Pain Management Network

aci.health.nsw.gov.au

Ophthalmology Network

Eye Emergency Manual

An illustrated guide

aci.health.nsw.gov.au

THIRD EDITION, DECEMBER 2023

This information is not a substitute for healthcare providers’ professional judgement.

Agency for Clinical Innovation aci.health.nsw.gov.au

Agency for Clinical Innovation

1 Reserve Road, St Leonards NSW 2065

Locked Bag 2030, St Leonards NSW 1590

Phone: +61 2 9464 4666 | Email: aci-info@health.nsw.gov.au | Web: aci.health.nsw.gov.au

Further copies of this publication can be obtained from the Agency for Clinical Innovation website at aci.health.nsw.gov.au

Disclaimer: the content within this publication was accurate at the time of publication.

© State of New South Wales (Agency for Clinical Innovation) 2023. Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivatives

4.0 licence. For current information go to: aci.health.nsw.gov.au. The ACI logo and cover image are excluded from

the Creative Commons licence and may only be used with express permission.

Title Eye Emergency Manual, 3rd Edition

Published December 2023

Next review 2028

Produced by ACI Ophthalmology Network

Preferred citation

NSW Agency for Clinical Innovation. Eye Emergency Manual, 3rd Edition.

Sydney: ACI; 2023.

TRIM ACI/D23/169 SHPN (ACI) 230806 ISBN 978-1-76023-644-1

ACI_8666 [11/23]

Agency for Clinical Innovation aci.health.nsw.gov.au

Eye Emergency Manual December 2023

Background 1

Introduction 3

Anatomy 4

Anatomy terms 5

Eye assessments 6

History to ascertain 7

Assessing the severely injured patient 15

Paediatric assessment 16

Examinations 18

Examination essentials 18

General inspection and assessment

of periocular and globe trauma 20

Visual acuity 23

Pupil examination 27

Visual field, eye movements

andeyelid examination 29

Eyelid eversion 33

Special eye examinations 34

Direct ophthalmoscope 34

Checking intraocular pressure 35

Slit lamp 37

Eye referrals and discharge advice 40

Traumacommunication checklist 40

Acute visual disturbance

communication checklist 40

Red eye or eyelid

communication checklist 40

Visual requirements for driving 41

Prevention of visual impairment 42

Eye trauma 43

Blunt ocular trauma 44

Chemical burns 46

Closed globe injury 49

Flash burns 51

Lid laceration 52

Non-accidental injury (NAI) 54

Open globe injury

(penetratingeye injury) 55

Orbital fracture 57

Retrobulbar haemorrhage

(orbital compartment syndrome) 59

Acute visual disturbance 61

Third (3rd) cranial nerve palsy 62

Fourth (4th) cranial nerve palsy 63

Sixth (6th) cranial nerve palsy 65

Central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) 66

Central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) 68

Central serous chorioretinopathy 69

Dry eye/exposure keratopathy 70

Giant cell arteritis (GCA)/anterior

ischaemic optic neuropathy (AION) 72

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH):

transientvisual obscuration 73

Intermittent angle closure/

acuteangle closure 75

Lens subluxation 76

Contents

Agency for Clinical Innovation aci.health.nsw.gov.au

Eye Emergency Manual December 2023

Macular haemorrhage in wet

age-related macular degeneration 77

Macular pathology 78

Migraine 78

Myasthenia gravis 79

Optic neuritis 80

Posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) 8 1

Retinal tear or detachment 83

Thyroid eye disease 84

Transient ischaemic attack

(amaurosis fugax) or retinal emboli 85

Visual pathway lesion 87

Vitreous haemorrhage 87

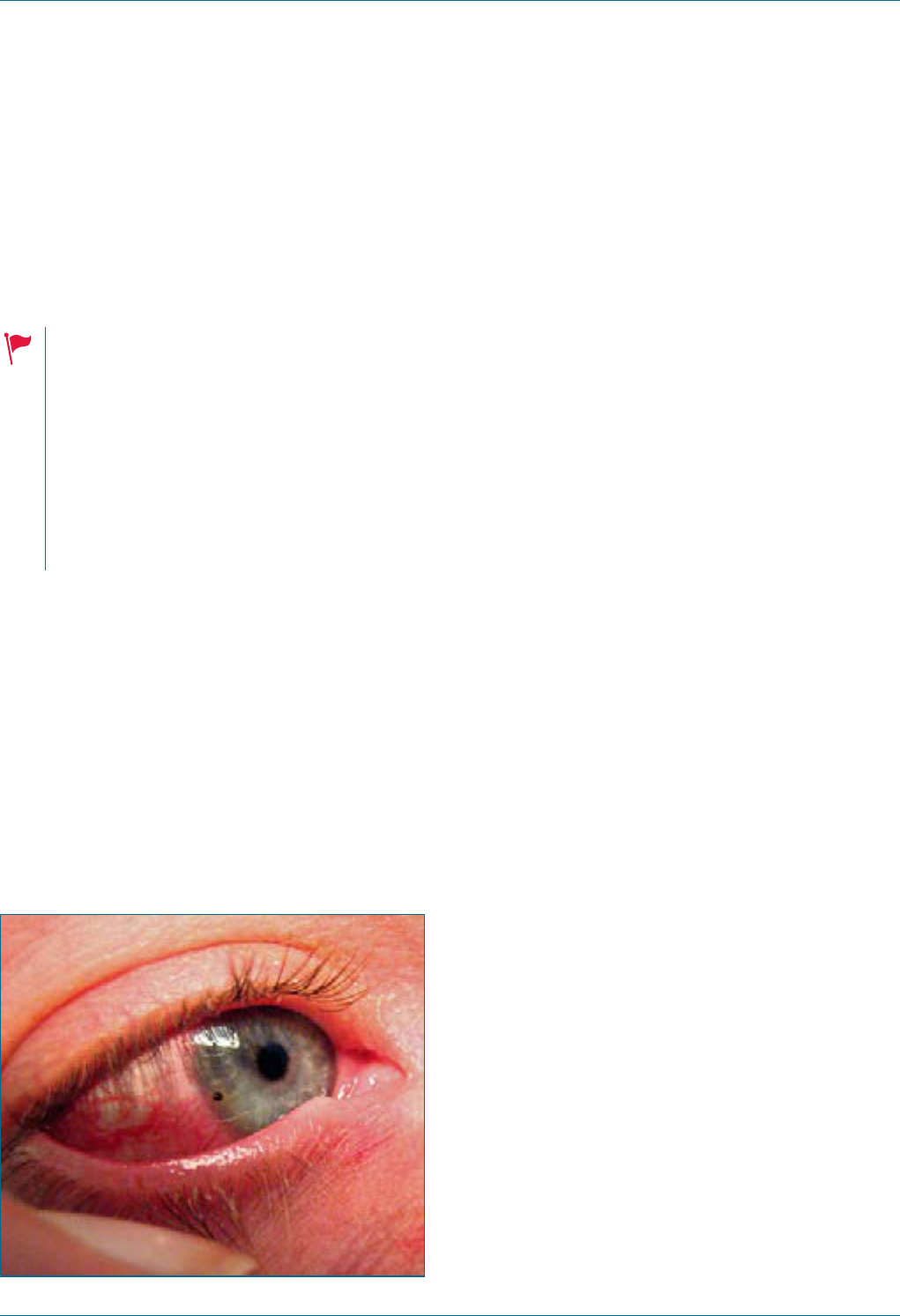

Acute red eye or eyelid 89

Acute red eye overview 90

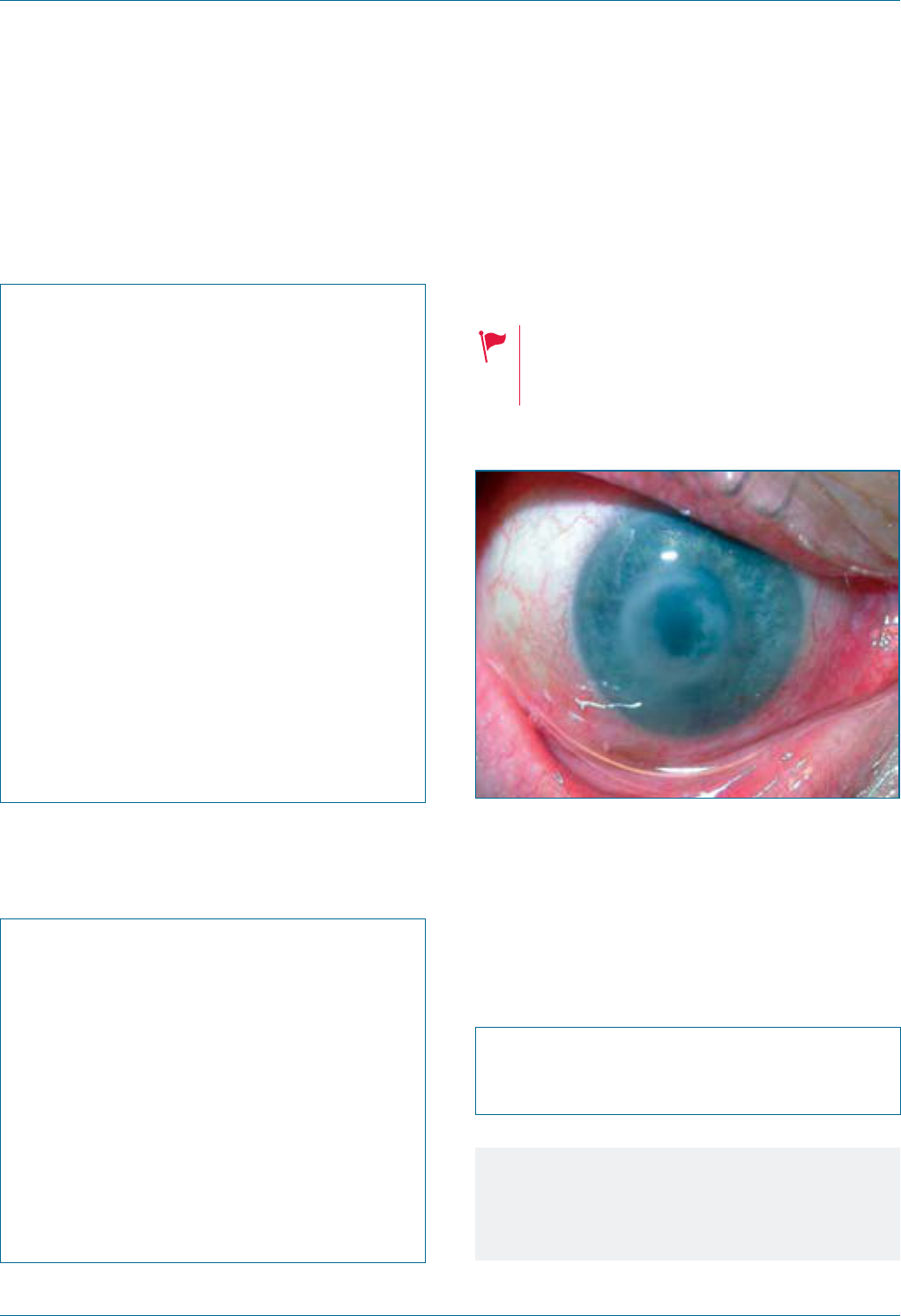

Acute angle closure crisis 91

Acute blepharitis 93

Allergic conjunctivitis 94

Iritis (anterior uveitis or an anterior

chamber inflammation) 95

Bacterial or acanthamoebal ulcer 96

Bacterial conjunctivitis 97

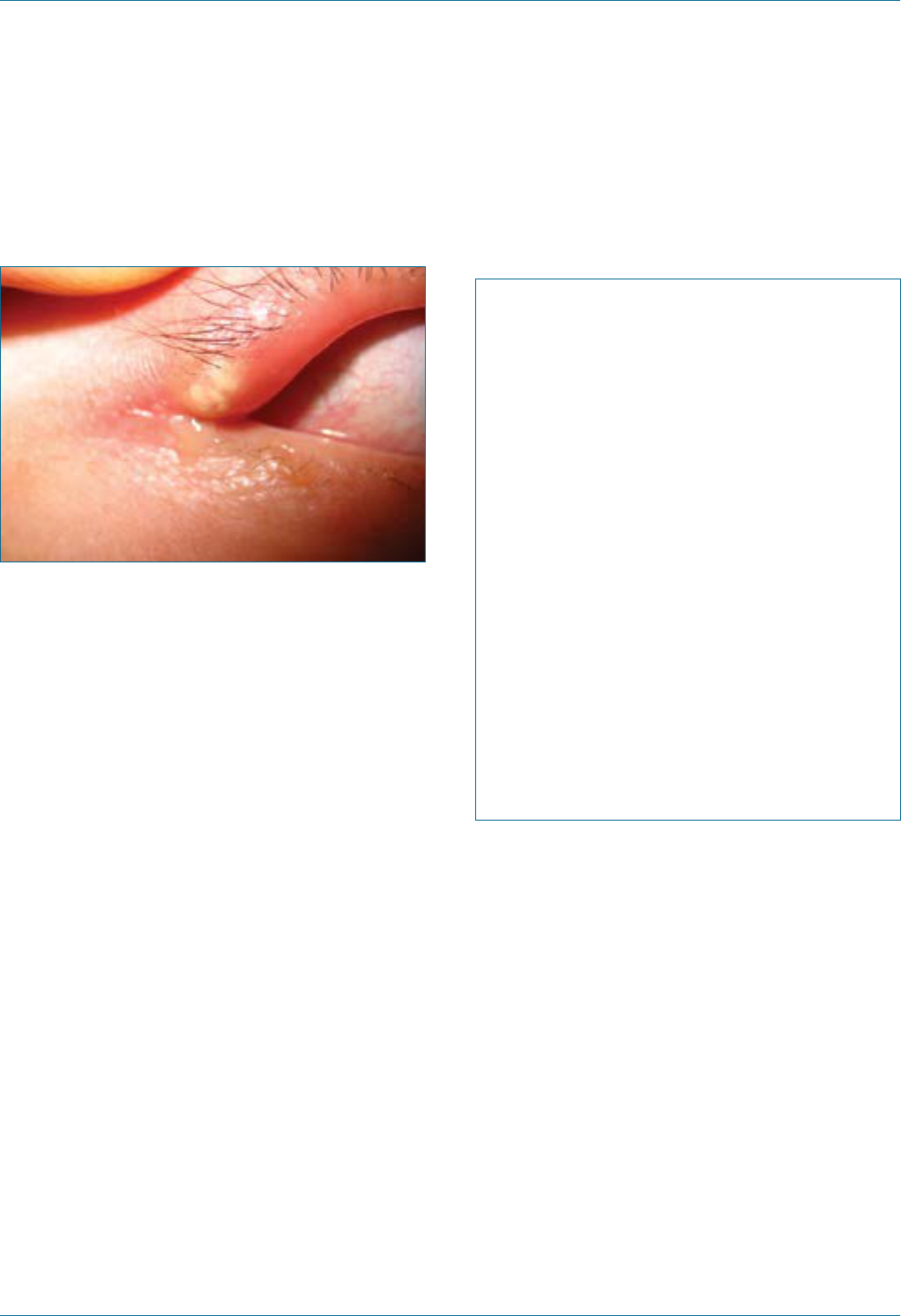

Chalazion/stye 98

Corneal or conjunctival foreignbody/

corneal abrasion 100

Ectropion 103

Entropion 104

Episcleritis 105

Eyelid lesion 106

Herpes simplex virus keratitis

(HSV/HSK) 106

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO)/

shingles 108

Hyphaema 109

Hypopyon 111

Marginal keratitis 112

Neovascular glaucoma 113

Ophthalmia neonatorum

(neonatal conjunctivitis) 114

Preseptal cellulitis

(periorbital cellulitis) 116

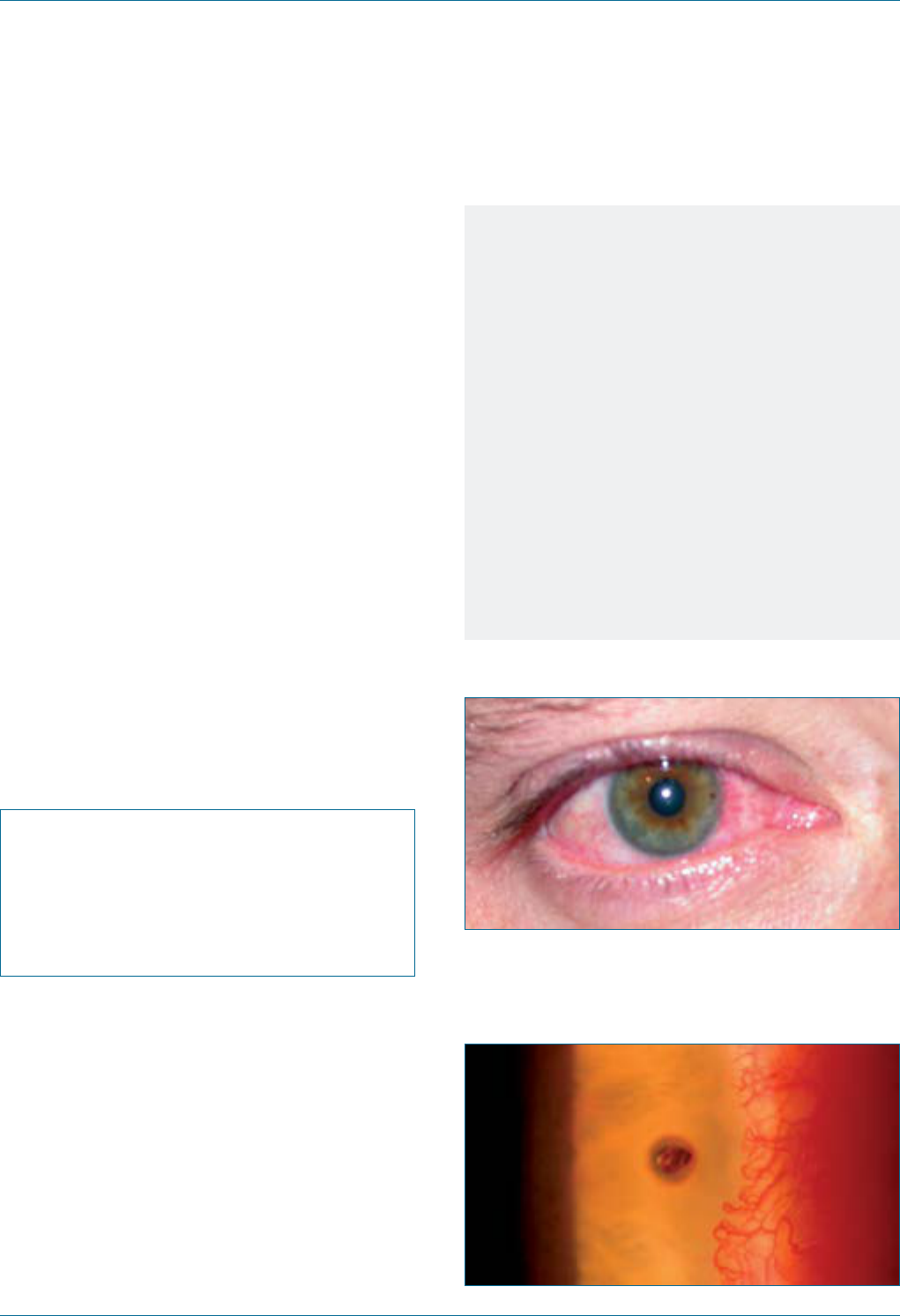

Pterygium 118

Scleritis 119

Subconjunctival haemorrhage 121

Trichiasis 122

Viral conjunctivitis 123

Treatments 125

Ocular drugs 126

How to put in eye drops 130

References 131

Appendix: Evidence base 133

PubMed search terms 133

Google search terms 133

Inclusion and exclusion criteria 133

Bibliography 133

Glossary 135

Eye Emergency Manual December 2023

Agency for Clinical Innovation 1 aci.health.nsw.gov.au

Background

The Eye Emergency Manual (EEM) is designed for medical, nursing and alliedhealth

staff in emergency departments and critical care, and for rural general practitioners.

The EEM has not undergone a formal process ofevidence-based clinical practice guideline development;

however, it is the result of consensus opinion determined by relevant experts. The EEM is not a denitive

statement on correct procedures; rather, it is a general guide to be followed subject to clinical judgement.

The EEM is based on the best information available at the time of writing.

The EEM was rst released in 2007 and last updated in 2009. The current review was undertaken by the ACI

Ophthalmology Network with oversight by a clinical working group led by Dr Parth Shah.

Method

The EEM was reviewed formally by members

of a working group, including clinicians in

ophthalmology, optometry, orthoptics, emergency

and critical care, and rural general practice

across NSW. Data for theEEM were drawn from

a literature search, consensus expert opinion of

the working group and consultation.

Rapid, targeted literature searches of PubMed

were conducted in June and July 2023. Searches

were related to: eye diseases OR eye injuries

AND emergency treatment AND guidelines

OR principles.

Grey literature searches were completed using

Google and Google Scholar.

Refer to "Appendix: Evidence base" for search

terms and reference list.

Consultation

The following groups were consulted for this

revision:

• Members of the working group

(as listed under ‘Acknowledgements’ below)

• ACI Networks

• Survey respondents

The Eye Emergency Manual is endorsed by the

Australian College of Emergency Nursing and

the Save Sight Institute, University of Sydney.

Eye Emergency Manual December 2023

Agency for Clinical Innovation 2 aci.health.nsw.gov.au

Acknowledgements

Parth Shah, Ophthalmologist, Prince of Wales

Hospital and Sydney Children’s Hospital

Claire Cuppitt, General Practitioner

Lin Davis, Nurse Educator, Rural Critical Care,

Hunter New England LHD

Michael Golding, Emergency Physician,

Prince of Wales Hospital

Paula Katalinic, Optometrist and Professional

Services and Advocacy Manager, Optometry

NSW/ACT

Yves Kerdraon, Ophthalmologist, Sydney

Hospital/ Sydney Eye Hospital and

ConcordHospital

Kerrie Martin, Ophthalmology Network and

Clinical Genetics Network Manager, Agency for

Clinical Innovation

Erin McArthur, Project Ofcer, Agency for

Clinical Innovation

Peter McCluskey, Professor and Chair of

Ophthalmology, University of Sydney and

Director, Save Sight Institute

Joanna McCulloch, Clinical Nurse Consultant

Ophthalmology, Sydney Hospital/Sydney

Eye Hospital

Danielle Morgan, Acting Deputy Head of

Orthoptic Department, Sydney Hospital/Sydney

Eye Hospital

David Murphy, Director of Emergency Medicine,

Prince of Wales Hospital

Eye Emergency Manual December 2023

Agency for Clinical Innovation 3 aci.health.nsw.gov.au

Introduction

The EEM is designed to provide a

quick and simple guide to recognising

important signs and symptoms, and

assisting with the management of

common eye emergencies. The EEM

will also assist with triaging patients

to appropriate care.

How to use this resource

For ease of use, the EEM has a large

amount of graphic content and is divided

into basic ophthalmic diagnostic

techniques/treatment and management

of common eye presentations.

Each condition includes

information about:

• immediate action (if any)

• history

• examination

• treatment

• communication checklist(s).

Each condition has red ags used

to increase the triage weighting or

indicate urgent ophthalmic referral

with an explanation of relevance.

Anatomy

Agency for Clinical Innovation 4 aci.health.nsw.gov.au

Eye Emergency Manual November 2023

Eye Emergency Manual December 2023

Agency for Clinical Innovation 5 aci.health.nsw.gov.au

Anatomy

Anatomy terms

Useful terms when describing an

eye lesion

• Right vs. left

• Globe vs. eyelids vs. periocular region

• Nasal (medial) vs. temporal (lateral)

• Superior vs. inferior (relative to the pupil)

• Corneal clock hours (as seen by the examiner,

e.g. 3 o’clock is the temporal limbus of the

left eye)

• Surface area of the cornea, e.g. 30% ulcer

Useful pathological terms

• Ulcer (loss of epithelium from the cornea,

conjunctiva or eyelid skin)

• White dot on the cornea or opacication: try to

differentiate between inltrate (abscess/

infection), long-standing scar, foreign body or

hazy cornea

• Redness on the conjunctiva: try to differentiate

between conjunctival injection, subconjunctival

haemorrhage and inamed conjunctival lesion,

e.g. pterygium or pingueculum

• Laceration (partial- or full-thickness if involving

the cornea, conjunctiva, sclera or eyelid)

• Blunt or sharp eye injury (depending on the

object used)

• Penetrating wound (which enters the full

thickness of the cornea or sclera)

• Leaking or sealed wound: use Seidel test to

determine if a penetrating wound is

actively leaking

Eye assessments

Agency for Clinical Innovation 6 aci.health.nsw.gov.au

Eye Emergency Manual November 2023

Eye Emergency Manual December 2023

Agency for Clinical Innovation 7 aci.health.nsw.gov.au

Eye assessments

History to ascertain

Basics

• Age

• Allergies

Reason for presentation

• Visual loss

• Eye pain

• Eye redness

• Trauma

• Foreign body

• Chemical injury

• Flashes/oaters

• Diplopia (double vision)

If a chemical injury is

suspected, postpone

further history-taking or

examination and

immediately begin

irrigation of the eye(s).

Mode of presentation

• Post trauma

• Self-presenting due to symptoms

• Via general practitioner (GP)

or optometrist

Past medical history

• Including microvascular

risk factors

• Social history

• Medications

Ophthalmic background

• Glasses: distance/reading/

bifocals/multifocals

• Contact lenses

• Eye surgery (when was it done,

where and by whom)

• Eye laser (what was it for)

• Eye drops (prescribed or

over-the-counter)

• Whether the patient is known to

anophthalmologist or

ophthalmology department

• When, where and who last saw the

patient and what problems were

being managed

Eye Emergency Manual December 2023

Agency for Clinical Innovation 8 aci.health.nsw.gov.au

Consider the following when conducting an

eye assessment:

• Demographics are crucial to the diagnosis of

many ophthalmic conditions. An ophthalmologist

will often ask you to go back and clarify a

patient’s age before moving on to the details of

the presentation.

• The most common reasons for patients to

present with ophthalmic problems are listed

above. Determining which of these is relevant to

the patient will focus your clinical assessment

and discussion with the ophthalmologist. Be

aware that this is a simplied approach and

there may be multiple reasons, such as visual

loss following trauma, or there may be

another symptom.

• Patients often confuse optometry and

ophthalmology, so be careful to make this

distinction yourself. If the patient refers to

advice given by their ‘eye doctor’ clarify exactly

who they mean and what advice was given.

Take note of drops that may have been

prescribed by a GP or an optometrist in the

recent past. Steroid drops are occasionally

prescribed for red eyes but can cause

blinding complications when used

inappropriately. Steroid eye drops should

only be prescribed following a

comprehensive ophthalmic examination

and in situations where close ophthalmic

follow-up can be provided.

• Ask if the patient drives and in what capacity.

• Ask if the patient is a carer for someone else, or

if they are cared for themselves.

Notes

You must specically ask if the patient has

had any eye surgery, laser or injections.

Remember that the patient may not volunteer

the information because they may not deem

it relevant, but it may be crucial to diagnosis.

Because many ophthalmic procedures are

done on an outpatient or day surgery basis,

with regional anaesthetic, and can be very

rapid, patients may omit to mention them

simply because they have forgotten. This is

particularly the case if the procedure was

performed many years ago

without complication.

Intravitreal injections are the modern

standard of care for certain types of

macular degeneration, diabetic

macular oedema and other

ophthalmic conditions, and hence are

very common. This treatment entails

regular injections, sometimes

monthly, and prevents blindness in

many thousands of patients. It also

exposes patients to the rare but

devastating complication of

intraocular infection

(endophthalmitis) following injection.

Any patient presenting with

ophthalmic symptoms following an

intravitreal injection requires urgent

ophthalmic review.

Although the most common ophthalmic

operation is cataract surgery, there are many

different operations that a patient may have

had, including retinal detachment surgery,

surgery for glaucoma or corneal

transplantation. It is very helpful if the

patient can tell you what they have had, so

try to elicit these details.

Eye Emergency Manual December 2023

Agency for Clinical Innovation 9 aci.health.nsw.gov.au

Visual loss

• When it occurred

• What the patient was doing

• What has happened since the visual loss

Ask the patient to describe the following:

• Total ‘black out’ or ‘blurry’

• Intermittent or constant

• Whole or part of the visual eld

• One or both eyes

• If the eyes are painful or painless

• Are the eyes red or white

• Preceding ashes/oaters OR brief

episodes of visual loss

• Any similar previous episodes

Consider whether the patient has associated

symptoms, such as:

• Headache

• Nausea or vomiting

Notes

Visual loss is potentially very serious

and should be accorded an

appropriate level of concern.

Of the numerous potential causes of visual

loss, some can be elucidated with the above

questions.

For example:

• Rapid, painful visual loss in a red eye with

associated headache and vomiting may be

due to an angle closure crisis (angle

closure glaucoma).

• Sudden vision loss in one eye that was

preceded by intermittent episodes in the

hours or days prior may be amaurosis

fugax, heralding an impending

cerebrovascular accident or anterior

ischaemic optic neuropathy due to giant

cell arteritis (GCA).

• Visual loss in one or both eyes that is

accompanied by headache may be due to

GCA or elevated intracranial pressure.

• Visual loss preceded by ashes/oaters

may be due to a retinal detachment.

If you are concerned about a neurological

cause for visual loss, it is reasonable to

proceed with appropriate neuroimaging prior

to contacting an ophthalmologist. An

ophthalmologist may help with the diagnosis

of some neurosurgical emergencies but

cannot treat them.

Flashes/oaters are a common reason for

presentation and may indicate the presence

of a retinal tear or may be innocuous. There is

no way to make this distinction from the

patient’s history. Therefore, a patient with

ashes/oaters should be regarded as

having a retinal tear until proven otherwise.

This requires a detailed examination of the

peripheral retina by an ophthalmologist with

specialised equipment and is beyond the

scope of an emergency department

(ED) assessment.

Patients may not notice loss of vision in one

eye and only come to realise this sometime

later when the good eye is covered for

another reason. This is not common, but can

occur once other causes of acute visual loss

have been excluded.

Abrupt vision loss in any patient over

50 years of age mandates

consideration of giant cell arteritis

(GCA) (see next).

Eye Emergency Manual December 2023

Agency for Clinical Innovation 10 aci.health.nsw.gov.au

Double vision (diplopia)

• Double vision (diplopia) can be a confusing

symptom for both the patient and the doctor.

Keep it simple by working through the

following questions:

• Is it only present with both eyes open?

• Is it present if one eye is closed? If so,

which eye?

If double vision is only present with both eyes open,

consider whether:

• the two images are side-by-side, on top of each

other, or vertically displaced

• the double vision resolves if the patient looks in

a particular direction

• the double vision gets worse (greater separation

between the images) in another direction.

Notes

• Consider whether it is truly double vision,

as opposed to one eye’s blurred image

superimposed on the other eye’s clear

image. This would suggest that visual loss

or blurring is the real issue.

• Binocular diplopia occurs if the double

vision is only seen with both eyes open.

This usually means that the eyes are

misaligned due to an imbalance of the

extraocular muscles.

Binocular diplopia is an emergency

as it may indicate a cranial nerve

palsy due to intracranial pathology,

for example, a third cranial nerve

palsy caused by an aneurysm of the

posterior communicating artery. Pay

close attention to the presence of

eyelid ptosis, pupil changes,

concurrent headache and other

neurological symptoms, and proceed

with urgent neuroimaging if you

deem it appropriate.

Binocular diplopia in any patient over

50 years of age mandates

consideration of giant cell arteritis

(GCA) (see next).

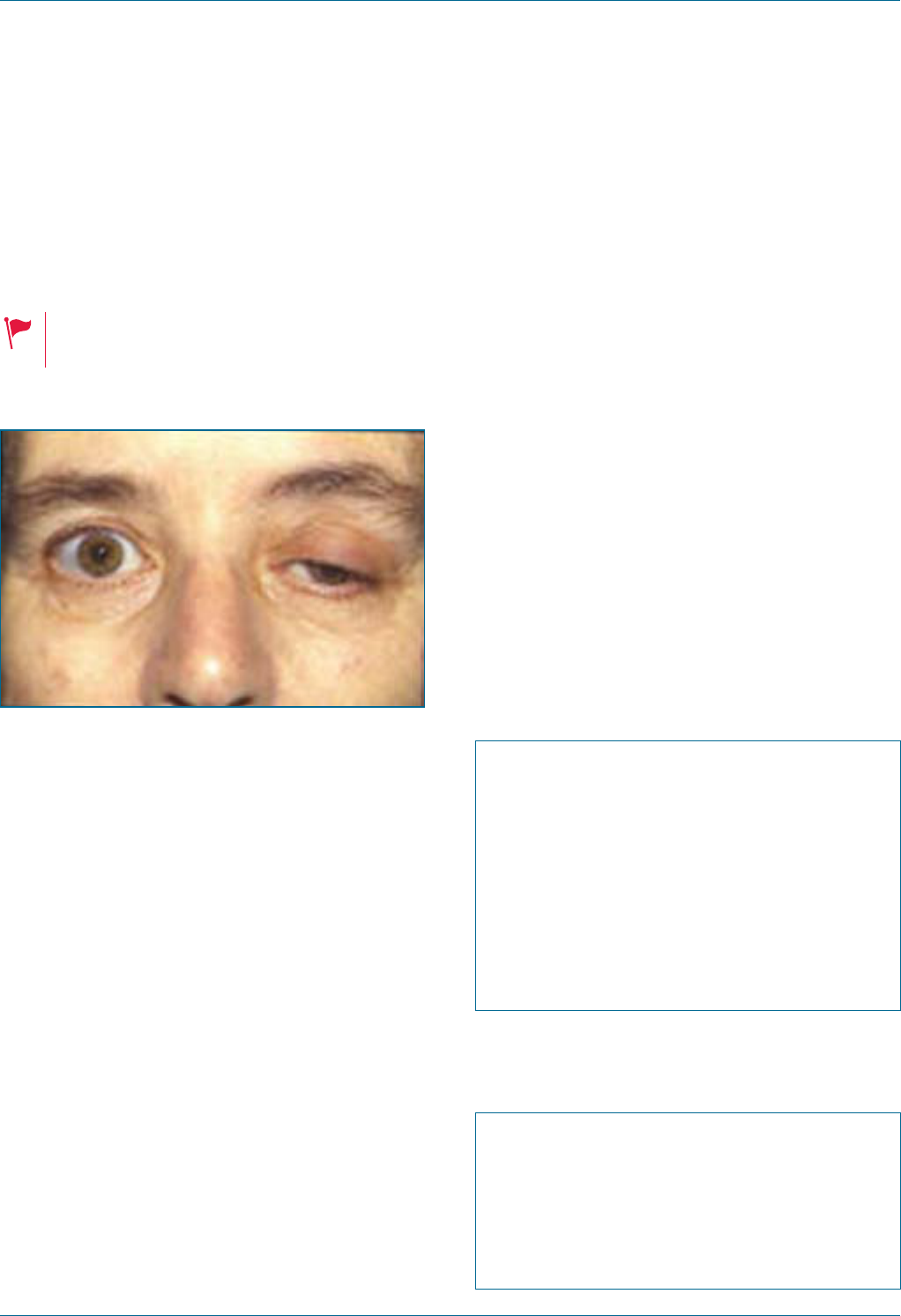

Other common causes of diplopia are other

cranial nerve palsies, myasthenia gravis,

thyroid eye disease and periorbital fractures,

so look for the clinical signs associated with

these disorders.

Eye Emergency Manual December 2023

Agency for Clinical Innovation 11 aci.health.nsw.gov.au

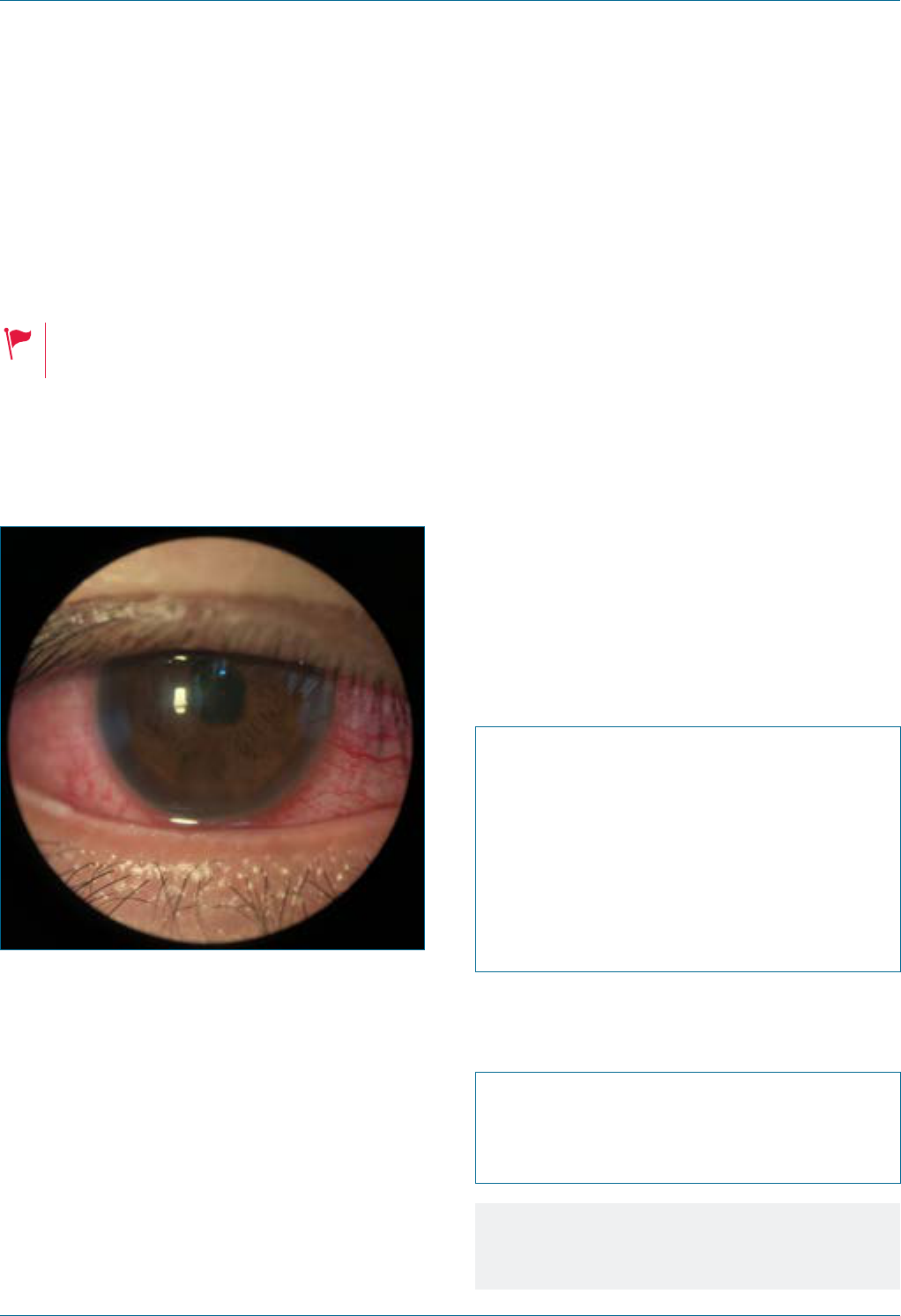

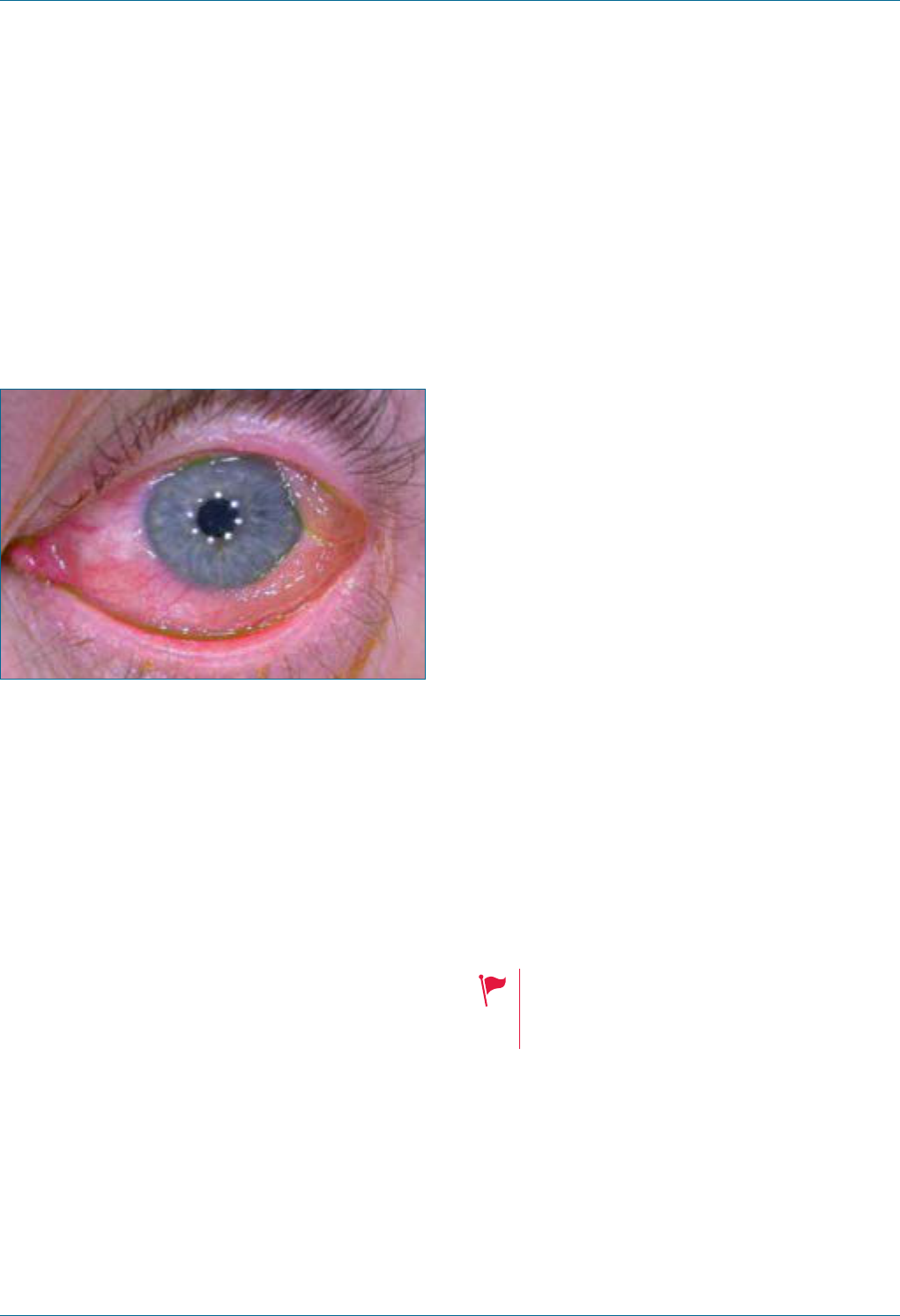

Painful or red eyes

Ask the patient the following questions:

• Has the patient had recent intraocular

surgery, laser or intraocular injections?

• Does the patient wear contact lenses?

If so, has the patient been swimming with,

sleeping with or overwearing the

contact lenses?

• Does the patient have decreased vision?

• Did the patient experience any prior

trauma, foreign body or ash from welding?

• What is the duration of symptoms?

• Does it affect one or both eyes? One eye

then the other?

• Are the eyes itchy?

• Is there discharge?

• Do family members or other contacts of the

patient have a red eye?

• Has the patient experienced any prior

similar episodes? If so, were they

investigated and what was the cause,

if known?

• Has the patient had prior herpetic

eye disease?

• Does the patient have any cold sores or

need for prior acyclovir?

• Does the patient have any systemic

symptoms such as rash, arthritis

or urethritis?

Notes

An urgent ophthalmic referral is

mandatory if a patient presents with

symptoms following a recent

ophthalmic procedure, especially any

eye surgery or intravitreal injection

(injection into the eye).

Similarly, any contact lens wearer

with red or painful eyes (or visual

changes) warrants an urgent

ophthalmic review.

Discharging, red eyes in a neonate

within one month of birth is an

ophthalmic emergency and requires

immediate input from ophthalmology,

paediatrics and infectious diseases.

• Red, painful eye(s) associated with visual

loss may be due to acute angle closure

crisis, corneal infection, severe

intraocular inammation, (e.g. iritis) or

intraocular infection (endophthalmitis).

• The presence of discharge usually

indicates a viral, bacterial or

allergic conjunctivitis.

• Herpetic eye disease tends to be

recurrent and can be associated with

signicant corneal scarring and visual

impairment. Patients may be aware of the

presence of corneal scars or that they

needed topical (or systemic) antivirals in

the past. Patients with herpetic eye

disease often need chronic low-dose

topical steroids or prophylactic systemic

antivirals, which may be a clue to

their diagnosis.

Eye Emergency Manual December 2023

Agency for Clinical Innovation 12 aci.health.nsw.gov.au

Trauma or chemical injury

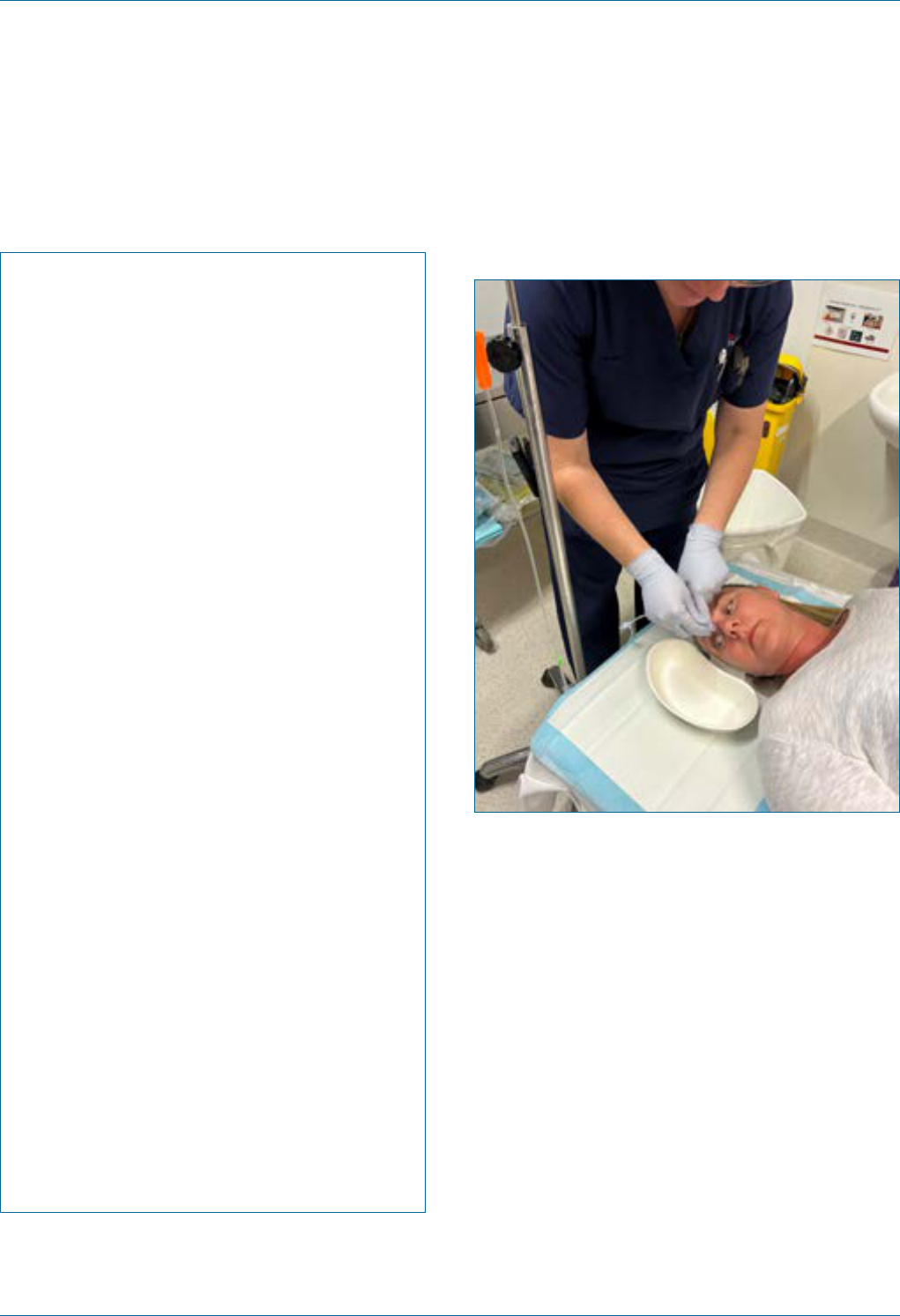

If a chemical injury is suspected, postpone

further history-taking or examination and

immediately begin irrigation of the eye(s).

Ask the patient the following questions:

• What time did the trauma/chemical

injury happen?

• Where did it happen?

• What was the mechanism?

• If a chemical injury is suspected, what was

the chemical?

• If a foreign body is suspected, what does

the patient think it might be?

• Was the patient doing any grinding or other

industrial activities before eye symptoms?

• Was any plant or organic material involved?

• Were the patient’s glasses or any protective

eyewear worn?

• How has vision been affected since

the injury?

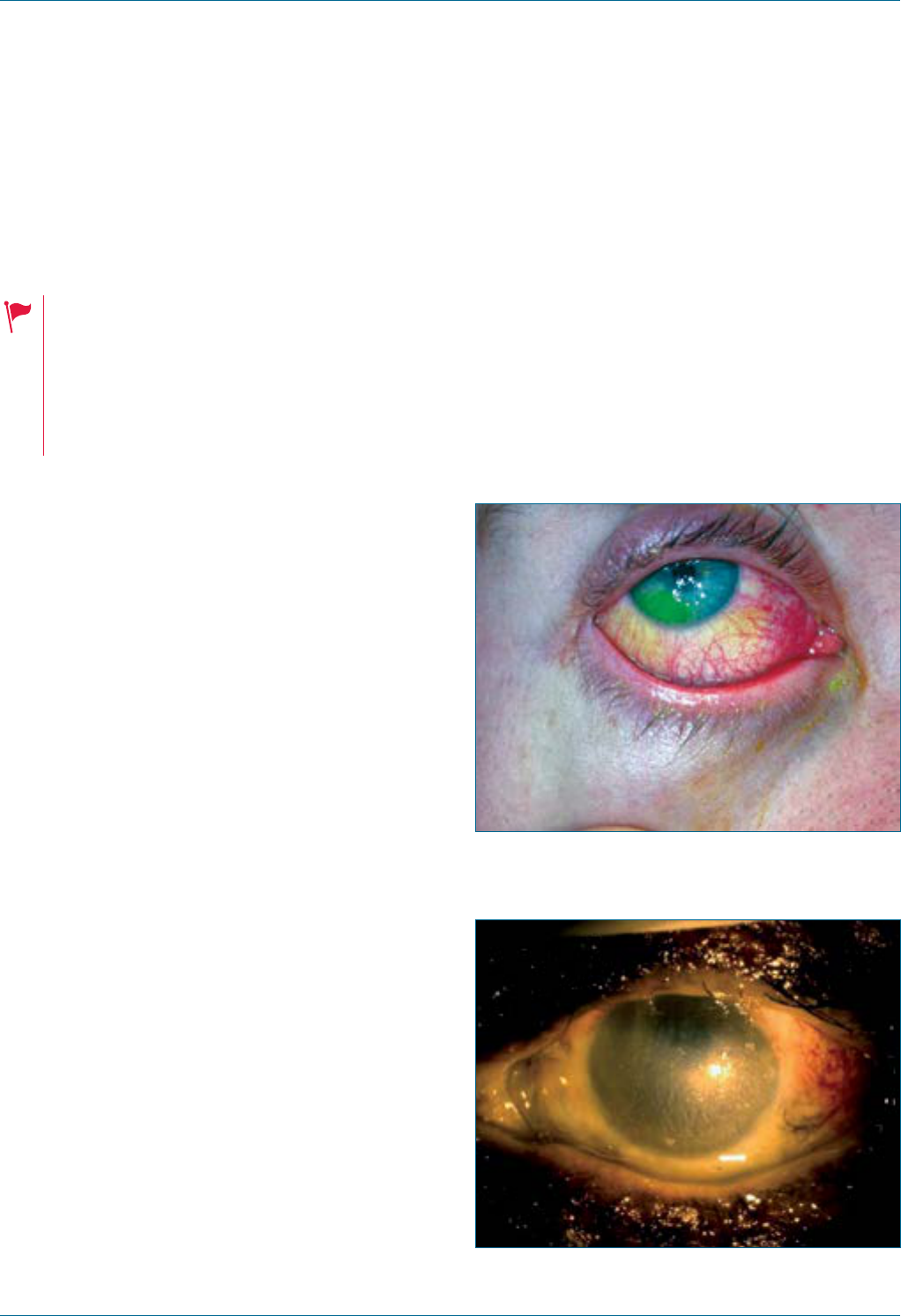

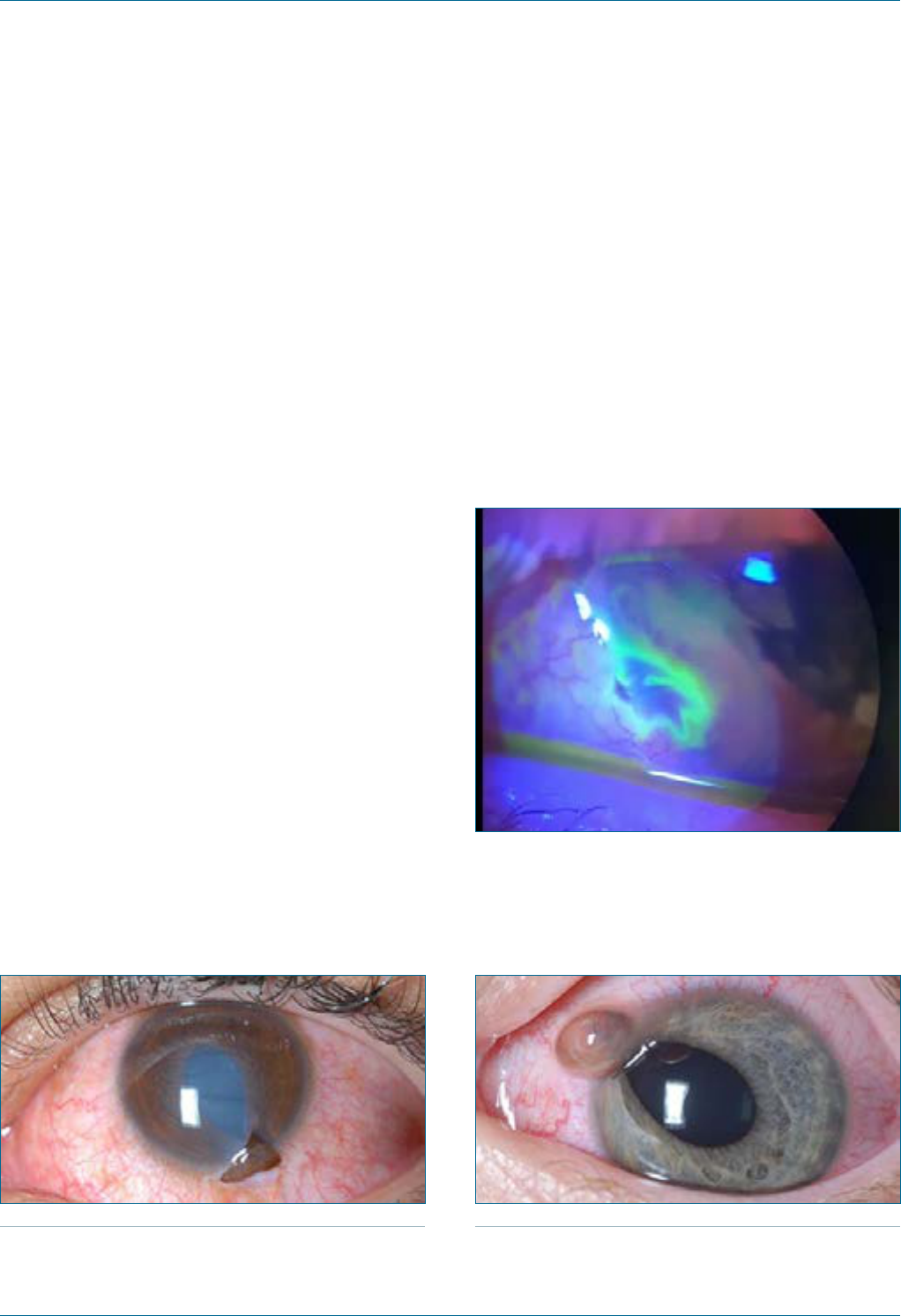

Figure 1. White blow-out fracture.

Notes

Ophthalmic trauma and chemical injuries are

potentially blinding. Because of this, the

normal sequence of history and examination

is sometimes suspended.

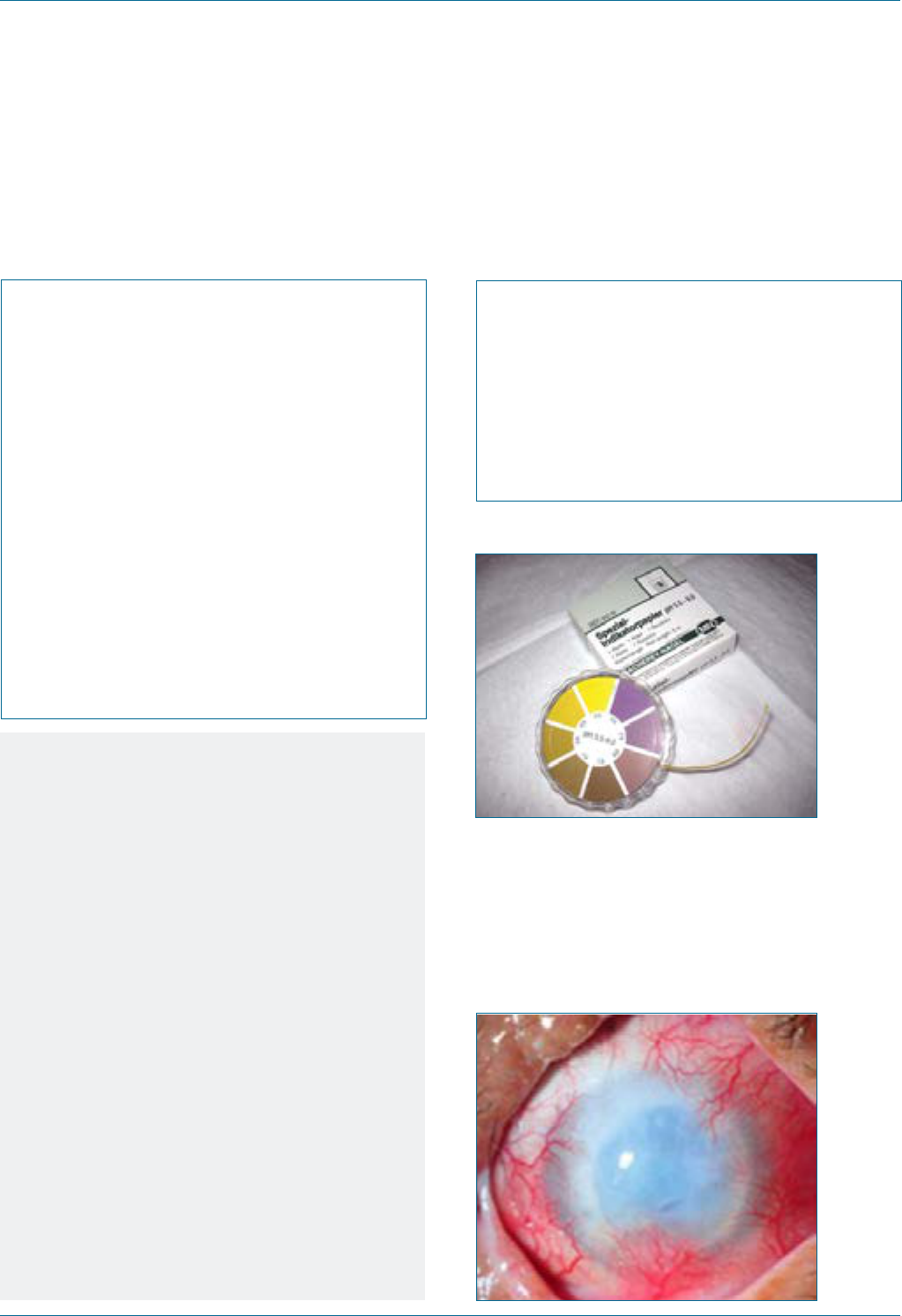

In the case of a chemical injury,

check the pH and immediately begin

copious irrigation until the pH is

normal. This is one situation in which

you do not need to check visual

acuity in the acute stage. Find out

what the chemical was, whether it

was acid or alkali and liaise with the

Poisons Information Centre (131 126)

for further information.

Globe ruptures can occur following

serious or seemingly innocuous

injuries and from both blunt or

penetrating trauma. If you suspect a

globe rupture, stop examining the

patient and immediately apply a clear

shield over the eye. Do not clean the

eye or perform any manipulation, as

this can worsen the injury. However,

you must still check the visual acuity.

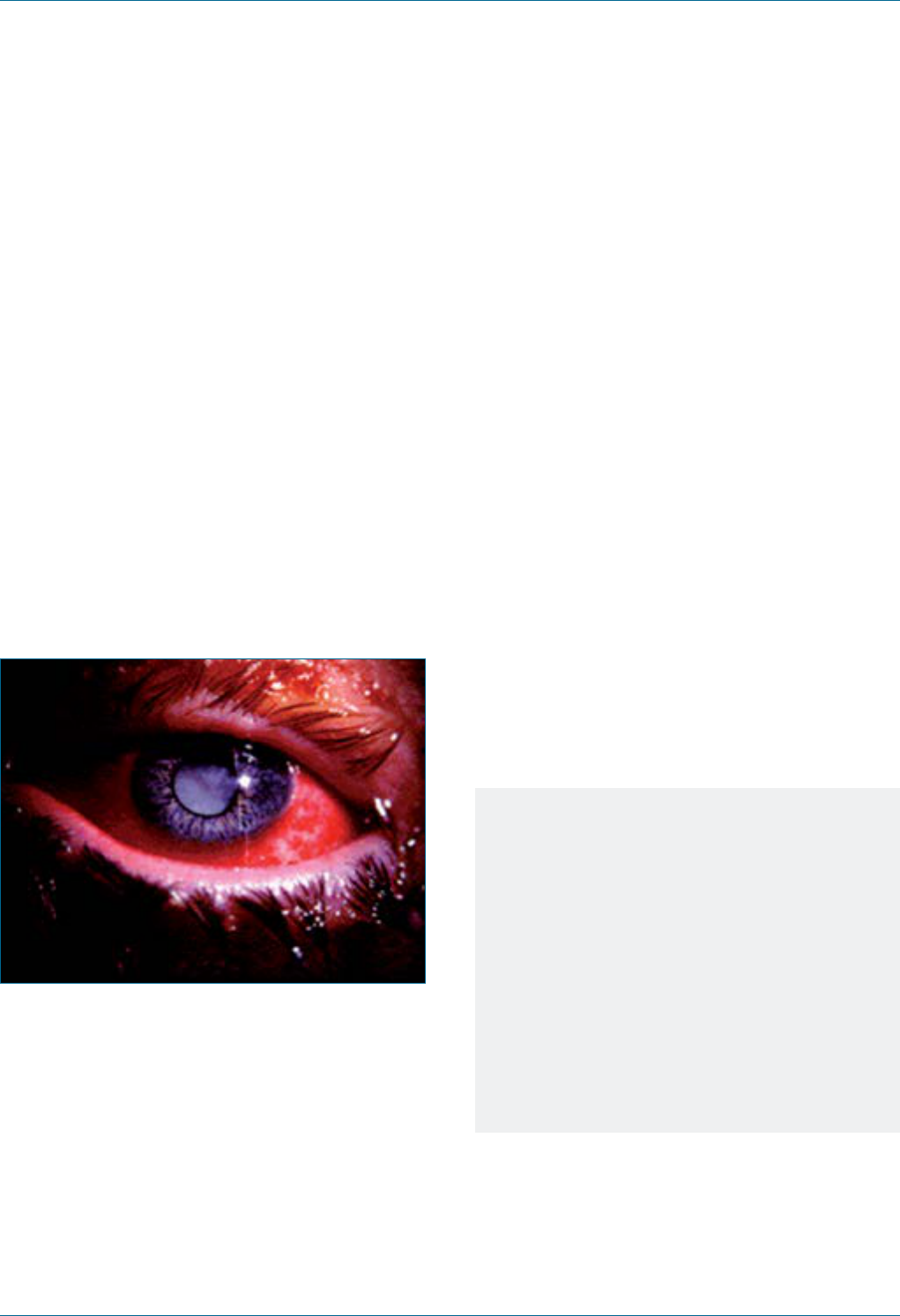

Retrobulbar haemorrhage is usually

dramatic and readily apparent from

an examination. It is a clinical

diagnosis, and you must check visual

acuity. If suspected, liaise urgently

with an ophthalmologist who can

perform emergency lateral

canthotomy and lower lid

cantholysis. This can sometimes also

be performed by plastic and

maxillofacial surgeons or ED

physicians, depending upon the skill

set possessed.

Eye Emergency Manual December 2023

Agency for Clinical Innovation 13 aci.health.nsw.gov.au

• If the eye has been scratched, determine

whether organic material was involved as

this increases the risk of infection,

especially fungal keratitis.

• Always document the mechanism of any

eye injury carefully, as it may have

medicolegal implications. If there is a

chemical injury, document whether the

exposure happened at work or in

the home.

• Be specic about the type of eye

protection worn at the time of injury,

including the patient’s own glasses,

specialised protective spectacles or

protective goggles.

• Glasses worn at the time of trauma can

shatter and pieces of the lens or frame

may contribute to ocular injury. Maintain a

low threshold of suspicion for penetrating

eye injury and, if possible, ask to examine

the glasses that may have been brought to

hospital with the patient.

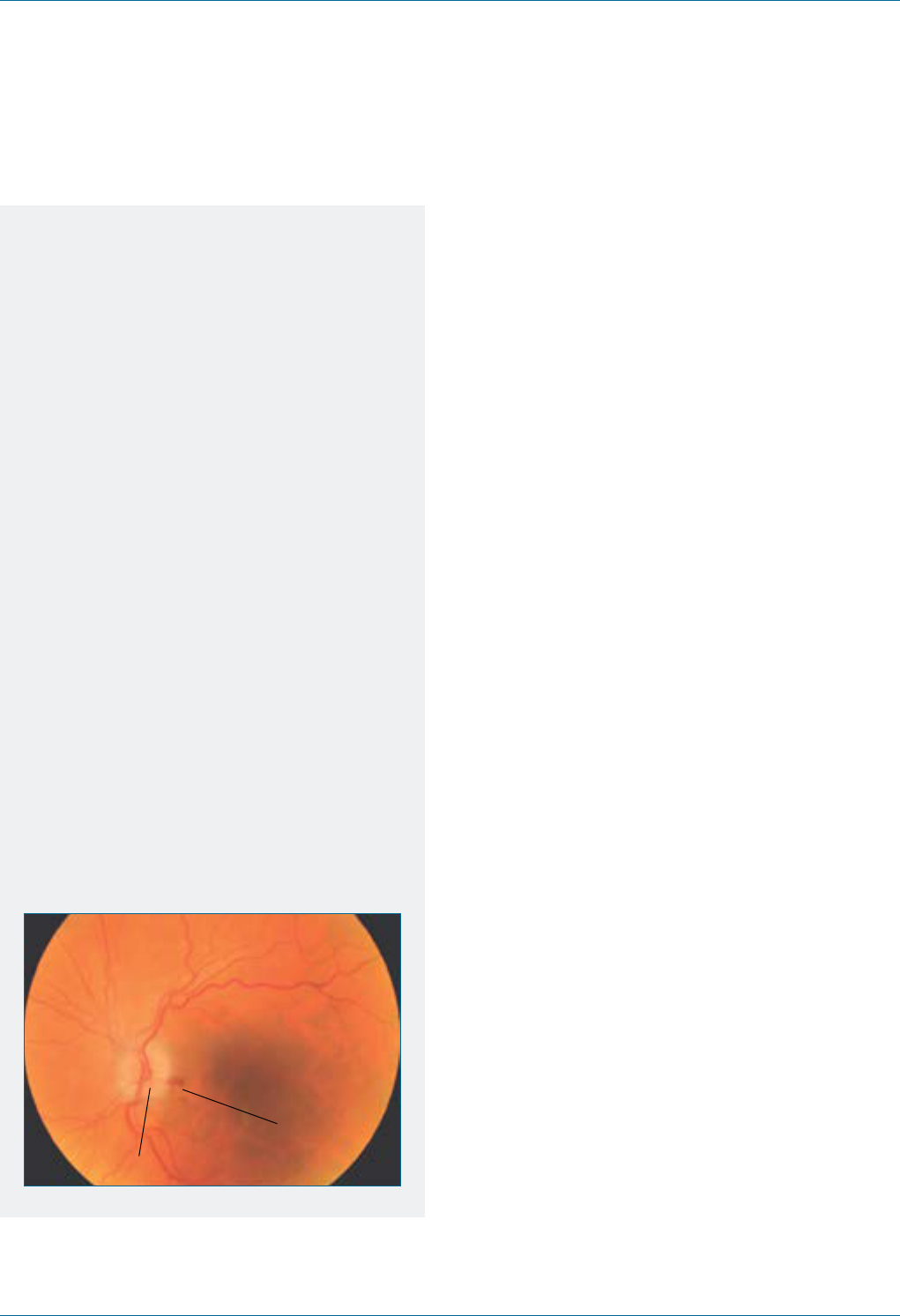

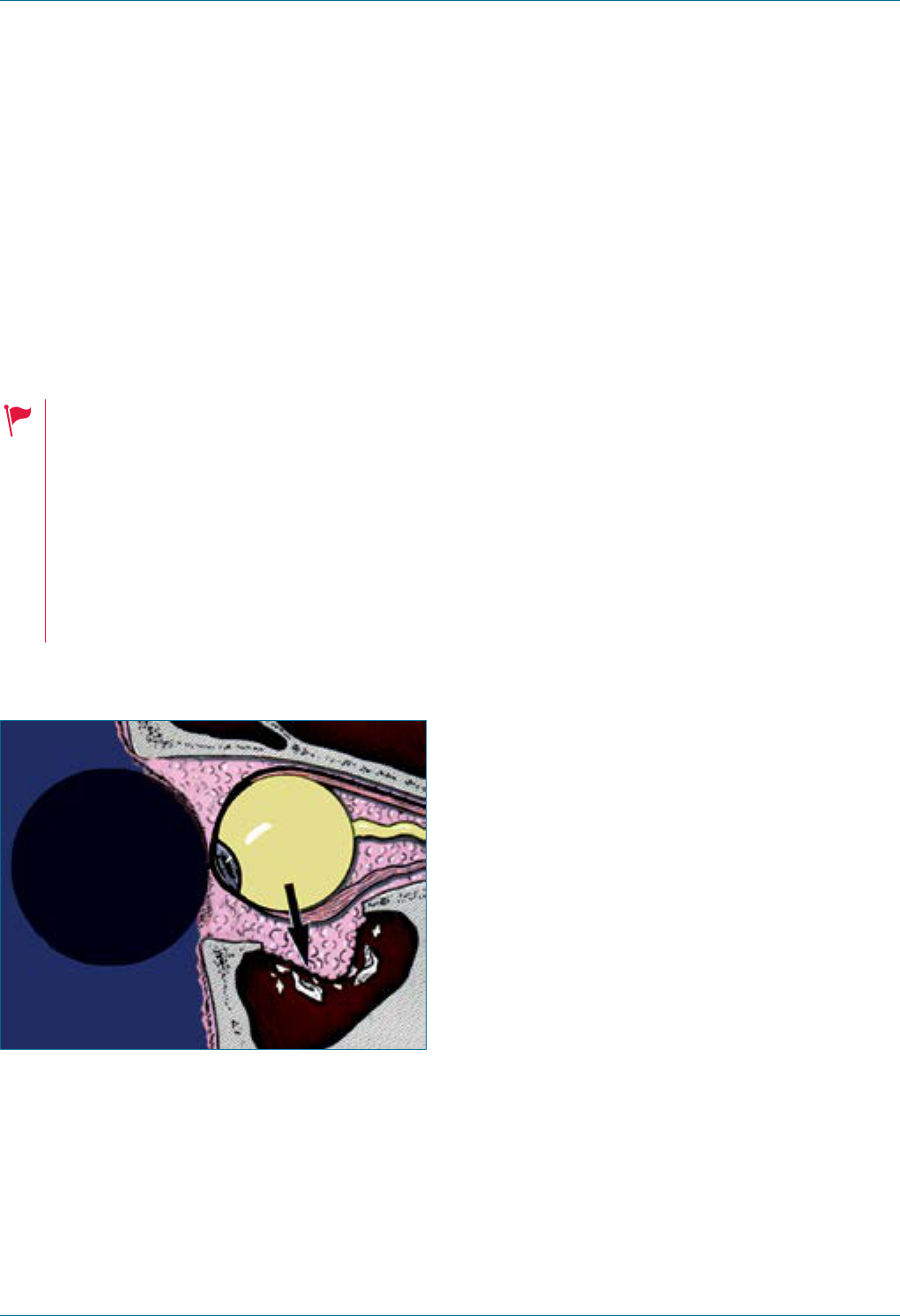

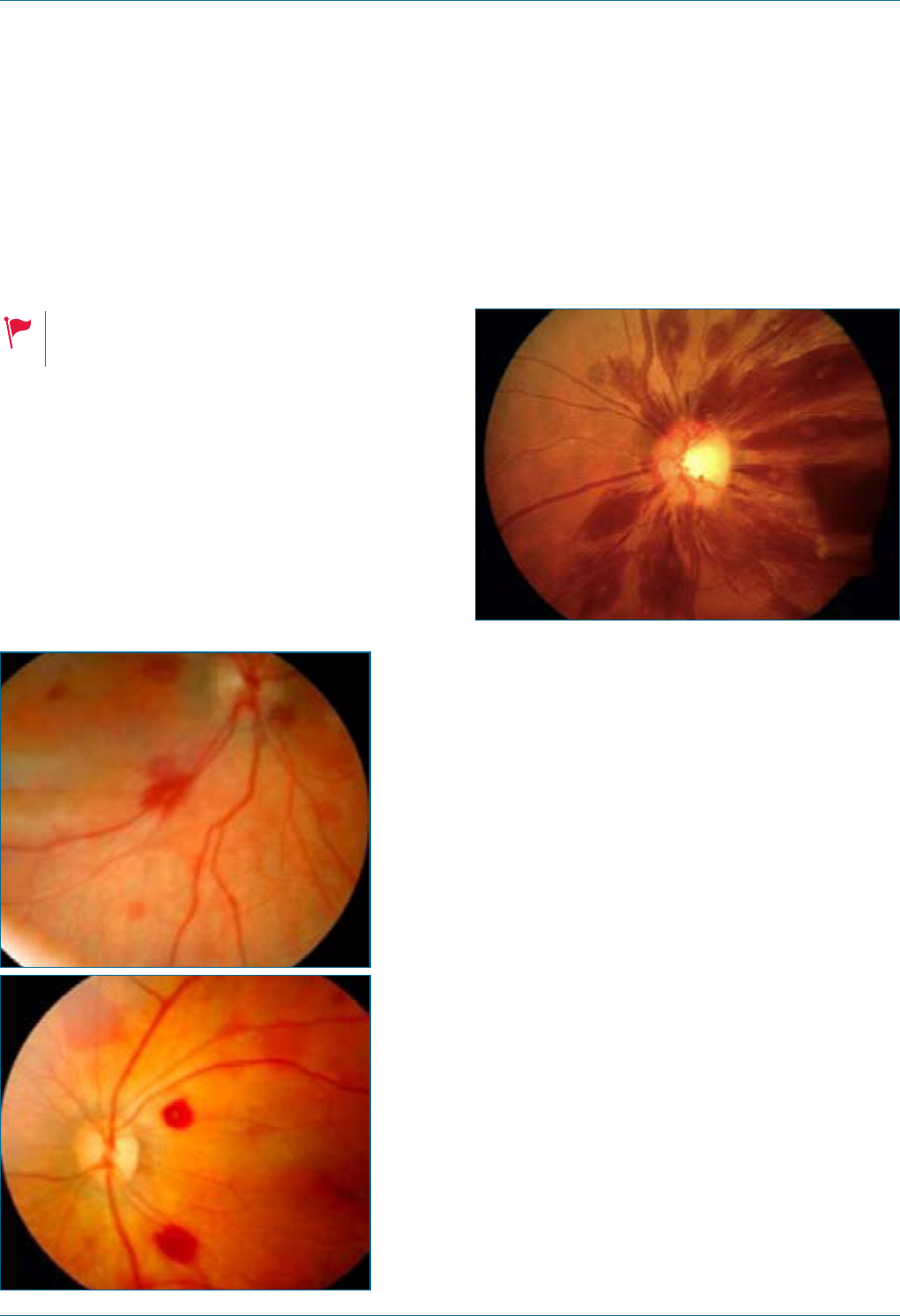

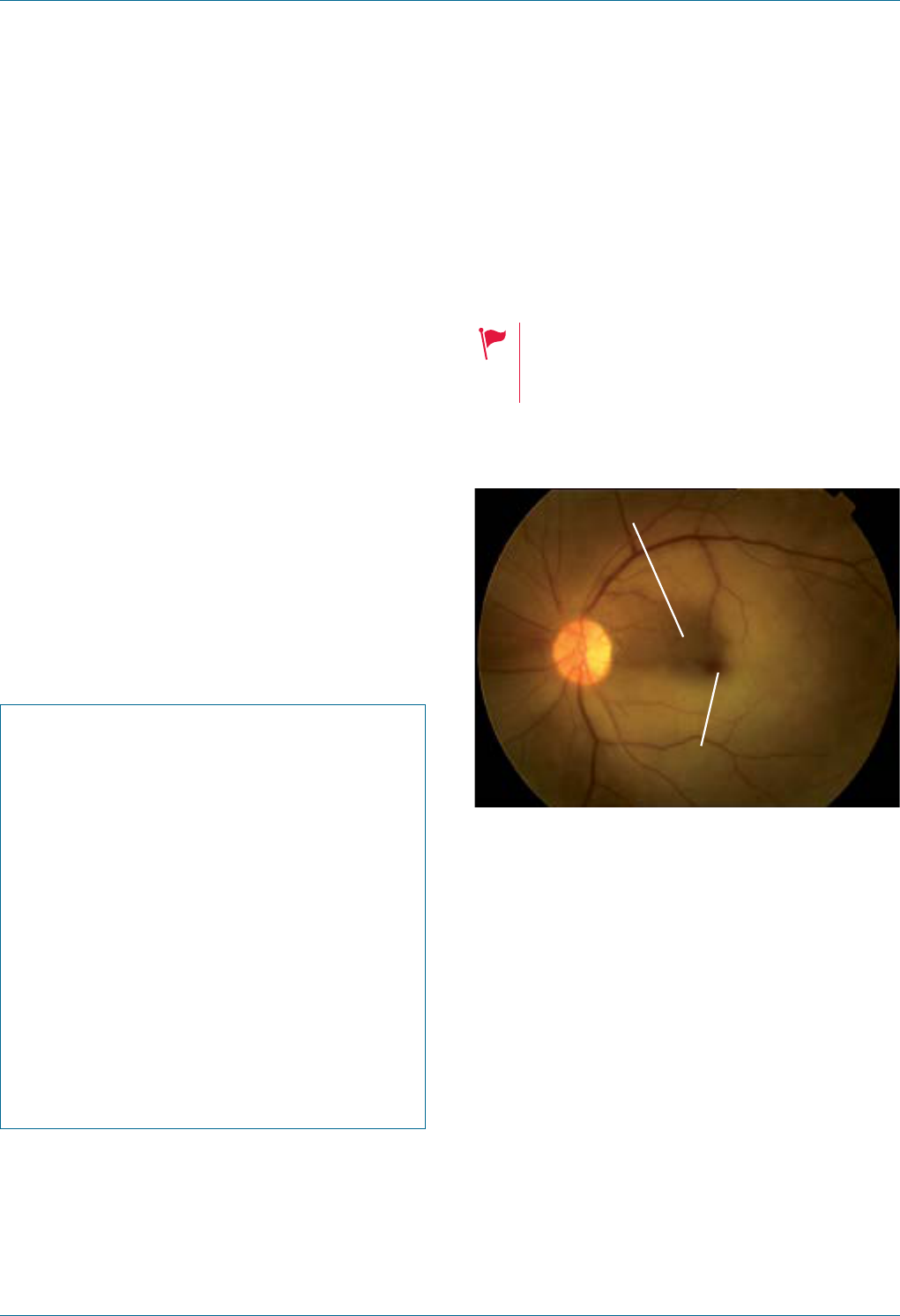

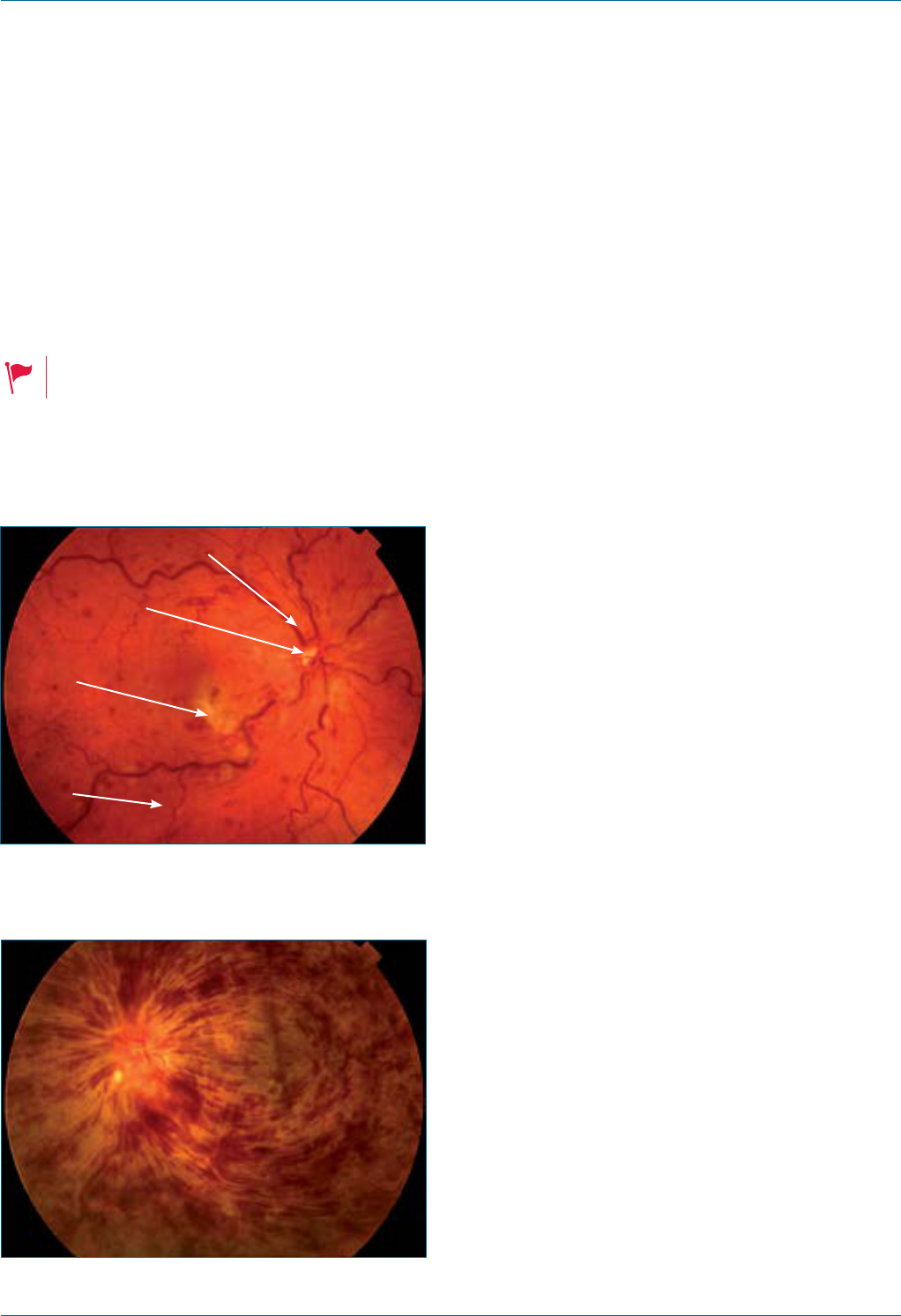

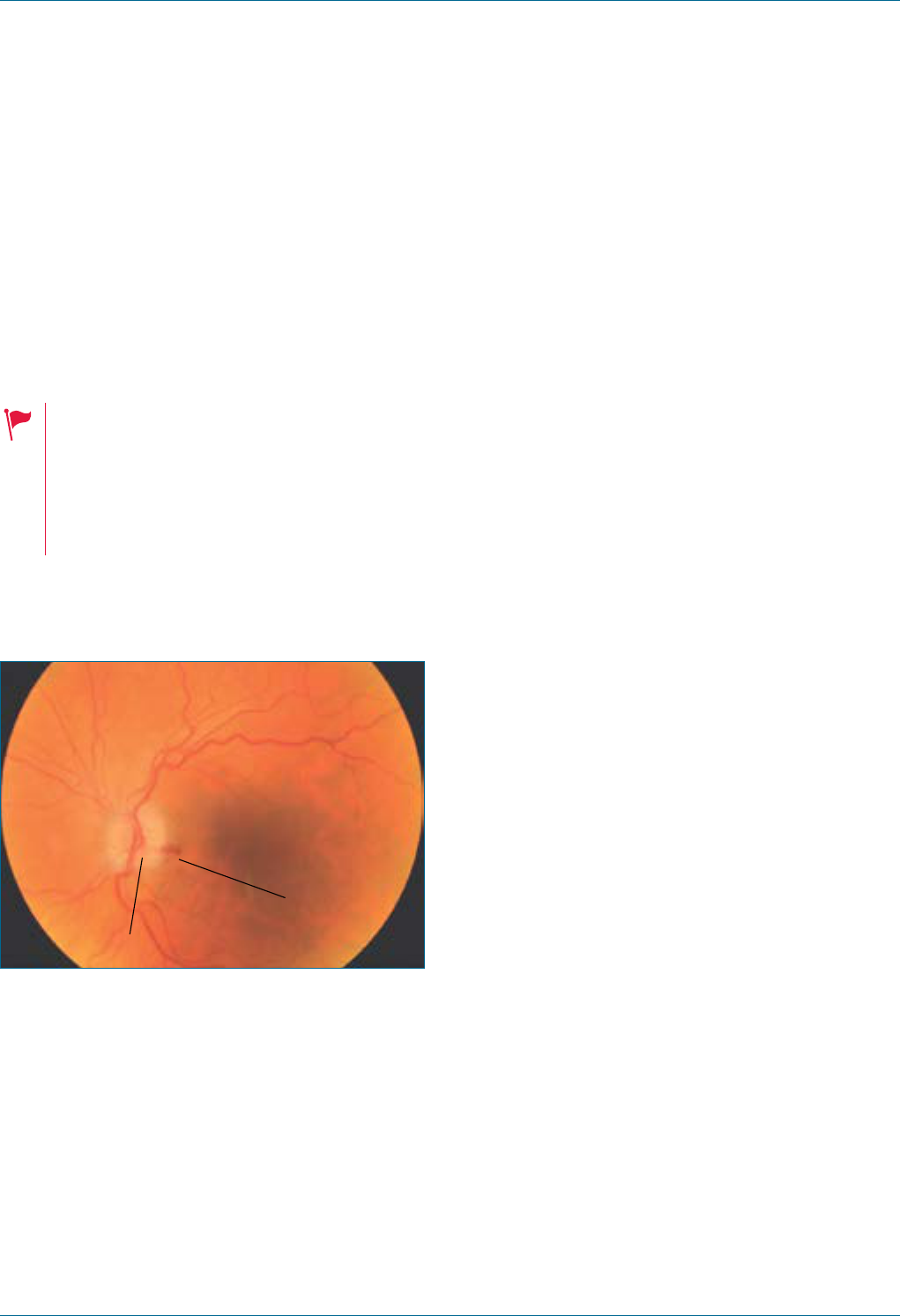

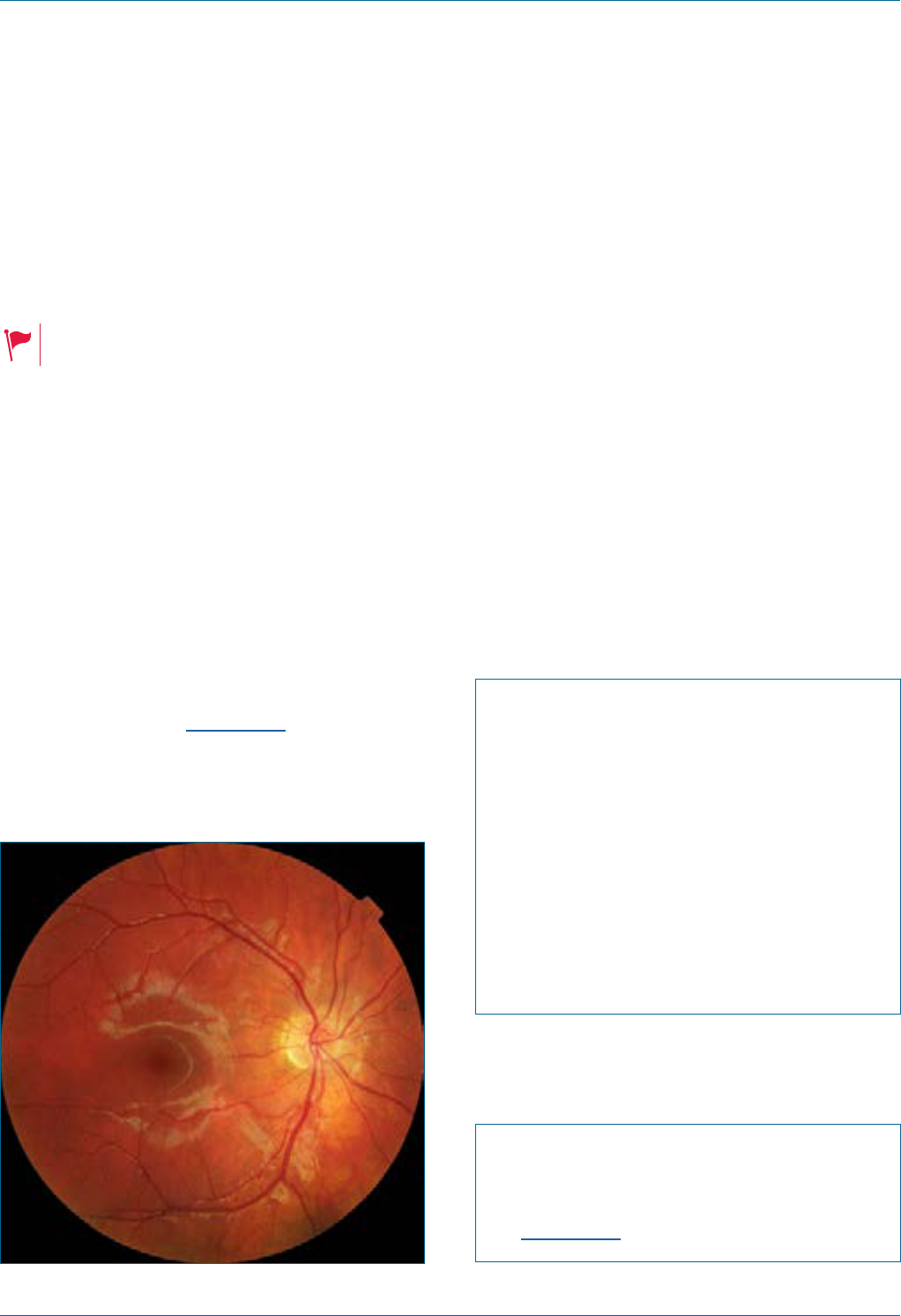

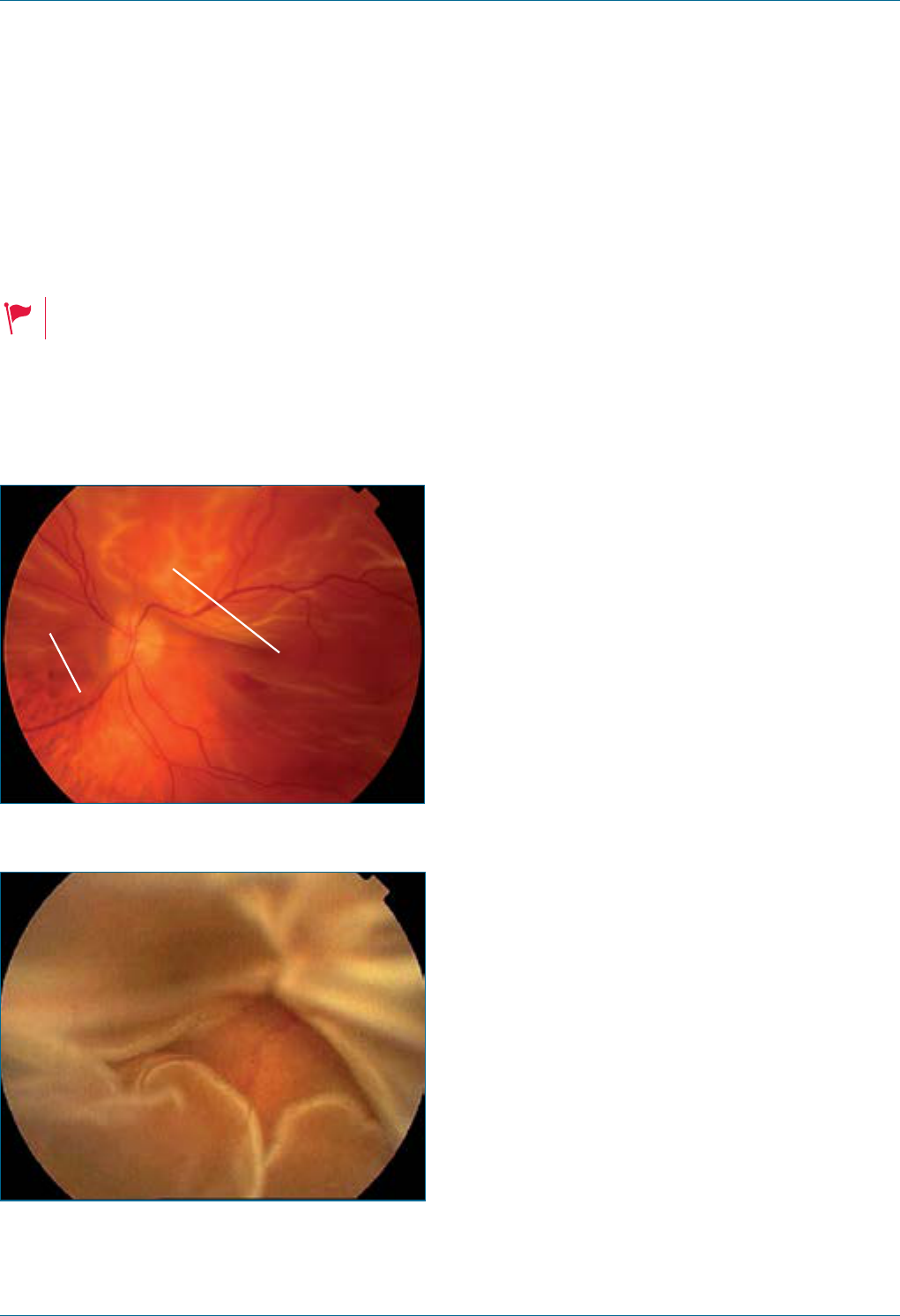

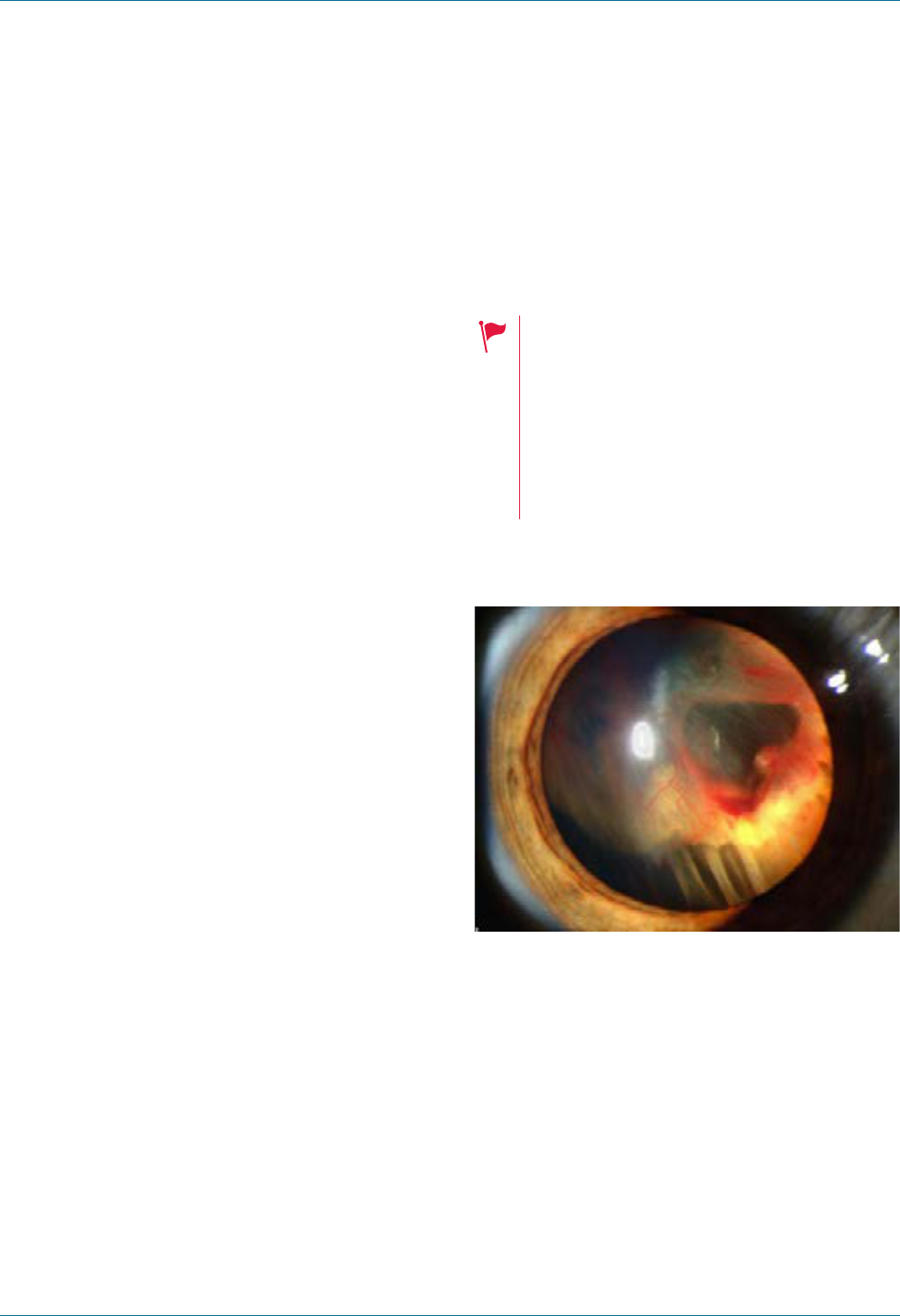

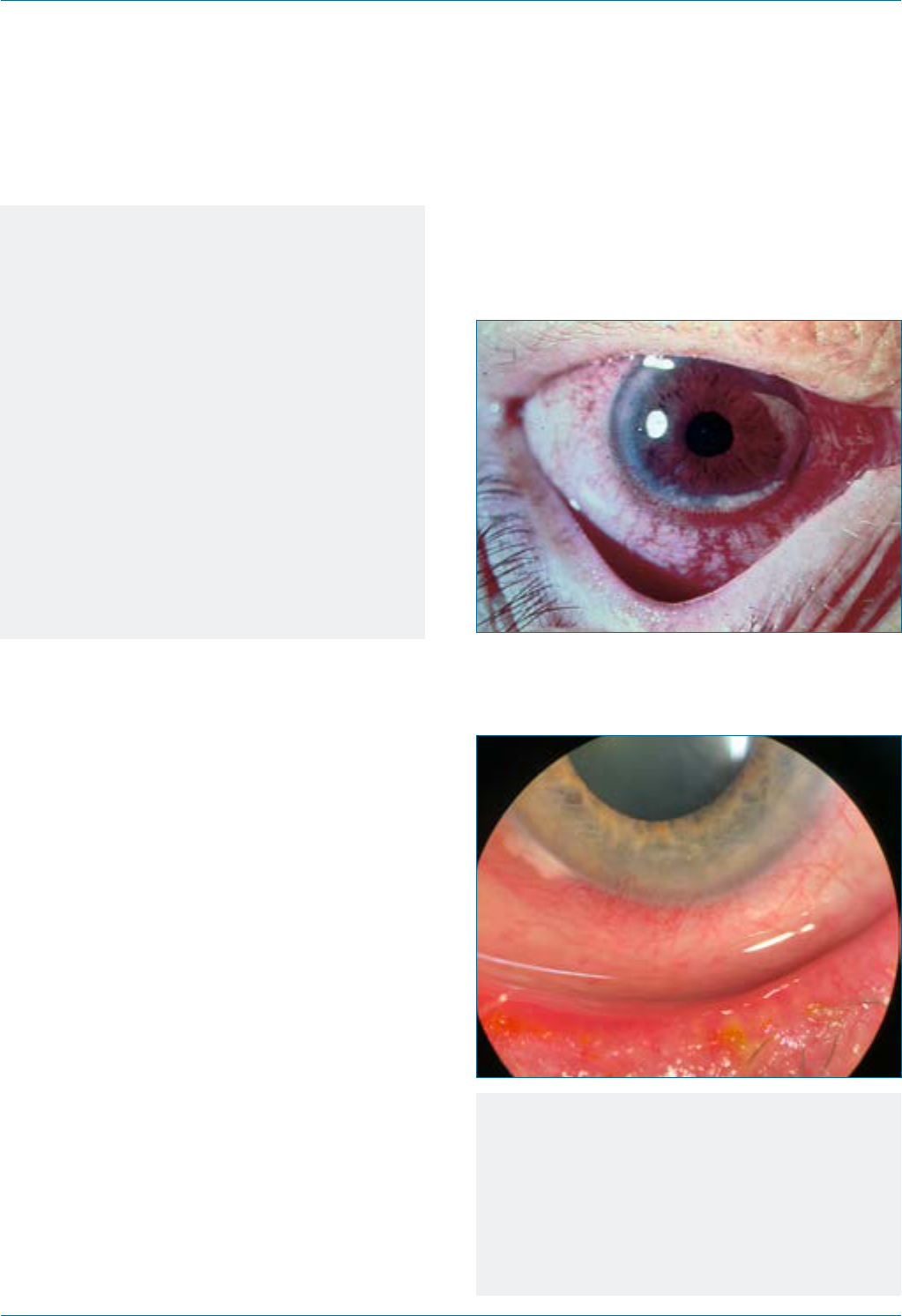

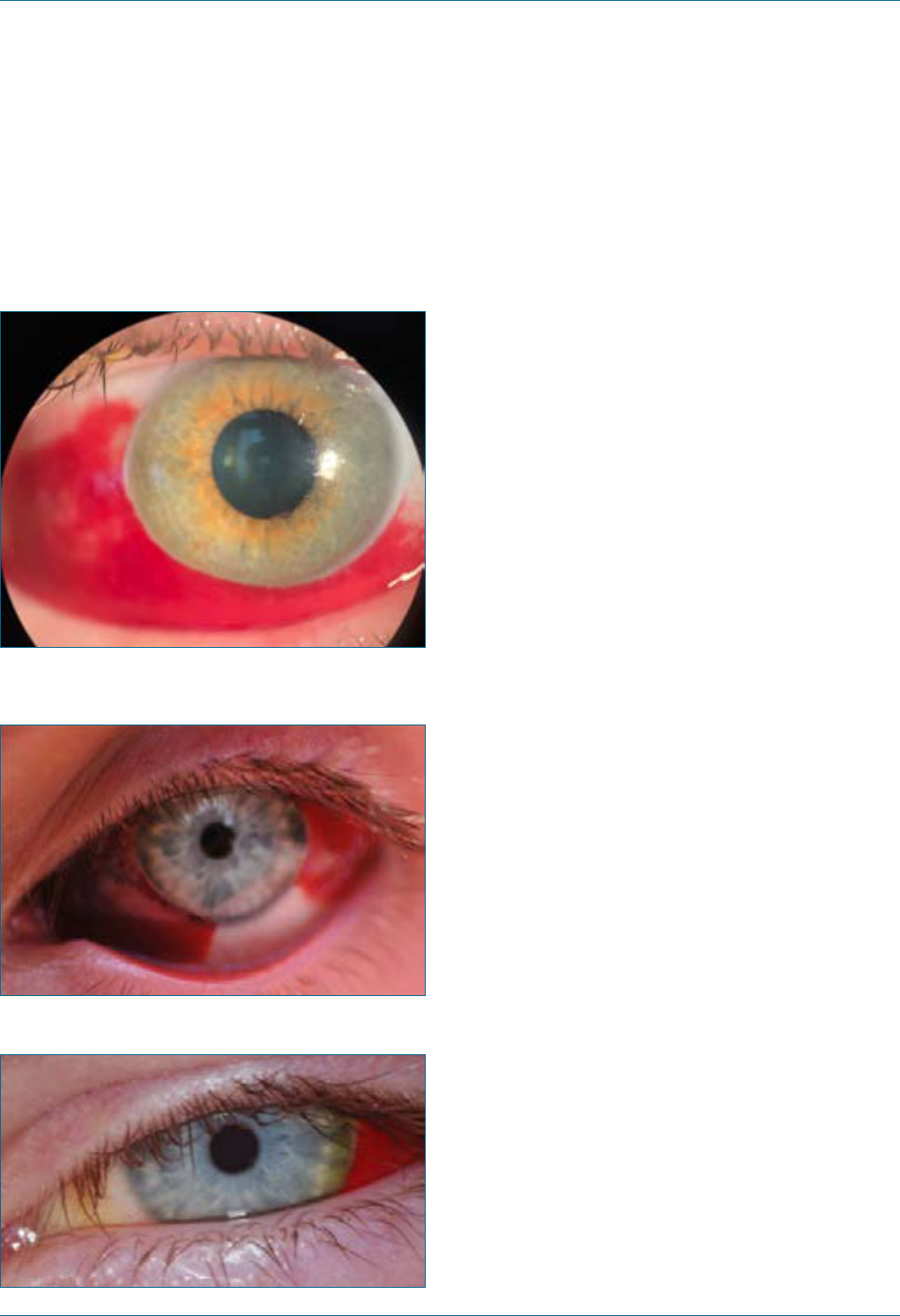

Figure 2. Swollen optic disc and

haemorrhage.

Haemorrhage

Swollen optic disc

Eye Emergency Manual December 2023

Agency for Clinical Innovation 14 aci.health.nsw.gov.au

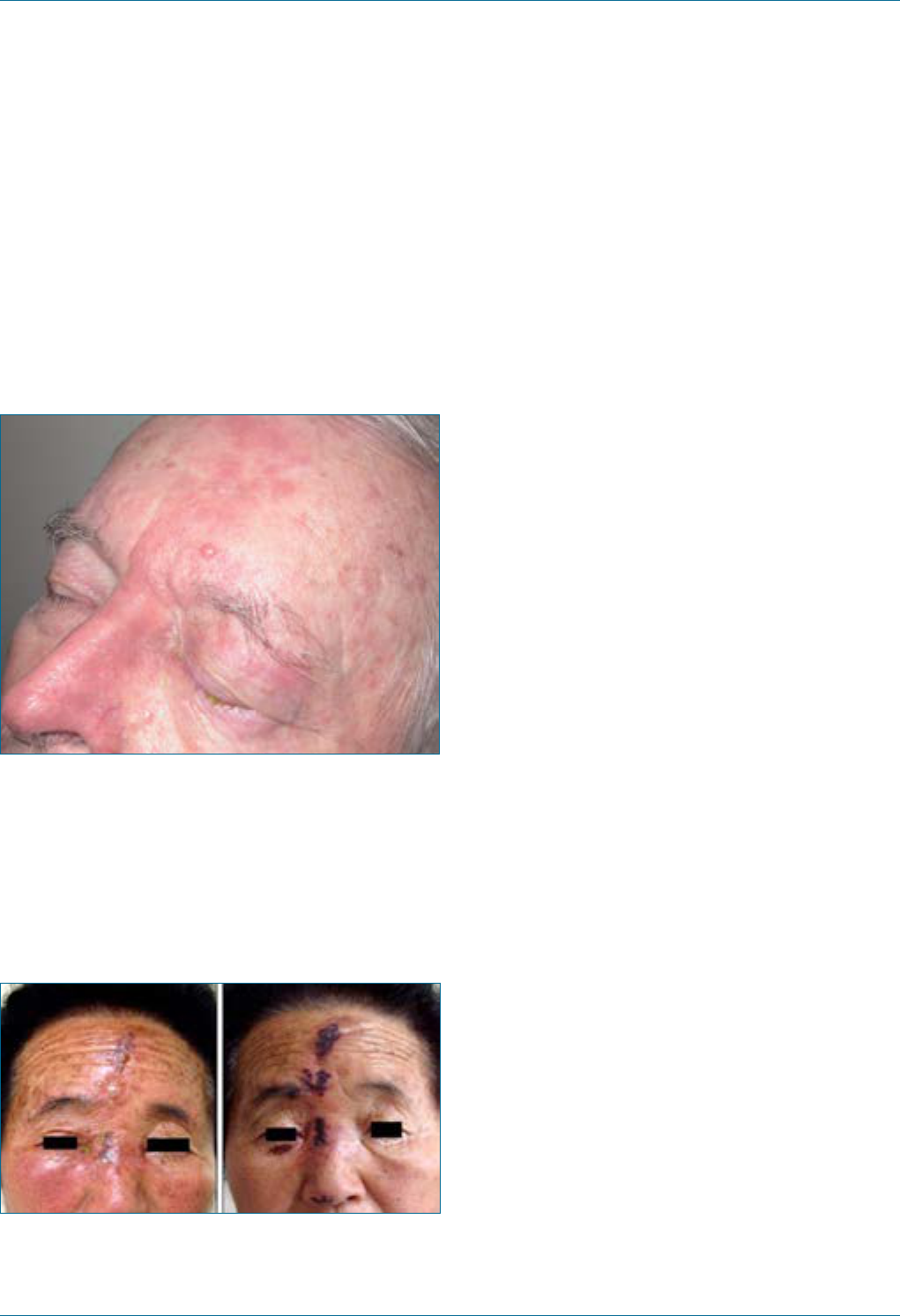

AION due to giant cell arteritis

Consider the following in determining if the patient

has giant cell arteritis (GCA):

• Abrupt, painless loss of vision in one or

both eyes

• Brief, transient visual loss in hours or days prior

• Double vision

• Headache (classically frontotemporal)

• Jaw or tongue claudication

(worse with chewing or talking)

• Discomfort on brushing hair over one or

both temples

• Weight loss

• Anorexia

• Polymyalgia rheumatica symptoms (pain and

stiffness in pelvic or shoulder girdles)

Notes

Suspect giant cell arteritis (GCA)

inany patient over 50 who presents

with visual changes or a cranial

nerve palsy.

• You may have already considered GCA if

the patient has visual loss or diplopia, but

take the opportunity to consider the

diagnosis again prior to contacting

an ophthalmologist.

• GCA can present insidiously and rapidly

progress to bilateral complete blindness,

in some cases despite

adequate treatment.

• The diagnosis of GCA is largely clinical, i.e.

it is based on history and supplemented

with inammatory markers, and only later

by a temporal artery biopsy. Treatment is

usually undertaken in the presence of

compelling history, regardless of

inammatory markers.

• If you suspect GCA, liaise urgently

with an ophthalmologist. Referrals to

endocrinology or rheumatology may also

be appropriate in certain

clinical scenarios.

• Jaw (or tongue) claudication can be

differentiated from other causes of dental

or temporomandibular pain by determining

that (as with all claudication) there is no

pain at the beginning of mastication, and

that pain develops after a specic amount

of time, abates after cessation of chewing

and recurs upon resumption.

• Document symptoms specically and in

point form, (e.g. ‘no headache, no jaw

claudication, no tongue claudication’)

rather than simply writing ‘no GCA

symptoms’ as this might be

challenged subsequently.

• The relevant clinical signs to elicit on

examination in suspected GCA are:

tenderness over the supercial temporal

arteries or paucity of pulsation on one or

the other side and the presence of a

relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD).

In acute GCA, the optic disc may be pale

and swollen, and while an effort may be

made to visualise the optic disc, this is

normally outside the scope of an

ED examination.

Eye Emergency Manual December 2023

Agency for Clinical Innovation 15 aci.health.nsw.gov.au

Assessing the severely

injured patient

Although life-threatening injuries take priority over

the assessment of the eye, it is not acceptable for

severe ocular injury to go unrecognised in a multi-

trauma patient once life-threatening issues have

been stabilised.

There are two main reasons for including an eye

assessment in the assessment of relevant

trauma patients:

• Firstly, damage to the eye can become the

dening injury for a patient who has survived

severe trauma, irrespective of the other injuries

they sustained. Hence, it is important to be

aware of these injuries early so that they can be

addressed appropriately.

• Secondly, although rare, some ocular injuries are

amenable to timely intervention that can

sometimes restore vision, e.g. retrobulbar

haemorrhage and chemical injury. Missing these

entities can contribute signicantly to a

patient’s morbidity.

Technique

Checking visual acuity in recumbent or restrained

patients or those in cervical collars can be difcult,

but this is vital if an ophthalmic injury is suspected.

Strategies include the following:

• Use another staff member to occlude the other

eye or hold a pinhole.

• Lower the patient’s bed without compromising

immobilisation of the spine.

• Hold a 3m chart above the patient’s bed. Ensure

your safety rst and foremost and adhere to

work health and safety regulations.

• Permanently tape a 3m or 6m chart to the

ceiling after measuring the distance between

the bed (putative position of the eyes) and the

ceiling. The acuity readings can be calibrated

based on the distance you have measured, e.g.

an eye that just sees the largest ‘E’ on a 6m

chart (labelled ‘60’) from a 2m distance should

be recorded as ‘2/60’.

While it is not possible to check visual acuity in

obtunded or intubated patients, you must still

undertake the following:

1. Perform a general inspection of the globe:

− check the integrity of the globe for rupture

− examine without putting pressure on the eye

− check for retrobulbar haemorrhage

− check for a bulging, tense, proptotic eye with

an inability to close the eyelids

− check for periocular and eyelid lacerations.

2. Check pupillary reactions for:

− direct and consensual pupil reaction

− RAPD and pupil size

This is the most important source of information in

obtunded patients (remember that the room must

be temporarily darkened to assess this).

Eye Emergency Manual December 2023

Agency for Clinical Innovation 16 aci.health.nsw.gov.au

Paediatric assessment

Paediatric assessment can be very difcult,

particularly if the child is injured or distressed. Do

not delegate the task of assessing a child to a junior

or an inexperienced member of the ED team and do

not separate the child from their parent(s) during

the assessment.

History

• Find out the child’s age, vaccination and

fasting status.

• Obtain a detailed history from an adult witness.

• A lot of information can be gathered by simply

observing the child while you take their history.

• Assess visual acuity for each eye based on the

patient’s age and ability to interact. Although

this can be difcult, it is vitally important and

cannot be deferred. Enlist the parent’s help for

an explanation, covering an eye or holding a

visual target. Check visual acuity before the

child becomes distressed, as may happen when

you examine them.

• Check visual acuity as appropriate for each

age group.

Babies

Assess the ability to x and follow light and

blink in response to bright lights (use a target

with a central, steady and maintained gaze). A

small child will x and reach for a bright object.

Toddlers

Assess the ability to identify and reach for a

small coloured target (e.g. single 100s and

1,000s sprinkles or similarly sized rolled up

piece of paper). Sprinkles (e.g. 100s and

1,000s) are commonly used to test ne vision

in children.

Infants

Assess visual acuity using a shape (or Snellen)

chart using a matching board (‘tumbling-E’s).

Age 5 or older

Assess using Snellen acuity test. Check pupils

and for an RAPD.

Some eyedrops will sting upon instillation.

Topical anaesthetic, although initially painful,

can be very useful as it will relieve pain for

about 20 minutes and may allow the child to

spontaneously open their eye after a

few minutes.

It may be necessary to gently restrain a child

to facilitate examination, or it may be feasible

to sedate the child in the ED, provided staff

with the appropriate training are available. In

some cases, it is necessary to plan an

examination under anaesthesia to complete

the assessment.

Eye Emergency Manual December 2023

Agency for Clinical Innovation 17 aci.health.nsw.gov.au

Notes

If a history is unavailable, always suspect an

injury or foreign body as a cause for a red or

painful eye in a child. If you suspect non-

accidental injury (NAI), contact the relevant

child protection service in your area.

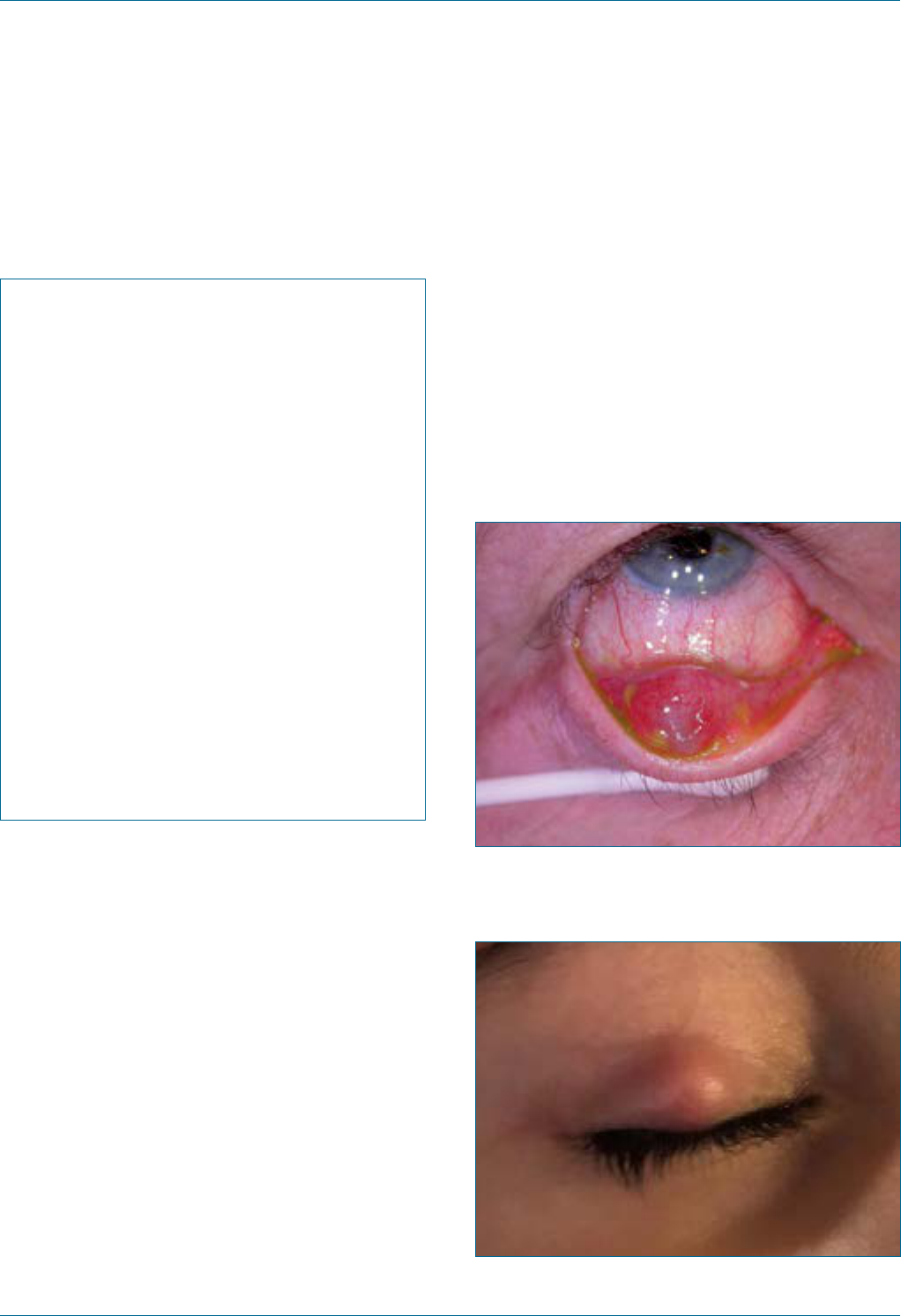

Periorbital cellulitis can be more aggressive in

children than in adults. It is normally treated by

admitting the child and placing them on

intravenous antibiotics under ophthalmology

and paediatric care.

Conjunctivitis in any child within one month of

birth is a medical emergency and requires input

from ophthalmology, infectious diseases and

potentially the child protection unit.

As is true for adult patients, do not put any

pressure on an eye that you suspect may be

ruptured. This is particularly an issue in children

where examination can be difcult. If you

suspect a globe rupture, put a shield on the eye,

fast the child and contact ophthalmology.

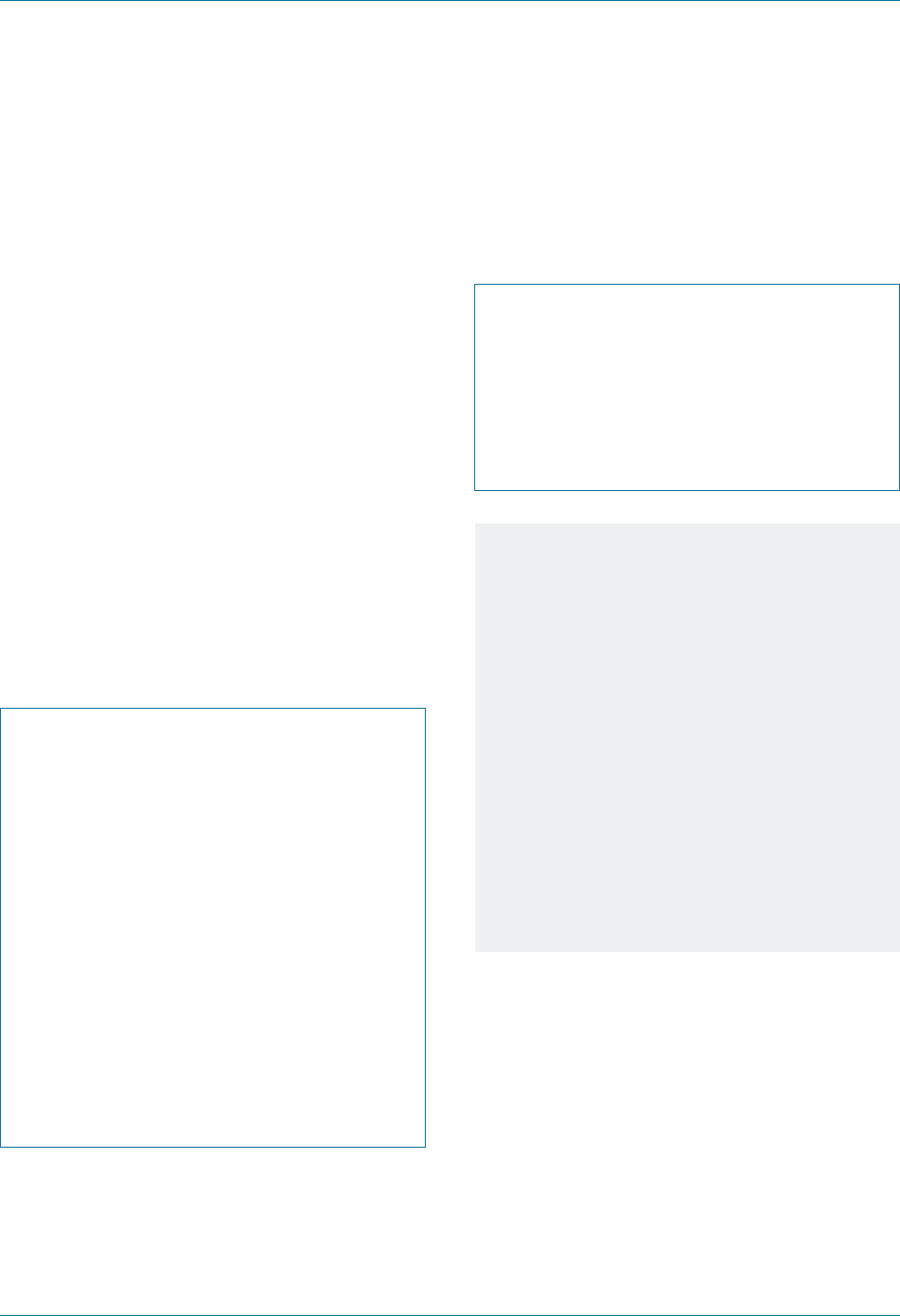

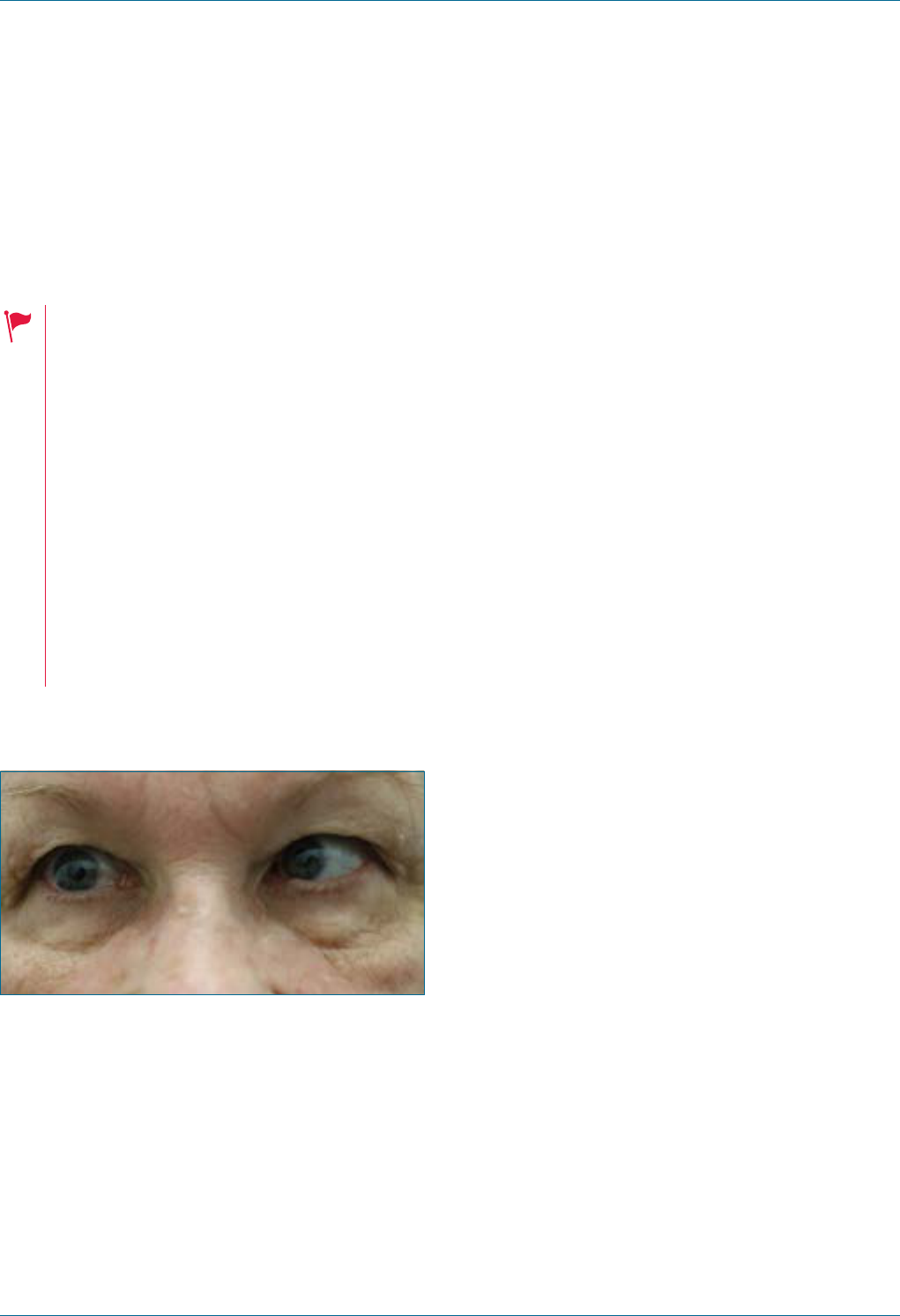

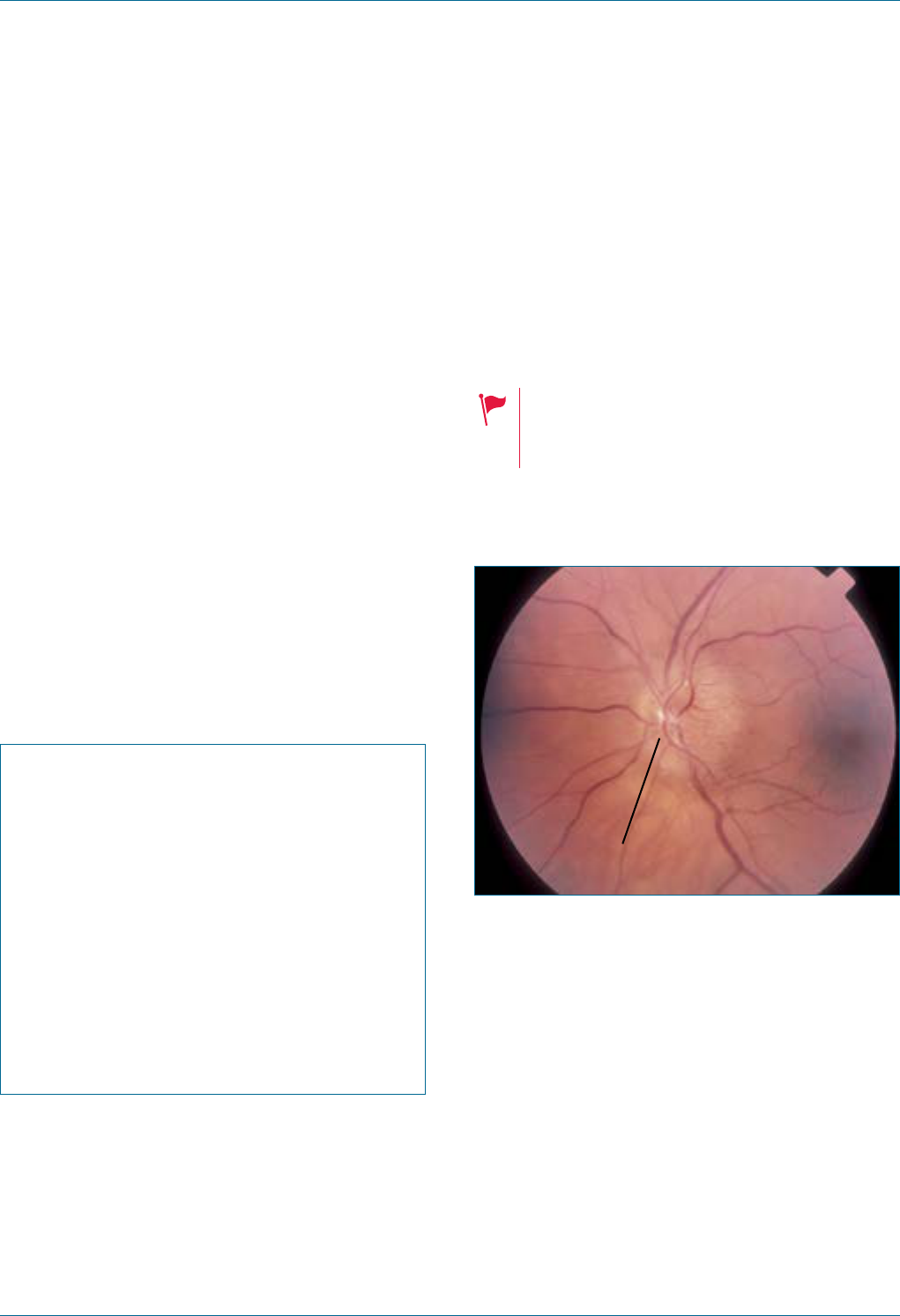

Orbital oor fractures in children are more

likely to adopt a greenstick conguration and

entrap part of the inferior rectus without

signicant external signs of injury. Be wary of

the classic presentation of the white-eye

blow-out fracture – a child presenting following

blunt periocular injury with an uninamed white

eye and inability to look up. They may be quite

unwell if they have a concurrent oculocardiac

reex (which is more common in children) and

this can provoke nausea, vomiting and

fatal bradyarrhythmias.

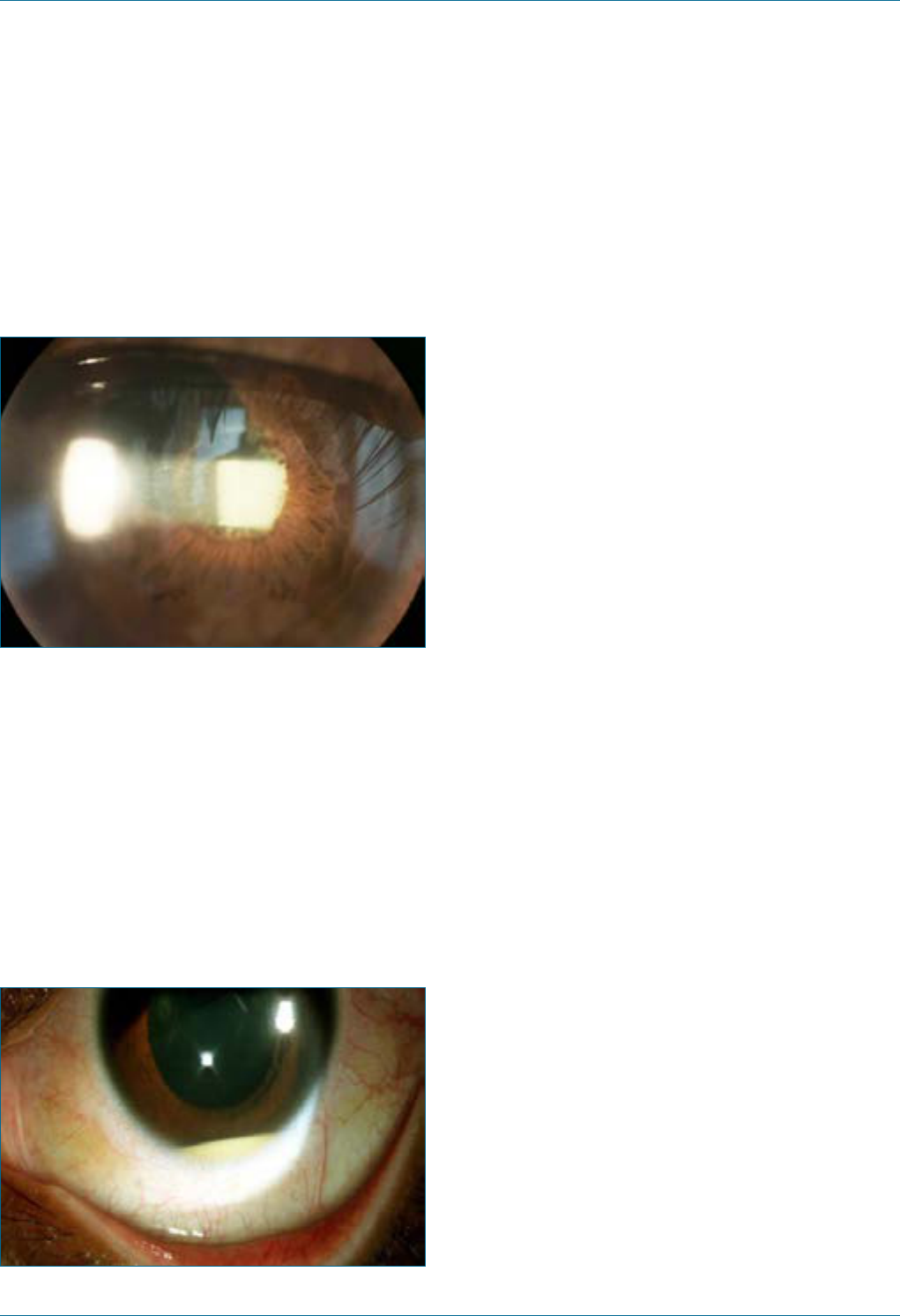

A child presenting at any age with no red reex

is said to have leukocoria. This may be noticed

by the parents, following a photograph that has

been taken, or by an optometrist. Several very

serious pathologies must be excluded in this

situation, chiey retinoblastoma. Leukocoria

requires urgent ophthalmic assessment.

As discussed in the visual acuity section,

amblyopia is a common cause of reduced vision

in adulthood. It occurs due to some sort of

visual impairment in children and cannot be

treated beyond approximately 10 years of age.

Ifyou discover unequal vision in a child whose

vision you have checked, the child may have

amblyopia that is still amenable to treatment.

Contact ophthalmology to arrange an

examination within 1–2 weeks.

Eye Emergency Manual December 2023

Agency for Clinical Innovation 18 aci.health.nsw.gov.au

Examinations

Examination essentials

Assessment of ophthalmology patients follows the same basic pattern of history and examination as in every

other area of medicine.

Below is a brief checklist for history and examination that should be used when assessing patients with

ophthalmic complaints. Please refer to it before contacting an ophthalmologist to ensure you have addressed

all the major points. The subsequent sections provide more information on each specic area.

Key points

Consider the following in examining patients:

• Take a history, check visual acuity, perform a

general inspection at arm’s length and look for

an RAPD for all patients.

• Selected other examinations may

be appropriate.

• It is usually not necessary to dilate pupils in ED.

Only dilate a patient’s pupils after you have

spoken with an ophthalmologist (and in cases of

trauma, the neurosurgery team).

History

• Age

• Basic demographics

• Medical history

Reasons for presentation

• Visual loss

• Diplopia (double vision)

• Painful or red eyes

• Trauma or foreign body

• Flashes and oaters

• Glasses/contact lenses/eye drops

• Prior or recent eye surgery/laser/injections

Examination

Essential

1. Visual acuity

− Without and with a pinhole for each eye

− 6/5 to 6/60, counting ngers (CF), hand

movements (HM), perception of light (PL)

orno perception of light (NPL)

Figure 3.

Snellen chart

using 6m eye

chart (visual

acuity ratio

inred).

6/60

6/36

6/24

6/18

6/12

6/9

6/6

6/5

6/4

2. General inspection

− Periocular injuries or injury to the globe

− Eye red or white

− Ptosis, proptosis or obvious misalignment

of the eye

− Gross surface anatomy of the orbit, lids,

lashes and eye

Eye Emergency Manual December 2023

Agency for Clinical Innovation 19 aci.health.nsw.gov.au

3. Pupils

− RAPD

− Direct and consensual response for each eye

− Size, shape and reactivity to light

4. Red reex with a direct ophthalmoscope

Essential in patients with visual loss or change or

neurological complaints

5. Visual elds

6. Eye movements

7. Cranial nerve examination

Additional

8. Slit lamp examination

9. Examination with direct ophthalmoscope

Contact an ophthalmologist immediately

after your assessment if you suspect

these conditions:

• Giant cell arteritis (GCA)

• Endophthalmitis

• Penetrating eye injury

• Retrobulbar haemorrhage

• Severe chemical injury

• Ophthalmia neonatorum

• Acute angle closure glaucoma

• Pain, redness or decreased vision in an

eye after any intraocular procedure

(surgery or injection) or in a contact

lens wearer

• Ophthalmic symptoms in any patient

withonly one eye (includes prosthetic

eye or long-standing poor vision in the

other eye)

Until proven otherwise

• Flashes and oaters = retinal tear

• Visual loss, visual change and diplopia in a

patient >50 years of age = GCA

• Serious periocular trauma = ruptured or

penetrated globe

• Serious periocular trauma = associated

intracranial injury

• Periocular lacerations contain a foreign body

• Eyelid lacerations are full thickness and involve

the globe

Reasons to defer visual acuity testing

• Chemical injury

• Obtunded, intubated or unconscious patient

• Severe life-threatening injury or

neurological concern

Diagnoses of exclusion

• Poor vision due to amblyopia

• Poor vision due to prior visual loss that has only

just become apparent to the patient

Reasons not to dilate a pupil

• Will not allow subsequent assessment for

an RAPD

• May precipitate angle closure

• Situations of head injury (will obviate pupil

measurements if the patient needs

neurological observations)

Eye Emergency Manual December 2023

Agency for Clinical Innovation 20 aci.health.nsw.gov.au

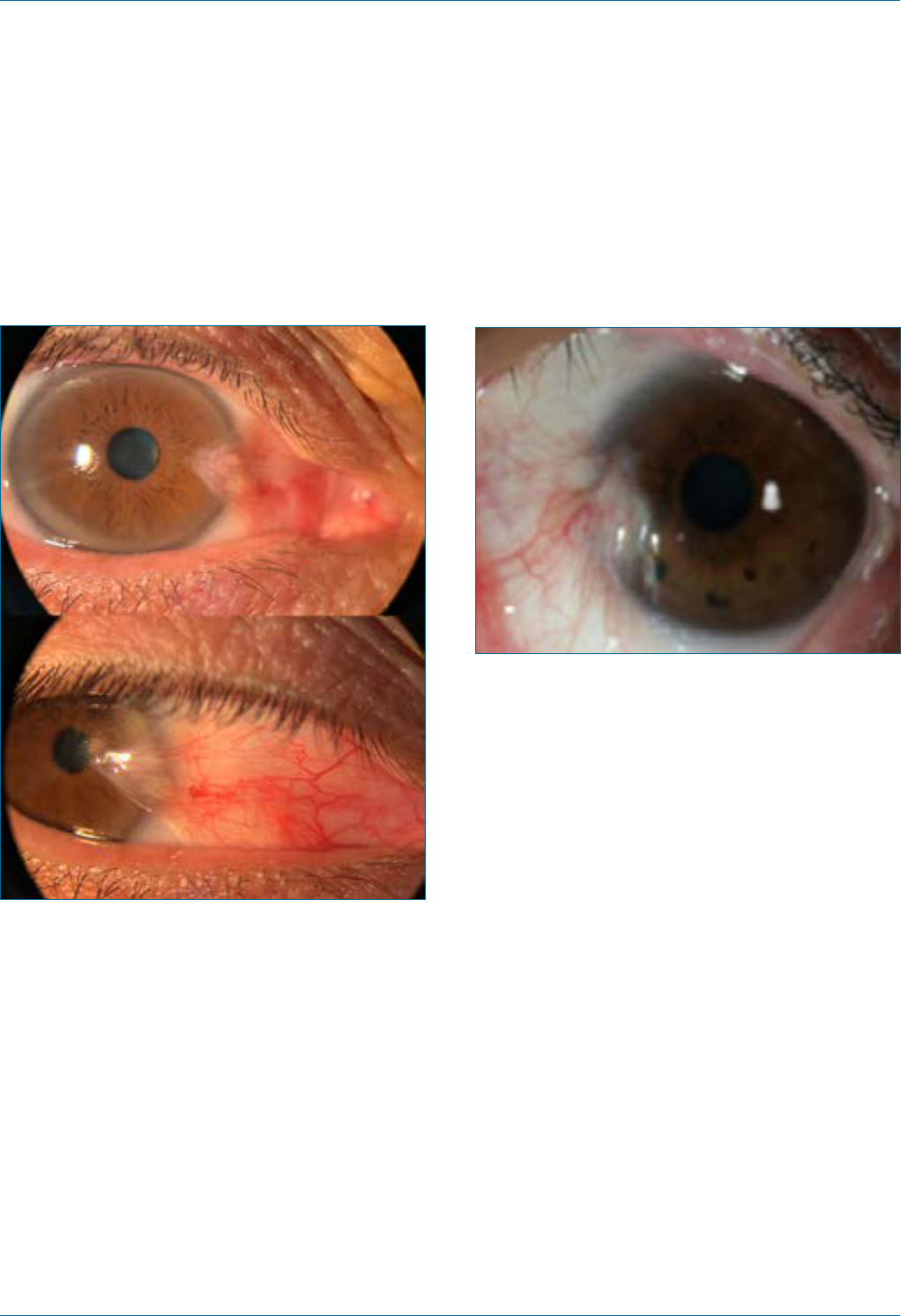

General inspection and assessment

of periocular and globe trauma

A general inspection provides a wealth of

information on all patients, particularly after trauma.

Most external eye ndings can be seen with a bright

pen torch or direct ophthalmoscope. Examine the

eye in an orderly fashion, i.e. lids, conjunctiva,

cornea, iris, pupil, anterior chamber, lens.

Address the following questions:

• Is the eye red or white?

• Is the globe ruptured or penetrated?

• Are there signs of

retrobulbar haemorrhage?

• Are there periocular lacerations

and ecchymoses?

• Are there signs of cranial nerve palsy?

• Is there cellulitis or swelling of the eyelids

or skin around the eye?

• Is there a foreign body in the lids, eye

or orbit?

Remember that in all serious trauma to the eye, a

penetrating eye injury and concurrent intracranial

injury must be excluded.

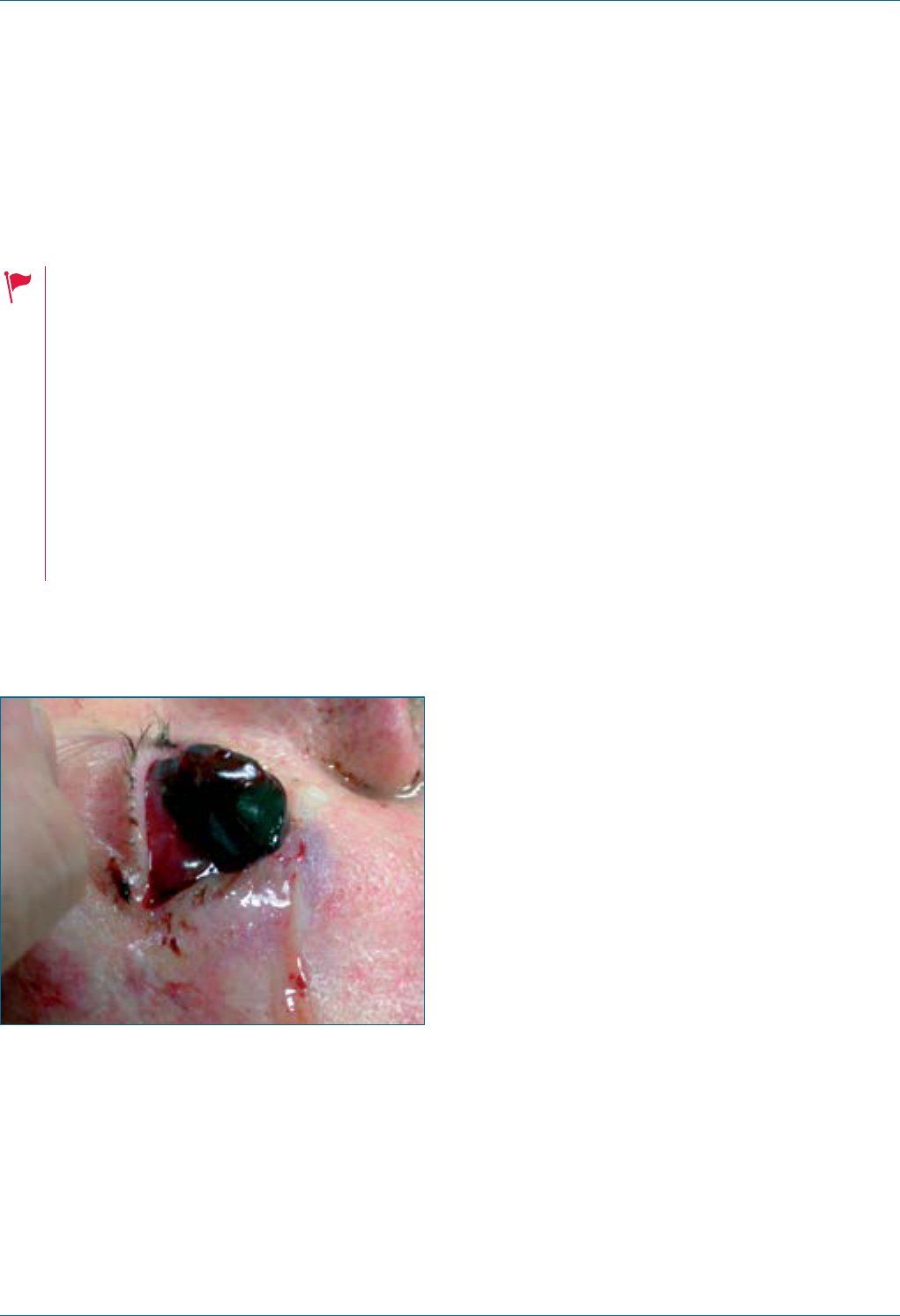

1. Is the globe intact?

Always begin with observation (see

questions above) and check visual acuity,

eye movements and pupils.

If you suspect globe rupture or penetrating

eye injury, examine with the utmost care.

Do not put any pressure on the eye. Gently

distract the eyelids by pressing ONLY on

the orbital margins.

External clues:

• Missile protruding from the eye: do not

remove it or touch it

• Swollen, haemorrhagic eyelids

• Obvious prolapse of uveal contents

• Distortion of the cornea or the globe

• Circumferential conjunctival swelling

and haemorrhage

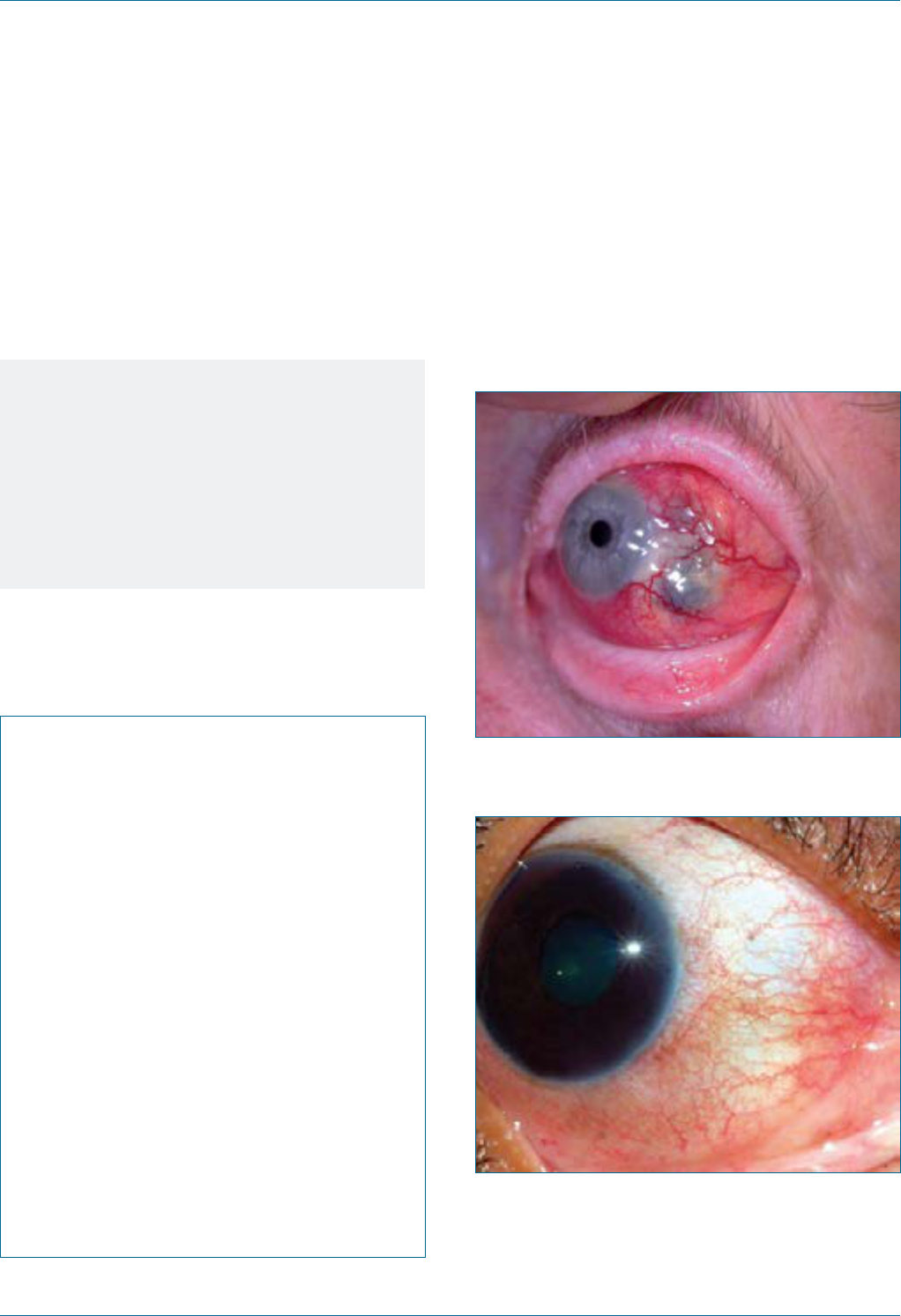

• Complete ‘8-ball’ hyphaema

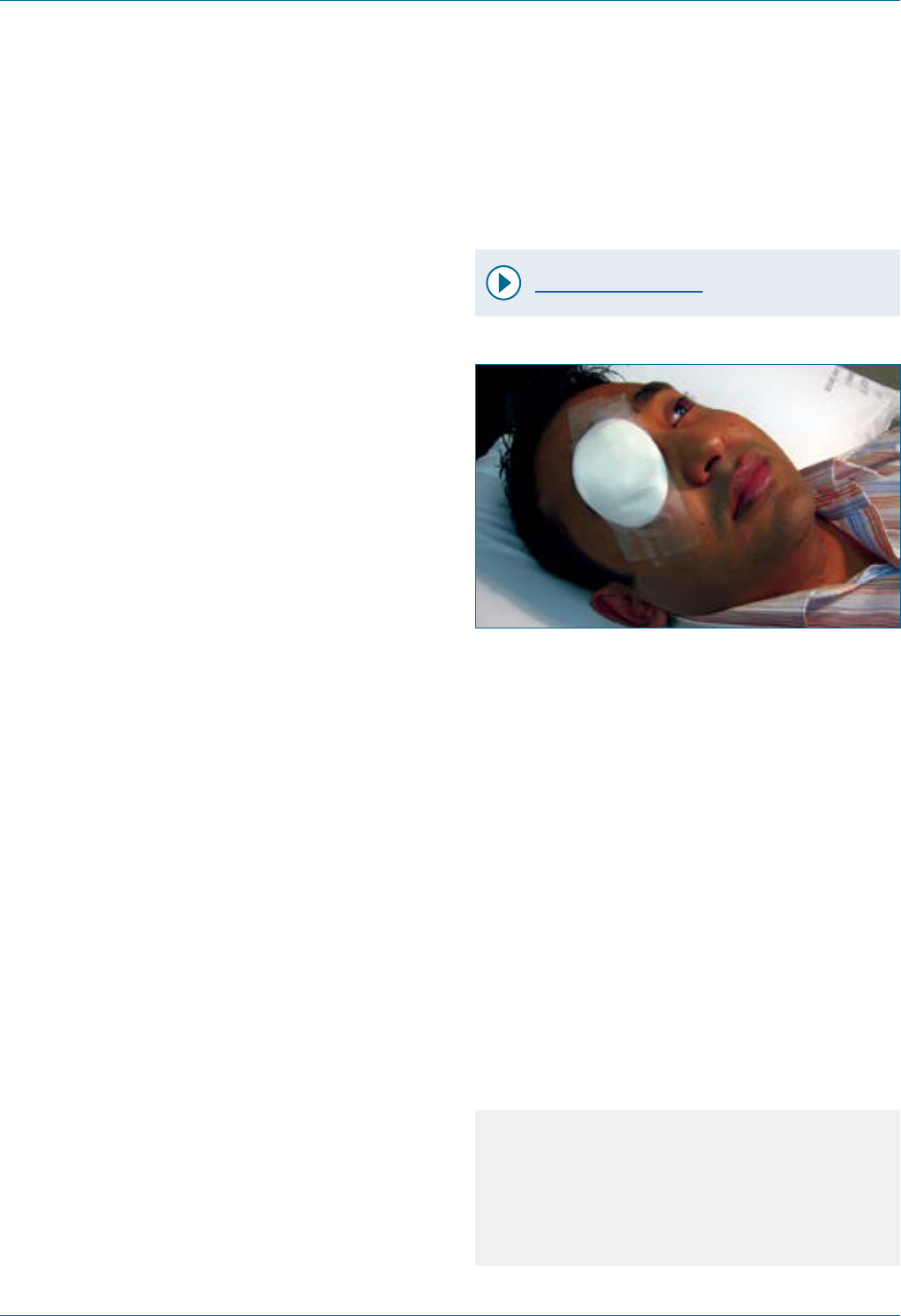

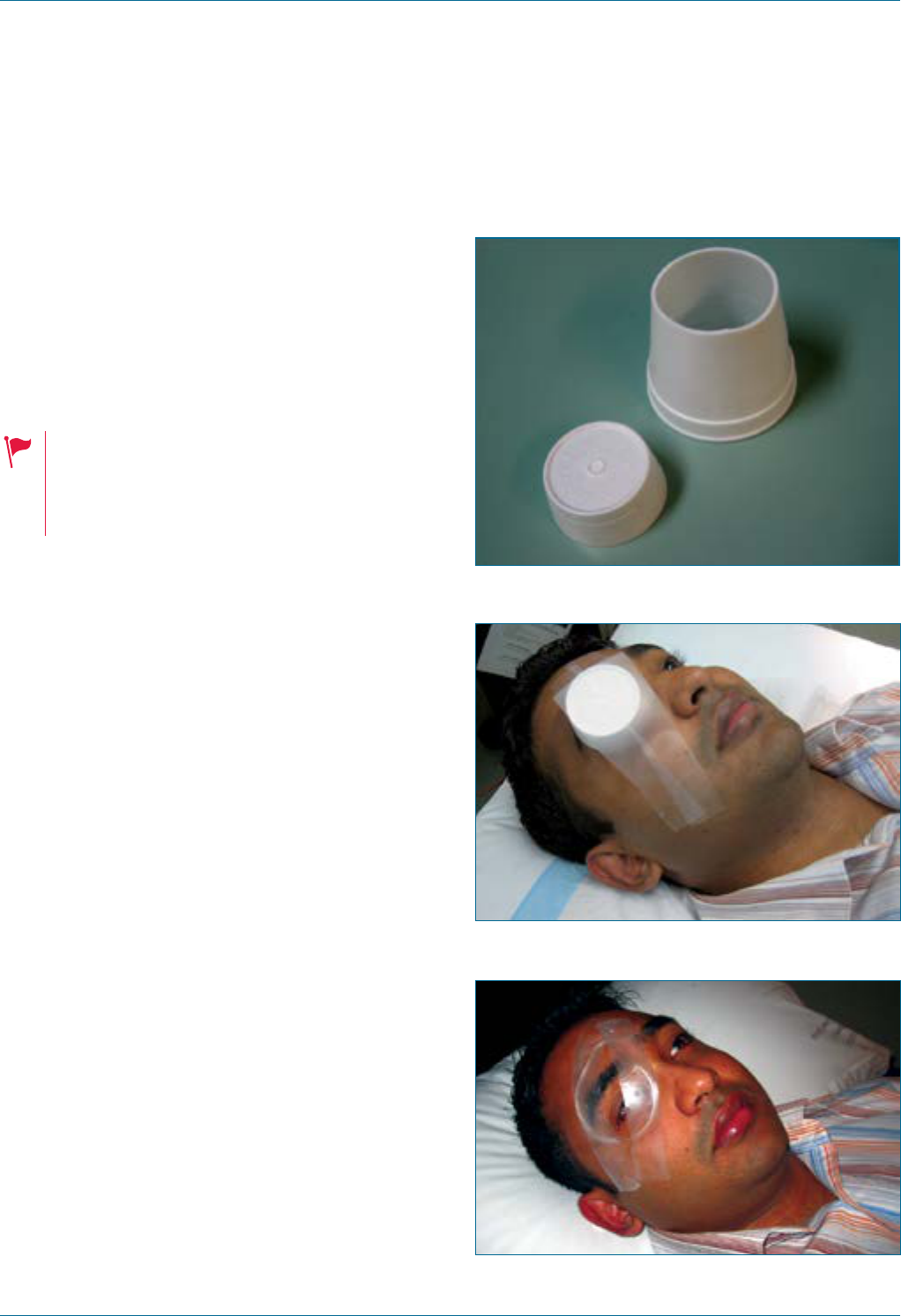

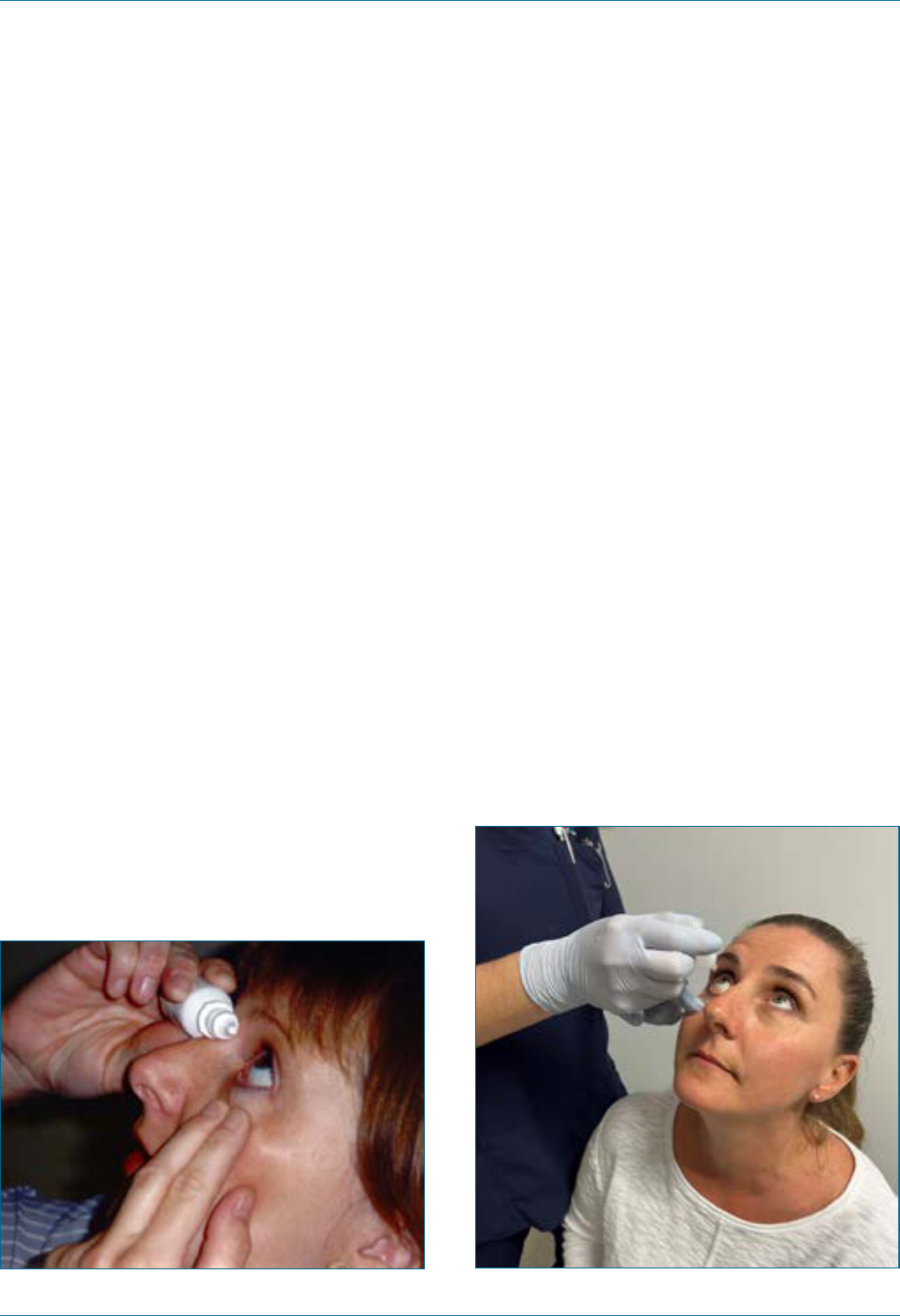

If you conrm globe rupture, do not

examine any further. Put a clear plastic

shield (or other makeshift mechanical

protection) over the eye, avoiding pads or

anything that might come in contact with

the eye. Contact ophthalmologist. Any

pressure put on the eye will exacerbate

the injury.

Eye Emergency Manual December 2023

Agency for Clinical Innovation 21 aci.health.nsw.gov.au

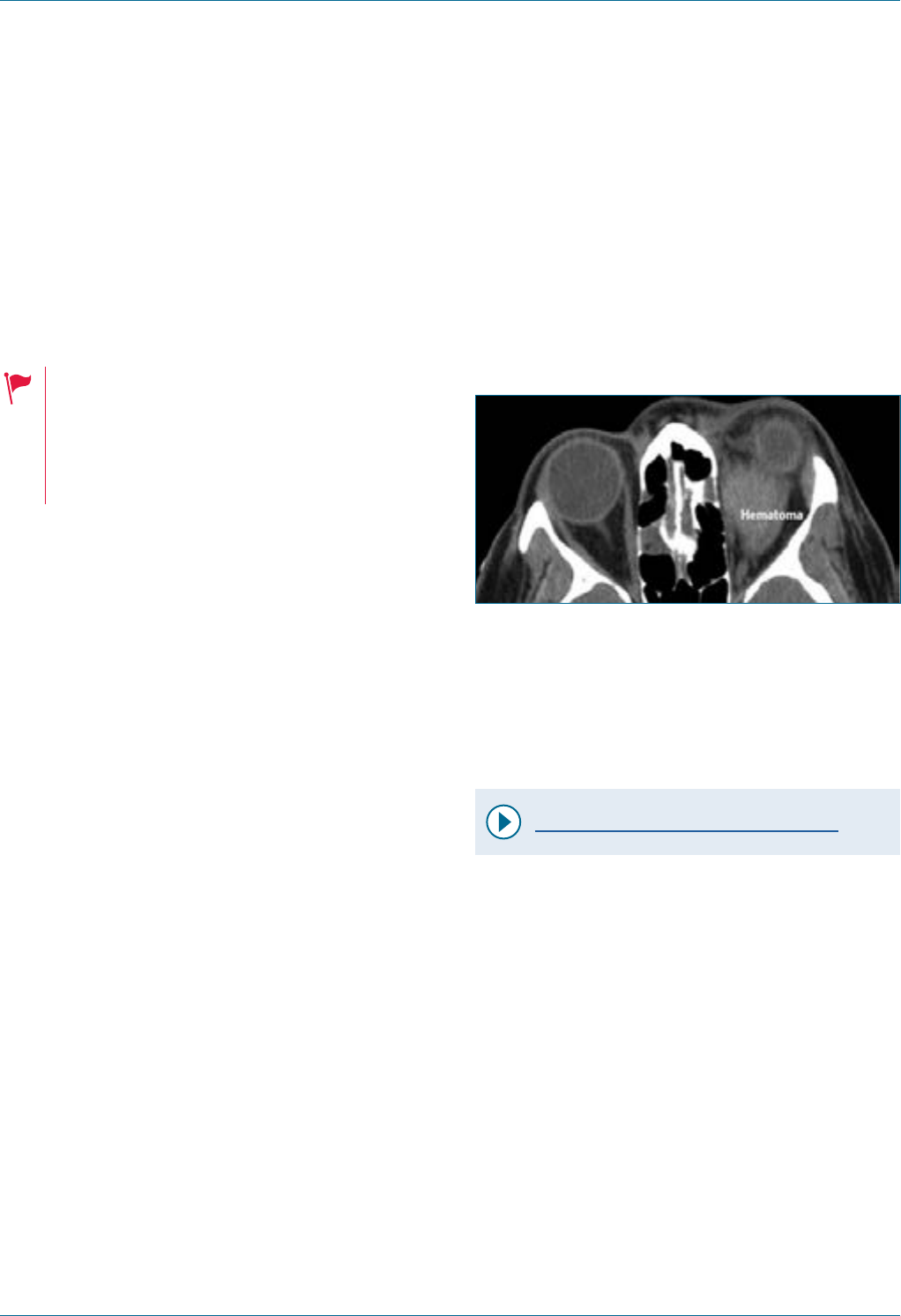

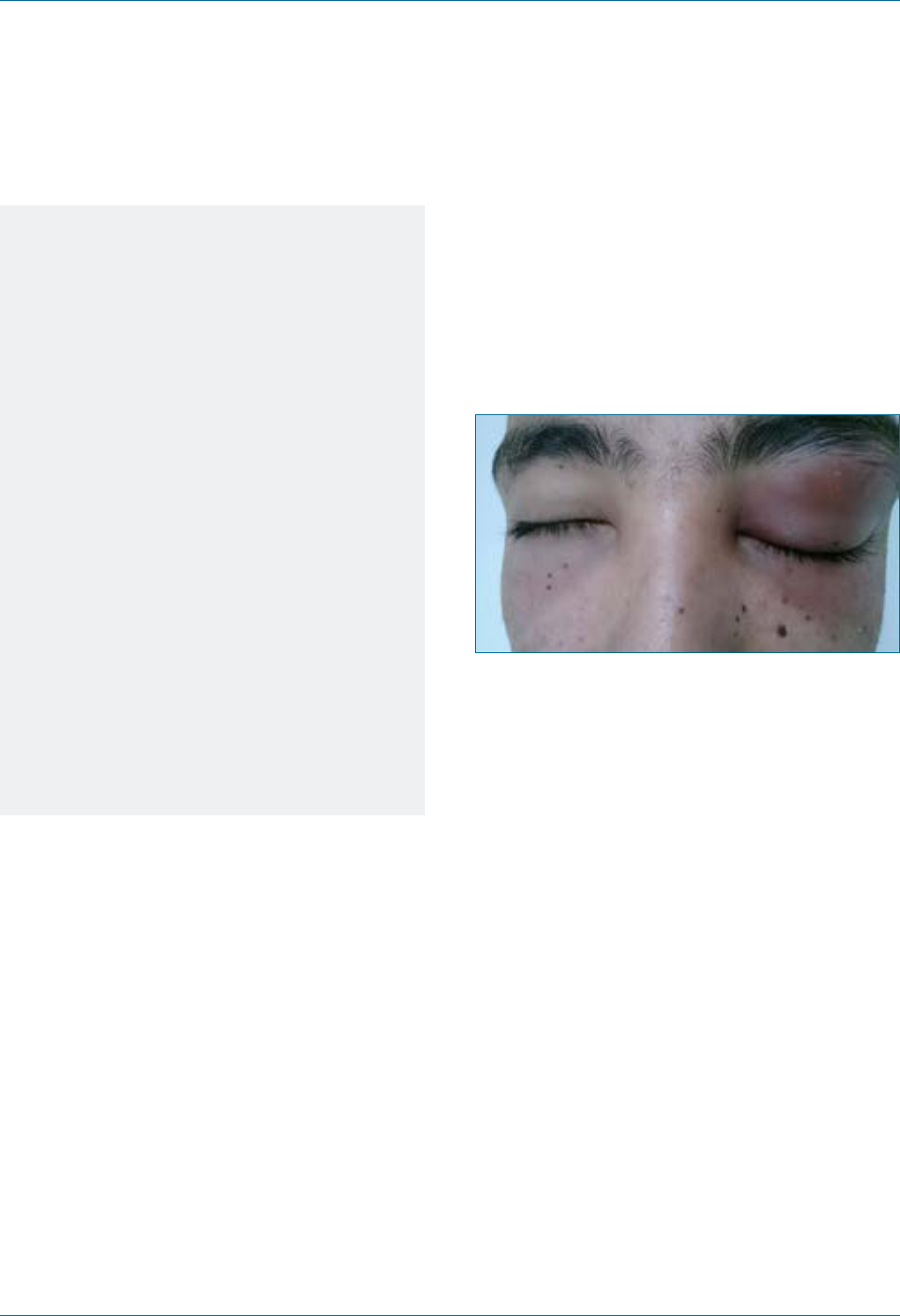

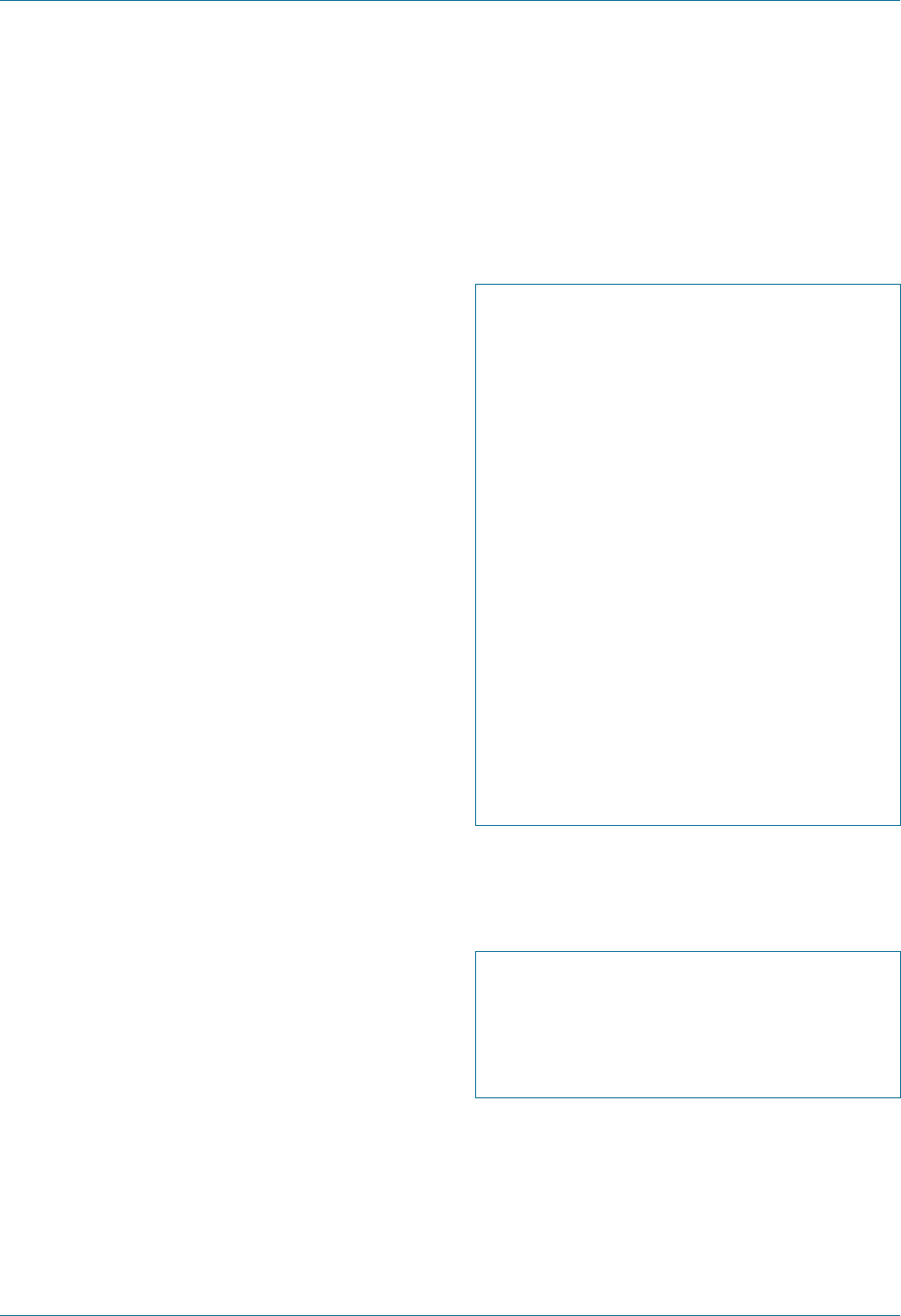

2. Is there a retrobulbar

haemorrhage?

External clues:

• Bulging, tense or proptotic eye with an

inability to close the eyelids following

blunt trauma

Check visual acuity and for an RAPD. The

presence of a periorbital fracture does

NOTpreclude a retrobulbar haemorrhage.

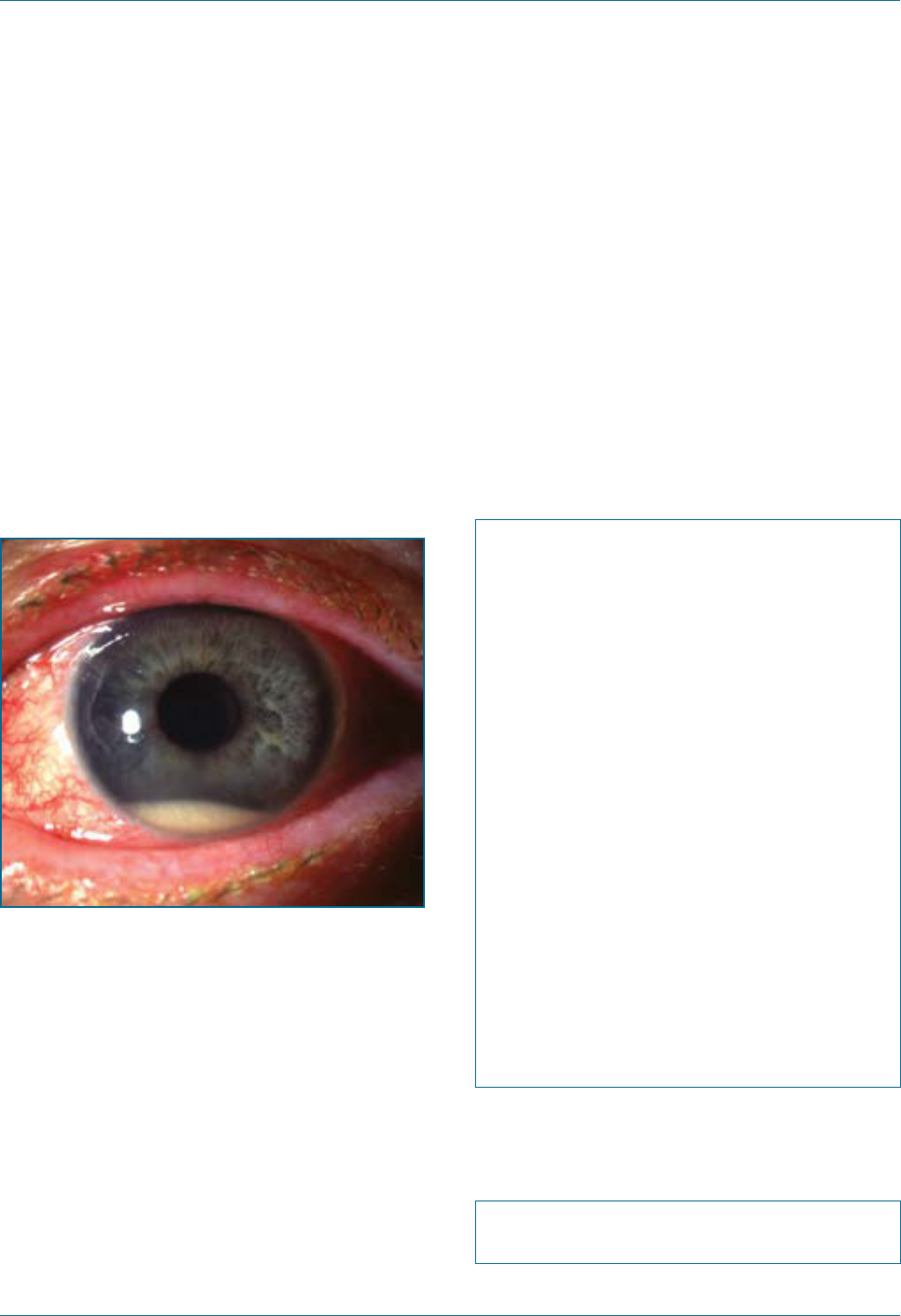

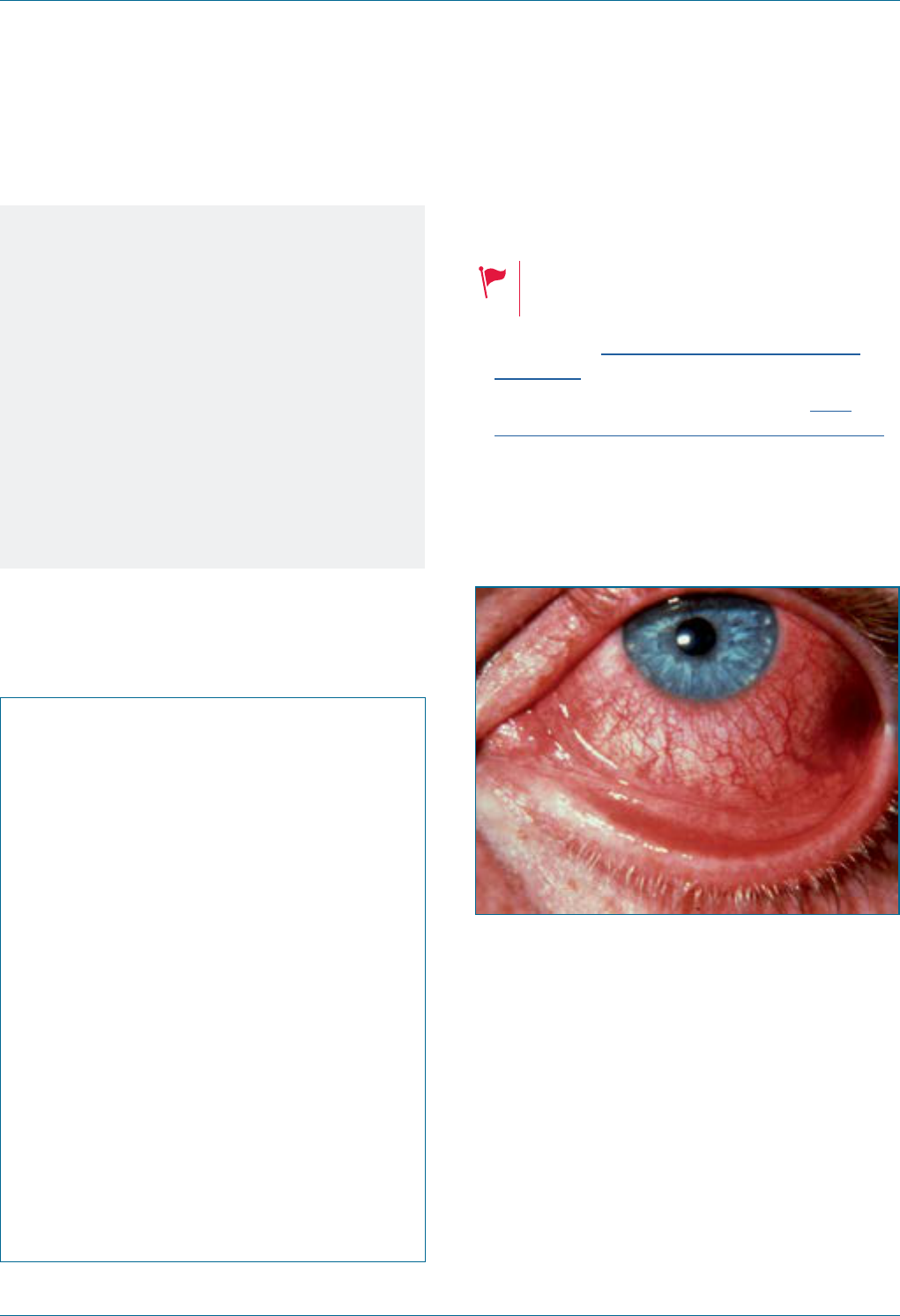

Retrobulbar haemorrhage is a clinical

diagnosis and does not need imaging for

conrmation. If you suspect it is present,

liaise urgently with an ophthalmologist,

emergency physician or a plastic or

maxillofacial surgeon to perform

canthotomy and lower lid cantholysis.

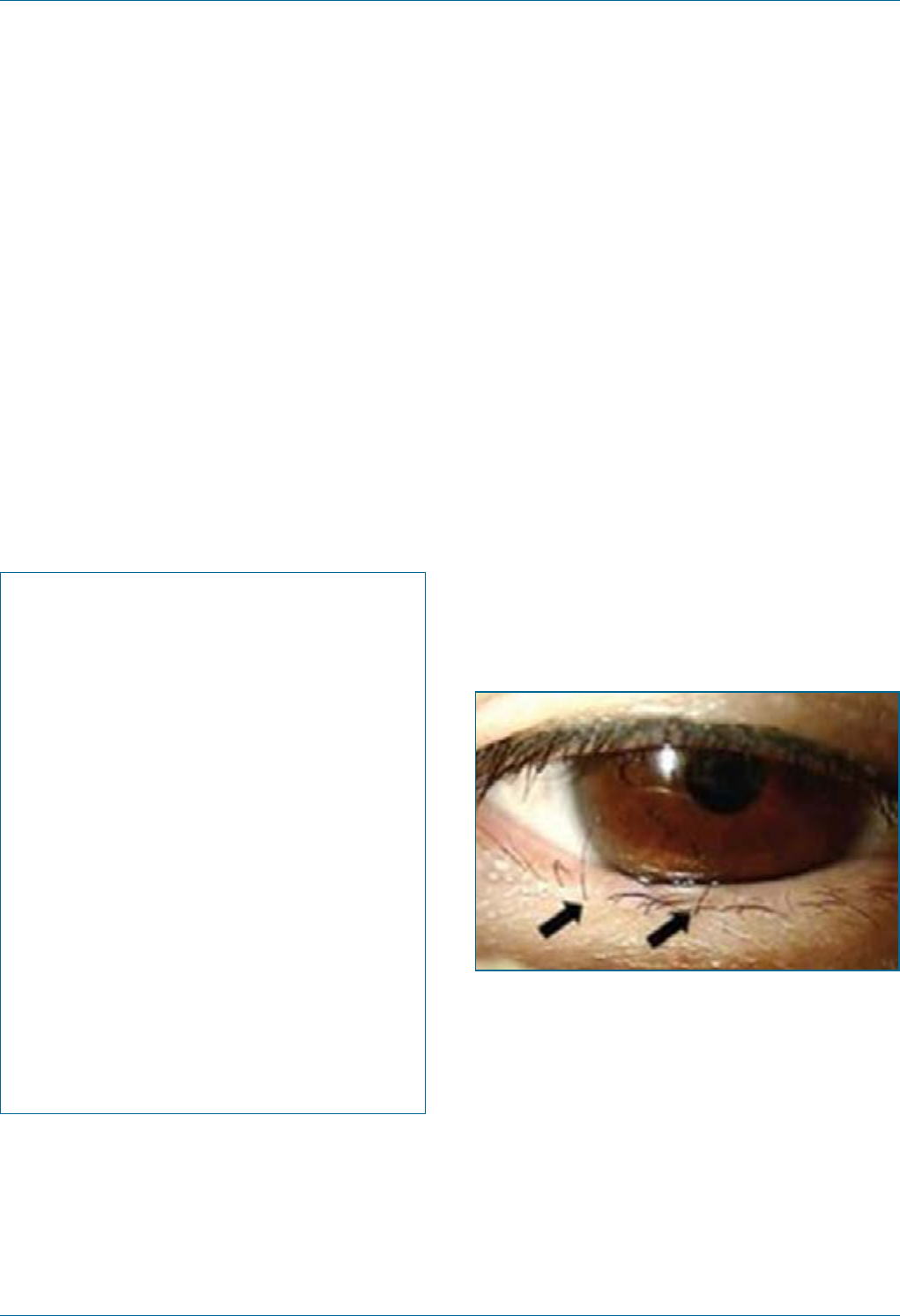

3. Are there periocular ecchymoses

(‘black eye’) and inammation?

External clues:

• Document presence and extent

Take note of any localised eyelid swellings which

may indicate abscesses or chalazia.

Bilateral periocular ecchymoses in a head trauma

patient is suggestive of a base of skull fracture.

4. Are there periocular and

eyelid lacerations?

External clues:

• Document number, size, location and depth

• All periocular lacerations must be assumed to

have a foreign body until proven otherwise

For eyelid lacerations, document which eyelid and

location (medial, middle or lateral third). Eyelid

lacerations must be assumed to be full-thickness,

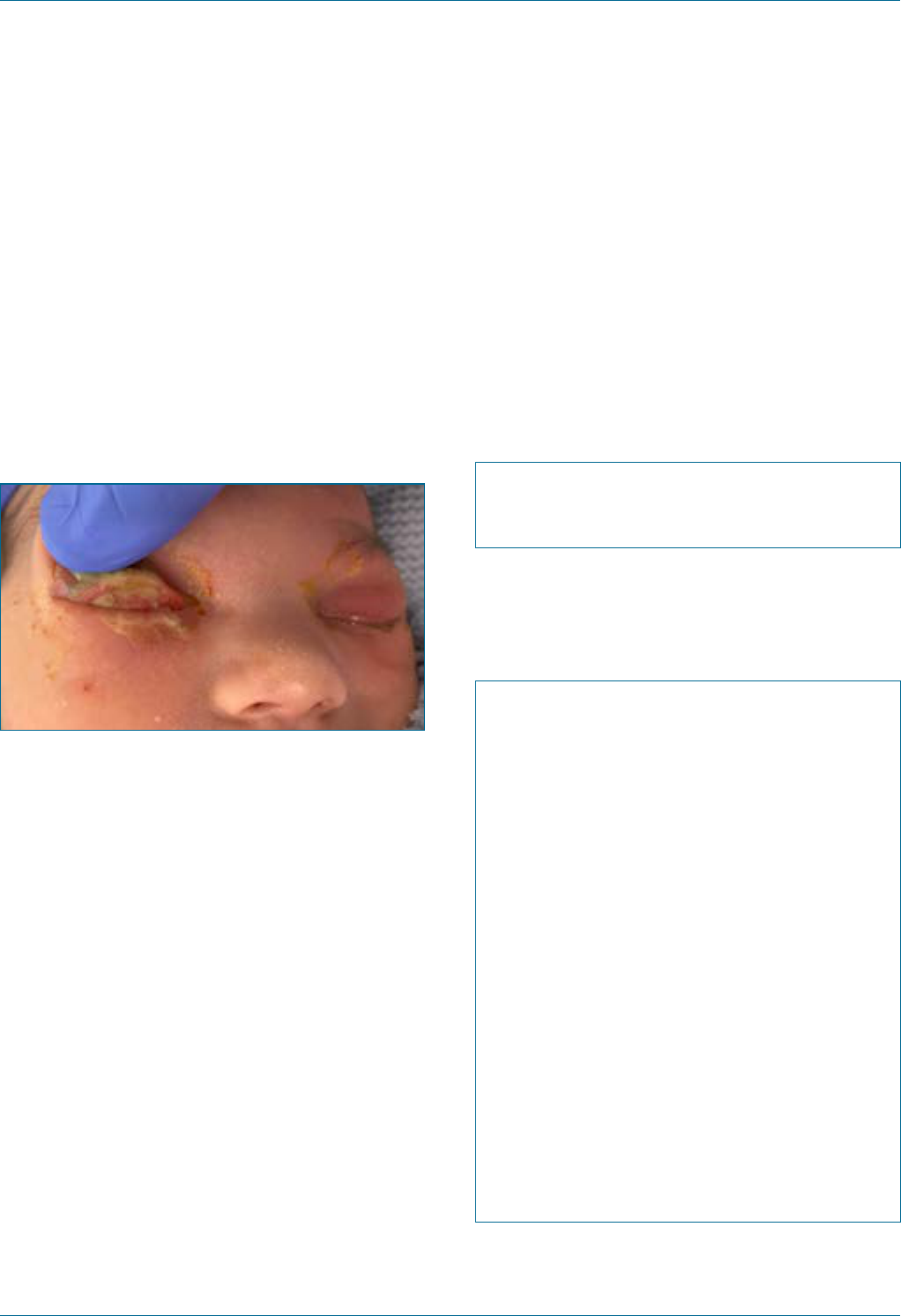

(i.e. through-and-through) until proven otherwise.

Severe eyelid lacerations may result in the

inability to close the eye and protect the

ocular surface. In such situations blinding

corneal exposure can rapidly occur.

Notes

• Lacerations involving the eyelid margin

need specialised repair.

• Lacerations involving the medial-most

portion of the eyelid may also involve the

lacrimal canaliculus and need

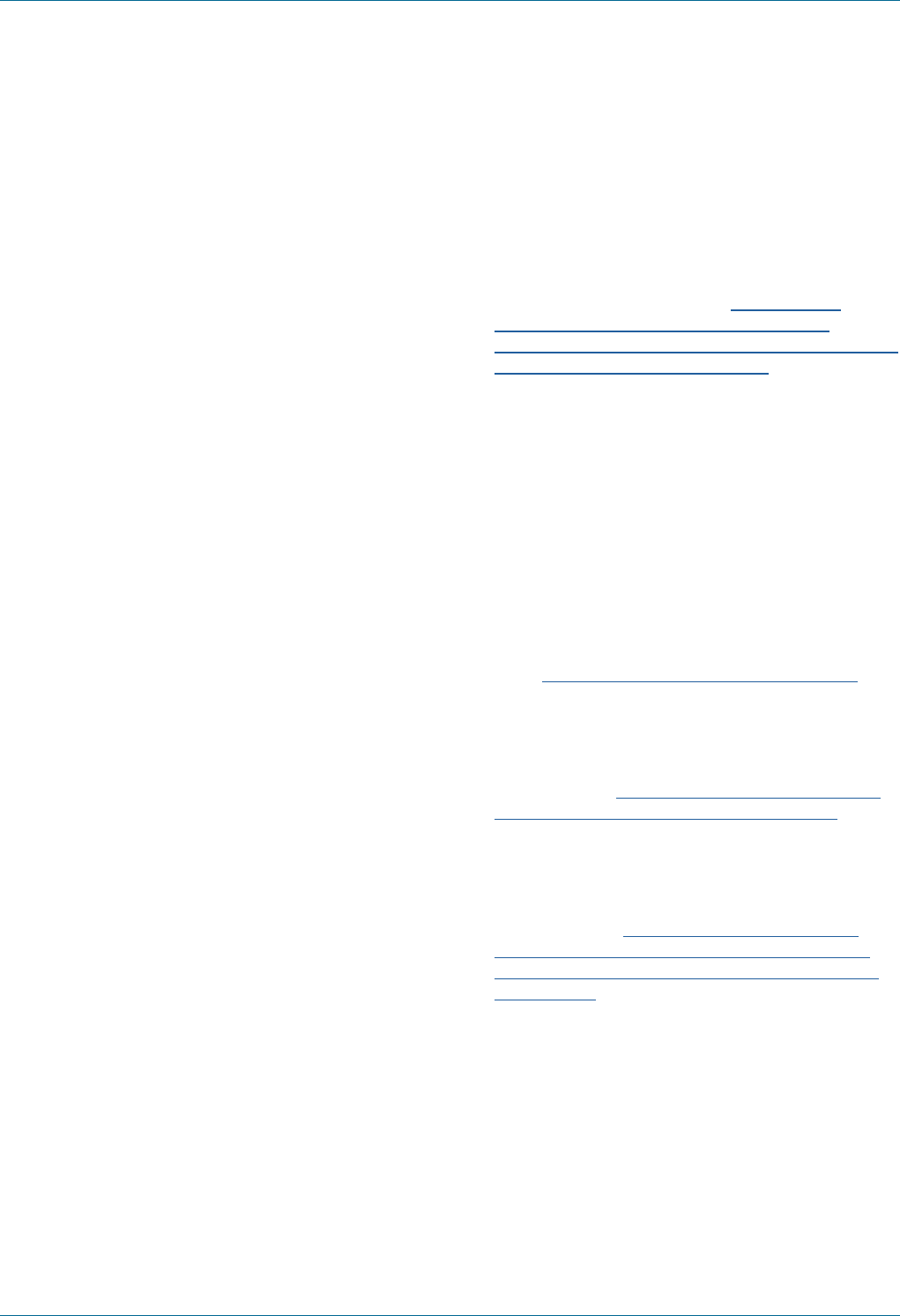

specialised repair.

• Periorbital cellulitis may complicate

lacerations, in this case, document the

extent of erythema.

5. Documentation

For external clues, draw a diagram and provide

accurate measurements at the initial assessment.

Note whether any lacerations have been sutured

prior to your assessment. Facial scarring can be

very disguring and patients may not be aware that

scarring will result, so it is important to explain this

and document that you have had this discussion.

In accordance with NSW Health policy, in

emergency situations a personal device can be

used to capture and store relevant clinical images

due to the urgent need for care, treatment or

advice. Images should be transferred to the local

health records management system as soon as

practical and the image permanently deleted from

the personal device.

Eye Emergency Manual December 2023

Agency for Clinical Innovation 22 aci.health.nsw.gov.au

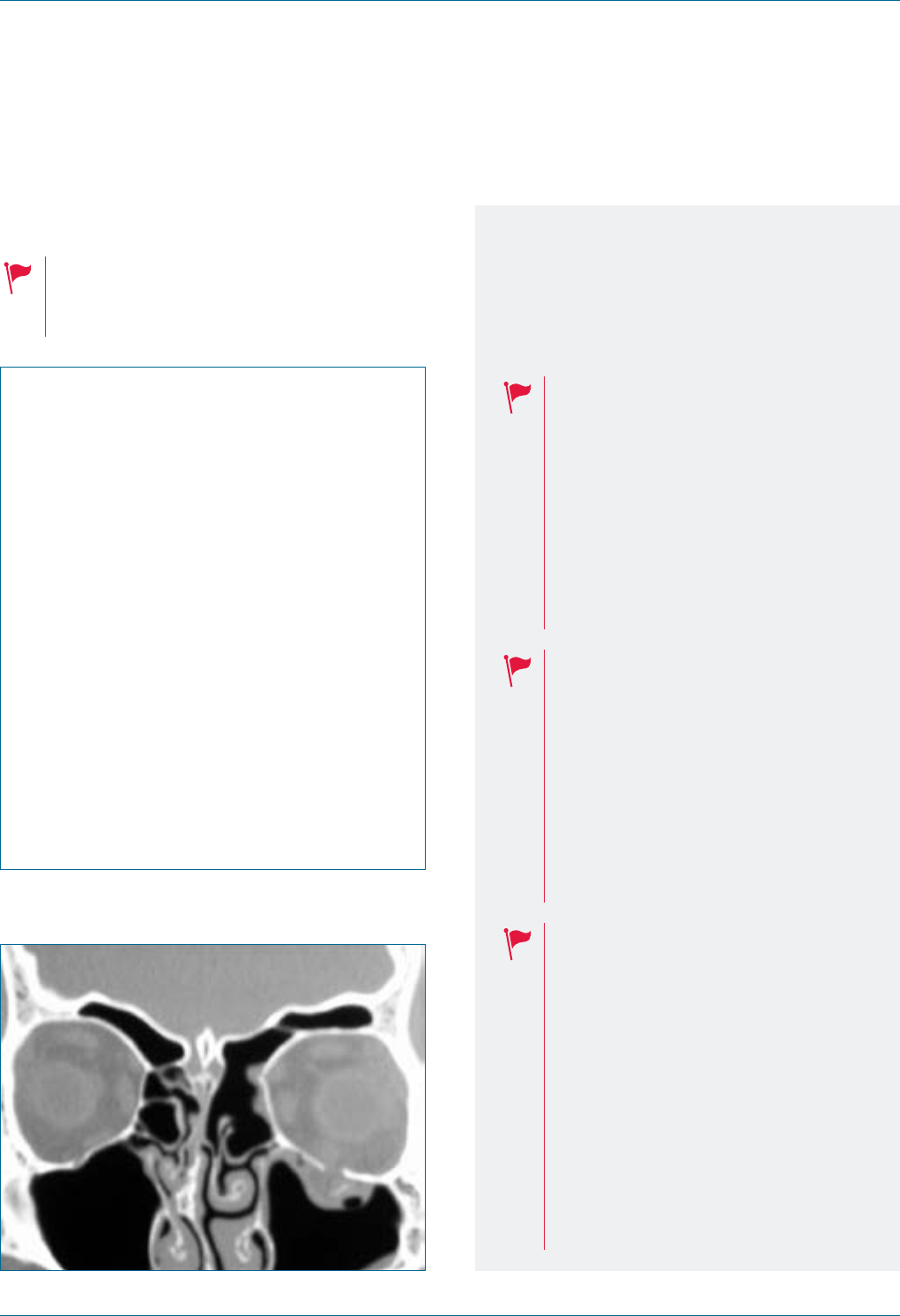

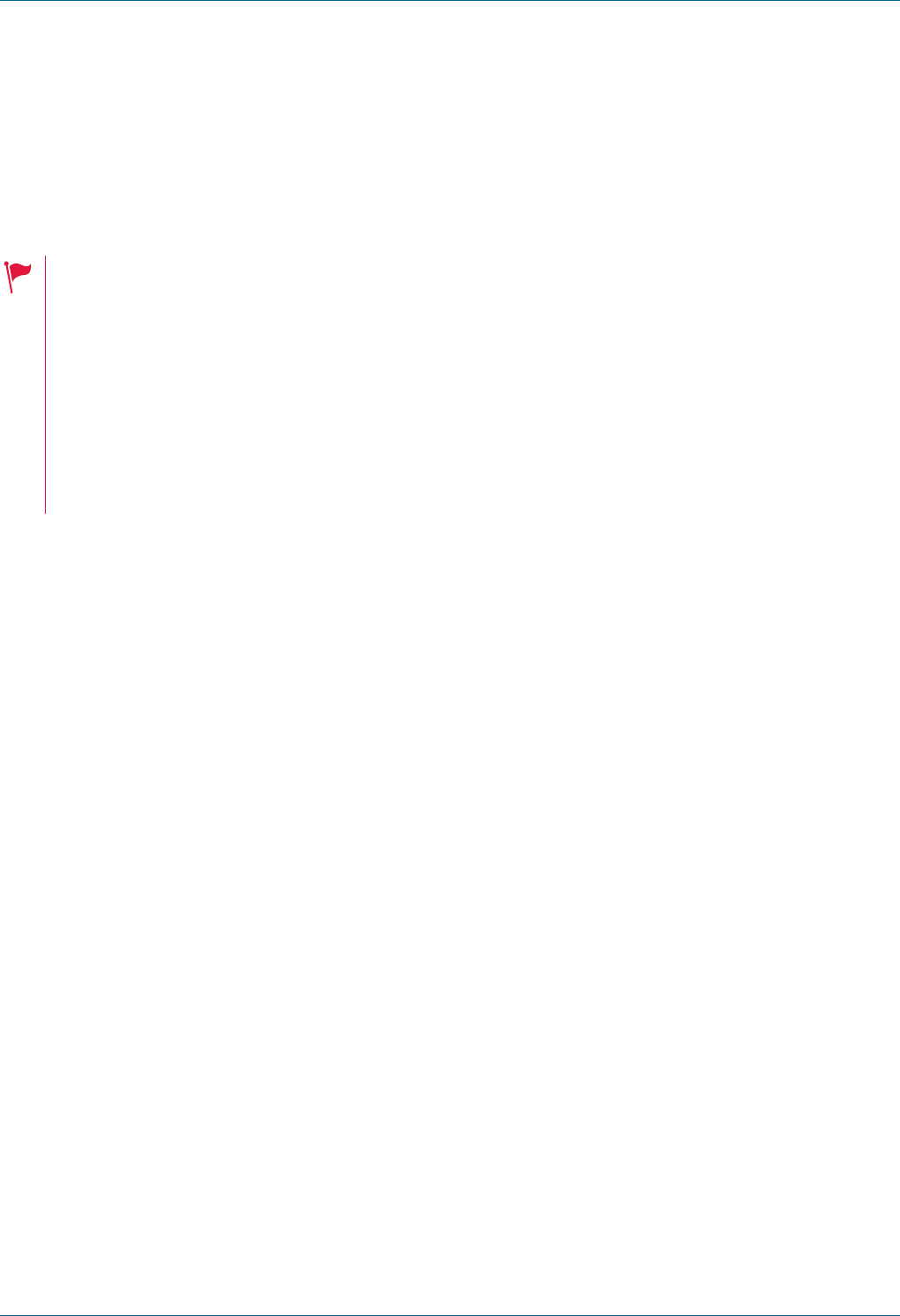

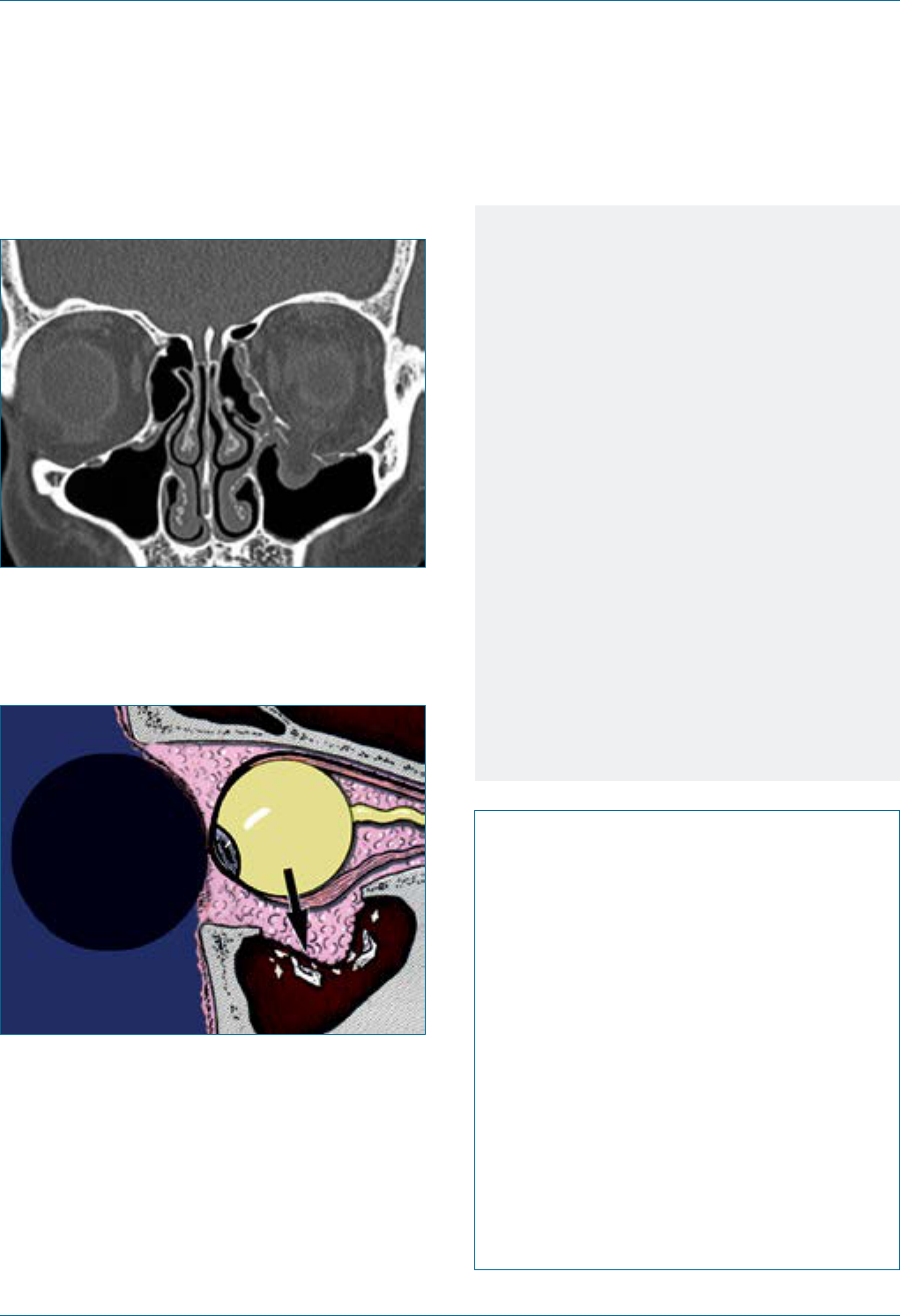

6. Imaging

Imaging is very important following periocular

trauma for the diagnosis of periorbital fractures

and to dene globe and soft tissue injuries.

Computed tomography (CT) imaging is often the

preferred modality in orbital pathology.

If a periorbital fracture is present with

entrapment of extraocular muscles, be

alert to the possibility of the oculocardiac

reex which can cause

life-threatening bradyarrhythmias.

In all serious periocular trauma, consider

that the patient may also have intracranial

trauma. Examine, image and liaise with

other specialties accordingly.

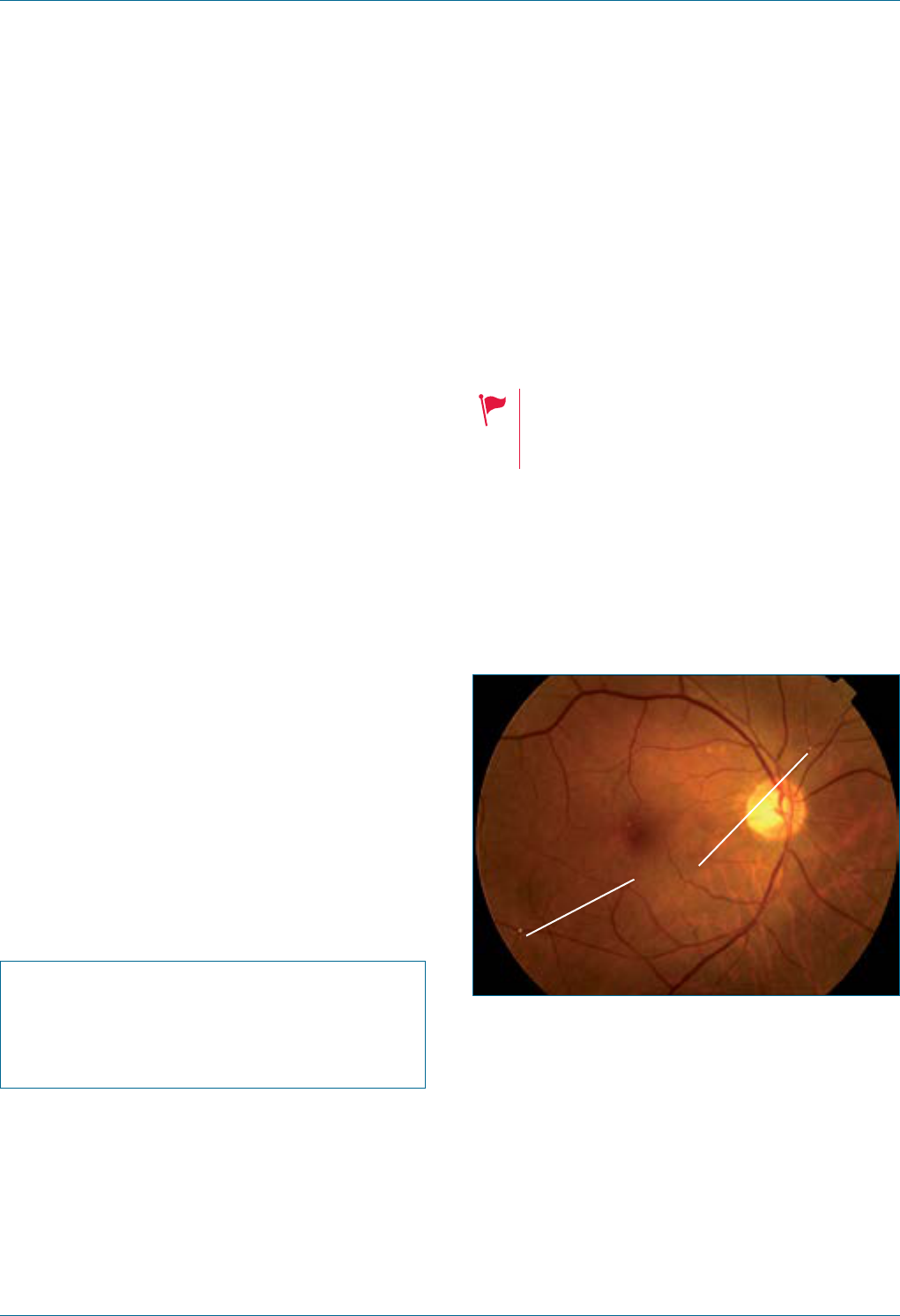

Figure 4. Orbital oor fracture.

7. Cranial nerve palsies

Consider the following:

• Perform a cranial nerve exam as you

would normally.

• See the relevant sections for specic

assessment of pupils, visual eld (for second

cranial nerve/optic nerve) and ocular movements

for third (3rd) and sixth (6th) cranial nerves.

• Signs of a 3rd cranial nerve palsy include ptosis

on one side, an eye that is misaligned downward

and laterally, and a dilated pupil.

• Signs of a unilateral or bilateral 6th cranial

nerve palsy include misalignment of the eye(s)

medially, in addition to the inability to abduct

the eye(s).

• Signs of a seventh (7th) cranial nerve palsy

include the inability to close the eye and

drooping of the lower eyelid and corner of

the mouth.

Eye Emergency Manual December 2023

Agency for Clinical Innovation 23 aci.health.nsw.gov.au

Visual acuity

Visual acuity provides the most important

information about how an eye is functioning and is

the basic means of examining an ophthalmology

patient. It is analogous to blood pressure

measurement or an electrocardiogram (ECG).

Visual acuity must be checked in any patient with

an ophthalmic complaint or periocular injury.

Visual acuity assessment is not complete

unless the following are performed:

• Checked in each eye separately

• With the patient’s distance correction

(distance glasses)

• Without then with a pinhole

• Documented in notes

Technique

Visual acuity assessment can be confusing, so

keep it simple.

1. Sit the patient 6m away from the chart or 3m

away from a mirror that is reecting a chart

positioned above their head, thus creating an

optical 6m. Make sure that the chart is

illuminated (either room lights are on, or the

globe is turned on behind the chart if it is a

retro-illuminated chart).

2. Ask the patient to put on their distance glasses

(the glasses they use for driving, not reading). If

you are unsure, try with and without; distance

glasses will improve the patient’s

distance vision.

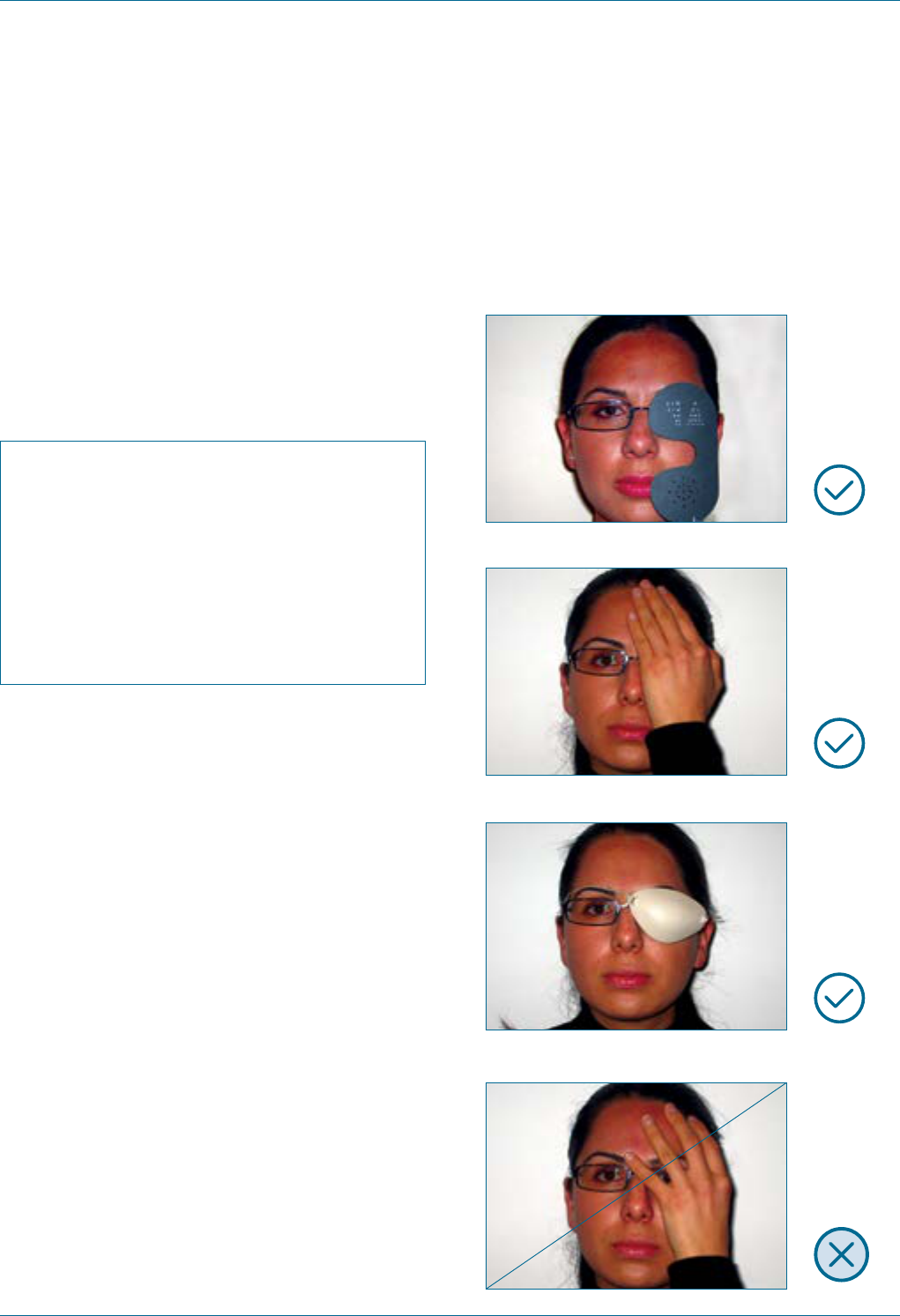

3. Use a solid object to occlude one eye. If the

patient is using their hand, ask them to hold the

palm of their hand gently up against their eye,

rather than their ngers, as it is possible to

peek through ngers.

Options to ensure the eye is fully occluded:

Figure 5. Correct.

Figure 6. Correct.

Figure 7. Correct.

Figure 8. Incorrect: beware of peeking!

Eye Emergency Manual December 2023

Agency for Clinical Innovation 24 aci.health.nsw.gov.au

4. Ask the patient to read as low down on the chart

as they can. Don’t correct the patient if they

make a mistake. Provide encouragement

irrespective of whether they are correct or

incorrect. Don’t let the patient give up once

things become blurry, instead encourage them

to keep going. It is not uncommon for patients

to give up several lines above their actual acuity

because it is blurry. Push them to get as low as

possible on the chart. A patient’s visual acuity is

dened as the line where they correctly guess

≥50% of the letters, whether they appear blurry

or not.

5. Document as you go, using the following

convention: the number ‘6’ over the number of

the lowest line that the patient can read (that is,

60, 36, 24, 18, 12, 9, 6, 5), giving you the familiar

fraction (6/60, 6/36, 6/24, 6/18, 6/12, 6/9, 6/6,

6/5). ‘RVA with glasses + pinhole is 6/18’ is

equivalent to saying that your patient, with

distance glasses and a superimposed pinhole,

can see at 6m what a normal person can see at

18m (6/18, which is a fraction less than 1, can be

thought of as less than normal vision). The top

number refers to the testing distance, (e.g. 6)

and the bottom number refers to the size of the

letters the patient sees (e.g. 6, 9, 12, 18, 24, 60).

6. Now test the eye looking through a pinhole. Use

an occluder with a pinhole, or, if not available,

poke a hole in a piece of paper with a 19G

needle (or even the tip of a pen). Look through it

yourself before giving it to the patient to ensure

that the aperture is clear. You may be surprised

to note that your vision improves as well. Do

NOT attempt to make a pinhole while the

patient is holding the paper over their eye. Ask

the patient to read the chart again and record

the pinhole acuity as above.

7. If the patient cannot read the largest line on the

chart, test if they can count how many ngers

you are holding up in front of their eye. Test

progressively at 30cm, 1m, 2m and 3m. If

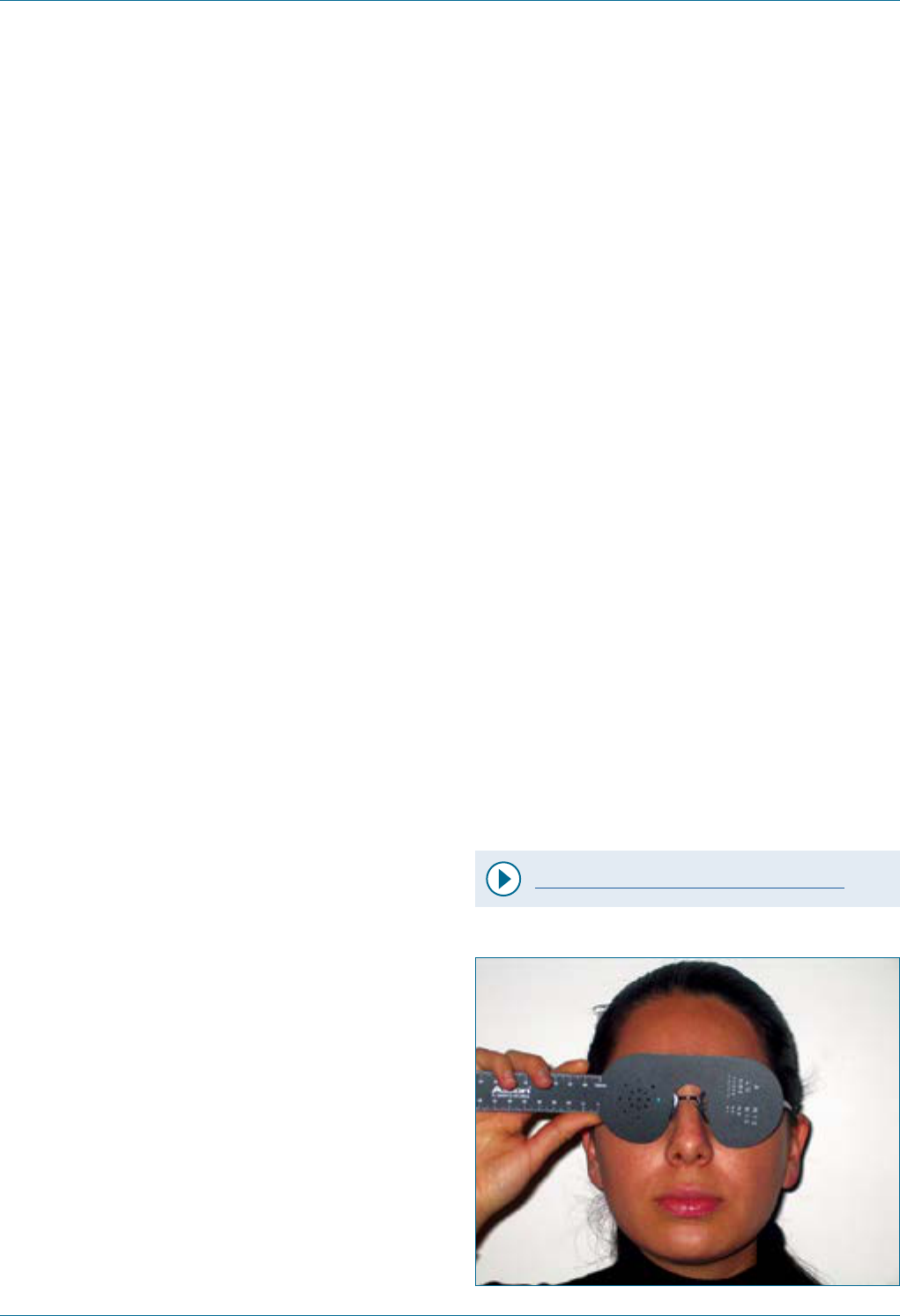

Figure 9. Pinhole occluder.

possible, record vision as CF and the distance at

which you measured.

8. If the patient cannot count ngers, assess

whether that eye can see your hand moving.

Wave your hand back and forth in front of their

eye at 30cm or more. If you are too close, they

may perceive light ickering, feel the air

movement on their face or hear your bracelets,

rather than see your hand moving. Ask the

patient to either describe the direction your

hand is moving or mirror the movement with

their hand. If possible, record vision as HM.

9. If the patient cannot perceive hand movements,

darken the room lights, ensure the other eye is

completely occluded and shine a bright light

into the eye from about 10cm. Ask if they can

see it. Shine the light on and off the eye

repeatedly and ask the patient to identify when

the light is on their eye. If they can, vision can be

recorded as light perception (LP or PL). If they

cannot, it is recorded as no light perception

(NLP or NPL).

10. Repeat the same process with the other eye.

Video - How to measure visual acuity

Eye Emergency Manual December 2023

Agency for Clinical Innovation 25 aci.health.nsw.gov.au

Notes

Visual acuity must be checked for every patient

with an ophthalmic complaint or periocular

injury. It is of vital importance for assessment

and prognosis. There are instances in which

visual acuity assessment can be deferred, e.g.

acute chemical injury, where irrigation takes

priority, or in severe life-threatening trauma

where attending to life-threatening injuries

takes priority. However, in both cases, visual

acuity must still be assessed at some stage to

ensure severe eye injuries are not missed.

Visual acuity must be documented in your

notes. Avoid writing ‘normal visual acuity’ or

‘blind’ as this does not provide any objective

information. Instead, record the specic acuity

in each eye without, then with, a pinhole. If this

is omitted, or the specic acuity is not

documented, the statement ‘normal visual

acuity’ can subsequently be challenged. This is

particularly an issue during handover in EDs,

where a colleague may have claimed to check

visual acuity but not recorded it.

It is unacceptable to say that a patient has

‘normal’ or ‘6/6’ vision because they can read

newspaper print, the writing on an IV bag, the

lowest line on a handheld chart or anything

other than the 6/6 line on a Snellen chart that is

6m away. Similarly, documenting vision as

counting ngers because that is all you have

checked and you do not have an acuity chart

means that the patient’s vision has not been

examined. It may be tempting to do these things

because measuring visual acuity using a chart

can be inconvenient, but it means visual acuity

has not been correctly checked, and there can

potentially be serious medical and

medicolegal repercussions.

A vision of 6/6 does not preclude serious

ocular pathology.

Test the eye that you suspect to have poorer

vision rst, to lessen the chance that the patient

will remember the letters when you test the

other eye. Observe the patient carefully during

the test to ensure that they are not looking

around the occluder or their hand or peeking in

another way. Visual acuity testing is an

objective test and the patient can either read

the letters or not, irrespective of whether they

are subjectively blurry or clear.

A patient must get at least 50% of the letters

correct on each line to be credited with that

acuity. It is possible to record mistaken letters

(on a line that was achieved) with a superscript

of -1, -2 or -3, or extra correct letters on the next

line (if the whole line was not achieved) with a

superscript of +1, +2 or +3 next to the visual

acuity. For example, you may record the acuity

as 6/12-1.

Patients may not know which glasses you mean

when you ask them to put on their ‘distance

glasses’. You can be more specic by asking

which glasses they use to drive or watch TV. If

there is still confusion, simply test the vision

with and without each pair. Multifocal glasses

provide distance correction when looking

through the top segment and near correction

when looking through the lower segment.

Ensure that the occluder used for the other eye

is not pushing multifocal glasses up the

patient’s nose, causing them to look through

the glasses’ reading segment.

Eye Emergency Manual December 2023

Agency for Clinical Innovation 26 aci.health.nsw.gov.au

A pinhole works by eliminating spherical

aberration, or the poorly focused rays of light

that are refracted at the periphery of a lens (in

this case, the eye’s tear lm, cornea and lens). A

pinhole eliminates most refractive error and

approximates a ‘universal’ lens, and this gives

vital information about an eye’s best possible

vision. Visual acuity testing is not complete until

pinhole acuity for each eye is tested and

recorded. Remember that visual acuity testing

should be done with glasses and then with a

pinhole as well. It is a common misconception

that testing with glasses and with a pinhole are

mutually exclusive. If a patient’s distance

glasses have not been updated for some time,

they may have signicantly better acuity when

tested with a pinhole as well.

‘Normal’ visual acuity or 6/6 means that the

patient can see at 6m the same target that a

person with normal vision can see at 6m. As the

denominator increases, the visual acuity

decreases, so a vision of 6/60 means that while

a person with normal vision could see the target

at 60m, the patient can only see it at 6m.

Similarly, 6/36 vision means that while a person

with normal vision could see the target at 36m,

the patient can only see it at 6m.

The distance to the chart is of paramount

importance. If the chart is closer, it will give an

inaccurate visual acuity. While it is possible to

mathematically adjust the ratio to reect a

shorter viewing distance, this adds an

unnecessary level of complexity to an ED

assessment. Keep it simple and check at 6m

(either directly or reected in a mirror).

Near acuity (or reading vision) as checked with a

handheld chart or a mobile phone app is an

alternate means of checking acuity but is NOT

readily interchangeable with distance acuity.

Snellen distance acuity is the standard method

of measuring a patient’s acuity and has the

most clinical relevance. It can create confusion

if a different method is used, particularly when

the acuity on presentation in ED is needed for

comparison at later stages in the

patient’s assessment.

An alternative to using a wall-mounted chart is

a scaled, handheld paper chart that is held at

3m. This is particularly useful for examining

bed-bound or recumbent patients. However, it is

more prone to inaccuracy as it is difcult to

calibrate exactly 3m from the patient’s eye and

charts that have been photocopied suffer a

degradation in contrast which can also

articially degrade visual acuity. Many of these

charts are also inaccurately labelled

concerning the visual acuity corresponding to

each line.

Patients who do not recognise the common

Snellen letters can be tested with the

‘tumbling-E’ chart. This replaces Snellen letters

with the letter ‘E’ in four different orientations:

up, down, left or right. The patient is asked to

point in the direction that the ‘E’ is pointing on

the chart.

If a patient is in pain, it is reasonable to instil a

drop of local anaesthetic to facilitate checking

visual acuity. Give the patient a few minutes

after anaesthetic instillation for the eyelid

spasm to subside.

Although amblyopia is a common cause of

unilateral poor vision in adults, do not attribute

reduced vision in ED to amblyopia. It is a

diagnosis of exclusion. Amblyopic eyes are as

prone to pathology as non-amblyopic eyes, and,

Eye Emergency Manual December 2023

Agency for Clinical Innovation 27 aci.health.nsw.gov.au

in some cases, more likely to be injured. Be

especially attentive if a patient describes

further worsening of vision in an eye that

was suspected to be amblyopic.

A vision of NLP has an extremely poor

prognosis and tends only to occur in the

very end stage of diseases such as

glaucoma, retinal detachment, injury to the

optic nerve or following serious injury. While

you may encounter patients in whom an eye

has been NLP for some years, if an eye

suddenly becomes NLP, then very serious

pathology is present. In patients over 50

years old, abrupt loss of vision to NLP

means GCA until proven otherwise. Liaise

with an ophthalmologist and commence

treatment to prevent a similar occurrence in

the other eye.

Common pathologies such as

cataracts, vitreous haemorrhage

and amblyopia do not cause vision

of NLP. The instances in which an

eye recovers some vision after

having been NLP are very rare.

Pupil examination

Pupil examination is a vital part of both the

ophthalmic and neurological assessment. It must

be done in all patients. In obtunded or severely

injured patients it may be the only type of

examination possible other than general inspection

and fundoscopy.

Pupil examination is not complete unless you have

assessed for an RAPD.

If a pupil abnormality is detected, you must also

examine the patient’s eye movements, eyelids and

visual eld.

Key aspects of pupil examination are size, shape

and reactivity. In ambient light, both pupils should

be of equal size and shape. Physiological anisocoria

is present in up to 15% of the population and does

not imply an RAPD.

Technique

Pupil examination technique requires the following:

1. Observe pupil size in the light. Ask the patient

to look at a target behind you, so that there is no

accommodation on a near target which will

inuence the size of the pupils. Look for a

difference in pupil size (anisocoria), difference

in iris colour (heterochromia) or irregularity of

the normally round shape.

2. Darken the room and check pupil size again.

Note whether any difference in pupil size is

more pronounced in the light or the dark.

3. Shine a bright light into one pupil and observe it

constricting to assess the direct pupil response

on that side.

Eye Emergency Manual December 2023

Agency for Clinical Innovation 28 aci.health.nsw.gov.au

4. Check that the other eye also constricts to

assess the consensual light reex. Repeat this

process by shining the light into the other eye.

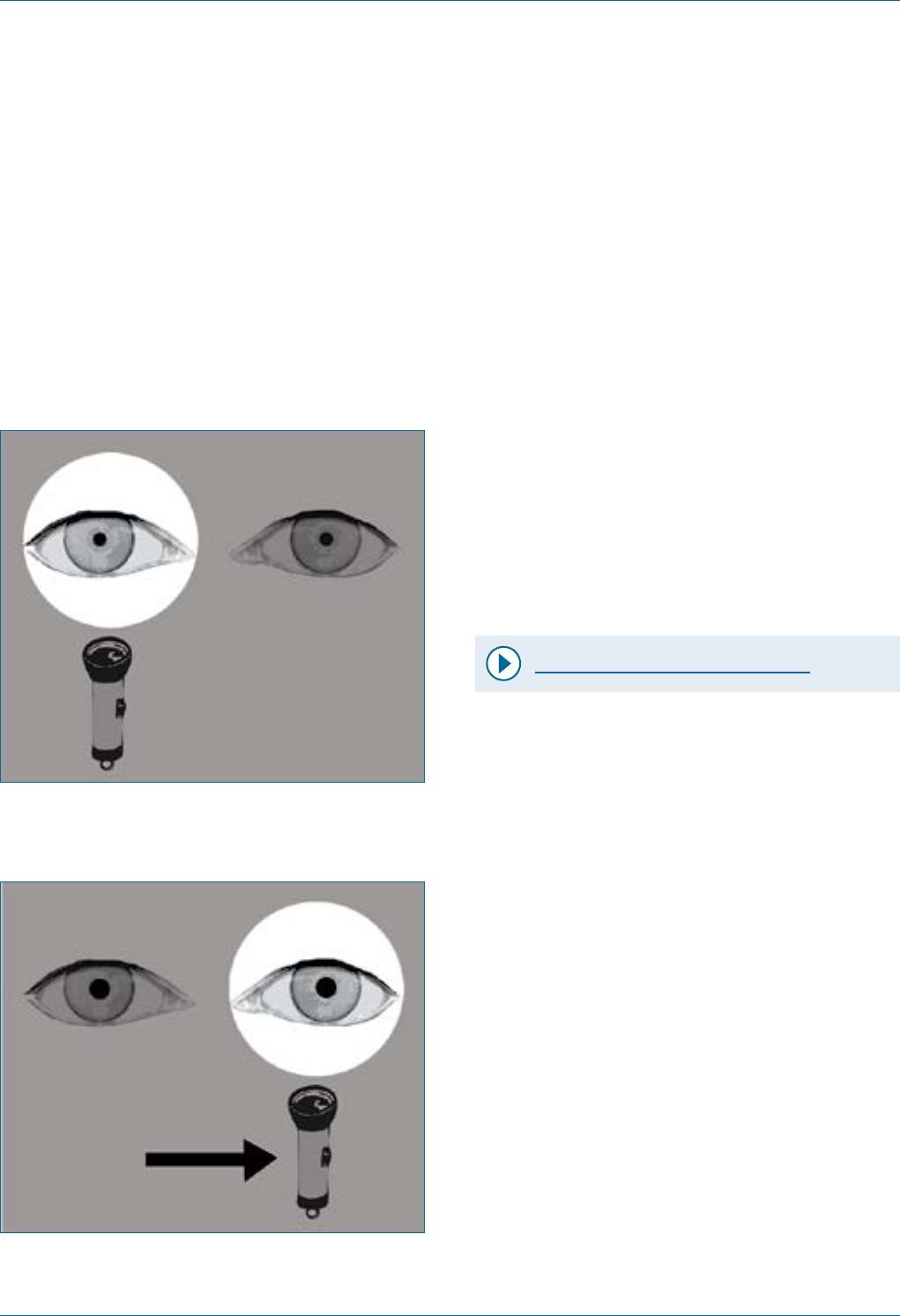

5. Check for an RAPD. Shine a bright light into one

pupil for 2–3 seconds, then rapidly ick the

light across to the other side, and hold it for the

same duration. An RAPD is present if the pupil

initially dilates (instead of initially constricting)

when icking across from the other side. You

can go back and forth several times until

convinced of the ndings, provided that the

time over each eye is the same and the time in

between the eyes is very short.

Video - How to examine an RAPD

Notes

Although an RAPD may be subtle in some

cases, it is a vitally important clinical sign to

elicit in situations of sudden visual loss and

ophthalmic trauma.

When pupils have been pharmacologically

dilated, it is not possible to test for an RAPD.

This is one of the principal reasons that

pupils are not dilated in ED prior to

ophthalmic assessment.

The key to detecting an RAPD reliably is to

ensure that each eye is exposed to the same

amount of bright light for the same amount of

time, with the briefest possible transit

between each eye. It is possible to mistakenly

give the impression of an RAPD if the light

intensity or the time over each eye varies.

The principle behind an RAPD is that by

alternately presenting each eye with a

symmetrical, intense light source, a subtle

unilateral optic nerve defect will be exposed.

If the optic nerve is damaged on one side,

when the light icks to that eye, the direct

response is less than the consensual

response from the recent contralateral light

stimulation, and so the pupil is observed to

dilate. It should be noted that this

observation is based on the direct and

consensual pupillary reexes being equal

in amplitude.

Vision loss in giant cell arteritis (GCA)

(or any other cause of optic neuropathy)

is associated with a relative afferent

pupillary defect (RAPD).

It may be hard to assess pupil size in the dark

if the patient has a dark-coloured iris.

Experiment with using a diffuse light shone

from above or below that allows you to see

the pupil without inuencing its size or with a

single-ash camera.

Remember that a unilaterally dilated

pupil on one side may indicate an

acute third (3rd) cranial nerve palsy

and urgent neuroimaging and liaison

with a neurosurgical service is

required if detected.

There are many situations in which pupils

may be abnormally shaped, including

intraocular inammation, prior surgery or

accidental trauma.

Eye Emergency Manual December 2023

Agency for Clinical Innovation 29 aci.health.nsw.gov.au

Swinging torch test

This involves demonstrating a left relative afferent

pupillary defect where the left pupil dilates after

prior consensual constriction with direct light

stimulation of the right eye.

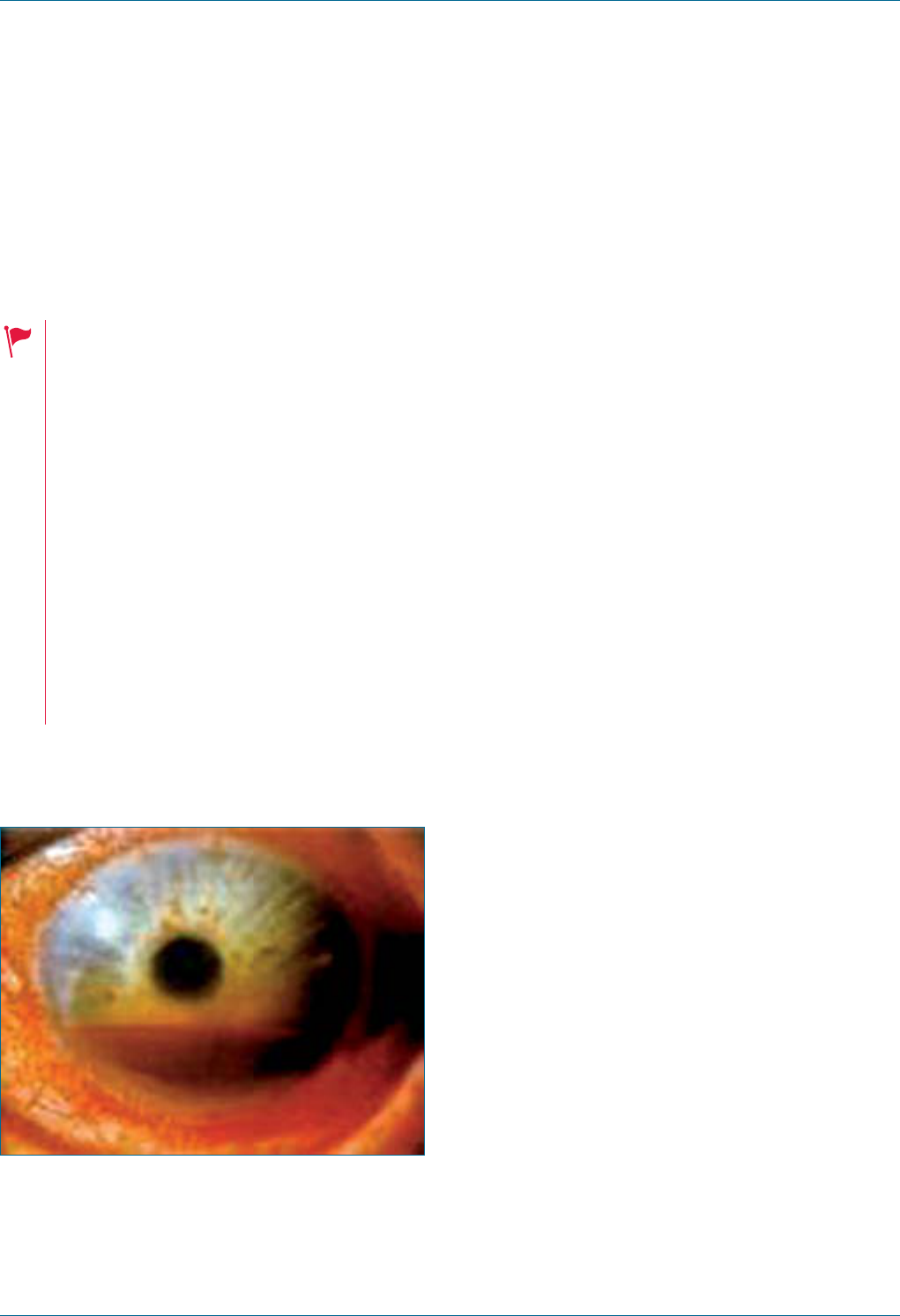

Figure 10. Swinging torch test

(consensual constriction).

Figure 11. Swinging torch test (left pupil

apparent dilation).

Visual eld, eye movements

andeyelid examination

Visual eld, eye movement testing and eyelid

examination are not mandatory in all ophthalmic

patients (for example, a simple foreign body) but

must be tested in anyone with visual changes or

suspected optic nerve, orbital or neurological

pathology. If a patient has a pupil abnormality,

these three examinations must be performed.

Given how rapidly and easily it can be done, have a

low threshold for testing it if you think it might

be relevant.

Technique for visual eld

Video - Technique for visual eld

1. Begin by explaining what you are going to do.

Telling the patient that you are testing their

‘peripheral vision’ can make it easier for the

patient to follow your instructions.

2. Ask the patient to remove their glasses so that

the rims do notinterfere with the assessment.

3. Sit opposite the patient with your eyes at the

same height, about 50cm away from their face.

4. Place a hand over one of your eyes and ask the

patient to mirror you, e.g. if you cover your left

eye, they cover their right eye.

5. Ask the patient to keep their eye covered, to

look directly at your eye with their uncovered

eye, and not to look away.

6. Clench the st of your free hand and hold it in a

reasonably peripheral position in one quadrant

of your peripheral vision.

Eye Emergency Manual December 2023

Agency for Clinical Innovation 30 aci.health.nsw.gov.au

7. Ask the patient how many ngers they see

and hold up a random number. Look at the

patient’s eye to ensure that they do not look at

your hand.

8. Test in all four quadrants in the same manner

and repeat the process on the other side.

9. Test for a scotoma by slowly moving your

nger from an area where the patient cannot

see to where they can. Repeat until you have

mapped the scotoma to your satisfaction.

Notes

Visual eld testing to confrontation is

unlikely to allow you to detect subtle or

small visual eld defects but larger defects

can be detected.

As you are sitting opposite the patient, your

visual eld is a reasonable approximation of

theirs. It is important to hold your hands in

the same coronal plane in each position and

equidistant from you and the patient.

Neglecting to do this distorts the eld that

you are assessing.

You can use the hand that was covering your

eye, provided you keep that eye closed and

remember the position of that monocular

visual eld with your hand in place. This

makes the examination more uid.

Alternatively, you can switch hands.

You can hold up several nger combinations

in each quadrant to ensure that the patient

can see them.

It is not uncommon for patients to

inadvertently look at your hand when they

realise your ngers are moving. The most

important thing is to recognise when this

happens, remind the patient to look at your

eye instead and repeat the step with a

different number of ngers.

A patient’s visual acuity must be at least

counting ngers to allow you to test their

eld to confrontation.

Eye Emergency Manual December 2023

Agency for Clinical Innovation 31 aci.health.nsw.gov.au

Technique for eye movements

Eye movement examination must be performed

in any patient with diplopia (double vision), pupil

or eyelid abnormalities.

Eye movement examination technique requires

the following:

1. Explain what you are going to do by asking

the patient to keep their head still and follow

your nger with their eyes.

2. Hold your index nger up in front of the

patient, then trace an ‘H’ pattern in a coronal

plane in front of them.

3. Ask the patient to tell you if they have double

vision, (e.g. ‘see two ngers’) in any position

of the ‘H’.

4. Following this, assess each eye separately by

asking the patient to cover one eye and

testing the movements of the other side.

5. Switch over so that both eyes are assessed in

this way. If the patient is experiencing

binocular diplopia, they will not experience

diplopia when one eye is covered.

Notes

When testing eye movements, it may help to

gently place a nger on the patient’s chin or

forehead to remind them not to follow with

their head.

If a patient has an eye movement disorder

you must check their pupils, eyelid and

visual eld.

In a sixth (6th) cranial nerve palsy, the

patient may not be able to abduct their eye.

In a third (3rd) cranial nerve palsy, the

patient may not be able to elevate, depress

or adduct the eye, and you may notice

associated pupil and eyelid changes.

In an orbital wall fracture, the patient may

not be able to move the eye in the opposite

direction, especially if there is associated

entrapment of the extraocular muscles

(e.g. inability to elevate the eye in an orbital

oor fracture).

Eye Emergency Manual December 2023

Agency for Clinical Innovation 32 aci.health.nsw.gov.au

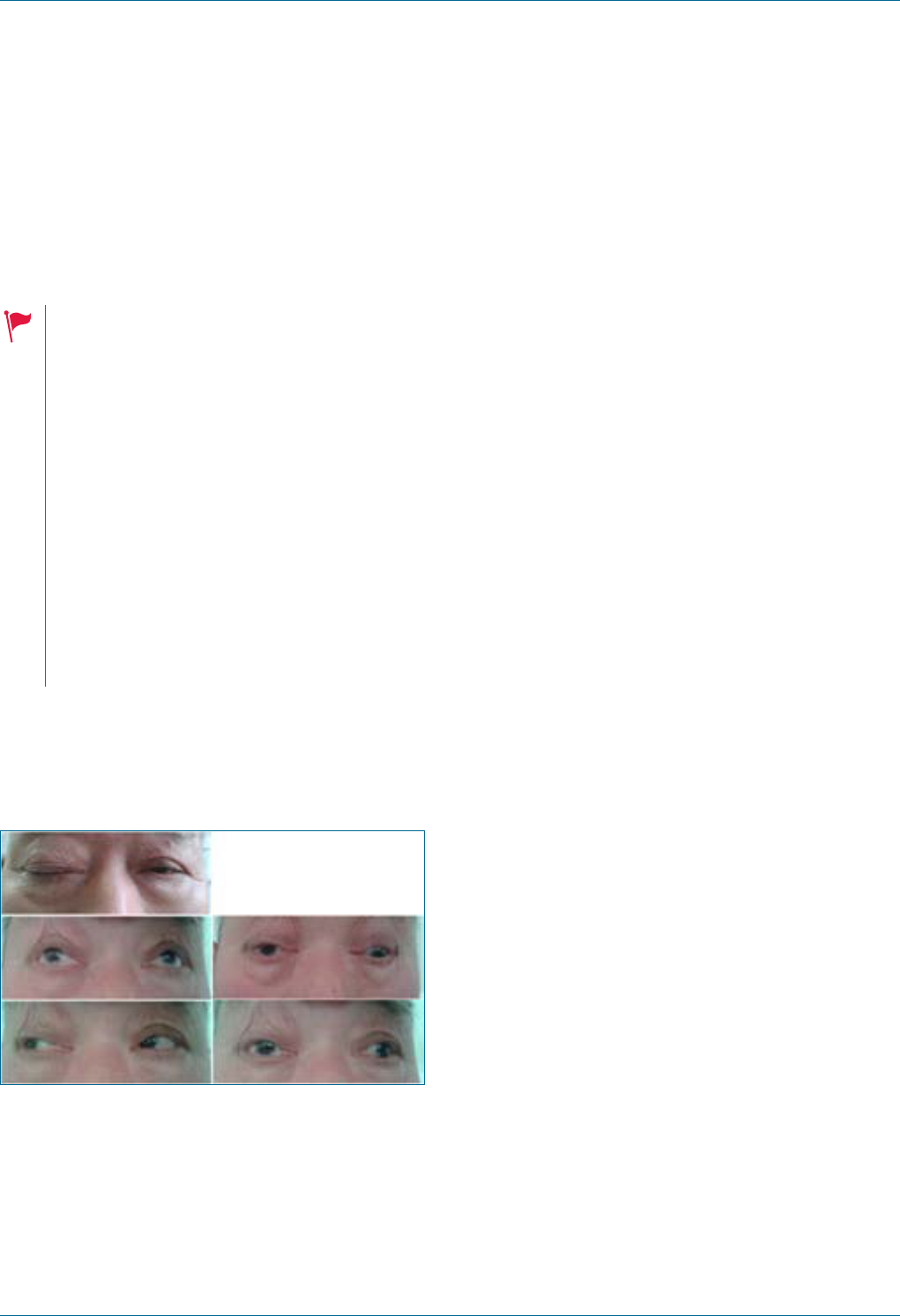

Eyelid examination

Eyelid examination must be performed in any

patient with diplopia (double vision), pupil

abnormalities or eye movement disorder and

requires the following:

• Observe for ptosis (drooping of the upper

eyelid over the eye, which may be unilateral or

bilateral). Compare the position of the upper

eyelid on one side with the other. This can be

done by simply judging the relation of the

upper eyelid to the top of the pupil or more

accurately by measuring the vertical height of

the palpebral aperture with a ruler.

• Ask the patient to close their eyes. Determine

whether there is any weakness in this action by

rst observing and then gently trying to part

the eyelids.

Notes

Opening the eye relies upon the third

(oculomotor) cranial nerve and the

sympathetic bres. Therefore, a lesion of the

oculomotor nerve causes ptosis, and if severe

enough, inability to open the eye. A lesion of

the sympathetic bres causes Horner

syndrome and less ptosis.

Other causes of ptosis include trauma,

swelling of the upper eyelid or age-related

degeneration of eyelid tissue.

Closing the eye relies upon the seventh (7th or

facial) cranial nerve. Lesion of the facial nerve

can result in an inability to close the eye, in

addition to drooping of the lower eyelid and

the corner of the mouth. Testing for eyelid

closure in this manner is the same manoeuvre

used in checking facial nerve function.

Inability to close the eye is called

lagophthalmos and, if severe, can

lead rapidly (within hours) to corneal

exposure, irreversible scarring

and blindness.

Eye Emergency Manual December 2023

Agency for Clinical Innovation 33 aci.health.nsw.gov.au

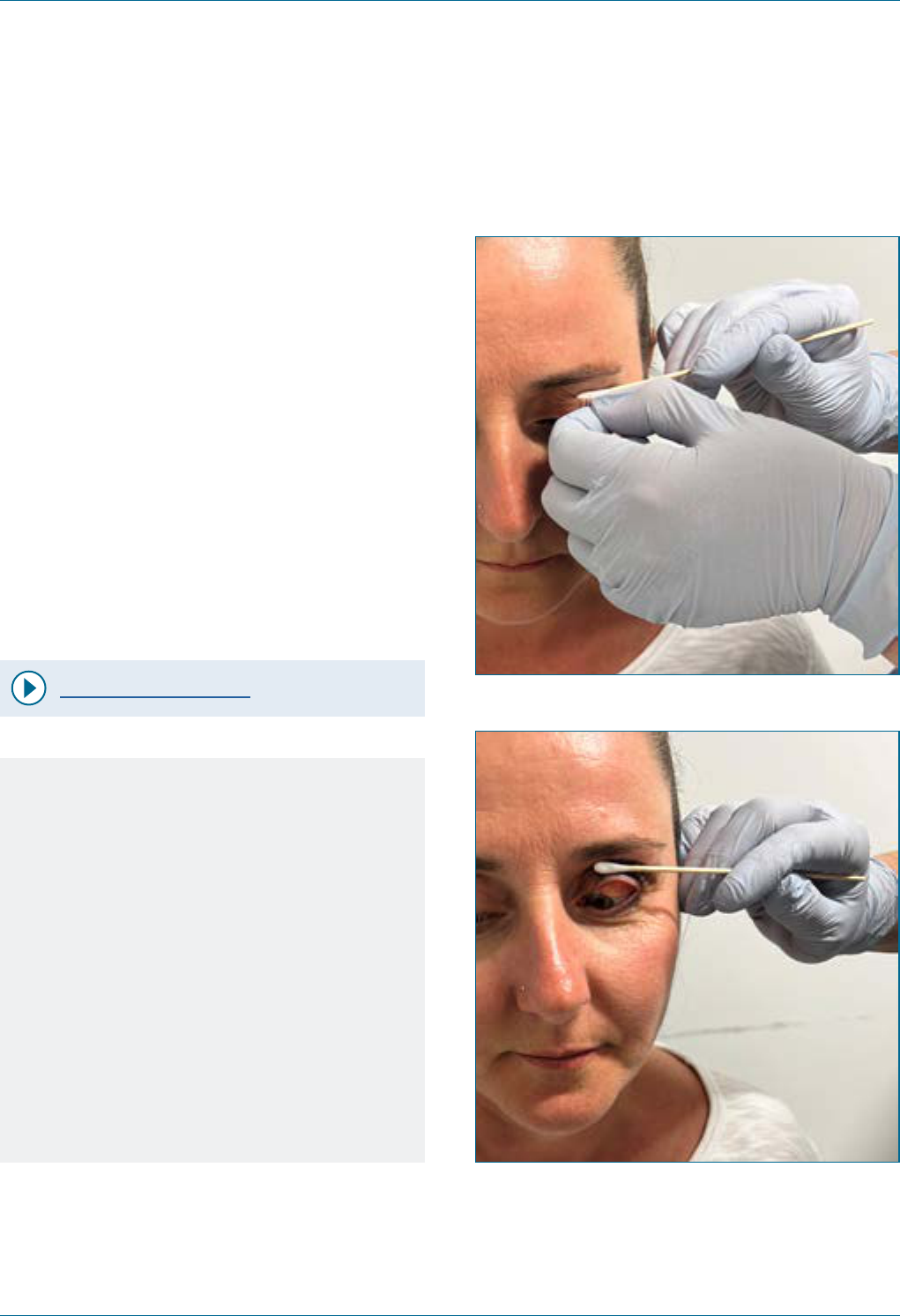

Eyelid eversion

Eyelids must be everted to exclude a subtarsal

foreign body.

Technique

1. Ask the patient to look down.

2. Gently pull the upper eyelid down and away

from the globe using the eyelashes.

3. Place a cotton bud at the midpoint on top of

the eyelid, then bend the eyelid up over the

cotton bud.

4. Slide the cotton bud out and either replace it

on the lid margin to hold the lid in position or

use your nger to do so.

Video - Eyelid eversion

Notes

It is most efcient to evert an eyelid at the

slit lamp, as your view of any potential

subtarsal foreign bodies will be better.

These may be gently removed with a moist

cotton bud.

Patients are often quite averse to having

their eyelids everted. Explain what you are

going to do, and that while it may feel

unusual, it should not be uncomfortable.

It may be easier to grip the edge of the

eyelid and eyelashes if you wear a glove.

Figure 12. Everting eyelid.

Figure 13. Everting eyelid.

Eye Emergency Manual December 2023

Agency for Clinical Innovation 34 aci.health.nsw.gov.au

Special eye examinations

Direct ophthalmoscope

It is not necessary to perform a detailed

examination with a direct ophthalmoscope for an

ED ophthalmology assessment, although it is very

helpful if you use it to determine whether the

patient has a red reex or not. Examination with a

direct ophthalmoscope does not take priority over

the simple assessment of visual acuity, pupils and

general inspection.

Do not dilate a patient’s pupils until you have

spoken with an ophthalmologist as it means that an

RAPD cannot be assessed and the patient cannot

have pupil observations for several hours.

Technique

Video -

Direct ophthalmoscope examination

1. Watch the video of direct

ophthalmoscope examination.

2. Darken the room and ask the patient to look at a

target behind you on the wall.

3. Adjust the dioptric correction to zero. Turn the

ophthalmoscope light on.

4. Use the same eye as the one you are examining

on the patient, i.e. your right eye for the

patient’s right eye.

5. Standing back from the patient, look through

the viewing aperture and shine the light into the

patient’s pupil. You should see a red reection

(‘red reex’).

6. If necessary, adjust the dioptric correction to

improve the clarity of the image.

7. To examine the retina, move in closer, keeping

the light focused on the red reex. You must get

very close to the patient (within 5cm).

8. When you are close enough you will see some

retinal detail, usually a retinal blood vessel.

Follow this vessel until you can see the

optic disc.

Notes

The direct ophthalmoscope provides a

highly magnied, narrow angle view of the

fundus. It cannot reliably be used to

examine the retina in sufcient detail to

exclude pathology. For this reason, patients

with suspected posterior segment

pathology such as optic disc swelling or

retinal tears need to be examined by

an ophthalmologist.

Other tools may be available in your ED also,

including a pan ophthalmoscope or a

non-mydriatic fundus camera. Acquiring one

of these is highly recommended.

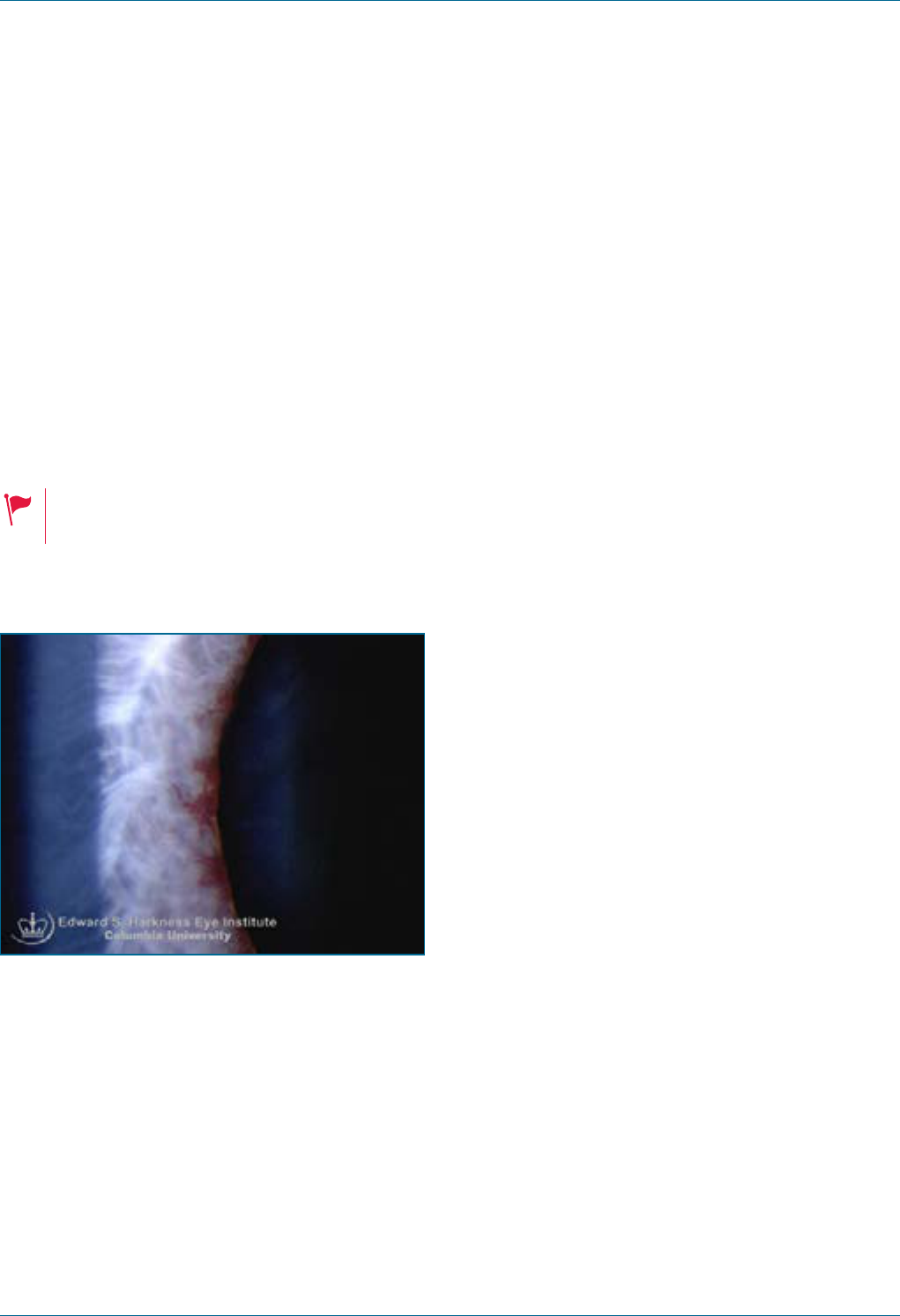

Loss of the red reex occurs in several

conditions (such as retinoblastoma,

cataract, vitreous haemorrhage or retinal

detachment) and this information can assist

greatly with triaging ophthalmic referrals.

It is much easier to examine the retina if the

patient’s pupil is pharmacologically dilated.

However, pupil dilation prevents subsequent

assessment for an RAPD, can rarely

precipitate acute angle closure in some

patients and obscures neurological

observations in patients with a head injury.

For these reasons, pupil dilation should only

be undertaken after discussion with an

ophthalmologist (and, in some cases,

a neurosurgeon).

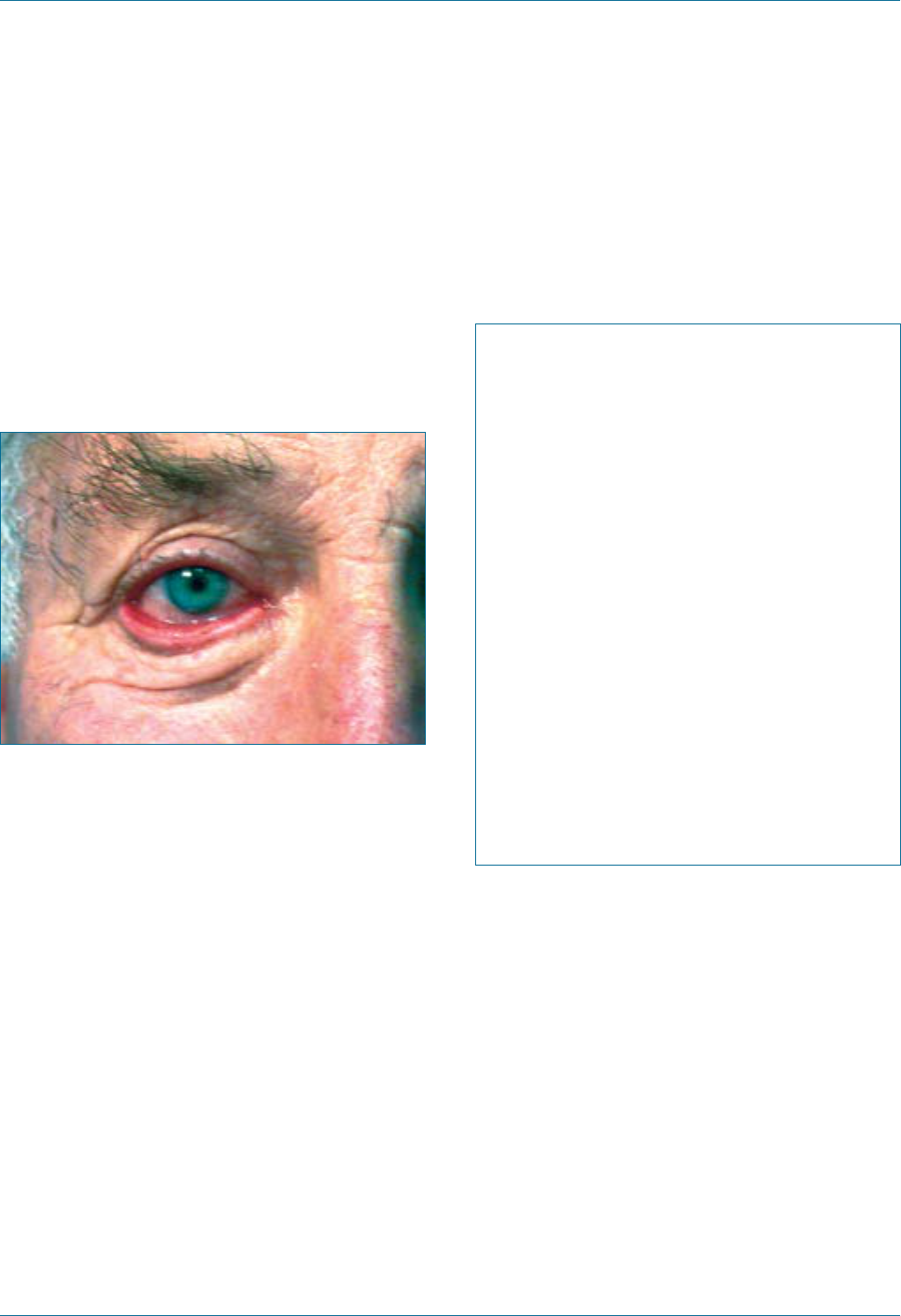

Eye Emergency Manual December 2023