UNIDIR/95/30

UNIDIR

United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research

Geneva

Disarmament and

Conflict Resolution Project

Managing Arms in Peace Processes:

Somalia

Paper: Clement Adibe

Questionnaire Analysis: LTCol J.W. Potgieter,

Military Expert DCR Project

Project funded by: the Ford Foundation, the United States Institute of Peace, The Winston Foundation,

the Ploughshares Fund, and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation; and the governments of

Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, the United Kingdom, the United States, Finland, France, Austria, the

Republic of Malta, the Republic of Argentina, and the Republic of South Africa.

UNITED NATIONS

New York and Geneva, 1995

NOTE

The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this

publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of

the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country,

territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its

frontiers or boundaries.

*

* *

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not

necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Secretariat.

UNIDIR/95/30

UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION

Sales No. GV.E.95.0.20

ISBN 92-9045-106-8

iii

Table of Contents

Page

Preface - Sverre Lodgaard ..................................... vii

Acknowledgements ...........................................ix

Project Introduction - Virginia Gamba ............................xi

Part I: Case Study ..................................... 1

Chapter 1: Introduction ...................................... 3

1.1 Background: The People, Government

and Politics of Somalia .............................. 4

1.2 The Origins and Character

of Somalia's Political Crisis .......................... 5

1.3 From Crisis to Conflict: The Principal Actors

in the Struggle for Power ........................... 10

Chapter 2: The Evolution of International Responses

to the Somali Conflict: Regional and

International Dimensions .......................... 19

2.1 The Emergence of a Consensus on an International

Emergency Relief Plan for Somalia ................... 25

Chapter 3: The Dynamics of UN Intervention in Somalia ......... 31

3.1 Phase I: The First United Nations Observer Mission

in Somalia (UNOSOM I) ........................... 39

3.2 Phase II: "Option 4", The United States,

Unified Task Force (UNITAF) and

"Operation Restore Hope" in Somalia ................. 48

Managing Arms in Peace Processes: Somalia

)))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))

iv

The Problem of Transition from UNITAF:

Differing Perspectives from the UN Secretariat

and the United States Government ................ 60

3.3 Phase III: The Second United Nations Operation

in Somalia (UNOSOM II) ........................... 61

Chapter 4: The Task of Implementing the Disarmament

Mandate in Somalia .............................. 69

4.1 Disarmament as a Mission Task in Somalia ............. 70

4.2 The Evolution of an Overall Concept and Plan

of Disarmament in Somalia.......................... 72

4.3 The New Four-Stage Concept of Disarmament .......... 88

4.4 The Consequences of Implementing the New Cost

Saving Concept of Disarmament

in Conditions of Anarchy ........................... 91

4.5 The 5 June 1993 Attack on UNOSOM II

Inventory Team................................... 93

4.6 The 3 October 1993 Attack on UNOSOM II

and its Aftermath.................................. 98

Chapter 5: Summary and Conclusion ........................ 101

Biographical Note .......................................... 111

Part II Bibliography ................................. 113

Part III Questionnaire Analysis ........................ 133

Analysis Report: Somalia .......................... 135

Table of Contents

)))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))

v

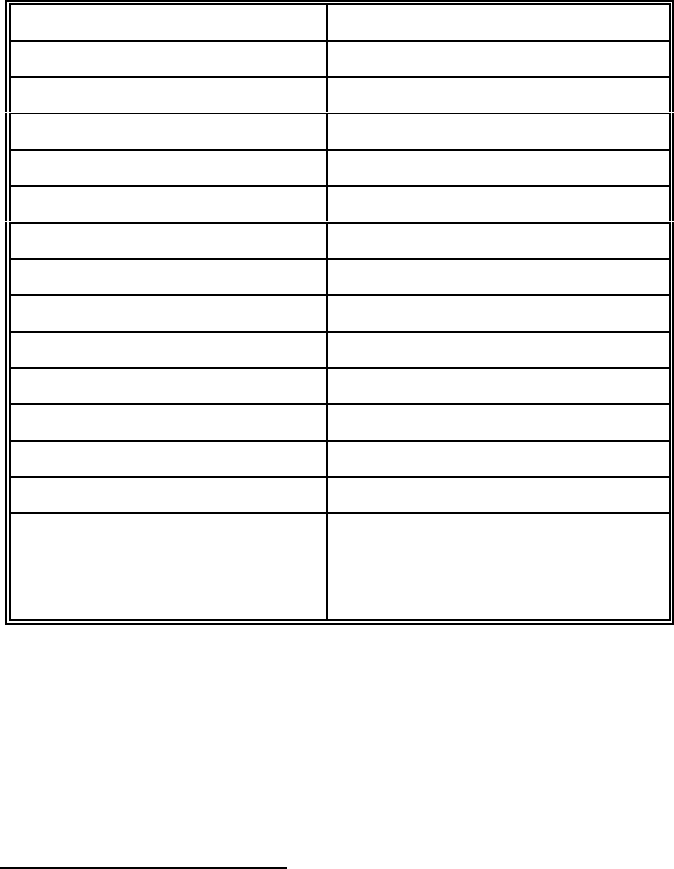

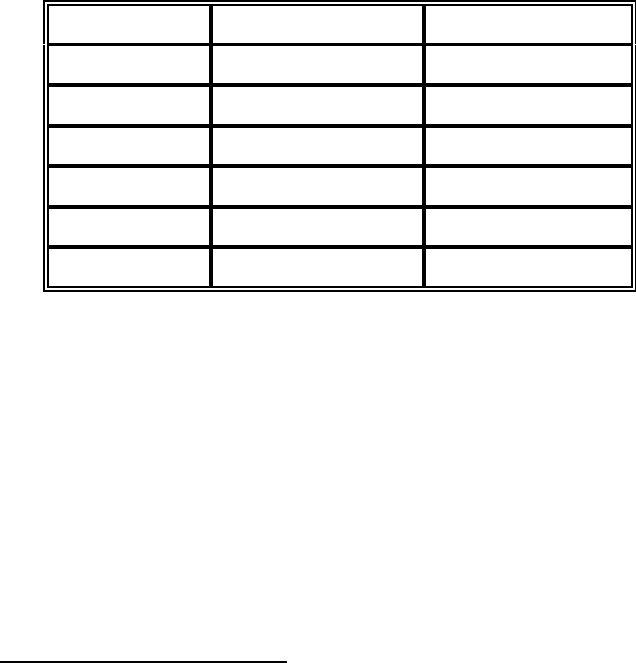

List of Tables

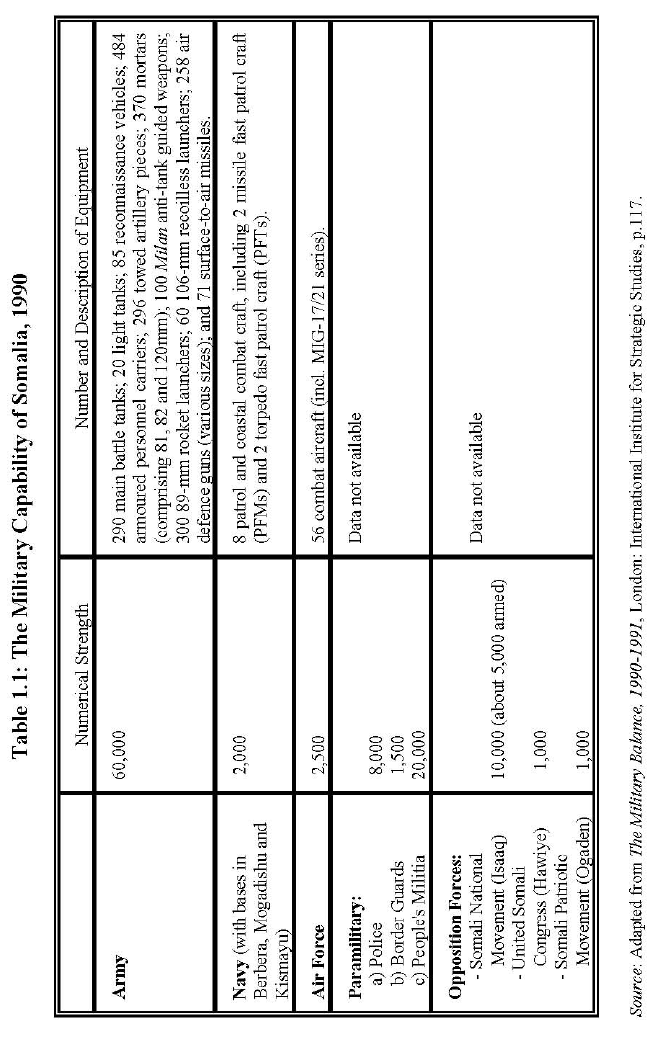

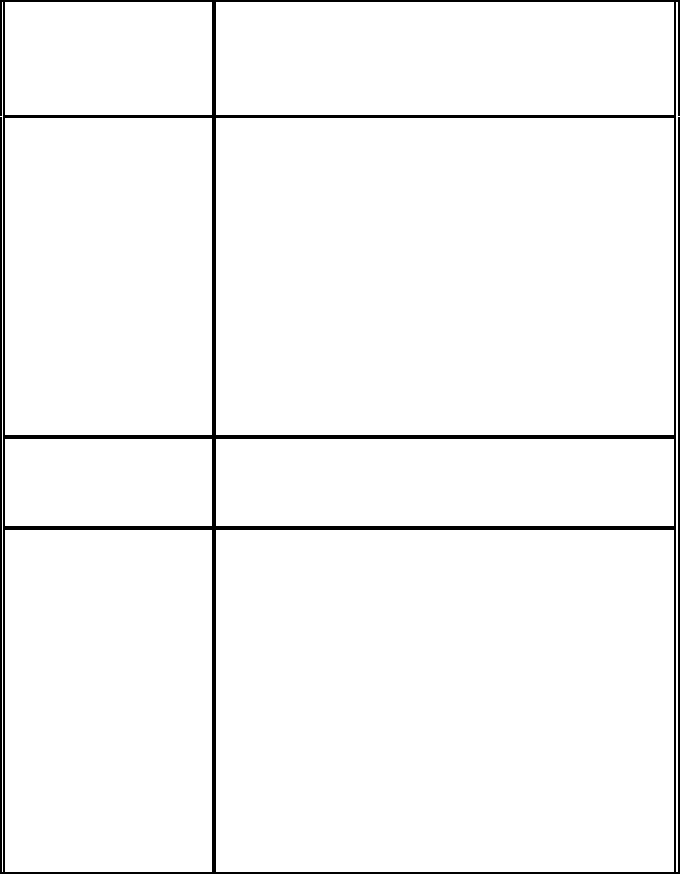

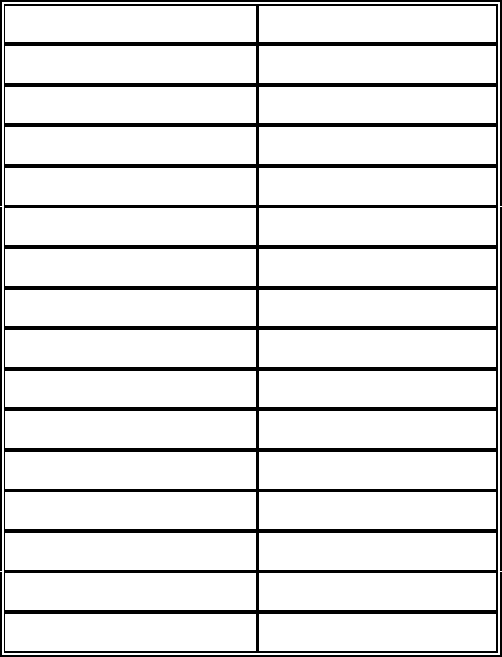

1.1 The Military Capability of Somalia, 1990 ................... 7

1.2 Principal Actors and Their Role in the Current

Somali Conflict ...................................... 10

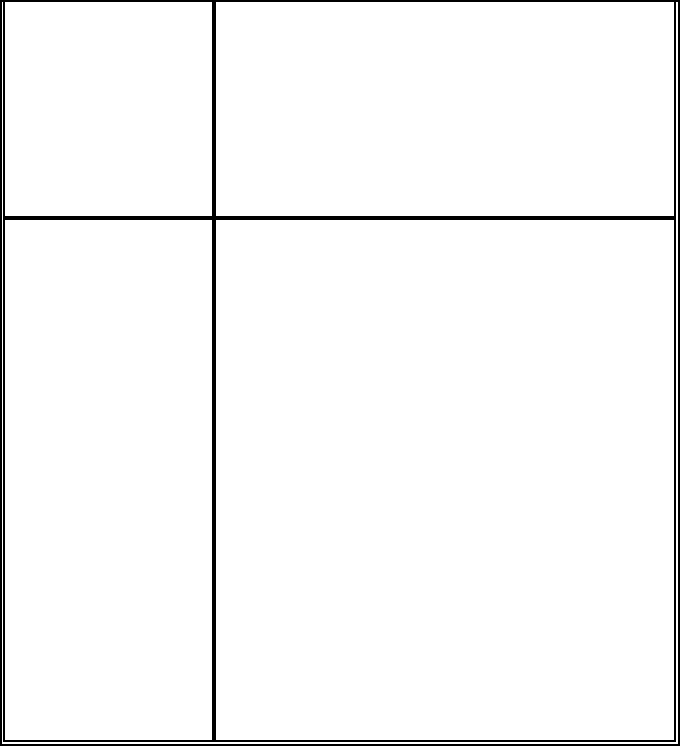

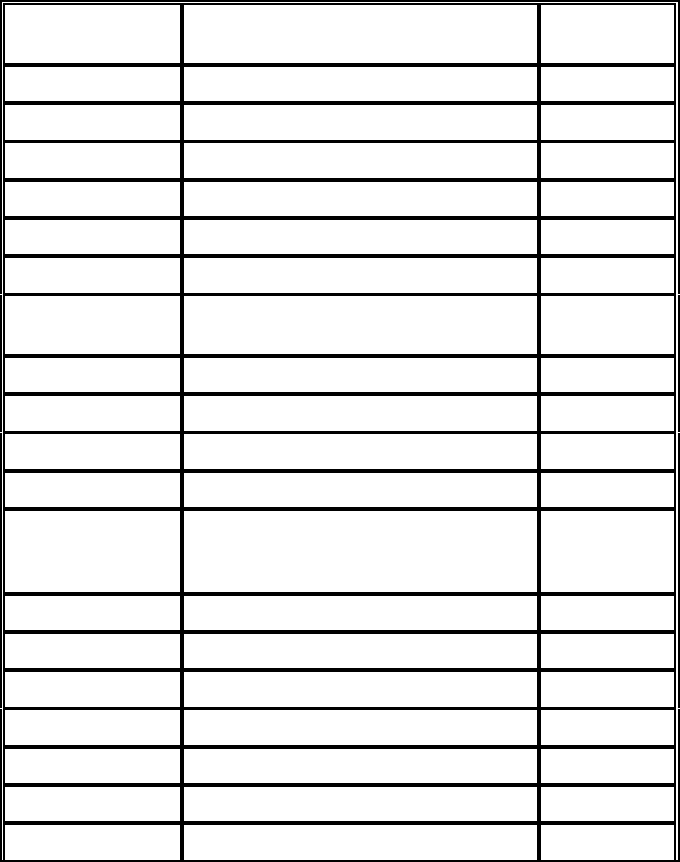

3.1 UN Intervention in Somalia: A Chronology of Major Events,

1991-95 ............................................ 31

3.2 Composition of UNITAF as at 7 January 1993 .............. 56

3.3 Composition of UNOSOM II as at 30 April 1993 ............ 65

3.4 Composition of UNOSOM II as at November 1993 .......... 67

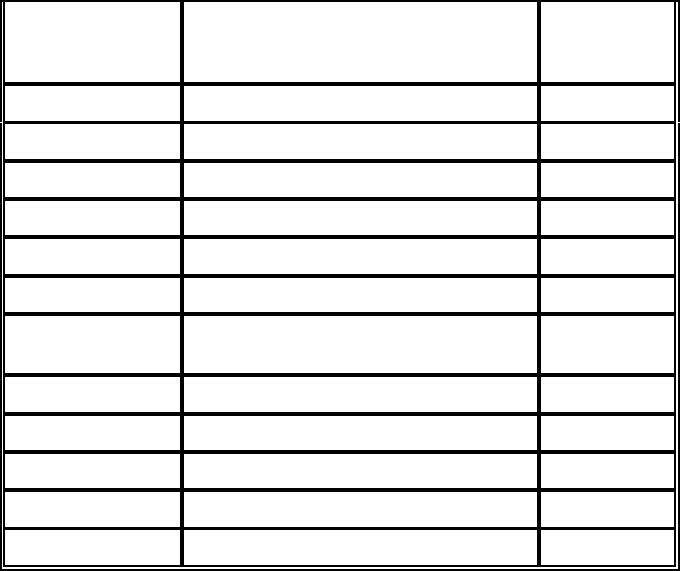

4.1 Comparative Statistics of Arms Deliveries to the States

of the Horn and Three Leading Arms Importers

in Sub-Saharan Africa, 1972-1990 (in US $) ................ 71

4.2 The Rules of Engagement for US-UNITAF ................ 75

4.3 The Rules of Engagement for UNOSOM II ................ 84

List of Maps

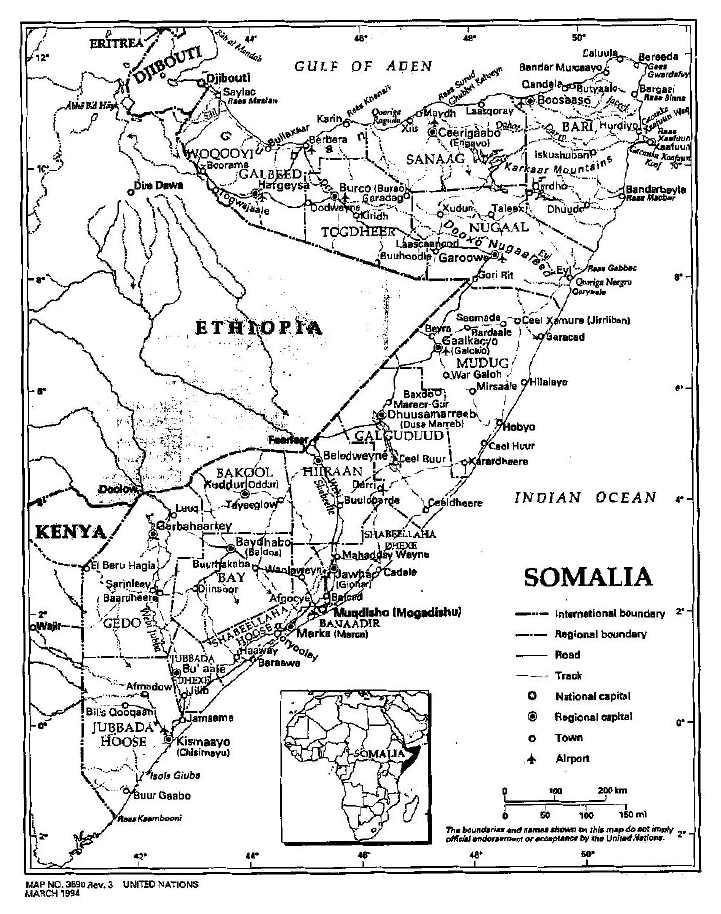

Somalia ........................................... 129

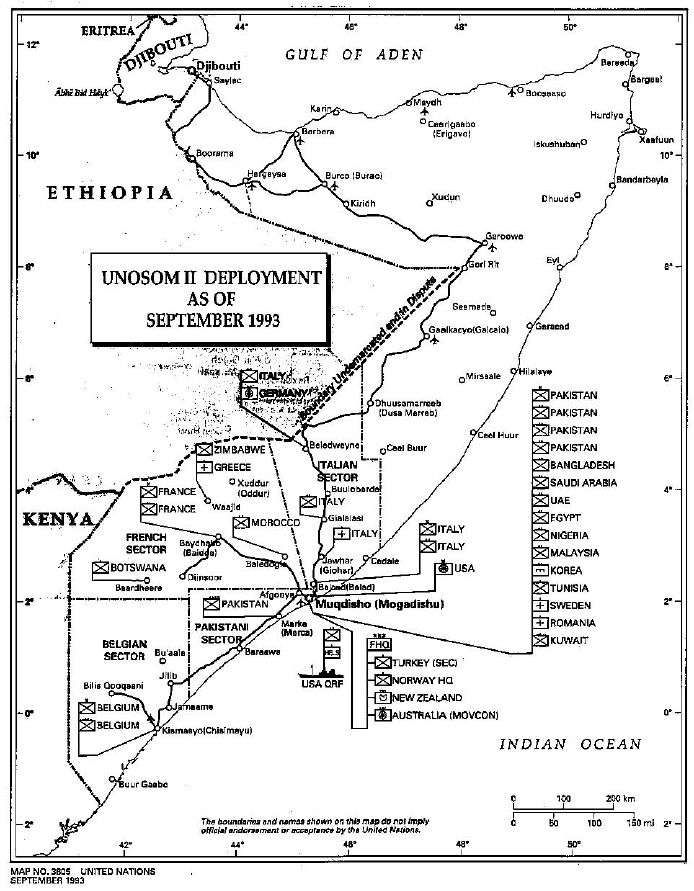

UNOSOM II Deployment as of September 1993 ........... 130

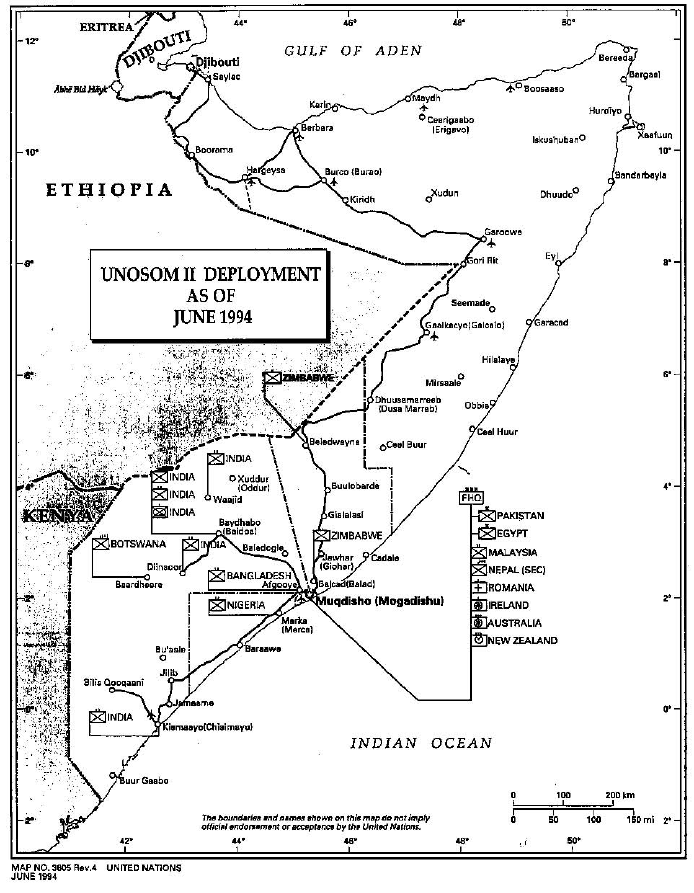

UNOSOM II Deployment as of September 1994 ........... 131

1

Document A/C.1/47/7, No 31, 23 October 1992.

2

Document 50/60-S/1995/1, 3 January 1995.

vii

Preface

Under the headline of Collective Security, UNIDIR is conducting a major

project on Disarmament and Conflict Resolution (DCR). The project examines the

utility and modalities of disarming warring parties as an element of efforts to

resolve intra-state conflicts. It collects field experiences regarding the

demobilization and disarmament of warring factions; reviews 11 collective

security actions where disarmament has been attempted; and examines the role

that disarmament of belligerents can play in the management and resolution of

internal conflicts. The 11 cases are UNPROFOR (Yugoslavia), UNOSOM and

UNITAF (Somalia), UNAVEM (Angola), UNTAC (Cambodia), ONUSAL

(Salvador), ONUCA (Central America), UNTAG (Namibia), UNOMOZ

(Mozambique), Liberia, Haiti and the 1979 Commonwealth operation in Rhodesia.

Being an autonomous institute charged with the task of undertaking

independent, applied research, UNIDIR keeps a certain distance from political

actors of all kinds. The impact of our publications is predicated on the

independence with which we are seen to conduct our research. At the same time,

being a research institute within the framework of the United Nations, UNIDIR

naturally relates its work to the needs of the Organization. Inspired by the

Secretary General's report on "New Dimensions of Arms Regulation and

Disarmament in the Post-Cold War Era",

1

the DCR Project also relates to a great

many governments involved in peace operations through the UN or under regional

auspices. Last not least, comprehensive networks of communication and co-

operation have been developed with UN personnel having field experience.

Weapons-wise, the disarmament of warring parties is mostly a matter of light

weapons. These weapons account for as much as 90% of the casualties in many

armed conflicts. UNIDIR recently published a paper on this subject (Small Arms

and Intra-State Conflicts, UNIDIR Paper No 34, 1995). The Secretary General's

appeal for stronger efforts to control small arms - to promote "micro

disarmament"

2

- is one which UNIDIR will continue to attend to in the framework

of the DCR Project.

To examine the peace operations where disarmament has been attempted, we

invited scholars from the regions of conflict. This Report on the peace operations

Managing Arms in Peace Processes: Somalia

)))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))

viii

in Somalia (UNOSOM, UNITAF) was written by Dr. Clement Adibe while

staying at UNIDIR in the winter/spring of 1995. It has been reviewed by Astrid

Arland (the Norwegian Institute of Foreign Affairs, Oslo), Steven John Stedman

(Johns Hopkins University, Washington) and by the project staff. It is the first in

a series of UNIDIR Reports on the disarmament dimension of peace operations.

There will be a Report on all of the cases mentioned above.

The authors of the case studies have drawn on the professional advice and

assistance of military officers intimately acquainted with peace operations. They

were Col. Roberto Bendini (Argentina), Lt. Col. Ilkka Tiihonen (Finland) and Lt.

Col. Jakkie Potgieter (South Africa). This Report also benefitted from a number

of briefings by military officers who worked in Somalia, among them Col. Cecil

Bailey (USA) and Gen. Bruno Loi (Italy). UNIDIR is grateful to all of them for

their invaluable contributions to clarifying and solving the multitude of questions

and problems we put before them.

Since October 1994, the DCR Project has developed under the guidance of

Virginia Gamba. Under her able leadership, the project has not only become the

largest in UNIDIR history: its evolution has been a source of inspiration for the

entire Institute.

UNIDIR takes no position on the views or conclusions expressed in the Report.

They are Dr Adibe's. My final word of thanks goes to him: UNIDIR has been

happy to have such a resourceful and dedicated collaborator.

UNIDIR takes no position on the views and conclusions expressed in these

papers which are those of their authors. Nevertheless, UNIDIR considers that such

papers merit publication and recommends them to the attention of its readers.

Sverre Lodgaard

Director, UNIDIR

ix

Acknowledgements

UNIDIR takes this opportunity to thank the many Foundations and

Governments who have supported the DCR Project. Among our contributors, the

following deserve a special mention and our deep appreciation: the Ford

Foundation; the United States Institute of Peace; the Winston Foundation; the

Ploughshares Fund; the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation; and the

governments of Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, the United Kingdom, the

United States, Finland, France, Austria, the Republic of Malta, the Republic of

Argentina, and the Republic of South Africa.

3

James S. Sutterlin, "Military Force in the Service of Peace", Aurora Papers, No 18,

Ottawa, Canada: Canadian Centre for Global Security, 1993, p.13.

xi

Project Introduction

Disarmament and Conflict Resolution

The global arena's main preoccupation during the Cold War centred on the

maintenance of international peace and stability between states. The vast network

of alliances, obligations and agreements which bound nuclear superpowers to the

global system, and the memory of the rapid internationalization of disputes into

world wars, favored the formulation of national and multinational deterrent

policies designed to maintain a stability which was often confused with

immobility. In these circumstances, the ability of groups within states to engage

in protest and to challenge recognized authority was limited.

The end of the Cold War in 1989, however, led to a relaxing of this pattern,

generating profound mobility within the global system. The ensuing break-up of

alliances, partnerships, and regional support systems brought new and often weak

states into the international arena. Since weak states are susceptible to ethnic

tensions, secession, and outright criminality, many regions are now afflicted by

situations of violent intra-state conflicts.

Intra-state conflict occurs at immense humanitarian cost. The massive

movement of people, their desperate condition, and the direct and indirect tolls on

human life have, in turn, generated pressure for international action.

Before and since the Cold War, the main objective of the international

community when taking action has been the maintenance and/or recovery of

stability. The main difference between then and now, however, is that then, the

main objective of global action was to maintain stability in the international

arena, whereas now it is to stabilize domestic situations. The international

community assists in stabilizing domestic situations in five different ways: by

facilitating dialogue between warring parties, by preventing a renewal of internal

armed conflict, by strengthening infrastructure, by improving local security, and

by facilitating an electoral process intended to lead to political stability

3

.

The United Nations is by no means the only organization that has been

requested by governments to undertake these tasks. However, the reputation of the

United Nations as being representative of all states and thus as being objective and

Managing Arms in Peace Processes: Somalia

)))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))

xii

trustworthy has been especially valued, as indicated by the greater amount of

peace operations in which it is currently engaged. Before 1991, the UN peace

operations presence enhanced not only peace but also the strengthening of

democratic processes, conciliation among population groups, the encouragement

of respect for human rights, and the alleviation of humanitarian problems. These

achievements are exemplified by the role of the UN in Congo, southern Lebanon,

Nicaragua, Namibia, Salvador, and to a lesser extent in Haiti.

Nevertheless, since 1991 the United Nations has been engaged in a number of

simultaneous, larger, and more ambitious peace operations such as those in

Angola, Bosnia, Croatia, Mozambique and Somalia. It has also been increasingly

pressured to act on quick-flaring and horrendously costly explosions of violence,

such as the one in Rwanda in 1995. The financial, personnel, and timing pressure

on the United Nations to undertake these massive short-term stabilizing actions

has seriously impaired the UN's ability to ensure long-term national and regional

stability. The UN has necessarily shifted its focus from a supporting role, in which

it could ensure long-term national and international stability, to a role which

involves obtaining quick peace and easing humanitarian pressures immediately.

But without a focus on peace defined in terms of longer-term stability, the overall

success of efforts to mediate and resolve intra-state conflict will remain in

question.

This problem is beginning to be recognized and acted upon by the international

community. More and more organizations and governments are linking success

to the ability to offer non-violent alternatives to a post-conflict society. These

alternatives are mostly of a socio-political-economic nature, and are national

rather than regional in character. As important as these linkages are to the final

resolution of conflict, they tend to overlook a major source of instability: the

existence of vast amounts of weapons widely distributed among combatant and

non-combatant elements in societies which are emerging from long periods of

internal conflict. The reason why weapons themselves are not the primary focus

of attention in the reconstruction of post-conflict societies is because they are

viewed from a political perspective. Action which does not award importance to

disarmament processes is justified by invoking the political value of a weapon as

well as the way the weapon is used by a warring party, rather than its mere

existence and availability. For proponents of this action, peace takes away the

reason for using the weapon and, therefore, renders it harmless for the post-

conflict reconstruction process. And yet, easy availability of weapons can, and

does, militarize societies in general. It also destabilizes regions that are affected

by unrestricted trade of light weapons between borders.

Project Introduction

)))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))

xiii

4

Fred Tanner, "Arms Control in Times of Conflict", Project on Rethinking Arms Control,

Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland, PRAC Paper 7, October 1993.

There are two problems, therefore, with the international community's approach

to post-conflict reconstruction processes: on the one hand, the international

community, under pressure to react to increasingly violent internal conflict, has

put a higher value on peace in the short-term than on development and stability in

the long-term; and, on the other hand, those who do focus on long-term stability

have put a higher value on the societal and economic elements of development

than on the management of the primary tools of violence, i.e., weapons.

UNIDIR's DCR Project and the Control of Arms during

Peace Processes (CAPP)

The DCR Project aims to explore the predicament posed by UN peace

operations which have recently focused on short-term needs rather than long-term

stability. The Project is based on the premise that the control and reduction of

weapons during peace operations can be a tool for ensuring stability. Perhaps

more than ever before, the effective control of weapons has the capacity to

influence far-reaching events in national and international activities. In this light,

the management and control of arms could become an important component for

the settlement of conflicts, a fundamental aid to diplomacy in the prevention and

deflation of conflict, and a critical component of the reconstruction process in

post-conflict societies.

Various instruments can be used to implement weapons control. For example,

instruments which may be used to support preventive diplomacy in times of crisis

include confidence-building measures, weapons control agreements, and the

control of illegal weapons transfers across borders.

4

Likewise, during conflict

situations, and particularly in the early phases of a peace operation, negotiations

conducive to lasting peace can be brought about by effective monitoring and the

establishment of safe havens, humanitarian corridors, and disengagement sectors.

Finally, after the termination of armed conflict, a situation of stability is required

for post-conflict reconstruction processes to be successful. Such stability can be

facilitated by troop withdrawals, the demilitarization of border zones, and

effective disarmament, demobilization and demining.

Managing Arms in Peace Processes: Somalia

)))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))

xiv

Nevertheless, problems within the process of controlling weapons have cropped

up at every stage of peace operations, for a variety of reasons. In most cases,

initial control of arms upon the commencement of peace operations has not

generally been achieved. This may be due to the fact that political negotiations

necessary to generate mandates and missions permitting international action are

often not specific enough on their disarmament implementation component. It

could also be that the various actors involved interpret mandates in totally

different ways. Conversely, in the specific cases where peace operations have

attained positive political outcomes, initial efforts to reduce weapons to

manageable levels - even if achieved - tend to be soon devalued, since most of the

ensuing activities centre on the consolidation of post-conflict reconstruction

processes. This shift in priorities from conflict resolution to reconstruction makes

for sloppy follow-up of arms management operations. Follow-up problems, in

turn, can result in future threats to internal stability. They also have the potential

to destabilize neighboring states due to the uncontrolled and unaccounted-for mass

movement of weapons that are no longer of political or military value to the

former warring parties.

The combination of internal conflicts with the proliferation of light weapons has

marked peace operations since 1990. This combination poses new challenges to

the international community and highlights the fact that a lack of consistent

strategies for the control of arms during peace processes (CAPP) reduces the

effectiveness of ongoing missions and diminishes the chances of long-term

national and regional stability once peace is agreed upon.

The case studies undertaken by the DCR Project highlight a number of recurrent

problems that have impinged on the control and reduction of weapons during

peace operations. Foremost among these are problems associated with the

establishment and maintenance of a secure environment early in the mission, and

problems concerned with the lack of co-ordination of efforts among the various

groups involved in the mission. Many secondary complications would be

alleviated if these two problems areas were understood differently. The

establishment of a secure environment, for example, would make the warring

parties more likely to agree on consensual disarmament initiatives. Likewise, a

concerted effort at weapons control early in the mission would demonstrate the

international community's determination to hold the parties to their original peace

agreements and cease fire arrangements. Such a demonstration of resolve would

make it more difficult for these agreements to be broken once the peace operation

was underway.

Project Introduction

)))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))

xv

The co-ordination problem applies both to international interactions and to the

components of the peace operation. A peace process will be more likely to

succeed if there is co-operation and co-ordination between the international effort

and the nations which immediately neighbor the striken country. But co-ordination

must not simply be present at the international level; it must permeate the entire

peace operation as well. To obtain maximum effect, relations must be co-ordinated

among and within the civil affairs, military, and humanitarian groups which

comprise a peace operation. A minimun of co-ordination must also be acheived

between intra- and inter-state mission commands, the civil and military

components at strategic, operational and tactical levels, and the humanitarian aid

organizations working in the field; these components must co-operate with each

other if the mission is to reach its desired outcome. If problems with mission co-

ordination are overcome, many secondary difficulties could also be avoided,

including lack of joint management, lack of unity of effort, and lack of mission

and population protection mechanisms.

Given these considerations, the Project believes that the way to implement

peace, defined in terms of long-term stability, is to focus not just on the sources

of violence (such as social and political development issues) but also on the

material vehicles for violence (such as weapons and munitions). Likewise, the

implementation of peace must take into account both the future needs of a society

and the elimination of its excess weapons, and also the broader international and

regional context in which the society is situated. In this sense, weapons that are

not managed and controlled in the field will invariably flow over into neighboring

countries, becoming a problem in themselves. Thus, the establishment of viable

stability requires that three primary aspects be included in every approach to

intra-state conflict resolution: (1) the implementation of a comprehensive,

systematic disarmament programme as soon as a peace operation is set-up; (2)

the establishment of an arms management programme that continues into

national post-conflict reconstruction processes; and (3) the encouragement of

close cooperation on weapons control and management programmes between

countries in the region where the peace operation is being implemented.

In order to fulfill its research mission, the DCR Project has been divided into

four phases. These are as follows: (1) the development, distribution, and

interpretation of a Practitioners' Questionnaire on Weapons Control,

Disarmament and Demobilization during Peacekeeping Operations; (2) the

development and publication of case studies on peace operations in which

disarmament tasks constituted an important aspect of the wider mission; (3) the

organization of a series of workshops on policy issues; and (4) the publication of

Managing Arms in Peace Processes: Somalia

)))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))

xvi

policy papers on substantive issues related to the linkages between the control of

arms during peace processes (CAPP) and the settlement of conflict.

Between September 1995 and March 1996, the Project foresees four sets of

publications. The first of these will involve eleven case studies, covering UN

peace operations in Somalia, Rhodesia (1979), Bosnia/Croatia, Central America

(ONUCA and ONUSAL), Cambodia, Angola, Namibia, Mozambique, Liberia and

Haiti. The second set of publications will include nine policy papers, addressing

topics such as Security Council Procedures, Mandate Specificity, Doctrine, Rules

of Engagement, Coercive versus Consensual Arms Control and Demobilization

Processes, Consensus, Intelligence and Media, and Training. A third set of

publications will involve three papers on the relationship between arms and

conflict in the region of Southern Africa. The last of the Project's published works

will be an overarching policy paper summarizing the conclusions of the research

and delineating recommendations based on the Project's findings.

Taking into account the existing material on some of the case studies, the DCR

project has purposefully concentrated on providing more information on the

disarmament and arms control components of the relevant international peace

operations than on providing a comprehensive political and diplomatic account of

each case.

This volume of the DCR series introduces the first of the Project's case studies,

focusing on Somalia. The case study is divided into three sections. The first

section analyzes the way in which three international peace processes (UNOSOM,

UNITAF, and UNOSOM II) struggled with the issue of controlling and managing

light weapons in Somalia so as to ensure the delivery of humanitarian assistance

to a famished and lawless population. The second section presents a full

bibliography of secondary and primary material used in the making of this study.

Finally, the third section provides an analysis of the responses on Somalia which

were obtained through the Project's own Practitioners' Questionnaire on

Weapons Control, Disarmament and Demobilization during Peacekeeping

Operations.

Virginia Gamba

Project Director

Geneva, August 1995

1

Part I:

Case Study

1

Stephen P. Riley, "War and Famine in Africa", Conflict Studies, No 268, London:

Research Institute for the Study of Conflict and Terrorism, 1994, p.18.

2

Ibid.

3

On the notion of "failed states," see, among others, Robert Jackson, "Why Africa's Weak

States Persist: The Empirical and Juridical in Statehood", World Politics, Vol. 35, No 1, 1988,

p.1; and Gerald B. Helman and Steven R. Ratner, "Saving Failed States", Foreign Policy, No

89, Winter 1992/93, p.3.

3

Chapter 1

Introduction

The collapse of the Somali state and the subsequent degeneration of the society

into anarchy in 1991 contrast sharply with the country's reputation among the

ancient Egyptians as the "Land of Punt, ... a fabled source of wealth and luxury far

beyond the upper reaches of the Nile..."

1

According to Stephen Riley, Somalia in

the late twentieth century has become "a byword for clan politics... and a symbol

of the hollow promises and contradictions of the "New World Order" in the

1990s."

2

How did this largely homogeneous and otherwise resourceful society

become an icon of failed states

3

after barely three decades of independence? The

purpose of this study is to examine in some depth the role of arms in explaining

the current Somali conflict and the difficulties of multinational intervention in

resolving this African tragedy.

This study is presented in five chapters. Chapter 1 briefly discusses the Somali

society and politics and provides the background to the conflict that ensued in

1991. Chapter 2 examines the regional and international contexts of the conflict,

focusing particularly on early efforts to bring the conflict to the attention of the

international community. Chapter 3 traces the involvement of the international

community and the United Nations through various phases. Chapter 4 focuses on

the evolution and implementation of the disarmament concept in Somalia. Chapter

5 discusses the lessons of the Somali experience for future UN involvement in

disarmament and conflict resolution.

Managing Arms in Peace Processes: Somalia

)))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))

4

4

Nii Wallace-Bruce, "The Statehood of Somalia and the United Nations", paper presented

at the 17th Annual Conference of the Academic Council on the United Nations System, The

Hague, The Netherlands, 23-25 June 1994, p.2.

5

Ibid., p.4.

1.1 Background: The People, Government

and Politics of Somalia

The state of Somalia is the result of the amalgamation of two separately

administered colonies: British Somaliland in the north and Italian Somaliland in

the south. The two colonies were inhabited by ethnic Somalis who may also be

found in Djibouti (French Somaliland), Kenya's Northern Frontier District (NFD)

and in the Ogaden region of Ethiopia. The majority of Somalis are Sunni Muslims,

but a small proportion are Christians. Unlike many African countries, Somalis are

united by one common language: Somali. In addition to the national language,

other languages widely spoken by segments of the population include Arabic,

English and Italian.

For a brief period during World War II, the "Somali people enjoyed a temporary

and partial

UreunificationU" following Italy's occupation of Ethiopia's Ogaden

region and Italian Somaliland (i.e. Rome's Africa Orientale Italiana) in addition

to British Somaliland in August 1940.

4

The enforced reunification of Somalia was

subsequently reversed in March 1941 when Britain defeated Italy in the Horn.

With the signing of the Paris peace treaty between Italy and the Allied Powers in

1947, Italy formally renounced title to its African colonies, including Italian

Somaliland. However, in 1949, the United Nations General Assembly, by

Resolution 289, decided to place Italian Somaliland "under the International

trusteeship system with Italy as the Administering Authority."

5

In 1950 Italy

formally began to administer its former colony, now known as the United Nations

Trust Territory of Somalia (hereafter referred to as the Trust Territory), for a

transitional period of ten years. As part of measures towards Somali independence

before the expiration of that mandate, Italy organised general elections in the Trust

Territory in 1959. That election was won by the Somali Youth League (SYL),

whose leader, Seyyid Abdullah Issa, emerged as the Prime Minister. On 1 July

1960, the Trust Territory joined British Somaliland, which attained its

independence on 26 June 1960, and the Republic of Somalia was formed. At

unification, the parallel institutions of government were merged, with Mr. Aden

Abdullah Osman (formerly president of the Legislative Assembly of British

Somaliland) as president and Seyidd Issa of SYL as Prime Minister. Following his

Introduction

)))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))

5

6

For a detailed country profile of Somalia, see The Europa World Yearbook, Vol. 1, 34th

edition, London: Europa Publications Ltd., 1993, pp.2358-2368.

7

Nii Wallace-Bruce, "The Statehood of Somalia and the United Nations", 1994, p.9.

8

Ibid., p.8. See also David Laitin and Said S. Samatar, Somalia: Nation in Search of a

State, Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1987, p.66.

9

This included Somalis in Djibouti, Kenya's NFD and Ethiopia's Ogaden region. The quest

for the reunification of all Somalis would later lead to the militarization of the region and two

major inter-state wars between Somalia and Ethiopia in 1964 and 1977/78.

10

For a comparative perspective, see A.I. Asiwaju (ed.), Partitioned Africans: Ethnic

Relations Across Africa's International Boundaries, 1884-1984, New York: St. Martin's Press,

1985.

early resignation, Seyidd Issa was replaced as Prime Minister by Dr. Abdirashid

Ali Shermarke (also of SYL).

6

The signs of the problems that would seriously impact on the stability of the

new republic were present from the start. According to Nii Wallace-Bruce,

The new Republic could not disguise the stark bi-reality. It had "two different judicial

systems; different currencies; different organization and conditions for service for the

army, the police and civil servants... The governmental institutions, both at the central

and local level, were differently organized and had different powers; the systems and

rates of taxation and customs were different, and so were the educational systems."

7

In addition, while British Somaliland had been conditioned by the colonial

government to political representation "on the basis of clans," the Trust Territory

was not.

8

However, these differences notwithstanding, the Somali political elite

was united in their quest for the unification of all Somalis under one state.

9

1.2 The Origins and Character

of Somalia's Political Crisis

Not unlike many immediate post-colonial African governments, the first

republican government of Somalia ran into severe obstacles soon after

independence because of an intense power struggle among the political elites.

10

In

Somalia, however, the intensity of the political struggle took on an added

dimension as a result of the nationalist and irredentist policies of the post-colonial

government. Upon unification, the Shermarke government made strong territorial

Managing Arms in Peace Processes: Somalia

)))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))

6

11

See Saadia Touval, Boundary Politics of Independent Africa, Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press, 1972; A.I. Asiwaju (ed.), Partitioned Africans, 1985; and Ioan M. Lewis, A

Modern History of Somalia, Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1988.

12

"International Implications of the Somali Crisis," n.n., n.d., p.3.

13

Ibid. See also Bereket Habte Selassie, Conflict and Intervention in the Horn of Africa,

New York: Monthly Review Press, 1980.

claims on its neighbours, especially Kenya and Ethiopia.

11

British and Western

governments' opposition to such blatant irredentism may have encouraged the

Shermarke government to seek the support of the Soviet Union. In the context of

the Cold War, Moscow seized on the opportunity to establish a politico-military

foothold in the strategic Horn of Africa.

Thus began the progressive expansion of the Somali armed forces through the

massive importation of Soviet arms and equipment. Between 1964-1969 the

national security apparatus grew from 5,000 police personnel to a standing army

of 12,000 persons.

12

In 1964, fighting broke out between Somalia and Ethiopia

over the Ogaden district, while tension characterised Somalia's relations with its

other neighbours, Kenya and Djibouti. By 1977, when Somalia initiated the

Ogaden War with Ethiopia, the strength of the Somali national armed forces had

increased markedly to 37,000, equipped with sophisticated Soviet land, aerial and

naval conventional weapons systems.

13

Thereafter (until the conflict of 1992), the

Somali Armed Forces grew to become a comparatively modern fighting force with

a wide range of basic and advanced weapons systems (see Table 1.1).

Introduction

)))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))

7

Managing Arms in Peace Processes: Somalia

)))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))

8

14

For a useful discussion of the coup d'état, see Ioan Lewis, "The Politics of the 1969

Somali Coup", The Journal of Modern African Studies, No 10, October 1972, esp. pp.397-400.

15

For useful insights into the dynamics of Somalia's socialist experiment, see John

Markakis and Michael Waller (eds), Military Marxist Regimes in Africa, London: Frank Cass,

1976; and Ahmed I. Samatar, Socialist Somalia: Rhetoric and Reality, London: Zed

Publishers, 1988.

16

Between 1976 and 1981, the URSS established extensive links with Somalia, the

Mogadishu naval base becoming one of the largest in the Indian Ocean. With this base,

simultaneous with the Soviet-Cuban intervention in Angola in 1975, a wide network for the

support of Soviet naval expansion and control of strategic passes was believed.

17

For details of Soviet influence and involvements in Somalia, see Robert G. Patman, The

Soviet Union in the Horn of Africa: The Diplomacy of Intervention and Disengagement,

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990. For insightful analysis of the embryonic crisis

in Somalia, see Osman Mohamoud, "Somalia: Crisis and Decay in an Authoritarian Regime",

Horn of Africa, Vol. 4, No 3, 1981.

18

"International Implications of the Somali Crisis", n.n., n.d., p.3 (emphasis added). For

further details, cf. Robin Theobold, "Patrimonialism", World Politics, No 34, 1982;

Christopher Clapham (ed.), Private Patronage and Public Power, London: Frances Pinter,

1985; Samuel N. Eisenstadt, Traditional Patrimonialism and Modern Neopatrimonialism,

London: Sage Publishers, 1972; Henry Bienen (ed.), Armies and Parties in Africa, New York:

Africana Publishing Company, 1979; and Samuel Decalo, "The Morphology of Military Rule

in Africa", in John Markakis and Michael Waller (eds), Military Marxist Regimes in Africa,

On 15 October 1969, President Shermarke was assassinated in a military coup

d'état. One week later, Major-General Mohammed Siad Barre, the Commander of

the national armed forces, assumed absolute power.

14

Consistent with the tradition

of military regimes, General Barre decreed the suspension of the Somali

constitution, dissolved the National Assembly, and in its place established an all-

military council known as the Supreme Revolutionary Council (SRC). In 1970,

General Barre formally declared Somalia a "socialist state."

15

In 1976, he

dissolved the SRC and replaced it with the Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party

(SRSP) as the sole political party in the country and the vanguard of the "people's

revolution." The members of the SRC became the politburo of the SRSP, with

General Barre as the Secretary-General. Backed by Moscow,

16

President Barre

sought to replicate the Soviet model and its entrenched patronage system of

nomenklatura in Mogadishu.

17

According to one study, Barre adapted the Soviet

model to suit his interests and the special conditions prevalent in Somalia. Thus,

for instance, in place of the nomenklatura, General Barre established "a

clanklatura system whereby clan relatives and other political loyalists" were

appointed "into positions of leadership, authority and power within the civil

service, armed forces, academies and institutes and social or civic associations."

18

Introduction

)))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))

9

London: Frank Cass., 1976.

19

The major Somali clans are Hawiye, Isaaq, Darod, Dir and Digil-Mirifle. For details, see

Ioan M. Lewis, A Modern History of Somalia, Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1988.

20

See Jeffrey Clark, "Debacle in Somalia: Failure of the Collective Response", in Lori F.

Damrosch (ed.), Enforcing Restraint: Collective Intervention in Internal Conflicts, New York:

Council on Foreign Relations Press, 1993, esp. pp.209-211.

21

Khalif Galaydh, "Notes on the State of the Somali State", Horn of Africa, Vol. 13, Nos 1-

2, 1990, p.26. Government campaigns against the Isaaq resulted in the massive emigration of

about 400,000 Isaaqs into refugee camps in Ethiopia and Djibouti following the destruction of

their principal city, Hargeisa, which is also Somalia's second-largest city. For details, see also

Jeffrey Clark, "Debacle in Somalia", 1993, pp.209-210.

22

Jeffrey Clark, "Debacle in Somalia: Failure of the Collective Response", 1993, p.210.

23

See Said Samatar, Somalia: A Nation in Turmoil, London: Minority Rights Group

Report, August 1991.

In the absence of major ethnic or religious cleavages in Somalia, Barre resorted

to manipulating the clan system as part of his overall strategy to maintain political

power despite his regime's deepening crisis of legitimation.

19

As challenges to his

dictatorship grew stronger, especially after Somalia's defeat by Ethiopia in 1978,

General Barre resorted to a "divide and rule" strategy which, by the late 1980s,

had resulted in several state-orchestrated mass murderings of elites belonging to

opposing clans.

20

In one such incident involving the massacre of Isaaq

professionals in Jasiira Beach in 1989, Khalif Galaydh recounts that "at least forty-

seven individuals, taken out of their homes in the middle of the night, [were]

confirmed to have been shot in cold blood and put in a mass grave."

21

According

to Jeffrey Clark, many more thousand Isaaqs who were fleeing the government

crack-down were strafed by Siad Barre's air force.

22

This heightened level of

violence was caused by an attempted coup d'état staged in 1978 against the Barre

regime by elements of the Somali military belonging to the Isaaq clan. Following

a government reprisal, the leaders of the failed coup fled initially to Ethiopia and

then to England where, in 1981, they formed a resistance movement, the Somali

National Movement (SNM), aimed at toppling the Barre dictatorship.

23

Managing Arms in Peace Processes: Somalia

)))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))

10

1.3 From Crisis to Conflict: The Principal Actors

in the Struggle for Power

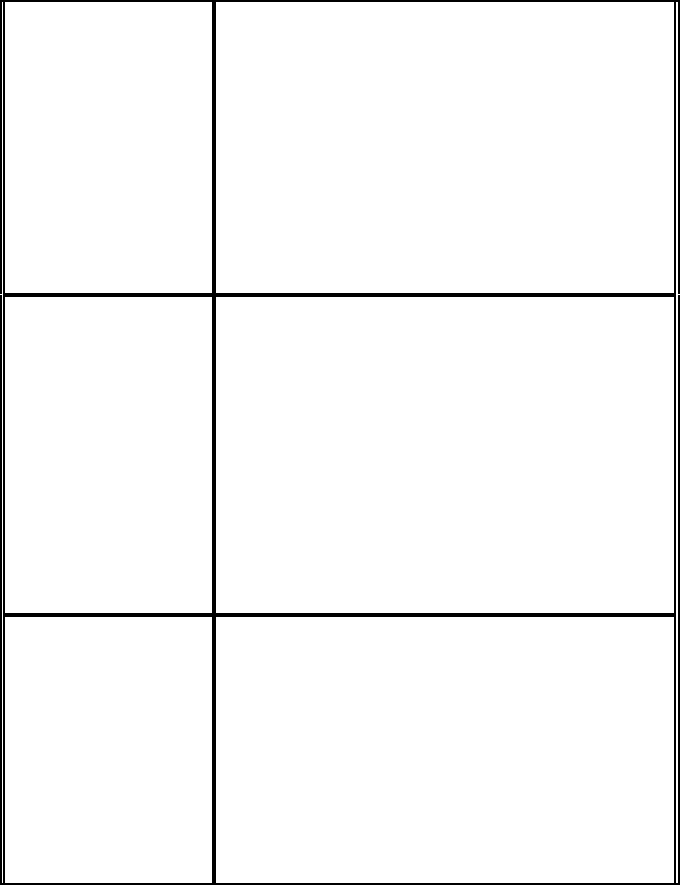

Table 1.2: Principal Actors and Their Role

in the Current Somali Conflict

Actor Role Description

General Siad Barre

Somali Army General who seized political

power through a coup d'état in 1969, and

whose rule generated the tensions that led to

the implosion of Somalia in 1991. In the

summer of 1992, he went into exile in Nigeria.

General Mohamed Farah

Aideed

Former General in the Somali Army who

helped defeat General Barre's forces in

Mogadishu as the military commander of the

United Somali Congress (USC). Following a

bitter struggle for power with Mr. Ali Mahdi,

his civilian colleague in the USC, General

Aideed formed the Somali National Alliance

(SNA), which soon became a key player in

Somalia's deepening conflict.

Ali Mahdi Mohamed

A cabinet minister in the First Republic and

prominent Mogadishu businessman, Mahdi

was a central figure in the USC and a key

player in Somalia's political tragedy. After the

exit of General Barre from Mogadishu, Mahdi

was pronounced interim President by the USC

on 29 January 1991 - an act that provoked a

violent power struggle between Mahdi and

General Aideed. Mahdi's faction, the USC

Manifesto Group, once exercised

unchallenged control over economic activities

in Mogadishu harbour and airports.

Introduction

)))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))

11

General Mohamed Said

Hersi (a.k.a. General

Morgan)

General Barre's son-in-law and a prime

beneficiary of the President's patronage,

serving as Defence Minister and head of

national security. In February 1993, General

Morgan captured a substantial part of

Kismayu from pro-Aideed forces led by Col.

Ahmed Omar Jess. This led to violent pro-

Aideed demonstrations in Mogadishu against

UNITAF which, because of its neutrality, was

alleged to have abetted General Morgan's

victory. In the spring of 1993, General

Morgan made a bungled last-ditch military

effort to return his father-in-law to power.

Colonel Ahmed Omar Jess

A pro-Aideed activist from the Ogaden clan

and former leader of the Somali People's

Movement, which was expelled from the

southern part of Kismayu by rival clans in the

Ogaden region.

General Mohamed Abshir

Musa

Former leader of the Somali Salvation

Democratic Front (SSDF), an anti-Aideed

faction. Educated in the US, Gen. Musa is

reputed to have taken sides with UN forces

against Aideed, and is regarded to be the

favourite of the Americans. His local support

base is in the northeast and southern Juba

region of Somalia.

Colonel Abdi Warsame

Leader of the Somali Salvation National

Movement (SSNM), Warsame left the Aideed

camp after Aideed engaged UN forces in

battle.

General Aden Nur Gabiyo

One-time Defence Minister under General

Barre, Gabiyo heads a faction of the Somali

People's Movement which supports Ali

Mahdi. General Gabiyo's forces control

Kismayu.

Managing Arms in Peace Processes: Somalia

)))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))

12

Mohamed Ali Hamad

Leader of the Somali Democratic Movement,

which draws its support from the Rahanwein

sub-clan based in Baidoa, the famine-ravaged

city in southern Somalia. Not known for his

loyalty to either Aideed or Mahdi, Mohamed

Hamad's relative neutrality may have

influenced the elders of his sub-clan to choose

him as leader of the SDM.

Ali Ismail Abdi

An ally of Aideed's, Abdia heads the Somali

National Democratic Union (SNDU), a

Leelkase Darod-based militia.

Mohamed Ramadan Arbo

Allied with Ali Mahdi's faction of the USC,

Mohamed Arbo leads the fragmented bantu

farming clans who live along the Shebelle and

Juba rivers, long regarded to be Somalia's

breadbasket.

General Omer Haji Maselle

A fellow Marehan-Darod clansman of Barre's

and former commander of Somali Armed

Forces, General Maselle is a prominent

member of the Somali National Front (SNF) -

a pro-Barre movement with strong support

from Barre's clan. Based in the famine-

stricken town of Bardere, General Maselle's

SNF has tried but failed in the past to take

advantage of the factionalization of the USC

to regain political power in Mogadishu.

Awad Ahmed Hashero

Reputed leader of a militia based in two Darod

sub-clans, Dolbahante and Warsengeli.

Introduction

)))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))

13

24

In a classic statement of this view, Andrew S. Natsios wrote in his "Food Through Force:

Humanitarian Intervention and US Policy", The Washington Quarterly, Vol. 17, No 1, 1993,

p.136, that: "The Somalis are by instinct a remarkably ethnocentric culture..." As evidence, he

cites a Somali proverb, suggesting their world view: "Me and Somalia against the world, Me

and my clan against Somalia, Me and my family against the clan, and Me against the family."

This echoes an earlier description of Somalis by Sir Richard Burton as "a fierce and turbulent

race of republicans" (quoted in Jeffrey Clark, "Debacle in Somalia," p. 207). The problem,

however, is that this view of the individual Somali as inherently force-prone, an iconic attribute

of the "zone of turmoil" about which relatively little can be done, projects a static view of the

Somali state and, as a consequence, is of limited use for purposes of analysis and prescription.

Umar Arteh Ghalib

A former Secretary of State for Foreign

Affairs, Ghalib was invited by interim

President Ali Mahdi to form a provisional

government that would prepare the country for

a return to democracy after the fall of Barre's

government. Ghalib accepted the offer and

formed a government on 2 February 1991. His

government was instantly denounced by

General Aideed and many international

observers as an attempt to dominate post-

Barre Somali politics.

Ibrahim Egal

Elected President of the Republic of

Somaliland, formerly British Somaliland in

the north, which unilaterally declared its

independence from Somalia on 17 May 1991.

However, the Republic of Somaliland has yet

to achieve diplomatic recognition from any

member of the United Nations.

The conflict and violence that eventually led to the implosion of Somalia in

1991 is not the product of a "first image" problematique - that is, the warlike and

ethnocentric nature of the Somalis, as some authors have suggested

24

- but that of

the "second image" par excellence. It is the problem of political governance, in

Managing Arms in Peace Processes: Somalia

)))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))

14

25

For a discussion of "First" and "Second Images" of the international system, see the

original formulation by Kenneth N. Waltz, Man, the State and War: A Theoretical Analysis,

New York: Columbia University Press, 1959. For further discussions, cf. Michael Doyle,

"Kant, Liberal Legacies and Foreign Affairs, Part I", Philosophy and Public Affairs, Vol. 12,

No 3, 1983, pp.205-235; "Liberalism and World Politics", American Political Science Review,

Vol. 80, No 4, 1986, pp.1151-1169; E. Weede, "Democracy and War Involvement", Journal of

Conflict Resolution, Vol. 28, No 4, 1984, pp.649-664; Francis Fukuyama, "Democratization

and International Security", Adelphi Papers, No 266, London: International Institute for

Strategic Studies, 1991/92; Robert Latham, "Democracy and War-Making: Locating the

International Liberal Context", Millennium: Journal of International Studies, Vol. 22, No 2,

1993, pp.139-164; Z. Maoz and N. Abdolali, "Regime Type and International Conflict, 1816-

1976", Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 33, No 1, 1989, pp.3-35; and Jack S. Levy, "The

Causes of War: A Review of Theories and Evidence", in Philip Tetlock, et al. (eds), Behavior,

Society and Nuclear War, Vol. 1, New York: Oxford University Press, 1988, pp.209-333.

26

Mohammed M. Sahnoun, "Prevention in Conflict Resolution: The Case of Somalia", Irish

Studies in International Affairs, Vol. 5, p.7, 1994 (emphasis added).

27

For a brilliant historical analysis of Somalia's steady slide towards anarchy, see Mohamed

Osman Omar, The Road to Zero: Somalia's Self-Destruction, London: Haan Associates, 1992.

this case the inherent anarchical tendency of Barre's authoritarian regime.

25

This

explanation is supported by the accounts of Mr. Mohammed Sahnoun, the former

Special Representative of the United Nations Secretary-General (SRSG) in

Somalia, which demonstrate that the disintegration of Somalia resulted from

uprisings which were:

fuelled both by clan-based rivalries and by wider political and economic considerations.

The northern part of Somalia, home of a large clan, the Isaak, as well as other smaller

tribes, came to resent the leadership of the southern tribal groups, whom they consider

to have monopolised political power since Siad Barré took over in a coup in 1969. The

inhabitants of the northern regions perceived themselves to be wronged and without the

possibility of democratic redress. Their revolt was led by the Somali National

Movement (SNM). Government forces, unable to prevent the uprising, unleashed a

bloody repression against the civilian population, using aircraft and heavy weapons.

26

The government's brutality was responded to in kind by the SNM and other

organised resistance movements based mainly in northern Somalia. Guerrilla

activities against government facilities intensified and so did Barre's repression,

thus institutionalising a cycle of violence in Somalia.

27

However, the government's

campaign of terror against the uprising in the north revealed the weakness of

Barre's army and served to encourage organised southern opposition groups to

take up arms against the regime. In 1989, southern opposition groups came

together under one politico-military umbrella, the United Somali Congress (USC).

Introduction

)))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))

15

28

Jeffrey Clark, Debacle in Somalia, 1993, p.210.

29

See Ioan Lewis, Making History in Somalia: Humanitarian Intervention in a Stateless

Society, Discussion Paper, No 6, London: Centre for the Study of Global Governance, 1993.

30

Robert G. Patman, "The UN Operation in Somalia", in Ramesh Thakur and Carlyle

Thayer (eds), UN Peacekeeping in the 1990s, Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1995, p.97. For

further detail, see Jonathan Stevenson, "Hope Restored in Somalia?", Foreign Policy, Vol. 91,

1993, p.143.

31

Jeffrey Clark, Debacle in Somalia, 1993, p.211.

By mid-1990, the political and territorial gains of the opposition forces, led by the

SNM in the north and the USC in the south, had severely weakened Barre's

governmental and military apparatus. In territorial terms, the government was left

with the capital city, Mogadishu, on which it maintained only a tenuous hold.

By now, the government, desperate for political power and control, resorted to

arming the "masses" to delay or forestall the fall of Mogadishu. To this end,

according to Jeffrey Clark, "Siad Barre desperately launched a massive

distribution of weapons and ammunition from his vast arsenals; his power all but

evaporated when he turned his army loose on Hawiye sections of the city,

destroying much of the infrastructure and provoking a violent and deadly uprising

in the process."

28

By mid-January 1991, the disintegration of Somalia was

completed with the largely unco-ordinated and riotous departure of General Barre

and his loyalists from Mogadishu.

29

According to Robert Patman,

Siad's retreating troops adopted a scorched-earth policy as they moved through Somalia's

farmland belt, in the Juba valley area, towards the region south of Mogadishu... The

troops slaughtered livestock, plundered crops and massacred local cultivators...

[Consequently], [d]evastation and starvation spread throughout southern Somalia.

30

Apart from destroying whatever social infrastructure existed in Mogadishu,

Barre and his fleeing loyalists also inflicted a profound psychological blow to the

city, thus leaving behind an urban population seething with inter- and intra-clan

hatred and violence. But, above all else, Barre's exit created a political vacuum in

Somalia. The USC, which played the principal role in defeating Barre's military

in Mogadishu, had splintered into two major factions once the goal of unseating

the government had been accomplished. In the ensuing struggle for supreme

political power, the two key figures in the USC, General Mohamed Farah Aideed

and Mr. Ali Mahdi - described as "a wealthy Mogadishu businessman" - turned

into bitter adversaries.

31

In the resulting confrontation in Mogadishu - a city which

was by now littered with "more than 500,000 weapons... abandoned by the former

Managing Arms in Peace Processes: Somalia

)))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))

16

32

M. Sahnoun, Prevention in Conflict Resolution, 1994, p.9.

33

Ibid., p.8.

34

Ibid.

35

Andrew Natsios, Vice President of World Vision and former Assistant Administrator of

the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), quoted in Jeffrey Clark,

Debacle in Somalia, 1993, p.212.

36

ICRC, Emergency Plan of Action - Somalia, Geneva: International Committee of the Red

Cross, 21 July 1992 (emphasis added).

37

See Jeffrey Clark, Debacle in Somalia, 1993, pp.212-213.

Somali army as the civil war reached its peak in January 1992" - the two leading

contenders for power turned to their sub-clans, the Habre Gedir-Hawiye and

Abgal-Hawiye, respectively, for mass support.

32

At this stage, according to

Mohammed Sahnoun, the power struggle between these two erstwhile allies "laid

waste to large areas of the city in November and December," claiming as many as

30,000 lives, in what has been described as "the worst part of an avoidable civil

war."

33

The multiplicity of actors and factions (see Table 1.2) and the terror they

unleashed on their society presented to the world the picture of Somalia as in

Hobbes's "state of nature", where life was literally nasty, brutish and pathetically

short. Thousands of Somalis died as much from violence directed by competing

"warlords" as from hunger. According to Sahnoun's account, by March 1992

... at least 300,000 people had died of hunger and hunger-related disease in the country

[of 8 million people]. Some 70% of the country's livestock had been lost and the farming

areas had been devastated, thus compelling the farming community to seek refuge in

remote areas or across the border in refugee camps. Some 500,000 people were in camps

in Ethiopia, Kenya and Djibouti.

34

The severity of the 1992 drought combined with Somali warlords to produce

what has been described as "the greatest humanitarian emergency in the world."

35

Unlike previous humanitarian emergencies which were limited to parts of a

country, the famine tragedy in Somalia was nation-wide, including the capital city,

Mogadishu. So grave and widespread was the famine that by mid-1992 the

International Committee of the Red Cross was estimating that malnutrition was

afflicting 95 percent of the entire population, "with 70 percent enduring severe

malnutrition."

36

By September 1992, ICRC estimated that 1.5 million Somalis

were threatened by imminent starvation, while other figures showed that 1.05

million Somalis had fled the country to escape the disaster.

37

Put simply, months

Introduction

)))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))

17

38

Ibid., p.213.

39

Mohammed Sahnoun, "Prevention in Conflict Resolution", 1994, p.9. Sahnoun was

referring to the UN relief programme in Somalia which he criticised for its ineffectiveness.

40

See Jeffrey Clark, Debacle in Somalia, 1993, pp.213-214.

after Barre's overthrow, a combination of civil war and famine had reduced

Somalia to a graveyard for the living dead.

While governments pondered and politicked over the Somali tragedy as it was

relayed by the international media, humanitarian relief organisations (HROs)

poured into Somalia on a rescue mission. However, these organisations were soon

overwhelmed by the magnitude of the human suffering and by the sheer

lawlessness that prevailed over the country. According to one description of the

plight of relief workers:

Relief officials were faced with the enormous hurdle of moving a minimally required

60,000 metric tons of emergency rations per month into a country with a destroyed

infrastructure and no functioning government, and were also confronted by the most

intensive looting ever to plague any relief operation.

By November 1992, some 80 percent of relief commodities were being confiscated. The

anarchy and chaos were diminishing the prospects that [the] relief effort would be even

minimally effective, and starvation was claiming in excess of a thousand victims a day

[thereby prompting widespread] reports that the entire relief operation would have to be

suspended, as the risk to the life of relief workers was rising well above acceptable

levels.

38

Essentially, therefore, Somalia had been thrown into a vicious cycle of famine

and violence. As Mohammed Sahnoun put it: "[t]ragically, not only was the...

assistance programme very limited but it was also so slowly and inadequately

delivered that it became counterproductive. Inevitably fighting erupted over the

meagre food supplied."

39

The point being made is that, at this stage in Somalia,

... food equalled money and power. Merchants stole food, hoarding it to keep the price

high; warlords stole it to feed armies. Hungry individuals possessing loaded automatic

rifles took (...) food [to feed themselves]. That is, the chaos and the overall shortage of

supplies available to relief groups resulted in a haphazard and uneven distribution of

food among clans; part of the looting was a violent and dangerous redistribution effort.

40

Paradoxically, however, a secure and orderly environment was required for a

balanced and effective distribution of food aid among Somalis. Such an

environment was lacking, and so the vicious cycle merely continued, with the

Managing Arms in Peace Processes: Somalia

)))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))

18

41

For detailed theoretical and empirical discussion of this problem, see Lawrence

Freedman, "Order and Disorder in the New World", Foreign Affairs, Vol. 71, No 1, 1992,

pp.20-37.

result being that more Somalis were dying as much from starvation as from

violence. The central policy challenge that confronted the international

community, therefore, was how to break the vicious cycle in order to restore hope

in Somalia. But to be of any assistance to Somalia, the international community

would first have to recover from its own "crisis fatigue."

41

1

Mohammed M. Sahnoun, "Prevention in Conflict Resolution: The Case of Somalia", Irish

Studies in International Affairs, Vol. 5, 1994, p.6 (emphasis added).

19

Chapter 2

The Evolution of International Responses

to the Somali Conflict: Regional and

International Dimensions

It has been argued that international intervention in the Somali crisis was

"slow" and pathetically erratic. This is puzzling because, according to

Mohammed Sahnoun,

Somalia, after all, was and remains a member of the League of Arab States [LAS] and

the Organisation of African Unity [OAU]. During the Carter and Reagan

administrations Somalia was a close ally of the United States, receiving hundreds of

millions of dollars in economic and military assistance. Somalia also retained good

relations with the former colonial powers of Britain and Italy, two important members

of the European Community. Finally, Somalia was a member of the UN. Any one of

these actors could have offered their services as mediators or supported the mediation

efforts timidly undertaken by neighbouring countries at various times... When the

international community finally did begin to intervene in early 1992, hundreds of

thousands of lives had already been lost.

1

The reasons for the sluggishness of international responses to the Somali

crisis are legion, but few are noteworthy. From the regional point of view,

Somalia's history of aggression towards its neighbours and its abiding interest

in "greater Somalia" had severely weakened whatever goodwill had existed

towards it from amongst the states of the Horn. Somalia's irredentist policy had

resulted in several instances of conflict with its neighbours, particularly Kenya

and Ethiopia. As an aspiration, "Greater Somalia" or "Somalia for all Somalis"

was not limited to the state, the elites and the two post-independence regimes.

Rather, it was an aspiration shared by many ordinary Somalis, as was also the

case in many African states where some ethnic groups had been split between

two colonial and post-colonial states. The defeat of Barre's army by Ethiopia

during the Ogaden conflict was seen by many Somalis as a betrayal of their

national cause by an incompetent regime. Not surprisingly, mass

Managing Arms in Peace Processes: Somalia

)))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))

20

2

Aside from the well known case of Mengistu's Ethiopia's military ties with Moscow,

Kenya was also an important military ally of a major power, the US. While prestige and the

geo-strategic imperatives of the Cold War might explain the behaviour of the superpowers, the

explanation for the behaviour of their African allies may be found in the "insecurity dilemma"

imposed on these states by their colonial inheritance of fragmented ethnic groups which

resulted in several cases of manifest and latent irredentism. For details, cf: Brian Job (ed.), The

Insecurity Dilemma: National Security of Third World States, Boulder, CO: Westview Press,

1992; Mohammed Ayoob, "The Security Problematic of the Third World", World Politics, Vol.

43, No 2, 1991, pp.257-283; "The New-Old Disorder in the Third World", Global Governance,

Vol. 1, No 1, 1995, p.59-77; and Donald Horowitz, Ethnic Groups in Conflict, Berkeley, CA:

University of California Press, 1985; Michael E. Brown (ed.), Ethnic Conflict and

International Security, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993.

disenchantment with the Barre regime became more vocal and more widespread

soon after the end of the Ogaden war. The consequence of Somalia's irredentist

attitude was that it created a nervousness amongst its neighbours who,

concerned about Somalia's potential for mounting a credible aggressive

campaign, sought and maintained close military co-operation with the major

military powers as a form of deterrence as well as insurance.

2

Logically,

therefore, these states were unwilling to invest their limited resources in any

significant effort to prevent the disintegration of Somalia in 1991.

In addition to the initial lack of enthusiasm on the part of Somalia's

neighbours, there was also the problem of inadequate institutional and financial

capacity for undertaking any serious regional diplomatic or military initiative

to arrest the anarchy and famine in Somalia. Somalia's immediate neighbours -

Ethiopia, Kenya and Djibouti - are each engrossed with some of the most

difficult problems of nation-building in Africa. Indeed, in 1991, Kenya, the

strongest of these states, was threatened by economic collapse and increased

political instability. Ethiopia was on the verge of collapse as a result of the

military successes of the separatist movement in Eritrea. In the light of this

regional circumstance, it was left to the OAU and LAS to assume the

responsibility for mediating the crisis and, if necessary, intervening to re-

establish some form of order. The OAU did attempt some mediation, but its

limited efforts were characteristically inadequate and lack lustre. On 18

December 1991, Dr. Salim Ahmed Salim, the Secretary-General of OAU, issued

a statement condemning the situation in Somalia: "I continue to be gravely

concerned at the continuing fratricidal fighting in Somalia... No differences

whatsoever, much less political differences, can justify the random and wanton

The Evolution of International Responses to the Somali Conflict

)))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))

21

3

Statement of 18 December 1991 by the Secretary-General of the Organisation of African

Unity Concerning the Situation in Somalia, Document S/23469, New York: The United

Nations Security Council, 23 January 1992,

Annex, p.2, para. 1.

4

Ibid., para. 2 (emphasis added).

5

Ibid., para. 3 (emphasis added).

6

Ibid., para. 4.

7

Resolution No. 5157 Adopted by the Council of the League at the Extraordinary Session

on 5 January 1992 Concerning the Situation in Somali, Document S/23448, New York: The

United Nations Security Council, 21 January 1992, Annex, p.3, para. 3.

killings we are now witnessing in Mogadishu."

3

He then appealed to the warring

factions to agree to an immediate cease-fire. In doing so, however, he struck a

raw nerve in Somalia by his reference to Ali Mahdi as president of the Interim

Government. In his own words:

The most urgent task at hand is to bring to a speedy end the mayhem and carnage now

raging in Mogadishu. In this regard, both parties involved in this fighting have

particular responsibility to ensure that there is an immediate cease-fire and normalcy

is restored to the city and thus paving the way to dialogue and a peaceful resolution to

the conflict. I would like to make a solemn appeal to President Mahdi of the Interim

Government and General Aedeed [sic] to exercise leadership and put an end to

violence and self-destruction which is being visited on the Somali people.

4

There was little indication from Salim's statement of what the OAU planned

to do in the face of the humanitarian disaster if Mahdi and Aideed failed to heed

the organisation's call for an immediate cease-fire. However, there was little

doubt that the organisation itself badly needed the initiative and assistance of the

international community in this regard: "I would... wish to appeal, once more,

to the international community at large to respond to the very urgent

humanitarian needs of the victims of the conflict in all parts of Somalia by

providing assistance especially of food and medicine."

5

On its part, the OAU

would "facilitate a meeting between all the parties involved... with a view to

elaborating a framework for constructive dialogue."

6

Following Egypt's request, the LAS took up the Somali problem from where

the OAU left off. At its extra-ordinary meeting held on 5 January 1992, the

organisation reviewed the Somali situation and decided "to provide Somalia

with emergency relief... so as to enable the Somali people to cope with their

tragic plight and avert the spectre of famine that threatens them..."

7

To this end,

the LAS sought voluntary contributions from its members and the entire Arab

Managing Arms in Peace Processes: Somalia

)))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))

22

8

Ibid., para. 4.

9

Letter dated 20 January 1992 from the Chargé d'Affaires A.I. of the Permanent Mission of

Somalia to the United Nations addressed to the President of the Security Council, Document

S/23445, New York, 20 January 1992, Annex, p.2, para. 3 (emphasis added).

10

Ibid., p.1 (emphasis added).

world. Accordingly, it instructed its Secretary-General "to open a special

account for Somalia and to take such measures as he may deem necessary to

determine and co-ordinate assistance in kind provided by the Member States,

and ensure orderly distribution."

8

Surprisingly, and quite in contrast to its

acknowledgement of the urgency of humanitarian assistance to Somalia, the

LAS relied on voluntary contributions rather than drawing from existing

resources. Needless to say that nothing of any significance came out of the LAS

resolution which called for an immediate humanitarian relief operation in

Somalia. Full-scale famine descended on Somalia towards the end of January,

just as the fighting between followers of Aideed and Mahdi intensified.

Any expectation of a regional plan to assist Somalia in any significant way

had evaporated by mid-January 1992. This realisation prompted a letter of

appeal dated 11 January 1992 from Mr. Omer Arteh Ghalib, Mahdi's hand-

picked Prime Minister of Somalia's Interim Government, calling on the United

Nations to rush to Somalia's aid:

I am confident that with the background knowledge of the new Secretary-General Dr.

Boutros-Ghali and his prior commitment to reconciliation in Somalia, the United

Nations will come up with a programme of effective action to end the fighting and

contribute to cementing peace and stability in the country.

9

In forwarding this letter to the Security Council on 20 January, Mr. Fatun

Mohamed Hassan, Somalia's Chargé d'affaires, added his voice to Mr. Arteh's

appeal by sounding a note of urgency which reflected the increasingly desperate

situation in Somalia and the fear that only a concerted UN-led international

effort could alter the path of anarchy in Somalia. According to Mr. Hassan, "[a]s

the civil war situation in Somalia is worsening by the day, I support Mr. Arteh's

appeal for the Security Council to convene immediately a meeting to consider

the deteriorating human dilemma prevailing in Somalia."

10

If Somalia's neighbours, the OAU and LAS could not respond quickly and

effectively to the security and humanitarian crises in the Horn, the situation is

even truer for the rest of the international community which first had to recover

from its own "crisis fatigue." Few people seriously expected the OAU or LAS

The Evolution of International Responses to the Somali Conflict

)))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))

23

11

For differing perspectives on the promises of the post-Cold War era, cf. Francis

Fukuyama, "The End of History?", The National Interest, Vol. 16, 1989, pp.3-18; John

Mearsheimer, "Why We Will Soon Miss the Cold War", The Atlantic Monthly, Vol. 266, No 2,

1990, pp.35-56; Charles Krauthammer, "The Unipolar Moment", Foreign Affairs, Vol. 70, No

1, 1991, pp.23-33; and Stanley Hoffmann, "A New World Order and its Troubles", Foreign

Affairs, Vol. 69, No 4, 1990, pp.115-122; Lawrence Freedman (1992), "Order and Disorder in

the New World", Foreign Affairs, Vol. 71, No 1, 1992, pp.20-37; Joseph S. Nye, Jr., "What

New World Order?", Foreign Affairs, Vol. 71, No 2, 1992, pp.83-96.

12

Mohammed Sahnoun argues quite passionately that the international community could

have prevented the Somali tragedy. See his Prevention in Conflict Resolution, esp. pp.5-9.

13

Lawrence Freedman, Order and Disorder in the New World, 1992, p.37.

to intervene in any significant way in Somalia, for neither of these organisations

has had successful experience in this regard. However, expectations were high

regarding the possibility and ability of western powers and the United Nations

to mount an effective operation to save Somalia from total collapse. Such high

expectation was based on the optimistic assumptions of post-Cold War

communitarianism; that is, the "peace dividend" of the "new world order."

11

That such high expectations of the international community were not

immediately met in Somalia was as avoidable as it was unexpected:

12

In all this a crisis fatigue may soon set in, for the process will be frustrating and the

results often dispiriting. It is by no means self-evident that the west Europeans have

the staying power to handle even a selection of the challenges thrown up by the

developing disorder in postcommunist Europe, let alone those left in the rest of the

world...

13

By the time the Somali crisis became leading news in the major press rooms

around the world in the spring and summer of 1992, the international