Spreading the Word: What Fiy Shades of Grey

Means for World Literature

Waiyee Loh, Department of English, Kanagawa University, Japan, waiy[email protected]

How does the global popularity of bestselling romance novel Fiy Shades of Grey complicate David

Damrosch’s seminal denion of World Literature as ‘literary works that circulate beyond their

culture of origin,’ and which are ‘acvely present within a literary system beyond that of [their]

original culture’? By oering a formal textual analysis of a novel few would call ‘literature,’ I explore

how Fiy Shades provides a test case for rethinking what World Literature is, how it travels, and how

we study it. With its ‘digital-like’ form and celebraon of aecve labour, Fiy Shades encourages

readers to publicise the novel by spreading fragments of its content through online social media

networks as a form of unpaid labour. This ‘spreading’ of the novel compels us to reconsider World

Literature in the light of digital media and fan parcipaon.

C21 Literature: Journal of 21st-century Wrings is a peer-reviewed open access journal published by the Open Library of

Humanies. © 2023 The Author(s). This is an open-access arcle distributed under the terms of the Creave Commons

Aribuon-NonCommercial 4.0 Internaonal License (CC-BY-NC 4.0), which permits unrestricted distribuon, reproducon

and adaptaon in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited, and that the material is not used for

commercial purposes. See hps://creavecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

OPEN ACCESS

Loh, Waiyee. 2023. “Spreading the Word: What

Fiy Shades of Grey Means for World Literature.”

C21 Literature: Journal of 21st-century Wrings 10(1):

pp. 1–24. DOI: hps://doi.org/10.16995/c21.4802

Journal of 21st-century

Writings

LITERATURE

2

Introducon

Much of the scholarship surrounding E. L. James’s bestselling romance novel Fifty

Shades of Grey (2012) expresses a striking reluctance to analyse the novel as a literary

text. Published in three volumes (Fifty Shades of Grey, Fifty Shades Darker, and Fifty Shades

Freed) spanning a total of 1,625 pages, the novel presents critics with the challenge of

explicating a text that is so thick with content yet seems so thin in terms of its meaning.

In a special issue of Sexualities on ‘Reading the Fifty Shades “Phenomenon”,’ IQ Hunter

(2013: 969) writes:

After only ninety dreadful pages of the first book, I knew I was in trouble. I couldn’t

think of anything worth writing about it, let alone anything scholarly and original....

my excited anticipation [had been] deflated by a close up and personal encounter

with a book far more engaging as a phenomenon than actually to read.

Hunter’s comments are typical of existing research on Fifty Shades of Grey (henceforth

Fifty Shades). Many scholars and cultural commentators give little weight to close

readings of the novel and focus instead on considering Fifty Shades as a social

phenomenon, examining the novel’s larger significance for the publishing industry;

the ethics of publishing fan fiction for commercial profit; reader reception; and what

the novel reveals about what women want, do not want, and should not want.

1

In other

words, many critics prefer to explore the social relations that connect the novel to

readers and publishers, rather than analyse the formal qualities that characterise Fifty

Shades as a literary text. Some of these critics also criticise Fifty Shades, or mention

that it has been heavily criticised by others, for its ‘bad writing.’ In a feature article

for Newsweek, Katie Roiphe (2012: 28) concludes that ‘what [is] most alarming about

the Fifty Shades of Grey phenomena [sic], what gives it its true edge of desperation,

and end-of-the-world ambience, is that millions of otherwise intelligent women are

willing to tolerate prose on this level.’

2

While hardly intending to do so, these critics

give the impression that it is not worth paying close attention to the form of Fifty Shades

because the novel is so badly written. The novel’s repetitive plot, flat characters, and

often painfully awkward choice of expression certainly tried this author’s patience.

Nevertheless, this article argues that attentiveness to literary form yields insights into

the ways in which the novel’s infamously ‘bad’ form has actually helped Fifty Shades to

become a global social phenomenon.

1

See, for example, Jamison (2013); Shaw (2012); Jones (2014); Deller and Smith (2013); and van Reenen (2014).

2

See also Jones (2014: 2–3); Deller, Harman, and Jones (2013: 860); and Hunter (2013: 971).

3

In fact, analysing the novel via close reading helps us to understand how and why

Fifty Shades and other similar works of contemporary fiction are read so widely around

the world. Circulation-oriented theories of World Literature often examine how literary

texts travel through translation, and some scholars have focused in particular on how the

formal qualities of a text might contribute to its being translated. Rebecca Walkowitz’s

‘born-translated’ novel, for example, self-consciously calls out for its own translation,

whereas David Damrosch’s ‘global’ literature deliberately erases local cultural

dierences to facilitate the process of translation.

3

In a radical variation of this approach

to World Literature, Franco Moretti calls for ‘distant reading’ – namely, the large-

scale quantitative analysis of data – to discern how literary forms, rather than specific

texts, travel across geographical, linguistic, and cultural boundaries.

4

The first part of

this article, however, makes a case for close reading as a productive means of analysing

how aesthetic form plays a crucial role in enabling Fifty Shades to transcend its original

context of production. The notoriously poor quality of E. L. James’s prose (repetitive plot,

verbatim repetitions, simplistic temporality and narratorial voice, formal incoherence,

and so on) enables readers to take the novel apart easily, and to disseminate or ‘spread’

fragments of its content online to other Internet users. The novel thus functions as an

example of what Henry Jenkins, Sam Ford, and Joshua Green have called ‘spreadable

media’ (2013). The second and third parts of the article build on this formal analysis to

explore 1) how Fifty Shades dramatises the concept of aective labour through the romantic

relationship between the two protagonists, and 2) how this romanticisation of aective

labour sheds light on the role of fan labour in ‘spreading’ media content. The work that

fans do in spreading word about Fifty Shades online represents an ambivalent example

of participatory culture: fans contribute to E.L. James’s commercial success by lovingly

remixing the novel through online forums, discussions, parodies, and commentaries, yet

they have not been given due credit for supporting Fifty Shades’s transformation from

Twilight fan fiction to international bestseller.

In particular, Fifty Shades introduces a new digital dimension to Damrosch’s (2003:4)

seminal definition of World Literature as ‘literary works that circulate beyond their

culture of origin,’ and which are ‘actively present within a literary system beyond that

of [their] original culture.’ Fifty Shades circulates widely around the world via digital

networks. This is not only because the e-book format oers a high degree of portability

and privacy (Shaw 2012), although these are important factors. Fifty Shades was initially

published online as the Twilight fan fiction story ‘Master of the Universe’ and then as a

print-on-demand digital book, before being picked up for mass publication by Vintage

3

See Walkowitz (2015); and Damrosch (2003: 18).

4

See More (2005; 2013).

4

in 2012.

5

While James and her publishers claimed that she had significantly revised

‘Master of the Universe’ for publication as Fifty Shades, fan accounts of the novel’s

controversial publication history suggest otherwise (Brennan & Large 2014: 29–30).

6

Fifty Shades appears to be an almost identical reproduction of its online fan fiction

precursor. These digital origins might explain why Fifty Shades’s stylistic form aligns

so closely with that of digital media – even in the print version of the novel – but it is

dicult to establish such a causal relationship without access to the author’s drafts,

reader comments, and online chapters of ‘Master of the Universe,’ which James took

down so that she could publish the work commercially. James’s removal of these online

records limits our ability to trace the evolution of Fifty Shades from a digital text to a

print novel that resembles a digital text. Nonetheless, the novel’s ‘digital-like’ form

encourages and enables readers to engage in a form of unpaid aective labour when they

share short passages of text from the novel through online social media networks, even

when this ‘born-digital’ text is translated into print. By applying the practice of close

reading to a novel few would call ‘literature,’ I use Fifty Shades as a test case for revising

our understanding of World Literature in light of digital media and fan participation.

From Naon to Social Network

As literary studies increasingly shifts its focus ‘from nation to network’ (C. Levine

2013), the global popularity of Fifty Shades draws our attention to digital media as a

paradigmatic example of networked literary production and consumption. Fifty Shades’s

infamously clunky prose actually makes it highly ‘spreadable’ (Jenkins, Ford & Green

2013) via digital social media networks such as fan forums, blogs, Twitter, and Facebook.

The judgment of bad writing that detractors of Fifty Shades have levelled at the novel

might be seen as a stylistic form that embodies the experience of reading digital texts.

This ‘digital-like’ form, which is embedded even in the print version of Fifty Shades,

encourages the reader to fragment the novel into bite-sized pieces for ‘sharing’ and

discussing online, thereby facilitating the novel’s circulation via social media.

Fifty Shades looks like bad writing because of its ambivalent relationship with the

nineteenth-century realist novel, to which it frequently alludes. Not only does Fifty

Shades invoke the marriage plot in its depiction of the romance between Christian Grey

and Anastasia Steele, it also cites canonical nineteenth-century texts and authors as a

shorthand for presenting the female protagonist ‘Ana’ as a bookish young woman who

miraculously wins the aection of a rich and handsome man, like a latter-day Jane Eyre.

Christian begins his courtship of Ana by giving her a first edition copy of Thomas Hardy’s

5

See Brennan and Large (2014) for an overview of Fiy Shades’s publicaon history.

6

See also Lie (2012); and Boog (n. dat.).

5

Tess of the d’Urbervilles, which he knows is one of the ‘classic British novel[s]’ that Ana

loves to read (James 2012a: 6). Christian’s copy of Tess comes in three volumes, which

mirror the number of volumes that make up Fifty Shades. In Fifty Shades Freed, the third

volume of the novel, Ana’s personified ‘subconscious’ busies herself with reading The

Complete Works of Charles Dickens (James 2012c: 33, 49, 121) and Jane Eyre (James 2012c:

346), while her libidinous ‘inner goddess’ enjoys sex with Christian. Readers who are

familiar with nineteenth-century novels, however, will quickly realise that Fifty Shades

appears to lack the formal characteristics of complexity, coherence, and character

development that literary scholars typically associate with nineteenth-century British

realism.

7

Unlike Thackeray’s Vanity Fair or Dickens’s Bleak House, Fifty Shades shows a

general lack of interest in ‘[w]hat connexion [there can] be’ (Dickens 2003: 256) between

events in the plot, and between the various people and places that appear in the novel.

The plot of Fifty Shades is extremely repetitive and monotonous. Christian and Ana

undergo the same cycle repeatedly: Christian tries to dominate Ana, Ana rebels and

they fight, Ana feels guilty and apologises for rebelling, and they make up by having

steamy sex. The novel also includes a large amount of inconsequential detail about

Ana’s thoughts and actions, which adds to its tediousness. Ana’s internal monologue

reads like a series of diary entries describing nitty-gritty everyday activities that do not

add meaningfully to the plot. For instance, in a scene that occurs close to the end of the

first volume, Christian takes Ana out to an International House of Pancakes café for

breakfast. They exchange innuendoes, the waitress is embarrassed by Christian’s good

looks (like all the other women in the novel), and they proceed to discuss their BDSM

contract, which, 450 pages into the book, the two protagonists are still contesting.

The scene comes to an end, and the IHOP café does not appear again in the rest of the

novel. This repetitive and pointless nature of many of the novel’s scenes means that the

reader does not have to make an eort to remember what comes before, and to make

connections between dierent parts of the text in order to understand what is going on.

Even on a syntactic level, Fifty Shades employs repetition to reduce the need for

the reader to make connections. The novel is written entirely in the first-person from

Ana’s perspective, and her narration is solely set in the present. Time in the narrative

therefore moves forward only in a linear direction, which makes narrative time (or

‘plot’) essentially coterminous with chronological time (or ‘story’). Instead of using

7

Scholars of nineteenth-century realism have acknowledged that, while it is very dicult to formulate a clear-cut den-

ion of realism’s formal properes, it is possible to idenfy several characteriscs that make up what Caroline Levine

(2012: 84–85), following Amanda Claybaugh, calls the ‘syndrome’ of Victorian realism. See, for example, G. Levine

(1981) on complexity; Williams (1974) on ‘organic’ coherence; and More (1987) on the socialisaon of the modern

subject in the bildungsroman.

6

flashbacks, the novel literally repeats phrases and sentences from earlier parts of the

text to indicate that Ana is thinking about the past:

As I lie staring into the darkness, I think of all the times he warned me to stay away.

Anastasia, you should steer clear of me. I’m not the man for you.

I don’t do the girlfriend thing.

I’m not a hearts and flowers kind of guy.

I don’t make love.

This is all I know. (James 2012a: 230)

Immediately some of the things he’s said spring into my mind.

I don’t want to lose you . . .

You’ve bewitched me . . .

You’ve completely beguiled me . . .

I’ll miss you, too . . . more than you know . . . (James 2012a: 398)

In both of these instances, the novel reproduces Christian’s words verbatim, literally

quoting itself to remind the reader of Christian’s contradictory expressions of love for

Ana. The novel uses this same technique to repeat information about the BDSM contract.

The contract is printed in full on pages 165 to 175, and then parts of it reappear on pages

255 to 258 and 499 to 500, as Christian and Ana negotiate the contract’s terms and

conditions. Once again, this practice of verbatim reproduction minimises demands on

the reader to hold the dierent parts of the narrative in his/her memory so as to articulate

the relations between these parts. Reading instead becomes quick and eortless.

Lastly, Fifty Shades’s multiple literary allusions also contribute to the novel’s lack of

formal coherence. The references to Hardy’s Tess in the first volume do little more than

position Ana as a virginal young woman and Christian as a composite figure combining

Alec d’Urberville’s debauchery and Angel Clare’s punishment of Tess for not living

up to his ideals. Rather than engaging with the tragic rape of Hardy’s heroine – Ana’s

response to Tess is summed up in the statement ‘Damn, that woman was in the wrong

place at the wrong time in the wrong century’ (James 2012a: 21) – the novel invokes Tess

rather perversely to celebrate its female protagonist’s growing desire to be ‘punished’

sexually by a domineering man. Like many other postfeminist heroines, Ana exercises

her autonomy by actively forsaking that autonomy, again and again.

8

Ana consistently

obeys Christian’s commands both in and outside of the bedroom. ‘I do as I’m told,’

she tells the reader repeatedly (James 2012a: 428). Unlike the nineteenth-century

8

For discussions of poseminist media, see Gill (2007: 258–61); and Tasker and Negra (2007).

7

bildungsroman that focuses attention on a single, highly individuated protagonist who

finds his/her place in the world (C. Levine 2012: 90), Fifty Shades presents a narrative of

character regression instead of development, with Ana becoming more submissive with

every iteration of the cycle (I will say more about this in the second section of the article

on female aective labour). After approximately three-quarters of the first volume, the

references to Tess disappear and are replaced by a plethora of literary references ranging

from Robinson Crusoe (James 2012b: 47) and The Little Prince (James 2012b: 223) to The

Complete Works of Charles Dickens (James 2012c: 33). These references have nothing in

common besides functioning as a kind of name-dropping that supposedly demonstrates

how cultured and intelligent Christian and Ana are. The novel thus thwarts attempts to

read it as a palimpsestic rewriting of earlier literary texts, presenting the reader instead

with a jumble of floating and fragmentary literary citations.

Fifty Shades thus comes across as a badly written novel because it flouts the

expectations of formal cohesion that E. L. James’s consistent employment of

intertextuality raises. On the one hand, the novel makes frequent allusions to the

tradition of nineteenth-century realism. On the other hand, the form of Fifty Shades

does not match conventional critical perceptions of realism, which, as Elaine

Freedgood (2019: ix) has recently argued, often imagine the ‘Victorian novel’ to be

‘integrated, coherent, and conservative.’

9

Yet the novel also does not align itself

with the avant-garde aesthetics of modernism, or the linguistic and epistemological

concerns of postmodernism. What makes Fifty Shades dierent from both realist and

non-realist forms of literature is its fragmentary form, which detractors of the novel

have neglected to analyse in detail because of its association with ‘bad writing.’ While

there are certainly suggestive parallels between Victorian serialised fiction and Fifty

Shades’s genesis as serialised fan fiction online, the fragmentariness of Fifty Shades is of

a dierent order. All serialised narratives are fragmentary insofar as they are consumed

in parts, but Fifty Shades strikingly lacks what Linda K. Hughes and Michael Lund

(1991) have described as the Victorian serial’s abiding concern with steady, continuous

development over time. In this sense, despite its serialised nature, Fifty Shades is also

very much unlike contemporary ‘complex’ television serials which, as Jason Mittell has

argued, foreground development, unity, and craftsmanship. Mittell (2015) claims that

‘complex TV’ shows such as ABC’s Lost (2004–2010) and HBO’s The Wire (2002–2008)

avoid giving explicit storytelling cues, thereby compelling viewers to pay close attention

to how the story is told, and to piece together evidence in order to make sense of the

story’s enigma. Such TV narratives ‘ask [viewers] to trust in the payo that [they] will

eventually arrive at a moment of complex but coherent comprehension’ (Mittell 2015:

9

Freedgood (2019: xi) argues that, from the 1850s to the 1960s – before the nineteenth-century realist novel became

instuonalised as a ‘great’ form of literature – the Victorian novel ‘was not always imagined as formally coherent or as

realisc in a good way.’

8

50). Fifty Shades, on the other hand, de-emphasises ‘continuity and a sense of long-

term memory,’ and does not display a ‘depth of references’ or ‘details that require

the liberal use of pause and rewind’ (Mittell 2010: 4). With its repetitive and episodic

plot structure and small cast of characters, Fifty Shades more closely resembles earlier

forms of ‘non-complex’ serialised television which, Mittell (2010: 4) argues, sought

to ‘create episodes that could be viewed in any order by a distracted viewer with only

casual attention.’

In other words, the piecemeal quality of Fifty Shades encourages a speedy and

fragmentary mode of reading that echoes not only how we used to watch television,

but also the ways in which we read digital texts such as online news stories, tweets,

Facebook posts, and YouTube videos. The novel in fact reproduces the experience of

reading email and mobile phone text messages, by presenting the messages that

Christian and Ana send to each other in a typographical format that mimics that of

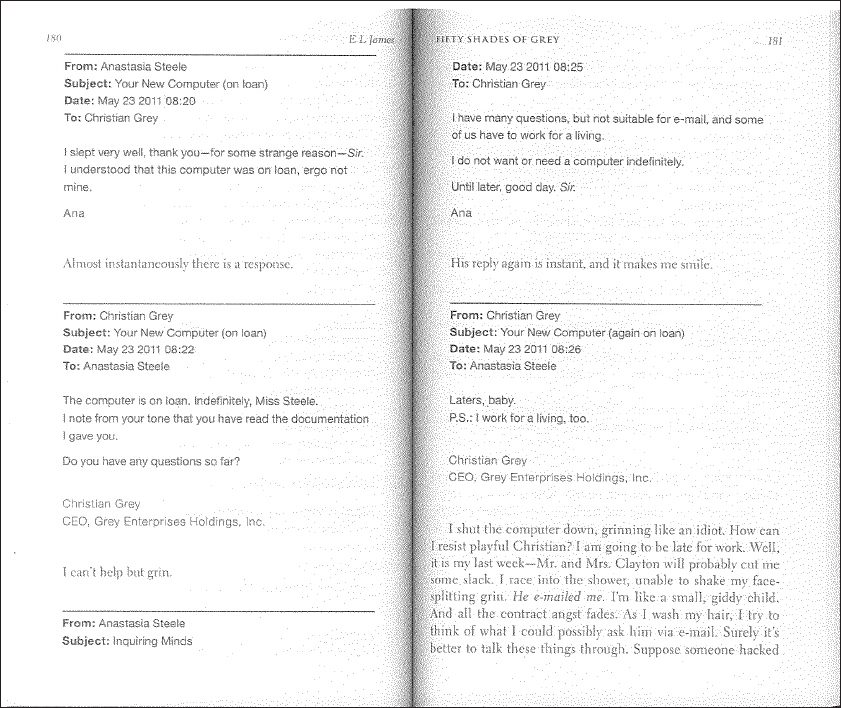

actual emails and text messages (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Chrisan and Ana discuss the BDSM contract via email (James 2012a: 180–81).

9

The novel presents what Christian and Ana see on their screens directly on the

printed page. This sense of immediacy is especially prominent in parts of the novel

where Christian and Ana send emails back and forth, and the emails are reproduced on

the printed page in a continuous sequence. Moreover, these verbatim transcriptions

of emails and text messages (as well as excerpts from the BDSM contract and even

quotations from Tess of the d’Urbervilles) break the text up visually, thereby making it

easy for the reader to skim the text quickly, and to even skip over sections to get to the

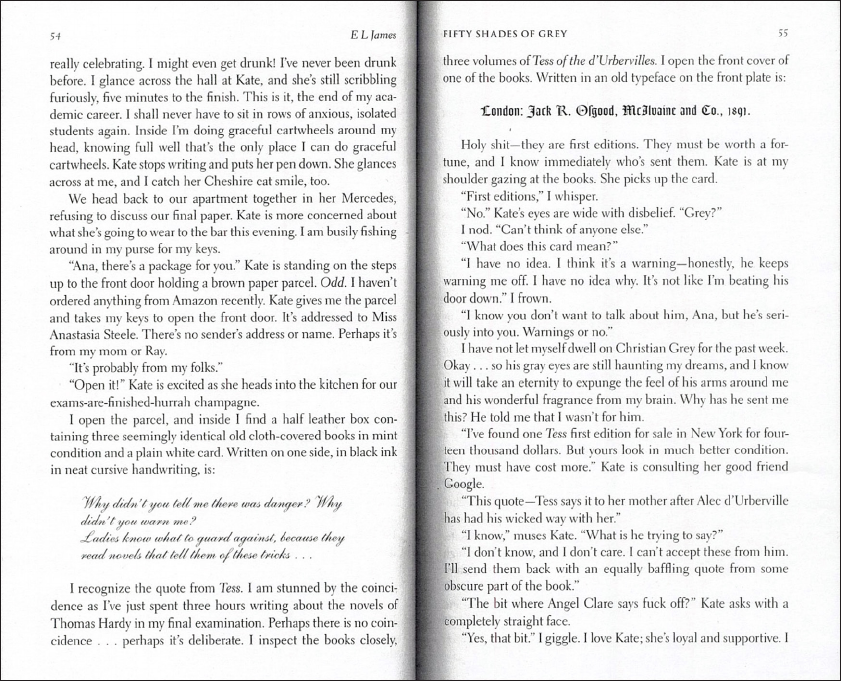

sex scenes or other passages that seem more interesting to the reader (Figure 2).

Repetition, inconsequential detail, narrative fragmentation, and the emails and

text messages in Fifty Shades collectively invoke a mode of reading digital texts that

Katherine Hayles (2012: 61) calls ‘hyper reading.’ Hyper reading is a form of superficial or

‘surface reading’ that is the opposite of close reading. Hayles (2007: 187–88) describes

this opposition as the contrast between ‘deep attention’ and ‘hyper attention’:

Figure 2: Christian’s quotation of Tess, as well as the publication details of the book,

visually break up the narrative into fragments (James 2012a: 54–55).

10

Deep attention, the cognitive style traditionally associated with the humanities, is

characterised by concentrating on a single object for long periods (say, a novel by

Dickens), ignoring outside stimuli while so engaged, preferring a single informa-

tion stream, and having a high tolerance for long focus times. Hyper attention is

characterised by switching focus rapidly among dierent tasks, preferring multiple

information streams, seeking a high level of stimulation, and having a low tolerance

for boredom. The contrast in the two cognitive modes may be captured in an image:

picture a college sophomore deep in Pride and Prejudice, with her legs draped over an

easy chair, oblivious to her ten-year-old brother sitting in front of a console, jam-

ming on a joystick while he plays Grand Theft Auto.

It is not a coincidence that Hayles references nineteenth-century realist novels by

Austen and Dickens as exemplary texts that require ‘deep attention,’ in contrast to Fifty

Shades, whose ambivalent relation to realist conventions primes the reader to engage in

‘hyper reading’ instead. In his polemical article ‘Is Google Making Us Stupid?’, Nicholas

Carr (2008) describes a similar opposition between deep reading and Internet reading

in more explicitly spatial terms: ‘My mind now expects to take in information the way

the Net distributes it: in a swiftly moving stream of particles. Once I was a scuba diver in

the sea of words. Now I zip along the surface like a guy on a Jet Ski.’ Whereas formalist

critics in recent years have proposed ‘surface reading’ as an alternative to historicist

and theoretical approaches to literary criticism, the mode of ‘surface reading’ that

Hayles and Carr describe completely rejects close reading, whether ‘deep’ or not.

10

This

digitally-inflected mode of surface reading deploys techniques such as skimming and

scanning, filtering by keywords, hyperlinking, and ‘pecking’ (pulling out a few items

from a longer text) to engage in what James Sosnoski refers to as ‘reader-directed,

screen-based, computer-assisted reading’ (qtd. in Hayles 2012: 61).

Rather than encouraging readers to take the time to make careful connections

between the dierent parts of a text, surface reading compels readers to fragment

texts in order to find the information they want as quickly as possible. Fragmentation

is key to Fifty Shades’s widespread circulation via online social media. New media, in

Lev Manovich’s seminal theorisation, are inherently open to fragmentation. Digital

10

Stephen Best and Sharon Marcus rst introduced the concept of ‘surface reading’ as an alternave to the ‘hermeneucs

of suspicion’ in their introducon to the 2009 special issue of Representaons on ‘The Way We Read Now.’ See also Love

(2010); and Levine (2015). These forms of ‘surface reading’ are essenally modes of close reading that focus exclus-

ively on tracking the development of formal paerns across the surface of the text. As such they have been cricised

for privileging descripon over interpretaon, and for creang a spurious antagonism between formal and contextual

analysis. See Tanoukhi (2016: 1426–29); and Goodlad (2015: 268–94).

11

media texts are ‘modular’: in other words, they are composed of discrete units of

information that can be combined into larger objects without losing their fundamental

separateness (Manovich 2001: 30–31). Manovich (2001: 30) gives the example of a

video clip inserted into a Microsoft Word document. Because of its modular nature,

the video clip can be edited or removed without impinging on the surrounding written

text. Likewise, in invoking surface reading, Fifty Shades invites the reader to treat

the novel as if it were a Word document that can be fragmented into discrete units of

information. These units can then be extracted and ‘shared’ online without aecting

the overall architecture of the novel’s plot and meaning. In Spreadable Media, Henry

Jenkins, Sam Ford, and Joshua Green (2013: 198) emphasise ‘portability’ as one of

several strategies for creating media content that is more likely to ‘spread’ online.

Echoing Manovich’s principles of digital media, Jenkins, Ford, and Green (2013: 198)

argue that, for media content to be ‘spreadable,’ online users should find it easy to

pick up the content and insert it elsewhere (for example, in a Facebook post). Despite

being a printed text, the form of Fifty Shades embodies this principle of modularity

characteristic of digital media, thereby facilitating the novel’s ‘spread’ via online social

media networks, albeit in fragmented form. Compared to the nineteenth-century

novels that Fifty Shades cites, and to more contemporary plot-driven forms of genre

fiction, it is much easier to ‘share’ and discuss fragments of Fifty Shades online without

having to connect the dierent elements in the text to make sense of it. Discussants

of Fifty Shades do not have to worry about ‘sharing’ too little of the novel for fellow

online users to understand what the novel is about. Nor do they have to worry about

‘sharing’ too much to the extent that they give the plot away and inadvertently spoil

the pleasure of reading the novel for others. By ‘sharing’ fragments from the text and

thereby spreading awareness of Fifty Shades, online users pique the interest of other

users, and encourage them (intentionally or not) to read the novel so that they too can

join in the conversation.

A brief look at online discussions of Fifty Shades demonstrates how the novel

circulates through this practice of ‘sharing’ extracts. In response to the question

‘What made you read Fifty Shades of Grey?’ on the Oh Fifty! A Fifty Shades Fansite forum,

a fan with the username ‘Felicia’ wrote that she bought all three volumes of the novel

based on a single excerpt from the first book, which she had found online. There is

also an entire thread in the forum in which fans list and discuss their favourite quotes

from the novel. More recently, fans on Twitter shared quotes from the novel to

build anticipation for the Fifty Shades Freed movie adaptation, which was released in

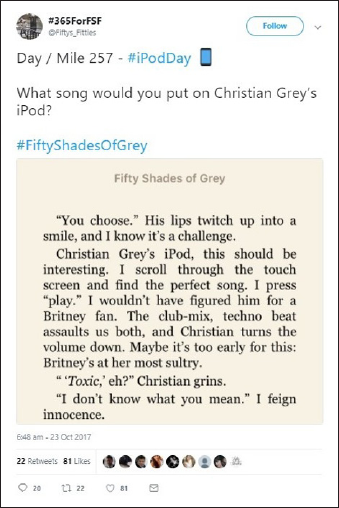

February 2018. For example, a user named @Fiftys_Fitties marked Day 257 in a year-

long countdown with a tweet asking fans what song they would put on Christian’s

12

iPod. The tweet includes an extract from Fifty

Shades of Grey, the first volume of the novel,

presumably as a starting point for discussion

(Figure 3).

Even critics of the novel engage in the same

practice of fragmentation, extraction, and

citation, but for the purpose of panning the

novel for its poorly written prose. The Honest

Trailers parody of the Fifty Shades of Grey movie

on YouTube, for example, lampoons both

adaptation and source material by listing several

‘horrible lines from the book that thankfully

didn’t make it into the movie.’ As Umberto Eco

(1986: 197–98) writes in Travels in Hyperreality,

a text’s openness to fragmentation is crucial in

determining its popularity:

What are the requirements for transforming a

book or movie into a cult object? The work must be loved, obviously, but this is not

enough. It must provide a completely furnished world so that its fans can quote char-

acters and episodes as if they were aspects of the fan’s private sectarian world.... I

think that in order to transform a work into a cult object one must be able to break,

dislocate, unhinge it so that one can remember only parts of it, irrespective of their

original relationship with the whole.

With its ‘digital-like’ stylistic form, Fifty Shades particularly invites fans and foes alike

to dismember the novel and spread its fragments far and wide, thereby contributing to

the novel’s ubiquity in the transnational networks of online digital culture.

Loving Work: Fans and Aecve Labour

Like all forms, the form of Fifty Shades has its ‘aordances’ (C. Levine 2015: 6–7),

but form alone does not ensure that a text will circulate widely. Fifty Shades became

popular worldwide not just because of its ‘digital-like’ form, but also because the

romance between Christian and Ana resonated with the kind of labour that fans often

engage in when showing aection for their favourite media texts. In Spreadable Media,

Jenkins et al. (2013: 19–21) take issue with the metaphor of ‘going viral’ because of

its denial of human agency in spreading content. While media producers can enhance

Figure 3: Tweet by @Fiftys_Fitties.

13

their content’s potential for spreading, Jenkins et al. (2013: 196) argue that online

users ultimately spread content because they want to do so. Fans, in particular, spread

content out of love, whether it is love for specific personages (such as idols) or specific

narratives (such as films, TV shows, and works of popular fiction). Fans of Fifty Shades

performed this labour of spreading the novel online – and in doing so they made use of

the novel’s capacity for fragmentation – partly because the marriage plot in the novel

idealises women’s participation in aective labour, of which fan labour is a significant

part. In celebrating aective labour in the context of post-Fordist capitalism, Fifty

Shades eectively celebrates the fan labour that has made its production and widespread

circulation possible. Reading Fifty Shades against the grain helps to illuminate the

nature of fan engagement with the novel.

The conventional marriage plot of the nineteenth-century novel usually ends with

the female protagonist subordinating herself to a man through marriage, in exchange

for her freedom from waged labour in the domestic sphere. Nancy Armstrong (1987:

41–42) has famously argued that domestic fiction naturalises this ‘sexual contract’

by presenting this exchange as a matter of private, romantic relationships rather than

a political and economic structure of power. Like its nineteenth-century precursors,

Fifty Shades romanticises the sexual contract – quite literally – but also updates it to

naturalise a highly exploitative relationship between capital and aective labour, which

is now both waged and unwaged under the conditions of late capitalism. Fifty Shades

appropriates the glamour of Christian and Ana’s BDSM relationship to glorify not only

Intimate Partner Violence, but also a particularly extreme form of capital’s domination

over labour.

11

Christian repeatedly invokes the idea of work in his romantic relationship

with Ana, blurring the boundaries between sex/love in the private sphere and paid work

in the public sphere. ‘Do the work,’ he commands Ana, ordering her to research BDSM

practices on Wikipedia as if she were one of his many employees at Grey Enterprises

Holdings, Inc. (James 2012a: 186). When Ana refuses to work in his multinational

corporation, Christian buys the publishing press that she works for, so that she ends

up working for him anyway. Moreover, the BDSM contract that constitutes the crux

of Christian and Ana’s relationship bears an uncanny resemblance to an employment

contract, with its stipulations about designated hours and conditions for dismissal

from service. Christian and Ana thus represent the positions of dominant capital and

submissive labour respectively. In this new version of the sexual contract, female

11

While Margot Weiss’s 2011 study of a BDSM community in San Francisco reveals that the BDSM subculture oen

enacts exisng instuonalised systems of dominaon in its role-play scenarios, it is open to debate whether ‘erociz-

ing . . . social inequality’ (Weiss 2011: 24) is equivalent to reproducing it. From the perspecve of many BDSM prac-

oners, Fiy Shades grossly misrepresents BDSM relaonships as abusive. See S. James (2012); and Smith (2015).

14

labour willingly subordinates itself to capital in exchange for both material wealth and

success in the workplace. Christian not only showers Ana with expensive gifts; at the

end of the novel, he makes her the owner of his publishing company.

Like the heroines of the nineteenth-century realist novel, Ana achieves upward

socio-economic mobility precisely because she does not desire it. In fact, Ana attains

success in both love and work because she actually enjoys subordinating herself to

Christian/capital. In Fifty Shades’s rendering of the relation between capital and labour,

the labour that Ana performs is doubly aective. Firstly, Ana engages in aective labour

when she submits to Christian’s will, thereby producing feelings of pleasure in Christian

and rearming their exploitative relationship. Aective labour, according to Michael

Hardt and Antonio Negri (2004: 108, 150), is ‘labour that produces or manipulates

aects such as a feeling of ease, well-being, satisfaction, excitement, or passion,’ and

that, in doing so, produces and maintains social relations.

12

Aective labour is a major

component of the kinds of work carried out in the childcare, healthcare, hospitality,

professional cleaning, and other service industries that focus on making people feel

comfortable and happy. As the exploitative relationship between Christian and Ana

demonstrates, this form of labour takes up all of the worker’s time and penetrates

all areas of the worker’s life. In The Soul at Work, Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi (2009) argues

that, as post-Fordist capitalism comes to focus more on communicating mental states

and feelings than on transforming physical matter, production becomes increasingly

structured as a global network in which workers create, process, and transfer digital

information. Workers cannot step back from this continuous flow of information for

fear of becoming irrelevant (Berardi 2009). As a result, the worker must be prepared to

receive commands from the network at any time, often through a mobile phone, which,

for Berardi (2009: 89–90), is the quintessential digital device that makes this state

of perpetual readiness possible. Fifty Shades dramatises (and idealises) this complete

co-optation of the worker’s time in the form of Christian stalking his Submissives.

Christian, representing the interests of capital, gives Ana an array of IT gadgets

(an Apple MacBook Pro laptop, a BlackBerry, and an iPad) so that he can track her

whereabouts and contact her at any time he wishes. Despite complaining that ‘[she is]

overwhelmed with technology’ (James 2012b: 115), Ana happily accepts these gadgets.

She willingly integrates herself into the digital network of production and its demand

that she provide aective labour whenever and wherever Christian/capital needs it. Ana

gladly subordinates herself in this way because she is aectively invested in her work

of producing aect. Giving pleasure to Christian gives her pleasure. For example, when

Ana has sex with Christian for the first time, she proclaims that ‘[she] will do anything

12

See also Hardt (1999); and Hardt and Negri (2000: 292–93).

15

he wants’ (James 2012a: 113), which apparently includes having instantaneous orgasms

at his command:

‘You. Are. Mine. Come for me, baby,’ he growls.

His words are my undoing, tipping me over the precipice. (James 2012a: 121)

Seen in this light, Ana loving Christian becomes an allegory of ‘loving one’s work of

loving.’ Ana thus embodies what Kathi Weeks (2011: 69–70) calls the ‘post-Fordist

work ethic,’ which drives workers in the new service-oriented global economy to

devote ‘not just the labour of the hand, but the labours of the head and the heart.’

Ana’s aective investment of time and energy into her ‘work’ for Christian parallels

that of the fans who spread media content from and about Fifty Shades online, not to

mention the fans who gave feedback and helped to edit the work when James was writing

it as ‘Master of the Universe.’ Fifty Shades thus celebrates the aective labour that has

contributed to its success. Fans of Fifty Shades demonstrate their love for the novel not

only by ‘sharing’ fragments extracted from it, but also by reworking these fragments

to accommodate their particular interests, such as in the case of the Twitter user who

‘shared’ an extract to start a discussion about Christian’s iPod playlist. This practice of

‘textual poaching,’ as Jenkins (2013: 3) puts it, is a labour of love that ‘mak[es] meaning

from materials others have characterised as trivial and worthless.’ Even detractors of

Fifty Shades engage in a kind of aective labour when they too participate in ‘textual

poaching,’ albeit for the purpose of criticising the novel. In their study on Fifty Shades

and ‘snark fandom,’ Sarah Harman and Bethan Jones (2013) reveal that ‘anti-fans’ of

the novel invest just as much time and energy as fans do in reading and talking about the

novel, but with a dierent objective in mind. For example, the ‘50shadesofWTF’ anti-fan

community on the blogging platform LiveJournal close-reads selected passages from

Fifty Shades to mock the novel for its gross misogyny (Harman and Jones 2013: 957–61):

I employ an exceptional team, and I reward them well.

KET: (Grey): With my dick.

GEHAYI: (Grey): And my riding crop.

KET: (Grey): At the same time.

GEHAYI: Do you suppose he ever gets them mixed up?

KET: He starts whacking away at some poor underling with his penis, leaving mush-

room-shaped bruises for days . . . (Ket Makura and Gehayi, qtd. in Harman and Jones

2013: 958)

16

In a twist on more straightforward fan communities, these anti-fans derive pleasure from

‘sharing’ extracts from the novel in order to satirise it. Although they dislike Fifty Shades

intensely, these anti-fans too engage in aective labour in ‘spreading’ Fifty Shades via

global online networks. Also, like their fan counterparts, they point to the convergence of

aective labour and fan labour under post-Fordist capitalism, and to the implications of

this convergence for how we approach World Literature as an object of study.

Digital Media, Fan Parcipaon, and World Literature

The ‘spreading’ of Fifty Shades online by fans and anti-fans provides an opportunity

for rethinking what World Literature is, how it travels, and how we study it. In a world

increasingly connected by digital networks of communication, how do we define what

counts as a ‘source culture’ or a ‘receiving culture’ (Damrosch 2003: 283)? Furthermore,

what does it mean for a digital or ‘digital-like’ text to be ‘actively present within a

literary system beyond that of its original culture’ (Damrosch 2003: 4)? Fifty Shades has

travelled from its ‘origin’ in an online Twilight fan fiction community to other online

social networks such as Twitter and Facebook, which cut across national boundaries

and span wide geographical distances. Fifty Shades’s perambulations suggest that, in

addition to examining how texts migrate from one geographical location to another,

perhaps we should look at how texts are now produced and consumed in online

social spaces that are divided along the lines of language use rather than national

and territorial boundaries. Fifty Shades has been translated into many languages, and

it certainly qualifies as a World Literature text in this regard. However, the novel’s

circulation in Anglophone online contexts suggests that a text can be ‘worldly’ even

when it travels in a single language. A similar situation applies to the phenomenally

popular Chinese Internet novel Mo Dao Zu Shi (Grandmaster of Demonic Cultivation). Even

before the ocial English translation was released in December 2021, the novel and its

multimedia adaptations had garnered many fans in the online Sinophone world. Texts

such as Fifty Shades and Mo Dao Zu Shi might not win the Booker Prize or be included

in the Norton Anthology of World Literature, but they deserve the attention of World

Literature scholars nonetheless, and not simply as sociological objects of analysis.

Besides reconfiguring existing definitions of World Literature, Fifty Shades also

prompts us to reconceptualise how World Literature moves around the world. The

transmedia travels of Fifty Shades demonstrate that World Literature in the age of digital

media circulates not only in the form of digital media adaptations – such as the video

game adaptation of Dante’s Inferno that Damrosch (2013) discusses in ‘World Literature

in a Postliterary Age’ – although the movie adaptations of Fifty Shades certainly contribute

to the hype. Neither does World Literature in the digital era necessarily circulate in the

form of electronic literature that is ‘born digital’ with no printed counterpart, such

17

as the poem-videos created by Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries and discussed in

Walkowitz’s Born Translated (2015) and Jessica Pressman’s chapter in Damrosch’s World

Literature in Theory (2014). As a novel that bears ‘the mark of the digital’ (Hayles 2008:

161), even the print edition of Fifty Shades travels through digital networks in the form of

textual fragments. These fragments point back to the novel in its entirety (for instance,

in the case of the fan who bought all three volumes after reading an excerpt online),

but also point forward to readers ‘remixing’ the novel in fan discussions, critical

commentaries, parodies, and so on. Furthermore, reader participation in ‘spreading’

these fragments of Fifty Shades on social media suggests that we might think about

circulation in World Literature not only in terms of literary influence or book sales, but

also in terms of online discussions and debates. When the first book of the Fifty Shades

trilogy took the world by storm in 2012, the American comedy TV programme Saturday

Night Live promptly lampooned both women readers of the novel and the online delivery

company Amazon in a parody of an Amazon Mothers’ Day advertisement (Figure 4).

‘This Mothers’ Day,’ the voiceover intones, ‘go to Amazon.com and get Mom what

she really wants.’ The comedy sketch was then uploaded onto YouTube a year later,

where it has since been viewed more than 5.6 million times.

13

One of the top-rated user

comments on the YouTube video laments that the user’s mother had bought a Kindle

simply in order to read the Fifty Shades trilogy: ‘She eventually gave it [the Kindle] to

me. The only books on it were all three Fifty Shades books >.>’ Many of the people who

talk about Fifty Shades online might not have read the novel in its entirety or at all,

but they are still able to understand the jokes in the Saturday Night Live sketch, and to

make further jokes about ‘Mommy Porn.’ Fifty Shades has travelled far and wide, but

not in the ways that scholars of World Literature conventionally consider. The fact that

13

“Amazon Mothers’ Day Ad,” YouTube. URL: hp://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mFte46jVFOg&t=4s (last accessed 13

March 2023).

Figure 4: SNL pokes fun at both Amazon and women readers of Fiy Shades.

18

Fifty Shades has become part of a common vocabulary suggests that we need to rethink

a text’s ‘activ[e] presen[ce]’ in world literary systems (Damrosch 2003: 4) from the

perspective of digital media and reader participation; in other words, what Jenkins,

Mizuko Ito, and danah boyd (2016) call ‘participatory culture in a networked era.’

This brings me to two final observations on how literary scholars might

approach a text such as Fifty Shades as World Literature. Firstly, in the early years of

World Literature’s emergence as a field, its most prominent proponents called for

scholars to examine not only source texts but also their permutations as they travel

across geographical and cultural borders. Damrosch (2003: 283–92), for instance,

foregrounded the transformative process of translation, while Moretti (2013: 50–59)

argued that literary forms from core areas of the world literary system become hybrid

when they make ‘compromises’ with local conditions in peripheral cultures. Fifty Shades

and other similar texts with a strong online presence not only rearm the need for

World Literature scholars to study both the source text and its transformations, but also

reveal that source texts are increasingly being adapted to the needs, the interests, and

even the political leanings of various transnational online constituencies. In the hands

of the ‘50shadesofWTF’ anti-fan community, seemingly romantic descriptions of

Christian and Ana’s relationship become tools for feminist critique. These adaptations

of Fifty Shades open up new areas of research that go beyond territorial notions of

cultural dierence, translation (whether linguistic or cultural), and hybridisation.

Secondly, studying source texts and their permutations in an online context

requires a careful approach to assessing fan labour, and especially to gauging how

much power readers (broadly understood) actually have in producing World Literature.

Digital social media enable readers to participate in selecting which works of amateur

online fiction get picked up by major publishers, and which of these books go on to

become international bestsellers. Fifty Shades would not have become the publishing

sensation that it is today had it not been for fans discussing James’s Twilight fan fiction

online, as well as for readers spreading word about Fifty Shades after the novel was

formally published. As Katy Shaw (2012) has observed, Fifty Shades’s success suggests

that power in publishing is shifting away from editors and the literary elite to readers

and grassroots communities. However, this increase in reader participation does not

necessarily mean that digital social media have made readers genuinely empowered in

producing World Literature. Fan participation in promoting Fifty Shades online serves

not only fan interests, but also the interests of the global literary publishing industry.

In the same way that Ana’s aective labour is plugged into an incessant communication

flow of emails, text messages, and phone calls, fan labour is integrated into the digital

network of capitalist production; in this case, the production of World Literature. While

many fans of Fifty Shades seem happy to do their ‘work’ of promoting the novel for free,

19

authors and the publishing industry benefit from their unpaid labour. Anne Jamison

(2013: 224–25) points out that James often downplays the fan fiction community’s

contributions to the success of Fifty Shades, even though she ‘benefited directly and

tangibly from the feedback, encouragement, interaction, and publicity [her] readership

oered.’ For Christian Fuchs (2014: 64), this counts as exploitation even though it does

not feel like it. Fuchs (2014: 56–57) criticises existing discussions of participatory

culture for being too celebratory, arguing that ‘[a]n Internet that is dominated by

corporations that accumulate capital by exploiting and commodifying users can in

the theory of participatory democracy never be participatory.’ Jenkins, Ito, and boyd

(2016: 1) express similar reservations when they begin their recent reassessment of

‘participatory culture’ by asking: ‘Does participation become exploitation when it takes

place on commercial platforms where others are making money o our participation

and where we often do not even own the culture we are producing?’ Apart from the

issue of Internet corporations such as Google and Facebook monetising users’ private

data, growing corporate interest in harnessing users’ participation for economic gain

(Jenkins, Ford, & Green 2013: 47–84) raises doubts about how much and what kind of

power readers possess in participating in world literary production.

While it is useful to avoid championing reader participation as an end in itself,

scholars of World Literature should also consider how the reading communities that

have developed around Fifty Shades and other similar texts online might provide what

Jenkins calls an ‘alternative’ to the digital network of capitalist production and other

forms of social inequality. Jenkins recognises that niche communities today are often

commercialised, and that they are seldom overtly resistant or oppositional (Jenkins,

Ito, & boyd 2016: 16). Nonetheless, they represent alternatives in the ways in which

they organise knowledge, structure social relations, or define their norms and values

(Jenkins, Ito, & boyd 2016: 16). Janice Radway makes a similar argument in Reading

the Romance (1991), where she examines the reading practices of a group of women

in the small American town of Smithton. Although the women often bought and read

romance novels, they were conscious that the novels did not adequately address some

of their desires (Radway 1991: 49–50). Like the readers of romance novels interviewed

in Radway’s study, fans of Fifty Shades read the novel in ways that the author and

publisher cannot fully control. While the ‘spreading’ of Fifty Shades has helped the

publishing industry to market its product, it has also given rise to online communities

of readers who problematize the status quo, such as the ‘50shadesofWTF’ anti-fans

and readers who criticise James for removing her fan fiction work from the public

domain to profit from it.

14

These online reading communities demonstrate that, in

14

See Jones (2014: 2–4); and De Kosnik (2009: 118–24).

20

Jenkins’ words, ‘[n]o matter how participatory culture is pulled towards dominant

practices, it cannot close o space for other, less mainstream interests if it is going to

remain truly participatory’ (Jenkins, Ito, & boyd 2016: 21). Although these communities

contribute to the ‘spreading’ of Fifty Shades in the service of the publishing industry,

they simultaneously divert the flow of information in small ways away from the

digital network of capitalist production towards the creation of social relations that

refuse to participate in commercialising fan labour or degrading women’s sexuality

for profit. Drawing on Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of the rhizome, Berardi (2009:

217) argues that we need to deterritorialise our points of contact in the digital network

of production, so as to break free from the network and form new connections and

communities. Perhaps, in producing Fifty Shades as World Literature, readers are also

subverting Fifty Shades’s exploitation of aective labour, and producing transnational

forms of community that can eect change for a better world.

21

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank all the readers who have commented on various dras of this arcle over

the years, including Ross Forman, Michael Gardiner, Anne Jamison, and the two anonymous peer-

reviewers.

Compeng Interests

The author has no compeng interests to declare.

References

Armstrong, Nancy. 1987. Desire and Domesc Ficon: A Polical History of the Novel. Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Berardi, Franco ‘Bifo.’ 2009. The Soul at Work: From Alienaon to Autonomy. Translated by Francesca

Cadel and Giuseppina Mecchia. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e).

Best, Stephen, and Sharon Marcus. 2009. “Surface Reading: An Introducon.” Representaons

108 (1): 1–21. DOI: hps://doi.org/10.1525/rep.2009.108.1.1

Boog, Jason. N.d. “The Lost History of Fiy Shades of Grey.” Galley Cat. hp://www.mediabistro.

com/galleycat/y-shades-of-grey-wayback-machines_b49124 (Last accessed 4 March 2019).

Brennan, Joseph, and David Large. 2014. “‘Let’s Get a Bit of Context’: Fiy Shades and the

Phenomenon of ‘Pulling to Publish’ in Twilight Fan Ficon.” Media Internaonal Australia 152: 27–39.

DOI: hps://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X1415200105

Carr, Nicholas. 2008. “Is Google Making Us Stupid?: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains.” The

Atlanc, July–August 2008. hp://www.theatlanc.com/magazine/archive/2008/07/is-google-

making-us-stupid/306868/ (Last accessed 23 May 2023).

Damrosch, David. 2003. What Is World Literature? Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Damrosch, David. 2013. “World Literature in a Postliterary Age.” Modern Language Quarterly 74 (2):

151–70. DOI: hps://doi.org/10.1215/00267929-2072971

De Kosnik, Abigail. 2009. “Should Fan Ficon Be Free?” Cinema Journal 48 (4): 118–24. JSTOR,

hp://www.jstor.org/stable/25619734. DOI: hps://doi.org/10.1353/cj.0.0144

Deller, Ruth A., and Clarissa Smith. 2013. “Reading the BDSM Romance: Reader Responses to Fiy

Shades.” Sexualies 16 (8): 932–50. DOI: hps://doi.org/10.1177/1363460713508882

Deller, Ruth A., Sarah Harman, and Bethan Jones. 2013. “Introducon.” Sexualies 16 (8): 859–63.

DOI: hps://doi.org/10.1177/1363460713508899

Dickens, Charles. 2003. Bleak House. Edited by Nicola Bradbury. London: Penguin.

Eco, Umberto. 1986. Travels in Hyperreality. London: Picador.

@Fiys_Fies. 2017. “Day/Mile 257 – #iPodDay What song would you put on Chrisan’s

iPod? #FiyShadesOfGrey.” Twier, October 23, 2017. hp://twier.com/Fiys_Fies/

status/922459706924371969 (Last accessed 1 November 2017).

22

Felicia. 2012. Comment on “What Made You Read Fiy Shades of Grey?” Oh Fiy! A Fiy Shades

Fansite. Forum post, June 2012. hp://ohy.com/forum/y-shades-of-grey/26-what-made-

you-read-fsog#37 (Last accessed 1 November 2017).

Freedgood, Elaine. 2019. Worlds Enough: The Invenon of Realism in the Novel. Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press. DOI: hps://doi.org/10.23943/princeton/9780691193304.001.0001

Fuchs, Chrisan. 2014. Social Media: A Crical Introducon. Los Angeles: Sage. DOI: hps://doi.

org/10.4135/9781446270066

Gill, Rosalind. 2007. Gender and the Media. Cambridge: Polity.

Goodlad, Lauren M. E. 2015. The Victorian Geopolical Aesthec: Realism, Sovereignty, and

Transnaonal Experience. Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: hps://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:

oso/9780198728276.001.0001

Hardt, Michael. 1999. “Aecve Labour.” Boundary 2 26 (2): 89–100.

Hardt, Michael, and Antonio Negri. 2000. Empire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hardt, Michael and Antonio Negri. 2004. Multude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire.

London: Penguin.

Harman, Sarah, and Bethan Jones. 2013. “Fiy Shades of Ghey: Snark Fandom and the Figure of

the An-Fan.” Sexualies 16 (8): 951–68. DOI: hps://doi.org/10.1177/1363460713508887

Hayles, N. Katherine. 2007. “Hyper and Deep Aenon: The Generaonal Divide in Cognive

Modes.” Profession: 187–99. JSTOR. hps://www.jstor.org/stable/25595866. DOI: hps://doi.

org/10.1632/prof.2007.2007.1.187

Hayles, N. Katherine. 2008. Electronic Literature: New Horizons for the Literary. Notre Dame:

University of Notre Dame Press.

Hayles, N. Katherine. 2012. How We Think: Digital Media and Contemporary Technogenesis. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press. DOI: hps://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226321370.001.0001

Hughes, Linda K., and Michael Lund. 1991. The Victorian Serial. Charloesville, VA: University Press

of Virginia.

Honest Trailers. 2015. “Fiy Shades of Grey.” YouTube. hp://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iopcfR1

vI5I&t=192s (Last accessed 1 November 2017).

Hunter, I. Q. 2013. “Pre-Reading and Failing to Read Fiy Shades of Grey.” Sexualies 16 (8): 969–73.

DOI: hps://doi.org/10.1177/1363460713508897

James, E. L. 2012a. Fiy Shades of Grey. London: Arrow Books.

James, E. L. 2012b. Fiy Shades Darker. London: Arrow Books.

James, E. L. 2012c. Fiy Shades Freed. London: Arrow Books.

James, Susan Donaldson. 2012. “BDSM Advocates Worry about Fiy Shades of Grey S ex .” ABC

News, October 2, 2012. hp://abcnews.go.com/Health/bdsm-advocates-worry-y-shades-grey-

sex/story?id=17369406 (Last accessed 1 November 2017).

Jamison, Anne. 2013. Fic: Why Fancon is Taking Over the World. Dallas: Smart Pop.

23

Jenkins, Henry. 2013. Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Parcipatory Culture, updated 20

th

Anniversary ed. New York: Routledge. DOI: hps://doi.org/10.4324/9780203114339

Jenkins, Henry, Mizuko Ito, and danah boyd. 2016. Parcipatory Culture in a Networked Era: A

Conversaon on Youth, Learning, Commerce, and Polics. Cambridge: Polity.

Jenkins, Henry, Sam Ford, and Joshua Green. 2013. Spreadable Media: Creang Value and Meaning

in a Networked Culture. New York: New York University Press.

Jones, Bethan. 2014. “Fiy Shades of Exploitaon: Fan Labour and Fiy Shades of Grey.”

Transformave Works and Cultures 15: n. p. hp://journal.transformaveworks.org/index.php/

twc/arcle/view/501/422%20 (Last Accessed 14 April 2016). DOI: hps://doi.org/10.3983/

twc.2014.0501

Levine, Caroline. 2013. “From Naon to Network.” Victorian Studies 55 (4): 647–66. DOI: hps://

doi.org/10.2979/victorianstudies.55.4.647

Levine, Caroline. 2015. Forms: Whole, Rhythm, Hierarchy, Network. Princeton, NJ: Princeton

University Press. DOI: hps://doi.org/10.23943/princeton/9780691160627.001.0001

Levine, George Lewis. 1981. The Realisc Imaginaon: English Ficon from Frankenstein to Lady

Chaerley. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lie, Jane. 2012. “Master of the Universe versus Fiy Shades by E. L. James Comparison.” Dear

Author, 13 March 2012. hp://dearauthor.com/features/industry-news/master-of-the-universe-

versus-y-shades-by-e-l-james-comparison (Last Accessed 3 May 2019).

Love, Heather. 2010. “Close but not Deep: Literary Ethics and the Descripve Turn.” New Literary

History 41: 371–91. DOI: hps://doi.org/10.1353/nlh.2010.0007

Manovich, Lev. 2001. The Language of New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. DOI: hps://doi.

org/10.22230/cjc.2002v27n1a1280

Miell, Jason. 2010. “Serial Boxes: The Cultural Values of Long-Form American Television.” Just TV,

20 January 2010. hp://jusv.wordpress.com/2010/01/20/serial-boxes/ (Last Accessed 4 March

2019).

Miell, Jason. 2015. Complex TV: The Poecs of Contemporary Television Storytelling. New York: New

York University Press.

More, Franco. 1987. The Way of the World: The Bildungsroman in European Culture. Translated by

Albert Sbragia. London: Verso.

More, Franco. 2005. Graphs, Maps, Trees. London: Verso.

More, Franco. 2013. “Conjectures on World Literature.” In Distant Reading, essays by Franco

More, 43–62. London: Verso.

Pressman, Jessica. 2014. “The Strategy of Digital Modernism: Young-hae Chang Heavy Industries’

Dakota (2008)”. In World Literature in Theory, edited by David Damrosch, 493–512. Chichester:

Wiley Blackwell.

Radway, Janice A. 1991. Reading the Romance: Women, Patriarchy, and Popular Literature. Chapel

Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

24

Roiphe, Kae. 2012. “She Works Crazy Hours. She Takes Care of the Kids. She Earns More Money.

She Manages her Team. At the End of the Day, She wants to be . . . Spanked?” Newsweek 159,

no. 17–18 (13 April 2012): 24–28. Business Source Complete, accession number 74412977 (Last

accessed 14 April 2016).

Saturday Night Live. 2013. “Amazon Mother’s Day Ad.” YouTube. hp://www.youtube.com/

watch?v=mFte46jVFOg&t=4s (Last Accessed 13 March 2023).

Shaw, Katy. 2012. “Fiy Shades of the Future.” Alluvium 1 (6): n. p. hp://www.alluvium-journal.

org/2012/11/01/y-shades-of-the-future/ (Last Accessed 14 April 2016). DOI: hps://doi.

org/10.7766/alluvium.v1.6.03

Smith, Anna. 2015. “Fiy Shades of Grey: What BDSM Enthusiasts Think.” The Guardian, 15 February

2015. hp://www.theguardian.com/lm/2015/feb/15/y-shades-of-grey-bdsm-enthusiasts

(Last Accessed 1 November 2017).

Tanoukhi, Nirvana. 2016. “Surprise Me If You Can.” PMLA 131 (5): 1423–34. DOI: hps://doi.

org/10.1632/pmla.2016.131.5.1423

Tasker, Yvonne, and Diane Negra, editors. 2007. Interrogang Poseminism: Gender and the Polics of

Popular Culture. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. DOI: hps://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1210217

Van Reenen, Dionne. 2014. “Is This Really What Women Want? An Analysis of Fiy Shades of Grey

and Modern Feminist Thought.” South African Journal of Philosophy 33 (2): 223–33. DOI: hps://doi.

org/10.1080/02580136.2014.925730

Walkowitz, Rebecca L. 2015. Born Translated: The Contemporary Novel in an Age of World Literature.

New York: Columbia University Press. DOI: hps://doi.org/10.7312/walk16594

Weeks, Kathi. 2011. The Problem with Work: Feminism, Marxism, Anwork Polics, and Postwork

Imaginaries. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. DOI: hps://doi.org/10.1215/9780822394723

Weiss, Margot. 2011. Techniques of Pleasure: BDSM and the Circuits of Sexuality. Durham, NC: Duke

University Press. DOI: hps://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11smtgc

Williams, Ioan M. 1974. The Realist Novel in England: A Study in Development. London: Macmillan.

Wrath91. 2019. Comment on “Amazon Mothers’ Day Ad.” YouTube. hp://www.youtube.com/

watch?v=mFte46jVFOg&t=4s (Last accessed 13 March 2023).