This classic chest

offers a lesson

in efficient

woodworking

BY CHRIS GOCHNOUR

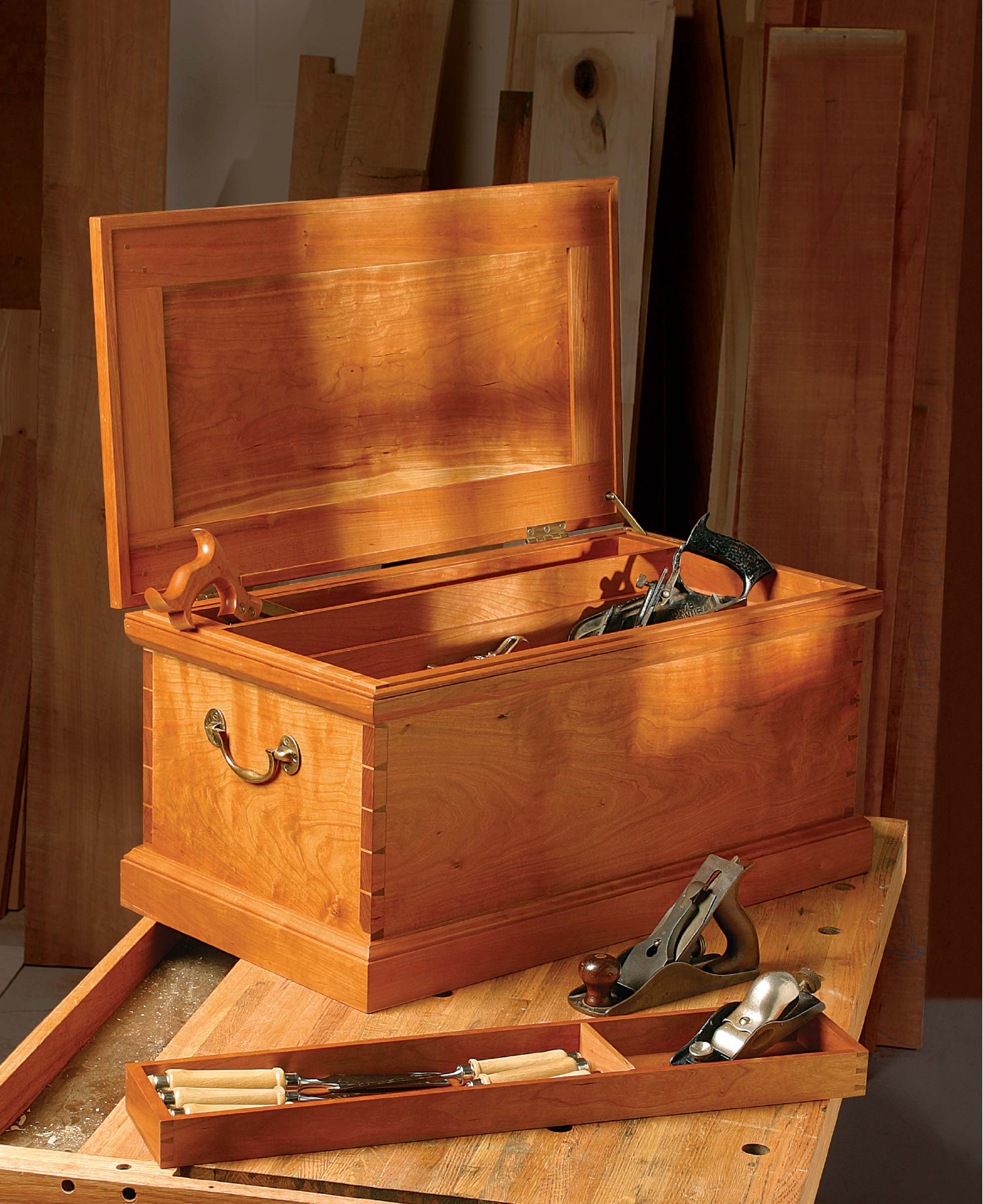

Heirloom Tool Chest

MARCH/APRIL 2004 37Photos, except where noted: Matt Berger; facing page: Michael Pekovich; drawings: Bob La Pointe

cabinetmaker’s tool chest embodies a certain nostalgia and

charm for modern woodworkers. It speaks of a time when

craftsmen had few tools but an abundance of skill. Tool

chests often served as a calling card to display a craftsman’s talents.

However, some were utilitarian, built simply to house tools.

The tool chest described in this article is of the latter kind—prac-

tical, enduring, and simple. But in a time when woodworkers have

an abundance of power tools at every turn, making this tool chest

with traditional hand-tool techniques can be a bridge to an era

past. I recommend using this project as a hand-tool exercise,

though power tools could be substituted for any of the operations.

Practicing the techniques involved in the chest’s construction will

make you more confident with hand tools, and you may find them

an indispensable resource in your day-to-day shop tasks.

Choose and mark the material

Select a medium-density hardwood that is worked easily with

hand tools. Because the tool chest is intended to be carried,

A

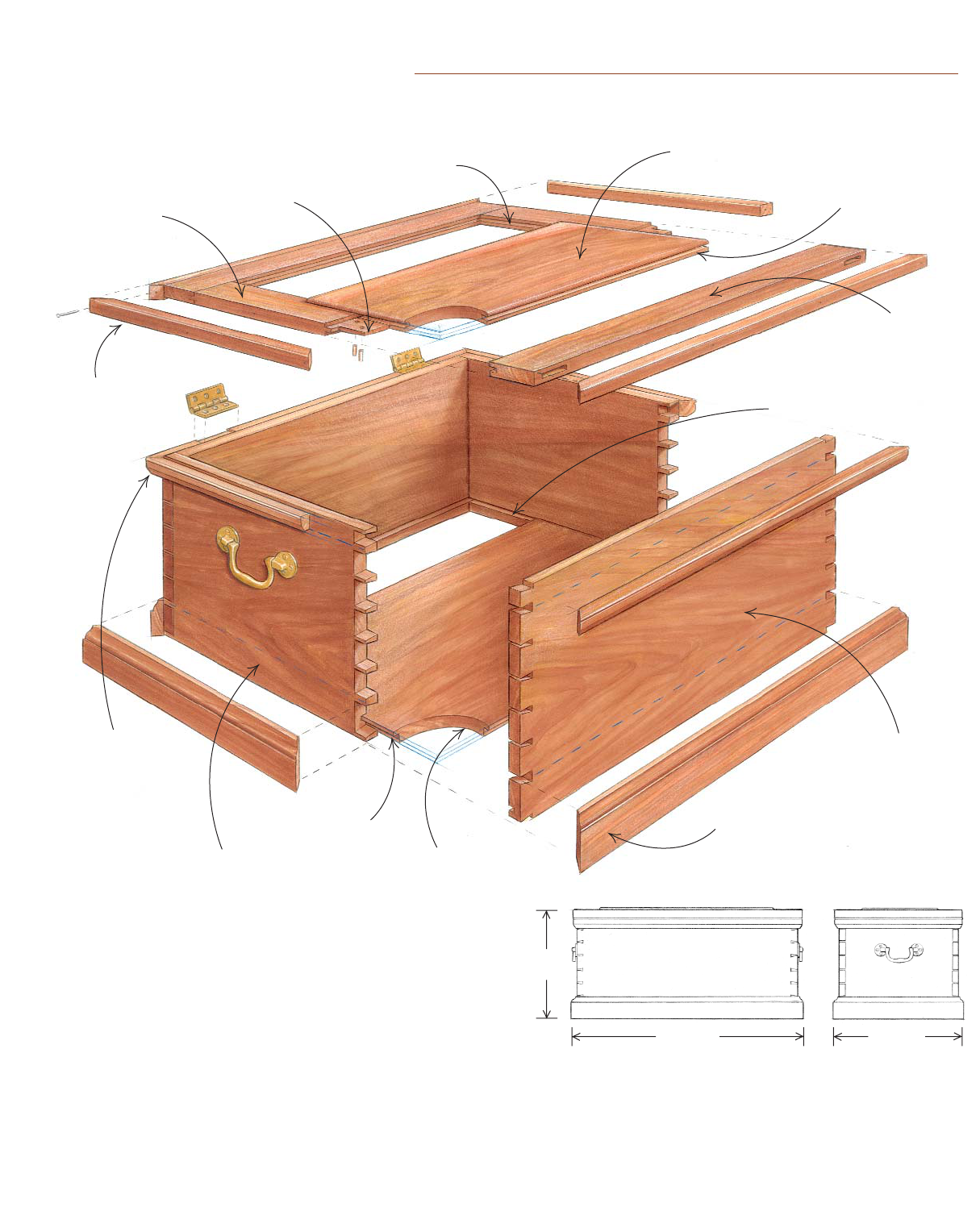

A COMFORTABLE HOME FOR TOOLS

Made of cherry and constructed entirely with hand tools, the tool chest incorporates

dovetail joinery, frame-and-panel construction, and applied molding.

Front and back,

3

⁄4 in. thick by

13 in. wide by

28 in. long

Groove,

3

⁄8 in. deep by

3

⁄8 in. wide, located

1

⁄2 in.

from the bottom edge

Sides,

3

⁄4 in.

thick by 13 in.

wide by 15 in.

long

Bottom panel,

3

⁄4 in. thick by

14 in. wide by

27

1

⁄4 in. long

Tongue,

3

⁄8 in. wide

by

3

⁄8 in.

long

Lid stiles,

3

⁄4 in. thick

by 2

1

⁄2 in. wide by

28

1

⁄8 in. long

Groove,

3

⁄8 in.

deep by

1

⁄4 in.

wide, centered

in thickness

Lid rails,

3

⁄4 in. thick

by 2

1

⁄2 in.

wide by

15

1

⁄8 in.

long

Haunched through-

tenons,

1

⁄4 in. thick

by 1

3

⁄4 in. wide by

2

1

⁄2 in. long

Lid panel,

7

⁄8 in.

thick by 10

5

⁄8 in.

wide by 23

5

⁄8 in. long

Groove,

3

⁄8 in. deep

by

1

⁄4 in. wide,

1

⁄4 in. from the

bottom edge

Base molding,

3

⁄4 in.

thick by 2

5

⁄8 in. wide,

with ogee profile

along top edge

Top molding,

3

⁄4 in. thick by

1

1

⁄4 in. high,

with

3

⁄16-in.-

radius bead

along top

edge and

1

⁄2-in.-wide

chamfer

along bottom

Lid molding,

11

⁄16 in. thick

by

7

⁄8 in. high

29

1

⁄2 in.

16

1

⁄2 in.

14 in.

38 FINE WOODWORKING

choose wood that is lightweight yet durable. For this box I chose

cherry, which is easy to work and attractive; however, woods such

as red alder, poplar, and white pine also are appropriate.

To reduce the likelihood of warp and twist, select clear, straight-

grained wood for the lid frame. This type of wood also is good for

the moldings because it will make them easier to work with mold-

ing planes. Knots are fine on panels, but keep them away from the

edges so that they will be out of the way of the joinery.

Once you’ve dimensioned the lumber for each part, mark them

with cabinetmaker’s triangles (see FWW #149, p. 90, 92). These tri-

angles clearly identify the face and the inside and outside edges of

each part. And they are helpful for identifying the orientation of

the pieces when you begin cutting joints.

From here, follow a sequential pattern of construction: Join the

box using dovetails; build the frame-and-panel lid with mortise-

and-tenon joinery; shape and apply moldings; and install the

hardware.

Practice and plan the carcase dovetails

I tell students that making dovetails is easy, but

controlling a handsaw can be difficult. Get

comfortable using a handsaw before you un-

dertake the dovetails, and practice dovetail-like

cuts on scraps of wood to improve your skill.

Clear and accurate layout is essential to

hand-cutting dovetails. Much of your success

will come down to your layout and your ability

to work to the lines and never cut beyond,

which comes with practice. The objective is to

cut precisely to the layout lines each step of the

way. This will greatly minimize cleanup and fit-

ting, making the entire process more efficient

and enjoyable.

Cut the tails two boards at a time—I cut the

tails first and then use them to lay out the pins.

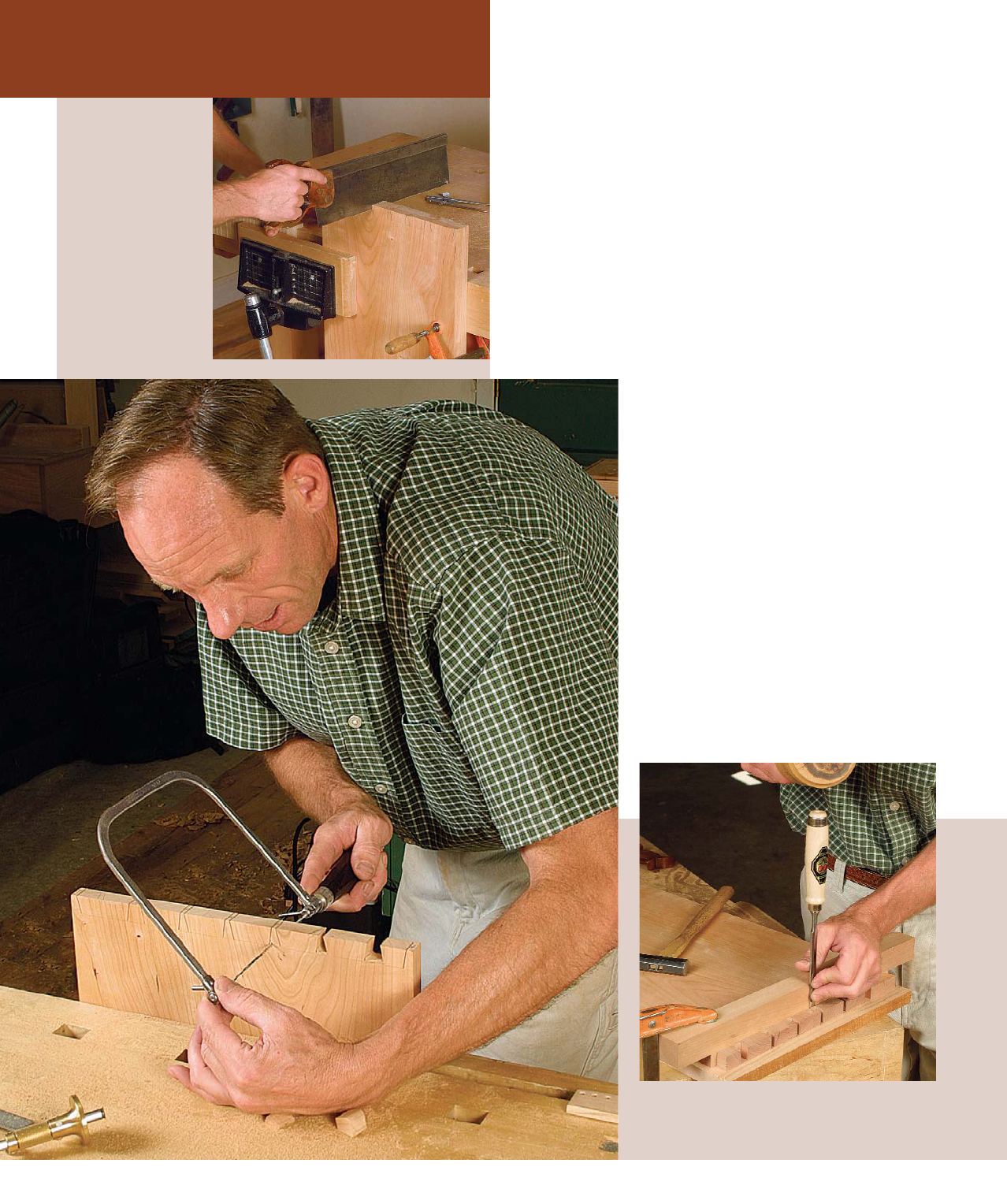

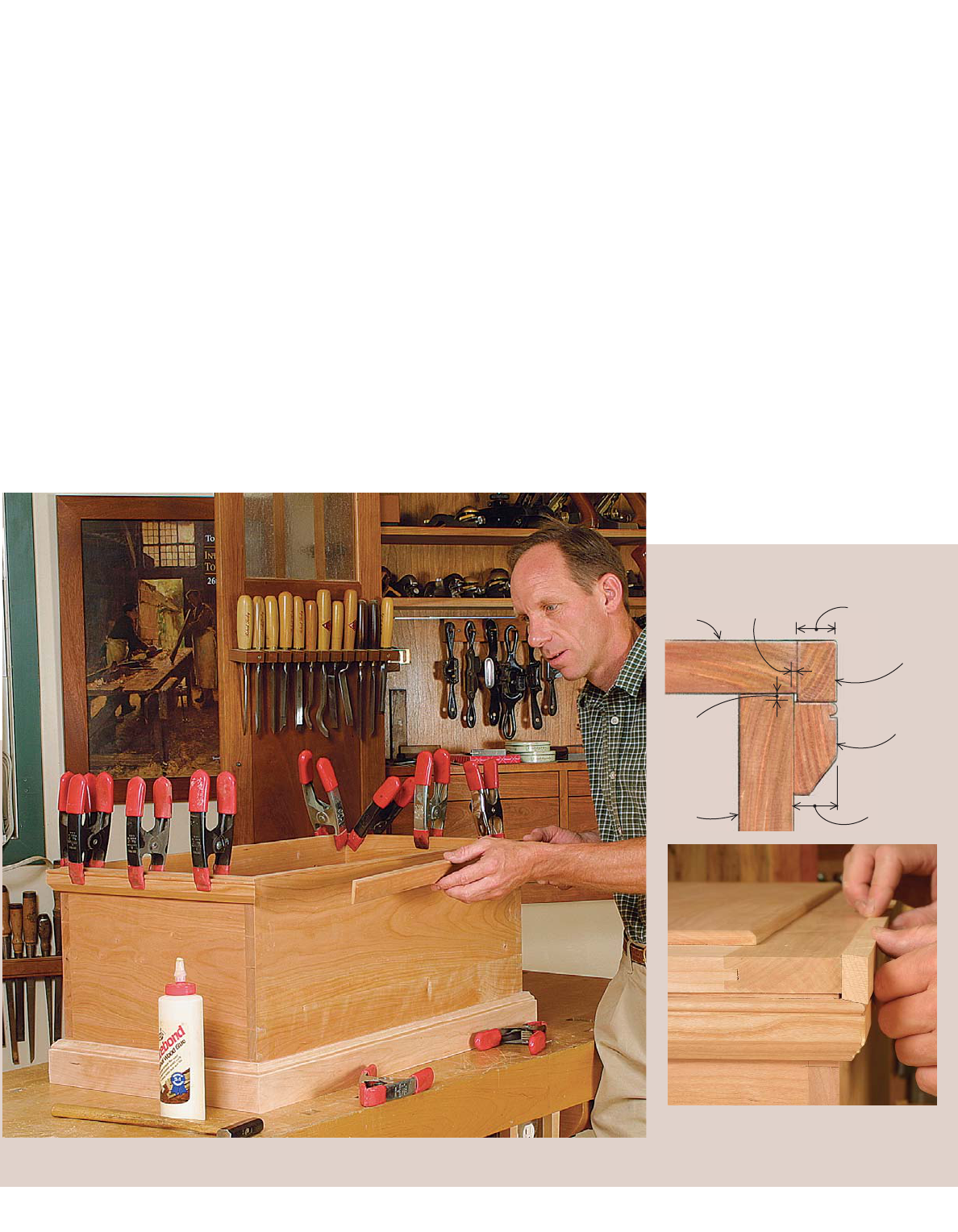

DOVETAIL AND ASSEMBLE THE CASE

Cut the tails. Clamp

both the front and

back of the chest in a

vise with the inside

faces touching (right).

Make the cuts with a

backsaw. Next, clean

out the waste one

board at a time with a

coping saw (below).

Make sure you do

not cut past the

scribe line.

Chop to the baseline with a chisel. Use a block

of wood, securely clamped along the scribe line, to

guide the chisel. Chop partway from both sides of

the board to avoid tearout.

MARCH/APRIL 2004 39

I also cut the tails on the front and back of the chest at the same

time with the two boards clamped together in a vise. It is faster and

more accurate because the saw has a longer line to follow as you

make the perpendicular cut along the end grain. Check your cab-

inetmaker’s triangles to see whether you have oriented the boards

correctly; the inside faces of the boards should be touching.

Next, remove the bulk of the waste with a coping saw one board

at a time. Finally, chop to the baseline with a chisel. This is a critical

step for the dovetails to fit together snug. One method I use is to

guide the chisel with a block of wood clamped in place along the

baseline. Chop halfway through from each side to avoid tearout.

Cut the pins to match the tails—The tails on the chest’s front

and back boards are used to lay out the pins. With one

board secured vertically in the bench vise, place the ad-

joining tail board on top, carefully aligned, and secure it

with a clamp.

Once again, make sure the box parts are oriented cor-

rectly, then define the pins on the end grain by tracing the

tails with a marking knife. Next, deepen the marks using

a broad chisel with its bevel facing the waste. This chisel

mark will help guide your saw. Continue the layout line

down the face of the board with a sharp pencil, stopping

at the scribed shoulder line.

The pins are cut much the same as the tails; however,

it is more critical here to cut to the line and not past it.

With the saw resting to the inside of your chisel mark,

make the vertical cuts down the waste side of the pins.

Next, remove the bulk of the waste with a coping saw

and pare to the baseline with a chisel.

Cut the bottom panel

The bottom panel of the chest must be sized and fitted

prior to glue-up. The panel floats in a groove plowed

on the inside of the sides, front, and back of the chest

carcase. Use a mortise gauge to scribe two lines

3

⁄8 in.

apart, about

1

⁄2 in. from the bottom. Now plow the groove with a

plow plane. The scored lines from the mortise gauge ensure

a clean cut.

The chest bottom is rabbeted, leaving a

3

⁄8-in. by

3

⁄8-in. tongue that

will be housed in the groove. Define the rabbet with two scribe

lines, then remove the material between these lines with a fillister

plane. Remember, the chest’s bottom panel should be free to

shrink and expand in the groove. Make sure it is slightly undersize,

and don’t glue it during assembly.

Glue up the chest carcase

Dry-fit the carcase prior to assembly to ensure that all of the

dovetails fit properly and that the bottom panel has room to

Mark the pins with the tails as your guide. With the tail

board clamped firmly in place, trace the tails onto the end

grain of the pin board with a marking knife. Deepen the marks

with a chisel to provide a kerf for the handsaw.

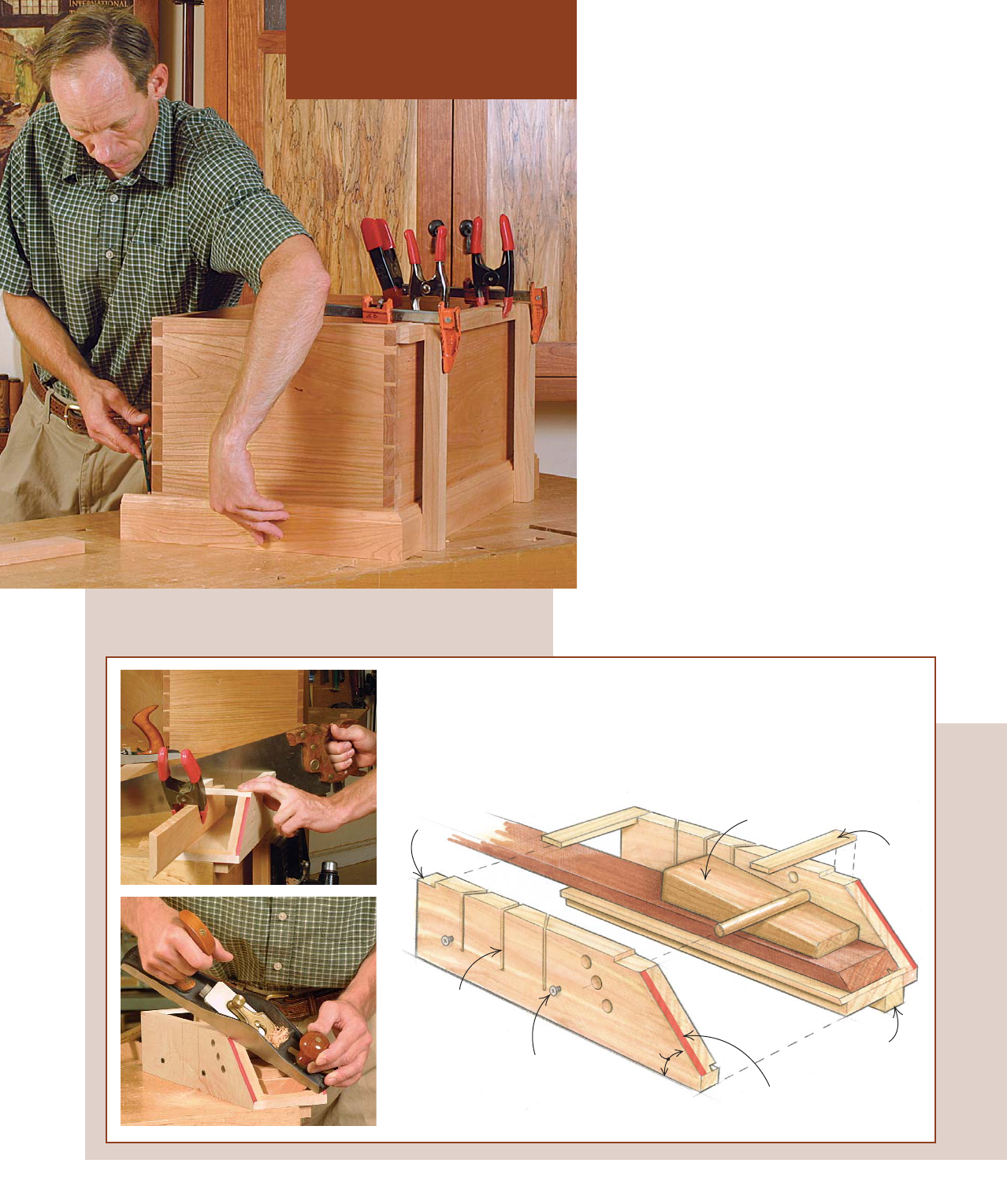

Glue up the carcase. After dry-fitting all of the pieces, coat the dovetail joints

with slow-setting wood glue and assemble. The rabbeted bottom panel floats in

the grooves plowed into the four sides. No glue is used.

40 FINE WOODWORKING

move. I’ve found that the glue-up can take some

time, so an extra pair of hands and slower-setting

glue can be helpful.

I prepared notched cauls that fit around the dovetail

pins to spread the clamp pressure evenly without get-

ting in the way of the joinery. Four clamps evenly

spaced are adequate for each side. Make sure the

chest is glued up squarely, and readjust your clamps

to correct any sides that are out of square.

Once the glue has dried, plane the dovetails clean

and flush, and turn your attention to the chest’s lid.

Through-tenons make a sturdy

frame-and-panel lid

For the lid’s frame, I used through mortise-and-

tenons. Through-tenons make the lid stronger be-

cause they provide more glue surface, and the strong,

long grain of the rails passes all the way through the

weak cross-grain of the stiles. In this way, the tenon

serves as a reinforcing cross-ply to the outside edge of

the lid. Through-tenons also minimize the chance of

twist in the frame. Because the mortises are chiseled

out from both sides at the same point, it is impossible

for the tenon to come through on an angle. Also,

chopping all the way through the stile is faster be-

cause you don’t have to clean the bottom of the mor-

tise, a difficult task.

The lid should be

1

⁄16 in. larger than the box on all

sides to provide clearance for the applied moldings.

Size your stiles and rails taking this into account. Also,

overcut the stiles by 2 in. to account for horns, which

A VERSATILE MITERING JIG

This simple maple jig works as a miter box, accommodating a panel saw in three

positions for cutting at 90° or 45° in either direction, and doubles as a miter jack. One

end is cut at 45° and is designed for fine-tuning miters with a bench plane. Once you

have sawn the miter, secure the workpiece in the shooting end of the jig with a cross

pin and wedge, and trim it to perfection.

Cut the front molding to size first. Once the front molding has been

fitted and clamped to the carcase, measure and cut the side moldings to

fit. The back piece is cut and fitted last.

APPLY THE MOLDINGS

Tips of screws help

secure a workpiece

during miter cuts.

Sawkerfs set

to cut 90° or

45° in either

direction

Removable dowel,

1

⁄2 in.

dia., and wedge secure

the workpiece for planing.

45°

Clamping rail fits

in a bench vise.

Body,

3

⁄4-in.-

thick maple

Brace,

1

⁄4 in. by

3

⁄4 in.

Color the miter-jack surface.

If it begins to fade, it means

the surface is no longer true.

MARCH/APRIL 2004 41

add strength to the material when cutting the mortises. The horns

are trimmed off after the lid has been assembled.

One setting on a mortise gauge is used throughout—On the

inside edge of the stiles, mark each end where the rails will inter-

sect the stiles. Then measure

3

⁄8 in. from these lines and draw two

more marks to define the width of the mortises. Because it is a

through-mortise, the lines also must be transferred across the face

to the outer edge of the stile.

Set up your mortise gauge precisely to mark the groove for the

lid panel as well as the mortises and tenons. Scribe all of these lines

referencing off the face of the boards. Last, lay out the tenon

cheeks, haunch, and shoulders with a marking knife.

Rough-cut the haunched tenons and then chop out the

mortises—Once the lines have been marked, begin rough-cutting

the tenons. Cut close to the lines, but leave material for final fitting

later. Then plow the groove on the inside edge of all of the stiles

and rails. Be sure to reference these plow cuts off the same face of

each part, guaranteeing a consistent alignment of the groove.

Finally, chisel the mortises. The key to successful mortising is to

use the right chisel—one with a thick blade to keep the chisel from

twisting and a long bevel to take a shearing cut. Clamp together the

two stiles in a wooden hand screw with the grooves facing up.

Clamping the boards will prevent them from splitting as you chisel

away the waste. Work your way through half the width of the stile

on all four mortises. Then flip over the stiles and finish chopping

from the other side. When you are all the way through, clear out the

debris and use a paring chisel to clean up any irregularities, ensuring

the mortise is straight and true on all four sides.

Once the mortises have been completed, fit the tenons. I used a

paring chisel or shoulder plane to fine-tune the shoulder and a

router plane set to the depth of the layout lines to fine-tune the fit

of the tenons. Dry-assemble the frame, and use this as one more

chance to get an accurate measurement for the panel.

Plow a groove in the panel and assemble—The panel should

be sized to fit into the groove with some extra room to accommo-

date expansion and contraction with humidity changes. Locate

and scribe a groove with the same setting on the mortise gauge as

used for the frame. However, this time register off the bottom side

of the panel. Then plow the groove on all four sides.

Next, shape a thumbnail molding on the

panel with a block plane. Before applying

glue, dry-fit the frame and panel to make

Glue the top molding. Later, after the hardware has been installed, nail the molding with fin-

ish nails to add additional holding power.

OFFSET THE MOLDINGS

TO CREATE A LIPPED LID

Lid

1

⁄8-in.

overhang

1

⁄16-in. gap

11

⁄16 in.

3

⁄4 in.

Case

side

Lid

molding

Top

molding

The lid molding masks minor warp or

twist in the frame-and-panel. Set the lid

on the box and apply the molding so that it

rests on the edge of the carcase molding.

42 FINE WOODWORKING

MAKE AND HANG TOOL TRAYS

Handplane tray,

3 in. deep by 5

1

⁄2 in. wide

by 26

1

⁄2 in. long, slides

along the cleat rabbet.

Handsaw box is

notched to fit over

the cleat.

Bottom panel,

1

⁄4 in.

thick, is glued flush to

the tray’s underside.

Chisel tray, 1

3

⁄4 in. deep by

5

1

⁄2 in. wide by 26

1

⁄2 in.

long, slides along the top

of the cleat.

Handsaw box, 6 in. deep

by 3

1

⁄2 in. wide by 26

1

⁄2 in.

long

Spacing of interior

dividers,

1

⁄4 in. thick, is

determined by the size

of the tools to be stored.

The interior tool trays slide along cleats attached

to the carcase sides. The sides and bottoms of

the trays are

1

⁄4 in. thick. The ends of the small

trays are

1

⁄2 in. thick. The ends of the saw box are

3

⁄4 in. thick and notched to fit the cleat.

Cleat

Saw box

Rabbets,

1

⁄4 in. deep

CLEAT DETAIL

1

⁄2 in.

1

⁄4 in.

3

⁄4 in.

4 in.

3 in.

1 in.

Trays slide on cleats inside

the chest. Nail the cleats to

the inside of the chest so that

the trays slide front to back.

The two shallow trays should

have enough clearance to

slide past each other.

Cleat,

1

⁄2 in. thick

(at its thickest)

by 4 in. wide by

13

1

⁄2 in. long

MARCH/APRIL 2004 43

sure all of the parts go together well. After gluing up the frame-

and-panel lid, trim off the horns and check that the lid is square to

the box and slightly oversize.

Top off the chest with molding

The molding on the tool chest is not only attractive, but it also

serves practical purposes. Along the bottom it provides a bumper

to protect the box as it is toted from place to place. On the top,

the molding seals the chest interior, keeping it relatively free

from dust and humidity.

I enjoy shaping and applying the molding because I love work-

ing with molding planes, and I like seeing the box begin to take

on its final form. Molding planes are simple tools, with only a con-

toured wooden body and a steel blade. They don’t require elec-

tricity like a router does, and the only noise they make is the sweet

sound of wood being sheared from a board edge in long, contin-

uous shavings. I enjoy the slight physical workout involved when

using molding planes and the satisfaction of seeing the molding

emerge from the board edge. The whole process takes me back to

a time when there was nothing between the board and the crafts-

man but a well-tuned tool.

I milled the base molding using a molding plane with an ogee

profile. A cove, quarter-round, or simple bevel profile would suit

the chest just as well. I shaped the molding for the upper portion

of the chest with

3

⁄16-in. beading on its top edge and a bevel on the

bottom. The band of moldings for the lid is shaped with

1

⁄8-in.

roundover, but only after it has been applied to the lid frame.

Begin by cutting miters on the front base

molding until the piece fits the carcase. Then

work your way around the chest measuring

and cutting the side pieces and finally the rear

section. Carefully fit each miter joint as you

move around the chest. I used a miter jack for

this (p. 40). Apply the moldings first with glue

and clamps, and then secure them later with

finish nails, being careful not to put nails

where the hinges and lid stay will be installed. Follow this series of

steps to install the lid and the lid moldings.

Build the sliding trays to fit

Because this tool chest is such a personal item, the inner tray sys-

tem can be personalized, too. I designed mine with three remov-

able sliding trays, which hold saws, chisels, handplanes, and a host

of other hand tools. The tray boxes are dovetailed, and the bottom

of each tray is glued flush in place. Two stepped cleats tacked on-

to the inner sides of the chest support the trays, allowing them

to slide forward and backward on different planes.

Install hardware and finish

Finish off the tool chest by installing the brass hardware, which

consists of two 90° stopped handles, two mortised hinges, and a lid

stay (Whitechapel Ltd.; 800-468-5534). The hinges are screwed on-

to the molding, which is why it’s a good idea to reinforce the mold-

ing with a few finish nails once the hardware has been installed.

I finished the chest with three coats of Tried and True oil/varnish

blend applied over several days, scuff-sanding between coats. Tool

chests often get abused, so I avoid built-up finishes such as shellac

or lacquer, which are prone to scratching and scuffing. But paint-

ing the chest would not be out of character with traditional tool

chests. Use a flat acrylic latex paint, which imparts a look similar to

milk paint, and top it off with a thin shellac topcoat.

Chris Gochnour makes custom furniture in Salt Lake City, Utah.

Dovetailed trays hold hand tools. The three

trays are sized specifically to hold Gochnour’s

chisels, planes, saws, and various other hand

tools. The sides are dovetailed, and the bottom

panels are glued flush to the trays.