

38

decision in New York

shows the difficulty of defining the range of administrative errors from which the provisional

voters should be held harmless. Even when the standard is “clerical error” judges can differ over

what that means exactly. Possibly a state law might be able to clarify a definition by giving

examples of clerical errors, but even then the definition is unlikely to be perfect.

35

Voting Order, November 2, 2004, Superior Court of New Jersey, Law Division, Middlesex County.

36

Connecticut: “Equal to or not less than 1% of the number of electors who are eligible to vote in any given district, or

such other number as the municipal clerk and the registrars agree is sufficient to protect voting rights. Conn. Gen.

Stat. Ann. § 9-232j.Delaware: Each County Department of Elections Office is required to provide to each election

district a number of provisional ballots equal to 6% of registered voters in that district, with a minimum allocation of 15

ballots. Additional supplies to be delivered when the supply becomes “very low.” Del.Code Ann. Tit 15 § 4948(e).

37

The Century Foundation, op. cit.

38

4 N.Y.3d 123, 824 N.E.2d 488 (N.Y. 2005) and Memorandum (LaPlante—Foley) Provisional Ballot Cases by State,

July 19, 2005.

23

.

1. State statutes or regulations should define a reasonable period for voters who lack the

HAVA-specified ID or other information bearing on their eligibility to provide it in order to

facilitate the state’s ability to verify that the person casting the provisional ballot is the

same one who registered. While there may be a concern to ensure that the individual

who returns with the ID may not be the same individual who cast the provisional ballot,

the spirit of HAVA demands that the opportunity to prove identity be provided after

Election Day. A signature match can go far in establishing that the individual who voted

and the individual returning later with identification is, in fact, the same person.

Encouraging a voter who lacks ID on Election Day to return later to help the verification

process by providing proper identification will strengthen the system and increase public

confidence in the electoral process. Our data indicate that some voters would prefer to

return with ID rather than to sign an affidavit, perhaps because of uncertainty about the

legal process involved in the affidavit. At least 11 states allow voters to provide ID or

other information one to 13 days after voting. Of particular interest is Kansas, which

allows voters to proffer their ID by electronic means or by mail, as well as in person.

39

2. More provisional ballots are counted in those states that verify ballots cast outside the

correct precinct.

40

While HAVA arguably leaves this decision up to the states, pointing

out the effect of the narrower definition on the portion of ballots counted could be useful

to the states in deciding this question. States should be aware, however, of the

additional burden placed on the ballot-evaluation process when out-of-precinct ballots

are considered. And tradeoffs are involved if out-of-precinct voters are unable to vote for

the local offices that might appear on the ballot in their district of residence. One option

for states is to involve the voters in the decision by pointing out that voters who cast their

provisional ballots in the wrong precinct may not be able to participate in the local

election. The voter could then decide to go to the correct precinct or vote provisionally

for the higher offices at the top of the ticket only.

3. Alternatively, if a state chooses to require voters to appear at their assigned precinct,