Prepared for

the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE)

at the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

by

Westat

October 2023

OFFICE OF BEHAVIORAL HEALTH,

DISABILITY, AND AGING POLICY

Addressing Homelessness Among

Older Adults: Final Report

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation

The Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) advises the Secretary of the U.S. Department

of Health and Human Services (HHS) on policy development in health, disability, human services, data,

and science; and provides advice and analysis on economic policy. ASPE leads special initiatives;

coordinates the Department's evaluation, research, and demonstration activities; and manages cross-

Department planning activities such as strategic planning, legislative planning, and review of regulations.

Integral to this role, ASPE conducts research and evaluation studies; develops policy analyses; and

estimates the cost and benefits of policy alternatives under consideration by the Department or

Congress.

Office of Behavioral Health, Disability, and Aging Policy

The Office of Behavioral Health, Disability, and Aging Policy (BHDAP) focuses on policies and programs

that support the independence, productivity, health and well-being, and long-term care needs of people

with disabilities, older adults, and people with mental and substance use disorders. Visit BHDAP at

https://aspe.hhs.gov/about/offices/bhdap for all their research activity.

NOTE: BHDAP was previously known as the Office of Disability, Aging, and Long-Term Care Policy

(DALTCP). Only our office name has changed, not our mission, portfolio, or policy focus.

This research was funded by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Assistant

Secretary for Planning and Evaluation under contract and carried out by Westat. Please visit

https://aspe.hhs.gov/topics/homelessness-housing for more information about ASPE research on

homelessness and housing.

ADDRESSING HOMELESSNESS AMONG OLDER ADULTS: FINAL REPORT

Authors

Kathryn A. Henderson, Ph.D.

Nanmathi Manian, Ph.D.

Debra J. Rog, Ph.D.

Evan Robison, MPH

Ethan Jorge

Monirah Al-Abdulmunem, MS

Westat

October 26, 2023

Prepared for

Office of Behavioral Health, Disability, and Aging Policy

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

The opinions and views expressed in this report are those of the authors. They do not reflect the views

of the Department of Health and Human Services, the contractor or any other funding organization. This

report was completed and submitted April 2023.

1

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of their colleagues, Ilene Rosin, for

assistance with data collection, and Dr. Andreea Balan-Cohen, Dr. Cindy Gruman, and

Dr. Beth Rabinovich for review of this report. We would also like to thank our project officers at

the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for

Planning and Evaluation, Lauren Anderson, Emma Nye, and Emily Rosenoff for providing us

guidance and support throughout the project.

We also thank the subject matter experts and service providers we interviewed for this project

for graciously providing us their time and knowledge. Most importantly, we are grateful to the

individuals with lived experience of homelessness in older adulthood who shared with us their

experiences and recommendations.

2

Table of Contents

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................. 4

SECTION 1. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 12

Overview of Report .............................................................................................................................. 13

Methodology ........................................................................................................................................ 13

SECTION 2. SIZE, CHARACTERISTICS, AND NEEDS OF THE POPULATION OF OLDER ADULTS

EXPERIENCING HOMELESSNESS ADULTS EXPERIENCING HOMELESSNESS .............................................. 14

Prevalence of Homelessness Among Older Adults .............................................................................. 14

Pathways into Homelessness for Older Adults .................................................................................... 15

Characteristics of Older Adults Experiencing Homelessness ............................................................... 17

Service Needs of Older Adults Experiencing Homelessness ................................................................ 19

SECTION 3. SYSTEMS AND SERVICES AVAILABLE TO SERVE OLDER ADULTS AT RISK OF OR

EXPERIENCING HOMELESSNESS ................................................................................................................. 27

Homelessness Assistance ..................................................................................................................... 28

Housing Programs and Residential Long-Term Care Options .............................................................. 32

Health Care, Long-Term Care, and Behavioral Health Services ........................................................... 39

Income Supports and Other Needs ...................................................................................................... 45

SECTION 4. GAPS AND POTENTIAL STRATEGIES ........................................................................................ 50

Gaps in Service Delivery and Coordination .......................................................................................... 50

Gaps in Knowledge ............................................................................................................................... 53

Potential Strategies .............................................................................................................................. 54

Conclusion ............................................................................................................................................ 56

APPENDIX: OVERVIEW OF METHODOLOGY .............................................................................................. 58

REFERENCES ................................................................................................................................................ 62

ACRONYMS ................................................................................................................................................. 77

3

List of Exhibits

Exhibit 1. Sample Racial/Ethnic Composition for Studies of Older Adults Experiencing

Homelessness ....................................................................................................................... 18

Exhibit 2. Comparison of Characteristics and Needs of Older Adults Experiencing

Homelessness ....................................................................................................................... 20

Exhibit 3. Systems Framework for Addressing Homelessness Among Older Adults ........................... 27

Exhibit 4. Types of Housing Assistance Available for Older Adults Experiencing

Homelessness ....................................................................................................................... 32

Exhibit 5. Types of Residential Long-Term Care Available for Older Adults Experiencing

Homelessness ....................................................................................................................... 36

Exhibit A-1. Key Words and Search Terms Used to Identify Relevant Published and

Unpublished Literature ........................................................................................................ 58

Exhibit A-2. Sources Searched to Identify Relevant Published and Unpublished Literature .................. 59

4

Executive Summary

The number of older adults at risk of and currently experiencing homelessness has increased

rapidly in recent years, a trend that is projected to continue and further accelerate (Culhane et

al., 2013; Culhane et al., 2019). Older adults at risk of or experiencing homelessness have

unique needs compared to other populations experiencing homelessness. As a first step in

understanding how to address the needs of this population, the U.S. Department of Health and

Human Services’ (HHS) Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation contracted

with Westat to conduct a study of what is known about older adults experiencing

homelessness, including an examination of the size, characteristics, and needs of this

vulnerable population and the services, housing, and supports needed and available to serve

them. The study included an environmental scan of published research, evaluations, and white

papers as well as discussions with subject matter experts, housing and service providers, and

people with lived experience of homelessness as older adults.

This report provides a roadmap for understanding the population of older adults at risk of or

experiencing homelessness and what services and supports are available to serve them. Using

an equity lens, we examine these topics with attention to what is known about racial and ethnic

groups disproportionately impacted by homelessness. We highlight the challenges older adults

face in accessing the assistance available; innovative practices, especially those implemented

during the Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, that could ease these challenges; and

remaining gaps that need to be filled to effectively tackle the problem. We end with

recommendations to better identify and serve older adults at risk of or experiencing

homelessness.

POPULATION OF OLDER ADULTS EXPERIENCING HOMELESSNESS

Older adults are the fastest-growing age group of those experiencing homelessness, composing

nearly half of the homeless population (Kushel, 2022) and their numbers are estimated to triple

by 2030 (Culhane et al., 2019). Older adults are especially vulnerable to homelessness as many

live on fixed incomes insufficient to cover all their expenses, especially housing expenses

(Sermons & Henry, 2010). Half of renters ages 50 and older pay more than 30 percent of their

income on housing (Joint Center for Housing Studies, 2018).

Two trends in the growth of homelessness among older adults are apparent: aging of those

who first experienced homelessness earlier in life and continue to experience homelessness as

older adults and, increasingly, people experiencing homelessness for the first time in older age.

The first group represents a cohort effect: individuals born in the second half of the post-World

War II baby boom (1954-1963) who throughout their lives have had an elevated risk of

homelessness due to limited employment opportunities, coupled with mental health and

substance use disorders. The second group of older adults are experiencing homelessness for

the first time after age 50 after having lived relatively stable lives including long periods of

employment and residential stability. For this group, homelessness is often preceded by

5

stressful life events, such as the death of a spouse or partner, divorce, loss of work, eviction, or

the onset of health problems, coupled with limited or fixed incomes (Cohen, 2004; Crane et al.,

2005).

CHARACTERISTICS OF OLDER ADULTS EXPERIENCING HOMELESSNESS

Older adults with earlier experiences of homelessness have had increased vulnerabilities

throughout their lives, including more adverse childhood experiences, more mental health

conditions, greater alcohol and drug use, higher rates of incarceration, and more

underemployment than those with later entry into homelessness (Brown et al., 2016). In

addition, this group has spent more time homeless both overall and in their current episodes

than those individuals whose first homelessness occurred in older age (Brown et al., 2016).

The few studies that have examined the racial and ethnic composition of older adults

experiencing homelessness are limited in their generalizability due to having small samples

drawn from limited geographic regions. Despite this limitation, their findings are consistent

with national level data in that the percentage of African Americans who are experiencing

homelessness is disproportionately large compared to the overall percentage of African

American older adults (HUD, 2023; Moses, 2019).

SERVICE NEEDS OF OLDER ADULTS EXPERIENCING HOMELESSNESS

Compared to their housed counterparts, older adults experiencing homelessness have higher

rates of health service utilization and more health and health-related concerns, including:

• Significantly shorter life spans (Metraux et al., 2011; Schinka & Byrne, 2018; Brown et al.,

2016; Kushel 2020).

• Higher prevalence and severity of physical and geriatric conditions including memory loss,

falls, difficulty performing activities of daily living (ADLs), cognitive impairment, and

functional impairments (Brown et al., 2011; Brown et al., 2017; Hahn et al., 2006; Hwang et

al., 1997).

• More complex health needs, comparable to housed individuals who are 10-20 years older

(Cohen, 1999; Gelberg et al., 1990; Homelessness Policy Research Institute [HPRI], 2019;

Brown et al., 2016).

• Higher rates of mental health and substance use disorders (Brown et al., 2011; CDC, 2008;

Spinelli et al., 2017).

“Like my body isn't so resilient. When I was younger,

I, mean, I went everywhere and bounced back. And

now it's harder to get up out of the chair, let alone

get up off the sidewalk if you're sleeping outside.”

– Adult currently experiencing homelessness, 59

6

As such, this population has greater need for health care supports, such as access to

medications, durable medical equipment, and assistive technology, as well as assistance with

ADLs, compared to their housed counterparts.

Compared to individuals younger than 50 years who are homeless, older adults experiencing

homelessness have higher rates of chronic illnesses, geriatric conditions, and cognitive

impairments as well as high blood pressure, arthritis, and functional disability (Garibaldi et al.,

2005; Gelberg et al., 1990). Among people experiencing homelessness, older adults and

younger adults have comparable rates of mental health and substance use disorders (DeMallie

et al., 1997; Gelberg et al., 1990; Gordon et al., 2012).

Among older adults experiencing homelessness, older adults who first experienced it earlier in

life have more behavioral health needs and service utilization than those who first experienced

homelessness after age 50. Differences are most pronounced in rates of current mental health

issues, including depressive symptoms, post-traumatic stress disorder, and substance use, as

well as hospitalizations for mental health conditions (Brown et al., 2016).

Finally, food insecurity, lack of transportation, and loss of community surface as additional

challenges for older adults experiencing homelessness. Older adults experiencing homelessness

have rates of food insecurity that are nearly two times higher than estimates among all people

living in poverty (Coleman-Jensen et al., 2016; Tong et al., 2018). Lack of transportation poses a

particularly significant barrier for older adults, who are more likely to have mobility limitations

due to health impairments, including poor eyesight and impaired cognition.

SYSTEMS AND SERVICES AVAILABLE TO SERVE OLDER ADULTS AT RISK OF OR EXPERIENCING

HOMELESSNESS

Homelessness Assistance

Older adults may face unique challenges accessing homelessness assistance, including limited

knowledge about the services available for which they are eligible, heightened anxiety about

and lack of trust in working with providers,

limited access to technology to complete online

applications (National Council on Aging [NCOA],

2022), and difficulty attending scheduled

appointments, providing documentation of

eligibility, or completing the necessary

paperwork (Grenier et al., 2013). As noted by experts, many crisis and interim housing facilities

may not be accessible to older adults with mobility challenges and difficulty performing ADLs or

these facilities may be unable to provide the kind of supports that older adults need. Although

some organizations and municipalities offer programs aimed specifically at older adults, most

communities do not provide this type of assistance.

Homelessness assistance includes

prevention services, identification,

engagement, and assessment services,

as well as crisis or interim housing.

7

Housing Assistance

Access to housing assistance can be difficult

given the current lack of availability and the high

and growing demand among low-income older

adults. Consequently, large numbers of older

adults who are eligible for rental assistance

either have a long wait time for assistance or do

not end up receiving the assistance (Public and

Affordable Housing Research Corporation

[PAHRC], 2020), a finding reflected in our

discussions with people with lived experience.

Experts also noted a lack of residential options

with sufficient support to enable older adults to

age in place.

Health Care, Long-Term Care, and Behavioral

Health Services

Older adults face a number of challenges

receiving the health care they need. Meeting

basic needs such as food and housing often takes

precedence over seeking treatment for physical

and behavioral health needs. Lack of available

providers within communities, limited provider

capacity, a lack of transportation, and mobility

challenges further exacerbate difficulties in

obtaining the health care that older adults experiencing homelessness need (Baggett et al.,

2011; Canham et al., 2020; Kushel et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2020; Ye et al., 2019).

Basic Needs Assistance

Older adults experiencing homelessness often

have difficulty accessing needed assistance.

Individuals without fixed addresses and those

with limited access to technology, as well as

those with health or behavioral health

conditions, may have difficulty establishing

eligibility for assistance or completing their

applications (Tong et al., 2018). Moreover, all of these basic needs programs may be limited in

rural areas.

Housing assistance includes programs

that provide time-limited assistance as

well as a wide range of permanent

subsidized housing options with and

without supportive services. These

include permanent supportive housing,

permanent subsidies, low-income tax

credit housing, and a range of residential

and institutional care settings that may

provide medical management, support

services, and social activities.

Health care, long-term care, and

behavioral health services, including

medications, are available for older

adults through a variety of federal and

state-funded mechanisms including

Medicare, Medicaid, VA benefits (for

eligible veterans), and OAA and SAMHSA

funded programs.

Assistance for basic needs, such as

income, food, transportation, and social

engagement are provided through a

range of federal, state, private, and non-

profit programs.

8

INNOVATIVE PROGRAMS TO SERVE OLDER ADULTS EXPERIENCING HOMELESSNESS

Numerous agencies and municipalities are implementing innovative programs to address the

specific challenges older adults experiencing homelessness face, including with accessing

needed assistance. A sample of the programs is highlighted throughout this report. For

example:

• The Native American Disability Law Center in New Mexico and Arizona creates accounts

for clients in an online benefits application portal to help individuals apply for energy

assistance and other public benefits.

• The Hearth program in Boston, Massachusetts provides outreach to older adults at risk

of or experiencing homelessness to apply for, locate, and move into subsidized housing.

• Serving Seniors in San Diego, California provides transitional housing with facilities

accessible to people with mobility challenges and supportive services focused on the

unique needs of older adults experiencing homelessness.

• The Southern California Clinical and Translational Science Institute in Los Angeles County

is pilot testing the integration of the Community Aging in Place--Advancing Better Living

for Elders (CAPABLE) program with permanent supportive housing to provide home-

based services, such as occupational therapists, nurses, and handypersons, to formerly

homeless older adults who experience difficulties with ADLs.

• St. Paul’s Programs of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) program in San Diego,

California, provides formerly homeless older adults subsidized housing with wrap-

around supportive services, including primary and specialty health services, medication

assistance, mental health services, occupational therapy, and dentistry, as well as meals

and nutrition counseling, social activities,

social services, and transportation

assistance.

Moreover, during the COVID-19 pandemic,

numerous federal, state, and local agencies

provided additional assistance to older adults

experiencing homelessness to access shelter,

housing, and services through increased funding,

policy changes or waivers, and new service

delivery models. Many of these innovations may

be continued or expanded to better serve

vulnerable older adults, especially those who

experience homelessness.

ADDRESSING GAPS IN SERVICE DELIVERY AND COORDINATION

The environmental scan and discussions identified a number of critical gaps in housing and

service availability, accessibility, delivery, and coordination. The following interventions and

Examples of Programs Implemented

During the Pandemic

• Expanded eviction prevention

resources.

• Placement of people experiencing

homelessness into motel rooms.

• Medicare coverage of telehealth

services.

• USDA’s SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot.

9

policy changes offer strategies to enable providers and policymakers to better meet the

housing and support needs of older adults experiencing housing instability and homelessness.

• Identification, outreach, and navigation services particularly targeted to older adults

experiencing homelessness who have specific barriers to receiving assistance, such as

fears of losing their independence or difficulty understanding eligibility requirements

Few non-homelessness providers with whom older adults are connected, such as health

clinics and benefits offices (e.g., Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program [SNAP]

offices), routinely screen for risk of homelessness. Older adults experiencing

homelessness for the first time may not know what types of assistance are available or

where to go to get it. They may also wait too long to request assistance to maintain

their housing. Older adults experiencing homelessness need resources and assistance to

learn about both the available supports for which they are eligible and the processes of

applying for and accessing these supports.

• Increased access to benefits and services to provide a greater number of older adults at

risk of or experiencing homelessness the assistance they need to address housing, health,

and other challenges. Experts noted that restrictive eligibility criteria such as strict income

and/or asset requirements, age or disability requirements, and other restrictions prevent

or complicate access to key services for older adults experiencing homelessness.

• Crisis and interim housing tailored to older adults. There is a need for emergency

shelter accommodations that include beds that are on the first floor or bottom bunk,

24-hour access to bedrooms and bathrooms, and refrigeration or locked storage for

medications and medical supplies, as well as crisis or interim housing accessible to older

adults with limited mobility, difficulties with ADLs, and needing assistance with limited

health care and medication management.

• Permanent supportive housing tailored to older adults with histories of homelessness.

Older adults with histories of homelessness often have greater functional impairments

and behavioral health challenges, as well as limited connection to their communities.

There is a need for permanent supportive housing with physical accommodations (e.g.,

wheelchair accessible buildings, grab bars in units) to address these needs as well as

access to the types of case management and nursing assistance (e.g., medication

management, wound care) that will allow them to age in place.

• Consistent case management assistance to assist older adults with accessing the

housing and other supports they need.

• Increased capacity of affordable housing. More permanent supportive housing is

needed, as well as a continuum of supports to provide tailored assistance to a diverse

population of individuals, ranging from those who may need only shallow rental

subsidies to those who need intensive medical management and support services.

• Coordination across systems to address the variety and unique needs of older adults

experiencing homelessness. Barriers to coordination include siloed funding streams,

varying eligibility criteria, overburdened staff, and data sharing barriers.

10

GAPS IN KNOWLEDGE

Gaps in knowledge include a lack of:

• Research around equity in services and outcomes.

• Research on the connection between health and homelessness among older adults.

• Documentation of the types of assistance available to older adults and their respective

eligibility criteria and enrollment requirements.

• Additional data on older adults experiencing homelessness.

POTENTIAL STRATEGIES

Through the information identified in this scan, we offer a number of potential strategies for

policymakers and service providers to better identify and serve older adults at risk of or

experiencing homelessness. Strategies for policymakers at federal, state, and local levels to

consider include:

• Additional prevention resources for older adults at risk of homelessness, including

short-term rental assistance, resources to help with property taxes, and assistance with

home maintenance costs.

• Assistance with other costs of living, including food, transportation, and other expenses

that would allow rent-burdened older adults to meet their needs.

• Additional types of affordable housing assistance, such as shallow subsidies and

affordable assisted living.

• Expanded state coverage for home and community-based services (HCBS), such as

assistance with medication management and wound care; assistance with ADLs; and

home management services, to help support individuals as they age.

• Identification of older adults by HUD as a key sub-population in its Annual

Homelessness Assessment Reports to provide more national data on older adults

experiencing homelessness.

• Better cross-system coordination, including through shared goals, flexible or blended

funding streams, better integrated data, and coordination between the No Wrong Door

Initiative with coordinated entry systems.

• Continuation of demonstration projects started during the pandemic, such as the U.S.

Department of Agriculture (USDA)’s SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot, that facilitated

access to services for older adults with limited mobility as well as flexibilities around

Medicaid enrollment and housing vouchers.

Potential strategies for service providers include:

• More proactive identification by service providers, such as health clinics and those

participating in the No Wrong Door Initiative, of older adults who are severely rent-

burdened or otherwise at risk of homelessness.

11

• Better documentation of services and supports available in local communities to enable

older adults at risk of or experiencing homelessness to know what assistance is

available and how they can access it.

• Additional assistance accessing medical equipment, such as eyeglasses and hearing

aids, that may be damaged or lost while people experience homelessness.

• Training for case management staff on issues specific to older adults.

• Improved access to income assistance for eligible individuals through programs such as

Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI)

Outreach, Access, and Recovery (SOAR) to provide a sustainable source of income for a

larger share of older adults experiencing homelessness.

12

Section 1. Introduction

The number of older adults living in poverty is

increasing (Li & Dalaker, 2021) due in part to the

aging of the United States population overall,

coupled with the growing affordable housing

crisis (Aurand et al., 2021) and the public health

and economic crises that resulted from the

Coronavirus Disease 19 (COVID-19) pandemic.

Older adults are increasingly likely to be housing

cost-burdened (i.e., housing costs require more

than 30 percent of household income) and

severely housing cost-burdened (i.e., housing

costs require more than 50 percent of household

income). In 2019, around 5 million households headed by someone aged 65 or older paid at

least 30 percent of their income on rent, and another 5 million paid at least 50 percent (Joint

Center for Housing Studies, 2019). Not surprisingly, the population of older adults at risk of or

experiencing homelessness is also growing rapidly and is projected to continue to grow over the

next decade (Culhane et al., 2013; Culhane et al., 2019). Until recently, older adults who

experience homelessness have largely struggled with housing issues throughout much of their

adult lives (Culhane et al., 2013), concomitant with other health and life challenges. Yet, recent

research has identified a growing subgroup of older adults who become homeless for the first

time after the age of 50, due largely to economic factors (Brown et al., 2016; Crane et al., 2005;

Shinn et al., 2007).

The growth in this population and the different pathways they follow into homelessness

underscore the critical importance of understanding the needs of this vulnerable population

and what services and housing can best address them. Drawing on published literature and

interviews with researchers, providers, and people experiencing homelessness, this report

provides an overview of the characteristics and needs of older adults at risk of or experiencing

homelessness, differences between individuals who are newly experiencing homelessness in

older age and those who first experienced homelessness earlier in life, and the types of

services, housing, and supports needed to serve them. Using an equity lens, we examine these

topics with attention to what is known about racial and ethnic groups disproportionately

impacted by homelessness. Finally, we add to this summary an exploration of the programs,

policies, services, and supports that exist to prevent and address homelessness across the

systems that serve older adults. Brought together, the research and systems’ offerings provide

a roadmap for determining what is available now to both prevent homelessness among those

at risk as well as what is available to serve those who are experiencing homelessness. We

highlight the challenges older adults face in accessing the assistance they need, innovative

practices, especially those implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic that could ease these

challenges, and remaining gaps that exist that need to be filled to effectively tackle the

problem.

Terminology

Throughout the report, we use the term

“older” adults to refer to people 50

years of age and older, and the term

“senior” to refer to people 62 years of

age and older. We use the term

“elderly” only when referring to specific

eligibility criteria for the various

programs and services discussed.

13

OVERVIEW OF REPORT

Section 2 provides a discussion of the population of older adults experiencing homelessness,

including the prevalence of and pathways into homelessness. We examine the characteristics

and needs of older adults experiencing homelessness, including sociodemographic

characteristics, health and behavioral health conditions, and basic needs. Where possible, we

compare these characteristics and needs to those of housed older adults as well as to younger

adults who are homeless to understand how the characteristics and needs of older adults

experiencing homelessness may be unique. Section 3 addresses the systems and services

available to serve older adults at risk of or experiencing homelessness, including homelessness

and housing supports, health and behavioral health services, income supports, and other basic

needs assistance programs. For each of these service areas, we describe the assistance

available to low-income older adults generally and to older adults experiencing homelessness

specifically. We highlight challenges older adults face in accessing assistance and innovative

programs or strategies available to serve them. We also address changes in policies or practices

during the COVID-19 pandemic to facilitate access to needed services for older adults

experiencing homelessness may be beneficial to continue post-pandemic. In Section 4, we

identify critical gaps in the housing and services available to meet the needs of older adults at

risk of or experiencing homelessness and in existing research. We end with potential strategies

to better identify and serve older adults at risk of or experiencing homelessness.

METHODOLOGY

This report incorporates findings from an environmental scan, including a review and synthesis

of published research, evaluations, and white papers, discussions with subject matter experts

and housing and service providers, and interviews with people with lived experience of

homelessness in older adulthood. Each of these methods is described in further detail in the

Appendix. For the environmental scan, we used a systems approach for identifying key

resources, including focused searches on literature and other resources within the fields of

homelessness and housing, health and behavioral health, and aging. We also conducted

discussions with a diverse set of subject matter experts and housing and service providers.

Throughout the report, these individuals are referred to as experts and providers. We also

collected data through tailored conversations from individuals between the ages of 56 and 74

who were experiencing or had experienced homelessness as older adults. Six people were

currently experiencing homelessness at the time of the discussion and were staying in shelters,

in tents, or on the sidewalk. Eight people were housed, with seven in permanent supportive

housing and one in low-income housing. The goals of these conversations were to learn more

about their experiences accessing the housing, supports they needed, and challenges they

faced.

14

Section 2. Size, Characteristics, and Needs of the Population of Older

Adults Experiencing Homelessness

PREVALENCE OF HOMELESSNESS AMONG OLDER ADULTS

Homelessness among older adults is increasing, with a growing proportion of the population

experiencing homelessness aged 50 and older.

1

People aged 50 and older are the fastest-growing age group of those experiencing

homelessness, and their numbers are estimated to triple by 2030 (Culhane et al., 2019).

According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), in 2021, people

aged 55 and older composed 19.8 percent of the sheltered homeless population (HUD, 2023),

an increase from 17.9 percent in 2020. This rate is even higher when we focus on adult-only

households experiencing homelessness: 28.7 percent in 2021 (HUD, 2023). Among sheltered

homeless adults with chronic patterns of homeless, those aged 55-64 made up the largest share

of people experiencing chronic homelessness (27.0 percent), and a total of 35.7 percent were

aged 55 and older in 2021 (HUD, 2023). The percentage of individuals aged 51 and older in

emergency shelters, transitional housing, and safe havens increased more than 10 percent in a

decade, from 23.0 percent in 2007 to 33.8 percent in 2017

2

(HUD, 2018). Among people

experiencing sheltered homelessness, people ages 55-64 compose a larger proportion (14.7

percent in 2021) than those ages 65 and older (5.1 percent in 2021) (HUD, 2023). In addition,

the percentage of older adults in permanent supportive housing grew during this time from

23.9 percent in 2007 to 38.7 percent in 2017 (HUD, 2018).

Age is the predominant way to define older adults experiencing homelessness, though the

specific age is not universally agreed upon in the literature or in practice.

Most current research on older adults at risk of or experiencing homelessness focuses on those

who are 50 and older. The experts with whom we spoke agreed that defining older adults in

this way makes sense for both research and practical purposes, because the health and mobility

of adults experiencing homelessness at age 50 is similar to that of housed adults who are 15-20

years older. Housing and service providers, on the other hand, noted that they are often

required to define older adults as age 55 and older or 62 and older because of eligibility

restrictions imposed by their programmatic funding sources. For example, Supportive Housing

for the Elderly vouchers provide rental assistance and supportive services to low-income

households that include at least one member who is 62 years or older. Individuals 55 and over

are eligible for other HUD-funded assistance for elderly and disabled households such as

1

In its Annual Homelessness Assessment Reports to Congress, HUD publishes the percentage of people

experiencing unsheltered homelessness only for three age groups: under 18, 18-24, and over 24. Data for older

adults (55-64 and 65 and older) are only available for sheltered populations.

2

In HUD’s Annual Homelessness Assessment Reports to Congress, the age categories for older adults changed in

2017 from 51-62 and 62 and older to 55-64 and 65 and older in 2018. Thus, we cannot measure changes over

time in the size of the population of older adults experiencing sheltered homelessness from before 2017 to

present.

15

Housing Choice Vouchers and public housing. Nutrition assistance, such as Meals on Wheels, is

provided by State Units on Aging and Area Agencies on Aging to adults aged 60 and older. To

provide services to individuals under 55, service providers often must use private funding

sources.

A couple of experts suggested, however, that defining “older adults” among those experiencing

homelessness, especially in relation to determining eligibility for assistance, should be based on

individuals’ health needs or functional limitations rather than age-based criteria alone. They

noted that many adults experiencing homelessness in their 40s and 50s have disabilities

requiring the same level of services and supports typically provided to older adults. Moreover,

due to increased mortality rates among people experiencing homelessness, many of these

individuals never reach “older adult” ages. One provider indicated, however, that there was

insufficient age granularity in data collected on adults experiencing homelessness to best

determine at which ages physical and mental health vulnerabilities are heightened, knowledge

that could help guide the categorization of older adults among those experiencing

homelessness.

PATHWAYS INTO HOMELESSNESS FOR OLDER ADULTS

Income supports for older adults at risk of homelessness are often insufficient to cover their

expenses.

SSI and SSDI are often the primary sources of income for older adults at risk of or experiencing

homelessness, with earned income, panhandling, and monetary assistance from relatives as

supplementary sources (Cohen et al., 1999; Garibaldi et al., 2005; Gonyea et al., 2010). These

income supports are often insufficient to cover the cost of housing and other expenses

(Airgood-Obrycki, 2019). Living on limited, fixed incomes, older adults experience housing cost

burden more frequently than the general population, potentially resulting in housing loss

(Sermons & Henry, 2010). According to the Joint Center on Housing Studies of Harvard

University, people older than age 50 have the highest risk of paying more than 30 percent of

their income on rent or mortgage, with as many as one half of renters ages 50 and older doing

so in 2018 (Joint Center for Housing Studies, 2018). Approximately 10 million households

headed by someone over age 65 pay at least 30 percent of their income on housing, and half of

those pay over 50 percent (Joint Center for Housing Studies, 2019). Nationally, more than 1.7

million extremely low-income renter households with an older adult are severely cost-

burdened, spending more than half their income on rent (Prunhuber & Kwok, 2021). Being cost-

burdened by housing limits resources available for other expenses, including health care,

transportation, and healthy food. With an overwhelming portion of their incomes dedicated to

rent, many severely rent-burdened older adults go without heat, food, or medication to pay

their rent (Prunhuber & Kwok, 2021). Cost-burdened older adults are more likely to report an

inability to fill a prescription or adhere to health care treatments due to cost (Center for

Housing Policy, 2015). Moreover, the challenge of affording housing on limited incomes is

exacerbated for Black and Latinx older renters, who are more likely than White older renters to

16

have insufficient income and few assets as they enter retirement years (Prunhuber & Kwok,

2021).

The population of older homeless adults is comprised of two subgroups with different

trajectories into homelessness.

The growth of homelessness among older adults can be attributed to two trends: aging of those

who first experienced homelessness earlier in life and continue to experience homelessness as

older adults, and those experiencing homelessness for the first time in older age.

Older adults who first experienced homelessness earlier in their lives represent a cohort effect:

individuals born in the second half of the post-World War II baby boom (1954-1963) who have

had an elevated risk of homelessness throughout their lives and have reached aged 50 and

older in the last decade (Culhane et al., 2013). This group of individuals became adults in a time

when there was an oversupply of workers and undersupply of housing, resulting in depressed

wages, high unemployment, and increased rents. These inauspicious circumstances combined

with back-to-back recessions in the late 1970s and early 1980s contributed to intermittent

employment in low-wage jobs and frequent periods of unemployment (Culhane et al., 2013),

and subsequently, increased vulnerability to housing instability and homelessness throughout

their lives. Moreover, this group of older adults experiencing homelessness typically have had

more risk factors (e.g., mental health and substance use disorders) for homelessness

throughout their lives than older adults who first experience homelessness after age 50, thus

increasing their vulnerability to homelessness throughout their lives (Culhane et al., 2013;

Brown et al., 2016). In discussions, experts and providers noted that whereas these individuals

may have initially entered homelessness as younger adults due to economic factors, they often

are unable to regain long-term stability due to physical or behavioral health challenges.

The second group of older adults are people who experience homelessness for the first time

after age 50, largely due to economic instability in their later years. In the Health Outcomes in

People Experiencing Homelessness in Older Middle Age (HOPE HOME) study, almost one-half of

the 350 older adults included in the sample (43 percent) had not experienced homelessness

before age 50 (Brown et al., 2016). In a qualitative study including 79 older adults experiencing

homelessness, Shinn and colleagues (2007) similarly found that over half of the respondents

lived relatively stable lives, typically involving long periods of employment and residential

stability, before becoming homeless at an average age of 59. In an international study of adults

aged 50 and older newly experiencing homelessness in Boston, England, and Melbourne, Crane

and colleagues found that only about one-third of the sample had experienced homelessness

prior to the current episode (Crane et al., 2005). For older adults experiencing homelessness for

the first time, homelessness is often caused by stressful life events, such as the death of a

spouse, divorce, loss of work, eviction, or the onset of health problems, coupled with limited or

fixed incomes (Cohen, 2004; Crane et al., 2005). Seniors and people with disabilities compose

nearly half of renters with extremely low incomes (i.e., at or below the poverty guideline or 30

percent of the area median income) (Aurand et al., 2021), making them vulnerable to

homelessness when stressful events occur (Brown et al., 2016; Kushel, 2020).

17

Experts and providers reinforced these findings: older adults relying on decreased or fixed

incomes often cannot withstand rising housing costs, including increasing rents, increasing

property taxes, and ongoing home maintenance costs. One expert noted that most states do

not have rent control or eviction protection. Another noted that few, if any, tax relief programs

are available nationally for older adults who cannot afford their property taxes, so increasing

house values can lead to financial strain even for those who own their own homes. Additional

factors experts and providers noted that can exacerbate older adults’ risk of homelessness

include financial exploitation, decreased perception of risk that can accompany cognitive aging,

and loss of social supports as family and friends move or pass away. Multiple interviewees

reported that individuals who have been self-reliant for many years often do not reach out for

assistance until their situation is dire due to shame or lack of knowledge about the supports

available offered and how to navigate the system.

These findings also were reflected in the

experiences of the people with lived experience

with whom we spoke. Among the 14 older adults

we engaged in conversation, the majority

indicated they had multiple experiences with

homelessness throughout their lifetimes; two

people experienced homelessness for the first

time as older adults. Both of the newly homeless

individuals reported their homelessness was

caused by changes in their incomes. One individual lost her housing when her rent increased

and her husband’s income declined. Another lost his housing when health problems prevented

him from doing his job. Among those who had previous experiences with homelessness, four

people attributed their recent experiences to mental health issues and substance use disorder,

and two people reported physical injuries led them to lose their jobs and subsequently their

housing. Two people reported having lost their most recent housing when a loved one passed

away and one person reported his house burned down and they had no other place to go. The

remaining three individuals did not cite a cause for their recent homelessness.

CHARACTERISTICS OF OLDER ADULTS EXPERIENCING HOMELESSNESS

Older adults who experienced homelessness earlier in life differ significantly on a range of

characteristics and needs from older adults who first experience homelessness after the age

of 50.

Early evidence suggests that older adults who experienced homelessness earlier in life have had

more vulnerabilities throughout their lives than older adults with later entry into homelessness.

Older adults with earlier experiences of homelessness have more adverse childhood

experiences, chronic medical conditions, drug use, and out-of-home placement during

childhood; more mental health, alcohol and drug use, and incarceration during young

adulthood; and more underemployment, drug use, and traumatic brain injury during middle

adulthood (Brown et al., 2016). In contrast, individuals with later onset homelessness have

“I got peripheral neuropathy in my

hands. My occupation was a ballet

accompanist. When my hands started

getting numb from the peripheral

neuropathy, I could not do that, the line

of work, anymore… That was the first

time that I was not working.” – Male, 65

18

typically been married, held jobs, and maintained housing in the past but experience

homelessness for the first time after age 50 (Brown et al., 2016; Shinn et al., 2007). Although

often living in poverty throughout their adult lives, these individuals have long work histories,

usually in low-paying, physically demanding work.

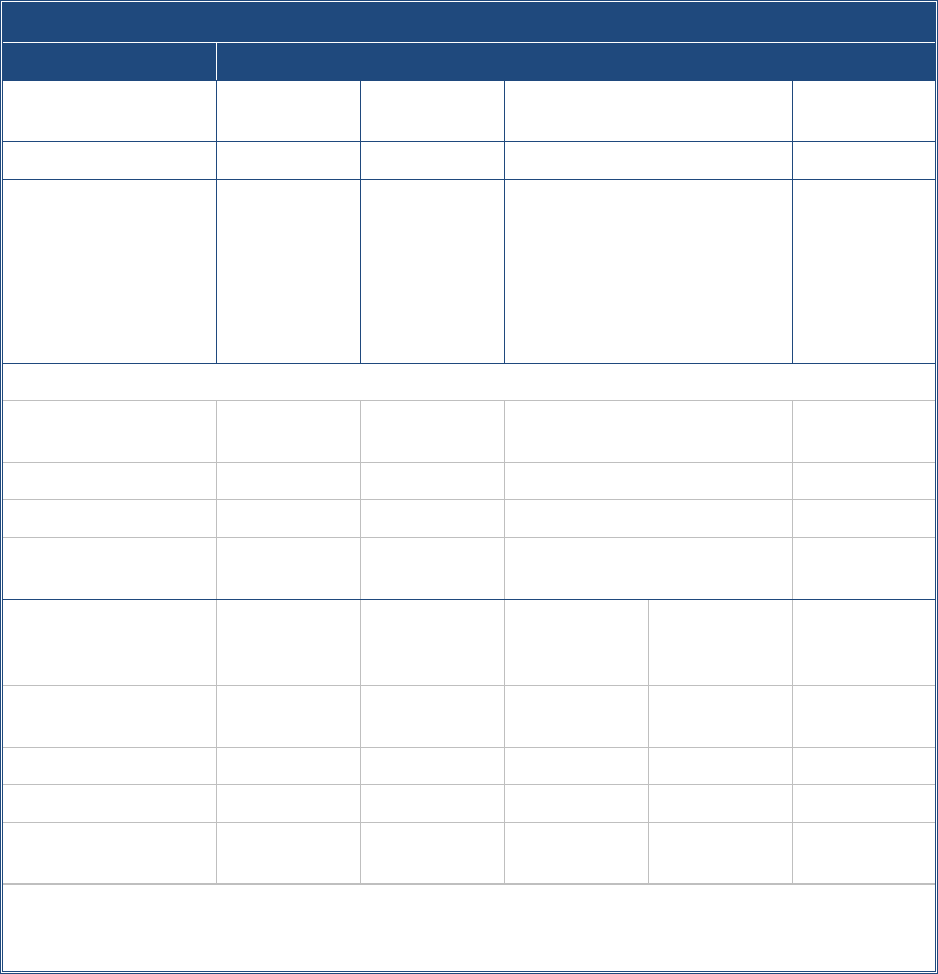

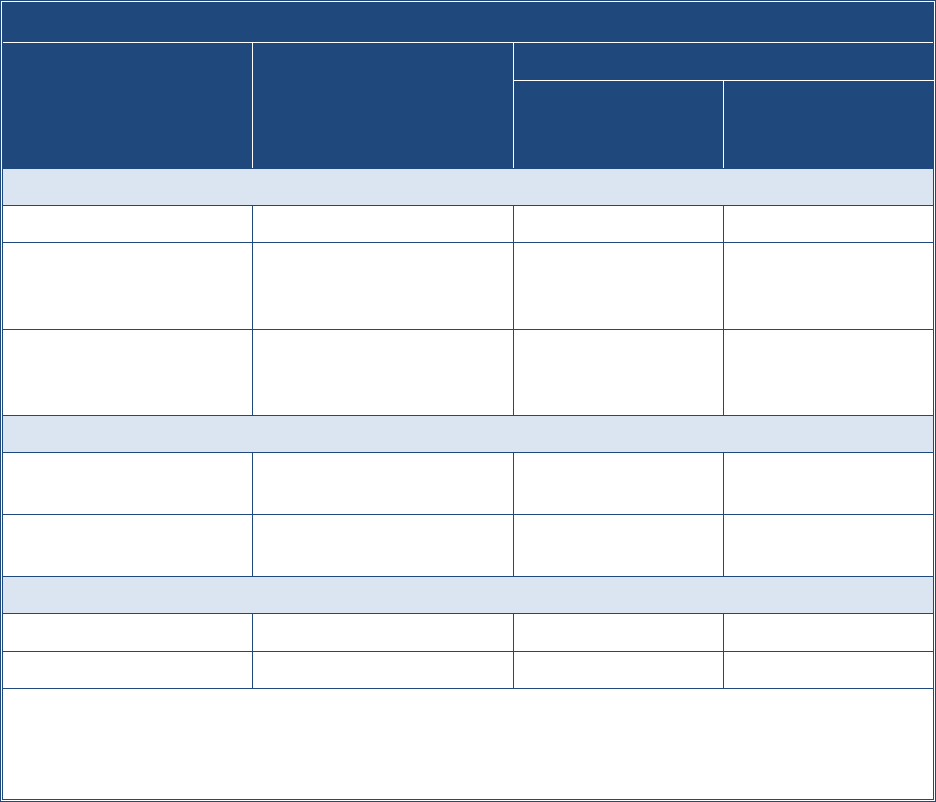

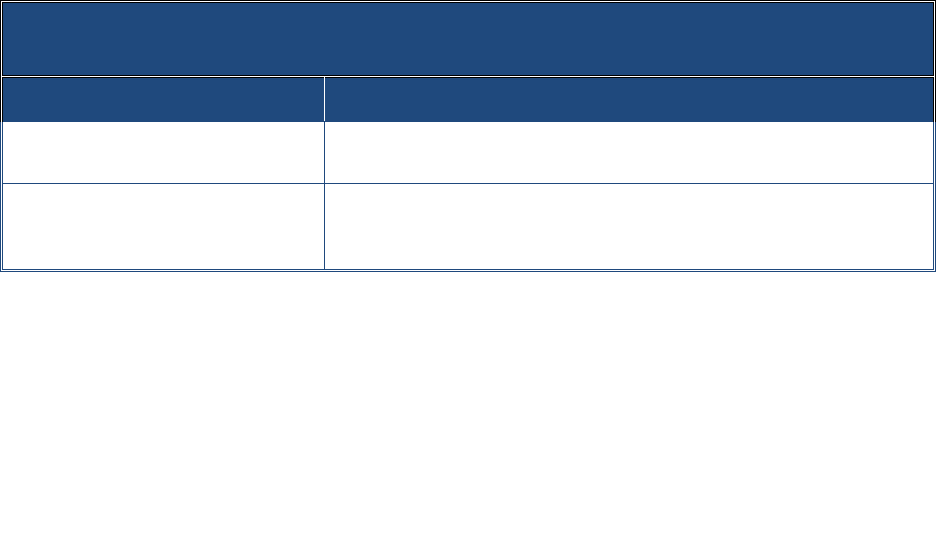

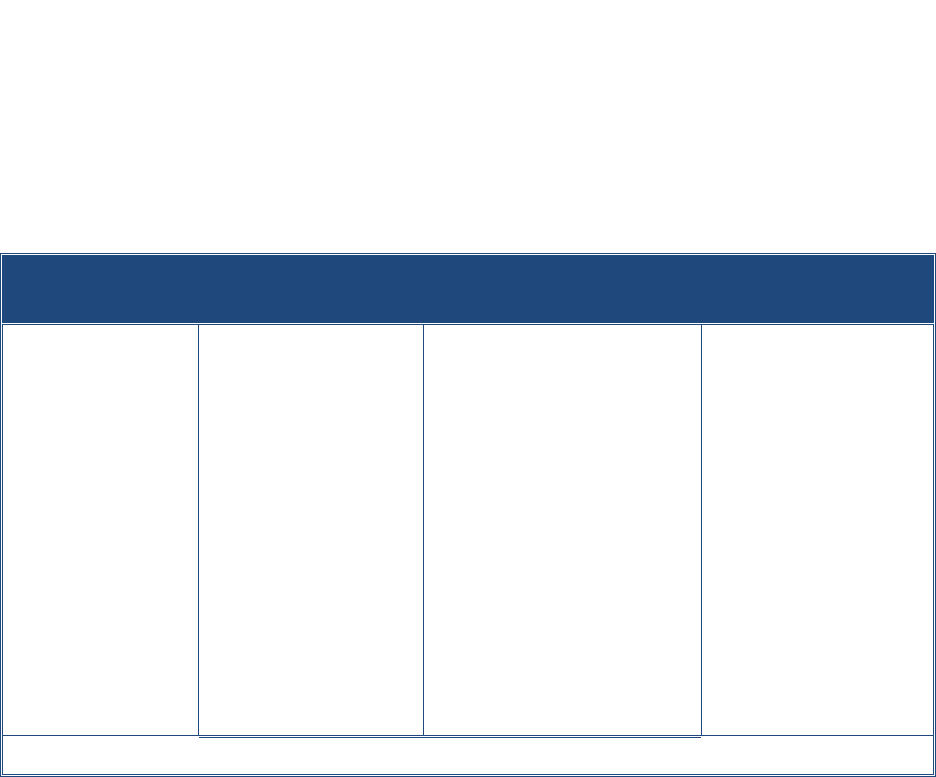

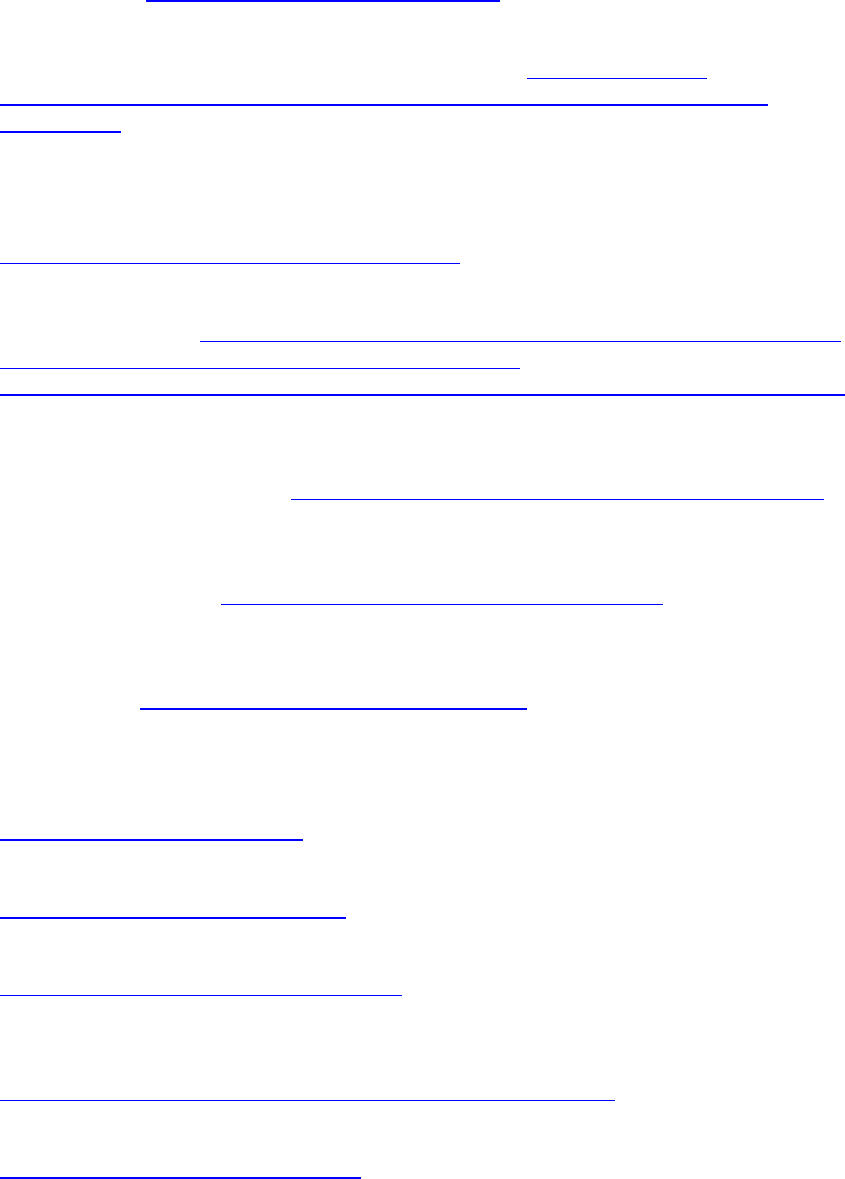

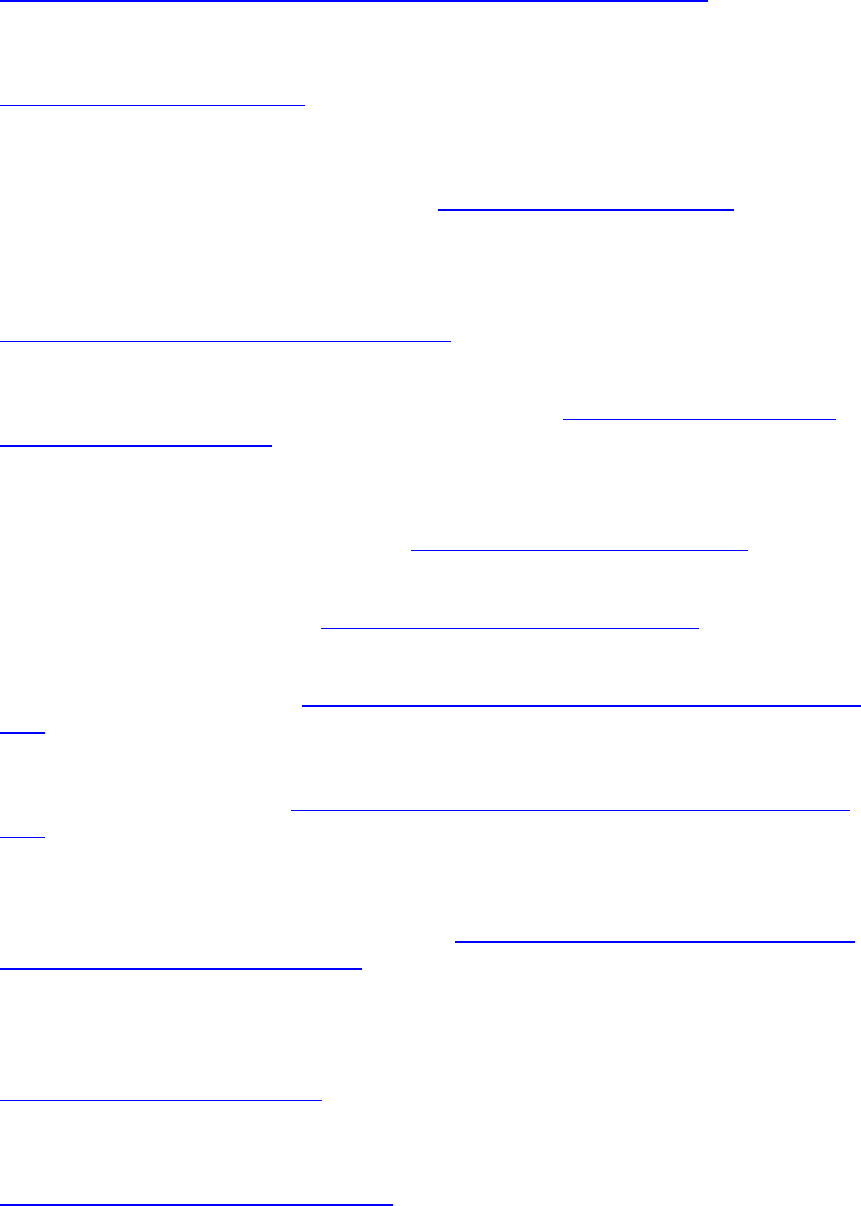

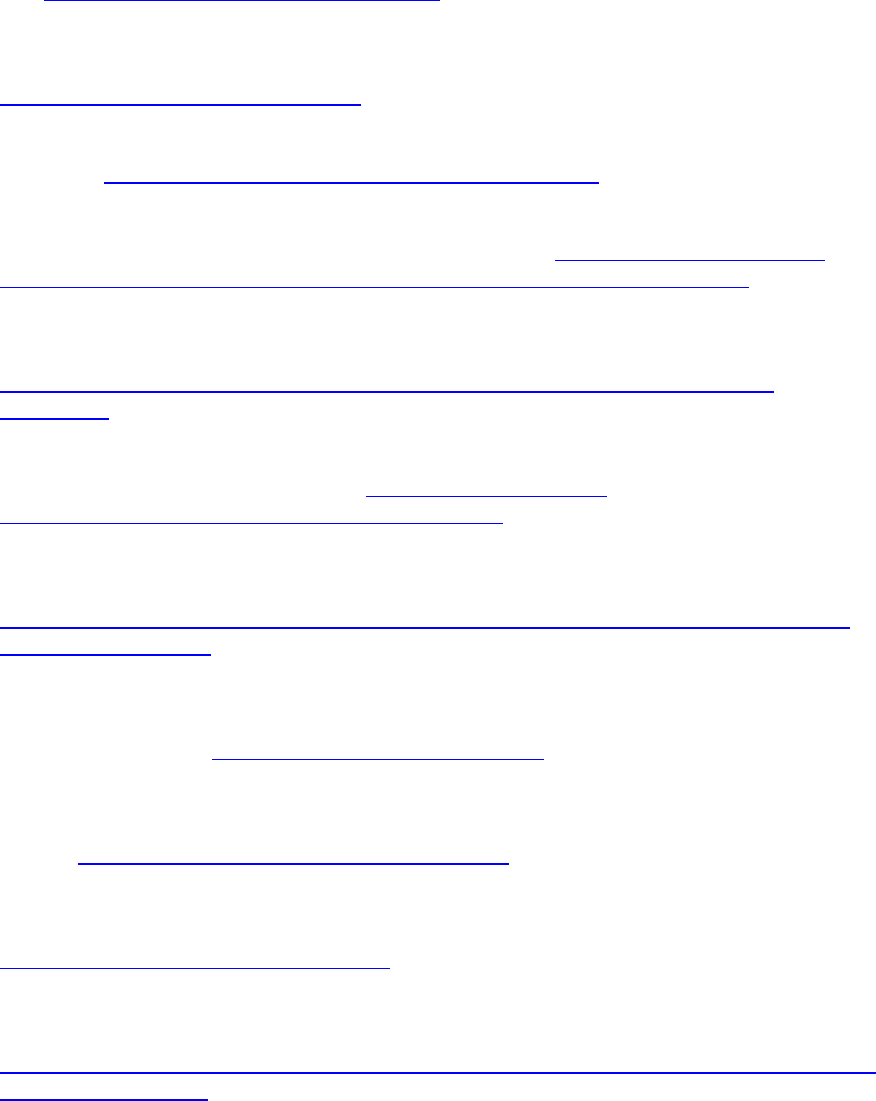

Exhibit 1. Sample Racial/Ethnic Composition for Studies of Older Adults Experiencing Homelessness

Category

Studies of Older Adults Experiencing Homelessness

Study

Brown et al.,

2010

Brown et al.,

2015

Garibaldi et al., 2005

Gordon et al.,

2012

Location

Oakland

Boston

Pittsburgh and Philadelphia

Multi-site

Sample

1

776 older

adult

attendees (50

and older) at

an outreach

event

204 older

adults (50 and

older)

recruited from

emergency

shelters

74 older adults (50 and older)

recruited from unsheltered

enclaves, shelters, and

transitional housing or single-

room occupancy dwellings

408 older

adults (55 and

older)

experiencing

homelessness

with mental

illness

Racial/Ethnic Composition of Sample

2

Black/African

American

54%

40%

81%

28%

White/Caucasian

29%

40%

19%

60%

Latino

8%

10%

--

--

Multiracial/Other

races

9%

9%

--

13%

Racial/Ethnic

Composition of Overall

Population

3

Oakland

Boston

Pittsburgh

Philadelphia

N/A

Black/African

American

22%

24%

23%

41%

White/Caucasian

29%

44%

64%

35%

Latino

27%

20%

4%

15%

Multiracial/Other

races

9%

10%

5%

5%

1

These samples of older adults are often sub-sets of larger samples included in the studies.

2

Terminology reflects that used in the included studies.

3

U.S. Census, 2021.

Those who first experienced homelessness prior to age 50 typically have experienced

homelessness for longer periods of time overall and in their current or recent episodes.

Not surprisingly, older adults who first experienced homelessness prior to age 50 have spent

more time homeless (4.2 years) than those individuals whose first homelessness occurred at

age 50 or older (2.0 years) (Brown et al., 2016). In the HOPE HOME study, the two groups also

19

differed in the length of their current episode of homelessness. Nearly three-fourths (73

percent) of those with first homelessness before age 50 were continuously homeless for one

year or longer in their current episode, compared to 60 percent of those who first experienced

homelessness after the age of 50 (Brown et al., 2016). Those with earlier experiences of

homelessness also spent a greater period of time during the three-year follow-up period living

in unsheltered and institutional settings (shelters, jails, transitional housing), whereas

individuals newly experiencing homelessness as older adults spent greater periods of time

cohabiting or living in rental housing during the follow-up period (Lee et al., 2016).

The limited data available on the racial/ethnic composition of the population of older adults

experiencing homelessness suggests an overrepresentation of people of color.

Data on racial/ethnic composition for this population are available only from a handful of

regional studies. Exhibit 1 provides the racial/ethnic background of each of the study

populations. These studies vary considerably in the geographic area in which they are set and in

the sampling strategies used to identify the population. Despite the differences in how they

were conducted and in their specific findings, each study found a larger percentage of African

Americans experiencing homelessness than the broader population, a finding that is similar to

national data on the overall population of people experiencing homelessness (HUD, 2020;

Moses, 2019).

SERVICE NEEDS OF OLDER ADULTS EXPERIENCING HOMELESSNESS

In this section, we review the service needs of older adults experiencing homelessness and how

they compare to the needs of older housed adults and younger adults experiencing

homelessness. Where available, we include evidence on the differences between the subgroups

of older adults experiencing homelessness for the first time compared to those who have

previously experienced homelessness and between racial/ethnic groups that are

disproportionately likely to experience homelessness.

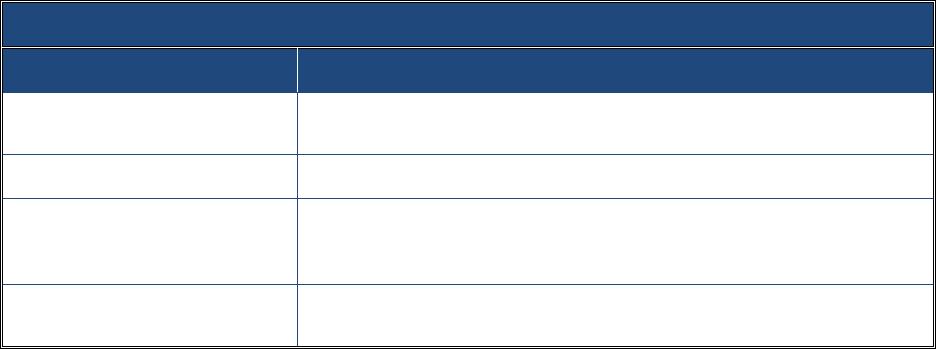

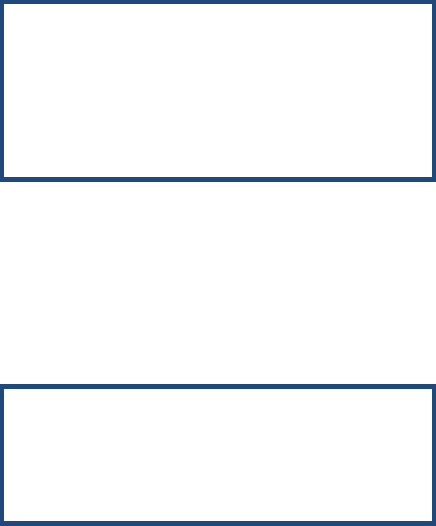

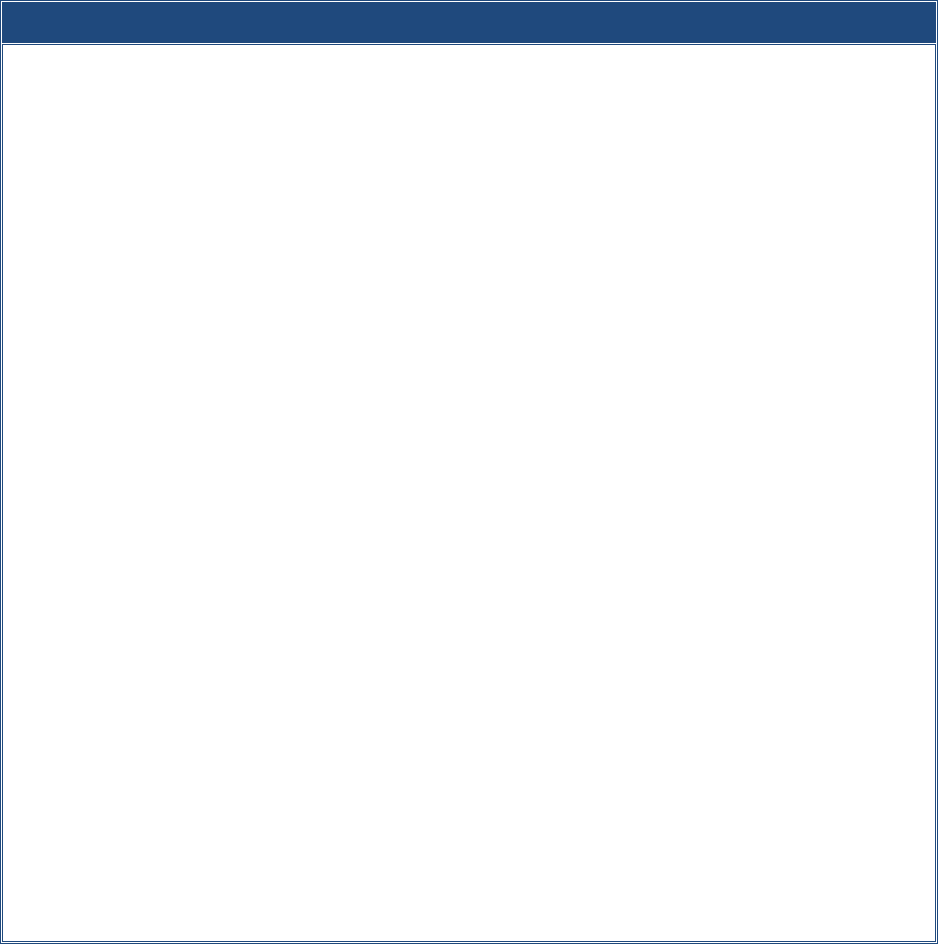

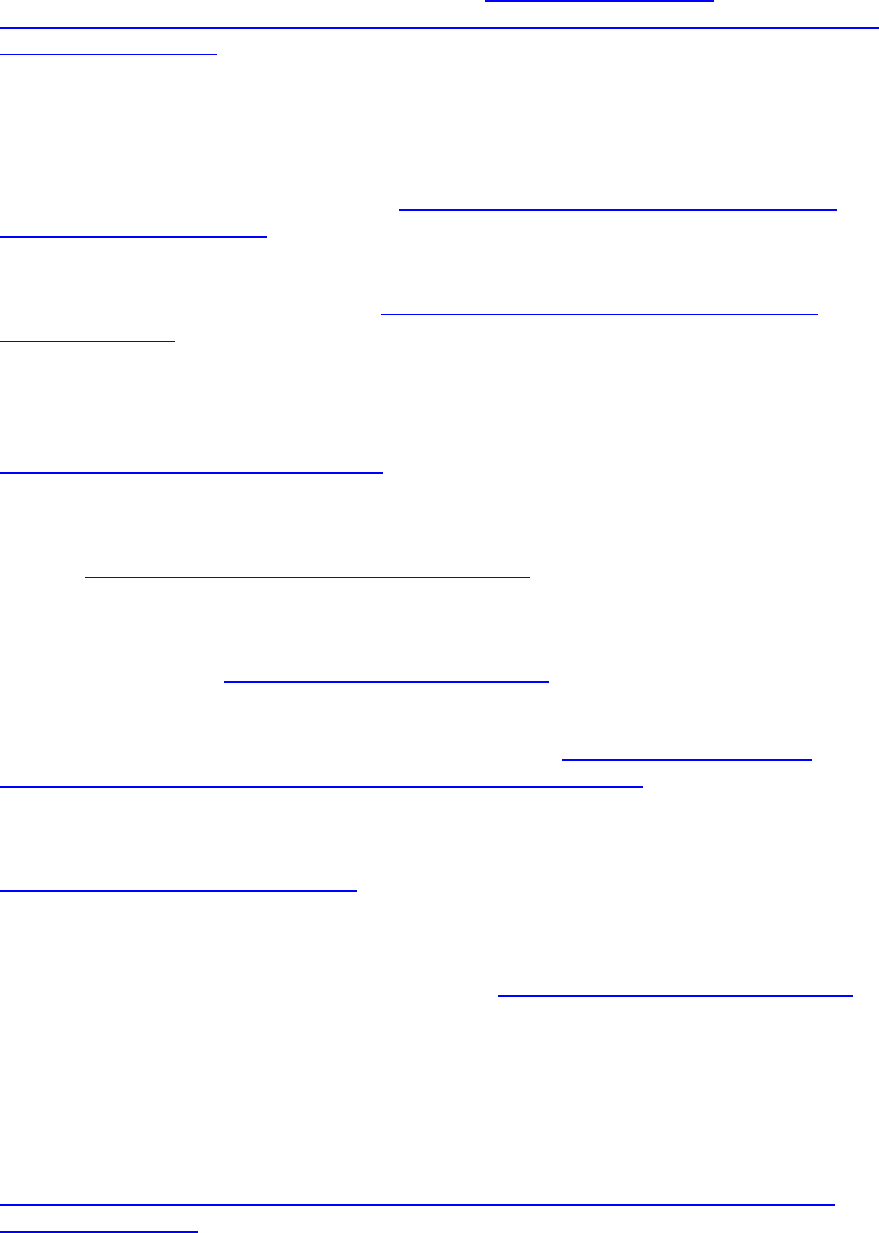

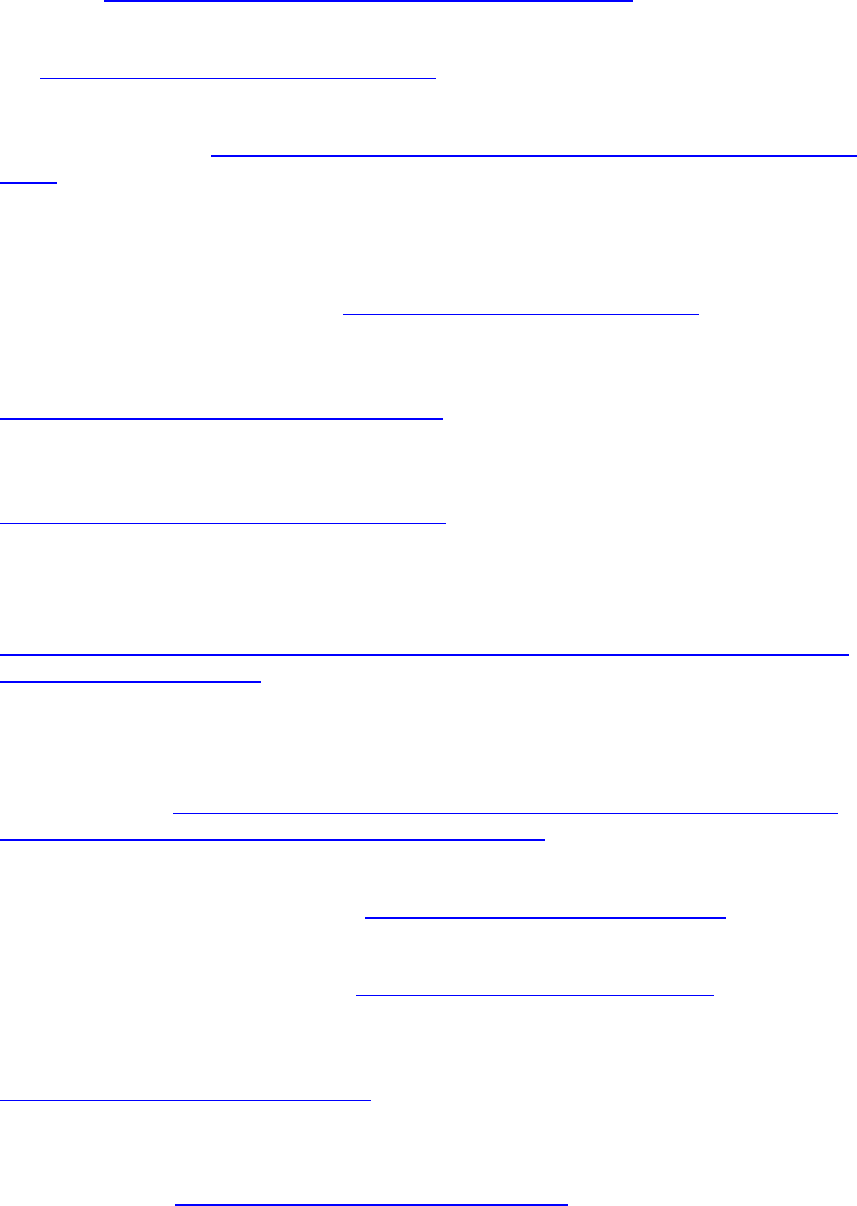

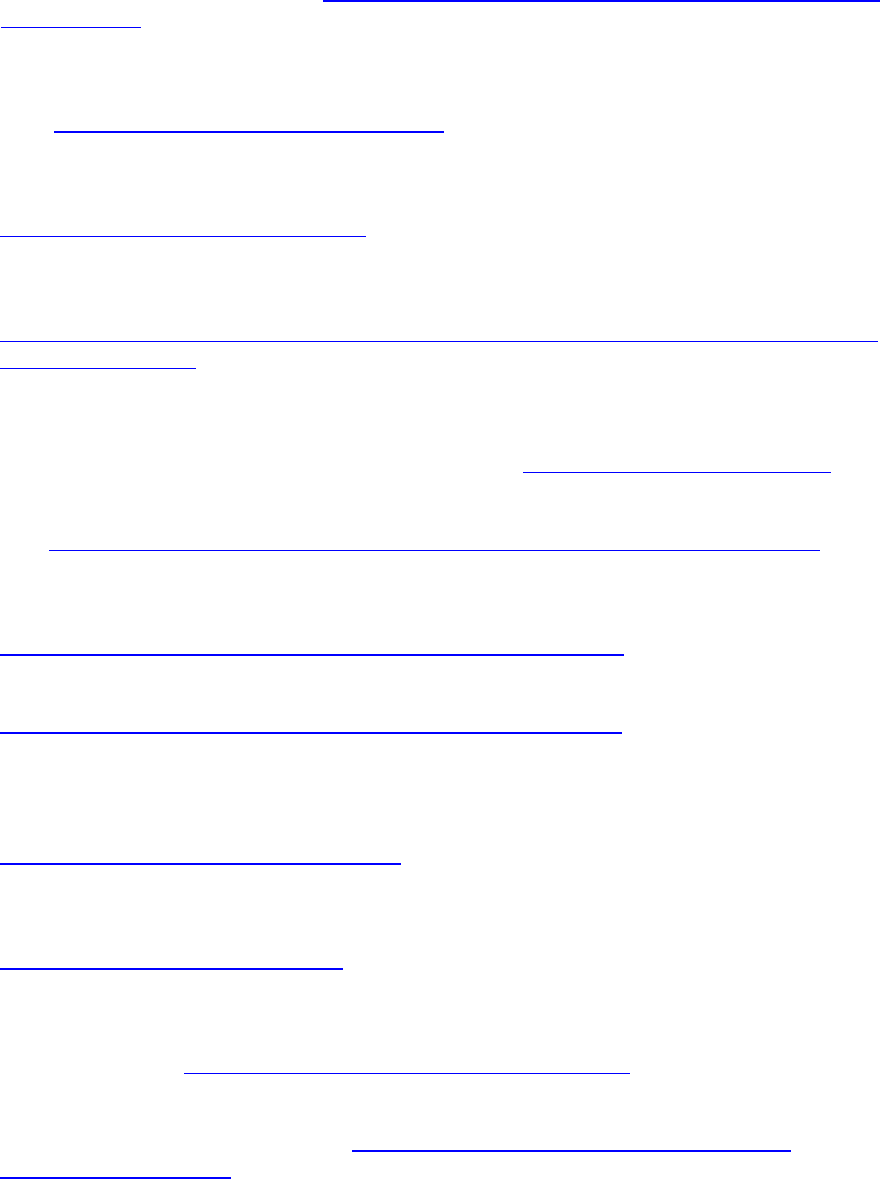

Exhibit 2 provides a summary of the characteristics and service needs of older adults

experiencing homelessness presented here in comparison to older housed adults and younger

homeless adults.

20

Exhibit 2. Comparison of Characteristics and Needs of Older Adults Experiencing Homelessness

Older Adults Experiencing

Homelessness

Finding

Compared to:

Older Housed Adults

Younger Adults

Experiencing

Homelessness

Physical Health Needs

Average life expectancy

64-69 years

Shorter life expectancy

---

Rates of health and

geriatric conditions

30-39% ADL impairment;

21-59% experience

hypertension

Higher rates

Higher rates

Utilization of acute

health care services

43-70% have emergency

department visits;

10-43% have hospitalizations

Higher utilization

Comparable rates

Behavioral Health Needs

Rates of mental health

conditions

~40%

Higher rates

1

No clear patterns

2

Rates of substance use

disorder

26-63%

Higher rates

No clear patterns

Basic Needs

Rates of food insecurity

~55%

Higher rates

3

Higher rates

Lack of transportation

---

---

---

1

As compared to 3 nationally representative samples of older adults.

2

Indicates studies show inconsistent findings on the differences between older and younger adults

experiencing homelessness.

3

As compared to national estimates of population living in poverty.

Physical Health Needs

Older adults experiencing homelessness have significantly shorter life spans than housed

older adults, though they die from similar chronic conditions.

Studies consistently document a shorter life span of older adults experiencing homelessness

despite the range of sub-populations studied, including individuals staying in shelters in New

York City (Metraux et al., 2011); veterans in transitional homeless programs (Schinka et al.,

2017; Schinka & Byrne, 2018); and individuals experiencing homelessness in Oakland, California

(Brown et al., 2016; Kushel, 2020). For example, Metraux and colleagues (2011) matched

administrative records for adults staying in the New York City shelter system with death records

from the Social Security Administration. They found that older adults experiencing

homelessness have a life expectancy of approximately 64 years for men and 69 years for

women (Metraux et al., 2011), compared to national life expectancies of 76 years for men and

81 years for women (Xu et al., 2020). Further, Hwang and colleagues (1997; 2008) found that

both older adults experiencing chronic homelessness and those who first became homeless

later in life had elevated mortality rates. Finally, although the most common causes of death

21

among older homeless adults are similar to housed older adults, for example, cancer and

cardiovascular disease, these illnesses occur approximately 20 years earlier (Kushel, 2020).

Older adults experiencing homelessness have health challenges similar to older adults who

are housed but who are of more advanced ages.

Adults experiencing homelessness between ages 50 and 62 often have health conditions that

are more severe than housed individuals their own age, but similar to those of housed people

who are 10-20 years older (Cohen, 1999; Gelberg et al., 1990; HPRI, 2019; Brown et al., 2016).

Compared to their housed counterparts, older adults experiencing homelessness have a higher

prevalence and severity of physical and geriatric conditions including memory loss, falls,

difficulty performing ADLs, and cognitive impairment (Brown et al., 2011; Brown et al., 2017;

Hahn et al., 2006; Hwang et al., 1997). Moreover, comorbid conditions among older adults

experiencing homelessness are common, including hypertension, arthritis, cognitive

impairment, frailty, hearing difficulty, and urinary incontinence (Kushel, 2020; Brown et al.,

2011, Brown et al., 2016; Brown, 2017; Gelberg et al., 1990). Additionally, in discussions,

experts and providers noted that sleep deprivation resulting from sleeping in unsheltered

locations such as tents or cars or in shelters that were crowded or offered limited hours of

access exacerbated older adults’ physical and mental health challenges and accelerated

cognitive decline.

Older adults have different health conditions than younger adults who are homeless, though

adults of all ages experiencing homelessness have poorer health status than those who are

housed.

Among those experiencing homelessness, older adults compared to younger adults have higher

rates of chronic illnesses such as high blood pressure; geriatric conditions, including arthritis,

and functional disability; and cognitive impairments (Garibaldi et al., 2005; Gelberg et al., 1990).

To illustrate, in a cross-sectional, community-based survey of homeless adults in two United

States cities, older adults were 3.6 times as likely to have a chronic medical condition as those

under age 50 (Garibaldi et al., 2005). Older adults also were more likely to report two or more

medical conditions (59 percent vs 28 percent) compared to the younger adults experiencing

homelessness (Garibaldi et al., 2005). A five-year study of 28,000 adults who received care at

the Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program reported death rates of almost 2.5 times

higher for those ages 45-64 compared to those ages 25-44 (Baggett et al., 2013). When

compared to the general housed population of the same ages, people 25-44 years old

experiencing homelessness had mortality rates 9 times higher, while people 45-64 years old

experiencing homelessness had mortality rates 4.5 times higher (Baggett et al., 2013).

Older adults experiencing homelessness utilize acute health care services at high rates and

significantly more than the general population of older adults.

Older adults experiencing homelessness use acute health care services at high rates, with rates

across studies ranging from 43 percent to 70 percent for emergency department visits and 10-

43 percent for inpatient hospitalizations (Brown et al., 2010; Brown et al., 2011; Raven et al.,

2017). Very few studies have compared national rates of acute health care services utilization

between older adults experiencing homelessness to those of their housed counterparts. In a

22

study comparing older adults experiencing homelessness in Boston to three nationally

representative samples of older adults, 43 percent of the older homeless adults had been

admitted to the hospital more than once in the prior year compared to 11 percent of the

nationally representative sample. Moreover, whereas 70 percent of the older adults

experiencing homelessness had more than one emergency department visit in the prior year,

only 19 percent of the nationally representative sample of older adults did (Brown et al., 2011).

Further, most older adults experiencing homelessness in the sample had received ambulatory

care (87 percent) within the previous 12 months (Brown et al., 2011). A study using a similar

sample of older adults experiencing homelessness found a small proportion of the sample

accounted for half of all emergency departments and inpatient visits; those who spent the

majority of the past six months homeless, either unsheltered or staying in shelters, had

significantly higher rates of emergency department visits than those who had spent most of

their time housed (Brown et al., 2010).

Older adults experiencing homelessness use the emergency department most frequently for

injuries and exposure to violence; complications resulting from substance use, including alcohol

and tobacco; and treatment of mental health disorders (Raven et al., 2017). Among people

experiencing homelessness, emergency departments remain a low-barrier access point to seek

pain management and medical treatment for chronic medical conditions and pain that could be

managed in outpatient settings. Although over two-thirds of the sample of adults 50 and older

experiencing homelessness in the study reported having a regular non-emergency place for

routine care, it was not associated with reduced use of the emergency department (Raven et

al., 2017).

Older adults and younger adults experiencing homelessness use acute health care services at

similar rates, despite differences in having health insurance and a regular health care place or

provider.

In Brown’s 2010 study of health care utilization by people experiencing homelessness, adults

aged 50 and older were more likely to have health insurance, a regular place for health care,

and a regular health care provider (e.g., medical doctor, nurse practitioner, or registered nurse)

than those under 50. However, both groups had similar rates of acute health care utilization in

the prior year, including emergency department visits (43 percent of older adults vs. 49 percent

of younger adults) and inpatient hospitalizations (32 percent of older adults vs. 40 percent of

younger adults) (Brown et al., 2010). This study showed no significant differences between age

groups in the type of visit; most visits were for physical ailments (85 percent for older adults vs.

88 percent for younger adults) as opposed to emotional problems (19.5 percent for both age

groups) (Brown et al., 2010).

Behavioral Health Needs

Older adults experiencing homelessness, especially women, are more likely to have mental

health conditions than older housed adults.

In studies with samples of older adults experiencing homelessness (Brown et al., 2011; Kaplan

et al., 2019), older adults in permanent supportive housing (Henwood et al., 2018), and

veterans (Schinka et al., 2012), between 40 percent and 58 percent either screened for or

23

reported mental health conditions. For example, 56 percent of older adults in permanent

supportive housing reported at least two chronic mental health conditions (Henwood et al.,

2018). Depression was the most common condition identified; other conditions include

schizophrenia and post-traumatic stress disorder. These rates of mental health conditions are

higher among older adults experiencing homelessness than older housed adults (which range

from 18 percent to 34 percent), measured both by diagnoses and symptomology (Brown et al.,

2011; U.S. CDC, 2008).

Some studies find evidence of gender differences in rates of mental health conditions among

older adults experiencing homelessness. Compared to older homeless men, older homeless

women were two and one-half times more likely to have any chronic mental health condition

and more likely to be diagnosed with more mental health conditions (Winetrobe et al., 2017;

Dickins et al., 2021).

Findings from the Health and Retirement Study indicate race and ethnic differences in the

behavioral health conditions of older adults experiencing homelessness. Compared to their

White counterparts, Black and African American older adults experiencing homelessness are

significantly more likely to report a history of illicit drug use and less likely to report a history of

mental illness or domestic violence than White older adults experiencing homelessness

(Chekuri et al., 2016).

Older adults experiencing homelessness also have more substance use disorders than the

general population.

Although there are no studies that directly compare older homeless adults to their housed

counterparts on substance use, a few studies have compared older homeless adults to

population-based samples and to other samples. Studies generally find that a higher percentage

of older adults experiencing homelessness

report alcohol and/or drug use than population-

based samples (e.g., CDC, 2008). In the HOPE

HOME cohort of older adults experiencing

homelessness, for example, rates of binge

drinking were significantly higher in older

homeless adults than in three large-scale studies

of older adults using population-based samples

(30 percent vs. 1 percent, 7 percent, and 3 percent) and a greater percentage of the older

adults experiencing homelessness reported moderate or greater severity of alcohol use (26

percent) than housed adults of all ages (5 percent) served in a U.S. Department of Veterans

Affairs (VA) primary care clinic (Brown et al., 2019). This sample also had a higher rate of

current illicit substance use (63 percent) than a national community-based sample of adults of

all ages experiencing homelessness (23 percent) (Spinelli et al., 2017).

“I've dealt with a lot of trauma as well. I lost

my best friend that I've known since I was

17 years old due to COVID, so there you go

again now. Setback is you start using again,

just to numb the pain, you know what I

mean?” – Male, 59

24

Studies to date yield inconsistent findings on the differences in mental health conditions and

substance use between older and younger adults experiencing homelessness.

It is unclear whether there are age differences in the prevalence of behavioral health conditions

among individuals experiencing homelessness. Whereas some studies have found a higher

prevalence of mental health conditions such as anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress

disorder (Garibaldi et al., 2005; Tompsett et al., 2009) among older adults experiencing

homelessness than among their younger counterparts, other studies have found either no

significant differences in the rates of these conditions (DeMallie et al.,1997; Gelberg et al.,

1990) or the opposite finding (Gordon et al., 2012).

Similarly, the limited studies that contrast rates of substance use between older and younger

adults experiencing homelessness yield mixed findings. Some studies suggest that, among

people experiencing homelessness, younger adults are more likely to use drugs than older

adults while older adults may be more likely to use alcohol (DeMallie et al., 1997; Gordon et al.,

2012). Yet other studies fail to find such differences (Hecht & Coyle, 2001; Gelberg et al., 1990)

or find that there is a lower prevalence of substance use disorders for older versus younger

adults experiencing homelessness (Burt et al., 1999; Dietz et al., 2009).

Preliminary evidence suggests older adults who first experienced homelessness earlier in life

are more likely to have behavioral health conditions than those who first experienced

homelessness after age 50.

In the only study to compare differences between newly and chronically homeless older adults,

Brown and colleagues (2016) found that participant characteristics and life course experiences

differed by age at first homelessness. Compared to

individuals whose first homelessness occurred at

age 50 or older, individuals with first homelessness

before age 50 showed a greater prevalence of

behavioral health disorders at different stages in

life. For example, this group had higher rates of

drug use in childhood and mental health problems

in young and middle adulthood, as well as a higher

prevalence of current mental health issues,

including depressive symptoms and post-traumatic

stress disorder, and drug use, and higher rates of

hospitalizations for mental health problems in

adulthood (Brown et al., 2016).

Individuals who had experienced homelessness as older adults reported high rates of physical

and behavioral health problems, echoing findings from the literature.

All of the older individuals with lived experience of homelessness with whom we spoke

discussed suffering from physical and behavioral health problems, including diabetes, HIV,

traumatic brain injury, glaucoma, arthritis, bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, and

substance use disorder. A few people also reported having experienced strokes or cancer in the

past. Many of the interviewees, including all of those who were homeless at the time of our

“I mean, I'm going to be 60 years old. It's

getting cold out and… I'm not settled

carrying a backpack around every

freaking day. It's like my back is starting

to bother me. I got health issues. I only

got one kidney that's functioning 40%

because I had cancer a little over a year

ago. That's the second time I had cancer

in 6 years. So, it's like, you know what? I

need to be settled down in a place.” –

Male, 59

25

interview, reported physical pain and mobility issues, often attributed to being unsheltered. For

example, one individual reported they had lost several toes due to frostbite contracted while

being outside in bad weather.

Basic Needs

Older adults experiencing homelessness have high rates of food insecurity.

Food insecurity coupled with insufficient nourishment complicates chronic disease

management and presents a major challenge for older homeless adults who have a high

prevalence of chronic disease and limited mobility (Brown et al., 2011; Patanwala et al., 2018).

Food insufficiency among older adults is associated with significantly greater odds of

hospitalization for any reason, psychiatric hospitalization, and high emergency department

utilization (Baggett et al., 2011). Individuals who are food insecure -- having limited access to

adequate food due to lack of resources -- have poorer health and are more likely to consume

foods deficient in nutrients (Robaina & Martin, 2013). Also, severely cost-burdened older adults

who are in the bottom income quartile reduce their spending on food by 30 percent more than

those who are not cost-burdened (National Association of Area Agencies on Aging [n4a], n.d. b).

Among participants in the HOPE HOME study, over half reported food insecurity, with one-third

reporting low food security and one-quarter reporting very low food security (Tong et al.,

2018), consistent with food insecurity estimates among other homeless populations (e.g.,

Parpouchi et al., 2016) and nearly two times higher than national estimates among the United

States population living in poverty (Coleman-Jensen et al., 2016).

Lack of transportation poses a significant barrier for older adults experiencing homelessness.

Adults experiencing homelessness commonly indicate their most used modes of transportation

include public transit and walking (Chan et al., 2014; North et al., 2017; Murphy, 2019), which

are more difficult for older individuals with mobility challenges. Lack of transportation has been

cited as a barrier for adults experiencing homelessness, as it reduces access to shelter and

housing, medical and behavioral health care, social engagement, food, and other supportive

services (Greysen et al., 2012; Hui & Habib, 2014, 2017; Niño, Loya, & Cuevas, 2009; Murphy,

2019; Turnbull, Muckle, & Masters, 2007). Among studies of older adults experiencing

homelessness, mobility challenges (i.e., difficulty walking without help) and challenges with

instrumental ADLs such as using public transportation are common (Henwood et al., 2018).

Thus, it is reasonable to conclude that older adults experiencing homelessness face

transportation barriers even beyond those of younger adults experiencing homelessness.

However, there is little available research focused on transportation issues specifically among

older adults experiencing homelessness.

Older adults experiencing homelessness, including those who are newly placed into housing,

experience loss of community.

Many of the experts and providers with whom we spoke noted that mobility limitations,

frequent address changes, receipt of housing assistance in a new neighborhood, and the death

of family and friends contribute to formerly homeless older adults having limited social

networks. Multiple interviewees noted that social and physical isolation among this population

can contribute to further cognitive and physical declines. One housing provider noted that

26

formerly homeless older residents in her organization’s properties often struggle to identify

someone who can serve as their medical power of attorney following years of social isolation.

27

Section 3. Systems and Services Available to Serve Older Adults at Risk

of or Experiencing Homelessness

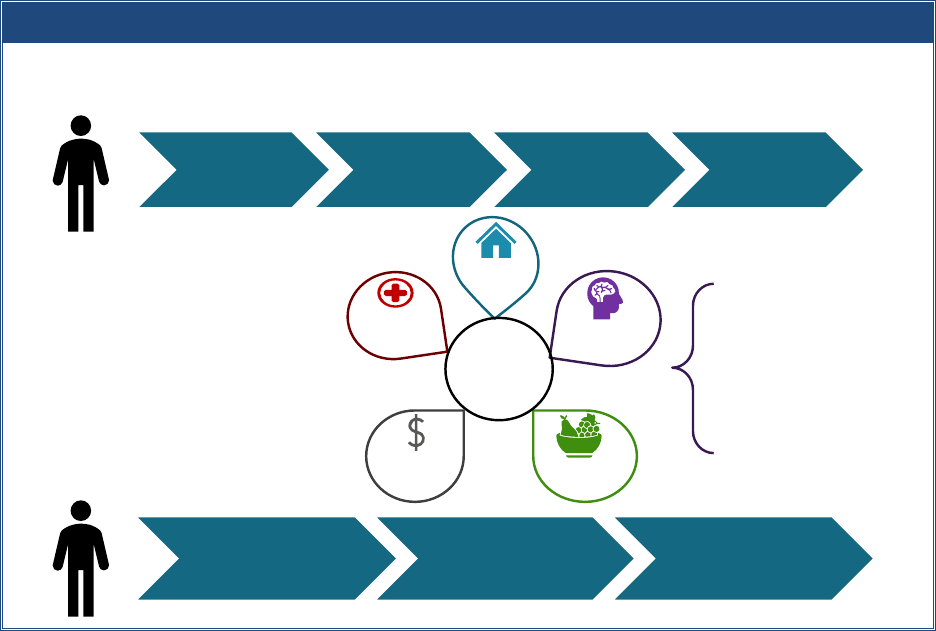

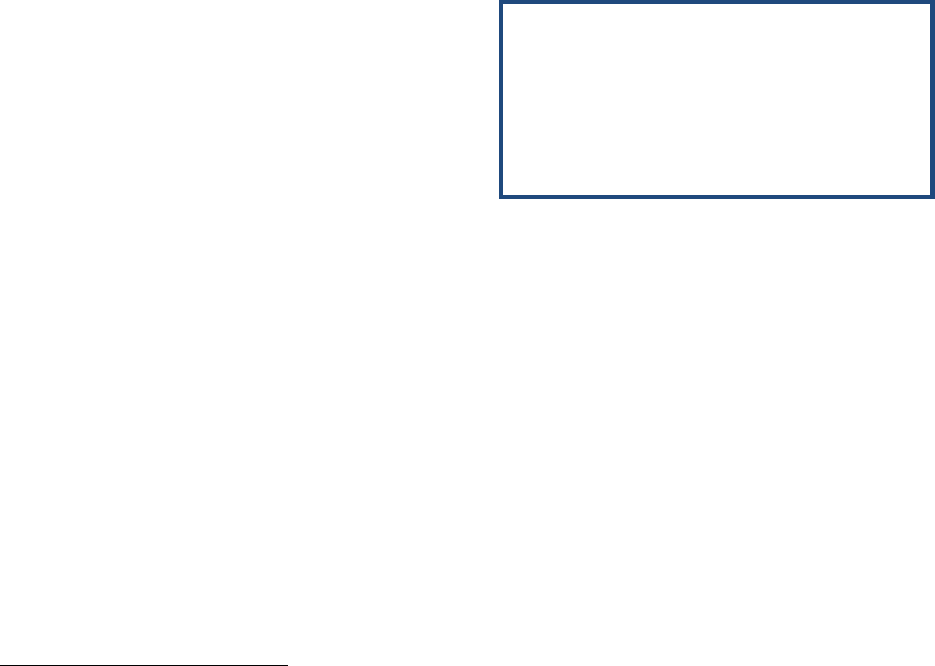

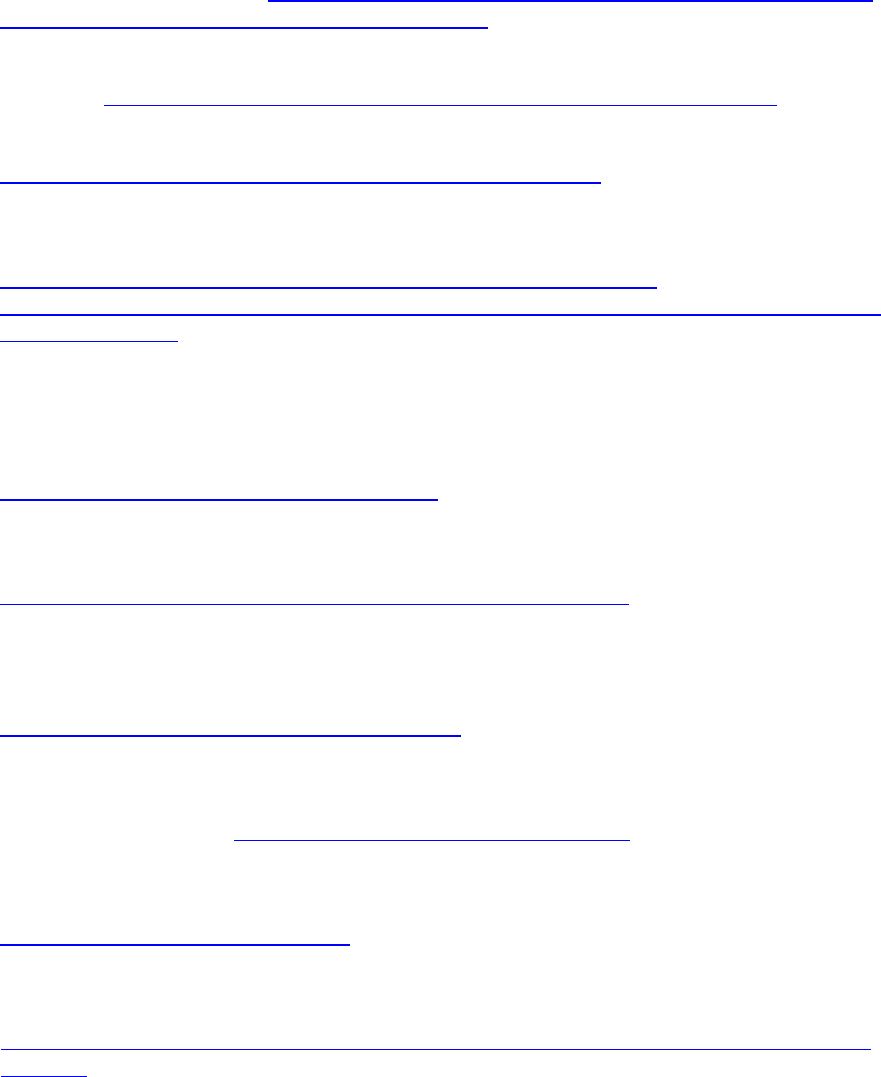

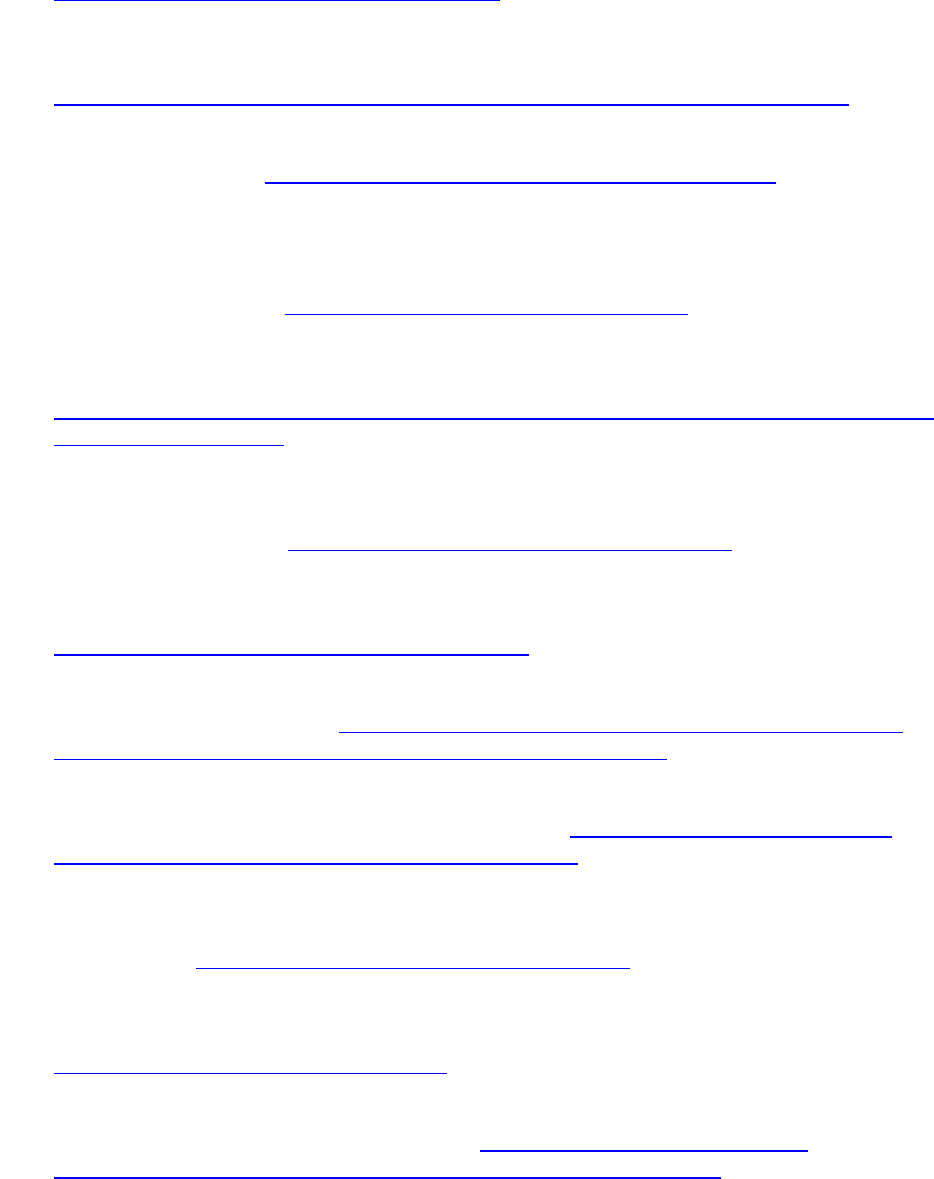

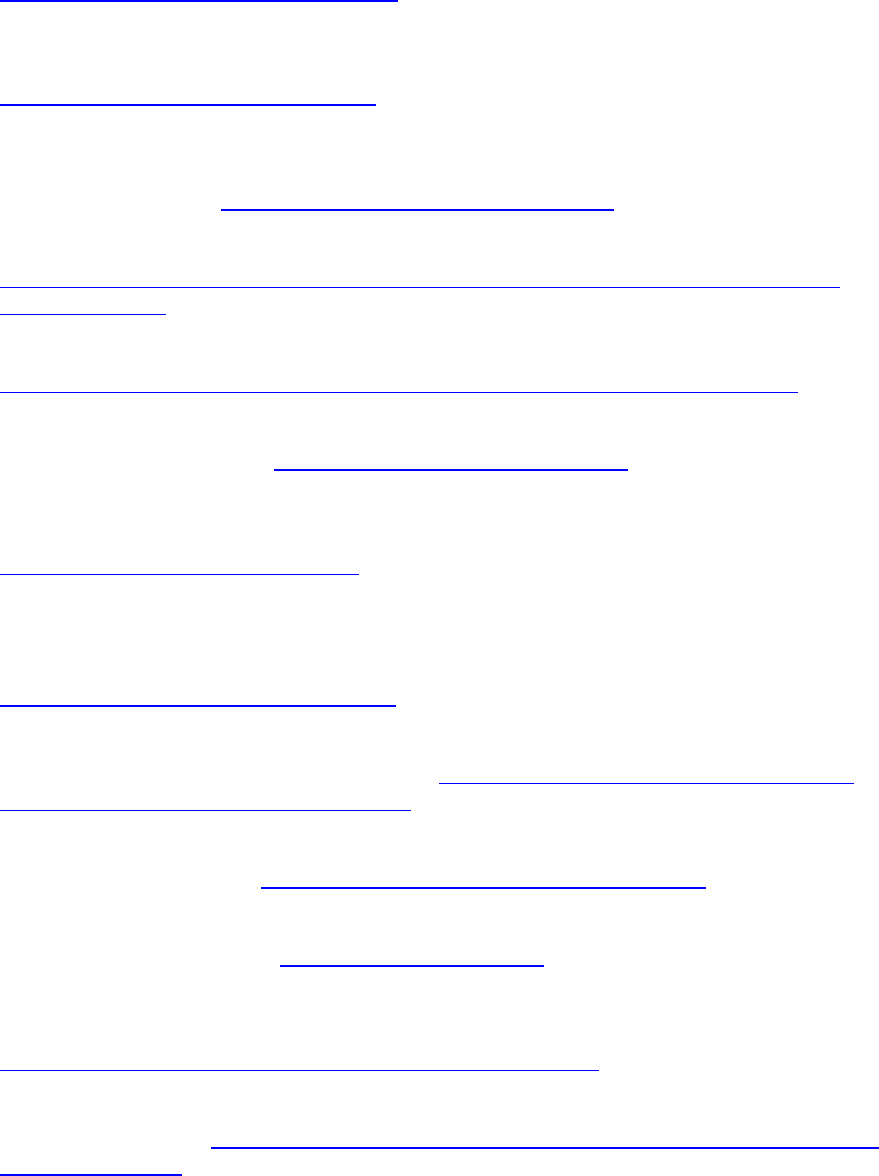

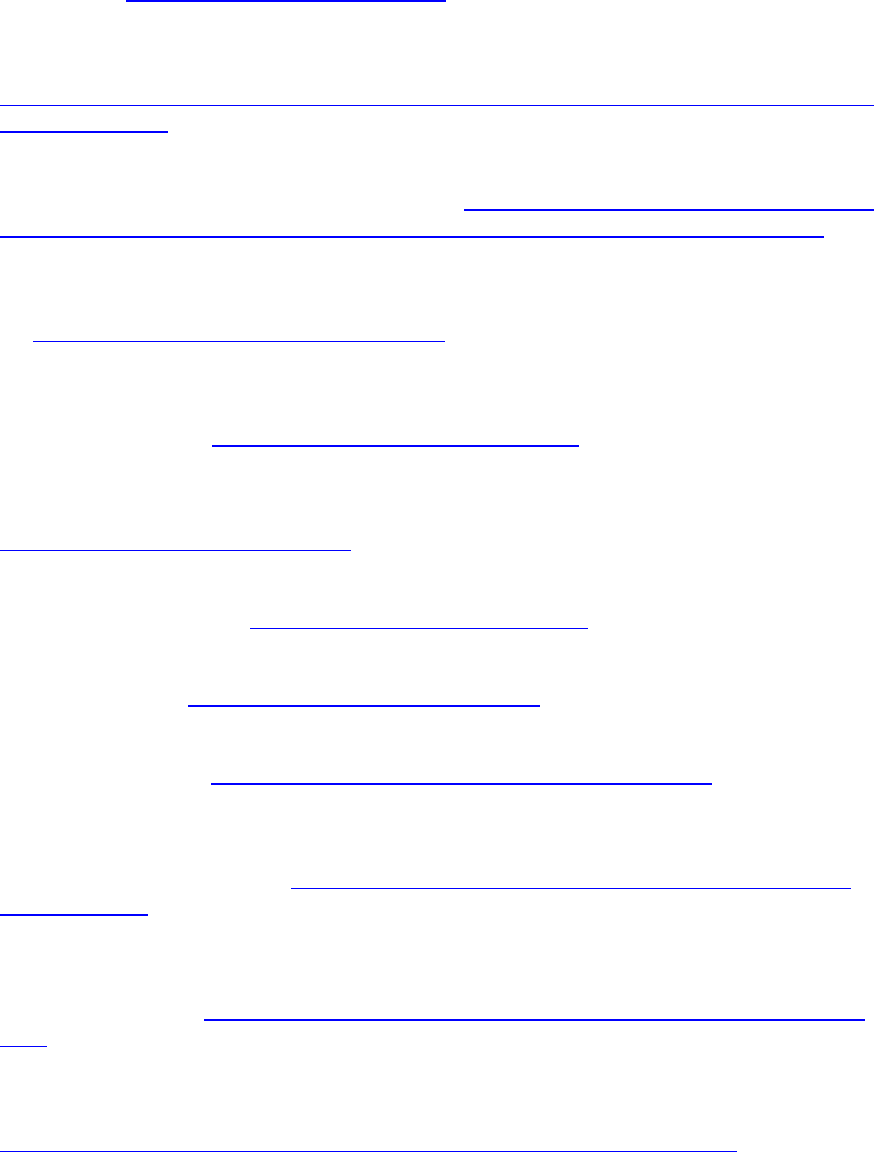

Exhibit 3 presents a conceptual systems framework for understanding the different services

needed by older adults experiencing homelessness and the service delivery systems that may

offer these services. The framework highlights the two subgroups of older adults experiencing

homelessness identified through recent studies and the pathways of services, housing, and

support likely needed to become stably housed. These two subgroups provide a rubric for

understanding the types of assistance older adults experiencing homelessness need, but within

the broader acknowledgement that each person has their own unique history and needs.

Exhibit 3. Systems Framework for Addressing Homelessness Among Older Adults

Older individuals who repeatedly experience homelessness often require extensive outreach

and emergency shelter before obtaining housing and supports. To achieve long-term stability,

many require ongoing case management to help link them to needed health and behavioral

health care, income supports, and other services. In contrast, older adults who have not

previously experienced homelessness, but have experienced adverse events that threaten their