•

CULINARY HISTORIANS OF NEW YORK

•

Volume 19, No. 2 Spring 2006

Continued on page 10

B

EFORE I LEFT MY HOME

in Manila to live in Hong Kong

many years ago, I made a spe

-

cial point of learning to cook one

recipe—my mother’s adobo. Today

this dish is still special to me in my

American home. It is the first thing

on my to-cook list when my Ameri

-

can husband is out of town, because

the smell of the odorous fermented

fish paste (bagoong) that I like to eat

with it makes him ill. It is the dish I

often cook to show American friends

or family what a typical Filipino dish

is. And it is what I’m likely to cook

when Filipino friends come to visit,

because we have unofficially anointed

it as our national dish. In fact, it has

acquired iconic status for members

Tasting Home: Filipino Adobo

of the Filipino diaspora.

How can a country with over

7,000 islands, 17 regions, 79 prov-

inces, and more than 111 spoken

languages have a national dish? Why

are Filipinos so staunchly united in

their devotion to this very simple

stew—essentially, pork or chicken

(sometimes both) cooked in a mix-

ture of vinegar and soy sauce with

smashed garlic, crushed peppercorns,

and bay leaves? There are count

-

less variations both regional and

personal, but what links them is the

sharp-smelling vinegar-soy base.

There is debate about the ori

-

gins of the dish. Many Filipinos

believe that adobo comes from

Spain, owing to the 333 years of

Ging Gutierrez Steinberg

Spanish colonial rule (1565–1898).

But adobo in Spanish cuisine is an

oil and vinegar-based marinade or

pickling sauce. (The name comes

from the Old French

adober, the

word for outfitting a knight in ar-

mor.) Some claim that during the

days of the Manila-Acapulco galleons

the dish was adopted from Mexico,

where adobos came to mean ground

seasoning pastes usually involving

dried red chiles, garlic, and vinegar

or another acid ingredient. They can

be marinades for different foods, or

directly used as a sauce base. Dishes

made with Mexican adobo mixtures

can be called adobos or described as

en adobo or adobado (“adobo-ized”).

Perhaps Filipino adobos descend

from those of Spain or Mexico. But

during the colonial era the native

peoples apparently began using local

ingredients to achieve a pucker-in-

ducing kind of sourness and saltiness

that Filipinos love. Early accounts

suggest that today’s Filipino flavor

principles were already developed

or developing in pre-colonial times.

Antonio Pigafetta, who sailed on

Magellan’s 1521 voyage, reported

that native Filipino food was “very

salty”; Spanish friars also described

it as salty and acidic.

The modern Filipino’s deep

attachment to adobo reflects this

preference together with a significant

olfactory appeal. The smell of adobo

cooking may not be attractive to non-

Filipinos, but for us the pungency

2

CHNY Steering Committee

2005–2006

Chair: Cathy Kaufman

Vice-Chair: Tae Ellin

Treasurer: Diane Klages

Secretary: Ellen J. Fried

Members-at-Large:

Kara Newman,

Membership

Linda Pelaccio,

Programs

Kathy Cardlin,

Publicity

CHNY Information Hotline:

(212) 501-3738

www.culinaryhistoriansny.org

CHNY Newsletter

Editor: Helen Brody

Lead Text Editor:

Anne Mendelson

Please send/e-mail member

news, book reviews, events

calendars to:

Helen Brody

PO Box 923

Grantham, NH 03753

helen@helenbrody.com

(603) 863-5299

(603) 863-8943 Fax

Papers demonstrating seri-

ous culinary history research

will be considered for inclu-

sion in issues of the CHNY

newsletters. Please contact

Helen Brody, newsletter editor.

Matriculating students of

culinary history or related top

-

ics are invited to contribute.

FROM THE CHAIR

T

HIS SPRING the Culinary

Historians of New York reaches

beyond its monthly programming

and semiannual newsletter to touch

the wider world of culinary history by

announcing its second Amelia Award

and calling for applications for its

second Amelia Scholar’s Grant.

Barbara Ketcham Wheaton

has been selected as the recipient

of CHNY’s second Amelia Award,

celebrating distinguished achieve-

ment in culinary history. Some of

you will recall that Wheaton spoke

in January 1986 to the newly-formed

Culinary Historians of New York

on her ground-breaking book, Sa-

voring the Past: The French Kitchen

from 1300-1789 (1983). Savoring the

Past remains the gold standard for

studies of the emergence of modern

French cuisine from the

service en

confusion (Wheaton’s wickedly funny

but accurate assessment) of medieval

cookery.

In addition to other writings and

teaching future generations how to

read cookbooks as historical docu-

ments, Wheaton has been heavily

involved in preserving our culinary

past, nurturing our present, and

projecting our future. She is the

honorary curator of the culinary

collection at Radcliffe’s Schlesinger

Library, is a Trustee of the Oxford

Symposium on Food & Cookery,

and has been a consultant to Mass-

achusetts Institute of Technology’s

Counter Intelligence Lab.

The

award ceremony will likely take place

in late September, as part of CHNY’s

20

th

anniversary celebration, so be on

the lookout for the invitation.

We are also soliciting applica

-

tions for the second Amelia Scholar’s

Grant—see article at right.

CHNY is transitioning into an

(almost) paperless organization by

encouraging all of our members

with e-mail access to receive pro-

gram notices electronically. With

a mailing list of nearly 400, e-mail

is cost effective, environmentally

gentle, and cuts down on the tedious

photocopying, envelope stickering,

sealing, and mailing required of the

CHNY volunteers every month. As

an added benefit, e-mail also allows

us to contact members quickly in the

event there is a change in program-

ming, such as cancellation due to

inclement weather or other unfore-

seen circumstance.

For those unsure whether we

have a current e-mail address for

you, or to change your e-mail ad-

dress, please e-mail information to

culinaryhistoriansny@verizon.net.

In the SUBJECT line please type

“e-mail update.” For those without

e-mail access, you can still receive

notices by regular mail by opting

into our “snail mail” delivery sys-

tem. Please fill out the form on page

9 of this newsletter and send it to

Culinary Historians of New York,

P.O. Box 3289, New York, New

York 10163, attention: Kara New

-

man (if you haven’t already done

so), with your name and mailing

address to continue receiving mailed

announcements of programs.

CHNY is not losing its addic

-

tion to paper entirely. Under Helen

Brody’s stewardship, CHNY will

continue to publish in hard copy

its semiannual newsletter. We have

instituted a reviewing board to vet

articles before publication to ensure

the highest scholarship, and my

thanks to those who have volun-

teered their expertise.

3

Letters to the Editor

To the Editor:

Tae Ellin’s article “Where the Buf

-

falo Roam… Again” in the fall 2005

CHNY newsletter is a delightful and

welcome treatment of an important

subject. But I’d like to call attention

to a couple of statements that per-

haps could use some qualifying.

As Ms. Ellin notes, American

bison long ago split into two popu-

lations generally called the “plains

buffalo” and the “wood buffalo”

(or bison). I do not think that today

most naturalists would classify them

as two separate species or use the

zoological names Bison bison and

Bison athabascae. They are generally

recognized as subspecies within the

species Bison bison and most often

identified as Bison bison bison (plains

bison) and Bison bison athabascae

(wood bison). It is not true that wood

bison are extinct and only plains

bison remain. Wood bison may no

longer exist in the United States,

but the subspecies still survives in

Canada, especially the province of

Alberta. See the report “Status of the

Wood Bison

(Bison bison athabascae)

in Alberta” by Jonathan A. Mitchell

and C. Cormack Gates, <www.3.gov.

ab.ca/srd/fw/status/reports/bison>.

I’m also concerned that the

paragraph beginning “The health

benefits of bison are unquestion-

able” may give an oversimplified

picture of bison meat’s nutritional

merits. Most nutritionists are leery

of numbers games that treat the

comparative “health benefits” of

different foods as matters of simple

more-and-less statistics. The figures

given in the article (2.42 grams of fat,

143 calories in a 100-gram serving)

are those that appear in literature of

the National Bison Association and

other industry groups with a product

to promote; probably they go back to

tables in a 1989 U.S.D.A. handbook

(Agriculture Handbook No. 8–17).

No mention is made of what cut of

meat might have been analyzed; we

all know that different cuts of beef

or parts of a chicken have different

compositions, and the same is true

for bison. What’s perhaps even more

important is that listing the relative

tallies of calories and fat for differ-

ent foods is an extremely superficial,

often misleading way of gauging

overall health benefits. It’s certainly

accurate and helpful to point out that

bison is a very lean meat compared

to beef. I would, however, mistrust

industry handouts as a source of

more specific information

Anne Mendelson

February, 2006

C

ULINARY HISTORIANS

of New York announces the

call for entries for the second

annual Amelia Scholar’s Grant.

Named after Amelia Simmons,

the author of American Cookery,

the first cookbook written in

America, the Amelia Scholar’s

Grant is designed to promote re-

search and scholarship in the field

of culinary history. The Amelia

Scholar’s Grant is intended to

fund one student or scholar whose

engaging, well-developed project

demonstrates commitment to the

field of culinary history.

One grant of $1,000 will be

awarded to help support ongoing

scholarship for research, books,

papers, articles, conferences, or

related projects. Further details

and application requirements are

available on the Culinary Histori-

ans of New York’s web site,

www.

culinaryhistoriansny.org.

Applications shall include

an essay (no more than 500

words) detailing the project

for which the Amelia Scholar’s

Grant is sought and one letter

of recommendation. Completed

applications must be postmarked

no later than April 30, 2006. It

is anticipated that the recipient

will be announced in June 2006.

The winner will be the featured

speaker at a Culinary Historians

of New York meeting during the

2007–08 season to share the fruits

of the funded research.

CALL FOR ENTRIES

The Amelia

Scholar’s Grant

Awarded by Culinary

Historians of New York

Finally, the legal reorganization

of Culinary Historians of New York

is complete. In late February, the

Internal Revenue Service granted

tax-exempt status to the newly

formed Culinary Historians of New

York, Inc. The corporation now

enjoys all of the benefits associated

with its nonprofit educational status

while protecting its members in

the event of legal claims against the

organization. Our deepest thanks to

the law firm of Patterson, Belknap,

Webb & Tyler, LLP, and especially

Antonia Grumback, Esq. and Derek

Dorn, Esq., for their tireless

pro bono

representation of CHNY, Inc. in this

important matter.

4

by Helen Studley

I

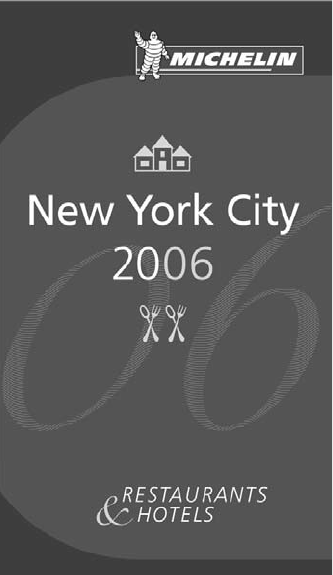

N NOVEMBER 2005 Michelin

made its much anticipated New

York debut with the release of

the Michelin Guide

®

New York City

2006 (Michelin Travel Publications,

Greenville, SC.). As it was Michelin’s

first guide in North America, expec

-

tations were high. Who would be

the illustrious few to receive three-

star billing? What chef would be

catapulted to sudden fame? What

restaurant would tumble?

The Michelin people held a com

-

ing out party attended by members of

the press, French dignitaries, and a ros

-

ter of popular chefs and restaurateurs.

Of the 500 restaurants and 50 hotels

rated, Alain Ducasse, Jean Georges,

Le Bernadin, and Per Se entered

Michelin’s hall of fame three-star sta

-

tus. Bouley, Daniel, Danube, and Masa

came in with two stars. There were 31

one-star nominations. No Chinese,

Mexican, Greek, Spanish, Thai, or

Vietnamese received a star, which

unleashed considerable public criti-

cism. The press ridiculed the guide’s

clumsy English and complained about

the poor quality of the pictures. Many

dismissed the Guide and returned to

the Zagat Survey which, despite some

flaws, is more in tune with the New

York public.

What, people wondered, had

prompted Michelin to take on New

York? Some suggested that the

guide’s prestige had suffered and

needed a boost. A former inspector’s

tell-all book had appeared in 2004

saying that Michelin had become lax

in its standards. Others mentioned

that since the Michelin Guide is

published by a French company, the

rating system is biased toward French

cuisine in a global economy.

The first Michelin Guide was

published in 1900 by André Mi

-

chelin to help wealthy gastronomes

find decent lodgings and food while

traveling by the new medium of the

motor car. The Guide included ad

-

dresses for gasoline stations, garages,

tire stock lists, and public toilets.

Until 1920 it was free.

In 1926, the Guide introduced

the star system to note “good places

to stop;” two and three stars were

added in the early 1930s. The mys

-

terious Michelin inspectors emerged

in 1933, visiting anonymously and

frequently dining alone.

The format utilized an extensive

system of symbols to describe each

establishment as briefly and accu-

rately as possible. There were five

levels to show good service, indicated

by crossed spoons and forks. Any

-

thing in red spelled super luxury. A

little bird in a rocking chair signaled

a quiet or secluded spot. To interpret

these symbols became a sport with

tourists who flocked in ever greater

numbers to France.

The Guide’s finest hour, how

-

ever, had nothing to do with stars

or crossed spoons. In the spring of

1944, as the great armada was pre-

paring for its landing on the coast

of Normandy, the Allied Chiefs of

Staff realized that progress through

France would be hampered because

road signs had all been either de-

stroyed or removed by the Germans.

After considerable research, and

with the permission of Michelin,

the Allies decided to reproduce the

last edition of the Guide—dated

l939—which contained hundreds of

detailed, up-to-date town and city

maps. Reproduced in Washington,

it was distributed to officers with

the cover stamped: “For official use

only.”

The Michelin Guide resumed

publication after the war. As tour

-

ism gained renewed momentum,

Michelin introduced guides to Bene

-

lux, Italy, Germany, Spain, Portugal,

Switzerland, Great Britain & Ireland,

and the “Main Cities of Europe.”

New York City, it turns out, was

only the first step for Michelin to

enter the U.S. market. There are

plans to produce a “red guide” to San

Francisco.

Helen Studley, a food and travel

writer, is the author of The Chicken

For Every Occasion Cookbook

and

The Life of a Restaurant: Tales and

Recipes of La Colombe d’Or

, the

former restaurant she and her husband

owned for twenty-three years.

The Red Michelin: Then and Now

5

Continued on page 6

Program Summaries

Some Like it Hot:

A History of the World’s

Hottest Cuisines

Presented by Clifford Wright

October 27, 2005

On a breezy fall evening at the Park

Avenue United Methodist Church

Clifford Wright, author of the re

-

cently published book, Some Like it

Hot: Spicy Favorites from the World’s

Hot Zones (Boston: Harvard Com-

mon Press, 2005), spoke about the

fiery cuisines of the world.

The focus of the program was

his research into why some groups of

people like hot food. He reviewed and

dismissed fourteen different common

and not so common hypotheses, con-

cluding with the simplest one that

says people prefer the way they taste.

He identified the fourteen centers of

spicy food culture as Western South

America, primarily Peru and Bolivia;

Mexico and Southwestern U.S.; Ca

-

jun Cuisine; Jamaica; Western coast

of Africa, primarily Senegal, Guinea,

Sierra Leone, Liberia, Ghana, and

Nigeria; North Africa of Algeria and

Tunisia; Eastern Africa, especially

Ethiopia; Yemen; India; Pakistan;

Thailand; Sichuan and Hunan prov

-

inces in China; and Korea.

Wright spoke of how chili pep

-

per migrated from its home in South

America to other countries around

the world and, although early on it

was not one of the most sought after

spices like black pepper or cinnamon,

once the New World was discovered

it replaced black pepper as the hottest

spice due in large part to the fact that it

was stronger in taste, cheaper to grow,

and adaptable to different climates.

Members and guests tasted

recipes made from Some Like It Hot

such as Manchamantel (Tablecloth

Stainer) from Oaxaca and Eggplant

Curry from India with pita bread and

green mangoes strips with a piquant

Tai spice mixture. A collection of

fresh and dried chili peppers were

also on display with explicit instruc-

tions not to touch or inhale because

chilies can burn three times—taste,

touch, and smell.

—Ammini Ramachandran

Dining With The Gods

Presented by Andrew Dalby

December 5, 2005

Sotheby Institute of Art’s exhibit of

ancient Greek dining vessels was

the perfect venue for “Dining With

the Gods,” a lecture on ancient food

rituals by Andrew Dalby.

Dalby, a trained classicist and lin

-

quist, is the author of many books on

ancient culinary history. He engaged

the audience in a scholarly discussion

of ancient Greece and the relation-

ships between gods and humans.

What part of an animal was offered

up to the gods hinted at the complex

human issue of how the ancients could

pay due homage and sacrifice without

wasting perfectly good food. The

stories that have been passed down

through time tell that humans and

gods socialized together on earth.

As an example, if a question

arose as to what parts of a roast oxen

should be offered to the gods and

which part to the humans, the choice

would be made eventually by the

gods. Prometheus, who had an affin-

ity toward the humans, decided that

he would help them get some of the

choicer meats by wrapping the thigh

bones with lush fat, making for some

delectable appearing treats. He then

placed them next to some choice cuts

that he cleverly covered with some

less attractive viscera. Prometheus

then declared that the gods them-

selves should decide which cuts they

would receive. Naturally they chose

the more attractive “lard-on-a-stick.”

Humans were then free to eat the

choice parts of the slaughtered animal

without feeling less devout.

Drawing on his skills as a linguist,

Dalby discussed the roots of the word

“toasting” as in lifting a glass of wine

to your host. In past history, a single

person doing the toasting might

actually share or give the cup to the

“toastee.” To not accept the cup, or

the gesture, was to offend. In a group,

however, toasting developed into a

more ritual raising of the glass in a

gesture of giving the cup.

Immediately following the lec

-

ture the audience delighted in period

food prepared by CHNY chair Cathy

Kaufman and based on recipes from

her forthcoming book, Cooking in the

Ancient World. The tasting included

an olive relish, must biscuits, honey

roasted pork, pomegranate-walnut

chicken turnovers, fried dates in

honey, and mini-cheesecakes. Spiced

wine sweetened with honey was

served as an accompaniment.

—David Araki

Gastronomy and

Gluttony in Early

Modern China

Presented by Joanna Waley-Cohen

January 31, 2006

In her talk, timed to coincide with

the Chinese New Year, Joanna Wal

-

ey-Cohen, Professor of History at

New York University, with a focus

on Chinese military history, left the

battlefields behind to explore the in-

6

Program Summaries

from page 5

Member Profile

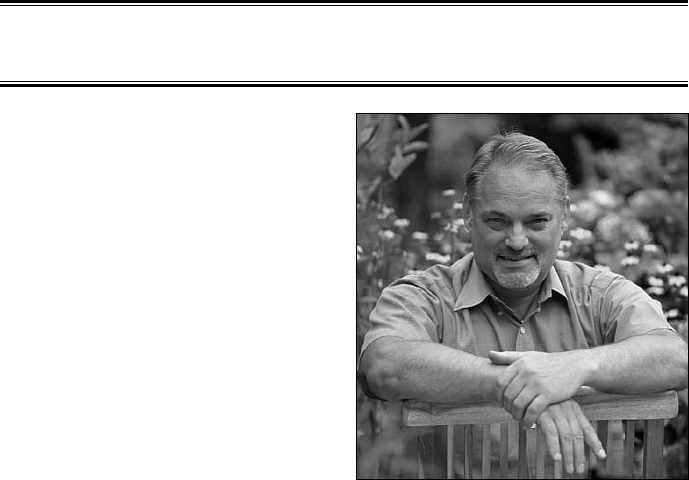

A

N OFFICE for most of us

consists of a telephone, a desk,

and a computer. For William Woys

Weaver, his office also includes the 21

raised beds of a kitchen garden near

his 1805 tavern named Roughwood.

“These are not the carefully mani

-

cured grounds intended for a garden

tour,” he warns those who might be

considering a casual walk through.

“They are my private laboratory of

plants in different stages of growth,

many even drying up and going to

seed, not always beautiful, I assure

you.” And no wonder he harbors a

sense of protection. These plants are

the source of a 4,000 heirloom seed

vegetable, herb, and fruit collection

—a repository that is drawn on by

growers all over the world.

Unlike Will’s heirloom seeds, the

seeds sold today by many corpora-

tions can not reproduce true plants,

meaning farmers cannot save and

replant their seeds. Known as F1 hy

-

brids, these seeds produce many of the

country’s major crops, and to continue

in business, the farmers are forced to

buy new and costly seed (from the

company) each year. Another major

downside to F1 hybrids, such as wheat,

corn, or soy, is that they are bred to

respond to particular pesticides and

fertilizers. If a virus that the plant is

designed to resist mutates, a large per-

centage of the nation’s crop could be

lost and the hybrid becomes worth-

less, causing food shortages. Such was

the case with corn back in the 1970s.

“In a sense,” Will says, “monoculture

hybrids are like one shoe to fit all feet

regardless of the soils, microclimate,

etc.” In other words, you can plant

William Woys Weaver

by Helen Brody

the seeds once and that would be it

for that product. What would appear

next is anybody’s guess and if you did

plant it, you might be sued for patent

infringement.

Enter the heirloom seed move

-

ment which developed in response

to this monoculture hybrid situation.

Unlike the corporate F1 hybrids,

heirloom hybrids are fixed in their

traits, resist mutation, and will re-

produce true plants, and their seeds

can be saved for replanting. Will’s

Roughwood Seed Collection assures

an established library of material to

draw on. Furthermore, these heir

-

loom treasures offer a variety of type

and flavor that corporate hybrids

cannot match.

But Will’s interests and involve

-

ments go far beyond the preservation

and selling of seeds. As a food his

-

torian who has traveled the world

tracking the origins of vegetables,

herbs, and fruits, he has discovered

a vast array of foods that that are no

longer part of our diet and is always on

the trail of some form of plant life that

he has seen mentioned in an histori-

cal text. Two of his oldest varieties in

continuous cultivation are the Cypriot

bottle gourd, datable to about 2,500

b.c. and the Perivan yacon, datable to

tersection of aesthetic and gustatory

taste in China.

While the Chinese have no word

for “sinful,” as in “sinful chocolate

cake,” the Chinese never looked

favorably upon gluttony. It served as

a metaphor for political corruption

and moral turpitude. Wise and good

rulers made sure that their subjects

had enough to eat, and conducted

their own lives and government with

frugality, moderation, and balance.

Learned people cultivated not only

their minds but also their bodies,

since both were viewed as intercon-

nected. Bad people were often said to

have gluttony among their failings.

Gastronomy, on the other hand,

ranked among the arts of the cultivat-

ed gentleman, along with knowledge

of painting and poetry. In the three

major periods that Waley-Cohen

examined—the late Song of the

thirteenth century, the late Ming

of the late sixteenth and early sev-

enteenth century, and the Manchu

Qing dynasty of the late eighteenth

century—an interest in gastronomy

was linked with a rise in consumerism.

In each of these diverse time periods,

an increased number of people had

money to spend on fine foods, lo-

cally grown or produced elsewhere in

China. Gustatory taste, especially in

the late Ming, became commodified,

like everything else, but also reflected,

despite its focus on pleasure, the mark

of a knowledgeable man. Authors,

painters, and poets represented the

epicurean life in their works (e.g.,

lavish descriptions of feasting on river

crabs and the proper way to make

snow orchid tea), and their works, in

turn, reveal the complex aesthetics

of taste in China, which encompass

satisfying the palate and obeying the

principles of balanced nutrition.

—Diana Pittet

Photo: Rob Cardillo

7

Elizabeth Andoh is an IACP and

James Beard award finalist for her

book Washoku: Recipes from the Japa-

nese Home Kitchen (Ten Speed Press,

Berkley, CA).

Rynn Berry, expert on the history

of vegetarianism, has just completed

seven entries for the Oxford Compan-

ion to Food and Drink in America to

be published in 2007 and edited by

member Andrew F. Smith. Rynn has

just released the twelfth edition of

The Vegan Guide to New York City.

The second and revised edition

of Taste of Malta by Claudia M.

Cauana was released in June, 2005,

by Hippocrene Books, New York.

In her recently published book,

The

Sex Life of Food (St. Martin’s Press,

New York, 2006),

Bunny Crum-

packer describes how food affects

every aspect of our lives, sex, table

manners, religion, digestion, soup to

nuts. Crumpacker is also the author of

The Old-Time Brand-Name Cook Book

and Old-Time Brand-Name Desserts.

Member News

Guidelines, and a comprehensive

nutrition dictionary.

Broadway Books, a division of Ran

-

dom House, Inc, New York, will

publish The Murray’s Cheese Handbook

by Rob Kaufelt this September.

To be published this month is

Tea

In the City: New York (Benjamin

Press, Perryville, KY) “a guide to

all things tea-related in Manhattan

and the boroughs” and written by

Elizabeth Knight, tea sommelier

for the historic St. Regis Hotel. It

features scores of colorful photos by

Bruce Richardson.

Alexandra Leaf continues her work

in chocolate, leading walking tours

to the city’s better chocolate shops

and conducting tasting classes for

the Institute of Culinary Education

and the 92nd St. Y. She is the prin

-

cipal organizer of the 92nd St. Y’s

Annual World Chocolate Tasting

at least 500 a.d. Currently he is in

pursuit of the name of the person who

developed the Atlantic Prize tomato

which began being marketed in 1889

in Atlantic County, New Jersey. “It

was the hottest tomato on the mar-

ket,” he says.

Of his 12 books, three have re

-

ceived International Association of

Culinary Professional (IACP)’s Jane

Grigson award for scholarship. He is

professor of Food Studies at Drexel

University, writes feature articles for

Mother Earth News, and is a contrib-

uting editor to Gourmet magazine,

for whom he has recently completed

an article on chef Alain Passard who

startled the gastronomic world by

changing his menu to include essen-

tially only vegetables. To complete

his resume, Will is working on a

doctorate at the University College

Dublin dealing with the “authentic-

ity” of the tourism food experience

—what foods the tourist expects

from his local visit versus what the

local residents actually eat at home.

Helen Brody

is CHNY newsletter

editor and the author/researcher of sev-

eral books including most recently New

Hampshire: From Farm to Kitchen

(Hippocrene Books, NY).

Betty Fussell appeared on a panel

at NYU’s Fales Library March 10

to discuss “Food Writers of Green

-

wich Village.” Members of CHNY

are welcomed at the Fales’ Critical

Topics series. Upcoming is “Women

Who Cook for a Living in New York

and Why There Aren’t More of

Them” on June 15, and “From There

to Here: the Chains and Systems of

Food” on October 19. Fussell also

appeared March 31 on a panel at the

IACP’s convention in Seattle to dis

-

cuss forms of food writing “Beyond

Cookbooks.”

Ann Heslin, MA, RD, CDN along

with Annette B. Natow, PhD and

Karen J. Nolan, PhD announce the

January 2006 release of the The Most

Complete Food Counter, 2nd Ed., a

Pocket Books trade paperback. The

book provides readers with an all-in-

one nutrition reference providing:

calories and nutrient values for over

21,000 foods, nutrition basics to

understand the function and need for

each nutrient counted, action points

for following the latest Dietary

IN MEMORY

Cecily Brownstone, a long-time

member of the Culinary Histori-

ans of New York, died in August

at the age of 96. For 39 years as

the Associated Press Food Editor,

Cecily was one of the most widely

distributed journalists in the

world, writing five recipe columns

and two features a week.

Her collection of more than

8,000 cookbooks, 5,000 cookery

pamphlets, and personal letters

are now part of the Fales Col

-

lection of New York University.

Donations in her memory may

be mailed to: Marvin Taylor,

Director, Fales Library, NYU, 70

Washington Square South, New

York, NY 10012.

—Christine Pines

Continued on page 8

8

Event which took place in March.

Active with Les Dames D’Escoffier,

she hosted an evening with anthro-

pologist Naomi Duguid to which

CHNY members were invited. In

April, she will host an evening at

the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts,

Richmond in conjunction with their

upcoming FEAST show and in May,

she will give a talk for the Beaux Arts

Alliance entitled “What Monet Ate

and How Toulouse Lautrec Drank:

The Art of the Table in Impression

-

ist France.”

David Leite is a finalist in both the

essay and internet categories of the

IACP’s Bert Greene Food Journalism

award, and received a nomination

in a new James Beard Foundation

category—“best internet website

for food.”

Susan McLellan Plaisted MS, RD,

CSP, LDN had her careers as a reg

-

istered dietitian and food historian

merge in Today’s Dietitian December

2005 with an article titled “Culinary

History and Preservation-Savoring

Tradition.”

Andrew F. Smith has completed a

book, Real American Food: A Culinary

Tour of America, coauthored with

Burt Wolf. It is a tour of ten Ameri

-

can cities with an examination of

their culinary heritage. It is sched

-

uled for publication by Rizzoli in

early June. He is also teaching classes

in Advanced Culinary History and

Professional Food Writing at the

New School.

Susan Yager’s article, “Incredible Ed-

ible East End Eggs,” concerning the

social, ethical, and environmental

benefits of eggs harvested from

humanely and sustainably raised

poultry, and the handful of farm

-

ers still raising chickens in this

way on Long Island, will be featured

in the spring edition of Edible East

End magazine.

Call for Authors for New Book Project

G

REENWOOD Publishing Group is seeking authors to contribute

entries for a new project on dining/entertaining through history. It

will be a three volume set arranged A-Z, with entries covering cultures

(Italian, Muslim, Japanese, etc), time periods (Ancient Rome, the Re

-

naissance, 19th Century, etc), objects (chopsticks, forks, finger bowls),

holidays and festivals, relating to the history of dining/entertaining.

The goal of this set is to identify for readers the entertaining practices

and traditions of various cultures throughout history, at festivals as well as

family events. It has an anthropological perspective explaining the links be

-

tween a culture’s political, economic, religious and/or social circumstances

and its methods of dining/entertaining. While the entries will not contain

recipes, foods and dishes should be mentioned where appropriate.

Contributors will receive writing credit and mention with bio in the

encyclopedia, but will not be paid.

If you are interested in contributing, please contact Francine Segan

October 1, 2006.

Help Save

Marcus Apicius!

M

OST CULINARY histori-

ans know about the cookery

manuscript attributed to Marcus

Apicius, the first century Roman

gourmand. Containing 500 recipes,

the manuscript was assembled and

hand copied in the fourth century. In

the ninth century, monks at the Fulda

monastery in Germany recopied

the recipes in a simple manuscript

adorned by red letters. This ninth

century manuscript has amazingly

survived through twelve hundred

years of wars and natural disasters

and is believed to be the earliest copy

of Apicius, the only recipe collection

we have from the ancient Mediter

-

ranean.

During the Reformation, the

manuscript was shipped to the Vati

-

can Library, which also owned

another, slightly later, set of Apicius’s

recipes. The Vatican sold the Fulda

manuscript to a private collector.

The manuscript was sold at auction

and eventually was given to the New

York Academy of Medicine. The

manuscript has been used by numer-

ous scholars, two of whom—Sally

Grainger and Dr. Christopher Gro-

cock—gave a presentation to the

Culinary Historians of New York

last year based on their forthcoming

re-translation of the manuscript.

The 1,200 year-old manuscript

is falling apart and needs to be re-

bound. The New York Academy of

Medicine approached a professional

manuscript restorer; the estimated

cost of rebinding is $15,000. In

cooperation with the Culinary Trust

of the International Association of

Culinary Professionals, Culinary

Historians of New York asks its

members to help save our culinary

Member News

from page 7

9

NYU and Beard Foundation

Host International Conference

F

ROM MAY 21 to 26, 2006, the

James Beard Foundation and

New York University’s Steinhardt

School of Education are co-hosting

a joint international conference titled

“The Mediterranean Diet: Fact &

Fiction.” The program, conducted

in English, will assemble Italian

and American experts on subjects

such as nutrition, culture, lifestyle

behaviors, artisanal and commercial

food production, and government

regulation to discuss the concept of

the Mediterranean diet using Italy

as a case study. Topics will include

how has the Mediterranean diet

has been (mis)understood and what

changes have gone on in Italian food

culture since the initial studies were

conducted. Among other program

highlights will be samplings of local

food and an informal conversation

with Frances Mayes, author of the

best-selling Under the Tuscan Sun.

Held at NYU’s spectacular 57-

acre Villa la Pietra, the conference

will afford participants—food enthu-

siasts, academics, nutritionists, and

others—an immersion in Italian food

culture. Tours of the villa, as well as

optional field trips to other points of

interest in the Tuscan countryside.

Registration forms, hotel infor

-

mation, and the conference program,

are available at http://education.nyu.

edu/conference/tuscandiet/.

heritage by donating to the Apicius

and similar restoration projects

through Culinary Historians of New

York. All funds collected will go

directly to restoration projects; all

those who contribute will be invited

to the Apicius restoration celebra

-

tion, likely in the Fall of 2006. Please

send contributions marked “culinary

heritage restoration” to:

Culinary Historians of

New York, Inc.

P.O.Box 3289

New York, NY 10163

Cathy Kaufman, CHNY

Andy Smith, CHNY and

IACP Culinary Trust

Attention! Important Changes!

We are moving over to the electronic age and in April will be sending program announcements by e-mail only un-

less you fill out the form below. We anticipate sending an initial notice approximately four weeks before a program,

plus a reminder one week before the program.

Please update our records by sending your correct e-mail address

In the SUBJECT

line type “e-mail update”

FOR THOSE WITHOUT INTERNET ACCESS

you must respond with the form below.

Mail paper announcements to:

Name: _____________________________________________________________________________________

Address:

____________________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Please return to CHNY, P.O. Box 3289, New York, NY 10163

Attn: Kara Newman

10

of the combined vinegar, soy, and

crushed garlic is instantly recogniz-

able—something that people take

for granted growing up but that is

transformed into the smell of home

when one has left. An Internet blog

-

ger who calls himself “The Wily

Filipino” muses:

“Anthropologists have always

prioritized only two or three of the

human senses… and the sense of

smell always ends up taking a back

seat. But smell is crucial to adobo—

the sting of vinegar in the nostrils the

minute after you pour it into the sim-

mering pot, the deep smell of chicken

cooking after the second hour—it’s

instantly recognizable anywhere.”

Although adobo is now eaten

by Filipinos of all classes, appar

-

ently this wasn’t always the case.

Historians note that in early colonial

times it used a lot of lard and was

typically made up in large quantities

and stored in the same clay vessels in

which it had been cooked; the vin-

egar and lard acted as preservatives.

As the Filipina novelist and essayist

Gilda Cordero-Fernando points out

in her book Philippine Food and Life,

such large-scale provisioning “im-

plied a surplus,” a sign of privilege.

Adobo was not everyday fare for the

Indios (natives), but something that

the colonists and principalia (wealthy

remnants of a pre-Hispanic native ar-

istocracy) could keep for long periods

of time against the visits of priests or

local dignitaries.

But somehow adobo ceased to be

the food of the conquerors. As I see

it, it was a dish intrinsically suited

to the natives’ sour-and-salty taste

preferences. First it became a dish

served to the peasantry on special

occasions like fiestas while the gentry

feasted on more elegant offerings.

Over time, people adapted it to lo

-

cal ingredients (palm or sugarcane

vinegar instead of Spanish wine

vinegar) and began making it with

the soy sauce brought by Chinese

immigrants (instead of salt). Dur-

ing the American occupation (1898

–1946) following the 1896 revolu-

tion against Spain, adobo became

typical everyday fare for an emerging

Filipino middle class. It was during

this period that Filipino cookbooks

first were published, and they show

home-cooked adobo holding its own

despite the powerful influence of

American-style convenience foods.

The 1960s saw the dramatic rise

of a local restaurant culture fueled

by increasing industrialization and

urbanization, with migrants from the

provinces trying their luck in the big

cities. These changes helped push

adobo to the forefront of a growing

popular or street-food scene as a

standby of the carinderias (open-air

food stalls with cheap but filling fare).

But at the same time they helped

bring the dish to other kinds of eat-

ing places, especially a new breed of

avowedly Filipino restaurants that

made a point of serving dishes associ-

ated with traditional home kitchens

—in contrast to the days when adobo

was usually the one token “native”

dish served in the more respectable

urban restaurants. By now Filipinos

as a group had begun identifying

adobo as their national dish.

As adobo moved across class lines

over the centuries, it also acquired a

huge number of variations that make

the whole meaning of “adobo” con-

fusing for non-Filipinos but that have

helped it to transcend not only class-

linked but regional identities and to

become a badge of national identity

as universal as Yankee Doodle Dandy.

Here is another secret of the dish’s

appeal: the ease with which you can

produce your own version. It is the

simplest thing to make because you

literally throw everything in the pot

and wait while it stews and the sauce

reduces. The ingredients are few,

inexpensive, readily available—and

incredibly flexible. Its very simplic

-

ity has made it easy for Filipinos to

apply their own variations over time.

In different islands and provinces,

people simply added to the basic

recipe whatever was locally thriving,

available, or specially liked, whether

it was coconuts from the plantations

or snipe and frogs to replace Span

-

ish pork and chicken. As Corazon S.

Alvina writes in an important con

-

tribution to the cookbook The Food

of the Philippines, “Every province

boasts of having the best version of

adobo. Manila’s is soupy with soy

sauce and garlic. Cavite cooks mash

pork liver into the sauce. Batangas

adds the orange hue of annatto,

Laguna likes hers yellowish and pi

-

quant with turmeric. Zamboanga’s

adobo is thick with coconut cream.”

There are not only regional adobo

variations, but countless personal

variations with their own changes

in technique or ingredients. As the

Filipina writer Felice de Sta. Maria

puts it, “There are as many adobo

recipes as there are cooks, and as

many favorite recipes as there are

childhoods.” I would be hard-pressed

to find another Filipino dish with this

many individual versions.

But the story doesn’t end there. It

continues in every part of the world

to which Filipinos have moved. It is

the Filipino diaspora that has elevat

-

ed adobo to iconic status. Filipino

college kids have been seen on U.S.

campuses wearing “Got Adobo?” or

“Love, Peace, and Adobo Grease”

T-shirts. You can buy adobo-themed

mugs, aprons, caps over the Web.

Adobo

from page 1

11

American food culture has picked up

on the idea that being Filipino means

eating or cooking adobo. It has be

-

come so powerfully associated with

being Filipino that the noun itself is

almost a synonym for national iden-

tity—the Website <adobo.com> has

nothing to do with the dish but is a

popular news and entertainment site

geared towards a Filipino audience.

I am reminded of Yael Raviv’s

comment (“Falafel: A National

Icon,”

Gastronomica, Vol. 3, No. 3,

pp. 20–25) that falafel seems to be

“most powerful as a symbol for out-

siders (such as Jews living abroad or

tourists) rather than for the people

of Israel.” Of course adobo also

carries intense meaning on Filipino

home ground. But invoking it abroad

carries great emotional weight. Mi

-

grants must try to find their own

place in a world different from the

world of their birth—and food, par-

ticularly their native country’s food,

is one thing that helps keep them

anchored in the familiar.

As Kenneth Minogue comments

in Nationalism, an immigrant to

America (or elsewhere) finds him

-

self situated in a world where “no

fixed structure exists by which he

can live in a traditional pigeonhole

or interpret the behavior of other

men… . In this new situation, where

social structure has largely gone, cul-

ture becomes far more important.”

Perhaps the most poignant manifes-

tations of “culture” in this sense are

food and the ways in which migrants

use it as a language to tell the world

who they really are. Thus adobo

of-

fers the Filipino exile the pleasure

of smelling, tasting, and savoring

something deeply familiar, a trip

down a memory lane of the palate.

Postscript: I did vary my mother’s

recipe a bit after I’d left home. I now

add more crushed garlic, and I fry

the pork pieces in olive oil instead of

lard. I’m still using a cooking fat of

my country’s ex-conquerors, but one

with different associations.

Ging Gutierrez Steinberg

, formerly

a marketing communications special-

ist, received her M.A. in Food Studies

and Food Management from New York

University in 2005 and is a graduate of

Le Cordon Bleu, Paris. She is currently

consulting and writing for a variety of

food-related publications.

FURTHER READING: To learn

more about adobo and other Filipino

foods, some works you may wish to

consult are Gilda Cordero-Fernando,

Philippine Food and Life (Anvil Pub-

lishing, 1992) and the many works

of the late Doreen G. Fernandez,

especially Tikim: Essays on Philippine

Food and Culture (Anvil Publishing,

1994) and the collaborative volume

The Food of the Philippines: Authentic

Recipes from the Pearl of the Orient

(Periplus, 1998). The restaurant

Cendrillon (45 Mercer St. NYC

10013) carries a selection of Filipino

food books.

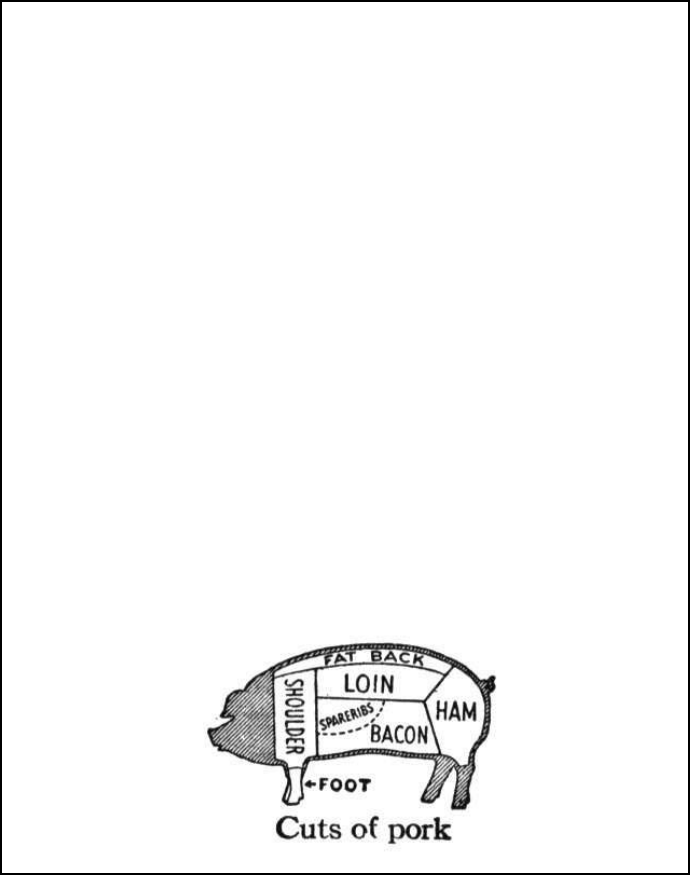

Pork Adobo — My Mother’s Recipe

2 pounds pork shoulder, cut into 2-inch pieces

10 cloves garlic, crushed and peeled

1 bay leaf

1 tsp. whole black peppercorns, lightly crushed

½ cup palm vinegar (or apple cider vinegar)

¼ cup soy sauce

2 tablespoons lard

In a large pot combine pork, garlic, bay leaf, peppercorns, vinegar,

soy sauce and two cups water. Bring to a boil. Reduce heat, cover,

and simmer until meat is tender, about 1 ½ hours. Remove garlic

pieces and pork from sauce and set aside. Discard bay leaf. Boil

sauce over medium heat until about 1 ½ cups remain, about 20

minutes. Transfer sauce to a bowl and set aside.

Brown pork pieces in lard in same pot. Add garlic pieces and fry

until lightly browned. Add reserved sauce to pot and simmer for 5

minutes. Serve with steamed white rice.

Makes 4 small servings

12

UPCOMING PROGRAMS

•CULINARY HISTORIANS OF NEW YORK•

PO Box 3289

New York, NY 10163

IN THIS ISSUE

Tasting Home ........................ 1

From the Chair ......................

2

Letters to the Editor ..............

3

Amelia Scholar’s Grant ..........

3

The Red Michelin .................

4

Program Summaries ..............

5

Member Profile .....................

6

Member News .......................

7

Important CHNY Changes ...

9

Monday, April 3 —

History of Spices and the Medieval Culinary Aes-

thetic by Paul Freeman

Paul Freedman, a medieval social historian and Chairman of the History

Department at Yale University, describes the medieval infatuation with

spices in both culinary and non-culinary terms—in relation to perfumes,

medicine, and what might be called “lifestyle products” resembling modern

aromatherapy—and discusses spices in relation to other traits of medieval

cuisine: the love of color, artifice, complexity, the preference for game, birds,

fish, the contempt for vegetables and dairy products. His forthcoming book,

Spices in the Middle Ages, will be published in 2007.

Wednesday, June 7 — Dining with Don Quixote by Janet Mendel

Inspired by the adventures of Don Quixote, Janet Mendel explores the foods

of Spain that have endured for centuries and their modern interpretations. Her

new book, Cooking From the Heart of Spain, will be published on the heels of the

2005 celebration of the IV Centenary of Don Quixote, and the inauguration

of the Don Quixote Route (

www.donquijotedelamancha2005.com).