Health Behavior Research Health Behavior Research

Volume 6

Number 4

Mentorship to Enhance Health

Behavior Research

Article 8

October 2023

A Longitudinal Examination of Multiple Forms of Stigma on A Longitudinal Examination of Multiple Forms of Stigma on

Minority Stress, Belongingness, and Problematic Alcohol Use Minority Stress, Belongingness, and Problematic Alcohol Use

Akanksha Das

Miami University

Rose Marie Ward

University of Cincinnati

Lauren Haus

Miami University

See next page for additional authors

Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/hbr

Part of the Clinical Psychology Commons, Health Psychology Commons, Social Justice Commons,

and the Social Psychology Commons

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Das, Akanksha; Ward, Rose Marie; Haus, Lauren; Heitt, Jackson; and Hunger, Jeffrey (2023) "A

Longitudinal Examination of Multiple Forms of Stigma on Minority Stress, Belongingness, and

Problematic Alcohol Use,"

Health Behavior Research

: Vol. 6: No. 4. https://doi.org/10.4148/

2572-1836.1204

This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for

inclusion in Health Behavior Research by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information,

please contact [email protected].

A Longitudinal Examination of Multiple Forms of Stigma on Minority Stress, A Longitudinal Examination of Multiple Forms of Stigma on Minority Stress,

Belongingness, and Problematic Alcohol Use Belongingness, and Problematic Alcohol Use

Abstract Abstract

College students who experience stigma report problematic alcohol use. However, the stigma-health link

focuses on one form of stigma, thereby excluding the intersectional oppression of experiencing multiple

forms of stigma. The present work has two primary aims: 1) evaluating whether additive intersectional

minority stress confers greater problematic alcohol use among multiply-stigmatized college students one

year later, and 2) whether that link can be explained by 1) lower belongingness and 2) greater drinking to

cope motives. Students (N=427) ranging in stigmatized identities (14.3% zero; 46.4% one; 29.5% two;

9.8% three or more), participated in an annual health survey at two subsequent fall semesters (2020 to

2021). Structural equation modeling tested the hypothesized model on relations between number of

stigmatized identities, minority stressors, belongingness, and coping motive on problematic drinking

(risky and problem drinking) one year later. As hypothesized, holding more stigmatized identities

predicted higher minority stress, which in turn predicted less belonging. Partially consistent with

expectations, lower belonging predicted more problem drinking, but

less

risky drinking. As expected,

higher minority stress predicted higher drinking to cope motives, which in turn, predicted more problem

drinking, and risky drinking. In conclusion, belongingness and drinking to cope may be potential

mechanisms through which multiply-stigmatized students experience future problem drinking, but that

may not always confer to more risky drinking. Implications for universities include implementation of 1)

campus-wide belonging interventions for students facing stigma, and 2) initiatives to teach alternative

coping strategies that reduce drinking to cope as a strategy to reduce the impact of minority stressors.

Keywords Keywords

Multiple stigmatized identities, alcohol, additive minority stress, college students, belonging, drinking to

cope

Acknowledgements/Disclaimers/Disclosures Acknowledgements/Disclaimers/Disclosures

We gratefully acknowledge our research participants without whom this work would not be possible.

Authors Authors

Akanksha Das, Rose Marie Ward, Lauren Haus, Jackson Heitt, and Jeffrey Hunger

This research article is available in Health Behavior Research: https://newprairiepress.org/hbr/vol6/iss4/8

A Longitudinal Examination of Multiple Forms of Stigma on Minority Stress,

Belongingness, and Problematic Alcohol Use

Akanksha Das, MA*

Rose Marie Ward, PhD

Lauren Haus,

Jackson Heitt

Jeffrey M. Hunger, PhD

Abstract

College students who experience stigma report problematic alcohol use. However, the stigma-

health link focuses on one form of stigma, thereby excluding the intersectional oppression of

experiencing multiple forms of stigma. The present work has two primary aims: (1) evaluating

whether additive intersectional minority stress confers greater problematic alcohol use among

multiple stigmatized college students one year later, and (2) whether that link can be explained by

lower belongingness and greater drinking to cope motives. Students (N = 427) ranging in

stigmatized identities (14.3% zero; 46.4% one; 29.5% two; 9.8% three or more), participated in an

annual health survey in two subsequent fall semesters (2020 to 2021). Structural equation

modeling tested the hypothesized model on relations between number of stigmatized identities,

minority stressors, belongingness, and coping motive on problematic drinking (risky and problem

drinking) one year later. As hypothesized, holding more stigmatized identities predicted higher

minority stress, which in turn predicted less belonging. Partially consistent with expectations,

lower belonging predicted more problem drinking, but less risky drinking. As expected, higher

minority stress predicted higher drinking to cope motives, which in turn, predicted more problem

drinking, and risky drinking. In conclusion, belongingness and drinking to cope may be potential

mechanisms through which multiple stigmatized students experience future problem drinking, but

that may not always confer to more risky drinking. Implications for universities include

implementation of (1) campus-wide belonging interventions for students facing stigma, and (2)

initiatives to teach alternative coping strategies that reduce drinking to cope as a strategy to reduce

the impact of minority stressors.

Keywords: multiple stigmatized identities, alcohol, additive minority stress, college students,

belonging, drinking to cope

* Corresponding author may be reached at [email protected]

Introduction

Excessive alcohol use in college poses a

significant public health concern that can

lead to increases in memory loss and higher

risks for injury or assault (White & Hingson,

2013). Importantly, college students holding

stigmatized identities, that is, culturally

devalued social identities (Crocker, Major, &

Steele, 1998), report greater problematic

alcohol use (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2011).

Furthermore, individuals who identify with

more than one stigmatized group (‘multiply-

stigmatized” individuals) (Remedios &

Snyder, 2018), report experiencing more

minority stressors (Remedios & Snyder,

1

Das et al.: INTERSECTIONAL MINORITY STRESS & ALCOHOL

Published by New Prairie Press, 2023

2018), and greater problematic alcohol use

than their singly-stigmatized peers (i.e., those

identifying with only one stigmatized

identity) (Cerezo & Ramirez, 2021). A

second study among college students showed

that compared to women experiencing no

discrimination, women experiencing

heterosexism and racism reported greater

alcohol use (Vu et al., 2019). Therefore, it is

important to understand the underlying

factors that explain the relationship between

intersectional minority stress and

problematic alcohol use.

Minority stress (Meyer, 2003),

psychological mediation (Hatzenbuehler,

2009), and intersectionality (Crenshaw,

1991) frameworks can help explain

relationships between intersectional minority

stress and problematic alcohol use. These

models suggest individuals exposed to stigma

(e.g., disadvantages due to having culturally

devalued social identities) experience

minority stress, or unique additional stressors

associated with exposure to oppression at the

structural, interpersonal, and intrapersonal

level. Minority stressors are defined as overt

or covert forms of oppression that are either

at the distal (e.g., structural and interpersonal

discrimination) or proximal (e.g., internally

perceived experiences of discrimination)

level. Multiple stigmatized individuals are

exposed to further additional intersecting

forms of oppression given the interconnected

nature of social identities. Following the

work of Remedios and Snyder (2018),

proximal intersectional minority stressors

evaluated in the present study include

experiences of perceived discrimination, felt

invisibility, and stereotype concern.

Hatzenbuehler’s mediation model (2009)

expands on Meyer’s (2003) minority stress

theory to characterize how minority stressors

require individuals to expend resources to

adapt or respond to hostile environments, and

therein, exposes them to elevated negative

psychological processes (drinking to cope,

lower belongingness) that ultimately result in

poorer health, including problematic alcohol

use. Although the aforementioned models by

Meyer (2003) and Hatzenbuehler (2009)

were developed with a focus on sexual

minorities, the fundamental model was

created following a long history of work

theorizing the experiences of individuals

holding a variety of stigmatized identities,

including on the basis of race, gender, class,

to name a few.

Given much of the existing research on

the oppression-health link focuses on a single

form of oppression (racism or sexism), the

generalizability to the real-world experiences

of people who identify with more than one

stigmatized group is limited (Cole, 2009).

Thus, it is less clear how minority stress tied

to intersectional oppression is associated with

problematic alcohol use.

In this study, we aimed to integrate the

three aforementioned models to examine

additive intersectional minority stress

processes and problematic alcohol use among

multiply stigmatized students. Consistent

with those frameworks, we sought to identify

the psychological processes that are (1)

established factors that drive alcohol-related

problems, and (2) uniquely arise from the

additional harms experienced because of

oppression (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2011;

Meyer, 2003) among students who identify

with a range of stigmatized identities (Cole,

2009). Extant literature provides support for

two established mediators of minority stress,

and problematic alcohol use: (1) a lack of

belonging, (Lewis et al., 2017; Napoli et al.,

2003; Rostosky et al., 2003) and (2) drinking

to cope (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2011; Lewis et

al., 2016). What follows is a review of

intersectional frameworks, hypothesized

pathways through belonging and coping, and

alcohol use among multiply-stigmatized

individuals.

2

Health Behavior Research, Vol. 6, No. 4 [2023], Art. 8

https://newprairiepress.org/hbr/vol6/iss4/8

DOI: 10.4148/2572-1836.1204

Intersectional Frameworks

The Combahee River Collective

(1977/1995), a group of Black feminist

scholar-activists, were first to highlight

problems associated with only accounting for

oppression that Black women face through

racism or sexism, but not racist sexism. That

work, later popularized as intersectionality

theory by Kimberlé Crenshaw (1991),

explicitly called for an examination of the

unique forms of oppression experienced by

individuals when subjected to oppression

across multiple stigmatized identities. That

said, quantitative psychological research of

intersectionality is continuously evolving

(Bauer et al., 2021). Some scholars approach

intersectional experiences through the

additive (versus interactive) lens of multiple

oppressed identities, such that a person who

identifies with stigmatized identities across

both race and gender would experience

double the stress as someone who is

stigmatized on the basis of only race or

gender (Remedios & Snyder, 2018).

Examining multiple identities in this manner

is also referred to as the double-disadvantage

hypothesis, or double-jeopardy hypothesis

(Beale, 1970; Dowd & Bengtson, 1978).

These approaches aim to capture the multiple

forms of harm, disadvantage, and stress that

multiply-stigmatized individuals experience

compared to those holding single or no-

stigmatized identities, and therein serve as

one attempt at approaching intersectionality.

Belongingness

Belongingness, or the sense that one is an

integral part of their surrounding systems, is

considered a fundamental human need that

predicts numerous mental, behavioral, and

social outcomes (Allen et al., 2021; Hamilton

& Dehart, 2019). Stigmatized students are

exposed to greater threats to belonging in

mainstream cultures, like the United States

(U.S.), which is built on their systematic

exclusion (Murdock-Perriera et al., 2019).

Such contexts can be threatening because

they communicate to those students that they

are devalued, not accepted, and thus, result in

feeling as though they do not fit in their

university (Allen et al., 2021). Indeed, first-

year racial-ethnic minority and first-

generation college students at four-year (but

not two-year) institutions reported lower

belonging than majority peers, which

predicted lower mental health (Gopalan &

Brady, 2020). Similar mediation patterns

emerge among lesbian, gay bisexual, and

asexual college students, who report higher

anxiety and depression, and lower happiness

via lower belonging and safety compared

heterosexual peers (Wilson & Liss, 2022).

Threats to one’s fundamental need to

belong are also associated with increased use

of alcohol. Among Native American

adolescents, students who reported lower

belonging in school reported higher lifetime

and current use of alcohol, among other

substances (Napoli et al., 2003). Decreases in

school belonging was associated with an

increased odds of alcohol use, and sexual

minority youth, specifically, reported lower

school belonging than their heterosexual

peers (Rostosky et al., 2003). Among lesbian

women, social isolation, a distinct but related

concept to belongingness (Asher & Weeks,

2013), mediated the link between higher

stigma-related stress, coping motives, and

alcohol-related problems (Lewis et al., 2017).

These studies underscore that stigmatized

individuals report belonging, which may be a

specific pathway for greater problematic

alcohol use.

Coping Motives

Coping motives, or the strategic use of

drinking to modulate, escape, or avoid

negative emotions (Cooper et al., 1995), is an

established risk factor for alcohol-related

3

Das et al.: INTERSECTIONAL MINORITY STRESS & ALCOHOL

Published by New Prairie Press, 2023

problems (Martens et al., 2008). Drinking to

cope is a mediator of the relationship between

perceived discrimination, a form of minority

stress, and alcohol-related problems among

several minoritized groups including women,

people of color, and gay, lesbian, and

bisexual individuals (Hatzenbuehler et al.,

2011; Lewis et al., 2016). Research with

sexual minority, gender expansive women of

color offers additional depth of

understanding on how coping with multiple

forms of oppression may relate to alcohol-

related outcomes. For instance, a qualitative

analysis among Latine and African-

American sexual minority, gender expansive

women revealed that drinking to cope as a

result of discrimination-related stress was

one of five major patterns of alcohol use

(Cerezo et al., 2020). Furthermore, among

Black lesbian women, sequential mediators

of rumination, psychological distress and

drinking to cope explained problematic

alcohol use (Lewis et al., 2016). Across these

studies, coping motives linked minority

stressors and alcohol use; however, more

research on associations between drinking to

cope with minority stressors more broadly

(perceived discrimination, stereotype

concerns, and felt invisibility) and alcohol-

related problems is needed.

Alcohol Use among Multiply-Stigmatized

Groups

College students holding multiple

stigmatized identities perceive more unfair

treatment, feel more invisible, and have more

concerns about being stereotyped than those

with zero or one stigmatized identity

(Remedios & Snyder, 2018). Experiencing

more forms of discrimination via multiple

stigmatized identities is associated with a

greater likelihood of experiencing major

depression and poorer physical health

(Grollman, 2014). Higher intersectional

minority stress (i.e., more sexism,

heterosexism, and racism) also predicts past

year substance use in bivariate correlations

(Cerezo & Ramirez, 2021). There are similar

longitudinal effects among Black, Latino,

and multiracial gay and bisexual men

(English et al., 2018). Namely, the interaction

of gay rejection sensitivity and racial

discrimination associates with

multiplicatively higher emotion regulation

difficulties, which in turn, predicts future

heavy drinking. Those findings highlight the

importance of intersectional approaches to

capture multiply-stigmatized people’s

experiences.

Conceptual Model

We extend previous literature through two

primary ways. First, we examine whether the

additive intersectional minority stress

associated with multiple stigmatized

identities confers greater problematic alcohol

use (i.e., risky and problem drinking) among

college students one year later. Second, we

examine whether that link can be explained

by (1) lower belongingness and (2) greater

drinking to cope motives. First, we aim to

replicate previous findings (Remedios &

Snyder, 2018), and hypothesize that holding

a greater number of stigmatized identities

will be associated with higher minority stress

(perceived discrimination, stereotype

concerns, and felt invisibility). Second, we

test the mediation pathway through

belongingness, and hypothesize that higher

minority stress will be correlated with

lowered belonging, which will in turn,

predict greater future risky drinking (i.e.,

higher peak number of drinks consumed in

one setting) and problem drinking (i.e.,

higher negative consequences from alcohol

use). Last, we test the pathway through

coping motives, and hypothesize that

minority stress will link to higher drinking to

cope motives, which will predict greater

future problematic alcohol use. Taken

4

Health Behavior Research, Vol. 6, No. 4 [2023], Art. 8

https://newprairiepress.org/hbr/vol6/iss4/8

DOI: 10.4148/2572-1836.1204

together, the three sets of hypotheses will

serve to demonstrate a link between a greater

number of stigmatized identities and

problematic alcohol use longitudinally over a

one-year period, consistent with

intersectional minority stress theories.

Methods

Procedure and Participants

Full-time students at a mid-sized U.S.

midwestern university were invited to

participate in an annual university student

health survey via Qualtrics collected at two

timepoints: fall 2020 and fall 2021 (18.1%

and 16.9% response, respectively). Although

the survey was designed as a cross-sectional

study, the present analyses included students

with complete data on relevant measures in

both 2020 and 2021 surveys (n = 427). Upon

completion at each timepoint, participants

received a $3 gift card.

Measures

Demographic Variables

Participants selected their current gender

identity and their current sexual orientation.

For gender identity, options included

Woman/Female, Man/Male, or Gender

Expansive. For sexual orientation, options

included: Heterosexual/straight, Bisexual,

Gay/lesbian, Asexual, Questioning, or not

listed. For race/ethnicity, participants could

choose all that apply from the following

identities: European American or White,

Asian or Asian American, Hispanic or

Latino/a, Black or African American, Native

American or Alaskan Native, Hawaiian or

Pacific Islander. Finally, participant Pell

grant eligibility status was merged into the

data prior to analysis.

Stigmatized Identities

Following Remedios and Snyder (2018),

we calculated a sum score of the number of

stigmatized identities (range 0-5) that the

participant reported on the bases of gender

(Man/Male = 0, Woman/Female = 1, Gender

Expansive = 2), sexual orientation

(Heterosexual/straight = 1, Bisexual,

Gay/lesbian, Asexual, Questioning, or not

listed = 2), racial/ethnic identity (European

American or White = 0, at least one of the

following identities: Asian or Asian

American, Hispanic or Latino/a, Black or

African American, Native American or

Alaskan Native, Hawaiian or Pacific

Islander), and social class (Pell Grant, not

eligible = 0, eligible = 1). Eligibility for the

Pell Grant was operationalized as an

indicator of stigma on the basis of social class

due to the awards being granted to students

from low-income households. Although four

categories of stigmatized identities were

measured, students identifying as gender

expansive were coded with a score of 2 in an

attempt to delineate from experiences of

students identifying as Woman/Female.

Minority Stress

We used three items from Remedios and

Snyder (2018) to measure minority stress.

Participants selected how much they agreed

with three statements using a 7-point Likert-

scale from Strongly disagree (1) to Strongly

agree (7). An example item is “I feel invisible

because of my identities (race/ethnicity,

gender, weight, sexual orientation, social

class).

Belonging

Belonging was measured with single item

adapted from the Perceived Cohesion Scale

(Bollen & Hoyle, 1990). Participants

reported their level of agreement to the

5

Das et al.: INTERSECTIONAL MINORITY STRESS & ALCOHOL

Published by New Prairie Press, 2023

statement: “I feel a sense of belonging – that

I “fit in” at [University name]” on a 6-point

Likert-scale from Strongly disagree (1) to

Strongly agree (6).

Drinking to Cope

The 5-item Coping Motives subscale of

the Cooper’s (1994) Revised Drinking

Motives Questionnaire assesses how often

someone drinks to reduce negative emotions.

Participants were asked to rate the frequency

they engaged a variety of coping motives on

a 5-point Likert-scale from Almost

never/never (1) to Almost always/Always (5).

Problematic Alcohol Use

Risky Drinking. Participants were provided

with the definition of a standard drink. They

indicated the number of standard drinks that

they consumed on their highest drinking

occasion in the past 30 days, which was

operationalized as risky drinking.

Problem Drinking. The 23-item Rutgers

Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI) (White &

Labouvie, 1989) assesses the frequency of 23

negative consequences that can result from

alcohol use over the past year. Example of

consequence include: “Got into fights, acted

bad, or did mean things,” “Not able to do

your homework or study for a test,”” Had

withdrawal symptoms, that is, felt sick

because you stopped or cut down on

drinking.” Participants were asked to choose

how frequently they experienced problems

on a scale from Never (1) to More than 10

times (4).

Data Analysis

Before fitting the structural equation

model, preliminary procedures were taken to

examine the data. Specifically, patterns of

missingness (Little’s MCAR) and

correlations between variables were

inspected, revealing patterns consistent with

that of missing at random or due to planned

missingness (i.e., due to the length of the

survey not every participant got every

measure) Outside of planned missingness,

1.2% or less was missing on each variable.

The model was run using full information

maximum likelihood to estimate missing

values in MPlus v8.6. (Muthén & Muthén,

1998). The following criteria were used to

examine the model: (1) theoretical relevance,

(2) global fit indices (chi-square, CFI, and

TLI), (3) microfit indices (RMSEA), and (4)

parsimony. A non-statistically significant

chi-square indicates that the data do not

significantly differ from the hypotheses

represented by the model. However, large

sample sizes rarely are able to achieve non-

significant chi-squares (Kenny, 2015). For

CFI and TLI, fit indices of above .90

indicated a well-fitting model (Hu & Bentler,

1999). Browne and Cudeck (1992) suggest a

RMSEA of less than .05 suggests a well-

fitting model.

Results

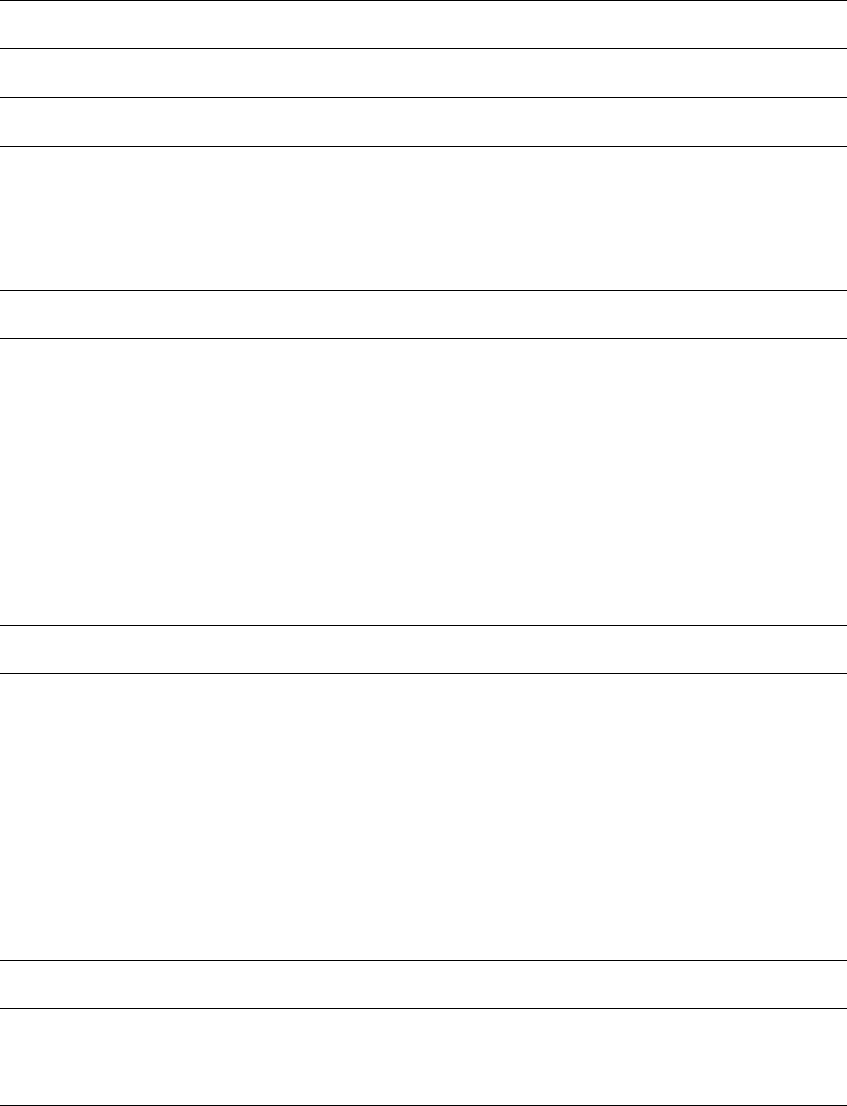

Table 1 presents the bivariate correlations,

mean, standard deviation, and Cronbach’s

alpha for measures.

6

Health Behavior Research, Vol. 6, No. 4 [2023], Art. 8

https://newprairiepress.org/hbr/vol6/iss4/8

DOI: 10.4148/2572-1836.1204

Table 1

Correlations, descriptive statistics, and reliability

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

1. Number of

Stigmatized

Identities

-

2. Minority Stress

.49***

-

3. Drinking to Cope

.05

-.05

-

4. Belongingness

-.26***

-.34***

.07

-

5. Risky Drinking

-.26***

-.29***

.38***

.16**

-

6. Alcohol Problems

-.05

-.02

.33***

.04

.37***

-

Mean

1.44

2.32

1.68

3.88

3.84

3.63

SD

.97

1.42

.82

1.32

4.05

6.53

Cronbach’s Alpha

-

.82

.87

-

-

.85

***p < .001; **p < .01; * p < .05.

Sample Characteristics

Table 2 shows participant characteristics

on each of the coded identities, and Table 3

for specific intersectional identities

represented in the sample. On average,

participants reported 1.44 (SD = .97)

stigmatized identities. For the total number of

stigmatized identities, which was the main

predictor variable, we summed across the

four categories (gender, race, sexual

orientation, and class) with codes ranging

from 0 to 5. In sum, 14.3% of participants (n

= 61) were coded as having zero stigmatized

identities, 44.3% (n = 189) coded as one;

30.2% (n = 129) coded as two; 9.8% (n = 42)

coded as three; and 1.6% (n = 7) coded as

four or five stigmatized identities.

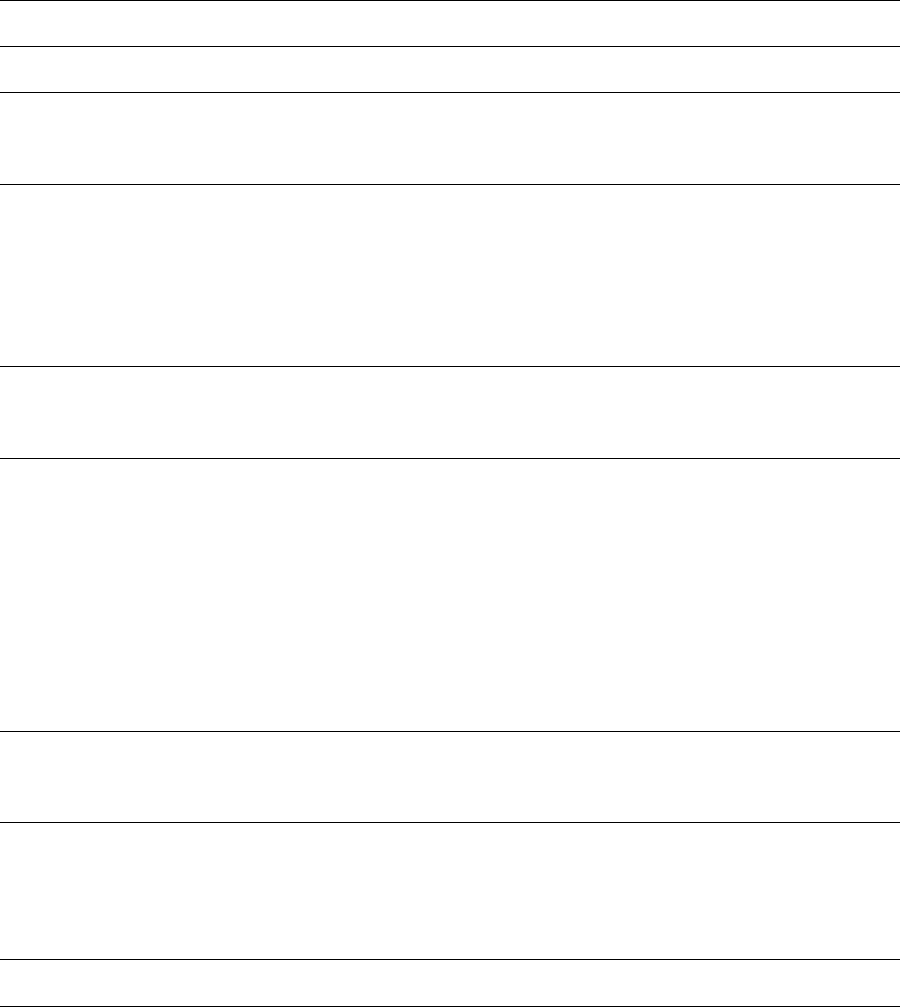

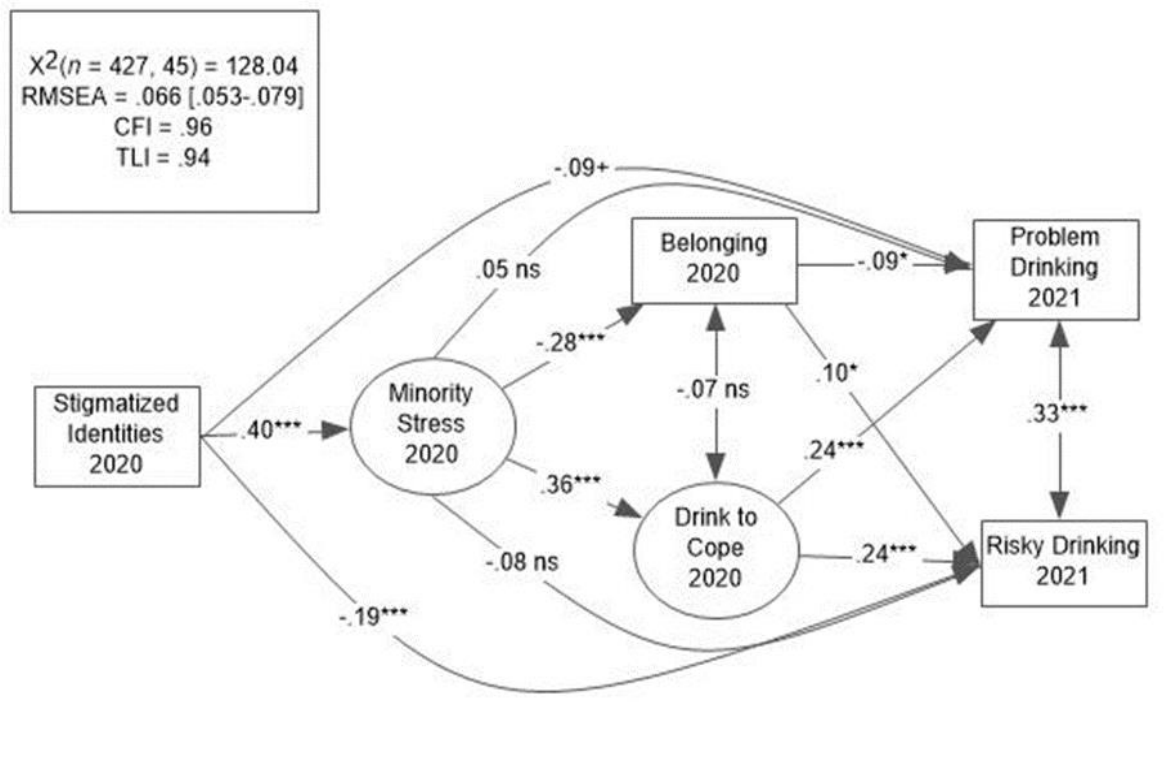

Structural Equation Model

The full model examined the relationship

between stigmatized identities, minority

stress, belongingness, drinking to cope, risky

drinking, and problem drinking (Figure 1),

and demonstrated good fit to the data, Χ

2

(n =

427, 45) =128.04, RMSEA = .066, CFI = .96,

TLI = .94. Most pathways were statistically

significant and in the predicted direction.

Consistent with expectations, bivariate

correlation and structural path model

revealed identifying with more stigmatized

identities was associated with higher

minority stress.

7

Das et al.: INTERSECTIONAL MINORITY STRESS & ALCOHOL

Published by New Prairie Press, 2023

Table 2

Participant characteristics

Characteristic

N (%)

Age

20.84 (SD = 5.12)

Gender

Woman/Female

316 (74.0%)

Man/Male

96 (22.5%)

Gender-expansive

a

15 (3.5%)

Race/Ethnicity

b

American White or Caucasian

380 (89.0%)

Asian or Asian American

41 (9.6%)

Hispanic or Latino/a

24 (5.6%)

Black or African American

18 (4.2%)

Native American or Alaskan Native

8 (1.9%)

Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

7 (1.6%)

Sexual Orientation

Heterosexual/straight

314 (73.5%)

Bisexual

57 (13.3%)

Gay/lesbian

21 (4.9%)

Asexual

11 (2.6%)

Questioning

5 (1.2%)

Not listed

10 (2.3%)

Pell Grant Status

Eligible

59 (13.8%)

Ineligible

368 (86.2%)

Note.

a

Gender-expansive identities include any of the following identities: transwoman; transman; genderqueer/gender non-

conforming; intersex; a gender not listed here.

b

N does not equal to total sample (427), as participants were instructed to select all that apply, and such would be double counted

8

Health Behavior Research, Vol. 6, No. 4 [2023], Art. 8

https://newprairiepress.org/hbr/vol6/iss4/8

DOI: 10.4148/2572-1836.1204

Table 3

Number of stigmatized identities

Intersections

N = 427 (100%)

0 SID

61 (14.1%)

1 SID

189 (44.3%)

N

% SID

% Total

Gender (Women)

160

86.7%

37.5%

Race/Ethnicity (REM)

12

6.3%

2.81%

Sexual Orientation (LGBTQ+)

9

4.8%

2.11%

Pell Grant (Awarded grant)

8

4.2%

1.87%

2 SIDs

129 (30.2%)

N

% SID

% Total

Gender X Race/Ethnicity

47

36.4%

11.01%

Gender X sexual orientation

56

43.4%

13.11%

Gender X Pell grant

18

14.0%

4.22%

Race/Ethnicity X sexual orientation

3

2.3%

0.70%

Race/Ethnicity X Pell grant

2

1.6%

0.47%

Sexual orientation X Pell grant

2

1.6%

0.47%

3 SIDs

42 (9.8%)

N

% SID

% Total

Gender X race X sexual orientation

15

31.8%

3.51%

Gender X race X Pell grant

6

14.3%

1.40%

Gender X sexual orientation X Pell grant

21

50%

4.92%

4 SIDs

7 (1.6%)

Note.

SID = stigmatized identity; REM = Racial/Ethnic Minority; LGBTQ+ = Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, Queer, and sexual

minority identities. Participants were coded as holding a stigmatized gender identity if they identified as woman/female (code =

1) or one of the following gender-expansive identities: transwoman; transman; genderqueer/gender non-conforming; intersex; a

gender not listed here (code = 2). Participants were coded as having a stigmatized identity on the basis of sexual orientation (code

= 1) if they selected any identity other than heterosexual/straight. Participants were coded as having a stigmatized racial/ethnic

identity (code = 1) if they selected at least one racial/ethnic category other than White (i.e., indicated biracial status). As a proxy

for a stigmatized social class identity, participants eligible for Pell grants were coded as one, as these awards are granted to

students from low-income households.

9

Das et al.: INTERSECTIONAL MINORITY STRESS & ALCOHOL

Published by New Prairie Press, 2023

Figure 1

Structural equation model of variables of interest

10

Health Behavior Research, Vol. 6, No. 4 [2023], Art. 8

https://newprairiepress.org/hbr/vol6/iss4/8

DOI: 10.4148/2572-1836.1204

Problematic Alcohol Use

A majority of participants reported having

had an alcoholic beverage at baseline (n =

365, 85.5%). On their peak drinking occasion

in the past 30 days, participants reported an

average of 3.84 (SD = 4.05) standard drinks.

Bivariate correlations were in expected

negative direction between number of

stigmatized identities, minority stress,

belonging, and drinking to cope motives.

Meditation Pathway through Belonging

As hypothesized, bivariate correlation and

structural model path indicated identifying

with more stigmatized identities and higher

minority stress was associated with lowered

belonging, which in turn, explained higher

problem drinking one year later. However,

unexpectedly, future risky drinking was

positively related to belonging, and

negatively related to minority stress and

number of stigmatized identities.

Mediation Pathway through Coping

Motives

Bivariate correlation and the structural

model path indicated, as expected, coping

motives and minority stress are negatively

related, and coping motives is positively

related to risky drinking and problem

drinking one year later. In other words, as

expected, higher minority stress predicted

higher drinking to cope motives, which in

turn, explained more problem drinking, and

risky drinking.

Discussion

The present work extends the literature on

problematic alcohol use among multiply-

stigmatized individuals by testing an additive

intersectional approach among individuals

facing multiple forms of oppression (Beale,

1970; Grollman, 2014). Problematic alcohol

use in the present study was characterized as

engaging in risky drinking and problem

drinking. Risky drinking was measured as the

peak number of drinks consumed in one

setting, wherein a large amount of alcohol

was consumed (i.e., higher negative

consequences from alcohol use).

Specifically, we tested whether greater risky

and problem drinking among multiply-

stigmatized students was associated with

greater reported minority stressors, indirectly

through lower belongingness, and greater

drinking to cope motives. A key strength of

the study is that it accounts for the experience

of individuals who identify with multiple

stigmatized identities, replicating previous

work on additive intersectional stressors and

support for the double-disadvantage

hypothesis (Beale, 1970; Grollman, 2014).

Taking an additive approach to the

intersections of multiple stigmatized

identities offers an initial step towards

understanding how exposure to multiple

forms of discrimination influences coping

motives, belonging, and problematic alcohol

use. Thus, the present study extends the

literature on potential mechanisms

explaining problem drinking behaviors and

risky drinking in college students facing

disproportionate exposure to discrimination.

A second strength is the longitudinal design

to test the mediation of several general and

unique stressors on future problematic

alcohol use over one year, consistent with

minority stress theory and the psychological

mediation model. We found partial support

for our three main hypotheses.

First, consistent with expectations, those

with more stigmatized identities reported

higher minority stress in bivariate

correlations and the structural model. This

relationship replicates previous findings

(Remedios & Snyder, 2018) that individuals

who identify with multiple (versus zero or

single) stigmatized identities report higher

11

Das et al.: INTERSECTIONAL MINORITY STRESS & ALCOHOL

Published by New Prairie Press, 2023

levels of discrimination, stereotype threat,

and felt invisibility.

Second, we found partial support for our

hypothesized mediation pathway through

belongingness on risky and problem

drinking. First, consistent with Murdock-

Perriera et al’s (2019) work suggesting that

those holding (multiple) stigmatized

identities may experience greater threats to

their belonging, we found higher minority

stress associated with lowered belonging.

However, mixed results between belonging

and risky and problem drinking emerged. For

problem drinking, in the structural model, as

hypothesized, lowered belonging predicted

greater problem drinking one year later, yet

we failed to find a bivariate correlation.

Notably, given we did find the expected

negative relationship between belonging and

problem drinking in the model, it may be the

case that when accounting for stigmatized

identities and minority stress, students

experiencing less belonging because of

oppressive environments, are also more

likely to drink with consequences. This

finding is consistent with Hatzenbuehler's

(2009) mediation framework of minority

stress, wherein minority stress is associated

with greater problem drinking, indirectly via

decreased belonging.

However, for risky drinking, or the

number of peak drinks consumed, we found

an unexpected, positive relation with

belongingness across both the model and

bivariate correlations. Although surprising, it

is possible that the positive relationship may

reflect norms of collegiate drinking.

Becoming involved in the drinking culture

may feel like a primary means to bolster

social capital and belonging (Gambles et al.,

2022; Olmstead et al., 2019). Indeed,

Hodgkins (2015) found drinkers versus non-

drinkers report greater social inclusion and,

in turn, life satisfaction. Further, Reid and

Hsu (2012) found (1) binge drinkers versus

non-binge drinkers report greater social

satisfaction, and (2) members from

stigmatized groups (women, racially

minoritized, low income) report equivalent

levels of social satisfaction as high-status

peers if they engaged in binge drinking than

if they did not. This suggests binge drinking

attenuated consequences of lower social

status on collegiate social satisfaction and

provides indirect evidence that drinking may

serve as a way through which social status

and belonging can be achieved. Thus, it is

possible that the belonging-alcohol pathway

may differ depending on the alcohol-related

behavior: (1) lowered belonging may serve

as an additional stressor and thus is a way in

which “stigma gets under the skin;” or (2)

greater threats to belonging may encourage

drinking as a way to “fit” in with others,

thereby lending to riskier drinking but

increased belonging. Future research should

explore those relations further. Specifically,

greater understanding of drinking cultures on

social activities and belonging for students

who identify with stigmatized identities is

needed.

Last, we found partial support for our final

mediation pathway through drinking to cope.

As expected, higher minority stress predicts

higher drinking to cope in the model, but this

association was not significant in bivariate

correlations. The discrepant finding may

suggest that when accounting for multiple

factors as in the model, the relationship

between increased minority stress and coping

to drink emerges. However, consistent with

previous research (Hatzenbuehler et al.,

2011), higher drinking to cope motives

predicted greater problem and risky drinking

across models. Importantly, similar to

belonging, direct associations between

minority stress, future risky and problem

drinking failed to reach significance, thereby

suggesting that among students who identify

with stigmatized identities, drinking to cope

is another specific mechanism through which

12

Health Behavior Research, Vol. 6, No. 4 [2023], Art. 8

https://newprairiepress.org/hbr/vol6/iss4/8

DOI: 10.4148/2572-1836.1204

stigmatized students may be vulnerable to

problematic alcohol use.

Of important note, when examining direct

relationships between minority stress and

alcohol consumption and problems,

additional mixed patterns emerge. Contrary

to expectations, higher minority stress

correlated with less risky drinking (i.e., fewer

peak number of drinks) in bivariate

associations, did not reach statistical

significance in the model, and was not

associated with problem drinking in either

analysis. This relationship also was observed

when examining the associations with the

number of stigmatized identities. These

findings are surprising in light of

Hatzenbuehler’s mediation framework

theory, which posits increased minority stress

may exacerbate psychological processes

associated with problematic alcohol use.

Examples of possibilities relevant to the

specific context of this sample may help to

explain our findings. First, negative and non-

significant associations may be confounded

by our majority White, woman sample (Table

3). Indeed, although Lewis et al. (2016)

found that among Black lesbian women

drinking to cope explained problematic

alcohol use, those findings did not replicate

among non-Hispanic White women. Second,

students sampled in the present study

experienced more social isolation than they

have in the past due to the COVID-19

pandemic. Consistent with the present

findings, there is a negative association

between substance use and discrimination in

spring 2020 among racially stigmatized

students (Hicks et al., 2022). Third, it is

possible that students experiencing minority

stress on campus may fear harsher

punishment for risky drinking, and as such

may reduce risky, problem drinking. Last,

another possibility is tied to the somewhat

unexpected positive bivariate relations

between belongingness, risky drinking, and

alcohol-related problems. As previously

mentioned, the positive relationship between

belonging and drinking may reflect an

influence of a drinking culture. It is possible

that students who are experiencing greater

minority stress, associated with less

belonging, may not seek out or feel included

in social interactions involving alcohol. Thus,

they may both be more aware of the negative

consequences of risky drinking and thus do

not engage in social drinking.

Limitations

First, whereas the present work is

grounded in intersectionality theory with a

review of literature at various intersections,

we applied an additive approach. As

intersectionality theorists have noted that

taking an additive rather than an interactive

approach can flatten or weaken our

understanding of the unique exposure to

oppression at intersection of two or more

stigmatized experiences. Due to the methods

and available data, unique constellations of

identities as in the reviewed literature (e.g.,

black queer women or gay men) were

collapsed, and thus, flattened experiences

across different forms of oppression. Indeed,

students who identify with two stigmatized

identities may experience notably different

forms of oppression across axes of their

identities (gendered racism, or classist

heterosexism) that are likely qualitatively

different. As a consequence, the results are

not able to test explicitly if mechanisms of the

oppression-alcohol link differ across specific

intersections of stigmatized identities.

Despite this limitation, in the current study,

we aimed to approach intersectionality as an

initial step towards understanding how

intersectional oppression may impact

problematic alcohol use. Findings support

continued research in larger samples on how

specific unique intersections of oppression

may relate to problematic alcohol use.

13

Das et al.: INTERSECTIONAL MINORITY STRESS & ALCOHOL

Published by New Prairie Press, 2023

Second, although the literature reviewed

focused on people with multiple stigmatized

identities, especially among racially

stigmatized groups, we acknowledge our

sample is mostly White women (59.7%),

with multiple stigmatized identities across

sexual orientation (13%), class (4%), and

their intersection (4%). Thus, with a student

sample of only 21% identifying as racially

stigmatized, we note that nuances of

intersectional oppression among racially

stigmatized college students are limited. This

may have influenced some of our non-

significant findings. To address the

limitations that prohibit generalizing to the

experiences of multiply-stigmatized college

students of color, future research with larger

samples of stigmatized students is necessary.

With a larger sample, generalizability could

be tested by examining minority stress

processes comparing multiply-stigmatized

racially diverse students versus those who are

not.

Finally, it is important to contextualize

that this study was conducted during the

COVID-19 pandemic and a period in which

we experienced renewed attention to racism

in the U.S. Thus, given the unprecedented

changes in the environment, our participants

may have been more socially isolated, and

issues related to racial minority stress may

have been particularly salient. Interestingly,

alcohol use was within expected norms for a

predominantly female-identified sample, and

the overall mean levels in minority stress was

slightly lower than in previous studies

(Remedios & Snyder, 2018). Nevertheless,

because the pandemic resulted in

unprecedented changes to the daily lives of

college students, replicating these findings is

needed to assess whether relationships

observed remained the same with the return

to campus and less isolation.

Future Directions

More research on the direction of the

relationship between belonging and drinking

behaviors is needed. Whereas previous

research points to negative associations

between lowered belonging and problematic

alcohol use, the present study’s results

suggest that there may be differential

associations between types of drinking

behaviors. That is, lowered belonging may be

associated with less risky drinking, but more

alcohol-related problems. The context in

which stigmatized college students drink may

be related to differing relations between

belonging and drinking: risky drinking may

be more likely in the context of social settings

(e.g., drinking games that require rapid

consumption of alcohol within short periods

of time), whereas drinking that lends to other

forms of alcohol consequences could result

from either isolated or social drinking, and

thus may associate with lowered belonging.

As such, future research should explicitly

examine whether the context in which

students from different stigmatized groups

participate in problematic drinking relates to

a sense of belonging. For instance, a daily

diary study among college students with

various stigmatized identities could examine

when and how these students drink and their

sense of belonging before and after drinking-

related events.

Given oppression exists at the internal,

individual, and structural level, future work

should consider extending findings to other

dimensions of stigma, such as interpersonal

and institutional discrimination. Examining

the impact of different policies or programs

at the university, county, or state level on

multiply-stigmatized students would be

fruitful. For instance, college campuses with

a greater number of policies and resources

affirming the inclusion of sexual and gender

minorities were shown to be associated

directly with lower reported discrimination,

14

Health Behavior Research, Vol. 6, No. 4 [2023], Art. 8

https://newprairiepress.org/hbr/vol6/iss4/8

DOI: 10.4148/2572-1836.1204

less distress, and higher self-acceptance

among LGBTQ students (Woodford et al.,

2018). However, student organizations and

networks are often based on single

stigmatized identities (e.g., women in STEM,

LGBTQ groups, and first-generation college

students), which only address a single axis of

identity (Dennissen et al., 2020). As such,

organizations focused on gender or sexuality,

for instance, may render students who are

exposed to racist heterosexism invisible and

unsupported. Given that a primary goal of

such organizations is to support belonging

and resources for coping with stress, colleges

should consider how students exposed to

stigma beyond one specific stigmatized

identity may need additional supports or

unique communities. For instance, extending

previous work of Woodford et al. (2018),

future research could examine the impact of

belonging to student organizations that center

students with more than one stigmatized

identity (e.g., women of color in STEM) on

minority stress and subsequent problematic

alcohol use. Given differences found in

belongingness among racially stigmatized

students in four-year versus two-year

universities (Gopalan & Brady, 2020),

researchers could also examine whether

problematic drinking among multiply-

stigmatized students differ depending on the

type of university. Specifically examining

what initiatives or factors foster

belongingness within two-year institutions

could also provide valuable insights for

supporting belonging among stigmatized

students at four-year universities. Doing so

could further our understanding of the

institutional factors related to belongingness

and more adaptive health behaviors among

minoritized students.

Implications for Health Behavior

Research

We extend the literature by examining the

longitudinal relationship between additive

minority stress (both general and unique to

intersectional oppression) associated with

exposure to multiple forms of oppression on

problematic drinking among college

students. Furthermore, we test whether that

link can be explained by lower

belongingness, and higher drinking to cope

motives. As expected, a greater number of

stigmatized identities were associated with

higher minority stress (discrimination,

stereotype concerns, and invisibility). This

finding underscores that the experiences of

minority stress vary as students are subjected

to multiple forms of oppression. Given the

implications of stigma on health behaviors

(Pascoe & Richman, 2009), understanding

the extent to which health behaviors may

differ among multiply-versus singly

stigmatized students is critical to supporting

adaptive outcomes among our stigmatized

students more broadly. Furthermore, as

expected, when accounted together, higher

coping motives explained the relation

between higher minority stress and future

risky, problem drinking. The implication of

that finding suggests that in order to reduce

problematic alcohol use, college

administrators and health behavior

practitioners should consider mitigating

minority stressors on their campuses and

introducing alternative coping strategies for

students facing stigma. Finally, mediation

pathways through belongingness were

mixed. Belonging may be an adaptive

process for reducing problem drinking, but

given the social nature of drinking in

colleges, belonging or fitting in that context

may lead to riskier drinking. Specifically,

given the differential implications of

belonging and the type of drinking behavior,

it will be important for practitioners to

15

Das et al.: INTERSECTIONAL MINORITY STRESS & ALCOHOL

Published by New Prairie Press, 2023

consider the nuances of how social aspects of

drinking may or may not be an adaptive

pathway to belonging. Taken together, given

these mixed findings, future health behavior

researchers should explore how underlying

mechanisms may portend different alcohol-

related behaviors in the discrimination-health

link.

Discussion Questions

The present study applied an additive

intersectional approach to understand

minority stress experiences of multiply-

stigmatized college students. How might

health behavior researchers use the

intersectional approach to address health

disparities?

In this study, we found the relationship

between belonging differed based on the

problematic alcohol use. Specifically,

belonging associates with less future problem

drinking, but more risky drinking

(consuming large amounts of alcohol during

a drinking event). Given the social nature of

drinking on college campuses, how might

belonging explain different types of alcohol

use, and how might health behaviorists try to

address this?

Ethical Approval

Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval

was obtained prior to data collection.

Conflict of Interests

The authors have no competing interests to

declare.

References

Allen, K.-A., Kern, M. L., Rozek, C. S.,

McInerney, D. M., & Slavich, G. M.

(2021). Belonging: A review of

conceptual issues, an integrative

framework, and directions for future

research. Australian Journal of

Psychology, 73(1), 87-102.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00049530.2021.1

883409

Asher, S. R., & Weeks, M. S. (2013).

Loneliness and belongingness in the

college years. In R. J. Coplan & J. C.

Bowker (Eds.), The handbook of solitude

(pp. 283-301). Wiley.

https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118427378.c

h16

Bauer, G. R., Churchill, S. M., Mahendran,

M., Walwyn, C., Lizotte, D., & Villa-

Rueda, A. A. (2021). Intersectionality in

quantitative research: A systematic

review of its emergence and applications

of theory and methods. SSM - Population

Health, 14, 100798.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100

798

Beale, F. (1970). Double jeopardy: To be

black and female. In T. Cade Bambara,

Black women: An anthology, (pp. 90-

100). New American Library.

Bollen, K. A., & Hoyle, R. H. (1990).

Perceived cohesion: A conceptual and

empirical examination. Social Forces,

69(2), 479.

https://doi.org/10.2307/2579670

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1992).

Alternative ways of assessing model fit.

SAGE Journals,

https://doi.org/10.1177/00491241920210

02005

Cerezo, A., & Ramirez, A. (2021).

Perceived discrimination, alcohol use

disorder and alcohol-related problems in

sexual minority women of color. Journal

of Social Service Research, 47(1), 33-46.

https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2019.1

710657

Cerezo, A., Williams, C., Cummings, M.,

Ching, D., & Holmes, M. (2020).

Minority stress and drinking: Connecting

16

Health Behavior Research, Vol. 6, No. 4 [2023], Art. 8

https://newprairiepress.org/hbr/vol6/iss4/8

DOI: 10.4148/2572-1836.1204

race, gender identity and sexual

orientation. Counseling Psychologist,

48(2), 277-303.

https://doi.org/10.1177/00110000198874

93

Cole, E. R. (2009). Intersectionality and

research in psychology. American

Psychologist, 64(3), 170-180.

https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014564

Combahee River Collective. (1995).

Combahee River Collective statement. In

B. Guy-Sheftall, Words of fire: An

anthology of African-American feminist

thought (pp. 232-240). New York: New

Press. (Original work published 1977)

Cooper, M. L. (1994). Motivations for

alcohol use among adolescents:

Development and validation of a four-

factor model. Psychological Assessment,

6(2), 117-128.

https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-

3590.6.2.117

Cooper, M. L., Frone, M. R., Russell, M., &

Mudar, P. (1995). Drinking to regulate

positive and negative emotions: A

motivational model of alcohol use.

Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 69(5), 990-1005.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-

3514.69.5.990

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins:

Intersectionality, identity politics, and

violence against women of color.

Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241-1299.

https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

Crocker, J., Major, B., & Steele, C. (1998).

Social stigma. In S. Fiske, D. Gilbert, &

G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social

psychology (Vol 2, pp. 504-553). New

York, NY: Wiley.

Dennissen, M., Benschop, Y., & van den

Brink, M. (2020). Rethinking diversity

management: An intersectional analysis

of diversity networks. Organization

Studies, 41(2), 219-240.

https://doi.org/10.1177/01708406188001

03

Dowd, J. J., & Bengtson, V. L. (1978).

Aging in minority populations: An

examination of the double jeopardy

hypothesis. Journal of Gerontology,

33(3), 427-436.

https://doi.org/10.1093/geronj/33.3.427

English, D., Rendina, H. J., & Parsons, J. T.

(2018). The effects of intersecting

stigma: A longitudinal examination of

minority stress, mental health, and

substance use among black, Latino, and

multiracial gay and bisexual men.

Psychology of Violence, 8(6), 669-679.

https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000218

Gambles, N., Porcellato, L., Fleming, K. M.,

& Quigg, Z. (2022). “If you don’t drink

at university, you’re going to struggle to

make friends:” Prospective students’

perceptions around alcohol use at

universities in the United Kingdom.

Substance Use & Misuse, 57(2), 249-255.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2021.2

002902

Gopalan, M., & Brady, S. T. (2020). College

students’ sense of belonging: A national

perspective. Educational Researcher,

49(2), 134-137.

https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X198976

22

Grollman, E. A. (2014). Multiple

disadvantaged statuses and health: The

role of multiple forms of discrimination.

Journal of Health and Social Behavior,

55(1), 3-19.

https://doi.org/10.1177/00221465145212

15

Hamilton, H. R., & Dehart, T. (2019). Needs

and norms: Testing the effects of

negative interpersonal interactions, the

need to belong, and perceived norms on

alcohol consumption. Journal of Studies

on Alcohol and Drugs, 80(3), 340-348.

https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2019.80.34

0

17

Das et al.: INTERSECTIONAL MINORITY STRESS & ALCOHOL

Published by New Prairie Press, 2023

Hatzenbuehler, M. L. (2009). How does

sexual minority stigma “get under the

skin”? A psychological mediation

framework. Psychological Bulletin,

135(5), 707-730.

https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016441

Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Corbin, W. R., &

Fromme, K. (2011). Discrimination and

alcohol-related problems among college

students: A prospective examination of

mediating effects. Drug and Alcohol

Dependence, 115(3), 213-220.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010

.11.002

Hicks, T. A., Chartier, K. G., Buckley, T.

D., Reese, D., Working Group, T. S. F.

S., Vassileva, J., ... & Moreno, O. (2022).

Divergent changes: abstinence and

higher-frequency substance use increase

among racial/ethnic minority young

adults during the COVID-19 global

pandemic. American Journal of Drug and

Alcohol Abuse, 48(1), 88-99.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00952990.2021.1

995401

Hodgkins, M. B. (2015). The importance of

fitting in: Drinker status, social

inclusion, and well-being in college

students [Colby College].

https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/honorst

heses/788

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff

criteria for fit indexes in covariance

structure analysis: Conventional criteria

versus new alternatives. Structural

Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1-55.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540

118

Kenny, D. (2015). SEM: Measuring model

fit.

http://www.davidakenny.net/cm/fit.htm.

Lewis, R. J., Mason, T. B., Winstead, B. A.,

Gaskins, M., & Irons, L. B. (2016).

Pathways to hazardous drinking among

racially and socioeconomically diverse

lesbian women: Sexual minority stress,

rumination, social isolation, and drinking

to cope. Psychology of Women Quarterly,

40(4), 564-581.

https://doi.org/10.1177/03616843166626

03

Lewis, R. J., Winstead, B. A., Lau-Barraco,

C., & Mason, T. B. (2017). Social factors

linking stigma-related stress with alcohol

use among lesbians. Journal of Social

Issues, 73(3), 545-562.

https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12231

Martens, M. P., Neighbors, C., Lewis, M.

A., Lee, C. M., Oster-Aaland, L., &

Larimer, M. E. (2008). The roles of

negative affect and coping motives in the

relationship between alcohol use and

alcohol-related problems among college

students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol

and Drugs, 69(3), 412-419.

https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2008.69.41

2

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress,

and mental health in lesbian, gay, and

bisexual populations: Conceptual issues

and research evidence. Psychological

Bulletin, 129(5), 674-697.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-

2909.129.5.674

Murdock-Perriera, L. A., Boucher, K. L.,

Carter, E. R., & Murphy, M. C. (2019).

Places of belonging: Person- and place-

focused interventions to support

belonging in college. In M. B. Paulsen &

L. W. Perna (Eds.), Higher education:

Handbook of theory and research (Vol.

34, pp. 291–323). Springer International

Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-

3-030-03457-3_7

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998).

Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Muthén &

Muthén.

Napoli, M., Marsiglia, F. F., & Kulis, S.

(2003). Sense of belonging in school as a

protective factor against drug abuse

among Native American urban

adolescents. Journal of Social Work

18

Health Behavior Research, Vol. 6, No. 4 [2023], Art. 8

https://newprairiepress.org/hbr/vol6/iss4/8

DOI: 10.4148/2572-1836.1204

Practice in the Addictions, 3(2), 25-41.

https://doi.org/10.1300/J160v03n02_03

Olmstead, S., Anders, K., Clemmons, D., &

Davis, K. (2019). First-semester college

students’ perceptions of and expectations

for involvement in the college drinking

culture. Journal of The First-Year

Experience & Students in Transition,

31(1), 51-67.

Pascoe, E. A., & Richman, L. S., (2009).

Perceived discrimination and health: a

meta-analytic review. Psychological

Bulletin, 135(4), 531.

https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016059.

Reid, L. D., & Hsu, C. L. (2012). Social

status, binge drinking, and social

satisfaction Among college students.

American Sociological Association

Annual Meeting, Denver, CO.

http://image.guardian.co.uk/sys-

files/Guardian/documents/2012/08/20/A

M_2012_Hsu_Study.pdf

Remedios, J., & Snyder, S. (2018).

Intersectional oppression: Multiple

stigmatized identities and perceptions of

invisibility, discrimination, and

stereotyping. Journal of Social Issues, 74,

265-281.

https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12268

Rostosky, S. S., Owens, G. P., Zimmerman,

R. S., & Riggle, E. D. B. (2003).

Associations among sexual attraction

status, school belonging, and alcohol and

marijuana use in rural high school

students. Journal of Adolescence, 26(6),

741-751.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.200

3.09.002

Vu, M., Li, J., Haardörfer, R., Windle, M.,

& Berg, C. J. (2019). Mental health and

substance use among women and men at

the intersections of identities and

experiences of discrimination: Insights

from the intersectionality framework.

BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1-13.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-

6430-0

Wilson, L. C., & Liss, M. (2022). Safety and

belonging as explanations for mental

health disparities among sexual minority

college students. Psychology of Sexual

Orientation and Gender Diversity, 9(1),

110. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000421.

White, A., & Hingson, R. (2013). The

burden of alcohol use: Excessive alcohol

consumption and related consequences

among college students. Alcohol

Research: Current Reviews, 35(2), 201-

218.

White, H. R., & Labouvie, E. W. (1989).

Towards the assessment of adolescent

problem drinking. Journal of Studies on

Alcohol, 50(1), 30-37.

https://doi.org/10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30

Woodford, M. R., Kulick, A., Garvey, J. C.,

Sinco, B. R., & Hong, J. S. (2018).

LGBTQ policies and resources on

campus and the experiences and

psychological well-being of sexual

minority college students: Advancing

research on structural inclusion.

Psychology of Sexual Orientation and

Gender Diversity, 5(4), 445-456.

https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000289

19

Das et al.: INTERSECTIONAL MINORITY STRESS & ALCOHOL

Published by New Prairie Press, 2023