REPORT TO THE

UTAH LEGISLATURE

Report No. 2002-01

A Performance Audit

of

Medical School Admissions

January 2002

Audit Performed by:

Audit Manager Tim Osterstock

Auditor Supervisor James Behunin

Audit Staff Mark Roos

Ivan Djambov

Aaron Eliason

Table of Contents

Page

Digest ................................................. i

Chapter I

Introduction ............................................ 1

Selection of a Medical School Class Is a Difficult Process ......... 2

Utah’s Selection Process Consists of Three Phases .............. 4

Steps Taken to Promote Fairness ..........................7

Audit Scope and Objectives .............................. 8

Chapter II

Rate of Acceptance Higher for Women and Minorities ............. 9

Gender Affects Likelihood of Acceptance ....................9

Minority Applicants Accepted At a Higher Rate .............. 14

Acceptance Rates for Other Variables Show Little Difference .... 17

Chapter III

Diversity Policy Explains the High Rate of Female and

Minority Admissions ..................................21

A Student’s Diversity Is Considered During the Admissions

Process ........................................... 21

Diversity Program Is Not a Population-based Quota System ..... 27

Diversity Policy Conflicts With Policy on Non-discrimination .... 30

Recommendations ....................................37

Chapter IV

Deviations from Admissions Process Have Raised Questions ....... 39

Office of the Utah Legislative Auditor General – 3 –

Table of Contents (Cont.)

Review Committee Decisions Are Not Always Followed ........ 39

Interview Problems Raise Question of Fairness ............... 44

Selection Committee Process Can be Streamlined ............. 49

Recommendations ....................................53

Appendices ............................................ 55

Agency Response ........................................ 75

-i-

Office of the Utah Legislative Auditor General – i –

The School of Medicine

seeks to enroll the

same portion of

minorities and women

found in the state’s

general population.

Women and minorities

are accepted at over

twice the rate of white

males.

Digest of

A Performance Audit of

Medical School Admissions

The University of Utah School of Medicine’s admissions practices have

changed in recent years to, among other things, better enable the school

to mirror the diversity of race and gender found in the general population.

This is a difficult task because relatively few women and minorities apply

to the School of Medicine. In seeking to enroll a class of students that

reflects the same general proportion of minorities and women, the school

has had to increase the rate of acceptance among minorities and women.

As a result, the fairness of the school’s admissions practices have been

questioned.

These questions arise because the school has elevated the importance

of diversity over academics and has conflicting internal policies. The

school’s diversity policy is, however, consistent with the policies of the

university administration and the Board of Regents. The policy on

diversity also fits within a broader strategy of affirmative action that is

promoted by the Association of American Medical Colleges.

The report’s main themes are summarized below.

Rate of Acceptance Higher for Women and Minorities

School of Medicine records show that over the past two years, roughly

one out of every two women who applied to medical school were

accepted while only one of five men were accepted. Similarly, about one

out of every two minority applicants were accepted during the past two

years but only one in five white applicants were accepted.

While gender and minority status appear to effect the rate of

acceptance, there is no significant difference in the rate of acceptance when

the applicant’s undergraduate college, rural/non-rural status or age is

considered. Also, we could not identify any systematic bias against

applicant’s religious background.

-ii-

– ii – A Performance Audit of Medical School Admissions

The high rate of

acceptance among

women and minorities

is explained by the

school’s efforts to

promote diversity.

Diversity Policy Explains the High Rate

of Female and Minority Admissions

The high rate of acceptance of women and minority applicants at the

School of Medicine can be attributed to the school’s effort to promote

diversity without relying on a rigid system of quotas. To gain greater

diversity in its student body, the School of Medicine has elevated the

importance of diversity-related selection criteria and reduced the

importance of academic achievement. The school has adopted lower

academic requirement (GPA and MCAT) for applicants it considers

disadvantaged while maintaining a higher set of standards for non-

disadvantaged applicants.

One obstacle to the school’s application of diversity is the apparent

conflict with the university’s policy on non-discrimination. Reconciliation

of the school’s promotion of racial and gender diversity within the student

body and the school’s often-stated prohibition against considering an

applicant’s gender, race, and religion, should be addressed.

We recommend that the School of Medicine adopt a single set of

academic standards, prohibit admission committee consideration of

applicant demographics, and consider providing under-represented

populations with, as needed, pre-admittance course work.

We recommend the Board of Regents examine the apparent conflicts

regarding its policies of diversity and non-discrimination.

Deviations from Admissions Process

Have Raised Questions

The school’s emphasis on the subjective evaluation of an applicant’s

character and background and its reduced consideration for an applicant’s

academic achievements has made it more difficult to evaluate applicants

consistently. In addition, inconsistencies in the administration of the

admissions process show there is a need to improve admissions procedures

and policies.

Central to the problems facing the admissions process is the

relationship between the school’s Dean of Admissions and the three

committees responsible for the selection of applicants. Although the

members of the admissions committee receive specific instructions from

-iii-

Office of the Utah Legislative Auditor General – iii –

Although 100

volunteers participate

on the admissions

committees, the Dean

of Admissions is often

the person that decides

whether an application

will receive further

consideration.

the school’s Office of Admissions, they are often unable or unwilling to

decide whether an application should continue in the system. This

indecision means that the Dean of Admissions often must decide whether

or not an applicant will receive further consideration. Reliance on the

Dean to ultimately decide so many of the applications appears to defeat

the school’s use of over 100 selection committee members to eliminate

individual bias.

Moreover, it appears that some applications sent to the selection

committee for final consideration may not be those considered to be the

best applicants by other admissions committees. Greater diligence in

policy and procedure control could eliminate a number of the problems

currently encountered.

We recommend the School of Medicine eliminate all courtesy

interviews and better define the relationship of admissions and

diversity.

We recommend interview forms be revised to eliminate confusion

regarding the results of an interview and limit the final evaluation

to either a “yes, forward to selection” or “no, reject applicant”.

We recommend the selection committee follow existing policies and

drop outlying scores and that all rankings be combined in order to

accept the next best scoring applicant.

-1-

Office of the Utah Legislative Auditor General – 1 –

Medical schools

throughout the

country are giving

special consideration

to students who add

diversity.

Chapter I

Introduction

The University of Utah School of Medicine’s (School of Medicine) has

followed a nationwide trend among medical schools to place greater

emphasis on subjective admissions criteria. Medical schools throughout

the United States are placing less emphasis on the objective indicators

such as a student’s MCAT score and GPA and are focusing more on

subjective factors such as a students character, leadership skills, and

compassion. In addition, special consideration is given to students who

can add diversity to a class of students. One result of the use of subjective

selection criteria is that many people who would like to apply to medical

school do not understand the requirements for admission and the relative

importance of objective factors such as the MCAT score and subjective

factors such as service in the community. The emphasis on subjective

criteria has also led some to question the fairness of the admissions

process.

The changes in selection criteria, particularly the heightened value of

diversity, has altered the demographics of students entering the School of

Medicine. Acceptance rates of various under-represented population

groups applying to the school have increased while rates for non-minority

males, who do not add to the school’s diversity, have decreased.

Although there is no evidence that unqualified individuals have been

admitted to medical school, the school’s emphasis on diversity has led to

claims by some applicants that they have not been given an equal

opportunity.

The school’s goal to create a diverse student body is an especially

difficult task in Utah because the state’s school of medicine tends to attract

a rather homogenous pool of applicants. The vast majority of applicants

are white males who tend to have similar backgrounds and experiences.

At the same time, relatively few women and minorities apply to medical

school in Utah. As a result, the school’s effort to enroll a diverse class can

make it difficult for a white male to stand out and be viewed as someone

who can offer something different. On the other hand, the push for

diversity tends to work in favor of female and minority applicants who,

because of their low numbers and varied backgrounds, find it relatively

easy to appear unique.

-2-

– 2 – A Performance Audit of Medical School Admissions

AAMC encourages

schools to place more

weight on an

applicant’s character

and background than

on GPA and MCAT.

An applicant with an

MCAT of 27 (or a 21 if

disadvantaged) is

considered to be as

equally prepared

academically as an

applicant with an

MCAT of 39.

Selection of a Medical School Class

Is a Difficult Process

The University of Utah School of Medicine has the difficult task of

selecting a medical school class of 102 students from 500 to 600 qualified

applicants each year. Like most other medical schools, the School of

Medicine follows an admissions process that is largely prescribed by the

Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC).

The AAMC processes a basic medical school application form that is

used jointly by medical schools throughout the country. In addition,

AAMC administers the Medical College Admissions Test (MCAT) and

advises the School of Medicine on the best admissions policies and

procedures. Occasionally, AAMC will provide training to the school’s

interviewers. Due to the school’s reliance on the national association, the

admissions procedures used by the School of Medicine are similar to those

used by medical schools in other states.

In recent years there have been two policies promoted by the AAMC

that have gained wide acceptance among the nation’s medical schools.

AAMC has encouraged medical schools to first, place less emphasis on

academic measures (MCAT and GPA) as selection criteria and second, to

adopt policies that promote diversity.

AAMC Discourages the Use of MCAT and GPA as Primary

Selection Criteria. In recent years, AAMC and many of its member

colleges have reconsidered their longstanding use of the applicant’s

academic achievements as the primary criteria for admission to medical

school. Instead, AAMC now encourages schools to place more weight on

an applicant’s character and background than on academics. This change

reflects an interest by many in the profession to select and train physicians

who can communicate effectively and be sensitive to the needs of patients.

It is ironic that the AAMC would discourage the use of the MCAT

and GPA as primary selection criteria because it is the organization that

administers the MCAT exam. In fact, the AAMC’s own research shows

that a student’s MCAT score and GPA correlate with their performance

during the first two years of medical school. Their concern, however is

that the test scores and grades (at least above certain levels) are not good

predictors of how effective a person might be as a physician. Instead, they

place more emphasis on an applicant’s character traits such as “altruism,

-3-

Office of the Utah Legislative Auditor General – 3 –

The medical school

has a goal to create a

student body with the

same proportion of

women and minorities

as the state’s general

population.

fervor for social justice, leadership, commitment to self sacrifice, empathy

for those in pain.”

In keeping with the suggestions of the AAMC’s president, the

University of Utah School of Medicine has adopted a policy of using the

MCAT score and the GPA only as a minimum standard for consideration.

Because academics do not seem to be as important as once thought,

minimum academic requirements for admission have been reduced. As

long as students have a GPA above a 3.2 and an MCAT of 27 (or, if

disadvantaged, a GPA of 2.5 and a MCAT of 21), then they are all

considered to be equally qualified in terms of their ability to handle the

curriculum of medical school. In other words, the applicant with an

MCAT of 27 )or a 21 if disadvantaged) is considered to be as equally

prepared academically as an applicant with an MCAT of 39.

By considering all applicants equal in terms of their academic

preparation, the School of Medicine can use their time to assess attributes

they associate with an effective physician. These other attributes include

leadership skills, communication skills, compassion, maturity,

understanding of the profession, humility and cultural sensitivity.

AAMC’s Push for Greater Diversity Is Followed by Most

Schools. AAMC’s President, Dr. Jordan J. Cohen, is a leading advocate

for expanding diversity within the nation’s medical schools. Speaking for

all medical schools, Dr. Cohen has said that “our mandate is to select and

prepare students for the profession who, in the aggregate, bear a

reasonable resemblance to the racial, ethnic, and, of course, gender

profiles of the people they will serve.” He also said “there is simply no

way we can select an adequately diverse class of medical students today

without taking race and ethnicity explicitly or implicitly into account.”

Like many other member schools, the University of Utah School of

Medicine supports the views of Dr. Cohen and the AAMC. For example,

school officials, with the support of the Board of Regents, have adopted

AAMC’s goal to create a student body that has the same proportion of

women and minorities as found in the state’s general population. In

addition, the School of Medicine offers special services and waives certain

requirements for five minority groups that the AAMC suggests are

“under-represented” in the state’s medical schools. These include

-4-

– 4 – A Performance Audit of Medical School Admissions

The medical school

uses ten cognitive and

non-cognitive selection

criteria.

• Native American

• African American

• Mexican American

• Native Hawaiian

• Mainland Puerto Rican

Specifically, applicants from these minority groups are offered advice and

assistance in their preparation for and application to medical school. In

addition, certain requirements imposed on non-resident applicants are

waived for those who belong to the above listed minority groups. The

following provides an overview of the admissions process used by the

School of Medicine and the changes the school has made in recent years to

promote a fair and objective selection process.

Utah’s Selection Process

Consists of Three Phases

The School of Medicine has declared that it evaluates each applicant

according to ten criteria that it says are used by medical school’s

nationally. The evaluation of applications is performed by three distinct,

independent committees. Each committee is assigned an evaluation

component and works to filter down the number of applications to the

point that a class is selected.

School of Medicine Uses AAMC Criteria

For its Selection Process

The ten cognitive and non-cognitive selection criteria promoted by the

AAMC and adopted by the University of Utah admissions program are

• Undergraduate GPA, overall and science

• MCAT, all sections

• Leadership/management skills

• Physician shadowing

• Exposure to patient care

• Community service

• Research experience

• Letters of recommendation

• Personal statements

• Interviews

-5-

Office of the Utah Legislative Auditor General – 5 –

Once the minimum

academic requirements

are met, an applicant’s

character and

background are the

primary consideration.

Although each application is evaluated against the above criteria, some

factors are given greater weight than others. In addition, the above list

does not include certain other factors that are considered, such as an

applicant’s compassion, motivation for services, and ability to add

diversity to the class of students. Two factors that are given relatively less

weight than other criteria are the GPA and MCAT score. The School of

Medicine uses GPA and MCAT scores only as minimum requirements for

consideration. Once the academic requirements are met, the applicant’s

character and background are the primary consideration.

In some respects, the personal essay, leadership positions, volunteer

service, and letters of recommendation are not really used as selection

criteria. Rather, they are the means used to consider a wide range of

attributes not specifically identified in its list of ten criteria. For example,

the applicant’s list of volunteer service is not used to merely identify the

extent of service rendered. The admissions committee also uses the list of

volunteer service to consider the applicant’s level of empathy, humility,

problem solving skills, exposure to other cultures, leadership skills, ability

to overcome hardships, openness to new/different ideas, and diversity of

experience. Although not specifically mentioned as selection criteria, these

character traits are all given considerable weight during the admissions

process.

Applicant Evaluation Is Divided

Into Three Committees

Operating under the control and guidance of the Dean of Admissions,

the medical school admissions process is carried out by three separate

committees. The three committees are described as follows:

• Review Committee - examines applicant’s basic qualifications and

determines whether the applicant should be interviewed.

• Interview Committee - holds interviews with applicants and

decides which applications should be presented to the Selection

Committee.

• Selection Committee - decides which of all the remaining

applicants should be accepted for admission to the medical school.

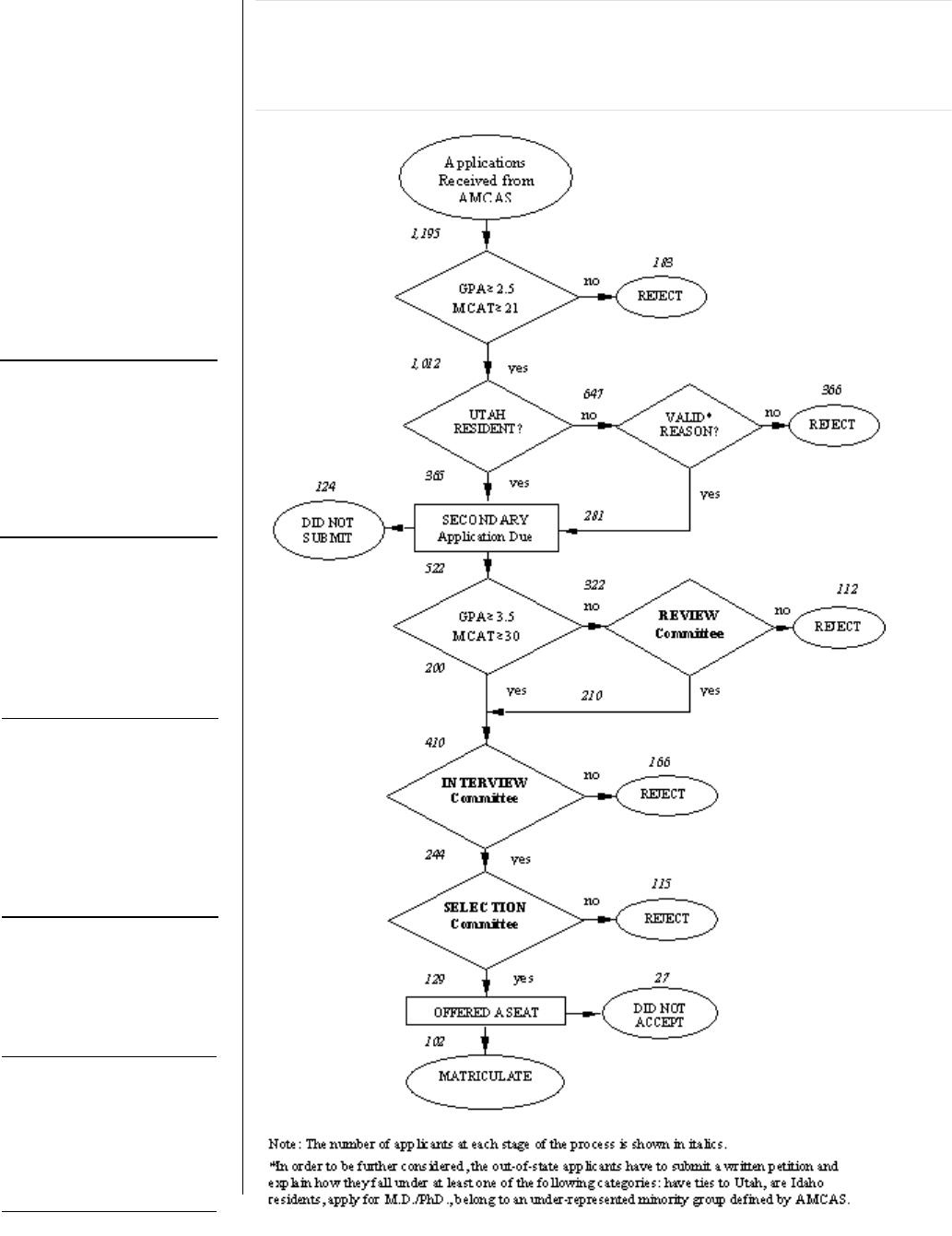

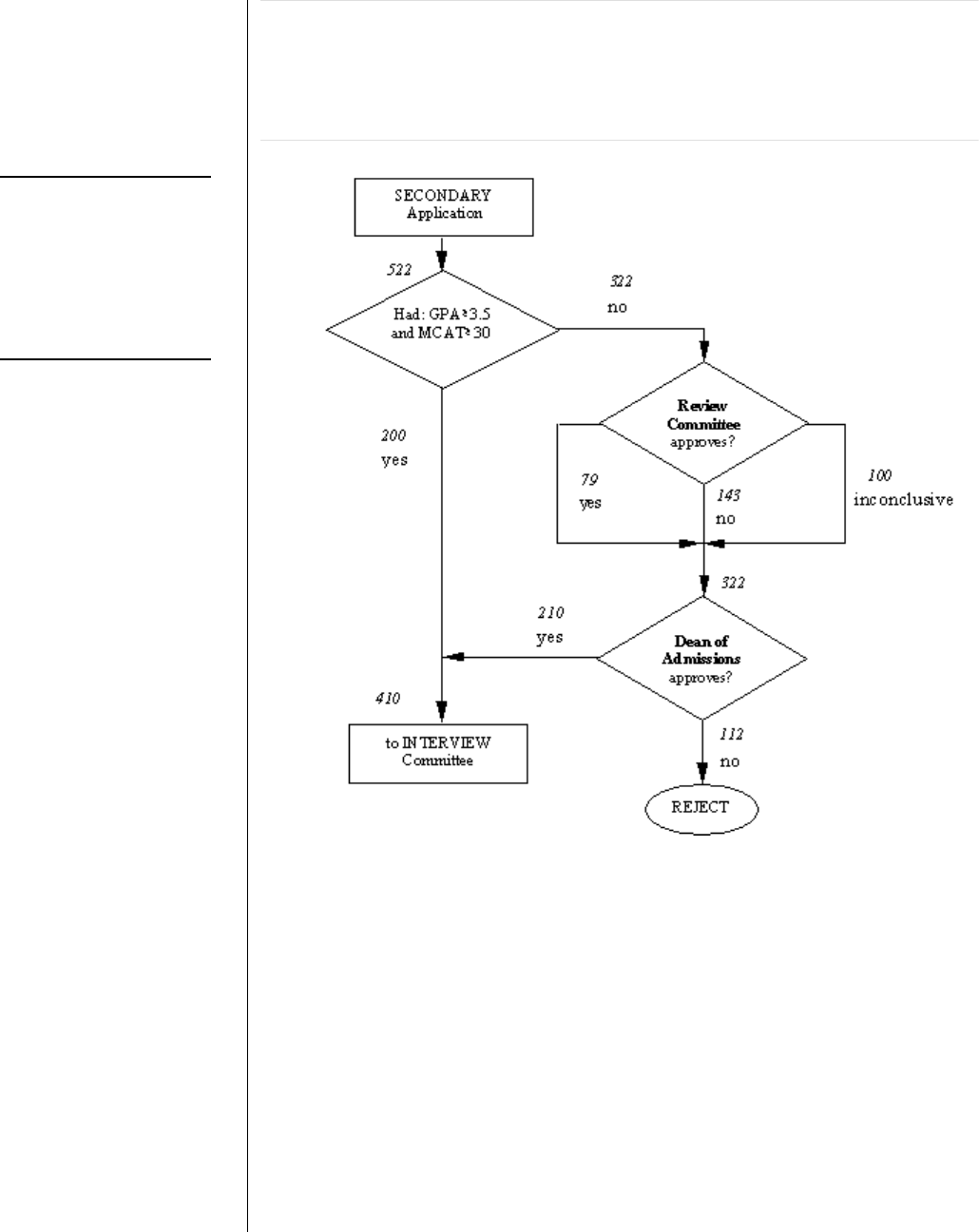

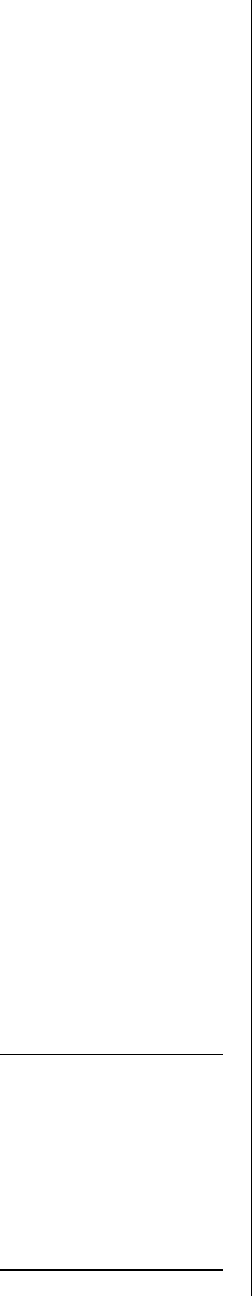

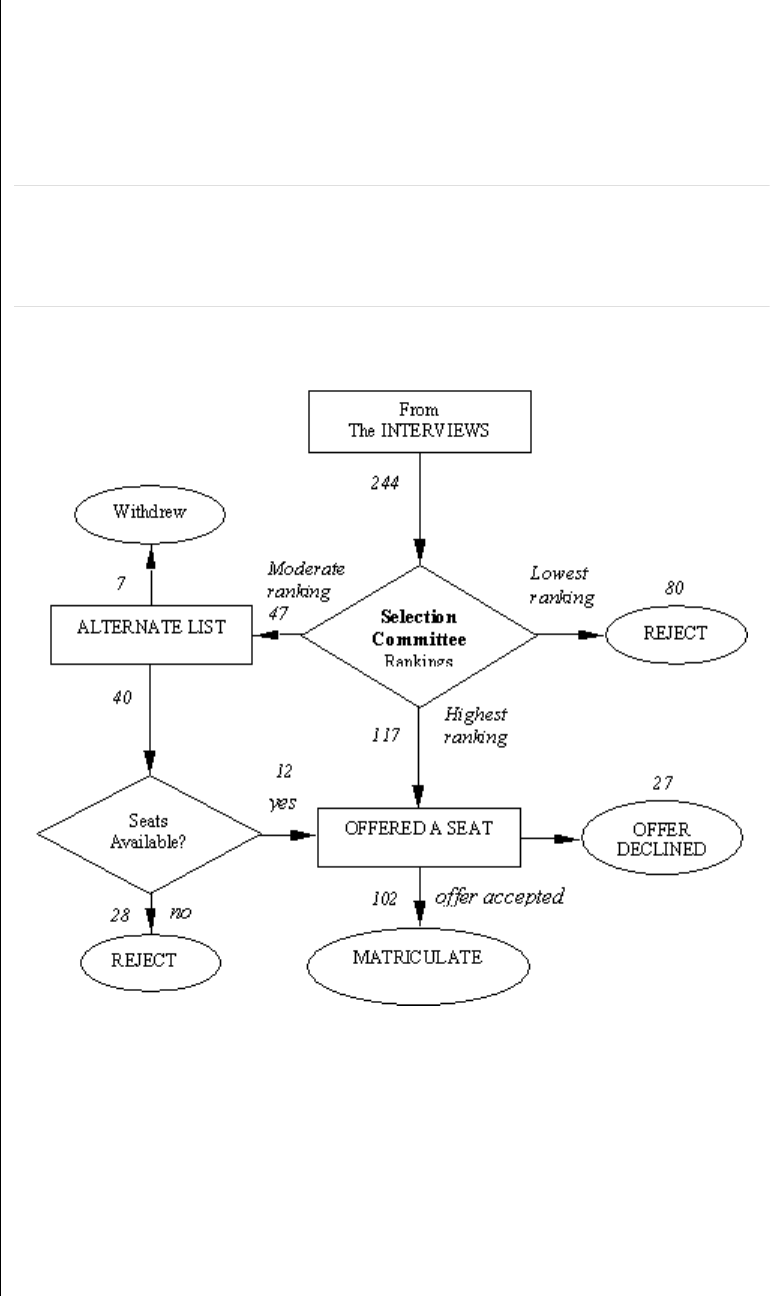

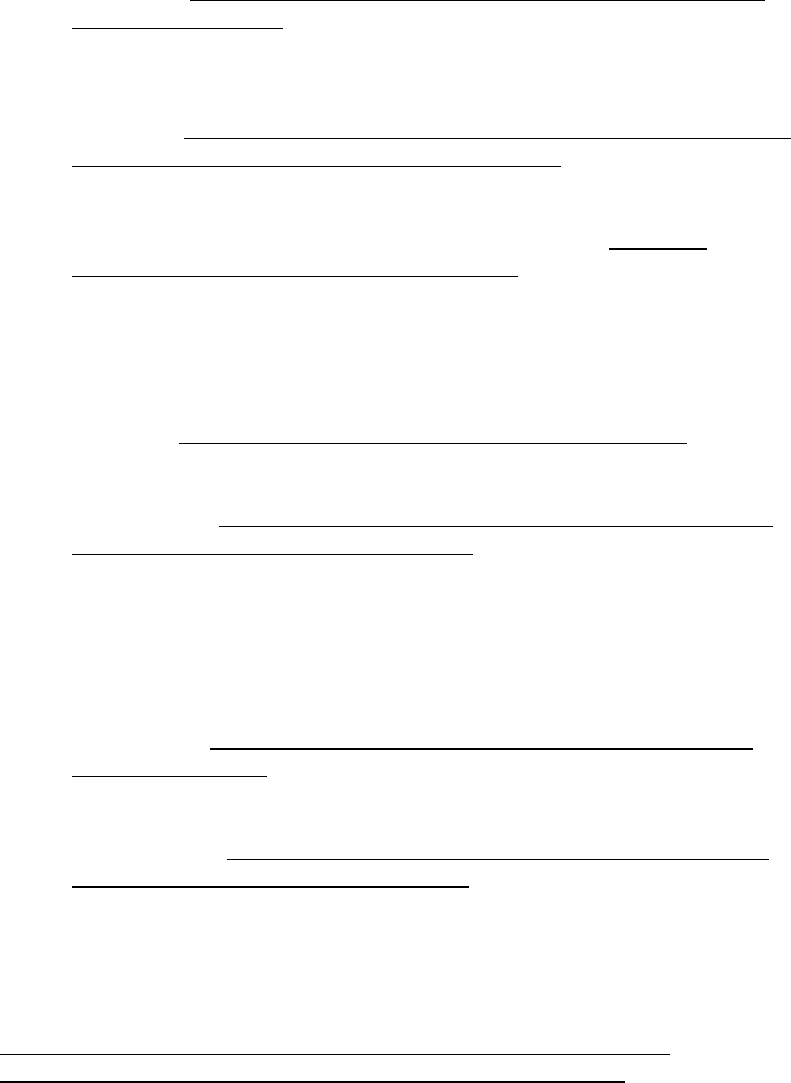

Figure 1 describes the flow of applications through the admissions

process.

-6-

– 6 – A Performance Audit of Medical School Admissions

Interview Comm ittee:

after conducting

interviews and

reviewing application,

committee

recommends

applicants for further

consideration.

Review Committee:

reviews academic

record and

disadvantaged status

to decide if applicant

should receive an

interview.

Selection Committee:

ranks and makes the

final class selection,

based on information

from the review and

interview committees.

Figure 1. The Application Process. During the 2001 recruitment

year, 1,195 individuals asked that their MCAT score be sent to the

University of Utah. Of those, only 522 completed the secondary

application form and 102 were admitted.

Office of the Utah Legislative Auditor General – 7 –

-7-

Three successive

committees pare down

the number of

applicants based on

selected criteria.

The School of Medicine

has taken steps to

prevent individual

committee members

from having too much

influence.

Figure 1 shows that 1,195 individuals asked that their MCAT scores

be sent to the University of Utah School of Medicine during the 2000-

2001 recruitment year. Of those, 522 completed the application by

submitting secondary forms requested by the University and by paying

their application fee. Of the 522 applicants, 200 were automatically

granted interviews, and the rest were considered by the Review

Committee.

The Review Committee approved interviews for an additional 210

applicants, and 112 were rejected because they did not meet the basic

requirements. The Interview Committee eliminated another 166

applicants and referred 244 applicants to the Selection Committee. Those

244 were each considered by the Selection Committee and given a

ranking or score by each member. The applicants with the highest

average score were sent letters of acceptance. In all, there are 102

positions available in the medical school. However, in order to fill those

positions, 129 applicants were sent letters of acceptance. Of those, 27

decided to attend other institutions.

Steps Taken to Promote Fairness

The selection process is fairly subjective because analyzing the selection

criteria is dependent on the perceptions of each Admissions Committee

member. Recognizing that each committee member has his or her own

unique set of biases and perspectives, the School of Medicine has taken

several steps to ensure that no single member of the admissions committee

has too much influence over the process. The following describes some of

the procedures that have been adopted in recent years:

• Committee members can participate on only one committee. Thus,

any one member cannot promote the cause of one individual applicant

through the entire admissions process. Instead, successful applicants

must receive approval from many committee members.

• No single individual selects the members for the admissions

committee. They are nominated by their organizations: departments

in the School of Medicine, community organizations, local hospitals,

senior medical students, alumni.

-8-

– 8 – A Performance Audit of Medical School Admissions

The school’s database

as well as applicant

admissions files were

used in the audit.

• More than 100 people serve on the admissions committee. Thus,

applications are considered from many different perspectives.

• Applicants have the opportunity to petition for an additional review if

they feel that the review committee has made a mistake or did not take

into consideration the applicant’s most recent accomplishments.

• Applicants who feel the interviewer was biased or asked unfair

questions, may request an additional interview.

• Personal background information regarding an applicant such as the

applicant’s home town, parents’ occupation, the college the applicant

attended, etc., are excluded from the materials presented to the

Selection Committee in order to prevent them from considering issues

that are not relevant.

Audit Scope and Objectives

The audit subcommittee asked that the primary focus of the audit be

the admissions process used by the University of Utah School of Medicine

but granted audit staff some flexibility to pursue other areas if instances of

bias were identified. In keeping with this request, the audit staff focused

mainly on matters relating to the admissions policies and procedures and

whether they were applied in a fair and consistent manner.

First, audit staff obtained a copy of the School of Medicine’s applicant

database and used that information to compile statistical information

describing the rates of admission for the past several years. Next, audit

staff conducted a detailed review of applications submitted for the class

beginning in the fall of 2001. Particular attention was given to the 410

applicants who reached the interview phase of the admissions process.

For each applicant, the written comments prepared by the Review

Committee and the Interview Committee were considered in light of the

school’s admissions policies.

The objective of the audit was to evaluate the fairness of th admissions

policies and procedures used by the School of Medicine.

Office of the Utah Legislative Auditor General – 9 –

-9-

The School of

Medicine accepts

women at a rate that

is two and one-half

times the rate of

acceptance for men.

Chapter II

Rate of Acceptance Higher for

Women and Minorities

There are significant differences in the rates at which men, women and

minorities are accepted to medical school. During the past two years,

roughly one out of every two women who applied to medical school was

accepted while only one of five men was accepted. Similarly, about one

out of every two minority applicants was accepted during the past two

years, but only one in five white applicants was accepted. There does not

appear to be a significant difference in the rate of acceptance when

considering the college where an applicant earned a pre-medical degree, an

applicant’s geographic origin, or age. We also found no evidence of bias

against applicants based on their religious affiliation.

The rate of acceptance among men, women and minorities is a useful

tool because it helps identify whether all applicants have an equal

opportunity to be admitted. According to its Student Information

Handbook, the School of Medicine embraces the concept of “equal

opportunity and non-discrimination.” Because the school says it does not

consider race or gender during the admissions process, one might expect

male, female and minority applicants to be accepted at roughly the same

rate at which they apply.

Gender Affects Likelihood of Acceptance

Men make up the majority of applicants to the University of Utah

School of Medicine and men also make up the majority of those admitted.

Although relatively few women apply, the School of Medicine accepts

women at a rate that is two and one-half times the rate of acceptance for

men. This difference in the rate of acceptance among men and women

sets Utah apart from most other medical schools in the nation. Most

schools have roughly the same number of men and women apply and

typically, with comparable acceptance rates, the schools admit a class of

students that is roughly half women and half men.

-10-

– 10 – A Performance Audit of Medical School Admissions

The number of

women who applied

to medical school

has declined in

recent years.

The University of Utah School of Medicine acknowledges the

difference between their admission rates and those at other schools but

can not explain why their admission rates would be higher for women and

minorities. Some school officials have speculated that the female

applicants are better qualified than the male applicants. Despite this

claim, we found no evidence to support it. In fact, school records show

that men and women applicants are roughly equal in terms of their

academic qualifications.

Female Acceptance Rates Have Increased

As Applications Have Declined

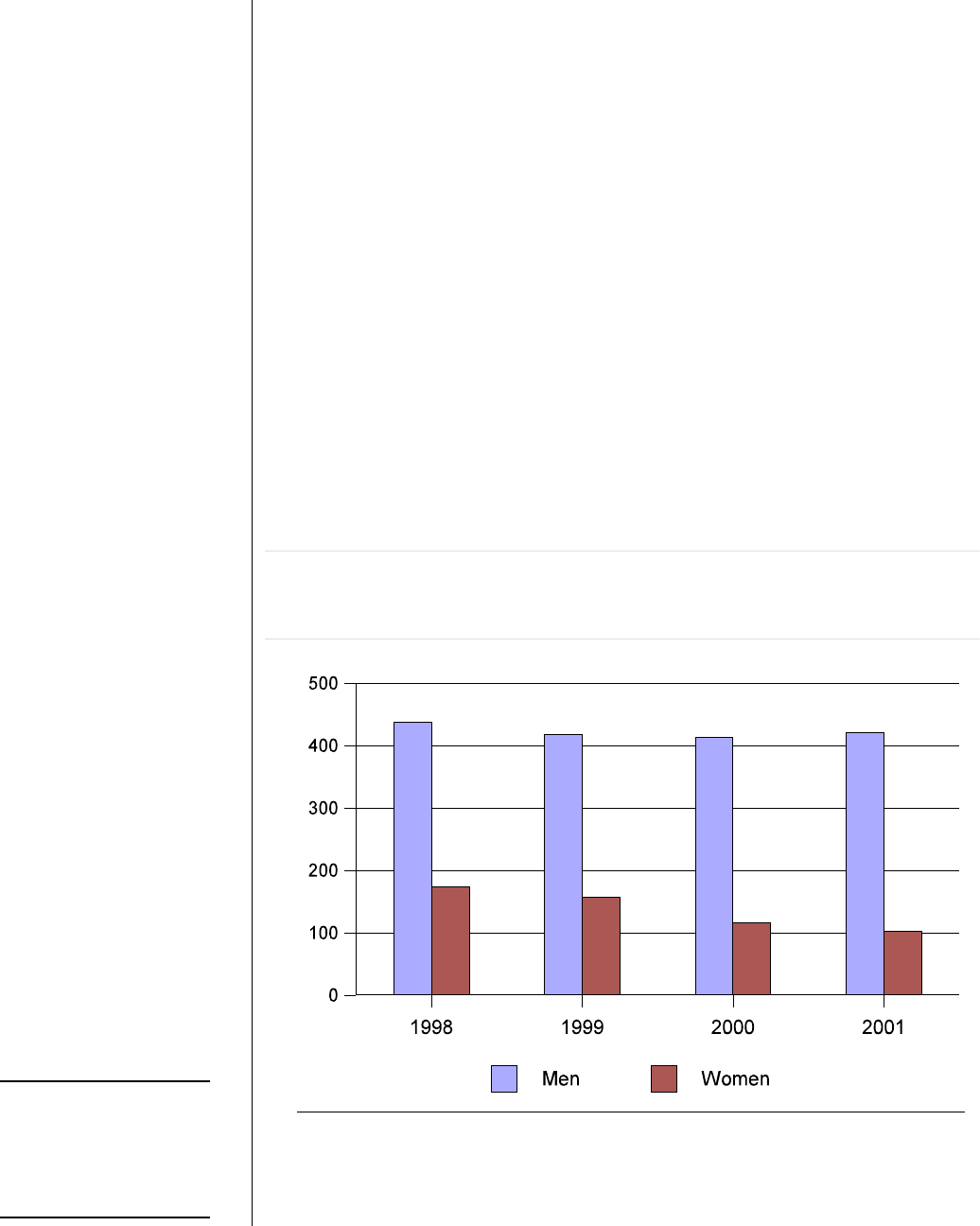

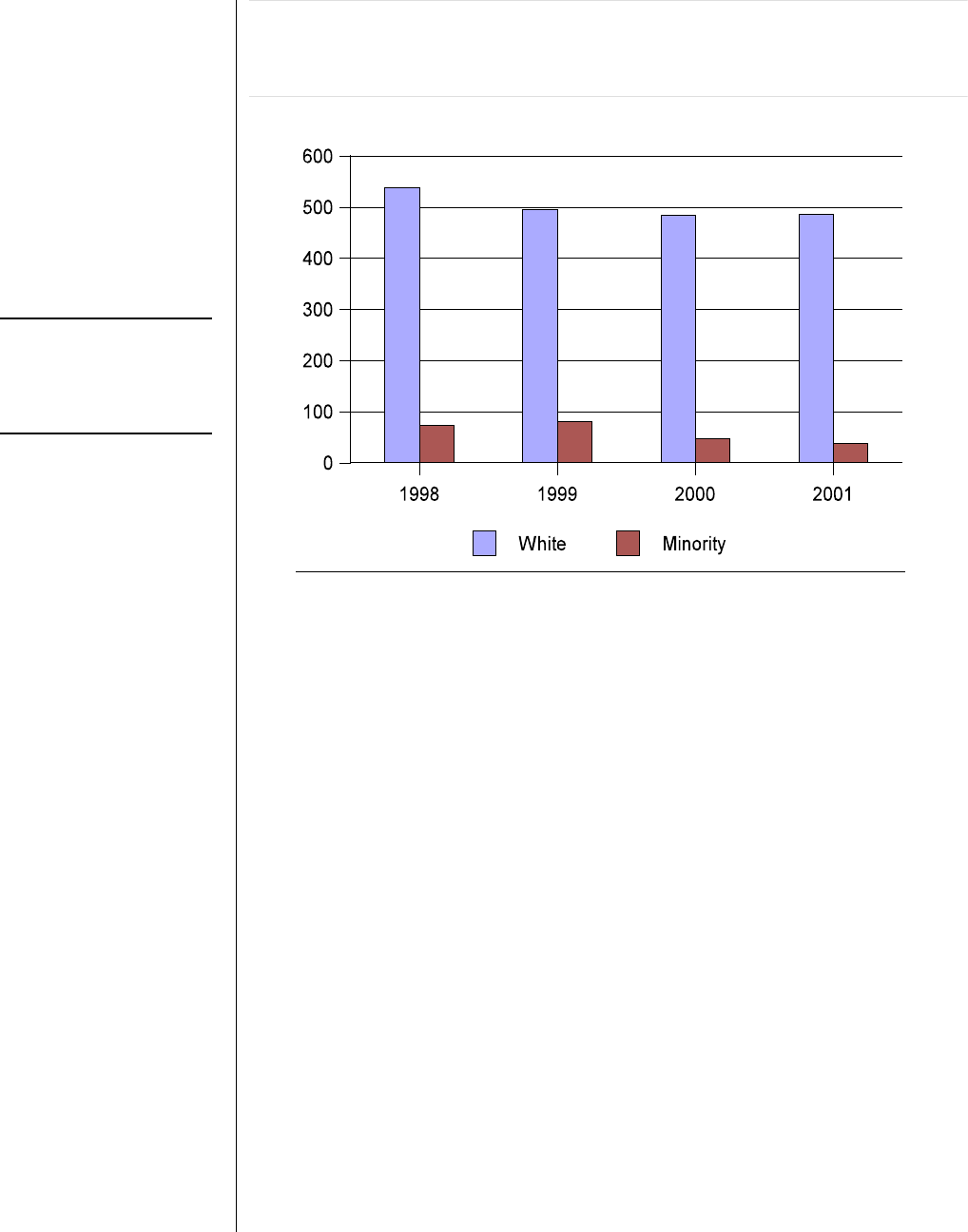

The number of men applying to the School of Medicine, as Figure 2

shows, has changed little during the past four years while the number of

women applicants, already relatively low compared to the number of male

applicants, has declined since 1998.

Figure 2. Number of Men and Women Applicants to the School

of Medicine, 1998 to 2001. The number of female applicants has

decreased by 40 % in recent years.

* See Appendix A for details.

Although Figure 2 shows the relatively low number of women

Office of the Utah Legislative Auditor General – 11 –

-11-

The number of

female applicants

accepted has

remained between

48 and 54 during the

past four years.

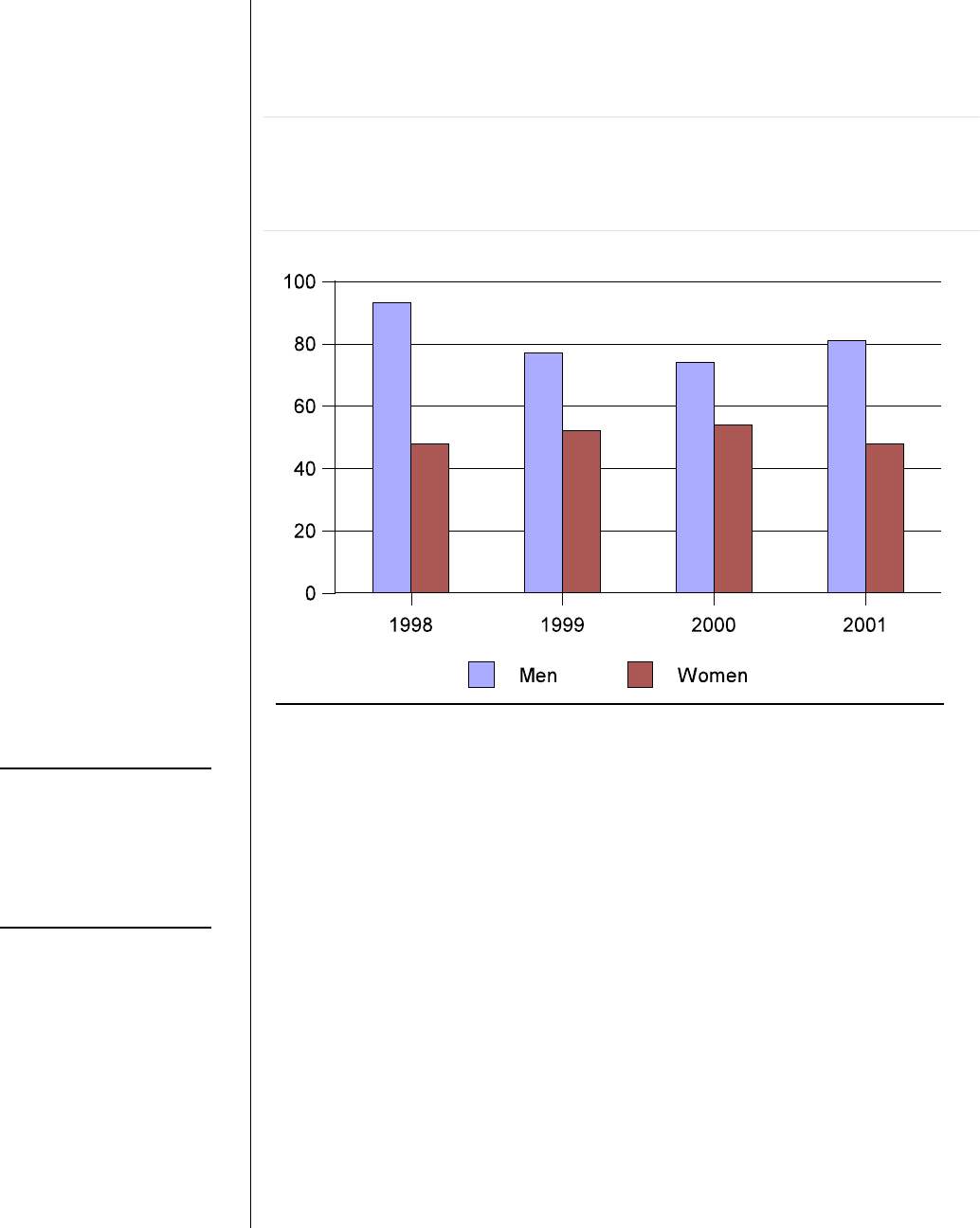

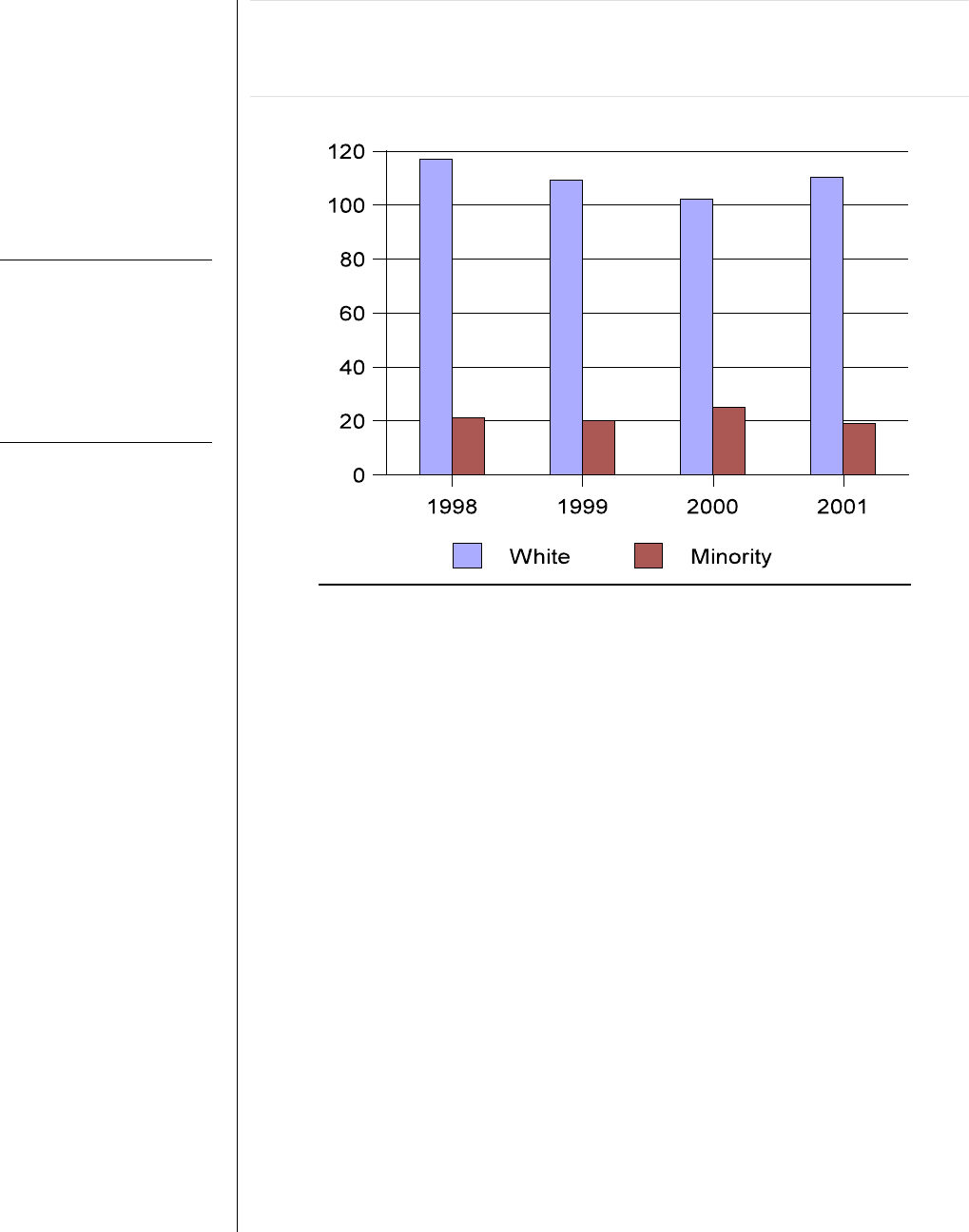

applying to medical school has declined in recent years, Figure 3 shows

the number of women accepted to the School of Medicine has remained

steady.

Figure 3. Number of Men and Women Accepted, 1998 to 2001.

The number of men accepted by the school has declined slightly

while the number of women accepted has remained relatively

constant.

* See Appendix A for details.

One effect of the declining number of female applicants, in

combination with a fairly constant number of women accepted, is that

female applicants have a much greater likelihood of being accepted than

they did just a few years ago. This increase in the acceptance rates for

women is described in Figure 4.

-12-

– 12 – A Performance Audit of Medical School Admissions

In the last two years,

nearly one out of

every tw o female

applicants was

accepted while only

one in five men was

accepted.

Figure 4. Rate of Acceptance of Female Applicants has

Increased. The percentage of females accepted has increased

significantly during the past four years while the percentage of males

accepted has decreased slightly.

* See Appendix A for details.

Of all those who qualified for medical school in 1998, women had a

slightly higher likelihood of being accepted than men. About 28 percent

of female applicants in 1998 were accepted and 21 percent of men were

accepted. Since that time, the likelihood of a female being accepted has

increased significantly to 47 percent while the percentage of men being

accepted has declined to 19 percent. Thus, nearly one out of every two

female applicants has been accepted to the medical school during the past

two years while only one in five men has been accepted.

Little Evidence to Support School’s Explanation

For the Higher Rate of Females Accepted

School officials offer three possible explanations for females being

accepted at higher rates than males, including

• Better preparation - women who apply are better prepared

candidates than their male counterparts; only the best prepared

women apply for medical school.

Office of the Utah Legislative Auditor General – 13 –

-13-

School officials say

that only the best

female applicants

apply.

Men and women

applicants had

comparable scores

on the verbal

reasoning section of

the MCAT.

• Better verbal communications - women have better interpersonal

and verbal skills that help them do better in interviews.

• Better writing skills - women commonly write better personal

essays than men.

Little Evidence That Only the Best Females Apply. School officials

have also suggested that, taken as a group, its women applicants are better

prepared than men because only the best prepared women apply. School

officials describe this phenomenon as “self-selection.” There is little

evidence supporting this claim, however.

Although self-selection may occur to some extent, nothing in the

school’s data would suggest that only the best prepared women apply to

medical school. The school’s application data demonstrates that there is

virtually no difference in the level of academic preparation (GPA and

MCAT). Both men and women earned comparable cumulative GPAs,

but the male applicants actually scored slightly higher on the MCAT than

the female applicants. Thus, female applicants appear no better prepared

academically to attend medical school than their male counterparts.

Little Evidence That Women Have Better Verbal and

Interpersonal Skills. School officials also suggest that women have

better interpersonal and verbal skills, and for this reason they perform

better during interviews than their male counterparts. Again, there is little

evidence to support this claim. One objective measure of an applicant’s

verbal skills is the verbal reasoning section of the MCAT exam. We found

that men and women applicants had comparable scores in this category

during the past four years. Similarly, we found little difference between

men and women’s verbal skills as tested by the verbal section of the SAT.

We could not find an objective measure of the interpersonal skills of

applicants. The school’s interviewers give each application a numeric

score for each of ten different selection criteria. In 2001, the interviewers

gave a slightly higher average overall rating to female applicants than they

did to male applicants. However, an interviewer’s evaluation of an

applicant is a subjective matter that tends to be influenced by the

interviewer’s own interests.

-14-

– 14 – A Performance Audit of Medical School Admissions

No difference was

found in the writing

ability of male and

female applicants.

Little Support Found for the Assertion That Women Write

Better Essays. School officials also suggested that women write better

essays. This assertion is also not supported by the facts. We found little

difference in the writing skills of male and female applicants, since male

and female applicants had similar scores on the written portion of the

MCAT exam.

It does appear, however, that while there is no difference in writing

ability, there may be a difference in the subject matter about which male

and female applicants choose to write. As a result, personal essay scores

given by School of Medicine reviewers are slightly higher for women than

for men on average. School officials have observed that women tend to

have more varied backgrounds and activities than their male counterparts,

write better personal statements, and are not as self-centered in their

personal experiences.

Minority Applicants Accepted

At a Higher Rate

In spite of efforts to increase the School of Medicine’s diversity, the

number of minority applications has decreased in the last few years.

However, the number of minorities accepted has remained relatively

steady. The decline in minority applicants, combined with the continued

acceptance of about 20 minority students each year has, in effect, doubled

the likelihood of a minority applicant being accepted.

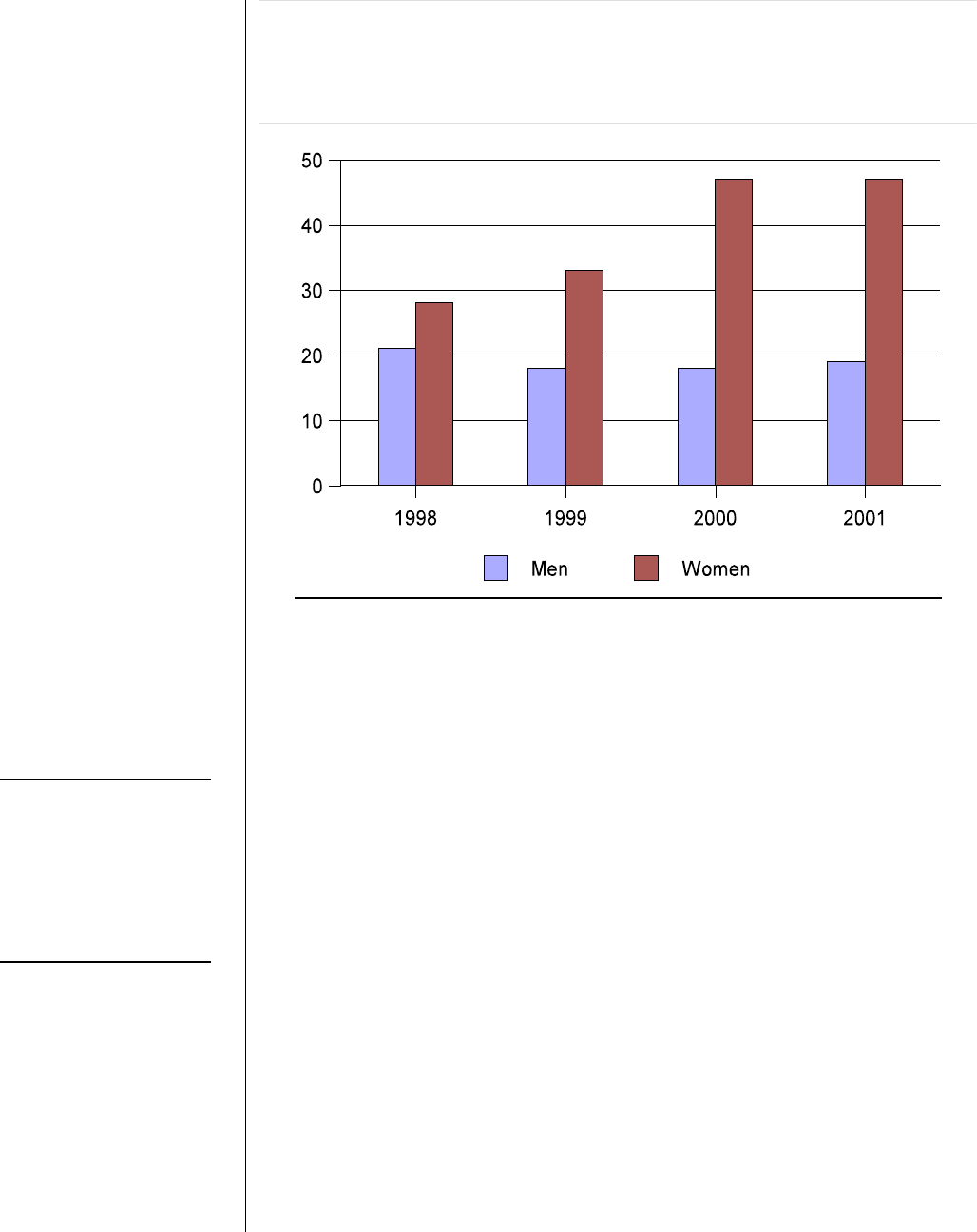

In 1998, approximately 11 percent of the School of Medicine’s

applicants described themselves as minorities. Over the last four years this

percentage has fallen to about 7 percent. During this same period, the

number of non-minority, or white applicants dropped slightly in the first

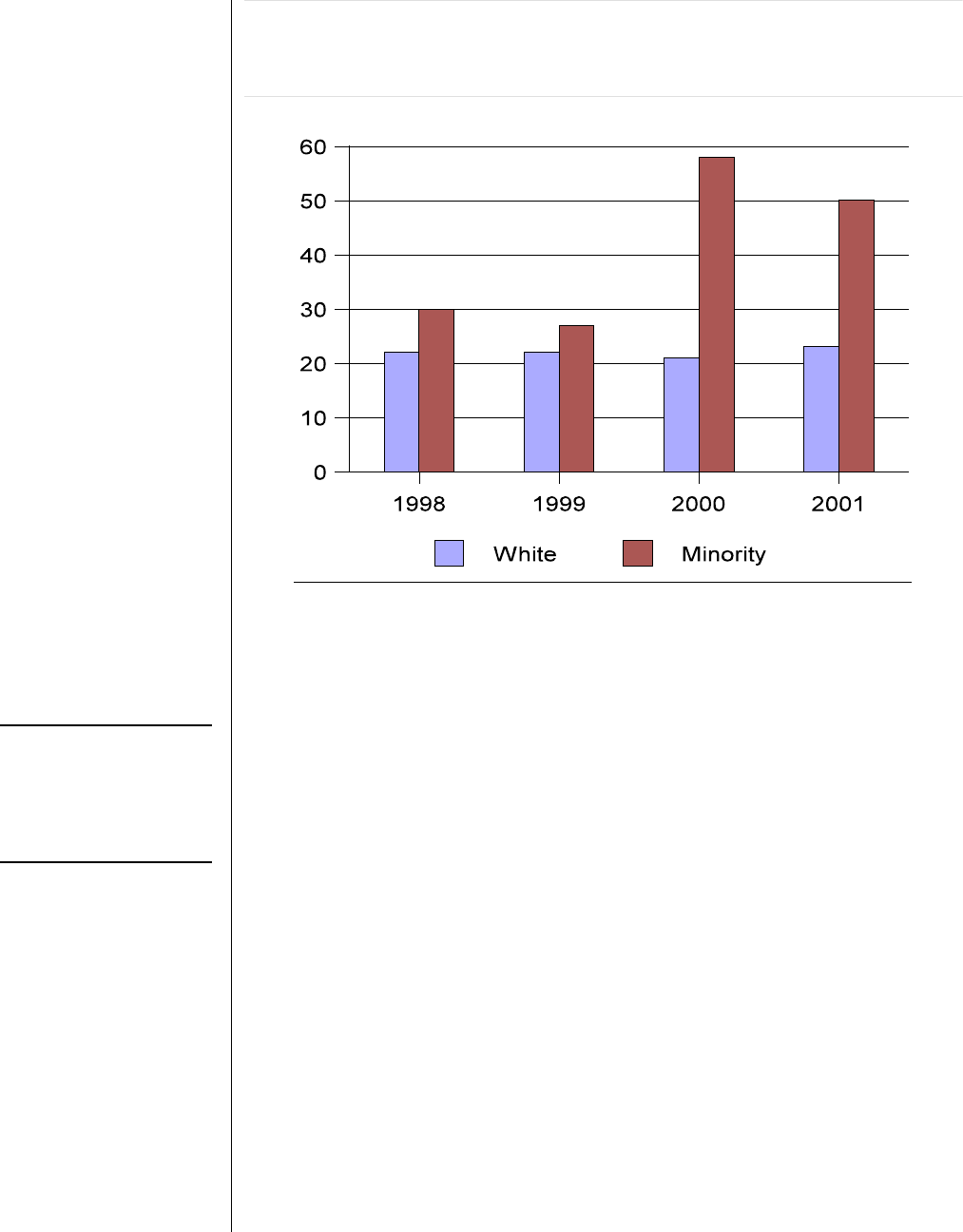

year and has since remained relatively constant. Figure 5 shows this

trend.

Office of the Utah Legislative Auditor General – 15 –

-15-

Since 1998, the

number of minority

applicants has

decreased.

Figure 5. Number of Applicants by Minority Status, 1998 to

2001. Since 1999, the number of white applicants has held steady

while the number of minority applicants has decreased.

*See Appendix A for details.

The slight overall decline in the number of applicants to the School of

Medicine reflects a national trend that school officials attribute to the

economy. Reportedly, university enrollment nationwide tends to decline

during an economic expansion. With the recent economic downturn, the

School of Medicine anticipates applications will rebound. The decline in

minority applicants is problematic for the School of Medicine where

minority recruitment has been difficult. When asked why minority

recruitment was declining, school officials could not provide an

explanation.

Although the school has received fewer applications from minorities in

recent years, the number of minority applicants accepted has not changed

significantly. Figure 6 shows this trend.

-16-

– 16 – A Performance Audit of Medical School Admissions

The num ber of both

minority and white

applicants accepted

has remained

relatively constant

over the last few

years.

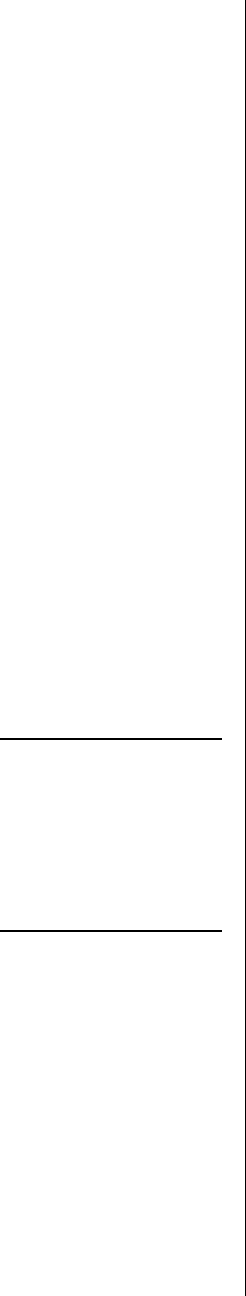

Figure 6. Minority Status of Accepted Applicants, 1998 to 2001.

The number of both minority and white applicants accepted has

remained relatively constant over the last few years.

*See Appendix A for details.

Because the number of minority applicants accepted has remained

constant during a period when fewer minorities have been applying, the

acceptance rate for minority applicants has increased dramatically. Figure

7 shows that in the last two years, minority applicants were much more

likely to be accepted than in the two previous years.

Office of the Utah Legislative Auditor General – 17 –

-17-

The acceptance rate

for minority

applicants has

increased in the last

few years.

Figure 7. Percentage of Applicants Accepted, Minority and

White, 1998 to 2001. The acceptance rate for minority applicants

has increased in the last few years.

*See Appendix A for details.

In years 2000 and 2001, one out of two minority applicants was

accepted by the School of Medicine. Applicants who did not describe

themselves as a minority were accepted at a rate of only one in five. In

previous years (1998 and 1999), minority acceptance rates were much

closer to the rate for non-minority, or white applicants. The rise in

minority acceptance rates appears to reflect the school’s increased

emphasis on diversity. This subject is discussed in some detail in Chapter

III.

Acceptance Rates for Other Variables

Show Little Difference

Although there is strong correlation between an applicant’s race and

gender and their likelihood of being accepted, there is little evidence that

an acceptant’s undergraduate college, age, geographic origin, or religion

affects the likelihood they would be accepted to the School of Medicine.

-18-

– 18 – A Performance Audit of Medical School Admissions

Those who attended

out-of-state schools

had a greater

likelihood of being

accepted than those

applying from in-

state schools.

For most of the groups tested, we found only modest differences in the

rates of acceptance. Most differences could be explained as random

variations. Some differences can also be explained by the fact that

applicants from some universities and age groups have a higher

proportion of white males. As a result, the slightly lower rates of

acceptance among some groups are best explained by the higher rate of

acceptance among female and minority applicants and not because of any

bias directed towards certain universities, age groups or applicants from a

rural background.

The use of admission rates is supplemented by regression analysis—a

statistical technique that identifies the correlation between various factors

and an applicant’s likelihood of gaining admission. The regression shows

little correlation between a person’s undergraduate institution, age, or

geographic origin and medical school acceptance. The regression does

show that applicant race and gender have the strongest influence on

acceptance (see Appendix B.)

Religious affiliation is not a part of the data collected for each

applicant, so it is impossible to determine whether the rate of admission

was higher or lower depending on the applicant’s religious affiliation.

However, it appears that any perceptions of bias against applicants from

certain religious affiliations are probably due to the lower rate of

acceptance among white males.

Acceptance Rates Are Similar

For Utah’s Undergraduate Colleges

There is also little evidence of bias towards the applicants because of

the undergraduate institution they attended. Although some significant

differences occurred from one year to the next in the number of students

accepted from different universities, these are likely explained as random

events. See Appendix A for the acceptance rates of individual institutions.

The one group who did appear to have an advantage in the admissions

process are the students from Utah who received their undergraduate

training at an out-of-state institution. Utahns attending out-of-state

schools were accepted by the School of Medicine at a rate of 35%. In

contrast, Utahns who attended in-state schools, such as University of

Utah, Brigham Young University, or Utah State University, were

accepted at an average rate of 24%.

Office of the Utah Legislative Auditor General – 19 –

-19-

As a group,

applicants aged 21-

23 were accepted at

a rate of one in four,

whereas only one in

five applicants aged

24-26 was accepted.

The fact that Utahns schooled out-of-state have a greater likelihood of

acceptance reflects the School of Medicine’s emphasis on diversity.

Applicants who attended out-of-state institutions were more likely to be

women and ethnic minorities. Due to their having lived out of state,

these applicants had a college experience that was different from most of

those applying from in-state schools.

In contrast, a higher portion of the applicants from in-state schools

were white males who tended to have similar experiences and

backgrounds. As a result, differences in the higher rate of acceptance for

Utah resident applicants from out-of-state schools does not necessarily

represent bias against certain institutions but the school’s desire to enroll a

diverse student body.

Age and Rural Acceptance Rate

Variations Appear Reasonable

There was some difference observed in acceptance rates for applicants

of different ages, but little difference was observed between applicants

from rural communities and those with no rural background. However,

there are reasonable explanations for the slight differences in acceptance

rates.

Most School of Medicine applicants are between 21 and 26 years old

with 24 being the average age. As a group, applicants aged 21-23 were

accepted at a rate of one in four, whereas only one in five applicants aged

24-26 was accepted. There are two possible explanations for these

differences.

First, the School of Medicine’s published criteria says that they want

applicants who are currently actively engaged in their education to show

they are academically-minded and a “life-long learner.” Second, the lower

rate for the older age group may be due, in part, to the higher percentage

of white males within that group. Eighty-six percent of the 24-to-26

year-old age group were white males and sixty percent of the 21-to-23 age

group were white males. As a result, the older group of applicants does

not offer as much racial and gender diversity as the younger applicants.

Over the four-year period (1998-2001), applicants from rural areas

-20-

– 20 – A Performance Audit of Medical School Admissions

An applicant’s

religious affiliation

is often known, but

there is little

evidence that it

affects the likelihood

of acceptance.

have been accepted at about the same rate as applicants from non-rural

areas. Applicants from rural communities make up a relatively small

portion of the total applicant pool—accounting for 13% of all applicants

and 12% of those accepted. The slight variations in the acceptance rates

among applicants from rural and non-rural communities is most likely a

random event.

Little Evidence That Religious Affiliation

Affects the Likelihood of Acceptance

We could not identify the rate of acceptance based on the religious

affiliation of applicants. Religious affiliation is not part of the data

collected by the AAMC or in the secondary forms that the School of

Medicine asks each applicant to fill out.

Applicant religious affiliation is often identified in the application if

they offered church-related volunteer service or served in a leadership

position within a religious organization. For example, if an applicant

provided religious missionary service, it would be listed among the

applicant’s “post-secondary experiences” on the AAMC form. For an

applicant not to include a major, time-consuming activity such as a

mission would be a glaring omission in the application for which the

school would request an accounting.

Although there were a few applicants who told us they felt their

interviewer was biased against their religious affiliation, such instances

were rare and certainly not the typical experience of most applicants. It

appears that any perception of bias against applicants from a certain

religious affiliation is probably due to the lower rate of acceptance among

white males.

Office of the Utah Legislative Auditor General – 21 –

-21-

Diversity,

considered in terms

of race or gender, is

an attribute

considered during

the admissions

process.

Chapter III

Diversity Policy Explains the High Rate of

Female and Minority Admissions

The high rate of acceptance of women and minority applicants at the

School of Medicine can be attributed primarily to the school’s effort to

promote diversity among its student body. Achieving a diverse student

body is a difficult task for the School of Medicine because the majority of

its applicants are white males. In order to achieve greater diversity, the

School of Medicine has set a goal to enroll roughly the same portion of

men, women and minorities as exist in Utah’s general population.

Although the School of Medicine does not rely on a system of quotas

to achieve its diversity goals, the school’s mission statement says that it is

guided by the “imperatives of affirmative action.” In keeping with its goal

for greater diversity, the school has taken several steps to encourage the

enrollment of greater numbers of women and minorities. The

consideration of diversity during the admissions process may, however,

conflict with the university’s policy on non-discrimination. It is unclear

how the school can follow a policy that promotes racial and gender

diversity and, at the same time, comply with a policy that prohibits the

consideration of an applicant’s gender, race, or religion as part of the

admissions process.

A Student’s Diversity Is Considered

During the Admissions Process

The School of Medicine’s selection criteria includes many factors such

as an applicant’s leadership experience, volunteer service, motivation for

becoming a physician, and familiarity with the profession. The

admissions committee also considers the extent to which a student might

add diversity to the student body. While there are many ways that a

medical school applicant might be viewed as someone who can add

diversity, an applicant’s race and gender are the attributes most often used

to identify their diversity. In fact, most of the School of Medicine’s

programs and policies for creating greater diversity are aimed at providing

more opportunities to women and minorities on campus.

-22-

– 22 – A Performance Audit of Medical School Admissions

The university’s

administration and

the Board of

Regents support

racial and ethnic

diversity.

The school wants

its student body to

mirror the

demographics of the

state’s population.

The School of Medicine’s policy on diversity is based on the following

beliefs:

(1) In order to better serve the public, the school needs to graduate

a class of physicians that has the same percentage of women and

minorities that exists in the community at large.

(2) The school can enhance the richness of the educational

experience by admitting a diverse student body with a broad range

of backgrounds and perspectives.

(3) Cultural and economic barriers prevent minorities from

performing well on standardized tests. For this reason, a different

set of MCAT and GPA standards should be applied to those who

have a disadvantaged background.

These principles are accepted by the Association of American Medical

Colleges and by medical schools throughout the country. The University

of Utah’s administration and the Board of Regents have also expressed

support for diversity.

Improved Medical Access Is the

Primary Goal of Diversity

One justification given for the School of Medicine’s diversity policy is

that women and minorities would have better access to health care

services if there were more female and minority physicians. Enrolling a

diverse student body is also considered an important way to help all

medical students become more sensitive to the needs of patients from

different ethnic communities.

Medical Students That Mirror the General Population May

Improve Access to Health Care. One goal of the School of Medicine is

to admit the same percentage of women and minorities that exist in the

general population. This goal is clearly stated in the school’s Statement on

Student Diversity:

The University of Utah seeks to recruit a student body that reflects

the diversity of the population as a whole. We feel that students

with different cultural and economic backgrounds as well as varied

life experiences add a valuable perspective to student life and

Office of the Utah Legislative Auditor General – 23 –

-23-

School officials

believe that diversity

helps medical

students appreciate

other cultures.

broaden the educational experience of all students. Therefore, the

School of Medicine seeks to foster the aspirations of women to

pursue careers in medicine, and is also committed to recruiting,

admitting and graduating qualified candidates from those minority

groups specifically recognized by the federal government as under-

represented in the health care professions: African-American,

American Indian, Mainland Puerto Rican, Mexican-American and

Native Hawaiians.

To support the above diversity statement, the School of Medicine cites

research suggesting that minority physicians are more likely to practice in

their own ethnic communities. School officials also contend that

minorities prefer to be cared for by physicians from their own ethnic

background. Because many of the state’s ethnic communities tend to have

poor access to health care, the school believes one solution is to admit

more applicants from those communities. As a result, the school’s

diversity policy is also viewed as a means of providing women and

minorities with better access to health care.

While relatively little research exists surrounding the above argument,

one study by the Commonwealth Fund found race is not one of the

primary criteria when minority patients select a doctor. The study showed

minority patients ranked a doctor’s “nationality/race/ethnicity” 12

th

out of

13 factors when selecting a physician. Respondents ranked the ability to

make an appointment quickly, their physician’s location, the doctor’s

reputation in the community and their professional credentials as the most

important factors in selecting a physician. Only two percent of the

African Americans and Hispanics and four percent of Asians surveyed

indicated problems with racial and ethnic differences between themselves

and their physician.

Due to the advent of managed health care plans, another researcher

suggests that patients tend to place more value on the amount of time

their doctors spend with them than their doctor’s race or ethnicity. In

these programs, patients tend to be cared for by a different doctor with

each visit. For these patients it is less likely that they will be able to

establish ties with a doctor of the same racial or ethnic heritage.

Diversity Can Enhance the Educational Experience of All

Students. School officials also believe that diversity helps improve the

-24-

– 24 – A Performance Audit of Medical School Admissions

education of all students. One representative of the School of Medicine

explained this sentiment as follows:

Discovering significant aspects of other cultures is valuable for all

physicians because they are called upon to care for patients of many

races and ethnic origins. This kind of cultural perspective can be

taught in a formal setting, but a more valuable way to experience it

is to get to know individuals of other races and cultures on an

informal basis. Only by having a diverse student body is this type

of experience possible.

The medical school believes that the best way to foster cultural

sensitivity is through the interaction of peers from different cultural

backgrounds.

Minorities Are Disadvantaged by Traditional

Measures of Academic Performance

That minority applicants have, in aggregate, lower MCAT scores and

lower total GPAs is not disputed. What is disputed is the relative value of

these measures for applicants who experienced certain hardships during

their high school and college years. Figure 8 shows how white and

minority applicants compare on MCAT scores and total GPA.

Figure 8. Comparison of Total MCAT and Overall GPA for

Minority and White Applicants to the U of U Medical School.

White applicants scored higher on the MCAT and had a higher GPA

than minority applicants during the last four years.

Average MCAT Average GPA

Year Minority White Minority White

1998 26.2 29.3 3.28 3.57

1999 26.4 29.5 3.32 3.60

2000 28.7 30.1 3.49 3.62

2001 28.8 30.3 3.51 3.63

Although many minority applicants have outstanding academic

records, school officials believe that, as a group, minorities have

Office of the Utah Legislative Auditor General – 25 –

-25-

School officials

believe some

allowance must be

made for the lower

test scores of

disadvantaged

applicants.

experienced social, economic and educational disadvantages that account

for their lower achievement on standardized tests. As a result, the School

of Medicine adopted a lower set of academic standards for

“disadvantaged” applicants, which includes many minority applicants.

They give two reasons for the lower set of academic standards:

(1) Many minorities’ disadvantaged backgrounds affect their

performance on standardized tests, and

(2) There is little correlation between level of academic preparation

and effectiveness as a physician.

For these reasons, disadvantaged applicants can gain entry to medical

school with an MCAT score as low as 21 and a GPA as low as 2.5 while

their non-disadvantaged classmates must have at least an MCAT of 27 and

a GPA of 3.2.

Many Minorities Come from Disadvantaged Backgrounds. The

school recognizes that minorities from disadvantaged backgrounds may

find it difficult to perform well in school. As an example, applicants who

use English as a second language can have difficulty performing on

standardized tests such as the MCAT. As a result, a minority student’s

abilities may not be accurately measured by the traditional measures of

academic achievement. This view is reflected in one of the comments by

an Associate Dean at the School of Medicine who said

Many under-represented minority students come from

disadvantaged educational and economic backgrounds that can

affect their performance on standard measures of academic

achievement. Many must work to support themselves during high

school and college, resulting in limited time for concentration on

academics. In addition, literature published on standardized

testing has indicated that minority groups often score lower on this

type of assessment and this can mask their true academic potential.

For these reasons, the predictors of success in medical school are

somewhat different for minority students.

So, instead of placing so much emphasis on academics, the school

emphasizes other factors in the selection process such as “motivation,

-26-

– 26 – A Performance Audit of Medical School Admissions

MCAT and GPA do

not predict

effectiveness as a

physician.

Once applicants are

approved by the

Review Committee,

they are considered

equally qualified in

terms of their

academic

preparation.

dedication and emotional stability.”

High Academic Scores Do Not Predict Effectiveness as a

Physician. The School of Medicine discounts the importance of MCAT

scores and GPA as indicators of a student’s ability to be an effective

physician. School officials acknowledge that MCAT and GPA scores are

good predictors of how well a student will perform during the first two

academically-focused years of medical school but cite little correlation in

later years.

School officials base their views regarding MCAT and GPA on the

statements of Dr. Jordan J. Cohen, President of the AAMC, whose

writings are included in the training manual for the members of its three

admissions committees. First, Dr. Cohen challenges the traditional view

that “students who have an easier time with tests in medical school make

better doctors.” He then states

Certainly we want our doctors to be smart and to have passed all of

their courses; no one, whether from a minority or majority

background, graduates from medical school who has not done so.

Just as no one practices medicine who has not passed all the

licensing examinations. But good doctoring requires a lot more

than passing requisite exams. And there is no reason to believe

that those other attributes we are looking for in our future doctors

—compassion, dedication, truthfulness, caring—correlate with

scores on multiple-choice exams.

Dr. Cohen then suggests that schools give less emphasis to GPA and

MCAT scores and place more attention on the applicant’s character. In

fact, most recently, Dr. Cohen proposed that medical schools abandon the

consideration of an applicant’s GPA and MCAT scores altogether.

In addition, school officials also believe that an applicant’s MCAT

score and GPA are not good predictors of how successful they might be as

a physician. For this reason, the School of Medicine places less weight on

an applicant’s academic record. Once students have passed the Review

Committee’s screening of their academic records, all applicants are

considered equally qualified in terms of their academic preparation for

medical school. From that point on, the Interview Committee and

Selection Committee only consider an applicant’s non-academic abilities

such as leadership, interpersonal communication skills, compassion,

curiosity and social awareness.

Office of the Utah Legislative Auditor General – 27 –

-27-

Preference may be

given to students

that offer diversity to

their class.

The School of

Medicine’s system

does not reserve

slots for minority or

female applicants.

The medical school has accepted disadvantaged students with MCAT

scores as low as 7 on each of the three parts of the MCAT and some with

GPAs less than 3.0. According to the school’s policy, however, these

lower scoring students were considered to be as equally qualified as

students with MCAT’s of 13s and 14s on each section of the test and

GPA’s of 4.0.

Diversity Program Is Not a

Population-based Quota System

The School of Medicine states that it does not use quotas to achieve its

diversity goals nor, in addressing its goals, does it admit unqualified

female and minority students. The school’s position is that, among

equally qualified applicants, preference can be given to female and

minority students that will offer diversity to their class. In this sense, the

School of Medicine is achieving the objectives of affirmative action

without resorting to the questionable admissions practices of past

affirmative action programs.

School of Medicine Supports the Principles of Affirmative Action.

The mission statement of the School of Medicine says that the school is

“guided by the imperatives of affirmative action.” For some, the term

affirmative action is reminiscent of race-based quotas and other policies

that mandated the hiring of a certain of under-represented groups whether

or not they are qualified. Many such policies have been overturned by the

courts.

Several outside observers (including the pre-med advisors from two

other universities in the state) told us that they believe a certain portion of

each freshman class is reserved for females and minorities. This, they say,

is supported by the enrollment figures from the past several years. Since

1998, roughly te same number of female and minorities have been

accepted even though the number of female and minority applicants has

declined.

The School of Medicine does not use an affirmative action quota

system. While the school does have a goal to enroll the same percentage

of women and minorities as in the general population, there are no slots

-28-

– 28 – A Performance Audit of Medical School Admissions

The school

measures diversity

in terms of the

number of women

and minorities that

have been enrolled.

The Office of

Diversity and

Community

Outreach provides

advice, services and

encouragement to

minority applicants.

reserved for minorities or women. Further, the school reports that all

students go through the same admissions process and are subjected to the

same admissions criteria—except for the lower standards applied to

disadvantaged students. The school does allocate a certain number of

positions based on state residency. The School of Medicine reserves 75 of

the 102 positions in each class for residents of Utah. Eight positions are

contracted to residents of Idaho, and the remaining 19 are available to

non-residents.

Medical School and University Administration Both Promote

Diversity. Although the University of Utah does not use quotas to

achieve its affirmative action goals, the school does what it can to

encourage the enrollment of minorities and women. There is an

expectation that the School of Medicine will try to enroll the same

proportion of women and minorities as exist in the general population.

Members of the three admissions committees clearly understand this goal

and that they should give preference to applicants who would add

diversity to the student body.

Although diversity means different things to different people, the term

is most often used to describe the need for an increase in minority and

female students. In fact, the school measures its progress toward its

diversity goals in terms of the number of women and minorities that have

been enrolled each year.

The university administration also encourages diversity through a

published Statement on Affirmative Action and through an annual

diversity award. In its Statement on Affirmative Action the University

states that “affirmative action continues to be needed as a vehicle for

achieving equal opportunity and a diverse population of students... .”

Furthermore, the University Diversity Award is handed out annually to

“programs and persons that have made important contributions to

diversity at the University, especially regarding inclusion of women and

minorities and related issues in the life of the University.” The award was

given to the School of Medicine in recognition of its success of increasing

the involvement of women and minorities within its programs.

Much of the effort to recruit women and minority students is carried

out by the medical school’s Office of Diversity and Community Outreach.

The office is charged with the task of “recruiting, admitting and

graduating qualified candidates from those minority groups” recognized

by AAMC as under-represented. One approach used to attract more

Office of the Utah Legislative Auditor General – 29 –

-29-

Some admissions

committee members

give higher ratings

to applicants they

consider diverse.

women and minorities to the health care profession is the Office’s

recruitment efforts. Occasionally, representatives from the Office of

Diversity and Community Outreach will visit local high schools and

colleges to encourage students to consider a profession in health care.

The Office of Diversity and Community Outreach also helps

minorities through the admissions process. The office contacts minorities

who have applied to the medical school and provides them with services

and advice concerning the application process. For example, they may

offer advice regarding how to write a personal essay or conduct mock

interviews with the applicant. Once an offer of acceptance is made, the

office will encourage minority students to enroll at the University of Utah.

Individual Admissions Committee Members Respond Differently

to the Diversity Policy. We found that members of the admissions

committee responds differently to the school’s goal for greater diversity.

Some members consider diversity specifically in terms of an applicant’s

race and gender. These members give higher ratings to minority and

female applicants because they believe the applicant’s race and gender will

help add to the diversity of the student body.

Other committee members told us that they would never consider

using race or gender as a criteria for selection, but they do look for

applicants with a background and experience that sets them apart from

others. For example, the dean points out that an applicant would be

considered adding diversity with an undergraduate degree in accounting

because the applicant would have a unique background and offer a

different perspective.

Many White Male Applicants Have Such Similar Backgrounds

That They Offer Little in Terms of Diversity. The need for greater

diversity is used to explain why women and minorities are accepted at

higher rates than white men. Women and minorities tend to have more

varied backgrounds and experiences than the typical white male applicant

from Utah. According to school officials, many male applicants from the

Wasatch Front tend to have very similar experiences during their years

leading up to medical school.

Most have attended BYU or the University of Utah, had similar pre-

med degrees, similar volunteer service, and sought out similar experiences

-30-

– 30 – A Performance Audit of Medical School Admissions

Many white male

applicants have

such similar

backgrounds that

they have difficulty

standing out.

to prepare them for medical school. On the other hand, most female and

minority applicants were less likely to pursue a traditional path to medical

school. As a result, the search for applicants with a unique set of

experiences and backgrounds tends to work against many of the white

male applicants and favor women and minorities.

Several Selection Committee members told us most of the applicants

sent to this committee appear quite similar to one another. Our review of

applications and discussions with committee members and school officials

showed this similarity also. So many applicants are highly qualified and

have such similar backgrounds that it is difficult to set them apart. As a

result, we are told, those who have unique experiences and backgrounds

tend to stand out and have a greater likelihood of being accepted. It is

interesting to note that the Selection Committee is not given the

applicants’ MCAT scores and GPAs—two factors that might help them

distinguish applicants who otherwise appear similarly qualified.

We also found through our own observations and discussions with

school officials that serving a mission for their church, while a positive

attribute, does not set applicants apart because so many have had that

same experience. Conversely, school officials told us that serving a

religious mission is a unique attribute for medical schools in other states.

This uniqueness may be one of the reasons why applicants from Utah tend

to have such great success gaining admittance to medical schools in other

states.

Diversity Policy Conflicts

With Policy on Non-discrimination

The goal of creating a diverse student body appears to conflict with

some other school policies. The very factors that make students diverse,

such as their ethnicity, gender, or geographic origin, are specifically

mentioned in the school’s non-discrimination policy as factors that

admissions committee members may not consider. Moreover, the

school’s decision to have lower admission standards for disadvantaged

students also contradicts the goal of the Board of Regents to increase the

academic requirements for admission to the University of Utah.

Office of the Utah Legislative Auditor General – 31 –

-31-

Diversity policy

appears to

contradict policy of

non-discrimination.

Some Attributes Considered as Signs of a Person’s Diversity

Are Listed in the School’s Non-discrimination Policy

It appears that the school’s diversity policy contradicts its policy on

non-discrimination. Although the school’s non-discrimination policies

prohibit the school from considering race, gender, geographic background

and other demographic attributes, the school’s diversity policy encourages

the admissions committee to consider such factors.

Policy on Non-discrimination Prohibits School from Considering

Race, Gender, and Other Attributes. The training manual provided to

each admissions committee member describes the following policy of non-

discrimination:

Factors such as social class, parents’ education and occupation, type

of education establishment attended, geographic location (rural vs

urban), race, ethnicity, gender religion, age, color... should not be

a part of any admissions decision.

Furthermore, representatives from the School of Medicine specifically

mentioned this policy when they met before the Legislative Audit

Subcommittee at its August 2001 meeting:

Being a state institution, we are not allowed to look at race,

gender, religion, geographic location, age, all of those other things

that we can’t look at. So, they are not part of our [selection]

process. They’re not part of our database.

The above statements seem to contradict the school’s policy to

promote the admission of females and minorities. In fact, race, gender,

religion, geographic location and age are all considered during the

admissions process. References to each of these personal attributes are

contained in the written comments made by admissions committee

members regarding applicants. In addition, race, gender, geography and

age are all part of the database of information kept for each student.

Committee Members Do Consider Race, Gender and Other

Demographic Attributes. We reviewed the written comments made by

both the Review Committee and the Interview Committee for each of

410 individuals who applied for the Fall 2001 class and who reached the

interview phase of the admissions process. Most committee members

-32-

– 32 – A Performance Audit of Medical School Admissions

Frequent reference

is made to an

applicant’s race.

Need for rural

physicians is often

cited by committee

members as a

reason to select an

applicant.

focus primarily on the established selection criteria they have been asked

to consider. These include such character traits as the applicant’s

leadership skills, community service, and awareness of the profession.

We did, however, identify 69 applications (or 16 percent) in which

references were made to race, gender, religion or other factors prohibited

by the school’s non-discrimination policy; but, which were listed among

the reasons to accept or reject the applicant. The following describes

some of the references found in applicants’ files regarding these factors

written by members of the Review Committee and Interview Committee:

• A person’s racial or ethnic background is often described favorably as

an indicator of an applicant’s diversity. There were 39 minority

applicants for the class beginning in the fall of 2001. Of those, there

were 30 applications in which one or more of the admissions

committee members made a reference to the applicants’ race as a

reason to consider the person for admission. Often an applicant’s

ethnic background was listed among the applicant’s “strengths” or

under the heading “unique qualities” about an applicant. In addition,

the person’s minority status was sometimes mentioned in the written

summary comments describing why the applicant offered diversity.

• Although the training manual specifically asks that “geographic

location (rural vs. urban)” not be considered, some committee

members are concerned that the school needs to admit more

physicians willing to serve in rural areas. We found 14 instances in

which the applicant was considered favorably because he or she came

from a rural area and expressed an interest in one day practicing

medicine in a rural community.

• Seven applications made reference to the applicant’s gender. Some

were used to describe a reason why the person should be admitted.

For example, one review committee member said that even though an

applicant’s MCAT score was low that the applicant should be

interviewed because the school needed more female students. In other

cases, interviewers made reference to the fact that applicants were

white and male and therefore did not stand out as someone who