WILLIAM

POOLE

Brown

University

Monetary

Policy

during

the

Recession

THE DEPTH

of

the

current

recession makes

it clear ex

post that government

stabilization

policy

should have been

less

contractionary

in

1974.

In

fact,

both

monetary and fiscal

policy were extremely

contractionary not only

relative

to the needs of

a

declining economy but

also relative to policy

during the

1972-73 boom.

During 1974, the full

employment budget sur-

plus rose

sharply and

monetary expansion slowed

markedly. My task in

this report

is

to

analyze the

monetary part of recent

stabilization policies.

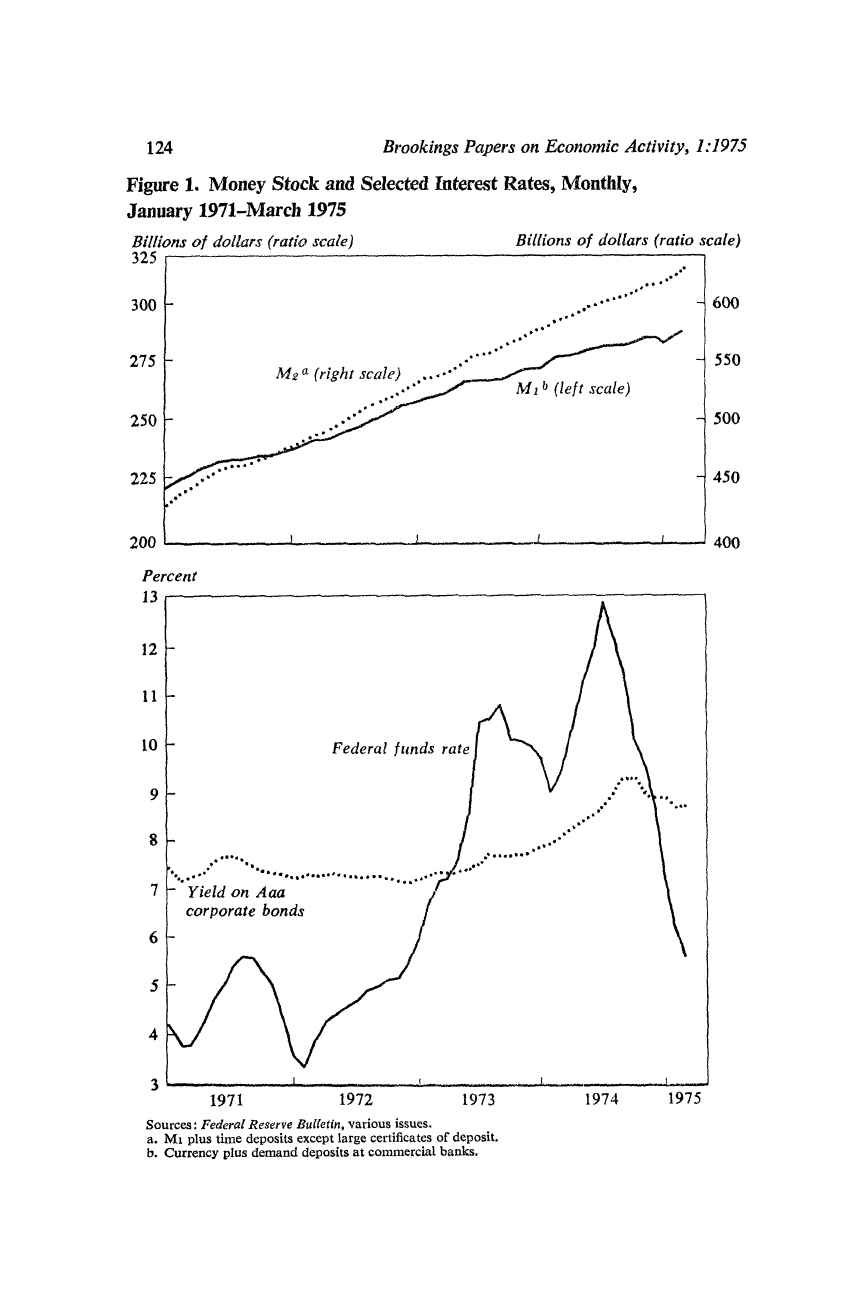

A

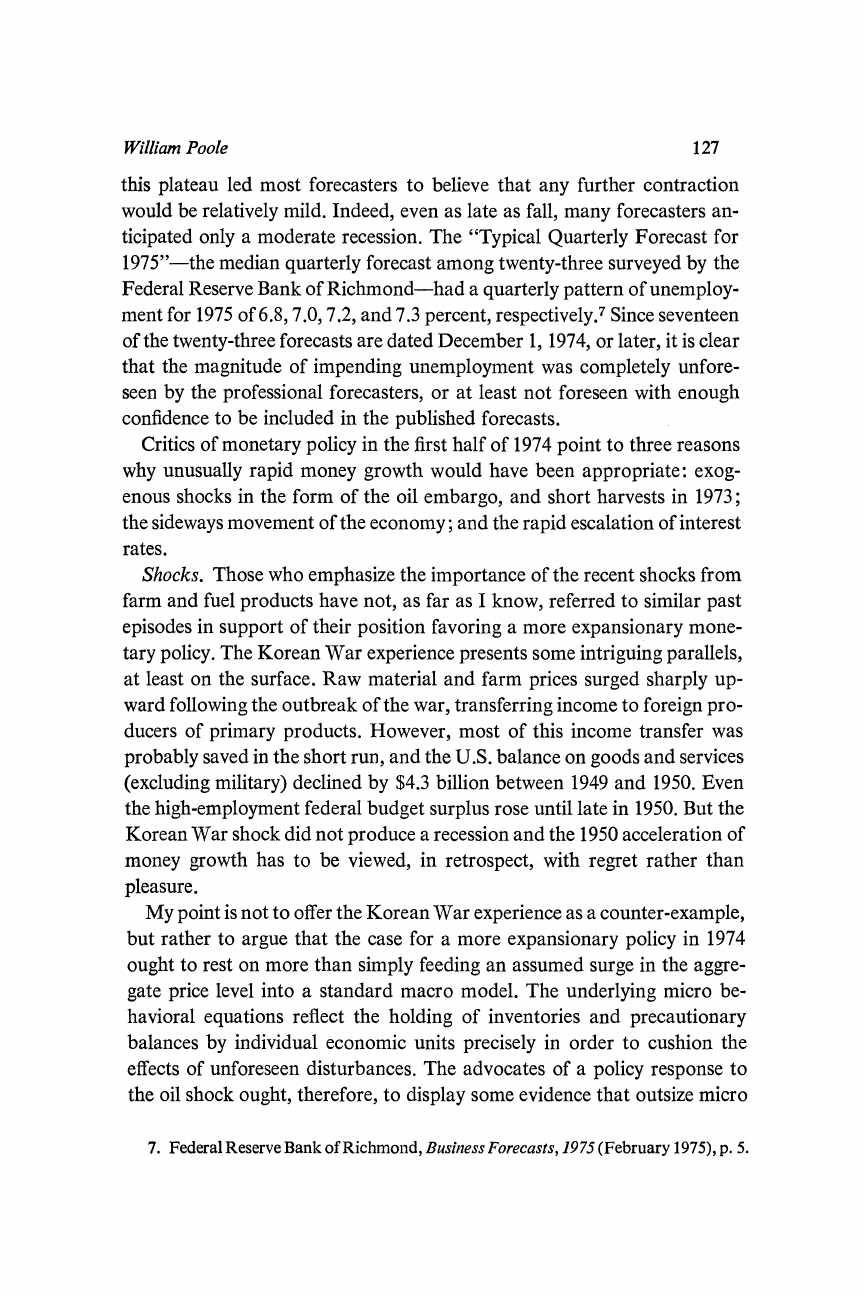

sharp

deceleration of

money growth (both

M1

and

M2) since mid-1974

is

evident in figure 1.1

Economists generally agree

that money growth in

the

second

half of

1974

was

too low, but split over the

proposition

that

money

growth

in the

first

half-6.2 percent for

M1

from December 1973

to

June

1974-was

about

right.2

As

I

argued

a

year ago,

an M1

growth target

of about

6

percent was appropriate on the

basis of

information available

in

early

and

mid-1974.3 Therefore,

I

applaud the Federal

Reserve

for

restrain-

Note:

I

want to thank

the Federal Reserve Bank

of Boston for research

support and

especially Ruth Kupfer

and Redenta de Leon of

the Bank for research assistance

and

typing.

The

views expressed,

however,

are

mine

and do not necessarily reflect those of the

Federal Reserve

Bank

of Boston.

1. I am

inclined to

believe that M2 is more closely

related to business conditions

than

M1, but have decided to

use M1 in most of my

analysis because the Federal

Reserve

tends to emphasize it

and

because the differences

in the recent behavior of the two

mea-

sures are relatively minor.

2. All

growth rates

in

this report are continuously

compounded

annual rates of

growth.

3. William

Poole,

"Reflections on U.S. Macroeconomic

Policy,"

BPEA

(1:1974),

pp.

233-46.

123

124

Brookings Papers

on

Economic

Activity,

1:1975

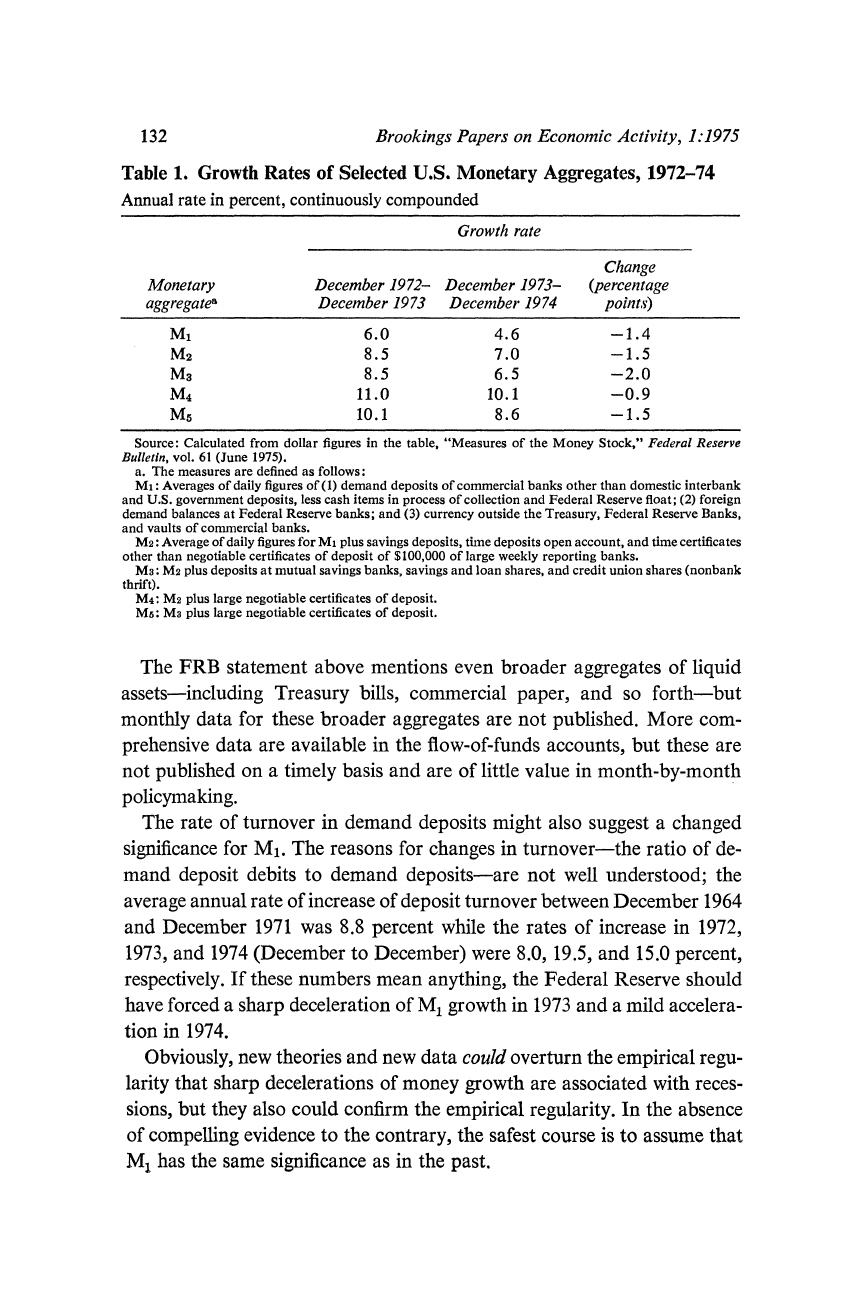

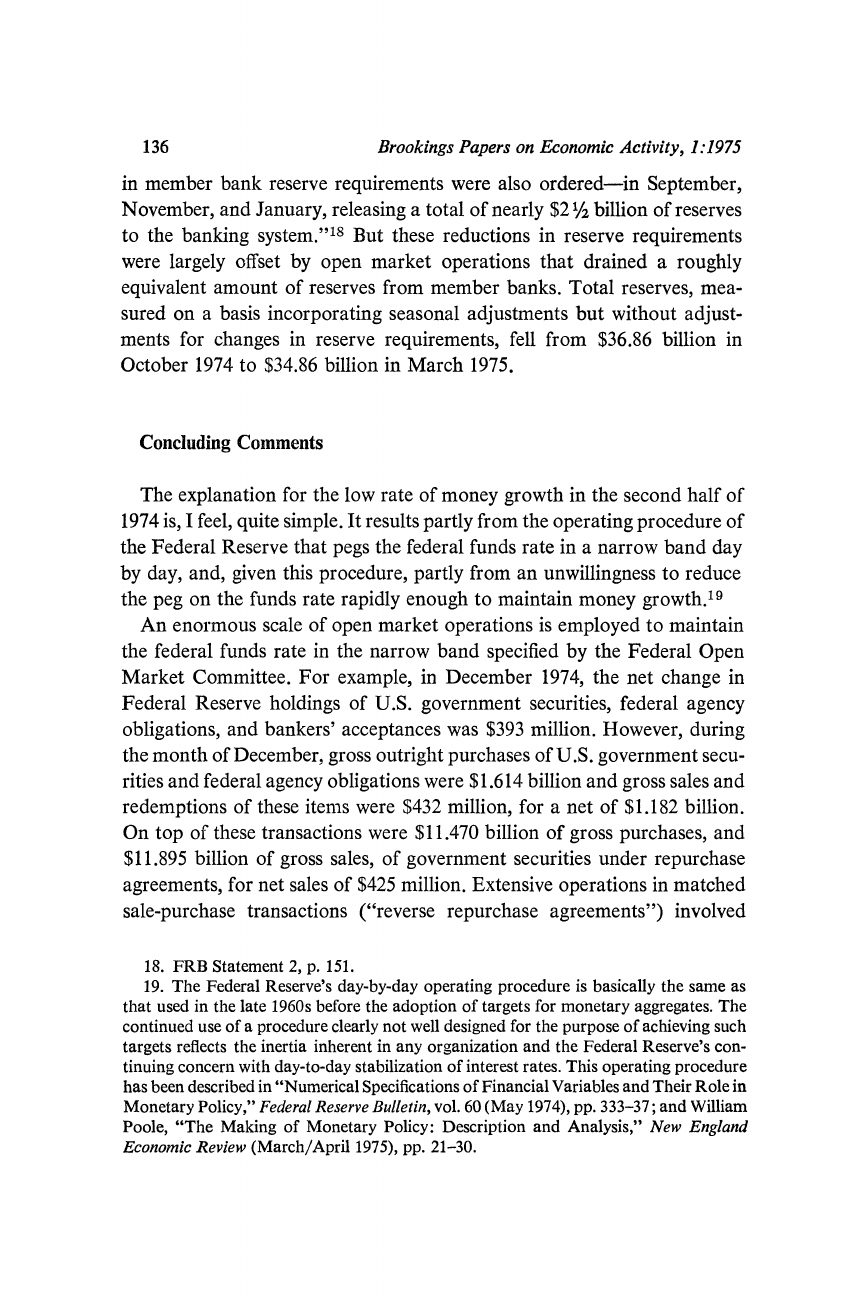

Figure

1.

Money

Stock

and Selected

Interest

Rates,

Monthly,

January 1971-March

1975

Billions of

dollars

(ratio scale)

Billions

of

dollars

(ratio scale)

325

300

.

600

275

-]550

275 10

MeMa,~-(right

scale) ~

250

500

225

Z

450

200

400

Percent

13

12

10

Federal

f

iunds

rate

9.

7

Yield

on Aaa

corporate

bonds

6

S

4

3

1971

1972

1973

1974

1975

Sources:

Federal

Reserve

Bulletin,

various

issues.

a. Ms

plus

time

deposits

except

large

certificates

of

deposit.

b.

Currency plus

demand

deposits

at

commercial

banks.

William

Poole 125

ing money growth

and

permitting

interest rates to

rise sharply

in the

first

half of 1974.

The next section is

devoted

to

a

defense of

the

proposition

that

a

6

per-

cent M1

growth

was

appropriate

in

1974.

There

follows

an

analysis

of

the

Federal

Reserve's explanation

of

monetary policy

in the second

half of

1974.

The

report

concludes with

a

few

general

comments on

what

the Fed-

eral Reserve should do, given

recent

experience.

Judging

the

Appropriateness of Monetary Policy

Policymaking

is

inherently

a

problem

of

decisionmaking under uncer-

tainty;

an

ex

post analysis

of

policy ought, therefore,

to be

cast

in the

same

terms. Judging

the

performance

of

policymakers requires

that

something

be

said

about

preferences

for

possible outcomes, especially

those related to

unemployment

and

inflation;

about

the

effect of events known

to

policy-

makers

when

decisions

are made on the odds of various

outcomes;

and

about the

impact on

the

odds

of

policy adjustments.

Although opinions

differ on the

relative

costs of

unemployment

and in-

flation,

I

know of no statements

by public

officials

suggesting

that the

cur-

rent

rapid

reduction in inflation has been worth the cost in terms of unem-

ployment.

On the

contrary, public officials have stressed repeatedly

that

inflation

must be reduced

slowly

in order to avoid

a

depression,

and that the

unavoidable cost

was

a

modest rise

in

unemployment.

Differences over the role of

preferences

arise

largely

because of

varying

views

of how the

world

works.

I

assign very

little

importance

to

inflation

per

se

but

feel

that

the

economic and

political dynamics

of inflation com-

bine

to

rule

out

any significant

chance of

simply stabilizing

the rate of in-

flation at 1973

or 1974 levels. Further acceleration of inflation very likely

would have generated vastly increased odds

of

deeper recession

in the

future.

I

basically agree, then, with

Milton

Friedman's argument

that the

real

choice is not between inflation and

unemployment,

but between

unemploy-

ment now

and

unemployment later.4

This is an

empirical

statement-cor-

rect or

incorrect-about the

way

the world works and not about

prefer-

ences. Nevertheless, the tradeoff between unemployment now and unem-

4.

Milton Friedman,

"The Role of

Monetary Policy," Americani Econlomic

Review,

vol.

58 (March 1968),

pp. 1-17 (especially

7-11).

126 Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1:1975

ployment later applies only within a certain range. After

a

point, more

unemployment now clearly brings more unemployment later, again for a

mixture of

economic and political reasons. When firms go bankrupt

and

are dismantled or fall far behind in their capital spending, an irreversible

loss occurs, and production and employment cannot be returned easily to

full employment levels. In addition, some government actions

taken in

response

to

unemployment, as

well

as

in

response

to

inflation,

reduce

eco-

nomic efficiency and interfere with the return to full employment.

I

also agree with the Modigliani-Papademos argument that the desirable

path for the economy is one involving the fastest possible recovery con-

sistent with

maintaining low odds of overshooting full employment

and

re-

accelerating inflation.5 I differ with Modigliani and Papademos not over

goals

but

over

the

odds of

achieving any given target path

for the

economy.

This

point

will be

discussed further in my comments on current policy,

but

it

is central to my analysis of Federal Reserve policy in 1974.

THE EVIDENCE OF

1974

Whatever

lessons

evolve

from the

sharp

rise

in

unemployment

in

late

1974 and

early 1975, an analysis of monetary policy

in

1974

should be

lim-

ited to the evidence available at the time the policy decisions were made.

The consensus

forecast

in

early 1974 was for

a flat

economy.

Pessimists

argued that

a

couple of quarters of declining real gross

national

product

were

likely and optimists thought a recession would be avoided. No

one

foresaw

either

a

deep recession or

a

boom.6

By June the forecasts became, if anything, a bit more optimistic. The

disruptive oil embargo had been lifted,

the

unemployment

rate

was the

same

as in

January,

and

the index of industrial

production actually

had

risen

a

bit since

April.

From

what is known

now,

the

business

cycle peak may

be

tentatively

placed at November 1973. However, after

a

significant decline

in the

early

months

of

1974,

the

economy

remained

basically

on a

plateau

until

autumn.

As

the

year continued,

the

consensus

forecast

was

revised downward,

but

5. See their paper in this issue.

6. It is fair to say that

a

year

ago many economists were concerned

over the

possi-

bility that maintaining a 6 percent

trend of money growth would

lead to a prolonged

period of economic slack, with

unemployment remaining above 6 percent,

and perhaps

rising slowly, for several years.

No one

I

know,

however, assigned any

significant

proba-

bility to

a

1975 unemployment

rate of the current magnitude.

William Poole 127

this plateau led most forecasters to believe that any further contraction

would be relatively mild. Indeed, even as late as fall, many forecasters

an-

ticipated only a moderate recession. The "Typical Quarterly Forecast for

1975"-the median quarterly forecast among twenty-three surveyed by the

Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond-had a quarterly pattern of unemploy-

ment for 1975 of

6.8, 7.0, 7.2,

and

7.3 percent, respectively.7 Since seventeen

of the twenty-three forecasts are dated December 1, 1974, or later, it is clear

that the magnitude of impending unemployment was completely unfore-

seen by the professional forecasters, or at least not foreseen with enough

confidence

to

be

included

in the

published forecasts.

Critics of

monetary policy

in

the

first half of 1974 point to three reasons

why unusually rapid money growth would

have been

appropriate: exog-

enous shocks

in the

form of the oil embargo, and short harvests in 1973;

the

sideways

movement of

the economy; and the rapid escalation of interest

rates.

Shocks.

Those who

emphasize

the

importance of the recent shocks from

farm and

fuel products have not,

as

far

as

I know, referred to similar past

episodes

in

support

of their

position favoring

a

more expansionary mone-

tary policy.

The Korean

War experience presents some intriguing parallels,

at least

on the

surface. Raw

material and

farm prices surged sharply up-

ward following

the outbreak of

the war, transferring income to foreign pro-

ducers of primary products. However, most of this income transfer

was

probably

saved

in the

short

run,

and

the

U.S.

balance on

goods

and services

(excluding military)

declined

by $4.3 billion between 1949 and 1950. Even

the

high-employment

federal

budget surplus rose until

late

in 1950.

But

the

Korean

War

shock

did not

produce

a

recession

and the

1950 acceleration

of

money growth

has

to be

viewed,

in

retrospect, with regret rather

than

pleasure.

My point

is

not to

offer the Korean

War experience

as a

counter-example,

but

rather to

argue

that the

case for a more expansionary policy in 1974

ought

to rest on more than

simply feeding

an assumed

surge

in

the

aggre-

gate price

level

into a standard

macro

model.

The

underlying micro

be-

havioral

equations

reflect the

holding of

inventories

and precautionary

balances by

individual

economic units precisely in order to cushion

the

effects of unforeseen

disturbances.

The

advocates of

a

policy response

to

the

oil

shock

ought, therefore,

to

display

some

evidence

that outsize micro

7. Federal Reserve

Bank

of Richmond, Business Forecasts, 1975 (February 1975), p.

5.

128 Brookings

Papers on Economic Activity,

1:1975

shocks in the past have

had

the macro effects postulated.

Historically,

there has been a tendency for economic policy to overreact

to external

events. Given the record, it seems best to maintain neutral

policy settings

in the absence of compelling evidence that a "clear and

present danger"

requires

a

policy response.

Sideways economy. The basically sideways movement of the

economy in

the

spring and summer of 1974 was

an

obvious danger sign.

The

pattern

was

not dissimilar, however, to that characterizing most of 1962

and

late

1966 through early 1967-periods that terminated in

renewed expansion

rather

than contraction. No solid criteria have been developed

to distinguish

the

economic "pause that refreshes" from one that forebodes

real trouble.

Interest escalation. The significance of the sharp escalation

of short-term

interest rates in early 1974 cannot be ignored even though

the

rise was

actually smaller than that in the first half of 1973. Rising

rates in 1973, as

in

most other

periods

of business

expansion,

were

appropriate

in

retrospect,

and the key question is whether sufficient information was

available to dis-

tinguish the 1974 case from the others. The economy was

obviously some-

what

weak in

1974,

but

given

the

lags

in the

effects of

a

changed

rate of

monetary growth, this weakness is relevant only insofar as it affects

the

economic

forecast for four

to

six quarters ahead. That forecast

held that

the

economy would level off,

or

fall

a

bit, and then resume its

expansion.

Interest

rates rose far more rapidly in the first half of 1974

than would

have

been

anticipated

at the

beginning of the year given

actual

money

growth.

The

proper response

of

monetary policy

to such

an

unexpected

change in interest rates depends crucially on whether the

change

is the

result

of

a

financial or

a

real disturbance. I have seen no

evidence suggesting

that it stemmed

from

a financial

disturbance.

In

U.S.

business

cycle experience, steady

or

accelerating

money growth

and rising short-term interest rates are generally associated with

expanding

economic activity; similarly, decelerating money growth

and

falling

interest

rates are standard recession

phenomena. Exceptions

are

few.

Given

these

patterns,

the

evidence

would have to be

very strong

to

prove

that the

proper

policy response

to

interest rate

pressures,

either

up

or

down,

is

a

sustained

acceleration or deceleration of

money growth.

Since

the

goal

of

monetary

policy

in

early

1974

was

to

permit

a

little slack to

develop

in the

economy

to

reduce the risk of a further acceleration in inflation,

the

Federal Reserve

appropriately

maintained

a

rate of

money growth roughly

equal

to

the

average

of the

preceding several years.

William

Poole

129

However,

monetary

policy in

the

second half

of 1974

was

ill-advised

for

exactly the

same

reasons.

Declining

money

growth in the

face of

downward

interest rate

pressures

should have

been

recognized as

characteristic of

re-

cession.

Even

ignoring

accompanying

interest

rate

movements, the

case

against

permitting

sharp

monetary

deceleration

is

overwhelming. Over

the

entire

period since

mid-1907 for

which

monthly

data

on the

money

stock

are

available, every

recession was

accompanied by

a

significant

deceleration

of

money

growth

and

every

significant

deceleration of

money

growth

was

accompanied by

recession.8

My

position

may be

summarized as

follows:

if

money

growth is

mea-

sured over

six-month

spans and

compared with

the

average rate

of

growth

over

the

preceding

two or

three

years,

most

accelerations

or

decelerations

of

2

percentage

points

or

more will

be

found to

have been

undesirable

under

almost any

preference

function.

Judgments vary

as to

the

importance

of

these

monetary

accelerations and

decelerations

in

generating

the business

cycle.

Nonetheless,

if

large

monetary

accelerations and

decelerations

are

typically

regretted

after

the fact,

then-even if

monetary

instability is

not

very

important-there is

no point

in

having

monetary

policy

push in

the

wrong

direction.

The

Federal

Reserve was

playing the

odds

correctly

in

the

first

half of

1974 by

holding

money

growth to

about 6

percent. But

by

per-

mitting the

sharp

monetary

deceleration

in the

second

half of

1974,

it was

playing

with

adverse odds

of at

least 8

to

1

calculated

from

1952-73

ex-

perience.9

The

adverse

odds were

very

much

higher if

the

extensive

prewar

recession

experience is

also

counted.

Moreover,

these

findings

were avail-

able

to the

Federal

Reserve in

the

second half

of 1974,

and

should

have

guided

policy

decisions.

There are

only

two

possible

defenses for

the

sharp

monetary deceleration

in

late

1974.

It

might be

argued,

first, that

persuasive

evidence

was

available

8.

See

William Poole,

"The

Relationship of

Monetary

Decelerations

to Business

Cycle

Peaks:

Another Look

at the

Evidence,"

Journal of

Finance, vol. 30

(forthcoming).

In

this paper the

meaning of

"significant

deceleration" is

defined

carefully.

9.

These odds

were

calculated by

measuring

money growth

over six-month

periods-

December-June,

and

June-December-and then

examining all

cases

between 1952 and

1973

in

which

money

growth was more

than 2

percentage

points below the

average for

the

preceding

three years.

The nine

periods of

sharply

decelerated money

growth were

both

halves of

1953, both

halves of

1957, the second

half of

1959, the first

half of

1960,

the

second

halves of 1966,

1969, and

1971. Given the

actual

performance of

the

economy

in

the months

following

these

decelerations, I

regard seven of

the nine

decelerations

as

clearly

inappropriate, the

1971

deceleration as

probably

inappropriate, and the

1966

deceleration as

possibly

appropriate.

130

Brookings

Papers on

Economic Activity,

1:1975

suggesting

that the

significance

of the

money

stock had

changed; or,

second,

that the Federal Reserve is

unable to control the money

stock and

therefore

is not responsible for the

sharp monetary deceleration.

These

two

argu-

ments will

now be

discussed

in turn.

Federal Reserve

Explanations

The

Federal Reserve's position

has been expressed clearly

in two recent

statements in

response to

proposed congressional legislation

concerning

the

conduct of monetary policy.10

A careful

reading

of these two statements raises questions

about

the

in-

ternal

consistency of

the Board's position. On the one

hand,

the

Board

seems to

accept

the

argument

presented in the previous section:

We appreciate the fact that

an expanding economy requires

an expanding sup-

ply of money, that any protracted

shrinkage of the money supply

may well lead

to shrinkage of economic activity,

and that attempts to encourage

growth

in

money and credit will lead to

a decline of short-term interest rates

when economic

activity

is

weak.

We

are well aware that an

expanding economy needs an expanding

supply

of

money and credit and that any

protracted shrinkage of the

money stock could

lead to or exacerbate a shrinkage

of economic activity."

On the

other hand,

the

Federal Reserve seems to argue

that lower

Ml

growth in the second half

of 1974 was acceptable because

the significance

10. In

regard to

H.R. 212,

"Statement by

Arthur F. Burns,

Chairman, Board

of Gov-

ernors

of the Federal

Reserve

System, before the

Subcommittee

on Domestic

Monetary

Policy

of the

Committee on Banking,

Currency and

Housing,

U.S. House of

Representa-

tives,

February 6,

1975," Federal

Reserve

Bulletin, vol. 61

(February 1975),

pp.

62-68

(hereafter

referred to

as

"FRB

Statement 1"); and in

regard to

Senate Concurrent Reso-

lution

18, "Statement

by Arthur F.

Burns,

Chairman, Board of

Governors of the

Federal

Reserve

System,

before the

Committee on

Banking, Housing

and Urban

Affairs, U.S.

Senate,

February 25,

1975," Federal

Reserve

Bulletin, vol. 61

(March 1975),

pp.

150-55

(hereafter

referred to

as "FRB Statement

2").

11. FRB

Statement

1, p. 63,

and

Statement 2, p. 153.

These

two statements,

however,

are less

precise than

they first

appear since

"shrinkage" of the

money stock,

interpreted

literally,

involves an

absolute decline

and

"protracted" involves a

period of

unspecified

length.

Given the

context of recent

monetary

analysis and the

frequent reference

to mone-

tary growth

rates

in

the

two

statements, it

is

reasonable to

interpret "shrinkage"

in

terms

of

a

decline

in

the

growth rate of

money. There

is no clear

interpretation of the word

"protracted," but the

Federal

Reserve has

frequently argued

that fluctuations

in

money

growth are

unimportant unless they

last for a

year or more.

William Poole

131

of

M1

has been changing. This argument, however, is

inconsistent with the

Board's

argument that

it

has attempted to achieve faster

growth in the

monetary

and credit

aggregates. Finally,

the

Federal Reserve

has argued

that it cannot control the money stock very precisely anyway.

CHANGES

IN THE

SIGNIFICANCE OF M1

The

argument that

the

significance

of M1

has changed

appears promi-

nently in both statements:

As

a rule consumers and businesses no longer hold all, or even

most, of their

spendable

funds as

currency

or

demand deposits. More and

more corporate

treasurers have learned how

to

get along with a minimum of

demand deposits; a

large part

of their transactions and

precautionary balances are

nowadays placed in

interest-bearing assets-negotiable certificates

of

deposit,

Treasury bills, com-

mercial paper, short-term municipal securities, and other forms.

Consumers, too,

have

learned

to

keep excess

funds

in

savings deposits

at

commercial

banks, shares

in

savings

and loan

associations,

certificates

of

deposit, Treasury

bills,

and

other

liquid instruments,

and

they

shift

their

liquid

resources

among

these

assets. The

result is

that no

single concept

of

money any longer

measures

adequately the

spendable

funds that are held

by

the

public.

For

example,

the

narrowly defined money

stock rose

by 41/2 per cent

during

1974.

But this

concept

of

the

money supply

has

lost

much of its

earlier

sig-

nificance.12

The

possibility

of

changing

economic

relationships

is a

constant source

of

concern

to

policymakers

and

advisers, properly

reflected

in

a

continuous

search

for evidence

of

change

and

a

willingness

to

shade

policy targets

de-

pending

on

the

strength

of the

evidence.

The

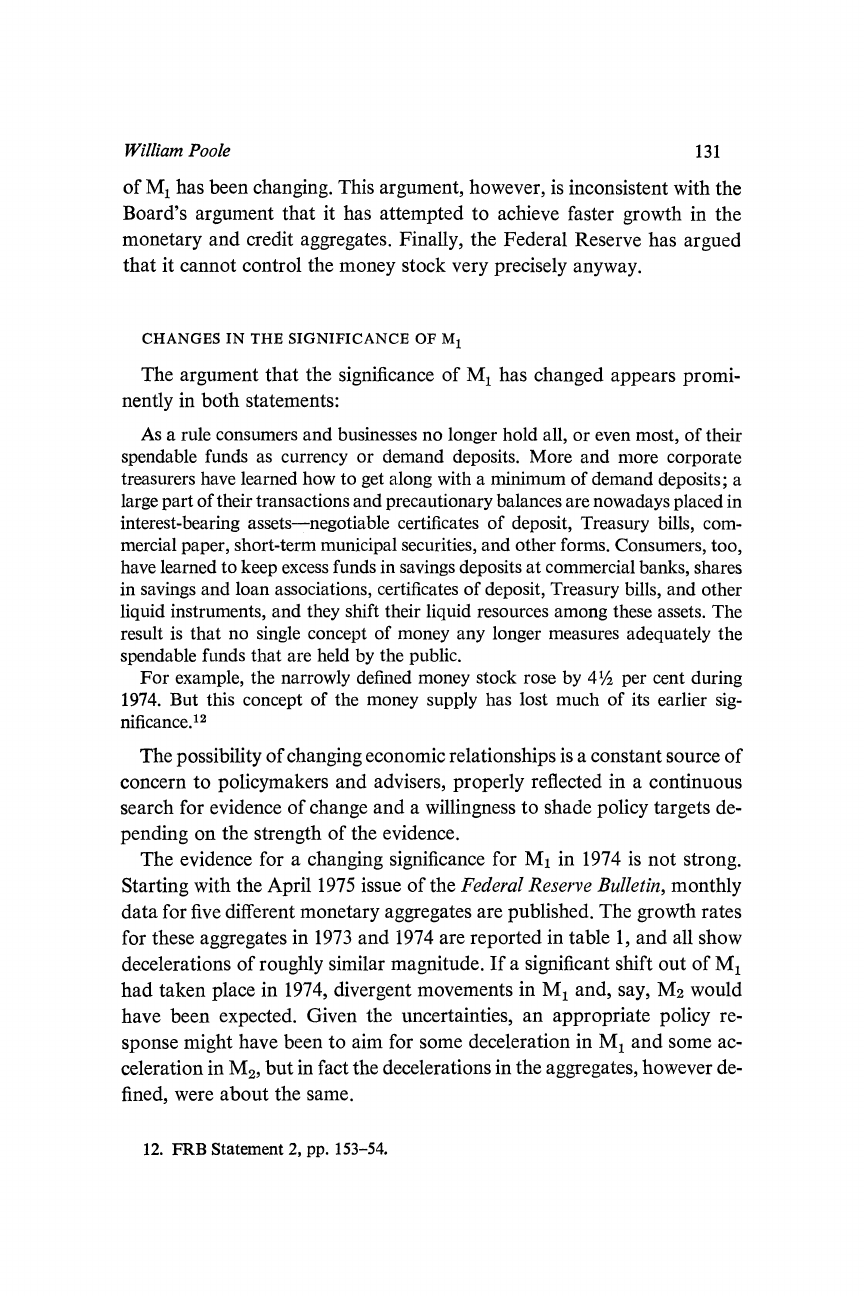

evidence

for

a

changing significance

for

M1

in 1974 is

not

strong.

Starting

with

the

April

1975 issue

of

the

Federal

Reserve

Bulletin, monthly

data

for

five

different

monetary aggregates

are

published.

The

growth

rates

for

these

aggregates

in

1973 and 1974

are

reported

in

table

1,

and

all

show

decelerations

of

roughly

similar

magnitude.

If

a

significant

shift out

of

M1

had taken

place

in

1974, divergent

movements

in

M1

and,

say, M2

would

have been

expected.

Given

the

uncertainties,

an

appropriate

policy

re-

sponse might

have

been

to aim for some deceleration

in

M1

and some ac-

celeration

in

M2,

but

in fact

the decelerations

in the

aggregates,

however

de-

fined,

were

about the

same.

12. FRB

Statement

2,

pp. 153-54.

132

Brookings Papers on Economic Activity,

1:1975

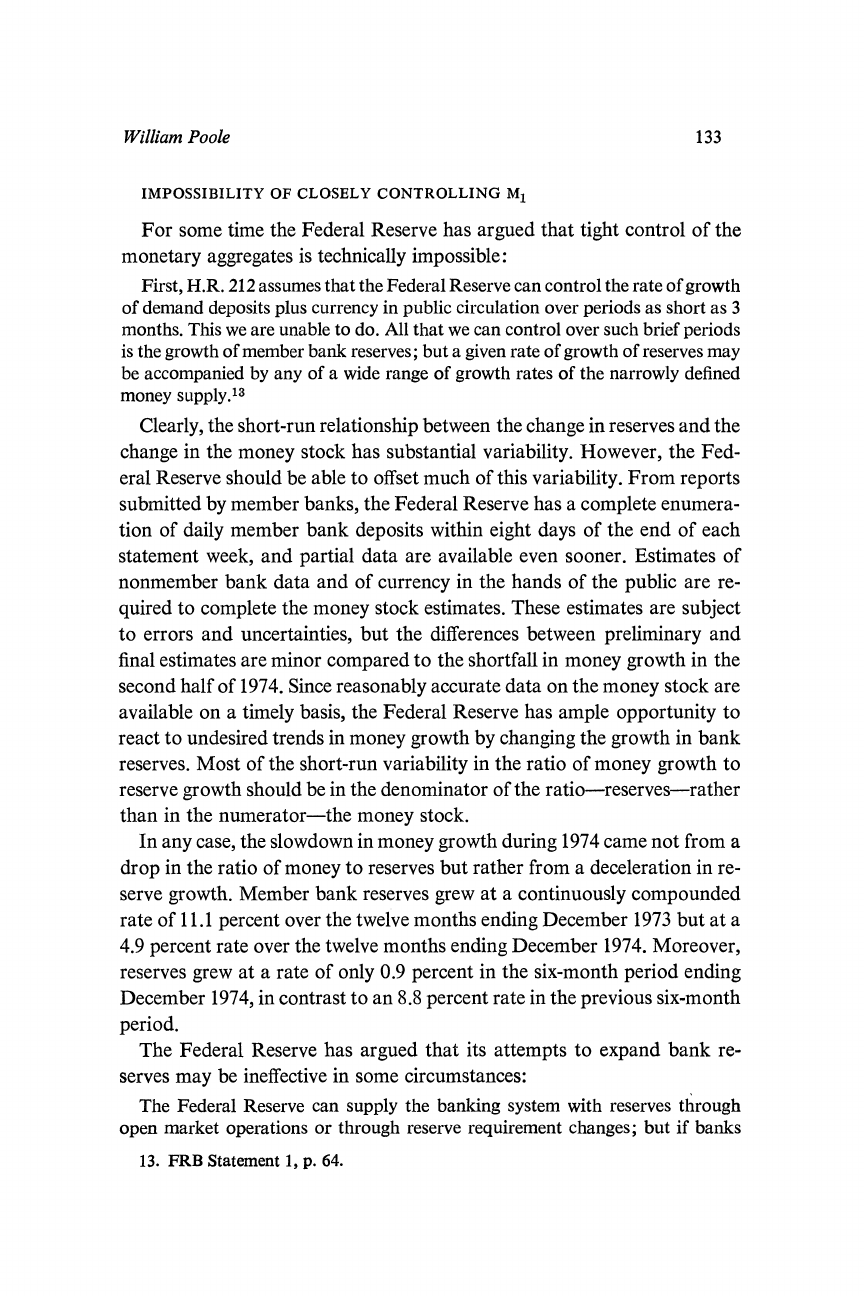

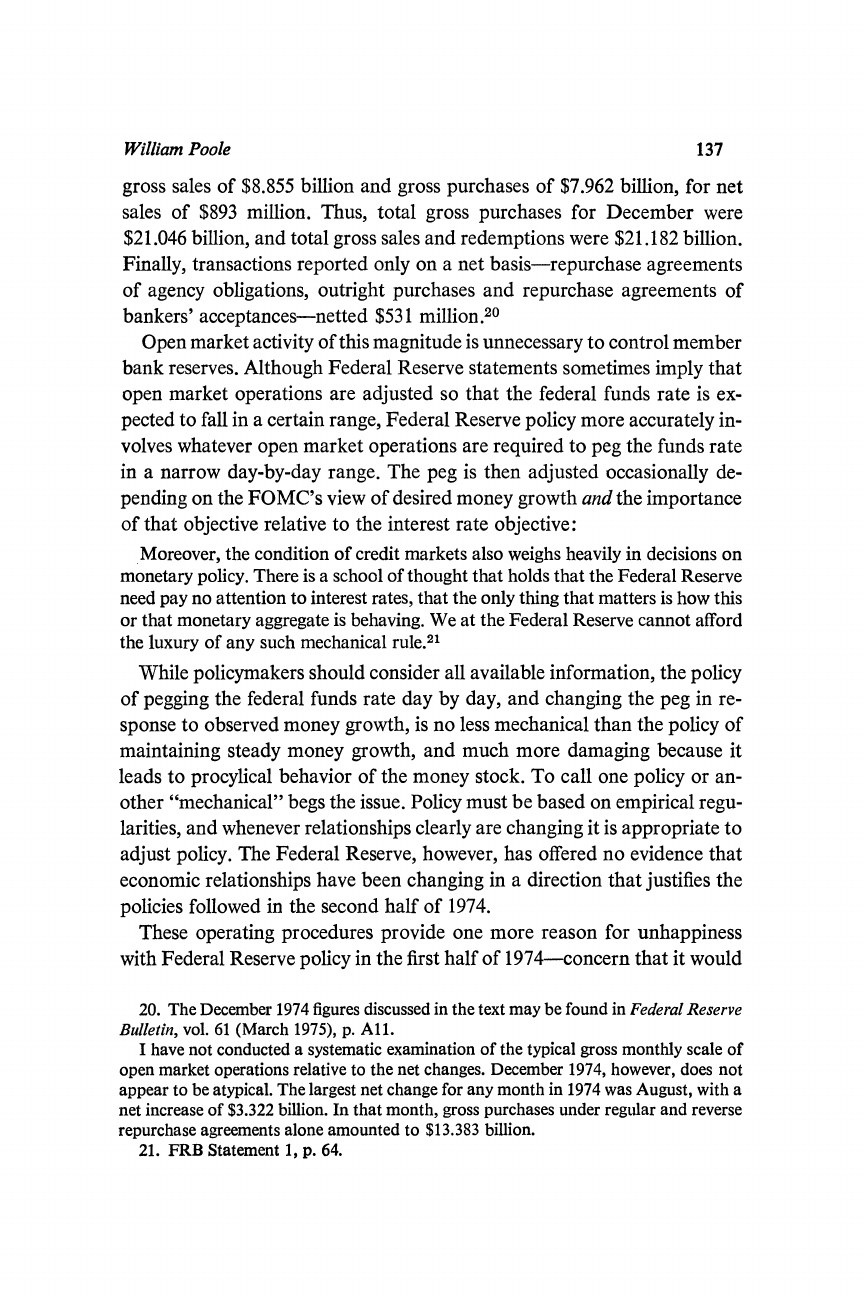

Table 1.

Growth Rates of Selected

U.S. Monetary

Aggregates, 1972-74

Annual

rate in

percent,

continuously compounded

Growth rate

Change

Monetary

December

1972-

December

1973- (percentage

aggregatea

December 1973 December 1974

points)

M1

6.0 4.6

-1.4

M2

8.5 7.0

-1.5

M3

8.5 6.5

-2.0

M4

11.0 10.1 -0.9

M5

10.1

8.6

-1.5

Source:

Calculated from dollar

figures

in

the

table, "Measures

of the

Money Stock,"

Federal Reserve

Bulletin,

vol. 61

(June 1975).

a.

The

measures

are defined as follows:

MI: Averages

of

daily figures

of

(1) demand deposits of commercial banks

other than domestic interbank

and U.S.

government deposits,

less cash items

in

process

of

collection and

Federal Reserve float; (2) foreign

demand

balances

at

Federal

Reserve banks; and (3) currency outside the

Treasury,

Federal Reserve

Banks,

and

vaults of

commercial

banks.

M2: Average

of

daily figures

for

Ml

plus savings deposits,

timne

deposits

open account,

and time certificates

other than negotiable

certificates

of

deposit of $100,000

of

large weekly

reporting banks.

M3: M2 plus deposits

at mutual

savings

banks,

savings

and

loan

shares,

and credit union shares

(nonbank

thrift).

M4: M2 plus large negotiable

certificates

of

deposit.

M5:

M3 plus large negotiable

certificates of

deposit.

The

FRB statement

above

mentions

even broader

aggregates

of

liquid

assets-including Treasury bills,

commercial

paper,

and so

forth-but

monthly

data

for

these

broader

aggregates

are

not

published. More

com-

prehensive

data are available in the

flow-of-funds

accounts,

but these are

not published

on a

timely

basis and are

of little value

in

month-by-month

policymaking.

The

rate of

turnover in demand

deposits might

also

suggest a changed

significance for M1. The

reasons

for

changes

in

turnover-the ratio of de-

mand

deposit

debits to demand

deposits-are not

well

understood; the

average

annual rate of increase of

deposit turnover between December 1964

and December

1971 was

8.8 percent while the

rates

of

increase

in

1972,

1973, and

1974

(December

to

December)

were

8.0, 19.5, and 15.0 percent,

respectively.

If these

numbers mean

anything,

the

Federal

Reserve

should

have forced

a

sharp

deceleration of M1

growth

in

1973

and a

mild accelera-

tion in 1974.

Obviously, new

theories

and new data

could overturn the empirical regu-

larity

that

sharp

decelerations of

money growth

are

associated

with

reces-

sions, but they also could confirm

the empirical regularity. In the absence

of

compelling evidence

to the

contrary,

the

safest course is to assume that

M1

has the

same

significance

as in the

past.

William Poole

133

IMPOSSIBILITY OF CLOSELY CONTROLLING

Ml

For some time the Federal Reserve

has

argued that tight control of the

monetary aggregates

is

technically impossible:

First, H.R. 212 assumes

that

the Federal Reserve

can

control

the rate of

growth

of demand deposits plus currency

in

public

circulation over

periods

as

short

as

3

months. This we are unable

to

do.

All

that we

can control over such brief periods

is the

growth

of

member

bank

reserves;

but

a

given

rate of

growth

of

reserves may

be accompanied by any of a wide range of growth

rates of the narrowly defined

money supply.'3

Clearly,

the

short-run

relationship

between

the

change in reserves and the

change

in the

money

stock has

substantial variability.

However, the Fed-

eral Reserve should be

able

to offset much of this variability. From reports

submitted

by

member

banks,

the

Federal Reserve

has a

complete

enumera-

tion

of

daily

member

bank

deposits

within eight days of

the end

of

each

statement

week, and partial

data are

available

even

sooner.

Estimates

of

nonmember

bank

data

and of

currency

in the

hands of the public

are re-

quired

to

complete the money

stock

estimates.

These

estimates

are

subject

to

errors and uncertainties,

but

the differences

between preliminary and

final estimates

are

minor

compared

to the shortfall

in

money growth

in the

second

half

of 1974.

Since

reasonably

accurate data on the

money

stock

are

available on

a

timely basis,

the

Federal

Reserve has

ample opportunity

to

react to undesired trends

in

money growth by

changing

the

growth

in

bank

reserves. Most of

the

short-run variability

in

the

ratio of money growth

to

reserve growth should

be in the

denominator

of

the

ratio-reserves-rather

than

in the

numerator-the

money

stock.

In

any case, the slowdown

in

money growth

during

1974 came

not

from a

drop

in

the

ratio of money

to

reserves

but

rather

from

a

deceleration

in re-

serve growth.

Member

bank

reserves grew

at

a

continuously compounded

rate of

11.1 percent over

the

twelve months ending

December 1973 but at

a

4.9 percent

rate

over

the twelve months ending December 1974. Moreover,

reserves grew

at

a

rate of

only 0.9 percent

in

the

six-month period ending

December

1974,

in

contrast

to an

8.8

percent

rate in

the

previous

six-month

period.

The

Federal Reserve

has

argued

that

its

attempts

to

expand

bank

re-

serves may

be ineffective

in some circumstances:

The Federal

Reserve

can

supply

the

banking system

with

reserves

through

open

market

operations

or

through

reserve

requirement

changes;

but if banks

13.

FRB

Statement

1,

p.

64.

134

Brookings

Papers

on Economic

Activity,

1:1975

choose

to

repay

debt

or rebuild their

liquidity,

these actions

will

have

little

impact

on

the

public's

money supply.'4

This position

raises questions

about two

effects of open

market operations:

the first,

on member

bank

borrowing

from the Federal

Reserve;

and the

second,

on

member bank

holdings

of excess

reserves.

Member

bank borrowing

at

the discount window

fluctuated substantially

in 1974, rising

from

a

December

1973 average

of

$1.3

billion to a

peak of

$3.4 billion

in August

1974,

and then

dropping to $0.7

billion

in

December.

The amount

of

outstanding

borrowing is,

of

course,

on the

books

of

the

Federal Reserve,

and hence

known

continuously. While

it

is true that

under

the current system

of

lagged

reserve

requirements-a

system

that fixes

in

advance

the

dollar amount

of

required

reserves

in

any particular

week-

increases

in

borrowings

cannot

be

immediately

offset

by open

market sales,

declines

in

borrowings

can nonetheless

be offset

by open

market

purchases.

The

Federal Reserve

has

argued:

"Of

late, open

market

policy

has been

reinforced

by

other

monetary

instruments.

The

discount rate was reduced

on

three occasions-in December,

January,

and

again

early this

month

[February]-from

8

per

cent to

63/4

per

cent."''5

But the

incentive for

banks

to use

the

discount

window

has declined substantially as open

market

interest rates have

fallen to

a

much

greater

extent.

The

federal funds

rate

averaged

12.01 percent

in

August

1974,

4

percentage

points above

the

dis-

count rate.

Four months

later,

in

December,

the

funds rate

averaged

8.53

percent,

or

about

3/4

of 1

percentage

point

above the discount

rate. By

March 1975

the federal

funds rate

averaged 5.54 percent,

about 1

'/4

per-

centage points

below

the

discount rate

of

63/4

percent.

The

sharp

decline

in

member

bank

borrowings

was

largely

predictable

due to this

sharp

change

in

the

spread

between

the

discount

rate and

open

market

rate.'6

For

a

given

quantity

of

total

reserves, attempts by

member banks

to

re-

build

liquidity

through

a

restructuring

of

their

assets can

contract

deposits

only

if

the banks

hold excess

reserves.

Member

bank

excess reserves

were

$262

million

in December

1973,

and

$131

million

and $339 million,

respec-

tively,

in

June

and

December

of

1974.

These small

swings

in

excess reserves

14. FRB

Statement 2, p.

152.

15. FRB

Statement 2, p.

151.

16. This

discussion

is

not

meant to

imply

that the discount

rate

should have

remained

4 percentage

points below

the

federal funds rate. The

discount

rate

is

best

held continu-

ously

above

the funds

rate;

but

having

failed

to

maintain such a

relationship

in

mid-1974,

the

Federal Reserve

should have

anticipated

the

sharp

decline in

borrowing

as

market

rates dropped

more

rapidly

than the discount rate.

William

Poole

135

are

clearly of

trivial

consequence

given

total reserves that

exceed

$35

billion.

The Federal

Reserve has also

argued

that there is a link

between

bank

loan

demand

and

money

creation:

The Federal

Reserve

can

have

a

marked influence

on

short-term

interest

rates

and

may

also have some indirect influence

on

other terms

of

credit.

But

it

cannot

force

businesses or

consumers to

borrow

from

their banks

and

thus to

expand

the

volume of bank

loans. The

Federal

Reserve

cannot force

people

to

hold

money in

the

form of demand

deposits

when

they

prefer

to

hold

their

transactions

or pre-

cautionary balances

in

income-earning

assets.'7

If

the

Federal Reserve

had maintained

a

higher

rate

of

growth of

total

member

bank

reserves,

and if member banks had

continued

their

long-

standing practice

of

holding only

minimal

amounts

of

excess

reserves

(which

earn no

interest),

then

deposit

growth

would

have

been

sustained.

Even

if

bank loan demand

had remained

sluggish,

banks would

have

pur-

chased securities

and

thus added

to

deposits

until their

liabilities

subject

to

reserve

requirements-predominantly

demand and time

deposits-had ex-

panded

sufficiently

to

absorb all of the

reserves

supplied

by

the

Federal

Reserve.

In terms of

the

composition

of

assets,

banks have

not

become

more

liquid.

Of total loans and investments for

all

commercial

banks,

loans

were

71.5

percent

at the end

of June

1974,

and

72.5 percent

at the end

of Decem-

ber.

Federal Reserve

policies

did

not

permit

banks to

increase

their

hold-

ings

of liquid

money-market

instruments.

That

banks

have

attempted, un-

successfully,

to

improve

their

liquidity

is

suggested

by

the

large

increase in

the

spread

between the

prime

rate and the commercial

paper rate.

In

June

and

July

of 1974 the

prime

rate was

only

a

little

above

the

commercial

paper

rate;

but

in

December

the

spread

was

about

1.5

percentage

points,

and it had increased somewhat further

by

March

1975.

If

the Federal

Reserve

had maintained the 1973 rate

of

growth

of bank

reserves

in

1974,

then interest rates on

open

market

securities

would

have

declined

sufficiently

to induce the nonbank

public

to

hold the

larger

quan-

tity

of demand and

time

deposits.

While

the

Federal

Reserve cannot

di-

rectly

control the

mix

of

demand

and

time

deposits,

it

certainly

can

ensure

that

sharply

reduced

rates

of

growth

do

not

occur

in

both M1

and

M2.

Finally,

the Federal Reserve

has

pointed

to

reductions in

reserve

require-

ments as

additional evidence

of

a

more

expansionary

policy:

"Reductions

17.

FRB Statement 2, p.

152.

136

Brookings Papers on Economic

Activity, 1:1975

in

member bank

reserve requirements were also

ordered-in September,

November, and January, releasing a total

of nearly $2 1/2 billion of reserves

to the banking system."18 But these

reductions

in

reserve requirements

were largely offset by open market

operations that drained a roughly

equivalent amount of reserves from

member banks. Total reserves, mea-

sured on a basis incorporating seasonal

adjustments but without adjust-

ments for

changes

in

reserve

requirements,

fell

from $36.86 billion

in

October 1974 to

$34.86 billion

in

March

1975.

Concluding Comments

The

explanation

for the

low

rate of

money growth in the second half of

1974

is,

I

feel, quite simple.

It

results

partly

from the

operating procedure

of

the Federal Reserve

that

pegs

the

federal funds rate in a

narrow band day

by day, and, given

this

procedure, partly

from

an

unwillingness

to reduce

the

peg

on

the

funds rate

rapidly enough

to

maintain

money growth.19

An enormous scale

of

open

market

operations

is

employed

to maintain

the federal funds

rate in the

narrow

band

specified by

the Federal

Open

Market

Committee.

For

example,

in December

1974,

the

net

change

in

Federal

Reserve

holdings

of

U.S. government

securities,

federal

agency

obligations,

and bankers'

acceptances was

$393 million. However, during

the month of

December, gross outright purchases

of

U.S. government

secu-

rities and federal

agency obligations

were

$1.614

billion and

gross

sales and

redemptions of these items were $432

million, for

a

net of $1.182 billion.

On

top

of these transactions were

$11.470

billion

of

gross purchases,

and

$11.895

billion

of

gross sales,

of

government

securities under

repurchase

agreements,

for

net

sales of

$425 million. Extensive

operations

in

matched

sale-purchase

transactions

("reverse repurchase

agreements")

involved

18. FRB Statement

2, p. 151.

19. The Federal

Reserve's day-by-day

operating procedure

is basically the same

as

that

used

in

the late 1960s before the adoption of targets

for

monetary aggregates.

The

continued

use of

a

procedure clearly

not well designed for the

purpose of achieving

such

targets

reflects

the

inertia

inherent

in

any organization

and

the

Federal Reserve's con-

tinuing

concern with

day-to-day

stabilization

of interest rates. This

operating procedure

has been described

in

"Numerical

Specifications

of Financial

Variables

and Their Role

in

Monetary Policy,"

Federal

Reserve Bulletin, vol. 60 (May 1974),

pp. 333-37;

and William

Poole, "The Making

of Monetary Policy:

Description and

Analysis," New

England

Economic

Review

(March/April 1975),

pp.

21-30.

William Poole

137

gross

sales

of $8.855

billion and

gross purchases of $7.962 billion, for

net

sales

of $893 million. Thus, total gross purchases for December

were

$21.046 billion, and total gross sales

and

redemptions were $21.182

billion.

Finally, transactions reported only

on

a net

basis-repurchase

agreements

of agency obligations, outright purchases

and

repurchase agreements

of

bankers' acceptances-netted $531 million.20

Open

market

activity

of this

magnitude

is

unnecessary to control member

bank

reserves. Although

Federal Reserve statements

sometimes imply that

open

market

operations

are

adjusted

so

that

the

federal

funds

rate is ex-

pected to fall in

a

certain range, Federal Reserve policy more accurately

in-

volves whatever

open

market

operations

are

required

to

peg

the

funds rate

in a

narrow day-by-day range.

The

peg is

then

adjusted occasionally

de-

pending on

the

FOMC's view

of desired

money growth and the importance

of that objective relative to the interest rate objective:

Moreover,

the condition

of

credit markets

also

weighs heavily

in

decisions

on

monetary policy. There is a school of thought that holds that the Federal

Reserve

need pay

no

attention

to interest

rates,

that the

only thing

that matters is

how this

or that monetary aggregate

is

behaving.

We

at the

Federal

Reserve

cannot

afford

the luxury

of

any such mechanical rule.21

While

policymakers

should consider

all

available

information,

the

policy

of

pegging

the federal funds

rate

day by day,

and

changing

the

peg

in re-

sponse

to

observed

money growth,

is no less

mechanical than

the

policy

of

maintaining steady money growth,

and

much

more

damaging

because it

leads to

procylical

behavior of the

money

stock.

To call

one

policy

or an-

other

"mechanical"

begs

the

issue.

Policy

must

be

based on

empirical regu-

larities,

and

whenever

relationships clearly

are

changing

it is

appropriate

to

adjust policy.

The Federal

Reserve, however,

has

offered no

evidence that

economic relationships have

been

changing

in

a

direction

that

justifies

the

policies followed

in the second

half of 1974.

These

operating procedures provide

one more reason

for

unhappiness

with

Federal

Reserve

policy

in the

first

half

of

1974-concern that it

would

20.

The December 1974

figures

discussed

in

the text

may

be found

in

Federal

Reserve

Bulletin,

vol. 61

(March

1975), p.

All.

I have not conducted

a systematic examination

of the typical gross

monthly scale of

open market operations

relative to the net

changes.

December

1974,

however,

does

not

appear to be atypical.

The

largest

net

change

for

any month

in

1974

was

August, with

a

net increase of $3.322

billion.

In

that month,

gross purchases under regular

and

reverse

repurchase agreements

alone

amounted

to $13.383

billion.

21. FRB Statement

1, p. 64.

138

Brookings Papers

on

Economic Activity,

1:1975

not permit

interest

rates to

drop rapidly

enough,

once

they

were

pushed up,

to maintain

money growth

at a

reasonable rate.

Indeed,

the Federal Re-

serve

seems

to

accept

this

argument

in the other direction as it

applies

currently:

If, for example,

we

presently

encourage

a

sharp decline

of

interest rates

on

top

of the decline

that

has

already

occurred

in

recent

months,

we would run

the

risk

of

seeing short-term

interest rates move

back up while the economy

is still receding.

There is,

moreover,

a

very

real

possibility

that,

as

a

result

of such a policy,

a

monetary base would

be

established for a new wave of inflation

in the future and

that market expectations

of

such a

development

would lead rather

promptly to a

rise

of

long-term

interest

rates.22

The fear

is

valid

under current Federal Reserve

operating

procedures.

Under

an FOMC

procedure

that

permits

only

slow and

"orderly" changes

in the

federal

funds

rate, money growth

is

likely

continually to

be

off target

as the adjustments

in the funds rate

lag

behind

market

pressures.

But

why

should

the Federal

Reserve maintain these

procedures?

No pos-

sible

gain

warrants

the costs

imposed

from

extensive

day-by-day

open

mar-

ket

operations

to limit

fluctuations

in

the federal

funds rate. Moreover, this

policy

has

obviously

failed

to stabilize

the

federal

funds rate

over spans

of

six

to twelve

months.

Excessive

money growth

over

several quarters

at

a

time-as

in 1967-68

and

1972-73-may temporarily

cushion

upward pres-

sures

on

interest

rates,

but

only

at the cost of

exacerbating inflationary

pressures

and

raising

the ultimate interest rate

peak.

Conversely,

abnor-

mally

low

money growth-as

in

1957 and late

1974-may temporarily

cushion

declines

in interest

rates,

but

only

at

the

cost

of

deepening reces-

sions.

The

Federal

Reserve

should

promptly

reform its

operating

procedures.

The FOMC should

direct

the

Open

Market

Manager to

achieve

the rate

of

growth

in nonborrowed reserves

necessary

to

attain the target

rate

of money

growth,

and

the federal

funds

rate

should

be

permitted

to

fluctuate without

limit.

The

goal

should

be

to return

promptly

to a 6

percent

money growth

path, projected

from June

1974,

in order to erase the

mistake of the second

half of 1974.

As of

April 1975,

the shortfall below

the

path

amounted to

$7.3 billion,

or

2.5 percent.

Once back on that 6

percent

path, the money

stock should

be

kept

there

until the

economy

has recovered

sufficiently

to

warrant

a

lower

trend rate of

money

growth

consistent with

long-run price

stability.

22. FRB

Statement

1, p. 64.

William Poole

139

Many economists

share the Modigliani-Papademos

position

that

a

much

more expansionary

monetary policy is

needed. I would agree

if I

were

con-

fident of model estimates

of the policies

required to engineer their

projected

employment path.

But

I

suspect that the

differences in the simulated

out-

comes under their

policy proposal

and my policy proposal

are, from past

experience, far smaller

than the model

errors themselves. The

safest course

is to

avoid major

departures from policy

settings that,

if

maintained five

years at a time, would

be expected to be

in the right range. The

recent fore-

casting fiascos

make it abundantly clear

that knowledge is

inadequate to

make

significant

departures from a trend

path of money growth

a good bet.

By trying to do

too much, policymakers

have put themselves

into a

vicious

"stop-go"

cycle

with

ever-widening

oscillations.

Each

period

of

monetary expansion

has been higher than

the previous one-considering

the

1965, 1967-68,

and

the 1972-73 expansions.

Each

of

the inflations since

1965 has been worse than the

previous

one. And

each setback

in real

ac-

tivity

since 1965 has been

deeper than

its predecessor-in

the sequence

1967, 1969-70,

1974-75. This pattern

must be broken,

and the only

method in which I have any confidence

is that of stabilizing

money growth

and

permitting the

economy

to

settle

down to a stable policy

environment.

The

discussiont

of this report is combinied with

that of the Modigliani-

Papademos report which follows.