Challenges to effective

EU cybersecurity policy

Briefing Paper

March 2019

2019EN

About the paper:

The objective of this briefing paper, which is not an audit report, is to provide an

overview of the EU’s complex cybersecurity policy landscape and identify the main

challenges to effective policy delivery. It covers network and information security,

cybercrime, cyber defence and disinformation. The paper will also inform any future

audit work in this area.

We based our analysis on a documentary review of publicly available information in

official documents, position papers and third party studies. Our field work was

carried out between April and September 2018, and developments up to December

2018 are taken into account. We complemented our work by a survey of the

Member States’ national audit offices, and through interviews with key stakeholders

from EU institutions and representatives from the private sector.

The challenges we identified are grouped into four broad clusters: i) the policy

framework; ii) funding and spending; iii) building cyber-resilience; iv) responding

effectively to cyber incidents. Achieving a greater level of cybersecurity in the EU

remains an imperative test. We therefore end each chapter with a series of ideas for

further reflection by policy-makers, legislators and practitioners.

We would like to acknowledge the constructive feedback received from the services

of the Commission, the European External Action Service, the Council of the

European Union, ENISA, Europol, the European Cybersecurity Organisation, and

national audit offices of the Member States.

2

Contents

Paragraph

Executive summary I-XIII

Introduction

01-24

What is cybersecurity? 02-06

How serious is the problem?

07-10

The EU’s action on cybersecurity

11-24

Policy 13-18

Legislation 19-24

Constructing a policy and legislative framework 25-39

Challenge 1: meaningful evaluation and accountability 26-32

Challenge 2: addressing gaps in EU law and its uneven

transposition

33-39

Funding and spending 40-64

Challenge 3: aligning investment levels with goals 41-46

Scaling up investment 41-44

Scaling up impact 45-46

Challenge 4: a clear overview of EU budget spending 47-60

Identifiable cybersecurity spending 50-56

Other cybersecurity spending 57-58

Looking ahead 59-60

Challenge 5: adequately resourcing the EU’s agencies 61-64

Building a cyber-resilient society 65-100

Challenge 6: strengthening governance and standards 66-81

Information security governance 66-75

Threat and risk assessments 76-78

Incentives 79-81

3

Challenge 7: raising skills and awareness 82-90

Training, skills and capacity development 84-87

Awareness 88-90

Challenge 8: better information exchange and coordination 91-100

Coordination among EU institutions and with Member States 92-96

Cooperation and information exchange with the private sector 97-100

Responding effectively to cyber incidents 101-117

Challenge 9: effective detection and response 102-111

Detection and notification 102-105

Coordinated response 106-111

Challenge 10: protecting critical infrastructure and societal

functions

112-117

Protecting infrastructure 112-115

Enhancing autonomy 116-117

Concluding remarks 118-121

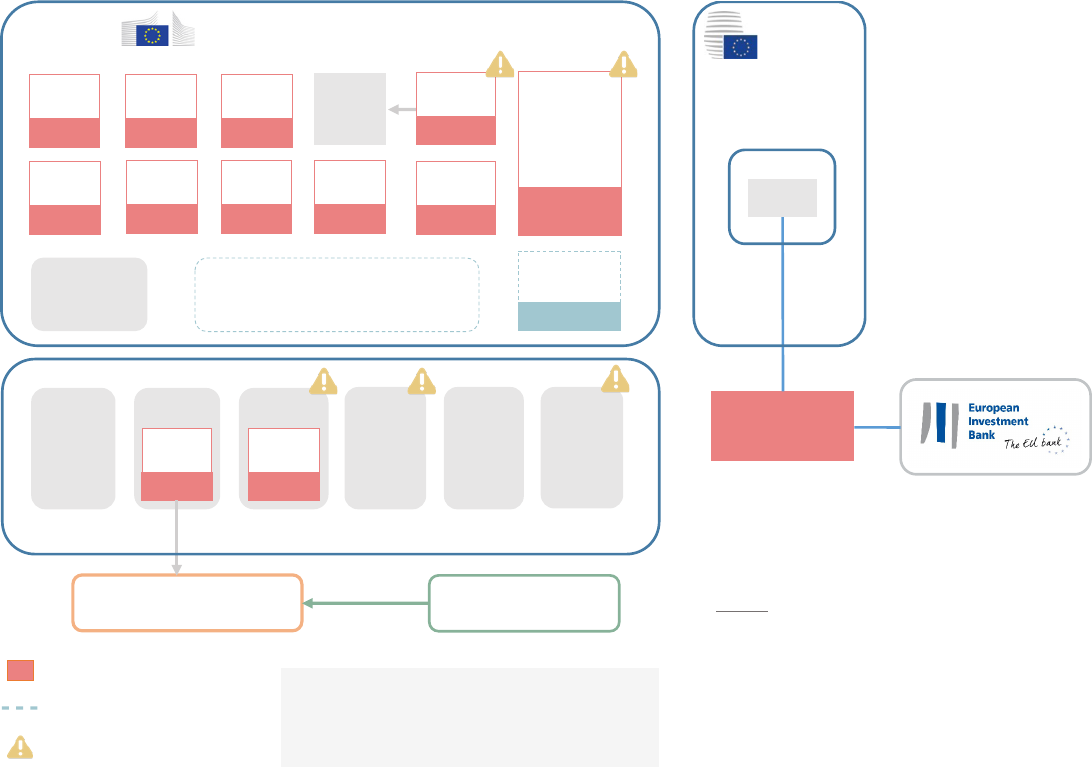

Annex I — A complex, multi-layered landscape with many actors

Annex II — EU spending on cybersecurity since 2014

Annex III — EU Member State audit office reports

Acronyms and abbreviations

Glossary

ECA team

4

Executive summary

I Technology is opening up a whole new world of opportunities, with new products

and services becoming integral parts of our daily lives. In turn, the risk of falling victim

to cybercrime or a cyberattack is increasing, the societal and economic impact of

which continues to mount. The EU’s recent drive since 2017 to accelerate efforts to

strengthen cybersecurity and its digital autonomy come therefore at a critical time.

II This briefing paper, which is not an audit report and is based on publicly available

information, aims to provide an overview of a complex and uneven policy landscape,

and to identify the main challenges to effective policy delivery. The scope of our paper

covers EU cybersecurity policy, as well as cybercrime and cyber defence, and also

encompasses efforts to combat disinformation. The challenges we identified are

grouped into four broad clusters: (i) the policy and legislative framework; (ii) funding

and spending; (iii) building cyber-resilience; and (iv) responding effectively to cyber

incidents. Each chapter includes some reflection points on the challenges presented.

The policy and legislative framework

III Developing action aligned to the EU’s cybersecurity strategy’s broad aims of

becoming the world’s safest digital environment is a challenge in the absence of

measurable objectives and scarce, reliable data. Outcomes are rarely measured and

few policy areas have been evaluated. A key challenge is therefore ensuring

meaningful accountability and evaluation by shifting towards a performance culture

with embedded evaluation practices.

IV The legislative framework remains incomplete. Gaps in, and the inconsistent

transposition of, EU law can make it difficult for legislation to reach its full potential.

Funding and spending

V Aligning investment levels with goals is challenging: this requires scaling up not

just overall investment in cybersecurity – which in the EU has been low and

fragmented– but also scaling up impact, especially in better harnessing the results of

research spending and ensuring the effective targeting and funding of start-ups.

VI Having a clear overview of EU spending is essential for the EU and its Member

States to know which gaps to close to meet their stated goals. As there is no dedicated

EU budget to fund the cybersecurity strategy, there is not a clear picture of what

money goes where.

5

VII At a time of heightened security-driven political priorities, constraints in the

adequate resourcing of the EU’s cyber-relevant agencies may prevent the EU’s

ambitions from being matched. Addressing this challenge includes finding ways of

attracting and retaining talent.

Building cyber-resilience

VIII Weaknesses in cybersecurity governance abound in the public and private

sectors across the EU as well as at the international level. This impairs the global

community’s ability to respond to and limit cyberattacks and undermines a coherent

EU-wide approach. The challenge is thus to strengthen cybersecurity governance.

IX Raising skills and awareness across all sectors and levels of society is essential,

given the growing global cybersecurity skills shortfall. There are currently limited EU-

wide standards for training, certification or cyber risk assessments.

X A foundation of trust is essential for strengthening overall cyber resilience. The

Commission itself has assessed that coordination in general is still insufficient.

Improving information exchange and coordination between the public and private

sectors remains a challenge.

Responding effectively to cyber incidents

XI Digital systems have become so complex that preventing all attacks is impossible.

Responding to this challenge is rapid detection and response. However, cybersecurity

is not yet fully integrated into existing EU-level crisis response coordination

mechanisms, potentially limiting the EU’s capacity to respond to large-scale, cross-

border cyber incidents.

XII The protection of critical infrastructure and societal functions is key. The

potential interference in electoral processes and disinformation campaigns are a

critical challenge.

XIII The current challenges posed by cyber threats facing the EU and the broader

global environment require continued commitment and an ongoing steadfast

adherence to the EU’s core values.

6

Introduction

01 Technology is opening up a whole new world of opportunities. As new products

and services take off, they become integral parts of our daily lives. However, with each

new development our technological dependence rises, and so too does the importance

of cybersecurity. The more personal data we put online and the more connected we

become, the more likely we are to fall victim to a form of cybercrime or cyberattack.

What is cybersecurity?

02 There is no standard, universally accepted definition of cybersecurity

1

. Broadly, it

is all the safeguards and measures adopted to defend information systems and their

users against unauthorised access, attack and damage to ensure the confidentiality,

integrity and availability of data.

03 Cybersecurity involves preventing, detecting, responding to and recovering from

cyber incidents. Incidents may be intended or not and range, for example, from

accidental disclosures of information, to attacks on businesses and critical

infrastructure, to the theft of personal data, and even interference in democratic

processes. These can all have wide-ranging harmful effects on individuals,

organisations and communities.

04 As a term used in EU policy circles, cybersecurity is not limited to network and

information security. It covers any unlawful activity involving the use of digital

technologies in cyberspace. This can therefore include cybercrimes like launching

computer virus attacks and non-cash payment fraud, and it can straddle the divide

between systems and content, as with the dissemination of online child sexual abuse

material. It can also cover disinformation campaigns to influence online debate and

suspected electoral interference. In addition, Europol sees a convergence between

cybercrime and terrorism

2

.

05 Different actors – including states, criminal groups and hacktivists – instigate

cyber incidents, moved by different motives. The fallout from these incidents is felt at

the national, European and even global level. However, the intangible and largely

borderless nature of the internet, and the tools and tactics used, often make it difficult

to identify an attack’s perpetrator (the so-called “attribution problem”).

7

06 The numerous types of cybersecurity threats can be classified according to what

they do to data – disclosure, modification, destruction or denied access – or the core

information security principles they violate, as shown in Figure 1 below. Some

examples of attacks are described in Box 1. As the attacks to information systems

increase in sophistication, our defence mechanisms become less effective

3

.

Figure 1 – Threat types and the security principles they put at risk

Source: ECA modified from a European Parliament study

4

. Padlock = security not impacted;

Exclamation mark = securi ty at risk

Unauthorised access

Disclosure

Modification

of Information

Destruction

Denial of service

Availability

Confidentiality Integrity

8

Box 1

Types of cyber attacks

Every time a new device comes online or connects with other devices, the so-called

cybersecurity “attack surface” increases. The exponential growth of the Internet of

Things, the cloud, big data and the digitisation of industry is accompanied by a growth

in the exposure of vulnerabilities, enabling malicious actors to target ever more

victims. The variety of attack types and their growing sophistication make it genuinely

difficult to keep pace

5

.

Malware (malicious software) is designed to harm devices or networks. It can include

viruses, trojans, ransomware, worms, adware and spyware. Ransomware encrypts

data, preventing users from accessing their files until a ransom is paid, typically in

cryptocurrency, or an action is carried out. According to Europol, ransomware attacks

dominate across the board, and the number of ransomware types has exploded over

the past few years. Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks, which make services

or resources unavailable by flooding them with more requests than they can handle,

are also on the rise, with one-third of organisations facing this type of attack in 2017

6

.

Users can be manipulated into unwittingly performing an action or disclosing

confidential information. This ruse can be used for data theft or cyberespionage, and

is known as social engineering. There are different ways to achieve this, but a

common method is phishing, where emails appearing to come from trusted sources

trick users into revealing information or clicking on links that will infect devices with

downloaded malware. More than half of Member States reported investigations into

network attacks

7

.

Perhaps the most nefarious of threat types are advanced persistent threats (APTs).

These are sophisticated attackers engaged in long-term monitoring and stealing of

data, and sometimes harbouring destructive goals as well. The aim here is to stay

under the radar without detection for as long as possible. APTs are often state-linked

and targeted at especially sensitive sectors like technology, defence, and critical

infrastructure. Cyberespionage is said to account for at least one-quarter of all cyber

incidents and the majority of costs

8

.

How serious is the problem?

07 Capturing the impact of being poorly prepared for a cyberattack is difficult due to

the lack of reliable data. The economic impact of cybercrime rose fivefold between

2013 and 2017

9

, hitting governments and companies, large and small alike. The

forecast growth in cyber insurance premiums from €3 billion in 2018 to €8.9 billion in

2020 reflects this trend.

9

08 While the financial impact of cyberattacks continues to grow, there is an alarming

disparity between the cost of launching an attack and the cost of prevention,

investigation and reparation. For example, a DDoS attack can cost as little as €15 a

month to carry out, yet the losses suffered by the targeted business, including

reputational damage, are considerably higher

10

.

09 Although 80 % of EU businesses having experienced at least one cybersecurity

incident in 2016

11

, acknowledgement of the risks is still alarmingly low. Among

companies in the EU, 69 % have no, or only a basic understanding, of their exposure to

cyber threats

12

, and 60 % have never estimated the potential financial losses

13

.

Furthermore, according to a global survey, one-third of organisations would rather pay

the hacker’s ransom than invest in information security

14

.

10 The global Wannacry ransomware and NotPetya wiper malware attacks in 2017

together affected more than 320 000 victims in around 150 countries

15

. These

incidents led to something of a global awakening of the threat posed by cyberattacks,

creating fresh momentum to bring cybersecurity into mainstream policy thinking. In

addition, 86 % of EU citizens now believe the risk of falling victim to cybercrime is

increasing

16

.

The EU’s action on cybersecurity

11 The EU became an observer organisation to the Council of Europe’s Convention

on Cybercrime Committee in 2001

17

(the Budapest Convention). Since then, the EU has

used policy, legislation and spending to improve its cyber resilience. Against a

background of an increasing number of major cyberattacks and incidents, activity has

accelerated since 2013, as Figure 2 shows. In parallel, Member States have adopted

(and in some cases already updated) their first national cybersecurity strategies.

12 The main EU actors with responsibility for cybersecurity are described in Box 2

and Annex I.

10

Box 2

Who is involved?

The European Commission aims to increase cybersecurity capabilities and

cooperation, strengthen the EU as a cybersecurity player, and mainstream it into

other EU policies. The main Directorates-General (DG) responsible for cybersecurity

policy are DGs CNECT (cybersecurity) and HOME (cybercrime), responsible for the

Digital Single Market and the Security Union respectively. DG DIGIT is responsible for

the IT security of the Commission’s own systems.

A host of EU agencies support the Commission, notably ENISA (European Union

Agency for Network and Information Security), the EU’s cybersecurity agency – a

mainly advisory body that supports policy development, capacity-building and

awareness-raising. Europol’s European Cybercrime Centre (EC3) was established to

strengthen the EU’s law enforcement response to cybercrime. A Computer

Emergency Response Team (CERT-EU), supporting all Union institutions, bodies and

agencies, is hosted by the Commission.

The European External Action Service (EEAS) leads on cyber defence, cyber

diplomacy and strategic communication, and hosts intelligence and analysis centres.

The European Defence Agency (EDA) aims to develop cyber defence capabilities.

Member States are primarily responsible for their own cybersecurity and, at the EU

level, act through the Council, which has numerous coordination and information-

sharing bodies (amongst them the Horizontal Working Party on Cyber Issues). The

European Parliament acts as co-legislator.

Private sector organisations, including industry, internet governance bodies, and

academia, are both partners and contributors to policy development and

implementation – including through a contractual public-private partnership (cPPP).

11

Figure 2 – An acceleration in policy development and legislation (as at 31 December 2018)

Source: ECA.

Key EU developments

First adoption of national

Cybersecurity Strategy

2000

2005

2010

2015

2018

2011

2012

2013

2014

2016

2017

EU Cybersecurity Strategy

EU Cyber Defence Policy F ramework

Digital Single Market

Strategy

European Agenda on

Security

EU Global Strategy

Cyber Diplomacy

Toolbox

Resilience, Deterrence and

Defence: Building strong

cybersecurity for the EU

Identification and designation of European

critical infrastructures and the assessment

of the need to improve their protection

Internet Policy and Governance

Strengthening Europe's Cyber Resilience

and F ostering a Competitive and

Innovative Cybersecurity Industry

Joint framework on

countering hybrid threats

Establishment of ENISA

Electronic communication

network and systems

Combating the sexual abuse

and sexual exploitation of

children and child pornography

Budapest Convention on Cybercrime

(Council of Europe)

Common framework for

electronic communications

networks and services

ePrivacy Directive

Update of ENISA

Regulation

Preparations for the roll-out of

smart metering systems

Attacks against Information Systems,

Directive

New ENISA

Regulation

Coordinated response to large-scale

cybersecurity incidents and crises

cPPP on Cybersecurity

NIS Directive

General D ata Protection Regulation

(GD PR)

Cybersecurity Act (ne w ma ndate for

ENISA and cybersecurity certification)

Combating fraud and counterfeiting

of non cash means of payments

2009

2008

2007

2006

Security rules for EU

classified information

Major cyberattacks and

breaches (non-exhaustive)

WannaCry

NotPetya

Red October

Stuxnet

Locky

Policy

Legislation

Equifax data breach

European Cloud Initiative

Mirai: first

IoT attack

Cyberattacks on Estonia

Yahoo data breach

‘Black Energy’: Ukraine powe r grid attacked

Proposed legislation

CryptoLocker

Operation Aurora

ZeuS

Electronic identification and trust

services Regulation

Production and Preservation Orders for

electronic evidence in criminal matters

Council Framework Decision on

attacks against information

systems (replaced 2013)

Ra ns om ware

Cyber warfare

Espionage

Data breach

Denial of service

Phishing /

Bank fraud

EU-NATO joint

declaration

(re newed 2018)

Disinformation /

influence campaign

Brexit referendum / US presidential election

German government “Informationsverbund Berlin-Bonn”

hacked

Tackling online disinformation:

a European approach

Combating fraud and

counterfeiting of non cash means

of payments (to be replaced 2018)

Establishment of EC3

Leaks

Snowden revelations of PRISM

programme

ePrivacy Regulation

Competence Centre Network and

Cybersecurity Competence Centre

EU Cyber Defence Policy Framework

(2018 upda te)

Macedonian referendum

Democratic National Committee email leak

Increasing resilience and bolstering

capabilities to address hybrid threats

European Strategy for a Better Internet

for Children

Convention

on the Protection of Children against Sexual

Ex ploitation and Sex ual Abuse (Council of

Europe)

2004

2003

2002

2001

Establishment of CERT-EU

Wiper malware

12

Policy

13 The EU’s cyber ecosystem is complex and multi-layered, cuts across an array of

internal policy areas, like justice and home affairs, the digital single market and

research policies. In external policy, cybersecurity features in diplomacy, and is

increasingly part of the EU’s emerging defence policy.

14 The cornerstone of the EU’s policy is the 2013 Cybersecurity Strategy

18

. The

Strategy aims to make the EU’s digital environment the safest in the world, while

defending fundamental values and freedoms. It has five core objectives: (i) increasing

cyber resilience; (ii) reducing cybercrime; (iii) developing cyber defence policies and

capabilities; (iv) developing industrial and technological cybersecurity resources; and

(v) establishing an international cyberspace policy aligned with core EU values.

15 The Cybersecurity Strategy interlinks with three subsequently adopted strategies:

— The European Agenda on Security’s (2015) objective is to improve law

enforcement and the judicial response to cybercrime, mainly by renewing

updating existing policies and legislation

19

. It also sets out to identify obstacles to

criminal investigations on cybercrime and enhance cyber capacity-building.

— The Digital Single Market Strategy

20

(2015) aims to create better access to digital

goods and services by creating the right conditions in which to maximise the

digital economy’s growth potential. Strengthening online security, trust and

inclusion is essential to this end.

— The 2016 Global Strategy

21

aims to boost the EU’s role in the world.

Cybersecurity forms a core pillar through a renewed commitment to cyber issues,

cooperation with key partners, and a resolve to address cyber issues across all

policy areas, including the rebuttal of disinformation through strategic

communication.

16 In recent years, as cyberspace has become increasingly militarised

22

and

weaponised

23

, it has come to be seen as the fifth domain of warfare

24

. Cyber defence

shields cyberspace systems, networks and critical infrastructure against attack by

military and other means. A Cyber Defence Policy Framework was adopted in 2014

and updated in 2018

25

. The 2018 updates identifies six priorities, including the

development of cyber defence capabilities, as well as the protection of the EU

Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) communication and information

13

networks. Cyber defence also forms part of the Permanent Structured Cooperation

Framework (PESCO) and EU-NATO cooperation.

17 The EU’s Joint Framework on countering hybrid threats (2016) tackles cyber

threats to both critical infrastructure and private users, highlighting that cyberattacks

can be carried out through disinformation campaigns on social media

26

. It also notes

the need to improve awareness and enhance cooperation between the EU and NATO,

which was given substance in the Joint EU-NATO Declarations of 2016 and 2018

27

.

18 In 2017 the Commission presented a new cybersecurity package, reflecting the

growing urgency of digital protection. This included a new Commission communication

updating the 2013 cybersecurity strategy

28

, a blueprint for a quick and coordinated

response to a major attack, and for the swift implementation of the Directive on

Security of Network and Information Systems (NIS Directive)

29

. Furthermore, the

package included a number of legislative proposals (see paragraph 22).

Legislation

19 Since 2002 legislation with varying degrees of relevance to cybersecurity has

been adopted.

20 As the main pillar of the 2013 cybersecurity strategy, the legal centrepiece is the

2016 Network and Information Security (NIS) Directive

30

, the first EU-wide legislation

on cybersecurity. The directive, which was to be transposed by May 2018, aims to

achieve a minimum level of harmonised capabilities by obliging Member States to

adopt national NIS strategies and create single points of contact and computer security

incident response teams (CSIRTs)

31

. It also sets security and notification requirements

for operators of essential services in critical sectors and digital service providers.

21 In parallel, the General Data Protection Regulation

32

(GDPR) came into force in

2016 and applied from May 2018. Its objective is to protect European citizens’

personal data by setting rules on its processing and dissemination. It grants data

subjects certain rights and places obligations on data controllers (digital service

providers) regarding the use and transfer of information. It also imposes notification

requirements in case of breach and, in some cases, can levy fines. Figure 3 illustrates

how the NIS Directive and the GDPR they complement each other in their aims to

strengthen cybersecurity and safeguard data protection.

14

22 Draft legislation currently under discussion includes the proposed Cybersecurity

Act to strengthen ENISA and establish an EU-wide certification mechanism

33

, the

proposed regulation on production and preservation orders for e-evidence

34

, and the

proposed directive on e-evidence

35

. The 2018 proposal for a European Cybersecurity

Industrial, Technology and Research Competence Centre and the Network of National

Coordination Centres (hereafter referred to as ‘network of cybersecurity competence

centres and a research competence centre’) forms part of the 2017 cybersecurity

package

36

.

23 It can be difficult to get a sense of the breadth of the policy and legislative

framework that touches on cybersecurity and how it affects our daily lives.

24 Figure 4 attempts to chart the intersection of different legislative acts and other

activities with the life of a fictitious European citizen.

15

Figure 3 – How the GDPR and the NIS Directive complement each other

Source: ECA.

General Data

Protection Regulation

(GDPR)

NIS Directive

Personal data security

Network security

Applies to any person or entity processing personal data

related to the offering of goods and services or to the

monitoring of their behaviour

Report breaches to supervisory authority

without delay

In some cases the data subjects (individuals)

need to be informed too

Operators of essential services processing information

about individuals are subject to both laws

Incident reporting to the Competent Authority by

Operators of essential services (energy,

transport, banking, health, water, digital

infrastructure)

Providers of digital services (online market

places, online search engines, cloud computing

services)

Highlights

Rights of the data subject

Obligations of data controllers

Rules for transferring personal data

Security and notification requirements apply to

operators of essential services and digital service

providers

Achievement of high level of security of network and information

systems within the Union so as to improve the functioning of the

internal market

Protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal

data and rules relating to the free movement of personal data

Scope

Targ e t

Notification

Requirements

Obligation for Member States to define:

a national strategy and to designate

competent authorities, single points of

contact and CSIRTs

Establishment of Cooperation Group

and CSIRTs Network

Penalties

Up to €20 million or 4 % of annual global turnover

Member States shall set penalties that are effective,

proportionate and dissuasive

16

Figure 4 – How the EU’s approach to cybersecurity fits into citizens’ daily lives

Source: ECA.

She has decided to spend

her summer job earnings

on a smartphone…

She signs a contract with a mobile

network operator and then goes

online via a Wi-Fi network

Later on, she downloads

a mobile banking app for

her teen current account

Unfortunately, the banking

app is not available, as the

bank is under a cyber attack

The attack is large scale and

requires coordination at EU Level

With a joined-up effort, the attack

is stopped and the crime

investigated and prosecuted

Meet Maria,

a 15

-year old school pupil

The proposal aims to increase trust through an EU-

wide cybersecurity certification and labelling scheme

for specific ICT products and services that could

foster a ‘security by design’ approach.

Proposal for the ‘Cybersecurity Act

’ Regulation (2017)

Directive 2016/1148 on Network and

Information Security (NIS Directive)

The

‘NIS Directive’ lays down measures to achieve

a high common level of security of network and

information systems within the Union, in

particular in key sectors and among digital service

providers where the maintenance of services are

vital for critical societal and economic activities.

Maria creates an account to access

the app store. She remembers the

importance of a strong password

from a Safer Internet Day at school

Safer Internet Day

This started as an EU initiative in 2004 and

is now celebrated in nearly 140 countries.

Each year this initiative aims to raise

awareness of emerging online issues of

concern and to promote the safe and

positive use of digital technology

www.saferinternetday.org

She first downloads all her favourite

social media apps in order to be in

touch with family and friends

GDPR’s aim (and that of the proposed ePrivacy

Regulation) is to provide standardised data protection

laws across the EU. This should make it easier for Maria

to understand how her data is being used and how she

can opt out or raise complaints.

The Gener al Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)

East StratCom

The ‘EU versus Disinformation’ campaign

is run by the EEAS East StratComTask

Force, which was initially set up to

challenge Russia’s

ongoing disinformation

campaigns

in March 2015.

Maria’s main source of news is through

social media. Sometimes she finds it hard

to know what is true and what is not

NIS Directive

Banking is one of the

key sectors covered by

the NIS Directive.

eIDAS Regulation

910/2014

The Regulation aims to enhance trust in

electronic transactions and sets rules for

electronic identification and trust services (like

electronic signatures, seals and timestamps, or

website authentication certificates).

To prevent unauthorised access to

her bank account, Maria uses her

token provided by a trust service

Maria needs to be ever vigilant to

protect her personal data,

including her banking details

Proposal for Directive on

combating fraud and

counterfeiting of non

-cash means of payment

Organised crime groups can trigger the

execution of payment by using payer

information obtained through phishing,

skimming or buying stolen credit card data on

the darknet. The proposal will help Member

States better deter and prosecutesuch crimes

Directive 2013/40 on attacks against

i nformation s ystems

The Directive establishes minimum rules

concerning the definition of criminal

offences and sanctions in the area of

attacks against inform ation syst ems.

The NIS Directive will require Maria’s

bank to notify the relevant national

authority of the serious cyber incident

NIS Directive

The Directive requires Member States to

establish national cybersecurity strategies,

and sets up cooperative mechanisms,

including the CSIRT (Computer Security

Incident Response Teams) Network. These

mechanisms help develop confidence and

trust to promote swift and effective

operational cooperation.

Proposal for Regulation on Production and

Pres ervation Orders for el ectronic evi dence

The proposal aims to ensure effective

investigation and prosecution of crimes by

improving cross-border access to e-evidence by

better judicial cooperation and an approximation

of rules and procedures. This would help reduce

delays and ensure access where it is currently

lacking, and improve legal certainty.

Coordinated response to large-scale

cybersecurity incidents and crises

The Commission proposed to set up an EU

Cybersecurity Crisis Response Framework

to improve political coordination and

decision-making, including how to make

use of the EU’s cyberdiplomacy ‘toolbox’

in applying sanctions to states to which a

cyber-attack is attributed.

Europol’s European Cybercrime

Centre can provide operational

support and digital forensic

expertise to Member States, and

participate in joint investigations.

Eurojust, another EU agency, was

established to improve the

handling of serious cross-border

and organised crime by

stimulating investigative and

prosecutorial co-ordination.

The key sectors covered by the

NIS Directive

are Energy, Transport, Financial market

infrastructure , Health, Drinking Water and

Digital Infrastructure

#DigitalSingleMarket

Increasing trust between

buyers and sellers of digital

products and services is an

essential component of

strengthening Europe’s Digital

Single Market

17

Constructing a policy and legislative

framework

25 The EU’s cyber ecosystem is complex and multi-layered, involving many

stakeholders (see Annex I). Bringing together all of its disparate parts is a considerable

challenge. Since 2013, there has been a concerted drive to bring coherence to the EU’s

cybersecurity field

37

.

Challenge 1: meaningful evaluation and accountability

26 Establishing a causal relationship between the 2013 strategy and any changes

seen is difficult, as the Commission has noted. The 2013 strategy’s objectives were

very broadly formulated, “expressing rather a vision than a measurable target”

38

.

Developing action aligned to these broad aims is a challenge in the absence of

measurable objectives. The updated cyber defence policy framework (2018) will aim to

develop objectives setting the minimum level of cybersecurity and trust to be

achieved. However, this will be limited to cyber defence; objectives defining the

desired level of resilience for the EU as a whole have not been set.

27 Outcomes are rarely measured and few policy areas have been evaluated

39

. This

is partly due to the recent implementation of many of the measures – legislative or

otherwise – hindering a full evaluation of their impact. The challenge is to define

meaningful assessment criteria that can help measure impact. Moreover, rigorous

evaluation has not yet become the norm for cybersecurity generally. A shift is

therefore needed towards a performance culture with embedded evaluation practices

and standardised reporting. ENISA’s current mandate does not extend to evaluating

and monitoring the state of EU cybersecurity and readiness.

28 Evidence-based policymaking depends on the availability of sufficient reliable

data and statistics to help monitor and analyse trends and needs. The absence of a

compulsory and common monitoring system makes reliable data scarce. Indicators are

often not readily available and are difficult to define

40

. Specific metrics have been

developed in some areas though, such as the EU Policy Cycle, used for tackling serious

and organised crime.

29 Few Member States regularly collect official data on cyber-related matters,

hindering comparability. The EU has given to date little indication on the need to

consolidate statistics at the European level

41

. There are also few independent EU-wide

18

analyses available covering key topics such as

42

: the economics of cybersecurity,

including behavioural aspects (misalignment of incentives, information asymmetries);

understanding the impact of cyber-failures and cybercrime; macro-statistics on cyber-

trends and expected challenges; and the best solutions to address threats.

30 In light of the absence of specific objectives and scarcity of reliable data and well-

defined indicators, assessment of the strategy’s achievements has been largely

qualitative to date. Progress reports often describe the activities carried out or

milestones achieved, without a thorough measure of results. Furthermore, baselines

for the assessment of systems’ resilience have not yet been established. In addition,

due to the lack of a codified definition of cybercrime it is nearly impossible to find

relevant European indicators that would aid monitoring and evaluation.

31 Independent oversight of the implementation of cybersecurity policy differs

between Member States. We surveyed national audit offices on their experience in

auditing this field. Half of all respondents

43

had never audited the area. For those that

had, the main focus of audits had been on: information governance; protection of

critical infrastructure; information exchange and coordination between key

stakeholders; incident preparedness, notification and response. Among the subjects

less covered were awareness-raising measures and the digital skills gap. The results of

these audits or evaluations are not always made public on the grounds of national

security. A list of published audit reports by national audit offices is included in

Annex III.

32 Limitations in cyber-related skills (see also paragraphs 82 to 90) and difficulties in

evaluating progress in cybersecurity were perceived as the main challenges to auditing

government measures in this field.

Challenge 2: addressing gaps in EU law and its uneven

transposition

33 The speed at which new technologies and threats emerge far outpaces the design

and implementation of EU legislation. The Union’s procedures were not designed with

the digital age in mind: developing innovative and flexible procedures to ensure a

policy and legal framework that is fit for purpose

44

to better anticipate and shape the

future, is a critical priority

45

.

34 Despite a drive for greater coherence, the legislative framework for cybersecurity

remains incomplete (for some examples, see Table 1). Fragmentation and gaps

19

hamper achievement of the overall policy objectives and lead to inefficiencies. Gaps

identified by the Commission in the strategy assessment included the Internet of

Things, the balance of responsibilities between users and providers of digital products,

and certain aspects left unaddressed by the NIS Directive. The proposed Cybersecurity

Act attempts to address this in part by promoting security-by-design through an EU-

wide certification scheme. Some stakeholders believe a clearly defined cyber industrial

policy and a common approach to cyberespionage are still noticeably absent

46

.

Table 1 – Gaps and uneven transposition in the legislative framework

(non-exhaustive)

Policy area

Examples

Digital Single

Market

o The present Consumer Sales Directive does not cover

cybersecurity. The proposed directives on digital content

47

and

online sales

48

aim to address this gap.

o There are limited and diverse legal frameworks for duties of care

in EU Member States, giving rise to legal uncertainty and

difficulty in enforcing legal remedies

49

.

o Policies on software vulnerability disclosures are being developed

at different speeds across Member States, with no overarching

legal framework at the EU level to enable a coordinated

approach

50

.

Strengthening

network and

information

security

o Member States are free to include sectors omitted from the NIS

Directive

51

. The accommodation industries, which are not

covered, can be a gateway for other crimes, including human and

drug trafficking and illegal immigration

52

.

Fighting

cybercrime

o Many Member States have not defined e-evidence in their

national legislation

53

(see also paragraph 22).

o The current framework decision on non-cash payment fraud does

not explicitly include non-physical payment instruments such as

virtual currencies, e-money and mobile money, nor does it cover

such acts as phishing, skimming and the possession and sharing

of payer information

54

.

o The Directive on Attacks against Information Systems does not

directly address illegal data acquisition from the inside (e.g.

cyberespionage), leading to challenges for law enforcement

55

.

o In the wake of the Court of Justice of the European Union

judgment on data retention

56

, differences in the application of

the legal framework among Member States has impeded law

enforcement, potentially resulting in the loss of investigative

leads and impairing effective prosecution of online criminal

activity

57

.

Source: ECA.

20

35 Applying some aspects of legislation remains voluntary both for national

authorities and private operators. For example, within the framework of the

Cooperation Group, evaluating the national strategies on the security of network and

information systems and the effectiveness of CSIRTs is voluntary. Also, under the

proposed certification scheme in the Cybersecurity Act, the application of certification

for ICT products and services will be voluntary.

36 In the EU, cybersecurity is a prerogative of the Member States. Despite this, the

EU has a critical role to play in creating the conditions for its Member States’ capacities

to improve, and for them to work together and generate trust. Yet given the wide

differences among the Member States in terms of capacity and engagement

58

, the

provision of sensitive (national security) information will remain voluntary.

37 The inconsistent transposition of EU law among Member States can result in legal

and operational incoherence, and prevents legislation from reaching its full potential.

For example, Member States have differing interpretations of how dual-use export

controls should be applied

59

, with the result that some EU-based companies may be

exporting technologies and services that can be used for cyber-surveillance and human

rights violations through censorship or interception. The European Parliament has

expressed concern about this

60

.

38 In addition, protecting privacy and the freedom of expression calls for a tailored

legislative response in order to strike the necessary balance between protecting

fundamental values and achieving the EU’s security imperatives. For example, how do

we ensure end-to-end encryption while finding the best way to support law

enforcement? Or how might we meet the aims of the GDPR while understanding its

implications on publicly available information on registrants of domain names and

holders of blocks of IP addresses? And how this can adversely affect law enforcement

investigations

61

?

39 Legislation alone does not guarantee resilience. While the NIS Directive’s

objective is to achieve a high level of security across the EU, it explicitly focuses on

achieving minimum, not maximum, harmonisation

62

. Gaps will continue to emerge as

the cyber-landscape evolves.

21

Reflection points – policy framework

- What critical steps are needed to prompt a shift by policy-makers and legislators

alike towards a stronger performance culture in cybersecurity, including defining

overall resilience?

- How can research better contribute to generating the necessary data and

statistics to enable meaningful evaluation?

- In what ways can the EU’s legislative processes be adapted to be more flexible

and take better account of the speed of technological and threat developments?

- How can the practice of developing metrics (indicators, targets) in the EU Policy

Cycle be adapted, scaled-up and replicated for the cybersecurity domain as a

whole?

- What can national audit offices learn from each other’s approaches to auditing

cybersecurity policies and measures?

- Which inconsistencies in the transposition and implementation of the EU legal

framework are undermining a more effective response to cybersecurity gaps and

cybercrime, and how could this be best addressed by Member States and EU

institutions?

- How effective are EU export controls on cyber goods and services in preventing

human rights abuses outside the EU?

22

Funding and spending

40 The EU has its sights set on becoming the world’s safest online environment.

Achieving this ambition requires significant efforts from all stakeholders, including a

sound and well-managed financial footing.

Challenge 3: aligning investment levels with goals

Scaling up investment

41 Total global cybersecurity spending as a percentage of GDP is estimated to be

about 0.1 %. In the United States

63

, this rises to about 0.35 % (including the private

sector). As a percentage of GDP, US federal government spending is around 0.1 %, or

around $21 billion budgeted for 2019

64

.

42 Spending in the EU has been low by comparison, fragmented and often not

backed by concerted government-led programmes. Figures are hard to come by, but

EU public spending on cybersecurity is estimated to range between one and two billion

euros per year

65

. Some Member States’ spending as a percentage of GDP is one-tenth

of US levels, or even lower

66

. The EU and its Member States need to know how much

they are investing collectively to know which gaps to close.

43 It is difficult to form a comprehensive picture in the absence of clear data owing

to cybersecurity’s cross-cutting nature and because cybersecurity and general IT

spending are often indistinguishable

67

. Our survey has confirmed that it is difficult to

obtain reliable statistics on spending in both the public and private sectors. Three-

quarters of the national audit offices reported having no centralised overview of cyber-

related government spending, and not one Member State obliged public entities to

report cybersecurity expenditure separately in their financial plans.

44 Scaling up public and private investment in Europe’s cybersecurity firms is a

particular challenge. Public capital is often available for the initial phases, but less so

for the growth and expansion stages

68

. Numerous EU funding initiatives exist but are

not being taken advantage of, largely due to red tape

69

. Overall, EU cybersecurity firms

underperform against their international peers: fewer in number, the average amount

of funding they raise is significantly lower

70

. Ensuring effective targeting and funding of

start-ups is therefore crucial to achieving the EU’s digital policy objectives.

23

Scaling up impact

45 Closing the cyber investment gap needs to yield useful outcomes. For example,

despite the strength of the EU’s research and innovation sector, results are not

sufficiently patented, commercialised or scaled up to help strengthen resilience,

competitiveness and digital autonomy

71

. This is especially the case when compared

with the EU’s global competitors. The paucity of properly harnessed results stems from

a range of factors

72

, including:

o the lack of a consistent transnational strategy to scale up the approach to fit the

EU’s wider digital needs for competiveness and increased autonomy;

o the length of the value chain cycle, which means tools soon become obsolete;

o the lack of sustainability as projects typically end with the dissolution of the

project team and a discontinuation of support, including updates and patching

solutions.

46 The Commission’s proposal to establish a network of cybersecurity competence

centres and a research competence centre is an attempt to overcome fragmentation in

the cybersecurity research field and to spur investment at scale

73

. In total, there are

some 665 centres of expertise across the EU.

Challenge 4: a clear overview of EU budget spending

47 A centralised overview of spending is important for transparency and improved

coordination. Without this, it is difficult for policymakers to see how spending aligns

with needs for meeting priority goals.

48 No dedicated budget funds the cybersecurity strategy. At the EU level,

cybersecurity spending instead comes from the EU’s general budget and Member

States’ co-funding. Our analysis reveals a complex set-up of at least ten different

instruments under the EU general budget, but no clear picture of what money goes

where (see Annex II).

49 Establishing a clear spending overview of a topic that cuts across many policy

areas is thus a sizeable challenge. Spending programmes are managed by different

parts of the Commission, each with its own goals, rules and timetables. The picture is

complicated further when factoring in Member States’ co-financing, like under the

Internal Security Fund (Police)

74

.

24

Identifiable cybersecurity spending

50 In the 2014 – 2018 period, the Commission spent at least €1.4 billion

implementing the Strategy

75

, allocating the largest share to Horizon 2020

76

(‘H2020’).

H2020’s funding is mainly channelled through the Secure Societies Challenge

programme and in Leadership in enabling and industrial technologies projects

77

. We

identified 279 contracted cybersecurity-related projects up to September 2018, with

total EU-financing of €786 million

78

. Figure 5 shows the typology of these projects

based on this analysis.

Figure 5 – H2020 contracted cybersecurity research projects (€ millions)

Source: ECA.

51 A contractual public-private partnership (cPPP) was set up in 2016 to spur on the

European cybersecurity industry. The aim was to channel €450 million from the H2020

programme into the cPPP and attract an additional €1.8 billion from the private sector

by 2020. In the 18-month period to 31 December 2017, €67.5 million was channelled

from H2020 into the cPPP and the private sector invested €1billion

79

.

52 The fight against cybercrime is also supported by the Internal Security Fund –

Police (ISF-P). The ISF-P supports studies, expert meetings, and communication

activities; these amounted to nearly €62 million between 2014 and 2017. Member

States can furthermore receive grants for equipment, training, research and data

25

collection under shared management. Nineteen Member States have taken up these

grants for €42 million.

53 Funds supporting judicial cooperation and the functioning of mutual legal

assistance treaties, with a specific focus on the exchange of electronic data and

financial information, amounted to €9 million under the Justice Programme managed

by DG JUST.

54 The NIS Directive explicitly states that the CSIRTs must have adequate resources

to effectively carry out their tasks

80

. Between 2016 and 2018, €13 million was available

annually from the Connecting Europe Facility, to which Member States could apply to

help implement the Directive’s requirements. There has been no study determining

the actual financial needs for the CSIRTs network and Cooperation Group to have an

impact.

55 Several of the agencies’ operational costs have been specifically aimed at

cybersecurity or cybercrime activities. It is difficult, however, to extract any exact

figures from the available public information.

56 The Budapest Convention (see paragraph 11) has formed the backbone for EU

external cyber spending. The EU spent around €50 million strengthening cybersecurity

beyond its borders in the 2014-2018 period. Nearly half of this was through the

Instrument contributing to Stability and Peace, with one main project – the

€13,5 million GLACY+ – aiming to strengthen capacities worldwide to develop and

implement cybercrime legislation and to increase international cooperation

81

.

Elsewhere the focus of spending by other EU financial instruments was largely on the

Western Balkans

82

, as well the European neighbourhood, for example the

Cybercrime@EaP project with the Eastern Partnership countries aims to improve

international co-operation on cybercrime and e-evidence.

Other cybersecurity spending

57 It is not always possible to identify specific cybersecurity spending within EU

programmes:

o H2020 funding has also been channelled through the Electronic Components and

Systems for European Leadership (ECSEL) joint undertaking for cyber-physical

systems. However, we were unable to determine what specifically related to

cybersecurity from among the 27 projects totalling €437 million between 2015

and 2016.

26

o Up to €400 million is available for spending on cybersecurity and trust services

under the European Structural and Investment Funds. This covers security and

data protection investments to enhance interoperability and interconnection of

digital infrastructure, electronic identification, and privacy and trust services.

58 In its 2018 operational plan, the European Investment Bank announced its

intention to increase the financing of dual-use technology, cybersecurity and civilian

security to up to €6 billion over a three-year period

83

.

Looking ahead

59 The €2 billion cybersecurity component of the proposed new Digital Europe

Programme

84

(DEP) for 2021-2027 is designed to strengthen the EU cybersecurity

industry and overall societal protection, including by aiding implementation of the NIS

Directive. The proposed network of cybersecurity competence centres and a research

competence centre, which aims to lead to a more streamlined approach, is expected

to form the main implementation mechanism for EU spending under the DEP.

60 Defence spending from the EU budget has recently increased through the

European Defence Industrial Development programme, with €500 million to be

allocated in 2019 and 2020

85

. This will focus on improving the coordination and

efficiency of Member States’ defence spending through incentives for joint

development. It aims to generate a total of €13 billion of defence capability

investment after 2020 through the European Defence Fund, some of which covers

cyber defence

86

.

Challenge 5: adequately resourcing the EU’s agencies

61 The three core bodies at the heart of the EU’s cybersecurity policy – ENISA,

Europol’s EC3, and CERT-EU (see Box 2) are facing resourcing challenges at a time of

heightened security-driven political priorities. The current allocation of human and

financial resources in the EU agencies remains a challenge for them to meet

expectations

87

.

62 The agencies’ requests for additional resources to meet rising demand have not

been fully satisfied, potentially jeopardising the (timely) meeting of policy objectives.

For example:

27

o Limited resources were a factor in preventing ENISA from fully achieving its

objectives in 2017

88

. Additional resources were proposed in the 2017 package to

match ENISA’s new mandate.

o The supply of analysts and investment in ICT capabilities at Europol EC3 have not

kept pace with demand

89

. Also, Europol EC’s Joint Cybercrime Action Taskforce (J-

CAT) is staffed by Member State and third country experts to support intelligence-

led investigations. But the costs are largely borne by the sending states,

discouraging the deployment of larger numbers of experts. A temporary, case-

basis deployment has been devised with some Europol or EU Policy Cycle funding

to permit participation by more countries.

63 Some constraints are self-inflicted. Many staff at CERT-EU and ENISA are contract

agents, the recruitment procedures for which are typically slow. Others, such as

attracting and retaining talent, stem from the agencies’ inability to compete with

private sector salaries or due to poor career progression prospects. ENISA therefore

outsourced much of its work between 2014 and 2016

90

.

64 Shortages in staff and the necessary tools can entail significant risks, especially

concerning the gathering of threat intelligence. The volume of data from open and

closed sources continues to swell and risks overwhelming analysts’ abilities to conduct

proper threat analyses. Without the right capabilities and tools in place to successfully

integrate and interconnect such data, it will not effectively translate into usable threat

intelligence that can be shared and analysed across the EU

91

.

Reflection points – Funding and spending

- In what ways can the Commission and legislators streamline EU cybersecurity

spending and more explicitly align it to clearly defined goals?

- How can the shortfalls in the resourcing of the EU agencies be addressed in an

over-arching manner taking account of the Union’s needs and goals?

- What measures are being identified at EU and Member State level to reduce

barriers to SMEs taking up investment capital to scale-up their activities?

- What concrete and sustained results are H2020 funds delivering to produce

cybersecurity solutions?

- How are EU capacity building exercises strengthening capacities beyond its

borders in line with EU values?

28

Building a cyber-resilient society

65 Cybersecurity governance deals with the management of threats and risks, the

strengthening of capacity and awareness, and coordination and information-sharing

built on a foundation of trust.

Challenge 6: strengthening governance and standards

Information security governance

66 Information security governance is about putting structures and policies in place

to ensure data confidentiality, integrity and availability. More than just a technical

issue, it requires effective leadership, robust processes, and strategies aligned with

organisational objectives

92

. A subset of this is cybersecurity governance, which deals

with all types of cyber-related threats, including targeted, sophisticated attacks,

breaches or incidents that are difficult to detect or manage.

67 Cybersecurity governance models differ between Member States, and within

them responsibility for cybersecurity is often divided among many entities. These

differences could obstruct the cooperation needed to respond to large-scale, cross-

border incidents and to exchange threat intelligence at the national – let alone the EU

– level. Our survey of national audit offices revealed that weaknesses in public

authorities’ governance arrangements and risk management were perceived as the

highest risks.

68 Although the consequences for private sector organisations can be severe,

weaknesses in cyber governance abound. Nearly nine in ten organisations say their

cybersecurity function does not fully meet their needs

93

, and cybersecurity officers are

often at least two levels removed from the board

94

.

69 The EU’s company law directives set no specific requirements on the disclosure of

cyber risks. In the United States, the Securities and Exchange Commission recently

issued non-binding guidance to assist public companies in preparing disclosures on

cybersecurity risks and incidents

95

. The Joint Committee of the European Supervisory

Authorities

96

(ESAs) warned of the increasing in cyber risks, encouraged financial

institutions to improve fragile IT systems, and to explore inherent risks to information

security, connectivity, and outsourcing

97

.

29

70 Strengthening the information security governance of SMEs is especially difficult

since, more often than not, they are unable to implement the appropriate systems.

SMEs lack suitable guidelines on applying information security and privacy

requirements and mitigating technology risks

98

. Key challenges are therefore better

understanding their needs and providing the necessary incentives and support.

71 The lack of a coherent, international cybersecurity governance framework

impairs the international community’s ability to respond to and limit cyberattacks. It is

important, therefore, to forge consensus on such a governance framework that best

reflects the EU’s interests and values

99

. Attempts to set binding international

cyberspace norms are becoming increasingly fraught, as seen in the lack of consensus

within the UN Group of Governmental Experts in 2017 on how international law should

apply to state responses to incidents.

72 To strengthen its agenda on cyberspace governance, the EU has also formalised

six cyber partnerships to establish regular policy dialogues aiming to build trust and

common areas for cooperation

100

. Outcomes are mixed; but, overall, in the

international domain, the EU cannot yet be considered a “major cybersecurity actor”

although it has raised its profile

101

.

Information security at the EU institutions

73 Each EU institution has its own information security governance rules. An inter-

institutional agreement provides for information security assistance from the

Commission for the other institutions and agencies. The EU institutions and bodies

have recognised the need to develop their cyber capacities and risk management

approaches in a coherent manner. The Commission, Council and EEAS are to present a

report in 2020 to the Horizontal Working Party on Cyber Issues on governance and the

progress made in clarifying and harmonising cybersecurity governance at the EU

institutions and agencies

102

.

74 Within the Commission, the Directorate-General for Informatics (DIGIT) is

responsible for the security of IT infrastructure and services (see Box 3). The

Commission’s Digital Strategy’s main IT security objectives are embedding IT security in

management processes; provision of (cost-) effective infrastructure and resilience;

widening the scope of incident detection and response; and integrating IT and security

governance

103

. The Commission, under its provider contract, ensures that almost all

software is actively maintained, and that only vendor-supported software is used

104

.

30

75 The importance of protecting the institutions also stretches to the EU’s CSDP

missions and structures worldwide. One of the priorities of the EU’s Cyber Defence

Policy Framework (2018 update) is to enhance the protection of CSDP communication

and information systems used by EU entities. An internal EEAS Cyber Governance

Board is now in place and met for the first time in June 2017

105

.

Box 3

Protecting the Commission’s information systems

The Commission’s roughly 1 300 systems and 50 000 devices are continuously targeted

by cyberattacks. Responsibility for IT is decentralised, as illustrated in the figure below.

Information and IT security are based on a common IT security plan set by DIGIT. The

Information Technology and Cybersecurity Board acts as the Commission’s de facto

Chief Information Security Officer and links the operational side of IT security to the

Commission’s top management, represented by the Corporate Management Board.

Source: ECA, based on Commission Decisions

106

.

DG Human Resources and Security’s (DG HR DS) main task is to protect the

Commission’s staff, information and assets. It also carries out security investigations of

incidents that have a broader security dimension than IT only, thus feeding into its

counter-intelligence and counter-terrorism activities.

LISO

Local informatics Security Officer

Corporate Management Board

DIGIT

System Owner

Data Owner

Users

HR DS

CERT-EU

Governance

Commission

Departments

Information Technology

and

Cybersecurity

Board

Advise / Consult

Security Instructions

Responsible for

security of data sets

Responsible for IT risks;

Ensures compliance with

IT security policy

Report on major incidents

Inform on incidents; cooperate

In charge of

Commission

information, IT security

inspections,

outsourcing framework

Information on security

threats; security standards

Propose standards

and strategy; reports

on execution

Ensure efficient use of IT

resources and investments;

oversees implementation of

Commission Digital Strategy;

Monitor IT risk

threat

landscape; define

IT security

strategy

Liaise

Ultimate accountability for IT

security; implement IT

security plan

Develop standards, assess

risks, support LISO

Involved when

other EU bodies

might be impacted

Notify about risks or exceptions

Preparedness, BAU

Incident Response

Legend

DIGIT is first incident

responder, HR DS takes

over if wider security

dimension concerned

Annual IT

security risk

report (2019+)

31

DIGIT is responsible for IT security and hosts CERT-EU (Computer Emergency Response

Team). Established in 2011, CERT-EU runs on an annual budget of about €2.5 million per

year and has about 30 staff. It is the first responder in any information security incident

that concerns several institutions yet does not operate on a 24/7 basis. It hosts an

information-sharing platform. In 2018, CERT-EU signed a non-binding memorandum of

understanding with ENISA, EC3 and the European Defence Agency to strengthen

cooperation and coordination. It also has a technical agreement with NATO’s computer

incident response capability (NCIRC).

Threat and risk assessments

76 Well-founded and continuous threat and risk assessments are important tools for

public and private organisations alike. However, there is no standard approach to

classifying and mapping cyber threats or to risk assessments, meaning assessments’

content varies considerably, posing a challenge to a coherent EU-wide approach to

cybersecurity

107

. Furthermore, they often rely on the same sources or even other

threat assessments, resulting in an echo chamber resounding with repeat findings

108

,

at the risk of paying insufficient attention to other threats. This is exacerbated by a

continued reluctance to share information and under-reporting of incidents.

77 The Hybrid Fusion Cell

109

embedded within the EEAS was established to improve

situational awareness and support decision-making through analysis-sharing but needs

to broaden its expertise, including in cybersecurity. In parallel, CERT-EU provides EU

institutions, bodies and agencies with reports and briefings regarding cyber threats

targeted at them.

78 ENISA has noted in the past that many Member States have a qualitative

understanding of threats and that there is a need for more cyber-threat modelling

110

.

Monitoring capacity for strategic analysis will strengthen overall understanding.

However, threat assessments could cover not only technological threats, but also

socio-political and economic threats to ensure a more comprehensive picture, as well

as threat drivers and actors’ motives.

Incentives

79 There are still too few legal and economic incentives for organisations to notify

and share information about incidents. Fearing reputational damage, many

organisations still prefer to handle cyberattacks discretely or to pay off the

perpetrators. It remains to be seen how effectively the NIS Directive will be in raising

32

the level of notifications. The Commission expects improvements to materialise

primarily at the national level, but the Cybersecurity Act will add an EU-wide view.

111

80 By embedding certain standards in its procurement, public authorities have

significant leverage over suppliers as buyers of digital products and services through

public procurement, and research and programme funding (for example, by requiring

the adoption of certain technical standards like Internet Protocol IPv6 to help in the

fight against cybercrime). Currently, though, there is no joint procurement framework

for cybersecurity infrastructure

112

. There is much that the Commission can do in this

regard. The proposed DEP for the next multiannual financial framework aims to

address the hitherto limited public sector investment in purchasing the latest

cybersecurity technology.

81 Through its regulatory capacity, the Commission can ensure that the right

standards are developed for widespread adoption to enhance security. The

Commission and Europol work with internet governance bodies like ICANN (see

paragraph 38) and RIPE-NCC

113

, which is essential to putting the right cybercrime

architecture in place to support law enforcement and the judicial authorities.

Challenge 7: raising skills and awareness

82 ENISA has pointed out that users play a critical role against cyberattacks and that

strengthening skills, education and awareness is key to building a cyber-resilient

society

114

. Individuals, at work or at home, who are well-versed in spotting the warning

signs and armed with the right techniques can slow down or prevent attacks.

83 Of particular concern is the growing asymmetry between the know-how needed

to commit a cybercrime or launch a cyberattack, and the skills needed to defend

against it. The crime-as-a-service model has lowered the barriers of entry to the

cybercriminal market: individuals without the technical knowledge to build them can

now rent botnets, exploit kits or ransomware packages.

Training, skills and capacity development

84 The world faces a growing cybersecurity skills shortfall; the workforce gap has

widened by 20 % since 2015

115

. Traditional recruitment channels are not meeting

demand, including for managerial and interdisciplinary positions

116

. Nearly 90 % of the

global cybersecurity workforce is male; the persistent lack of gender diversity restricts

33

the talent pool further

117

. Moreover, at universities, cyber-related subjects are under-

represented on non-technical programmes.

85 Training and education is needed across the board, among civil servants, law

enforcement officers, judicial authorities, the armed forces and educators. For

example, the judicial courts need to be able to deal with the fast-changing technical

particularities of cybercrime and its victims

118

; there are currently no EU-wide

standards for training and certification

119

. At the EU institutions, getting the right skills

mix is important. Without the right skills mix in place, the institutions may be unable to

properly define scope, identify the right partners and security needs, or lack the

capacity to manage programmes. This in turn may undermine the effectiveness of EU

programmes or policy development.

86 While Member States are responsible for education policies at the EU level,

numerous training activities (see Table 2) and exercises (see Box 4) are already taking

place. The EU can help work EU-wide standards into the learning curricula across all

relevant disciplines

120

. In the area of digital forensics, for example, common training

standards are necessary to facilitate the path to evidence admissibility in Member

States. Due to the cross-border nature of cybercrime multiple jurisdictions can be

involved, which requires training at the EU level. And yet, CEPOL, the EU’s law

enforcement training agency, has noted that more than two-thirds of Member States

do not provide regular cyber training to law enforcement officials

121

. The EU can also

potentially identify ways to synergise education and training between the civilian and

military spheres

122

. That said, ENISA has found that while current training

opportunities in critical sectors are extensive, they do not sufficiently target the

resilience of critical infrastructure

123

.

Table 2 – Some of the EU’s cyber-related training initiatives

European Defence Agency projects,

e.g. exercise s upport by the private

sector and the Cyber Ranges

project

European Security and Defence

College network (providing civilian-

military training), including Cyber

Education, Training Exercise and

Evaluation Platform

ENISA training, offering training

programmes where the

commercial market may fail to

provide them

Europol, CEPOL, ECTEG

124

tra i ning

progra mmes – i ncluding the