Vanderbilt University Law School Vanderbilt University Law School

Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law

Vanderbilt Law School Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship

2023

Education and Electronic Medical Records and Genomics Education and Electronic Medical Records and Genomics

Network, Challenges and Lessons Learned from a Large-Scale Network, Challenges and Lessons Learned from a Large-Scale

Clinical Trial Using Polygenic Risk Scores Clinical Trial Using Polygenic Risk Scores

Ellen Wright Clayton

John J. Connolly

et al.

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/faculty-publications

Part of the Medical Jurisprudence Commons

REVIEW

Education and electronic medical records and

genomics network, challenges, and lessons learned

from a large-scale clinical trial using polygenic risk

scores

ARTICLE INFO

Article history:

Received 2 February 2023

Received in revised form

17 May 2023

Accepted 18 May 2023

Available online 26 May 2023

Keywords:

Education

eMERGE

Genome-Informed Risk Report

Polygenic risk score

PRS

ABSTRACT

Polygenic risk scores (PRS) have potential to improve health care by identifying individuals that

have elevated risk for common complex conditions. Use of PRS in clinical practice, however,

requires careful assessment of the needs and capabilities of patients, providers, and health care

systems. The electronic Medical Records and Genomics (eMERGE) network is conducting a

collaborative study which will return PRS to 25,000 pediatric and adult participants. All par-

ticipants will receive a risk report, potentially classifying them as high risk (~2-10% per con-

dition) for 1 or more of 10 conditions based on PRS. The study population is enriched by

participants from racial and ethnic minority populations, underserved populations, and pop-

ulations who experience poorer medical outcomes.

All 10 eMERGE clinical sites conducted focus groups, interviews, and/or surveys to understand

educational needs among key stakeholders—participants, providers, and/or study staff.

Together, these studies highlighted the need for tools that address the perceived benefit/value of

PRS, types of education/support needed, accessibility, and PRS-related knowledge and under-

standing. Based on findings from these preliminary studies, the network harmonized training

initiatives and formal/informal educational resources.

This paper summarizes eMERGE’s collective approach to assessing educational needs and

developing educational approaches for primary stakeholders. It discusses challenges encoun-

tered and solutions provided.

© 2023 American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics.

Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Introduction

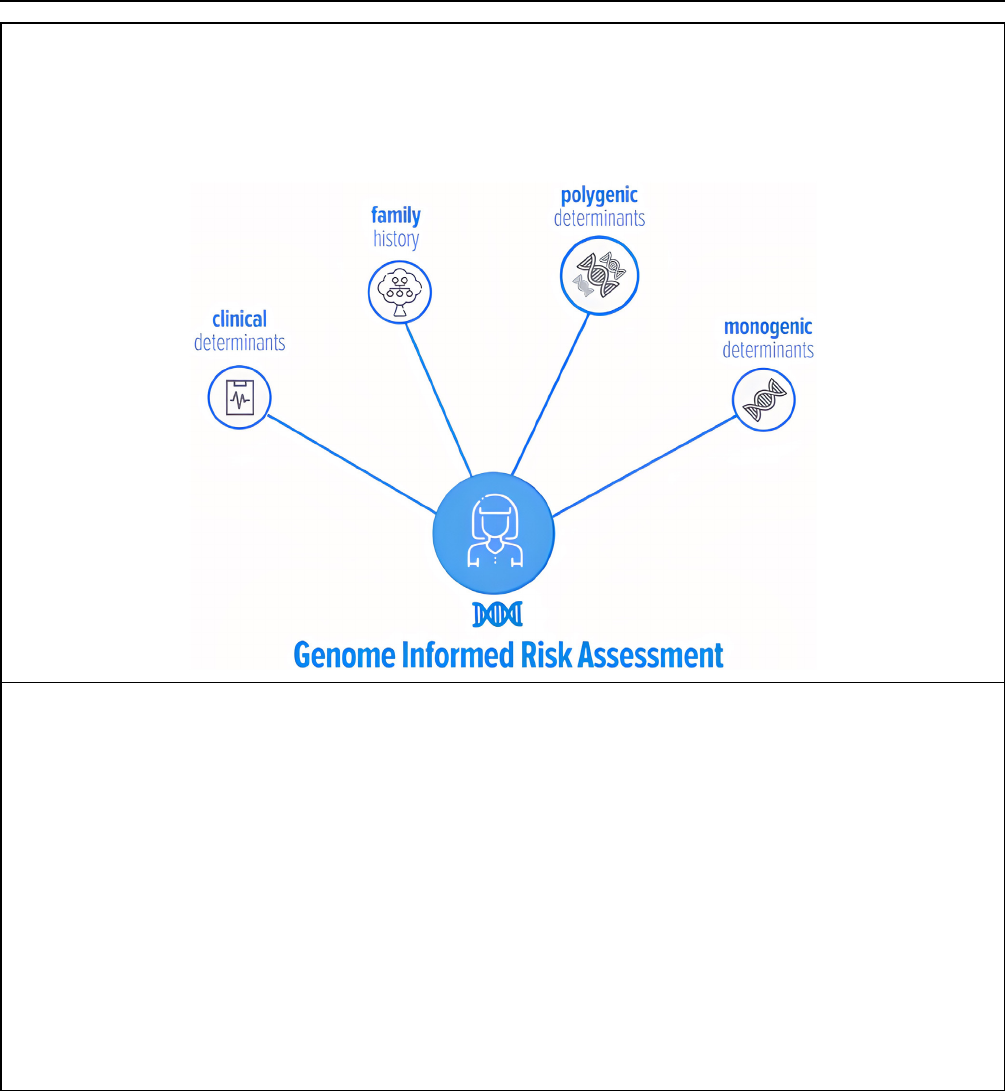

The electronic Medical Records and Genomics (eMERGE)

network was established in 2006 and aims to develop,

disseminate, and apply approaches to research that combine

biorepositories with electronic medical record (EMR) sys-

tems for genomic discovery and genomic medicine

implementation research. In July 2020, Phase IV of the

eMERGE program was launched with the objective of

recruiting 25,000 participants across 10 clinical sites—all of

whom will receive a risk report that includes polygenic risk

scores (PRS), monogenic risk (adults only), family history,

and clinical risk factors. The report is called the Genome

Informed Risk Assessment (GIRA).

*

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to John J. Connolly, Center for Applied Genomics, 3615 Civic Center Blvd, Abramson

Building Suite 1216F, Philadelphia, PA 19104. Email address: [email protected] OR Maya Sabatello, Center for Precision Medicine & Genomics,

Department of Medicine, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, NY 10032. Email address: [email protected]

A full list of authors and affiliations appears at the end of the paper.

Genetics in Medicine (2023) 25, 100906

www.journals.elsevier.com/genetics-in-medicine

doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gim.2023.100906

1098-3600/© 2023 American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Unlike a single research study focused on a specific

condition or population, the results of the eMERGE study

will inform not only how PRS can be used to identify people

at high risk for common conditions but, importantly, if

receiving this risk information helps patients and their pro-

viders make health care decisions to improve the patient’s

overall health. With minimal stated exclusion criteria (eg,

unable to consent, recent bone marrow transplant, or no

medical record at recruitment site), participants are not

selected for presence/absence of disease or susceptibility to

disease. They span a wide spectrum of ages (3-75 years) and

are geographically diverse, recruited from health care cen-

ters across the United States (though biased tow ard prox-

imity to recruitment sites in large urban areas in which

eMERGE sites are based).

In selecting phenot ypes for PRS-based return of results

(RoR), netw ork leaders prioritized the need to generat e

feasible, actionable, and translatable scores for individuals

across 4 groups: African, Asian, European, and Hispanic/

Latino. PRS for a range of phenotypes are promising for

their potential to improve health care/outcomes and have

been shown to outperform clinical predictors for several

diseases.

1-3

Supplemental Table 1 summarizes the final

conditions and thresholds/logic for return. Although condi-

tions such as breast cancer and coronary heart disease are

relatively mature in terms of the validity and potential for

clinical application of relevant PRS, other conditions are

less well established. For this reason, the network collec-

tively conducted an extensive process of PRS validation for

all phenotypes. Phenotype selection and validation pro-

cesses are summarized elsewhere.

4

Returning PRS for multiple conditions, in a clinical

environment, is relatively novel. Best practices are only

beginning to take shape, though forerunners such as the

Polygenic Risk Score Reporting Standards, a joint collab-

oration between the Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen)

Complex Disease Working Group,

5

have been influential.

As outlined in Box 1, eMERGE’s custom GIRA report

classifies participants at “high risk” (or not) for 11 condi-

tions, based on a range of risk factors. For 10 of the 11

conditions, PRS are the primary driver of high-risk reporting

and for most are prerequisite to returning other risk factors

such as family history and/or clinical history for most con-

ditions (ie, for most conditions, high clinical/family history

risk is not retur ned in the absence of high risk PRS—see

Supplemental Table 1 for more details). The relative novelty

of returning and integrating PRS for multiple conditions

represents an exciting research opportunity but also poses

educational challenges.

Importantly, PRS performance diff ers by group. Scores

for many condition s were originally developed using ge-

notypes from individuals of European ancestries and

therefore tended to perform better in European cohorts.

6-8

A

major goal of the eMERGE network is to tackle a long-

documented bias in who participates in genomics resear ch.

In the US where health disparities are significantly higher

than in other high- and middle-income countries,

9,10

it is

especially important that PRS-linked phenotypes be vali-

dated in historically underrepresented cohorts. Per the rele-

vant National Institutes of Health Requests for Application

(HG-19-014), “Minority” (also non-European ancestry) re-

fers to individuals from the following populations: African

American or Black, Asian, American Indian or Alaska

Native, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, or Latino/

Hispanic. Six of the 10 eMERGE sites aim to recruit at least

75% of their participants from racial or ethnic minority

populations, underserved populations, or populations that

experience poorer medical outcomes. The remaining 4 sites

have a 35% recruitment target for minority/underserved

communities. PRS for all conditions implemented in

eMERGE-IV were validated across at least 2 of 4 groups

(African, Asian, European, and Hispanic/Latino). From an

educational perspective, network members agreed upon the

importance of both acknowledging the historical short-

comings of the genomics community in delivering equitable

resources and the urgent effort to address this imbalance.

Multiple clinical sites led independent projects engaging

local communities and underrepresented populations to

assist in designing educational materials and approaches,

recruitment strategies, and offer guidance on study imple-

mentation. Additionally, the eMERGE network has been

transparent about the fact that not all PRS are validated for

all 4 groups .

In addition to marginalized racial and ethnic populations,

eMERGE has made efforts toward inclusion of people with

disability, in which health disparities are among the largest

in the United States.

11

Despite research indicating that many

people with disability express high interest in participation

in precision medicine resear ch, they often also experience

numerous barriers for participation in mainstream

research.

12

Key barriers include accessibility of facilities

and study materials and limited knowledge among re-

searchers and research staff about how to design inclusive

studies. To address some of these challenges, eMERGE

collects self-reported disability status information among

other demographic questions in its baseline survey. The

development of educational material for the network

similarly considered issues of accessibility.

Overall, PRS will be returned to a large cohort (N =

25,000), therefore requiring scalable educational resources.

Across all sites, approximately 24% of research participants

are expected to be classified as high risk for at least 1

condition (see Supplemental Table 1), necessitating coor-

dination between clinical sites for consistency in study

design and risk reporting.

The latest phase of the eMERGE program constitutes a

model of genomic medicine that is potentially generalizable

and scalable to a large proportion of the US population and

other countries with genomics capacity and access to EMRs.

Education will be a key component in helping to develop a

comprehensive suite of resources and know-how that sup-

port the use of genomic information in clinical care of

diverse populations. It will also be critical for promoting

team-oriented genomic care, encompassing patients,

2 J.J. Connolly et al.

research participant, health care provider, or study team

member. The experiences, processes, and lessons learn ed

from eMERGE IV can shed light on these issues and inform

other consortia that are considering simil ar issues or related

work.

A crucial component of this coordinated approach is the

need to unders tand and subsequently address the educa-

tional requirements of eMERGE participants, providers, and

site representatives (eg, study coordinators, recruiters, and

clinical staff returning results). For this purpose, an Edu-

cation Subgroup was created to develop and coordinate the

work surrounding educational material. The Education

Subgroup comprises members from all eMERGE sites and

diverse expertise. This paper will review the network’s

collective approach to education through needs assessment

and subsequent resource development. It specifically

Box 1. Main elements of the genome-informed risk assessment (GIRA). Genetic results, along with family and medical

history are used to estimate participants’ risk of developing 11 common conditions (Supplemental Table 1). The GIRA can

classify participants at “high risk” of developing a condition based on several factors. For 2 conditions (break cancer and

CHD), an integrated absolute risk score is presented; for the others, the information is displayed separately.

4

Note, in

addition to the GIRA, a PRS report and monogenic report (if relevant) are produced separately and appended to the GIRA.

Polygenic results: In eMERGE, PRS are calculated for 10 of the 11 conditions implemented. Each phenotype has a specific PRS

percentile cut-off (2%-10%) that is associated with high risk. The participant’s exact percentile is not provided. For breast cancer

and coronary heart disease, PRS are integrated with other risk factors to achieve a global score, incorporating the other risk

elements discussed below. Breast cancer used the BOADICEA model.

20

Monogenic results: Adult participants (18+ YO) provide an additional biosample, which is assessed for monogenic susceptibility across

a 16-gene panel. Relevant conditions tested are the following: Constitutional mismatch repair deficiency syndrome (CMMR-D), Lynch

syndrome, BRCA1/BRCA2-Associated Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC) syndrome, PALB2-related conditions, PTEN-related

conditions, Li Fraumeni syndrome (LFS), Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS), Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH), and LMNA-related

conditions.

21

Family history: Participants are asked to provide their family health history for all conditions using an online tool called MeTree,

developed at Duke University.

22

For some conditions (eg, coronary heart disease), positive family history alone can trigger high risk.

For other conditions (eg, hypercholesterolemia) positive family history is returned only if a participant is at high PRS/monogenic

risk for the same condition.

Clinical risk factors: Data from participant self-report surveys and the EMR will be used to calculate risk, or contextualize high genetic

risk. Examples of these clinical risk factors include most recent hemoglobin A1C, reported physical activity, and BMI, when

available. Similar to family history, high risk for any given condition is only returned if a participant is at high PRS/monogenic risk

for the same condition.

J.J. Connolly et al. 3

addresses (1) assessment of educational needs around PRS,

(2) the process of developing educational resources, and (3)

challenges and lessons learned.

Assessment of educational needs around PRS

To facilitate RoR and study coordination, eMERGE leaders

developed a range of initiatives to understand and address

educational requirements for its many constituents as sum-

marized in Table 1. Key to these were Ethical, Legal, and

Social Implication (ELSI) studies conducted at member sites

in the first 2 years of the eMERGE study. These ELSI

studies differed in scope and methods used (eg, inte rviews

or focus groups) but all explored perspe ctives and needs

related to study implementation. Ultimately, these studies

informed the development of educational resources, which

are summarized in Table 2. The resources address

eMERGE’s primary stakeholders: patients/participants,

providers, and study teams.

In addition to the wi de-range of ELSI studies that

informed study design and relevant educational initiatives, a

huge effort was undert aken across the network to solicit

input from a broad spectrum of individuals. Sites directly

engaged with different community groups and advisory

boards, including those representing Black/African Amer-

ican community members, pediatric- and adult-specific

subcohorts, health care providers with a range of back-

grounds, and hospital leadership. Collectively, these

generated feedback on study design, knowledge of genetics,

and interest in participating in the study. Feedback from

these groups, though not (necessarily) captured in “formal”

research design, provided important discussion points for

consideration by eMERGE education leadership.

Development of educational resources

Design of the GIRA

All 25,000 participants across the eMERGE network will

receive a novel report - the GIRA. This includes approxi-

mately 6000 participants expected to be identified as high

risk. The GIRA was custom-developed for returning results

to participants, with relevant features including PRS,

monogenic risk, family history, and clinical risk.

In developing the network-wide risk report, several fea-

tures specific to the eMERGE study were important to

consider, including the novelty of the study objectives

(particularly PRS), the diversity of participants, (particularly

in terms of race, ethnicity, and age), and the different

backgrounds/needs of providers and patients in interacting

with relevant content. The goals of the GIRA were to inform

participants of their study results, to provide educational

material about the associated condition, and to provide care

recommendations for the participant and their provider. In-

dividual eMERGE sites drafted risk report language and

recommendations for the condition(s) led by that site.

Relevant material included educational content to help pa-

tients/providers understand the conditions, the implications

of their risk result, and available options for next steps to

reduce high risk. This approach was the most pragmatic

because it allowed the network to leverage local expertise

and resources specific of the site(s) leading respective con-

ditions. However, it yielded substantial variability in the

requisite detail and language level . Once drafts wer e created,

a GIRA development subgroup worked to standardize the

language and graphics for all 11 eMERGE conditions.

Educational resources for research participants

Concepts such as “monogenic” and “polygenic” risk are

unlikely to be familiar to this broadly healthy research

cohort, presenting a challenge for returning

results—particularly for individuals not identified as high

risk, who may not have the opportunity to discuss results

with a health professional. Informal education resources can

play a major role in addressing this issue. Surveys show that

the majority of internet users in the United States use online

sources as their primary source of health information.

23,24

However, the lack of reliable infor mation has been well

documented, sowing distrust among users.

25

Authoritative

print, video, and internet multimedia developed by univer-

sities, hospitals, and science centers can help to address the

communication gap between research/medical communities

and the general public. A large consensus in the scientific

community favors the free dissemination of information as

widely as possible.

26

To this end, the eMERGE network

clinical sites developed educational materials for online

dissemination, aiming to engage participants to be fully

informed decision makers throughout their participation.

Study website. Much of the educational content pro-

duced for the GIRA, along with many other efforts across

the network, was repurposed for a participant-facing website

www.emerge.study. This website organizes the broad

spectrum of participant-facing educational materials in one

location for current and prospective participants to refer-

ence. Participants can use this website throughout their

participation in eMERGE, from finding contact information

for their site to register for eMERGE, all the way up to

viewing the GIRA frequently asked questions (FAQs) and

condition-specific education pages while waiting for their

results.

In creating the web resource, an eMERGE web team dis-

cussed scenarios most likely to be relevant to users, agreeing

upon 4: (1) prospective participants interested in learning

more about the study, (2) enrolled participants interested in

learning about next steps or discu ssing questions, (3) in-

dividuals looking to contact a local eMERGE site for any

reason, and (4) providers with questions about the eMERGE

study and/or GIRA recommendations. A dedicated section

was built around each of these scenarios with separate FAQs

for providers/participants, and similarly distinct discussion of

study protocols tailored to respective users.

All material was created in both English and Spanish and

made openly-available to the general public, with no re-

quirements for registration. Before launch, usability-testing

4 J.J. Connolly et al.

Table 1 Key eMERGE stakeholders and respective educational objectives. A one-size-fits-all approach to education is unsuitable for a

program involving heterogeneous stakeholders with disparate educational objectives. Acknowledging the numerous constituents across the

research clinical-spectrum, the eMERGE Education Subgroup identified 3 primary target groups: research participants, research staff, and

health care providers. These groups have necessarily different competencies and priorities, which require targeted approaches to capturing

learning needs and developing educational resources. This table summarizes the main research considerations considered for each group and

the respective educational objectives addressed:

A. General public: Broadly healthy population. Non-medically oriented individuals.

B. Health care providers: Medically-trained individuals working in the clinical domain. The individual will have direct contact with the

eMERGE participant as a patient at their clinical site. However, 2 important criteria are consistent across the network: (1) High risk reports

are returned in-person; (2) Reports that do not include a high-risk result are returned to the participant without in-person consultation.

C. Study staff: Medical- and/or research-orientated individual that is a member of an eMERGE

a

clinical or support center

b

.

Unless explicitly stated, the points delineated below arose from eMERGE ’ s preliminary ELSI studies.

A. Research Participants:

Research Considerations

Objective(s) of Educational

Resources Relevant Findings and Lessons Learned

Develop a novel risk report (the

GIRA) that integrates PRS,

monogenic risk, family history,

and clinical risk factors.

Ensure patient-participants

understand the risk report

(GIRA).

• Patients may struggle to understand PRS-based reports.

13

• Misinterpreting percentiles as absolute risk is a common

mistake.

13

• Patients prefer absolute risk information and a continuous

result (vs, high risk/not high risk) report design.

13

• Patients have a preference for visualization.

13

• Patients/community members express a need for simple

language,

13

including Spanish versions among target sub-

cohorts.

All 25,000 participants will

receive a GIRA risk report. Of

these, ~6000 will be identified

as high-risk for 1 or more

conditions

Avoid harm by worry.

Avoid false reassurance for

individuals not at high risk.

• Clarify that “high risk” and “low risk” are not indicative of a

diagnosis.

• For high-risk participants, results should be returned directly

by a genetic counselor, physician, or trained clinical research

professional.

• Provide system navigation for those who are at high risk For

participants not at high-risk for any conditions, results can be

returned to the EMR and/or by letter. In this instance, edu-

cation is reliant upon the clarity and comprehensiveness of

the risk report, and supplemented by informal educational

resources including brochures, video, and study website.

Facilitate easy access to reliable

information about PRS and the

eMERGE study

Develop accessible study website

to engage participants to be

fully informed decision makers

throughout their entire

participation.

• Delineate subsections likely to be relevant to users. For

eMERGE this includes:

○

Prospective participants interested in learning more about

the study.

○

Enrolled participants with questions about next steps.

○

Individuals looking to contact a local eMERGE site.

○

Providers with questions about the eMERGE study and/or

GIRA.

• Translate content if targeting a sub-cohort with different

language capacity.

• Apply usability testing to address functionality, clarity, and

relevance.

• Capture and review analytics.

Minority Enriched: Six of the 10

eMERGE sites aim to recruit at

least 75% of their participants

from racial or ethnic minority

populations, underserved

populations, or populations

who experience poorer medical

outcomes.

Provide cohort-appropriate

educational material and

approaches.

• Leverage off-line forms of communication, including

community-based newspapers, magazines, and radio.

• Opportunities for interpersonal conversations are important

for participants of racial or ethnic minority populations for

responding to questions and concerns.

• Per above, Spanish versions of educational material can help

target sub-cohorts.

(continued)

J.J. Connolly et al. 5

Table 1 Continued

A. Research Participants:

Research Considerations

Objective(s) of Educational

Resources Relevant Findings and Lessons Learned

Age Spectrum: Participants span

a pediatric-adult age spectrum

(3-75 years).

Pediatric and adult participants

receive different GIRA reports,

with different conditions

relevant to each. In addition,

adults will receive a

monogenic risk report for a

discrete number of conditions.

Understand needs of different

sub-cohorts in terms of

expectations.

Communicate clearly implications

of respective phenotypes.

• Parents face barriers in acting on recommendations,

14

which

reflect previously-reported limitations for minority and un-

derrepresented communities.

15,16

Perhaps the most notable

barrier that participants reported was existing behavioral

health issues in their children. Given the high prevalence of

conditions such as ADHD (9.4%),

17

behavioral conduct

(7.4%), and anxiety problems (7.1%),

18

behavioral health

clearly needs to be taken into consideration when strategizing

risk reduction in children.

• Younger participants (20s and 30s) may be lower resourced

and/or less motivated to address a risk in the future (vs older

participants).

B. Healthcare Providers

Research Considerations Educational Objective(s) Relevant Findings and Lessons Learned

Large-scale return of results

leveraging PRS is novel.

Improve genomic knowledge by

providing templates and

resources to facilitate return

of results and

recommendations for follow-

up care.

Provide educational resources

that can be shared with

patients.

• Providers probed for their reactions to PRS reports of different

designs, reported that

13

:

○

The report is more than just communicating a result, but

integral to the whole interaction with the patient.

○

The Limitations section of the GIRA report should make it

very clear what these mean for the patient.

○

Education can help in becoming comfortable with their

“spiel.”

• Providers request different types of educational

materials—some that would enhance their own knowledge

and some that could be shared with patients.

Primary care providers and health

care providers may not be

aware of the eMERGE study

Provide as-needed resources to

support encounters in which

the program may be

unfamiliar.

Provide an online resource that

clearly outlines program goals

and report implications.

• Many PCPs are inexperienced with PRS and may feel

uncomfortable using it in clinical practice. In particular,

clinicians may not be comfortable returning results that are

not within their immediate expertise and they have limited

time to do so.

• PCPs express a preference for easy to use, non-time-

consuming material—preferably, info that can be found by

clicking a link and consumed quickly (eg, versus watching a

video).

• Many providers would prefer forewarning of pending genetic

report information

• Endorsement or actual guidelines from relevant specialty

societies would promote trust in test reports.

• Some providers were interested in technical information

regarding GIRA development, available outcome data, and

other published research. Links to peer reviewed journal

articles would promote trust in the test reports.

• Online resource should include the following:

○

Sources for guidelines and recommendations.

○

Contact details for local teams.

• Supporting educational initiatives preferred by providers

include:

○

An online webinar with CME.

○

Available online recording.

○

Separate online webinar to practices where recruitment will

be high.

○

The option to provide in-person “lunch and learn” sessions.

○

Modeling of results return by a PCP for both high- and low-

risk scores.

(continued)

6 J.J. Connolly et al.

was performed on a small convenience sample of in-

dividuals (N = 5), which addressed functionality, clarity,

and appropriateness of resources, yielding minor revisions

in content structure and language. To monitor usage of the

site, analytics are captured and reviewed on a monthly basis,

with the opportunity to formatively adapt to relevance/

popularity of content on an ongoing basis. (However, it is a

requirement of the central institutional review board [IRB]

that all study material on the website be approved by the

IRB, necessarily limiting the speed with which any content

can be updated.) The site follows Section 504 of the 1973

Rehabilitation Act to prevent discrimination on the basis of

disability. Care was taken to ensure broad representation in

images, including diversity in race, ethnicity, disability,

gender, and age. This approach was similarly applied in

developing other content for dissemination across eMERGE

stakeholders (brochures, flyers, etc.).

Education resources for health care providers

In addition to receiving the GIRA directly (either through a

patient portal or by mail), high-risk participants are contacted

by a genetic counselor, clinician, or trained health profes-

sional, who recommend that the high-risk participant follows

up with their local primary care provider (PCP) where addi-

tional testing/referral may be required. Importantly, the

majority of PCPs across eMERGE will likely be naive to the

eMERGE study and may encounter the GIRA for the first

time during a clinical encounter with a participant-patient. A

range of educational approaches are therefore required to

support providers in discussing and acting upon GIRA health

care recommendations.

We learned from our ELSI studies that, though

comfortable explaining risk to patients, many PCPs are

inexperienced with PRS technology and may feel uncom-

fortable using it as a tool in clinical practice. They also

expressed concerns about being caught “off guard,” not

having heard about the study in advance, and they had

questions and concerns about the validity of the PRS and

implications for prevention and treatment. This gap between

knowledge and practice with PRS is a potential obstacle for

uptake among providers, with downstream ramifications for

(possible difficulty in) implementing care recommendations.

Moreover, clinicians may not be comfortable discussing

results that are beyond thei r immediate expertise, in partic-

ular when time constrained. Rather, they expressed a pref-

erence for easy to use, non-time-consuming material,

Physicians were also interested in accessible fact sheets for

sharing with patients. eMERGE education initiatives that

address these findings include the provision of clinical de-

cision support (CDS), development of custom web content,

Table 1 Continued

B. Healthcare Providers

Research Considerations Educational Objective(s) Relevant Findings and Lessons Learned

Provide clinical decision support:

(CDS) to facilitate reporting

and downstream health care

implementation

A well-designed CDS

development and validation

plan can facilitate

implementation of PRS-based

recommendations.

• Reflecting a theme from previous work,

19

PCPs expressed a

desire for CDS targeted to primary care that may include

actionable steps in the EMR such as the following:

○

Modification of the problem list.

○

Reviewing provider education.

○

Provision of patient-family education.

○

Referrals to specialists, and/or

○

Ordering a preventive medication.

C. Study Staff

Research Considerations Educational Objective(s) Relevant Findings and Lessons Learned

Recruiters, Coordinators,

Resource Developers, and

Other Research Staff are highly

diverse in terms of

background, experience, and

training. Staff require answers

regarding study components

and key research objectives.

Need for accessible educational

resources that address

misperceptions.

Disseminate standard resources/

messaging across the network.

Collective need to coordinate and share know-how and resources.

Core elements required for centralized access:

• (Electronic) data capture and tracking.

• (Electronic) consent driven by a single IRB.

• Standard operating procedures (SOPs) for sample management

and ordering, and engagement.

• Provision of regular training.

A centralized database accessible to clinical sites can streamline

and standardize Network supports (eMERGE utilized REDCap for

this purpose):

• Support data integration from third-party providers for shared

SOP development and to facilitate collective testing and

training.

a

Clinical sites: Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC), Columbia University, Mass General

Brigham, Mayo Clinic, Mount Sinai, Northwestern University, University of Alabama At Birmingham, University of Washington, and Vanderbilt University

Medical Center.

b

Support Sites: Coordinating Center: Vanderbilt University Medical Center; Genotyping Center: Broad; Monogenic Sequencing: Invitae; Family History:

MeTree (Duke University).

J.J. Connolly et al. 7

Table 2 Resources developed by eMERGE network sites. Unless otherwise stated in Column 1, relevant resources are used network-wide by

all eMERGE sites (resources delineated as site-specific were nevertheless shared with network partners).

Resource Stakeholder Description

GIRA Report Participant and Provider The GIRA (Genome Informed Risk Assessment), the novel result report issued in this

study, caters to both patients and providers through its accessible phrasing and

diagrams, as well as separate FAQ sections for participants and providers.

Infographics Participant Infographics were developed through an iterative process, including 10 “think

aloud” sessions in English and Spanish with community members. The

infographics explain the components of a GIRA, the meaning of genetic

predisposition for a disease, and general recommendations for both high-risk and

not at high-risk individuals.

Participant and Provider

facing website

(www.emerge.study)

Participant and Provider The website is a resource for participants to learn about the goals of the study, the

timeline of participation, and information about results. A subgroup led by CHOP

was formed to spearhead the development of the website. They used the services

of third-party vendor Culture Shift to design the website and translate it into

Spanish. In addition, the website follows requirements for disability accessibility

Participant and provider

FAQ’s/patient

education pages

Participant and Provider Centrally-developed educational material included a plain-language brochure,

common FAQs, and patient/provider education pages for use across the network.

Clinician education

resources (site-specific)

Provider Several sites developed local CDS to facilitate on-demand education, focused on

implementing GIRA guidelines. Although network members shared expertise and

methodologies, individual sites developed individualized CDS to align with local

institutional infrastructure and policy.

Bilingual content Participant Although not a “resource” in the traditional sense, the provision of educational

material in Spanish as well as English was important to addressing representation

and included here as a core component of Education strategy.

Animated recruitment

video to explain

eMERGE

Prospective participant Animated 2-minute video developed by collaborators across the Network and made

available to all prospective and existing participants.

Participant-facing online

presentations/webinars

[site-specific]

Participant Two sites made short (~7-minute) presentations available to (prospective)

participants. These focused on explaining PRS, their clinical use, and current

limitations, including increased accuracy in populations with origins from Europe

compared with other populations. They also defined genetic terms, such as 'DNA',

'gene', and 'genetic variants'. Additionally, a vignette where a patient was offered

a PRS for hypercholesterolemia was incorporated to help contextualize the

application of PRS for common health conditions

Provider-facing in-person

presentations

[site-specific]

Provider Provider-facing presentations introducing eMERGE study, implementation, and

basic concepts around PRS were given at primary care recruitment sites (a) at the

start of recruitment and (b) leading up to return of results. Presentations also

directed providers to the eMERGE.study website and staff contact information.

Presentations were given at grand rounds, lab-meetings, departmental meetings,

and scheduled informational sessions.

Provider-facing online

presentations/webinars

[site-specific]

Provider Following the same format as in-person presentations, 15 to 20-minute webinars

were recorded and made available online for provider access.

Provider-facing PRS online

media

Provider Easily navigable online resource containing practical information about the study,

specifically designed for use during routine patient care activity.

Clinical hotline

[site-specific]

Provider One site developed an expert clinician hotline to connect clinicians with study

experts to address any questions related to study results.

Staff-facing PowerPoint Study Team PowerPoint presentation given to all eMERGE research staff members. Disseminated

Network-wide over a series of “classes” to introduce the basics of eMERGE and

create a shared baseline of knowledge amongst staff members. Creating these

slides was a network wide effort undertaken by the education workgroup. The

presentation was given by multiple members of this workgroup.

(continued)

8 J.J. Connolly et al.

and creation of a range of learning sessions, and are dis-

cussed immediately below.

CDS. Interviews with providers at several eMERGE

sites indicated a preference for CDS to help implement GIRA

recommendations. CDS is an important component of edu-

cation strategy, addressing the need for continuous and cur-

rent knowledge in daily practice

27

and can also address the

complex sociotechnical factors that arise from genomic test

results.

19

Reflecting a theme from previous work,

19,28

in-

terviews with providers underline a desire for CDS targeted

at primary care that may include actionable steps in the EMR,

such as modification of the problem list, reviewing provider

education, provision of patient-family education, referrals to

specialists, and/or ordering a preventive medication. PCPs

welcomed CDS for positive results only, with a strong

preference for clear recommendations and next steps.

Custom web content for providers. To facilitate easy

access to reliable information about PRS and the eMERGE

study, the emerge.study website was updated with provider-

specific content. Interviews with physicians and clinical

leaders indicated that links to peer-reviewed papers and

endorsement or actual guidelines from relevant specialty

societies would make them more like ly to trust and use these

tests. The site was updated with links to source material and

guidelines, on which GIRA recommendations are based. In

addition, provider-specific FAQs were published, in which a

range of themes incl uded a program overview, the role of

the health care provider in eMERGE, the patient/participant

experience, and data privacy.

Webinars and other learning sessions. Although

recognizing a preference for informal, just-in-time, resources,

several initiatives were developed for providers preferring

more increased engagement. These are particularly pertinent

to health care practices/clinics enriched for eMERGE patient-

participants and include the following:

• An online webinar with Continuing Medical Educa-

tion—several sites offered Continuing Medical Edu-

cation credits centered on PRS and the GIRA

• Targeted online webinars in practices in which

recruitment will be highest

• Provision of webinar recordings available to PCPs

online

• In-person “lunch and learn” sessions at practices with a

high level of eMERGE participation.

These initiatives were considered necessary to supplement

resources that are intentionally not time consuming and

providing a more in-depth perspective on the goals and impli-

cations of the eMERGE program. Webinars and presentations

focused on explaining PRS, their clinical use, and current

limitations, including increased accuracy in populations with

origins from Europe compared with other populations. Sites

focused on recruiting Hispanic individuals offered relevant

educational resources in both Spanish and English.

RoR training sessions were developed to help coordinate

RoR and to ensure that individuals felt confident to discuss

this new form of results. A content guide was developed that

collected network resources, including, lecture series, articles,

and tools to aid return. Talking points for high-risk pediatric

PRS results, high-risk adult PRS results, monogenic results,

and edge cases were also generated. The network also pro-

vided staff the option to participate in mock roleplay sessions.

Potential scenarios and mock GIRAs were generated, and

those who wanted the additional practice had the opportunity

to gain feedback on ways to better manage the RoR session.

Understanding the need for ongoing communication and

Table 2 Continued

Resource Stakeholder Description

Research assistant office

hours

Study Team Biweekly meetings open to any Network member focused on answering the

questions and addressing the concerns of coordinators/recruiters/research

assistants. Open space to solicit advice from others and collaboratively solve

problems and share tips.

Centralized staff support

and training

Study Team The Network Coordinating Center hosted frequent education/training program for

staff at all sites and developed several standard operating procedure documents

consisting relevant to study implementation and general utilization of the

interface.

Return of return of result

staff training materials

Study Team Several tools were created by the Network for return of result staff members to

utilize and prepare for the sessions. A content guide was developed to provide

staff with educational resources needed to efficiently explain results to

participants. Talking points for the various return of result sessions were created

to help outline the sessions and to guide sessions. Finally, mock roleplay sessions

were held among various members across the Network to allow individuals to

practice returning results scenarios in a training environment.

Return of results round

tables

Study Team Biweekly meetings open to any Network member who is involved in the return of

results process to discuss shared experiences. Opportunity to gain feedback on

how the sessions went and ways to improve the discussion of results.

CDS, clinical decision support; CHOP, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia; eMERGE, electronic Medical Records and Genomics; FAQs, frequently asked

questions; GIRA, Genome Informed Risk Assessment; PRS, plygenic risk scores.

J.J. Connolly et al. 9

feedback about RoR sessions, the network also hosted

biweekly round tables for staff members to share experiences

and learn from the experiences of other s.

Education resources for recruiters and study coordinators

Any large program will require delegation of workload

across several subgroups. Although essential from an

organizational perspective, an unwelcome consequence is

the potential for respective workgroups to become siloed

and detached from the broader mission. In the context of

eMERGE, this is of particular concern to team members

directly interacting with participants and who are required to

cogently address participants’ questions and concerns. To

provide the requisite resources for participant engagement,

the network developed and conducted a series of training

sessions for coordinator and recruitment teams, which

reviewed program goals and approaches and anticipated

questions from (prospective) participants. The goal was to

ensure study members meet a standard minimum in terms of

baseline knowledge of the eMERGE program and imple-

mentation requi rements.

The primary staff education initiative was developed and

coordinated to begin 1 to 2 months before the first partici-

pants were enrol led. A 2.5-hour training curriculum was

developed for recruiters and study coordinators across all 10

clinical sites and focused on program goals and relevant

study themes such as genetics; PRS; disease risk; and lim-

itations of disease risk prediction for certain groups study

privacy, study partners, and consent language.

Importantly, a series of form ative assessments were in-

tegrated into the session, facilitating real-time feedback from

attendees, with the opportunity to pivot accordingly. A set

of multiple-choice questions addressing the major topics

covered in the training sessions were prepared in advance

and integrated into a polling feature, which allo ws the

audience members to answ er questions and have their an-

swers recorded and displayed for the group. These questions

were asked after each topic was presented and used to assess

whether the audience had unders tood the content, reinforce

major points, and add additional explanations if indicated.

Coordination. Additional suppor t focused on know-

how related to the use of genomic information in clinical

care. This leveraged a centralized data capture portal built in

REDCap,

29,30

which allowed participants to electronically

consent and enter survey data, while also providing sites the

ability to track participants and send/receive data from

Network data partners. The Network Coordinating Center

(Vanderbilt University Medical Center [VUMC]) hosted

frequent education/training programs for staff at all sites and

developed several standard operating procedure docum ents

consisting relevant to study implementation and general

utilization of the interface.

Challenges and Lessons Learned

Although each clinical site necess arily has distinct de-

mographic and institutional priorities, common themes from

eMERGE’s coll ective research and approaches have been

critical in driving network-wide collaboration. We hope that

our shared initiatives can be instructive to other consortia

and/or individual sites similarly involved in operationaliz-

ing/expanding precision medicine programs and propose

several discussion points.

Need for harmonization

Among the biggest challenges, educationally, for eMERGE

has been to harmonize the efforts of 10 different sites,

operating from 10 different funded proposals, albeit with

shared goals. Clinical sites in eMERGE are individually

focused on disparate target populations (eg, African, Asian,

European, and Hispanic), age groups (adult/pediatric), and

institutional priorities. These align with different language

or communication preferences. An important part of edu-

cation strategy is making sure these priorities are all repre-

sented and messaging is consistent across groups. Virtually

all eMERGE sites used community engagement and input

from relevant community groups was important in high-

lighting requirements, as well as potential gaps in under-

standing. The importance of consultation with these groups

early in the planning process should be stressed because

relevant feedback was adopted into educational materials

through FAQs, videos, and presentations.

Centralized coordination was c ritical to the harmoniza-

tion process. Although somewhat unwieldy from a logistical

perspective, the network’s use of a single IRB greatly

facilitated harmonization of educational material—ensuring

all sites were working from a common resource set. Simi-

larly, using a single site (VUMC) to generate the GIRA

ensured sites were working from a level playing field in

terms of the validity of the final product being returned. This

further ensured that content created for patients and pro-

viders was applicable to all sites. Similarly, training and

educational material for study teams was the same for all

sites and based on a report (GIRA) that is consistent for all

research participants.

Targeting different stakeholders

Aone-size-fits-all approach to education is unsuitable for a

program with heterogeneous stakeholders who have disparate

educational objectives. Acknowledging the numerous con-

stituents across the research-clinical spectrum, the eMERGE

Education Subgroup identified 3 primary target groups:

research participants, research staff, and health care pro-

viders. These groups have necessarily different competencies

and priorities, which require targeted approaches to capturing

learning needs and developing educational resources.

Awareness of barriers for participants

A common theme in genetic literature is the difficulty pa-

tients/participants have in inte rpreting risk, and this theme is

10 J.J. Connolly et al.

borne out again in relation to PRS.

31,32

From an educational

perspective, it is clear that resources should be spent

determining the extent to which participants understand risk

as reported to them, to plainly stress that they are at higher

than normal risk where this is relevant, and to simulta-

neously avoid genetic determinism. Including next steps and

ways to reduce risk are practical educational steps that may

facilitate implementation.

Relatedly, several ELSI studies in eMERGE identified

obstacles participants face in following through on health

care recommendations. Collectively, these obstacles stress

that the risk result does not exist in a vacuum and that

numerous factors can affect a participant’s likelihood of

following recommendations. For example, for parents of

pediatric participants, a high-risk report may need to

“compete” with existing behavioral health issues in chil-

dren.

14

Similarly, adults face competing priorities and as is-

sues of access that influence the feasibility of some

recommendations. It is critical that health care providers be

aware of such barriers (eg, other medical/behavioral problems

or resource/time scarcity) and address them where relevant.

Providers interacting with risk reports should be reminded of

these factors, whereas recommendations for patients/partici-

pants need to be cognizant of the wider psychosocial context.

Finally, these findings underscore the importance of trust

between patients and providers. Participants in this study

emphasized the importance of access to a trusted resource

with whom they could review the results and ask questions.

33

Cognizance of implementation barriers for

providers

Studies from several sites found that clinicians may not be

comfortable returning results that are not within their im-

mediate expertise and have limited time to do so. Given the

novelty of PRS in the clinical environment, this presents an

educational challenge to provider support for RoR, and also

prompts ELSI-related discussions on the readiness of pro-

viders to interact with these types of results. As mentioned

above, the language and formatting of the GIRA is critical to

the patient-provider interaction and may be the centerpiece

of the clinical encounter. This stresses the need for plain and

uncomplicated language, as well as an awareness of diffi-

culties in risk-perception among many participants. Simi-

larly, from a practical educat ional perspective, the

limitations section of the risk report should be very clear on

implications for the patient.

The provision of effective CDS can facilitate provider

interactions with the GIRA and was highlighted as a

requirement among providers in interviews at 2 sit es.

Visualization and risk preferences matter

Health and genomic literacy can affect genomic utilization

and participation in genomic research, but studies indicate

that genomic literacy in the United States is limited.

34,35

Challenges are pronounced for individuals with limited

oral, print, or graph-reading literacy and further augmented

for individuals whose first language is other than English.

Infographics can be an important tool in increasing health

literacy

36-38

and in particular addressing deficits in under-

standing complex health concepts,

37

including genomics

and genetic risk factors.

39

For eMERGE, infographics were

developed through an iterative process, including modified

“think aloud” sessions with English and Spanish-speakers

(overall n = 10) to explain the components of a GIRA

and the meaning of genetic predisposition for a disease, as

well as recommendations for both high-risk and not at high-

risk individuals.

Centralized training for study teams

Finally, given the novelty, large scale , and wide scope of the

project, centralized training of study teams is strongly rec-

ommended as an educational output. Clinical and research

teams at diff erent sites differ greatly in terms of knowledge,

experience, and understanding of study goals and health care

best practices. A major effort was undertaken by the coordi-

nating center to standardize enrollment tools and reporting

resources, requiring the generation and implementation of

SOPs for all major aspects of the program (including, but not

limited to, education). Although this effort involves a massive

investment of time and human resources, it ultimately yields a

standardized protocol, which should greatly facilitate out-

comes analyses later in the project.

Assessment

A key component of the eMERGE study is to assess the

impact of return of PRS and GIRA results on health care be-

haviors and outcomes for participants and their providers. It

will be essential to re-evaluate relevant educational methods

and the clinical utility of the information once outcomes data

are available. Toward the end of the eMERGE study timeline,

a wide range of studies are planned that address the efficacy

and acceptability of the tools and approaches used. Analyses

of EHR and self-report data will assess differences in clinical

care for participants who received high-risk reports versus

those who did not. In tandem, a series of studies across the

network will assess outcomes that speak more directly to the

efficacy of educational approaches delineated herein. These

include interviews with participants (or their parents in the

case of pediatric participants), interviews with providers and a

network-wide provider survey. Leveraging these approaches,

we will assess the extent to which participants and providers

struggled to understand reports and act upon relevant infor-

mation. Although several of the ELSI studies outlined above

utilized hypothetical risk report aimed to replicate the RoR

scenario, the real-world “ road test” will be most critical to

relevant outcomes. This will yield formative data and the

opportunity to further update educational material/methods

for the utility of future PRS-based programs.

J.J. Connolly et al. 11

A limitation of the eMERGE program pertains to the

representativeness of the pilot study participants to the full

cohort of 25,000 participants. It may be that findings from

the preliminary ELSI studies are biased given that they re-

flected the views of participants in these small-scale studies

rather than the general population. However, similar to the

eMERGE network more generally, these preliminary studies

comprised primarily of individuals from minority/un der-

represented racial and ethnic communities, reflecting a

recruitment goal across the 10 clinical eMERGE sites.

Conclusions

In developing a comprehensive education strategy, consid-

eration should be given to (1) the necessity of thinking

through the educational needs of different stakeholders, (2)

the necessity for different approaches to ascertaining those

needs, including targeted studies and stakeholder engage-

ment, (3) that this all takes a huge amount of resources, and

(4) that much of what is learnt and developed can be shared

across projects, lowering a potentially massive barrier for

other projects. For its part, eMERGE is committed to

sharing the resources it has put together, which continues to

be consolidated as the study progresses, which can be

accessed via the network’s coordinating center.

40

Data Availability

Data used in this manuscript are available upon request by

contacting the corresponding author. Requests should be sent

to the corresponding author with a description of the reason for

the request and the qualifications of those requesting the data.

Acknowledgments

The network would like to thank our eMERGE participants and

their families for graciously taking part in this study and the

patient and physician advisory groups that helped shape study

design, report content, and education materials. Because of the

structure of the U01 cooperative agreement, the recruitment

sites, coordinating center, and funding agency collaborated on

the study design, as well as collection, management, analysis,

and interpretation of the data. This trial was registered with

clinicaltrials.gov under identifier NCT05277116.

Funding

This phase of the eMERGE network was initiated and funded

by the NHGRI through the following grants: U01HG011172

(Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center),

U01HG011175 (Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia),

U01HG008680 (Columbia University), U01HG011166

(Duke University), U01HG011176 (Icahn School of Medi-

cine at Mount Sinai), U01HG008685 (Mass General Brig-

ham), U01HG006379 (Mayo Clinic), U01HG011169

(Northwestern University), U01HG011167 (University of

Alabama at Birmingham), U01HG008657 (University of

Washington), U01HG011181 (Vanderbilt University Medi-

cal Center), and U01HG011166 (Vanderbilt University

Medical Center serving as the Coordinating Center).

Author Information

Conceptualization: J.J.C., E.S.B., M.Sm., M.Sa.; Data Cura-

tion: J.J.C., S.L.; Formal Analysis: J.J.C., E.S.B., M.Sm., S.L.,

S.T., M.Har., M.Sa.; Funding Acquisition: J.J.C., E.S.B.,

M.Sm., M.Har., S.S., I.A.H., K.D., C.N., A.K., R.L.C.,

W.-Q.W., H.T.B., E.W.C., J.E.L., N.A.L., L.A.O., J.W., H.H.,

M.Sa.; Investigation: J.J.C., E.S.B., M.Sm., S.L., S.T., M.Har.,

D.K., S.S., I.A.H., K.D., C.N., A.K., R.L.C., A.A., W.-Q.W.,

H.T.B., E.W.C., E.R.S., J.E.L., N.A.L., A.M., S.N., H.B.,

M.Ham., A.S., A.C.F.L., E.P., L.A.O., M.A.-D., S.C., J.W.,

H.H., M.Sa. Methodology: J.J.C., E.S.B., M.Sm., S.L., S.T.,

M.Har., D.K., S.S., I.A.H., K.D., C.N., A.K., R.L.C., A.A.,

W.-Q.W., H.T.B., E.W.C., E.R.S., J.E.L., N.A.L., A.M., S.N.,

H.B., M.Ham., A.S., A.C.F.L., E.P., L.A.O., M.A.-D., S.C.,

J.W., H.H., M.Sa.; Project Administration: J.J.C., C.N., A.K.,

H.T.B., E.W.C., E.R.S., A.M., E.P., T.K.R.-B.; Writing-

Original Draft: J.J.C., E.S.B., M.Sm., S.L., S.T., M.Har., D.K.,

C.N., A.M., E.P., L.A.O., T.K.R.-B., J.W., M.Sa.; Writing-

Review & Editing: J.J.C., E.S.B., M.Sm., S.L., S.T., M.Har.,

D.K., S.S., I.A.H., K.D., C.N., A.K., R.L.C., A.A., W.-Q.W.,

H.T.B., E.W.C., E.R.S., J.E.L., N.A.L., A.M., S.N., H.B.,

M.Ham., A.S., A.C.F.L., E.P., L.A.O., T.K.R.-B., M.A.-D.,

S.C., C.L.S., J.W., H.H., M.Sa.

Ethics Declaration

The studies discussed in this reviewed were all conducted

according to the guidelines of the Declarat ion of Helsinki

and approved by the Institutional Rev iew Board of VUMC

and/or local Institutional Review Boards. Informed consent

is required from all enrolled individuals.

Conflict of Interest

Emma Perez is a paid consultant for Allelica Inc. Lori

Orlando and Tejinder Rakhra-Burris are founders of a

company developing MeTree. Maureen Smith is a Section

Editor for the Journal of Genetic Counseling. Maya

Sabatello serves as IRB member of the All of Us

Research Program. All other authors declare no conflicts of

interest.

12 J.J. Connolly et al.

Additional Information

The online version of this article (http s://doi.org/10.1016/j.

gim.2023.100906) contains supplemental material, which

is available to authorized users.

Authors

John J. Connolly

1,*

, Eta S. Berner

2

, Maureen Smith

3

,

Samuel Levy

1

, Shannon Terek

1

, Margaret Harr

1

,

Dean Karavite

4

, Sabrina Suckiel

5

, Ingrid A. Holm

6

,

Kevin Dufendach

7

, Catrina Nelson

8

, Atlas Khan

9

,

Rex L. Chisholm

10

, Aimee Allworth

11

, Wei-Qi Wei

12

,

Harris T. Bland

12

, Ellen Wright Clayton

13,14,15

,

Emily R. Soper

5,16

, Jodell E. Linder

17

, Nita A. Limdi

18

,

Alexandra Miller

19,20

, Scott Nigbur

19

, Hana Bangash

19

,

Marwan Hamed

19

, Alborz Sherafati

19

,

Anna C.F. Lewi s

21,22

, Emma Perez

23

, Lori A. Orlando

24

,

Tejinder K. Rakhra-Burris

24

, Mustafa Al-Dulaimi

25

,

Selma Cifric

25

, Courtney Lyn am Scherr

26

, Julia Wynn

27

,

Hakon Hakonarson

1,28,29,30

, Maya Sabatello

31,32,*

Affiliations

1

Center for Applied Genomics, Children’s Hospital of

Philadelphia, PA;

2

Department of Health Services Admin-

istration, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birming-

ham, AL;

3

Center for Genetic Medicine, Department of

Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL;

4

Depart-

ment of Biomedical and Health Informatics, Children’s

Hospital of Philadelphia, PA;

5

The Institute for Genomi c

Health, Department of Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine

at Mount Sinai, New York, NY;

6

Division of Genetics and

Genomics, Boston Children’s Hospital; Department of Pe-

diatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA;

7

Depart-

ment of Pediatrics, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati,

OH;

8

Center for Autoimmune Genomics and Etiology,

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati,

OH;

9

Division of Nephrology, Dept of Medicine, Vagelos

College of Physic ians & Surgeons, Columbia University,

New York, NY;

10

Center for Genetic Medicine, Feinberg

School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL;

11

Department of Medical Genetics, University of Wash-

ington, Seattle, WA;

12

Department of Biomedical Infor-

matics, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nas hville,

TN;

13

Division of Genetic Medicine, Department of Medi-

cine, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN;

14

Center for Biomedical Ethics and Society, Vanderbilt

University, Nashville, TN;

15

Vanderbilt University Law

School, Nashville, TN;

16

Division of Genomic Medicine,

Department of Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at

Mount Sinai, New York, NY;

17

Vanderbilt Institute for

Clinical and Translational Research, Vanderbilt University

Medical Center, Nashville, TN;

18

Department of Neurology,

Heersink School of Medicine, University of Alabama at

Birmingham, Birmingham, AL;

19

Department of Cardio-

vascular Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN;

20

Department of Clinical Genomics, Mayo Clinic, Roches-

ter, MN;

21

Edmond and Lily Safra Center for Ethics, Har-

vard, MA;

22

Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA;

23

Mass General Brigham Personalized Medicine, Brigham

and Wome n’s Hospital, Boston, MA;

24

Department of

Medicine, Duke University, Durham, NC;

25

Department of

Biology, The College of Idaho, Caldwell, ID;

26

School of

Communication | Department of Communication Studies,

Northwestern University, Chicago, IL;

27

Department of

Pediatrics, Columbia University Irving Medical Center,

New York, NY;

28

Department of Pediatrics, The Perelman

School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadel-

phia, PA;

29

Division of Human Genetics, Children's Hos-

pital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA;

30

Division of

Pulmonary Medicine, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia,

Philadelphia, PA;

31

Center for Precision Medicine & Ge-

nomics, Department of Medicine, Columbia University

Irving Medical Center, New York, NY;

32

Division of

Ethics, Department of Medical Humanities & Ethics,

Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, NY

References

1. Maas P, Barrdahl M, Joshi AD, et al. Breast cancer risk from modifi-

able and nonmodifiable risk factors among white women in the United

States. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(10):1295-1302. http://doi.org/10.1001/

jamaoncol.2016.1025

2. Schumacher FR, Al Olama AA, Berndt SI, et al. Association analyses

of more than 140,000 men identify 63 new prostate cancer suscepti-

bility loci. Nat Genet. 2018;50(7):928-936. http://doi.org/10.1038/

s41588-018-0142-8

3. Sharp SA, Rich SS, Wood AR, et al. Development and standardization

of an improved Type 1 diabetes genetic risk score for use in newborn

screening and incident diagnosis. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(2):200-207.

http://doi.org/10.2337/dc18-1785

4. Linder JE, Allworth A, Bland HT, et al. Returning integrated genomic

risk and clinical recommendations: the eMERGE study. Genet Med.

2023;25(4):100006. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.gim.2023.100006

5. Wand H, Lambert SA, Tamburro C, et al. Improving reporting stan-

dards for polygenic scores in risk prediction studies. Nature.

2021;591(7849):211-219. http://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03243-6

6. Kessler MD, Yerges-Armstrong L, Taub MA, et al. Challenges and

disparities in the application of personalized genomic medicine to

populations with African ancestry. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12521. http://

doi.org/10.1038/ncomms12521

7. Martin AR, Gignoux CR, Walters RK, et al. Human demographic

history impacts genetic risk prediction across diverse populations. Am J

Hum Genet. 2017;100(4):635-649. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.

03.004

8. Kim MS, Patel KP, Teng AK, Berens AJ, Lachance J. Genetic disease

risks can be misestimated across global populations. Genome Biol.

2018;19(1):179. http://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-018-1561-7

9. Hero JO, Zaslavsky AM, Blendon RJ. The United States leads other

nations in differences by income in perceptions of health and health

care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(6):1032-1040. http://doi.org/10.

1377/hlthaff.2017.0006

10. Williams DR, Priest N, Anderson NB. Understanding associations

among race, socioeconomic status, and health: patterns and prospects.

Health Psychol. 2016;35(4):407-411. http://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000242

J.J. Connolly et al. 13

11. Krahn GL, Walker DK, Correa-De-Araujo R. Persons with disabilities

as an unrecognized health disparity population. Am J Public Health.

2015;105(suppl 2):S198-S206. http://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.

302182

12. Sabatello M, Chen Y, Zhang Y, Appelbaum PS. Disability inclusion in

precision medicine research: a first national survey. Genet Med.

2019;21(10):2319-2327. http://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-019-0486-1

13. Lewis ACF, Perez EF, Prince AER, et al. Patient and provider per-

spectives on polygenic risk scores: implications for clinical reporting

and utilization. Genome Med. 2022;14(1):114. http://doi.org/10.1186/

s13073-022-01117-8

14. Terek S, Del Rosario MC, Hain HS, et al. Attitudes among parents

towards return of disease-related polygenic risk scores (PRS) for their

children. J Pers Med. 2022;12(12). http://doi.org/10.3390/

jpm12121945

15. Fisher EB, Fitzgibbon ML, Glasgow RE, et al. Behavior matters. Am J

Prev Med. 2011;40(5):e15-e30. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2010.

12.031

16. Patel N, Ferrer HB, Tyrer F, et al. Barriers and facilitators to healthy

lifestyle changes in minority ethnic populations in the UK: a narrative

review. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2017;4(6):1107-1119. http://

doi.org/10.1007/s40615-016-0316-y

17. Danielson ML, Bitsko RH, Ghandour RM, Holbrook JR, Kogan MD,

Blumberg SJ. Prevalence of parent-reported ADHD diagnosis and

associated treatment among U.S. Children and adolescents, 2016.

J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2018;47(2):199-212. http://doi.org/10.

1080/15374416.2017.1417860

18. Ghandour RM, Sherman LJ, Vladutiu CJ, et al. Prevalence and treat-

ment of depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in US children.

J Pediatr. 2019;206:256-267.e3. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.

09.021

19. Pennington JW, Karavite DJ, Krause EM, Miller J, Bernhardt BA,

Grundmeier RW. Genomic decision support needs in pediatric primary

care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24(4):851-856. http://doi.org/10.

1093/jamia/ocw184

20. Lee A, Mavaddat N, Wilcox AN, et al. Boadicea: a comprehensive

breast cancer risk prediction model incorporating genetic and nonge-

netic risk factors. Genet Med. 2019;21(8):1708-1718. http://doi.org/10.

1038/s41436-018-0406-9

21. invitae.com. Invitae eMERGE Panel. Invitae. Accessed January 18,

2023.

22. Orlando LA, Buchanan AH, Hahn SE, et al. Development and vali-

dation of a primary care-based family health history and decision

support program (MeTree). N C Med J. 2013;74(4):287-296. http://doi.

org/10.18043/ncm.74.4.287

23. Brown SN, Jouni H, Marroush TS, Kullo IJ. Effect of disclosing ge-

netic risk for coronary heart disease on information seeking and

sharing: the MI-GENES study (myocardial infarction genes). Circ

Cardiovasc Genet. 2017;10(4). http://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCGE-

NETICS.116.001613

24. Saks E, Tyson A. Americans Report More Engagement with Science

News than in 2017. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.

org/fact-tank/2022/11/10/americans-report-more-engagement-with-

science-news-than-in-2017/

25. Funk C, Hefferon M, Kennedy B, Johnson C. Trust and mistrust in

Americans’ views of scientific experts; 2019. Pew Research Center.

https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2019/08/02/trust-and-mistrust-

in-americans-views-of-scientific-experts/

26. De Castro P, Marsili D, Poltronieri E, Calder

´

on CA. Dissemination of

public health information: key tools utilised by the NECOBELAC

network in Europe and Latin America. Health Info Libr J.

2012;29(2):119-130. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2012.00977.x

27. Konstantinidis ST, Bamidis PD. Why decision support systems are

important for medical education. Healthc Technol Lett. 2016;3(1):56-

60. http://doi.org/10.1049/htl.2015.0057

28. Pet DB, Holm IA, Williams JL, et al. Physicians’ perspectives on

receiving unsolicited genomic results. Genet Med. 2019;21(2):311-318.

http://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-018-0047-z

29. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG.

Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven

methodology and workflow process for providing translational

research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381.

http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

30. Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: building

an international community of software platform partners. JBiomed

Inform. 2019;95:103208. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208

31. Nightingale SD. Risk preference and laboratory test selection. J Gen

Intern Med. 1987;2(1):25-28. http://doi.org/10.1007/BF02596246

32. Huhn JM III, Potts CA, Rosenbaum DA. Cognitive framing in action.

Cognition. 2016;151:42-51. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2016.02.

015

33. Suckiel SA, Braganza GT, Agui

˜

niga KL, et al. Perspectives of diverse

Spanish- and English-speaking patients on the clinical use of polygenic

risk scores. Genet Med. 2022;24(6):1217-1226. http://doi.org/10.1016/

j.gim.2022.03.006

34. Lea DH, Kaphingst KA, Bowen D, Lipkus I, Hadley DW. Commu-