sunset advisory Commission

staff report with Commission deCisions

State Board of Dental Examiners

2016–2017

85th LegisLature

sunset advisory Commission

Representave Larry Gonzales Senator Van Taylor

Chair Vice Chair

Representave Cindy Burke Senator Juan “Chuy” Hinojosa

Representave Dan Flynn Senator Robert Nichols

Representave Richard Peña Raymond Senator Charles Schwertner

Representave Senfronia Thompson Senator Kirk Watson

William Meadows LTC (Ret.) Allen B. West

Ken Levine

Director

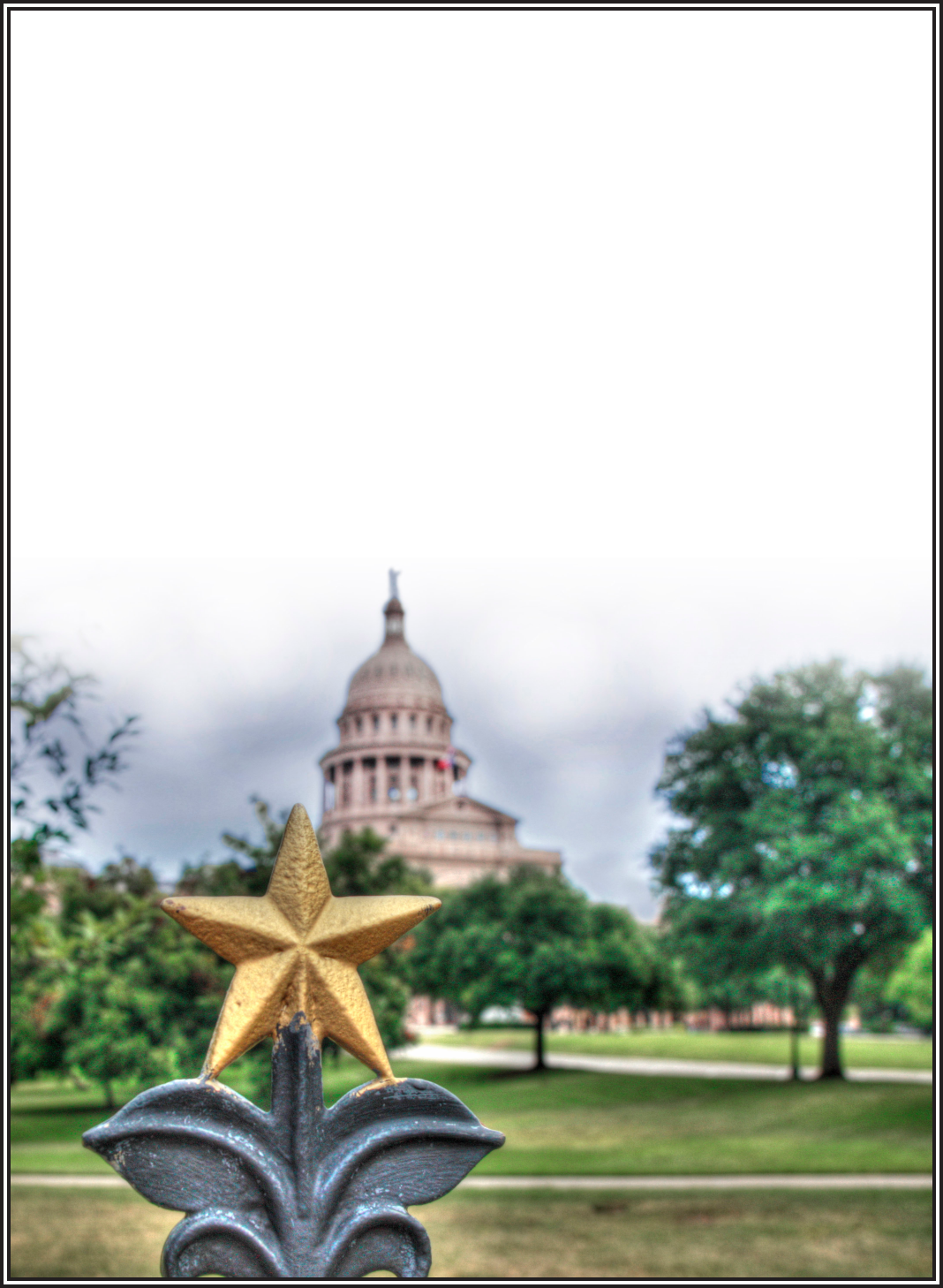

Cover Photo: The iron perimeter fence was installed in the 1890s, a few years after the completion of the Texas State

Capitol. The fence surrounds approximately 22 acres of the Capitol Grounds but only on the east, west, and south sides

due to the addition of the Capitol Extension to the north in the early 1990s. Photo Credit: Janet Wood

State Board of dental examinerS

SunSet Staff report with CommiSSion deCiSionS

2016–2017

85th legiSlature

How to Read SunSet RepoRtS

Each Sunset report is issued three times, at each of the three key phases of the Sunset process, to compile

all recommendations and action into one, up-to-date document. Only the most recent version is posted

to the website. (e version in bold is the version you are reading.)

1. SunSet Staff evaluation PhaSe

Sunset sta performs extensive research and analysis to evaluate the need for, performance of,

and improvements to the agency under review.

F V: The Sunset Staff Report identifies problem areas and makes specific

recommendations for positive change, either to the laws governing an agency or in the form of

management directives to agency leadership.

2. SunSet CommiSSion Deliberation PhaSe

e Sunset Commission conducts a public hearing to take testimony on the sta report and the

agency overall. Later, the Commission meets again to vote on which changes to recommend to

the full Legislature.

Second VerSion: e Sunset Sta Report with Commission Decisions, issued after the

decision meeting, documents the Sunset Commission’s decisions on the original sta

recommendations and any new issues raised during the hearing, forming the basis of the

Sunset bills.

3. legiSlative aCtion PhaSe

e full Legislature considers bills containing the Sunset Commission’s recommendations on

each agency and makes nal determinations.

T V: e Sunset Sta Report with Final Results, published after the end of the

legislative session, documents the ultimate outcome of the Sunset process for each agency,

including the actions taken by the legislature on each Sunset recommendation and any new

provisions added to the Sunset bill.

taBle of ContentS

page

SunSet CommiSSion deCiSionS

State Board of Dental Examiners ............................................................................. A1

Adopted Language .................................................................................................... A7

Summary of SunSet Staff reCommendationS

.................................................................................................................................. 1

agenCy at a glanCe

.................................................................................................................................. 7

iSSueS/reCommendationS

1 e Unusually Large Dental Board Inappropriately Focuses on Issues

Unrelated to Its Public Safety Mission ..................................................................... 11

2 State Regulation of Dental Assistants Is Unnecessary to Ensure Public

Protection and Is an Inecient Use of Resources ..................................................... 19

3 e Board Lacks Key Enforcement Tools to Ensure Dentists Are Prepared

to Respond to Increasing Anesthesia Concerns ....................................................... 27

4 Key Elements of the State Board of Dental Examiners’ Licensing and

Regulatory Functions Do Not Conform to Common Licensing Standards ............ 33

5 A Continuing Need Exists for the State Board of Dental Examiners ..................... 39

appendiCeS

Appendix A — Historically Underutilized Businesses Statistics .............................. 45

Appendix B — Equal Employment Opportunity Statistics ...................................... 49

Appendix C — State Board of Dental Examiners Comprehensive

Enforcement Data ........................................................................... 51

Appendix D — Sta Review Activities .................................................................... 53

SunSet CommiSSion deCiSionS

a1

State Board of Dental Examiners Staff Report with Commission Decisions

Sunset Commission Decisions

Sunset Advisory Commission January 2017

SunSet CommiSSion deCiSionS

Summary

e following material summarizes the Sunset Commission’s decisions on the sta recommendations

for the State Board of Dental Examiners, as well as modications and new issues raised during the

public hearing.

For a relatively small agency, the dental board has been bueted by more than its share of problems

due to high turnover among its leadership ranks. At 15 members, the dental board itself is oversized

compared to its shrinking duties, leading to board involvement in operational matters well beyond its

proper role and the agency’s needs. Dentist board members have pursued high prole rule packages

that appear more motivated by business interests than demonstrated concern for public safety; all the

while other emerging problems like regulating the administration of anesthesia went largely unaddressed.

In light of high-prole media cases exposing gaps in the board’s regulation of dental anesthesia, the

commission’s recommendations aim to strengthen anesthesia regulation through clear enforcement tools,

improved training and education requirements for permit holders, and broader avenues for stakeholder

input. ese recommendations are consistent with the ndings of a blue ribbon panel commissioned

by Sunset to assess the dental anesthesia problems. Other changes would address deciencies in the

agency’s regulation of dental assistants and update licensing and enforcement processes that have not

kept up with best practices. e Sunset Commission recommends continuing the agency for 12 years.

iSSue 1

The Unusually Large Dental Board Inappropriately Focuses on Issues Unrelated

to Its Public Safety Mission.

Recommendation 1.1, Modied — In lieu of the sta recommendation, sweep the board and reduce

the size of the board from 15 to 11 members, including six dentists, three hygienists, and two public

members. To allow for staggering of terms, the recommendation would provide that all current board

member terms expire on September 1, 2017, with the governor making initial appointments as specied

below. Current members would be eligible for re-appointment if so determined by the governor to

maintain needed expertise. Board members serving on August 31, 2017 would continue to serve until

a majority of new appointments are made.

•

Two dentists and one dental hygienist to initial terms expiring February 1, 2019.

•

Two dentists, one dental hygienist, and one public member to initial terms expiring February 1, 2021.

•

Two dentists, one dental hygienist, and one public member to initial terms expiring February 1, 2023.

Recommendation 1.2, Adopted — Allow the board’s statutory advisory groups to expire and direct

the board to establish clearer processes for stakeholder input in rule.

Recommendation 1.3, Modied — Clarify the use and role of board members at informal settlement

conferences and strike language in the Dental Practice Act regarding informal settlement conferences

State Board of Dental Examiners Staff Report with Commission Decisions

Sunset Commission Decisions

a2

January 2017 Sunset Advisory Commission

(Texas Occupations Code, sections 263.007, 263.0075, and 263.0076) and replace with more detailed

language on structure and conduct of informal proceedings. (See Adopted Language, page A7)

•

Dental review committee. Create a state Dental Review Committee consisting of nine governor-

appointed members, including six dentists and three dental hygienists, to serve at informal settlement

conferences on a rotating basis.

iSSue 2

State Regulation of Dental Assistants Is Unnecessary to Ensure Public Protection

and Is an Inefficient Use of Resources.

Recommendation 2.1, Modied — In lieu of the sta recommendation, combine the board’s four dental

assistant certicate programs into one registration for dental assistants. (See Adopted Language, page A9)

iSSue 3

The Board Lacks Key Enforcement Tools to Ensure Dentists Are Prepared to

Respond to Increasing Anesthesia Concerns.

Recommendation 3.1, Modied — Authorize the board to conduct inspections of dentists administering

parenteral anesthesia in oce settings. Provide four levels of anesthesia permits and require the board

to establish minimum standards, education, and training for dentists administering anesthesia. Allow

additional limitations on anesthesia administration for high-risk or pediatric patients. (See Adopted

Language, page A10)

•

Blue ribbon panel. As a management action, Sunset directed the board to quickly establish

an independent 5- to 10-member blue ribbon panel that reviewed de-identied data, including

condential investigative information, related to dental anesthesia deaths and mishaps over the last

ve years, as well as evaluate emergency protocols. e Committee made recommendations to the

Legislature and the Sunset Commission at its January 11, 2017 meeting.

Recommendation 3.2, Modied — As a statutory instead of a management recommendation, direct

the board to revise rules to ensure dentists with one or more anesthesia permits maintain related written

emergency management plans. Also provide that level 2–4 sedation/anesthesia permit holders’ emergency

plans must include current Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) rescue protocols and advanced

airway management techniques. For level 2–4 sedation/anesthesia permit holders treating pediatric

patients emergency management plans must include current Pediatric Advanced Cardiac Life Support

(PALS) rescue protocols and advanced airway management techniques.

iSSue 4

Key Elements of the State Board of Dental Examiners’ Licensing and Regulatory

Functions Do Not Conform to Common Licensing Standards.

Recommendation 4.1, Adopted — Require the board to monitor licensees for adverse licensure actions.

a3

State Board of Dental Examiners Staff Report with Commission Decisions

Sunset Commission Decisions

Sunset Advisory Commission January 2017

Recommendation 4.2, Adopted — Authorize the board to deny applications to renew a license if an

applicant is not compliant with a board order.

Recommendation 4.3, Adopted — Authorize the board to require evaluations of licensees suspected of

being impaired and require condentiality for information relating to the evaluation and participation

in treatment programs.

Recommendation 4.4, Adopted — Remove unnecessary qualications required of applicants for

licensure or registration.

Recommendation 4.5, Adopted — Direct the board to make data on the board’s enforcement activity

information publicly available on its website. (Management action – nonstatutory)

Recommendation 4.6, Adopted — Direct the board to stagger registration and certicate renewals.

(Management action – nonstatutory)

iSSue 5

A Continuing Need Exists for the State Board of Dental Examiners.

Recommendation 5.1, Adopted — Continue the State Board of Dental Examiners for 12 years.

Recommendation 5.2, Modied — Update the standard Sunset across-the-board provision regarding

conicts of interest and apply the newly updated Sunset across-the-board recommendation on board

member training.

adopted new iSSueS

Dental Anesthesia

Advisory committee. Create a standing advisory committee on dental anesthesia to advise the board

on the development and revision of rules related to dental sedation and anesthesia:

•

Require the board chair to appoint nine members to include, but not be limited to: dentists, dentist

anesthesiologists, oral and maxillofacial surgeons, pediatric dentists and physician anesthesiologists.

e board chair may not appoint an active dental board member to the advisory committee.

•

Require the board to provide the committee with a board attorney who will act as counsel to the

committee members. e board attorney shall be present during committee meetings and the

committee’s deliberations to advise the committee on legal issues.

•

Require the committee to report their recommendations and other ndings to the dental board

on an annual basis, or more frequently as necessary to provide input on rulemaking and make this

information available on the board’s website.

Data reporting. Direct the board to track and quarterly report anesthesia-related data and to make

publicly available on its website aggregate enforcement data by scal year and type of license. (Management

action – nonstatutory; see Adopted Language, page A10)

State Board of Dental Examiners Staff Report with Commission Decisions

Sunset Commission Decisions

a4

January 2017 Sunset Advisory Commission

Emergency preparedness. Require the board to develop rules establishing minimum emergency

preparedness standards necessary prior to administering sedation /anesthesia including requirements

related to

•

having an adequate, unexpired supply of necessary drugs and anesthetic agents;

•

having an onsite automated external debrillator (AED) immediately available;

•

periodic equipment inspections in a manner and on a schedule determined by the board; and

•

maintenance and retention of an equipment readiness log that shall be made available to the board

upon request and to board sta during inspections.

Portability permits. Provide for the following statutory changes to portability requirements:

•

Dene “portability” as the ability of a permit holder to provide permitted anesthesia services in a

location other than a facility or satellite facility, consistent with the denition in rule.

•

Require the board to establish in rule requirements and methods for a dental sedation and anesthesia

permit holder to obtain a portability permit.

•

Require the board to establish advanced didactic and clinical training requirements necessary for a

portability permit, with consideration for additional requirements for those using their portability

permit to treat pediatric and/or high-risk patients.

Prescription Monitoring Program

Dentist requirements. Beginning September 1, 2018, require dentists to search the Prescription

Monitoring Program and review a patient’s prescription history before prescribing opioids, benzodiazepines,

barbiturates, or carisoprodol. A dentist who does not check the program before prescribing these drugs

would be subject to disciplinary action by the dental board.

Dental board requirements. Require the dental board to query the Prescription Monitoring Program

on a periodic basis for potentially harmful prescribing patterns among its licensees. e dental board

would work with the pharmacy board to establish potentially harmful prescribing patterns that the

dental board should monitor by querying the database for dentists who meet those prescribing patterns.

Based on the information obtained from the Prescription Monitoring Program, the dental board would

be authorized to open a complaint for possible non-therapeutic prescribing.

Fiscal Implication Summary

Overall, the Sunset Commission’s recommendations would result in a positive scal impact to the General

Revenue Fund of approximately $47,900 annually from reducing the size of the board and enhancing

licensing and enforcement eorts.

e recommendation to decrease the number of board members by four would result in a small annual

savings of about $8,300 to the General Revenue Fund resulting from decreased travel costs. Requiring

nine members to attend informal settlement conferences on a rotating basis would cost approximately

$5,400 per year in travel costs, assuming each member attended informal settlement conferences two

times per year.

a5

State Board of Dental Examiners Staff Report with Commission Decisions

Sunset Commission Decisions

Sunset Advisory Commission January 2017

e recommendation to authorize the board to inspect dental oces administering anesthesia would not

have a signicant scal impact to the state, though actual implementation would have costs associated

with extra sta, travel, and equipment. ese costs could be mitigated by an adjustment to existing

anesthesia permitting fees.

e recommendation to query the National Practitioner Data Bank would require a $3 increase in

licensing fees to cover the board’s cost and would result in a small revenue gain of approximately $45,000

annually. is gain would result from applicants paying the fee who ultimately do not meet the standards

for licensure and thus do not require of queries the data bank.

State Board of Dental Examiners Staff Report with Commission Decisions

Sunset Commission Decisions

a6

January 2017 Sunset Advisory Commission

a7

State Board of Dental Examiners Staff Report with Commission Decisions

Sunset Commission Decisions

Sunset Advisory Commission January 2017

adopted language

Recommendation 1.3

Modication Language

Include the following as statutory changes.

Informal Proceedings

•

e board by rule shall adopt procedures governing informal disposition of a contested case. Rules

must require that

(1) not later than the 180th day after the date the board’s ocial investigation of the complaint

is commenced, the board shall determine a future date on which to hold an informal settlement

conference to consider disposition of the complaint or allegation, unless good cause is shown by the

board for scheduling the informal settlement conference after that date;

(2) the board give notice to the licensee of the time and place of the meeting not later than the 45th

day before the date the informal settlement conference is held;

(3) the complainant and the licensee be provided an opportunity to be heard;

(4) the board’s legal counsel or a representative of the attorney general be present to advise the

board or the board’s sta; and

(5) a member of the board’s sta be at the meeting to present to the Informal Settlement Conference

Panel the facts the sta reasonably believes it could prove by competent evidence or qualied

witnesses at a hearing.

•

An aected licensee is entitled to reply to the sta ’s presentation and present the facts the licensee

reasonably believes the licensee could prove by competent evidence or qualied witnesses at a hearing.

•

After ample time is given for the presentations, the Informal Settlement Conference Panel shall

recommend that the investigation be closed or shall make a recommendation regarding the disposition

of the case, unless applicable concerning contested cases requires a hearing.

•

If the license holder has previously been the subject of disciplinary action by the board, the board

shall schedule the informal settlement conference as soon as practicable but not later than the 180th

day after the date the board’s ocial investigation of the complaint is commenced.

•

Notice must be accompanied by a written statement of the nature of the allegations and the

information the board intends to use at the meeting. If the board does not provide the statement

or information at that time, the license holder may use that failure as grounds for rescheduling the

informal meeting. If the complaint includes an allegation that the license holder has violated the

standard of care, the notice must include a copy of the report by the expert dentist reviewer. e

licensee must provide to the board the licensee’s rebuttal at least 15 business days before the date of

the meeting in order for the information to be considered at the meeting.

•

e board by rule shall dene circumstances constituting good cause for not meeting the 180-day

deadline, including an expert dentist reviewer’s delinquency in reviewing and submitting a report

to the board.

State Board of Dental Examiners Staff Report with Commission Decisions

Sunset Commission Decisions

a8

January 2017 Sunset Advisory Commission

•

e board by rule shall dene circumstances constituting good cause to grant a licensee’s request for

a continuance of the informal settlement conference.

•

Information presented by the board or board sta in an informal settlement conference is condential.

•

On request by a licensee under review, the board shall make a recording of the informal settlement

conference proceeding. e recording is a part of the investigative le and may not be released to a

third party unless authorized. e board may charge the licensee a fee to cover the cost of recording

the proceeding. e board shall provide a copy of the recording to the licensee on the licensee’s request.

Board Representation in Informal Proceedings

•

Dene the informal settlement conference panel to include members of the Board and the Dental

Review Committee.

•

In an informal settlement conference, at least two Informal Settlement Conference Panel members

shall be appointed to determine whether an informal disposition is appropriate. At least one of the

panelists must be a dentist.

•

Pursuant to Board rules, one panelist must be physically present at the ISC, but one panelist may

appear by video conference.

•

An informal settlement conference may be conducted by one panelist if the aected licensee waives

the requirement that at least two panelists conduct the informal proceeding. If the licensee waives

that requirement, the panelist may be either a dentist, dental hygienist, or a member who represents

the public.

•

Only one panel member is required in an informal settlement conference proceeding conducted by

the board to show compliance with an order or remedial plan of the board.

Roles and Responsibilities of Participants in Informal Proceedings

•

An informal settlement conference panel member that serves as a panelist at an informal settlement

conference shall make recommendations for the disposition of a complaint or allegation. e member

may request the assistance of a board employee at any time.

•

Board employees shall present a summary of the allegations against the aected licensee and of the

facts pertaining to the allegation that the employees reasonably believe may be proven by competent

evidence at a formal hearing.

•

A board attorney shall act as counsel to the panel members and shall be present during the informal

settlement conference and the panel’s deliberations to advise the panel on legal issues that arise

during the proceeding. e attorney may ask questions of participants in the informal settlement

conference to clarify any statement made by the participant. e attorney shall provide to the panel a

historical perspective on comparable cases that have appeared before the board, keep the proceedings

focused on the case being discussed, and ensure that the board’s employees and the aected licensee

have an opportunity to present information related to the case. During the panel’s deliberations,

the attorney may be present only to advise the panel on legal issues and to provide information on

comparable cases that have appeared before the board.

•

e panel and board employees shall provide an opportunity for the aected licensee and the

licensee’s authorized representative to reply to the board employees’ presentation and to present

a9

State Board of Dental Examiners Staff Report with Commission Decisions

Sunset Commission Decisions

Sunset Advisory Commission January 2017

oral and written statements and facts that the licensee and representative reasonably believe could

be proven by competent evidence at a formal hearing.

•

An employee of the board who participated in the presentation of the allegation or information

gathered in the investigation of the complaint, the aected licensee, the licensee’s authorized

representative, the complainant, the witnesses, and members of the public may not be present during

the deliberations of the panel. Only the members of the panel and the board attorney serving as

counsel to the panel may be present during the deliberations.

•

e panel shall recommend the dismissal of the complaint or allegations or, if the panel determines

that the aected licensee has violated a statute or board rule, and that violation supports action by

the board, the panel may recommend board action and terms for an informal settlement of the case.

•

e panel’s recommendations must be made in writing and presented to the aected licensee and the

licensee’s authorized representative. e licensee may accept the proposed settlement within the time

established by the panel at the informal meeting. If the licensee rejects the proposed settlement or

does not act within the required time, the board may proceed with the ling of a formal complaint

with the State Oce of Administrative Hearings.

Recommendation 2.1

Modication Language

In lieu of the sta recommendation, remove the separate certication provisions for dental assistants

from law and require one registration for dental assistants who provide the following dental support

services to a licensed dentist: dental x-rays, pit and ssure sealants, coronal polishing, and nitrous oxide

monitoring. A dental assistant would not be authorized to perform any of the four services above without

rst obtaining registration from the board.

Services provided by a registered dental assistant would be performed under the direct supervision of

a licensed dentist, but not to be construed to authorize a dental assistant to practice dentistry or dental

hygiene. Dentists remain responsible for acts delegated to the registered dental assistant. ese changes

would not aect the board’s authority to determine which acts a licensed dentist may delegate to non-

registered dental assistants. is recommendation would establish registration requirements for dental

assistants, as follows:

•

A person may not practice as a dental assistant to perform the four dental support services listed

above after September 1, 2018 unless the person has registered with the board and received a

certicate of registration.

•

e board, by rule, shall establish minimum education requirements for registration as a dental

assistant. Requirements must include a high school diploma or equivalent; and a course of instruction

and examination to demonstrate competency in the following dental support services: dental x-rays,

pit and ssure sealants, coronal polishing, and nitrous oxide monitoring; and training in basic life

support, infection control, jurisprudence, and any other requirements the board determines necessary.

•

e board could consider approving courses of instruction and examinations provided by outside

entities such as the Dental Assisting National Board to qualify for this registration.

•

Dental assistant registrations shall be renewed biennially on a staggered basis, as established by the

board.

State Board of Dental Examiners Staff Report with Commission Decisions

Sunset Commission Decisions

a10

January 2017 Sunset Advisory Commission

•

e board shall establish continuing education requirements as a condition of renewing registration

as a registered dental assistant.

•

e board shall establish standards for taking disciplinary action against a registered dental assistant.

•

e board shall establish fees for initial registration and renewals to cover the cost of regulation.

Recommendation 3.1

Modication Language

Include the following as statutory changes.

•

Denitions. Dene “pediatric” as patients ages 0–12. Dene “high-risk patient” as patients with

an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) rating of level 3 or 4 or older than 75.

•

Permitting. Require an annual permit for each of the four dierent levels of anesthesia, dened

based on the depth of the intended procedure to alter the patient’s mental status and the method

of drug delivery.

– Level 1: Minimal Sedation

– Level 2: Moderate Sedation (Enteral)

– Level 3: Moderate Sedation (Parenteral)

– Level 4: Deep Sedation or General Anesthesia

Require the board to develop rules establishing minimum standards for training, education, and other

standards for dierent permit levels. For level 2–4 permit holders, education/training requirements

must include training on pre-procedural patient evaluation including the evaluation of the patient’s

airway and physical status as currently dened by the ASA, ongoing monitoring of sedation and

anesthesia, and management of emergencies.

Require level 2–4 permit holders to provide proof of additional training for the treatment of pediatric

and/or high risk patients including advanced didactic and clinical training requirements. Dentists

would not be allowed to treat pediatric and/or high-risk patients without proof of specialized education.

Allow the board to establish additional limitations on the administration of anesthesia on pediatric

and/or high risk patients.

•

Inspections. Allow the board to conduct pre-permit, random, and compliance inspections. Require

the board to determine an appropriate risk-based inspection schedule for on-site inspections of dental

oces of dentists with a level 2, 3 or 4 permit. Allow the board to stagger inspections as long as all

relevant oces are inspected at least once every 5 years. Allow the board to determine education

and training requirements for inspectors. Require the board to maintain records of inspections.

Data Reporting New Issue

Adopted Language

Direct the board to track and report the following data. All information related to an investigation is

condential, except that the agency shall provide the following information on a quarterly basis to the

a11

State Board of Dental Examiners Staff Report with Commission Decisions

Sunset Commission Decisions

Sunset Advisory Commission January 2017

board and the standing advisory committee on dental anesthesia, and to legislative oces upon request:

de-identied, case specic data reecting information about jurisdictional, led complaints resolved

during the reporting period related to anesthesia/sedation including the following.

1. Source of initial complaint: public, other agency, self-report of death, self-report of hospitalization,

or initiated by the board

2. Information about licensee:

a. Whether respondent is Medicaid provider

b. Respondent’s highest sedation/anesthesia permit level

c. Whether respondent holds portability privileges

d. Respondent’s self-reported practice area

3. Information about patient:

a. Patient ASA rating (identied in respondent’s dental records and/or determined by dental review

panel)

b. Patient age: 12 and under, between 13 and 18, between 19 and 75, and over 75

c. Location of treatment investigated by the agency: dental oce, hospital, ASC, oce of other

practitioner

d. Level of sedation/anesthesia administered: local, nitrous, level I, level II, level III, level IV

(determined by dental review panel)

e. Sedation/anesthesia administrator: respondent, other dentist, doctor of medicine, certied

registered nurse anesthetist (determined by dental review panel)

f. Whether treatment investigated by the agency was paid by Medicaid

4. Information about investigation:

a. Allegation categories identied in preliminary investigation

b. Disposition of ocial investigation — dismissed by enforcement, dismissed by legal — no

violation, dismissed by board vote, closed by administrative citation/remedial plan/disciplinary

action

c. If disposition is public action (administrative citation, remedial plan, or disciplinary action), the

violations identied in the public action resolving the ocial investigation

e board must make publicly available on their website aggregate data by scal year and type of license

about the following areas:

1. Number of licensees at the end of the scal year

2. Total number of complaints against licensees originating in that scal year

3. For all resolved complaints in that scal year, break down the resolution by each type of action taken

(nonjurisdictional, dismissed, warning, probation, suspension, revocation, etc.)

State Board of Dental Examiners Staff Report with Commission Decisions

Sunset Commission Decisions

a12

January 2017 Sunset Advisory Commission

4. For all resolved complaints in that scal year, break down the resolution by the nature of the complaint

allegation (standard of care, impairment, dishonorable conduct, continuing education violation, etc.)

5. Number of cases open longer than one year

6. Average administrative penalty assessed

7. Number of cases referred to informal settlement conferences

8. Number of cases resolved in informal settlement conferences

9. Number of cases referred to the State Oce of Administrative Hearings (default + non-default)

10. Number of contested cases heard at the State Oce of Administrative Hearings

11. Number of cases that went on to district court

12. Average number of days to resolve a complaint from complaint received to investigation completed

13. Average number of days to resolve a complaint from complaint received to nal order issued

14. Average number of days to issue a license

15. Number of cases involving mortality and morbidity

16. Total number of anesthesia complaints against licensees originating in that scal year by permit level

17. For all resolved anesthesia complaints in that scal year, break down the resolution by each type of

action taken (dismissed, warning, probation, suspension, revocation, etc.) by permit level

18. For all resolved anesthesia complaints in that scal year, break down the resolution by type of

complication that violated the standard of care by permit level.

Summary of SunSet

Staff reCommendationS

1

State Board of Dental Examiners Staff Report with Commission Decisions

Summary of Sunset Staff Recommendations

Sunset Advisory Commission January 2017

Turnover among the agency’s

leadership ranks has had

a significant effect on the

agency and governing board.

Summary

For a relatively small agency, the State Board of Dental Examiners has had

more than its share of problems over the years. e agency infamously was

abolished through its 1993 Sunset review amid a legislative skirmish not of

its own making. After its re-creation in 1995, the agency was placed under

another Sunset review out of its regular order in 2003 because of concerns

about serious enforcement deciencies. In its last ve years, the agency has

been bueted by high turnover among its leadership ranks, going through four

executive directors and general counsels in that time.

While the older events do not necessarily explain the current situation at the

agency, they do provide an important historical context. Of greater signicance is

the more recent history of employee turnover and the eect it

has had on the agency and the governing board. e revolving

door of executive directors and general counsels means that

senior sta must constantly play catch-up to gain a complete

understanding of the basic elements of the job. e agency

loses institutional knowledge for how and why policies and

procedures were developed, lessons learned, and what works

and what does not. Most important, however, the agency

loses the vision to see emerging problems and the leadership to help address

strategic agency needs, qualities that take time to develop. With experience in

the job and time to see things through, senior sta can work more eectively

with the board to ensure that the agency has the resources — both sta and

systems — and the tools and statutory authority to do its job well. Finally,

sound agency leadership gives condence to the Legislature that the resources

and tools will be used appropriately to protect the public.

In such an environment of high turnover at the top of the organization, the

board itself would understandably emerge to ll the void and take on a larger

role in running the agency. Further, because board members typically have

longer tenure than the agency’s senior sta, they would understandably play a

larger role in calling the shots for the agency. However, at such a disadvantage

to the board, sta is far less likely to take initiative and far more likely to defer

to the board on matters even when the board may need to hear sta ’s more

objective voice.

e issue of board involvement in agency operations is not new to the dental

board. Sunset sta raised the issue in the last review of 2002, noting that the

board no longer developed and administered its own dental examination and

thus had less need for its then-18 members to do its job. Sunset sta ’s initial

recommendation to reduce the board size to 11 members was changed to the

current 15 members through the legislative process.

Sate Board of Dental Examiners Staff Report with Commission Decisions

Summary of Sunset Staff Recommendations

2

January 2017 Sunset Advisory Commission

In the current review, this situation of an oversized board has only continued. e board has even less to

do because of legislation from 2013 eliminating its role in reviewing standard of care complaints, though

dentist board members still nd ways to get involved in such cases. Dentist board members have also

pursued high prole rule packages that appear more motivated by business interests than demonstrated

concern for public safety; all the while other emerging problems like regulating the administration of

anesthesia went largely unaddressed.

is Sunset review occurs at an opportune time for the board. Positive signs are emerging from the

current eorts of the agency’s senior sta, implementing the Legislature’s 2013 operational changes and

other initiatives such as new approaches for engaging stakeholders. While these changes have occurred

with the blessing of the board, the same dynamic that has governed the agency in recent years is still

in place. At the time of this review, the executive director has only been in that position seven months;

the general counsel, less than two years; and the dental director, less than two and a half years. Key

departures could still threaten the progress made.

Structural changes to reduce the size of the board are needed to focus it on its public protection mission

and help ensure the ongoing eectiveness of the agency. Other changes would better focus stakeholder

processes for dental hygienists and dental laboratories; address deciencies in the agency’s regulation

of dentists’ administration of anesthesia; deregulate dental assistants by eliminating the unworkable

patchwork of certicate programs that provides little public protection; and update licensing and

enforcement processes that have not kept up with best practices. Sunset sta recommends continuing

the agency for 12 years.

e following material summarizes all of the Sunset sta ndings and recommendations on the State

Board of Dental Examiners.

Issues and Recommendations

Issue 1

The Unusually Large Dental Board Inappropriately Focuses on Issues Unrelated

to Its Public Safety Mission.

A shift in responsibility for technical complaint reviews to a panel of contracted experts in 2013

signicantly decreased the workload for dentist board members. With less to do, the board, at the behest

of dentist members, pursued signicant rule changes more related to business practices than demonstrated

public safety problems and despite widespread concern by stakeholders and other interests and a lack

of broad consensus. Dentist members also continue their involvement in case resolution, ultimately

undermining those eorts. Better aligning the number of dentist board members with the amount of

technical expertise needed by the agency will help focus the board squarely on issues of public protection

and make better use of sta resources.

In addition, board processes for stakeholder input hold promise for improved involvement, eliminating

the need for two statutorily created advisory committees, the Dental Hygiene Advisory Committee and

the Dental Laboratory Certication Council. Removing advisory committees from statute will allow the

board more exibility to convene more diverse groups of stakeholders for input on an as needed basis.

3

State Board of Dental Examiners Staff Report with Commission Decisions

Summary of Sunset Staff Recommendations

Sunset Advisory Commission January 2017

Key Recommendations

•

Reduce the size of the board from 15 to nine members and adjust its composition to consist of four

dentists, two dental hygienists, and three public members.

•

Allow the board’s statutory advisory groups to expire and direct the board to establish clearer processes

for stakeholder input in rule.

Issue 2

State Regulation of Dental Assistants Is Unnecessary to Ensure Public Protection

and Is an Inefficient Use of Resources.

e board’s regulation of dental assistants has expanded over the past 25 years to consist of four separate

certicate programs for commonly delegated tasks, though assistants can legally perform some work

without holding any certicate. In scal year 2015 the board issued 50,469 dental assistant certicates,

more than all other board issued credentials combined.

State regulation of dental assistants is not needed to protect public safety. Dental assistants can only

work under the delegated authority of the dentist, who remains responsible for patient care and safety.

Because they can only perform reversible tasks, they have very low volume of meaningful complaint and

enforcement activity, little, if any, of which relates to standard of care. In addition, gaps in regulatory

requirements undermine the very promise of public safety the regulations were supposed to provide. e

regulatory program wastes licensing and legal resources and diverts board and sta focus from higher-

risk agency responsibilities. Ultimately, addressing deciencies to x these regulations is not an option

without dramatically expanding the scope of their practice, because the risk to the public relating to the

current practice is so low. National credentialing and private market forces can provide any training or

oversight of dental assistants desired by employers or the public. Removing regulatory responsibility

for dental assistants from the board will allow the agency to focus on licensees that pose a higher risk

to patients and the public.

Key Recommendation

•

Discontinue the board’s dental assistant certicate programs.

Issue 3

The Board Lacks Key Enforcement Tools to Ensure Dentists Are Prepared to

Respond to Increasing Anesthesia Concerns.

Dentists administer anesthesia for a variety of dental procedures. In recent years, the board has seen an

increase in related complaints involving serious patient harm and sometimes death. e board lacks the

authority and resources to routinely inspect the oces of dentists providing some anesthesia services

and does not require written emergency action plans for any dentist administering anesthesia to help

ensure thoughtful planning and readiness for the unexpected. Dentists in other states and Texas doctors

administering anesthesia in oces are subject to related routine inspections, and oce-based Texas

physicians providing anesthesia must maintain written emergency action plans. Allowing the board to

conduct inspections of dentists administering anesthesia in oce settings and requiring related written

emergency management plans of dentists providing anesthesia will incentivize dentists to be prepared

for anesthesia-related complications and train support sta accordingly.

Sate Board of Dental Examiners Staff Report with Commission Decisions

Summary of Sunset Staff Recommendations

4

January 2017 Sunset Advisory Commission

Key Recommendations

•

Authorize the board to conduct inspections for dentists administering parenteral anesthesia in oce

settings.

•

Direct the board to revise rules to ensure dentists with one or more anesthesia permit and maintain

related written emergency management plans.

Issue 4

Key Elements of the State Board of Dental Examiners’ Licensing and Regulatory

Functions Do Not Conform to Common Licensing Standards.

In reviewing the board’s regulatory authority, Sunset sta found that certain licensing and enforcement

processes do not match model standards or common practices observed through Sunset sta ’s experience

reviewing regulatory agencies. Specically, the board does not do enough to ensure licensees are free

from disciplinary action in other states or have complied with past board orders before renewing their

licenses. e board is also unable to require evaluations for licenses suspected of impairment due to

substance abuse or mental illness, and cannot protect the condentiality of licensees participating in

assistance programs.

Key Recommendations

•

Require the board to monitor licensees for adverse licensure actions in other states.

•

Authorize the board to deny applications to renew a license if an applicant is noncompliant with

a board order.

•

Authorize the board to require evaluations of licensees suspected of being impaired and require

condentiality for information relating to the evaluation and participation in treatment programs.

•

Direct the board to make data on the board’s enforcement activity information publically available

on its website.

Issue 5

A Continuing Need Exists for the State Board of Dental Examiners.

Regulating the practice of dentistry and supporting functions continues to support the state’s interest in

protecting the public. Alternative organizational structures, including the transfer of regulatory programs

to other agencies, oer no substantiated benet at this time. Continuing the board in its current form

will provide an independent agency responsible for ensuring quality, safe dental care.

Key Recommendation

•

Continue the State Board of Dental Examiners for 12 years.

5

State Board of Dental Examiners Staff Report with Commission Decisions

Summary of Sunset Staff Recommendations

Sunset Advisory Commission January 2017

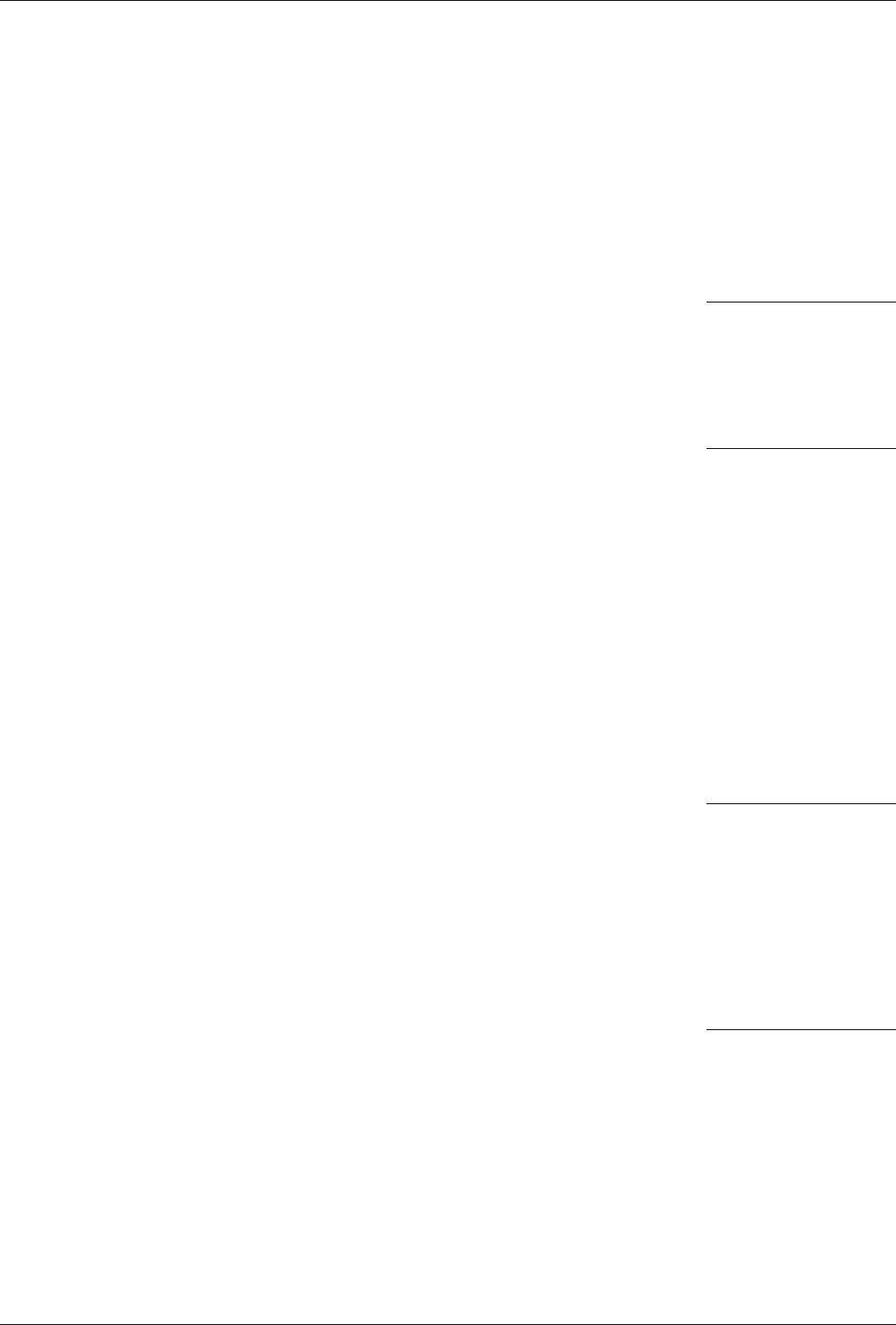

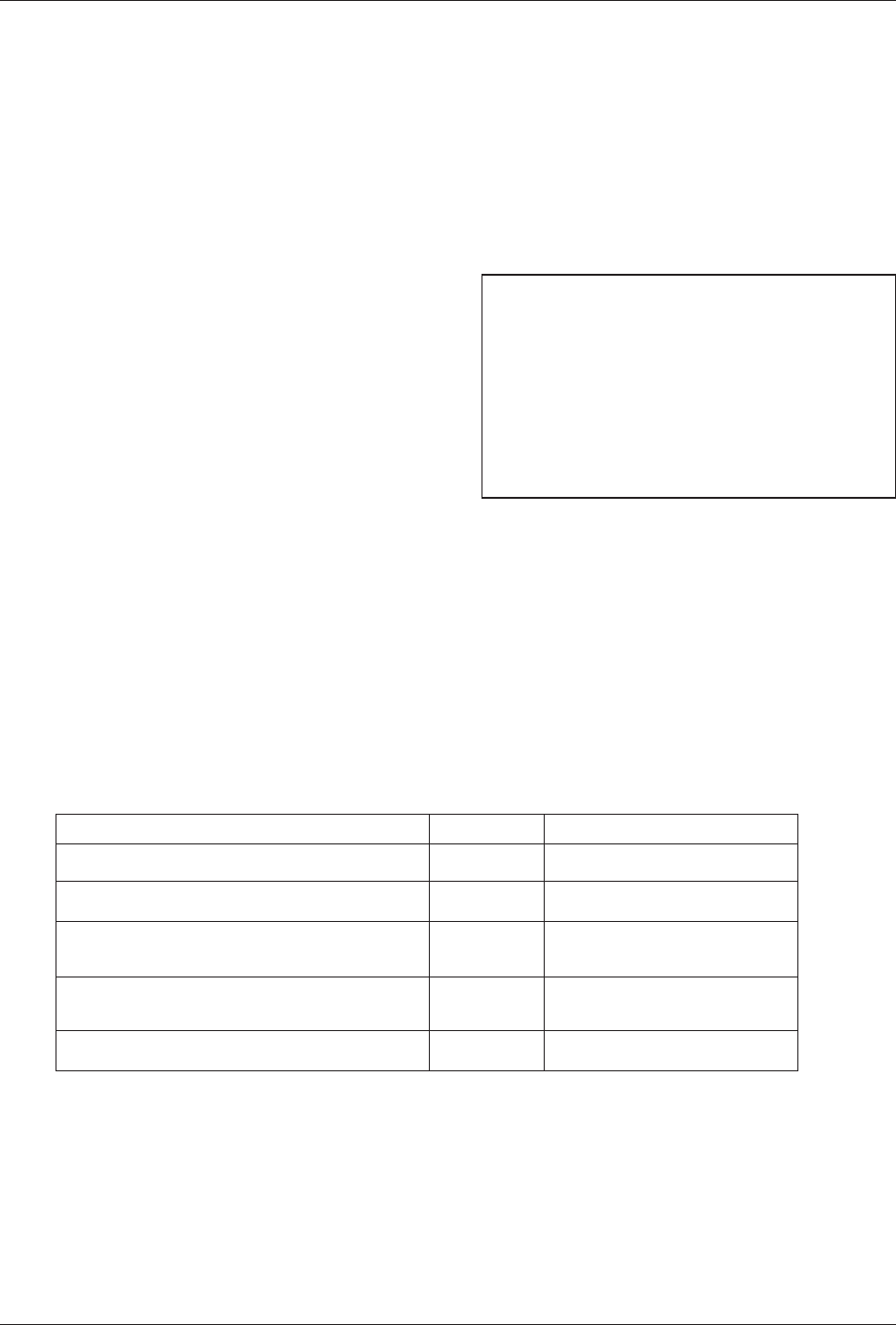

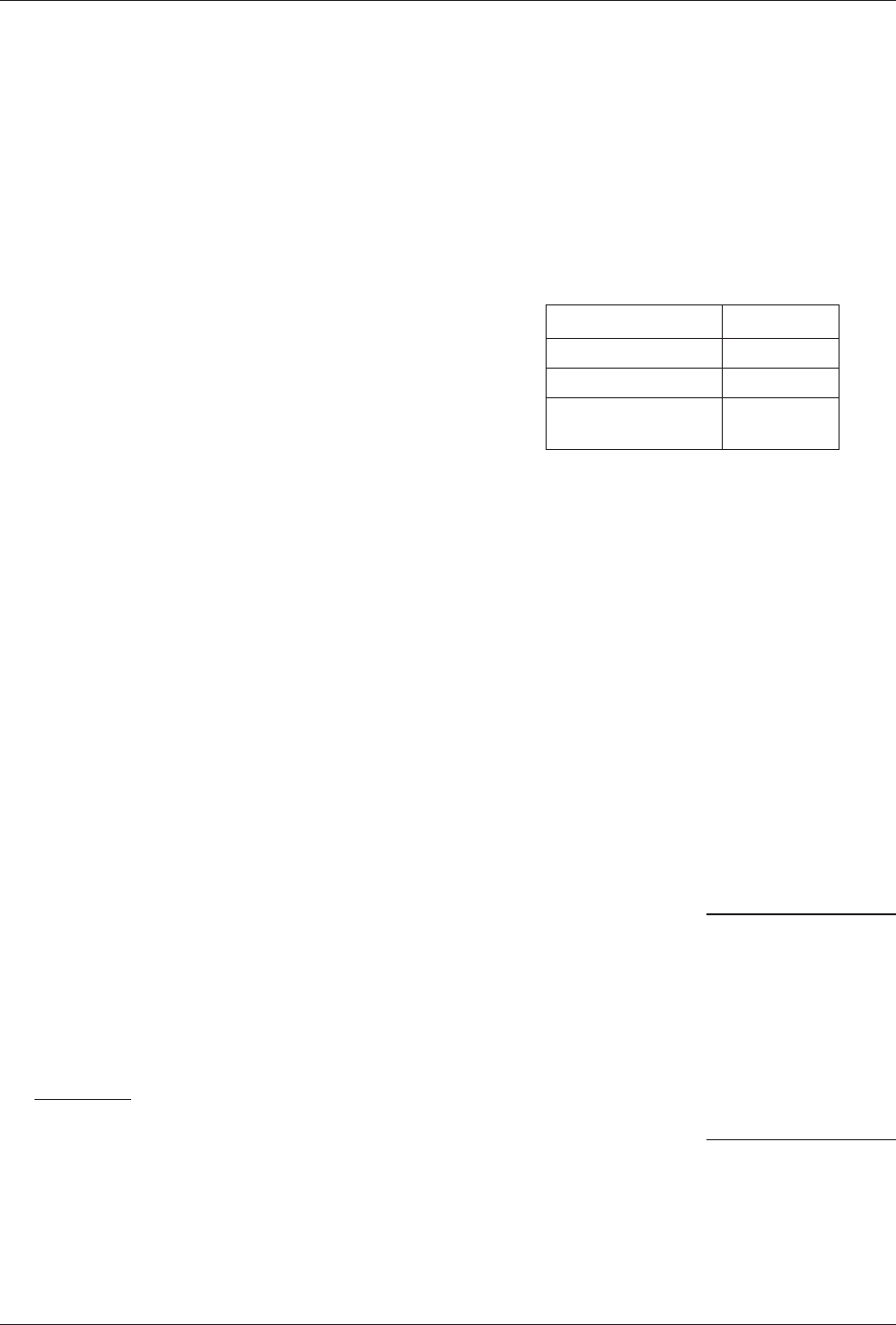

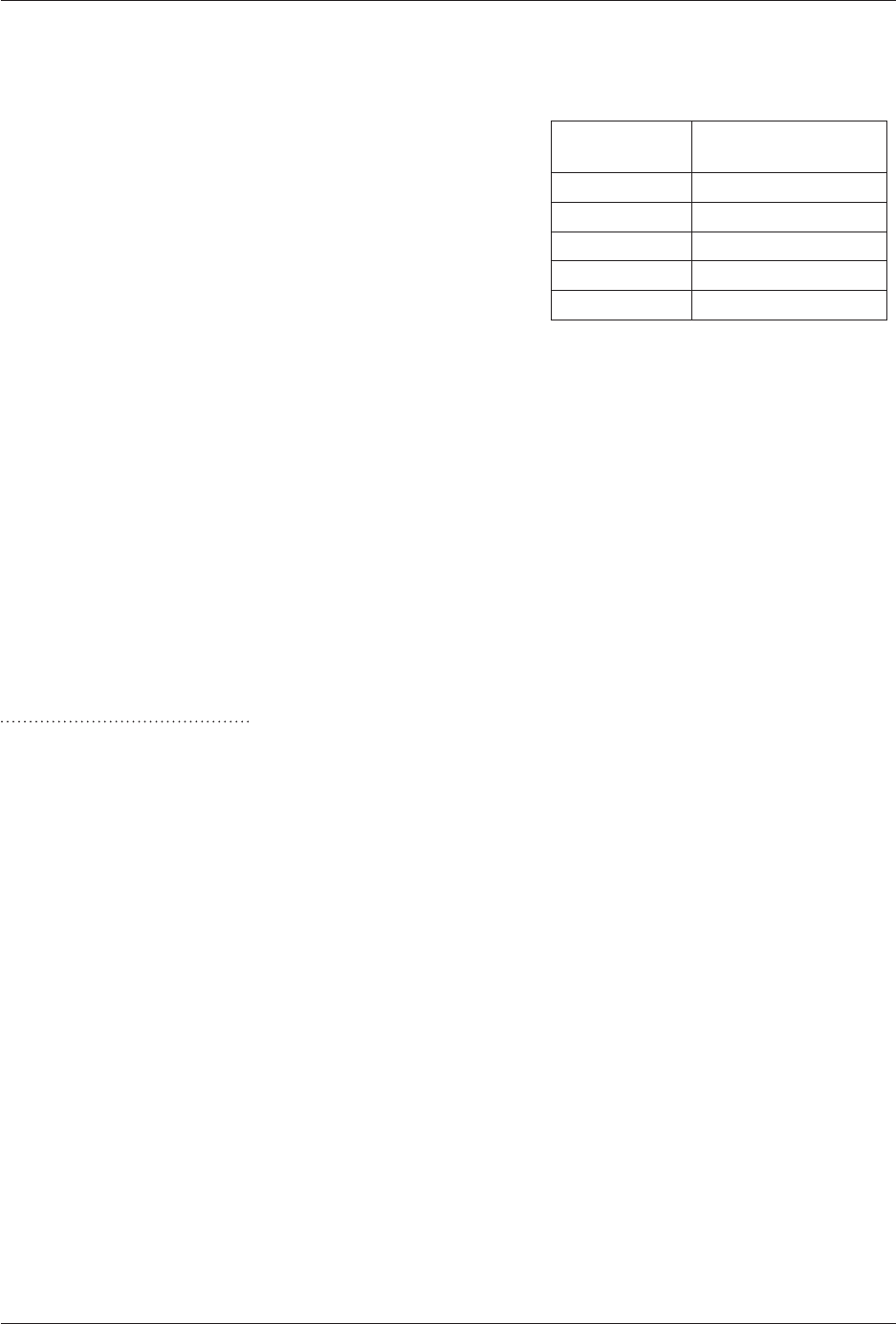

Fiscal Implication Summary

Overall, recommendations in this report would result in a negative scal impact to the General

Revenue Fund of approximately $1,402,000 over the next ve years. e impact comes from ending

the occupational licensing programs for dental assistants, reducing the size of the board, and enhancing

licensing and enforcement eorts.

Issue 1 — Decreasing the number of board members by six would result in a small annual savings of

about $13,000 to the General Revenue Fund resulting from decreased travel costs.

Issue 2 — e recommendation to deregulate dental assistants would have a negative impact to the

General Revenue Fund of about $1.46 million per year resulting from the loss of fee revenue collected

from dental assistants in excess of the cost of regulation.

Issue 3 — Providing the authority for the board to inspect dental oces administering anesthesia

would not have a signicant scal impact to the state, though actual implementation would have costs

associated with extra sta, travel, and equipment. ese costs could be mitigated by an adjustment to

existing anesthesia permitting fees.

Issue 4 — ese recommendations would result in a small revenue gain of approximately $45,000

annually, associated with the $3 increase in licensing fees to cover the board’s cost to query the National

Practitioner Data Bank. is gain would result from applicants paying the fee who ultimately do not

meet the standards for licensure and thus do not require of queries the data bank.

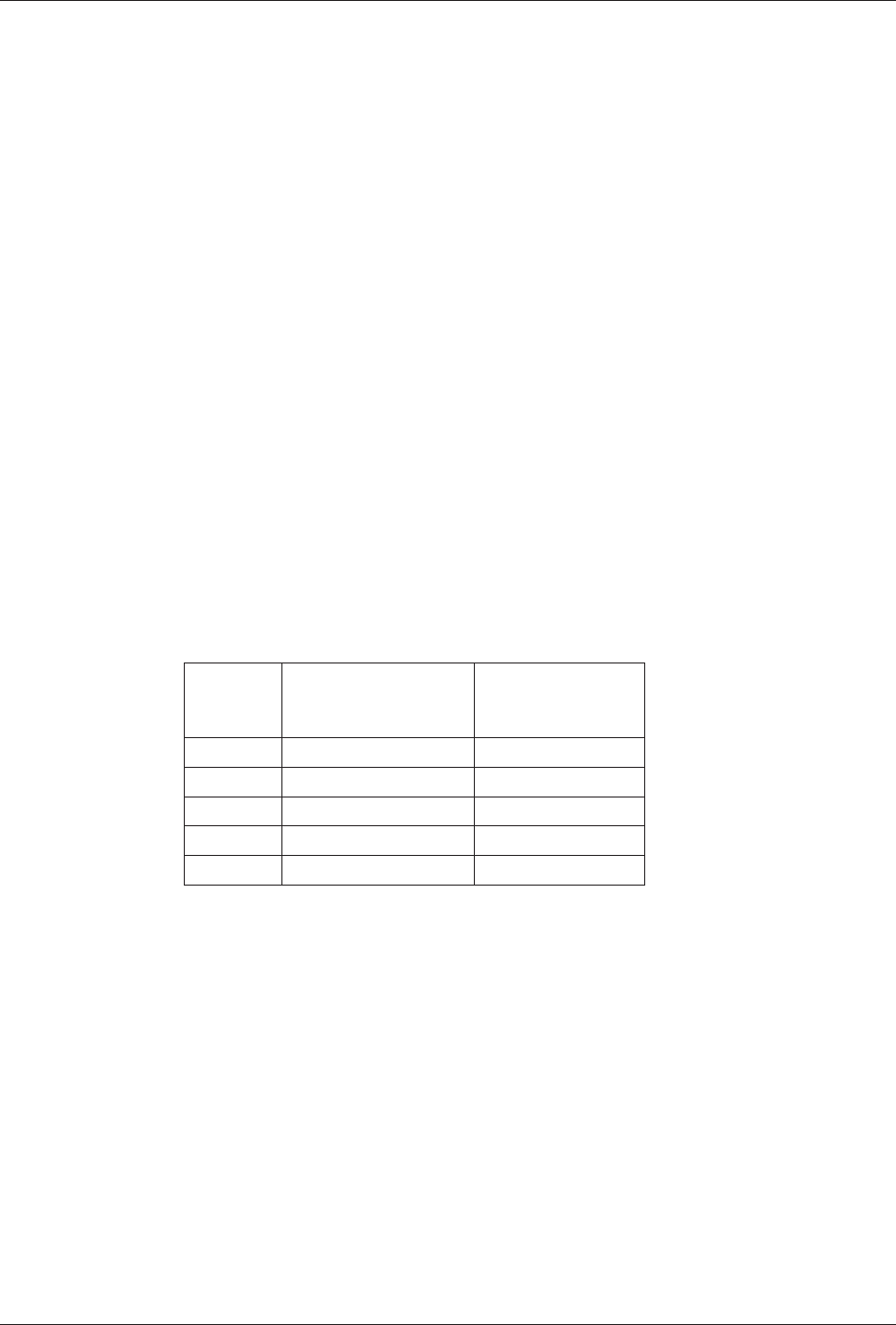

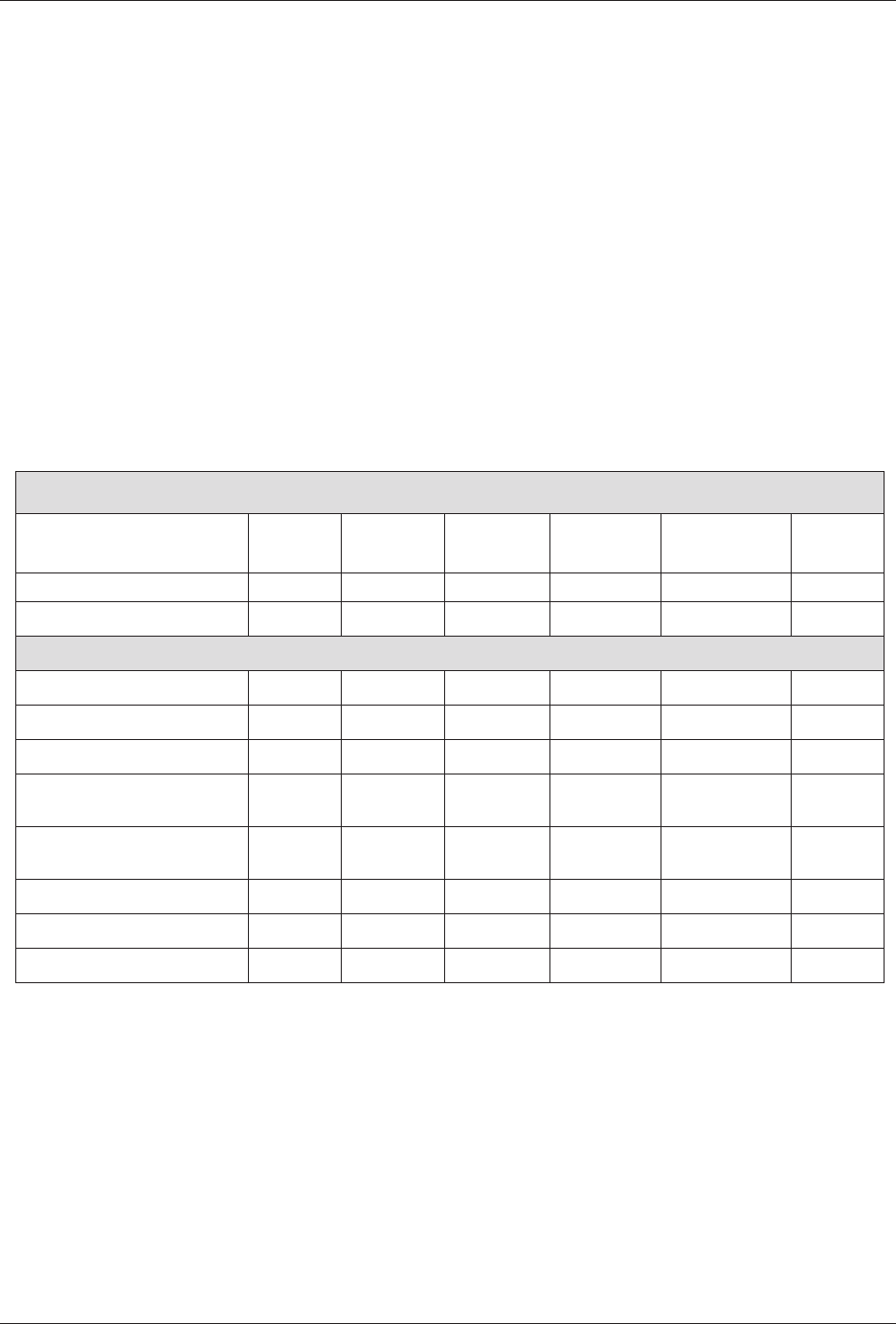

State Board of Dental Examiners

Fiscal Loss to the General

Change in the

Number of FTEs

Year Revenue Fund From FY 2017

2018 $1,402,000 -3

2019 $1,402,000 -3

2020 $1,402,000 -3

2021 $1,402,000 -3

2022 $1,402,000 -3

Sate Board of Dental Examiners Staff Report with Commission Decisions

Summary of Sunset Staff Recommendations

6

January 2017 Sunset Advisory Commission

agenCy at a glanCe

april 2016

7

State Board of Dental Examiners Staff Report with Commission Decisions

Agency at a Glance

Sunset Advisory Commission January 2017

agenCy at a glanCe

e State Board of Dental Examiners (the board) seeks to safeguard public health and safety by regulating

dental care in Texas, a responsibility the board has had since its creation in 1897. To meet its mission

of ensuring high quality and safe dental care, the board

•

licenses dentists and dental hygienists and registers dental assistants, laboratories, and mobile dental

facilities;

•

enforces the Dental Practice Act and board rules by investigating complaints against licensees and

registrants and taking disciplinary action against violators;

•

monitors compliance of disciplined licensees and registrants; and

•

provides a peer assistance program for licensees and registrants who are impaired.

Key Facts

•

State Board of Dental Examiners. e board consists of 15 members: eight dentists, two dental

hygienists, and ve public members. All members are appointed by the governor, with the advice

and consent of the Senate, for no more than two six-year terms. e presiding ocer is chosen by

the governor and must be a dentist; the board annually elects a member to act as secretary. Two

statutorily created advisory committees assist the board. e Dental Hygiene Advisory Committee

is composed of three dental hygienists and two public members appointed by the governor, as well

as one dentist appointed by the board, but not a member of the board. e Dental Laboratory

Certication Council consists of three certied dental technicians appointed by the board.

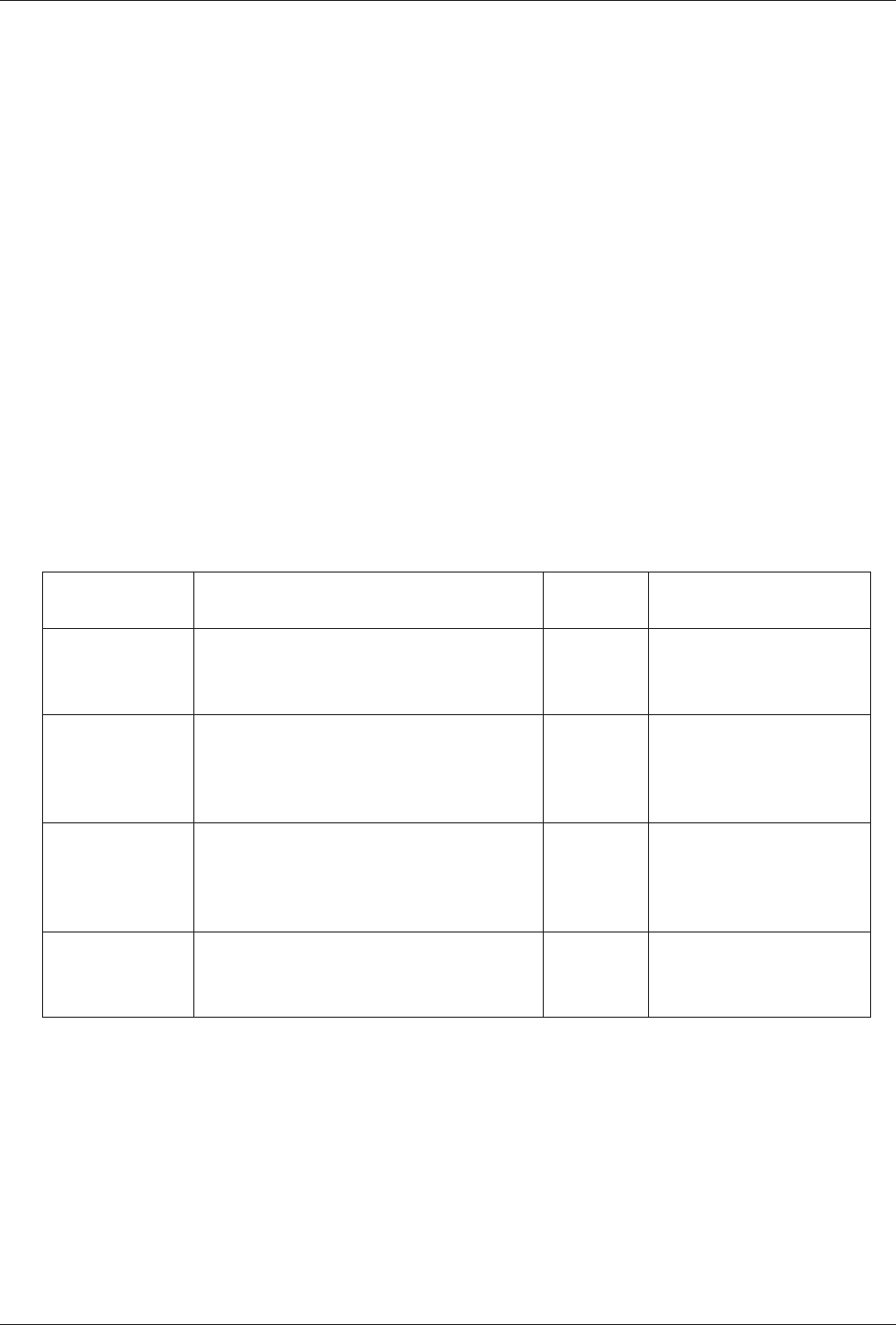

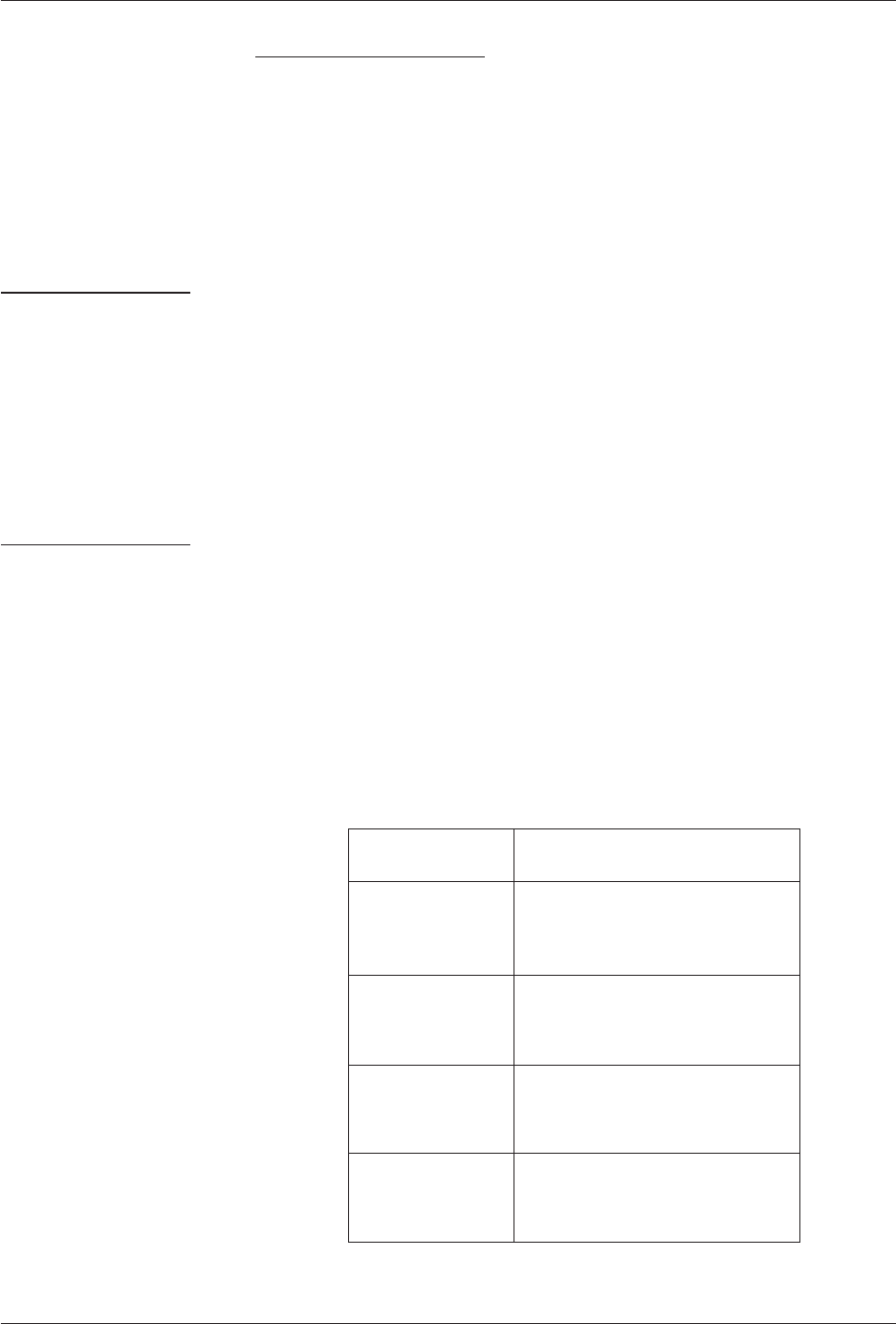

•

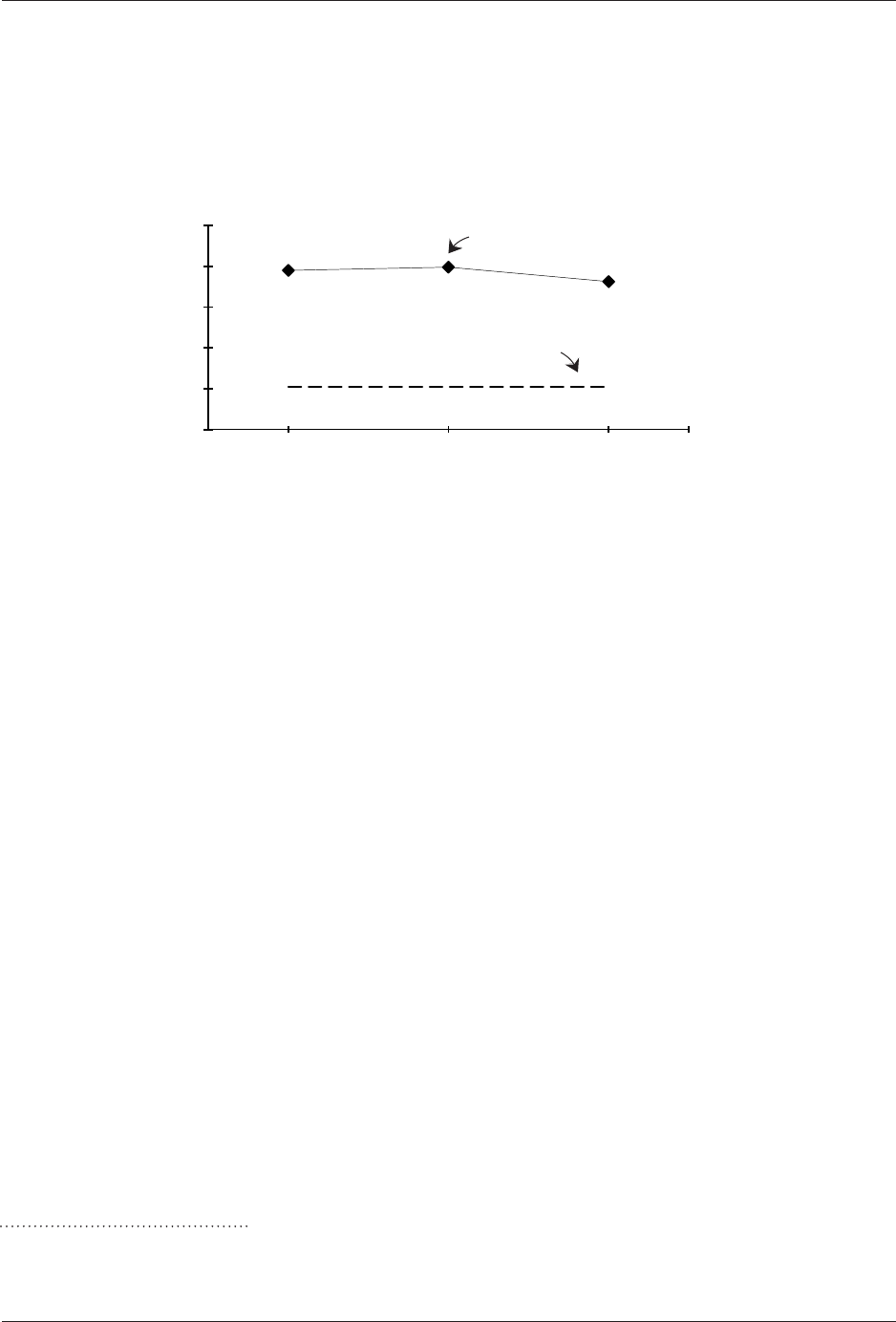

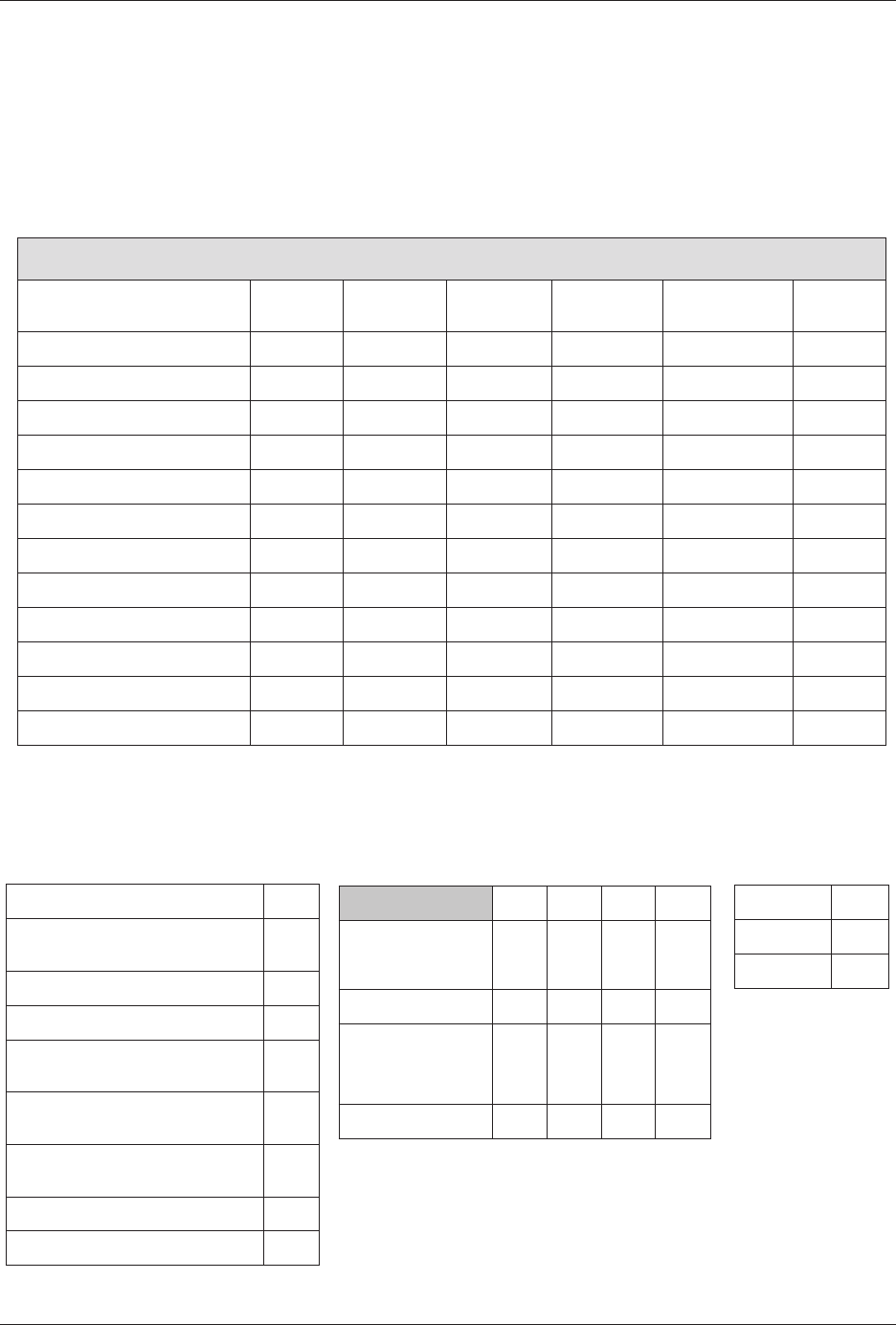

Funding. In scal year 2015, the board operated on a total budget of $4,203,605 with 93 percent of

its funding coming from the General Revenue Fund and the remainder from appropriated receipts.

Revenue generated through fees paid by dentists, dental hygienists, dental assistants, and other entities

regulated by the board is deposited in the General Revenue Fund and more than covers the board’s

operating costs. e pie chart, State Board of Dental Examiners Expenditures by Program, shows the

board’s expenditures in each major program area. Investigating and resolving complaints accounts

for almost two-thirds of total board expenditures.

Peer Assistance Program

$124,250 (3%)

Indirect Administration

$156,882 (4%)

Texas.gov

$300,054 (7%)

Licensure & Registration

$835,900 (20%)

Complaint Resolution

$2,786,519 (66%)

Total: $4,203,605

State Board of Dental Examiners Expenditures by Program

FY 2015

State Board of Dental Examiners Staff Report with Commission Decisions

Agency at a Glance

8

January 2017 Sunset Advisory Commission

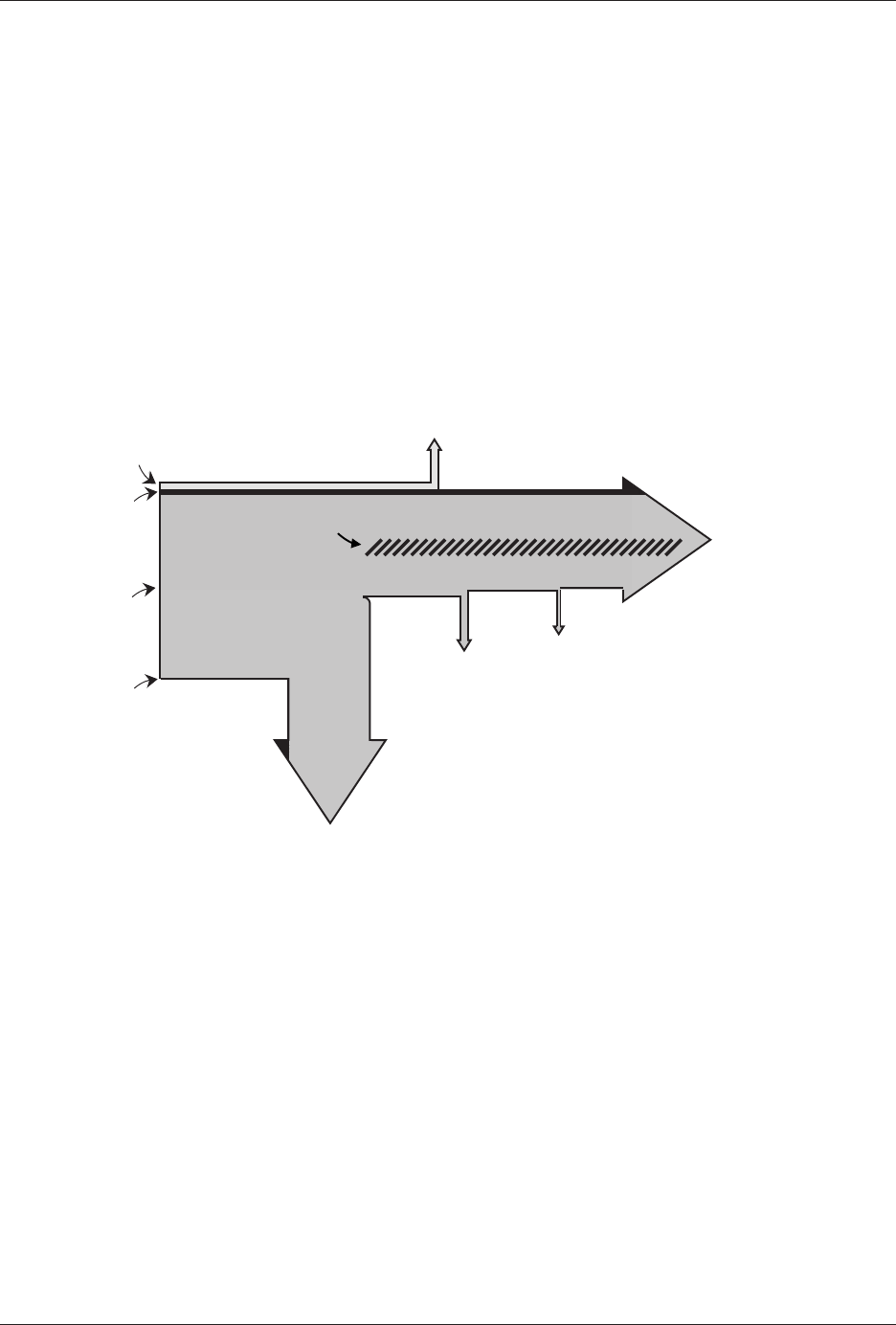

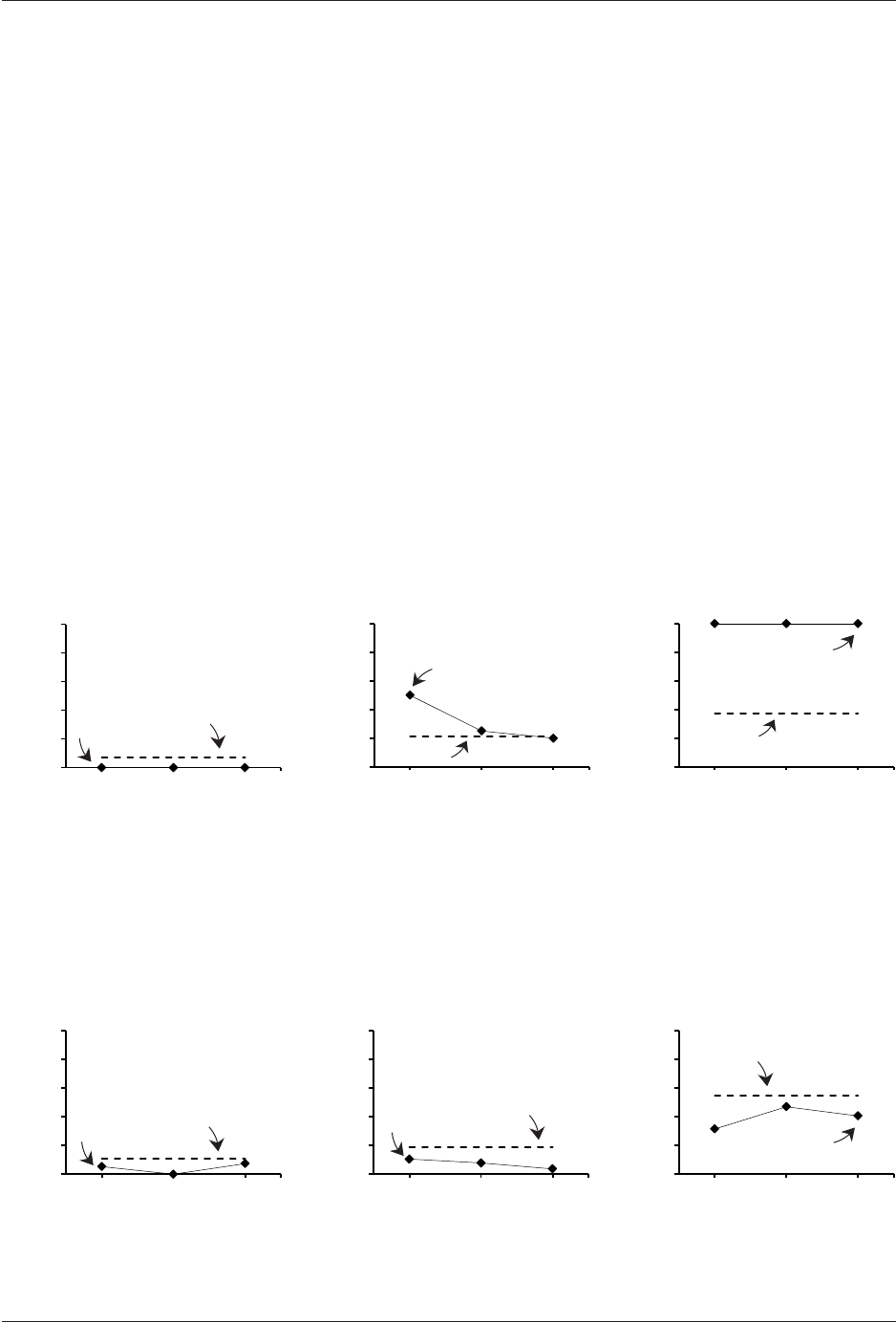

Historically, the board has generated revenue through various fees and charges far in excess of

what is needed to cover agency expenditures. In scal year 2015, the board generated revenue of

$11,814,143, including more than $3 million from the professional fee paid by dentists directly to the

General Revenue Fund and the Foundation School Fund. Although the Legislature discontinued

this professional fee in 2015, the board is still expected to bring in almost $3.8 million more from

its operating fees in scal year 2016 than budgeted to run the agency and pay for employee benets,

as shown in the chart, Flow of State Board of Dental Examiners Agency Revenue and Expenditures. A

description of the board’s use of historically underutilized businesses in purchasing goods and services

for scal years 2013–2015 is included in Appendix A, Historically Underutilized Businesses Statistics.

Texas.gov Fees

$250,000

Texas.gov

$250,000

Agency Costs

$4,586,954

Appropriated

Receipts

$258,500

Agency Fees

and Charges

$8,388,285

Professional Fees

$67,600

Health Professions

Council

$247,019

Peer Assistance

$124,250

General Revenue

$3,756,162

Total: $8,964,385

Employee Benets

$817,093

Flow of State Board of Dental Examiners Agency Revenue and Expenditures

FY 2016 (Budgeted)

•

Stang. e board had 58 authorized positions at the end of scal year 2015 and actually employed

55 individuals. Most employees work in the central oce in Austin, with 16 investigators and

inspectors working in eld oces throughout the state. Additionally, the board is a member of

the Health Professions Council, which provides supplemental information technology stang for

the board and other health professional licensing agencies. A comparison of the board’s workforce

composition to the percentage of minorities in the statewide civilian workforce for the past three

scal years is included in Appendix B, Equal Employment Opportunity Statistics.

•

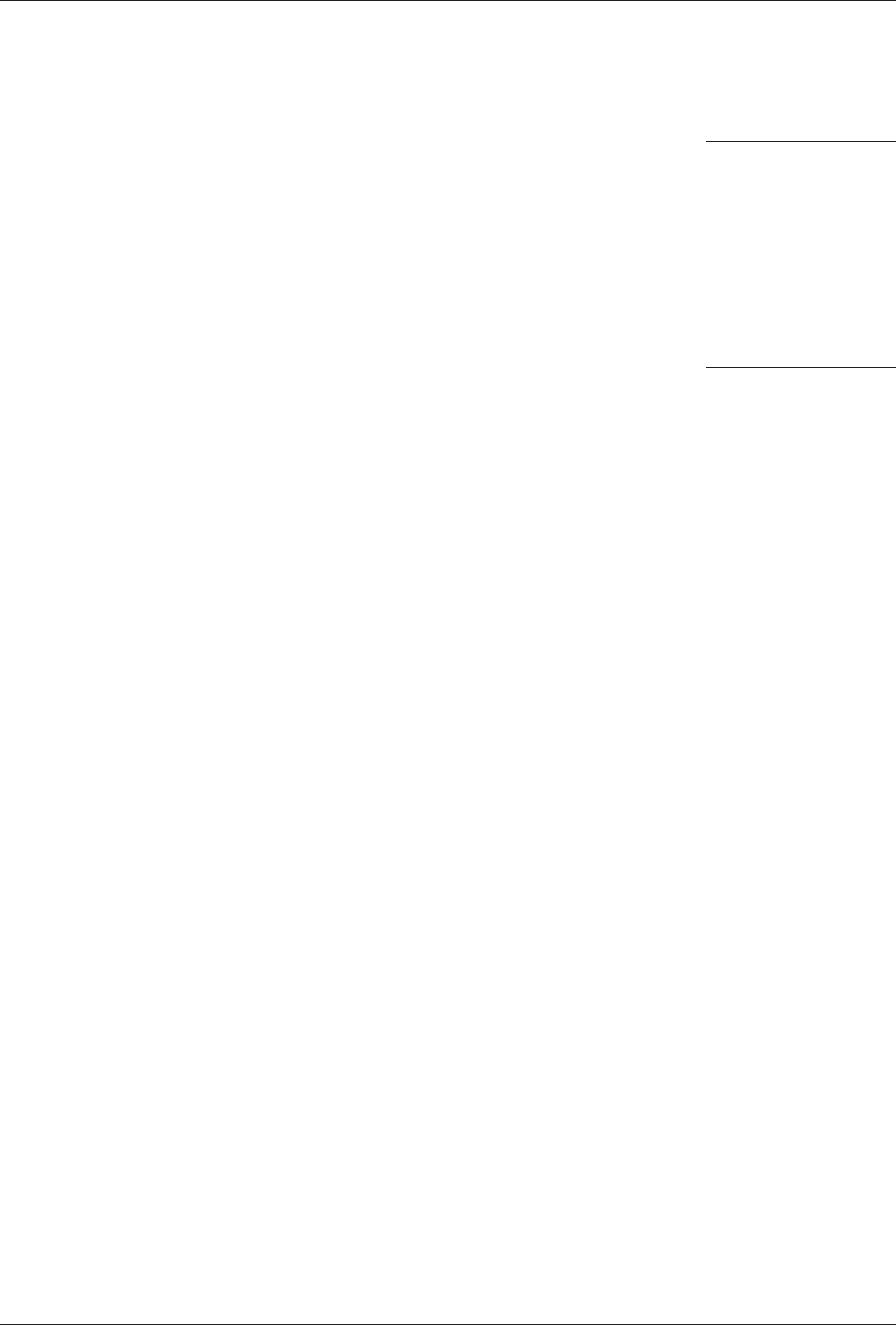

Licensing and Registration. e board processes initial applications, renewals, and reinstatements

for three regulated dental occupations and two facility types. e table on the following page, Licenses

or Registrations by Type, shows credentials issued by type by the board in scal year 2015. Since

1994, the board has outsourced responsibility for administering licensing examinations for dentists

and dental hygienists to the Western Regional Examining Board. In addition to these licenses and

registrations, the board issues permits for dentists using anesthesia. In calendar year 2016, the board

9

State Board of Dental Examiners Staff Report with Commission Decisions

Agency at a Glance

Sunset Advisory Commission January 2017

will begin monitoring professional involvement with

dental service organizations through a cooperative

agreement with the secretary of state.

•

Complaints, Investigations, and Enforcement.

The board is responsible for receiving and

investigating complaints against licensees. e board

resolves complaints by dismissing those in which no

violation is found or proven, or when a violation is

found, by issuing a recommendation for education

or practice changes, imposing a remedial plan as

a non-disciplinary action, or ordering disciplinary

action. e table, Board Enforcement Data, details

the number of complaints received, subject

of complaints, and disposition of complaints

resolved in scal year 2015. In the same year, the

board averaged 447 days to resolve a total of 943

complaints.

•

Compliance. Sta monitors licensees’ compliance

with disciplinary actions and remedial plans to

ensure that the terms and conditions of board

orders are actually met. e board has two sta

responsible for ensuring compliance of 354 total

open cases at the end of the scal year 2015.

•

Peer Assistance. The agency contracts for

peer assistance services for licensees who may

be impaired by substance abuse or dependence

or mental illness. Through this program,

dentists, dental hygienists, and dental assistants

are evaluated to determine if they are safe to

practice, and if not, may be subject to treatment

and monitoring before being allowed to practice.

Eighty-nine practitioners participated in the peer

assistance program in scal year 2015.

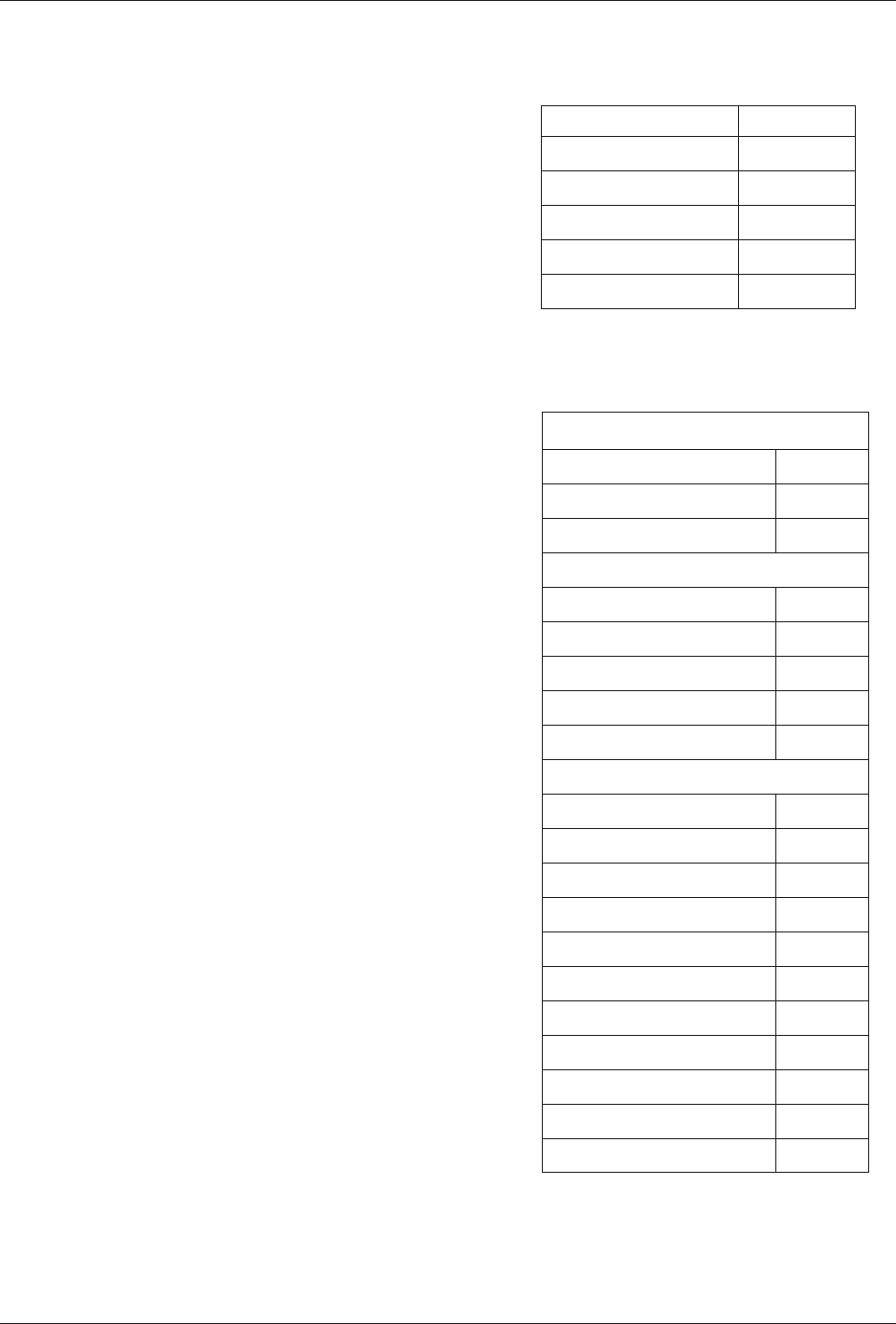

Licenses or Registrations by Type

FY 2015

Dentist 17,540

Dental hygienist 13,740

Dental assistant

50,469

1

Dental laboratory 847

Mobile dental facility 62

Total 82,658

Board Enforcement Data

FY 2015

Complaints Received*

From the public 1,127

Initiated by sta 109

Total 1,236

Subject of Complaints Received*

Dentist 1,137

Dental hygienist 21

Dental assistant 41

Regulated facility 5

Unregulated entity 32

Disposition of Complaints Resolved*

Dismissed 710

Remedial plan 46

Warning or reprimand 128

Administrative penalty 5

Probation 23

Suspension 4

Voluntary surrender 8

Revocation 3

Cease-and-desist order 6

Other 10

Total complaints resolved

943

* Does not include enforcement actions

initiated after criminal history reviews or for

non-jurisdictional cases.

State Board of Dental Examiners Staff Report with Commission Decisions

Agency at a Glance

10

January 2017 Sunset Advisory Commission

1

is number represents the total number of dental assistant registrations issued in scal year 2015 for four separate certicate

programs and does not reect the total number of unique dental assistants registered with the board.

iSSueS

11

State Board of Dental Examiners Staff Report with Commission Decisions

Issue 1

Sunset Advisory Commission January 2017

iSSue 1

The Unusually Large Dental Board Inappropriately Focuses on Issues

Unrelated to Its Public Safety Mission.

Background

e structure of the State Board of Dental Examiners governing body was last changed following the

2002 Sunset review of the agency, when the number of board members decreased from 18 to 15. e

board now consists of eight dentists, two dental hygienists, and ve public members.

Four standing committees support the board: the Executive, Licensing, Enforcement, and Quality

Control committees. e presiding ocer appoints ad hoc committees to work on special projects or

potential rulemaking eorts. Eight ad hoc committees have been created since 2013 to focus on issues

such as advertising, strategic planning, and ownership of dental practice. Every ad hoc committee

created in recent years has consisted entirely of board members, with mostly dentist board members

participating. Rules allow the board to appoint committees of various stakeholders to advise the board

about contemplated rulemaking.

1

e rst work group in recent history with stakeholder members was

established in February 2016 to examine anesthesia permitting and related inspections.

Two statutorily created advisory groups also

work with the board: the Dental Hygiene

Advisory Committee and the Dental Laboratory

Certication Council. e committee advises

the board, reviews and comments on proposed

rules, and may recommend rules related to the

practice of dental hygiene. e council reviews

applications for laboratory registration and may

also recommend rules related to laboratories to

the board. e Board Advisory Group Composition

textbox lists the membership of each group.

2

Findings

A decline in board duties requiring dental expertise has left

dentist members of the board with less to do.

e board’s oversized number of dentist members is a holdover from when

members had a much larger role in daily agency operations and is no longer

necessary to conduct agency business. In 2013, the Legislature reassigned

standard of care complaint review from the board’s dentist members to a

panel of expert dentists and dental hygienists designated by the board.

3

is

process removes dentist board members from serving as both investigator

and judge in enforcement matters, a position which would aect their ability

to render impartial decisions. ese expert reviewers also represent a much

broader range of dental specialty than is possible on the board. e continuous

availability on a contract basis of the 130 expert reviewers enables a much faster

Board Advisory Group Composition

Dental Hygiene Advisory Committee

•

ree dental hygienists appointed by the Governor

•

Two public members appointed by the Governor

•

One dentist member appointed by the board

Dental Laboratory Certication Council

•

ree members who must be dental technicians or

owners, managers, or employees of a registered dental

laboratory, appointed by the board

State Board of Dental Examiners Staff Report with Commission Decisions

Issue 1

12

January 2017 Sunset Advisory Commission

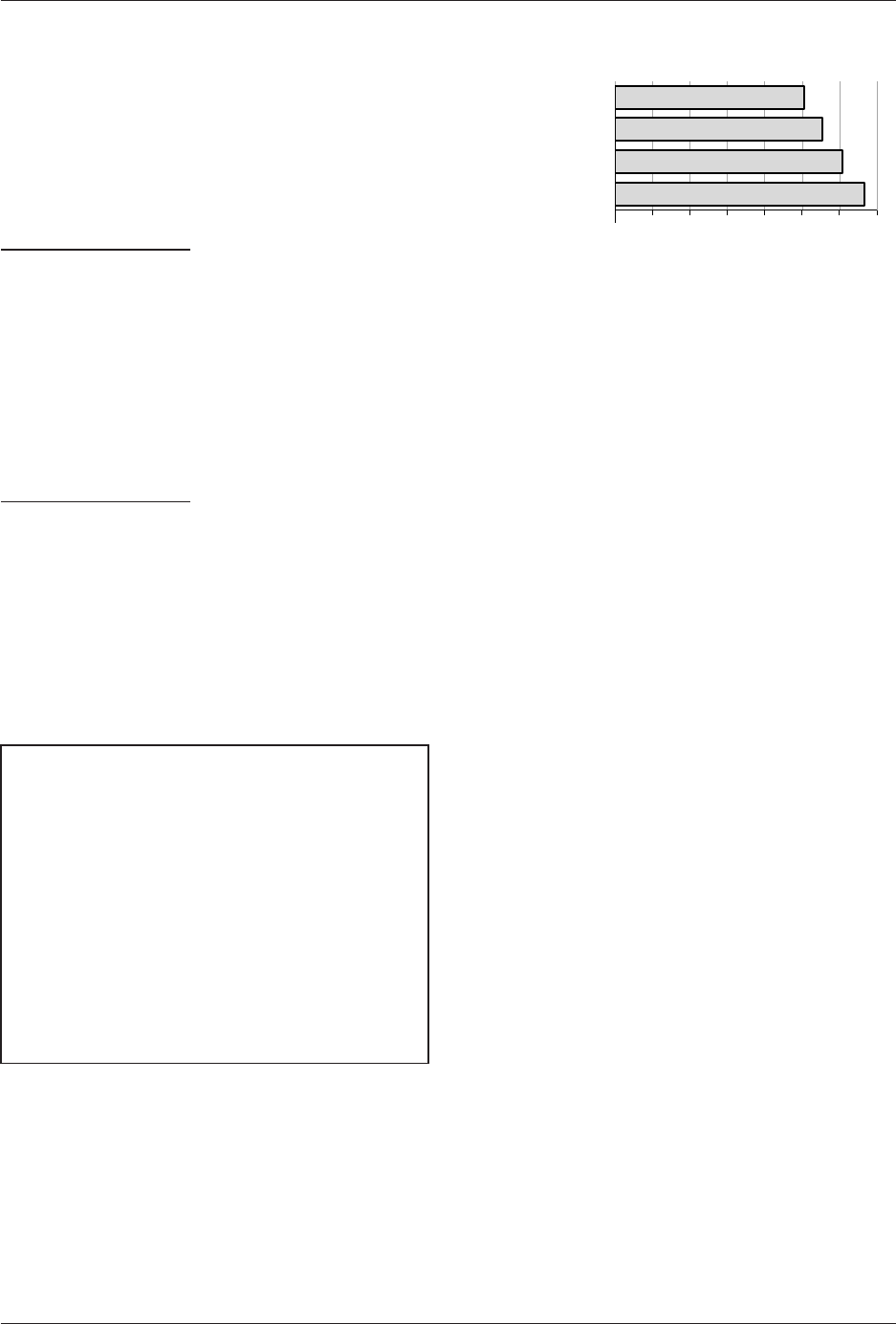

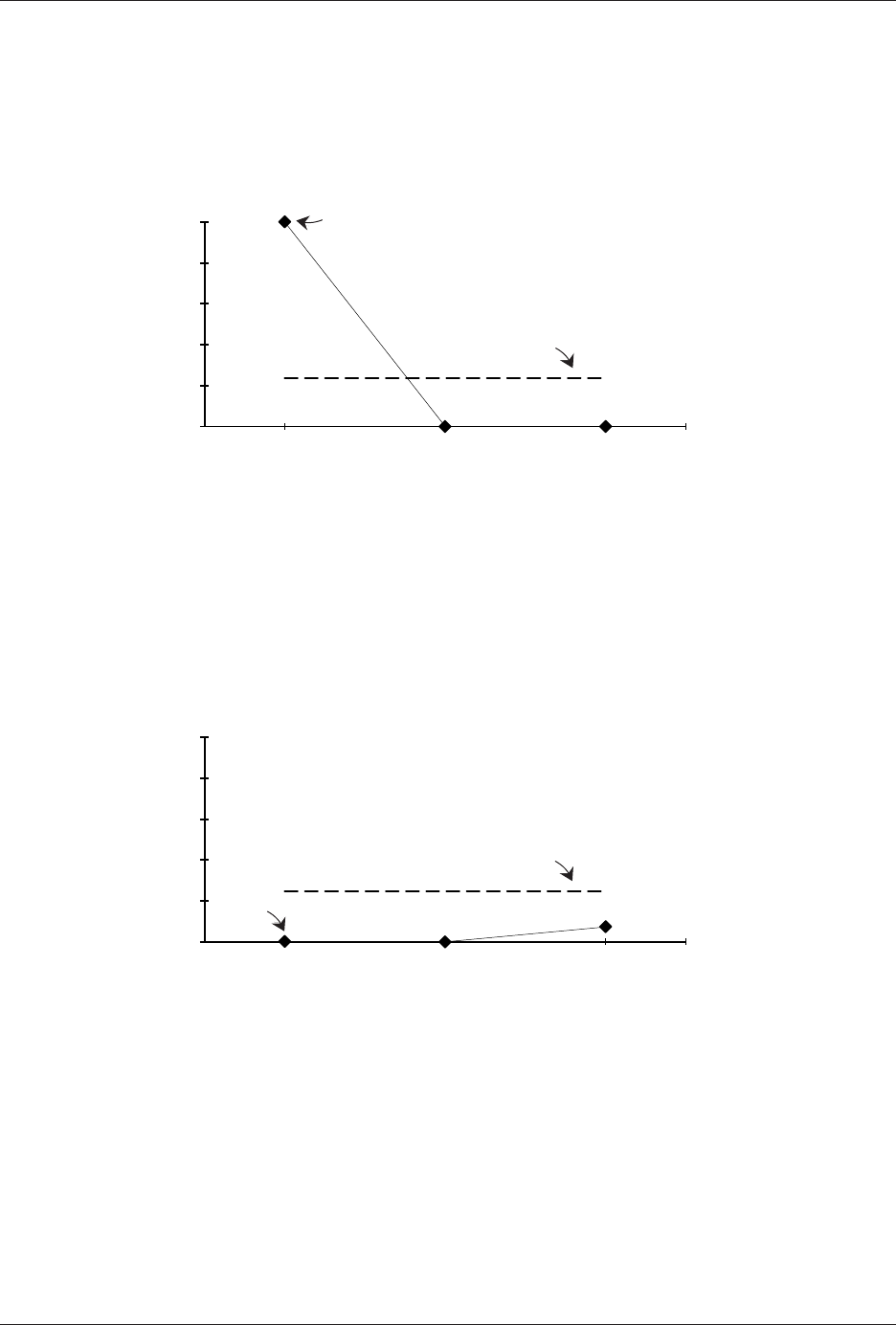

turnaround of reviews for the growing

number of incoming standard of care

complaints shown in the accompanying

chart. e use of panels has relieved

dentist board members of hundreds of

hours of work each year, sped up the

investigative process, and helped the

board make progress on its persistent

backlog of enforcement cases.

With fewer requirements to consume their time, dentist

board members have focused on matters that do not have a

demonstrated public safety impetus, undermining the agency’s

processes and wasting its resources.

•

Ill-fated rule packages. At the behest of dentist members, the board

has shown a propensity to push business-oriented matters without clear

evidence of patient harm. Two recent rulemaking eorts show the board’s

disregard for stakeholder concerns, legislative and legal interests, and the

lack of broad support and consensus.

One set of such proposed rules, regarding dental oce ownership

arrangements, purported to address patient care relating to non-dentist

owners of dental oces, although the board lacks data to suggest that

practice models or ownership arrangements are associated with a higher

incidence of complaints alleging compromised patient safety or demonstrated

harm. Yet, the board’s related ad hoc committee repeatedly promoted rule

revisions addressing the perceived issue in both 2014

and 2015. e board persisted in this matter even in

the face of pointed criticism from the Federal Trade

Commission, opposition from numerous stakeholders,

and requests by six members of the Legislature to

defer to the Legislature on the issue. Federal attention

to state agency rulemaking is unusual; the textbox,

Federal Trade Commission Comments, highlights some

of its comments on the proposed rules.

4

e rules

were ultimately withdrawn, but not before the eort

consumed ve board meetings, six ad hoc committee

meetings, and countless hours of sta support between

May 2014 and May 2015.

e other notable rulemaking eort regarding specialty advertising has a

considerably longer history. e rules reect the board’s long reliance on

a national association for advertising specialty designations. Although

the rules were not challenged for several decades, the regulatory climate

shifted. In 2011, the board began another review of its advertising rules,

an eort spanning numerous board and ad hoc committee meetings.

Ultimately, the board re-adopted rules restricting the advertising of dental

Federal Trade Commission Comments

“Proposed regulations to limit commercial relationships

between dentists and non-licensed entities should

be carefully examined to determine if they are based

on credible and well-founded safety, quality, or other

legitimate justications.”

“e proposed rules appear unnecessary to address any

concerns about the independent judgment of dental

professionals… we urge the Board to consider the

potential anticompetitive eects of the proposed rules,

including higher prices and reduced access to dental

services... and to reject both proposed [rules].”

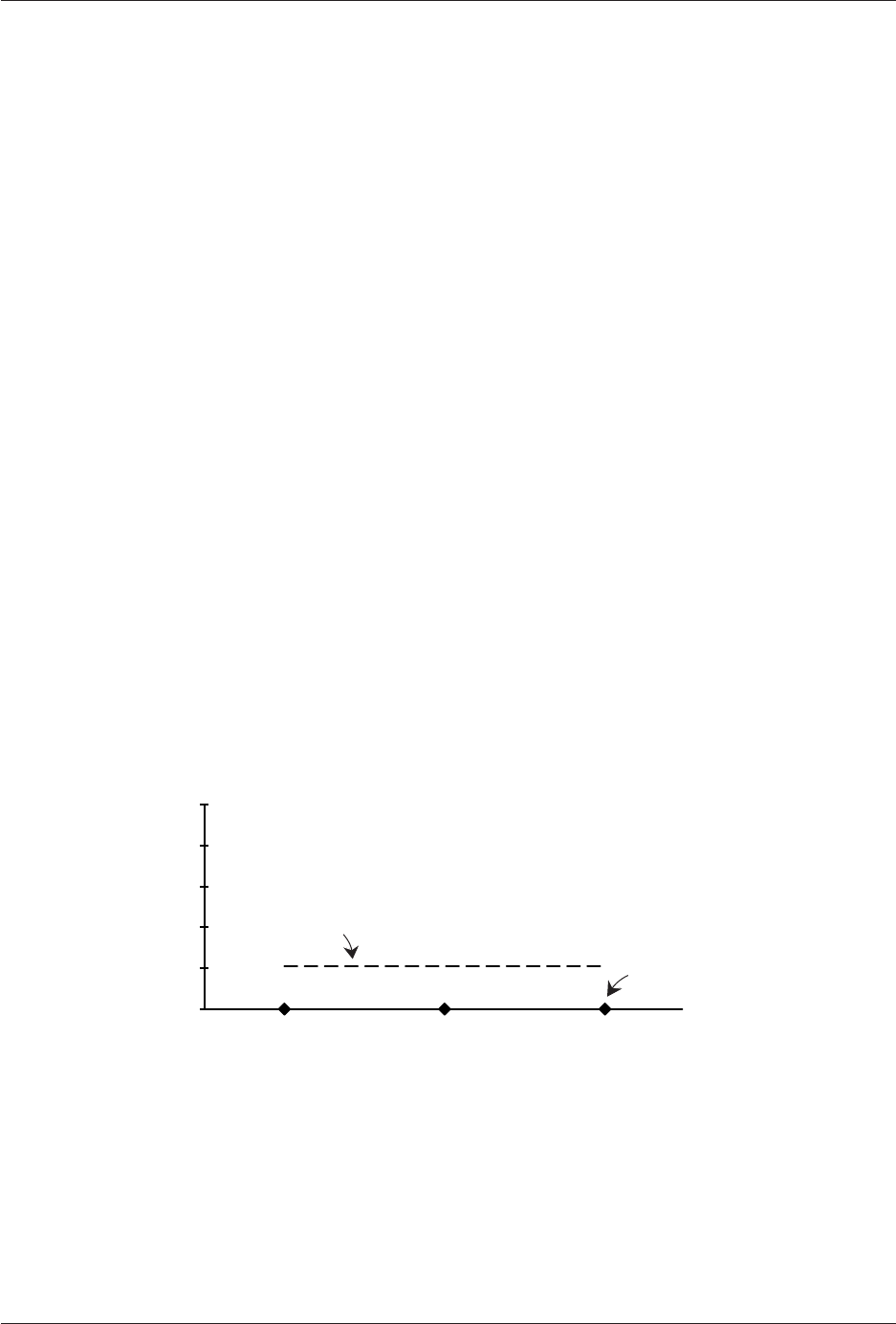

499

455

416

379

0 75 150 225 300 375 450 525

Standard of Care Complaints

FYs 2012–2015

2012

2013

2014

2015

Number of Complaints

The board

has shown a

propensity to

push business–

oriented matters

without clear

evidence of

patient harm.

13

State Board of Dental Examiners Staff Report with Commission Decisions

Issue 1

Sunset Advisory Commission January 2017

specialties in 2012 and 2013 without clear evidence of patient harm from

an alternative approach to regulating advertising and despite unfavorable

trends in litigation on the subject.

5

e board was sued over the rules

and recently lost, drawing the rebuke of a U.S. District Court in January

2016. As evidenced by the textbox, Specialty Advertising Court Decision,

Federal District Court Judge Sam Sparks’ opinion questioned the board’s

motivation for re-adopting the rules.

6

Despite numerous opportunities to

address the issues raised in the lawsuit and in the court’s ruling, as suggested

by agency sta and stakeholders, the board continues to pursue its own

course, with little apparent concern for the legal liability and potential

nancial impacts its actions could bring on the agency.

Specialty Advertising Court Decision

“Defendants have produced no evidence of actual deception associated with

advertising as specialists in non-ADA [American Dental Association]-recognized

elds, there is no evidence to suggest any of the Plaintis’ elds are illegitimate or

unrecognized, and there has been no accusation any of the Plaintis’ organizations

are shams.”

“Defendants do not oer any competent evidence to substantiate these fears

and admit they did not review any studies, surveys or other evidence regarding

the impact of specialty advertisements before promulgating the Rule. Instead,

Defendants appeal to their own professional judgment and “vast experience dealing

with customers of dental services.” e State Dental Board’s collective common

sense is not a substitute for the “tangible evidence” required…”

“e right to advertise as a specialist in Texas is undoubtedly a nancial boon to

dentists in the state. While ostensibly promulgated to protect consumers from

misleading speech, it appears from the dearth of evidence [the Rule’s] true purpose

is to protect the entrenched economic interests of organizations and dentists in

ADA [American Dental Association]-recognized specialty areas.”

The board missed

opportunities to

address issues

more clearly

related to patient

harm, such

as anesthesia-

related

complaints.

Regulatory boards clearly have exibility to pursue matters they reasonably

believe are within their mission to protect the public, and they should be

given some forgiveness when they miss the mark. However, while this

board was pursuing these two dead-end rule packages — and still has

another regarding sleep apnea being challenged in court — it missed

numerous signs that it was on the wrong road. More importantly, while

these matters were occupying the board’s time, it missed opportunities to

address issues much more clearly related to patient harm, such as a rise

in anesthesia-related complaints. As discussed in Issue 3, board guidance

for strengthening agency oversight of dental anesthesia had been largely

lacking until the board established a work group in February 2016, at the

suggestion of the board’s new executive director, after a spate of media

attention elevated the concern.

e board’s recent misadventures in rulemaking highlight another concern

about obtaining public and stakeholder input on dicult, contentious

issues. e board follows the Administrative Procedure Act and properly

posts rule changes in the Texas Register, but without doing more to include

State Board of Dental Examiners Staff Report with Commission Decisions

Issue 1

14

January 2017 Sunset Advisory Commission

stakeholders earlier in the rulemaking process, the board gave an appearance

that it had already determined its course of action and was not concerned

with the eect of its policies and regulations on stakeholders. In February

2015, agency sta put a process in place for stakeholders to provide input

on proposed rules earlier, in their formative stages, where they can raise

potential problem areas or identify blind spots that can result without such

a broad perspective. is new process oers promise, but must continue

to focus the board’s rulemaking eorts and ensure that they best serve its

public safety mission.

•

Eect on case resolution. Involvement in the case resolution processes

reects the diculty dentist board members have had accepting the

board’s diminished role. rough the board’s Quality Control Committee,

these members revisit standard of care complaint cases recommended for

dismissal by expert panel reviewers. While the review of dismissed cases is

within the board’s purview, having a standing committee expressly created

to review the work of its appointed experts slows down the resolution of

enforcement cases for little practical result, as detailed in the textbox, Quality

Control Committee Case Review. Of the 10 cases returned to the expert

panel from the Quality Control Committee, only three have resulted in

additional action — requiring nondisciplinary remedial plans. Ultimately,

the committee reects the dentist members’ antipathy for its own dental

review panel, whose members the dentist board members pointedly refuse

to call expert reviewers, despite the designation in law.

7

Quality Control Committee Case Review

September 2014–February 2016

•

290 – Number of cases reviewed

•

7-8 – Weeks, on average, cases wait for committee review

•

10 – Cases returned to expert review panel for additional examination

•

6.7 – Months, on average, added to case resolution for re-reviewed cases

•

2 – Cases dismissed following committee initiated re-review

•

3 – Cases closed by remedial plan following committee initiated re-review

•

5 – Cases pending action following committee initiated re-review

Reviewing work

of appointed

experts slows

case resolution

for little practical

result.

rough informal settlement conferences, board members and agency sta

seek to resolve complaints without going to contested case hearings at the

State Oce of Administrative Hearings. Most settlement conferences

are attended by dentist members to clarify technical issues and questions.

However some dentist board members question the ndings of their own

expert review panel that was designed to provide specic expertise regarding

the specialty of the dentist subject to the complaint. Such freelancing

has the eect of revisiting the facts of the case and revising the agency’s

position, which is not the role of board members at the conferences. It

can also result in less consistent and potentially unfair outcomes for those

15

State Board of Dental Examiners Staff Report with Commission Decisions

Issue 1

Sunset Advisory Commission January 2017

accused, ultimately undermining the settlement process. Some dentist

board members involve themselves more than others; for example, of six

informal conferences not settled from September 2014 to January 2016, ve

had the same dentist presiding. e regulatory process should work more

consistently and predictably to ensure the fairness and overall eectiveness

of enforcement activities.

•

Sta turnover. Signicant turnover in the executive director and general

counsel positions has left stakeholders and sta without a consistent

vision for agency operations. From 2011 to 2015, the board employed

four separate executive directors and general counsels. Increased funding

for the executive director position in the 84th Legislative Session should

help promote stability for the position. However, board behavior has an

undeniable impact on agency sta in terms of morale and motivation to

do the dicult work of regulating dentistry. Ultimately, the board must

foster an environment to maintain the consistency in leadership and legal

support necessary to focus the board and the agency squarely on clear

issues of public safety and protection.

Recent events highlight the heightened expectations on

occupational licensing boards to adhere to a higher standard of

behavior to protect the public.

•

A recent U.S. Supreme Court ruling put a spotlight on state occupational

licensing board behavior that may be considered anticompetitive.

8

e

impact of the ruling has been to focus attention on board actions that do

not have clear public safety implications, especially actions by active market

participants who may be motivated to act in their self interest. Board

members must clearly show their decisions focus on the agency’s mission

to protect the public.

•

In the 84th Legislative Session, in the heat of the board’s maneuvering

on the dental oce ownership issue, a bill was introduced to single out

the dental board as needing training on the scope and limitations of its

rulemaking authority and establishing a code of conduct.

9

While the bill

was not pursued, the perceived need for such a directed measure indicates

an awareness that existing board training has not resonated with current

board members. e inappropriate actions of dentist board members begs

for a refocusing eort directed toward issues of clear public protection

supported by board licensing and enforcement data.

Statutorily created advisory groups are no longer necessary to

conduct board business and receive input.

•

e Texas Sunset Act states that advisory committees are abolished on

the date set for abolition of an agency unless the committee is expressly

continued by law. e Act also directs the Sunset Commission and sta to

make recommendations on the future of agency advisory committees using

Board behavior

has an impact

on staff morale

and motivation.

Recent court

rulings have

focused attention

on board actions

that do not have

public safety

implications.

State Board of Dental Examiners Staff Report with Commission Decisions

Issue 1

16

January 2017 Sunset Advisory Commission

the same criteria to evaluate both committees and their host agencies.

10

e Dental Hygiene Advisory Committee and the Dental Laboratory

Certication Council do not eciently support the board and could be

removed from statute without a negative eect on licensees or the public.

•

e board’s advisory groups have outlived their necessity and are no longer

necessary as separate statutorily created entities for eective input to the

board. e Dental Hygiene Advisory Committee has met just four times