EXECUTIVE BOARD

EB148/7

148th session

13 January 2021

Provisional agenda item 6

Political declaration of the third high-level meeting

of the General Assembly on the prevention and

control of non-communicable diseases

Report by the Director-General

1. The report is submitted in response to decision WHA72(11) (2019), in which the Health Assembly

requests the Director-General “to consolidate reporting on the progress achieved in the prevention and

control of noncommunicable diseases and the promotion of mental health with an annual report to be

submitted to the Health Assembly through the Executive Board, from 2021 to 2031, annexing reports

on implementation of relevant resolutions, action plans and strategies, in line with existing reporting

mandates and timelines.” Table 1 sets out the corresponding elements of this report.

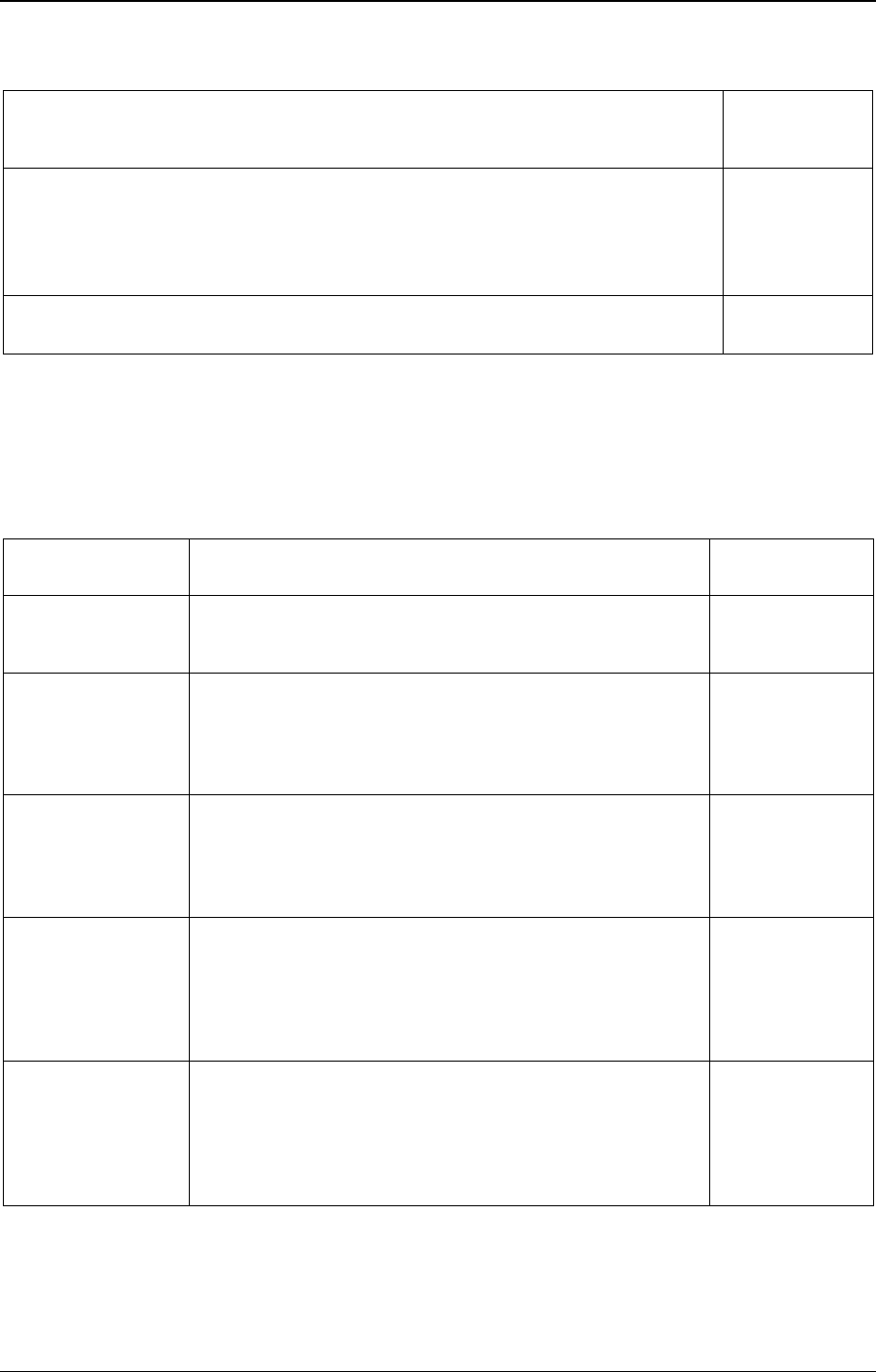

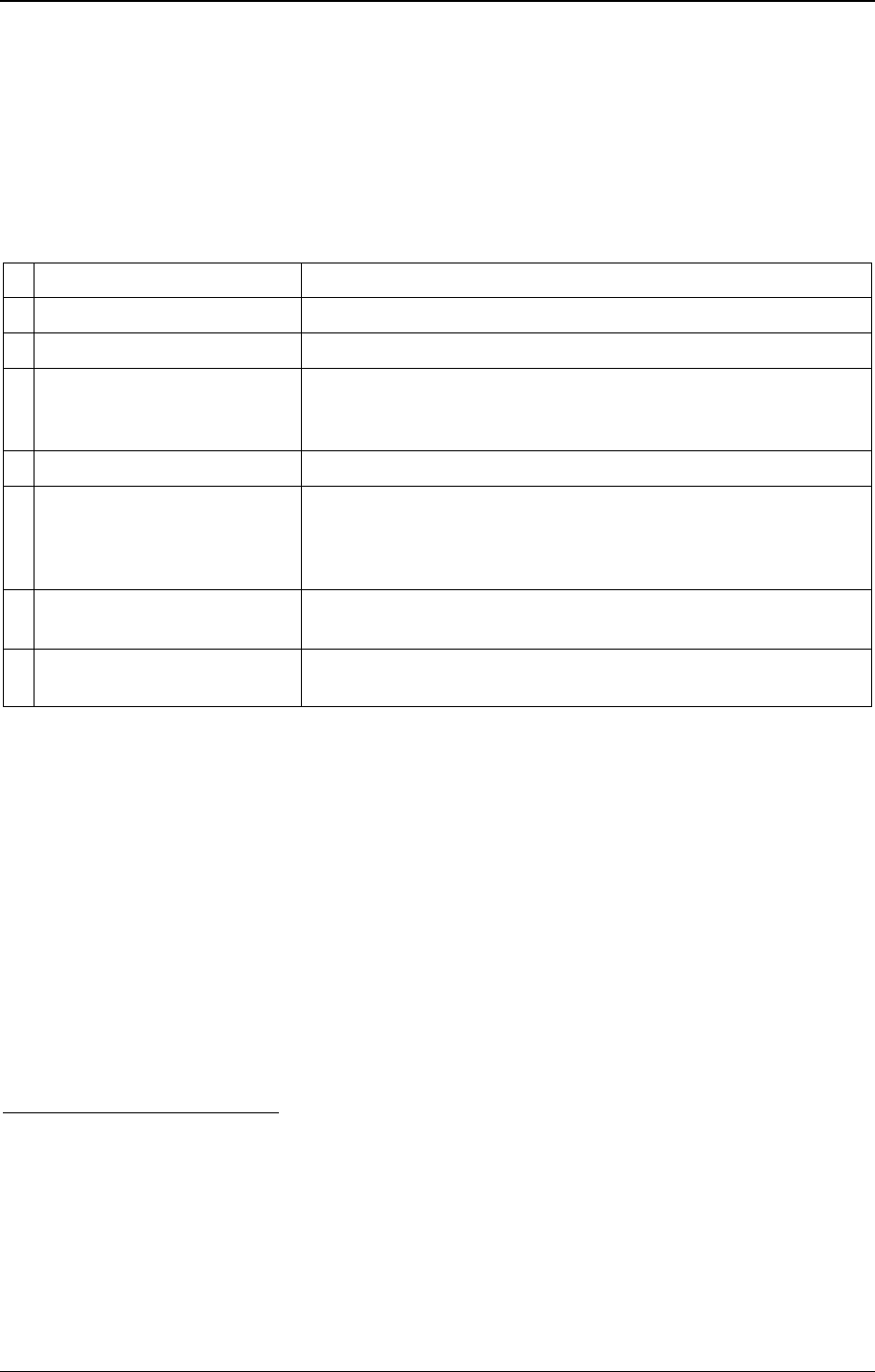

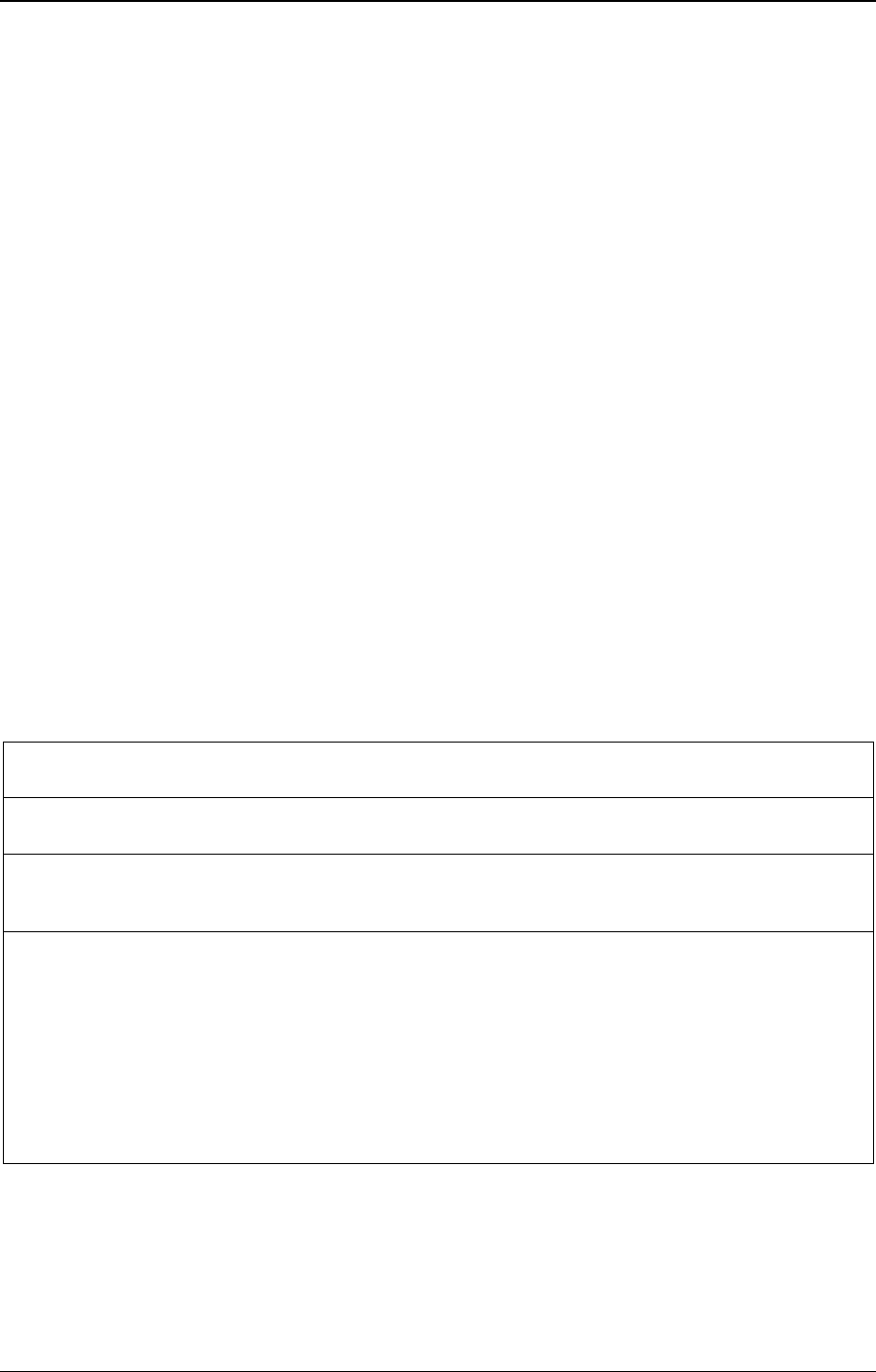

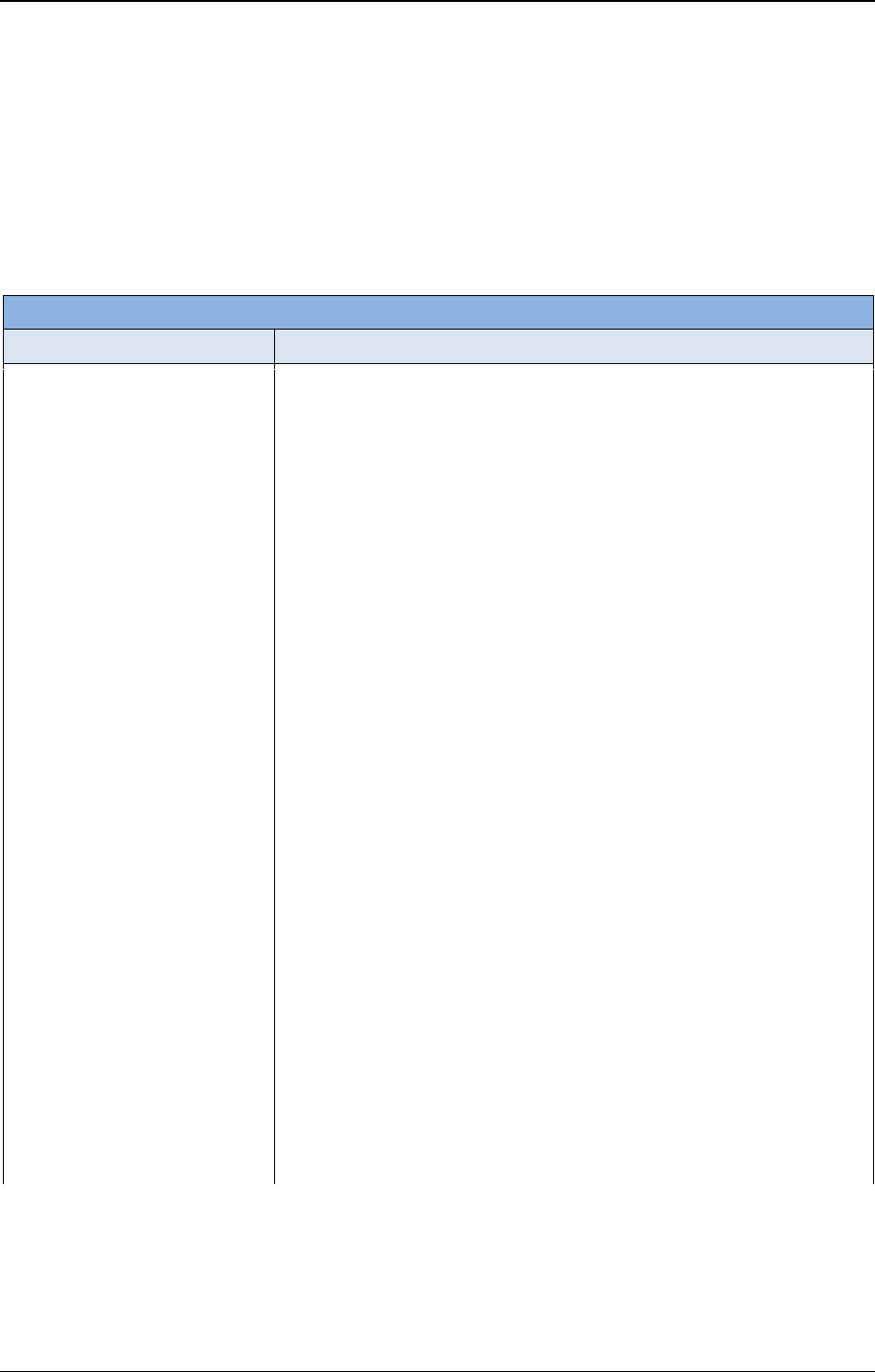

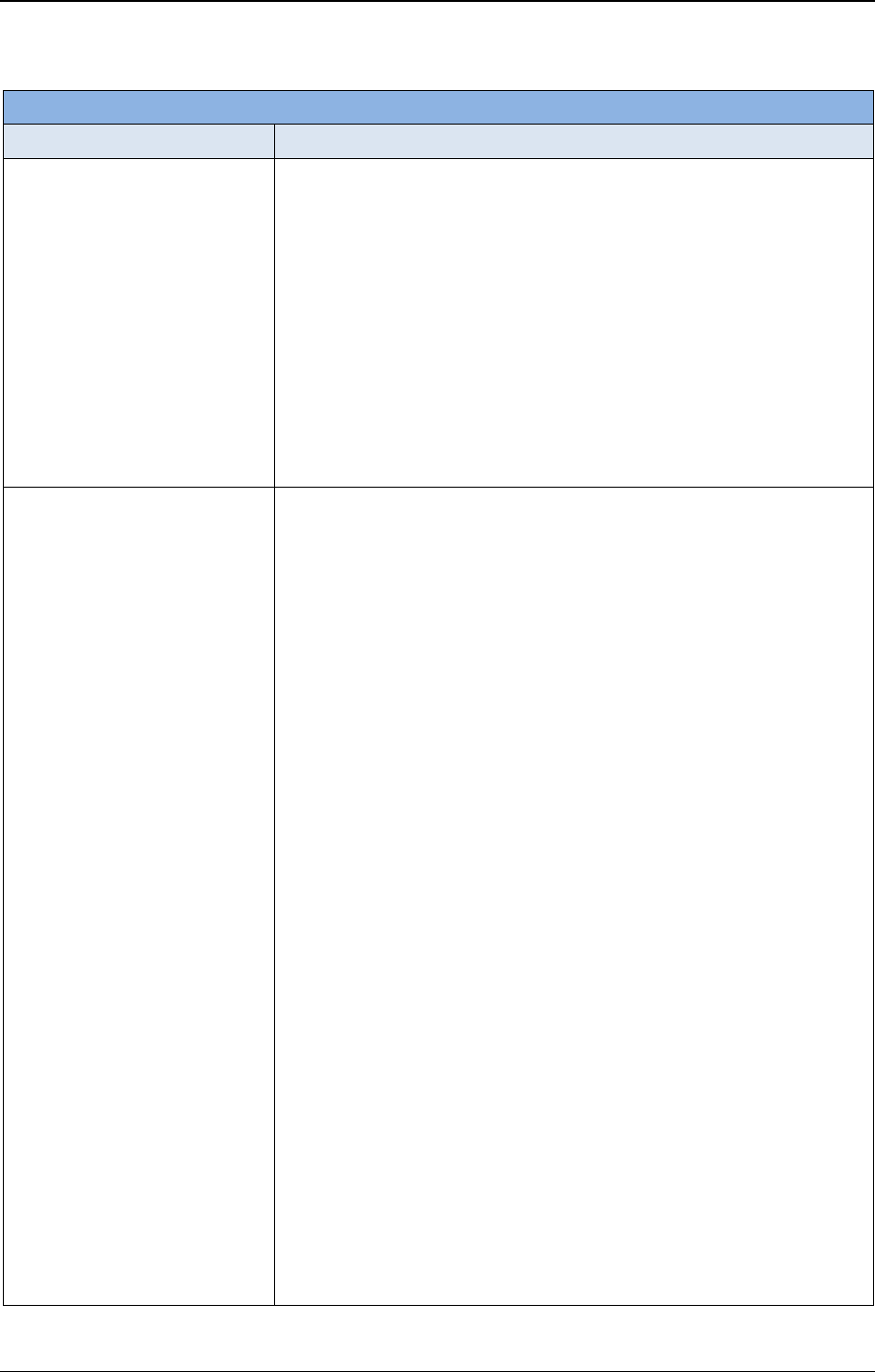

Table 1. Mandates from paragraph 3(e) in decision WHA72(11) for progress reports in this

document.

Progress achieved in the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases and

the promotion of mental health, including the following topics and the mandating

resolution or decision:

Location in this

document

• resolution WHA53.17 (2000) on prevention and control of noncommunicable

diseases

• resolution WHA66.10 (2013) on follow-up to the Political Declaration of the High-

level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Prevention and Control of Non-

communicable Diseases

• decision WHA72(11) on the follow-up to the political declaration of the third high-

level meeting of the General Assembly on the prevention and control of non-

communicable diseases

Paragraphs

2 to 43

• resolution WHA70.12 (2017) on cancer prevention and control in the context of an

integrated approach

Annex 1

• resolution WHA57.17 (2004) on the global strategy on diet, physical activity and

health

• resolution WHA71.6 (2018) on WHO’s global action plan on physical activity

2018–2030

Annex 2

• resolution WHA65.6 (2012) on comprehensive implementation plan on maternal,

infant and young child nutrition

Annex 3

EB148/7

2

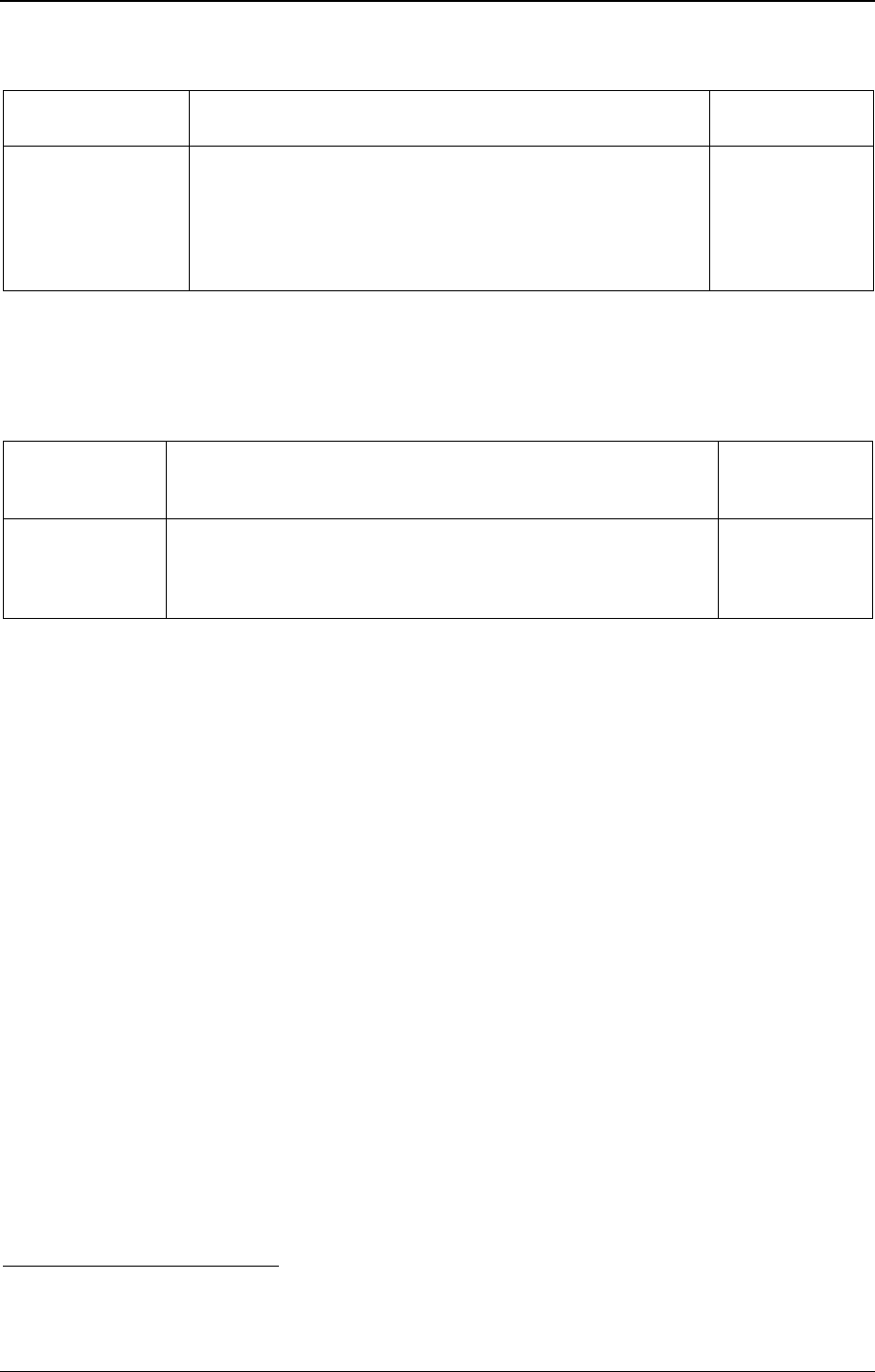

Progress achieved in the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases and

the promotion of mental health, including the following topics and the mandating

resolution or decision:

Location in this

document

• resolution WHA68.19 (2015) on outcome of the Second International Conference

on Nutrition

• decision WHA70(19) (2017) on report of the Commission on Ending Childhood

Obesity: implementation plan

• resolution WHA71.9 (2018) on infant and young child feeding

• resolution WHA68.8 (2015) on health and environment: addressing the impact of air

pollution and decision WHA69(11) (2016) on the related road map

Annex 4

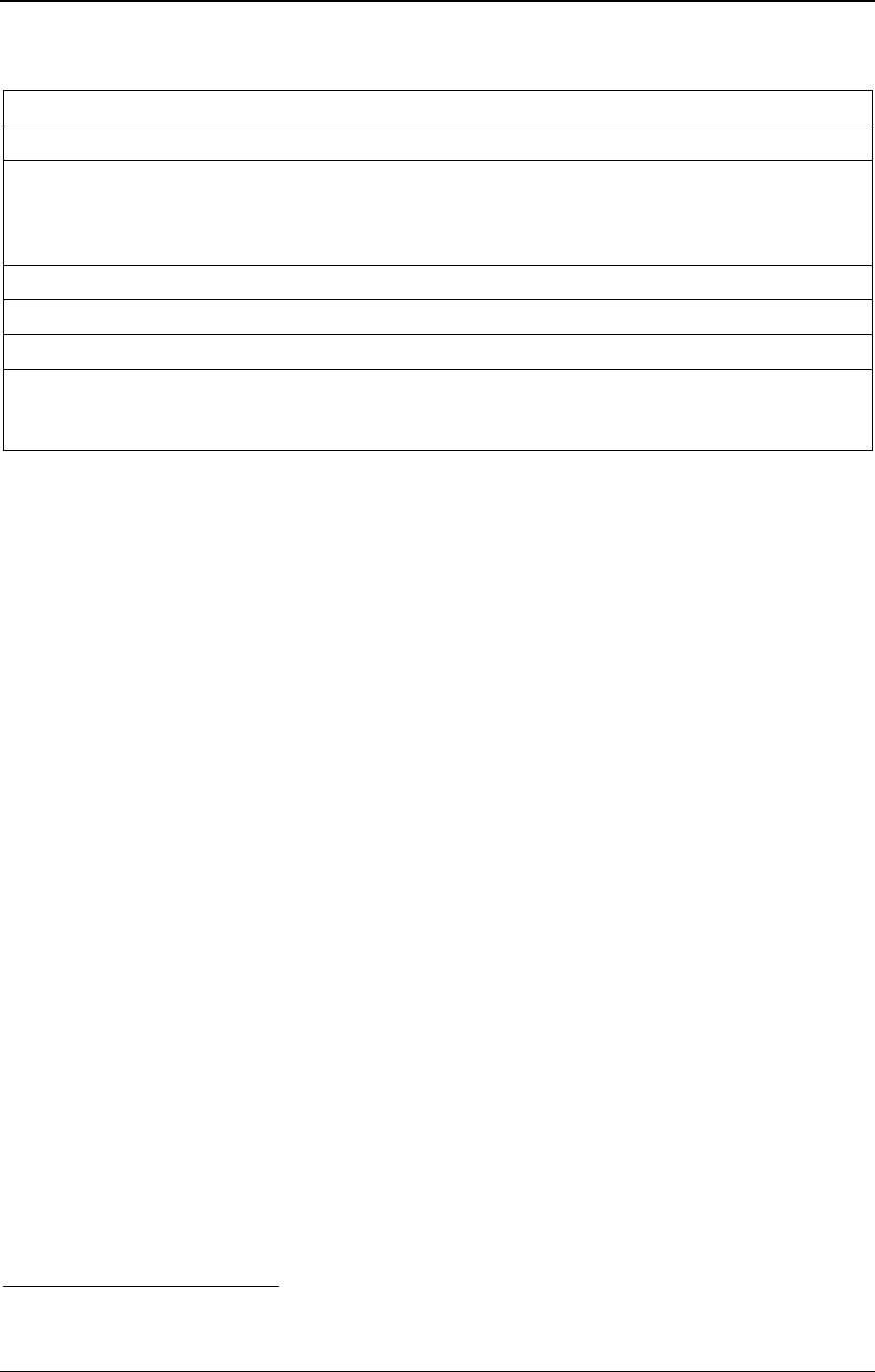

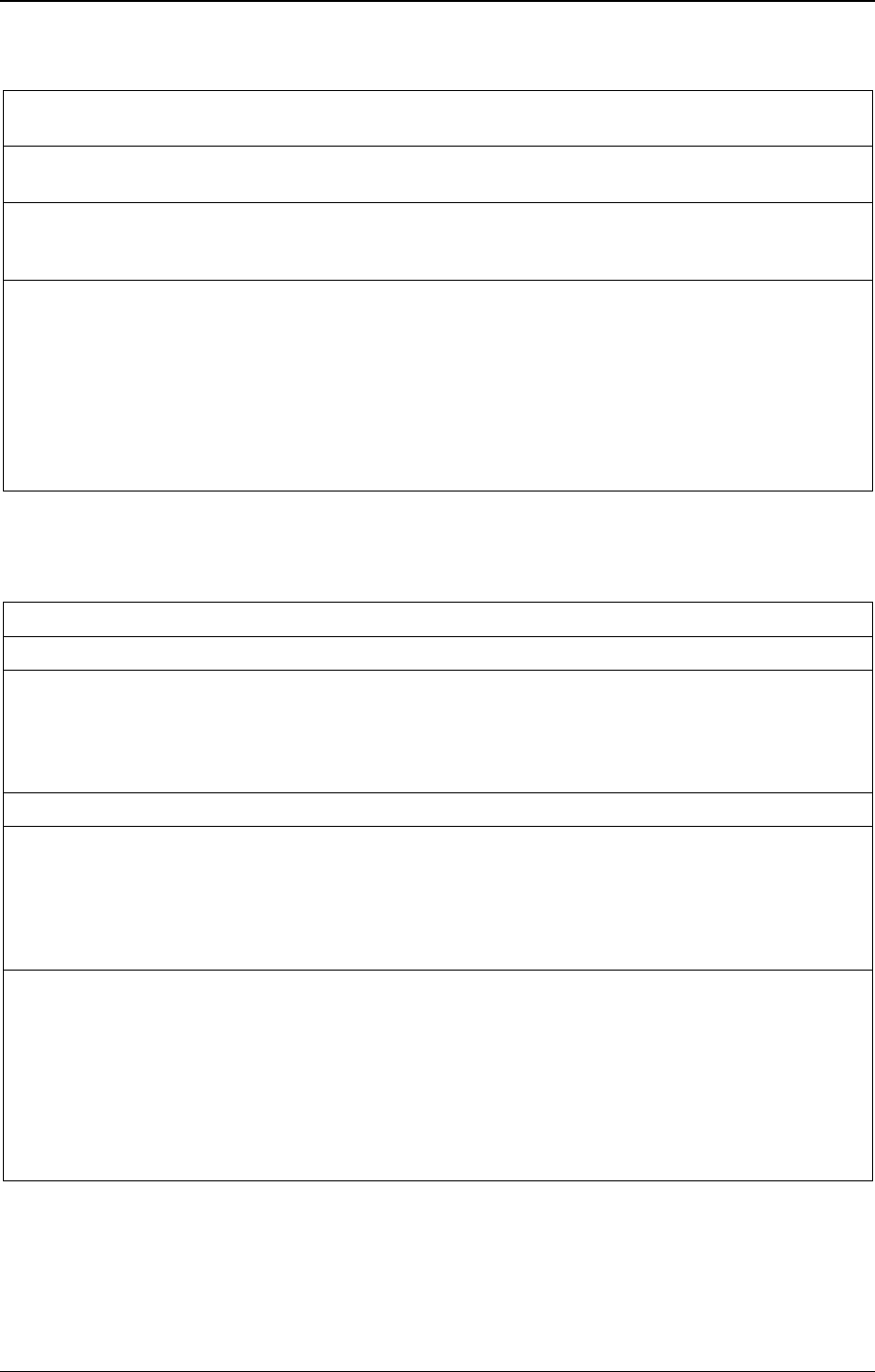

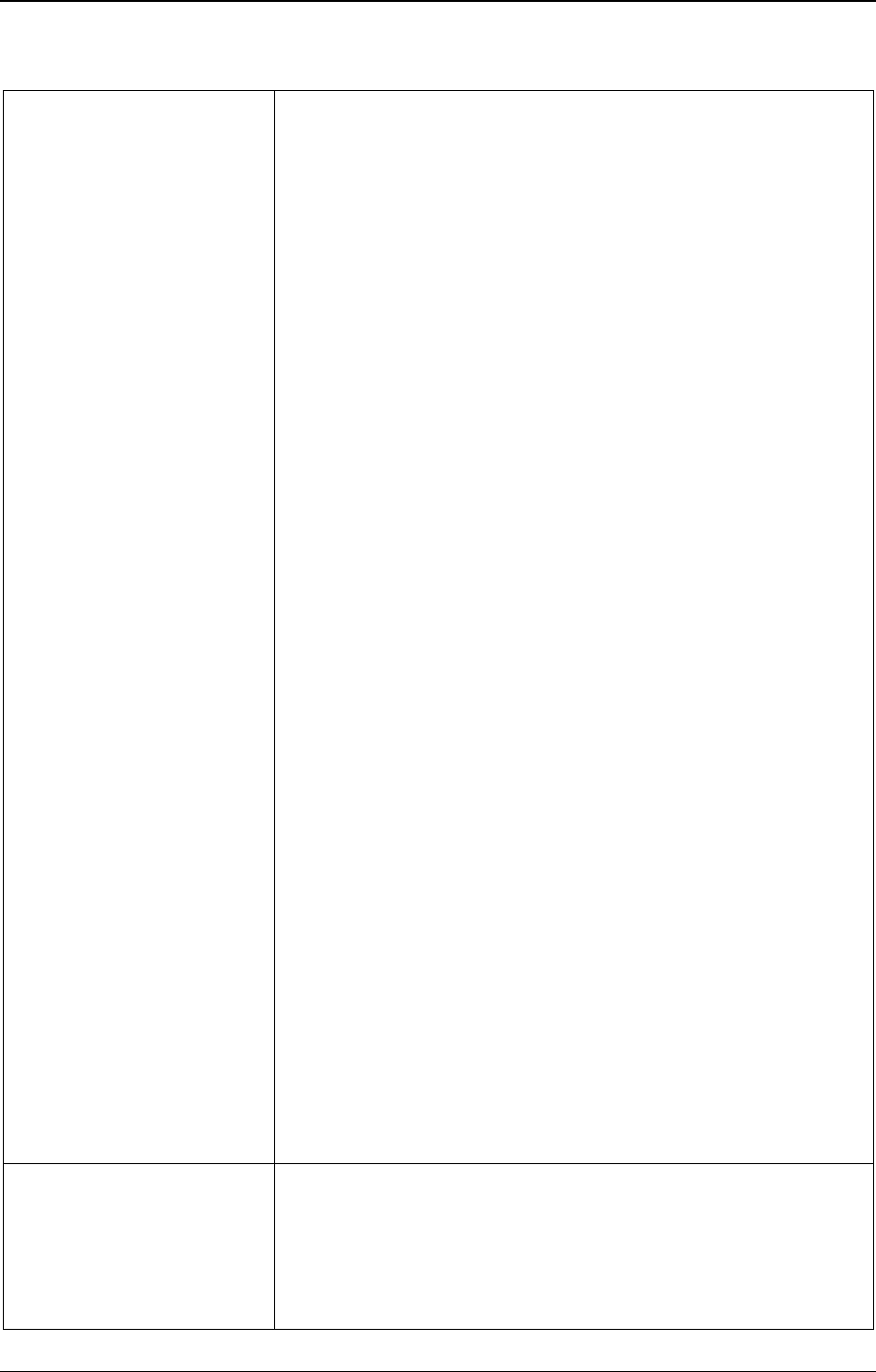

2. In addition, in decision WHA72(11) (2019) the Health Assembly requests the Director-General

to submit information about the following requested actions to the Seventy-fourth World Health

Assembly, through the Executive Board. See Table 2.

Table 2. Further actions requested of the Director-General in decision WHA72(11) (2019)

Relevant

paragraph

Action

Location in this

document

3(a)

to propose updates to the appendices of WHO’s comprehensive

mental health action plan 2013–2030

Annex 5

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

3(f)

to provide further concrete guidance to Member States in order

to strengthen health literacy through education programmes and

population-wide targeted and mass- and social-media campaigns

to reduce the impact of all risk factors and determinants of

noncommunicable diseases

Annex 6

3(g)

to present, based on a review of international experiences, an

analysis of successful approaches to multisectoral action for the

prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases, including

those that address the social, economic and environmental

determinants of such diseases

Annex 7

3(h)

to collect and share best practices for the prevention of

overweight and obesity, and in particular to analyse how food

procurement in schools and other relevant institutions can be

made supportive of healthy diets and lifestyles in order to

address the epidemic of childhood overweight and obesity and

reduce malnutrition in all its forms

Annex 8

1 and paragraph 40

of United Nations

General Assembly

resolution 73/2

(2018)

to provide support for implementation of the following action:

strengthen the design and implementation of policies, including

for resilient health systems and health services and infrastructure

to treat people living with noncommunicable diseases and

prevent and control their risk factors in humanitarian

emergencies

Annex 9

EB148/7

3

Relevant

paragraph

Action

Location in this

document

United Nations

Economic and Social

Council resolution

2014/10

to inform the World Health Assembly on a regular basis about

progress made by the United Nations Inter-Agency Task Force

for the Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases

in the implementation of the WHO’s global action plan for the

prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases

2013–2030.

Annex 10

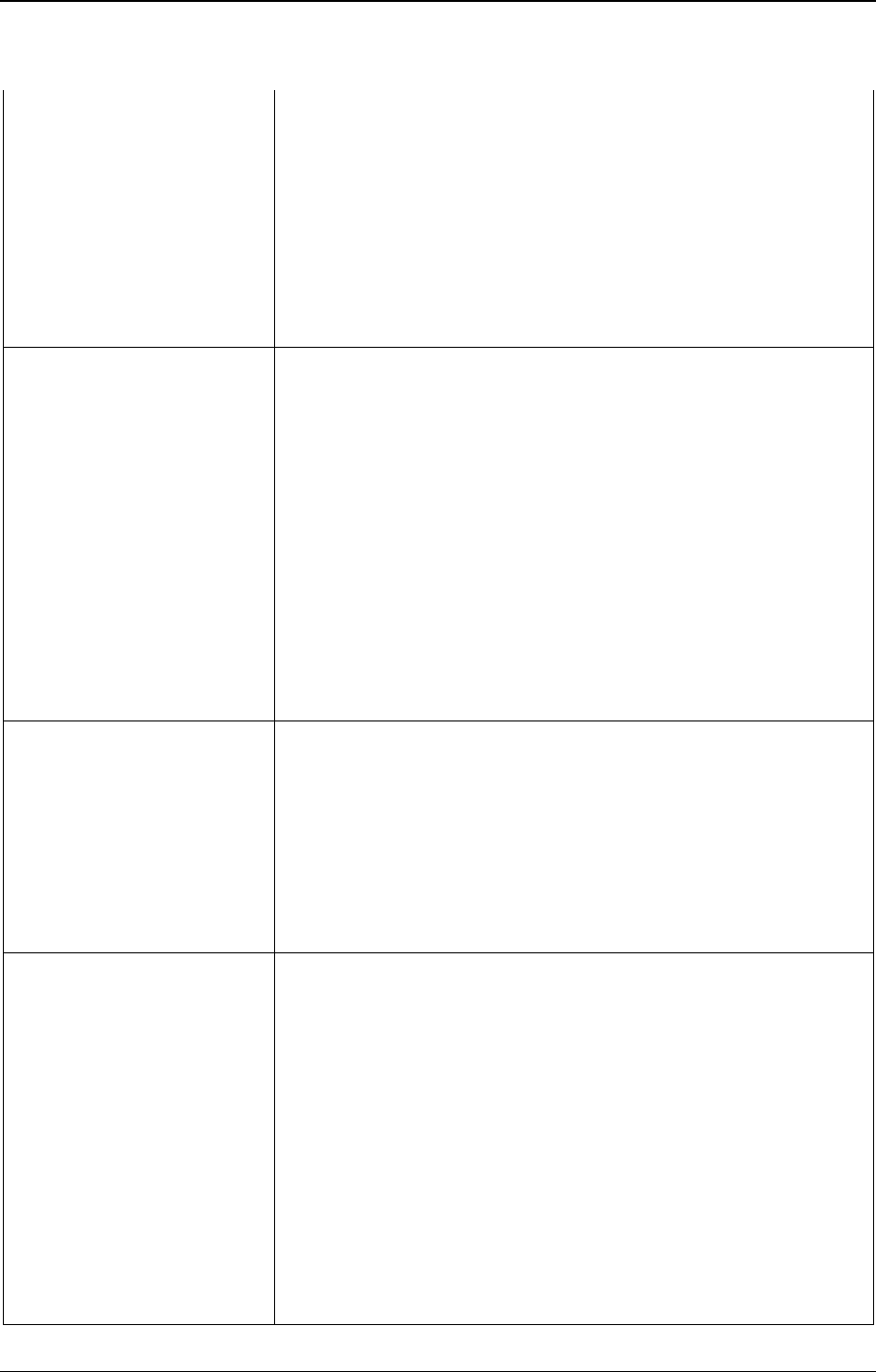

3. Table 3 lists two other mandated evaluations, which are discussed briefly below (see paragraphs

45–47) and will be published separately.

Table 3. Two further mandated evaluations, with source of mandate and document number

Resolution

WHA66.10

(2013)

Mid-point evaluation of the WHO’s global action plan for the

prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases

Document

EB148/7 Add.1

Document

A67/14 Add.1,

Appendix 1,

paragraph 19

Final evaluation of the Global coordination mechanism on the

prevention and control of noncommunicable disease

Document

EB148/7 Add.2

THE BURDEN OF NONCOMMUNICABLE DISEASES (NCDS): WHERE WE STAND

TODAY

1

4. WHO’s World health statistics 2020 reveal that, compared with the advances against

communicable diseases, progress in preventing and controlling premature death from NCDs has been

inadequate.

5. An estimated 41 million people worldwide died of NCDs in 2016, equivalent to 71% of all deaths.

Four NCDs caused most of those deaths: cardiovascular diseases (17.9 million), cancer (9.0 million),

chronic respiratory diseases (3.8 million), and diabetes (1.6 million).

6. An estimated 15 million people worldwide died of NCDs between the ages of 30 and 70 years,

defined as premature death. The probability (risk) of premature death from any one of the four main

NCDs decreased by 18% globally between 2000 and 2016. The most rapid decline was seen for chronic

respiratory diseases (40% lower), followed by cardiovascular diseases and cancer (both 19% lower).

Diabetes, however, showed a 5% increase in premature mortality during the same period.

7. Despite the rapid progress made between 2000 and 2010 in reducing the risk of premature death

from any one of the four main NCDs, the momentum of change has dwindled during 2010–2016, with

annual reductions in premature mortality rates slowing for the main NCDs. In high-income countries,

even though the premature mortality rate due to diabetes decreased from 2000 to 2010, it increased in

2010–2016. In low- and middle-income countries, the premature mortality rate due to diabetes increased

across both periods.

1

WHO. World health statistics 2020: monitoring health for the SDGs. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020

(https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/332070).

EB148/7

4

8. The rising mortality rates from diabetes are associated with – among other factors – the increasing

prevalence of obesity. Since 2000, the prevalence of obesity among adults (18 years and older) globally

has increased 1.5 times and the prevalence in children (5–18 years) more than doubled (from 2.9% to

6.8%) in 2016.

9. In 2016, the prevalence of physical inactivity for adults aged 18 years or more was 27.5%. Levels

of inactivity are twice as high in high-income countries as in low-income countries, and insufficient

activity increased by 5% in high-income countries between 2001 and 2016.

10. Global prevalence of hypertension decreased by 11% from 2000 to 2015. The prevalence of

hypertension was highest in low-income countries (28.4%) and lowest in high-income countries (17.7%)

in 2015.

11. Tobacco use has decreased steadily globally. A little under one quarter (23.6%) of adults (15 years

and older) globally used tobacco in some form in 2018, down from one third (33.3%) in 2000. The total

number of adult tobacco users remains very high, however: about 1.3 billion in 2018.

12. The burden of mental health conditions remains high. According to the latest global burden of

disease estimates (for 2017), mental, neurological and substance use disorders make up 11.1% of

disability-adjusted life years lost worldwide and 26.7% of years lived with disability (compared to

10.2% and 26.8% respectively in 2012), and an estimated 971 million people have a mental disorder

(compared to 916 million people in 2012). Almost 800 000 people die by suicide each year; it is the

second leading cause of death in 15–29-year-olds.

13. Worldwide, alcohol consumption, measured in litres of pure alcohol per person of 15 years or

older, has been relatively stable since 2010 and was estimated at 6.2 litres in 2018. However, trends

observed and projections made before the pandemic of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) forecast an

increase in global alcohol consumption per capita by 2025. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on

the levels of alcohol consumption worldwide and predicted trends still needs to be assessed.

14. In 2016, nine out of 10 people breathed air that did not meet the WHO air quality guidelines and

more than half the world’s population was exposed to air pollution levels at least 2.5 times above the

safety standard set by WHO. Although the proportion of the global population with access to clean

cooking fuels and technologies has increased steadily since 2000 and reached 63% in 2018, the actual

number of people without clean cooking has remained relatively constant over the past three decades.

PROGRESS TOWARDS TARGET 3.4 OF SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOAL

AND RELATED TARGETS: WHERE WE STAND TODAY

15. Target 3.4 of Sustainable Development Goal 3 is to reduce premature mortality from NCDs by a

third by 2030 relative to 2015 levels, and to promote mental health and well-being. Only 17 countries

are on track to meet that target for women and 15 for men.

1

There is some reduction in the global

1

NCD Countdown 2030 Collaborators. NCD Countdown 2030: pathways to achieving Sustainable Development

Goal target 3.4. The Lancet, 2020; 396(10255):918-934 (https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-

6736(20)31761-X/fulltext, accessed 29 October 2020).

EB148/7

5

age-standardized suicide rate

1

(8% reduction from 2010 to 2016)

2

but the indicator (3.4.2) shows that

the suicide rate is still far from achieving the target.

16. Target 3.8 is to achieve universal health coverage. All income categories of countries have

demonstrated almost no progress since 2000 in expanding the “universal health coverage service

capacity and access coverage” for the prevention, screening, early diagnosis and appropriate treatment

of NCDs.

3

In particular, between 2010 and 2019, many countries showed lagging performance on

effective coverage indicators for NCDs compared with those for communicable diseases and maternal

and child health, suggesting that many health systems are not keeping pace with the rising NCD burden.

There is a growing awareness that global ambitions to accelerate progress towards universal health

coverage are increasingly unlikely to be realized without concerted action on NCDs.

4

17. Overweight among children has shown a concerning upward trend. Worldwide, an estimated

5.6% – or 38.3 million children under five years of age – were overweight in 2019, compared with about

30.3 million in 2000.

18. Target 3.5 is to strengthen the prevention and treatment of substance abuse, including the harmful

use of alcohol, which is a risk factor for NCDs and other health conditions. Since 2010 little progress

has been made in reducing the harmful use of alcohol, and development and implementation of effective

alcohol control measures have been uneven between countries and WHO regions.

19. Target 3.a is to strengthen the implementation of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco

Control in all countries, where progress is measured by the age-standardized prevalence of current

tobacco use among persons aged 15 years and older. WHO estimates that the prevalence of current

tobacco use among persons aged 15 years and older has declined globally since 2015, from 24.9% in

2015 to 23.6% in 2018.

5

However, the implementation progress has been uneven for different articles

of the Convention. Only 32 Member States are currently on track to achieve WHO’s voluntary target of

a relative reduction in tobacco use prevalence of 30% between 2010 and 2025.

20. Over the past decade, the number of countries monitoring and reporting on air quality (indicator

11.6.2 on annual mean levels of fine particulate matter) has improved. Globally, the population exposed

1

WHO. Mental health atlas 2017. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018

(https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/272735).

2

WHO (https://www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/2020/EN_WHS_2020_Main.pdf?ua=1,

accessed 29 October 2020).

3

WHO. Primary health care on the road to Universal Health Coverage: 2019 Monitoring report. Geneva: World

Health Organization; 2019 (https://www.who.int/healthinfo/universal_health_coverage/report/uhc_report_2019.pdf?ua=1,

accessed 29 October 2020).

4

GBD 2019 Universal Health Coverage Collaborators. Measuring universal health coverage based on an index of

effective coverage of health services in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden

of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet, 2020; 396(10258):1250-1284

(https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30750-9/fulltext, accessed 29 October 2020).

5

WHO. The Global Health Observatory. Geneva: World Health Organization

(https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/age-standardized-prevalence-of-current-tobacco-

smoking-among-persons-aged-15-years-and-older, accessed 7 December 2020).

EB148/7

6

to PM2.5 levels above the current WHO air quality guidelines (annual average of 10 μg/m

3

) has fallen

by 4%, from 94% in 2010 to 90% in 2016.

1

21. In 2018, 63% (range 56–68%) of the global population had access to clean cooking fuels and

technologies, leaving the global population without such access at 2.8 billion people,

2

a figure

unchanged for around two decades now (indicator 7.1.2 on proportion of population with primary

reliance on clean fuels and technology). Without prompt action, universal access will fall short of the

relevant Goals by almost 30%.

22. In a growing recognition of air pollution as a public health threat, countries are scaling up

commitments to implement air quality policies and to align climate and air quality. At the 2019 Climate

Action Summit, 50 countries with in total more than one billion people committed themselves to reach

WHO air quality guideline values and align climate and air quality policies by 2030.

23. For the poorest one billion people of the world, NCDs account for more than a third of their

burden of disease. That includes almost 800 000 deaths annually among those aged younger than

40 years, more than HIV, tuberculosis and maternal deaths combined.

THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC: A DEADLY INTERPLAY WITH THE NCD EPIDEMIC

24. In May 2020, WHO conducted a rapid assessment survey of the impact of the COVID-19

pandemic on NCD resources and services,

3

to which 163 Member States (84%) responded. In

122 countries, governments are collecting or collating data on comorbidities between persons infected

with SARS-CoV-2 and persons living with NCDs. The Secretariat is analysing the data in order to derive

global estimates on these comorbidities. Initial results seem to indicate that persons living with

hypertension and/or diabetes appear to be two-to-four times more vulnerable to becoming severely ill

with or die from the virus. People living with obesity or using tobacco may be suffering from

undiagnosed or untreated hypertension or diabetes, which may be one of the reasons for a differential

social impact of COVID-19 within countries.

25. More than 80 countries reported complete or partial disruptions to management services for

people with hypertension or diabetes and diabetic complications. Countries most commonly reported

that they used triaging in response to the disruptions to NCD-related services; telemedicine was also

very widely used. However, the disruption of health services is particularly problematic for those living

with NCDs who need regular care.

26. Several examples from countries show how the disruption of NCD services has directly affected

people. Screening, case identification and referral systems for cancer have all been affected by the

COVID-19 pandemic, resulting in a substantial decrease in cancer diagnoses. The fact that fewer patients

with acute coronary syndrome are admitted to hospital often means increases in out-of-hospital deaths

and long-term complications of myocardial infarction. The Secretariat is conducting a modelling

1

Shaddick G, Thomas ML, Mudu P, Ruggeri G, Gumy S. Half the world’s population are exposed to increasing air

pollution. npj Climate and Atmospheric Science 2020; 3:23 (https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-020-0124-2, accessed

7 December 2020).

2

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Statistics Division. Ensure access to affordable,

reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all (https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2020/goal-07/, accessed 7 December 2020).

3

WHO. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on noncommunicable disease resources and services: results of a

rapid assessment. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 (https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/334136).

EB148/7

7

exercise to forecast the long-term upsurge in premature deaths from NCDs resulting from the disruption

of health services.

27. WHO’s interim operational guidance on maintaining health services in the COVID-19 context

includes considerations for NCDs, mental health and nutrition.

1

The joint policy brief on responding to

NCDs during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic provides examples of NCD-specific actions that

could be considered in the development of national COVID-19 response and recovery plans.

2

28. In September 2020, the United Nations General Assembly in its resolution 74/306 on a

comprehensive and coordinated response to the COVID-19 pandemic called upon Member States “to

further strengthen efforts to address non-communicable diseases as part of universal health coverage,

recognizing that people living with non-communicable diseases are at a higher risk of developing severe

COVID-19 symptoms and are among the most impacted by the pandemic”.

3

THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC: RESPONDING TO THE MENTAL HEALTH,

NEUROLOGICAL AND SUBSTANCE USE CONSEQUENCES

29. The COVID‐19 pandemic is profoundly affecting mental health and well-being. Mental and

neurological manifestations, such as depression, anxiety and delirium/encephalopathy, are reported in

COVID-19 patients. Many people with pre-existing mental, neurological and substance use disorders

are facing exacerbation of symptoms due to stressors, while the limited available services are disrupted.

Some people cope with stressors in harmful ways such as turning to alcohol, drugs or risky patterns of

potentially addictive behaviours, including video gaming and gambling. Adversity is a potent risk factor

for mental and behavioural disorders, such as depression and alcohol use disorders.

30. The Secretariat has assessed the impact of COVID-19 on services for mental, neurological and

substance use disorders through a rapid survey between June and August 2020.

4

Out of 130 countries,

121 (93%) countries reported disruptions in one or more of their services for these disorders and

116 (89%) reported that mental health and psychosocial support was part of their national COVID-19

response plans. Countries are responding to the disruptions through teletherapy interventions (70%),

crisis hotlines (68%) and training for health-care providers (60%). The General Assembly

resolution 74/306 encouraged Member States “to address mental health in their response to and recovery

from the pandemic by ensuring widespread availability of emergency mental health and psychosocial

support”.

31. The Secretariat is coordinating different pillars of its COVID‐19 response to integrate mental

health and psychosocial support into the COVID‐19 response effort.

5

WHO co‐chairs the Inter‐Agency

Standing Committee Reference Group on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency

1

WHO. Maintaining essential health services: operational guidance for the COVID-19 context: interim guidance,

1 June 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 (https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/332240).

2

WHO, United Nations Development Programme. Responding to non-communicable diseases during and beyond the

COVID-19 pandemic. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 (https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/334145).

3

United Nations General Assembly, resolution 74/306 (2020), Comprehensive and coordinated response to the

coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic: operative paragraph 9.

4

WHO. The impact of COVID-19 on mental, neurological and substance use services: results of a rapid assessment.

Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 (https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/335838).

5

Tedros AG. Addressing mental health needs: an integral part of COVID-19 response. World Psychiatry 2020;

19(2):129-130 (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/wps.20768, accessed 30 October 2020).

EB148/7

8

Settings. A wide range of resources, available in numerous languages and formats, has been developed

by WHO and its partners.

1

WHO established the Global Forum on Neurology and COVID-19 in order

to exchange knowledge and enhance clinical practices.

BUILDING BACK BETTER

32. Over the past 20 years, NCDs have changed the world. They have become the leading cause of

death in most countries, resulting in 200 million premature deaths among people aged between 30 and

70 years, most living in low- and middle-income countries. During the next 10 years, another 150 million

people will die from NCDs between the ages of 30 and 70 years. Most deaths can be avoided or delayed.

33. In adopting resolution WHA53.17 in 2000, the Health Assembly recognized for the first time that

the long-term needs of people living with NCDs are rarely dealt with. Accordingly, the Political

Declaration of the High-level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Prevention and Control of

Non-communicable Diseases in 2011 included a commitment from governments to explore the

provision of adequate resources through, inter alia, domestic and bilateral channels. In 2016, NCDs

represented 27% of domestic public spending and 9% of external funds for health across a dataset

including 16 low-income countries and 24 middle-income countries.

2

Today, NCDs remain the largest,

most internationally-underfunded public health issue globally, where most lives could be saved or

improved.

34. Bilateral donors have not shown increased appetite for funding activities specifically earmarked

as addressing NCDs to establish even the minimal critical capacity, mechanisms and mandates needed

in low- and middle-income countries to pursue change. In the absence of such funding, groups with

economic, market and commercial interests stepped up their efforts to lobby against implementation of

interventions by WHO, discrediting WHO’s scientific knowledge, available evidence and reviews of

international experience, and bringing legal challenges against countries to oppose progress.

3

35. The response to the COVID-19 pandemic must address precisely these failures that are being

exposed and exploited by the pandemic. Investment in the prevention and control of NCDs as part of

COVID-19 recovery is attractive, as cost-effective, high-impact interventions already exist but are not

sufficiently implemented and scaled up in low- and middle-income countries. Tackling NCDs in general

must be an integral part of the immediate response to COVID-19 and of the recovery at global, regional

and national levels, as well as part of the strategies to build back better.

36. Pathway analyses show that every country still has options today for achieving target 3.4 of

Sustainable Development Goal 3. No country could achieve the target by addressing only prevention or

only counselling, screening, early diagnosis and appropriate treatment of NCDs.

1

WHO. Mental health & COVID-19 (https://www.who.int/teams/mental-health-and-substance-use/covid-19,

accessed 30 October 2020).

2

WHO. Public spending on health: a closer look at global trends. Geneva: World Health Organization;

2018 (https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/276728), p. 29.

3

Seventy-first World Health Assembly. Preparation for the third High-level Meeting of the General Assembly on the

Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases, to be held in 2018: report by the Director-General. Geneva: World

Health Organization; 2018. Document A71/14, Table 5, row (v) (https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/276368).

EB148/7

9

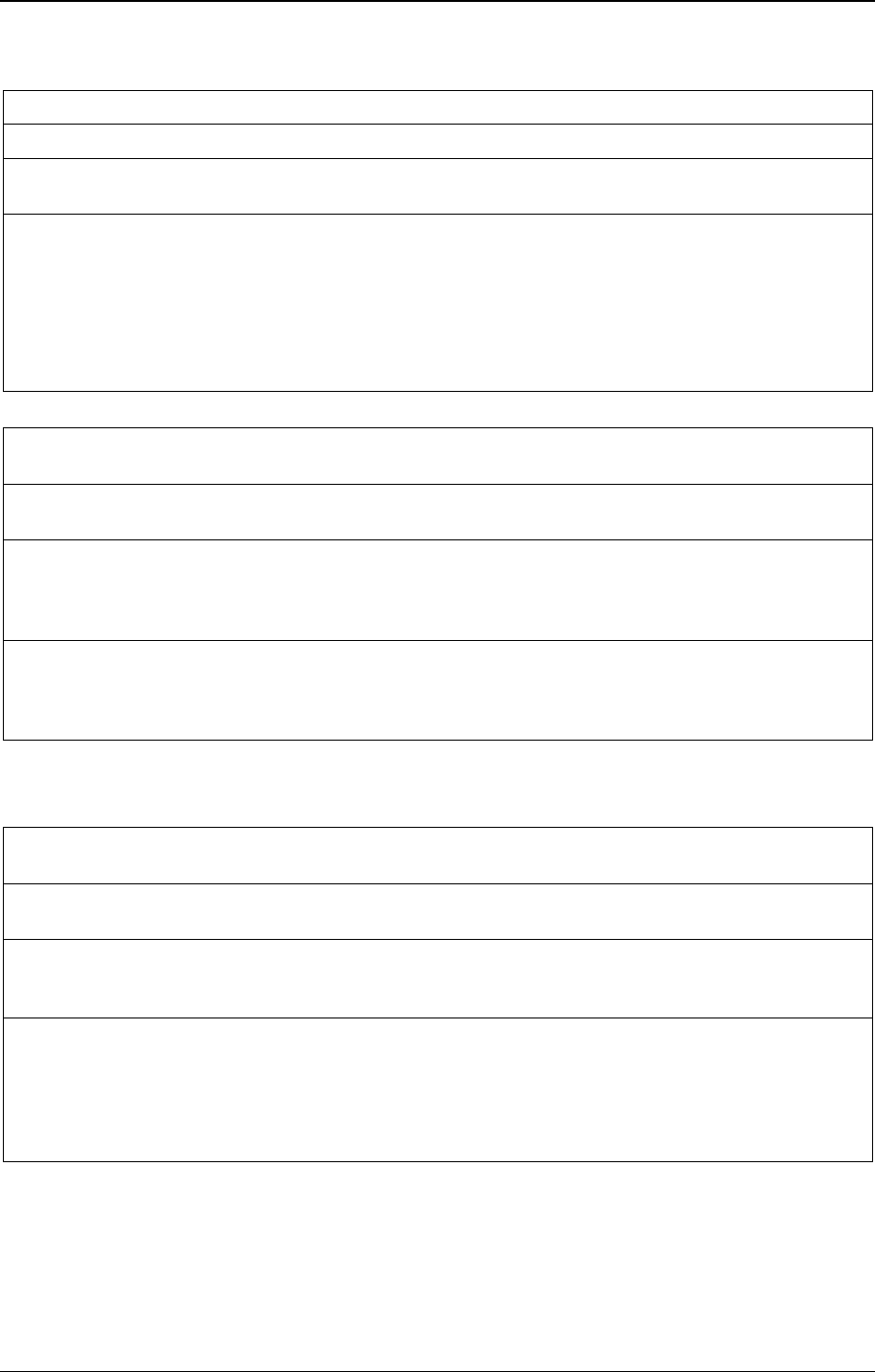

37. The final report of WHO’s Independent High-level Commission on Non-communicable Diseases

1

recommended a specific set of the most effective and feasible interventions that should be considered

as a priority to accelerate progress towards target 3.4, reducing premature mortality from NCDs by one

third (Table 4).

Table 4. Interventions against specific risk factors and diseases

Risk factor or disease

2

Interventions

1

Tobacco use

• WHO mPOWER policy package

3

2

Excess sodium consumption

• WHO SHAKE technical package

3

Cervical, liver, colon and other

cancers

• Hepatitis B and human papillomavirus vaccination

• Detection, screening and treatment of cervical and preventable or

treatable cancers

4

Hypertension

• WHO HEARTS technical package for cardiovascular disease

5

Household air pollution

• World Bank: Household Energy for Cooking: Project Design

Principles

• WHO Guidelines for indoor air quality: household fuel

consumption

6

Consumption of industrially-

produced trans-fatty acids

• WHO REPLACE action package

• WHO protocol for measuring trans-fatty acids in foods

7

Harmful use of alcohol

• Taxation; limitation of places and hours of sale; restrictions on

marketing, promotion, and sponsorships

38. The report of the WHO/The Lancet’s NCD Countdown 2030 in 2020 showed that essential

components of any strategy to achieve target 3.4 of Goal 3 must include control of tobacco use and of

the harmful use of alcohol, detection and treatment of hypertension and diabetes, primary and secondary

prevention of cardiovascular diseases in high-risk individuals through multidrug treatment, and

bronchodilators and low-dose inhaled corticosteroids for asthma and selected patients with chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease.

4

39. Progress in noncommunicable diseases towards relevant targets needs a major boost. The

Secretariat is scaling up its programme on NCDs. The immediate aim is to catalyse tangible progress

towards target 3.4 within the next three years, especially through new and bold innovative solutions that

have a multiplier effect across the Sustainable Development Goals.

1

WHO. WHO Independent high-level commission on noncommunicable diseases: final report: it’s time to walk the

talk. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019 (https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/330023).

2

Physical inactivity is not included, owing to lack of adequate data.

3

Derived from key demand reduction measures in the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, thus

supporting the achievement of SDG target 3.a.

4

NCD Countdown 2030 collaborators. NCD Countdown 2030: pathways to achieving Sustainable Development

Goal target 3.4. The Lancet, 2020; 396(10255):918-934 (https://www.thelancet.com/action/showPdf?pii=S0140-

6736%2820%2931761-X, accessed 7 December 2020).

EB148/7

10

40. A major contribution to attaining target 3.4 will come from WHO’s new initiative to eliminate

cervical cancer in the next 100 years and reaching the 90-70-90 triple-intervention target by 2030:

• 90% of girls fully vaccinated against human papillomavirus by the age of 15 years;

• 70% of women screened using a high-performance test by the age of 35 years and again by the

age of 45 years;

• 90% of women identified with cervical disease receive treatment (90% of women with

pre-cancer treated and 90% of women with invasive cancer managed).

41. The Secretariat will develop similar strategic cross-cutting initiatives for diabetes, childhood

cancer and breast cancer.

42. The current capacities for NCD surveillance remain inadequate in many countries and urgently

require strengthening. Currently, many countries have few usable mortality data and weak information

on risk factor exposure and morbidity. Data on NCDs are often not well integrated into national health

information systems. Improving country-level surveillance and monitoring remains a top priority in the

fight against NCDs. The Secretariat will continue to support the scaling up of national efforts to

strengthen NCD surveillance and data systems, and expand the provision of strategic information for

policy-making, service provision and accountability.

43. Other organizations in the United Nations system are also committed to aligning their relevant

activities with the comprehensive United Nations response to COVID-19, for example through:

(i) raising national awareness on the return on investment in NCD prevention and treatment so as to

secure domestic budgetary allocations and international finance; (ii) supporting countries in including

NCDs into their socioeconomic plans for the COVID-19 response; and (iii) participating in the WHO

Working Group on COVID-19 and NCDs. The United Nations Inter-Agency Task Force on the

Prevention and Control of NCDs and the Global Action Plan for Healthy Lives and Well-being for All

continue to provide important platforms for many United Nations organizations to work through.

PREPARATORY PROCESS LEADING TO THE FOURTH HIGH-LEVEL MEETING

OF THE UNITED NATIONS GENERAL ASSEMBLY ON THE PREVENTION AND

CONTROL OF NCDs IN 2025

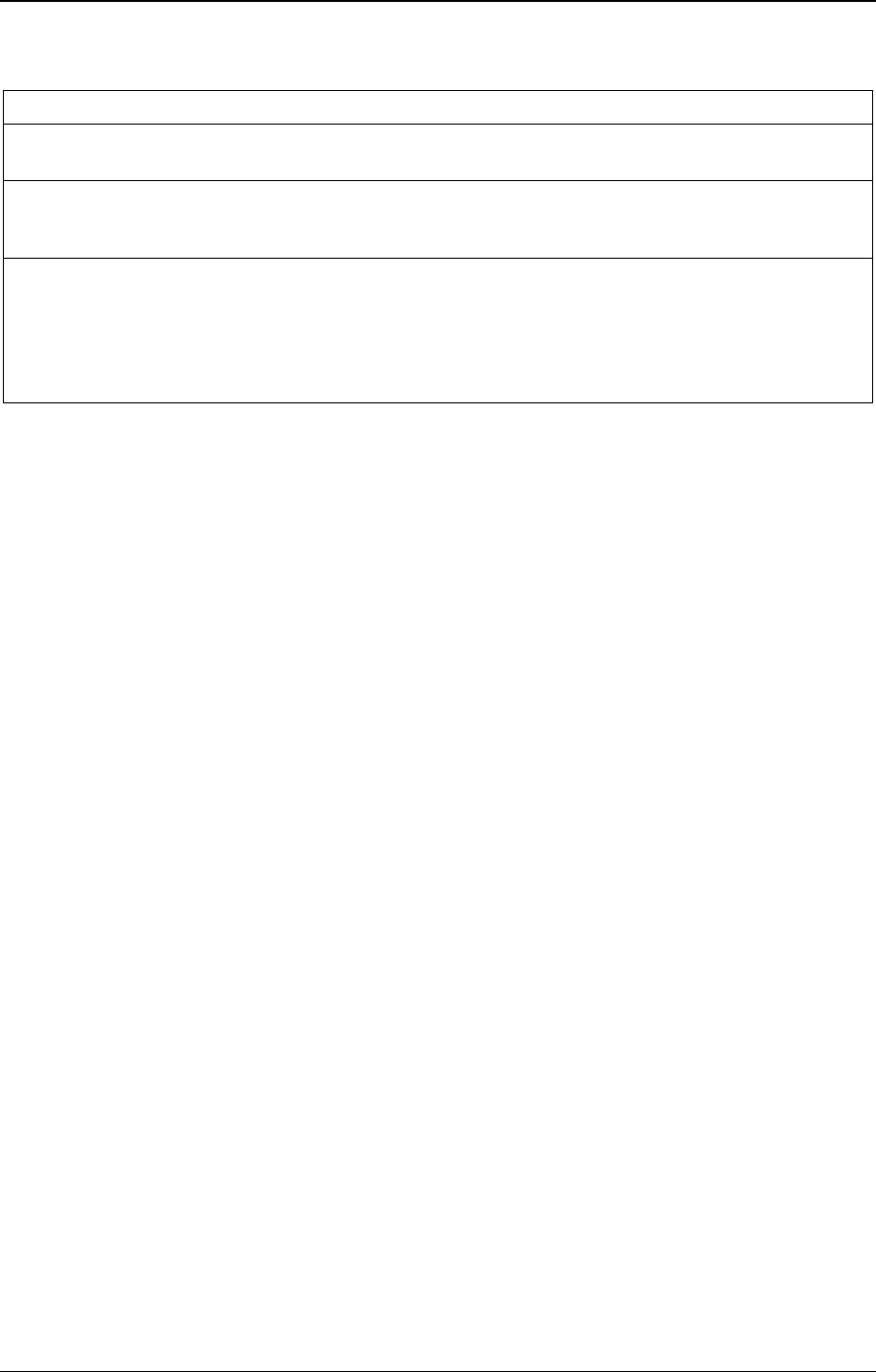

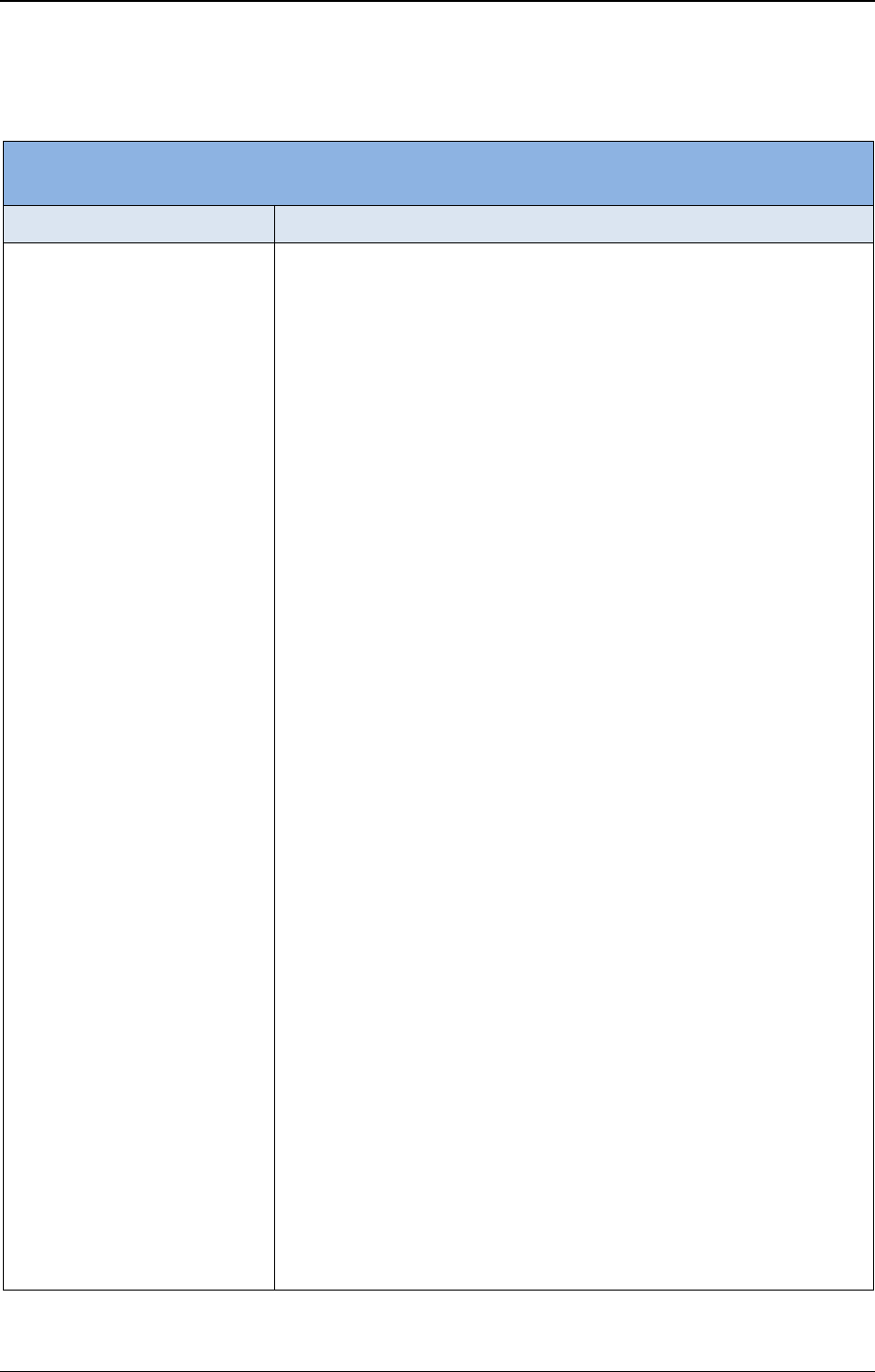

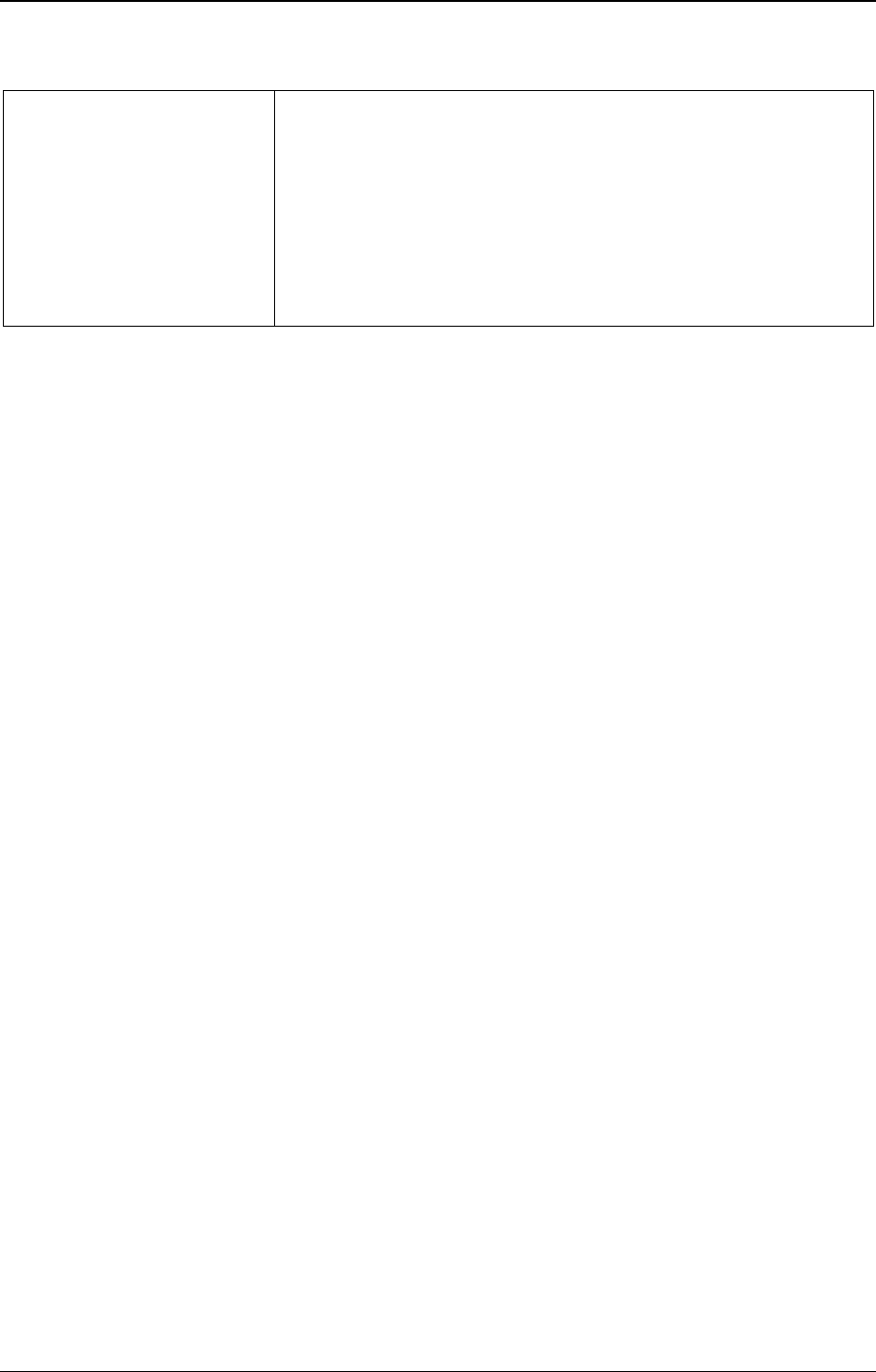

44. Table 5 sets out the process and scheduled meetings in preparation for the fourth high-level

meeting of the General Assembly on the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases.

Outcomes will serve as an input into the process.

Table 5. Meetings planned to prepare for the fourth high-level meeting of the General Assembly

on the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases

2021

• Second WHO global dialogue on financing national NCD responses

• Ninth session of the Conference of the Parties to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control

• Second Session of the Meeting of the Parties to the Protocol to Eliminate Illicit Trade in Tobacco

Products

2022

EB148/7

11

• Third WHO global meeting of national NCD Programme Directors and Managers

2023

• First WHO global ministerial conference for Small Island Development States on the prevention and

control of NCDs

• Tenth session of the Conference of the Parties to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control

• Third Session of the Meeting of the Parties to the Protocol to Eliminate Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products

2024

• Third WHO global ministerial conference on the prevention and control of NCDs

2025

• United Nations dialogue with civil society and the private sector

• Fourth high-level meeting of the General Assembly on the Prevention and Control of Non-communicable

Diseases

EVALUATIONS

45. In accordance with paragraph 60 of the Global action plan for the prevention and control of

noncommunicable diseases 2013–2020, in 2019 the Secretariat convened a representative group of

stakeholders, including Member States and international partners, to conduct a mid-point evaluation of

implementation of the global action plan. Its purpose was to assess progress towards the six objectives

of the global action plan and identify the lessons learned throughout its implementation by Member

States, by international partners and by the three levels of the Organization. The evaluation aimed to

document successes and identify challenges and gaps in the implementation of the global action plan

since 2013; to make strategic recommendations for improving implementation up until 2030; and to

provide inputs into WHO’s next global status report on noncommunicable diseases and other relevant

reports. The Secretariat’s Evaluation Office will submit an executive summary of the mid-point

evaluation to the Seventy-fourth World Health Assembly, through the Executive Board (see document

EB148/7 Add.1).

46. As specified in the terms of reference for the Global coordination mechanism on the prevention

and control of noncommunicable diseases,

1

a final evaluation of the mechanism took place in 2020 in

order to assess its effectiveness, its added value and its continued relevance to the achievement of the

2025 voluntary global targets, including its possible extension. The Evaluation Office will submit an

executive summary of the final evaluation to the Seventy-fourth World Health Assembly, through the

Executive Board (see document EB148/7 Add.2).

47. In line with the terms of reference of the United Nations Inter-Agency Task Force on the

Prevention and Control of NCDs, the evaluation of its contribution to the implementation of WHO’s

Global Action plan was described in the mid-point evaluation of that plan.

1

Document A67/14 Add.1, Appendix 1.

EB148/7

12

ACTION BY THE EXECUTIVE BOARD

48. The Board is invited:

• to note the report and its annexes;

• to provide guidance on the continued relevance of WHO’s Global action plan for the prevention

and control of noncommunicable diseases and on any corrective measures which may be taken

where actions have not been effective, and to reorient parts of the plan, as appropriate, in

response to the 2030 Agenda on Sustainable Development and/or the United Nations

Comprehensive Response to COVID-19, as appropriate;

• to provide guidance on the continued relevance of WHO’s Global coordination mechanism for

the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases and the possible extension of its

lifespan, taking into account the evaluation mentioned in paragraph 46, and decision

WHA72(11) (2019), which extended the lifespan of WHO’s Global action plan for the

prevention and control of non-communicable diseases 2013–2020 to 2030.

49. The Board is further invited to consider the following draft decision:

The Executive Board, having considered the report of the Director-General on the political

declaration of the third high-level meeting of the General Assembly on the prevention and control

of non-communicable diseases,

1

decided to recommend to the Seventy-fourth World Health

Assembly the adoption of the following decision:

The Seventy-fourth World Health Assembly, having considered the report of the

Director-General, decided to adopt the proposed updates to the appendices of WHO’s

comprehensive mental health action plan 2013–2030 (contained in document EB148/7,

Annex 5, appendices 1 and 2).

1

Document EB148/7.

EB148/7

13

ANNEX 1

CANCER PREVENTION AND CONTROL IN THE CONTEXT OF AN

INTEGRATED APPROACH

1. In 2017, the Seventieth World Health Assembly adopted resolution WHA70.12 (2017) on cancer

prevention and control in the context of an integrated approach and requested the Director-General: to

develop, before the end of 2019, the first periodic public health- and policy-oriented world report on

cancer; to prepare a comprehensive technical report on pricing approaches and their impact on the

availability and affordability of cancer medicines; to develop tool kits to establish and implement

comprehensive cancer prevention and control programmes; to strengthen the capacity of the Secretariat

both to support the implementation of cost-effective interventions and country-adapted models of care

and to work with international partners; and to provide technical assistance, including support for the

establishment of centres of excellence. This annex describes progress made in implementing the

resolution.

2. The Secretariat has undertaken the following activities.

3. WHO report on cancer.

1

The report and accompanying cancer country profiles

2

were launched

on World Cancer Day (4 February 2020), in coordination with the launch by the International Agency

for Research on Cancer of its World Cancer Report on cancer research for cancer prevention. The

content of both documents was harmonized.

4. The WHO report included an investment case for cancer, in line with the mandate from resolution

WHA70.12, that demonstrated every US$ 1 invested in cancer control yields a full social return based

on both direct productivity and societal gains of US$ 9.50. By investing US$ 2.70 per person in

low-income countries, US$ 3.95 per person in lower-middle-income countries and US$ 8.15 per person

in upper-middle-income countries, an additional 7.3 million lives could be saved by 2030.

5. Technical report on cancer medicine pricing approaches. The requested comprehensive

technical report on pricing of cancer medicines and its impacts was submitted to and noted by the

Executive Board at its 144th session.

3

In 2020 WHO updated the WHO guideline on country

pharmaceutical pricing policies to support national policy development and implementation.

4

6. Toolkit for cancer prevention and control. Among its multiple toolkits to support Member

States with cancer policy formulation and guidance, WHO, working with the International Agency for

1

WHO. WHO report on cancer: setting priorities, investing wisely and providing care for all. Geneva: World Health

Organization; 2020 (https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/330745).

2

WHO cancer country profiles. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 (https://www.who.int/cancer/country-

profiles/en/, accessed 30 October 2020).

3

Technical report: pricing of cancer medicines and its impacts: a comprehensive technical report for the World

Health Assembly Resolution WHA70.12 (2017): operative paragraph 2.9 on pricing approaches and their impacts on

availability and affordability of medicines for the prevention and treatment of cancer. Geneva: World Health Organization;

2020 (https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/277190) and document EB144/2019/REC/2, summary records of the tenth

meeting.

4

WHO. WHO guideline on country pharmaceutical pricing policies, 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization;

2020 (https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/335692).

EB148/7 Annex 1

14

Research on Cancer, has developed one that is linked to the OneHealth tool.

1

It allows for stepwise and

resource-stratified scale-up in cancer prevention and control for adult and childhood cancers. It provides

evidence on the most cost-effective interventions for all age groups and has been used to support five

Member States in implementing cancer interventions.

7. WHO, working with the International Atomic Energy Agency, issues guidance, providing a

framework for Member States to establish comprehensive cancer centres.

8. Technical support to countries. The Secretariat has provided broad technical support to Member

States in the development and formulation of comprehensive programmes and policies on cancer

prevention and control.

9. WHO collaborated with the International Atomic Energy Agency to support countries in enabling

radiotherapy procurement by prioritizing radiotherapy technology aligned with health system capacity.

Technical specifications for radiotherapy were jointly developed as part of inter-agency guidance on

technical specifications for radiotherapy equipment in cancer treatment.

10. WHO has also worked with the International Atomic Energy Agency to increase coordination and

support provided to Member States participating in an “imPACT review”. The imPACT methodology

has been revised to improve the service and to provide more effective and coordinated support to

Member States, including broad partner collaboration.

11. Elimination of cervical cancer. In resolution WHA73.2 (2020), the Seventy-third World Health

Assembly adopted the global strategy to accelerate the elimination of cervical cancer as a public health

problem. The global strategy outlines the 90-70-90 targets to be reached by 2030, on the basis of human

papillomavirus vaccination, screening, and treatment of pre-invasive and invasive cancers, including

palliative care. For the third target of the global strategy (the appropriate management of 90% of women

identified with invasive cervical cancer), the Secretariat is preparing a framework for strengthening and

scaling-up services for the management of invasive cervical cancer.

12. WHO global initiative for childhood cancer. In September 2018, this global initiative was

launched. It aims to double the probabilities of survival from childhood cancer, which would save one

million more lives by 2030, by improving access to and quality of services including treatment and

palliative care. A technical package, CureAll, will be launched in 2021. Support to Member States has

started in 12 countries.

2

13. Collaboration with stakeholders. The Secretariat has strengthened engagement with broad

multisectoral stakeholders within and beyond existing WHO initiatives. This has included enhanced

coordination between the International Agency on Cancer Research and WHO at the management and

working levels, as reflected in the development of standard operating procedures and routine

communication on IARC Handbooks of Cancer Prevention.

3

1

OneHealth Tool. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 (https://www.who.int/choice/onehealthtool/en/,

accessed 30 October 2020).

2

Ghana, Mali, Morocco, Myanmar, Pakistan, Peru, Philippines, Senegal, Timor-Leste, Ukraine, Uzbekistan and

Zambia.

3

Coordination and Communication Mechanisms between IARC and WHO – at management and working levels.

Governing Council, Sixtieth Session (document GC/60/13). Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2018

(https://governance.iarc.fr/GC/GC60/En/Docs/GC60_13_CoordinationWHO.pdf, accessed 30 October 2020).

Annex 1 EB148/7

15

14. The Secretariat has strengthened capacity, as requested, by increasing the number of staff working

on cancer prevention and control, with more than 20 new staff positions and consultancy posts, equally

distributed among all levels of the Organization. The result has been increased intensity and frequency

of support to Member States.

15. The Secretariat will continue to support Member States in their efforts to prevent, identify and

address cancer prevention and control through integrating cancer care within noncommunicable diseases

policies and programmes and broader work to strengthen national health systems as part of universal

health coverage.

EB148/7

16

ANNEX 2

GLOBAL STRATEGY ON DIET, PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND HEALTH AND

GLOBAL ACTION PLAN ON PHYSICAL ACTIVITY 2018–2030

1. This annex sets out the progress made in implementing resolutions WHA57.17 (2004) on global

strategy on diet, physical activity and health and WHA71.6 (2018) on global action plan on physical

activity 2018–2030.

GLOBAL STRATEGY ON DIET, PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND HEALTH:

PROGRESS TO DATE

2. To support Member States in implementing the set of recommendations on physical activity, the

Secretariat produced a series of supporting global technical resources. In addition, regional technical

tools and resources supported policy action across key settings and populations.

3. In 2010, WHO launched the first global recommendations on physical activity for health

1

outlining the substantial range of health benefits of regular physical activity for different age groups.

These guidelines affirmed the substantial health benefits of regular physical activity for healthy growth

and development, prevention of leading noncommunicable diseases and injuries, and improvement of

mental health and well-being.

4. In 2013, the Health Assembly agreed the first global target to reduce physical inactivity by 10%

by 2025 as part of the set of nine voluntary targets to reduce noncommunicable disease by 2025.

2

The

global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2013–2020 had

identified public awareness campaigns as a cost-effective intervention (“best buy”), and in 2017 an

updated set of best buys identified an extended set of effective interventions

3

to increase population

levels of physical activity across the life course.

5. In all regions, technical support and multi-country training were developed and capacity-building

workshops conducted, resulting in an increasing number of countries developing national policies or

plans and surveillance. In addition, countries across all regions commenced, or updated, their

surveillance of physical activity in adults and, to a lesser extent, adolescents.

6. Although in all WHO regional offices limited human and financial capacity dedicated to physical

activity constrained the pace and scale of technical assistance to countries, the Regional Office for

1

WHO. Global recommendations on physical activity for health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010

(https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44399).

2

Resolution WHA66.10 (2013).

3

WHO. Tackling NCDs: “best buys” and other recommended interventions for the prevention and control of

noncommunicable diseases. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017 (https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/259232).

Annex 2 EB148/7

17

Europe developed a regional strategy on physical activity for the period 2016–2025

1

and the Regional

Office for the Eastern Mediterranean issued a regional call for action.

2

7. In 2016, the Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity reaffirmed the importance of addressing

physical inactivity in children, especially young children.

3

Its subsequent implementation plan

4

called

for countries to prioritize and strengthen the promotion of physical activity to children through schools

and child care, to parents and families, and through supportive urban design and transport systems.

8. Throughout the period 2004–2016, the global strategy contributed to increased recognition

globally of the importance of regular physical activity. Overall, however, the impact on the development

and implementation of national policy and approaches was slow and uneven, and mostly limited to

high-income countries. Rising concerns about the lack of progress in reducing levels of physical

inactivity and the apparent widening of disparities prompted the request for a global action plan on

physical activity, drawing on the latest scientific evidence on effective approaches and aligned with the

goals of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

GLOBAL ACTION PLAN ON PHYSICAL ACTIVITY 2018–2030: PROGRESS TO DATE

9. In resolution WHA71.6 (2018), the Seventy-first World Health Assembly endorsed the global

action plan on physical activity 2018–2030, which provided an updated set of 20 evidence-based policy

recommendations for accelerating progress towards the interim 2025 target, namely a 10% improvement

in physical activity.

10. The Health Assembly requested five specific actions: (1) implementation of the actions for the

Secretariat in the global action plan, including providing necessary support to Member States for

implementation of the plan, in collaboration with other relevant partners; (2) finalization of a monitoring

and evaluation framework on the implementation of the global action plan; (3) production of a global

status report on physical activity, building on the latest evidence including that on sedentary behaviours;

(4) updating the global recommendations on physical activity for health 2010; and (5) reporting on

progress made in implementing the global action plan to the Health Assembly in 2021, 2026 and 2030.

The following paragraphs respond to that request and outline key priorities for the remainder of the

biennium 2020–2021 and challenges and opportunities for promoting physical activity.

1

WHO Regional Office for Europe. Physical activity strategy for the WHO European Region 2016–2025. World

Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe; 2016 (https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/329407).

2

WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Promoting physical activity in the Eastern Mediterranean

Region through a life-course approach. Cairo: World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean;

2014 (https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/116901).

3

See decision WHA69(12) (2016).

4

Welcomed by the Health Assembly in decision WHA70(19) (2017). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018

(https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/275415).

EB148/7 Annex 2

18

Responding to requests from Member States to support national efforts for implementing

the recommendations of the global action plan

11. In 2018, WHO launched ACTIVE: a technical package on effective interventions to promote

physical activity.

1

It provides guidance for Member States on how to plan, start and scale up the

implementation of the policy recommendations across the four strategic areas of the global action plan,

including strengthening governance and national policy frameworks and multisectoral collaboration.

12. Technical support on how to reduce disparities in physical activity between subpopulations will

be described in modules on promoting physical activity to older adults, people living with disabilities or

chronic disease, and strengthening community sport-health initiatives and partnerships.

13. At the regional level, tools and resources to support Member States’ actions on physical activity

and for sharing regional best practices have also been developed in priority areas including:

communication campaigns, health-promoting schools, counselling in primary health care, workplaces,

healthy ageing, and healthy cities.

14. Training courses have been held to strengthen skills and knowledge on physical activity within

context of health promotion and/or NCD prevention programmes at the global, regional and national

levels. Often these have been conducted in collaboration with WHO collaborating centres and supported

by stakeholders; during 2018–2019 more than 100 countries have participated.

15. New global comparative analyses of levels and trends in physical activity estimated that in 2016

one quarter of adults and three quarters of adolescents did not meet global recommendations, with

negligible improvements since 2001.

2

Furthermore, gender disparities between men and women, and

boys and girls, appeared to be widening.

Updating the global recommendations on physical activity for health 2010

16. In 2019–2020, the Secretariat completed the requested updating of the global recommendations

from 2010. The work was supported by a 27-member Guideline Development Group and included a

web-based public consultation.

17. WHO’s new guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour

3

have been finalized for

children and adolescents (aged 5–17 years), adults (18–64 years), older adults (65 years and above) and

include, for the first time, specific recommendations on physical activity in subpopulations such as

pregnant women and those living with chronic conditions or disability. The guidelines are thus aligned

with the goals of the global action plan. The global launch took place on 25 November 2020.

4

1

WHO. ACTIVE: a technical package for increasing physical activity. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018

(https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/275415).

2

WHO. The Global Health Observatory: noncommunicable diseases: risk factors

(https://www.who.int/gho/ncd/risk_factors/physical_activity/en/, accessed 2 November 2020).

3

WHO. WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020

(https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/336656).

4

WHO. Every move counts towards better health – says WHO (https://www.who.int/news/item/25-11-2020-every-

move-counts-towards-better-health-says-who, accessed 7 December 2020).

Annex 2 EB148/7

19

18. To support preparation and accelerate country adoption of the new global guidelines, virtual

workshops were held in each of WHO’s six regions (June–July 2020), bringing together more than

67 Member States responsible for national guideline development across multiple ministries. The

workshops and piloting of the adoption framework will support Member States to develop or update

their national physical activity guidelines.

Developing a global monitoring and evaluation framework to track progress on

implementation of a global action plan

19. In developing a monitoring and evaluation framework the Secretariat has included identification,

where possible, of existing indicators and data sources suitable for tracking progress on implementation

of the 20 policy recommendations (see paragraph 9 of this annex). Consultation with Member States

and relevant stakeholders began with an expert meeting in November 2018 and continues, for instance

with organizations in the United Nations development system, particularly United Nations Development

Programme, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization and United Nations

Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat), to ensure alignment with other relevant monitoring

frameworks and Sustainable Development Goals.

20. The framework, comprising a set of process, outcome and impact indicators, is scheduled for

publication as a technical report on the WHO website by the end of 2020.

Global status report on physical activity

21. Preparation of the requested first global status report on physical activity began in parallel with

work on the monitoring and evaluation framework. During 2019–2020 relevant data, including those

from WHO’s global survey in 2019 of national capacity for NCD prevention and control

1

and WHO’s

road safety survey 2018,

2

were analysed.

22. Workplans for 2020, including proposed global and regional consultations, collection and launch

(scheduled for December 2020) of country best practice case studies, have been heavily disrupted by

COVID-19. Consequently, the publication of this report has been postponed to 2021 to allow for full

engagement of all relevant stakeholders.

23. The emerging findings reaffirm that progress on physical activity remains modest and uneven in

reach and scale between and within regions. Further, the rate of country implementation suggests that

continuing a “business as usual” approach is unlikely to achieve the global target of a 15% reduction in

the global prevalence of physical inactivity by 2030. Impediments to implementing recommended,

cost-effective actions at national and subnational levels must be identified and mitigated in order to

accelerate global progress and impact.

Major obstacles to increasing physical activity

24. Impediments identified across all regions include: (1) a lack of prioritization of policy on physical

activity within and beyond the health sector; (2) lack of human and financial resources within the

1

WHO. Assessing national capacity for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases: report of the 2019

global survey. Geneva: World Health Organization 2020 (https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331452).

2

WHO. Global status report on road safety 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018

(https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/276462).

EB148/7 Annex 2

20

Secretariat and countries to develop, disseminate and implement policy actions on physical activity;

(3) weak capacity to integrate approaches across multiple sectors and implement whole-of-system

approaches; and (4) insufficient capacity to engage and sustain civil society, research communities and

other key partners at national and subnational levels, particularly between health and relevant authorities

for sport, transport, urban planning, design and environment.

Accelerating increases in physical activity

25. In most Member States multiple opportunities exist to strengthen and accelerate actions aimed at

retaining or increasing physical activity, particularly through walking and cycling, with the achievement

of multiple other policy priorities. Areas of strong policy alignment include: healthy ageing; road safety;

climate change mitigation; air quality; environmental sustainability; liveable cities and communities;

and reduction of inequalities.

26. To support the scaling up of country efforts, WHO has strengthened partnership with

stakeholders, including the sport and technology sectors, and established dialogues with the relevant

private sector operators

1

to engage and align their efforts towards achieving common goals of the global

action plan.

27. Progress in implementation of the global action plan can also be accelerated by increased

investment in the promotion of physical activity to youth and adolescents; expansion of workforce

capacity and skills in the promotion of physical activity; strengthening national multisectoral

coordination; investment in research and knowledge transfer, particularly in low- and middle-income

countries; and removing social, environmental and economic barriers to participation.

Impact of COVID-19 on physical activity and responses

28. COVID-19 has had an unprecedented impact on how, where and for how long people can be

physically active. Ensuring that the importance and protective benefits of physical activity on mental

and physical health are recognized in countries’ responses to COVID-19 is vital, as is securing the

inclusion of policies that embed equitable opportunities for physical activity in strategies to “build back

better”.

1

WHO. Engagement with the private sector for SDG target 3.4 on NCDs and mental health

(https://www.who.int/ncds/governance/private-sector/en/, accessed 9 November 2020).

EB148/7

21

ANNEX 3

ENDING ALL FORMS OF MALNUTRITION

1. Sustainable Development Goal 2 (End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and

promote sustainable agriculture) has set the ambitious targets to eliminate all forms of malnutrition by

the year 2030. The Health Assembly has been concerned about nutrition since its early years. In the past

two decades it has dealt with unhealthy diets through the global strategy on diet, physical activity and

health, endorsed in 2004 (resolution WHA57.17); all forms of malnutrition through the comprehensive

implementation plan on maternal, infant and young child nutrition, endorsed in 2012

(resolution WHA65.6 and later resolution WHA71.9 (2018) on infant and young child feeding); and the

implementation plan of the Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity, welcomed in 2017 (decision

WHA70(19)). The Health Assembly also endorsed the Rome Declaration, the outcome of the Second

International Conference on Nutrition in 2014 (resolution WHA68.19 (2015)), and progress on its

implementation has subsequently been reported biennially, together with the progress on the United

Nations Decade of Action on Nutrition, 2016–2025.

2. This annex provides an overview of the progress in the global nutrition situation and the policy

response and reports more specifically on the outcomes of the Second International Conference on

Nutrition. Progress in implementing resolutions WHA65.6 (2012) and WHA71.9 (2018) and decision

WHA70.19 (2017) are reported in greater detail in the biennial reports delivered in even years.

PROGRESS IN ACHIEVING GLOBAL TARGETS ON DIET AND NUTRITION

3. The concept of “all forms of malnutrition” is reflected in the global nutrition targets established

by the Health Assembly in 2012 (resolution WHA65.6),

1

which cover child wasting, stunting and

overweight; anaemia in women of reproductive age; low birth weight; and exclusive breastfeeding. The

first four targets are included in the formal monitoring system for the Sustainable Development Goals.

In addition, in 2013 the Health Assembly endorsed the global action plan for the prevention and control

of noncommunicable diseases 2013–2020 and adopted its nine voluntary global targets for 2025 in

resolution WHA66.10 (2013), including the targets of halting the rise in diabetes and obesity and

reducing the intake of salt/sodium.

4. The prevalence of adult obesity continues to rise in all WHO regions, from 11.8% in 2012 to

13.1% in 2016, so that the global target to halt the rise in obesity by 2025 is unlikely to be achieved.

Excessive salt consumption is still responsible for an estimated three million deaths from heart disease,

stroke and related causes.

5. In addition, in 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic, almost 690 million people (8.9% of the

global population) were undernourished and two billion people (25.9% of the global population)

experienced hunger or did not have regular access to nutritious and sufficient food.

1

Document WHA65/2012/REC/1, Annex 2 (Comprehensive implementation plan on maternal, infant and young

child nutrition) (https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA65-REC1/A65_REC1-en.pdf).

EB148/7 Annex 3

22

6. Unhealthy diets account for an additional 11 million deaths. Sub-optimal diets are now

responsible for 20% of premature (disease-mediated) mortality worldwide, as well as for 20% of all

disability-adjusted life years lost to ill-health.

PROGRESS IN THE IMPLEMENTATION OF FOOD AND NUTRITION POLICIES

7. WHO’s Global database on the Implementation of Nutrition Action

1

contains information on

national policies and strategies with nutrition goals, strategies or indicators in 194 Member States, of

which 180 have comprehensive or topic-specific nutrition policies (on, for example, healthy diet,

anaemia and breastfeeding). A third

Global Nutrition Policy Review is in process.

8. National strategies that include specific goals, objectives, and actions to promote healthy

diets. Most countries have adopted the global nutrition targets for 2025, covering for example stunting

(117 Member States), anaemia in women (104), low birth weight (119), child overweight (137),

exclusive breastfeeding (130) and wasting (111). The vast majority (186 Member States) include actions

to promote healthy diets in their national policies and strategies, aiming to reduce consumption of fats

(100 Member States), salt/sodium (142) or sugars (86). Population information policies through

counselling or media campaigns are more common (181 Member States) than those that seek to change

the food environment through nutrition labelling, marketing restrictions, fiscal policies or

reformulation (156).

9. Labelling and health claim. Nutrition labelling was the intervention that saw the largest increase

between WHO’s first and second global nutrition policy reviews in 2009–2010 and 2016–2017,

respectively. National nutrition-labelling legislation defines the details on the information that should

be available to consumers on pre-packaged food, including list of ingredients, nutrient declaration and

the health or nutrient claims producers make on labels. As reported to the second review, 73 countries

provided detailed information on their implementation of nutrient declaration and 69 countries on their

regulation of nutrition and health claims.

10. Promotion of food products consistent with a healthy diet. Reformulation of food and

beverage products is being implemented to reduce the content of saturated fatty acids, trans-fatty acids,

sugars and salt/sodium. The recent WHO report on global trans-fatty acid elimination 2020

2

found that

58 countries so far have introduced laws to eliminate trans-fatty acids from the food supply; if

successful, elimination will protect 3.2 billion people from those harmful substances by the end of 2021.

11. Fiscal policies. Currently 73 Member States impose taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages,

although the definitions, type and level of tax and range of products covered vary greatly. Twenty-nine

Member States identify subsidies on healthy foods and beverages (for instance, fruits and vegetables)

as suitable approaches to support healthy diets in their national strategies.

1

WHO. Global database on the Implementation of Nutrition Action (GINA)

(https://extranet.who.int/nutrition/gina/en).

2

WHO. News release: more than 3 billion people protected from harmful trans fat in their food. Geneva: World

Health Organization; 2020 (https://www.who.int/news/item/09-09-2020-more-than-3-billion-people-protected-from-harmful-

trans-fat-in-their-food, accessed 7 December 2020).

Annex 3 EB148/7

23

12. Food programmes. Among the respondents to the Global Nutrition Policy Review 2016–2017,

1

85 countries reported food distribution programmes as part of their social safety nets employed to

address underlying causes of malnutrition, typically either emergency food aid programmes or special

foods for infants and young children (or both).

13. School policies and programmes. The Global Nutrition Policy Review 2016–2017

recommended the strengthening of school health and nutrition programmes to ensure nutrition-friendly

schools where policies, curriculum, environments and services are designed to promote healthy diets

and support good nutrition. Most countries (89% of 160) reported having school health and nutrition

programmes, but individual components of school programmes had largely deteriorated since the first

Global Nutrition Policy Review in 2009–2010.

14. Health and other services. Among respondents to the Global Nutrition Policy Review

2016–2017, 153 countries reported employing nutrition professionals (that is, trained nutritionists or

dieticians). However, the density was low (particularly in the African Region) – six countries had no

nutrition professionals, and the global median among 126 countries providing details was only

2.3 trained nutrition professionals per 100 000 population. Pre-service and in-service training of health

professionals in maternal, infant and young child nutrition was reported to be offered in 140 countries,

although the number of hours in the pre-service curriculum dedicated to this topic was generally less

than the number of hours dedicated to this subject area in WHO’s breastfeeding training course curricula.

SECOND INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON NUTRITION AND THE UNITED

NATIONS DECADE OF ACTION ON NUTRITION

15. Following up on the outcomes of the Second International Conference on Nutrition, governments,

organizations in the United Nations system, civil society and the private sector have been active in

improving awareness and stimulating action to respond to a new nutritional reality characterized by all

forms of malnutrition. A second report of the United Nations Secretary-General on the implementation

of the United Nations Decade of Action on Nutrition was published on 13 April 2020.

2

Mid-term review

16. In keeping with the United Nations Economic and Social Council’s resolution E/RES/1989/84 on

international decades, commitments made in the Rome Declaration on Nutrition should be reviewed at

mid-term and at the end of the Decade of Action on Nutrition, in an open and participatory process.

17. The mid-term review foresight paper

3

summarizes the progress in the six action areas of the

Decade:

(a) Sustainable, resilient food systems for healthy diets. In growing numbers, high-level

reports and resolutions have underlined the crucial role of sustainable, resilient food systems for

1

WHO. Global Nutrition Policy Review 2016–2017: country progress in creating enabling policy environments for

promoting healthy diets and nutrition. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2018

(https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/275990).

2

UN General Assembly. Implementation of the United Nations Decade of Action on Nutrition (2016–2025).

New York: United Nations; 2020 (https://undocs.org/en/A/74/794).

3

United Nations Decade of Action on Nutrition (2016-2025). Mid-term review foresight paper

(https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nutritionlibrary/departmental-news/mid-term-review---un-decade-of-action-on-

nutrition/nutrition-decade-mtr-foresight-paper-en.pdf?sfvrsn=c3c14085_8, accessed 7 December 2020).

EB148/7 Annex 3

24

healthy diets and improved nutrition. Numerous alliances have been established to bring together

different actors, beyond the traditional nutrition actors, for sustainable food systems. Recognition

of agroecology and biodiversity, increased consideration of sustainability issues in national

food-based dietary guidelines, growing implementation of measures to reduce food loss and

waste, and action to enhance resilience of the food supply in crisis-prone areas have been noticed.

Measures to reduce or eliminate industrially-produced trans-fatty acids have been accelerated,

and voluntary or mandatory reformulation of processed food products has been carried out to

reduce their salt/sodium content.

(b) Aligned health systems providing universal coverage of essential nutrition actions. A

clear understanding of the effective interventions to be delivered by health systems has emerged

during the first half of the Decade, but there has been significant under-investment in both

ensuring adequate coverage of high-impact nutrition interventions and improving their quality.

To accelerate progress on wasting in children under five years of age, a United Nations global

action plan on child wasting: a framework for action to accelerate progress in preventing and

managing child wasting and the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals

1

was

published on 9 March 2020. This plan will enable organizations of the United Nations

development system to develop a more targeted road map for action in 2021. Strong health

systems are needed to deliver nutrition actions, and the increasing political momentum for

achieving universal health coverage presents new opportunities for expanding coverage and for

mainstreaming WHO’s essential nutrition actions

2

through the life-course.

(c) Social protection and nutrition education. The contributions of social protection to food

security and nutrition will depend on its integration at policy level. To ensure that social protection

policies holistically combat all forms of malnutrition, a nutrition-sensitive approach needs to be

applied in their design and implementation. Policy measures for improving food access, social

protection and food assistance are prevalent in some WHO regions, while in other WHO regions

this continues to be an area of under-investment. Nutrition education is widely implemented in

schools, but policies to ensure that education is supported by healthy school environments are

lacking and implementation of school health and nutrition programmes has deteriorated in recent

years. Although most countries train health workers on nutrition, the level of training is often

inadequate and, more generally, nutrition action continues to be hampered by a lack of trained

nutrition professionals. The potential of multi-component school-based programmes to educate

about food and nutrition has been increasingly recognized as an important programmatic area for

sustainable development.

(d) Trade and investment for improved nutrition. Trade can be a key element in enhancing

food security and nutrition, but there has been increasing recognition of the need for coherence

between trade policy and nutrition action and the importance of governance and cross-sectoral

cooperation. A finance gap persists, despite the need for responsible and sustainable investments

in agriculture and food systems. Certain global value chains and agri-food industries currently

produce environmentally unsustainable food products which commonly are rich in unhealthy fats,

sugars and/or salt/sodium. Increased globalization of the food supply means populations are more

1

WHO. Global action plan on child wasting: a framework for action to accelerate progress in preventing and

managing child wasting and the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals. Geneva: World Health Organization;

2020 (https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/global-action-plan-on-child-wasting-a-framework-for-action, accessed

7 December 2020).

2

WHO. Essential nutrition actions: mainstreaming nutrition through the life-course. Geneva: World Health

Organization; 2019 (https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/326261).

Annex 3 EB148/7

25

exposed to different food hazards. Rather than driving healthy diets, trade and investment policies

are exacerbating malnutrition in all its forms. Increased foreign direct investment, for example,

has been linked to higher consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages. Prioritizing health over

short-term economic gain has been shown to lead to greater economic gains in the long term.

(e) Safe and supportive environments for nutrition at all ages. Creation of healthy food

environments – encompassing availability, affordability, promotion and quality of food

supporting healthy diets – has become a central consideration in nutrition policy-making. There

is increasing momentum for the creation of healthy urban environments, with food environments

an important element. Policies to create healthy food environments in schools, to protect and