49

CHAPTER 3

Research Ethics and

Philosophies

The primary focus of this chapter is on research ethics. While each methods chapter in

this book provides a discussion of ethical issues devoted specifically to a particular method

(e.g., experimental design, survey), this chapter will highlight the general ethical

considerations everyone should consider before beginning his or her research. Every

researcher needs to consider how to practice his or her discipline ethically. Whenever we

interact with other people as social scientists, we must place great importance on the

concerns and emotional needs that shape their responses to our actions. It is here that

ethical research practice begins, with the recognition that our research procedures involve

people who deserve respect. At the end of the chapter, we conclude with a brief discussion

of different social research philosophies that will set the stage for the remainder of the

book.

WHAT DO WE HAVE IN MIND?

Consider the following scenario: One day as you are drinking coffee and reading the

newspaper during your summer in California, you notice a small ad recruiting college

students for a study at Stanford University. You go to the campus and complete an

application. The ad read as follows:

Male college students needed for psychological study of prison life. $80 per day

for 1–2 weeks beginning Aug. 14. For further information & applications, come to

Room 248, Jordan Hall, Stanford U. (Zimbardo 1973: 38)

After you arrive at the university, you are given an information form with more details

about the research (Zimbardo 1973).

FUNDAMENTALS OF RESEARCH IN CRIMINOLOGY AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE

50

Purpose: A simulated prison will be established somewhere in the vicinity of Palo Alto, Stanford [sic], to

study a number of problems of psychological and sociological relevance. Paid volunteers will be randomly

assigned to play the roles of either prisoners and guards [sic] for the duration of the study. This time

period will vary somewhat from about five days to two weeks for any one volunteer—depending upon

several factors, such as the “sentence” for the prisoner or the work effectiveness of the guards. Payment

will be $80 a day for performing various activities and work associated with the operation of our prison.

Each volunteer must enter a contractual arrangement with the principal investigator (Dr. P. G. Zimbardo)

agreeing to participate for the full duration of the study. It is obviously essential that no prisoner can

leave once jailed, except through established procedures. In addition, guards must report for their 8-hour

work shifts promptly and regularly since surveillance by the guards will be around-the-clock—three work

shifts will be rotated or guards will be assigned a regular shift—day, evening, or early morning. Failure

to fulfill this contract will result in a partial loss of salary accumulated—according to a prearranged

schedule to be agreed upon. Food and accommodations for the prisoners will be provided which will meet

minimal standard nutrition, health, and sanitation requirements. A warden and several prison staff will

be housed in adjacent cell blocks, meals and bedding also provided for them. Medical and psychiatric

facilities will be accessible should any of the participants desire or require such services. All participants

will agree to having their behavior observed and to be interviewed and perhaps also taking psychological

tests. Films of parts of the study will be taken, participants agreeing to allow them to be shown, assuming

their content has information of scientific value.

[The information form then summarizes two of the “problems to be studied” and provides a few more details.]

Thanks for your interest in this study. We hope it will be possible for you to participate and to share

your experiences with us.

Philip G. Zimbardo, PhD

Professor of Social Psychology

Stanford University

Source: Zimbardo (1973).

Prison Life Study: General Information

First, you are asked to complete a long questionnaire about your family background,

physical and mental health history, and prior criminal involvement. Next, you are

interviewed by someone, and then you finally sign a consent form. A few days later, you

are informed that you and 20 other young men have been selected to participate in the

experiment. You return to the university to complete a battery of “psychological tests” and

are told you will be picked up for the study the next day (Haney, Banks, & Zimbardo

1973: 73).

The next morning, you hear a siren just before a squad car stops in front of your house.

A police officer charges you with assault and battery, warns you of your constitutional

rights, searches and handcuffs you, and drives you off to the police station. After

fingerprinting and a short stay in a detention cell, you are blindfolded and driven to the

“Stanford County Prison.” Upon arrival, your blindfold is removed and you are stripped

naked, skin-searched, deloused, and issued a uniform (a loosely fitting smock with an ID

number printed on it), bedding, soap, and a towel. You don’t recognize anyone, but you

CHAPTER 3 Research Ethics and Philosophies

51

notice that the other “prisoners” and the “guards” are college-age, apparently almost all

middle-class white men (except for one Asian) like you (Haney et al. 1973; Zimbardo et al.

1973).

The prison warden welcomes you:

As you probably know, I’m your warden. All of you have shown that you are

unable to function outside in the real world for one reason or another—that

somehow you lack the responsibility of good citizens of this great country. We of

this prison, your correctional staff, are going to help you learn what your

responsibilities as citizens of this country are. . . . If you follow all of these rules

and keep your hands clean, repent for your misdeeds and show a proper attitude

of penitence, you and I will get along just fine. (Zimbardo et al. 1973: 38)

Among other behavioral restrictions, the rules stipulate that prisoners must remain silent

during rest periods, during meals, and after lights out. They must address each other only by

their assigned ID numbers, they are to address guards as “Mr. Correctional Officer,” and

everyone is warned that punishment will follow any rule violation (Zimbardo et al. 1973).

You look around and can tell that you are in the basement of a building. You are led

down a corridor to a small cell (6’ x 9’) with three cots, where you are locked behind a steel-

barred black door with two other prisoners (Exhibit 3.1). Located across the hall, there is a

small solitary confinement room (2’ x 2’ x 7’)

for those who misbehave. There is little

privacy, since you realize that the uniformed

guards, behind the mirrored lenses of their

sunglasses, can always observe the prisoners.

After you go to sleep, you are awakened by a

whistle summoning you and the others for a

roll call periodically through the night.

The next morning, you and the other eight

prisoners must stand in line outside your cells

and recite the rules until you remember all 17

of them. Prisoners must chant, “It’s a wonderful

day, Mr. Correctional Officer.” Two prisoners

who get out of line are put in the solitary

confinement unit. After a bit, the prisoners in

Cell 1 decide to resist: They barricade their cell

door and call on the prisoners in other cells to

join in their resistance. The guards respond by

pulling the beds out from the other cells and

spraying several of the inmates with a fire

extinguisher. The guards succeed in enforcing

control and become more authoritarian, while

the prisoners become increasingly docile.

Punishments are regularly meted out for

infractions of rules and sometimes for

Exhibit 3.1

Prisoner in His Cell

Source: From The Lucifer Effect, by Philip Zimbardo

2008, p. 155. Reprinted with permission.

FUNDAMENTALS OF RESEARCH IN CRIMINOLOGY AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE

52

seemingly no reason at all; punishments include doing push-ups, being stripped naked,

having legs chained, and being repeatedly wakened during the night. If this were you, would

you join in the resistance? How would you react to this deprivation of your liberty by these

authoritarian guards? How would you respond given that you signed a consent form allowing

you to be subjected to this kind of treatment?

By the fifth day of the actual Stanford Prison Experiment, five student prisoners had to

be released due to evident extreme stress (Zimbardo 2008). On the sixth day, Philip

Zimbardo terminated the experiment. A prisoner subsequently reported,

The way we were made to degrade ourselves really brought us down and that’s

why we all sat docile towards the end of the experiment. (Haney et al. 1973: 88)

One guard later recounted his experience:

I was surprised at myself. . . . I made them call each other names and clean the

toilets out with their bare hands. I practically considered the prisoners cattle, and I

kept thinking: “I have to watch out for them in case they try something.”

(Zimbardo et al. 1973: 174)

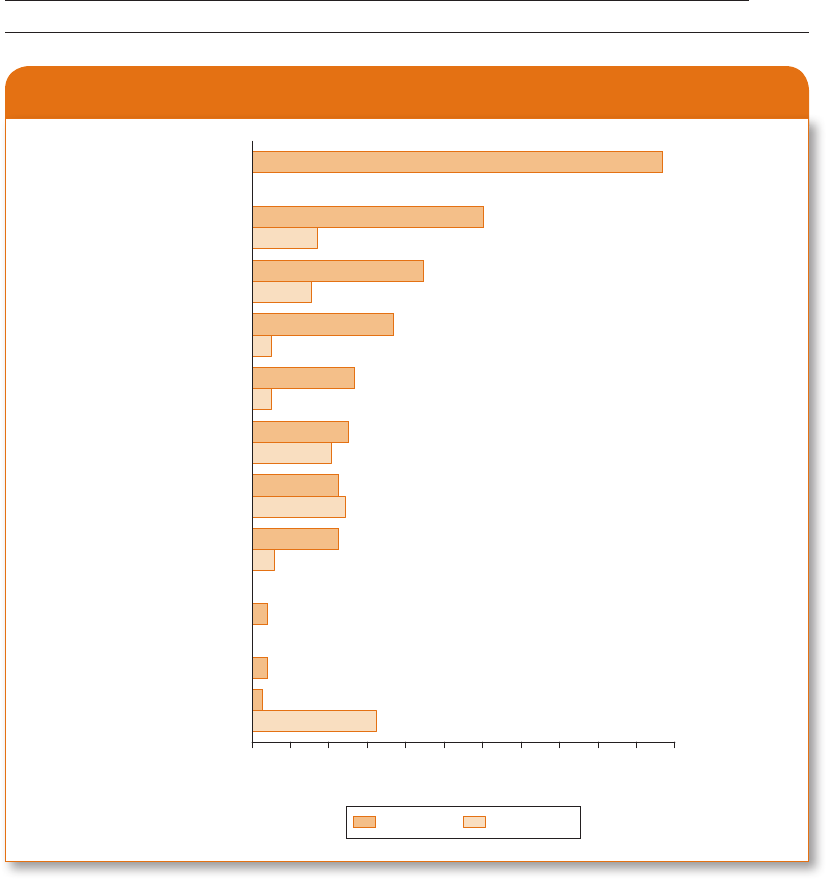

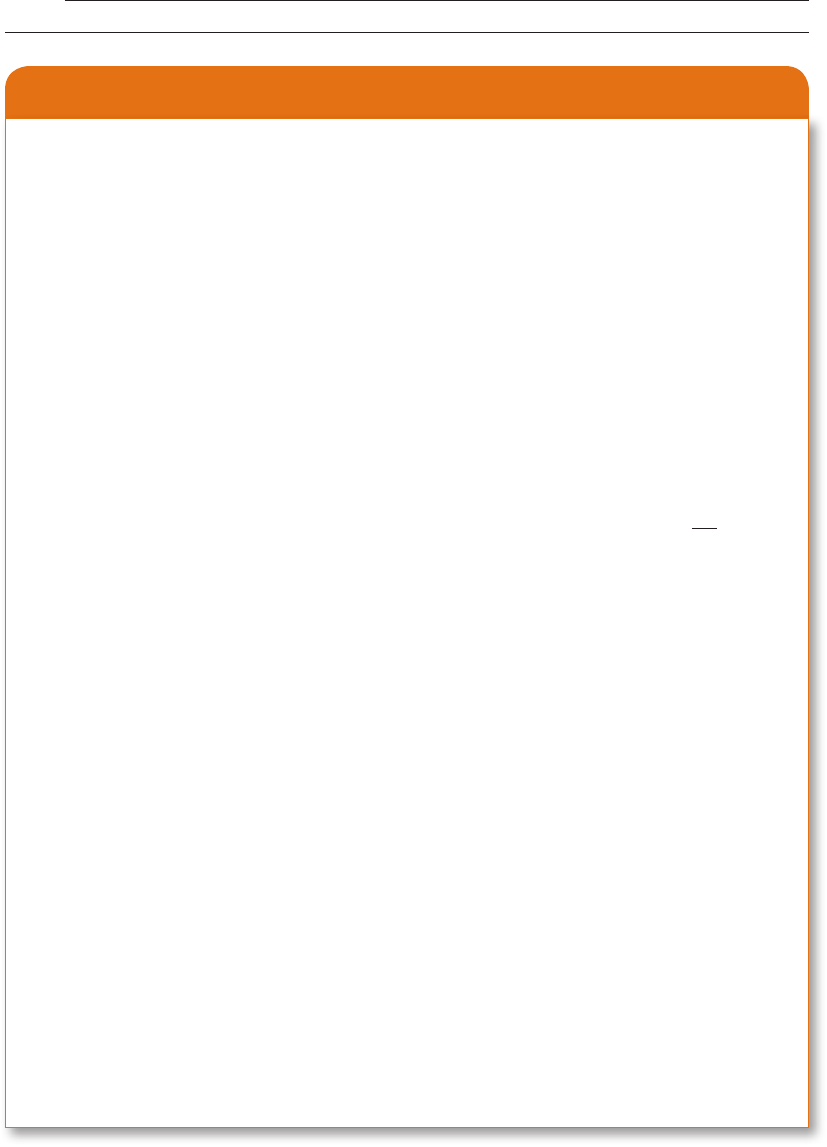

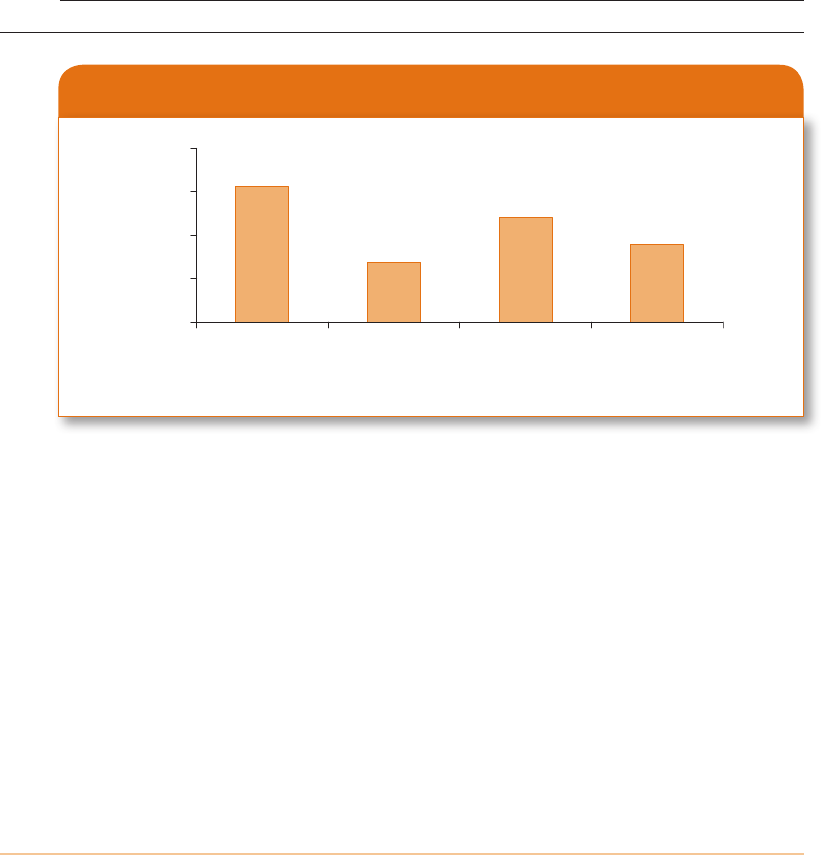

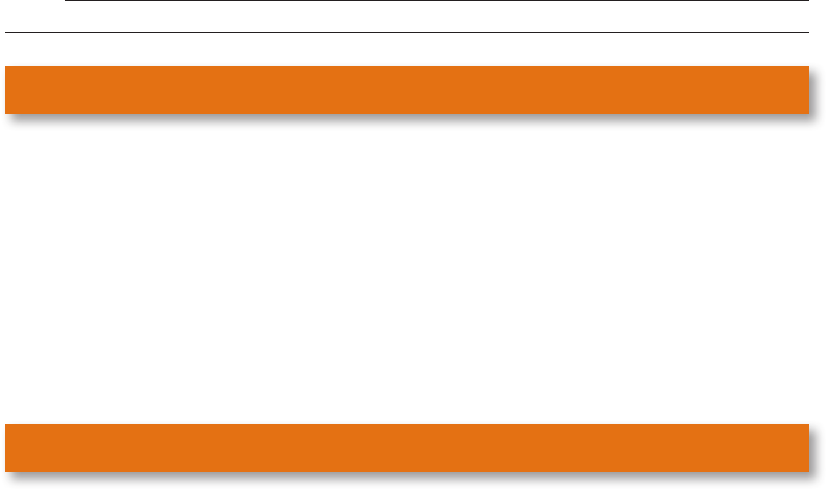

Exhibit 3.2 gives some idea of the difference in how the prisoners and guards behaved.

What is most striking about this result is that all the guards and prisoners had been screened

before the study began to ensure that they were physically and mentally healthy. The roles

of guard and prisoner had been assigned randomly, by the toss of a coin, so the two groups

were very similar when the study began. Something about the “situation” appears to have

led to the deterioration of the prisoners’ mental states and the different behavior of the

guards. Being a guard or a prisoner, with rules and physical arrangements reinforcing

distinctive roles, changed their behavior.

Are you surprised by the outcome of the experiment? By the guard’s report of his

unexpected, abusive behavior? By the prisoners’ ultimate submissiveness and the

considerable psychic distress some felt? (We leave it to you to assess how you would have

responded if you had been an actual research participant.)

Of course, our purpose in introducing this small “experiment” is not to focus attention

on the prediction of behavior in prisons but to introduce the topic of research ethics. We

will refer to Philip Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison Experiment throughout this chapter, since

it is fair to say that this research ultimately had a profound influence on the way that social

scientists think about research ethics as well as on the way that criminologists understand

behavior in prisons. We will also refer to Stanley Milgram’s (1963) experiments on

obedience to authority, since that research also pertains to criminal justice issues and has

stimulated much debate about research ethics.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Formal procedures regarding the protection of research participants emerged only after the

revelation of several very questionable and damaging research practices. A defining event

CHAPTER 3 Research Ethics and Philosophies

53

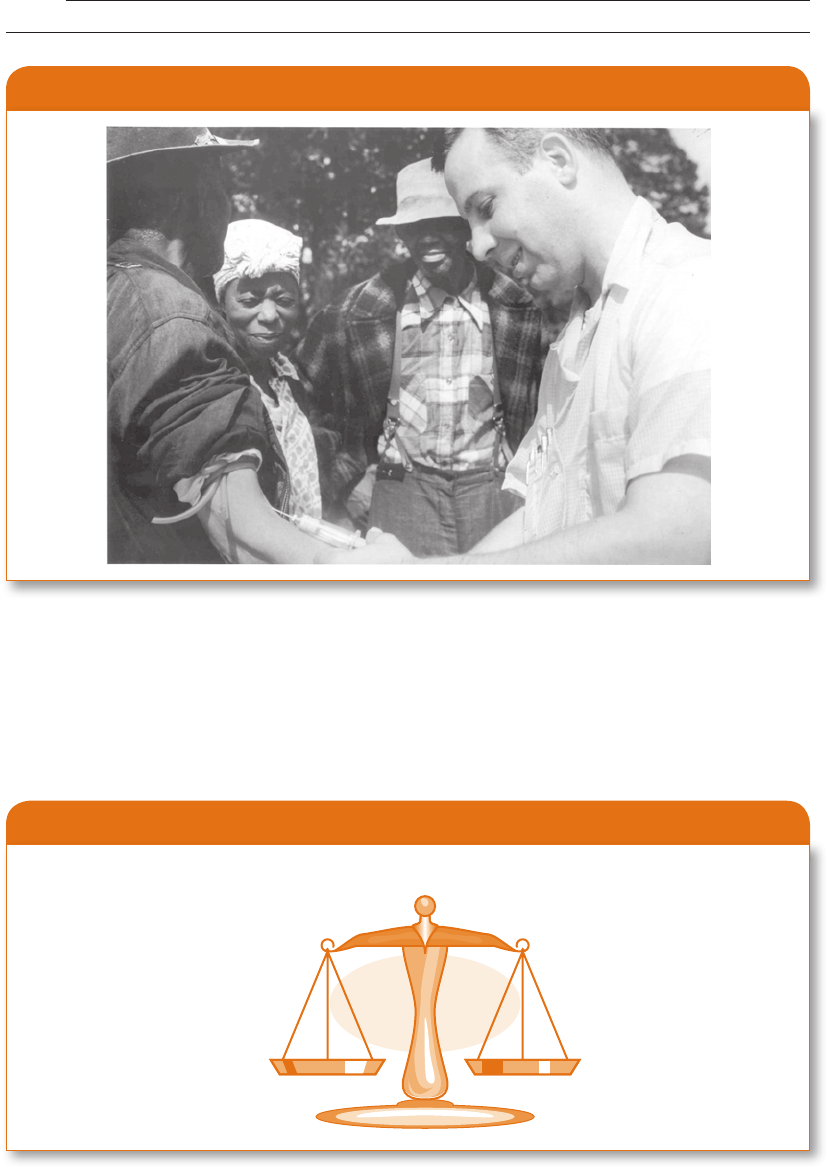

occurred in 1946, when the Nuremberg War Crime Trials exposed horrific medical

experiments conducted by Nazi doctors and others in the name of “science.” In the 1970s,

Americans were shocked to learn that researchers funded by the U.S. Public Health Service

had followed 399 low-income African American men with syphilis in the 1930s, collecting

data to study the “natural” course of the illness (Exhibit 3.3). Many participants were not

informed of their illness and were denied treatment until 1972, even though a cure

(penicillin) was developed in the 1950s.

Commands

Insults

Deindividuating

reference

Aggression

Threats

Questions

Information

Use of

instruments

Individuating

reference

Helping

Resistance

0102030405060

Frequency

70 80 90 100 110

Guards Prisoners

Exhibit 3.2

Chart of Guard and Prisoner Behavior

Source: From The Lucifer Effect by Philip G. Zimbardo, copyright © 2007 by Philip G. Zimbardo, Inc. Used by permission of

Random House Inc.

FUNDAMENTALS OF RESEARCH IN CRIMINOLOGY AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE

54

Horrible violations of human rights similar to these resulted, in the United States, in the

creation of a National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and

Behavioral Research. The commission’s 1979 Belmont Report (from the Department of

Health, Education, and Welfare) established three basic ethical principles for the protection

of human subjects (Exhibit 3.4):

Exhibit 3.3

Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment

Source: Tuskegee Syphilis Study Administrative Records. Records of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National

Archives—Southeast Region (Atlanta).

Respect for Persons

Beneficence Justice

Exhibit 3.4

Belmont Report Principles

CHAPTER 3 Research Ethics and Philosophies

55

• Respect for persons: Treating persons as autonomous agents and protecting those

with diminished autonomy

• Beneficence: Minimizing possible harms and maximizing benefits

• Justice: Distributing benefits and risks of research fairly

The Department of Health and Human Services and the Food and Drug Administration

then translated these principles into specific regulations that were adopted in 1991 as the

Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects. This policy has shaped the course of

social science research ever since. This section introduces these regulations.

Federal regulations require that every institution, including universities that seek federal

funding for biomedical or behavioral research on human subjects, have an institutional

review board (IRB) to review research proposals. IRBs at universities and other agencies

adopt a review process that is principally guided by federally regulated ethical standards

but can be expanded by the IRB itself (Sieber 1992). To promote adequate review of ethical

issues, the regulations require that IRBs include members with diverse backgrounds. The

Office for Protection From Research Risks in the National Institutes of Health monitors

IRBs, with the exception of research involving drugs (which is the responsibility of the

federal Food and Drug Administration).

The Academy of Criminal Justice Sciences (ACJS) and the American Society of

Criminology (ASC), like most professional social science organizations, have adopted

ethical guidelines for practicing criminologists that are more specific than the federal

regulations. The ACJS Code of Ethics also establishes procedures for investigating and

resolving complaints concerning the ethical conduct of the organization’s members. The

Code of Ethics of the ACJS (2000) is available on the ACJS Web site (www.acjs.org). The ASC

follows the American Sociological Association’s code (ASA 1999).

ETHICAL PRINCIPLES

Achieving Valid Results

A commitment to achieving valid results is the necessary starting point for ethical research

practice. Simply put, we have no business asking people to answer questions, submit to

observations, or participate in experimental procedures if we are simply seeking to verify

our preexisting prejudices or convince others to take action on behalf of our personal

interests. It is the pursuit of objective knowledge about human behavior—the goal of

validity—that motivates and justifies our investigations and gives us some claim to the right

to influence others to participate in our research. If we approach our research projects

objectively, setting aside our personal predilections in the service of learning a bit more

about human behavior, we can honestly represent our actions as potentially contributing

to the advancement of knowledge.

The details in Zimbardo’s articles and his recent book (2008) on the prison

experiment make a compelling case for his commitment to achieving valid results—to

learning how and why a prison-like situation influences behavior. In Zimbardo’s (2009)

own words,

FUNDAMENTALS OF RESEARCH IN CRIMINOLOGY AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE

56

Social-psychological studies were showing that human nature was more pliable

than previously imagined and more responsive to situational pressures than we

cared to acknowledge. . . . Missing from the body of social-science research at the

time was the direct confrontation . . . of good people pitted against the forces

inherent in bad situations. . . . I decided that what was needed was to create a

situation in a controlled experimental setting in which we could array on one side

a host of variables, such as . . . coercive rules, power differentials, anonymity. . . .

On the other side, we lined up a collection of the “best and brightest” of young

college men. . . . I wanted to know who wins—good people or an evil situation—

when they were brought into direct confrontation.

Zimbardo (Haney et al. 1973) devised his experiment so the situation would seem

realistic to the participants and still allow careful measurement of important variables and

observation of behavior at all times. Questionnaires and rating scales, interviews with

participants as the research proceeded and after it was over, ongoing video and audio

recording, and documented logs maintained by the guards all ensured that very little would

escape the researcher’s gaze.

Zimbardo’s (Haney et al. 1973) attention to validity is also apparent in his design of the

physical conditions and organizational procedures for the experiment. The “prison” was

constructed in a basement without any windows so that participants were denied a sense

of time and place. Their isolation was reinforced by the practice of placing paper bags over

their heads when they moved around “the facility,” meals were bland, and conditions were

generally demeaning. This was a very different “situation” from what the participants were

used to—suffice it to say that it was no college dorm experience.

However, not all social scientists agree that Zimbardo’s approach achieved valid

results. British psychologists Stephen Reicher and S. Alexander Haslam (2006) argue

that guard behavior was not so consistent and that it was determined by the instructions

Zimbardo gave the guards at the start of the experiment, rather than by becoming a

guard in itself. For example, in another experiment, when guards were trained to

respect prisoners, their behavior was less malicious (Lovibond, Mithiran, & Adams

1979).

In response to such criticism, Zimbardo (2007) has pointed to several replications of his

basic experiment that support his conclusions—as well as to the evidence of patterns of

abuse in the real world of prisons, including the behavior of guards who tormented

prisoners at Abu Ghraib during the war in Iraq.

Do you agree with Zimbardo’s assumption that the effects of being a prisoner or guard

could fruitfully be studied in a mock prison, with “pretend” prisoners? Do you find merit

in the criticisms? Will your evaluation of the ethics of Zimbardo’s experiment be influenced

by your answers to these questions? Should our ethical judgments differ when we are

confident a study’s results provide valid information about important social processes?

As you attempt to answer such questions, bear in mind that both Zimbardo and his

critics support their conflicting ethical arguments with assertions about the validity (or

invalidity) of the experimental results. It is hard to justify any risk for human subjects,

or any expenditure of time and resources, if our findings tell us nothing about the reality

of crime and punishment.

CHAPTER 3 Research Ethics and Philosophies

57

Honesty and Openness

The scientific concern with validity requires that scientists openly disclose their methods

and honestly present their findings. In contrast, research distorted by political or personal

pressures to find particular outcomes or to achieve the most marketable results is unlikely

to be carried out in an honest and open fashion. To assess the validity of a researcher’s

conclusions and the ethics of his or her procedures, you need to know exactly how the

research was conducted. This means that articles or other reports must include a detailed

methodology section, perhaps supplemented by appendices containing the research

instruments or websites or an address where more information can be obtained.

Philip Zimbardo’s research reports seemed to present an honest and forthright account

of the methods used in the Stanford experiment. His initial article (Haney et al. 1973)

contained a detailed description of study procedures, including the physical aspects of the

prison, the instructions to participants, the uniforms used, the induction procedure, and

the specific data collection methods and measures. Many more details, including forms and

pictures, are available on Zimbardo’s website (www.prisonexperiment.org) and in his

recent book (Zimbardo 2008).

The act of publication itself is a vital element in maintaining openness and honesty. It

allows others to review and question study procedures and generate an open dialogue with

the researcher. Although Zimbardo disagreed sharply with his critics about many aspects

of his experiment, their mutual commitment to public discourse in publications resulted

in a more comprehensive presentation of study procedures and a more thoughtful

discourse about research ethics (Savin 1973; Zimbardo 1973). Almost 40 years later, this

commentary continues to inform debates about research ethics (Reicher & Haslam 2006;

Zimbardo 2007).

Openness about research procedures and results goes hand in hand with honesty in

research design. Openness is also essential if researchers are to learn from the work of

others. In spite of this need for openness, some researchers may hesitate to disclose their

procedures or results to prevent others from building on their ideas and taking some of the

credit. Scientists are like other people in their desire to be first. Enforcing standards of

honesty and encouraging openness about research are the best solutions to this problem.

Protecting Research Participants

The ACJS code’s standards concerning the treatment of human subjects include

federal regulations and ethical guidelines emphasized by most professional social science

organizations:

• Research should expose participants to no more than minimal risk of personal

harm. (#16)

• Researchers should fully disclose the purposes of their research. (#13)

• Participation in research should be voluntary, and therefore subjects must give

their informed consent to participate in the research. (#16)

• Confidentiality must be maintained for individual research participants unless it is

voluntarily and explicitly waived. (#14, #18, #19)

FUNDAMENTALS OF RESEARCH IN CRIMINOLOGY AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE

58

Philip Zimbardo (2008) himself decided that his Stanford Prison Experiment was

unethical because it violated the first two of these principles: First, participants “did suffer

considerable anguish . . . and [the experiment] resulted in such extreme stress and

emotional turmoil that five of the sample of initially healthy young prisoners had to be

released early” (pp. 233–234). Second, Zimbardo’s research team did not disclose in

advance the nature of the arrest or booking procedures at police headquarters nor did they

disclose to the participants’ parents how bad the situation had become when they came to

a visiting night. Nonetheless, Zimbardo (Zimbardo et al. 1973; Zimbardo 2008) argued that

there was no long-lasting harm to participants and that there were some long-term social

benefits from this research. In particular, debriefing participants—discussing their

experiences and revealing the logic behind the experiment—and follow-up interviews

enabled the participants to recover from the experience without lasting harm (Zimbardo

2007). Also, the experience led several participants in the experiment, including Zimbardo,

to dedicate their careers to investigating and improving prison conditions. As a result,

publicity about the experiment has also helped focus attention on problems in prison

management.

Do you agree with Zimbardo’s conclusion that his experiment was not ethical? Do you

think it should have been prevented from happening in the first place? Are you relieved to

learn that current standards in the United States for the protection of human subjects in

research would not allow his experiment to be conducted?

In contrast to Zimbardo, Stanley Milgram (1963) believed that his controversial

experiments on obedience to authority were entirely ethical, so debate about this study

persists today. His experiments raise most of the relevant issues we want to highlight here.

Milgram had recruited community members to participate in his experiment at Yale

University. His research was prompted by the ability of Germany’s Nazi regime of the 1930s

and 1940s to enlist the participation of ordinary citizens in unconscionable acts of terror

and genocide. Milgram set out to identify through laboratory experiments the conditions

under which ordinary citizens will be obedient to authority figures’ instructions to inflict

pain on others. He operationalized this obedience by asking subjects to deliver electric

shocks (fake, of course) to students supposedly learning a memory task. Subjects

(“teachers”) were told to administer a shock to the learner each time he gave a wrong

response and to incrementally raise the voltage with each incorrect response. They were

told to increase the shocks over time and many did so, even after the “students,” behind a

partition, began to cry out in (simulated) pain (Exhibit 3.5). The participants became very

tense, and some resisted as the shocks increased to the (supposedly) lethal range, but many

still complied with the authority in that situation and increased the shocks. Like Zimbardo,

Milgram debriefed participants afterward and followed up later to check on their well-

being. It seemed that none had suffered long-term harm (Milgram 1974).

As we discuss how the ACJS Code of Ethics standards apply to Milgram’s experiments,

you will begin to realize that there is no simple answer to the question, “What is (or isn’t)

ethical research practice?” The issues are just too complicated and the relevant principles

too subject to different interpretations. But we do promise that by the end of this chapter,

you will be aware of the major issues in research ethics and be able to make informed,

defensible decisions about the ethical conduct of social science research.

CHAPTER 3 Research Ethics and Philosophies

59

Avoid Harming Research Participants

Although this standard may seem straightforward, it can be difficult to interpret in

specific cases and harder yet to define in a way that is agreeable to all social scientists.

Does it mean that subjects should not be harmed at all, psychologically or physically?

That they should feel no anxiety or distress whatsoever during the study or even after

their involvement ends? Should the possibility of any harm, no matter how remote,

deter research?

Before we address these questions with respect to Milgram’s experiments, a verbatim

transcript of one session will give you an idea of what participants experienced (Milgram

1965):

150 volts delivered. You want me to keep going?

165 volts delivered

. That guy is hollering in there. There’s a lot of them here.

He’s liable to have a heart condition. You want me to go on?

180 volts delivered. He can’t stand it! I’m not going to kill that man in there!

You hear him hollering? He’s hollering. He can’t stand

it. . . . I mean who is going to take responsibility if

anything happens to that gentleman?

[The experimenter accepts responsibility.] All right.

Experimenter

Teacher

Student

Exhibit 3.5

Diagram of Milgram’s Experiment

FUNDAMENTALS OF RESEARCH IN CRIMINOLOGY AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE

60

195 volts delivered. You see he’s hollering. Hear that? Gee, I don’t know.

[The experimenter says: “The experiment requires that

you go on.”] I know it does, sir, but I mean—Hugh—he

don’t know what he’s in for. He’s up to 195 volts.

210 volts delivered.

225 volts delivered.

240 volts delivered. (p. 67)

This experimental manipulation generated “extraordinary tension” (Milgram 1963):

Subjects were observed to sweat, tremble, stutter, bite their lips, groan and dig

their fingernails into their flesh. . . . Full-blown, uncontrollable seizures were

observed for 3 subjects. [O]ne . . . seizure [was] so violently convulsive that it was

necessary to call a halt to the experiment [for that individual]. (p. 375)

An observer (behind a one-way mirror) reported, “I observed a mature and initially poised

businessman enter the laboratory smiling and confident. Within 20 minutes he was

reduced to a twitching, stuttering wreck, who was rapidly approaching a point of nervous

collapse” (p. 377).

Psychologist Diana Baumrind (1964) disagreed sharply with Milgram’s approach,

concluding that the emotional disturbance subjects experienced was “potentially harmful

because it could easily affect an alteration in the subject’s self-image or ability to trust adult

authorities in the future” (p. 422). Stanley Milgram (1964) quickly countered, “As the

experiment progressed there was no indication of injurious effects in the subjects; and as

the subjects themselves strongly endorsed the experiment, the judgment I made was to

continue the experiment” (p. 849).

When Milgram (1964) surveyed the subjects in a follow-up, 83.7% endorsed the

statement that they were “very glad” or “glad” “to have been in the experiment,” 15.1%

were “neither sorry nor glad,” and just 1.3% were “sorry” or “very sorry” to have

participated (p. 849). Interviews by a psychiatrist a year later found no evidence “of any

traumatic reactions” (p. 197). Subsequently, Milgram (1974) argued that “the central moral

justification for allowing my experiment is that it was judged acceptable by those who took

part in it” (p. 21).

Milgram (1964) also attempted to minimize harm to subjects with post-experimental

procedures “to assure that the subject would leave the laboratory in a state of well being”

(p. 374). A friendly reconciliation was arranged between the subject and the victim, and an

effort was made to reduce any tensions that arose as a result of the experiment. In some

cases, the “dehoaxing” (or “debriefing”) discussion was extensive, and all subjects were

promised (and later received) a comprehensive report (p. 849).

In a later article, Baumrind (1985) dismissed the value of the self-reported “lack of harm”

of subjects who had been willing to participate in the experiment—and noted that 16% did

not endorse the statement that they were “glad” they had participated in the experiment

(p. 168). Baumrind also argued that research indicates most students who have participated

CHAPTER 3 Research Ethics and Philosophies

61

in a deception experiment report a decreased trust in authorities as a result—a tangible

harm in itself.

Many social scientists, ethicists, and others concluded that Milgram’s procedures had

not harmed the subjects and so were justified for the knowledge they produced, but others

sided with Baumrind’s criticisms (Miller 1986). What is your opinion at this point? Does

Milgram’s debriefing process relieve your concerns? Are you as persuaded by the subjects’

own endorsement of the procedures as was Milgram?

Would you ban such experiments because of the potential for harm to subjects? Does

the fact that Zimbardo’s and Milgram’s experiments seemed to yield significant insights

into the effect of a social situation on human behavior—insights that could be used to

improve prisons or perhaps lessen the likelihood of another holocaust—make any

difference (Reynolds 1979)? Do you believe that this benefit outweighs the foreseeable

risks?

Obtain Informed Consent

The requirement of informed consent is also more difficult to define than it first appears.

To be informed consent, it must be given by the persons who are competent to consent,

can consent voluntarily, are fully informed about the research, and comprehend what they

have been told (Reynolds 1979). Still, even well-intentioned researchers may not foresee

all the potential problems and may not point them out in advance to potential participants

(Baumrind 1985). In Zimbardo’s prison-simulation study, all the participants signed con-

sent forms, but they were not “fully informed” in advance about potential risks. The

researchers themselves did not realize that the study participants would experience so

much stress so quickly, that some prisoners would have to be released for severe negative

reactions within the first few days, or that even those who were not severely stressed would

soon be begging to be released from the mock prison. But on the other hand, are you con-

cerned that real harm “could result from not doing research on destructive obedience” and

other troubling human behavior (Miller 1986:138, italics original)?

Obtaining informed consent creates additional challenges for researchers. The language

of the consent form must be clear and understandable to the research participants yet

sufficiently long and detailed to explain what will actually happen in the research.

Examples A (Exhibit 3.6) and B (Exhibit 3.7) illustrate two different approaches to these

trade-offs.

Consent form A was approved by the University of Delaware IRB for in-depth interviews

with former inmates about their experiences after release from prison. Consent form B is

the one used by Philip Zimbardo. It is brief and to the point, leaving out many of the details

that current standards for the protection of human subjects require. Zimbardo’s consent

form also released the researchers from any liability for problems arising out of the

research (Such a statement is no longer allowed.).

As in Milgram’s (1963) study, experimental researchers whose research design requires

some type of subject deception try to minimize disclosure of experimental details by

withholding some information before the experiment begins but then debrief subjects at

the end. In the debriefing, the researcher explains to the subjects what happened in the

experiment and why, and then addresses participants’ concerns or questions. A carefully

FUNDAMENTALS OF RESEARCH IN CRIMINOLOGY AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE

62

INFORMED CONSENT

ROADS DIVERGE: LONG-TERM PATTERNS OF RELAPSE, RECIDIVISM, AND DESIS TANCE

FOR A RE-ENTRY COHORT (National Institute of Justice, 2008-IJ-CX-0017)

PURPOSE: You are one of approximately 300 people being asked to participate in a research

project conducted by the Center for Drug and Alcohol Studies at the University of Delaware.

You were part of the original study of offenders in Delaware leaving prison in the 1990s, and we

want to find out how things in your life have changed since that time. The overall purpose of this

research is to help us understand what factors lead to changes in criminal activity and drug use

over time.

PROCEDURES: If you agree to take part in this study, you will be asked to complete a survey,

which will last approximately 60 to 90 minutes. We will ask you to provide us with some contact

information so that we can locate you again if we are able to do another follow up study in the

future. You will be asked about your employment, family history, criminal involvement, health his-

tory, drug use, and how these have changed over time. We will use this information, as well as

information that you have previously provided or which is publicly available. We will not ask you

for the names of anyone, or the specific dates or specific places of any of your activities. The

interviews will be tape-recorded, but you will not be identified by name on the tape. The tapes will

be stored in a locked cabinet until they can be transcribed to an electronic word processor. After

the tapes have been transcribed and checked for accuracy they will be destroyed. Anonymous

transcribed data will be kept indefinitely – no audio data will be kept.

RISKS: There are some risks to participating in this study. You may experience distress or dis-

comfort when asked questions about your drug use, criminal history, and other experiences.

Should this occur, you may choose not to answer such questions. If emotional distress occurs,

our staff will make referrals to services you may need, including counseling, and drug abuse

treatment and support services.

The risk that confidentiality could be broken is a concern, but it is very unlikely to occur. You will

not be identified on the audiotape of the interview. We request that you not mention names of

other people or places, but if this happens, those names will be deleted from the audiotape prior

to transcription. All study materials are kept in locked file cabinets. Only three members of [the]

research team will have access to study materials.

BENEFITS: You will have the opportunity to participate in an important research project, which

may lead to the better understanding of what factors both help and prevent an individual’s recov-

ery from drug use and criminal activity.

COMPENSATION: You will receive $100 to compensate you for your time and travel costs for

this interview.

CONFIDENTIALITY: Your records will be kept confidential. They will be kept under lock and key

and will not be shared with anyone without your written permission. Your name will not appear

on any data file or research report.

Exhibit 3.6

Consent Form A

CHAPTER 3 Research Ethics and Philosophies

63

A Privacy Certificate has been approved by the U.S. Department of Justice. The data will be

protected from being revealed to non-research interests by court subpoena in any federal, state,

or local civil, criminal, administrative, legislative or other proceedings.

You should understand that a Privacy Certificate does not prevent you or a member of your

family from voluntarily releasing information about yourself or your involvement in this research.

If you give anyone written consent to receive research information, then we may not use the

Certificate to withhold that information.

The Privacy Certificate does not prevent research staff from voluntary disclosures to authorities

if we learn that you intend to harm yourself or someone else. These incidents would be reported

as required by state and federal law. However, we will not ask you questions about these areas.

Because this research is paid for by the National Institute of Justice, staff of this research office

may review copies of your records, but they also are required to keep that information confidential.

RIGHT TO QUIT THE STUDY: Participation in this research project is voluntary and you have

the right to leave the study at any time. The researchers and their assistants have the right to

remove you from this study if needed.

You may ask and will receive answers to any questions concerning this study. If you have any

questions about this study, you may contact Ronet Bachman or Daniel O’Connell at (302) 831-

6107. If you have any questions about your rights as a research participant you may contact the

Chairperson of the University of Delaware’s Human Subjects Review Board at (302) 831-2136.

CONSENT TO BE INTERVIEWED

I have read and understand this form (or it has been read to me), and I agree to participate in the

in-depth interview portion of this research project.

____________________________________________

Participant Signature Date

____________________________________________

Signature of Witness/Interviewer Date

CONSENT TO BE CONTACTED IN FUTURE

I have read and understand this form (or it has been read to me), and I agree to be recontacted

in the future as part of this research project.

____________________________________________

Participant Signature Date

____________________________________________

Signature of Witness/Interviewer Date

Ronet Bachman, PhD

Principal Investigator

University of Delaware

Telephone: (302) 831-6107

FUNDAMENTALS OF RESEARCH IN CRIMINOLOGY AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE

64

CONSENT

Prison Life Study

Dr. Zimbardo

August 1971

__________________________________________________________

(date) (name of volunteer)

I, _________________________________________, the undersigned, hereby consent to par-

ticipate as a volunteer in a prison life study research project to be conducted by the Stanford

University Psychology Department.

The nature of the research project has been fully explained to me, including, without limi-

tation, the fact that paid volunteers will be randomly assigned to the roles of either “prison-

ers” or “guards” for the duration of the study. I understand that participation in the research

project will involve a loss of privacy, that I will be expected to participate for the full duration

of the study, that I will only be released from participation for reasons of health deemed

adequate by the medical advisers to the research project or for other reasons deemed

appropriate by Dr. Philip Zimbardo, Principal Investigator of the project, and that I will be

expected to follow directions from staff members of the project or from other participants in

the research project.

I am submitting myself for participation in this research project with full knowledge and

understanding of the nature of the research project and of what will be expected of me. I specifi-

cally release the Principal Investigator and the staff members of the research project, Stanford

University, its agents and employees, and the Federal Government, its agents and employees,

from any liability to me arising in any way out of my participation in the project.

________________________________________________________

(signature of volunteer)

Witness: ________________________________________________

If volunteer is a minor:

________________________________________________________

(signature of person authorized to consent for volunteer)

Witness: ________________________________________________

________________________________________________________

(relationship to volunteer)

Exhibit 3.7 Consent Form B

CHAPTER 3 Research Ethics and Philosophies

65

designed debriefing procedure can help the research participants learn from the

experimental research and grapple constructively with feelings elicited by the realization

that they were deceived (Sieber 1992). However, even though debriefing can be viewed as a

substitute, in some cases, for securing fully informed consent prior to the experiment,

debriefed subjects who disclose the nature of the experiment to other participants can

contaminate subsequent results (Adair, Dushenko, & Lindsay 1985). Unfortunately, if the

debriefing process is delayed, the ability to lessen any harm resulting from the deception

may also be compromised.

If you were to serve on your university’s IRB, would you allow this type of research to

be conducted? Can students who are asked to participate in research by their professor

be considered able to give informed consent? Do you consider “informed consent” to be

meaningful if the true purpose or nature of an experimental manipulation is not

revealed?

The process and even possibility of obtaining informed consent must take into

account the capacity of prospective participants to give informed consent. For example,

children cannot legally give consent to participate in research. Instead, minors must in

most circumstances be given the opportunity to give or withhold their assent or

compliance to participate in research, usually by a verbal response to an explanation

of the research. In addition, a child’s legal guardian typically must grant additional

written informed consent to have the child participate in research (Sieber 1992). There

are also special protections for other populations that are likely to be vulnerable to

coercion—prisoners, pregnant women, mentally disabled persons, and educationally

or economically disadvantaged persons. Would you allow research on prisoners, whose

ability to give “informed consent” can be questioned? If so, what special protections do

you think would be appropriate?

Avoid Deception in Research, Except in Limited Circumstances

Deception occurs when subjects are misled about research procedures in an effort to deter-

mine how they would react to the treatment if they were not research subjects. In other

words, researchers deceive their subjects when they believe that knowledge of the experi-

mental premise may actually change the subjects’ behavior. Deception is a critical compo-

nent of many experiments, in part because of the difficulty of simulating real-world

stresses and dilemmas in a laboratory setting. The goal is to get subjects “to accept as true

what is false or to give a false impression” (Korn 1997: 4). In Milgram’s (1963) experiment,

for example, deception seemed necessary because the subjects could not be permitted to

administer real electric shocks to the “student,” yet it would not have made sense to order

the subjects to do something that they didn’t find to be so troubling. Milgram (1992)

insisted that the deception was absolutely essential. The results of many other experiments

would be worthless if subjects understood what was really happening to them while the

experiment was in progress. The real question is this: Is that sufficient justification to allow

the use of deception?

There are many examples of research efforts that employ placebos, ruses, or guises

to ensure that participants’ behavior is genuine. For example, Piliavin and Piliavin

(1972) staged fake seizures on subway trains to study helpfulness. Would you vote to

FUNDAMENTALS OF RESEARCH IN CRIMINOLOGY AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE

66

allow such deceptive practices in research if you were a member of your university’s

IRB? What about less dramatic instances of deception in laboratory experiments with

students like yourself? Do you react differently to the debriefing by Milgram compared

to that by Zimbardo?

What scientific or educational or applied “value” would make deception justifiable, even

if there is some potential for harm? Who determines whether a nondeceptive intervention

is “equally effective” (Miller 1986: 103)? Diana Baumrind (1985) suggested that personal

“introspection” would have been sufficient to test Milgram’s hypothesis and has argued

subsequently that intentional deception in research violates the ethical principles of self-

determination, protection of others, and maintenance of trust between people and so can

never be justified. How much risk, discomfort, or unpleasantness might be seen as affecting

willingness to participate? When should a post-experimental “attempt to correct any

misconception” due to deception be deemed sufficient?

Can you see why an IRB, representing a range of perspectives, is an important tool for

making reasonable, ethical research decisions when confronted with such ambiguity?

Maintain Privacy and Confidentiality

Maintaining privacy and confidentiality is another key ethical standard for protecting research

participants, and the researcher’s commitment to that standard should be included in the

informed consent agreement (Sieber 1992). Procedures to protect each subject’s privacy, such

as locking records and creating special identifying codes, must be created to minimize the

risk of access by unauthorized persons. However, statements about confidentiality should be

realistic: In some cases, laws allow research records to be subpoenaed and may require report-

ing child abuse; a researcher may feel compelled to release information if a health- or life-

threatening situation arises and participants need to be alerted. Also, the standard of

confidentiality does not apply to observation in public places and information available in

public records.

There are two exceptions to some of these constraints: The National Institute of Justice

can issue a “Privacy Certificate,” and the National Institutes of Health can issue a

“Certificate of Confidentiality.” Both of these documents protect researchers from being

legally required to disclose confidential information. Researchers who are focusing on

high-risk populations or behaviors, such as crime, substance abuse, sexual activity, or

genetic information, can request such a certificate. Suspicions of child abuse or neglect

must still be reported, as well as instances where respondents may immediately harm

themselves or others. In some states, researchers also may be required to report crimes

such as elder abuse (Arwood & Panicker 2007).

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) passed by Congress in

1996 created much more stringent regulations for the protection of health care data. As

implemented by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services in 2000 (and revised in

2002), the HIPAA Final Privacy Rule applies to oral, written, and electronic information that

“relates to the past, present, or future physical or mental health or condition of an individual.”

The HIPAA rule requires that researchers have valid authorization for any use or disclosure

of “protected health information” (PHI) from a health care provider. Waivers of authorization

can be granted in special circumstances (Cava, Cushman, & Goodman 2007).

CHAPTER 3 Research Ethics and Philosophies

67

The Uses of Research

Although many scientists believe that personal values should be left outside the laboratory,

some feel that it is proper—even necessary—for scientists to concern themselves with the

way their research is used. Philip Zimbardo made it clear that he was concerned about the

phenomenon of situational influence on behavior precisely because of its implications for

people’s welfare. As you have already learned, his first article (Haney et al. 1973) high-

lighted abuses in the treatment of prisoners. In his more comprehensive book, Zimbardo

(2007) used his findings to explain the atrocities committed at Abu Ghraib. He also urged

reforms in prison policy.

It is also impossible to ignore the very practical implications of Milgram’s investigations,

which Milgram (1974) took pains to emphasize. His research highlighted the extent of

obedience to authority and identified multiple factors that could be manipulated to lessen

blind obedience (such as encouraging dissent by just one group member, removing the

subject from direct contact with the authority figure, and increasing the contact between

the subject and the victim).

The evaluation research by Lawrence Sherman and Richard Berk (1984) on the police

response to domestic violence provides an interesting cautionary tale about the uses of

science. As you will recall from Chapter 2, the results of this field experiment indicated that

those who were arrested were less likely to subsequently commit violent acts against their

partners. Sherman (1992) explicitly cautioned police departments not to adopt mandatory

arrest policies based solely on the results of the Minneapolis experiment, but the results were

publicized in the mass media and encouraged many jurisdictions to change their policies

(Binder & Meeker 1993; Lempert 1989). Although we now know that the original finding of

a deterrent effect of arrest did not hold up in other cities where the experiment was repeated,

Sherman (1992) later suggested that implementing mandatory arrest policies might have

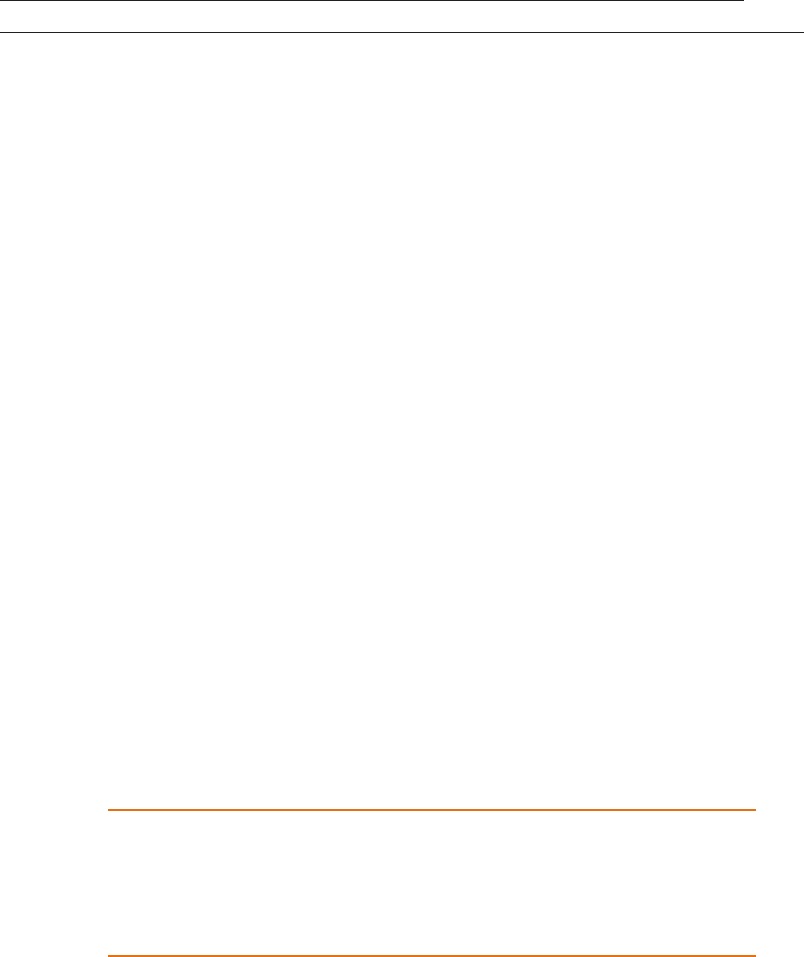

prevented some subsequent cases of spouse abuse. JoAnn Miller’s (2003) analysis of victims’

experiences and perceptions concerning their safety after the mandatory arrest experiment

in Dade County, Florida, found that victims reported less violence if their abuser had been

arrested (or assigned to a police-based counseling program called “Safe Streets”) (Exhibit 3.8).

Should this Dade County finding be publicized in the popular press so it could be used to

improve police policies? What about the results of the other replication studies where arrest

led to increased domestic assault? The answers to such questions are never easy.

Social scientists who conduct research on behalf of specific organizations may face

additional difficulties when the organization, instead of the researcher, controls the final

report and the publicity it receives. If organizational leaders decide that particular research

results are unwelcome, the researcher’s desire to have findings used appropriately and

reported fully can conflict with contractual obligations. Researchers can often anticipate

such dilemmas in advance and resolve them when the contract for research is negotiated—

or simply decline a particular research opportunity altogether. But other times, such

problems come up only after a report has been drafted, or the problems are ignored by a

researcher who needs a job or needs to maintain particular professional relationships.

These possibilities cannot be avoided entirely, but because of them, it is always important

to acknowledge the source of research funding in reports and to consider carefully the

sources of funding for research reports written by others.

FUNDAMENTALS OF RESEARCH IN CRIMINOLOGY AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE

68

0

10

20

30

40

Control Arrest Safe Streets Arrest and

Safe Streets

Treatment Condition

Percent

Exhibit 3.8

Victim Reports of Violence Following Police Intervention

Source: Adapted from Miller (2003: 704).

The withholding of a beneficial treatment from some subjects also is a cause for ethical

concern. Recall that the Sherman and Berk (1984) experiment required the random

assignment of subjects to treatment conditions and thus had the potential of causing harm

to the victims of domestic violence whose batterers were not arrested. The justification for

the study design, however, is quite persuasive: The researchers didn’t know prior to the

experiment which response to a domestic violence complaint would be most likely to deter

future incidents (Sherman 1992). The experiment provided clear evidence about the value

of arrest, so it can be argued that the benefits outweighed the risks.

In later chapters, we will continue to highlight the ethical dilemmas faced by research

that utilizes particular types of methods. Before we begin our examination of various

research methods, however, we first want to introduce you to the primary philosophies.

SOCIAL RESEARCH PHILOSOPHIES

What influences the decision to choose one research strategy over another? The motive for

conducting research is critical: An explanatory or evaluative motive generally leads a researcher

to use quantitative methods, whereas an exploratory motive often results in the use of qualitative

methods. Of course, a descriptive motive means choosing a descriptive research strategy.

Positivism and Postpositivism

A researcher’s philosophical perspective on reality and on the appropriate role of the

researcher also will shape his or her choice of methodological preferences. Researchers with

a philosophy of positivism believe that there is an objective reality that exists apart from the

perceptions of those who observe it; the goal of science is to better understand this reality.

CHAPTER 3 Research Ethics and Philosophies

69

Whatever nature “really” is, we assume that it presents itself in precisely the same

way to the same human observer standing at different points in time and space. . . .

We assume that it also presents itself in precisely the same way across different

human observers standing at the same point in time and space. (Wallace 1983: 461)

This philosophy is traditionally associated with science (Weber 1949), with the expectation

that there are universal laws of human behavior, and with the belief that scientists must be

objective and unbiased to see reality clearly.

Postpositivism is a philosophy of reality that is closely related to positivism.

Postpositivists believe that there is an external, objective reality, but are very sensitive to

the complexity of this reality and the limitations of the scientists who study it. Social

scientists, in particular, recognize the biases they bring to their research as they are social

beings themselves (Guba & Lincoln 1994: 109–111). As a result, they do not think scientists

can ever be sure that their methods allow them to perceive objective reality. Rather, the goal

of science can only be to achieve intersubjective agreement among scientists about the

nature of reality (Wallace 1983: 461). For example, postpositivists may worry that

researchers’ predispositions may bias them in favor of deterrence theory. Therefore, they

will remain somewhat skeptical of results that support predictions based on deterrence

until a number of researchers feel that they have found supportive evidence. The

postpositivist retains much more confidence in the ability of the community of social

researchers to develop an unbiased account of reality than in the ability of any individual

social scientist to do so (Campbell & Russo 1999: 144).

Positivist Research Guidelines

To achieve an accurate understanding of the social world, a researcher operating within the

positivist or postpositivist tradition must adhere to some basic guidelines about how to

conduct research:

1. Test ideas against empirical reality without becoming too personally invested in a

particular outcome. This guideline requires a commitment to “testing,” as opposed

to just reacting to events as they happen or looking for what we want to or expect

to see (Kincaid 1996: 51–54).

2. Plan and carry out investigations systematically. Social researchers have little hope

of conducting a careful test of their ideas if they do not fully think through in

advance how they should go about the test and then proceed accordingly.

3. Document all procedures and disclose them publicly. Social researchers should

disclose the methods on which their conclusions are based so that others can

evaluate for themselves the likely soundness of these conclusions (Kincaid 1996).

4. Clarify assumptions. No investigation is complete in itself. Whatever the

researcher’s method(s), the effort rests on some background assumptions. For

example, research to determine whether arrest has a deterrent effect assumes that

potential law violators think rationally and that they calculate potential costs and

benefits prior to committing crimes.

FUNDAMENTALS OF RESEARCH IN CRIMINOLOGY AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE

70

5. Specify the meaning of all terms. Words often have multiple or unclear meanings.

“Recidivism,” “self-control,” “poverty,” “overcrowded,” and so on can mean

different things to different people. In scientific research, all terms must be defined

explicitly and used consistently.

6. Maintain a skeptical stance toward current knowledge. The results of any particular

investigation must be examined critically, although confidence about

interpretations of the social or natural world increases after repeated investigations

yield similar results.

7. Replicate research and build social theory. No one study is definitive by itself. We

cannot fully understand a single study’s results apart from the larger body of

knowledge to which it is related, and we cannot place much confidence in these

results until the study has been replicated.

8. Search for regularities or patterns. Positivist and postpositivist scientists assume

that the natural world has some underlying order of relationships, so that unique

events and individuals can be understood at least in part in terms of general

principles (Grinnell 1992: 27–29).

Real investigations by social scientists do not always include much attention to theory,

specific definitions of all terms, and so forth. However, all social researchers should be

compelled to study these guidelines and to consider the consequences of not following any

with which they do not agree.

A Positivist Research Goal: Advancing Knowledge

The goal of the traditional positivist scientific approach is to advance scientific knowledge.

This goal is achieved when research results are published in academic journals or pre-

sented at academic conferences.

The positivist approach regards value considerations to be beyond the scope of science.

In Max Weber’s (1949) words, “An empirical science cannot tell anyone what he should

do—but rather what he can do—and under certain circumstances—what he wishes to do”

(p. 54). The idea is that developing valid knowledge about how society is organized, or how

we live our lives, does not tell us how society should be organized or how we should live

our lives. The determination of empirical facts should be a separate process from the

evaluation of these facts as satisfactory or unsatisfactory (p. 11).

Intersubjective agreement An agreement by different observers on what is happening in

the natural or social world

Positivism The belief, shared by most scientists, that there is a reality that exists quite

apart from our own perception of it, although our knowledge of this reality may never be

complete

Postpositivism The belief that there is an empirical reality but that our understanding of

it is limited by its complexity and by the biases and other limitations of researchers

CHAPTER 3 Research Ethics and Philosophies

71

Interpretivism and Constructivism

Qualitative research is often guided by a philosophy of interpretivism. Interpretive

social scientists believe that reality is socially constructed and that the goal of social

scientists is to understand what meanings people give to reality, not to determine how

reality works apart from these interpretations. This philosophy rejects the positivist

belief that there is a concrete, objective reality that scientific methods help us to under-

stand (Lynch & Bogen 1997); instead, interpretivists believe that scientists construct an

image of reality based on their own preferences and prejudices and their interactions

with others.

Here is the basic argument: The empirical data we collect all come to us through our

own senses and must be interpreted with our own minds. This suggests that we can never

be sure that we have understood reality properly, or that we ever can, or that our own

understandings can really be judged more valid than someone else’s.

Searching for universally applicable social laws can distract from learning what

people know and how they understand their lives. The interpretive social

researcher examines meanings that have been socially constructed. . . . There is

not one reality out there to be measured; objects and events are understood by

different people differently, and those perceptions are the reality—or realities—

that social science should focus on. (Rubin & Rubin 1995: 35)

The paradigm of constructivism extends interpretivist philosophy by emphasizing the

importance of exploring how different stakeholders in a social setting construct their

beliefs (Guba & Lincoln 1989: 44–45). It gives particular attention to the different goals of

researchers and other participants in a research setting and seeks to develop a consensus

among participants about how to understand the focus of inquiry. The constructivist

research report will highlight different views of the social program or other issue and

explain how a consensus can be reached among participants.

Interpretivism The belief that reality is socially constructed and that the goal of social

scientists is to understand what meanings people give to that reality. Max Weber termed

the goal of interpretivist research verstehen, or “understanding.”

Constructivism A perspective that emphasizes how different stakeholders in social

settings construct their beliefs

Constructivist inquiry uses an interactive research process, in which a researcher

begins an evaluation in some social setting by identifying the different interest groups

in that setting. The researcher goes on to learn what each group thinks, and then

gradually tries to develop a shared perspective on the problem being evaluated (Guba

& Lincoln 1989: 42).

FUNDAMENTALS OF RESEARCH IN CRIMINOLOGY AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE

72

Interpretivist/Constructivist Research Guidelines

Researchers guided by an interpretivist philosophy reject some of the guidelines to which

positivist researchers seek to adhere. In fact, there is a wide variety of specific approaches

that can be termed “interpretivist,” and each has some guidelines that it highlights. For

those working within the constructivist perspective, Guba and Lincoln (1989) suggest four

key steps for researchers, each of which may be repeated many times in a given study:

1. Identify stakeholders and solicit their “claims, concerns, and issues.”

2. Introduce the claims, concerns, and issues of each stakeholder group to the other

stakeholder groups and ask for their reactions.

3. Focus further information collection on claims, concerns, and issues about which

there is disagreement among stakeholder groups.

4. Negotiate with stakeholder groups about the information collected, and attempt

to reach consensus on the issues about which there is disagreement (p. 42).

An Interpretivist or Constructivist Research Goal: Creating Change

Some social researchers with an interpretivist or constructivist orientation often reject

explicitly the traditional positivist distinction between facts and values (Sjoberg & Nett

1968). Bellah et al. (1985) have instead proposed a model of “social science as public phi-

losophy.” In this model, social scientists focus explicit attention on achieving a more just

society.

Whyte (1991) proposed a more activist approach to research called participatory action

research. As the name implies, this approach encourages social researchers to get “out of

the academic rut” and bring values into the research process (p. 285).

In participatory action research, the researcher involves as active participants some

members of the setting studied. Both the organizational members and the researcher are

assumed to want to develop valid conclusions, to bring unique insights, and to desire

change, but Whyte (1991) believes these objectives are more likely to be obtained if the

researcher collaborates actively with the persons studied.

An Integrated Philosophy

It is tempting to think of positivism and postpositivism as representing an opposing

research philosophy to interpretivism and constructivism. Then it seems that we should

choose the one philosophy that seems closest to our own preferences and condemn the

other as “unscientific,” “uncaring,” or perhaps just “unrealistic.” But there are good reasons

to prefer a research philosophy that integrates some of the differences between these phi-

losophies (Smith 1991).

And what about the important positivist distinction between facts and values in social

research? Here, too, there is evidence that neither the “value-free” presumption of

positivists nor the constructivist critique of this position is entirely correct. For example,

Savelsberg, King, and Cleveland (2002) examined influences on the focus and findings of

CHAPTER 3 Research Ethics and Philosophies

73

published criminal justice scholarship. They found that criminal justice research was more

likely to be oriented to topics and theories suggested by the state when it was funded by

government agencies. This reflects a political influence on scholarship. However,

government funding did not have any bearing on the researchers’ conclusions about the

criminal justice processes they examined. This suggests that scientific procedures can

insulate the research.

Which philosophy makes the most sense to you? Do you agree with positivists and

postpositivists that scientific methods can help us understand the social world as it is, not

just as we would like to think it is? Does the interpretivist focus on meanings sound like a

good idea? Whatever your answers to these questions, you would probably agree that

developing a valid understanding of the social world is not an easy task for social

scientists.

CONCLUSION

The extent to which ethical issues present methodological challenges for researchers

varies dramatically with the type of research design. Survey research, in particular,

creates few ethical problems. In fact, researchers from Michigan’s Institute for Social

Research Survey Center interviewed a representative national sample of adults and found

that 68% of those who had participated in a survey were somewhat or very interested in

participating in another; the more times respondents had been interviewed, the more

willing they were to participate again. Presumably, they would have felt differently if they

had been treated unethically (Reynolds 1979). On the other hand, some experimental

studies in the social sciences that have put people in uncomfortable or embarrassing

situations have generated vociferous complaints and years of debate about ethics

(Reynolds 1979; Sjoberg 1967).

The evaluation of ethical issues in a research project should be based on a realistic

assessment of the overall potential for harm and benefit to research subjects rather than

an apparent inconsistency between any particular aspect of a research plan and a specific

ethical guideline. For example, full disclosure of “what is really going on” in an experimental

study is unnecessary if subjects are unlikely to be harmed. Nevertheless, researchers

should make every effort to foresee all possible risks and to weigh the possible benefits of

the research against these risks. They should consult with individuals with different

perspectives to develop a realistic risk–benefit assessment, and they should try to

maximize the benefits to, as well as minimize the risks for, subjects of the research (Sieber

1992).

Ultimately, these decisions about ethical procedures are not just up to you, as a

researcher, to make. Your university’s IRB sets the human subjects’ protection standards for

your institution and will require researchers—even, in most cases, students—to submit

their research proposal to the IRB for review. So we leave you with the instruction to review

the human subjects guidelines of the ACJS or other professional association in your field,

consult your university’s procedures for the conduct of research with human subjects, and

then proceed accordingly.

FUNDAMENTALS OF RESEARCH IN CRIMINOLOGY AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE

74

KEY TERMS

Belmont Report

Beneficence

Certificate of Confidentiality

Code of Ethics

Constructivism

Debriefing

Federal Policy for the

Protection of Human

Subjects

Institutional review board (IRB)

Interpretivism

Intersubjective agreement

Nuremberg War Crime Trials

Office for Protection From

Research Risks in the

National Institutes of

Health

Participatory action research

Philip Zimbardo’s Stanford

Prison Experiment

Positivism

Postpositivism

Privacy Certificate

Respect for persons

Stanley Milgram’s experiments

on obedience to authority

Verstehen

HIGHLIGHTS

• Philip Zimbardo’s prison-simulation study and Stanley Milgram’s obedience experiments led

to intensive debate about the extent to which deception could be tolerated in social science

research and how harm to subjects should be evaluated.

• Egregious violations of human rights by researchers, including scientists in Nazi Germany and

researchers in the Tuskegee syphilis study, led to the adoption of federal ethical standards for

research on human subjects.

• The 1979 Belmont Report, developed by a national commission, established three basic

ethical standards for the protection of human subjects: respect for persons, beneficence, and

justice.

• The Department of Health and Human Services adopted in 1991 a Federal Policy for the

Protection of Human Subjects. This policy requires that every institution seeking federal

funding for biomedical or behavioral research on human subjects have an institutional review

board (IRB) to exercise oversight.

• The ACJS standards for the protection of human subjects require avoiding harm, obtaining

informed consent, avoiding deception except in limited circumstances, and maintaining

privacy and confidentiality.

• Scientific research should maintain high standards for validity and be conducted and reported

in an honest and open fashion.

• Effective debriefing of subjects after an experiment can help reduce the risk of harm resulting

from the use of deception in the experiment.

• Positivism is the belief that there is a reality quite apart from one’s own perception of it that

is amenable to observation.

• Intersubjective agreement is an agreement by different observers on what is happening in the

natural or social world.

CHAPTER 3 Research Ethics and Philosophies

75

• Postpositivism is the belief that there is an empirical reality but that our understanding of it is

limited by its complexity and by the biases and other limitations of researchers.

• Interpretivism is the belief that reality is socially constructed, and the goal of social science

should be to understand what meanings people give to that reality.

• The constructivist paradigm emphasizes the importance of exploring and representing the

ways in which different stakeholders in a social setting construct their beliefs. Constructivists

interact with research subjects to gradually develop a shared perspective on the issue being

studied.

EXERCISES

Discussing research

1. What policy would you recommend that researchers such as Sherman and Berk follow in

reporting the results of their research? Should social scientists try to correct misinformation

in the popular press about their research, or should they just focus on what is published in

academic journals? Should researchers speak to audiences like at police conventions in order

to influence policies related to their research results?

2. Now go to this book’s study site at www.sagepub.com/bachmanfrccj2e and choose the

Learning From Journal Articles option. Read one article based on research involving human

subjects. What ethical issues did the research pose, and how were they resolved? Does it seem

that subjects were appropriately protected?

3. Outline your own research philosophy. You can base your outline primarily on your reactions

to the points you have read in this chapter, but try also to think seriously about which

perspective seems the most reasonable to you.