A ROUTE TO

NET ZERO EUROPEAN

AVIATION

Destination 2050 – A route to net zero European aviation

Preface

Aviation has brought enormous benefits to European society and its economy. It has allowed people to visit

other cities and countries and facilitated the transport of goods in ways that previous generations could only

have dreamed of. Passenger traffic has enjoyed remarkable growth over the last ten years, reaching a total of

over 11.1 million movements in the 44 European countries of the ECAC area

1

in 2019.

Yet with this growth, the role of aviation and its environmental impact are now the subject of greater scrutiny

in society, most notably in relation to carbon emissions. While climate change already had a high profile in

Europe, the entry into force of the Paris Agreement undoubtedly contributed to pushing this to the top of the

political agenda. Recognising this, the current College of European Commissioners (2019-2024) led by

Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has said that making Europe the first climate-neutral continent will

be the 'greatest challenge and opportunity of our times' and with it, her Commission’s number one priority as

laid out in the European Green Deal.

It is right to expect the aviation sector to meet its responsibilities in this regard. Aviation accounts for around 2-

3% of CO

2

emissions globally, and 4% in Europe. While the fuel efficiency of aircraft operations has been

improving by an average of over 2% per year between 2009 and 2019, we acknowledge that further action is

needed to bring down the absolute level, even if traffic levels increase. We must do this in an ambitious way in

order to meet the EU’s goal of net zero CO

2

emissions by 2050. We believe that this is desirable and should be

achievable – not only for European society and the economy as a whole, but also for the aviation industry and

future generations of travellers.

Our five associations, representing aircraft manufacturers, airlines, airports and air navigation service providers

in Europe, have therefore come together to plan a route to achieve this – an initiative we have called

“Destination 2050” to reflect our common end goal. Recognising that the whole European air transport

ecosystem must act together decisively, our intention is to identify the measures which our members can apply

to achieve this decarbonisation collectively. In some cases these may be new measures, while in others there

may be existing programmes that need to be approached in a new and better way.

We asked the Netherlands Aerospace Centre (NLR) and SEO Amsterdam Economics to support us in providing a

scientific basis for this project. They have identified measures across four pillars which are presented in this

report:

1. Aircraft and engine technology

2. Air traffic management and aircraft operations

3. Sustainable Aviation Fuels

4. Smart economic measures

Destination 2050 does not describe the only pathway to net zero CO

2

emissions. Assumptions may change and

other factors and opportunities may enter into the equation, such as the role of intermodal travel. Equally, the

report does not address the financing of the tremendous effort required for a socially compatible

transformation that ensures European citizens’ and businesses’ connectivity.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and its negative consequences for aviation have been a complicating

factor in producing this report, but we do not see the downturn in traffic since March 2020 or the higher profile

1

See https://www.ecac-ceac.org/member-states

of the crisis as an excuse for inaction. Once passenger traffic has returned to 2019 levels, we expect the

number of flights to resume its upward trend. The time to start implementing our plan is now.

The undersigned five associations have used the conclusions of this report to develop a set of commitments,

representing our contribution to the EU Pact for Sustainable Aviation, a forthcoming initiative resulting from

the Round Table Report on the Recovery of European Aviation

2

(November 2020). In fact, we cannot undertake

this decarbonisation journey on our own. To be successful, we will need support from European and national

policy makers to create the right policy frameworks and, in some cases, to provide financial assistance to

develop and apply new technologies. We take the lead but call on policy makers to play their part, as well (both

at a European and worldwide level) to help our industry achieve its climate goals.

Together we are confident that we can find a route to net zero European aviation.

Thomas Reynaert, Managing Director, Airlines for

Europe (A4E)

Tanja Grobotek, Director Europe Affairs, CANSO

(Civil Air Navigation Services Organisation)

Montserrat Barriga, Director General, ERA

(European Regions Airline Association)

Olivier Jankovec, Director General, Airports Council

International-EUROPE (ACI)

Jan Pie, Secretary General,

Aerospace & Defence Industries Association of Europe (ASD)

2

See: https://canso.org/eu-aviation-maps-a-sustainable-post-crisis-future-in-round-table-report/

1

PUBLIC

NLR – Royal Netherlands Aerospace Centre

SEO Amsterdam Economics

CUSTOMER: A4E, ACI-EUROPE, ASD, CANSO, ERA

Destination 2050

A Route To Net Zero European Aviation

NLR-CR-2020-510 | February 2021

i

UNLIMITED DISTRIBUTION

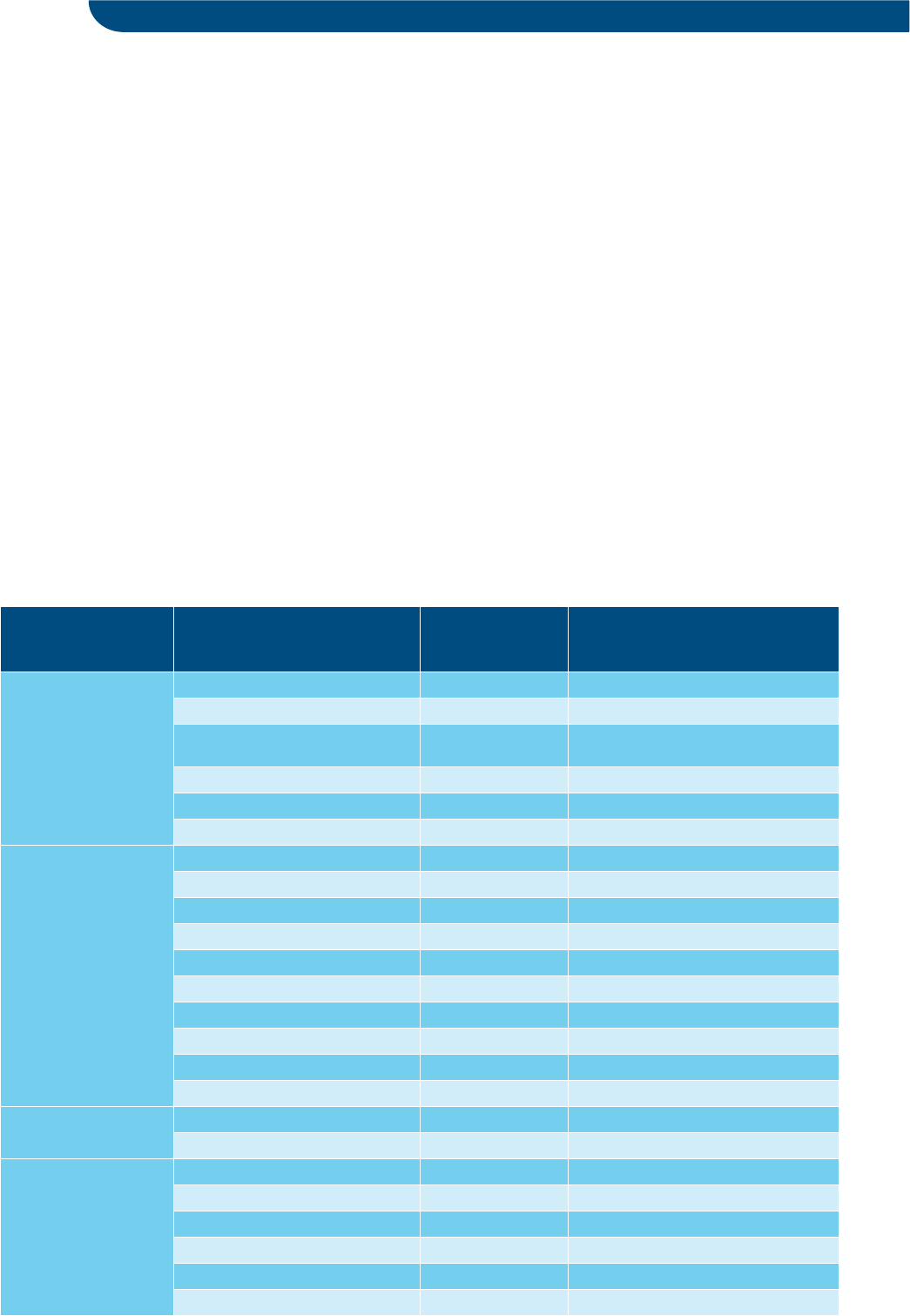

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

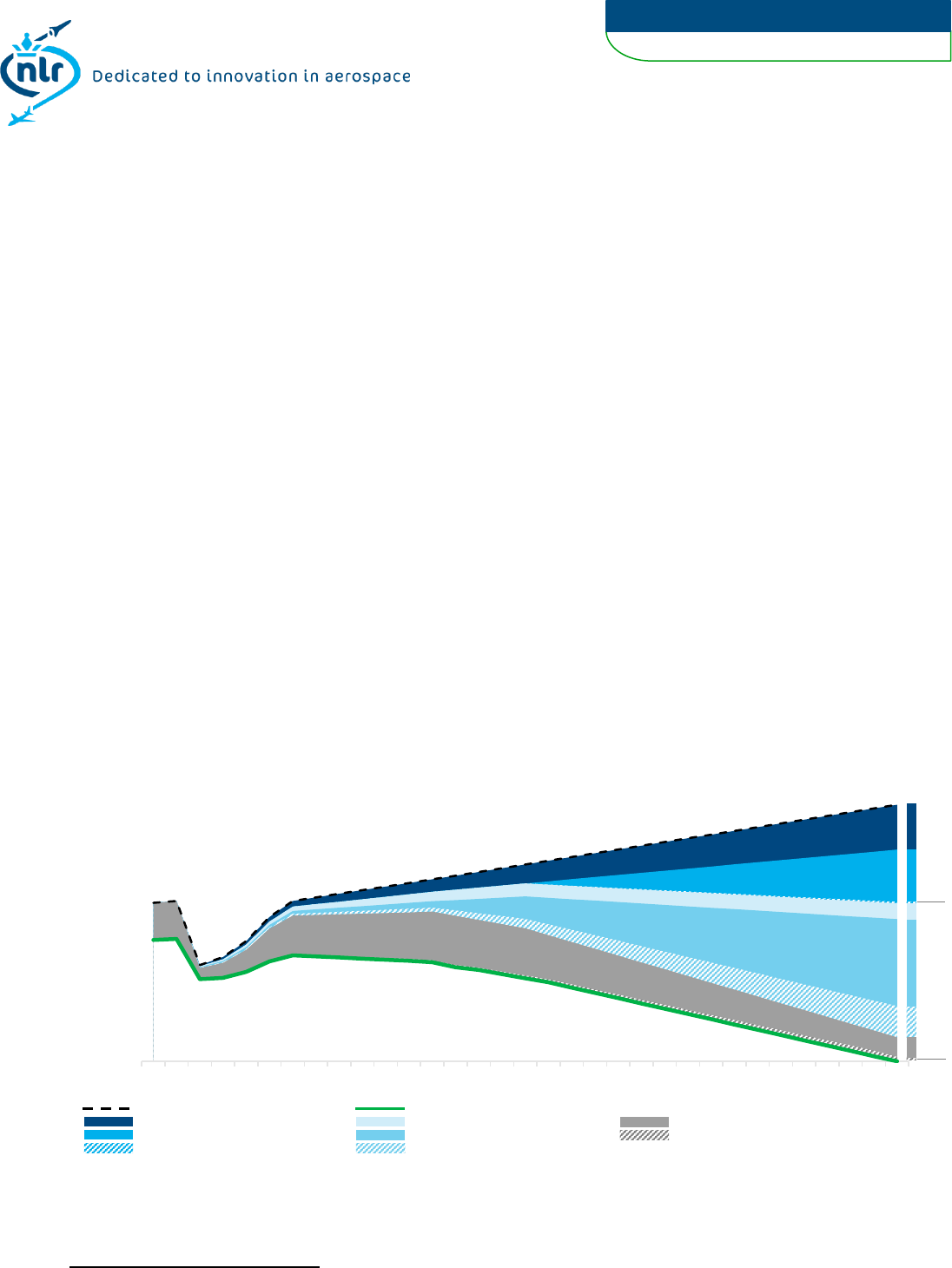

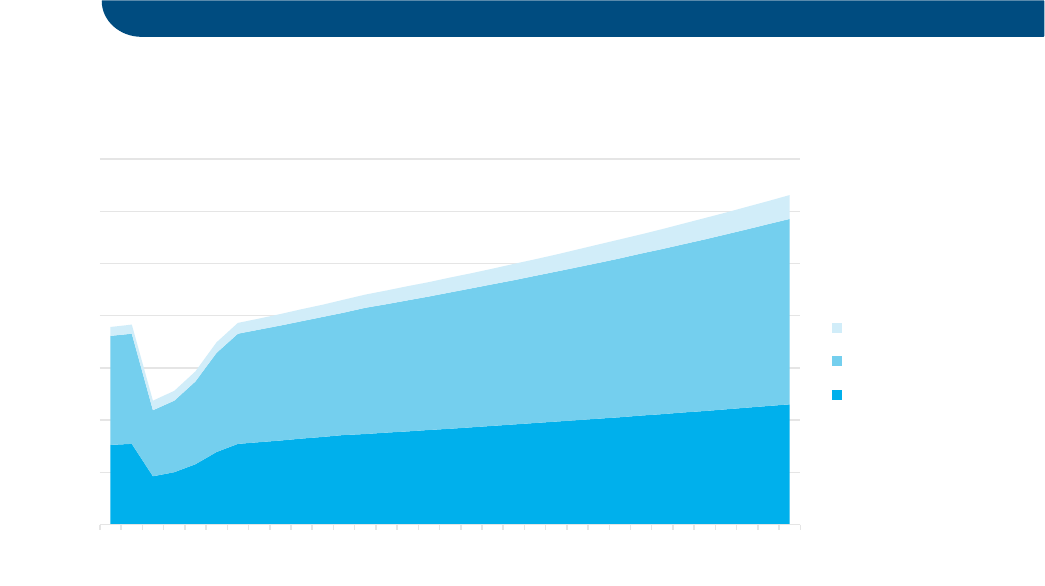

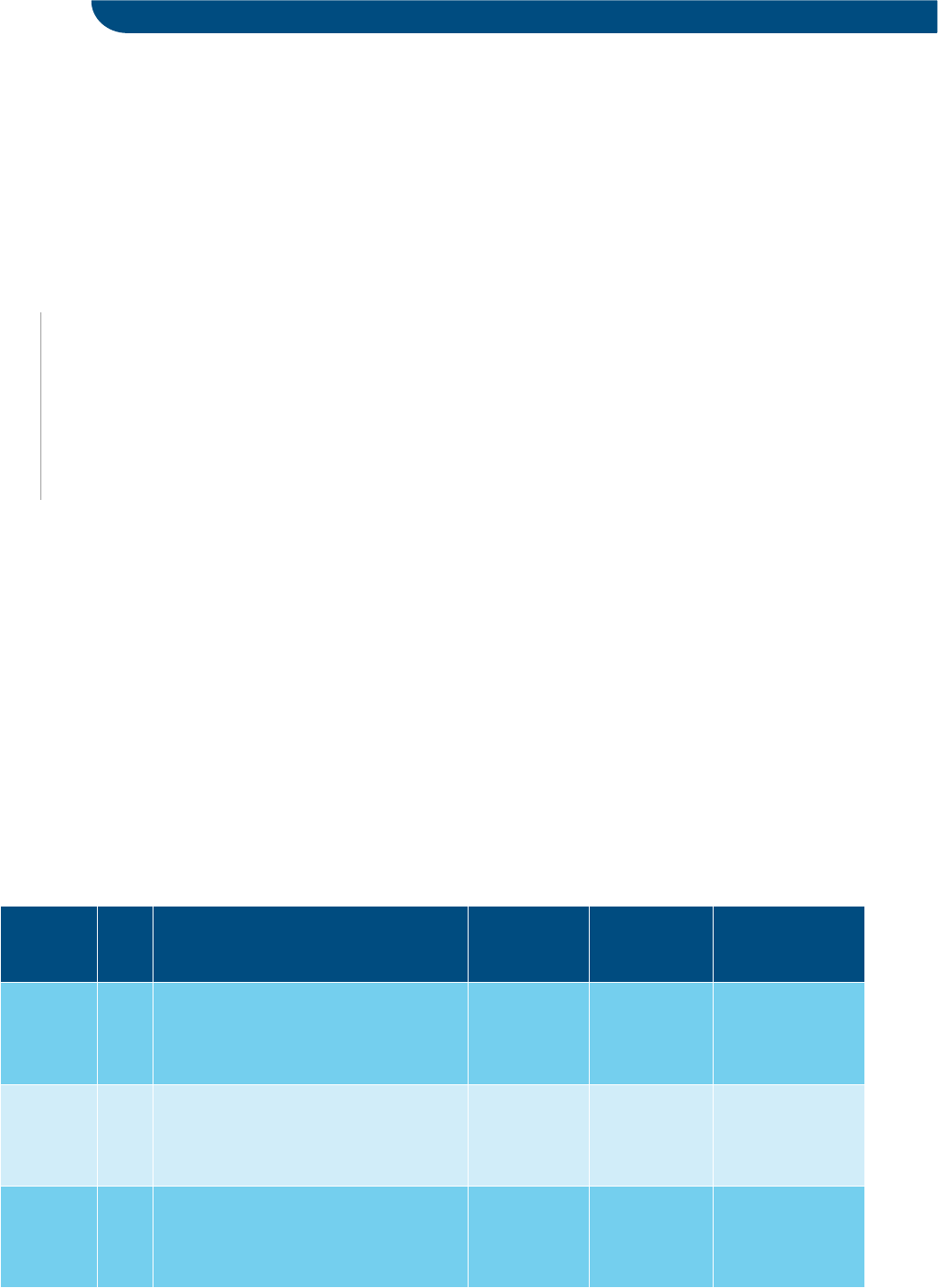

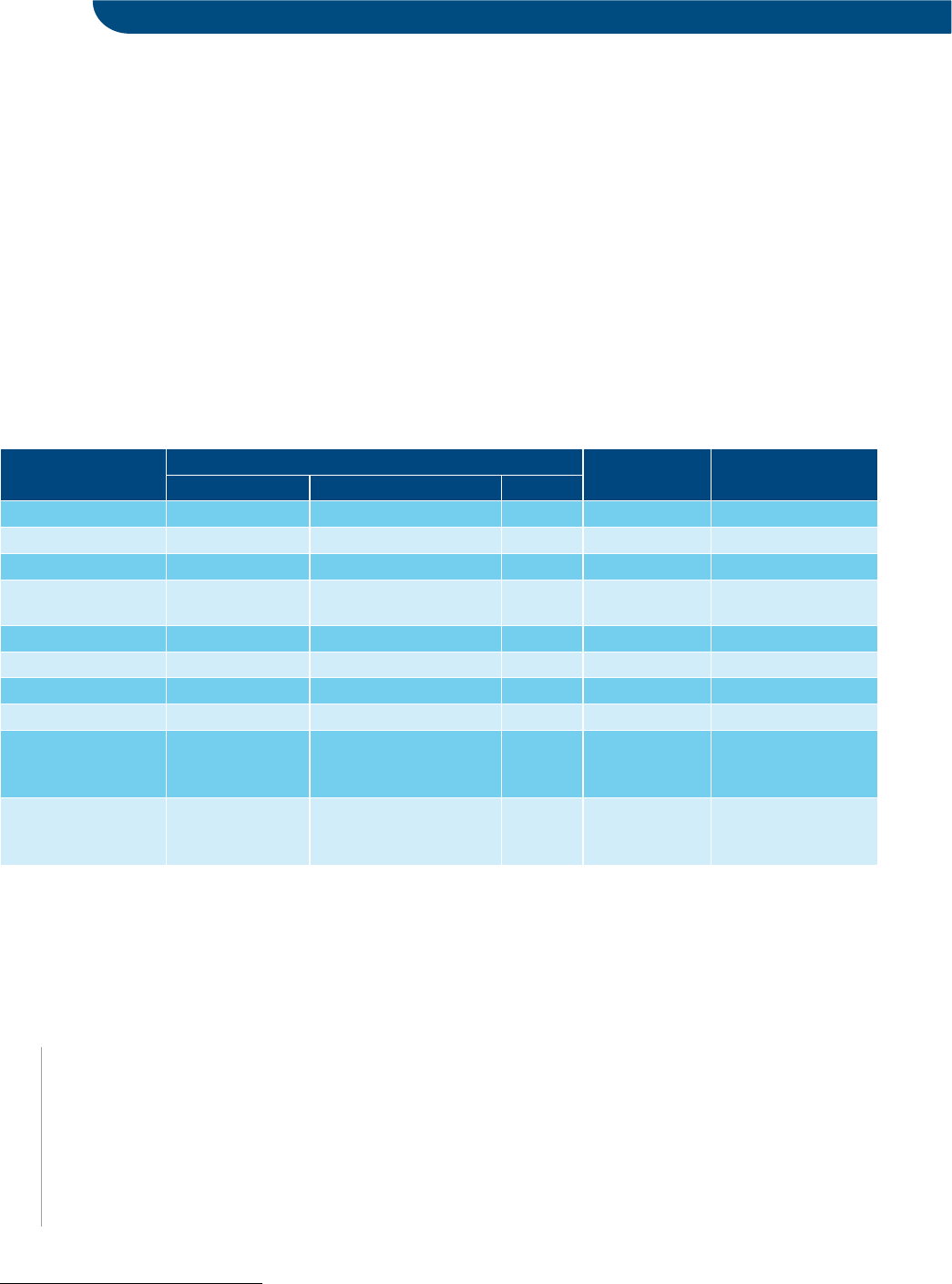

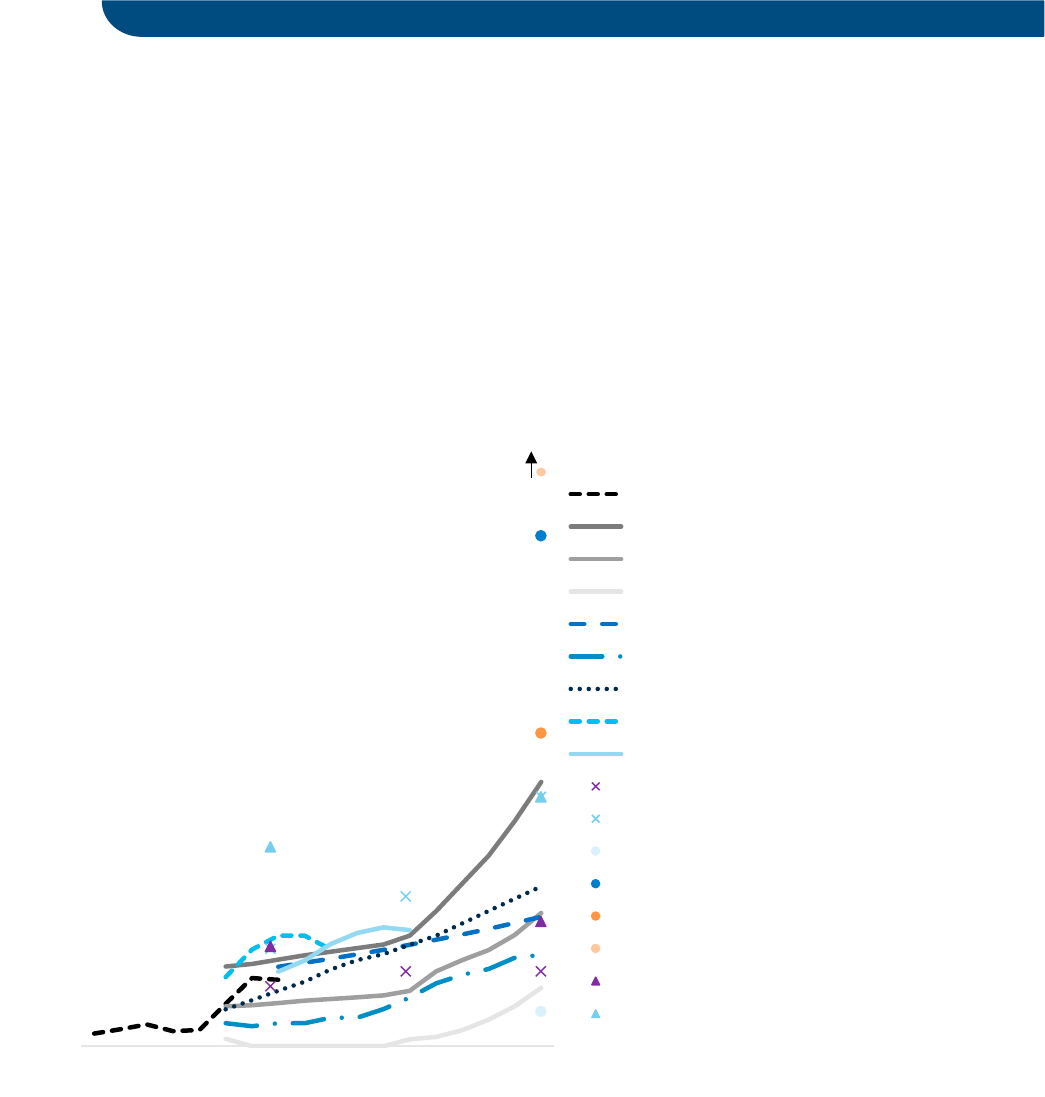

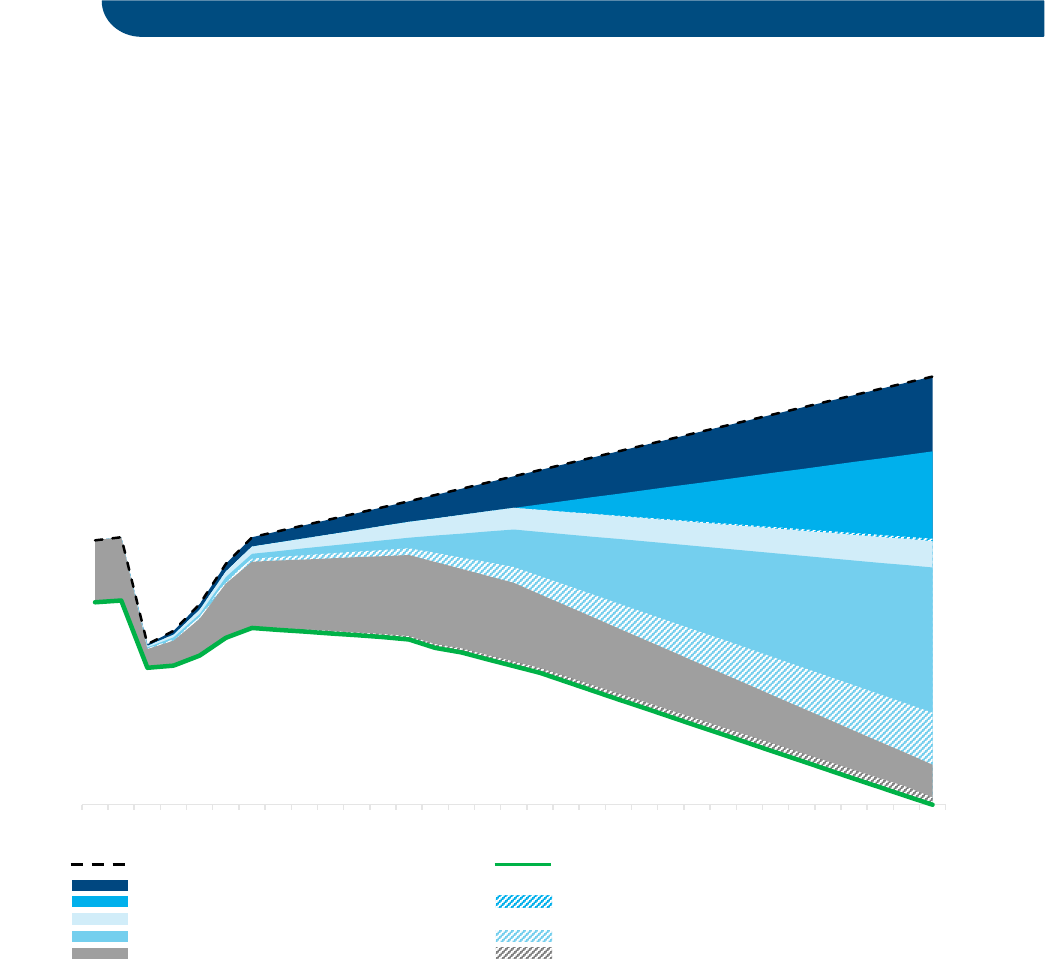

Net zero CO

2

emissions

1

from all flights within and departing from the EU

2

can be achieved by 2050 through joint,

coordinated and decisive industry and government efforts. The European aviation industry is committed to

reaching this target and contribute to the goals set in the European Green Deal and the Paris Agreement.

Destination 2050 shows a possible pathway that combines new technologies, improved operations, sustainable

aviation fuels and economic measures. Absolute emissions are reduced by 92%, while the remaining 8% is removed

from the atmosphere through negative emissions, achieved through natural carbon sinks or dedicated technologies.

Royal Netherlands Aerospace Centre and SEO Amsterdam Economics conducted this study commissioned by the

representatives of European airports, airlines, aerospace manufacturers and air navigation service providers. It

assesses to what extent four groups of sustainability measures are able to reduce carbon emissions until 2050,

strongly influenced by policies and actions. The effects of these measures are compared to a hypothetical reference

scenario taking into account continuous demand growth and the recent COVID-19 impact. These sustainability

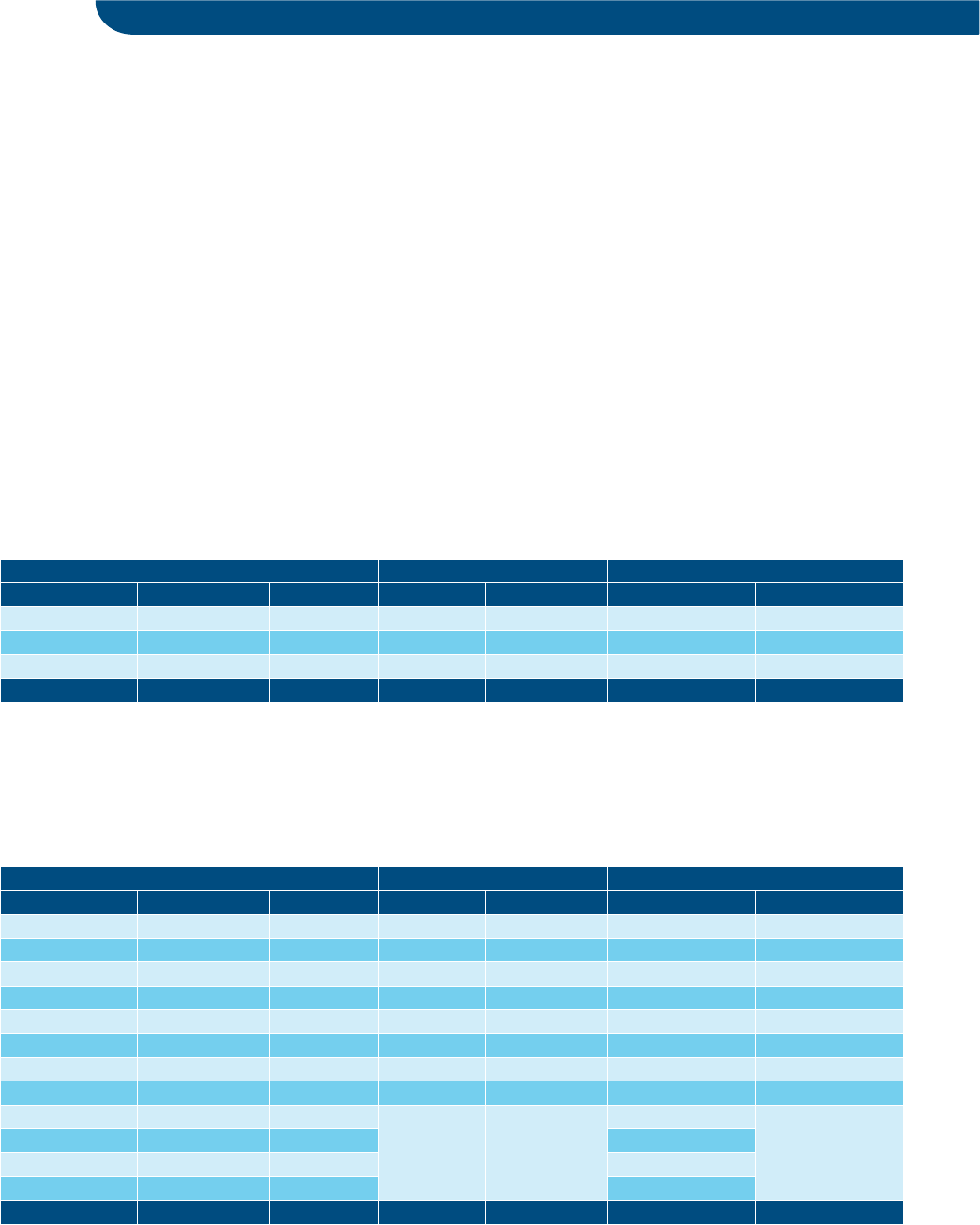

measures result in the following net CO

2

emissions reductions in the year 2050:

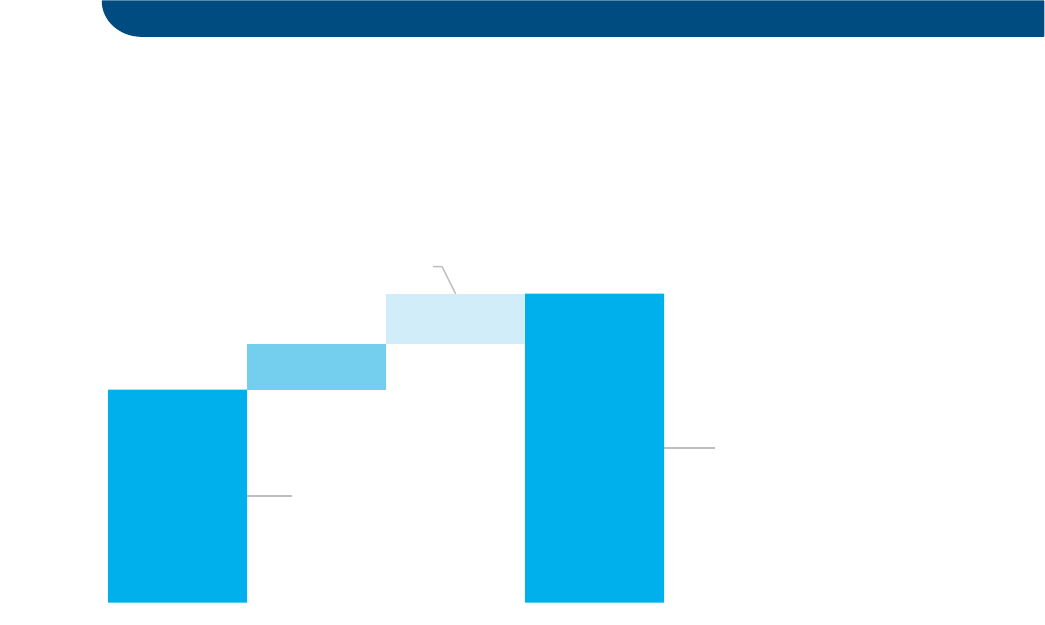

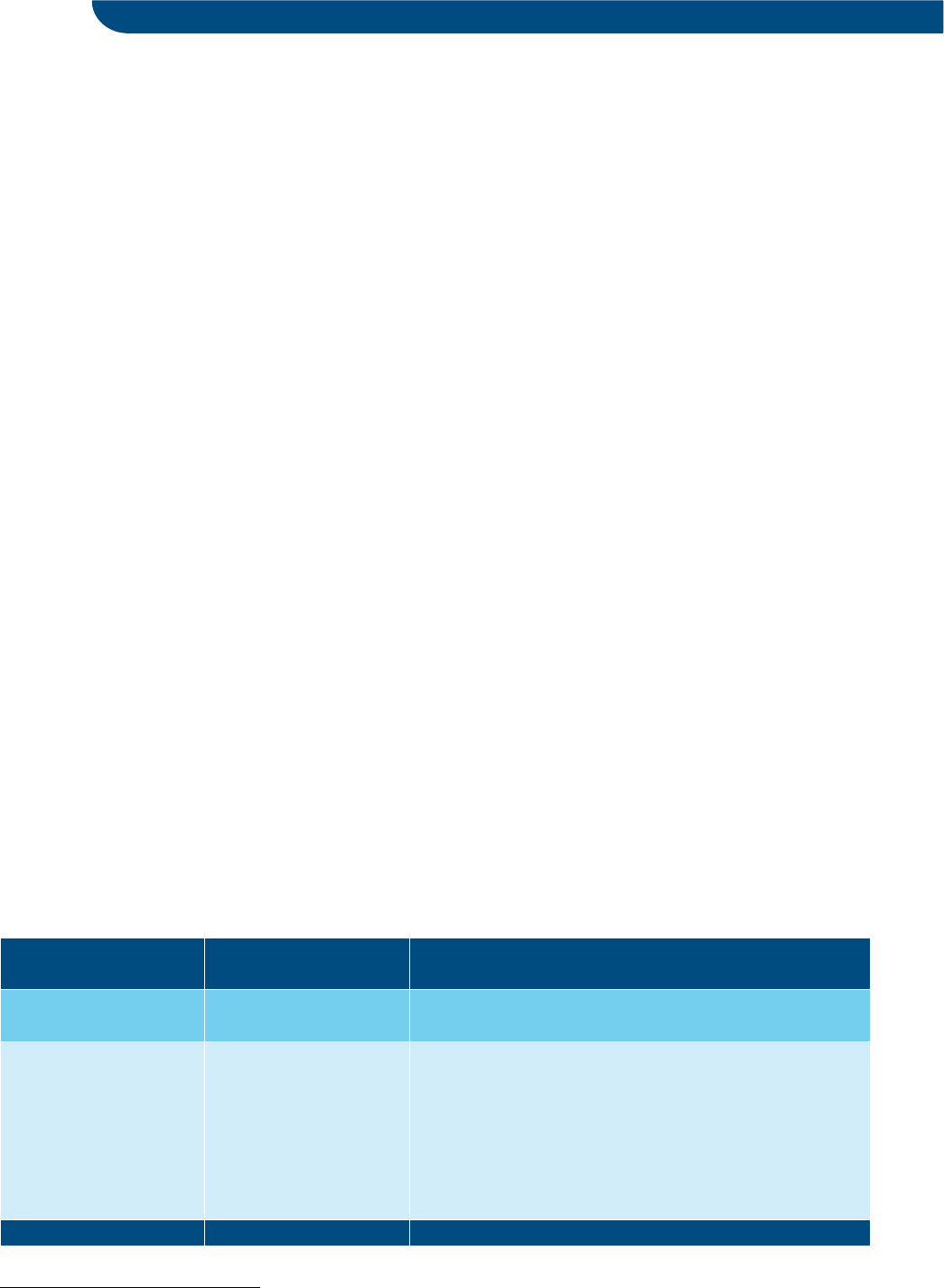

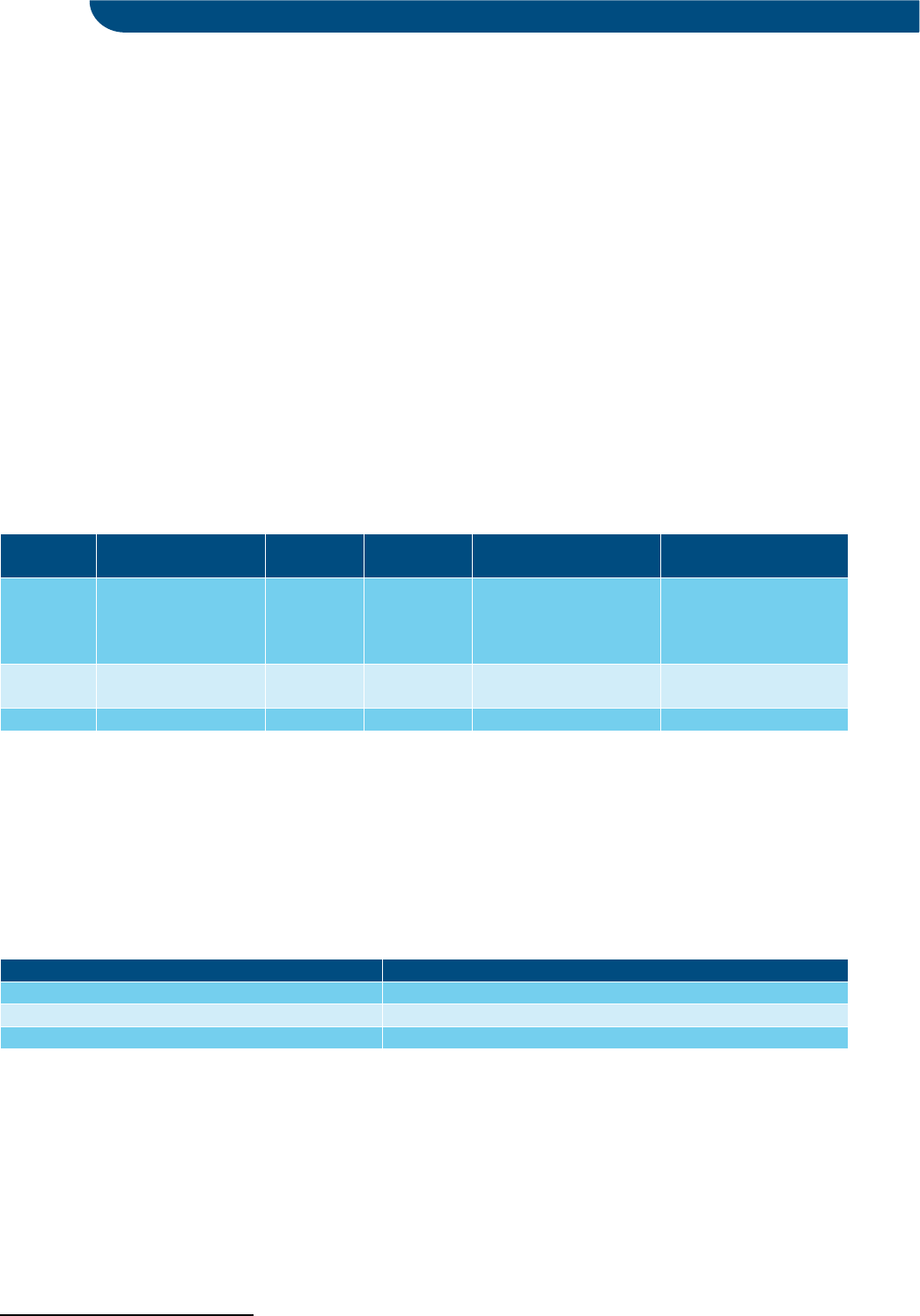

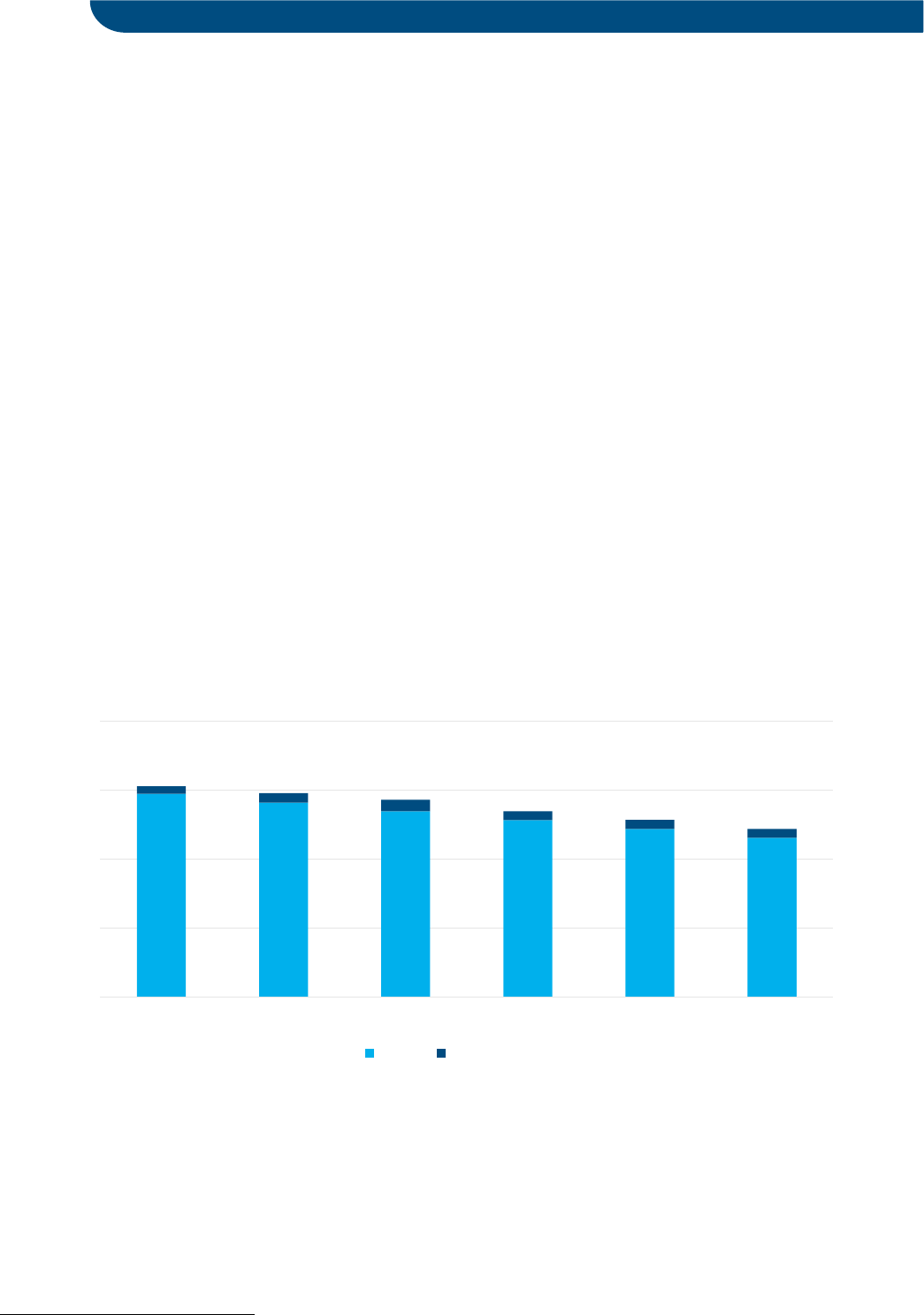

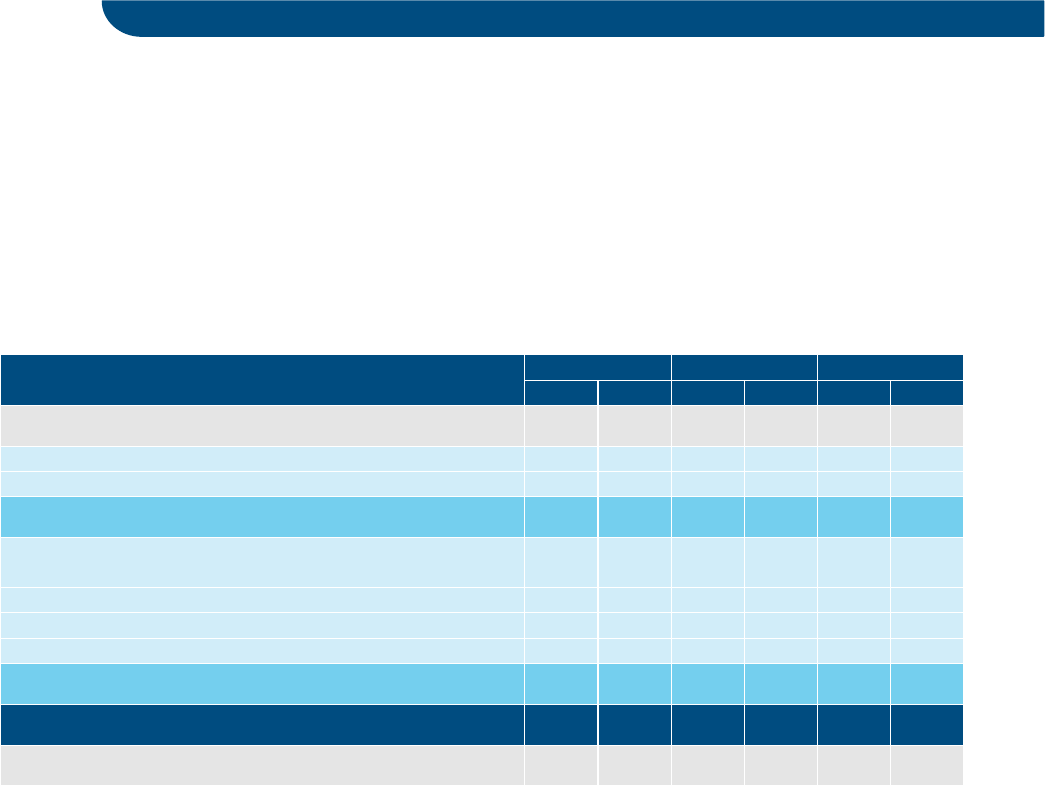

• 111 MtCO

2

through improvements in aircraft and engine technology:

o 60 MtCO

2

by hydrogen-powered aircraft on intra-European routes and

o 51 MtCO

2

by kerosene-powered or (hybrid-)electric aircraft;

• 18 MtCO

2

through improvements in air traffic management (ATM) and aircraft operations;

• 99 MtCO

2

through using drop-in sustainable aviation fuels (SAF);

• 22 MtCO

2

through economic measures (carbon removal projects only).

The combined cost of these sustainability measures is modelled to impact ticket prices, resulting in a lower air travel

demand. This would avoid 43 MtCO

2

whilst maintaining an average compound annual passenger growth rate of 1.4%.

Results are presented for all flights within and departing from the EU region

2

. Improving aircraft and engine

technology, ATM and aircraft operations, SAF and economic measures all hold decarbonisation potential. Modelled for

2030 and 2050, the impacts are linearly interpolated. The base year for this study is 2018.

1

While acknowledging that aviation is also responsible for non-CO

2

climate impacts, the scope of this study is limited to a quantitative assessment of CO

2

emissions.

Further study is required to develop a roadmap to take these non-CO

2

emissions into account.

2

Specifically, the European Union (EU), the United Kingdom (UK), and the European Free Trade Association (EFTA).

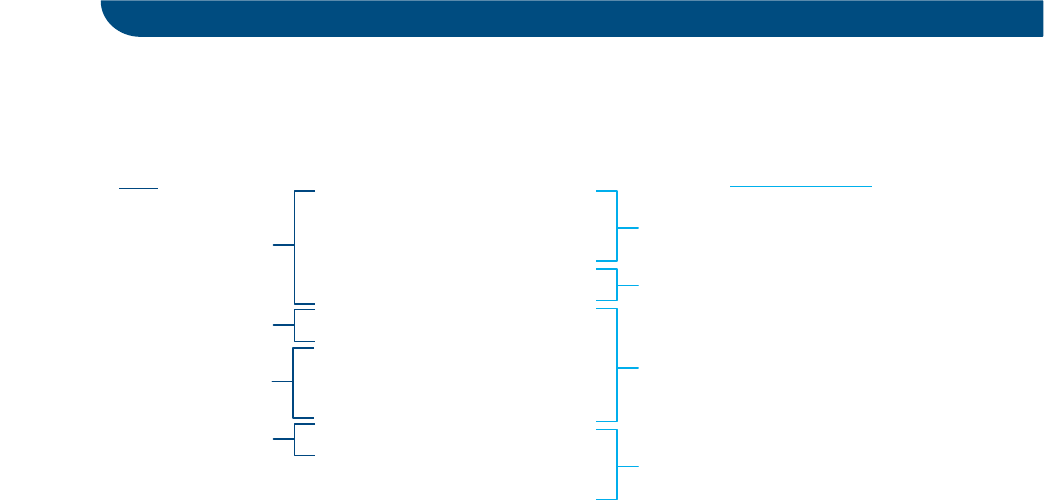

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

2018 2030 2050

EU+ aviation net CO

2

emissions (Mt)

Decarbonisation Roadmap for European Aviation

Destination 2050

Improved technology (kerosene)

Improved ATM and operations

Sustainable aviation fuels (SAF)

Effect of SAF on demand

Improved technology (hydrogen)

Hypothetical reference scenario

Net CO

2

emissions

Effect of hydrogen on demand

Economic measures

Effect of economic measures on demand

17%

20%

6%

34%

12%

8%

2%

1%

ii

UNLIMITED DISTRIBUTION

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

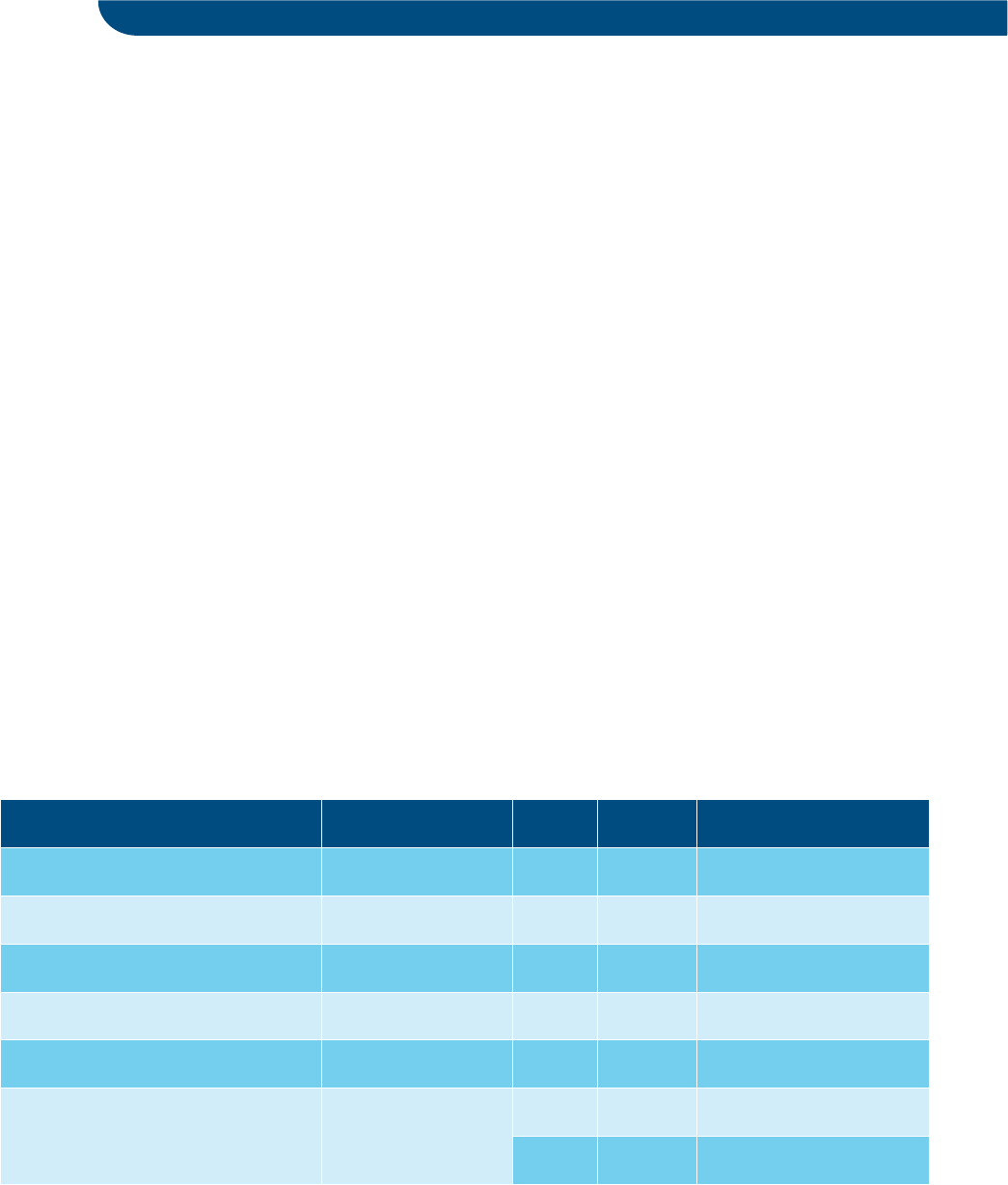

A pathway to 2050

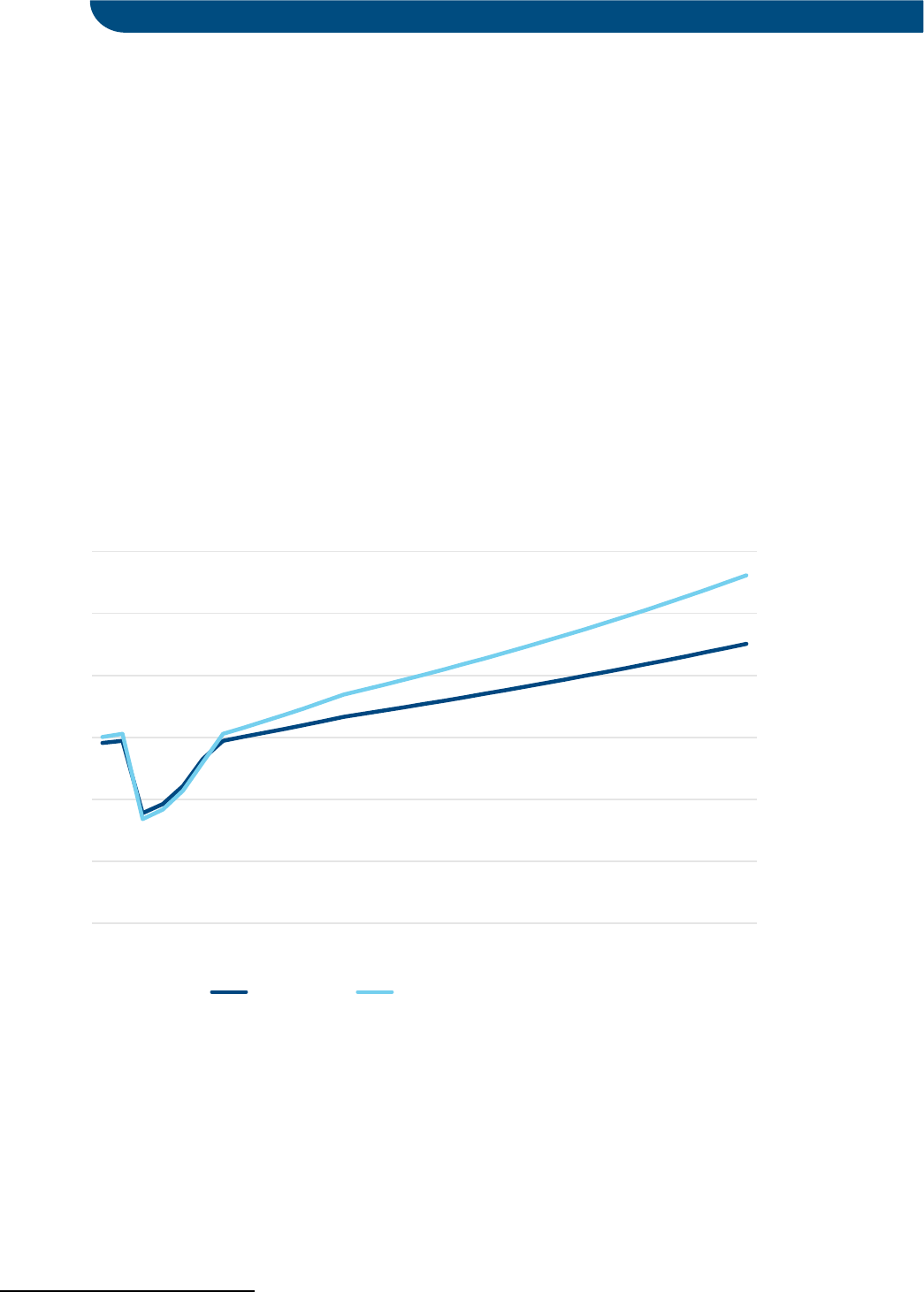

Implementing these measures could make 2019 the peak year in absolute CO

2

emissions from European aviation,

thereby surpassing the industry target of carbon neutral growth from 2020 onwards. In the year 2030, net CO

2

emissions are reduced by 45% compared to the hypothetical reference scenario as a result of continued fleet renewal,

improvements in ATM and aircraft operations and a substantial reliance on economic measures. Compared to the CO

2

emissions in the year 1990, on which European Green Deal targets are based, this however means a 36% increase of

net CO

2

emissions from European aviation. This is due to the fact that most substantial emission reductions measures

– a next generation of aircraft and substantial uptake of sustainable aviation fuel – take more time to materialise. It is

nonetheless essential that the foundations for post-2030 reductions are laid in the coming years, to realise net zero

CO

2

emissions in 2050 and reduce reliance on economic measures.

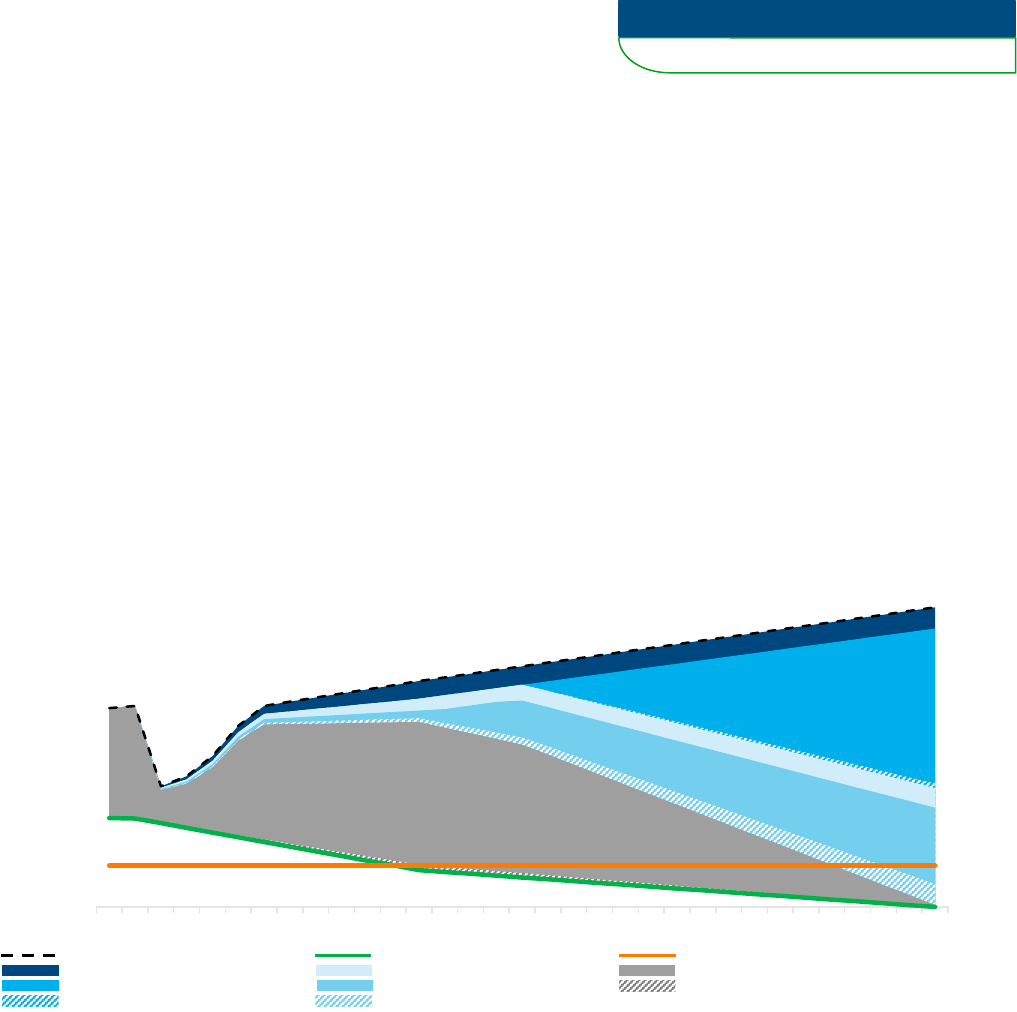

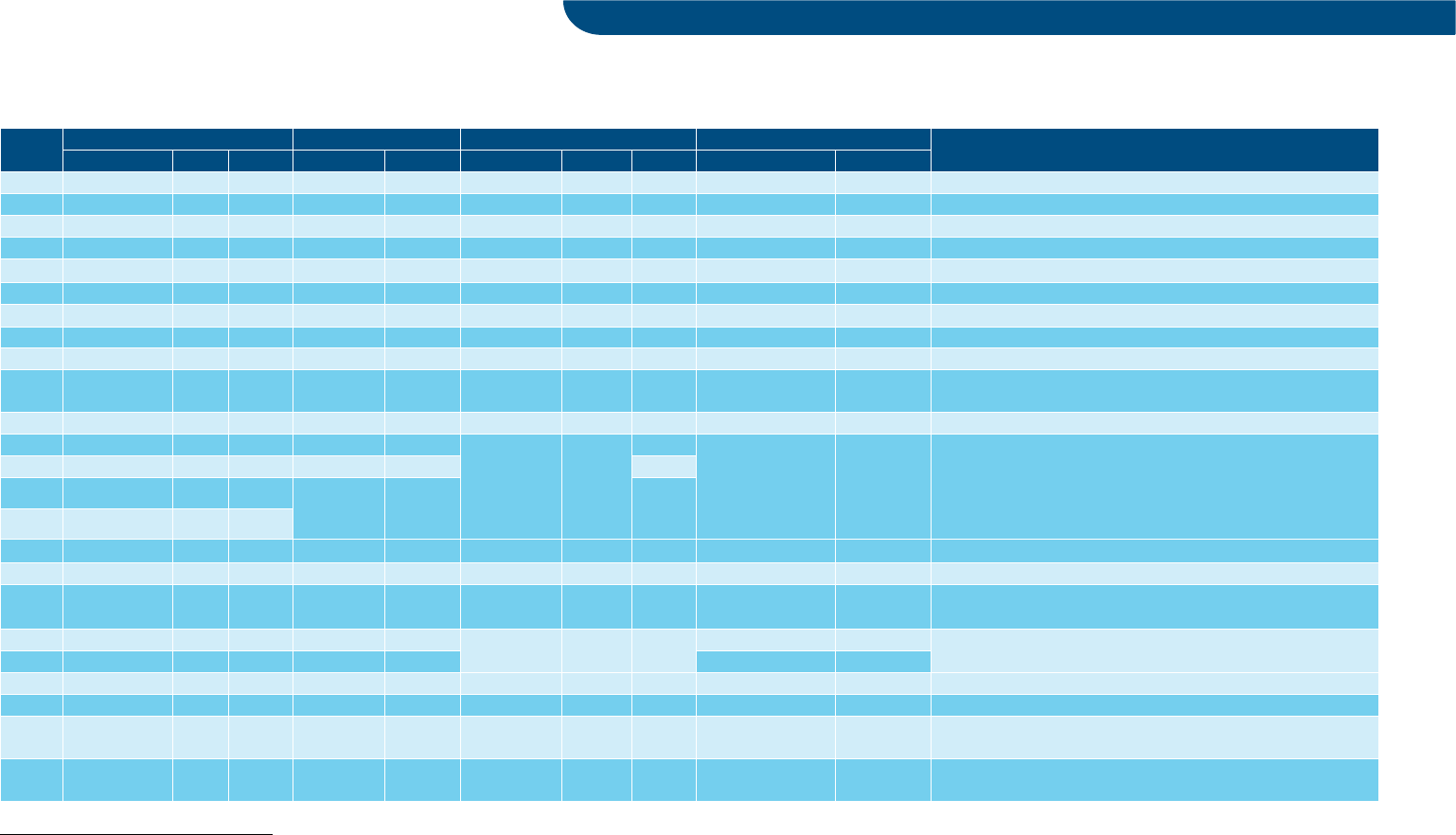

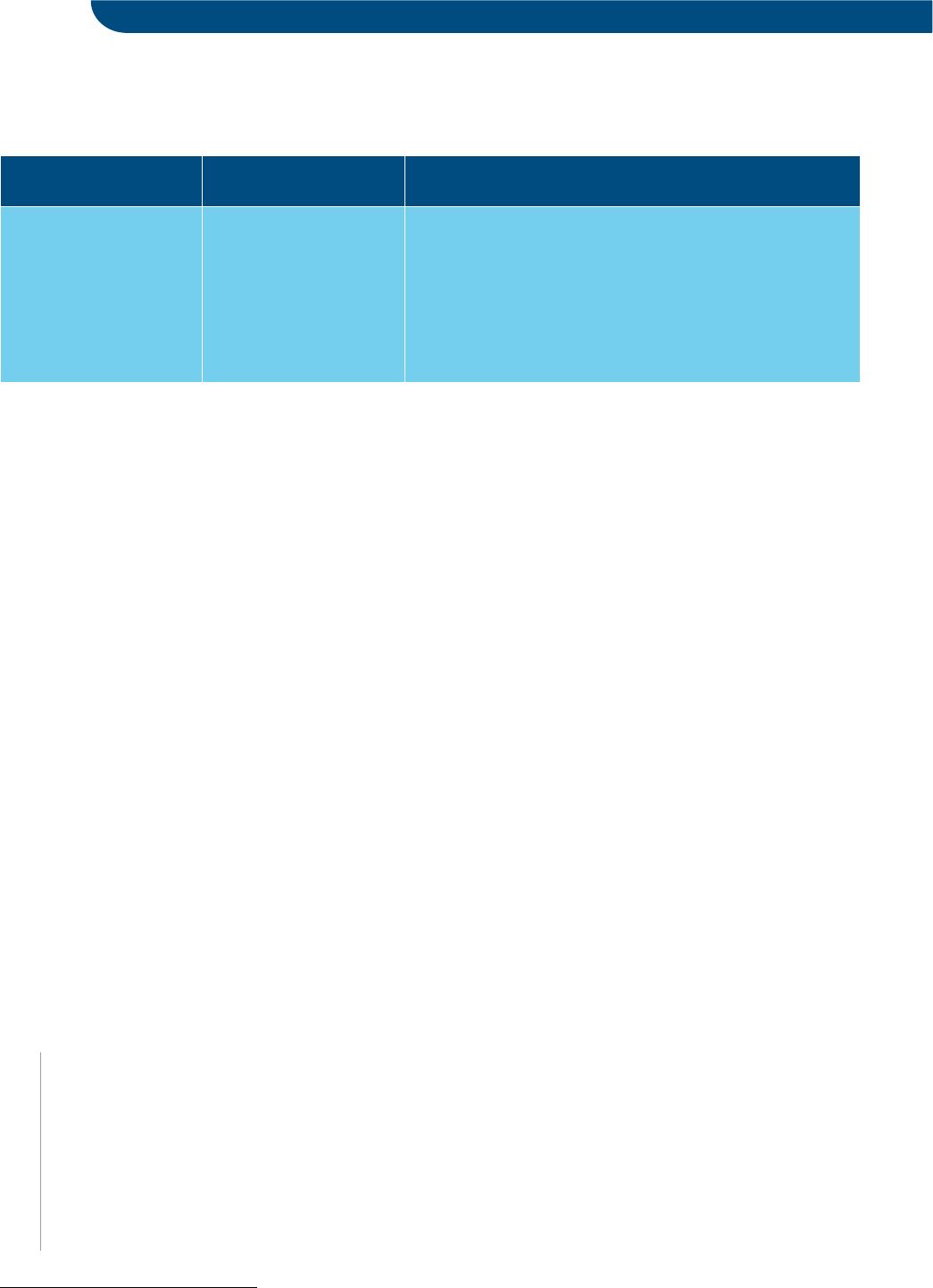

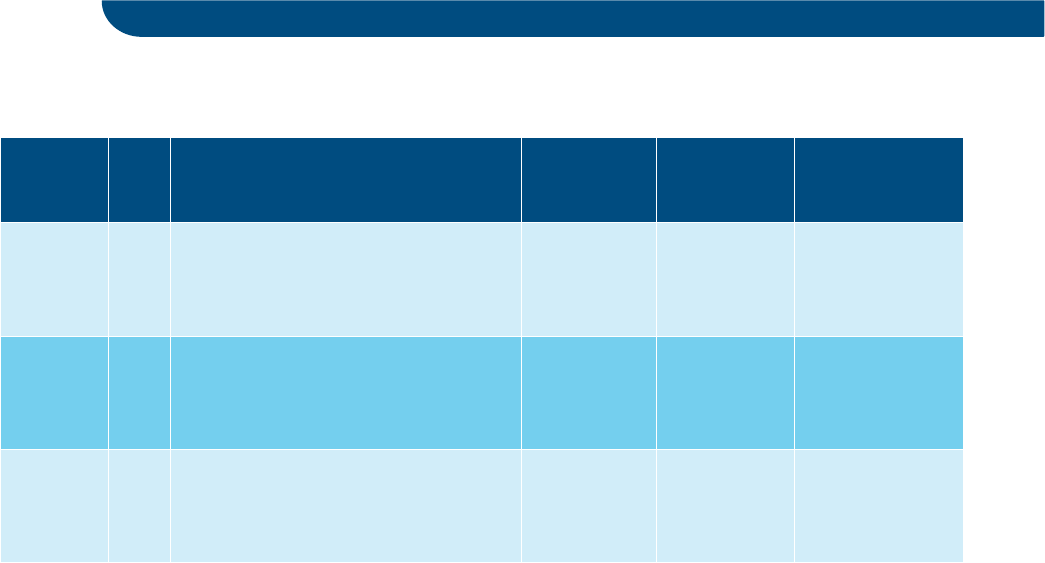

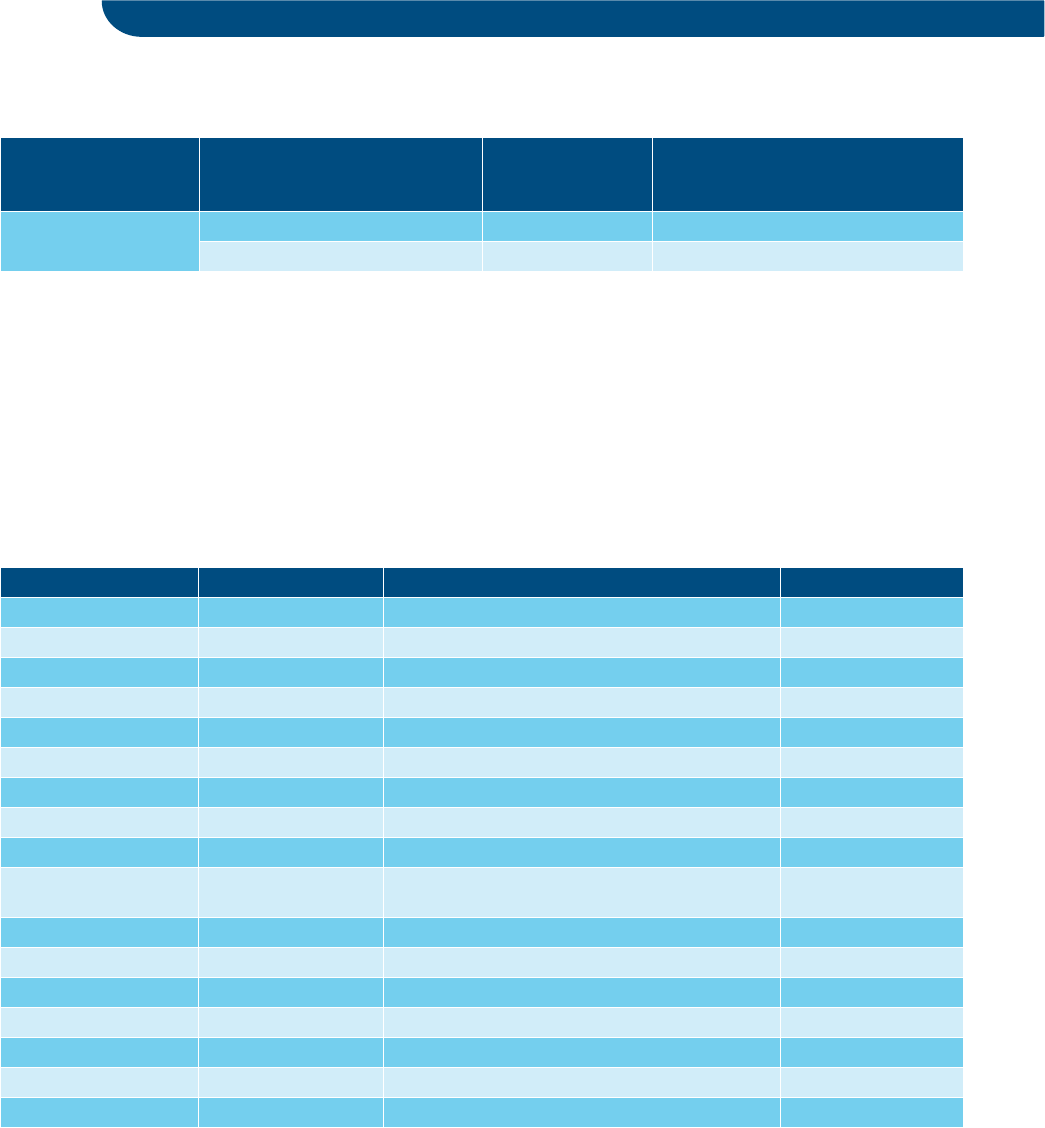

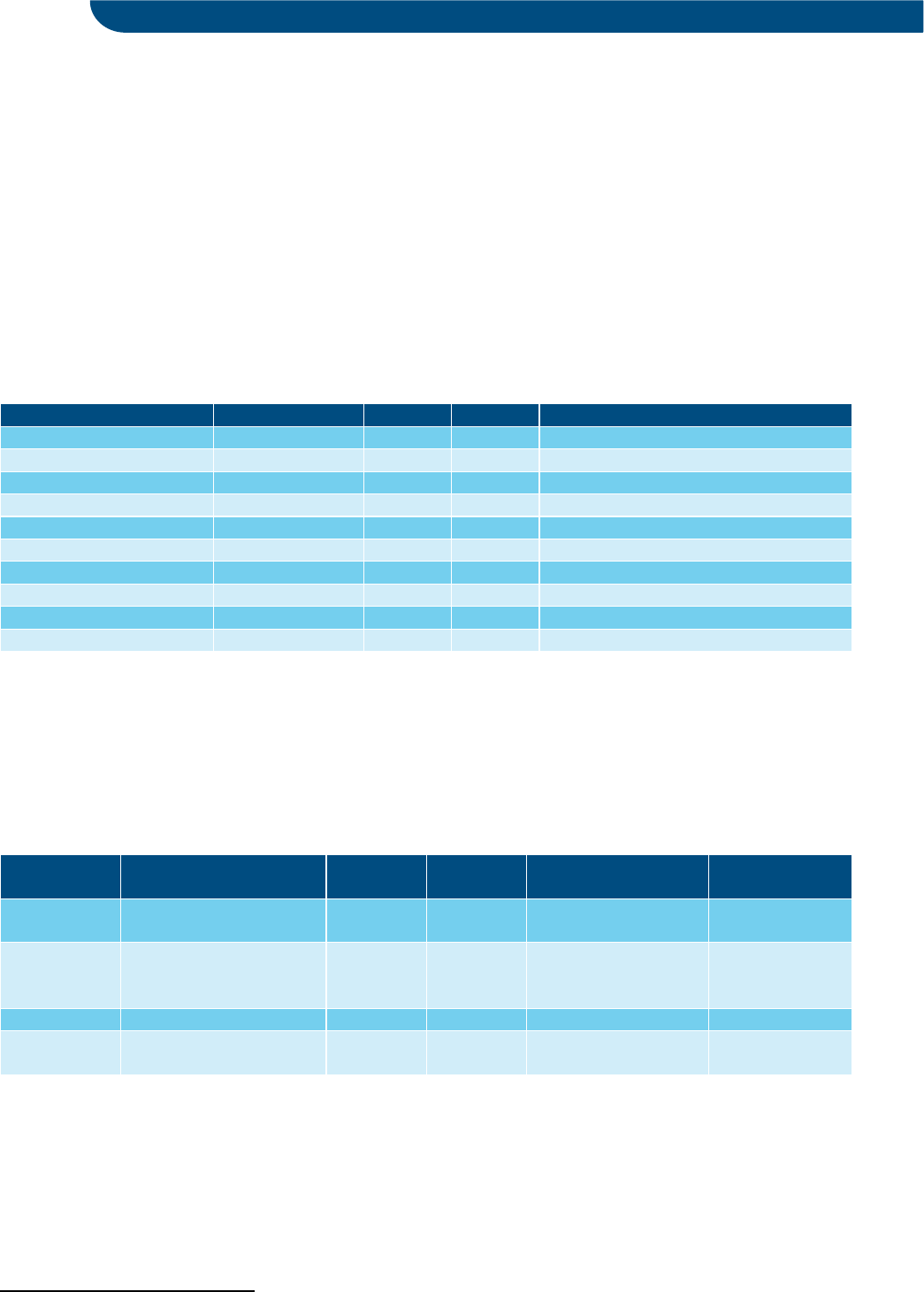

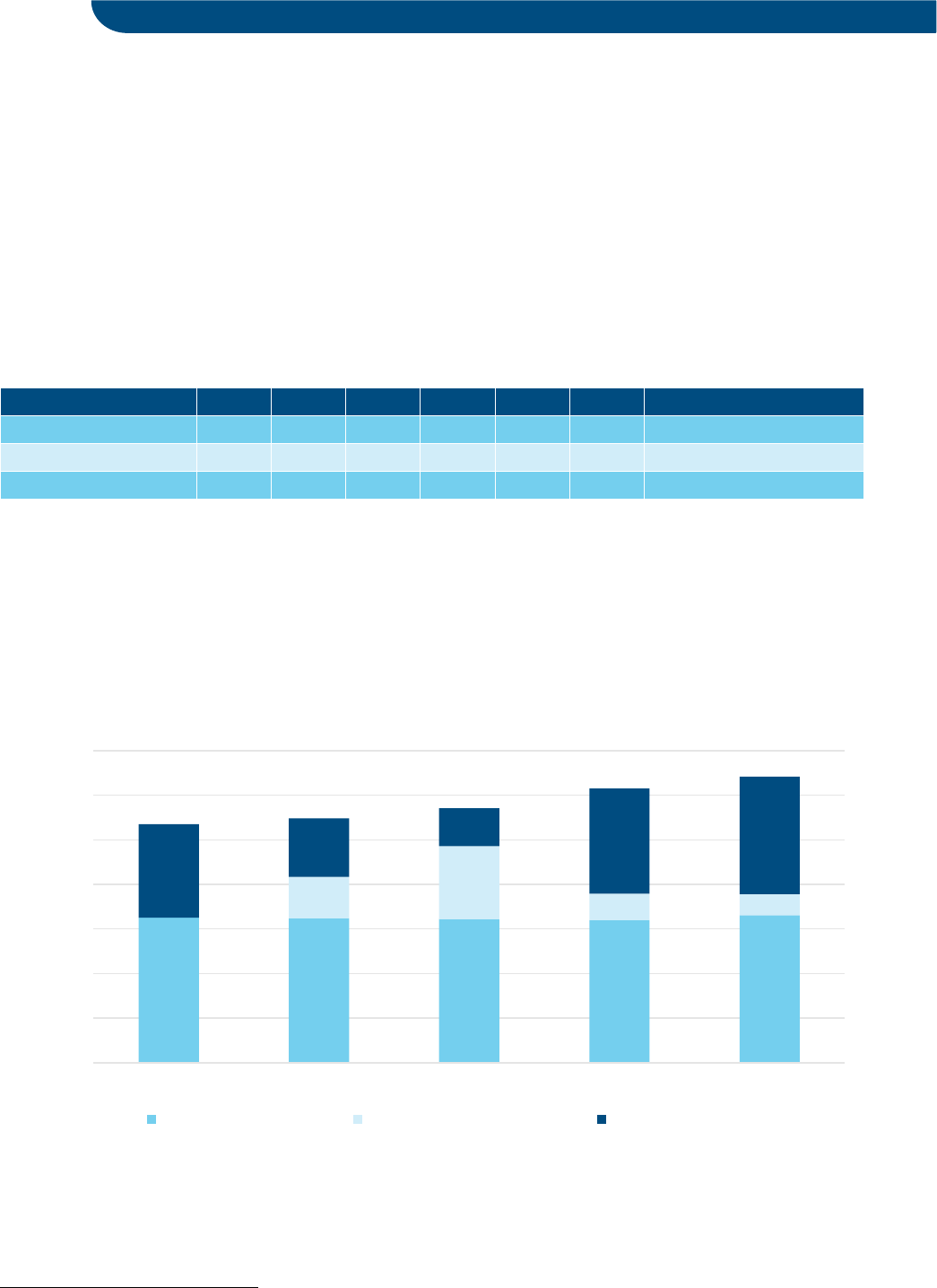

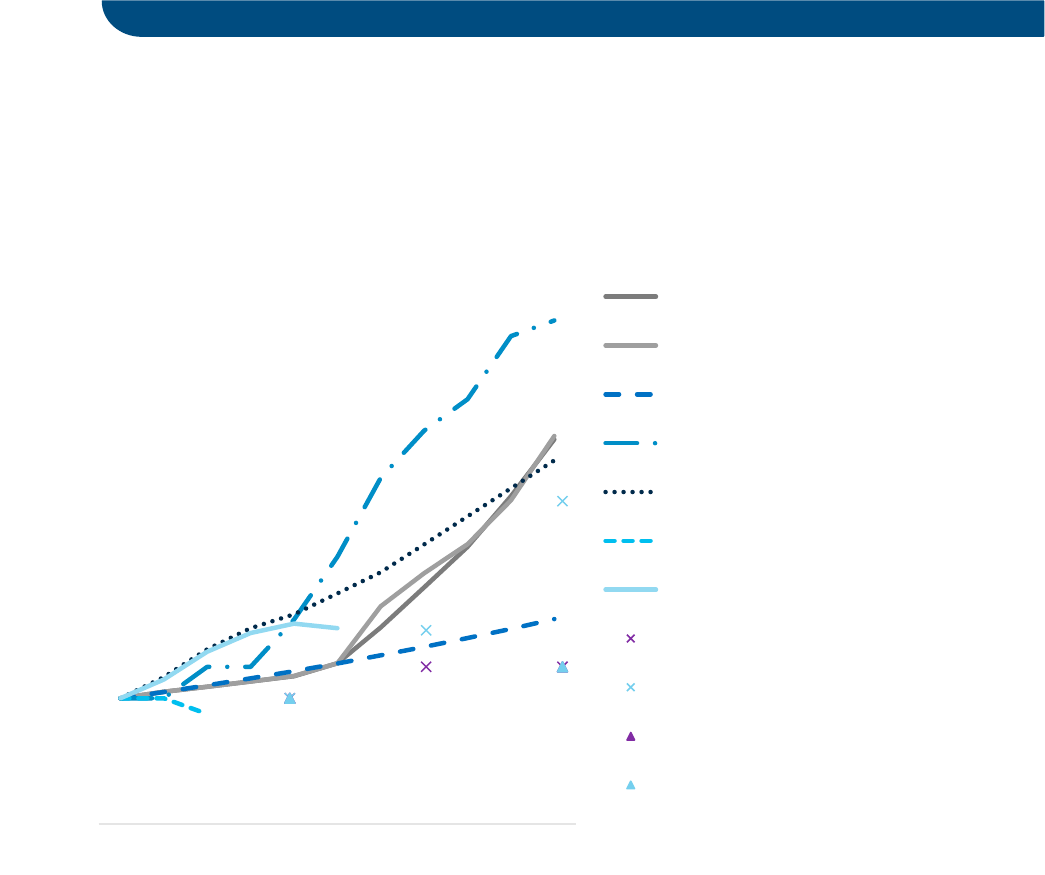

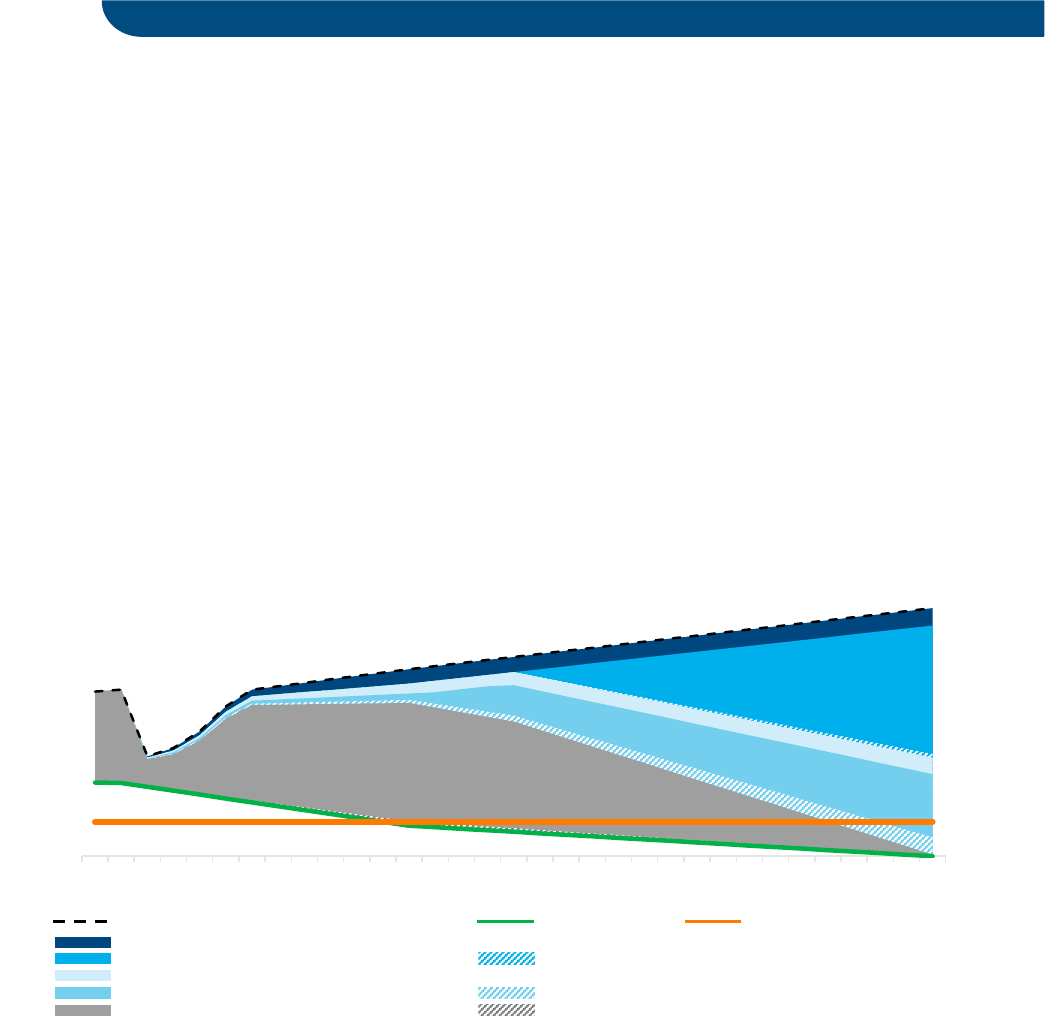

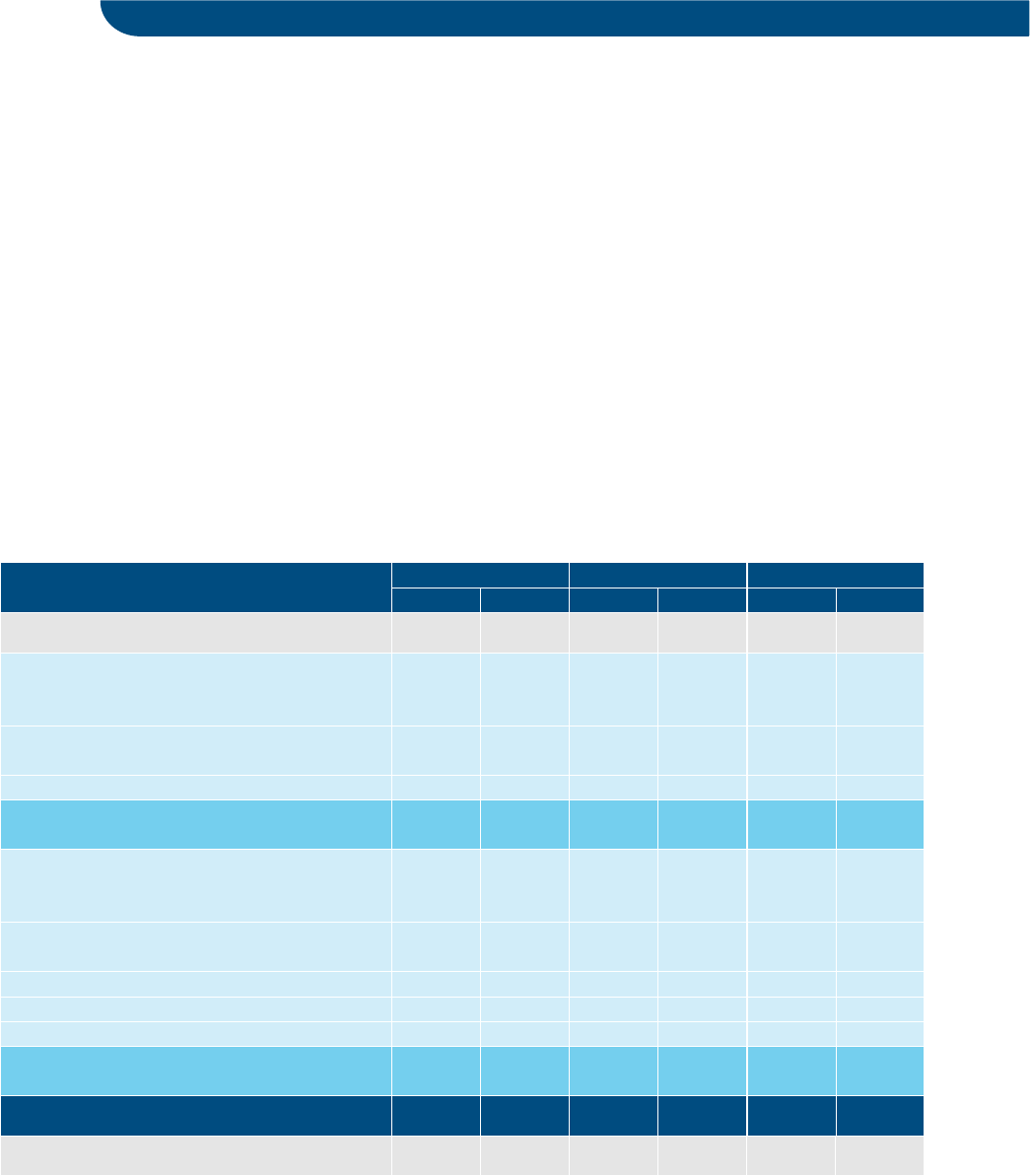

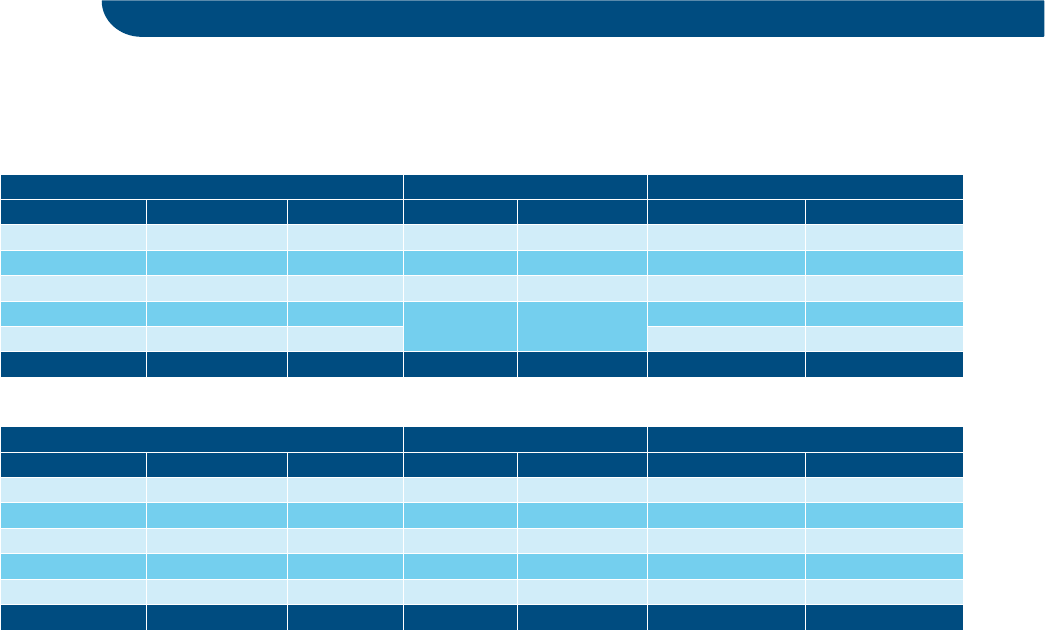

A detailed look at flights within the EU

For flights within the EU

2

, the results highlight that net zero CO

2

emissions in the year 2050 can be achieved with close

to zero economic measures. The largest contribution is made by hydrogen-powered aircraft introduced in 2035

followed by sustainable aviation fuels. Net emissions can be limited to 13 MtCO

2

in the year 2030, estimated to be

55% below the emission levels in 1990 and thereby contributing to the implementation of the European Green Deal.

Intra-EU

2

only. Modelled for 2030 and 2050, the impacts are linearly interpolated. The base year for this study is 2018.

Recommendations to industry and government

The measures leading to net zero CO

2

emissions from European aviation need to be realised through collective

policies and actions by governments and industry. Both should work towards global commitment to a net zero

carbon future for aviation, to avoid differentiated policies, carbon leakage and transfer of activity. Europe should

maintain and evolve its leading position in sustainable aviation by the following policies and actions:

Industry should

Continue to substantially invest in decarbonisation

Develop more fuel-efficient aircraft and bring these

into operation through continued fleet renewal

Develop hydrogen-powered and (hybrid-)electric

aircraft and associated supporting (airport)

infrastructure and bring these into the market

Scale up drop-in SAF production and uptake

Implement the latest innovations in ATM and flight

planning

Compensate remaining CO

2

emissions by removing

carbon dioxide from the atmosphere

Governments should

Support industry investments by direct stimuli or by

reducing investment risk through a consistent and

long-term policy framework

Stimulate further development and deployment of

innovations by funding research programmes and

promoting carbon removal technologies

Work with the energy sector to ensure sufficient

availability of renewable energy at affordable cost

Support the development of the SAF industry

Contribute to optimising ATM, in particular by fully

implementing the Single European Sky

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

2018 2030 2050

intra-

EU+ aviation net CO

2

emissions

(Mt)

Flights within the EU+ region

Improved technology (kerosene)

Improved ATM and operations

Sustainable aviation fuels (SAF)

Effect of SAF on demand

Improved technology (hydrogen)

Hypothetical reference scenario

Net CO

2

emissions

Effect of hydrogen on demand

Economic measures

Effect of economic measures on demand

55% of 1990 CO

2

iii

UNLIMITED DISTRIBUTION

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

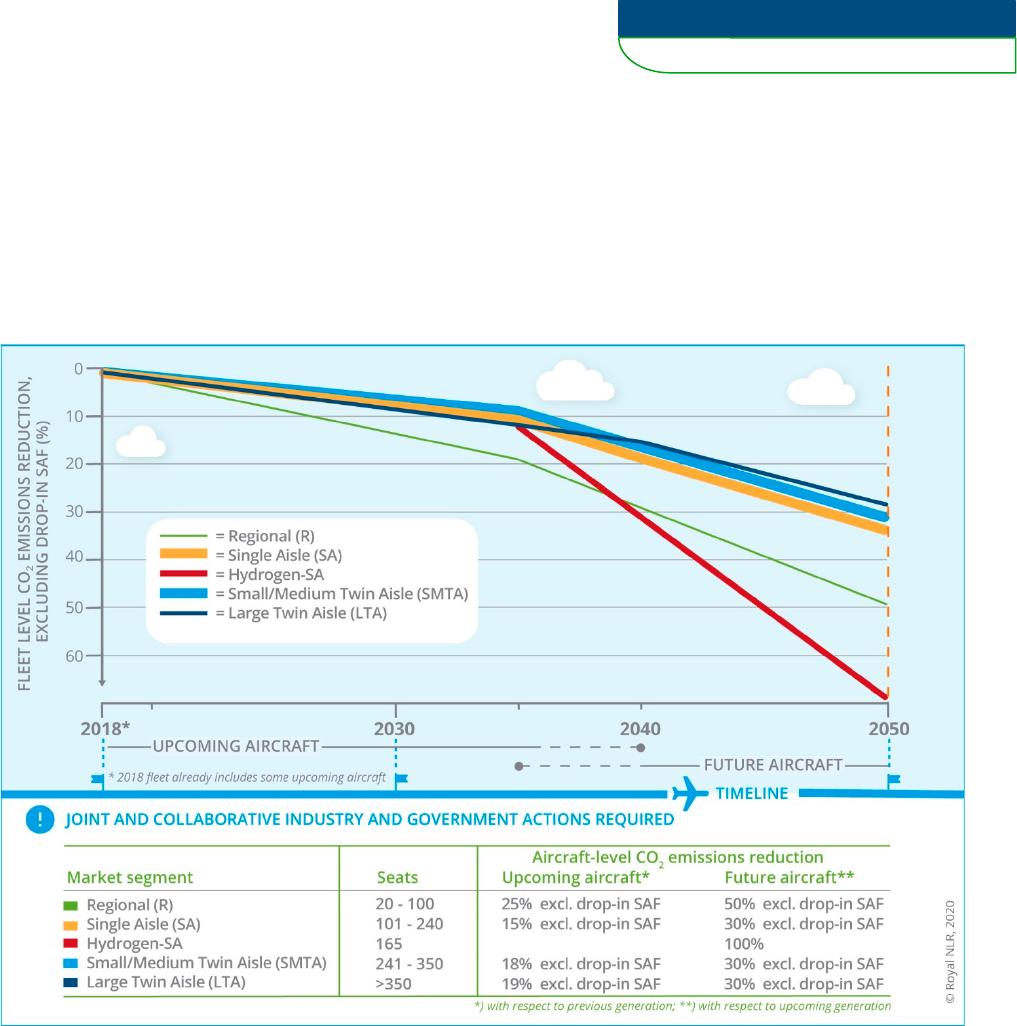

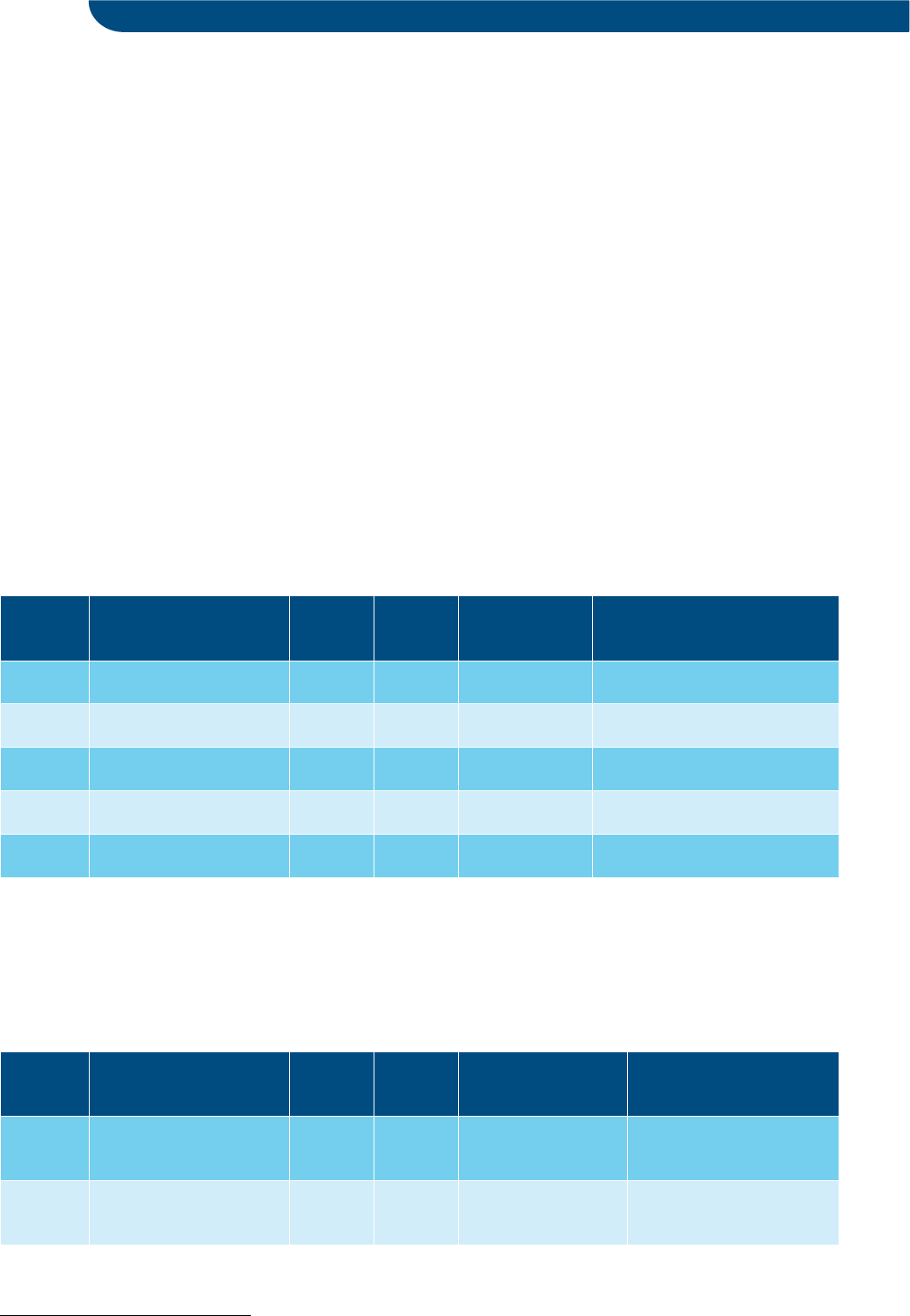

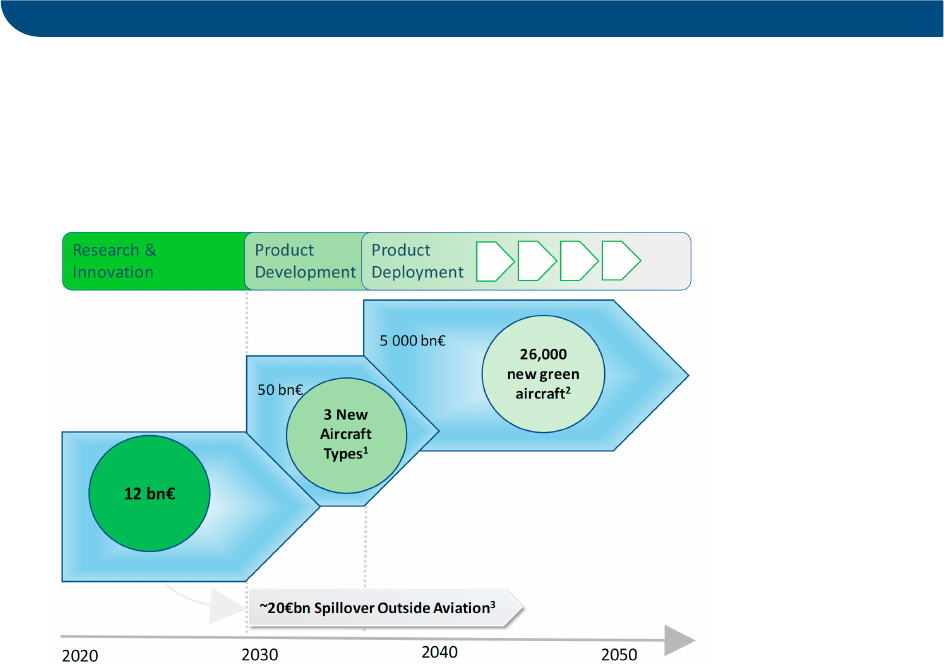

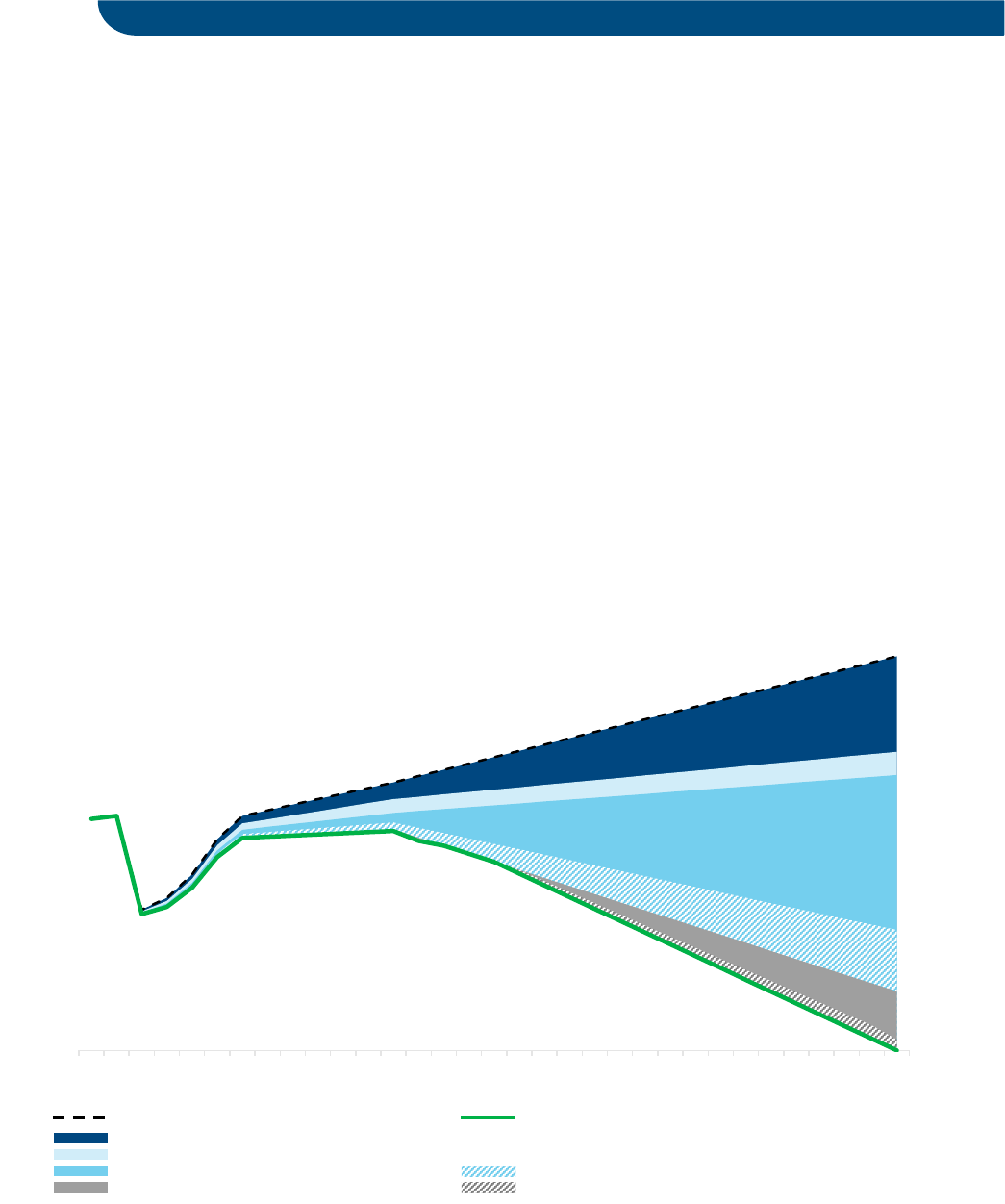

Improvements in aircraft and engine technology

By 2050, improvements in aircraft and engine technology and subsequent fleet replacement hold the largest promise

for decarbonising European aviation. This includes the introduction of a hydrogen-powered single-aisle aircraft on

intra-European routes in 2035. The generation of commercial passenger aircraft to be developed in the next 10 years

has potential to realise a step-change in energy efficiency. Introduced from 2035 onwards, these aircraft types are

forecast to reduce fuel burn by 30% or more per flight compared to predecessors. Range and capacity optimised

hybrid-electric regional aircraft are anticipated to bring down CO

2

emissions by 50% per flight in that market segment.

Future small aircraft and rotorcraft, introduced from 2030, may become drivers for larger aircraft development.

Continued replacement of current aircraft with upcoming models would reduce emissions until 2040. Next-generation

future aircraft would yield aircraft-level CO

2

emissions reduction of 30 to 50% compared to upcoming aircraft types.

Specifically for the intra-European market, a hydrogen-powered aircraft would enable zero-CO

2

flight. At fleet level the

CO

2

emissions reduction by upcoming and future aircraft reaches levels of 28 to 67% in 2050.

Future aircraft availability by 2035 requires technology readiness by 2027 to 2030. The proposed Partnership for

Clean Aviation provides a well-structured stimulus framework to realise this. A collaborative research programme

should also address more disruptive technologies modelled in this study, such as hydrogen-powered or other zero-

CO

2

emission aircraft. Collaboration and cross-pollination with other European and national R&D programmes and

instruments should be ensured. New technologies should be swiftly incorporated in commercial products, helped by

efficient new certification for disruptive technologies. Additional improvements should be delivered by accelerating

previous R&D results for market uptake, through new product offerings or upgrades to in-production aircraft.

Expedited replacement of older aircraft by state-of-the-art models may realise CO

2

emission reductions even earlier.

Besides substantially reducing fuel consumption and fostering green technologies by design, the policies and actions

recommended in this roadmap would more firmly establish the European aviation sector as leading the way towards

sustainable aviation. With environmental concerns intensifying around the world, this offers Europe an important

first-mover advantage.

iv

UNLIMITED DISTRIBUTION

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

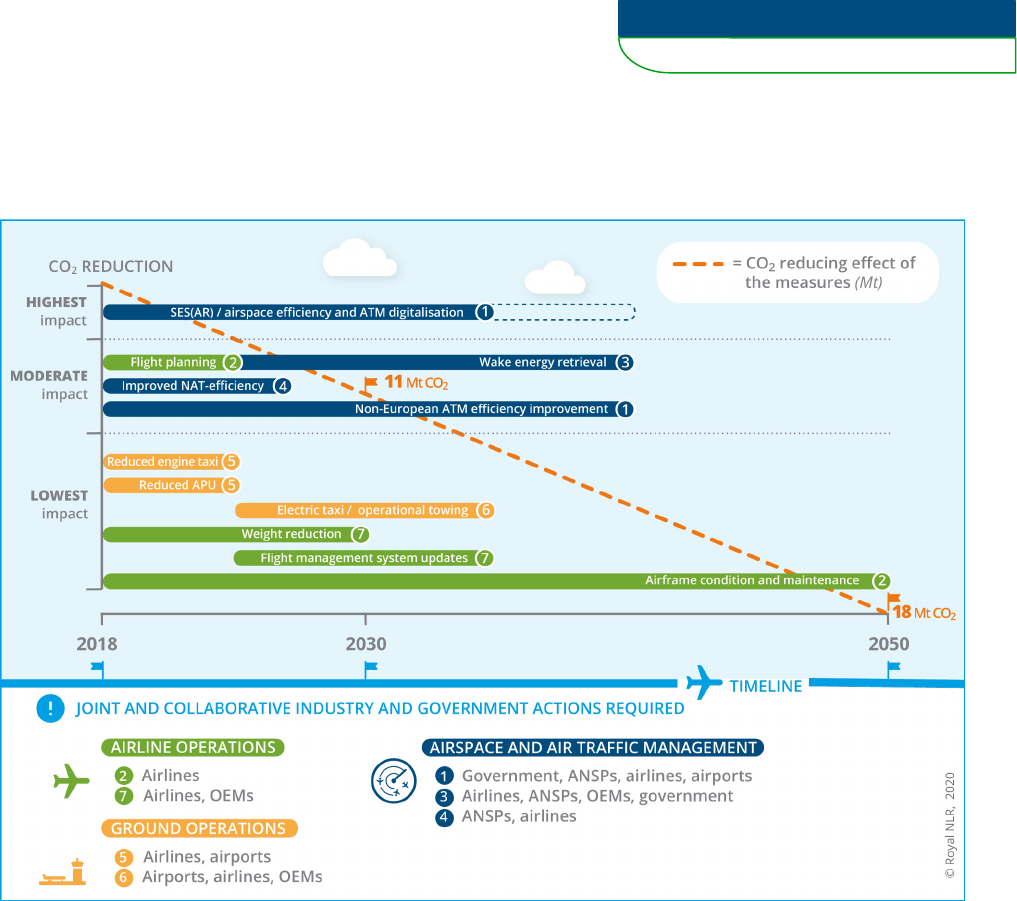

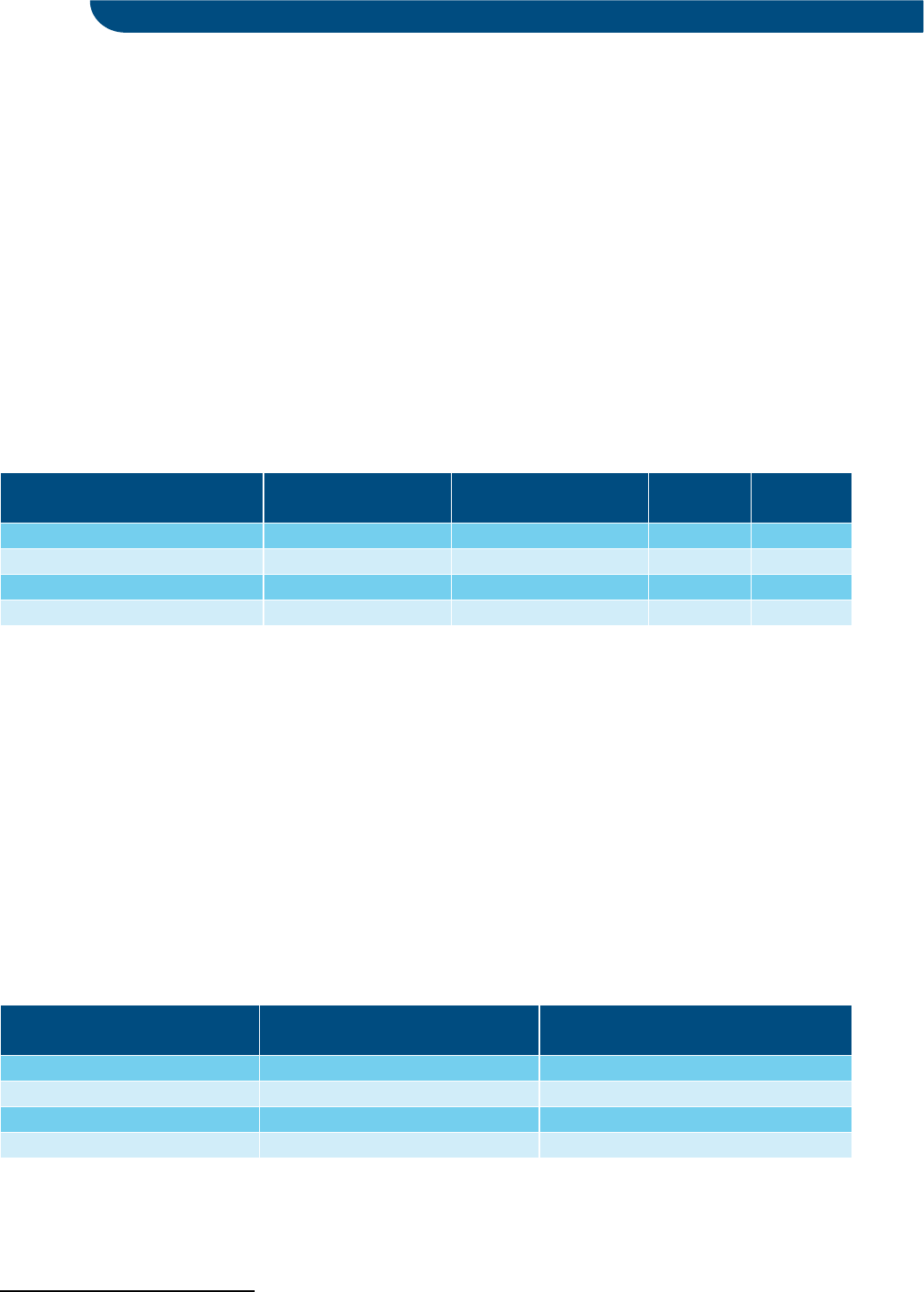

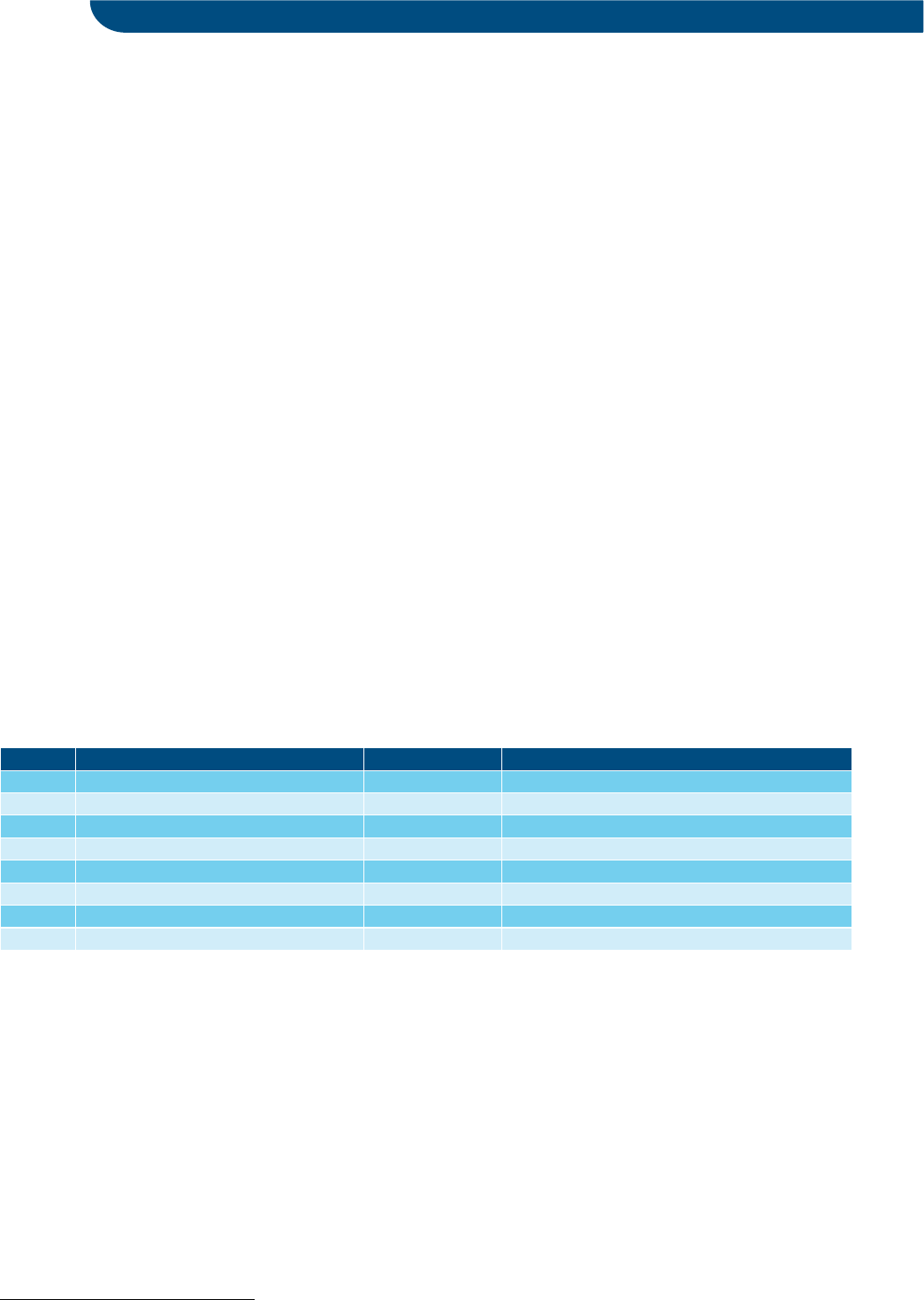

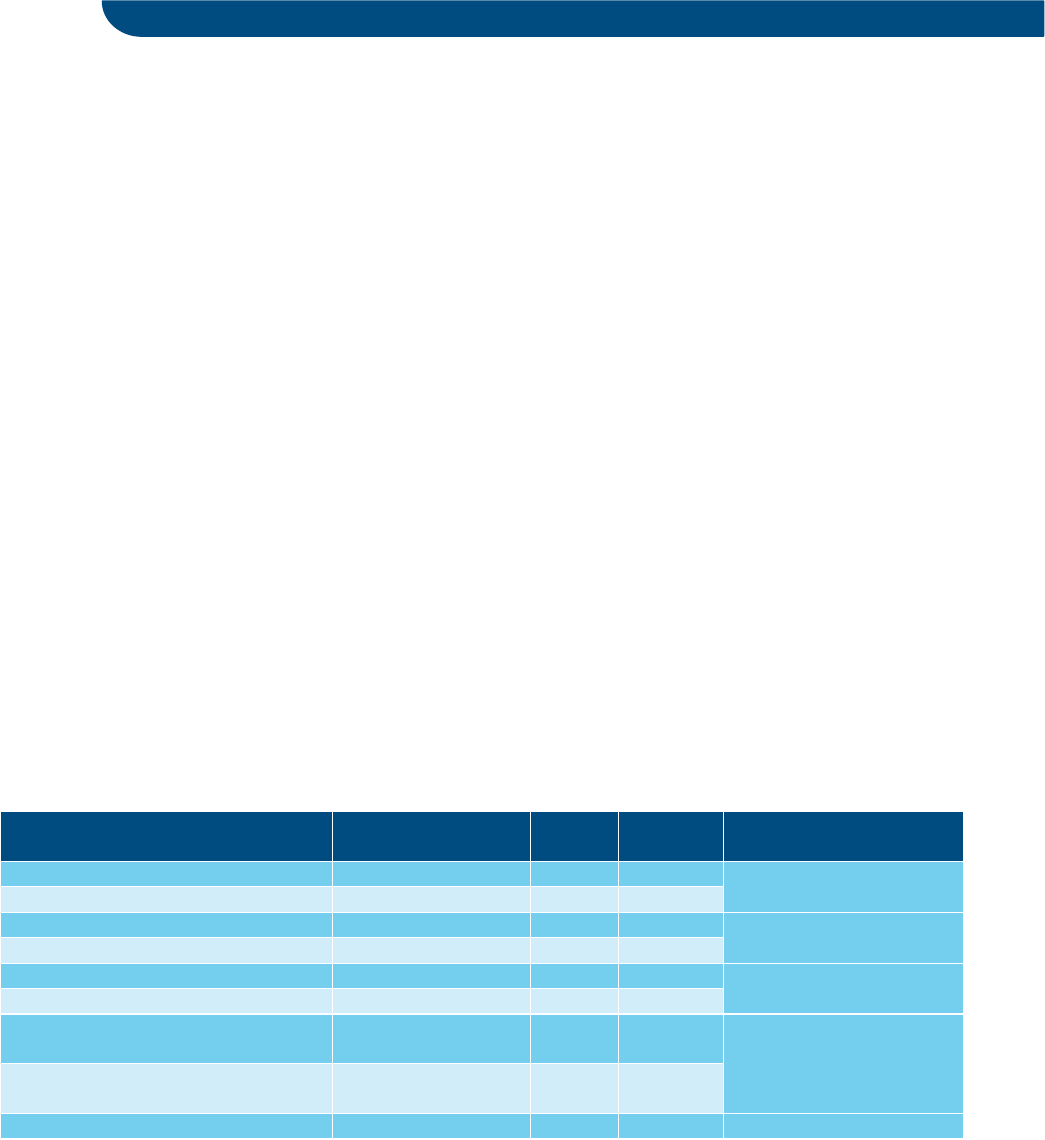

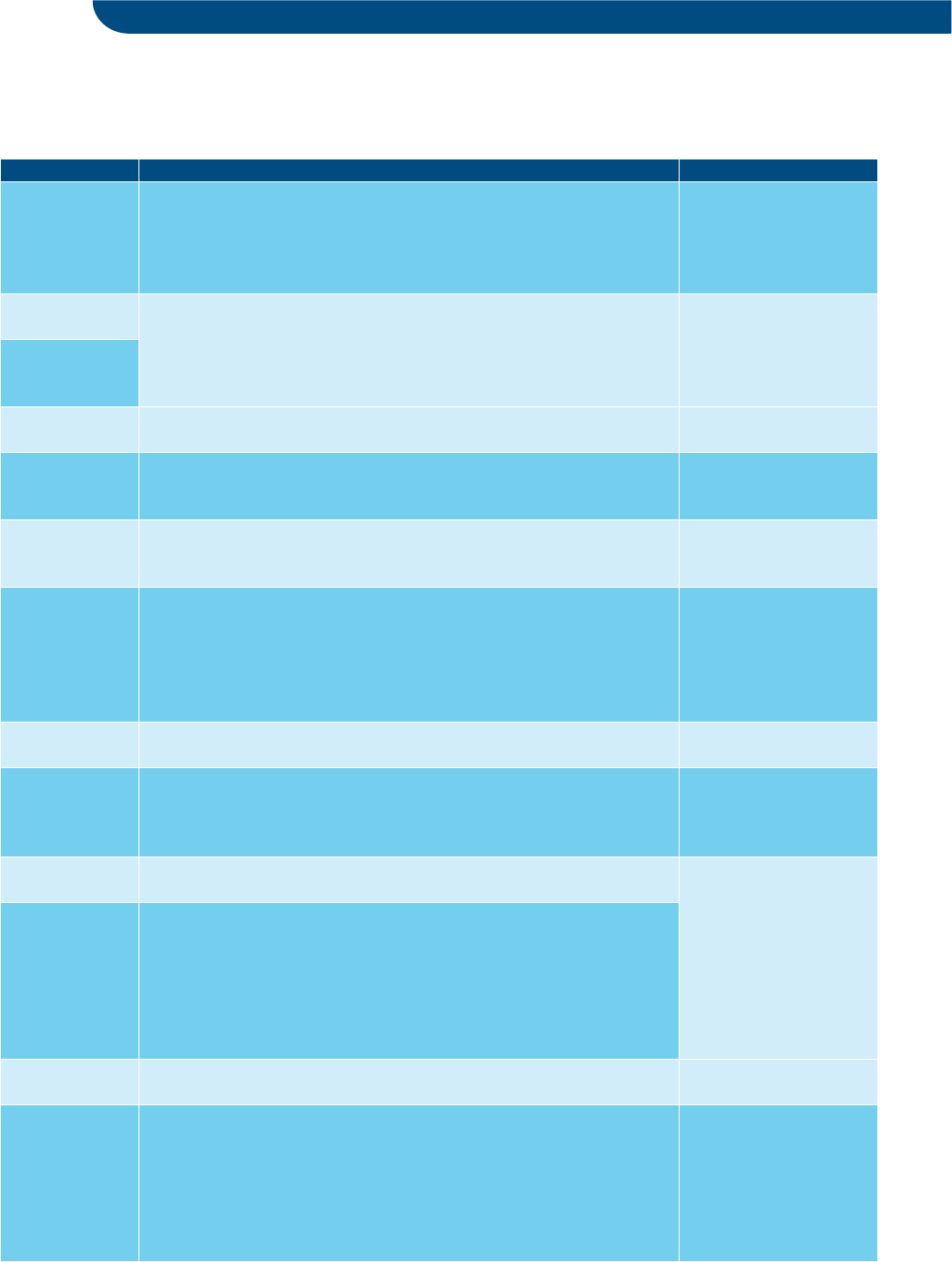

Improvements in air traffic management and aircraft operations

Improvements in ATM and aircraft operations are estimated to be a crucial opportunity to reducing CO

2

emissions in

the short to medium term. Ensuring full and complete implementation of most measures by 2035 at the latest would,

furthermore, allow such benefits to continue yielding impacts between 2035 and 2050.

An array of improvements in ATM and aircraft operations yields a 5 to 6% system-level CO

2

emissions reduction in 2030

and 2050 compared to the reference scenario. Requiring actions from all industry actors and governments, most of

these improvements could be realised by 2035. Within each of the three groups (highest / moderate / lowest impact),

the measures have not been sorted according to impact.

For Europe’s residents and visitors to enjoy the full benefits of the Single European Sky, it is imperative to move more

towards a network-centric and digital ATM sys

tem and requires political willingness to implement many of the

SESAR solutions. Regulation and R&D efforts must optimally support that goal. First and foremost, such a system

would include a renewed set of KPIs with clearly defined accountabilities; a seamless upper airspace; and an R&D

policy ensuring steady progress of new technology development and deployment. Better quantifying the anticipated

benefits following from fuel and CO

2

optimized routing are near-term priorities.

Innovation in communication, navigation and surveillance equipment and processes should also be encouraged, such

that these can be swiftly put into practice. Beyond SES and SESAR, European governments and industry should

globally stimulate regions and States to improve ATM efficiency.

Finally, regulations and incentives should enable and encourage the rapid decarbonisation of ground operations.

Electric operational towing or taxiing solutions should be developed for all common aircraft and, when parked, aircraft

should use renewable energy. Along with possibly stimulating or supporting companies to make such investments,

European governments have a crucial role to ensure the supply of renewable energy can match its increased demand.

v

UNLIMITED DISTRIBUTION

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

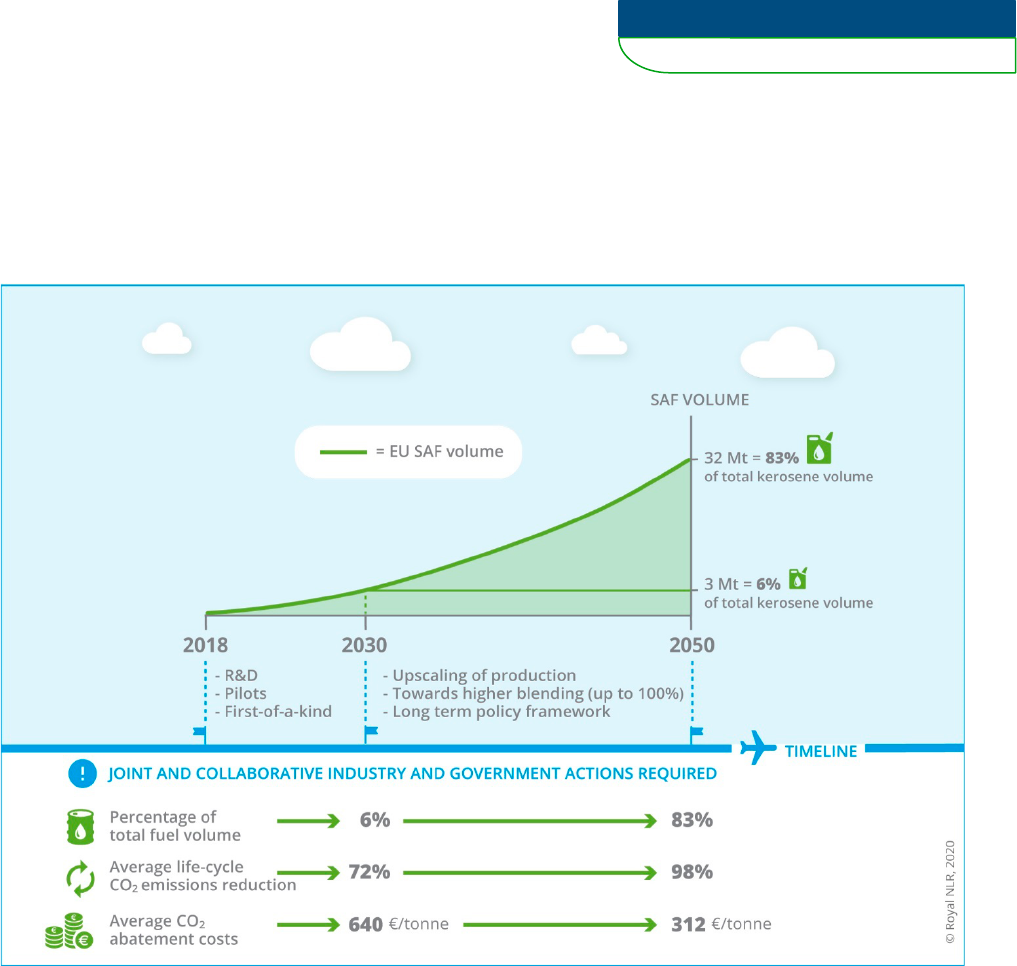

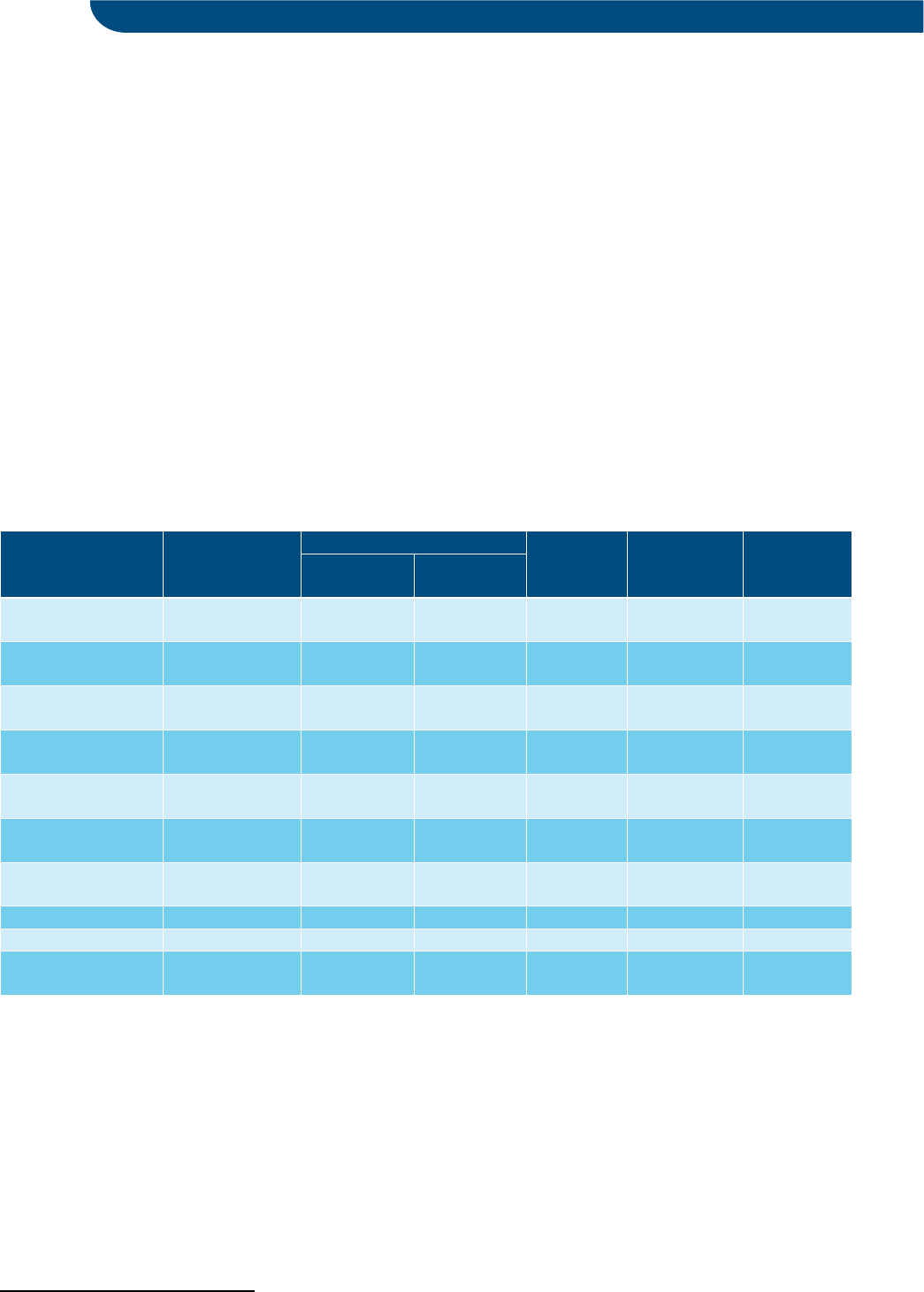

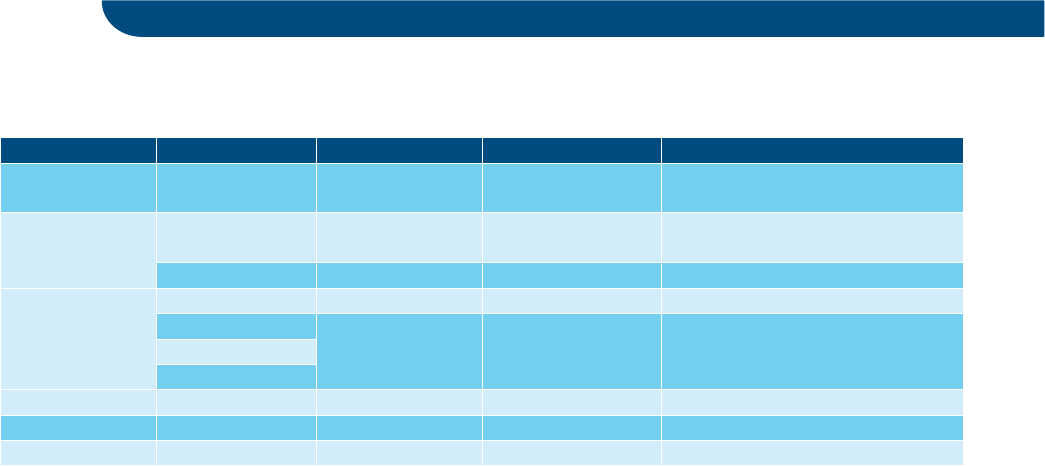

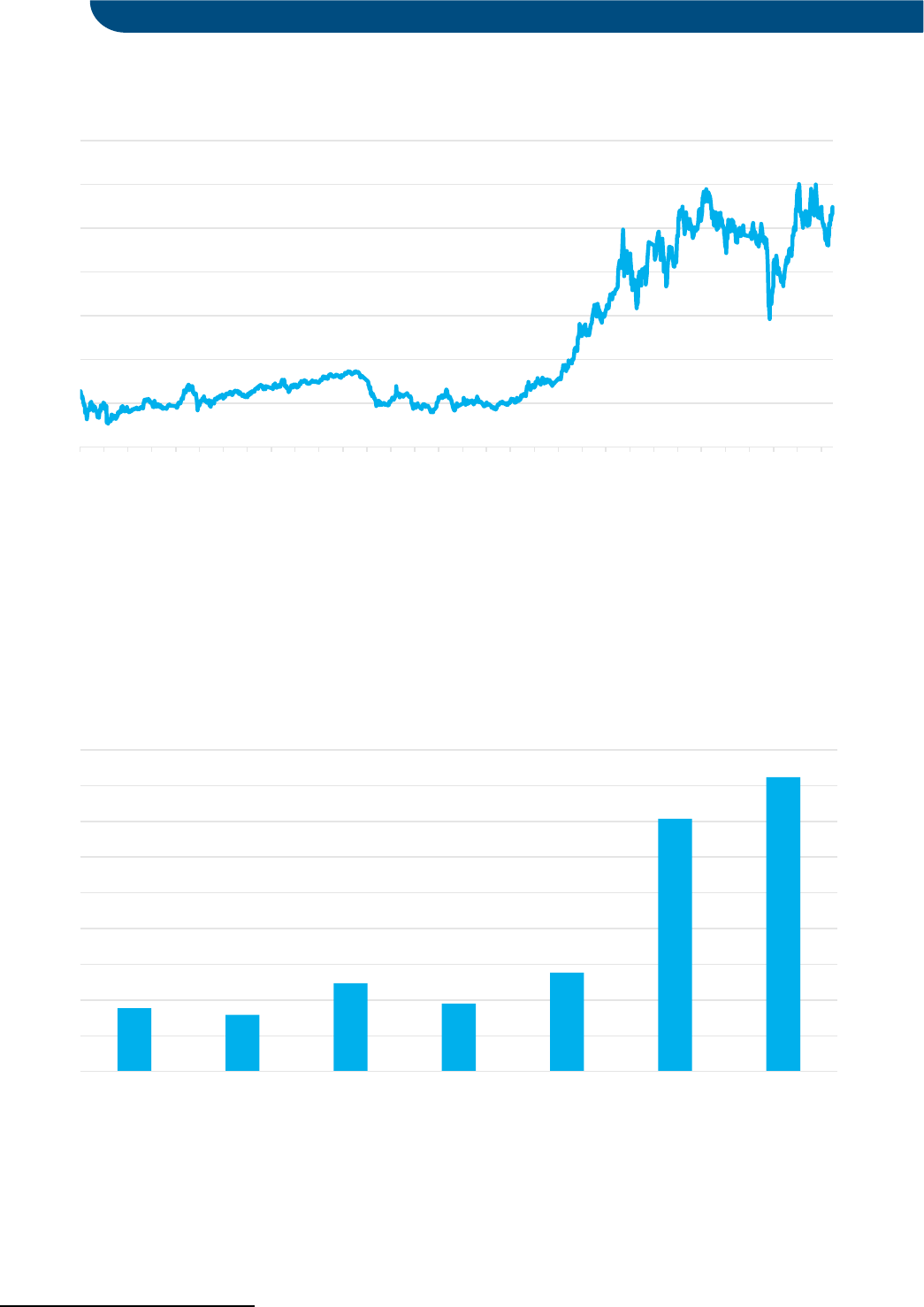

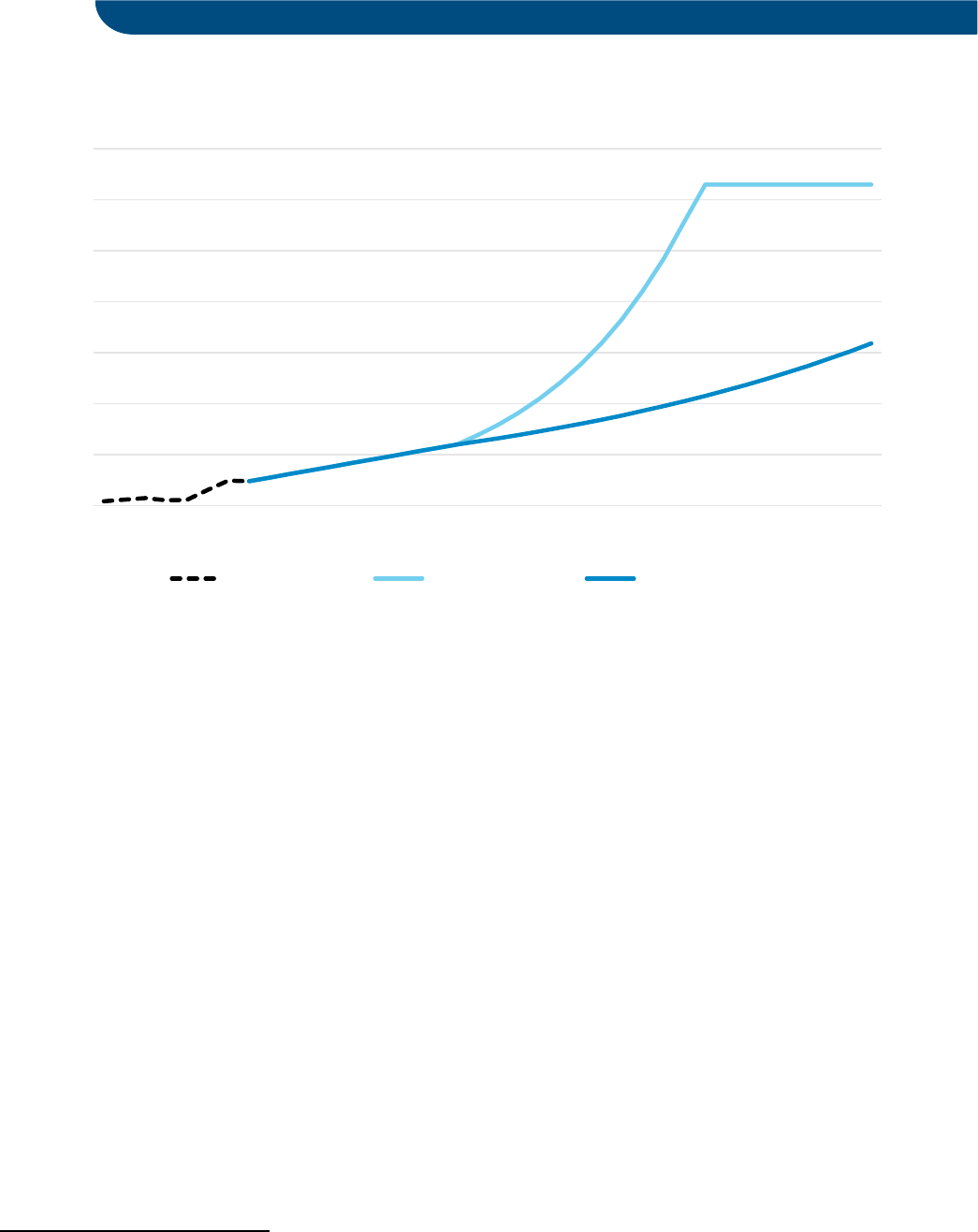

Sustainable aviation fuel

SAFs deliver a major contribution to achieving net zero carbon emissions in 2050. The supply of SAF may increase

from 3 Mt in 2030 to 32 Mt in 2050, equal to 83% of the total kerosene consumption. The SAF contribution is directly

linked to the development of industrial production capacity and strongly influenced by a supporting long-term policy

framework. SAF contribution in 2030 may be increased if a strong political support is given to SAF development. Over

time, life-cycle CO

2

reduction increases to nearly 100% while production costs decrease.

Over time, SAF production volumes and life-cycle CO

2

reductions increase while production costs decrease.

Crucial steps must be taken to scale up and commercialise SAF deployment. While making robust and transparent

sustainability criteria the foundation of a long-term policy framework, a diversified and sustainable feedstock base

should be established. This would combine biofuels from wastes, residues and non-food (lignocellulosic) crops as well

as e-fuels from renewable electricity and CO

2

sourced from direct air capture. Multiple production pathways should be

tested in pilot and first-of-a-kind facilities. This increases technological learning, reduces risk and decreases production

costs. If the price gap with fossil fuels is overcome, SAFs could fulfil the entire kerosene demand from intra-European

flights, necessitating increasing the blending ratio allowed by ASTM certification from 50% currently to 100%.

To effectively address the price difference with fossil fuel throughout the value chain and thereby make SAF more

affordable, policies need to include measures to de-risk investments and boost production and off-take. These

measures could include financial incentives (e.g. carbon pricing, subsidies, auctioning mechanisms and capital grants)

and regulatory measures such as the implementation of an EU wide blending obligation. The timing and conditions

for implementing these measures are currently being investigated in ReFuelEU Aviation. To further reduce cost and

increase emissions reductions, a transparent monitoring and accounting framework should be implemented, similar

to the framework for renewable electricity. This would give airlines the possibility to claim the use of SAF in the most

economically efficient way across the fleet, regardless of where SAF has been physically uplifted.

vi

UNLIMITED DISTRIBUTION

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

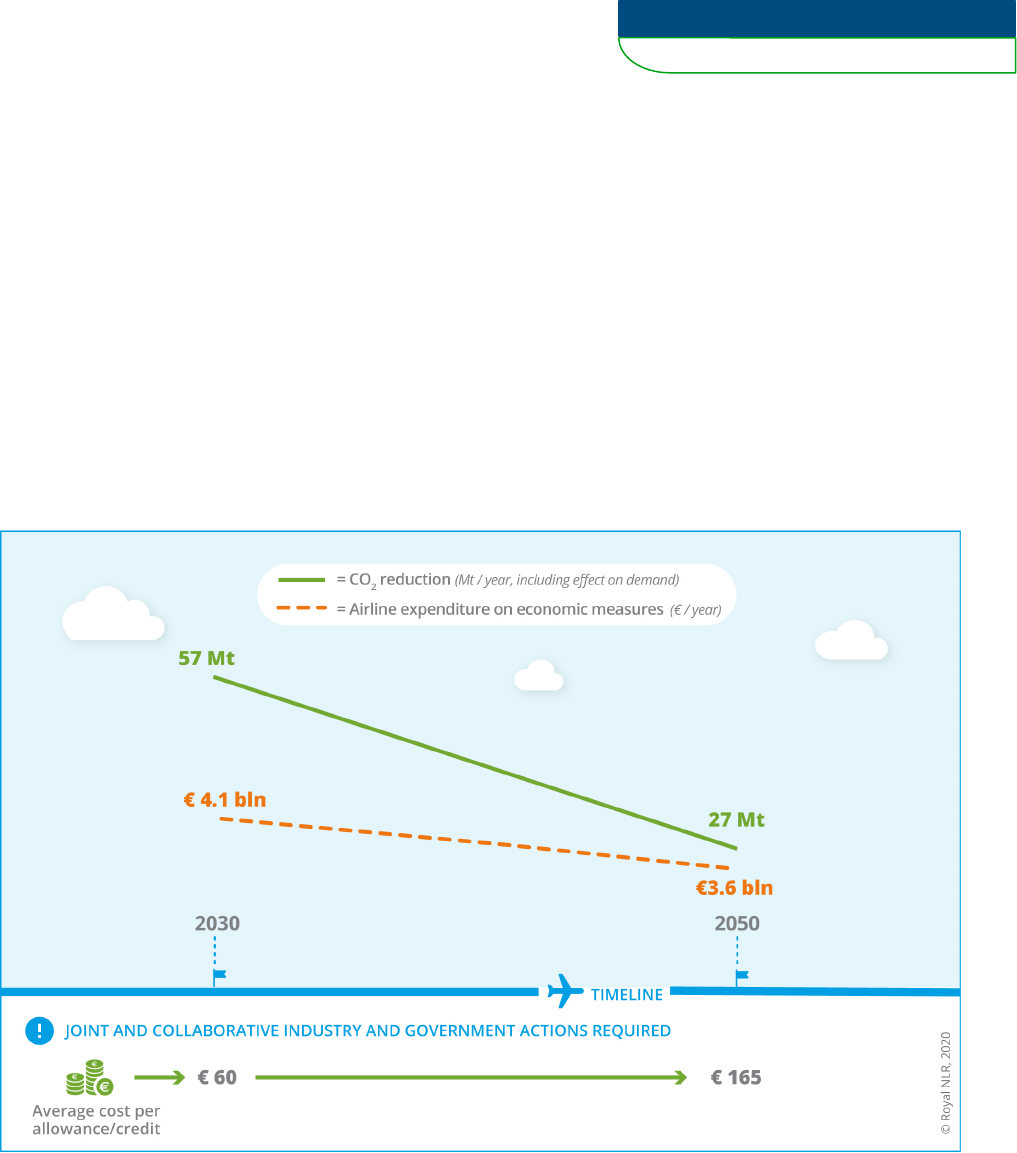

Economic measures

In the short term, smart economic measures are central in the reduction of carbon emissions from aviation. Such

measures assign a price to CO

2

emissions ensuring that airlines take climate costs explicitly into account in their

business decisions. To ensure cost-effectiveness, economic measures must be market-based. The European Emission

Trading Scheme (EU ETS) is the mechanism that is implemented in Europe and which is complemented by the ICAO

CORSIA scheme for international flights. They trigger the acceleration towards the energy transition and bridge the

gap until breakthrough technologies and SAFs become widely available. By 2030, economic measures are expected

to reduce net CO

2

emissions by 27% compared to the reference scenario.

Over time, breakthrough technologies and the use of SAF reduce the role of economic measures. The price of

allowances and carbon credits will increase as they become increasingly scarce. This will eventually lead to a price

whereby carbon removal projects become economically attractive to investors. In 2050, any remaining emissions can

therefore be balanced by carbon removal projects, which are assumed to lead to the issuance of additional emissions

allowances and carbon credits. A global approach is critical to prevent market distortion and carbon leakage.

Smart economic measures are a key mechanism to reducing carbon emissions, especially in the short term when

radical breakthrough technologies and SAFs are not yet widely available. The compliance costs to European airlines

would add up to around 3.6 billion euros by 2050 – € 165 per tonne CO

2

– as allowances and carbon credits become

increasingly scarce.

Guaranteeing the quality of carbon credits through both industry action and policy intervention is key to realising

these necessary reductions in CO

2

. Implementing the global economic measure CORSIA is crucial to keeping

international aviation on track to reduce emissions and contribute to the net zero ambition globally. Earmarking of

revenues ensures the economic measures fully contribute to the development of aviation decarbonisation solutions.

Direct Air Capture is seen as important enabling technology for deployment in the short to medium term in order to

create high quality carbon allowance and credits.

PUBLIC

NLR – Royal Netherlands Aerospace Centre

SEO Amsterdam Economics

Destination 2050

A Route To Net Zero European Aviation

NLR-CR-2020-510 | February 2021

CUSTOMER: A4E, ACI-EUROPE, ASD, CANSO, ERA

AUTHOR(S):

Elisabeth van der Sman

NLR

Bram Peerlings

NLR

Johan Kos

NLR

Rogier Lieshout

SEO

Thijs Boonekamp

SEO

2

NLR-CR-2020-510 | February 2021

Contents

1 Introduction 4

1.1 Context 5

1.2 Approach 11

1.3 Objective 11

1.4 Scope 12

1.5 Reading guide 15

2 Reference scenario 16

2.1 Introduction 16

2.2 Assumptions 16

2.3 Results 22

3 Improvements in aircraft and engine technology 26

3.1 Introduction 26

3.2 Upcoming technology 28

3.3 Future technology 31

3.4 Drivers and barriers 45

3.5 Policies and actions 47

4 Improvements in ATM and aircraft operations 53

4.1 Introduction 53

4.2 Airline operations 54

4.3 Airspace and air traffic management 57

4.4 Ground operations at airports 67

4.5 Drivers and barriers 70

4.6 Policies and actions 73

5 Sustainable aviation fuels 81

5.1 Introduction 81

5.2 Sustainability 82

5.3 Current EU policy framework 86

5.4 Feedstocks and production processes 86

5.5 ASTM certification 89

5.6 Production cost 90

5.7 Supply potential in 2030 94

5.8 Supply potential in 2050 98

5.9 Drivers and barriers 104

5.10 Policies and actions 106

6 Economic measures 114

6.1 Introduction 114

6.2 Types of pricing mechanisms 115

6.3 Smart economic measures 116

3

NLR-CR-2020-510 | February 2021

6.4 Approach 126

6.5 Drivers and barriers 131

6.6 Policies and actions 132

7 System changes and radical ideas 134

8 Assumption and impact modelling 137

8.1 Improvements in aircraft and engine technology 138

8.2 Improvements in ATM and aircraft operations 140

8.3 Sustainable aviation fuels 141

8.4 Economic measures 142

9 Destination 2050 144

9.1 Introduction 145

9.2 CO

2

reduction 145

9.3 Overall policies and actions 151

References 154

Appendix A Abbreviations 171

Appendix B Consulted parties 176

Appendix C Class-averaged improvement potential of upcoming aircraft 177

Appendix D Future aircraft concept studies 179

Appendix D.1 Aircraft with drop-in fuels 179

Appendix D.2 Aircraft with non-drop-in fuels 181

Appendix E Comparison to Waypoint 2050 184

4

NLR-CR-2020-510 | February 2021

1 Introduction

Since the foundation of the first airlines over a century ago, aviation has developed to become a crucial element of

modern society. Connecting people, businesses and families around the globe, it has contributed to global economic

wealth development and increased our understanding and appreciation for different continents and cultures. With

that understanding of the world we live in, however, also comes increased knowledge of how our consumption and

travel patterns affect our planet. Over the past few years, sustainability has grown to become a top priority for

governments, consumers and industry. Various sectors – such as energy generation, industry and automotive – are

making progress in reducing the environmental impact of both their own activities and their products and services.

Maintaining the benefits that aviation brings to the global community, the European air transport industry also has

committed to play its part in that sustainability transition (Aviation Round Table, 2020). Notwithstanding the

achievements realised in terms of reducing fuel consumption per passenger kilometre, reduced circa 45% between

1968 to 2014 (Kharina & Rutherford, 2015) and 80% since the introduction of the first jet aircraft (EUROCONTROL,

2019c), absolute CO

2

emissions have continued to increase. Before the impact of COVID-19 drastically reduced air

travel, aviation was responsible for 2 to 3% of global anthropogenic CO

2

emissions and it is expected that these

numbers are to rise tenfold if aviation does not change its course while other industries do (Cames, Graichen,

Siemons, & Cook, 2015; Pidcock & Yeo, 2016; Becken & Pant, 2020). Social phenomena such as flygskam (flight shame)

and wider questions about future mobility are also affecting the industry’s licence to operate and grow (Topham,

2019; BBC, 2019; EUROCONTROL, 2019c).

This report, initiated by European representatives of (regional) airlines, airports, aerospace manufacturers, and air

navigation service providers and prepared by Royal Netherlands Aerospace Centre and SEO Amsterdam Economics,

identifies pathways to substantially reduce aviation carbon emissions. Potential carbon emission reductions from

future aircraft and engine technology, improvements in air traffic management and aircraft operations, the use of

sustainable aviation fuels and economic measures are first identified. These are subsequently modelled and assessed

against a hypothetical reference scenario that includes activity growth as well as the recent COVID-19 impact in order

to identify the extent to which these efforts can help realise European and international goals. The report focusses on

areas where the initiators and governments (both European and Member States) play a leading role in developments.

Additional initiatives besides the ones included in this study are welcomed and other actors are encouraged to take

responsibility where they can. This concerns both the CO

2

emissions considered in this study as well as other

environmental or sustainability impacts.

In addition to quantifying potential improvements, policies and actions are defined to help make the possibilities

identified a reality. As such, this report – as well as the five initiating parties – hope to inspire all stakeholders in the

aviation industry and governments to take action now to make Europe’s climate ambitions for 2030 and 2050 a

reality.

The remainder of this chapter is structured as follows. Section 1.1 presents the context of the study, providing among

other an overview of current environmental goals, the climate effect of aviation and past efforts to reduce this. Next,

Section 1.2 goes into detail on the approach taken and Sections 1.3 and 1.4 formally define the objective and scope of

the project. Last, Section 1.5 details the structure of the report and thereby serves as a reading guide to the remainder

of the report.

5

NLR-CR-2020-510 | February 2021

1.1 Context

This section discusses the context of this study in greater detail. Although some aspects have been highlighted in the

introductory paragraphs of this chapter, a thorough overview and understanding of this context is deemed critical for

the correct appreciation of the results presented in this report.

Section 1.1.1 first discusses the various international environmental goals and related policy developments. Next, the

costs and benefits of the aviation industry are put into perspective in Section 1.1.2. Then, relevant characteristics of

industry itself are discussed in Section 1.1.3. Last, Section 1.1.4 treats the impact of climate change on society and the

aviation sector in particular.

1.1.1 Climate and CO

2

emissions reduction goals and policy

developments

According to the latest reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the rise of global average

temperatures – when compared to pre-industrial levels – has to be limited to 1.5° to 2° Celsius to prevent doing

further and irreversible harm to our planet (NASA, 2020; Sustainable Aviation, 2020a; Lamontagne, Reed, Marangoni,

Keller, & Garner, 2019; Becken & Pant, 2020). During the 21

st

Conference of the Parties of the United Nations

Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in Paris in 2015, the world set a climate goal based on these

insights: “Holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and to

pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, recognising that this would

significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change” (UNFCC, 2015, Art. 2). The IPCC has determined that in

order to meet the 1.5° or 2° scenarios, net zero carbon must be achieved by 2050 or 2070

3

, respectively (IPCC, 2018b).

DEFINITION: NET ZERO CARBON AND CARBON NEUTRALITY

The IPCC (2018a) states that “[n]et zero carbon dioxide (CO

2

) emissions are achieved when anthropogenic CO

2

emissions

are balanced globally by anthropogenic CO

2

removals over a specified period”. It does not limit CO

2

removal to either

natural (e.g. afforestation efforts) or artificial sinks (e.g. dedicated technologies, such as Direct Air Capture and Storage).

Carbon reductions through avoided emission projects in other sectors, defined as activities that “result in a lower emissions

scenario compared to a hypothetical business-as-usual scenario as a result of a specific intervention” (Carrillo Pineda &

Faria, 2019), are not compatible with the IPCC definition.

Carbon neutrality is used by the IPCC as synonym for net zero CO

2

emission. There are also organisations that use a broader

definition of carbon neutrality, in which it includes avoided emission projects. As these are excluded from this analysis, the

text refers to ‘net zero carbon’ or ‘net zero CO

2

’.

More recently, the European Commission announced its European Green Deal aiming to become a climate neutral

(requiring net zero greenhouse gas emissions) continent by 2050 and presented its proposal for a European Climate

Law (EC, 2019i; EC, 2020d). With that, the Commission subscribes to the 1.5° C IPCC scenario. “All relevant climate-

related policy instruments” are to be reviewed and possibly revised by June 2021 (EC, 2019i, pp. 4-5). Possible changes

include reductions in the amount of free allowances for aviation in the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (EU-ETS) and

updates to both to the Renewable Energy Directive

4

(Simon, 2019) and the Energy Taxation Directive

5

. The

Commission has furthermore noted that “the price of transport must reflect the impact it has on the environment”

3

“In model pathways with no or limited overshoot of 1.5°C, global net anthropogenic CO

2

emissions decline by about 45% from 2010 levels by 2030 (40-60%

interquartile range), reaching net zero around 2050 (2045-2055 interquartile range). For limiting global warming to below 2°C CO

2

emissions are projected to decline by

about 25% by 2030 in most pathways (10-30% interquartile range) and reach net zero around 2070 (2065-2080 interquartile range). Non-CO

2

emissions in pathways that

limit global warming to 1.5°C show deep reductions that are similar to those in pathways limiting warming to 2°C. (high confidence)” (IPCC, 2018b)

4

Council Directive 2018/2001/EU, an update to the original renewable energy directive, 2009/28/EC.

5

Council Directive 2003/96/EC, recently reviewed by the European Commission (2019e). The European Commission has communicated to “look closely at the current tax

exemptions including for aviation and maritime fuels” (EC, 2019i, p. 10).

6

NLR-CR-2020-510 | February 2021

and that “fossil-fuel subsidies should end” (EC, 2019i, p. 10). For 2030, the European Commission proposed a

reduction of greenhouse gas emissions of 55% with respect to 1990 (Simon, 2020a) whereas the European Parliament

voted for a higher reduction of 60% (Simon, 2020b).

Specific to the aviation sector, various industry and governmental organisations have also formulated objectives

(Peerlings, 2020). The International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) set goals for annual fuel efficiency

improvements (2% p.a. through 2050) and carbon-neutral growth (CNG) from 2020 (ICAO, 2016). The newly-launched

Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA), which starts its pilot phase in 2021, was

designed to achieve that latter goal. That target is also supported by the International Air Transport Association (IATA)

and Air Transport Action Group (ATAG), alongside the goal of reducing net emissions to 50% of 2005-levels by 2050

(IATA, 2020d; ATAG, 2020a). Going beyond that, the oneworld airline alliance committed to net zero carbon by 2050

(oneworld, 2020). At a European level, different participants in the aviation chain such as ACI EUROPE, the

International Airlines Group (IAG) and Sustainable Aviation UK have committed to reaching net zero CO

2

emissions by

2050 (ACI Europe, 2019; IAG, 2019; Mace, 2019; Sustainable Aviation, 2020a)

6

.

Air France and British Airways offset

carbon emissions of all domestic flights since January 2020 and easyJet has done so for all flights from November 19

th

,

2019 (Air France, 2019; British Airways, 2019; easyJet, 2019). Finally, ICAO (2019b) has prioritised the development of

“a long-term global aspirational goal for international [civil] aviation CO

2

emissions reduction” in October 2019,

targeting its definition in 2022 (ICAO, n.d.).

EU-ETS AND CORSIA

The EU-ETS and CORSIA are two important elements of the existing environmental aviation policy context in Europe.

Although both are economic measures, there are important differences between the two. The EU-ETS is a so-called cap and

trade system. Sectors to which the EU-ETS applies can emit no more emissions than allowed by the cap and need emission

allowances matching their emissions. Businesses get part of their allowances for free and can buy additional allowances on

the market. If there are no more allowances, no more greenhouse gases can be emitted. As the cap is progressively

reduced, the total amount of CO

2

emissions is reduced as well.

CORSIA, on the other hand, is an offsetting scheme. This means that there is no cap on the total amount of CO

2

emitted into

the atmosphere. Rather, the scheme requires participants (airlines) to offset the amount of CO

2

they emit on top of a pre-

determined baseline value. Offsetting regularly takes the form of planting trees (such that an equivalent amount of CO

2

is

captured and stored in biomass) or financing CO

2

reductions in other industries. This way, the underlying market

mechanism aims to abate CO

2

emissions in the most cost-effective way.

Additional details on EU-ETS and CORSIA are provided in Sections 6.3.1 and 6.3.2, respectively. The two mechanisms are

compared side-by-side in Table 34 in Section 6.3.3.

It is important to note that the targets just discussed concern emissions reductions expressed in absolute terms,

whereas goals in the past often used to discuss emissions reduction per passenger or per passenger-kilometre. A well-

known example are the goals set by a high level group commissioned by the European Commission in Flightpath 2050

and the related Strategic Research and Innovation Agenda submitted by the Advisory Council for Aviation Research

and Innovation in Europe. These aim to reduce CO

2

and NO

X

emissions per revenue passenger kilometre by 75% and

90% respectively, and decrease perceived noise levels by 65%, all with respect to aircraft from the year 2000 (EC,

2011). Furthermore, these goals have steered the various Clean Sky programmes (Clean Sky, n.d.). The challenge with

such relative efficiency metrics is that the absolute emissions levels could continue to increase even if efficiency

continued to improve.

6

The UK commitments likely follow from the advice by the UK Committee on Climate Change (2019) to its government to include international aviation and shipping in

its (binding) national net zero 2050 targets

7

NLR-CR-2020-510 | February 2021

1.1.2 Aviation as part of society

The European Parliament notes the aviation sector supports around 5 million jobs and contributes € 110 billion to the

European GDP per year (Erbach, 2018). If secondary – indirect, induced and catalytic – effects are included, these

numbers rise to 12 million jobs and a € 700 billion plus GDP contribution (ATAG, 2019). Similarly, the recent Aviation

Round Table (2020) notes almost 10 million jobs and € 672 billion in economic activity. Given EU totals of 227 million

jobs and € 17 trillion total GDP, aviation is estimated to be directly responsible for 1 in every 100 EU jobs

(approximately 5 per 100 with secondary effects) and slightly more than 1% of the EU GDP (rising to over 4% with

secondary effects) (IMF, 2019b; eurostat, 2019; Aviation Round Table, 2020). Without aviation, leisure and business

travel would not be the same as we know it today, and modern conveniences such as next-day global deliveries would

be limited. Put differently: through the connectivity it provides, aviation has grown to become an unmistakable

component of modern society and people’s need for mobility.

Benefits, however, do not come without costs. Limiting the present discussion to the scope of this report – CO

2

emissions as part of broader environmental impact – pre-COVID worldwide commercial aviation was computed to be

responsible for between 2 and 3% of anthropogenic CO

2

emissions (ATAG, 2018; EEA, EASA & EUROCONTROL, 2019;

Erbach, 2018). The most detailed computation states 2.4% (Graver, Zhang, & Rutherford, 2019), equal to 918 million

tonnes in 2019 (Graver, Rutherford, & Zheng, 2020). To that figure, passenger travel contributed the most at 85%,

with freight carriage (including belly cargo) causing the remaining 15% (Graver, Rutherford, & Zheng, 2020). In Europe,

departing flights in 2016 were responsible for 171 million tonnes of CO

2

– approximately one-fifth of global aviation

emissions. European commercial aviation emissions have almost doubled between 1990 and 2016 (EEA, EASA &

EUROCONTROL, 2019) and correspond to 4.3 to 5.6% of total EU CO

2

emissions

7

and 3.6 to 3.9% of total EU

greenhouse gas emissions

8

in 2016 (UNFCCC, n.d.; EEA, 2019). Taking other greenhouse gases and global warming

effects into account, the contribution from global aviation is approximated to be two to three times as large as CO

2

alone (Grewe, et al., 2017; Grewe, 2019; Lee, 2018; Lee D. , et al., 2020; Lee D. , et al., 2009; EASA, 2020).

CO

2

AND NON-CO

2

INFLUENCES ON GLOBAL WARMING

In addition to CO

2

, there are other effects that have a positive or negative influence on global warming. This influence is

measured as radiative forcing (RF), expressed in Watts (of energy) per square metre (of the Earth’s surface area). Whereas

the CO

2

contribution to RF is “well-understood” (Lee, 2018, p. 2), substantial uncertainty exists about other sources – such

as contrail formation and induced cirrus cloudiness.

Following the recent publication of EASA’s updated analysis of the non-CO2 climate impacts of aviation (EASA, 2020), the

European Commission commented that “unlike CO

2

impacts, which directly correlate to the amount of fuel burned, the

complexity of measuring non-CO

2

climate impacts – and the uncertainty regarding trade-offs between the various impacts –

makes targeted policy development in this area more challenging” (EC, 2020j). As further discussed in Section 1.4.2, non-

CO

2

effects are not included in the present study.

1.1.3 Workings of the aviation industry

What started out with linen and wood in a grass field over a century ago has evolved into a truly global industry, built

up of an intricate and complex network of stakeholders, suppliers, integrators, operators and authorities that

contribute to air transport. Despite the tremendous growth that the aviation industry has seen, profit margins are

limited and risks are substantial (Doganis, 2010).

7

3,941,273 kilotonnes without land use, land use change and forestry (LULUFC); 3,185,038 with LULUFC (UNFCCC, n.d.).

8

Total EU greenhouse gas emissions in 2016 were 4,441 million tonnes (EEA, 2019), yielding a share of 171 / 4441 = 3.85%. The European Aviation Environmental Report

states 3.6% (EEA, EASA & EUROCONTROL, 2019).

8

NLR-CR-2020-510 | February 2021

Innovation is a key driver for the aviation industry. The sector generally takes a long-term perspective. Aircraft are

designed to have a lifespan of 20 to 30 years. It can take 15 years to develop from concept to production. This is

partially explained by the focus on safety and associated stringent certification requirements. Programmes normally

break even only after ten to twenty years of production (Sadraey, 2013; Buxton, Farr, & Maccarthy, 2006; Johansson,

2014) and manufacturers are often said to bet their entire company’s worth when committing to a new aircraft

(Raymer, 2002). Especially in times of major change – such as the transitions from wood to metal aircraft, or from

propeller-driven types to jets – not all manufacturers manage to survive, either because they committed to the new

technology too early, committed to the new technology not early enough, or committed to the wrong technology.

Manufacturers often develop families of aircraft, with each type offering different capacity and range. Similarly, new

concepts are regularly based on designs already in production. Due to the complexity of the product, intermediate

upgrades are difficult: a new engine usually requires changes to the wing, which in turn affects other parts of the

aircraft. Nevertheless, continuous and incremental developments are incorporated over the production lifetime of

aircraft.

These characteristics have a clear impact on the capability of the airlines together to take up novel aircraft in their

fleets. Long financial lifetimes make it very costly to replace existing technology frequently and airlines are dependent

on what new products are offered in the market. Another difficulty for airlines is that network and fleet planning have

a much longer time horizon than the day-to-day operations. Seemingly good decisions (buying an expensive but fuel

efficient new aircraft) might end up very different if circumstances change (decrease in oil price). Given limited profits,

an intense focus on operating costs is unsurprising.

Infrastructure planning challenges that airports face see a similarly long time horizon. Alike as well are the significant

investment costs related to infrastructure, comparable to what is observed in aircraft development. This is true for

terminal expansions or changes, but even more so for the addition of runways or new airport development. When

airports are located close to residential areas – as is quite common in Europe – land may not be readily available and

surrounding communities may be concerned about the impact on their local environment or on global warming, as

the London Heathrow expansion case shows (Morgan, 2020). Notwithstanding the validity of these interests, pre-

COVID aviation growth projections show the “capacity crunch” currently faced by various airports throughout Europe

is unlikely to lessen (EUROCONTROL, 2018b) – causing increasing delays and preventing more and more people from

travelling by air.

1.1.4 Effects of climate change on society and aviation

According to the UN IPCC there is scientific consensus that the climate is changing. As a result, the chance of extreme

weather events increases. Such events have a significant human cost, reduce economic productivity and increase the

costs associated with damage prevention or restoration.

Over the past 30 years damages resulting from climate-related weather events increased by a factor 20 (Swiss Re,

2018). In 2017 the weather-related damages amounted to $ 330 billion in 2017, making it the most costly year on

record. Around two-thirds of the damages were caused by hurricanes in the North Atlantic (Munich Re, 2018). In

addition, climate-related weather events are a main cause of humanitarian crises, such as food shortages. In 2018,

around 2 million people were displaced as a result of climate related weather events such as drought, floods and

storms (WMO, 2019). In 2017, between 8,000 and 10,000 people lost their lives due to extreme weather events (Swiss

Re, 2018; Munich Re, 2018), with heat being the most deadly. Adapting to climate change is also costly, especially for

9

NLR-CR-2020-510 | February 2021

small island economies and low-income countries. Required investments for developing countries are estimated at

$ 140 – 300 billion in 2030 and $ 280 – 500 billion in 2050 (IMF, 2019a).

Weather related damages in Europe amounted to $ 24 billion in 2017 (Swiss Re, 2018). Going forward, the EEA

expects that the damages will be largest in Southern Europe (EEA, 2017). Extreme weather events may also enhance

the speed in which the climate changes. The emissions from wildfires in Italy and Portugal in 2017 for instance were

among the highest ever recorded (EC, 2019g). By the year 2100, two-thirds of the European population could be

affected by weather-related disasters, compared with 5% in 2018 (EC, 2018b).

The aviation sector is affected by climate change through changes in temperatures, precipitation, wind and storm

patterns and sea-levels.

Temperature

The years 2015 – 2018 were the four warmest on record (WMO, 2019). Europe experienced extreme heatwaves over

this period. Human-induced warming had already reached 1° C above pre-industrial levels (1850-1900) and is

increasing at approximately 0.2° C per decade (EC, 2018b). Temperatures in Europe are expected to rise faster than

the global average. In winter, warming is estimated to be strongest in north-eastern Europe and Scandinavia. In

summer warming is expected to be strongest in southern Europe. How does warming affect the aviation sector?

Warmer air is less dense which reduces the lift of aircraft. This means that the operational capacity of runways is

reduced. Airlines may experience runway length issues and could be forced to reschedule heavier aircraft to cooler

times of day, reduce payloads or depart with a higher thrust setting causing more noise and emissions (ICAO, 2018a).

Furthermore, airports may need to invest more in air conditioning systems. Extreme heat also causes damage to

runways and taxiways (EUROCONTROL, 2018a). In regions where temperatures and drought increase, there is a

heightened risk of desertification and sand storms, which may disrupt airport operations and damage aircraft. In

February 2020, sand storms in the Canary Islands for instance led to the closing of most of its airports. Extreme cold

on the other hand, may lead to the freezing of airport equipment. Furthermore, there will be a larger need for aircraft

de-icing, with anticipated associated increases in emissions. This reduces the efficiency of airport operations and may

lead to delays and cancellations (ICAO, 2018a). Temperature changes may also lead to changes in demand patterns

(EEA, 2017), not only in terms of destination (region) but also in terms of seasonality. Demand for destinations which

face extreme heat and water scarcity may decline. The same holds for winter sport destinations that are affected by a

reduction in snowfall (ICAO, 2018a). Demand changes not only affect airports and airlines but also the ANSPs.

Precipitation and humidity

Expectations with respect to precipitation (rain and snow) differ regionally. In Europe, wet regions are likely to get

wetter (Northern and Eastern parts) especially during winter, while dry regions (South of Europe) are getting dryer

especially in summer (EEA, 2017). Heavy precipitation reduces the efficiency of airport operations. Snow-clearance for

instance may cause delays and cancellations. In extreme cases, drainage systems may be inadequate causing damage

to airport infrastructure and assets and disrupting operations for a longer period of time. Less rain and longer periods

of drought calls for active water management (EUROCONTROL, 2018a). In some regions there may be an increase in

the level of humidity which increases the chance of morning fog (ICAO, 2018a). At airports without a modern ILS, this

also leads to disruptions.

Wind patterns

Temperature differences lead to changes in wind directions and speeds. The northern parts of central and western

Europe may see an increase in extreme wind speeds, whereas the opposite is true for southern Europe. Changes to

the prevailing wind directions affect runway use. Strong crosswinds reduce airport capacity and disrupt operations

when winds are too heavy to take off or land. Air turbulence may also increase which can cause re-routings, less

comfortable flights and heightened maintenance costs (EUROCONTROL, 2018a).

10

NLR-CR-2020-510 | February 2021

Storm patterns

In some regions storm frequency and intensity may increase, whereas in others they may decrease (ICAO, 2018a).

Northern, north-western and central Europe may see an increase in severe autumn and winter storms. Also there

could be an increase in the number of cyclones in central Europe. In the Mediterranean the number of cyclones may

decrease in number, but increase in intensity. Heavy storms reduce airport and airspace capacity, causing delays,

cancellations, re-routings and additional fuel burn. Furthermore, storms may damage infrastructure and equipment.

Tropical storm Jebi, for instance, led to the inundation of Kansai airport in 2018, leaving thousands of passengers

stranded (WMO, 2019). With more heavy storms, the risk of lightning strikes also increases. Although aircraft are

designed to withstand lightning, it may cause damage to aircraft (EUROCONTROL, 2018a; ICAO, 2018a).

Sea-level rise

Rising temperatures also lead to a rise in sea-levels due to the melting of glaciers and ice. Over the 1993-2018 period,

the average sea-level rose by 3.15 mm per year. The 2018 sea-level was the highest ever recorded (WMO, 2019).

There is scientific consensus that sea-level rise will continue and possibly at an increasing pace (ICAO, 2018a). A

temperature increase of 1.5 ° to 2 °C, for instance, could trigger an irreversible loss of the Greenland ice sheet which

could lead to 7 meters of sea level rise, directly affecting coastal areas and low-lying lands and islands in Europe (EC,

2018b). Airports are sometimes located near large bodies of water away from built areas, which makes them

vulnerable to sea-level rise. Research indicates that a one metre rise in sea-level is expected to increase the risk of

inundation at 96 European airports when no further protectionist measures (such as building higher levees) are taken

(EUROCONTROL, 2018a). Airport infrastructure may need to be adapted or relocated which comes at a significant cost

(ICAO, 2018a).

To sum it up, extreme weather events reduce the efficiency of airport and airline operations, which may lead to delays

and flight cancellations. Disruptions in one region may have knock-on effects in other regions. Reduced operational

efficiency leads to additional costs. Damage to infrastructure and equipment as well as additional maintenance further

inflates costs.

A survey among European aviation stakeholders

9

showed a quarter of them is already experiencing the impacts of

climate change (EUROCONTROL, 2018a). On a global scale 74 percent of the stakeholders is experiencing the impacts

of climate change, as indicated by a survey

10

of the ICAO Committee on Aviation Environmental Protection (CAEP)

(ICAO, 2018a). Both surveys indicate that most stakeholders expect their business to be impacted by climate change in

the future. The most severe impacts are expected from increasing temperatures, changes in wind conditions and

increased precipitation. Sea-level rise was indicated as a potential risk by fewer respondents, probably because the

issue is more localised (ICAO, 2018a; EUROCONTROL, 2018a).

To limit the impacts of climate change, aviation stakeholders can implement adaptation measures. This requires a risk

analysis and a corresponding adaptation strategy (ACI World, 2020a). The survey among European stakeholders

showed that 52 percent have already started implement adaptation and resilience plans (EUROCONTROL, 2018a). On

a global scale the percentage is somewhat lower: 30 percent (ICAO, 2018a).

In addition to mitigation, the aviation sector also needs to take action to reduce its climate impact. Limiting the

climate impact will reduce the costs of adaptation measures in the future.

9

In total 93 responses were received including airlines, airports, ANSPs, civil aviation authorities and manufacturers across Europe. The authors indicate that there may

be a degree of self-selection bias with organizations that have a larger interest in the issue or are already taking measures being more likely to take part in the survey.

10

In total 88 responses were received including airlines, airports, ANSPs and member states.

11

NLR-CR-2020-510 | February 2021

1.2 Approach

European aviation industry trade organisations ACI EUROPE, Airlines for Europe (A4E), ASD Europe, European Regions

Airline Association (ERA) and CANSO initiated this study and jointly identified the need to develop a roadmap for 2020

up to 2050 listing current and proposed future policies and actions that can contribute to meeting international

climate goals as set out in Section 1.1.

Rather than choosing either a top-down or bottom-up methodology, the current report fuses elements of the two in

order to combine the strengths of both. In this hybrid approach, an ambition level was determined that is both

consistent with realistic expectations of future developments in the areas of aircraft and engine technologies, air

traffic management and aircraft operations, sustainable aviation fuel, economic measures, as well as with

(international) climate and sustainability policymaking. These expectations were based on an extensive literature

review to which iteratively input was given by industry and research professionals – the full list of which is included in

Appendix B. Using this approach, this report presents a possible pathway towards the decarbonisation of international

aviation in Europe.

Notwithstanding the rigour with which this study was conducted, it is emphasised here that there are uncertainties to

this document – as holds for any work aiming to predict a thirty-year future. Conclusions and recommendations will

have to be updated as time progresses. Some developments might not bring the benefits anticipated from them,

whereas others – possibly even breakthroughs entirely unforeseen today – might surpass expectations. Similarly,

while some policies and actions now focus on developing innovative technologies and associated measures, others

will need to follow that support the delivery of their benefits to all stakeholders. It is thereby emphasised that this

report presents a pathway towards decarbonising European aviation but does not necessarily present the only way.

Uncertainty, however, can also lead to inaction – inaction that no-one can afford. As such, this report is presented as a

well-supported foundation for tackling the challenge of decarbonising aviation and guiding government and industry

action in the crucial following years to come.

1.3 Objective

This report has the objective to identify opportunities to achieve net zero CO

2

emissions from all flights within and

departing from the EU

11

by 2050. Following the definition of ‘net zero’ carbon by the IPCC (2018a), this means that all

possibly remaining carbon emissions will have to be removed from the atmosphere through negative emissions,

achieved through natural carbon sinks (e.g. forests) or dedicated technologies (carbon capture and storage).

Destination 2050 considers improvements in aircraft and engine technology; improvements in ATM and aircraft

operations; sustainable aviation fuels; and economic measures. Most significantly, solutions of this kind will allow

retaining the social and economic benefits of aviation, while delivering substantial improvements in the level of CO

2

emissions. The report does not merely list possible improvements, but also pays attention to the way these

improvements can be realised. This way, this study does not aim to be just an overview of opportunities, but a

document that initiates action from all parties involved.

11

The exact geographical scope of this study is defined in Section 1.4.1.

12

NLR-CR-2020-510 | February 2021

This report is targeted at various audiences. First: industry professionals, which are the ones to commit to researching,

developing and implementing the innovations that are required. Second: European and national policy makers, which

play an essential role in setting the conditions that make innovation and market introduction possible, and ensure that

aviation can continue to benefit Europe’s economy and society. Last, fitting with the scale of the effort ahead and the

societal expectations concerning this topic, this report also hopes to inform a wider array of opinion leaders interested

in the decarbonisation of European aviation. Section 1.5 at the end of this chapter highlights the most relevant

sections of this report for each of these audiences.

1.4 Scope

This study is limited in scope in terms of geography (Section 1.4.1), emissions and emissions accounting (Sections 1.4.2

and 1.4.3) and flights considered (Section 1.4.4). Last, Section 1.4.5 defines and shortly explains the four areas in

which improvements are sought in the context of this study.

1.4.1 Geographical scope

In geographical scope, the study is limited to commercial flights departing from airports within the European Union

(EU), the United Kingdom (UK), and the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), consisting of Iceland, Liechtenstein,

Norway and Switzerland. This is visualised in Figure 1. For brevity and legibility reasons, EU+ is used to refer to EU27 +

UK + EFTA, unless explicitly stated otherwise.

Figure 1: Geographical scope: commercial flights departing from airports within the European Union (EU), the United

Kingdom (UK), and the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), consisting of Iceland, Norway, Switzerland and

Liechtenstein.

Norway and Iceland cooperate with current EU targets in aiming to reduce GHG emissions in 2030 by at least 40%

compared to 1990 levels. Both countries take part in the EU ETS since 2008 and as of 2021 will implement Effort

13

NLR-CR-2020-510 | February 2021

Sharing regulation and LULUCF regulation. In 2017, Switzerland and the EU agreed to link their emissions trading

systems. The agreement entered into force on January 1

st

, 2020. Switzerland keeps a separate system, but its scope is

similar to the EU ETS and also includes aviation. The linking has resulted in the mutual recognition of EU and Swiss

emission allowances (EC, 2019g).

1.4.2 Emissions

This study is limited to CO

2

emissions. Although, as described in Section 1.1, the impact of aviation on climate change

is wider, these effects are less well understood.

Although other emissions and climate effects, such as NO

X

, noise and contrail formation, are not modelled, some

attention is paid to these in a qualitative sense – in case impacts are expected to go hand in hand with the reduction

of CO

2

emissions, or imply trade-offs. Carbon dioxide emissions related to surface airport access (both ingress and

egress), aircraft production and maintenance, and energy supply and heating of (airport) buildings are not taken into

account in this report, either due to resource limitations or data availability, or because these types of emissions are

addressed in other programmes

12

.

1.4.3 Emissions accounting

To assess aviation’s carbon emissions in the EU+, all emissions from a flight departing from country of origin A towards

country of destination B are attributed to country A. This aligns with the UNFCCC reporting framework and the IPCC

Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories (IPCC, 2006). The EU greenhouse gas emission inventories assign

emissions from international aviation to countries where the associated fuel is bunkered, and as such also only

incorporate emissions from departing flights (eurostat, 2019). These data are also submitted to the UNFCCC, and

represent the official data for international and EU climate policies. The global characteristic of the aviation industry is

also reflected in the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories (IPCC, 2006), which state that

“emissions from fuel use on […] aircraft engaged in international transport should not be included in national totals.

To ensure global completeness, these emissions should be reported separately.”

Arriving flights from outside the EU+ are excluded from the scope in order to respect international accounting

standards, and to avoid double counting of aviation emissions. Nevertheless, various parties in the air transport

system are making an effort to also reduce emissions on inbound intercontinental flights. The accounting rules applied

for this study do not undermine the importance of such efforts.

1.4.4 Flights

The analyses in this study primarily focus on scheduled passenger flights on subsonic aircraft. For these flights, impacts

of sustainability measures on emissions, passenger demand and number of flights offered are taken into account. In

12

For example, in 2019, ACI EUROPE has celebrated the 10 year anniversary of its Airport Carbon Accreditation programme, which focuses on reductions of emissions of

airports under direct control of airport operators. At the higher levels of the programme, it also requires monitoring of airline and other third party emissions, as well as

associated stakeholder engagement.

14

NLR-CR-2020-510 | February 2021

addition, emissions from scheduled cargo operations are considered. However, estimation of demand impacts for air

freight – either carried in passenger or all-cargo aircraft – are out of scope.

Non-scheduled passenger and cargo operations are out of scope for the quantitative assessments. This includes all

charter flights, general and business aviation, cargo flights carried out by integrators (such as UPS, DHL and FedEx),

and all other forms of air traffic not included in OAG Schedules Analyser (Official Airline Guide, 2019)

13

.

In addition, the study is limited to operational emissions generated by commercial aircraft. Although this includes both

air and ground components (such as taxiing and the use of auxiliary power units for ground power), emissions related

to airport facility operation and aircraft manufacturing or maintenance are (as substantiated in Section 1.4.2) not

considered. Finally, modal shifts (to e.g. high-speed rail or future developments such as Hyperloop) are not part of the

study, although the importance of air-rail complementarity is acknowledged.

1.4.5 Improvements

As indicated earlier in this introduction, this report looks at the possible reductions in CO

2

emissions that can be

delivered by four groups – or pillars – of improvements:

• improvements in aircraft and engine technology, including alternative energy sources, which are materialised

through replacement of current aircraft by new types;

• improvements in air traffic management (ATM) and aircraft operations, which can be implemented without

replacement of current aircraft;

• drop-in sustainable aviation fuels; and

• economic measures.

These pillars are slightly different and more extensive than the ones adhered to by e.g. IATA, being “technology”,

“operations”, “infrastructure” and a “global market-based measure” (IATA, 2020b). Specifically, sustainable aviation

fuels

14

are taken separately from other technology developments. Operations and infrastructure improvements, the

latter of which IATA describes as the modernisation of air traffic management, however, are grouped in the present

report. The scope for economic measures is expanded beyond global market-based measures. Figure 2 provides a

graphical overview of the different groupings.

Recent industry publications, such as ATAG’s Waypoint 2050 (ATAG, 2020b), adhere to a structure more closely

matching Destination 2050: taking (drop-in) sustainable aviation fuels separately from technology and grouping

operations and infrastructure together.

13

General and business aviation is estimated to account for about 2% of total aviation CO

2

worldwide (ICCT, 2019). Integrator and charter flights are likely to account

only for a small share of aviation emissions.

14

Which is an appropriately more narrow scope than the “low-carbon fuels” mentioned by IATA (2020b).

15

NLR-CR-2020-510 | February 2021

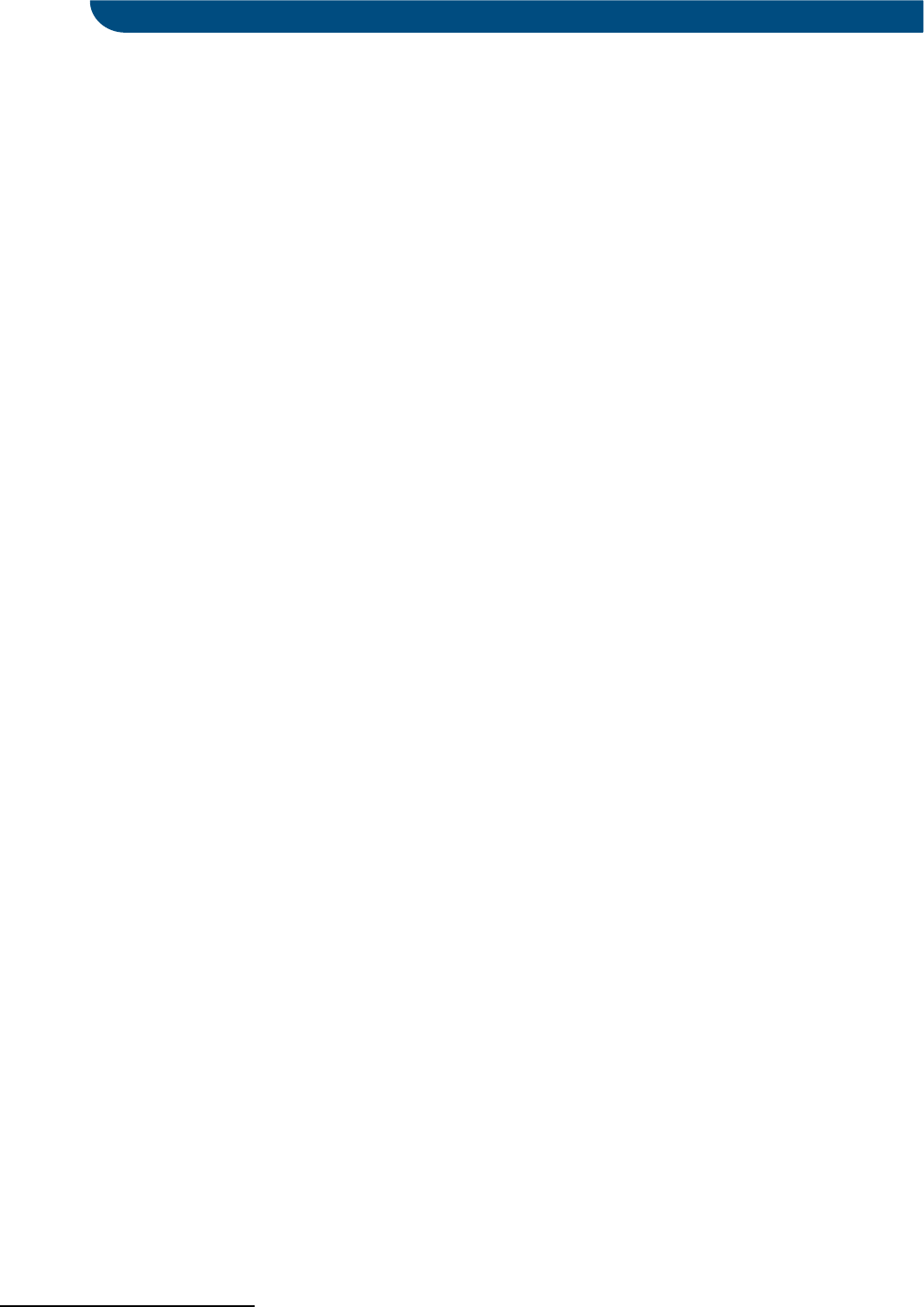

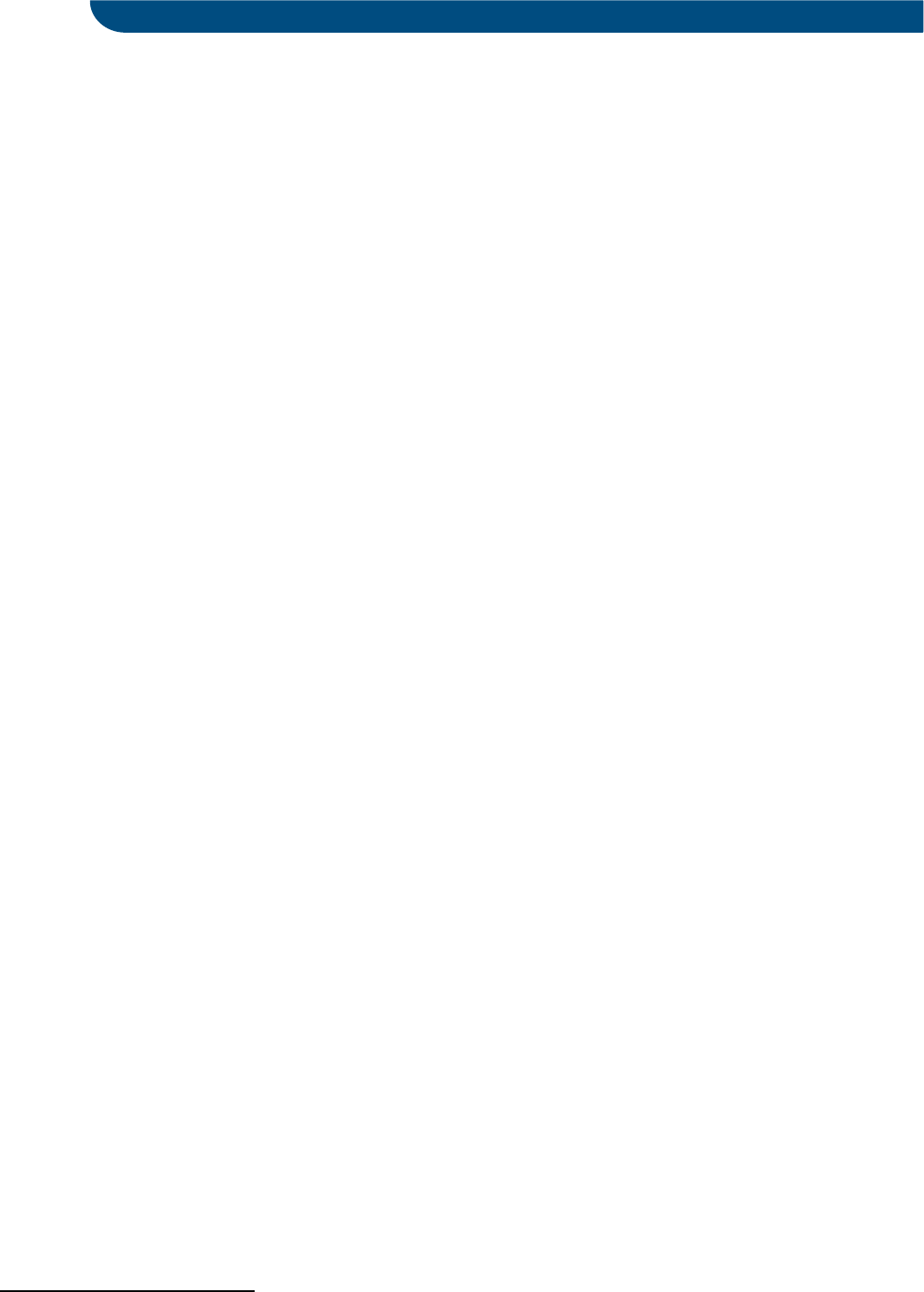

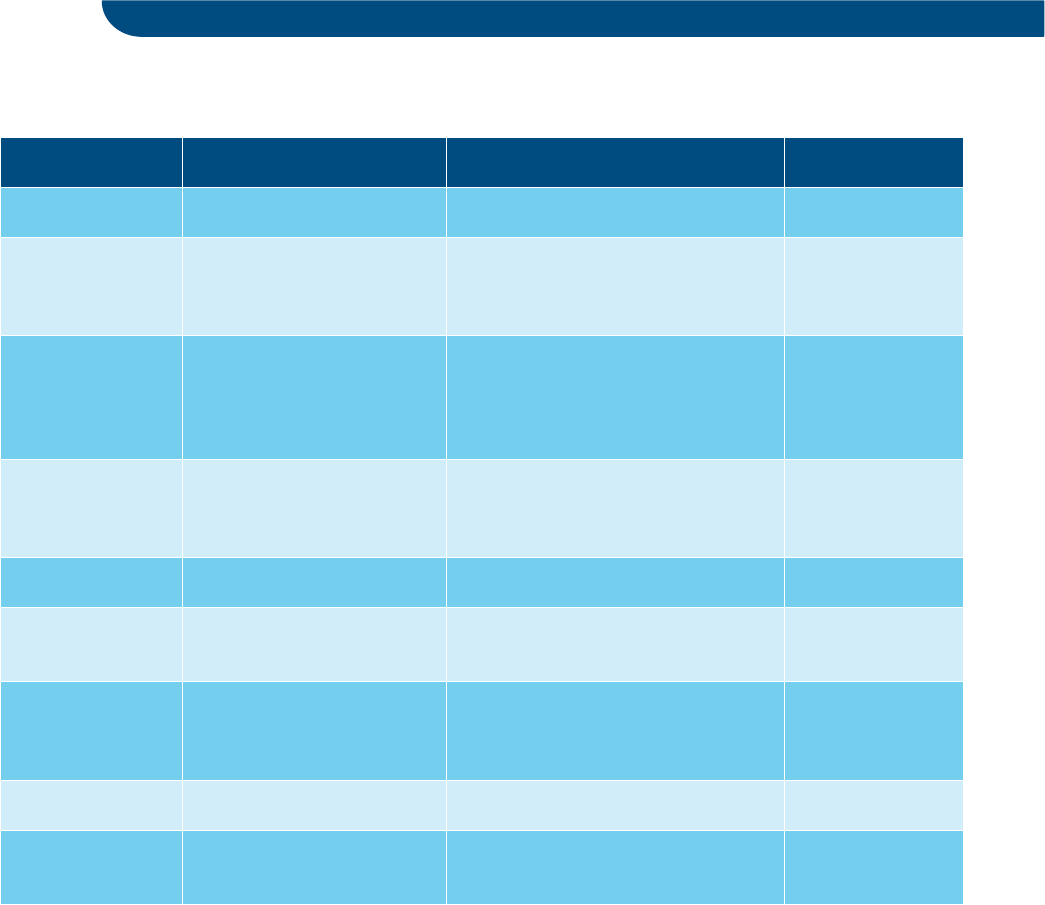

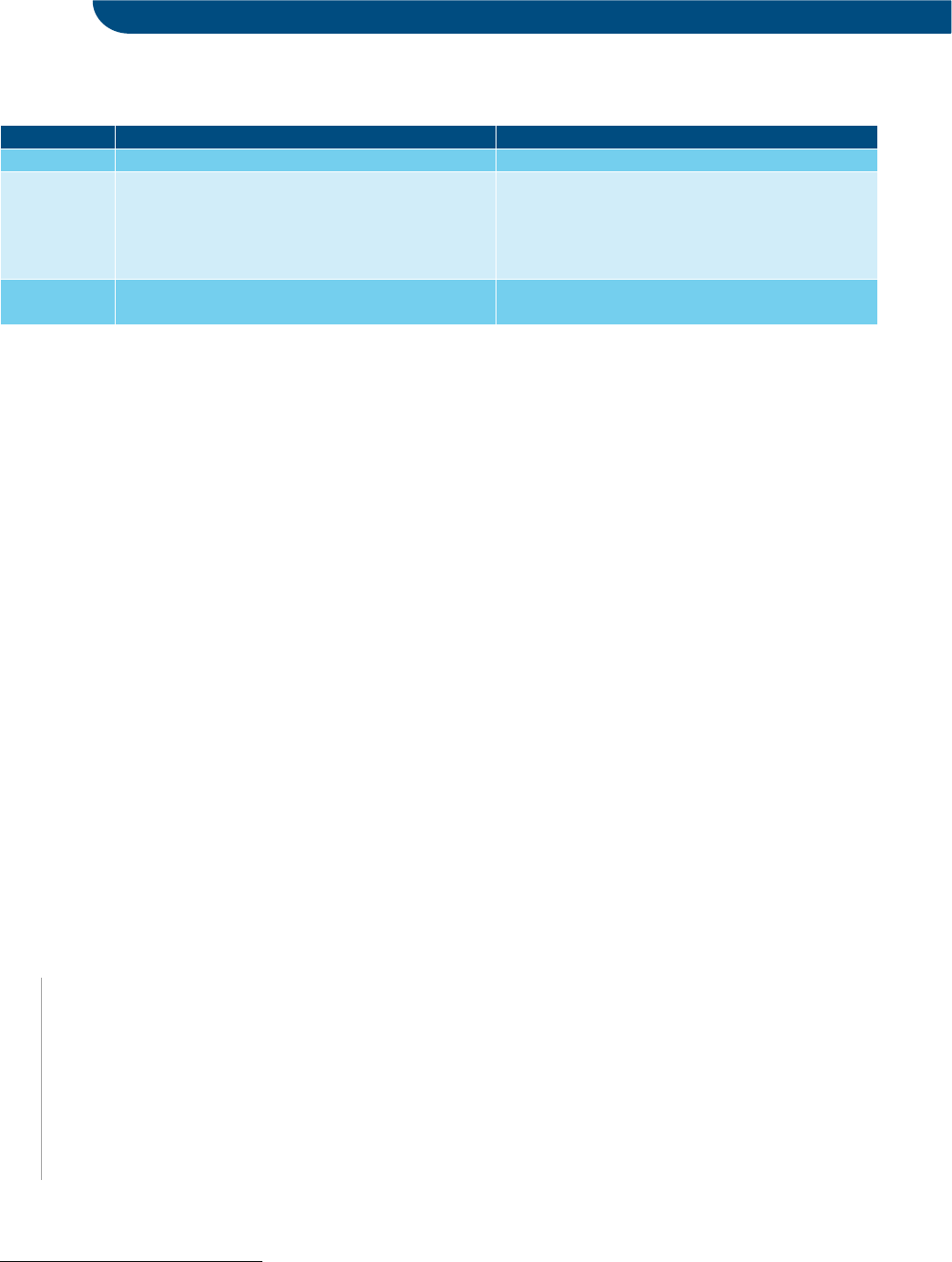

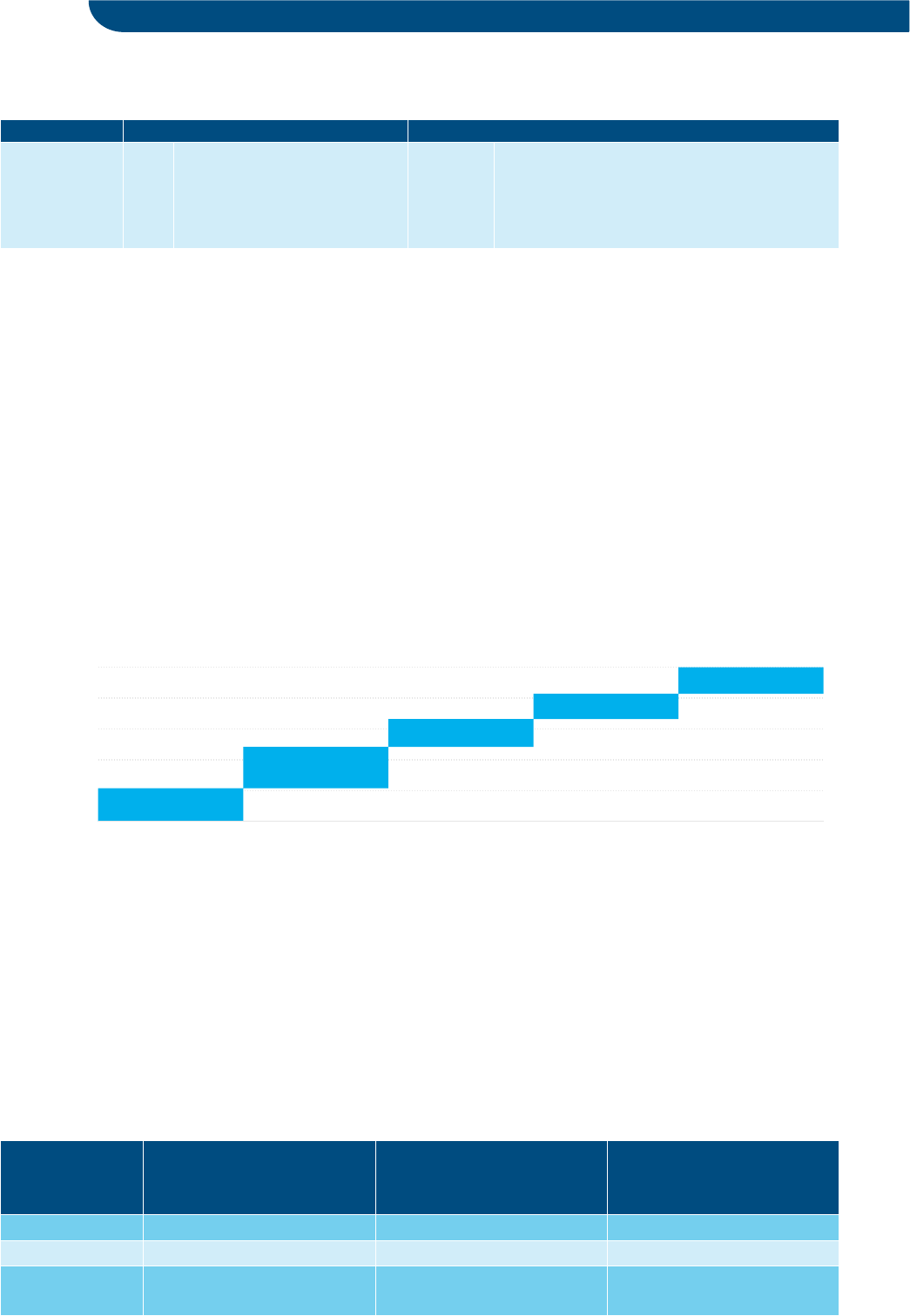

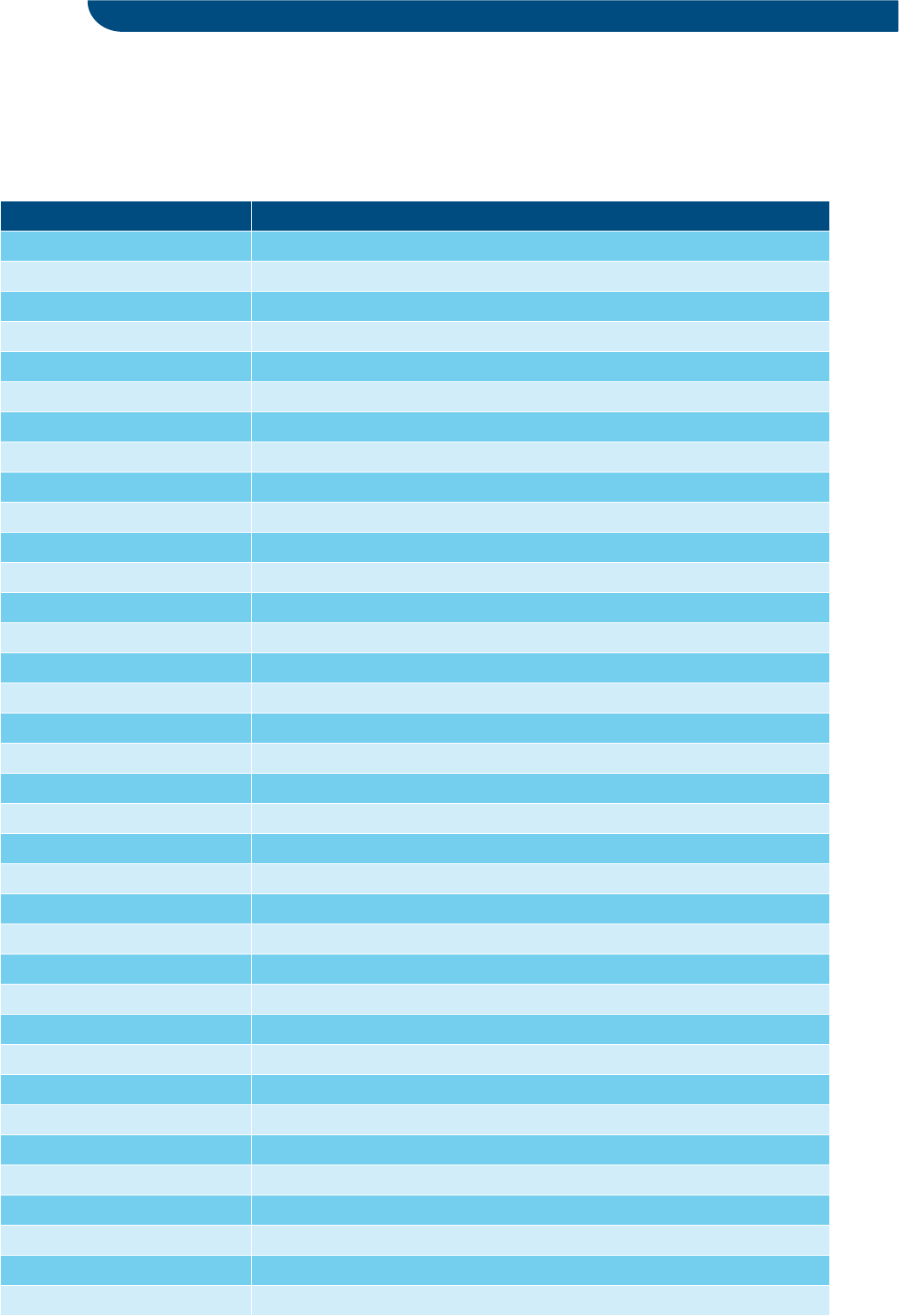

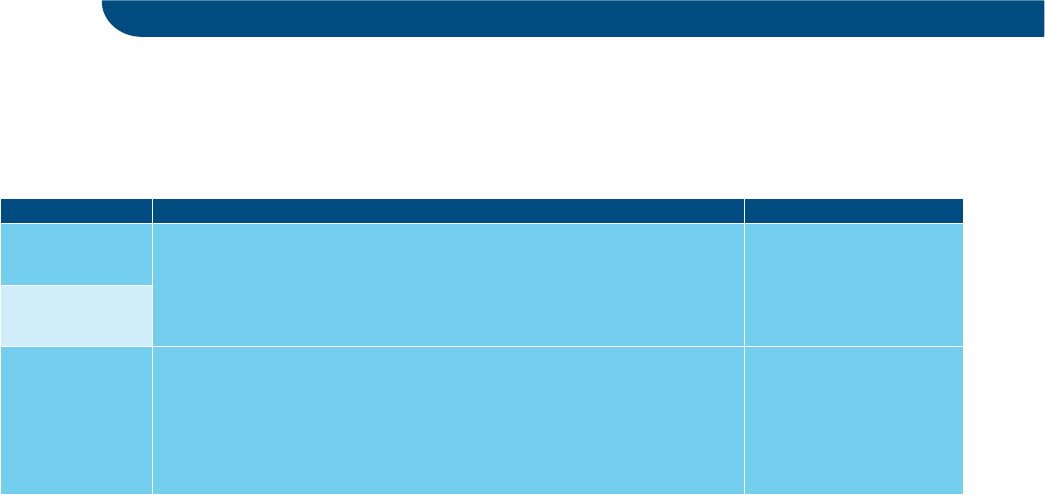

Figure 2: Comparison of groups ('pillars') of improvements between IATA (2020b) and Destination 2050

1.5 Reading guide

The main body of this report starts with presenting the reference scenario used as a basis for the analyses presented

in this report. This is the subject of Chapter 2.

Then, Chapters 3, 4, 5 and 6 each discuss one of the four groups of measures considered in the study:

• improvements in aircraft and engine technology;

• improvement in ATM and aircraft operations;

• sustainable aviation fuels; and

• economic measures.

Each of these chapters is structured in a similar fashion. Following an introduction, the main content of each chapter is

formed by a number of sections that detail possible improvements and measures and estimate their impact. Then,

drivers and barriers – or: challenges – that influence the effectiveness and adoption speed of the measures are

treated. As political and societal pressures to reduce CO

2

emissions are drivers for all measures, these are not

repeated in the specific chapters. The last section of each of the Chapters 3, 4, 5 and 6 discusses policies and actions

that are needed to realise the benefits discussed. Often, these policies and actions are specifically intended to

strengthen drivers and mitigate or circumvent barriers.

Following the chapters related to the four groups of measures, Chapter 7 discusses a number of possible changes to

the air transport system at large, thereby spanning multiple domains. Next, Chapter 8 discusses the impact modelling

of the various potential improvements. Chapter 9 presents the main findings of this study and presents the path

forward to Destination 2050. This includes a comparison with current industry and governmental targets and lists a

number of policies and actions that are relevant to all measures considered in this study. A list of references and

supplementary appendices are included at the end of the report.

In addition to Chapter 9, which presents the key results, and Chapter 8, which summarises input values used for the

impact modelling, readers interested in the details of the measures and the methodology using which their impacts

are assessed are recommended to focus their attention on Chapters 3, 4, 5 and 6. Specific sections in each these

chapters present key actions and policies, of which industry professionals and policymakers should take note. Last,

Section 1.1 and the parts of Chapters 3 through 6 that discuss drivers and barriers are suggested to audiences

interested in deepening their understanding of the system-level challenges of decarbonising European aviation.

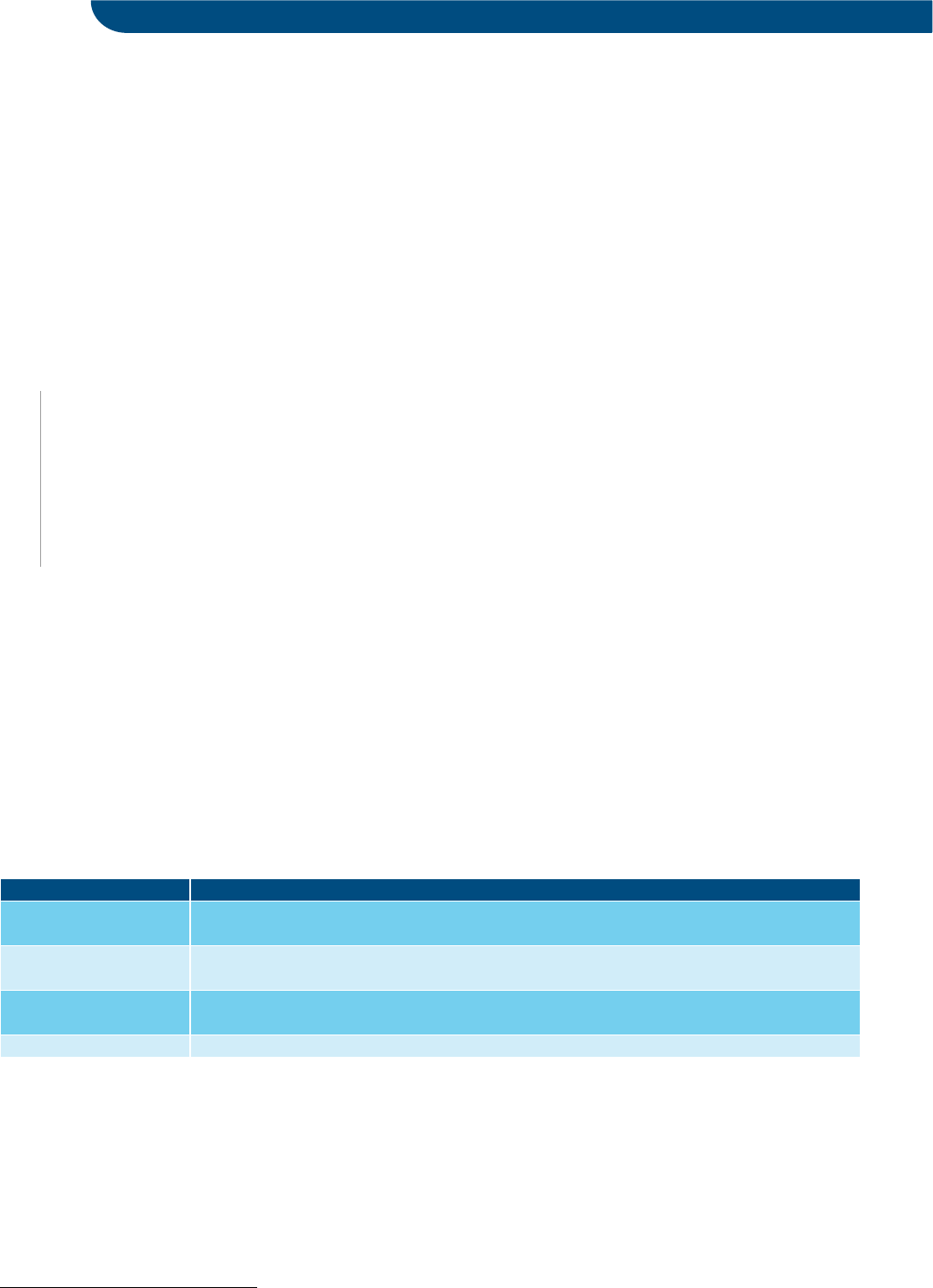

IATA

Destination 2050

aircraft technology

engine technology

sustainable aviation fuels

aircraft operations

air traffic management

ground operations

global market-based

other economic measures

technology

operations

infrastructure

global market-based measure

aircraft and engine technology

(drop-in) sustainable aviation fuels

ATM and aircraft operations

economic measures

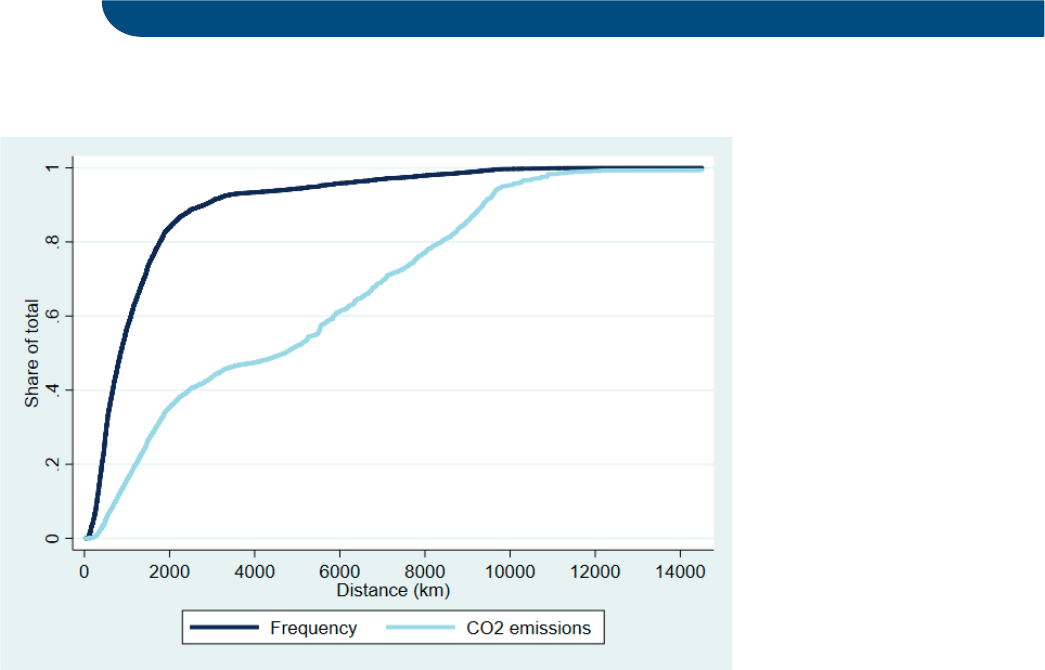

16

NLR-CR-2020-510 | February 2021

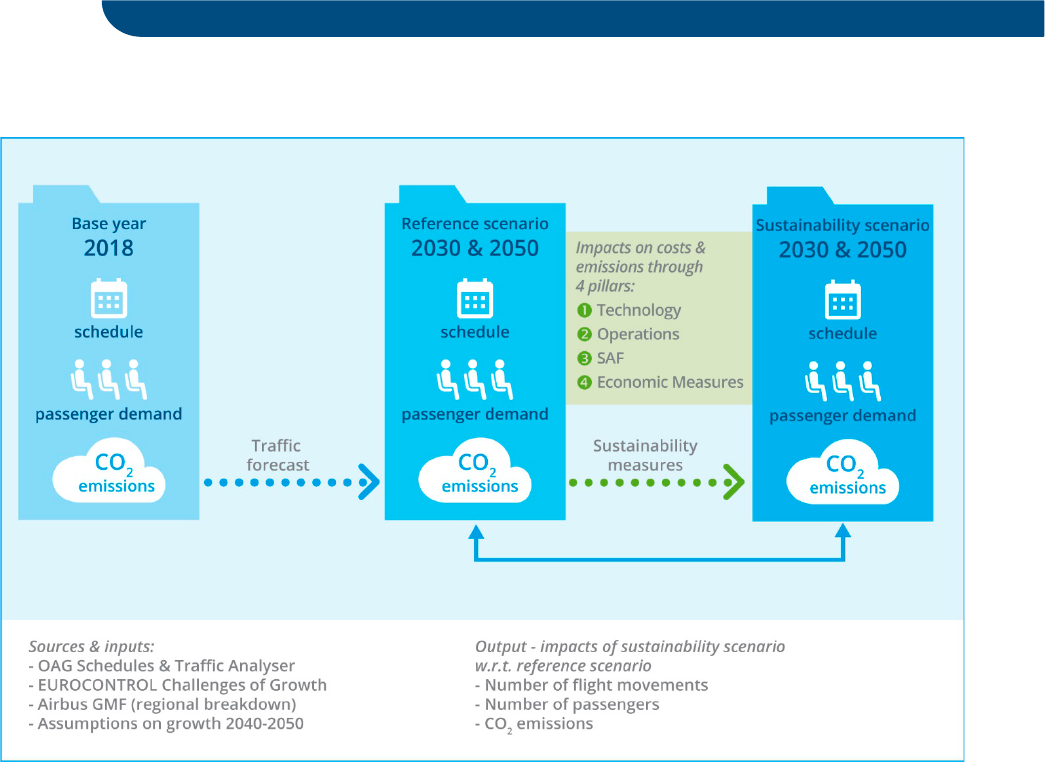

2 Reference scenario

A hypothetical ‘no-action’ scenario is used as a reference for evaluating the impacts of the

sustainability scenario developed in this study. The reference scenario is based on EUROCONTROL’s

Challenges of Growth forecast. The impact of COVID-19 is taken into account by assuming that

traffic gradually recovers to pre-crisis levels by 2024. Growth factors per flight region are

subsequently applied to schedule data from OAG. Emissions are determined at flight level using a

combination of EUROCONTROL’s Base of Aircraft Data and the ICAO Emissions Databank. Load

factors and aircraft size are assumed to increase by 0.3% per year.

In the reference scenario traffic increases to 11.3 million departing flights and 1.4 billion passengers

in 2050. CO

2

emissions in 2050 are estimated at 320 Mt. Compared to 2018 levels, this comes down

to increases of 55% (flights), 87% (passengers) and 67% (CO

2

emissions).

2.1 Introduction

Destination 2050 seeks to identify different sustainability measures that could be implemented in the aviation sector,

and assess the impacts of these measures against a reference scenario. Estimated impacts are expressed in terms of (i)

passengers, (ii) aircraft movements, and (iii) CO

2

emissions. For the horizon years 2030 and 2050, Chapter 8 presents

the reduction of CO

2

emissions resulting from the proposed sustainability measures, compared against the reference

scenario presented in this chapter.

The reference scenario is a hypothetical ‘no-action’ growth scenario with regards to fuel efficiency improvements,

operational improvements and sustainable aviation fuels. This means that CO

2

emissions in the reference scenario are

estimated based on the assumption that aircraft deployed until 2050 have the same fuel efficiency as in the base year,

2018. It should be noted that such a scenario is purely hypothetical. Even without additional sustainability measures,

fuel efficiency is likely to improve due to already implemented climate policies and a continued focus of airlines to

reduce fuel consumption. However, distinguishing between improvements in a ‘business as usual’ scenario compared

to an ambitious technology scenario requires additional assumptions on what is ‘business as usual’. Thus, using a

hypothetical ‘no-action’ scenario is the best way to provide a full picture of all the sustainability measures taken.

This chapter is structured as follows. Section 2.1 describes the assumptions made in the reference scenario regarding

the development of air traffic, load factors, aircraft size and fuel efficiency. Section 2.3 presents the reference scenario

in terms of passengers, aircraft movements and carbon emissions.

2.2 Assumptions

This section lists assumptions concerning traffic scenario, load factor development and aircraft size growth and

environmental regulation.

17

NLR-CR-2020-510 | February 2021

2.2.1 Traffic forecast

An individual route level forecast for 2030 and 2050 is made, allowing estimation of the impact of various

sustainability measures at a detailed level. The worldwide airline schedule of 2018 forms the basis for the supply-side

forecast. This schedule is obtained from OAG Schedules Analyser, which provides information on scheduled passenger

flights by airline, route and aircraft type deployed. In addition, the source provides information on the elapsed time

between scheduled departure and arrival

15

, which is used to estimate fuel consumption and emissions for each flight

(see box). On the demand side, origin-destination (O&D) 2018 passenger booking data from OAG Traffic Analyser

forms the basis for the analysis.

EMISSIONS MODEL

For the study we apply a highly detailed emissions model which estimates fuel consumption for each individual aircraft

operation during each flight phase. For the climb, cruise and descent phases the fuel consumption data is based on

EUROCONTROL’s Base of Aircraft Data (BADA). BADA is used extensively in the (scientific) literature to estimate fuel

consumption. It does not contain data for all aircraft types in operation, but recommends which types to use as synonyms.

For the LTO phase, fuel consumption is taken from ICAO’s Engine Emissions Databank. This databank contains fuel

consumption data for individual engine types in the LTO phase. To each aircraft type we attach a common engine type

based on the EUROCONTROL ANP database. CO

2

emissions are directly related to fuel consumption and follow directly from