JOINT LEGISLATIVE AUDIT

AND REVIEW COMMISSION

Report to the Governor and the General Assembly of Virginia

Commonwealth of Virginia

September 12, 2023

Virginia’s K–12 Teacher Pipeline

2023

COMMISSION DRAFT

JLARC Report 576

©2023 Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission

jlarc.virginia.gov

Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission

Senator Janet D. Howell, Chair

Delegate Robert D. Orrock, Sr., Vice Chair

Delegate Terry L. Austin

Delegate Kathy J. Byron

Delegate Betsy B. Carr

Delegate Barry D. Knight

Senator Mamie E. Locke

Senator Jeremy S. McPike

Senator Thomas K. Norment, Jr.

Delegate Kenneth R. Plum

Senator Lionell Spruill, Sr.

Delegate Luke E. Torian

Delegate R. Lee Ware

Delegate Tony O. Wilt

Staci Henshaw, Auditor of Public Accounts

JLARC sta

Hal E. Greer, Director

Justin Brown, Senior Associate Director

Lauren Axselle - Principal Legislative Analyst, Project Leader

Christine Wolfe, Senior Legislative Analyst

Laura White, Associate Legislative Analyst

Information graphics: Nathan Skreslet

Managing editor: Jessica Sabbath

Contents

Summary i

Recommendations and Policy Options vii

Chapters

1. Virginia’s Public K–12 Teacher Pipeline 1

2. Trends in Virginia’s Supply of K–12 Teachers 5

3. Virginia’s Teacher Preparation Pathways 11

4. Virginia’s Teacher Licensing Process 29

5. Teacher Recruitment and Retention 37

Appendixes

A: Study resolution 43

B: Research activities and methods 44

C: Teacher vacancies by school division 52

D: Agency response

Online Appendixes

E: Inventory of state-supported K–12 teacher pipeline programs and initiatives

F: Traditional teacher preparation programs at public institutions

Commission draft

i

Summary: Virginia’s K–12 Teacher Pipeline

WHAT WE FOUND

Statewide, teacher vacancies and reliance on less than fully licensed

teachers has increased

Having enough, high quality teachers is among the most important factors necessary

for a quality education system. The latest available

data shows continued declines in the number of

teachers in Virginia’s K–12 system and the propor-

tion of them who are fully licensed:

• 4.8 percent of teaching positions were va-

cant at the start of the 2023–24 school year,

up from 3.9 percent in the prior school year

(and less than 1 percent in years prior to the

pandemic); and

• 16 percent of Virginia’s teachers were not

fully licensed or not teaching “in field” in

SY2022–23, up from 14 percent in the prior

school year (and 6 percent a decade ago).

Some divisions are facing substantial

teacher workforce problems, but other divisions are not

The severity of the teacher workforce problems varies widely across the state. Some

divisions have much higher than average teacher vacancy rates, while others have very

few or no vacant teaching positions. Virginia school divisions with large populations

of Black students have especially high teacher vacancy rates.

As with vacancies, school divisions’ reliance on teachers who are not fully licensed

varies widely. For example, two divisions reported that all their teachers were fully li-

censed, while two reported that only about half of their teachers were. Similarly, two

divisions reported that all their teachers were teaching “in field,” while two reported

only about two-thirds of their teachers were.

Direct pathways to licensure tend to better prepare teachers to be

successful in the classroom

In general, teachers who use direct pathways to become a fully licensed teacher are

better prepared for the classroom. The most common direct pathway by far in Virginia

is graduating from a traditional higher education teacher preparation program as a fully

licensed teacher. Traditional higher education-based preparation programs prepare

WHY WE DID THIS STUDY

In 2022,

the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Com-

mission (JLARC) directed staff to review the adequa

cy

of the supply of qualified K

–12 teachers in Virginia.

ABOUT

VIRGINIA’S K-12 TEACHER PIPELINE

Virginia’s “teacher pipeline” consists of the programs

and proce

sses that attract, prepare, licens

e, recruit, and

retain public K

–

12 teachers. While the Commonwealth’s

134

local school divisions individually recruit and retain

teachers, the state plays a role in

the teacher pipeline

through higher education institutions that administer

teacher preparation programs, VDOE’s licensure of

teachers, and funding for initiatives to promote the

teaching profession.

Summary: Virginia’s K–12 Teacher Pipeline

Commission draft

ii

about 2,600 teachers annually in Virginia. These programs include important compo-

nents of effective teacher preparation, including pedagogical coursework, student

teaching and mentorship from experienced teachers, and college-level subject area

coursework.

School divisions believe traditional higher education preparation programs better

prepare people to teach than indirect pathways. For example, 46 percent of school

divisions surveyed by JLARC reported that provisionally licensed teachers are very

poorly or poorly prepared to be teachers, while only 3 percent of school divisions re-

ported poor preparation among individuals who attended traditional higher educa-

tion preparation programs.

Teacher residency programs also produce well prepared teachers. Residency pro-

grams involve an extended co-teaching placement while simultaneously completing

coursework. Residency programs have a rigorous design and are low cost to partici-

pants because of the financial assistance provided. Residency programs, though, are

expensive to administer and currently have limited capacity in Virginia. State-sup-

ported residency programs prepared just under 100 individuals for teaching in

SY2022–23.

In January 2023, VDOE initiated a registered teacher apprenticeship program.

VDOE has distributed funds to six partnerships between school divisions and higher

education institutions to implement programs. Apprenticeship programs can pro-

duce teachers that are well prepared, according to experts. They also pay individuals

during their preparation and have the advantage of being able to use federal work-

force funds to cover a portion of program costs. If implemented effectively, Vir-

ginia’s new registered apprenticeships should result in additional well-prepared teach-

ers without the financial barriers associated with traditional preparation.

Indirect pathways give individuals flexibility to obtain credentials

over time and cost less

In recent years, an increasing number of individuals have been entering teaching

through Virginia’s indirect pathways to fill current teacher vacancies. These indirect

pathways include provisional licensure, career switcher programs, and division-led

preparation programs. Individuals using these pathways to become a teacher are typi-

cally less well prepared in the short term, but can move through those pathways at

substantially less cost and benefit from more flexible pacing and delivery format (fig-

ure, next page). For example, most provisionally licensed teachers take required

courses at their convenience, often online, while working as a teacher. Tuition can still

be costly for these courses, but many divisions offer tuition reimbursement for provi-

sionally licensed teachers, and several divisions offer in-house preparation at no cost

to participants.

In Virginia, provisional

teaching

licenses are

non

-

renewable and valid

for three years.

In 2018,

the General Assembly

passed legislation allow-

ing provisional license

es

to

receive up to two,

one

-year extensions if a

teacher has satisfactory

performance evaluations

and receives a recom-

mendation from the divi-

sion superintendent.

Summary: Virginia’s K–12 Teacher Pipeline

Commission draft

iii

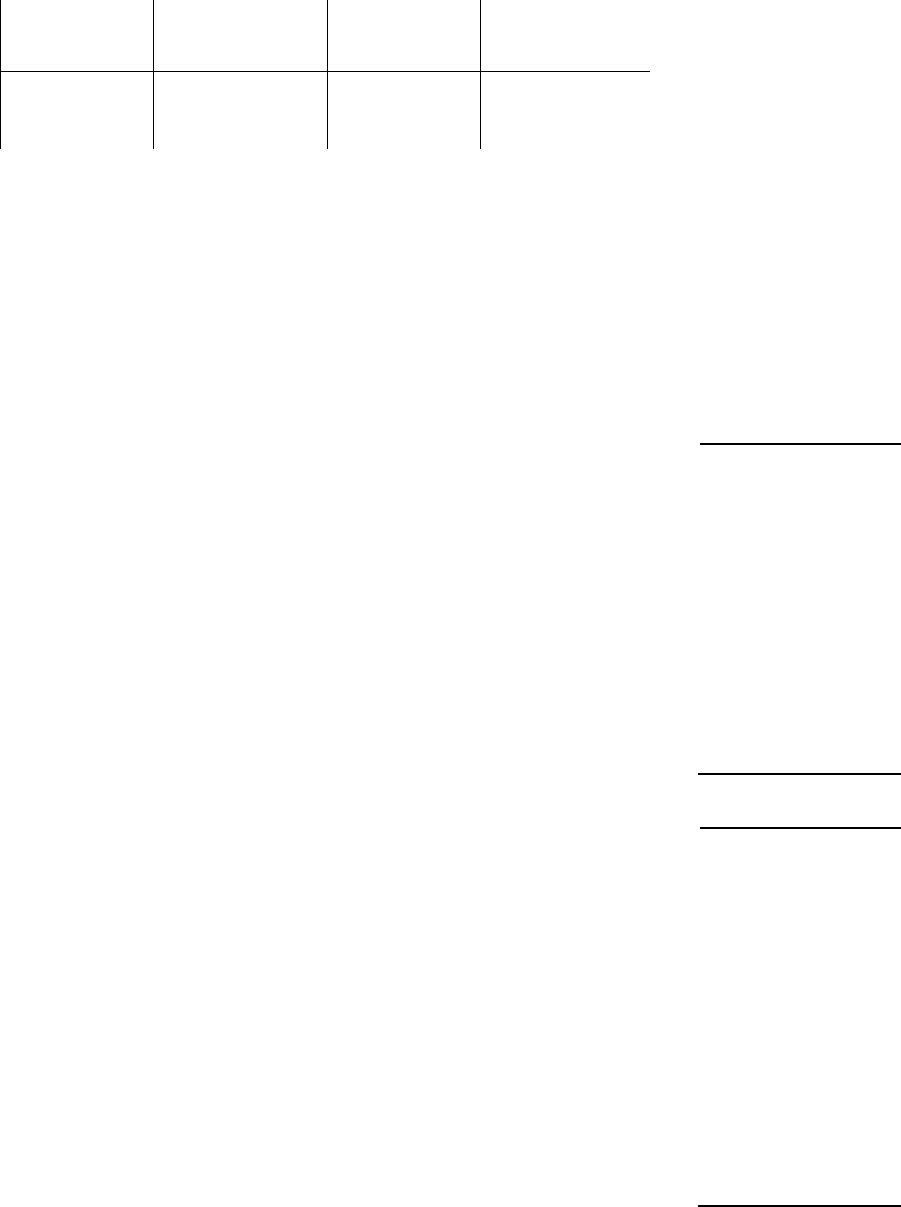

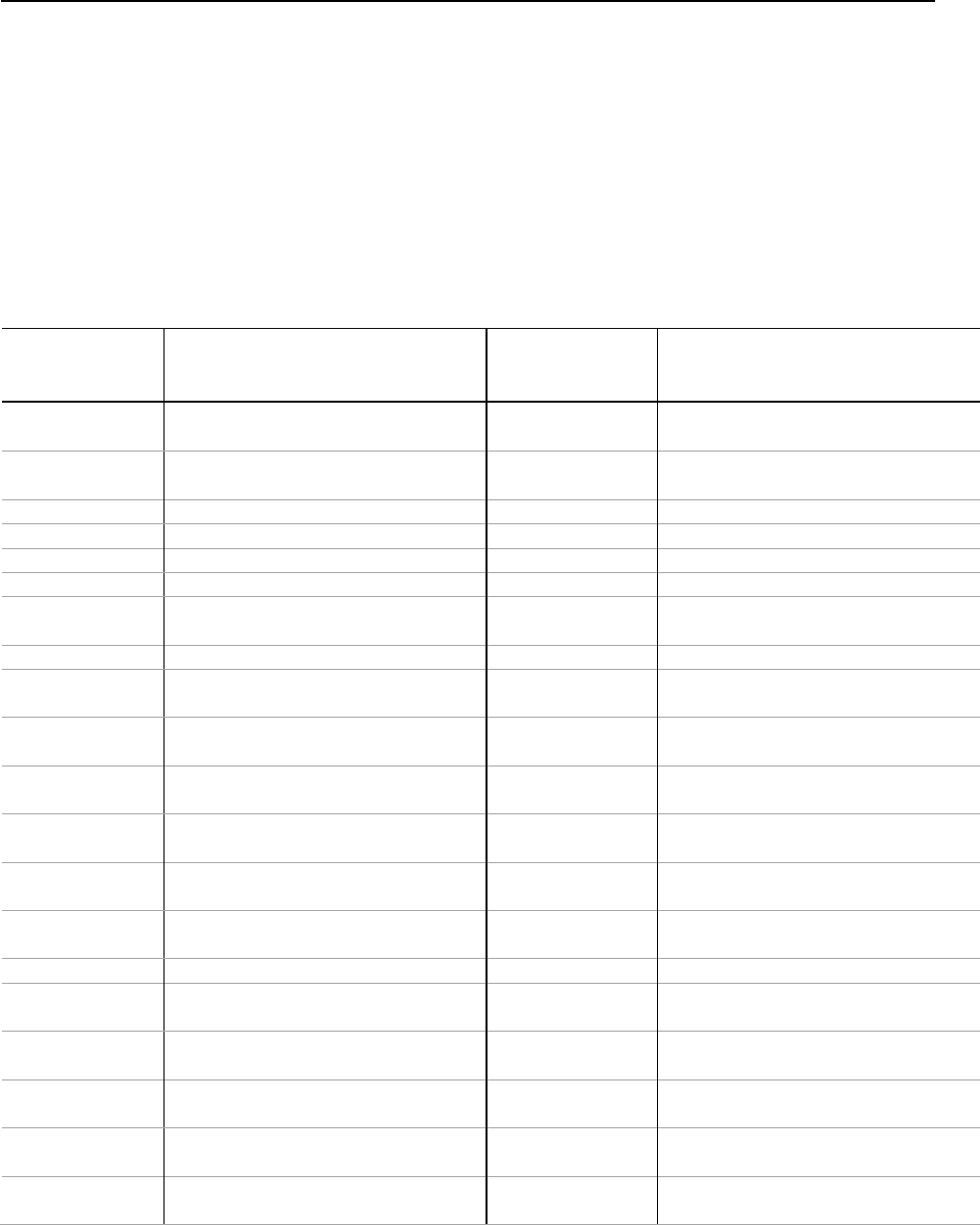

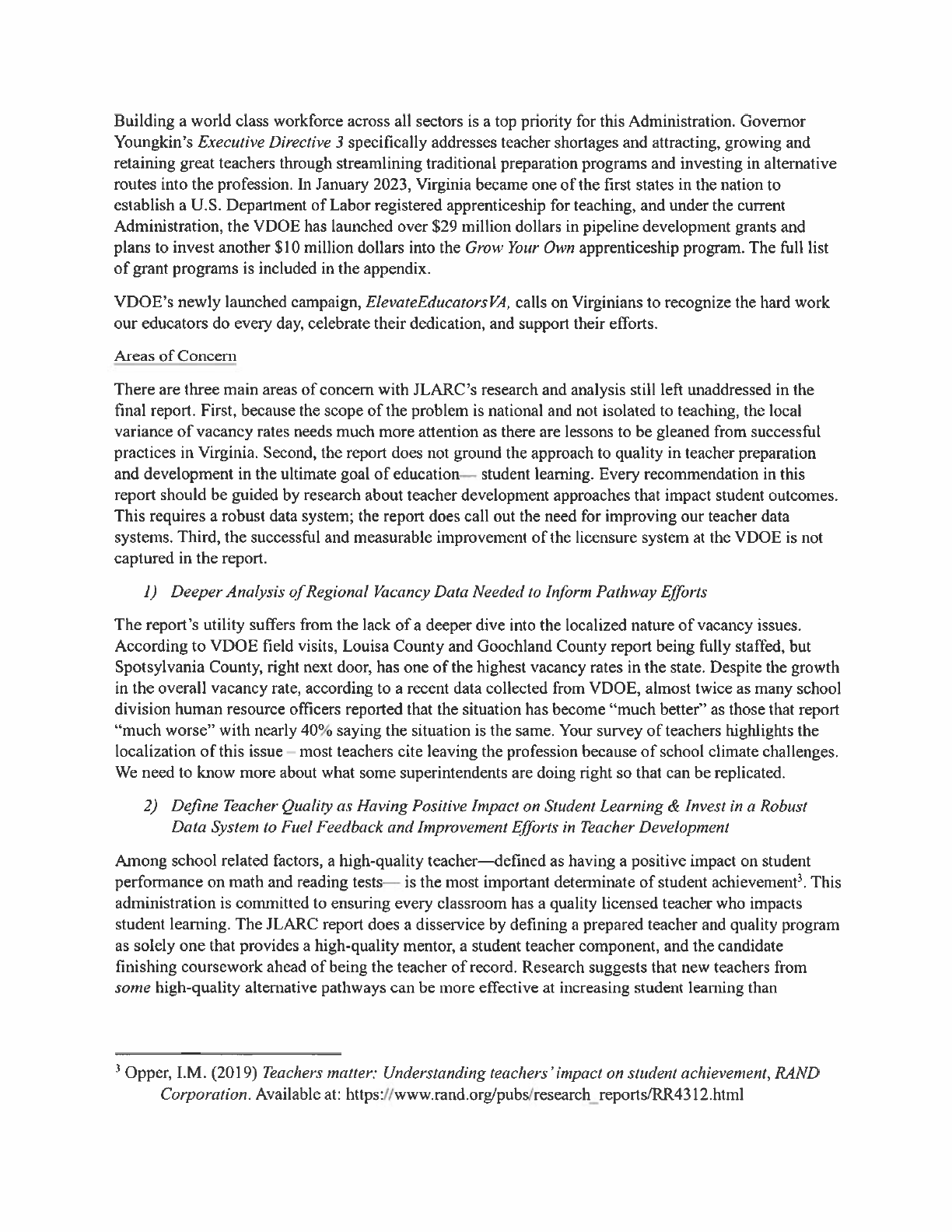

Teacher pathways have tradeoffs between quality and affordability

Program quality /

Participant preparedness

Participant

affordability

Direct pathways

Traditional teacher preparation programs

●

○

Teacher residency programs

●

●

a

Registered apprenticeship programs

-

b

-

b

Indirect pathways

Provisional license, classes as needed over time

○

c

◑

Special education provisional license

◑

◑

Career switcher programs

◑

◑

Division-led preparation

Varies

●

SOURCE: JLARC staff analysis.

NOTES: Program quality / participant preparedness = High quality mentor provided; student teaching component;

candidate finishes content and pedagogical coursework prior to being teacher of record. Participant affordability =

cost of tuition and fees; ease of holding paid employment.

A new indirect pathway—online courses through a private provider called iTeach—has recently been approved in

Virginia but is not yet operating.

a

Teacher residency programs are affordable for participants but often costly for the state or sponsoring division.

b

A new direct pathway—registered apprenticeship programs— is currently being implemented in Virginia. Vir-

ginia’s program is too new to evaluate.

c

Preparedness measured when provisional licensee becomes teacher of record; preparedness varies and is likely to

increase as classes are completed.

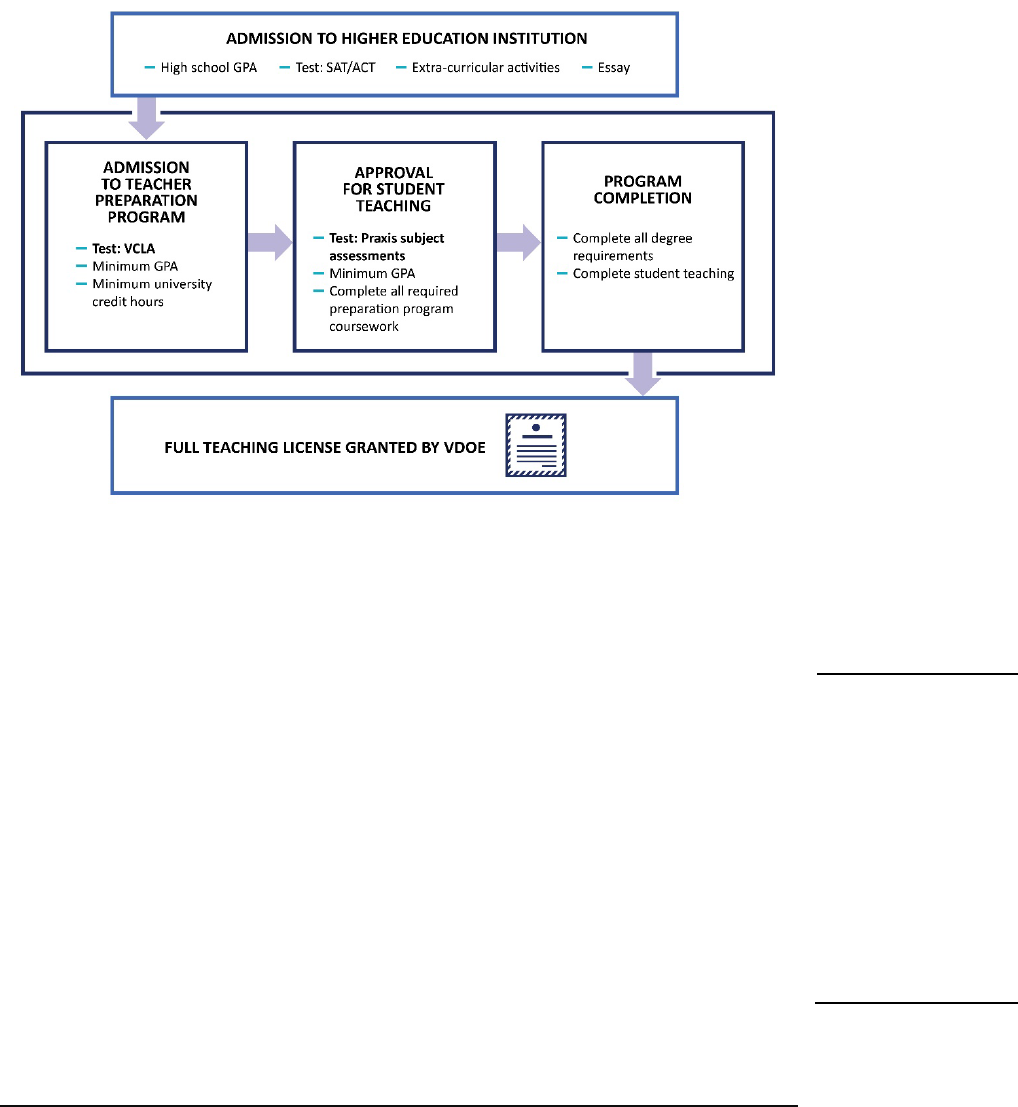

Virginia-specific assessment required for traditional teacher

preparation programs may be an unnecessary barrier

A Virginia-specific test (which is separate from the nationally used and recognized

Praxis subject assessments) is preventing some individuals from enrolling in and com-

pleting traditional higher education teacher preparation programs. The Virginia Com-

munication and Literacy Assessment (VCLA) is a Virginia-specific test with two sub-

tests that measure reading comprehension and written communication skills. While 86

percent of test takers eventually pass the VCLA, an average of about 630 test takers

(14 percent) did not pass it each year over the last six years.

The VCLA may present an unnecessary barrier to admission to or completion of tra-

ditional teacher preparation programs when the state needs more people to enter the

teacher pipeline. According to staff at 11 of the 14 Virginia public teacher preparation

programs, failure to pass required assessments such as the VCLA is a top reason indi-

viduals are unable to enroll in and/or complete preparation programs. The test, which

was developed in 2007 and has not been updated, is outdated and tests prospective

teachers on skills that are not relevant for some types of teachers to be effective.

Summary: Virginia’s K–12 Teacher Pipeline

Commission draft

iv

Tuition, assessments, and unpaid student teaching present financial

barrier to some participants in traditional preparation programs

Costs associated with traditional higher education teacher preparation programs are

another barrier to participation in these high quality programs. Seventy-three percent

of new teachers surveyed by JLARC who attended traditional preparation programs

reported at least one cost associated with preparation (tuition and fees, cost of licens-

ing tests, unpaid student teaching) to be a moderate or significant barrier to complet-

ing their preparation program. In addition, staff from 10 of the 14 traditional prepa-

ration programs at Virginia’s public higher education institutions cited financial

concerns as a top reason why teacher candidates did not enter or complete their pro-

gram.

Virginia has a relatively small ongoing program to reduce the cost of tuition for tra-

ditional teacher preparation for some students. The Virginia Teaching Scholarship

Loan Program (VTSLP) awards up to $10,000 for tuition and fees to teacher candi-

dates at public or private institutions pursuing teaching in a critical shortage disci-

pline or who are minority teacher candidates. The program requires recipients to

teach for at least two years in the critical shortage discipline or in a school where

more than half of the students are eligible for free or reduced lunch.

Recently, $708,000 in annual VTSLP funding has facilitated scholarship loans to 75

recipients per year. This represents an estimated 10 percent of all graduates of Vir-

ginia’s traditional teacher preparation programs who have financial need (based on

Pell grant eligibility). Higher education teacher preparation programs report there is

substantially more demand for this program than current funding levels support. For

example, one large public institution reported having at least 50 additional individuals

eligible for scholarship loans every year who were not able to receive them.

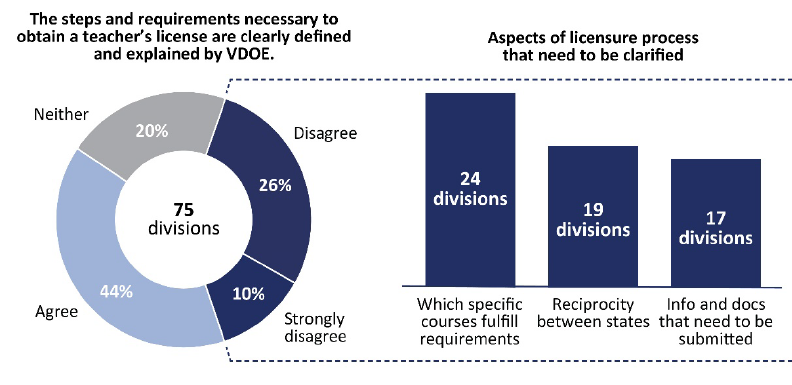

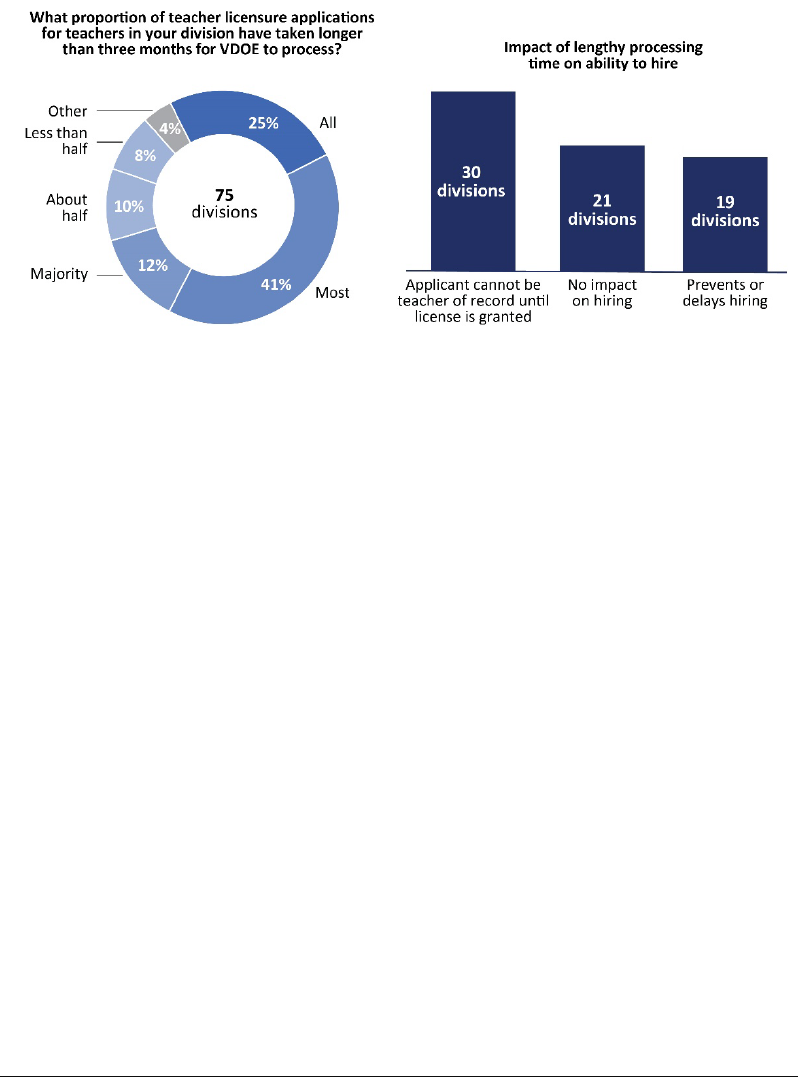

Licensure requirements and process can seem complex and be unclear

to some applicants

School division HR staff surveyed by JLARC expressed mixed opinions on how clearly

defined the requirements are to obtain a Virginia teaching license. Thirty-six percent

of division staff “strongly disagreed” or “disagreed” that teacher licensure require-

ments are sufficiently clear. When asked on a JLARC survey, one new teacher said:

“The process to apply for a license is so complicated and draining.”

The lack of clarity about licensure requirements can be especially challenging for

teachers with provisional licenses and fully licensed teachers in other states interested

in teaching in Virginia. VDOE does not publish information specifying which courses

meet licensure requirements. As a result, provisionally licensed teachers may take

courses that do not fulfill Virginia’s licensure requirements, which can be costly and

delay their ability to teach. Similarly, VDOE does not publish information on the spe-

cific license types and endorsement areas that are comparable between Virginia and

other states. As a result, teachers from another state seeking a Virginia license must

Summary: Virginia’s K–12 Teacher Pipeline

Commission draft

v

submit a full application to VDOE to learn whether their license and/or endorsement

area will be accepted.

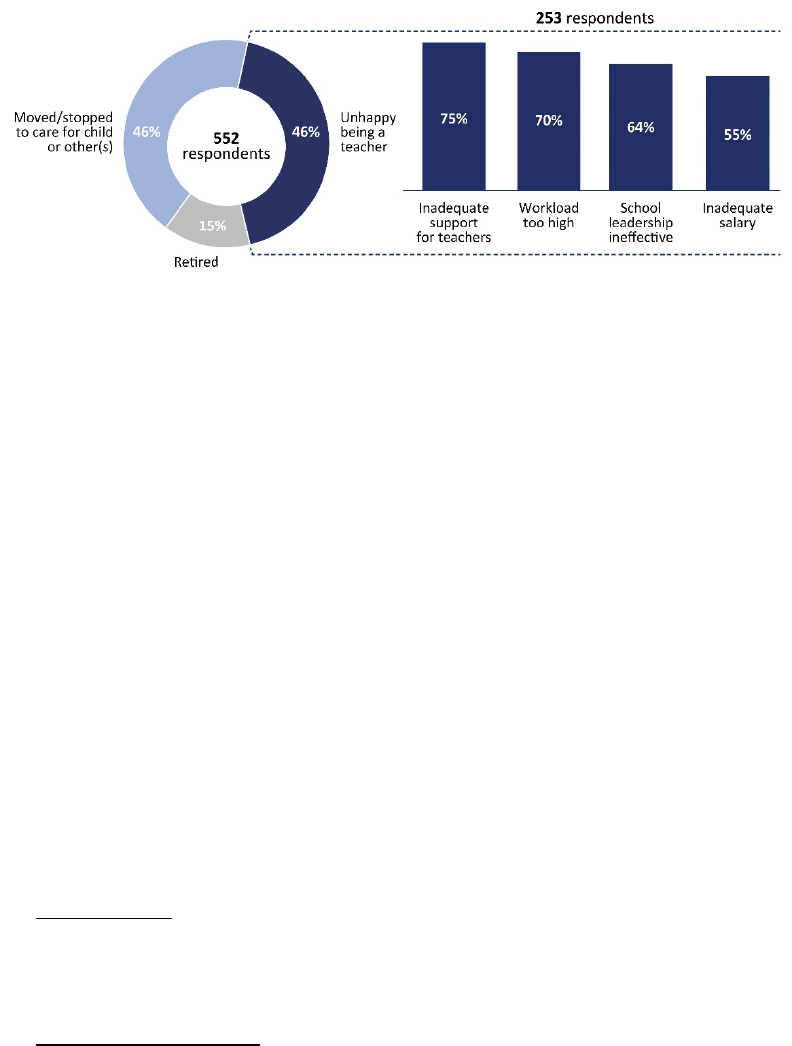

Factors other than barriers to preparation program participation and

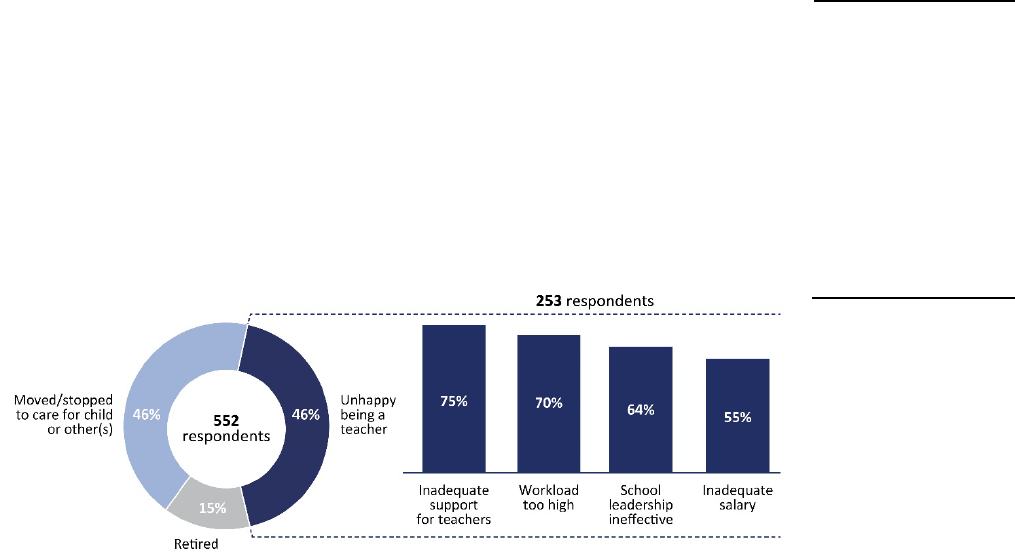

the licensure process are primary reasons for state’s teacher shortage

Though the state can improve the teacher preparation and licensure processes, Vir-

ginia’s teacher shortage will not materially improve until the root causes of the short-

age are addressed. Teachers in Virginia have left the profession primarily either for

personal reasons (e.g., family moving to another location), or because they were un-

happy with the job. Inadequate support for teachers generally, high workload, ineffec-

tive school leadership, and low salary are the top reasons cited for their unhappiness

with being a teacher (figure), according to a JLARC survey.

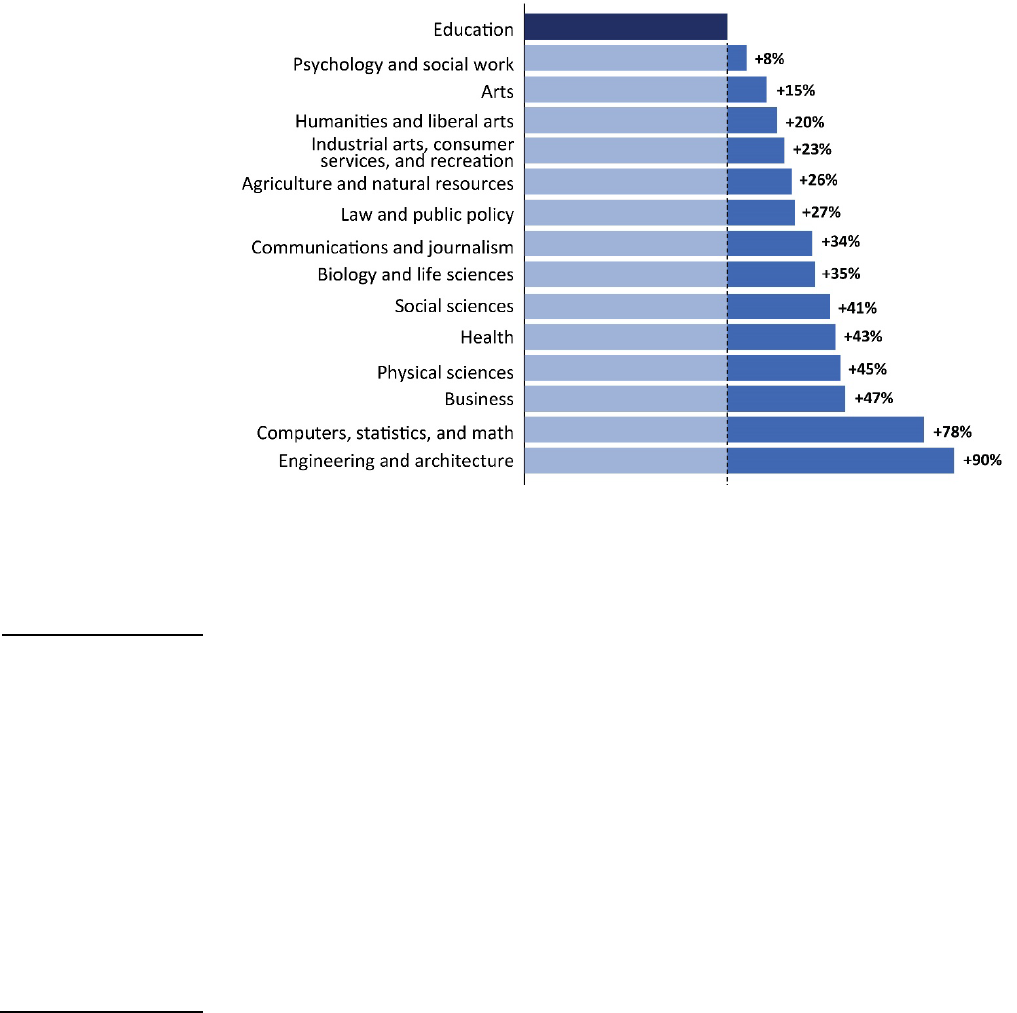

Reasons licensed teachers left positions in Virginia public schools

SOURCE: JLARC survey of licensed teachers who are not currently teaching in a Virginia public school.

NOTE: Respondents could select more than one response. Some respondents provided other reasons for leaving

their jobs in Virginia public schools, including deciding to pursue another career and deciding they no longer

wanted to work for pay.

Other, recent JLARC reports have recommended ways to address issues related to

teacher support and workload (e.g., more instructional assistants), and salary (e.g.,

changing the SOQ formula inputs to more accurately reflect actual teacher salaries).

Therefore, the potential benefits of the recommendations and policy options in this

report related to the teacher pipeline must be considered in the context of these

broader factors that more heavily influence teacher recruitment and retention.

WHAT WE RECOMMEND

Legislative action

• Authorize a waiver that allows higher education teacher preparation pro-

grams to recommend qualified individuals who have not passed the VCLA

to receive full teacher licensure.

• Increase funding for the Virginia Teaching Scholarship Loan Program.

JLARC surveyed

individuals with Virginia

teaching licenses who

were not working in

Virginia public schools

in July 2023. The survey

was sent to individuals for

whom VDOE had em

ail

addresses. JLARC re-

ceived 1,164 responses

for an overall response

rate of 34 percent.

Summary: Virginia’s K–12 Teacher Pipeline

Commission draft

vi

Executive action

• Replace the VCLA with a relevant and nationally recognized test, or remove

it as a requirement for full teacher licensure.

• List on the VDOE website the (i) courses that fulfill licensure requirements

in each endorsement area for provisionally licensed teachers pursuing full

licensure and (ii) license types and endorsement areas that qualify for reci-

procity with selected other states.

• Report on the program participation, size, and funding levels of the new

registered teacher apprenticeship program.

The complete list of recommendations is available on page vii.

Commission draft

vii

Recommendations and Policy Options: Virginia’s K-

12 Teacher Pipeline

JLARC staff typically make recommendations to address findings during reviews.

Staff also sometimes propose policy options rather than recommendations. The three

most common reasons staff propose policy options rather than recommendations are:

(1) the action proposed is a policy judgment best made by the General Assembly or

other elected officials, (2) the evidence indicates that addressing a report finding is not

necessarily required, but doing so could be beneficial, or (3) there are multiple ways in

which a report finding could be addressed and there is insufficient evidence of a single

best way to address the finding.

Recommendations

RECOMMENDATION 1

The General Assembly may wish to consider including language in the Appropriation

Act directing the Virginia Department of Education to report (i) which higher educa-

tion institutions and school divisions have been approved to have apprentice pro-

grams, (ii) when they expect to begin preparing prospective teachers, (iii) how many

individuals are expected to be prepared through each program annually, and (iv) how

each program will be funded. The report should be submitted to the Board of Edu-

cation and House Education and Senate Education and Health committees by June

30, 2024. (Chapter 3)

RECOMMENDATION 2

The General Assembly may wish to consider including language in the Appropriation

Act directing the Virginia Board of Education to either (i) replace the Virginia Com-

munications and Literacy Assessment with a nationally recognized teacher licensure

test that is more relevant for assessing prospective teachers or (ii) eliminate the Virginia

Communications and Literacy Assessment as a requirement for a full 10-year renewa-

ble Virginia teaching license. (Chapter 3)

RECOMMENDATION 3

The General Assembly may wish to consider amending the Code of Virginia to create

a waiver through which the Board of Education shall issue a full 10-year renewable

Virginia teaching license to qualified individuals attending approved higher education

teacher preparation programs who have not passed the Virginia Communication and

Literacy Assessment but meet established criteria. (Chapter 3)

Recommendations: Virginia’s K-12 Teacher Pipeline

Commission draft

viii

RECOMMENDATION 4

The Virginia Board of Education should revise section 8-VAC-20-543-50 of the Vir-

ginia Administrative Code to remove the incentive traditional higher education teacher

preparation programs currently have to establish admission policies that unnecessarily

restrict the number of individuals enrolling in such programs. (Chapter 3)

RECOMMENDATION 5

The General Assembly may wish to consider including language and funding in the

Appropriation Act to increase the annual funding for the Virginia Teaching Scholar-

ship Loan Program. (Chapter 3)

RECOMMENDATION 6

The Virginia Department of Education should work with Virginia higher education

institutions that offer teacher preparation courses to develop, publish on its website,

and periodically update a list of specific professional studies and subject-matter courses

that fulfill licensure requirements in each endorsement area for provisionally licensed

teachers pursuing full licensure. (Chapter 4)

RECOMMENDATION 7

The Virginia Department of Education should list and periodically update on its web-

site the specific teacher license types and endorsement areas in other states that qualify

for a Virginia teaching license through reciprocity, prioritizing states from which Vir-

ginia receives the most reciprocity applications. (Chapter 4)

RECOMMENDATION 8

The Virginia Department of Education should report on the status of its teacher li-

censure process, staffing, and information technology improvements to the Board of

Education and House Education and Senate Education and Health committees by

December 15, 2023, and again by June 30, 2024. (Chapter 4)

RECOMMENDATION 9

The General Assembly may wish to consider including language and funding in the

Appropriation Act directing the Virginia Department of Education to (i) hire a con-

tractor to develop a database that can store and maintain teacher information; (ii) reg-

ularly collect information on the teacher preparation pathway, licensure status, place

of employment, indicators of instructional quality, and public K–12 teaching tenure

for each teacher who is prepared in Virginia; and (iii) share such information about

these teachers with the Virginia preparation programs from which they graduated.

(Chapter 5)

Recommendations: Virginia’s K-12 Teacher Pipeline

Commission draft

ix

RECOMMENDATION 10

The General Assembly may wish to consider amending the Code of Virginia to direct

the Virginia Department of Education to biennially report on the preparedness and

tenure of teachers prepared through each of Virginia’s teacher preparation pathways

and programs and recommend improvements to specific preparation pathways and

programs as needed. The report should be submitted to the Board of Education and

House Education and Senate Education and Health committees by November 1 every

other year. (Chapter 5)

Policy Options to Consider

POLICY OPTION 1

The General Assembly could include language and funding in the Appropriation Act

to create a pilot program for provisionally licensed teachers to complete a curriculum

and instruction course or classroom and behavior management course by the end of

their first semester as a teacher of record at no cost. (Chapter 3)

POLICY OPTION 2

The General Assembly could include language and funding in the Appropriation Act

for the Virginia Department of Education to increase funding for teacher residency

programs to help cover the cost of preparation for additional teacher residents. (Chap-

ter 3)

POLICY OPTION 3

The General Assembly could include language and funding in the Appropriation Act

to provide state general funds for the Competitive Grant for Praxis and Virginia Li-

censure and Certification Assessment program. (Chapter 3)

POLICY OPTION 4

The General Assembly could include language and funding in the Appropriation Act

to provide state general funds for the Paid Internship Scholarship for Aspiring Virginia

Educators program. (Chapter 3)

POLICY OPTION 5

The General Assembly could include language and funding in the Appropriation Act

directing the Virginia Department of Education to administer a three-year pilot pro-

gram that provides targeted mentorship assistance to divisions with high teacher va-

cancies using mentors trained and coordinated by Virginia higher education institu-

tions. (Chapter 5)

Recommendations: Virginia’s K-12 Teacher Pipeline

Commission draft

x

Commission draft

1

1

Virginia’s Public K

–12 Teacher Pipeline

In 2022, the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (JLARC) directed staff

to review the adequacy of the supply of qualified K–12 teachers in Virginia. Staff were

directed to identify the number of K–12 teachers needed and available; evaluate fac-

tors contributing to the decline in individuals entering teacher preparation programs;

evaluate the state process for determining the qualifications and credentials teachers

need to be fully licensed; and identify effective or innovative practices used in other

states to maintain or increase the number of individuals entering and graduating from

teacher preparation programs and becoming fully licensed teachers (Appendix A).

To address the study resolution, JLARC analyzed data related to public K–12 teacher

licensure and employment; surveyed new teachers in Virginia, individuals who are li-

censed in Virginia but not currently teaching, and school division human resources

staff; interviewed staff at the Virginia Department of Education (VDOE), staff at

public and private teacher preparation programs, staff at local school divisions, stake-

holder groups and associations, and state and national experts in teacher preparation

and retention; and reviewed effective teacher pipeline practices in existing research

literature and other states. (See Appendix B for a detailed description of research

methods.)

Multiple entities, programs, and processes comprise

Virginia’s K–12 teacher pipeline

Virginia’s “teacher pipeline” consists of multiple programs and processes that help

attract, prepare, license, recruit, and retain public K–12 teachers. While the Common-

wealth’s 134 local school divisions individually recruit and retain teachers, the state

plays a role in the teacher pipeline through higher education institutions that adminis-

ter teacher preparation programs, VDOE’s licensure of teachers, and funding for ini-

tiatives to promote or incentivize the teaching profession.

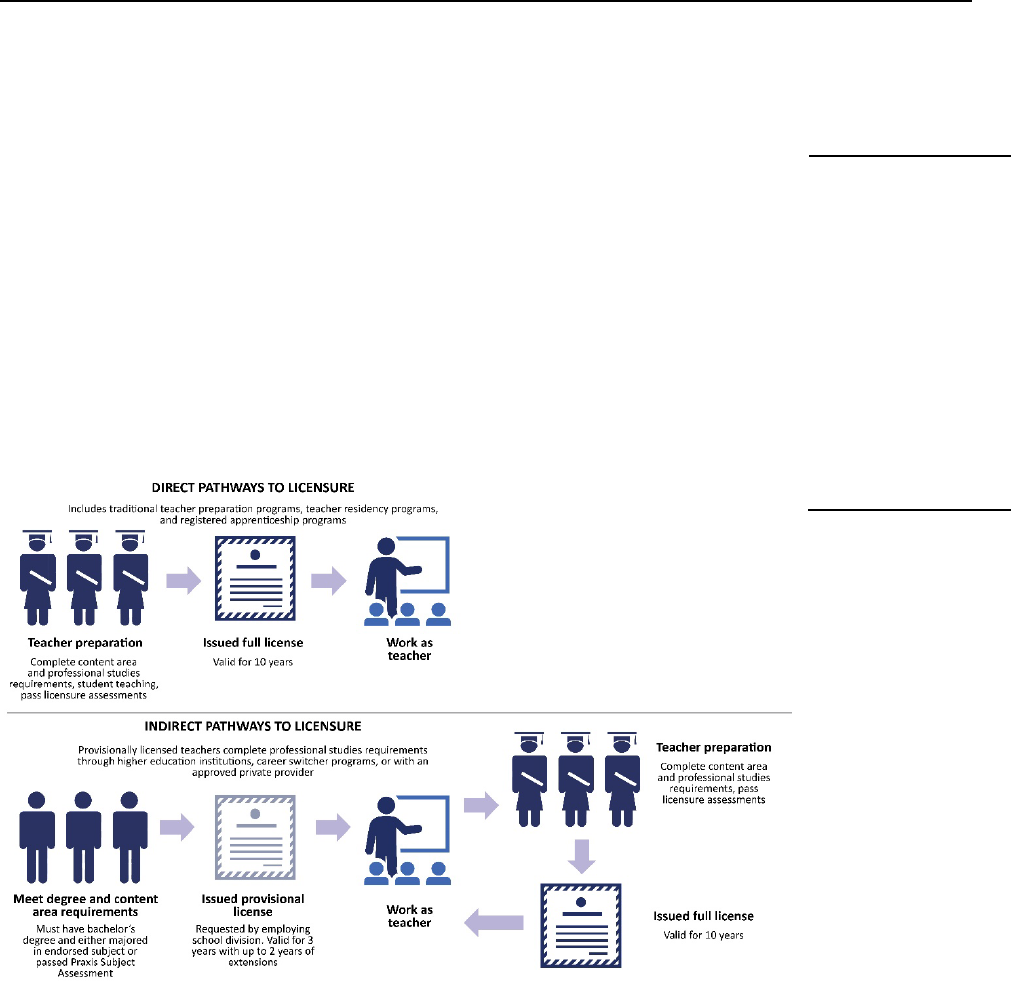

Virginia offers several options to become a teacher

There are several different pathways individuals can take to progress through Virginia’s

teacher pipeline. Virginia’s direct pathways to licensure include traditional higher edu-

cation programs and teacher residency or apprenticeship programs. The state’s indirect

pathways to licensure include career switcher programs, division-led preparation pro-

grams, special education provisional licensee programs, and individuals who take

courses ad hoc after obtaining a provisional license. New teachers, as well as individuals

licensed in other states who want to teach in Virginia, then submit teacher licensure

applications to VDOE for review and approval. Virginia public school divisions recruit

Though this report spe-

cifically focuses on the

public K

-12 teacher pipe-

line,

JLARC has released

other

reports about K–

12

education during the

past decade.

These re-

ports address a wide

range of topics, including

(i)

Virginia’s K–12 fund-

ing f

ormula, (ii) the pan-

demic

’s effect on public

K

–12 education, (iii) the

operations and perfor-

mance of the Virginia

Department of Educa-

tion

, (iv) special educa-

tion services

, and (v) ur-

ban high poverty

schools.

Chapter 1: Virginia’s Public K–12 Teacher Pipeline

Commission draft

2

teachers to fill needed positions and provide ongoing support to retain existing teach-

ers.

Various entities are part of Virginia’s teacher pipeline, making it highly decentralized.

VDOE reviews and accredits teacher preparation programs and reviews and approves

teacher licensure applications. Separately, 14 public higher education institutions, 23

private higher education institutions, several community colleges, and at least six local

school divisions train teachers through teacher preparation programs and courses that

are designed and implemented differently. Virginia’s 134 local school divisions recruit

and retain teachers, each using different strategies and incentives. Although some col-

laboration occurs, the entities involved in the pipeline generally operate independently.

Virginia recently created a registered teacher apprentice program. Virginia is one of

several states approved by the U.S. Department of Labor to offer a teacher apprentice

program. The new program will allow Virginia school divisions to hire unlicensed

school employees (e.g., classroom aides, paraprofessionals, substitute teachers) and

support them while they complete the coursework and training needed to become fully

licensed teachers.

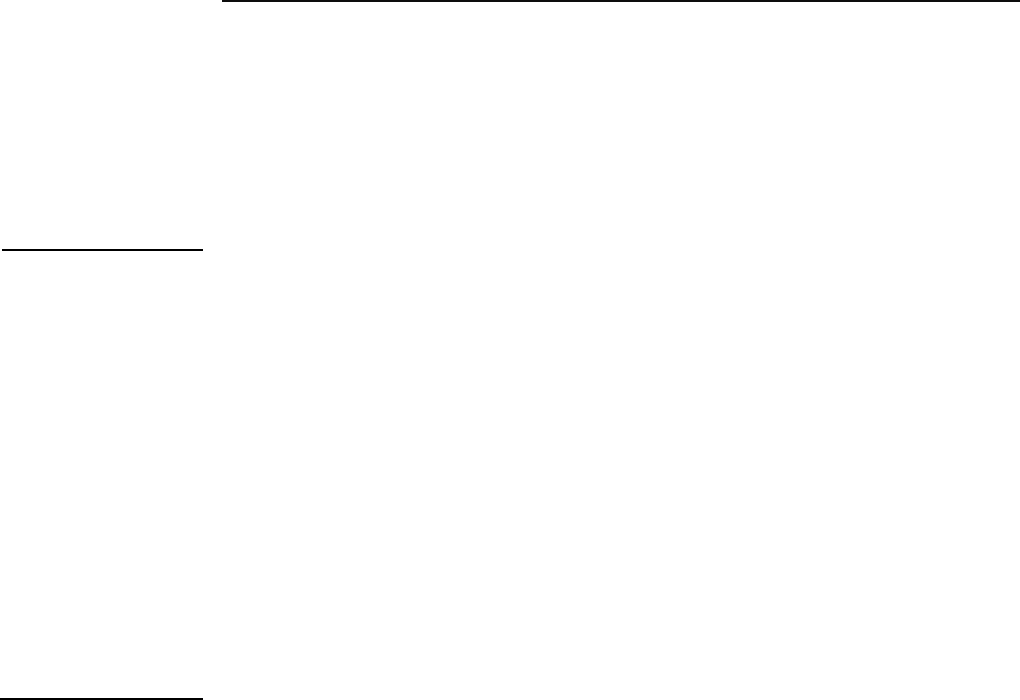

VDOE administers Virginia’s teacher licensure process

While likely not a major determining factor affecting people’s interest in becoming a

teacher, the process individuals must navigate to become licensed has historically been

administratively complex and cumbersome. The process to obtain a license previously

required mailing a check and paper application to VDOE. This manual process re-

sulted in delays, longer than expected processing times, and frustration from applicants

who could not easily obtain information about the status of their application.

Efforts over the last few years to re-engineer the licensure process have not fixed key

deficiencies, but VDOE reports being close to having a new system available. In 2019,

the General Assembly appropriated $348,500 for VDOE to automate the license ap-

plication process. However, efforts to automate the process had several limitations

(sidebar). During 2023, VDOE has been making new efforts to automate the process

and make it more efficient. VDOE hired a new IT vendor in February 2023, and a

new automated system is planned for implementation in October 2023.

State provides funding to support teacher preparation, recruitment,

and retention

In FY23, the state provided over $16 million for at least 19 additional initiatives de-

signed to help individuals advance through the teacher pipeline or remain in teaching

positions. Additional state funding also helps support the operations of traditional

teacher preparation programs. (See Appendix E for an inventory of programs and

initiatives that comprise Virginia’s K–12 teacher pipeline.)

VDOE also allocated $5 million of pandemic relief funding to a new registered

teacher apprenticeship program. VDOE awarded over $1 million to six partnerships

V

DOE began automat-

ing the li

censure system

in

2019. The new system

enabled

individuals to

submit licensure applica-

tions and pay licensure

fees online.

However, the

new system had several

limitations, including (1)

additional documents

could not be uploaded

after applications were in-

itially submitted

;

(2) appli-

cations for adding en-

dorsements or converting

from provisional to full li-

censure could not be

completed online

; (3) the

system did not indicate

whether applications had

satisfied licensure re-

quirements

; and (4) appli-

cations co

uld not be as-

signed to VDOE staff for

review

through the sys-

tem

.

Chapter 1: Virginia’s Public K–12 Teacher Pipeline

Commission draft

3

between school divisions and higher education institutions in July 2023 to implement

apprenticeship programs. As of early September 2023, at least one partnership en-

rolled an apprentice in fall 2023, and at least three partnerships plan to begin enrolling

apprentices in spring 2024.

Several factors that affect interest in teaching

profession have worsened since pandemic

Research has found that the classroom environment, compensation, and support out-

side of the classroom are among the factors people consider when deciding whether

to be a teacher and in which division to teach. For example, a 2022 Annenberg Institute

study found that in addition to salaries and benefits, teachers also value having access

to key support staff (e.g., counselors) and other expertise (e.g., special education).

The pandemic’s disruptions to K–12 education created several challenges for teachers.

For example, according to a 2022 JLARC survey, teachers cited the following issues as

the most serious problems they faced after the pandemic:

• Classroom environment - a more challenging student population, including

behavior issues (56 percent indicated this was a very serious issue), student

anxiety and mental health (43 percent), and higher workload because of un-

filled vacancies (40 percent).

• Compensation - lower than desired salary given the demands of the profes-

sion (51 percent).

• Outside the classroom - lack of respect from parents and the public (47

percent).

This report is not evaluating these factors because prior JLARC reports have identified

issues related to these factors and made recommendations to address them. For exam-

ple, in 2022 JLARC recommended several ways to better support teachers in the class-

room by addressing challenging student behavior, funding more instructional aides, or

expanding student access to mental health supports. Similarly, in July 2023, JLARC

recommended changing the K–12 funding formula to more accurately reflect actual

teacher compensation in each division, which would increase state funding for teacher

salaries. The recommendations and policy options in this report must be considered

in the context of these broader factors that influence teacher recruitment and reten-

tion.

Reduction in quantity and quality of teachers

complicates quickly improving teacher pipeline

Several key teaching positions have historically been difficult to fill, such as special

education teachers. However, in recent years, divisions had difficulty recruiting and

Chapter 1: Virginia’s Public K–12 Teacher Pipeline

Commission draft

4

retaining enough teachers generally—as evidenced by the increase in vacant teaching

positions (discussed in Chapter 2).

Divisions are not only having difficulty hiring and retaining enough teachers, but are

also having difficulty finding and keeping enough qualified teachers. Recently, divisions

have relied more on provisionally licensed teachers and teachers working outside their

“endorsed” direct field of expertise or training (sidebars).

The challenges associated with hiring enough teachers to fill vacant positions has ex-

acerbated the challenge of ensuring teacher quality. As divisions have had more diffi-

culty filling vacant positions, their focus has understandably been on finding teachers

for the positions, which has led to a willingness to hire more teachers who are not fully

licensed or not endorsed in the area in which they are hired to teach. One division

human resources director stated: “I’m surprised when we get an application from a

fully qualified teacher.”

Practically, until the supply and demand for teachers stabilizes, school divisions will

need to continue to rely on teachers who are provisionally licensed or teaching outside

their field. Reducing reliance on provisionally licensed teachers and teachers teaching

outside their fields must, therefore, be a longer term goal.

The Virginia Administra-

tive Code defines a provi-

sional license

as a “non-

renewable license valid

for a period not to ex-

ceed three years issued to

an individual who has al-

lowable deficiencies for

full licensure

” (8VAC20-

23

-50). A provisionally li-

censed teach

er is not re-

quired to have taken any

teacher preparation

courses. A school division

can request a provisional

license for an individual it

hires to fill a teacher va-

cancy.

T

eachers are “endorsed“

in

their content area if

they have taken the ap-

propriate courses and/or

passed t

he appropriate li-

censing exam for the en-

dorsed content area.

VDOE must verify and ap-

prove that the require-

ments have been fulfilled

for endorsement.

Commission draft

5

2

Trends in Virginia’s Supply of K–12

Teachers

JLARC’s 2022 review of the pandemic’s impact on K–12 public education found that

Virginia school divisions faced substantial recruiting and retention challenges. These

challenges were also faced by other states. Legislative interest in helping to address

these challenges prompted this JLARC review of the public K–12 teacher pipeline.

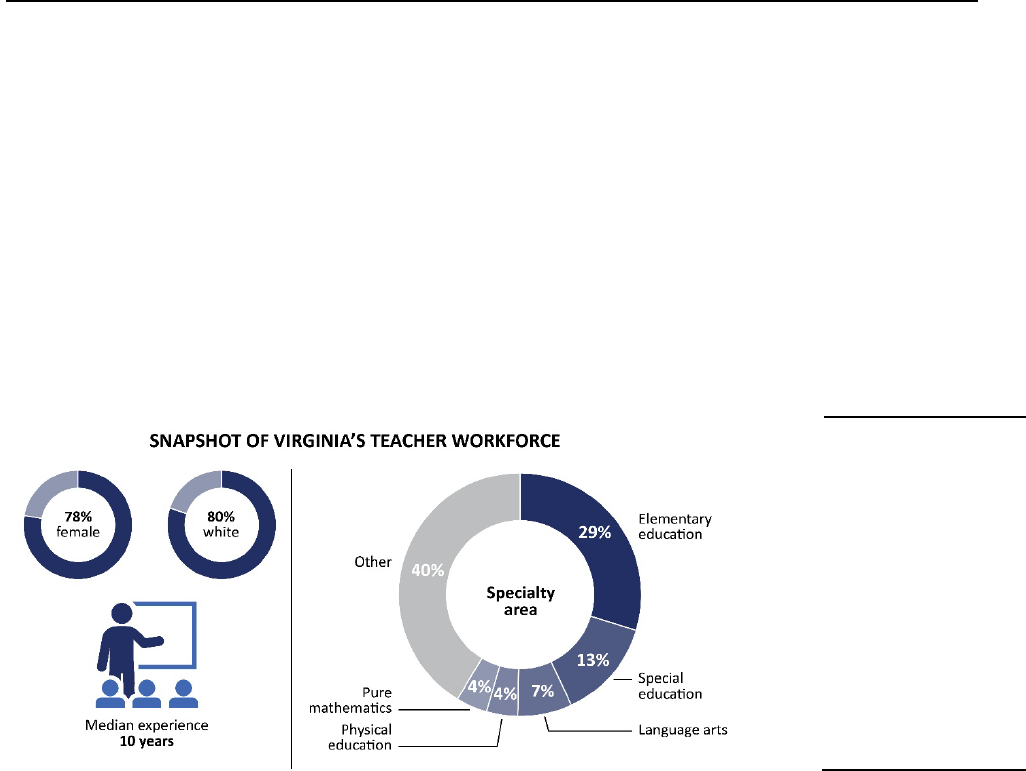

Virginia school divisions employed about 87,000 K–12 teachers in SY2022–23 (Figure

2-1). Most of Virginia’s public K–12 teacher workforce is female and white. The me-

dian Virginia public K–12 teacher has 10 years of experience and is 43 years old. About

29 percent of teachers are elementary education teachers. Special education teachers

were the next largest group (13 percent), followed by language arts teachers (7 percent).

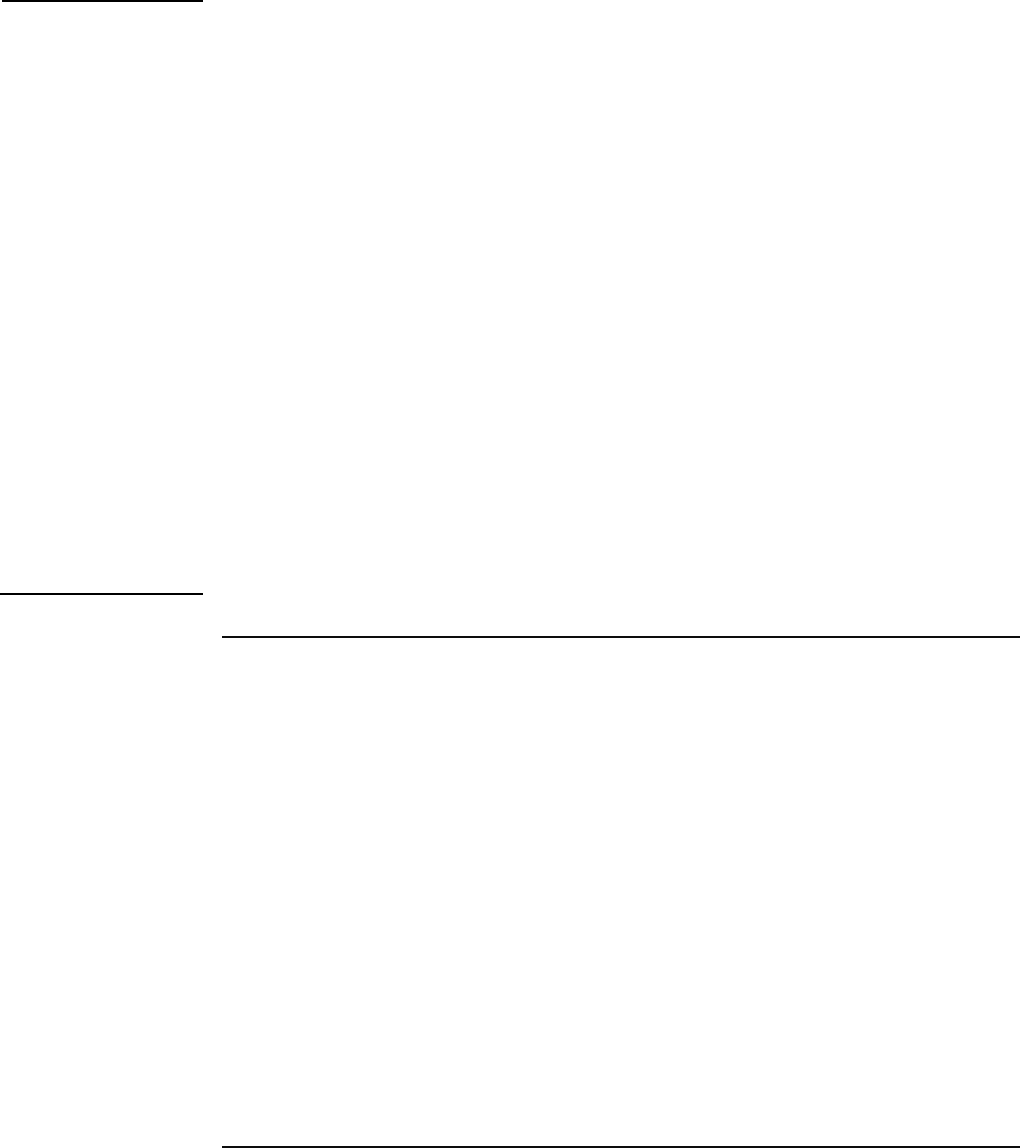

FIGURE 2-1

Virginia had about 87,000 public K–12 teachers in SY2022-23

SOURCE: JLARC staff analysis of Virginia Department of Education data, school year 2022–23.

NOTES: Elementary education includes kindergarten through fifth grade. Pure mathematics is one of the state’s cat-

egories of math teachers and can include subject areas such as algebra.

Teacher vacancies increased statewide, though some

divisions still have no or few teaching vacancies

Teacher vacancies can create a variety of problems for teachers and students. Just one

vacant teaching position can create substantial challenges for schools, requiring either

the use of a long-term substitute or larger class sizes. For example, an elementary

school with 80 third-grade students that planned to have four teachers may be forced

to substantially increase class sizes if it can only hire three teachers. Rather than having

four classes of 20 students, the school may start the year with three classes of either

Virginia’s public K

–12

teacher workforce

has

similar demographic

characteristics compared

to other

states’ teacher

workforces, according to

results of the National

Center

for Education Sta-

tistic’s 2020

–21 National

Teacher and Principal

Survey. Teacher gender,

ethnicity, and median age

in Virginia w

ere

similar to

the national average.

Chapter 2: Trends in Virginia’s Supply of K–12 Teachers

Commission draft

6

26 or 27 students. Larger class sizes typically make it more challenging for teachers and

can reduce the quality of instruction students receive—especially for students needing

individualized or small group assistance. In addition, teacher vacancies can require

schools to reduce the types of courses they offer, such as advanced placement or elec-

tive courses. Finally, teacher vacancies often create a greater workload for remaining

staff, which contributes to lower morale and lower job satisfaction.

Statewide number of vacant teaching positions has substantially

increased

The latest available data shows that 4.8 percent of teaching positions were reported

vacant on the first day of SY2023–24. This represents a 23 percent increase from the

prior year’s vacancy rate of 3.9 percent. These vacancies represented a substantial in-

crease from prior years (Figure 2-2).

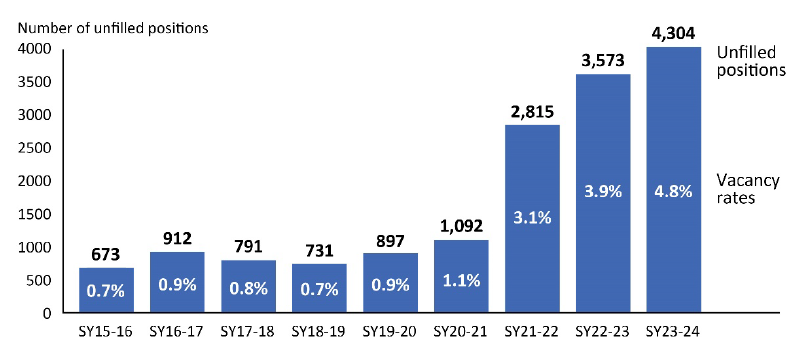

FIGURE 2-2

School divisions reported over 4,000 vacant teaching positions at the start of

SY2023–24

SOURCE: JLARC staff analysis of Virginia Department of Education data, school years 2015–16 to 2023–24.

NOTE: Vacant public K-12 positions are full-time equivalent positions reported by divisions as of October 1, 2022

for SY15–16 through SY22–23. SY23–24 vacancy data reflects actual or assumed to be vacant public K–12 full-time

equivalent positions on the first day of school for 123 divisions.

Statewide, over half (57 percent) of teacher vacancies are in elementary education or

special education positions. Elementary education (defined to include pre-kindergar-

ten through sixth grade) has the most vacancies, representing 30 percent of all teacher

vacancies statewide at the start of SY2023–24. Special education accounted for over

one-fourth (26 percent) of all vacancies at the start of SY2023–24. Special education

and elementary education had such a large number of teacher vacancies in part be-

cause a large portion of the state’s total teaching positions are in these two areas.

Chapter 2: Trends in Virginia’s Supply of K–12 Teachers

Commission draft

7

Some divisions have no vacancies; others have substantial vacancies,

especially those with more Black students

While the statewide average rate for teacher vacancies is 4.8 percent, some divisions

have no vacancies, while others have very high vacancy rates (Table 2-1 and Appendix

C). Ten divisions reported no vacant teaching positions at the start of SY2023–24. In

contrast, 15 divisions reported at least 10 percent of their teaching positions vacant.

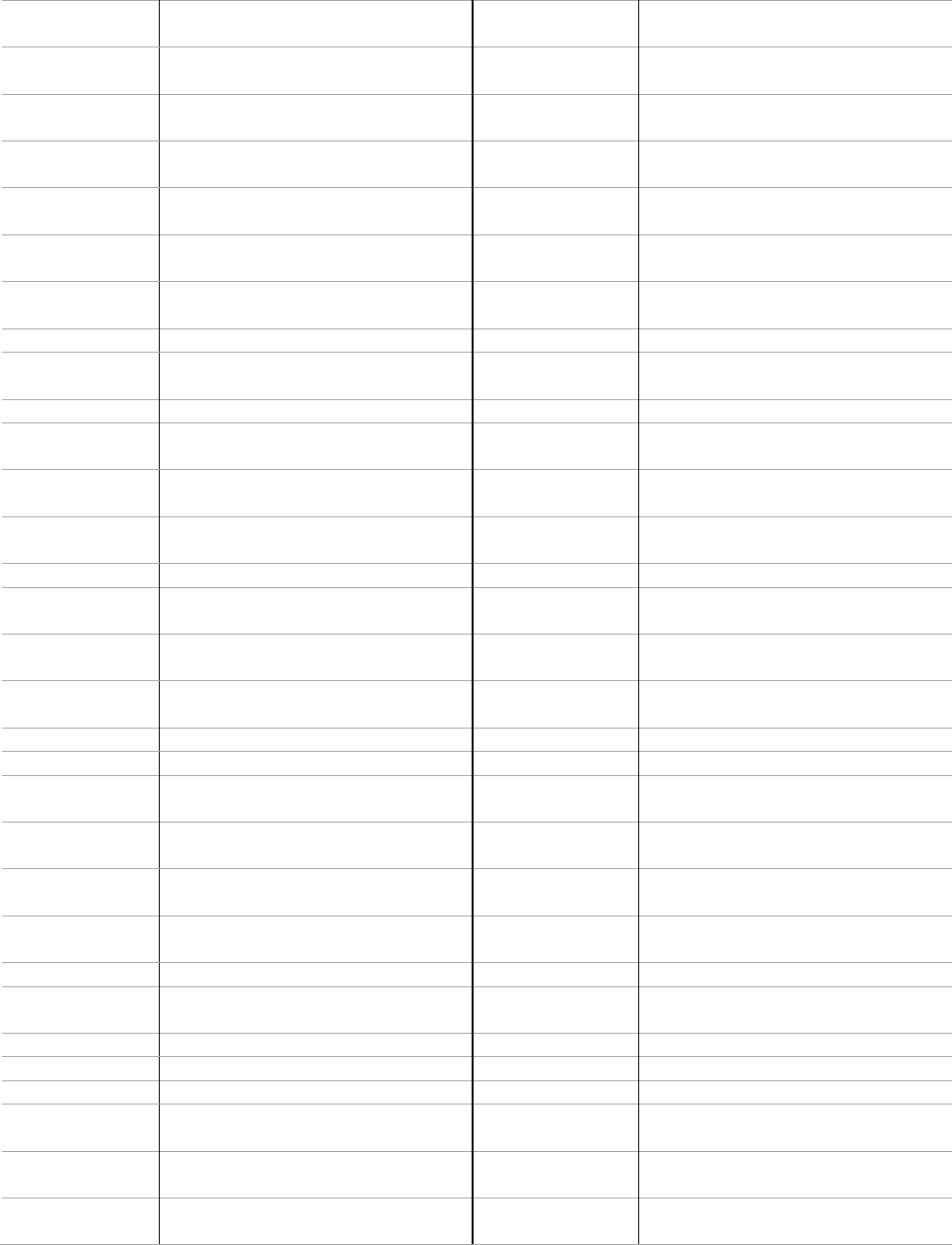

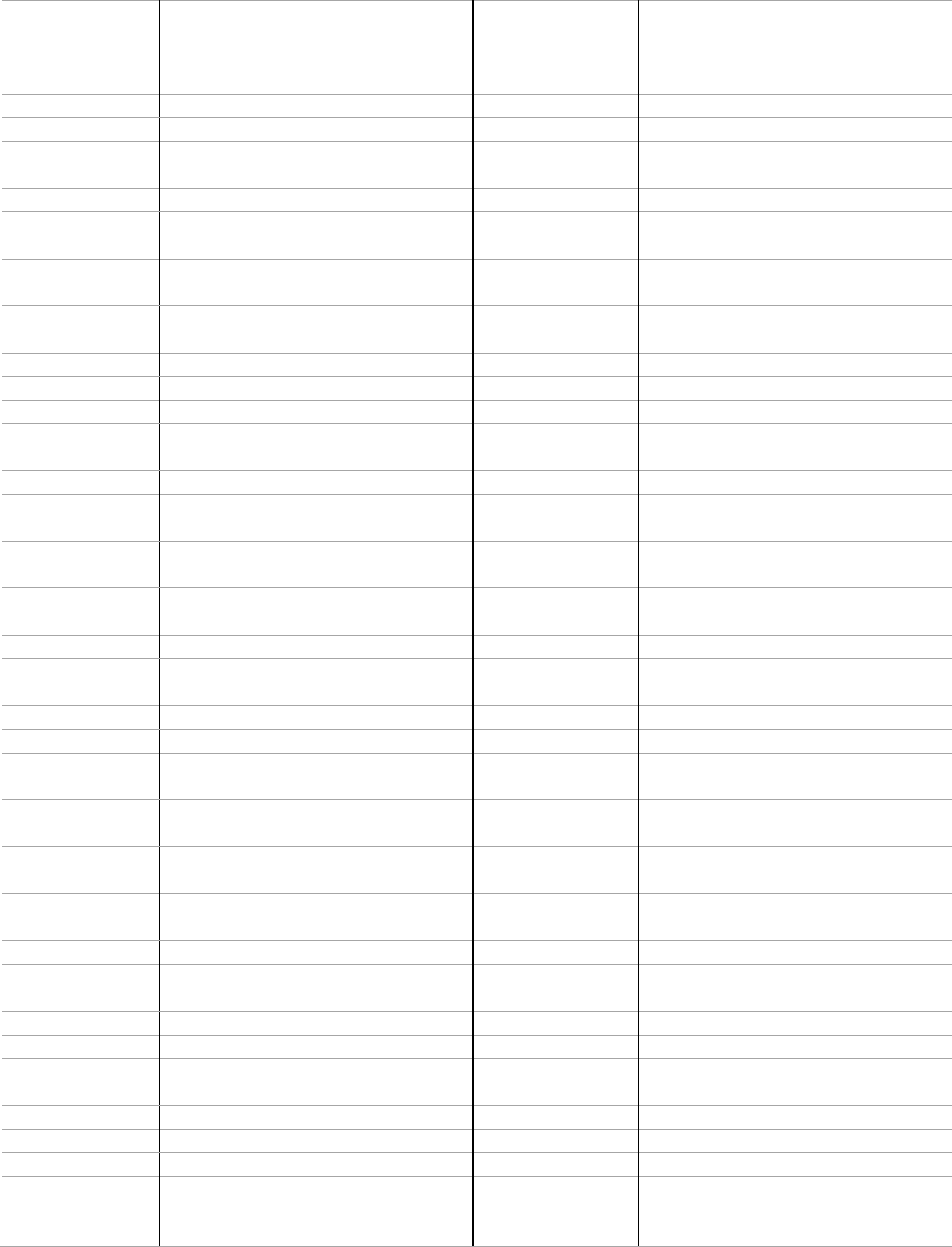

TABLE 2-1

Some Virginia school divisions have high vacancy rates while others have no

vacancies

10 divisions with

highest teacher vacancy rates

10 divisions with

lowest teacher vacancy rates

Division

Vacant

Division

Vacant

Danville City

40.4%

Botetourt County

0%

Charles City County

21.5

Carroll County

0

Suffolk City

17.7

Clarke County

0

Lancaster County

17.0

Colonial Beach

0

Norfolk City

16.8

Falls Church City

0

Essex County

15.1

Fluvanna County

0

Cumberland County

14.7

Grayson County

0

Poquoson City

14.3

Lexington City

0

Caroline County

13.7

Russell County

0

Pulaski County

13.2

Staunton City

0

Source: JLARC analysis of Virginia Department of Education data, school year 2023–24.

NOTE: Vacancy data includes actual or assumed to be vacant public K–12 full-time equivalent positions on the first

day of school for 123 divisions. See Appendix C for a complete list of teacher vacancies by school division.

As with individual divisions, there is variation in teacher vacancy rates across regions.

The Southside region had the state’s highest rate of vacant teaching positions, 6.8 per-

cent, a decline from the prior year’s vacancy rate of 7.4 percent. The Tidewater and

Eastern Shore region included divisions with, on average, 6.3 percent of their teaching

positions vacant, slightly higher than last year. The Northern Virginia and Middle Pen-

insula region’s teacher vacancy rate of 5.2 percent was above the state average and

substantially increased from the prior year’s vacancy rate of 2.9 percent.

Virginia school divisions with large populations of Black students tend to have higher

teacher vacancy rates. According to a data analysis conducted by JLARC staff (side-

bar), divisions with mostly Black students had teacher vacancy rates in SY2022–23 that

were 6 percentage points higher than divisions with almost no Black students, control-

ling for other differences across divisions.

JLARC staff conducted a

multivariate regression

analysis

to estimate the

factors most strongly re-

lated

to division-level var-

iations

in teacher

vacancy

rates

in SY2022-23. The

dependent var

iable was

the public K

-12 teacher

vacancy rate

, and the in-

dependent variables in-

cluded: (1) %

students by

race and ethnicity

; (2) %

disadvantaged students

;

(3) % disabled students;

(4) composite index; (5)

VDOE region; and (6) de-

gree of in

-person instruc-

ti

on during COVID-19

pandemic. See Appendix

B for more information

on the methodology and

results of this analysis.

Chapter 2: Trends in Virginia’s Supply of K–12 Teachers

Commission draft

8

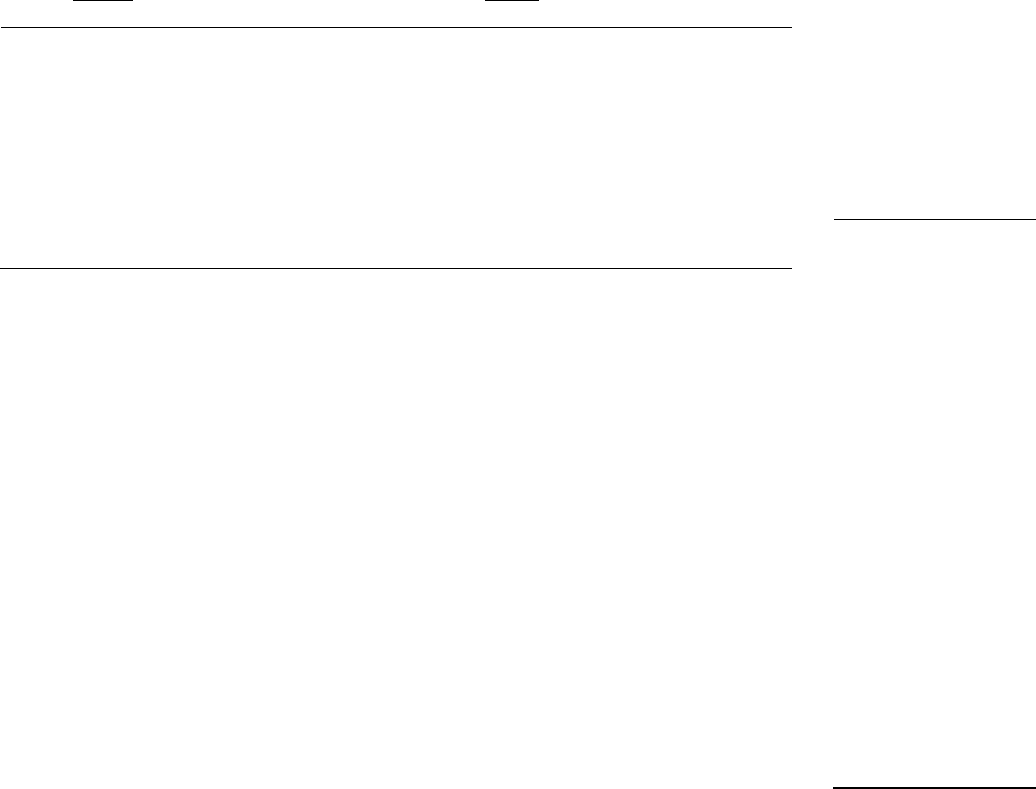

Deficit of teachers has grown because more teachers

are leaving than entering the profession in Virginia

Increasing vacancies can be partially explained by the widening deficit between teach-

ers leaving the profession and newly licensed teachers (Figure 2-3). The deficit between

newly licensed teachers and those leaving averaged about 1,250 annually in the years

preceding the pandemic. (Individuals licensed to teach for the first time in Virginia are

a key indicator of the total teacher supply, because they account for more than 85

percent of the total number of teachers entering Virginia’s teacher workforce each

year.)

After the pandemic, though, the number of teachers leaving began to far outpace the

number of newly licensed teachers. The deficit between newly licensed teachers and

those leaving the profession was about 3,000 after SY2020–21, and jumped to nearly

5,500 after SY2021–22. In a positive development, the number of newly licensed

teachers stabilized in SY2022–2023. Data about teachers who have left the profession

after SY2022–23 will not be available until early 2024.

FIGURE 2-3

More teachers have been leaving than are newly licensed, creating a deficit

SOURCE: JLARC staff analysis of Virginia Department of Education data, school years 2015–16 to 2022–23.

NOTES: *2023 data on teachers leaving not available until early 2024. Counts of newly licensed teachers entering

the workforce each school year reflect VDOE’s licensure data as of June 2023 and differ from data cited in JLARC’s

2022 review of Pandemic Impact on Public K–12 Education because of data updates.

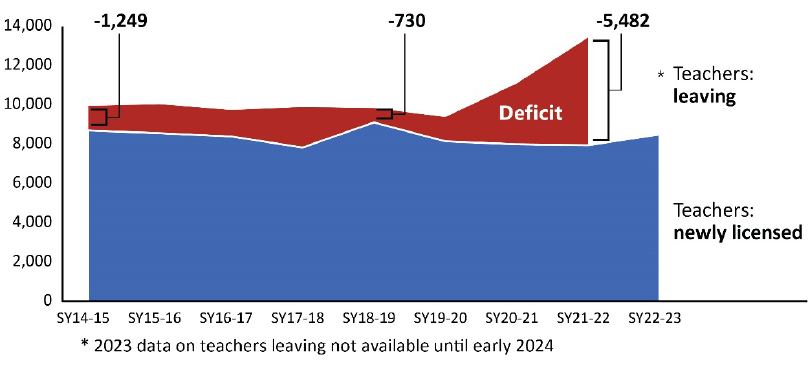

Fewer teaching positions are occupied by teachers

who are fully licensed and teaching “in field”

As more teachers leave Virginia’s teacher workforce, divisions are increasingly relying

on teachers who are not yet fully licensed or teaching out of their endorsed field. For

example, the combined proportion of Virginia’s public K–12 teacher workforce that

Chapter 2: Trends in Virginia’s Supply of K–12 Teachers

Commission draft

9

was not fully licensed or teaching out of field was 6 percent in SY2012–13 but in-

creased to 14 percent by SY2021–22 and 16 percent by SY2022–23 (Figure 2-4).

Teachers who lack full licensure may not have completed the coursework on methods

of teaching (pedagogy) that Virginia requires for full licensure, which contributes to

teacher effectiveness. Teachers who are teaching out of field have not demonstrated a

minimum level of competency in the content area they are teaching and may be less

effective.

There is wide variation across divisions in the proportion of teachers who are not yet

fully licensed or teaching out of field. In SY2022–23, two divisions reported having all

their teachers fully licensed, while two others each had only about half of their teachers

fully licensed. Similarly, two divisions reported all their teachers were teaching in their

field, while two others had only about two-thirds of their teachers teaching in their

field of expertise.

FIGURE 2-4

Smaller proportion of teachers are fully licensed than a decade ago

SOURCE: JLARC staff analysis of Virginia Department of Education data, school years 2012–13 and 2022–23.

NOTE: “Other” includes individuals such as long-term substitutes.

Chapter 2: Trends in Virginia’s Supply of K–12 Teachers

Commission draft

10

Commission draft

11

3

Virginia’s Teacher

Preparation Pathways

An effective K–12 system needs fully prepared teachers. Teachers who are less than

fully prepared typically do not provide the same quality of educational experience for

students, according to research literature.

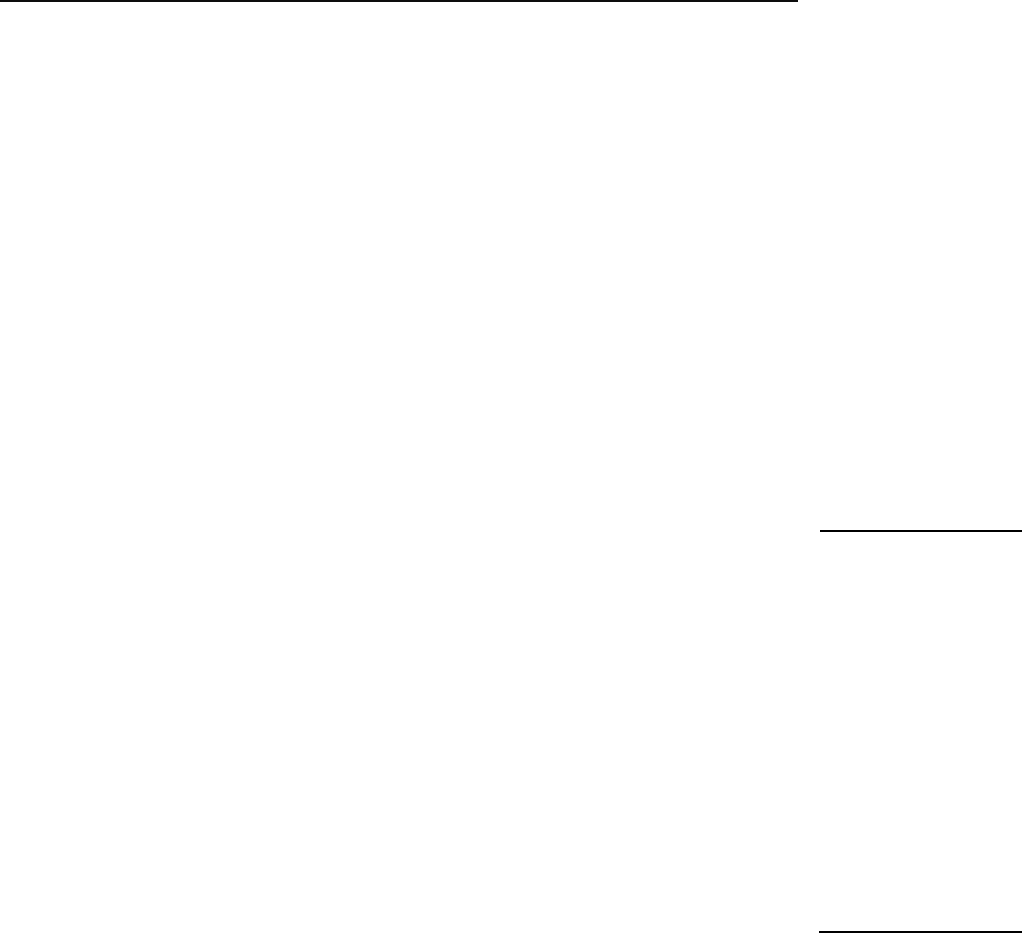

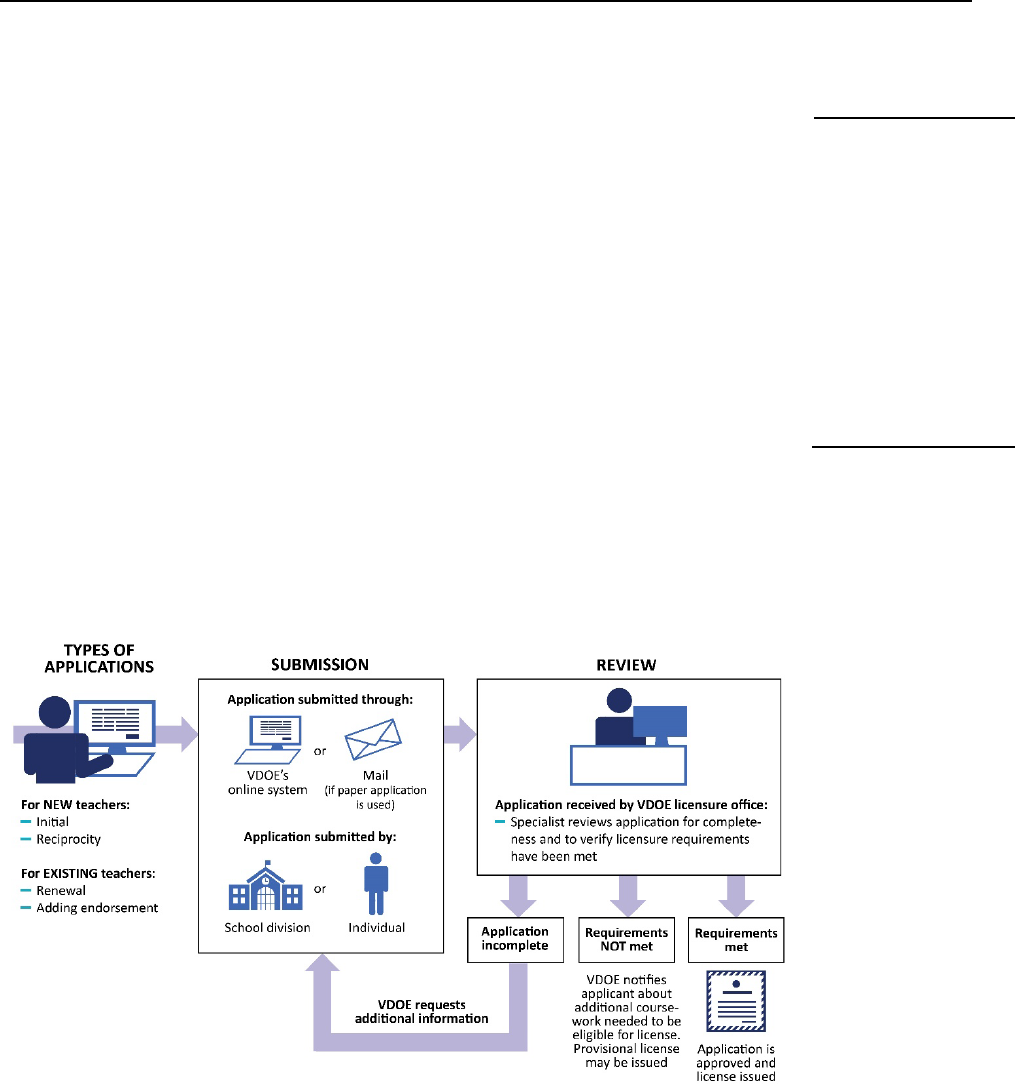

Virginia has multiple pathways individuals can follow to complete the preparation

courses and training needed to become public K–12 teachers. Some pathways, such

as traditional higher education-based programs and teacher residency programs, pro-

vide a direct route to full licensure and qualify individuals for a 10-year renewable

teaching license upon completion (Figure 3-1). Other pathways, such as career

switcher programs, division-led programs, and taking courses ad hoc are indirect, al-

lowing individuals to teach under a temporary provisional license (sidebar) while they

complete the preparation courses required for full licensure.

FIGURE 3-1

Direct and indirect pathways offer different routes to teacher licensure

NOTE: Career switcher programs have a different indirect pathway, where students receive the majority of their in-

struction prior to being issued a provisional license.

In Virginia

, provisional

teaching

licenses are

non

-

renewable and valid

for three years

. In 2018,

the General Assembly

passed legislation allow-

ing provisional license

es

to

receive up to two,

one

-year extensions if a

teacher

has satisfactory

performance evaluations

and receives a recom-

mendation from the divi-

sion superintendent.

Chapter 3: Virginia’s Teacher Preparation Pathways

Commission draft

12

TABLE 3-1

Indirect pathways for K-12 teaching in Virginia

Indirect pathway

Description

Provisional license, classes

as needed over time

Individual works as teacher of record while completing require-

ments for full licensure (e.g., professional studies courses, assess-

ments).

Special education

provisional license

After completing prerequisite course, individual works as teacher

of record while completing remaining requirements for full licen-

sure. Some candidates complete an approved program at a higher

education institution, while others complete courses at their own

pace.

Career switcher

programs

Individuals complete accelerated coursework and brief field experi-

ence before becoming teacher of record on a career switcher pro-

visional license. Career switchers can be granted full licensure after

at least one year of teaching and 20 hours of additional seminars.

Division-led

preparation

Individuals work as teacher of record while completing profes-

sional studies coursework for full licensure provided by division

staff or in partnership with external providers (e.g., iTeach).

SOURCE: Virginia Administrative Code and interviews with VDOE staff.

NOTE: Teacher of record is the teacher who is responsible for the delivery of instruction. The teacher of record

must hold a license issued by the Virginia Board of Education.

Limited data is available on the proportion of individuals who pursue teaching

through Virginia’s various direct and indirect preparation pathways. Data that is

available indicates just less than half of all newly licensed teachers are provisionally

licensed, while the remainder are prepared through a direct pathway or licensed

through reciprocity with another state. The percentage of newly licensed teachers in

Virginia using indirect pathways has grown as school divisions are increasingly hiring

provisionally licensed teachers to fill teacher vacancies. Half of Virginia’s newly li-

censed teachers each year are prepared in Virginia, and half are prepared in other

states (sidebar). (See Chapter 2 for more information on trends in Virginia’s teacher

supply.)

Direct pathways prepare teachers better but require

more time and cost more than indirect pathways

Ideally, Virginia school divisions would be able to fill all teaching positions with well-

prepared teachers. However, there are not enough teachers completing direct, higher

education preparation programs to fill vacancies with fully licensed teachers. Many

divisions are increasingly relying on provisionally licensed teachers who have not

completed their preparation.

An individual’s path to become a teacher is not always determinative of their effec-

tiveness in the classroom. School division staff and experts frequently cite examples

of teachers from varied backgrounds and training who are extremely effective teach-

ers. No reliable or comprehensive data exists, however, about the effectiveness of

About

half of newly li-

censed teachers were

prepared outside of Vir-

ginia

in SY2021–22.

These individuals include

new graduates from

preparation programs in

other states who pursue

initial licensure in Vir-

ginia and experienced

teachers licensed by reci-

procity.

Some licensed

teachers from out of

state who do not qualify

for reciprocity initially

teach in Virginia with a

provisional license.

Chapter 3: Virginia’s Teacher Preparation Pathways

Commission draft

13

each teacher in Virginia. In the absence of this information, staff developed a meth-

odology to help understand the relative differences among pathways to become a

teacher.

In general, teachers who use direct pathways to become a fully licensed teacher are

better prepared for the classroom (Table 3-2). These programs, though, typically cost

more for the participant or provider because they take longer and are more compre-

hensive. Teacher residency programs, which involve an extended co-teaching place-

ment while simultaneously completing coursework, have the most rigorous design and

are low cost to participants because of the financial assistance provided. Residency

programs, though, are expensive to administer and currently have limited capacity in

Virginia. The state is beginning to build teacher apprenticeship programs, which can

also effectively foster preparation through required coursework and in-classroom ex-

perience.

Individuals using indirect pathways are typically less well prepared in the short term,

but can move through those pathways at substantially less cost and benefit from more

flexible pacing and delivery format. Individuals using indirect pathways are also typi-

cally able to maintain paid employment while they are taking the required coursework

or assessments.

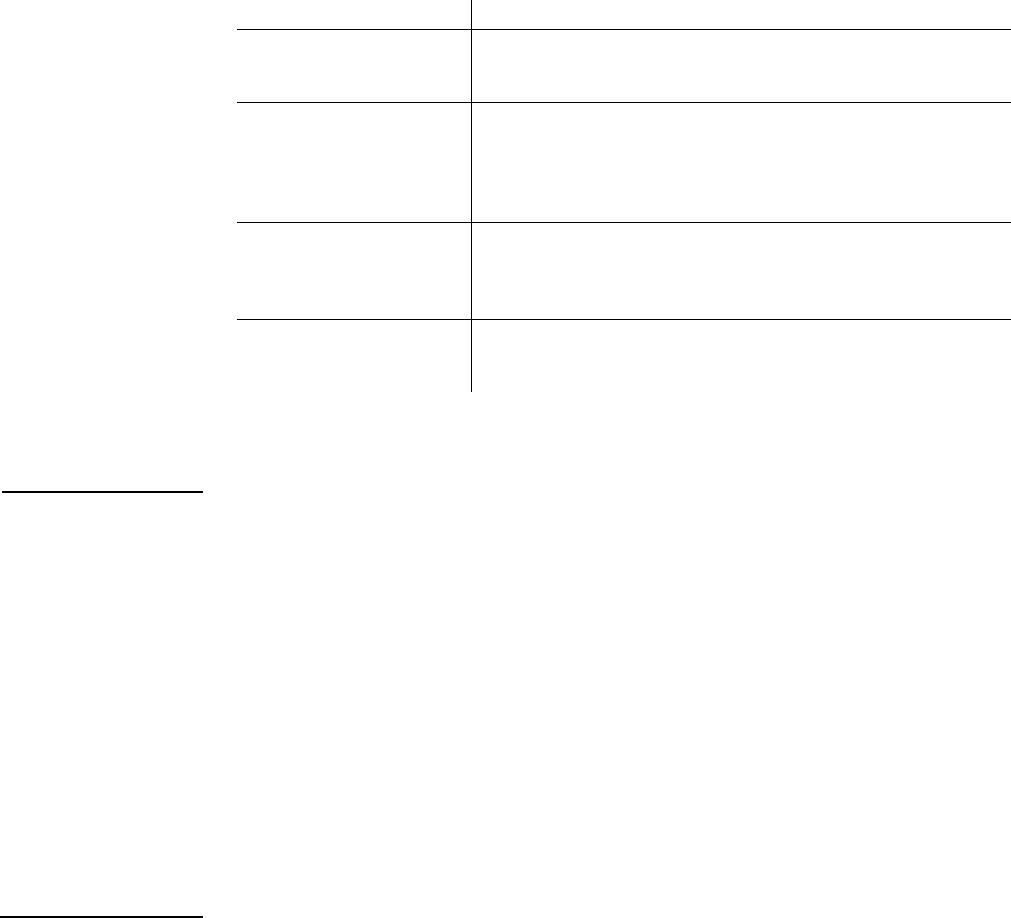

TABLE 3-2

Teacher pathways have tradeoffs between quality and affordability

Program quality /

Participant preparedness

Participant

affordability

Direct pathways

Traditional teacher preparation programs

●

○

Teacher residency programs

●

●

a

Registered apprenticeship programs

-

b

-

b

Indirect pathways

Provisional license, classes as needed over time

○

c

◑

Special education provisional license

◑

◑

Career switcher programs

◑

◑

Division-led preparation

Varies

●

SOURCE: JLARC staff analysis.

NOTES: Program quality / participant preparedness = High quality mentor provided; student teaching component;

candidate finishes content and pedagogical coursework prior to being teacher of record. Participant affordability =

cost of tuition and fees; ease of holding paid employment.

A new indirect pathway—online courses through a private provider called iTeach—has recently been approved in

Virginia but is not yet operating.

a

Teacher residency programs are affordable for participants but often costly for the state or sponsoring division.

b

A new direct pathway—registered apprenticeship programs— is currently being implemented in Virginia. Vir-

ginia’s program is too new to evaluate.

c

Preparedness measured when provisional licensee becomes teacher of record; preparedness varies and is likely to

increase as classes are completed.

Chapter 3: Virginia’s Teacher Preparation Pathways

Commission draft

14

The differences in the quality and nature of preparation between direct and indirect

pathways likely matter less as a teacher gains experience in the classroom. Research

shows that teacher experience is positively associated with student achievement

throughout their career. As teachers gain experience and learn on the job, differences

in initial preparation may have less of an impact over time.

Direct pathways through traditional higher education programs

typically produce teachers who are better prepared for the classroom

Direct pathways through traditional higher education preparation programs generally

produce higher quality new teachers than indirect pathways. Traditional higher edu-

cation-based programs include important components of effective teacher prepara-

tion, including pedagogical coursework, student teaching and mentorship from expe-

rienced teachers, and college-level subject area coursework. (See Appendix F for

more information on Virginia’s traditional teacher preparation programs at public in-

stitutions.) In contrast, individuals using indirect pathways can become responsible

for a classroom (called the “teacher of record”) without completing any pedagogical

preparation or obtaining classroom experience through student teaching.

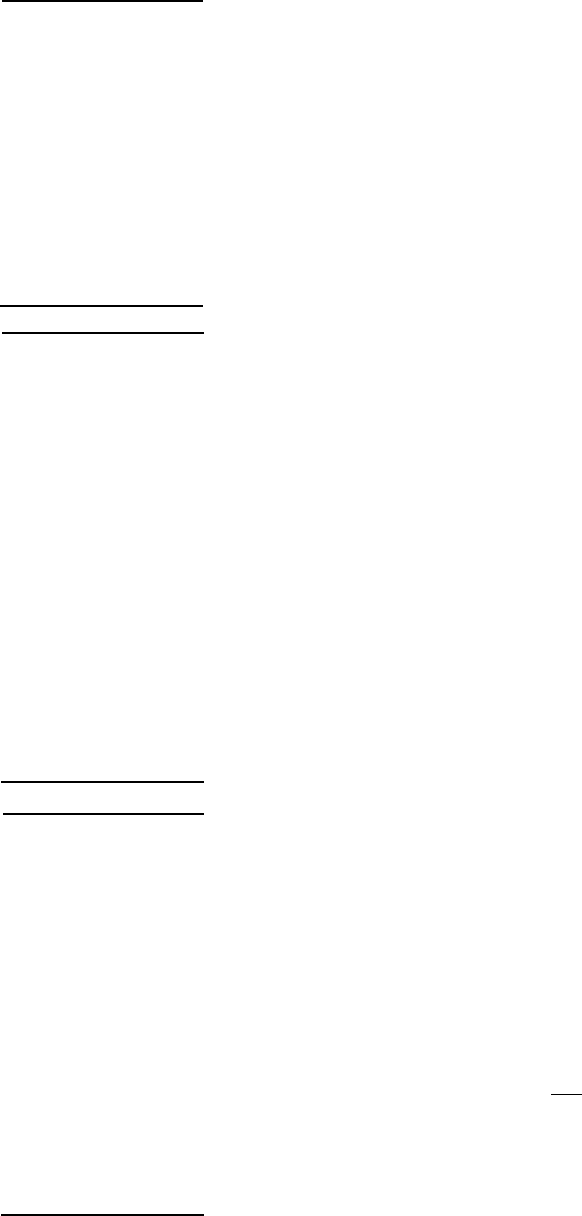

School divisions and new Virginia teachers believe traditional higher education prep-

aration programs (direct pathway to full licensure) better prepare people to teach

than indirect pathways. For example, 46 percent of school divisions surveyed by

JLARC (sidebar) reported that provisionally licensed teachers are very poorly or poorly

prepared to be teachers, while only 3 percent of school divisions reported poor prep-

aration among individuals who attended traditional higher education preparation

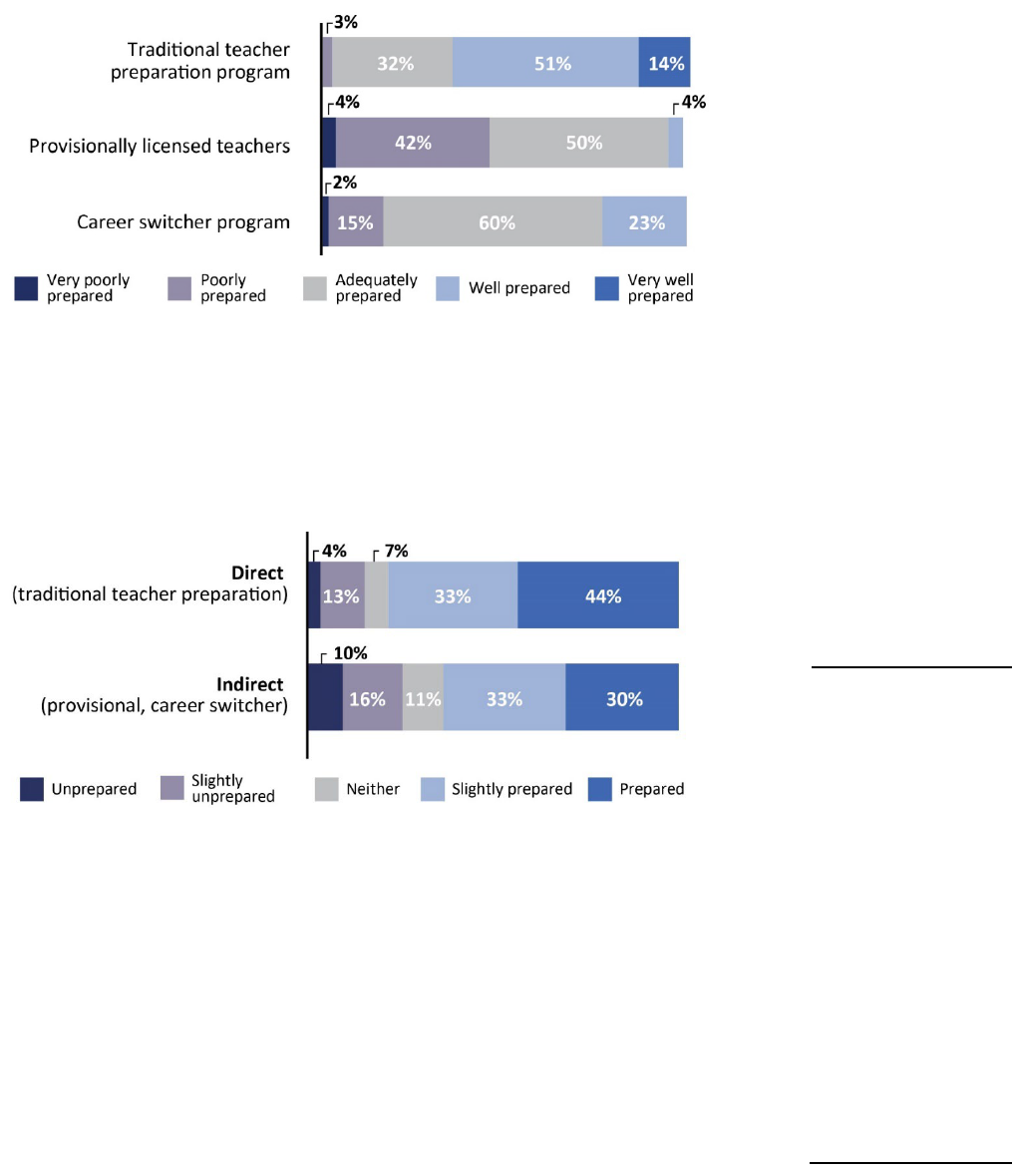

programs (Figure 3-2). Similarly, 44 percent of new teachers who responded to a

JLARC survey (sidebar) and attended a traditional higher education preparation pro-

gram reported feeling prepared in their first year of teaching, compared with 30 per-

cent of new teachers who took an indirect pathway for preparation (e.g., career

switcher, provisional licensee) (Figure 3-3).

Research literature indicates that provisionally licensed teachers have shorter tenures

than fully licensed teachers; yet Virginia’s experience has shown only a small differ-

ence. Subject matter experts emphasize that preparation plays a role in teacher reten-

tion and effectiveness (sidebar). According to Virginia data over the last decade,

teachers with provisional licenses typically have a slightly shorter tenure than fully li-

censed teachers. Comparing the bottom quartile by tenure of fully licensed and

provisionally licensed teachers, the bottom quartile of fully licensed teachers leave

within four years or less; the bottom quartile of provisionally licensed teachers leave

within three years or less. In addition, in Virginia, 27 percent of provisionally licensed

teachers over the past 20 years did not go on to obtain full licensure after three years.

However, it is too soon to assess how these trends may have changed during the

pandemic (provisional licenses issued after 2019 are still valid).

J

LARC staff surveyed

new K

–12 public school

teachers in Virginia

about their teacher prep-

aration, experiences with

the state licensure pro-

cess, and first year of

teaching. New teachers

were defined to include

individuals who began

teaching in a Virginia

public school after J

anu-

ary 1, 2022

. JLARC re-

ceived responses from

917 teachers (25 percent

response rate). See Ap-

pendix B for more infor-

mation.

JLARC surveyed human

resources staff from

Virginia school divisions

in July 2023 to ask about

the state’s teacher licen-

sure process, new teacher

support programs, and

divisions’ supply of public

K

–12 teachers. JLARC re-

ceived responses

from 75

divisions for an overall re-

sponse rate of 5

6

percent.

Subject matter experts

like the National Council

on Teacher Quality say

that

high quality prepa-

ration is important

for

teacher retention

, par-

ticularly in the early years

of a new teacher’s career.

Student teaching is a

critical co

mponent of

preparation, and candi-

dates who are trained

under a quality mentor

have been shown to be

more effective

instruc-

tionally

.

Chapter 3: Virginia’s Teacher Preparation Pathways

Commission draft

15

FIGURE 3-2

Divisions reported teachers from traditional higher education preparation

programs were the most prepared to be a teacher

SOURCE: JLARC survey of Virginia school divisions, summer 2023.

NOTE: Because there are only a small number of residency programs in the state, most divisions do not have new

teachers who graduated from residency programs.

FIGURE 3-3

New teachers from Virginia’s traditional preparation programs reported feeling

more prepared than teachers using indirect pathways

SOURCE: JLARC survey of new Virginia teachers, summer 2023.

NOTE: Results for residencies not reported because of small number of respondents.

To better prepare new provisionally licensed teachers for success in the classroom

from the outset, the state could consider piloting a program that would eventually

require all provisionally licensed teachers to complete a curriculum and instruction

course or a classroom and behavior management course by the end of their first se-

mester of employment as a teacher of record (sidebar). Both of these courses are

already required for full licensure. A curriculum and instruction course covers compe-

tencies that include the principles of learning, methods of communication with stu-

dents, and the selection and use of materials, curricula, and methodologies to support

student learning. A classroom and behavior management course covers research-based

Provisionally licensed

teachers are required to

complete six profes-

sional studies courses

for most endorsement

areas:

curriculum and in-

struction, classroom and

behavior management,

assessment of and for

learning, human devel-

opment and learning,

foundation

s

of education

and the teaching profes-

sion,

and language and

literacy.

Provisionally li-

censed teachers cur-

rently must

complete

these

courses prior to

the expiration of their li-

cense.

Chapter 3: Virginia’s Teacher Preparation Pathways

Commission draft

16

classroom and behavior management techniques, classroom community building, pos-

itive behavior supports, and individual interventions.

The state could initially award grants to several higher education institutions to provide

the course to all new provisionally licensed teachers in a subset of divisions. The pro-

gram could be evaluated based on the feedback of participating provisionally licensed

teachers and school administrators. The course would be most effective if it is offered

online at times compatible with the teacher workday, taught live by a qualified instruc-

tor who is available to help students outside of class time, and is free of charge to

participants. The program could be applied to new teachers once it becomes available,

not retroactively.

POLICY OPTION 1

The General Assembly could include language and funding in the Appropriation Act

to create a pilot program for provisionally licensed teachers to complete a curriculum

and instruction course or classroom and behavior management course by the end of

their first semester as a teacher of record at no cost.

Indirect pathways give individuals flexibility to obtain credentials

over time and cost less

More individuals have been entering teaching through Virginia’s indirect pathways to fill

current teacher vacancies. To help their provisionally licensed teachers achieve full li-

censure, more divisions have shown interest in offering in-house preparation or part-

nering with external entities to offer required professional studies coursework. In 2019,

the General Assembly allowed divisions to petition the Board of Education to approve

alternative coursework and assessments to meet requirements for licensure. Under this

regulation, iTeach, the online private provider, has recently been approved to offer

preparation to provisionally licensed teachers in multiple divisions.

Though generally lower quality than direct pathways, indirect pathways to becoming a

teacher typically allow more flexibility and are lower cost. For example, most provi-

sionally licensed teachers take required courses at their convenience, often online,

while working as a teacher. Tuition can still be costly for these courses, but many divi-

sions offer tuition reimbursement for provisionally licensed teachers, and several divi-

sions offer in-house preparation at no cost to participants. In contrast, teacher candi-

dates at traditional preparation programs often pay tens of thousands of dollars in

tuition and fees (Table 3-3). Possibly as a result of being lower cost and more flexible,

indirect pathways have attracted more Black teachers than direct pathways, which can

be beneficial for student learning outcomes (sidebar).

Researchers have found

that

diverse teacher

workforces that mirror

their student population

are important for stu-

dent outcomes

.

Students

with at least one teacher

with the same racial or

ethnic background tend

to have higher test

scores, lower rates of

chronic absenteeism,

fewer susp

ensions, and

higher rates of high

school graduation and

college enrollment.

Chapter 3: Virginia’s Teacher Preparation Pathways

Commission draft

17

TABLE 3-3

Indirect pathways are more affordable than traditional teacher preparation

Traditional

program

Career switcher

program

Division prepa-

ration program

Provisional

license, taking

classes as needed

Cost to

participant

$15K-$96K $2K-$6K $0 $0K-$12K

a

SOURCE: JLARC data collection from public higher education institutions, interviews with division staff, and analysis

of publicly available tuition data

a

Provisionally licensed teachers can take classes online or in-person at higher education institutions, community

colleges, or with approved providers. Many divisions offer tuition reimbursements for courses taken by provisional

licensees pursuing full licensure. Reimbursement amounts vary, but some divisions cover the full cost of courses. In

addition, some higher education institutions offer discounted tuition to provisionally licensed teachers.

Teacher residency programs produce well-prepared teachers and

prepare them to work in hard-to-staff schools

Residency programs are Virginia’s most rigorous teacher preparation pathway (side-

bar), but they have limited capacity and therefore prepare a small number of teachers.

Virginia currently has three state-supported teacher residency programs that prepare

individuals for teaching through a co-teaching placement of at least a year while par-

ticipants simultaneously complete coursework. State-supported residency programs

prepared just under 100 individuals for teaching in SY2022–23 (traditional higher ed-

ucation-based preparation programs prepared approximately 2,600 teachers in the

most recent year for which data is available). Residency programs are costly to admin-

ister because they typically cover the cost of preparation and provide a stipend to

participants, limiting the number of resident positions available. Several divisions also

have partnerships with traditional higher education teacher preparation programs to

offer residency placements for selected teacher candidates (sidebar).

In addition to providing high quality teacher preparation, teacher residencies also help

improve teacher recruitment in divisions with high teacher vacancies. (JLARC recom-

mended expanding teacher residency programs in its 2014 Low Performing Schools in Ur-

ban High Poverty Communities.) Virginia residency program participants are placed in

hard-to-staff schools, and they are required to teach in those schools for several years

after completing residency programs. These requirements help divisions experiencing

significant teacher vacancies recruit new teachers. Many Virginia school divisions with

large populations of Black students and limited resources have especially high teacher

vacancy rates, according to a JLARC staff analysis, making teacher residency programs

an especially useful recruiting tool in these schools. (See Chapter 2 and Appendix C

for more information about divisions’ teacher vacancies.)

Additional state funding for teacher residency programs in Virginia could increase the

number of students able to receive high quality preparation each year and direct more

well-prepared teachers to divisions with the most teacher vacancies. State funding

Division

-

funded teacher

residency partnerships

offer financial support

and an extended field

placement to students in

traditional teacher prep-

aration programs. Part-

nerships vary in design,

but

residents may fill va-

cant support positions

like long

-term substi-

tutes or instructional

aides. Partnerships may

also include a service ob-

ligation.

Subject matter experts

consider teacher resi-

dencies

the most effec-

tive method for

training

teachers

because re-

search shows residency

participants

have higher

teacher retention and

f

eel better prepared to

teach. Residencies also

attract diverse candi-

dates

and fill critical va-

cancies.

Chapter 3: Virginia’s Teacher Preparation Pathways

Commission draft

18

could either be used to develop new or expand existing higher education-based teacher

residency programs or division teacher residency partnerships, as both models are de-

signed to provide high quality preparation to prospective teachers.

POLICY OPTION 2

The General Assembly could include language and funding in the Appropriation Act

for the Virginia Department of Education to increase funding for teacher residency

programs to help cover the cost of preparation for additional teacher residents.

New registered teacher apprenticeship program should provide

rigorous preparation and be cost-effective due to federal funding

Registered teacher apprenticeship programs are another pathway that can provide

high-quality teacher preparation, while addressing the financial barriers that can pre-

vent individuals from pursing teaching. Apprenticeship programs can produce teach-

ers that remain in teaching positions longer and feel better prepared to teach than

individuals who use less rigorous pathways, according to experts. Apprenticeship pro-

grams also pay individuals during their preparation, which research shows facilitates a

more diverse teacher workforce.

Registered teacher apprenticeship programs use a preparation model that is similar to

teacher residency programs, but their funding sources can differ, and apprenticeship

programs must meet certain federal requirements. Similar to residencies, registered ap-

prenticeship programs require individuals to complete extensive on-the-job training

while simultaneously completing courses required for teacher licensure. In addition,

individuals are paid during the program, and they work with experienced teachers ra-

ther than immediately becoming the “teacher of record.” Unlike residencies, however,

registered apprenticeship programs can receive federal workforce funds to cover a

portion of program costs. Registered apprenticeship programs must also meet certain

federal requirements, including providing 2,000 on-the-job training hours per year, 144

hours of related technical instruction hours per year (e.g., degree and statutory require-

ments), and progressive wage increases as apprentices gain skills.

If implemented effectively, Virginia’s new registered apprenticeships should result in

additional well-prepared teachers and remove the financial barriers associated with tra-

ditional preparation. VDOE distributed funding to six partnerships between school

divisions and higher education institutions in July 2023 for registered apprenticeship

programs. As of early September 2023, at least one partnership enrolled an apprentice

in fall 2023, and at least three partnerships plan to begin enrolling apprentices in spring

2024.

As this new program is implemented, VDOE should report on program participation,

size, and funding. Eventually, the role that apprenticeship programs play in Virginia’s

pipeline should be reported and assessed in the context of other pathways (recom-

mendations 9 and 10). If registered apprenticeships begin to prepare a large number

Chapter 3: Virginia’s Teacher Preparation Pathways

Commission draft

19

of prospective teachers soon, there may be less need for the state to invest additional

funding in teacher residencies (Policy Option 2).

RECOMMENDATION 1

The General Assembly may wish to consider including language in the Appropriation

Act directing the Virginia Department of Education to report (i) which higher educa-

tion institutions and school divisions have been approved to have apprentice pro-

grams, (ii) when they expect to begin preparing prospective teachers, (iii) how many

individuals are expected to be prepared through each program annually, and (iv) how

each program will be funded. The report should be submitted to the Board of Edu-

cation and House Education and Senate Education and Health committees by June

30, 2024.

State can reduce barriers to participation in higher

education teacher preparation programs

The state could address barriers that prevent individuals from participating in the

largest direct pathway—traditional higher education teacher preparation programs.

Doing so will not immediately result in a substantial increase in graduates from these

programs. Over time, though, reducing or eliminating some of these barriers may re-