Journal of Family Strengths Journal of Family Strengths

Volume 11 Issue 1 Article 10

November 2011

Connecting the Dots: Families and Children with Special Needs in Connecting the Dots: Families and Children with Special Needs in

a Rural Community a Rural Community

Saundra Starks

Western Kentucky University

Dana J. Sullivan

Western Kentucky University

Vella Mae Travis

Western Kentucky University

Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/jfs

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Starks, Saundra; Sullivan, Dana J.; and Travis, Vella Mae (2011) "Connecting the Dots: Families and

Children with Special Needs in a Rural Community,"

Journal of Family Strengths

: Vol. 11: Iss. 1, Article 10.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58464/2168-670X.1015

Available at: https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/jfs/vol11/iss1/10

The Journal of Family Strengths is brought to you for free

and open access by CHILDREN AT RISK at

DigitalCommons@The Texas Medical Center. It has a "cc

by-nc-nd" Creative Commons license" (Attribution Non-

Commercial No Derivatives) For more information, please

contact [email protected].tmc.edu

Over the past 20 years, there has been a rise in diagnoses of autism

spectrum disorders as well as other developmental disorders and delays

(Autism Speaks, n.d.). While low-birth weight babies are more likely to

survive due to advanced medical care and technology, these babies are

also more likely to have delays and disabilities (Carpenter, 2000). Autism

is the fastest growing developmental disability and has an incidence rate

of 1 in 110 births (formally 1 in 150 until 2009 and 1 in 10,000 in the early

1990’s). For males, the rate is 1 in 70 births, unsurprising since boys are

four times more likely than girls to be diagnosed with the disorder. The

number of children with autism is more than the numbers of children with

AIDS, cancer, and diabetes combined (Autism Speaks, n.d.). According

to the 2010 Kentucky KIDS COUNT Data Book, the number of children in

a south-central Kentucky Area Development District receiving social

security income due to disability in 2000 totaled 1,183, whereas in 2008

when the count was updated, the number jumped to 1,512 (Kentucky

Youth Advocates, 2010).

It takes a village to address these increasing social phenomena of

the rise in numbers of families with special needs children. Whether these

children have autism spectrum disorders, pervasive developmental

disorders, or any myriad number of other limiting physical, psychological,

social, or emotional issues, the habilitative response has to be

collaborative and well integrated. This village must include, but not be

limited to, the families, the professionals in the special needs community,

the students/interns in training, and the agencies and facilities that provide

the services. So what would the creation of such a village look like in a

rural southern community with both a university and a community

committed to having such services? What theories would support and

ground such an initiative? What system of inquiry would be used to

explore the needs and the gaps in services? What results would come

from such an initiative?

The following discussion answers the above questions and

presents not only the theoretical models but also the process of

developing a special needs forum that applied training, support, and

research to issues of families and children with special needs in a rural

community. The exploration of these needs and gaps within the rural

community is critical since rural communities in general are often

considered communities in transition (Ginsberg, 2005) and can lag behind

urban areas in terms of resource development and social service delivery.

The strengths perspective and systems model are integral

components of all social work education and practice (Zastrow, 2002) and

1

Starks et al.: Connecting the Dots

Published by DigitalCommons@TMC, 2011

are critical to service development and delivery. The strengths

perspective provides an orientation that

emphasizes the client’s resources, capabilities, support systems

and motivation to meet challenges and overcome adversity. . . . It

emphasizes the client’s assets that can be used to achieve and

maintain individual and social well-being. (Barker, 2003, p. 420)

In order to connect the dots for services for the special needs community,

the village would need a clear understanding of how all the elements work

together. Systems theories inform us about the interrelatedness and

interconnectedness of people, issues, and elements. Any discussion of,

or planning for, a response to major biopsychosocial issues should

ethically include an understanding of systems theory. Thus begins the

process in a village that includes a small force of individuals connected by

their commitment to address the issues of families with special needs.

Functioning as a Clinical Education Complex (CEC) connected to a

university in rural south-central Kentucky, this village proceeded to move

beyond services as usual. The CEC is comprised of six programs that

provide services in the areas of 1) acquired brain injury, 2) communication

disorders, 3) early childhood education/intervention, 4) family counseling,

5) family resources, and 6) autism support. These programs work

together collaboratively to provide services to individuals, families, and

professionals in this rural community. Research and multidisciplinary

training complement the service delivery and are critical to the mission of

a CEC in an academic setting.

The Family Resource Program (FRP) of the CEC is a

service/resource program staffed with social work faculty, students, and

community volunteers. Comprehensive family needs assessments are

provided to families to evaluate their needs and connect them to services

within the CEC as well as community, state, and national resources.

Support networks are encouraged and fostered through the services of the

FRP. Education and support are also available to families who have a

child newly diagnosed with autism or any other developmental disorders.

Professional staff and interns are available to meet with family members

and significant others to provide information, resource material, screening

services, case management, counseling, and referrals.

As an integral part of a university community, the FRP strives to

proactively empower individuals and caregivers. While building bridges

between individuals and needed services within the community, the FRP

enhances the community’s knowledge and awareness of individual and

family needs. The services at the FRP are offered to individuals and

families referred from other programs within the CEC, from the community

2

Journal of Family Strengths, Vol. 11 [2011], Iss. 1, Art. 10

https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/jfs/vol11/iss1/10

DOI: 10.58464/2168-670X.1015

agencies and programs, and from area schools; they are also available to

anyone seeking resource assistance in the region.

Overall, the FRP’s goals are to provide resource information and

referrals to individuals and families in need of services, to identify

individual strengths and assess individual needs, to assist families in

connecting with needed resources in the community, especially families

who have children with special needs, and to encourage and promote

community partnerships in service delivery.

Historical Perspective

In 2010, the Family Resource Program (FRP), in collaboration with the

other five CEC programs, developed a forum to target professionals in the

community as well as parents and caregivers of children with special

needs. The first forum was titled “Special Needs Family Summit” and was

presented to the community in May 2010. This event was modeled after

“The Family Café,” an annual conference for individuals and families with

special needs in Florida. The annual statewide conference of Florida’s

special needs community provides information on resources and services

available to the special needs community, while also involving the families

in the programs, agendas, and entertainment of the conference (The

Family Café, n.d.).

“The Family Café” annual conference’s mission is “to provide

individuals with disabilities and their families with an opportunity for

collaboration, advocacy, friendship, and empowerment by serving as a

facilitator of communication, a space for dialogue, and a source of

information” (The Family Café, n.d.) This conference, reportedly the

largest of its kind in the country, has impacted over 40,000 individuals

through “education, training, and networking,” providing families and

individuals with the opportunity to collaborate with professionals and other

families (The Family Café, n.d.)

The state of Florida has a unique history of responding to the needs

of children with special needs since 1994 (Stoutimore, Williams, Neff, &

Foster, 2008). Several initiatives, which included placing behavioral

analysts in child welfare programs as well as in-home placements for

parent coaching and training, were implemented. Collaboration was a key

element in the success of the programs developed. A training curriculum

of behavioral management skills and tools was utilized for caregivers.

Using the Florida conference or “Family Café” as a model, the FRP

proceeded with the assistance of a committee comprised of other CEC

program directors, interns, parent volunteers, and faculty to develop the

first Summit. Sessions were provided on the following: “Feeding

3

Starks et al.: Connecting the Dots

Published by DigitalCommons@TMC, 2011

Disorders,” “Common Psychiatric Disorders in Children,” “Waiver

Services,” “Applied Behavioral Analysis,” and “Play-based Parenting

Strategies,” along with a psycho-drama and panel presentation on “How to

be an Effective Advocate as a Parent with a Child with Special Needs in

the Public School System.” Area health-care providers and other

professionals were given the opportunity to earn continuing education

credits through this forum.

Like the Florida conference, the Summit provided similar

information and activities, although on a much smaller scale. One

difference in the two forums was the research component. The Special

Needs Family Summit provided an opportune time for data collection

around the issues of resource availability, accessibility, and gaps in

services as well as an assessment of needs directly from the stakeholders

or those most impacted. This very unique Summit was the first of its kind

in the area and was repeated the following year (2011) as the “Special

Needs Summit.”

The 2011 Summit expanded on the original with an increase in

continuing education offerings and opportunities for education and

activities. The Summit concluded with a panel of college-aged students,

all with a diagnosis on the autism spectrum. These students contributed

their personal reflections of opportunities experienced through the service

delivery programs of the CEC, in particular the mentoring and tutoring

offered through the autism program.

The success of both of the Summits will be discussed further in the

results and discussion sections of this article. The results from both not

only provided answers to the research questions but also were consistent

with the current literature on families and children with special needs.

Literature Review

A review of the literature on the issues faced by families of children with

special needs produces several common themes. Parents of children with

special needs tend to 1) experience chronic stress in caring for their child

with special needs, 2) be more prone to feelings of social isolation, 3)

experience financial difficulties in caring for their child, 4) be likely to

experience frustration in trying to locate and access services, and 5)

experience frequent anxiety and worry over their child’s future or life span

issues (Abery, 2006; Aitken et al., 2009; Autism Speaks, n.d.; Barr, 2010;

Benson & Karlof, 2009; Freedman & Boyer, 2000; Sloper, 1999). For the

scope of this article, families are defined in a broad context that includes

biological parents, adoptive parents, grandparents, extended family

members, siblings, and fictive kin. The term “parents” refers to individuals

4

Journal of Family Strengths, Vol. 11 [2011], Iss. 1, Art. 10

https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/jfs/vol11/iss1/10

DOI: 10.58464/2168-670X.1015

in the parenting or caregiving role for the child with special needs. The

terms “parents” and “families” will be used interchangeably due to the

primary relationships between the children and those individuals in the

parenting or caregiving role.

Stress

Several studies indicate the connection between a child’s disability or

health condition with parental stress and mental health issues such as

depression. Parents of children with special needs are more likely to

experience stress than parents of children who are considered to be

typically developing (Abery, 2006; Benson & Karlof, 2009; Sloper, 1999).

Having a child with a disability has a ripple effect on the family across

several domains.

Specifically, studies have shown that parents of children with ASD

(autism spectrum disorders) are at greater risk for mental health issues,

including depression, than parents of children with disabilities other than

autism. According to Benson and Karlof (2009), the symptoms and

behaviors of children with ASD, which are often pervasive and chronic,

may disrupt family roles and activities in multiple ways such as finances,

employment, and social interaction. This in turn may lead to parental

depression and other issues. In their study of parents of children with

ASD, Benson and Karlof (2009) found that having a child with ASD can

lead to considerable “psychological distress” (p. 358), including

comparatively higher levels of depressed mood and anger.

For families who have children with special needs, higher levels of

parental stress could contribute to higher parental divorce rates; however,

it is difficult to draw conclusions due to the existence of contradictory

studies. Differing divorce rates for families who have children with special

needs seem to be related to the type and severity of disability. For

example, in families where a child has autism, divorce rates appear to be

higher. In studies of families with an infant who has a health condition or

health risk, the family is more likely to experience parental divorce and

parental separation, and the family is more likely to have a stay-at-home

mother, in addition to a father with reduced work hours. In these same

families, the mother is more likely to rely on public assistance (Reichman,

Corman, & Noonan, 2008), probably due to the family’s loss of income.

However, one study by the Vanderbilt Kennedy Center found that

the divorce rate is actually lower than the national average for families

who have a child with Down Syndrome (Barr, 2010). Regardless of the

actual divorce rates for families of children with special needs, there is a

general consensus that these families need extra support due to the

5

Starks et al.: Connecting the Dots

Published by DigitalCommons@TMC, 2011

higher levels of stress experienced, especially in families where a child

presents challenging behaviors (Osborne & Reed, 2009), including

sleeping problems (Williams, Sears, & Allard, 2004).

For parents of children with special needs, finding appropriate and

affordable child care can add to family stress (Reichman et al., 2008).

Perhaps because locating affordable and quality child care is difficult,

many parents of children with special needs choose to remain at home to

care for their child or one or both parents reduce their work hours in order

to provide care at home (Reichman et al., 2008). Concern about how their

child would be treated by caregivers outside the family could also

contribute to parents’ decisions to care for their child at home. For some

families, their child’s challenging behaviors result in one parent remaining

at home to care for the child.

Social Isolation

Parents of children with special needs tend to have lower rates of social

participation than parents without a child with a disability (Reichman et al.,

2008), which may contribute to parental depression. In general, parents of

children with special needs are more prone to social isolation than their

peers who do not have children with special needs (Autism Speaks, n.d.;

Abery, 2006). In a preliminary study by the organization Autism Speaks

and the Kennedy Krieger Institute (2011), extremely challenging behaviors

resulted in social isolation for the whole family, due to the family remaining

home in order to stick to routines and avoid challenging behaviors in

public, as well as the public’s response to their child’s behaviors.

Financial Difficulties

Financial issues and work issues are significant stressors for families of

children with special needs (Aitken et al., 2009; Bachman & Comeau,

2010; Kogan et al., 2008; Lindley & Mark, 2010; Porterfield & McBride,

2007). Several factors contribute to special needs families experiencing

financial difficulties; these factors include the cost of treatments and

therapies, cost of child care, loss of income due to parents’ not being able

to work or work full-time, the time needed to receive appropriate therapies

and treatments, and the costs of money and time to transport children to

and from appointments (Parish & Cloud, 2006).

Not having adequate income means that families will not be able to

access or purchase services and resources that their children need.

Families with children who have special needs tend to have lower incomes

compared to other families; this exacerbates the process of obtaining

needed services and treatments (Bachman & Comeau, 2010). Since

6

Journal of Family Strengths, Vol. 11 [2011], Iss. 1, Art. 10

https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/jfs/vol11/iss1/10

DOI: 10.58464/2168-670X.1015

children with special needs are more likely to be living in poverty than

children in general, financial worries greatly contribute to family stress

(Bachman & Comeau, 2010; Porterfield & McBride, 2007). In rural areas

with high poverty rates, higher levels of stress produced by financial

strains may be experienced.

Contributing to financial difficulties is the lack of access to and

affordability of adequate insurance coverage (Bumbalo, Ustinich,

Ramcharran, & Schwalberg, 2005; Freedman & Boyer, 2000). Of those

with insurance, many have found that insurance does not cover needed

interventions such as physical therapy, speech-language services,

occupational therapy, applied behavior analysis, case management, and

parent support (Kennedy Krieger Institute, 2011).

Locating and Accessing Services

In order to make informed decisions about their children’s care, parents

need information about available resources and programs (Freedman &

Boyer, 2000). However, information about their child’s condition or

diagnosis, available services, available financial resources, material

supports, and respite is often missing (Sloper, 1999). In one study by

Davis et al. (2010), families reported that they did not feel supported by

services that they accessed. Another study found that lower-income

families frequently hold negative perceptions about existing community

resources (Silverstein, Lamberto, DePeau, & Grossman, 2008). Without

effective case managers who can connect families with services and

resources across several agencies, the family may be forced to

“piecemeal” services and thus experience higher levels of stress and

frustration (Freedman & Boyer, 2000).

Special needs families often require interventions and services from

multiple agencies, such as health-care, social services, education, federal,

and state agencies; this leads to contact with numerous service providers

(Abery, 2006; Ello & Donovan, 2005; Sloper, 1999). Having several

agencies or programs involved with the family without a “key” or single

point of contact leads to fragmentation of services and lack of coordination

of care (Sloper, 1999). In addition, the families who receive the least

services may be those in greatest need, including single-parent families,

lower-income families, and large families (Sloper, 1999). Families need

help in navigating the complex system of services (Freedman & Boyer,

2000).

In one study, parents often perceived that programs or agencies

involved in their children’s care did not communicate with each other,

duplicated paperwork and procedures, and provided contradictory

7

Starks et al.: Connecting the Dots

Published by DigitalCommons@TMC, 2011

information. Thus, they identified a need for agencies to communicate

and collaborate, as well as the need for a single point of entry for services

(Freedman & Boyer, 2000).

Life Span Issues

A major concern for parents of children with special needs is worry over

what will happen to the children after the parents die. Easter Seals, along

with the Autism Society of America, conducted the Living with Autism

study, in which 1,652 parents of children with autism and 917 parents of

typically developing children were surveyed regarding their daily lives,

relationships, employment, finances, healthcare, independence, and so

forth. This study found that close to 80% of parents with autism reported

that they are extremely concerned or very concerned about their child’s

ability to be independent as an adult, in stark contrast to only 32% of

parents with typically developing children. In comparison to parents of

children who are typically developing, much smaller percentages of

parents felt their child with autism would be able to make life decisions,

befriend others in the community, take part in recreational/leisure

activities, or have a life partner or spouse (Easter Seals, 2008).

Strengths

In spite of the increased demands and increased stress on families of

children with special needs, many families not only cope with the

additional demands and stress but find ways to thrive. In families of

children with developmental disabilities, parents often find ways to cope

with caregiving demands, build strong marriages, and raise children

without disabilities who appear to be well adjusted (Abery, 2006). As

mentioned earlier, in families with a child who has Down Syndrome, the

parental divorce rate was actually lower than the national average (Barr,

2010).

Some positive benefits to the family have been identified in families

with a child who has an intellectual disability. Though having a child with

an intellectual disability is not stress-free, it can be very rewarding and

enriching. Family members may have positive experiences which

contribute to an overall appreciation of life. For siblings of children with an

intellectual disability, several positive outcomes included “increased

empathy, love, sense of social justice, advocacy for those in need,

protection-nurturance, loyalty, implicit understandings and acceptance of

difference” (Dykens, 2005, p. 361).

Several factors have been identified as contributing to families’

success in raising a child with a disability, including the meanings that

8

Journal of Family Strengths, Vol. 11 [2011], Iss. 1, Art. 10

https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/jfs/vol11/iss1/10

DOI: 10.58464/2168-670X.1015

family members attribute to their situational demands and capacity to meet

those demands, the resources used by or available to the family, and the

coping behaviors used by family members to balance demands and

resources (Abery, 2006). Programs such as those examined in this study

aid families in navigating the needed services and resources as they strive

to maintain and promote the well-being of their children and entire family.

Resource Centers for Families with Special Needs

Across the United States, there are several resource centers serving

families of children with special needs. The Southwest Autism Research

& Resource Center (SARRC), located in Phoenix, Arizona, carries out its

mission to “advance research and provide a lifetime of support for

individuals with autism and their families” (Southwest Autism Research &

Resource Center, n.d.). SARRC provides services and support to children

and families with autism, while conducting research and providing

trainings for and presentations to family members and professionals in the

special needs community (Southwest Autism Research & Resource

Center, n.d.).

Another center that serves professionals in the autism community

as well as families of children with autism is the University of Louisville

Autism Center at Kosair Charities, located in Louisville, Kentucky. The

center combines different departments in the university to provide

evaluations, treatment, and interventions for children while providing

training and information to parents, caregivers, and professionals. The

goal is to provide children, caregivers, and professionals a single place

where they can obtain information, treatment, and referrals (University of

Louisville, n.d.).

In Austin, Texas, the Johnson Center for Child and Health

Development provides diagnostic services, health-care services,

behavioral therapy, educational assessments, community outreach, and

education while also conducting research. This center’s mission is “to

advance the understanding of childhood development through clinical

care, research, and education” (Johnson Center for Child and Health

Development, n.d.). Formerly called the Thoughtful House, the Johnson

Center serves individuals, families, and professionals within the

developmental disorders community (Johnson Center for Child and Health

Development, n.d.).

Located at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, the

Vanderbilt Kennedy Center offers several programs for children, parents,

and professionals within the special needs community. The center

provides information, treatment, interventions, and support for families

9

Starks et al.: Connecting the Dots

Published by DigitalCommons@TMC, 2011

who have a member with developmental disabilities. Within the Vanderbilt

Kennedy Center is the Family Outreach Center, which serves as the point

of entry for families needing services and resources offered at Vanderbilt

University and services offered within the community (Vanderbilt Kennedy

Center, n.d.). All of these centers, including the Clinical Education

Complex (CEC), share similar core values and missions in serving

individuals, families, caregivers, and professionals within the special

needs community while also conducting research to further the knowledge

of evidence-based practices within multiple disciplines. These

multidisciplinary centers provide services, training, and research within the

village of the special needs community.

Method

Consistent with the village approach, inductive methods of research

produce the most effective and user-friendly methods of inquiry.

Grounded theory can be used to capture the multiple dimensions of

phenomena. According to Denzin and Lincoln (2000), grounded theory is

currently the most widely used interpretive paradigm in the social

sciences. The inductive nature of this partially qualitative research

method provides a systematic set of procedures to develop a theory about

a phenomenon that is grounded in data and the experiences of the

participants (Tillman, 2002). Data collection, analysis, and theory

construction are regarded as reciprocally related. This interweaving is a

way to increase insights and clarify the parameters of emerging theory to

ensure that the analysis is based on the data and not on presumptions

(Padgett, 2008; Wilson, 2008). Subsequently, the emergent theory here is

specifically focused on capturing themes related to the needs of families

and children with special needs as well as the professionals who develop

and provide services to them.

This study evaluated the community Summits held over two years

by the CEC to determine if the training was useful and helpful and if it

contributed to the knowledge and skills of the conference participants.

Given the needs of children with special needs and their families, the

researchers also wanted to explore whether participants thought that the

resources were adequate in the area and to get more of a sense of

training and service needs. The training evaluation instrument selected

for this study has been utilized in several studies involving child welfare

and mental health professionals (Antle, Barbee, & van Zyl, 2008; Sullivan,

Antle, van Zyl, & Faul, 2009); it has been found to be a good measure of

training utility and, in the Antle et al. study, appeared to be a factor in

retention of knowledge gained in training. The instrument contained

10

Journal of Family Strengths, Vol. 11 [2011], Iss. 1, Art. 10

https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/jfs/vol11/iss1/10

DOI: 10.58464/2168-670X.1015

questions measured on a 5-point Likert scale. The instrument asked

participants to rate areas such as the training atmosphere, the methods

utilized in the training, the confidence they felt to practice in the topic area,

the usefulness of the material, the amount of material covered, and overall

satisfaction with training. In addition, some needs assessment questions

were asked to determine what supports and services were needed by

families with children with special needs and the professionals who serve

those families. In this study, the researchers wanted to know if the

participants thought the available resources were adequate and wanted to

explore themes around the needs of this targeted population, in order to

consider possible interventions and begin to develop theory around gaps

in services, unmet needs and a continuum of care for these children and

families. Some demographic questions were included to capture

information such as educational level, role of the participant (parent,

professional, student, etc.), age, ethnicity, and length of time involved in

the special needs community.

This study used a convenience sample of training attendees at the

Summit. There was a consent preamble inviting the participants to

complete the survey. They were informed that completing the survey and

participating in the study were voluntary and that they could discontinue

participation in the study at any time. The consent preamble indicated that

their completion of the survey communicates their consent to voluntary

participation in the study. The consent preamble and survey were

included in the participant’s training packet.

Results

Over the two years the Summit was held, 38 participants responded to the

invitation to complete the survey, 20 the first year and 18 the second year.

There were 128 total Summit participants over the two years, which made

this a response rate of 29.6%. Of the participants, 92% were female.

When asked about their ethnic origin, 76% identified themselves as

Caucasian, 18% African American, 3% Hispanic/Latino and 3% selected

the option “other.” The participants had varying levels of education, with

the majority of participants having a Master’s degree (n = 17) or Master of

Social Work degree (n = 7), 10 having Bachelor’s degrees (2 were in

social work), 1 each having a high school diploma and associate’s degree,

and 2 holding doctoral degrees.

The participants were asked their role within the special needs

community. Thirty-two percent said they worked in an agency serving

children with special needs and their families, 26% worked in a university

setting, 16% were in some sort of private practice, 8% worked for public

11

Starks et al.: Connecting the Dots

Published by DigitalCommons@TMC, 2011

school systems, and 3% were volunteers (number does not equal 100

because some chose “none of the above”). The participants represented

different roles when attending the conference. Most respondents (73%)

were attending as professionals that serve special needs children, 11%

were parents of special needs children, and 16% were students. In terms

of their length of involvement working with the special needs community,

over half the sample had been involved for more than 6 years (51%), only

5% had less than a year’s involvement, while 32% had been involved 1 to

3 years and 11% between 4 and 6 years. Those who work in the field had

been employed an average of 4 years (Mean = 48, SD = 42.3, Range = 8

– 156 months [one outlier of 39 years removed from analysis]).

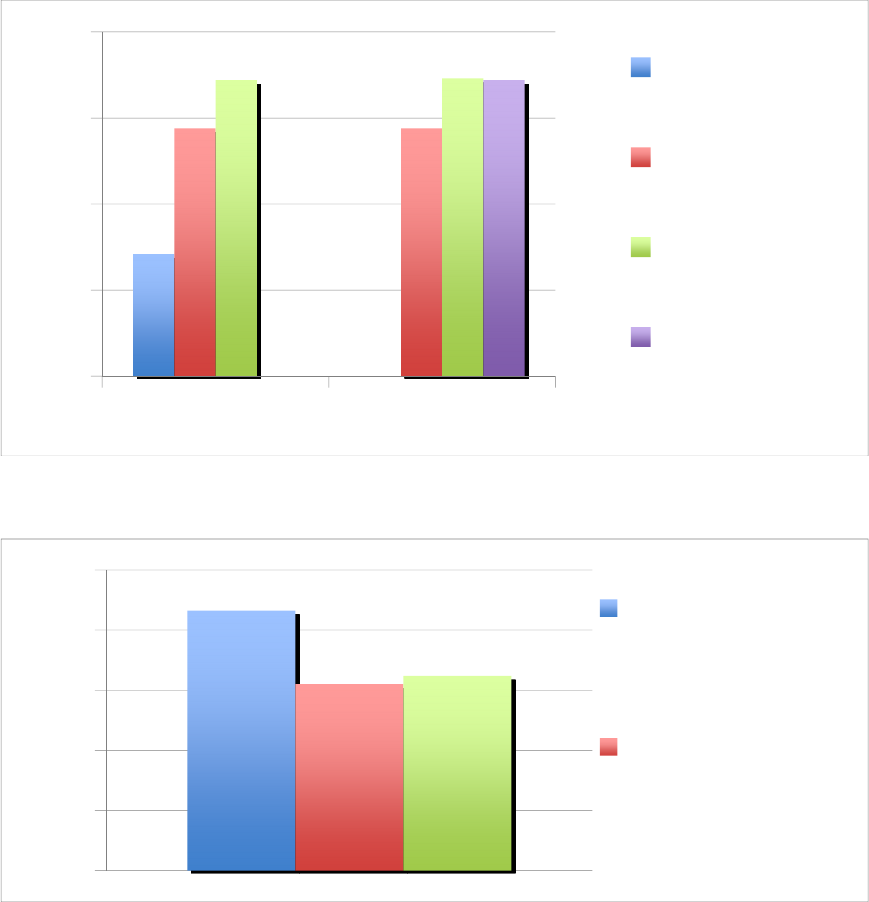

Overall, the participants reported a high level of satisfaction with the

training. When asked about the importance of the training, on a 5-point

Likert scale, the mean was 4.38 (SD = .83), with 89% indicating they

agreed or strongly agreed about the importance of the training. Their

ratings of the helpfulness and practicality of the various training methods

(role play, handouts, and lecture) were very high, ranging from 87% to

97% when combining the “agree” and “strongly agree” responses. See

Figure 1 for a graph of these results. Nearly all respondents (97%)

indicated that the method of training delivery was effective.

The training was seen as useful by 97% of the respondents, and

86.5% said their knowledge had increased as a result of participating in

the Summit. More than half of the sample (62%) indicated the training had

increased their skill in this area, and 65% indicated an increase in their

confidence to practice in this area. A large majority (89%) indicated their

likelihood to apply the knowledge gained from the training, with scores

ranging from 2-5 on a 5-point Likert scale, with a mean score of 4.35 (SD

= .89). See Figure 2 for a summary of these items.

12

Journal of Family Strengths, Vol. 11 [2011], Iss. 1, Art. 10

https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/jfs/vol11/iss1/10

DOI: 10.58464/2168-670X.1015

Figure 1. Helpfulness and practicality of training methods (combining

“agree” and “strongly agree”).

Figure 2. Impact of training on practice.

The majority of the participants (89.2%) indicated that they agreed

or strongly agreed regarding the importance of the training, and the

majority (86.5%) indicated their knowledge on the topic had increased

after attending the training. Nearly two-thirds (64%) indicated the amount

of material covered was the right amount while 21.4% indicated they

would have liked more material to be covered during the event. When

asked if they felt more equipped to be an advocate for special needs

80

85

90

95

100

Helpful Practical

Role Playing

Handouts

Lecturing

Training

Overall

0

20

40

60

80

100

Increase

Knowledge

Increase Skill,

Confidence in

Practice

13

Starks et al.: Connecting the Dots

Published by DigitalCommons@TMC, 2011

children after attending the training, 88% indicated they did. Almost all of

the participants (94%) indicated they felt more informed about children

with special needs after attending the Summit. Several themes emerged

regarding how participants felt more equipped to be advocates for children

with special needs. Participants mentioned areas such as feeling better

equipped for families when children have feeding concerns, feeling more

comfortable working with this population, gaining a better understanding of

autism spectrum disorders and related interventions/treatment, and

gaining knowledge to pass on to others to raise awareness about how to

best assist children and families.

Slightly over half (56.3%) indicated that the resources for special

needs children and their families are adequate within the community.

Some of the needed resources listed were as follows: help for learning

resources when new to the area; awareness in the general population to

the needs of children with ASD; more resources for feeding issues;

decreased waiting lists; greater social interaction and assistance with

activities of daily living; more play groups and support groups; financial

resources; transportation to services; more in-home services; and respite

care.

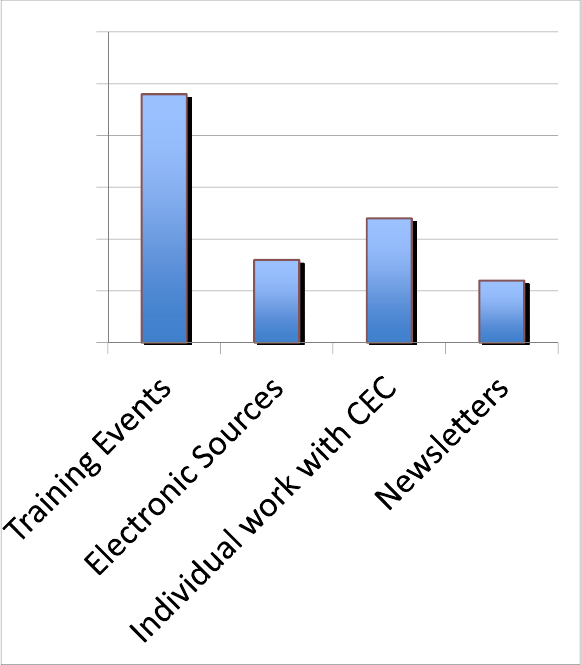

The preferred format for receiving information about working with

special needs children was training events (n = 34), followed by individual

work with staff (n = 12), then electronic sources (n = 8) and newsletters (n

= 6). See Figure 3 for a summary. The training topics most requested by

participants for future events were as follows: strategies for low-

functioning autism, physical disabilities, feeding, sensory issues, speech

behavior, auditory processing/hearing impairment, and in-depth

information on therapy and intervention techniques.

14

Journal of Family Strengths, Vol. 11 [2011], Iss. 1, Art. 10

https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/jfs/vol11/iss1/10

DOI: 10.58464/2168-670X.1015

Figure 3. Preferred format for receiving information about working with

special needs children

Discussion

The participants in this study had several years of work experience with

children with special needs and had been involved in the special needs

community for some time. They had varying levels of education, and

more than half had been involved with the special needs community for

more than 6 years. Professionals, parents, and students were all

represented and came together to gain more information about children

with special needs. Those who had worked in the field had been working

there an average of 4 years, indicating that the sample had some

experience already with this population and began the training with some

familiarity of the issues related to this population.

Overall, the participants rated the training as useful, important, and

practical. The qualitative comments indicated that the participants liked

the speakers, that the training was interesting and helpful, and that a great

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

15

Starks et al.: Connecting the Dots

Published by DigitalCommons@TMC, 2011

deal of good information was covered. Needed resources and future

training topics were identified. Many of these topics are in line with the

literature, which indicates these families need assistance in areas such as

accessing services (Freedman & Boyer, 2000). The majority of

participants indicated they felt better equipped after the training to be

advocates for children with special needs. They were highly satisfied with

the training and indicated an increase in knowledge, skills, and confidence

to practice in this area. Even though many in this sample indicated that

there are adequate resources for children with special needs, the small

sample size limits the generalizability of these findings. Future studies

should continue to explore the needs of children with special needs and

their families as well as to examine outcomes from programs such as the

CEC, programs which are designed to help meet these multiple needs.

Conclusion

The rise in prevalence of children with special needs presents challenges

for families and communities. A child’s disability affects several areas of

family life, and parental well-being impacts the child’s well-being.

Therefore, it is imperative to address the whole family’s needs and not just

the needs of the individual with a disability. Particularly in rural areas, as

more and more children are diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders

and other developmental disabilities, families often struggle to locate

information, support, and referrals for various therapies, services, and

resources.

A review of the literature identifies several issues faced by parents

of children with special needs such as chronic stress, social isolation,

financial issues, difficulty locating and accessing services, and life span

issues. In order to meet the needs of families with special needs, a

holistic approach is critical (Freedman & Boyer, 2000). This holistic

approach was supported by the results of the research conducted in this

study. Linking families with needed resources and giving parents options

to make choices and decisions about the services their children receive

empowers them, and all family members benefit.

The Special Needs Summit was developed by a Clinical Education

Complex (CEC) to provide education, support, and training for families,

professionals, paraprofessionals, and students within the special needs

community. The Summit provided the following for its participants, who

were parents, caregivers, professionals, paraprofessionals, and students:

workshops on relevant topics, continuing education credit, informational

booths, panel of college students with autism spectrum disorders, a talent

show featuring children with special needs, and family festival activities.

16

Journal of Family Strengths, Vol. 11 [2011], Iss. 1, Art. 10

https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/jfs/vol11/iss1/10

DOI: 10.58464/2168-670X.1015

This forum allowed an opportunity for research, and data were

collected through the use of an evaluation training instrument.

Participants were able to provide feedback through the use of a survey

that requested information about the following: 1) relevance of the

training, 2) future needs for training, 3) needs for development of

additional resources, and 4) the best vehicle for service delivery.

Based on data from participants, the majority agreed the training

was important and rated highly the helpfulness and practicality of the

training methods. As a result of the Summit, participants reported their

knowledge and skill in a particular area had increased. Participants

indicated they felt more equipped to advocate for children with special

needs, and almost all felt more informed about children with special needs

after attending the Summit. Some of the gaps in services or needed

resources which were identified included: help in locating and accessing

services when new to the area, community awareness of children with

autism spectrum disorders, financial resources, transportation, and respite

care; this list corresponds to the needs of parents found in the literature.

The feedback from participants in this study will also contribute to the

existing literature on diversity as it relates to families of children with

special needs.

More studies are needed to further explore the challenges of

members within the special needs community, particularly families. More

detailed feedback regarding specific needs would be helpful in developing

future Summits and parent training and support events. Forming a

coalition of service providers dedicated to serving families with special

needs could make service provision more effective and responsive to

families. In order to connect the dots for these families, it will take a

village approach. This village should be multidisciplinary, inclusive of

parents, siblings, formal and informal caregivers, and the professional and

academic communities.

17

Starks et al.: Connecting the Dots

Published by DigitalCommons@TMC, 2011

References

Abery, B. H. (2006). Family adjustment and adaptation with children with

Down Syndrome. Focus on Exceptional Children, 38(6), 1-18.

Aitken, M. E., McCarthy, M. L., Slomine, B. S., Ding, R., Durbin, D. R.,

Jaffe, K. M. . . . & Mackenzie, E. J. (2009). Family burden after

traumatic brain injury in children. Pediatrics, 123(1), 199-206.

Antle, B. A., Barbee, A. P., & van Zyl, M. (2008). A comprehensive model

for child welfare training evaluation. Children and Youth Services

Review, 30(9), 1063-1080.

Autism Speaks Incorporated. (n.d.). What is autism? Retrieved from

http://www.autismspeaks.org/what-autism

Bachman, S. S., & Comeau, M. (2010). A call to action for social work:

Minimizing financial hardship for families of children with special

health care needs. Health & Social Work, 35(3), 233-238.

Barker, R. L. (Ed.). (2003). The social work dictionary (5th ed.).

Washington, DC: NASW Press.

Barr, K. N. (2010, February). When parents of children with special needs

divorce. Exceptional Parent Magazine, 4-7.

Benson, P. R., & Karlof, K. L. (2009) Anger, stress proliferation, and

depressed mood among parents of children with ASD: A

longitudinal replication. Journal of Autism and Developmental

Disorders, 39, 350-362.

Bumbalo, J., Ustinich, L., Ramcharran, D., & Schwalberg, R. (2005).

Economic impact on families caring for children with special health

care needs in New Hampshire: The effect of socioeconomic and

health-related factors. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 9(2

Suppl.), S3-S11.

Carpenter, B. (2000). Sustaining the family: Meeting the needs of families

of children with disabilities. British Journal of Special Education,

27(3), 135-144.

Davis, E., Shelly, A., Waters, E., Boyd, R., Cook, K., Casey, E., . . .

Reddihough, D. (2010). The impact of caring for a child with

cerebral palsy: Quality of life for mothers and fathers. Child: Care,

Health, and Development, 36(1), 63-73.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2000). Handbook of qualitative research.

Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Dykens, E. M. (2005). Happiness, well-being, and character strengths:

Outcomes for families and siblings of persons with mental

retardation. Mental Retardation, 43(5), 360-364.

Easter Seals. (2008). Living with autism study. Retrieved from

18

Journal of Family Strengths, Vol. 11 [2011], Iss. 1, Art. 10

https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/jfs/vol11/iss1/10

DOI: 10.58464/2168-670X.1015

http://www.easterseals.com/site/PageServer?pagename=ntlc8_livin

g_with_autism_study_home

Ello, L. M., & Donovan, S. J. (2005). Assessment of the relationship

between parenting stress and a child’s ability to functionally

communicate. Research on Social Work Practice, 15(6), 531-544.

Freedman, R. I., & Boyer, N. C. (2000). The power to choose: Supports for

families caring for individuals with developmental disabilities. Health

& Social Work, 25(1), 59-68.

Ginsberg, L. H. (Ed.). (2005). Social work in rural communities (4th ed.).

Alexandria, VA: Council on Social Work Education.

Johnson Center for Child and Health Development. (n.d., para. 1).

What is the Johnson Center for Child Health and

Development?.Retrieved from http://www.johnson-

center.org/index.php/site/FAQ

Kennedy Krieger Institute. (2011). Interactive autism network research

report: Family stress—part 1. Retrieved from

http://www.autismspeaks.org/news/news-item/ian-research-report-

family-stress-%E2%80%94-part-1

Kentucky Youth Advocates. (2010). Kentucky KIDS COUNT county data

book. Jeffersonville, KY: Kentucky Youth Advocates.

Kogan, M. D., Strickland, B. B., Blumberg, S. J., Singh, G. K., Perrin, J.

M., & van Dyck, P. C. (2008). A national profile of the health care

experiences and family impact of autism spectrum disorder among

children in the United States, 2005-2006. Pediatrics, 122(6), e1149-

e1158.

Lindley, L. C., & Mark, B. A. (2010). Children with special health care

needs: Impact of health care expenditures on family financial

burden. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19, 79-89.

Osborne, L. A., & Reed, P. (2009). The relationship between parenting

stress and behavior problems of children with autistic spectrum

disorders. Exceptional Children, 76(1), 54-73.

Padgett, D. K. (2008). Qualitative methods in social work research (2nd

ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Parish, S. L., & Cloud, J. M. (2006). Financial well-being of young children

with disabilities and their families. Social Work, 51(3), 223-232.

Porterfield, S. L., & McBride, T. D. (2007). The effect of poverty and

caregiver education on perceived need and access to health

services among children with special health care needs. American

Journal of Public Health, 97(2), 323-329.

19

Starks et al.: Connecting the Dots

Published by DigitalCommons@TMC, 2011

Reichman, N. E., Corman, H., & Noonan, K. (2008). Impact of child

disability on the family. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 12, 679-

683.

Silverstein, M., Lamberto, J., DePeau, K., & Grossman, D. C. (2008). “You

get what you get”: Unexpected findings about low-income parents’

negative experiences with community resources. Pediatrics, 122(6),

e1141-e1148.

Sloper, P. (1999). Models of service support for parents of disabled

children: What do we know? What do we need to know? Child:

Care, Health, and Development, 25(2), 85-99.

Southwest Autism Research & Resource Center. (n.d.) About SARRC.

Retrieved from

http://www.autismcenter.org/about_sarrc.aspx

Stoutimore, M. R., Williams, C. E., Neff, B., & Foster, M. (2008). The

Florida child welfare behavior analysis services program. Research

on Social Work Practice, 18(5), 367-376.

Sullivan, D. J., Antle, B. F., van Zyl, M. A., & Faul, A. C. (2009).

Implementing evidence-based practice into public mental health

settings: Evaluation of the Kentucky Medication Algorithm Program.

Best Practices in Mental Health, 5(2), 112-128.

The Family Café. (n.d., para 1). The Family Café: About Us. Retrieved

from

http://familycafe.net/index.php?option=com_content&view=section&

id=3&Itemid=90

Tillman, L. C. (2002). Culturally sensitive research approaches: An

African-American perspective. Educational Researcher, 31(9), 3-

12.

University of Louisville Autism Center at Kosair Charities. (n.d.) Our

mission statement. Retrieved from http://louisville.edu/autism/

Vanderbilt Kennedy Center (n.d.) The Family Outreach Center. Retrieved

from

http://kc.vanderbilt.edu/site/services/disabilityservices/default.aspx

Williams, P. G., Sears, L. L., & Allard, A. (2004). Sleep problems in

children with autism. Journal of Sleep Research, 13, 265-268.

Wilson, S. (2008). Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods.

Winnipeg, Canada: Fernwood Publishing.

Zastrow, C. (2002). The practice of social work (7th ed.). Pacific Grove,

CA: Brookes/Cole Publishers.

20

Journal of Family Strengths, Vol. 11 [2011], Iss. 1, Art. 10

https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/jfs/vol11/iss1/10

DOI: 10.58464/2168-670X.1015