GAO

United States Government Accountabilit

y

Office

Report to Congressional Requesters

HOME MORTGAGES

Provisions in a 2007

Mortgage Reform Bill

(H.R. 3915) Would

Strengthen Borrower

Protections, but Views

on Their Long-term

Impact Differ

July 2009

GAO-09-741

What GAO Found

United States Government Accountability Office

Why GAO Did This Study

Highlights

Accountability Integrity Reliability

Jul

y

2009

HOME MORTGAGES

Provisions in a 2007 Mortgage Reform Bill (H.R. 3915)

Would Strengthen Borrower Protections, but Views

on Their Long-term Impact Differ

Highlights of GAO-09-741, a report to

congressional requesters

GAO estimates that almost 75 percent of securitized nonprime mortgages

originated from 2000 through 2007 would not have met H.R. 3915’s safe harbor

requirements, which include, among other things, full documentation of

borrower income and assets, and a prohibition on mortgages for which the

loan principal can increase over time. The extent to which mortgages met

specific safe harbor requirements varied by origination year. For example, the

percentage of nonprime mortgages with less than full documentation rose

from 27 percent in 2000 to almost 60 percent in 2007. Consistent with the

consumer protection purpose of the bill, GAO found that certain variables

associated with the safe harbor requirements influenced the probability of a

loan entering default (i.e., 90 or more da

y

s delinquent or in foreclosure) within

24 months of origination. For example, on the basis of statistical analysis,

GAO estimates that, all other things being equal, less than full documentation

was associated with a 5 percentage point increase in the likelihood of default

for the most common type of nonprime mortgage product. GAO also found

that other variables—such as house price appreciation, borrowers’ credit

scores, and the ratio of the loan amount to the house value—were associated

with default rates.

Research on state and local anti-predatory lending laws and the perspectives

of mortgage industry stakeholders do not provide a consensus view on the

bill’s potential effects on the availability of mortgage credit. Some research

indicates that anti-predatory lending laws can have the intended result of

reducing loans with problematic features without substantially affecting credit

availability. However, it is difficult to generalize these findings to all anti-

predatory lending laws or the potential effect of the bill, in part, because of

differences in the design and coverage of these laws. Mortgage industry and

consumer group representatives with whom GAO spoke disagreed on the bill’s

potential effect on credit availability and consumer protection. For example,

mortgage industry officials generally said that the bill’s safe harbor, securitizer

liability, and other provisions would limit mortgage options and increase the

cost of credit for nonprime borrowers. In contrast, consumer groups generally

stated that these provisions needed to be strengthened to protect consumers

from predatory loan products.

H.R. 3915 (2007), a bill introduced,

but not enacted by the 110th

Congress, was intended to reform

mortgage lending practices to

prevent a recurrence of problems in

the mortgage market, particularly in

the nonprime market segment. The

bill would have set minimum

standards for all mortgages (e.g.,

reasonable ability to repay) and

created a “safe harbor” for loans

that met certain requirements.

Securitizers of safe harbor loans

would be exempt from liability

provisions, while securitizers of

non-safe harbor loans would be

subject to limited liability for loans

that violated the bill’s minimum

standards. In response to a

congressional request, this report

discusses (1) the proportions of

recent nonprime loans that likely

would have met and not met the

bill’s safe harbor requirements and

factors influencing the performance

of these loans, and (2) relevant

research and the views of mortgage

industry stakeholders concerning

the potential impact of key

provisions of the bill on the

availability of mortgage credit. To

do this work, GAO analyzed a

proprietary database of securitized

nonprime loans, reviewed studies of

state and local anti-predatory

lending laws, and met with financial

regulatory agencies and key

mortgage industry stakeholders.

What GAO Recommends

GAO makes no recommendations

in this report.

View GAO-09-741 or key components.

For more information, contact William B.

Shear at (202) 512-8678 or [email protected].

Page i GAO-09-741

Contents

Letter 1

Background 5

Most Recent Nonprime Mortgages Would Not Have Been Safe

Harbor Loans and Certain Variables Associated with the Safe

Harbor Requirements and Other Factors Influenced Defaults 17

Relevant Research and Stakeholder Perspectives Do Not Provide a

Consensus View on the Bill’s Potential Impact 35

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation 43

Appendix I Objectives, Scope, and Methodology 45

Appendix II Description of the Econometric Analysis of

Safe Harbor Requirements 50

Appendix III Comments from the National Credit Union

Administration 62

Appendix IV GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments 63

Tables

Table 1: Nontraditional Mortgage Products 6

Table 2: Percentage of Nonprime Mortgages That Were Safe Harbor

and Non-safe Harbor Loans by Racial, Ethnic, and Income

Groupings, 2000-2007 25

Table 3: Percentage of Nonprime Mortgages That Were Safe Harbor

and Non-Safe Harbor Loans by Credit Score Groupings,

2000-2007 26

Table 4: Estimated Probability of Nonprime Purchase Mortgages

Defaulting within 24 months of Origination with and

without Full Documentation, 2000-2006 Loans 29

Table 5: Estimated Probability of Nonprime Purchase Mortgages

Defaulting within 24 months of Origination under Different

Assumptions for the Safe Harbor Spread Requirement,

2000-2006 Loans 30

Impact of Mortgage Reform

Table 6: Estimated Percentage of Nonagency Securitized Subprime

and Alt-A Loans in the LP Database, 2001-2007 46

Table 7: Safe Harbor Requirements and LP Variables Used to

Duplicate the Requirements or Develop Proxies 47

Table 8: Variables Used in the Model 51

Table 9: Mean Values for Short-term Hybrid ARMs with DTI

Information 54

Table 10: Mean Values for Fixed-rate mortgages with DTI

Information 54

Table 11: Mean Values for Longer-term ARMs with DTI information 55

Table 12: Mean Values for Payment-option ARMs with DTI

Information 56

Table 13: Estimation Results for Short-term Hybrid ARMs with DTI

Information 58

Table 14: Estimation Results for Fixed-rate Mortgages with DTI

Information 59

Table 15: Estimation Results for Longer-term ARMs with DTI

Information 60

Table 16: Estimation Results for Payment-option ARMs with DTI

Information 61

Figures

Figure 1: H.R. 3915 Loan Standards 16

Figure 2: Estimated Proportions of Nonprime Mortgages Meeting

and Not Meeting the Safe Harbor Requirements, 2000-2007 18

Figure 3: Estimated Proportions of Nonprime Mortgages Not

Meeting Documentation and Amortization Requirements,

2000-2007 20

Figure 4: Estimated Proportions of Nonprime Mortgages Not

Meeting Interest Rate and Debt Burden Requirements,

2000-2007 22

Figure 5: Estimated Proportions of Nonprime Mortgages Not

Meeting the Fully Indexed Rate Requirement, 2000-2007 24

Figure 6: Estimated Probability of Nonprime Purchase Mortgages

Defaulting within 24 Months under Different House Price

Appreciation, Credit Score, and LTV Ratio Assumptions,

2000-2006 Loans 34

Page ii GAO-09-741 Impact of Mortgage Reform

Abbreviations

APR annual percentage rate

ARM adjustable-rate mortgage

DTI debt-service-to-income

FHA Federal Housing Administration

FTC Federal Trade Commission

GSE government-sponsored enterprises

HMDA Home Mortgage Disclosure Act

HOEPA Home Ownership and Equity Protection Act

HPA house price appreciation

HUD Department of Housing and Urban Development

LIBOR London Interbank Offered Rate

LP LoanPerformance

LTV loan-to-value

MBS mortgage-backed securities

MSA metropolitan statistical area

NCUA National Credit Union Administration

OCC Office of the Comptroller of the Currency

OTS Office of Thrift Supervision

RESPA Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act

SEC Securities and Exchange Commission

TILA Truth in Lending Act

VA Department of Veterans Affairs

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety

without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain

copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be

necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Page iii GAO-09-741 Impact of Mortgage Reform

Page 1 GAO-09-741

United States Government Accountability Office

Washington, DC 20548

July 31, 2009

The Honorable Barney Frank

Chairman

Committee on Financial Services

House of Representatives

The Honorable Adam H. Putnam

House of Representatives

The U.S. housing and mortgage markets are experiencing severe stress,

with over 3.2 million home mortgages 90 or more days delinquent or in the

foreclosure process in the first quarter of 2009. The rise in delinquencies

and foreclosures has been particularly acute in the nonprime segment of

the mortgage market. Nonprime mortgages, which include subprime and

Alt-A loans, grew dramatically in terms of dollar volume and share of the

mortgage market from 2001 through 2006.

1

In 2001, lenders originated

$215 billion in nonprime loans, but by 2006, had increased originations to

$1 trillion. Likewise, the share of the nonprime market as a percentage of

the total mortgage market increased from around 10 percent in 2001 to

almost 34 percent in 2006. Further, investment banks increased the volume

of nonprime loans they bundled into private label mortgage-backed

securities (MBS) over this period.

2

In 2001, they bundled 46 percent of

nonprime loans into private label MBS, but by 2006, were bundling 81

percent of these loans. The market for nonprime mortgages contracted

sharply in mid-2007, as the nation entered a credit crisis and has not

rebounded.

1

The conventional mortgage market (i.e., mortgages not insured or guaranteed by the

federal government) comprises prime loans for the most creditworthy borrowers and

nonprime loans (i.e., subprime and Alt-A loans). The subprime market generally serves

borrowers with blemished credit and features higher interest rates and fees than the prime

market. The Alt-A market generally serves borrowers whose credit histories are close to

prime, but the loans often have one or more higher-risk features, such as limited

documentation of income or assets.

2

Securitization allows lenders to sell loans from their portfolios, transferring credit risk to

investors, and use the proceeds to make more loans. Private label MBS, which are bought

and sold on the secondary market, are backed by mortgages that do not conform to

government-sponsored enterprise (GSE) purchase requirements because they are too large

or do not meet GSE underwriting criteria.

Impact of Mortgage Reform

As we reported in October 2007, an easing of underwriting standards for

nonprime mortgages and wider use of certain loan features associated

with poorer loan performance contributed to increases in mortgage

delinquencies and foreclosures.

3

These features included mortgages with

higher loan-to-value ratios (the amount of the loan divided by the value of

the home), adjustable interest rates, limited or no documentation of

borrower income or assets, and deferred payment of principal or interest.

In some cases, lenders engaged in predatory practices that resulted in

loans with onerous terms and conditions.

4

Often, borrowers could not

repay these loans and found themselves facing foreclosure or bankruptcy.

Some of these predatory practices included providing the borrower with

misleading information, manipulating the borrower through aggressive

sales tactics, or taking unfair advantage of the borrower’s lack of

information about the loan terms and their consequences.

To prevent a recurrence of problems in the mortgage market, the House of

Representatives passed the Mortgage Reform and Anti-Predatory Lending

Act of 2007 (bill) on November 15, 2007 (H.R. 3915). The Senate did not

pass companion legislation by the end of the 110th Congress, so the bill

did not become law.

5

The bill, among other things, would have set

minimum standards for mortgages requiring that consumers had a

“reasonable ability to repay” at the time the loan was made and that they

received a “net tangible benefit” from mortgage refinancings. One of the

key provisions of H.R. 3915 would have been the creation of a “safe

harbor” from potential liability for assignees and securitizers of mortgages

(i.e., entities that purchase or hold mortgages in the secondary market),

provided that the loans met certain requirements.

6

Assignees would have

3

GAO, Information on Recent Default and Foreclosure Trends for Home Mortgages and

Associated Economic and Market Developments, GAO-08-78R (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 16,

2007).

4

While there is no uniformly accepted definition of predatory lending, a number of

practices are widely acknowledged to be predatory. These include, among other things,

charging excessive fees and interest rates, lending without regard to borrowers’ ability to

repay, refinancing borrowers’ loans repeatedly over a short period of time without any

economic gain for the borrower, and committing outright fraud or deception—for example,

falsifying documents or intentionally misinforming borrowers about the terms of a loan.

5

On May 7, 2009, the House of Representatives passed the Mortgage Reform and Anti-

Predatory Lending Act of 2009 (H.R. 1728, 111th Congress), which has a similar purpose to

H.R. 3915.

6

For ease of presentation, we use the term “assignee” to mean either an assignee or a

securitizer.

Page 2 GAO-09-741 Impact of Mortgage Reform

been subject to limited liability if they securitized loans that fell outside

the bill’s safe harbor. Language in the bill and the accompanying House

report suggests that the safe harbor and other provisions were intended to

strengthen consumer protections for nonprime mortgage products

associated with higher levels of default and foreclosure. Additionally,

congressional hearings and debate about the bill highlighted, among other

things, the challenge of designing safe harbor requirements that protect

consumers from nonprime mortgage products that put them at high risk of

default and foreclosure, while maintaining broad access to mortgage

credit.

Given the serious problems facing the mortgage market, particularly those

associated with nonprime mortgages, and congressional interest in

protecting consumers and ensuring credit availability, you asked us to

assess the potential impact of the bill were it to become law. Accordingly,

this report (1) assesses the proportion of recent nonprime loans that

would likely have met and not met the bill’s safe harbor requirements, and

how variables associated with those requirements affect loan

performance, and (2) discusses relevant research and the views of

mortgage industry stakeholders concerning the potential impact of key

provisions of the bill on the mortgage market. The scope of our analysis

was limited to nonprime mortgages.

To assess the proportions of recent nonprime loans that would likely have

met and not met H.R. 3915’s safe harbor requirements, we analyzed a

proprietary database of securitized nonprime loans from

LoanPerformance (LP).

7

This database covered about 87 percent of the

subprime and 98 percent of the Alt-A securitized mortgage originations

from January 2001 through July 2007. Nonprime mortgages that were not

securitized (i.e., mortgages that lenders held in portfolio) may have

different characteristics and performance histories than those that were

securitized. In this report, we define subprime loans as mortgages in

subprime securitization pools and Alt-A loans as mortgages in Alt-A

securitization pools. Specifically, we analyzed loans in the LP database

originated from 2000 through 2007. For each year, we estimated the

proportion of mortgages with terms and underwriting characteristics that

were consistent with the safe harbor requirements and those that were not

consistent with such requirements. When the data did not allow us to

duplicate a specific safe harbor requirement, we developed reasonable

7

LoanPerformance is a unit of First American CoreLogic, Inc.

Page 3 GAO-09-741 Impact of Mortgage Reform

proxies. Additionally, incorporating data from the Census Bureau, we

examined the proportions of safe harbor and non-safe harbor loans within

different census tract and borrower groupings. Finally, to examine factors

that could explain the performance of nonprime loans, we developed a

statistical model to estimate the relationship between variables associated

with the safe harbor requirements and other variables and the probability

of loan default within 24 months of origination.

We assessed the reliability of the data by interviewing LP representatives

about the methods they use to collect and ensure the integrity of the

information. We also reviewed supporting documentation about the

database, including LP’s estimates of the database’s market coverage. In

addition, we conducted reasonableness checks on the data to identify any

missing, erroneous, or outlying figures. We found the data elements we

used to be sufficiently reliable.

To describe relevant research on the bill’s potential effects on the

nonprime mortgage market, we identified and reviewed empirical studies

on the effects of state and local anti-predatory lending laws on key

nonprime mortgage indicators. The indicators used in these studies

included mortgage originations and the cost of credit. We reviewed the

studies’ overall conclusions concerning the impact of the laws and

identified any limitations in the researchers’ methodologies. We also

interviewed selected authors to ensure that we interpreted their results

correctly. To obtain the views of mortgage industry participants and

stakeholders, we interviewed officials from organizations representing

mortgage lenders, mortgage brokers, securitizers, and consumer interests.

We also interviewed officials from a large mortgage lender and a major

investment bank involved in the securitization of mortgages. Finally, we

interviewed officials from the federal banking regulators, Department of

Housing and Urban Development (HUD), Federal Trade Commission

(FTC), and Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

We conducted this performance audit from March 2008 to July 2009, in

accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those

standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient,

appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and

conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence

obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions

based on our audit objectives. Appendix I explains our objectives, scope,

and methodology in greater detail.

Page 4 GAO-09-741 Impact of Mortgage Reform

Background

The primary mortgage market features a variety of loan products and

relies, in part, on the process of securitization to provide funds for

mortgage lending. Over the years, a number of federal and state laws and

regulations were implemented to protect mortgage borrowers. In 2007, the

bill was introduced to strengthen consumer protections and included

provisions that would have created a safe harbor for loans that met certain

requirements.

Mortgage Markets and

Securitization

The primary mortgage market has several segments and offers a range of

loan products:

• The prime market serves borrowers with strong credit histories and

provides the most attractive interest rates and mortgage terms.

• The Alt-A market generally serves borrowers whose credit histories are

close to prime, but the loans often have one or more higher-risk features,

such as limited documentation of income or assets.

• The subprime market generally serves borrowers with blemished credit

and features higher interest rates and fees than the prime market.

• Finally, the government-insured or -guaranteed market primarily serves

borrowers who may have difficulty qualifying for prime mortgages but

features interest rates competitive with prime loans in return for payment

of insurance premiums or guarantee fees. HUD’s Federal Housing

Administration (FHA) and the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA)

operate the two main federal programs that insure or guarantee

mortgages.

Across all of these market segments, two types of loans are common:

fixed-rate mortgages, which have interest rates that do not change over the

life of the loans and adjustable-rate mortgages (ARM), which have interest

rates that change periodically based on changes in a specified index. Other

more unique loan products, referred to as nontraditional mortgage

products, grew in popularity over the last decade (see table 1). Hybrid

ARMs—which are fixed for a given period and then reset to an adjustable

rate—also became popular in recent years, especially in the subprime

market. In particular, a significant portion of subprime loans originated

from 2003 through 2006 were 2/28 or 3/27 hybrid ARMs—that is, they were

fixed for the first 2 or 3 years before resetting to often much higher

interest rates and correspondingly higher mortgage payments. Other

nontraditional mortgage products included interest-only or payment-

Page 5 GAO-09-741 Impact of Mortgage Reform

option loans, which allowed borrowers to defer repayment of principal

and possibly part of the interest for the first few years of the loan.

8

Table 1: Nontraditional Mortgage Products

Adjustable rate loans Initial period Remaining loan period

Hybrid ARMs (2/28s, 3/27s) For an initial period of usually 2 or 3 years, loan is

fixed at an introductory rate.

After the initial fixed period, the rate will eventually

adjust to a “fully indexed” interest rate equal to a

floating index, such as the London Interbank

Offered Rate (LIBOR), plus a fixed margin.

Although reaching the fully indexed rate is often a

gradual process because incremental increases

are capped, even the first increases, which

average approximately 2 percent, can cause

payment shock.

Interest-only mortgages For an initial period, typically the first 3 to 10 years,

borrowers can defer principal payments.

After the initial period, the mortgage is “recast” to

require higher monthly payments that cover

principal as well as interest and to pay off

(amortize) the outstanding balance over the

remaining term of the loan.

Payment-option mortgages For an initial period of typically 5 years or when the

loan balance reaches a specified cap, borrowers

can make minimum payments that do not cover

principal or all accrued interest, thereby, in some

cases, resulting in increased loan balances over

time (negative amortization).

After the initial period, payments are recast to

include an amount that will fully amortize the

outstanding balance over the remaining years of

the loan.

Source: GAO.

A number of loan features also became more common over the past

decade. While these features potentially expanded access to mortgage

credit, they are often associated with higher default rates. These features

included the following:

• Low and no-documentation loans. Originally intended for borrowers who

had difficulty documenting income, such as the self-employed, these loans

were made with little or no verification of a borrower’s income or assets.

• High loan-to-value (LTV) ratios. As homebuyers made smaller down

payments, the ratio of loan amount to home value increased.

8

GAO, Alternative Mortgage Products: Impact on Defaults Remains Unclear, but

Disclosure of Risks to Borrowers Could Be Improved, GAO-06-1021 (Washington, D.C.:

Sept. 19, 2006).

Page 6 GAO-09-741 Impact of Mortgage Reform

• Prepayment penalties. Some loans contained built-in penalties for

repaying part or all of a loan in advance of the regular schedule.

Many loans were originated with a number of these features, a practice

known as risk layering.

The secondary mortgage market and the process of securitization play

important roles in providing liquidity for mortgage lending. Mortgage

lenders originate and then sell their loans to third parties, freeing up funds

to originate more loans. Securitization, in this context, is the bundling of

mortgage loans into investment products called residential MBS that are

bought and sold by investors. The secondary market consists of (1) Ginnie

Mae-guaranteed MBS, which are backed by cash flows from federally-

insured or -guaranteed mortgages; (2) government-sponsored enterprise

(GSE) MBS, which are backed by mortgages that meet the criteria for

purchase by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac; and (3) private label MBS,

which are backed by mortgages that do not conform to GSE purchase

requirements because they are too large or do not meet GSE underwriting

criteria.

9

Investment banks have traditionally bundled most subprime and

Alt-A loans into private label MBS, although since 2007, the market has

slowed dramatically.

Federal Mortgage Lending

Laws

The Truth in Lending Act (TILA), which was enacted in 1968, and the

Home Ownership and Equity Protection Act of 1994 (HOEPA), which

amended TILA in 1994, are among the primary federal laws governing

mortgage lending.

10

TILA was designed to provide consumers with

accurate information about the cost of credit. Among other things, TILA

requires lenders to disclose information about the terms of loans—

including the amount financed, the finance charge, and the annual

percentage rate (APR)—that can help borrowers understand the overall

costs of their loans. Congress enacted HOEPA to amend TILA, in response

to concerns about predatory lending. HOEPA regulates and restricts the

terms and characteristics of certain kinds of high-cost mortgage loans that

9

The GSEs Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are private, federally chartered companies created

by Congress to, among other things, provide liquidity to home mortgage markets by

purchasing mortgage loans, thus, enabling lenders to make additional loans. To be eligible

for purchase by the GSEs, loans (and borrowers receiving the loans) must meet specified

requirements. In September 2008, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were placed into federal

government conservatorship.

10

TILA, as amended, is codified at 15 U.S.C. §§ 1601 – 1666j.

Page 7 GAO-09-741 Impact of Mortgage Reform

exceed certain thresholds in their APRs or fees (often referred to as “rate

and fee triggers”). The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

(Federal Reserve) implements TILA and HOEPA through Regulation Z,

which was amended in 2001 and 2008 with respect to high-cost lending. As

a result of the most recent rulemaking in 2008, Regulation Z will restrict

mortgage lending in the following ways, as of October 1, 2009:

11

• Higher-priced loans: First-lien loans with APRs that equal or exceed an

index of average prime offer rates by 1.5 percentage points above an index

of average prime offer rates—a category meant to include virtually all

loans in the subprime market, but generally exclude loans in the prime

market—are called “higher-priced mortgage loans.”

12

Creditors are

prohibited from making these loans without regard to the borrower’s

ability to repay from income and assets other than the home’s value, and

creditors must verify the income and assets they rely upon to determine a

borrower’s repayment ability. Also, prepayment penalties are prohibited

for these loans if the payment can change in the first 4 years of the loan;

for loans where the payment is fixed for at least the first 4 years,

prepayment penalties are limited to 2 years. In addition, creditors must

establish escrow accounts for this category of loans for property taxes and

homeowners’ insurance.

• High-cost HOEPA loans: First-lien loans with APRs that exceed the yield

on Treasury securities of comparable maturity by more than 8 percentage

points or with total points and fees that exceed the greater of 8 percent of

the loan amount or $583, are called “high-cost HOEPA loans.”

13

For these

11

HOEPA imposes substantive restrictions and special pre-closing disclosures on

particularly high-cost refinancings and home equity loans secured by the borrower’s

principal dwelling. These restrictions and disclosures have been in effect since 1995. When

Congress enacted HOEPA in 1994, it authorized the Federal Reserve to adopt new or

expanded restrictions, as needed, to protect consumers from unfairness, deception, or

evasion of HOEPA in connection with mortgage loans. The Federal Reserve is also

authorized to prohibit acts or practices in connection with refinancings that are associated

with abusive lending practices or are otherwise not in the interest of the borrower. In 2008,

the Federal Reserve used this authority to put in place special protections for certain

higher-priced loans secured by the borrower’s principal dwelling, including home purchase

loans, as well as refinancing and home equity loans.

12

Second lien loans are also subject to TILA and HOEPA restrictions, but have higher rate

triggers.

13

HOEPA requires the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System to adjust this

dollar figure, initially set at $400, every year according to changes in the Consumer Price

Index. For loans made in 2009, the adjusted dollar figure is $583. 73 F.R. 46190 (Aug. 8,

2008).

Page 8 GAO-09-741 Impact of Mortgage Reform

loans, the law restricts prepayment penalties, prohibits balloon payments

(i.e., a large balance due at maturity of the loan term) for loans with terms

of less than 5 years, prohibits negative amortization, and contains certain

other restrictions on loan terms or payments.

14

• General provisions: For all loans, regardless of whether they fall into one

of the above categories, Regulation Z includes a number of basic

disclosure requirements and prohibits certain activities considered to be

unfair, deceptive, misleading, abusive, or otherwise problematic, such as

coercing a real estate appraiser to misstate a home’s value, and abusive

collection practices by loan servicers.

Each federal banking regulator is charged with enforcing TILA and

HOEPA with respect to the depository institutions it regulates, and the

FTC has responsibility for enforcing the statutes for mortgage brokers and

most financial entities other than banks, thrifts, and federal credit

unions.

15

The Federal Reserve has concurrent authority to enforce T

and HOEPA for non-bank subsidiaries of bank holding companie

ILA

s.

In addition to TILA and HOEPA, some other federal laws govern aspects of

mortgage lending. For example, the Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act

(RESPA), passed in 1974, seeks to protect consumers from unnecessarily

high charges in the settlement of residential mortgages by requiring

lenders to disclose details of the costs of settling a loan and by prohibiting

kickbacks (payments made in exchange for referring a settlement service)

and other costs. HUD has primary rule-writing authority and is responsible

14

Prepayment penalties are prohibited on high-cost HOEPA loans unless (a) the monthly

payment will not change during the first 4 years of the loan; (b) the consumer’s total

monthly debts with the mortgage do not exceed 50 percent of the consumer’s monthly

gross income, as verified by the consumer’s signed financial statement, a credit report, and

payment records for employment income; (c) the penalty is limited to 2 years; and (d) the

source of the prepayment funds is not a refinancing by the creditor or an affiliate of the

creditor. Negative amortization occurs when loan payment amounts do not cover the

interest accruing on a loan, resulting in an increasing outstanding principal balance over

time. See 15 U.S.C. § 1639(f).

15

In the context of this report, the term “federal banking regulators” refers to the Federal

Reserve, the federal supervisory agency for state-chartered banks that are members of the

Federal Reserve System; Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, which supervises

national banks and their subsidiaries; Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the federal

regulator responsible for insured state-chartered banks that are not members of the

Federal Reserve System; Office of Thrift Supervision, the primary federal supervisory

agency for federally insured thrifts and their subsidiaries; and National Credit Union

Administration (NCUA), which supervises federally insured credit unions.

Page 9 GAO-09-741 Impact of Mortgage Reform

for enforcing RESPA. HUD coordinates on RESPA issues, as it deems

appropriate, with federal banking regulators and other federal agencies,

such as the FTC and the Department of Justice. In addition, the federal

banking agencies, under section 8 of the Federal Deposit Insurance Act,

examine for and enforce compliance with RESPA’s requirements with

respect to the institutions they supervise.

16

Finally, the Federal Deposit

Insurance Act and Federal Credit Union Act allow federal banking

regulators to use their supervisory and enforcement authorities to ensure

that an institution’s conduct with respect to consumer protection laws

does not affect its safety and soundness or that of an affiliated institution.

17

Banking Regulator

Guidance

In conjunction with enforcing federal statutes, federal banking regulators

have issued guidance to their institutions—including federally-regulated

banks, thrifts, credit unions, holding companies and their subsidiaries—

about nontraditional and subprime lending.

• In September 2006, banking regulators issued final guidance clarifying

how institutions can offer nontraditional mortgage products in a safe and

sound manner, and in a way that clearly discloses the risks that borrowers

may assume. The guidance provides specific steps institutions should take

to help ensure that loan terms and underwriting standards are consistent

with prudent lending practices, including considering a borrower’s

repayment capacity; ensuring strong risk management standards,

including capital levels; and ensuring that consumers have sufficient

information to clearly understand loan terms and associated risks.

18

• In June 2007, banking regulators issued a final statement on subprime

lending, in response to concerns about certain types of loans that could

result in payment shock to borrowers. The statement warned institutions

about risks associated with subprime loans with adjustable rates with low

16

See 24 C.F.R. § 3500.19(a), “It is the policy of the [HUD] Secretary regarding RESPA

enforcement matters to cooperate with Federal, State, or local agencies having supervisory

powers over lenders or other persons with responsibilities under RESPA. Federal agencies

with supervisory powers over lenders may use their powers to require compliance with

RESPA.”

17

For more information on federal laws and statutes related to mortgage lending, see GAO,

Consumer Protection: Federal and State Agencies Face Challenges in Combating

Predatory Lending, GAO-04-280 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 30, 2004).

18

71 Fed. Reg. 58609 “Interagency Guidance on Nontraditional Mortgage Product Risks,”

(Oct. 4, 2006).

Page 10 GAO-09-741 Impact of Mortgage Reform

initial payments, based on fixed introductory rates that expire after a short

period, limited or no documentation of income, prepayment penalties that

were very high or that extended beyond the initial fixed rate period, and

other product features likely to result in frequent refinancing to maintain

an affordable monthly payment.

19

State Mortgage Lending

Laws

In response to concerns about the growth of predatory lending over the

past decade, many states have enacted laws to restrict the terms or

provisions of certain types of mortgage loans. According to the

Congressional Research Service, at least 30 states and the District of

Columbia had enacted a wide array of such laws, as of November 2008.

20

Many of these state laws are similar to HOEPA in that they regulate and

restrict the terms and characteristics of certain kinds of high-cost

mortgages exceeding certain interest rate or fee thresholds that require

enhanced protections. Like HOEPA, these laws often restrict certain loan

features that can, in certain cases, be abusive—such as prepayment

penalties, balloon payments, negative amortization, and loan flipping—and

many laws also require enhanced disclosures and credit counseling. While

some laws are only minimally different than HOEPA, others are more

comprehensive.

Significant debate has taken place as to the advantages and disadvantages

of state predatory lending laws. In several cases, regulators of federally

supervised financial institutions have determined that federal laws

preempt state predatory lending laws for the institutions they regulate. In

making these determinations, two regulators—the Office of the

Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) and Office of Thrift Supervision

(OTS)—have cited federal law that provides for uniform regulation of

federally chartered institutions and have noted the potential harm that

state predatory lending laws can do to legitimate lending. Many state

officials and consumer advocates are opposed to federal preemption of

state predatory lending laws.

21

They maintain that federal laws related to

19

72 Fed. Reg. 37569 “Statement on Subprime Mortgage Lending,” (Jul. 10, 2007). Banking

regulators have issued other guidance on subprime lending, including Interagency

Guidance on Subprime Lending, Mar. 1, 1999; and Expanded Guidance for Subprime

Lending Programs, Jan. 31, 2001.

20

Congressional Research Service, A Predatory Lending Primer: The Homeownership and

Equity Protection Act (HOEPA), RL34259 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 2008).

21

A recent Supreme Court case (Cuomo v. The Clearing House Association) allows states to

bring lawsuits against national banks to enforce state fair lending and consumer protection

laws.

Page 11 GAO-09-741 Impact of Mortgage Reform

predatory lending are insufficient, and that preemption, therefore,

interferes with their ability to protect consumers in their states.

22

The first state predatory lending law, the North Carolina Anti-Predatory

Lending Law of 1999, has been the subject of particular attention by

researchers and policymakers. The law was more restrictive than HOEPA

was at the time. Among other things, it banned prepayment penalties on all

home loans with a principal amount of $150,000 or less, and prohibited

loan flipping (refinancings of consumer home loans that do not provide a

reasonable, net tangible benefit to the borrower). It included more

restrictions for a category of high-cost loans, which were defined to

include lower points and fee triggers than HOEPA, as well as a third

trigger that included any loan with a prepayment penalty that could be

collected more than 30 months after closing or that was greater than 2

percent of the amount paid.

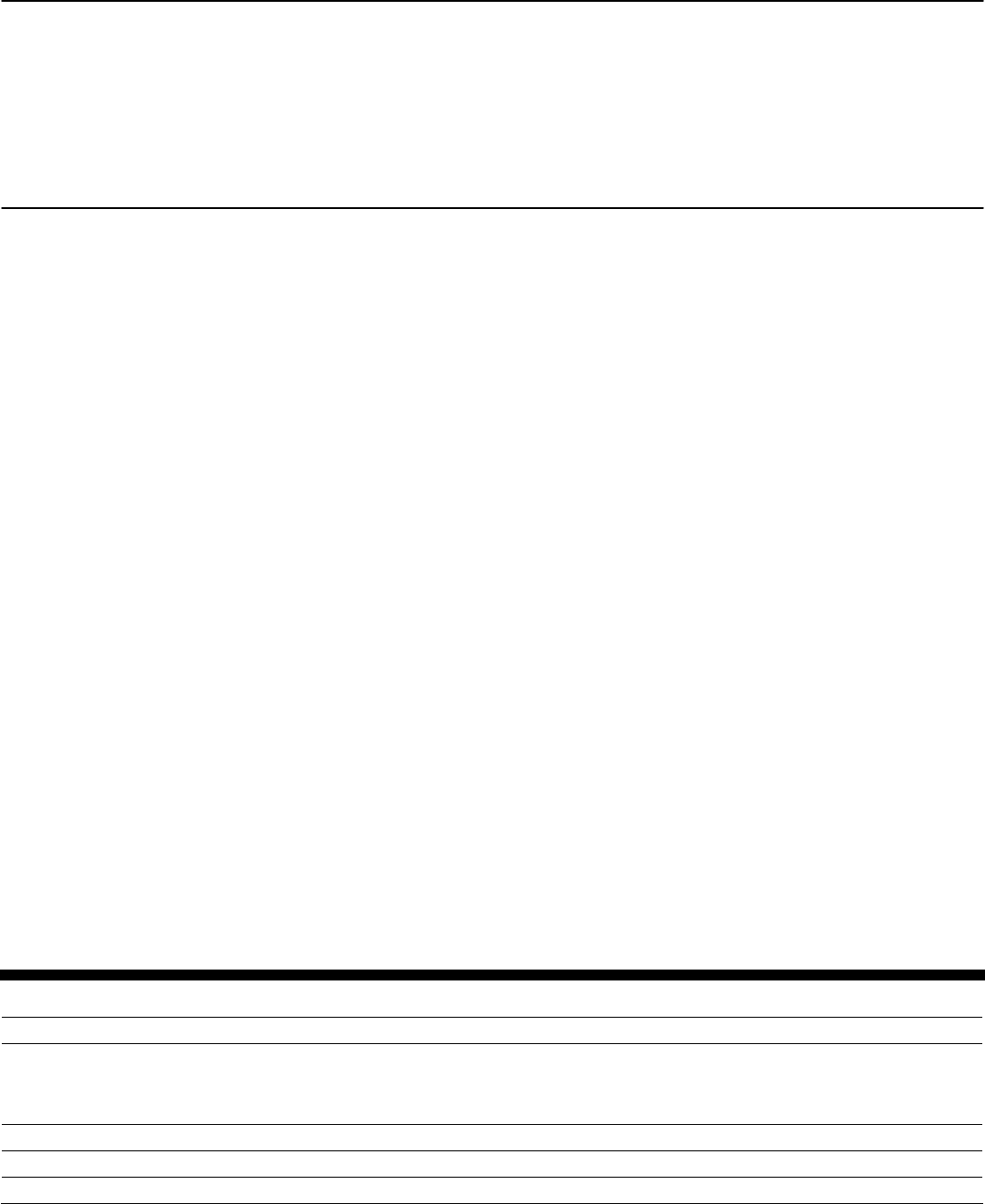

H.R. 3915

The U.S. House of Representatives passed H.R. 3915—the Mortgage

Reform and Anti-Predatory Lending Act of 2007—on November 15, 2007,

in response to significant increases in mortgage defaults and foreclosures,

especially among subprime borrowers.

23

Although the bill was passed by

the U.S. House of Representatives, it was not enacted into law before the

end of the 110th Congress. The bill would have reformed mortgage lending

by, among other things, setting minimum standards for residential

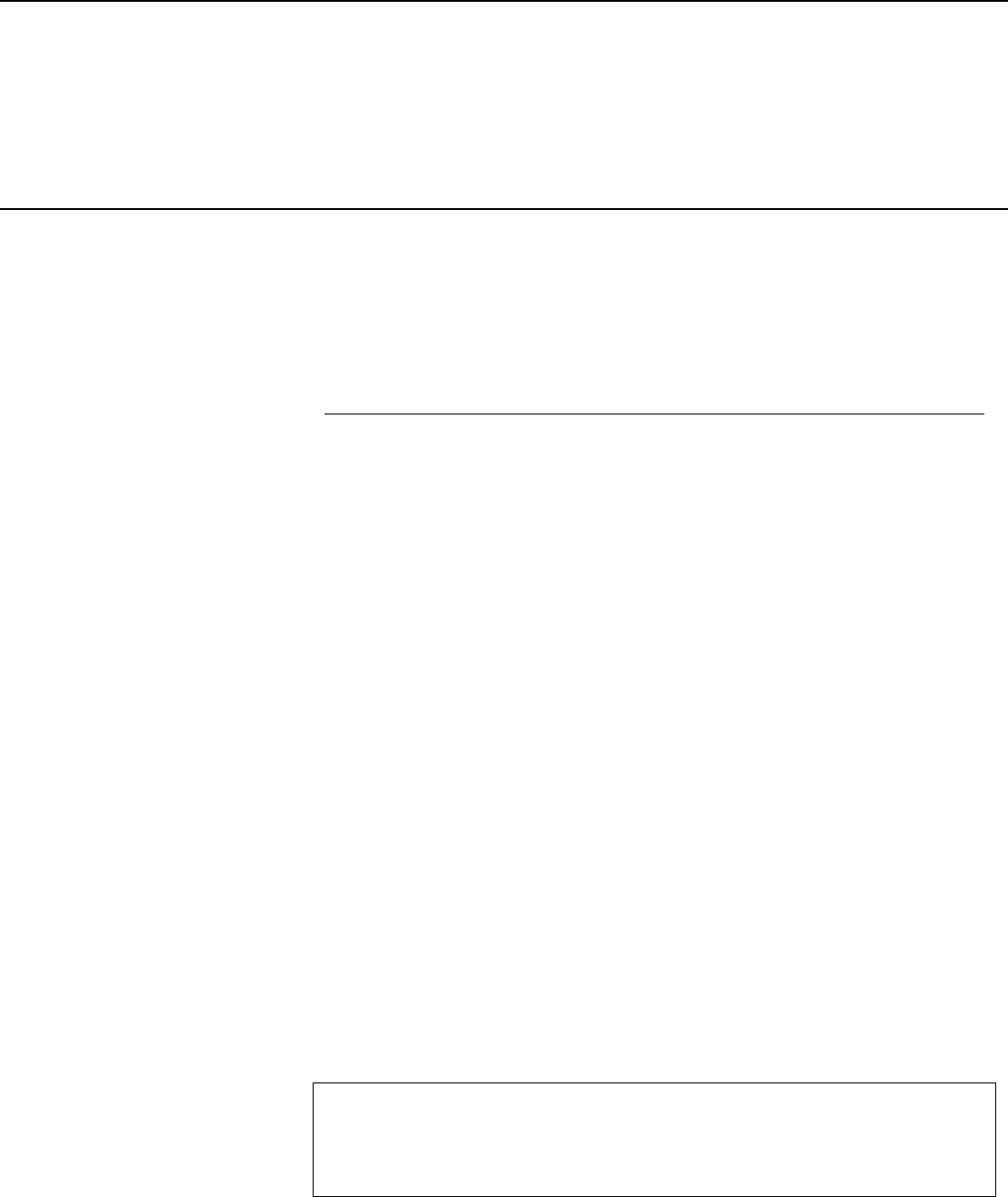

mortgage loans (see fig. 1). The two standards included:

• Reasonable ability to repay. The bill would have created a “reasonable

ability to repay” standard by prohibiting a creditor from making a

residential mortgage loan without making a determination based on

verified and documented information that a consumer was likely to be

able to repay the loan, including all applicable taxes, insurance, and

assessments. Such a determination was to be based on the consumer’s

credit history, current and expected income, obligations, debt-service-to-

22

For more information about preemption, see GAO-04-280; GAO, OCC Preemption

Rulemaking: Opportunities Existed to Enhance the Consultative Efforts and Better

Document the Rulemaking Process, GAO-06-8 (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 17, 2005); and GAO,

OCC Preemption Rules: OCC Should Further Clarify the Applicability of State Consumer

Protection Laws to National Banks, GAO-06-387 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 28, 2006).

23

H.R. 3915 was one of several bills introduced during the 110th Congress to address

concerns about rising foreclosures and abusive lending practices. See also S. 2452, 110th

Congress (2007), Home Ownership Preservation and Protection Act of 2007.

Page 12 GAO-09-741 Impact of Mortgage Reform

income (DTI) ratio, employment status, and financial resources other than

any equity in the real property securing the loan. Additionally, the bill

would have required lenders making ARMs to qualify borrowers at the

fully indexed rate. However, the actual standard was to be prescribed in

regulation by the federal banking agencies, in consultation with the FTC.

• Net tangible benefit. The bill would have created a “net tangible benefit”

standard by prohibiting a creditor from refinancing a loan without making

a reasonable good faith determination that the loan would provide a net

tangible benefit to the consumer. The bill stated that a loan would not

meet the standard if the loan’s costs exceeded the amount of newly

advanced principal, without any corresponding changes in the terms of the

refinanced loan that were advantageous to the consumer. However, the

term “net tangible benefit” was to be defined in regulation by the federal

banking agencies.

The specific responsibilities of lenders to meet the standards, and the

rights of consumers to take action against lenders to claim standards had

not been met, depended on the category of the loan. Under the bill, loans

are classified into three basic categories:

• Qualified mortgages would have had relatively low APRs, be insured by

FHA, or made or guaranteed by VA. This category was intended to include

most prime loans. Specifically, a loan would have been considered a

qualified loan if either the APR was less than 3 percent above the yield on

comparable Treasury securities, or less than 1.75 percent above the most

recent conventional mortgage rate (a term that would have been more

explicitly defined in regulation). For second-lien loans, the limits were 5

and 3.75 percent, respectively. Qualified mortgages would have been

presumed under the law to meet the “ability to repay” and “net tangible

benefit” standards, and for these loans, the creditor’s presumption could

not be rebutted by borrowers.

• Qualified safe harbor mortgages would have fallen outside of the

definition of qualified mortgages (i.e., would not have met this standard),

but would have met certain underwriting requirements. This category was

intended to include subprime loans that did not contain certain high-risk

features. Specifically, these mortgages were required to (1) have full

documentation, (2) be underwritten to the fully indexed rate, (3) not

negatively amortize, and (4) have a fixed rate for at least 5 years, have a

variable rate with an APR less than 3 percentage points over a generally

accepted interest rate index, or meet a DTI ratio to be established in

Page 13 GAO-09-741 Impact of Mortgage Reform

regulation.

24

Qualified safe harbor mortgages, like qualified mortgages,

would have been presumed under the law to meet the “ability to repay”

and “net tangible benefit” standards. Unlike borrowers with qualified

mortgages, however, borrowers with these mortgages would have had the

right to challenge a creditor’s presumption that these loans met the “ability

to repay” and “net tangible benefit” standards.

• Nonqualified mortgages would have fallen outside of the two definitions

above (i.e., would not have met either standard). This category was

intended to include subprime loans with high-risk features. For these

loans, the law would have required lenders to meet the reasonable ability

to repay and net tangible benefit standards, as well as provide borrowers

with the ability to challenge such determinations by creditors and

assignees.

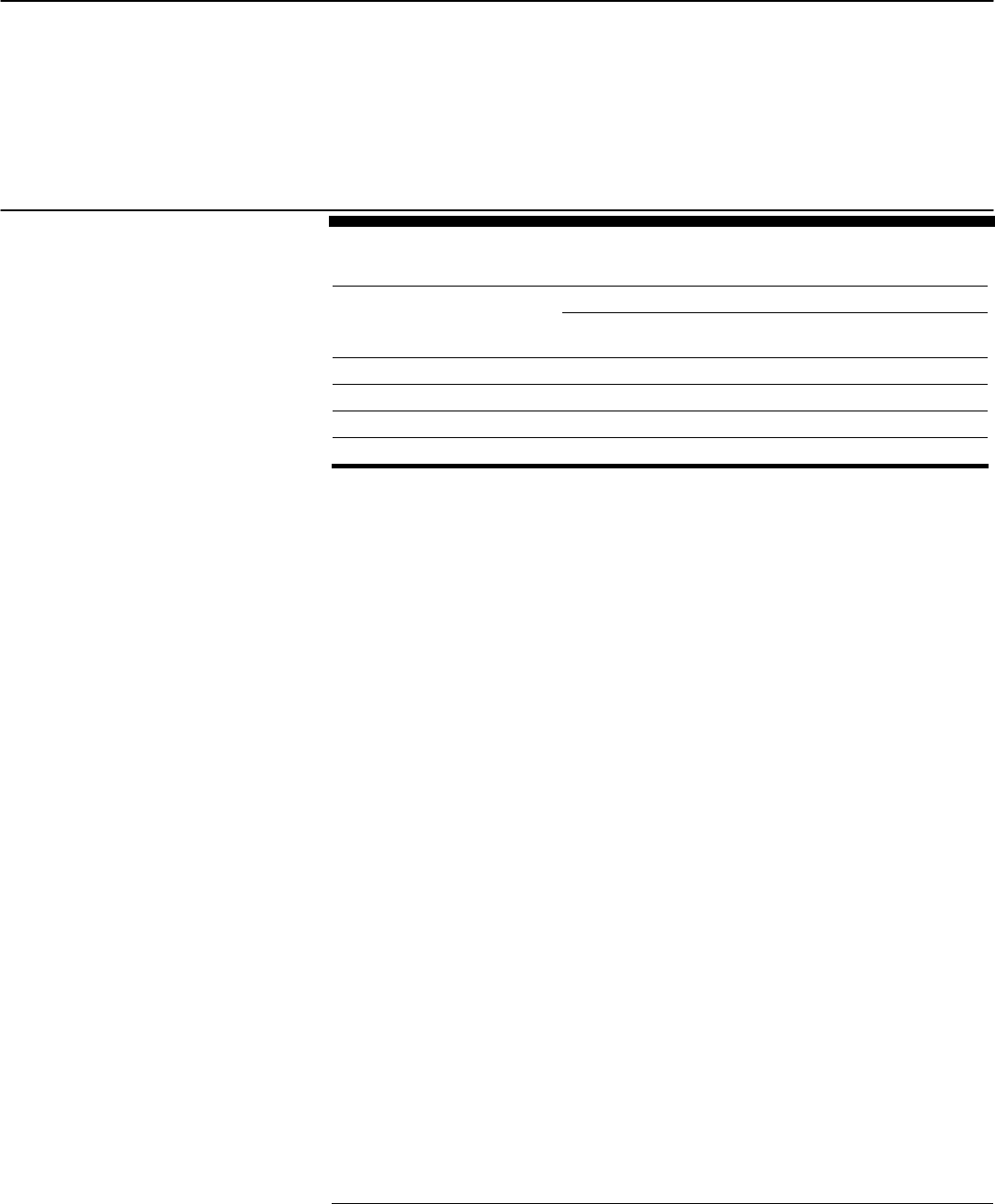

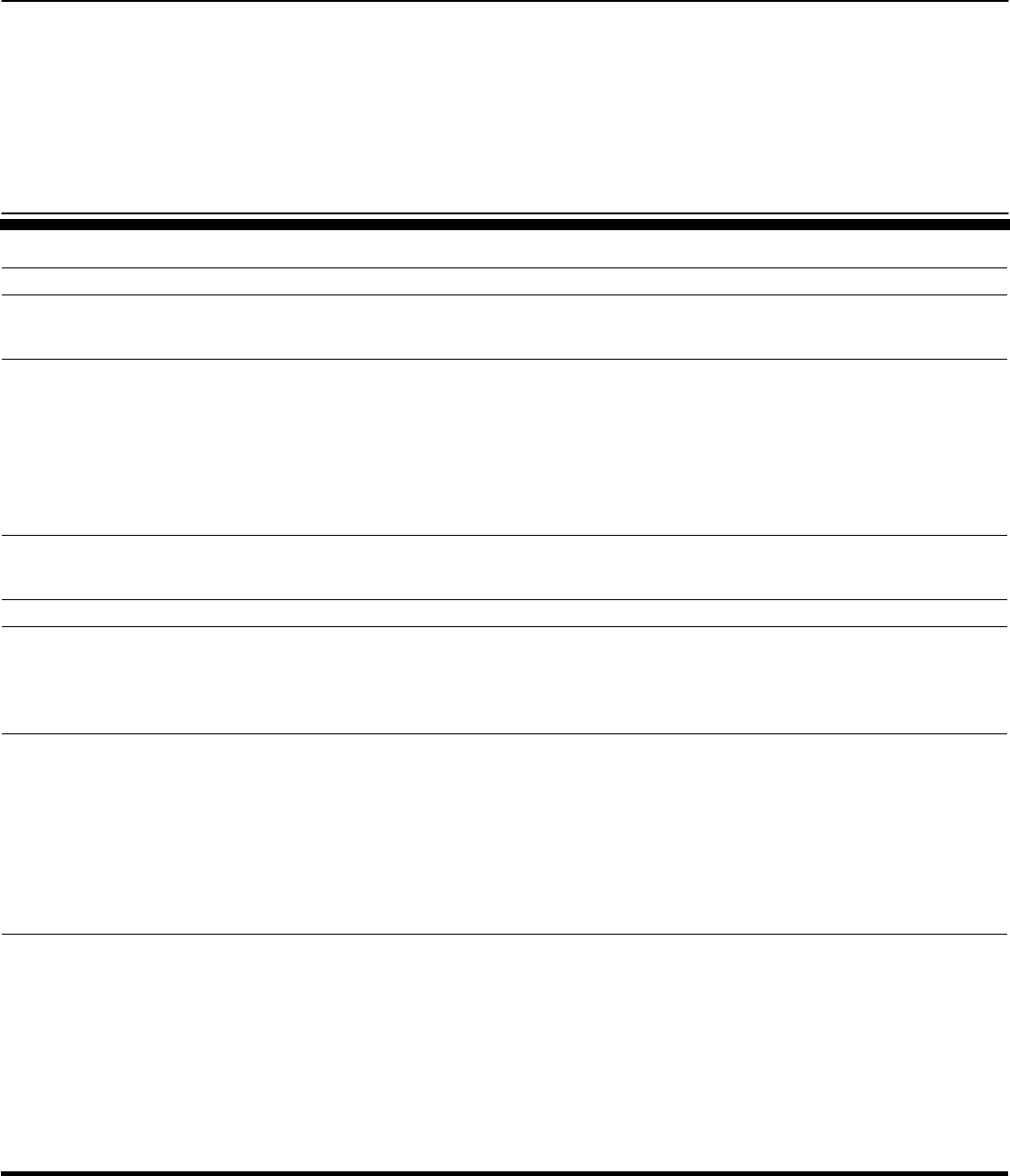

As shown in figure 1, the bill would also have imposed restrictions on

specific loan terms, depending on the loan category. First, the bill would

have prohibited prepayment penalties for loans that were not qualified

mortgages and would have required the penalties on all qualified

mortgages with an adjustable interest rate to expire 3 months before the

initial interest rate adjustment. Second, negative amortization loans to

first-time borrowers would have been prohibited, unless the creditor made

certain disclosures to the consumer and the consumer had received

homeownership counseling from a HUD-certified organization or

counselor. Finally, single-premium credit insurance and mandatory

arbitration on mortgage loans would have been prohibited for all loans.

25

The bill would have established additional liability for creditors of

qualified safe harbor and nonqualified mortgages (see fig. 1).

26

In addition,

24

The bill provided the federal banking agencies the authority to jointly prescribe

regulations to revise, add to, or subtract from these safe harbor provisions to the extent

necessary and appropriate to meet the purposes intended in the law, to prevent

circumvention or evasion of the provisions, or to facilitate compliance with the provisions.

25

Credit insurance is a loan product that repays the lender should the borrower die or

become disabled. In the case of single-premium credit insurance, the full premium is paid

all at once—by being added to the amount financed in the loan—rather than on a monthly

basis. Because adding the full premium to the amount of the loan unnecessarily raises the

amount of interest borrowers pay, single-premium credit insurance is generally considered

inherently abusive.

26

Under the terms of the bill, the liability of rescission faced by creditors would have been

“[i]n addition to any other liability” under TILA for violating the minimum standards. H.R.

3915, § 204. Those additional liabilities include individual and class action damages. See 12

U.S.C. §1640.

Page 14 GAO-09-741 Impact of Mortgage Reform

it would have established limited liability for assignees of nonqualified

mortgages. Borrowers would have been able to bring civil actions against

creditors or assignees if loans violated the “reasonable ability to repay” or

“net tangible benefit” standards. Creditors would have been liable for the

rescission of a loan and the borrower’s cost associated with the rescission

unless they could make the loan conform to minimum standards within 90

days. In addition, assignees would have been liable for the rescission (i.e.,

cancellation) of a loan and for borrower costs associated with the

rescission unless the loan could be made to conform to the minimum

standards within 90 days, or unless the assignee (1) had a policy against

buying loans that were not qualified loans or qualified safe harbor loans,

(2) exercised reasonable due diligence, as defined in regulation by the

federal banking agencies and the SEC, and (3) had agreements with the

seller or assignees of loans requiring that certain standards be met and

certain steps be taken. The bill included additional provisions to resolve

situations in which the parties could not agree on loan changes and set

certain time frames for addressing challenges to these changes. Liability

would not have been extended to pools of loans, including the

securitization vehicles, or investors in pools of loans. According to the

House Committee Report on the bill, it was not intended to apply to

trustees or titleholders who held loans solely for the benefit of the

securitization vehicle.

27

27

Committee Report, 110th Congress, 1st Session, Report 110-441.

Page 15 GAO-09-741 Impact of Mortgage Reform

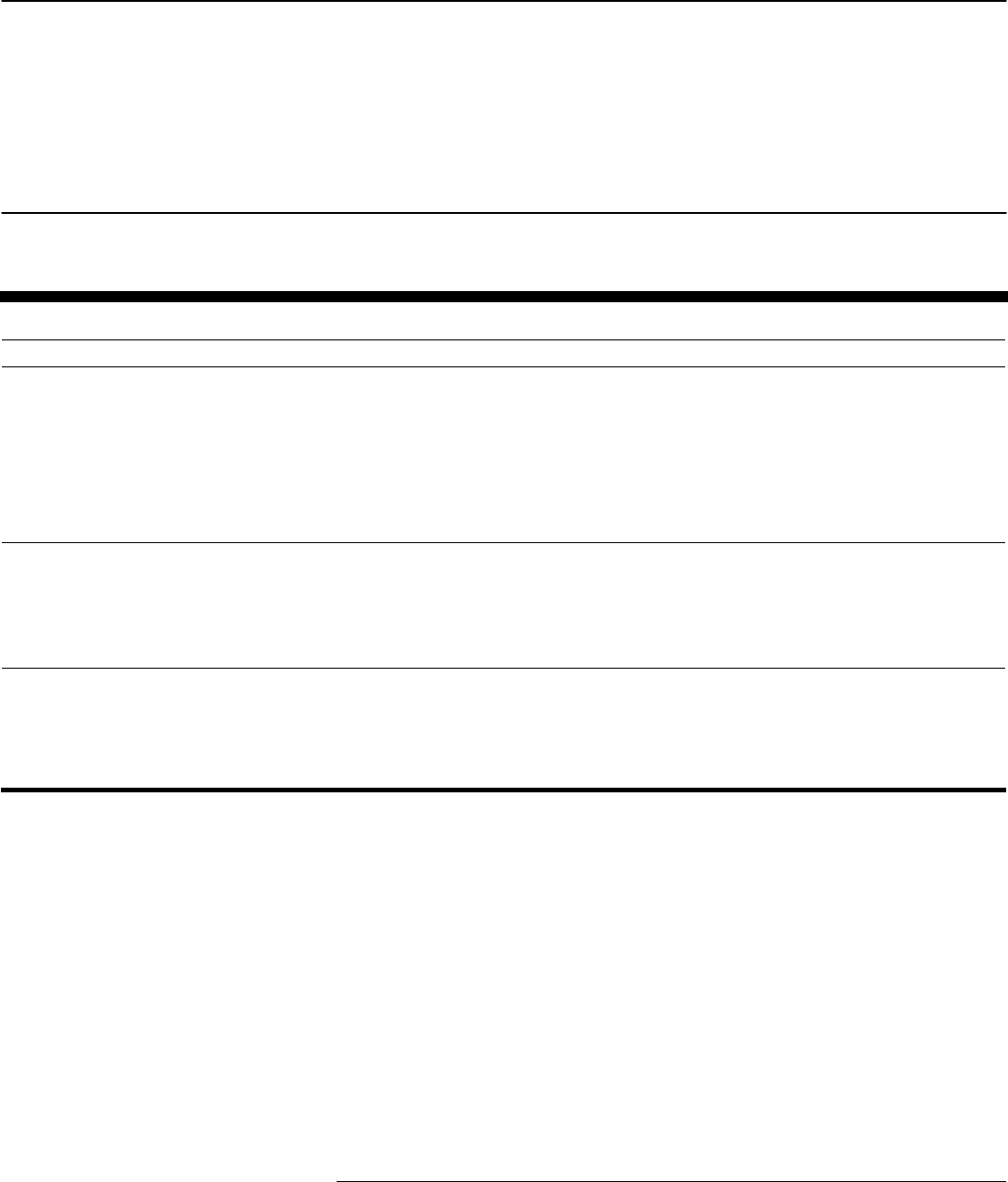

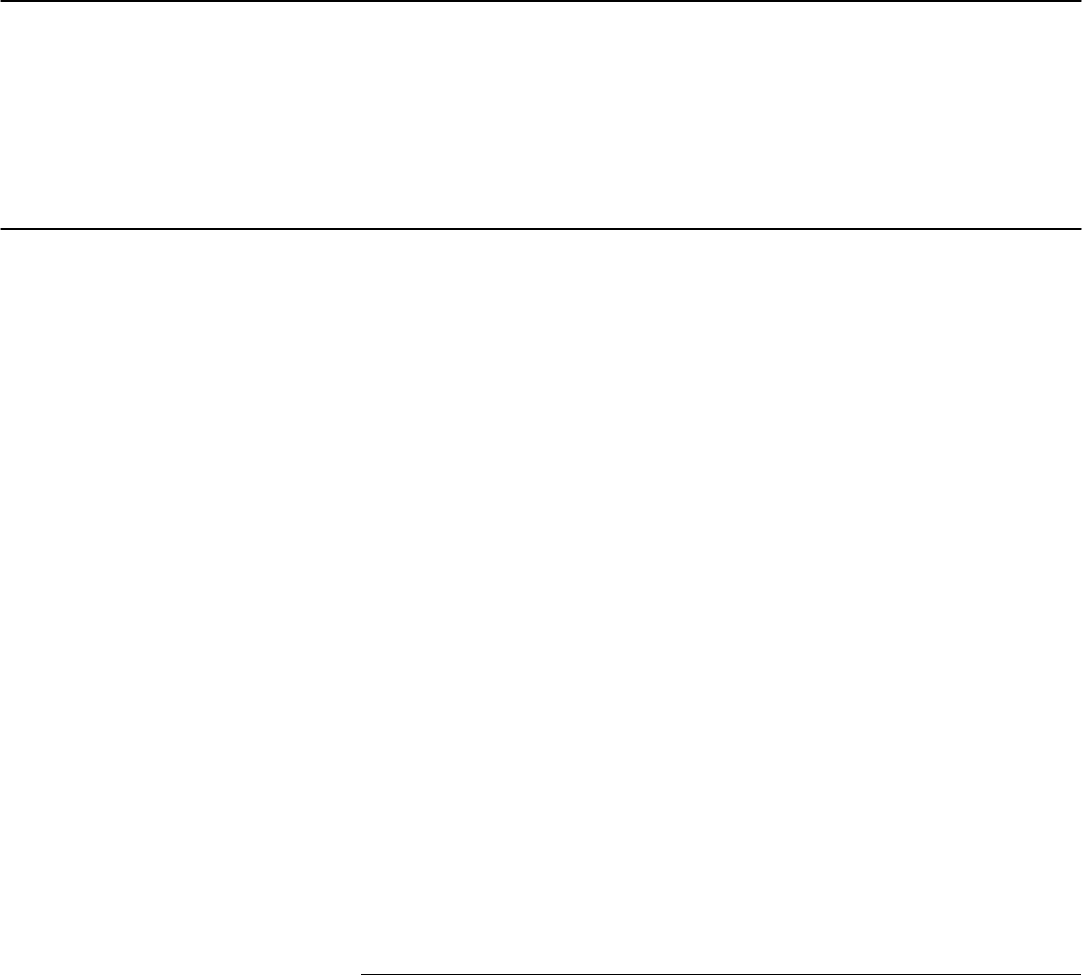

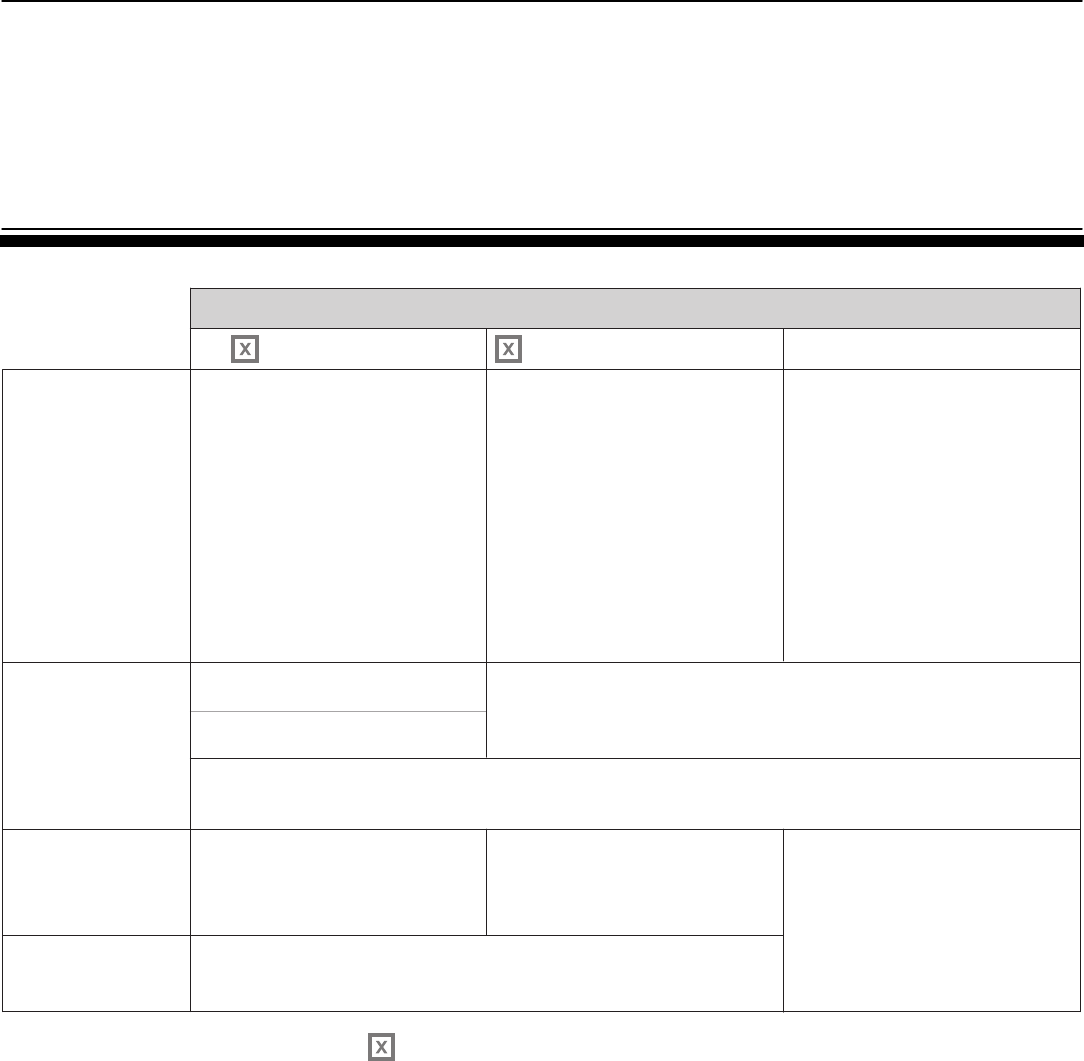

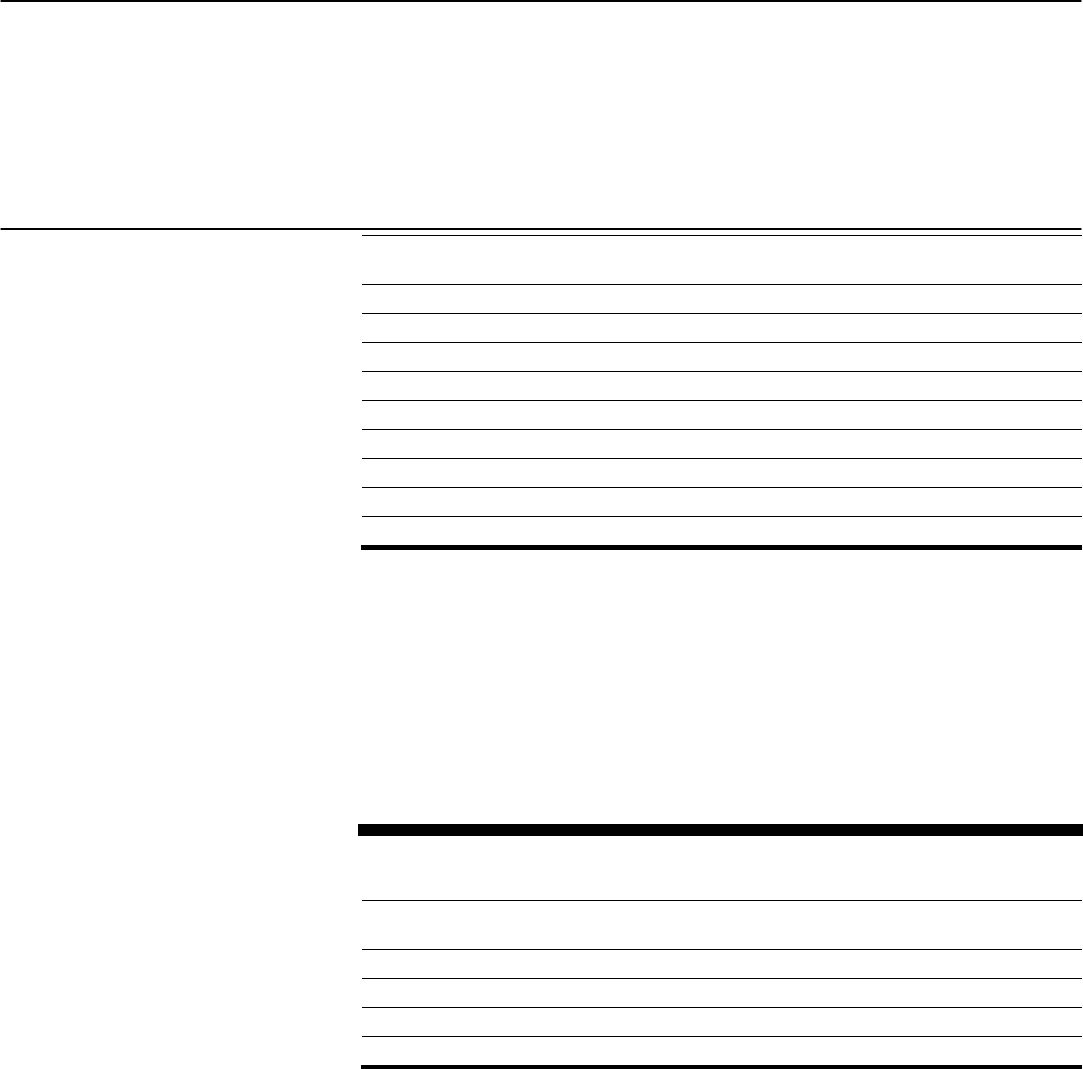

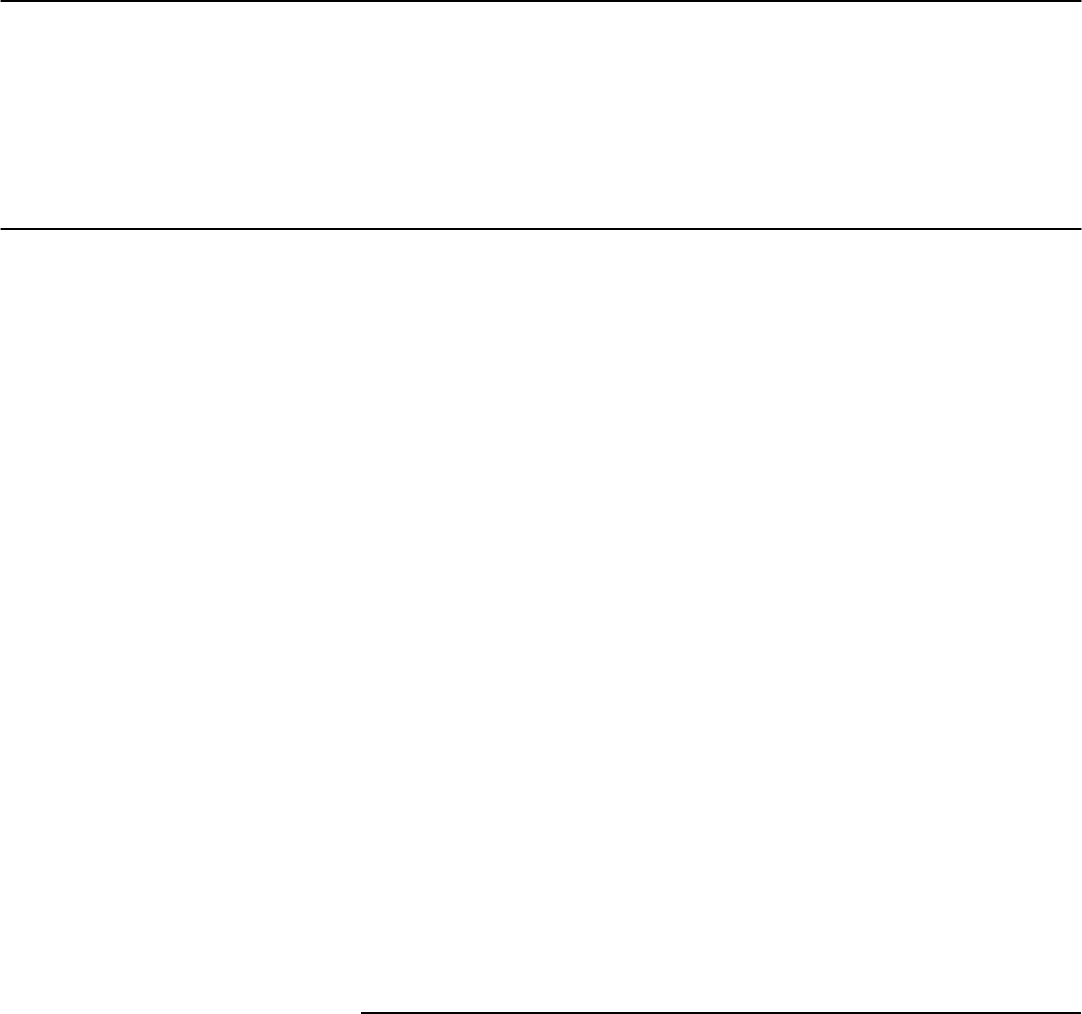

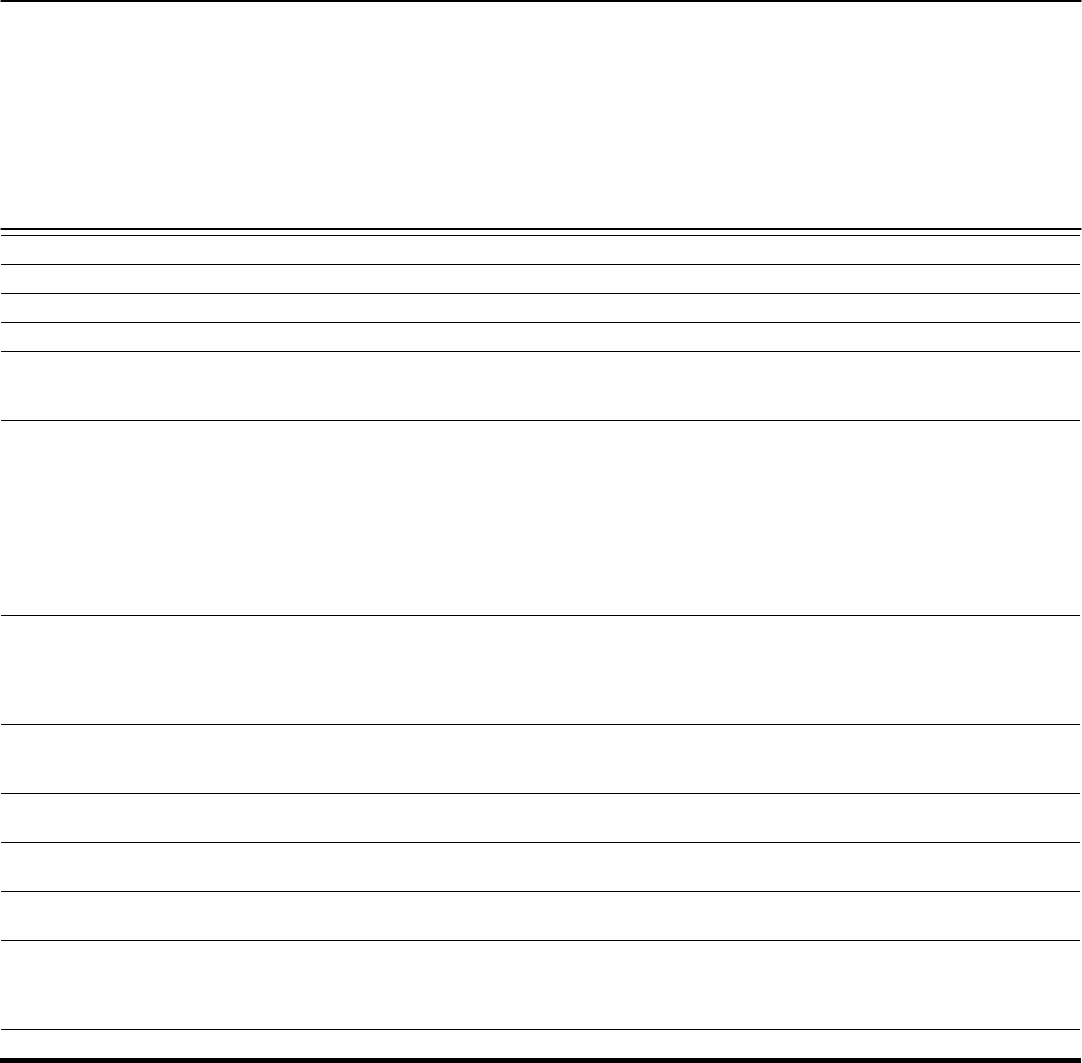

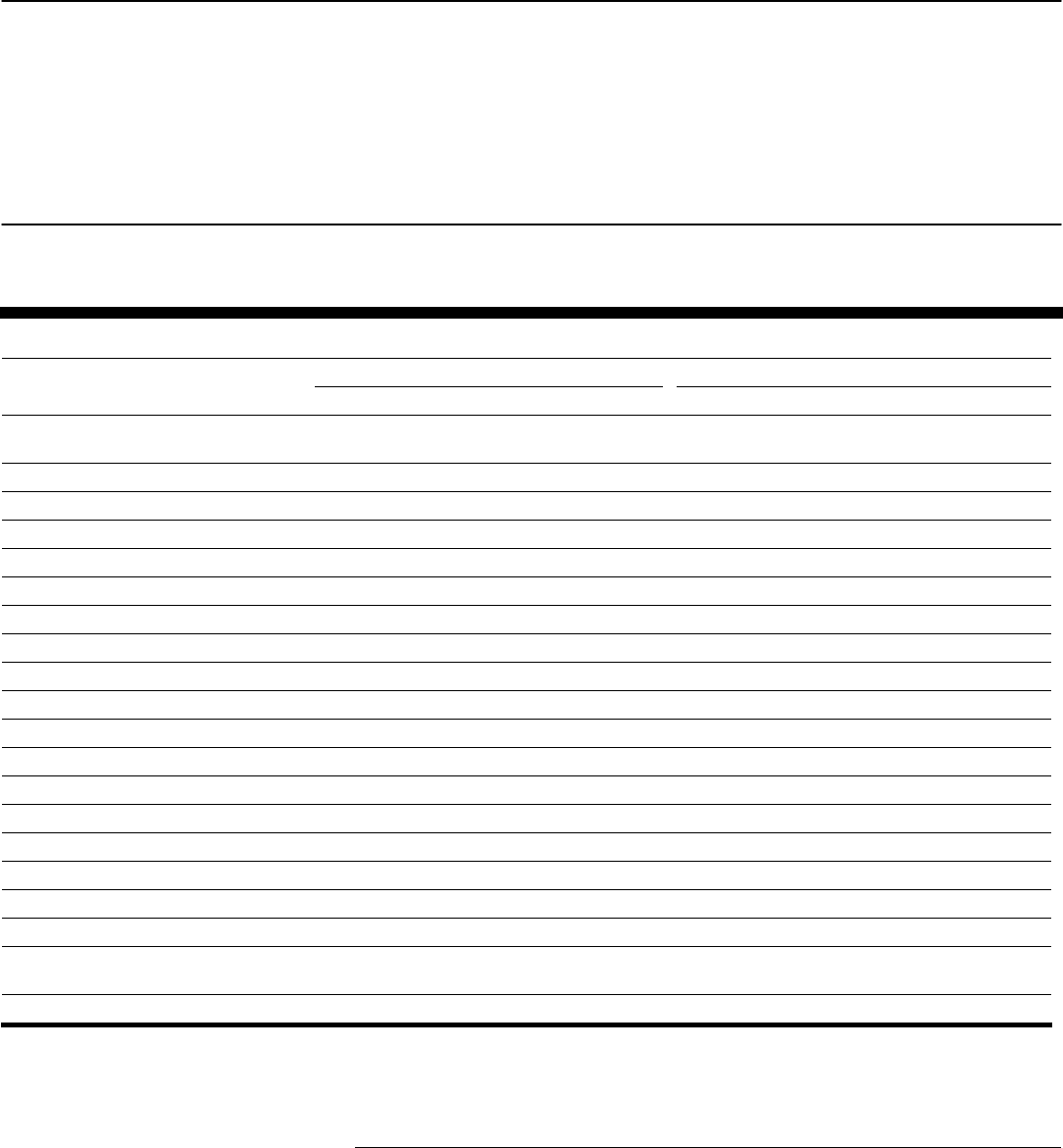

Figure 1: H.R. 3915 Loan Standards

APR requirements

and underwriting

standards

Qualified mortgages

Loan categories

Qualified safe harbor mortgages Nonqualified mortgages

Loan terms

and

standards

Liability for

creditors

Liability for

assignees and

securitizers

Presumed to meet minimum lending standards (i.e., “reasonable ability to repay” and “net tangible benefit”)

• APR less than three percent above yield on

comparable Treasury securities or less

than 1.75 percent above most recent

conventional mortgage rate (to be defined

in regulation)

• Second lien (subordinate loan): APR less

than 5 percent above yield on

comparable Treasury securities or 3.75

percent above most recent conventional

mortgage rate (to be defined in regulation)

• Loan is insured by FHA

• Loan is made or guaranteed by V

A

• Limits on prepayment penalities for first

3 years

• No prepayment penalties after initial fixed

term expires on hybrid-ARM

• No liability for creditors

• No liability for assignees and securitizers

• Potential liability for rescission or cure of

loans (presumption of having met minimum

lending standards is rebuttable if borro

wer

can prove a violation of the miniumum

lending criteria)

a

• Potential liability for rescission or cure of

loans if borrower can prove loan violation

of minimum lending standards

a

• Prohibits prepayment penalties

• Prohibits single premium credit insurance from being financed

• Prohibits requirement of arbitration

• Do not meet standards established for

qualified mortgages or qualified safe

harbor mortgages

Mortgages must meet all four underwriting

standards:

(1) Full documentation

(2) No negative amortization

(3) Underwritten to the fully indexed rate

(4) Have ONE of the following features:

-

fixed interest rate for at least 5 years, or

- variable rate mortgage where the

APR has a margin less than 3 percent

over a generally-accepted interest

rate index, or

- meet a DTI ratio to

be established in regulation

Source: GAO.

a

Liability of creditors for rescission would be in addition to other liabilities (e.g., damages) that

currently exist in TILA.

The bill would also have expanded the definition of “high-cost” loans

under HOEPA. Specifically, the bill would have included home purchase

loans in the definition, reduced the points and fees trigger from 8 to 5

percent—the APR trigger would stay at 8—and expanded the definition of

points and fees for high-cost mortgages. The bill would have also added a

third high-cost trigger for loans with prepayment penalties that applied for

more than 3 years or exceeded 2 percent of the prepaid amount. Further,

Page 16 GAO-09-741 Impact of Mortgage Reform

the bill would have enhanced existing HOEPA restrictions on lending

without repayment ability by presuming that creditors engaged in a

pattern or practice of making high-cost mortgages without verifying or

documenting consumers’ repayment ability were violating HOEPA.

Finally, the bill would have established a federal duty of care for mortgage

originators; prohibited steering of consumers eligible for qualified

mortgages to nonqualified mortgages; established a licensing and

registration regime for loan originators; established an Office of Housing

Counseling within HUD and imposed additional counseling requirements;

made changes to mortgage servicing and appraisal requirements; and

provided protections for renters in foreclosed properties.

We estimate that almost three-quarters of securitized nonprime mortgages

originated from 2000 through 2007 would not have been safe harbor loans.

The extent to which mortgages would have met the individual safe harbor

requirements varied substantially by origination year, reflecting changes in

market conditions and lending practices over the 8-year period. We also

found that the proportions of safe harbor and non-safe harbor loans varied

across different census tract and borrower groupings. Our statistical

analysis of loan data shows that certain variables associated with the safe

harbor requirements—documentation of borrower income and assets, in

particular—were associated with the probability of a loan default. We

found that other variables, such as house price appreciation and borrower

credit score, were also associated with default rates.

Most Recent

Nonprime Mortgages

Would Not Have Been

Safe Harbor Loans

and Certain Variables

Associated with the

Safe Harbor

Requirements and

Other Factors

Influenced Defaults

Most Recent Nonprime

Loans Would Not Have Met

the Bill’s Safe Harbor

Requirements

To illustrate the potential significance of the safe harbor requirements

under different lending environments and market conditions, we applied

those requirements to nonprime mortgages originated from 2000 through

2007 and calculated the proportions of loans that likely would and would

not have met the requirements. Because of data limitations and

uncertainty about how federal regulators would have interpreted some of

the safe harbor requirements, our analysis includes a number of

assumptions discussed in this section. (See appendix I for details about

our methodology.)

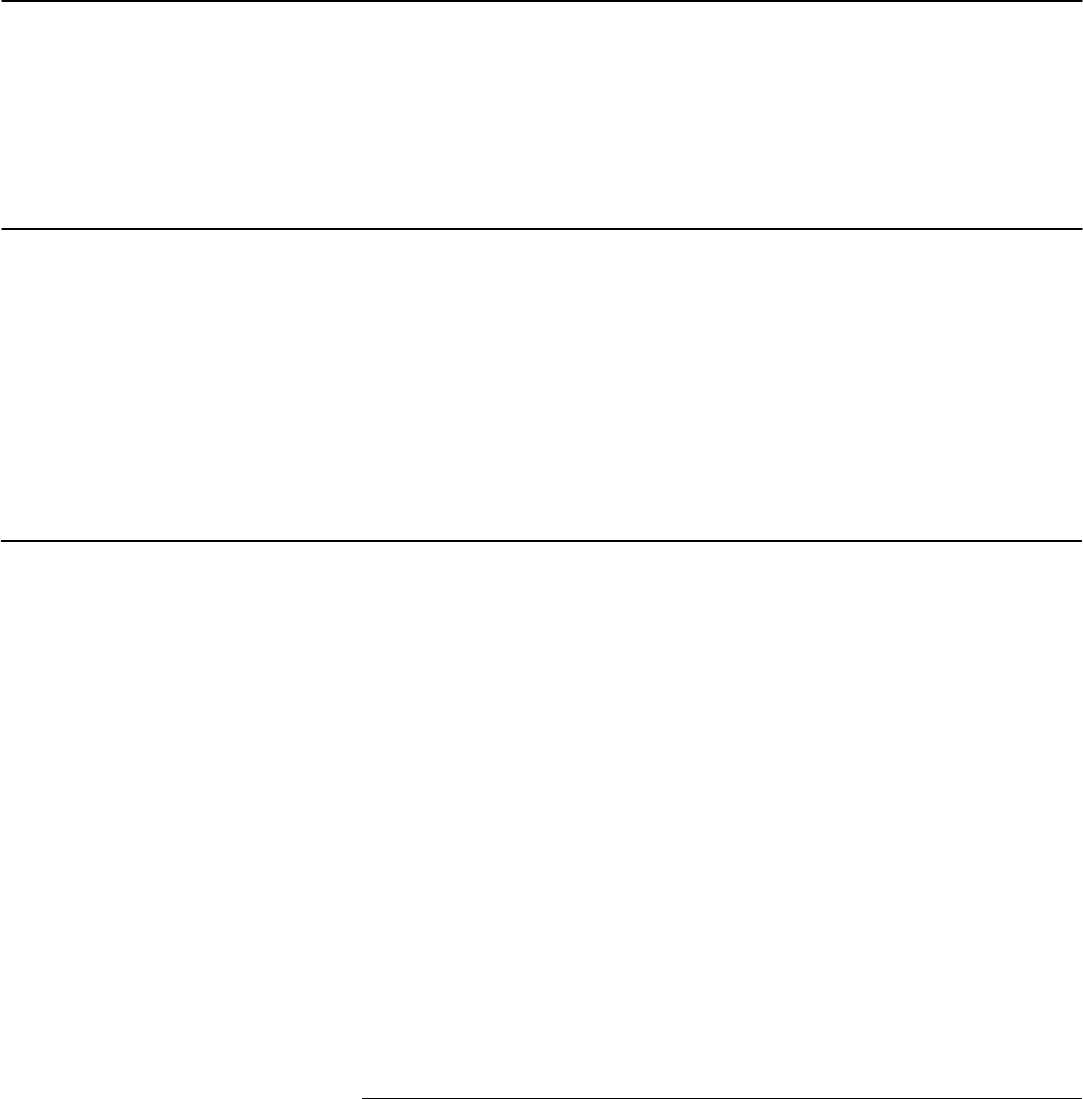

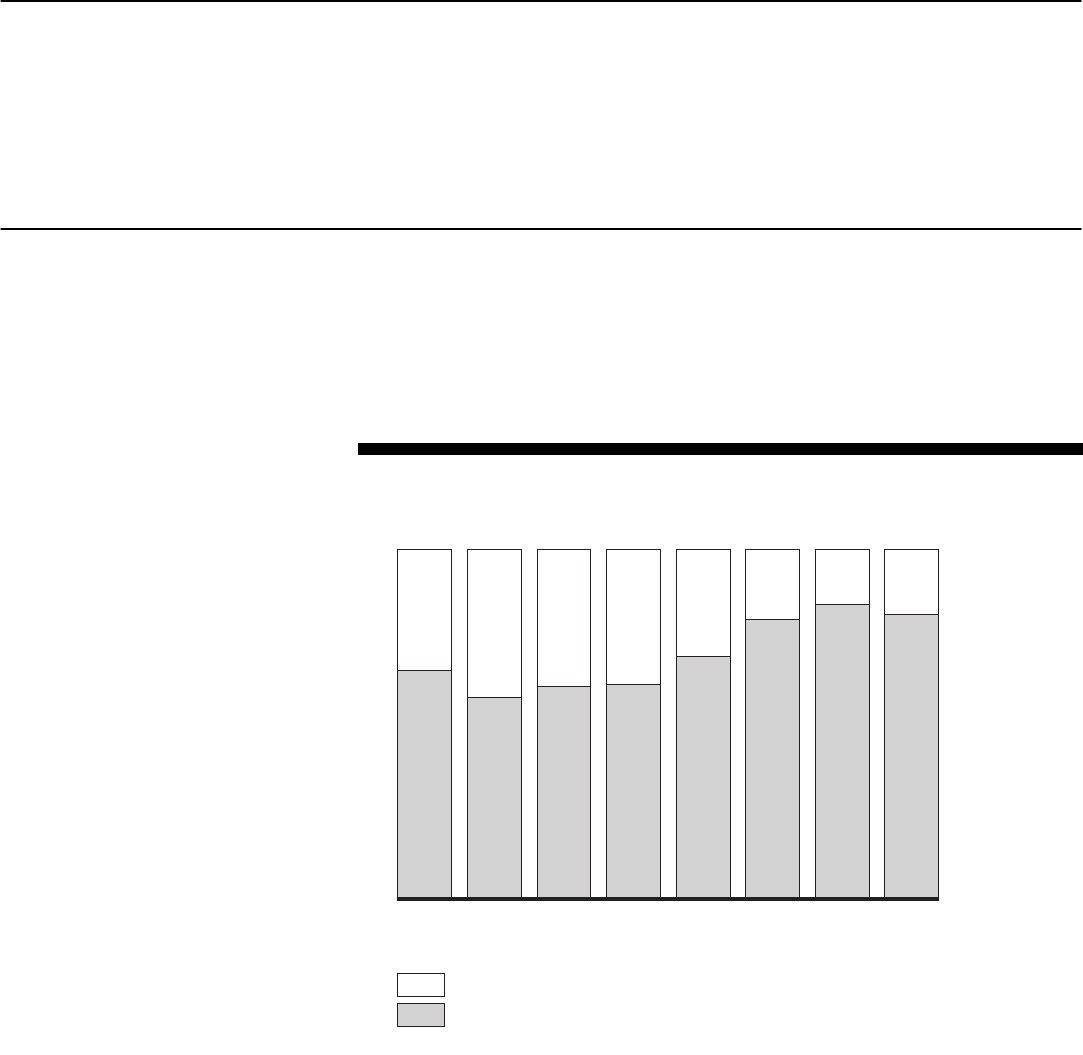

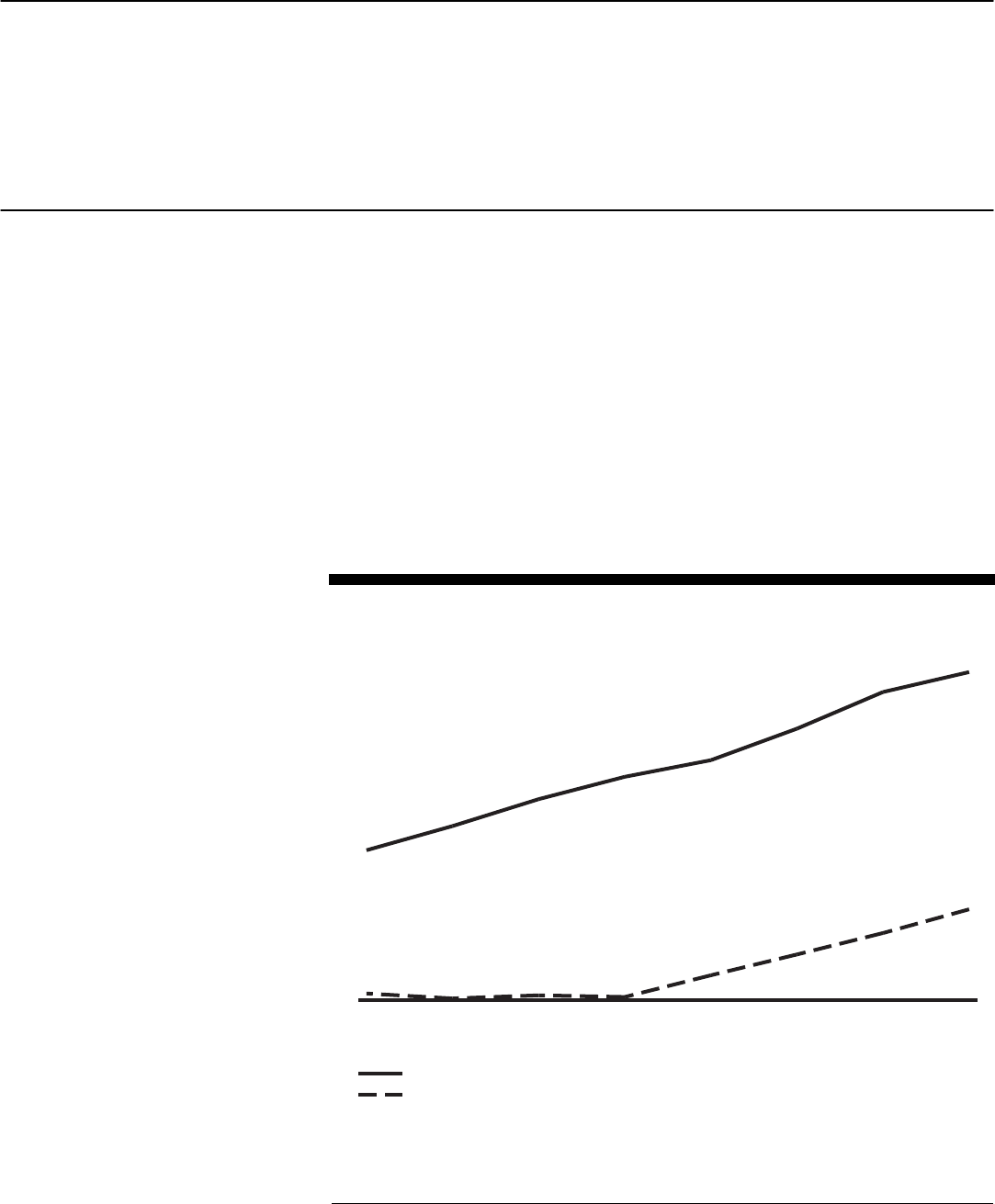

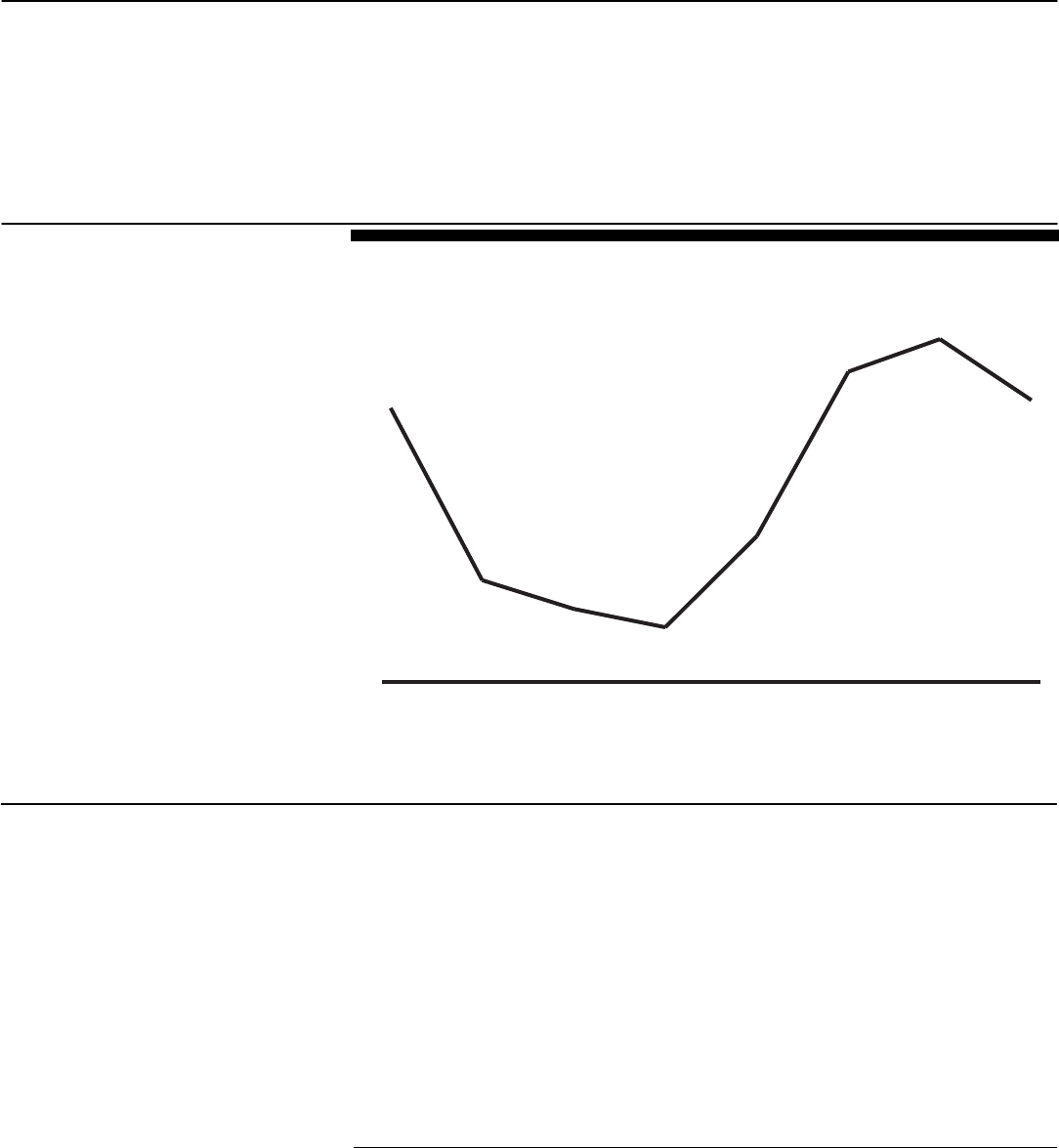

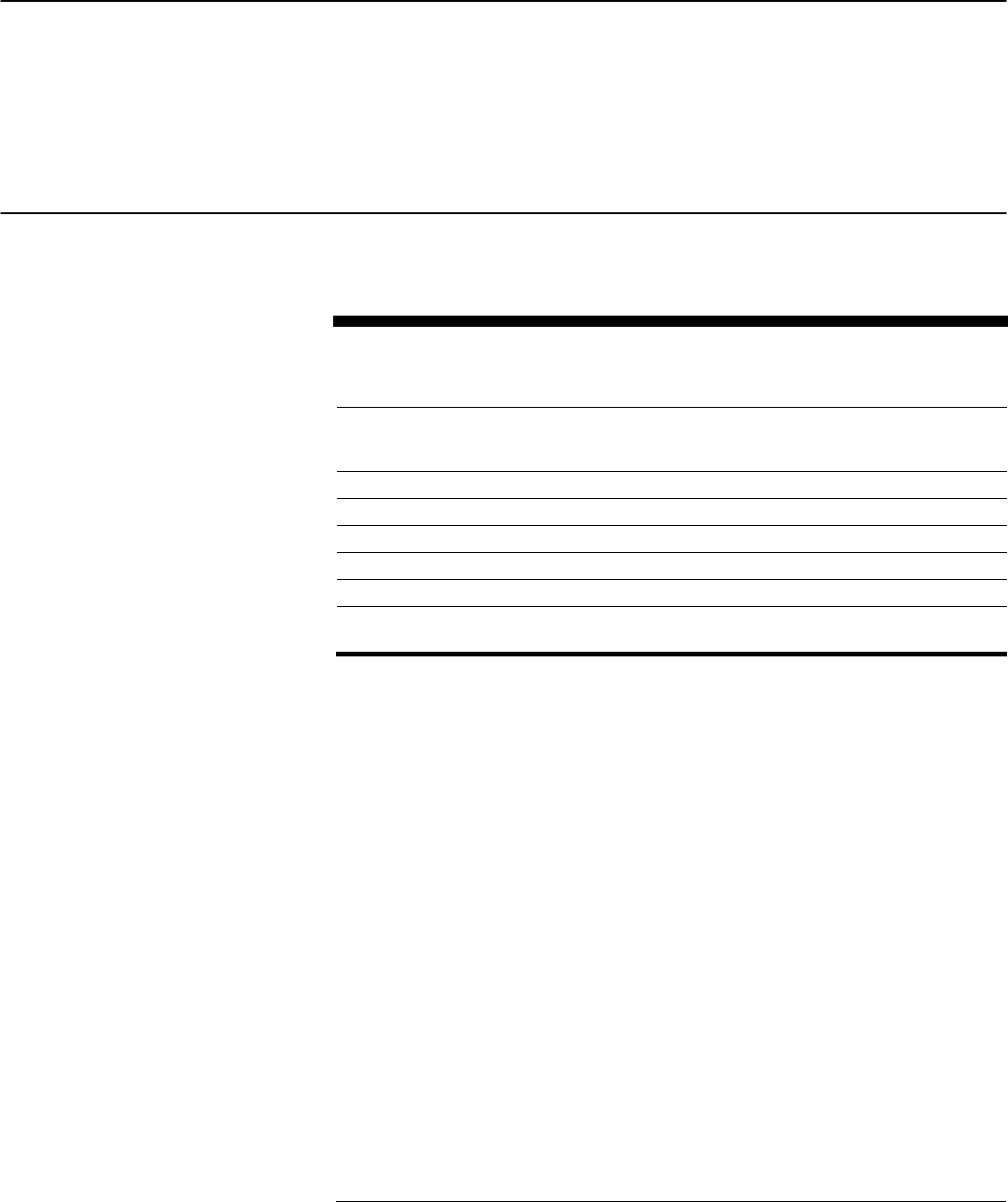

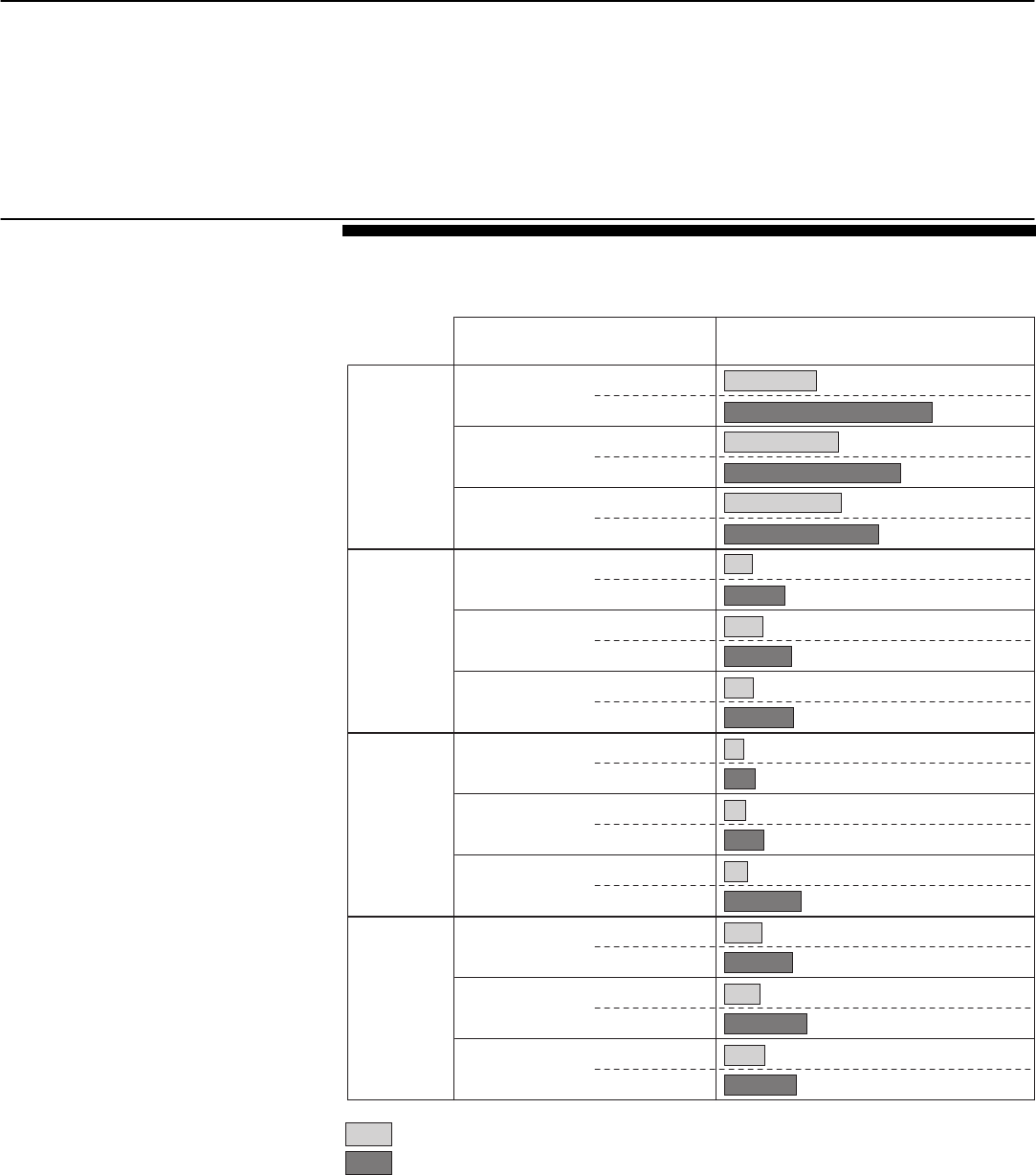

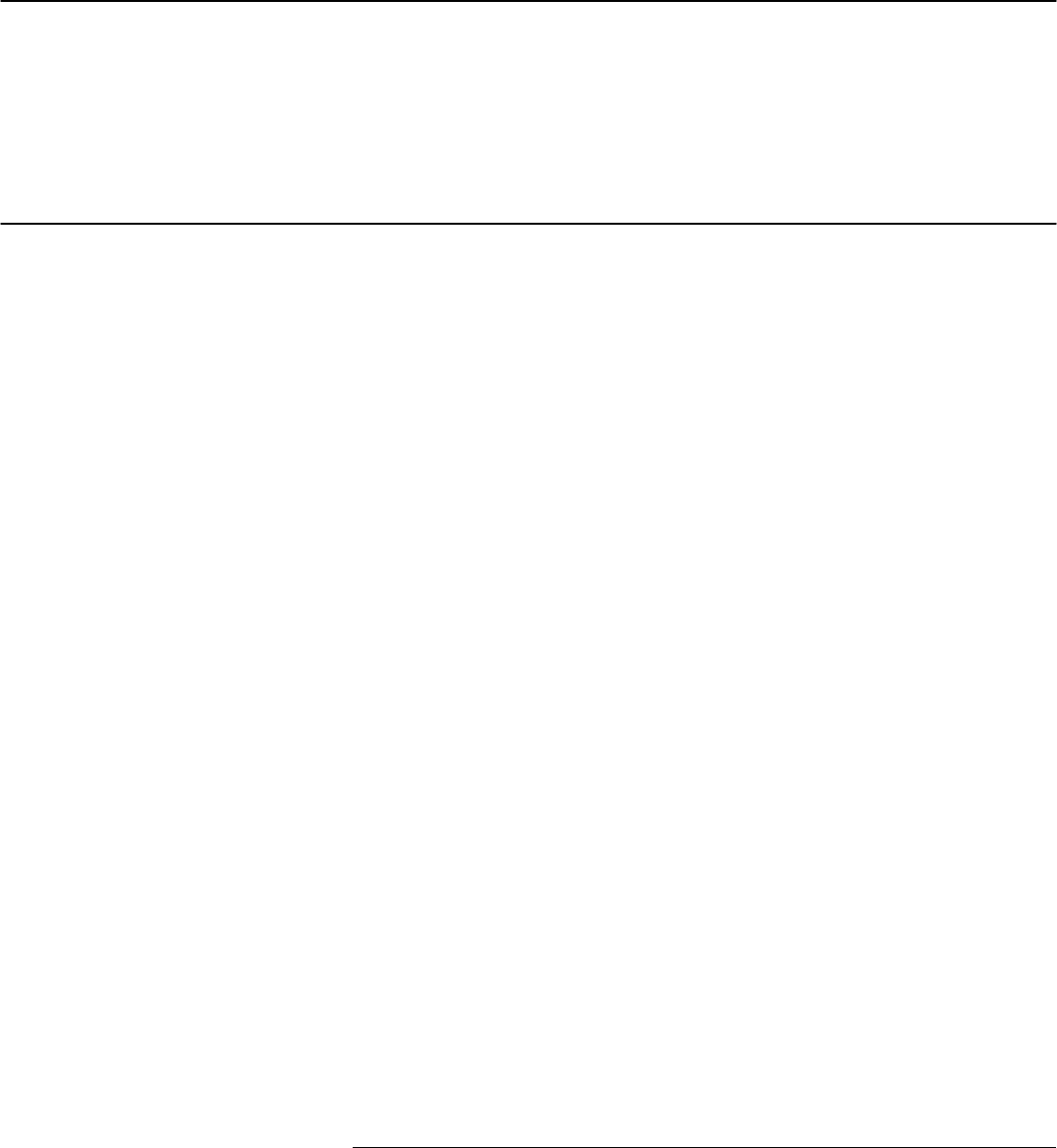

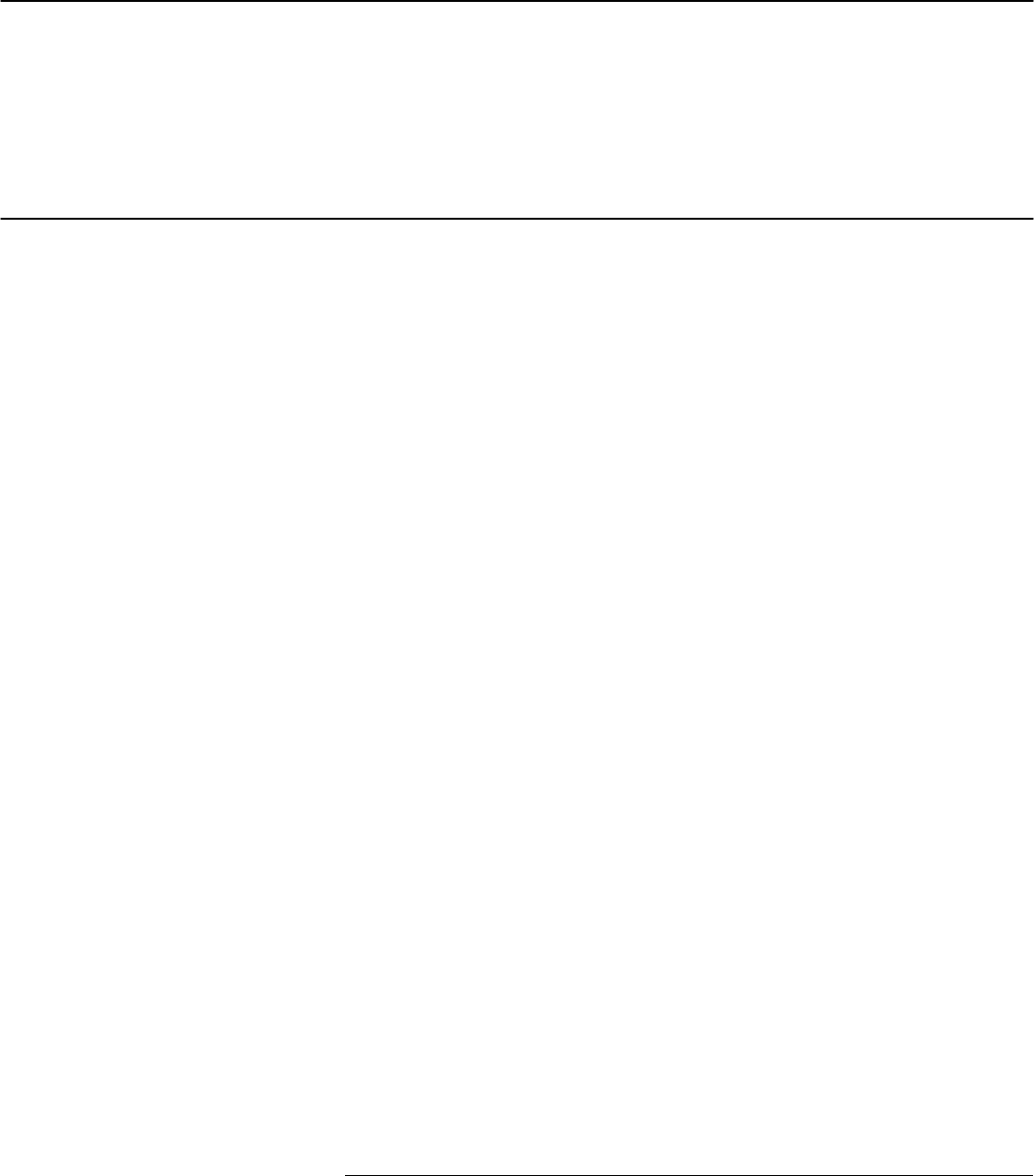

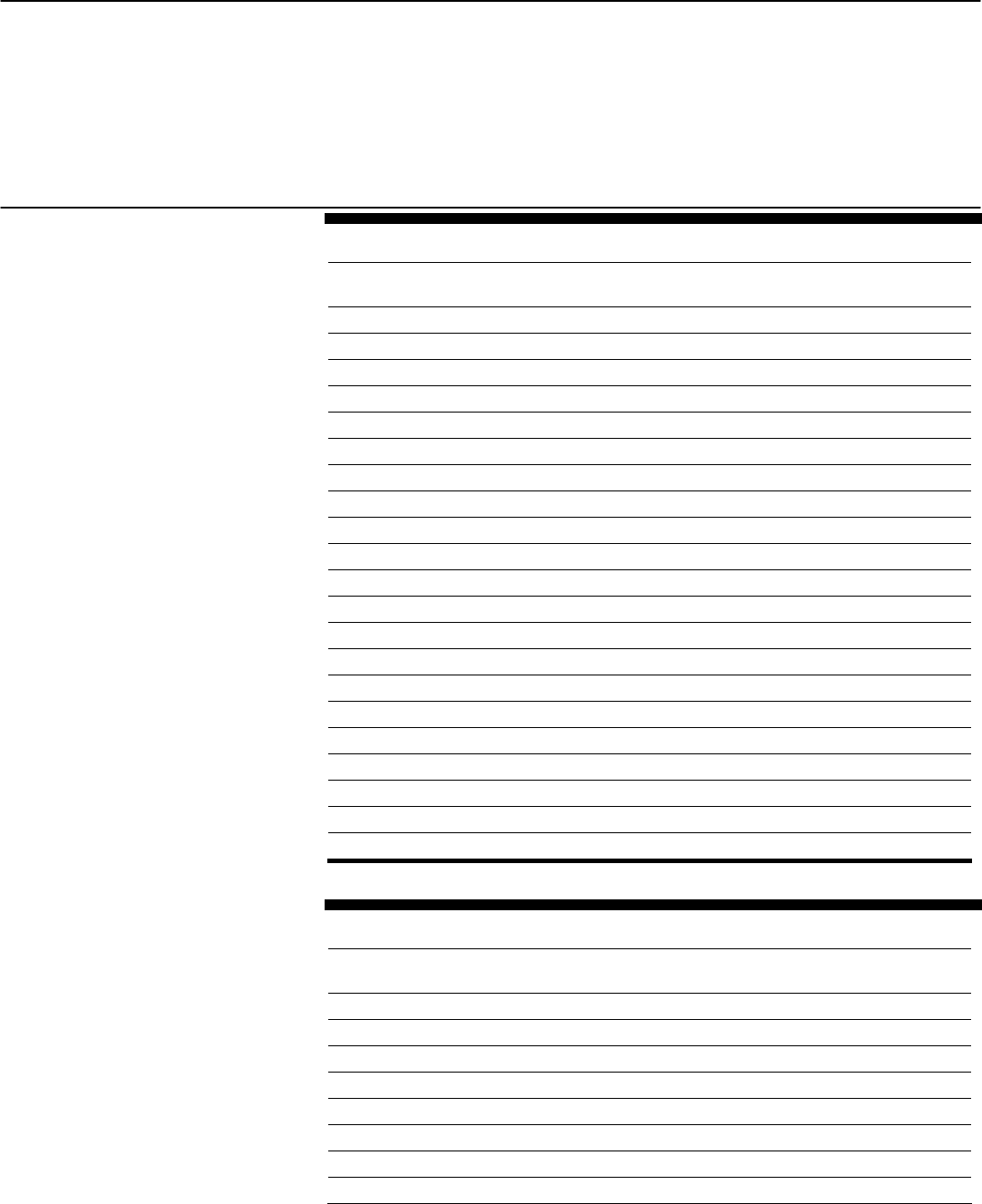

We estimate that almost 75 percent of nonprime mortgages originated

from 2000 through 2007 would not have met the bill’s safe harbor

requirements. More specifically, the estimated proportion of non-safe

harbor loans ranged from a low of 58 percent for 2001 to a high of 84

Page 17 GAO-09-741 Impact of Mortgage Reform

percent for 2006 (see fig. 2). The non-safe harbor loans were primarily

ARMs, while the safe harbor loans were largely fixed-rate mortgages. For

all 8 years combined, Alt-A mortgages represented about 37 percent of

non-safe harbor loans, or slightly more than the Alt-A share of the

nonprime market over this period (35 percent). Over this same period,

subprime mortgages comprised about 63 percent of non-safe harbor loans,

or slightly less that their 65 percent share of the nonprime market.

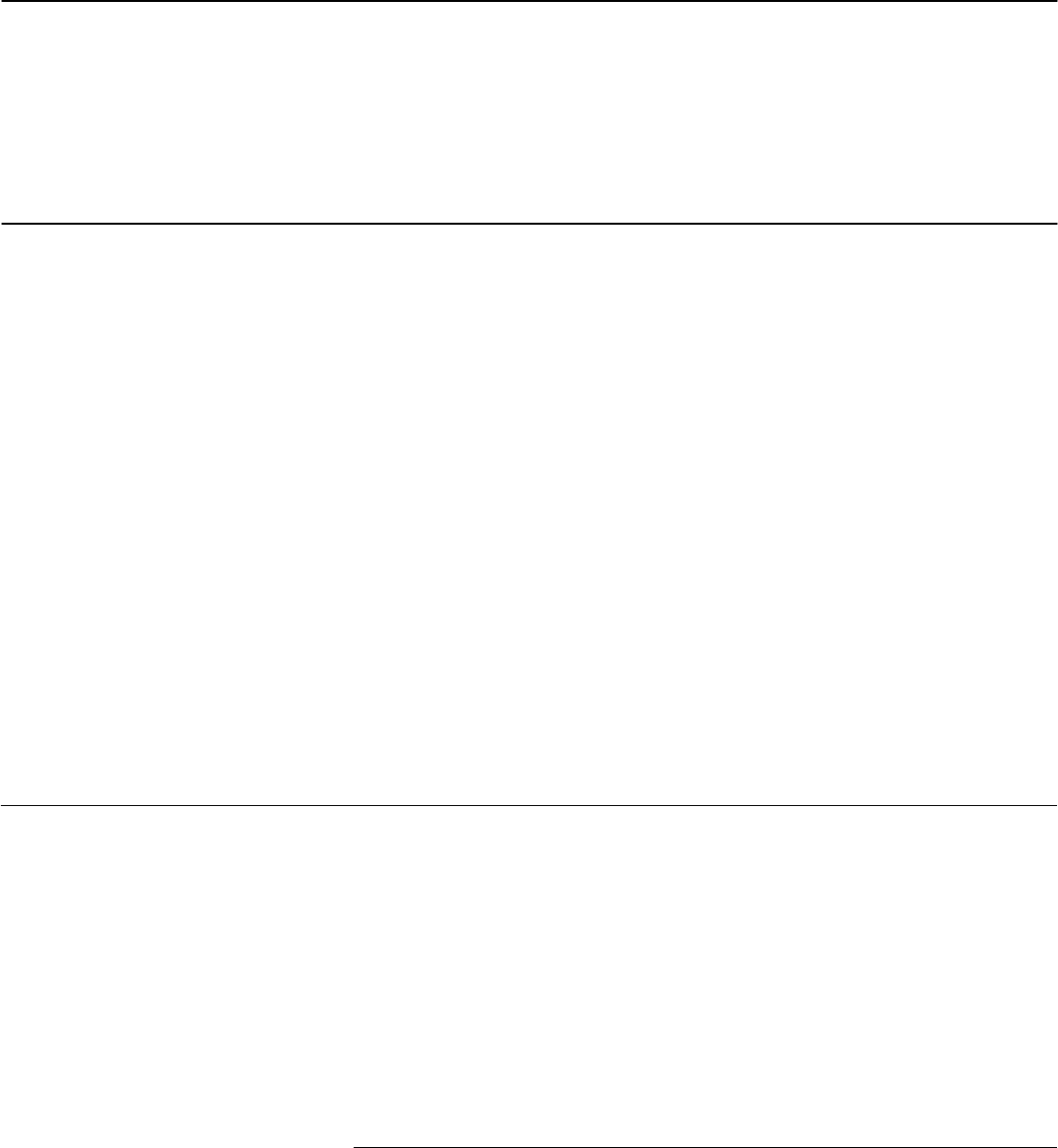

Figure 2: Estimated Proportions of Nonprime Mortgages Meeting and Not Meeting

the Safe Harbor Requirements, 2000-2007

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

20072006200520042003200220012000

Percentage

Year

Safe harbor loans

Non-safe harbor loans

Source: GAO analysis of LP data.

The significance of particular safe harbor requirements varied by

origination year. As previously noted, the safe harbor requirements include

the following:

• Documentation and amortization. The mortgage would have to be

underwritten based on full documentation of the borrower’s income and

assets and could not have a negative amortization feature.

• Interest rate and debt burden. The mortgage would be required to have

either (1) a fixed interest rate for at least 5 years, (2) a DTI ratio within a

Page 18 GAO-09-741 Impact of Mortgage Reform

level to be specified in regulation (we used the 41 percent ratio that serves

as a guideline in underwriting FHA-insured mortgages), or (3) an ARM

with an APR of less than 3 percentage points over a generally accepted

interest rate index.

28

Because the loan data we used did not include APRs,

we instead compared the initial interest rate on each loan to the relevant

interest rate index.

29

• Fully indexed rate. The mortgage would have to be underwritten to the

fully indexed interest rate (which the bill defines as the initial interest rate

index, plus the lender’s margin). We could not determine from the data we

used whether a mortgage was underwritten to the fully indexed rate. We

created a proxy by assuming that the mortgage satisfied this requirement if

the fully indexed rate was 1 percentage point or less over the initial

interest rate, indicating a reasonable likelihood that the borrower could

have qualified for a loan underwritten to the fully indexed rate.

30

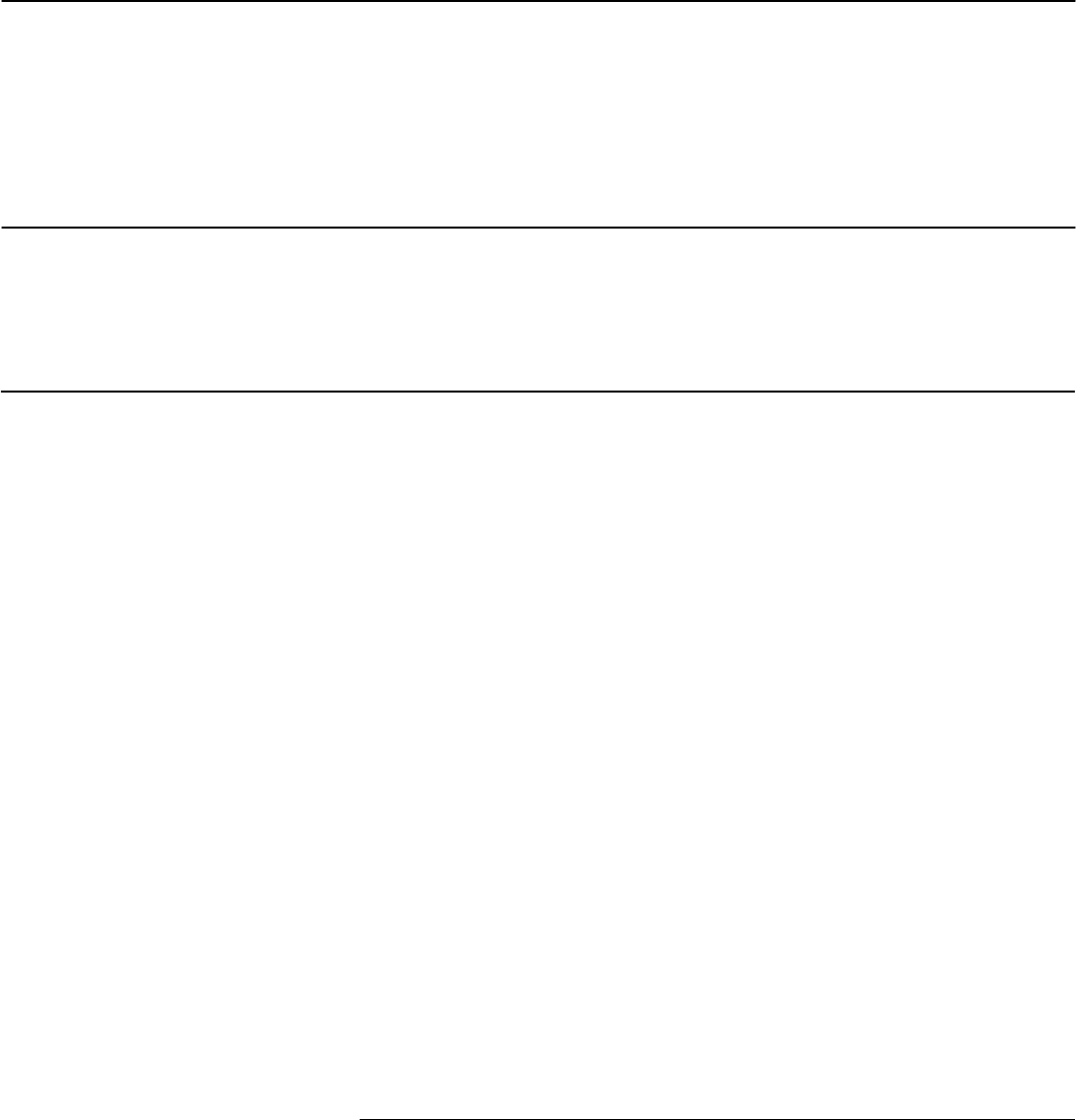

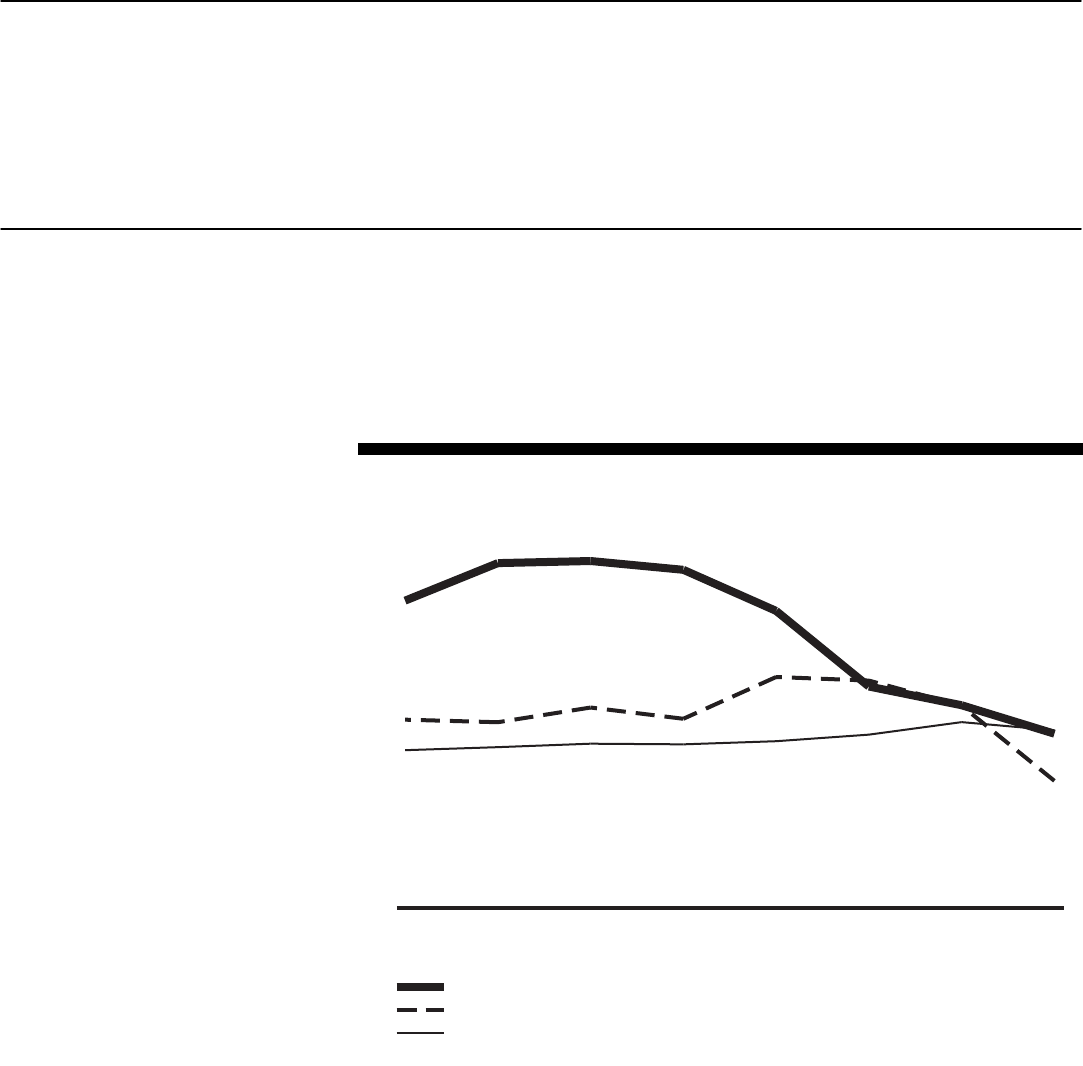

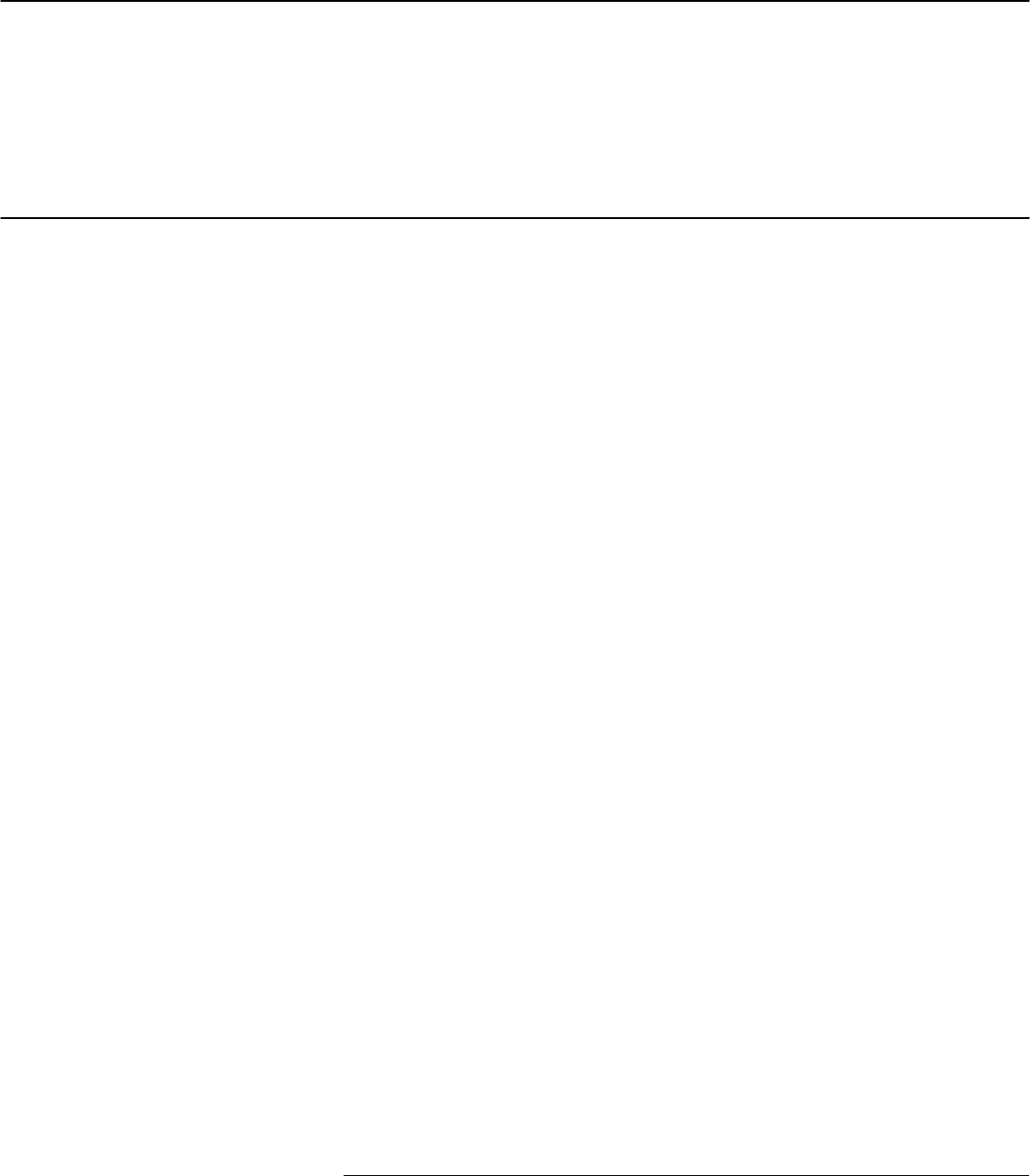

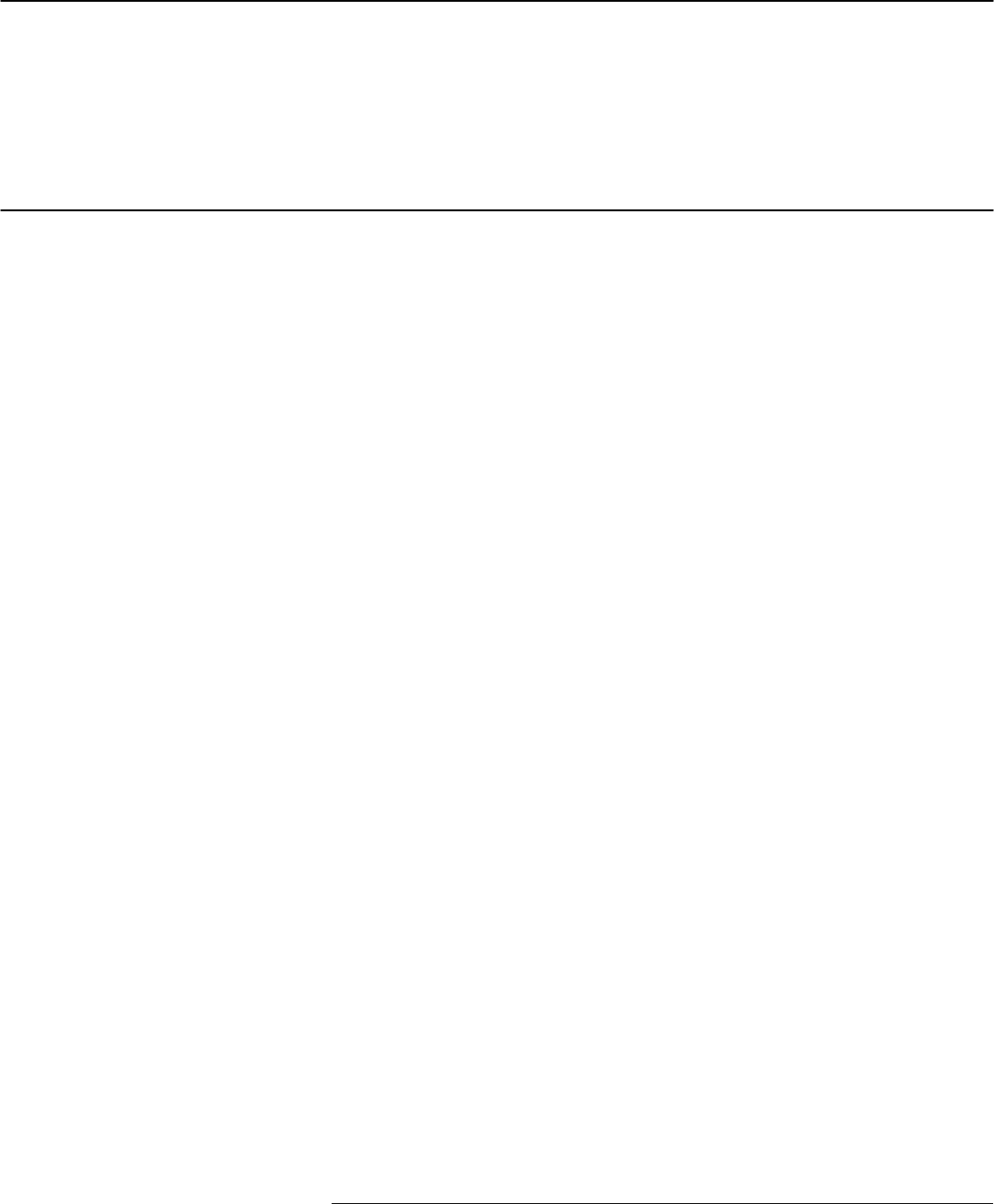

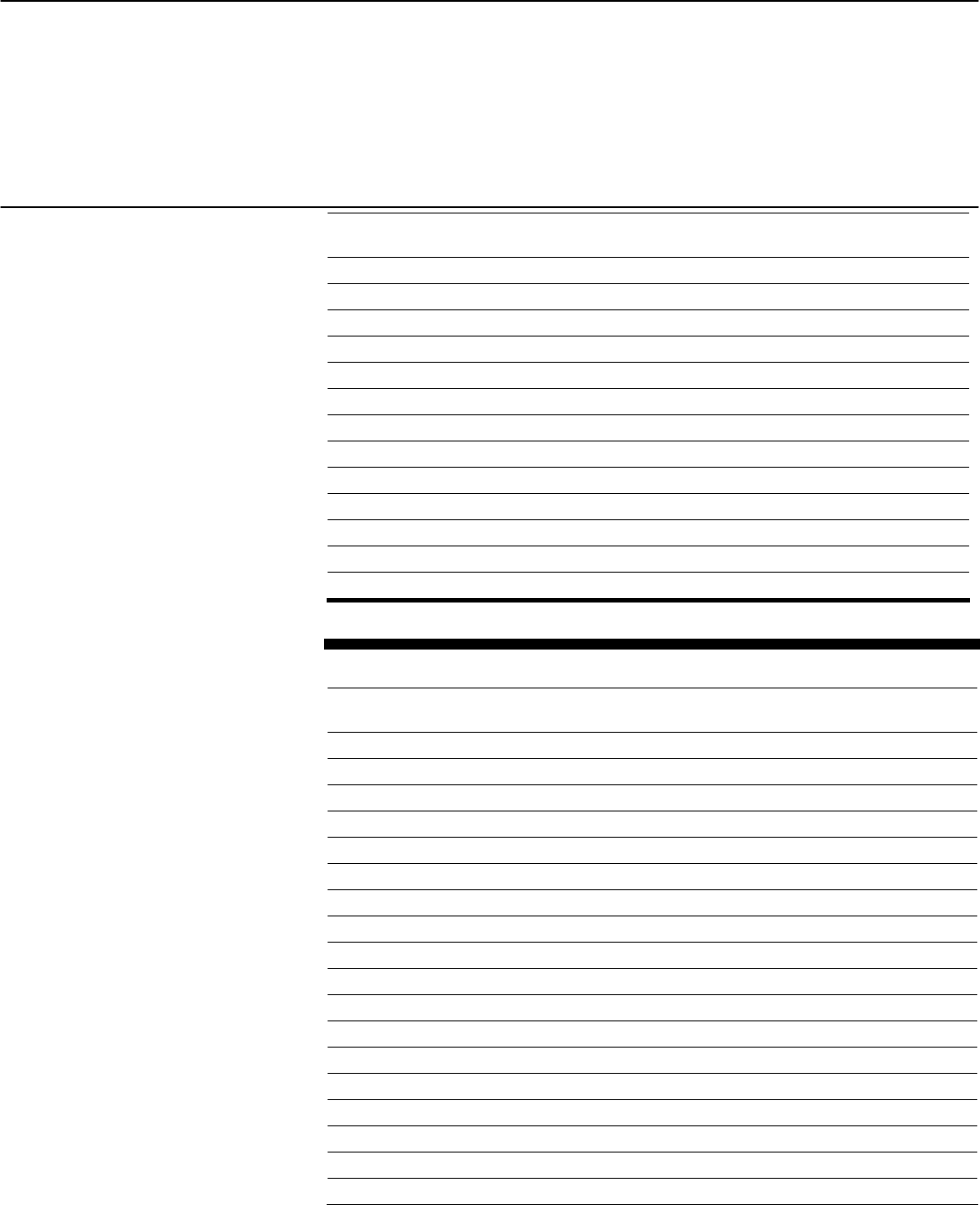

As shown in figure 3, there was an increasing trend in the proportion of

nonprime loans originated from 2000 through 2007 that would not have

met the safe harbor documentation and amortization requirements. More

specifically, the estimated percentages of nonprime loans without full

documentation ranged from a low of 27 percent in 2000 to a high of almost

60 percent in 2007.

31

Also, from 2004 through 2007, the proportion of

nonprime loans with a negative amortization feature increased steadily.

The growth in these percentages reflects the increased use of low-

documentation mortgages in both the subprime and Alt-A markets and

28

We used the FHA guidelines because FHA primarily serves borrowers with credit

characteristics somewhat similar to those of nonprime borrowers.

29

Because the APR is generally higher than the initial interest rate, our results may

overestimate the number of loans that would meet this requirement. The bill did not specify

particular interest rate indexes, so we used the Treasury 2-year constant maturity rate for

short-term hybrid ARMs (e.g., 2/28 and 3/27 mortgages), the Treasury 5-year constant

maturity rate for longer-term ARMs, and the Treasury 10-year constant maturity rate for

fixed-rate mortgages.

30

One industry and one consumer group representative told us that nonprime lenders often

underwrote loans to less than the fully indexed rate. We based our assumption on the

policy of a major subprime lender, which underwrote its riskiest loans at one percentage

point below the fully indexed rate. To the extent that lenders underwrote loans to more

than one percentage point below that rate, our approach would tend to underestimate the

proportion of loans meeting the fully indexed rate requirement.

31

While our analysis examined the documentation requirement in the context of the bill’s

safe harbor provisions, the bill’s minimum lending standards include a similar requirement,

as discussed in the Background section of this report.

Page 19 GAO-09-741 Impact of Mortgage Reform

mortgages with negative amortization features (e.g., payment-option

ARMs) in the Alt-A market. In both cases, these products were originally

intended for a narrow population of borrowers but, ultimately, became

more widespread. For example, as we reported in 2006, payment-option

ARMs were once specialized products for financially sophisticated

borrowers who wanted to minimize mortgage payments to invest funds

elsewhere or borrowers with irregular earnings who could take advantage

of minimum monthly payments during periods of lower income and could

pay down principal when they received an increase in income.

32

However,

according to federal banking regulators and a range of industry

participants, as home prices increased rapidly in some areas of the

country, lenders began marketing payment-option ARMs as affordability

products and made them available to less creditworthy and lower income

borrowers. borrowers.

Figure 3: Estimated Proportions of Nonprime Mortgages Not Meeting Figure 3: Estimated Proportions of Nonprime Mortgages Not Meeting

Documentation and Amortization Requirements, 2000-2007

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

2007

2006200520042003200220012000

Percentage

Source: GAO analysis of LP data.

Year

Documentation requirement

Amortization requirement

32

GAO-06-1021.

Page 20 GAO-09-741 Impact of Mortgage Reform

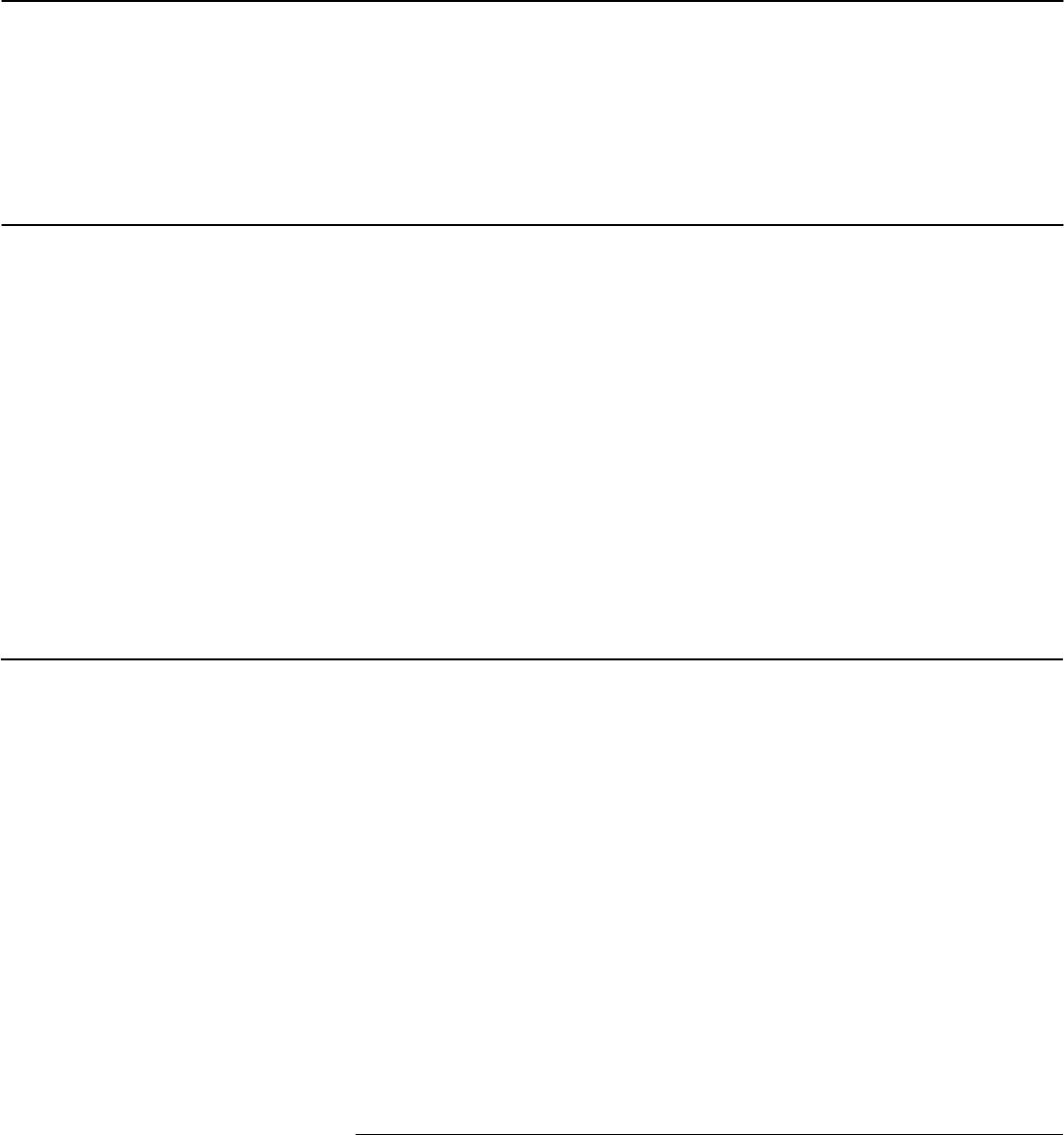

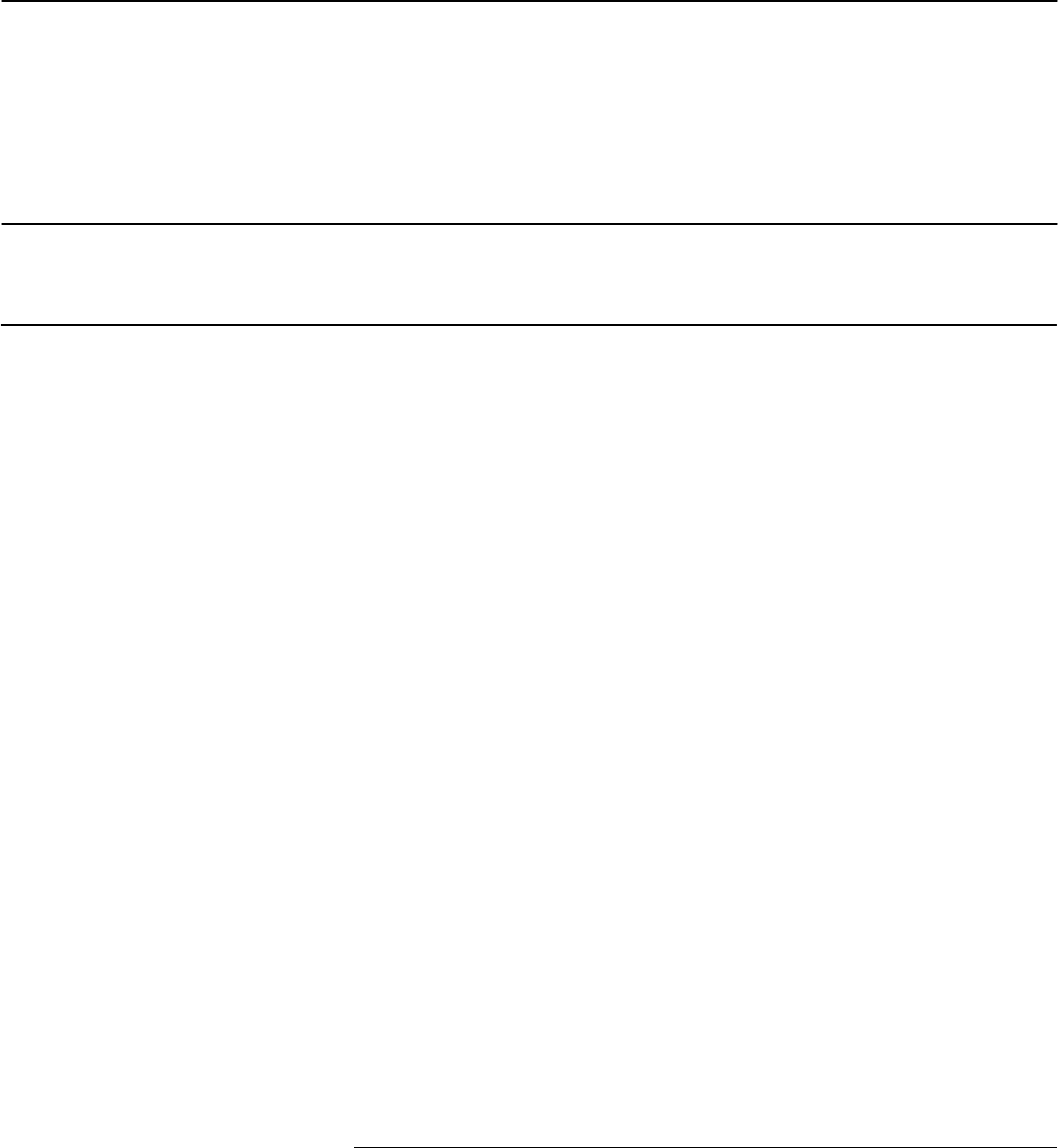

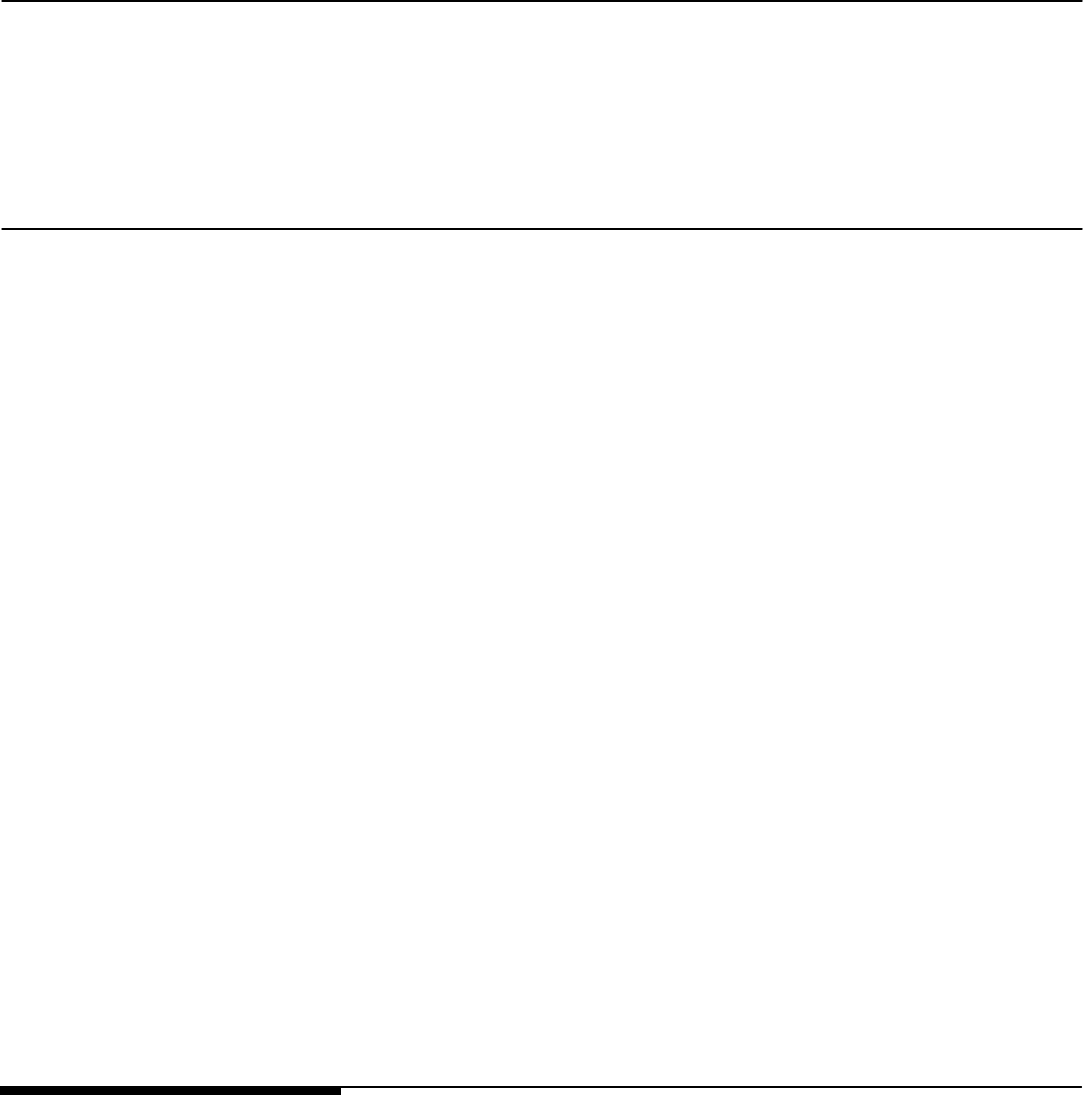

Substantial proportions of the nonprime loans made over the 8-year period

we examined also did not meet the safe harbor interest rate and debt

burden requirements, although the proportions varied by year:

• The proportion of nonprime originations that did not have a fixed interest

rate for at least 5 years rose from 52 percent in 2000 to 64 percent in 2004

(see fig. 4). This increase can be attributed primarily to a shift in the Alt-A

market away from fixed-rate mortgage products to adjustable-rate

products. For example, in 2000 about 88 percent of Alt-A loans were fixed

rate, but by 2004 this figure had dropped to about 38 percent. Beginning in

2005, the percentage of nonprime originations with adjustable rates began

falling, reaching 37 percent in 2007. The decline was due in large part to a

trend in the Alt-A market toward fixed-rate mortgages.

• As figure 4 also shows, the proportion of nonprime originations that did

not have a DTI ratio under 41 percent grew over the 8-year period, rising

from 43 percent in 2000 to 51 percent in 2006, although it fell slightly in

2007. The generally increasing trend is partly a result of house prices

growing faster than borrowers’ incomes over the period and of lenders

allowing borrowers to take out larger mortgages relative to their incomes.

For example, from 2000 through 2006, average home prices grew by 38

percent nationally, while over the same period, average incomes grew by

just 23 percent.

• Finally, the proportion of nonprime ARM originations with initial interest

rates not less than 3 percentage points over a generally accepted interest

rate index (3 percent test) ranged from a high of 96 percent in 2002 to a

low of 48 percent in 2007 (see fig. 4). The changing proportions over time

were largely due to movements in the interest rate indexes used to set

ARM interest rates that affected the size of the gap between the initial

rates and the index values. For example, when the 2-year Treasury

constant maturity rate (a common interest rate index) dropped from 2000

through 2002, the proportion of nonprime ARMs that did not meet the 3

percent test rose. But when the 2-year Treasury rate rose from 2004

through 2006, the proportion declined sharply.

The bill’s interest rate and debt burden requirements for safe harbor

mortgages were structured so that a loan would only have to meet one of

the three requirements. As a result, some loans could have met one of the

requirements, but not one or both of the other requirements and still could

have qualified as safe harbor loans. To illustrate, of the safe harbor loans

that met the bill’s safe harbor requirements by having a fixed interest rate

for 5 or more years, almost one-half would not have met the DTI ratio

requirement, assuming the 41 percent ratio we used for our analysis. Some

Page 21 GAO-09-741 Impact of Mortgage Reform

of the banking regulators we interviewed said that the DTI ratio was an

important factor in assessing a borrower’s ability to repay a mortgage loan.

They said that all borrowers should be required to meet some DTI ratio in

order for their loans to be eligible for the bill’s safe harbor. Consistent

with this view, H.R. 1728, which was passed by the House earlier this year,

requires borrowers of safe harbor loans to meet a DTI ratio to be

established by regulation.

Figure 4: Estimated Proportions of Nonprime Mortgages Not Meeting Interest Rate

and Debt Burden Requirements, 2000-2007

Note: About 37 percent of the loans in the LP database did not have information on the DTI ratio. We

compared the credit score distribution for loans with DTI data to the distribution for loans without this

information, and found them to be very similar. As a result, we believe that the DTI data we present

are a reasonable reflection of trends in the nonprime market as a whole.

Over the 8-year period we examined, about 38 percent of the nonprime

loans originated would not have met the safe harbor fully indexed rate

0

20

40

60

80

100

2007

2006200520042003200220012000

Percentage

Source: GAO analysis of LP data.

Year

ARM interest rate requirement

Fixed interest rate requirement

DTI requirement

Page 22 GAO-09-741 Impact of Mortgage Reform

requirement, although the proportions varied by year (see fig. 5).

33

As

previously noted, we assumed that if the fully indexed rate—that is, the

index rate at origination plus the lender’s margin—was more than 1

percentage point above the initial interest rate, the mortgage did not meet

the requirement. The variation by year largely reflected changes in the

index used to determine the fully indexed rate. More specifically, during

years in which a commonly used index such as the 6-month LIBOR was

relatively high (e.g., 2000 and 2005 through 2006), a larger proportion of

the nonprime loans would not have met the requirement because the fully

indexed rate would have been well above the initial interest rate of the

loan. In contrast, during years in which the index was low (e.g., 2001

through 2004), a greater proportion of loans would have met the

requirement because the fully indexed rate would have been close to the

initial rate. For example, in 2000, when the average 6-month LIBOR was

6.7 percent, the proportion of nonprime loans that did not meet the fully

indexed rate requirement was 47 percent. In 2003, when the average 6-

month LIBOR was 1.2 percent, the proportion was 9 percent. A potential

shortcoming of this requirement is that many ARMs could meet this

requirement when interest rates were low, but the mortgages could

become unaffordable if interest rates were to rise and the borrower’s

payments adjusted upward to reflect the higher rates. However, it may be

difficult to design a more stringent fully indexed rate requirement to

provide protection during low interest rate environments without possibly

reducing the availability of ARMs during high interest rate environments.

33

While our analysis examined the fully indexed rate requirement in the context of the bill’s

safe harbor provisions, the bill’s minimum lending standards include a similar requirement,

as discussed in the Background section of this report.

Page 23 GAO-09-741 Impact of Mortgage Reform

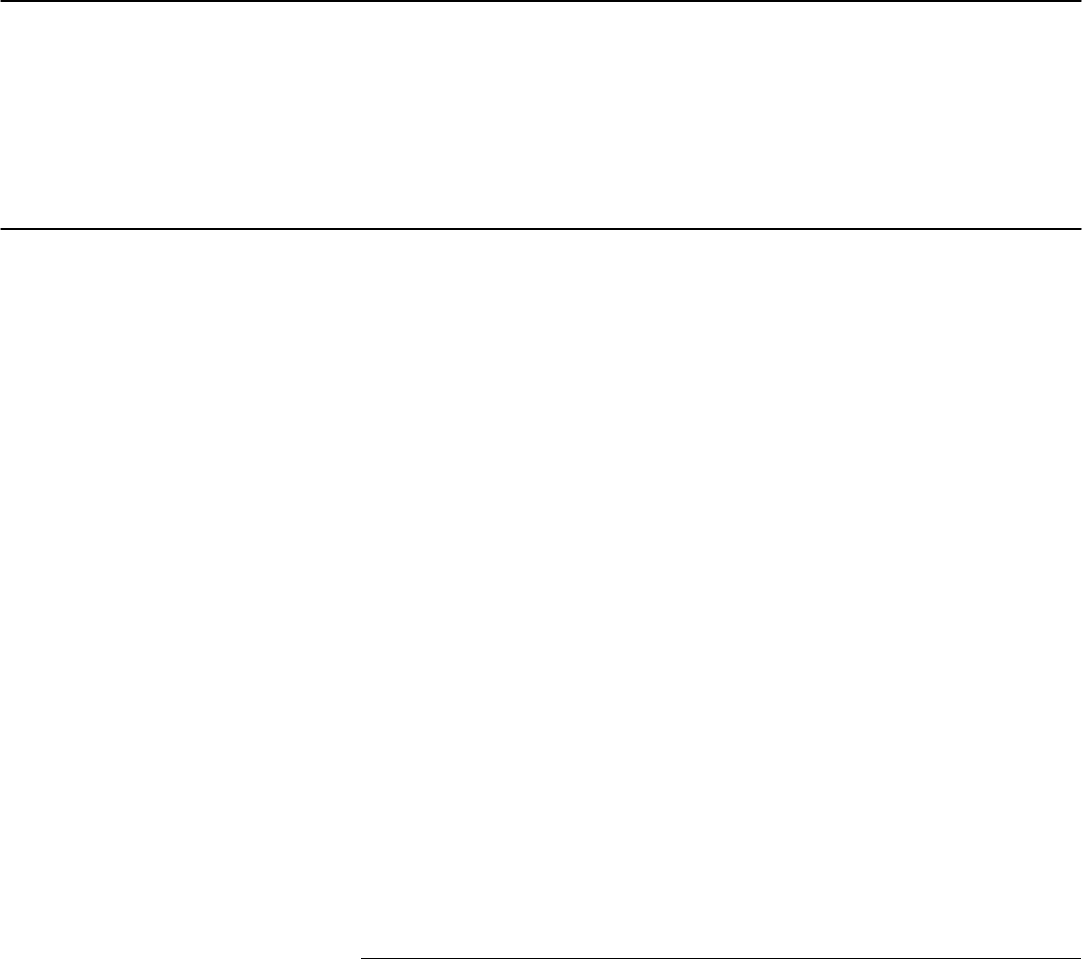

Figure 5: Estimated Proportions of Nonprime Mortgages Not Meeting the Fully

Indexed Rate Requirement, 2000-2007

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

2007

2006200520042003200220012000

Percentage

Source: GAO analysis of LP data.

Year

The Proportions of Safe

Harbor and Non-Safe

Harbor Loans Differed

across Zip Code and

Borrower Groupings

Prior research has indicated that nonprime lending occurred

disproportionately in areas with higher proportions of minority, low-

income, and credit-impaired residents.

34

Therefore, in contemplating the

potential impact of the Bill, one consideration is the extent to which

nonprime mortgages made to these groups of borrowers would have fallen

inside or outside of the safe harbor. For groups with higher proportions of

non-safe harbor mortgages, the Bill’s impact on the availability of these

loans and consumer protections for them may be particularly important.

Accordingly, we examined the estimated proportions of safe harbor and

non-safe harbor loans within various zip code and borrower groupings.

35

34

GAO, Federal Housing Administration: Decline in the Agency’s Market Share Was

Associated with Product and Process Developments of Other Mortgage Market

Participants, GAO-07-645 (Washington, D.C.: June 29, 2007) and Mayer and Pence,

“Subprime Mortgages: What, Where, and to Whom?”, Finance and Economics Discussion

Series 2008-29, Federal Reserve Board (2008).

35

We did not examine the reasons for differences among the various groupings as part of

our analysis.

Page 24 GAO-09-741 Impact of Mortgage Reform

Specifically, we looked at zip codes grouped by race, ethnicity, and

income characteristics, as well as borrowers grouped by credit score.

36

Our analysis of safe harbor and non-safe harbor loans by race and

ethnicity groupings found that zip codes with higher percentages of

households that Census identified as black or African-American had lower

percentages of non-safe harbor loans than the nonprime borrower

population as a whole. For example, in zip codes where black or African-

American households made up 75 percent or more of the household

population, the proportion of non-safe harbor loans was 68 percent,

compared with 75 percent for all nonprime borrowers (see table 2). In

contrast, in zip codes with higher percentages of households that Census

identified as Hispanic or Latino, the percentages of non-safe harbor loans

were higher than for nonprime borrowers as a whole. For example, in zip

codes where Hispanic or Latino households comprised 75 percent or mor

of the household population, the percentage of non-safe harbor loans was

80 percent, or 5 percentage points higher than for all nonprime

borrowers.

e

n

e as

ime borrower population.

38

37

Our analysis by income groupings found that the proportio

of non-safe harbor loans for each grouping was essentially the sam

that for the entire nonpr

Table 2: Percentage of Nonprime Mortgages That Were Safe Harbor and Non-safe

Harbor Loans by Racial, Ethnic, and Income Groupings, 2000-2007

Zip code population

grouping

Percentage of safe

harbor loans

Percentage of non-safe

harbor loans

All nonprime borrowers 25 75

Black or African-American

Less than 5% 25 75

5% to 24% 26 74

25% to 74% 29 71

75% or greater 32 68

36

We used the Census 2000 data for our analysis.

37

Individuals who classify themselves as Hispanic or Latino include people of different

racial backgrounds.

38

We defined low-, moderate-, and upper-income census tracts as those with median

incomes that were less than 80 percent, at least 80 percent but less than 120 percent, and

120 percent and above, respectively, of the median income for the associated metropolitan

statistical area.

Page 25 GAO-09-741 Impact of Mortgage Reform

Zip code population

grouping

Percentage of safe

harbor loans

Percentage of non-safe

harbor loans

Hispanic or Latino

Less than 5% 31 69

5% to 24% 24 76

25% to 74% 20 80

75% or greater 20 80

Median income

Low income 26 74

Moderate income 25 75

Upper income 24 76

Source: GAO analysis of LP and Census data.

We also analyzed safe harbor and non-safe harbor loans by credit score

groupings. We used four groupings that ranged from the least creditworthy

borrowers (scores of 599 and less) to the most creditworthy borrowers

(scores of 720 and above). We found that borrowers with scores of 599

and less (the lowest category) had the smallest percentage of non-safe

harbor loans (69 percent), while borrowers with scores of 600 to 719 (the

second highest category) had the largest percentage of non-safe harbor

loans (see table 3).

Table 3: Percentage of Nonprime Mortgages That Were Safe Harbor and Non-Safe

Harbor Loans by Credit Score Groupings, 2000-2007

Credit score

grouping

Percentage of safe harbor

loans

Percentage of non-safe

harbor loans

599 and less 31 69

600-659 25 75

660-719 22 78

720 and above 26 74

Source: GAO analysis of LP and Census data.

Page 26 GAO-09-741 Impact of Mortgage Reform

Prior research has shown that a number of different loan, borrower, and

economic variables influence the performance of a loan. To see if the bill’s

provisions appear to fulfill their consumer protection purpose, we

developed a statistical model, based on the data available to us, to

examine the relationship between safe harbor requirements, as well as a

subset of other variables known to affect performance, and the probability

of a loan defaulting within the first 24 months of origination.

39

We defined

a loan as being in default if it was delinquent by at least 90 days, in the

foreclosure process (including loans identified as in real-estate-owned

status), paid off after being 90 days delinquent or in foreclosure, or had

already terminated with evidence of a loss.

Some of the Safe Harbor

Requirements and Other

Factors Were Associated

with the Likelihood of

Default

We focused on 24-month performance because a large proportion of

nonprime borrowers—particularly those with hybrid ARMs—prepaid their

loans (e.g., by refinancing) within 2 years. Using a 24-month time frame

allowed us to include these loans in our model. The variables we used in

the model included variables based on the individual safe harbor

requirements, house price appreciation, borrower credit scores, and LTV