Building the City of Solutions

Evaluating the Addiction

Crisis Response

in Huntington/Cabell County WV

Principle Investigator

-Todd Davies, PhD

Quantitative Team Lead

-Hannah Redman, MSHI, MHA

Team

-Tim Babine, MS, MSHI

-Jonathan Willis, MS

-Jing Tian, MS

Qualitative Team Lead

-Taylor Maddox-Rooper, MS

Team

-Ryan Crouse, MA

-Fortune Ezemobi, MPH

-Kassandra Flores, MS

-Paris Johnson, MPH

-Benjamin Thompson, MS

-Sarah Matson, MPH

Tool Development

-Debra Koester, PhD, DNP,

MSN, RN

MARSHALL TEAM

Evaluation Lead

-Debra Dekker, PhD

Directoral Support

-Chris Aldridge, PhD, MSW

-Aaron Alford, PhD, MPH, PMP

Fidelity Team

-Shawna Newton

-Kellie Hall

-Caden Gabriel

NACCHO TEAM

Project Lead

-Michael Meit, MPH, MA

ACEs Team

-Lucianna Rocha, MPH

-Michelle Dougherty, MPH

-Victoria Hallman

-Megan Heffernan, MPH

-Margaret Cherney

Partner Analytics

-Brandon Sepulvado, PhD

-Keshav Vemuri, MS

NORC TEAM

Project Director

-Christopher Jones,

PharmD, DrPH, MPH

Project Coordination

-Brian Corry, MS

-Akadia Kacha-Ochana,

MPH

Technical Assistance

-Steven Sumner, MD

-Gaya Myers, MPH, CHES

-Manisha Patel, MD, MS

-Vikram Krishnasamy, MD

CDC TEAM

© MUSOM 2021| www.jcesom.edu

Addiction Response | September 2021

Understanding Declining Rates of Drug Overdose Mortality in Eastern Kentucky NORC at the University of Chicago

jcesom.marshall.edu September 2021

Introduction

By 2014, Huntington/Cabell County found itself in

the midst of an addiction epidemic that put the

entire community into crisis mode. The community

came together to create a response to the

epidemic, which was built on an unprecedented

level of collaboration. This report evaluates the

development of that response and outlines the

critical timing and resources that made it

successful.

Prior to the community response, Huntington, WV

and surrounding Cabell County was much like

many communities in regards to addiction. The

focus of services were primarily on the clinical

aspects of treatment and recovery. Agencies

operated separately and often functioned as

competitors. Medication assisted treatment (MAT)

providers and peer-based or 12-step programs

spoke of each other with distain. The local

governmental approach to addiction was

channeled through the police department. As the

number of people struggling with addiction

increased across the community, it became clear to

many that those approaches were not sufficient to

address the growing problem. Frontline workers

often felt that with control over the resources (Key

Stakeholders) did not understand the full

consequences of addiction and were not

empowered to address many critical issues.

“I think we spend a lot of time with

people with initials after their names

thinking they have the answer and the

only thing they've been in is a book.”

- Frontline Worker

Those attitudes changed when the political, health,

and university leadership publically admitted that

the community was in trouble and worked together

to create an

environment

of

collaboration

across the

community.

Frontline

workers and

patients were

sought out for their expertise and encouraged to

build natural connections between agencies. The

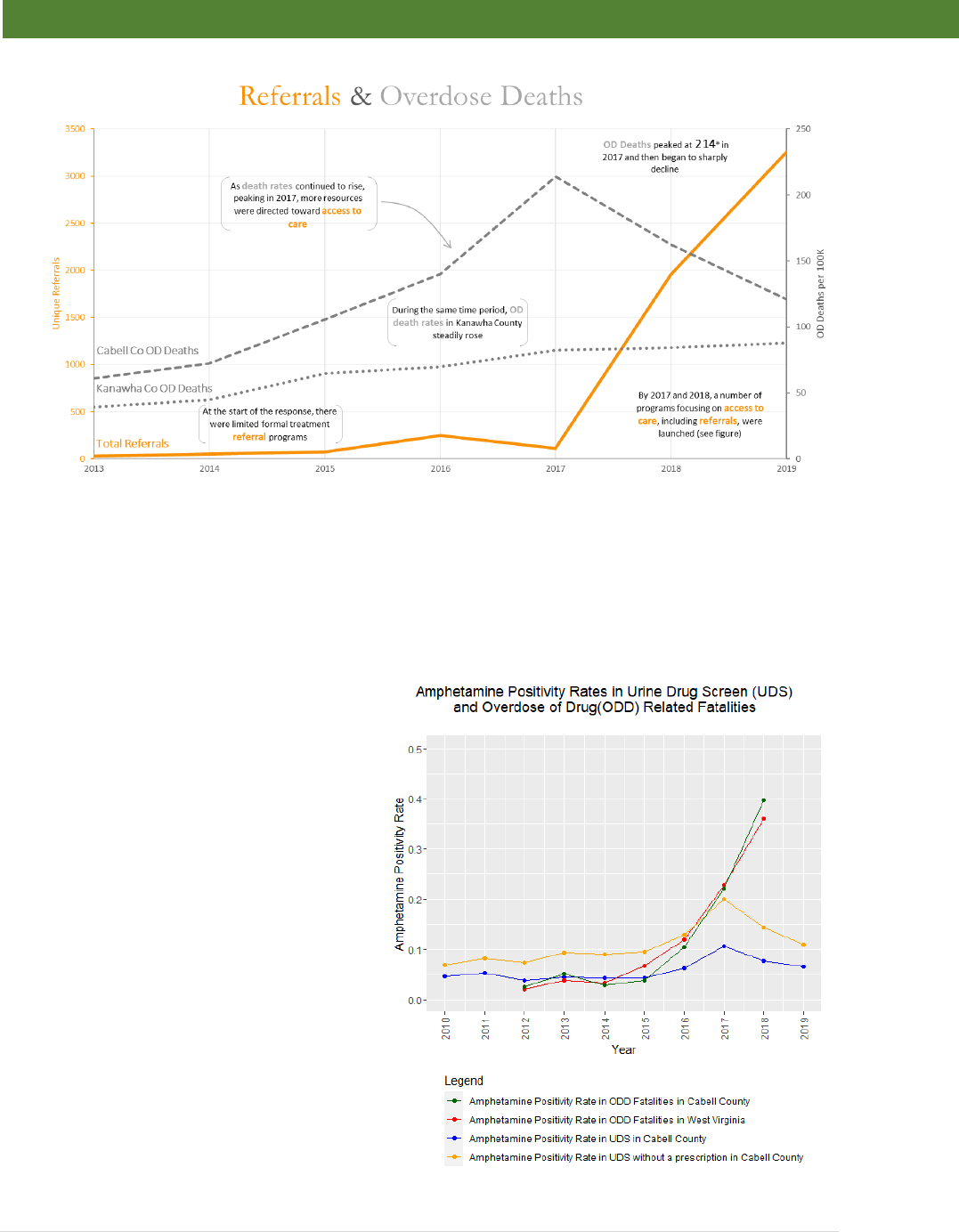

overall result was a large increase in referrals to

treatment and a decrease in overdose deaths.

Project Description

With funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Association of County and

City Health Officials (NACCHO), the Division of Addiction Sciences within the Joan C. Edwards School of Medicine at

Marshall University (Marshall) conducted this study to Identify and describe the impact of critical elements of a

community-wide response in Huntington/Cabell County, WV to the addiction epidemic. The community response resulted

in an increase in the number of individuals with substance use disorder identified and referred to treatment that correlated

with a two-year drop in overdose deaths just prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. This study describes the severity of the

epidemic including the significant barriers. Key actionable components for other communities are reported with the

approach and timing required to deploy them.

Building the City of Solutions

Evaluating the Addiction Crisis Response in Huntington/Cabell County WV

Executive Summary

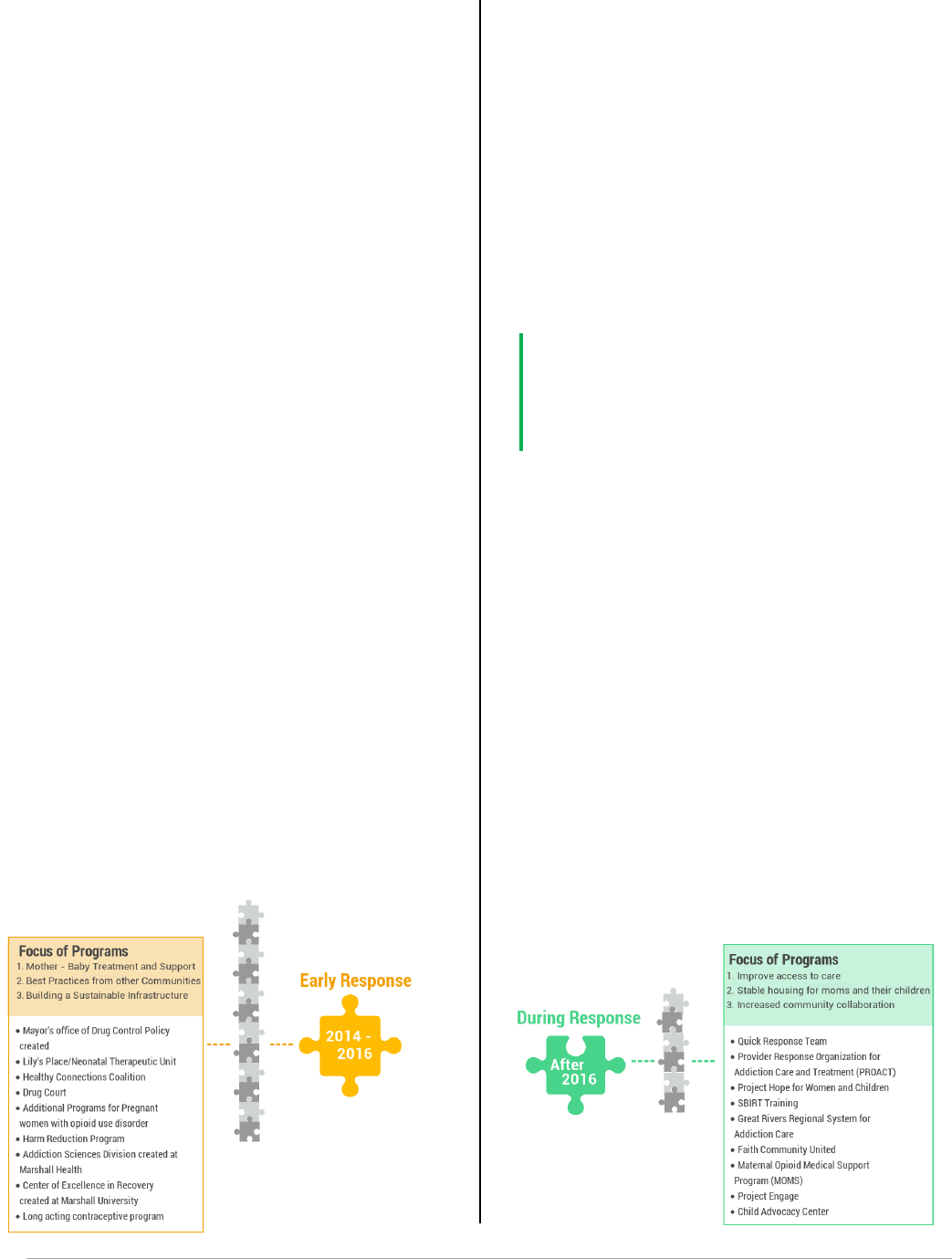

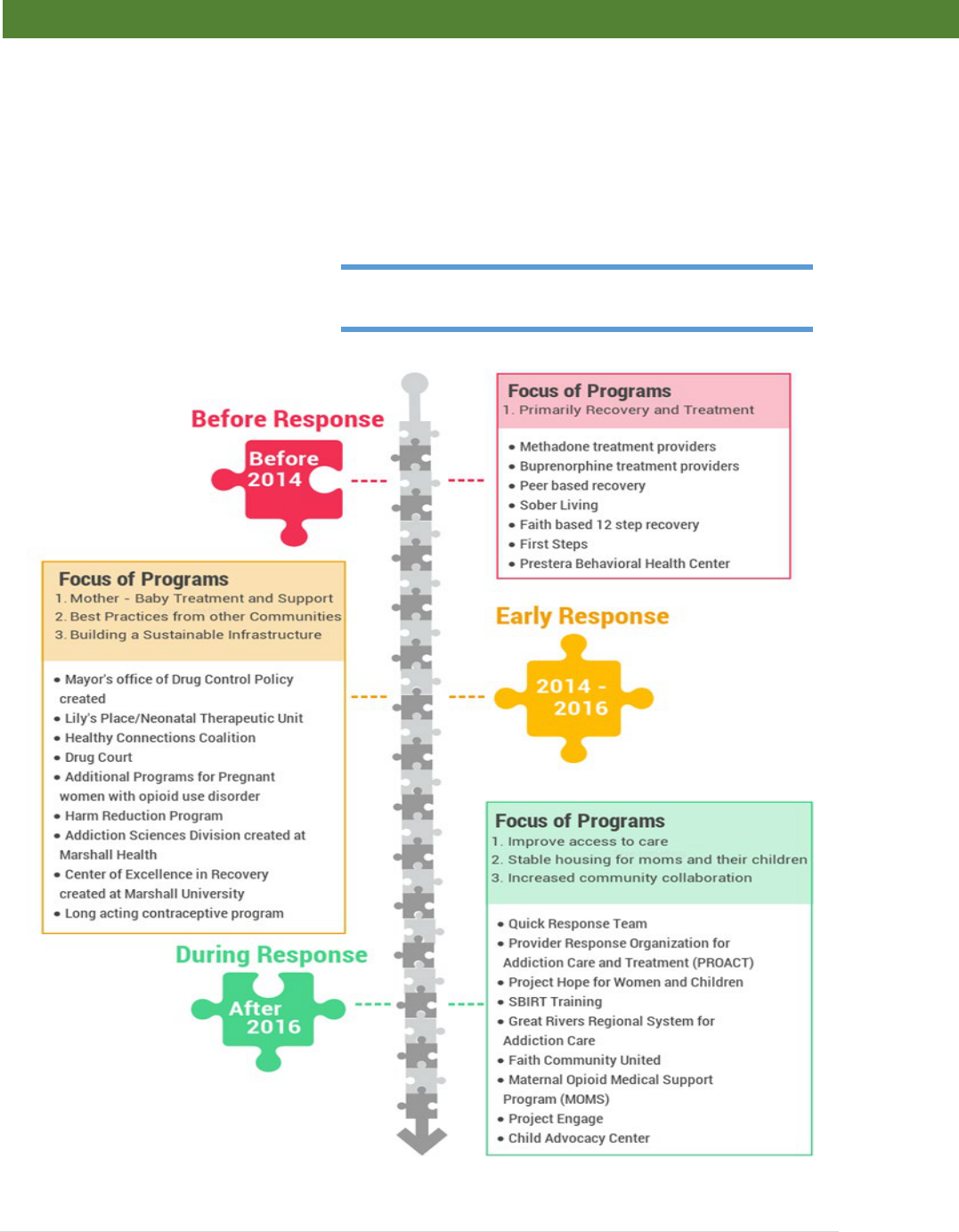

Figure 1: Programs prior to response

Figure 2: Critical leadership entities.

© MUSOM 2021| www.jcesom.edu

Addiction Response | September 2021

Figure 3: Programs early in the response

Methods

A multi-layered mixed methods approach was

used by evaluators. Data was collected and

analyzed use a variety of complementary

methodologies.

• Qualitative data from those involved

with the Huntington/Cabell County

addiction epidemic response was

collected by semi-structured

interviews with 44 Key Stakeholders

(administrative level) and 56 Frontline

Workers (those who with work directly

with those affected by substance use).

• A non-affiliated “client survey” was

conducted of individuals with

substance use disorder (SUD) to

collect the patient perspective of the

response.

• A partnership survey and network

analysis was used to determine the

level of agency collaboration.

• Evaluators also conducted a review of

SUD and Cabell County-related media

activity.

• A community shared data system was

developed to aggregate clinical data to

determine success of the evaluation

through existing data.

Findings

Building the Response

The response to the addiction epidemic in

Huntington/Cabell County, WV was a process with

the community searching for answers. The key

attribute that made the response successful was

the attitude and approach of leadership that the

community should search for answers

together. Community buy-in was still a challenge early

on, so efforts were focused on adopting best practices

from other communities (such as establishing a drug

court) while building a sustainable infrastructure that

would allow the community to react quickly as the

consequences of widespread addiction.

As part of creating infrastructure, local government,

county health officials, and university members

emphasized the collection and analysis of more real-

time data for the community to convince State and

Federal agencies of the critical nature of the situation.

Data available to these agencies was not timely or

representative of the size of the problem, making it

difficult to secure grant funding for the area.

“I think having access to data, just

information is so crucial because people

don't understand what's happening.”

- Key Stakeholder

Community agencies began immediately building

collaborations, but with an emphasis on mother –

baby resources. As part of the epidemic, Cabell

County was experiencing an alarming number of

births in which the neonate was prenatally exposed

to drugs. Most of the community viewed these babies

as innocent, and community support for these

resources met with minimum stigma.

Buy-in from the larger community for patients with

substance use disorder outside of exposed neonates

did not happen until August 2016 when the area

experienced 26 overdoses in a single day. After this

day, the response became focused on improving

access to care and building community collaboration.

These later efforts were directly responsible for the

success of the response, but would not have been

possible without the earlier infrastructure and

collaboration already in place.

Figure 4: Programs during the full response

Evaluating the Addiction Crisis Response in Huntington/Cabell County WV

Division of Addiction Sciences Research

© MUSOM 2021| www.jcesom.edu

Addiction Response | September 2021

What Worked?

Key Stakeholders and Frontline Workers agreed that collaboration, community buy-in, and a client-centered

approach are what made the response effective. The collaboration structure in Huntington/ Cabell County, WV

is unstructured, denoting an environment of collaboration and not a controlled process. There was a strong

sense from the community members that participated in data collection that, while the new programs are an

important part of the response, the collaborative approach was the key to identifying and deploying the

programs that were best suited to this community specifically. Culture, or cultural specificity, was an important

part of the overall process. All of the programs developed after 2016 also have a peer component in order to

extend that cultural sensitivity directly to the clients in need of support or care.

Key Stakeholders also discussed that data collection and the willingness to try new methods and approaches

were key factors, while Frontline Workers and surveyed clients focused on more practical aspects of recovery

(access to care, transportation, fulfilling personal commitments, etc.).

Recommendations for other

communities:

•

Admit there is a problem:

This will likely

require strong political leadership

•

Empower existing resources:

Many

answers were found existing within the

community already

•

Create an environment of

Collaboration:

Natural collaborations are

the most effective, but can require

encouragement.

•

Focus attention on whole life recovery

and families:

Every patient represents a

larger group that needs support.

•

Treat patients as human beings:

Services will not be utilized to the fullest

extent if the clients don’t feel welcome.

•

Control the message with shared data:

Tell others about your community; don’t

wait for them to decide who you are.

•

Watch out for compassion fatigue:

Those in the thick of the fight need to

know that their efforts are worthwhile.

ABOUT NAACHO

National Association of County and City Health Officials

(NACCHO) was established in 1965 to improve the

health of communities by strengthening and advocating

for local health departments. NACCHO currently serves

over 3000 local health departments and is the leader in

providing cutting-edge, skill-building, professional

resources and programs, seeking health equity, and

supporting effective local public health practice and

systems. NACCHO is dedicated to supporting local

health departments, optimizing strategic partnerships

and alliances, and advocating for local health

departments.

ABOUT MU Joan C. Edwards School of Medicine

The Joan C. Edwards School of Medicine at Marshall

University is a community-based, Veterans Affairs

affiliated medical school established in 1977 to address

health disparities in rural tri-state region of southern

West Virginia, southeastern Ohio, and eastern Kentucky

and dedicated to providing high quality medical

education and post graduate training programs to foster

a skilled physician workforce to meet the unique

healthcare needs of the population we serve. The

mission was and still is today to provide healthcare and

education to Appalachia.

Table of Contents

Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 1

Background .................................................................................................................. 1

A Community in Trouble ............................................................................................... 2

Methodology ......................................................................................................................... 5

Interviews ..................................................................................................................... 5

Surveys ........................................................................................................................ 6

Quantitative Methodology ............................................................................................ 6

Media Analysis ............................................................................................................. 7

Findings ............................................................................................................................... 8

Addressing the Barriers ................................................................................................ 8

Building Collaboration is a multi-Step Process ........................................................... 10

Evaluation of Community Collaborative Structure ...................................................... 10

Process of Developing a Community-Wide Collaborative Environment ...................... 12

Finding Common Ground ................................................................................... 12

Leadership ......................................................................................................... 13

Community Response Approach ....................................................................... 16

Collaboration Creates Opportunity for Sustainable Programs ................................... 20

Stigma, Misunderstanding, and Educating the Community ........................................ 21

Financing the Response-Data is the Key ................................................................... 24

Indicators of Success ................................................................................................. 25

Future Directions .................................................................................................................. 30

Limitations ............................................................................................................................ 32

Conclusion ............................................................................................................................ 33

Lessons for Other Communities ........................................................................................... 34

Index of Response Participants Mentioned in Evaluation: .................................................... 35

Resources ............................................................................................................................ 36

Funding from the CDC was made possible through the Center for State, Tribal, Local, and

Territorial Support (CSTLTS) Cooperative Agreement OT18-1802 "Strengthening Public Health

Systems and Services through National Partnerships to Improve and Protect the Nation's

Health.”

1 | Evaluating the Addiction Crisis Response in

Huntington/Cabell County WV

Introduction: For the last few decades, a major epidemic grew and the United States saw an

increase in the incidence and complication rates of drug addiction.

1

This epidemic would result

in deaths by drug poisoning surpassing death by suicide, homicide, firearms and motor vehicles

accidents by 2017.

2

A culmination of events placed the small Appalachian city of Huntington,

West Virginia at the epicenter. Huntington and surrounding Cabell County, developed a

community response that included an unprecedented level of collaboration and a number of

novel solutions. In Dec 2019, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) through

the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO) funded an evaluation of

the community response to the addiction epidemic to:

1. Identify and describe the impact of critical elements defined as part of the response in

Huntington/Cabell County, WV

2. Understand the role of public health system partners on the effectiveness of system

delivery and utilization in the response in Huntington/Cabell County

3. Identify the actionable factors for translating the Huntington/Cabell County response to

other communities.

Utilizing a mixed methods approach, evaluators conducted 100 interviews with Key

Stakeholders (administrative level) and Frontline workers (those who work directly with those

affected by substance use). By conducting a partnership survey to determine the level of

agency collaboration; a client survey of individuals with substance use disorder (SUD); a review

of SUD-related media activity and a quantitative clinical data system, evaluators were able to

report on the response to the addiction epidemic in Huntington/Cabell County. This report will

describe the severity of the epidemic, the response, and report indicators of effectiveness. The

ultimate goal is to identify the key components of the response that may be adapted and used in

other communities to respond to public health crises.

Background: Cicero et al demonstrated that the pattern of first opioid use changed significantly

in the last 40 to 50 years. Eighty percent of individuals who had their first opioid use in the

1960’s reported that first exposure to be heroin. Contrast this with the 2000’s, where 75% of

users reported prescription opioids as their first exposure.

3

Despite an increased likelihood of

abuse, only 4.2% of those using opioids non-medically turned to heroin

4

. Some researchers

speculate OxyContin abuse may have increased the rates of heroin abuse,

5

6

but as OxyContin

prescribing decreases heroin use continues to rise.

5

As efforts continue to reduce the over-prescribing of opioids, availability of opioids made

significant inroads. Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) WONDER

Database found increases in overdose deaths associated with heroin and synthetic opioids like

fentanyl.

7

8

In fact, heroin related overdose deaths jumped from 1,842 in 2000 to 10,574 in

2014

9

with heroin use increasing significantly in most demographic groups.

4

The influence of

overprescribing on the addiction epidemic may have waned with prescribing restrictions, but the

substance abuse continued to grow as an increasing number of patients reported heroin as their

first opioid

8

, reversing the trend of the previous few decades.

By 2015, claims were being made of Middle America being specifically targeted by opioid

producers and “Mexican drug lords.”

11

Heroin became more readily available in areas not

traditionally considered centers for drug distribution

12

and the cost per gram dropped from

$2,690 in 1982 to less than $600.

13

2 | Evaluating the Addiction Crisis Response in

Huntington/Cabell County WV

This increased availability and lower cost of heroin, coupled with the poor economic conditions

and isolating terrain throughout Central Appalachia, created a fertile soil for this targeted drug

activity to grow. West Virginia (WV), the only state located entirely in Central Appalachia, ranks

consistently as one of the worst states for health and economic status. WV had the highest age-

adjusted death rate from drug poisoning in the country.

14

The state reported a rapid growth in

the rates of opiate overdoses,

15,16

Hepatitis C and other communicable diseases related to

sharing needles, and Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS)

17

throughout WV with the most

severe effect on Southern WV.

18

This culmination of evidence indicates that West Virginia was,

likely, the most impacted state in the union and Huntington/Cabell County was the most affected

part of the state.

Numerous anecdotal accounts report the

majority living in the Huntington or Cabell

County, WV either struggled with SUD or

had a loved one who did. Because of the

widespread personal impact, the

community was quick to set aside biases

and individual agendas to work toward a

comprehensive solution.

A Community in Trouble: Prior to 2013,

during the building stages of the epidemic, there were a few already aware of the continued

increase in substance use in Huntington/Cabell County. The number and variety of available

SUD resources suited a community its size, but would prove inadequate in the face of the high

volume of individuals with SUD within the community. There were faith-based programs, like

Celebrate Recovery and Loved One’s, as well as both Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics

Anonymous. Huntington’s numerous sober living houses demonstrated some success helping

those who

sought

recovery. A

peer-based

recovery

facility that

would

eventually

become

Recovery Point

of West

Virginia

opened in

2011. In 2012,

First Steps

Wellness &

Recovery

Center opened

to serve people

experiencing homelessness and the opioid using population. During this time, the Huntington

Comprehensive Treatment Center and Valley Heath Systems provided medication-assisted

treatment options to the community. All of this was in addition to the county’s behavioral health

I always kind of have to smile to myself when I hear

people talk about how the opioid crisis became a

big thing in the 2000s, because, I was here in

ninety-seven and it was already a fairly big thing

then. It was, of course, more pain pills at that time.

– Key Stakeholder

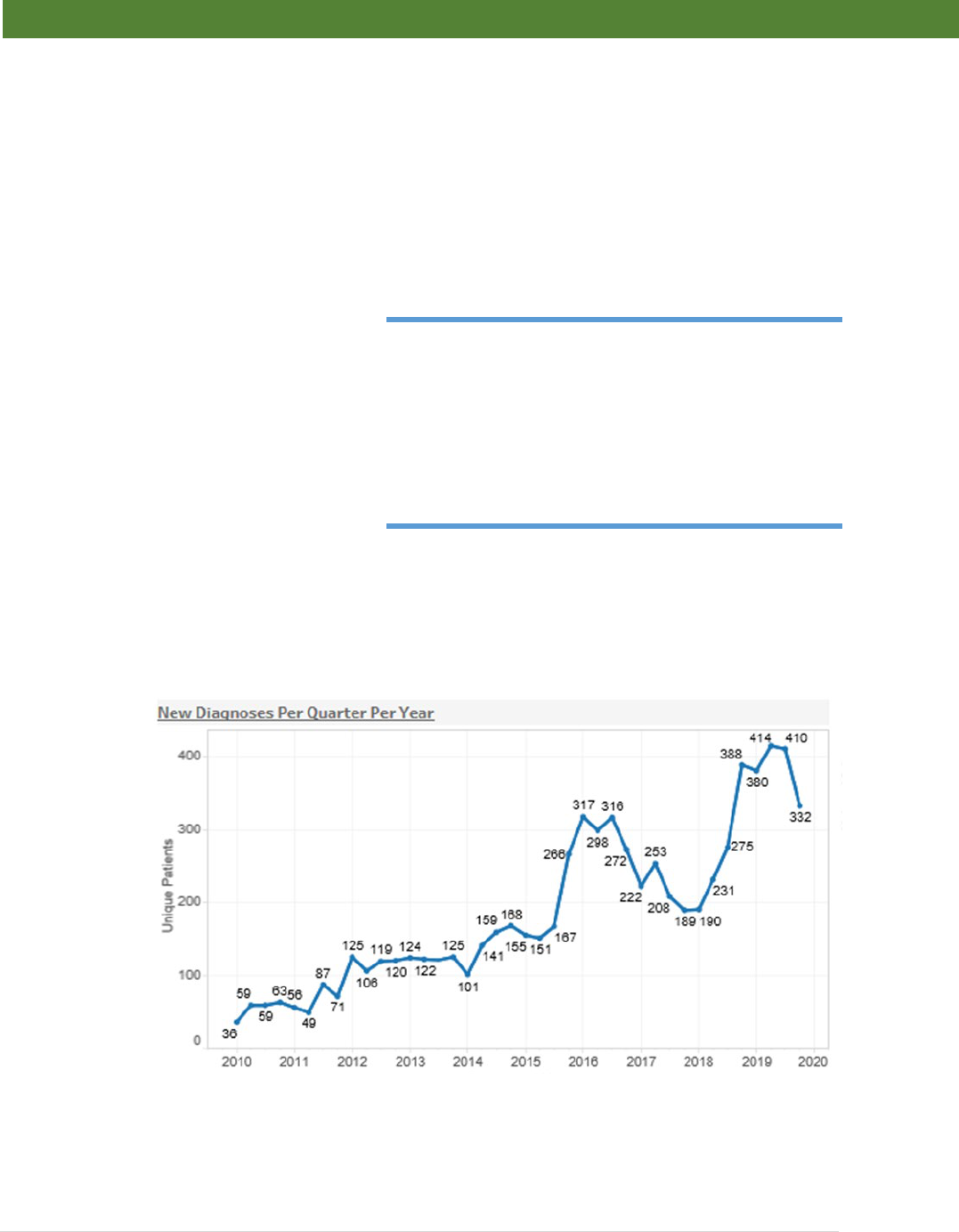

Figure 1: Incidence of new diagnosis of opioid use disorder within WV CAD partner agencies.

3 | Evaluating the Addiction Crisis Response in

Huntington/Cabell County WV

facility, Prestera Center, which ran a variety of programs across the community for decades by

this time.

While many resources existed in the

community, they were largely working

in isolation. Independently, those

involved in these organizations were

noticing a sharp rise in patient volume.

Data would later confirm these observations, but official reports of both incidence and

prevalence are often years behind. A retrospective report using data assembled from the CDC’s

Wonder Database shows that, in 2014, West Virginia led the U.S. in Overdose Death Rate with

35.5 deaths per 1000, almost 2.5 times the national average and 35% more than the next

closest state (New Mexico and New Hampshire are tied with 26.2 deaths per 1000 each).

19

Overdose deaths were not the only data to demonstrate the severity of the substance use

problem at the time. The number of individuals diagnosed with opioid use disorder (OUD)

continued to rise during this period. (Figure 1) Hepatitis C (HCV) infection present in infants at

the time of delivery in West

Virginia was the highest in the

nation at 22.6 per 1000 live in

2014

20

, suggesting that the

number of substance abusers

was quite high the area. Anil

and Simmons published a

comprehensive report on

Hepatitis B (HBV) and HCV

incidence in WV.

21

The

incidence of acute HBV

infection in 2015 was 14.7 per

every 100,000 West Virginia

residents, nearly 14 times the

national average. By 2015,

West Virginia had almost 5

times the HCV infection rate as

the rest of the country

combined (3.4 per 100,000

compared to 0.7 per 100,000)

21

. In developed countries,

about 90% of people infected

It doesn't seem like the community became aware

at the same time, but we felt little changes

happening – Frontline Worker

The initial reaction was, frankly, one of being overwhelmed with the sheer number of

patients we were caring for… but also overwhelming resources and not being able to care

for babies that truly needed an intensive care unit and having to turn those patients away. –

Sean Loudin: Former Medical Director of Lily’s Place and Cabell-Huntington Hospital

Neonatal Therapeutic Unit

Figure 2: Verified number of babies born prenatally-exposed to opioids in

Cabell County, WV per 1000 births Between 2010 and 2019.

4 | Evaluating the Addiction Crisis Response in

Huntington/Cabell County WV

with HCV are former or current injection drug users

22

. Although increased infectious disease

transmission rates are a significant part of the overall societal cost, infection rates are

dependent on several factors (harm reduction, sexual activity, transmission rates, etc.) and does

not include non-injection misuse of opioids exclusively.

Perhaps the most impactful and alarming aspect of the addiction epidemic was the surge of

babies born with in utero exposure to opioids and other substances and those that developed

Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS). Among 28 states with publicly available data in the

Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project during 1999-2013, the overall NAS incidence increased

300% from 1.5 per 1000 hospital births in 1999, to 6 per 1000 hospital births in 2013. Using

state-based data, the CDC reports that WV has the highest rate of babies born with NAS in

2013 at 33.4 per 1000

17

. It has also been reported using the WV Health Care Authority (HCA)

database and the Uniform Billing Database that southeastern region of WV has the highest

incidence of NAS in the state at 48.76 per 1000 births.

18

Based on a comprehensive review of

cases from Cabell County’s primary birthing hospital, Cabell Huntington Hospital (CHH), it is

possible that the numbers from these databases vastly under-reported the true severity of the

situation. The 33.4 per 1000 NAS patients for West Virginia in 2013 is much lower than the 76.4

per 1000 patient treated for severe withdrawal due to prenatal exposure in the same year and

163.9 neonates per 1000 live births with known in utero exposure to drugs, also in 2013. Those

numbers continued to increase and were reported as 94.3 neonates with severe withdrawal per

1000 live births and 185.8 per 1000 with known in utero exposure in 2015.

23

That number rose

to 236 per 1000 by its peak with 123 per 1000 of those neonates exhibiting severe enough

symptoms to be diagnosed with NAS. (Figure 2)

Of course, in 2011 and 2012, none of these statistics were available. Tolia et al reported in 2015

that NAS was increasing in frequency and represented a large percentage of admissions to

some NICUs across the country.

24

This was certainly true in Huntington/Cabell County. The

NICU at Cabell-Huntington Hospital was so inundated with withdrawing neonates that newborns

with more severe medical needs were often sent to regional hospitals hours away.

Huntington and the surrounding community were desperate for solutions. Those who treated

SUD felt isolated, community sentiment to those suffering was unkind, and there was a distinct

lack of leadership. While the members of this small community suffered across the board, the

data lagged behind the reality of the devastation. State and Federal agencies, who only had

access to data that was years old, were largely dismissive of the gravity of the problem. Without

numbers to reinforce the claims, the outside world could not see the signs of the epidemic

ravaging on the inside. Discussions of SUD and Cabell County, WV were rarely held outside the

region. The community felt invisible. As the epidemic increased in intensity, the community went

from relative obscurity to intense scrutiny. By 2017, four percent (4%) of all media and social

media coverage related to addiction worldwide mentioned Huntington or Cabell County. That

number had dropped to less than 2% by 2019.

In the face of doubt, feelings of isolation, and general hopelessness the Huntington/Cabell

County community developed a collaborative response perceived by the individuals connected

to the local SUD population as being highly successful. This response has been credited for a

decrease in overdose deaths and building the infrastructure necessary for long-term community-

wide recovery. Many communities face, or will face, similar public health crises and could

potentially benefit by developing a similar response. An evaluation of the community response

to the addiction epidemic was conducted to fully understand the key components, aggregate the

community-wide measures of success, and create a roadmap for other communities.

5 | Evaluating the Addiction Crisis Response in

Huntington/Cabell County WV

Methodology: A mixed methods approach was applied to explore the perceived effectiveness

of the addiction epidemic response in Huntington/Cabell County by key stakeholders, frontline

workers, and individuals in treatment. Participants were asked to identify the effective

components of the response, barriers, and remaining gaps. To support this data, a partnering

survey was conducted to determine the level of interagency collaboration across the community

and a media analysis was completed for 2014 through 2019. One or all of the above

instruments were used to collect data representing 67 separate agencies or major divisions

including representation for treatment, recovery, public health, education, recovery and family

services, criminal justice, economic/workforce development, and advocacy. The Marshall

Institutional Review Board (IRB) reviewed and approved all study mechanics and participant

interactions. Before each interview, the interviewer conducted informed consent with the

participant to assure voluntary participation.

Interviews:

1. Definitions:

a. Key stakeholders (KS) – defined as individuals that were directly involved

with the response and had decision-making authority (or significant influence

over decision making authority) for an agency with regular interaction with

the SUD population

i. Data was collected from 44 KS by in-person individually interviews.

b. Frontline workers (FL) – defined as individuals who had substantial direct

client contact with individuals with SUD or their family members during the

response.

i. The original intent was to conduct focus groups of FL based on sector

representation. COVID-19 restrictions required a shift to individual

telephone interviews. Fifty-six (56) FL were interviewed.

2. Interview Design: An interview guide was developed for each population type (KS

and FL) to maintain consistency between interviews. Conduct of the interviews

were semi-structured to allow participants to express themselves freely thus

allowing for more accurate data capture. As Marshall University is imbedded in the

Huntington/Cabell County community; evaluators had internal knowledge and

experience of the response. This knowledge was augmented by additional local

stakeholders not related to the study team, including individuals with lived

experience, to formulate value-based questions aimed at identifying the critical

elements of the response in Huntington/Cabell County, WV. Interview guides were

then independently reviewed by members of NACCHO and the CDC for

appropriateness and project relevance. In addition to an accounting of the history

of the development of the community response, questions identifying critical areas

are best surmised with the following questions:

1. At a community level what is working and how has the community gaged that

progress or success? How do you know it is ‘working’?

2. What barriers must be overcome?

3. What gaps remain currently in the community response? Has the community

tried to address them to date – why or why not?

4. What changes occurred at the community level as a result of the community

response in Huntington/Cabell County?

5. What are the most important ways in which the community responded from

2015 to 2019 that other communities should understand?

6 | Evaluating the Addiction Crisis Response in

Huntington/Cabell County WV

Participants were initially identified based on their association with agencies known

to participate in the response or interact with a significant portion of the SUD

population in Huntington/Cabell County. Further participants were identified using

snowball sampling. Interviews were recorded and transcribed. Partners at NACCHO

independently screened interviews to assure fidelity and identify bias prior to

analysis. The research team conducted an analysis of qualitative data using NVivo

qualitative analysis software (QSR International Pty Ltd., Melbourne, Australia). We

developed a codebook to identify themes and topics of interest based on the

research hypotheses.

Surveys:

1. Partnering Survey – Individuals participating in the KS and FL interviews were provided

a partnering survey at the conclusion of the interview. The survey received 75.7%

participation with all agencies represented. Participants were provided a comprehensive

list of agencies involved with the SUD population and asked to rate the relationship

based on the level of collaboration with their own agency. The strength of the tie

between agencies was rated on a scale from 0 to 5.

a. No Interaction (0): No interaction with your organization at all.

b. Networking (1): Aware of organization - Loosely defined roles - little

communication - All decisions are made independent from this organization.

c. Cooperation (2): Provide information to each other - Somewhat defined roles -

Formal communication - All decisions are made independently

Figure 3: Distribution of community interviews by organization type.

7 | Evaluating the Addiction Crisis Response in

Huntington/Cabell County WV

d. Coordination (3): Share information and resources - Defined roles - Frequent

communication - Some shared decision making

e. Coalition (4): Share ideas - Share resources - Frequent and prioritized

communication - All members have a vote in decision making

f. Collaboration (5): Members participate in programs that function as one system -

Frequent communication is characterized by mutual trust - Consensus is reached

on many or all decisions.

2. Anonymous Client Survey: Individuals in SUD treatment or served by recovery

supportive programs were surveyed to determine client perceptions of the response.

Questions were designed to determine, in the last five years, which programs were most

helpful in their recovery journey, key factors in recovery, barriers to recovery, and

changes in access to care. Surveys were distributed to individuals in all aspects of

addiction, treatment, or recovery throughout the community including Medication

Assisted Treatment (MAT) programs, peer-based programs, sober living facilities, those

with SUD that are experiencing homelessness, and individuals served by Lily’s Place

NAS treatment facility. Surveys were provided online and email using Qualtrics

(Qualtrics, Provo, UT) or via paper. Paper surveys were later entered into the system by

research staff.

Quantitative Methodology: In addition to the primary qualitative and survey data collection

mechanisms, the West Virginia Community Data System (WV CAD) was developed to

aggregate substance use disorder data from multiple agencies. WV CAD brings the data from

different agencies using different data collection systems into a single-dimensional database

that can identify unique individuals across the community system in a way that protects patient

privacy utilizing a “Safe Harbor” concept. Our methodology allows us to aggregate private

health information (PHI) while complying with regulations promulgated under HIPAA, HITECH,

42 C.F.R. Part 2 (in regards to PHI, and other substance use disorder information as

contemplated by the confidentiality regulations of 42 CFR Part 2), as well as W. Va. Code § 27-

3C-1 and W. Va. Code § 16-3C-1 et seq., as amended.

WV CAD currently houses data from ten separate programs and agencies representing 70-80%

of the substance use treatment and related programs (by patient volume - approximately

440,000 unique patients that receive care in Cabell County, WV) in Huntington, WV. Data

elements include treatment, program utilization, success measures, substance use data, and a

variety of social determinants of health. Initial quantitative data representing referrals to

treatment, increases in those receiving treatment, and 90-day success rates related directly to

the response, as well as SUD population demographics, were extracted from this system.

Media Analysis: Data was collected Cision Communications Cloud (Cision, Chicago, Il) for

media monitoring of the keywords: substance use disorder, addiction, opioids, opioid use

disorder, drug epidemic, opioid epidemic co-mentioned with Huntington or Cabell County, West

Virginia between 2014 and 2019. Cision combs a collection of global online news, blogs, social,

print and broadcast channels for relevant mentions. Then, we analyzed those mentions by key

topics, audience reach, ad value equivalency, and sentiment.

8 | Evaluating the Addiction Crisis Response in

Huntington/Cabell County WV

Findings: Addressing the Barriers: Interviewees reported that attitudes across the

community varied from compassionate to outright hostile towards individuals with SUD in

the early 2010’s. The broader community was not aware of the severity of the situation and

a great deal of stigma permeated the community. When asked about the barriers that

needed to be overcome both KS (40.9% of interviews) and FL (28.8% of interviews)

answered “stigma” more often than any other answer. (Figure 4) The two groups similarly

agreed for the need of funding as the second most significant barrier. Finances were a

common theme across the interviews as many referred to a data gap between what was

available to federal agencies and the local reality as a major struggling in attracting funding

in the early days of the response. Both groups also mentioned lack of education along with

poor understanding of addiction and mental health. Beyond those main issues, there was

some variance between the groups. KS, whose responsibilities are primarily

administrative, discussed agency level barriers, such as silos between agencies, employee

burnout, access to care, and the politicizing of SUD. Frontline workers focused more on

patient levels barriers like access, long-term facilities, housing, and transportation.

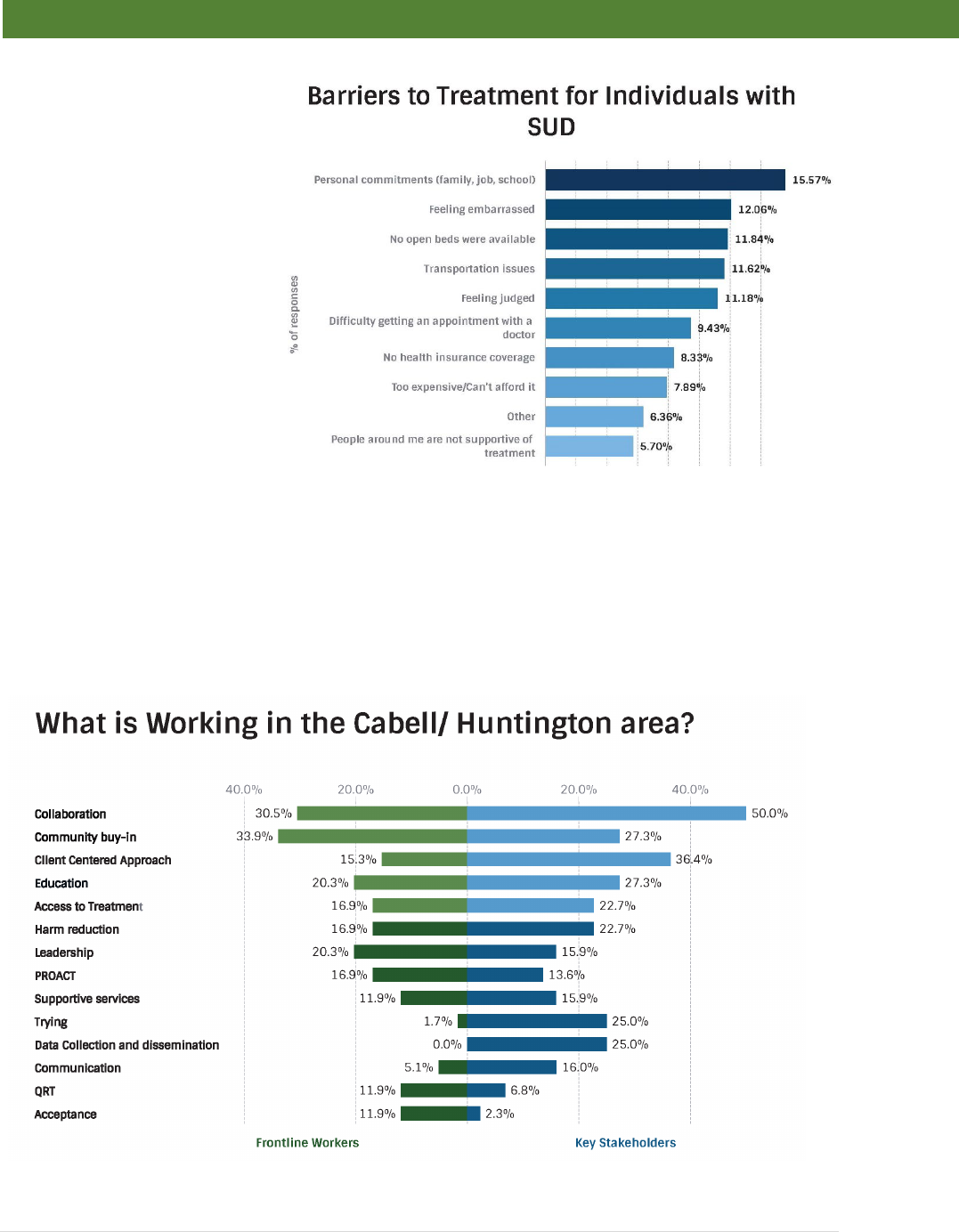

The perception of the most impactful barriers by KS and FL were slightly different from those

identified by those with SUD. An anonymous survey of clients receiving services in the

community showed that “personal commitments” was the biggest barrier. A second tier of

barriers were reported by clients that suggest issues with access to care (“transportation and

“no open beds available”) and stigma (“feeling embarrassed” and “feeling judged”). (Figure 5)

While stigma is important to all of the groups, it seems to be viewed as a more significant

barrier by KS and FL than the clients; who see their personal commitments and basic access

as larger barriers.

Figure 4: Answers given to the question, "What were the barriers?" answered by more than 10% of interviewees.

9 | Evaluating the Addiction Crisis Response in

Huntington/Cabell County WV

Despite these barriers, the

overwhelming tone from the

interviews was in regards to

a remarkable level of

collaboration. Both KS

(50.0%) and FL (30.5%)

reported “collaboration”

more than any other

response when asked,

“What is working?” (Figure

6) Many KS and FL

interviews also mentioned

community buy-in,

education, and a client-

centered approach as

functional aspects of the

community response. Similar

to the barriers question, the

consensus answers from FL

interviewees focused on

their impression of what

helped the clients directly, naming a number of specific programs (PROACT and QRT). While

KS interviewees mentioned access to care and approach issues, many discussed how efforts

to collect and disseminate data was critical to attracting funding and changing policies. Another

theme by KS was coded as “trying,” or the willingness of a variety of individuals and agencies to

step outside of their standard procedures to attempt new methods and approaches.

Figure 5: Patients with SUD were asked to identify the barriers to treatment with the

question: "

Whenever you’ve thought about getting treatment (either residential or

outpatient), which of the following would you say are the biggest barriers for you

to get

into a treatment program?” N=456

Figure 6: Answers given to the question, "What is working?" answered by more than 10% of interviewees.

10 | Evaluating the Addiction Crisis Response in

Huntington/Cabell County WV

While KS listed siloes between agencies and competition between agencies as barriers, those

barriers were often considered less critical than others. Several FL interviewees did discuss

problems in the continuity of care while others associated access to care issues with poor

communication between agencies. These barriers may have been more impactful than

suggested by discussing specific issues. There was agreement across the interviews that the

mechanism for overcoming many of the identified and potentially unidentified barriers was an

unprecedented level of collaboration. Unity of purpose and a collaborative spirit was

overwhelmingly credited as the primary reason for the success of the community response to

the addiction epidemic.

Building Collaboration is a multi-Step Process: Collaboration was identified as the key factor

in the Huntington/Cabell County Response to the Addiction Epidemic. While the participants in

the response were, by their own admission, learning as they went, the process that developed

was deliberate and should be replicable. The tangible elements of the response came into effect

because of the community-wide sense of collaboration. This allowed Huntington/Cabell County

to identify and address gaps quickly by optimizing existing programs and creating a few new

programs strategically to take advantage of limited resources. Creating this collaborative

environment required a number of key elements and followed a precarious timing of events. The

steps of the process and the timing of those steps were equally important.

Evaluation of Community Collaborative Structure: An analysis of the collaborative structure

in the Huntington/Cabell County community showed a lot of collaboration that was unstructured.

The absence of central point, or even cluster of collaboration suggests that the community

developed an environment of collaboration that encouraged natural connections to occur

instead of an institutionally driven collaborative structure.

In order to understand the nature of this community-wide collaboration, we conducted a

partnering survey in which we asked agencies from across the community to rate the strength of

the tie between their agency and a list of 80 different organizations across the community on a

scale from 0 to 5. With a 75.7% response rate to the survey, there were 52 organizations

represented in the survey response data (39 of which were among the 80 partners included as

questionnaire items). Of these 52 organizations, 35 were represented by at least one FL

respondent, 27 were represented by at least one KS respondent, and 10 were represented by at

least one of each type of respondent. Participants were requested to indicate the level of

interaction between their agencies and 79 other agencies based from 0 to 5. No Interaction (0):

No interaction with your organization at all. Networking (1): Aware of organization - Loosely

defined roles - Little communication - All decisions are made independent from this

organization. Cooperation (2): Provide information to each other - Somewhat defined roles -

Formal communication - All decisions are made independently. Coordination (3): Share

information and resources - Defined roles - Frequent communication - Some shared decision

making. Coalition (4): Share ideas - Share resources - Frequent and prioritized communication -

All members have a vote in decision making. Collaboration (5): Members participate in

programs that function as one system - Frequent communication is characterized by mutual

trust - Consensus is reached on many or all decisions. There was no clear community structure

indicated by either group. A- Key stakeholders were evenly distributed while B- Frontline

workers were either weak (<3) or strong (5). Lighter lines represents weaker collaboration

strength while darker lines represent stronger collaboration strength. There were 4 instances

where 2 FL respondents from the same organization participated in the survey and 4 more

instances where 2 KS respondents from the same organization participated in the survey; we

11 | Evaluating the Addiction Crisis Response in

Huntington/Cabell County WV

obtained a single response vector in each of these cases by taking the entry-wise maximum of

the dual responses present.

Organizations tend to be listed as

collaborators by roughly 20 other

organizations normally distributed

between Key Stakeholders and

Frontline workers (in-degree), while

the collaborations an organization

claims to have are uniformly

distributed (out-degree) (Figure 7).

This is an indication that many

organizations are less collaborative

than they report, particularly when

reported by Key Stakeholders. The

differential distribution pattern is

likely an indication of a collaborative

environment in which there was

social pressure to appear

collaborative. Even with the variance

of in-degree vs (no comma) out-

degree distribution patterns, the large

amount of interagency collaboration

mentioned in the interviews appears

to be functional.

Key Stakeholders, most having administrative authority, reported a strong sense of collaboration

and the expectation of collaboration from the community. The partner survey responses indicate

this phenomenon. Undirected network maps show an even distribution of the strength of

interagency collaborations, but no clear community structure is indicated. (Figure 8A) This

suggests an effective environment of collaboration instead of a specifically directed structure.

FL had a slightly different distribution by reporting primarily either weak (<3) or very strong

collaboration (=5). FL partnering analysis still failed to show a clear community structure.

(Figure 8B)

Weak ties in social networks are associated with distant clusters within a social system. As this

study is measuring across a community, it is likely that weak ties (<3) are more representative of

Figure 8: The partnership study results for A- Key stakeholders and B- Frontline workers.

A

B

Figure 7: Distribution of partner survey collaborators. Organizations tend

to be listed as collaborators by roughly 20 other organizations. (in-

degree) This number tends to be normally distributed. The number of

collaborations that an organization says it has tends to vary uniformly.

(out-degree) “Count” indicates the strength of collaboration (0-5).

“Degree” is the number of agencies indicated as having some a level of

collaboration >0.

12 | Evaluating the Addiction Crisis Response in

Huntington/Cabell County WV

individual relationships interacting across agencies. Strong ties (=5) are official or public

collaborations recognized by every level of the organization. Intermediate ties (3,4) in this study

would represent the interagency collaboration that go beyond individual relationships, but are

not yet official or public agency connections. Under the suggested model of a widespread

environment of collaboration, this data would then suggest that KS, as the administrative

officials, have a wider view of agency collaboration. FL on the other hand see the most

collaboration at a personal level or when the collaboration reaches widely across the

organization, but not necessarily collaboration in the intermediate stages.

Process of Developing a Community-Wide Collaborative Environment: Several

interviewees credited the togetherness of the Appalachian culture for the collective nature of the

response to the addiction epidemic. It is unclear how much of the cooperation was cultural, or if

the desire to work together for the common good is necessarily unique to Appalachia. The data

suggests however, in addition to the general building of infrastructure, that major components

were necessary to allow the community to come together in such a way. Based on interview

responses and the timeline and focus of the efforts; three key approaches were determined to

be a necessary part of overcoming

the barriers and building an

environment of collaborative healthy

recovery in the face of the epidemic.

• Finding Common Ground

• Leadership

• Community Response Approach

1. Finding Common Ground:

Despite community-wide stigma,

there was one population who

shared ubiquitous support, the

prenatally-exposed neonate. One

Key Stakeholder summed up the

consensus that prenatally-exposed

children were not subject to the

same stigma presented to others in

the SUD population by stating, “…it

is easy to get people to support

babies, even if they won’t support

their mothers.” The large number of

babies who had become victims of

the addiction epidemic became a

rallying point for the community.

Interview respondents, regardless of

position, discussed a need for support for children, particularly those exposed to substances in

utero. Supporting this perception, the first programs developed that enjoyed broad community

support were related to these youngest victims of the epidemic.

While Prestera Center had women and children’s program for years, a number of new

programs changed the landscape of treatment for pregnant women with SUD. Marshall Health

developed the Maternal Addiction Recovery Center, a medication assisted treatment program

You know, the building for Lily's place donated by a

prominent family, each nursery room within Lily's

place was donated, every bit of that facility; the

flooring, the cribs, the paint, the furniture within each

nursery was donated by a family or a church or

something. That Lily's place has never bought or

purchased a diaper in its existence in 2014 because

the community has always donated diapers and

wipes and baby clothing and bubble bath and

everything else. So that, you know, that is how this

community has rallied around that you will see.

We've seen children forgoing their birthday parties or

presence at their birthday parties so that they could

throw a baby shower for a little place…

…because it’s babies.

– Sean Loudin: Former Medical Director of Lily’s Place

and Cabell-Huntington Hospital Neonatal Therapeutic

Unit

13 | Evaluating the Addiction Crisis Response in

Huntington/Cabell County WV

for pregnant women up to six weeks postpartum. Valley Health System, a local Federally

Qualified Health Center, developed their own pregnancy program, co-currently. Cabell-

Huntington Hospital created a specialized unit just for withdrawing neonates. These programs

helped provide the necessary infrastructure to handle the rapidly growing need, but one effort

captured the community psyche more than any other— Lily’s Place. Despite the fact that this

outside facility had a lower capacity than the hospital’s Neonatal Therapeutic Unit, interviewees

from both groups, who mentioned babies or NAS, also mentioned Lily’s Place.

Lily’s Place is a private not-for-profit facility where prenatally exposed babies with no other

medical problems can recover in a more homebound setting. Lily’s Place uses therapeutic

handling methods and weaning techniques to treat patients. Developing this unique facility was

truly a community effort with donations from around the community and shared resources with

other medical facilities. Lily’s Place

changed the discussion. It was a

positive story of helping the helpless

that allowed many within the

community to begin to see the

severity of the epidemic. Once the

community rallied around saving the

neonates, it was a short step to

getting support to get more

resources to their mothers, leading

eventually to the coalition Healthy

Connections, Project Hope for

Women and Children, Hope House,

and numerous programs and

resources targeted at helping new

mothers with SUD.

2. Leadership

When it comes to identifying those

primarily for the response, a few

names rose to the top. However, it

was very clear that Key Stakeholders and Frontline workers all felt that the

Huntington/Cabell County response to the addiction epidemic was a broad effort with too

many champions to mention. At the end of the day, everyone was expected to do their

part and most delivered above and beyond expectation. This community collaboration

did not happen in a vacuum.

Although early on it was important to give the community a single program on which to focus

support there were other more difficult programs critical to an effective response that required

taking political risks. The individuals who took those risks were identified by key stakeholders in

the community as the primary champions of the response. It likely is no accident that the

named champions represent the most influential organizations in Cabell County, i.e, the City of

Huntington, the Cabell-Huntington Health Department, and Marshall University. It is clear that

the leadership had to come from these three entities (Figure 9) while being supported strongly

by the two major hospitals in town (St. Mary’s Hospital and Cabell-Huntington Hospital), the

County’s Behavioral Health Center - Prestera Center, and the area’s largest Federally Qualified

Health Center – Valley Health System. These agencies developed their own response while

Political Leader

(Mayor)

Top Public Health

Official (County

Health

Department)

Most Trusted non-

Political Agency

(Marshall

University)

Figure 9: Three major leadership components in Huntington/Cabell

County

14 | Evaluating the Addiction Crisis Response in

Huntington/Cabell County WV

working together to create an environment that allowed a single unified community response

that started with treating those patients already on the front lines of the epidemic and

approaching patients as the content experts. Thus, it was not just that the recognized

community leaders came together, but the approach they used empowered those most able to

make the critical changes. Many Frontline personnel interviewed indicated that prior to the

founding of the Mayor’s Office of Drug Control Policy and the Division of Addiction Sciences at

Marshall University, they and their counterparts were often underappreciated.

Of the six individuals named by more than ten percent of interviewees as “Champions” of the

community response (Figure 10) to the addiction epidemic, four (Mayor Steve Williams, Dr.

Michael Kilkenny, Dr. Stephen Petrany,

and Former Police Chief Jim Johnson)

admitted to having a steep learning

curve. Some of the critical individuals

involved with making the response a

success knew very little about addiction

or recovery at the beginning. However,

each was able to put their reservations

and biases aside to bring the

community together and focus on

developing a response based on best

practice and improving the community

as a whole.

a. Mayor Steve Williams – City of Huntington

In 2014, shortly after being elected Mayor, Steve Williams responded to citizen complaints

about the growing epidemic by supporting the “River to Jail” program, which took a at law

enforcement approach to addressing the addiction problem. Like many before him, Mayor

Williams thought that increased arrests and drug seizures would stem the tide of drugs entering

Huntington. The Mayor quickly realized that he did not understand the epidemic that was now

plaguing the City in which he was

responsible. So, leaving politics aside

(as many might not do), he changed

his approach.

In 2015, the Mayor’s Office of Drug

Control Policy (MODCP) was

established. Former Police Chief Jim

Johnson, and Fire Chief Jan Rader

were tasked with developing a

comprehensive plan for the community. Chief Johnson and Chief Rader used the influence of

their office to bring together anybody and everybody who were spending resources to address

SUD or were strongly affected by the epidemic. Stakeholders in the community responded well

to the formation of the new office. Everyone involved with the Mayor’s Office of Drug Control

Policy used each meeting to learn from those who had been working with the substance using

population. In addition to the specific question of “Champions,” Jan Rader was mentioned

specifically throughout the interview transcripts. Her association with the MODCP was noted as

Figure 10: Top responses of both KS and FL In response to the

ques

tion, "Who are the Champions?" in discussion of the response.

I didn't go to city council and ask for an action on it.

This is just something that we needed to do. I called it

the Mayor's Office of Drug Control Policy. We just got

moving, started meeting with people. Now, I was a

bit naive at the time in January of 2015. – Steve

Williams: Mayor Huntington, WV

15 | Evaluating the Addiction Crisis Response in

Huntington/Cabell County WV

important for changing the perception of the SUD population. Experts in addiction from across

the area started to feel more empowered than isolated, and the siloes started to break.

While actively working to establish a community resolve to respond to the addiction epidemic,

the City of Huntington began a campaign to address the critical data gap. Police data analyst

Scott Lemley was assigned to create a database of addiction related information. Through this

effort, the Mayor’s Office of Drug Control Policy was able to demonstrate that a large portion of

crime in the City of Huntington was drug related and that the number of overdoses in the City

were rising rapidly well ahead of the State Medical Officer’s report on overdose deaths.

b. Michael Kilkenny, MD – Cabell-Huntington Health Department

As the Mayor’s office was establishing its response, the Cabell-Huntington Harm Reduction

Program (CHHRP) began at the Cabell-Huntington Health Department (CHHD). This program

began providing an array of harm

reduction services including

infectious disease care, wide-

spread naloxone distribution, as

well as providing syringes to 1,155

Cabell County residents that were

persons who inject drugs (PWID),

primarily heroin and drugs sold as

heroin

25

in the first year. Harm

reduction has been a critical part of

controlling infectious disease outbreaks during the epidemic while providing a path to

treatment for PWIDs. By keeping his message focused on best practice and scientific

methodology while engaging and addressing concerns, Dr Kilkenny and his staff were able to

gain tentative acceptance in a resistant community to establish this program. Thus, despite

public resistance, Cabell County has widely distributed naloxone and maintained a functional

syringe exchange program.

As in the efforts of the Mayor’s Office, CHHD focused on utilizing the data collected to obtain

more accurate estimates of the epidemic. The City and Dr. Kilkenny alike were confronted with

sorting the differences between available data and the reality on the ground.

c. Marshall University

Marshall University has always had a special relationship with the City of Huntington. While this

is true of many universities, a full community response would not have been possible in

Huntington/Cabell County without the full participation of Marshall. This is why the University

was one of the earliest visits made by the Mayor’s office.

The University reacted immediately along two major efforts paths. 1) The Marshall University

President created a task force to coordinate University resources directed at addressing the

epidemic. This effort coordinated a variety of activities from a number of different colleges and

departments. 2) Developed the Division of Addiction Science within the Joan C. Edwards

School of Medicine to provide infrastructure for research and expanded SUD treatment. The

physician’s group of the medical school (Marshall Health) would also provide clinical

infrastructure for the creation of sustainable programs. In 100 of 100 interviews, Marshall was

mentioned as a partner, champion, or key to a long-term successful response in addressing

SUD in the community. Throughout the response, various Marshall University Colleges and

departments were collaborating in dozens of different community efforts. Per the interviews,

The champions, can I say the Health Department as

one of the champions? They would be one of the

champions because it's a group effort, it’s not just

harm reduction, it’s nurses, it’s environmental.-

Frontline Worker

16 | Evaluating the Addiction Crisis Response in

Huntington/Cabell County WV

many Key Stakeholders and Frontline workers did not specifically name an individual,

department, or project at the University. More than a dozen individuals from Marshall University

were identified as “Champions,” but only two were indicated by at least 10% of interviewees.

• Dr. Stephen Petrany, Chair of the Department of Family and Community Health in

Marshall’s medical school, created the Division of Addiction Sciences which would

provide the infrastructure for sustaining new programs (described below) designed to fill

critical gaps in the continuum of care across the community.

• Bob Hansen, former CEO of Prestera Center was hired as the first Director of the

Division of Addiction Science, becoming the primary architect for major components of

the full community response. After serving as Director, Bob moved on to lead the Office

of Drug Control Policy for the State of West Virginia.

Results from the frontline worker interviews clearly show a strong emphasis on the overall

sense of collaboration across the community and that the groundwork laid for the NAS focused

response and the leadership framework were critical to the response being effective and timely.

Without the coordination of resources and the support from those who managed such

resources, a collaborative effort of community members would have proven ineffective. As

evidence, on May 22, 2005 four teens were found dead in Huntington after prom in a violent

crime that was a direct result of illegal drug activity. Police reported that one of the teens was

targeted while the rest were killed to eliminate witnesses.

27,28

The community rallied and there

were many “calls to action,” community coalitions started to form, and the event even garnered

national attention.

27

The incident was severe enough to capture the attention of the community

as was the 28 person in one day overdose event of 2016, which caused the community to

respond. However, without a concerted effort from the community leaders, who largely

disregarded events of a growing addiction problem in the community and considered the

circumstances a police matter, there was little in the way of effective response.

Huntington still celebrates a “Day of

Hope” on the anniversary of these

murders. Two projects developed

from the efforts of private citizens,

Hope House and what would become

Recovery Point of WV, but both

programs struggled for 5+ years

before becoming an effective part of

the Huntington/Cabell County

recovery community.

Community Response Approach: Having little knowledge of the collective opinion of the KS,

FL, and clients across the community, local leaders set out to understand how to address the

growing issues. The first step in this process was for the community leaders to admit there was

a problem and face the epidemic. KS and FL interviews often (53 of 100) mentioned that a key

component in beginning a response was the willingness of social and political leadership to

admit that the community was in trouble. How they approached the next phase was equally

important. Several interviewees commented that having a number of KS in certain positions

with extensive experience as Frontline workers made a big difference in the response

approach.

I think that the mayor really was being honest and

open about what the problem were, that the city was

having problems and he was willing to talk about it.

You know, there are other mayors and other political

officials around the country and certainly in West

Virginia that wouldn’t face issues. –Key Stakeholder

17 | Evaluating the Addiction Crisis Response in

Huntington/Cabell County WV

While the leadership in

Huntington/Cabell County pulled

together in both purpose and

approach, agencies across the

community came together quickly in

response. Clinical agencies and

those that deal with substance using

populations joined the effort very

quickly. This was particularly true of efforts or resources directed specifically at helping

newborn babies who were prenatally exposed to opioids and other neuroactive substances.

Many of the existing agencies began collaborating despite long-held differences based on

philosophical differences in recovery approach. Agencies that had programs in place noted

by both Key Stakeholders and Frontline workers as early contributors and collaborators in

the response are as follows (alphabetical order):

• Cabell County Drug Court

• Cabell County Prosecutor’s Office

• Cabell County Child Protective Services

• Harmony House (including First Steps) - a day shelter for people experiencing

homelessness and families

• Lifehouse – Sober living facility

• Lily’s Place – Independent treatment facility for neonates experiencing withdrawal

• Marshall’s Maternal Addiction Recovery Center – MAT program for pregnant women

• Mountain Health Network - owns the Cabell Huntington Hospital and St. Mary’s Medical

Center in Huntington

• Prestera Center – County Behavioral Health Center

• Recovery Point of West Virginia – Residential peer recovery facility

According to many interviewees,

the community at large came

along more slowly, despite the fact

that a growing number of families

were directly affected by the

epidemic. Individuals outside the

agencies that routinely deal with

an SUD population, particularly

those in the faith community,

reported a growing sense of

urgency and often felt isolated

dealing with the increases in

crime, used syringe litter, and

trying to find help for loved ones. A

response to the epidemic was

underway, but it was not yet a full

community response.

On 15 August, 2016 everything

changed. That was the day that

Not a normalization of an opioid epidemic. But

making it no longer something that has to be hidden,

I think is one of the first steps of a much stronger

response. -Frontline Worker

Twenty six overdose calls are called within a four hour

period. Twenty eight people overdosed that day.

However, two of the individuals were never called in.

They used drugs by themselves. They both,

unfortunately did pass. But however, all 26 people

who were called in on that single day, all were saved

from an overdose. And that was the first time that we

knew that we had a band from heroin to fentanyl and

car fentanyl mixed into the drugs being far more

potent. And that's all public knowledge because of

some court papers. Certainly went after the individual

who distributed those drugs in the community. So on

that day, it became national and international news.

So if you had had your head buried in the sand, it was

no longer possible. –Key Stakeholder

18 | Evaluating the Addiction Crisis Response in

Huntington/Cabell County WV

fentanyl and fentanyl analogs arrived and were responsible for 28 overdoses in Cabell

County. Twenty six of these overdoses were responded to by emergency medical services

within 4 hours.

26

This single event galvanized the majority of the community into a single

response, because the leadership had been preparing a response and could offer

immediate, well-vetted answers. Cries of “What can we do?” and “Who is going to stop this?”

were quickly marginalized with people asking, “What can I do?” More than half (23 of 44) of

the Key Stakeholders mentioned this day as a seminal event in the response. After August

2016, whatever remained of the interagency siloes were (temporarily) torn down.

Agencies and services for SUD prior to the addiction epidemic and subsequent response in

Huntington/Cabell County were primarily focused on recovery and treatment. As the increasing

number of individuals with SUD were

recognized by frontline agencies across the

community, programs were developed that

either focused on the agreed sub-population

(prenatally-exposed babies) and adopted as

best practice from other communities (Drug

Court, Harm Reduction), or were attempts by

leadership organizations to develop a

functional plan (Mayor’s Office, Marshall)

(Figure 12). These programs were largely

developed in isolation or with a limited group of

interested parties that simply did what they

could. After the events of August 15, 2016, the

establishment of programs became more

directed.

In meetings joint hosted by Marshall University’s Division of Addiction Science and the Mayor’s

Office of Drug Control Policy, community members that work with SUD populations were asked

for their opinion of what should be the focus of the community response. For the many

individuals and agencies that had felt underappreciated from traditional approaches, this was a

significant change in approach. In that meeting several needs were identified:

• Lack of Detox Beds

• Poor access to care across the population, i.e., need to “meet population where they

are.”

• Not enough housing for new mothers with SUD

• Programs do not work well together

New programs developed after this meeting largely addressed one of these defined needs.

Prestera Center immediately doubled the number of Detox beds. Project Hope for Women and

Children was developed to address

the need for more housing for new

mothers with SUD. Collaborative

efforts designed programs that either

Improved access to care or

developed a community

collaboration to continuously improve

Figure 11: One example of the national reports about the

overdoses on 15 August, 2016 in Huntington/Cabell

County.

I think we spend a lot of time with people with initials

after their names thinking they have the answer and

the only thing they've been in is a book. –Frontline

Worker

19 | Evaluating the Addiction Crisis Response in

Huntington/Cabell County WV

system optimization (Figure 12). These new programs developed quickly because agencies in

the community were willing to share infrastructure. All of the post-Aug 2016 programs went from

concept to implementation in less than two years, with early results realized by early in 2018.

Timing seems to have been critical. Many interviewees reported a lack of public support prior to

Aug 2016. However, had the leadership structures not been in place when the events of that

day occurred, there is a strong possibility that the overall response would have been too slow to

effectively change the course of the epidemic.

Prior to the response (before 2014)

programs largely focused on

treatment or recovery exclusively.

Without widespread support,

Figure 12: Programs for individuals and Families with SUD in Huntington/ Cabell County established before the response,

early in the response, or during the full community effort.

We had people hiding in plain sight. –Key Stakeholder

20 | Evaluating the Addiction Crisis Response in

Huntington/Cabell County WV

agencies created the programs that were sustainable through medical reimbursement claims.

As these agencies were at the forefront of addiction in the community, they often understood

the need for additional services and recovery support, but did not have the resources to fund

such efforts with grants that are time consuming and unreliable long-term. Thus, many

programs developed by community agencies throughout the years prior to the epidemic were

ultimately short-lived.

In the early days of the response, public support for those struggling with addiction was largely

restricted to prenatally-exposed babies. Thus, the steps taken to establish the Mayor’s Office of

Drug Control Policy, the Cabell-Huntington Harm Reduction Program, and the Marshall

University Division of Addiction Sciences and Center of Excellence for Addiction Care required

leaders to shoulder a fair amount of political risk.

The Client Survey (n=219) identified PROACT and Harmony House (a drop in center for

individuals experiencing homelessness) as the most impactful organizations by being used by

>30% of respondents with >90% of those that used the agencies labeling them as ‘helpful.’ All

of the agencies labeled in Figure 13, with the exception of PROACT, existed prior to the

response, but have made significant changes to their services during the response.

Figure 13: Indication of usefulness of agencies in the response to the addiction epidemic in Huntington/ Cabell County, WV.

Participants in the client survey (n=219) identified which community services they utilized which agency or services they uti

lized

and indicated which (yes/no) if that agency or service was helpful to their recovery. Labeled organizat

ions represent those

agencies who were identified as used by >30% of participants and 80% of those who used the agency in their recovery indicated

that agency as ‘helpful.’

Harmony House and PROACT very closely overlap in the figure.

21 | Evaluating the Addiction Crisis Response in

Huntington/Cabell County WV

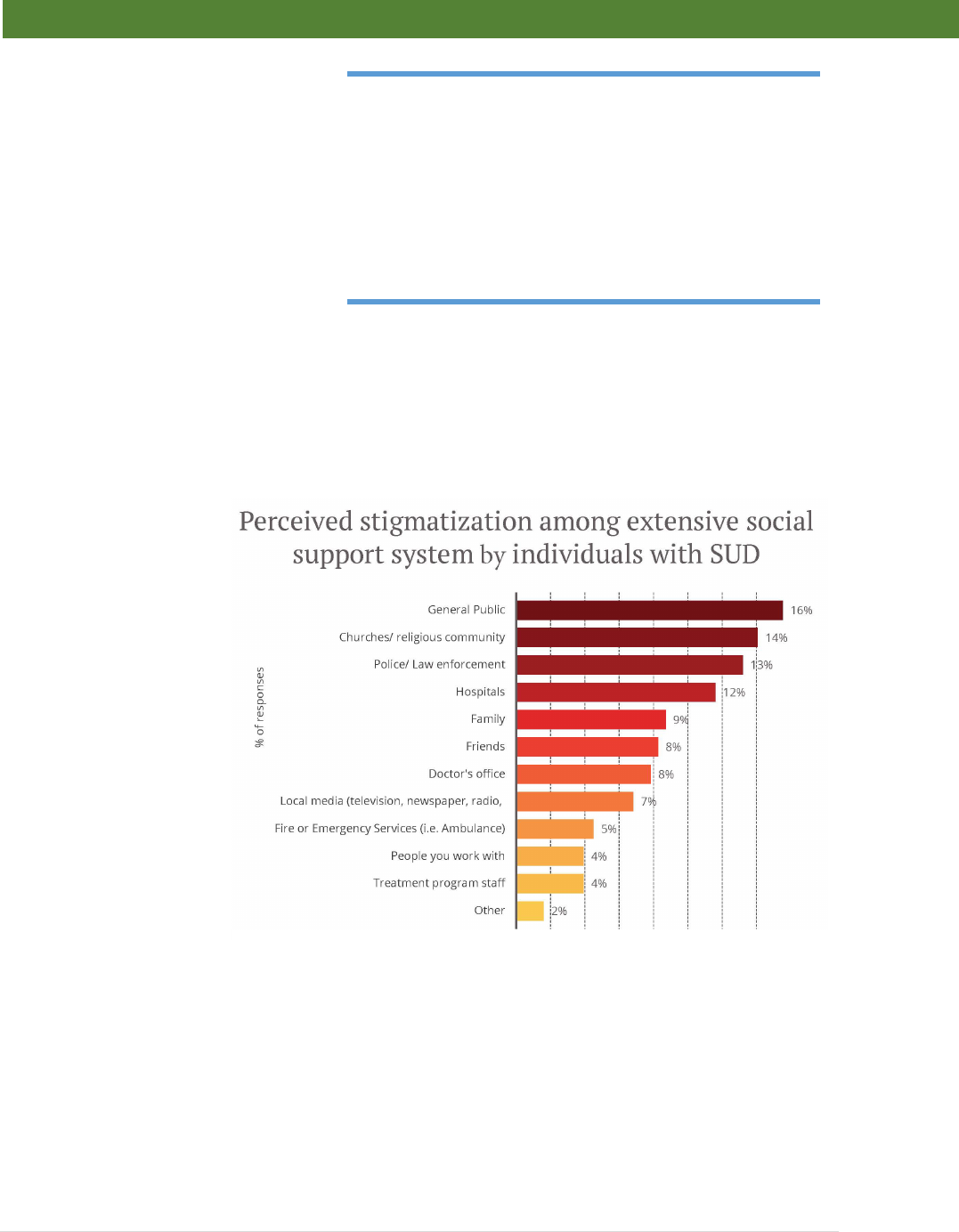

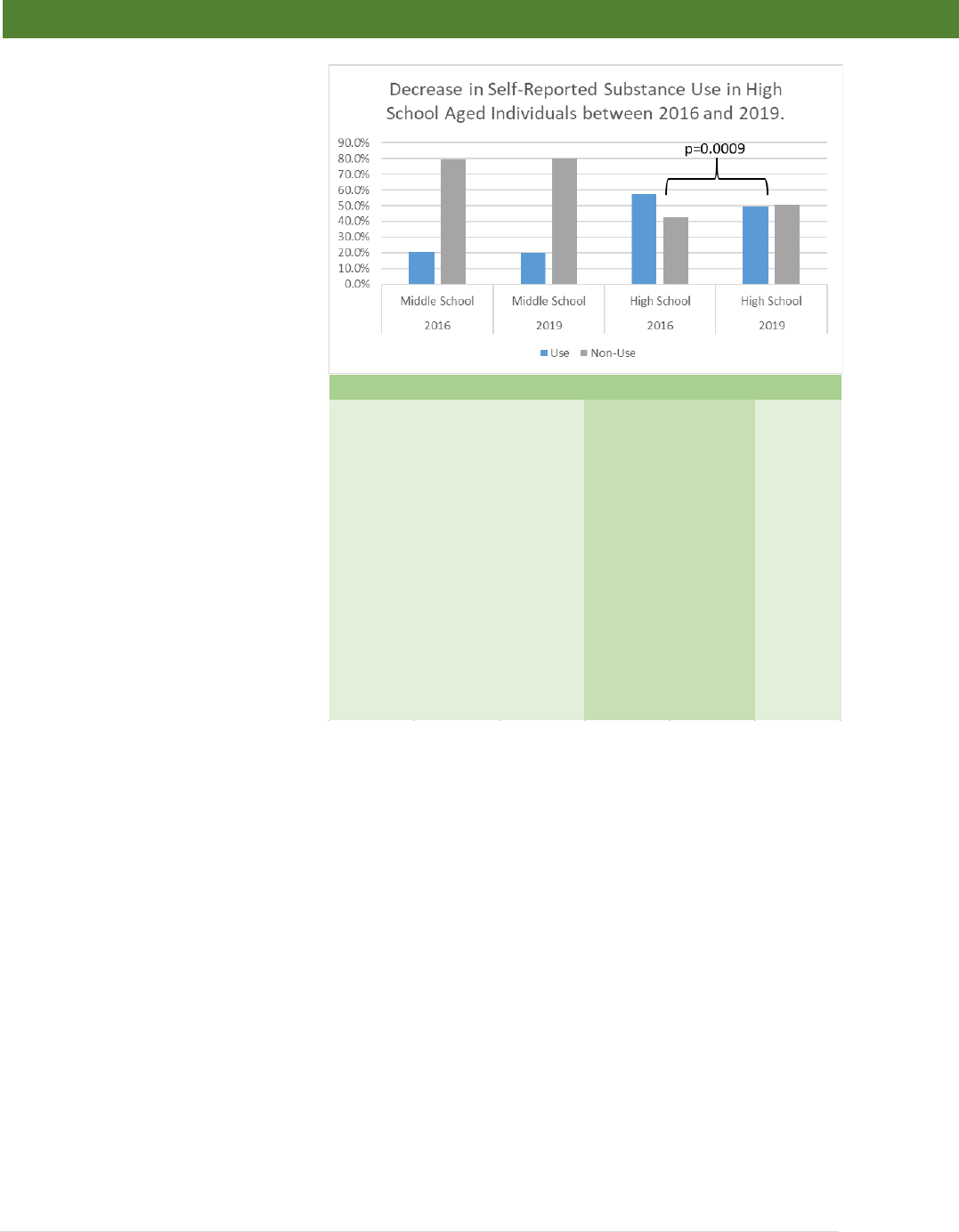

Collaboration Creates Opportunity for Sustainable Programs: All 44 Key Stakeholders

reported that expanded services either improved utilization or created new programs during the

response. Many attributed open dialogue across the community or better communication with