Can Implicit Associations Distinguish True and

False Eyewitness Memory? Development and

Preliminary Testing of the IATe

Rebecca K. Helm

*

, Stephen J. Ceci and Kayla A. Burd

Eyewitness identification has been shown to be fallible and prone to false memory. In

this study we develop and test a new method to probe the mechanisms involved in the

formation of false memories in this area, and determine whether a particular memory

is likely to be true or false. We created a seven-step procedure based on the Implicit

Association Test to gauge implicit biases in eyewitness identification (the IATe). We

show that identification errors may result from unconscious bias caused by implicit

associations evoked by a given face. We also show that implicit associations between

negative attributions such as guilt and eyewitnesses’ final pick from a line-up can help

to distinguish between true and false memory (especially where the witness has been

subject to the suggestive nature of a prior blank line-up). Specifically, the more a

witness implicitly associates an individual face with a particular crime, the more likely

it is that a memory they have for that person committing the crime is false. These find-

ings are consistent with existing findings in the memory and neuroscience literature

showing that false memories can be caused by implicit associations that are outside

conscious awareness. Copyright # 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Cognitive psychology has provided extensive insight into human memory, pointing out

that memory is fallible, prone to error, and context-dependent (see, for example

Brainerd & Reyna, 2005; Ceci & Bronfenbrenner, 1991; Loftus, 2003; Shaw & Porter,

2015). This is clearly important for eyewitness identification in the criminal justice

system – the Innocence Project notes that eyewitness misidentification contributes to

more than 70% of wrongful convictions revealed by DNA exonerations (Innocence

Project Report on Eyewitness Misidentification, 2015).

In 2011, the New Jersey Supreme Court issued a ruling changing the legal standard

for assessing eyewitness evidence (State v. Henderson, 2011). As a result of this ruling,

defendants who can show some evidence of suggestive influence are entitled to a hearing

in which all factors that might have a bearing on the eyewitness evidence are explored

and weighed (Schacter & Loftus, 2013). If, after weighing the evidence presented at

the hearing, it is decided to admit the eyewitness evidence into trial, then the judge will

provide instructions to guide jurors on how to evaluate the evidence. While this ruling is

important, it relies on an understanding of the factors that affect eyewitness testimony

and the factors related to true or false eyewitness memory. Currently, there are few cog-

nitive methods for distinguishing true from false memory (Schacter & Loftus, 2013).

* Correspondence to: Rebecca K. Helm, Department of Human Development, Martha Van Rensselaer Hall,

Department of Human Development, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY

Copyright # 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Behavioral Sciences and the Law

Behav. Sci. Law 34: 803–819 (2016)

Published online 23 January 2017 in Wiley Online Library

(wileyonlinelibrary.com) DOI: 10.1002/bsl.2272

This paper introduces a new tool to assess false eyewitness identification memory,

our adaption of the Implicit Associations Test (IAT)/Autobiographical Implicit

Associations Test (aIAT), to investigate: (i) whether it can provide insight into the

mechanisms behind false memory (particularly false memory based on suggestion);

and (ii) whether it can be used to determine if a particular memory is likely to be true

or false. We will refer to this new version as the Implicit Associations Test for

Eyewitness Identification (IATe).

Research provides support for a link between implicit associations and false memory

(see Online Supplemental Material). This suggests that the strength of associations

between concepts can be important in the creation of false memory and that this pro-

cess occurs outside of effortful and perhaps even conscious processing.

In a forensic context, associations that witnesses have may be significant in

predicting whether they will be susceptible to false memory. Specifically, the extent

to which they associate or classify an innocent individual with a crime may be predictive

of how likely they will be to have a false memory for that person committing a crime

even when the actual perpetrator appears in the same line-up. If the presentation of

an individual face arouses a network of associations that are linked to guilt, this can,

in theory, result in mistaken identification, particularly if the associations of the face

with guilt are greater than are the associations of the face of the actual perpetrator.

Importantly, this form of implicit association is thought to operate outside conscious

awareness, thus not triggering self-initiated behaviors to monitor or reverse it.

1

Numerous researchers have examined the neural correlates of false memory, and

several theories have been put forward to explain the role of implicit semantic associa-

tions in false memory, such as Fuzzy Trace Theory (FTT; see Online Supplemental

Material for details).

The Implicit Associations Test

In order to examine the predicted relationship between implicit associations and false

memory, we developed a task based on the Implicit Associations Test (IAT) and its

derivative, the Autobiographical Implicit Associati ons Test (aIAT). The IAT measures

the strength of associations between concepts (e.g. women) and evaluations (e.g. good)

and stereotypes (e.g. athletic) (Greenwald, McGhee, & Schwartz, 1998). It provides a

measure of the strength of an association by measuring the difference between perfor-

mance speeds during two classification tasks in which associative strengths influence

performance (Greenwald, Nosek, & Banaji, 2003).

To illustrate how the IAT works, take the example of measuring an association

between men and science. Participants would initially complete two practice tasks –

first, classifying a list of disciplines (e.g., physics, music, chemistry, poetry) into either

1

This dual-process distinction between fast, relatively unconscious processes and those that are slower,

more deliberative and effortful dates back to the seminal work on reasoning biases by Kahneman and Tversky

in the early 1970s (Kahneman, 2011), and goes by various names in the psychological science literature, with

some referring to it as “automatic versus controlled” processing, “System 1 versus System 2” processing,

“implicit versus explicit processing, “Type 1/Type 2″ processing, etc. (for a review of the pervasiveness of this

distinction in explaining various psychological outcomes, see Chapter 2 of Stanovich, West, & Toplak, 2016).

The essential distinction is between processes that are triggered spontaneously by an aspect of the stimulus

environment and which do not require limited attentional resources as opposed to those that require con-

trolled effort and are resource-intensive.

804 Helm R. K. et al.

Copyright # 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Behav. Sci. Law 34: 803–819 (2016)

DOI: 10.1002/bsl

“arts” or “sciences” by clicking specified keys on a keyboard. Next, participants classify

a list of people (e.g. father, mother, brother, sister) into male or female. They are asked

to sort the items into the respective categories as quickly as possible. Then participants

perform tasks where they categorize disciplines and people at the same time (so they

categorize the people that appear according to their gender and the disciplines that

appear according to whether they are an arts or a science). For example, participants

might press “e” for both male and science and “i” for both female and arts (see

Figure 1). The task will then switch so the participants are instructed to press “e” for

both male and sciences and “i” for female and arts.

The IAT is scored using reaction times and at no time are participants made explic-

itly aware of a linkage between gender and disciplines. The association of men with

sciences is inferred by the quicker classification of sciences into the correct category

when they appear with male (so you press the same button for men and for sciences)

and slower to group sciences into the correct category when they appear with female.

The difference in reaction times between these two types of task provides the basis

for the IAT measure (Greenwald, Poehlman, Uhlmann, & Banaji, 2009). This task

has been shown to significantly exceed self-report measures of association in detecting

stereotypes (Greenwald et al., 2009), and it has been validated in a variety of ways, such

as predicting international sex differences in math and science achievement in 34

countries, whereas conscious self-report measur es added nothing to the prediction over

and above the unconscious measures (see Nosek et al., 2009)

The autobiographical IAT or aIAT was developed from the IAT and has been used

to evaluate which one of two personally experienced autobiographical events is true.

The participant is presented with stimuli from one of four categories: sentences that

are always true (I am in front of a computer), or always false (I am climbing a moun-

tain), and sentences that are true or false for a particular participant (e.g. I went on

holiday to Paris last year or I went on holiday to London last year). In this task, the true

autobiographical event gives rise to faster reaction times when it shares the same motor

response (i.e. the same key has to be pressed to place it in the correct category) with

Figure 1. An example slide from an Implicit Associations Test (IAT) examining implicit associations

between gender and arts/science subjects. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Development and preliminary testing of the IATe 805

Copyright # 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Behav. Sci. Law 34: 803–819 (2016)

DOI: 10.1002/bsl

true sentences. A recent review found that this task had more than 90% accuracy in

detecting true memory (Agosta & Sartori, 2013).

Researchers have used the aIAT to detect true and false memory in a

Deese–Roediger–McDermott (DRM) task (Marini, Agosta, Mazzoni, Dalla Barba, &

Sartori, 2012). This task assessed the association of presented words (e.g. “I heard

the word sharp”) and critical lures (e.g. “I heard the word needle”) with the logical

dimension “true”. Results showed that there was a greater association between

presented target words with the logical dimension “true” than there was between

non-presented critical lures with the logical dimension “ true”. This research with

semantically organized word lists suggests that an adaptation of the IAT/aIAT might

be useful to examine the relationship between true and false memory in eyewitness

identifications, a challenge we take up next.

The Implicit Associations Test and Eyewitness Memory – the Present

Study

In order to test our predictions, we adapted the IAT/aIAT to measure the extent to

which eyewitnesses implicitly associated specific individuals (including the true

perpetrator and foils) with committing a crime after witnessing that crime being com-

mitted. To do this, we designed an implicit categorization task in which participants

had to classify two categories of things, true and false statem ents, and faces of a target

(the person they had seen witnessing a crime) and foils (other similar-looking individ-

uals). The faces were intended to have a similar gist but be differe nt enough that an

individual seeing all the faces at once could readily distinguish between them. We

administered our task in seven blocks, following the procedure described in Greenwald

et al. (2003). First, participants were asked to categorize easy statements that were

either true (2 + 2 = 4) or false (2 + 2 = 10). Secondly, participants grou ped pictures

of individuals (the target and foils) with the statements regarding crime or gender

(e.g., this person committed the crime or this person is a man) into crime or gender

categories. Participants then completed two sets of categorizations (one block of 20

trials and one block of 40 trials) consisting of both statements about faces from the

narrative and true/false statements. In these tasks, true appeared with (and shared a

motor response with) crime-related and false appeared with (and shared a motor

response with) gender-related. Participants categorized the true/false statements into

true or false and the faces with accompanying statements into crime-related or

gender-related.

In the fifth task, participants practiced categorizing true and false statements when

their position on the screen (and the motor response associated with them) was re-

versed, to avoid position effects. In the sixth and seventh tasks, participants categorized

statements about faces from the narrative and true/false statements (in one block of 20

trials and one block of 40 trials). In these tasks, false appeared with (and shared a motor

response with) crime-related and true appeared with (and shared a motor response

with) gender-related. As in the third and fourth blocks, participants categorized the

true/false statements into true or false and the faces with accompanying statements into

crime-related or gender-related.

Our reasoning is as follows: participants associating an individual with a crime

should group the picture of him with the statement “this person committed the crime”

into the crime category faster when this statement shares a motor response with “true”

806 Helm R. K. et al.

Copyright # 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Behav. Sci. Law 34: 803–819 (2016)

DOI: 10.1002/bsl

(as in Figure 2), and conversely we reasoned that participants associating an individual

with a crime would group the picture of him with the statement “this person stole the

purse” into the crime category more slowly when this statement shared a motor

response with “false” (as in Figure 3). These twin expectations follow directly from

the logic of the IAT. We refer to this adaptation of the IAT/aIAT for use with eyewit-

nesses making an identification as the IATe.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were 350 undergraduate students at a large east coast university that

contains both a public, state university and a private university within a single

Figure 3. An example slide from a classification task where crime related shares a motor response with false.

[Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Figure 2. An example slide from a classification task where crime-related shares a motor response with true.

[Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Development and preliminary testing of the IATe 807

Copyright # 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Behav. Sci. Law 34: 803–819 (2016)

DOI: 10.1002/bsl

administrative structure (35% male, 65% female). Students participated in the study

for course credit. They ranged in age from 18 to 24 (M = 19.33, SD = 1.22). The most

common racial identity of participants was White (56.5%), followed by Chinese

(10.4%) and Black/African American (7.6%). The largest religious affiliation was no

religion (30.1%), with substantial numbers also identifying as Catholic (26.6%), Prot-

estant (17.6%) and Jewish (13.7%).

Crime Scenario and Initial Identification

Participants were first told that police were investigating an incident that took place

about a week ago (they did not receive instructions prior to this and did not know that

they would subsequently complete an identification task). They were presented with an

illustrated narrative of the incident. Specifically they read a short (approximately 150

words) description of a crime, accompanied by pictures of characters in the narrative.

In the narrative, participants were told that they had been walking along the side of a

road in New York with a friend when they saw movement ahead of them and stopped

to see what was happening. They were told that they saw one person (pictured)

approach another person (pictured) and grab her purse from her then run away. They

were also told that they saw two people (pictured) attempt to follow the purse-snatcher

but fail to find him. Pictures of each of the char acters (the purse-snatcher, the two pur-

suers, and the victim) accompanied the narrative and were presented as that character

appeared in the narrative, so the participants saw a clear picture of the purse-snatcher

(the perpetrator). We rotated the faces of the characters in the story, assigning them

randomly to one of three faces (“Face 1”, “Face 2”,or“Face 3”) to control for any

stimulus-specific effects that could later lead to biased line-up selections. All of our

perpetrators (and all faces appearing in subsequent line-ups) were young White males

with short dark hair and dark eyes; however, they were intended to be different enough

that an individual looking at the faces all together could readily distinguish between

them. The victim in all scenarios was a young White woman. All faces were of real

people, taken from an online face bank.

Participants were able to view this crime scenario for as long as they wanted. After

viewing the crime scenario, participants completed a buffer task for approximately

20 minutes and were then randomly assigned to one of three line-up conditions from

which they were asked to pick the suspect in a two-person matchup. Participants were

not given formal line-up instructions and were just asked to identify who they saw steal

the bag. This initial line-up was given in order to subject some participants to sugges-

tion through a target-absent line-up. The target-absent line-up was intended to foster

false memory because participants could subsequently misremember the suspect they

picked from the line-up as the person who committed the crime – a source misattribu-

tion error. The line-up contained either “Face 1” and “Face 2” (conditi on 1), “Face 1”

and “Face 3” (condition 2), or “Face 2” and “Face 3” (condition 3). This meant that a

participant would see either a target-present line-up in which t he real perpetrator was in

the line-up (in two-thirds of cases) or a target-absent line-up in which the real perpetra-

tor was not in the line-up (in one-third of cases). For example, if a person saw “Face 1 ”

as the perpetrator, conditions 1 and 2 would be target-present, and condition 3 would

be target-absent. After picking a suspect from this line-up, participants completed

another buffer task, for approximately 10 minutes. They then completed the IATe

(our version of the autobiographical IAT) to measure the extent to which they

808 Helm R. K. et al.

Copyright # 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Behav. Sci. Law 34: 803–819 (2016)

DOI: 10.1002/bsl

associated the perpetrator and foils with guilt. They then completed a final line-up

identification task, which was target-present for all participants.

Implicit Associations Test for Eyewitnesses

Participants then completed our seven-step IATe, which we created to examine mem-

ory phenomena. Participants completed seven sections of this IATe. First, they com-

pleted two practice tasks in which they had to group true and false statements into

either true or false, categories and statements about faces (these faces were the three

faces used in the prior crime narrative they had been shown) into crime-related or

gender-related statements. In the third task, participants completed 20 categorizations,

consisting of both statements about faces from the narrative and true/false statements.

In this task, true appeared with (and shared a motor response with) crime-related and

false appeared with (and shared a motor response with) gender-related. The fourth task

was the same as the third task but participants completed 40 categorizations. The logic

of this procedure is as follows: we would expect participants who implicitly associated a

face with guilt to group a statement about that face saying “this person stole the purse”

into crime-related more quickly in these tasks, as crime-related appeared, and shared a

motor response, with true.

In the fifth task, participants practiced categorizing true and false statements when

their position on the screen (and the motor response associated with them) was

reversed, to avoid position effects. In the sixth task, participants completed 20 catego-

rizations, consisting of both statements about faces and true/false statements. In this

task, false appeared with (and shared a motor response with) crime-related and true

appeared with (and shared a motor response with) gender-related. The final task was

the same as the sixth task but participants completed 40 categorizations. The logic of

the IAT leads to the expectation that participants who implicitly associated a face with

guilt would group a statement about that face saying “this person stole the purse” into

crime-related less quic kly in these tasks, as crime-related appeared with, and shared a

motor response with, false.

To summarize, tasks 3 and 6 were the same except that, in 3, true appeared with (and

shared a motor response with) crime-related and in 6 false appeared with (and shared a

motor respon se with) crime-related. Similarly, tasks 4 and 7 were the same except that

in 4 true appeared with (and shared a motor response with) crime-related and in 7 false

appeared with (and shared a motor response with) crime-related. In these tasks, partic-

ipants who associate a statement about a face that related to a crime (for example “this

person stole the purse”) with being true, we would expect them to be faster to group this

statement into crime-related when crime-related appears with (and shares a motor

response with) true than when crime-related appears with (and shares a motor response

with) false. So, a relatively fast reaction time in tasks 3 and 4 and a relatively slow reac-

tion time in tasks 6 and 7 would indicate a strong association with guilt.

Participants saw every face and had to categorize it at least once in each of tasks 3, 6,

4, and 7. To score the IAT, we took the average response time (in milliseconds) for cat-

egorizing the statement “this person stole the purse” into crime-related for each face, in

each of tasks 3, 4, 5, and 6. We took each participant’s score in task 3 and subtracted it

from their score in task 6 (hereafter referred to as 6–3), and each participant’s score in

task 4 and subtracted it from their score in task 7 (referred to as 7–4). Finally, we took

the mean of 6–3 and 7– 4. We did this for each of the three faces they saw in the IAT,

Development and preliminary testing of the IATe 809

Copyright # 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Behav. Sci. Law 34: 803–819 (2016)

DOI: 10.1002/bsl

resulting in three raw scores (in milliseconds); each of these reflect the extent to which

the participant associated each of these characters with guilt. A positive score in

milliseconds means that the participant responded faster when the crime statement

(stating that the individual committed the crime) was grouped with true than when it

was grouped with false, and a negative score in milliseconds means that the participant

responded faster when the crime statement (stating that the individual committed the

crime) was grouped with false than when it was grouped with true. In other words, a

positive score meant that a participant associated the individual more with being guilty

than with being not guilty, and a negative score meant that a participant associated the

individual more with being not guilty than with guilty.

Final Identification

Finally, participants were presented a target-present line-up that contained all three

faces – so for each participant the line-up contained the perpetrator and two innocent

suspects. In every condition, the three faces in this line-up were the same (and were

all young White males with dark hair), differing solely in which face represented the

perpetrator (purse-snatcher) in the illustrated narrative.

RESULTS

Initial Descriptive Statistics

Overall, 121 participants saw “Face 1” as the perpetrator, 120 participants saw “Face

2” as the perpetrator, and 109 participants saw “Face 3” as the perpetrator. A total of

106 participants saw a target-absent line-up, and 244 participants saw a target-present

line-up. Of participants who saw “Face 1” as the perpetrator, 35 saw a targ et-absent

line-up and 86 saw a target-present line-up; of participants who saw “Face 2” as the

perpetrator, 39 saw a target-absent line-up and 81 saw a target-present line-up; of

participants who saw “Face 3” as the perpetrator, 32 saw a target-absent line-up and

77 saw a target-present line-up.

When viewing the final target-present line-up, 34 of the 106 participants who

initially saw a target-absent line-up (32.1%) had a false memory (i.e. picked someone

other than the target), and 67.9% picked the target. Twenty-six of the 244 participants

who initially saw a target-present line-up (10.7%) had a false memory (i.e. picked

someone other than the target) when picking from the final target-present line up,

and 89.3% picked the target. The number of correct identifications and false identifica-

tions of each participant is displayed in Table 1. Because level of false identifications for

Table 1. Rates of correct and false identifications for each perpetrator

Correct identifications False identifications

Target present Target absent Target present Target absent

Face 1 73 21 4 8

Face 2 77 28 15 9

Face 3 68 22 7 18

810 Helm R. K. et al.

Copyright # 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Behav. Sci. Law 34: 803–819 (2016)

DOI: 10.1002/bsl

each face indicates some asymmetry in facial association with guilt and/or with false

memory, in all subsequent analyses these three faces were analyzed as a between-

subjects factor to preclude any undue influence of a given face or its association with

guilt. There were no significant differences in the extent to which each perpetrator

was associated with guilt, even when controlling for the perpetrato r each participant

had seen – the mean association of participant 1 with guilt was 200.75 milliseconds,

the mean association of participant 2 with guilt was 160.27 milliseconds, and the

mean association of participant 3 with guilt was 114.87 milliseconds.

The Relationship Between Implicit Associations and Final Pick

Firstly, we wanted to see whether participants associated the person they picked from

the final line-up with guilt more than the other “ suspects”, and whether this varied

depending on whether the participant had a false memory for a suspect who was not

the target. To examine this, we conducted a repeated-measures ANOVA using

association with guilt as a repeated measure (association of the suspect’s face picked

with guilt vs. the average association of two innocent suspects’ faces with guilt), and

true or false memory as a between-subjects factor. We ran this ANOVA first including

all subjects, and secondly including only subjects who had seen an initial target-absent

line up.

Including all Subjects

In this ANOVA there was a significant main effect of association with guilt – partici-

pants associated the person they went on to pick with guilt more than they associated

the other two suspects with guilt [Δ = 205.19, 95% CI: 88.70–321.69;

F(1,348) = 12.16, p < 0.001, η

p

2

= 0.033].

2

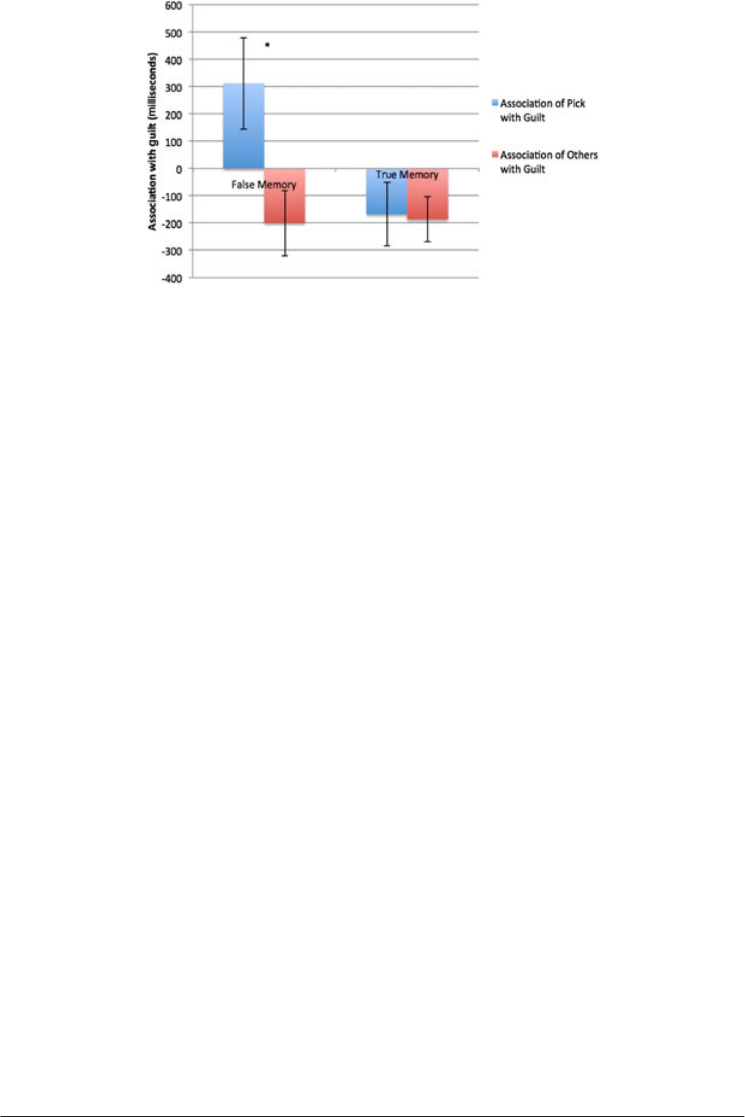

There was also a significant interaction

between association with guilt (face picked vs. other faces) and type of memory (true

or false) [F(1,348) = 6.11, p = 0.014, η

p

2

= 0.017]. For participants who had a false

memory, there was a significant difference in association with guilt between the face

they picked and the two other suspects, so that they associated the face they picked with

guilt more than the other two suspects (Δ = 351.60, 95% CI: 139.51–563.68,

p = 0.001, η

p

2

= 0.030). For participants who did not have a false memory, there was

no significant difference in association with guilt between their pick and the other sub-

jects (Δ = 58.79, 95% CI: –37.68–155.26, p = 0.231, η

p

2

= 0.004). This interaction is

illustrated in Figure 4.

In light of the asymmetry of faces associated with a false memory reported earlier, we

also ran this ANOVA with face used for perpetrator as a between-subjects factor, in

order to ensure that the effects were not driven by false memory for a particular face

or by an association of a particular face with guilt. The significant effects remained

the same, and this factor was not significant, nor did it significantly interact with any

of the other factors. We also ran the ANOVA with gender as a between-subjects factor,

and ran the ANOVA with race as a between-subjects factor.

3

In both ANOVAs, the

2

η

p

2

= partial eta squared.

3

When including race as a between-subjects factor we split race into four groups to ensure sufficient sample

size – White, Black/African American, Chinese, and Other.

Development and preliminary testing of the IATe 811

Copyright # 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Behav. Sci. Law 34: 803–819 (2016)

DOI: 10.1002/bsl

significant effects remained the same, and gender and race were not significant and did

not significantly interact with any of the other factors.

Including only Subjects who Initially Saw a Target-absent Line-up

Focusing only on participants who were initially presented with a target-absent line-up,

the results of this ANOVA replicated the results of the ANOVA including all subjects:

once again, there was a main effect of association with guilt – participants associated the

person they went on to pick with guilt more than they associated the other subjects with

guilt (Δ = 265.45, 95% CI: 80.02–450.90; F(1, 104) = 8.06, p = 0.005, η

p

2

= 0.072),

and there was a significant interaction between association with guilt (face picked vs.

others) and type of memory (true or false) [F(1, 104) = 6.96, p = 0.010, η

p

2

= 0.063] .

As in the previous ANOVA, for participants who exhibite d a false memory there was

a significant difference in association with guilt between their pick and other suspects

(Δ = 512.16, 95% CI: 206.48–817.84, p = 0.001, η

p

2

= 0.096], whereas for participants

who had a true memory, there was no significant difference in association with guilt

between their pick and other subjects (Δ = 18.74, 95% CI: –191.32–228.80,

p = 0.860, η

p

2

= 0.001).

Again, we ran this ANOVA with face used for perpetrator as a between-subjects

factor, in order to ensure the effects were not driven by false memory for a particular

face or association of a particular face with guilt. The significant effects remained the

same, and this factor was not significant and did not significantly interact with any

other factor. We also ran the ANOVA with gender as a between-subjects factor, and

ran the ANOVA with race as a between-subjects factor.

4

In both ANOVAs, the

4

When including race as a between-subjects factor we split race into four groups to ensure sufficient sample

size – White, Chinese, and Other.

Figure 4. Significant interaction between association with guilt(pick vs. others) and type of memory (true vs.

false). Error bars represent standard error. Association with guilt is the time taken to group a statement that

the person was guilty into a crime statement when a motor response was shared with true minus the time

taken to group a statement that the person was guilty into a crime statement when a motor response was

shared with false. In other words, a positive association with guilt score suggests that the participant associ-

ated the statement that the person committed the crime with being true more than they associated it with

being false. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

812 Helm R. K. et al.

Copyright # 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Behav. Sci. Law 34: 803–819 (2016)

DOI: 10.1002/bsl

significant effects remained the same, and gender and race were not significant and did

not significantly interact with any of the other factors.

Distinguishing True and False Memories Using Implicit Associations –

Logistic Regression

Next, a logistic regression was conducted, to determine whether implicit association

scores could distinguish between true and false memories in our participants. We used

type of memory (true or false) as the dependent variable and association of final pick

with guilt and mean association of others with guilt as predictors. We used standardized

scores (Z scores) for these variables due to the large range of associations. Association

of pick with guilt was a significant predictor in this regression (B = .299, SE = 0.153,

p = 0.026, OR = 0.712). As a participant’s implicit association of their pick with guilt

increased, the more likely it was that their memory was false. Mean association of

non-picks with guilt was non-significant in the oth er direction (B = 0.291, SE = 0.153,

p = 0.058, OR = 1.338).

5

We tested our logistic regression model using the Hosmer

and Lemeshow test. The results of this test indicated that our model did fit the data

at an acceptabl e level (p = 0.127).

Results remained the same when including gender as a predictor, and gender itself

was not a significant predictor. When including race as a predictor, race itself was

not a significant predictor but mean association of non-picks with guilt became

significant, such that the more non-picks were associated with guilt, the more likely a

memory was to be true (B = 0.330, SE = 0.158, p = 0.037, OR =1.390).

We then ran the same regression with face used for perpetrator as a predictor, in

order to ensure the effects were not driven by false memory for a particular face or

association of a particular face with guilt. When this was included as a predictor, it

was not significant and association with pick remained significant (B = 0.319,

SE = 0.153, p = 0.038, OR =0.727), such that the higher the association of the pick

with guilt, the more likely it was that a memory was false. Mean association of non-

picks with guilt also became significant (B = 0.303, SE = 0.154, p = 0.049, OR

=1.354), such that the higher the association of non-picks with guilt, the more likely

it was that a memory was true.

Distinguishing True and False Memories Using Implicit Associations –

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curves.

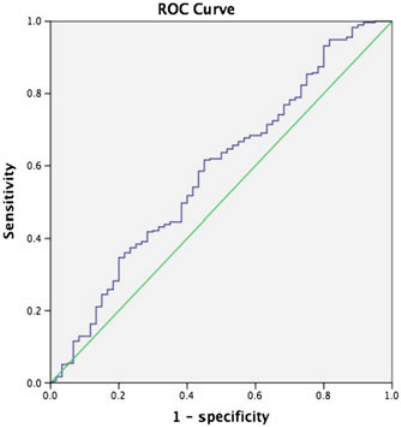

Our ANOVAs and regressions suggested that we could distinguish participants who

had a true or false memory by looking at the difference between the association of the

pick with guilt and the association of others with guilt. Participants with a false memory

tended to have higher implicit associations between their pick and guilt, and lower

associations between non-picks and guilt. We calculated areas under ROC curves to

investigate how accurately the difference between the association of the pick with guilt

5

We also conducted this regression with type of line-up viewed (target-present or target-absent) as an addi-

tional predictor in the regression. In this regression, participants who saw a target-absent line-up were more

likely to have a false memory (B = 2.509, p < 0.001). Association of pick with guilt just missed significance

(B = 0.299, SE = 1.53, p = 0.05, OR =0.741) and mean association of non-picks with guilt remained

non-significant (B = 0.287, SE = 1.58, p = 0.070, OR =1.332).

Development and preliminary testing of the IATe 813

Copyright # 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Behav. Sci. Law 34: 803–819 (2016)

DOI: 10.1002/bsl

and the mean association of non-picks with guilt could indicate whether a particular

memory was likely to be true or false.

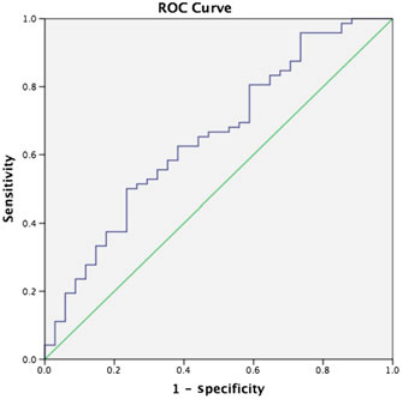

First, we calculated the area under an ROC curve using the difference between the

association of the pick with guilt and the mean association of non-picks with guilt, as a

predictor of whether a memory was true or false for all participants (participants who

saw a target-present line-up and participants who saw a target-absent line-up). We

expected the memory of participants with a larger difference between association of

the pick with guilt and mean association of non-picks with guilt to be more likely to

be false. The ROC curve for this test is displayed in Figure 5. The area under this curve

was 0.585, and was significantly different from an area of 0.5 (p = 0.039).

Next, we calculated the area under an ROC curve using the same difference score to

predict whether a memory was true or false in participants who had been subject to sug-

gestibility (specifically, participants who had seen an initial target absent line up).

Again, we expected the memory of participants with a larger difference between associ-

ation of the pick with guilt and mean association of non-picks with guilt to be more

likely to be false. The ROC curve for this test is displayed in Figure 6. The area under

the curve was 0.654 and was significantly different from an area of 0.5 (p = 0.011).

DISCUSSION

These results suggest that the retrieval of a false memory (caused by the inherently sug-

gestive nature of previously viewing a target-absent line-up and subsequently being

offered to choice of one of the faces from it) is often the result of activating implicit

Figure 5. Receiver operating characteristic curve showing sensitivity and 1 – specificity when using differ-

ences between the association of the pick with guilt and association of others with guilt to predict true or false

memory in all participants. The green line represents what would be expected from a test that is no better than

random guessing. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

814 Helm R. K. et al.

Copyright # 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Behav. Sci. Law 34: 803–819 (2016)

DOI: 10.1002/bsl

semantic or associative processes during encoding and that this process occurs mainly

outside of conscious awareness. Participants with a false memory had implicitly associ-

ated their final (incorrect) line-up pick with criminal behavior more than they

associated the other two characters in the final target-present line-up with criminal

behavior. This negative association was not present in participants with a true memory,

further supporting the causal role of the implicit negative attribution process during

encoding: participants with a true memory had no signi fi cant difference in implicit

association with criminal behavior between their final pick and the two innocent char-

acters (see Figure 4). In addition, the level of negative association was a significant pre-

dictor of false memory. Participants with a higher implicit association between their

pick and criminal behavior were more likely to have a memory that was false (meaning

they picked the incorrect character at the final target-present line-up). This suggests

that participants with a false memory were influenced by implicit associations outside

consciousness, but participants with a true memory were not. This is consistent with

our predictions based on FTT that: adults have a preference for reliance on gist

memory; implicit associations infuse gist memory and cause participants relying on gist

memory to make false identifications; and in line-ups where suspects all have similar

characteristics, where gist is not infused by implicit associations, eyewitnesses would

be forced to rely on verbatim processing, resulting in a true categorization (as long as

the verbatim memory was still accessible).

Thus, the extent to which eyewitnesses associated a given target with a particular

crime was predictive of how likely they were to have a false memory for that person

committing the crime. This may be because the presentation of that suspect’s face

aroused a network of negative associations implying guilt and infused the eyewitness’s

gist memory of the perpetrator, resulting in mistaken identification. Therefore, a key

finding in this study is that participants who exhibited a false memory were significantly

Figure 6. Receiver operating characteristic curve showing sensitivity and 1 – specificity when using differ-

ences between the association of the pick with guilt and association of others with guilt to predict true or false

memory in participants who were subject to suggestion. The green line represents what would be expected

from a test that is no better than random guessing. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Development and preliminary testing of the IATe 815

Copyright # 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Behav. Sci. Law 34: 803–819 (2016)

DOI: 10.1002/bsl

more likely to have associated the face they picked with a negative attribute than was

the case with non-picked faces. Supporting this causal interpretation, there was a

dose–response relationship: as a participant’s association of the face they picked with

a negative attribute increased, the more likely it was that their memory was false. Since

this was true even when target-present line-ups were used, it indicates that the process

was implicit rather than conscious. This has both theoretical and practical implications

which we discuss in the following. When considering these implications, it is important

to note that our study focused specifically on eyewitness identifications of a perpetrator,

and therefore our results may not be generalizable to other crime-specific details such

as the weapon or the victim.

Theoretical Implications

Eyewitness identification errors have been framed in terms of perceptual similarity

between the foil and target faces, often at a level of conscious featural matching wherein

the witness compares line-up faces with a memory of the perpetrator (“I think the thief

is #2 because I remember he also had brown eyes, high cheekbones, and a receding

hairline, and he didn’t have the kind of haircut that #1 has and he was taller than

#3.”). The so-called elimination procedure pioneered by Pozzulo and her colleagues

(e.g., Pozzulo, Dempsey, & Gascoigne, 2009) was developed to reduce the impact of

these kinds of relative comparisons by asking eyewitnesses to engage in a series of judg-

ments, beginning with picking the person who looks most similar to the perpetrator

(relative judgment), and then eliminating the remaining faces before deciding whether

the chosen face is that of the actual perpetrator (absolute judgment). During a simulta-

neous line-up, witnesses may perform the relative judgments by consciously comparing

the line-up faces with their memory of the thief. In contrast, absolute judgments can

occur outside conscious reasoning processes, as in pop-out effects in which the eyewit-

ness quickly selects a face but often is not aware of the basis used (Ross, Benton,

McDonnell, Metzger, & Silver, 2007).

The current findings suggest another framing that can supplement conscious feature

matching in relative judgments. Namely, witnesses’ choices may be influenced by

unconscious biases that occur at the time of encoding and which are independent from

conscious perceptual analysis. Certain faces may elicit a witness’s predisposition to

negatively categorize them. This claim is intuitively reasonable – some faces may seem

to a witness more sinister than others, some faces may seem more likely to be associated

with certai n crimes than others, and witnesses are aware of such inferences and can

readily report them. For example, Valla, Williams, and Ceci (2011) provided empirical

evidence that participants can match unfamiliar faces with speci fic crimes (rape, mur-

der, arson, drug-dealing, white collar fraud) at a rate that is better than chance, and

Todorov and his colleagues, among others, have repeatedly shown that participants

can correctly infer political orientation, competence, and personality attributes from

faces (e.g., Todorov, Mandisodza, Goren, & Hall, 2005). Unlike these conscious pro-

cesses, however, witnesses’ choices in the present study were influenced by biases that

may have operated outside of conscious awareness and that are so subtle that their pres-

ence requires measurement in milliseconds, using a paradigm employed by stereotype

researchers specifically to uncover unconscious biases (e.g., Nosek et al., 2009), rather

than by memory researchers studying conscious decision-making. Such biases as

revealed through the use of the IATe may not require on the part of witnesses any

816 Helm R. K. et al.

Copyright # 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Behav. Sci. Law 34: 803–819 (2016)

DOI: 10.1002/bsl

conscious criminal association and they can be detected by the presence of a miniscule

delay in response time to categorize a face in a positive or negative pairing.

In the Introduction we noted that on tasks that involve automatic spreading seman-

tic activation, such as the DRM paradigm, there are often reverse developmental find-

ings (e.g., Brainerd, Reyna, & Ceci, 2008). This is because older individuals possess

greater semantic knowledge than children and, as a result, it is more likely that when

they encode a word, its associations become activated, leading to a form of source mis-

attribution in which they later misattribute these activated associations as having been

presented. However, it is possible that this same mechanism when applied to the con-

text of face processing will operate for young children as well as or even more so than

for adults. Unlike word knowledge, which clearly grows with age, facial stereotypes

may be available to children, perhaps to an even greater extent than for adults who have

experienced similar faces in contexts that disconfirm the negative stereotype. This is an

empirical question, and research will be needed to test it.

Practical Implications

These findings could have implications for the legal system. The results are germane in

attempting to distinguish true from false memory in eyewitness testimony. Although

our seven-step IATe is not appropriate to give to eyewitnesses directly, understanding

the link between implicit associations and false memory can assist researchers in the

future in designing tests to probe the potential accuracy of eyewitness memory. Such

tests could assess the extent to which a witness implicitly/automatically associated a

suspect with guilt. This could be probed by assessing similar associations that a witness

might make using carefully designed questions (e.g., a witness may associate a particu-

lar crime with a defendant of a particular race or age). Clearly, such tests would not be

definitive, but they could be one of many tools to help those in the legal arena (forensic

experts, attorneys, law enforcem ent personnel) distinguish between true and false

memories. Even without a test of implicit associations, knowledge that false memory

is often relate d to implicit associations may assist experts in assessing the accuracy of

eyewitness testimony and in making evaluations of accuracy for jurors. Secondly,

understanding the relationship between implicit associations and false memory, along

with knowledge of the types of implicit associations that people are likely to make,

may help when selecting foils to appear in a line-up (alongside a defendant). If foils

activate similar implicit associations to a defendant then any identification would have

to be made based on recollec tion and not implicit associations.

Conclusions and Future Directions

This research is the first step in a validation attempt that will require a great deal of

future research. Now that we have developed the IATe and reported statistical data

regarding its theoretical feasibility, future research is needed to establish its external

validity (e.g., field testing in crime-related scenarios, with realistic timing between

event and identification so that emotionality is comparable to that in the modal case,

and the effects of memory deterioration can be examined). Future research should con-

trol the amount of time that a witness sees the perpetrator, to investigate whether this

has an effect. The present study is best viewed as a proof-of-concept, demonstrating

the link between millisecond differences in a seemingly unrelated categorization task

Development and preliminary testing of the IATe 817

Copyright # 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Behav. Sci. Law 34: 803–819 (2016)

DOI: 10.1002/bsl

and subsequent false memory; numerous ‘next steps’ will be needed to make this link

legally relevant. Future research should also test potential ways to reduce the relation-

ship betw een implicit association and false memory (drawing on existing research on

unconscious bias).

There are other interesting findings raised by this study that should be followed up

further. For example, certain faces were more likely to be falsely identified than others

(Face 1 was falsely identified in 12 cases, whereas Face 3 was falsely identified in 40

cases). This may be because generally Face 3 was more associated with guilt overall

than Face 1. Our results support this somewhat, as Face 3 did have the highest overall

association with guilt; however, this is not conclusive, as the difference in association

with guilt between Face 3 and Face 1 was not significant.

Our study examined eyewitness identifications using only young White males,

meaning that there were no dramatic differences between our perpetrators. This means

that our findings may not apply where there are more obvious differences between a

true perpetrator and crime suspects, such as differences in race or gender. Future

research should probe the effects of implicit associations between race/gender and

criminality. In addition, although the present study is focused on eyewitness identifica-

tions, it would seem to open new possibilities for psycholegal researchers: it could some

day prove fruitful in examining subtle processing-time differences as a predictor of a

host of outcomes, such as guilt verdicts, mistaken eyewitness identifications, compe-

tency determinations, and length of sentencing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Logan Kenney, Madison Ulczak, Garrett Heller,

HyeEon Park, Isabella Esposito, Leona Sharpstene, Stephanie Matthews-Carpenter,

and Danielle Bubniak for their help with collecting and analyzing the data for this

article.

REFERENCES

Agosta, S., & Sartori, G. (2013). The autobiographical IAT: a review. Frontiers in Psychology, 4,1–12.

doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00519.

Brainerd, C. J., & Reyna, V. F. (2005). The Science of False Memory. New York: Oxford University Press.

Brainerd, C. J., Reyna, V. F., & Ceci, S. J. (2008). Developmental reversals in false memory: a review of data

and theory. Psychological Bulletin, 134(3), 343–382. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.134.3.343.

Ceci, S. J., & Bronfenbrenner, U. (1991). On the demise of everyday memory: The rumors of my death are

greatly exaggerated. American Psychologist, 46,27–31.

Greenwald, A. G., McGhee, D. E., & Schwartz, J. L. (1998). Measuring individual differences in implicit

cognition: the implicit association test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(6), 1464–1480.

doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1464.

Greenwald, A. G., Nosek, B. A., & Banaji, M. R. (2003). Understanding and using the implicit association

test: an improved scoring algorithm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 197–216.

doi:10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.197.

Greenwald, A. G., Poehlman, T. A., Uhlmann, E. L., & Banaji, M. R. (2009). Understanding and using the

implicit association test: a meta-analysis of predictive validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

97,17–41. doi:10.1037/a0015575.

Innocence Project Report on Eyewitness Misidentification (2015). Retrieved from http://www.

innocenceproject.org/causes-wrongful-conviction/eyewitness-misidentification.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

818 Helm R. K. et al.

Copyright # 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Behav. Sci. Law 34: 803–819 (2016)

DOI: 10.1002/bsl

Loftus, E. (2003). Make-believe memories. American Psychologist, 58(11), 864–873.

Marini, M., Agosta, S., Mazzoni, G., Dalla Barba, G., & Sartori, G. (2012). True and false DRM memories:

differences detected with an implicit task. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 310. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00310.

Nosek, B. A., Smyth, F. L., Sriram, N., Lindner, N. M., Devos, T., Ayala, A., … Greenwald, A. G. (2009).

National differences in gender-science stereotypes predict national sex differences in science and math

achievement. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(26), 10592–10597.

Pozzulo, J. D., Dempsey, J. L., & Gascoigne, E. (2009). Eyewitness accuracy when making multiple

identifications using the elimination line-up. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 16(1), 101–111.

Ross, D. F., Benton, T., McDonnell, S., Metzger, R., & Silver, C. (2007). When accurate and inaccurate

eyewitnesses look the same: A limitation of the ‘pop-out’ effect and the 10- to 12-second rule. Applied

Cognitive Psychology, 21(5), 677–690. doi:10.1002/acp.1308.

Schacter, D. L., & Loftus, E. F. (2013). Memory and law: what can cognitive neuroscience contribute?

Nature Neuroscience, 16, 119–123. doi:10.1038/nn.3294.

Shaw, J., & Porter, S. (2015). Constructing rich false memories of committing crime. Psychological Science,

26(3), 291–301. doi:10.1177/0956797614562862.

Stanovich, K. E., West, R. F., & Toplak, M. E. (2016). The rationality quotient. Cambridge, MA: M.I.T.

Press.

State v. Henderson. (2011). 208 N.J. 208.

Todorov, A., Mandisodza, A., Goren, A., & Hall, C. (2005). Inferences of competence from faces predict

election outcomes. Science, 308, 1623–1626.

Valla, J., Williams, W., & Ceci, S. J. (2011). The accuracy of inferences about criminality based on facial

appearance. Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology (journal retitled Evolutionary Behavioral

Sciences), 5(1), 66–91. doi:10.1037/h0099274.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at

the publisher's web site.

Development and preliminary testing of the IATe 819

Copyright # 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Behav. Sci. Law 34: 803–819 (2016)

DOI: 10.1002/bsl