JUNE 2022

RECENT MIGRATION

TRENDS IN THE

AMERICAS

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reect the views of the International

Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the publication do

not imply expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city

or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries.

IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benets migrants and society. As an intergovernmental

organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of

migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and

uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants.

_____________________________

Publisher: International Organization for Migration (IOM)

Regional Oce for South America

Buenos Aires, Argentina

Tel: +(54) 11 4813 3330

Email: robuepr[email protected]

Website: www.robuenosaires.iom.int

International Organization for Migration (IOM)

Regional Oce for Central America, North America and the Caribbean

San José, Costa Rica

Tel: +(506) 2212 5300

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.rosanjose.iom.int

___________________________

This publication was issued without formal editing by IOM.

This publication was issued without IOM Publications Unit (PUB) approval.

Programme coordinators: Susanne Melde, Raúl Soto

Research team: Ignacio Bustinza, Sofía Arce, Andrea Ortiz, Mark McCarthy and inputs form country oces in the

Americas and from the Oce of the Director General’s Special Envoy (OSE).

Cover photo: Puerto Limón, Panama Migrants from all over the world dreaming of US arrive extenuated in Puerto Limón

after braving dangerous Darien Gap. © IOM March 2022 / Gema CORTES.

© IOM 2022

Required citation: International Organization for Migration (IOM), 2022. Recent Migration Trends in the Americas. IOM,

Buenos Aires and San José.

The maps used in this publication are for illustration purposes only. The boundaries and names shown and the designations

used on this map do not imply ocial endorsement or acceptance by the International Organization for Migration.

Some rights reserved. This work is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0

IGO License (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 IGO).*

For further specications please see the Copyright and Terms of Use.

This publication should not be used, published or redistributed for purposes primarily intended for or directed towards commercial

advantage or monetary compensation, with the exception of educational purposes, e.g. to be included in textbooks.

Permissions: Requests for commercial use or further rights and licensing should be submitted to [email protected]

* https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/igo/legalcode

RECENT MIGRATION

TRENDS IN THE

AMERICAS

JUNE 2022

iv

RECENT MIGRATION TRENDS IN THE AMERICAS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This report seeks to inform the discussions at the Summit of the

Americas in June 2022 by providing background on migration on the

continent and in particular recent dynamics pending data availability.

The Global Compact of Migration recognized in the objective 1 the

need to collect and utilize accurate and disaggregated data as a basis

for evidence-based policies and interventions which guarantee that

migration takes in a safe, orderly and regular manner. Data are the

foundation for designing evidence-based public policies, informing

public discourse, monitoring and evaluating implementation of

commitments over time and developing concrete actions which

maximize the benets of migration.

As of mid-2020, several countries in the Americas hosted

important numbers of immigrants, in particular in Northern

America, with the highest number of international migrants

worldwide residing in the United States, as well as South

America. Various countries on the continent have experienced

signicant emigration, notably in Central American and the

Caribbean. Intra-regional migration is high in South America,

demonstrating that the region also accounts for a considerable

number of emigrants that have moved to other countries or

outside the region (UN DESA, 2020). At the same time, the

United States – Mexico border is the deadliest land border

worldwide (IOM MMP, 2021), underlining the need to ensure

that migration takes place in a safe, orderly and regular manner.

Both immigrants and emigrants played and continue to play

an important role in the response to and recovery from

the COVID-19 pandemic and make contributions to human

development more generally in societies in destination countries

and origin communities, despite often having been the most

aected by the public health emergency

In terms of vulnerability, as of early May 2022, more than 5

million Venezuelan refugees and migrants were hosted by other

countries on the continent, mostly in South America (R4V,

2022). According to indications from IOM´s Displacement

Tracking Matrix (DTM)

1

data in Chile, the main transit route

from the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela (hereafter Venezuela)

to Chile is via the Andean corridor. However, routes on the

continent continue to be dynamic.

Drivers of migration, such as poverty, inequality, slow economic

growth, lack of decent jobs, labour market needs in destination

countries, political instability, the impact of the COVID-19

pandemic, natural disasters, environmental degradation,

climate change, violence, human rights violations, insecurity,

and family ties continue to push migrants to move elsewhere

on the continent or immigrate to the Americas from other

regions. Due to border closures, visa requirements and lack

of documentation, public health requirements and a general

lack of regular pathways for some nationalities, many migrants

from within the continent and others, traverse borders on

the continent irregularly. Crossings across the Darien gap

between Colombia and Panama spiked in 2021 to an all-time

high (nearly 134,000) compared to the past decade (nearly

118,000), predominantly by Haitians and Cubans and children

of Haitians (SNM, 2022a). In 2022 irregular entries into Panama

via this dangerous jungle stretch continue, but with Venezuelan

refugees and migrants representing the majority who then tend

to transit via Central America to the North. Other current

routes include migrants from the Caribbean directly moving via

Central American countries such as Nicaragua and Honduras.

Such journeys pose high protection risks and increase migrants’

vulnerability. These transit movements pose challenges for

migration governance that can only be addressed in a holistic,

gender-responsive regional approach, ensuring the protection of

the rights of migrants and in particular of the most vulnerable,

including children and LGBTIQ+ persons. In response to

movements of Venezuelans in particular, many countries in Latin

America have created regularization programmes and are using

existing regional agreements or exceptional visa categories. The

latter also applies to migrants from countries such as Haiti,

Cuba and Ukraine.

1

The Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM) is a modular system that IOM uses to capture, process and disseminate information on human mobility, routes and places of displacement,

the degree of vulnerability and the main needs of protection of these populations.

Ecuadorians returning to their country due to the crisis in Ukraine | @ IOM Ramiro AGUILAR, Ecuador, 2022

RECENT MIGRATION TRENDS IN THE AMERICAS

BACK TO CONTENTS

v

CONTENTS

Introduction 1

1. General overview 1

Migrant deaths and disappearances 3

2. Recent key trends in the region 3

Venezuelan refugees and migrants 4

Data available by country of destination / transit 5

Brazil 5

Chile 6

Peru 7

Ecuador 8

Colombia 8

Crossing via the Darién Gap: Colombia – Panama Border 9

Risks and vulnerabilities during the journey via the Darién Gap 10

Paso Canoas Border, Panama-Costa Rica 11

Costa Rica-Nicaragua 11

Nicaragua-Honduras 11

Tapachula, Mexico 12

Mexico 13

Returns 14

Haiti – forced returns statistics 14

Returns to countries of northern Central America 15

United States Southwest Land Border Encounters 15

3. Regular Pathways 16

Visas and permits granted in South America 16

Visas and permits granted in the United States, Mexico and the Caribbean 18

Permanent Resident Cards (Green cards) 18

Temporary Protected Status (TPS) 18

Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) 19

Migrant Workers in the United States and Canada 19

H2A Temporary Agricultural Program in the United States 19

H2B Temporary Non-agricultural Program in the United States 20

Regional Visitor Card (TVR) in Mexico 20

CARICOM and OECS 20

4. Migrants’ contribution to sustainable development 21

COVID-19 pandemic 21

Remittances 21

Diasporas 22

5. Climate and environmental change as a driver of human mobility 24

Bibliography 25

RECENT MIGRATION TRENDS IN THE AMERICAS

BACK TO CONTENTS

1

INTRODUCTION

Migration in the region takes place in a context marked by deep

historical, political, economic and social ties between countries,

signicant internal and intraregional socioeconomic disparities,

political instability, insecurity, and violence in some countries,

as well as severe and frequent natural hazards compounded by

slow-onset environmental changes. The COVID-19 pandemic,

the restrictions on international and domestic mobility, socio-

economic consequences and health risks have led to changes in

human mobility patterns, accelerating existing ones and raising

new challenges for migration governance in the Americas.

Governments and authorities have implemented primarily route

restrictions which limit the entry of travelers arriving from,

transiting through or having been to specied countries or other

territories. Visa requirements modied by governments also

aected international mobility in the Americas (IOM; MPI, 2022a).

At the same time, migrants have been key parts of the response to

the COVID-19 pandemic and make important contributions during

the recovery as well as to human development more generally.

Inequality, political crises, insecurity, and instability in the region

and globally as well as natural disasters continue to impact

countries on the continent, representing important push

factors. Recent increases in ination in Latin America and the

Caribbean in 2021 not seen since the global nancial crisis in

2008 (ECLAC, 2022a) 2 and food insecurity (Idem; FAO, 2022)

continue to add to existing drivers of mobility and are expected

to rise further in the next months. Over the past 2.5 years, the

migration of Venezuelan nationals to South American countries,

albeit at a slower pace than in previous years, continued: as of

April 2020, around 4.3 million Venezuelan refugees and migrants

were recorded in Latin America, according to data from the

Interagency Coordination Platform for Refugees and Migrants

from Venezuela (R4V), while by April 2022 there were more

than 5 million, representing an increase of almost 20 per cent

within two years. The actual gure may well be higher (R4V,

2022). Changes in mobility in the region include the return of

Venezuelans to their country of origin, where, as of December

2021, almost 28,000 Venezuelans had returned according to

ocial gures (Ministry of Popular Power for Foreign Aairs

of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, 2021). In the case of

these returns, it is not known how many returnees plan to stay

or are leaving again.

On the other hand, it is worth mentioning the sharp increase

in irregular crossings by Caribbean, South American and

extra-continental migrants via the Colombia-Panama border

through the Darién gap with the intention of reaching North

America, reaching record levels in 2021, representing serious

risks and threats to their physical integrity and human rights

(SNM, 2022a).

This report aims to provide an overview of migration and

mobility trends in the Americas as of May 2022, highlighting key

overall dynamics and spotlighting more recent ones, to inform

discussions at the Ninth Summit of the Americas in June 2022. It

does not claim to be comprehensive but hopes to provide existing

and updated data and information to support policy discussions.

The rst section provides a general overview based on

internationally comparable estimates available, for mid-

2020. Section two focuses on more recent trends including

of Venezuelan refugees and migrants, Haitians, Cubans and

migrants from within and other continents moving. Section three

presents data on regular migration pathways such as residency

permits, and other specic visa categories/programmes and

recent protection programmes for Ukrainian nationals. The

fourth section highlights the contribution of migrants to human

development. The last section details available information

on natural disasters and other data on human mobility in the

context of environmental degradation and climate change.

Where available, the report presents data disaggregated by sex

and age to foster gender- responsive migration governance,

taking the best interests of the child into consideration.

1. GENERAL OVERVIEW

Based on international and latest comparable data available from

the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Aairs

(UN DESA), as of mid-2020, one out of four (26 per cent) of

all international migrants worldwide resided on the American

continent, amounting to a total 73.5 million. The main destination

region is North America, led by far by the United States which

hosts the largest number of international migrants worldwide

(almost 51 million) and Canada (8 million), followed by South

America (Argentina with 2.3 million, Colombia 1.9 million, among

others, see table 1). Intraregional migration is particularly high

in South America, where almost four out of ve migrants are

estimated to reside in another country in the American sub-

region (79%) (UN DESA, 2020). Furthermore, migrants have

moved on to other countries on the continent, a tendency

further detailed in the next section.

The international migrant population on the continent

represented 7.2 per cent of the total population in mid- 2020,

which is double the world average (Idem), indicating the

importance of immigration in the region. Female international

migrants represented 51.3 per cent of all international migrant

population in the continent, which is higher than the global

average of 48.1 (Idem), indicating that slightly more women

than men migrated to or within the continent. By mid-2020

an estimated 47.2 million emigrants from the Americas resided

elsewhere, including in other countries on the continent.

Emigration is particularly high from some countries in Central

America and the Caribbean (Idem, see table 1).

2

Excluding Argentina, the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela (Venezuela hereafter), Haiti and Suriname as their ination rates have been much higher consistently and would thus aect

representativeness for the regional dynamics.

2

RECENT MIGRATION TRENDS IN THE AMERICAS

BACK TO CONTENTS

2

For purposes of comparability, this table shows data from the UN DESA international migrant stock that may dier from other sources.

Source: UN DESA, 2020.

SUB-

REGION

TOTAL NUMBER

OF IMMIGRANTS

MAIN COUNTRIES

OF ORIGIN

TOP 5 COUNTRIES WITH

HIGHEST IMMIGRANT

POPULATION

TOP 5 COUNTRIES

OF EMIGRATION

South America 10,887,474

Venezuela:

Colombia:

Paraguay:

Bolivia :

Peru:

4,103,204

1,329,616

749,084

635,043

534,230

Argentina:

Colombia:

Chile:

Venezuela:

Peru:

2,281,728

1,900,000

1,645,015

1,300,000

1,200,000

Venezuela:

Colombia:

Brasil:

Peru:

Ecuador:

5,400,000

3,000,000

1,900,000

1,500,000

1,000,000

Central America 2,302,001

United States:

Nicaragua:

Venezuela:

Colombia:

Guatemala:

861,487

395,784

218,960

99,665

93,792

Costa Rica:

Panama:

Guatemala:

Belize:

El Salvador:

520,729

313,165

84,311

62,043

42,767

El Salvador:

Guatemala:

Honduras:

Nicaragua:

Costa Rica:

1,599,058

1,368,431

985,077

718,154

150,241

Caribbean 1,605,148

Haiti:

United States:

France:

Venezuela:

Dominican

Republic:

567,956

230,255

108,253

95,834

77,714

Dominican

Republic:

Trinidad

and Tobago:

Bahamas:

Barbados:

Antigua and

Barbuda:

603,794

78,849

65,583

34,869

29,386

Haiti:

Cuba:

Dominican

Republic:

Jamaica:

Guyana:

1,769,671

1,757,300

1,608,567

1,118,931

438,413

North America 58,708,795

Mexico:

India:

China:

Philippines:

Viet Nam:

10,939,885

3,444,419

2,883,364

2,696,634

1,585,458

United States:

Canada:

Mexico:

50,632,836

8,049,323

1,197,624

Mexico:

United States:

Canada:

11,185,737

2,996,223

1,292,329

TABLE 1: TOTAL NUMBER OF MIGRANTS AND MAIN COUNTRIES OF ORIGIN BY SUB-REGION AT MID-2020

3

GRAPH 1: COUNTRIES WITH THE LARGEST INTERNATIONAL

MIGRANT POPULATION IN THE AMERICAS BY MID-2020 (IN MILLIONS)

Source: UN DESA, 2020.

United States

Of America

50.6

8

1.9

1.6

2.3

Canada Argentina Colombia Chile

RECENT MIGRATION TRENDS IN THE AMERICAS

BACK TO CONTENTS

3

4

Data collection on migrant fatalities face specic limitations, as the majority of deaths are of migrants travelling by irregular means, bodies are not always found quickly and deaths may

not be systematically reported to authorities. Also, when deaths occur at sea or in other bodies of water, many of the deceased may not be recovered. Few ocial sources collect and

publish data on migrant deaths. Often incidents come to light through media sources, which may have incomplete and infrequent coverage. Furthermore, data on missing migrants tend

to over-represent parts of the world where there is better media coverage and ocial reporting of deaths (IOM Missing Migrants, 2022).

Source: IOM Missing Migrants Project, 2022.

TABLE 2: AVAILABLE DATA DISAGGREGATED BY SEX ON MISSING AND DECEASED MIGRANTS REGISTERED BY THE IOM MISSING

MIGRANTS PROJECT IN 2021 AND JANUARY-MARCH 2022, BY SUB-REGION

SUB-REGION IN THE

AMERICAS

TOTAL NUMBER OF

DEAD AND MISSING

MIGRANTS

WOMEN MEN CHILDREN (UNDER 18)

Caribbean 296 32% 68% 5%

South America 183 28% 72% 5%

Central America 402 19% 81% 7%

Northern America 646 22% 78% 2%

Total for the Americas 1527 22% 78% 5%

MIGRANT DEATHS AND DISAPPEARANCES

Migration journeys are not always safe and, in many cases,

lead to the loss of life. IOM´s Missing Migrant Project (MMP)

recorded 1,248 deaths in 2021 in the Americas, a 57 per cent

increase compared to the 796 deaths and missing migrants

registered in 2020. During the rst four months of 2022, 279

deaths and missing migrants were reported in the Americas,

while for the same period of 2021 there were 356 (Missing

Migrants Project (MMP), 2022). In the rst Quarter of 2022,

seven deaths were registered at the border point of Colchane

(Chile-Bolivia), including three Venezuelans (R4V, 2022).

Several incidents also aected Haitian migrants travelling by

boat in the Caribbean Sea, with the most notable accident

causing eleven deaths near the Puerto Rican coast in May

2022. The true scale of migrant deaths and disappearances

remains dicult to estimate given signicant time taken in

reporting andunder-reporting. In general, most deaths and

missing migrants were reported for North America, which

is also due to data coverage issues. The border between the

United States and Mexico, 3,145 kilometers long, covers a

variety of landscapes from urban areas to deadly deserts and

rivers with strong currents. Nearly 3,000 people lost their

lives during migration between 2014-2020, the largest number

recorded by IOM´s MMP on any land border worldwide and

thus making it the most dangerous according to the data

(IOM, MMP, 2021).

Although much of the data on deaths and those missing are

not disaggregated by sex yet, available data covering 60 per

cent of the reported cases for 2021 and 2022 in the Americas

show that 22 per cent were women and 78 per cent men. 5

per cent of the victims registered were children under the

age of 18. Making migration safe needs to be a priority in

the region, taking into account that the data points to higher

recorded deaths and missing persons among men and protect

in particular also children. It is worth noticing that as a result

of the National Search Commission (CNB) eorts, alongside

the families of missing migrants and the civil organizations that

accompany them, a Search Taskforce for Missing Migrants

was created in the scope of the National Search System for

Persons (SNBP) last November 2021 in Mexico.

2. RECENT KEY TRENDS IN THE REGION

As the latest comparable estimates for the continent date

two years back (to mid-2020), this section highlights more

recent data where possible. Given the magnitude, information

on Venezuelans refugees and migrants is presented, together

with data on Haitians, Cubans and migrants from other

regions if available and by destination/transit country, ordered

geographically from south to north. Those migrants tend to

be particularly vulnerable due to a lack of access to regular

pathways, sanitary health requirements that impact mobility,

lack of access to necessary documentation and information.

BACK TO CONTENTS

COUNTRIES WITH THE MAJORITY OF PERMITS GRANTED AS OF MAY 2022

Brazil

214,300

Colombia

730,000

Mexico

43,000

Panama

79,700

Chile

636,400

Peru

362,800

Ecuador

202,500

Argentina

324,700

Fuente: R4V, 2022.

* Note: May cover, in some countries, residence permits not currently in force, but also duplication or triplication of cases (a person with more than one permit granted). It does not cover

tourist stay permits.

VENEZUELAN REFUGEES AND MIGRANTS

MAP 1: VENEZUELAN REFUGEES AND MIGRANTS IN LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN (MAY 2022)*

of Venezuelan refugees

and migrants live in Latin

American and Caribbean

countries.

Approx. Venezuelan refugees

and migrants in Latin

America and Caribbean

Total approx. Venezuelan

refugees and migrants

in the world including the

United States and Canada

of all Venezuelan refugees

and migrants worldwide

live in Colombia, Peru and

Ecuador.

Venezuelan refugees and

migrants live in North

American, Central American,

and Caribbean countries:

Out of these 50 percent live

in United States, 14 percent

in Panama, and 13 percent in

the Dominican Republic.

residence permits and regular

stays have been granted, 90

per cent of these permits

have been issued in Latin

American and Caribbean

countries (R4V, 2022). *

82%82%

5.08M5.08M

6.13M6.13M

60%60%

Around Around

924,416 924,416

As of April 2022As of April 2022

2,708,9942,708,994

4

RECENT MIGRATION TRENDS IN THE AMERICAS

ARGENTINA

CHILE

URUGUAY

PARAGUAY

BOLIVIA

SURINAME

GUYANA

COLOMBIA

ECUADOR

PANAMA

COSTA

RICA

NICARAGUA

HONDURAS

EL SALVADOR

GUATEMALA

BELIZE

MEXICO

CUBA

PUERTO

RICO

DOMINICAN

REPUBLIC

HAITI

JAMAICA

ARUBA

CURAZAO

TRINIDAD

& TOBAGO

PERU

VENEZUELA

UNITED STATES

FRENCH

GUYANA

BRAZIL

The boundaries and names shown and the designations used in this map do not imply official endorsement or

acceptance by the United Nations. Creation date: May 2022, more information available in: http://R4V.info

Mexico

Costa Rica

Panama

Colombia

Peru

Brazil

Guyana

Trinidad and Tobago

Aruba

Curacao

Dominican Republic

Argentina

Uruguay

Bolivia

Central America & Mexico

The Southern Cone

The Caribbean

Other Countries

1.05 M

Chile

Ecuador

Paraguay

83.0 K

29.9 K

121.6 K

1.84 M

448.1 K

1.29 M

513.9 K

345 K

24.5 K

28.5 K

17.0 K

14.2 K

115.3 K

170.3 K

20.6 K

12.4 K

5.92 K

RECENT MIGRATION TRENDS IN THE AMERICAS

BACK TO CONTENTS

5

DATA AVAILABLE BY COUNTRY OF DESTINATION /

TRANSIT

Brazil

Since 2017, Brazil has become one of the top ve destination

countries of Venezuelan migration in Latin America (see map

1). As of April 2022, Brazil hosts approximately 345,000

Venezuelan refugees and migrants, 78 per cent of whom have

entered the country through the Northern border in the state

of Roraima (IOM, 2022b). The Brazilian Federal Government

has responded to the situation by establishing a national

humanitarian response, Operation Welcome (Operação

Acolhida, in Portuguese), to provide emergency assistance to

this population in need.

Operation Welcome has also assisted eligible Venezuelan

refugees and migrants located at the Northern border to

safely relocate to other cities in Brazil (for family reunication,

employment or other reasons), thus facilitating their socio-

economic integration in the country. To date, more than

74,000 Venezuelan refugees and migrants have been voluntarily

relocated from Roraima into other states with the support

of the Brazilian Government, UN agencies and civil society

organizations (IOM, 2022d). Concerning the prole of the

population assisted, the majority (89%) travelled in family groups.

47 per cent were women and 38 per cent were children. Main

destination states are Paraná, Santa Catarina, Rio Grande do

Sul and Sao Paulo, followed by Mato Grosso and Minas Gerais.

IOM Brazil has deployed DTM tools to perform ow monitoring

and collect demographic data on Venezuelan refugees and

migrants. In the state of Roraima, surveys have been conducted

since 2018. Data from the latest DTM Round May 2021

showed that 87 per cent of the respondents lived in rented

accommodation and 65 per cent were either employed or self-

employed - however, only 6 per cent of those were employed

in the formal labour market, and 76 per cent reported their

economic situation worsened during the pandemic (IOM, 2021a).

The DTM conducted in the state of Amazonas showed that 58

per cent of the respondents earned less than the minimum wage,

and 36 per cent had diculty accessing food items in the previous

months (IOM, 2021b). More recently, IOM Brazil also deployed a

National DTM focused on indigenous Venezuelan migrants, with

3,319 indigenous Venezuelans interviewed. The R4V Platform

estimates that 6,000 indigenous people from Venezuela have

migrated to Brazil, belonging to the Warao, E’ñepá, Ka’riña,

Pemón (Taurepang), Wayuu, Ye’kwana, and Baniva ethnic groups.

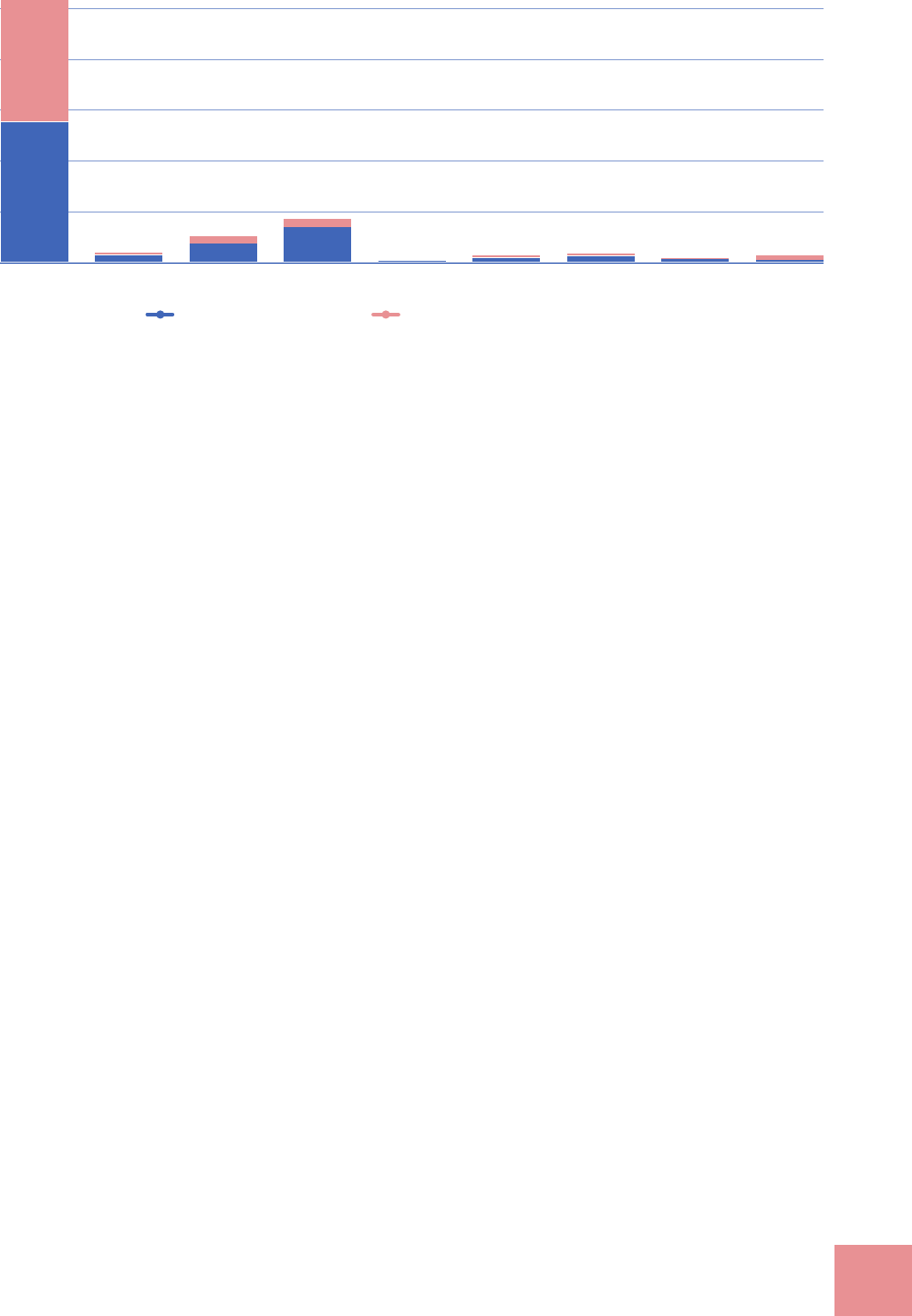

GRAPH 2: NUMBER OF RESIDENCE PERMITS AND ASYLUM CLAIMS OF VENEZUELAN REFUGEES AND MIGRANTS IN BRAZIL PER

MONTH AND YEAR (JANUARY 2017 - MARCH 2022)

Source: CG-CONARE E STI-MAR, 2022

263

273

1.342

1.301

1.480

1.252

2.400

3.791

3.570

3.638

2.602

2.843

3.944

5.652

4.526

6.080

6.193

6.594

10.829

11.059

7.706

10.450

11.236

10.096

14.398

11.661

8.911

8.963

10.329

9.893

10.765

13.914

12.180

15.692

15.246

12.094

13.181

11.060

9.546

605

307

1.227

1.801

3.123

3.829

3.643

4.510

4.504

2.874

2.402

2.943

3.472

3.200

3.241

9.184

11.038

10.876

13.309

16.533

16.863

15.670

12.353

13.806

2017

2018 2019 2020 2021

2022

Requests for recognition of refugee status Residence Records

6

RECENT MIGRATION TRENDS IN THE AMERICAS

BACK TO CONTENTS

Chile

May 1st, 2022, the Government of Chile normalized cross-border

transits with the reopening of all international Points of Entry

(PoEs) that had been previously closed due to the COVID-19

pandemic public health emergency (Suramérica Abierta, 2022).

During 2021 and the beginning of 2022, with the border

closures, a considerable increase -when compared to 2020

gures- of migrants and refugees entered Chile through

unocial PoEs along the north of the country. Colchane, a

small town along the shared border with the Plurinational

State of Bolivia (hereafter Bolivia), in the northern Tarapacá

Region, was the principal access point.

In January 2022, IOM conducted a DTM in northern regions of the

country (Arica y Parinacota, Tarapacá, Antofagasta, and Coquimbo),

with a total number of 300 Venezuelan refugees and migrants

surveyed. Those surveyed were found to be predominately in

transit to other locations in the country (IOM, 2022c).

Main ndings of the 6th DTM Report:

• Age composition: Of the total number of Venezuelans

surveyed, 70 per cent were between the ages of 18 and

34 years old. Those over 45 years of age represented 9 per

cent of all respondents (4% men and 5% women). In total,

81 per cent of Venezuelans surveyed were of working age.

• Duration of stay: About half of all respondents (56%) declared

to have arrived in Chile less than a month before surveyed, with

29 per cent between one and six months, and a further 15 per

cent over six months. These ndings highlight that the majority

of Venezuelans surveyed had only recently arrived in Chile.

• Transit routes: All Venezuelans surveyed (100%) declared to

have entered Chile by land, with 98 per cent stating that Chile

was their destination country, reinforcing integration needs. The

capital of Santiago was the predominant city for nal destination

(42%), followed by the city of Arica as a distant second (18%).

82 per cent of the migrants surveyed traveled with a member of

their family, with 71 per cent traveling with children.

• Countries of stay before entry into Chile: Data recollected

indicates that 50 per cent of Venezuelans surveyed stated

to have resided in Peru before entering Chile, followed by

Colombia (45%), Ecuador (30%), Bolivia (14%), and, lastly,

Brazil (2%). As such, these preliminary insights point toward

the Andean Corridor as a main route of transit between

Venezuela and Chile.

• Documentation: A majority of those surveyed (80%) stated

that a Venezuelan national identication card was the only

identication document used for border crossings, while 18

per cent stated to be in possession of a passport and a

nal 2 per cent declaring to be without any identication

documents at the time of the survey.

• Challenges during migration routes: Nearly 1 out of every

10 Venezuelans surveyed (7%) declared to have been forced

to worked against their will during their journey prior to

arriving in Chile. Additionally, 28 per cent of those surveyed

conrmed to have witnessed emotional or physical abuse,

followed by a further 17 per cent reporting to have

witnessed gender-based acts of violence (a gure equally

reported between male and female respondents).

• Diculties in Chile: An alarming 84 per cent of Venezuelans

surveyed highlighted the lack of economic resources as

their main diculty in Chile, followed by the availability of

safe places to sleep and access to food and water (53%),

and means of transport (41%). These indicators point

to considerable socio-economic integration needs and

vulnerabilities.

• Reasons for travelling to Chile

5

: Economic mobility-

associated motives are predominant factors of attraction,

with 76 per cent of Venezuelans surveyed indicating work

GRAPH 3: NUMBER OF VENEZUELAN REFUGEES AND MIGRANTS SUPPORTED WITH VOLUNTARY RELOCATION IN BRAZIL PER

MONTH AND YEAR

4,972

2018

2019

2020

2021 2022

0

500

1000

1500

2000

2500

3000

3500

abr/18

mai/18

jun/18

jul/18

ago/18

set/18

out/18

nov/18

dez/18

jan/19

fev/19

mar/19

abr/19

mai/19

jun/19

jul/19

ago/19

set/19

out/19

nov/19

dez/19

jan/20

fev/20

mar/20

abr/20

mai/20

jun/20

jul/20

ago/20

set/20

out/20

nov/20

dez/20

jan/21

fev/21

mar/21

abr/21

mai/21

jun/21

jul/21

ago/21

set/21

out/21

nov/21

dez/21

jan/22

fev/22

469

939

1057

1103

1509

2304

2171

2717

2497

3069

2503

1890

3010

3110

2199

1004

1095

1025

1203

1300

1348

1500

1239

1356

1360

1109

1260

1228

1467

1842

2443

2073

1892

1798

1779

2263

1908

270

265

_

299

316

1401

744

588

1089

1417

Federal government IOM Civil Society

22,228

19,389 19,668 4,171

Source: CG-CONARE E STI-MAR 2022

RECENT MIGRATION TRENDS IN THE AMERICAS

BACK TO CONTENTS

7

opportunities as the main reason for travelling to Chile.

Furthermore, 38 per cent reported reasons pertaining to

family reunication, 15 per cent cited reunication with

friends and acquaintances, and a nal 12 per cent declared

their intention to settle in Chile.

• Discrimination

6

: Prior to arriving in Chile, almost 60 per

cent of Venezuelans surveyed stated to have suered

discriminated, with a vast majority (97%) citing nationality-

based discrimination followed by 14 per cent citing

economic-based conditions.

• Pregnant women and healthcare: Of the total number of

Venezuelans surveyed, 3 per cent were pregnant women,

of whom 60 per cent had not received pre-natal healthcare.

• Leading short-term needs

7

: Findings highlight that 72 per

cent of Venezuelans surveyed required assistance with

employment and income generation, followed by 51 per

cent stating to be in need of food and legal assistance.

Child and young migrants identied along the routes through Chile:

The majority (72%) of the people surveyed reported traveling

with at least one child or adolescent. When disaggregated by age,

68 per cent of the children and adolescents in travel groups were

between 0 and 9 years old, 25 per cent were between 10 and

14 years old, and 7 per cent were between 15 and 17 years old.

When asked about the education of children and adolescents,

and as a result of the displacement process, 68 per cent of

those surveyed stated that children and adolescents have not

completed their formal education on a continuous basis.

Peru

On 14 February 2022, after two years of being closed, the border

between Peru and Ecuador was reopened. Since 2019, Peru

requires a visa for Venezuelans to enter the country. (IOM, 2022d).

According to DTM data, among 1,740 Venezuelan refugees

and migrants entering Peru via Tumbes using non-ocial

crossings, 62 per cent were men and 38 women (Idem).

The majority of women (58%) travels in family groups, while

86 per cent of men travel in non-family groups.

Origins: 45 per cent of the interviewed persons used to reside

in Colombia prior to entering Peru, 28 per cent in Venezuela

and 27 per cent in Ecuador.

Main destinations inside Peru: Lima 60 per cent, Tumbes 9 per

cent, Piura 6 per cent, Trujillo 6 per cent and Chiclayo 5 per cent.

Main nal destinations countries: 56 per cent responded that

Peru was their nal destination, and in second place Chile with

43 per cent (Idem).

5

Multiple choice question, percentages may exceed 100%.

6

Multiple choice question, percentages may exceed 100%.

7

Multiple choice question, percentages may exceed 100%.

Source: IOM DTM Peru Flow Monitoring on Venezuelan Population - Round 14, March 2022.

TABLE 3: TRAVELLING MODE BY SEX

TYPE OF GROUP MEN WOMEN

Family Group 42% 58%

Non- Family Group 86% 14%

GRAPH 4: INTERVIEWED RESPONDENTS BY SEX AND AGE GROUPS

Source: IOM DTM Peru Flow Monitoring on Venezuelan Population - Round 14, March 2022

32%

16%

23%

15%

6%

6%

1%2%

MEN

18 to 25

26 to 35

36 to 45

46 to 60

WOMEN

8

RECENT MIGRATION TRENDS IN THE AMERICAS

BACK TO CONTENTS

Ecuador

According to Ecuador’s Ministry of Government (2022),

in 2021 10,530 entries from Venezuelan nationals were

registered through ocial Points of Entry (PoE) into the

country, and 18,723 exits at the same time. Between January-

May 2022, ocials recorded 7,411 entries and 11,921 exits,

likely indicating higher gures for 2022 than for 2021 if current

trends continue. In terms of importance, the main PoE’s are

the international airports of Quito and Guayaquil, followed by

the International Bridge in Rumichaca at the northern border

with Colombia.

• Considering the proles of Venezuelan refugees and

migrants, data collected through DTM surveys in 2021 and

2022 show that this group is predominantly young, and

approximately three quarters are between 18 and 39 years

old. More than half of this surveyed population identies as

male, while less than 1 per cent identify as non-binary (IOM

DTM Ecuador, 2022).

• Border closures due to the COVID-19 pandemic may be

associated with an observed rise of irregular crossings into

the country: from 43.2 per cent in the rst quarter of 2021

to 58.3 per cent in the same period for 2022. Surveys

show that nearly 8 out of 10 Venezuelan migrants have an

irregular migratory status, so entries are likely much higher

than those registered ocially (Idem).

• Almost half of the surveyed population in February-March

travelled with close relatives, and do not see Ecuador as

their nal destination (50.9% indicatingindicating Peru as

their destination, 25.8% Chile and 12.3% other countries

including Venezuela and Argentina) (Idem).

• In terms of the labour status of the surveyed population,

20.8 per cent said they were unemployed (Idem).

• By February-March 2022, only 12.1 per cent had not

received a COVID-19 vaccine, marking a huge decrease

since June 2021 where almost 95 per cent stated not having

received any vaccine (Idem).

Colombia

According to ocial data, in 2021 260,000 Venezuelan

nationals entered Colombia and 250,000 exited via air, land

and sea borders. The most dynamic month was December

2021, when 22 per cent of the entries and 20 per cent of the

exits took place (Migración Colombia, 2022a).

As part of IOM’s humanitarian response addressed to refugees

and migrants from Venezuela, IOM used the DTM approach

and interviewed 5,548 Venezuelan nationals in 24 shelters run

by IOM distributed in 13 departments in Colombia in April

2022 where they received humanitarian assistance

9

(IOM

DTM Colombia, 2022).

8

The Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM) is a modular system that IOM uses to capture, process and disseminate information on human mobility, routes and places of displacement, the

degree of vulnerability and the main needs of protection of these populations. Neither DTM deployed in Colombia nor in Peru show results from a probabilistic surveys nor sampling.

Data on both country sections is non probabilistic.

9

Interviewed Venezuelan refugees and migrants per Assistance shelter: Antioquia (130), Arauca (166), Atlántico (37), Bogotá D.C. (131), Bolívar (21), Casanare (781), Cundinamarca

(198), La Guajira (411), Nariño (1,057), Norte de Santander (2,017), Santander (304), Tolima (101), Valle del Cauca (194).

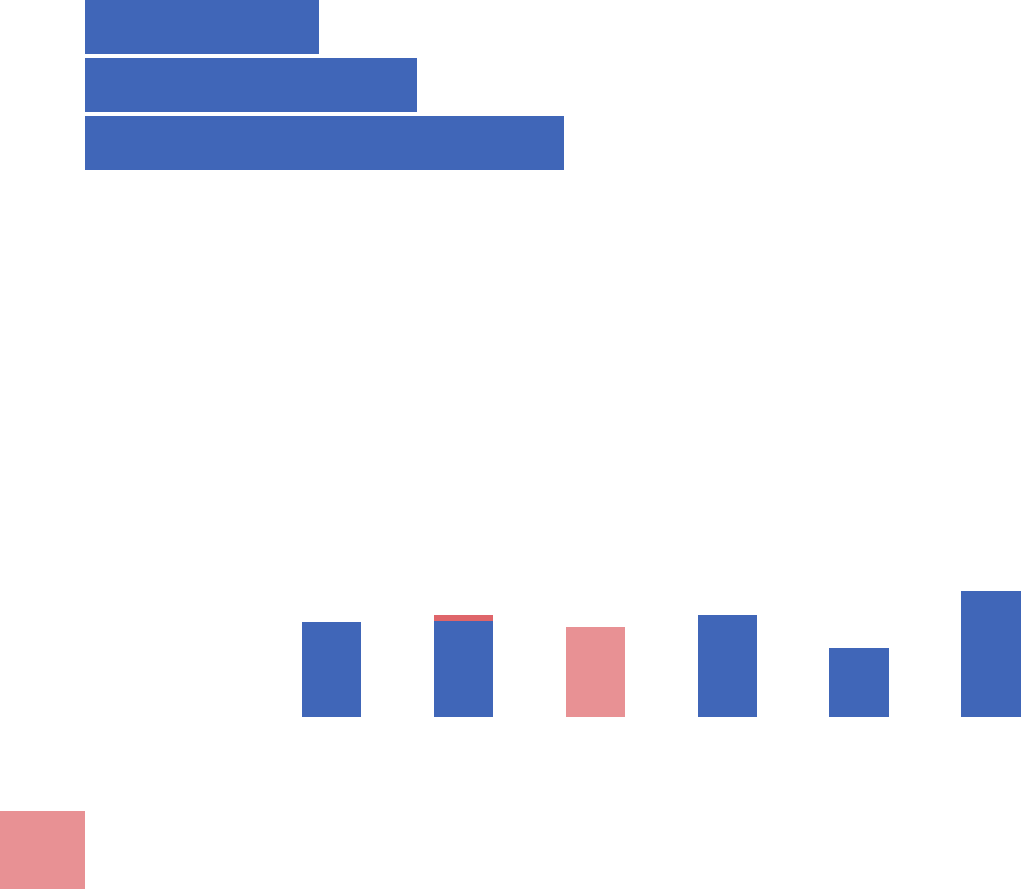

GRAPH 5: VENEZUELAN REFUGEES AND MIGRANTS IN COLOMBIA APRIL 2021 AND APRIL 2022

Source: IOM DTM Colombia - Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela - Flow Monitoring Emergency and Stabilization Program, April 2022

198

134

143

110

418

383

430

405

390

152

132

372

489

518

528

471

336

333

811

728

426

542

472

264

223

539

430

279

307

441

249

183

73

350

251

176

245

179

157

77

274

233

179

31

65

33

192

295

166

360

324

208

246

214

230

186

98

125

1-Apr2 -Apr 3-Apr4 -Apr 5-Apr6 -Apr 7-Apr8 -Apr 9-Apr1 0-Apr1 1-Apr1 2-Apr1 3-Apr1 4-Apr1 5-Apr1 6-Apr1 7-Apr1 8-Apr1 9-Apr2 0-Apr2 1-Apr2 2-Apr2 3-Apr 24-Apr 25-Apr 26-Apr 27-Apr 28-Apr 29-A pr 30-A pr

2021 2022

According to the accommodation registers for April 2022, the ow of Venezuelan nationals decreased from 11,404 to 5,548

compared to the same month of the previous year, and the analysis for March 2022 shows a decrease in the inow of Venezuelan

national migrants (Idem).

RECENT MIGRATION TRENDS IN THE AMERICAS

BACK TO CONTENTS

9

MAP 2: MAIN STATES OF ORIGIN IN VENEZUELA AND DESTINATION COUNTRIES

Source: IOM DTM Colombia - Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela - Flow Monitoring Emergency and Stabilization Program, April 2022.

The following data compares the daily distribution during April (Idem) 2021 and April 2022 of refugees and migrants from

Venezuela, indicating so far lower numbers that month in 2022 than in 2021.

82 per cent of the interviewed Venezuelan nationals indicated

that they entered Colombia directly from Venezuela,

highlighting new or repeat movements. A smaller proportion

came from other countries such as Peru (10%), Ecuador

(6%) and Chile (2%).

Compared to April 2021, in April 2022 9 per cent less

respondents indicated that their destination country was

Colombia. At the same time, comparing April 2021 and 2022,

the intention of Venezuelan refugees and migrants to move on

to Peru remained the same (14%). In contrast, the percentage

of those intending to return to Venezuela has increased by 11

per cent, which could explain why less Venezuelans intend to

remain in Colombia and thus return instead (Idem).

Crossing via the Darién Gap: Colombia –

Panama Border

Transits from South America to North America of migrants

from the Caribbean, Asia and Africa have been developing

for around a decade. Migration ows have reached a record-

high and surpassed the last 10 years combined in 2021 due

to the socioeconomic crisis brought about by the COVID-19

pandemic, disasters, and political instability in countries of

origin and residence (IOM, 2021c). Some nationals from

Haiti, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and African and Asian

countries already living in Latin America, and others that

arrived more recently, were forced to migrate or made the

decision to migrate to other destinations in the north of the

continent (Idem). Certain migrants from the Caribbean and

African and Asian countries have children who are nationals

PANAMA

ECUADOR

PERU

BRAZIL

GRAPH 6: DESTINATION COUNTRIES FOR VENEZUELAN REFUGEES AND MIGRANTS (APRIL 2021 VS APRIL 2022)

Source: IOM DTM Colombia - Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela - Flow Monitoring Emergency and Stabilization Program, April 2022.

62%

53%

14% 14%

14% 10%

6%

17%

3%

5%

1%

APR

APR

2021 2022

Colombia

Peru

Ecuador Venezuela Other country of destination. Does not know / Does not respond

10

RECENT MIGRATION TRENDS IN THE AMERICAS

BACK TO CONTENTS

of a South American country, so they are not exclusively

migrants from the Caribbean and other regions, but also

nationals from South American countries in transit to North

America (Idem).

Due to the lack of accessible regular routes for most of

these migrants from other continents and the Caribbean,

these movements tend to occur in an irregular manner

(Idem). 2021 registered almost 134,000 irregular crossings

from Colombia to Panama via the Darién Gap, a gure higher

than the sum of the previous 11 years (amounting to almost

118,000). During 2021, Haitian was the main nationality

representing 62 per cent of the total number of entries,

followed by Cuban with 14 per cent, then Chilean with 7

per cent and Brazilian with 6 per cent (mostly representing

children of Haitian-born parents) (SNM, 2022a). Venezuelan

is the main nationality for 2022, followed by Haitian, Cuban,

Senegalese and Brazilian (in particular Brazilian children born

to Haitian parents) (SNM, 2022b).

According to ocial data for January-April 2022, 811,502

regular entries

10

into Panama were registered. This gure is

almost three times the one observed during the same period

2021, which shows higher international mobility after the

pandemic (SNM, 2022a; 2022b). Ocial gures for January-

April 2022 registered 19,092 irregular entries, higher than

those recorded for the same period in 2021, reaching 11,487.

This represents an increase of 66 per cent (SNM, 2022b). It

is important to recall that 2021 had the highest number of

irregular entries so if the current trend for 2022 continues,

2022 will have higher number of irregular entries (Idem),

increasing male dominance in these ows.

Between January and April 2022, men represented almost

three out of four (74%) of all persons crossing the Darien,

while women only made up 26 per cent. Compared to the

same period in 2021, this shows an 8 per cent decrease in the

share of men, who represented 66 per cent in 2021 (Idem).

10

Regular entries refer to visits rather than individual records of people, which means that a person can enter several times through an ocial point and be recorded as one visit.

GRAPH 7: MAIN NATIONALITIES IN IRREGULAR TRANSIT THROUGH THE BORDER WITH COLOMBIA TOTAL 2022

Source: Prepared by IOM based on tránsito irregular de extranjeros por la frontera con Colombia between 2010 y 2021 of SNM Panama to December 2021.

* Includes all other nationalities identied and those yet to be identied by SENAFRONT - Darien Regional. (1) Children of Haitian nationals whose birth records correspond to these countries.

Venezuelan

6,951

36%

2,195

11%

1,579

8%

1,355

7%

934

5%

Haitian Cuban Senegalese Angolan

GRAPH 8: IRREGULAR ENTRIES BETWEEN JANUARY AND APRIL 2021 AND 2022 VIA THE DARIEN

Source: SNM, 2022.

2021 2022

6,000

5,000

4,000

3,000

2,000

1,000

0

January

1,071

MarchFebruary April

4,442

4,014

1,857

2,694

4,959

5,865

5,667

RECENT MIGRATION TRENDS IN THE AMERICAS

BACK TO CONTENTS

11

Risks and vulnerabilities during the journey via

the Darién Gap

The duration of the journey varies between 6 and 10 days,

depending on the season, and the trek includes crossing

hills and rivers with strong currents (IOM, 2021c). The lack

of basic services, such as drinking water and medical care

along the way, leads to a situation of extreme vulnerability.

Risks associated with the characteristics of the road put

children at particular risk of diarrhea, respiratory diseases

and dehydration (UNICEF, 2021a). A major risk factor is the

presence of criminal gangs in the Darién Gap that expose

migrants to violence, including sexual abuse, human tracking

and extortion (Idem). The dangers of crossing the Darien

rainforest are also associated with geographical and climatic

factors such as being a thick tropical rainforest with an

ecosystem that gathers dangerous animals and insects (IOM,

2021c). According to UNICEF, the use of sexual violence

against women and minors as an instrument of intimidation

has increased (UNICEF, 2021).

Between January 2021 and April 2022, 56 deaths and missing

of migrants have been registered in the Darién Gap. Available

gures indicate that out of those 33 who have been identied,

approximately 40 per cent were female, 30 per cent male and,

30 per cent children (Missing Migrants Project (MMP)).

Paso Canoas Border, Panama-Costa Rica

According to the ow monitoring DTM in the Paso Canoas

border applied between 1 and 30 April 2022:

• About 5,136 people were recorded as departing from

Panama heading to Costa Rica through the Paso Canoas

border, which represents a 6 per cent increase in ows

compared to the previous month (4,837 people leaving

Panama in March 2022 according to DTM) (IOM, 2022e).

Main ndings:

• Most of the migration ow is composed of men (76% men

and 24% women). The average age is 32 years, with a majority

of people (81%) between 26 and 45 years of age (Idem).

• The main countries of residence of the people identied in

mobility at the Paso Canoas border (countries where people

lived for one year or more before starting their journey), are

Venezuela (44%), Colombia (11%), Brazil (8%), Ecuador (8%),

Peru (7%) and 22 per cent among 10 other countries. (Idem)

• Based on the same DTM report, the identied route of

migrants interviewed begins in Brazil and Bolivia, continuing

to Peru (mainly to the city of Lima), and then to Quito in

Ecuador. From Ecuador, the route forks into two routes; one

to Medellín and the other to Necoclí in Colombia. Another

route directly leads from Venezuela to Colombia, mainly

to Medellin. From Medellín, there is one ow that indicates

heading directly to David in Panama, and two others that

travel to Necoclí or Darién in Panama, and from there, the

routes are distributed among various transit cities reported

in Panama, mainly through the communities of Puerto Limón,

Panama City, Gualaca and Chiriquí (Idem).

• Regarding the countries of destination, the United States

of America was identied as the main destination country

(83%), followed by Mexico (17%), among others (Idem).

• Lack of economic resources and access to food and services

were the main diculties identied in the migration process

of the migrant population moving through the Americas,

while during their stay in Costa Rica, access to food, access

to health and security became important (Idem).

Costa Rica-Nicaragua

The irregular mixed ow monitoring DTM in Las Tablillas

border point, applied from October 26th, 2021, to February

15th, 2022, obtained the following key ndings:

• Las Tablillas is the monitoring point that records a higher

proportion of outows than inows (78% of its recorded ows

are outows), indicating it is primarily used to leave the country.

• The ow of persons in transit through the Americas in Las

Tablillas was constant in December 2021, January and the

rst half of February 2022.

• The main reasons for migration, for both men and women,

are family reunication and the search for better economic

conditions (IOM, 2022f).

GRAPH 9: MAIN NATIONALITIES IDENTIFIED IN TRANSIT THROUGH THE PASO CANOAS BORDER TO COSTA RICA, MARCH 2022.

Source: OM DTM,Flow Monitoring of people in mobility situation through the Americas, round 5-April 2022.

Note: The Others category includes the following countries of origin: Afghanistan, Cameroon, Colombia, Ecuador, Eritrea, Ghana, Democratic Republic of Congo, Senegal, and Somalia.

Venezuelan

2,979

50%

484

10%

483

10%

435

9%

1,130

21%

Haitian Cuban Senegalese Angolan

12

RECENT MIGRATION TRENDS IN THE AMERICAS

BACK TO CONTENTS

11

http://www.politicamigratoria.gob.mx/es/PoliticaMigratoria/Boletines_Estadisticos

Nicaragua-Honduras

According to the Instituto Nacional de Migración of Honduras

(INM for its acronym in Spanish), approximately 400 people have

entered daily through irregular border crossing points in the

municipality of Trojes (on the border of Honduras, coming from

Nicaragua) from January to April 2022. They are not receiving

immediate assistance due to several reasons: lack of personnel in

the migration delegations in the municipalities of Trojes and Danlí,

an increase in requests to complete the procedures and pay the

administrative ne or to have the vulnerability test applied and be

exempted from the nes and considering that migrants cross the

border at night (IOM, 2022g).

According to the Catholic Church, most of the groups

entering the territory continue to be made up of a high per-

centage of males (67%), of whom 59 per cent are over 17

years of age and 7 per cent under 17 years of age, and 33 per

cent of females, 27 per cent over 17 years of age and 7 per

cent under 17 years of age (Idem).

The INM delegation in Danlí has informed that many Cuban

migrants in irregular situations pay the administrative ne of

200 US dollars; however, the rest of the nationalities request

the application of the vulnerability test due to economic

limitations for the payment of the ne (Idem).

On November 22, 2021, the Nicaraguan Ministry of the

Interior established free entry visas for Cubans.

This facilitates the entry and transit of these migrants in

Honduras (Ministerio de Gobernación de Nicaragua, 2021).

Based on information from the INM, between 1 January and

6 April 2022, a total of 16,214 migrants in irregular conditions

have been identied in Honduras. 64 per cent of the total

were people between 21 and 40 years old. In addition, 7

per cent of the total were minors between 0 and 10 years

(Migración Honduras, 2022).

Tapachula, Mexico

The latest DTM executed in March 2022, in the Guatemala-

Mexico border, observing 1141 migrants, 871 in Tapachula and

270 persons in Tenosquique, presented the following key results:

• Access to health services shows a dierentiated behavior

among cities because migrants in Tapachula receive care mainly

at government health centers, while in Tenosique NGOs are

the main means of accessing medical services. On the other

hand, the main obstacles reported by those who were not able

to access medical services in both cities are lack of information

and lack of money (IOM, 2022h).

• Tapachula is the city most frequented by extra-regional

migrants because it is a city with an important oer of medical

services. However, Tenosique has begun to be a point of

passage for other nationalities (idem), such as Haitians who

traditionally were not detected in this city.

• The predominant group surveyed was between 26 and 30

years of age (25%), followed by the group between 18 and 25

years of age (23%) (Idem).

• The analysis by city shows that the highest percentage of

young people (between 18 and 25 years of age) was found in

Tenosique, while in Tapachula the distribution is more equitable

between the ages of 18 to 40 (Idem).

• 74 per cent of respondents were refugee claimants in Mexico

(Idem).

• 7 per cent of women were pregnant only 71 per cent of them

have received mother-child care (Idem).

• 21 per cent of migrants reported suering from one or more

non-communicable diseases, mainly cardiovascular (Idem).

• Between the two cities, the distribution of migrants by

nationality is uneven. People coming from the Central American

region were mainly identied in the city of Tenosique, while

GRAPH 10: MAIN NATIONALITIES IDENTIFIED IN IRREGULAR CONDITIONS IN HONDURAS

Source: Migración Honduras, 2022.

Note: The “Others” category includes: 170 Senegalese, 149 Nicaraguans, 125 Brazilians, 93 Bangladeshi and 962 non-specied records.

12,526

77%

0,474

3%

1,031

6%

0,445

3%

0,249

2%

1,499

9%

Venezuelan HaitianCuban Ecuadorian Angolan Others

RECENT MIGRATION TRENDS IN THE AMERICAS

BACK TO CONTENTS

13

those from the Caribbean, South America, and Central and

Southeast Africa were surveyed mostly in Tapachula (Idem).•

The highest percentage of the migrant population has

completed primary school (33%) and high school (29%),

while 16 per cent have a university or postgraduate degree.

About ve per cent have no education at all; this category is

represented mostly by men (75%) (Idem).

Mexico

After the apparent stagnation of migratory ows that

occurred in 2020 because of the pandemic and the closure of

borders, since 2021 there has been a continuous increase in

presentation events by U.S. and Mexican authorities, showing

gures higher than 2019. The trend remains constant in 2022

(as of May).

According to the Migration Policy Unit (Unidad de Política

Migratoria, in Spanish), during the rst months of 2022, there

has been a continuous increase in return events of Mexicans

from the United States. Comparing data from January and

February 2021 with the same period of the current year, an

increase of 66.35 per cent stands out; during this period,

in 2021 24,788 events were registered, while in 2022 there

have been 41,231, of which 86.8 per cent are men, and 13.2

per cent are women (UPM, 2022). Likewise, the Migration

Policy Unit has published that during the rst months of 2022,

46,688 events of foreign persons presented to the migratory

authority have been registered. The main nationalities of the

people presented are: Honduran (25%), Guatemalan (24.7%)

and Cuban (11.8%).

From October to December 2021, IOM carried out a data

collection exercise using the DTM in order to collect reliable

and disaggregated information on the migratory ows of

people of Haitian origin in Mexico. Among the most relevant

ndings, it stands out that the main countries of the last

residence of those surveyed are Brazil (50%) and Chile (46%).

The factors that motivated them to migrate are associated

with security issues, favorable socioeconomic conditions,

political stability, access to refugee determination processes,

and family reunication. Currently, 85 per cent of migrants of

Haitian origin in the country are unemployed and in search

of employment. However, of the total number of people

interviewed, three out of four Haitians (74%) expressed

their desire to stay in Mexico, highlighting the importance of

supporting their integration (IOM, 2022h).

GRAPH 11: RETURN EVENTS OF MEXICANS FROM THE

UNITED STATES, JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2021-2022

Source: UPM, 2022.

GRAPH 12: RETURN EVENTS OF MEXICANS FROM

UNITED STATES, JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2021-2022, BY SEX

Source: UPM, 2022.

86.77%

MEN

13.23%

WOMEN

GRAPH 13: RESULTS OF THE DTM ON HAITIANS IN MEXICO - MIGRATION DRIVERS

Source: UPM, 2022.

Security Favorable

socioeconomic

conditions

Political

stability

Access to refugee

determination

process

Family

reunication

41%41% 36%36% 15%15% 5%5% 3%3%

2021

24,788

2022

41,237

14

RECENT MIGRATION TRENDS IN THE AMERICAS

BACK TO CONTENTS

Staying in

Mexico

Try to reach

the U.S.

Try to reach

the Canada

Return to their

country or the

last country of

residence

In terms of migratory ows of Venezuelan migrants to

Mexico, there has been a signicant reduction of arrivals

since the visa enforcement in January 2022 for Venezuelans.

As a result of the Visa Decree, air arrivals decreased by 86.49

per cent for the period between December 2021 to January

2022, and February to March 2022 in Mexico.

RETURNS

HAITI – FORCED RETURNS STATISTICS

As of 30 April 2022, IOM Haiti had assisted more than 11,600

migrants with reception and post-arrival assistance in all of

2022, in addition to nearly 20,000 assisted in 2021. The vast

majority of those returned by air and sea arriving in Port-

au-Prince or Cap-Haïtien since the beginning of 2021 were

returned on ights from the United States, while smaller

proportions were returned by air and sea by other countries

and territories in the region, mainly from the Bahamas Cuba,

Mexico and Saint Kitts and Nevis (IOM, 2022i, IOM, 2022j).

Of all those forcibly returned between the beginning of 2021

and the end of April 2022, 57 per cent were adult men, 25

per cent were adult women and 18 per cent were minors

(9% girls and 9% boys) (Ibid). Most of the returned migrants

previously resided in Chile or Brazil and were returned by

the United States after journeying northward (IOM, 2022i).

Based on voluntary registration records collected between

October 2021 and February 2022, 20 per cent of the 9,260

migrants returned in this period were born outside of Haiti

(most of these between the ages of 0 and 2) (IOM, 2022j).

Close to 90 per cent of respondents reported the intention

to migrate again following return, with most citing lack of

economic opportunities (94% of those intending to leave

again), safety and security (67%) and the recent increase

in kidnapping (61%) as the key reasons for not wanting

to remain (IOM, 2022j). While the main immediate need

expressed by returned migrants across the country are

nancial assistance (28%) and housing (22%), 70 per cent

of those returned to Port-au-Prince expressed safety and

security as one of their three top priority needs (IOM, 2022j).

A phone survey conducted at the start of 2022 with adult

migrants repatriated between September and December

2021 showed that over three in ve adult returned migrants

relied on assistance from family and friends as their main

source of income, with only eight per cent reporting that

they had worked to earn income in the 30 days prior to data

collection (IOM, 2022i).

GRAPH 14: RESULTS OF THE DTM ON HAITIANS IN MEXICO - INTENTIONS IN MEXICO

74%74% 23%23% 2%2% 1%1%

Source: UPM, 2022.

GRAPH 15: FORCED RETURNS BY AIR AND SEA TO HAITI RECORDED DURING 2021-2022 (JANUARY- APRIL)

Source: IOM, 2021i; 2022j.

207

4,523

1,613

2,561

803

2,923

909

601

February MarchJanuary April

2021 2022

RECENT MIGRATION TRENDS IN THE AMERICAS

BACK TO CONTENTS

15

GRAPH 16: RETURNS TO GUATEMALA, HONDURAS, AND EL SALVADOR, 2019-2022 (JANUARY-APRIL)

Source: NTMI, 2022.

Along the land border with the Dominican Republic, it is

estimated that several thousand migrants are deported in

accordance with the 1999 bilateral Protocol or expelled every

month, with anecdotal evidence of an increasing trend since

the last quarter of 2021.

RETURNS TO COUNTRIES OF NORTHERN

CENTRAL AMERICA

• During 2021, approximately 125,257 migrant returns

11

to

northern Central American countries were recorded, an

increase by 39 percent compared to the total number of

returns in 2020.

• 73 per cent of returns in 2021 were sent from Mexico and

27 per cent from the United States. During January - April

2022, Mexico was the country from which most returns

took place. Of the more than 69,000 returns recorded

between January-April 2022, Mexico has returned 57 per

cent of Central American migrants and the United States

43 per cent. (Northern Triangle Migration Information

Initiative (NTMI), 2022)

• The total number of returned migrants between January-

April of 2022 compared to the same period in 2021, has

shown an increase of 265 per cent for El Salvador, 124 per

cent for Guatemala and 83 per cent for Honduras (Idem).

11

The numbers of returns presented do not consider information on voluntary returnees but only forced returns.

2019 255,282

2020 93,013

2021 125,257

2022 69,188

108,762 (43%)

45,605 (49%)

63,808 (51%)

31,635 (46%) 32,512 (47%)

52,968 (42%)

8,481 (7%)

5,041 (7%)

36,558 (39%) 10,840 (12%)

109,185 (42%) 37,335 (15%)

UNITED STATES SOUTHWEST LAND BORDER

ENCOUNTERS

Asylum The Encounters statistics reect the migration control

actions carried out by the US Border Protection and Oces

of Field Operations (OFO), including Title 8 Apprehensions

(temporary detainment of a person who is not lawfully in the

United States, which may or may not result in an detention

procedure), Title 8 inadmissions (refers to individuals

encountered at ports of entry who are seeking lawful admission

into the United States but are determined to be inadmissible),

and Title 42 Expulsions (refers to individuals encountered by

USBP and OFO and expelled to the country of last transit or

home country in the interest of public health) (CBP, 2021).

According to U.S. Customs and Border Protection (C B P,

2022), during the rst quarter of 2022, records of encounters

have been continuously increasing. In January 2022, 154, 816

encounters were registered, 165,900 in February, 222,144

in March and 234,088 in April. When comparing data for

January-April 2021 with the same period for 2022, an

increase of 46 per cent is observed: since in 2021, in that

period, 531, 585events were registered, while 776,948 were

registered in 2022. (Idem)

On 21 March 2020, expulsions under Title 42 became

eective, this implied that individuals encountered by US

Border Protection and Oces of Field Operations (OFO)

were expelled to the country of last transit or home country

in the interest of public health. In total, there were 234,088

encounters along the southwest land border in April 2022

– surpassing March’s record-setting total of 222,144, the

highest total in 22 years (Idem).

Guatemala Honduras El Salvador

GRAPH 17: ENCOUNTERS ON THE SOUTHWESTERN UNITED STATES BORDER, BY DEMOGRAPHIC GROUPS,

2021-2022 JANUARY-APRIL

Source: CBP, Southwest Land Border Encounters, 2022.

2021

2,035,602

2022 776,948

Single Adults

Minors Family Units

1,255,959 (62%)

577,468

(74%)

48,101

(6%)

151,379

(20%)

173,763

(8%)

605,889

(30%)

16

RECENT MIGRATION TRENDS IN THE AMERICAS

BACK TO CONTENTS

For 2021 the top 10 countries of origin of migrants encountered

were: Mexico (706,647), Honduras (353,504), Guatemala

(311,814) El Salvador (116,448), Venezuela (106,755), Nicaragua

(86,316), Ecuador (82,113), Brazil (78,983), Cuba (53,825) and

Haiti (37,765), historically Central American nationalities have

accumulated the highest number of encounters, i but for the

period from January-April 2022 the trend has been changing,

with now the nationality with the highest number of encounters

being Mexican followed by Cuban. (CBP, 2022).

From 2020 onward, and continuing into 2022, Mexican nationals

(mainly adults traveling alone) have again been the most

identied group amongst registered encounters, encompassing

as high as 66 per cent (362,251) of total encounters in 2020,

35 per cent in 2021 and 39 per cent in the rst four months of

2022. Large numbers of unaccompanied and separated children

(UASC) continue to be encountered at the southwest US

border – after reaching 37,916 in 2020, the total increased to

172,436 in 2021 and 47,324 already in the rst four months of

2022. (Idem)

On 1 April 2022 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

(CDC) in the United States, in consultation with the DHS,

announced the termination of its Title 42 Public Health Order

which had suspended the right to introduce migrants into the

United States as a COVID-19 mitigation protocol (CDC, 2022).

Under this order, as of 23 May 2022, DHS was due to no longer

process families and single adults for expulsion pursuant to Title

42, instead processing them for removal under Title 8 (Ibid).

However, a US District Judge issued a nationwide injunction

blocking the end of Title 42 (Aguilera and Carlisle, 2022).

As such, the policy – and consequently, Title 42 expulsions –

remain active at the time of writing.

GRAPH 18: TOP 10 NATIONALITIES WITH THE HIGHEST RECORDS OF ENCOUNTERS IDENTIFIED IN 2022 (JANUARY -APRIL)

Source: CBP, Southwest Land Border Encounters, 2022.

301,657

93,248

73,291

57,857

41,659

34,007

29,681

23,912

12,872

Mexican

Cuban

Guatemalan

Honduran

Nicaraguan

Colombian

Venezuelan

Salvadoran

Ukrainian

Haitian

3. REGULAR PATHWAYS

While irregular movements dominate political agendas

and media reporting, the vast majority of migrants enter

countries on the continent regularly. Asylum and migratory

regularizations processes (both ordinary and extraordinary)

are in themselves considered a protection mechanism and one

of the most eective ways to guarantee migrants’ human rights

and a more perdurable socio-economic integration of foreign

populations in hosting societies. In Latin America in recent

years, several countries have adopted major regularization

programmes, especially for Venezuelan refugees and migrants.

This section presents available data on those regular pathways

(ordinary and extraordinary mechanisms), established through

regional and bilateral agreements, extraordinary visa policies,

among other measures.

VISAS AND PERMITS GRANTED IN SOUTH AMERICA

In 2002, countries in South America took a fundamental step

towards achieving the free movement of people and advancing

the rights of migrants through the Agreement on Residence

for Nationals of the States Parties of MERCOSUR, Bolivia

and Chile (then extended to Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and

Venezuela

12

).

The Agreement established common rules for citizens from

signatory countries soliciting residency in another signatory

member. The rules include “MERCOSUR nationality”

criteria that, jointly with the lack of criminal records and

the presentation of certain personal records, constitute the

basic requisites for obtaining residency. The Agreement also

exempts migrants in irregular situations who meet the criteria

and obtain residency from paying penalties or monetary

sanctions for their irregularity (IOM, 2022k).

The Agreement facilitates managing residence permits

and visas, easing the procedures and reducing application-

processing times. Since its entry into force in 2009 and until

12

The Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela was suspended from MERCOSUR in 2016.

RECENT MIGRATION TRENDS IN THE AMERICAS

BACK TO CONTENTS

17

2020 (until which data are available), more than 3.3 million

residence permits were granted, with Argentina issuing the

most, followed by Chile and Brazil (IOM, 2022L).

As concerns Venezuelan nationals, Argentina and Uruguay use

the MERCOSUR agreement and apply it to those nationals.

Other countries, use extraordinary regularization measures

for Venezuelans.

From May 2021, when the Temporary Protection Statute

was implemented in Colombia, until May 2022, 1.38 million

Venezuelan citizens have accessed to a regular status,

representing 52 per cent of more than 2 million applicants

(Migración Colombia, 2022b). In Brazil, between January 2017

and March 2022 200,000 residencies have been granted to

Venezuelan migrants, 90 per cent correspond to a two-year

permit and 10 per cent for an undetermined period (IOM,

2022b). Ecuador and Peru also implement regularization

programmes for Venezuelan refugees and migrants.

Brazil also continues to be a destination country for nationals

from Haiti. Following the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, Brazil

oered a regular pathway through humanitarian visas and

other legal options to facilitate migration and regularize

migrants from that country. According to ocial data, there

are approximately 150,000 to 200,000 Haitians registered

in Brazil. The vast majority is single (76%) and male (62%),

between the ages of 25 and 40 years old (59%) (IOM, 2021e).

VISAS AND PERMITS GRANTED IN THE UNITED

STATES, MEXICO AND THE CARIBBEAN

Permanent Resident Cards (Green cards)

Lawful permanent resident (LPRs) status, also known as a

“green card,” legally authorizes non-citizens to live permanently

within the United States. LPRs may also apply to become U.S.

citizens if they meet certain requirements.

According to data from the United States Department of

Homeland Security, between Fiscal Years (FY) 2016 and 2020

(spanning October through September), nearly 1.9 million

nationals of Central America, North America and the Caribbean

newly obtained lawful permanent residence (“green cards”)

in the United States, the largest proportion of whom were

nationals of Mexico (41%), Cuba (14%), Dominican Republic

(14%), El Salvador (6%) and Jamaica (5%). Nationals of the region

also receive a notable proportion of the approximately 140,000

employment based LPRs made available in the United States each