Guidelines on surveillance among

populations most at risk for HIV

UNAIDS/WHO Working Group

on Global HIV/AIDS and STI Surveillance

WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

Procurement process resource guide.

(WHO Medical device technical series)

1.Appropriate technology. 2.Equipment and supplies - supply and distribution. 3.Technology

assessment, Biomedical I.World Health Organization.

ISBN 978 92 4 150137 8 (NLM classification: WX 147)

© World Health Organization 2011

All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from WHO

Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41

22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to

reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution

– should be addressed to WHO Press, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; e-mail:

The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not

imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization

concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or

concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent

approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement.

The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that

they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others

of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of

proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters.

All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify

the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being

distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. The responsibility for

the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall the World

Health Organization be liable for damages arising from its use.

Design & layout: L’IV Com Sàrl, Le Mont-sur-Lausanne, Switzerland.

Guidelines on surveillance among

populations most at risk for HIV

UNAIDS/WHO Working Group

on Global HIV/AIDS and STI Surveillance

ii

Acknowledgements

Global surveillance of HIV and sexually transmitted infections is a joint effort of the World Health Organization

(WHO) and the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). The UNAIDS/WHO Working Group

on Global HIV/AIDS and STI Surveillance, initiated in November 1996, provides technical guidance on

conducting HIV and STI surveillance. Its mandate is to improve the quality of data available for informed

decision-making and planning at the national, regional and global levels.

This document is based on experience in countries and expert reviews from WHO/UNAIDS and the Centers

for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), USA, which have contributed to the writing and revision of the

final document. All the persons involved declared no conflicts of interest.

WHO and UNAIDS would like to thank the individuals who contributed to this document including: Donna

Stroup, Carolyn Smith, members of the UNAIDS/WHO Working Group on HIV and STI Surveillance, and

members of the US Government’s Surveillance and Surveys Technical Working Group.

Guidelines on surveillance among populations most at risk for HIV

1

Contents

Acknowledgements ii

1 Introduction 3

1.1. Purpose 3

1.2. Background 4

1.3. Classification of HIV epidemics 4

1.4. Ethical issues with populations most at risk for HIV 5

Protect participants’ privacy and rights 5

Provide benefits to the community 5

Handle incentives for participation ethically 5

Protect young people 5

Provide protection to participants with illegal behaviours 6

1.5. Process 6

2 Plan surveillance of populations most at risk for HIV 7

2.1. Step 1: Prepare to set up the surveillance system 7

2.1.1 Collaborate with stakeholders 7

2.1.2 Conduct a pre-surveillance assessment 8

2.1.3 Identify populations at increased HIV risk from high-risk behaviour 9

2.1.4 Estimate the size of populations at increased risk for HIV 10

2.1.5 Decide on the geographical areas 10

2.1.6 Consider special issues related to each population of interest 10

2.1.7 Integrate with existing surveillance and monitoring plans 13

2.2 Step 2: Decide on the surveillance design 13

2.2.1 HIV case reporting 13

2.2.2 Programme data used for surveillance 14

2.2.3 Sentinel surveillance 14

2.3. Step 3: Decide on a surveillance sampling strategy 15

2.3.1 Simple random sampling 15

2.3.2 Stratified sampling 16

2.3.3 Cluster or targeted sampling 17

2.3.4 Snowball sampling 17

2.3.5 Respondent-driven sampling 18

2.3.6 Convenience sampling 20

2.3.7 Time–location sampling 20

2.3.8 Sample size 21

2.3.9 Sampling strategies for populations most at risk for HIV 22

3 Conduct surveillance of populations most at risk for HIV 25

3.1 Step 4: Address operational issues 25

3.1.1 Plan staffing and training 25

3.1.2 Develop data collection instruments 26

3.1.3 Plan handling of specimens and HIV testing 27

3.2. Step 5: Data management 27

3.2.1 Plan the data management system 27

3.2.2 Use data management best practices 28

3.2.3 Create a dataset for analysis 28

3.2.4 Document the steps used to create the database 28

3.2.5 Maintain confidentiality and security 29

2

3.3. Step 6: Data analysis 29

3.3.1 Handling non-response 29

3.3.2 Using weighting 29

3.3.3 Determining HIV prevalence 30

3.3.4 Determining HIV prevalence trends 30

3.3.5 Determining HIV incidence 30

3.3.6 Dealing with uncertainty 31

3.3.7. Ensuring validity 31

4 Use the results/Evaluate the surveillance plan 32

4.1.1 Share the results 32

4.1.2 Develop a dissemination plan 32

4.1.3 Protect the population from stigma or legal action 32

4.1.4 Use the results to improve programmes 33

4.2. Step 8: Evaluate the system 34

Appendix A: List of additional surveillance resources 35

Appendix B: Glossary and acronyms 36

Appendix C: Links 39

References 40

Guidelines on surveillance among populations most at risk for HIV

3

The overall goal of this document is to provide guidance on how to develop and maintain HIV surveillance

among populations most at risk for HIV. Ultimately, these surveillance activities should improve the overall

understanding of HIV in countries and improve the response to HIV.

This guide complements the second generation surveillance guidelines on how to conduct HIV surveillance

activities in low- and middle-income countries. Those guidelines recommend that all countries conduct HIV

surveillance among populations with behaviours that increase their risk for HIV, or populations most at risk

for HIV infection.

1.1. Purpose

This document provides guidance on methods for conducting surveillance among populations most at risk

for HIV.

Public health surveillance for HIV is the systematic, ongoing collection of data on the occurrence, distribution

and trends in HIV infection. In general, the objectives of surveillance include:

n to estimate the magnitude of a health problem in a population at risk

n to understand the natural history of a disease

n to evaluate prevention and control activities

n to monitor changes in trends in the epidemic

n to detect changes in health practices or risk factors

n to identify research needs and facilitate research

n to contribute to the planning process (1).

Additional reasons to conduct HIV surveillance among populations most at risk for HIV are:

n to guide HIV prevention programming at the local level

n to inform priority-setting and resource allocation at the national level

n to contribute to the scientific understanding of HIV transmission in populations most at risk for HIV

infection as a result of high-risk behaviour

n to inform disease burden and treatment needs among most-at-risk populations.

When monitoring the HIV epidemic, it is important to identify populations that are most at risk for infection.

The sexual and drug-use behaviours of populations contribute to the overall burden of HIV in the country.

People with these behaviours are often the first to become infected and are at risk of being infected at a

higher rate than those in the general population.

The primary target audience of this guide includes surveillance specialists. In addition, this guide will be

useful for programme managers at national and subnational levels to better understand the strengths

and weaknesses of the data they are using to make decisions. Finally, this guide will also be useful for

donor agencies that support HIV surveillance activities and measure the success of their activities through

surveillance data.

Most countries and their development partners already have some form of HIV surveillance among most-

at-risk populations. This guide is intended to help refine and standardize their HIV strategies and activities

for HIV surveillance among these populations. It presents different approaches along with their advantages

and disadvantages. It is hoped that this guide will empower managers and decision-makers to consider

additional options for strengthening their HIV surveillance systems so that they are able to compare trends

over time.

1. Introduction

4

This guide does not cover all the issues related to HIV surveillance; rather, it serves as a general hands-

on reference specifically for surveillance among most-at-risk populations. It cites additional materials and

resources for further information on surveillance and includes country examples.

1.2. Background

This document complements a number of other guidelines that provide further information on specific

surveillance activities. A complete list of reference materials is provided in Appendix A. These guidelines

are available on the UNAIDS and WHO web sites.

Some of the core sources include the following:

n Guidelines for estimating the size of populations most at risk to HIV presents a process for creating local

and national size estimates.

n An update to Guidelines on second generation surveillance explores new tools and techniques from a

field perspective to enhance the first guideline published in 2000.

There are a number of documents that describe monitoring and evaluation activities among populations

most at risk for HIV, including the Framework for monitoring and evaluating HIV prevention programmes

among most-at-risk populations (2007). (http://data.unaids.org/pub/Manual/2008/jc1519_framework_for_

me_en.pdf). Operational guidelines for the monitoring and evaluation of HIV-related programmes targeting

persons who inject drugs and men who have sex with men are anticipated in 2011.

For more in-depth information on the topics covered here as well as a self-teaching manual on surveillance

among most-at-risk populations, see Surveillance of most-at-risk populations (http://globalhealthsciences.

ucsf.edu/PPHG/surveillance/surv_modules.html).

1.3. Classification of HIV epidemics

UNAIDS/WHO and partners have identified three epidemic categories to help countries focus surveillance

activities. These categories are suggestions. Countries should know best where new infections are coming

from and what type of epidemic exists in their country.

Each country has a unique epidemic and usually has multiple subepidemics within different parts of the

country. Because of the diversity among HIV epidemics, it is critical to “know your epidemic”. That means

understanding how the epidemic differs within subpopulations and in geographical areas. Surveillance

data will provide the information to allow programme managers to better know their epidemics. Moreover,

they will allow programme managers to respond more effectively to the epidemic. As more surveillance

data become available, surveillance officers should evaluate their surveillance system to ensure that it is

appropriate for the type of epidemic. Table 1.1 will help determine where to focus the surveillance system

and whether the focus needs to shift over time.

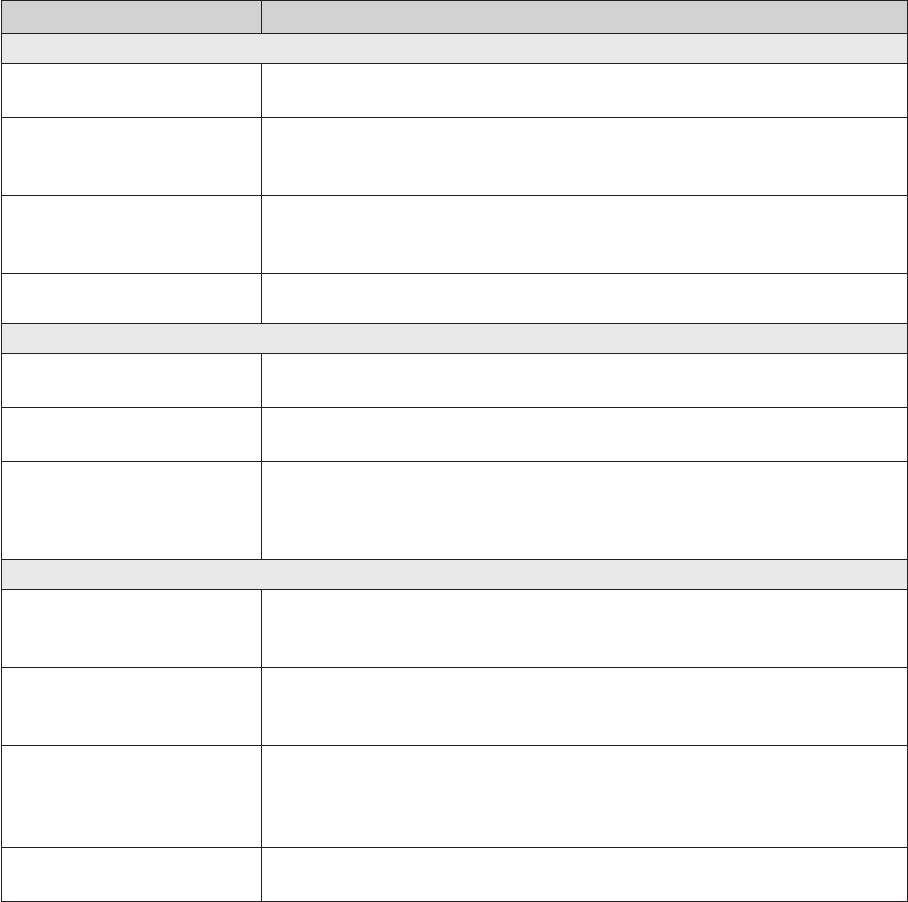

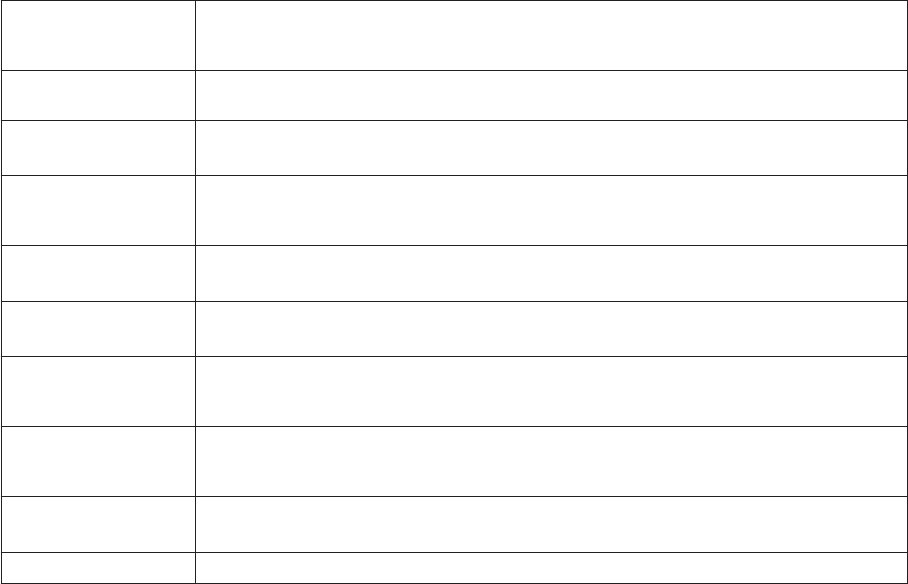

Table 1.1. Base surveillance activities on the type of epidemic

Epidemic state, situation Surveillance focus

Low-level

n HIV has not reached significant levels in populations most at

risk for HIV infection as a result of high-risk behaviour.

n HIV is largely confined to people within populations most at risk

for HIV infection as a result of high-risk behaviour.

n Focus surveillance activities in populations most at risk for HIV.

Concentrated

n HIV has spread rapidly in one or more populations most at risk

for HIV infection as a result of high-risk behaviour.

n The epidemic is not yet well established in the general

population.

n Continue surveillance among most-at-risk populations.

n Begin surveillance activities in the general population,

especially in urban areas.

Guidelines on surveillance among populations most at risk for HIV

5

Generalized

n The epidemic has matured to a level where transmission occurs

in the general population, independent of populations most at

risk for HIV.

n Without effective prevention, HIV transmission continues at

high rates in populations most at risk.

n With effective prevention, prevalence will drop in populations

most at risk before they drop in general population.

n Focus routine surveillance on the general population.

n Conduct surveillance among populations most at risk for HIV.

As described in Table 1.1, each type of epidemic should maintain some surveillance of populations most at

risk for HIV. Use these guidelines to facilitate surveillance in all settings.

1.4. Ethical issues with populations most at risk for HIV

Collection of any data requires attention to human subjects’ concerns. Before considering surveillance of

populations most at risk for HIV, the following principles should be considered.

Protect participants’ privacy and rights

In many cases, populations that are the target of HIV surveillance are vulnerable and might be accorded

special protection under ethical regulations. Handling of data on risk behaviours and HIV status may increase

the risk of harm to these populations due to stigma, economic loss or legal liability (2).

Participating in surveillance activities should either be voluntary or, in specific circumstances, should be

based on unlinked anonymous testing of blood samples. Unlinked anonymous testing should be used as

a surveillance strategy only when data from clinical settings and other studies cannot provide an accurate

measure of the prevalence or trends of HIV infection (3). Respect each person’s right to privacy. It is critical

to offer privacy and assurances of confidentiality during data collection. Keep data confidential. In turn, the

perception of confidentiality will influence the completeness of reporting and disclosure of risk.

Provide benefits to the community

Public health research should always provide a benefit to society. Extend the ethical principle of do no harm

to providing benefits to surveillance subjects. Whenever possible, provide individuals participating in the

survey with:

n test results

n information about HIV and AIDS

n counselling (on preventing HIV or on other health or social needs)

n treatment and care to the extent possible with local resources

n referrals to other services.

Consider how the results will be used before starting a surveillance activity among most-at-risk populations.

The results should be used for the good of public health while minimizing any harm to the participants.

Handle incentives for participation ethically

Providing benefits in the form of cash payment or vouchers for goods and services is often a useful

recruitment and retention technique (4). However, the use of incentives should be considered carefully

during the ethical review. Any incentive must consider the customs of the community but should not be so

large that it is considered coercive or exploitative (5). The ethical concern here is that the offer of financial

compensation, medical services or some goods might cause participants to consider only their short-term

benefits and they might underestimate the long-term costs. This might entice some participants to provide

data and could create a bias to the results (6).

Protect young people

When surveillance of most-at-risk populations includes collecting data from adolescents, additional ethical

issue arise. Young people may be particularly vulnerable to exploitation, abuse and other harmful outcomes

(legal, physical and social). Follow the guidelines for collecting data on adolescents (4,7).

6

Provide protection to participants with illegal behaviours

Safeguard participants from situations in which they might face legal persecution. This is critical for HIV

surveillance in any context. Some of the behaviours that cause increased risk for HIV are illegal in some

settings. Legal protection of confidentiality are constantly in flux (8). This can be avoided by including

members of the population who can provide information on the local context in surveillance pre-planning.

For additional information, see Ethical issues to be considered in second generation surveillance (http://www.

who.int/hiv/pub/epidemiology/en/sgs_ethical.pdf). Additional guidelines on ethics and HIV surveillance will

be available on the WHO web site shortly.

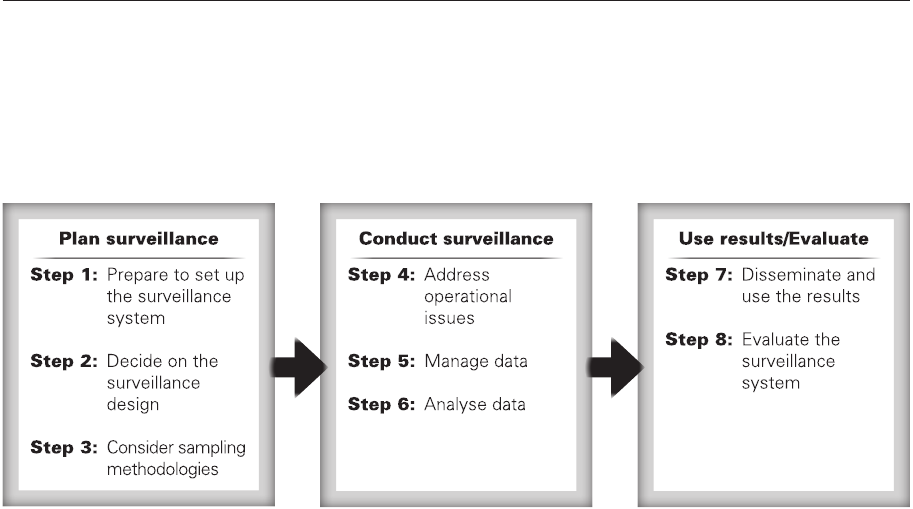

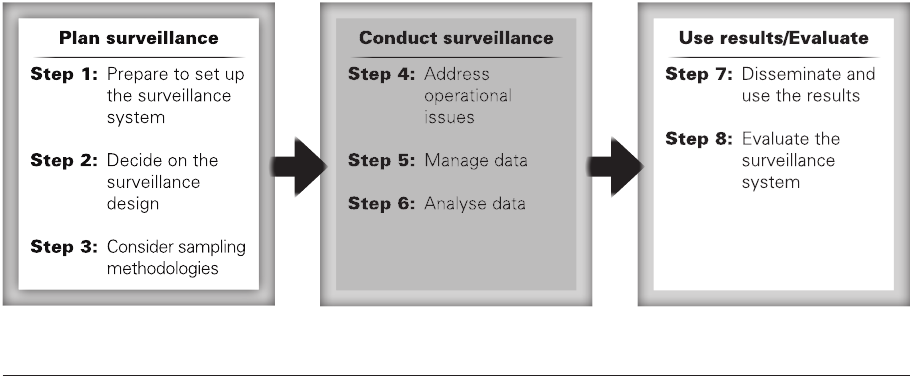

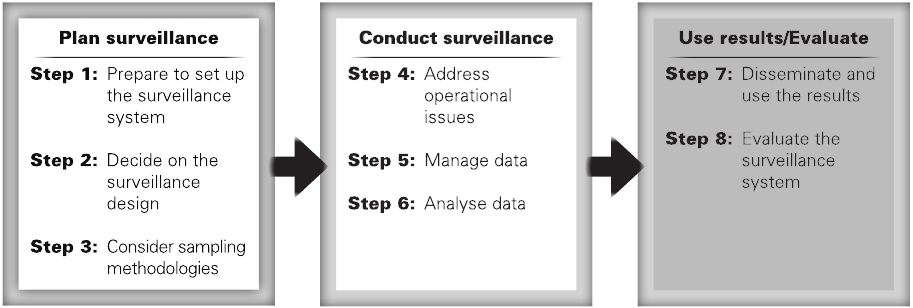

1.5. Process

Planning and conducting surveillance among populations most at risk for HIV can be summarized by the

eight steps shown below.

Figure 1.1. Planning and conducting surveillance among populations most at risk for HIV

The remainder of this document discusses the processes shown in Figure 1.1. Guidance and examples are

provided on methods:

n to plan surveillance activities, steps 1–3, Section 2

n to conduct surveillance, steps 4–6, Section 3

n to disseminate results and evaluate the surveillance system, steps 7–8, Section 4.

Guidelines on surveillance among populations most at risk for HIV

7

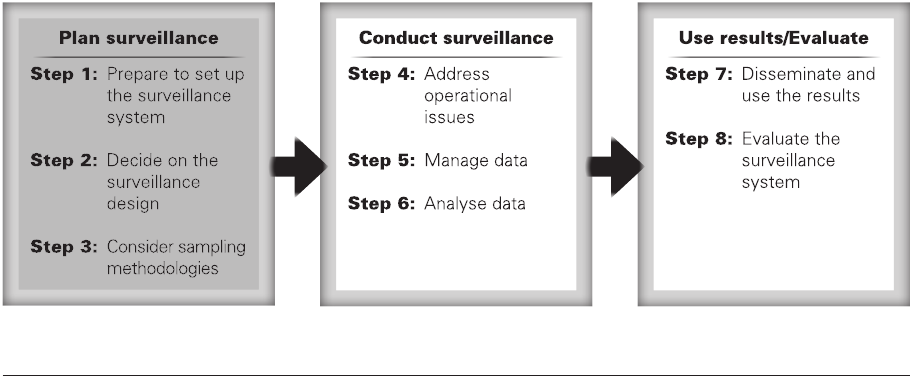

The first three steps of the process are general preparations for conducting surveillance among populations

most at risk for HIV. Some countries might have an existing surveillance system. It might still be useful to

review the first steps to ensure that the system is well designed.

Figure 2.1. Plan HIV surveillance among populations most at risk for HIV

2.1. Step 1: Prepare to set up the surveillance system

While preparing the surveillance system, it is important to develop a protocol to ensure the success of the

surveillance system. This will help ensure that accurate, appropriate and useful data will be captured by the

surveillance system. Be sure the protocol covers the following areas:

n how surveillance stakeholders will be involved in activities

n planned pre-surveillance assessment

n populations of interest, with explicit definitions of these populations, based on the behaviours that put

them at increased risk for HIV

n the size of the population or populations

n geographical boundaries, sites or location of surveillance

n coverage and descriptions of the representativeness of the population

n frequency of surveillance

n how surveillance activities will be merged with other monitoring and evaluation plans.

2.1.1 Collaborate with stakeholders

HIV surveillance cannot be done in isolation. Use a team approach to improve the quality and credibility

of the results. Table 2.1 provides a list of possible stakeholders and what they can bring to the surveillance

activities. Plan to involve members of HIV prevention programmes, monitoring and evaluation programmes,

and resource planning structures. Identify a team of stakeholders to help in designing and implementing

HIV surveillance activities.

2. Plan surveillance of populations most

at risk for HIV

8

Table 2.1. Potential stakeholders to include in planning surveillance activities among populations most at

risk for HIV

Stakeholder What they bring

Members of the populations most at risk for HIV n Provide insight into:

• thetimingofsurveillance

• theappropriatenessofthesamplingstrategy

• thewordingforthequestionnaire,and

• instrumentdesign

n Provide study legitimacy in the community

n Provide the legal and social context

Nongovernmental organizations or civil society

organizations working with most-at-risk populations

n Provide information on the needs of most-at-risk populations

n Have experience in reaching the population to inform the sampling

strategy and instrument design

HIV prevention experts Ensure that the surveillance results provide information on a timely basis for

programme planning or advocacy

Survey and census implementers n Advice on sampling strategies

n Additional data for size estimation activities

Monitoring and evaluation staff n Ensure that surveillance activities are part of the national monitoring and

evaluation plan

n Reduce the chances that efforts will be duplicated by different

organizations

n Combine data/analysis of results with other monitoring and evaluation

activities

n Disseminate combined results

Staff engaged in surveillance for sexually transmitted

infections

Improve efficiency by combining HIV surveillance activities with surveillance

for sexually transmitted infections

2.1.2 Conduct a pre-surveillance assessment

Conduct a pre-surveillance assessment before starting surveillance activities. The purpose of this assessment

is to understand the epidemic in the country. Review existing HIV and STI surveillance results as well as

findings from behavioural surveys. Consider which populations are at increased risk for HIV and how their

behaviours put them at increased risk. Guidelines on how to conduct a pre-surveillance assessment are

available at: http://data.unaids.org/pub/Manual/2005/20050101_gs_guidepresurveillanceassmnt_en.pdf.

In brief, pre-surveillance activities should gather information on the subpopulations and geographical areas

to be included in the surveillance. The assessment should include qualitative fieldwork

• toidentifyandverifyhotspots,

• toverifythedenitionofthepopulation,and

• toguidetheplanningandlogisticsofsurveillanceeldwork.

The pre-surveillance assessment will ensure that the right subpopulations are being considered and are

defined correctly. If the population is defined incorrectly, the surveillance team might fail to detect emerging

epidemics and miss the opportunity to target interventions where they will make the most difference.

Qualitative research is necessary to describe the patterns of behaviour, points of access and barriers to

surveillance for the populations (9). Surveillance methods will differ depending on whether the person is

self-identified and, if so, whether the person is part of a subculture (10).

It is worth taking the extra time and effort to go through the pre-surveillance process to plan appropriately

and refine the surveillance protocol. Conducting the assessment could help avoid mistakes that might

ultimately cost lives, time and money.

Guidelines on surveillance among populations most at risk for HIV

9

2.1.3 Identify populations at increased HIV risk from high-risk behaviour

Specific behaviours put individuals at increased risk for HIV. During the pre-surveillance assessment, the

available resources are compiled to help identify populations with these behaviours. Very high transmission

rates are found in groups that engage in the following behaviours:

n inject drugs with used needles

n have anal sex

n have sex with many partners without protection.

Specific populations with behaviours that put individuals at increased risk for HIV have been identified as

being important for HIV surveillance (11):

n Sex workers

n Clients of sex workers

n People who inject drugs

n Men who have sex with men.

Identify the actual behaviour that puts people at increased risk for HIV when selecting subpopulations for

surveillance activities. For example:

n Sex workers have large numbers of partners, often within a very short time, increasing their exposure to

HIV and sexually transmitted infections. Sex workers are often at a disadvantage in negotiating condom

use because their partners pay for their services.

n Clients of sex workers are also at increased risk for infection because of the sex workers’ high turnover

of sex partners. Clients of sex workers often act as a bridge to low-risk populations, which means that

they are often the link between the populations with behaviours that put them at increased risk for HIV

and low-risk populations. For example, a client of a sex worker may transmit HIV to his regular partner.

n Persons who inject drugs are at increased risk because of the high transmissibility of HIV when injecting

equipment is shared. When a needle, syringe or other injecting equipment is shared, the blood from the

first injector is often still in the equipment. It is injected into the next user’s body. This is a very efficient

method for transmitting HIV or hepatitis B and C.

n Men who have sex with men are often identified as another population at increased risk for HIV. This is

because unprotected anal sex has much higher transmissibility than vaginal sex.

n Women who receive anal sex are also at increased risk for HIV.

Carefully consider the difference between vulnerable populations (such as persons with disabilities) and

populations with behaviours that put them at increased risk. Conducting surveillance among vulnerable

populations whose risk-taking behaviours are not well understood is not useful (although it might be useful

for programming for those populations).

Transgender persons often have unique networks of sexual partners or clients. The risk behaviours are

often the same as described above – anal sex or selling sex – but they take place in select venues or with

select populations. Given the high levels of HIV prevalence among this population, it is important to carry

out special surveys to estimate the size of this population and estimate the HIV prevalence in this population.

Transgender populations can vary from an individual who dresses as the other sex (transvestite) to persons

who have had surgery to modify body parts (trans-sexual). The population is difficult to categorize and

often identifies with different terminology. Formative research is critical among this population to ensure

that the correct terms and questions are included in any survey. Participation from the community is also

essential. For guidance on how to conduct surveys among transgender populations, see http://transpulse.

ca/documents/OHTN-%20Best%20Practices%20for%20Trans%20Participants-%20GBauer%202009%20

vFINAL.pdf

10

Decide on a clear and specific definition of the populations that will be covered with surveillance activities.

Here are some examples:

n Sex workers – “Women who have received money for sex at a brothel in the past six months”

n Persons who inject drugs – “Persons who have injected any non-medical drug in the past three weeks”.

Definitions will depend on the surveillance strategy and design so no global guidance can be provided

on these definitions. Keep in mind that definitions should be precise, time-bound, measurable, valid and

reliable.

Proxy populations

It is often necessary to use proxy definitions for at-risk populations that are not a distinct social group. A

proxy definition uses a sociodemographic characteristic of a group, such as occupation, or places where

persons engaging in risk behaviours are likely to be found (such as men at bars, male migrants living in

dormitories, etc.).

The proxy definition is not the cause of the increased risk for HIV. For example, truck drivers are often used

as a proxy definition for clients of sex workers because some studies show that a higher proportion of

truckers are reported to be clients of sex workers than men in the general population. However, on its own,

driving a truck is not a risk for acquiring HIV. Similarly, prisoners are often a proxy definition for most-at-risk

populations. In some settings, prisoners have been found to inject drugs or have anal sex.

A proxy definition is almost always imperfect:

n Some people who meet the proxy definition may not engage in the risk behaviour.

n Some people who have the risk behaviour may not meet the proxy definition.

A proxy definition is useful only if there is evidence that a large proportion of individuals in the group

practise the high-risk behaviour of interest. When using data from proxy groups to describe the epidemic,

be clear why a proxy group has been adopted. Document any local data which demonstrate that the proxy

group does define a population with higher risk behaviours.

2.1.4 Estimate the size of populations at increased risk for HIV

Estimates of the size of at-risk populations are critical for interpreting surveillance results and can be used to

justify surveillance activities to stakeholders and funders. Estimates can be a strong force in policy change

and resource allocation by describing the potential population at risk. In addition, estimates of population

size inform the development, implementation, and monitoring and evaluation of interventions.

Population sizes can often be estimated at the same time as surveillance activities. Information on how to

conduct size estimation studies is available in the Guidelines on estimating the size of populations most at

risk to HIV (12).

2.1.5 Decide on the geographical areas

Population members in different regions of the country may have different behaviours and thus different

risks. These differences are important for planning surveillance efforts.

Differences by region may make it difficult to generalize surveillance results from one city to the rest of the

country. Surveillance activities will be needed in multiple locations within the country to ensure that these

differences are captured.

Again, the information gathered during the pre-surveillance assessment should assist in deciding on the

geographical regions where surveillance will be conducted.

2.1.6 Consider special issues related to each population of interest

Sex workers

Sex workers – people who exchange sex for money or goods – are an important group in the HIV epidemics

of many countries, especially in countries where condom use by sex workers and their clients is low. Sex

workers may have a higher prevalence of HIV than other populations because of their high turnover of

sexual partners and financial incentives by clients to not use condoms.

Guidelines on surveillance among populations most at risk for HIV

11

Sex workers differ markedly from one place to another and by the level of the HIV epidemic (13). In addition,

there may be many different categories of sex work. In pre-surveillance activities, it is especially important

to get the community to support the research so that they can provide input on the surveillance design.

In addition, researchers should forge alliances with individuals and organizations in a position to deliver

specific intervention programmes. These include:

n sex workers’ groups

n local authorities

n gatekeepers, such as brothel owners

n women’s groups.

Data that should be collected in addition to HIV status include: frequency of sex work, time since initiation

in sex work, frequency of condom use, non-client partners, questions on the reach of prevention and care

programmes available in the area, other high-risk behaviours and other relevant variables.

Clients of sex workers

Clients of sex workers are at increased risk of infection because they have sex with sex workers who have

large numbers of sex partners. As described earlier, clients of sex workers act as a bridging population to

the general population. Surveillance among clients of sex workers is increasingly being conducted among

clients recruited at sex work venues (14,15, 16).

Surveillance of client populations can also be done using proxy populations that are believed to have sexual

contact with sex workers. These include:

n commercial drivers

n military personnel

n patients at STI clinics who report visiting sex workers.

In addition to HIV status, some additional data which should be collected among clients include: frequency

of visits to sex workers, sexual behaviour with regular partners, condom use frequency, other high-risk

behaviours and other relevant variables.

Persons who inject drugs

In most societies, the illegal nature of injecting drug use and its associated stigma mean that persons who

inject drugs are often a hidden population (17). Implementing surveillance among persons who inject drugs

requires some general principles:

n Combine HIV surveillance activities with a larger surveillance framework, including other health issues

such as hepatitis B and C surveillance.

n Work with organizations that have links to drug users:

• formerusers

• drug-abusetreatmentprogrammes

• lawenforcementsettings

• communityoutreachworkerswhooftenarerecruitedfromamongcurrentusers

• treatmentandrehabilitationcentres(18).

In many countries, the population of those who inject drugs varies from year to year, so plan to conduct size

estimation studies regularly rather than relying on old data. As described earlier, preventive services for

persons who inject drugs should accompany HIV surveillance activities (19).

Collect data on risk and preventive behaviours, including information on screening and vaccination for

hepatitis. Include needle-sharing, sexual activity (such as condom use), access to free sterile injection

equipment, participation in prevention activities and access to antiretroviral treatment (20, 21). See Technical

guide for countries to set targets for universal access to HIV prevention, treatment and care for injecting

drug users. (http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/idu/idu_target_setting_guide.pdf)

Different drug-injecting behaviours may contribute to HIV transmission, for example:

n needle-sharing

n indirect sharing (“backloading” or “frontloading”)

n sharing filters or cookers.

12

In indirect sharing, one syringe is used to prepare the drug solution, which is then divided into one or more

syringes for injection. The solution is transferred between syringes with the needle removed (frontloading)

or plunger removed (backloading). This allows virus transmission if the preparation syringe is not clean.

The importance of each of these methods of sharing may depend on local behaviour. For example, if

direct sharing has been virtually eliminated due to intervention programmes and behaviour change, then

surveillance should monitor indirect sharing.

Surveillance should also monitor sharing that involves many different “sharing partners” within a short

period (“rapid partner-change” behaviour), since this behaviour is associated with rapid transmission of HIV

among persons who inject drugs. Technical guidelines that provide specific guidance on monitoring and

evaluating interventions for injecting drug use are available. (http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/idu/idu_target_

setting_guide.pdf)

Finally, collect information on access to sterile injecting equipment. Easy access to sterile injection equipment

is critical for HIV prevention among persons who inject drugs.

In summary, surveillance among persons who inject drugs should incorporate:

n data on drug injection risk behaviour

n sexual risk behaviour

n size and growth of the population

n patterns of drug use

n access to sterile injecting equipment

n participation in prevention activities, including screening for hepatitis

n access to antiretroviral therapy.

Men who have sex with men

HIV among men who have sex with men is increasing in many countries of the world (22,23,24). Surveillance

in this population has often underestimated the magnitude of infection and risk among this population.

Many countries do not include men who have sex with men in their regular surveillance activities because

homosexuality is illegal and highly stigmatized (25).

The impact of risk among men who have sex with men varies, depending on the level of the epidemic.

Even in some regions with a generalized epidemic, men who have sex with men may have a higher HIV

prevalence than among the general population (26).

Use formative research to enlist the cooperation of the community.

Behavioural questions that should be included in surveys with men who have sex with men include: the

number of partners, sexual behaviour and frequency of sex with female partners, time since initiation of

male-to-male sex, frequency of condom use, participation in HIV prevention or care programmes and other

relevant variables.

Other populations

In some countries, access to populations most at risk for HIV may be limited. As a result, surveillance

activities may be planned among proxy populations. In some cases, regular and consistent HIV testing and

counselling will be available from proxy populations (for example, prisoners), providing an opportunity to

analyse potential trends. It is important to ensure that ethical processes were followed to generate these

data before using them.

Surveillance systems based on proxy populations might not be adequate. Although they can be useful for

supplementing surveillance, they will typically not provide full and representative information on the actual

group of interest. As a result, they suffer from the same problems and weaknesses of such sampling or

selection biases (sampling biases and weaknesses are described later in this document). Additional variables

that should be asked of these populations depend on the behaviour that puts the group at increased risk.

Guidelines on surveillance among populations most at risk for HIV

13

Incarcerated populations

Persons in prison might be more likely to engage in behaviours that increase their risk for acquiring HIV

through injecting drugs, engaging in anal sex with fellow prisoners (27,28) or tattooing (29). While these

behaviours occur in many prison settings, incarcerated populations are not a proxy population for all

injecting drug users or men who have sex with men.

Prison populations are often used as proxy populations. Surveillance among prisoners should include the

reason for each prisoner’s incarceration (this can provide potential information to determine if they were

infected before imprisonment).

Keep in mind that incarcerated persons may have been infected before they were incarcerated.

Military recruits

In some countries, military recruits are more likely to visit sex workers. This makes them a useful proxy

population for clients of sex workers. In addition, this population is often routinely tested for sexually

transmitted infection (including HIV) through existing medical systems.

However, being in the military is not on its own a risk factor for HIV infection so interpret results with caution.

2.1.7 Integrate with existing surveillance and monitoring plans

After conducting all of these preliminary activities, including the formative assessment and size estimation,

revise and review the HIV surveillance protocol. Ensure that the protocol documents the decisions made

and plans future surveillance activities on a timeline. Make sure that the surveillance protocol is incorporated

into the national monitoring and evaluation plan to avoid overburdening staff and duplicating efforts. Use

the surveillance protocol to develop funding requests for surveillance activities.

2.2 Step 2: Decide on the surveillance design

Surveillance results will help determine:

n how many people are infected with HIV among the population most at risk, and

n the factors that might be associated with their HIV status.

Therefore, surveillance activities must collect biological and behavioural data.

There are a few ways to collect biological data. Options include:

n HIV case reporting

n using programme data for surveillance

n sentinel surveillance.

Regardless of the biological surveillance design, behavioural data should also be collected. Tracking HIV

prevalence or incidence may show the progress in implementing prevention programmes. However,

these data alone will not indicate why the programmes succeeded or failed. Behavioural data can show

associations with particular aspects of risk.

Historically, surveillance activities for biomarkers and for behavioural indicators were conducted as separate

activities. When planning surveillance activities that collect information on biomarkers, it is currently

recommended to also collect data on risk and preventive behaviours.

2.2.1 HIV case reporting

Many developed countries rely on HIV case reporting (and the self-reported transmission route) for

surveillance among most-at-risk populations. However, this method has several limitations:

n Many individuals are not diagnosed until long after they have been infected, or not at all, leading to

underreporting.

n The self-reported mode of transmission is potentially biased, as individuals may not want to disclose

high-risk behaviours to health-care providers.

n HIV case reporting generally provides only limited data on the risks of HIV transmission or behaviour.

14

Therefore, if HIV case reporting will be used, it is important to conduct alternative or additional surveillance

activities to supplement the case reporting data.

Because of the time lag of almost a decade between infection and development of AIDS, AIDS case reporting

does not reflect the recent dynamics of the HIV epidemic. In addition, as the number of people receiving

antiretroviral therapy increases, the number of new AIDS cases will decline. AIDS case reporting is therefore

not very useful for surveillance. Instead, building on systems for the delivery of antiretroviral therapy,

surveillance of advanced HIV is recommended (30).

Case reporting often needs to be based on names or national identity numbers to avoid double counting.

If individuals are required to report on behaviours that might be illegal or highly stigmatized, storing

identifying information along with self-reports of those data might be unethical.

2.2.2 Programme data used for surveillance

Many countries collect biological results from their programmes, such as sexually transmitted infection

(STI) clinics or HIV testing and counselling services. Routine programmes often focus on populations at

increased risk for HIV.

STI clinics or voluntary counselling and testing services collect information on risk behaviours. This allows

programme managers to separate the test results of men who have sex with men, women who have anal

sex, sex workers and persons who inject drugs. Annual measures of the HIV prevalence in these separate

populations provide an indication of HIV trends in most-at-risk populations.

However, data from voluntary counselling and testing and other services are often biased, depending on

who decides to participate in these services. For example, when the services charge fees, these services will

be attended by more wealthy members of the population. Moreover, the bias is likely to change over time

as more or less people access these services as programmes expand or undergo budgetary restrictions.

Similar to case reporting, this method relies on self-reported behaviours provided in a setting that might

not be confidential. Data may be biased depending on the stigma attached to the behaviour in the country.

2.2.3 Sentinel surveillance

Sentinel surveillance uses selected sites for collecting measures of HIV prevalence in a population.

Sentinel surveillance can take the form of:

n a community survey or

n a facility-based survey.

Both require the identification of subgroups of the population who are at increased risk. The section on

sampling later in this document describes the methods available for sentinel surveillance.

Similar to case reporting, this method relies on self-reported behaviours to determine the mode of

transmission. In many survey settings, interviewers are unknown to the respondent. This ensures some

level of confidentiality.

Sentinel surveillance at the community level has several challenges. All of these factors influence the validity

of the data and the generalizability of the data to a larger population.

n Sampling of most-at risk-populations is often challenging because no complete sampling frame (list

of members of the population) is available. Because of this, the resulting sample may be biased and

difficult to replicate over time.

n When random selection rules are not used, interviewer and self-selection sampling biases may result.

As a result, the survey may under-sample members of a given population who do not occupy obvious

niches in the community or who do not approach outreach workers. In other words, the survey may not

reach hidden subpopulations.

Guidelines on surveillance among populations most at risk for HIV

15

n Sampling of subgroups of interest may only recruit those who are at higher risk for HIV infection and

only later recruit those at lower risk (31).

n In sampling populations of interest, geographical areas may not be sampled in proportion to numbers

of the population of interest. For example, drug users may not be sampled in proportion to the intensity

of drug use in the region. The probability of selecting drug users may not be known.

All of these issues are discussed further in the section on sampling.

2.3. Step 3: Decide on a surveillance sampling strategy

Surveillance is conducted to allow comparisons of data from the same group over time. Thus, samples

should be:

n representative of the population

n able to be repeated (or replicable) in a later survey.

For most-at-risk populations, it is difficult to replicate surveys. Populations may be difficult to reach (hidden)

or transient; that is, people move into or out of the population. To address these issues, HIV prevalence

studies among most-at-risk populations often use probability, convenience or snowball sampling methods,

which are not always replicable over time.

While selecting a sampling strategy, consider the following:

n It should be feasible to sample from the same population in future surveys.

n The sample should be as representative of the population as possible.

n The sampling strategy should match available resources for this round and future rounds of the survey.

n It should be possible to carry out the survey (reaching all persons in the sample) in a reasonably short

period of time.

n The cost involved should be affordable.

n Legal and ethical issues of implementing the sampling strategy should be taken into account.

2.3.1 Simple random sampling

Description

The way a sample is selected determines the scientific viability of the study. A simple random sample is the

gold standard for sampling considerations. Simple random sampling assumes that everyone in the target

population has the same, known probability of being included in the sample, like drawing numbers or

names from a hat. More commonly, each member of the population is identified by a number and random

number tables or computer algorithms are used to select the required sample size.

Advantages

From a statistical perspective, simple random sampling:

n eliminates bias from a sample of volunteers who might have different characteristics than the complete

population

n provides each member of the population with the same chance of being selected

n provides a sample that contains members with characteristics similar to the population as a whole.

Limitations

As straightforward as this seems, implementing a true simple random sample in fieldwork can be expensive,

inconvenient or impossible:

n Implementing a random sample requires a sampling frame or list of the target population. Clearly, this

requirement is not met for many populations at increased risk for HIV. (See Box 1.)

n Even if a list does exist, the sample population might be dispersed throughout a geographical area,

making it expensive and time-consuming to carry out.

n A random sample may miss people or behaviours that are not common in the population.

16

In cases where a sampling frame and easy access to the population are not available, alternatives are

necessary. Excellent reviews of conventional sampling techniques can be found elsewhere (32,33,34). Several

variants of classical sampling are important for surveillance among populations at increased risk for HIV (35).

These variants are presented below.

Box 1: What is a sampling frame?

A sampling frame is simply a list of all of the individuals eligible to be in the survey. Persons participating

in the survey are selected from the sampling frame and are considered the survey sample. An

incomplete sampling frame can result in a biased sample and inaccurate results if the people excluded

from the frame have different characteristics than those included in the sampling frame.

2.3.2 Stratified sampling

Description

Stratified sampling is modified simple random sampling. Stratified sampling may provide an economic

saving over simple random sampling:

n Divide the target population into groups (strata) that are more similar within the group than the groups

are to each other.

n Now take a simple random sample from each group independently.

Define strata by the nature of the sampling question. For example, if the variable of interest is condom use,

and different types of sex workers used condoms at different frequencies, the strata could be defined as the

various types of sex workers (street-based, brothel-based, home-based) in the population.

Advantages

When data are collected in this way, statistical methods allow weighting schemes to be used to estimate the

variability and potential error of the survey due to the sampling design (36). (See Box 2.)

Limitations

It is important to have a clear understanding of the population and the differences within the population

to be able to stratify it. In the example above, we would need to know the different types of sex workers

and their behaviours. Once the strata are known, a sampling frame is needed for each stratum. Choose the

sample from these lists.

Box 2: How to weigh survey results

When a sample is drawn from a sampling frame, it is common to draw more from one section of the

population than another. This is referred to as stratified or cluster sampling.

When stratified sampling is used, it is possible to correct the bias in the sample by calculating a

variable that truly represents the population of interest. For example:

n If one subgroup of the population is overrepresented in the survey, give this subgroup a weight of

less than one.

n If a subgroup is underrepresented in the survey, give them a weight greater than one.

n The overall weighted frequency is equal to the total number of people in the survey.

All survey variables are then calculated using these weights to correct for the biases introduced from

the sampling strategy. In addition, weights are used to calculate the precision of the estimate and the

potential error as a result of the survey design or the design effect.

Guidelines on surveillance among populations most at risk for HIV

17

2.3.3 Cluster or targeted sampling

Description

Cluster or targeted sampling is also a modified simple random sampling. The target population may

be naturally divided into groups (as with stratified sampling). Within the groups there is diversity in the

variable of interest but, on average, one group is similar to the other. Each cluster should be a fairly good

representation of the entire population on a smaller scale. Often, clusters are geographical areas, such as:

n villages

n regions of a rural area

n sections of a town or city

n physical units such as brothels, bars or streets.

To conduct cluster sampling, randomly select the clusters and then perform simple random sampling within

the clusters (37).

Advantages

As with stratified sampling, weighting allows for calculation of the sampling error (38). Using the sex worker

example, if most of the population of interest is street-based, cluster sampling may be appropriate. Cluster

sampling commonly uses maps to guide the stratification. This allows for a greater generalizability to a

geographical area.

Limitations

It is usually easy to break groups into clusters when using geographical areas. Use mapping of the population

to be sure that a sample of the entire population in the region is included. A sampling frame from which to

draw the sample is needed for each cluster.

As described earlier, stratified and cluster samples can use weighting schemes to create statistical estimates

of variability and errors. This means that they can produce probability samples. Properly conducted, these

adaptations can produce estimates with as much or more accuracy as simple random sampling but with a

substantial saving of resources.

However, these designs could lead to higher estimates of error compared with that from simple random

sampling. When surveys are structured with stratifications or clusters, they are described as having a design

effect. The design effect of the study needs to be considered when planning the sampling strategy and

calculating sample sizes. Involve a statistician on the surveillance team for these types of issues.

The first three options described above are often not feasible when working with most-at-risk populations.

There are usually no sampling frames if the entire most-at-risk population in a geographical area is

considered the sampling universe. Therefore, non-probability sampling is often necessary for surveillance

of most-at-risk populations.

2.3.4 Snowball sampling

Description

Snowball sampling is one type of non-probability sampling. Persons already interviewed or measured are

used to find study subjects. Generally, subjects first contacted are asked to name acquaintances who are

then approached, interviewed and asked for additional names. In this way, a sufficient number of subjects

can be accumulated to give a study adequate power (39).

For example, if the goal is to study persons who inject drugs, sampling from needle exchange programmes,

while accessible, will miss many women, youth and those who have recently started injecting. This would

produce a statistically representative sample of an unrepresentative part of the target population. Snowball

sampling was developed to address this problem by reaching individuals in diverse social networks.

Advantage

The method allows the sampling of populations that are networked when there is no sampling frame.

18

Limitations

Snowball sampling has many limitations.

n If the goal is repeated surveillance on the same group, snowball sampling will not be appropriate. There

can be no way to compare the results over time.

n Bias can result since most people tend to name acquaintances who are similar to themselves

demographically: by race, ethnicity, education, income or religion.

2.3.5 Respondent-driven sampling

Description

Respondent-driven sampling is a modification of snowball sampling which uses a mathematical model to

weight the sample data to compensate for the fact that the sample is not a simple random sample (40,41).

Respondent-driven sampling is an important method for sampling hard-to-reach groups, including when

the groups may be small relative to the general population or when a list (sampling frame) of population

members does not exist.

To conduct respondent-driven sampling:

n Identify and recruit seeds (initial survey respondents). The number of seeds required varies by the total

sample size required and the diversity of the target population.

n Give each seed coupons and ask them to recruit three to five acquaintances.

n Each recruit who visits the study site brings a coupon that identifies (by number) who referred them.

n No names are provided, just study identification numbers combined to develop a list of the numbers of

acquaintances per study participant.

n Give each recruit coupons and ask them to recruit three to five acquaintances.

n Recruiting may go on for several waves.

n A mathematical model based on the Markov chain theory and network theory weights the sample to

address the probability that people will refer their friends, making the sample less random.

Advantages

The resulting statistical theory controls for the biases associated with chain-referral methods, providing

both population estimates and estimates of variability for those estimates (42).

Individuals are accessed through their social networks, making it more likely to reach those who shun large

public venues and avoid the street.

Limitations

As a method, respondent-driven sampling is costly and time-consuming. Sources of significant bias can

exist if the population is not well networked. Entire sections of the population of interest can be missed if

they are not connected to the initial seeds.

Depending on the number of initial seeds, the start-up of a respondent-driven sampling study can be slow.

Respondent-driven sampling requires specific software for analysis (available at: http://www.

respondentdrivensampling.org/main.htm). Recent research has found that there is large variation in the

estimates produced through respondent-driven sampling. Large sample sizes should improve on the

estimates (43).

There have been mixed results using respondent-driven sampling with different most-at-risk populations.

In some contexts, the populations were not well networked, making respondent-driven sampling a difficult

sampling strategy.

A more detailed description of how to conduct respondent-driven sampling is available at: http://www.

respondentdrivensampling.org/.

Guidelines on surveillance among populations most at risk for HIV

19

Respondent-driven sampling in Beijing, China

Respondent-driven sampling was used for three rounds of surveys to recruit men who have sex with

men in Beijing, China in 2004, 2005 and 2006. The surveys included a structured interview to collect

behavioural data and blood specimens to test for HIV, syphilis, hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus.

The number of participants in the surveys was 325, 427 and 540 in the 2004, 2005 and 2006 surveys,

respectively. In the 2004 survey, only one seed was recruited; in the 2005 and 2006 surveys, 10 and 8

seeds were recruited, respectively.

Special software (RDSAT) was used to adjust for the chain referral recruitment process used to select

the sample for the survey. The software allowed researchers to make adjustments to reflect the make-

up of the target population based on information from the networks of the respondents.

Once adjusted, the results were representative of the population, allowing the researchers to compare

the results over time. The researchers found a rise in HIV prevalence among men who have sex with

men in Beijing over the three years and recommended urgent services for this population to slow the

spread of HIV. This study was one of the first to use respondent-driven sampling for basic surveillance

– comparing prevalence trends. (41)

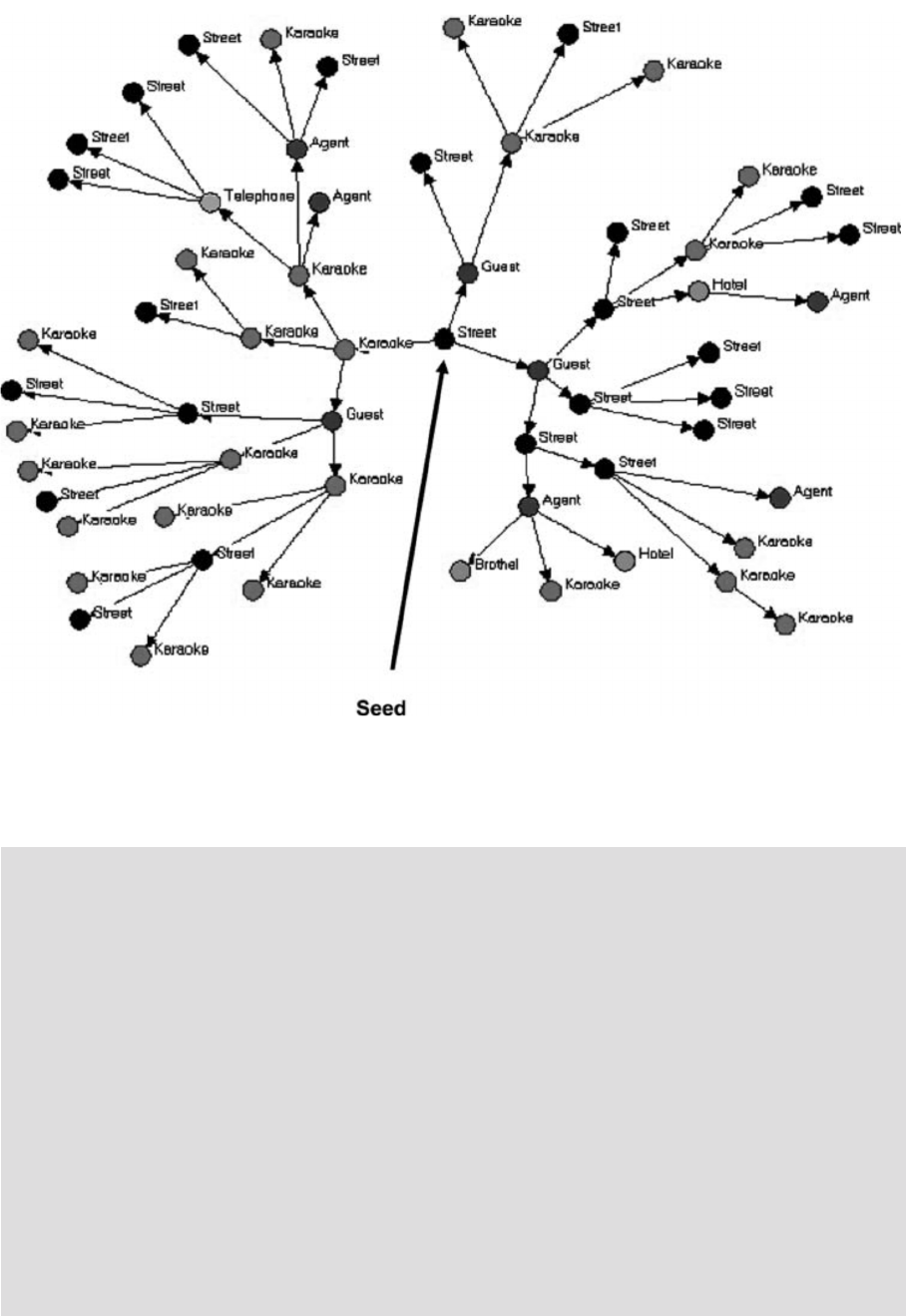

Figure 2.2. Respondent-driven sampling recruitment network for one seed by type of female sex worker

in Viet Nam

Source: Johnston LG et al. Effectiveness of respondent-driven sampling to recruit female sex workers in two cities in Vietnam.

Journal of Urban Health,

2006, 83 (Suppl 7):16–28.

http://www.springerlink.com/content/j31w862u2v65538n

20

2.3.6 Convenience sampling

Description

A convenience sample includes persons in the sample who are easy to reach or convenient to sample. An

example might be testing and interviewing all sex workers attending an STI clinic.

Advantages

Although convenience sampling is not a form of probability sampling, data from convenience samples may

be the only information available on populations most at risk for HIV transmission.

Limitations

In convenience sampling, no rules are used for sample selection. There is no way to estimate error or bias

in this sampling scheme.

2.3.7 Time–location sampling

Description

Many of the sampling methods discussed above rely on non-probability methods or tend to overestimate

people who are more networked. Time–location sampling methods can avoid these limitations.

This is a probability-based surveillance method that relies on a sampling frame derived from the times

when and locations where members of a target population congregate rather than where they live (44).

To conduct time–location sampling:

n List all the venues where the population congregates as the primary sampling unit. For example, the

population may meet in certain clubs.

n Randomly select specific times, days and venues.

n The selected venues are visited during the day and time specified.

n Subjects are systematically approached and asked to participate.

This represents a probability-based sample if:

n Every member of the target population has an equal probability of being at the venue at any given time

or day.

n Every person selected agrees to participate.

n Everyone gives truthful responses.

Time–location sampling requires good-quality formative research to ensure that no bias is entered into

selection of the venue, day and time.

Advantages

A time–location sample can be derived from key informant interviews which describe where members of

the population congregate. Once a full census of these sites has been identified, a random selection of

these sites can be chosen for inclusion in the sample. This information will also be useful for prevention

activities.

Limitations

A number of limitations exist.

n The venues selected might not necessarily be frequented by all of the target population.

n It is difficult to estimate the probability of missing someone who does not attend any of the venues.

n Some venues offer little privacy for disclosure of sensitive information.

n The accuracy of self-reported data given in a public setting is questionable.

n Identifying venues that most-at-risk populations frequent could be exposing them to unwanted attention.

Although it is time- and labour-intensive, time–location sampling does have utility for surveillance among

groups at higher risk for HIV infection as a result of high-risk behaviour (45).

More guidance on how to conduct a time–location survey can be found at: http://globalhealthsciences.ucsf.

edu/PPHG/assets/docs/tls-res-guide.pdf.

Guidelines on surveillance among populations most at risk for HIV

21

Time–location sampling in Harare, Zimbabwe

“Spatial–temporal” sampling, or time–location sampling, was used for a cross-sectional survey in

Harare, Zimbabwe of men who frequent beer halls. These men are a proxy group for men who have

high-risk sexual behaviour or frequent sex workers. To create the sample, the researchers:

n created a list of all beer halls owned by one operator (which accounted for 75% of the beer halls in

Harare),

n created a calendar of 4-hour recruitment events,

n randomly selected the beer halls to fill each calendar event,

n approached every third man who entered the beer hall to assess his eligibility for the survey

(eligibility criteria included that the man was not intoxicated).

Interviews were conducted in the privacy of nearby vans and biological samples were taken to test for

HIV. Prevention efforts were provided at the same time as the survey. Prevalence of HIV was found to

be 30% among men attending beer halls in Harare. Sex while intoxicated, unprotected sex with casual

partners, and paying for sex were highly correlated with recent HIV seroconversion. The results of this

study suggested that prevention efforts should be focused on patrons of beer halls (46).

Comparison of time–location sampling and respondent-driven sampling

Time–location sampling and respondent-driven sampling are the most common sampling techniques

currently used among populations most-at-risk for HIV. They both have limitations. Sometimes one is

preferred over the other (47).

Use respondent-driven sampling when:

n the target population is truly hidden

n it is useful to understand the social connections within the population for programme planning.

Use time–location sampling when:

n the target population is visible

n knowledge of the environment will also assist with programme planning.

2.3.8 Sample size

Sample size is an important aspect of the sample design and requires a number of considerations.

n What are the key variables in the study (usually HIV prevalence or behavioural factors)?

n How precise do the estimated results for those variables need to be?

n Does the survey need to be large enough to detect change over time between surveys or differences

between key subgroups?

In general, larger sample sizes are better than smaller ones:

n Larger samples provide the ability to distinguish true differences among subgroups of the population

or to analyse trends in incidence and risk behaviour. Because most hidden or high-risk populations are

themselves heterogeneous, surveillance requires large sample sizes to analyse subgroups.

n Larger samples are needed to make the sample more likely to accurately represent the population (i.e.

there is less uncertainty around the estimate).

n It is important to note that a large sample does not necessarily guarantee estimates that are unbiased. It

is possible to have a very precise estimate of a biased value.

For more detailed information on calculating sample size, see Surveillance of populations at high risk for

HIV transmission (48).

22

2.3.9 Sampling strategies for populations most at risk for HIV

Sex workers

Sex workers may be working legally or illegally:

n If they are legal and registered, routine screening for sexually transmitted infection may be required. If

so, a list of workers may be available from authorities or clinics. In this case, simple random sampling

or enumeration may be possible from the list. If no such list is available, time–location sampling may be

used. For reasons of comparability, surveillance should be conducted during the same period each year.

n For illegal sex workers who are venue based, time–location sampling at street, brothel, agent or other

venues can be used for HIV surveillance. If sex workers are not venue based but are well networked,

respondent-driven sampling might be appropriate.

Surveillance in institutional settings such as clinics is less subject to refusal bias, but more subject to

participation bias when compared with population-based surveillance. Clinics may overrepresent sex

workers at either end of the economic spectrum, depending on whether services are free or not. Some

populations may avoid clinics due to legal implications or stigma toward their behaviour.

Clients of sex workers

Researchers may use time–location sampling focusing on the locations where persons meet sex workers to

provide estimates of behavioural risk and infection prevalence (49). Researchers may also use convenience

sampling. In this case, an interviewer approaches clients leaving the room of a female sex worker to invite

the client for an interview and to provide an oral fluid sample for rapid testing (15,16). Clients of sex workers

are often not well networked so snowball or respondent-driven sampling is not effective in this population.

Persons who inject drugs

For out-of-treatment drug users, street- or venue-based sampling or network sampling will be necessary. For

in-treatment drug users, convenience samples can be useful. For example, needle exchange programmes

can be useful in assessing the changing characteristics of illicit drug markets, even though the data are

not representative of the broader population of persons who inject drugs (18). Behavioural surveillance is

important to document the effectiveness of prevention programmes in this population (20). Injecting drug

users are often well networked in order to purchase drugs so network sampling methods are appropriate.

Men who have sex with men

Sampling approaches for HIV surveillance among men who have sex with men again depends on the stigma

attached to the behaviour.

Convenience sampling, such as patients at a clinic (50) is often difficult as few countries have clinics devoted

to men who have sex with men. In those that do, such clinics are usually limited to large urban centres.

For men who have sex with men, it may be more appropriate to conduct repeated biological and behavioural

surveys at venues identified through formative research. If the population is hidden and venues are not

available, respondent-driven sampling can be used. Repeating these surveys at consistent sites will be

crucial for tracking trends over time.

Guidelines on surveillance among populations most at risk for HIV

23

Surveillance among men who have sex with men in Bangkok, Thailand

Three cross-sectional surveys were carried out in Bangkok, Thailand between 2003 and 2007. The

surveys focused on men who have sex with men using a time–location sampling methodology.

Venues where the men congregated were identified through a mapping exercise followed by a count

of the men attending each venue. Venues were then selected for participation in the survey.

HIV prevalence was calculated and regression analyses were used to evaluate differences and trends

over time adjusting for time–location cluster sampling. HIV prevalence in 2003, 2005 and 2007 was

17.3%, 28.3% and 30.8%, respectively.

There was a significant increase between 2003 and 2005 but the difference between 2005 and 2007 was

not significant. Additional analysis was done by looking at proxy measures of incidence and changes

in behaviour over time (see section 3.3.5). Based on the prevalence levels and the behavioural data,

the authors identified key prevention strategies that would be useful for reversing the epidemic among

men who have sex with men in Bangkok (51).

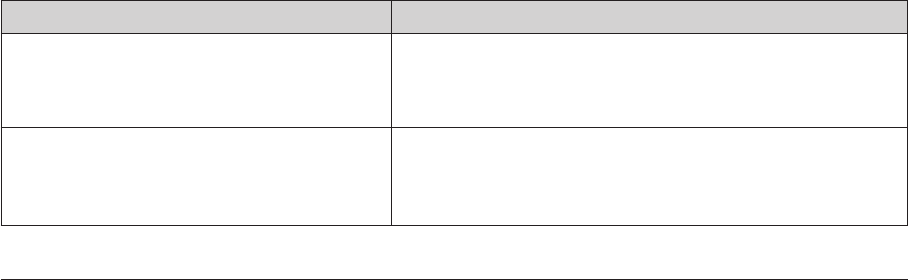

Table 2.2 provides a quick overview of sampling strategies for populations at higher risk for HIV because of

high-risk behaviour.

Table 2.2. Sampling strategies for various populations

At higher risk Possible sampling strategies

Sex workers n Time–location sampling: At hotspots where sex workers sell their trade

n Convenience: List of registered sex workers

n Convenience: List of STI clinics attendees

Clients of sex workers n Cluster sampling: survey of proxy populations (truck drivers, fishermen)

n Time–location sampling: hotspots where clients meet sex workers

n Convenience: list of STI clinic attendees reporting sex worker visits

Persons who inject drugs n Respondent-driven sampling: starting seeds from an injecting arcade

n Time–location sampling: at street venues where people inject

n Convenience: List of treatment centre attendees

Men who have sex with men n Respondent-driven sampling: starting seeds from a club

n Time–location sampling: at venues (bars, parks, etc.)

n Cluster sampling: using surveys of proxy populations (prisoners)

24

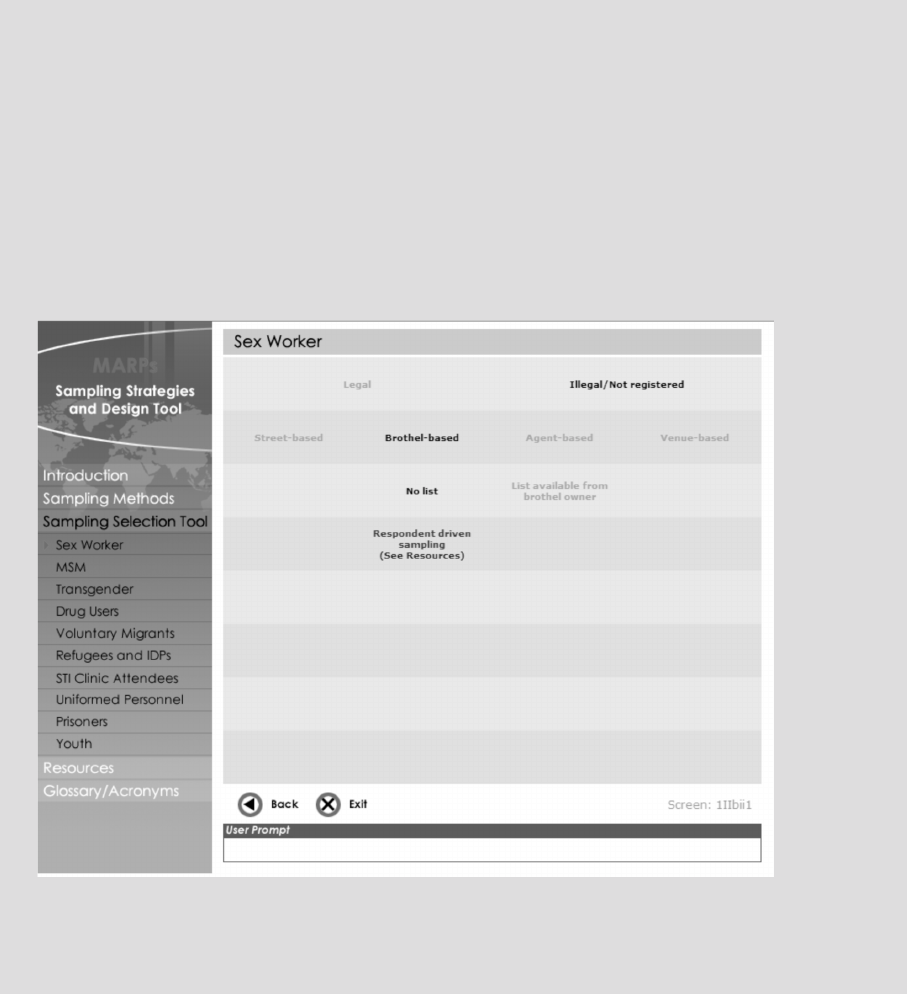

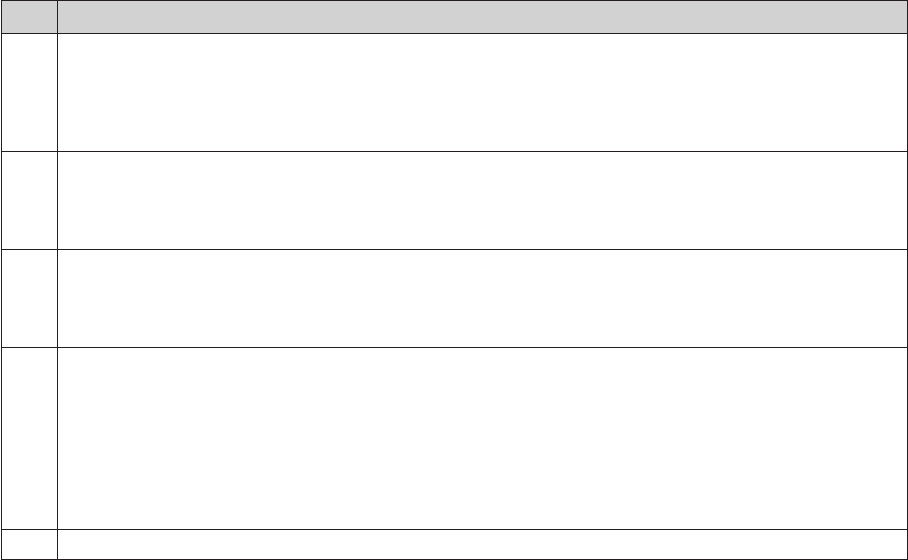

Sampling strategies and design tool

A useful tool for determining the most appropriate sampling tool is hosted at

http://globalhealthsciences.ucsf.edu/PPHG/surveillance/CDC-MARPs/sampling_selection.htm.

This tool provides sampling strategies based on the population that is being surveyed. It includes most-

at-risk populations as well as some populations that are commonly considered proxy populations for

surveillance of those most at risk. Figure 2.3 provides a snapshot of the tool and the results for brothel-

based sex workers.

Figure 2.3. Example from the sampling strategies and design tool

Developed for Centers for Disease Control and Prevention by Design and Learning Interactive, Inc.,

www.designandlearning.com, a Northrop Grumman subcontractor, 2009.

Guidelines on surveillance among populations most at risk for HIV

25

The next part of the process concerns conducting surveys. Populations most at risk for HIV have special

requirements. Focus on their special needs and how to avoid legal repercussions and stigma.

Figure 3.1. Conduct surveillance of most-at-risk populations

3.1 Step 4: Address operational issues

3.1.1 Plan staffing and training

Recruiting and training staff for a surveillance project is a critical and challenging task. The surveillance

programme staff should include:

• managementandtechnicalpersonnel

• supportstaff

• eldworkstaff

• dataentrystaff

• analysisstaff.

3. Conduct surveillance of populations

most at risk for HIV

26

Table 3.1 provides a surveillance staff list and job responsibilities. Regular and ongoing training of staff is

critical to ensure the success of the surveillance programme. All staff should be aware of all aspects of the

programme. Use every opportunity to cross-train staff. For example, give data entry staff field experience in

collecting data. They will be better team members.

Table 3.1 Example responsibilities of surveillance programme staff

Staff categories Example responsibilities

Surveillance management and technical personnel

Surveillance director n Overall surveillance, statistical and financial direction

n Technical lead for the project

Surveillance and statistical specialist n Surveillance methods, statistical survey design, enumeration areas, sampling frames

n Fieldstafftraining,supervision,qualitycontrol

n Data management, statistical analysis, report writing

Financial manager n Surveillance budget accounts

n Spending monitor

n Contractsandacquisitions

Support staff n General administrative support for surveillance staff

(May include drivers and tracking of fuel and mileage)

Fieldwork

Team leader n Team supervisor

n Meetings with community leader and members

Interviewer n Interviewing and obtaining specimens for HIV testing

n Completingquestionnairesandeditstoquestionnaires

Laboratory technician n Obtaining specimens for HIV tests if the survey protocol does not allow interviewers to do

this

n Performing tests in the laboratory

n Quality control of laboratory data

Data entry and processing

Data manager Manager for:

n Data entry, program and database development

n Dataediting,qualitycontrol

Data entry personnel n Questionnaire management

n Final hand-editing

n Dataentryfromquestionnairesintoelectronicdatales

Analyst n Supervisor, construction of documentation

n Data analysis

n Interpretation of results for relevant audiences