Eduardo Navas

THE AESTHETICS OF SAMPLING

••••• •••••

.000

•

00.00

.000.

00000

.000.

•

0000

••

0

••

00.00

0.0.0

00000

••••• •••••

.0.0

•

00.00

00.00

00.00

.00.0

•

0000

.000

•

00.00

0.0.0

00000

•

000.

•••••

.000

•

00.00

.000.

00000

•••••

•

000

•

••••• ••••• •••••

.000

•

00.00

.000.

•

0000

•

000

•

.000

•

0.0.0

00.00

••••• •••••

•

000

•

•••••

00.00

00.00

.000.

•

0000

.000

•

.00.0

00.00

00.00

•

000.

••••• •••••

.000

•

00.00

SpringerWienNewYork

Eduardo Navas, Ph.D.

Post-Doctoral Research Fellow

Information Science and Media Studies

University of Bergen, Norway

With financial support of The Department of Information Science and Me-

dia Studies at The University of Bergen, Norway.

This work is subject to copyright.

All rights are reserved, whether the whole or part of the material is con-

cerned, specifically those of translation, reprinting, re-use of illustrations,

broadcasting, reproduction by photocopying machines or similar means,

and storage in data banks.

Product Liability: The publisher can give no guarantee for all the informa-

tion contained in this book. The use of registered names, trademarks, etc.

in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific state-

ment, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and

regulations and therefore free for general use.

© 2012 Springer-Verlag/Wien

SpringerWienNewYork is part of

Springer Science+Business Media

springer.at

Cover Image: Eduardo Navas

Cover Design: Ludmil Trenkov

Printing: Strauss GmbH, D-69509 Mörlenbach

Printed on acid-free and chlorine-free bleached paper

SPIN 86094050

With 60 figures

Library of Congress Control Number: 2012939340

ISBN 978-3-7091-1262-5 SpringerWienNewYork

Contents

Acknowledgments [vii]

Preface [xi]

Introduction: Remix and Noise [1]

Chapter One: Remix[ing] Sampling [9]

Sampling Defined (11) —The Three Chronological Stages of Mechanical Repro-

duction (17) —The Four Stages of Remix (20) — Analytics: From Photography to

Remix Culture (22) — The Regressive Ideology of Remix (27)

Chapter Two: Remix[ing] Music [33]

A Night at Kadan, San Diego, CA (35) — Dub, B Sides and Their [re]versions in

the Threshold of Remix (36) — The Threshold in Dub (37) — Dub: From Acetate

to Digital (39) — Subversion and the Threshold (42) — Analytics: From Reggae

to Electronic Dub (44) — Dub in Hip Hop, Down Tempo and Drum ‘n’ Bass (47)

— Dub ‘n’ Theory (50) —Dub-b-[ing] the Threshold (53) — Dub ‘n’ Remix (58)

— Bonus Beats: Remix as Composing (60)

Chapter Three: Remix[ing] Theory [63]

Remix Defined (65) —Allegory in Remix (66) — Analytics: Variations of the Re-

flexive Remix in Music (68) — The Regenerative Remix (73) — Remix in Art

(76) — The Waning of Affect in Remix (86) — Remix in the Culture Industry

(89) — Mashups Defined (93) — From Music to Culture to Web 2.0 (100) —

Web Application Mashups (101) — The Ideology Behind the Reflexive Mashup

(103) Analytics: From Music Video to Software Mashups (105) — Sampling and

the Reflexive Mashup (108) — Resistance in Remix (109) — Remix in History

(111) — Remix in Blogging (120) — Bonus Beats: Remix in Culture (124)

Chapter Four: Remix[ing] Art [129]

A Late Night in Berlin (131) — Remix is Meta (133) — The Role of the Author

and the Viewer in Remix (134) — The Role of the Author and the Viewer in Per-

formance and Minimalism (137) — New Media’s Dependence on Collaboration

(141) — The Curator as Remixer (146) — Online Practice and Conceptualism

(150) — The Regressive Ideology of Remix Part 2 (155) — Bonus Beats: The

transparency of Remix (157)

Conclusion: Noise and Remix [161]

Periférico, Mexico City (163) — After the Domestication of Noise (167) — Bo-

nus Beats: the Causality of Remix (170)

Index [175]

Remix Theory

3

We must know the right time to forget

as well as the right time to remember,

and instinctively see when it is necessary

to feel historically and when unhistorically.

Friedrich Nietzsche

My goal in this analysis is to evaluate how Remix as discourse is at play

across art, music, media, and culture. Remix, at the beginning of the

twenty-first century, informs the development of material reality depend-

ent on the constant recyclability of material with the implementation of

mechanical reproduction. This recycling is active in both content and form;

and for this reason throughout this book I discuss the act of remixing in

formal and conceptual terms. I focus on Remix as opposed to remix cul-

ture, which means that I consider the reasoning that makes the conception

of remix culture possible. Remix culture, as a movement, is mainly preoc-

cupied with the free exchange of ideas and their manifestation as specific

products. Much has already been published about Remix under the um-

brella of remix culture in terms of material development: how it is pro-

duced, reproduced, and disseminated. Its conflicts of intellectual property

are also a central point discussed by activists such Lawrence Lessig, a

copyright lawyer whom I reference throughout my investigation. As I

evaluated the principles of Remix for this analysis, I came to the conclu-

sion that as a form of discourse Remix affects culture in ways that go be-

yond the basic understanding of recombining material to create something

different. For this reason, my concern is with Remix as a cultural variable

that is able to move and inform art, music, and media in ways not always

obvious as discussed in remix culture. Remix culture is certainly founded

on Remix, and for this reason it is referenced repeatedly through my

chapters; but remix culture is not the subject of this investigation mainly

because it is a global cultural activity often linked specifically to copy-

right; and Remix, itself, cannot be defined on these terms.

Throughout the chapters that follow, whenever I refer to Remix as dis-

course I use a capital “R.” Discourse is commonly understood in the hu-

manities as an ever-changing set of ideas up for debate in written and oral

form. However, I also consider discourse to include all forms of communi-

cation, not just writing and oral communication. When the term is used in

the humanities, it is often linked to Michel Foucault. My use of discourse

is certainly informed by his definition (debates within and among special-

ized fields of knowledge), and I do extend Foucault’s definition to media

Eduardo Navas

4

at large, because at the beginning of the twenty-first century it is media as

a whole that is treated as a form of writing; or rather, media is discourse.

1

Therefore I argue that Remix is not an actual movement, but a binder—a

cultural glue. Based on this proposition, the analysis performed in the fol-

lowing chapters should demonstrate that Remix is more like a virus that

has mutated into different forms according to the needs of particular cul-

tures.

2

Remix, itself, has no form, but is quick to take on any shape and

medium. It needs cultural value to be at play; in this sense Remix is para-

sitical. Remix is meta—always unoriginal. At the same time, when imple-

mented effectively, it can become a tool of autonomy. An example of this

can be found in the beginnings of Remix in music.

Remix has its roots in the musical explorations of DJ producers; in par-

ticular, hip-hop DJs who improved on the skills of disco DJs, starting in

the late sixties. DJs took beatmixing and turned it into beat juggling: they

played with beats and sounds, and repeated (looped) them on two turnta-

bles to create unique momentary compositions for live audiences. This is

known today as turntablism. This practice made its way into the music stu-

dio as sampling, and eventually into culture at large, contributing to the

tradition of appropriation.

Cut/copy and paste is a common feature found in all computer software

applications, and currently is the most popular form of sampling practiced

by anyone who has access to a computer. Cut/copy and paste extends

many of the principles explored by DJs and previous cultural producers in

the twentieth century. Keeping in mind the link of sampling and appro-

priation to cut/copy and paste, I argue that Remix is a discourse that en-

capsulates and extends shifts in modernism and postmodernism; for if

modernism is legitimated by the conception of a Universal History, post-

modernism is validated by the deconstruction of that History. Postmod-

ernism has often been cited to allegorize modernism by way of fragmenta-

tion, by sampling selectively from modernism; thus, metaphorically

speaking, postmodernism remixes modernism to keep it alive as a valid

epistemological project.

3

To come to terms with the importance of Remix during the first decade

of the twenty-first century, then, we must consider its historical develop-

ment. This will enable us to understand the dialectics at play in Remix,

which at the beginning of the twenty-first century is the foundation of

1

For the concepts of discourse and episteme, see Michel Foucault, The Order of Things (New

York: Routledge, 2001).

2

This is a reference to William Burroughs’s views on language as a virus. See Williams S. Bur-

roughs, The Ticket That Exploded (New York: Grover Press, 1987).

3

This is a reference to the critical positions of Jean Francois Lyotard and Fredric Jameson.

Their ideas are discussed in chapter three.

Remix Theory

5

remix culture. Remix came about as the result of a long process of experi-

mentation with diverse forms of mechanical recording and reproduction

that reached a meta-level in sampling, which in the past relied on direct

copying and pasting. Certain dynamics had to be in place in the process of

mechanical recording and reproduction for sampling to become part of the

everyday, and they first manifested themselves in music at the end of the

nineteenth century, framed by the contention of representation and repeti-

tion.

Political economist Jacques Attali has reflected at length on the relation

of representation and repetition, arguing that the power of the individual to

express herself through performance, a primary form of representation,

particularly of musical material, shifted when recording devices were mass

produced. Once recording took place, repetition—not representa-

tion—became the default mode of reference in daily reality; a common ex-

ample, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, is the willingness of

individuals to purchase and listen to a music compilation in CD or MP3

format. This form of musical experience is different from a live perform-

ance. Following Attali’s line of thinking, the power of repetition here is in

the fact that the user sees a practicality in listening to a recording as fre-

quently as desired. Going to a performance, on the other hand, implies a

different experience that requires a deliberate commitment to a social ac-

tivity. Often the material one expects to hear live is compositions of which

one already bought recordings, or at least heard previously on the radio;

thus the live performance is linked to some form of reproduction, defined

by repetition. For these reasons I argue that repetition and representation

have a contentious relationship in contemporary culture and play a key role

in modernism, postmodernism, and new media during the first decade of

the twenty-first century.

Attali sees music as the domestication of noise during the nineteenth

century. Music became, and is, a political medium that enables Capital to

become the default form of cultural exchange. He considers this domesti-

cation important in the understanding of culture throughout modernity and

argues that it is in the domestication of noise where one can learn about the

effects of the world:

More than colors and forms, it is sounds and their arrangements that fashion societies.

With noise is born disorder and its opposite: the world. With music is born power and its

opposite: subversion. In noise can be read the codes of life, the relations among men.

Clamor, Melody, Dissonance, Harmony; when it is fashioned by man with specific tools,

when it invades man’s time, when it becomes sound, noise is the source of purpose and

power, of the dream—music.

4

4

Jacques Attali, Noise The Political Economy of Music (Minneapolis: Minnesota Press, 1985), 6.

Eduardo Navas

6

Using Attali’s theory as a conceptual framework and starting point, my

goal is to demonstrate how Remix is closely linked to the domestication of

noise, which eventually became a model for autonomy in modernism and

postmodernism. I approach Remix as Attali approaches Music. He consid-

ers music the result of the domestication of noise; I consider Remix to be

the result of the domestication of noise on a meta-level of power and con-

trol, as simulacrum and spectacle. Applying Attali’s theory of noise to

Remix exposes how and why Remix is able to move with ease across me-

dia and culture, both formally and conceptually. For this reason, my inves-

tigation of Remix in art, music, and media is not primarily concerned with

productions or objects popularly considered remixes, such as music

remixes or video mashups; instead the popular understanding of remix is

taken as the point of departure to look at works and activities that clearly

use principles of Remix, but may or may not be called remixes. My analy-

sis also considers how Remix principles originally found in the concrete

form of sampling as understood in music remixes move on to other forms,

though not always in terms of actual sampling, but as citations of ideas or

other forms of reference. In other words, my investigation traces how prin-

ciples found in the act of remixing in music become conceptual strategies

used in different forms in art, media, and culture.

I argue that Remix, starting in the nineteenth century, has a solid foun-

dation in capturing sound, complemented with a strong link to capturing

images in photography and film. Given the role of these media in art prac-

tice, it became evident to me that art is a field in which principles of remix

have been at play from the very beginning of mechanical reproduc-

tion—hence the prevalence of art aesthetics throughout the chapters.

During the 1970s the concept of sampling became specifically linked to

music, and, towards the end of the ‘90s, all forms of media in remix cul-

ture. It is the computer that made the latter shift possible. This does not

mean that Remix is not informed or intimately linked with other cultural

developments; on the contrary, Remix thrives on the relentless combina-

tion of all things possible. However, for the sake of precision, I emphasize

the role of textuality in terms of structural and poststructural theory. Ad-

mittedly, my definition of Remix privileges music because it is in music

where the term was first used deliberately as an act of autonomy by DJs

and producers with the purpose to develop some of the most important

popular music movements of the 1970s: disco and hip-hop.

I also pay specific attention to the foundation of Remix in music be-

cause, according to Attali, it is in the domestication of music where we can

find the roots of modernism proper: “For twenty-five centuries, Western

knowledge has tried to look upon the world. It has failed to understand that

the world is not for the beholding. It is for the hearing. It is not legible, but

Remix Theory

7

audible.”

5

Attali, by providing a critical reading of music as domesticated

noise, is able to expose how specific conflicts are at play in different areas

of culture; conflicts such as subversion of individual expression in an

economy of specialization, as well as the control of knowledge in a global

class struggle. My focus on the origin of Remix in music aims to have a

similar effect for remix culture, as well as new media, in close relation to

art practice. My reading of Remix and its intimate relation to music should

be viewed, then, as one way of theorizing about a culture defined by recy-

clability and appropriation. My hope is that my research will be considered

complementary to other studies of Remix and remix culture. Throughout

the chapters I implement cultural analytics methodologies, meaning that I

make use of statistics and graphs, and other types of data visualization in

order to better understand information that otherwise would function as

abstract footnote references. The implementation of cultural analytics

makes this publication a contribution to the interdisciplinary research

practice of the digital humanities, which consists of the adoption of com-

puting by the humanities.

6

The four chapters of this book were written to note how Remix has its

roots in the early stages of mechanical recording and reproduction, starting

in the nineteenth century. As noted above, a crossover between art, media

and music was inevitable, hence the chapters reflect on these fields in or-

der to demonstrate how the principles of Remix constantly shift across

media. To accentuate how Remix is at play in a micro and macro level,

some of the chapters contain personal anecdotes in which Remix was ex-

perienced.

According to the critical framework that I have proposed in this intro-

duction, chapter one, “Remix[ing] Sampling,” defines the roots of Remix

in early forms of mechanical reproduction. It outlines seven stages begin-

ning in the nineteenth century with the development of the photo camera

and the phonograph that lead up to the current state of Remix, and evalu-

ates how recorded material redefines people's concept of representation.

The first three stages are called “Stages of Mechanical Reproduction,” and

the remaining four “Stages of Remix.” The chapter also outlines the differ-

ence in sampling at play in visual culture and music culture, and explains

how such differences collapsed with the rise of the computer.

Chapter two, “Remix[ing] Music,” explains the rise of dub in Jamaica

during the 1960s and ‘70s, the experimentation with remixing in New

York City during the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, the development of remix as

a style from the mid ‘80s to the late ‘90s, and the global rise of remix cul-

5

Ibid, 3.

6

To learn more about cultural analytics, see http://lab.softwarestudies.com/

Eduardo Navas

8

ture from the end of the ‘90s to the time of this writing. Chapter two also

expands on the definition of Remix outlined in chapter one to demonstrate

how Remix moves beyond basic material production into an ideological

realm, where it becomes a political tool. To accomplish this, the chapter

re-evaluates the writings of Hommi Bhabha and Michael Hardt & Antonio

Negri in relation to Remix as a form of critical production. This is done to

reflect upon not just the historical development, but also the cultural poli-

tics that inform Remix.

Chapter three “Remix[ing] Theory” consists of a concise definition of

Remix as a proper action in music. It makes use of the historical and cul-

tural contextualization set in the previous two chapters to define specific

forms of Remix. Chapter three focuses on Remix’s beginning in music

during the 1970s and its eventual influence in art and media. It includes

analysis of modern and networked art projects, software applications and

literature, including Remix’s evolution as blogging. Attali’s definition of

noise and music are explained extensively, and linked to arguments by

Theodor Adorno. Craig Owens’s and Fredric Jameson’s theories of post-

modernism are discussed in detail throughout the chapter in order to gain a

better understanding of the development of modernism and postmodernism

in the twentieth century. Chapter three explores Remix in art, music, and

media, and lays the ground for the study of other critical strategies that

also inform Remix, which are considered in the last chapter and conclu-

sion.

Chapter four, “Remix[ing] Art” expands on how principles of sampling

considered in chapter one share strategies as a political tool with forms of

appropriation at play in conceptualism, minimalism, and performance art.

It examines specific new media works in order to assess the interchange-

able role of artists and curators. This chapter applies the theories of author-

ship by Roland Barthes, as well as Michel Foucault to networked projects

to better understand how collaboration has become a conventional act in

media culture, informed by the concept of textuality and reading as defined

in terms of critical discourse. Sampling is linked in this case to the preoc-

cupation with reading and writing as an extended cultural practice beyond

textual writing onto all forms of media. In the conclusion, I reflect on the

history and theory I outlined throughout the four chapters of the book.

In this publication, I deliberately leave an open-ended position for the

viewer to reflect on the implications of cultural recyclability. I do not at-

tempt to provide a specific answer, but rather offer material for critical re-

flection that may be considered a contribution to various fields of research

in the humanities and social sciences. I do, however, take a critical position

which I believe is already apparent in this introduction, but is further de-

veloped throughout the following chapters.

Chapter One: Remix[ing] Sampling

© Springer-Verlag/Wien 2012

E. Navas,

Remix Theory

Remix Theory

11

Before Remix is defined specifically in the late 1960s and ‘70s, it is neces-

sary to trace its cultural development, which will clarify how Remix is in-

formed by modernism and postmodernism at the beginning of the twenty-

first century. For this reason, my aim in this chapter is to contextualize

Remix’s theoretical framework. This will be done in two parts. The first

consists of the three stages of mechanical reproduction,

1

which set the

ground for sampling to rise as a meta-activity in the second half of the

twentieth century. The three stages are presented with the aim to under-

stand how people engage with mechanical reproduction as media becomes

more accessible for manipulation. The three stages can be marked with the

first beginning in the 1830s, when the rise of early photography took place;

followed by the second in the 1920s, when experimentation of cut up

methods were best expressed in collage and photomontage; and ending

with the third, when Photoshop was introduced in the late 1980s. I also re-

fer to the last as the stage of new media. The three stages are then linked to

four stages of Remix, which take place between the 1970s to the present;

they overlap the second and third stage of mechanical reproduction. This

chapter, then, defines three stages in the development of mechanical re-

production to show how sampling became a vital element in acts of appro-

priation and recycling in modernism that then became conventions in

postmodernism, which eventually evolved to inform and support Remix in

culture.

Sampling Defined

Some specialists might propose sampling as a term reserved for music.

However, the principle of sampling at its most basic level had been at play

as a cultural activity well before its common use in music during the

1970s. I do not argue to change the term recording for sampling when dis-

cussing film, photography or early music recording; rather, my goal is to

point out that recording and sampling are terms used at specific times in

history in part due to cultural motivations. Sampling as an act is basically

what takes place in any form of mechanical recording—whether one cop-

1

Mechanical reproduction here is understood according to Walter Benjamin’s well-known essay,

“The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” At the time that Benjamin wrote

his essay, it was not possible for him to see completely where new technologies would lead

the mass-produced image. Yet, he did set a methodological precedent to deal with possibili-

ties when he explained how mechanical reproduction freed the object from cult value. Once

taken out of its original context, the object gains the potential of infinite reproducibility; it

enters the realm of exhibit value. See, Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the End of Me-

chanical Reproduction,” Illuminations (New York, Schocken, 1968), 217-251.

Eduardo Navas

12

ies, by taking a photograph, or cuts, by taking a part of an object or sub-

ject, such as cutting part of a leaf to study under a microscope.

The concept of sampling developed in a social context that demanded

for a term that encapsulated the act of taking not from the world but an ar-

chive of representations of the world. In this sense, sampling can only be

conceived culturally as a meta-activity, preparing the way for Remix in the

time of new media. Early recording, in essence, is a form of sampling from

the world that may not appear as such to those used to the conventional

terms in which the concepts of recording and sampling are understood.

According to the basic definition of capturing material (which can then be

re-sampled, re-recorded, dubbed and re-dubbed), sampling and recording

are synonymous following their formal signification.

Sampling is the key element that makes the act of remixing possible. In

order for Remix to take effect, an originating source must be sampled in

part or in whole. However, sampling favors fragmentation over the whole.

At the moment that mechanical recording became a norm to evaluate, un-

derstand, and define the world in early modernism, the stage was set for

postmodernism. Postmodernism is dependent on a particular form of frag-

mentation, whose foundation is in early forms of capturing image and

sound through mechanical recording, which, technically speaking, sampled

from the world beginning in the nineteenth century.

Recording is a form of sampling because it derives from the concept of

cutting a piece from a bigger whole. Because cutting was commonly un-

derstood as a form of taking a sample, the disturbing element of photogra-

phy is that an exact copy appeared to be taken, as though it had been “cut”

from the world, yet the original subject apparently stayed intact. To better

understand this, it is necessary to evaluate the basic definition of sampling.

Random House Dictionary states: “a small part of anything or one of a

number, intended to show the quality, style, or nature of the whole; speci-

men.”

2

This general definition defaults to cutting, not copying materially.

Looking back on the history of mechanical reproduction, it becomes evi-

dent that this definition was in part contingent upon the technology avail-

able for capturing images. It was in the nineteenth century when mechani-

cal copying became possible, with machines designed to copy at an

affordable price. The first form of mechanical copying with certain accu-

racy was the lithograph, which became quite popular in the 1830s.

3

So,

2

Dictionary.com Unabridged (v 1.1)

Based on the Random House Unabridged Dictionary, Random House, Inc. 2006,

http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/sample.

3

Barbara Rhodes & Heraldry Bindery, “Materials & Methods/The Art of Copying,” Before

Photocopying: The Art & History of Mechanical Copying, 1780-1938 (Massachusetts: Oak

Knoll Press & Heraldry Bindery, 1999), 21.

Remix Theory

13

while the notion of copying from pre-existing texts or sampling a piece to

represent a whole may have been at play to some degree in this time pe-

riod, it was so with great possibility of inaccuracy or error in having some

of the information missing. Prior to the popularization of mass printing, it

would be up to scribes to copy as accurately as possible, but during the

nineteenth century other forms of copying would start to be employed

more pervasively.

4

Once the idea of capturing from the real world (as a form of copying)

entered the material world via mechanical reproduction, a major shift in

culture began to take place in the nineteenth century with photography: the

first technology that is fully invested in capturing as a form of sampling.

While printing can be argued to have the basic elements of recording by

way of sampling, the difference with photography is that photo media

could in theory record an image of anything—it created accurate copies of

the world; of course in the beginning this was unstable, as the success of

developing an actual image from, say a calotype required great devotion

and care in the process. Eventually, even text would be treated as another

element from which to copy, capture (sample) in part or in whole: the mi-

crofilm is the most obvious example of this transition. Before digital scan-

ning was possible, microfilm was one of the first databases of information

relying on scanning as understood in new media. Most importantly, pho-

tography introduced the possibility for everyone to record images. In other

words, with a broad sense of the term: to sample the world as they wished.

Potentially, any person with the right equipment could take a piece of the

world by making an image copy of a moment in time.

This challenged the control over mechanically produced material. The

principle that enabled people to use a medium for private use was not the

direct intent of print; if anything, print promoted the contrary. Print was

and still is a one-way form of communication, in which the publisher holds

ultimate control on what is printed. While it can be argued that today read-

ers have greater power on what is published, it is still the publisher who

will decide so based on politics. Print, then, is about quality control; its

authority lies in the fact that from the very beginning only few people

could learn and afford how to edit and print books properly. Today this is

further complicated with the rising complexity of copyright.

5

Photography

challenged this control during its cultural introduction. During its early

stages, photography validated itself as a mass medium by promoting the

opportunity for anyone potentially to take photographs; so in photography

4

Ibid, 7.

5

A good account of publishing control directly connected to emerging technologies, especially

online can be found in, Lawrence Lessig, The Future of Ideas: The Fate of the Commons in

the Connected World (New York: Vintage Books, 2002), 111-112.

Eduardo Navas

14

a tendency that is vital to new media and Remix at the beginning of the

twenty-first century manifested itself as a mass phenomenon: the acknowl-

edgment of the user to complete the work, or do the actual labor.

Sampling, then, has its seeds in 1839, as Lev Manovich argues when he

cites a Parisian who commented on what followed after Louis Daguerre’s

famous presentation of his daguerreotype: “A few days later, ‘opticians’

shops were crowded with amateurs panting for daguerreotype apparatus,

and everywhere cameras were trained on buildings. Everyone wanted to

record the view from his window, and he was lucky who at first trial got a

silhouette of roof tops against the sky.”

6

And this frenzy is a natural ele-

ment of new media culture, taken as a given.

To fully grasp the importance of sampling in modernism, however, we

must also consider how recording in music evolved to incorporate sam-

pling as a vital part of music production. At the time of this writing, sam-

pling is commonly understood to imply copying in material form, not by

capturing from the real world, but from a pre-existing recording. This prin-

ciple of sampling, which became popular in the 1970s with DJ producers

of disco and eventually hip-hop, is a meta-activity that follows early forms

of sound capturing. Early sound recordings, with a similar approach as

photography’s, were also tools used to copy (sample) from the world.

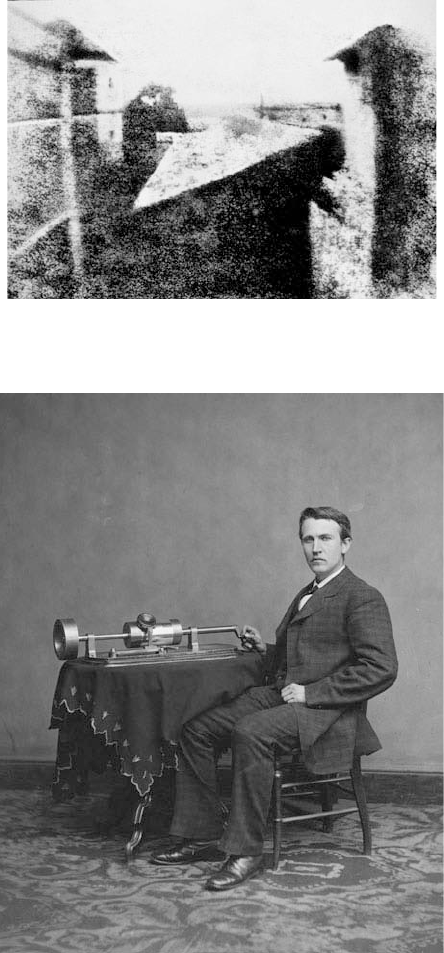

Thomas Edison developed the phonograph in 1877 to record sound (Figure

1.2); his interest was not the recording of music but of voices.

7

It was not

until much later, around 1910, that the phonograph, along with the gramo-

phone, would be commonly used not to record but to listen to music. Edi-

son did not pursue recording music as he was interested in providing a

dictating service for corporations. (This pursuit was not successful.)

8

Thus,

the phonograph, like the photograph was developed with the same pur-

pose: to capture (sample) a moment and relive it later. This is particularly

true from Edison’s point of view. It must be noted here that while the kind

of sampling taking place in photography can be argued to be technically a

different process from capturing sound, from a cultural perspective it was

collapsed in film by Edison’s conceptual approach. He deliberately

thought of capturing images equivalent to capturing sound. He theorized

that “photographic emulsion could attach images to a cylinder, and they

could be played back like a phonograph.”

9

And he openly considered the

Kinetoscope a visual phonograph. Here we begin to see an intimate rela-

6

Cited by Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media (Cambridge, Massachusetts: 2001), 21.

7

Theresa M. Collins, Lisa Gitelman, and Gregory Jankunis, “Invention of the Phonograph, as

recalled by Edison’s Assistant, by Charles Batchelor,” Thomas Edison and Modern America:

A Brief History with Documents (New York: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2002), 64.

8

Ibid, 23.

9

Ibid, 20.

Remix Theory

15

tionship between image and sound; however, the process of capturing

would not become the same for them until the introduction of the com-

puter, a machine that treats both image and sound the same: as binary data

to be manipulated at will by the user. While early recording technology

carried this trace, people would not think of image and sound as equivalent

forms of recording; further, these two forms would not be called “sam-

pling” at this time, because the notion of sampling as it is used during the

first decade of the twenty-first century was not conceivable—in part be-

cause the conception of appropriating recorded material would not take

place until the beginning of the twentieth century.

Technically speaking, when considering the basic definition of sam-

pling, this is what takes place in this first stage; early technology enabled

people to sample from the world and eventually from sampled material. In

current times the latter becomes a default state with the computer: to sam-

ple means to copy/cut & paste. Most importantly, this action is the same

for image, sound and text. In this sense, the computer is a sampling ma-

chine: from a wide cultural point of view, the ultimate remixing tool. The

reason for this has to do with two levels of operation in culture, which I

define as The Framework of Culture. The first takes place when an ele-

ment is introduced in culture, and the second when once that element has

attained cultural value it is re-evaluated, either by social commentary, ap-

propriation, or sampling.

10

These strategies are vital to the practice of

Remix as the act of remixing takes place in the latter stage with the combi-

nation of formal and ideological strategies. Both the photograph and the

phonograph functioned at the first stage, setting the ground for appropria-

tion and sampling in modernism commonly understood mainly as forms of

recording primary sources. Photography and sound recording would take

full effect as a meta-action in postmodernism, to become friendly to the

simulacrum, once enough material had been gathered to be remixed.

10

This statement does not imply that the content is some how “new” along the lines of some-

thing completely “original,” but rather that the material introduced is different enough for

people to evaluate how it redefines conventions previously established. Once such material is

assimilated it can enter the second layer of the framework of culture. Some obvious examples

are the photograph, the phonograph, the computer and the Internet, which are all innovative

re-combinations of technology developed by many people, not a sole individual.

Eduardo Navas

16

Figure 1.1 Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, View from the Window at Le Gras, Eight

hour exposure. Heliograph. Taken in 1826 or 1827, in Saint-Loup-de-Varennes.

Figure 1.2 Thomas Edison and his early phonograph. Circa 1877, Brady-Handy

Photograph Collection (Library of Congress) Author: Levin C. Handy.

Remix Theory

17

The Three Chronological Stages of Mechanical

Reproduction

Based on the material surveyed above, there are three stages of Mechanical

Reproduction (Figure 1.3): the first consists of early photography, begin-

ning around the 1830s (extended in film), and sound recording with the

phonograph in the 1870s and ‘90s; at this stage, it is the world itself that is

recorded—represented with images and sounds. The act of sampling as

known today was not relevant at this stage; instead, recording was the

word most often linked with early forms of mechanical reproduction. Once

mechanical recording became conventionalized and paradigms developed,

and most importantly, enough material was recorded and archived, the

second stage of mechanical reproduction is found beginning in the 1920s

in photo collages and photomontages, which relied mainly in cutting and

pasting. This is the first stage of recycling—an early form of meta-media

preceding sampling as commonly understood in new media. Social com-

mentary dependent on the recycling of mechanically reproduced media be-

comes feasible in this second stage, which first manifested itself most visi-

bly in photomontage, but became pervasive in music sampling during the

1970s, once sampling machines became readily available. In music, cut-

ting gave way to copying. During the ‘70s, music sampling leaned towards

leaving the original music composition intact; and with the right equip-

ment, music samples could sound just as good as the originating source.

The final stage of sampling is found in new media beginning in the

1980s—which I also refer to as the second stage of recycling. This stage

privileges pre-existing material over the real world. The tendency to look

for already recorded material prevalent in early music remixes, which be-

came the staple practice in hip-hop music, is now a shared tendency com-

monly found in new media when people opt to search for information in

databases—whether it be text, image, or video. In this case, both of the

previous stages are combined at a meta-level, thus giving the user the op-

tion to cut or copy based on aesthetics, rather than limitations of media.

This is not to say that new media does not have limitations, but rather that

most people adept in emerging technologies could concentrate with greater

ease in developing their ideas with efficient forms of recording and sam-

pling that simulated (to a believable degree) previously existing media.

Eduardo Navas

18

Figure 1.3

Let us examine each of these three stages in more detail. To begin, photog-

raphy in its initial stage samples, in the strict sense of the definition, by

capturing a moment in time that can be reproduced as a print, assuming

that the negative is well taken care of, which is most obvious in one of the

first recorded images by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, View from the Window

Remix Theory

19

at Le Gras, circa 1826, (Figure 1.1) a heliograph which took several hours

to achieve.

11

The capture of time would be pushed by film language by

creating a series of images that when played in sequence gave a sense of

actual time lapse. During the second stage of mechanical representation,

cutting from images to create other images was explored as a legitimate

aesthetic. A prime example of this stage is the work of Hannah Höch, who

sampled by cutting directly from magazines and other publications. John

Heartfield is another artist who sampled by cutting to then create photo-

graphs (better known as photomontages) to be published in magazines.

While Höch may have a closer relationship to the notion of sampling by

taking actual pieces from a bigger whole, Heartfield and his contemporar-

ies offer a transitional moment; they set the ground for the kind of recy-

cling found in new media that privileges copying not cutting. Heartfield

explored copying or sampling as defined by the first stage found in pho-

tography when he produced cut and paste compositions to be photo-

graphed to then find their final form in the print Magazine AIZ, as criti-

cism on the politics of Adolf Hitler.

12

What is crucial in Heartfield and his

contemporaries practicing photomontage is that he developed work spe-

cifically for reproduction; they explored the visual language that would

become fundamental during the early ‘90s for the software application

Photoshop, where cut/copy & paste is essential to develop basic new me-

dia imagery. This is the default mode of photographic reproduction for

people who have access to computer technology at a professional or ama-

teur level. Photoshop, then, marks the third stage of mechanical reproduc-

tion, which I also refer to as the stage of new media, and the second stage

of recycling. This stage was marked in music a decade earlier, when DJs

turned producers during the late 1970s and early ‘80s were able to take bits

of different songs with sampling machines to create their own composi-

tions. This tendency now is part of remix culture.

Now that the three stages of mechanical reproduction have been defined

and contextualized theoretically, it is time to look at how these stages are

historically linked to four more stages that specifically support the devel-

opment of Remix in postmodernism and our current state of new media

production.

11

Mary Warner Marien, “The Invention of Photographies,” History of Photography: A Cultural

History (New York: Prentice Hall, 2006), 9.

12

David Evans,“From Idea to Page: The Making of Heartfield’s Photomontages,”John Heart-

field: AIZ (New York: Kent Gallery, Inc, 1992), 20-29.

Eduardo Navas

20

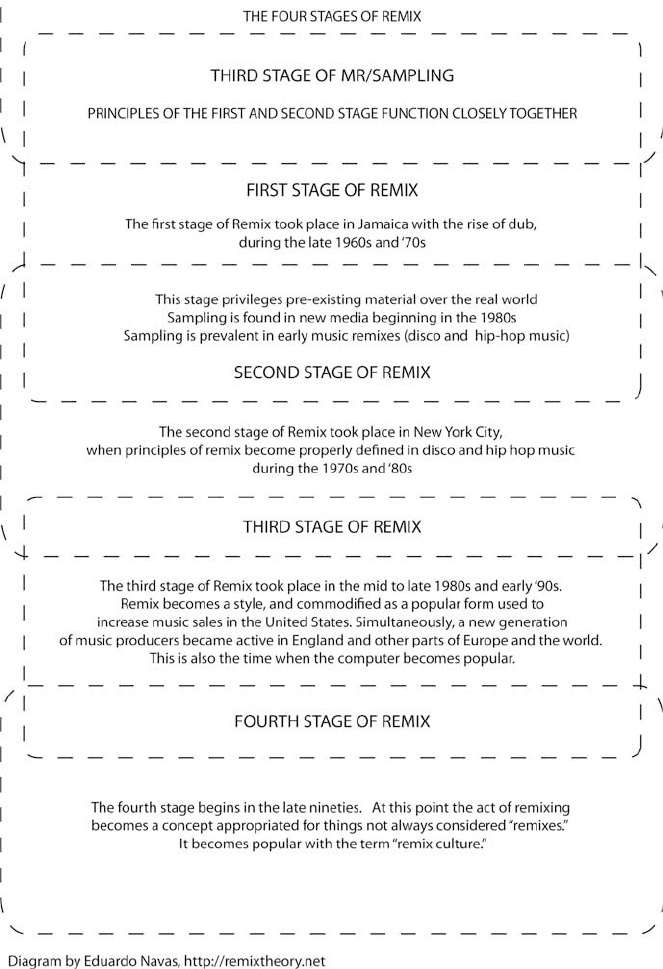

The Four Stages of Remix

The four stages of Remix overlap the second and third stage of mechanical

reproduction (Figure 1.4). As noted, the third stage of mechanical repro-

duction begins in visual culture when Photoshop was introduced; however,

as also noted, this shift happened in music a few years earlier during the

1980s with the introduction of sampling machines used to experiment with

different forms of remix. While this is taking place, the computer was in-

troduced to the mass public during the first years of the 1980s. IBM’s per-

sonal computer 5150 was officially released in 1980. And Apple’s Lisa

was released in 1983.

13

In this way, the aesthetics of constantly taking bits

and pieces of content begins to be shared across media, and is not limited

to music. Here we find a parallel in the aesthetics of sampling, which

would be combined in the late ‘90s in Remix. However, it is the concept of

remixing in music, as we will see that became appropriated to encapsulate

the tendency to recycle material in all media.

The first stage of Remix took place in Jamaica with the rise of dub,

during the late 1960s and ‘70s; that is, at the end of the second stage of

mechanical reproduction. The second stage of Remix took place during the

1970s and ‘80s when principles of remixing are defined in New York City.

The third stage takes place, during the mid to late ‘80s and ‘90s, when

Remix becomes a style, and therefore commodified as a popular form used

to increase music sales in the United States, at which time a new genera-

tion of music producers became active in England as well as other parts of

Europe and the world. This is also the time when the computer becomes

more popular and the aesthetics of new media are implemented with the

introduction of Photoshop. While the United States began to sell music

clearly informed by remix aesthetics as mainstream commodities, people

in Europe developed a subculture based on the principles of Remix defined

during the 1970s and early ‘80s. The North American styles of Detroit

Techno, Chicago House, New York Garage, along with the rise of main-

stream hip-hop, became the points of reference for subcultures to develop

their own material. The result was music genres such as trip-hop, down-

tempo, breakbeat and jungle, which were perfected throughout Europe, but

most clearly defined in England.

13

Paul Freiberger & Michael Swaine, Fire in the Valley (New York: McGraw Hill, 2000), 329 –

354.

Remix Theory

21

Figure 1.4

Eduardo Navas

22

The fourth stage of Remix takes place when the act of remixing becomes a

concept appropriated for things not always considered “remixes.” Remix

becomes an aesthetic to validate activities based on appropriation. This

stage takes place during the late ‘90s, and becomes most pronounced with

the concept of remix culture, as defined by Lawrence Lessig. The popular

online community resource ccMixter is perhaps the most obvious example

of how the principles of remixing, explored in the previous stages inform

online collaboration.

14

ccMixter encourages its members to share music

tracks and remix them, as long as participants respect the copyright li-

censes which have been adopted by the original track producers. But the

less obvious examples would fall in the diverse uses of Creative Commons

licenses which are designed to cover all forms of intellectual property pro-

duction, including, image, music, and text.

15

Here, Remix is in place, and

we are currently living through the fourth stage.

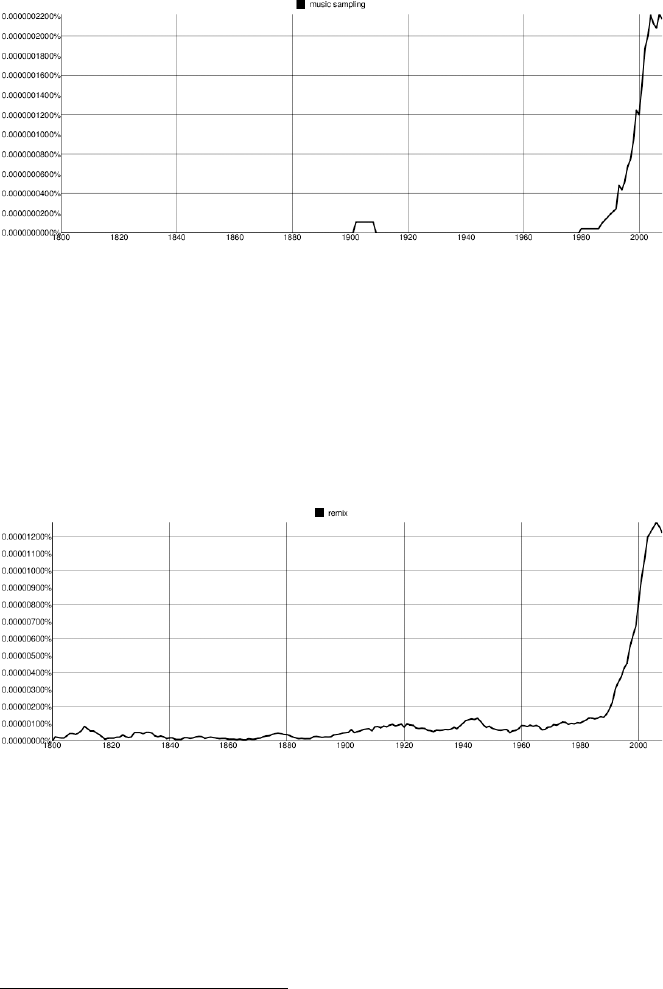

Analytics: From Photography to Remix Culture

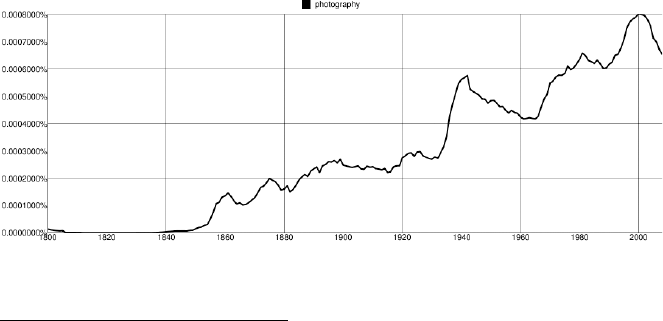

The three stages of mechanical reproduction and the four stages of Remix become evident

in the use of key terms in print between the 1800s and 2000s. The visualizations that follow

demonstrate the rise of sampling moving towards Remix as discussed throughout this

chapter. Note that the queries are limited to books in English.

The Cultural Understanding of Photography and Film in

Print

The following graphs demonstrate how the words “photography” and “film” were popular

in print publications between 1800 and 2008.

14

ccMixter, http://ccmixter.org/

15

Creative Commons, http://creativecommons.org/

Remix Theory

23

Figure 1.5 The usage of the term “photography” increases dramatically beginning in the

1840s.

16

This is shortly after Louis Daguerre’s innovations. This corresponds with the First

stage of mechanical reproduction.

Figure 1.6 The term “film” appeared in print prior to the 1840s.

17

This, however, was likely

in relation to other denotations of the term. The term’s use increases around the 1860s. This

falls in line with the innovations by Thomas Edison and his contemporaries. The usage of

photography and film in print corresponds with the first stage of mechanical reproduction.

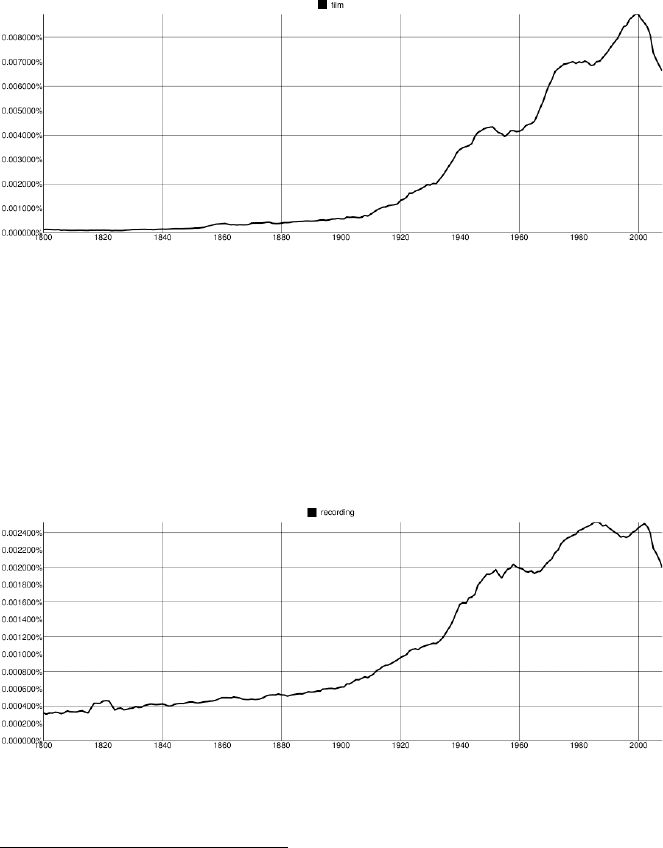

The Cultural Understanding of Recording and Sampling

in Print

The following graphs demonstrate how the words “recording” and “sampling” were popular

in print publications between 1800 and 2008.

Figure 1.7 The usage of the term “recording” increases from left to right, moving towards

contemporary times.

18

16

Google nGram: http://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=photography&year_start=

1800&year_end=2008&corpus=0&smoothing=3

17

Google nGram: http://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=film&year_start=

1800&year_end=2008&corpus=0&smoothing=3

18

Google nGram: http://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=recording&year_start=

1800&year_end=2008&corpus=0&smoothing=3

Eduardo Navas

24

Figure 1.8 The usage of the term “sampling” is basically non-existent in print until the be-

ginning of the 1880s. This corresponds with the relation of the concept of sampling with the

archiving of mechanically reproduced material from which to sample in order to create

collages and photomontages during the second stage of mechanical reproduction.

19

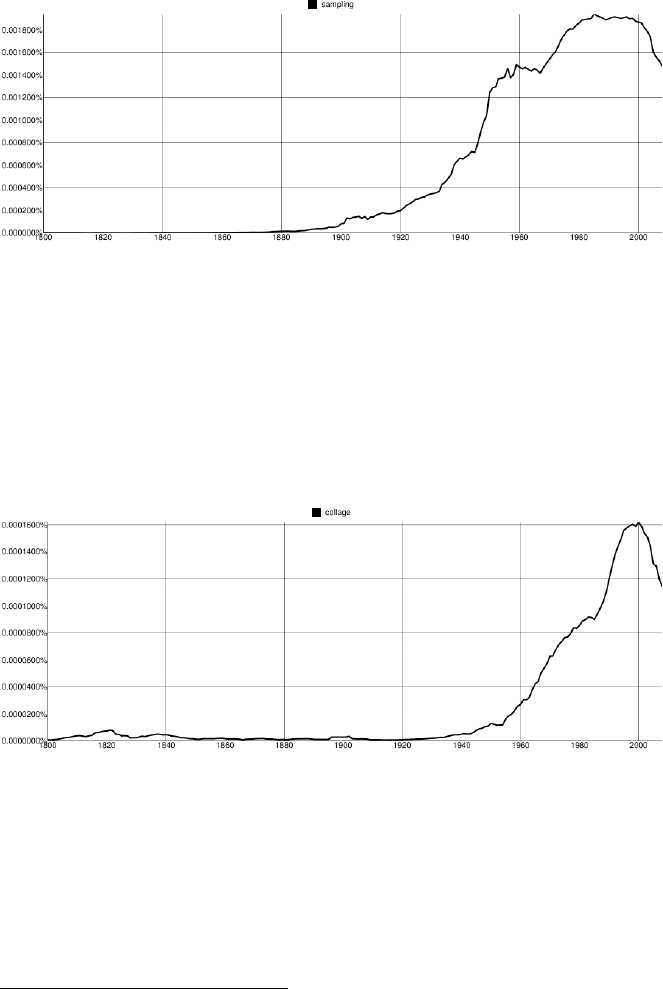

The Cultural Understanding of Collage and Photomon-

tage in Print

The following graphs demonstrate how the words “collage” and “photomontage” were

popular in print publications between 1800 and 2008.

Figure 1.9 The term collage did not increase in usage until around the 1920s. This corre-

sponds with the second stage of mechanical reproduction.

20

19

Google nGram: http://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=sampling&year_start=

1800&year_end=2008&corpus=0&smoothing=3

20

Google nGram, http://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=collage&year_start=1800

&year_end=2008&corpus=0&smoothing=3

Remix Theory

25

Figure 1.10 The term “photo montage” was not in print until about the 1930s.

21

Performing

the search for “photomontage” results in a slightly different pattern, which still corresponds

with the rise of the concept of photomontage in culture during the 1930s. I searched for two

words, as opposed to one because this would be the way the concept was initially printed.

The popularity of photomontage in print corresponds with the second stage of mechanical

reproduction.

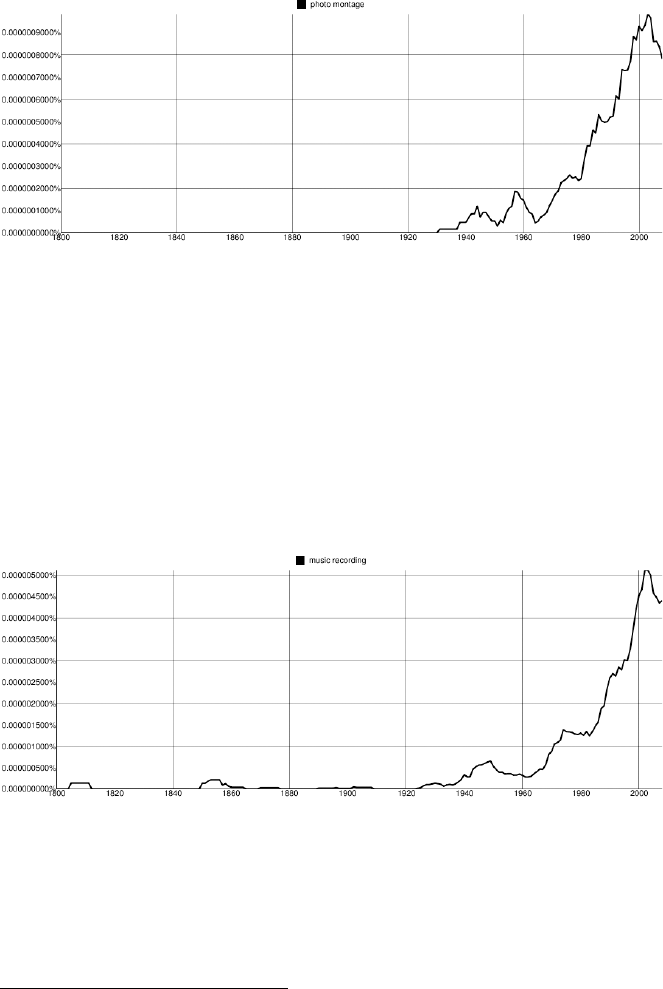

The Cultural Understanding of Music Recording and Mu-

sic Sampling in Print

The following graphs demonstrate how the words “music recording” and “music sampling”

were popular in print publications between 1800 and 2008.

Figure 1.11 The term “music recording” does not increase in popular usage until the 1930s,

and takes a major rise in the late ‘40s, and then again in the ‘80s.

22

This corresponds with

the second and third stage of mechanical reproduction, and the first stage of Remix.

21

Google nGram, http://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=photo+montage&year_start=

1800&year_end=2008&corpus=0&smoothing=3

22

Google nGram: http://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=music+recording&

year_start=1800&year_end=2008&corpus=0&smoothing=3

Eduardo Navas

26

Figure 1.12 Music sampling, although it had an apparent relevance at the beginning of the

1900s, is not consistently popular until the beginning of the 1980s.

23

This corresponds with

the rise of remixing in music within the first and second stages of Remix, eventually lead-

ing to the concept of remix culture.

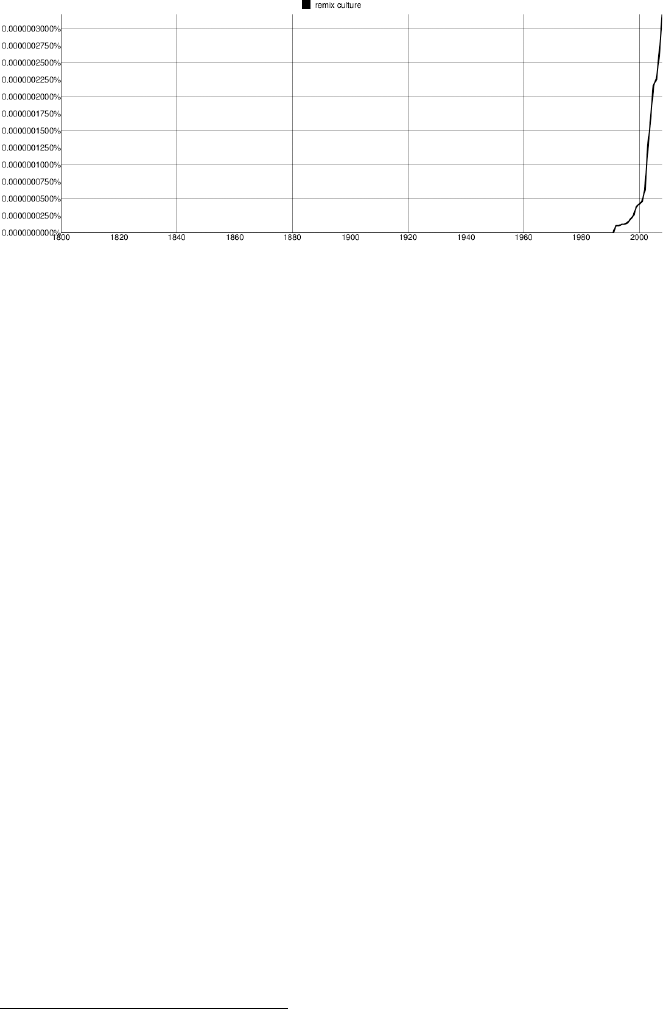

The Cultural Understanding of Remix and Remix Culture

in Print

The following graphs demonstrate how the words “remix” and “remix culture” were popu-

lar in print publications between 1800 and 2008.

Figure 1.13 This graph demonstrates that the term “remix” was in use during the 1800s;

however, it becomes evident that the term’s popularity increased exponentially during the

1980s, which is also the time when dance club and hip-hop remixes became popular.

24

This

corresponds with the first and second stages of Remix.

23

Google nGram: http://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=music+sampling&year_start=

1800&year_end=2008&corpus=0&smoothing=3

24

Google nGram: http://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=remix&year_start=

1800&year_end=2008&corpus=0&smoothing=3

Remix Theory

27

Figure 1.14 The term “remix culture” was not in print prior to the 1990s, when it began to

be used to promote changes to copyright law by Lawrence Lessig and his contemporaries.

25

This corresponds with the third and fourth stages of Remix.

The Regressive Ideology of Remix

A theoretical evaluation of the fourth stage of Remix is necessary to un-

derstand better Remix’s development. The notion of time that was ex-

plored in music sampling during the 1970s became proliferated throughout

postmodern culture during the ‘80s. In the ‘90s—and certainly in the early

2000s—the notion of sampling became the intricate and undeniable default

form of consumption available to average listeners who normally would

not be considered content producers; users who, from time to time, may

want “to play DJ” by selecting music in their ipods, or “remixers” by re-

blogging on subjects of interest. Inevitably, because of the state of spe-

cialization which makes modernism and postmodernism possible, access to

sampling and ability to remix (of appropriating material which carries

cultural value and tends to reference itself) falls into the danger of sub-

verting history; and younger generations who may not know where the

sample came from may treat remixed material as original. This is key to

sampling in media at large, and this was the great fear of critical theorist

Theodor Adorno when he discusses the regressive listener in mass cul-

ture—the individual who the industry would gladly keep at a juvenile

stage, and can tell what to consume.

26

An example of this occurrence is the hip-hop song “Rappers Delight”

by the Sugarhill Gang, which during the early ‘80s was a popular hit, rid-

ing on the coat tails of hip-hop subculture. Early electrofunk artists, like

Grandmaster Flash dismissed the song as a cooption by the culture indus-

25

Google nGram: http://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=remix+culture&year_start=

1800&year_end=2008&corpus=0&smoothing=3

26

Theodore Adorno, The Culture Industry (London, New York: Routtledge, 1991), 50 - 52

Eduardo Navas

28

try of the thriving developments in the Bronx.

27

Some people thought of it

as the first rap song, but it was not; and further, it sampled from a song ti-

tled “Good Times” by Chic. The producers did not acknowledge the sam-

ple. Here we note how historical citation is by default subverted in Remix.

People were expected to recognize the “Good Times” baseline loop while

the MCs rapped on top. Giving credit and also royalties to music artists

whose samples were used would become a major issue in copyright law in

the 80s.

28

As can be noted with “Rappers Delight,” Remix, even when

used in regressive fashion, with a short history span, still demands that

people recognize some trace of history. Thus the power of sampling is al-

ways based on a diversion, one that can be presented, as a state of re-

pressed desire that is completely mediated, showing no solution except to

point to itself.

29

Part of the interest in sampling within the culture industry,

then, is in taking a bit of music that the listener will recognize, who will in

turn most likely become excited when she recognizes the sample. At this

point, sampling manifests itself as loops that can potentially go on forever.

It begins to expose the basic aesthetic of loops as vehicles of ideology in

consumer culture. Repetition, as defined by political economist Jacques

Attali, subverts representation, making the recording the primary form of

experience in everyday life; it becomes part of reality at this moment.

30

And with this form of mechanical repetition, with loops, time gives way to

space, because in modularity, time is not marked linearly, but circularly,

for the sake of consumption and regression. One can go back to a favorite

recording to experience it over and over again, thus making it the main

point of reference in one’s understanding of the world.

This is also the power of the photograph as defined by Roland Barthes.

For him, the punctum is a static form of repetition; it captures, freezes a

moment in time that the viewer can play over and over in his/her mind,

similarly to a music recording. For Barthes the punctum is a sublime expe-

rience with which the viewer tries to come to terms by negotiating space

and time. Barthes argued that an acknowledgment of a person’s inevitable

death is pronounced:

This punctum, more or less blurred beneath the abundance and the disparity of

contemporary photographs, is vividly legible in historical photographs: there is always a

27

Ulf Poschardt, DJ Culture (London: Quartet Books, 1998), 193-194.

28

Bill Brewster and Frank Broughton, Last Night a DJ save my Life (New York: Grover Press,

2000), 244-246.

29

This is an observation made on postmodern culture by Fredic Jameson. See, Fredric Jameson,

Postmodernism or, The Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham: Duke University Press, 1991),

51-54. Also, see my analysis of his work in chapter three, 86-88.

30

Attali, 7-22, see introduction for full citation, 5.

Remix Theory

29

defeat of Time in them: that is dead and that is going to die. […] At the limit, there is no

need to represent a body in order for me to experience this vertigo of time defeated.

31

For Barthes the ability of photography to freeze a moment in time was not

only a pronouncement of death in the future, but also the capture of death

within the image itself. It is because of the sense of “cutting” that was un-

derstood when people saw an apparently accurate reproduction of reality

why the punctum was at play. It appeared as though a “sample” from real

life had been stolen. The photograph records time, turning it into a frag-

ment that spans across space: a material record of a person’s mortality.

This disturbing element of photography, which is crucial as an early form

of recording, culminated in the power of film—in which the punctum

noted by Barthes is extended overtly pronouncing space over time.

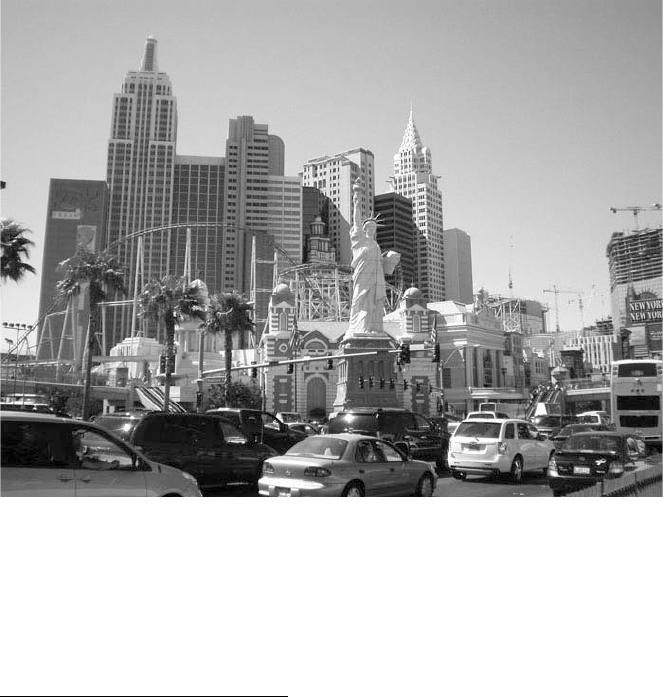

Figure 1.15 View of New York, New York Casino, Las Vegas, Summer 2008

During the first decade of the twenty-first century, stills and moving im-

ages, informed by photo and film language, are used to advertise all sorts

of commercial brands. Images are displayed on billboards found all over

New York City and Los Angeles, Las Vegas, and Tokyo to name but a few

31

Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida Trans. Richard Howard, (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981),

96.

Eduardo Navas

30

major international centers. In Las Vegas, as a concrete example, image

and sound are strategically repeated incessantly to create a seamless spec-

tacular loop. In this city with no clocks anywhere to be found, time is sus-

pended—night and day become one timeless loop, encouraging people to

stay up as much as possible and spend all of their time at the gambling ta-

bles. Kitsch art exhibitions and collections are promoted as just another

major spectacle on the strip; nightly performances by cover bands of The

Beatles, along with Elvis Presley impersonators, are naturally juxtaposed

with actual performers, including Cher, Prince, and Wayne Newton—as if

they belong to the same time period. In Las Vegas time stands still in the

name of the spectacle. With the efficiency in production and simulation

that mechanical reproduction has reached, the concept of time, and with it,

history, give way to privileging space—simulacrum in space. Thus, Las

Vegas specializes in presenting an ever-growing simulacrum of the world.

One no longer needs to go to Paris to experience the Eiffel tower, but to

Las Vegas to experience the pure myth of Parisian culture. What Las Ve-

gas offers is a culture where the copy is revered for being a fake. And that

fakeness attains authenticity based on the honest act of trying to be a par-

ody of, and admirable reference to the original. Vegas is the ultimate ex-

periment in appropriation—where critical distance is absent, where time is

dismissed and space is presented as something modular, which can be rep-

licated as simulacra proper, a never ending stage of make believe.

32

The

punctum is taken to its limit.

The ideology that makes Las Vegas powerful has a reciprocal relation-

ship with new media technology: once the computer database entered eve-

ryday reality, linear representation gave way to modular representation.

This consists of privileging the paradigm over syntagm; meaning that it is

not the story but the parts of the story that become emphasized as forms of

interest. Database logic consists of making information access the goal in

cultural production,

33

and narrative is subverted by the drive for efficient

information access that need not have a beginning, middle, or end to be of

interest to the user.

Music sampling was a transitional period toward privileging the frag-

ment over the whole; and it is no accident that sampling in music became

popular during the postmodern period. Fragments became the subject of

cultural tension. While it was the medium of photography that came to de-

fine our relationship of the world through recorded (sampled) representa-

tions, this tendency would take its first major shift towards what is known

32

My concept of the simulacrum is informed by Jean Baudrillard’s theory on simulacra. See,

Jean Baudrillard, “The Precession of Simulacra,” Simulacra and Simulation (Ann Arbor:

University of Michigan Press, 2007), 1-43.

33

Manovich, 218 – 221.

Remix Theory

31

today as modularity not in visual culture but in music culture, in the explo-

rations of composers, like Stockhausen, who with tape loops aesthetically

alluded to what the computer actually does today. Tape loops run repeat-

edly until they are turned off, or fall apart from wear and tear; similarly,

computers check themselves in loops in fractions of seconds to decide

what to do at all times.

34

Looping, or modular repetition is what defines

media culture, and Remix as a form of discourse; in this sense, Las Vegas

is just one example of how this understanding of repetition is accepted by

the average consumer in the form of spectacle: images repeat with no be-

ginning or end. Looping in culture at large functions similarly to the

punctum in photography as noticed by Barthes: the loop repeats a moment

in time, just like a photograph presents a moment in time. Repetition, the

stability and negation of the passing of time towards death, is found in

consumer culture, not as a conscious recognition of history, but as super-

fluous and indifferent fragments of apparently unrelated events.

Hence, the principles of appropriation privileged in visual culture at

large during the first decade of the twenty-first century started in early

photography and printed media, moving on to sampling in music, finding

their way back into culture once the computer became a common item in

people’s homes. And today, principles of Remix in new media blur the line

between high and low culture (the potential that photography initially of-

fered), allowing average people and the elite to produce work with the very

same tools. Choice and intention, then, become the crucial defining ele-

ments in new media; digital tools can be used to support all types of agen-

das—which fall between commerce and culture.

34

Rob Young, “Pioneers. Roll Tape: Pioneer Spirits in Musique Concrete,” Modulations, ed.

Peter Shapiro (New York: Caipirinha Productions and D.A.P., 2000), 8 – 20.