United States Employment Impact Review of the

U.S. - Singapore Free Trade Agreement

Pursuant to section 2102(c)(5) of the Trade Act of 2002, the United States Trade Representative,

in consultation with the Secretary of Labor, provides the following United States Employment

Impact Review of the U.S. - Singapore Free Trade Agreement. The report was prepared by the

Department of Labor.

1

United States Employment Impact Review of

the U.S.-Singapore Free Trade Agreement

Table of Contents

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

I. Introduction: Overview of the Employment Impact Review Process

A. Scope and Outline of the Employment Impact Review

B. Legislative Mandate

C. Public Outreach and Comments

1. Responses to Federal Register Notice

2. Reports of the Labor Advisory Committee for Trade Negotiations

and Trade Policy (LAC) and Other Advisory Committees

II. Background and Contents of the FTA

A. Bilateral Economic Setting

1. Population and the Economy

2. Labor Force

a. U.S. Labor Force

b. Singapore’s Labor Force

3. International Trade in Goods

a. Global and Bilateral Trade

b. U.S. Merchandise Exports to Singapore

c. U.S. Merchandise Imports from Singapore

4. International Trade in Services

5. Foreign Direct Investment

B. Current Barriers to Bilateral Trade

1. Trade in Goods

2. Trade in Services, Investment, and Temporary Entry of Business

Persons Related to these Activities

C. Major Elements of the FTA

III. Potential Economic and Employment Effects of the FTA

A. Aggregate Economic Effects

2

B. Sectoral Employment Effects

C. Potential U.S. Labor Market Effects

1. Industry

a. Sectors Likely to Expand as the Result of the FTA

b. Sectors Likely to Contract as the Result of the FTA

c. Rules of Origin, Phase-in of the FTA, and Safeguards

2. Occupation and Compensation

3. Gender Issues

IV. Special Issues Selected for Review

A. Labor Chapter, Including the Labor Cooperation Mechanism

1. Labor Chapter in the FTA

a. Overview

b. Labor and the Trade Act

c. Summary of FTA Chapter 17: Labor

2. Labor Cooperation Mechanism

B. Investment

1. Overview

2. Employment Impact

C. Temporary Entry Provisions for Business Persons in the FTA

1. Categories of Temporary Entry under the FTA

a. Business Visitor

b. Traders and Investors

c. Intra-company Transferees

d. Professionals

2. Areas in Which this FTA Extends New Temporary Entry Rights

3. Potential U.S. Labor Market Impacts

D. Trade Adjustment Assistance and Other Federal Programs to Assist

Displaced Workers

1. New Enhanced Trade Adjustment Assistance Program

2. Benefits and Services Provided to Dislocated Workers

3. Grant Programs to the States for the Provision of Health Insurance

Assistance

Endnotes

3

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This employment impact review is the first-ever U.S. employment impact review of a

new U.S. trade agreement prepared pursuant to section 2102(c)(5) of the Trade Act of

2002 which requires the President to review and report to the Congress on the impact of

future trade agreements on U.S. employment, including labor markets. This review

presents an overview of the employment impact review process, the background and

contents of the U.S-Singapore Free Trade Agreement (FTA), and assessments of the

potential economic and employment effects of the FTA. In addition, the review

considers four selected issues related to the FTA that are relevant to employment and

labor markets in the United States: the labor provisions of the FTA; the investment

provisions in the FTA; the temporary entry provisions for business persons in the FTA;

and trade adjustment assistance (TAA) and other federal programs to assist U.S. workers

who may be displaced by international trade. The Trade Act of 2002 not only included

the Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) but also renewed the TAA program and greatly

expanded and enhanced the coverage, benefits, and services available to workers certified

under the program.

The major finding of this review is, given the current volume, composition, and structure

of bilateral trade between Singapore and the United States, the U.S.-Singapore FTA is not

expected to have any significant effects on employment in the United States. The

absence of any significant domestic employment effects from the FTA is attributable to,

among other factors, substantial amounts (85 percent) of imports from Singapore already

enter the United States duty free, the gradual removal over a 10-year period of the

remaining U.S. tariffs on imports from Singapore, and safeguards for increases in imports

that may cause serious injury to a domestic industry.

As Singapore’s markets become more open to U.S. goods and services with the

introduction of the U.S.-Singapore FTA, and U.S. goods become more competitive in the

Singaporean market, it is expected that U.S. services and merchandise exports to

Singapore will increase. This especially ought to be the case for the current leading U.S.

merchandise exporters and service providers to Singapore in areas such as capital and

industrial goods, including aircraft, computers, machinery and equipment, chemicals, and

measuring instruments, and financial and other business related services, including

banking, financial services, and insurance. New U.S. export opportunities may also arise

in the areas of agriculture, manufacturing, and services as the Singaporean market—

though relatively small—becomes more open. U.S. imports from Singapore are also

expected to increase as the result of the FTA, especially in products such as wearing

apparel, chemicals, prepared foods, jewelry, machinery, computers and electronic

equipment, electrical motors and appliances, and scientific instruments.

4

I. Introduction: Overview of the Employment Impact Review Process

A. Scope and Outline of the Employment Review

This employment impact review consists of three additional parts. Part II discusses the

background and contents of the U.S.-Singapore FTA, including the bilateral economic

setting, current barriers to bilateral trade, and the major elements of the FTA. Part III

considers the potential economic and employment effects of the FTA, with special

emphasis on industrial employment and occupational labor markets in the United States.

Part IV considers four special issues related to the FTA that are relevant to employment

and labor markets in the United States and have been raised by the public in the context

of the FTA negotiations: (1) the labor provisions of the FTA, including a labor

cooperation mechanism; (2) the investment provisions in the FTA and their implications

for employment in the United States; (3) the temporary entry provisions for business

persons in the FTA; and (4) the availability of trade adjustment assistance and other

federal programs to assist U.S. workers that may be displaced by increased imports or

companies transferring their production overseas.

B. Legislative Mandate

This review of the employment impact of the U.S.-Singapore FTA has been prepared

pursuant to section 2102(c)(5) of the Trade Act of 2002 (“Trade Act”) (Pub. L. No. 107-

210). Section 2102(c)(5) provides that the President shall:

review the impact of future trade agreements on United States

employment, including labor markets, modeled after Executive Order

13141 to the extent appropriate in establishing procedures and criteria,

report to the Committee on Ways and Means of the House of

Representatives and the Committee on Finance of the Senate on such

review, and make that report available to the public.

The President, by Executive Order 13277 (67 Fed. Reg. 70305), assigned the

responsibility of conducting reviews under section 2102(c)(5) to the United States Trade

Representative (USTR), who delegated such responsibility to the Secretary of Labor with

the requirement that reviews be coordinated through the Trade Policy Staff Committee

(67 Fed. Reg. 71606).

The employment impact review is modeled, to the extent appropriate, after Executive

Order 13141; the guidelines developed for the implementation of that order provided

guidance for the development of procedures and the determination of the scope of this

employment review.

1

Because of the short time frame between the completion of the

negotiation of the U.S.-Singapore FTA and the submission due date of the employment

impact review, there was not sufficient time to seek public comments on a draft review.

The U.S. Department of Labor and USTR would welcome comments on the organization,

content, and usefulness of this review that would lead to improvements in the

employment impact reviews of future trade agreements.

5

C. Public Outreach and Comments

1. Responses to Federal Register Notice

The U.S. Department of Labor and USTR jointly issued a notice on October 21, 2002 in

the Federal Register announcing the initiation of a review of the potential impact on U.S.

employment of the proposed U.S.-Singapore FTA, including the effects on domestic

labor markets, and requesting written public comment on the review and the provision of

information on potentially significant sectoral or regional employment impacts (both

positive and negative) in the United States as well as other likely labor market effects of

the FTA.

2

Four submissions were received in response to the notice:

(i) The Rubber and Plastic Footwear Manufacturers Association (RPFMA),

representing domestic manufacturers of fabric-upper, rubber-soled footwear and

protective footwear, noted that the impact on domestic employment of the FTA

can only be adverse since there are not likely to be increases in U.S. exports of

footwear to Singapore as the result of the FTA and that the phase-out of U.S.

tariffs on these products should be done over a 15-year period.

(ii) The American Apparel & Footwear Association (AAFA), a national

association of apparel and footwear industries, argued the employment impacts of

the FTA in the industrial sectors it represents will be negligible because Singapore

is a very small supplier of apparel and footwear to the U.S. market, Singapore

represents a small market for U.S. apparel and footwear, and given the already

high level of import penetration in the U.S. market any further growth in apparel

and footwear imports is likely to come at the expense of other foreign suppliers

rather than displacing U.S. production and employment.

(iii) The American Yarn Spinners Association, a national trade association

representing the yarn put-up-for-sale manufacturing industry, observed that

Singapore is not competitive with other Asian countries in yarn production and

would likely source yarn and fibers for apparel production from Asian sources

rather than U.S firms (i.e., they did not anticipate any significant export

opportunities resulting from the FTA). The Association argued further that

preferences under the FTA should be available only for apparel goods made

completely of U.S. or Singaporean yarns (i.e., not yarns from a third country),

claiming that without such a requirement domestic apparel jobs would be

jeopardized by imports of finished apparel using third-country-sourced yarn or

fibers as well as employment in domestic yarn mills to the extent that the use of

third-country-sourced yarn displaces domestic customers for U.S. made yarn.

(iv) The American Dehydrated Onion and Garlic Association argued duty-free

treatment of dehydrated onion and garlic from Singapore constituted an

unacceptable risk of transshipments of lower-than-fair-value products from China

6

that would severely affect employment opportunities within the U.S. dehydrated

onion and garlic industry and U.S. tariffs on these products should be phased-out

over a 15-25 year period.

2. Reports of the Labor Advisory Committee for Trade Negotiations

and Trade Policy (LAC) and Other Advisory Committees

Section 2104(e) of the Trade Act requires that advisory committees provide the President,

USTR, and Congress with reports under Section 135(e)(1) of the Trade Act of 1974, as

amended, not later than 30 days after the President notifies Congress of his intent to enter

into an agreement. The advisory committee reports are available on the USTR web site

at: http://www.ustr.gov/new/fta/Singapore/advisor_reports.htm.

The Advisory Committee on Trade Policy and Negotiations (ACTPN) and the other 29

trade advisory committees virtually all expressed the view that the U.S.-Singapore FTA is

in the economic interests of the United States and stated their support for the FTA. The

findings of a majority of the ACTPN found that the FTA will “substantially improve

market access for American farm products, industrial and other non-agricultural goods,

and services;” a labor representative on the ACTPN dissented from the positive views of

other ACTPN members. The Industry Sector Advisory Committees (ISACs) on Capital

Goods (ISAC-2) and on Transportation, Construction, and Agricultural Equipment

(ISAC-16), in particular, commented that the FTA would benefit the exports of their

respective industries. ISAC-13 (Services) noted that the temporary entry provisions in

the FTA are constructive. The ACTPN and a number of other trade advisory committees

also indicated that the investment provisions of the FTA are especially noteworthy as

they significantly improve the opportunities and conditions for U.S. investments in

Singapore.

The Labor Advisory Committee for Trade Negotiations and Trade Policy (LAC)

submitted its report to the President on February 28, 2003. Contrary to the 30 other

advisory committees, the LAC argued in its report that the FTA will lead to a

deteriorating trade balance and lost jobs, citing their views of NAFTA and the

establishment of permanent normal trade relations with China. They noted that

Singapore’s tariffs on U.S. exports are already zero and claimed that the main focus of

the FTA was on removing obstacles to increased U.S. investment in Singapore at the

expense of the United States, with a consequent loss of U.S. jobs.

3

[This issue is

addressed in section IV.B of this review.]

The LAC was also critical of the FTA’s labor provisions that commit the Parties to

enforce their own labor laws without any enforceable obligation for those laws to meet

international standards as defined by the ILO. The LAC interpreted the FTA’s dispute

resolution procedure as providing for longer timelines and lower penalties for violations

of the Labor Chapter than for other violations and that requiring financial penalties be

used to improve labor standards reduced their punitive value. [These issues are discussed

in section IV.A of this review.] The LAC also opined that FTA provisions on the

temporary entry of professionals erode basic protections for U.S. workers in the domestic

labor market, and that the FTA provisions on investment, procurement, and services

7

would constrain the ability of the U.S. government to regulate in the public interest and

provide public services. [These issues are addressed in section IV.C of this review.]

8

II. Background and Contents of the FTA

A. Bilateral Economic Setting

1. Population and the Economy

Singapore’s population is 4.2 million, 1.4 percent of that of the United States, and its land

size is only 3.5 times that of Washington, DC. Singapore is a small city-state, and

approximately 19 percent of its population are foreigners (mainly migrant workers and

professionals). Located amid one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes, its economy is

heavily dependent on both imports and exports. Singapore’s total imports and exports

exceed its GDP. In 2002, Singapore’s GDP totaled $92.3 billion (at current market

prices)—about one percent of the U.S. GDP of $10.4 trillion, while its total goods trade

(exports plus imports) was $241.4 billion. Singapore’s GDP growth rate has decelerated

from the high annual rates seen from 1965-1997, in part due to regional and global

economic effects, but also due to the maturation of Singapore into a developed economy.

In 2001, real GDP declined 2 percent, but recovered in 2002 to show positive growth of

2.2 percent. Singapore’s labor force of approximately 2.1 million in 2002 is roughly 1.5

percent of that of the United States. Singapore’s gross national income (GNI) per capita

in 2001 was $21,500, which was just between that of Italy ($19,390) and Canada

($21,930) and approximately 63 percent of that of the United States ($34,280).

4

2. Labor Force

a. U.S. Labor Force

In 2002, the U.S. labor force totaled 145 million workers. The service-producing

industries, also known as the service sector, are the major source of employment in the

United States. In 2002, service-producing industries accounted for 77 percent of total

U.S. employment; within this group, services, including personal, private, business, and

other services, accounted for 38 percent of total U.S. employment and wholesale and

retail trade accounted for 21 percent. Other major sectors of employment include

manufacturing which accounted for 13 percent of total U.S. employment, mining and

construction which accounted for about 7 percent and agriculture which accounted for

slightly over 2 percent.

5

On an occupational basis, approximately 31 percent of all the

employed persons were in either managerial professions (15 percent of total employment)

or professional specialty occupations (16 percent of total employment); other major

occupational categories of U.S. employment were technical, sales, and administrative

support occupations (29 percent of total employment) and service occupations (14

percent of total employment). On the industrial basis used for cross-country analysis,

6

U.S. employment in 2000 was distributed across industrial sectors as follows: 2 percent

in the agricultural sector,

7

22 percent in industry,

8

and 75 percent in the service sector.

9

Nearly 47 percent (67.4 million) of the civilian U.S. labor force in 2002 was female.

10

The annual average unemployment rate in the United States was 5.8 percent for 2002, an

increase over its recent low point of 3.8 percent in April 2000.

11

The majority of the U.S.

9

unemployed in 2002, as is typical, included job losers and those who had completed

temporary jobs (55 percent). Reentrants to the labor force made up 28 percent of the

unemployed in 2002, new entrants represented 6 percent, and job leavers accounted for

10 percent. From an industry standpoint, job losses during 2002 were in mining,

construction, manufacturing, retail trade, and transportation. These losses were countered

in part by an increase in jobs in the services and government industries.

12

Education appears to have been a favorable influence on finding and keeping a job. Of

workers 25 years or older, 10 percent of the employed had less than a secondary degree,

31 percent had finished secondary schooling, 27 percent had some tertiary schooling, and

32 percent had a college degree in 2002.

13

Of the unemployed in 2002, 19 percent had

not completed secondary school, 35 percent had completed secondary schooling, 27

percent had attended some college (including those receiving an associate degree), and 20

percent had a college degree.

14

In 2002, business sector labor productivity rose 4.8 percent, a sharp increase from the 1.1

percent annual average labor productivity growth in 2001.

15

Overall, labor productivity

in manufacturing increased 4.5 percent on average in 2002, compared to labor

productivity increases for durable goods and nondurable goods within the manufacturing

sector of 5.6 percent and 2.8 percent, respectively.

16

Between 1990 and 2000, labor

productivity increased in 111 of the 119 industries in the manufacturing sector.

17

On average, U.S. workers worked 39.2 hours per week during 2002; the average full-time

worker put in 42.9 hours per week. Persons working in agriculture reported more work

hours per week, 41.1 hours on average (46.8 hours for full-time workers), than those in

nonagricultural industries, 39.1 hours per week (42.8 hours for full-time workers).

b. Singapore’s Labor Force

Singapore’s labor force was comprised of approximately 2.1 million workers in June

2002.

18

The major sectors of employment in Singapore in 2002 were: community, social

and personal services (26 percent); manufacturing (18 percent); wholesale and retail trade

(21 percent); business and financial services (17 percent); and transport, storage and

communications (11 percent). The top occupational groups in 2002 were: production

craftsmen, operators, cleaners and laborers (30 percent); professionals and managers (25

percent); technicians and associate professionals (17 percent); clerical workers (13

percent); and service and sales workers (11 percent).

19

In 2002, female workers made up

44 percent of the total Singaporean labor force.

20

The female labor force was composed

of 927 thousand workers, and had an employment rate of 95 percent.

Unemployment in Singapore reached a high of 4.6 percent in September 2002, but fell

back to 4.2 percent by the end of the year. Job losses have come mainly in the

manufacturing sector.

21

The top occupational categories of the unemployed in 2002

were: production craftsmen, operators, cleaners and laborers (23 percent); service and

sales workers (16 percent); clerical workers (16 percent); professionals and managers (13

percent); and technicians and associated professionals (12 percent).

22

10

The Singapore Ministry of Manpower estimates that labor productivity decreased by 5.4

percent in 2001.

23

Standard hours worked were 42.6 per week in 2001, and average

weekly overtime hours were 3.6. In 2001, 38 percent of the labor force had a post-

secondary education, 42 percent had completed secondary or lower secondary schooling,

and 20 percent had a primary school or lower education.

24

About 33 percent of the

economically active residents between the ages of 15 and 64 years were engaged in “job-

related structured training” over the 12-month period ending June 2001.

3. International Trade in Goods

a. Global and Bilateral Trade

Trade in goods represented 18 percent of U.S. GDP in 2001. U.S. goods trade with the

world amounted to $1.8 trillion ($666.0 billion exports and $1,132.6 billion imports) in

2001. Based on available statistics from the World Trade Organization (WTO), the

United States was the world’s number one exporter and number one importer in 2000.

25

Singapore’s trade in goods (excluding re-exports) represented 167 percent of its GDP in

2000, while its trade in goods and services represented 220 percent of its GDP. During

2001, Singapore’s total goods trade with the world amounted to $237.1 billion ($121.5

billion exports and $115.6 billion imports). Singapore is a regional hub for Asian trade,

with almost 43 percent of its total exports consisting of re-exports of products from other

countries. In 2000, its total exports to the world totaled $137.9 billion, while exports of

Singaporean domestic products totaled only $78.9 billion. Similarly, total imports

measured $134.5 billion in 2000, while imports for Singapore’s domestic consumption

measured $75.6 billion. Based on available statistics from the WTO, Singapore was the

world’s 22

nd

largest exporter and the 18

th

largest importer in 2000.

26

U.S. bilateral goods trade with Singapore represented 2.4 percent ($15.8 billion) of

overall U.S. exports to the world

and 1.3 percent ($14.9 billion) of overall U.S. imports

from the world in 2001. Singapore ranked as the 11

th

largest U.S. export market and the

13

th

largest source for U.S. goods imports in 2001. In contrast, the United States was

Singapore’s second largest export partner and second largest import supplier in 2001,

accounting for 15 percent of Singapore’s total exports and 17 percent of Singapore’s total

imports. Between 1997 and 2001, U.S. exports to Singapore have increased by less than

one percent while imports from Singapore have decreased by over 25 percent. The U.S.

goods trade surplus with Singapore was $.9 billion in 2001, a $4.0 billion swing from the

$3.1 billion trade deficit in 2000.

In 2002, Singapore ranked as the 11

th

largest U.S. export market and the 16

th

largest

source for U.S. goods imports. U.S. goods exports to Singapore amounted to $14.7

billion in 2002 and U.S. goods imports from Singapore were $14.1 billion. The U.S.

goods trade surplus with Singapore was $.6 billion in 2002, down slightly from 2001.

b. U.S. Merchandise Exports to Singapore

11

U.S. goods exports to Singapore amounted to $15.8 billion in 2001. Almost 71 percent

were accounted for by the top-10 3-digit export-based Standard Industry Classification

(SIC) industries covering a variety of manufactured products, including: aircraft;

electronic components and machinery; office machines; construction, industrial, and

mining machinery and equipment; measuring instruments; and petroleum products (See

Table 1).

27

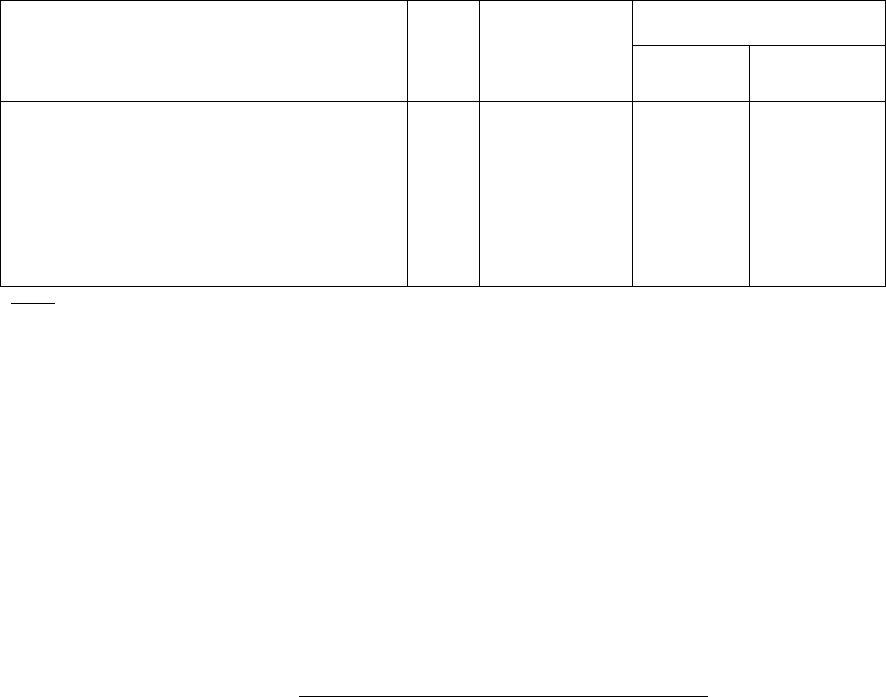

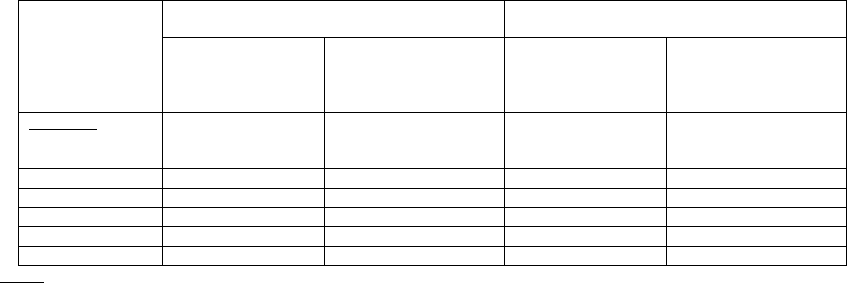

Table 1: Top-10 SIC-based U.S. Exports to Singapore in 2001

Percent of

U.S. Export Industry

SIC

Code

Value of U.S.

Exports to

Singapore ($mil.)

Total U.S.

Industry

Exports

All U.S. Exports

to Singapore

Aircraft and Parts, not specifically provided for 372 4,118 7.4 26.1

Electronic Components and Accessories 367 2,175 4.5 13.8

Office, Computing, and Accounting Machines 357 1,409 3.7 8.9

Construction, Mining, and Materials Handling Machines 353 694 4.4 4.4

Instruments for Measuring Non-electric Quantities 382 672 3.3 4.3

Petroleum Refinery Products 291 475 6.3 3.0

General Industrial Machines and Equipment 356 417 2.8 2.6

Electrical Machinery 369 412 5.2 2.6

Special Industry Machines, not specifically provided for 355 386 4.5 2.4

Manufactured Commodities Not Identified by Kind 3XX 386 2.0 2.4

Source: U.S. Department of Labor tabulations of official U.S. trade data from the U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the

Census.

Viewed from the vantage point of Singapore’s published statistics which include re-

exports, during 2000 Singapore imported more than $500 million from the United States

in each of several 2-digit Standard International Trade Classification (SITC) product

categories; these imports of U.S. goods accounted for more than 10 percent of

Singapore’s imports for: Electrical Machinery ($5.9 billion; 15 percent); Office Machines

($2.3 billion; 14 percent); Specialized Machinery ($2.0 billion; 36 percent); Scientific

Instruments ($1.5 billion; 44 percent); Miscellaneous Manufactures ($988 million; 26

percent); Transport Equipment ($867 million; 46 percent); General Industrial Machinery

($775 million; 18 percent); Chemical Materials ($566 million; 39 percent); and Power

Generating Machinery ($521 million; 21 percent).

c. U.S. Merchandise Imports from Singapore

U.S. goods imports from Singapore amounted to $14.9 billion in 2001. Almost 90

percent were accounted for by the top-10 3-digit import-based SIC industries covering a

variety of manufactured products including computer and office machines, electronic

components, drugs, medical instruments, radios and TVs, measuring devices,

communications equipment, petroleum products, and industrial organic chemicals (See

Table 2).

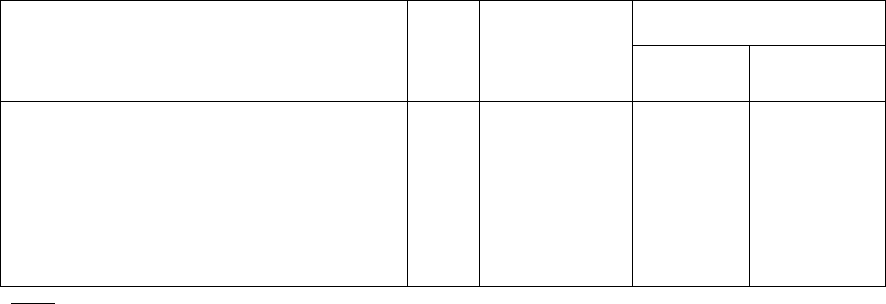

Table 2: Top-10 SIC-based U.S. Imports from Singapore in 2001

12

Percent of

U.S. Import Industry

SIC

Code

Value of U.S.

Imports from

Singapore ($mil.)

Total U.S.

Industry

Imports

All U.S. Imports

from Singapore

Computer and Office Equipment 357 7,942 10.6 53.3

Electronic Components 367 2,108 4.4 14.1

U.S. Goods Returned 980 994 2.9 6.7

Drugs 283 672 2.0 4.5

Medical and Dental Instruments 384 420 3.5 2.8

Radio/TV Sets; Phonographs 365 332 1.4 2.2

Measuring and Controlling Devices 382 289 1.9 1.9

Communication Equipment 366 287 0.8 1.9

Petroleum Refinery Products 291 187 0.5 1.3

Industrial Organic Chemicals 286 158 1.0 1.1

Source: U.S. Department of Labor tabulations of official U.S. trade data from the U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the

Census.

Several items, not in the top-10, imported from Singapore that accounted for more than

one percent of total U.S. imports of the item in 2001 include the following SIC-based

import groups: Aircraft and Nautical Instruments—SIC 381 ($31 million; 2 percent);

Ship Repair—SIC 373 ($22 million; 2 percent); and Manifold Business Forms—SIC 276

($71 thousand; 1 percent).

Again, viewed from the vantage point of Singapore’s statistics which include re-exports,

during 2000 the United States imported more than $250 million in goods from Singapore

in each of several 2-digit SITC sectors including: (also provided is the U.S. percentage of

Singapore exports of each category): Office Machines ($10.7 billion; 35 percent);

Electrical Machinery ($7.3 billion; 17 percent); Telecommunications Equipment ($1.2

billion; 15 percent); Apparel ($1.0 billion; 57 percent); Scientific Instruments ($611

million; 30 percent); Miscellaneous Manufactures ($389 million; 8 percent); Organic

Chemicals ($344 million; 11 percent); Petroleum Products ($323 million; 3 percent);

Transportation Equipment ($265 million; 19 percent); and General Industrial Machinery

($251 million; 9 percent).

4. International Trade in Services

U.S. exports of private commercial services (i.e., excluding military and government) to

Singapore were $4.1 billion out of total U.S. services exports of $266 billion in 2001

(about 1.5 percent of total U.S. services exports), and U.S. services imports from

Singapore were $2.0 billion out of the total U.S. imports of $192 billion (about 1.0

percent of total U.S. services imports).

U.S. exports of services to Singapore in 2001 consisted of $314 million in travel (or

about 8 percent of U.S. services exports to Singapore), $68 million in passenger fares

(about 2 percent), $601 million in transportation (about 15 percent), $923 million in

royalties (about 23 percent), and $2,175 million of other private services (about 53

percent). U.S. imports of services from Singapore in 2001 consisted of $423 million in

travel (or about 21 percent of U.S. services imports from Singapore), $171 million in

passenger fares (about 9 percent), $792 million in transportation (about 39 percent), $52

13

million in royalties (about 3 percent), and $572 million in other private services (about 28

percent).

Sales of services in Singapore by majority U.S.-owned affiliates were $5.4 billion in

2000, while sales of services in the United States by majority Singapore-owned firms

were $979 million.

5. Foreign Direct Investment

Net inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI) in 2000 accounted for 22 percent of

Singapore’s gross capital formation and 7 percent of GDP. FDI accounts for 70 percent

of total investment in the manufacturing sector.

28

The stock of U.S. foreign direct

investment in Singapore was $27.3 billion in 2001. U.S. FDI in Singapore is

concentrated largely manufacturing (notably industrial machinery, semiconductors and

other electronics, and pharmaceuticals), petroleum, and financial service sectors.

29

The stock of Singapore’s FDI in the United States was $6.5 billion in 2001, down slightly

from $7.8 billion in 2000, but up considerably from $2.6 billion in 1997, $1.8 billion in

1998, and $1.4 billion in 1999.

30

B. Current Barriers to Bilateral Trade

1. Trade in Goods

Virtually all of Singapore’s imports enter duty free except for four tariff lines involving

alcoholic products. Singapore does levy excise taxes on a number of products (most of

which are not produced domestically) including motor vehicles, tobacco products,

alcohol products, gasoline, and motor oil. Singapore has no restrictions or duties on

imports of textiles and apparel. Although Singapore’s current applied tariffs are zero for

most products, its average WTO bound duty rate (which only covers 71 percent of its

tariffs) was 9.7 percent in 1999 and is projected to decline to 6.9 percent in 2005.

Of the $14.9 billion of U.S. merchandise imports from Singapore in 2001, $12.6 billion

(85 percent) entered normal trade relations (NTR) duty free. Of the remaining $2.3

billion that was subject to duty, $833 million entered duty-free under either the

Harmonized Tariff System (HTS) 9802 program ($10.6 million) or other special tariff

provisions ($822.4 million).

31

Of the $1.4 billion (10 percent) that was actually assessed

duties, the average ad valorem duty rate was 6.7 percent. Over $235 million of these

dutiable imports were subject to an ad valorem duty rate of less than or equal to one

percent. Another $299 million was assessed duties between one and two percent, $353

million between two and five percent, $164 million at between 5 and 10 percent, $185

million at between 10 and 20 percent, $52 million between 20 and 30 percent, and $65

million above 30 percent.

32

Total estimated annual tariff revenue collected by the United

States on imports from Singapore was $96.5 million, which was about 0.5 percent of total

14

U.S. tariff revenues in 2001.

2. Trade in Services, Investment, and Temporary Entry of Business

Persons Related to these Activities

Singapore has a generally open investment regime, and no overarching screening process

for foreign investment.

33

Singapore does maintain limits on foreign investment in

broadcasting, the news media, domestic retail, banking, property ownership, and in some

government-linked companies. There are no restrictions on reinvestment or repatriation

of earnings and capital. In the service sector, Singapore maintains restrictions in several

sectors. For example, the local free-to-air broadcasting, cable and newspaper sectors are

effectively closed to foreign firms; in the professional services—law, architecture,

engineering, and accounting—Singapore maintains certification and registration

requirements not unlike those required to practice these professions in the United States.

In addition, foreign law firms with offices in Singapore are unable to practice Singapore

law, cannot employ Singapore lawyers to practice Singapore law, and cannot litigate in

local courts. There are also restrictions on engineering and architectural services as well

as on accounting and tax services. Foreign banks in the domestic retail banking sector

face significant restrictions and are not accorded national treatment. There are also

restrictions on offshore banking and Singapore dollar lending.

The U.S. services and investment regimes are open.

34

Such restrictions as exist are fully

consistent with international obligations under the WTO and bilateral and multilateral

agreements. Cabotage laws reserve domestic routes to U.S. operators and U.S.-flag

vessels. The United States restricts foreign ownership and control of U.S. air transport

carriers, and the provision of domestic air service is restricted to U.S. carriers. The

United States also restricts foreign investment in telecommunications, radio broadcast,

atomic energy, and energy pipelines. Insurance is subject to sub-federal regulation at the

state level, which frequently limits competition from other U.S. states and foreign

providers, unless they establish a commercial presence in the state. Professional services

are similarly regulated by the states. Finally, under the Exon-Florio Amendment to the

Defense Production Act, the President has the authority to suspend or prohibit foreign

mergers, acquisitions, and takeovers, where there is credible information of a threat to

national security.

Temporary entry of business persons is an important counterpart to the facilitation of

trade in goods and services and investment. Separate from the question of professional

licenses or accreditation, the degree to which these persons can enter another country can

affect the ability of firms and persons to carry out activities that are important to trade in

goods or services or the conduct of investment.

Singapore’s existing temporary entry system includes three tiers: the worker pass (WP),

the employment pass (EP), and the social visit pass (SVP). Unskilled and semi-skilled

workers are admitted by means of the worker pass (WP). The social visit pass (SVP) is

available for short-term visits (less than 90 days) during which the entrant is not

permitted to work within the domestic economy. Persons entering for longer periods of

15

time and/or in order to work under an employment contract in Singapore must obtain an

employment pass (EP). The EP is issued for up to 2 years, but may be renewed in

increments of up to 3 years if the individual continues to work for the same employer. A

new EP is required when changing employers in Singapore. Neither SVP nor EP entries

are numerically capped.

Under the U.S. temporary admission system, applicants are only admitted for specific

types of activities, and must be fully qualified to engage in those activities at the time of

entry. For the temporary entry categories of traders or investors (E-1, E-2 visas), intra-

company transferees (L-1), and professionals (H-1B), work authorization is issued along

with the grant of temporary entry. However, traders and investors are only admitted from

countries that have entered into treaties of commerce and navigation with the United

States. The United States does not numerically limit entries of business visitors (B-1),

traders or investors, or intra-company transferees, but it does impose a worldwide

limitation on professional entries under its H-1B visa program. Singaporean

professionals desiring to enter the United States have had to compete with other foreign

nationals for entry under this program.

C. Major Elements of the FTA

The U.S.-Singapore FTA consists of 21 chapters and associated annexes: Establishment

of a Free Trade Area (including a preamble) and Definitions; National Treatment and

Market Access for Goods; Rules of Origin; Customs Administration; Textiles; Technical

Barriers to Trade; Safeguards; Cross Border Trade in Services; Telecommunications;

Financial Services; Temporary Entry of Business Persons; Competition Policy;

Government Procurement; Electronic Commerce; Investment; Intellectual Property;

Labor; Environment; Transparency; Administrative and Institutional Arrangements

(including dispute settlement procedures); and General Provisions (including general

exceptions). The complete text of the FTA and summary fact sheets are available on

USTR’s web site at http://www.ustr.gov.

Following is a summary of the FTA provisions that are most relevant to this employment

impact review.

• Preamble (Chapter 1)

Although it does not create specific obligations, the Preamble to the FTA (contained in

Chapter 1) frames the FTA’s obligations and sets out the broad aims and objectives of the

Agreement. The Preamble recognizes that liberalized trade in goods and services will

assist the expansion of trade and investment flows, raise standards of living, and create

new employment opportunities in the two countries.

• National Treatment and Market Access for Goods (Chapter 2)

The FTA market access provisions set out the schedules for the elimination of tariffs on

goods originating in the two countries. Most tariffs will be eliminated immediately, with

16

remaining tariffs phased out over three to ten years. For the United States, the import

sensitivity of goods is generally reflected in the tariff phase-out schedules.

• Rules of Origin, Customs Administration and Enforcement Cooperation

Regarding Import and Export Restrictions (Chapters 3 and 4)

The FTA provides clear, simple, and enforceable rules of origin to ensure that only

eligible products from the FTA Parties receive preferential treatment. Certain non-

sensitive information technology products that already enter MFN duty-free into each

Party’s territory, such as lower-end information and communications components, are

considered to be products of the Parties when exported to the other Party even if they are

not manufactured in a Party’s territory. The FTA requires transparency and efficiency in

customs administration, with commitments on publishing laws and regulations on the

Internet, and ensuring procedural certainty and fairness. Both Parties agree to share

information to combat illegal transshipment of goods.

• Textiles (Chapter 5) and Market Access for Textiles (Chapter 2)

Chapter 5, Textiles and Apparel, establishes extensive monitoring and anti-circumvention

commitments—such as reporting, licensing, and unannounced factory checks—to assure

that only Singaporean-originating textiles and apparel receive tariff preferences. In

addition, the chapter contains provisions for Bilateral Textile and Apparel Safeguard

Actions under which emergency measures may be taken on textile or apparel imports

causing serious damage during a 10-year transition period.

The market access provisions in Chapter 2 establish that textile and apparel will be

admitted duty-free immediately if they meet the FTA’s rule of origin. The rule of origin,

a “yarn-forward” rule, requires that an apparel item be made from yarn or fabric

manufactured in Singapore or the United States to benefit from duty-free admission.

There are some departures from this rule that allow a limited yearly amount of textiles

and apparel containing non-U.S. or non-Singaporean yarns, fibers, or fabrics to qualify

for duty-free treatment.

• Technical Barriers to Trade (Chapter 6)

The FTA includes an enhanced co-operation program to exchange information on

subjects covered by the WTO Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade (WTO TBT

Agreement), which addresses technical regulations, standards, and conformity assessment

procedures. The FTA does not contain any additional obligations beyond those contained

in the WTO TBT Agreement.

• Government Procurement (Chapter 13)

The FTA’s Government Procurement Chapter builds on the existing commitments in the

WTO Government Procurement Agreement (GPA), which ensures non-discrimination,

transparency, predictability, and accountability in the government procurement process

17

and provides appropriate reciprocal, competitive government procurement opportunities

to U.S. suppliers in Singapore’s government procurement market. The chapter on

government procurement provides additional coverage to the WTO GPA Agreement, in

particular in the area of government owned/controlled entities. The chapter also contains

exceptions for non-discriminatory measures necessary to protect human, animal or plant

life or health.

• Safeguards (Chapter 7)

The FTA Safeguards Chapter allows a Party to restore the MFN duty if a product is

being imported in such increased quantities so as to be a substantial cause of serious

injury or threat thereof to a domestic producer of a like or directly competitive product.

A safeguard action may be taken only during the 10-year transition period and generally

not be in place for longer than 2 years. The Party taking the action must provide

compensation or be subject to withdrawal of substantially equivalent concessions by the

other Party. The Parties’ WTO rights are reserved. A Party taking a global safeguard

action may exclude the imports of the other Party if such imports are not a substantial

cause of injury.

• Services (Chapter 8 and related provisions)

The FTA’s core commitments regarding services are modeled on obligations and

concepts in the WTO General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS), the North

American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and other FTAs to which the United States is

a Party. These include provision for national treatment and most-favored-nation

treatment for services suppliers in like circumstances; obligations on transparency in

regulatory processes; and exclusions for services supplied in the exercise of

governmental authority, i.e., any service that is supplied neither on a commercial basis,

nor in competition with one or more services suppliers.

The FTA disciplines will apply across a broad range of services sectors in Singapore.

35

As a result, U.S. service suppliers are afforded substantially improved market access

opportunities in Singapore, with very few exceptions. The FTA’s disciplines apply both

to cross-border supply of services (such as those delivered electronically, or through the

travel of services professionals across borders) and the right to establish a local services

presence in Singapore.

• Temporary Entry (Chapter 11)

Mutual commitments for the temporary mobility of business visitors, traders and

investors, intra-company transferees, and professionals are set forth in Chapter 11,

Temporary Entry of Business Persons. Its provisions do not affect policies regarding

visa issuance and screening procedures related to national security. This chapter promotes

transparency by detailing the circumstances under which FTA temporary labor mobility

will be authorized. Apart from the FTA professional category, for which U.S. legislation

will be necessary, all temporary entry commitments will be implemented through existing

18

immigration law. This agreement will form the basis for a Singaporean national’s access

to the treaty trader and treaty investor classifications for temporary entry into the United

States.

• Investment (Chapter 15)

The FTA’s Investment Chapter contains a comprehensive set of well-established

standards found in investment agreements throughout the world, including provisions

obligating each Party to treat investors of the other Party and their investments no less

favorably then its own investors and their investments in like circumstances (national

treatment) and no less favorably than the investors of other countries and their

investments in like circumstances (most-favored-nation treatment). Likewise, the chapter

contains disciplines on imposing listed “performance requirements” on investors of the

other Party as a condition of the investment. However, the chapter does provide

exceptions for non-discriminatory health, safety, and environmental requirements, as well

as requirements related to locating production and training and employing workers in the

territory of a Party.

The chapter also incorporates a number of modifications to investment provisions in prior

agreements that respond to Congress’ guidance on investment objectives in the Trade

Act. In particular, the provisions on minimum standard of treatment of investors and

expropriation, together with supplementary annexes, provide more detail and context to

the Parties’ understanding of these obligations to ensure that they are properly interpreted

and applied. The FTA’s provisions on investor-State dispute settlement procedures (a

mechanism allowing an investor to pursue a claim in international arbitration against a

host government for alleged breach of its investment obligations) include a significant

number of innovations to improve the transparency of arbitral proceedings and to help

assure that arbitral panels properly interpret the FTA’s investment provisions.

• Labor (Chapter 17)

The Labor Chapter of the FTA is consistent with the guidance from the Congress in the

Trade Act. The Agreement includes promotion of internationally recognized core labor

standards as a chapter within the main text of the Agreement, obligates the Parties to

effectively enforce their labor laws, and makes the effective enforcement of a Party’s

labor laws subject to the same State-to-State dispute settlement procedures that apply to

the commercial chapters. It also includes procedural guarantees ensuring that interested

persons have access to the relevant courts and/or tribunals necessary for the enforcement

of a Party’s labor laws.

Consistent with the guidance of the Congress on other priorities, the Agreement includes

provisions for consultations to resolve issues that may arise under the chapter and

establishes a Labor Cooperation Mechanism for cooperation on labor issues between the

Parties to promote respect for the principles embodied in the ILO Declaration on

Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work and its Follow-up and compliance with ILO

19

Convention 182 Concerning the Prohibition and Immediate Action for the Elimination of

the Worst Forms of Child Labor.

• Environment (Chapter 18)

The FTA’s Environment Chapter incorporates Trade Act guidance through a number of

core obligations concerning effective enforcement of environmental laws, providing for

high levels of environmental protection, and not weakening environmental laws to

encourage trade or attract investment. The FTA also includes articles on environmental

cooperation, procedural guarantees (e.g., commitments by each Party to provide certain

basic remedies for violations of its environmental laws, and to provide appropriate public

access to environmental enforcement proceedings), and a consultative mechanism for

implementing the provisions of the chapter. Consistent with Trade Act guidance, the

effective enforcement provision is enforceable through the FTA’s State-to-State dispute

settlement provisions.

• Transparency (Chapter 19)

The FTA’s Transparency Chapter, modeled on the NAFTA, requires both Parties to

publicize their laws, regulations, procedures and administrative rulings of general

applicability respecting matters covered by the Agreement such as to enable interested

persons to become acquainted with them. Also, to the extent possible, such proposed

measures shall be published in advance to provide interested persons a reasonable

opportunity to comment on them.

• Dispute Settlement Procedures (Chapter 20)

The FTA sets out detailed provisions providing for speedy and impartial resolution of

government-to-government disputes over the implementation of the Agreement.

Consistent with Trade Act guidance, the FTA’s core obligation to effectively enforce

labor laws (as well as the analogous obligation in the FTA’s environmental provisions) is

subject to the dispute settlement provisions. An innovative enforcement mechanism

includes monetary penalties as a way to enforce commercial, labor, and environmental

obligations of the trade agreement. Special provisions give guidance on factors panels

should take into account in considering the amount of monetary assessments in

environmental and labor disputes, and provide for assessments to be paid into a fund to

be expended for appropriate environmental and labor initiatives.

The dispute settlement provisions also set high standards for openness and transparency,

including provisions for open public hearings, public release of legal submissions, and

rights for interested third parties to submit views.

• Institutional Provisions (Chapter 20)

20

The FTA establishes a Joint Committee composed of government officials to review the

FTA’s general functioning and consider specific matters related to its operation and

implementation with respect to labor, among other areas, and to establish a subcommittee

on labor affairs as necessary. Recognizing the importance of transparency and openness,

the Parties reaffirm their respective practices of considering the views of members of the

public in order to draw upon a broad range of perspectives in the FTA’s implementation.

21

III. Potential Economic and Employment Effects of the FTA

The focus of this review is on the potential employment and labor market impacts of the

U.S.-Singapore FTA in the United States. This assessment is based upon qualitative

assessments of the current structure and volume of U.S. trade with Singapore, including

the potential effects of removing barriers to trade, as well as publicly available

independent quantitative assessments (econometric modeling) of the economic and

employment effects of a U.S.-Singapore FTA.

A. Aggregate Economic Effects

A review of the economic modeling literature revealed only two independent academic

quantitative assessments of a U.S.-Singapore FTA have been conducted. One study was

performed by Professors Drusilla Brown (Tufts University), Alan Deardorff and Robert

Stern (University of Michigan), employing their Michigan Model of World Production

and Trade that they have used to evaluate the economic effects (including sectoral

employment changes) of various proposed U.S. trade agreements.

36

The Michigan Model is a computable general equilibrium (CGE) model of world

production and trade containing 18 economic sectors in each of 20 countries or world

regions. The model incorporates some aspects of increasing returns to scale,

monopolistic competition, and product variety. The model assumes full employment or

that total employment in each economy does not change, while employment in each

economic sector is permitted to adjust to a new equilibrium after the introduction of the

FTA with sectors either expanding or contracting their production in response to changes

in bilateral trade flows.

37

The other study of a U.S.-Singapore FTA was conducted by Robert Scollay (University

of Auckland) and John P. Gilbert (Washington State University) as part of their

examination of the economic effects of various regional trade agreements in the Asia-

Pacific region.

38

Scollay and Gilbert used a CGE model, under the assumption of perfect

competition, with 22 countries or world regions and 21 economic sectors. Their study

reports only the aggregate economic effects of the FTA and does not provide estimates of

changes in sectoral employment resulting from the FTA.

The Brown, Deardorff, and Stern (BDS) study found that the U.S.-Singapore FTA would

boost global welfare by $25.1 billion, with U.S. welfare increasing by $17.5 billion (0.2

percent of U.S. GNP), Singapore’s welfare increasing by $2.5 billion (3.4 percent of

Singapore’s GNP), and the rest of the world would benefit as well.

39

The Scollay and Gilbert study found that the U.S.-Singapore FTA would boost

Singapore’s welfare by 0.7 percent of its GDP, with a negligible effect on U.S. welfare.

Scollay and Gilbert also estimate that as the result of a U.S.-Singapore FTA, U.S. exports

would increase by 0.2 percent and those of Singapore would increase by 0.9 percent,

while U.S. imports would increase by 0.2 percent and those of Singapore by 0.9 percent.

As the modelers note in their study, however, their results tend to be relatively small

22

compared to other CGE models that are dynamic or account for imperfect competition in

some sectors—as the BDS model does; models taking the latter into account have a

tendency to produce larger estimates.

The measures of welfare changes only consider how national aggregate consumption

possibilities may change and do not consider how it is distributed amongst the

population; hence, an increase in a country’s welfare does not necessarily imply that all,

or even a majority, of the population is better off.

B. Sectoral Employment Effects

According to the BDS study, the sectoral employment effects in the United States of the

FTA would be very small (less than 0.2 percent of employment in every sector affected)

with expected increases in employment in the agricultural and manufacturing sectors

balancing expected job losses in services. U.S. employment would be expected to

expand in 15 sectors and to contract in 3 sectors as the result of the FTA (See Table 3).

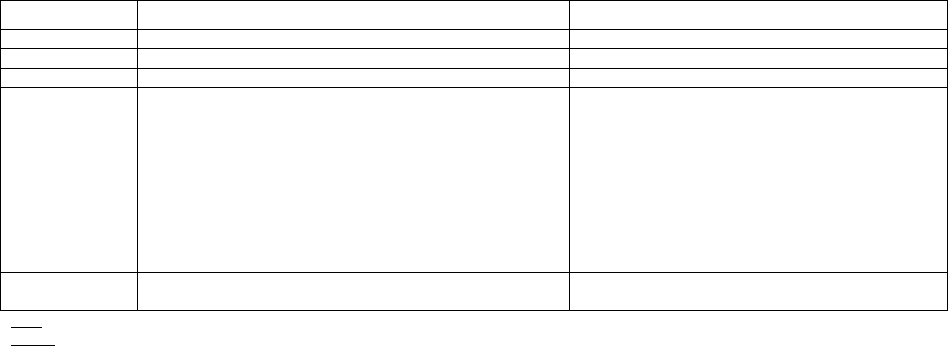

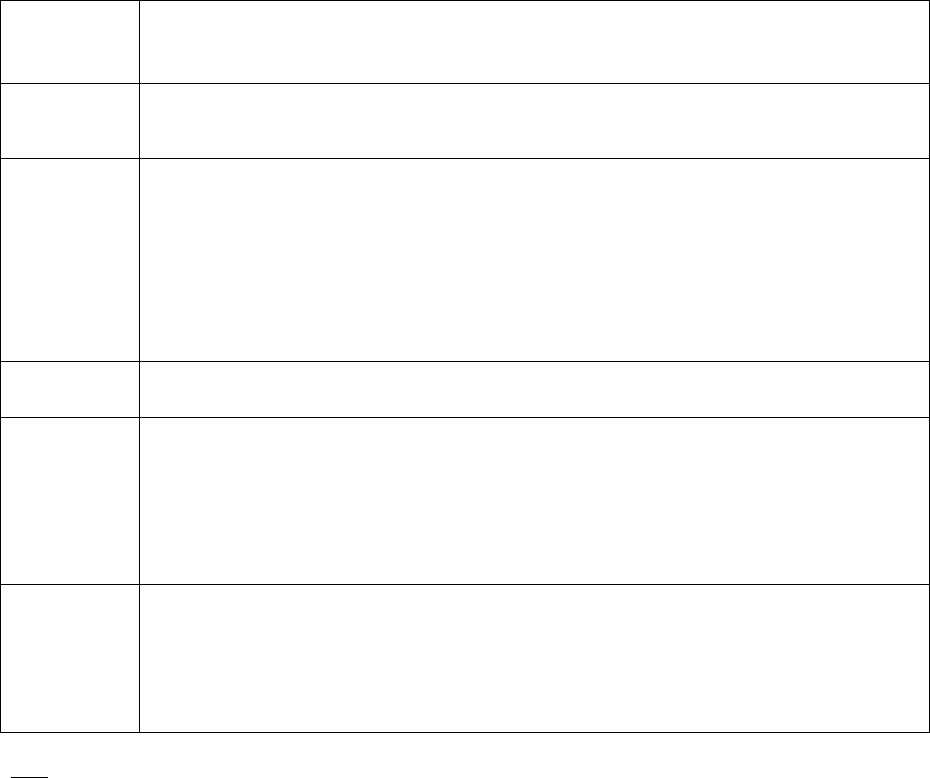

Table 3: Sectoral Employment Effects in the United States of a U.S.-Singapore FTA

Based on Simulations Using the Michigan Model of World Production and Trade

(number of workers and percent of sector employment)

U.S. Sector Employment Increasing Employment Decreasing

Agriculture Agriculture (4,216 workers or 0.10 percent) --

Mining Mining (616 workers or 0.09 percent) --

Construction Construction (38 workers or z percent) --

Manufacturing Machinery and Equipment (4,222 workers or 0.15 percent);

Other Manufactures (3,511 workers or 0.19 percent);

Metal Products (2,045 workers or 0.07 percent);

Chemicals (1,769 workers or 0.06 percent);

Wood and Wood Products (1,231 workers or 0.03 percent);

Transportation Equipment (1,231 workers or 0.06 percent);

Food, Beverages and Tobacco (1,146 workers or 0.04 percent);

Textiles (581 workers or 0.05 percent);

Non-metallic Mineral Products (338 workers or 0.04 percent)

Leather Products and Footwear (275 workers or 0.19 percent).

Wearing Apparel (-300 workers or -0.03 percent)

Services Government Services (1,254 workers or z percent);

Electric, Gas and Water (409 workers or 0.01 percent).

Trade & Transport (-22,013 workers or –0.07 percent);

Other Private Services (-569 workers or z percent).

Note: z percent = less than 0.005 percent.

Source: Drusilla K. Brown, Alan V. Deardorff, and Robert M. Stern, “Multilateral, Regional, and Bilateral Trade-Policy Options for

the United States and Japan,” Research Seminar in International Economics Discussion Paper No. 490 (Ann Arbor, MI: The

University of Michigan, School of Public Policy, December 16, 2002), Table 8.

The expected sectoral employment changes under the BDS study are either quite small or

negligible (especially when compared to the employment size of the affected sector or the

normal turnover—quits, separations, and new hires—in the U.S. labor market). The

largest expected absolute U.S. employment gains (sectors likely to expand) are

Machinery and Equipment, Metal Products, Chemicals, Wood and Wood Products,

Transportation Equipment, and Food Products—all strong and competitive U.S. export

sectors, while the largest expected employment declines (sectors likely to contract) are

Trade and Transport Services, Other Private Services, and Wearing Apparel.

These estimated levels of job changes in Table 3 (sectoral employment adjustments to a

new equilibrium following the full implementation of the FTA) are quite insignificant,

23

particularly given that they are likely to occur over a number of years. In a typical month

in 2002, 1.5 million U.S. workers were laid off or discharged while 4.2 million were

hired. In addition, the estimated job losses do not necessarily imply that current workers

in these industries will actually lose their jobs (although that could happen). Many of the

expected employment losses may be achieved simply by not hiring new workers to

replace workers voluntarily leaving their jobs.

C. Potential U.S. Labor Market Effects

1. Industry

a. Sectors Likely to Expand as the Result of the FTA

Current export patterns and the BDS modeling results suggest that U.S. employment in

several manufacturing industries is likely to increase due to the FTA. The industries

likely to gain jobs include: Food, Beverages, and Tobacco (SIC 20 & 21), Lumber and

Wood Products (SIC 24), Chemicals (SIC 28), Primary and Fabricated Metals (SIC 33 &

34), Industrial Machinery (SIC 35), Electrical Machinery (SIC 36), Transportation

Equipment (SIC 37); smaller or insignificant gains may occur in Textiles (SIC 22), Non-

Metallic Mineral Products such as stone, clay, and, glass products (SIC 32), and Leather

Products and Footwear (SIC 31). The projections of the BDS study also suggest

employment gains in construction and several service sectors.

b. Sectors Likely to Contract as the Result of the FTA

Based upon the current pattern of U.S. imports from Singapore and their current duty

treatment, both the BDS modeling results and current import patterns suggest that the

only major U.S. manufacturing industry likely to be negatively affected by the FTA is the

apparel industry. Of the $301.2 million in imports from Singapore in 2001 that faced

U.S. duties of more than 10 percent, $276.9 million (or 92 percent) were apparel items.

Included in this category are a broad range of items including cotton and synthetic, and

men’s and women’s shirts, trousers, coats, sweatshirts, pajamas, and sweaters. The phase

out of tariffs may lead to some employment declines in the United States for those

employed in this sector. However, apparel items currently account for only 2 percent of

U.S. imports from Singapore, and the gradual phase out of tariffs should allow for

adjustment in this sector. Further, the modeling of the FTA by BDS does not take into

account the potential effects of the yarn forward rule for qualifying apparel goods, which

could offset potential losses in other parts of the industry.

The BDS model assumes full employment (i.e., total U.S. employment does not change)

and as a result projected increases in sectoral employment must be matched by sectoral

employment declines elsewhere in the economy. Under the BDS study, employment

increases are projected for agriculture, mining, construction, and manufacturing (only one

goods-producing industry—apparel—is expected to contract in employment as the result

of the FTA), so nearly all of the employment declines (99 percent of the estimated 22,882

employment losses) are expected to occur in the service-producing industries and, in

24

particular, those in the trade and transport services sector. This sector in the BDS model,

however, represents an aggregation of two fairly large major groups within the service-

producing sector that includes wholesale and retail trade (where employment stood at

30.4 million in December 2002) and transportation services (where employment stood at

4.3 million in December 2002); together these two major groups account for about one-

third of all service-producing jobs. The predicted employment losses in trade and

transport services are likely to result not from direct import competition from Singapore,

but from economy-wide secondary effects. For example, lower prices for imports are

likely to draw expenditures away from the services sector, and higher prices for exports

are likely to draw productive resources (i.e., labor) away from the service-producing

sectors. The FTA is expected to result in a more efficient allocation of resources away

from some of the service-providing industries—such as wholesale and retail trade and

transportation services—into more productive export-oriented industries. Given the

relatively large size of the trade and transport services sector, and the lengthy FTA phase-

in period, the estimated employment losses need not imply actual job displacements but

may simply mean slower employment growth in these services sectors than would have

occurred otherwise.

The only goods-producing industry likely to be negatively affected by the FTA is the

apparel industry where employment has been contracting over the last several decades

and where employment declines were occurring even during the 1990s when the overall

economy experienced rather strong employment growth. The majority of the employment

losses, however, are estimated to occur in the service sector, which has seen rather

healthy employment growth over the last several decades. Again, any such losses would

be a negligible share of U.S. employment in these sectors. Indeed, the opening of

Singapore’s market to U.S. service suppliers (banking, insurance, etc.) is expected to

provide new and more widespread opportunities for U.S. service providers.

c. Rules of Origin, Phase-in of the FTA, and Safeguards

Features have been built into the FTA to help ease the adjustment process in the United

States during the transition to bilateral free trade with Singapore and help assure that only

imports from Singapore benefit from the FTA. These include strict rules of origin, rules

to protect against transshipment of goods (e.g., a third country using Singapore as an

export platform to the United States), the gradual phase-out of U.S. tariffs on goods

originating from Singapore, and mechanisms to address surges in imports from

Singapore.

Rules of Origin and Anti-Circumvention Provisions: The FTA contains strict rules of

origin to assure that only products grown or produced in each country are afforded the

benefits under the FTA. These rules generally include requirements which specify that

items must undergo substantial transformation within the United States or Singapore to

be eligible for benefits under the FTA—namely, a change in HTS classification (either a

change to another subheading within or outside the group, a new heading, or a new

chapter) and, in addition, some items must meet a specific regional content rule of 35-45

percent of the value of the item, depending on the method of valuation used.

25

As discussed above, textile and apparel goods produced or assembled in Singapore must

meet a yarn forward rule (i.e., be produced from yarns or fabrics that originated in either

the United States or Singapore) in order to be considered as a product of the United States

or Singapore and be eligible for preferential treatment under the FTA.

The FTA contains a de minimis provision for goods that do not meet the requirements of

the Agreement to be considered as originating from one of the Parties. Generally, if the

value of materials used in the production of a good does not undergo the required change

in HTS classification and does not exceed 10 percent of the adjusted value of the good,

and the good otherwise meets all other applicable criteria, it qualifies as an originating

good. There are, however, some exceptions to this general rule.

40

The Integrated Sourcing Initiative (ISI) in Chapter 3 of the FTA exempts certain

information technology (IT) products and medical devices from specific complex

documentation requirements in Singapore and the United States. Importantly, the ISI

does not confer new tariff preferences on products of other third-country (non-Party)

origin; it eliminates certain origin-related import procedures and a nominal fee for a list

of products that already enter the United States duty-free under the 1996 WTO

Information Technology Agreement (ITA).

41

By further enabling manufacturers to

purchase components from modern, competitive facilities, the ISI reduces unnecessary

red tape, and encourages the use of high-technology facilities.

The FTA contains provisions that commit each Party to enforce its own laws related to

circumvention and its prevention. Circumvention means providing false declaration or

information for the purpose or effect of violating or avoiding existing customs, country of

origin labeling, or trade laws of the respective Parties. Examples of circumvention

include illegal transshipment and false declarations concerning country of origin and

product content or description.

Regarding textile and apparel goods exported to the United States, Singapore has

committed to instituting registration of exporting establishments in Singapore or operated

by Singaporean companies in third countries under an outward processing arrangement to

help monitor the importation, production, exportation, and processing or manipulation in

free trade zones. To receive preferential treatment under the FTA, textile and apparel

establishments in Singapore that export to the United States must be registered with the

government of Singapore. These registered establishments are required to maintain

detailed records for a period of five years on all export shipments to the United States as

well as records related production capabilities and number of employees to support or

verify claimed production.

Gradual Phase-out of Tariffs: Table 4 summarizes the scheduled phase-out of tariffs by

the United States on goods originating from Singapore under the FTA and estimates of

the U.S. customs duties foregone by each staging category going duty free, based on

2002 U.S. import data and NTR tariff rates.

26

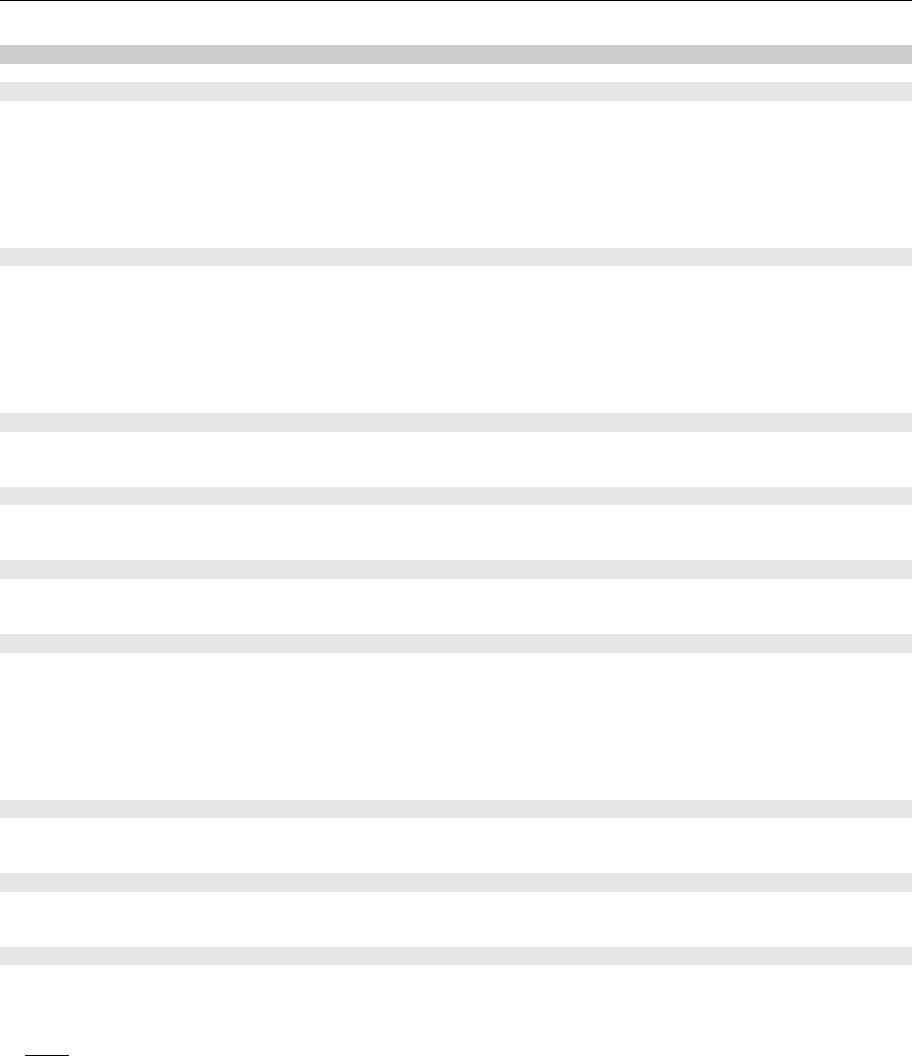

Table 4: Phase-Out of U.S. Tariffs on Originating Goods from Singapore under the U.S.-Singapore

FTA and U.S. Customs Duties Foregone

Value and Percent of U.S. Imports from

Singapore Going Duty-Free under the FTA

Value and Percent of Duties Foregone by

Staging Category Going Duty-Free

Staging

Category:

Duty-Free

In Year of FTA

2002 Import Value

($million)

Percent of Total

Import Value

Duties Foregone

($million)

Percent of Total Duties

Foregone

Immediate

MFN Duty-Free

Other

11,998.1

962.7

85.5

6.9

0.2

63.0

0.3

72.0

Year 4 762.3 5.4 1.9 2.1

Year 5 274.1 2.0 9.1 10.4

Year 8 12.3 0.1 Less than 0.05 0.0

Year 10 18.0 0.1 13.3 15.2

Total 14,028.1 100.0 87.5 100.0

Source: Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, Office of Asia and the Pacific.

Nearly 90 percent of U.S. imports from Singapore entered the United States duty-free in

2001. Only 10 percent of the total value of U.S. imports from Singapore were assessed

U.S. import duties in 2001; 85 percent of the total value of U.S. imports from Singapore

entered NTR duty-free and slightly less than 6 percent entered duty-free under special

tariff provisions. Under the FTA, the United States will phase-out all of its import tariffs

on goods originating from Singapore over a period of 10 years. As Table 4 shows, based

data for 2002, the bulk of U.S. imports from Singapore (92 percent by value, accounting

for 72 percent of foregone duties) will be duty-free upon the initiation of the FTA, with

most of the balance becoming duty-free by year 5 of the FTA and only a small number of

the most-sensitive items becoming duty-free after 8 years of the FTA. The 5-year and

10-year staging categories, which contain some of the most import-sensitive items,

together account for about 26 percent of duties foregone, but only slightly over 2 percent

of the total import value.

27

Table 5 presents a summary of the product content of each tariff phase-out category

(tariff staging category) for U.S. tariffs on goods originating from Singapore.

Table 5: U.S. Tariff Staging for Imports from Singapore under the FTA

Duty Free

Beginning

of Year

Tariff Staging Category and Product Content

0

(immediate)

E: Items now duty-free, continue duty-free.

A: Some agricultural and food products and the majority of consumer and industrial goods currently subject to duty.

G: Items now duty-free under bond, become duty-free without bond (e.g., items imported for samples, repair, exhibit,

etc.).

4

B: Some agricultural and food products, including certain poultry and meats; meals and flour; fish; snails; milk

products and dairy spreads; cheese; fresh onions, cauliflower, radishes, and other vegetables; dried vegetables; fruits

and melons; green tea; fresh sugar cane; certain seed oils; some syrups; some cocoa preparations and chocolate;

uncooked pastas; certain fruit juices; some tobacco and cigars. Some industrial and consumer goods, including some

chemicals; plastics and plastic products; certain conveyor belts; some leather and leather goods; plywood; willow

wicker baskets and luggage; some wool; some sports and other footwear; hats; some umbrellas; stone; porcelain and

ceramic products; glass and glass products; cultured pearls; some metal products; iron or steel screws; aluminum pipes

and tubes; tungsten, molybdenum, and manganese; certain hand tools; tableware; steam turbines; toasters; video

monitors; Christmas tree lights; fishing equipment; saw blades; pens and pencils; musical instruments; lamps and

lighting equipment; bicycles; combs; binoculars and telescopes; cameras; watches and clocks; certain measuring

devices.

5

F: Certain cotton and manmade fiber textile and apparel items subject to tariff preference levels, including some coats

and suits, jackets, skirts, dresses, trousers, shorts, braziers and undergarments, t-shirts, panty hose, sweaters, swim

wear, stocking and hosiery, ties and handkerchiefs, gloves, baby garments.

8

C: Certain agricultural and food products, including preserved citrus, prepared artichokes and tomatoes, lobsters and

crabs, soybean and cotton oils, nuts, rice, cereals, melons, fruits and berries, sturgeon roe, some milk and cheese

products, dried eggs, broccoli, cucumbers, carrots, spinach, potatoes, and other vegetables, and cigarettes. Certain

industrial goods, including some brooms, slide fasteners, parts of lamps, quilts, sporting and hunting rifles, watches and

clocks & pts, instruments, telescopic equipment, bicycles, railway or train cars, cathode ray television or monitor tubes,

flashlights and parts, various chemicals and dyes, molybdenum ores, unwrought manganese, titanium, and

molybdenum, iron or steel screws, ferrosilicon chromium, kitchen and tableware utensils, glassware, float glass, china

and tableware, ceramic flags and tiles, jewelry and precious stones, umbrella frames, artificial flowers, footwear, wood

blinds, articles of natural cork, wood cases and pallets, and leather gloves.

10

D: Certain agricultural products, including beef*, liquid dairy products*, cheese*, milk powder*, butter*, other dairy

products*, peanuts*, sugar*, cotton*, and tobacco*. Some other agricultural and food products, including certain

frozen turkey offal and cuts, asparagus, sweet corn, dried onions and garlic, dates, hops, sardines and tuna, citrus juice,

and rum. Certain industrial products, including brooms, military rifles, motor vehicles for transport of goods,

glassware, porcelain or china tableware, footwear, luggage and flat goods of rattan, and paperboard containers and

handbags with vulcanized fiber surface.

H: Foreign value added to item entered under HTS 9802 provisions; spare parts for vessels installed before first entry

into the United States; certain protective ski-racing wearing apparel.

Notes: * with a tariff-rate quota (i.e., immediately duty-free up to a specified quantitative limit [quota] with staged tariffs applied to

the amount in excess of the quota; quotas expire at the end of the staging period and the item is then duty-free in unlimited quantities).

The staging categories are defined as follows:

A: Duty-free January 1 of year 1 of the FTA.

B: Four equal annual reductions, beginning Jan 1 of year 1; duty-free January 1 of year 4.

C: Eight equal annual reductions, beginning Jan 1 of year 1; duty-free January 1 of year 8.