Report to the

North Carolina General Assembly

Study of Subbasin Transfers per SL 2020-79 (4)

January 15, 2021

Division of Water Resources

NORTH CAROLINA

DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY

Page | 3

Directive

Session Law 2020-79 (4) directed the Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) to study the

statutes and rules governing subbasin transfers and make recommendations as to whether the

statutes and rules should be amended. More specifically, DEQ was asked to:

(1) examine whether transfers of water between subbasins within the same major river basin

should continue to be required to comply with all of the same requirements under G.S.

143-215.22L as transfers of water between major river basins; and

(2) consider whether the costs of complying with specific requirements, including financial

costs and time, are justified by the benefits of the requirements, including the production

of useful information and public notice and involvement.

Background

North Carolina has a long history regulating interbasin transfers, dating back to the 1950’s. The

purpose of the Interbasin Transfer (IBT) Law is to ensure it is good public policy to move water

from one basin into another. An interbasin transfer, as defined in § 143-215.22G, is the

withdrawal, diversion or pumping of surface water from one river basin that is then discharged

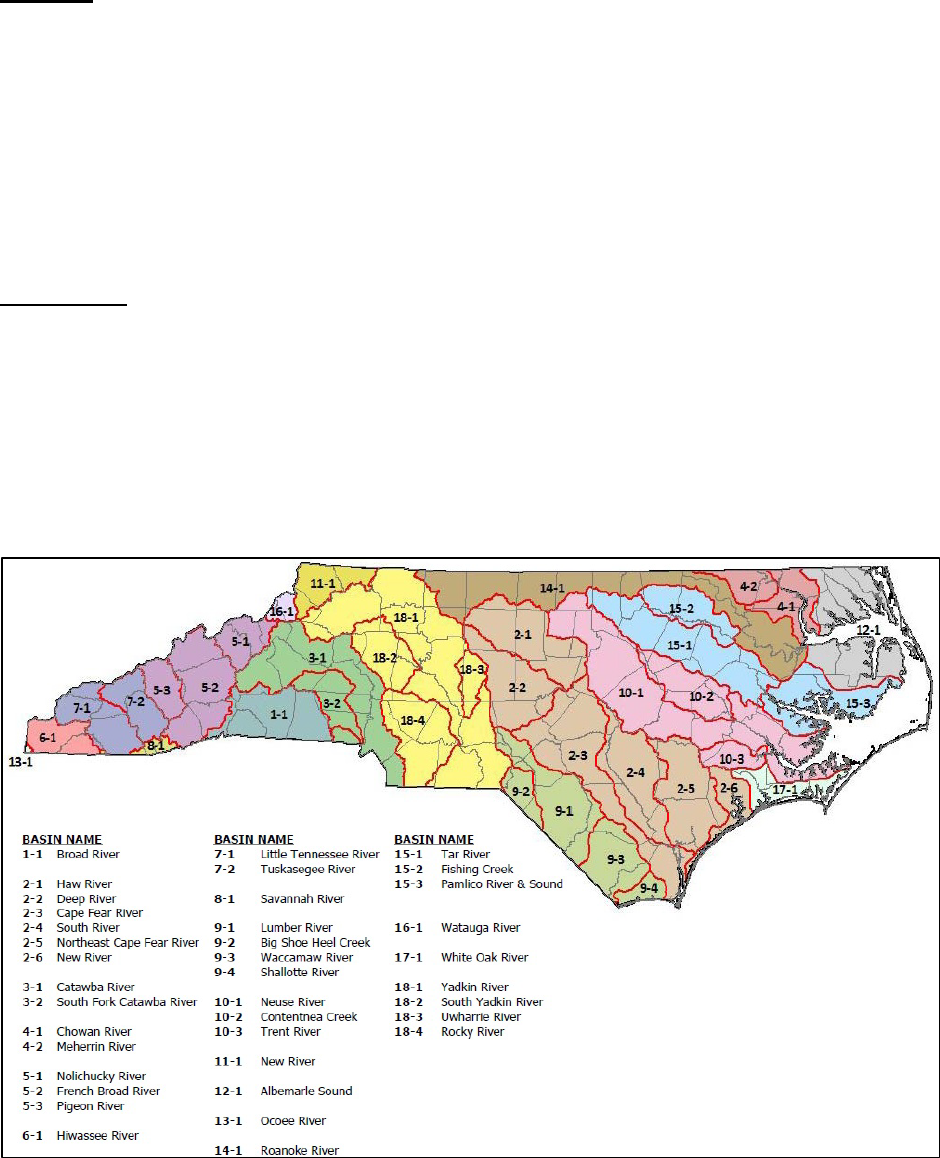

into a different river basin. § 143-215.22G establishes 18 major river basins and 38 subbasins, as

designated on the map entitled “Major River Basins and Sub-basins in North Carolina” and filed

in the Office of the Secretary of State on April 16, 1991.

Figure 1. IBT Basins as defined in § 143-215.22G

Page | 4

Importance of Major and Subbasin Boundaries

How basins are defined is critical since a receiving basin’s water needs are subordinate to the

source basin’s water needs. The State’s policy on IBTs states:

§ 143-215.22L

(t) Statement of Policy. - It is the public policy of the State to maintain, protect, and

enhance water quality within North Carolina. It is the public policy of this State

that the reasonably foreseeable future water needs of a public water system with

its service area located primarily in the receiving river basin are subordinate to

the reasonably foreseeable future water needs of a public water system with its

service area located primarily in the source river basin. Further, it is the public

policy of the State that the cumulative impact of transfers from a source river

basin shall not result in a violation of the antidegradation policy set out in 40

Code of Federal Regulations § 131.12 (1 July 2006 Edition) and the statewide

antidegradation policy adopted pursuant thereto.

IBT Certificate

An IBT Certificate

1

from the N.C. Environmental Management Commission (EMC) is required

to:

(1) initiate a transfer of 2,000,000 gallons of water or more per day, calculated as a daily

average of a calendar month and not to exceed 3,000,000 gallons per day in any one day,

from one river basin to another;

(2) increase the amount of an existing transfer of water from one river basin to another by

twenty-five percent (25%) or more above the average daily amount transferred during

the year ending 1 July 1993 if the total transfer including the increase is 2,000,000

gallons or more per day; or

(3) increase an existing transfer of water from one river basin to another above the amount

approved by the Commission in a certificate issued under G.S. 162A-7 prior to 1 July

1993.

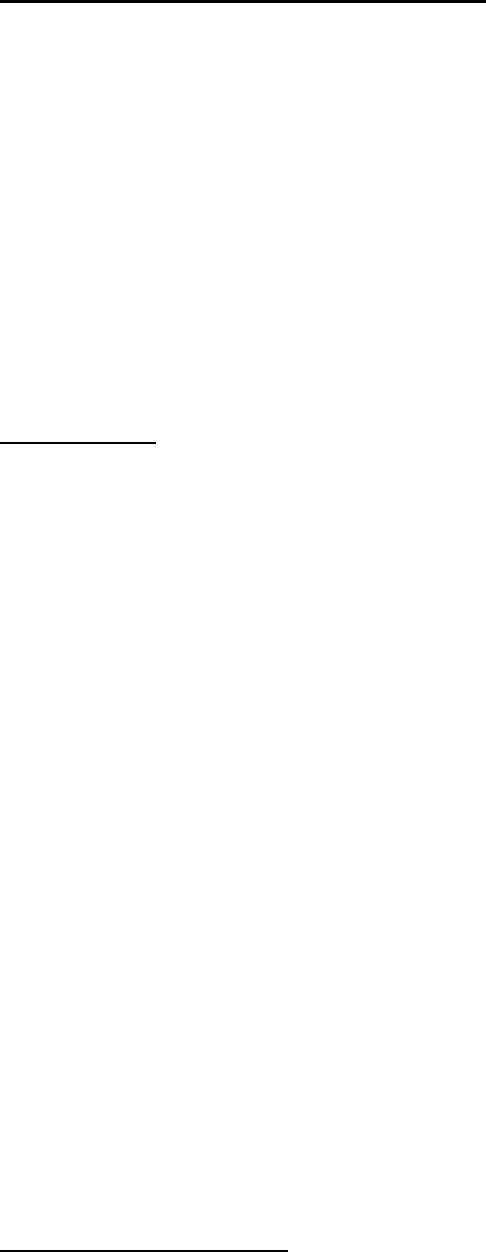

An applicant for an IBT Certificate first submits a Notice of Intent (NOI) to file a petition and

then holds at least three public meetings. Next the applicant submits a draft environmental

document, either an Environmental Assessment (EA) or an Environmental Impact Statement

(EIS), and the EMC holds at least one public hearing. After DEQ issues either a Finding of No

Significant Impact (FONSI) on the EA or a Record of Decision (ROD) on the EIS, the applicant

shall petition the EMC for an IBT Certificate. After issuing a draft determination on the petition,

the EMC holds at least two public hearings prior to issuing their final determination. (Figure 2)

1

An IBT Certificate shall not be required to transfer water from one river basin to another up to the full capacity of a

facility to transfer water from basin to another if the facility was in existence or under construction on July 1, 1993.

Page | 5

Figure 2. IBT Process per § 143-215.22L

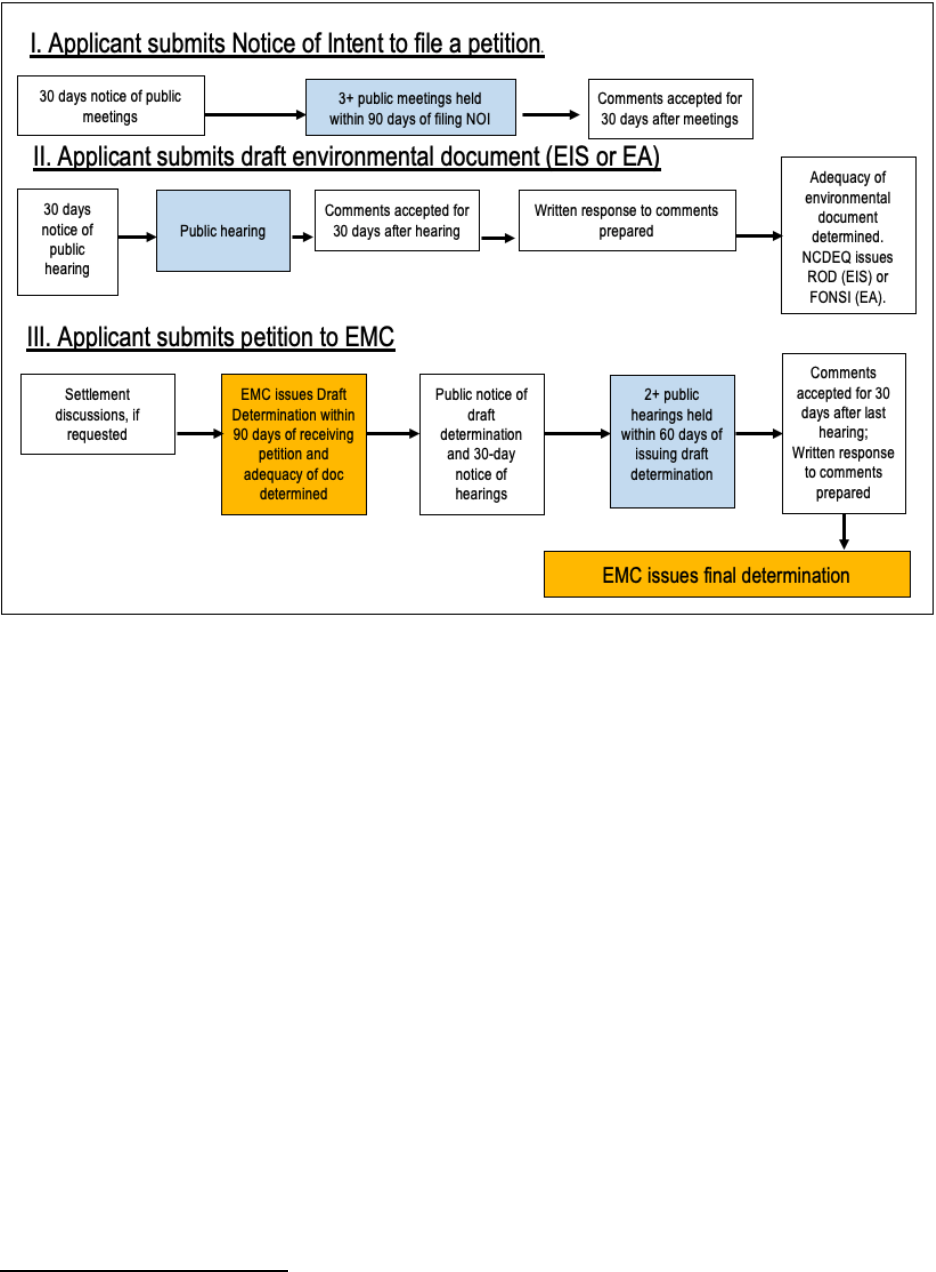

In the coastal counties and reservoirs constructed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers,

projects

2

may follow a truncated process. First the applicant shall submit a Notice of Intent to

file a petition with the EMC, however no public hearings are required at this step. Next the

applicant submits a draft environmental document (an EA or EIS), again no public hearings are

required at this step. Finally, upon determining the documentation is adequate, DEQ holds a

public hearing on the petition and accepts public comments for a minimum of 30 days prior to

the EMC issuing their final determination (Figure 3).

2

See § 143-215.22L (w) for full description of projects that fall under the truncated process.

Page | 6

Figure 3. Truncated IBT Process per § 143-215.22L (w)

Status of Surface Water Transfers

Currently, there are 133 public water systems across North Carolina that transfer surface water

between river basins. Of the 133 surface water transfers, 27 systems are transferring more than 1

million gallons per day (MGD), with 11 of those 27 systems regulated under nine IBT

certificates.

Since 1993, nine IBT certificates have been issued by the EMC. Five of the nine IBT certificates

transfer water between major river basins (Piedmont Triad RWA, Charlotte Water, Greenville

Utilities, Brunswick County, and Kerr Lake RWS). Two of the nine IBT certificates transfer

water between subbasins, but the water remains within the respective major river basins (Union

County and Pender County). Finally, two IBT certificates transfer a portion of water between

subbasins, with the remaining portion transferred between major river basins (Cary-Apex and

Concord-Kannapolis). (Table 1)

In addition to the public water systems with IBT certificates, there are ten public water systems

that have a grandfathered allowance for their surface water transfers that exceed the 2 MGD

threshold requiring a certificate

1

. Of the ten public water systems with a grandfathered

allowance, three are transferring water between subbasins. (Table 1)

There are also six water systems below the IBT certificate threshold that are transferring between

1 and 2 MGD. Of those six systems, one is transferring surface water between subbasins. (Table

1)

Page | 7

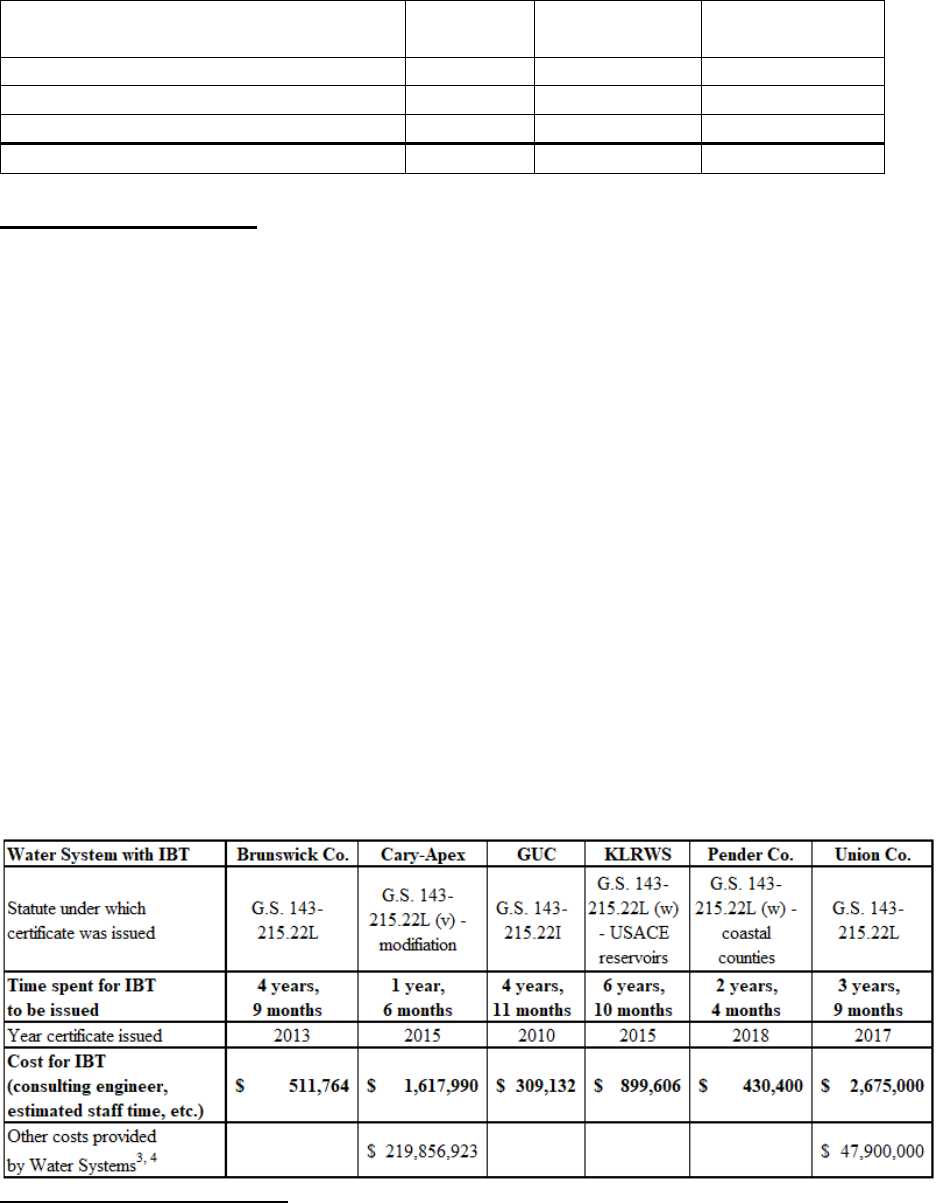

Table 1. Water Systems Transferring More Than 1 MGD

Water system transfer classification

Subbasin

transfer

Major basin

transfer

Total number

transfers

Systems with IBT certificate

2

9

11

Systems with grandfathered allowance

3

7

10

Systems transferring 1.0-2.0 MGD

1

5

6

All Systems transferring >1.0 MGD

6

21

27

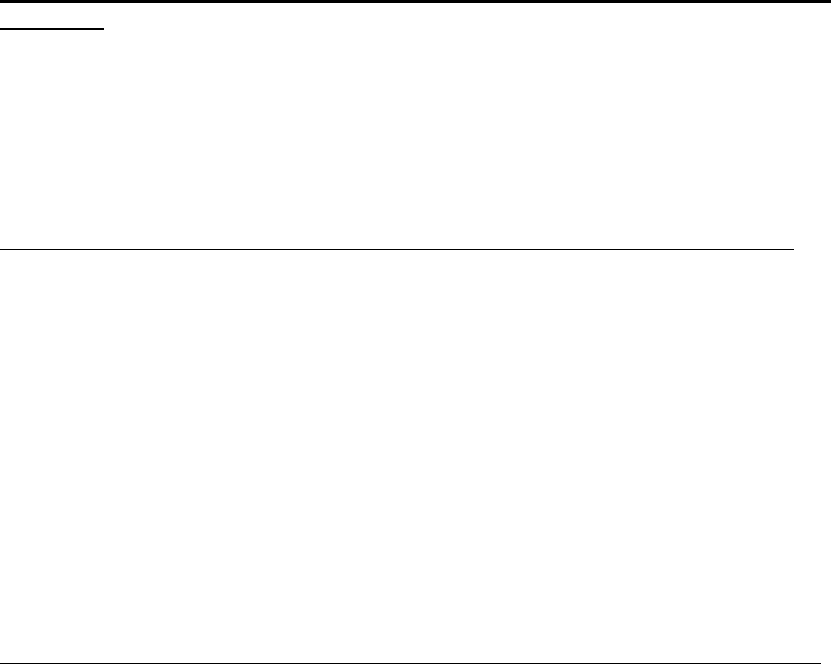

Time and Cost Estimates

The six public water supply systems that have received an IBT certificate in the past 10 years

were contacted by the Division of Water Resources and asked to provide an estimate of the time

and cost involved in obtaining their IBT certificates (Table 2). The categories and values were

provided directly by the applicants with little direction from NCDEQ staff.

The time spent for an IBT, from NOI submission to IBT certificate issuance, ranged from 18

months to over six years (Table 2). Just as every water system is a unique entity, so too is every

proposed IBT, with its own particular set of conditions and variables. This can create

widely differing timetables for the issuance of an IBT Certificate. The range in time can be

attributed to issues including, application of different subsections of the statute (i.e., processes)

under which a certificate would be issued; legislative changes to the statute while an applicant

was pursuing an IBT certificate; length of time to produce the environmental document or other

required analyses; and settlement discussions as allowed under N.C.G.S. 143-215.22L (h).

Importantly, time spent in planning phases before the submittal of the NOI to the EMC is not

captured in the table.

The costs borne by the applicant to go through the IBT process varied greatly as well (Table 2).

Systems such as Greenville Utilities Commission (GUC) and Kerr Lake Regional Water System

(KLRWS) provided a total cost with no itemization, while Cary-Apex

3

and Union County

4

included line items that are beyond the anticipated scope of a typical IBT.

Table 2. Time and Cost Estimates for IBT Certificates Issued from 2010-2018

3

Cary-Apex:

$

458,000 for Attorney-IBT & contested case support and

$

219,398,923 for the Western Wake

Regional Wastewater Management Facility to be in compliance with the IBT Certificate

4

Union Co:

$

1,400,000 for Attorney-IBT & contested case support;

$

8,500,000 for settlement commitments; and

$

38,000,000 for 5-year construction delay

Page | 8

Potential Impacts from Changing Statutory Requirements for Transfers Between

Subbasins

When examining whether transfers of water between subbasins within the same major river basin

should continue to be required to comply with all of the same requirements under G.S. 143-

215.22L as transfers of water between major river basins, DEQ considered changing the

requirement for transfers between subbasins to follow the truncated process (Figure 3) outlined

in G.S. 143-215.22L (w). The advantages and disadvantages to both are discussed in more detail

below.

Advantages to Changing Statutory Requirements for Transfers Between Subbasins

If the current statutory requirements for surface water transfers were eliminated for subbasins, it

would save substantial time and money for those systems seeking to transfer water between

subbasins (see above) by not having to go through a lengthy IBT certificate process. Changing

the requirements to follow the truncated process outlined in subsection (w) would reduce the cost

and time to obtain an IBT certificate. The current statutory requirements identify three separate

points in the process through public notices to solicit review and comment as well as public

hearings. The initial public meetings following the NOI are often not well attended as the

proposed project is in the scoping stage with many aspects of the project still unknown.

Changes in the requirements, either through truncation or elimination, for subbasin transfers

could make it easier for neighboring systems to have interconnections. This could increase water

systems’ resiliency to water shortage conditions such as drought or emergency situations such as

line breaks.

Disadvantages to Changing Statutory Requirements for Transfers Between Subbasins

Changes to, or the elimination of, the current requirements for subbasin transfers could reduce

opportunities for public involvement and transparency, and adequate review to protect both the

source and receiving river subbasins’ water users and the environment.

Many of the current requirements for obtaining an IBT certificate are in place to protect the

state’s water resources and comply with the federal Clean Water Act. Without a thorough

environmental review of a proposed surface water transfer, there could be impacts not identified,

resolved or mitigated to both water users and the environment in both the source and receiving

river basins. This is a significant concern to ensure adequate protection of both water quality and

quantity for the affected river basins. There could be sensitive areas with protected species,

impaired waters, segments of a river disproportionately impacted, or different water systems

more at risk during water shortages. Without thorough environmental review and

documentation, water systems may be at increased risk for litigation.

Public involvement is a key element in the current statutory process required for water systems

seeking an IBT certificate. Public involvement provides a more complete picture to both DEQ

and the EMC, including additional facts and perspectives. Eliminating the opportunity for public

notice, review and comment throughout the process could result in critical issues being left

unaddressed or coming to light late in the review process. It can also make the decisions seem

less legitimate and ultimately more susceptible to litigation.

Page | 9

Recommendation

DEQ finds that the current process for obtaining an IBT certificate for transfers between

subbasins within the same major river basin is appropriate and protective of the state’s water

resources and recommends that such transfers should continue to be required to obtain an IBT

certificate. However, if changes to the process are deemed necessary, DEQ recommends that

transfers between subbasins within the same major river basin should follow the truncated

process (Figure 2) outlined in G.S. 143-215.22L (w) instead of the full IBT process outlined

throughout G.S. 143-215.22L. Such an approach would likely provide time and cost savings for

the water systems seeking to transfer water between subbasins while preserving an

environmental review process. There would still be public involvement, though reduced, and

transparency throughout the process. It should be noted that specific landscape, infrastructure, or

flow conditions may necessitate a full review of a sub-basin IBT to avoid potentially significant

detrimental impacts.