BRIEFING

EPRS | European Parliament Research Service

Author: Ionel Zamfir

Members’ Research Service

PE 620.229 – April 2018

EN

Towards a binding international treaty

on business and human rights

SUMMARY

With its extended value chains, economic globalisation has provided numerousopportunities, while

also creating specific challenges, including in the area of human rights protection. The recent history

of transnational corporations contains numerous examples of human rights abuses occurring as a

result of their operations. Such corporations are known to have taken advantage of loose regulatory

frameworks in developing countries, corruption, or lack of accountability resulting from legal rules

shielding corporate interests.

This situation has created a pressing need to establish international norms regulating business

operations in relation to human rights. So far, the preferred approach has been 'soft', consisting of

the adoption of voluntary guidelines for businesses. Several sets of such norms exist at international

level, the most notable being the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.

Nevertheless, while such voluntary commitments are clearly useful, they cannot entirely stop gross

human rights violations (such as child labour, labour rights violations and land grabbing) committed

by transnational corporations, their subsidiaries or suppliers. To address the shortcomings of the

soft approach, an intergovernmental working group was established within the UN framework in

June 2014, with the task of drafting a binding treaty on human rights and business.

After being reluctant at the outset, the EU has become involved in the negotiations, but has insisted

that the future treaty's scope should include all businesses, not only transnational ones. The EU's

position on this issue has been disregarded by the UN intergovernmental working group until now,

which raises some questions about the fairness of the process. The European Parliament is a staunch

supporter of this initiative and has encouraged the EU to take a positive and constructive approach.

This is an updated edition of a briefing published in July 2017: PE 608.636.

In this Briefing

Background

The need for a binding international instrument: a

complex debate

The proposed business and human rights treaty – key

content and controversial issues

Binding legal initiatives at EU and Member State level

Stakeholders' positions

European Union position

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

2

List of acronyms used

ILO International Labour Organization

OBE Other business enterprises

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

OEIWG Open-ended intergovernmental working group

TNCs Transnational corporations

UNGPs United Nations Guiding Principles on business and Human Rights

UNHRC UN Human Rights Council

Background

Human rights abuses committed by businesses

have been a cause of serious public concern for

decades. Examples of such abuses include: use of

forced and child labour, lack of respect for labour

rights, including the right to associate and form

unions, poor safety and health conditions at work,

land grabbing, including from indigenous

communities, unlawful violence perpetrated by

private security staff, pollution and destruction of

the environment, including of water sources, to

name but a few.

What makes such abuses particularly problematic

is that access to justice and means of redress are

often insufficient, due to multiple factors.

Identifying the competent court the victims should

address is particularly problematic when dealing

with transnational corporations (TNCs). Another

aggravating factor is the lack of codification of

certain human rights abuses in penal codes. Many

obstacles to access to justice persist, particularly

when victims search for justice abroad, such as the

high costs for representationor the complexity and

length of proceedings. In developing countries,

corruption among state officials can undermine

legal proceedings. Victims and the defendants of

their rights can face intimidation, violence and

even murder, commissioned by the businesses

involved, with the acquiescence of corrupt state

authorities. Appropriate non-judicial remedies are

also of crucial importance, but are often lacking. As

recognised in a recent opinion issued by the EU

Agency for Fundamental Rights, many obstacles

also persist in EU's single market, where 'it is harder

for victims to seek redress from companies based

elsewhere or when rights violations happen

abroad'. To remedy the situation, numerous

international, regional and national-level initiatives

have been launched, which have privileged a soft

approach based on voluntary standards.

Five 'internationally recognised standards'

– 2011 UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human

Rights (hereafter referred to as UNGPs): guidelines to

prevent, address and remedy human rights violations

committed in business operations.

– 2000 UN Global Compact: the world's largest voluntary

corporate sustainability initiative encouraging businesses

to align their strategies and operations with universal

human rights, labour, environment and anti-corruption

principles, and take actions that advance societal goals.

– 1976 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

Development (OECD) Guidelines for Multinational

Enterprises (last revised in 2011) are 'recommendations

addressed by governments to multinational enterprises

operating in or from adhering countries. They provide

non-binding principles and standards for responsible

business conduct in a global context consistent with

applicable laws and internationally recognised standards.

The [OECD] Guidelines are the only multilaterally agreed

and comprehensive code of responsible business conduct

that governments have committed to promoting.'

– Launched in 2010 by the International Organization for

Standardization, the ISO 26000 Guidance Standard on

Social Responsibility provides guidance on how

businesses and organisations can operate in a socially

responsible way. This means acting in such an ethical and

transparent way as would contribute to the health and

welfare of society. As the standard provides guidance

rather than requirements, it cannot be certified, unlike

other ISO standards.

– The International Labour Organization's Tripartite

Declaration of Principles concerning Multinational

Enterprises and Social Policy: adopted in 1977 and last

amended in March 2017, offers guidelines to

multinational enterprises, governments and employers'

and workers' organisations in areas such as employment,

training, conditions of work and life, and industrial

relations. This guidance is based mainly on principles laid

down in international labour conventions and

recommendations.

Towards a binding international treaty on business and human rights

3

The EU has shown commitment to the international business and human rights governance regime

and has undertaken various actions

1

under the main instruments mentioned above. Of all these, the

EU has beenmost engaged with the UNGPs. It hassupported their development and considers them

the overarching instrument in the field. The EU is, together with many of its Member States, at the

forefront of the UNGPs' implementation, for example with regard to establishing the required

national action plans.

Increased recognition for the relationship between human rights

and business

The issue of human rights and business started receiving increased public attention in the 2000s.

Consequently, an explicit reference to human rights was introduced in the OECD and ILO standards

mentioned above. The adoption of the UNGPs in 2011 marked a decisive step forward. Today, these

principles enjoy quasi-universal recognition, being unanimously endorsed by the UN Human Rights

Council (UNHRC). They impose commitments on both states and businesses and put special

emphasis on remedies for human rights abuses committed by corporations. Nevertheless,

according to a 2017 study for the European Parliament, although much progress has been achieved

in implementing the UNGPS (for example, the OECD Guidelines have been aligned to the UNGPs

and new tools have been developed), human rights abuses by corporations persist. According to

critics, this is possibly due to the absence of a central mechanism to ensure their implementation,

and to their non-binding character.

A binding international treaty could prevent such issues. A first attempt towards such a treaty was

the Draft UN Norms on the Responsibilities of Transnational Corporations and other Business

Enterprises with Regard to Human Rights. However, this, failed in the UN Commission on Human

Rights in 2004. It contained obligations for TNCs to respect and protect the whole array of

internationally recognised human rights and to provide remedy in case of violations.

The need for a binding international instrument: a complex

debate

Timeline of events relating to the binding treaty initiative

June 2011

The UNGPs were adopted unanimously by the UNHRC

September 2013

Ecuador called for a new binding treaty to be negotiated

June 2014

Ecuador's resolution on a binding treaty was adopted in the UNHRC with thin

support

A parallel resolution tabled by Norway reaffirming the importance of the

UNGPs and calling for an examination of the benefits and limitations of a

binding treaty was unanimously adopted

October 2015

First session of the open-ended intergovernmental working group (OEIGWG)

tasked with drafting the new treaty

October 2016

OEIGWG's second session

October 2017

The Chair of the OEIGWG published a guiding document entitled 'Elements'

for the draft binding treaty

October 2017

Third OEIGWG session

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

4

March 2018

The UNHRC endorsed the 'Elements' and authorises the OEIGWG to continue

its work

June 2018

First draft of the treaty expected to be released

October 2018

Fourth OEIGWG session planned to take place

When, in September 2013, Ecuador proposed the creation of an open-ended intergovernmental

working group to negotiate a treaty instrument in the UN framework, its initiative received strong

support from civil society organisations. However, support from among the UNHRC members was

moderate. Ecuador's resolution (A/HRC/26/L22), tabled at the 26th UNHRC Session on 26 June 2014

and co-sponsored by Bolivia, Cuba, South Africa and Venezuela, was adopted with only 20 votes in

favour, 14 against and 13 abstentions. It was rejected by the industrialised members, including the

EU Member States sitting on the UNHRC, while most Latin American members abstained.

The mandate provided by the resolution is to 'elaborate an international legally binding instrument

to regulate, in international human rights law, the activities of transnational corporations and other

business enterprises' (paragraph 1). The resolution does not define TNCs; it only explains in a

footnote what is meant by 'other business enterprises' (OBEs): this concept 'denotes all business

enterprises that have a transnational character in their operational activities, and does not apply to

local businesses registered in terms of relevant domestic law'.

Again at the 26th UNHRC session, a second resolution (A/HRC/26/L.1) on the same subject, drafted

by Norway and supported by 22 other countries from all regions, was tabled in what was a unique

situation. It requested that the UN Working Group on Business and Human Rights (established in

2011 by UNHRC resolution 17/4) to prepare a report considering, among other things, the benefits

and limitations of a legally binding instrument. It furthermore requested the High Commissioner for

Human Rights to initiate a consultative process with stakeholders exploring 'the full range of legal

options and practical measures to improve access to remedy for victims of business-related human

rights abuses'. The resolution was adopted by consensus.

The open-ended intergovernmental working group on transnational corporations and other

business enterprises with respect to human rights (OEIGWG), established under the above-

mentioned resolution A/HRC/26/9, held its first session in October 2015 and a second one in October

2016. These sessions 'were dedicated to conducting constructive deliberations on the content,

scope, nature and form of the future international instrument', in accordance with the UNHRC

mandate. On 19 October, the OEIGWG Chair published the 'Elements for the draft legally binding

instrument', which were then debated in the third OEIGWG session in October 2017.

Impunity for corporate abuses at transnational level

While it would be clearly unfair to accuse all TNCs of committing systematic human rights abuses, it

is no less true that the recent history of human rights abuses committed by or resulting from the

activities of such corporations contains a number of cases of shockingly irresponsible corporate

behaviour. Moreover, victims of such abuses have oftentimes faced huge obstacles both in

accessing justice and in obtaining redress.

This is mainly due to the complexities of the rules applicable to TNCs: they can easily use the most

favourable jurisdiction to fend off responsibility and to shift it instead to their subsidiaries and

suppliers. In a 2014 publication on corporate abuses and remedies, Amnesty International examines

the negative implications for human rights protection of the doctrine of 'separate legal personality'

(the 'corporate veil'): 'each separately incorporated member of a corporate group is considered to

be a distinct legal entity that holds and manages its own separate liabilities. [...] This doctrine implies

that the liabilities of one member of a corporate group will not automatically be imputed to another,

merely because there is an equity relationship between them'. This makes it quasi-impossible to sue

Towards a binding international treaty on business and human rights

5

parent companies either in the countries where their subsidiaries operateor in their home countries.

Moreover, victims who look for redress in foreign courts also face huge obstacles. When criminal

liability is at stake, those who have the ultimate responsibility for corporate abuses can find

protection in their home state's jurisdiction or in investment protection treaties.

There is thus a profound asymmetry between TNCs' rights and obligations. While they enjoy

substantial rights secured through trade and investment agreements, their human rights

obligations are less clearand more difficult to enforce. Given the power of TNCs in today's globalised

world, the expectation that domestic law would be sufficient to impose human rights-related

obligations and to hold TNCs accountable for abuses is simply unrealistic. The long supply chains

make it extremely difficult to establish responsibility and hold accountable those in the highest

position of command in such chains. States hosting powerful TNCs often lack the capacity to act

against them or do not take action over fear of losing foreign investment. Nor do TNCs' home states

take action, to avoid placing them at a competitive disadvantage.

Limits of the soft law/hard law approaches

Dissatisfaction with the slow and ineffective implementation of the UNGPs – though they were

much acclaimed at the time of their adoption – has driven the initiative to draft a binding

international treaty. The limits and shortcomings of the UNGPs have been widely recognised by

both governments and civil society organisations. Their non-binding character has been portrayed

as a particular weakness. Their defenders have responded to this criticism by pointing out that, as

they have only been around for a few years, more time is needed to assess their impact.

Furthermore, with respect to the binding treaty, many experts in the field point to the huge

complexity of the business and human rights subject. This was initially used as an argument for

preferring the soft-law approach of the UNGPs to a binding treaty. UN rapporteur John Ruggie, who

drafted the UNGPs, expressed strong reservations about such a treaty. The subject area it would

have to cover would be too vast, since it 'includes all human rights, all rights holders, all business –

large and small, transnational and national'. The inherent risk with such a complex treaty is that

negotiations would last many years, without leading to a conclusive outcome endorsed by all. The

EU, through the statement delivered by its Delegation to the UN at the third OEIGWG session, has

also expressed serious reservations about an all-encompassing treaty, marking its preference

instead for more precise and specific international legal instruments based on existing norms.

A related criticism is that the treaty would be of little practical significance given its overly general

character, and it could be used by states to obscure their incapacity to uphold human rights by

pointing the finger at transnational companies. Actually, many of the countries that have actively

promoted the treaty have very poor human rights and labour rights records, which raises serious

questions about their commitment to the cause of human rights. The EU has also expressed

concerns that a new treaty will not be of much help to victims of human rights violations caused by

the incapacity or unwillingness of certain states to uphold their existing human rights obligations.

According to the defenders of the UNGPs, the pursuit of a binding treaty would also risk weakening

their implementation by driving public attention and resources away, and by implicitly

acknowledging their limitations. However, this concern has not materialised, as there has been a lot

of progress in implementing the principles, including national action plans and legislative attempts

to regulate due diligence.

A more balanced view acknowledges that the UNGPs and the proposed treaty both have

advantages and disadvantages of their own. Therefore, the best strategy may be to continue with

several initiatives in order to 'enhance victims' access to remedies and to teach corporations how to

pursue effective due diligence in order to prevent potential human rights abuses'. While initially the

two camps – those supporting and those rejecting a binding treaty – were highly polarised,

2

the

division between them has diminished. Today, there are more people who believe that the two

initiatives could complement each other well, rather than compete with each other.

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

6

The proposed business and human rights treaty – key

content and controversial issues

A major challenge for the drafters of the treaty is to select from among the huge range of issues

those that are the most relevant and capable of securing the necessary final consensus. During its

2015 and 2016 sessions, the OEIGWG debated a broad range of issues. Taking into account the

published 'Elements for the treaty', as well as the positions expressed by civil society and other

stakeholders, several issues have emerged as elements for possible inclusion in the treaty.

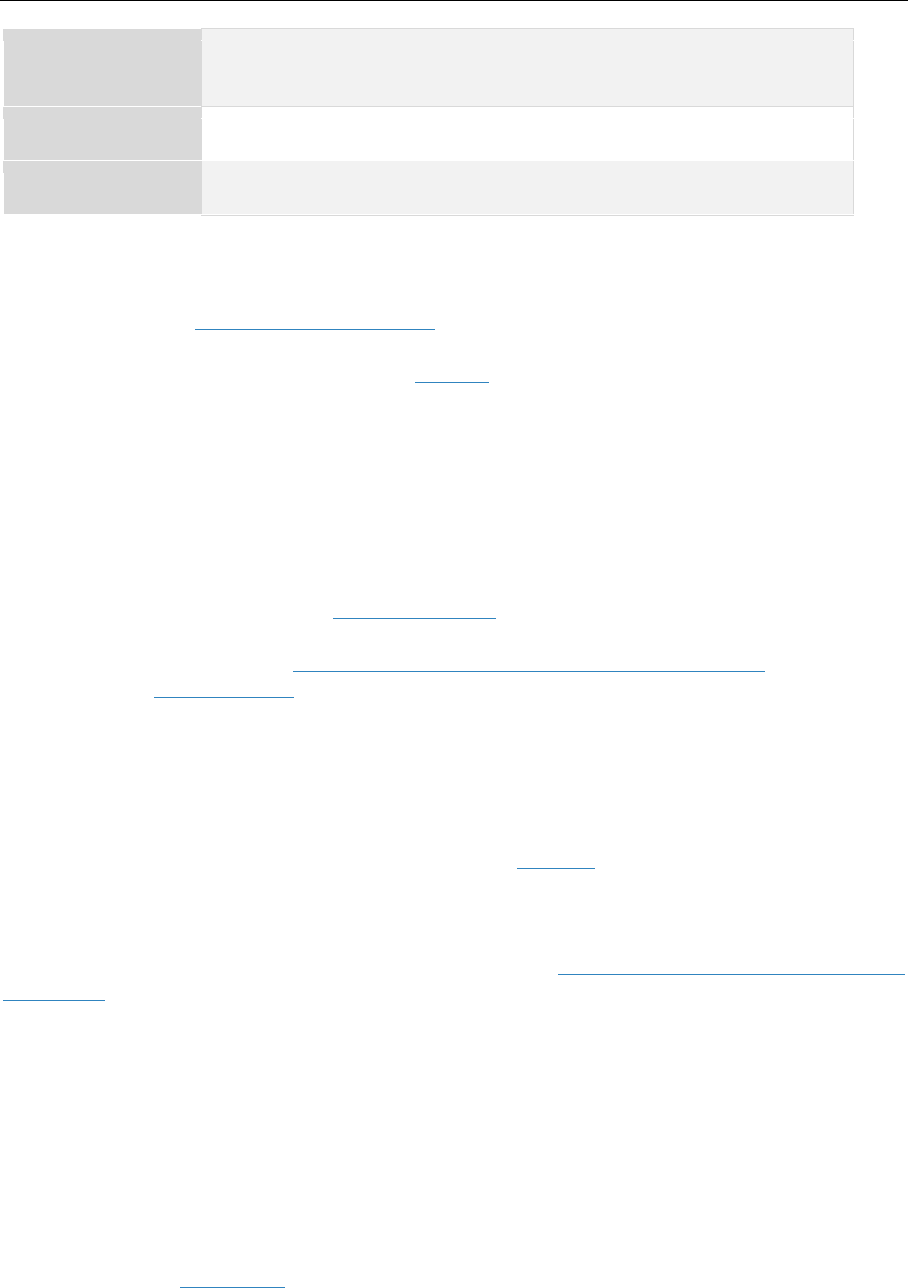

Figure 1 – Potential elements of the future treaty

Source: EPRS, 2018.

Among the most debated issues are:

The obligation for companies to demonstrate due diligence: According to the option

highlighted in the 'Elements', the states parties shall adopt legislative and other

measures to make due diligence

3

mandatory for TNCs and OBEs, including with respect

to their subsidiaries;

Strengthening legal liability: According to the 'Elements', states parties shall regulate

the legal liability of TNCs and OBEs from an administrative, civil and penal point of view

with respect to violations of human rights resulting from their activities. In particular, all

states should recognise the criminal liability of companies;

A broad concept of jurisdiction is required, allowing victims to have access to justice

either in the country where the violation occurred or in the country where the parent

company has its seat;

Provision of effective remedies has to be guaranteed: The right to effective remedies is

central to human rights law and to theUNGPs; nevertheless, victims of corporate abuses

have difficulty getting access to remedies. The treaty is expected to impose an

obligation on states to guarantee access to justice and effective remedies;

Establishing remedial mechanisms at international level: The 'Elements' propose an

International Court on Transnational Corporations and Human Rights and special

chambers of existing international and regional courts. The 'Elements' also put forward

the proposal for a non-judicial mechanism, namely an international committee

composed of experts, which would examine progress made by states parties, issue

reports and receive communications;

Towards a binding international treaty on business and human rights

7

Improving judicial cooperation among states parties is another objective. The

'Elements' provide for the facilitation of mutual legal assistance and for the recognition

of relevant court decisions.

An important issue on which the planned treaty could bring clarity is the recognition of the extra-

territorial obligations of states with respect to human rights and business. The UNGPs state that, 'At

present, states are not generally required under international human rights law to regulate the

extra-territorial activities of businesses domiciled in their territory and/or jurisdiction. Nor are they

generally prohibited from doing so, provided there is a jurisdictional basis.' On the other hand,

international law contains the principle that a state should not allow the use of its territory and its

jurisdiction to cause damage in the territory or jurisdiction of another state. Some human rights

treaty bodies recommend that states take steps to prevent abuse abroad by businesses within their

jurisdiction. The 'Elements' provide that the future treaty should 'reaffirm that State Parties’

obligations regarding the protection of human rights do not stop at their territorial borders'.

So far, the most controversial point of the debate has been whether the envisaged treaty should be

limited to TNCs andOBEs involved in transnational operations, or should also cover local companies.

The EU has insisted that it should cover all business enterprises, and from the beginning has made

this approach into a pre-condition of its participation in the drafting process. The EU argues that the

treaty would otherwise be incoherent, as many human rights violations are committed by purely

local companies. Also the treaty would put transnational companies at a competitive disadvantage

in relation to their local competitors, which could commit certain human rights violations with

impunity. Contrary to the EU's position, the 'Elements' clearly limit the scope of the treaty to 'TNCs

and OBEs involved in transnational operations. During the debates in the third session, the EU's

position did not find much support among other states.

Some analysts believe that there are substantial reasons for drafting a treaty only applicable to TNCs

and other business enterprises with transnational operations, as provided for in the mandate, and

not to local companies. They argue that the treaty is expected to fill a gap in the international rules

on determining the liability of parent or controlling companies beyond the jurisdiction of the state

where the violations occurred. At present, TNCs benefit the most from this governance gap.

According to a South Centre policy advisor, limiting the scope of the proposed treaty to TNCs and

business enterprises with transnational activities would not be discriminatory towards these in

relation to domestic companies, but would put them on the same footing. TNCs are often able to

avoid responsibility because of their transnational structure.

A further issue up for debate concerns the human rights covered. The international human rights

regime includes numerous rights – such as certain social and economic rights – some of which are

more difficult to enforce in a court of law. The 'Elements' propose a broad approach covering all

internationally recognised human rights, as reflected in all human rights treaties, as well as in

international conventions on labour rights, environment and corruption. According to critics, this

could push the treaty to such a level of abstraction that would make it practically ineffective.

A further point of controversy refers to the responsibility for fulfilling the obligations defined under

the treaty. The 'Elements' propose that they include, in addition to states and international

organisations with an economic remit, TNCs and OBEs, as well as natural persons. According to

critics of this approach, this move to hold corporations directly liable under international law for

their human rights abuses would be unprecedented. It would contravene the traditional approach

of international law to holding states accountable for human rights abuses committed by

corporations in their territory.

4

This was most likely also the reason the previous attempt in the UN

to establish binding norms on business and human rights failed (see page 3). Furthermore, states

could use the treaty to shun their responsibility for protecting human rights. Asking businesses to

implement elaborate human rights policies could also pose enormous practical difficulties, given

the complicated, partly unpredictable and sometimes contradictory implications economic

activities can have on human rights. International law does not provide any guidance on trade-offs

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

8

between different human rights. According to Danny Bradlow, professor in international law, 'it

would be imprudent to establish binding rules on how businesses should manage human rights

issues before we fully understand how to draft such rules without causing unintended

consequences... It [human rights law] has not yet worked out how to deal with human rights

situations that require making trade-offs, setting priorities, and managing risk. These are standard

in business'.

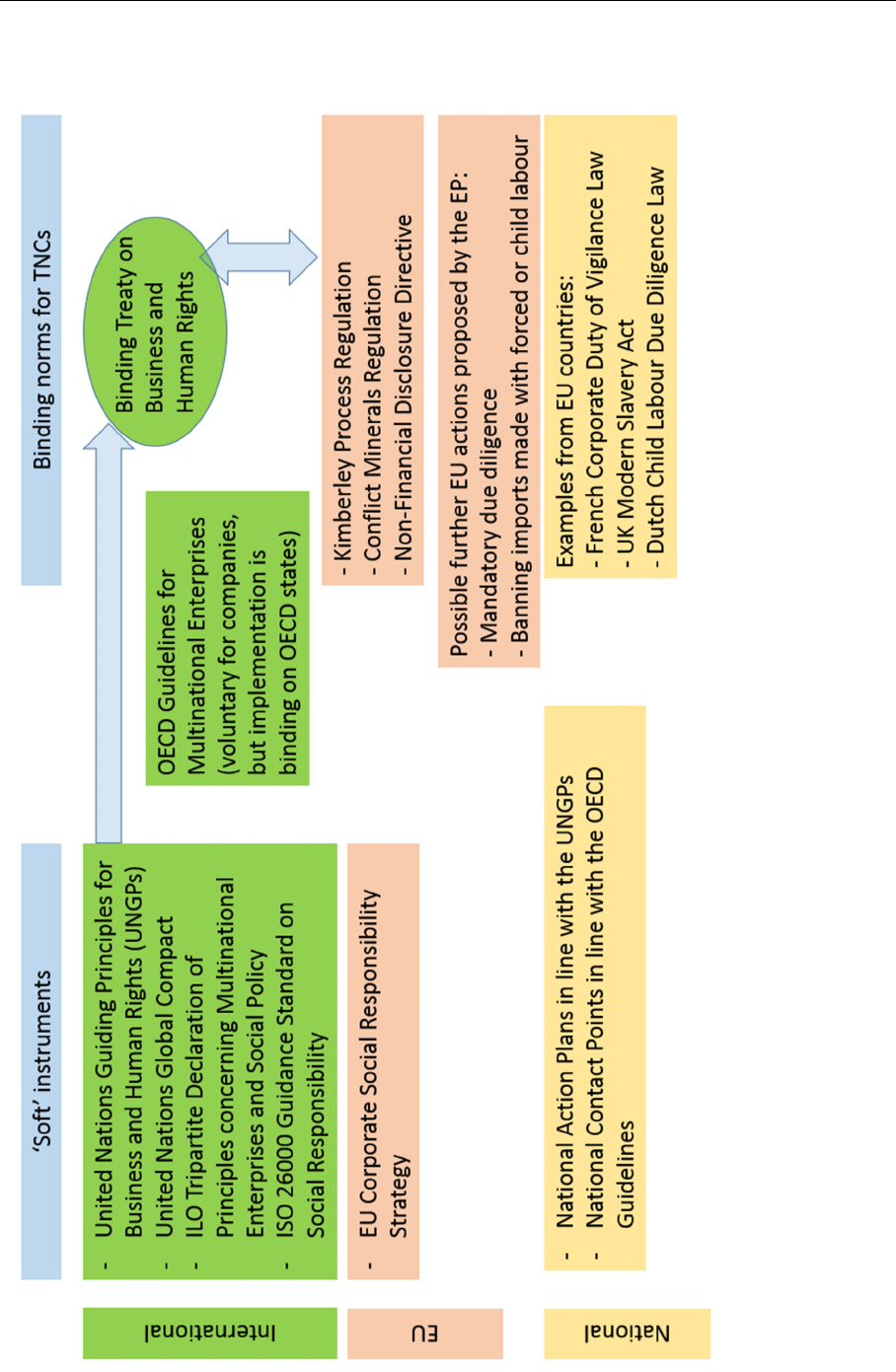

Binding legal initiatives at EU and Member State level

EU level

Existing legal initiatives could serve a path-finding role in the drafting of the treaty, as already

recognised in the preparatory OEIGWG debates. At global level, there are several examples of such

initiatives, with the EU and a few of its Member States being among the frontrunners in the area.

The EU's Non-financial Reporting Directive (Directive 2014/95/EU),

5

which entered into force in 2014

and whose transposition deadline was 6 December 2016, provides obligations for companies

operating abroad to disclose their compliance inter alia with human rights norms. The directive

incorporates the concept of due diligence in EU legislation (Article 19a (b)), and human rights are

among the issues to be covered under the due diligence reporting obligations it sets. Around 6 000

large companies listed on EU markets or operating in the banking and insurance sectors will be

expected to publish their first reports (for the financial year 2017) in 2018. As the application of this

directive is in an incipient phase, assessing its impact on the extent to which businesses respect

human rights will take some time. Another legislative initiative imposing due diligence obligations

on EU companies is the recently adopted Conflict Minerals Regulation, which will take full effect on

1 January 2021. Importers of four minerals (tin, tantalum, tungsten and gold) into the EU will be

obliged to check the likelihood that the rawmaterials could be financing conflict or could have been

extracted using forced labour.

EU Member State level

In March 2017, France adopted a law on the duty of vigilance of parent and subcontracting

companies, imposing on large French companies the requirement to assess and prevent the

negative impacts of their activities and of those of their subsidiaries, suppliers and subcontractors

on the environment and on human rights. Businesses' failure to comply with this legal obligation

entails payment of a compensation. Civil society organisations hope this law could serve as a model

for EU-wide legislation, in line with the precedent set by the French law on non-financial reporting,

which preceded the above-mentioned EU directive on the subject.

Inspired by the French move, eight EU national parliaments have expressed their support for a green

card initiative, namely the parliaments of Estonia, Lithuania, Slovakia and Portugal, the UK House of

Lords, the Dutch House of Representatives, the Italian Senate, and the French National Assembly.

The initiative calls for a duty of care towards individuals and communities whose human rights and

local environment have been affected by the activities of EU-based companies. Nevertheless, the

European Commission's response has been that it has 'no plans to adopt further legislation at this

stage, but is carefully monitoring, in close collaboration with the main stakeholders, how the

situation is evolving in the Member States and in the international bodies involved in the corporate

social responsibility process'.

In February 2017, the lower chamber of the Dutch Parliament adopted a Child Labour Due Diligence

Law for companies. If the Senate also approves it, the law will be effective as of 2020 and will oblige

companies to determine not only whether there is a 'reasonable suspicion' that their first supplier is

free from child labour but also – where possible – whether child labour occurs further down the

production chain.

Towards a binding international treaty on business and human rights

9

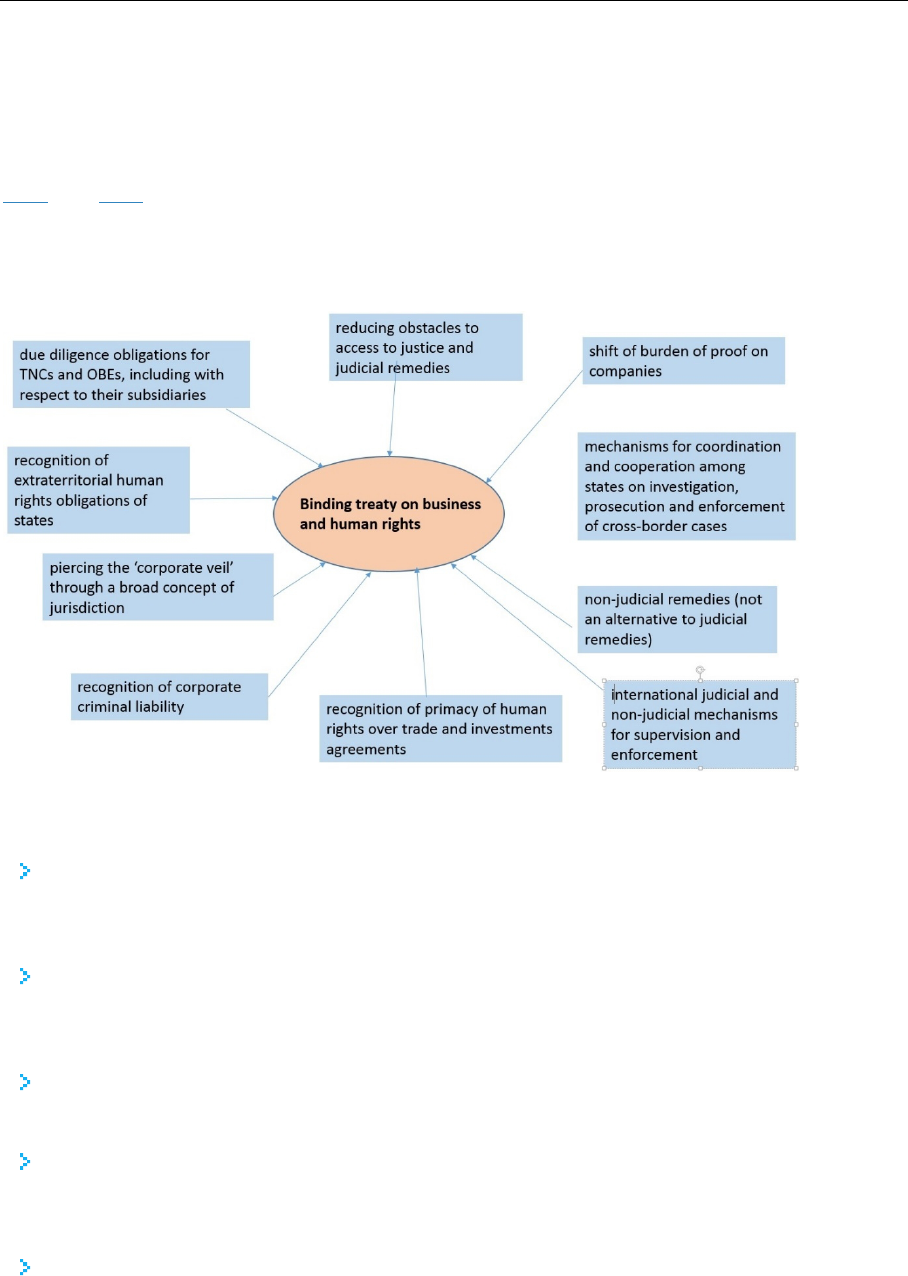

Figure 2 – The proposed treaty in the current business and human rights-governance

system

Source: EPRS, 2017

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

10

Stakeholders' positions

A broad alliance of civil society organisations (the Treaty Alliance) has been built in order to support

the treaty negotiation process, with the objectives to '(1) enhance the protection of affected

individuals and communities against violations related to the operation of TNCs and OBEs, and (2)

provide them with access to effective remedies, in particular through judicial mechanisms'.

According to the alliance, the treaty must stipulate the primacy of human rights law over corporate

rights.

On the other hand, the International Organisation of Employers has expressed its opposition to a

binding treaty, pointing out that it would undermine the UNGPs. In a statement delivered at the

second OEIGWG session, it stated that the problem is not the governance gap at the international

level, but the lack of capacity at the national level to effectively implement and enforce laws.

Inappropriate working conditions and negative impacts on the environment are due to 'a high

prevalence of informality, ineffective governmental inspection, a lack of governance frameworks,

high levels of corruption, and ineffective judiciary systems' at national level. Global supply chains

most often have a positive impact on local working conditions by setting higher standards.

However, other business organisations have come out in favour of the binding treaty, albeit with

some caveats. Accordingly, the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) and

a number of partners (the International Organisation of Employers; the International Chamber of

Commerce; and the Business and Industry Advisory Committee to the OECD), submitted a joint

advocacy paper for the second OEIGWG session. The paper highlighted their main

recommendations that the jurisdictional scope of the treaty must include all business enterprises;

the UN treaty process should build on the UN 'protect-respect-remedy' framework defined in the

UNGPs and respect the established division of roles between states and companies; and that access

to remedy must be local to be effective.

The International Commission of Jurists, an organisation composed of 60 eminent judges and

lawyers from all regions of the world, has laid out its Proposals for Elements of a Legally Binding

Instrument on Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises. Access to remedy and

justice is an essential part of its vision. While considering that the mandate and scope of the treaty

should not be limited to TNCs, the organisation argues that a one-size-fits-all approach is not the

best approach, either.

In Europe, various stakeholders such as academics, politicians, global justice campaigners and NGOs

have come out in favour of the treaty.

Support for the treaty has also been building at national level. For example, in France, civil society

organisations, together with a significant number ofparliamentarians,have urged their government

to support the UN process.

European Union position

After dropping its initial reluctance, the EU has been constructively involved in the UN process for

drafting the treaty, being represented by its Delegation to the UN in Geneva. The EU has observer

status in the UN Human Rights Council, the body which oversees the drafting process. The positions

defended by the EU Delegation in the UN framework are agreed beforehand among all Member

States.

The EU has set two main requirements for a legally binding international treaty: 1) ensuring that the

scope of the discussion is not limited to TNCs (see page 7), and 2) the treaty should be firmly rooted

in the UNGPs, making sure that their implementation is not undermined. The EU insists that the

UNGPs have allowed for tangible progress on better protecting human rights in relation with

business activities and they provide an efficient framework, which needs to be implemented.

Towards a binding international treaty on business and human rights

11

At the third session in October 2017, the EU expressed serious concerns about the way the process

had been conducted. More specifically, the 'Elements of the Treaty' were published much later than

initially scheduled and the programme of work for the discussions was made available only very

shortly before the meeting, hampering stakeholders in preparing their positions, raising serious

questions about the validity of the outcome. The EU expressed its regret that the scope of the

negotiation has not been widened to cover all companies. The 'Elements' were endorsed by the

March 2018 UN Human Rights Council, without taking into account the EU's position. The EU has

not expressed an official position on this development. Its participation in the process will most

likely continue based on the same requirements (see above).

European Parliament's position

The Parliament is a staunch supporter of the binding treaty initiative. It has expressed its full support

for the UN-level preparatory work to this effect and has argued against any obstructive actions.

6

The

Parliament has called on the EU to show its full commitment to such an instrument and to actively

engage in the debates.

7

It has also emphasised the need to build the principle of accountability into

the planned treaty, which could be achieved by including a grievance mechanism in it.

8

The Parliament has also recognised the insufficiency of voluntary action. For example, in its recent

legislative initiative report, EU flagship initiative on the garment sector, the Parliament expressed

concern that the existing voluntary initiatives aimed at achieving sustainability of the garment

sector's global supply chain have not been effective enough in addressing human rights- and labour

rights-related issues in the sector.

MAIN REFERENCES

Amnesty International, Injustice Incorporated – Corporate abuses and the human right to remedy, 2014.

Faracik, Beata, Implementation of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, European

Parliament, Directorate-General for External Policies, February 2017.

Business & Human Rights Resource Centre, Binding Treaty, a vast collection of resources on the treaty

initiative.

Ruggie, John, Get real or we'll get nothing: Reflections on the First Session of the Intergovernmental

Working Group on a Business and Human Rights Treaty, 22 July 2015.

ENDNOTES

1

For an overview of EU actions in the area, see the following studies: The EU's engagement with the main Business

and Human Rights instruments (Stephanie Bijlmakers, Mary Footer, Nicolas Hachez, Frame Project, November 2015), and

Implementation of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (Beata Faracik, European Parliament Study,

February 2017, especially pp. 38-40).

2

It is not unusual that at the outset of negotiations on new international treaties, parties would adopt more hard-

line positions, but would soften them up later.

3

While the UNGPs do not define this concept clearly, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCHR)

defines it as follows: 'In the context of the Guiding Principles, human rights due diligence comprises an ongoing

management process that a reasonable and prudent enterprise needs to undertake, in light of its circumstances (including

sector, operating context, size and similar factors) to meet its responsibility to respect human rights.' A proposal by civil

society envisages inclusion into the treaty of a provision 'that all human rights due diligence should be conducted

according to, at minimum, the international standards of the [UN] Guiding Principles'.

4

On the issue of state versus companies' obligations, see Direct Corporate Obligations by David Bilchitz and Carlos

López.

5

Under the directive, certain large companies are required to disclose in their management report information

on their policies, main risks and outcomes relating to environmental matters, social and employee aspects, respect for

human rights, anticorruption and bribery issues, and diversity in their board of directors. Companies may rely on

international, European or national guidelines (such as the UN Global Compact, the OECD Guidelines for Multinational

Enterprises and ISO 26000). See the European Commission's webpage on the matter.

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

12

6

See European Parliament resolution of 14 December 2016 on the Annual report on human rights and democracy

in the world and the European Union's policy on the matter 2015; European Parliament resolution of 25 October 2016 on

Corporate liability for serious human rights abuses in third countries; European Parliament resolution of 21 January 2016

on the EU's priorities for the UNHRC sessions in 2016.

7

See European Parliament resolution of 17 December 2015 on the Annual report on human rights and democracy

in the world 2014 and the European Union's policy on the matter; resolution of 12 March 2015 on the EU's priorities for the

UN Human Rights Council in 2015; and resolution of 12 March 2015 on the Annual report on human rights and democracy

in the world 2013 and the European Union's policy on the matter.

8

In its resolution of 14 February 2017 on the revision of the European Consensus on Development, the Parliament

asked the EU to support the adoption of a legally binding international instrument to hold companies accountable for

their human rights violations. In its resolution of 14 April 2016 on the Private sector and development, the Parliament

asked the EU to support such an instrument since it would provide effective remedies for victims in cases where domestic

jurisdiction is unable to prosecute companies effectively. The inclusion of a grievance mechanism in such a binding

instrument is also called for in Parliament's resolution of 19 May 2015 on Financing for development.

DISCLAIMER AND COPYRIGHT

This document is prepared for, and addressed to, the Members and staff of the European Parliament as

background material to assist them in their parliamentary work. The content of the document is the sole

responsibility of its author(s) and any opinions expressed herein should not be taken to represent an official

position of the Parliament.

Reproduction and translation for non-commercial purposes are authorised, provided the source is

acknowledged and the European Parliament is given prior notice and sent a copy.

© European Union, 2018.

Photo credits: © hramovnick / Fotolia.

[email protected]u (contact)

www.eprs.ep.parl.union.eu (intranet)

www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank (internet)

http://epthinktank.eu (blog)