1

INTRODUCTION

The Equal Pay Act, passed over a half century ago,

prohibits sex-based wage discrimination (U.S. Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission 2020).

But the gender pay gap remains substantial: full-

time, year-round women workers earn 18 percent

less than their male counterparts (Hegewisch and

Mariano 2020). A lack of knowledge about who

makes what within organizations contributes to

this continuing disparity. A growing body of research

suggests that pay transparency – improving such

knowledge – reduces the gender wage gap (Baker

et al. 2019; Bennedsen et al. 2019; Gamage et al.

2020; Kim 2015).

Pay transparency advances other aspects of

workplace equity as well. Asymmetric wage

information, whereby employers know more than

workers about pay rates, undermines workers’

ability to negotiate for higher pay. Improving

pay transparency is an essential step towards

empowering workers and ensuring corporate

accountability.

In principle, the National Labor Relations Act

(NLRA) protects workers’ rights to discuss their

pay. In practice, however, the NLRA has many

loopholes limiting its effectiveness in protecting

workers against employer retaliation for violating

pay secrecy policies, such as the exclusion of

workers with supervisory responsibilities (National

Women’s Law Center 2019a). The Paycheck

POLICY BRIEF

Research Highlights

• Compared to men, women are more

likely to work under a pay secrecy policy

and to violate a formal pay secrecy

policy.

• Between 2017-2018, nearly half of

full-time workers reported they were

either discouraged or prohibited from

discussing wages and salaries.

• Over the past decade, despite increased

state legislation preventing pay secrecy,

informal pay secrecy has increased.

• Public sector and unionized workers are

less likely to be subject to pay secrecy

policies compared to their private sector

and non-union counterparts.

IWPR #C494

January 2021

ON THE BOOKS, OFF THE RECORD:

EXAMINING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF PAY SECRECY LAWS IN THE U.S.

Shengwei Sun, Institute for Women’s Policy Research

Jake Rosenfeld, Washington University in St. Louis

Patrick Denice, University of Western Ontario

2

Fairness Act would strengthen protections and remedies, but Congress has failed to adopt it

every year since its initial introduction in 2010 (National Women’s Law Center 2019b).

In 2010, IWPR conducted a national survey on pay transparency and found that policies and

practices restricting workers’ rights to discuss their pay were widespread. At that time, about

half of all workers (51 percent of women and 47 percent of men) – and 62 percent of women

and 60 percent of men in the private sector – reported that they were either discouraged or

prohibited from discussing wage and salary information (Hayes and Hartmann 2011).

Since then, more than a dozen states plus the District of Columbia have adopted legislation

banning pay secrecy rules in the workplace. How have these laws affected pay secrecy policies?

Do such policies stop discussions about pay? This brieing paper examines whether recent

legislation has enhanced pay transparency, reveals what types of workers are still subject

to pay secrecy policies, and provides the irst analyses of whether employees abide by these

workplace speech restrictions.

METHODOLOGY

In the fall of 2017, we partnered with the survey research irm GfK Knowledge Networks (now

Ipsos) to ield a national survey of U.S. workers; we then re-surveyed a subsample in late fall

2018. The survey was restricted to full-time employees aged 18 and over who were not self-

employed. We obtained 2,568 complete surveys in 2017, and 1,694 from the follow-up, for a total

sample of 4,262 valid responses.

1

We weighted the samples to produce estimates representing

the adult (18 years and over) U.S. population who are full-time employees. Analyses based on

the 2017/2018 survey update the results of the original IWPR survey.

The survey results suggest that, between 2010

and 2018, a declining share of workers reports

workplace policies that formally prohibit discussion

of pay. At the same time, however, pay secrecy rules

appear to have shifted from formal prohibition to

informal discouragement of pay transparency.

Private sector and non-unionized workers are

especially likely to work under pay secrecy policies.

Moreover, women continue to be more likely than

men to be subject to pay transparency bans, but

women are also more likely than men to discuss

pay even when prohibited. Understanding where

and how recent state-level anti-secrecy laws

fall short can help identify effective strategies

for empowering workers, especially women. This

paper concludes with a discussion of the policy

implications of our indings for closing the gender

pay gap.

1

The follow-up survey was designed to measure changes in work-

place policies and respondents’ characteristics between 2017 and

2018, an aspect of the research not discussed in this brief.

3

A DECADE OF CHANGE:

PROGRESS AND LIMITS OF PAY TRANSPARENCY LAWS SINCE 2010

IWPR’s 2010 national survey asked workers whether they were allowed to discuss their pay

or were subject to workplace rules, formal or informal, that discourage or ban workers from

discussing wages and salaries with one another (Hayes and Hartmann 2011). Courts have

consistently ruled that discussions about wages and salaries constitute “concerted activity”,

and thus are protected against employer interference under Section 7 of the NLRA (Gely and

Bierman 2003). Given this legal protection, the survey results were surprising: nearly one in

ive workers said their employer had a formal prohibition against discussing pay, and roughly

half of all workers – rising to more than 60 percent of private-sector workers – said they were

subject to a pay secrecy policy of some kind (Rosenfeld 2017).

The prevalence of pay secrecy

practices in the workplace may

partly low from the loopholes

in and weak enforcement of the

NLRA. The law permits employers

with a “legitimate and substantial

business justiication” to institute

secrecy policies. It excludes

supervisors (broadly deined),

public sector workers, domestic

workers, agricultural workers, and

workers employed by railroads

or airlines (National Women’s

Law Center 2019a). In addition,

employers who are found to

violate the law are usually subject

only to minor ines and penalties.

Following the publication of IWPR’s 2010 survey, and faced with the defeat of the Paycheck

Fairness Act in the Republican-controlled Senate, lawmakers turned to other strategies

to combat pay secrecy (National Women’s Law Center 2019a). In 2014, President Obama

issued an executive order barring irms that contracted with the federal government from

maintaining pay secrecy policies. Upon signing the order, the President declared, “Pay secrecy

fosters discrimination and we should not tolerate it” (Eilperin 2014). In just the past decade,

over a dozen states and the District of Columbia joined California (strengthening an earlier

prohibition), Illinois, Colorado, Maine, Michigan, and Vermont in passing their own legislation

banning pay secrecy rules. The scope of these anti-secrecy laws varies across states, but they

all explicitly ban retaliation against workers who discuss pay and prohibit employers from

requiring workers to waive their right to discuss pay (Harris 2018).

4

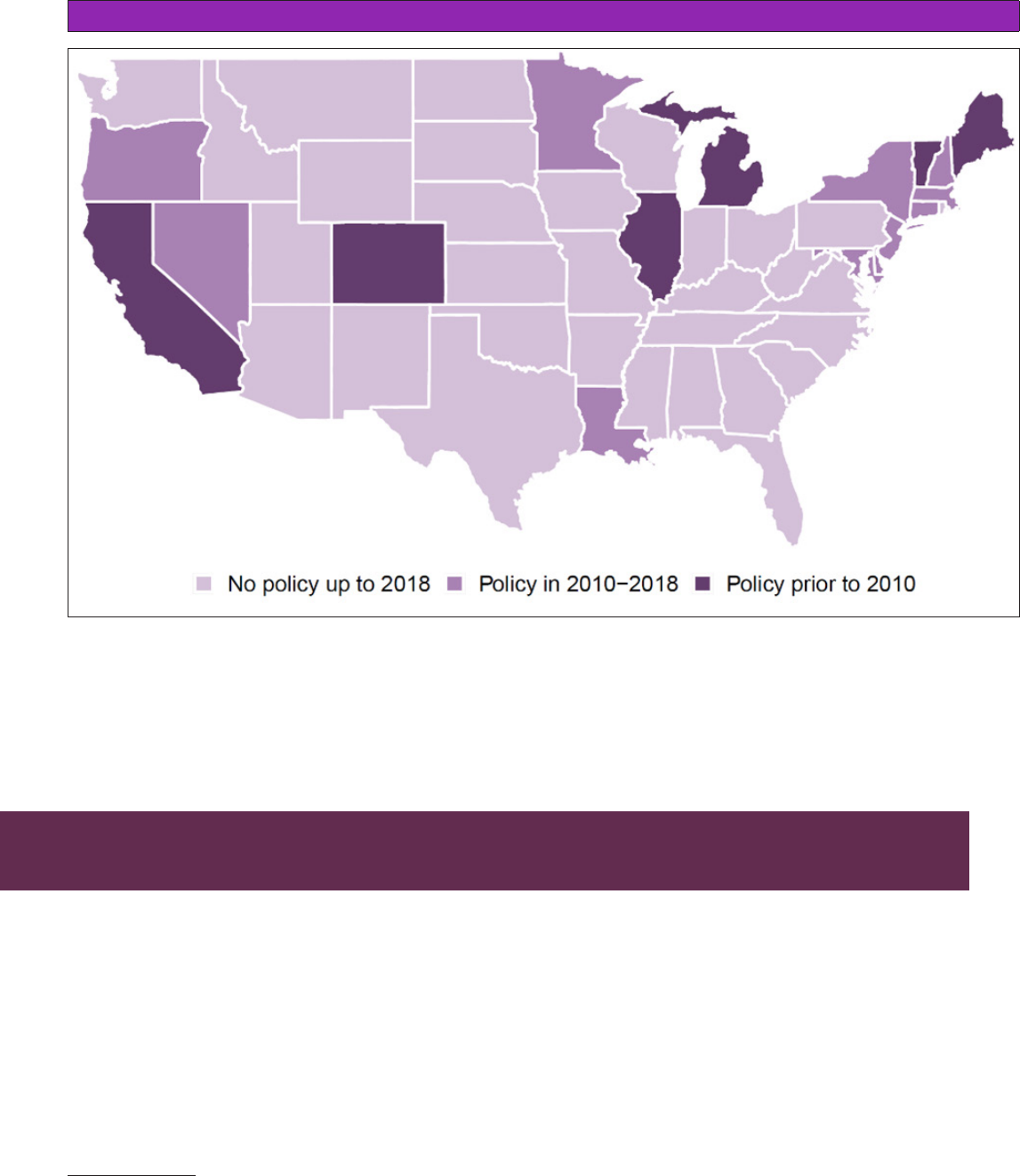

FIGURE 1. U.S. states regulating pay secrecy policies

Notes: This map shows the states with policies regulating pay secrecy in the workplace as of 2018. Six states (California,

Illinois, Colorado, Maine, Michigan, and Vermont) had policies in place prior to 2010. Eleven states (Connecticut, Delaware,

Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, and including the District

of Columbia) instituted policies between 2010 and 2018. We ielded our survey in the fall of 2017 and 2018. Since then,

lawmakers in Hawaii, Nebraska, Virginia, and Washington have taken action to curb pay secrecy policies in their states. We

classify these states as “no policy up to 2018” since they had not passed legislation at the time of our survey.

Source: Authors’ analysis of state legislation.

WITH TIGHTENED LEGAL RESTRICTIONS, FORMAL WORKPLACE PROHIBITIONS

DECLINED, YET PAY SECRECY POLICIES REMAIN PREVALENT

In our 2017-2018 survey, we replicated IWPR’s original pay secrecy question to ask whether

respondents’ employers publicized wage and salary information, permitted discussions of

wages and salaries, discouraged such discussions, or prohibited them outright. Nationally, in

2017/2018 about half of all workers (48.2 percent) reported that they were either banned

or discouraged from discussing their pay (Figure 2), relecting little change from 2010 (48.4

percent).

2

The share of workers reporting formal prohibitions declined from 18.1 percent in

2010 to 12.8 percent – a substantial change.

3

At the same time, however, the share of workers

whose employers discouraged pay discussion actually increased from 30.3 percent to 35.4

percent.

4

These results may relect employers switching from formal to informal pay secrecy

rules in the wake of increased national attention and state-level legislation.

2

See Figure 1 in Rosenfeld (2017).

3

As note 2 above.

4

Some of the apparent changes may be due to different samples: whereas the 2010 IWPR survey included part-time work-

ers, the 2017/2018 surveys only include full-time workers.

5

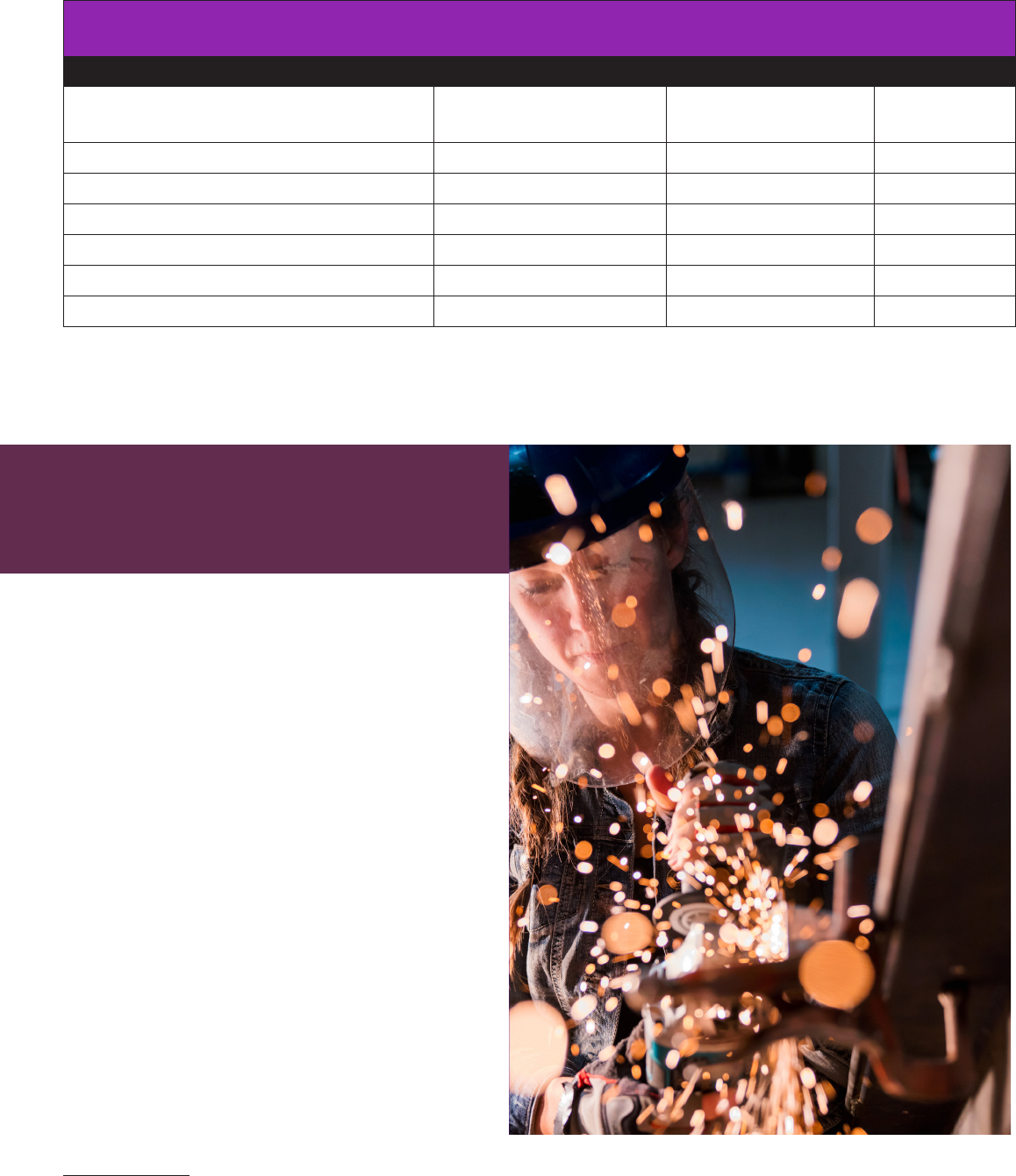

FIGURE 2. Pay secrecy policies among U.S. workers, 2017/2018

Notes: Figure shows the percentage of U.S. workers subject to each pay secrecy policy. Percentages are weighted using survey

weights.

Source: Authors’ analysis of the 2017/2018 Pay Secrecy survey.

These national results include workers in states

with pay secrecy laws as well as workers in states

without such protections. Table 1 disaggregates

survey responses into three groups: workers in

states with no statutes against pay secrecy at

the time of the survey, workers in states that

banned pay secrecy policies before 2010, and

workers in states that enacted pay secrecy

prohibitions between 2010 and 2018. The

analysis inds that workers in states with

no pay secrecy bans are the least likely of all

groups to report that pay information is public

(23.1 percent) or that discussion is permitted

(23.2 percent). Interestingly, workers in states

with recently-adopted pay secrecy prohibitions

report relatively similar results: 26.2 and 24.7

percent respectively. Employees in states with

policies in place prior to 2010 are most likely to

work for transparent organizations.

While restrictions on discussions about pay are more prevalent in those states that have not

enacted legislative bans, even in states with pay secrecy bans, nearly one in ten workers is

formally barred from discussing pay. These results suggest that state-level action has been

only marginally effective, especially when the policy has been in place for a signiicant period.

6

TABLE 1. Workers in States with Recent Pay Transparency Laws Are Not Substantially More

Likely to Report Pay Transparency than Workers in States with No Such Laws

Pay secrecy policies among U.S. workers, by state-level legislation

Pay secrecy policy No policy up to 2018

Policy between

2010 and 2018

Policy prior

to 2010

Public 23.1 26.2 26.5

Discussion is permitted 23.2 24.7 30.6

Discussion is discouraged 35.6 37.3 32.9

Discussion is formally prohibited 15.5 9.4 8.4

Refused/Don’t know 2.5 2.4 1.6

Unweighted N 2,489 874 899

Notes: This table presents the percentage of U.S. workers working under pay secrecy policies, by whether their state has

passed legislation regulating such policies. Percentages are weighted. See Figure 1 for the states included in each group.

Source: Analysis of 2017/2018 Pay Secrecy survey.

PUBLICSECTOR WORKERS AND

UNIONIZED WORKERS ARE LESS

LIKELY TO BE SUBJECT TO PAY

SECRECY

Prior research indicates two workforce

characteristics that inluence the

likelihood of being subject to a pay

secrecy policy: labor market sector and

union membership (Rosenfeld 2017). In

2010, only 15.1 percent of government

employees said that their employer

discouraged or prohibited them from

talking about pay, and less than a third

of union members reported that they

worked under a pay secrecy policy.

5

As

Figure 3 shows, government employees

and union members continued to

experience greater pay transparency in

2017-18. As in 2010, the large majority

of public sector employees (nearly 75

percent) work in organizations that

publicize pay. By contrast, just one in ten

private sector workers report that pay

information is public at their workplace,

even lower than the 2010 level (17

percent).

6

5

See Table 2 of Rosenfeld (2017).

6

See Figure 1 of Institute for Women’s Policy Research (2017).

7

The majority of the U.S. labor force works for a

private sector, for-proit organization.

7

Altogether, 60 percent of workers in the for-

proit, private sector work under a pay secrecy

policy of some sort, just six percentage points

lower than in 2010 (66 percent).

8

The proportion

of private-sector workers who reported that

they are formally prohibited from discussing

their pay fell from 25 percent in 2010 to 16

percent in 2017-18, but at the same time, the

share of private-sector workers reporting that

they are discouraged from discussing their pay

increased from 41 percent to 44 percent.

9

While workers in non-proit organizations are more likely than workers in private, for-proit

organizations to report transparent pay policies, on the whole pay policies in the non-proit

sector are much closer to the restrictive practices used in the private sector than to the more

transparent policies in the public sector (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3. Just One in Ten Private Sector Workers but

Seven in Ten Public Sector Workers Report Full Pay Transparency

Pay secrecy policies among U.S. workers by sector, 2017/2018

Notes: Figure shows the percentage of U.S. workers subject to each pay secrecy policy, by sector

(government; private, for-proit; non-proit). Percentages are weighted. Sample excludes those who

responded “refused/don’t know” to the questions about either pay secrecy policy or sector (n=118).

Source: Analysis of the 2017/2018 Pay Secrecy survey.

7

Authors’ calculation based on labor force statistics from the Current Population Survey, available at https://www.bls.gov/

web/empsit/cpsee_e05.htm.

8

As note 6 above.

9

As note 6 above.

8

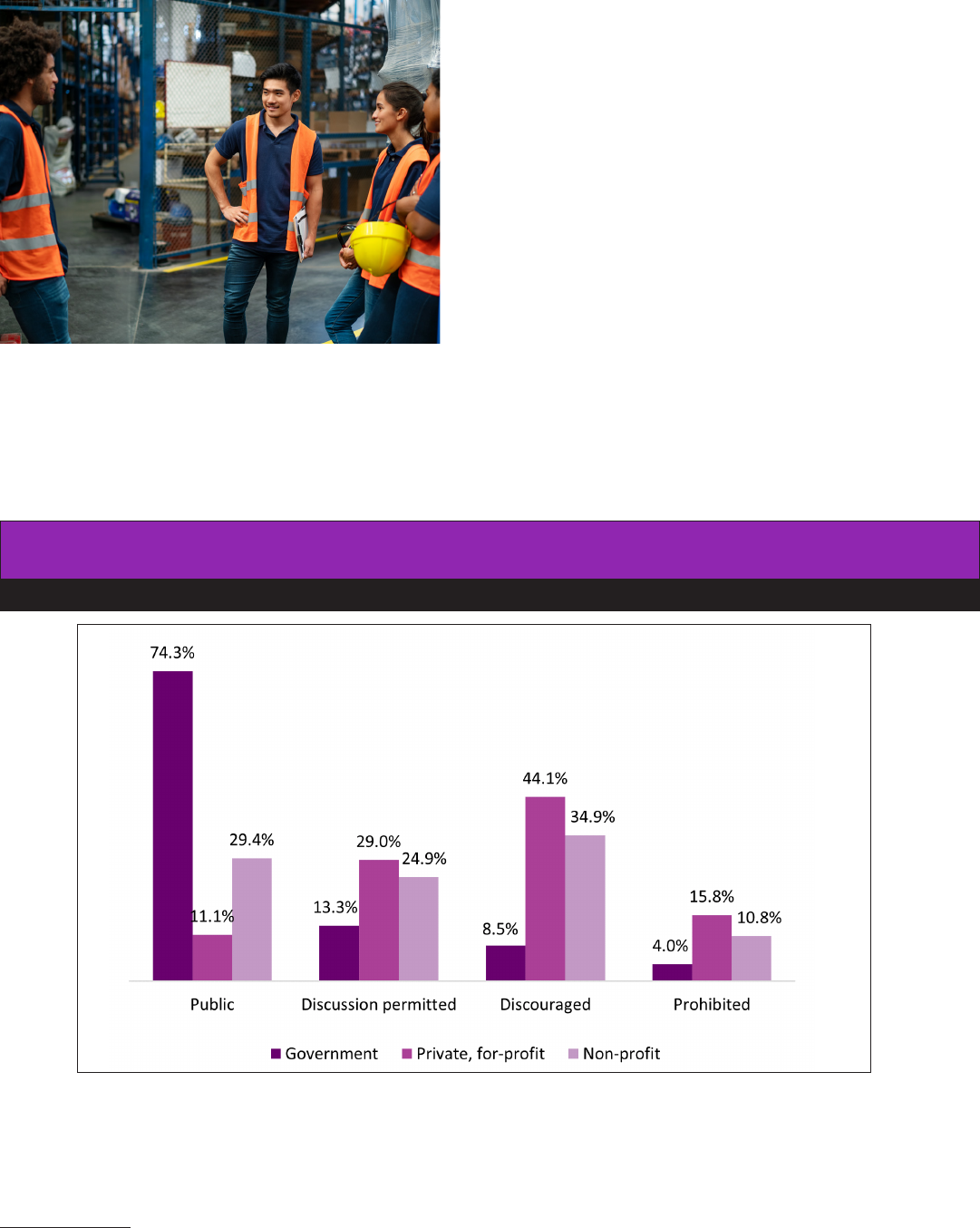

UNIONIZATION PROVIDES GREATER PAY TRANSPARENCY

What about the effect of unionization? Figure 4 below conirms what past research has shown:

unionized workers are much less likely to report that their workplaces have a pay secrecy

policy. Over two-thirds of unionized respondents (68.7 percent) say that pay is public at their

organization; another 20 percent report they are permitted to discuss pay. The majority of

workers without union representation work under a pay secrecy policy (55.7 percent), including

14.9 percent who say that their employer formally bars talking about pay with one’s peers.

The unionization rate in the United States today has fallen to just over 10 percent; in the private

sector it is closer to 6 percent, just one-ifth of the rate in the public sector (33.9 percent; U.S.

Bureau of Labor Statistics 2019). The majority of full-time workers (63.3 percent) in our sample

were non-union workers employed by private, for-proit irms. Among this group, almost two-

thirds (63.5 percent) are subject to a pay secrecy policy (Figure 5).

FIGURE 4. Non-Union Workers Are Far More Likely than

Union Workers to be Prohibited or Discouraged from Discussing Pay

Pay secrecy policies among U.S. workers by union membership, 2017/2018

Notes: Figure shows the percentage of U.S. workers subject to each pay secrecy policy, by whether

the worker belongs to a union. Percentages are weighted. Sample excludes those who responded

“refused/don’t know” to the questions about either pay secrecy policy or union membership (n=112).

Source: Analysis of the 2017/2018 Pay Secrecy survey.

9

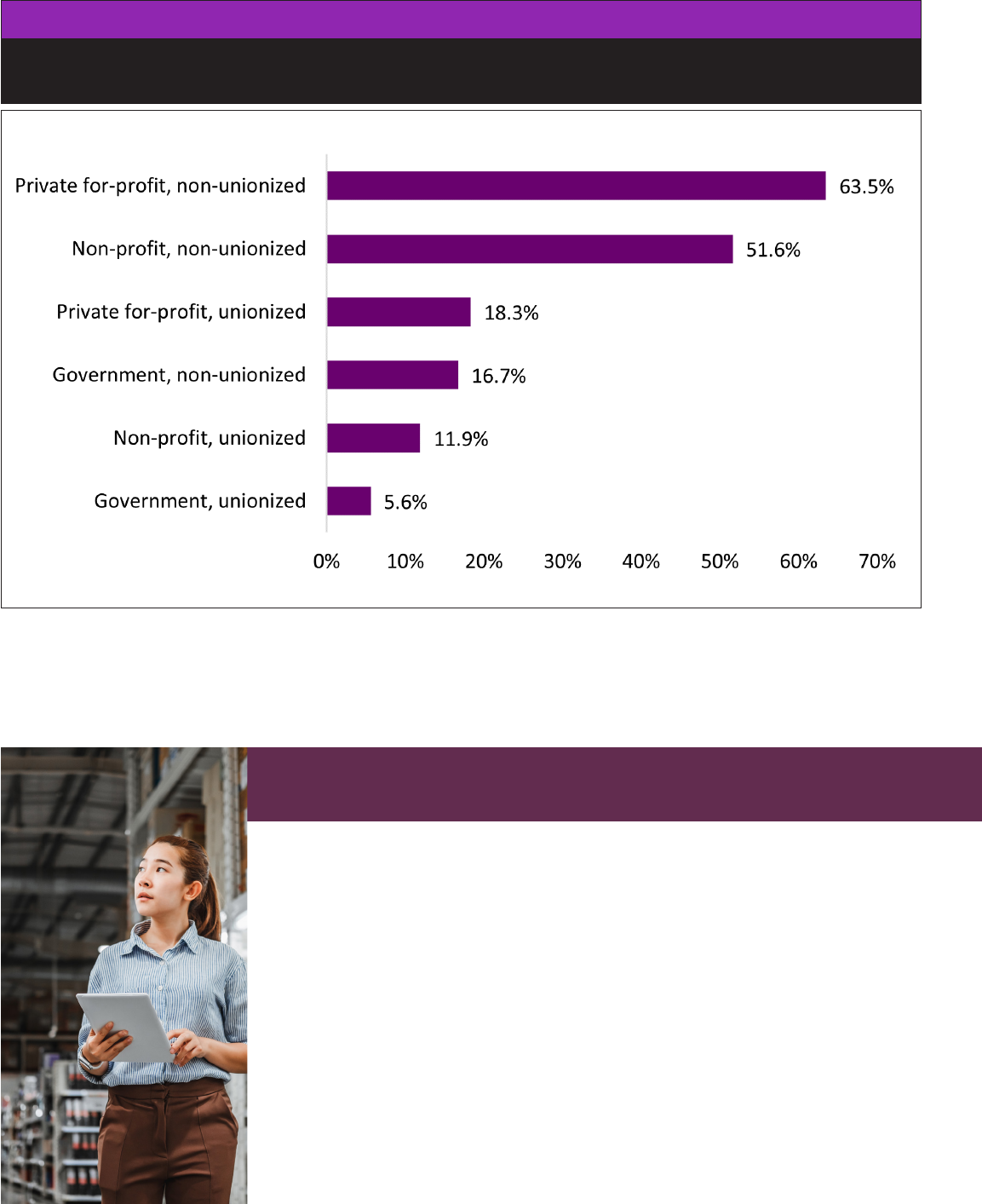

FIGURE 5. Pay Secrecy Policies are Most Common for Non-Union Private Sector Workers

Percentage of workers subject to pay secrecy policies,

by employment sector and union membership status, 2017/2018

Notes: Figure shows the percentage of U.S. workers subject to pay secrecy policies (either discouraged or prohibited from

discussing pay), by sector (government; private, for-proit; non-proit) and union member status. Percentages are weighted.

Sample excludes those who responded “refused/don’t know” to the questions about either pay secrecy policy, sector, or union

member status (n=146).

Source: Analysis of 2017/2018 Pay Secrecy survey.

WOMEN ARE MORE LIKELY THAN MEN TO WORK UNDER A PAY

SECRECY POLICY

The primary impetus behind lawmakers’ efforts to prohibit pay

secrecy policies is to eliminate a means by which employers can,

intentionally or not, discriminate against women in setting pay.

Information about co-workers’ pay can reveal ongoing or past

instances of unlawful wage and salary disparities. The absence of

such information means many women may never become aware

of discriminatory pay gaps. In 2010, women were not signiicantly

more likely to report working under a pay secrecy rule compared

with men (54.2 percent of women and 52.3 percent of men;

Rosenfeld 2017). This had changed by 2017/2018, when 52.2 percent

of women and 46.8 percent of men reported working under a pay

secrecy policy (Figure 6). Women were signiicantly more likely than

men to report that their employer formally barred discussing pay

(15.7 percent and 10.9 percent, respectively).

10

FIGURE 6. Women Are More Likely Than Men to be Subject to Formal Pay Secrecy Rules

Pay secrecy policies among U.S. workers by gender, 2017/2018

Notes: Figure shows the percentage of U.S. workers subject to each pay secrecy policy, by gender. Percentages are weighted.

Sample excludes those who responded “refused/don’t know” to the questions about pay secrecy policy (n=80).

Source: Analysis of the 2017/2018 Pay Secrecy survey.

DO PAY SECRECY POLICIES WORK?

Do workers take pay secrecy policies seriously and abide by their

restrictions? The 2017/2018 survey asked respondents whether

they talk about wages and salaries with their colleagues.

10

Of

particular interest is whether workers who lack access to pay

information nonetheless discuss pay. Pay information could be

empowering for these workers.

11

Among this group, as one would

expect, workers who report that they are permitted to discuss

their pay are signiicantly more likely to do so than workers who

are discouraged or prohibited from doing so. In workplaces with

no speech prohibitions, over half of all workers (52.3 percent)

report discussing pay with their peers. In workplaces that

discourage workers from discussing pay, well over a third of

workers (36.8 percent) say they nonetheless discuss pay. And

in establishments with a formal ban on discussing pay, just

under a third of workers (30.4 percent) say they engage in such

talk (Table 2). The comparatively low proportion of workers

reporting pay discussions in organizations where pay rates are

publicly available (33.8 percent) likely stems from the lack of a

need to talk about something to which everyone has access.

10

The 2010 survey did not include such a question.

11

This part of our analysis excludes those who have access to pay information as a condition of their jobs (for example, HR

managers).

11

Table 2. Share of workers who discuss their pay with

their coworkers, by pay secrecy policy

Pay secrecy policy Percent

Public 33.8

Discussion is permitted 52.3

Discussion is discouraged 36.8

Discussion is formally prohibited 30.4

Refused/Don’t know 10.3

Overall 38.6

Unweighted N 3,455

Notes: Table shows the percentage of U.S. workers who discuss their pay, by the pay secrecy policy at their workplace. Sam-

ple restricted to those who are not granted access to pay information as part of their jobs. Percentages are weighted.

Source: Analysis of the 2017/2018 Pay Secrecy survey.

In short, not everyone who is permitted to discuss pay actually does so (though having that

permission makes it signiicantly more likely) and not everyone who is prohibited or discouraged

from discussing their pay heeds that prohibition (though such prohibitions make it much less

likely that pay is discussed). Does the willingness to violate workplace pay secrecy policies vary

by gender?

On the one hand, women

may uncover possible

gender pay disparities by

discussing their pay, and

thus may be expected to

be more likely to ignore

pay secrecy rules. On the

other hand, prior research

suggests that women

are less likely to engage

in risky behavior in the

workplace,

12

and thus

women may be less likely to

violate formal or informal

policies against discussing

pay. The 2017/2018 survey

supports the former—

that women are signiicantly more likely to break the rules: 35.3 percent of women but just

24.0 percent of men subject to a formal pay secrecy policy say they talk about pay (Figure 7).

Women are also more likely than men to discuss wages and salaries in those workplaces that

publicize pay (37.4 percent compared with 30.7 percent).

Men, on the other hand, are more likely to report discussing pay where there are no prohibitions,

and men and women are equally likely to talk (or not talk) about pay in contexts where employers

discourage such discussions (Figure 7).

12

For research on gendered patterns of rule-breaking in the workplace, see Huiras et al. (2000) and Morrison (2006).

12

FIGURE 7. Women Are Signiicantly More Likely than Men

to Discuss Pay Even When Doing So Is Formally Prohibited

Share (%) of workers who discuss their pay, by gender and pay secrecy policies, 2017/2018

Notes: Figure shows the percentage of U.S. workers who discuss their pay, by gender and pay secrecy policy. Sample is

restricted to those who are not granted access to pay as part of their jobs, and excludes those who responded “refused/don’t

know” to the question about pay secrecy policy (n=80; 38 women and 42 men). Percentages are weighted.

Source: Analysis of the 2017/2018 Pay Secrecy survey.

Altogether, among workers who are formally prohibited from discussing pay, one in three women

violate such policies, compared with one in four men. These indings point to a conundrum

faced by women in the workplace. They likely have more to gain from knowing what colleagues

earn, and yet they are more likely than men to be subject to formal pay secrecy policies. Women

workers are pushing back against pay secrecy rules, but by doing so, they may be more likely to

face adverse consequences.

13

CONCLUSIONS AND POLICY IMPLICATIONS

This brieing paper presents updated data on organizations’ pay secrecy policies across the

United States. The 2017/2018 survey indings suggest that pay secrecy policies remain common

despite recent media attention, executive action, and state-level legislation meant to curtail

them. Since 2010, there has been a clear drop in the proportion of workers who report that their

employer formally prohibits pay discussions, but there has been no corresponding increase in

the share of workers reporting that they are free to discuss their pay, or work in organizations

where pay rates are publicly available. Instead of greater transparency, the share of workers

reporting that they are discouraged from discussing their pay has increased. Overall, existing

legislative changes have not been suficient to rid workplaces of rules against discussing pay.

Restrictions on workers’ freedom to discuss their pay are concentrated in private-sector,

non-union organizations. While pay secrecy policies are not universally effective in stopping

discussions about pay—a substantial share of workers report talking about their pay with

colleagues despite restrictions—the presence of such a policy is associated with reduced pay

discussions among workers.

The survey inds substantial gender differences: Women are more likely than men both to

work under a formal pay secrecy policy and to violate that policy. This suggests a greater

dissatisfaction with the status quo by women. Women are much more likely than men to

report experiencing gender-based discrimination in pay and promotions, and to see gender

discrimination as a major problem in the workplace (Parker and Funk 2017; Saad 2015). Yet,

research also points to the perils of leaving it to individual women to seek out information

and negotiate their salaries. Several studies suggest that women and men do not fare equally

when they do negotiate for higher pay, that women tend to be penalized for attempting to

do so, and that, even when men and women request the same salary, women receive lower

offers than men (Artz et al. 2018; Exley et al. 2020; Hernandez-Arenaz and Iriberri 2018; Säve-

Söderbergh 2019).

Nevertheless, workplace transparency practices can likely help equalize opportunities at the

bargaining table. Existing research suggests that gender differences in negotiation outcomes

are less pronounced when the terms of negotiation and the bargaining range are clear, whereas

ambiguity ampliies the gender difference (Recalde and Vesterlund 2020). Thus, initiatives to

enhance workplace pay transparency would not only allow women to uncover whether they

are being illegally underpaid, they may also beneit them at the negotiation table. Moreover,

in organizations where pay is public and where there is less reliance on individual negotiation,

such as in the federal government or in unionized workplaces, gender wage gaps are smaller

(Hegewisch and Ahmed 2019; U.S. GAO 2020).

Not knowing what one’s colleagues earn, and not being able to ind out, disadvantages workers

subject to bias and provides cover for employers engaged in pay discrimination, whether

intentional or not. State-level pay transparency laws were designed to lower this barrier, by

explicitly prohibiting retaliation against workers for discussing wages and salaries. Legislation

alone, however, does not appear to be enough to shift entrenched workplace norms and

practices regarding pay secrecy. There is a need to understand better why these laws have

had limited effects on the ground and to suggest improvements.

14

Legislation alone might not be enough to shift entrenched workplace norms and practices

regarding pay secrecy. Many workers subject to a pay secrecy policy may not know that these

policies are illegal, and employers imposing illegal restrictions may not believe that there

is a realistic threat of enforcement. Legislation should be backed up by enforcement and

information. Future research should also investigate how to address employers’ informal pay

secrecy practices and how to challenge longstanding “salary taboos” among workers.

Moreover, while these laws protect workers from retaliation for discussing wages and

salaries, they do not mandate transparency practices by the employers and they leave the

responsibility for inding out about pay to individual (women) workers. Anti-secrecy laws

can be more effective when complemented by other approaches, such as limiting employers’

reliance on salary history during recruitment and selection, mandating employers to provide

job applicants with the salary range for the advertised position, strengthening measures to

increase employers’ analysis of their own pay policies, and adding pay reporting to employers’

obligation to report equal employment opportunity data (for example, see Frye 2020).

Last but not least – given that public-sector workers and unionized workers are much less

likely to be subject to pay secrecy, and also tend to beneit from lower gender wage gaps

– strengthening workers’ rights to unionize and supporting investment in public-sector jobs

would likely be particularly effective in increasing pay transparency as well as improving pay

equity.

This brieing paper was written by Shengwei Sun at the Institute for Women’s Policy Research

(IWPR), Jake Rosenfeld at Washington University in St. Louis, and Patrick Denice at the University

of Western Ontario. The authors thank Ariane Hegewisch (IWPR) for her editorial advice and

comments on multiple drafts of this paper, Andrea Johnson at the National Women’s Law

Center for reviewing this brief, participants at the Equal Pay Today (EPT!) roundtable, Jeffrey

Hayes (IWPR) for advice, and Adiam Tesfaselassie (IWPR) for editorial assistance. Financial

support for this research was provided by National Science Foundation (Award #1727350), the

Ford Foundation, Pivotal Ventures, and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

All photos from Getty Images.

15

REFERENCES

Artz, Benjamin, Amanda H. Goodall, and Andrew J. Oswald. 2018. “Do Women Ask?”

Industrial Relations 57(4): 611-636.

Baker, Michael, Yosh Halberstam, Kory Kroft, Alexandre Mas, and Derek Messacar. 2019. “Pay

Transparency and the Gender Gap.” NBER Working Paper 25834.

Bennedsen, Morten, Elena Simintzi, Margarita Tsoutsoura, and Daniel Wolfenzon. 2019. “Do

Firms Respond to Gender Pay Gap Transparency?” NBER Working Paper 25435.

Eilperin, Juliet. 2014. “Obama Takes Executive Action to Lift the Veil of ‘Pay Secrecy.’”

Washington Post, April 8. <https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/post-politics/

wp/2014/04/08/obama-takes-executive-action-to-lift-the-veil-of-pay-secrecy/> (accessed

December 22, 2020).

Exley, Christine L., Muriel Niederle, and Lise Vesterlund. 2020. “Knowing When to Ask: The

Cost of Leaning In.” Journal of Political Economy 128(3).

Frye, Jocelyn. 2020. “Why Pay Data Matter in the Fight for Equal Pay.” Washington,

DC: Center for American Progress <https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/women/

reports/2020/03/02/480920/pay-data-matter-ight-equal-pay/> (accessed December 22,

2020).

Gamage, Danula K., Georgios Kavetsos, Sushanta Mallick, and Almudena Sevilla. 2020. “Pay

Transparency Initiative and Gender Pay Gap: Evidence from Research-Intensive Universities

in the UK.” IZA Working Paper 13635.

Gely, Rafael, and Leonard Bierman. 2003. “Pay Secrecy/Conidentiality Rules and the

National Labor Relations Act.” University of Pennsylvania Journal of Labor and Employment

Law 6: 121-156.

Harris, Benjamin. 2018. “Information Is Power: Fostering Labor Market Competition through

Transparent Wages.” Hamilton Project, Brookings Institution. <https://www.hamiltonproject.

org/assets/iles/information_is_power_harris_pp.pdf> (accessed December 22, 2020).

Hayes, Jeffrey, and Heidi Hartmann. 2011. “Women and Men Living on the Edge: Economic

Insecurity after the Great Recession.” IWPR Report #C386. Washington, DC: Institute for

Women’s Policy Research. <https://iwpr.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/C386.pdf >

(accessed December 22, 2020).

Hegewisch, Ariane, and Tanima Ahmed. 2019. “Growing the Numbers of Women in the

Trades: Building Equity and Inclusion through Pre-Apprenticeship Programs.” Brieing paper.

National Center for Women’s Equity in Apprenticeship and Employment at Chicago Women

in the Trades. <http://womensequitycenter.org/best-practices/> (accessed December 22,

2020).

Hegewisch, Ariane, and Halie Mariano. 2020. “Same Gap, Different Year. The Gender Wage

Gap: 2019 Earnings Differences by Gender, Race, and Ethnicity.” IWPR Report #C495.

Washington, DC: Institute for Women’s Policy Research. <https://iwpr.org/wp-content/

uploads/2020/09/Gender-Wage-Gap-Fact-Sheet-2.pdf> (accessed December 22, 2020).

Hernandez-Arenaz, Iñigo, and Nagore Iriberri. 2018. “Women Ask for Less (Only from Men):

Evidence from Bargaining in the Field.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 152:

192-214.

16

Huiras, Jessica, Christopher Uggen, and Barbara McMorris. 2000. “Career Jobs, Survival

Jobs, and Employee Deviance: A Social Investment Model of Workplace Misconduct.” The

Sociological Quarterly 41: 245-263.

Institute for Women’s Policy Research. 2017. “Private Sector Workers Lack Pay Transparency:

Pay Secrecy May Reduce Women’s Bargaining Power and Contribute to Gender Wage Gap.”

Quick Figures, IWPR #Q068. Washington DC: The Institute for Women’s Policy Research.

<https://iwpr.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Q068-Pay-Secrecy.pdf> (accessed

December 22, 2020).

Kim, Marlene. 2015. “Pay Secrecy and the Gender Wage Gap in the United States.” Industrial

Relations 54: 648-667.

Morrison, Elizabeth W. 2006. “Doing the Job Well: An Investigation of Pro-Social Rule

Breaking.” Journal of Management 32: 5-28.

National Women’s Law Center. 2019a. “Combating Punitive Pay Secrecy Policies.” Fact

Sheet. Washington, DC: National Women’s Law Center <https://nwlc.org/wp-content/

uploads/2019/02/Combating-Punitive-Pay-Secrecy-Policies.pdf> (accessed December 22,

2020).

———. 2019b. “The Paycheck Fairness Act: Closing the ‘Factor Other Than Sex’ Loophole to

Strengthen Protections against Pay Discrimination.” Fact Sheet. Washington, DC: National

Women’s Law Center <https://nwlc-ciw49tixgw5lbab.stackpathdns.com/wp-content/

uploads/2019/03/PFA-Closing-the-Loophole.pdf> (accessed December 22, 2020).

Parker, Kim, and Cary Funk. 2017. “Women Are More Concerned Than Men about Gender

Discrimination in Tech Industry.” Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. <https://www.

pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/10/10/women-are-more-concerned-than-men-about-

gender-discrimination-in-tech-industry/> (accessed December 22, 2020).

Recalde, Maria, and Lise Vesterlund. 2020. “Gender Differences in Negotiation and Policy for

Improvement.” NBER Working Paper 28183.

Rosenfeld, Jake. 2017. “Don’t Ask or Tell: Pay Secrecy Policies in U.S. Workplaces.” Social

Science Research 65: 1-16.

Saad, Lydia. 2015. “Working Women Still Lag Men in Opinion of Workplace Equity.” Gallup.

<https://news.gallup.com/poll/185213/working-women-lag-men-opinion-workplace-equity.

aspx> (accessed December 22, 2020).

Säve-Söderbergh, Jenny. 2019. “Gender Gaps in Salary Negotiations: Salary Requests and

Starting Salaries in the Field.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 161: 35-51.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2019. “Union Membership (Annual Release: Union

Members--2018.” Economic News Release, January 18. <https://www.bls.gov/news.release/

archives/union2_01182019.htm> (accessed December 22, 2020).

U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. 2020. Equal Pay Act of 1963 (Pub. L.

88-38). Washington, DC. <https://www.eeoc.gov/statutes/equal-pay-act-1963> (accessed

December 22, 2020).

U.S. Government Accountability Ofice (GAO). 2020. Gender Pay Differentials: The Pay Gap

for Federal Workers Has Continued to Narrow, but Better Quality Data on Promotions Are

Needed. GAO-21-67, December, report to congressional requesters. <https://www.gao.gov/

assets/720/711014.pdf> (accessed January 14, 2021).

17

We win economic equity for all women and eliminate barriers to their full participation

in society. As a leading national think tank, we build evidence to shape policies that

grow women’s power and inluence, close inequality gaps, and improve the economic

well-being of families.

OUR MISSION | A just future begins with bold ideas.