Swarthmore College Swarthmore College

Works Works

English Literature Faculty Works English Literature

Fall 2017

Solomon Northup’s Singing Book Solomon Northup’s Singing Book

Lara Langer Cohen

Swarthmore College

, lcohen2@swarthmore.edu

Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-english-lit

Part of the English Language and Literature Commons

Let us know how access to these works bene<ts you

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Lara Langer Cohen. (2017). "Solomon Northup’s Singing Book".

African American Review

. Volume 50,

Issue 3. 259-272. DOI: 10.1353/afa.2017.0032

https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-english-lit/334

This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in

English Literature Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact

myworks@swarthmore.edu.

Lara Langer Cohen

Solomon Northup's Singing Book

When Steve McQueen's film adaptation of Solomon Northup's 1853 slave

narrative, Twelve Years a Slave, appeared in 2013, it was accompanied by a

soundtrack album of music "from and inspired by" the movie. Executive producer

John Legend combined selections from the film score, spirituals, and new material

from contemporary artists to impressive ends: "12 Years a Slave Leads Contemporary

Soundtrack Revival," announced Billboard Magazine (Gallo).1 But 160 years before

Music from and Inspired by 12 Years a Slave, the book came with its own soundtrack.

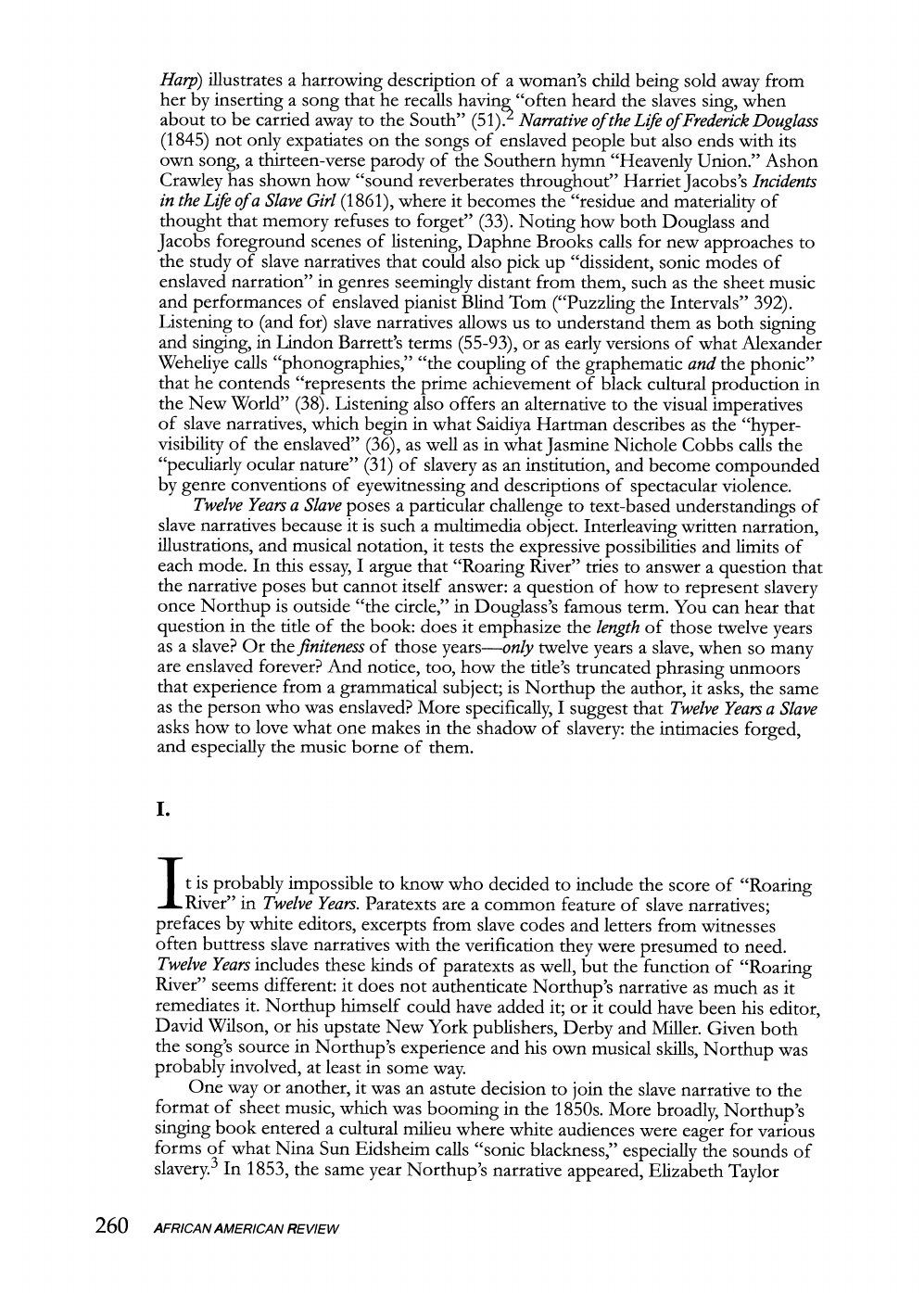

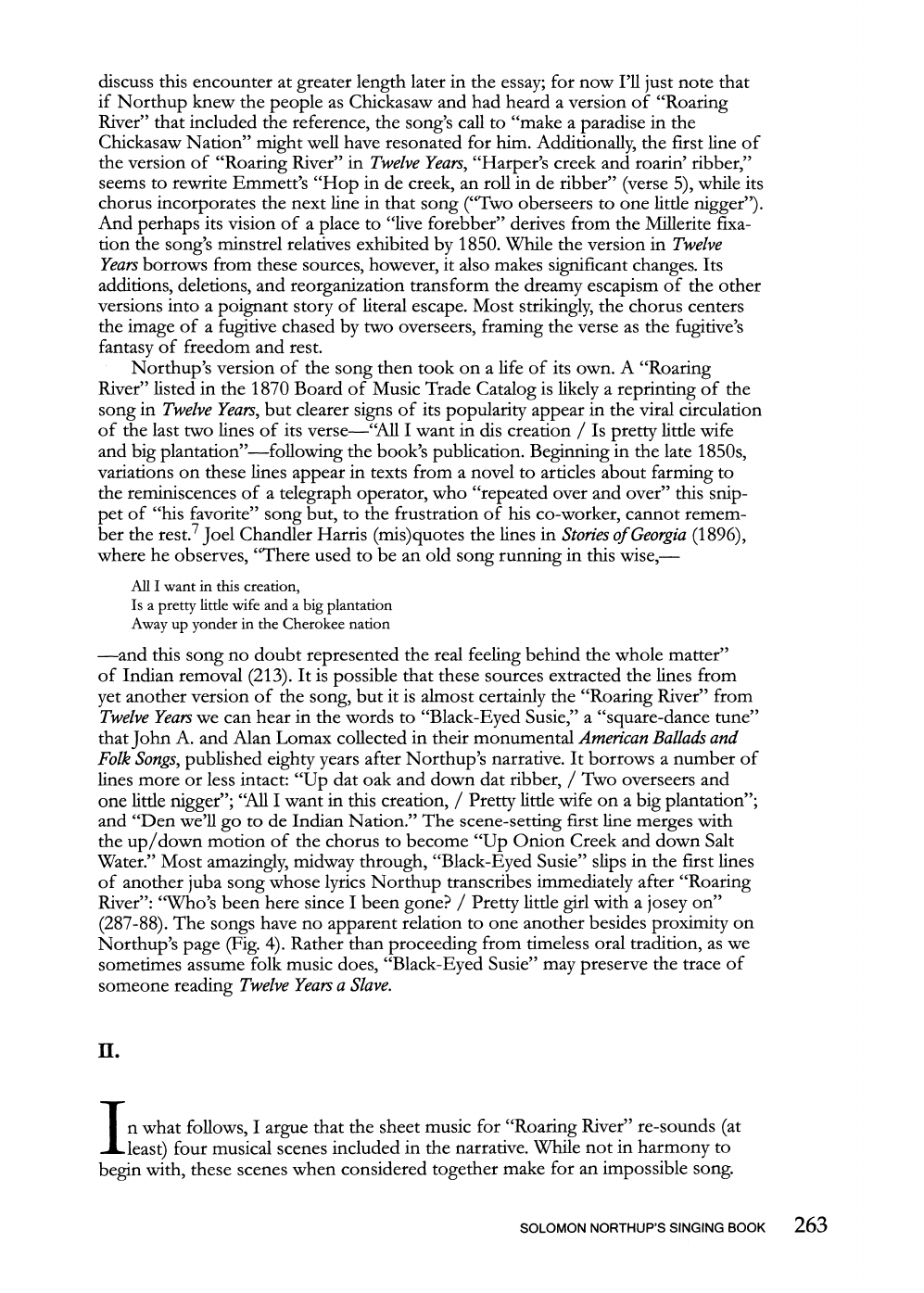

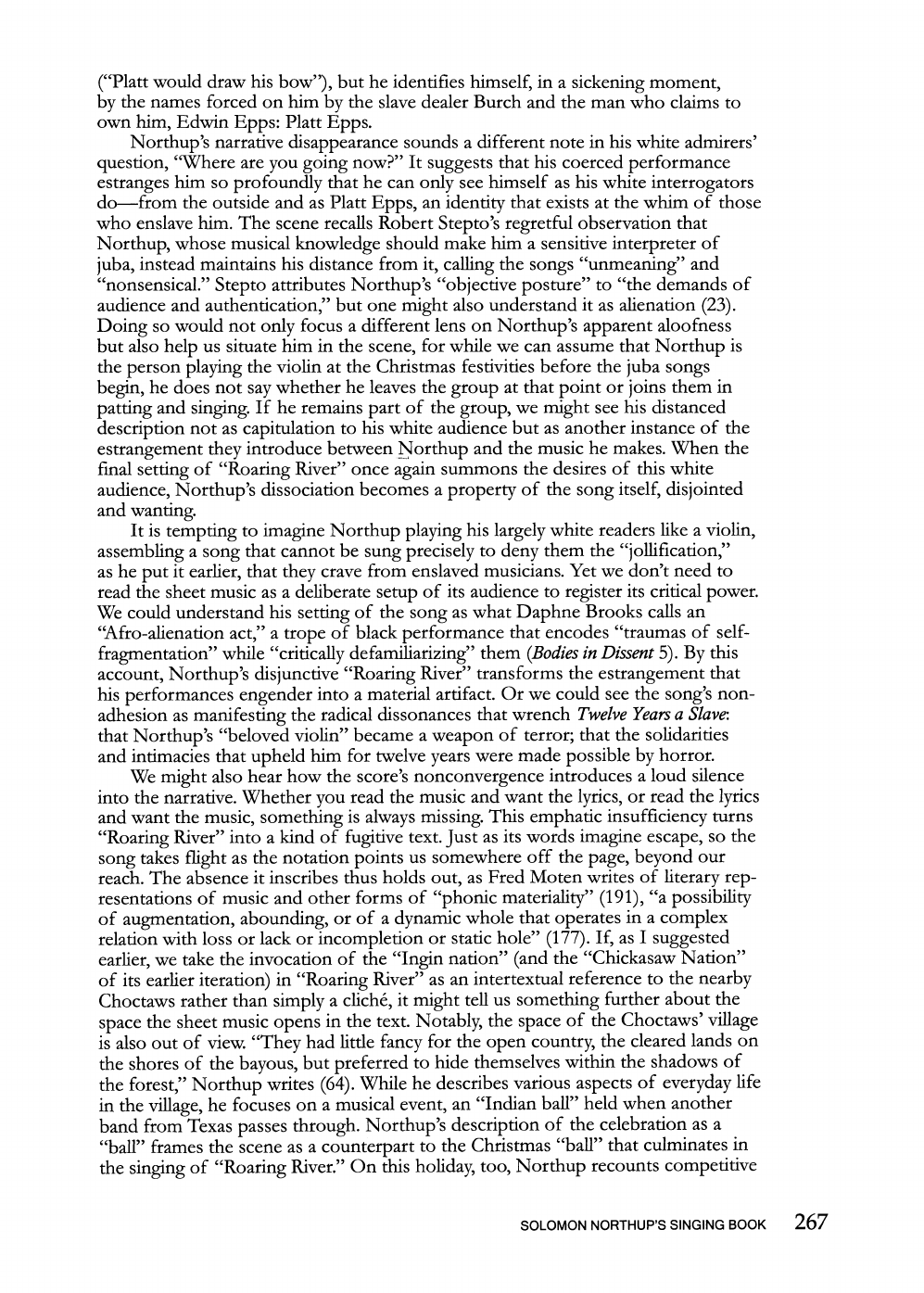

At the end of the narrative, Northup, a talented violinist, includes a musical score:

a setting of a song called "Roaring River" that, as he recounted earlier in the book,

he heard enslaved people on the Red River plantation singing as they patted juba at

a Christmas celebration (Fig. 1). The study of slave narratives has been profoundly

shaped by Henry Louis Gates, Jr.'s argument that its foundational trope is the "talking

book," a set piece in which the not-yet-print-literate narrator puts ear to book to see

if it will talk (127-69). With "Roaring River," however, Twelve Years a Slave asks us

also to consider the meaning of a "singing book."

Once we attune ourselves to the voices as well as the words of slave narratives,

its surprising how much music they make. In the Narrative of William W. Brown,

A Fugitive Slave (1847), Brown (who also edited the antislavery songster The Anti-Slavery

BOABING BIVEB.

A REFRAIN Of TIUI RED RIVER PLANTATION.

• Harper'* creek And roar in' ribber,

Tbar, my dear, wall lira forebber;

Den wall go to da Iitgin ntlioo,

All I want in dla creation,

la preU/ liUla wifa and big plantation.

CHORDS.

Up dat oak and down dat ribber,

Two oTaraaera and ooa little niggar*

Fig. 1: "Roaring River; A Refrain of the Red River Plantation,"

in Solomon Northup, Twelve Years a Slave (Auburn: Derby and Miller, 1853).

African American Review 50.3 (Fall 2017): 259-272 ~ j-q

© 2017 Saint Louis University and Johns Hopkins University Press /.Dy

This content downloaded from 130.58.34.40 on Mon, 09 Aug 2021 17:07:37 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Harp) illustrates a harrowing description of a woman's child being sold away from

her by inserting a song that he recalls having "often heard the slaves sing, when

about to be carried away to the South" (51). Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass

(1845) not only expatiates on the songs of enslaved people but also ends with its

own song, a thirteen-verse parody of the Southern hymn "Heavenly Union." Ashon

Crawley has shown how "sound reverberates throughout" Harriet Jacobs's Incidents

in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861), where it becomes the "residue and materiality of

thought that memory refuses to forget" (33). Noting how both Douglass and

Jacobs foreground scenes of listening, Daphne Brooks calls for new approaches to

the study of slave narratives that could also pick up "dissident, sonic modes of

enslaved narration" in genres seemingly distant from them, such as the sheet music

and performances of enslaved pianist Blind Tom ("Puzzling the Intervals" 392).

Listening to (and for) slave narratives allows us to understand them as both signing

and singing, in Lindon Barrett's terms (55-93), or as early versions of what Alexander

Weheliye calls "phonographies," "the coupling of the graphematic and the phonic"

that he contends "represents the prime achievement of black cultural production in

the New World" (38). Listening also offers an alternative to the visual imperatives

of slave narratives, which begin in what Saidiya Hartman describes as the "hyper

visibility of the enslaved" (36), as well as in what Jasmine Nichole Cobbs calls the

"peculiarly ocular nature" (31) of slavery as an institution, and become compounded

by genre conventions of eyewitnessing and descriptions of spectacular violence.

Twelve Years a Slave poses a particular challenge to text-based understandings of

slave narratives because it is such a multimedia object. Interleaving written narration,

illustrations, and musical notation, it tests the expressive possibilities and limits of

each mode. In this essay, I argue that "Roaring River" tries to answer a question that

the narrative poses but cannot itself answer: a question of how to represent slavery

once Northup is outside "the circle," in Douglass's famous term. You can hear that

question in the title of the book: does it emphasize the length of those twelve years

as a slave? Or the Jiniteness of those years—only twelve years a slave, when so many

are enslaved forever? And notice, too, how the title's truncated phrasing unmoors

that experience from a grammatical subject; is Northup the author, it asks, the same

as the person who was enslaved? More specifically, I suggest that Twelve Years a Slave

asks how to love what one makes in the shadow of slavery: the intimacies forged,

and especially the music borne of them.

I.

It is probably impossible to know who decided to include the score of "Roaring

River" in Twelve Years. Paratexts are a common feature of slave narratives;

prefaces by white editors, excerpts from slave codes and letters from witnesses

often buttress slave narratives with the verification they were presumed to need.

Twelve Years includes these kinds of paratexts as well, but the function of "Roaring

River" seems different: it does not authenticate Northup's narrative as much as it

remediates it. Northup himself could have added it; or it could have been his editor,

David Wilson, or his upstate New York publishers, Derby and Miller. Given both

the song's source in Northup's experience and his own musical skills, Northup was

probably involved, at least in some way.

One way or another, it was an astute decision to join the slave narrative to the

format of sheet music, which was booming in the 1850s. More broadly, Northup's

singing book entered a cultural milieu where white audiences were eager for various

forms of what Nina Sun Eidsheim calls "sonic blackness," especially the sounds of

slavery.3 In 1853, the same year Northup's narrative appeared, Elizabeth Taylor

260 AFRICAN AMERICAN REVIEW

This content downloaded from 130.58.34.40 on Mon, 09 Aug 2021 17:07:37 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Greenfield, the celebrated concert singer born in slavery who became known as the

"Black Swan," made her New York City debut before embarking on an English

tour. Blackface minstrelsy began to move away from the "comic" modes of the

1830s and '40s and increasingly featured sentimental songs that claimed to present

the true feelings of enslaved people. The publication of Uncle Tom's Cabin in 1852

led to a burst of "Tom shows," both minstrel burlesques and earnest musical

dramatizations, and dozens of songs from these performances circulated as sheet

music.4 The Hutchinson Family Singers, one of the country's most famous white

singing troupes, became increasingly vocal abolitionists during the 1850s, and the

Luca Family Singers, a black troupe who also sang abolitionist songs, toured widely.

This musical context may well have shaped the decision to include the score of

"Roaring River," which invites the largely white readers of Northup's narrative not

only to "hear" enslaved voices but themselves to sing in them. And in fact, Twelve

Years proved hugely popular, selling 25,000 copies in its first year—which likely made

"Roaring River" one of the best-selling songs of the year during a time when sheet

music publishers considered sales of 5,000 units highly successful for a popular song

(Sanjek 76). Sales of the book continued strongly through the 1850s and several

new editions appeared in the 1880s and '90s, once the original copyright had

expired (Pope). Although we'll never know how many readers actually played or

sang "Roaring River," these sales mean that it was probably one of the more widely

distributed songs of the nineteenth century.5

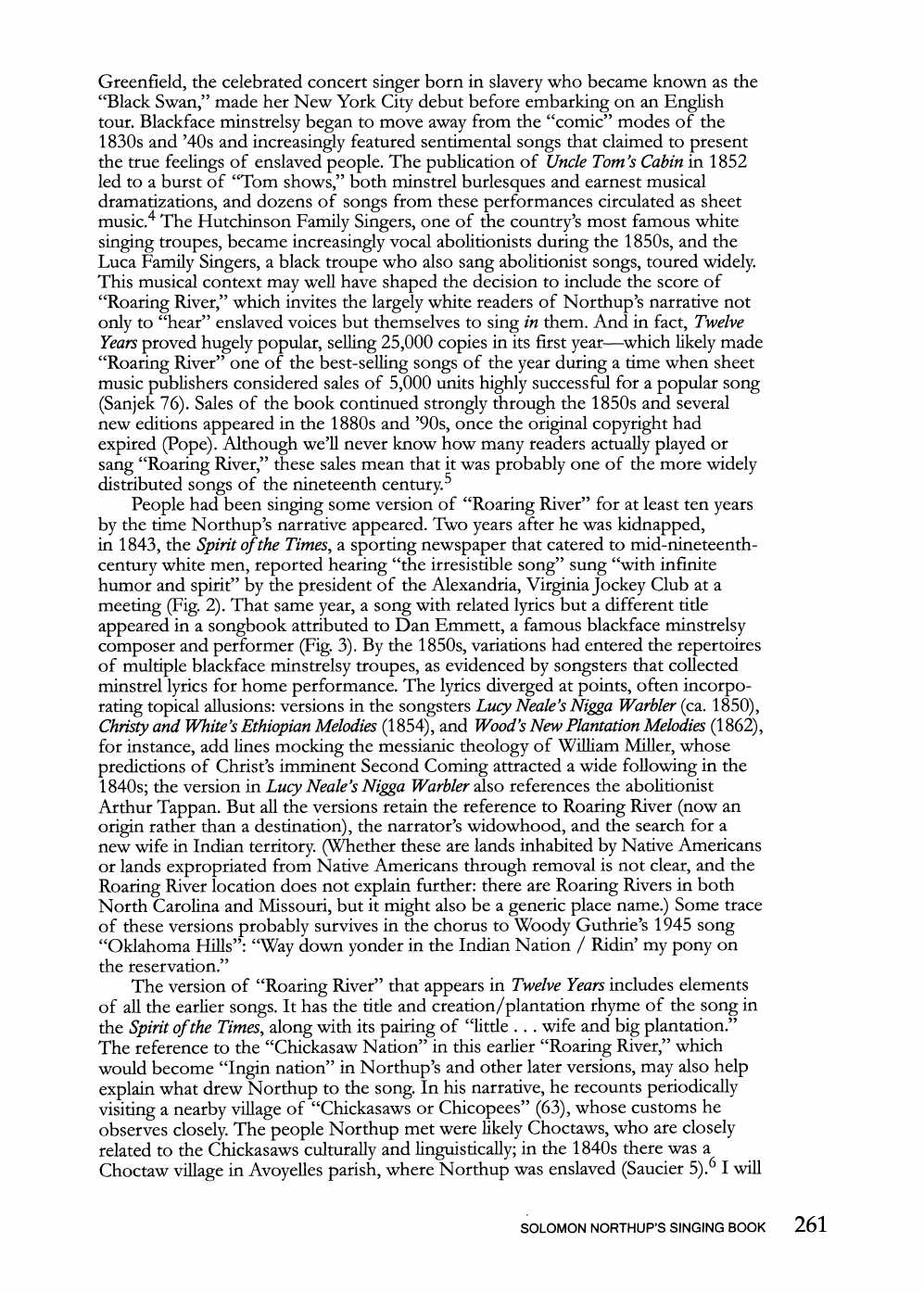

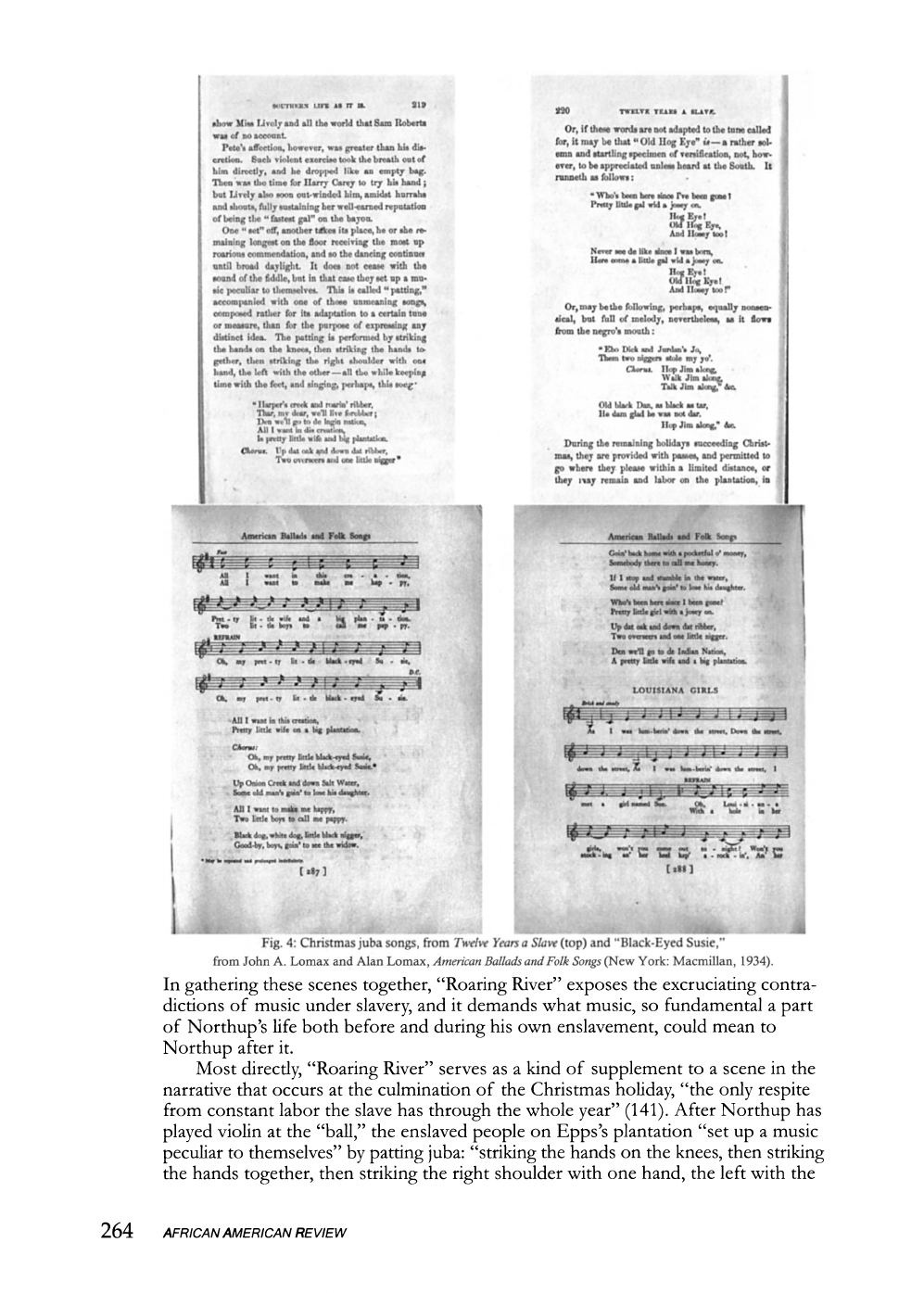

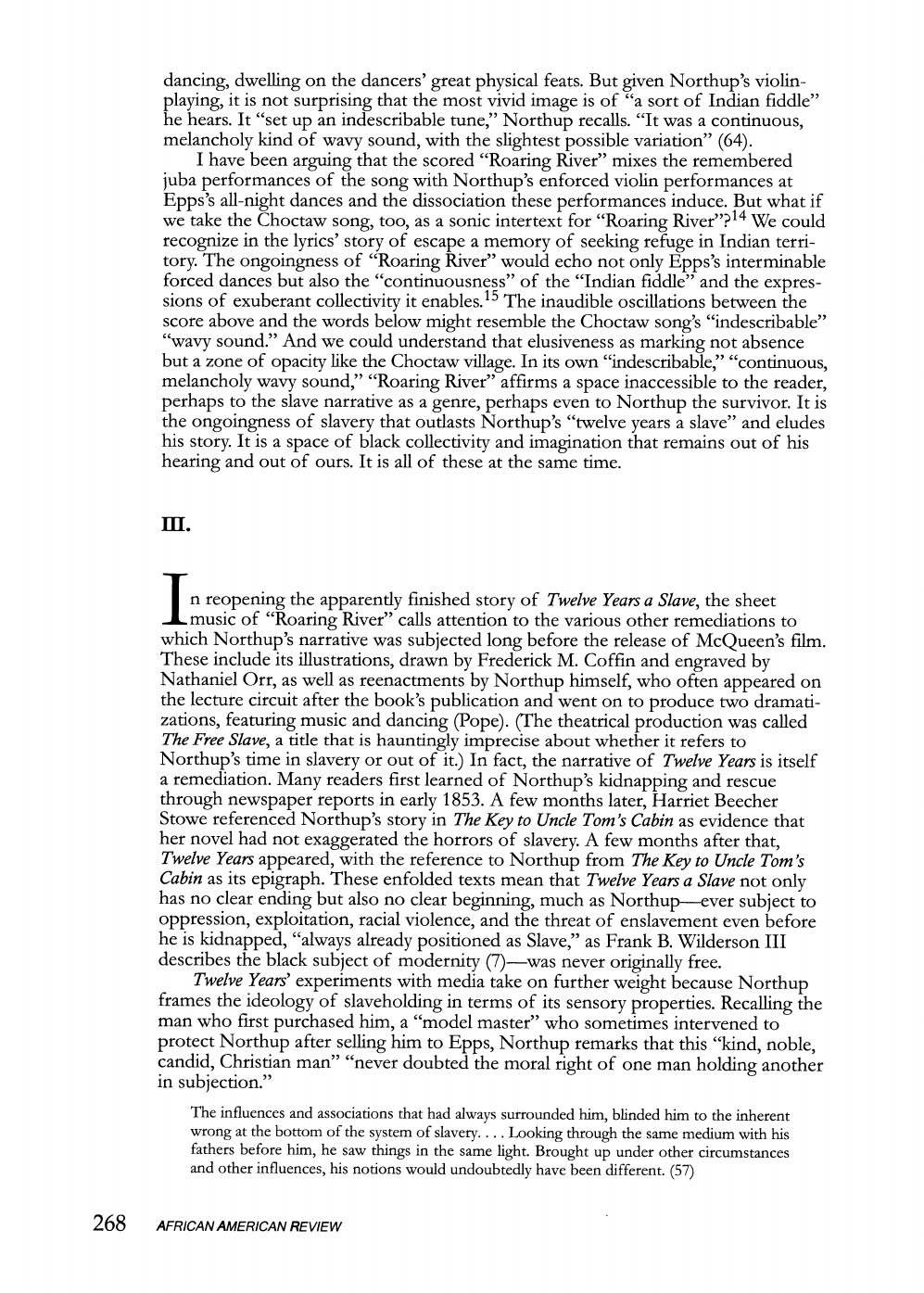

People had been singing some version of "Roaring River" for at least ten years

by the time Northup's narrative appeared. Two years after he was kidnapped,

in 1843, the Spirit of the Times, a sporting newspaper that catered to mid-nineteenth

century white men, reported hearing "the irresistible song" sung "with infinite

humor and spirit" by the president of the Alexandria, Virginia Jockey Club at a

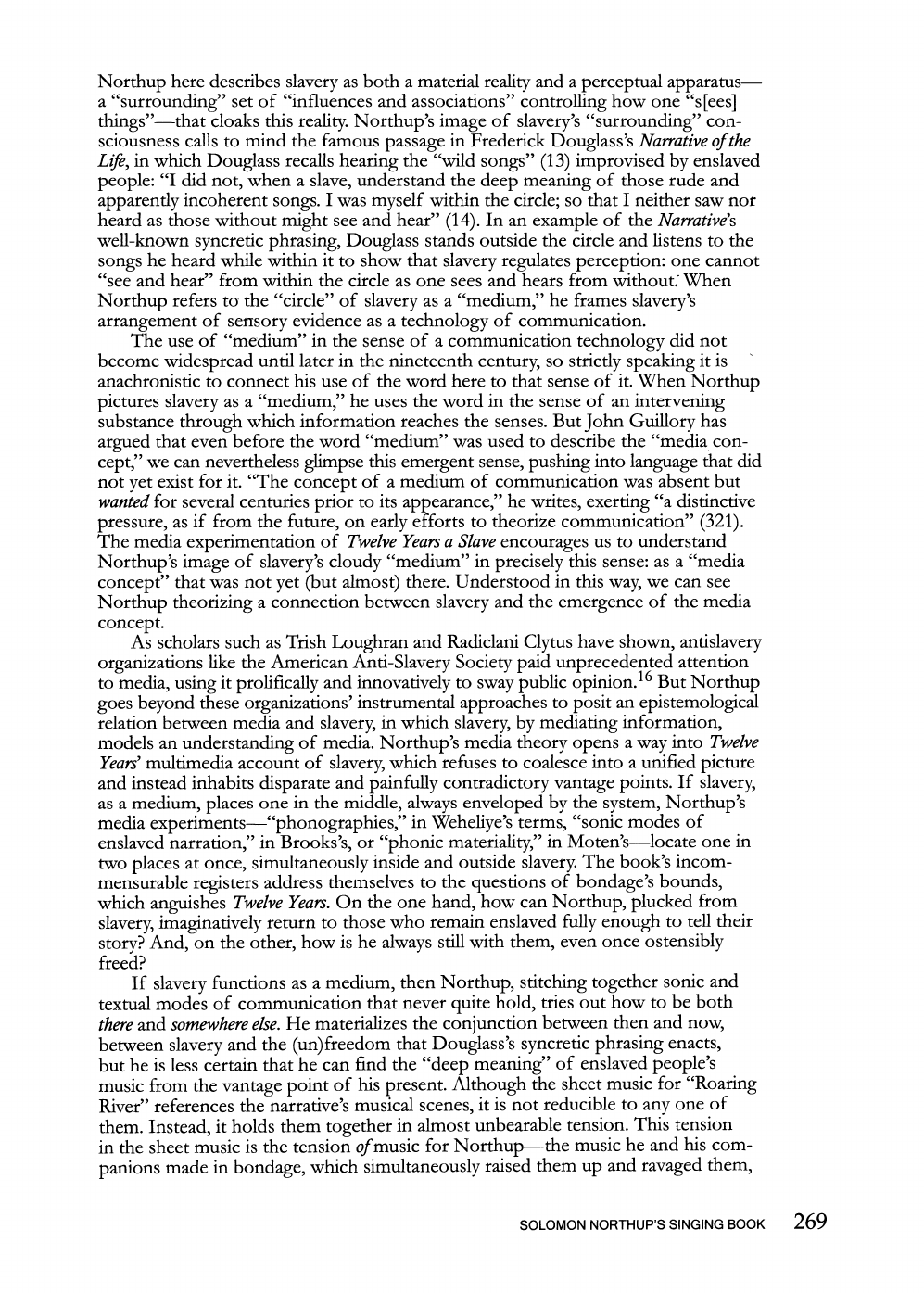

meeting (Fig. 2). That same year, a song with related lyrics but a different title

appeared in a songbook attributed to Dan Emmett, a famous blackface minstrelsy

composer and performer (Fig. 3). By the 1850s, variations had entered the repertoires

of multiple blackface minstrelsy troupes, as evidenced by songsters that collected

minstrel lyrics for home performance. The lyrics diverged at points, often incorpo

rating topical allusions: versions in the songsters Lucy Neale's Nigga Warbler (ca. 1850),

Christy and White's Ethiopian Melodies (1854), and Wood's New Plantation Melodies (1862),

for instance, add lines mocking the messianic theology of William Miller, whose

predictions of Christ's imminent Second Coming attracted a wide following in the

1840s; the version in Lucy Neale's Nigga Warbler also references the abolitionist

Arthur Tappan. But all the versions retain the reference to Roaring River (now an

origin rather than a destination), the narrator's widowhood, and the search for a

new wife in Indian territory. (Whether these are lands inhabited by Native Americans

or lands expropriated from Native Americans through removal is not clear, and the

Roaring River location does not explain further: there are Roaring Rivers in both

North Carolina and Missouri, but it might also be a generic place name.) Some trace

of these versions probably survives in the chorus to Woody Guthrie's 1945 song

"Oklahoma Hills": "Way down yonder in the Indian Nation / Ridin' my pony on

the reservation."

The version of "Roaring River" that appears in Twelve Years includes elements

of all the earlier songs. It has the title and creation/plantation rhyme of the song in

the Spirit of the Times, along with its pairing of "litde . .. wife and big plantation."

The reference to the "Chickasaw Nation" in this earlier "Roaring River," which

would become "Ingin nation" in Northup's and other later versions, may also help

explain what drew Northup to the song. In his narrative, he recounts periodically

visiting a nearby village of "Chickasaws or Chicopees" (63), whose customs he

observes closely. The people Northup met were likely Choctaws, who are closely

related to the Chickasaws culturally and linguistically; in the 1840s there was a

Choctaw village in Avoyelles parish, where Northup was enslaved (Saucier 5).6 I will

SOLOMON NORTHUP'S SINGING BOOK

261

This content downloaded from 130.58.34.40 on Mon, 09 Aug 2021 17:07:37 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Thotc who remember the "/tieriu£ Rivtr"—4be irreaietihle eong of the i

i Pre* idem of the Alexandria Jockey Club—Col. J. McC , of Virginia—

j which he givea with each infinite humor end spirit, when surrounded by bia

friend* at a Club dinner—will think o« fur giving, from memory, the first atan

zas, if it revive in any degrre the pleasant aasocutiou< incident to such meet

ing# at the e.«cial board in the Old Dominion

I bed e wife, and now I'm a widower.

On mv way to the floariof Ri*er,

Where 1 expect to get another, I

Every tit at food a* t' other.

Ob dear! for the Chickaaaw Nation,

The fineat place In the wholeneat ton!

! A Utile *mall wile and a bic plantation

Make a paradlee In tbe Chickasaw Nation.

Fig. 2: From the Spirit of the Times, 12 Aug. 1843.

OLD DAN EMMIT *S

, i '♦v. ^ \

0 I.I'D GALS (MB ME Ac

I. rrrfuar^ k) IW Vaxirh

IU-'m ftMKM k) f H k'» CIM tmn M

j<5'*—-r:- —I

|<4^ . J.llljll Ml ,

( />' - 5 " = T" = T" = T" = T ' T « T: T

) • < > i i > > > i > < i i i i < <

<5'; ; • • ; : '

r.« ~ . . rm

it st t * t t tit

f: i . >

i in""'

itt . t t

I - : - '_1L' > ' 8 J • • <

ft r 1 J | 'if' ' • ;

I hath ■ Uf .1r mftw . kr?, «Ar> -i MnBiba I («• • b. d* <f • >)

\f, • r~, rm. =• : . ,

ta*£- - : - f~# ~ - - 5 :

i ^r. — '•& &u ■—■ •

I «» ijjsiujmi iiu ]jjj nu ua u;

2 1

turf*. Jn« ■ p«j»» ** *

Art to ■> M- Mi »-•(■*— "N- k~. —« <• k— —

M, .Ik'. IM »r> • «Mn, lbvk.Hr OMt. r*br<

W *, mmj (m nn nkkn T«« •» —» »*W

OMpklr. O W «*.'*•

Mj 4*mi w rn (rt aaMf

P.m., 1Mb Mxk r*l Jt«l-k» MAW.

OU|A *«.

IM> my M W««. M •*—»

OM|<k 4c.

Fig. 3: Old Dan Emmit's Original Banjo Melodies (Boston: Charles H. Keith, 1843).

262 AFRICAN AMERICAN REVIEW

This content downloaded from 130.58.34.40 on Mon, 09 Aug 2021 17:07:37 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

discuss this encounter at greater length later in the essay; for now I'll just note that

if Northup knew the people as Chickasaw and had heard a version of "Roaring

River" that included the reference, the song's call to "make a paradise in the

Chickasaw Nation" might well have resonated for him. Additionally, the first line of

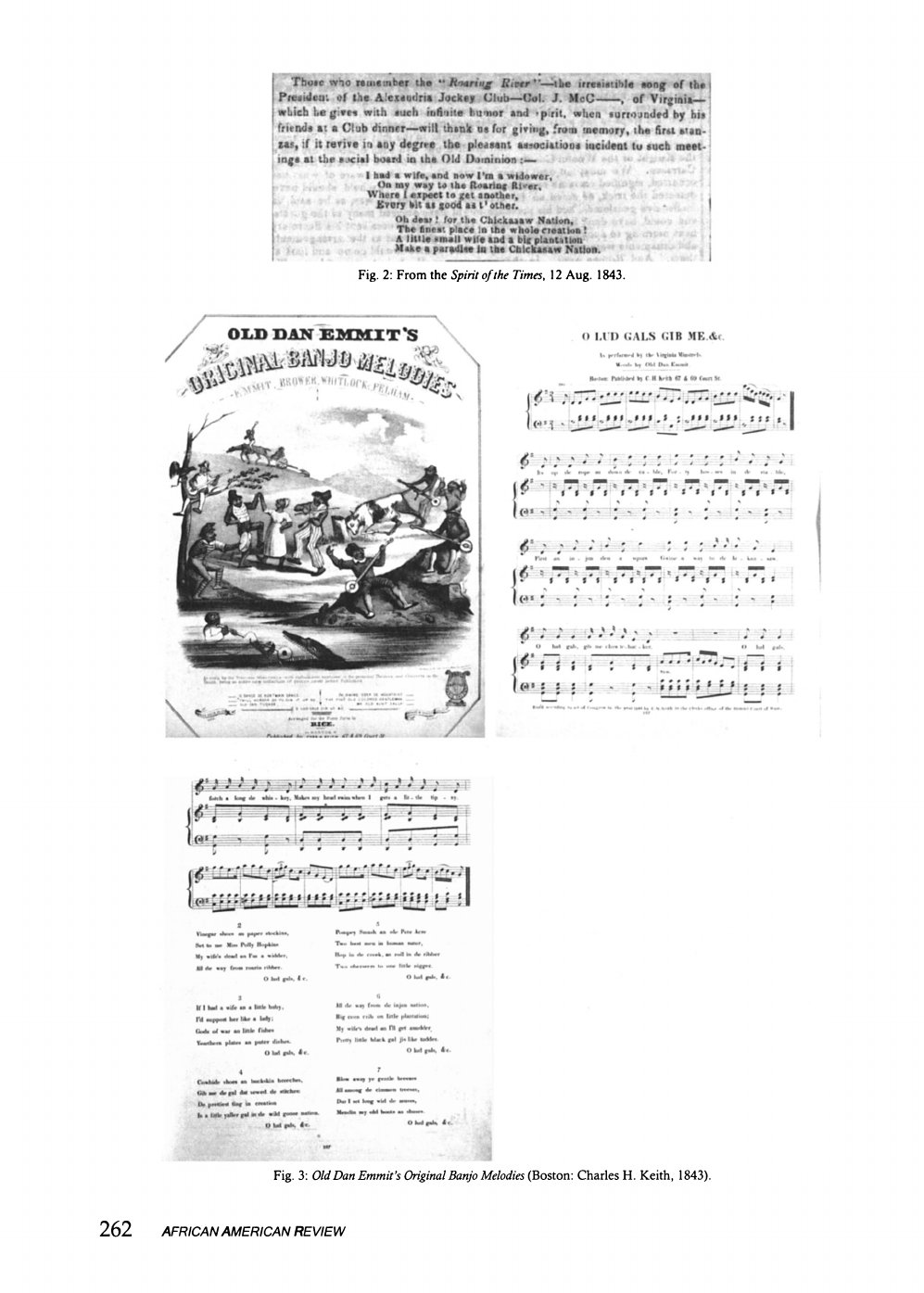

the version of "Roaring River" in Twelve Years, "Harper's creek and roarin' ribber,"

seems to rewrite Emmett's "Hop in de creek, an roll in de ribber" (verse 5), while its

chorus incorporates the next line in that song ("Two oberseers to one little nigger").

And perhaps its vision of a place to "live forebber" derives from the Millerite fixa

tion the song's minstrel relatives exhibited by 1850. While the version in Twelve

Years borrows from these sources, however, it also makes significant changes. Its

additions, deletions, and reorganization transform the dreamy escapism of the other

versions into a poignant story of literal escape. Most strikingly, the chorus centers

the image of a fugitive chased by two overseers, framing the verse as the fugitive's

fantasy of freedom and rest.

Northup's version of the song then took on a life of its own. A "Roaring

River" listed in the 1870 Board of Music Trade Catalog is likely a reprinting of the

song in Twelve Years, but clearer signs of its popularity appear in the viral circulation

of the last two lines of its verse—"All I want in dis creation / Is pretty little wife

and big plantation"—following the book's publication. Beginning in the late 1850s,

variations on these lines appear in texts from a novel to articles about farming to

the reminiscences of a telegraph operator, who "repeated over and over" this snip

pet of "his favorite" song but, to the frustration of his co-worker, cannot remem

ber the rest.7 Joel Chandler Harris (mis)quotes the lines in Stories of Georgia (1896),

where he observes, "There used to be an old song running in this wise,—

All I want in this creation,

Is a pretty little wife and a big plantation

Away up yonder in the Cherokee nation

—and this song no doubt represented the real feeling behind the whole matter"

of Indian removal (213). It is possible that these sources extracted the lines from

yet another version of the song, but it is almost certainly the "Roaring River" from

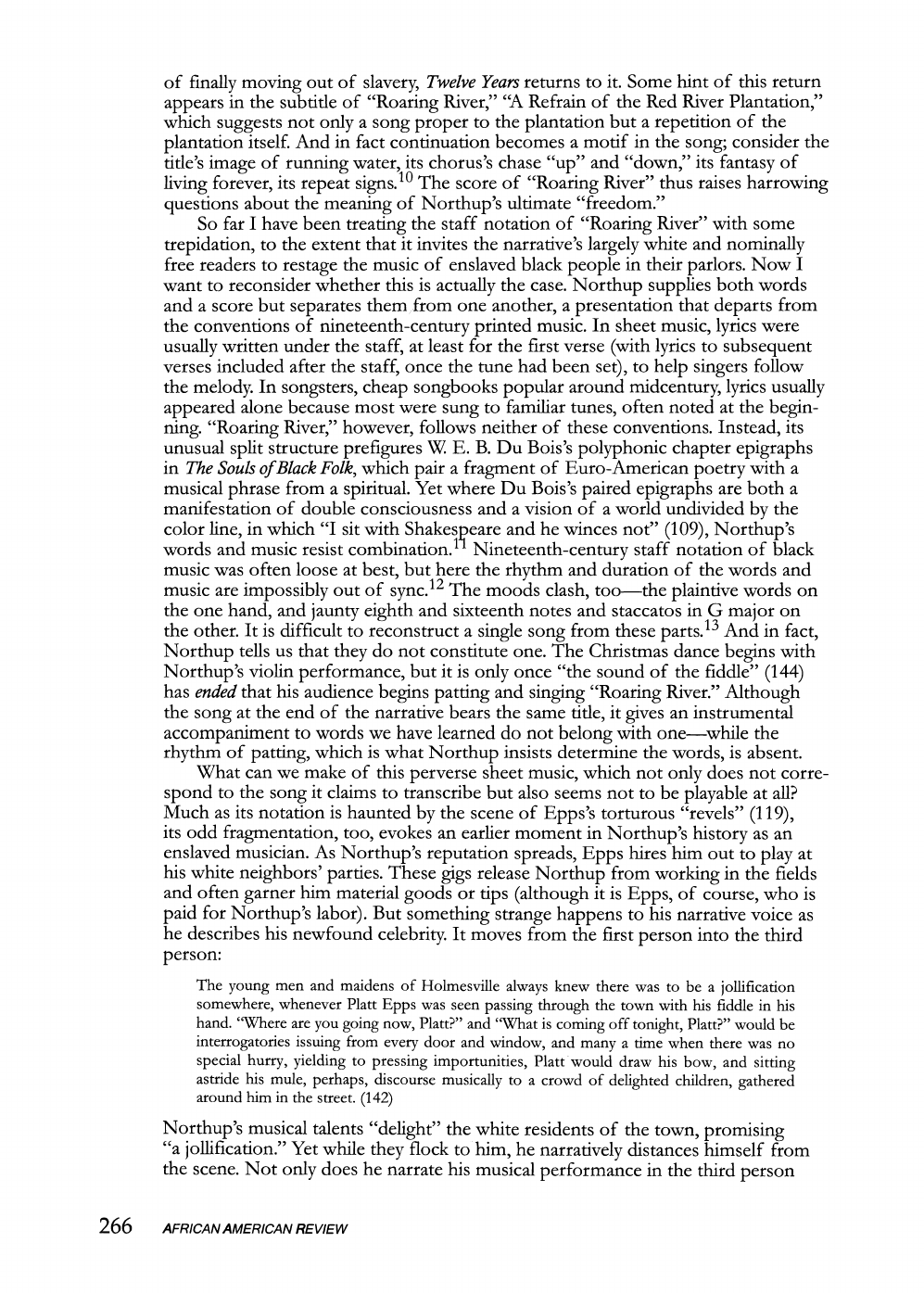

Twelve Years we can hear in the words to "Black-Eyed Susie," a "square-dance tune"

that John A. and Alan Lomax collected in their monumental American Ballads and

Folk Songs, published eighty years after Northup's narrative. It borrows a number of

lines more or less intact: "Up dat oak and down dat ribber, / Two overseers and

one little nigger"; "All I want in this creation, / Pretty little wife on a big plantation";

and "Den we'll go to de Indian Nation." The scene-setting first line merges with

the up/down motion of the chorus to become "Up Onion Creek and down Salt

Water." Most amazingly, midway through, "Black-Eyed Susie" slips in the first lines

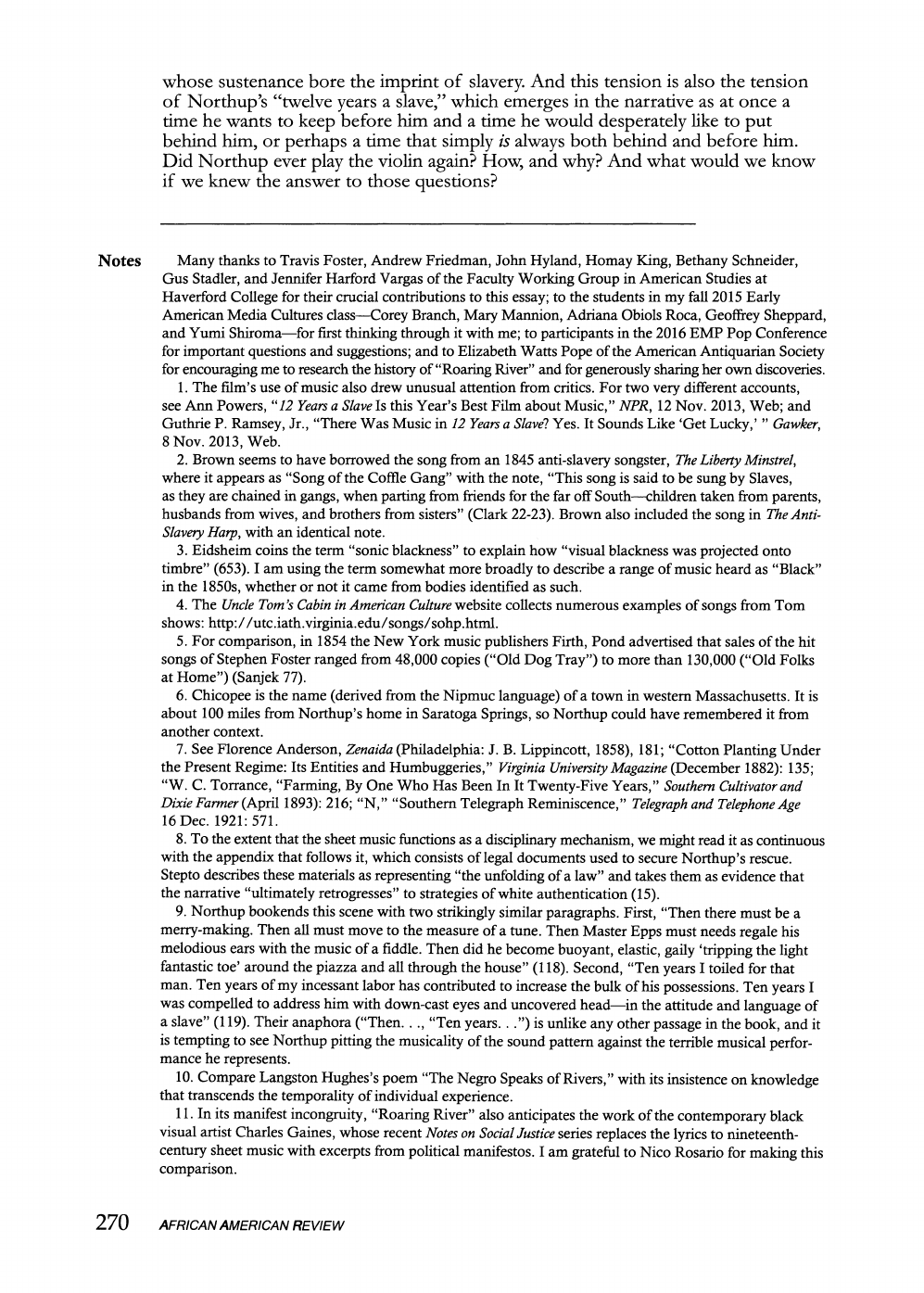

of another juba song whose lyrics Northup transcribes immediately after "Roaring

River": "Who's been here since I been gone? / Pretty little girl with a josey on"

(287-88). The songs have no apparent relation to one another besides proximity on

Northup's page (Fig. 4). Rather than proceeding from timeless oral tradition, as we

sometimes assume foils music does, "Black-Eyed Susie" may preserve the trace of

someone reading Twelve Years a Slave.

n.

In what follows, I argue that the sheet music for "Roaring River" re-sounds (at

least) four musical scenes included in the narrative. While not in harmony to

begin with, these scenes when considered together make for an impossible song.

SOLOMON NORTHUP'S SINGING BOOK 263

This content downloaded from 130.58.34.40 on Mon, 09 Aug 2021 17:07:37 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

k'tTHUt LIT* am.

sit

«0

TVKLTI TUN A iUTX.

•bow Mia. Urolj and all the world that Sam Itoberta

waa of do aoeoant

Pate's affection, howerer, was greater than hi* dia

cretion. Bach violent eicrtue took the breath oat of

him direct!/, and be dropped like an empty bag.

Then waa the time for Harry Carey to try his hand ;

bat IJreiy also soon out-winded him, amidst hurrahs

and sbouta, full/ sustaining her wall-earned reputation

of being the " fastest gal" on the bayou.

One " set" off, another Ukea its placa, he or she re

maining longeat on the floor receiving the moat op

roarious commendation, and so the dancing continue*

until broad daylight. It doea not cease with the

aoand of the fiddle, bat in that caae they act up a mu

sic peculiar to tlteraselvee. This is called " patting,"

accompanied with one of thaae unmeaning songs,

composed rather for ita adaptation to a certain tone

or meaaore, than for the purpose of expressing any

diatinct idea. The patting ia performed by striking

the ban da on the kneoa, then atriking the handa to

gether, then striking the right shoulder with out

band, the left with the other—all the while keeping

time with the feet, and singing, per ha pa, this aocg'

" llarprr's crr«fc and Paris' nl.brr,

TW, IDI drtr, wall lit*

IV« *r^l f. to <W tape Mtka,

All I -an* ia d- ™.,«,

k ytrtty littk aUk aoj plants!»«.

OUrua. l>dat.*kandd"aa.ktnbUr1

Tee in trarer* stui una liuie tcpr *

Or, if these words are not adapted to the tune called

for, it may be that u Old Ilog Eye" is— a rather aoi

emn and atartling specimen of rsrsification, not, bow*

erer, to be appreciated unlaaa beard at the South. It

runneth aa follows:

-Who's bam hws siiwa lSe bs*a raat

I'mij littk gal wVl a jnaejr est.

And I lamj tool

Never M de lik* Sim I waa Uen,

Uses enme s link gal aid a jumty en.

Hog Era!

OUIkgKyet

And Ilaaagr loo!"

Or, may be the following, perhapa, equally nonsen

sical, bnt foil of melody, nevertheleaa, aa it flowe

from the negro's mouth:

- Ebo Die* and J an lac's Jo,

Ham t*u nlflgrr* at. J# mj jo".

CW Hop Jim ak*«

Walk Jim aim,

Talk Jim atuv," &c

Old Uari Dan, as Uark as tar,

Ha dam glad U «sa aat dar.

Hop Jim along." to.

During the remaining holidayi aucceeding Christ

mas, they are provided with paasas, and permitted to

go where they pleaae within a limited diatance, or

they i\ay remain and labor on the plantation, in

American Ballad, aad Folk bags

t - f \

tyi 6 5t=j

Al I aaat m

A1 I —* to

Pm-IT h - ih m4 s k-a pUa - u - ooa.

T»» It • da keys to J ft • FT

Ok. m, fmt.tr »• - «*• -

Aaaaric— Walla* and Fefc Sesp

M wak s pocketful o* noaef

U I «op sad «

WW. bsea ker* Met I kass |W

Pwij fads girl «tt s Hr sa.

Up dst ask sad down d* nbber.

Ts» r

Dm well gs to ds lads* Nstiaa,

A peaKy link ails sad s kig plantatma.

Ok. »r r*" «7 fa

All I waai ia das

ds Mack - «y*4 £ - aa.

• aa s kg plaatatooa.

Ok, mj pretty fatk ilack-cyad SaM,

Ok, air Ptttr fatk black-eyad Sads.*

Up Oaioa Cfak sad dowa Salt Water.

AH 1 want ta auks aw kappy>

Tea link bey* to call mt pappy.

Black dog, white dog, fatk black siggsr,

Cood-by. bays, goia' to sss tks widow.

[»«7l

LOUISIANA GIRLS

c "rr 5 :

[•ID

Fig. 4: Christmas juba songs, from Twelve Yean a Slave (top) and "Black-Eyed Susie,"

from John A. Lomax and Alan Lomax, American Ballads and Folk Songs (New York: Macmillan, 1934).

rig. 4: Christmas juba songs, from Twelve Yean a Slave (top) and "Black-Eyed Susie,

from John A. Lomax and Alan Lomax, American Ballads and Folk Songs (New York: Macmillan, 1934).

In gathering these scenes together, "Roaring River" exposes the excruciating contra

dictions of music under slavery, and it demands what music, so fundamental a part

of Northup's life both before and during his own enslavement, could mean to

Northup after it.

Most direcdy, "Roaring River" serves as a kind of supplement to a scene in the

narrative that occurs at the culmination of the Christmas holiday, "the only respite

from constant labor the slave has through the whole year" (141). After Northup has

played violin at the "ball," the enslaved people on Epps's plantation "set up a music

peculiar to themselves" by patting juba: "striking the hands on the knees, then striking

the hands together, then striking the right shoulder with one hand, the left with the

264 AFRICAN AMERICAN REVIEW

This content downloaded from 130.58.34.40 on Mon, 09 Aug 2021 17:07:37 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

other—all the while keeping time with the feet, and singing, perhaps, this song,"

whose lyrics Northup then transcribes (144). Saidiya Hartman has described juba

as a "form of redressive action" (71) that uses one's captive body "for one's own

ends" (72). Put differently, the song represents "freedom as a bodily practice,"

as Walter Johnson has argued of another musical moment in the narrative, Northup's

recollections of birds singing in the trees above the Red River plantation (210).

In doing so, it holds out a version of freedom beyond Northup's individual, legal

freedom, which otherwise structures the narrative. Its inclusion thus breaks the

focus Twelve Years places on Northup's exceptionality—his virtuosic violin playing,

his talents as an engineer, his remarkable rescue. Instead, it raises the voices of those

still enslaved, whom he left behind.

When the song reappears at the end of the narrative, however, translated into

staff notation with accompanying lyrics, it is not their voices we hear. What was

once a kind of music "peculiar to" enslaved people is repackaged as a commodity

for the home entertainment of the book's largely white and nominally free readers,

who are invited to sing in the voices of the enslaved. In this transformation, Twelve

Years itself participates in the blackface minstrelsy genealogy of "Roaring River"

and perhaps helps script its continuation. More broadly, the juba song's translation

into staff notation converts the song from a living expression into an artifact,

formalizing and nailing down a process of collective improvisation. Following the

narrative's scenes of brutal violence, including the attempted lynching of Northup

and the binding of Patsey to stakes, it is hard not to flinch at all these black note

heads (there is not a white one among them) suspended on bars, upside-down and

right-side up.8

In its regimentation, its intimations of black bodies in agony, its fast-paced

dance rhythm (all eighth and sixteenth notes, with no rests), and its conversion of a

reparative practice into material for white people's amusement, the score echoes an

earlier scene in the narrative. Since he was young, playing the violin had been

Northup's "ruling passion" (7); he marvels, "had it not been for my beloved violin,

I scarcely can conceive how I could have endured the long years of bondage" (143).

Yet while Northup's violin sustains him, he writes with horror of the humiliation

and suffering it unwillingly assists. He recalls evenings when Epps would call the

people he owned into the house, and "no matter how worn out and tired" they

were, demand that they dance. Then Northup's violin becomes an instrument of

violence, "ruling" over others:

Usually his whip was in his hand, ready to fall about the ears of the presumptuous thrall,

who dared to rest a moment, or even stop to catch his breath. . . . With a slash, and crack,

and flourish of the whip, he would shout again, "Dance, niggers, dance," and away they

would go once more, pell-mell, while I, spurred by an occasional sharp touch of the lash,

sat in a corner, extracting from my violin a marvelous quick-stepping tune. . . . Frequendy

we were thus detained until almost morning. Bent with excessive toil—actually suffering for

a litde refreshing rest, and feeling rather as if we would cast ourselves upon the earth and

weep, many a night in the house of Edwin Epps have his unhappy slaves been made to

dance and laugh. (119)9

In this extraordinarily brutal scene, it might be the "marvelous quick-stepping tune"

that jangles most painfully. You can hear Northup's love of music, the pleasure he

takes in his talents, and the comfort his violin offers, all curdle. Where his violin was

once a "beloved" companion, now he wrings music from it as they both become

links in a cruel chain of "extraction": Epps extracts the playing from Northup that

will extract the music from the violin that will extract the dancing from the "unhappy

slaves."

In the final setting of "Roaring River," we find an afterimage of this scene's

violence. Its reappearance contravenes the finite duration of Northup's "twelve

years a slave" as well as the customary trajectory of the slave narrative, for instead

SOLOMON NORTHUP'S SINGING BOOK 265

This content downloaded from 130.58.34.40 on Mon, 09 Aug 2021 17:07:37 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

of finally moving out of slavery, Twelve Years returns to it. Some hint of this return

appears in the subtitle of "Roaring River," "A Refrain of the Red River Plantation,"

which suggests not only a song proper to the plantation but a repetition of the

plantation itself. And in fact continuation becomes a motif in the song; consider the

title's image of running water, its chorus's chase "up" and "down," its fantasy of

living forever, its repeat signs.10 The score of "Roaring River" thus raises harrowing

questions about the meaning of Northup's ultimate "freedom."

So far I have been treating the staff notation of "Roaring River" with some

trepidation, to the extent that it invites the narrative's largely white and nominally

free readers to restage the music of enslaved black people in their parlors. Now I

want to reconsider whether this is actually the case. Northup supplies both words

and a score but separates them from one another, a presentation that departs from

the conventions of nineteenth-century printed music. In sheet music, lyrics were

usually written under the staff, at least for the first verse (with lyrics to subsequent

verses included after the staff, once the tune had been set), to help singers follow

the melody. In songsters, cheap songbooks popular around midcentury, lyrics usually

appeared alone because most were sung to familiar tunes, often noted at the begin

ning. "Roaring River," however, follows neither of these conventions. Instead, its

unusual split structure prefigures W E. B. Du Bois's polyphonic chapter epigraphs

in The Souls of Black Folk, which pair a fragment of Euro-American poetry with a

musical phrase from a spiritual. Yet where Du Bois's paired epigraphs are both a

manifestation of double consciousness and a vision of a world undivided by the

color line, in which "I sit with Shakespeare and he winces not" (109), Northup's

words and music resist combination.1' Nineteenth-century staff notation of black

music was often loose at best, but here the rhythm and duration of the words and

music are impossibly out of sync.12 The moods clash, too—the plaintive words on

the one hand, and jaunty eighth and sixteenth notes and staccatos in G major on

the other. It is difficult to reconstruct a single song from these parts. ^ And in fact,

Northup tells us that they do not constitute one. The Christmas dance begins with

Northup's violin performance, but it is only once "the sound of the fiddle" (144)

has ended that his audience begins patting and singing "Roaring River." Although

the song at the end of the narrative bears the same title, it gives an instrumental

accompaniment to words we have learned do not belong with one—while the

rhythm of patting, which is what Northup insists determine the words, is absent.

What can we make of this perverse sheet music, which not only does not corre

spond to the song it claims to transcribe but also seems not to be playable at all?

Much as its notation is haunted by the scene of Epps's torturous "revels" (119),

its odd fragmentation, too, evokes an earlier moment in Northup's history as an

enslaved musician. As Northup's reputation spreads, Epps hires him out to play at

his white neighbors' parties. These gigs release Northup from working in the fields

and often garner him material goods or tips (although it is Epps, of course, who is

paid for Northup's labor). But something strange happens to his narrative voice as

he describes his newfound celebrity. It moves from the first person into the third

person:

The young men and maidens of Holmesville always knew there was to be a jollification

somewhere, whenever Piatt Epps was seen passing through the town with his fiddle in his

hand. "Where are you going now, Piatt?" and "What is coming off tonight, Piatt?" would be

interrogatories issuing from every door and window, and many a time when there was no

special hurry, yielding to pressing importunities, Piatt would draw his bow, and sitting

astride his mule, perhaps, discourse musically to a crowd of delighted children, gathered

around him in the street. (142)

Northup's musical talents "delight" the white residents of the town, promising

"a jollification." Yet while they flock to him, he narratively distances himself from

the scene. Not only does he narrate his musical performance in the third person

266

AFRICAN AMERICAN REVIEW

This content downloaded from 130.58.34.40 on Mon, 09 Aug 2021 17:07:37 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

("Piatt would draw his bow"), but he identifies himself, in a sickening moment,

by the names forced on him by the slave dealer Burch and the man who claims to

own him, Edwin Epps: Piatt Epps.

Northup's narrative disappearance sounds a different note in his white admirers'

question, "Where are you going now?" It suggests that his coerced performance

estranges him so profoundly that he can only see himself as his white interrogators

do—from the outside and as Piatt Epps, an identity that exists at the whim of those

who enslave him. The scene recalls Robert Stepto's regretful observation that

Northup, whose musical knowledge should make him a sensitive interpreter of

juba, instead maintains his distance from it, calling the songs "unmeaning" and

"nonsensical." Stepto attributes Northup's "objective posture" to "the demands of

audience and authentication," but one might also understand it as alienation (23).

Doing so would not only focus a different lens on Northup's apparent aloofness

but also help us situate him in the scene, for while we can assume that Northup is

the person playing the violin at the Christmas festivities before the juba songs

begin, he does not say whether he leaves the group at that point or joins them in

patting and singing. If he remains part of the group, we might see his distanced

description not as capitulation to his white audience but as another instance of the

estrangement they introduce between Northup and the music he makes. When the

final setting of "Roaring River" once again summons the desires of this white

audience, Northup's dissociation becomes a property of the song itself, disjointed

and wanting.

It is tempting to imagine Northup playing his largely white readers like a violin,

assembling a song that cannot be sung precisely to deny them the "jollification,"

as he put it earlier, that they crave from enslaved musicians. Yet we don't need to

read the sheet music as a deliberate setup of its audience to register its critical power.

We could understand his setting of the song as what Daphne Brooks calls an

"Afro-alienation act," a trope of black performance that encodes "traumas of self

fragmentation" while "critically defamiliarizing" them (Bodies in Dissent 5). By this

account, Northup's disjunctive "Roaring River" transforms the estrangement that

his performances engender into a material artifact. Or we could see the song's non

adhesion as manifesting the radical dissonances that wrench Twelve Years a Slave-.

that Northup's "beloved violin" became a weapon of terror; that the solidarities

and intimacies that upheld him for twelve years were made possible by horror.

We might also hear how the score's nonconvergence introduces a loud silence

into the narrative. Whether you read the music and want the lyrics, or read the lyrics

and want the music, something is always missing. This emphatic insufficiency turns

"Roaring River" into a kind of fugitive text. Just as its words imagine escape, so the

song takes flight as the notation points us somewhere off the page, beyond our

reach. The absence it inscribes thus holds out, as Fred Moten writes of literary rep

resentations of music and other forms of "phonic materiality" (191), "a possibility

of augmentation, abounding, or of a dynamic whole that operates in a complex

relation with loss or lack or incompletion or static hole" (177). If, as I suggested

earlier, we take the invocation of the "Ingin nation" (and the "Chickasaw Nation"

of its earlier iteration) in "Roaring River" as an intertextual reference to the nearby

Choctaws rather than simply a cliche, it might tell us something further about the

space the sheet music opens in the text. Notably, the space of the Choctaws' village

is also out of view. "They had little fancy for the open country, the cleared lands on

the shores of the bayous, but preferred to hide themselves within the shadows of

the forest," Northup writes (64). While he describes various aspects of everyday life

in the village, he focuses on a musical event, an "Indian ball" held when another

band from Texas passes through. Northup's description of the celebration as a

"ball" frames the scene as a counterpart to the Christmas "ball" that culminates in

the singing of "Roaring River." On this holiday, too, Northup recounts competitive

SOLOMON NORTHUP'S SINGING BOOK

26 7

This content downloaded from 130.58.34.40 on Mon, 09 Aug 2021 17:07:37 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

dancing, dwelling on the dancers' great physical feats. But given Northup's violin

playing, it is not surprising that the most vivid image is of "a sort of Indian fiddle"

he hears. It "set up an indescribable tune," Northup recalls. "It was a continuous,

melancholy kind of wavy sound, with the slightest possible variation" (64).

I have been arguing that the scored "Roaring River" mixes the remembered

juba performances of the song with Northup's enforced violin performances at

Epps's all-night dances and the dissociation these performances induce. But what if

we take the Choctaw song, too, as a sonic intertext for "Roaring River"?14 We could

recognize in the lyrics' story of escape a memory of seeking refuge in Indian terri

tory. The ongoingness of "Roaring River" would echo not only Epps's interminable

forced dances but also the "continuousness" of the "Indian fiddle" and the expres

sions of exuberant collectivity it enables.15 The inaudible oscillations between the

score above and the words below might resemble the Choctaw song's "indescribable"

"wavy sound." And we could understand that elusiveness as marking not absence

but a zone of opacity like the Choctaw village. In its own "indescribable," "continuous,

melancholy wavy sound," "Roaring River" affirms a space inaccessible to the reader,

perhaps to the slave narrative as a genre, perhaps even to Northup the survivor. It is

the ongoingness of slavery that outlasts Northup's "twelve years a slave" and eludes

his story. It is a space of black collectivity and imagination that remains out of his

hearing and out of ours. It is all of these at the same time.

m.

In reopening the apparently finished story of Twelve Years a Slave, the sheet

music of "Roaring River" calls attention to the various other remediations to

which Northup's narrative was subjected long before the release of McQueen's film.

These include its illustrations, drawn by Frederick M. Coffin and engraved by

Nathaniel Orr, as well as reenactments by Northup himself, who often appeared on

the lecture circuit after the book's publication and went on to produce two dramati

zations, featuring music and dancing (Pope). (The theatrical production was called

The Free Slave, a title that is hauntingly imprecise about whether it refers to

Northup's time in slavery or out of it.) In fact, the narrative of Twelve Years is itself

a remediation. Many readers first learned of Northup's kidnapping and rescue

through newspaper reports in early 1853. A few months later, Harriet Beecher

Stowe referenced Northup's story in The Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin as evidence that

her novel had not exaggerated the horrors of slavery. A few months after that,

Twelve Years appeared, with the reference to Northup from The Key to Uncle Tom's

Cabin as its epigraph. These enfolded texts mean that Twelve Years a Slave not only

has no clear ending but also no clear beginning, much as Northup—ever subject to

oppression, exploitation, racial violence, and the threat of enslavement even before

he is kidnapped, "always already positioned as Slave," as Frank B. Wilderson III

describes the black subject of modernity (7)—was never originally free.

Twelve Years' experiments with media take on further weight because Northup

frames the ideology of slaveholding in terms of its sensory properties. Recalling the

man who first purchased him, a "model master" who sometimes intervened to

protect Northup after selling him to Epps, Northup remarks that this "kind, noble,

candid, Christian man" "never doubted the moral right of one man holding another

in subjection."

The influences and associations that had always surrounded him, blinded him to the inherent

wrong at the bottom of the system of slavery. . . . Looking through the same medium with his

fathers before him, he saw things in the same light. Brought up under other circumstances

and other influences, his notions would undoubtedly have been different. (57)

268 AFRICAN AMERICAN REVIEW

This content downloaded from 130.58.34.40 on Mon, 09 Aug 2021 17:07:37 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Northup here describes slavery as both a material reality and a perceptual apparatus—

a "surrounding" set of "influences and associations" controlling how one "s[ees]

things"—that cloaks this reality. Northup's image of slavery's "surrounding" con

sciousness calls to mind the famous passage in Frederick Douglass's Narrative of the

Life, in which Douglass recalls hearing the "wild songs" (13) improvised by enslaved

people: "I did not, when a slave, understand the deep meaning of those rude and

apparendy incoherent songs. I was myself within the circle; so that I neither saw nor

heard as those without might see and hear" (14). In an example of the Narrative's

well-known syncretic phrasing, Douglass stands outside the circle and listens to the

songs he heard while within it to show that slavery regulates perception: one cannot

"see and hear" from within the circle as one sees and hears from without; When

Northup refers to the "circle" of slavery as a "medium," he frames slavery's

arrangement of sensory evidence as a technology of communication.

The use of "medium" in the sense of a communication technology did not

become widespread until later in the nineteenth century, so stricdy speaking it is

anachronistic to connect his use of the word here to that sense of it. When Northup

pictures slavery as a "medium," he uses the word in the sense of an intervening

substance through which information reaches the senses. But John Guillory has

argued that even before the word "medium" was used to describe the "media con

cept," we can nevertheless glimpse this emergent sense, pushing into language that did

not yet exist for it. "The concept of a medium of communication was absent but

wanted for several centuries prior to its appearance," he writes, exerting "a distinctive

pressure, as if from the future, on early efforts to theorize communication" (321).

The media experimentation of Twelve Years a Slave encourages us to understand

Northup's image of slavery's cloudy "medium" in precisely this sense: as a "media

concept" that was not yet (but almost) there. Understood in this way, we can see

Northup theorizing a connection between slavery and the emergence of the media

concept.

As scholars such as Trish Loughran and Radiclani Clytus have shown, antislavery

organizations like the American Anti-Slavery Society paid unprecedented attention

to media, using it prolifically and innovatively to sway public opinion.16 But Northup

goes beyond these organizations' instrumental approaches to posit an epistemological

relation between media and slavery, in which slavery, by mediating information,

models an understanding of media. Northup's media theory opens a way into Twelve

Years' multimedia account of slavery, which refuses to coalesce into a unified picture

and instead inhabits disparate and painfully contradictory vantage points. If slavery,

as a medium, places one in the middle, always enveloped by the system, Northup's

media experiments—"phonographies," in Weheliye's terms, "sonic modes of

enslaved narration," in Brooks's, or "phonic materiality," in Moten's—locate one in

two places at once, simultaneously inside and outside slavery. The book's incom

mensurable registers address themselves to the questions of bondage's bounds,

which anguishes Twelve Years. On the one hand, how can Northup, plucked from

slavery, imaginatively return to those who remain enslaved fully enough to tell their

story? And, on the other, how is he always still with them, even once ostensibly

freed?

If slavery functions as a medium, then Northup, stitching together sonic and

textual modes of communication that never quite hold, tries out how to be both

there and somewhere else. He materializes the conjunction between then and now,

between slavery and the (un)freedom that Douglass's syncretic phrasing enacts,

but he is less certain that he can find the "deep meaning" of enslaved people's

music from the vantage point of his present. Although the sheet music for "Roaring

River" references the narrative's musical scenes, it is not reducible to any one of

them. Instead, it holds them together in almost unbearable tension. This tension

in the sheet music is the tension o/music for Northup—the music he and his com

panions made in bondage, which simultaneously raised them up and ravaged them,

SOLOMON NORTHUP'S SINGING BOOK

269

This content downloaded from 130.58.34.40 on Mon, 09 Aug 2021 17:07:37 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

whose sustenance bore the imprint of slavery. And this tension is also the tension

of Northup's "twelve years a slave," which emerges in the narrative as at once a

time he wants to keep before him and a time he would desperately like to put

behind him, or perhaps a time that simply is always both behind and before him.

Did Northup ever play the violin again? How, and why? And what would we know

if we knew the answer to those questions?

Notes

Many thanks to Travis Foster, Andrew Friedman, John Hyland, Homay King, Bethany Schneider,

Gus Stadler, and Jennifer Harford Vargas of the Faculty Working Group in American Studies at

Haverford College for their crucial contributions to this essay; to the students in my fall 2015 Early

American Media Cultures class—Corey Branch, Mary Mannion, Adriana Obiols Roca, Geoffrey Sheppard,

and Yumi Shiroma—for first thinking through it with me; to participants in the 2016 EMP Pop Conference

for important questions and suggestions; and to Elizabeth Watts Pope of the American Antiquarian Society

for encouraging me to research the history of "Roaring River" and for generously sharing her own discoveries.

1. The film's use of music also drew unusual attention from critics. For two very different accounts,

see Ann Powers, "12 Years a Slave Is this Year's Best Film about Music," NPR, 12 Nov. 2013, Web; and

Guthrie P. Ramsey, Jr., "There Was Music in 12 Years a Slave! Yes. It Sounds Like 'Get Lucky,' " Gawker,

8 Nov. 2013, Web.

2. Brown seems to have borrowed the song from an 1845 anti-slavery songster, The Liberty Minstrel,

where it appears as "Song of the Coffle Gang" with the note, "This song is said to be sung by Slaves,

as they are chained in gangs, when parting from friends for the far off South—children taken from parents,

husbands from wives, and brothers from sisters" (Clark 22-23). Brown also included the song in The Anti

Slavery Harp, with an identical note.

3. Eidsheim coins the term "sonic blackness" to explain how "visual blackness was projected onto

timbre" (653). I am using the term somewhat more broadly to describe a range of music heard as "Black"

in the 1850s, whether or not it came from bodies identified as such.

4. The Uncle Tom's Cabin in American Culture website collects numerous examples of songs from Tom

shows: http://utc.iath.virginia.edu/songs/sohp.html.

5. For comparison, in 1854 the New York music publishers Firth, Pond advertised that sales of the hit

songs of Stephen Foster ranged from 48,000 copies ("Old Dog Tray") to more than 130,000 ("Old Folks

at Home") (Sanjek 77).

6. Chicopee is the name (derived from the Nipmuc language) of a town in western Massachusetts. It is

about 100 miles from Northup's home in Saratoga Springs, so Northup could have remembered it from

another context.

7. See Florence Anderson, Zenaida (Philadelphia; J. B. Lippincott, 1858), 181; "Cotton Planting Under

the Present Regime: Its Entities and Humbuggeries," Virginia University Magazine (December 1882): 135;

"W. C. Torrance, "Farming, By One Who Has Been In It Twenty-Five Years," Southern Cultivator and

Dixie Farmer (April 1893): 216; "N," "Southern Telegraph Reminiscence," Telegraph and Telephone Age

16 Dec. 1921: 571.

8. To the extent that the sheet music functions as a disciplinary mechanism, we might read it as continuous

with the appendix that follows it, which consists of legal documents used to secure Northup's rescue.

Stepto describes these materials as representing "the unfolding of a law" and takes them as evidence that

the narrative "ultimately retrogresses" to strategies of white authentication (15).

9. Northup bookends this scene with two strikingly similar paragraphs. First, "Then there must be a

merry-making. Then all must move to the measure of a tune. Then Master Epps must needs regale his

melodious ears with the music of a fiddle. Then did he become buoyant, elastic, gaily 'tripping the light

fantastic toe' around the piazza and all through the house" (118). Second, "Ten years I toiled for that

man. Ten years of my incessant labor has contributed to increase the bulk of his possessions. Ten years I

was compelled to address him with down-cast eyes and uncovered head—in the attitude and language of

a slave" (119). Their anaphora ("Then. . ., "Ten years. . .") is unlike any other passage in the book, and it

is tempting to see Northup pitting the musicality of the sound pattern against the terrible musical perfor

mance he represents.

10. Compare Langston Hughes's poem "The Negro Speaks of Rivers," with its insistence on knowledge

that transcends the temporality of individual experience.

11. In its manifest incongruity, "Roaring River" also anticipates the work of the contemporary black

visual artist Charles Gaines, whose recent Notes on Social Justice series replaces the lyrics to nineteenth

century sheet music with excerpts from political manifestos. I am grateful to Nico Rosario for making this

comparison.

270 AFRICAN AMERICAN REVIEW

This content downloaded from 130.58.34.40 on Mon, 09 Aug 2021 17:07:37 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

12. "The best that we can do, however, with paper and types, or even with voices, will convey but a faint

shadow of the original," Allen, Ware, and Garrison write in their introduction to Slave Songs of the United

States (v). Staff notation was invariably reductive, but as Radano reminds us, white writers' professions of

its impossibility projected an almost mystical racial difference, which "depicted the experience of the

slave sound world as a peculiarly audible sensation whose special properties tested the outer limits of the

Western imagination" (508).

13. In a fascinating post on the Sounding Out! blog, Lingold discusses the significance of Northup's

fiddle to Twelve Years and experiments with playing the violin melody for "Roaring River," but notes that

"the lyrics are ill-fitting for the fiddle tune provided."

14. The influence of the Choctaw song on "Roaring River" may be representative of a broader musical

tradition. As Byrd reminds us, the "blues epistemologies and blues aesthetics" that arose from slavery and

its afterlife in the Mississippi Delta did so in close proximity to Chickasaw and Choctaw people's musical

practices (122). See Byrd 118-22.

15. If in escaping from slavery Northup left behind people he loved and the music they created together,

then the Choctaw song's "continuous, melancholy kind of wavy sound" might hold out the promise that

Snead finds in black techniques of repetition: that "the thing (the ritual, the dance, the beat) is 'there for

you to pick it up when you come back to get it' " (67).

16. See Trish Loughran, The Republic in Print: Print Culture in the Age of U.S. Nation Building (New York:

Columbia UP, 2007), 303-61; and Radiclani Clytus, " 'Keep It Before the People': The Pictorialization of

American Abolitionism," in Early African American Print Culture, Lara Langer Cohen and Jordan Alexander

Stein, eds. (Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P, 2012), 290-317.

Works

Cited

Allen, William Francis, Charles Pickard Ware, and Lucy McKim Garrison. Introduction. Slave Songs of

the United States. New York: A. Simpson, 1867. i-xxxviii.

Barrett, Lindon. Blackness and Value: Seeing Double. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1999.

"Black-Eyed Susie." Lomax and Lomax 287-88.

Brooks, Daphne A. Bodies in Dissent: Spectacular Performances of Race and Freedom, 1850-1910. Durham:

Duke UP, 2006.

—-. " 'Puzzling the Intervals': Blind Tom and the Poetics of the Sonic Slave Narrative." The Oxford

Handbook of the African American Slave Narrative. Ed. John Ernest. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2014. 391-414.

Brown, William Wells. Narrative of William W. Brown, A Fugitive Slave. Boston: Anti-Slavery Office, 1847.

Byrd, Jodi. The Transit of Empire: Indigenous Critiques of Colonialism. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 2011.

Clark, George W. The Liberty Minstrel. New York: Leavitt and Alden, 1845.

Cobb, Jasmine Nichole. Picture Freedom: Remaking Black Visuality in the Early Nineteenth Century. New York:

New York UP, 2015.

Crawley, Ashon. "Harriet Jacobs Gets a Hearing." CurrentMusicology 93 (Spring 2012): 33-55.

Douglass, Frederick. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. Written by Himself. Boston:

Anti-Slavery Office, 1845.

Du Bois, W. E. Burghardt. The Souls of Black Folk: Essays and Sketches. Chicago: A. C. McClurg, 1903.

Eidsheim, Nina Sun. "Marian Anderson and 'Sonic Blackness' in American Opera." Sound Clash:

Listening to American Studies. Ed. Kara Keeling and Josh Kun. Spec, issue of American Quarterly 63.3

(2011): 641-71.

Gallo, Phil. "12 Yearsa Slave Leads Contemporary Soundtrack Revival." Billboard Magazine 11 Dec. 2013.

Web. 15 Mar. 2017.

Gates, Henry Louis, Jr. The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of Afro-American Literary Criticism. New York:

Oxford UP, 1988.

Guillory, John. "Genesis of the Media Concept." Critical Inquiry 36.2 (2010): 321-62.

Harris, Joel Chandler. Stories of Georgia. New York: American Book, 1896.

Hartman, Saidiya V. Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America.

New York: Oxford UP, 1997.

Johnson, Walter. River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom. Cambridge: Harvard UP,

2013.

Lingold, Mary Caton. "Fiddling with Freedom: Solomon Northup's Musical Trade in 12 Years a Slave."

Sounding Out! 16 Dec. 2013. Web. 15 Mar. 2017.

Lomax, John A., and Alan Lomax. American Ballads and Folk Songs. New York: Macmillan, 1934.

Moten, Fred. In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 2003.

Northup, Solomon. Twelve Years a Slave. 1853. New York: Penguin, 2012.

Old Dan Emmit's Original Banjo Melodies. Boston: Charles H. Keith, 1843.

Pope, Elizabeth Watts. " Twelve Years a Slave, the Book: Dramatizations, Illustrations, and Editions."

Past is Present. 2014. Web. 15 Mar. 2017.

SOLOMON NORTHUP'S SINGING BOOK 271

This content downloaded from 130.58.34.40 on Mon, 09 Aug 2021 17:07:37 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Radano, Ronald. "Denoting Difference: The Writing of the Slave Spirituals." Critical Inquiry 22.3 (1996):

506-44.

Sanjek, Russell. American Popular Music and Its Business: The First Four Hundred Years. Vol. 2. New York:

Oxford UP, 1988.

Saucier, Corinne L. History of Avoyelles Parish, Louisiana. New Orleans: Pelican, 1943.

Snead, James A. "Repetition as a Figure of Black Culture." Black Literature and Literary Theory. Ed. Henry

Louis Gates, Jr. New York: Methuen, 1984. 59-80.

Stepto, Robert B. From Behind the Veil: A Study of Afro-American Narrative. Urbana: U of Illinois P, 1979.

Weheliye, Alexander G. Phonographies: Grooves in Sonic Afro-Modernity. Durham: Duke UP, 2005.

Wilderson, Frank B., III. Red, White, and Black: Cinema and the Structure of U.S. Antagonisms. Durham:

Duke UP, 2010.

272 AFRICAN AMERICAN REVIEW

This content downloaded from 130.58.34.40 on Mon, 09 Aug 2021 17:07:37 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms