32

(Re)thinking the Adopon of Inclusive Educaon Policy

in Ontario Schools

A y m a n M a s s o u

University of Western Ontario

Abstract

The purpose of this article is to advance a proposal for the analysis of how inclusive education policies

in Ontario schools are adopted. In particular, I use the notion of Policy Enactment to re-conceptualize

the processes of putting inclusive education policies into practice. The argument is that the traditional

implementation model to analyze the adoption of inclusive education policies devalues the signicant

role of context in both policy analysis research and practice. Analyzing education policies based on the

construct of enactment offers a context-informed approach that can help policy actors and researchers to

better understand how inclusive education policies are incorporated into practices. The paper concludes

that a policy enactment perspective empowered by the constructs of Neo-Institutionalism theory is a more

robust tool for analyzing inclusive education policies as their translation is far from being a mere upfront

conversion of text into action.

Keywords: inclusive educaon policy, implementaon, enactment, context, Ontario schools,

policy actors, pracce, policy analysis

Introducon

Despite the existence of a large body of research on inclusive education policies (Bourke, 2010; Johnstone

& Chapman, 2009; Kelly, Devitt, O’Keffee, & Donovan, 2014; Peters, 2007), little knowledge exists on

how such policies are incorporated into practices (Ahmmed & Mullick, 2014; Forlin, 2010a; Naicker,

2007; Poon-McBrayer & Wong, 2013) from a policy enactment and institutional perspective. This paper

seeks to provide a conceptual framework for the analysis of the adoption of inclusive education policies

through the lens of policy enactment (Ball, Maguire, & Braun, 2012) that examines the interpretation and

translation of policy texts into context-relevant practices. As it will be evidenced in my critical review of

the literature, the enactment construct has not been sufciently used in policy research that particularly re-

late to inclusive education in Ontario. Instead, policy analysis and the practice of inclusive education have

been widely examined through the implementation model. The implementation model is a perspective

that portrays policy adoption as a hierarchical, top-down, and formal transfer of text into action without

attention to the policy’s contextual dimensions, namely the social, organizational, and cultural dimensions

that are highly signicant in policy practice and research (Ball et al., 2012).

Globally speaking, the existence of challenges associated with the implementation of policies, partic-

ularly those related to the inclusion of students with special needs, is evident in the literature (Engelbrecht,

Nel, Smit, & van Deventer, 2016; Hamdan, Anuar, & Khan, 2016; Mosia, 2014; Vorapanya & Dunlap,

2014). After examining many policy implementation studies, Werts and Brewer (2015) found that the aims

of education policies are not usually in line with what teachers believe, as well as the motivations and

capacities they have. Addressing the signicance of context, Heimans (2014) claims that contextual fac-

Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy, 185, 32-44

33

CJEAP, 185

tors are rarely considered in education policy research. Giving priority to the element of context can help

us to understand how “policies are taken up, variously inected, translated and interpreted” (Heimans,

2014, p. 308). According to Singh, Heimans, and Glasswell (2014), context is an analytic construct that

allows policy enactment researchers to realize how policies are translated and incorporated into actions

and practices in schools. They contend that the notions of enactment and context together constitute a

signicant contribution that supports the literature of critical policy analysis, such as inclusive education

policy research and practice.

Adding to the critique of formal implementation models, Werts and Brewer (2015) state that education

policies do not anticipate any democratic engagement at the place where they are practiced, but they tend

to marginalize “the perspectives and experiences of those living out the policy” (p. 224), the policy actors.

This potential for marginalization highlights the need to reconsider the relation between the social, the

cultural, and the organizational context and a given mandated institutional policy, and how such a relation

informs policy outcomes. Therefore, in my view, the enactment construct is a more workable approach to

be used in the analysis of the adoption of inclusive education policies and practice. For Vekeman, Devos,

and Tuytens (2015), policy makers do not often recognize the multiple interpretations and concerns of

those who are acting out or translating a policy into practices. They contend that what makes policy prac-

tice more difcult is the existence of multiple interpretations, even within the same organization. Thus,

the translation of a given institutional policy such as Ontario’s Equity and Inclusive Education Strategy

(Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014) into practices may not fulll the policy’s objectives that have been

initially set. This policy calls upon school boards in Ontario and their personnel, particularly teachers,

to “understand, identify, address, and eliminate the biases, barriers, and power dynamics that limit stu-

dents’ prospects for learning, growing, and fully contributing to society” (OME, 2014, p. 6). However,

transforming these ethical objectives into real-life practices become subject to the various social, cultural,

organizational, and belief systems at schools. Therefore, it is best to offer some space for policy actors to

interpret a mandated policy according to their situated context and within the policy’s institutional frame-

work (Vekeman et al., 2015). According to Heimans (2014), the policy enactment perspective shifts the

direction of policy analysis from understanding the conceptual meaning of policies to the examination

of the contextual practices of local policy actors. Here, Ball (1994) reminds us that policies are never

straightforward, rather “they create circumstances in which the range of options available in deciding what

to do are narrowed or changed, or particular goals or outcomes are set” (p. 19). Thus, with the enactment

perspective, policy goals, practices, and outcomes become negotiable, context-informed, and dependent

on the meanings that policy actors make in their own situated context.

In addition to the concept of enactment, this paper draws from Neo-Institutionalism theory (NI) (Pow-

ell & DiMaggio, 1991) as a macro level component that can enhance the analysis of the adoption of inclu-

sive education policies. NI theory emphasizes how particular institutional rules, norms, and regulations

have their share in shaping the ways policy actors view themselves in interpreting and translating inclusive

education policies. Having said that, policy analysis researchers should not only consider the micro level

framework within which policy actors perform their practices but also to attend to the macro level one, the

institutional. This paper claims that the enactment model and NI together can offer a new tool to examine

and analyze the adoption of complex inclusive education policies in Ontario. I argue that this could be

accomplished by devoting particular attention to the interplay of the micro level (local context), and the

macro level (policy making), and how this interplay informs the practices of local policy actors. With

this argument, policy researchers are provided with a new and wider conceptual framework to utilize in

understanding how inclusive education policies are and can be fused into the practices of policy actors in

Ontario schools.

The Adopon of Inclusive Educaon Policies: Learning from Internaonal Cases

The adoption of inclusive education policies continues to be a challenging task across the world due to

the underestimation of many factors including the context. For instance, Naicker (2007) noted that the im-

plementation of inclusive education policies in South African schools remains problematic due to beliefs

that have fostered exclusion for years. He claimed that in South Africa, inclusive education policy did not

develop in line with the pedagogical revolution (inclusive teaching and learning in a digital age) and got

“stuck at a political level since it ignored epistemological issues in the training of educationists” (Naicker,

2007, p. 2). Naicker’s study highlights the disparity between the inclusive policy agenda and the profes-

34

Massouti

sional development and educational strategies at the school level. In Bangladesh, Ahmmed and Mullick

(2014) found that the implementation of inclusive education (IE) initiatives faces multiple complexities in

practice. They believe that “contextually relevant strategies to address these complications and implement

IE reform policies successfully” (Ahmmed & Mullick, 2014, p. 168) are needed. The struggle with the

implementation model is embedded in (1) resource allocation for inclusive education, (2) parental engage-

ment in the school activities and decision-making, and (3) the need for advanced teacher development and

school leaders’ empowerment (Ahmmed & Mullick, 2014). Consequently, translating policy into practice

rests on a robust organization and serious collaborative work at the local level among all policy actors

(Johnstone & Chapman, 2009). Collaboration practices for Kim (2013) serve as a signicant factor that

promotes teachers’ professional development in the inclusive classroom and in turn the achievement of

policy goals such as successful learning experiences and assured well-being for all learners.

Sensemaking and Policy Adopon

Within the competitive Korean learning environment where academic achievement is of high concern

among parents, Kim (2013) noted that it is very challenging to implement an inclusive education ap-

proach as students are under pressure due to their parents’ high expectations. To adopt inclusion policies,

Kim believes that an “insufcient understanding and inactive participation from principals of the regular

school act as one of the barriers to inclusion” (p. 81). According to Dudley-Marling and Burns (2013), the

enactment of the US law PL 94-142 states that all children with special needs must learn together with

their non-disabled peers in the Least Restrictive Environment (LRE) and be provided with an appropriate

education. However, the outcomes of these objectives rest on local teachers’ denitions of disability and

inclusion (Dudley-Marling & Burns, 2013). In this vein, Weick (1995) contends that the implementation

of policy in organizations such as schools depends on the existing organizational processes and how local

teachers make sense of policy. Kelly, Devitt, O’Keffee, and Donovan (2014) argue that Irish legislation

and educational policies do facilitate inclusion by offering guidelines; however, the ways in which such

policies are being incorporated into practices remains subject to the multiple interpretations of actors in

schools. They found that students with special education needs (SEN) continue to move from mainstream

schools to special schools due to the presence of an exclusion-oriented environment in the former. I argue

that these studies contribute collectively to the signicance of context which must be taken more seriously

in policy practice and policy making research if to alleviate policy-associated challenges.

Policy Adopon and the Local Context

Referring to context, Kelly et al. (2014) contend that “the fundamental criteria necessary for implementing

a change in an educational system were not explored sufciently prior to implementation” (p. 79). The

shift from segregation to inclusion requires an adjustment of school culture and attitudes even with the

implementation model being fully supported (Kelly et al., 2014). That is, at the school level, the imple-

mentation of inclusive education has to overcome many obstacles including lack of teacher training, inad-

equate educational assessment of students with SEN, and incompatible curriculum and resources (Kelly et

al., 2014). With the existence of many inclusive education policies and approaches, Sailor (2015) from the

US, argues that there is a clear continuous emphasis on the complexity of differentiating instruction to ac-

commodate all learners. Referring to the crucial role of context, he notes that “what better way to approach

this complex problem than to attend to the entire ecology of the learning situation?” (Sailor, 2015, p. 95).

Relatedly, Forlin (2010a) found that the contextual factors that obstruct a signicant adoption of inclusive

education at schools in Hong Kong include lack of teachers’ autonomy, lack of inclusion-oriented expe-

riences, xed curricula, and high working demands. To overcome the challenges of adopting an inclusive

education policy model she adds, the external control on students’ achievement, such as the dilemma of

testing requirements according to the Canadian context, should be minimized to allow classroom teachers

to develop their inclusive skills and monitor their students’ academic progress (Forlin, 2010a).

The Role of the Macro Level System in Policy Adopon

In their study, Johnstone and Chapman (2009) argued that it is unacceptable to train only some teachers in

particular schools on how to practice a new inclusive policy and assume that untrained teachers in other

school contexts will conform to that practice. In this vein, Peters (2007) stresses the fact that inclusive

35

CJEAP, 185

education policies get “shaped by people (actors) in the context of society, whether locally, nationally, or

globally” (p. 100). For her, the practicality of the inclusive approach lies in changing the discourses about

SEN students in related policy documents that tend to be exclusive rather than inclusive (Peters, 2007).

Alternatively, Bourke (2010) argued that the inclusive education policy models in Queensland are being

introduced in the school system without signicant attention to how school contexts impact both teachers

and students. She noted that although many initiatives towards inclusive education have been offered,

school structures and strategies continue to reect an exclusive practice and teachers continue to feel con-

fused and frustrated about the term inclusion (Bourke, 2010). That is, the disparity between policy making

and policy-in-practice persists. Young and Lewis (2015) looked at Finnish schools. They found that these

schools are offered “considerable autonomy to organize special education according to local values, rely-

ing on a culture of trust” (Young & Lewis, 2015, p. 9). In other words, the Finnish education system seems

to offer its local schools a chance to interpret and translate new policies according to their organizational

context. By looking at the Finnish system, a critical reader could argue that transforming complex inclu-

sive education policies into practices is not an up-to-bottom process but a context-informed one.

The Crique of the Implementaon Model: Towards a Context-Informed Ap-

proach

Many studies have examined the theoretical and practical work of inclusive education and its related

policies towards advancing the learning of all students in the inclusive classroom (Ainscow, 2007; Forlin,

2010b; Keefe, Rossi, de Valenzuela, & Howarth, 2000; Loreman, 2010; Mittler, 2000; Slee, 2010). How-

ever, a question to which the answer remains vague is how can we best understand the processes by which

inclusive education policies are translated into practices at schools. The knowledge about translating pol-

icy into practice tends to be mostly framed by the implementation model. As noted above, this model

is insufcient if we aim to offer a context-sensitive account of how inclusive policies are analyzed and

incorporated into practices. Embedded in the context, the enactment model becomes a more promising

approach in the analysis of inclusive education policies.

I claim that inclusive education is a contested concept and has become the subject of debates in aca-

demic and policymaking circles all over the world. Relatedly, a published report about inclusive education

by the Council of Ministers of Education in Canada (2008) identied the inclusion approach as a chal-

lenging route. According to the report, it takes a serious contribution from all of those concerned about

inclusion to eliminate the barriers to students’ success. This is a promising recognition of the role played

by both the macro and the micro level systems. In Ontario, Canada, Inclusive education policies aim to

accommodate the learning of all students including those with special learning needs and provide them

with the necessary tools and strategies to overcome their challenges and achieve their potential (OME,

2014). However, a context-free translation of these policies into practices is problematic. Johnstone and

Chapman (2009) remind us that the ultimate aim of education policies is to ensure they are translated into

practices at schools; however, the adoption phase remains complex while actors continue to face chal-

lenges in interpreting and assessing those policies’ objectives. This explicates the idea that policies are

tools that “sanction, encourage, and disseminate desired practice” (Johnstone & Chapman, 2009, p. 131),

a practice that is often institutionalized and conforms to pre-set norms and rules. Having said that, the

struggles of policy implementation in educational organizations such as schools, returns to those involved

in policy making who in many cases, tend to disregard the complexities of schools and their context and

how these inform the policy actors’ practices. This contempt for context, in line with the implementation

model can be exemplied in the following quote:

While teacher training is an essential component of launching a policy with implications for class-

room practice, many policy-makers gamble that, once launched, those practices will be more widely

adopted. Their hope is that demonstrating the effectiveness of an intervention on a small scale, but

in a way that is highly visible to a wider audience, will create a local demand for wider implemen-

tation. (Johnstone & Chapman, 2009, p. 132)

The assumption that policies are generalizable and transferable to all contexts seems difcult, especially in

light of the multiple meanings, representations, and discourses that circulate in educational organizations.

In response to this decontextualized view of policy practices and adoption, Riveros and Viczko (2016)

argue that the enactment perspective offers a “way to talk about the transformations and adaptations of

36

Massouti

educational policy that overcomes the limitations of the instrumentalist models in policy analysis” (p. 67)

such as those of policy implementation.

For the purpose of policy analysis, researchers have identied many shortcomings in the policy imple-

mentation construct (May, 2015). These inadequacies for May (2015) are due to the lack of acknowledg-

ment of the “basic conicts among the actors charged with carrying out policies” (p. 279). Over time, it is

becoming more evident that policies calling for action at a governmental level, such as education reform,

are experiencing challenges in practice at the local level. In May’s view, such challenges depend on the

evolution of policies while they are in the translation phase, and the context-associated demands and con-

ditions. These demands and conditions are embedded in the institutional and organizational frameworks

that shape the means by which these policies are practiced, or more specically, enacted. Thus, disre-

garding the policy context can lead to undesirable outcomes because context serves as the milieu within

which policy meanings are constructed. The context here mirrors the place, norms, and the values of its

inhabitants including the teachers, students, administrators, and other school personnel. Werts and Brewer

(2015) claim that the limited positive impact of policy in schools “is due to continual attempts to under-

stand local actors, not on their terms but, instead, in relationship to the reformer’s goals” (p. 207). Having

said that, inclusive education policies and their translation into practice will remain unclear if a top-down

managerial approach towards policy analysis and practice continues to exist. This persistence promotes

us to reconsider the way we look at these policies. This is to say that with respect to pre-set institutional

guidelines on policy practice, we need to analyze the adoption of policies from local perspectives and to

be continuously aware of how context speaks to the policy’s various outcomes.

Fixsen, Naoom, Blase, Friedman, and Wallace (2005) noted that a consensus exists about adoption

being “a decidedly complex endeavor, more complex than the policies, programs, procedures, techniques,

or technologies that are the subject of the implementation efforts” (p. 2). Regarding the practical problems

associated with the incorporation of inclusive education policies into practices, Florian (1998) noted that

while inclusion is one of a human's rights and the focal point of inclusive education policies, concerns

remain about the inclusive schools’ learning and teaching practices. Consequently, by overlooking the

contextual elements of policies, we continue to bring about less valuable outcomes. Although the inclu-

sion concept is highly recognized today in Global North countries such as Canada and the US (see Forlin,

2010b), inclusive policies, and how they inform the practices of teachers, administrators, and school

principals are still unclear. Relatedly, Thompson, Lyons, and Timmons (2015) realized the ambiguity in

conceptualizing the adoption of inclusive education policy. They found that while the inclusion approach

is evident at the public policy level, a gap between policy and practice still exists. Similarly, in the Swedish

context, Ineland (2015) asserts that Swedish classrooms are promised with the inclusive learning envi-

ronment, yet the practice of inclusion reveals, “fragmented organizational structures [and] professional

attitudes together with vague guiding principles for inter-professional collaboration” (p. 54).

Policy Enactment and Policy Actors

Attention to the institutional positions and experiences of the policy actors is a promising task that claries

how policies are put into practice (Maguire, Braun, & Ball, 2015; Werts & Brewer, 2015). According to

Sin (2014a), policy can be molded and re-molded. That is, when policy is enacted, it becomes subject to

multiple understandings depending on its situated context. The enactment of policy has been viewed as

assemblage (Riveros & Viczko, 2016) in which “people, their material objects, and their discursive prac-

tices are brought together to enact policy in productive ways” (Koyama, 2015, p. 548). Assemblage, ac-

cording to Koyama (2015) represents a collection of various practices, plans, processes, materials, and the

imagination of new forms of policies. Further, Mulcahy (2015) argues that policy enactment is not only

about written texts but also about how policies are perceived and put into practice. Similarly, enactment

has been conceptualized as “a meshwork of policy practices. These practices draw on divergent material

and discursive resources for their ongoing emergent (re)constitution” (Heimans, 2012, p. 317).

Viczko and Riveros (2015) contend that the analysis of policy processes should not view schools as

organizations that lack context, or a place where policies are translated similarly by all actors. In their

view, to understand the realities of policy actors and to conceptualize alternative ways of policy trans-

lation, it is imperative to examine “what comes to be performed through policy” (p. 480). According to

Sin (2014b), two factors are considered when we look at policy research outcomes in higher education.

These factors are the policy process itself including the making of it and its translation into practice, as

37

CJEAP, 185

well as the policy actors. Every policy actor plays a role or performs a set of activities that add to the

understanding of how policy is enacted. Ball (2015) reminds us that “policies are ‘contested’, mediated

and differentially represented by different actors in different contexts” (p. 311). These policy actors and

contexts are important factors in negotiating, constructing, and enacting policy (Sin, 2014b). That is, the

beliefs of policy actors regarding a policy are subject to contextual circumstances that impact how policies

are translated (Sin, 2014b).

Maguire et al. (2015) inform us that further attention has been devoted in recent years to multiple pol-

icy reforms, particularly assessment, curriculum, and teacher education with the aim to advance students’

academic achievement. Therefore, in future policy research, it becomes “useful to consider what some of

the more senior school managers have to say about policy work. What comes across is their understanding

of the wider context as well as their decision-making capacity – their capacity to interpret and dene”

(Maguire et al., 2015, p. 496). It is worth noting here that few studies have examined how policies such

as those related to inclusion get enacted through the actions of policy actors in schools and other institu-

tions (Maguire et al., 2015). Consequently, understanding these actors’ positions helps policy researchers

and policy decision makers to conceptualize how policies need to be constructed and disseminated. Ball

(2015) maintains that when we study policy text, we should focus on how language is being used in docu-

ments and practices. However, policy as a discourse attends to a discursive and meaningful understanding

of the different practices to make sense of how education is constituted (Ball, 2015).

Policy enactment then offers a venue to re-conceptualize policy adoption as it recognizes texts and

documents as complex structures to decode (Braun, Ball, Maguire, & Hoskins, 2011). Policy enactment

research attends to the relation between the policy process and its context. In this regard, Braun et al.

(2011) assert that translating a policy such as Ontario’s Equity and Inclusive Education Strategy into

practice requires attention to the relation between the objective conditions and “a set of subjective ‘inter-

pretational’ dynamics and thus acknowledge that the material, structural and relational are part of policy

analysis in order to make better sense of policy at the institutional level” (p. 588). Regarding the material

context, Braun et al. (2011) stated that in schools, the staff, available technology, the space, and the layout

of buildings play key roles in policy enactment. In other words, enacting an inclusive education-related

policy for instance in a particular school depends on the organizational structure and perhaps the nancial

and professional capacities of that school. Thus, it becomes illogical to assume that all schools will prac-

tice policies similarly. Therefore, the need to consider the context in policy analysis research is relevant

because “policy making and policy makers tend to assume ‘best possible’ environments for ‘implementa-

tion’: ideal buildings, students and teachers and even resources” (Braun et al., 2011, p. 595). This assump-

tion allows us as policy researchers to understand that what policy actors do, may not necessarily reect

the intended policy outcomes since the actors’ practices depend on their understanding of that policy

(Maguire et al., 2015).

Compleng the Picture with a Neo-Instuonal Perspecve to Analyze Policy

Pracces

A complex denition for institution has been given by March and Olsen (2006). For them, it is a combina-

tion of “rules and organized practices, embedded in structures of meaning and resources that are relatively

invariant in the face of turnover of individuals and relatively resilient to the idiosyncratic preferences and

expectations of individuals and changing external circumstances” (March & Olsen, 2006, p. 3). Simply

put by Schmidt (2010), institutions are “socially constituted and culturally framed rules and norms” (p. 2).

For Scott (2014), institutions are a set of “rules, norms and beliefs to which individuals and organizations

conform” (p. xi). However, advocates of new institutionalism have not agreed upon a standard denition

for institutions as they do not share a similar methodological and research agenda (Immergut, 1998).

New institutionalists according to Immergut (1998), reject behavior as the sole idea behind NI as it is not

enough to explain complex social-political phenomena, such as institutions. In NI, attention is devoted to

the institutional rules as well as the routines and the procedures followed by actors within organizations

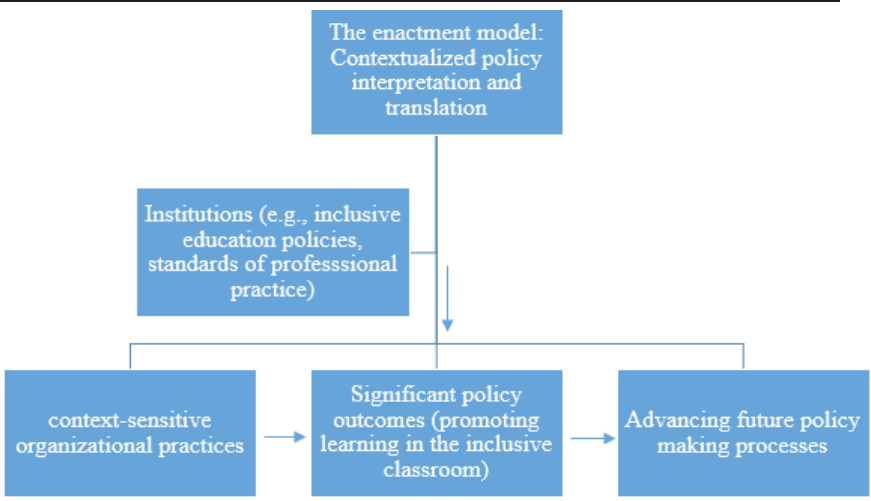

in response to given policies. Figure 1 describes how the enactment perspective with Neo-Institutionalism

contributes to a contextual understanding of policy practices that fulll institutional objectives such as

students’ academic achievement.

38

Massouti

Figure 1. The relevance of context in policy analysis and policy practices in schools.

These ideas have led Immergut (1998) to suggest that new policy decisions (e.g., inclusive education pol-

icies) change the social structure of the organizations.

It is argued that institutions through their rules and norms tend to shape the perceptions of policy

actors (Ineland, 2015). In turn, these perceptions may inform the practices and strategies followed by

those individuals while enacting policies of inclusive education in a public organization such as a school.

Having said that, I propose that using both the idea of enactment (Ball, Maguire, & Braun, 2012) and the

theory of Neo-Institutionalism (NI) (Meyer & Rowan, 1977; Powell & DiMaggio, 1991; Scott, 1995)

constitute a new analytical framework to understand how inclusive education policies are translated into

practices in Ontario schools. I argue that through the notion of enactment, we can analyze policies and

policy practices by attending to their situated context whereas NI offers us a chance to step back and

realize how certain institutional macro level rules, norms, and guidelines tend to guide and frame those

practices. Further, I would say that addressing policy making processes in future policy analysis research

from an NI perspective will invite public institutions such as Ministry of Education, school boards, and the

Ontario College of Teachers (OCT) to re-conceptualize their mandated policies. A re-conceptualization

that realizes the impact of context on the educational organizations’ policy practices in ways that allow for

a better learning experience for all learners in Ontario schools.

Revising the Concept of Organizaons

According to Ineland (2015), studies of organizational analysis show us how organizations, such as public

schools, seek to adapt required institutional changes to gain continuous support and legitimacy. These in-

stitutional changes can be represented here as the new policies issued by Ontario’s Ministry of Education

that relate to educating all students in the same classroom. For Ineland (2015), organizations are “not as

rational and consistent but largely as open systems that are sensitive to expectations in the institutional en-

vironment” (p. 56). Inside these organizations, attitudes including beliefs and values are subject to the in-

stitutional rules (Powell & DiMaggio, 1991) that shape how practices such as those that relate to inclusion,

are managed and organized. For Radaelli, Dente, and Dossi (2012), institutions play a fundamental role in

the policy process and policy actors are required to examine the extent to which institutional frameworks

impact their practices. Further, they believe that merging both policy analysis and the institutional analysis

is a promising step towards strengthening NI as a perspective that would provide a situated understanding

of the role of different actors in policy action.

39

CJEAP, 185

Scott and Meyer (1991) found that policy research does not only focus on decision making but on

policy practices as well. For them, “in one policy arena after another, examination revealed that far from

being automatic, the implementation of public policy decisions is highly problematic” (Scott & Meyer,

1991, p. 113). Thus, responding to new policies requires attention to how organizations are structured

and how they link policy makers with the enactors (Scott & Meyer, 1991). Over the years, the old institu-

tionalism’s focus on behaviors and xed structures got shifted to an emphasis on policy actors’ practices

and their impact on institutions, creating what is called today New-Institutionalism (Lecours, 2005). This

emphasis on practices according to Schatzki, Cetina, and Savigny (2001), showcases that individuals’

interactions with the surrounding structures and systems can illuminate how social groups are constituted.

For these authors, the focus on practice portrays language as “a type of activity (discursive) and hence a

practice phenomenon, whereas institutions and structures are effects” of that practice (Schatzki, Cetina, &

Savigny, 2001, p. 12). A signicant argument of NI is that institutions inuence the actions and “shape the

perceptions of actors, and through this mechanism, leads to behavior that favors the reproduction of insti-

tutions” (Lecours, 2005, p. 17). That is, institutions maintain the prevailing dominant norms and beliefs in

society and constrict the actors’ agency and the possibilities for organizational change. Such a claim can

be examined by attending to the ways actors in schools interpret and translate institutional policies, such

as those of inclusive education, into practices that support all students in the inclusive classroom.

It is worth noting that NI rejects two perspectives on the relation between institutions and the practices

performed by policy actors. The rst perspective is that institutions are restrictions-free instruments ma-

nipulated and adjusted by the actors to serve their interests. NI responds to this perspective by noting that

actors operate within frameworks shaped by their interests, so their capacity for practice and change are

central to understanding the organization (Lecours, 2005). The second perspective considers institutions

as neutral, xed, and unchangeable, stressing that institutions do not conform to a contextual change (Le-

cours, 2005). This perspective is rejected in NI by further acknowledging the meaning making capacities

and the contextualized practices of actors, which are discounted in the old institutionalism. With these two

responses, NI continues to offer policy analysis a wider framework to study how policy actors interpret

and translate policies according to their context, a framework that suggests the existence of an environ-

ment that entails constrains and affords possibilities for action.

The Instuonalizaon of Policy Pracces

NI proposes that the structure of formal organizations, such as schools, is constructed upon “institutional

forces, including rational myths, knowledge legitimated through the educational system and by the profes-

sions, public opinion, and the law” (Powell, 2007, p. 1). The conceptualization of organizations as struc-

tures inuenced by political and social environments suggests that organizational practices correspond, in

a substantive way, to these structures (Powell, 2007). Thus, organizational practices can reect how policy

actors in Ontario schools interpret, for instance, inclusive education policies. From a sociological perspec-

tive, Sehring (2009) noted that NI “seeks to understand how institutions inuence orientations (prefer-

ences, perceptions), anticipations, interests, and objectives of actors and therefore the ways solutions to

problems are sought” (p. 32). For example, institutional rules set by Ontario’s Ministry of Education and

the Ontario College of Teachers in relation to inclusive education inuence the ways policy actors adopt

inclusion policies and incorporate them into their practices. As a practical example, funding discrepancies

among schools in Ontario (George, Gopal, & Woods, 2014) inuence school teachers’ capacities in ac-

commodating their students’ diverse learning needs. In the same vein, Powell and Colyvas (2008) contend

that the aims and interests of the policy actors are institutionalized, meaning that institutions can frame

and limit their actions.

DiMaggio and Powell (1991) claim that both the cognitive and the normative features of institutions

inform the actions of policy actors. Indeed, institutions “regulate humans’ conduct, but indirectly via the

membership of individual agents in a common institutionalized realm of discourse” (Bidwell, 2006, p.

35). Such regulation requires the agents, for instance the policy actors who are enacting an inclusive edu-

cation policy, to align their interests with established societal norms and values. Nevertheless, DiMaggio

and Powell (1991) remind us that institutions “establish the very criteria just by which people discover

their preferences” (p. 11). Thus, it could be argued that inclusive education policy practices performed by

school actors are inuenced by the institutional context that relates not only to that policy but to the actors’

beliefs, values, and particular historical circumstances. Related to this idea, March and Olsen (2006) argue

40

Massouti

that the actions of policy actors are framed by rules and beliefs that have been deemed socially acceptable

in the wider society. However, the enactment of these rules remains subject to the available material,

professional resources, and the capabilities of the policy actors (March & Olsen, 2006) that may relate,

according to this study, to inclusive education.

For Scott (2014), institutionalized practices means practices that are infused “with values beyond

the technical requirements of the task at hand” (p. 24). Whether these practices are institutionalized or

not depends on “the position and role occupied by the actor” (Zucher, 1991, p. 86) as well as the context

within which these practices are carried out. Organizations become institutionalized as they embody a set

of values such as clear objectives and goals, and seek to preserve these values. The embodiment of these

values explains institutionalization as a mechanism that continues to regulate the organizational practices

until they become the norm among the multiple actors (Palmer, Biggart, & Dick, 2008). Powell and Coly-

vas (2008) note that in institutional research, a micro-level analysis would involve “theories that attend to

enacting, interpretation, translation and meaning” (p. 276) of rules and norms by the individual actors. For

them, this approach does not only examine the organizational structure but interrogates as well how actors

understand their context and view themselves in the social environment. Since institutions tend to man-

date the values, identities, and the interests of organizations such as schools (Lawrence, 2008), it becomes

necessary from the NI lens, to understand how actors in these organizations enact certain policies such as

those of inclusive education.

Conclusion

The analysis of the adoption of inclusive education policies in Ontario schools must be viewed as a com-

plex and context-sensitive process. Many studies have concluded that a de-contextualized analysis of pol-

icy practice has contributed to a limited understanding of policy implementation (Johnstone & Chapman,

2009; Naicker, 2007; Vekeman, Devos, & Tuytens, 2015; Werts & Brewer, 2015). In this essay, I stressed

the necessity to recognize that policy practices in Ontario schools is framed by contextual and institutional

settings, and I defend that this perspective is vital in policy analysis, research, and practice. This paper has

advanced a conceptual framework through which the analysis of inclusive education policies, particularly

in Ontario, could be undertaken. My argument shows that using both the enactment perspective and NI

theory would offer a signicant theoretical framework to analyze inclusive education policies and their

translation into practices. The rationale for using this framework resides on the much-needed emphasis on

context and the recognition of the role of institutions in shaping organizational practices. It is worth noting

that the suggested framework recognizes the policy actors’ orientations, beliefs, and values as powerful

elements in how policies are practiced. Nonetheless, attending to the constraints that institutions may im-

pose upon policy actors may help with the overall understanding of how inclusive education policies are

interpreted and translated.

As these limitations are viewed as a contextual element in policy practice, the use of the notion of en-

actment to analyze inclusive policy adoption becomes signicant. The enactment perspective emphasizes

the role of context in shaping, altering, and informing the ways policy actors see themselves in translating

policies such as those of inclusive education into practices. The translation of inclusive education policies

in a diverse province such as Ontario is a complicated endeavor that requires a critical look regarding

where, and under what conditions, these policies are practiced. This paper aimed to advance the literature

of policy studies by offering a new approach to inclusive education policy analysis. It showed how atten-

tion to the local context (e.g., schools), as well as to the policy processes at the macro level (e.g., Ministry

of Education, school boards, OCT), including the making of policies, could reorient the analysis of the

translation of inclusive education policies into practices. Looking at the larger picture that shows how

policy text, policy in practice, and the context are intermingled is an approach that can help us to better

analyze policy adoption in schools.

References

Ahmmed, M., & Mullick, J. (2014). Implementing inclusive education in primary schools in Bangla-

desh: Recommended strategies. Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 13(2), 167-180.

doi:10.1007/s10671-013-9156-2

41

CJEAP, 185

Ainscow, M. (2007). From special education to effective schools for all: A review of progress so far. In

L. Florian (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of special education (pp. 146-159). London, UK: SAGE.

Ball, S. J. (1994). Education reform. A critical and post-structural approach. Buckingham, UK: Open

University Press.

Ball, S. J. (2015). What is policy? 21 years later: Reections on the possibilities of policy research.

Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 36(3), 306-313. doi:10.1080/01596306.2

015.1015279

Ball, S. J., Maguire, M., & Braun, A. (2012). How schools do policy: Policy enactments in secondary

schools. New York, NY: Routledge.

Bidwell, C. (2006). Varieties of institutional theory: Traditions and prospects for educational research. In

H. D. Meyer, & B. Rowan (Eds.), The new institutionalism in education (pp. 33-50). Albany, NY:

State University of New York Press.

Bourke, P. E. (2010). Inclusive education reform in Queensland: Implications for pol-

icy and practice. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 14(2), 183-193.

doi:10.1080/13603110802504200

Braun, A., Ball, S. J., Maguire, M., & Hoskins, K. (2011). Taking context seriously: Towards explain-

ing policy enactments in the secondary school. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of

Education, 32(4), 585. doi:10.1080/01596306.2011.601555

Council of Ministers of Education in Canada. (2008). Report Two: Inclusive Education in Canada: The

Way of the Future. Retrieved from Council of Ministers of Education Canada website http://www.

cmec.ca/Publications/Lists/Publications/Attachments/122/ICE2008-reportscanada.en.pdf

DiMaggio, P., & Powell, W. W. (1991). Introduction. In W. W. Powell, & P. DiMaggio (Eds.), The new

institutionalism in organizational analysis (pp. 1-38). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Dudley-Marling, C., & Burns, M. B. (2013). Two perspectives on inclusion in the United States. Global

Education Review, 1(1), 14-32.

Engelbrecht, P., Nel, M., Smit, S., & van Deventer, M. (2016). The idealism of education policies and

the realities in schools: The implementation of inclusive education in South Africa. International

Journal of Inclusive Education, 20(5), 520-535. doi:10.1080/13603116.2015.1095250

Fixsen, D. L., Naoom, S. F., Blase, K. A., Friedman, R. M., & Wallace, F. (2005). Implementation

research: A synthesis of the literature. Tampa, FL: University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte

Florida Mental Health Institute, The National Implementation Research Network (FMHI Publica-

tion #231).

Florian, L. (1998). An examination of the practical problems associated with the implementation of

inclusive education policies. Support for Learning, 13(3), 105-108. doi:10.1111/1467-9604.00069

Forlin, C. (2010a). Developing and implementing quality inclusive education in Hong Kong: Impli-

cations for teacher education. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 10, 177-184.

doi:10.1111/j.1471-3802.2010.01162.x

Forlin, C. (Ed.). (2010b). Teacher education for inclusion: Changing paradigms and innovative ap-

proaches. New York, NY: Routledge.

George, P., Gopal, T. N., & Woods, S. (2014). Look at my life: Access to education for the remand popu-

lation in Ontario. Canadian Review of Social Policy, (70), 34-47.

Hamdan, A. R., Anuar, M. K., & Khan, A. (2016). Implementation of co-teaching approach in an inclu-

sive classroom: Overview of the challenges, readiness, and role of special education teacher. Asia

Pacic Education Review, 17(2), 289-298. doi:10.1007/s12564-016-9419-8

Heimans, S. (2012). Coming to matter in practice: Enacting education policy. Discourse: Studies in the

Cultural Politics of Education, 33, 313–326. doi:10.1080/01596306.2012.666083

Heimans, S. (2014). Education policy enactment research: Disrupting continuities. Discourse: Studies in

the Cultural Politics of Education, 35(2), 307-316. doi:10.1080/01596306.2013.832566

Immergut, E. M. (1998). The theoretical core of the new institutionalism. Politics & Society, 26(1), 5-34.

Ineland, J. (2015). Logics and ambivalence – professional dilemmas during implementation of an inclu-

sive education practice. Education Inquiry, 6(1), 53. doi:10.3402/edui.v6.26157

Johnstone, C. J., & Chapman, D. W. (2009). Contributions and constraints to the implementation of

inclusive education in Lesotho. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education,

42

Massouti

56(2), 131-148. doi:10.1080/10349120902868582

Keefe, E. B., Rossi, P. J., de Valenzuela, J. S., & Howarth, S. (2000). Reconceptualizing teacher prepa-

ration for inclusive classrooms: A description of the dual license program at the University of New

Mexico. Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps, 25(2), 72–82.

Kelly, A., Devitt, C., O’Keffee, D., & Donovan, A. M. (2014). Challenges in implementing inclusive

education in Ireland: Principal’s views of the reasons students aged 12+ are seeking enrollment

to special schools. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 11(1), 68-81.

doi:10.1111/jppi.12073

Kim, Y. W. (2013). Inclusive education in Korea: Policy, practice, and challenges. Journal of Policy and

Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 10(2), 79-81. doi:10.1111/jppi.12034

Koyama, J. (2015). When things come undone: The promise of dissembling education policy. Discourse:

Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 36(4), 548–559.

Lawrence, T. (2008). Power, institutions, and organizations. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, K. Sahlin, &

R. Suddaby (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of organizational institutionalism (pp. 170-197). London,

UK; Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

Lecours, A. (2005). New institutionalism: issues and questions. In A. Lecours (Ed.), New institutional-

ism: Theory and analysis (pp. 3-25). Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Loreman, T. (2010). Essential inclusive education-related outcomes for Alberta preservice teachers.

Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 56(2), 124.

Maguire, M., Braun, A., & Ball, S. (2015). ‘Where you stand depends on where you sit’: The social

construction of policy enactments in the (English) secondary school. Discourse: Studies in the

Cultural Politics of Education, 36(4), 485-499. doi:10.1080/01596306.2014.977022

March J. G., & Olsen J. P. (2006). Elaborating the “new institutionalism”. In R. A. W. Rhodes, S. A.

Binder, & B. A. Rockman (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of political institutions (pp. 3-22). Oxford,

UK: Oxford University Press.

May, P. J. (2015). Implementation failures revisited: Policy regime perspectives. Public Policy and Ad-

ministration, 30(3-4), 277-299. doi:10.1177/0952076714561505

Meyer, J., & Rowan, B. (1977). Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony.

American Journal of Sociology, 83, 5577.

Mittler, P. J. (2000). Working towards inclusive education: Social contexts. London, UK: D. Fulton

Publishers.

Mosia, P. A. (2014). Threats to inclusive education in Lesotho: An overview of policy and implementa-

tion challenges. Africa Education Review, 11(3), 292-292. doi:10.1080/18146627.2014.934989

Mulcahy, D. (2015). Re/assembling spaces of learning in Victorian government schools: Policy enact-

ments, pedagogic encounters and micropolitics. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of

Education, 36(4), 500–514.

Naicker, S. (2007). From policy to practice: A South-African perspective on implementing inclusive

education policy. International Journal of Whole Schooling, 3(1), 1.

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2014). Equity and inclusive education in Ontario schools: Guidelines

for policy development and implementation: Realizing the promise of diversity. Toronto, ON:

Author.

Palmer, D., Biggart, N., & Dick, B. (2008). Is the new institutionalism a theory? In R. Greenwood, C.

Oliver, K. Sahlin, & R. Suddaby (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of organizational institutionalism

(pp. 739-768). London, UK; Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

Peters, S. J. (2007). Education for all? A historical analysis of international inclusive education policy

and individuals with disabilities. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 18(2), 98-108. doi:10.1177/1

0442073070180020601

Poon-McBrayer, K. F., & Wong, P. (2013). Inclusive education services for children and youth

with disabilities: Values, roles and challenges of school leaders. Children and Youth Services

Review, 35(9), 1520-1525. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.06.009

Powell, W. W. (2007). The new institutionalism. In The international encyclopedia of organization

studies. London, UK: Sage Publishers. Retrieved from http://web.stanford.edu/group/song/papers/

NewInstitutionalism.pdf

43

CJEAP, 185

Powell, W. W., & Colyvas, J. A. (2008). Microfoundations of institutional theory. In R. Greenwood, C.

Oliver, K. Sahlin, & R. Suddaby (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of organizational institutionalism

(pp. 276-298). London, UK; Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

Powell, W. W., & DiMaggio, P. (1991). The new institutionalism in organizational analysis. Chicago, IL:

University of Chicago Press.

Radaelli, C. M., Dente, B., & Dossi, S. (2012). Recasting institutionalism: Institutional analysis and

public policy. European Political Science, 11(4), 537.

Riveros, A., & Viczko, M. (2016). The enactment of professional learning policies: Performativity and

multiple ontologies. In M.Viczko, & A. Riveros (Eds.), Assemblage, enactment and agency: Edu-

cational policy perspectives (pp. 55-69). New York, NY: Routledge.

Sailor, W. (2015). Advances in schoolwide inclusive school reform. Remedial and Special

Education, 36(2), 94-99. doi:10.1177/0741932514555021

Schatzki, T.R., Cetina, K. K., & Savigny, E. V. (Eds.) (2001). The practice turn in contemporary theory.

New York, NY: Routledge.

Schmidt, V. A. (2010). Taking ideas and discourse seriously: Explaining change through discursive insti-

tutionalism as the fourth ‘new institutionalism’. European Political Science Review, 2(1), 1-25.

Scott, W. R. (1995). Institutions and organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Scott, W. R. (2014). Institutions and organizations: Ideas, interests, and identities (4th ed.). Thousand

Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Scott, W. R., & Meyer, J. W. (1991). The organization of societal sectors: Propositions and early evi-

dence. In W. W. Powell, & P. DiMaggio (Eds.), The new institutionalism in organizational analysis

(pp. 108-140). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Sehring, J. (2009). The politics of water institutional reform in neo-patrimonial states: A comparative

analysis of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. Wiesbaden, Germany: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Sin, C. (2014a). Lost in translation: The meaning of learning outcomes across national and institutional

policy contexts. Studies in Higher Education, 39(10), 1823-1837. doi:10.1080/03075079.2013.80

6463

Sin, C. (2014b). The policy object: A different perspective on policy enactment in higher educa-

tion. Higher Education, 68(3), 435-448. doi:10.1007/s10734-014-9721-5

Singh, P., Heimans, S., & Glasswell, K. (2014). Policy enactment, context and performativity: Ontologi-

cal politics and researching Australian national partnership policies. Journal of Education Poli-

cy, 29(6), 826-844. doi:10.1080/02680939.2014.891763

Slee, R. (2010). Political economy, inclusive education and teacher education. In C. Forlin (Ed.), Teach-

er education for inclusion: Changing paradigms and innovative approaches (pp. 13-22). New

York, NY: Routledge.

Thompson, S. A., Lyons, W., & Timmons, V. (2015). Inclusive education policy: What the leadership of

Canadian teacher associations has to say about it. International Journal of Inclusive Education,

19(2), 121-140. doi:10.1080/13603116.2014.908964

Vekeman, E., Devos, G., & Tuytens, M. (2015). The inuence of teachers’ expectations on principals’

implementation of a new teacher evaluation policy in Flemish secondary education. Educational

Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 27(2), 129-151. doi:10.1007/s11092-014-9203-4

Viczko, M., & Riveros, A. (2015). Assemblage, enactment and agency: Educational policy perspec-

tives. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 36(4), 479-484. doi:10.1080/01596

306.2015.980488

Vorapanya, S., & Dunlap, D. (2014). Inclusive education in Thailand: Practices and challenges. Interna-

tional Journal of Inclusive Education, 18(10), 1014-1028. doi:10.1080/13603116.2012.693400

Weick, K. E. 1995. Sensemaking in organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Werts, A. B., & Brewer, C. A. (2015). Reframing the study of policy implementation: Lived experience

as politics. Educational Policy, 29(1), 206-229. doi:10.1177/0895904814559247

Young, T., & Lewis, W. D. (2015). Educational policy implementation revisited. Educational Policy,

29(1), 3-17. doi:10.1177/0895904815568936

Zucker, L. G. (1991). The role of institutionalization in cultural persistence. In W. W. Powell, & P.

44

Massouti

DiMaggio (Eds.), The new institutionalism in organizational analysis (pp. 83-107). Chicago, IL:

University of Chicago Press.