Case Western Reserve Law Review Case Western Reserve Law Review

Volume 70 Issue 2 Article 12

2019

Defamatory Political Deepfakes and the First Amendment Defamatory Political Deepfakes and the First Amendment

Jessica Ice

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev

Part of the Law Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Jessica Ice,

Defamatory Political Deepfakes and the First Amendment

, 70 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 417

(2019)

Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol70/iss2/12

This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University

School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an

authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons.

Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 70·Issue 2·2019

417

— Note —

Defamatory Political Deepfakes

and the First Amendment

Contents

Contents ......................................................................................... 417

Introduction .................................................................................. 417

I. What Are Deepfakes? ............................................................ 420

A. The Technology Behind Deepfakes ...................................................... 420

B. How Deepfakes Got Their Name ......................................................... 423

C. Defining Deepfakes .............................................................................. 426

II. Deepfakes of Political Figures ............................................. 427

III. Defamation Law as a Remedy ................................................. 431

IV. Satire or Parody as a Defense .............................................. 435

V. Injunctions as a Remedy ......................................................... 437

A. Injunctions and the First Amendment ................................................ 438

B. Constitutionally Permissible Injunctions on Expression ...................... 440

1. Obscenity ...................................................................................... 440

2. Copyright ...................................................................................... 441

C. Injunctions on Defamatory Speech...................................................... 442

VI. Injunctions on Defamatory Deepfakes .................................. 448

VII. Appropriate Scope for Injunctions Against Political

Defamatory Deepfakes ......................................................... 450

VIII. Injunctions and Third-Party Providers ................................ 451

Conclusion ...................................................................................... 454

Introduction

After logging onto Facebook, you see that your friend has posted a

video on your wall titled: “Donald Trump Pee Tape Released.”

Surprised, you click on the link and are directed to a YouTube video of

several young, scantily clad Russian women bouncing on a bed in what

appears to be the infamous Presidential Suite at the Ritz Carlton in

Moscow.

1

Donald Trump walks into the room and heads towards the

1. President Obama reportedly stayed in the Presidential Suite of the Ritz

Carlton in Moscow during a diplomatic trip to Russia. Michelle Goldberg,

Lordy, Is There a Tape?, N.Y. Times (Apr. 16, 2018), https://www.

nytimes.com/2018/04/16/opinion/comey-book-steele-dossier.html [https://

perma.cc/FB5T-GGWF]. Later, Donald Trump was alleged to have

stayed in the same room and hired Russian prostitutes to pee on the same

bed where President Obama slept. Id.

Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 70·Issue 2·2019

Defamatory Political Deepfakes and the First Amendment

418

women. You hear Trump’s voice say, “let’s have some fun, ladies.” The

girls laugh and you hear Trump again: “How about we show Obama

what we think of him. Why don’t you pee on his bed?” The tape cuts

off in an instant and you feel shocked. Could this video actually be real?

The video in the hypothetical above could easily be what is

described colloquially as a “deepfake.” The definition of a deepfake is

“still in flux, as technology develops.”

2

However, a deepfake is generally

understood to be a video made with the use of machine-learning to swap

one real person’s face onto another real person’s face. This ability

essentially makes it possible to ascribe the conduct of one individual

who has been previously videotaped to a different individual.

3

That is,

a deepfake is a digital impersonation of someone. This impersonation

occurs without the consent of either the person in the original video or

the person whose face is superimposed on the original. Individuals in

the public eye have already been a major target for deepfakes.

4

Political

figures likely will be the targets of future deepfakes, especially by those

with an interest in spreading discord and undermining public trust.

5

Deepfakes of political figures pose serious challenges for our political

system and even national security, but legal remedies for these videos

are complicated. Every legal remedy to combat the negative effects of

political deepfakes must go through a careful balancing test. On one

side you have a special interest in protecting high-value political speech

and furthering public discourse under the First Amendment. On the

other side you have the potential for severe public harm by undermining

elections and eroding trust in public officials. Although some political

deepfakes might be satirical and promote public discourse about the

2. James Vincent, Why We Need a Better Definition of ‘Deepfake’, The

Verge (May 22, 2018, 2:53 PM), https://www.theverge.com/2018/5/22/

17380306/deepfake-definition-ai-manipulation-fake-news [https://perma.cc/

55JA-SH67].

3. Robert Chesney & Danielle Keats Citron, Deep Fakes: A Looming

Challenge for Privacy, Democracy, and National Security, 107 Calif. L.

Rev. (forthcoming 2019) (manuscript at 4–5).

4. Samantha Cole, AI-Assisted Fake Porn Is Here and We’re All Fucked,

Vice: Motherboard (Dec. 11, 2017, 2:18 PM), https://motherboard.vice

.com/en_us/article/gydydm/gal-gadot-fake-ai-porn [https://perma.cc/

4PQW-KCVE].

5. James Vincent, US Lawmakers Say AI Deepfakes ‘Have the Potential to

Disrupt Every Facet of Our Society’, The Verge (Sept. 14, 2018, 1:17

PM),

https://www.theverge.com/2018/9/14/17859188/ai-deepfakes-national-

security-threat-lawmakers-letter-intelligence-community [https://perma.cc/

WE3U-BCLN]; Ana Romano, Jordan Peele’s Simulated Obama PSA Is a

Double-Edged Warning Against Fake News, Vox (Apr. 18, 2018, 3:00

PM), https://www.vox.com/2018/4/18/17252410/jordan-peele-obama-

deepfake-buzzfeed [https://perma.cc/3B9H-SX4X].

Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 70·Issue 2·2019

Defamatory Political Deepfakes and the First Amendment

419

merits of an individual candidate or issue,

6

many deepfakes will likely

cross over the line into pure defamation.

Given this careful balancing test, what remedies are available for

defamatory political deepfakes that survive First Amendment scrutiny?

If deepfakes are found to be truly defamatory, such speech would only

receive limited First Amendment protection and victims could recoup

monetary damages from successful defamation lawsuits.

7

For most

political figures, however, damages will be difficult, if not impossible,

to determine, and any monetary damages will come too late to truly

remedy the reputational harm inflicted during a campaign or their

tenure as a public figure. Thus, injunctions are likely a quicker and

more effective remedy for defamatory political deepfakes.

Although injunctions against deepfakes may seem like a logical

remedy, they will likely face major First Amendment hurdles. The

Supreme Court has yet to provide a definitive answer on whether

injunctions against defamatory speech are permissible under the First

Amendment.

8

Some lower courts have found injunctions to be

impermissible because they are not sufficiently tailored, effectively

creating a prior restraint on constitutionally protected speech.

9

Other

courts have suggested that narrowly crafted injunctions against

defamatory speech may be permissible.

10

Even if an injunction against

a defamatory political deepfake survives a First Amendment challenge,

victims might still be unable to remove that deepfake if its creator is

unreachable by United States courts.

11

This Note argues that narrowly crafted injunctions against

defamatory political deepfakes should be permitted under the First

6. See Hustler Magazine, Inc. v. Falwell, 485 U.S. 46, 54 (1988) (“Despite

their sometimes caustic nature . . . graphic depictions and satirical cartoons

have played a prominent role in public and political debate.”).

7. Ashcroft v. Free Speech Coalition, 535 U.S. 234, 245–46 (2002) (“The

freedom of speech has its limits; it does not embrace certain categories of

speech, including defamation.”).

8. See Tony v. Cochran, 544 U.S. 734 (2005) (discussing but not resolving

the permissibility of an injunction against defamatory speech).

9. See Sindi v. El-Moslimany, 896 F.3d 1, 34 (1st Cir. 2018); McCarthy v.

Fuller, 810 F.3d 456, 461–62 (7th Cir. 2015); see also infra Part V.

10. See San Antonio Cmty. Hosp. v. S. Cal. Dist. Council of Carpenters, 125

F.3d 1230, 1238 (9th Cir. 1997) (upholding an injunction against

fraudulent speech); Brown v. Petrolite Corp., 965 F.2d 38, 51 (5th Cir.

1992) (permitting a limited injunction against defamatory speech);

Lothschuetz v. Carpenter, 898 F.2d 1200, 1208 (6th Cir. 1990) (Wellford,

J., concurring in part and dissenting in part) (permitting a limited

injunction against defamatory speech); David S. Ardia, Freedom of

Speech, Defamation, and Injunctions, 55 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 1, 41 (2013).

11. Chesney & Citron, supra note 3, at 44–45.

Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 70·Issue 2·2019

Defamatory Political Deepfakes and the First Amendment

420

Amendment. First, this Note gives an overview of deepfakes and the

technology used to propagate them. Then, it addresses the potential

defamatory and non-defamatory uses of political deepfakes and how

defamatory political deepfakes would be analyzed under the First

Amendment’s heightened scrutiny standard that is used to analyze

political speech. Third, it gives an overview of injunctions on speech

under First Amendment jurisprudence and provides some examples of

permissible injunctions on expression. Fourth, borrowing from obscen–

ity and copyright law, this Note discusses injunctions as a remedy for

defamatory political deepfakes and whether such injunctions should be

considered impermissible prior restraints on speech. Finally, it addresses

the issue of unreachable defendants and provides a potential solution

by extending to deepfakes the requirements for copyrighted materials

under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act.

12

I. What Are Deepfakes?

The notion of what a deepfake is might seem intuitive at first

glance—deepfakes seem to be a simple fake or face-swapping video. But

such a simple definition grossly oversimplifies the technology behind

deepfakes and lacks the specificity needed to properly address deepfakes

from a legal perspective.

A. The Technology Behind Deepfakes

Traditionally, any individual who wanted to edit a photo or video

would have to upload the photo or video into a computer program and

manually make any desired edits. Computer programs have gradually

made the editing process easier, but a complete manual overhaul of a

video with realistic final results is still very time- and resource-

intensive.

13

For instance, when the creators of Rogue One: A Star Wars

Story decided to bring back the character of Grand Moff Tarkin

through

a digital recreation, the Rogue One visual-effects supervisor described

the digital recreation process as “extremely labor-intensive and

expensive.”

14

12. 17 U.S.C. § 1201 (2012).

13. Donie O’Sullivan, Deepfake Videos: Inside the Pentagon’s Race Against

Disinformation, CNN (Jan. 28, 2019), https://www.cnn.com/interactive/

2019/01/business/pentagons-race-against-deepfakes/ [https://perma.cc/

PQ2H-PK59]; Scott Ross, Why VFX House Lose Money on Big Movies,

The Hollywood Reporter (Mar. 7, 2013, 5:00 AM), https://www

.hollywoodreporter.com/news/why-life-pi-titanic-vfx-426182 [https://perma

.cc/Z8KF-X2HZ].

14. Grand Moff Tarkin was originally played by the late Peter Cushing but

Cushing died prior to the filming of Rogue One: A Star Wars Story. Dave

Itzkoff, How ‘Rogue One’ Brought Back Familiar Faces, N.Y. Times

Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 70·Issue 2·2019

Defamatory Political Deepfakes and the First Amendment

421

Deepfakes, however, do not require human labor to manually

manipulate videos; instead, a computer’s processing power does all the

work.

15

The technology that makes deepfakes possible stems from “a

branch of Machine Learning that focuses on deep neural networks”

called “deep learning.”

16

Deep learning loosely imitates the way the

brain works by processing information through a series of nodes (similar

to neurons) in an artificial neural network. For a neural network to

replicate an image, it must take in a multitude of information from a

particular source (often called an “input layer”) and then run that

information through various nodes until it produces an “output layer.”

17

Neural networks are “trained” by adjusting the weights at each node

to try to improve the final “output layer” to be as close as possible to

the desired result.

18

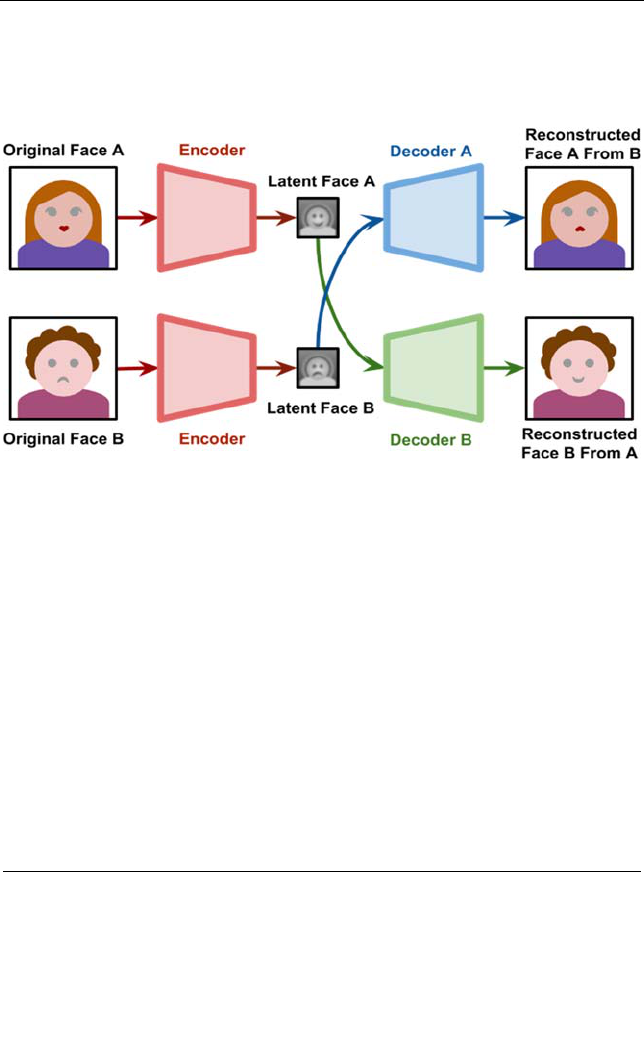

Deepfakes add an extra layer of complexity onto this process

because they ultimately have two input sources: (1) the face in the

original scenario video (“original face”), and (2) the face swapped into

the original scenario video (“swapped face”). To facilitate this process,

a computer must generate two separate neural networks for each image,

each that has enough in common with the other to be able to swap

images on a shared facial structure.

19

A basic way to achieve this result

is through an autoencoder.

20

An autoencoder is a “neural network that

is trained to attempt to copy its input to its output.”

21

In order for the

face swapping to be successful, the computer must construct two

separate neural networks, one for the original face and another for the

swapped face, and both must be trained separately.

22

Once the

individual networks have been built with enough accuracy through

training, then a portion of the networks called the decoders can be

swapped, effectively pasting the swapped face onto the network of the

(Dec. 27, 2016), https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/27/movies/how-rogue-

one-brought-back-grand-moff-tarkin.html [https://perma.cc/F9B7-8K62].

15. O’Sullivan, supra note 13.

16. Alan Zucconi, An Introduction to Neural Networks and Autoencoders,

Alan Zucconi Blog (Mar. 14, 2018), https://www.alanzucconi.com/2018/

03/14/an-introduction-to-autoencoders/ [https://perma.cc/HJ6F-MJXS].

17. Id. (explaining that image-based applications are often built on

convolutional neural networks).

18. Id.

19. Alan Zucconi, Understanding the Technology Behind DeepFakes, Alan

Zucconi Blog (Mar. 14, 2018), https://www.alanzucconi.com/2018/

03/14/understanding-the-technology-behind-deepfakes/ [https://perma.cc/

L7UE-2WWF].

20. Zucconi, supra note 16.

21. Ian Goodfellow et al., Deep Learning 499 (2016) (ebook).

22. Zucconi, supra note 19.

Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 70·Issue 2·2019

Defamatory Political Deepfakes and the First Amendment

422

original face. Using such technology allows the swapped face to mimic

any expressions originally made by the original face in the original

video.

23

24

Face generation can be made even more realistic through the use of

a Generative Adversarial Network (“GAN”).

25

Similar to autoencoding,

GANs attempt to recreate images using deep-learning techniques.

26

GANs achieve this result by using two components: (1) a generator,

which creates natural looking images, and (2) a discriminator, which

decides whether the images are real or fake.

27

Essentially the “generator

tries to fool the discriminator by generating real images as far as

possible.”

28

Through this adversarial process between the generator and

discriminator, the network is able to produce more consistently realistic

images than it could through a traditional autoencoding structure.

Most recently, mathematicians and computer scientists have

attempted to combine GANs with a specialized type of autoencoding

called “variational autoencoding” (collectively, “VAE-GANs”) to

23. Id.

24. Id.

25. Chesney & Citron, supra note 3, at 6; see also Ian Goodfellow et al.,

Generative Adversarial Nets, arXiv (June 10, 2014), https://arxiv.org/

pdf/1406.2661.pdf [https://perma.cc/K2HH-PL2M].

26. Chesney & Citron, supra note 3, at 7.

27. Prakash Pandey, Deep Generative Models, Medium (Jan. 23, 2018), https://

medium.com/@prakashpandey9/deep-generative-models-e0f149995b7c

[https://perma.cc/5NXU-MHC8].

28. Id.

Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 70·Issue 2·2019

Defamatory Political Deepfakes and the First Amendment

423

produce the most realistic output layers or generated images to date.

29

VAE-GANs work by using the autoencoding process to provide an

image to the GAN’s generator.

30

The GAN’s discriminator then checks

the image through an iterative process to make it seem more realistic.

31

In addition to the advancements in deepfake videos, researchers have

also made strides in improving fake audio through GANs

32

and other

techniques.

33

These advancements are only the beginning of computer-

image and audio regeneration. Deepfake creators report that the

technology behind deepfakes “is improving rapidly,” and the creators

“see no limit to whom they can impersonate.”

34

B. How Deepfakes Got Their Name

Although the technology (and mathematics) behind deepfakes is

complex, using deepfake technology is relatively simple.

35

This is

especially true after an anonymous user on reddit named “deepfake”

posted computer code on a subreddit forum in late 2017 that allowed

hobbyists to create deepfakes.

36

In early 2018, another reddit user

29. Enoch Kan, What The Heck Are VAE-GANs?, Towards Data Science

(Aug. 16, 2018), https://towardsdatascience.com/what-the-heck-are-vae-

gans-17b86023588a [https://perma.cc/D9J8-NURV].

30. Anders Larsen et al., Autoencoding Beyond Pixels Using a Learned Similarity

Metric, ArXiv (Feb. 10, 2016), https://arxiv.org/pdf/1512.09300.pdf

[https://perma.cc/XK4U-AQ3C].

31. Id.; Kan, supra note 29.

32. See generally Chris Donahue et al., Adversarial Audio Synthesis, ArXiv

(Feb. 12, 2018), https://arxiv.org/pdf/1802.04208.pdf

[https://perma.cc/UQ3J-892W]; Yang Gao et al., Voice Impersonation

Using Generative Adversarial Networks, ArXiv (Feb. 19, 2018),

http://arxiv.org/abs/1802.06840.pdf [https://perma.cc/FJ6K-9LC8].

33. Chesney & Citron, supra note 3, at 7; O’Sullivan, supra note 13.

34. Drew Harwell, Fake-Porn Videos Are Being Weaponized to Harass and

Humiliate Women: ‘Everybody Is a Potential Target’, Wash. Post (Dec.

30, 2018), https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2018/12/30/fake-

porn-videos-are-being-weaponized-harass-humiliate-women-everybody-is-

potential-target/?utm_term=.8693f1f740f5 [https://perma.cc/7TDN-662W].

35. Alan Zucconi, How to Install FakeApp, Alan Zucconi Blog (Mar. 14,

2018), https://www.alanzucconi.com/2018/03/14/how-to-install-fakeapp/

[https://perma.cc/T3G4-PEMB].

36. Jeevan Biswas, What Exactly Is Deepfakes and Why Is This AI-Based

Creation a Menace, Analytics India Mag. (Feb. 8, 2018), https://

www.analyticsindiamag.com/deepfakes-ai-celebrity-fake-videos/ [https://

perma.cc/K6E6-NJMA]. The actual month that the subreddit was created

is contested by various Internet sources. Compare id. (claiming the

“deepfakes” subreddit was created in November 2017), with Aja Romano,

Why Reddit’s Face-Swapping Celebrity Porn Craze is a Harbinger of

Dystopia, Vox (Feb. 7, 2018, 5:55 PM), https://www.vox.com/2018/1/31/

16932264/reddit-celebrity-porn-face-swapping-dystopia [https://perma.cc/

Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 70·Issue 2·2019

Defamatory Political Deepfakes and the First Amendment

424

adapted that code into a user-friendly application called FakeApp.

37

Users of the original code and FakeApp did not need to understand the

complex mathematical and computational underpinnings of deepfake

technology. Instead, users merely needed above average computer

literacy and a sufficiently powerful Graphics Processing Unit (“GPU”)

in their computer to create deepfakes.

38

News of the user-friendly application spread quickly, and users

began posting their own computer-generated face-swapping videos on

the “deepfake” subreddit.

39

User and commentators began to call the

videos “deepfakes” after the subreddit where they were born.

40

Many

users used the technology to perverse ends, often swapping celebrities’

faces (primarily female) onto pornographic videos.

41

Users also

generated “revenge porn” deepfakes by swapping their ex-girlfriends’

faces onto pornographic videos.

42

Not all users made pornographic

deepfakes. Many users enjoyed splicing Nicholas Cage’s face onto

various movie and television characters.

43

Over 80,000 people partic–

ipated in the subreddit before it was eventually shut down due to the

XP3Q-UDN7] (claiming the “deepfakes” subreddit was created in September

2017).

37. Biswas, supra note 36.

38. Zucconi, supra note 35.

39. Damon Beres & Marcus Gilmer, A Guide to ‘Deepfakes,’ the Internet’s

Latest Moral Crisis, Mashable (Feb. 2, 2018), https://mashable.com/

2018/02/02/what-are-deepfakes/#xUHFJsuHqqV [https://perma.cc/

NLP6-FBGF].

40. Julia Pimentel, Twitter and Reddit Have Banned ‘Deepfake’ Celebrity

Porn Videos, Complex (Feb. 7, 2018), https://www.complex.com/life/2018/

02/twitter-reddit-and-more-ban-deepfake-celebrity-videos [https://perma

.cc/K5TL-GHF9].

41. Cole, supra note 4; Alex Hern, AI Used to Face-Swap Hollywood Stars

into Pornography Films, The Guardian (Jan. 25, 2018), https://www

.theguardian.com/technology/2018/jan/25/ai-face-swap-pornography-emma-

watson-scarlett-johansson-taylor-swift-daisy-ridley-sophie-turner-maisie-

williams [https://perma.cc/3VDX-A5ZB].

42. Larry N. Zimmerman, Cheap and Easily Manipulated Video, 87 J. Kan.

B. Ass’n, no. 4, Apr. 2014, at 20, https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.ksbar.org/

resource/dynamic/blogs/20180410_111450_30470.pdf [https://perma.cc/

9938-ADYD].

43. Reid McCarter, Idiots on the Internet Are Getting Really Good at Splicing

Nic Cage’s Face Onto Every Movie, AV Club (Sept. 4, 2018, 10:30 AM),

https://news.avclub.com/idiots-on-the-internet-are-getting-really-good-

at-splic-1828799192 [https://perma.cc/RP9Z-QFFZ]; Sam Haysom,

Nicolas Cage is Being Added to Random Movies Using Face-Swapping

Technology, Mashable (Jan. 31, 2018), https://mashable.com/2018/01/

31/nicolas-cage-face-swapping-deepfakes/#WGhEd3yKgiqw [https://perma

.cc/SQQ3-D9M8].

Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 70·Issue 2·2019

Defamatory Political Deepfakes and the First Amendment

425

largely nonconsensual pornographic nature of the posted content.

44

Other major platforms such as Twitter, PornHub, Gyfcat, and Discord

have also banned pornographic deepfakes.

45

As of this writing, however,

FakeApp is still available online.

46

Although many commentators have described the ease of creating

deepfakes, it should be noted that downloading and using FakeApp is

probably still too cumbersome for the average computer user. First, to

“train” a neural network in a reasonable amount of time, a computer

needs an adequately sophisticated GPU.

47

As of 2019, a typical laptop

does not have the appropriate GPU to perform deep learning and

generate deepfakes.

48

In addition, although there are many tutorials on

how to download and use FakeApp,

49

the process requires above-

44. Beres & Gilmer, supra note 39. Later the subreddit was removed. Alex

Hern, Reddit Bans ‘Deepfakes’ Face-Swap Porn Community, The

Guardian (Feb. 8, 2018) https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/

feb/08/reddit-bans-deepfakes-face-swap-porn-community [https://perma.cc/

9T4L-YCDV].

45. Megan Farokhmanesh, Deepfakes Are Disappearing from Parts of the

Web, But They’re Not Going Away, The Verge (Feb. 9, 2018, 9:00 AM),

https://www.theverge.com/2018/2/9/16986602/deepfakes-banned-

reddit-ai-faceswap-porn [https://perma.cc/C4E5-D2PH].

46. FakeApp Download, https://www.malavida.com/en/soft/fakeapp/#gref

[https://perma.cc/P87C-SEGP] (last visited Nov. 13, 2018).

47. Zucconi, supra note 35; Slav Ivanov, Picking a GPU for Deep Learning,

Slav Ivanov Blog (Nov. 22, 2017), https://blog.slavv.com/picking-a-

gpu-for-deep-learning-3d4795c273b9 [https://perma.cc/UZZ5-SX66].

48. See Nicholas Deleon, Why Even Non-Gamers May Want a Powerful

Graphics Card in Their Next Computer, Consumer Reports (Aug. 29,

2018), https://www.consumerreports.org/computers/why-even-non-gamers-

may-want-a-powerful-graphics-card/ [https://perma.cc/JVS7-7DA3]

(indicating that consumers need to elect to upgrade their laptops to include

GPUs at the time of purchase); Janakiram MSV, In the Era of Artificial

Intelligence, GPUs Are the New CPUs, Forbes (Aug. 7, 2017, 10:14AM),

https://www.forbes.com/sites/janakirammsv/2017/08/07/in-the-era-of-

artificial-intelligence-gpus-are-the-new-cpus/#6e5d76755d16 [https://perma

.cc/TU2T-J49H] (noting that for the average consumer GPUs were purely

optional); Zucconi, supra note 35 (stating the training the neural network

without a GPU would take weeks instead of hours).

49. See generally Zucconi, supra note 35; tech 4tress, Deepfakes Guide: Fake

App 2 2 Tutorial. Installation (Totally Simplified, Model Folder Included),

YouTube (Feb. 21, 2018), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lsv38PkLsGU&

t=83s [https://perma.cc/FVL3-23WU]; Irrelevant Voice, Deepfakes

Tutorial (FakeApp) (Fake Adult Videos of Celebrities), YouTube (Jan.

28, 2018), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ghTb2kZSpZE [https://

perma.cc/YV6C-5PGQ]; Oliver Lardner, Tutorial for Mac: Deepfakes—

Reddit [MIRROR], Medium (Feb. 7, 2018), https://medium.com/@

oliverlardner/tutorial-for-mac-deepfakes-reddit-mirror-d75eb8069a16 [https://

perma.cc/ER5V-T9PW].

Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 70·Issue 2·2019

Defamatory Political Deepfakes and the First Amendment

426

average computer literacy, including understanding torrenting, path

configuration, file structures, and application versioning.

50

Although the

GPU and technological skills necessary to create deepfakes may be

hurdles for the average computer user, they are far less cumbersome for

an avid computer-hobbyist or gamer. As of 2018, individuals could buy

GPUs sufficient to create deepfakes for as low as $160.

51

Although

regular laptops may be inadequate for creating deepfakes, gaming

laptops regularly feature sufficiently powerful GPUs.

52

As developers

create more user-friendly deepfake applications, average computer users

will likely gain greater deepfake-creating capabilities. But even if the

process of creating deepfakes becomes easier, it will likely always

involve deliberate affirmative actions on behalf of the creator (such as

selecting which faces or scenarios to swap).

C. Defining Deepfakes

As noted above, the technology driving deepfakes and computer-

generated images is still rapidly evolving. Thus, defining deepfakes is

especially tricky and researchers are still struggling with a uniform

definition.

53

Legal scholars Robert Chesney and Danielle Citron

describe deepfake technology as “leverag[ing] machine-learning algor–

ithms to insert faces and voices into video and audio recordings of

actual people and enabl[ing] the creation of realistic impersonations out

of digital whole cloth.”

54

Building on this definition, legal scholar

Richard Hasen defined deepfakes as “audio and video clips manipulated

using machine learning and artificial intelligence that can make a

politician, celebrity, or anyone else appear to say or do anything the

manipulator wants.”

55

Artificial intelligence researcher Miles Brundage

noted that the term “deepfake” generally refers to a “subset of fake

video that leverages deep learning . . . to make the faking process

easier.”

56

Technologist Aviv Ovadya said that deepfakes can be

50. Zucconi, supra note 35.

51. Ivanov, supra note 47.

52. Gordon Mah Ung & Alaina Yee, How to Pick the Best Gaming Laptop

GPU, PCWorld (Sept. 5, 2018, 4:53 PM), https://www.pcworld.com/

article/3237991/laptop-computers/how-to-pick-the-best-gaming-laptop-

gpu.html [https://perma.cc/ES33-UZX2].

53. Vincent, supra note 2.

54. Chesney & Citron, supra note 3, at 4.

55. Richard L. Hasen, Deep Fakes, Bots, and Siloed Justices: American

Election Law in a Post-Truth World, St. Louis U. L. J., 9 (forthcoming

2020). This Note quotes and cites this article with Professor Hasen’s

permission.

56. Vincent, supra note 2; Miles Brundage et. al., The Malicious Use of

Artificial Intelligence: Forecasting, Prevention, and Mitigation, Future

of Human. Inst. (Feb. 2018), https://img1.wsimg.com/blobby/go/

Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 70·Issue 2·2019

Defamatory Political Deepfakes and the First Amendment

427

described as “audio or video fabrication or manipulation that would

have been extremely difficult and expensive without AI advances.”

57

All of these definitions include the method of creation (by deep

learning or artificial intelligence) as a key way to distinguish deepfakes

from other faked videos. This distinction is very important because the

use of deep learning in a video’s creation implies that such a video can

be created more easily than a manually manipulated video. In addition,

as the technology improves, videos created by deep learning have the

potential to look more realistic than manually altered videos. Another

important element of deepfake videos is the “faking” of a face or a

scenario in a pre-existing video or image. Although to date most

deepfakes have primarily focused on face-swapping and voice alter–

ations, the technology could be used to swap out other components in

a video, such as background or objects in a video. A final definition

must be flexible enough to incorporate any “faking” of an original video

possible by deep learning technology. Combining all the key elements

above, we can use this simplified definition: Deepfakes are videos,

images, and audio created using deep learning to alter the content of

an original video, image, and/or audio file by face-swapping or scenario

alterations.

II. Deepfakes of Political Figures

As we have seen in Part I, deepfakes have a wide range of uses and

raise many legal issues. This Note focuses solely on the impact of

deepfakes targeting political figures, or “political deepfakes.” Through–

out history, individuals have been inclined to use the latest

communications technology to mock, comment about, and criticize

politicians.

58

Persons in power have been suspicious of such technology,

often banning or severely restricting its dissemination, usually at the

expense of growth and the exchange of ideas.

59

For instance, upon the

invention of the printing press in 1456, French King Charles VII sent a

spy to Mainz to investigate how the device might be used to spread

political ideas.

60

Charles was concerned that the technology could

disseminate information very quickly; he was relieved once he learned

that government leaders placed strict controls on what information

3d82daa4-97fe-4096-9c6b-376b92c619de/downloads/1c6q2kc4v_50335.pdf

[https://perma.cc/ZRA2-69RE].

57. Vincent, supra note 2.

58. Craig Smith et al., The First Amendment—Its Current Condition, in The

First Amendment—The Challenge of New Technology 9–12 (Sig

Mickelson & Elena Mier Y. Teran eds., 1989).

59. Id.

60. Id. at 9–10.

Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 70·Issue 2·2019

Defamatory Political Deepfakes and the First Amendment

428

could be published.

61

History teaches us that if we choose to attempt to

mitigate the risks of a new communication technology, such restrictions

should be as limited as possible so as not to curtail the benefits of that

technology.

From the printing press to the Internet, deepfakes are simply the

next in a long line of disruptive communications technology that can

be used to further civic discourse, or misused to deceive and undermine

public trust. Individuals have already used deepfakes to further public

discussion. Jordan Peele created a political deepfake of President

Obama to warn the public of the dangers of political deepfakes in April

of 2018.

62

Many political deepfakes, such as Jordan Peele’s, will likely

be viewed by courts as “speech on public issues,” which deserves a place

on the “‘highest rung of the hierarchy of First Amendment values’ and

is entitled to special protection.”

63

Given the possible beneficial uses of

deepfakes by satirists, educators, and artists, an outright ban on

deepfake technology is not only ill-advised but also likely uncon–

stitutional.

However, because deepfakes use deep learning to reduce the effort

needed to “fake” a previously made video, bad actors will have a special

incentive to use this technology not only to mock, but potentially to

frame, undermine, or blackmail political figures. Chesney and Citron

outlined eight potential harms to society resulting from the use of

deepfakes: (1) distortion of democratic discourse, (2) manipulation of

elections, (3) eroding trust in institutions, (4) exacerbating social

divisions, (5) undermining public safety, (6) undermining diplomacy,

(7) jeopardizing national security, and (8) undermining journalism.

64

Political deepfakes are the most likely candidates to perpetrate almost

all of the harms outlined by Chesney and Citron. For instance, if a

political deepfake depicting a candidate taking a bribe gets released on

the eve of an election, such a tape could simultaneously change the

election results, distort discourse about the candidates, and erode trust

in public figures and institutions. If the tape agitates activist groups

enough that they begin to hold public protests or demonstrations, such

demonstrations could turn violent and undermine public safety. If a

news outlet runs the story believing it is real and only later finds out it

is fake, the deepfake could also undermine the public’s faith in

61. Id.

62. David Mack, This PSA About Fake News from Barack Obama Is Not What

it Appears, BuzzFeed News (Apr. 17, 2018), https://www.buzzfeednews

.com/article/davidmack/obama-fake-news-jordan-peele-psa-video-buzzfeed#

.el7Eqkeo7A [https://perma.cc/PDW2-DQSV].

63. Snyder v. Phelps, 562 U.S. 443, 444 (2011) (quoting Connick v. Myers,

461 U.S. 138, 145 (1983)).

64. Chesney & Citron, supra note 3, at 20–28.

Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 70·Issue 2·2019

Defamatory Political Deepfakes and the First Amendment

429

journalism. Although this doomsday scenario may seem extreme,

deepfakes that manifest even one of these threats to society could still

cause severe harm.

The deepfake threat has not gone unnoticed by Congress. In July

2018, Senator Marco Rubio mused on a potential danger of deepfakes

as “the ability to influence the outcome [of an election] by putting out

a video of a candidate on the eve before the election doing or saying

something strategically placed, strategically altered, in such a way to

drive some narrative that could flip enough votes in the right place to

cost someone an election.”

65

Senator Rubio characterized such a

situation as “not a threat to our elections, but a threat to our Repub–

lic.”

66

Senator Mark Warner also specifically addressed deepfakes in his

draft white paper outlining various policy proposals to regulate social

media and large technology firms.

67

On September 13, 2018,

Representatives Adam Schiff, Stephanie Murphy, and Carlos Curbelo

sent a letter to Director of National Intelligence Dan Coates specifically

asking the intelligence community to “report to Congress and the public

about the implications of new technologies that allow malicious actors

to fabricate audio, video, and still images.”

68

Some legislators have even gone so far as to introduce specific

legislation to address deepfakes.

69

On December 21, 2018, Senator Sasse

introduced a bill attempting to criminalize the “malicious creation and

distribution of deepfakes” entitled the “Malicious Deep Fake

Prohibition Act of 2018.”

70

The bill makes it a crime punishable by up

to ten years imprisonment to:

65. Senator Marco Rubio, Keynote Remarks at The Heritage Foundation’s

Homeland Security Event on Deep Fakes (July 19, 2018), video available

at Deep Fakes: A Looming Challenge for Privacy, Democracy, and National

Security, The Heritage Foundation, at 15:00–15:21, https://www.

heritage.org/homeland-security/event/deep-fakes-looming-challenge-privacy-

democracy-and-national-security [https://perma.cc/G97A-HK5J].

66. Id.

67. Senator Mark R. Warner, Potential Policy Proposals for Regulation of

Social Media and Technology Firms 2 (Aug. 20, 2018) (White Paper

Draft), https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/public_comments/

2018/08/ftc-2018-0048-d-0104-155263.pdf [https://perma.cc/8Y5F-DUQP].

68. Letter from Adam B. Schiff, Stephanie Murphy, and Carlos Curbelo,

Representatives, U.S. House of Representatives, to Daniel R. Coats, Dir.,

Office of Nat’l Intelligence (Sept. 13, 2018), https://schiff.house.gov/imo/

media/doc/2018-09%20ODNI%20Deep%20Fakes%20letter.pdf [https://

perma.cc/D82S-TPQV].

69. Kaveh Waddell, Lawmakers Plunge into “Deepfake” War, Axios (Jan.

31, 2019), https://www.axios.com/deepfake-laws-fb5de200-1bfe-4aaf-9c93-

19c0ba16d744.html [https://perma.cc/JCP3-9HDF].

70. Id.; S. 3805, 115th Cong. § 2 (2018). The bill defines “deep fake” as “an

audiovisual record created or altered in a manner that the record would

Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 70·Issue 2·2019

Defamatory Political Deepfakes and the First Amendment

430

(1) create, with the intent to distribute, a deep fake with the

intent that the distribution of the deep fake would facilitate

criminal or tortious conduct under Federal, State, local, or Tribal

law; or

(2) distribute an audiovisual record with –

(A) actual knowledge that the audiovisual record is a deepfake;

and

(B) the intent that the distribution of the audiovisual record

would facilitate criminal or tortious conduct under Federal, State,

local or Tribal law.

71

The bill includes the limitation that “any activity protected by the

First Amendment” is not punishable under the Act.

72

Although the bill

expired at the end of 2018, Sasse’s office indicated that it intends to

reintroduce the bill.

73

Representative Clarke of New York introduced a

bill entitled the “DEEP FAKES Accountability Act in June of 2019.”

74

This bill requires deepfake creators to include either a watermark or

disclosure that the audio or video is altered.

75

Deepfake creators who

do not comply with the watermark or disclosure requirements may face

civil penalties of up to $150,000 per record in fines, five years in jail, or

both.

76

The bill also allows for injunctive relief to comply creators to

use watermarks or disclosures.

77

In addition to the legislation proposed

by Congress, several states, including New York, Texas, and Maine,

introduced legislation to address the harms of deepfakes.

78

In October

falsely appear to a reasonable observer to be an authentic record of the

actual speech or conduct of an individual.” Id. Strikingly, the bill’s

definition of deepfake does not restrict the manner of creation to videos

created through deep learning. See id.; supra Part I.C.

71. S. 3805, 115th Cong. § 2 (2018). Law professor and commentator Orin

Kerr noted his concern that Senator Sasse’s bill reaches too far, creating

“federal crimes that prohibit acts undertaken in furtherance of any

criminal law or tort.” Orin Kerr, Should Congress Pass a “Deep Fakes”

Law?, The Volokh Conspiracy (Jan. 31, 2019), http://reason.com/

volokh/2019/01/31/should-congress-pass-a-deep-fakes-law [https://perma

.cc/43DG-9WBU].

72. S. 3805, 115th Cong. § 2 (2018).

73. Waddell, supra note 69.

74. H.R. 3230, 116th Cong. § 1 (2019).

75. Id. § 2.

76. Id.

77. Id.

78. Nina Iacono Brown, Congress Wants to Solve Deepfakes by 2020, Slate

(July 15, 2019, 7:30A.M.), https://slate.com/technology/2019/07/congress-

Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 70·Issue 2·2019

Defamatory Political Deepfakes and the First Amendment

431

of 2019, California passed legislation penalizing the distribution of

deepfakes of political candidates within 60 days of an election.

79

Although both federal and state level legislatures have attempted to

address the harms of deepfakes, whether these measures will comport

with the First Amendment has yet to be tested in court.

Given all of these concerns, this Note must return to our original

hypothetical. Imagine that you believe that the Donald Trump’s Pee

Tape video posted by your friend is real. Imagine that you are not the

only one. Thousands of people believe that this video is the smoking

gun that proves both that the Russians had information that could have

compromised Trump and that Russia largely controlled him throughout

the 2016 election and into his presidency. The video contains imagery

so graphic that even the Republican base turn against Trump.

Democratic activist groups are primed to believe such a video and take

to the streets, protesting in outrage. The House votes to impeach

Trump on newly discovered evidence of corruption. Republican

Senators, fearing the repercussions of not acting, ultimately decide to

remove Trump from office. Only after all of this has taken place does

video forensics reveal that the video was a deepfake. In this scenario,

could Trump recover damages from the video’s creator? What would

those damages be?

III. Defamation Law as a Remedy

For defamatory deepfakes in general, individuals or companies may

have legal remedies to protect their property or publicity under

copyright law or the tort of right to publicity.

80

However, politicians

will likely struggle to recover under either of these legal theories.

Regarding copyright law, political figures often do not own much of the

video taken of them, barring them from any recovery.

81

Even if a

political figure owns the video of themselves, courts will likely not

punish an individual who uses the video to comment on the political

deepfake-regulation-230-2020.html [https://perma.cc/HT5S-HBVN]; Scott

Thistle, Maine Joins ‘Deepfake’ Flight: Might Ban in Political Ads,

Governing (Jan. 30, 2020), https://www.governing.com/next/Maine-

Joins-Deepfake-Fight-Might-Ban-in-Political-Ads.html [https://perma.cc/

3CFY-WBM4].

79. Colin Lecher, California has Banned Political Deepfakes During Election

Season, Verge (Oct. 7, 2019), https://www.theverge.com/2019/10/7/

20902884/california-deepfake-political-ban-election-2020 [https://perma.cc/

88Y7-4AA2].

80. Chesney & Citron, supra note 3, at 34–35.

81. Hustler Magazine, Inc. v. Moral Majority, Inc., 796 F.2d 1148, 1151 (9th

Cir. 1986) (noting the first element of copyright infringement is

“ownership of the copyright by the plaintiff”).

Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 70·Issue 2·2019

Defamatory Political Deepfakes and the First Amendment

432

figure in a non-commercial way, categorizing such commentary as “fair

use.” For instance, in Dhillon v. Doe,

82

the United States District Court

for the Northern District of California held that a non-commercial

website’s use of a politician’s headshot to criticize the politician was

“transformative” and “such a use is precisely what the Copyright Act

envisions as a paradigmatic fair use.”

83

Public figures will likely also

struggle to recover under the right of publicity, or “the inherent right

of every human being to control the commercial use of his or her

identity.”

84

First, only about thirty states even recognize such a right.

85

Second, and even more importantly, the right to publicity only protects

the use of someone’s persona for a commercial gain.

86

As in the Trump

hypothetical, many political deepfakes do not seek to profit from their

creations, so the right of publicity will not provide an appropriate legal

remedy.

This brings us to the pièce de résistance: the tort of defamation.

Defamation law covers both libel (written communications or commun–

ications that persist similarly to written works) and slander (spoken

communications).

87

Although the actual elements of defamation vary

from state to state, the tort generally consists of several elements as

outlined in the Second Restatement of Torts:

To create liability for defamation there must be:

(a) a false and defamatory statement concerning another;

(b) an unprivileged publication to a third party;

(c) fault amounting to at least negligence on the part of the

publisher; and

(d) either actionability of the statement irrespective of special

harm or the existence of special harm caused by the publication.

88

82. No. C 13-01465 SI, 2014 WL 722592 (N.D. Cal. Feb. 25, 2014).

83. Id. at *5.

84. 1 J. Thomas McCarthy, Rights of Publicity and Privacy § 3:1

(2d ed. 2018).

85. Amanda Tate, Note, Miley Cyrus and the Attack of the Drones: The Right

of Publicity and Tabloid Use of Unmanned Aircraft Systems, 17 Tex.

Rev. Ent. & Sports L. 73, 84 (2015).

86. McCarthy, supra note 84.

87. Robert D. Sack, Sack on Defamation: Libel, Slander, and

Related Problems §§ 2:4.1–.2 (4th ed. 2010).

88. Restatement (Second) of Torts § 558 (Am. Law Inst. 1977).

Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 70·Issue 2·2019

Defamatory Political Deepfakes and the First Amendment

433

However, in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan,

89

the Supreme Court

replaced the traditional third element of “fault amounting to at least

negligence” with a higher standard, requiring proof that the speech’s

publisher acted with actual malice in publishing speech directed at

public officials.

90

Actual malice is found when the statement is made

“with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether

it was false or not.”

91

Mere negligence does not suffice to meet an actual-

malice standard.

92

The actual-malice standard creates an exceptionally high burden of

proof for public officials in defamation suits, as it is very difficult to

prove that a publisher knew the information she published was false or

that her actions regarding the information’s truthfulness rose to the

level of recklessness. The Supreme Court created such a high burden to

balance the competing interests of public officials who sought to protect

their reputations from defamation against the First Amendment’s

safeguarding of high-value political speech. The Court reasoned that

erroneous statements are “inevitable in free debate,” adding that even

erroneous statements should be protected to provide the freedom-of-

expression principle the adequate “breathing space” it needs to

survive.

93

The Court held that when public officials bring a defamation

suit, any mental state on behalf of the publisher lower than actual

malice is “constitutionally deficient [in its] failure to provide the

safeguards for freedom of speech and of the press that are required by

the First and Fourteenth Amendments.”

94

Such a standard still

provides recourse for political figures because if they can prove that

individuals acted with actual malice when publishing false and defam–

atory statements about them, then the statement is not protected under

the First Amendment.

95

Applying this rigorous standard to political deepfakes is relatively

straightforward. Deepfakes are intended to be “fakes” or falsehoods.

Unlike an article where an individual might not be sure about one

particular fact regarding a political figure, creators of deepfakes know

89. 376 U.S. 254 (1964).

90. Id. at 283; Restatement (Second) of Torts § 558 (Am. Law Inst.

1977). The Court later extended the holding from Sullivan to apply not

only to public officials but also to public figures. Curtis Publishing Co. v.

Butts, 388 U.S. 130, 150 (1967).

91. Sullivan, 376 U.S. at 280.

92. Id. at 287–88.

93. Id. at 271–72.

94. Id. at 264.

95. See Ashcroft v. Free Speech Coalition, 535 U.S. 234, 245–46 (2002) (“The

freedom of speech has its limits; it does not embrace certain categories of

speech, including defamation . . . .”).

Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 70·Issue 2·2019

Defamatory Political Deepfakes and the First Amendment

434

that the content they are creating is false. Creating a deepfake requires

a person with above-average computer literacy to download a program

and take a series of non-trivial, affirmative steps to swap someone’s face

onto another video.

96

Even as technology makes it easier to create

deepfakes, it will still be hard to prove that an individual “accidentally”

created a video of a public figure in a compromising situation. Deep–

fakes are designed to look realistic and to make others believe that the

face swapped onto the fake video is in fact the person it seems to be.

The old adage “seeing is believing” still holds as videos are generally

considered highly reliable evidence of past events.

97

A deepfake creator

will not only know that what she is creating is false, but since she is

creating a video, many more persons are likely to believe that what the

video depicts is true.

Nevertheless, good-faith deepfake creators will have a rather easy

shield against culpability: any indication, either in the video itself or on

the location (webpage) where the video was posted, that the video is a

fake. If a deepfake creator supplies a watermark or disclaimer, clearly

indicating the video is a fake, such information could be used as

compelling evidence that the creator reasonably believed that others

would not treat the video as an actual representation of the political

figure. If a third party could not reasonably believe the video was a

depiction of the political figure, then the video is not defamatory.

98

Given the ease of providing such a disclaimer or watermark, this will

also work against bad actors who intend to use the video to deceive. If

an individual creates a defamatory deepfake without providing any

indication that the video is fake, it seems likely that she knew or had

reckless disregard for the video’s falsity.

In addition to the actual-malice standard, politicians will also have

to establish the other elements of defamation: “a false and defamatory

statement concerning another,” “an unprivileged publication to a third

party,” and “either actionability of the statement irrespective of special

harm or the existence of special harm caused by the publication.”

99

The

Second Restatement of Torts defines a defamatory statement as one

that “tends so to harm the reputation of another as to lower him in the

estimation of the community or to deter third persons from associating

or dealing with him.”

100

Some videos will be completely innocuous (e.g.,

96. See supra Part I.B.

97. Brundage et. al., supra note 56, at 46.

98. See Hustler Magazine, Inc. v. Falwell, 485 U.S. 46, 57 (1988) (holding

that the publisher was not liable for defamation because the parody ad

“could not be reasonably understood as describing actual facts about

[respondent]”).

99. Restatement (Second) of Torts § 558 (Am. Law Inst. 1977).

100. Id. § 559.

Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 70·Issue 2·2019

Defamatory Political Deepfakes and the First Amendment

435

a video of a politician watering her garden) and thus, not defamatory.

Bad actors, however, are likely to be more interested in using deepfake

technology to place political figures in compromising situations, aiming

to lower the reputation of those political figures. The trier of fact will

have the final word on whether the content is deemed defamatory.

Political figures seeking to recover damages will also have to prove

that the deepfake was published and that they were harmed by that

publication. A statement is published through “any act by which the

defamatory matter is . . . communicated to a third person.”

101

Posting

a deepfake online would certainly constitute a publication. Finally, the

political figure could argue that the publication caused her special harm

(or some kind of monetary loss), such as the loss of an election or

reduced campaign donations.

102

Even if the political figure did not suffer

a particularized harm, she could argue that the publication caused

general societal harm (such as the harms outlined in Part II).

IV. Satire or Parody as a Defense

A good-faith deepfake creator’s most readily available defense is an

acknowledgement in or near the video that the video is false. The more

obvious the disclaimer or watermark, the less likely such a video will

be misconstrued by a member of the general public that such a video

is actually real. Some political satirists, however, might not want to be

constrained by the addition of a watermark or disclaimer and instead

may claim a privilege by satire or parody. The Supreme Court noted

the importance of satire in the political-discourse context in Hustler

Magazine, Inc. v. Falwell, stating that “[d]espite their sometimes

caustic nature . . . graphic depictions and satirical cartoons have played

a prominent role in public and political debate.”

103

In that case, Jerry Falwell sued Hustler Magazine for defamation

and intentional infliction of emotional distress after Hustler editors

drew a cartoon in which Falwell discussed his “first time” as a “drunken

incestuous rendezvous with his mother.”

104

At trial, the jury rejected

Falwell’s defamation claim based on its findings that no reasonable

person would believe that the cartoon described actual facts; however,

it found in favor of Falwell on his intentional infliction of emotion

distress claim.

105

On appeal, Hustler Magazine claimed that awarding

damages for intentional infliction of emotional distress violated its First

101. Id. § 577 cmt. a.

102. Ardia, supra note 10, at 9.

103. 485 U.S. 46, 54 (1988).

104. Id. at 48.

105. Id. at 49.

Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 70·Issue 2·2019

Defamatory Political Deepfakes and the First Amendment

436

Amendment rights.

106

Falwell contended that the cartoon was so

“outrageous” that it was distinguishable from a traditional political

cartoon.

107

The Court, inherently suspicious of an “outrageousness”

argument, rejected Falwell’s position, noting:

“Outrageousness” in the area of political and social discourse has

an inherent subjectiveness about it which would allow a jury to

impose liability on the basis of the jurors’ tastes or views, or

perhaps on the basis of their dislike of a particular expression. An

“outrageousness” standard thus runs afoul of our longstanding

refusal to allow damages to be awarded because the speech in

question may have an adverse emotional impact on the

audience.

108

The Court instead held that “public figures . . . may not recover

for the tort of intentional infliction of emotional distress by reason of

[satirical] publications . . . without showing in addition that the

publication contains a false statement of fact which was made with

‘actual malice.’”

109

The Court adopted New York Times’s actual-malice

standard to the tort of intentional infliction of emotional distress to

provide “adequate ‘breathing space’ to the freedoms protected by the

First Amendment.”

110

The Supreme Court’s view of outrageousness might seem like a

blank check for satirists and parody makers to use deepfakes to mock

politicians. The question remains, however, whether deepfakes can be

considered satirical works in general. The satire at issue in Hustler was

a hand-drawn caricature that the jury found could not “reasonably be

understood as describing actual facts about [respondent] or actual

events in which [he] participated.”

111

Deepfakes, unlike caricatures and

other parodies, could reasonably be understood to depict facts about an

individual. This reasonableness element is crucial for establishing

liability against a defendant asserting a parody or satire defense. In

Farah v. Esquire,

112

the United States Court of Appeals for the District

of Columbia Circuit noted that “satire is effective as social commentary

precisely because it is often grounded in truth.”

113

Thus, “[t]he test [for

satire] . . . is not whether some actual readers were misled, but whether

106. Id. at 50.

107. Id. at 55.

108. Id.

109. Id. at 56.

110. Id.

111. Id. at 49.

112. 736 F.3d 528 (D.C. Cir. 2013).

113. Id. at 537.

Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 70·Issue 2·2019

Defamatory Political Deepfakes and the First Amendment

437

the hypothetical reasonable reader could be (after time for

reflection).”

114

What it takes to mislead the “hypothetical reasonable

reader” will certainly evolve as deepfake technology improves to mirror

true human interaction. If the video is extremely realistic, and the

actions are outrageous but within the realm of possibility, a court may

find that a deepfake intended to be a satire is actually defamatory

speech because a reasonable viewer would not be able to distinguish the

fake video from reality.

V. Injunctions as a Remedy

If a political figure can prove that a publisher acted with actual

malice to create a defamatory deepfake, and that the deepfake could

not be considered a satire, then the political figure will be able to

recover the traditional tort remedy of monetary damages.

115

Despite the

attraction of monetary damages, they do nothing to stop the ongoing

reputational loss caused by the deepfake’s continued existence on the

Internet.

116

Nor do monetary damages remedy the societal damages

caused by the video if it is allowed to persist in the public sphere.

Moreover, many bad actors posting deepfakes might be judgment-proof,

denying the political figure any recovery.

Given the inadequacy of monetary damages, injunctions may be a

better avenue to address some of the harms caused by deepfakes. Unlike

monetary damages, an injunction is an equity-based remedy designed

to “order the defendant to refrain from specified conduct.”

117

Political

figures are likely to favor injunctions because removing the original

video from the Internet will remedy the imminent issue of reputational

loss caused by a defamatory political deepfake.

118

Courts can grant

permanent injunctions that occur after an adjudication on the merits

of the claim, or preliminary injunctions that occur prior to adjudications

based on the likelihood of success on the merits.

119

Although preliminary

injunctions may be favored because they remove an offending video

from the Internet sooner than other remedies, they face a heightened

First Amendment hurdle because they risk censoring protected

114. Id.

115. Ardia, supra note 10, at 7.

116. Id. at 16.

117. Id. at 14.

118. Id. at 9, 15–16.

119. Mark A. Lemley & Eugene Volokh, Freedom of Speech and Injunctions

in Intellectual Property Cases, 48 Duke L.J. 147, 149–50 (1998).

Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 70·Issue 2·2019

Defamatory Political Deepfakes and the First Amendment

438

speech.

120

Thus, this Note focuses primarily on the potential use of

permanent injunctions against defamatory political deepfakes.

A. Injunctions and the First Amendment

The First Amendment protects individuals’ rights to freedom of

religion, speech, the press, and assembly.

121

Since the founding of the

United States, courts have been keen to avoid prior restraints on speech,

or restraints on expression before occurs.

122

In Near v. Minnesota,

123

the

Supreme Court established that injunctions against free speech and the

press usually amount to a prior restraint on expression.

124

In Near, the

Court held a state statute that perpetually enjoined individuals or

corporations (including the press) who published “a malicious,

scandalous and defamatory newspaper or other periodical” was an

unconstitutional prior restraint on freedom of the press.

125

The broad

nature of the statute led to the “effective censorship” of any publisher

who was convicted of publishing an “offending newspaper or

periodical,” because all future publications regarding the offending

matter (defamatory or not) would be subject to court review.

126

The

Court held that the threat of enjoining the press’ constitutionally

protected activity outweighed the potential that publishing scandalous

and defamatory information may disturb the public peace.

127

Similarly, the Supreme Court struck down injunctions against press

activities in both New York Times Co. v. United States (Pentagon

Papers)

128

and Nebraska Press Association v. Stuart

129

as uncon–

stitutional prior restraints on the freedom of speech and the press. In

Pentagon Papers, the Second Circuit enjoined the New York Times and

the Washington Post from publishing the “Pentagon Papers,” a Defense

Department study of American activities in Southeast Asia, after the

government argued that the information’s publication would endanger

120. See id. at 150.

121. U.S. Const. amend. I.

122. See Anthony Lewis, Make No Law: The Sullivan Case and the

First Amendment 51 (1991); Ardia, supra note 10, at 32. The perception

that injunctions were prior restraints on speech and therefore invalid as

an equitable remedy was so pervasive commentators described it as the

“no injunction rule.” Id. at 18.

123. 283 U.S. 697 (1931).

124. Id. at 722–23.

125. Id. at 702–03, 722–23.

126. Id. at 712.

127. Id. at 721–22.

128. (Pentagon Papers) 403 U.S. 713 (1971) (per curiam).

129. 427 U.S. 539 (1976).

Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 70·Issue 2·2019

Defamatory Political Deepfakes and the First Amendment

439

national security.

130

In Nebraska Press, a state court feared that

reporting on a sensational criminal trial in a small community would

endanger the defendant’s right to a fair trial.

131

The court crafted a

restrictive order prohibiting the press from reporting on certain aspects

of the trial.

132

In both cases, the Supreme Court grappled with a careful

balancing test between constitutionally protected speech and important

governmental interests (national security) or individual rights (the right

to a fair trial).

133

And in both cases, the Supreme Court held that the

First Amendment’s free-speech guarantee outweighed either competing

interest.

134

In the case of deepfakes, courts must also balance the speech

contained in defamatory political deepfakes against important

governmental interests, such as safeguarding free elections, promoting

trust in public officials, defending national security, and protecting

truth itself.

135

It is important to note that in Near, Pentagon Papers,

and Nebraska Press, the balancing test involved either a statute or a

court-ordered remedy that both targeted an entire industry (the press)

and included speech that likely was not libelous.

136

None of the cases

addressed an individual or private wrong of one person defaming

another. For political deepfakes, it is likely the defamatory threat would

not come from the press, but instead from a private individual

intentionally attempting to disparage a political figure. In addition,

unlike the cases discussed above, the expression in the deepfake would

be clearly false.

137

Thus, if an injunction could be carefully crafted to

include only the speech in the defamatory deepfake itself, the resulting

balancing-test analysis would pit unprotected false and defamatory

speech against important governmental interests. To determine

whether a court might hold that the important (some might even say

“compelling”) governmental interests outweigh any free-speech con–

cerns, we must take a closer look at several constitutionally permissible

prior restraints on expression.

130. Pentagon Papers, 403 U.S. at 714.

131. Nebraska Press, 427 U.S. at 543–45.

132. Id. at 543–44.

133. Pentagon Papers, 403 U.S. at 718; Nebraska Press, 427 U.S. at 543.

134. Pentagon Papers, 403 U.S. at 714; Nebraska Press, 427 U.S. at 570.

135. See supra Part II.

136. Near v. Minnesota, 283 U.S. 697, 702–03 (1931); Pentagon Papers, 403

U.S. at 714; Nebraska Press, 427 U.S. at 570.

137. See supra Part I.

Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 70·Issue 2·2019

Defamatory Political Deepfakes and the First Amendment

440

B. Constitutionally Permissible Injunctions on Expression

Although prior restraints on expression bear “a heavy presumption

against [their] constitutional validity,” not all prior restraints are pro–

hibited by the Constitution.

138

In Near, the Supreme Court outlined

four exceptions to the prior-restraint rule: (1) key issues of national

security, such as troop movements or sailing dates; (2) obscene

publications; (3) incitement to acts of violence or attempts to overthrow

the government; and (4) to “protect private rights” in accordance with

the rules of courts of equity.”

139

Other than the national-security

exception, all the exceptions outlined in Near relate to speech that falls

outside of the First Amendment’s traditional protective scope.

140

1. Obscenity

Obscenity has no protection under the First Amendment.

141

In Roth

v. United States, the Court held that “obscenity is not within the area

of constitutionally protected speech or press.”

142

The Court reasoned

that “lewd and obscene . . . utterances are no essential part of any

exposition of ideas, and are of such slight social value as a step to truth

that any benefit that may be derived from them is clearly outweighed

by the social interest in order and morality.”

143

Since obscenity provides

such low social value, the Court in Miller v. California

144

affirmed a

broader test to determine what constitutes obscenity. A trier of fact

must determine whether (1) “‘the average person, applying contemp–

orary community standards’ would find that the work, taken as a whole,

appeals to the prurient interest”;

145

(2) the work depicts offensive sexual

conduct; and (3) “the work, taken as a whole, lacks serious literary,

artistic, political, or scientific value.”

146

Given that obscenity receives no constitutional protection, states

have some ability to censor lewd and obscene publications as long as

they take precautions to avoid censoring protected speech. In Times

138. Pentagon Papers, 403 U.S. at 714; Near, 283 U.S. at 716.

139. Near, 283 U.S. at 716.

140. Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc. v. Nation Enters., 471 U.S. 539, 555, 559

(1985); Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444, 448–49 (1969); Roth v. United

States, 354 U.S. 476, 485 (1957).

141. Roth, 354 U.S. at 485.

142. Id.

143. Id. (quoting Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U.S. 568, 571–72 (1942)).

144. 413 U.S. 15 (1973).

145. Id. at 16 (quoting Roth, 354 U.S. at 489).

146. Id.

Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 70·Issue 2·2019

Defamatory Political Deepfakes and the First Amendment

441

Film Corp. v. City of Chicago,

147

the Supreme Court upheld a local

ordinance requiring filmmakers to submit their films to a review board

and obtain approval from the city prior to a public exhibition.

148

The

Court clarified this holding in Freedman v. Maryland,

149

where it

affirmed that states could use noncriminal processes, including prior

submission, to censor obscenity in films.

150

However, the prior

submission must “take[] place under procedural safeguards designed to

obviate the dangers of a censorship system.”

151

2. Copyright

A copyright holder has “the right to exclude others from using his

property.”

152

Individuals cannot copyright facts or ideas, but they can

copyright a particular “expression.”

153

Although copyright law creates

a restriction on speech, the Supreme Court held in Harper & Row,

Publishers, Inc. v. Nation Enterprises

154

that the First Amendment does

not protect speech that infringes on another’s copyright.

155

Under the

Copyright Act of 1976, a federal court “may . . . grant temporary and

final injunctions on such terms as it may deem reasonable to prevent

or restrain infringement of a copyright.”

156

Under this statute, modern

courts have been willing to grant not only permanent injunctions but

also preliminary injunctions to protect a plaintiff’s property interests.

157

The practice of granting injunctions in copyright and patent cases

became so pervasive that in 2006 the Supreme Court reminded lower

courts that in granting injunctions, they should not abandon

“traditional equitable considerations.”

158

In eBay Inc. v. MercExchange,

L.L.C., the Supreme Court noted that it has “consistently rejected

invitations to replace traditional equitable considerations with a rule

that an injunction automatically follows a determination that a

147. 365 U.S. 43 (1961).

148. Id. at 46.

149. 380 U.S. 51 (1965).

150. Id. at 58.

151. Id.

152. eBay, Inc. v. MercExchange, L.L.C., 547 U.S. 388, 392 (2006) (quoting

Fox Film Corp. v. Doyal, 286 U.S. 123, 127 (1932)).

153. Lemley & Volokh, supra note 119, at 166.

154. 471 U.S. 539 (1985).

155. Id. at 555–60; Lemley & Volokh, supra note 119, at 150, 166.

156. 17 U.S.C. § 502(a) (2012).

157. Lemley & Volokh, supra note 119, at 150, 158–59.

158. eBay Inc. v. MercExchange, L.L.C., 547 U.S. 388, 392 (2006).

Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 70·Issue 2·2019

Defamatory Political Deepfakes and the First Amendment

442

copyright has been infringed.”

159

Under eBay, a copyright- or patent-

holding plaintiff must satisfy a four-factor test before a permanent

injunction can be granted to protect her intellectual property interest.

160

The four factors are: (1) the plaintiff “has suffered an irreparable

injury”; (2) “remedies available at law . . . are inadequate to compensate

for [the] injury”; (3) “considering the balance of hardships between [the

parties], a remedy in equity is warranted”; and (4) “the public interest

would not be disserved by a permanent injunction.”

161

Although eBay

was a patent case, lower courts have extended its holding to copyright

cases involving preliminary- or permanent-injunction requests.

162

C. Injunctions on Defamatory Speech

Like obscenity and copyrights, defamatory speech has only limited

protection under the First Amendment.

163

Unlike obscenity and

copyrights, however, courts have been hesitant to allow injunctions on

defamatory speech.

164

The Supreme Court did not formally address the

issue of injunctions against non-press related defamation until 2005.

165

In Tory v. Cochran,

166

the Court accepted a case on post-trial

injunctions against defamatory speech, but Cochran’s untimely death

prevented a final resolution of the issue.

167

The Tory case arose out of

a dispute between renowned attorney Johnnie Cochran and Ulysses

Tory, a disgruntled prior client of Cochran’s law firm.

168

Dissatisfied

with Cochran’s services, Tory picketed outside Cochran’s office with

159. Id. at 392–93.

160. Id. at 391.

161. Id.

162. Salinger v. Colting, 607 F.3d 68, 77 (2nd Cir. 2010) (holding that “eBay

applies with equal force (a) to preliminary injunctions (b) that are issued