PAVING THE WAY

C

areers guidance in secondary schools

Erica Holt-White, Rebecca Montacute, Lewis Tibbs

March 2022

1

About the Sutton Trust

The Sutton Trust is a foundation which improves social mobility in the UK through evidence-

based programmes, research and policy advocacy.

Copyright © 2022 Sutton Trust. All rights reserved. Please cite the Sutton Trust when using material

from this research.

About the authors

Erica Holt-White is Research and Policy Officer at the Sutton Trust

Rebecca Montacute is Senior Research and Policy Manager at the Sutton Trust

Lewis Tibbs is Research, Policy and Communications Intern at the Sutton Trust

2

Contents

Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................ 3

Foreword ...................................................................................................................................... 4

Key Findings ................................................................................................................................. 5

Recommendations ......................................................................................................................... 7

Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 9

The policy landscape ................................................................................................................... 11

Existing evidence on careers education ......................................................................................... 20

Methodology ............................................................................................................................... 26

Current provision ......................................................................................................................... 28

Young people’s experiences of careers education ........................................................................... 39

Discussion .................................................................................................................................. 50

Appendix 1 ................................................................................................................................. 57

3

Acknowledgements

Case studies for this report were written with contributions from Gemma Collins, Senior Programmes

Manager at the Sutton Trust.

The authors would like to thank David Andrews (Independent CEG Consultant & NICEC Fellow); Tristram

Hooley (Professor of Careers Education at the Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences, and at the

University of Derby) and Jonathan Kay (Education Endowment Foundation) for reviewing the full report

and recommendations.

The authors would also like to thank Joanna Bailey (Tees Valley Collaborative Trust); Professor Sir John

Holman (University of York); Anna Morrison CBE and Lucy Springett (both Amazing Apprenticeships);

Sue John (Challenge Partners); members of the Career Development Policy Group; and members of the

Sutton Trust’s Alumni Leadership Board for their views on the report’s recommendations.

4

Foreword

Giving young people from all backgrounds the information and experiences to make choices about their

future has been at the heart of the Sutton Trust’s work over the past 25 years.

Young people make important decisions about their education and careers throughout their schooling.

From GCSE and A Level subject choices, to post-16 options and apprenticeships, to which university

and course to apply to. These choices have a big impact on their future education and career.

But not everyone receives the same level of support. Young people in families with highly educated

parents and better networks are more likely to receive the support they need to navigate their way through

competitive pathways. Independent schools and some sixth forms devote substantial resources to

supporting university applications.

Over 25 years, our programmes have given over 50,000 young

people from low and moderate income backgrounds the

opportunity to change their lives and experience a leading

university environment, as well as providing invaluable support for

their applications. But to ensure a more level playing field, we

need to ensure that every school and college – especially those

serving the most disadvantaged pupils – is geared up to delivering

high quality, independent advice and guidance for vital decisions

on university, apprenticeships and jobs.

Careers guidance in England has seen a total overhaul over the

last decade. After years of neglect, a new structure is being built

by the Careers and Enterprise Company to help schools deliver high quality support – but there is more

that needs to be done. Today’s research gives a comprehensive picture on how guidance is working on

the ground and how we can improve it further.

I’d like to thank the Sutton Trust team, in particular lead author Erica Holt-White, for this vital research.

Sir Peter Lampl

Founder and Executive Chairman of the Sutton Trust, Chairman of the Education Endowment

Foundation

“Giving young people

from all backgrounds

the information and

experiences to make

choices about their

future has been at the

heart of the Sutton

Trust’s work over the

past 25 years.”

5

Key Findings

Overview

When the Sutton Trust last looked at careers provision back in 2014, our research found a major decline

in the quality and quantity of careers provision happening in schools, with a ‘postcode lottery’ of

provision.

Our findings here suggest there have been improvements since then, but there is still too often variability

in careers provision, with differences between state and private schools and between state schools with

more and less deprived intakes.

Existing careers provision

• A wide range of career related activities are available in schools. The most common activities

reported as taking place by senior leaders in English state schools include sessions with a

Careers Adviser (85%), careers fairs or events (84%), and links to possible careers within

curriculum lessons (80%).

• Classroom teachers in English state schools are less likely than senior leaders to say links to

possible careers are being made within curriculum lessons, at 59% vs 80%, perhaps reflecting

some ambitions for careers guidance not filtering down into classroom practice.

• Almost all state schools now have a Careers Leader, a role responsible for a school’s careers

programme, with 95% of state school senior leaders reporting their school has such a role.

• 73% of state school headteachers said their school works with the government funded Career

and Enterprise Company (CEC). However, just 48% of headteachers said their school was part

of a CEC Careers Hub - designed to bring together schools, colleges, employers and

apprenticeship providers in a local area.

• The majority (94%) of state school senior leaders are aware of the Gatsby benchmarks, the

current framework for careers guidance. However, awareness is much lower among classroom

teachers in state schools (40%), again showing some elements of guidance are not necessarily

making it into day to day practice.

• Alongside differences in the range of activities available in schools reported by teachers, there

are also differences in students’ self-reported access. Overall, 36% of students in the UK said

they had not taken part in any careers related activities. State school pupils are more likely to

report not having taken part (38%) compared to pupils at private schools (23%).

• Students’ self-reporting of career activities is higher for those in later year groups. For

example, while only 7% of those in years 8-9 report learning about apprenticeships, this was

26% for year 13s. Similarly, while only 2% of those in years 8-9 had visited a university, 42%

of year 13s have done so. But even for year 13s, figures for many of these activities remain

low, with for example just 17% having learnt about career opportunities in their local area, and

just 30% having done work experience.

• Nearly half (46%) of 17- and 18-year olds (year 13) say they have received a large amount of

information on university routes during their education, compared to just 10% who say the

same for apprenticeships.

6

• Less than a third (30%) of students in year 13 have completed work experience.

• Around a third (36%) of secondary school students do not feel confident in their next steps in

education and training, with only just over half (56%) feeling confident. The proportion not

feeling confident is lower, but still sizable, for students in year 13 (22%).

• More pupils in state secondary schools report not being confident in their next steps in

education and training than in private schools (39% vs 29%).

Barriers to good quality provision

• Over three quarters of state school teachers (88%) felt that their teacher training didn’t

prepare them to deliver careers information and guidance to students.

• Over a third (37%) of senior leaders think their school does not have adequate funding and

resources to deliver careers advice and guidance.

• Just under a third (32%) of teachers in state schools report they don’t have enough funding to

deliver good quality careers education and guidance, compared to just 6% saying the same in

private schools. Just over half (51%) of teachers in state schools think there isn’t enough staff

time to do so, compared to just 34% saying the same in private schools.

• Schools in more deprived areas are less likely to have access to a specialist Careers Adviser,

with 21% of teachers in the most deprived areas reporting non-specialists delivered personal

guidance, compared to 14% in more affluent areas.

• 72% of teachers think the pandemic has negatively impacted their school’s ability to deliver

careers education and guidance. This figure was 16 percentage points higher for teachers in

state schools, at 75%, vs 59% in private schools.

Teachers’ views on improving careers guidance

• Almost half (47%) of state school teachers want to see additional funding for careers

guidance, more than four times as many as in private schools (11%). State schools want to

use additional funding to allow a member of staff to fully focus on careers guidance, with

teachers also wanting to see better pay and recognition for the Careers Leader role in schools.

• Many senior leaders in English state schools also want to see additional visits from employers

(47%) and more visits from apprenticeship providers (39%).

7

Recommendations

For government

1. The government should develop a new national strategy on careers education. Provision

would benefit from a clear overarching strategy now that the government’s 2017 careers

strategy has lapsed. The strategy should sit primarily in the Department for Education, but

with strong cross-departmental links, to join up what are currently disparate elements in the

system. The strategy should look at the very start of a child’s education, all the way through to

the workplace. It should be formed in partnership with employers, with a view to help prepare

young people for future labour market trends, and link clearly into the government’s levelling

up strategy.

2. At the centre of this strategy should be a core ‘careers structure’ outlining a minimum

underlying structure for careers provision in all schools. There is too much variation in the

careers provision available to students. This underlying architecture, with adequate funding

behind it, would help tackle this inconsistency, by putting in place the same standard

underlying set up in all schools, to aid them to deliver guidance as set out in the Gatsby

benchmarks.

This offer should guarantee that all schools:

• Have a Careers Leader with the time, recognition, and resources to properly fulfil their

role

• Are part of a Careers Hub

• Have access to a professional career adviser for their students (qualified to at least

Level 6)

3. Greater time should be earmarked and integrated within the overall curriculum, and within

subject curricula, to deliver careers education and guidance, to reflect its centrality to

students’ future prospects. With competing demands on the school day, setting clearer

requirements on the time schools should be spending on careers education, both on overall

careers guidance (for example in PSHE lessons or as a scheduled careers week for pupils), and

for subject specific careers guidance within lessons, would help give the topic the required

priority within schools. This should be accompanied by better training for teachers on careers

education within initial teacher training.

4. All pupils should have access to work experience between the ages of 14 and 16.

Experience in the workplace can be extremely impactful for students, allowing them to gain

important insights into the world of work and develop essential skills, with support given to

help them find relevant placements. This should also be accompanied by additional funding

for schools, to allow them to pay for the staff time needed to support students to organise good

quality placements.

5. Better support and guidance should be made available for schools and colleges on

apprenticeships, with better enforcement of statutory requirements. More investment

should be made in national information sources and programmes on technical education

routes to improve the advice available. Evidence suggests that too many schools are not

meeting their statutory requirements under the ‘Baker Clause’. Better enforcement should be

introduced, for example looking at incentives such as limiting Ofsted grades in schools who do

not comply with the clause.

8

For the Career and Enterprise Company (CEC)

1. All secondary schools should be part of a Careers Hub, with schools serving the most

deprived intakes prioritised. Plans for the Careers Hub network to be expanded are to be

welcomed, but now is the time to expand the network to reach all schools. Given the

disparities in careers provision identified here, it is vital that the most deprived schools are

prioritised in this expansion plan. Evaluation of the programme should continue to ensure that

expansion is impactful.

2. The CEC should continue to roll out pilot programmes of promising interventions based on

evidence, again where possible with a focus on the most deprived schools. We welcome

recent pilot programmes, including partnerships with businesses, to help to give young people

greater insights into the world of work. Further such work should continue, with programmes

likely to benefit the most deprived schools prioritised.

For schools, colleges and their governing boards

1. Additional support for employability and career education should be seen as a key part of

catch-up plans for education post pandemic. Many students have missed out on important

aspects of career education and guidance during school closures, when core learning had to be

prioritised. School catch-up plans should include a strategy on how students will be supported

to make up for the opportunities to learn about careers which they have missed during the

pandemic. This should be accompanied by additional catch-up funds from government to

support schools to do this work.

2. There should be clear responsibility for careers guidance within a school’s senior

leadership team. How this is done may differ between schools, for example by having a

Careers Leader themselves sit within a school’s senior leadership team (SLT), or if this role is

held by a middle leader, by having a member of SLT who is clearly responsible for the school’s

strategy on careers. The member of SLT with responsibility for careers should work with the

school’s Pupil Premium Lead to ensure the school’s career strategy takes into account the

needs of this group of students.

3. Every school should have at least one governor who oversees careers provision. This

governor role should engage with a school’s Careers Leader to give strategic oversight of a

school’s careers programme, as well as potentially helping to link their school up with local

employers through any contacts on the governing board. It should also work together with a

school’s pupil premium governor, again to ensure the school’s strategy is successfully catering

to this group of students.

9

Introduction

High quality careers education, information, advice and guidance is vital to ensure young people can

access jobs that suit their talents and aspirations. For those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, this

advice is particularly important, as they are less likely to have access to support from family and friends,

or to have networks which provide an insight into a wide range of career options. Accessing independent

and impartial advice on education, training and career paths is therefore a central plank of social

mobility, empowering young people to make informed decisions about their future pathways.

In this report, the term careers guidance is used to cover all careers-related activities delivered in schools

and colleges, including under the Gatsby benchmarks. Careers guidance is delivered in a variety of forms,

from in-class workshops to visits from an employer. That advice, when done well, introduces a variety of

potential career paths, and helps to facilitate the transition from secondary education to further

education and employment.

1

When we last published research on careers guidance in our report

Advancing Ambitions

in 2014,

2

guidance was seen too often as a postcode lottery, with significant variability between schools. The

coalition government had made significant changes to provision in 2011, scrapping the Connexions

service (which held the main responsibilities for careers guidance from 2000 until 2011) and giving

responsibilities to schools, but without the necessary funding and guidance to support delivery. This left

behind a fragmented system, with the most disadvantaged students losing out on services that were cut

by their local authority at a time of austerity.

In response to the changes made by the coalition government, our report called for improvements to

statutory guidance, more funding for Careers Advisers in schools and greater recognition of careers

guidance in Ofsted assessments. Since then, the policy landscape has changed considerably, with the

government publishing statutory guidance for schools and colleges in England in 2015,

3

built around

the Gatsby Foundation’s benchmarks for good careers guidance.

4

These were designed to bring the varied

elements of guidance that cover education, training and employment into a coherent whole. The Careers

and Enterprise Company was also founded in 2015 to support schools in achieving the benchmarks, and

to create better networks for schools and colleges to work with employers and share effective strategies.

However, relatively little is known about how well those changes are being implemented on the ground,

and research has continued to find inequalities in access.

Furthermore, since our last report, significant changes have happened in the further education space,

such as the introduction of T-Levels and degree apprenticeships. But evidence so far suggests these

routes have not been treated equally to more academic routes, with technical and vocational pathways

too often given less prominence in careers education. To tackle this issue, the government made it a

statutory requirement in 2015 for education providers to offer a range of education and training providers

the opportunity to inform students in years 8 to 13 about technical and further education routes.

5

But

previous research has found this requirement is not being implemented consistently - two in five students

believe more information and advice would have led to them making better choices, and almost a third

1

Cedefop, European Commission, ETF, ILO, OECD, UNESCO (2021) Investing in career guidance. European Trading

Foundation. Available at: https://www.etf.europa.eu/en/publications-and-resources/publications/investing-career-guidance

2

A. G. Watts, J. Matheson and T.Hooley (2014) Advancing Ambitions. The Sutton Trust. Available at:

https://www.suttontrust.com/our-research/advancing-ambitions/

3

Department for Education (2015) Careers guidance and access for education and training providers. Gov.uk. Available at:

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/careers-guidance-provision-for-young-people-in-schools

4

J. Holman (2014) Good careers guidance. The Gatsby Charitable Foundation. Available at:

https://www.gatsby.org.uk/uploads/education/reports/pdf/gatsby-sir-john-holman-good-career-guidance-2014.pdf

5

Department for Education (2015) Careers guidance and access for education and training providers. Gov.uk. Available at:

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/careers-guidance-provision-for-young-people-in-schools

10

of students had not received any information about apprenticeships from their school.

6

As there have

been many recent changes in the technical education landscape, it is more important than ever for a

range of post-16 options to be covered in the advice given to young people.

Ensuring equal access to careers guidance is particularly vital as we continue to move through the

economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, during which many young people’s opportunities to take

part in work experience and other workplace learning were impacted. Our research in July 2020 found a

reduction in work experience opportunities during the pandemic, with 61% of the employers surveyed

saying that they had cancelled work placements for the summer of 2020.

7

Additionally, in more recent

research from the Institute for Employment Studies, interviews with young people revealed that school-

age pupils are concerned about the lack of preparation for the world of work after missing out on work

experience opportunities as well as the increased pool of competition for entry level roles.

8

Against this context particularly, it is essential that from a young age all children and young people can

access high quality careers guidance, regardless of background, so that they can make informed

decisions about their next steps. This should cover a wide range of pathways and take into account up

to date information on changes in the labour market. The Trust’s own programme work - with around

8,000 young people each year – helps young people with high potential from lower income homes to

make choices about their futures that are well informed, and supports them to realise those aspirations.

But a system-wide, well-funded, high quality and impartial careers and advice function is a prerequisite

of a fair and effective education system.

This report looks in detail at the advice now available to young people, engagement with related

opportunities and any barriers to improving provision in schools and colleges, including polling of both

secondary school pupils and teachers.

6

UCAS (2021) Where Next? What influences the choices school leavers make? Available at:

https://www.ucas.com/file/435551/download?token=VUdIDVFh

7

E. Holt-White & R. Montacute (2020) Covid-19 and social mobility impact brief #5: Graduate recruitment and access to the

workplace. The Sutton Trust. Available at:

https://www.suttontrust.com/our-research/coronavirus-workplace-access-and-graduate-

recruitment/

8

C. Orlando (2021) Not just any job, good jobs! Youth voices from across the UK. The Health Foundation. Available at:

https://www.employment-studies.co.uk/system/files/resources/files/Not%20just%20any%20job%2C%20good%20jobs%21.pdf

11

The policy landscape

Careers provision across the UK

The current careers education and guidance system in England is mainly delivered in schools and

colleges, who follow statutory guidance written by the Department for Education, with significant

involvement from external arms-length organisations like the Careers and Enterprise Company (CEC) and

National Careers Service (NCS).

Policies in the devolved nations are outlined in the box below.

The following section outlines the current legislation in place for careers guidance in England, and

summarises the role of key organisations in this space.

Careers guidance in other UK nations

Wales

- Careers guidance in Wales is offered by schools and the Careers Wales Service. Established in 2012,

the service delivers external support which is funded by government. Young people can interact with the

service’s Careers Advisers online and over the phone.

Careers Wales promote partnerships between schools and local employers to ensure young people are

experiencing the world of work. They also work with schools to train teachers in using their resources and

show how to incorporate guidance into the curriculum. These activities are co-ordinated by a team of Careers

Advisers, with advisers acting as ‘account executives’ for individual schools.

There is no statutory guidance currently in place for careers guidance in Wales, but guidance is currently

being developed by the government and a team of Careers and the World of Work (CWOW) co-ordinators who

sit within Careers Wales.

Scotland -

The key universal careers service for young people in Scotland is Skills Development Scotland.

All state schools partner with the organisation, who can access a team of qualified careers staff to deliver

drop-in services, one to one meetings and group activities as well as a range of online resources for teachers

to use in the classroom. The service also works with employers to deliver targeted outreach activities related

to particular industries.

Various services are funded by the UK and Scottish governments as well as the European Union, including

Skills Development Scotland and Jobcentre Plus, but provision and engagement in careers guidance

activities are significantly variable between regions. A

2020 strategy from the Scottish government sets out

plans to create “a national model for career education, information, advice and guidance services with

shared principles adopted across education, training and employability services”.

Northern Ireland -

All Northern Irish schools have a partnership agreement with the country’s careers

service. Schools and parents are advised to encourage students to use this service, particularly in years 10

and 12.

In 2015, a 5-year strategy was set jointly by the Department for Education and the Department for the

Economy for the whole population. Policy commitments in the strategy include re-introducing the statutory

duty of delivering careers education, improving work experience offered to young people and providing

additional support for disadvantaged groups.

12

The Gatsby benchmarks

In 2013, the Gatsby Foundation, led by Sir John Holman, put together a report outlining the

requirements for high quality careers guidance.

9

The report reviewed existing literature in the field and

visited independent schools to gather information about good practice. The authors also visited 6 other

countries (the Netherlands, Germany, Hong Kong, Finland, Canada and Ireland) who had been identified

as having both good career guidance offers in schools and strong educational results. The organisation

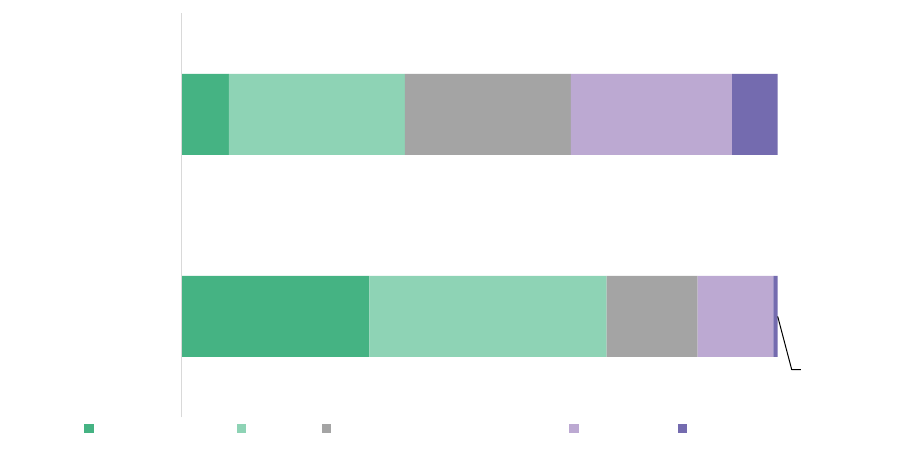

formulated a set of 8 criteria known as the Gatsby benchmarks (shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Gatsby benchmarks

The benchmarks are designed to bring the varied elements of guidance that cover education, training

and employment into a coherent whole. This involves ‘push’ factors (such as individualised guidance

and discussing careers in the classroom) that are based in schools, and ‘pull’ factors (such as offering

visits to the workplace and running group workshops) that come from employers. Each benchmark has

associated indicators which can be used to measure progress. They have formed the core of the most

recent statutory guidance on careers guidance from the Department for Education.

A recent evaluation of the Gatsby benchmarks found that, when integrated into a school’s careers

provision, achieving the benchmarks can contribute to a significant improvement in students’ career

readiness.

10

On a wider level, a positive relationship was also seen with classroom engagement, as

9

J. Holman (2014) Good careers guidance. The Gatsby Charitable Foundation. Available at:

https://www.gatsby.org.uk/uploads/education/reports/pdf/gatsby-sir-john-holman-good-career-guidance-2014.pdf

10

J. Hanson

et al.

(2021) An evaluation of the North East of England pilot of the Gatsby Benchmarks of good careers guidance.

The University of Deby and the International Centre for Guidance Studies. Available at:

https://www.gatsby.org.uk/uploads/education/ne-pilot-evaluation-full-report.pdf

13

students were more aware of why they were learning particular topics and how the skills developed from

lessons link to future careers.

Statutory guidance

In 2015, the government published statutory guidance for schools and colleges for delivering careers

guidance, with an updated version published in 2021.

11

This followed a review led by CooperGibson

which highlighted that whilst a wide range of careers activities were taking place in most schools, the

most common forms of guidance were led by in-school staff during lesson time rather than qualified

careers staff.

12

The review also found that around half of respondents’ schools did not have formal links

with employers, 13% did not offer workplace visits and 8% did not offer work experience opportunities.

The review suggested more work considering students’ experiences with careers provision in schools,

targeted provision for individual needs and improved relationships between schools and employers.

The statutory guidance sets out the duty for all local-authority maintained schools to secure access to

impartial guidance for pupils from years 8 to 13 (ages 12 to 18), with securing independent guidance

for pupils a funding requirement for all further education (FE) and sixth form colleges. Most academies

and free schools also have duties regarding careers guidance in their funding agreements; if they do not,

they are still encouraged to follow government guidance as a sign of good practice.

Only two areas are legal requirements: offering impartial guidance and meeting the Baker Clause

(discussed below). Points preceded with ‘should’ are policies schools should follow unless there is a good

reason not to. One of these points is a recommendation for all schools to work towards a Quality in

Careers Standard award, which is awarded by the Quality in Careers consortium

(partly funded by the

DfE). To gain the award, schools must meet a set of assessment criteria that align to the Gatsby

benchmarks. In their statutory guidance, the DfE recommend that schools work towards achieving this

award. 32% of state secondary schools and 30% of colleges currently hold an award.

13

The work of the Career Development Institute (CDI) is also highlighted in the statutory guidance; a

professional body for all organisations working in the careers guidance field and also offer postgraduate-

level qualifications on careers.

14

Schools and colleges are encouraged to use the organisation’s Career

Development Framework (which clarifies the skills, knowledge and attitudes that individuals should

achieve from careers guidance) to shape their careers programme.

15

The guidance also states that schools

should follow the CDI’s recommendation of Careers Advisers being qualified to at least Level 6.

The guidance sets out suggestions for achieving all 8 of the Gatsby benchmarks and highlights

government policies that will help to facilitate this. The guidance also highlights the importance of a

Careers Leader and the benefits of being part of a Careers Hub; managed by the Careers and Enterprise

Company.

11

Department for Education (2021) Careers guidance and access for education and training providers. Gov.uk. Available at:

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/748474/181008_schools_stat

utory_guidance_final.pdf and Department for Education (2015) Careers guidance and access for education and training

providers. Available at:

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/7491

51/Careers_guidance-

Guide_for_colleges.pdf

12

S. Gibson

et al.

(2015) Mapping careers provision in schools and colleges in England. Department for Education. Available at:

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/447134/Mapping_careers_prov

ision_in_schools_and_colleges_in_England.pdf

13

Award Holders. Quality in Careers. Accessed March 2022. Available at: https://www.qualityincareers.org.uk/what-is-the-quality-

in-careers-standard/award-holders/

14

About us. The Career Development Institute. Accessed March 2022. Available from: https://www.thecdi.net/About

15

T. Hooley (2021) Career Development Framework. The Career Development Institute. Available at:

https://www.thecdi.net/write/CDI_90-Framework-Career_Development_skills-web.pdf

14

Careers and Enterprise Company

The DfE set up the Careers and Enterprise Company in 2015 in order to link secondary education

providers and employers to deliver high quality careers guidance. Investment from the Department of

Education has increased since the organisation’s inception, when £6million was awarded, up to an

allocation of nearly £28million for 2021/22 (Table 1).

16

Table 1: Funding allocated by the Department for Education to the Careers and Enterprise

Company (2015/16 – 2021/22)

2015/16

2016/17

2017/18

2018/19

2019/20

2020/21

2021/22 (allocated)

£6m

£16m

£18.8m

£30.2m

£20.6m

£25.9m

£28m

The CEC offer a range of resources and tools to be used by Careers Leaders, as well as wider advice to

schools. The organisation suggest that a Careers Leader should ideally be a senior role within a school,

who oversees a school’s careers programme, ensuring progress is made towards the Gatsby benchmarks

and connecting the school to external partners.

17

The CEC also says that Careers Leaders should manage

or commission a Careers Adviser, who is responsible for delivering personal guidance either to individuals

or groups of pupils. A Careers Leader should also work with all staff and partners that are involved in a

school’s programme; for instance, they should collaborate with an enterprise adviser, who is a volunteer

from a business who can use their external expertise to shape a school’s careers programme.

18

This

voluntary opportunity is managed by a network of enterprise co-ordinators led by the CEC, who connect

business volunteers with schools.

Tools available to Careers Leaders include Compass, which allows a school to evaluate their careers

programme against the Gatsby benchmarks, and Compass+, which can be used to manage, track and

report on careers provision at an individual student level. Training for Careers Leaders is also offered by

CEC, where leaders can develop the skills and knowledge required to lead an extensive careers

programme. Ensuring all schools had a named Careers Leader by the end of 2020 was set as a key target

in the government’s most recent careers strategy, published in 2017 (discussed in more detail below).

Careers Hubs are also managed by the CEC. These are groups of 20 to 40 neighbouring secondary schools

who are joined together to work towards the Gatsby benchmarks; each Hub has a Lead to co-ordinate

activities, access to training bursaries and a central fund of around £1,000 per school or college.

19

They

are designed to connect education providers to employers, working locally to test, trial and evaluate

interventions that can be shared within the wider network of Hubs. As of December 2019, there were

32 Hubs that reached 1,300 schools, with further expansions of the programme announced in 2020

reaching almost half of state schools in England.

20

Being part of a Hub has been associated with a higher likelihood of working with employers; in a review

of the programme one year after its inception, 66% of schools in a Hub run regular encounters with

16

Department for Education Freedom of Information request. Responses received 2nd and 8th of November 2021.

17

The Careers and Enterprise Company. Understanding the role of the Careers Leader. Available at:

https://www.careersandenterprise.co.uk/media/uhtkww5h/understanding-careers-leader-role-careers-enterprise.pdf

18

The Careers and Enterprise Company. Become an Enterprise Adviser. Accessed March 2022. Available at:

https://enterpriseadviser.careersandenterprise.co.uk/

19

The Careers and Enterprise Company. Careers Hubs. Accessed March 2022. Available at:

https://www.careersandenterprise.co.uk/about-us/our-network/careers-hubs

20

LEP Network (2020) LEPs drive Careers Hubs extension to boost recovery. LEP network, 24 June. Available at:

https://lepnetwork.net/news-and-events/2020/june/leps-drive-careers-hubs-extension-to-boost-recovery/

15

employers compared to 33% of schools and colleges that are not in a Hub.

21

Research has also shown

that being part of a Hub increases the likelihood of a school holding a Quality in Careers Standard

award.

22

It is therefore encouraging that the rollout of Careers Hubs has been supported in the

government’s recent ‘Skills for Jobs’ white paper,

23

and funding has been awarded to the Careers and

Enterprise Company for a third rollout of the scheme, which will reach nearly half of all state schools.

24

Programme pilots in the primary education space have also been led by the Careers and Enterprise

Company. Working with the Centre for Education and Youth (CFEY), the CEC launched the Primary

Careers Resources Platform, which provides information and resources to help put career-related learning

into the curriculum and engage parents as well as external stakeholders in the area.

25

It also conducts

activities that can be run in primary classes. The CEC feature several reports in this area on their website,

showing that high quality careers guidance from a young age helps pupils to understand the relevance

of what they are learning and broadens pupil’s knowledge of career sectors that they would not typically

gain elsewhere at such an age.

26

In their 2020 review, the organisation highlighted that schools, colleges

and businesses across the country are starting to work together in this area, building good foundations

for economic recovery, but continued investment in the sector focusing on national rollout through

Careers Hubs is vital.

27

The Careers and Enterprise Company release a

‘State of the Nation’

report each year, which typically

looks at progress towards the Gatsby benchmarks and analyses key trends in the careers landscape over

the past year. The most recent report, published at end of 2021, reflected on the past 2 years and how

the Covid-19 pandemic affected careers provision.

28

Progress was seen in terms of coverage of careers

during lesson time and delivery of personal guidance – for example, around 80% of secondary schools

reported providing most students with a qualified Careers Adviser interview by the end of year 11 (up

from 74% in 2019). However, progress towards some benchmarks had receded – 39% of schools

reported that most of their students had access to a workplace experience by the end of year 11,

compared to 57% in 2019, although this is likely at least in part due to impacts of the pandemic. It is

also notable that progress over time is not reported for all benchmarks.

National Careers Service

Outside of provision in schools and colleges, the DfE also funds the National Careers Service (NCS).

Since 2012, the NCS has provided impartial online and over-the-phone advice on career options.

29

Whilst

young people can use this service, the NCS is an information source for anyone of working age, so is not

specifically tailored to an audience of students or school aged children.

21

Hutchinson, J.

et al

. (2019) Careers Hubs: One year on. The Careers and Enterprise Company. Available at:

https://www.careersandenterprise.co.uk/media/ku0akyn2/careers-hubs-one-year-on.pdf

22

The Careers and Enterprise Company. Compass results for the secondary schools and colleges in England with the Quality in

Careers Standard 2021. Accessed March 2022. Available at:

https://www.qualityincareers.org.uk/wp-

content/uploads/2022/01/Compass-results-and-Quality-in-Careers-Standard-7.1.2022.pdf

23

Department for Education (2021) Skills for jobs: lifelong learning for opportunity and growth. Available at:

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/957856/Skills_for_jobs_lifelon

g_learning_for_opportunity_and_growth__web_version_.pdf

24

LEP Network (2020) LEPs drive Careers Hubs extension to boost recovery. LEP network, 24 June. Accessed March 2022.

Available at: https://lepnetwork.net/news-and-events/2020/june/leps-drive-careers-hubs-extension-to-boost-recovery/

25

The Careers and Enterprise Company. Primary Careers Resources. Accessed March 2022. Available at: https://primary-

careers.careersandenterprise.co.uk/

26

Research. The Careers and Enterprise Company Primary Careers Resources. Accessed February 2022. Available at:

https://primary-careers.careersandenterprise.co.uk/practice/research

27

The Careers and Enterprise Company (2020) Careers Education in England’s schools and colleges 2020. Careers and

Enterprise Company. Available at:

https://www.careersandenterprise.co.uk/our-research/careers-education-englands-schools-and-

colleges-2020

28

The Careers and Enterprise Company (2021) 2021: Trends in careers education. Careers and Enterprise Company. Available

at: https://www.careersandenterprise.co.uk/media/xadnk1hb/cec-trends-in-careers-education-2021.pdf

29

National Careers Service. Accessed March 2022. Available at: https://nationalcareers.service.gov.uk/

16

The NCS budget was allocated by the department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS)

(previously the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills; BIS) until 2017. Funding from the DfE

has been variable; £74.5 million was awarded in the 2017/18 financial year, with £70.4 million

allocated for 2021/22.

30

Funding ranged between £57 million and £64 million in the years between.

The skills assessment feature, consisting of an online test that suggests potential careers to users based

on their responses, has been a particularly hot topic in recent months due to job losses during the Covid-

19 pandemic. Those who had lost roles were encouraged to re-skill and re-train, with funding announced

in the government’s Plan For Jobs and a significant revamp of the platform set out in the Skills white

paper.

31

However, a previous government-commissioned review found no evidence of using the service

leading to a higher likelihood of employment (albeit there were more positive associations when

considering education and training pathways).

32

Indeed, after an additional £32 million was allocated to

the NCS in 2020, there have been several concerns around the current funding arrangements,

highlighted in an open letter to Gillian Keegan from over 90 signatories, including Careers England and

the Career Development Institute.

33

As set out in the Skills white paper, the government plans to improve the alignment between the NCS

and the CEC to create a more comprehensive system. However, commentators have flagged that this will

require bringing together two differing ways of working, which could be challenging, - currently, the NCS

works with subcontractors to target provision to specific cohorts of adults, such as NEETs, with the only

part of the service for young people being the website and phone service, whereas the CEC work more

closely with government departments.

34

The service has recently been updated to offer more content for young people – a hub was added in

January 2022 to provide a single hub of information on all post-16 pathways. A recent life skills

campaign,

Get The Jump

, has been launched to attract young people to the website.

35

Policy on technical education and apprenticeships

In January 2018, the Baker Clause was introduced to ensure all schools and colleges are offering

information on apprenticeships and other further education pathways, to recognise the importance of

technical educational routes.

36

The law states that schools should be ensuring pupils from year 8 to year

13 are receiving information advice on technical education and apprenticeships from a range of

employers and providers. This policy statement must be published on a school’s website.

30

Department for Education Freedom of Information request. Responses received 2nd and 8th of November 2021.

31

Department for Education (2021) Skills for Jobs: Lifelong Learning for Opportunity and Growth. Gov.uk. Available at:

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/957856/Skills_for_jobs_lifelon

g_learning_for_opportunity_and_growth__web_version_.pdf

32

M. Lane

et al

. (2017) An economic evaluation of the National Careers Service. Department for Education, gov.uk. Available at:

https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/28677/1/National_Careers_Service_economic_evaluation.pdf

or for a summary see: FE News (2017) An

economic evaluation of the National Careers Service. FE News. Available at: https://www.fenews.co.uk/fevoices/13607-an-

economic-evaluation-of-the-national-careers-service

33

Careers England, Careers Development Institute, Careers Research Advisory Centre (CRAC), University of Derby and

International Centre for Guidance Studies (2020) An open letter to the secretary of state for Apprenticeships and Skills.

Available at: https://www.careersengland.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Dear-Gillian-Keegan-Open-lettter-final-2-page.pdf

and

Careers England (2020) Risks to Rishi Sunak’s Extra Investment in Careers Advice in the ‘Plan For Jobs’. FE News, September

30. Available at: www.fenews.co.uk/featured-ar

ticle/55658-risks-to-rishi-sunak-s-extra-investment-in-careers-advice-in-the-plan-

for-jobs

34

J. Staufenberg (2021) Can the government fix the ‘confusing’ careers landscape? FE Week. Available at:

https://feweek.co.uk/can-the-government-fix-the-confusing-careers-landscape/

35

Explore your choices. National Careers Service. Accessed March 2022. Available at:

https://nationalcareers.service.gov.uk/explore-your-education-and-training-choices

36

J. Burke (2017) Baker clause: Schools obliged to let FE providers talk to pupils from January. FE Week. Available at:

https://feweek.co.uk/2017/11/23/baker-clause-schools-will-have-to-open-doors-to-fe-providers-from-january/

17

The Baker Clause also features in the House of Lord’s Skills and Post-16 Education Bill, whereby an

amendment from the government states that pupils should expect two mandatory visits from providers

of technical education and apprenticeships over the course of their secondary education.

37

However, the

plans have been criticised by the creator of the clause, Lord Baker, who has said the fact that the

government have reserved the right to specify further details in secondary legislation weakens the intent

of the proposals. A stronger clause was proposed by Lord Baker to make it obligatory for schools to

arrange three mandatory encounters with technical education and training providers over the course of

their secondary education,

38

however this amendment was scrapped by the government.

39

Information on apprenticeships and other technical education routes is available from the government’s

apprenticeships website, which offers online guidance for prospective apprentices as well as employers.

40

The DfE has also funded the Apprenticeship Support and Knowledge for Schools and Colleges (ASK)

programme; a source of support in delivering information about apprenticeships, traineeships and T-

Levels for education providers.

41

Additionally in this space, organisations like Amazing Apprenticeships

offer online support, resources for education providers and conduct outreach activities.

42

The OfS also

has an online guide for degree apprenticeships,

43

and UCAS have a range of information and resources

available on their website.

44

The Sutton Trust itself has also launched its first ever Apprenticeship

Summer School to highlight the benefits and routes into degree level apprenticeships.

The Gatsby benchmarks also cover guidance on further technical education. Benchmark 7 states that all

pupils should understand all academic and vocational routes that are available to them, with the

expectation that by age 16 all pupils should have had at least one meaningful encounter with a provider

associated with each option. The Gatsby Foundation have argued that the embedding of their benchmarks

across different levels of education before post-16 is vital in order for young people to be able to be

prepared and informed to take up roles that arise as technical education as well as UK industry grow.

45

Without this, young people will not be equipped for the large number of technical jobs that are part of

the government’s industrial strategy.

46

Reviews and regulation

In 2017, the DfE published a careers strategy, aiming to improve social mobility, as part of the

government’s long term industrial strategy aiming to raise earning power and productivity.

47

The

document introduces a set of key milestones involving the expansion of programmes supported by the

CEC (notably including a new round of the CEC’s Investment Fund to target support at the most

disadvantaged groups), improvements to the NCS and offering at least one opportunity per year for all

37

Skills and Post-16 Education Bill. Paliamentary Bills, UK Parliament. Accessed March 2022. Available at:

https://bills.parliament.uk/bills/2868

38

S. Chowen (2021) Baker to take on government over ‘inadequate’ careers guidance laws. FE Week. Available at:

https://feweek.co.uk/baker-to-take-on-government-over-inadequate-careers-guidance-laws/

39

S. Chowen (2021) Government strips popular Lords amendments from Skills Bill. FE Week. Available at:

https://feweek.co.uk/government-strips-popular-lords-amendments-from-skills-bill/

40

HM Government. Connecting people with amibition to businesses with vision. Accessed March 2022. Available at:

https://www.apprenticeships.gov.uk/

41

HM Government. Influencers – the ASK programme. Accessed March 2022. Available at:

https://www.apprenticeships.gov.uk/influencers/ask-programme-resources

42

Amazing Apprenticeships. Accessed March 2022. Available at: https://amazingapprenticeships.com/about-us/

43

Office for Students. Degree apprenticeships – guide for apprentices. Accessed March 2022. Available at:

https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/for-students/degree-apprenticeships-guide-for-apprentices/

44

UCAS. Apprenticeships. Interested in apprenticeships? Find out everything you need to know. Accessed March 2022.

Available at: https://www.ucas.com/understanding-apprenticeships

45

The Gatsby Charitable Foundation. Good careers guidance. Accessed March 2022. Available at:

https://www.gatsby.org.uk/education/focus-areas/good-career-guidance

46

Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy. (2017) Industrial Strategy: the 5 foundations. Available at:

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/industrial-strategy-the-foundations/industrial-strategy-the-5-foundations

47

Department for Education (2017) Careers strategy: making the most of everyone’s skills and talents. Gov.uk. Available at:

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/careers-strategy-making-the-most-of-everyones-skills-and-talents

18

students to interact with employers. All milestones in the strategy were set out to be achieved by the end

of 2020 – although no evaluation has yet been published to indicate whether the aims of the strategy

have been met.

There has not yet been an updated careers strategy published by the government. However there have

been some significant policy changes outlined in other documents. As part of the government’s recent

Skills for Jobs white paper, careers guidance in schools is set to become compulsory for year 7s upwards,

with updated statutory guidance due to be published.

48

There are also calls for careers guidance to

become mandatory for even younger age groups; for instance, the House of Lords Youth Unemployment

Committee want to see careers education compulsory from Key Stage 1 to Key Stage 4.

49

This call comes

alongside a recommendation for the government to ensure that the curriculum covers the knowledge and

skills that are relevant to both emerging and existing sectors in the economy which are currently

experiencing skills gaps and shortages.

The Skills white paper also stated that the Careers Hub rollout would continue and more investment

would be made in Careers Leaders through the CEC, with the work of the CEC becoming more closely

aligned with that of the National Careers Service. Although these new policies have been welcomed,

some MPs want to see better links between the CEC and schools so that pupils can access knowledge of

other careers that their teachers may not know about.

50

Concerns over a lack of clear timelines for

improvements to the CEC in the white paper as well as the level of influence the organisation has over

schools were also flagged in a House of Lords debate in 2021.

51

Careers guidance was also mentioned in a section of the Augar Review, published in 2019 focusing on

post-18 education and funding.

52

Although the review’s main focus is higher education, one of the

recommendations is for the government’s careers strategy to be rolled out nationwide across all secondary

schools, with funding increased to a level which allows all schools to be part of a Careers Hub and all

Careers Leaders to receive further training, so that young people can be well informed about the post-18

options available. The review also calls for schools to be held to account for their provision, ensuring that

the requirement of apprenticeship and technical education providers to visit all schools is being met.

Moreover, the Labour Party have pledged to give all schools access to a professional Careers Adviser at

least one day per week and introduce two weeks of compulsory work experience.

53

Careers guidance is also mentioned briefly in the government’s levelling up strategy document, published

in February 2021.

54

Unifying local delivery partners from the Department for Work and Pensions and the

48

Department for Education (2021) Skills for jobs: lifelong learning for opportunity and growth. Gov.uk. Available at:

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/957856/Skills_for_jobs_lifelon

g_learning_for_opportunity_and_growth__web_version_.pdf

49

House of Lords, Youth Unemployment Committee (2021) Skills for every young person. Report of sessions 2021-22. Available

at:

https://committees.parliament.uk/committee/506/youth-unemployment-committee/news/159184/urgent-action-needed-to-

tackle-and-prevent-youth-unemployment/

50

Esther McVey- Hansard Extract (Careers Guidance in Schools) Bill. Commons Chamber. Available at:

https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/2021-09-10/debates/B2372DF6-9B7A-4534-A07D-

3649824F7901/Education(CareersGuidanceInSchools)Bill?highlight=careers#contribution-29F26518-54AC-4831-A016-

C5F06D5DB207

51

Lord Patel – Hansard extract. House of Lords. Available at: https://hansard.parliament.uk/Lords/2021-07-

19/debates/AEC59D02-6B02-425C-B795-10908C197C83/SkillsAndPost-16EducationBill(HL)?highlight=cec#contribution-

ADA2B02D-F2F6-463E-94E0-52580B648BCE

52

Department for Education (2019) Post-18 review of education and funding: independent panel report. Gov.uk. Available at:

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/post-18-review-of-education-and-funding-independent-panel-report

53

Labour Party (2021) Labour would make sure every child leaves school job-ready and life-ready. Available at:

https://labour.org.uk/press/labour-would-make-sure-every-child-leaves-school-job-ready-and-life-ready/

54

HM Government (2022) Levelling up the United Kingdom. Gov.uk. Available at:

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1052706/Levelling_Up_WP_H

RES.pdf

19

DfE, including careers services, is pledged in order to support people into jobs that fulfil local skills

needs.

In terms of regulation, the schools inspectorate Ofsted report on personal development, which is where

career information and guidance sits.

55

Schools should be providing an effective careers programme in

line with the government’s statutory guidance on careers guidance that offers pupils information on a

variety of career options and what is needed to succeed in them.

56

The House of Lords Youth Unemployment Committee, the House of Commons Education Select

Committee and the think tank IPPR have all suggested that Ofsted should assess compliance with the

Clause, with suggestions also made that local authorities should work with local employers and directly

contact parents with wide ranging advice not just focussed on technical education. This year, Ofsted

penalised a school for the first time for failing the Baker Clause, indicating that the body may have

listened to the calls for the clause to be a consideration in the inspection process.

57

Indeed, in the recent

Skills white paper, the DfE pledged they will be tougher on schools not complying with the clause.

58

The Covid-19 pandemic has also shaped recent policy developments in the careers guidance field, as

have immigration specific labour market issues following both Brexit and the pandemic. As the country’s

economy recovers from the pandemic, adapts to Brexit, and the government works towards its ‘Levelling

Up’ strategy, the importance of careers guidance has also come to the forefront, with increased funding

for careers guidance being part of the chancellor’s Plan For Jobs. An extra £32 million was announced

for the National Careers Service as part of the Covid-19 recovery package, which came with a pledge to

reach over 250,000 more young people (although, the way that this funding was allocated made it

difficult for the service to actually spend it).

59

New Youth Hubs have also been set up for young people

to find training and job opportunities.

60

These changes are vital to ensure young people have the right

information and advice for an ever-changing job market.

Gaining an insight into the current state of play in the careers guidance space is key to understanding

the feasibility of achieving the aims set out in these documents. It is clear that there has been a large

amount of change since the Sutton Trust last looked at this policy area, including the creation of the

Careers and Enterprise Company and the introduction of new statutory guidance for schools and colleges.

While many of these individual strands of careers guidance are positive, as it stands, there is not a clear

careers strategy that brings all of the important aspects of careers advice and guidance together, and

how these changes are translating into the provision available within schools is less clear.

55

Ofsted (2018) Ofsted: schools, early years, further education and skills. Building confidence, encouraging aspiration. Available

at: https://educationinspection.blog.gov.uk/2018/06/12/building-confidence-encouraging-aspiration/

56

Ofsted (2019) School inspection handbook. Gov.uk. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/school-

inspection-handbook-eif

57

B. Camden (2020). Ofsted raps first school over Baker Clause. FE Week. Available at:

https://feweek.co.uk/2020/05/15/school-slammed-by-ofsted-after-failing-baker-clause/

and F. Whieldon (2021) Pressure mounts

on Ofsted to limit grades by Baker Clause compliance. FE Week. Available at: https://feweek.co.uk/pressure-mounts-on-ofsted-to-

limit-grades-by-baker-clause-compliance/

58

F. Whittaker. (2021) DfE to toughen up Baker Clause and extend careers requirement to year 7s. Schools Week. Available at:

https://schoolsweek.co.uk/dfe-to-toughen-up-baker-clause-and-extend-careers-requirement-to-year-7s/

59

T. Hooley. (2020) Gillian Keegan needs to free the National Careers Service to do its job. FE Week. Available at:

https://www.fenews.co.uk/exclusive/gillian-keegan-needs-to-free-the-national-careers-service-to-do-its-job/

60

Department for Work and Pensions (2021) Over 110 new Youth Hubs offer job help. Available at:

https://www.gov.uk/government/news/over-110-new-youth-hubs-offer-job-help

20

Existing evidence on careers education

The following section looks at what is known in the research literature on what makes for good quality

careers guidance, existing issues with provision and potential barriers, with a focus on guidance in

schools.

For disadvantaged young people, a significant barrier to their desired career is having access to

information about what a particular path involves and the best subjects to study in order to access it.

Those from poorer backgrounds are also less likely to know about the range of career choices on offer in

the first place. Knowledge of particular careers or subject choices can often come from sources both

inside and outside of the classroom, such as friends and family, but it is those from the poorest

backgrounds who are least likely to receive such insights. As a result, they may have lower aspirations

for their future career that do not reflect their potential.

High quality careers guidance from a school or college can open the door to a post-16 pathway that a

young person from a lower socioeconomic background would not have otherwise known about.

Alternatively, when it comes to the most competitive careers such as law, politics or medicine, they may

be aware of the roles but not be sure of the pathway to reach them. Indeed, previous research has found

that careers guidance in schools is the main source of guidance for students who grew up in families

where the top earners were in low-skilled roles and-or had not gone to university,

61

and advice received

can overcome barriers that are created by socioeconomic background. But currently, access to such

provision appears to be a postcode lottery.

62

The value of careers guidance

Receiving high quality careers guidance can have an effect not just on the years following education but

also much further into the life course. In a comprehensive, international literature review by the

Education Endowment Foundation (EEF), 67% of the papers reviewed provided robust evidence that

activities like work-related learning positively impacted economic outcomes and 62% found a positive

association with social outcomes such as career maturity (the level of preparedness for making career-

related decisions) and career identity (the ability to link interests and skills to particular careers).

63

Furthermore, the review concluded that disadvantaged students were more likely to be unsure regarding

choosing the correct qualifications to match their ideal career. The research makes it clear that careers

guidance provided in education settings has the potential to reach all students and, when tailored to

individual needs, can meet the needs of students looking for guidance regarding their next steps.

The OECD have also produced a wealth of research in this space. A recent report on teenagers’ career

expectations, analysing data from 41 countries, has found that there is a misalignment with young

people’s aspirations and the qualifications they think are required to access them.

64

It also finds that

high attaining disadvantaged young people are less likely to hold ‘ambitious’ aspirations compared to

high attainers from privileged backgrounds. The report highlights the need for careers guidance to cover

the qualifications required for particular pathways, as well as opportunities to experience encounters

61

G. Haynes

et al

. (2012) Young people’s decision making; the importance of high quality school-based careers education,

information, advice and guidance. Research Papers in Education. Available at:

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02671522.2012.727099

62

A. G. Watts, J. Matheson and T.Hooley (2014) Advancing Ambitions. The Sutton Trust. Available at:

https://www.suttontrust.com/our-research/advancing-ambitions/

63

D. Hughes

et al.

(2016) Careers education: international literature review. The Education Endowment Foundation. Available

at: https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/public/files/Presentations/Publications/Careers_review.pdf

64

A. Mann

et al.

(2020) Dream Jobs? Teenagers career aspriations and the future of work. The OECD. Available at:

https://www.oecd.org/education/dream-jobs-teenagers-career-aspirations-and-the-future-of-work.htm

21

with employers. Additionally, the OECD highlighted the importance of covering the labour market

changes associated with the Covid-19 pandemic in the guidance delivered in schools, and recommended

that individual guidance should be tailored to account for this.

65

They have warned that in previous times

of economic turbulence it was disadvantaged students who were more likely to experience poor levels of

career readiness.

The importance of starting early

The evidence review from the OECD concluded that careers guidance is most successful when advice is

personalised to individuals and is accessed from an early age, before starting secondary school. The

value of careers guidance activities from an early stage is also made clear in a large-scale, global study

by the charity Education and Employers, which found that the patterns in ideal jobs of 7 year-olds are

often reflected in the choices made by 17 year olds.

66

The study identified that nearly 2 in 5 (36%) of

primary school children under the age of 7 base their aspirations on people they know, with a significant

proportion on the remaining children (45%) saying they were influenced by the media, such as TV and

film. Less than 1% of children said that visitors to their school had told them about a career. In the UK

specifically, whilst career aspirations were similar across levels of deprivation overall, several high-

earning professions (such as engineers, lawyers and vets) are more likely to be aspired to by students in

more affluent schools.

These findings are particularly concerning, given that disadvantaged young children are less likely to

have friends and family from a wide range of careers (particularly those that are paid highly) to influence

their aspirations at a young age and, as the Education and Employers report discusses, this could

negatively impact their labour market choices later on in life. By educating children about careers from

a young age, connections between the classroom and careers as an adult can be established, and any

stereotypes associated with gender, ethnicity and class can be broken down.

67

Guidance on options for the future is important not only in primary school, but also in the early years of

secondary school. Based on analysis of a survey of 18 to 20 year-olds in the UK, UCAS found that 1 in

3 students begin to think about higher education when in primary school, with disadvantaged students

1.4 times less likely to do so compared to more affluent peers.

68

The report also highlighted the

importance of individual guidance when it comes to deciding which subjects to study at school - two in

five students felt more information and advice would have led to them making better subject choices to

match their degree, with these students almost three times as likely to report not being able to study a

degree course that might have interested them at university or college due to not holding the necessary

subjects (30% of students vs. 11% of students). Based on their findings, UCAS have called for broader,

personalised guidance to be available from a young age, with more targeted outreach activities taking

place in primary schools and the lower years of secondary school.

65

A. Mann, V. Denis and C. Percy (2020) Career Ready? How schools can better prepare young people for working life in the era

of COVID-19. Available at: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/career-ready_e1503534-en

66

N. Chambers

et al.

(2018) Drawing the future. Education and Employers. Available at:

https://www.educationandemployers.org/drawing-the-future-report-published/

67

P. Musset and L. Mytna Kurekova (2018)Working it out: Career Guidance and Employer Engagement, OECD Education

Working Papers, No. 175, OECD. Available at:

https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/working-it-out_51c9d18d-

en;jsessionid=cHcPcm6vhEE-YBCs9kJx_G5y.ip-10-240-5-92

68

UCAS (2011) Where next? What influences the choices school leavers make? UCAS. Available at:

https://www.ucas.com/file/435551/download?token=VUdIDVFh

22

Regional inequalities

The fragmented nature of careers guidance, across not just England but the whole of the UK, often

appears in the literature, with regional patterns of careers provision often mirroring patterns of social

class, which could be exacerbating inequalities.

69

Regional variation has also been seen in previous

research looking at engagement with employers, with levels of recalled engagements by those under the

age of 25 who have left school 22% higher in the South East of England than in Scotland and North

East England.

70

There are also sector specific challenges. For example, in a report on innovation and invention, NESTA

found that less than 1.5% of schools are currently involved in schemes aimed to attract students to

inventing, with those in the South twice as likely to have taken part compared to students in the

Midlands.

71

It was also found that schools with better-off pupil populations were more likely to be involved

and are six times as likely to send pupils to invention competitions and then reach the final. Although

this research only considers one particular area, it provides insight into the regional inequalities in STEM-

related provision, and highlights important improvements. The organisation has called for better co-

ordination between schools and providers; one way of doing this could be for businesses to create long-

term relationships with local schools. Similarly, the Local Government Association (LGA) have called for

funding and control of employment schemes to go to back to local authorities to bring the ‘patchwork’

of careers activities to an end (they previously held responsibility before the implementation of the 2011

Education Act and the dissolution of the Connexions service).

72

Previous research has also identified a link between Ofsted ratings and Gatsby benchmark performance,

with higher-rated schools performing better,

73

further emphasising the view that careers guidance is a

postcode lottery. But it may be wrong to assume that lower-rated schools do not have any careers

education provision in place; it is common to see that careers services have self-referral systems, which

could disadvantage those who are less aware of the value of careers guidance and the variety of advice

available.

74

Guidance can also be affected by biases of both schools and careers staff, such as

encouraging children to choose post-16 options at the school they are currently at,

75

or unconscious bias

leading to lower-ability pathways being suggested for students that are in fact capable of more.

76

Insight to the workplace

A key part of careers guidance is young people getting to speak to employers and visit workplaces to find

out what particular careers are like. This is particularly important for those interested in an

apprenticeship, as they will be entering a workplace whilst also studying. Previous research has shown

69

J. Moote and L. Archer (2018) Failing to deliver? Exploring the current status of career education provision in England,

Research Papers in Education, 33:2, 187-215. Available at:

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02671522.2016.1271005

70

A. Mann

et al.

(2016) Contemporary transitions: Young Britons reflect on life after secondary school and college. Education

and Employers. Available at:

https://www.educationandemployers.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Contemporary-Transitions-30-

1-2017.pdf

71

M. Gabriel

et al.

(2018) Opportunity Lost: How inventive potential is squandered and what to do about it. Nesta. Available at:

https://www.nesta.org.uk/report/opportunity-lost-how-inventive-potential-squandered-and-what-do-about-it/

72

LGA (2019) Thousands of young people missing out on vital careers support, Councils warn. Policy Mogul, 29 October.

Available at:

https://policymogul.com/key-updates/5441/thousands-of-young-people-missing-out-on-vital-careers-support-

councils-warn

73

R. Long and S. Hubble (2018) Careers guidance in schools, colleges and universities. House of Commons Library, Briefing

Paper 07236. House of Commons. Available at: https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/30886/1/CBP-7236%20.pdf

74

J. Moote and L. Archer (2018) Failing to deliver? Exploring the current status of career education provision in England,

Research Papers in Education, 33:2, 187-215. Available

at:https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02671522.2016.1271005

75

N. Foskett

et al.

(2008) The influence of the school in the decision to participate in learning post-16. British Educational

Research Journal 34, no. 1: 37–61. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01411920701491961

76