CONDITIONS OF WORK AND EMPLOYMENT SERIES No. 101

Zero-Hours Work in the United Kingdom

Abi Adams

Jeremias Prassl

INWORK

Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 101

Inclusive Labour Markets, Labour Relations

and Working Conditions Branch

Zero-Hours Work in the United Kingdom

Abi Adams

*

Jeremias Prassl

*

*

* Associate Professor in the Department of Economics and Fellow of New College.

** Associate Professor in the Faculty of Law and Fellow of Magdalen College.

INTERNATIONAL LABOUR OFFICE - GENEVA

Copyright © International Labour Organization 2018

Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention.

Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated.

For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publications (Rights and Licensing),

International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour

Office welcomes such applications.

Libraries, institutions and other users registered with a reproduction rights organization may make copies in accordance

with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to find the reproduction rights organization in your

country.

Conditions of work and employment series ; no. 101, ISSN: 2226-8944 (print); 2226-8952 (web pdf)

First published 2018

Cover: DTP/Design Unit, ILO

The designations employed in ILO publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the presentation

of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Labour Office

concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its

frontiers.

The responsibility for opinions expressed in signed articles, studies and other contributions rests solely with their authors,

and publication does not constitute an endorsement by the International Labour Office of the opinions expressed in them.

Reference to names of firms and commercial products and processes does not imply their endorsement by the International

Labour Office, and any failure to mention a particular firm, commercial product or process is not a sign of disapproval.

Information on ILO publications and digital products can be found at: www.ilo.org/publns.

Printed in Switzerland.

Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 101 iii

ExecutiveSummary

In this report, we provide a detailed study of zero-hours work in the United Kingdom. An initial section

defines zero-hours work, emphasising key characteristics as well as overlaps between zero-hours work

and other casual work arrangements, and draws parallels both with historic instances of on-demand work

and current experiences of ‘if and when’ contracts in the Republic of Ireland.

Section two presents the most recent available data on the prevalence and key characteristics of zero-

hours workers and employers, explaining the evolution of such work arrangements as well as the technical

issues which make measuring the phenomenon through official labour market statistics particularly

difficult. Section three complements the empirical evidence with an analysis of the effects of zero-hours

work for workers, employers, and society more broadly. Our focus is not limited to the legal situation of

those working under such arrangements, but also includes questions of social security entitlements, and

wider implications such as business flexibility, cost savings, and productivity growth.

As the fourth section explains, a growing awareness of the growth of zero-hours contracts from 2011

onwards brought about a marked increase in public discussion of the phenomenon, leading eventually to

(limited) legislative intervention. We explore the positions taken by the social partners, before analysing

historical as well as recent legislative responses, and setting out a case study of Parliament’s response to

a particularly egregious instance of labour standards violations in warehouses operated by the sports

equipment chain Sports Direct. A brief concluding section, finally, turns to a series of policy

recommendations and broader considerations, with a view to finding a model in which (some of) the

flexibility of zero-hours work arrangements might be preserved, without however continuing to pose a

real threat to decent working conditions in the United Kingdom’s labour market.

iv Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 101

TABLEOFCONTENTS

Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................................. iii

1. Defining Zero-Hours Work .............................................................................................................................. 1

a. The ‘Zero-Hours Contract’ ............................................................................................................................ 1

i. Common Parlance, Statistical, and Legal Definitions .............................................................................. 1

ii. Relationship to other casual work arrangements....................................................................................... 3

b. Parallels and Precedent ................................................................................................................................. 4

i. Historical Development ............................................................................................................................. 4

ii. The Irish Experience .................................................................................................................................. 5

2. Prevalence ........................................................................................................................................................... 7

a. Key Statistics ................................................................................................................................................... 7

i. Measurement .............................................................................................................................................. 7

ii. Numbers ..................................................................................................................................................... 9

b. Detailed Characteristics ............................................................................................................................... 12

i. Earnings on ZHCs .................................................................................................................................... 12

ii. Hours and Working Patterns .................................................................................................................... 13

iii. Worker Characteristics ............................................................................................................................ 15

iv. Employer Characteristics ......................................................................................................................... 18

v. Social Care ............................................................................................................................................... 20

3. The Impact of Zero-Hours Work .................................................................................................................. 21

a. What’s the Counterfactual? .......................................................................................................................... 21

b. Workers ......................................................................................................................................................... 22

i. Flexibility? ............................................................................................................................................... 22

ii. Income and Social Security ..................................................................................................................... 23

iii. Legal Implications ................................................................................................................................... 26

iv. Other Factors ............................................................................................................................................ 30

c. Business ......................................................................................................................................................... 31

d. Government and Society ............................................................................................................................... 33

4. Policy Responses .............................................................................................................................................. 34

a. The Position of the Social Partners .............................................................................................................. 34

i. Trade Unions ............................................................................................................................................ 34

ii. Employer Representatives ....................................................................................................................... 35

b. Legislative Responses ................................................................................................................................... 36

c. Parliamentary Inquiry .................................................................................................................................. 37

d. National Minimum Wage Act 1998 .............................................................................................................. 38

5. Conclusion and Recommendations ................................................................................................................ 39

i. Employment Law ..................................................................................................................................... 39

ii. Social Security ......................................................................................................................................... 40

iii. Government Commissioning ................................................................................................................... 40

iv. Broader Outlook ....................................................................................................................................... 40

Conditions of Work and Employment Series ......................................................................................................... 41

Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 101 1

1. DefiningZero‐HoursWork

This section addresses a series of fundamental definitional issues. We turn, first, to the many different

definitions of the contractual arrangements underpinning zero-hours work: despite widespread

assumptions to the contrary, there is no such thing as ‘the’ zero-hours contract (ZHC). It is important to

see zero-hours work as a wide spectrum of contractual arrangements, centred on the absence of guaranteed

hours for the worker. Having set out different definitions and sample clauses, we situate zero-hours work

in the broader context of precarious or casual work arrangements. A second sub-section addresses a

further set of misconceptions: that zero-hours work is a relatively novel phenomenon, found exclusively

in UK labour markets. In reality, examples of zero-hours work in its current instantiation can be found as

early as the 1970s; functionally equivalent short-term hire models reach back several centuries, from the

hosiery industry to dock workers in the 19

th

century. Similar arrangements also exist in the Republic of

Ireland, under the label of ‘if and when’ contracts.

a. The‘Zero‐HoursContract’

As the then Secretary of State for Business, Innovation and Skills, Dr Vince Cable MP noted during a

2013 Opposition Day debate in Parliament, definitional problems are at the heart of any discussion of

zero-hours contracts:

There is an issue about what zero-hours contracts actually are; they are not clearly defined.

[…] There are a whole lot of contractual arrangements […] They are enormously varied.

1

In public discourse, the zero-hours label is applied to a wide range of arrangements in which workers are

not guaranteed any hours of work in a particular period. At least in theory, workers party to such

arrangements are often thought at liberty to reject any offer of work made by their employer. The scope

of the term in colloquial usage has expanded in recent years as a result of media attention, not least

because of the rise of the “gig economy”.

i. CommonParlance,Statistical,andLegalDefinitions

A series of definitions can be found in the academic literature, official government policy documents,

statutory enactments, and statistical surveys. While a necessary element of definitions is a lack of

guaranteed hours, as we shall see, there is a great deal of heterogeneity in the realities of work that falls

under the label “zero-hours contracts”. Simon Deakin and Gillian Morris suggest that zero-hours

arrangements encompass all

cases ‘where the employer unequivocally refuses to commit itself in advance

to make any given quantum of work available.’

2

Mark Freedland and Nicola Kountouris bring out this

diversity even more clearly, when they refer to ‘work arrangements in which the worker is in a personal

work relation with an employing entity […] for which there are no fixed or guaranteed hours of

remunerated work. These arrangements are variously described as ‘on-call’, ‘intermittent’, or ‘on-

demand’ work, or sometimes referred to as ‘zero-hours contracts’.’

3

1

HC Deb 16 October 2013, vol 567, col 756.

2

S Deakin and G Morris, Labour Law (6th edn Hart 2012) 167.

3

M Freedland and N Kountouris, The Legal Construction of Personal Work Relations (OUP, 2012) 318-319.

2 Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 101

Parliament intervention in 2015, resulting in section 27A of the Employment Rights Act of 1996 (‘ERA

1996’),

4

stipulates that:

(1) In this section “zero hours contract” means a contract of employment or other worker’s

contract under which—

(a) the undertaking to do or perform work or services is an undertaking to do so

conditionally on the employer making work or services available to the worker, and

(b) there is no certainty that any such work or services will be made available to the

worker.

(2) For this purpose, an employer makes work or services available to a worker if the employer

requests or requires the worker to do the work or perform the services.

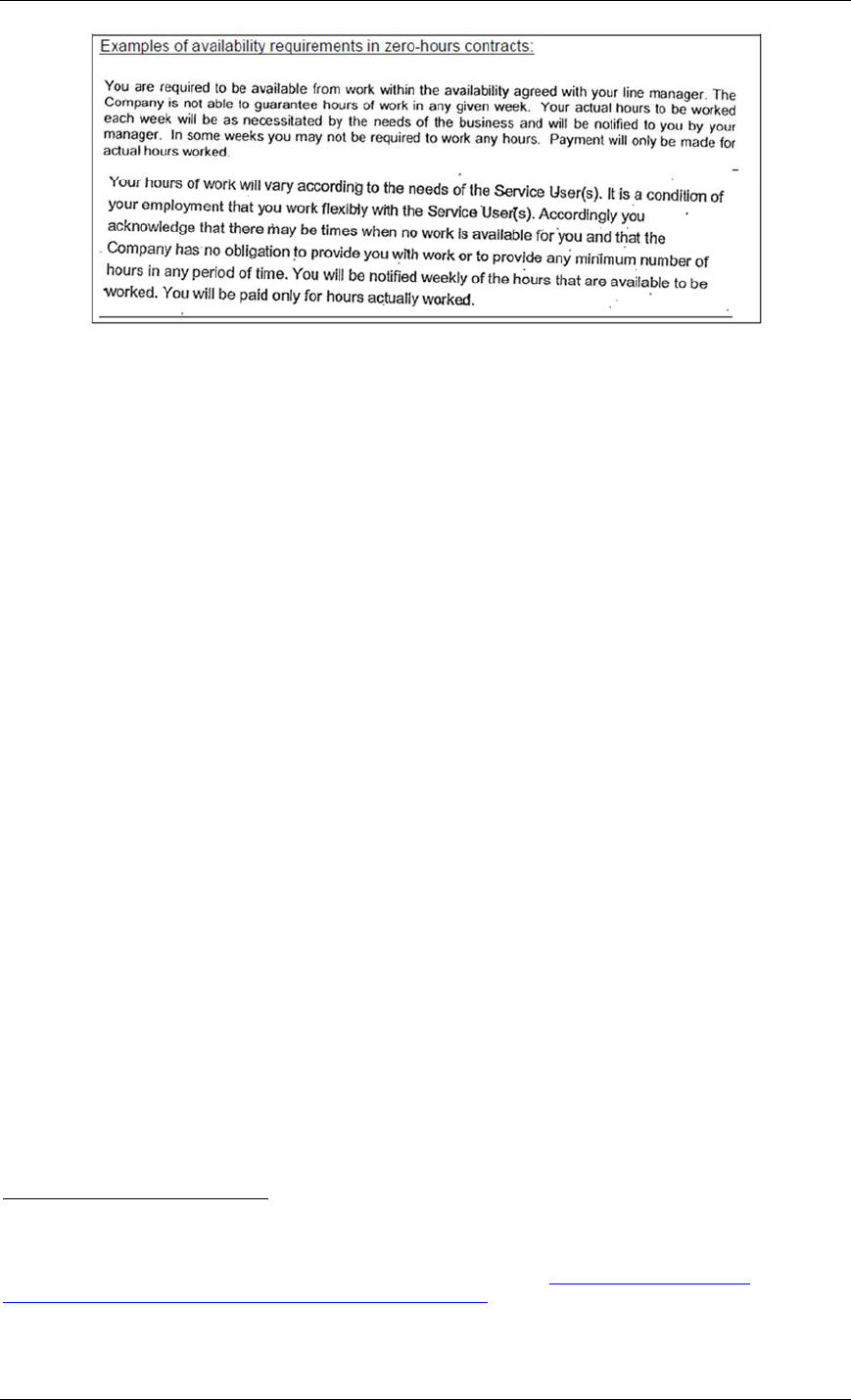

This definition builds on official consultation documents on the use and regulation of zero-hours

arrangements, published by the government in December 2013. There a zero-hours contract was defined

as ‘an employment contract in which the employer does not guarantee the individual any work, and the

individual is not obliged to accept any work offered.’ The consultation illustrated the technical

implementation of such arrangements by means of a specific ‘example of a clause in a zero-hours contract

which does not guarantee a fixed number of hours work per week’:

“The Company is under no obligation to provide work to you at any time and you are under

no obligation to accept any work offered by the Company at any time.”

5

While zero-hours contracts do not guarantee a minimum number of hours, there is heterogeneity across

contracts in stated expectations of work availability and the degree of notification given of when work

will be available. Additional contractual examples to highlight this are given below.

6

Under some

contracts, time when a worker must be available to work if needed must be agreed upon;

7

under others

no such commitment is required. Some contracts state that workers will be notified on a weekly basis

about available work; in others, this commitment is missing. The Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration

Service (Acas) documents that many workers are often not aware that their contracts do not guarantee

any hours as the reality of their day-to-day work experience suggest otherwise. In their opinion, “many

workers experience a false sense of security when it comes to their contractual relationship”.

8

4

For an earlier example of an attempted statutory definition of Zero-Hours Contracts, see the Zero Hours Contracts HC Bill (2013-14) 79

introduced by Andy Sawford MP in the summer of 2013, with a view to making it ‘unlawful to issue a zero hours contract.’ (cl 1(1)). That Bill

sought to define such arrangements in its clause 3(1), identifying them through a combination of factors as follows:

A zero hours contract is a contract or arrangement for the provision of labour which fails to specify guaranteed working

hours and has one or more of the following features—

(a) it requires the worker to be available for work when there is no guarantee the worker will be needed;

(b) it requires the worker to work exclusively for one employer;

(c) a contract setting out the worker’s regular working hours has not been offered after the worker has been employed for

12 consecutive weeks.

5

BIS, Consultation: Zero Hours Employment Contracts (London, December 2013) [‘Consultation’] [11] – [12].

6

N. Pickavance, Zeroed Out: the place of zero-hours contracts in a fair and productive economy (London, 2014), 9 [‘Pickavance’].

7

See discussion of contract terms in House of Commons Business, Innovation and Skills Committee, Employment Practises at Sports

Direct: Third Report of Session 2016-17, 7.

8

Acas, ‘Give and take? Unravelling the true nature of zero-hours contracts’ (2014) Acas Policy Discussion Papers, 6.

Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 101 3

Some have responded to this factual complexity by developing more refined categories. Hugh Collins,

Keith Ewing and Aileen McColgan, for example, draw a distinction between zero-hours contracts, where

‘the employee promises to be ready and available for work, but the employer merely promises to pay for

time actually worked according to the requirements of the employer’ and ‘arrangements for casual work’

where ‘again the employer does not promise to offer any work, but equally in this case the employee does

not promise to be available when required.’

9

This distinction is relevant for comparisons of the UK and

Republic of Ireland experiences. In Ireland, a distinction is drawn between zero-hours contracts, which

do not guarantee work but an individual is contractually required to make themselves available to work,

and ‘if-and-when contracts’, which do not guarantee works and do not require an individual to be

available for work at any point.

10

The heterogeneity in work experiences under zero-hours contracts has created significant difficulties in

measuring the prevalence and characteristics of ‘the’ phenomenon. The main official data source on

information on zero-hours contracts is the Labour Force Survey (LFS), which is administered by the

Office for National Statistics (ONS). Here, the work arrangement is defined as:

“[A zero hours contract] is where a person is not contracted to work a set number of

hours, and is only paid for the number of hours that they actually work”

11

However, this definition is only provided to respondents if they ask explicitly for clarification of the term.

The precise working definition of a zero-hours contract in the LFS is, therefore, deeply unclear as

classification is primarily a matter of respondent self-identification. This has caused deep reservations

about the quality of the statistical evidence, to which we return in Section 2.

ii. Relationshiptoothercasualworkarrangements

Given the diverse set of work arrangements that the term applies to, the ‘zero-hours contract’ label should

not be seen as representing a clear or overarching category or organising principle of precarious work.

There is a considerable degree of heterogeneity of temporary work,

12

reflected in ‘a growing

nomenclature of ‘atypical’ and ‘non-standard’ work, apart from commonly used categories such as

temporary, part-time and self-employed work. Terms include ‘reservist’; ‘on-call’, and ‘as and when’

contracts; ‘regular casuals’; ‘key-time’ workers; ‘min-max’ and ‘zero-hours’ contracts.’

13

Indeed, the

9

H Collins, K Ewing and A McColgan, Labour Law (CUP 2012) 243.

10

M O’Sullivan et al, A Study on the Prevalence of Zero Hours Contracts among Irish Employers and their Impact on Employees (University

of Limerick, 2015).

11

User Guide: Volume 3 – Details of LFS Variables, Labour Force Survey, February 2014. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/guide-

method/method-quality/specific/labour-market/labour-market-statistics/index.html

12

D McCann, Regulating Flexible Work (OUP 2008) 102.

13

L Dickens, ‘Exploring the Atypical: Zero Hours Contracts’ (1997) 26 ILJ 263.

4 Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 101

various categories of ‘atypical’ work can frequently overlap, for example where agency work

incorporates a ‘zero-hours contract dimension’.

14

Relationship to Self-Employment and “Gig Work”. The distinction between zero-hours work

arrangements and self-employment has particular economic and legal significance in the UK. The self-

employed are not subject to minimum wage legislation nor working time regulation. Self-employment is

also tax advantaged for both workers and firms; National Insurance Contributions (NICs) are 3% lower

for the self-employed compared to employees, and employers pay 13.8% NICs on employee income.

These differences in tax rates are not met with significant differenc es in social security entitlements.

15

The distinction between the self-employed and zero-hours workers has acquired greater urgency in the

last year with increasing media and policy interest in the rise of the on-demand economy and “gig-work”.

Developments in communications technology have supposedly led to the emergence of new forms of

employment ‘located in the grey and often uncharted territory between employment contracts and

freelance work’.

16

There is a great deal of heterogeneity in the types of working relationships that are

labelled as part of this phenomenon. Among the most salient examples in the UK are ‘ride-sharing’ app,

Uber, and food delivery company, Deliveroo.

17

Firms in this sector, including Uber and Deliveroo, insist that their workers are independent contractors,

while recent UK Employment Tribunal rulings suggest that their workforce should be classified as

individuals working on zero-hour contracts. For example, in Aslam v Uber BV, the tribunal ruled that

Uber drivers are workers within sec 230(3)(b) of the ERA 1996 given the high degree of control exerted

by the firm.

18

We return to this point in Section 3.

b. ParallelsandPrecedent

In defining the zero-hours contract, it is equally important to note what zero-hours work is not: the

phenomenon is neither a recent labour market development, nor is it unique to the United Kingdom.

i. HistoricalDevelopment

In exploring the historical development of zero-hours work, two important dimensions should be

highlighted. First, that as regards modern labour markets, arrangements akin to zero-hours work have

been recorded in the literature and judicial proceedings at least since the 1970s, most recently coming to

public consciousness in the 1990s. Second, that historical examples can even be found much further back:

a vast number of industries in the 19

th

century, from hosiery manufacturing to dock labour, were built

around an employment model in which workers were not guaranteed any amount of fixed work from one

week, or even one day, to the next.

Modern use of zero-hours arrangements should thus not be seen as a new phenomenon but rather part of

a much larger ‘tendency toward numerical flexibility [which has been] particularly marked [since] the

1980s’.

19

Litigation arising from the use of zero-hours contracts to allow employers numerical flexibility

14

J O’Connor, ‘Precarious Employment and EU Employment Regulation’ in G Ramia, K Farnsworth and Z Irving, Social Policy Review 25:

Analysis and Debate in Social Policy’ (OUP 2013) 238.

15

A Adams, J Freedman and J Prassl, Different Ways of Working (Oxford, 2016).

16

J. Prassl and M. Risak, ‘Uber, Taskrabbit & Co: Platforms as Employers? Rethinking the Legal Analysis of Crowdwork’ (2017), 37

Comparative Law and Policy Journal 619.

17

J Prassl, Humans as a Service (OUP 2018).

18

Aslam, Farrar and Ors v Uber (Case No 2202550/2015; decision of 28 October 2016). See also R Hunter and J Prassl, Worker Status for

App-Drivers: Uber-rated?, Oxford Human Rights Hub Blog 21

st

November 2016.

19

S Fredman, ‘Labour Law in Flux: The Changing Composition of the Workforce’ (1997) 26 ILJ 337, 339. The effects were originally

particularly marked in the case of female workers (339-340) and industries such as construction and dock-working (340), or trawler working.

See also P Leighton and R Painter, ‘“Task” and “Global” Contracts of Employment’ (1986) 15 ILJ 127; A McColgan, Just Wages for Women

(OUP 1997) 391.

Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 101 5

and attempt to avoid the application of statutory protection can be traced back nearly forty years.

20

In the

1978 decision of Mailway,

21

for example, the claimant postal packer ‘could and would only attend for

work in accordance with the need expressed by the employers.’

22

Discussion of zero-hours contracts can also be found in the academic literature prior to their recent rise

to notoriety.

23

A study by Katherine Cave in the 1990s showed the already widespread use of ‘something

that could be classified as zero hours contracts’;

24

with a strong growth trend as an area where there has

been abuse’

25

continuing in the subsequent decade.

26

The work arrangement even merited an explicit

mention in New Labour’s 1998 White Paper on ‘Fairness at Work’;

27

perhaps in response to one of the

earliest examples of public controversy, when Burger King’s practice to pay staff only for time spent

actually serving customers was exposed in the mid-1990s.

28

The (then) government there welcomed

‘views on whether further action should be taken to address the potential abuse of zero hours contracts

and, if so, how to take this forward without undermining labour market flexibility.’

29

ii. TheIrishExperience

Parallels can also be drawn with other contemporary labour markets, notably in the Republic of Ireland.

There, a distinction is drawn between zero-hours and ‘if and when’ contracts, as referenced in Section

1(a). The key difference between the use of the two terms in Ireland is whether individuals are

contractually required to make themselves available for work with an employer: zero-hours contracts

require individuals to be available for work while if-and-when contracts do not.

30

A recent study the

University of Limerick, commissioned by the Irish government’s Department of Jobs, Enterprise and

Innovation, provides a detailed examination of contracts with no guaranteed hours in the context of the

Irish economy.

31

Similar issues regarding definition, measurement, legal status, and policy arise in the

UK and Irish contexts. As we shall explore in later sections, the debate in the Irish context is similarly

skewed by a focus on the benefits of flexibility by employers’ organisation and on income insecurity by

trade unions.

In the UK, if-and-when work arrangements would be classified as zero-hours arrangements. It is unclear

how many of the zero-hours arrangements in the UK would be classified as if-and-when contracts if the

Irish definitions were applied. However, the recent UK ban on so-called ‘exclusivity clauses’, which

prevent workers on zero-hours arrangements from accepting work from another employer, might have

limited the prevalence of zero-hours contracts in the Irish sense of the term.

Policy recommendations arising from the University of Limerick report are more substantive than those

arising from the UK consultation, aiming to provide mechanisms to regularise work patterns to provide

stability for workers whilst retaining flexibility for employers. The proposals include legislative

provisions for guaranteeing hours and providing notice of work and its cancellation. It is suggested that

employers provide a written statement of terms and conditions of employment on the first day of work,

20

In the instance cited, the employer’s minimum guarantee payment for employees within the meaning of s 22(1) of the Employment

Protection Act 1975.

21

Mailway (Southern) Ltd v Willsher [1978] ICR 511 (EAT).

22

ibid 513G. See H Collins, K Ewing and A McColgan, Labour Law (CUP 2012) 163.

23

The earliest mention of the label in the leading specialist journal appears to be in L Watson, ‘Employees and the Unfair Contract Terms

Act’ (1995) 24 ILJ 323, 323.

24

K Graven, Zero Hours Contracts: a Report into the Incidence and Implications of Such Contracts (University of Huddersfield, 1997); as

discussed in L Dickens, ‘Exploring the Atypical: Zero Hours Contracts’ (1997) 26 ILJ 262, 263.

25

J Lourie, Fairness at Work – Research Paper 98/99 (HC Library, London 1998) 26-27.

26

B Kersley et al, Inside the Workplace: First Findings from the 2004 Workplace Employment Relations Survey (DTI, London 2005).

27

DTI, Fairness at Work (White Paper, Cm 3968, 1998) [3.14]ff. For a critical analysis on point, see B Simpson, ‘Research and Reports’

(1998) 27 ILJ 245, 251; D McCann, Regulating Flexible Work (OUP 2008) 167ff.

28

see eg B Clement, ‘Burger King pays £ 106,000 to Staff Forced to “Clock Off”’ The Independent (London, 19 December 1995). Today this

practice would no longer be possible under the Minimum Wage Act 1998.

29

Fairness at Work (n 27) [3.16].

30

M O’Sullivan et al, A Study on the Prevalence of Zero Hours Contracts among Irish Employers and their Impact on Employees (University

of Limerick, 2015).

31

Ibid.

6 Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 101

including a statement of working hours that are a “true reflection” of the hours required. We will return

to these themes in Section 4.

Finally, the UK and Republic of Ireland are not alone in their use of zero-hours arrangements. They can

be found in varying forms across other European and Commonwealth countries, subject to varying

degrees of regulation as summarised in Table 1.

32

Table 1. Zero Hours Contracts in Europe

Allowed Allowed, heavil

y

re

g

ulated Not

g

enerall

y

allowed Not used/rare

Cyprus

Finland

Ireland

Malta

Norway

Sweden

United Kingdom

Germany

Italy

Netherlands

Slovakia

Austria

Belgium

Czech Republic

Estonia

France

Lithuania

Luxembourg

Bulgaria

Croatia

Denmark

Hungary

Poland

Romania

Slovenia

Spain

Source: A Study on the Prevalence of Zero Hours Contracts among Irish Employers and their Impact on Employees (University of Limerick,

2015); Flexible Forms of Work: ‘very atypical’ contractual arrangements (European Observatory of Working Life, 2010); Full Fact, Zero hours

contracts: is the UK “the odd one out”?

32

Note that some caution is required in cross-country studies of zero-hours arrangements. As noted, their heterogeneity creates issues of

definition and measurement within countries, let alone between. Further, zero-hours contracts may be rarely used in some labour markets if

employers rely on self-employment or substitute forms of casual labour to a greater degree.

Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 101 7

2. Prevalence

This section presents the most recent available data from the Labour Force Survey, ONS Business Survey,

and National Minimum Data Set for Social Care among others, on the prevalence and key characteristics

of zero-hours work in the United Kingdom. A first sub-section sets out the key statistics, explaining the

evolution of zero-hours work and focussing on some of the technical issues which make measuring the

phenomenon through official labour market statistics particularly difficult. A second sub-section then

turns to the specific characteristics of those involved in zero-hours work arrangements, whether as

employees or employers.

In summary, our calculations show that approximately 6% of contracts on which work is performed in

the UK do not guarantee minimum hours and 10% of employers make some use of zero hours work

arrangements. Wage rates and hours worked are significantly lower on average under zero-hours

arrangements compared to alternative work arrangements. Zero-hours contracts are associated with a 35%

lower median hourly wage and ten fewer hours worked per week on average when compared to other

types of contracts. Controlling for worker and job characteristics still leaves a 10% zero-hours pay gap

on top of that usually associated with part-time work. Zero-hours work is particularly concentrated

amongst younger workers and students. Women, migrants, non-white workers, and workers with

disabilities are also disproportionately employed under zero hours work arrangements.

a. KeyStatistics

Before setting out the most recent headline figures available in official government statistics and from

private data sources, it is important to sound a note of caution as regards the reliability of key indicators.

i. Measurement

The following paragraphs first address a series of historical problems with the recording of zero-hours

work in the official Labour Force Survey. They highlight, in particular, the impact that an increased

awareness through public dialogue has had on key indicators, and explain recent changes in ONS

methodology enacted to provide reliable estimates of the number of zero-hours workers in the UK

economy.

The LFS is the largest regular social survey of private households in the UK administered by the Office

for National Statistics (ONS). It samples around 40,000 individuals each quarter and collects information

on their employment status. Estimates of the prevalence of zero-hours arrangements come from a question

that relates to work arrangements that might vary weekly or daily. A zero-hours contract is defined as

“where a person is not contracted to work a set number of hours, and is only paid for the number of hours

that they actually work”

33

33

User Guide: Volume 3 – Details of LFS Variables, Labour Force Survey, February 2014. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/guide-

method/method-quality/specific/labour-market/labour-market-statistics/index.html

8 Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 101

Some people have special working hours arrangements that vary daily or weekly. In your (main) job

is your agreed working arrangement any of the following… (up to 3 coded)

a. flexitime

b. annualised hours contract

c. term-time working

d. job sharing

e. nine-day fortnight

f. 4.5 day week

g. zero hours contract

h. on call working

i. none of these

FLEX10 (Applies if in work during reference week.)

2014 Measurement Controversy. Given the aforementioned definitional issues, it should not be

surprising that accurate measurement of zero-hours work is a key challenge for statistical agencies. In

2014, these measurement issues became salient enough to warrant media attention in their own right as

empirical evidence in the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills’ (‘BIS’) official consultation

document came under attack.

Until 2012 the empirical evidence on zero-hours contracts (ZHC) in the UK did not suggest significant

cause for concern. Statistics concerning the prevalence and characteristics of ZHCs were instead

suggestive of a relatively benign labour market phenomena; the prevalence of zero-hours contracts

appeared relatively low,

34

with majority apparently content with the number of hours worked in an

average week.

35

In the final quarter of 2012, responses to the Labour Force Survey suggested that a

negligible percentage of the workforce, a mere 0.8%, were employed on a ZHC.

36

Indeed, the historical

evidence presented in the consultation document suggested that the percentage of workers on a ZHC had

not exceeded 0.9% of total employment since the early 2000s.

37

However, the consensus is now that previous LFS methodology resulted in a gross underestimate of the

prevalence of zero-hours contracts. The LFS estimate in the fourth quarter of 2012 suggested that 250,000

people were on zero-hours contracts.

38

However, this figure was recognised as incredible in the face of

evidence from other sources. For example, Skills for Care, the partner in the sector skills council for

social care, estimates that 307,000 individuals were employed on zero-hours contracts in the social care

sector alone in May 2013.

39

Under the instruction of Sir Andrew Dilnot, the Office for National Statistics revised its estimates of the

prevalence of ZHCs in 2013 to reflect the evidence presented in independent estimates.

40

This, alongside

rising public awareness of the term, led to a substantial increase in estimates of the prevalence of zero

hour contracts. In 2013, the ONS estimated that 582,935 workers were on ZHC contracts,

41

a three-fold

increase in the numbers of individuals working under such arrangements since 2008 (as estimated by the

LFS).

42

34

Consultation 12.

35

Consultation 12.

36

ONS, Zero hours contract levels and percent 2000 to 2012, ad hoc analysis, 31 July 2013

37

Consultation 9.

38

Note that these numbers were revised upwards from 200,000 to 250,000 in late 2013. See for example, Office for National Statistics,

Corporate Information: Zero hour contract levels and percent 2000-2012, July 2013.

39

Sir Andrew Dilnot, Zero-hours employment statistics, Correspondence to Chuka Umunna MP, 7 August 2013.

40

Office for National Statistics, Statement: ONS urges caution on zero-hours estimates, March 2014.

41

Ibid.

42

Authors’ calculation from ONS.

Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 101 9

Measurement Challenges. A number of factors contributed to the under-recording of ZHCs in the LFS.

First, the survey prevented individuals from simultaneously identifying themselves as, e.g., working shift

work and being employed on a ZHC. This issue has now been resolved, with certain ‘check and box’

questions. Further, the question on ZHCs is not asked in all quarters, excluding the recording of seasonal

workers on ZHCs.

More fundamentally, the LFS is based upon the responses of individuals, who frequently do not have the

necessary information about, or understanding of, their contractual situation to provide reliable evidence

in this regard. For example, in an interview given to the Resolution Foundation, a further education

lecturer in Bradford suggested that he:

‘had no idea [that he] had signed a zero-hours contract. When I applied for the job it

was advertised a being for between three and twenty-one hours work a week.”

43

This problem is compounded by the fact that awareness of the term has been increasing in recent years,

increasing the likelihood that individuals will self-identify with the ‘zero-hours’ label. This makes an

analysis of trends in the prevalence of ZHCs particularly problematic.

Finally, only respondents who work a positive number of hours or who are ‘temporarily away from their

job’ in the reference week are asked about the nature of their work contract. This is not a problem for

individuals who worked a positive number of paid hours during the reference week: they can be

unambiguously classed as having been in employment. However, it appears that the ‘in employment’

criterion might be of issue for those who were not assigned any work during the survey reference week,

a phenomenon that we shall see is very common in the next section.

In response to these difficulties, the ONS now also includes questions on zero-hours work in their survey

of businesses because firms are thought to be better placed to respond to questions about the contractual

arrangements of their workers.

44

Rather than ask about zero-hours contracts explicitly, the ONS came to

the conclusion that the most useful definition for purposes of this survey was “contracts that do not

guarantee a minimum number of hours”.

45

This has been justified by reference to the fact that it is the

lack of guaranteed hours that is the salient common feature of all current definitions of zero-hours

contracts.

46

This survey records contracts rather than workers, even if no hours were worked on those

contracts in the survey reference period.

ii. Numbers

Through a series of graphs, tables, and brief explanatory paragraphs, this section sets out the most recent

numbers of zero-hours workers and contracts, as well as the number of business users of such employment

arrangements. While the precise figure varies across surveys, the best evidence suggests that

approximately 6% of contracts on which work is performed do not guarantee minimum hours.

Approximately 2.8% of the UK workforce was employed on a zero-hours contracts for their ‘main job’

in 2016.

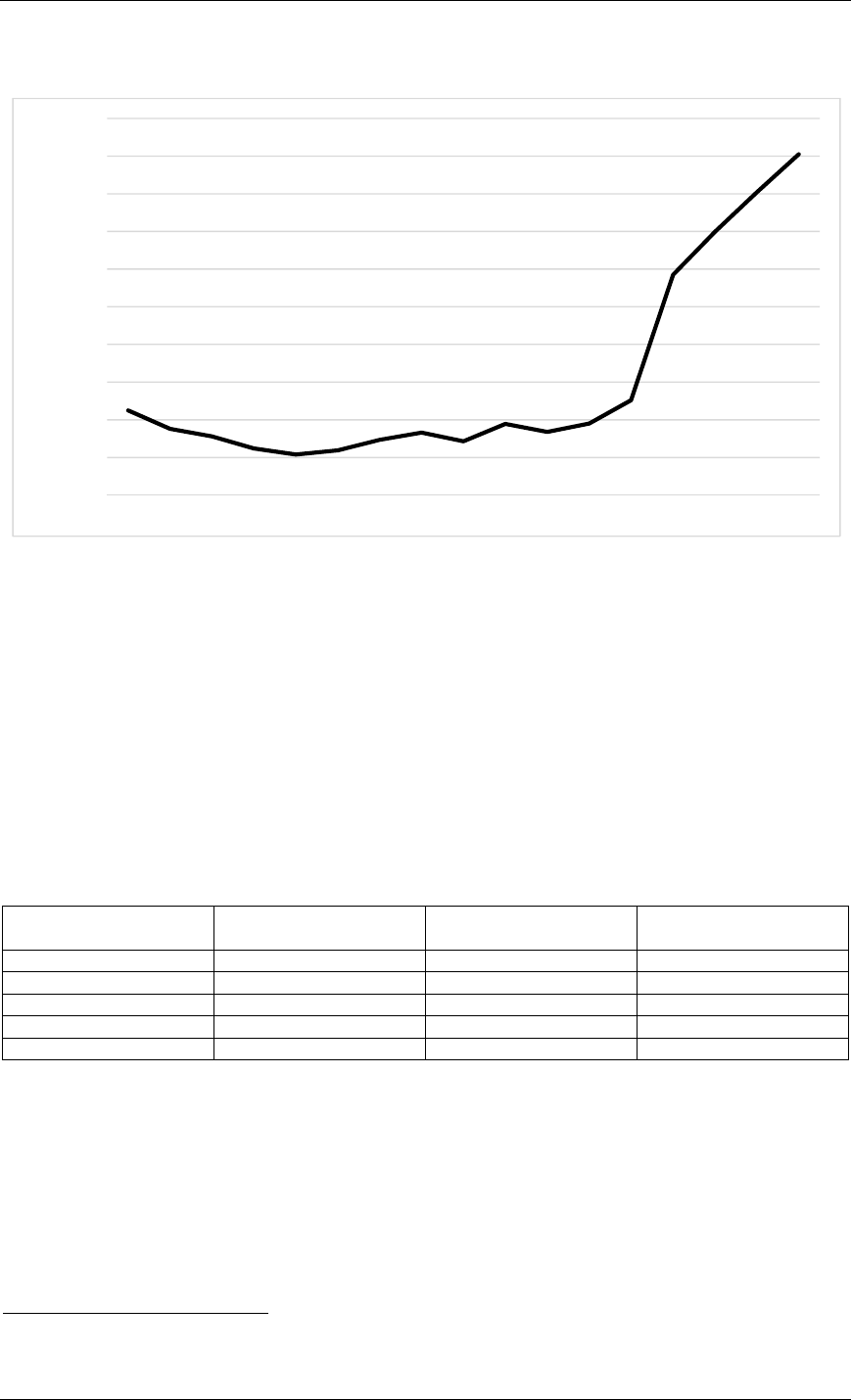

Labour Force Survey. The latest estimate from the LFS for October to December 2016 suggests that

905,000 individuals, or 2.8% of the workforce, were employed on a ZHC for their main job. This is 13%

higher than the figure for the same period in 2015 in which 804,000 individuals were thought to be

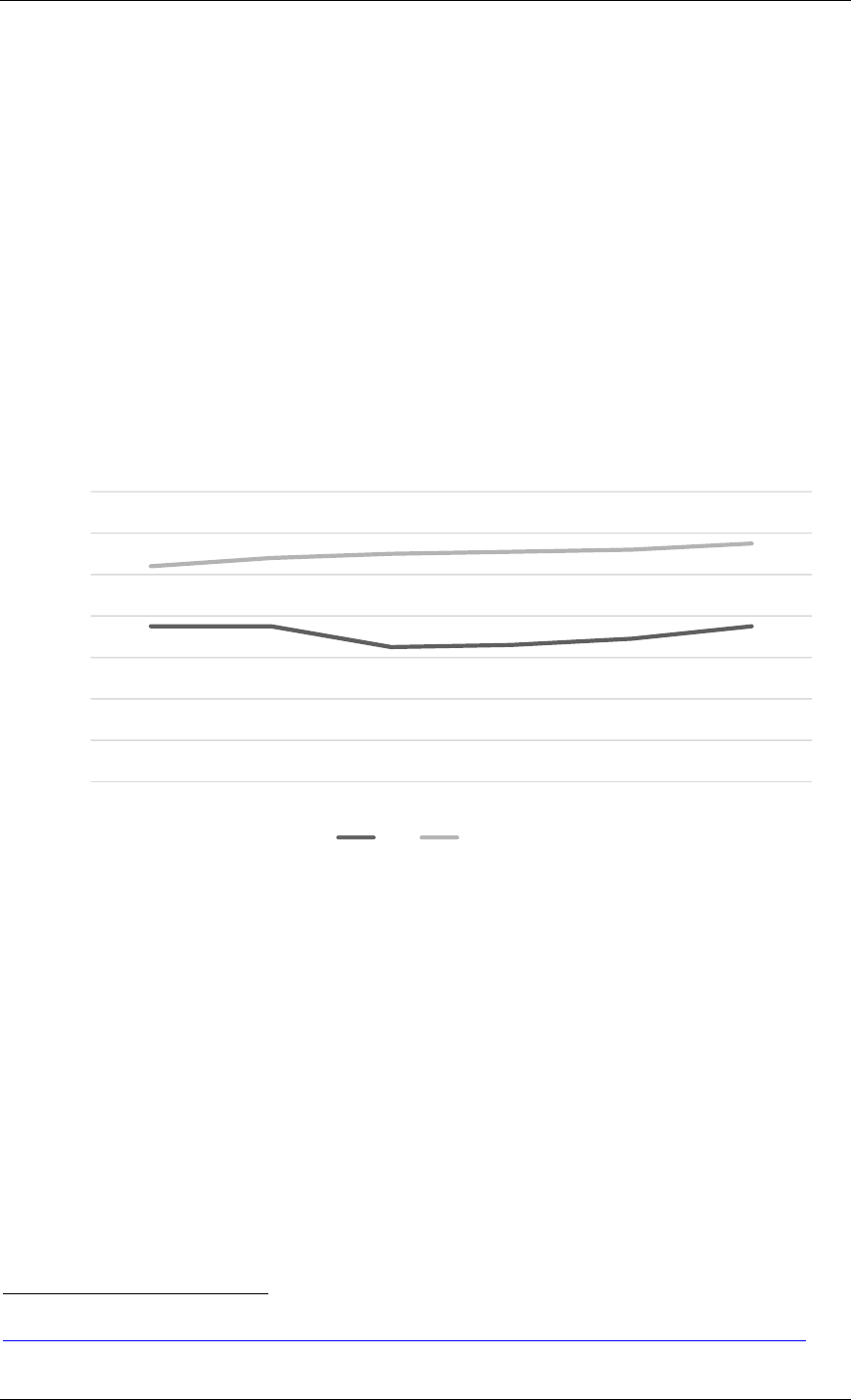

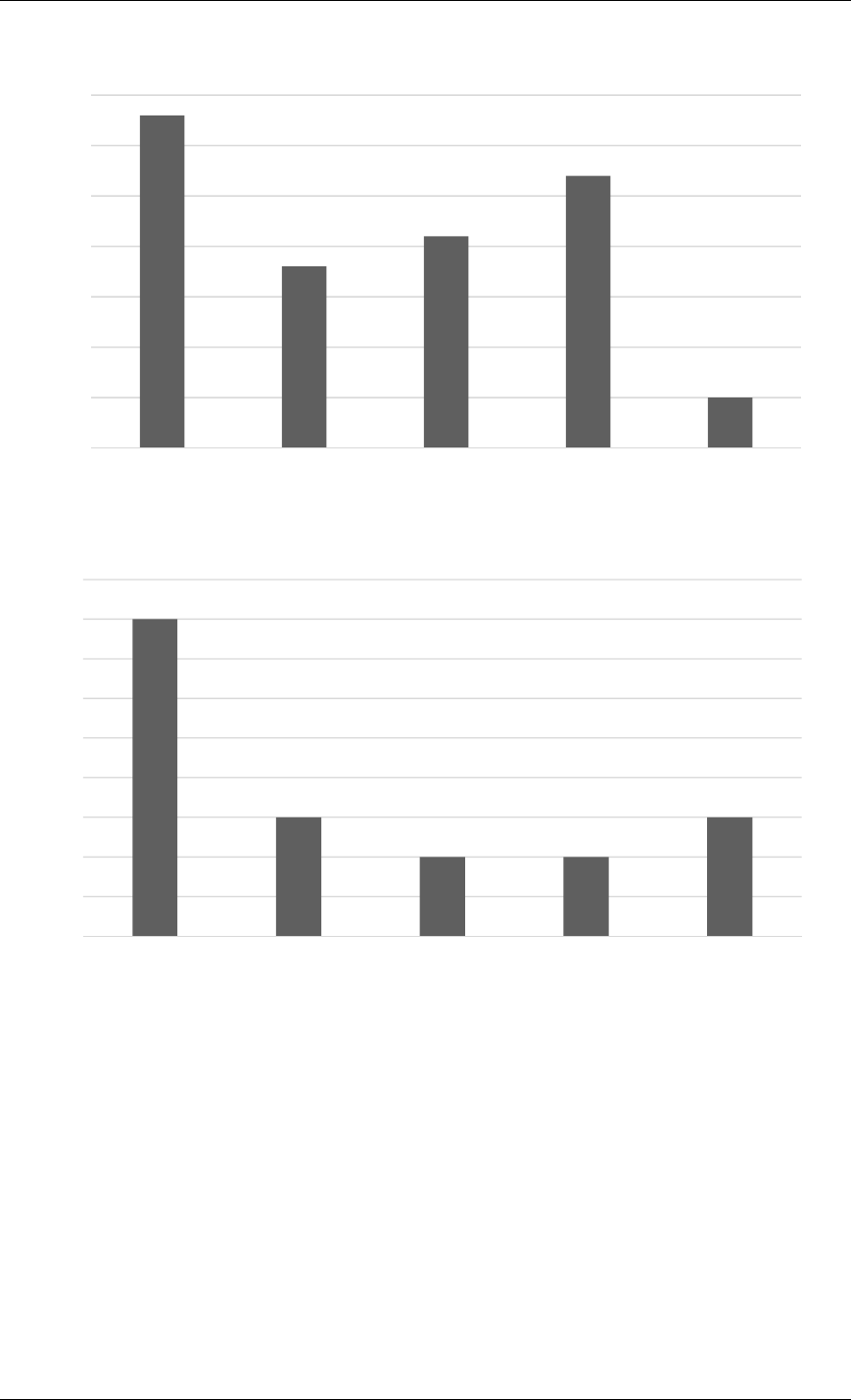

employed on ZHCs. A naïve analysis of Figure 1 might suggest that there has been fast growth in the

prevalence of zero hours work since 2011. We would like to caution against this interpretation, however,

given the aforementioned measurement issues.

43

M Pennycook, G Cory, and V Alakeson, A Matter of Time: The rise of zero-hours contracts (Resolution Foundation, London 2013) [‘Matter

of Time’].

44

Office for National Statistics, Press Release: ONS announces additional estimate of zero-hours contracts, 22 August 2013.

45

Analysis of Contracts that Do Not Guarantee a Minimum Number of Hours, Office for National Statistics, April 2014.

46

M Chandler (2016), Measurement of zero-hours contracts, ONS Presentation.

https://www.ukdataservice.ac.uk/media/604638/chandler.pdf

10 Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 101

Figure 1. Main Job as Zero Hours Contract, Q4 2000-2016, LFS

Source: Author Calculations from Labour Force Survey

Business Survey. To overcome reporting biases associated with surveying individuals about the terms of

their employment contract (see above), data on the prevalence of ‘contracts that do not guarantee a

minimum number of hours’ (NGHCs) is now collected annually in the ONS Business Survey. Table 2

gives the currently available statistics on the number of NGHCs in the UK. Approximately 6% of all

contracts on which work was carried out in the reference period did not guarantee any hours of work. The

survey estimates that 10% of businesses make use of this work arrangement. In addition to the 1.7million

contracts on which work was carried out in November 2015, there were an additional 2 million contracts

on which no work was performed. It is unclear whether no work was performed because individuals did

not accept work offered or because an employer offered no work.

Table 2. Contracts with no guaranteed hours, ONS Business Survey

Reference Period Number NGHCs in which

work carried out

% Contracts that are

NGHCs

% Business making use of

NGHCs

Jan 2014 1.4 5 13

Aug 2014 1.8 6 11

Jan 2015 1.5 6 11

May 2015 2.1 7 11

Nov 2015 1.7 6 10

Source: Office for National Statistics Business Survey

47

The Business Survey suggests a higher prevalence of ZHCs than the LFS. It is unclear which is the ‘best’

measure to use. Employer surveys record contracts that cover a variety of arrangements, as opposed to a

single individual’s ‘main employment’. This measure thus includes contracts for those who work on an

irregular basis. Employers are also more likely to be aware of their employees formal contractual

arrangements. This may differ may differ from the perception of employees if their normal working hours

are relatively stable or if changes in hours are mainly as a result of personal choice.

47

Office for National Statistics, Contracts that do not guarantee a minimum number of hours: March 2016.

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

800

900

1000

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016

Hundred thousands

Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 101 11

Social Care. Given the difficulties in assessing trends over time from the LFS, we present data from the

social care sector in which the prevalence of ZHCs has, arguably, been better measured since 2012.

Indeed, administrative data on the prevalence of ZHCs in the social care sector was used in 2014 as

evidence of the limitations of previous LFS estimates. The National Minimum Data Set for Social Care

is a workforce planning tool managed by Skills for Care which is used to analyse employment practises

and workforce composition in the sector. There were 315,000 people employed on ZHCs in March 2016,

or 24% of the workforce. The percentage of workers on zero hours contracts in social care grew by 3

percentage points between 2012/13 and 2015/16 due to increases in the proportion of care workers and

registered nurses working under these arrangements.

Table 3. % Social Care Workforce on ZHC, NMDS-SC

Job Role 2012/13 2013/14 2014/15 2015/16

All 21 23 25 24

Senior Mana

g

ement 4 4 4 4

Registered Manager 3 2 2 3

Social Worker 3 3 3 3

Occ. Therapist 3 3 2 3

Registered Nurse 16 18 19 18

Senior Care Worker 9 9 9 10

Care Worker 30 33 35 33

Support 15 15 14 15

Source: NMDS-SC

48

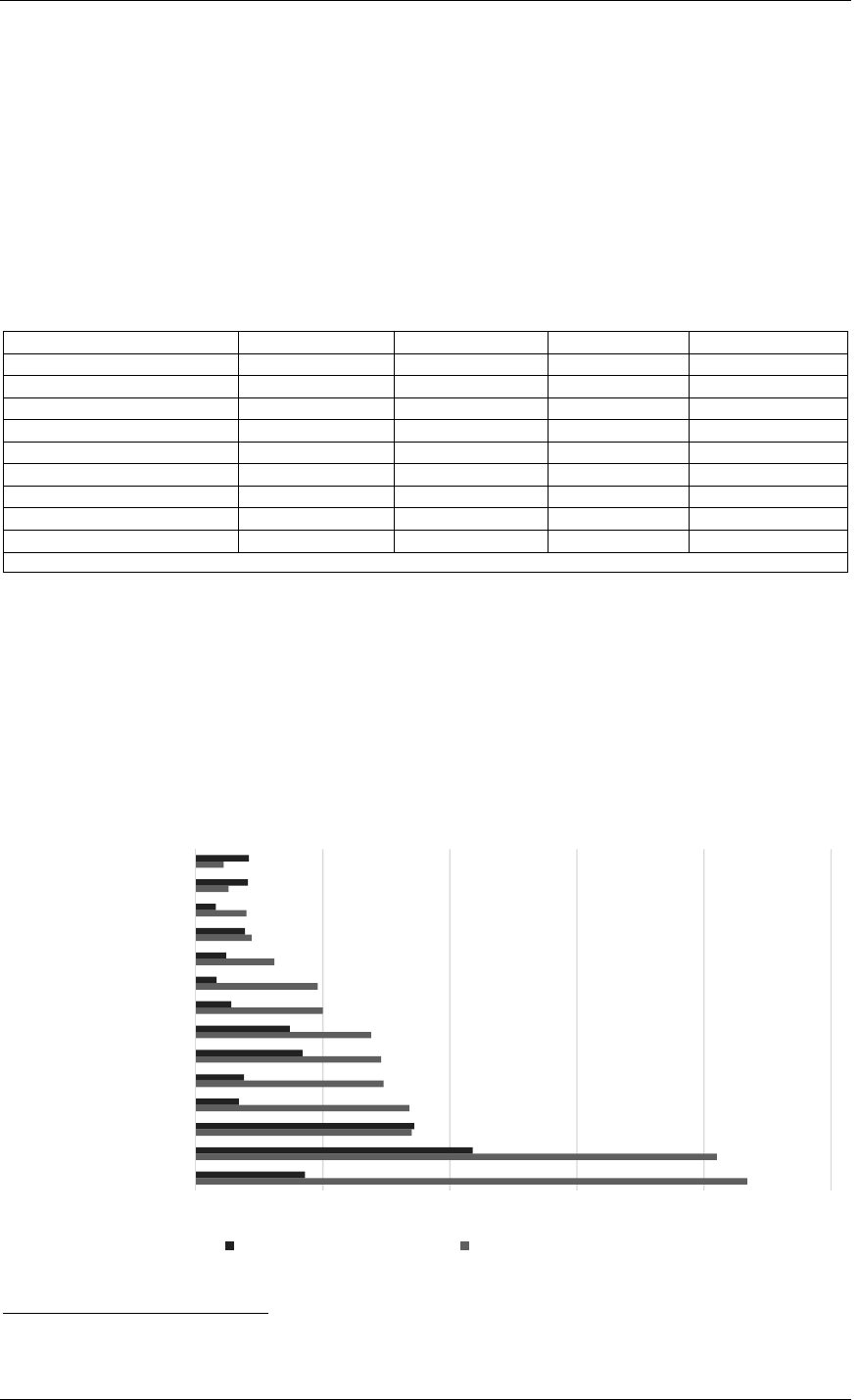

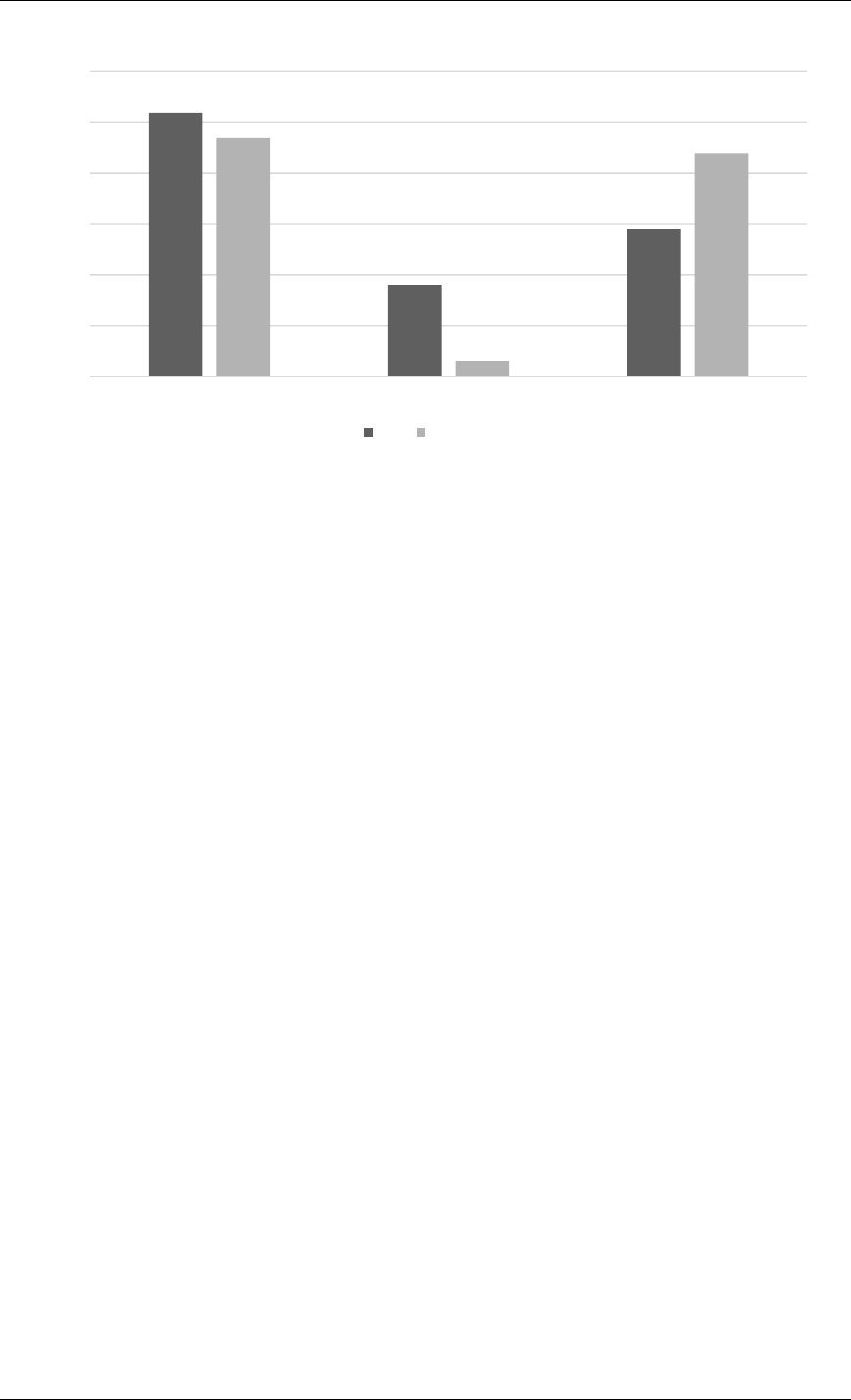

Prevalence Across Industries. The prevalence of zero-hours work arrangements varies markedly across

industries. Figure 2 shows the percentage of people in each industry employed on a zero-hours contract

and the distribution of those on zero-hours contracts across industries. Responses to the Labour Force

Survey show that the over two-fifths of workers on zero-hours contracts for their main job are located in

Social Care, Health, Accommodation and Food Services. Zero-hours contract workers make up 11% of

total employment in Accommodation and Food Services, 9% of employment in the Arts sector and just

over 4% of employment in Health and Social Care.

Figure 2. Zero-hours work across Sectors, Oct-Dec 2016

Source: Author Calculations from Labour Force Survey October-December 2016

48

Skills for Care, The state of the adult social care sector and workforce in England, September 2016.

0 5 10 15 20 25

Health & Social Work (Q)

Hotels & Restaurants (I)

Arts (R.)

Retail (G)

Education (P)

Admin & Support (N)

Transport (H)

Manufacturing ©

Finance & IT (J, K, L, M)

Construction (F)

Other (S, T, U)

Public Admin (O)

Mining & Utilities (B, D, E)

Agriculture (A)

% Workers in Industry on ZHC % of ZHC Workers in Industry

12 Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 101

b. DetailedCharacteristics

Discussion now turns to an analysis of the key features of work and remuneration, the characteristics

workers engaged, and employers offering work, under zero-hours arrangements.

i. EarningsonZHCs

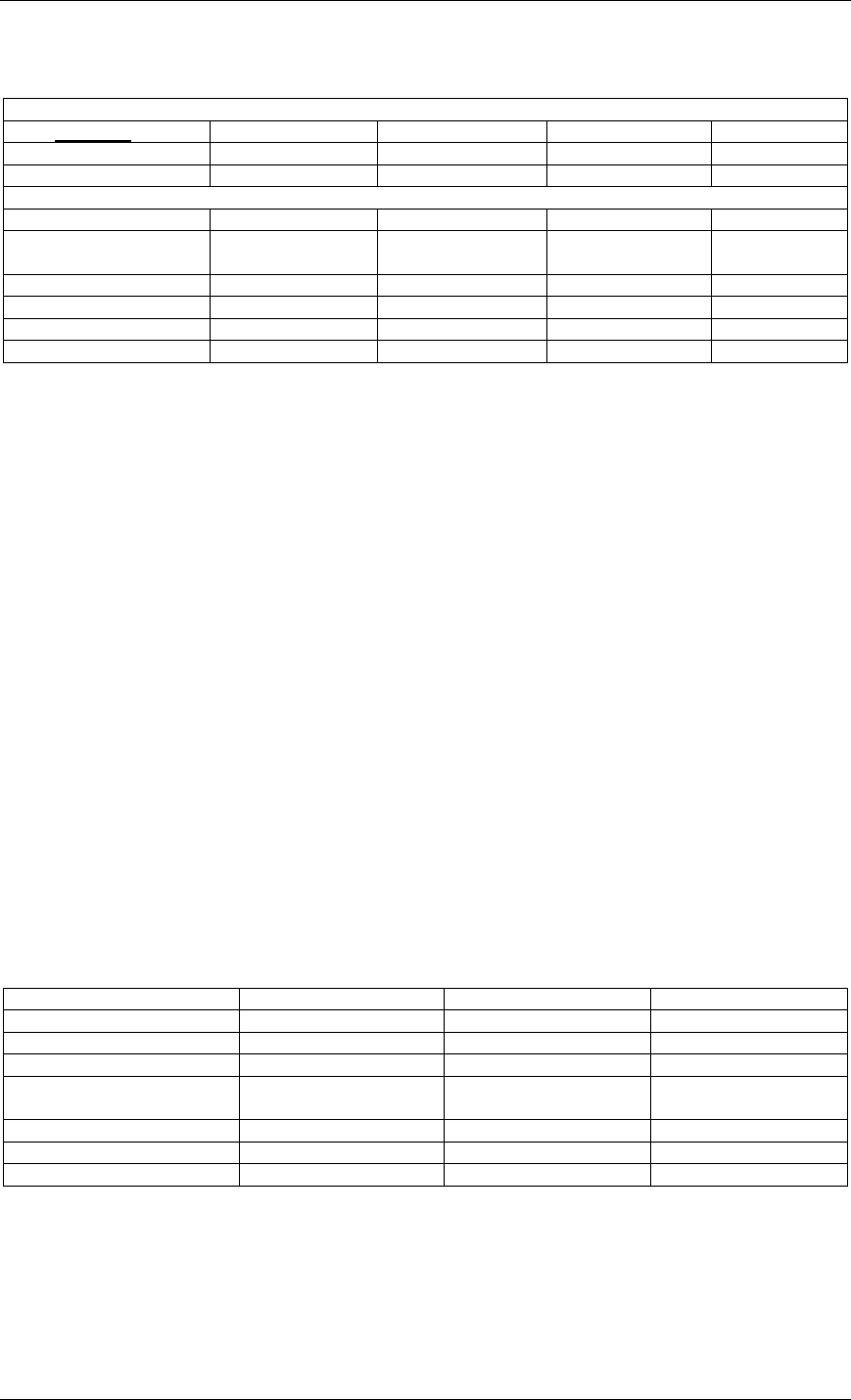

Hourly wage rates on zero hours work arrangements are significantly lower than average. The median

wage rate for ZHC work is approximately 35% less than that for all workers. In real terms (adjusting for

CPIH inflation), wages on ZHC fell by 13.8% between 2011 and 2015, while real wages for non-ZHC

workers stayed approximately flat. Zero hours work is thus likely to be highly affected by increases in

the national minimum wage which was increased to £7.50 on 1

st

April 2017.

Figure 2. Median Hourly Wage, ZHCs and All Workers

Source: Author calculations from Labour Force Survey

There are many reasons why remuneration might be lower on ZHC contracts. Zero hours work might be

relatively concentrated in lower paying sectors, workers employed on ZHCs might have less experience

or be less productive, or the nature of the contracts could provide opportunities for value extraction by

employers or render the nature of work less productive.

The Resolution Foundation have previously estimated that approximately four-fifths of the overall hourly

pay gap between ZHC and full time work can be accounted for by the characteristics of the workers doing

them and the lower average pay in the occupations that the contracts are concentrated in.

49

We repeat this

analysis for the most recent data finding that a 10% ‘precarity pay gap’ remains after controlling for

observable differences between those working on zero-hours contracts and those working on other types

of contrast. Our analysis is robust to whether one considers the mean or median hourly pay. While it is of

course possible that this pay gap could be driven by other worker or job characteristics not measured in

the data, the analysis does provide relatively compelling evidence that there is a pay penalty associated

with zero hours work beyond that associated with part-time work more broadly.

49

Resolution Foundation, Zero hours contract workers face a ‘precarious pay penalty’ of £1,000 per year, December 2016

http://www.resolutionfoundation.org/media/press-releases/zero-hours-contract-workers-face-a-precarious-pay-penalty-of-1000-a-year/

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016

Median Hourly Pay, £

ZHC Not ZHC

Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 101 13

Table 4. Hourly Wage Regression Analysis, LFS Q4 2016

Log hourly wage

Mean Regression (1) (2) (3) (4)

ZHC -.449*** -.243*** -.102*** -.09***

(0.04) (0.03) (0.03) (0.03)

Controls:

Worker Characteristics

Industry & Occupation

Characteristics

Part-Time

N 10,244 9,676 9,594 9,591

R

2

0.0160 0.2778 0.4476 0.4484

A

d

j

R

2

0.0159 0.2769 0.4459 0.4466

ii. HoursandWorkingPatterns

Here, we focus on working time data, including average working hours of workers under zero-hours

contracts and, to the extent that such data is available, on the variability of their work schedules. We also

link to the broader debates and statistics on underemployment in recent years.

The LFS records actual hours worked during the survey reference week. Figures below are again the

latest available from the LFS October-December 2016 unless otherwise stated. Note that to appear in the

statistics, respondents must have done at least one hour of paid work in the week before they were

interviewed or to have reported that they were temporarily away from their job. Therefore, this source is

likely to miss those who did no work on under a zero hours work arrangement.

Actual Hours. The majority of people on ZHCs (65%) report that they worked part-time, compared with

26% of other workers. Average actual weekly hours in zero hours work are thus unsurprisingly lower at

22.0 hours per week compared with the average actual weekly hours for all workers at 31.8 hours. This

shows a similar pattern to usual hours worked, that is, the weekly hours usually worked throughout the

year, which were 25.2 and 36.4 for people on “zero-hours contracts” and all workers respectively. Table

5 shows that this hours gap closes slightly but remains significant when controlling for observed worker

and job characteristics (e.g. female, have children, age).

Table 5. Hours Worked Regression Analysis, LFS Q4 2016

Hours in Reference Week (1) (2) (3)

ZHC -10.2*** -8.2*** -7.4***

(0.59) (0.57) (0.59)

Worker Characteristics

Industry & Occupation

Characteristics

N 34,623 32,845 28,222

R

2

0.0086 0.1222 0.1568

Adj R

2

0.0086 0.1219 0.1559

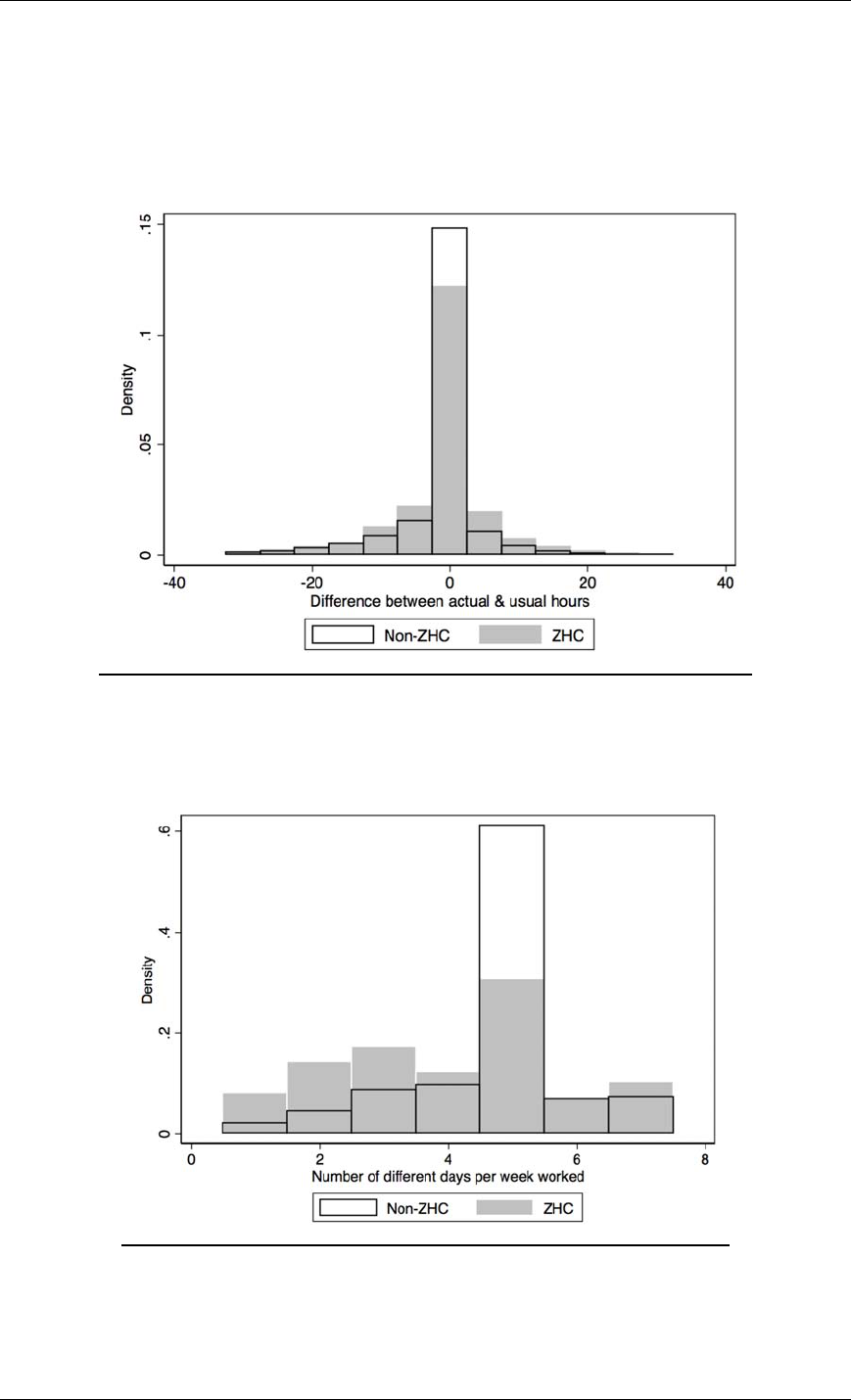

Hours Variability. Zero hours work is associated with greater weekly hours variation when compared

to all work as shown in Figure 3. For October to December 2016: 43% ZHC workers worked their usual

hours compared with 58% of other workers, while 35% of ZHC workers worked less than their usual

14 Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 101

hours compared with 30% of other workers. Note again however that the LFS might under-record those

who work zero hours when they might usually work a positive number. Those on zero-hours contracts

are also much less likely to work 5-day weeks, the norm amongst those on other types of contracts. This

pattern is depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 3. Variability in Actual Hours versus Usual, Oct-Dec 2016

Figure 4. Number of Days per Week Worked, Oct-Dec 2016

Source: Author Calculations from Labour Force Survey

Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 101 15

Underemployment. There is compelling evidence of underemployment amongst workers on ZHCs. A

quarter (25%) of those on ZHCs want to work more hours compared with 9% of people in employment

not on these contracts. 9% of those doing zero-hours work would like a different job with more hours

compared with 1% for other people in employment, while the remainder would like more hours in their

current job or an additional job. Disaggregating underemployment figures by key worker characteristics

is suggestive that while underemployment is a problem across all groups, men, immigrants and those with

disabilities (according to Equality Act 2010 criteria) are particularly affected. While men and women

employed on other types of contracts are equally likely to report being underemployed, women on zero-

hours contracts are less likely to be underemployed than men suggesting that some women who want low

hours might be selecting into this form of work. There is also some suggestion that a similar phenomenon

might be at work with students.

Table 6. Underemployment by Worker Characteristics, Oct-Dec 2016

ZHC Non-ZHC

Age

Youn

g

er workers 31% 15%

Older 22% 7%

Diff 9%** 8%***

Gender

Female 22% 9%

Male 29% 7%

-7%** 2%***

Disabled

Disability 31% 10%

No Disability 24% 8%

7%* 2%***

Immigrant

Migrant 33% 11%

Not Migrant 23% 8%

Difference 10%** 3%***

Student

Student 26% 12%

Not Student 24% 8%

Difference 2% 4%***

Source: Author’s calculations from the Labour Force Survey

iii. WorkerCharacteristics

Here, we focus on whether zero hours work is associated with particular groups of workers (such as

migrant workers, or those in particular sectors). In short, those doing zero-hours work are more likely to

be young, migrants and either still studying or less educated.

The relationship between age and work under zero-hours arrangements is particularly striking. A third of

zero-hours works are aged under 25, and 8% of those employed in this age group work on a zero-hours

contract compared to 2% of those aged 25 and over.

16 Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 101

Figure 5a. Age Distribution of ZHC Workers

Figure 5b. % Workers in Each Age Group on ZHC

Source: Author Calculations from Labour Force Survey

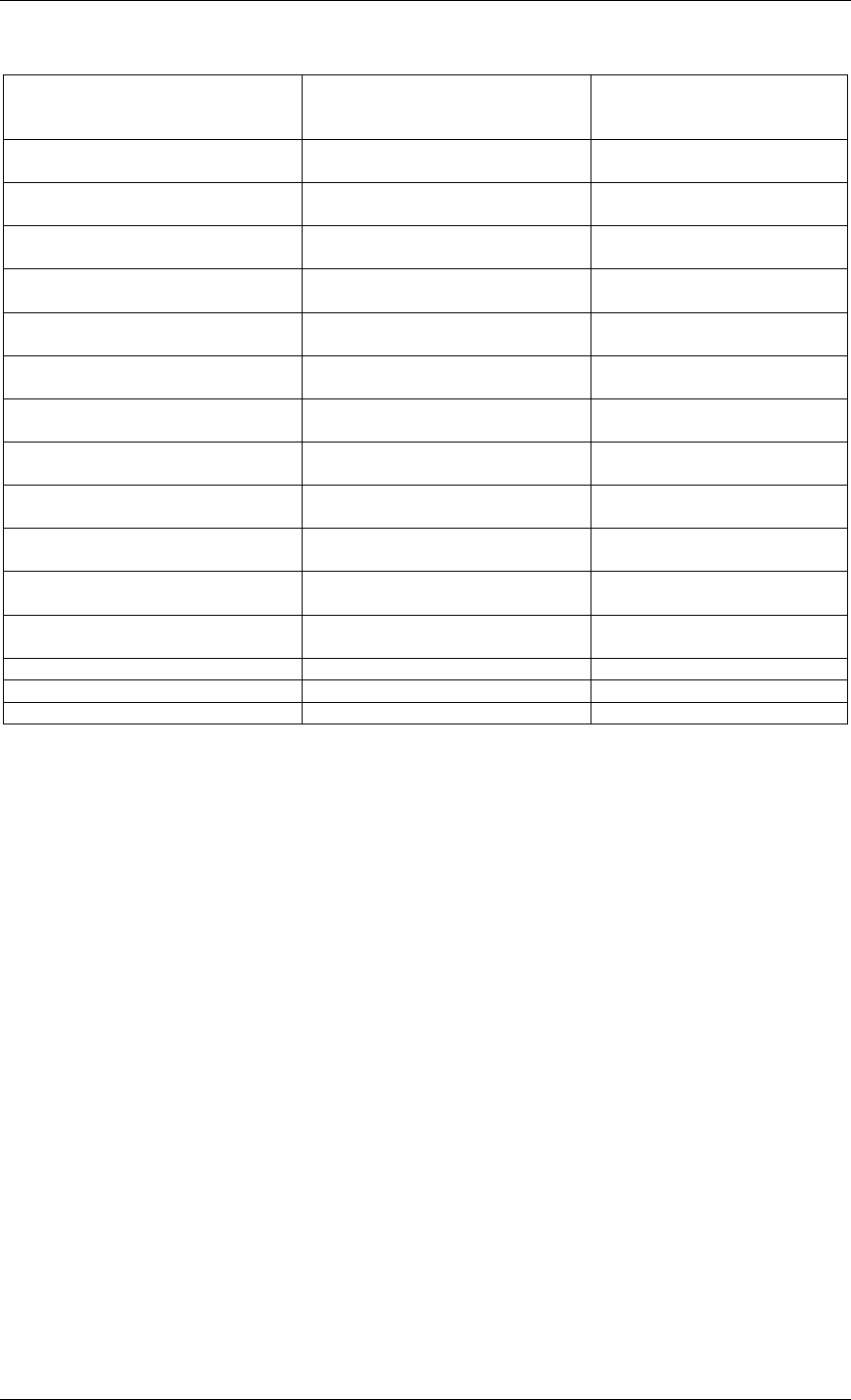

Women, students and those with lower education are over-represented among zero-hours contract

workers. However, it is important to note that zero-hours arrangements still account for a relatively small

share of overall employment for most groups. While 52% of zero-hours workers are women, only 3% of

women in employment are on a zero-hours contract. However, for students, zero-hours work does account

for a bigger share of overall employment: 8% of students in work are employed on zero-hours

arrangements.

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

16-24 25-34 35-49 50-64 65+

%

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

16-24 25-34 35-49 50-64 65+

%

Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 101 17

Figure 6. Characteristics of ZHC Workers, Q4 2016

Source: Author Calculations from Labour Force Survey

To control for the impact of various characteristics simultaneously, we run a multivariate logistic

regression of an indicator of whether an individual was employed on a zero-hours contracts on various

characteristics. An odds ratio of more than one indicates that workers with this characteristic are more

likely to work under a zero-hours arrangement. An odds ratio of less than one indicates that workers with

this characteristic are less likely to work under a zero-hours arrangement. We give results with and

without controls for industry and occupation.

The most salient themes match those of our graphical analysis: that zero-hours work is much more

common amongst workers under age 25, current students, and, amongst those who have finished

studying, those who do not have any qualifications higher than A-Levels (awarded at age 18 in the UK).

There is also evidence for the work arrangement being more prevalent amongst those classified as

disabled according to Equality Act 2010 criteria; 16% of those on zero hours arrangements are classified

as disabled under this measure, compared to 12% employed on other types of contract. Non-native UK

workers are also disproportionately employed on ZHCs; 20% of workers on ZHCs were born outside the

UK compared to 15% on other types of contract. Those who self-identify with a non-white ethnicity are

similarly over-represented amongst zero-hours work (14% to 10%). Women are more likely to be

working under zero-hours arrangements but this is largely because the industries and occupations that

women work in are more likely to use zero-hours contracts. Controlling for industry and occupation in

the second column of Table X results in the relationship between women and zero-hours arrangements

becoming insignificant.

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

Female Student More than A-Level

%

ZHC Not-ZHC

18 Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 101

Table 6. ZHC Worker Characteristics, Logistic Regression

ZHC (1)

Odds Ratio

(Std Error)

(2)

Odds Ratio

(Std Error)

Age 16-24 3.89***

(0.43)

2.72***

(0.34)

Age 25-34 1.56***

(

0.17

)

1.42***

(

0.17

)

Age 50-64 1.38***

(0.15)

1.33**

(0.16)

Age 65+ 1.42*

(0.28)

1.78***

(0.38)

More than A-Levels 0.59***

(0.05)

1.03

(0.10)

Student 2.06***

(0.20)

1.84***

(0.20)

Female 1.23***

(0.08)

0.95

(0.08)

Disability 1.60***

(0.15)

1.39***

(0.14)

Immigrant 1.58***

(0.16)

1.26**

(0.14)

Non White 1.30**

(0.15)

1.24*

(0.16)

Children 0.95

(.15)

0.94

(0.08)

Constant 0.01

(0.00)

0.08

(0.12)

Industry & Occupation

N 33,334 28,540

Psuedo R

2

0.0593 0.1419

Benefit Receipt. Workers on zero-hours contracts are more likely to be in receipt of some state benefits

compared to those not on these contracts. 30% of those working on zero-hours contracts are in receipt of

benefits compared to 25% of workers employed under alternative work arrangements. We will return to

a wider discussion of this point in Section 3.

Unionisation. Unionisation rates are lower amongst zero-hours workers. 22% of workers employed on

other types of contracts are a member of a trade union, compared to only 8% of workers employed on

zero-hours contracts. The negative association between zero-hours work and unionisation continues to

hold even after controlling for worker characteristics, industry, and occupation.

iv. EmployerCharacteristics

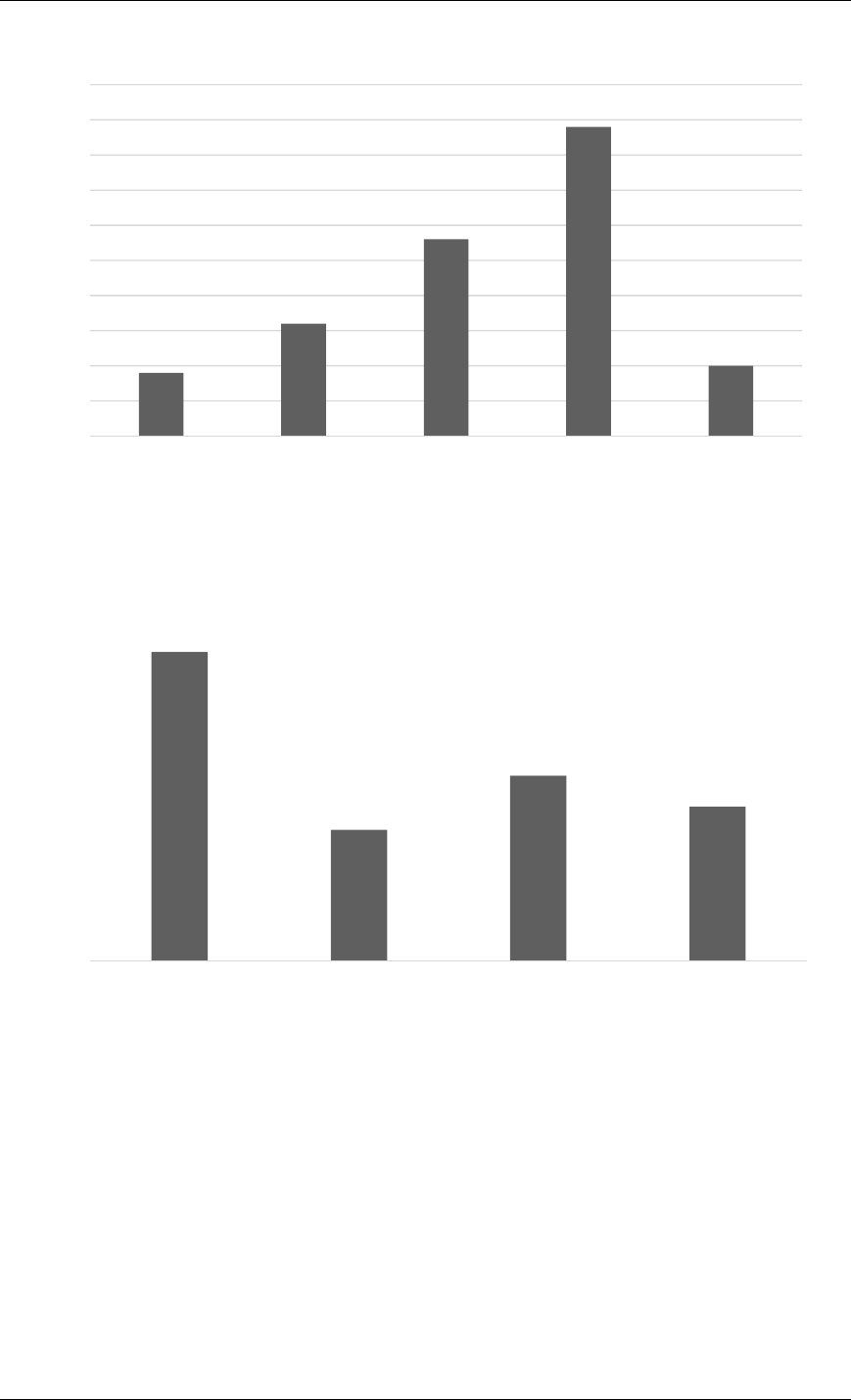

Zero-hours contract workers are more likely to be found in small firms – 40% of those employed on zero-

hours contracts in October-December 2016 where in firms with fewer than 25 employees. 20% of zero-

hours workers were in the smallest category of firm size, at firms with fewer than 10 employees. However,

it seems that a higher proportion of very large firms make use of zero-hours contracts than smaller firms

(there are just few large firms in the UK).

Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 101 19

Figure 7a. Proportion of Businesses Making Some Use of NGHCs by Business Size, Nov 2015

Source: ONS Business Survey

Figure 7b. Distribution of ZHCs by Firm Size, Oct-Dec 2016

Source: Labour Force Survey

We gave the breakdown of zero-hours contracts by industry earlier in this section, finding that they are

particularly prevalent in Health & Social Care and Accommodation and Food. Zero-hours arrangements

also appear relatively more common in private than public-sector organisations; 13% of zero-hours

workers are employed in the public sector compared to 23% of workers on other types of arrangements.

Agency Work. There is an important overlap between agency work and zero-hours arrangements. 10% of

workers employed by agencies are on zero-hours arrangements. Thus, hybrid forms of work organisation

are possible. Agency-ZHC work seems to be particularly important in the care sector. 30% of care workers

employed through agencies are on zero-hour contracts according to the LFS.

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

0-9 employees 10-19 employees 20 to 249 employees 250 or more

employees

Total

%

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

1-24 employees 25-49 employees 50-249 employees 250 or more employees

%

20 Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 101

v. SocialCare

Given the heavy use of zero-hours contracts in the care sector, we provide a more in-depth study of their

use and characteristics in the sector. Skills for Care administrative data reveal that approximately a quarter

of all social care workers were employed on zero-hours contracts in 2015/16 (see Table 3). This is more

than estimated in the LFS or ONS Business Survey which might again give reason to believe that these

sources continue to underestimate the prevalence of zero hours work arrangements.

Domiciliary Care. Zero-hours contracts are particularly concentrated within care workers as opposed to

managers or administrative staff. Further they are very common within adult domiciliary care (care given

within an individual’s own home). In 2015/16, a large 58% of care workers and 57% of registered nurses

working in domiciliary care were employed on zero hours contracts.

50

80% of domiciliary care workers

on zero hours contracts were employed on a permanent basis on these contracts. There is also some

evidence that zero-hours contracts are clustered within particular types of provider. Unison and a review

for the Department of Health found that a large number of independent domiciliary care providers used

zero hours contracts for all staff but this was not the case for local authority providers.

51

Zero-hours contracts are sometimes justified as arising from employers need for flexibility, enabling them

to scale the size of their workforce to fluctuating demand. While demand for social care is systematically

high and constant across the week, homecare is time and location specific with some peaks and troughs

over the day. This feature of service delivery combined with ‘chronic underfunding’ and the

commissioning model used by most local councils leads to the use of zero-hours arrangements.

The majority of workers in social care are employed by private firms. However, as the UK Homecare

Association explains, ‘local councils buy around 70% of all homecare, meaning that they effectively have

a near monopsony of purchasing power in their local care market. The purchasing decisions of councils,

and the available funding from central government, largely determine the operation of the sector.’

52

It is widely acknowledged that councils do not usually pay for travel time; research by Unison suggests

that more than 65% of councils only pay for the time a carer actually spends in a service user's home.

Funding pressures have led councils to freeze the fees they pay to providers or providing only nominal

annual increases.

53

Care providers have been ‘very clear’ in arguing that the use of zero-hours contracts

is necessary because of the extremely low rates that local authorities pay for care, and the practise of

councils paying for care by the hour.

54

Indeed, ‘the majority of providers told [the UK Homecare

Association] that their services would be unsustainable on the current levels of funding, without the use

of zero hours contracts.’

55

There is thus little if no scope for many providers to remunerate workers fully

for travel and on-call time. In addition to likely resulting in the use of ZHCs, as we will discuss further

in Section 4, this practise has led to violations of National Minimum Wage regulations.

50

Skills for Care, The state of the adult social care sector and workforce in England (Skills for Care 2016).

51

Unison, Outsourcing the Cuts: Pay and Employment Effects of Contracting Out (The Smith Institute 2014).

52

C Angel, The use of zero hours contracts in the homecare sector (Acas Blog 2014) http://m.acas.org.uk/index.aspx?articleid=4901

53

House of Common Communities and Local Government Committee, Adult Social Care: Ninth Report of Session 2016-17, HC 1103 March

2017.

54

Angel (n 52).

55

ibid.

Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 101 21

3. TheImpactofZero‐HoursWork

In the third section of this report, we complement the numerical evidence just set out with an extended

analysis of the effects of zero-hours work for workers, employers, and society more broadly. Our focus

is not limited to the legal situation of those working under such arrangements, but also includes questions

of social security entitlements, and wider implications for business flexibility, cost savings, and

productivity growth.

a. What’stheCounterfactual?

Before turning to a detailed discussion of the benefits and limitations of zero hours work for key

stakeholders, we first explore the important issue of what constitutes the relevant counterfactual. While

there might be drawbacks to the use of zero hours working arrangements, it might be the case that they

are preferable to the alternatives that would exist in their absence. Some job is often thought better than

no job at all.

Indeed, flexible work arrangements such as zero hours are suggested by some to have contributed to the

UK’s ‘employment miracle’ since the financial crisis. The UK employment rate is now at its highest level

since records began at 74.6% of the working age population. As zero hours arrangements enable firms to

take on workers with limited risk if demand falls short of expectations, there might have been higher

unemployment over the recession if such work arrangements were not available. The CBI, for example,

predicts that unemployment would have risen by an extra 500,000 people had firms not been able to resort

to these work arrangements.

56

This is supported by evidence that a third of all workers and more than half

of workers between 16-24 years old say that they are on these contracts because they cannot find a job

with regular fixed hours.

57

This is important because a large body of research highlights the long-term

damage of unemployment spells for individuals and society as people lose skills, lose confidence, and

face difficulty returning to employment.

58

Zero hours arrangements might also function as a stepping-stone to ‘better’ employment. The

Government consultation, for example, argues that ZHCs provide people with “opportunities to enter the

labour market and a pathway to other forms of employment.”

59

It is thus plausible that for certain groups

of individuals facing a lacklustre labour market, the opportunity to work on a zero hours contracts

represents a real benefit over the alternatives available.

However, that being said, there is evidence that zero hours contracts are used by some employers not

because positions that guarantee hours are economically unviable but rather because of poor management

practises. As we will explore in Section 3(b), many businesses stress that there exist more efficient means

of workforce management. Many CEOs and HR managers interviewed as part of an independent review

on zero hours contracts in the UK argued that, in the current economic climate, reliance on zero hours

contracts represents “lazy management”, an “unsophisticated way of managing workplace flexibility”,

and an “ineffective way of motivating people”.

60

Further, the link between forms of temporary and causal work and positive future labour market outcomes

is weak. Indeed, economists David Autor and Susan Houseman found that temporary help placements

might even harm subsequent employment and earnings outcomes in their study of the Work First

programme in Michigan.

61

According to Norman Pickavance, the lack of training and the emergence of

a two-tier workforce that can be associated with reliance on zero hours arrangements have ‘broken’ the

56

http://www.publicsectorexecutive.com/Public-Sector-News/vital-role-for-zero-hours-contracts-cbi-

57

Pickavance 5.

58

See, e.g. D Bell and D Blanchflower (2011), ‘Young People and the Great Recession’, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 27(2); W

Aruampalan, A. Booth and M. Taylor (2000), ‘Unemployment Persistence’, Oxford Economic Papers 52.

59

Consultation 13.

60

Pickavance 13.

61

D Autor and S Houseman, ‘Do Temporary-Help Jobs Improve Labour Market Outcomes for Low-Skilled Workers? Evidence from “Work

First”’ (2010) American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 2.

22 Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 101

ladders that normally allow people to progress through the ranks of an organisation.

62

Thus, it is not

unambiguously clear that zero-hours contracts necessarily have a positive effect on future labour market

prospects.

With the difficulty of the counterfactual point raised, we now turn to a detailed discussion of the benefits

and costs of zero hours work arrangements for workers, businesses, and society at large.

b. Workers

Zero-hours work arrangements are simultaneously lauded as good and bad for workers. On the positive

side, employment on zero hours work arrangements is argued to reflect a ‘preference for flexibility’

amongst students, older workers, and women with care giving responsibilities. Further, as mentioned

above, employment on a zero hours contract might be better than no employment at all. However, workers

are subject to much greater income risk on these contracts and face greater uncertainty over the scope of

their employment rights. Difficult questions also arise in relation to the social security system, particular

as part of the on-going shift to the so-called Universal Credit (‘UC’) system, and broader issues from

work-life balance to worker health.

i. Flexibility?

In principle, zero-hours arrangements allow individuals a greater say over when and how much they

work. In theory they permit, for example, students to fit in paid employment while studying and allow

women to work around childcare duties. There is evidence that a preference for flexibility is relevant for

some workers. For example, a CIPD study suggested that 47% of workers were ‘very satisfied’ or

‘satisfied’ with having no guaranteed hours.

63

Interview responses to a Resolution Foundation study in

2013 also suggested that certain types of workers valued these work arrangements, whilst acknowledging

that they would not suit everyone:

“I really value the flexibility of working on zero hours because it allows me to fit

other things into my life and if I don’t get enough hours one week I can always

make them up the next by taking on more. I can see that for families with a

mortgage the situation would be seriously nerve wracking and of course I have to

trust my line manager to deliver those hours and that’s far from ideal but it has

worked for me so far.”

(Male domiciliary care worker, Edinburgh)

64

However, it is important to note that flexibility is not a universally valued characteristic. In the CIPD

study quoted above, 27% reported that they were ‘very dissatisfied’ or ‘dissatisfied’ with having no

guaranteed hours.

65

Recent academic evidence also suggests that the great majority of workers do not

value flexible working arrangements; most workers are not willing to pay for flexible scheduling and

traditional Monday-Friday 9-5pm schedules are preferred by most job seekers.

66

There is also some uncertainty as to the extent to which zero-hours work is genuinely flexible for workers.

Acas argues that the problem of “effective exclusivity clauses” is a “very major concern”.

67

Their

experience suggests that workers are often frightened to turn down work in case their employer starts

‘zeroing in’ on their hours. They conclude that these anxieties “reflect the imbalance of power between

the worker and the employer in these contractual arrangements as workers are also fearful of raising

62

Pickavance 12.

63

CIPD, Labour Market Outlook 2013.

64

Matter of Time 16.

65

CIPD, Labour Market Outlook 2013.

66

A Mas and A Pallais, ‘Valuing Alternative Work Arrangements’, Working Paper.

67

Acas, ‘Give and take? Unravelling the true nature of zero-hours contracts’ (2014) Acas Policy Disucssion Papers.

Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 101 23

queries regarding their rights and entitlements.”

68

A union representative interviewed as part of a wider

study of zero-hours contracts in the UK retail sector explains that:

69