Bradley M. Allan and Roland G. Fryer, Jr.

The Power and Pitfalls of Education Incentives

DISCUSSION PAPER 2011-07 | SEPTEMBER 2011

The Hamilton Project seeks to advance America’s promise

of opportunity, prosperity, and growth.

We believe that today’s increasingly competitive global economy

demands public policy ideas commensurate with the challenges

of the 21st Century. The Project’s economic strategy reflects a

judgment that long-term prosperity is best achieved by fostering

economic growth and broad participation in that growth, by

enhancing individual economic security, and by embracing a role

for effective government in making needed public investments.

Our strategy calls for combining public investment, a secure social

safety net, and fiscal discipline. In that framework, the Project

puts forward innovative proposals from leading economic thinkers

— based on credible evidence and experience, not ideology or

doctrine — to introduce new and effective policy options into the

national debate.

The Project is named after Alexander Hamilton, the nation’s

first Treasury Secretary, who laid the foundation for the modern

American economy. Hamilton stood for sound fiscal policy,

believed that broad-based opportunity for advancement would

drive American economic growth, and recognized that “prudent

aids and encouragements on the part of government” are

necessary to enhance and guide market forces. The guiding

principles of the Project remain consistent with these views.

MISSION STATEMENT

The Hamilton Project • Brookings 1

The Power and Pitfalls of

Education Incentives

Bradley M. Allan

EdLabs

Roland G. Fryer, Jr.

Harvard University, EdLabs

SEPTEMBER 2011

NOTE: is discussion paper is a proposal from the author. As emphasized in e Hamilton Project’s

original strategy paper, the Project was designed in part to provide a forum for leading thinkers across the

nation to put forward innovative and potentially important economic policy ideas that share the Project’s

broad goals of promoting economic growth, broad-based participation in growth, and economic security.

e authors are invited to express their own ideas in discussion papers, whether or not the Project’s sta or

advisory council agrees with the specic proposals. is discussion paper is oered in that spirit.

2 The Power and Pitfalls of Education Incentives

Abstract

ere is widespread agreement that America’s school system is in desperate need of reform, but many educational interventions

are ineective, expensive, or dicult to implement. Recent incentive programs, however, demonstrate that well-designed

rewards to students can improve achievement at relatively low costs. Fryer and Allan draw on school-based field experiments

with student and teacher incentives to oer a series of guidelines for designing successful educational incentive programs. e

experiments covered more than 250 urban schools in ve cities and were designed to better understand the impact of nancial

incentives on student achievement. Incentives for inputs, such as doing homework or reading books, produced modest gains

and might have positive returns on investment, and thus provide the best direction for future programs. Additionally, this paper

proposes directions for future incentive programs and concludes with implementation guidelines for educators and policymakers

to implement incentive programs based on the experiments’ research ndings and best practices. Incentive programs are not

enough to solve all the problems in America’s educational system, but they can denitely play a role in the larger solution.

The Hamilton Project • Brookings 3

Table of Contents

ABSTRACT 2

CHAPTER 1: EDUCATION IN AMERICA 5

CHAPTER 2: STUDENT INCENTIVE PROGRAM DETAILS AND RESULTS 8

CHAPTER 3: TEACHER INCENTIVE PROGRAM DETAILS AND RESULTS 12

CHAPTER 4: THE 10 DO’S AND DON’TS OF EDUCATION INCENTIVES 15

CHAPTER 5: MOVING FORWARD ON EVALUATING EDUCATION INCENTIVES 22

CHAPTER 6: STRUCTURING AND IMPLEMENTING INCENTIVE PROGRAMS 23

CONCLUSION 28

AUTHORS 29

ENDNOTES 30

REFERENCES 31

4 The Power and Pitfalls of Education Incentives

The Hamilton Project • Brookings 5

Chapter 1: Education in America

M

any believe that there is a “crisis” in American

education. On the Program for International

Student Assessment (OECD 2009), out of thirty-

four countries, our ninth graders rank twenty-h in math,

seventeenth in science, and fourteenth in reading achievement.

1

Seventy percent of American students graduate from high

school, which ranks the United States in the bottom quartile of

OECD countries (OECD 2007). In large urban areas with high

concentrations of blacks and Latinos, educational attainment

and achievement are even bleaker, with graduation rates as

low as 38 percent in Detroit and 31 percent in Indianapolis

(Swanson 2009). Of the eighteen districts in the National

Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) Trial Urban

District Assessment (TUDA) sample, at least half of the black

students in fourteen of these districts score at the “below basic”

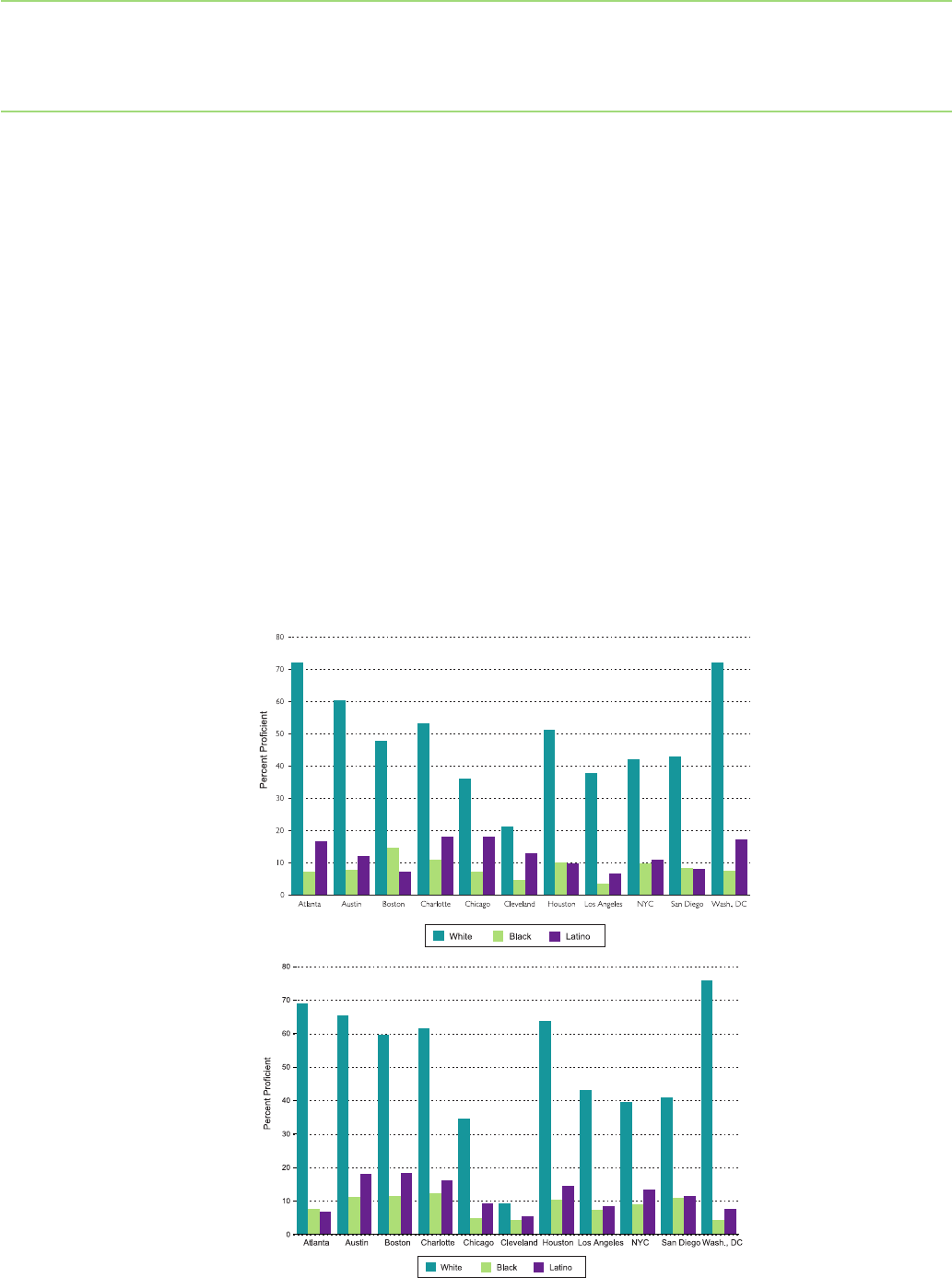

level on eighth-grade math. And, as Figure 1 demonstrates,

there is not a major city in the United States in which even

one fourth of black or Latino eighth graders are procient in

reading or math. In Detroit, for example, only 4 percent of

black fourth graders are procient in math; by eighth grade,

only 3 percent are procient. e performance of black and

Latino students on international assessments is roughly equal

to national performance in Mexico and Turkey—two of the

lowest-performing OECD countries.

FIGURE 1

Racial Differences in Achievement on NAEP, 8th Grade

Reading

Mathematics

Note: All means are calculated using sample weights. N=16,473.

Source: Fryer 2010.

Note: All means are calculated using sample weights. N=17,110.

6 The Power and Pitfalls of Education Incentives

In an eort to increase achievement and narrow dierences

between racial groups, school districts have become

laboratories for reforms. ese reforms include smaller schools

and classrooms (Krueger 2003; Nye, Fulton, Boyd-Zaharias,

and Cain 1995); mandatory summer school (Jacob and Lefgren

2004); aer-school programs (Lauer, Akiba, Wilkerson,

Apthorp, Snow, and Martin-Glenn 2006); budget, curricula,

and assessment reorganization (Borman, Slavin, Cheung,

Chamberlain, Madden, and Chambers 2007); policies to lower

the barrier to teaching via alternative paths to accreditation

(Decker, Mayer, and Glazerman 2004; Kane, Rocko, and

Staiger 2008); single-sex education (Shapka and Keating

2003); data-driven instruction (Datnow, Park, and Kennedy

2008); ending social promotion (Greene and Winters 2006);

mayoral or state control of schools (Henig and Rich 2004;

Wong and Shen 2002, 2005); instructional coaching (Knight

2009); local school councils (Easton, Flinspach, O’Connor,

Paul, Qualls, and Ryan 1993); reallocating per pupil spending

(Guryan 2001; Marlow 2000); providing more culturally

sensitive curricula (Banks 2001, 2006; Protheroe and Barsdate

1991; ernstrom 1992); renovated and more technologically

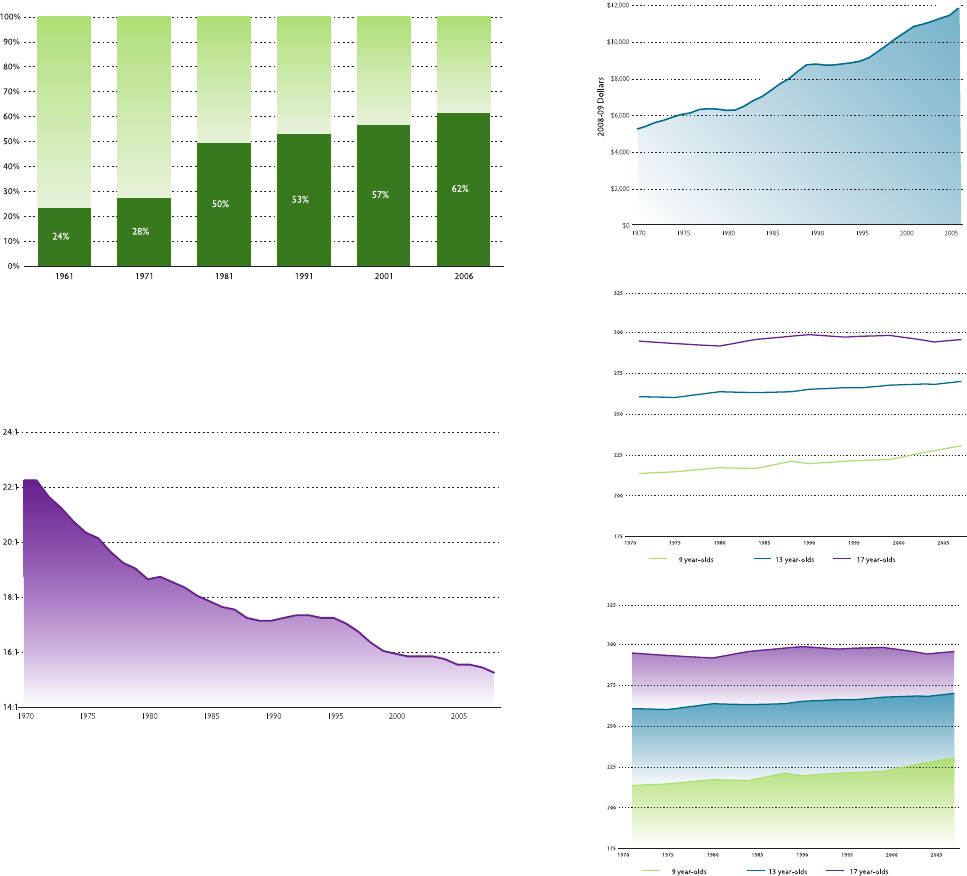

FIGURE 2

Conventional Wisdom Has Failed – Despite well-intentioned and intuitive reforms,

performance has been at since the 1970s.

Source: Snyder and Dillow 2010.

Percentage of Teachers with a Master’s Degree or Higher

Total Expenditure Per Pupil (In 2008-09 US Dollars)

Student to Teacher Ratio

Mean Reading and Math Achievement, 1971-2008

HS Graduates as a Ratio of 17 Year-Old Population

The Hamilton Project • Brookings 7

savvy classrooms (Goolsbee and Guryan 2006; Krueger and

Rouse 2004); professional development for teachers and other

key sta (Boyd, Grossman, Lankford, Loeb, and Wycko 2008;

Rocko 2008); and increasing parental involvement (Domina

2005).

Consider Figure 2. In 1961, 23.5 percent of teachers had a

master’s degree or higher. In 2001, 56.8 percent of teachers

had at least a master’s degree. Student-to-teacher ratios in

public schools have decreased from more than 22 to 1 in 1970

to 16 to 1 in 2000, a decrease of almost 30 percent in class

size in thirty years. America spends more on education than

ever: per pupil spending has increased (in 2008–2009 dollars)

from approximately $5,200 per student in 1970 to more than

$12,000 in 2007 (Snyder and Dillow 2011). Despite these

and many other intuitive eorts in the past three decades to

increase student achievement, even the most reform-minded

districts have shown little progress.

One potentially cost-eective strategy that has received

considerable attention recently is providing short-term

nancial incentives for students, teachers, parents, or

principals to achieve or exhibit certain behaviors correlated

with student achievement. eoretically, providing such

incentives could have one of three possible eects. (1) If

individuals lack sucient motivation, dramatically discount

the future, or lack accurate information on the returns to

schooling to exert optimal eort, then providing incentives

for achievement will yield increases in student performance.

(2) If individuals lack the structural resources or knowledge

to convert eort to measurable achievement or if their success

depends on forces out of their control (e.g., eective teachers,

motivated students, engaged parents, or peer dynamics), then

incentives will have very little impact. (3) Some argue that

nancial rewards for students (or any type of external reward

or incentive) will undermine intrinsic motivation and lead to

negative outcomes.

Between the 2007–2008 and 2010–2011 school years, we

conducted incentive experiments in public schools in ve

prototypically low-performing urban school districts—

Chicago, Dallas, Houston, New York City, and Washington,

DC—distributing a total of $9.4 million to roughly 36,000

students in 250 schools (including treatment and control

schools).

2

All experiments were randomized control trials

that varied from city to city on several dimensions: what was

rewarded, how oen students were given incentives, the grade

levels that participated, and the magnitude of the rewards.

e key features of each experiment consisted of monetary

payments to students, teachers, parents—and sometimes

all three—for performance according to a simple incentive

scheme. e incentive schemes were designed to be simple and

politically feasible. It is important to note at the outset that

these incentive schemes barely scratch the surface of what is

possible. We urge the reader to interpret any results as specic

to these incentive schemes and refrain from drawing more

general conclusions. Many more programs need to be tried

and evaluated before we can form more general conclusions

about the ecacy of incentives writ large.

e goal of this paper is three-fold. First, we provide an

overview of the literature on incentives in education and

develop a broad sense of the potential power (or, in many

cases, lack thereof) of incentives as a tool in a reformer’s

toolkit. Second, using the experimental evidence as a guide, we

develop a list of “10 Do’s and Don’ts” for the use of incentives

in education. ird, we provide a “How To” guide for policy-

makers or school districts that are interested in implementing

nancial incentives for teachers, students, or parents. In all

sections, we draw on scholarly work from Fryer (forthcoming),

which provides additional analysis of education incentive

experiments.

We begin by providing some key details of our experiments

on incentives and their implementation in ve cities (see

Fryer (forthcoming) for further details). We concentrate on

the incentive experiments implemented by the Education

Innovation Laboratory at Harvard University (EdLabs)

because of our access to important information about every

phase of the implementation and evaluation process, which

allows more adequate comparisons across experimental sites.

Chapters 2 and 3 provide a high-level summary of the results

of these experiments and how they compare with estimates

gleaned from other experimental analyses. Based on our

set of incentive experiments for students and teachers and

the literature, Chapter 4 exposits “10 Do’s and Don’ts” of

education incentive programs. Chapter 5 oers considerations

for evaluating incentive programs in the future, and Chapter 6

is an implementation supplement that provides guidelines for

structuring and implementing an incentive program.

America spends more on education than ever: per pupil

spending has increased from approximately $5,200 per

student in 1970 to more than $12,000 in 2007.

8 The Power and Pitfalls of Education Incentives

Chapter 2: Student Incentive Program Details

and Results

T

his section examines the evidence on student incentive

programs. Students in cities across the United States

were paid for inputs, such as reading books, completing

math assignments, and attending school, or for outputs, such as

grades and test scores. Although programs rewarding outputs

showed no signicant results, incentive programs can be a

cost-eective strategy to raise achievement if the incentives

are targeted for eective inputs, such as reading books and

completing math assignments.

STUDENT INCENTIVE PROGRAM DESIGN

Table 1 provides an overview of each experiment and species

conditions for each site. In total, experiments were conducted

in 250 schools across ve cities, distributing $9.4 million

to roughly 36,000 students. In all cities, the students in the

experimental sample were predominantly black or Latino.

In all cities except Washington, DC, more than 90 percent

of students were free lunch eligible, meaning that they were

Reward Structure Amounts Earned Operations

A. Input Experiments

Dallas Students earned $2 per book to read Average: $13.81 $126,000 total cost.

(2nd graders) books and pass a short test to ensure Max: $80 80% consent rate. One dedicated

they read it. project manager.

Washington DC Students were rewarded for meeting Average: $532.85 $3,800,000 distributed. 99.9% consent

(6th-8th graders) behavioral, attendance, and performance- Max: $1322 rate. 86% of students understood the

based metrics. They could earn up to basic structure of the program. Two

$100 every two weeks - up to $1500 dedicated project managers.

for the year.

Houston Students and parents earned $2 for each Student $870,000 distributed. 99.9% consent rate.

(5th graders) math objective the student mastered by Average: $228.72 Two dedicated project managers.

passing a short test, and parents earned Max: $1392

$20 for each teacher conference attended. Parent

Average: $254.27

Max: $1000

B. Output Experiments

NYC Students were paid for interim tests similar 4th grader $1,600,000 distributed. 82% consent rate.

(4th graders and 7th graders) to state assessments. 4th graders could Average: $139.43 90% of students understood the basic

earn up to $25 per test and $250 per year. Max: $244 structure of the program. 66% opened

7th graders could earn up to $50 per test 7th grader bank accounts. Three dedicated project

and $500 per year. Average: $232 managers.

Max: $495

Chicago Students earned money for their report Average: $422.93 $3,000,000 distributed. 88.97% consent

(9th graders) card grades. The scheme was A=$50, Max: $1000 rate. 91% of students understood the

B=$35, C=$20, D=$0, and F=$0 (and basic structure of the program. Two

resulted in $0 for all classes). They could dedicated project managers

earn up to $250 per report card and $2,000

total. Half of the rewards were given

immediately; the other half at graduation.

Notes: Each column describes a different aspect of treatment. Entries are school districts where the experiments were held. See Fryer (forthcoming) for further details.

TABLE 1

Student Incentive Treatments by School District

The Hamilton Project • Brookings 9

economically disadvantaged. In Washington, DC, more than

70 percent of students t this criterion.

e incentives can be divided into two general categories:

incentives for inputs and incentives for outputs. e output

of interest is student achievement, which is measured through

test scores or class grades. An input is anything that can

contribute to student learning. Generally, this category

includes high-quality teachers, a safe learning environment,

and student eort. In Dallas, Houston, and Washington, DC,

students were paid for inputs that were under their control.

ese included tasks such as reading books, doing homework,

attending school, or wearing a school uniform. In New York

City and Chicago, incentives were based on outputs.

e input experiments in Dallas, Houston, and Washington,

DC oered students incentives for either engaging in positive

behaviors or completing certain tasks. In Dallas, students

were rewarded for reading books and completing quizzes

based on the books. Students were allowed to select and read

books of their choice at the appropriate reading level and at

their leisure. Students were paid $2 for each book they read for

up to twenty books per semester.

Student incentives in Washington, DC, were based on a

combination of ve inputs, including attendance and behavior.

3

A typical scheme included attendance, behavior, wearing a

school uniform, homework, and class work. Students were

given as much as $10 per day for satisfying the ve criteria.

4

e Houston experiment applied incentives to students,

parents, and teachers. Students were given customized math

assignments that focused on their areas of weakness. Students

worked on these assignments at home with their parents or at

school outside of regular school hours and then took a quiz to

show that they had mastered the content. ey earned $2 for

each quiz they passed. Teachers could hold eight conferences

each year to update parents on their child’s progress. Both

parents and teachers were paid for each conference that they

attended. Parents could also earn money if their child passed

quizzes, as long as they attended at least one conference.

In addition, teachers and principals were both eligible for

bonuses through the HISD (Houston Independent School

District) ASPIRE (Accelerating Student Progress Increasing

Results and Expectations) program.

e output incentive programs paid students for test scores

and grades. In New York City, students took ten interim

assessments. For each test, fourth graders earned $5 plus

an amount proportional to their score. e magnitude of

the incentive was doubled for seventh graders. In Chicago,

students were paid for their grades in ve core courses.

5

STUDENT INCENTIVE PROGRAM RESULTS

Table 2 presents the results from the experiments described

above and includes estimates from the literature. e nal

columns report intent-to-treat (ITT) estimates from the

experiments. e ITT estimates capture the impact of

being oered a chance to participate in a nancial incentive

program, not of actually participating. An important potential

limitation of this set of experiments is that it was designed to

capture relatively large eects, and so some incentive programs

may generate positive returns even though they do not show

statistically signicant results.

6

Incentives can be a cost-effective strategy to raise

achievement among even the poorest minority students

in the lowest-performing schools.

10 The Power and Pitfalls of Education Incentives

Effect Effect in

in Standard Months of

Incentive Outcome Deviations Schooling

A. Input Experiments

Dallas $2 per book ITBS 2nd grade Reading Comp. 0.180** 2.250**

(0.075) (0.938)

Logramos 2nd grade Reading Comp. -0.165* -2.063*

(0.090) (1.125)

Washington DC Up to $100 per week for DC-CAS 6th-8th grade Reading 0.142 1.775

school-determined goals (0.090) (1.125)

DC-CAS 6th-8th grade Math 0.103 1.288

(0.104) (1.300)

Houston $2 per math objective Accelerated Math Objectives Mastered 0.985*** ______

(0.121)

TAKS 5th Grade Math 0.074* 0.925*

(0.044) (0.550)

B. Output Experiments

NYC Up to $250 for test results NY State Assmt. 4th grade ELA -0.026 -0.325

(0.034) (0.425)

NY State Assmt. 4th grade Math 0.062 0.775

(0.047) (0.588)

Up to $500 for test results NY State Assmt. 7th grade ELA 0.004 0.050

(0.017) (0.213)

NY State Assmt. 7th grade Math -0.031 -0.388

(0.037) (0.463)

Chicago Up to $250 per report card for PLAN 9th grade Reading -0.006 -0.075

grades (0.028) (0.350)

PLAN 9th grade Math -0.010 -0.125

(0.023) (0.288)

C. Other Incentive Programs

Rural Ohio Cash for test scores Terra Nova, Ohio Achievement, Math 0.133** 1.663**

(0.049) (0.609)

Kenya Scholarships for test scores Kenya Cert. of Primary Ed. Exam 0.12** 1.50**

(0.07) (0.88)

Israel Cash for test scores Bagrut HS Matriculation Exam 0.067* 0.838*

(0.036) (0.450)

Notes: The first three columns describe the treatment and its location. The last two columns are intent-to-treat estimates of the effect of being offered a chance to participate in treatment on the

outcome listed in column three. All regressions control for demographic factors and previous test scores and include all members of the experimental group with non-missing reading or math

test scores. Results marked with *, **, and *** are significant at the 10%, 5%, and 1 percent levels, respectively. Entries are school districts where the experiments were held. Conversion factor

of 0.08 standard deviations=1 month of schooling. See Fryer (forthcoming) for further details.

TABLE 2

Average Effects of Student Incentive Programs

The Hamilton Project • Brookings 11

Results are reported in standard deviations (Column 4) and

months of schooling (Column 5). A standard deviation is

the distance between ranking in the middle of the class and

ranking at the 84th percentile. A student typically improves

by about 1.0 standard deviation over the course of 1.4 years

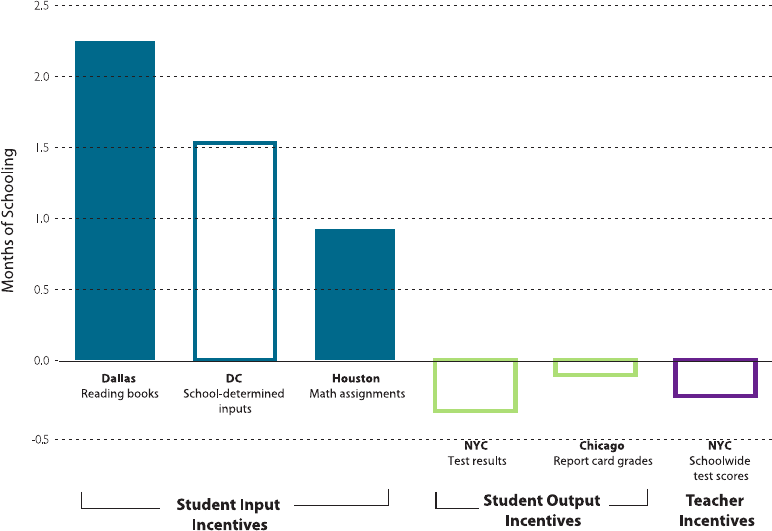

academic school years, or 12.5 months. Figure 3 summarizes

the results of all the incentive experiments.

Figure 3 (and the rst three rows of table 2) demonstrate that

incentives can be a cost-eective strategy to raise achievement

among even the poorest minority students in the lowest-

performing schools if the incentives are given for certain

inputs to the educational production function. Paying students

to read books yields large and statistically signicant increases

in reading comprehension. Paying students for attendance,

good behavior, wearing their uniforms, and turning in their

homework yields a similar estimate; due to imprecision,

however, the eects are not statistically signicant.

In Houston, where parents, students, and teachers were all

given incentives for a student’s mastery of math objectives,

students who were given incentives mastered 125 percent more

objectives than did students who were not given incentives.

However, because the focus of the math quizzes was not

tightly aligned with the topics that appeared on the statewide

test, the eects on measured mathematics achievement on the

state test were more muted.

7

Conversely, the output experiments demonstrate less-

promising results. Paying for performance on standardized

tests in New York City did not signicantly aect test scores

in math or reading. Rewarding ninth graders in Chicago for

their grades similarly has no eect on achievement test scores

in math or reading.

ese experimental results are broadly consistent with

international results that show mixed eects for output

incentives. Kremer, Miguel, and ornton (2009) evaluated a

merit scholarship program in Kenya, where girls in the top 15

percent of the two participating districts received scholarships

to oset school fees. ey found that the program raised test

scores by 0.13 standard deviations. Angrist and Lavy (2009)

examined a program in Israel that oered scholarships to

students from low-achieving schools for passing the Bagrut,

but they do not nd signicant eects.

8

FIGURE 3

Impact of Incentive Programs on Student Achievement

Notes: Solid bars represent impacts that are extremely unlikely to have occurred through chance. These results are statistically significant at the 10% level. Results are impacts on standardized

tests, averaged over subjects and grade levels where applicable. See Fryer (forthcoming) for further details.

Source: Fryer (forthcoming) and data from the authors.

12 The Power and Pitfalls of Education Incentives

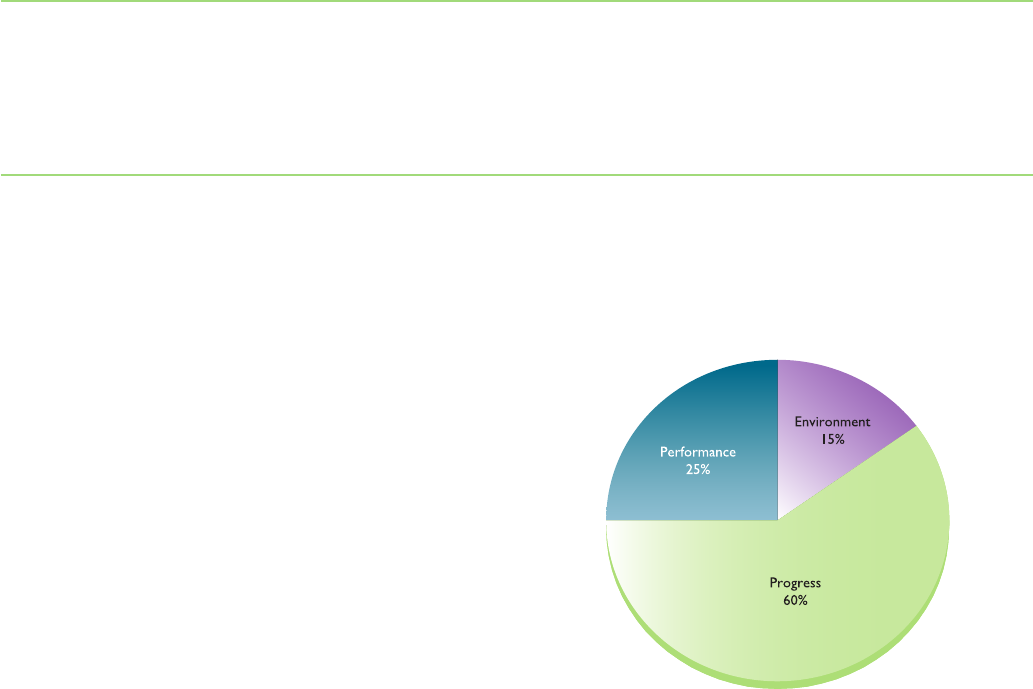

FIGURE 4

Progress Report Card Metrics

Chapter 3: Teacher Incentive Program Details

and Results

E

xperiments with teacher incentive programs in the

United States, such as one in New York City, nd

that nancial incentives given to teachers for student

achievement are not eective. is result may depend on

the structure of the particular incentive program tested. A

great deal more research is needed on the ecacy of teacher

incentives.

NEW YORK CITY

On October 17, 2007, New York City’s mayor, schools

chancellor, and the president of the United Federation of

Teachers (UFT) announced an initiative to provide teachers

with nancial incentives to improve student performance,

attendance, and school culture. Schools that met their

achievement target would be awarded $3,000 per teacher,

and schools that met 75 percent of their target would receive

$1,500 per teacher. Each school decided at the beginning of the

year how the bonus would be distributed among teachers and

other sta, but incentives were not allowed to be distributed

according to seniority. Schools could have chosen to distribute

the incentives to teachers based on which classes showed the

most improvement in students’ achievement, but instead an

overwhelming majority of schools chose an incentive scheme

that gave teachers more or less the same award, varied only by

position held in the school.

Figure 4 shows how the progress report card score, which is

the basis for awarding incentives to schools, is calculated. In

each of the three categories—learning environment, student

performance, and student progress—schools were evaluated

by their relative performance in each metric compared to their

peer schools and all schools in the city, with performance

relative to peer schools weighted three times as heavily as

performance relative to all schools citywide. However, because

it is calculated using many metrics and because scores in each

metric are calculated relative to other schools, it is not obvious

how much eort is needed to raise the progress report card

score by, say, one point.

Subscore Example Criteria

Environment 5% Attendance, 10% Learning Environment

Survey results

Progress Elementary/Middle schools: Average change

in state exam proficiency rating among level

1 and 2 students, average change in state

exam proficiency ratings among level 3 and 4

students, percentage of students making a year

of progress among the bottom third

High schools: Percentage of students earning

more than 10 credits among the bottom third,

weighted Regents pass rates, average comple-

tion rates of remaining Regents

Performance Elementary/Middle schools: Proportion

of students at state ELA and math exam

performance level 3 or 4, state exam median

proficiency ratings

High schools: 4- and 6-year graduation rates,

diploma-weighted graduation rates

Source: New York Department of Education (2011a, 2011b).

The Hamilton Project • Brookings 13

Results of the New York City teacher incentive scheme are

presented in Table 3, and the total eect is compared to

the impacts of student incentives in Figure 3. Across eight

outcomes, there is no evidence that teacher incentives increase

student performance, attendance, or graduation, nor is there

any evidence that the incentives change teacher behavior. If

anything, the evidence suggests that teacher incentives may

decrease student achievement, especially in larger schools.

Elementary Middle School High School

Outcome Standard Months of Standard Months of Standard Months of

Deviations Schooling Deviations Schooling Deviations Schooling

A. Effects on Student Achievement

NY State Assessment ELA -0.011 -0.138 -0.032** -0.400** --- ---

(0.020) (0.250) (0.011) (0.138)

NY State Assessment Math -0.015 -0.188 -0.048** -0.600** --- ---

(0.024) (0.300) (0.017) (0.213)

Regents Exam ELA --- --- --- --- -0.003 -0.038

(0.044) (0.550)

Regents Exam Math --- --- --- --- -0.011 -0.138

(0.031) (0.388)

Attendance Rate -0.018 --- -0.019 --- -0.014 ---

(0.020) (0.022) (0.050)

GPA -0.001 --- 0.001 --- -0.004 ---

(0.040) (0.031) (0.029)

4-year Graduation Rate --- --- --- --- -0.044** ---

(0.021)

B. Effects on Teacher Behavior

Retention in District 0.002 --- -0.006 --- --- ---

(0.006) (0.011)

Retention in School -0.007 --- -0.027 --- --- ---

(0.021) (0.017)

Personal Absences 0.275 --- -0.440 --- --- ---

(0.212) (0.403)

Notes: The first column describes the outcome of interest for that row. The last five columns are intent-to-treat estimates of the effect of being offered a chance to participate in treatment on

the outcome listed in column one. All regressions control for demographic factors and previous test scores and include all members of the experimental group or subgroup with non-missing

reading or math test scores. Results marked with *, **, and *** are significant at the 10%, 5%, and 1 percent levels, respectively. Entries are school districts where the experiments were held.

Conversion factor of 0.08 standard deviations=1 month of schooling.

TABLE 3

Average Effects of Teacher Incentive Programs

14 The Power and Pitfalls of Education Incentives

OTHER INCENTIVE PROGRAMS

An individual-based teacher incentive program elsewhere

in the United States similarly found no impact on student

achievement. Springer and colleagues (2010) evaluated teacher

incentives in Nashville. Middle school math teachers were

awarded $5,000, $10,000, and $15,000 bonuses if their students

performed at the 80th, 90th, and 95th percentiles, respectively,

in the historical distribution of class performance. Springer

and colleagues found no signicant eects on student

achievement or teaching practices.

ere are a couple of nonexperimental evaluations of teacher

incentive programs in the United States, both of which

report nonsignicant impacts on student achievement

(Glazerman, McKie, and Carey 2009; Vigdor 2008). e

Teacher Advancement Program (TAP) in Chicago rewarded

teachers based on classroom observations (50 percent) and

schoolwide student growth on Illinois state exams (50 percent).

Evaluations of TAP in its rst two years nd no impact on

student achievement, but further time is needed to determine

the program’s eect, especially because the structure of the

program is still changing and teachers can adapt to new

incentives (Glazerman and Seifullah 2010).

9

Other schools also have implemented performance pay

programs for teachers, but there is little rigorous evidence on

their eectiveness. Most school districts that have implemented

performance pay for teachers use similar metrics to those

used in New York City to measure teacher’s performance. For

example, Houston’s ASPIRE program uses measures of the

impact of both schools and individual teachers on student

test score growth in state exams to reward the top 50 percent

of teachers, with the top 25 percent receiving an extra bonus.

Alaska’s Public School Performance Incentive Program

divides schoolwide student achievement into six categories

and rewards teachers based on the average movement up to

higher categories. Florida’s STAR uses a similar approach, but

at a teacher level instead of a school level. Virginia is piloting

a program with individual incentives for teachers at hard-to-

sta schools.

Other experimental evaluations come from other countries.

Duo and Hanna (2005) provided schools in rural India with

incentives to reduce absenteeism and found positive eects

on teacher attendance and student achievement. In India,

Glewwe Ilias, and Kremer (2010) found that group incentives

for teachers based on test scores increased test scores in the

short run, but that students did not retain the gains aer the

program ended. Finally, Muralidharan and Sundararaman

(forthcoming) investigate the eect of individual and group

incentives in India, nding increases in student achievement

from both types of incentives, although individual incentives

were more successful in the second year.

e eectiveness of teacher incentives can vary a good

deal depending on the context; more research is needed on

incentive design and eectiveness. One common feature of

incentive programs tested is that they compare teachers’ or

schools’ performance to the distribution of performance

in the district. In this system, teachers may feel that their

measured performance is not entirely in their control because

it also depends on how well teachers at other schools are doing

(since teachers are compared to other teachers). Additionally,

the incentives experimented with in New York City were

awarded based on overall school performance. Because

schools then chose to distribute the incentives more or less

equally internally, teachers were not awarded based on their

individual eort. is ambiguity—the likelihood of receiving

an incentive depends on one’s own eort and the eort of

others—may make increased eort seem less worthwhile.

Another possibility is that these programs simply have not

been in place for long enough for teachers to properly react

and adapt their teaching habits.

The effectiveness of teacher incentives can vary a good deal

depending on the context…

The Hamilton Project • Brookings 15

Chapter 4: The 10 Do’s and Don’ts of

Education Incentives

T

his section expatiates “10 Do’s and Don’ts” of education

incentive programs based on our set of incentive

experiments for students and teachers and the literature

from elsewhere in the United States and around the world.

1. DO PROVIDE INCENTIVES FOR INPUTS, NOT

OUTPUTS, ESPECIALLY FOR YOUNGER CHILDREN.

Economic theory predicts that incentives based on outputs or

achievements, such as test scores or grades, will work better

than incentives based on inputs, such as a required time for

reading and homework. e theory would suggest that not

all students learn the same, and they individually know what

works best for them with regard to activities such as time

spent doing homework, reading books, and listening in class

to achieve the best outcome. Incentives for inputs are basically

rewards for specic behaviors that may lead students to focus

on that input (i.e., reading or better behavior) even if it is not

the input that will most help them achieve higher grades.

Incentives for the desired output or achievement would instead

empower each student to decide how to improve his output.

As any parent knows, however, this simple set of assumptions

does not always hold true; therefore, in some cases, it can be

more eective to provide incentives for inputs. In the end, this

is the result that our research supported.

In our experiments, input incentives were more eective than

output incentives, suggesting that students do not know how

to increase their test scores. If students only have a vague

idea of how to increase their test scores, then when provided

with incentives for performance, they may not be motivated

to increase eort. In Dallas, Houston, and Washington, DC,

students were not required to know how to increase their test

scores: they only needed to know how to read books on their

grade level, master math objectives, attend class, behave well,

wear their uniforms, and so on. In other words, they were

rewarded for inputs. In New York City, students were required

either to know how to improve test scores or to know someone

who could help them with the task. In Chicago, students faced

a similar challenge—they were required to undertake the

necessary steps to improve their performance.

In addition to our quantiable ndings, there is also qualitative

data supporting the theory that students do not respond well

to the general challenge of improving their performance, or

output. During the 2008–2009 school year, seven full-time

qualitative researchers in New York City observed twelve

students and their families, as well as ten classrooms. From

detailed interview notes, the researchers gathered that students

were uniformly excited about the incentives and the prospect

of earning money for school performance. In a particularly

illuminating example, one of the treatment schools asked their

students to propose a new “law” for the school, a pedagogical

tool to teach students how bills make their way through

Congress. e law that students chose to study, by a nearly

unanimous vote, was a proposal that students take incentive

tests every day.

Despite showing that students were excited about the incentive

programs, the qualitative data also demonstrate that students

had little idea about how to translate their enthusiasm into

tangible steps designed to increase their achievement. Aer

each of the ten exams administered in New York City, our

qualitative team asked students how they felt about the

rewards and what they could do to earn more money on

the next test. Every student found the question about how

to increase his or her scores dicult to answer. Students

answering this question discussed test-taking strategies rather

than salient inputs into the education production function or

improving their general understanding of a subject area. For

instance, many of the students expressed the importance of

“reading the test questions more carefully,” “not racing to see

who could nish rst,” or “re-reading their answers to make

sure they had entered them correctly.” Not a single student

mentioned reading the textbook, studying harder, completing

homework, or asking teachers or other adults for help with

confusing topics.

Two focus groups in Chicago conrmed the more

systematically collected qualitative data from New York City.

e focus groups included a total of thirteen students, evenly

split (subject to rounding) between blacks and Latinos, males

and females. Again, students reported excitement about

receiving nancial incentives for their grades. Students also

reported that they attended school more, turned in more

homework, and listened more in class. Yet when probed about

16 The Power and Pitfalls of Education Incentives

why other inputs to the educational production function were

not used—reading books, staying aer school to work on more

problems, asking teachers for help when they were confused,

reviewing homework before tests, or doing practice problems

presented in textbooks—one female student remarked, “I

never thought about it.” e basic themes from students in

Chicago centered on the excitement generated by the program

at the beginning of the year. is excitement triggered more

eort initially—coming to school, paying attention in class,

and so on. Students indicated that they did not notice any

change in their performance on quizzes or tests, however, so

they eventually stopped trying. As one student put it, “Classes

were still hard aer I tried doing my homework.”

A similar argument may partially explain the ineectiveness

of the teacher incentives tested. It is plausible that teachers do

not know how to increase student achievement without proper

coaching and development. If true, teachers face the same

challenges as students in responding to the general challenge

of improving student performance, or output. Rather, future

teacher incentive programs may try to link additional

compensation to activities, behaviors, or training that policy-

makers believe are correlated with student performance.

2. DO THINK CAREFULLY ABOUT WHAT TO

INCENTIVIZE.

Ideally, providing incentives for a particular activity would

have spillover eects on many other activities. For instance,

paying students to read books might make them equally

excited about math. Or paying students for attendance and

behavior—as we did in Washington, DC—might increase

enthusiasm for school so much that students engage in new

ways with their teachers. From our set of experiments, these

eects did seem to take place. Incentives seem to change

what people do, and not who they are. Unfortunately, since

the standard errors are so large in our DC experiment, it is

unclear whether this principle holds there, because we cannot

rule out modest-sized eects in either direction.

Across our set of experiments, we collected self-reported

measures of eort and investigated achievement on

dimensions in which we did not provide incentives. In every

experiment the data were clear: students did precisely what

they were paid to do, and not any more. Indeed, our team

of qualitative researchers reported general excitement by

students about earning rewards, but the students seem to have

focused their behavioral changes on precisely those elements

that were incentivized.

us, one has to think very carefully about what to provide

incentives for and target those incentives to achievement-

enhancing activities. For instance, it is plausible that some

of the inputs for which we provided incentives—behavior,

attendance, turning in homework regardless of the quality—

are not well suited to achievement gains. As discussed

above, we cannot rule out the possibility that the experiment

produced modest gains on these dimensions. But, due to

imprecision, the achievement eects of this experiment are

only marginally signicant.

3. DO ALIGN INCENTIVES.

Among the incentive programs tried, the one that has shown

the most power on direct outcomes is our experiment in

Houston that aligned the incentives of teachers, students, and

parents. Recall that treatment students mastered 125 percent

(or 0.985 standard deviations) more objectives than control

students. Furthermore, according to student and parent

surveys, parents of students in treatment attended 87 percent

(or 0.829 standard deviations) more teacher conferences than

parents of control students.

Since teachers, students, and parents can all play a role in

learning, incentives may be more eective when they are

all nudged toward the same goal. ere may be important

factors outside of a student’s or teacher’s control that aect

performance. For instance, student incentives may need to be

coupled with good teachers, an engaging curriculum, eective

parents, or other inputs in order to produce output. In Dallas,

students were encouraged to read books independently and at

their own pace. In Washington, DC, we provided incentives

for several inputs, many of which may be complementary. It

is plausible that increased student eort, parental support and

guidance, and high-quality schools would have been necessary

and sucient conditions for test scores to increase during our

Chicago or New York City experiments. An anecdote from

our qualitative interviews illustrates the potential power of

parental involvement and expectations coupled with student

incentives to drive achievement. Our interviewers followed

a high-performing Chinese immigrant student home when

she told an illiterate grandmother that she had earned $30 for

her performance at school. Her grandmother immediately

retorted, “But Jimmy next door won more than you!”

The Hamilton Project • Brookings 17

4. DON’T THINK THE EFFECTS GO AWAY

IMMEDIATELY AFTER THE INCENTIVES ARE

REMOVED.

A central question in the study of incentives is what happens

when the incentives are taken away. Many believe that

students will have decreased intrinsic motivation and that

their achievement will be negative once the incentives are

discontinued. (See Kohn 1993 and references therein.)

Contrary to this view, the point estimate one year aer the

Dallas experiment is roughly half of the original eect in

reading and larger in math. e nding for reading is similar

to the classic “fade-out” eect that has been documented in

other successful interventions, such as Head Start, a high-

quality teacher for one year, or a reduced class size (Nye,

Hedges, and Konstantopoulos 1999; Puma, Bell, Cook, and

Heid 2010).

Furthermore, fading of test score gains does not necessarily

mean that there are no positive long-term outcomes. One

study that links kindergarten test scores with adult wages

nds that even when test score gains disappear in later grades,

the eects appear again in earnings as an adult (Chetty,

Friedman, Hilger, Saez, Schanzenbach, and Yagan 2011). In

the experiment, kindergarteners were randomly assigned to

dierent classrooms. Some of these classrooms had better

teachers or meshed together better. Chetty and colleagues

identied kindergarteners who received a boost in their test

scores from being randomly assigned to better classrooms.

ese students did not score signicantly better on tests in later

grades, but earned more as adults. One possible explanation

is that good kindergarten classes teach other skills, such as

patience and work ethics, that may not inuence test scores

later on, but do inuence income.

5. DON’T BELIEVE THAT ALL EDUCATION INCENTIVES

DESTROY INTRINSIC MOTIVATION.

One of the major criticisms of the use of incentives to boost

student achievement is that the incentives may destroy a

student’s “love of learning.” In other words, providing external

(extrinsic) rewards can crowd out a student’s internal (intrinsic)

motivation. ere is an active debate in psychology as to

whether extrinsic rewards crowd out intrinsic motivation.

11

In a review of the literature surrounding the detrimental eects

of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation, Eisenberger and

Cameron (1996) conclude that although there can be negative

eects on intrinsic motivation from certain uses of extrinsic

reward structures, these circumstances are restricted and

do not eliminate the use of extrinsic rewards altogether.

Eisenberger and Cameron claim, however, that there are many

uses of incentives that do not diminish student motivation.

12

To test the impact of our incentive experiments on intrinsic

motivation, we administered the Intrinsic Motivation

Inventory, developed by Ryan (1982), to students in our

experimental groups. e inventory has been used in several

experiments related to intrinsic motivation and self-regulation

(e.g., Deci, Eghrari, Patrick, and Leone 1994; Ryan, Koestner,

and Deci 1991). e instrument assesses participants’ interest/

enjoyment, perceived competence, eort, value/usefulness,

pressure and tension, and perceived choice while performing

a given activity. ere is a subscale score for each of those six

categories. We include only the interest/enjoyment subscale in

our surveys because it is considered the self-report measure

of intrinsic motivation. e interest/enjoyment instrument

consists of seven statements on the survey: (1) I enjoyed doing

this activity very much. (2) is activity was fun to do. (3) I

thought this was a boring activity. (4) is activity did not

hold my attention at all. (5) I would describe this activity as

very interesting. (6) I thought this activity was quite enjoyable.

(7) While I was doing this activity, I was thinking about how

much I enjoyed it. Respondents are asked how much they

agree with each of the above statements on a seven-point

Likert scale ranging from “not at all true” to “very true.” To

get an overall intrinsic motivation score, we added the values

for these statements (reversing the sign on Statements [3] and

[4]). Only students with valid responses to all statements are

included in our analysis of the overall score, as nonresponse

may be confused with low intrinsic motivation.

Table 4 reports the impact of our set of experiments on the

intrinsic motivation of students in each city. Contrary to

Deci (1972), Kohn (1993), and others, these results show that

our incentive programs had little to no eect on intrinsic

motivation. is suggests that the hyperconcern of some

educators and social psychologists that nancial incentives

destroy a student’s intrinsic motivation may be unwarranted

in this context.

Incentives seem to change what

people do, and not who they

are…. In every experiment the

data were clear: students did

precisely what they were paid to

do, and not any more.

18 The Power and Pitfalls of Education Incentives

6. DON’T WORRY THAT STUDENTS WASTE THE

MONEY THEY EARN.

e spending habits of our subjects was a common query, and

in response we asked detailed questions in every experiment

about what students spent their money on, how much was

saved, and how much their parents took away from them. e

results were enlightening, and are summarized in Table 5.

13

Our incentives experiments produced a large eect on students’

saving habits: in Washington, DC, treatment students were

27.8 percent more likely than control students to have saved

over $50, while in Houston, treatment students were 45.4

percent more likely to have saved over $50. Both estimates

are signicant at the 1 percent level. On the other hand, in

Washington, DC, paying students produced signicant

negative eects on student spending on entertainment (–$9.96

per month), clothing (–$25.84 per month), food (–$12.84

per month), and even household bills (–$6.96 per month).

Likewise, in Houston point estimates revealed large negative

eects: –$14.57, –$6.76, –$2.55, and –$0.03, respectively. All

DC results were signicant below the 5 percent level, while in

Houston, only the decrease in spending on entertainment was

statistically signicant, albeit at the 1 percent level.

ese ndings demonstrate that apprehension over paying

students for fear that they will spend their earnings quickly

is misguided. Students in our programs showed a strong

proclivity not only to spend less than nonearning peers, but

also to save more. Each of our experiments involved educating

students on nancial literacy and helping students establish

bank accounts. A well-designed incentive program can

incorporate nancial literacy education that promotes savings

behaviors and a sense of personal responsibility. Recall

that MDRC’s Opportunity NYC conditional cash transfer

TABLE 4

Average Effects of Student Incentive Programs On Intrinsic Motivation

Dallas Washington DC Houston NYC Chicago

7th

Intrinsic Motivation -0.020 0.067 -0.003 -0.048 0.017

Inventory (0.068) (0.052) (0.055) (0.049) (0.065)

Notes: Each column label describes the district where the experiment took place. This table reports intent-to-treat estimates of the effect of being offered a chance to participate in treatment on

the outcome listed in column one. All dependent variables are normalized to be mean zero, standard deviation 1, and all point estimates are in standard deviations from the normalized mean.

Regressions control for demographic factors and previous test scores and include all members of the experimental group with non-missing survey data. Results marked with *, **, and *** are

significant at the 10%, 5%, and 1 percent levels, respectively. See Fryer (forthcoming) for further details.

TABLE 5

Average Effects of Student Incentive Programs On Spending Habits

Entertainment Clothing Food Household Bills Saved more

than $50?

Washington DC -9.956** -25.844*** -12.840*** -6.961** 0.276***

(3.852) (6.810) (3.061) (2.814) (0.070)

Houston -14.571*** -6.759 -2.553 -0.033 0.454***

(3.478) (5.725) (2.051) (1.263) (0.079)

Notes: Each column label describes a category of expenditure where students reported spending their money. The first four columns report intent-to-treat estimates (in $) of the effect of being

offered a chance to participate in treatment on the amount of money an individual spends on each category. The final column, labeled “Savings” reports coefficient on treatment from a probit

regression on a binary variable of whether or not a student has $50 or more in savings. Regressions control for demographic factors and previous test scores and include all members of the

experimental group with non-missing survey data. Results marked with *, **, and *** are significant at the 10%, 5%, and 1 percent levels, respectively. Entries are school districts where the

experiments were held. Observations where students reported spending more than $300 on any single component of a given category were set to missing.

The Hamilton Project • Brookings 19

Health and Human Services designed “Opportunity NYC” in

partnership with MDRC to closely mirror the PROGRESA

(Programa de Educación, Salud y Alimentación) experiment

in Mexico by providing cash incentives to parents (and

sometimes students) for a range of behaviors and outcomes

including school attendance, student achievement, preventive

healthcare participation, and human capital development.

e evaluation of Opportunity NYC showed promise for

reducing some of the immediate hardships linked to poverty

by mitigating hunger, increasing healthcare participation,

and decreasing reliance on alternative banking institutions,

but the program demonstrated no impacts on academic

dimensions, including all academic outcomes for elementary

school, middle school, and lower-achieving high school

students. However, among well-prepared high school students,

Opportunity NYC appears to have modest positive eects on

attendance, course grades, credits earned, and standardized

test achievement (MDRC 2010).

It is possible that one of the reasons that incentive schemes

such as PROGRESA were eective in Mexico but not New York

City is that the social safety net in America is very dierent

from the safety net in Mexico. In other words, the incentives

in programs such as Opportunity NYC provide marginal

incentives above and beyond what individuals already have.

If there are dierences across places in the level of baseline

incentives, the eect of an additional incentive program can

vary dramatically.

8. DO STAY THE COURSE.

Few educational policies provoke as strong a negative visceral

reaction among the general public as tying nancial incentives

to learning. In a 2010 PDK/Gallup poll, only 23 percent of

Americans said they supported “the idea of school districts

paying small amounts of money to students to, for example,

read books, attend school or get good grades.” Seventy-

six percent opposed the idea, with 1 percent undecided. As

points of contrast, consider the results from another recent

public opinion poll. In 2008, an ABCNEWS poll found that

26 percent of Americans say grade-school teachers should be

allowed to spank kids at school, with even higher approval

rates in the South (35 percent) and the Midwest (31 percent).

In other words, the concept of paying students in school is less

palatable than the concept of spanking students in school.

Despite the public’s negative opinion of nancial incentives

for students, reform-minded school leaders are increasingly

interested because they recognize that conventional wisdom

is simply not producing results (see Figure 2). While the initial

phases of implementation can lead to negative publicity and

pushback from within the community, what ultimately matters

program successfully decreased reliance on alternative

banking institutions and increased savings by providing cash

incentives to parents and students. More research is needed,

but preliminary results suggest that implementing these

kinds of programs early on for our youth may help promote a

culture of savings and help students develop a higher level of

uency and comfort within the context of traditional nancial

institutions.

To be sure, the exact spending habits of recipients of rewards

in education incentive programs may not be important at all

if the incentives themselves have a positive impact on student

achievement. Of course, understanding that students (perhaps

unexpectedly) save a large portion of their rewards might make

the idea of an incentive program more palatable to districts

and schools. But student achievement is the most important

outcome, and if incentive programs improve achievement and

students spend their earnings on video games and junk food,

from our perspective, that is a desirable set of outcomes.

7. DO IMPLEMENT WHAT WORKS.

Implement what has been shown to work, not what tickles

your intuition, and do not generalize the results too broadly.

Aer we nished the rst round of our incentives work, we

briefed a top-ranking policy ocial in Washington, DC.

Aer hearing that paying students $2 per book read yielded

statistically signicant eects on reading comprehension

scores, his response was, “Excellent. Based on these results I

want to implement a policy that rewards kids with nonnancial

incentives for doing their homework.” But our results showed

that paying students for doing general homework was not

an eective way to increase achievement, and nonnancial

incentives may not have the same eect as nancial incentives.

e results discussed here are from demonstration projects on

nancial incentives across the United States. We are condent

that the impacts of these particular programs are accurately

estimated. We are less condent that the same program

implemented in a dierent city will give similar answers. And,

perhaps more importantly, we have absolutely no condence

that a program with multiple variations in any city will have

similar results.

Also, we need to be careful about extrapolating results from

other countries. Incentives given to students and teachers in

other countries are given in a dierent context from those

given in the United States. In Mexico, incentives were shown

to have a large positive impact on student attendance and

growth and development outcomes, such as child health

and early childhood cognitive development. In the United

States, though, we have not seen any such increases with

similar incentives. Indeed, the New York City Department of

20 The Power and Pitfalls of Education Incentives

is student achievement; the challenge for policy-makers is to

educate their constituents about the results. Results change

minds, and the body of evidence suggests that a properly

implemented incentive program can be a cost-eective means

of improving student learning outcomes.

In a similar poll by USA TODAY in 2008, more than half of

the seventy-four CEOs and other senior executives that were

surveyed supported nancial incentives in schools, and exactly

half reported instituting similar ideas for their own children.

While this sample is small and still divided, it suggests that

those individuals who have perhaps the most experience

with the power of nancial incentives in the marketplace—

businesspersons whose prots are driven by recruiting,

retaining, and motivating their workers to perform at their

peak—are far more likely than the general public to support

similar incentives in schools.

9. DON’T BE CHEAP.

Deciding the appropriate price to pay students for dierent

behaviors or levels of achievement can be dicult; given

scal constraints, policy-makers and educators may worry

about spending extra money that will not produce results.

Our research found, however, that when incentives work,

increasing the amount of the incentive also brings about a

larger impact. Students respond to the incentives, and when

we unexpectedly increase the price, students put in even more

eort.

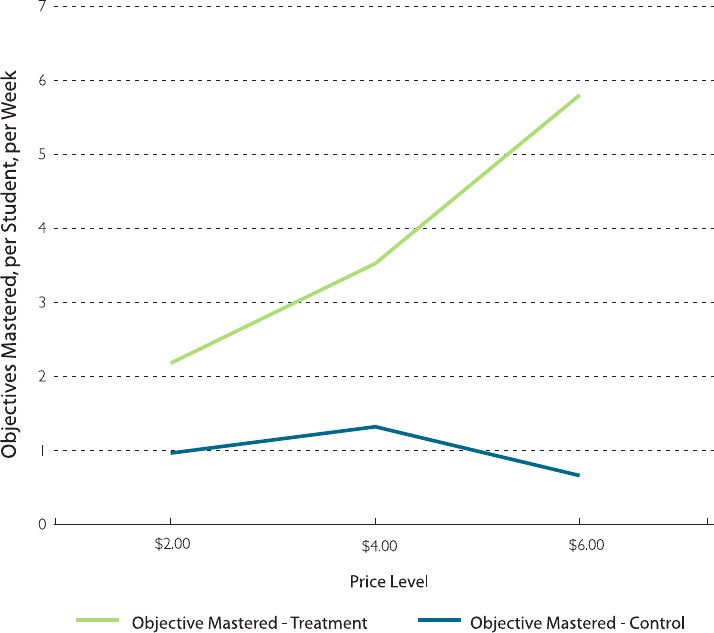

Figure 5 demonstrates this fact from our incentive experiment

in Houston. Students in treatment were paid $2 per math

objective mastered. (Students in control were not paid for

mastering objectives.) Under this incentive format, students

mastered roughly two objectives per week. In mid-February,

we unexpectedly increased the price to $4 per objective for

four weeks. During the following four weeks, the average

FIGURE 5

Math Stars Houston, Objectives Mastered by Price Level

Source: Data from the authors.

The Hamilton Project • Brookings 21

all. Eect sizes from incentive programs in America range from

statistically zero (or even negative) to 0.256 standard deviations,

or about three months of additional schooling. Relative to the

education “crisis” described in the introduction, these are modest

eects. For instance, black and Latino students are typically

1.0 standard deviation behind whites on standardized tests.

us, even under the most optimistic assumptions, and even if

we provided incentives only to minority students, they would

decrease the gap by one fourth. Again, the gain from incentive

programs is not large relative to the gap, but is large relative to its

cost. e ideal of students internalizing the incentive structure

and then demanding more (and better) education from their

teachers and parents is not consistent with the data.

Similarly, the hope that providing struggling teachers with

incentives will miraculously increase their eort, make them

better teachers, and increase student achievement is not

consistent with the experimental evidence to date. Teacher

incentive experiments in Tennessee provided incentives that

were roughly 22 percent of their annual salary. Still, the program

yielded no long-term eects.

number of objectives mastered per week increased to more

than three and a half in the treatment group and stayed

constant in the control group (where students were not being

paid for mastering objectives). Aer this bonus period was

over, students again were paid $2 per objective mastered. Two

months later, we again announced a price increase—this time

to $6 per objective mastered. Figure 5 shows that students

responded by mastering almost six objectives per week.

Using these three data points, a simple calculation shows that

for every 10 percent increase in payments, students increase

their eort by 8.7 percent. Compared to traditional measures

of labor supply elasticities of adult males—which average

about 0.32 (Chetty 2011)—this elasticity of 0.87 is relatively

high, meaning that students in our incentive program are

highly price sensitive and will likely respond to increased

incentives.

10. DON’T BELIEVE THE HYPE: INCENTIVES ARE NOT

A PANACEA.

Incentives can have a large return on investment, but they will

not eliminate the educational problems of the United States or

eliminate the racial achievement gap. at is, they are a wise

investment in a diverse portfolio of reforms, but not a cure-

Incentives are a wise investment in a diverse portfolio of reforms,

but not a cure-all.

22 The Power and Pitfalls of Education Incentives

Chapter 5: Moving Forward on Evaluating

Education Incentives

T

he set of experiments discussed here has generated three

broad lessons: (1) that incentives for certain inputs such

as reading and doing math homework will raise student

achievement, (2) that incentives for output seem less eective,

and (3) that group-level incentives for teachers do not appear to

be eective. Much more remains to be done and some areas for

research are discussed below:

PROVIDE INCENTIVES FOR STUDENTS OR TEACHERS

TO TRY NEW STRATEGIES.

Incentive programs provide the opportunity to experiment

with new approaches to learning and to nd out which

student behaviors and teaching strategies actually work.

Testing out incentives for innovative inputs is essential for

designing eective programs, and can also provides broader

insight into what works in the learning process. For example,

teachers could be given incentives for using technology in the

classroom, or students could be asked to watch educational

videos at home.

TRY VARYING THE INCENTIVES.

Incentives can vary in amount or type (nancial or

nonnancial). Every community is dierent and we encourage

education leaders to try new and dierent ideas to test what

works best in their schools. Changing the amount and type

of incentive can help determine the combinations with the

highest returns, and variation during the program itself helps

keep students engaged and motivated. During the Houston

experiment, for example, the reward for passing math quizzes

was increased during certain weeks. Interestingly, student

mastery per day rose dramatically when rewards increased, but

student participation (i.e., the percentage of eligible students

who mastered at least one objective and thereby received

rewards) did not increase. e higher reward amount did not

encourage more students to participate, but it made students

already participating more eager to complete the quizzes.

TRY NONFINANCIAL INCENTIVES, ESPECIALLY FOR

TEACHERS.

Mobile phone minutes and other nonnancial incentives

can save money for incentive programs by cutting down on

distribution costs. Nonnancial incentives may be more cost-

eective if students or teachers put a higher value on them

than their cost. For example, popcorn and pizza parties are

relatively low cost, but students enjoy them because they

provide opportunities to celebrate. Similarly, gi cards that

can be purchased in bulk at a discounted price might also

have excess value because they cut down on transaction costs

and render rewards nontransferable to other family members.

Teachers may not respond well to nancial incentives, but they

may be enticed by benets such as vacation time or changes

to the work environment. In Canada, teachers are allowed to

defer a portion of their salary each year to self-fund a leave of

absence. e popularity of this program shows that teachers

may prefer nonmonetary rewards to additional pay (Jacobson

and Kennedy 1997).

DO MORE WITH PARENTS.

Parent incentives were tested only as a part of the package

of incentives for teachers, parents, and students in Houston;

results showed that parents with incentives were signicantly

more invested than were other parents. Future programs could

incentivize only parents or they could provide incentives for

more specic behaviors outside of going to conferences, such as

enforcing a homework time for their children or encouraging

them to read for a given amount of time. Parent incentive

programs have potential to improve student achievement, but

we need to experiment with them further.

The Hamilton Project • Brookings 23

Chapter 6: Structuring and Implementing

Incentive Programs

T

his section discusses how to structure and implement

an incentive program. e guidelines provided are

based on the actual implementation of incentive

programs designed and evaluated by EdLabs at Harvard in

partnership with school districts. An online appendix provides

a full description of how these programs were designed and

implemented including approaches taken in dierent project

sites (please visit www.hamiltonproject.org for this online

appendix). is implementation guide draws lessons from

those experiences, but is written with the idea that districts and

schools can design and execute incentive programs on their

own. As long as schools are implementing incentive programs

that have been proven successful, then there may not be a role

for an implementation and evaluation partnership.

CONSTRUCTING AN INCENTIVES STRUCTURE

e structure of an incentive program can and will vary from

district to district and from school to school; each district

or school can pick and choose which tasks and behaviors to

provide incentives for, the amount of incentives to be paid,

and payment structure. If a particular district struggles

with reading scores or a particular school suers from low

attendance rates, the opportunity for a tailored yet properly

implemented incentive program could be especially fruitful.

Our prescription for constructing a workable incentives

structure follows from our two central claims about incentive

programs: First, unlike other major education initiatives of

the past few decades, a large proportion (approximately 70–

80 percent) of expenditures should be directed to students,

parents, or teachers in the form of incentives payments.

Past education initiatives—from reducing school and

classroom sizes and providing mandatory aer-school

programs, to providing renovated and more technologically

savvy classrooms and professional development for teachers

and other key sta—spend a far higher percentage of total

expenditures on indirect costs such as building renovation,

training, and computers than our incentive programs.

In incentive programs, most funds should go directly to

students, teachers, or parents. e proportion of expenditures

devoted to administration should be small but will vary

depending in part on the scale of the incentive program.

Consider a districtwide incentive program in which students

earn money for doing homework and are able to gain a

maximum of $100 during the school year. Two thousand

students from twenty schools participate, and the average

student receives $50 total. Students are paid by check every

three weeks, ten times total. Incentives payments for the year

would total approximately $100,000. In this hypothetical

example, the most signicant marginal costs for an internally

driven incentive program are a full-time program manager

and covering payment-processing fees. e program manager

would be responsible for all payment calculation, auditing,

and reward distribution. Where payments could be tied to the

employee payroll cycle, the cost of payment processing may be

minimized; where a bank partnership is necessary to process

Unlike other major education initiatives of the past few decades, a large

proportion (approximately 70-80 percent) of expenditures for incentive

programs should be directed to students, parents, or teachers...

24 The Power and Pitfalls of Education Incentives

and print checks, the cost will be similar to contracting with

an external payroll vendor (usually a per check or per deposit

rate between $0.30 and $0.50).

Now consider a single school incentive program in which

students can earn up to $180 for wearing their uniform to

school every day. Five hundred students participate and the

average student receives $120 during the school year. Students

are paid in cash at the end of every month by their assistant

principal, using Title I funds. Although the incentives

payments total is $60,000, in this instance there is no need

for a dedicated program manager and no cost associated with

processing the payments.

e second claim underlying our guidelines for implementing

incentive programs is that the incentive programs described

herein are eminently scalable within school districts or even

individual schools. is claim is based on our reliance on

district-based teams to help manage the day-to-day operations

in our own experiments and ensure delity of implementation.

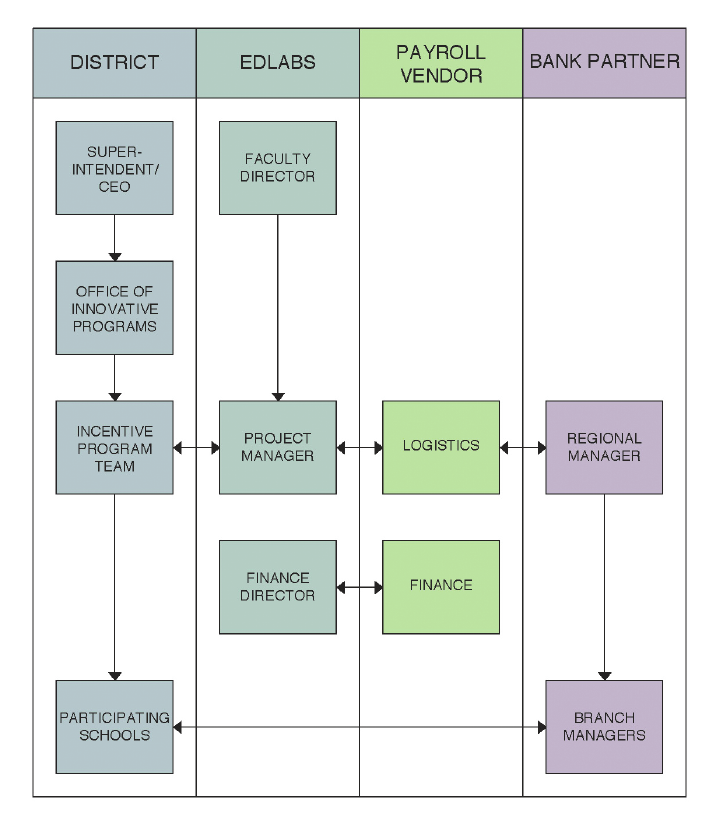

At a district level, program implementation would be driven

entirely within a district department, with incentive payments

oered either along the employee payroll cycle or through a

third-party payroll vendor (see Payment Calculation and

Distribution, below). Following our ve guidelines can lead to

successful in-district implementation.

IMPLEMENTING INCENTIVE PROGRAMS

e implementation of an incentive program must be

a coordinated eort to ensure that students, parents,

teachers, and key school sta understand the particulars of

each program; that schools are constantly monitoring the

performance of students; and that payments are distributed

on time and accurately. Five guidelines are key to realizing

these objectives:

1. Students and their families are provided with extensive

information about the programs, with additional

mechanisms to check understanding.

2. Explicit structures of communication and responsibility

are created between districts and third-party vendors,

including procedures to govern the ow of data,

information, and reporting.

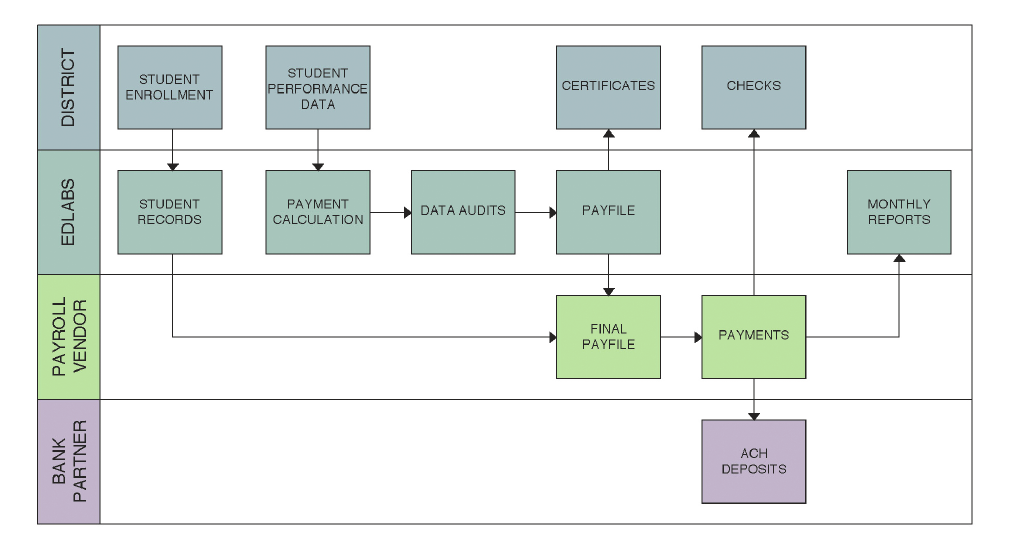

3. A payment algorithm is created to generate reward amounts

from student performance data, and procedures are

established to both run the algorithm on a predetermined

schedule and to distribute rewards.

4. Regular reporting is done on subject (student or parent)

performance, including metrics such as participation,

average earnings, and rened budget projections.

5. A culture of success is built by recognizing student

performance with assemblies, certicates, and bonuses.

A general summary of each guideline is included below.

Additional details, based on our research, can be found

in the online appendix. ese examples are based on our

work through EdLabs and should be replicable, whether a

school district works independently or with another outside

implementation and evaluation partner.

1. Informing Subjects. One of the truly distinguishing

features of our incentives experiments is the concentrated

eort made to fully inform students and their families not

only of the particulars of each program (i.e., incentive scheme,

reward schedule, etc.), but also the potential risks involved

in participating.

14

Students and families can be briefed in a

number of dierent ways, but we recommend the following