1

Strategic Plan for Preventing and Mitigating

Drug Shortages

Food and Drug Administration

October 2013

2

TABLE OF CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................3

INTRODUCTION...............................................................................................................7

I. UNDERSTANDING AND RESPONDING TO DRUG SHORTAGES ...............8

A. R

ECENT CHANGES TO FDA OVERSIGHT OF DRUG SHORTAGES ............................... 9

B. R

OOT CAUSES OF DRUG SHORTAGES .....................................................................

11

C. C

URRENT FDA EFFORTS TO PREVENT AND MITIGATE DRUG SHORTAGES............

12

D. I

NTERNAL AND EXTERNAL COMMUNICATION AND ENGAGEMENT ........................

15

II. CONTINUING PROGRESS: FDA’S STRATEGIC PLAN...............................17

A. GOAL

#1: STRENGTHEN MITIGATION RESPONSE ................................................. 18

B. GOAL

#2: DEVELOP LONG-TERM PREVENTION STRATEGIES............................... 20

III. ACTIONS OTHER STAKEHOLDERS SHOULD CONSIDER ........................21

A. M

ANUFACTURING INCENTIVES ...............................................................................

22

B. U

SE OF QUALITY DATA ..........................................................................................

22

C. R

EDUNDANCY, CAPABILITY, AND CAPACITY .........................................................

23

D. T

HE GRAY MARKET................................................................................................

23

CONCLUSION .................................................................................................................23

APPENDIX A: FEDERAL REGISTER NOTICE .........................................................25

APPENDIX B: STATUTORY ELEMENTS...................................................................28

APPENDIX C:

COLLECTING INFORMATION ON DRUG SHORTAGES..............29

APPENDIX D: FDA OFFICES ENGAGED IN DRUG SHORTAGE EFFORTS......

31

APPENDIX E: COORDINATING DRUG SHORTAGE EFFORTS IN CDER ..........

34

APPENDIX F: COMMUNICATING WITH EXTERNAL GROUPS...........................

37

3

Strategic Plan for Preventing and Mitigating

Drug Shortages

Executive Summary

On July 9, 2012, the President signed into law the Food and Drug Administration Safety and

Innovation Act (FDASIA).

1

Among other things, Title X of FDASIA directs the Food and Drug

Administration (FDA or the Agency) to establish a task force on drug shortages to develop and

submit to Congress a Strategic Plan to enhance FDA’s response to preventing and mitigating

drug shortages.

Understanding and Responding to Drug Shortages

Shortages of drugs and biologics pose a significant public health threat, delaying, and in some

cases even denying, critically needed care for patients. Preventing drug shortages remains a top

priority for FDA.

Although FDA cannot directly affect many of the business and economic decisions that

contribute to drug shortages, FDA is well positioned to play a significant role as manufacturers

work to restore lost production of life-saving medications. FDA can be most effective when

there is time to plan; thus, it is critical that manufacturers notify FDA as soon as possible when

manufacturing disruptions are expected. Early notification about possible shortages, as

requested in the President’s Executive Order 13588 and then codified into law by Congress, has

enabled FDA to work with manufacturers to restore production of many lifesaving therapies.

There has been a 6-fold increase in notifications to FDA since the Executive Order. These

increased notifications combined with allocation of additional FDA resources have resulted in

real progress in addressing shortages―FDA helped prevent close to 200 drug shortages in 2011

and more than 280 in 2012. The total number of new shortages decreased from 251 in 2011 to

117 in 2012.

If notified of a potential disruption in production, FDA can take a number of steps to help

prevent or mitigate a shortage, including:

Determine if other manufacturers are willing and able to increase production

Expedite inspections and reviews of submissions

Exercise temporary enforcement discretion for new sources of medically necessary drugs

Work with the manufacturer to ensure adequate investigation into the root cause of the

shortage

1

Public Law 112-144.

4

Review possible risk mitigation measures for remaining inventory

When selecting specific regulatory tools, FDA works closely with manufacturers and chooses

tools that are appropriate to the specific situation. FDA also makes certain that drug shortages

are considered before taking an enforcement action or issuing a Warning Letter. Additionally,

FDA communicates up-to-date information about a shortage to affected stakeholders and

continues to monitor a shortage until it is resolved.

FDA’s efforts to date demonstrate that FDA is an important part of the solution to the drug

shortages problem. By working closely with manufacturers experiencing problems, as well as

potential alternative manufacturers, and by exercising regulatory flexibility in appropriate cases,

FDA has had a substantial positive impact on the shortage situation. However, FDA cannot

address the drug shortage threat alone. An examination of FDA’s response to drug shortages

underscores the importance of strong collaboration and constant communication between FDA,

industry, health professionals, and patients. In addition, ensuring that critical drugs are available

to the patients who need them will require further action by manufacturers and other

stakeholders.

FDA’s Drug Shortage Strategic Plan

In its Drug Shortage Strategic Plan (Strategic Plan), FDA identifies two central goals to address

drug shortages: improving our mitigation response to imminent or existing shortages, and

implementing strategies for the long-term prevention of shortages by focusing on the root causes

of shortages. The Strategic Plan outlines specific tasks under each goal.

Goal #1: STRENGTHEN MITIGATION RESPONSE

Improve and streamline FDA’s current mitigation activities once the

Agency is notified of a supply disruption or shortage

TASK 1.1

Revise and standardize procedures to more accurately reflect and

Develop and/or Streamline enhance the interactions between units within FDA and maximize the

Internal FDA Processes efficiency of FDA’s response to a notification of a disruption in supply.

TASK 1.2

Improve Data and Response

Tracking

Improve Agency databases related to shortages and the tracking

procedures FDA uses to manage shortages. Improved tracking will

enable FDA to better assess progress on preventing and mitigating

shortages.

TASK 1.3

Clarify Roles/Responsibility

of Manufacturers

Clarify roles/responsibilities of manufacturers by finalizing the

proposed rule explaining when and how to notify FDA

of a

discontinuance or interruption in manufacturing, working with

manufacturers on remediation efforts, and encouraging manufacturers

to engage in best practices to avoid or mitigate shortages.

5

TASK 1.4

Enhance Public

Communications about Drug

Shortages

Continue to improve FDA’s public communications about drug

shortages by developing a smartphone application so that individuals

can instantaneously access drug shortage information, updating the

website to include the therapeutic category(ies) for shortage products,

and improving the functionality of the website by adding sort and

search capabilities.

Goal #2: DEVELOP LONG-TERM PREVENTION STRATEGIES

Develop long-term prevention strategies to address the underlying causes of supply disruptions

and prevent drug shortages

TASK 2.1

Develop Methods to

Incentivize and Prioritize

Manufacturing Quality

Identify ways FDA can implement positive incentives to promote and

sustain manufacturing and product quality improvements.

TASK 2.2

Use Regulatory Science to

Identify Early-Warning

Signals of Shortages

Continue to develop risk-based approaches to identify early warning

signals for manufacturing and quality problems to prevent supply

disruptions.

TASK 2.3

Increase Knowledge to

Develop New Strategies to

Address Shortages

Continue to work with stakeholders to further develop our

understanding of issues related to shortages, including whether a

Qualified Manufacturing Partner Program would be feasible and

beneficial. This additional information could help inform new

strategies to address shortages.

Actions for Other Stakeholders to Consider

Stakeholders outside FDA have a significant role to play in mitigating and preventing drug

shortages. Because there are limits to what FDA can do on its own to address shortages, any

comprehensive drug shortages plan must also discuss other stakeholders’ roles and potential

contributions. FDA has identified four specific areas that merit external stakeholder attention:

Manufacturing incentives: Many shortages are caused by manufacturing quality issues.

FDA is exploring ways to use its existing authorities to promote and sustain quality

manufacturing. However, our ability to offer financial or other economic incentives for

innovation and new investments in high-quality manufacturing is limited. Given the

importance of quality and its link to shortages, payers might explore financial or

economic incentives to encourage high-quality manufacturing that could help reduce the

occurrence and severity of shortages.

Use of data on manufacturing quality in purchasing decisions: FDA makes certain

information publicly available about manufacturers’ historical ability to produce quality

products. However, FDA cannot influence whether or how these quality data are used by

buyers, such as hospitals, pharmacies, and other group purchasing organizations, when

they make purchasing decisions. Better use of this information could help incentivize

manufacturers to focus on quality and, ultimately, prevent shortages.

6

Redundancy, capability, and capacity: A disruption in supply is exacerbated if there is

limited manufacturing capacity and capability, market concentration, or just-in-time

inventory practices that result in minimal product inventory being on hand at any given

time. However, FDA cannot prevent manufacturing concentration or require redundancy

of manufacturing capability and capacity. Nor can FDA require a company to

manufacture a drug, maintain a certain level of inventory of drug product, or reverse a

business decision to cease manufacturing. Manufacturers could consider opportunities

for building redundant manufacturing capacity, holding spare capacity, or increasing

inventory levels to lower the risks of shortages; and other stakeholders might explore

how to incentivize such practices.

Gray market: In the context of drug shortages, the term gray market is used to reference

the downstream distribution of approved drug products at significantly marked-up prices.

FDA has limited data on the gray market and limited influence on its workings (for

example, we have no authority regarding product pricing). However, there is evidence

that gray market activities can worsen the impact of drug shortages. Actions on the part

of other stakeholders to minimize gray market activities when such activities exacerbate

the impact of drug shortages could play a role in mitigating the impact of shortages and

reducing risks to patients.

Conclusion

Drug shortages remain a significant public health issue in the United States, and addressing

shortages remains a top priority for FDA. Early and open dialogue between FDA and

manufacturers is critical to successfully mitigating and preventing shortages. Recent important

actions by the President and Congress have enabled FDA to learn more about possible shortages

before they occur. These actions, combined with an increase in the resources FDA is devoting to

drug shortages, have helped prevent numerous recent shortages—more than 280 in 2012.

Nevertheless, substantial challenges remain, and more work by all relevant stakeholders is

needed. This Strategic Plan identifies a number of activities to improve the Agency’s ability to

address drug shortages, focusing on two goals:

Strengthening FDA’s ability to respond to notices of a disruption in supply, including

improving our mitigation tools

Developing long-term prevention strategies to address the underlying causes of supply

disruptions and prevent drug shortages

Recognizing that manufacturers and other stakeholders have important roles to play in ensuring

that drugs are available to the patients who need them, the Strategic Plan also identifies actions

others can consider that show promise in helping to prevent shortages.

FDA looks forward to implementing this Strategic Plan as part of a collaborative and sustained

effort to address drug shortages in the United States.

7

FDA’s Strategic Plan for Preventing and

Mitigating Drug Shortages

Introduction

On July 9, 2012, the President signed into law the Food and Drug Administration Safety and

Innovation Act (FDASIA). Title X of FDASIA pertains to drug shortages and defines a shortage

or drug shortage as a period of time when the demand or projected demand for a drug within the

United States exceeds the supply of the drug.

2

Among other things, FDASIA directed FDA to

establish a task force on drug shortages to develop and submit to Congress a Strategic Plan to

enhance FDA’s response to preventing and mitigating drug shortages. FDASIA specifically

required the Drug Shortages Strategic Plan (Strategic Plan) to include the following:

Plans for enhanced inter- and intra-agency coordination, communication,

and decision-making

Plans to ensure drug shortages are considered when FDA initiates a

regulatory action that could precipitate or exacerbate a drug shortage

Plans for effective communication with external stakeholders

Plans for considering the impact of drug shortages on clinical trials

An examination of whether to establish a “qualified manufacturing partner

program” as further described in FDASIA

Appendix B includes a table indicating where each statutory element is discussed in this

document.

Since the passage of FDASIA, FDA has convened a Drug Shortages Task Force (Task Force),

representing multiple disciplines, centers, and offices within FDA.

3

This Strategic Plan

4

is the

culmination of the efforts of the Task Force over the last several months. The Plan also reflects

input received from a wide variety of sources, including discussions with outside stakeholders

2

Section 506C(h)(2) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) (21 USC 356c(h)(2), as amended by

Title X of FDASIA.

3

Information on drug shortages, including the members of the Task Force can be found at

http://www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/drug

shortages/default.htm (drug shortages). Information about biologics

shortages can be found at http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/SafetyAvailability/Shorta

ges/default.htm

(biologics shortages).

4

The Strategic Plan encompasses both drugs and biologics—although shortages of drugs outnumber shortages of

biologics, both can have a similar and equally troubling impact on patient care. Unless otherwise indicated, we use

the term drug to refer to both drugs and biologics.

8

and comments responding to a Federal Register notice FDA published on February 12, 2013

(Appendix A).

5

FDA also recognizes that numerous other groups are examining drug shortages,

including the Government Accountability Office (GAO) and several private organizations.

Following this Introduction, the Strategic Plan consists of three sections. The first section

explains FDA’s oversight of drug shortages, examines what is known about the causes of

shortages, and describes FDA’s current efforts to resolve existing shortages and respond to

disruptions in supply. The second section is the Strategic Plan: it explains the actions FDA is, or

will be, taking to strengthen and expand its efforts to address shortages. Recognizing that FDA

cannot address this problem alone, the third section outlines potential actions for other

stakeholders to consider.

I. Understanding and Respondi

ng to Drug Shortages

Drug shortages pose a significant public health threat, affecting critically important drugs

including those intended for intravenous administration (e.g., chemotherapy, nutritional support,

and antibiotics). A shortage can result in delaying or denying needed care to patients and may

cause practitioners to prescribe an alternative therapy that may be less effective for the patient or

that poses greater risk.

6

Drug shortages have even disrupted clinical trials, potentially delaying

research on important new therapies.

The number of new drug shortages quadrupled from approximately 60 in 2005 to more than 250

in 2011. These statistics reflect the number of new shortages reported in a given year, but

because shortages typically continue for extended amounts of time, the actual number of

shortages at a given point in time is likely to be higher. As a result, although the number of new

shortages significantly decreased in 2012 to 117 (from 251 in 2011), more than 300 shortages

remained active at the end of 2012.

7

Behind these statistics are individual patients from across the United States who are in need of

drugs to treat life-threatening diseases, including cancer and serious infections. Preventing drug

shortages has been, and continues to be, a top priority for FDA. Working within the confines of

the current statutory and regulatory framework and in partnership with manufacturers and other

stakeholders, FDA helped prevent close to 200 drug shortages in 2011 and more than 280

shortages in 2012.

5

The Federal Register notice and the submitted comments can be found online at http://www.regulations.gov,

Docket No. FDA-2013-N-0124.

6

Berg N, Kos K, et al. Report on the ISPE 2013 Drug Shortages Survey. June 2013. Tampa, FL: International

Society for Pharmaceutical Engineering. Available at www.ispe.org/drugshortages/2013JuneReport

.

7

FDA drug shortage statistics can be found at

http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/DrugSho

rtages/ucm050796.htm.

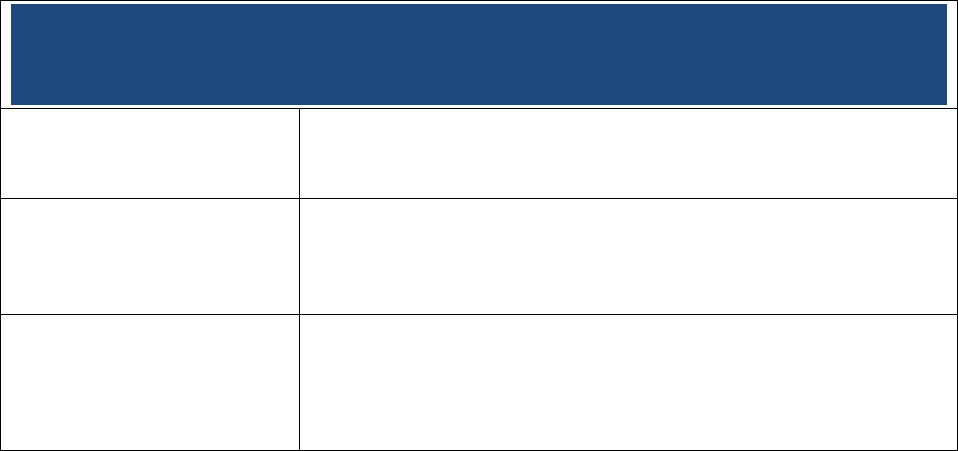

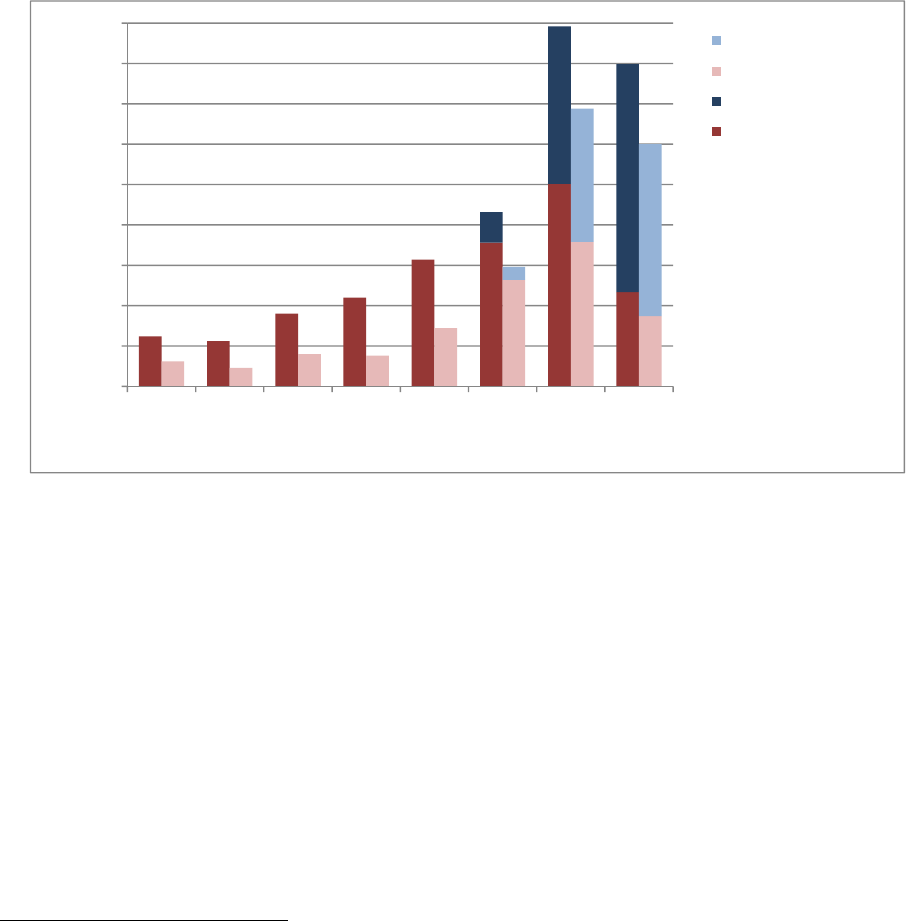

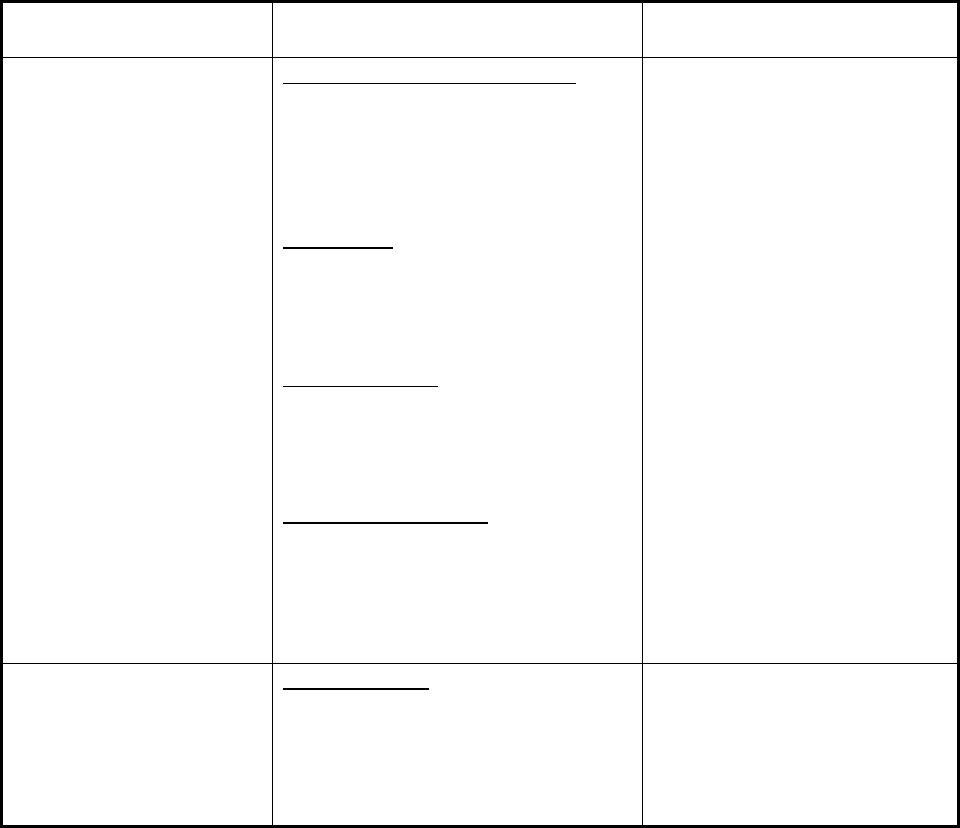

Figure 1 illustrates the number of new drug shortages by year from 2005-2012 and the number of

prevented shortages by year from 2010-2012 (FDA began tracking prevented shortages in 2010).

Figure 1 also shows that shortages predominantly affect sterile injectable products and reflects

FDA’s focus on preventing nationwide shortages of these critical drugs

8

.

Figure 1. Number of New and Prevented Shortages by Dosage Form, 2005-2012

62

56

90

110

157

178

251

117

38

195

282

31

23

40

38

72

132

179

87

16

165

213

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

400

450

2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012

NumberofShortages

CalendarYear

Injectables‐Prevented

Injectables‐New

All‐Prevented

All‐New

Source:DatafromFDA’s

internaldrugandbiologics

shortagesdatabases.

A. Recent Changes to FDA Oversight of Drug Shortages

Authorities granted by Congress as part of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C

Act) have enabled FDA to coordinate with manufacturers to help prevent or mitigate drug

shortages. However, FDA’s ability to take effective action depends on the relevant manufacturer

notifying FDA in a timely fashion of a disruption or possible disruption in supply. FDA has at

its disposal a variety of mitigation tools (more fully described in section C.3) that the Agency

can use when working with a manufacturer (or manufacturers) to prevent a possible shortage or

to take appropriate remedial actions once a shortage has occurred; but these tools are only useful

to the extent that FDA receives early notification about the supply disruption. Lack of, or late,

notification severely limits FDA’s ability to coordinate a timely response with manufacturers.

8

There are regional or local shortages of certain products. However, these are often the result of distribution issues

that can be resolved locally and are not indicative of a national supply and demand imbalance. In general, FDA

focuses its resources on nationwide drug shortages of medically necessary products that have the most significant

impact on public health across the country.

9

10

Recently, the White House and Congress have taken important and welcome steps to expand

early notification of interruptions and discontinuations, enhancing FDA’s ability to address drug

shortages. Before FDASIA, notification under section 506C of the FD&C Act was limited in

scope, applying only to sole manufacturers; only to a discontinuance (which could be read to

imply a permanent shutdown); and only to certain approved drugs (e.g., unapproved drugs and

biologics were excluded).

9

The following actions have expanded the scope of early notification

requirements and the rate of early reporting:

October 31, 2011, Executive Order 13588 – Reducing Prescription Drug

Shortages

10

: acknowledged the need for a “multifaceted approach” to address the many

different factors that contribute to drug shortages, and, among other things, directed FDA

to “[u]se all appropriate administrative tools” to require drug manufacturers to provide

advance notice of manufacturing discontinuances that could lead to shortages.

11

December 19, 2011, Interim Final Rule (IFR)

12

: published in response to the Executive

Order, the IFR amended FDA’s regulations related to early notification to improve the

likelihood of FDA receiving advance notification of a potential drug shortage.

13

July 9, 2012, FDASIA: broadens the scope of the early notification provisions by

requiring all manufacturers of certain medically important prescription drugs

14

(approved

9

See 21 CFR 314.80(b)(3)(iii) (as amended by the Interim Final Rule of December 19, 2011).

10

Executive Order 13588, available at http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2011/10/31/executive-order-

reducing-prescription-drug-shortages.

11

On October 31, 2011, FDA also released a review of the Agency’s approach to drug shortages, available at

http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/Repo

rtsManualsForms/Reports/ucm277749.htm and sent a letter to drug and

biologic manufacturers, encouraging them to voluntarily report potential shortages to FDA, beyond what was

required under the FD&C Act.

12

76 FR 78530 (December 19, 2011). The IFR is a final rule implementing the pre-FDASIA section 506C.

FDASIA significantly amended section 506C and requires FDA to initiate a new rulemaking process to implement

the amended section 506C. FDA is in the process of developing a proposed rule for public comment implementing

the new drug shortages provisions of FDASIA. Once final, the rule will supersede the IFR.

13

As a complement to the IFR, the Agency also published a draft guidance for industry on drug shortages on

February 21, 2012, available at

http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplian

ceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM292426.pdf.

The draft guidance was issued for public comment, and: (1) further discussed the Agency’s interpretation of the

mandatory early notification requirements in the IFR; (2) explained a policy of encouraging additional voluntary

reporting; and (3) discussed the role that manufacturers play in preventing or responding to drug shortages,

including that many shortages arise from quality or other issues experienced during the manufacturing process.

14

Specifically, the requirement currently applies to prescription drugs that are not biologics, and that are: (1) life-

supporting; life-sustaining; or intended for use in the prevention or treatment of a debilitating disease or condition,

including any such drug used in emergency medical care or during surgery; and “(2) … not a radio pharmaceutical

drug product….” FD&C Act § 506C(a).

11

or unapproved) to notify FDA of a permanent discontinuance or (temporary) interruption

in manufacturing. FDASIA also allows FDA to require, by regulation, early notification

of discontinuances or interruptions in the manufacturing of biologics, and requires FDA

to send a noncompliance letter to firms that fail to notify the Agency in accordance with

FDASIA.

15

B. Root Causes of Drug Shortages

In addition to understanding the legal and regulatory authorities related to drug shortages, it is

important to explain why drug shortages occur. In most cases, a shortage is preceded by a

production disruption (i.e., a discontinuance or interruption in manufacturing). Once a

manufacturer experiences a discontinuance or interruption in manufacturing, a shortage will

occur if there is no other manufacturer to step in to fill the gap in supply, or if other

manufacturers cannot increase production quickly enough to make up the loss.

16

A production disruption can be triggered by several factors, including a natural disaster or other

unexpected event not within a manufacturer’s control, or a business decision to permanently

discontinue production of a drug (e.g., because the product is no longer profitable or is less

profitable than other products that could be produced with the limited production capacity

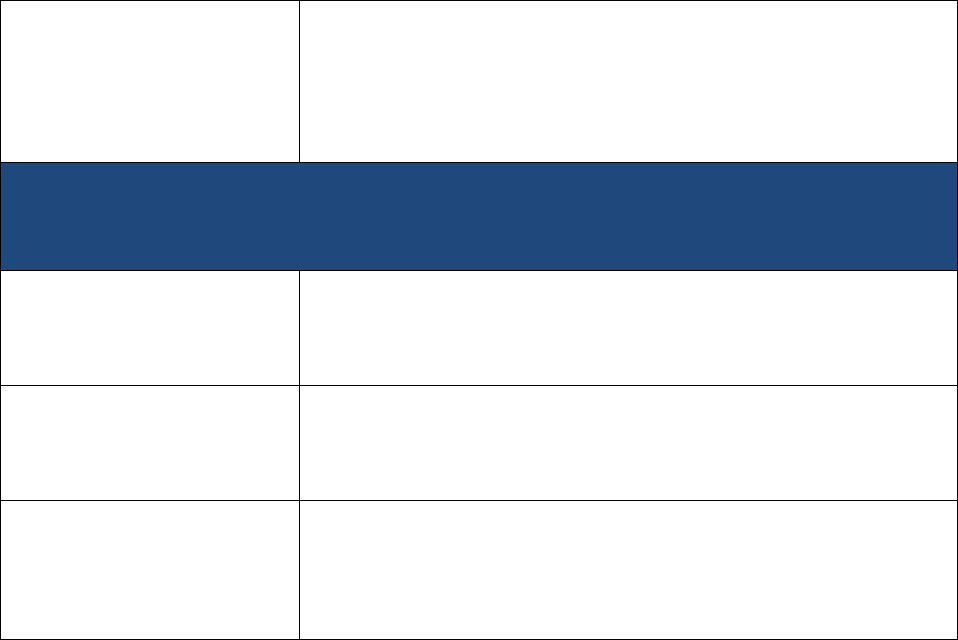

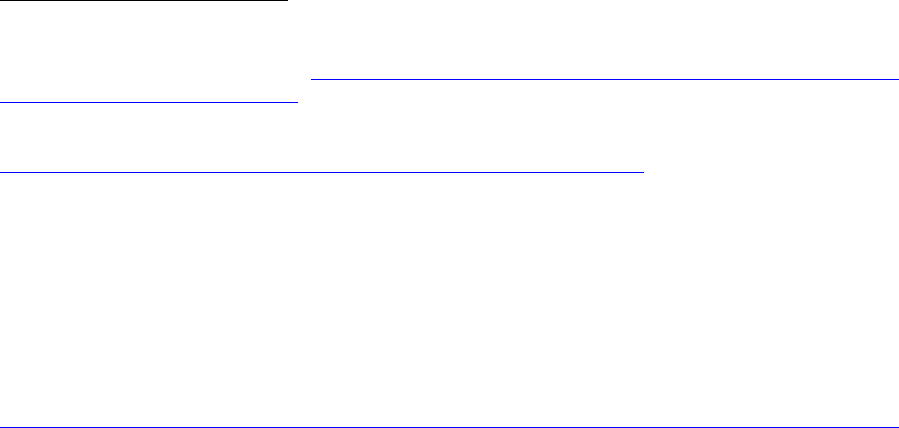

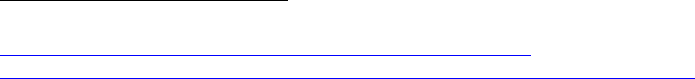

available to the firm) (Figure 2).

More often, however, failures in product or facility quality are the primary factor leading to

disruptions in manufacturing (Figure 2). In 2012, for example, based on information collected

from manufacturers, FDA determined that the majority of production disruptions (66%) resulted

from either (1) efforts to address product-specific quality failures (31%, labeled Quality:

Manufacturing Issues in Figure 2) or (2) broader efforts to remediate or improve a problematic

manufacturing facility (35%, labeled Quality: Remediation Efforts in Figure 2). Quality or

manufacturing concerns can involve compromised sterility, such as roof leakage; mold in

manufacturing areas; or unsterilized vials or containers to hold the product—issues that could

pose extreme safety risks to patients.

Since 2011, the number of shortages associated with shutdowns or slowdowns in manufacturing

to address overall facility quality (remediation) has not changed significantly, although there has

been a decline in the number of shortages due to quality concerns related to a specific product

(e.g., particulates, contamination). Remediation efforts can lead to a short-term risk of a

shortage for specific products while facility upgrades are made, but this risk is balanced by the

15

Under FDASIA, FDA must issue a final rule implementing certain of the FDASIA shortages provisions by

January 9, 2014.

16

See Woodcock J, Wosinska, M. Economic and technological drivers of generic sterile injectable drug shortages.

Clin Pharmacol Ther. 93:170-176 (2013), pp. 174-75 (discussing why one manufacturer’s disruption in supply may

result in a market-wide shortage).

expectation that improvements will lead to long-term, stable, high-quality manufacturing

capacity, thus reducing the long-term risk of shortages.

17

Figure 2. Drug Shortages by Primary Reason for Disruption in Supply in 2012

35%

31%

14%

8%

2%

6%

4%

Quality:Facility

RemediationEfforts

Quality:Product

ManufacturingIssues

Discontinuationof

Product

RawMaterials(API)

Shortage

OtherComponent

Shortage

IncreasedDemand

LossofManufacturing

Site

Source:Datafrom

FDA’sinternaldrug

andbiologics

shortagesdatabases.

C. Current FDA Efforts to Prevent and Mitigate Drug Shortages

Preventing or mitigating drug shortages requires a careful and coordinated response by FDA,

which begins with a notification to FDA of a potential disruption in supply. This notification

allows FDA to assess the risk of a shortage developing and subsequently deploy one or more

regulatory tools, as appropriate, to prevent or mitigate the shortage. FDA largely focuses its

efforts on ensuring that a disruption in production does not result in a shortage, or on mitigating

the impact of the shortage should it become unavoidable.

1. Notifying FDA of a Disruption in Supply

The most important way to prevent or mitigate a drug shortage is for FDA to learn about a

disruption in production as soon as possible. The sooner FDA is notified of a discontinuance or

interruption in manufacturing, the more time FDA has between the disruption and the potential

shortage to help coordinate the manufacturers’ response. Notification of a disruption in

production can come from a variety of sources outside the agency, including a drug

manufacturer, a professional organization, interest groups, patients, and health care

professionals, or through internal channels at FDA. Since the Executive Order was issued in

17

Berg N, Kos K, et al. Report on the ISPE 2013 Drug Shortages Survey. June 2013. Tampa, FL: International

Society for Pharmaceutical Engineering. Available at http://www.ispe.org/drugshortages/2013JuneReport

.

12

13

October 2011, FDA has seen a six-fold increase in the num

ber of notifications from

manufacturers (from 10 notifications per month prior to the Executive Order to an average of 60

per month since the Executive Order). These early notifications have had a direct impact on the

number of shortages FDA has been able to prevent.

2. Assessing the Risk of Shortage

Once FDA’s shortage staff has been alerted to a discontinuance or disruption in production, they

first verify if an actual shortage exists or may occur. The shortage staff may take the following

actions to do this:

Use a market research database to collect initial information to determine whether or not

the current supply of product across manufacturers is stable

Contact product manufacturer(s) to collect up-to-date inventory information, rate of

demand (units/month), manufacturing schedules, and any changes in ordering patterns.

Although manufacturers are not required to provide this information to FDA, voluntarily

sharing this information greatly facilitates the management of shortages

Evaluate product inventory in the distribution chain to the extent possible. This

information can help predict how quickly a shortage may develop (if at all)

Additional information on how FDA collects and uses data to assess the risk of a shortage can be

found in Appendix C.

When the shortage staff determines that a shortage either exists or is likely to occur imminently,

shortage staff members lead and coordinate the mitigation efforts with multiple other offices

within FDA. Working with FDA’s drug review division and/or professional organizations, they

determine if the drug is medically necessary.

18

FDA uses the information about whether or not a

drug is medically necessary to prioritize its response to a shortage overall and to inform the risk-

benefit assessment for the specific product in question.

3. Mitigating an Actual or Imminent Shortage

Mitig

ation efforts begin once FDA has confirmed that a shortage exists or could occur and that

the drug is medically necessary. The actions FDA can take to mitigate a shortage include, as

appropriate:

Identify the extent of the shortfall and determine if other manufacturers are willing and

able to increase production to make up the gap

18

A medically necessary drug product is a product that is used to treat or prevent a serious disease or medical

condition for which there is no alternative drug in adequate supply that is judged by medical staff to be an

appropriate substitute. Off-label uses are taken into account when making medical necessity determinations. CDER

MAPP 6003.1, Drug Shortage Management at 2, available at

http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AboutFDA/Cen

tersOffices/CDER/ManualofPoliciesProcedures/ucm079936.pdf.

14

Expedite FDA inspections and reviews of submissions from manufacturers attempting to

restore production

Expedite FDA inspections and reviews of submissions from competing manufacturers

who are interested in starting new production or increasing existing production of

products in shortage

Exercise temporary enforcement discretion for new sources of medically necessary drugs

Work with the manufacturer to ensure adequate investigation into the root cause of the

shortage

Develop risk mitigation measures for a batch(es) of product initially not meeting

established standards

FDA may use one or more of these mitigation tools, or may seek to develop other options,

depending on the severity of the shortage and the circumstances surrounding the shortage. When

selecting specific tools, FDA continues to work with the manufacturer to tailor its response to the

specific situation. FDA also frequently communicates available information about a shortage to

affected stakeholders and monitors a shortage until it is resolved. Additional information on how

FDA collects and uses data to manage a shortage can be found in Appendix C.

It is important to note that FDA’s standards of safety, efficacy, and quality do not change in a

shortage situation. FDA’s preferred solution to a shortage is a supply of approved drugs

sufficient to meet patient demand. However, FDA recognizes that there can also be risks to

patients when treatment options are not available for critical conditions, and understands the

importance of using the appropriate tools to prevent or mitigate a shortage. FDA also makes

certain that drug shortages are considered before taking an enforcement action or issuing a

Warning Letter. In appropriate cases, temporary exercise of regulatory flexibility has proven to

be an important tool in ensuring access to treatment options for health care practitioners and

patients in critical need.

For example, when particulate matter (including glass and metal particles) was found in an

injectable drug product that was medically necessary and vulnerable to shortage, FDA exercised

discretion to allow distribution of the product along with a letter, included in the drug’s

packaging, warning health care professionals to use a filter when administering the drug. The

exercise of discretion was temporary, and was conditioned on the manufacturer’s ability to

demonstrate to FDA that the filter did not affect the way the drug works and could successfully

remove the particulate. FDA also worked with the manufacturer while the manufacturer

identified and addressed the root cause of the problem, so that it could resume producing a drug

product that did not need the work-around involving the filter. In the last two years, FDA has

exercised temporary regulatory flexibility involving the use of filters for eight important drugs,

including life-saving components of IV nutrition for newborns, children, and other patients who

are unable to eat or drink by mouth.

In contrast, a drug that is contaminated with bacteria or fungi presents a more extreme risk to

patients, one that cannot be mitigated through a work-around such as the one described above.

In such cases, the manufacturer must correct the conditions leading to the contamination before

the product is safe for use, even if correcting the conditions ultimately leads to a shortage. Each

situation must be carefully evaluated to determine the public health impact, keeping in mind that

a given action may have unintended, and potentially long-term, consequences.

19

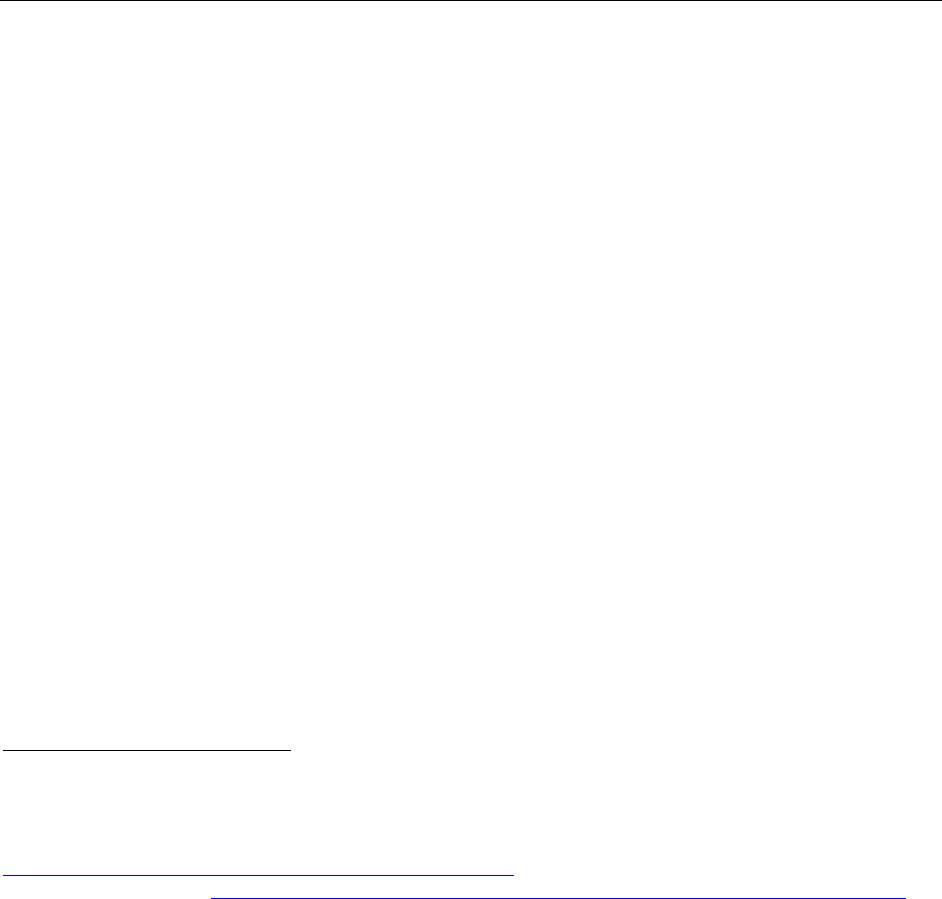

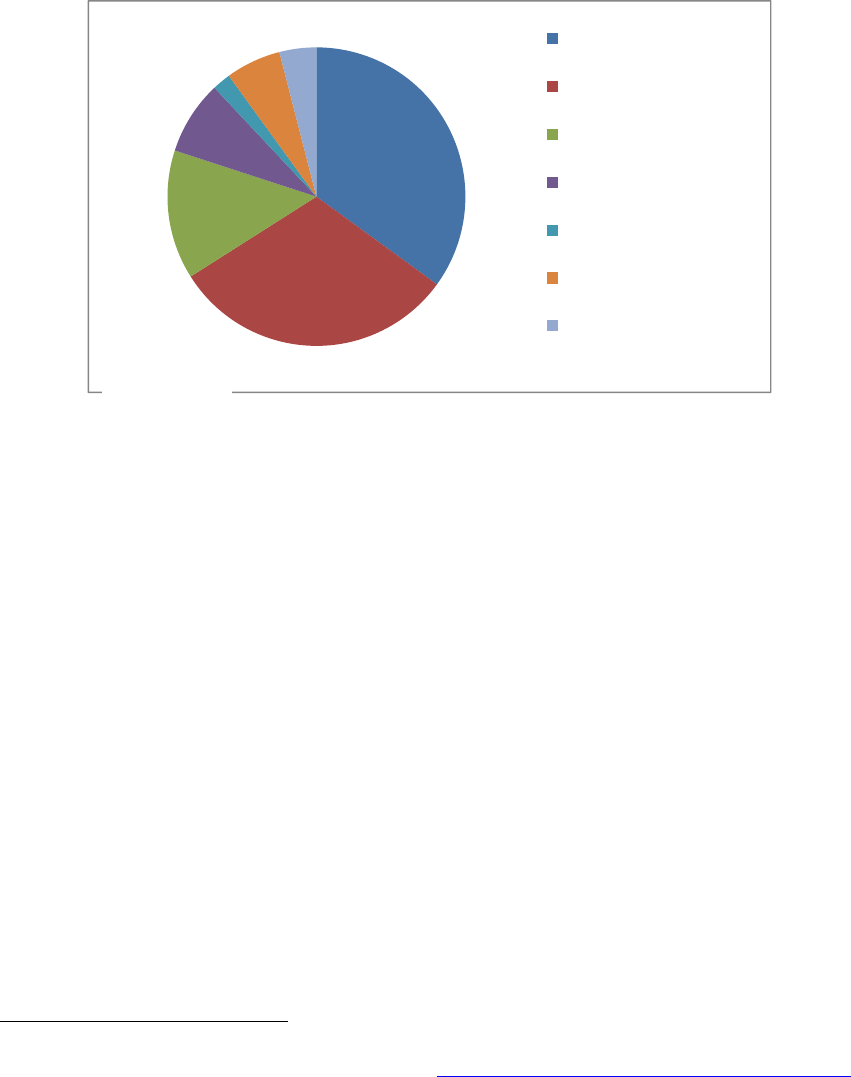

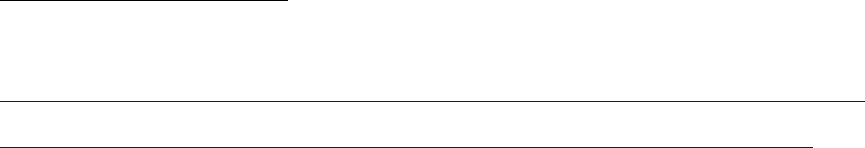

D. Internal and External Communication and Engagement

FDA communication and collaboration processes are essential to effectively prevent and manage

drug shortages. These types of interactions, both internally and externally, occur in a variety of

ways and with a variety of stakeholders (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Internal and External Communication During Shortage Management

1. Internal Coordination

The Agency’s response to a notification of a discontinuance or production disruption involves

multiple offices within FDA and often requires a cross-functional team of up to 25 individuals to

respond to a specific shortage or potential shortage. Appendix D lists examples of specific

offices and their roles in managing drug shortages. Appendix E lists specific examples of the

types of communication that occur within the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER)

to manage a drug shortage.

In response to the recent increase in drug shortages, CDER has nearly tripled the number of staff

directly responsible for shortages, from 4 employees in 2011 to 11 employees in 2013. The

office has also been elevated within the Center to indicate the priority FDA has placed on this

topic. Although this staff serves as the primary point of contact for drug shortage-related issues,

shortage staff members work with a large number of other offices and divisions within FDA.

19

For example, if the use of enforcement discretion signals to industry that FDA is willing to exercise flexibility to

ensure the availability of any critical product, this could create a long-term disincentive for manufacturers to invest

in manufacturing upgrades or other quality improvements to avoid disruptions in supply, exacerbating the risk of

shortages over the long term.

15

16

2. External Communication and Engagement

In addition to internal communication and coordination to facilitate FDA decision-making, it is

essential for FDA to adequately maintain communication with the many external groups affected

by drug shortages, including patients, health professionals, federal partners, and international

groups. Appendix F describes these communications in greater detail.

One straightforward and accessible method for enhancing communication with these groups has

been through FDA’s website. In response to feedback from numerous stakeholders, including

those who responded to the Federal Register notice, FDA has significantly improved its drug

and biologics shortage websites in the past year. For example, CDER’s website now includes

the following features:

More frequent updates to the CDER shortage website, including biweekly updates on

postings from manufacturers about progress on specific shortages

Icons to highlight new listings and update dates

Improved layout for easier navigation, including the creation of a Current Drug Shortage

Index, and separating the shortage list into sections of the alphabet for each page

Information about the causes of shortages

A page for additional news and information, such as extensions of expiry date for a

specific lot of product to prevent shortage

Another important shortage website is maintained by the American Society of Health-System

Pharmacists (ASHP) and the Drug Information Service at the University of Utah.

20

FDA, the

Drug Information Service, and ASHP exchange information on a routine basis, sharing

notifications and public information on the status of the drug supply. This collaborative effort

has greatly improved FDA’s ability to monitor product disruptions. ASHP’s website also

provides recommendations about therapeutic alternatives.

Communication with manufacturers is also a key component of FDA’s coordination efforts.

FDA’s drug shortages staff interact with manufacturers on an ongoing basis to understand

specific issues related to possible or ongoing shortages. For example, when the shortage staff

hears about a potential disruption in production, FDA may contact other manufacturers to see if

they have experienced an increase in demand; determine the status of their on-hand supply; and

if a shortage appears imminent, determine whether the manufacturer is willing to initiate or

increase production. FDA then works with those manufacturers as they increase production.

During a shortage, FDA also continues to work with the manufacturer causing the shortage to aid

in recovery efforts. For instance, when a firm shuts down to address manufacturing and/or

quality problems, FDA works with the firm as it remediates the problem to restore or maintain

the availability of critical medicines. To maintain some level of supply during remediation, FDA

may recommend creating a priority list that emphasizes continued manufacture of shortage

20

Available at http://www.ashp.org/shortages.

products; encourage allocation programs to hold back supply of shortage products; or

recommend third-party quality review for release of manufactured batches.

Finally, FDA understands the important role that the public plays in discussing and identifying

solutions to drug shortage issues. FDA is actively involved in meetings with outside

stakeholders to help guide FDA’s regulatory and policy decision making, as well as to increase

our understanding of the issues facing these stakeholders. In 2012, FDA staff participated in

more than 45 such meetings with academics, patient groups, pharmacy organizations,

distributors, and manufacturers.

II. Continuing Progress: FDA’s Strategic Plan

As described previously, Title X of FDASIA requires FDA to establish a task force to develop

and submit to Congress a Strategic Plan to enhance FDA’s ability to address drug shortages. In

response, FDA convened a Task Force representing multiple centers, offices, and disciplines

within FDA. The Task Force has identified two central goals and related tasks for FDA to focus

on to address drug shortages, stated below. Specific tasks are discussed in further detail in the

sections that follow.

STRENGTHEN MITIGATION RESPONSE.

Goal #1

Improve and streamline FDA’s current mitigation activities once the

Agency is notified of a supply disruption or shortage.

DEVELOP LONG-TERM PREVENTION STRATEGIES.

Goal #2

Develop prevention strategies to address the underlying causes of

production disruptions to prevent drug shortages.

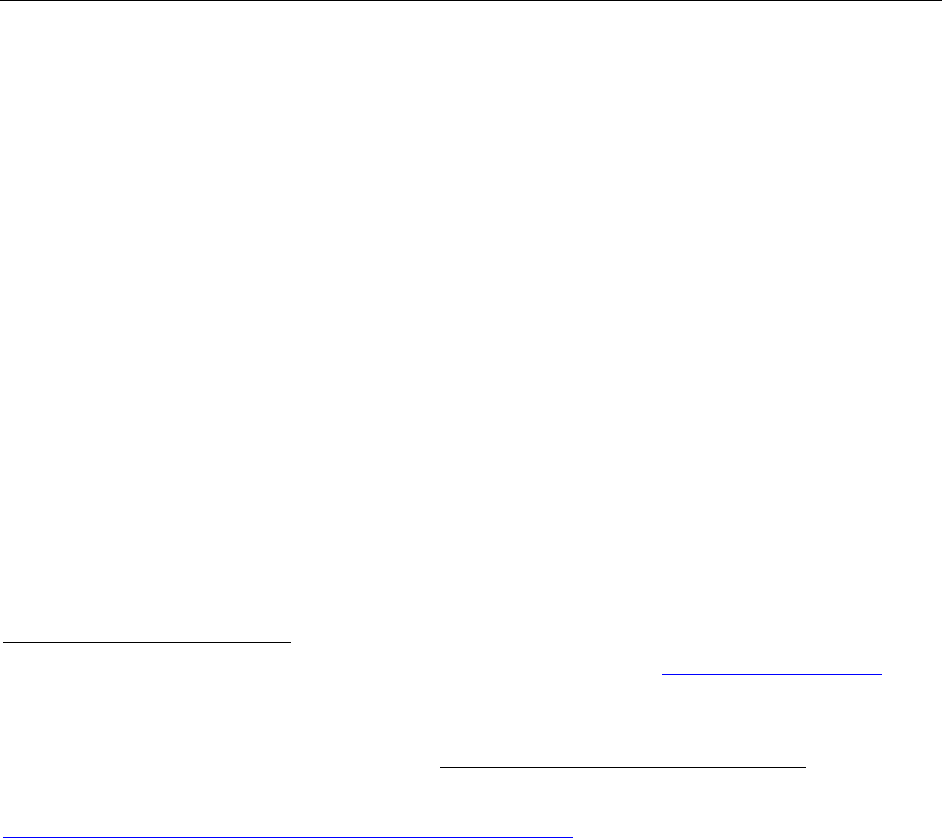

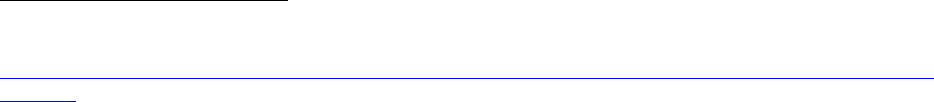

As depicted in the Figure 4, mitigation activities are directed at preventing supply disruptions

from turning into actual shortages. Long-term prevention strategies are intended to address the

underlying causes of shortages to prevent supply disruptions from occurring in the first place.

Figure 4. Addressing Drug Shortages: Mitigation Activities and Long-Term Prevention

17

Supply

Disruption

MITIGATION

Quality

Problems &

Other Factors

PREVENTION

Drug

Shortage

18

A. GOAL #1: Strengthen Mitigation Response

The Task Force identified the following tasks to strengthen FDA’s ability to respond to a

notification of a production disruption to prevent a shortage or to mitigate an unavoidable

shortage.

TASK 1.1: Develop and/or Streamline Internal FDA Processes

While coordinating the increased number of drug shortages over the last few years, FDA has

continued to improve its approaches to the management of shortages. Revising and

standardizing procedures will more accurately reflect and enhance the working interactions

between units within FDA and will maximize the efficiency of FDA’s response to a shortage.

As a part of this work, the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) is undertaking

a review of its internal procedures to address shortages, including revising its standard operating

policy and procedure on CBER-regulated product shortages.

21

In addition, CDER is revising its

Manual of Policies and Procedures (MAPP) on Drug Shortage Management.

22

Specifically, FDA

intends to:

Standardize the risk-benefit assessment process prior to compliance actions

23

Update the process for interacting with the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) in

the event of a shortage of a controlled substance, including updating a memorandum of

understanding between the two agencies that will improve the sharing of important

information

Develop and implement a process for issuing a noncompliance letter for failure to notify

FDA as required by FDASIA

Explore new approaches to extend expiration dating to temporarily mitigate a shortage

TASK 1.2: Improve Data and Response Tracking

FDA is working to improve its databases related to shortages and the tracking procedures it uses

to manage them. FDA has several databases that it uses to support efforts to address shortages,

but they were not created specifically for the purposes of assisting shortage-related activities.

24

21

CBER Standard Operating Policy and Procedure 8506, Management of Shortages of CBER-Regulated Products,

available at

http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVacci

nes/Guidan

ceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/ProceduresSOPPs/ucm29

9304.htm.

22

CDER MAPP 6003.1, Drug Shortage Management.

23

This work is also responsive to FDASIA, which directed FDA to evaluate certain risks and benefits prior to an

enforcement action or issuance of a warning letter that could reasonably be expected to lead to a meaningful

disruption in the supply of a drug covered by section 506C. FD&C Act § 506D(c).

24

Examples include databases supporting the Orange and Red Books, and the databases that collect information

about the inspections of manufacturing facilities.

19

In addition to these more general databases, CDER has created a dedicated database that focuses

solely on collecting data related to shortages. This improved tracking will enable FDA to better

assess progress on preventing and mitigating shortages and will enhance FDA’s ability to

compile the information necessary for the required annual report to Congress on drug shortages.

TASK 1.3: Clarify Roles/Responsibility of Manufacturers

Patients expect and deserve high-quality drugs, and it is the manufacturer’s responsibility to

ensure that its products are safe, effective, and of high quality. FDA is committed to working

with industry to resolve quality or manufacturing problems that arise, or avoid them if possible.

Where justified, FDA may exercise regulatory flexibility to prevent or mitigate a shortage. To

facilitate its work with industry, FDA intends to:

Finalize the proposed rule on Notification to FDA of a Discontinuance or Interruption in

Supply of Certain Drug or Biological Products

Work with manufacturers as needed to remediate manufacturing problems, facilitate their

return to full production, and discuss how to prioritize drugs in shortage as they address

manufacturing deficiencies

Encourage manufacturers to engage in practices to avoid or mitigate shortages. These

practices are listed in the table below:

Practices to Avoid or Mitigate Shortages

Create Allocation Plans Design an allocation plan in advance, in the event that a product

shortage occurs.

Communicate with

Contract Manufacturing

Organizations

Communicate frequently with contract manufacturers to ensure up-to-

date knowledge of their manufacturing processes and facilities and to

anticipate potential problems that might lead to a shortage

Manage Inventory Build robust inventories before major manufacturing changes, such as

upgrades to manufacturing facilities or transfer of facility ownership

Develop Short- and

Long-Term Proposals

Provide short- and long-term proposals to address issues that could

cause a shortage, either as part of the notification to FDA of a

potential shortage or shortly thereafter

Communicate with FDA Engage in dialogue with FDA to work on a long-term solution to a

shortage, including remediation efforts

Investigate Root Causes Provide a realistic timeline for investigation of product defects and

scheduled restart after shut downs

Consider Clinical Trials Consider the possibility of shortages during initial clinical trial design

and developing and implementing contingency plans for handling a

shortage during the clinical trial, should one arise (see Appendix F for

additional discussion of this point).

TASK 1.4: Enhance Public Communications about Drug Shortages

Comments received in response to the Federal Register notice made clear that ongoing efforts by

FDA to improve external communications have enhanced our response to shortages or potential

20

shortages. Additionally, groups requested up-to-the-minute and customized information about

shortages. FDA will continue to improve our public communications about drug shortages by:

Developing a smartphone application so that individuals can access the drug shortage

information currently posted online instantaneously from their mobile phones or tablets

Updating the website to include the therapeutic category (or categories) for the products

listed in shortage

Improving the functionality of the drug shortages website so that users will be able to sort

by therapeutic or other categories and view the relevant products confirmed to be in

shortage nationally

B. GOAL #2: Develop Long-Term Prevention Strategies

Developing long-term strategies focused on the underlying causes of production disruptions can,

ultimately, prevent drug shortages. Efforts to build on existing tools to mitigate or prevent

existing shortages are an important piece of the Strategic Plan. However, a comprehensive

strategy must also recognize the importance of addressing the underlying causes of shortages,

including sustaining manufacturing quality. While keeping in mind the role other stakeholders

play in ensuring manufacturing quality, FDA is also exploring actions it can take, both alone and

in collaboration with other groups.

TASK 2.1: Develop Methods to Incentivize and Prioritize Manufacturing Quality

The majority of drug shortages are the result of production disruptions caused by manufacturing

problems, particularly problems that affect product quality (see Figure 2). Ultimately,

prevention of future drug shortages means improving the quality of manufacturing facilities and

manufactured products. In addition to regulatory enforcement, FDA is exploring what it can do

to provide more positive incentives for quality improvements and to make manufacturing quality

a priority, taking into account the responses we received to the Federal Register notice. For

example, FDA is:

Examining the broader use of manufacturing quality metrics to assist in the evaluation of

product manufacturing quality

Implementing internal organizational improvements to focus on quality, including the

creation of an Office of Pharmaceutical Quality within CDER

Considering public recognition of manufacturers who have demonstrated a consistent

record of high quality manufacturing

Continuing expedited review to mitigate shortages, including the review of submissions

for facility upgrades to improve quality

TASK 2.2: Use Regulatory Science to Identify Early Warning Signals of Shortages

Understanding the factors contributing to supply disruptions and drug shortages and identifying

potential warning signals of future production disruptions could help FDA and manufacturers in

their efforts to prevent them. However, identifying these factors and signals is a challenging

21

undertaking. To further this effort, FDA will explore risk-based approaches to identifying the

early warning signals of manufacturing and quality problems that could lead to production

disruptions. In addition, to gain a better understanding of the factors and forces contributing to

manufacturing and quality problems, FDA will work with stakeholders to identify vulnerabilities

at manufacturing sites that could put the production of quality drugs at that facility at risk, and

thereby contribute to shortages.

TASK 2.3: Increase Knowledge to Develop New Strategies to Address Shortages

A wide variety of stakeholders have collected and analyzed data on drug shortages and potential

approaches to their prevention, and it is essential that FDA continue to work with these

stakeholders to fill gaps in our understanding of issues around shortages. This additional

information could help inform new strategies to address shortages. Specifically, FDA intends to:

Work with the International Society for Pharmaceutical Engineering (ISPE) to analyze

data from a recent global survey ISPE conducted on the technical, scientific,

manufacturing, quality, and compliance issues that have resulted in drug shortages

Join with other stakeholder groups, such as groups convened by the American Society of

Anesthesiologists and ASHP, and with individual companies, patient groups, and group

purchasing organizations to discuss shortages

Work with manufacturers to identify best practices for avoiding disruptions in production

Continue to explore (through the Department of Health and Human Services) the

potential benefit, and assess the identified challenges, of establishing a Qualified

Manufacturing Partner Program (QMPP)

25

III. Actions Other Stakeholders Should Consider

FDA can play a significant role in addressing drug shortages and has identified several additional

ways to enhance its efforts. It is clear, however, that FDA cannot address the threat of drug

shortages alone. Success in addressing drug shortages requires a collective effort by all

stakeholders—manufacturers, federal partners, researchers, professional organizations, and

patients. In preparing this Strategic Plan, FDA has identified four key areas that merit

consideration by the broader community for their potential to reduce drug shortages. FDA

limitations in these areas and possible roles for others are discussed in the following sections.

25

FDASIA requires FDA to examine the value of establishing a QMPP. FDA asked for public input on the

feasibility and advisability of a QMPP in the Federal Register notice. We asked commenters to address several

significant challenges FDA identified with such a program, including lack of funding to incentivize participation and

a potentially unlimited scope of applicable products. Many public comments supported the idea of a QMPP, but did

not address the challenges FDA raised. In follow up to these comments, the Department of Health and Human

Services will explore further the feasibility of creating a QMPP.

22

A. Manufacturing Incentives

Advances in drug discovery and development have been and continue to be encouraged and

supported through a variety of economic incentives, such as listed patent protection, various

forms of statutory market exclusivity, and tax credits. Yet, the need for innovation goes beyond

drug discovery and approval—manufacturing processes and technologies must keep pace with

advances in drug research and development. In many cases pharmaceutical manufacturing

processes, facilities, and equipment lag behind innovation in drug development. Some processes

and facilities have become outdated, resulting in quality problems that can lead to drug

shortages.

FDA Limitations: FDA is exploring ways to use its existing authorities to promote and sustain

quality manufacturing. However, our ability to offer financial or other economic means to

promote innovation in quality manufacturing is limited.

Opportunities for Others: Given the importance of quality and its link to shortages, other

stakeholders might explore economic, financial, or other means to incentivize innovation and

new investments in manufacturing quality drugs to reduce the occurrence and severity of

shortages.

B. Use of Data on Manufacturing Quality

Within the limits set by disclosure law, FDA makes certain information publicly available about

the historical ability of manufacturers to produce quality products. Several indicators of

historical quality, including a manufacturer’s history of inspection outcomes and classification,

recalls, and shortages, are publicly available. Nevertheless, numerous comments to the Federal

Register notice suggested that buyers (e.g., hospitals, health maintenance organizations, group

purchasing organizations, and others) do not consider or value this potentially important

information. This decoupling of quality considerations from purchasing decisions makes cost

the major factor in purchasing decisions, most likely intensifying price competition, leading

manufacturers to focus more on reducing costs than on maintaining quality, and potentially

contributing to shortages.

FDA Limitations: Although FDA makes certain quality information public, buyers ultimately

decide how or whether they will use this data when they make purchasing decisions.

Opportunities for Others: An effort by buyers to use publicly available information to take

quality into account when making drug purchasing decisions—for example, by buying only from

manufacturers with a history of good quality, or including “failure to supply” clauses in

purchasing contracts—could further incentivize manufacturers to invest in quality improvements,

and ultimately prevent drug shortages.

23

C. Redundancy, Capability, and Capacity

A disruption in supply is exacerbated by limited manufacturing capacity and capability, market

concentration, and just-in-time inventory practices that result in minimal product inventory being

on hand at any given time. If these factors are present, a disruption in supply is more likely to

result in a nationwide shortage. Many stakeholders, including commenters to the Federal

Register notice, have suggested that building redundancy, holding spare capacity, and increasing

inventory levels could lower the risks of shortages.

FDA Limitations: FDA does not regulate manufacturing concentration and cannot require

redundancy of manufacturing capability or capacity. Nor can FDA require a company to

manufacture a drug, maintain a certain level of inventory of drug product, or reverse a business

decision to cease manufacturing.

Opportunities for Others: Manufacturers could explore building redundant manufacturing

capacity, holding spare capacity, or increasing inventory levels to lower the risks of shortages.

Other stakeholders could consider how to incentivize such practices.

D. The Gray Market

In the context of drug shortages, the term gray market is often used to reference the downstream

distribution of approved drug products at significantly marked-up prices. A shortage offers a

unique opportunity for this to occur, because large-scale buyers are often willing to pay any price

to obtain a much-needed product in short supply. When a gray market distributor handles a

product that it normally would not distribute, there can also be safety issues that put patients at

risk – if, for example, the product is not stored or handled appropriately. These activities do not

cause shortages, but may exacerbate the impact of an existing shortage.

FDA Limitations: FDA has limited data on the gray market and limited influence on its

workings (including no authority regarding product pricing). However, there is evidence that

gray market activities exacerbate the impact of drug shortages.

Opportunities for Others: Actions on the part of other stakeholders to minimize gray market

activities could play a role in mitigating the impact of shortages and reducing risks to patients.

Conclusion

Drug shortages remain a significant public health issue in the United States and a top priority for

FDA. FDA works with manufacturers to help prevent shortages from occurring. In this respect,

early and open dialogue between FDA and manufacturers is critical to successfully preventing a

shortage. Because of recent important actions by the President and Congress, FDA has been able

to learn of many possible shortages before they occur. These actions, along with increases in the

24

resources FDA is devoting to drug shortages, have helped prevent numerous recent shortages—

more than 280 in 2012.

Despite these achievements, substantial challenges remain, and more work is needed on the part

of manufacturers and other relevant stakeholders. This Strategic Plan identifies a number of

activities to improve the Agency’s ability to address drug shortages. Activities center around

two key goals: (1) strengthening FDA’s ability to respond to notices of a disruption in supply,

including improving our mitigation tools, and (2) developing long-term strategies to prevent drug

shortages by addressing the underlying causes of shortages.

FDA recognizes that manufacturers and other stakeholders have important roles to play in

ensuring that drugs are available to the patients who need them. Thus, the Task Force has also

identified actions outside stakeholders can consider that show promise in helping to prevent

shortages.

FDA looks forward to implementing this Strategic Plan as part of a collaborative and sustained

effort to address drug shortages in the United States.

25

APPENDIX A: Federal Register Notice

http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2013-02-12/html/2013-03198.htm

[Federal Register Volume 78, Number 29 (Tuesday, February 12, 2013)]

[Notices]

[Pages 9928-9929]

From the Federal Register Online via the Government Printing Office

[www.gpo.gov]

[FR Doc No: 2013-03198]

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

Food and Drug Administration

[Docket No. FDA-2013-N-0124]

Food and Drug Administration Drug Shortages Task Force and

Strategic Plan; Request for Comments

AGENCY: Food and Drug Administration, HHS.

ACTION: Notice; request for comments.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

SUMMARY: To assist the Food and Drug Administration (FDA or Agency) in

drafting a strategic plan on drug shortages as required by the Food and

Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act, the Agency is seeking

public comment from interested persons on certain questions related to

drug and biological product shortages.

DATES: Submit either electronic or written comments by March 14, 2013.

ADDRESSES: You may submit comments, identified by Docket No. FDA-2013-

N-0124, by any of the following methods:

Electronic Submissions:

Submit electronic comments in the following way:

Federal eRulemaking Portal: http://www.regulations.gov.

Follow the instructions for submitting comments.

Written Submissions:

Submit written submissions in the following way:

Mail/Hand delivery/Courier (for paper or CD-ROM

submissions): Division of Dockets Management (HFA-305), Food and Drug

Administration, 5630 Fishers Lane, rm. 1061, Rockville, MD 20852.

Instructions: All submissions received must include the Agency name

and Docket No. FDA-2013-N-0124. All comments received may be posted

without change to http://www.regulations.gov, including any personal

information provided. For additional information on submitting

comments, see the ``Comments'' heading of the SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

section of this document.

Docket: For access to the docket to read background documents or

comments received, go to http://www.regulations.gov and insert the

docket number, found in brackets in the heading of this document, into

the ``Search'' box and follow the prompts and/or go to the Division of

Dockets Management, 5630 Fishers Lane, rm. 1061, Rockville, MD 20852.

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Kalah Auchincloss, Center for Drug

Evaluation and Research, Food and Drug Administration, 10903 New

Hampshire Ave., Bldg. 51, rm. 6208; Silver Spring, MD 20993, 301-796-

0659.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

I. Background

On July 9, 2012, the President signed into law the Food and Drug

Administration Safety and Innovation Act (FDASIA) (Pub. L. 112-144).

Section 1003 of FDASIA adds section 506D to the Federal Food, Drug, and

Cosmetic Act (the FD&C Act) to require the formation of a task force to

26

develop and implement a strategic plan for enhancing the Agency's

response to preventing and mitigating drug shortages. Section 506D of

the FD&C Act (21 U.S.C. 356D) requires that the drug shortages

strategic plan include the following:

-Plans for enhanced interagency and intra-agency coordination, communication,

and decisionmaking;

-Plans for ensuring that drug shortages are considered when the Secretary

initiates a regulatory action that could precipitate a drug shortage or

exacerbate an existing drug shortage;

-Plans for effective communication with outside stakeholders, including who

the Secretary should alert about potential or actual drug shortages, how the

communication should occur, and what types of information should be shared;

-Plans for considering the impact of drug shortages on research and clinical

trials; and

-An examination of whether to establish a ``qualified

manufacturing partner program'' as described in section 506D(a)(1)(C)

of the FD&C Act.

II. Scope of Public Input Requested

Per the directive in section 506D, FDA has formed an internal Drug

Shortages Task Force (Task Force) to develop and implement the drug

shortages strategic plan. The Task Force is seeking comments from the

public on issues related to the development of this strategic plan.

Importantly, although FDASIA refers only to a drug shortages strategic

plan, we anticipate that the strategic plan will consider prevention

and mitigation of both drug and biological product shortages.

Accordingly, we are interested in receiving comments on these questions

from all parties, including those with an interest in biological

products. The Task Force is specifically interested in seeking public

input on the following questions:

1. In an effort to address the major underlying causes of drug and

biological product shortages, FDA is seeking new ideas to encourage

high-quality manufacturing and to facilitate expansion of manufacturing

capacity.

a. To assist in the evaluation of product manufacturing quality,

FDA is exploring the broader use of manufacturing quality metrics. With

that in mind, FDA would like input on the following issues: What

metrics do manufacturers currently use to monitor production quality?

To what extent do purchasers and prescribers use information about

manufacturing quality when deciding how to purchase or utilize

products? What kinds of manufacturing quality metrics might be valuable

for purchasers and prescribers when determining which manufacturers to

purchase from or which manufacturers' products to prescribe? What kinds

of manufacturing quality metrics might be valuable for manufacturers

when choosing a contract manufacturer? How frequently would such

metrics need to be updated to be meaningful?

b. The use of a qualified manufacturing partner program similar to

one used under the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development

Authority (BARDA) has been suggested as a potentially useful approach

to expanding manufacturing capacity and preventing shortages. FDA

recognizes that there are important potential differences between the

BARDA program and the use of a parallel program to address shortages.

For example, the BARDA program covers a relatively stable and limited

number of products, but drugs at risk of shortage are many, may change

rapidly over time, and are difficult to predict in advance. In

addition, FDA does not have funding to pay manufacturers to participate

in a drug shortages qualified manufacturing partner program or to

27

guarantee purchase of the end product. With these differences in mind,

is it possible to design a qualified manufacturing partner program that

would have a positive impact on shortages?

c. Are there incentives that FDA can provide to encourage

manufacturers to establish and maintain high-quality manufacturing

practices, to develop redundancy in manufacturing operations, to expand

capacity, and/or to create other conditions to prevent or mitigate

shortages?

2. In our work to prevent shortages of drugs and biological

products, FDA regularly engages with other U.S. Government Agencies.

Are there incentives these Agencies can provide, separately or in

partnership with FDA, to prevent shortages?

3. When notified of a potential or actual drug or biological

product shortage, FDA may take certain actions to mitigate the impact

of the shortage, including expediting review of regulatory submissions,

expediting inspections, exercising enforcement discretion, identifying

alternative manufacturing sources, extending expiration dates based on

stability data, and working with the manufacturer to resolve the

underlying cause of the shortage. Are there changes to these existing

tools that FDA can make to improve their utility in managing shortages?

Are there other actions that FDA can take under its existing authority

to address impending shortages?

4. To manage communications to help alleviate potential or actual

shortages, FDA uses a variety of tools, including posting information

on our public shortages Web sites and sending targeted notifications to

specialty groups. Are there other communication tools that FDA should

use or additional information the Agency should share to help health

care professionals, manufacturers, distributors, patients, and others

manage shortages more effectively? Are there changes to our public

shortage Web sites that would help enhance their utility for patients,

prescribers, and others in managing shortages?

5. What impact do drug and biological product shortages have on

research and clinical trials? What actions can FDA take to mitigate any

negative impact of shortages on research and clinical trials?

6. What other actions or activities should FDA consider including

in the strategic plan to help prevent or mitigate shortages?

III. Comments

Interested persons may submit either electronic comments regarding

this document to http://www.regulations.gov or written comments to the

Division of Dockets Management (see ADDRESSES). It is only necessary to

send one set of comments. Identify comments with the docket number

found in brackets in the heading of this document. Received comments

may be seen in the Division of Dockets Management between 9 a.m. and 4

p.m., Monday through Friday, and will be posted to the docket at

http://www.regulations.gov.

Dated: February 7, 2013.

Leslie Kux,

Assistant Commissioner for Policy.

[FR Doc. 2013-03198 Filed 2-11-13; 8:45 am]

28

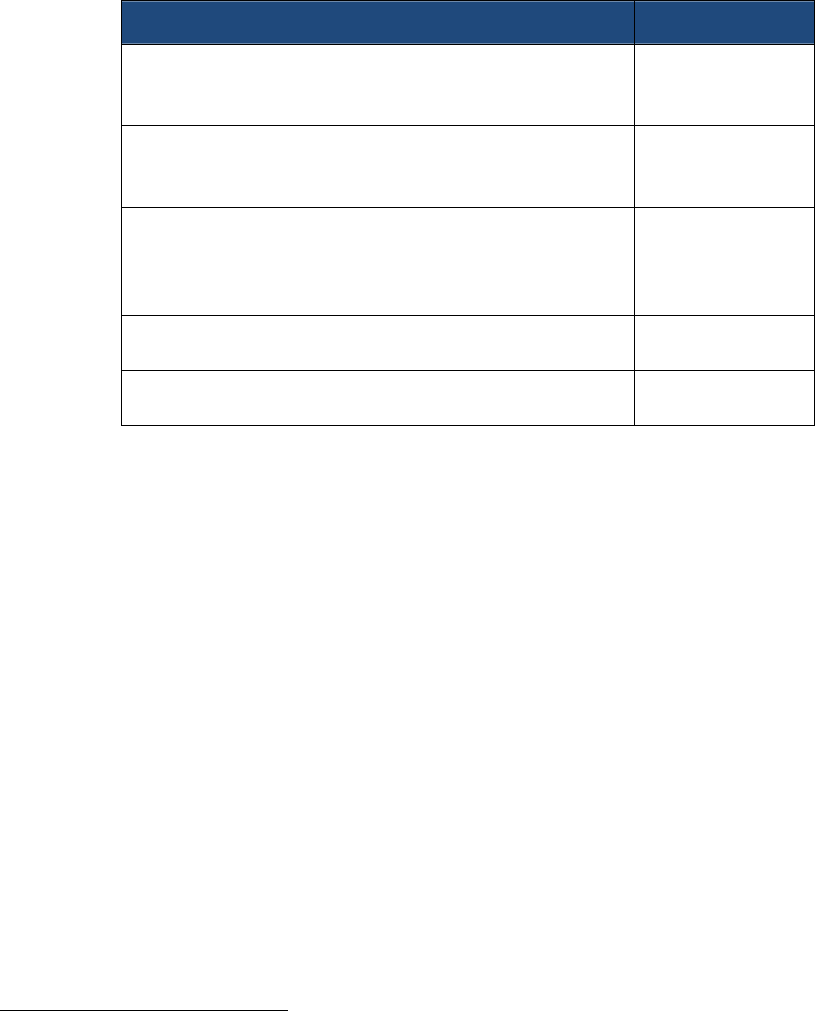

APPENDIX B: Statutory Elements

26

The following table indicates where in this Strategic Plan the reader can find discussion of

specific topics required by FDASIA.

Element Section&Task

Enhancedinter‐agencyandintra‐agencycoordination,

communication,anddecision‐making

Task1.1

SectionI.C.2

SectionII.A

Ensuredrugshortagesareconsideredbeforeinitiating

aregulatoryactionthatcouldprecipitateor

exacerbateadrugshortage

Task1.1

Section1.C.1

Effectivecommunicationwithexternalstakeholders Task1.4

Task2.3

SectionI.C.2

SectionII.A

Impactofdrugshortagesonresearchandclinicaltrials Task1.3

SectionI.C.2

Examinationofestablishinga“qualifiedmanufacturing

partnerprogram”

Task2.3

SectionII.B

26

Section 506D(a)(1)(B) (added by FDASIA) requires FDA to consider certain elements when developing the

Strategic Plan.

29

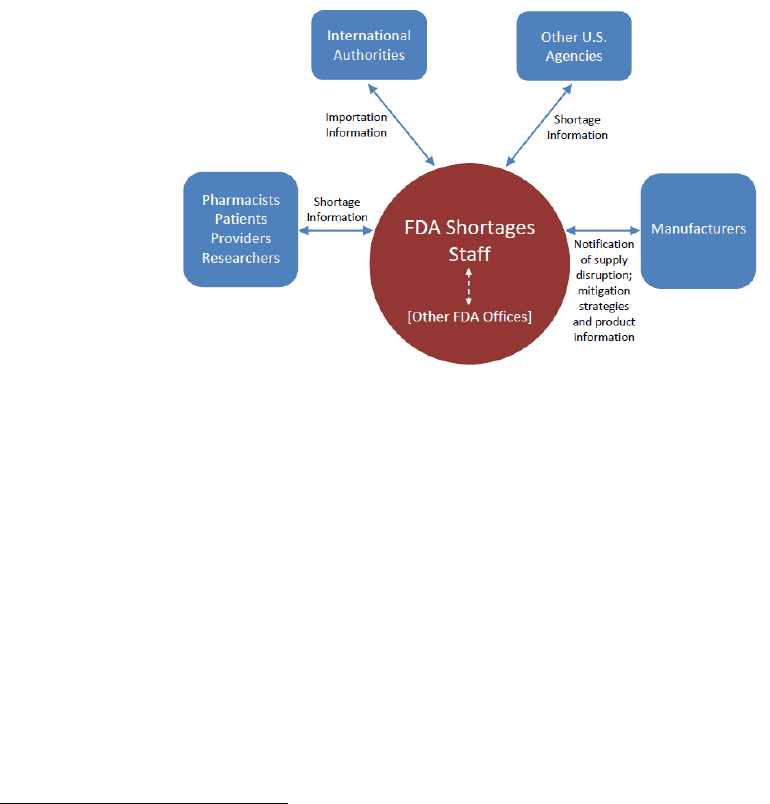

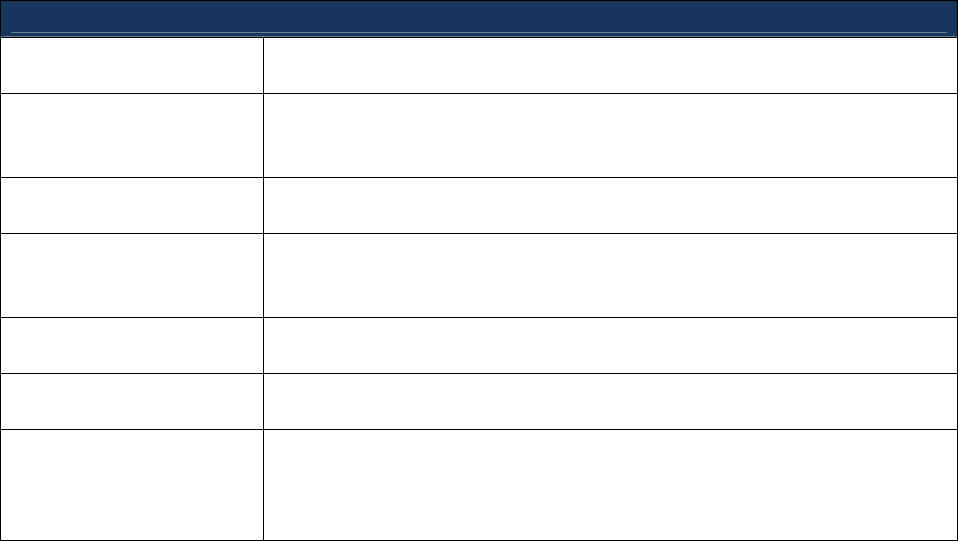

APPENDIX C: Collecting Information on Drug Shortages

Recognizing the complexity of drug manufacturing and the importance of having up-to-date data

to manage shortages, FDA draws on a variety of sources for information on whether a shortage

exists and how best to manage a shortage. The table below lists various sources of information

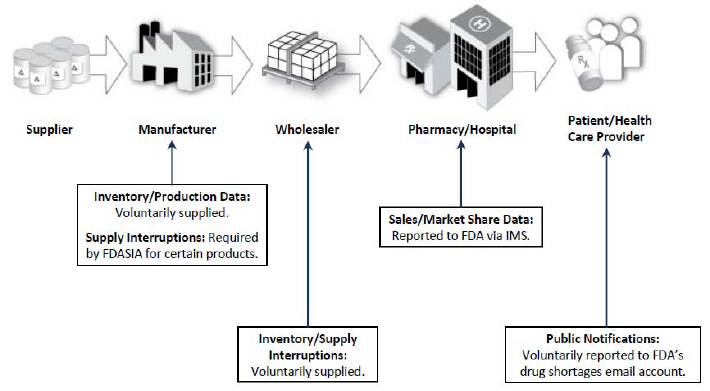

and the type of information obtained from each source. Figure 5 illustrates some of these

sources of information in the context of the drug supply chain.

Source TypeofInformation

OrangeBookorDrugs@FDA Informationontherapeuticequivalents

NationalDrugCode(NDC)product

directory

IdentificationofNDCsforproducts

InternalFDAdatabases

Informationonmanagingandtracking

drugandbiologicslicenseapplications;

inspectionsandregisteredmanufacturing

establishments;andlotdistributionand

releasedata

IMSHealth(healthcareanalyticsfirm)

Informationonthepharmaceutical

market,includinghistoricalsupplyand

demand

RedBook

Informationoncurrentsuppliersof

products

Emailsfromprescribers,patients,

pharmacies,manufacturers,andother

stakeholders

Notificationsofadisruptioninsupplyand

informationontheimpactofashortage

ASHPshortagewebsite

Additionalinformationonexisting

shortagesandtherapeuticalternatives

Otheragencies,suchDEA,theCenters

forDiseaseControlandPrevention

(CDC),andNIH

Dataonotherfactorsthatmaybe

influencingtheshortage

Figure 5. FDA’s Key Supply Chain Information Sources

However, although extremely useful, these data provide only part of the picture. For example,

key aspects of drug manufacture and distribution are not transparent, such as production

schedules, distribution of production volume across various contract manufacturing facilities, the

amount of inventory stored by a manufacturer, and wholesaler and pharmacy/hospital supply and

purchasing practices. Additionally, the role that other sources of products (e.g., gray market

distribution, compounding, unapproved drugs) play in contributing to shortages or in the

reactions to shortages is not clearly understood.

30

31

APPENDIX D: FDA Offices Engaged in Drug Shortage Efforts

1. FDA’s Drug Shortage Task Force

This overarching group, which includes individuals from across CBER, CDER, and the Office of

Regulatory Affairs (ORA), was formed in 2012, per the directive in FDASIA. The Task Force

coordinates the development of consistent policy with regard to FDA’s handling of drug

shortages, facilitates intra- and inter-agency communications around shortages, and provides a

forum for individuals working on shortage issues within FDA to discuss policy issues related to

shortages, including the development of this Strategic Plan.

2. CBER’s Product Shortage Coordinator

The Product Shortage Coordinator within CBER’s Office of Compliance and Biologics Quality,