Examining Religion as A Preventative Factor

to Delinquency

Russell K. VanVleet

Jeff Cockayne

Timothy R. Fowles

August 1999

2

Table of Contents

Executive Summary ....................................................... Page 3

Penitentiaries of the Past ................................................... Page 5

Parameters and Purpose of the Study ......................................... Page 6

Religious Attendance...................................................... Page 7

Other Factors-Forced Religion .............................................. Page 7

Religious Involvement of High School Seniors ................................. Page 8

Morals and Values ....................................................... Page 11

Hellfire and Delinquency .................................................. Page 12

The Ecology Theory ..................................................... Page 12

The Provo Study Testing Hellfire and Delinquency ............................. Page 13

Defining and Resting Religiosity Correctly.................................... Page 14

Other Factors to Consider When Evaluating Religiosity.......................... Page 14

Quality of Research ...................................................... Page 14

Is Religiosity Connected to Delinquency ..................................... Page 15

Conclusion ............................................................. Page 16

References ............................................................. Page 17

1

Religiosity is a term researchers use to quantify an individual’s commitment to any

particular religion. Although the terms “religion”, “religiousness”, and “religiosity” are often

used interchangeably, many researchers prefer “religiosity” because it denotes a specific measure

of individual commitment (like “velocity” as a scientific measure in physics) rather than simply

common belief held by a number of people.

3

Executive Summary

Throughout the past, clergymen, church members, and social scientists, have assumed

that religious beliefs and church attendance are effective deterrent to delinquent behavior. Many

hypothesized that the more religious a person was, the less likely he or she will be to participate

in delinquent behavior. As time and technology progressed researchers began looking more

empirically at the connection between religion and delinquency. Unfortunately, science has

neither confirmed nor refuted the age old hypothesis that religion deters delinquency. “During

the 1970's and 1980's several studies using more sophisticated methodologies and statistical

analysis produced mixed results.” (Chadwick, and Top, 1993) These mixed results allow church

officials, legislators, and social workers to pick and choose research that supports their particular

view. However, an overall analysis reveals that no theory can account for all the research. As

Tittle and Welch (1983) point out, religiosity

1

cannot in and of itself be conclusively held as a

deterrent for delinquency.

Despite numerous theoretical reasons for expecting religion to contribute to social conformity,

social scientists cannot say with any confidence whether religiosity actually inhibits deviant

behavior. Over forty years of research has produced results which are often interpreted as

inconclusive or even contradictory.

A large amount of the inconsistency between various studies in the ways in which

researchers have operationalized religiosity and delinquency. Many studies choose to define

religiosity simply as church attendance. This provides an easy way to quantify religiosity, and

4

therefore is easy to analyze statistically. In addition, many studies show that church attendance

is declining, which concerns those who believe in religion as an important component of crime

prevention. However, this measure of delinquency is confounded by a number of factors

including forced attendance at church, attendance based on sentimental rather than commitment,

component skewing research.

Other attempts to define religion attempt to include morals and values, cultural context,

and individual determining factors. Defining delinquency is often just as difficult. Researchers

must decide whether deviant behavior must be misdemeanors and felonies, drug use, etc.

Because of differing definitions, studies report differing results. Consequently, social science

has yet to make a definitive statement regarding the connection between religion and

delinquency.

5

Penitentiaries of the Past

Throughout history, the line separating crime and sin has been blurry at best, and

in most cases non-existent. During the eighteenth century, many thought deviant behavior was

caused by evil spirits, supernatural powers, or the result of individual free choice. (Schafer and

Knudten, 1970) In 1790, Philadelphia’s Walnut Street Jail was converted into a penitentiary,

where penance was adopted as the new ideology. Penance is defined as, “The act of self

punishment as reparation for guilt, sins, etc.” (Abate, 1998, emphasis added) Institutions were

initially named penitentiaries because the question of crime with sin necessitated a means of

reformation for “unclean” offenses. The first “penitentiaries” were founded on the religious

philosophy that the offenders should make amends with society and accept responsibility for

their own misdeeds. In the eighteenth century prisons, “Penance was the primary vehicle

through which rehabilitation was anticipated, and the study of the Bible was strongly

encouraged.” (Schmalleger, 1997) Capital punishment, often conducted in public, made

offenders examples in order to discourage crime. The death sentence was used as a consequence

all manners of crimes including, “murder and arson, horse stealing, and children’s disrespect for

their parents.” (Rothman, 1971, pg15)

The late eighteenth century marked a paradigm shift from corporal punishment towards

imprisonment with the hope of conforming the will of the individual. Early prison systems used

solitary confinement and congregate silent systems in an attempt to compel offenders to reflect

on the damage they had caused to others and society. Eighteenth century lawmakers aspired to

establish penitentiaries, “free of corruptions and dedicated to the proper training of the inmate,

Religion and Delinquency

2

This paper was a literature search intended to examine the varioius studies and materials

regarding the effects of religiosity on delinquency. It was not an experimental study, nor an

empirical analysis drawing its own conclusions, but simply an overview of the studies already

conducted.

6

[penitentiaries] would inculcate the discipline the negligent parents, evil companions, taverns,

houses of prostitution, theaters, and gambling halls had destroyed.” (Rothman 1971, pg 82) In

many ways, this type of religiously driven penal goal starkly contrasts our modern system. The

United States no longer believes in public executions, and has detached the taut correlation of

religion and delinquency from that of the past,

Contemporary society often claims sciences such as psychology, sociology, and

criminology as empirical solutions to religiously driven penal systems; however, there is

still much debate on how much of a bearing religion has on deviant behavior. “As

observations on the influence of religion in the formation and volume of delinquency are

scattered and inconclusive, the exact relationship between religion on one hand and delinquency

and criminality on the other is unknown.” (Schafer & Knudten, 1970) Throughout the decades of

research, various studies have conclusively shown conflicting results. This report

2

examines the

effects of religion as a preventative factor in delinquency using the following parameters:

1. What is religiosity, and how has it been measured?

2. Why is there such a vast disparity in the correlation of religiousness and delinquent

behavior?

3. Is religion directly correlated to delinquency, and to what extent?

Religion and Delinquency

3

Bachman, Johnson & O’Malley, working at the University of Michigan’s Institute for

Social Research, conducted an ongoing cross-sectional study questioning youth extensively

about various issues. The results were reported yearly in a work titled Monitoring the Future.

7

Church Attendance: A Poor Measure of Religiosity

Religion is a multi-faceted word with many implications, which makes describing

religion extremely difficult and often subjective. For some, being religious means simply

attending church, for others it includes specific beliefs and practices such as prayer, rituals, and

accepting certain values and morals. This ambiguity makes operationalizing religion difficult for

researchers. As a result many narrowly define one’s religiosity, or commitment to religion

simply as church attendance. Hirschi and Stark (1969) illustrate why:

We shall not here be concerned with what religiosity really is. Instead we shall take for

granted the view that religiosity is many things...The usual beginning point in studies of the

effects of religion is a measure of church attendance. In our opinion this is as it should be.

Another reason researchers operationalize religiosity as church attendance is because

data shows that youth are attending church less and less. Lawmakers and parents alike want to

know to what extent relaxed attitudes toward church contribute to delinquency. Data collected

by Bachman, Johnston & O’Malley (various years

3

) contributes to the idea that church

attendance is declining among today’s youth.

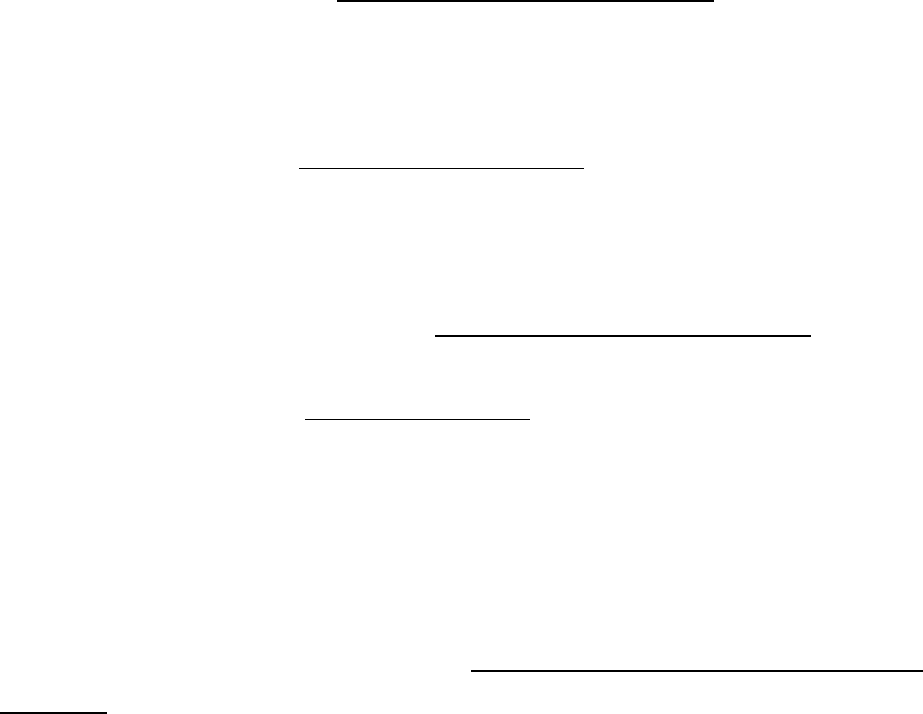

Researchers at the Institute for Social Research conducted a long-term study examining the

beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors of young adults 19-32 in the United States (see Figure 1). They

examined 420 public and private schools between 1976 and 1991. In 1976, approximately

40.7% of high school seniors attended church weekly. During 1991, the average attendance of

Religion and Delinquency

8

high school seniors was 31.2%; indicated a 9.5% decline in religious attendance during a fifteen

year period. The survey also depicts an increase in the population of high school seniors that

consider religion “Not Important,” from 12.7% in 1976 to 15.3% in 1991.

Figure 1:

Religious involvement of high school seniors: 1976 to 1991

SOURCE: University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research, Monitoring the Future, various

years.

Religious activity Percent of Seniors

and level of interest

1976 1978 1980 1982 1984 1985

Frequency of attending religious services:

Weekly................. 40.7 39.4 43.1 37.3 37.7 35.3

1-2 times a month. 16.3 17.2 16.3 17.4 16.2 16.6

Rarely.................. 32.0 34.4 32.0 35.8 35.8 37.0

Never................... 11.0 9.0 8.6 9.6 10.2 11.1

Importance of religion in life:

Very important.... 28.8 27.8 32.4 28.4 29.7 27.3

Pretty Important.. 30.5 33.0 32.6 33.0 32.6 32.4

A little................. 27.8 27.9 25.3 27.9 26.7 27.6

Not important..... 12.9 11.2 9.8 10.7 11.0 12.7

Religious activity Percent of Seniors

and level of interest

1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991

Frequency of attending religious services:

Weekly................ 34.4 31.8 31.9 31.4 30.4 31.2

1-2 times a month. 16.8 15.6 17.3 16.6 15.7 16.8

Rarely.................. 36.9 39.6 39.0 38.5 39.7 37.6

Never.................. 12.0 13.0 11.7 13.5 14.1 14.4

Importance of religion in life:

Very important.... 26.3 24.9 26.1 27.2 26.4 27.7

Pretty important.. 32.7 31.7 31.9 30.3 29.5 30.0

A little................. 27.8 28.8 28.4 27.8 28.7 27.0

Not important.......... 13.3 14.5 13.6 14.7 15.5 15.3

Although these figures indicate that church attendance and importance of religion may be

Religion and Delinquency

4

Yochelson and Samenow in their book The Criminal Personality describe various

characteristics of criminality they believe are inherent to certain individuals. Because this

criminality is a part of their personality, they propose, church attendance most likely does not

motivate them to change - rather, it is simply one dimension of their personality.

9

on the decline among today’s youth, analysis such as these have been criticized because of their

superficial view of religiousness. Stark, Kant, and Doyle (1982) point out that:

Many people who attend church frequently who are not particularly religious in any other way–

they do not believe in the theology of their church, they do not pray (except as part of the ritual of

church services), nor do they think of themselves as concerned about religion. By the same token

many persons who are very devout in other ways are infrequent churchgoers, and some such

persons never attend at all. Thus, if one is interested in measuring inner religiousness, church

attendance is not as good a measure as are direct inquiries about what a person believes and feels.

Moreover, in the case of teenage boys, this measurement error is likely to be magnified because,

compared to most adults, youth have less control over whether or not they go to church. It is this

less accurate measurement provided by church attendance that produces the weaker correlations

between church attendance and delinquency...

Stark et. al. points out that many teenagers and delinquents are coerced into going to

church. This “forced religion” can skew research findings, and weaken the connection between

religiosity and delinquency. Correlations may also be confounded by the “conscience factor,”

which has an influence on deviants attending church. Delinquents consciences’ may weigh them

down, causing an increased frequency of church attendance for purification of the soul.

Yochelson and Samenow (1977) illustrate this phenomenon when describing “the criminal

personality

4

:

Criminals of all ages have periods of self-doubt and may go to church themselves. This

state of mind sometimes lasts no longer than the church service itself and is concurrent with

criminality. Church-going serves as a palliative measure for the criminal’s conscience.

(Yochelson, and Samenow, 1977)

Religion and Delinquency

10

Even the non-criminal may attend church for reasons other than devotion. For example,

some attend services simply out of tradition or sentiment, rather than commitment to ideals and

values preached within the denomination. This too leads researchers to question using church

attendance as a measure of true religiosity.

Religion still serves another function: it is of sentimental value to some. The criminal may cling

to the religion of his childhood. Walking into a church, hearing the music, reading psalms, and

participating in the ritual may evoke a strong nostalgia. This sentimentality may be a factor in

frequent church attendance. (Yochelson, and Samenow, 1977)

Research conducted by Hirschi and Stark (1969) confirms the problem with using church

attendance as a measure of religiousness. In an exhaustive survey involving 4,077 students of

Western Contra Costa, California, Hirschi and Stark’s well known study entitled “Hellfire and

Delinquency” found no casual relationship between church attendance and delinquency.

In conclusion, although church attendance may be declining among today’s youth, this

decline does not clearly correlate to rates of delinquency. Therefore, church attendance along is

an ineffective way to measure religiosity.

Moral Poverty and Ecological Theory

Religion and Delinquency

11

In an attempt to better understand religion’s contribution to preventing delinquency,

researchers have attempted to focus studies more on the moral contributions of religious activity.

When researchers use cultural, moral, and societal influences, to examine religiousness, the

research reveals correlations between religion and delinquency more effectively. Since many of

the moral ideals within a given society stem from religion, morals and values are crucial factors

when observing religiosity. Morals can be defined as acceptable behaviors, that do not violate

the norms of society; or right moral conduct. (Abate, 1998)

Sadly, many believe that the current “norms of society” are moving further and further

away from true morality. The Advertising Council’s Strategic Task Force observed, “Americans

are convinced that today’s youth face a crisis...not in their economic or physical well-being but

in their values and morals.” (Merkly Newman Harty, Public Agenda Foundation) Their

observation was based on a sample of 2,000 randomly selected adults aged 18 years and older,

and of 600 randomly selected youth between 12 and 17; both conducted in December 1996. The

study contends that parents are fundamentally responsible for the aberrant condition of their

youth, and that children are suffering because of the disinterest of the parents. According to their

findings, most Americans view today’s teenagers with trepidation, considering them

undisciplined, disrespectful, and unfriendly. But is this really true? If so, what is the source of

declining morality among today’s youth?

Social scientists have long accepted poverty and low socio-economic status as

contributing risk factors for delinquency; however, Sagi and Eisikovits (1981) propose a new

risk factor: moral poverty. “Moral Poverty,” as explained by Sagi and Eisikovits, is a deficiency

Religion and Delinquency

12

of concerned adults capable of teaching their children right from wrong. This moral deprivation

may be partly responsible for the increasing number of crimes committed by juveniles.

Presently, many youth are without parents and other authorities to habituate them to feel others

joy and pain, or happiness when doing what is right, and remorse when doing what is wrong.

(DiIulio, 1997)

Religion plays a major role in dictating contemporary views of morality. Therefore,

another factor contributing to moral poverty could be the continued attempts to divorce religion

from society. In the name of tolerance, many accept what traditional religion would call

immoral. Furthermore, in attempts to separate church and state, governments often end up

separating religion from the state. If researchers can effectively correlate moral depravity and

delinquency, a more religious community might be our most effective tool for eradicating moral

poverty.

Results of studies including moral variables reveal new implications about the connection

between morality and religion. During the early 1980's a new ideology was presented that shed a

new light on why there were conflicting results with religion and delinquency surveys.

Parameters of religiosity have changed since the Hellfire and Delinquency (see pg 10 and

annotated bibliography) test, and “As a consequence, virtually every published work subsequent

to Hirschi and Stark’s has found evidence of a statistically significant, inverse, bivariate

relationship [opposite] between some indicator of religiosity and various indicators of delinquent

or deviant behavior.” (Cochran, Akers, 1989) However, most of this research hinges on the

cultural cont or “religious ecology” in which the study is conducted. As Chadwick and Top

Religion and Delinquency

5

When the Provo Study was administered, in 1972, the population of Provo was

approximately 50,000 people; the overwhelming majority of which were members of The

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. At the time, Utah stood first among states in terms

of church membership rates, and the Provo-Orem metropolitan area stood first among American

cities with the rate of 966 per 1,000; compared to the 320 per 1,000 for the San Francisco-

Oakland area, in which Richmond is located. (The area where Hirschi and Stark administered

their survey) (Stark, Kant, Doyle, 1982)

13

(1993) explain, “Religion is negatively associated with deviance only when it is part of widely

accepted social values and norms prohibiting such behavior.” The study done by Chadwick and

Top (1993) helped to settle some controversy concerning the ecological explanation used by

researchers in the 1980's including Stark, Kant, and Doyle (1982) who observed,

...conflicting findings stem from variations in the religious ecology of the communities studied. In

communities where religious commitment is the norm, the more religious an individual, the less likely

he or she will be delinquent. However, in highly secularized communities, even the most devout

teenagers are no less delinquent than the most irreligious.

Presently, many sociologists would agree that conflicting results from studies of the past (Hirschi

and Stark) are from ecological conditions or the religious climate of the community studied.

The Provo Study

5

tested the ecological theory and compared the youth of Provo to the

area of Hirschi and Stark’s. The data was based on a sample of boys from Provo, Utah. As

cited, “Indeed, while Hirschi and Stark found that only 37 percent of white boys in Richmond

attended church weekly, 55 percent of the boys in Provo attended at least that often, and 30

percent of them went to church at least three times a week.” (Stark, Kant, Doyle, 1982) Due to

the different conclusions and sampling methods, other studies were conducted to bring about

some clarification on the validity of the ecology theory. “The inconsistent support discovered

for the religious ecology explanation justifies additional exploration of whether religion’s

Religion and Delinquency

6

William Sims Bainbridge is a professor in the Department of Sociology, Anthropology,

and Social Work at Illinois State University. He conducted a survey titled, “The Religious

Ecology of Deviance.” His data was collected from the 75 American metropolitan areas outside

New England. Delinquency was measured by suicide, crime, homosexuality, and cultism;

religiosity was the rate of church membership. Their findings were that although many forms of

crime and cultism are directly deterred by religion, the influence of religion upon suicide and

homosexuality appears indirect, if it exists at all. (Bainbridge, 1989)

14

relationship to delinquency is a function of social cohesion or whether religious beliefs and

values are related to such behaviors independent of the moral ecology.” (Chadwick, Top, 1993)

Other researchers expanded the ecological systems view when examining the religion-

delinquency connection. Bainbridge

6

(1989) suggested that old age, poverty levels, and

education can all influence correlations in delinquency and religiosity. According to Bainbridge

(1989), effective evaluation of religion and delinquency requires controlling for a wide variety of

variables:

...divorce might be an interesting variable through which religion affects deviance... Other factors

that influence rates of each kind of deviance must also be employed as controls, especially those

that might be associated with religiousness. Suicide is stimulated by despair that sometimes

accompanies old age, and many kinds of crime may be more common where substantial portions

of the population experience economic and social frustrations.

The ecological theory gave researchers an effective alternative to using church

attendance as their only method of operationalizing religiosity. As cited above, this led to

important breakthroughs in examining religion and delinquency; however, this did not provide

authoritative answers, nor did it settle controversy over the true correlation.

Religion and Delinquency

15

Is Religiosity Connected To Delinquency?

Although studies define religiosity and delinquency differently, creating contradictions

and ambiguous conclusions, research does tend to support several generalizations. Correlations

can be shown when religiosity is defined according to an individual’s social, moral, and cultural

context. For example, Chadwick and Top (1993) conclude:

Two measures of religiosity, private religious behavior and feelings of integration, also made

significant contributions to predicting delinquency. The more frequent the private religious

behavior and the stronger the feelings of being accepted in the local congregation the lower

was the level of delinquency. (Chadwick, Top, 1993)

However, whenever correlations between religion and delinquency are examined, a

certain degree of scientific skepticism must be reserved. Geographical locations, predominant

areas of religion, family structure, socio-economic status, divorce, and poverty; all affect

correlations. The methods of measuring religion, and delinquency respectively also largely

determines the results of any study. Therefore, despite advances in theory and methodology,

social science cannot conclude that overall religiosity is directly correlated with delinquency, not

that any casual relationship exists. However, specific studies indicate that certain attributes of

religion definitely have an impact of delinquency.

Religion deters some deviant acts, but not others. If religion lacks a particular community,

it may have had an influence before and may still have an influence elsewhere. (Bainbridge, 1989)

Religion and Delinquency

16

Conclusion

For parents, lawmakers, and other community leaders, scientific results may not be

conclusive, but they do make important implications. Religion should not be abandoned as a

possible variable in the prevention of delinquency. Nor should inconclusive evidence further

promote the separation of religion from the community. The place of religion in prevention of

delinquency may not be clear, but it is there nonetheless.

Religion and Delinquency

17

References

Bachman, J.G., Johnston, L.D., & O’Malley, P.M.. (various years). Monitoring the

Future. University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research.

Bainbridge, W.S. (1989). The Religious Ecology of Deviance. American Sociological

Review 54: pg. 288-95.

Benda, B.B. (1997). Examination of a Reciprocal Relationship Between Religiosity and

Different Forms of Delinquency Within a Theoretical Model. Journal of Research in Crime and

Delinquency 34,2 (May): pg. 163-186.

Blum, R. & Rinehart, P.M.. (1997). Reducing the Risk: Connections that Make a

Difference in the Lives of Youth. Youth Studies Australia 16, N 4 (December): pg. 37-50.

Burkett, S.R. & White, M. (1974). Hellfire and Delinquency: Another Look. Journal for

the Scientific Study of Religion 13, N 1 (March): pg. 455-62.

Chadwick, B.A. & Top, B.L. (1993). Religiosity and Delinquency among LDS

Adolescents. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 32, N 1 (March): pg. 51-67.

Cochran, J.K. & Akers, R.L. (1989). Beyond Hellfire: An Exploration of the variables

affects religiosity on adolescent marijuana and alcohol use. Journal of Research in Crime and

Delinquency 26, N 1 (February): pg. 198-225.

Cortes, J.B. & Gatti, F.M.. (1972). Delinquency and Crime: A Biopsychosocial

Approach. Seminar Press, New York and London.

DiIulio, J.J.Jr. (1997). Lack of Moral Guidance Causes Juvenile Crime and Violence. In

Sadler, A.E. (Editor). Juvenile Crime: Opposing Viewpoints. Greenhaven Press, Inc. San Diego,

California. Pg. 107-117.

Ellis, L. (1985). Religiosity and Criminality Evidence and Explanations of Complex

Relationships. Sociological Perspectives 28, N4 (October): pg. 501-15.

Evans, T.D., Cullen, F.T., Burton, V.S. Jr., Dunaway, R.G., Payne, G.L., Kethineni, S.R.

(1996). Social Bonds, and Delinquency. Deviant Behavior 17, N 1 (January-March): pg. 43-70.

Religion and Delinquency

18

Fernquist, R.M.. (1995). Research Note on the Association Between Religion and

Delinquency. Deviant Behavior 16, N 2 (April-June): pg. 169-175.

Hirshi, T. & Stark, R. (1969). Hellfire and Delinquency. Social Problems 17, N 1: pg.

202-13.

Abate, F. (Editor). (1998). The Oxford American Desk Dictionary. New York: Oxford

University Press.

Merkly Newman Harty and the Public Agenda Foundation. (1997). Kids These Days:

What Americans Really Think About the Next Generation.

Rothman, D.J. (1971). The Discovery of the Asylum. Little, Brown and Company,

Boston, Toronto.

Safi, A. & Eisikovits, Z. (1981). Juvenile Delinquency and Moral Development.

Criminal Justice and Behavior 8, N 1 (March): pg. 79-93.

Schafer, S. & Knudten, R.D. (1970). Juvenile Delinquency: An Introduction. Random

House, Inc. Toronto, Canada. pg. 234-238.

Schmalleger, F. (1997). Criminal Justice Today. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, New

Jersey. Pg. 432-443.

Stark, R., Kent, L. & Doyle, D.P. (1980). Religion Delinquency: The ecology of a “lost”

relationship. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 19, N 1 (January): pg. 4-24.

Tittle, C.R. & Welch, M.R. (1983). Religiosity and Deviance: Toward a Contingency

Theory of Constraining Effects. Social Forces 61, N 3 (March): pg. 653-682.

Yochelson, S. & Samenow, S.E. (1977). The Criminal Personality, Volume 1: A Profile

for Change. Jason Aronson, New York. pg. 297-308.