acy Merchant Education Multi-jurisdictional Agreement Outlet D

ualitative or Anecdotal Data Quantitative Data Shoulder Tap Social Host Law Social Ma

Source Investigation Program Synar Checks Teen Party Ordinance Zero Tolerance 24

olerance Policy 4 Ps of Marketing Alcohol Purchase Survey CleanAir Laws Community

Beyond the Basics: Topic-Specific Publications for Coalitions

The Coalition Impact:

Environmental Prevention

Strategies

Community Anti-Drug Coalitions of America

National Community Anti-Drug Coalition Institute

About this Publication

CADCA’s National Coalition Institute published a

series of seven primers that coincide with and

help coalitions navigate the elements of the Sub-

stance Abuse and Mental Health Services Admin-

istration’s Strategic Prevention Framework. This

is the first in a new series—Beyond the Basics:

Topic-Specific Publications for Coalitions—that

work in conjunction with the Primer Series. They

are meant to assist coalitions expand their

knowledge about planning for population-level

change. As is true with the primers, they work

as a set, however, each also can stand alone.

This publication provides an overview of the envi-

ronmental strategies approach to community

problem solving. It includes real examples of ef-

forts where environmental strategies aimed at

preventing and reducing community problems

related to alcohol and other drugs were imple-

mented. No one approach or set of strategies

will fix every community problem, but with an

appropriate environmental assessment, a coali-

tion can determine what aspects of environmen-

tal prevention will best serve their community.

Topics covered in this publication include:

WHAT are environmental strategies and why are

coalitions best suited to plan and implement

them?

WHAT data collection and analysis is essential in

the investigation of environmental conditions

of a community to effectively choose and

implement strategies?

HOW can a coalition build capacity to commit to

the long-term investment that is necessary

for environmental strategies to succeed?

WHERE do environmental strategies fit into a

comprehensive community plan?

HOW will your coalition evaluate the success and

impact of environmental strategies?

CADCA’s National Coalition Institute

The National Community Anti-Drug Coalition

Institute (Institute), a part of the Community

Anti-Drug Coalitions of America (CADCA), serves

as a center for training, technical assistance,

evaluation, research and capacity building for

community anti-drug coalitions throughout the

United States. The Institute was created in 2002

by an act of Congress and supports coalition

development and growth for Drug Free Commu-

nities Support Program (DFC) grantees and other

community coalitions.

The Institute offers an exceptional opportunity to

move the coalition field forward. Its mission and

objectives are ambitious but achievable. In short,

the Institute helps grow new, stronger and

smarter coalitions.

Drug Free Communities Support Program

In 1997, Congress enacted the Drug-Free Com-

munities Act to provide grants to community-

based coalitions that serve as catalysts for multi-

sector participation to reduce local substance

abuse problems. As of September 2010, more

than 1,700 local coalitions have received or are

receiving funding to work on two main goals:

• Reduce substance abuse among youth

and, over time, among adults by

addressing the factors in a community

that increase the risk of substance abuse

and promoting the factors that minimize the

risk of substance abuse.

• Establish and strengthen collaboration

among communities, private nonprofit

agencies and federal, state, local and

tribal governments to support the efforts

of community coalitions to prevent and

reduce substance abuse among youth.

Table of Contents

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION TO AN ENVIRONMENTAL APPROACH 1

What are environmental strategies? 1

Roots of environmental approaches 1

Advantages of environmental strategies 1

CHAPTER 2: LAYING THE FOUNDATION FOR COMMUNITY CHANGE 4

The Public Health Model 4

Institute of Medicine Model—A useful planning approach for coalitions 4

A broader look at policy 5

Coalitions: The organizational structure for environmental strategies 5

CHAPTER 3: THE SPF AND ENVIRONMENTAL STRATEGIES 10

Cultural implications in assessing the community and planning strategies 10

Environmental assessment 11

Environmental scanning 12

Assess conditions with marketing’s 4 Ps 12

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) 12

Understanding problem environments 13

Involving youth in assessment 14

Commitment through capacity building 14

Whom do we need around the table? 14

Bolstering coalition leaders 16

The planning process 17

CHAPTER 4: ENVIRONMENTAL PREVENTION IN ACTION 19

Seven strategies for community change: A brief explanation 19

Implementing environmental approaches using the seven strategies 20

Media and environmental approaches 22

Evaluation of environmental strategy implementation 24

Conclusion 26

COALITION EXAMPLES

Shawnee County Meth Awareness Project 3

North Coastal Prevention Coalition 6

Hood River County Alcohol Tobacco and Other Drug Prevention Coalition 15

Salt Lake City Mayor’s Coalition on Alcohol Tobacco and Other Drugs 25

ENDNOTES 29

GLOSSARY 29

RESOURCES 31

The Coalition Impact: Environmental Prevention StrategiesCADCA’s National Coalition Institute 1

This publication launches a new series—Beyond

the Basics: Topic-Specific Publications for Coali-

tions—that work in conjunction with the Institute’s

popular Primer Series, based on the Substance

Abuse and Mental Health Services Administra-

tion’s (SAMHSA) Strategic Prevention Framework

(SPF). It can help your coalition start planning and

implementing environmental strategies, but it

does not provide a set design for any individual

community or coalition.

The publication includes brief case studies from

four local coalitions that have implemented envi-

ronmental strategies to successfully address their

communities’ most pressing issues. Each group

used an environmental approach, but none imple-

mented identical strategies in the same ways.

Environmental strategies must be tailored to local

community characteristics. Your coalition must ad-

dress the root causes and local conditions around

the specific problem you are trying to change.

What are environmental strategies?

Grounded in the field of public health, which em-

phasizes the broader physical, social, cultural and

institutional forces that contribute to the problems

that coalitions address, environmental strategies

offer well-accepted prevention approaches that

coalitions use to change the context (environment)

in which substance use and abuse occur.

Environmental strategies incorporate prevention

efforts aimed at changing or influencing commu-

nity conditions, standards, institutions, structures,

systems and policies. Coalitions should select

strategies that lead to long-term outcomes. In-

creasing fines for underage drinking, moving to-

bacco products behind the counter, not selling

cold, single-serving containers of beer in conven-

ience stores and increasing access to treatment

services by providing Spanish-speaking counselors

are all examples of environmental strategies.

Roots of environmental approaches

1

Interest in the scientific study of environmental

strategies and the corresponding use of alcohol

policy dates back to the mid-1970s. In the United

States this approach was embraced in the mid-

1980s by communities looking for mechanisms to

address the growing problems of alcohol outlet-

related crime and violence, drinking and driving,

underage access to alcohol and other community-

based alcohol problems.

Three key publications have attracted attention to,

provided a foundation for and offered evidence

that by implementing environmental approaches,

communities and local municipalities develop suf-

ficient power to reduce alcohol-related problems.

These publications include:

• Alcohol Control Policies in Public Health

Perspective

2

—sponsored by the World Health

Organization (WHO), was published in 1975

and drew the attention of governments

around the world that sought to rationally ad-

dress alcohol availability and consumption.

• Alcohol Policy and Public Good

3

—another

WHO-sponsored book, published in 1994,

opened the door for increased scientific

research into the approach’s efficacy.

• In 2003, Alcohol: No Ordinary Commodity—

Research and Public Policy,

4

provided an

updated summary of the significant litera-

ture on the evidential underpinnings of

environmental approaches.

Today, ample evidence and little doubt exist that

well-conceived and implemented policies—local,

state and national—can reduce population-based

alcohol, tobacco and other drug problems.

Advantages of environmental strategies

Environmental strategies can produce quick wins

and instill commitment toward long-term impact

on practices and policies within a community.

But, they also require substantial commitment

from various sectors of the community to con-

tribute to sustainable community change. Such

approaches potentially reach entire populations

and reduce collective risk. They create lasting

change in community norms and systems,

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION TO AN ENVIRONMENTAL APPROACH

The Coalition Impact: Environmental Prevention StrategiesCADCA’s National Coalition Institute 2

producing widespread behavior change and, in

turn, reducing problems for entire communities.

Individual strategies, such as drug education

classes, are based on the premise that substance

abuse develops because of deficits in knowledge

about negative consequences, inadequate resist-

ance skills, poor decision making abilities and low

academic achievement. But these efforts, while

important in a multiple strategy approach, do little

to independently alter the overall environment in

which people live and work.

For example, numerous education campaigns and

public awareness efforts related to heart disease

exist. We are encouraged to avoid certain foods,

exercise daily and get regular check-ups. This in-

formation is familiar and repeated often, yet we

live in a society where heart disease remains an

insidious public health problem.

Telling individuals what to do is different than

limiting food options in grocery stores or providing

exercise breaks for employees. Likewise, simply

telling an individual that substance use/abuse is

dangerous will not necessarily affect their behav-

ior in a significant manner.

Individuals do not become involved with sub-

stances solely on the basis of personal character-

istics. They are influenced by a complex set of

factors, such as institutional rules and regulations,

community norms, mass media messages and

the accessibility of alcohol, tobacco and other

drugs (ATOD). When a comprehensive, multi-

strategy effort is in place, coalitions contribute to

achieving population-level change by focusing on

multiple targets of sufficient scale and scope to

make a difference communitywide.

Costs associated with implementation, monitoring

and political action within a community can be

considerably lower than those associated with on-

going education, services and therapeutic efforts

applied to individuals. The bottom line is environ-

mental strategies are effective in modifying the

settings where a person lives, which plays a part

in how that person behaves.

CSAP’s Centers for the Application of Prevention Technologies (CAPT), West CAPT.

Environmental Prevention Strategies: Putting

Theory Into Practice Presentation

, retrieved from web,

http://captus.samhsa.gov/western/resources/ppt/index.cfm

, March 2008.

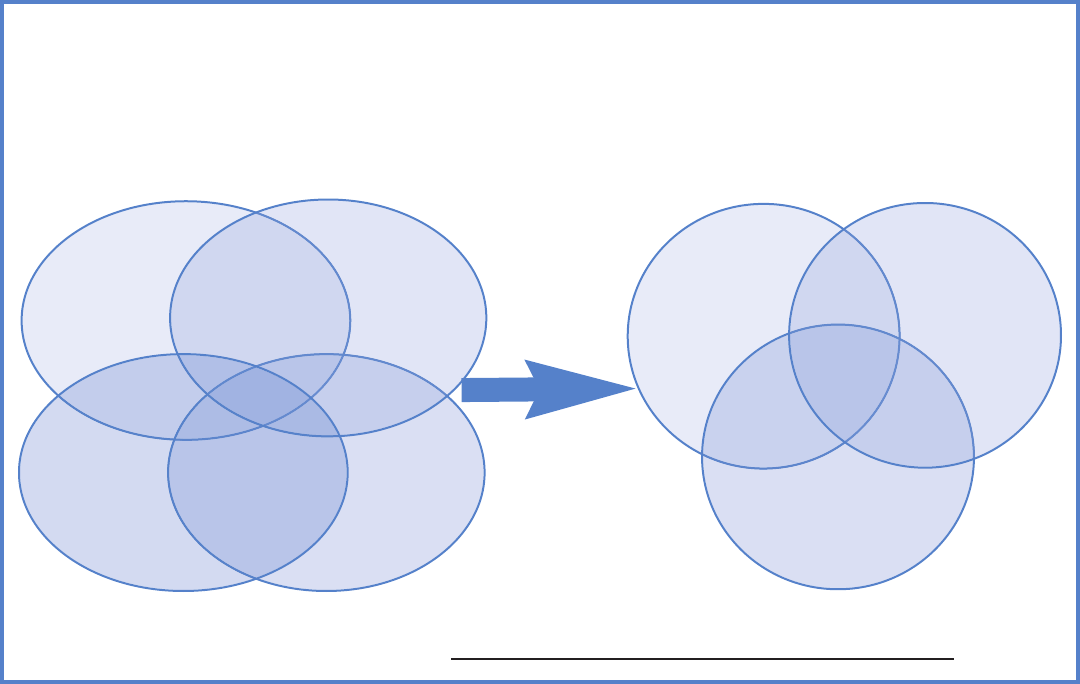

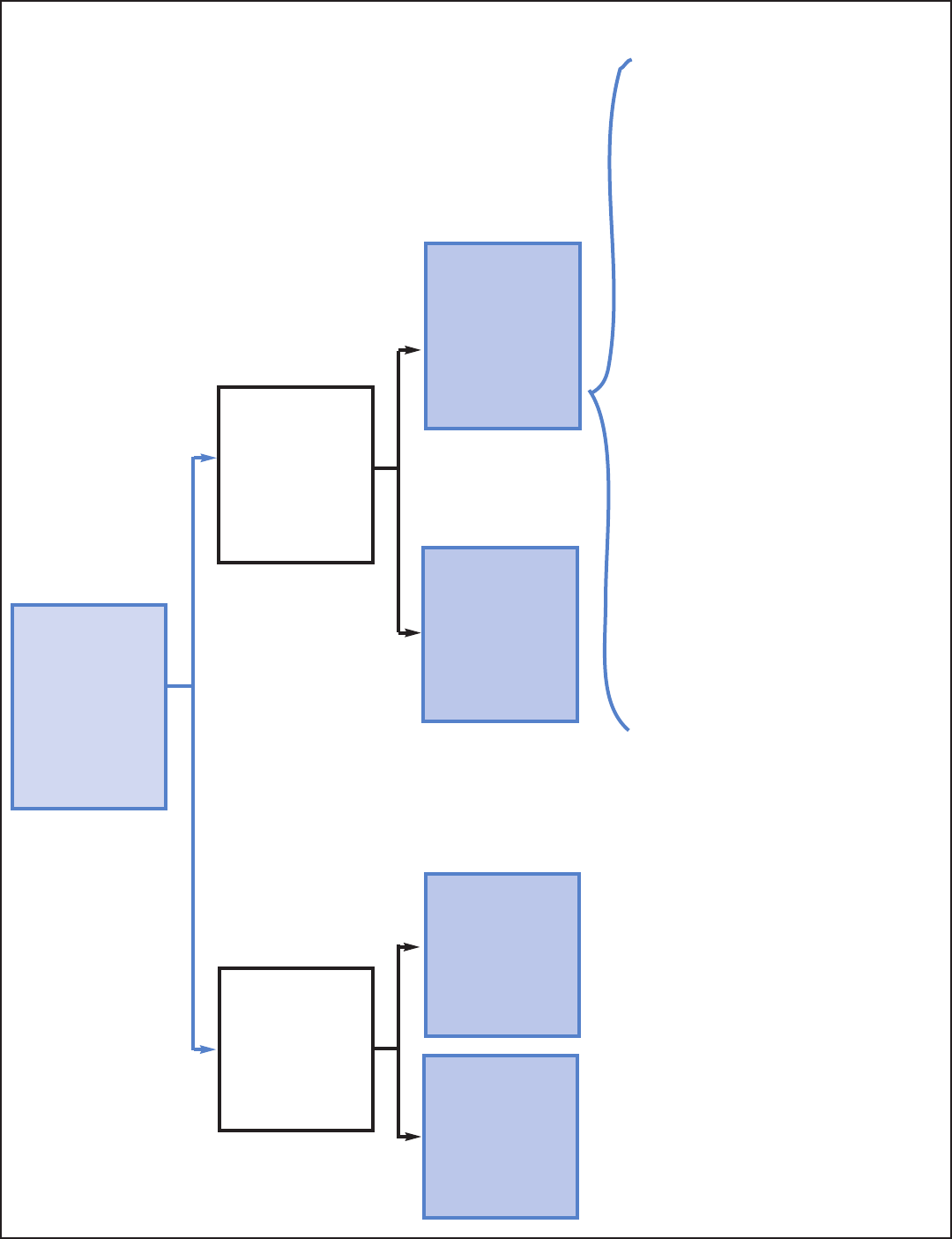

Figure 1: Prevention strategies attempt to alter two kinds of environments

Strategies Targeting

Individualized Environments

Strategies Targeting the

Shared Environment

Socialize, Instruct, Guide, Counsel

Support, Thwart

ALL YOUTH

Norms Regulations

Availability

Family

School

Faith

Community

Health

Care

Providers

INDIVIDUAL YOUTH

The Coalition Impact: Environmental Prevention StrategiesCADCA’s National Coalition Institute 3

Lessons Learned:

Develop actionable steps to implement. Education is necessary to create awareness and start a movement in your

community. However, coalition members and stakeholders need actionable steps to gain momentum.

Create and share the

basic tools needed to achieve success. For example, the Shawnee County coalition, through the Kansas Methamphetamine Pre-

vention Project, provided technical assistance and resources to local communities to address meth production. They developed

a kit with ready-to-use information for neighboring counties to implement similar, but not necessarily identical, strategies.

Avoid placing blame when bringing others on board. Ask for help and support the efforts of community members. The

Kansas Meth Prevention Project worked with the farming community to reduce access to anhydrous ammonia tanks, taking care

not to blame farmers. The coalition educated farmers on the importance of locking their tanks and obtained funding to pay for

locks that they distributed to the local agricultural community. This demonstrated the coalition’s willingness to work with farmers

instead of pointing the finger and expecting them to implement a strategy without support.

Be creative when presenting to different groups. Present visuals when possible—in Shawnee County, coalition leaders used

a map to plot the lab seizures in the community which helped fight denial that the drug problem was permeating everyone’s

neighborhoods. Drug seizures were happening throughout the community and did not exclude rural areas, locations near ele-

mentary schools, or the local shopping mall.

Provide small start-up funds to encourage community development. The average funding received in this case was $900

per county. It served as a catalyst to convene the community. Once people mobilize around an issue, the possibilities are

endless. With the right resources, support and the proper strategies aligned, people can do much with a little money.

Residents in Shawnee County, Kans., mobilized to address an

increase in the number of methanphetamine (meth) labs

throughout the county. At the time, Kansas law did not prevent

purchasing large amounts of products containing pseudo-

ephedrine, a substance commonly found in over-the-counter

cough and cold medicines and used in meth production. When

two local substance abuse prevention professionals entered a

store and observed a suspicious sale, they reported it to their

Director of Regional Prevention and started to plan a commu-

nity mobilization strategy to address the problem.

Residents of the county formed a coalition—the Shawnee

County Meth Awareness Project—incorporating local and state

government, law enforcement, agriculture, education and busi-

ness, and focusing on reducing local meth production.

The group took advantage of their partnerships and existing

relationships that those partners brought to the table. These

collaborations ensured the coalition a high level of capacity to

reduce meth production locally.

Guided by ongoing community assessment, the group concen-

trated its efforts on limiting access to pseudoephedrine and

anhydrous ammonia—commonly used in meth production. The

coalition’s multiple-strategy approach started with an educa-

tion campaign, concentrating particularly on retail merchants,

residential landlords and hotel/motel managers and the

agriculture community about the issue.

They worked with local farmers to ensure that tanks of anhy-

drous ammonia—designed for use as a fertilizer—remained

locked when not in use. The coalition received funding to sup-

port the farming community by paying for the locks.

The Shawnee County coalition’s broad community reach

resulted in development of new initiatives; one of which grew

into the Kansas Retail Meth Watch Program, a nationally

recognized initiative aimed at deterring theft or purchase

of products used in meth production.

Their local successes led to requests from neighboring counties

that hoped to implement similar strategies. The coalition

then began to provide training and technical assistance to

other communities that wanted to address meth production

and use.

As the movement grew, it gained significant media attention

and opportunities for state-level change emerged. In October

2002, the Kansas Methamphetamine Prevention Project, a

statewide initiative was launched to reduce and prevent pro-

duction and use of meth in the state. The initiative developed

a statewide training program called “Crank it up! Community

Methamphetamine Prevention Training.”

The grassroots mobilization success of the Shawnee County

project demonstrates how community coalitions can create

a “domino effect,” starting at the local level, spreading to

surrounding counties and ultimately producing state- and

national-level results.

The coalition advocated for action from the state legislature

and neighboring states began passing meth precursor laws. In

2005, Kansas passed a law limiting the sale of ephedrine and

pseudoephedrine in retail stores throughout the state. This

local effort has spread throughout the United States and con-

tributed to an overall reduction in the number of meth labs.

SHAWNEE COUNTY METH AWARENESS PROJECT

Selective Prevention Interventions target specific

subgroups that are believed to be at greater risk

for substance abuse than others. Risk groups may

be identified on the basis of biological, psychologi-

cal, social or environmental risk factors known to

be associated with substance abuse and addic-

tion. Interventions are designed to address the

identified risk indicators of the targeted subgroup.

Indicated Prevention Interventions target

individuals who exhibit early signs of substance

use disorders and other problem behaviors associ-

ated with such disorders, including early sub-

stance use, school failure, interpersonal social

problems, delinquency, other anti-social behaviors

and psychological problems such as depression.

Although most environmental strategies are

aimed at the general population (universal), they

also can impact a smaller segment of the commu-

nity. The IOM model is, therefore, a useful frame-

The Coalition Impact: Environmental Prevention StrategiesCADCA’s National Coalition Institute 4

CHAPTER 2: LAYING THE FOUNDATION FOR COMMUNITY CHANGE

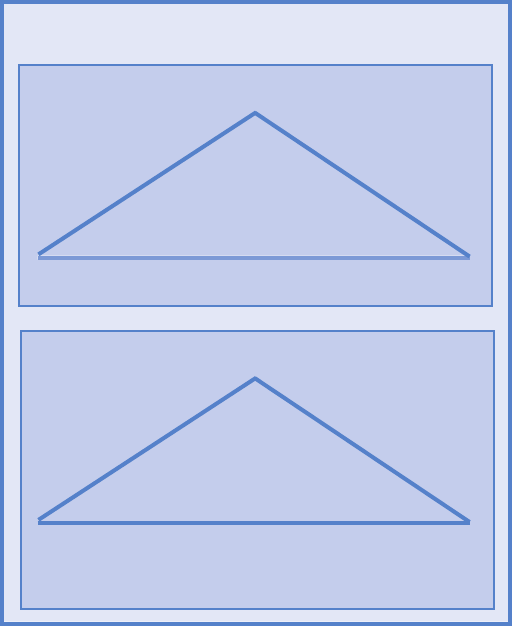

Figure 2. The Public Health Model

Agent

EnvironmentHost

Alcohol

Physical &

Social Context

Individual

The Public Health Model

The public health model demonstrates that prob-

lems arise through relationships and interactions

among an agent (e.g., the substance, like alcohol

or drugs), a host (the individual drinker or drug

user) and the environment (the social and physical

context of substance use).

For example, health risks from smoking became

clear in 1964 with the Surgeon General’s warning.

This stepped up efforts to implement tobacco edu-

cation and cessation programs. However, signifi-

cant reductions in tobacco consumption occurred

only when strategies were implemented to change

the settings (e.g., airplanes) where the agent (e.g.,

tobacco smoke) and the host (e.g., flight atten-

dants, passengers) came together. Groundbreak-

ing, smoke-free policies implemented by major

airlines led to passage of similar policies in work-

places and public buildings across the country.

Today, many states and localities have enacted

and are enforcing Clean Air Laws and pushing

smoking outside of public buildings and spaces.

Institute of Medicine Model—A useful

planning approach for coalitions

In 1994, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) proposed

a new framework for classifying prevention. The

IOM model divides the continuum of care into

three parts: prevention, treatment and mainte-

nance. Prevention interventions are divided into

three classifications--universal, selective and indi-

cated. Although the system distinguishes between

prevention and treatment, intervention in this con-

text is used in its generic sense.

Universal Prevention Interventions address the

general population with programs aimed at delay-

ing substance use and preventing abuse. Partici-

pants are not specifically recruited for the pre-

vention activities. Universal prevention activities

also can include efforts to bring community mem-

bers together to plan for services and to change

norms and laws reducing risk factors and promot-

ing a more protective environment.

The Coalition Impact: Environmental Prevention StrategiesCADCA’s National Coalition Institute 5

work for classifying environmental efforts. By

improving systems to better support a subset of

the community—for example, individuals return-

ing to the community after incarceration—bene-

fits can be derived for the former inmates, their

families and the population as a whole.

A broader look at policy

Environmental approaches tend to center on

policy that shapes perception in communities,

homes or workplaces in local, state or national

venues. Environmental strategies focus on pop-

ulations and affect large numbers of people

through the adoption of systems and policy

change and ongoing effective enforcement.

Policies, formal or informal, can be enacted

locally. Informal policy change can occur at a

high school, police department or with local mer-

chants. For example, if local alcohol retailers are

willing to attend merchant education sessions

voluntarily, formal policy change is unnecessary.

However, if your community determines that par-

ents and other adults are the main suppliers of

alcohol to underage drinkers, existing ordinances

and laws related to social host issues may require

more formal policy change.

Do not immediately head to the state house to

get laws enacted. In many instances, it is easier

for coalitions to achieve policy success at the

local level—particularly as they relate to alcohol

and underage drinking. Start at home and learn

about existing policies that may simply need more

proactive enforcement.

Continuing enforcement creates lasting environ-

mental change. For example, if the local school

district enacts a 24/7 Zero Tolerance Policy,

prohibiting students from consuming or posessing

alcoholic beverages, enforcement augments the

environmental work. Consistent enforcement for

policy violations leads to widespread adoption.

Just passing a policy does not ensure that a com-

munity will change. Enforcement of a policy that

responds to a community problem provides the

greatest impact. The consequences for violating

a policy must be appropriate and swift.

Coalitions: The organizational structure

for environmental strategies

Environmental strategies are carried out most

effectively in the context of a community problem-

solving process conducted by coalitions. Coalitions

can harness the community’s power to create

change. A well-functioning coalition engages

residents, law enforcement, schools, nonprofit

organizations, the faith community, youth and

other key groups to work in tandem to address

community concerns. Coalitions are well posi-

tioned to ensure sustained action on pervasive

community problems that have eluded simple

solutions. And, coalitions enable residents to

contribute to making a difference and creating the

political will necessary to influence development

and implementation of lasting policy.

Finally, environmental strategies are cost effective

given the potential magnitude of change. Commu-

nity mobilization is central to creating population-

level change. After data have been collected and

analyzed, coalitions must assess their capacity to

effectively address the identified problem(s). This

is especially important when using environmental

approaches. Historically, many coalitions have

consisted largely of members whose focus has

been working with individuals, families and other

small groups to elicit change in knowledge, skills

and attitudes. Implementing environmental strate-

gies requires different skills, such as community

organizing and/or development, and the involve-

ment of different community actors.

Individual strategies Environmental strategies

Focus on behavior and Focus on policy and policy

behavior change change

Focus on the relationship Focus on the social, political

between the individual and and economic context of

alcohol/drug-related problems alcohol/drug-related problems

Short-term focus on Long-term focus on policy

program development development

Individual generally does not People gain power by

participate in decision making acting collectively

Individual as audience Individual as advocate

The Coalition Impact: Environmental Prevention StrategiesCADCA’s National Coalition Institute 6

Lessons Learned:

Focus on local policies first. You do not have to change state laws or create ordinances to make environmental changes.

Businesses also have the power to change policies. In this case, the coalition approached street fair promoters, getting

them to understand the scope of the problem. They presented pictures and data, helping them to see the value in banning

products with pro-drug messages.

Monitor enforcement of policy. Once a policy change is made, the work is not over because having a policy in writing, does

not guarantee enforcement! The

NCPC members continue to be the “eyes and ears” at street festivals to ensure that vendors

are following the policy. Your coalition may have to take responsibility for such surveillance to guarantee compliance. Law en-

forcement in communities often is stretched very thin and they appreciate assistance.

Take advantage of windows of opportunity for change. It often is difficult to mobilize people around a particular issue

unless a significant event is involved. These events can be great levers for changing community norms and attitudes and to

get people on board with your coalition’s proposed strategies. In this case, one festival helped raise visibility of the problem.

Document it. Take pictures and share them with your community through Web-based photo sharing sites such as Flickr.

Make it easy for partners to get on board. In this case, the coalition went to the street fair promoters with a plan. They told

them that the coalition would monitor vendor compliance and would bring this information back to the promoters. The promoters

only needed to agree to change the policy language. Offer support to partners. Business people will be more willing to agree to

your terms if it does not seem like an extra burden for them.

The North Coastal Prevention Coalition (NCPC) serving

North San Diego County, including the cities of Carlsbad,

Oceanside and Vista, Calif., developed a comprehensive

plan to address youth marijuana use when assessments

revealed that more San Diego County youth smoked mari-

juana than cigarettes. At the time, the community envi-

ronment was saturated with pro-drug messages on the

radio, in retail stores and at local street fairs. As part of

their plan, the coalition collaborated with a countywide

initiative called HARM (Health Advocates Rejecting Mari-

juana) to eliminate messages portraying marijuana use

as “fun” and “harmless.”

The county holds about 40 public festivals each year,

making the problem visible to the general community,

particularly youth. NCPC leaders determined that they

could have success in eliminating drug paraphernalia

and pro-drug items at local street fairs.

When a music festival, saturated with pro-marijuana mes-

sages came to Oceanside, drawing large crowds of youth

and young adults, the coalition saw a prime opportunity

to document the problem. Coalition members went to

the festival and took a collection of photographs they

used later to advocate for their position and display the

magnitude of the problem.

This visual documentation proved extremely helpful when

the coalition approached the city council to amend an

existing “headshop” ordinance, to require drug parapher-

nalia, such as bongs and pipes, to be sold inside licensed

buildings. The city council agreed to the amendment, but

the coalition realized this was only part of the problem.

The original ordinance did not prevent street vendors from

selling and displaying items such as t-shirts, jewelry and

posters that sent messages to local youth that could be

construed as supporting marijuana use.

The coalition went to the Chamber of Commerce, the

sponsor of “Harbor Days,” an annual festival held at the

Oceanside Harbor. They believed that if they could compel

the “Harbor Days” event planners to change their policies,

others might follow. The coalition worked with the Cham-

ber of Commerce to add language to their vendor policy

banning vendors from selling “tobacco products, to-

bacco/drug paraphernalia or any item that promotes the

use of illicit substances.” This was a huge success, but

many more festivals remained. The coalition had to be cre-

ative. Instead of pushing for an ordinance, they decided to

get street fair promoters on their side.

One company was responsible for sponsoring most street

fairs across North San Diego County. The coalition called

the promoters to seek voluntary adoption of a policy

against the sale of pro-drug items. As they hoped, the

change made by “Harbor Days,” led the promoter to

voluntarily ban the pro-drug items from other fairs.

These efforts led the coalition to successfully advocate

environmental change at 14 fairs throughout the North

County. They continue to monitor activity, ensuring that

festivals are positive environments for families and youth.

NORTH COASTAL PREVENTION COALITION

The Coalition Impact: Environmental Prevention StrategiesCADCA’s National Coalition Institute 7

Think about coalition membership in terms of a

business. Successful companies recruit and hire

employees only after an analysis of their skills and

abilities. Within a company, leadership strives to

collectively gather the best mix of individuals who,

working together, leverage the breadth of their

skills and perform in a cohesive manner. New

projects may mean new employees or an adjust-

ment in positions. Approach coalition work in the

same way: a company, with a set of leaders

(Board of Directors) and divisions (subcommittees)

engaged in planning and implementing the work,

while keeping common goals and measures of

success in sharp focus.

Do your homework

Coalitions that are planning to implement environmental strategies must do a considerable amount of investiga-

tion to learn what formal and informal policies exist that influence environmental factors. For example, not know-

ing local ordinances related to alcohol and tobacco will hinder progress. Coalitions should learn about state and

local laws related to the sale of alcohol and tobacco products. In other words, coalitions must do their homework.

It becomes the coalition’s job to know everything that might be helpful.

Examples of homework for coalitions:

• Locate and read your state’s alcohol/tobacco laws

• Locate and read local alcohol/tobacco ordinances/policies

• Understand the process for obtaining an alcohol/tobacco retail license

• Understand the process for enforcement of alcohol/tobacco retail licenses

• Understand the process for creating and modifying local land use regulations, i.e., zoning

• Learn about local law enforcement agencies and their roles within your community (i.e., jurisdictions,

current efforts)

• Learn about the roles and responsibilities of judicial officers (i.e., magistrates, judges) in your community

• Learn the political process in your community (i.e., election cycles, who is currently serving and their

agendas, etc.)

• Conduct a local/state policy analysis (what already exists)

• Conduct a power analysis in your community (who has the power to change policy)

• Determine what other local agencies are doing to address the problem your coalition is concerned about

The Coalition Impact: Environmental Prevention StrategiesCADCA’s National Coalition Institute 8

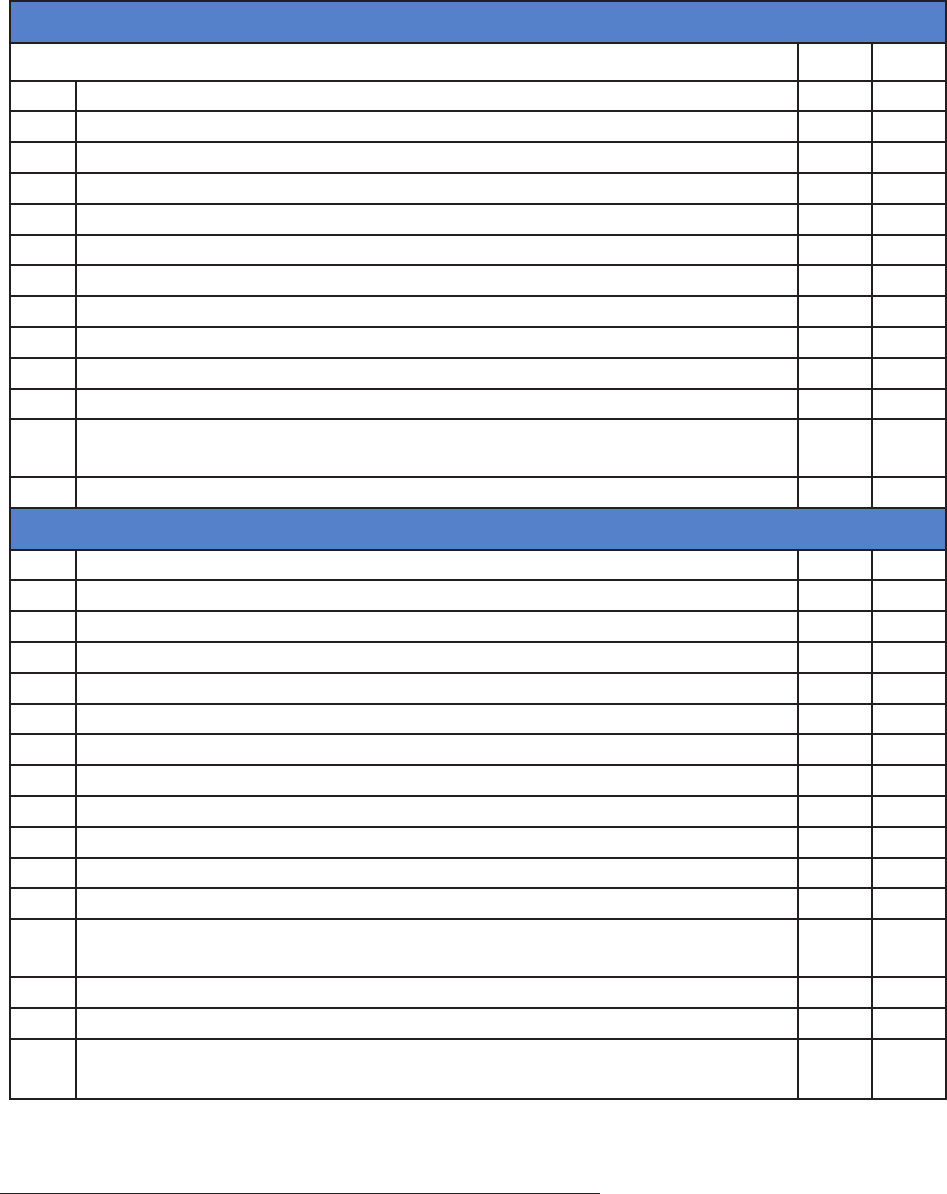

ALCOHOL—Public Policies

Yes No

Excise taxes (local)

Limits on hours or days of sale

Restrictions of density, location, or types of outlets

Mandatory server training and licensing

Dram shop and social host liability

Restrictions on advertising and promotion

Mandatory warning signs and labels

Restrictions on consumption in public places

Prevention of preemption of local control of alcohol regulation (home rule)

Minimum bar entry age

Keg registration/tagging ordinances

Compulsory compliance checks for minimum purchase age and administrative

penalties for violations

Establishment of minimum age for sellers

ALCOHOL—Organizational Policies

Restrictions on alcohol advertisements (media)

Restrictions on alcohol use at work and work events (businesses)

Restrictions on sponsorship of special events (communities, stadiums)

Police walkthroughs at alcohol outlets

Undercover outlet compliance checks (law enforcement agencies)

Responsible beverage service policies (outlets)

Mandatory checks of age identification (businesses)

Server training (businesses)

Incentives for checking age identification (businesses)

Prohibition of alcohol on school grounds or at school events (schools)

Enforcement of school policies (schools)

Prohibition of beer kegs on campus (colleges)

Establishment of enforcement priorities against adults who illegally provide

alcohol to youth

Sobriety checkpoints (law enforcement agencies)

Media campaigns about enforcement efforts (media)

Identification of source of alcohol consumed prior to driving-while-intoxicated arrests

(law enforcement agencies)

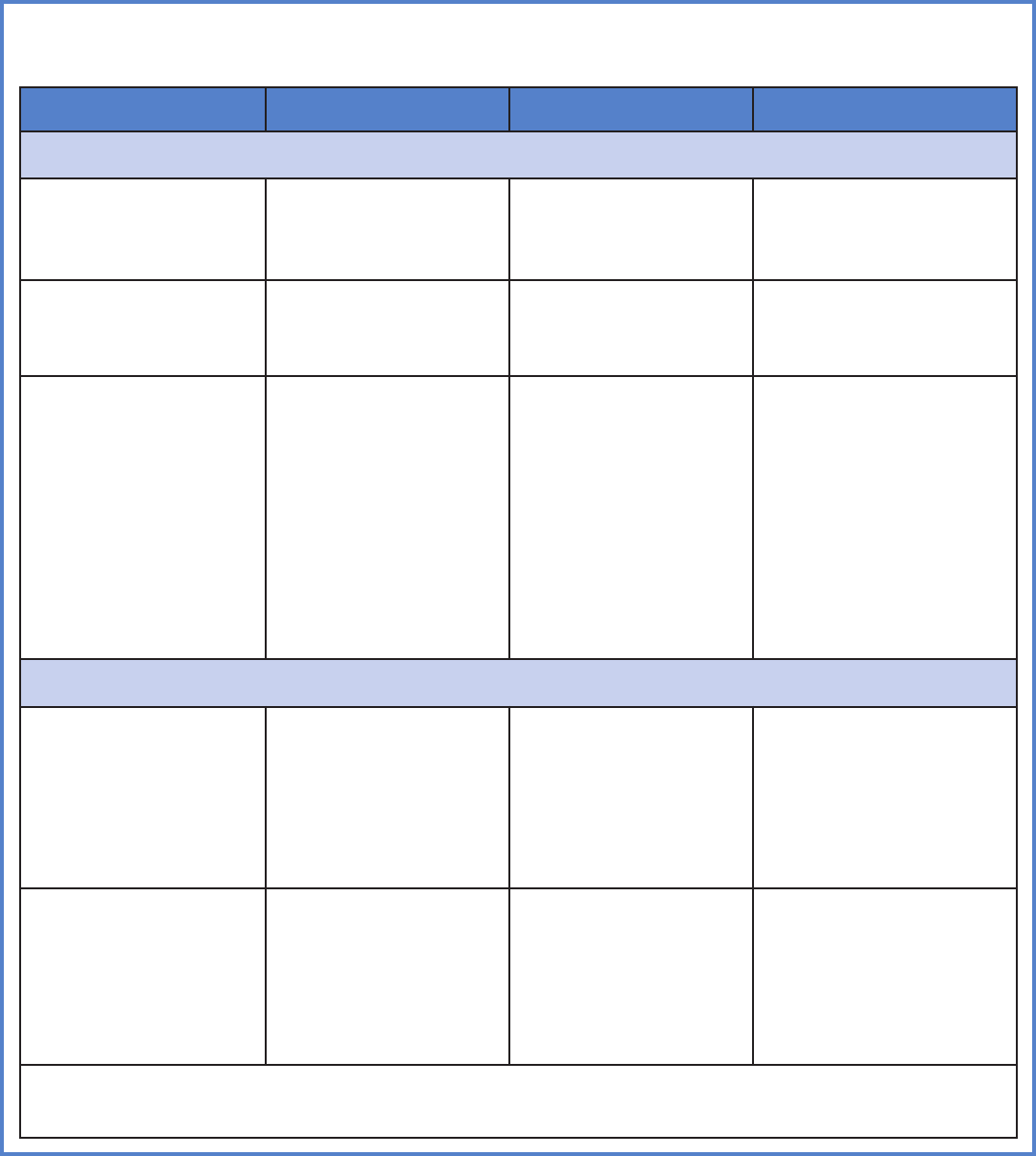

Checklist of policy indicators for alcohol,

tobacco and other drugs

This checklist can help you to assess the number and types of policies within your community

and where you might best extend your efforts.

Source: Center for Prevention Research and Development, Institute of Government & Public Affairs,

University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana, Retreived from the Internet at

http://www.cprd.uiuc.edu/Pep/docs/Checklist_of_Policy_Indicators.RTF

, March 2008.

T

able 1.

The Coalition Impact: Environmental Prevention StrategiesCADCA’s National Coalition Institute 9

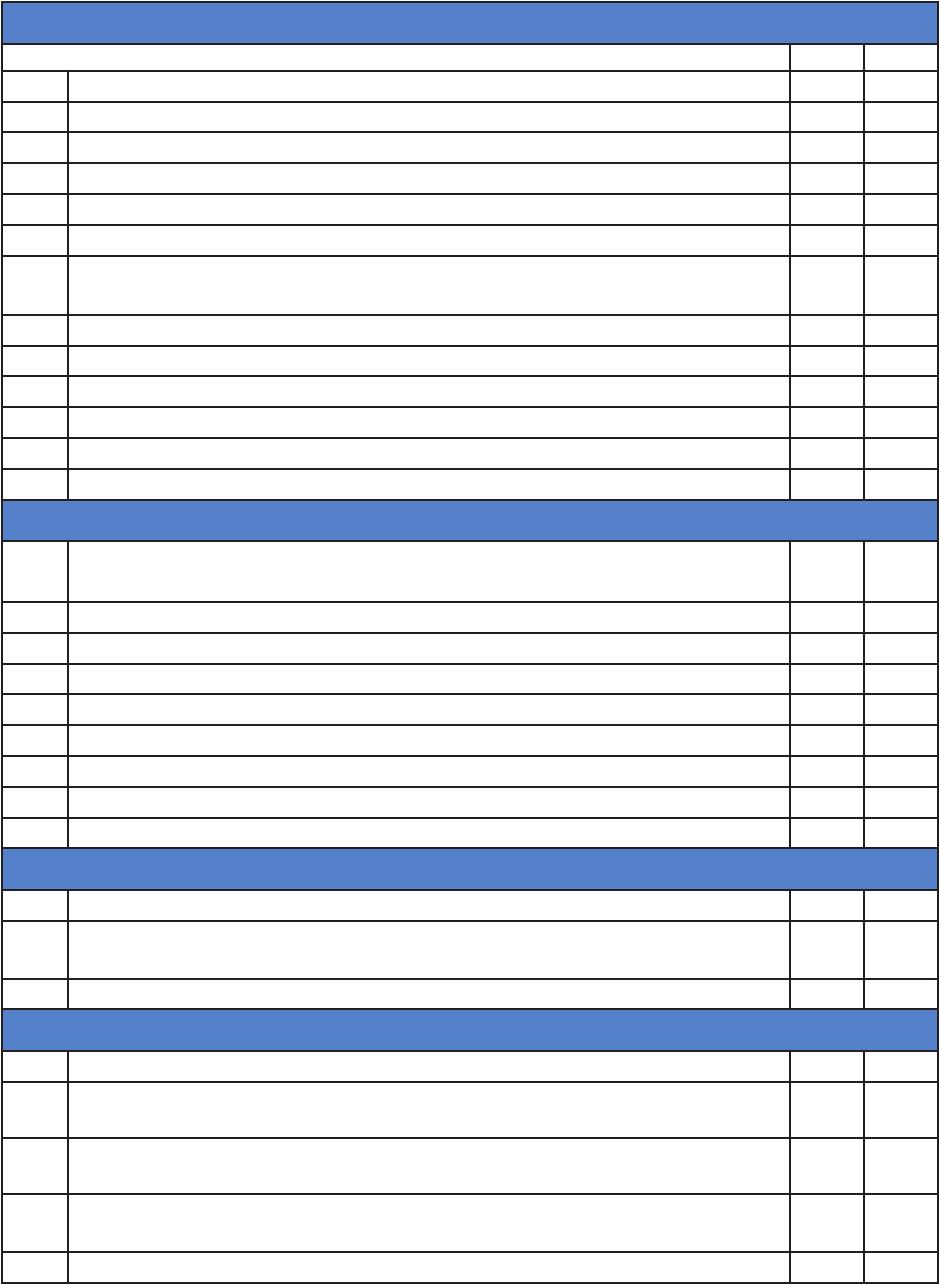

TOBACCO—Public Policies

Yes No

Excise taxes (local)

Tobacco sales licensing system

Prohibition of smoking in public places

Prevention of preemption of local control of tobacco sales

Restrictions on advertising and promotion

Ban on vending machines

Compulsory compliance checks for minimum purchase age and

administrative penalties for violations

Minimum age sales of age 18

Warning labels

Mandatory seller training

Ban on self - service sales (all tobacco behind the counter)

Minimum age for sellers

Penalty for underage use

TOBACCO—Organizational Policies

Establishment of smoke-free settings (restaurants, workplaces, hospitals, stadiums,

malls, day care facilities)

Counter advertising (media)

Restrictions on sponsorship of special events (communities, colleges, stadiums)

Prohibition of tobacco use on school grounds, in buses and at school events

Enforcement of school policies (schools)

Mandatory checks for age identification (businesses)

Seller training (businesses)

Incentives for checking age identification (businesses)

Undercover shopper or monitoring program (businesses)

OTHER DRUGS—Public Policies

Control of production and distribution

Zoning and building codes that discourage drug activity and penalties for

property owners who fail to address known drug activity

Mandated school policies

OTHER DRUGS—Organizational Policies

Employer policies (businesses)

Surveillance of high-risk public area (law enforcement agencies, neighborhood

watch groups)

Enforcement of zoning and building codes (law enforcement agencies,

building authorities)

Appropriate design and maintenance of parks, streets, and other public places

(e.g., lighting, traffic flow) (city agencies, housing authorities)

Enforcement of school drug policies (schools)

The Coalition Impact: Environmental Prevention StrategiesCADCA’s National Coalition Institute 10

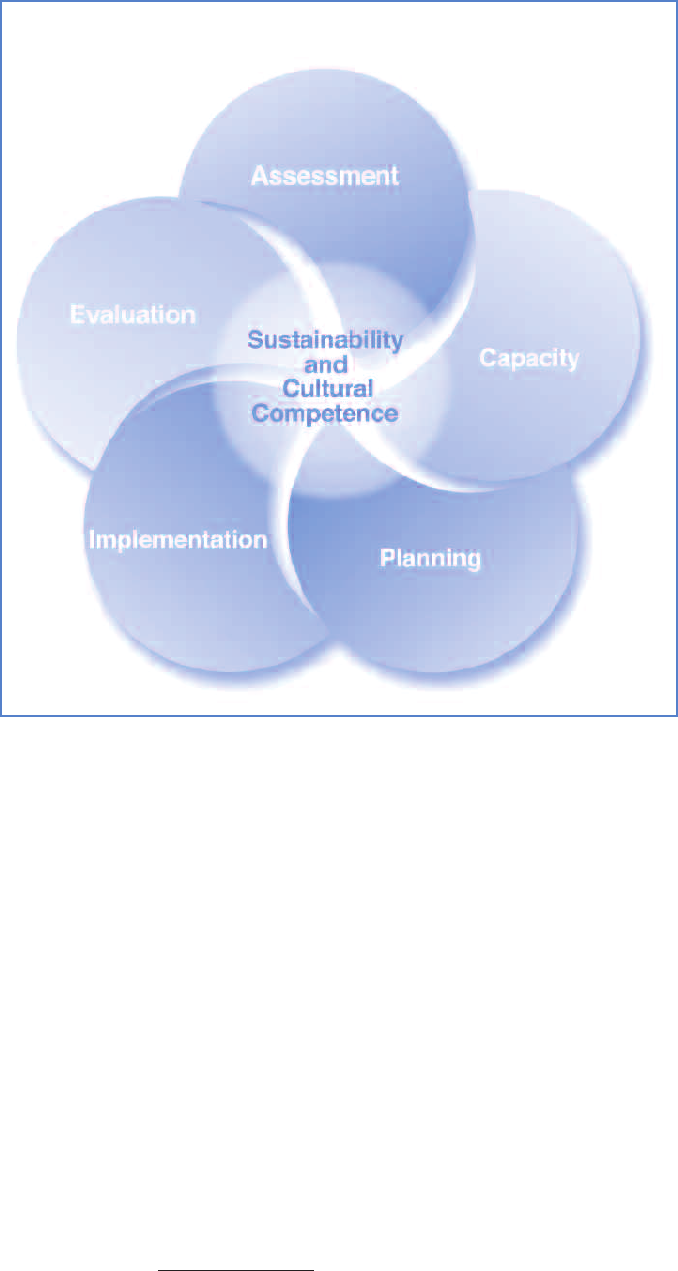

In this chapter, we take a look at the

elements of the Strategic Prevention

Framework (SPF) and how each re-

lates to environmental approaches.

No “cookie cutter” response to envi-

ronmental strategies exists. You can-

not select a “model” program and

hope it will work in your community.

You must do your homework—study

your community, know the people,

the neighborhoods and, yes, the local

context. Then your coalition can craft

environmental strategies tailored to

your community characteristics.

CADCA utilizes the SPF to assist

community coalitions in developing

the infrastructure needed for

community-based, public health

approaches that can lead to effective

and sustainable reductions in alco-

hol, tobacco and other drug (ATOD)

use and abuse. The elements shown

Figure 3, at right, include:

• Assessment. Collect data to de-

fine problems, resources, and

readiness within a geographic area to

address needs and gaps.

• Capacity. Mobilize and/or build capacity

within a geographic area to address needs.

• Planning. Develop a comprehensive strategic

approach that includes policies, programs,

and practices creating a logical, data-driven

plan to address problems identified in

the assessment.

• Implementation. Implement evidence-based

prevention strategies, programs, policies

and practices.

• Evaluation. Measure the impact of the SPF

and the implementation of strategies,

programs, policies and practices.

The elements of sustainability and cultural compe-

tence—central to community-based approaches—

are shown in the center of the graphic indicating

their importance to each of the other elements.

Cultural implications in assessing the

community and planning strategies

Coalitions considering implementation of environ-

mental strategies need to work with diverse popu-

lations within their communities. Representatives

from those communities must be involved as early

as possible to avoid miscommunication or percep-

tions that “outsiders” want to change their norms,

traditions, policies or environments. Environmen-

tal strategies planned without consideration of

cultural impact will not be accepted by the larger

community and most likely will not produce the

desired results. Such involvement also requires

that the coalition commit to fostering cultural

competence at all levels of activity. The Institute’s

Cultural Competence Primer may help your

coalition and is available in PDF format online at

www.cadca.org

.

CHAPTER 3: THE SPF AND ENVIRONMENTAL STRATEGIES

Figure 3. SAMHSA’s Strategic Prevention Framework

The Coalition Impact: Environmental Prevention StrategiesCADCA’s National Coalition Institute 11

Note: in many communities across the country,

problem environments tend to be concentrated in

economically disadvantaged, minority neighbor-

hoods. These areas often have a high concentra-

tion of liquor outlets, liquor and tobacco billboards

and advertisements, as well as abandoned hous-

ing that foster illicit drug use. These communities

often are marginalized and disenfranchised and

high-risk conditions exist that would not be toler-

ated in more affluent neighborhoods. Community

coalitions must involve formal and informal lead-

ers from such communities to bring about mean-

ingful environmental change that will lead to im-

proved community health in areas that are dispro-

portionally impacted by myriad problems.

Carefully consider how your coalition will address

issues of cultural diversity and competence as you

work through the elements of the SPF. For exam-

ple, how will you conduct an accurate assessment

of diverse sectors of your community? How will

you ensure broad representation of minority popu-

lations in your coalition? How will you build capac-

ity in economically disadvantaged communities?

How your coalition responds to these issues likely

will determine your ultimate success in imple-

menting environmental strategies and reducing

substance abuse rates in your community.

Environmental assessment

Coalitions should take the necessary time to

complete an assessment that includes key factors

to determine the most appropriate environmental

strategies for a community. Create a picture of

the state of affairs locally and surface problems

the community sees as its most pressing issues.

Move beyond just collecting student consumption

and attitudinal data for a more detailed under-

standing of the deep-rooted causes in the commu-

nity. The Institute’s Assessment Primer provides

in-depth information on how to complete a com-

munity assessment and is available in PDF format

online at www.cadca.org

.

Data collection can present challenges. Coalitions

should seek data on their targeted geographic

area and/or create data that are aggregated down

to the level they need (i.e., zip codes, a town, etc.).

When searching for data, remember to collect

them at the smallest level necessary to thoroughly

understand the issues in the target population or

community. It may be necessary to dig deeper as

your data investigation progresses. If the county

has been chosen as the targeted area, then col-

lecting county-level data is a good place to start.

Today’s approach to environmental strategies had

beginnings more than 150 years ago when Dr.

John Snow—a pioneer in the science of epidemiol-

ogy—was able to stem an outbreak of Asiatic

cholera in South London by tracing it to a single

source of polluted water.

By interviewing families of victims where the out-

break occurred, he was able to identify a single

pump as the epicenter of the outbreak. And, by

creating a map that showed all the pumps in the

South London area in relation to cholera deaths,

he convinced authorities to remove the pump han-

dle, stopping the spread of cholera immediately.

This example of the benefits of well-researched

epidemiology forms the foundation for environ-

mental assessments being conducted by coali-

tions today. Snow used both qualitative data

(personal interviews) and quantitative data

(mapping locations of deaths) to make his case.

Further, he looked at where the deaths were

most concentrated to pinpoint the source of

the infection and compel skeptical policymakers

to take action.

Community assessment

Issues may be considered “pressing” when:

a. The problem occurs frequently (FREQUENCY)

b. The problem has lasted for a while (DURATION)

c. The problem affects many people (SCOPE)

d. The problem is intense (SEVERITY)

e. The problem deprives people of legal or human rights

(SOCIAL IMPORTANCE)

f. The problem is perceived to be important (PERCEPTION).

University of Kansas Community Tool Box, retrieved from the Internet

at

ctb.ku.edu

, March 2008. Used with permission.

The Coalition Impact: Environmental Prevention StrategiesCADCA’s National Coalition Institute 12

Environmental scanning

Environmental scanning is a useful assessment

method coalitions can employ to gather visible in-

formation on local conditions surrounding alcohol,

tobacco and other drugs. In determining the envi-

ronmental strategies that best fit your community,

coalitions may find it valuable to physically assess

the landscape. Using the context of substance

use/abuse as a starting point, coalitions can

become sensitive to environmental cues evident

when viewing the community context.

To conduct an environmental scan, your coalition

must first develop a methodology to document

the information. This includes questions you want

answered and the ability to collect additional infor-

mation that comes to the forefront during the

scanning process. Recruit coalition members and

enlist other community residents (i.e., law enforce-

ment officers, youth, etc.) who will complete the

scans and bring back the information.

While conducting a scan, visit local alcohol out-

lets, other retail and commercial properties, resi-

dential neighborhoods, parks and recreation areas

(rivers, streams, wooded areas, etc.). Collect infor-

mation about what you see, including the number

of billboards, advertising, lighting, signage, loca-

tion of police and fire stations, schools, day care

centers, churches and other physical elements of

the community. Take photographs and post the on

your coalition’s website, blog or social networking

site such as Flickr or Photobucket (photo sharing

sites). Use the data gathered to further inform

your assessment process and alert your coalition

membership of environmental elements that were

not previously discovered.

Assess conditions with marketing’s 4 Ps

When engaging in environmental scanning, work

to find conditions that make illegal or excessive

substance use and abuse easier. A concept known

as the marketing mix, or marketing’s four Ps, can

help identify issues your coalition may need to

address. Consider:

Price: How much does a 22-ounce beer cost when

compared to a 12-ounce can of soda? Is alcohol

less expensive in certain settings or time of day?

What is the excise tax on tobacco?

Product: Do specific products appeal to certain

populations (i.e., alcopops or flavored ciga-

rettes)? Is beer provided in single cans with a

high alcohol content?

Promotion: What Happy Hour regulations exist

(i.e., time, price of alcohol, etc.)? Does the com-

munity allow “2 for 1 specials?” Are there com-

munity festivals that revolve around alcohol

use? What are the regulations related to free

samples of wine at the grocery store or chewing

tobacco on a military base?

Place: Is beer next to soda in the cooler of local

convenience stores? Do “beer caves” make

large amounts of cold beer available? Are prod-

ucts displayed where they can be stolen easily?

Geographic Information Systems (GIS)

In addition to the data sources already listed, the

prevention field has sophisticated technology that

can further illustrate the context of the environ-

ment and its current conditions.

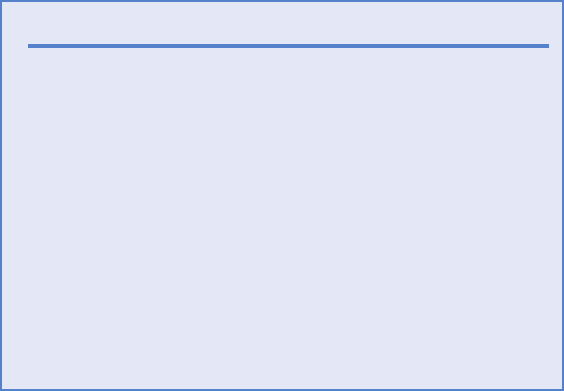

Figure 4. Marketing’s Four Ps

The marketing mix, or 4 Ps of marketing, can help coalitions

determine where in the community change needs to occur. For

a community environmental approach, the target market seen

above informs initiative planning and implementation. Graphic

adapted from

NetMBA.com

.

Product

Place Promotion

Price

TARGET

MARKET

Through Geographic Information Systems

(GIS), information can be digitally mapped,

creating visual displays that indicate problem

environments or “hot spots” of activity. For ex-

ample, GIS mapping can have one layer that

shows the locations of alcohol outlets across

a county; a second that indicates areas where

underage drinking violations have occurred

and a third illustrating crimes including van-

dalism, public intoxication and loitering. In

areas where the data are concentrated, a

coalition can pinpoint an area of high activity

where environmental factors should be inves-

tigated further. Where are alcohol retail out-

lets and crime rates most concentrated? GIS

mapping provides correlations among data

sets, so communities can determine problem

settings and move toward addressing the en-

vironmental factors that create opportunities

for high-risk behaviors and related crime.

Learn more about GIS mapping on the Find

Youth Information website, www.Find

YouthInfo.gov. Many states and law enforce-

ment and military agencies utilize GIS map-

ping in their day-to-day operations. Check

with your local police or National Guard

Bureau for help in compiling GIS maps for your

community. See the Resources Section on

page 31 for more information.

Understanding problem environments

For success in planning environmental strategies,

determine what specific locations in the commu-

nity might be considered high-risk or problematic.

For example, during the course of a community

assessment that includes environmental investiga-

tion (i.e., environmental scanning and GIS map-

ping), a community discovers that there is a high

density of alcohol outlets within a two-block area

of the downtown district. In that area, crime, such

as vandalism, noise ordinance violations and drug

dealing, also are significant. Understanding this, a

coalition may identify environmental factors—i.e.,

overgrown vacant lots or bars that allow underage

patrons to drink—that must be addressed.

In some instances, a single outlet can wreak

havoc on an entire community. GIS mapping can

The Coalition Impact: Environmental Prevention StrategiesCADCA’s National Coalition Institute 13

show how one “bad apple” can affect the commu-

nity. Dealing with that one location might improve

conditions in the entire community.

Consider demographic and geographic features

within the environmental context. Pay close atten-

tion to the following:

• Lakes and rivers: Are youth allowed to use

their parents’ boats on the water with little or

no supervision? Are boat patrols a regular

part of enforcement activities?

• Homes with large land areas: Are these

areas ideal for underage drinking parties?

• Homes with basements: Can youth easily

conceal a party from negligent adults?

• Youth with working parents: Is supervision

an issue?

• Rural communities: Are the driving distances

long and do they contribute to driving under

the influence? Are open fields or wooded

areas common gathering spots for youth?

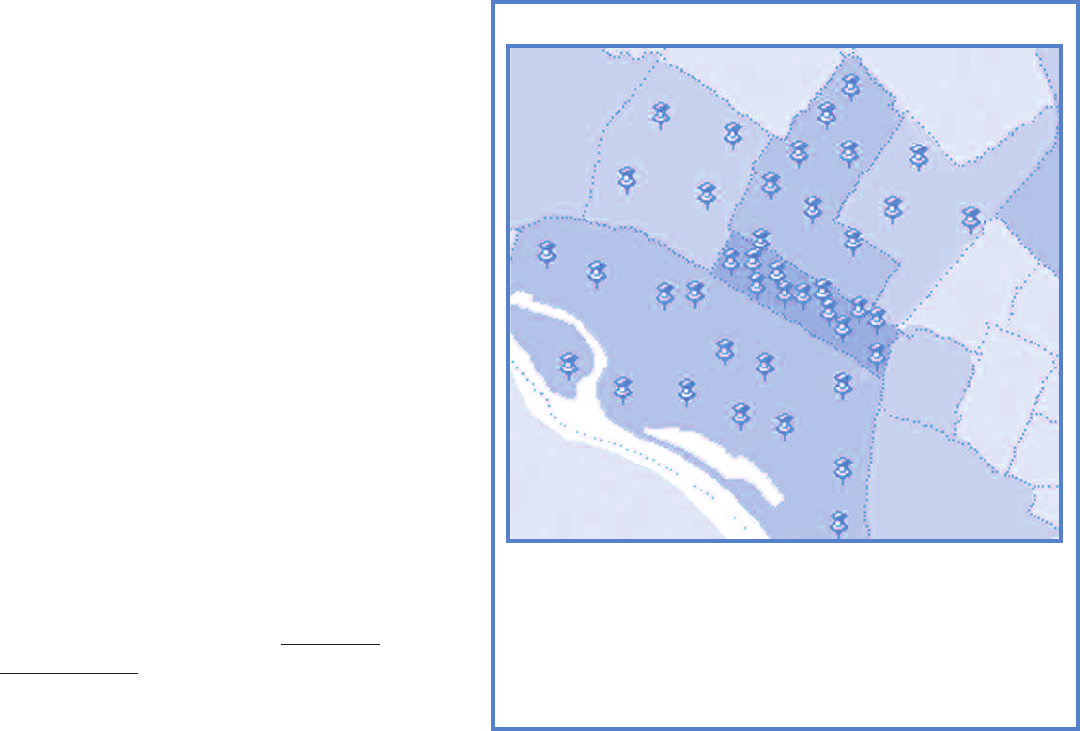

Figure 5: Sample GIS map

The map illustrates a GIS map indicating the correlation in the crime

rate (including loitering, vandalism, noise ordinance violations, drug

dealing, public drunkenness and robbery) and alcohol outlet density

in a five county area. Crime rates are shown by color (with darker color

indicating higher crime rates), while alcohol outlets are illustrated by

pins in the map.

The Coalition Impact: Environmental Prevention StrategiesCADCA’s National Coalition Institute 14

• Economically disadvantaged communities:

Are abandoned buildings used for drug

sales or use?

• Major highways/ports: Does your city have a

major highway or port that becomes part of

the trafficking issue and increases the local

supply of illegal drugs?

Again, communities must consider ALL salient

factors when determining where problem environ-

ments are and how to most appropriately plan to

address them.

Involving youth in assessment

Youth involvement in coalitions is essential and

young people can become great “data detectives.”

They may see the community through a different

lens than most adult coalition members. Youth

can be recruited and organized to carry out inter-

views with neighborhood residents, count and

map alcohol and tobacco outlets and locate and

photograph settings to further illustrate local con-

ditions. They can create and administer surveys

and present data in easy-to-understand reports,

and coordinate town hall meetings and recruit

participants. See the case study on page 15 to

learn about how the Hood River Coalition engaged

youth in the environmental assessment process.

The context in which a young person lives certainly

influences his/her behavior and how that context

becomes an influence is different than that of an

adult. With adult support and guidance, youth

have the skills and ability to go out into the com-

munity and collect information. And, their knowl-

edge of technology can be invaluable. Involving

and utilizing their skills in GIS mapping is not only

an effective way to get this type of data collection

underway, but also to educate youth on the princi-

ples of environmental strategies and how physical

design can be modified.

Commitment through capacity building

Successful implementation of environmental

strategies does not happen overnight. Results

take long-term commitment from coalition

members and membership must be adapted and

adjusted as implementation progresses. Imple-

menting environ-

mental strategies

requires more com-

munity involvement

than individual

strategies and re-

quires participation

of those most af-

fected for crafting

and carrying out

solutions.

Coalition members

should become

savvy agents of

change to modify

risky environments

and affect improve-

ments in systems to

discourage alcohol,

drug and tobacco

use. Remember,

the strategies and tactics needed to bring about

environmental change differ from those required

to select and implement programs for individuals.

Coalitions that employ environmental approaches

must learn to generate political capital and garner

support from those in positions of authority.

Elected officials, school and hospital administra-

tors, business and labor union leaders, faith and

cultural organizations and media all have the

power to shape policies and deploy resources.

When such leaders also are coalition members,

they can act as catalysts for change by enlisting

support from others in their sphere of influence.

Encourage them as “champions for change” for

the coalition’s policies and practices.

Whom do we need around the table?

Determine whether your coalition includes all the

stakeholder groups it needs to improve the likeli-

hood that your initiatives will succeed. Using the

problem(s) identified from your community

assessment data as a starting point, ask the fol-

lowing questions to begin to analyze if your coali-

tion membership is comprehensive:

DFC requirements

DFC coalitions must include a

minimum of one member/

representative from each of

these 12 community sectors:

• Youth (persons less than or

equal to 18 years of age)

• Parents

• Business community

• Media

• Schools

• Youth-serving organization

• Law enforcement agencies

• Religious or fraternal

organizations

• Civic and volunteer groups

• Healthcare professionals

• State, local, or tribal

governmental agencies

• Other organizations involved

in reducing substance abuse

The Coalition Impact: Environmental Prevention StrategiesCADCA’s National Coalition Institute 15

Lessons Learned:

Involve youth in your coalition work. Youth are powerful and persuasive advocates that can speak on behalf of the

coalition to key leaders and stakeholders in the community. Youth can push the coalition to do the work because they

are anxious for results. Involve them in the assessment and evaluation processto help paint a picture of the

environment, using methods such as GIS mapping, photography and video. However, involving youth takes

planning to facilitate success.

Build capacity through training opportunities. The coalition’s affiliation to the Oregon Research Institute was a key

component to their success because of the training provided. Never underestimate the power of training. It can greatly

increase a coalition’s chances for success. The coalition leader was taught community mobilization; focusing on specific

skills including working with the media, networking with key leaders, sharing data, and motivating and engaging commu-

nity members. Active youth members also received training that built their capacity to reach their goals.

Work with your community. The Hood River Coalition had little pushback from the community because of their overall

approach and their deep roots in the community. It is best if you can keep the coalition from being the “bad guy.” Work with

businesses, not against them. Provide incentives and reminders to keep community members involved.

From 1992 to 1999, the Hood River County Alcohol Tobacco

and Other Drug Prevention Coalition, in partnership with the

Oregon Research Institute in Eugene, Ore., implemented Proj-

ect SixTeen, to prevent and reduce tobacco use by adults and

youth in their community. The project was comprehensive, in-

volving multiple strategies to reduce access and sales of

tobacco to underage youth, increase perception of harm and

parental disapproval of tobacco and increase tobacco-free

places and events.

What is unique about Hood River’s strategies is they involve-

ment of youth in every step of the coalition process. The

coalition engages youth as agents of change in its action plan

because of the receptive environment toward youth in the

overall community. Involving youth in coalition work empowers

them, builds their leadership skills and bonds them to the

community. They also can show the community youth’s role in

positive community change.

To recruit youth members to assist in developing coalition

activities, coalition leaders began in the local high school.

They identified interested youth in classrooms and student

clubs to help implement strategies and activities to mobilize

the community to reduce exposure to tobacco smoke, de-

crease exposure to tobacco advertising and create barriers to

tobacco sales to underage youth. By first engaging youth in

poster contests, t-shirt exchanges and strategy development,

the coalition strategically planned for how to systematically

achieve the goals of their initiative.

Youth passionately expressed their desire for stronger school

policies prohibiting tobacco use on school grounds, at commu-

nity events and in local restaurants, retail outlets and other

venues where youth gathered. They worked closely with school

administrators and presented to the school board fact-filled

and persuasive arguments supporting a tobacco-free campus.

These efforts led to adoption of policies restricting tobacco

advertising, paraphernalia, use and possession in the schools,

on campus and at school events. The policies applied to all

students, employees and visitors to the school and banned to-

bacco use on campus outside of regular school hours.

The success of these efforts empowered youth to address the

tobacco issue beyond school grounds. They worked to extend

the school policy to include local restaurants, bars, motels and

businesses; advocating for a Smoke-Free Workplace Law in

Hood River County. They presented in front of city council

members, county commissioners, and individual businesses,

among others to influence change. Youth created petitions at

the high school, and surveyed peers, to demonstrate to local

business owners that banning smoking in their facility was a

profitable decision.

As a result of their hard work, 87 percent of local restaurants

and bars voluntarily adopted tobacco-free policies before the

first state laws were passed in 1998. In addition, three local

businesses removed vending machines from their bars and

eight Quick Stop groceries put tobacco products behind the

counter. Once these local businesses were on board, the

coalition youth were prepared to present their successes at

the state level. These efforts helped lead to the passage of

Oregon’s Smoke-Free Workplace Law in 1999. The coalition

continues to engage about 30 youth in prevention work each

year through youth-led education, media and testimony to

local and state policy makers on the impact of second hand

smoke and the need to increase the tobacco tax as an

effective reduction tool.

HOOD RIVER COUNTY ALCOHOL TOBACCO AND OTHER DRUG PREVENTION COALITION

The Coalition Impact: Environmental Prevention StrategiesCADCA’s National Coalition Institute 16

• Who is directly affected by the problem(s)?

• Who else cares enough to want to solve the

problem(s)?

• Who benefits if the problem is resolved?

• What individuals or groups can resolve the

problem?

Resist the urge to respond to these questions with

the common answer, “Everyone!” Identify specific

environmental conditions that underlie problems

and clearly identify those groups and individuals

who can enhance your efforts—human resources,

community resources, political power, etc.

In the environmental approach, the community is

not simply the site for the intervention, but the ve-

hicle for change. To truly reflect community needs

and solutions, coalitions must include residents

and others who experience the alcohol and other

drug-related problems directly, on a regular basis.

These might include residents living near a park

where drugs are sold and consumed; teenagers

with direct knowledge of underage drinking par-

ties and the effects on their friends and class-

mates; or persons recovering from addiction who

understand how relapse and recovery are affected

by high-risk environments where alcohol and other

drugs are easily available.

People who directly experience a problem are

more invested in finding solutions. In the final

analysis, community members can help sustain

environmental change strategies by overseeing

the implementation of efforts over the long term.

Take the opportunity to learn and cultivate your

community members’ skills, talents, abilities,

interests and resources. Your members will

remain active when they are called to contribute

to the cause. Remember that coalition members

need to feel as though there is purpose and

definition to their role within the coalition.

Bolstering coalition leaders

Coalition leaders set the tone for their coalition’s

capacity to engage the community from grass-

roots to policymakers. As a coalition leader, your

main role is as a community mobilizer. Individuals

in leadership positions must be able to clearly

convey what environmental strategies are and why

they should be a focus of the coalition. Relation-

ship building and collaboration are vital to sustain-

ability and must correspond to the coalition’s

collective vision for long-term commitment and

measurable community change.

Engaging law enforcement and judicial officers

Environmental strategies that require law enforcement agencies can be part of a comprehensive, multi-strategy

approach. The coalition’s role is to investigate existing policies and procedures that can benefit the community.

Learn how your coalition can help local law enforcement in analyzing gaps and enforcing current laws.

Consider tapping into non-traditional law enforcement agencies (i.e., game wardens, natural resource officers,

code enforcement, animal protection, fraud investigators, etc.). These agencies face the same problems as the city

police or county sheriff’s departments, but in a different environment or context. Coalitions in rural communities

should consider these agencies valuable partners in addressing environments that are more difficult to reach.

Judicial officers and systems are a large part of policy enforcement. Without their support, violators may not be

convicted or consequences may not be enforced. Consider how the coalition can make their job easier. Failure to

engage local judicial officers may hinder the forward progression of enforcement operations and create tension

among local law enforcement and the judges they stand before in court. Coalitions can seek Attorney Generals’

opinions to support law enforcement and help them effectively defend cases.

In doing your homework, coalitions should:

• Investigate current arrangements among all local law enforcement agencies regarding enforcement (multi-ju-

risdictional agreements, multi-aid agreements, etc.)

• Work to improve and bolster relationships between law enforcement agencies

• Involve local judicial officers and systems prior to an increase in enforcement operations (i.e., Compliance

Checks, Shoulder Taps, DUI Enforcement)

The Coalition Impact: Environmental Prevention StrategiesCADCA’s National Coalition Institute 17

Coalitions that provide direct services or whose

membership consists predominantly of service

providing organizations may find environmental

strategies difficult to implement. Thus, grassroots

mobilization that includes residents, parents,

neighborhood associations, formal and informal

leaders is essential. These individuals can become

the voice of change without the fear of repercus-

sion from an employer or appearing to be acting

solely in their employers’ interests.

Informal leaders can be as effective and influen-

tial as formal leaders. For example, residents are

the “eyes and ears” of the community and can

hold policy makers and other institutions account-

able for ensuring that system changes and poli-

cies are enforced on an ongoing basis.

Leaders—formal and informal—can benefit from

training that develops the skills required to plan

and implement environmental strategies. Some

examples include, but are not limited to:

• Community mobilization including relationship

building skills;

• Training on environmental strategies and their

effects;

• Analyzing and developing effective, enforce-

able policies, including the process for develop-

ing local land use restrictions;

• Appropriate engagement of media;

• Knowledge of how local, state and federal gov-

ernment processes operate;

• Knowledge of community policing;

• Knowledge of alcohol and other drug-related

community problems;

• Knowledge of how local decisions are made

and who makes them;

• Strong communication and facilitation skills;

and

• Comfort working in environments with consid-

erable community dialogue and disparate

opinions.

These are skills generally associated with commu-

nity mobilizers—people who motivate others into

action, fade into the background and share credit

for success. Emphasize the community process to

engage residents and key stakeholders in defining

issues and participating in the development and

implementation of environmental solutions.

Your coalition must continue to build its bench

strength, planning for growth and change over

time. Good leaders move coalition partners and

other stakeholders from the simple to the com-

plex, mediate disagreements and coach members

to represent and articulate coalition positions.

The planning process

Like the processes of community assessment and

capacity building, coalition planning works best

when it incorporates multiple sectors of the com-

munity. Coalition leaders must make planning an

inclusive process, beginning with the prioritization

of the root causes identified in the community

assessment and acknowledgement of underlying

conditions, such as high crime locations.

The choice of how to name and frame issues

should reflect what works for your community,

the language that motivates citizens into action

and sets the stage for a comprehensive response

to shared problems. Listening to community

member—beginning with assessment—and

involving them throughout the planning process

lays the strong foundation a coalition needs to

change environments. Refer to the Institute’s

Assessment and Planning Primers for more

information on data collection and developing a

logic model to inform your coalition’s process for

selecting interventions and activities.

Choosing environmental strategies and planning

for their implementation should be carefully

mapped out by the coalition. Again, no single

strategy will provide the desired results and local-

izing strategies is allowable and encouraged. A

carbon copy of what was done in another commu-

nity will not be the best solution for your commu-

nity. To achieve real, long-term success, take the

time to think through what is viable and what will

create the identified changes. See page 18 for a

chart that illustrates examples of environmental

strategies aimed at specific problems.

The Coalition Impact: Environmental Prevention StrategiesCADCA’s National Coalition Institute 18

Strategy Alcohol Tobacco Illicit Drugs

Environmental policies to limit access

Purchase laws

Compliance checks:

Minimum purchase age

laws actively enforced

Removal of cigarette

machines

Laws prohibiting sale,

possession and

distribution

Price controls

Excise tax;

Ban on “2 for 1” drink

specials

Excise tax;

No free tobacco samples

on military bases

Increase supply reduction to

raise prices

Restrictions on retail

sales or sellers

Limit number of sales

licenses within a

county/city/town

Synar checks;

Limit number of sales

licenses;

Fines for selling to youth

Land use ordinances

enforced on blighted/

abandoned properties;

physical design changes

(increase lighting; plant

shrubs, etc.);

restrictions on sale of

pseudoephedrine and

ephedrine and other meth

precursor chemicals

Environmental policies to influence norms

Legal deterrence

Zero Tolerance laws for

youth under 21 years;

You Use/You Lose laws;

Social Host laws

Source Investigation

Programs

Fines for selling tobacco

to youth

Workplace initiatives;

Asset forfeiture laws

Counteradvertising Ban alcohol sponsorship;

Advertising restrictions

Surgeon General’s

Warning/The Truth

Campaign;

Restriction on samples and

coupons;

Ban television advertising

National Anti-Drug Youth

Media Campaign ads/

websites

Adapted from

Environmental Prevention Strategies: An Introduction and Overview

, Deborah A. Fisher, Ph.D.,

used with permission.

Examples of environmental policies for alcohol, tobacco and illicit drugs

T

able 2.

The Coalition Impact: Environmental Prevention StrategiesCADCA’s National Coalition Institute 19

The environmental strategies approach recognizes

that risks associated with substance use are, in

part, a function of the interplay between the envi-

ronments where an individual uses and the sub-

stances he/she uses (agent). In the environmental

approach, place matters. We recognize that man-

aging the availability of alcohol and other drugs in

specific environments impacts the substances in-

dividuals choose and the amount they use. These

decisions determine the level of risk individuals

and communities experience. The ability to shape

individual’s behavior by structuring what is ex-

pected or permitted in specific environments can

reduce alcohol- and other drug-related problems.

Seven strategies for community change:

A brief explanation

Seven methods that can bring about community

change have been adopted as a useful framework

by CADCA’s Institute. Each of these strategies rep-

resents a key element to build and maintain a

healthy community. In the planning process, utilize

all seven strategies to be as comprehensive as

possible to achieve population-level change. When

focusing on implementation of environmental

strategies, consider the types of information, skill-

building and support activities necessary to move

your interventions forward. You will see that the

strategies overlap and reinforce each other.

CHAPTER 4: ENVIRONMENTAL PREVENTION IN ACTION

Seven strategies to affect community change

1. Provide information—Educational presentations, workshops or seminars, and data or media presentations (e.g., public

service announcements, brochures, billboard campaigns, community meetings, town halls, forums, web-based

communication).

2. Enhance skills—Workshops, seminars or activities designed to increase the skills of participants, members and staff

(e.g., training, technical assistance, distance learning, strategic planning retreats, parenting classes, model programs

in schools).

3. Provide support—Creating opportunities to support people to participate in activities that reduce risk or enhance

protection (e.g., providing alternative activities, mentoring, referrals for services, support groups, youth clubs, parenting

groups, Alcoholics or Narcotics Anonymous).

4. Enhance access/reduce barriers**—Improving systems and processes to increase the ease, ability and opportunity to

utilize systems and services (e.g., access to treatment, childcare, transportation, housing, education, special needs,

cultural and language sensitivity).