Medicare Managed Care Manual

Chapter 21 – Compliance Program Guidelines

and

Prescription Drug Benefit Manual

Chapter 9 - Compliance Program Guidelines

Table of Contents

(Chapter 21 - Rev. 110, 01-11-13)

(Chapter 9 - Rev. 16, 01-11-13)

Transmittals for Chapter 21

10 – Introduction

20 – Definitions

30 – Overview of Mandatory Compliance Program

40 – Sponsor Accountability for and Oversight of FDRs

50 – Elements of an Effective Compliance Program

50.1 – Element I: Written Policies, Procedures and Standards of Conduct

50.1.1 – Standards of Conduct

50.1.2 – Policies and Procedures

50.1.3 – Distribution of Compliance Policies and Procedures and

Standards of Conduct

50.2 – Element II: Compliance Officer, Compliance Committee and High Level

Oversight

50.2.1 – Compliance Officer

50.2.2– Compliance Committee

50.2.3 – Governing Body

50.2.4 – Senior Management Involvement in Compliance Program

50.3 – Element III: Effective Training and Education

50.3.1 – General Compliance Training

50.3.2 –Fraud, Waste, and Abuse Training

50.4 – Element IV: Effective Lines of Communication

50.4.1 – Effective Lines of Communication Among the Compliance

Officer, Compliance Committee, Employees, Governing Body, and FDRs

50.4.2 – Communication and Reporting Mechanisms

50.4.3 – Enrollee Communications and Education

50.5 – Element V: Well-Publicized Disciplinary Standards

50.5.1 – Disciplinary Standards

50.5.2 – Methods to Publicize Disciplinary Standards

50.5.3 – Enforcing Disciplinary Standards

50.6 – Element VI: Effective System for Routine Monitoring, Auditing and

Identification of Compliance Risks

50.6.1 – Routine Monitoring and Auditing

50.6.2 – Development of a System to Identify Compliance Risks

50.6.3 – Development of the Monitoring and Auditing Work Plan

50.6.4 – Audit Schedule and Methodology

50.6.5 – Audit of the Sponsor’s Operations and Compliance Program

50.6.6 – Monitoring and Auditing FDRs

50.6.7 – Tracking and Documenting Compliance and Compliance

Program Effectiveness

50.6.8 – OIG/GSA Exclusion

50.6.9 – Use of Data Analysis for Fraud, Waste and Abuse Prevention and

Detection

50.6.10 – Special Investigation Units (SIUs)

50.6.11 – Auditing by CMS or its Designee

50.7 – Element VII: Procedures and System for Prompt Response to Compliance

Issues

50.7.1 – Conducting a Timely and Reasonable Inquiry of Detected

Offenses

50.7.2 – Corrective Actions

50.7.3 – Procedures for Self-Reporting Potential FWA and Significant

Non Compliance

50.7.4 – NBI MEDIC

50.7.5 – Referrals to the NBI MEDIC

50.7.6 – Responding to CMS-Issued Fraud Alerts

50.7.7 – Identifying Providers with a History of Complaints

Appendix A: Resources

Appendix B: Laws and Regulations to Consider in Standards of Conduct and/or Training

10 – Introduction

(Chapter 21 - Rev. 109, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-

20-12)

(Chapter 9 - Rev. 15, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-20-

12)

These compliance program guidelines reflect the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid

Services (CMS) interpretation of the Compliance Program requirements and related

provisions for Medicare Advantage Organizations (MAO) and Medicare Prescription

Drug Plans (PDP) (Chapter 42 of the Code of Federal Regulations, Parts 422 and 423,

hereinafter collectively referred to as “Parts C & D”). This chapter is designed to assist

sponsors to establish and maintain an effective compliance program.

These compliance program guidelines apply fully to the prescription drug benefit

programs of sections 1833 and 1876 Cost Plans. In addition, these compliance program

guidelines apply to the prescription drug benefit programs of Program of All-Inclusive

Care for the Elderly (PACE) plans only with respect to those portions of this chapter that

pertain to Elements 6 and 7, which are embodied in 42 C.F.R. 423 §§504(b)(4)(vi)(F) and

(G) respectively. These compliance program guidelines do not apply to the PACE plans

or to sections 1833 and 1876 Cost Plans that do not have a prescription drug benefit

program. However, given the Office of Inspector General (OIG) guidance promoting

compliance programs for all sponsors, the CMS strongly encourages sponsors to

voluntarily develop and implement effective compliance programs.

This guidance is subject to change as policy, technology and Medicare business practices

continue to evolve.

Each sponsor must implement an effective compliance program that meets the regulatory

requirements set forth at 42 C.F.R. §§422.503(b)(4)(vi) and 423.504(b)(4)(vi). Sponsors

should apply the principles outlined in these guidelines to all relevant decisions,

situations, communications and developments. Any new rule-making or interpretive

guidance (e.g., annual call letter or Health Plan Management System (HPMS) guidance

memoranda) may update the guidance provided in this document. Sponsors may also

wish to consult the resources listed in the Appendices, which provide additional

information on some topics addressed in this chapter.

In this chapter, the word “must” is used to reflect requirements created by statute or

regulation. The word “should” is used to indicate expectations created by this guidance.

Recommendations are noted as “best practices.”

Chapter 9 previously addressed the prevention of fraud, waste and abuse (FWA) by only

Part D sponsors. In contrast, this chapter provides interpretive rules and guidance to help

all sponsors to establish and maintain an effective compliance program to prevent, detect,

and correct FWA and Medicare program noncompliance

These guidelines, published in both Pub. 100-18, Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit

Manual, chapter 9 and in Pub. 100-16, Medicare Managed Care Manual, chapter 21, are

identical and allow organizations offering both Medicare Advantage (MA) and

Prescription Drug Plans (PDP) to reference one document for guidance.

20 – Definitions

(Chapter 21 - Rev. 109, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-

20-12)

(Chapter 9 - Rev. 15, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-20-

12)

The following definitions apply for purposes of these guidelines only:

Abuse includes actions that may, directly or indirectly, result in: unnecessary costs to the

Medicare Program, improper payment, payment for services that fail to meet

professionally recognized standards of care, or services that are medically unnecessary.

Abuse involves payment for items or services when there is no legal entitlement to that

payment and the provider has not knowingly and/or intentionally misrepresented facts to

obtain payment. Abuse cannot be differentiated categorically from fraud, because the

distinction between “fraud” and “abuse” depends on specific facts and circumstances,

intent and prior knowledge, and available evidence, among other factors.

Act refers to the Social Security Act.

Appeal (Part C Plan): Any of the procedures that deal with the review of adverse

organization determinations on the health care services an enrollee believes he or she is

entitled to receive, including delay in providing, arranging for, or approving the health

care services (such that a delay would adversely affect the health of the enrollee), or on

any amounts the enrollee must pay for a service as defined in 42 C.F.R. § 422.566(b).

These procedures include reconsideration by the MA Plan and, if necessary, an

independent review entity, hearings before Administrative Law Judges (ALJs), review by

the Medicare Appeals Council (MAC), and judicial review.

Appeal (Part D Plan): Any of the procedures that deal with the review of adverse

coverage determinations made by the Part D plan sponsor on the benefits under a Part D

plan the enrollee believes he or she is entitled to receive, including a delay in providing

or approving the drug coverage (when a delay would adversely affect the health of the

enrollee), or on any amounts the enrollee must pay for the drug coverage, as defined in 42

C.F.R. §423.566(b). These procedures include redeterminations by the Part D plan

sponsor, reconsiderations by the independent review entity (IRE), Administrative Law

Judge (ALJ) hearings, reviews by the Medicare Appeals Council (MAC), and judicial

reviews.

Audit is a formal review of compliance with a particular set of standards (e.g., policies

and procedures, laws and regulations) used as base measures.

Cost Plan is a Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) or Competitive Medical Plan

(CMP) with a cost-reimbursement contract under section 1876(h) of the Act (See 42

C.F.R. §417.1, §423.4). Cost Plan sponsors may contract to offer prescription drug

benefits under the Part D program. (See, 42 C.F.R. §423.4.)

Data Analysis is a tool for identifying coverage and payment errors, and other indicators

of potential FWA and noncompliance.

Deemed Provider or Supplier means a provider or supplier that has been accredited by

a national accreditation program (approved by CMS) as demonstrating compliance with

certain conditions.

DHHS is the Department of Health and Human Services. CMS is the agency within

DHHS that administers the Medicare program.

DOJ is the Department of Justice.

Downstream Entity is any party that enters into a written arrangement, acceptable to

CMS, with persons or entities involved with the MA benefit or Part D benefit, below the

level of the arrangement between an MAO or applicant or a Part D plan sponsor or

applicant and a first tier entity. These written arrangements continue down to the level of

the ultimate provider of both health and administrative services. (See, 42 C.F.R. §,

423.501).

Employee(s) refers to those persons employed by the sponsor or a First Tier,

Downstream or Related Entity (FDR) who provide health or administrative services for

an enrollee.

Enrollee means a Medicare beneficiary who is enrolled in a sponsor’s Medicare Part C or

Part D plan.

External Audit means an audit of the sponsor or its FDRs conducted by outside auditors,

not employed by or affiliated with, and independent of, the sponsor.

FDR means First Tier, Downstream or Related Entity.

First Tier Entity is any party that enters into a written arrangement, acceptable to CMS,

with an MAO or Part D plan sponsor or applicant to provide administrative services or

health care services to a Medicare eligible individual under the MA program or Part D

program. (See, 42 C.F.R. § 423.501).

Formulary means the entire list of Part D drugs covered by a Part D plan and all

associated requirements outlined in Pub. 100-18, Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit

Manual, chapter 6.

Fraud is knowingly and willfully executing, or attempting to execute, a scheme or

artifice to defraud any health care benefit program or to obtain (by means of false or

fraudulent pretenses, representations, or promises) any of the money or property owned

by, or under the custody or control of, any health care benefit program. 18 U.S.C. § 1347.

FWA means fraud, waste and abuse.

Governing Body means that group of individuals at the highest level of governance of

the sponsor, such as the Board of Directors or the Board of Trustees, who formulate

policy and direct and control the sponsor in the best interest of the organization and its

enrollees. As used in this chapter, governing body does not include C-level management

such as the Chief Executive Officer, Chief Operations Officer, Chief Financial Officer,

etc., unless persons in those management positions also serve as directors or trustees or

otherwise at the highest level of governance of the sponsor.

GSA means General Services Administration.

Internal Audit means an audit of the sponsor or its FDRs conducted by auditors who are

employed by or affiliated with the sponsor.

Medicare is the health insurance program for the following:

• People 65 or older,

• People under 65 with certain disabilities, or

• People of any age with End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) (permanent kidney

failure requiring dialysis or a kidney transplant).

Monitoring Activities are regular reviews performed as part of normal operations to

confirm ongoing compliance and to ensure that corrective actions are undertaken and

effective.

NBI MEDIC means National Benefit Integrity Medicare Drug Integrity Contractor

(MEDIC), an organization that CMS has contracted with to perform specific program

integrity functions for Parts C and D under the Medicare Integrity Program. The NBI

MEDIC’s primary role is to identify potential FWA in Medicare Parts C and D.

OIG is the Office of the Inspector General within DHHS. The Inspector General is

responsible for audits, evaluations, investigations, and law enforcement efforts relating to

DHHS programs and operations, including the Medicare program.

Pharmacy Benefit Manager (PBM) is an entity that provides pharmacy benefit

management services, which may include contracting with a network of pharmacies;

establishing payment levels for network pharmacies; negotiating rebate arrangements;

developing and managing formularies, preferred drug lists, and prior authorization

programs; performing drug utilization review; and operating disease management

programs. Some sponsors perform these functions in-house and do not use an outside

entity as their PBM. Many PBMs also operate mail order pharmacies or have

arrangements to include prescription availability through mail order pharmacies. A PBM

is often a first tier entity for the provision of Part D benefits.

PDP means Prescription Drug Plan.

Related Entity means any entity that is related to an MAO or Part D sponsor by common

ownership or control and

(1) Performs some of the MAO or Part D plan sponsor’s management functions

under contract or delegation;

(2) Furnishes services to Medicare enrollees under an oral or written agreement; or

(3) Leases real property or sells materials to the MAO or Part D plan sponsor at a

cost of more than $2,500 during a contract period. (See, 42 C.F.R. §423.501).

Special Investigations Unit (SIU) is an internal investigation unit responsible for

conducting investigations of potential FWA.

Sponsor refers to the entities described in the Introduction to these guidelines.

TrOOP (True Out of Pocket) Costs are costs that an enrollee must incur on Part D

covered drugs to reach catastrophic coverage. (These incurred costs are defined in

regulation at §423.100 and Pub. 100-18, Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit Manual,

chapter 5, section 30). In general, payments counting toward TrOOP include payments

by enrollee, family member or friend, Qualified State Pharmacy Assistance Program

(SPAP), Medicare’s Extra Help (low income subsidy), a charity, manufacturers

participating in the Medicare coverage gap discount program, Indian Health Service,

AIDS Drug Assistance Programs, or a personal health savings vehicle (flexible spending

account, health savings account, medical savings account). Payments that do NOT count

toward TrOOP include Part D premiums and coverage by other insurances, group health

plans, government programs (non-SPAP), workers’ compensation, Part D plans’

supplemental or enhanced benefits, or other third parties, drugs purchased outside the

United States, and over-the counter drugs and vitamins.

Waste is the overutilization of services, or other practices that, directly or indirectly,

result in unnecessary costs to the Medicare program. Waste is generally not considered

to be caused by criminally negligent actions but rather the misuse of resources.

30 – Overview of Mandatory Compliance Program

(Chapter 21 - Rev. 109, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-

20-12)

(Chapter 9 - Rev. 15, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-20-

12)

Section 1860D-4(c)(1)(D) of the Act, 42 C.F.R. §§ 422.503(b)(4)(vi), 423.504(b)(4)(vi)

All sponsors are required to adopt and implement an effective compliance program,

which must include measures to prevent, detect and correct Part C or D program

noncompliance as well as FWA.

The compliance program must, at a minimum, include the following core requirements:

1. Written Policies, Procedures and Standards of Conduct;

2. Compliance Officer, Compliance Committee and High Level Oversight;

3. Effective Training and Education;

4. Effective Lines of Communication;

5. Well Publicized Disciplinary Standards;

6. Effective System for Routine Monitoring and Identification of Compliance Risks;

and

7. Procedures and System for Prompt Response to Compliance Issues.

In order to be effective, a sponsor’s compliance program must be fully implemented, and

should be tailored to each sponsor’s unique organization, operations and circumstances.

A compliance program will not be effective unless sponsors devote adequate resources to

the program. Adequate resources include those that are sufficient to do the following:

1. Promote and enforce its Standards of Conduct

2. Promote and enforce its compliance program;

3. Effectively train and educate its governing body members, employees and FDRs;

4. Effectively establish lines of communication within itself and between itself and

its FDRs;

5. Oversee FDR compliance with Medicare Part C and D requirements;

6. Establish and implement an effective system for routine auditing and monitoring;

and

7. Identify and promptly respond to risks and findings.

CMS will consider a sponsor’s size, structure, business model, activities, the extent of its

delegation of responsibilities to other entities, the breadth of its operation, and the risks it

faces in evaluating whether adequate resources have been devoted to the compliance

program.

40 – Sponsor Accountability for and Oversight of FDRs

(Chapter 21 - Rev. 109, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-

20-12)

(Chapter 9 - Rev. 15, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-20-

12)

42 C.F.R. §§ 422.503(b)(4)(vi), 422.504(i), 423.504(b)(4)(vi), 423.505(i)

Sponsors may enter into contracts with FDRs to provide administrative or health care

services for enrollees on behalf of the sponsor. Sponsors may not delegate compliance

program administrative functions (e.g., compliance officer, compliance committee,

compliance reporting to senior management, etc.) to entities other than its parent

organization or corporate affiliate; however, sponsors may use FDRs for compliance

activities such as monitoring, auditing, and training.

The sponsor maintains the ultimate responsibility for fulfilling the terms and conditions

of its contract with CMS, and for meeting the Medicare program requirements.

Therefore, CMS may hold the sponsor accountable for the failure of its FDRs to comply

with Medicare program requirements.

Medicare program requirements apply to FDRs to whom the sponsor has delegated

administrative or health care service functions relating to the sponsor’s Medicare Parts C

and D contracts. These requirements do not apply to persons and entities whose

administrative contracts with the sponsor do not relate to the sponsor’s Medicare

functions, for example, a contract between a sponsor and a real estate broker in

connection with the rental of office space.

Below are examples of functions that relate to the sponsor’s Medicare Parts C and D

contracts:

• Sales and marketing;

• Utilization management;

• Quality improvement;

• Applications processing;

• Enrollment, disenrollment, membership functions;

• Claims administration, processing and coverage adjudication;

• Appeals and grievances;

• Licensing and credentialing;

• Pharmacy benefit management;

• Hotline operations;

• Customer service;

• Bid preparation;

• Outbound enrollment verification;

• Provider network management;

• Processing of pharmacy claims at the point of sale;

• Negotiation with prescription drug manufacturers and others for rebates, discounts

or other price concessions on prescription drugs;

• Administration and tracking of enrollees’ drug benefits, including TrOOP balance

processing;

• Coordination with other benefit programs such as Medicaid, state pharmaceutical

assistance or other insurance programs;

• Entities that generate claims data; and

• Health care services.

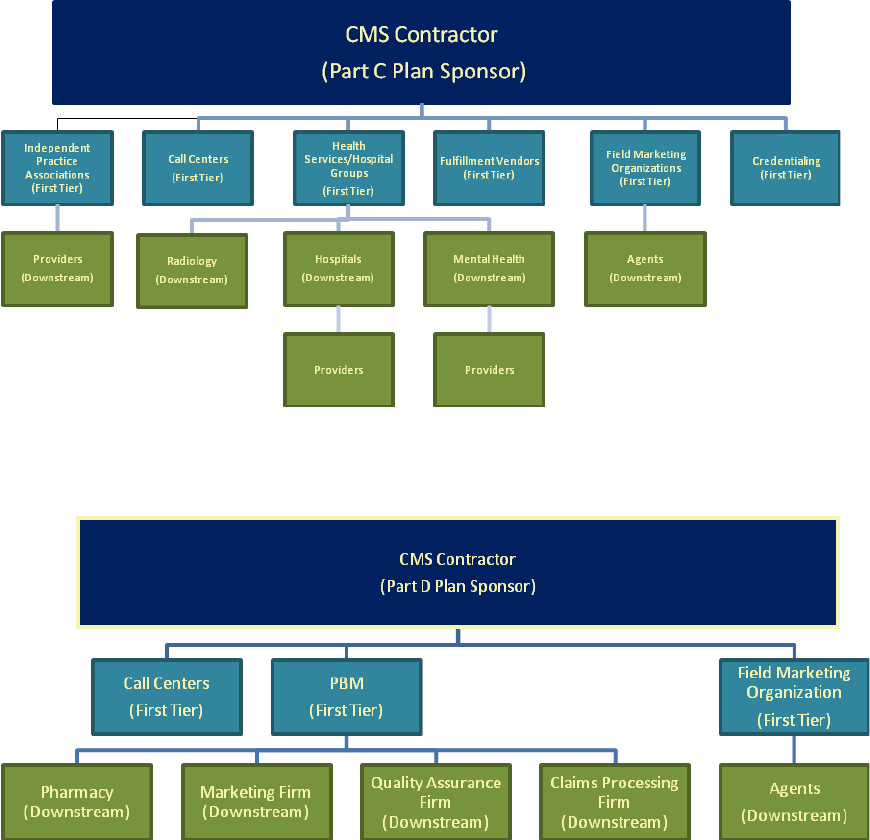

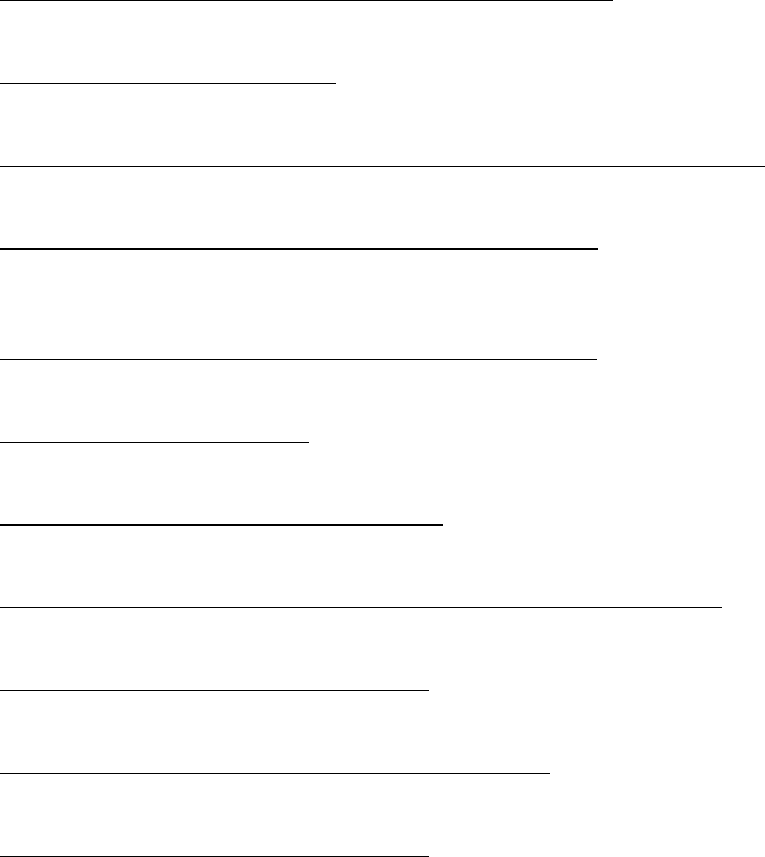

Stakeholder Relationship Flow Charts

First tier and related entities may contract with downstream entities to fulfill their

contractual obligations to the sponsors. A field marketing organization (first tier entity)

may contract with a smaller brokerage firm (downstream entity) to sell the sponsors’

Medicare Parts C and D products. That smaller brokerage firm may further contract with

individual sales agents (downstream entities) to perform the day-to-day sales work. A

related entity may also be either a first tier entity or a downstream entity.

It is critical that sponsors correctly identify those entities with which they contract that

qualify as FDRs. Sponsors are required to comply with CMS requirements for FDRs.

Unless it is very clear that an entity is or is not an FDR, the determination of FDR status

requires an analysis of all of the circumstances. Sponsors should have clearly defined

processes and criteria to evaluate and categorize all vendors with which they contract.

Below are some factors to consider in determining whether an entity is an FDR:

• The function to be performed by the delegated entity;

• Whether the function is something the sponsor is required to do or to provide

under its contract with CMS, the applicable federal regulations or CMS guidance;

• To what extent the function directly impacts enrollees;

• To what extent the delegated entity has interaction with enrollees, either orally or

in writing;

• Whether the delegated entity has access to beneficiary information or personal

health information;

• Whether the delegated entity has decision-making authority (e.g., enrollment

vendor deciding time frames) or whether the entity strictly takes direction from

the sponsor;

• The extent to which the function places the delegated entity in a position to

commit health care fraud, waste or abuse; and

• The risk that the entity could harm enrollees or otherwise violate Medicare

program requirements or commit FWA.

The method by which the analysis is performed is left to the discretion of the sponsor.

Some sponsors use a multi-functional committee, consisting of members from the

compliance and legal departments as well as the business owner of the FDR function, to

make the determination.

The sponsor’s compliance officer, working with the sponsor’s compliance committee,

must develop procedures to promote and ensure that all FDRs are in compliance with all

applicable laws, rules and regulations with respect to Medicare Parts C and D delegated

responsibilities. The sponsor must have a system in place to monitor FDRs. Sponsors are

free to choose the method for monitoring their FDRs’ compliance with Medicare program

requirements. Sponsors must be able to demonstrate that their method of monitoring is

effective. It is a best practice to use metrics to assist in observing compliance

performance and operational trends.

For more information on requirements for contracts with FDRs, see Pub. 100-16,

Medicare Managed Care Manual, chapter 11, §110.

50 – Elements of an Effective Compliance Program

(Chapter 21 - Rev. 109, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-

20-12)

(Chapter 9 - Rev. 15, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-20-

12)

42 C.F.R. §§ 422.503(b)(4)(vi), 423.504(b)(4)(vi)

This section discusses the seven elements of an effective compliance program, as set

forth in the applicable Federal regulations governing Parts C and D.

50.1 – Element I: Written Policies, Procedures and Standards of

Conduct

(Chapter 21 - Rev. 109, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-

20-12)

(Chapter 9 - Rev. 15, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-20-

12)

42 C.F.R. §§ 422.503(b)(4)(vi)(A), 423.504(b)(4)(vi)(A)

Sponsors must have written policies, procedures and standards of conduct that –

1. Articulate the sponsor’s commitment to comply with all applicable Federal and

State standards;

2. Describe compliance expectations as embodied in the Standards of Conduct;

3. Implement the operation of the compliance program;

4. Provide guidance to employees and others on dealing with suspected, detected or

reported compliance issues;

5. Identify how to communicate compliance issues to appropriate compliance

personnel;

6. Describe how suspected, detected or reported compliance issues are investigated

and resolved by the sponsor; and

7. Include a policy of non-intimidation and non-retaliation for good faith

participation in the compliance program, including, but not limited to, reporting

potential issues, investigating issues, conducting self-evaluations, audits and

remedial actions, and reporting to appropriate officials.

The requirements that are discussed in this section must be included as part of the

compliance program but may be stated either in policies and procedures or in Standards

of Conduct. They may, but need not, appear in both documents.

50.1.1 – Standards of Conduct

(Chapter 21 - Rev. 109, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-

20-12)

(Chapter 9 - Rev. 15, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-20-

12)

42 C.F.R. §§ 422.503(b)(4)(vi)(A), 423.504(b)(4)(vi)(A)

Standards of Conduct, also known in some organizations as the “Code of Conduct” or by

other similar names, state the overarching principles and values by which the company

operates, and define the underlying framework for the compliance policies and

procedures. Standards of Conduct should describe the sponsor’s expectations that all

employees conduct themselves in an ethical manner; that issues of noncompliance and

potential FWA are reported through appropriate mechanisms; and that reported issues

will be addressed and corrected.

The Standards of Conduct may be stated in a separate Medicare-specific stand-alone

document or within the corporate Code of Conduct. Sponsors should update the

Standards of Conduct to incorporate changes in applicable laws, regulations, and other

program requirements, such as those listed in Appendix B.

Standards of Conduct communicate to employees and FDRs that compliance is

everyone’s responsibility from the top to the bottom of the organization. For that reason,

and because Standards of Conduct are the most fundamental statement of the sponsor’s

governing principles, Standards of Conduct should be approved by the sponsor’s full

governing body.

It is a best practice of some sponsors to include a resolution of the full governing body

stating the sponsor’s commitment to compliant, lawful and ethical conduct. This

communicates to employees and FDRs that compliance and ethics are valued and

important to those at the highest levels of authority in the company.

50.1.2 – Policies and Procedures

(Chapter 21 - Rev. 109, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-

20-12)

(Chapter 9 - Rev. 15, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-20-

12)

42 C.F.R. §§ 422.503(b)(4)(vi)(A), 423.504(b)(4)(vi)(A)

Compliance policies and/or procedures are detailed and specific, and describe the

operation of the compliance program. Compliance policies may address issues such as

sponsors’ compliance reporting structure, compliance and FWA training requirements,

the operation of the hotline or other reporting mechanisms, and how suspected, detected

or reported compliance and potential FWA issues are investigated and addressed and

remediated. Sponsors should update the policies and procedures to incorporate changes

in applicable laws, regulations, and other program requirements.

50.1.3 – Distribution of Compliance Policies and Procedures and

Standards of Conduct

(Chapter 21 - Rev. 109, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-

20-12)

(Chapter 9 - Rev. 15, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-20-

12)

42 C.F.R. §§ 422.503(b)(4)(vi)(A), 423.504(b)(4)(vi)(A)

In order to be effective, compliance policies and procedures and Standards of Conduct

must be distributed to employees who support the sponsor’s Medicare business.

Distribution must occur within 90 days of hire, when there are updates to the policies,

and annually thereafter. Sponsors may choose their distribution method. Some examples

are furnishing hard copies at the time of hire and electronic copies thereafter, emailing an

electronic copy, or posting on the company intranet. The sponsors should have a method

to demonstrate that the Standards of Conduct and policies and procedures were

distributed to employees.

The Standards of Conduct should be written in a format that is easy to read and

comprehend. Sponsors should consider translating Standards of Conduct and policies

and procedures into other languages as necessary.

In order to communicate the sponsor’s compliance expectations for FDRs, sponsors

should ensure that Standards of Conduct and policies and procedures are distributed to

FDRs’ employees. Sponsors may make their Standards of Conduct and policies and

procedures available to their FDRs. Alternatively, the sponsor may ensure that the FDR

has comparable policies and procedures and Standards of Conduct of their own.

The sponsors should have a method to demonstrate that Standards of Conduct and

policies and procedures were distributed to FDRs’ employees. Sponsors or the FDR may

make the policies available through methods such as a fax blast, placement on an FDR

portal, in contract materials, etc. A best practice is to include appropriate contract

provisions in the FDR contract, coupled with periodic monitoring of a sample of FDRs

based on risk assessment, including a review of the FDRs’ compliance policies and

procedures and Standards of Conduct.

50.2 – Element II: Compliance Officer, Compliance Committee and

High Level Oversight

(Chapter 21 - Rev. 109, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-

20-12)

(Chapter 9 - Rev. 15, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-20-

12)

42 C.F.R. §§ 422.503(b)(4)(vi)(B), 423.504(b)(4)(vi)(B)

The sponsor must designate a compliance officer and a compliance committee who report

directly and are accountable to the sponsor’s chief executive or other senior management.

1. The compliance officer, vested with the day-to-day operations of the compliance

program, must be an employee of the sponsor, parent organization or corporate

affiliate. The compliance officer may not be an employee of an FDR.

2. The compliance officer and the compliance committee must periodically report

directly to the sponsor’s governing body on the activities and status of the

compliance program, including issues identified, investigated, and resolved by the

compliance program.

3. The sponsor’s governing body must be knowledgeable about the content and

operation of the compliance program and must exercise reasonable oversight with

respect to the implementation and effectiveness of the compliance program.

50.2.1 – Compliance Officer

(Chapter 21, Rev. 110, Issued:01-11-13, Effective:01-11-13; Implementation:01-11-13)

(Chapter 9, Rev. 16, Issued: 01-11-13, Effective: 01-11-13; Implementation: 01-11-13)

42 C.F.R. §§ 422.503(b)(4)(vi)(B), 423.504(b)(4)(vi)(B)

The compliance officer position should be full-time. The sponsor is not required to have a

separate compliance officer (“Medicare Compliance Officer”) dedicated only to its

Medicare Parts C and D business, although CMS strongly recommends a dedicated

Medicare compliance officer. Sponsors must assess the scope of the existing compliance

officer’s responsibilities, the size of the organization, and the organization’s resources

when determining whether a single compliance officer can effectively implement the

Medicare compliance program and the sponsor’s commercial or other governmental

business.

The compliance officer must be an employee of the sponsor (preferred) or of its parent

company or corporate affiliate. Sponsors may not delegate the compliance officer

position or compliance program functions to first tier or downstream entities. When the

compliance officer is not employed by the sponsor itself, but by the sponsor’s parent

company or corporate affiliate, the sponsor must ensure that the compliance officer has

detailed involvement in and familiarity with the sponsor’s operational and compliance

activities.

The sponsor must ensure that reports from the compliance officer reach the sponsor’s

senior-most leader (typically the CEO or President). The direct reporting relationship

between the compliance officer and the senior-most leadership refers to the direct

reporting of information, not necessarily to a supervisory reporting relationship. This can

be accomplished through a dotted line or matrix reporting.

The compliance officer must have express authority to provide unfiltered, in-person

reports to the sponsor’s senior-most leader. The compliance officer’s reports should not

be routed to the CEO or President through operational management such as the COO,

CFO, GC (General Counsel) or other executives responsible for operational areas. For

example, the compliance officer’s report to the CEO should not be filtered through the

CFO. However, the compliance officer’s reports may be relayed to the sponsor’s senior-

most leader through divisional Presidents. For example, the compliance officer may

report directly to the President of the division that houses the Medicare program, who

then reports to the CEO of the sponsor on the status and activities of the Medicare

compliance program.

The compliance officer’s reports to the sponsor’s governing body must be made through

the compliance infrastructure. The compliance officer must have express authority to

provide unfiltered, in-person reports to the sponsor’s governing body at his/her

discretion.

The Medicare compliance officer may report compliance issues directly to the corporate

compliance officer and/or the compliance committee, who then provide compliance

reports directly to the sponsor’s governing body. The compliance officer, in his/her

discretion, need not await approval of the sponsor’s governing body to implement needed

compliance actions and activities, provided that those actions and activities, as

appropriate, are reported to the governing body or governing body committee at its next

scheduled meeting. It is a best practice for sponsors who have both a corporate

compliance officer and a Medicare compliance officer to allow the Medicare compliance

officer to regularly attend meetings of the sponsor’s governing body and to make in-

person reports to the sponsor’s governing body. A related best practice is to allow the

compliance officer to meet in Executive Session with the governing body.

The compliance officer should be independent. The compliance officer should not serve

in both compliance and operational areas (e.g., where the compliance officer is also the

CFO, COO or GC). This leads to self-policing in the operational area(s) in which he/she

serves, which is a conflict of interest.

Because the compliance officer must be free to raise compliance issues without fear of

retaliation, it is a best practice to require governing body approval before the compliance

officer can be terminated from employment.

The compliance officer is responsible for the implementation of the compliance program.

The compliance officer defines the program structure, educational requirements,

reporting, and complaint mechanisms, response and correction procedures, and

compliance expectations of all personnel and FDRs.

The compliance officer should have training and/or experience working with MA, MA-

PD or PDP programs and, with regulatory authorities. It is a best practice for the

compliance officer to be a member of senior management.

Duties of the compliance officer may include, but are not limited to:

• Ensuring that Medicare compliance reports are provided regularly to the sponsor’s

corporate compliance officer (if any), governing body, CEO, and compliance

committee. Reports should include the status of the sponsor’s Medicare

compliance program implementation, the identification and resolution of

suspected, detected or reported instances of noncompliance, and the sponsor’s

compliance oversight and audit activities;

• Being aware of daily business activity by interacting with the operational units of

the sponsor;

• Creating and coordinating, by appropriate delegation, if desired, educational

training programs to ensure that the sponsor’s officers, governing body,

managers, employees, FDRs, and other individuals working in the Medicare

program are knowledgeable about the sponsor’s compliance program, its written

Standards of Conduct, compliance policies and procedures, and all applicable

statutory and regulatory requirements;

• Developing and implementing methods and programs that encourage managers

and employees to report Medicare program noncompliance and potential FWA

without fear of retaliation;

• Maintaining the compliance reporting mechanism and closely coordinating with

the internal audit department and the SIU, where applicable;

• Responding to reports of potential FWA, including the coordination of internal

investigations with the SIU or internal audit department and the development of

appropriate corrective or disciplinary actions, if necessary. To that end, the

compliance officer should have the flexibility to design and coordinate internal

investigations;

• Ensuring that the DHHS OIG and Government Services Administration (“GSA”)

exclusion lists have been checked with respect to all employees, governing body

members, and FDRs monthly and coordinating any resulting personnel issues

with the sponsor’s Human Resources, Security, Legal or other departments as

appropriate;

• Maintaining documentation for each report of potential noncompliance or

potential FWA received from any source, through any reporting method (e.g.,

hotline, mail, or in-person);

• Overseeing the development and monitoring of the implementation of corrective

action plans;

• Coordinating potential fraud investigations/referrals with the SIU, where

applicable, and the appropriate NBI MEDIC. This includes facilitating any

documentation or procedural requests that the NBI MEDIC makes of the sponsor.

Similarly, the compliance officer should collaborate with other sponsors, State Medicaid

programs, Medicaid Fraud Control Units (MCFUs), commercial payers, and other

organizations, where appropriate, when a potential FWA issue is discovered that involves

multiple parties; and

• The compliance officer should have the authority to:

o Interview or delegate the responsibility to interview the sponsor’s employees

and other relevant individuals regarding compliance issues;

o Review company contracts and other documents pertinent to the Medicare

program;

o Review or delegate the responsibility to review the submission of data to CMS

to ensure that it is accurate and in compliance with CMS reporting

requirements;

o Independently seek advice from legal counsel;

o Report potential FWA to CMS, its designee or law enforcement;

o Conduct and/or direct audits and investigations of any FDRs;

o Conduct and/or direct audits of any area or function involved with Medicare

Parts C or D plans; and

o Recommend policy, procedure, and process changes.

50.2.2– Compliance Committee

(Chapter 21 - Rev. 109, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-

20-12)

(Chapter 9 - Rev. 15, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-20-

12)

42 C.F.R. §§ 422.503(b)(4)(vi)(B), 423.504(b)(4)(vi)(B)

Sponsors must have a compliance committee in place that oversees the Medicare

compliance program. The sponsor need not have a separate Medicare compliance

committee, as long as the committee addresses Medicare compliance issues. In many

organizations, the compliance committee is chaired by the compliance officer. The

compliance committee serves to advise the compliance officer. The compliance

committee is accountable to, and must provide regular compliance reports to, the

sponsor’s senior-most leader and governing body. Reports on the status of the

compliance program are usually reported through the chairperson of the committee.

Duties of the compliance committee may include, but are not limited to:

• Meeting at least on a quarterly basis, or more frequently as necessary to enable

reasonable oversight of the compliance program;

• Developing strategies to promote compliance and the detection of any potential

violations;

• Reviewing and approving compliance and FWA training, and ensuring that

training and education are effective and appropriately completed;

• Assisting with the creation and implementation of the compliance risk assessment

and of the compliance monitoring and auditing work plan;

• Assisting in the creation, implementation and monitoring of effective corrective

actions;

• Developing innovative ways to implement appropriate corrective and preventative

action;

• Reviewing effectiveness of the system of internal controls designed to ensure

compliance with Medicare regulations in daily operations;

• Supporting the compliance officer’s needs for sufficient staff and resources to

carry out his/her duties;

• Ensuring that the sponsor has appropriate, up-to-date compliance policies and

procedures;

• Ensuring that the sponsor has a system for employees and FDRs to ask

compliance questions and report potential instances of Medicare program

noncompliance and potential FWA confidentially or anonymously (if desired)

without fear of retaliation;

• Ensuring that the sponsor has a method for enrollees to report potential FWA

• Reviewing and addressing reports of monitoring and auditing of areas in which

the sponsor is at risk for program noncompliance or potential FWA and ensuring

that corrective action plans are implemented and monitored for effectiveness; and

• Providing regular and ad hoc reports on the status of compliance with

recommendations to the sponsor’s governing body.

The compliance committee should include individuals with a variety of backgrounds, and

reflect the size and scope of the sponsor. Members of the compliance committee should

have decision-making authority in their respective areas of expertise. Sponsors should

include members of senior management (e.g., CFO, COO), as well as auditors,

pharmacists, registered nurses, and nationally certified pharmacy technicians on the

compliance committee (to the extent that their organization has those positions on staff.).

Other committee members might include personnel experienced in legal issues, statistical

analysts, and staff/managers from various departments within the organization who

understand the vulnerabilities within their respective areas of expertise.

50.2.3 – Governing Body

(Chapter 21 - Rev. 109, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-

20-12)

(Chapter 9 - Rev. 15, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-20-

12)

42 C.F.R. §§ 422.503(b)(4)(vi)(B), 423.504(b)(4)(vi)(B)

The sponsor’s governing body (e.g., Board of Directors or Board of Trustees) must

exercise reasonable oversight with respect to the implementation and effectiveness of the

sponsor’s compliance program. The governing body of the organization that contracted

with CMS or its parent company may oversee the Medicare compliance program. When

compliance issues are presented to the sponsor’s governing body, it should make further

inquiry and take appropriate action to ensure the issues are resolved.

The sponsor’s governing body may delegate compliance program oversight to a specific

committee of the governing body (e.g., Board Audit Committee or Board compliance

committee), but the governing body as a whole remains accountable for reviewing the

status of the compliance program. The scope of the delegation from the full governing

body to the governing body committee must be clear in the committee’s charter and

reporting.

The governing body must receive training and education as to the structure and operation

of the compliance program. The governing body should be knowledgeable about

compliance risks and strategies, should understand the measurements of outcome, and

should be able to gauge effectiveness of the compliance program.

Reasonable oversight by the governing body (assisted by a committee, if desired)

includes, but is not limited to:

• Approving the Standards of Conduct (this should be performed by the full

governing body and not a committee);

• Understanding the compliance program structure;

• Remaining informed about the compliance program outcomes, including results

of internal and external audits;

• Remaining informed about governmental compliance enforcement activity such

as Notices of Non-Compliance, Warning Letters and/or more formal sanctions;

• Receiving regularly scheduled, periodic updates from the compliance officer and

compliance committee; and

• Reviewing the results of performance and effectiveness assessments of the

compliance program.

The following are examples of activities in which the governing body, or a governing

body committee, may wish to have involvement. Alternatively, the governing body may

delegate some or all of these activities to senior management or to the compliance

committee:

• Development, implementation and annual review of compliance policies and

procedures;

• Approval of compliance policies and procedures;

• Review and approval of compliance and FWA training;

• Review and approval of compliance risk assessment;

• Review of internal and external audit work plans and audit results;

• Review and approval of corrective action plans resulting from audits;

• Review and approval of appointment of the compliance officer;

• Review and approval of performance goals for the compliance officer;

• Evaluation of the senior management team’s commitment to ethics and the

compliance program; and

• Review of dashboards, scorecards, self-assessment tools, etc., that reveal

compliance issues.

The governing body should collect and review measurable evidence that the compliance

program is detecting and correcting Medicare program noncompliance on a timely basis.

It is a best practice for the governing body to be provided with data showing that the

program has reduced the risks of program noncompliance and FWA. Some indicators of

an effective compliance program are:

• Use of quantitative measurement tools (e.g., scorecards, dashboard reports, key

performance indicators) to report, and track and compare over time, compliance

with key Medicare Parts C and D operations such as enrollment, appeals and

grievances, prescription drug benefit administration;

• Use of monitoring to track and review open/closed corrective action plans, FDR

compliance, Notices of Non-Compliance, warning letters, CMS sanctions,

marketing material approval rates, training completion/pass rates, etc.;

• Implementation of new or updated Medicare requirements (e.g., tracking HPMS

memo from receipt to implementation) including monitoring or auditing and

quality control measures to confirm appropriate and timely implementation;

• Increase or decrease in number and/or severity of complaints from employees,

FDRs, providers, beneficiaries through customer service calls or the Complaint

Tracking Module (CTM), marketing misrepresentations, Parts A and B issues,

etc.;

• Timely response to reported noncompliance and potential FWA, and effective

resolution (i.e., non-recurring issues);

• Consistent, timely and appropriate disciplinary action; and

• Detection of noncompliance and FWA issues through monitoring and auditing:

o Whether root cause was determined and corrective action appropriately

and timely implemented and tested for effectiveness;

o Detection of FWA trends and schemes via daily claims reviews, outlier

reports, pharmacy audits, etc.; and

o Actions taken in response to compliance reports submitted by FDRs.

The sponsor should ensure that CMS is able to validate, through review of governing

body meeting minutes or other documentation, the active engagement of the governing

body in the oversight of the Medicare compliance program. A governing body that is

appropriately engaged asks questions, requires follow-up on issues and takes action when

necessary.

50.2.4 – Senior Management Involvement in Compliance Program

(Chapter 21 - Rev. 109, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-

20-12)

(Chapter 9 - Rev. 15, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-20-

12)

42 C.F.R. §§ 422.503(b)(4)(vi)(B), 423.504(b)(4)(vi)(B)

An effective compliance program cannot be achieved unless the CEO (or senior-most

leader) and other senior management, as appropriate, are engaged in the compliance

program. The CEO and senior management must recognize the importance of the

compliance program in the sponsor’s success.

In situations where the contract holder engages in multiple lines of business (e.g.,

commercial, Medicare, etc.), with each line of business having its own CEO, the senior-

most leader of the contract holder must be engaged in compliance program oversight.

The CEO and senior management should ensure that the compliance officer is integrated

into the organization and is given the credibility, authority and resources necessary to

operate a robust and effective compliance program. The CEO must receive periodic

reports from the compliance officer of risk areas facing the organization, the strategies

being implemented to address them and the results of those strategies. The CEO must

also be advised of all governmental compliance enforcement activity, from Notices of

Non-compliance to formal enforcement actions.

50.3 – Element III: Effective Training and Education

(Chapter 21 - Rev. 109, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-

20-12)

(Chapter 9 - Rev. 15, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-20-

12)

42 C.F.R. §§ 422.503(b)(4)(vi)(C), 423.504(b)(4)(vi)(C)

The sponsor must establish, implement and provide effective training and education for

its employees, including the CEO, senior administrators or managers, and for the

governing body members, and FDRs.

The training and education must occur at least annually and be made a part of the

orientation for new employees, including the chief executive and senior administrators or

managers, governing body members, and FDRs.

FDRs who have met the FWA certification requirements through enrollment into the

Medicare program or accreditation as a Durable Medical Equipment, Prosthetics,

Orthotics, and Supplies (DMEPOS) are deemed to have met the training and educational

requirements for fraud, waste, and abuse.

Effectiveness of Training and Education

Effectiveness of training, education, compliance policies and procedures, and Standards

of Conduct will be apparent through sponsor’s compliance with all Medicare program

requirements. Sponsors must ensure that employees are aware of the Medicare

requirements related to their job function.

50.3.1 – General Compliance Training

(Chapter 21 - Rev. 109, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-

20-12)

(Chapter 9 - Rev. 15, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-20-

12)

42 C.F.R. §§ 422.503(b)(4)(vi)(C), 423.504(b)(4)(vi)(C)

The sponsor’s employees (including temporary workers and volunteers), and governing

body members, must, at a minimum, receive general compliance training within 90 days

of initial hiring, and annually thereafter. The following are examples of how sponsors

may satisfy the general compliance training requirements:

• Classroom training;

• Online training modules; or

• Attestations that employees have read and received the sponsor’s Standards of

Conduct and/or compliance policies and procedures.

Sponsors must be able to demonstrate that their employees have fulfilled these training

requirements. Examples of proof of training may include copies of sign-in sheets,

employee attestations and electronic certifications from the employees taking and

completing the training.

Sponsors must ensure that general compliance information is communicated to their

FDRs. The sponsor’s compliance expectations can be communicated through

distribution of the sponsor’s Standards of Conduct and/or compliance policies and

procedures to FDRs’ employees. Distribution may be accomplished through Provider

Guides, Business Associate Agreements or Participation Manuals, etc.

Sponsors should review and update, if necessary, the general compliance training

whenever there are material changes in regulations, policy or guidance, and at least

annually.

The following are examples of topics the general compliance training program should

communicate:

• A description of the compliance program, including a review of compliance

policies and procedures, the Standards of Conduct, and the sponsor’s commitment

to business ethics and compliance with all Medicare program requirements;

• An overview of how to ask compliance questions, request compliance

clarification or report suspected or detected noncompliance. Training should

emphasize confidentiality, anonymity, and non-retaliation for compliance related

questions or reports of suspected or detected noncompliance or potential FWA;

• The requirement to report to the sponsor actual or suspected Medicare program

noncompliance or potential FWA;

• Examples of reportable noncompliance that an employee might observe;

• A review of the disciplinary guidelines for non-compliant or fraudulent behavior.

The guidelines will communicate how such behavior can result in mandatory

retraining and may result in disciplinary action, including possible termination

when such behavior is serious or repeated or when knowledge of a possible

violation is not reported;

• Attendance and participation in compliance and FWA training programs as a

condition of continued employment and a criterion to be included in employee

evaluations;

• A review of policies related to contracting with the government, such as the laws

addressing gifts and gratuities for Government employees;

• A review of potential conflicts of interest and the sponsor’s system for disclosure

of conflicts of interest;

• An overview of HIPAA/HITECH, the CMS Data Use Agreement (if applicable),

and the importance of maintaining the confidentiality of personal health

information;

• An overview of the monitoring and auditing process; and

• A review of the laws that govern employee conduct in the Medicare program.

See Appendix B for other examples of laws and regulations that may be discussed in

training.

50.3.2 –Fraud, Waste, and Abuse Training

(Chapter 21 - Rev. 109, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-

20-12)

(Chapter 9 - Rev. 15, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-20-

12)

42 C.F.R. §§ 422.503(b)(4)(vi)(C), 423.504(b)(4)(vi)(C)

The sponsor’s employees (including temporary workers and volunteers), and governing

body members, as well as FDRs’ employees who have involvement in the administration

or delivery of Parts C and D benefits must, at a minimum, receive FWA training within

90 days of initial hiring (or contracting in the case of FDRs), and annually thereafter.

Additional, specialized or refresher training may be provided on issues posing FWA risks

based on the individual’s job function (e.g., pharmacist, statistician, customer service,

etc.). Training may be provided:

• upon appointment to a new job function;

• when requirements change;

• when employees are found to be noncompliant;

• as a corrective action to address a noncompliance issue; and

• when an employee works in an area implicated in past FWA.

Sponsors may choose to tailor the training in response to circumstances surrounding

potential FWA and specific functions performed by FDRs.

Sponsors must be able to demonstrate that their employees and FDRs have fulfilled these

training requirements as applicable. Examples of proof of training may include copies of

sign-in sheets, employee attestations and electronic certifications from the employees

taking and completing the training.

Sponsors must provide the FWA training directly to their FDRs or provide appropriate

FWA training materials to their FDRs.

To reduce the potential burden on FDRs, CMS has developed and provided a

standardized FWA training and education module. The module is available through the

CMS Medicare Learning Network (MLN) at http://www.cms.gov/MLNProducts. Using

CMS’ training module is optional and a sponsor may use another method. However, this

training meets CMS’ FWA training requirements so sponsors should accept FDRs’ use of

this FWA training option. For details on accessing the FWA training and education on

the MLN website, see the May 8, 2012, HPMS memo regarding Fraud, Waste and Abuse

Training and Education Guidance.

Topics that should be addressed in FWA training include, but are not limited to the

following:

• Laws and regulations related to MA and Part D FWA (i.e., False Claims Act,

Anti-Kickback statute, HIPAA/HITECH, etc.);

• Obligations of FDRs to have appropriate policies and procedures to address

FWA;

• Processes for sponsors and FDR employees to report suspected FWA to the

sponsor (or, as to FDR employees, either to the sponsor directly or to their

employers who then must report it to the sponsor);

• Protections for sponsor and FDR employees who report suspected FWA; and

• Types of FWA that can occur in the settings in which sponsor and FDR

employees work.

Sponsors are accountable for maintaining records for a period of 10 years of the time,

attendance, topic, certificates of completion (if applicable), and test scores of any tests

administered to their employees, and must require FDRs to maintain records of the

training of the FDRs’ employees.

FDRs who have met the FWA certification requirements through enrollment into Parts A

or B of the Medicare program or through accreditation as a supplier of DMEPOS are

deemed to have met the FWA training and education requirements. No additional

documentation beyond the documentation necessary for proper credentialing is required

to establish that an employee or FDR or employee of an FDR is deemed. In the case of

chains, such as chain pharmacies, each individual location must be enrolled into

Medicare Part A or B to be deemed. See examples of such entities in Pub. 100-16,

Medicare Managed Care Manual, chapter 6 §70.

50.4 – Element IV: Effective Lines of Communication

(Chapter 21 - Rev. 109, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-

20-12)

(Chapter 9 - Rev. 15, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-20-

12)

42 C.F.R. §§ 422.503(b)(4)(vi)(D), 423.504(b)(4)(vi)(D)

The sponsor must establish and implement effective lines of communication, ensuring

confidentiality between the compliance officer, members of the compliance committee,

the sponsor’s employees, managers and governing body, and the sponsor’s FDRs. Such

lines of communication must be accessible to all and allow compliance issues to be

reported including a method for anonymous and confidential good faith reporting of

potential compliance issues as they are identified.

50.4.1 – Effective Lines of Communication Among the Compliance

Officer, Compliance Committee, Employees, Governing Body, and

FDRs

(Chapter 21 - Rev. 109, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-

20-12)

(Chapter 9 - Rev. 15, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-20-

12)

42 C.F.R. §§ 422.503(b)(4)(vi)(D), 423.504(b)(4)(vi)(D)

Sponsors must have an effective way to communicate information from the compliance

officer to others. Such information should include the compliance officer’s name, office

location and contact information; laws, regulations and guidance for sponsors and FDRs,

such as statutory, regulatory, and sub-regulatory changes (e.g., HPMS memos); and

changes to policies and procedures and Standards of Conduct.

Methods to communicate information may include physical postings of information, e-

mail distributions, internal websites, and individual and group meetings with the

compliance officer. The dissemination of information from the compliance officer must

be made within a reasonable time and to all appropriate parties.

50.4.2 – Communication and Reporting Mechanisms

(Chapter 21 - Rev. 109, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-

20-12)

(Chapter 9 - Rev. 15, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-20-

12)

42 C.F.R. §§ 422.503(b)(4)(vi)(D), 423.504(b)(4)(vi)(D)

The sponsor’s written Standards of Conduct and/or policies and procedures must require

all employees, members of the governing body, and FDRs to report compliance concerns

and suspected or actual violations related to the Medicare program to the sponsor.

Sponsors must have a system in place to receive, record, respond to and track compliance

questions or reports of suspected or detected noncompliance or potential FWA from

employees, members of the governing body, enrollees and FDRs and their employees.

Reporting systems must maintain confidentiality (to the greatest extent possible), allow

anonymity if desired (e.g., through telephone hotlines or mail drops), and emphasize the

sponsor’s / FDR’s policy of non-intimidation and non-retaliation for good faith reporting

of compliance concerns and participation in the compliance program. FDRs that partner

with multiple sponsors may train their employees on the FDR’s reporting processes

including emphasis that reports must be made to the appropriate sponsor.

Sponsors must adopt, widely publicize, and enforce a no-tolerance policy for retaliation

or retribution against any employee or FDR who in good faith reports suspected FWA.

Employees and FDRs must be notified that they are protected from retaliation for False

Claims Act complaints, as well as any other applicable anti-retaliation protections.

The methods available for reporting compliance or FWA concerns and the non-retaliation

policy must be publicized throughout the sponsor’s or FDR’s facilities. This information

can be publicized, for example, through the use of posters, table tents, mouse pads, key

cards and other prominent displays. General compliance training should include the

reporting requirements and the available methods for reporting.

Sponsors must make the reporting mechanisms user friendly, easy to access and navigate,

and available 24 hours a day for employees, members of the governing body, and FDRs.

It is a best practice for sponsors to establish more than one type of reporting mechanism

to account for the different ways in which people prefer to communicate or feel

comfortable communicating.

When a suspected compliance issue is reported, it is a best practice for sponsors to

provide the complainant with information regarding expectations of a timely response,

confidentiality, non-retaliation and progress reports.

50.4.3 – Enrollee Communications and Education

(Chapter 21 - Rev. 109, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-

20-12)

(Chapter 9 - Rev. 15, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-20-

12)

42 C.F.R. §§ 422.503(b)(4)(vi)(D), 423.504(b)(4)(vi)(D)

Sponsors must educate their enrollees about identification and reporting of potential

FWA. Education methods may include flyers, letters, pamphlets that can be included in

mailings to enrollees (such as enrollment packages, Explanation of Benefits (“EOB”),

and information published on sponsor websites (especially on enrollee links), etc.).

50.5 – Element V: Well-Publicized Disciplinary Standards

(Chapter 21 - Rev. 109, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-

20-12)

(Chapter 9 - Rev. 15, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-20-

12)

42 C.F.R. §§ 422.503(b)(4)(vi)(E), 423.504(b)(4)(vi)(E)

Sponsors must have well-publicized disciplinary standards through the implementation of

procedures which encourage good faith participation in the compliance program by all

affected individuals. These standards must include policies that:

1. Articulate expectations for reporting compliance issues and assist in their

resolution;

2. Identify noncompliance or unethical behavior; and

3. Provide for timely, consistent, and effective enforcement of the standards when

noncompliance or unethical behavior is determined.

50.5.1 – Disciplinary Standards

(Chapter 21 - Rev. 109, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-

20-12)

(Chapter 9 - Rev. 15, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-20-

12)

42 C.F.R. §§ 422.503(b)(4)(vi)(E), 423.504(b)(4)(vi)(E)

Sponsors must establish and implement disciplinary policies and procedures that reflect

clear and specific disciplinary standards. The disciplinary policies must describe the

sponsor’s expectations for the reporting of compliance issues including noncompliant,

unethical or illegal behavior, that employees participate in required training, and the

expectations for assisting in the resolution of reported compliance issues. In addition, the

disciplinary policies must identify noncompliant, unethical or illegal behavior, through

examples of violative conduct that employees might encounter in their jobs. Further, the

policies must provide for timely, consistent and effective enforcement of the standards

when noncompliant or unethical behavior is found. Finally, the disciplinary action must

be appropriate to the seriousness of the violation.

50.5.2 – Methods to Publicize Disciplinary Standards

(Chapter 21 - Rev. 109, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-

20-12)

(Chapter 9 - Rev. 15, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-20-

12)

42 C.F.R. §§ 422.503(b)(4)(vi)(E), 423.504(b)(4)(vi)(E)

To encourage good faith participation in the compliance program, sponsors must

publicize disciplinary standards for employees and FDRs. The standards should include

the duty and expectation to report issues or concerns. The following are examples of the

types of publication mechanisms that could be used:

• Newsletters;

• Regular presentations at department staff meetings;

• Communications with FDRs;

• General compliance training;

• Intranet site;

• Posters prominently displayed throughout employee work and break areas; and

• Cafeteria table tents.

50.5.3 – Enforcing Disciplinary Standards

(Chapter 21 - Rev. 109, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-

20-12)

(Chapter 9 - Rev. 15, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-20-

12)

42 C.F.R. §§ 422.503(b)(4)(vi)(E), 423.504(b)(4)(vi)(E)

Sponsors must be able to demonstrate to CMS that disciplinary standards are enforced in

a timely, consistent and effective manner. Records must be maintained for a period of 10

years for all compliance violation disciplinary actions, capturing the date the violation

was reported, a description of the violation, date of investigation, summary of findings,

disciplinary action taken and the date it was taken. Sponsors should periodically review

these records of discipline to ensure that disciplinary actions are appropriate to the

seriousness of the violation, fairly and consistently administered and imposed within a

reasonable timeframe. Sponsors may consider including compliance as a measure on an

individual’s annual performance review. In addition, a best practice followed by some

sponsors is to publish de-identified disciplinary action in employee publications, such as

a newsletter, in order to demonstrate to employees that disciplinary action is imposed for

violations.

50.6 – Element VI: Effective System for Routine Monitoring, Auditing

and Identification of Compliance Risks

(Chapter 21 - Rev. 109, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-

20-12)

(Chapter 9 - Rev. 15, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-20-

12)

42 C.F.R. §§ 422.503(b)(4)(vi)(E), 423.504(b)(4)(vi)(E)

Sponsors must establish and implement an effective system for routine monitoring and

identification of compliance risks. The system should include internal monitoring and

audits and, as appropriate, external audits, to evaluate the sponsor’s, including FDRs’,

compliance with CMS requirements and the overall effectiveness of the compliance

program.

50.6.1 – Routine Monitoring and Auditing

(Chapter 21 - Rev. 109, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-

20-12)

(Chapter 9 - Rev. 15, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-20-

12)

42 C.F.R. §§ 422.503(b)(4)(vi)(F), 423.504(b)(4)(vi)(F)

Sponsors must undertake monitoring and auditing to test and confirm compliance with

Medicare regulations, sub-regulatory guidance, contractual agreements, and all applicable

Federal and State laws, as well as internal policies and procedures to protect against

Medicare program noncompliance and potential FWA.

Monitoring activities are regular reviews performed as part of normal operations to

confirm ongoing compliance and to ensure that corrective actions are undertaken and

effective. An audit is a formal review of compliance with a particular set of standards

(e.g., policies and procedures, laws and regulations) used as base measures.

Sponsors must develop a monitoring and auditing work plan that addresses the risks

associated with the Medicare Parts C and D benefits. The compliance officer and

compliance committee are key participants in this process.

Sponsors must have a system of ongoing monitoring and auditing that is reflective of its

size, organization, risks and resources to assess performance in, at a minimum, areas

identified as being at risk. The monitoring and auditing work plan must be coordinated,

overseen and/or executed by the compliance officer, assisted if desired by the compliance

department staff and/or the compliance committee. The compliance officer may

coordinate with the audit department, if any, in connection with these activities. The

compliance officer must receive regular reports from the audit department or from those

who are conducting the audits regarding the results of auditing and monitoring and the

status and effectiveness of corrective actions taken. It is the responsibility of the

compliance officer or his/her designee to provide updates on monitoring and auditing

results to the compliance committee, the CEO, senior leadership and the sponsor’s

governing body. In addition, for specific work coordinated with the audit department, the

compliance officer and Chief Audit Executive may share the responsibility to provide

updates on monitoring and auditing results to the compliance committee, the CEO, senior

leadership and the sponsor’s governing body.

50.6.2 – Development of a System to Identify Compliance Risks

(Chapter 21 - Rev. 109, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-

20-12)

(Chapter 9 - Rev. 15, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-20-

12)

42 C.F.R. §§ 422.503(b)(4)(vi)(F), 423.504(b)(4)(vi)(F)

Sponsors must establish and implement policies and procedures to conduct a formal

baseline assessment of the sponsor’s major compliance and FWA risk areas, such as

through a risk assessment. The sponsor’s assessment must take into account all Medicare

business operational areas. Each operational area must be assessed for the types and

levels of risks the area presents to the Medicare program and to the sponsor. Factors that

sponsors may consider in determining the risks associated with each area include, but are

not limited to:

• Size of department;

• Complexity of work;

• Amount of training that has taken place;

• Past compliance issues; and

• Budget.

Areas of particular concern for Medicare Parts C and D sponsors include, but are not

limited to, marketing and enrollment violations, agent/broker misrepresentation, selective

marketing, enrollment/disenrollment noncompliance, credentialing, quality assessment,

appeals and grievance procedures, benefit/formulary administration, transition policy,

protected classes policy, utilization management, accuracy of claims processing,

detection of potentially fraudulent claims, and FDR oversight and monitoring.

Risks identified by the risk assessment must be ranked to determine which risk areas will

have the greatest impact on the sponsor, and the sponsor must prioritize the monitoring

and auditing strategy accordingly. Risks change and evolve with changes in the law,

regulations, CMS requirements and operational matters. Therefore, there must be

ongoing review of potential risks of noncompliance and FWA and a periodic re-

evaluation of the accuracy of the sponsor’s baseline assessments. Risk areas identified

through CMS audits and oversight, as well as through the sponsor’s own monitoring,

audits and investigations are priority risks. The results of the risk assessment inform the

development of the monitoring and audit work plan.

50.6.3 – Development of the Monitoring and Auditing Work Plan

(Chapter 21 - Rev. 109, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-

20-12)

(Chapter 9 - Rev. 15, Issued: 07-27-12, Effective: 07-20-12; Implementation: 07-20-

12)

42 C.F.R. §§ 422.503(b)(4)(vi)(F), 423.504(b)(4)(vi)(F)

Once the risk assessment has been completed, a monitoring and auditing work plan must

be developed. The compliance officer may coordinate with each department to develop a

monitoring and auditing work plan based upon the results of the risk assessment. The

work plan may include:

• The audits to be performed;