BEST PRACTICES: CARIES-RISK ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT

THE REFERENCE MANUAL OF PEDIATRIC DENTISTRY 301

Purpose

e American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD)

recognizes that caries-risk assessment and management proto-

cols, also called care pathways, can assist clinicians with

decisions regarding treatment based upon a child’s age, caries

risk, and patient compliance and are essential elements of con-

temporary clinical care for infants, children, and adolescents.

ese recommendations are intended to educate healthcare

providers and other interested parties on the assessment of

caries risk in contemporary pediatric dentistry and aid in

clinical decision making regarding evidence- and risk-based

diagnostic, uoride, dietary, and restorative protocols.

Methods

is document was developed by the Council on Clinical

Aairs, adopted in 2002

1

, and last revised in 2019

2

. To update

this document, an electronic search was conducted of publi-

cations from 2012 to 2021 that included systematic reviews/

meta-analyses or reports from expert panels, clinical guidelines,

and other relevant reviews using the terms: caries risk assess-

ment AND diet, sealants, uoride, radiology, nonrestorative

treatment, active surveillance, caries prevention. Five hundred

ninety-two articles met these criteria. Papers for review were

chosen from this list and from references within selected

articles. When data did not appear sucient or were incon-

clusive, recommendations were based upon expert and/or

consensus opinion by experienced researchers and clinicians.

Background

Caries-risk assessment

Risk assessment procedures used in medical practice generally

have sucient data to accurately quantitate a person’s disease

susceptibility and allow for preventive measures. However, in

dentistry, suciently-validated multivariate screening tools to

determine which children are at higher risk for dental caries

are limited.

3,4

Two caries risk assessment tools, namely the

Cariogram

5

and CAMBRA tools

6

, have been validated in clinical

trials and clinical outcomes studies. Several other published

caries-risk assessment tools utilize similar components but

have not been clinically validated.

5,7

Nevertheless, caries-risk

assessment:

1. fosters the treatment of the disease process instead of

treating the outcome of the disease.

2. allows an understanding of the disease factors for a

specic patient and aids in individualizing preventive

discussions.

3. individualizes, selects, and determines frequency of

preventive and restorative treatment for a patient.

4. anticipates caries progression or stabilization.

Caries-Risk Assessment and Management for

Infants, Children, and Adolescents

Latest Revision

2022

How to Cite: American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Caries-risk

assessment and management for infants, children, and adolescents.

The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry. Chicago, Ill.: American

Academy of Pediatric Dentistry; 2023:301-7.

Abstract

This best practice reviews caries-risk assessment and patient care pathways for pediatric patients. Presented caries-related topics include

caries-risk assessment, active surveillance, caries prevention, sealants, fluoride, diet, radiology, and nonrestorative treatment. Caries-risk

assessment forms are organized by age: 0-5 years and ≥6 years old, incorporating three factor categories (social/behavioral/medical, clin-

ical, and protective factors) and disease indicators appropriate for the patient age. Each factor category lists specific conditions to be graded

“Yes” if applicable, with the answers tallied to render a caries-risk assessment score of high, moderate, or low. The care management

pathway presents clinical care options beyond surgical or restorative choices and promotes individualized treatment regimens dependent

on patient age, compliance with preventive strategies, and other appropriate strategies. Caries management forms also are organized by

age: 0-5 years and ≥ 6 years old, addressing risk categories of high, moderate, and low, based on treatment categories of diagnostics, pre-

ventive interventions (fluoride, diet counseling, sealants), and restorative care. Caries-risk assessment and clinical management pathways

allow for customized periodicity, diagnostic, preventive, and restorative care for infants, children, adolescents, and individuals with special needs.

This document was developed through a collaborative effort of the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry Councils on Clinical Affairs and

Scientific Affairs to offer updated information and recommendations regarding assessment of caries-risk and risk-based management protocols.

KEYWORDS: CARIES-RISK ASSESSMENT; CARIES PREVENTION; CLINICAL MANAGEMENT PATHWAYS; DENTAL SEALANTS; FLUORIDE

ABBREVIATION

AAPD: American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry.

BEST PRACTICES: CARIES-RISK ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT

302 THE REFERENCE MANUAL OF PEDIATRIC DENTISTRY

Caries-risk assessment is part of a comprehensive treatment

plan approach based on age of the child, starting with the age

one visit. Caries-risk assessment models currently involve a

combination of factors including diet, uoride exposure, a

susceptible host, and microora that interplay with a variety of

social, cultural, and behavioral factors.

8

Caries-risk assessment

is the determination of the likelihood of the increased inci-

dence of caries (i.e., new cavitated or incipient lesions) during

a certain time period

9,10

or the likelihood that there will be a

change in the size or activity of lesions already present. With

the ability to detect caries in its earliest stages (i.e., noncavitated

or white spot lesions), health care providers can help prevent

cavitation.

11

Caries risk factors are variables that are thought to cause

the disease directly (e.g., microora) or have been shown useful

in predicting it (e.g., life-time poverty, low health literacy)

and include those variables that may be considered protective

factors. e most-used caries-risk factors include low salivary

ow, visible plaque on teeth, high frequency sugar consump-

tion, presence of appliance in the mouth, health challenges,

sociodemographic factors, access to care, and cariogenic

microora.

11

e presence of caries lesions, either noncavitated

or cavitated, also has been shown in numerous studies to be

a strong indicator of caries risk. Clinical observation of caries

lesions, or restorations recently placed because of such lesions,

are best thought of as disease indicators rather than risk

factors since these lesions do not cause the disease directly or

indirectly but, very importantly, indicate the presence of the

factors that cause the disease. Protective factors in caries risk

include a child’s receiving optimally-uoridated water, having

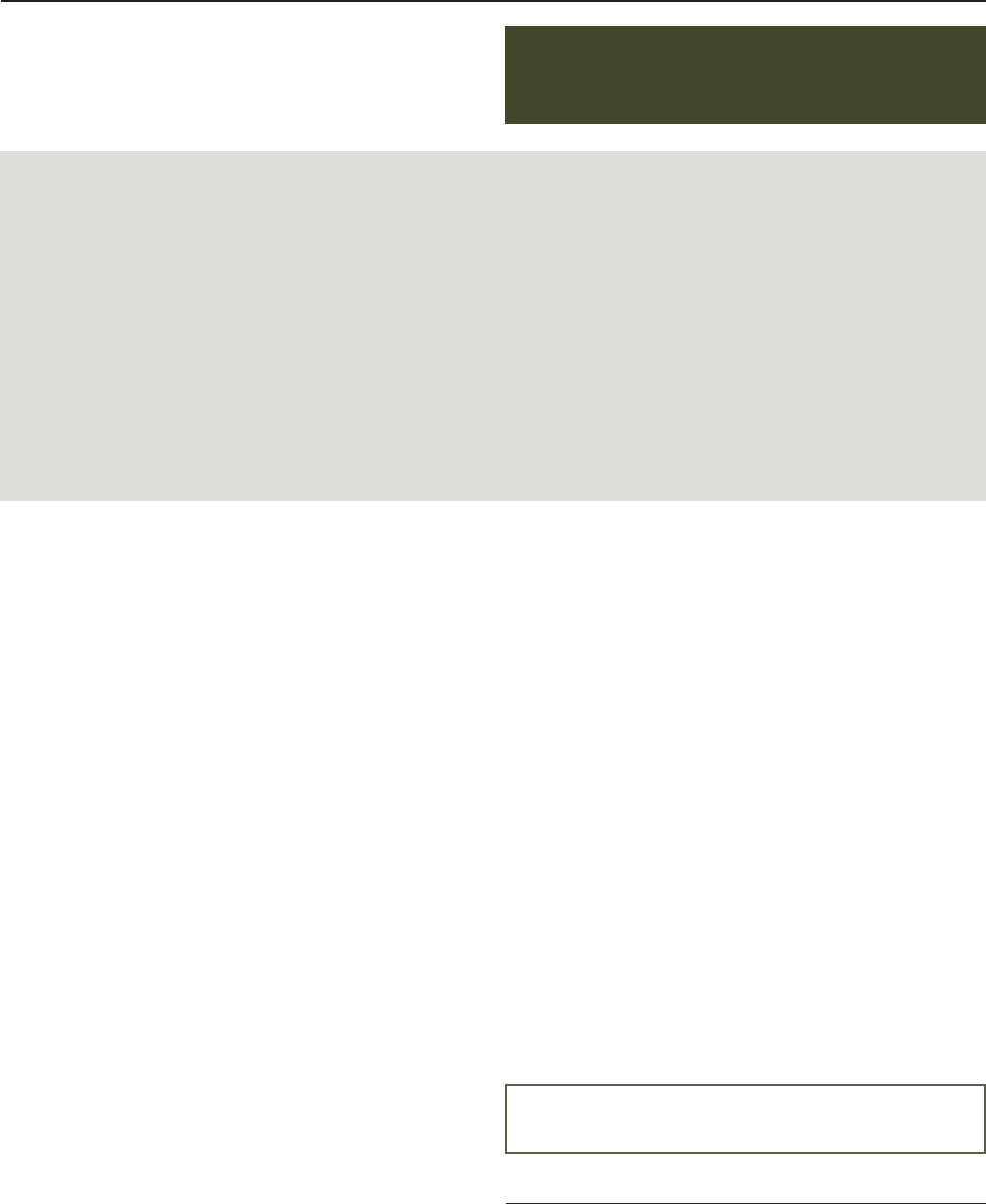

Table 1. Caries-risk Assessment Form for 0-5 Years Old

Use of this tool will help the health care provider assess the child’s risk for developing caries lesions. In addition, reviewing specic

factors will help the practitioner and parent understand the variable inuences that contribute to or protect from dental caries.

Factors

High risk Moderate risk Low risk

Risk factors, social/behavioral/medical

Mother/primary caregiver has active dental caries Yes

Parent/caregiver has life-time of poverty, low health literacy Yes

Child has frequent exposure (>3 times/day) between-meal sugar-containing

snacks or beverages per day

Yes

Child uses bottle or nonspill cup containing natural or added sugar frequently,

between meals and/or at bedtime

Yes

Child is a recent immigrant Yes

Child has special health care needs

α

Yes

Risk factors, clinical

Child has visible plaque on teeth Yes

Child presents with dental enamel defects Yes

Protective factors

Child receives optimally-uoridated drinking water or uoride supplements Yes

Child has teeth brushed daily with uoridated toothpaste Yes

Child receives topical uoride from health professional Yes

Child has dental home/regular dental care Yes

Disease indicators

ß

Child has noncavitated (incipient/white spot) caries lesions

Yes

Child has visible caries lesions Yes

Child has recent restorations or missing teeth due to caries Yes

α

Practitioners may choose a dierent risk level based on specic medical diagnosis and unique circumstances, especially conditions that aect

motor coordination or cooperation.

ß

While these do not cause caries directly or indirectly, they indicate presence of factors that do.

Instructions: Circle “Yes” that corresponds with those conditions applying to a specic patient. Use the circled responses to visualize the balance

among risk factors, protective factors, and disease indicators. Use this balance or imbalance, together with clinical judgment, to assign a caries

risk level of low, moderate, or high based on the preponderance of factors for the individual. Clinical judgment may justify the weighting of one

factor (e.g., heavy plaque on the teeth) more than others.

Overall assessment of the child’s dental caries risk: High Moderate Low

Adapted with permission from the California Dental Association, (Ramos-Gomez et al. )

33

Copyright © October 2007.

BEST PRACTICES: CARIES-RISK ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT

THE REFERENCE MANUAL OF PEDIATRIC DENTISTRY 303

teeth brushed daily with uoridated toothpaste, receiving

topical uoride from a health professional, and having regular

dental care.

11,12

Some limitations with the risk factors include the

following:

• Past caries experience is not particularly useful in young

children, and activity of lesions may be more important

than number of lesions.

• Low salivary ow is dicult to measure and may not

be relevant in young children.

13

• Frequent sugar consumption is hard to quantitate.

• Sociodemographic factors are just a proxy for various

exposures/behaviors which may aect caries risk.

• Predictive ability of various risk factors across the life

span and how risk changes with age have not been

determined.

14

• Genome-level risk factors may account for substantial

variations in caries risk.

Risk assessment tools can aid in the identication of

specic behaviors or risk factors for each individual and allow

dentists and other health care professionals to become more

actively involved in identifying and referring high-risk children.

Tables 1 and 2 incorporate available evidence into practical

tools to assist dental practitioners, physicians, and other non-

dental health care providers in assessing levels of risk for

caries development in infants, children, and adolescents. As

new evidence emerges, these tools can be rened to provide

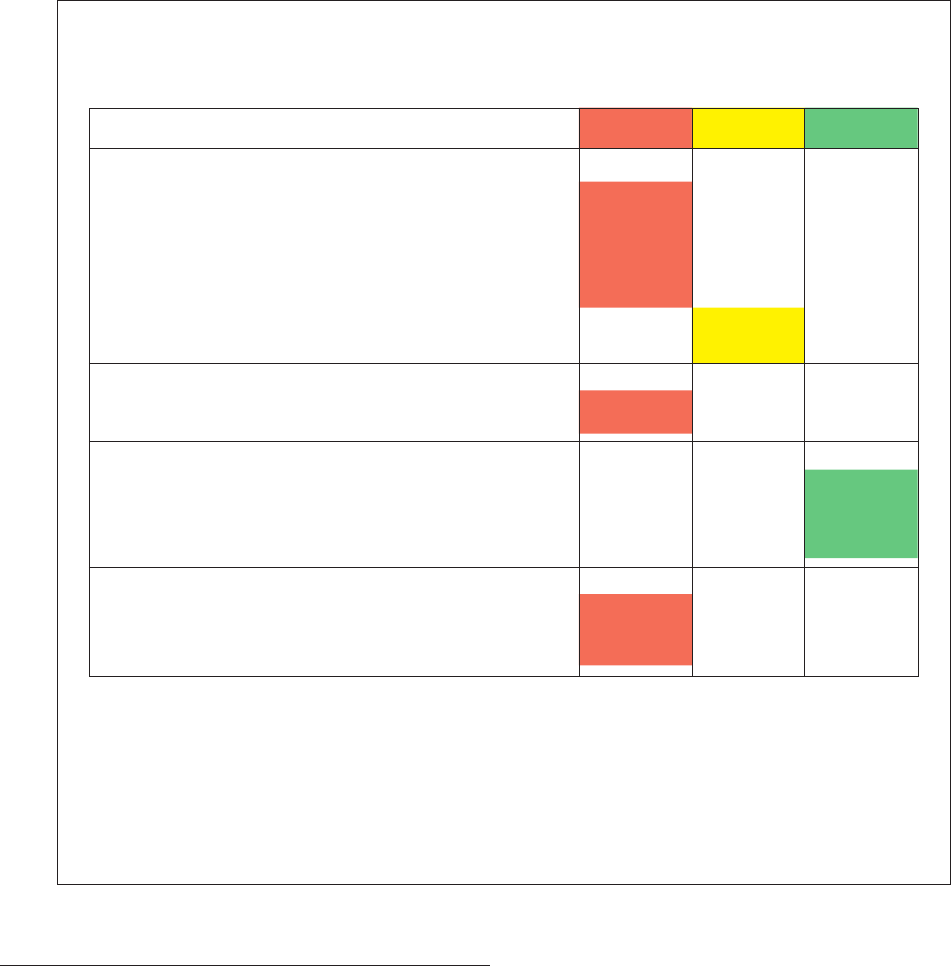

Table 2. Caries-risk Assessment Form for ≥6 Years Old

25

(For Dental Providers)

Use of this tool will help the health care provider assess the child’s risk for developing caries lesions. In addition, reviewing specic

factors will help the practitioner and patient/parent understand the variable inuences that contribute to or protect from dental caries.

Factors

High risk Moderate risk Low risk

Risk factors, social/behavioral/medical

Patient has life-time of poverty, low health literacy Yes

Patient has frequent exposure (>3 times/day) between-meal sugar-containing

snacks or beverages per day

Yes

Child is a recent immigrant Yes

Patient uses hyposalivatory medication(s) Yes

Patient has special health care needs

α

Yes

Risk factors, clinical

Patient has low salivary ow Yes

Patient has visible plaque on teeth Yes

Patient presents with dental enamel defects Yes

Patient wears an intraoral appliance Yes

Patient has defective restorations Yes

Protective factors

Patient receives optimally-fluoridated drinking water Yes

Patient has teeth brushed daily with fluoridated toothpaste Yes

Patient receives topical fluoride from health professional Yes

Patient has dental home/regular dental care Yes

Disease indicators

ß

Patient has interproximal caries lesion(s) Yes

Patient has new noncavitated (white spot) caries lesions Yes

Patient has new cavitated caries lesions or lesions into dentin radiographically Yes

Patient has restorations that were placed in the last 3 years (new patient) or

in the last 12 months (patient of record)

Yes

α

Practitioners may choose a dierent risk level based on specic medical diagnosis and unique circumstances, especially conditions that aect

motor coordination or cooperation.

ß

While these do not cause caries directly or indirectly, they indicate presence of factors that do.

Instructions: Circle “Yes” that corresponds with those conditions that apply to a specic patient. Use the circled responses to visualize the balance among

risk factors, protective factors, and disease indicators. Use this balance or imbalance, together with clinical judgment, to assign a caries risk level of

low, moderate, or high based on the preponderance of factors for the individual. Clinical judgment may justify the weighting of one factor (e.g.,

heavy plaque on the teeth) more than others.

Overall assessment of the dental caries risk: High Moderate Low

Adapted with permission from the California Dental Association, (Featherstone et al.)

34

Copyright © October 2007.

BEST PRACTICES: CARIES-RISK ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT

304 THE REFERENCE MANUAL OF PEDIATRIC DENTISTRY

greater predictably of caries in children prior to disease initia-

tion. Furthermore, the evolution of caries-risk assessment tools

and care pathways can assist in providing evidence for and

justifying periodicity of services, modication of third-party

involvement in the delivery of dental services, and quality of

care with outcomes assessment to address limited resources

and workforce issues.

Care pathways for caries management

Care pathways are documents designed to assist in clinical

decision making; they provide criteria regarding diagnosis and

treatment and lead to recommended courses of action.

15

e

pathways are based on evidence from current peer-reviewed

literature and the considered judgment of expert panels, as

well as clinical experience of practitioners. Care pathways for

caries management in children aged 0-2 and 3-5 years old

were rst introduced in 2011.

16

Care pathways are updated

frequently as new technologies and evidence develop.

Historically, the management of dental caries was based

on the notion that it was a progressive disease that eventually

destroyed the tooth unless there was surgical/restorative inter-

vention. Decisions for intervention often were learned from

unstandardized dental school instruction and then rened by

clinicians over years of practice. It is now known that surgical

intervention of dental caries alone does not stop the disease

process. Additionally, many lesions do not progress, and tooth

restorations have a nite longevity. erefore, modern manage-

ment of dental caries should be more conservative and includes

early detection of noncavitated lesions, identification of an

individual’s risk for caries progression, understanding of the

disease process for that individual, and active surveillance to

apply preventive measures and monitor carefully for signs of

arrest or progression.

Care pathways for children further rene the decisions

concerning individualized treatment and treatment thresholds

based on a specic patient’s risk levels, age, and compliance

with preventive strategies (Tables 3 and 4). Such clinical path-

ways yield greater probability of success, fewer complications,

and more ecient use of resources than less standardized

treatment.

15

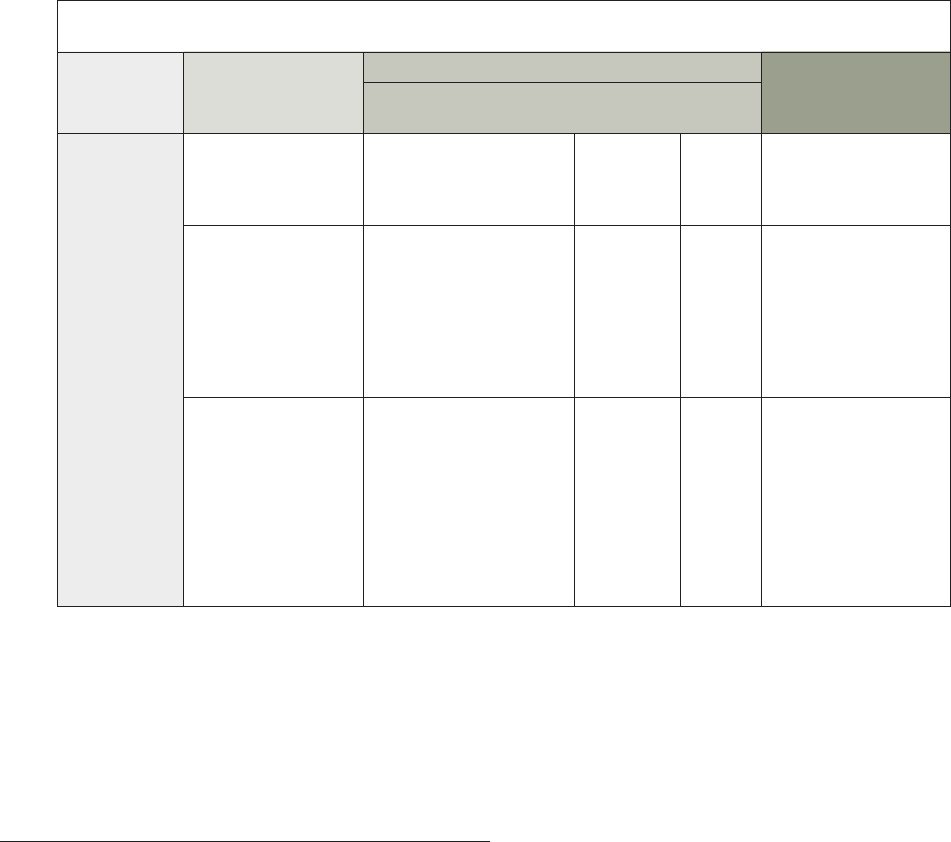

Table 3. Example of Caries Management Pathways for 0-5 Years Old

Risk category Diagnostics

Preventive interventions

Restorative

interventions

Fluoride Dietary

counseling

Sealants

Low risk – Recall every six to 12

months

– Radiographs every 12

to 24 months

– Drink optimally-uoridated

water

– Twice daily brushing with

uoridated toothpaste

Yes Yes – Surveillance

Moderate risk – Recall every six months

– Radiographs every six

to 12 months

– Drink optimally-uoridated

water (alternatively, take

uoride supplements

with uoride-decient

water supplies)

– Twice daily brushing with

uoridated toothpaste

– Professional topical treatment

every six months

Yes Yes – Active surveillance of non-

cavitated (white spot)

caries lesions

– Restore cavitated or

enlarging caries lesions

High risk – Recall every three months

– Radiographs every six

months

– Drink optimally-uoridated

water (alternatively, take

uoride supplements

with uoride-decient

water supplies)

– Twice daily brushing with

uoridated toothpaste

– Professional topical treatment

every three months

– Silver diamine uoride on

cavitated lesions

Yes Yes – Active surveillance of non-

cavitated (white spot)

caries lesions

– Restore cavitated or

enlarging caries lesions

– Interim therapeutic

restorations (ITR) may

be used until permanent

restorations can be

placed

Notes for caries management pathways table:

Twice daily brushing: Parental supervision of a “smear” amount of uoridated toothpaste for children under age three, pea-size amount

for children ages three through ve.

Surveillance: Periodic monitoring for signs of caries progression; active surveillance: active measures by parents and oral health professionals

to reduce cariogenic environment and monitor possible caries progression.

Silver diamine uoride: Use of 38 percent silver diamine uoride to assist in arresting caries lesions; informed consent: particularly

highlighting expected staining of treated lesions.

Sealants: e decision to seal primary and permanent molars should account for both the individual-level and tooth-level risks.

BEST PRACTICES: CARIES-RISK ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT

THE REFERENCE MANUAL OF PEDIATRIC DENTISTRY 305

Content of the present caries management protocol is

based on results of systematic reviews and expert panel

recommendations that provide better understanding of and

recommendations for diagnostic, preventive, and restorative

treatments. Recommendations for the use of uoridated

toothpaste are based on four systematic reviews

17-20

,

dietary

uoride supplements are based on the Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention’s uoride guidelines

21

, professionally-

applied and prescription strength home-use topical uoride are

based on two systematic reviews

19,22

, the use of silver diamine

uoride to arrest caries lesions also is based on two systematic

reviews

23,24

.

Radiographic diagnostic recommendations are

based on the uniform guidelines from national organizations.

25

Recommendations for pit-and-ssure sealants are based on

two systematic reviews

26,27

, with only the American Dental

Association/AAPD review addressing sealants for primary

teeth. Dietary interventions are based on a systematic review of

strategies to reduce sugar-sweetened beverages.

28

Caries risk is

assessed at both the individual level and tooth level. Treatment

of caries with interim therapeutic restorations is based on

the AAPD policy and recommended best practices.

29,30

Active

surveillance (prevention therapies and close monitoring) of

enamel lesions is based on the concept that treatment of

disease may only be necessary if there is disease progression,

31

and that caries can arrest without treatment.

32

Other approaches to the assessment and treatment of dental

caries will emerge with time and, with evidence of eectiveness,

may be included in future guidelines on caries-risk assessment

and care pathways.

Recommendations

1. Dental caries-risk assessment, based on a child’s age,

social/behavioral/medical factors, protective factors, and

clinical ndings, should be a routine component of new

and periodic examinations by oral health and medical

providers.

2. While there is not enough information at present to have

quantitative caries-risk assessment analyses, estimating

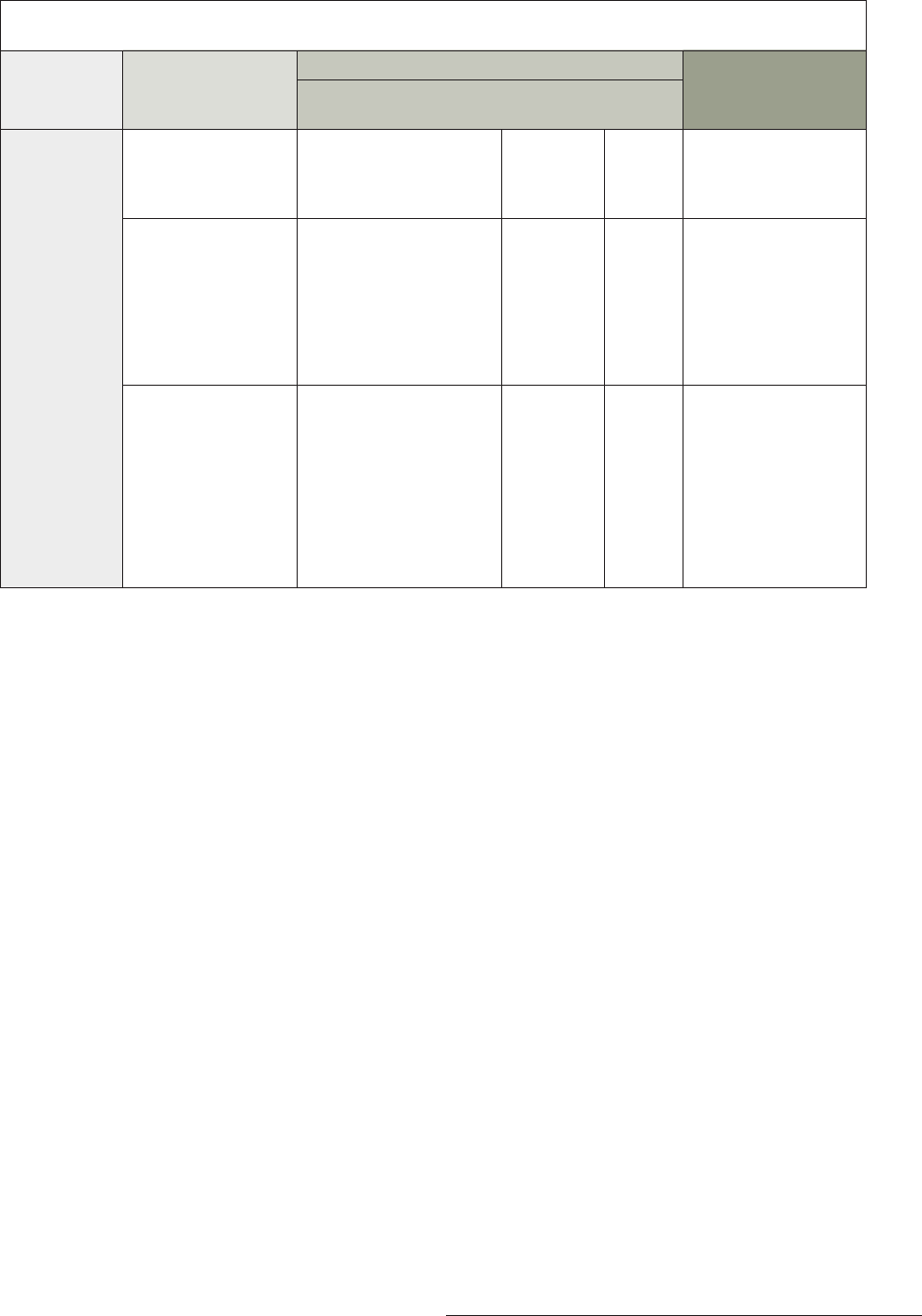

Table 4. Example of a Caries Management Pathways for ≥6 Years Old

Risk category Diagnostics

Preventive interventions

Restorative

interventions

Fluoride Dietary

counseling

Sealants

Low risk – Recall every six to

12 months

– Radiographs every

12 to 24 months

– Drink optimally-uoridated

water

– Twice daily brushing with

uoridated toothpaste

Yes Yes – Surveillance

Moderate risk – Recall every six months

– Radiographs every

six to 12 months

– Drink optimally-uoridated

water (alternatively, take

uoride supplements

with uoride-decient

water supplies)

– Twice daily brushing with

uoridated toothpaste

– Professional topical treatment

every six months

Yes Yes – Active surveillance of non-

cavitated (white spot)

caries lesions

– Restore cavitated or

enlarging caries lesions

High risk – Recall every three

months

– Radiographs every

six months

– Drink optimally-uoridated

water (alternatively, take

uoride supplements

with uoride-decient

water supplies)

– Brushing with 0.5 percent

uoride gel/paste

– Professional topical treatment

every three months

– Silver diamine uoride on

cavitated lesions

Yes Yes – Active surveillance of non-

cavitated (white spot)

caries lesions

– Restore cavitated or

enlarging caries lesions

– Interim therapeutic

restorations (ITR) may

be used until permanent

restorations can be

placed

Notes for caries management pathways table:

Twice daily brushing: Parental supervision of a pea-size amount of uoridated toothpaste for children six years of age.

Surveillance: Periodic monitoring for signs of caries progression; active surveillance: active measures by parents and oral health professionals

to reduce cariogenic environment and monitor possible caries progression.

Silver diamine uoride: Use of 38 percent silver diamine uoride to assist in arresting caries lesions; informed consent: particularly

highlighting expected staining of treated lesions.

Sealants: Although studies report unfavorable cost/benet ratio for sealant placement in low caries-risk children, expert opinion favors

sealants in permanent teeth of low-risk children based on possible changes in risk over time and dierences in tooth anatomy. e

decision to seal primary and permanent molars should account for both the individual-level and tooth-level risks.

BEST PRACTICES: CARIES-RISK ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT

306 THE REFERENCE MANUAL OF PEDIATRIC DENTISTRY

children at low, moderate, and high caries risk by a

preponderance of risk and protective factors and disease

indicators will enable a more evidence-based approach to

medical provider referrals, as well as establish periodicity

and intensity of diagnostic, preventive, and restorative

interventions.

3. Care pathways, based on a child’s age and caries risk,

provide health providers with criteria and protocols for

determining the types and frequency of diagnostic,

preventive, and restorative interventions for patient-

specic management of dental caries.

References

1. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. e use of a

caries-risk assessment tool (CAT) for infants, children,

and adolescents. Pediatr Dent 2002;24(7):15-7.

2. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Caries-risk

assessment and management for infants, children, and

adolescents. e Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry.

Chicago, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry;

2019:220-4.

3. Cagetti MG, Bonta G, Cocco F, Lingstrom P, Strohmenger

L, Campus G. Are standardized caries risk assessment

models eective in assessing actual caries status and future

caries increment? A systematic review. BMC Oral Health

2018;18(1):123.

4. Moyer V. Prevention of dental caries in children from

birth through age 5 years: U.S. Preventive Services Task

Force recommendation statement. Pediatrics 2014;133

(6):1102-10.

5. Bratthall D, Hansel Petersson G. Cariogram--A

multifactorial risk assessment model for a multifactorial

disease. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2005;33(4):

256-64.

6. Featherstone JBD, Domejean-Orliaguet S, Jenson L, et al.

Caries risk assessment in practice for age 6 through adult.

J Calif Dent Assoc 2007;35(10):703-13.

7. Featherstone JDB, Crystal YO, Alston, P, et al. A compar-

ison of four caries risk assessment methods. Front Oral

Health 2021;2:656558. Available at: “https://www.

frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/froh.2021.656558/full”.

Accessed August 26, 2022.

8. Harrison-Barry L, Elsworthy K, Pukallus M, et al. e

Queensland Birth Cohort Study for Early Childhood

Caries: Results at 7 years. JDR Clin Trans Res 2022;7(1):

80-9.

9. Fontana M, Carrasco-Labra A, Spallek H, Eckert G,

Katz B. Improving caries prediction modeling: A call for

action. J Dent Res 2020;99(11):1215-0.

10. Kirthiga M, Murugan M, Saikia A, Kirubakaran R. Risk

factors for early childhood caries: A systematic meta-

analysis of case control and cohort studies. Pediatr Dent

2019;41(2):95-112.

11. American Dental Association. Guidance on caries risk

assessment in children, June 2018. Available at: “https:

//www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/DQA/CRA_Report.pdf

?la=en”. Accessed March 11, 2022.

12. Machiulskiene V, Campus G, Carvalho JC, et al. Termi-

nology of dental caries and dental caries management:

Consensus report of a workshop organized by ORCA

and Cariology Research Group of IADR. Caries Res

2020;54(1):7-14.

13. Alaluusua S, Malmivirta R. Early plaque accumulation:

A sign for caries risk in young children. Community

Dent Oral Epidemiol 1994;22(10):273-6.

14. Divaris K. Predicting dental caries outcomes in childhood:

A “risky” concept. J Dent Res 2016;95(3):248-54.

15. Rotter T, Kinsman L, James E, et al. e eects of clini-

cal pathways on professional practice, patient outcomes,

length of stay, and hospital costs: Cochrane systematic

review and meta-analysis. Eval Health Prof 2012;35(1):

3-27.

16. Ramos-Gomez F, Ng MW. Into the future: Keeping

healthy teeth caries free. Pediatric CAMBRA protocols. J

Cal Dent Assoc 2011;39(10):723-32.

17. Santos APP, Nadanovsky P, Oliveira BH. A systematic

review and meta-analysis of the eects of uoride tooth-

paste on the prevention of dental caries in the primary

dentition of preschool children. Community Dent Oral

Epidemiol 2013;41(1):1-12.

18. Wright JT, Hanson N, Ristic H, et al. Fluoride toothpaste

efficacy and safety in children younger than 6 years. J

Am Dent Assoc 2014;145(2):182-9.

19. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network: SIGN 138:

Dental interventions to prevent caries in children, March

2014. Available at: “https://www.sign.ac.uk/assets/sign

138.pdf ”. Accessed March 17, 2022.

20. Walsh T, Worthington HV, Glenny AM, Marinho VCC,

Jeroncic A. Fluoride toothpastes of dierent concentra-

tions for preventing dental caries. Cochrane Database

Sys Rev 2019;3(3):CD007868. Available at: “https://

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6398117/”.

Accessed September 12, 2022.

21. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommen-

dations for using uoride to prevent and control dental

caries in the United States. MMWR Recomm Rep 2001;

50(RR14):1-42.

22. Weyant RJ, Tracy SL, Anselmo T, et al. Topical uoride

for caries prevention: Executive summary of the updat-

ed clinical recommendations and supporting systematic

review. J Am Dent Assoc 2013;144(11):1279-91.

23. Crystal YO, Marghalani AA, Ureles SD, et al. Use of

silver diamine uoride for dental caries management in

children and adolescents, including those with special

health care needs. Pediatr Dent 2017;39(5):135-45.

BEST PRACTICES: CARIES-RISK ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT

THE REFERENCE MANUAL OF PEDIATRIC DENTISTRY 307

24. Slayton R, Araujo M, Guzman-Armstrong S, et al.

Evidence-based clinical practice guideline for non-

restorative management of dental caries. J Am Dent Assoc

2018;149(10):837-49.

25. U.S. Food and Drug Administration, American Dental

Association, Department of Health and Human Services.

Dental Radiographic Examinations for Patient Selection

and Limiting Radiation Exposure, 2012. Available at:

“https://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Member%20Center

/FIles/Dental_Radiographic_Examinations_2012.pdf”.

Accessed March 17, 2022.

26. Wright JT, Tampi MP, Graham L, et al. Sealants for

preventing and arresting pit-and-ssure occlusal caries in

primary and permanent molars. A systematic review of

randomized controlled trials–A report of the American

Dental Association and the American Academy of

Pediatric Dentistry. Pediatr Dent 2016;38(4):282-94.

E1-E4. Erratum in: Pediatr Dent 2017;39(2):100. Avail-

able at: “https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27557916/”.

September 12, 2022.

27. Ahovuo‐Saloranta A, Forss H, Walsh T, Nordblad A,

Mäkelä M, Worthington HV. Pit and ssure sealants for

preventing dental decay in permanent teeth. Cochrane

Database Sys Rev 2017;7(7):CD001830. Available at:

“https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC63

98117/”. September 12, 2022.

28. Vercammen KA, Frelier JM, Lawery CM, McGlone ME,

Ebbeling CB, Bleich SN. A systematic review of strategies

to reduce sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among

0-year to 5-year-olds. Obes Rev 2018;19(11):1504-24.

29. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on

interim therapeutic restorations (ITR). The Reference

Manual of Pediatric Dentistry. Chicago, Ill.: American

Academy of Pediatric Dentistry; 2022:78-9.

30. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Pediatric

restorative dentistry. e Reference Manual of Pediatric

Dentistry. Chicago, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatric

Dentistry; 2022:401-14.

31. Parker C. Active surveillance: Toward a new paradigm in

the management of early prostate cancer. Lancet Oncol

2004;5(2):101-6.

32. Ekstrand KR, Bakhshandeh A. Martignon S. Treatment

of proximal superficial caries lesions on primary molar

teeth with resin infiltration and fluoride varnish versus

fluoride varnish only: Efficacy after 1 year. Caries Res

2010;44(1):41-6.

33. Ramos-Gomez FJ, Crall J, Gansky SA, Slayton RL,

Featherstone JDB. Caries risk assessment appropriate for

the age 1 visit (infants and toddlers). J Calif Dent Assoc

2007;35(10):687-702.

34. Featherstone JBD, Domejean-Orliaguet S, Jenson L, et

al. Caries risk assessment in practice for age 6 through

adult. J Calif Dent Assoc 2007;35(10):703-13.