59

7. CREDIT AND INSURANCE

The Federal Government offers direct loans and loan

guarantees to support a wide range of activities includ-

ing home ownership, student loans, small business,

farming, energy, infrastructure investment, and exports.

In addition, Government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs)

operate under Federal charters for the purpose of en-

hancing credit availability for targeted sectors. Through

its insurance programs, the Federal Government insures

deposits at depository institutions, guarantees private-

sector defined-benefit pensions, and insures against some

other risks such as flood and terrorism. These programs

are also exposed to climate-related financial risks, which

the private sector is increasingly taking into account in

the pricing of financial products. For a discussion of cli-

mate risks faced by Federal housing loans, please see the

“Analysis of Federal Climate Financial Risk Exposure”

chapter of this volume.

This chapter discusses the roles of these diverse pro-

grams. The first section discusses individual credit

programs and GSEs. The second section reviews Federal

deposit insurance, pension guarantees, disaster insurance,

and insurance against terrorism and other security-relat-

ed risks. The final section includes a brief analysis of the

Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP).

I. CREDIT IN VARIOUS SECTORS

Housing Credit Programs

Through its main housing credit programs, the Federal

Government promotes homeownership among various

groups that may face barriers to owning a home, includ-

ing low- and moderate-income people, veterans, and rural

residents. By expanding affordable homeownership op-

portunities for underserved borrowers, these programs

can advance equity. In times of economic crisis, the

Federal Government’s role and target market can expand

dramatically.

Federal Housing Administration

The Federal Housing Administration (FHA) guar-

antees single-family mortgages that expand access to

homeownership for households who may have difficulty

obtaining a conventional mortgage. In addition to tradi-

tional single-family “forward” mortgages, FHA insures

“reverse” mortgages for seniors (Home Equity Conversion

Mortgages, described below) and loans for the construc-

tion, rehabilitation, and refinancing of multifamily

housing, hospitals, and other healthcare facilities.

FHA Single-Family Forward Mortgages

FHA has been a primary facilitator of mortgage cred-

it for first-time and minority homebuyers, a pioneer of

products such as the 30-year self-amortizing mortgage,

and a vehicle to enhance credit for many low- to moder-

ate-income households. One of the major benefits of an

FHA-insured mortgage is that it provides a homeowner-

ship option for borrowers who, though they can only make

a modest down payment, can show that they are credit-

worthy and have sufficient income to afford the house

they want to buy. First-time homebuyers accounted for 82

percent of new FHA purchase loans in 2023 and, for cal-

endar year (CY) 2022, the low-income homebuyer share

was over 40 percent. In the market as a whole, more than

half of all Black and Hispanic borrowers who obtained

low down payment mortgages (less than 5 percent down)

in CY 2022 relied on FHA.

FHA Home Equity Conversion Mortgages

Home Equity Conversion Mortgages (HECMs), or “re-

verse” mortgages, are designed to support aging in place

by enabling elderly homeowners to borrow against the eq-

uity in their homes without having to make repayments

during their lifetime (unless they sell, refinance, or fail

to meet certain requirements). A HECM is known as a

“reverse” mortgage because the change in home equity

over time is generally the opposite of a forward mortgage.

While a traditional forward mortgage starts with a small

amount of equity and builds equity with amortization of

the loan, a HECM starts with a large equity cushion that

declines over time as the loan accrues interest and pre-

miums. The risk of HECMs is therefore weighted toward

the end of the mortgage, while forward mortgage risk is

concentrated in the first 10 years.

FHA Mutual Mortgage Insurance (MMI) Fund

FHA guarantees for forward and reverse mortgages

are administered under the Mutual Mortgage Insurance

(MMI) Fund. At the end of 2023, the MMI Fund had $1.38

trillion in total mortgages outstanding and a capital ra-

tio of 10.51 percent, a minor decrease from the 2022 level

of 11.11 percent. For more information on the financial

status of the MMI Fund, please see the Annual Report

to Congress Regarding the Financial Status of the FHA

Mutual Mortgage Insurance Fund, Fiscal Year 2023.

1

FHA’s new origination volume in 2023 was $209 billion

for forward mortgages and $16 billion for HECMs, and

the Budget projects $220 billion and $18 billion, respec-

tively, for 2025.

1

https://www.hud.gov/sites/dfiles/PA/documents/2023FHAAnnualRe

portMMIFund.pdf

60

ANALYTICAL PERSPECTIVES

FHA Multifamily and Healthcare Guarantees

In addition to the single-family mortgage insurance pro-

vided through the MMI Fund, FHA’s General Insurance

and Special Risk Insurance (GISRI) loan programs con-

tinue to facilitate the construction, rehabilitation, and

refinancing of multifamily housing, hospitals, and other

healthcare facilities. The credit enhancement provided by

FHA enables borrowers to obtain long-term, fixed-rate fi-

nancing, which mitigates interest rate risk and facilitates

lower monthly mortgage payments. This can improve

the financial sustainability of multifamily housing and

healthcare facilities, and may also translate into more af-

fordable rents and lower healthcare costs for consumers.

GISRI’s new origination loan volume for all programs

in 2023 was $17 billion and the Budget projects $18 bil-

lion for 2025. The total amount of guarantees outstanding

on mortgages in the FHA GISRI Fund were $167 billion

at the end of 2023.

VA Housing Loan Program

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) assists vet-

erans, members of the Selected Reserve, and active duty

personnel in purchasing homes in recognition of their

service to the Nation. The VA housing loan program effec-

tively substitutes a Federal guarantee for the borrower’s

down payment, meaning more favorable lending terms for

veterans. Under this program, VA does not guarantee the

entire mortgage loan, but typically fully guarantees the

first 25 percent of losses upon default. In fiscal year 2023,

VA guaranteed a total of 320,274 new purchase home

loans, providing approximately $119.4 billion in guaran-

tees. VA also guaranteed 5,000 Interest Rate Reduction

Refinance loans and veteran borrowers lowered inter-

est rates on their home mortgages through streamlined

refinancing. VA provided approximately $144 billion in

guarantees for 400,695 VA loans in fiscal year 2023. That

followed $257 billion in guarantees for 746,091 VA loans

closed in fiscal year 2022.

VA, in cooperation with VA-guaranteed loan servicers,

also assists borrowers through home retention options

and alternatives to foreclosure. VA intervenes when

needed to help veterans and servicemembers avoid fore-

closure through loan modifications, special forbearances,

repayment plans, and acquired loans, as well as assis-

tance to complete compromised sales or deeds-in-lieu of

foreclosure. These standard efforts helped resolve over 96

percent of defaulted VA-guaranteed loans and assisted

145,480 veterans retain homeownership or avoid foreclo-

sure in 2023. These efforts resulted in over $2.5 billion in

avoided guaranteed claim payments. VA has responded

to the COVID-19 crisis by providing special CARES Act

(Public Law 116-136) forbearances to support otherwise-

current borrowers through the pandemic. As of September

30, 2023, 24,833 VA borrowers were participating in a

special COVID-19 forbearance.

Rural Housing Service

The Rural Housing Service (RHS) at the U.S.

Department of Agriculture (USDA) offers direct and guar-

anteed loans to help very-low- to moderate-income rural

residents buy and maintain adequate, affordable housing.

RHS housing loans and loan guarantees differ from other

Federal housing loan programs in that they are means-

tested, making them more accessible to low-income, rural

residents. The single family housing guaranteed loan

program is designed to provide home loan guarantees

for moderate-income rural residents whose incomes are

between 80 percent and 115 percent (maximum for the

program) of area median income.

RHS has traditionally offered both direct and guar-

anteed homeownership loans. The direct single family

housing loans have been historically funded at $1.2 billion

a year, while the single family housing guaranteed loan

program, authorized in 1990 at $100 million, has grown

into a $30 billion loan program annually.USDA also of-

fers direct and guaranteed multifamily housing loans, as

well as housing repair loans.

Education Credit Programs

The Department of Education (ED) direct student loan

program is one of the largest Federal credit programs,

with $1.34 trillion in Direct Loan principal outstand-

ing in 2023. The Federal student loan programs provide

students and their families with the funds to help meet

postsecondary education costs. Because funding for the

loan programs is provided through mandatory budget

authority, student loans are considered separately for

budget purposes from other Federal student financial as-

sistance programs (which are largely discretionary), but

should be viewed as part of the overall Federal effort to

expand access to higher education.

Loans for higher education were first authorized un-

der the William D. Ford program, which was included in

the Higher Education Act of 1965 (Public Law 89-329).

The direct loan program was authorized by the Student

Loan Reform Act of 1993 (subtitle A of title IV of Public

Law 103–66). The enactment of the SAFRA Act (subtitle

A of title II of Public Law 111–152) ended the guaranteed

Federal Financial Education Loan program. On July 1,

2010, ED became the sole originator of Federal student

loans through the Direct Loan program.

Under the current direct loan program, the Federal

Government partners with over 5,500 institutions of high-

er education, which then disburse loan funds to students.

Loans are available to students and parents of students

regardless of income, and only Parent and Graduate PLUS

loans include a minimal credit check. There are three

types of Direct Loans: Federal Direct Subsidized Stafford

Loans, Federal Direct Unsubsidized Stafford Loans, and

Federal Direct PLUS Loans, each with different terms.

The Direct Loan program offers a variety of repay-

ment options, including income-driven repayment ones

for all student borrowers. Depending on the plan, month-

ly payments are capped at no more than 5 to 15 percent

of borrower discretionary income, with any remaining

balance after 10 to 25 years of payments forgiven. In ad-

dition, borrowers working in public service professions

while making 10 years of qualifying payments are eligible

for Public Service Loan Forgiveness.

7. CREDIT AND INSURANCE

61

The Department of Education also operates the

Historically Black College and Universities (HBCU)

Capital Financing Program. Since fiscal year 1996, the

Program has provided HBCUs with access to low-cost

capital financing for the repair, renovation, and, in ex-

ceptional circumstances, construction or acquisition of

educational facilities, instructional equipment, research

instrumentation, and physical infrastructure.

Small Business and Farm Credit Programs

The Government offers direct loans and loan guarantees

to small businesses and farmers, who may have difficulty

obtaining credit elsewhere. It also provides guarantees

of debt issued by certain investment funds that invest in

small businesses. Two GSEs, the Farm Credit System and

the Federal Agricultural Mortgage Corporation, increase

liquidity in the agricultural lending market.

Small Business Administration

The Small Business Administration (SBA) ensures that

small businesses across the Nation have the tools and re-

sources needed to start, grow, and recover their business.

SBA’s lending programs complement credit markets by of-

fering creditworthy small businesses access to affordable

credit through private lenders when they cannot other-

wise obtain financing on reasonable terms or conditions.

In 2023, SBA provided $26 billion in loan guarantees

to assist small business owners with access to affordable

capital through its largest program, the 7(a) General

Business Loan Guarantee program. This program pro-

vides access to financing for general business operations,

such as operating and capital expenses. In addition,

through the 504 Certified Development Company (CDC)

and Refinance Programs, SBA supported $6 billion in

guaranteed loans for fixed-asset financing and provided

the opportunity for small businesses to refinance existing

504 CDC loans. These programs enable small business-

es to secure financing for assets such as machinery and

equipment, construction, and commercial real estate, and

to free up resources for expansion. The Small Business

Investment Company (SBIC) Program also supports pri-

vately-owned and -operated venture capital investment

firms that invest in small businesses. In 2023, SBA sup-

ported $4 billion in SBIC venture capital investments.

In addition to these guaranteed lending programs, the

7(m) Direct Microloan program supports the smallest

of businesses, startups, and underserved entrepreneurs

through loans of up to $50,000 made by non-profit inter-

mediaries. In 2023, SBA facilitated a record $52 million

in microlending.

Community Development Financial Institutions

Since its creation in 1994, the Department of the

Treasury’s (Treasury) Community Development Financial

Institutions (CDFI) Fund has, through different grant,

loan, and tax credit programs, worked to expand the

availability of credit, investment capital, and financial

services for underserved people and communities by sup-

porting the growth and capacity of a national network of

CDFIs, investors, and financial service providers. Today,

there are more than 1,480 Certified CDFIs nationwide,

including a variety of loan funds, community development

banks, credit unions, and venture capital funds. CDFI

certification also enables some non-depository financial

institutions to apply for financing programs offered by

certain Federal Home Loan Banks.

Unlike other CDFI Fund programs, the CDFI Bond

Guarantee Program (BGP), enacted through the Small

Business Jobs Act of 2010, does not offer grants, but is

instead exclusively a Federal credit program. The BGP

was designed to provide CDFIs greater access to low-cost,

long-term, fixed-rate capital.

Under the BGP, the Treasury provides a 100 percent

guarantee on long-term bonds of at least $100 million is-

sued to qualified CDFIs, with a maximum maturity of 30

years. To date, the Treasury has issued nearly $2.5 billion

in bond guarantee commitments to 27 CDFIs, over $1.6

billion of which has been disbursed to help finance af-

fordable housing, charter schools, commercial real estate,

community healthcare facilities, and other eligible uses in

34 States and the District of Columbia.

Farm Service Agency

Farm operating loans were first offered in 1937 by the

newly created Farm Security Administration (FSA) to

assist family farmers who were unable to obtain credit

from a commercial source to buy equipment, livestock, or

seed. Farm ownership loans were authorized in 1961 to

provide family farmers with financial assistance to pur-

chase farmland. Presently, FSA assists low-income family

farmers in starting and maintaining viable farming op-

erations. Emphasis is placed on aiding beginning and

socially disadvantaged farmers. Legislation mandates

that a portion of appropriated funds are set aside for ex-

clusive use by those underserved groups.

FSA offers operating loans and ownership loans, both of

which may be either direct or guaranteed loans. Operating

loans provide credit to farmers and ranchers for annual

production expenses and purchases of livestock, machin-

ery, and equipment, while farm ownership loans assist

producers in acquiring and developing their farming or

ranching operations. As a condition of eligibility for direct

loans, borrowers must be unable to obtain private credit

at reasonable rates and terms. As FSA is the “lender of

first opportunity,” default rates on FSA direct loans are

generally higher than those on private-sector loans. FSA-

guaranteed farm loans are made to more creditworthy

borrowers who have access to private credit markets.

Because the private loan originators must, in most situ-

ations, retain 10 percent of the risk, they exercise care in

examining the repayment ability of borrowers. The subsi-

dy rates for the direct programs fluctuate largely because

of changes in the interest component of the subsidy rate.

In 2023, there were more than 22,000 direct or guaran-

teed loan obligations totaling over $4.7 billion. The entire

portfolio of outstanding debt as of September 30, 2023,

totaled $33 billion, serving 122,000 farmers and ranchers.

In 2023, the amount of lending declined in both dollar and

volume terms, down 19 and seven percent, respectively.

Lending in dollar terms for real estate purchases de-

62

ANALYTICAL PERSPECTIVES

creased for both direct loans (decreasing two percent) and

guaranteed loans (decreasing 42 percent). Operating loan

obligations also fell in dollar terms for guaranteed loans

(decreasing 14 percent), but increased for direct loans (in-

creasing six percent). The decline in 2023 obligations was

not unexpected, particularly for farm ownership loans

where increased real estate values and rising interest

rates resulted in decreased demand for land purchases

and real estate refinancing. Direct operating loans that

provide working capital to farmers and ranchers did see

an increase in 2023 as rising interest rates and cost of in-

puts pressuring farm profits and resulting in an increased

need for the favorable rates and terms provided by the di-

rect operating loan program. This cyclicality is typical for

farm loan programs and underscores the importance of

FSA’s Farm Loan Programs as a safety net.

A beginning farmer is an individual or entity who: has

operated a farm for not more than 10 years; substantially

participates in farm operation; and, for farm ownership

loans, the applicant cannot own a farm larger than 30

percent of the average size farm in the county at time

of application. If the applicant is an entity, all entity

members must be related by blood or marriage, and all

members must be eligible beginning farmers. Beginning

farmers received 60 percent of direct and guaranteed

loans in 2023. Direct and guaranteed loan programs pro-

vided assistance totaling $2.7 billion to nearly 13,600

beginning farmers. Additionally in 2023, loans for socially

disadvantaged farmers totaled nearly $1.1 billion to near-

ly 6,000 borrowers, of which $748 million was in the farm

ownership program and $339 million in the farm operat-

ing program.

The FSA Microloan program increases overall direct

and guaranteed lending to small niche producers and mi-

norities. This program dramatically simplifies application

procedures for small loans and implements more flexible

eligibility and experience requirements.Demand for the

micro-loan program continues to grow while delinquen-

cies and defaults remain at or below those of the regular

FSA operating loan program.

Energy and Infrastructure Credit Programs

The Department of Energy (DOE) administers four

credit programs: Title XVII Innovative Technology Loan

Guarantee Program (Title XVII), the Advanced Technology

Vehicle Manufacturing (ATVM) Loan Program, the Tribal

Energy Loan Guarantee Program, and the Carbon Dioxide

Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation

Program. Section 1703 of title XVII of the Energy Policy

Act of 2005, as amended (Public Law 109–58) authorizes

DOE to issue loan guarantees for clean energy projects

that employ innovative technologies or are supported by

State Energy Financing Institutions to reduce, avoid, or

sequester air pollutants or man-made greenhouse gases.

To date, under Title XVII, DOE has issued five loan guar-

antees totaling over $15 billion to support the construction

of two new commercial nuclear power reactors, a clean

hydrogen production and storage project, and a solar plus

storage virtual power plant project. DOE has three active

conditional commitments totaling $1.5 billion. DOE is ac-

tively working with applicants proceeding to conditional

commitment and financial close to utilize the $3.5 billion

in appropriated credit subsidy and $73 billion in available

loan guarantee authority currently available.

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009

(Public Law 111–5) amended section 1705 of Title XVII

and appropriated credit subsidy to support loan guaran-

tees on a temporary basis for commercial or advanced

renewable energy systems, electric power transmission

systems, and leading-edge biofuel projects. Authority

for the temporary program to extend new loans expired

September 30, 2011. $16 billion in loans and loan guaran-

tees was disbursed via 24 loan guarantees issued prior to

the program’s expiration.

Public Law 117-169, commonly referred to as the

Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (IRA) further amended

section 1706 to the Title XVII program’s authorizing

statute and appropriated $4.8 billion in credit subsidy to

support loan guarantees for projects that retool, repower,

repurpose, or replace energy infrastructure and avoid,

reduce, or sequester air pollutants or man-made green-

house gases. Appropriated authority for the section 1706

program expires September 30, 2026. DOE is actively

working with applicants toward conditional commitment

and financial close.

Section 136 of the Energy Independence and Security

Act of 2007 (Public Law 110–140) authorizes DOE to

issue loans to support the development of advanced tech-

nology vehicles and qualifying components. In 2009, the

Congress appropriated $7.5 billion in credit subsidy to

support a maximum of $25 billion in loans under ATVM.

From 2009 to 2011, DOE issued five loans totaling over $8

billion to support the manufacturing of advanced technol-

ogy vehicles. Since 2021, DOE has issued 11 conditional

commitments totaling over $19 billion, of which two loans

have reach financial close. DOE has $4.6 billion in credit

subsidy balances with no loan limitation and is actively

working with applicants proceeding to conditional com-

mitment and financial close.Title XXVI of the Energy

Policy Act of 1992, as amended (Public Law 102-486) au-

thorizes DOE to guarantee up to $20 billion in loans to

Indian Tribes for energy development. The Congress has

appropriated over $80 million in credit subsidy, cumula-

tively, to support tribal energy development. DOE issued

a revised solicitation in 2022 and is actively working with

applicants proceeding to conditional commitment and fi-

nancial close.

Section 40304 of the Infrastructure Investment and

Jobs Act (IIJA; Public Law 117-58) amended Title IX of

the Energy Policy Act of 2005 by authorizing DOE to issue

loans, loan guarantees, and grants to support the devel-

opment of carbon dioxide transportation infrastructure

(e.g., pipelines). The law provided $3 million for program

start-up costs in 2022 and an advance appropriation of

$2.1 billion in 2023 budget authority for the cost of loans,

loan guarantees, and grants to eligible projects. DOE is

actively working to establish the program.

7. CREDIT AND INSURANCE

63

Electric and Telecommunications Loans

Rural Utilities Service (RUS) programs of the USDA

provide grants and loans to support the distribution of

rural electrification, telecommunications, distance learn-

ing, and broadband infrastructure systems.

In 2023, RUS delivered $6.9 billion in direct electrifica-

tion loans (including $1.87 billion in Federal Financing

Bank (FFB) Electric Loans, $900 million in electric under-

writing, and $201.5 million rural energy savings loans),

$17.1 million in direct and FFB telecommunications loans,

and $1.99 billion in Reconnect broadband loans. RUS also

helped a rural Kentucky electric utility. As a result, RUS

made an operating loan to a local cooperative for $122.8

million, which also unlocked an additional $12.3 million

in energy efficiency initiatives.

USDA Rural Infrastructure and

Business Development Programs

USDA, through a variety of Rural Development (RD)

programs, provides grants, direct loans, and loan guar-

antees to communities for constructing facilities such as

healthcare clinics, police stations, and water systems,as

well as to assist rural businesses andcooperatives in cre-

ating new community infrastructure (e.g., educational and

healthcare networks) and to diversifythe rural economy

and employment opportunities.In 2023, RD provided $1.1

billion in Community Facility (CF) direct loans, which are

for communities of 20,000 or less. The CF programs have

the flexibility to finance more than 100 separate types of

essential community infrastructure that ultimately im-

prove access to healthcare, education, public safety and

other critical facilities and services. RD also provided $1.1

billion in water and wastewater (W&W) direct loans, and

guaranteed $2 billion in rural business loans, which will

help create and save jobs in rural America. Since 2020, CF

and W&W loan guarantees have been for communities of

50,000 or less.

Water Infrastructure

The Environmental Protection Agency’s Water

Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (WIFIA)

program accelerates investment in the Nation’s wa-

ter infrastructure by providing long-term, low-cost

supplemental loans for projects of regional or national

significance. To date, WIFIA has closed 120 loans total-

ing $19 billion in credit assistance to help finance over

$43 billion for water infrastructure projects and create

143,000 jobs. The selected projects demonstrate the broad

range of project types that the WIFIA program can fi-

nance, including wastewater, drinking water, stormwater,

and water reuse projects.

In addition, the WIFIA Program, authorized by the

Water Resources Reform and Development Act of 2014,

as amended (Public Law 113-121), allows the U.S. Army

Corps of Engineers to issue loans and loan guarantees

for eligible non-Federal water resources projects. The

Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021 (Public Law 116-

260) provided $12 million for the cost of loans and loan

guarantees for dam safety projects at non-Federal dams

identified in the National Inventory of Dams. The IIJA

provided an additional $64 million for this purpose. The

Corps of Engineers is actively working to establish this

new Federal credit program, including developing imple-

menting regulations.

Transportation Infrastructure

The Department of Transportation (DOT) adminis-

ters credit programs that fund critical transportation

infrastructure projects, often using innovative financ-

ing methods. The two predominant programs are the

Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation

Act (TIFIA) and the Railroad Rehabilitation and

Improvement Financing (RRIF) loan programs. DOT’s

Build America Bureau administers both of these pro-

grams, as well as Private Activity Bonds. The Bureau

serves as the single point of contact for State and local

governments, transit agencies, railroads and other types

of project sponsors seeking to utilize Federal transpor-

tation innovative financing expertise, apply for Federal

transportation credit programs, and explore ways to ac-

cess private capital in public-private partnerships.

Transportation Infrastructure Finance

and Innovation Act (TIFIA)

Established by the Transportation Equity Act for the

21st Century (TEA-21; Public Law 105-178) in 1998,

the TIFIA program is designed to fill market gaps and

leverage substantial private co-investment by providing

supplemental and subordinate capital to transportation

infrastructure projects. Through TIFIA, DOT provides

three types of Federal credit assistance to highway,

transit, rail, intermodal, airport, and transit-oriented

development projects: direct loans, loan guarantees, and

lines of credit. TIFIA can help advance qualified, large-

scale projects that otherwise might be delayed or deferred

because of size, complexity, or uncertainty over the tim-

ing of revenues.For example, in 2023 the TIFIA program

provided a $501 million loan to the I-25 Express Lanes

project in Colorado, which will add 52 miles of express

toll lanes between Denver and Fort Collins. The IIJA

authorized $250 million annually for TIFIA for fiscal

years 2022-2026, and the Budget fully reflects the IIJA-

authorized level for 2025.

Railroad Rehabilitation and

Improvement Financing (RRIF)

Also established by TEA–21 in 1998, the RRIF pro-

gram provides loans or loan guarantees with an interest

rate equal to the Treasury rate for similar-term securities

for terms up to 75 years. The RRIF program allows bor-

rowers to pay the subsidy cost of a loan (a “Credit Risk

Premium”) using non-Federal sources, thereby allowing

the program to operate without Federal subsidy appro-

priations. The RRIF program assists rail infrastructure

projects that improve rail safety and efficiency, support

economic development and opportunity, or increase the

capacity of the national rail network. For example, in

2023 the RRIF program provided a $27.5 million loan to

64

ANALYTICAL PERSPECTIVES

the Double Track Project in Northwest Indiana, to im-

prove connections between the region and Chicago.

International Credit Programs

Through 2023, seven unique Federal agencies pro-

vide or have existing portfolios of direct loans, loan

guarantees, and insurance to a variety of private and

sovereign borrowers: USDA, the Department of Defense,

the Department of State, the Treasury, the U.S. Agency

for International Development, the Export-Import Bank

(ExIm), and the U.S. International Development Finance

Corporation (DFC). These programs are intended to level

the playing field for U.S. exporters, deliver robust support

for U.S. goods and services, stabilize international finan-

cial markets, enhance security, and promote sustainable

development.

Federal export credit programs provide financing sup-

port for American businesses involved in international

trade and to counteract unfair foreign trade financing.

Various foreign governments provide their exporters of-

ficial financing assistance, usually through export credit

agencies. The U.S. Government has worked since the

1970s to constrain official credit support through a mul-

tilateral agreement in the Organisation for Economic

Cooperation and Development (OECD). This agreement

has established standards for Government-backed financ-

ing of exports. In addition to ongoing work in keeping

these OECD standards up-to-date, the U.S. Government

established the International Working Group on Export

Credits to set up a new framework that will include China

and other non-OECD countries, which were not previously

subject to export credit standards. The process of estab-

lishing these new standards, which is not yet complete,

advances a congressional mandate to reduce subsidized

export financing programs.

Export Support Programs

When the private sector is unable or unwilling to pro-

vide financing, ExIm fills the gap for American businesses

by equipping them with the financing support necessary

to level the playing field against foreign competitors.

ExIm support includes direct loans and loan guarantees

for creditworthy foreign buyers to help secure export

sales from U.S. exporters. It also includes working capi-

tal guarantees and export credit insurance to help U.S.

exporters secure financing for overseas sales. USDA’s

Export Credit Guarantee Programs (GSM programs)

similarly help to level the playing field. Like programs

of other agricultural exporting nations, GSM programs

guarantee payment from countries and entities that want

to import U.S. agricultural products but cannot easily ob-

tain credit. The GSM 102 program provides guarantees

for credit extended with short-term repayment terms not

to exceed 18 months.

Exchange Stabilization Fund

Consistent with U.S. obligations in the International

Monetary Fund (IMF) regarding global financial stabil-

ity, the Exchange Stabilization Fund (ESF) managed

by the Treasury may provide loans or credits to a for-

eign entity or government of a foreign country. A loan or

credit may not be made for more than six months in any

12-month period unless the President gives the Congress

a written statement that unique or emergency circum-

stances require that the loan or credit be for more than

six months. The CARES Act established within the ESF

an Economic Stabilization Program with temporary au-

thority for lending and other eligible investments, which

included programs or facilities established by the Board

of Governors of the Federal Reserve System pursuant to

section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act. The Consolidated

Appropriations Act, 2021 rescinded this authority, though

loans and investments already made remain active until

obligations are liquidated.

Sovereign Lending and Guarantees

The U.S. Government can extend short-to-medium-

term loan guarantees that cover potential losses that

might be incurred by lenders if a country defaults on its

borrowings; for example, the U.S. may guarantee another

country’s sovereign bond issuance. The purpose of this tool

is to provide the Nation’s sovereign international part-

ners access to necessary, urgent, and relatively affordable

financing during temporary periods of strain when they

cannot access such financing in international financial

markets, and to support critical reforms that will enhance

long-term fiscal sustainability, often in concert with sup-

port from international financial institutions such as the

IMF. The goal of sovereign loan guarantees is to help lay

the economic groundwork for the Nation’s international

partners to graduate to an unenhanced bond issuance in

the international capital markets. For example, as part of

the U.S. response to fiscal crises, the U.S. Government has

extended sovereign loan guarantees to Jordan and Iraq to

enhance their access to capital markets while promoting

economic policy adjustment.

Development Programs

Credit is an important tool in U.S. bilateral assistance

to promote sustainable development. The DFC provides

loans, guarantees, and other investment tools such as

equity and political risk insurance to facilitate and in-

centivize private-sector investment in emerging markets

that will have positive developmental impact, and meet

national security objectives.

The Government-Sponsored Enterprises (GSEs)

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac

The Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie

Mae) created in 1938, and the Federal Home Loan

Mortgage Corporation (Fredie Mac) created in 1970, were

established to support the stability and liquidity of a sec-

ondary market for residential mortgage loans. Fannie

Mae’s and Freddie Mac’s public missions were later

broadened to promote affordable housing. The Federal

Home Loan Bank (FHLB) System, created in 1932, is

comprised of eleven individual banks with shared liabili-

ties. Together they lend money to financial institutions,

mainly banks and thrifts, that are involved in mortgage

7. CREDIT AND INSURANCE

65

financing to varying degrees, and they also finance some

mortgages using their own funds. The mission of the

FHLB System is broadly defined as promoting housing

finance, and the System also has specific requirements to

support affordable housing.

Together these three GSEs currently are involved, in

one form or another, with approximately half of residen-

tial mortgages outstanding in the U.S. today.

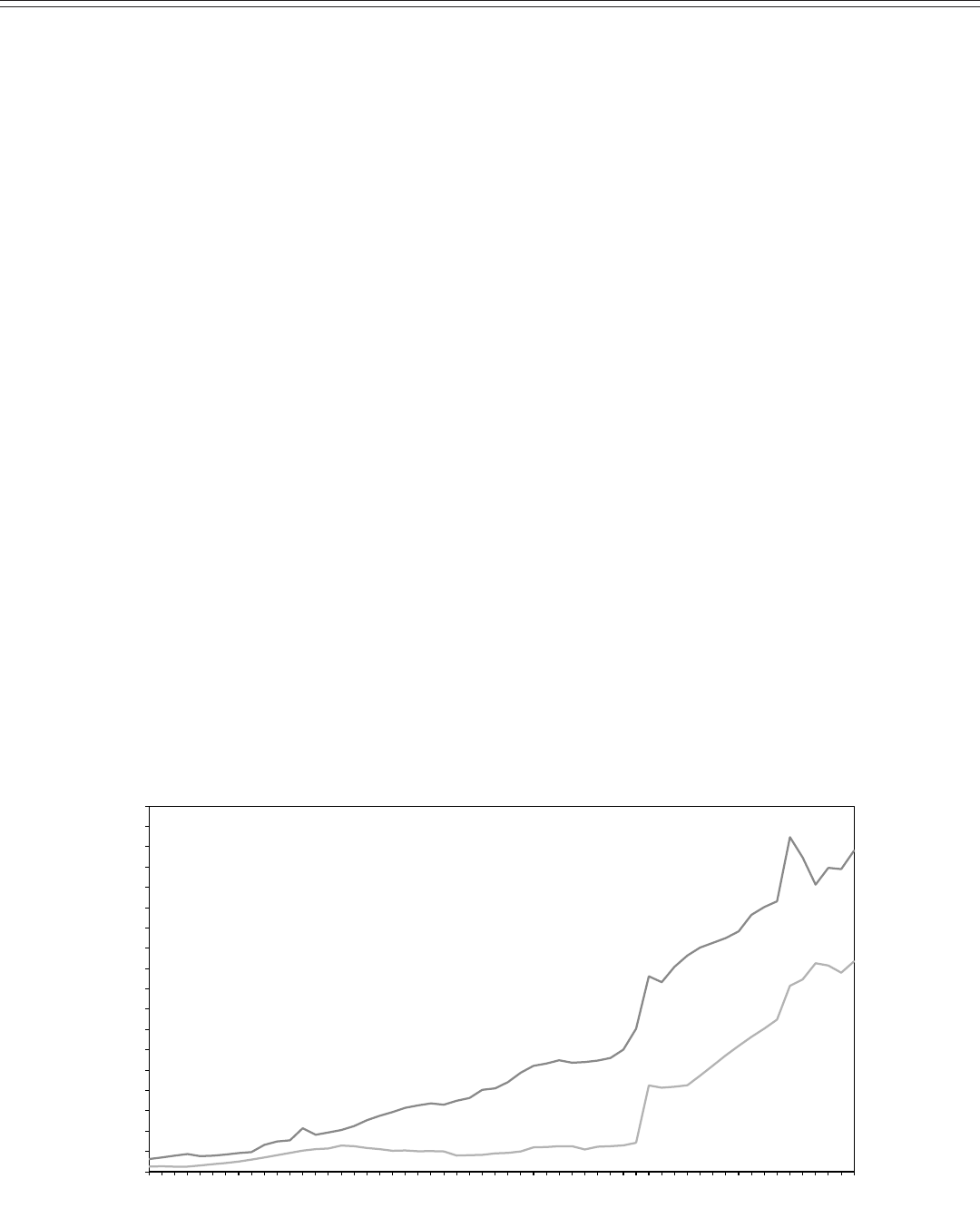

History of the Conservatorship of Fannie Mae

and Freddie Mac and Budgetary Effects

Growing stress and losses in the mortgage markets

in 2007 and 2008 seriously eroded the capital of Fannie

Mae and Freddie Mac. Legislation enacted in July 2008

strengthened regulation of the housing GSEs through the

creation of the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA),

a new independent regulator of housing GSEs, and pro-

vided the Treasury with authorities to purchase securities

from Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

On September 6, 2008, FHFA placed Fannie Mae and

Freddie Mac under Federal conservatorship. The next day,

the Treasury launched various programs to provide tem-

porary financial support to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac

under the temporary authority to purchase securities.

The Treasury entered into agreements with Fannie Mae

and Freddie Mac to make investments in senior preferred

stock in each GSE in order to ensure that each company

maintains a positive net worth. The cumulative funding

commitment through these Preferred Stock Purchase

Agreements (PSPAs) with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac

was set at $445.5 billion. In total, as of December 31,

2023, $191.5 billion has been invested in Fannie Mae

and Freddie Mac. The remaining commitment amount is

$254.1 billion.

The PSPAs also generally require that Fannie Mae

and Freddie Mac pay quarterly dividends to the Treasury,

though the terms governing the amount of those dividends

have changed several times pursuant to agreements be-

tween the Treasury and Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

Notably, changes announced on January 14, 2021, per-

mit the GSEs to suspend dividend payments until they

achieve minimum capital levels established by FHFA

through regulation. The Budget projects those levels will

not be reached during the Budget window and according-

ly reflects no dividends through 2034. Through December

31, 2023, the GSEs have paid a total of $301.0 billion in

dividend payments to the Treasury on the senior pre-

ferred stock.

The Temporary Payroll Tax Cut Continuation Act of

2011 (Public Law 112–78) amended the Housing and

Community Development Act of 1992 (Public Law 102-

550) by requiring that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac

increase their annual credit guarantee fees on single-

family mortgage acquisitions between 2012 and 2021 by

an average of at least 0.10 percentage points. This sun-

set was extended through 2032 by the IIJA. The Budget

estimates these fees, which are remitted directly to the

Treasury and are not included in the PSPA amounts,

will result in deficit reduction of $69.7 billion from 2025

through 2034.

In addition, effective January 1, 2015 FHFA directed

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to set aside 0.042 percent-

age points for each dollar of the unpaid principal balance

of new business purchases (including but not limited to

mortgages purchased for securitization) in each year to

fund several Federal affordable housing programs cre-

ated by the Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008

(Public Law 110-289), including the Housing Trust Fund

and the Capital Magnet Fund. The 2025 Budget projects

these assessments will generate $4.9 billion for the af-

fordable housing funds from 2025 through 2034.

Future of the Housing Finance System

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are in their fifteenth

year of conservatorship, and the Congress has not yet

enacted legislation to define the GSEs’ long-term role

in the housing finance system. The Administration is

committed to housing finance policy that increases the

supply of housing that is affordable for low- and moder-

ate-income households, expands fair and equitable access

to homeownership and affordable rental opportunities,

protects taxpayers, and promotes financial stability. The

Administration has a key role in shaping, and a key inter-

est in the outcome of, housing finance reform, and stands

ready to work with the Congress in support of these goals.

The Farm Credit System (Banks and Associations)

The Farm Credit System (FCS or System) is a GSE.

Its banks and associations constitute a nationwide net-

work of borrower-owned cooperative lending institutions

originally authorized by Congress in 1916. Their mission

is to provide sound and dependable credit to American

farmers, ranchers, producers or harvesters of aquatic

products, farm cooperatives, and farm-related businesses.

The institutions also serve rural America by providing

financing for rural residential real estate; rural commu-

nication, energy, and water/wastewater infrastructure;

and agricultural exports. In addition, maintaining special

policies and programs for the extension of credit to young,

beginning, and small (YBS) farmers and ranchers is a leg-

islative mandate for the System.

The financial condition of the System’s banks and as-

sociations remains fundamentally sound. The ratio of

capital to assets was 14.7 percent on September 30, 2023,

compared with 14.9 percent on September 30, 2022. An

increase in interest rates, which reduced the fair value of

existing fixed-rate investment securities, contributed to

the decline in the capital-to-assets ratio in 2023. Capital

that is available to absorb losses amounted to $72.3 bil-

lion, which is mainly composed of retained earnings

(high-quality capital). For the first nine months of calen-

dar year 2023, net income equaled $5.5 billion compared

with $5.4 billion for the same period the previous year.

Over the 12-month period ended September 30, 2023,

System assets grew 6.1 percent, primarily because of

higher cash and investment balances and increased

loan volume primarily in rural infrastructure, process-

ing and marketing, production and intermediate-term,

and real estate mortgage loans. During the same period,

nonperforming assets as a percentage of the dollar vol-

66

ANALYTICAL PERSPECTIVES

ume of loans and other property owned was 0.53 percent

on September 30, 2023, compared with 0.51 percent on

September 30, 2022.

The number of FCS institutions continues to decrease

because of intra-System consolidation. As of September

30, 2023, the System consisted of four banks and 59 as-

sociations, compared with five banks and 84 associations

in September 2011. Of the 67 FCS banks and associations

rated, 62 had a rating of 1 or 2 on a safety and sound-

ness scale of 1 to 5 (1 being most safe and sound) and

accounted for 99.1 percent of System assets. Five FCS in-

stitutions had a rating of 3.

Dollar volume outstanding increased for both total

System lending and YBS lending. Total System loan vol-

ume outstanding increased by 9.4 percent. Loan volume

outstanding to young farmers increased by 6.3 percent, to

beginning farmers by 9.6 percent, and to small farmers

by 5.3 percent. The growth rate of outstanding loans was

lower in 2022 than it was in both 2020 and 2021. While

the total number of loans outstanding for the System de-

creased by 0.6 percent, the number of outstanding loans

to young and beginning farmers increased modestly,

whereas the number of small farmer loans outstanding

contracted slightly.

The dollar volume of loans made in 2023 decreased

for the System as a whole and for the YBS categories.

The System’s total new loan dollar volume decreased

by 1.7 percent while new loan volume to young farmers

decreased by 12.5 percent, to beginning farmers by 17.9

percent, and to small farmers by 25.3 percent. The num-

ber of total System loans made during the year decreased

by 17.2 percent. The number of loans to young farmers

decreased by 17.1 percent, to beginning farmers by 18.9

percent, and to small farmers by 22.9 percent.

Several factors led to reduced System lending in 2023:

•

Rising interest rates and fewer refinanced loans

•

Changing economic conditions and less demand for

rural properties

•

End of the Paycheck Protection Program

The System has recorded strong earnings and capital

growth in 2023. The System also faces risks associated

with its portfolio concentration in agriculture and rural

America, the System, including labor shortages due to a

tight labor market, interest expenses and tightening farm

profit margins, and regional drought. After reaching re-

cord highs in 2022, farm income in 2024 is expected to

decline for the second consecutive year and near histori-

cal averages.

Federal Agricultural Mortgage

Corporation (Farmer Mac)

Farmer Mac was established in 1988 by the Agricultural

Credit Act of 1987 (Public Law 100-233) as a federally

chartered instrumentality of the United States and an

institution of the System to facilitate a secondary mar-

ket for farm real estate and rural housing loans. Farmer

Mac is not liable for any debt or obligation of the other

System institutions, and no other System institutions

are liable for any debt or obligation of Farmer Mac. The

Farm Credit System Reform Act of 1996 (Public Law

104-105) expanded Farmer Mac’s role from a guarantor

of securities backed by loan pools to a direct purchaser

of mortgages, enabling it to form pools to securitize. The

Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008 (Public Law

110-246) expanded Farmer Mac’s program authorities by

allowing it to purchase and guarantee securities backed

by rural utility loans made by cooperatives.

Farmer Mac continues to meet core capital and regu-

latory risk-based capital requirements. As of September

30, 2023, Farmer Mac’s total outstanding program volume

(loans purchased and guaranteed, standby loan purchase

commitments, and AgVantage bonds purchased and guar-

anteed) amounted to $27.7 billion, which represents an

increase of 9.2 percent from the level a year ago. Of total

program activity, on-balance-sheet loans and guaranteed

securities amounted to $23 billion, and off-balance-sheet

obligations amounted to $4.7 billion. Total assets were

$28.3 billion, with nonprogram investments (including

cash and cash equivalents) accounting for $5.7 billion

of those assets. Farmer Mac’s net income attributable to

common stockholders for the first three quarters of cal-

endar year 2023 was $132 million, compared with $114.4

million for the same period in 2022.

II. INSURANCE PROGRAMS

Deposit Insurance

Federal deposit insurance promotes stability in the U.S.

financial system. Prior to the establishment of Federal

deposit insurance, depository institution failures often

caused depositors to lose confidence in the banking system

and rush to withdraw deposits. Such sudden withdrawals

caused serious disruption to the economy. In 1933, in the

midst of the Great Depression, a system of Federal de-

posit insurance was established to protect depositors and

to prevent bank failures from causing widespread disrup-

tion in financial markets.

Today, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation

(FDIC) insures deposits in banks and savings associa-

tions (thrifts) using the resources available in its Deposit

Insurance Fund (DIF). The National Credit Union

Administration (NCUA) insures deposits (shares) in most

credit unions through the National Credit Union Share

Insurance Fund (SIF). (Some credit unions are privately

insured.) As of September 30, 2023, the FDIC insured

$10.6 trillion of deposits at 4,623 commercial banks and

thrifts, and as of September 30, 2023, the NCUA insured

nearly $1.7 trillion of shares at 4,645 Federal and feder-

ally insured State-chartered credit unions.

Since its creation, the Federal deposit insurance sys-

tem has undergone many reforms. As a result of the 2008

financial crisis, several reforms were enacted to protect

7. CREDIT AND INSURANCE

67

both the immediate and longer-term integrity of the

Federal deposit insurance system. The Helping Families

Save Their Homes Act of 2009 (division A of Public Law

111–22) provided NCUA with tools to protect the SIF and

the financial stability of the credit union system. Notably,

the Act established the Temporary Corporate Credit

Union Stabilization Fund, which has now been closed

with its assets and liabilities distributed into the SIF. In

addition, the Act:

•

Provided flexibility to the NCUA Board by permit-

ting use of a restoration plan to spread insurance

premium assessments over a period of up to eight

years, or longer in extraordinary circumstances, if

the SIF equity ratio falls below 1.2 percent; and

•

Permanently increased the Share Insurance Fund’s

borrowing authority to $6 billion.

The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer

Protection Act of 2010 (Dodd-Frank Act; Public Law 111-

203) established new DIF reserve ratio requirements. The

Act required the FDIC to achieve a minimum DIF reserve

ratio (ratio of the deposit insurance fund balance to total

estimated insured deposits) of 1.35 percent by 2020, up

from 1.15 percent in 2016. On September 30, 2018, the

DIF reserve ratio reached 1.36 percent. However, as of

June 30, 2020 the DIF reserve ratio fell to 1.30 percent,

below the statutory minimum of 1.35 percent. The decline

was a result of strong one-time growth in insured depos-

its. On September 15, 2020, FDIC adopted a Restoration

Plan to restore the DIF reserve ratio to at least 1.35 per-

cent by 2027.

In addition to raising the minimum reserve ratio, the

Dodd-Frank Act also:

•

eliminated the FDIC’s requirement to rebate premi-

ums when the DIF reserve ratio is between 1.35 and

1.5 percent;

•

gave the FDIC discretion to suspend or limit rebates

when the DIF reserve ratio is 1.5 percent or higher,

effectively removing the 1.5 percent cap on the DIF;

and

•

required the FDIC to offset the effect on small in-

sured depository institutions (defined as banks with

assets less than $10 billion) when setting assess-

ments to raise the reserve ratio from 1.15 to 1.35

percent. In implementing the Dodd-Frank Act, the

FDIC issued a final rule setting a long-term (i.e.,

beyond 2028) reserve ratio target of 2 percent, a

goal that FDIC considers necessary to maintain a

positive fund balance during economic crises while

permitting steady long-term assessment rates that

provide transparency and predictability to the bank-

ing sector.

The Dodd-Frank Act also permanently increased the

insured deposit level to $250,000 per account at banks or

credit unions insured by the FDIC or NCUA.

Recent Fund Performance

As of September 30, 2023, the FDIC DIF balance stood

at $119.3 billion on an accrual basis, a one-year decrease

of $6.2 billion. The decline in the DIF balance is primarily

a result of bank failures that occurred in early 2023. As a

result, the reserve ratio on September 30, 2023, declined

by 12 basis points from 1.25 percent one year prior to 1.13

percent.

As of September 30, 2023, the number of insured in-

stitutions on the FDIC’s “problem list” (institutions with

the highest risk ratings) totaled 44, which represented a

decrease of 95 percent from December 2010, the peak year

for bank failures during the 2008 financial crisis, but an

increase of two banks from the year prior. Moreover, the

assets held by problem institutions were 87 percent below

the level in December 2009, the peak year for assets held

by problem institutions.

The NCUA-administered SIF ended September 2023

with assets of $20.9 billion and an equity ratio of 1.27

percent. In December 2023, NCUA continued to maintain

the normal operating level of the SIF equity ratio at 1.33

percent of insured shares after, in December 2022, the

NCUA Board reduced the ratio from 1.38 to 1.33 percent.

If the equity ratio exceeds the normal operating level, a

distribution is normally paid to insured credit unions to

reduce the equity ratio.

The health of the credit union industry has markedly

improved since the 2008 financial crisis. As of September

30, 2023, NCUA reserved $214 million in the SIF to cov-

er potential losses, up 16 percent from the $185 million

reserved as of December 31, 2022. The ratio of insured

shares in troubled institutions to total insured shares has

remained stable from the end of 2022 through September

2023. The ratio increased slightly from 0.29 percent

in December 2022 to 0.33 percent in June 2023 before

declining to 0.28 percent in September 2023. This is a sig-

nificant reduction from a high of 5.7 percent in December

2009.

Budget Outlook

The Budget estimates DIF net outlays of -$162.3 bil-

lion over the current 10-year budget window (2025–2034).

This includes the repayment of $93.3 billion in principal

on FFB financing transactions executed in 2023 and 2024

(see below), as well as the current anticipated impact

of a special assessment to recover the DIF’s estimated

losses associated with uninsured depositors following the

closures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, af-

ter the Secretary of the Treasury announced on March

12, 2023, that uninsured depositors would be covered to

avoid systemic risk to the financial system. The final rule

implementing this special assessment was approved by

the FDIC Board of Directors on November 16, 2023. The

Budget projects that FDIC’s Restoration Plan will remain

in effect until 2027, when the DIF is estimated to reach the

statutory reserve ratio target of 1.35 percent. The Budget

also assumes that the DIF will reach the historic long-run

reserve ratio target of 1.5 percent over the 10-year budget

window. Although the FDIC has authority to borrow up

68

ANALYTICAL PERSPECTIVES

to $100 billion from the Treasury to maintain sufficient

DIF balances, the Budget does not anticipate FDIC uti-

lizing this direct borrowing authority. In 2023, the FDIC

engaged in a financing transaction with the FFB to pur-

chase a $50 billion note guaranteed by the FDIC in its

corporate capacity as deposit insurer and regulator. The

Budget reflects this as an exercise of borrowing authority

and reflects additional transactions totalling $43.3 billion

in January 2024.

Pension Guarantees

The Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC)

insures the pension benefits of workers and retirees in

covered defined-benefit pension plans. PBGC operates

two legally and financially separate insurance programs:

single-employer plans and multiemployer plans.

Single-Employer Insurance Program

When an underfunded single-employer plan termi-

nates, PBGC becomes the trustee and pays benefits, up to

a guaranteed level. This typically happens when the em-

ployer sponsoring an underfunded plan insured by PBGC

goes bankrupt, ceases operation, or can no longer afford

to keep the plan going. PBGC’s claims exposure is the

amount by which guaranteed benefits exceed assets in in-

sured plans. In the near term, the risk of loss stems from

financially distressed firms with underfunded plans. In

the longer term, loss exposure also results from the pos-

sibility that well-funded plans become underfunded due

to inadequate contributions, poor investment results, or

increased liabilities, and that the firms sponsoring those

plans become distressed.

PBGC monitors companies with large, underfunded

plans and acts to protect the interests of the pension in-

surance program’s stakeholders where possible. Under its

Early Warning Program, PBGC works with plan sponsors

to mitigate risks to pension plans posed by corporate trans-

actions or otherwise protect the insurance program from

avoidable losses. However, PBGC’s authority to manage

risks to the insurance program is limited. Most private

insurers can diversify or reinsure their catastrophic risks

as well as flexibly price these risks. Unlike private insur-

ers, Federal law does not allow PBGC to deny insurance

coverage to a defined-benefit plan or adjust premiums ac-

cording to risk. Both types of PBGC premiums, the flat

rate (a per person charge paid by all plans) and the vari-

able rate (paid by underfunded plans), are set in statute.

Claims against PBGC’s insurance programs are highly

variable. One large pension plan termination may result

in a larger claim against PBGC than the termination of

many smaller plans. The future financial health of the

PBGC will continue to depend largely on the potential ter-

mination of a limited number of very large plans. Finally,

PBGC’s financial condition is sensitive to market risk.

Interest rates and equity returns affect not only PBGC’s

own assets and liabilities, but also those of PBGC-insured

plans.

Single-employer plans generally provide benefits to the

employees of one employer. When an underfunded single-

employer plan terminates, PBGC becomes trustee of the

plan, applies legal limits on payouts, and pays benefits.

To determine the amount to pay each participant, PBGC

considers: a) the benefit that a participant had accrued

in the terminated plan; b) the availability of assets from

the terminated plan to cover benefits; c) how much PBGC

recovers from employers for plan underfunding; and d)

the legal maximum benefit level set in statute. The guar-

anteed benefit limits are indexed (i.e., they increase in

proportion to increases in a specified Social Security wage

index) and vary based on the participant’s age and elected

form of payment. For plans terminating in 2024, the max-

imum guaranteed annual benefit payable as a single life

annuity under the single-employer program is $85,295 for

a retiree at age 65.

Multiemployer Insurance Program

Multiemployer plans are collectively bargained pension

plans maintained by one or more labor unions and more

than one unrelated employer, usually within the same or

related industries. PBGC does not trustee multiemployer

plans. In the Multiemployer Program, the event trigger-

ing PBGC’s guarantee is plan insolvency (the inability to

pay guaranteed benefits when due), whether or not the

plan has terminated. PBGC provides insolvent multiem-

ployer plans with financial assistance in the statutorily

required form of loans sufficient to pay PBGC guaranteed

benefits and reasonable administrative expenses. Since

multiemployer plans generally do not receive PBGC as-

sistance until their assets are fully depleted, financial

assistance is almost never repaid unless the plan receives

special financial assistance under the American Rescue

Plan Act of 2021 (ARPA; Public Law 117-2).

Benefits guaranteed under the multiemployer program

are calculated based on: a) the benefit a participant would

have received under the insolvent plan, subject to; b) the

multiemployer guarantee limit set in statute. The guar-

antee limit depends on the participant’s years of service

and the level of the benefit accruals. For example, for a

participant with 30 years of service, PBGC guarantees

100 percent of the pension benefit up to a yearly amount

of $3,960. If the pension exceeds that amount, PBGC

guarantees 75 percent of the rest of the pension benefit

up to a total maximum guarantee of $12,870 per year for

a participant with 30 years of service. This limit has been

in place since 2001 and is not adjusted for inflation or

cost-of-living increases.

PBGC’s FY 2022 Projections Report shows the

Multiemployer Program is likely to remain solvent over

the 40-year projection period. Prior to the enactment

of the ARPA, PBGC’s Multiemployer Program was pro-

jected to become insolvent in 2026. ARPA amended the

Employee Retirement and Income Security Act of 1974

(Public Law 93-406) and established a new Special

Financial Assistance program that provides funding from

the Treasury’s General Fund for lump-sum payments to

eligible multiemployer plans. This program allows PBGC

to provide funding assistance to eligible plans so they can

pay projected benefits at the plan level through 2051. By

providing special financial assistance to the most finan-

cially troubled multiemployer plans, ARPA significantly

7. CREDIT AND INSURANCE

69

extends the solvency of PBGC’s Multiemployer Program.

ARPA also assists plans by providing funds to reinstate

previously suspended benefits.

Disaster Insurance

Flood Insurance

The Federal Government provides flood insurance

through the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP),

which is administered by the Department of Homeland

Security’s Federal Emergency Management Agency

(FEMA). Flood insurance is available to homeowners,

renters, businesses, and State and local governments in

communities that have adopted and enforce minimum

floodplain management measures. Coverage is limited to

buildings and their contents. As of November 30, 2023,

the program had 4.7 million policies worth $1.3 trillion in

force in over 22,600 communities.

2

The Congress established the NFIP in 1968 via the

National Flood Insurance Act of 1968 (Title XIII of Public

Law 90-448) to make flood insurance coverage widely

available, to combine a program of insurance with flood

mitigation measures to reduce the Nation’s risk of loss

from floods, protect the natural and beneficial functions

of the floodway,

3

and to reduce Federal disaster-assis-

tance expenditures on flood losses. The NFIP requires

participating communities to adopt certain land use or-

dinances consistent with FEMA’s floodplain management

regulations and to take other mitigation efforts to reduce

flood-related losses in high flood hazard areas (“Special

Flood Hazard Areas”) identified through partnership with

FEMA, States, and local communities. These efforts have

resulted in substantial reductions in the risk of flood-re-

lated losses nationwide. Legislation enacted in 2012 and

2014 established a Reserve Fund that is available to meet

the expected future obligations of the flood insurance pro-

gram and invest available resources. The Reserve Fund

is funded by an assessment and fixed annual surcharge.

Legislation also introduced a phase-in to higher full-risk

premiums for structures newly mapped into the Special

Flood Hazard Area until full-risk rates are achieved,

capped annual premium increases at 18 percent for most

structures, and created the Office of the Flood Insurance

Advocate.

As of April 1, 2023, FEMA has fully implemented

NFIP’s new pricing approach, Risk Rating 2.0, The ap-

proach leverages industry best practices and cutting-edge

technology to enable FEMA to deliver rates that are ac-

tuarially sound, equitable, and better reflect a property’s

flood risk. Since the 1970s, rates had been predominantly

based on relatively static measurements, emphasizing a

property’s elevation within a zone on the Flood Insurance

2

Community - anyStateor area or political subdivision thereof, or

any Indian Tribe or authorized tribal organization, or Alaska Native

village or authorized native organization, which has authority to adopt

and enforceflood plain management regulationsfor the areas within

its jurisdiction.

3

A regulatory floodway is the channel of a river or other water-

course and the adjacent land areas that must be reserved in order to

discharge the base flood without cumulatively increasing the water

surface elevation more than a desig-nated height

Rate Map (FIRM). The 1970s legacy methodology did not

incorporate as many flooding variables as today’s pricing

approach. FEMA is building on years of investment in

flood hazard information by incorporating private sector

data sets, catastrophe models, and evolving actuarial sci-

ence. In addition, the 1970s legacy rating methodology did

not account for the cost of rebuilding a home. Policyholders

with lower-valued homes may have been paying more

than their share of the risk while higher -valued homes

may have been paying less than their share of the risk.

Today’s NFIP pricing approach enables FEMA to set rates

that are fairer and ensures up-to-date actuarial principles

based upon new technology, including modeling. With the

implementation of the NFIP’s pricing approach, FEMA is

now able to equitably distribute premiums across all poli-

cyholders based on home value and a property’s flood risk.

FEMA’s Community Rating System offers discounts on

policy premiums in communities that adopt and enforce

more stringent floodplain land use ordinances than those

identified in FEMA’s regulations and/or engage in miti-

gation activities beyond those required by the NFIP. The

discounts provide an incentive for communities to imple-

ment new flood protection activities that can help save

lives and property when a flood occurs. Further, NFIP of-

fers flood mitigation assistance grants for planning and

carrying out activities to reduce the risk of flood damage

to structures covered by NFIP, which may include demoli-

tion or relocation of a structure, elevation or flood-proofing

a structure, and community-wide mitigation efforts that

will reduce future flood claims for the NFIP. In particular,

flood mitigation assistance grants targeted toward repeti-

tive and severe repetitive loss properties not only help

owners of high-risk property, but also reduce the dispro-

portionate drain these properties cause on the National

Flood Insurance Fund (NFIF). The IIJA provided signifi-

cant additional resources of $3.5 billion over five years for

the flood mitigation assistance grants. The flood grants

are a Justice40 covered program.

Due to the catastrophic nature of flooding, with

Hurricanes Harvey, Katrina, and Sandy as notable ex-

amples, insured flood damages can far exceed premium

revenue and deplete the program’s reserves. On those

occasions, the NFIP exercises its borrowing authority

through the Treasury to meet flood insurance claim ob-

ligations. While the program needed appropriations in

the early 1980s to repay the funds borrowed during the

1970s, it was able to repay all borrowed funds with inter-

est using only premium dollars between 1986 and 2004.

In 2005, however, Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, and Wilma

generated more flood insurance claims than the cumula-

tive number of claims paid from 1968 to 2004. Hurricane

Sandy in 2012 generated $8.8 billion in flood insurance

claims. As a result, in 2013 the Congress increased the

borrowing authority for the fund to $30.425 billion. After

the estimated $2.4 billion and $670 million in flood in-

surance claims generated by the Louisiana flooding of

August 2016, and Hurricane Matthew in October 2016,

respectively, the NFIP used its borrowing authority

again, bringing the total outstanding debt to the Treasury

to $24.6 billion.

70

ANALYTICAL PERSPECTIVES

In the fall 2017, Hurricanes Harvey and Irma struck

the southern coast of the United States, resulting in

catastrophic flood damage across Texas, Louisiana, and

Florida. To pay claims, NFIP exhausted all borrowing

authority. The Congress provided $16 billion in debt can-

cellation to the NFIP, bringing its debt to $20.525 billion.

To pay Hurricane Harvey flood claims, NFIP also received

more than $1 billion in reinsurance payments as a result of

transferring risk to the private reinsurance market at the

beginning of 2017. FEMA continues to mature its reinsur-

ance program and transfer additional risk to the private

market. In September 2022 Hurricane Ian hit the south-

ern coast of Florida. Based on FEMA’s NFIP claims data

as of January 31, 2024, FEMA estimates that Hurricane

Ian could potentially result in flood claims losses between

$4.9–$5.2 billion, including loss adjustment expenses.

Budget projections rely on both NFIF and Reserve

Fund balances to make up for annual deficits between

collections from policyholders and NFIF expenses, until

2027-2032 when NFIF would utilize borrowing author-

ity for any shortfalls. FEMA has submitted 17 legislative

proposals to reform the NFIP, achieve long-term reautho-

rization, and better protect policyholders. These proposals

include eliminating the debt, reducing borrowing author-

ity, and collecting congressional equalization payments.

The 2022-2026 FEMA Strategic Plan creates a shared

vision for the NFIP and other FEMA programs to build a

more prepared and resilient Nation. The Strategic Plan

outlines a bold vision and three ambitious goals designed

to address key challenges the agency faces during a pivot-

al moment in the field of emergency management: Instill

Equity as a Foundation of Emergency Management, Lead

Whole of Community in Climate Resilience, and Promote

and Sustain a Ready FEMA and Prepared Nation. While

the NFIP supports all three goals, it is central to lead-

ing whole of community in climate resilience. To that end,

FEMA is pursuing initiatives including:

•

providing products that clearly and accurately com-

municate flood risk;

•

helping individuals, businesses, and communities

understand their risks and the available options like

the NFIP to best manage those risks;

•

transforming the NFIP into a simpler, customer-

focused program that policyholders value and trust;

and

•

increasing the number of properties covered by flood

insurance (either through the NFIP or private insur-

ance).

Crop Insurance

Subsidized Federal crop insurance, administered by

USDA’s Risk Management Agency (RMA) on behalf of the

Federal Crop Insurance Corporation (FCIC), assists farm-

ers in managing yield and revenue shortfalls due to bad

weather or other natural disasters. The program is a co-

operative partnership between the Federal Government

and the private insurance industry. Private insurance

companies sell and service crop insurance policies. The

Federal Government, in turn, pays private companies an

administrative and operating expense subsidy to cover

expenses associated with selling and servicing these poli-

cies. The Federal Government also provides reinsurance

through the Standard Reinsurance Agreement and pays

companies an “underwriting gain” if they have a profitable

year. For the 2025 Budget, the combined payments to the

companies are projected to be $4.51 billion. The Federal

Government also subsidizes premiums for farmers as a

way to encourage farmers to participate in the program.

The most basic type of crop insurance is catastrophic

coverage (CAT), which compensates the farmer for losses

in excess of 50 percent of the individual’s average yield

at 55 percent of the expected market price. The CAT

premium is entirely subsidized, and farmers pay only

an administrative fee. Higher levels of coverage, called

“buy-up,” are also available. A portion of the premium for

buy-up coverage is paid by FCIC on behalf of producers

and varies by coverage level – generally, the higher the

coverage level, the lower the percent of premium subsi-

dized. The remaining (unsubsidized) premium amount

is owed by the producer and represents an out-of-pocket

expense.

For 2023, the four principal crops (corn, soybeans,

wheat, and cotton) accounted for over 74 percent of total

crop liability, and approximately 89 percent of the total

U.S. planted acres of the 10 principal row crops (also

including barley, peanuts, potatoes, rice, sorghum, and

tobacco) were covered by crop insurance. Producers can

purchase both yield- and revenue-based insurance prod-

ucts, which are underwritten on the basis of a producer’s

actual production history (APH). Revenue insurance

programs protect against loss of revenue resulting from

low prices, low yields, or a combination of both. Revenue

insurance has enhanced traditional yield insurance by

adding price as an insurable component.

In addition to price and revenue insurance, FCIC has

made available other plans of insurance to provide protec-

tion for a variety of crops grown across the United States.

For example, “area plans” of insurance offer protection

based on a geographic area (most commonly a county),

and do not directly insure an individual farm. Often, the

loss trigger is based on an index, such as one on rainfall,

which is established by a Government entity (for example,

the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration).

One such plan is the pilot Rainfall Index plan, which

insures against a decline in an index value covering

Pasture, Rangeland, and Forage. These pilot programs

meet the needs of livestock producers who purchase in-