Eastern Illinois University Eastern Illinois University

The Keep The Keep

Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications

Summer 2022

Problematic Social Media Use and Depression in College Problematic Social Media Use and Depression in College

Students: A Mediation Study Students: A Mediation Study

Morgan Hummel

Eastern Illinois University

Follow this and additional works at: https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses

Part of the Clinical Psychology Commons, and the Counseling Psychology Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Hummel, Morgan, "Problematic Social Media Use and Depression in College Students: A Mediation Study"

(2022).

Masters Theses

. 4955.

https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/4955

This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The

Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more

information, please contact [email protected].

Running head: PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 1

Problematic Social Media Use and Depression in College Students: A Mediation Study

Morgan Hummel

Eastern Illinois University

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 2

Table of Contents

Abstract 4

Introduction 5

Social Media Use in College Students 7

Positive Effects of Social Media Use 8

Negative Effects of Social Media Use 9

Social Media Addiction and Problematic Social Media Use 10

Social Comparison 12

Rumination 15

Relationship between Social Media Addiction and Depression 17

Covid-19 Pandemic and Social Media Use 20

Research Question 20

Method 21

Overview 21

Participants 21

Procedure 22

Measures 23

Problematic Social Media Use 23

Social Comparison 24

Depressive Symptoms 24

Data analysis 24

Results 25

Mediation Analysis 26

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 3

Discussion 28

Limitations 29

Clinical Implications 30

References 31

Table 1 43

Table 2 43

Table 3 43

Appendix A 44

Appendix B 45

Appendix C 46

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 4

Abstract

Recent research has shown a relationship between problematic social media use and

depression symptoms in adults in the United States. Social comparison has been identified as a

mediator in this relationship in previous studies. Little research has explored the underlying

mechanisms in social media use and the onset of depression symptoms in college aged students.

The present study examines whether social comparison mediates the relationship between

problematic social media use and depression symptoms in 102 college students in the US. The

participants completed measures of problematic social media use, social comparison, and

depression symptoms. The results indicated a positive relationship between problematic social

media use and depression symptoms. A mediation analysis was conducted and found a partial

mediation of social comparison in this presented relationship.

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 5

Introduction

Social media has gained popularity within many groups since its invention in 1997.

Social media has not only grown exponentially in recent years, but it has also had a large impact

on the daily lives of young people. Social media can be defined as “any online resource that is

designed to facilitate engagement between individuals” (Bishop, 2019). Several studies have

shown that engaging in social media usage can have a negative impact on individual’s daily

living and well-being (Okeeffe & Clarke-Pearson, 2011). The majority of research focuses on the

effects of social media on adolescents; however, college students are also shown to have high

levels of usage when compared to other age groups. The Pew Research Center found that 84% of

18-29 use social media in February 2021, the largest percentage of individuals in a group who

use various social media platforms (2021). Of this age group, 48% reported being online almost

constantly (Perrin, Andrew, & Atske, 2021). The most popular social media sites in the U.S.

amongst this age group as of February 2021 is YouTube (95%), Instagram (71%), Facebook

(70%), Snapchat (65%), TikTok (48%), and Twitter (42%) (Auxier & Anderson, 2021). One

study also found that individuals with higher education are more likely to use social media than

those with lower education; 76% of college graduates use social media, 70% of those with some

college, and 54% of those with a high school degree or less use social media (Greenwood,

Perrin, & Duggan, 2016).

In addition to the rise of social media, depression has been recognized as one of the most

common health challenges during this time period in the U.S in adults (Wang et al., 2018). The

college student population has been shown to be particularly vulnerable to depression (Mahmoud

et al., 2012). In a 2014 study, there was an increase in the reported number of major depressive

episodes in adolescents and young adults (Mojtabai, Olfson & Han, 2016). This study also found

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 6

an increase in mental health related hospitalizations and prescription medications in this

population. There was no cause identified for the increase in major depressive episodes. Many

recent studies show a link between social media use and depression. Scrolling through social

media, or passive social media use, was found to be positively correlated with symptoms of

depression such as feeling down and inferior (Aalbers et al., 2019). Likewise, a study of 19-to-

32-year old's found the more times a participant visited social media in a week, the higher they

scored on the depression scale that was administered (Lin et al., 2016). This shows the necessity

for more research to be conducted on the relationship between social media and depression in

college students.

Young adulthood has been recognized as a vulnerable period of time for the onset of

depression symptoms to begin showing (Hankin et al., 1998). Due to the correlation of social

media use and depression, this is an important topic to look at. Although social media addiction

and depression have been linked in past studies, there is a gap in the causal relationship between

these variables. Prior studies have focused on the relationship between these two variables in

teenagers. There is a lack of research on this topic in college students. In addition, college is a

critical time in development for individuals due to the quick changes that occur during this time

such as new relationships, new residency, and the diversity of this environment (Zuschlag &

Whitbourne, 1994). This developmental period makes this population vulnerable to different

types of changes in their mental health. In order to make a step towards filling this gap, our study

used a mediation model to test the role of social comparison in the relationship between

problematic social media use and depressive symptoms in college students.

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 7

Social Media Use in College Students

Social media use in emerging adulthood has been at its peak within the last couple of

years. As stated above, the largest group of social media users is young adults who are in the age

range of 18-to-29-year old's. Within this age group belongs college students who are susceptible

to social media use due to the constant connection to social media sites through mobile devices.

95% of undergraduate college students own a laptop, smartphone, or tablet, and 30% of

undergraduate students own all three of these devices. (Brooks & Pomerantz, 2017). A study

which measured social media use in undergraduate college students through automatic

programming logs found participants spent an average of 1.5 hours using social media sites per

day and visited these sites on an average of 118 times per day (Wang at al., 2015), although this

study points out the average visits could be an overestimate due to counting every switch of

social media site URLs.

The use of social media has been found to have both positive and negative effects on

college students. A study conducted at the University of Florida did not find significant results

with positive and negative effects from the sites; rather they found the way the students use the

sites affects the outcome (Mastrodicasa & Metellus, 2013). Wang et al (2015) concluded that

individuals create their own patterns of social media use as a response to their needs that are

experienced daily. Social media also has a dual impact on academic achievement in college

students (Talaue et al., 2018). This study found social networks can be beneficial for academic

development when used appropriately, however, it can also be used as a means to spend free

time which can have negative impacts on development. Although there is a great deal of research

focusing on social media use in high school aged students, there is limited research on social

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 8

media use and the college student population. This section will now explore the current research

of positive and negative effects of social media use on college students.

Positive Effects of Social Media Use

Social media use was found in a 2017 study to have positive effects on college students

(Kim & Kim, 2017). The relationships created through social media use were positively related

to the subjective well-being of the students. Students can use social media sites to stay connected

with high school friends and maintain long distance friendships (Subrahmanyam et al., 2008).

Not only is this helpful for college students who are experiencing a time of transition, but it has

been shown to be linked with higher life satisfaction. Facebook use has been shown to have a

relationship with bridging social capital in college students (Kim & Kim, 2017). Using social

media as a tool to bridge social capital can be beneficial for creating relationships and ties

between communities to create unity amongst student groups and non-student groups.

Students can use social media as a tool for learning. Education can be pursued through

social networking sites through research, collaboration, sharing of information, writing, and

posting class-related information (Siddiqui & Singh, 2016). Students can be taught to use social

media in ways that are beneficial to their own development intellectually and can encourage

reserved students to participate. College students reported positive use of social media sites for

academic purposes through sharing and creating new ideas and found the social media sites used

for their studies were enjoyable (Amin et al., 2016). Although students tend to make social media

part of their daily routine, the participants in this study found they were able to use the sites in a

meaningful way for their academic work.

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 9

Negative Effects of Social Media Use

There are also several negative effects of social media use patterns in college-aged

students. College students showed continual social media checking reported feelings of lack of

control (Wang et al., 2015). Results also showed that the more the participants check their social

media sites, the less positive their mood is. Students reported feeling isolated when using social

media (Kitsantas et al., 2016). Social media sites have prevented face to face contact and can

lead to negative effects such as isolation. The lack of self-regulation was correlated with constant

checking of social media sites (Wang et al., 2015). Social media users reported behaviors that

exuded lack of self-control behaviors such as routine social media usage to procrastinate, pass

time, and avoid studying. Students are also influenced on decisions through social media sites.

Social media posts in favor of smoking were positively related to students’ attitudes and

behaviors of smoking (Yoo, Yang, & Cho, 2016). Similarly, exposure to alcohol-related posts on

social media sites was a predictor for drinking behaviors in the participant in the following 6

months (Boyle et al., 2016).

Social media use can have a negative impact on student’s academic performance. Ajjan et

al (2019) found problematic social media use amongst college students had a negative impact on

academic performance. A study found students who used social media sites frequently during

class has a lower grade point average than those who did not use social media during class

(Landry, 2015). In addition, students who reported never using social media sites had higher

grade point averages. Similarly, reports of more time spent using social media sites is positively

correlated with lower grade point averages (Al-Menayes, 2014). The implication is that students

are using social media sites in replacement of the time which could be spent doing activities that

would benefit their grade point averages.

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 10

Social Media Addiction and Problematic Social Media Use

Problematic social media use is defined as compulsive behaviors that involve excessively

using social media sites which can lead to negative outcomes in an individual’s personal, social,

and/or professional life (Hawi & Samaha, 2017; Bányai et al., 2017). Although problematic

social media use does not currently have a consistent definition, for the purpose of defining the

term in this study, we have borrowed defining characteristics from research on addiction to

define problematic social media use. Social media addiction is the dependency on online social

media sites where an individual has an out-of-control urge to use social media sites and acts upon

these urges (Hou et al., 2019). Behavioral addiction identifies addiction as performing excess

behaviors that are rewarding for an individual, yet have negative consequences (Starcevic, 2013).

It is characterized by loss of control, tolerance, withdrawal, desired mood-altering effects,

negative consequences, and as a result neglects other areas of daily life. Asking questions such as

“How often do you find that you spend more time on social media than intended?” can

demonstrate tolerance for use of social media to achieve a satisfied effect (Cabral, 2008). A

sample found 47.9% of the respondents reported they find themselves saying “just a few more

minutes” some of the time or often, which shows a higher level of tolerance for social media

usage. We chose to highlight social media addiction to describe the condition of the individual.

Whereas problematic social media use represents the problematic behavior. Both social media

addiction and problematic social media use are categorized by compulsion.

Social media addiction and problematic social media use have overlapping characteristics

and will be used interchangeably in this study. Both terms show an act of compulsion when

using social media. Problematic social media use is the method of using social media in a way

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 11

that creates a problem for the user and can be classified as a behavioral addiction. Social media

addiction is viewed an addiction because there are signs of tolerance and withdrawal.

Problematic social media use can lead to social media addiction in many cases, but social media

addiction is characterized by problematic social media use. This study will use problematic

social media use as the appropriate term to focus more on the behaviors of social media use

rather than grouping the participants into this category and to eliminate stigma of addiction. In

this study, problematic social media use will be explored in its relation to depressive symptoms

in college students by assessing the frequency of social media use and how the individual spends

their time using social media.

Social media addiction and problematic social media use behaviors can have negative

impacts on mental health. For example, a study of young people found that life satisfaction

decreased the more they used Facebook within a 2-week period (Kross et al., 2013). The more

people check their social media sites within a specified time frame, the more it can be

categorized as an addiction because social media addiction involves having an urge to check

social media sites. Social media addiction has been shown to have a negative relationship with

poor mental health due to social media use lowering self-esteem levels (Hou et al., 2019). This

study proposed mental health declines as a result of using social media sites. Similarly, a study of

college students found those who scored higher on social media addiction scales also scored

lower on the self-esteem reports (Hawi & Samaha, 2017). Those who use social media sites with

an intention to strengthen their own self-image may not only be at risk of lower self-esteem, but

also may develop more urges to log on to social media. Users who were considered continual

checkers reported feeling out of control of their social media habits (Wang et al., 2015).

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 12

There has been an increase in research on problematic social media use in the recent

years. This could be because of the rise of users who report problematic social media use when

online. 44% of social media users reported aligning with behaviors of problematic social media

use in a study of young adults (Shensa et al., 2017). Problematic social media users reported

sending more messages to friends, check and respond to more notifications, and were more likely

to deactivate their accounts, which points to negative perception’s an individual may hold about

their own social media use (Cheng, Burke & Davis, 2019). Those who were considered as using

social media problematically also said social media sites were more valuable to them when

compared to non-problematic users. Shensa et al. (2017) found problematic social media use to

be strongly correlated with symptoms of depression. The problematic use of social media could

lead to lack of in person interactions, lack of exercise, and difficulty sleeping (Choi et al., 2009;

Moreno et al., 2013; Younes et al., 2016). These behaviors, which are associated with

depression, show the neglect a person has for other areas of living making the social media use a

problem in their day-to-day life.

Social Comparison

The process of social comparison is defined as ‘thinking of information about one or

more other people in relation to the self’ (Wood, 1996). This implies looking for similarities and

differences between oneself and the other, which then leads to making judgements about the self

or confirming beliefs about one’s attributes and the other’s attributes in relation to one another.

Self-esteem is usually correlated with social comparison (Wood et al., 1994). This research

suggests social comparison can have both positive and negative effects on self-esteem. Positive

effects of social comparison may include comparing oneself to a superior and believe they align

with their positive characteristics, known as upward comparison (Collins, 2000). Downward

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 13

comparisons such as comparing one’s situation to another and believing others have it worse can

also promote positive self-esteem levels (Buunk et al., 1990). One who participates in downward

comparison may also believe their current status can decline, which can decrease self-esteem

levels. Whereas upward comparisons can also have a negative impact on self-esteem due to

feelings of inferiority (Wheeler & Miyake, 1992).

Engaging in social comparison thoughts and behaviors can have effects on mental health.

Social comparison theory describes social influence and competitive behaviors derive the drive

of our own self-evaluation and the evaluation from others based on comparison (Festinger,

1954). A meta-analysis study found social comparison has a significant association with

symptoms of depression and anxiety (McCarthy & Morina, 2020). Higher levels of social

comparison may show a risk factor for depression onset. Undergraduate students who used

Facebook reported they agreed that other users were happier and had better lives. Those who had

many Facebook friends whom they did not personally know also reported that others had better

lives (Chou & Edge, 2012). A study in Singapore found that social comparison through

Instagram use and self-esteem mediated the outcome of social anxiety in adults (Jiang & Ngien,

2020). When it comes to amount of time spent on social media or number of online friends,

engaging in social comparison was more influential on development of depression and anxiety

symptoms (Keles, McCrae, & Grealish, 2020).

The rise of social media use has made it easier to engage in social comparison. In a study

that explored social comparison levels in undergraduate students, participants who had higher

levels of social comparison also spent more time on Facebook when compared with the

participants who had lower levels of social comparison (Vogel et al., 2015). This also supports

the idea of social media users indirectly recognizing the opportunities for social comparison

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 14

through social media, thus using their sites more frequently. In the context of social comparison

orientation, individuals who engaged in upward social comparison showed lower self-evaluation

levels after spending time on Facebook (Vogel et al., 2014). This study suggests that the people

who spent time on profiles with positive content were comparing themselves to the people on the

social media account and reflecting negatively on themselves which led to lower self-esteem in

those participants. Social media use popularity has introduced the concept of the selfie to post on

social media and has had an impact on how one compares themself to others.

Social comparison and rumination often coexist as processes that occur as a result of one

another or even simultaneously. In a study of college students use of social media, social

comparison was positively linked with ruminating (Yang et al., 2018). This study suggests the

students are more susceptible to comparison due to being in a time of transition, so they begin to

ruminate when they perceive other’s posts as doing well. A study that measured frequency of

rumination and social comparison method reported those who participated in the rumination

process were also likely to engage in upward social comparison (Dibb & Foster, 2021). These

factors were also shown to lead to loneliness as discussed above. In a study that links social

comparison to negative mental health outcomes, comparing oneself to another on social media is

a large risk factor for engaging in more rumination (Feinstein et al., 2013). Social comparison on

Facebook predicted increased levels of ruminations at a 3-week follow-up. The possible

explanation for this result is that individuals tend to post more positive information online than

what is shared outside of online sources (Qiu et al., 2012), so they believe others live “better

lives,” which may lead to more comparison and thinking of their own negative attributes.

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 15

Rumination

Rumination is described as the repetition of thoughts or behaviors of depression

symptoms, causes of depression, and consequences of one’s own depressive symptoms (Nolen-

Hoeksema, 1991; Wang et al., 2018). Rumination does not involve taking action to solve an

issue; rather it causes a person to remain focused on the problem and their emotions (Nolen-

Hoeksema, Wisco & Lyubomirsky, 2008). According to the response styles theory, when an

individual becomes stuck in the cycle of rumination, being consumed in the depressive thoughts

and behaviors can draw out these symptoms which can increase the possibility of the symptoms

of the depression becoming more chronic (Spasojevic et al., 2004). The frequency and amount of

depressive, ruminating thoughts can determine the severity of development of depression

(Nolen-Hoeksema, 2004). An individual who engages in frequent rumination can experience

episodes of major depressive disorder. Ruminating thoughts can be experienced in examples

such as: “What is wrong with me?” “Why can’t I get over this?” and “No one cares about me.”

The process of rumination has been linked to depression. Rumination was correlated with

significant increase of depression symptoms when there were low levels of emotional

differentiation, or the ability to recognize identified emotions (Liu, Gilbert, & Thompson, 2019).

A longitudinal study of adolescents found major depressive disorder and minor depressive

disorder were predicted by high levels of rumination (Wilkinson, Croudace, & Goodyer, 2013).

Depressive symptoms were also predicted by rumination one year later. A study of university

students reported participants who were clinically non-depressed experienced rumination as a

response to their symptoms of depression (Just & Alloy, 1997). These participants were more

likely to experience a depressive episode than those who were able to stay distracted from their

depressive symptoms within 18 months. Rumination is associated with being fixated on

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 16

emotions rather than taking a problem-solving approach. Rumination is positively correlated

with resistance to change and therefore were also both predictors of depressive development

including the severity of depression (Koval et al., 2012).

Rumination tendencies can also be identified through social media use. Scrolling through

social media sites can result in comparing oneself to others and reflecting on one’s own life

success. Social comparison on social networking sites was a risk factor for rumination, which

was then a predictor of depression (Feinstein et al., 2013). Similarly, another study found

competition-based social comparison prompts the rumination process that produce negative

emotions (Yang et al., 2018). Rumination was found to be the mediator between social media

addiction and depression, while rumination and depression were stronger for individuals with

lower levels of self-esteem (Wang et al., 2018). A sample of Facebook users reported rumination

was positively associated with loneliness (Dibb & Foster, 2021). This study suggests that

individuals may engage in ruminating behaviors while on social media that can be associated

with negative outcomes.

There are several explanations for how social media addiction can influence the

rumination process. For example, Facebook offers the option to update your status for other users

to view. Through this feature, users can share their thoughts online which can impact rumination

based on the interactions the post receives such as likes, reactions, and comments, or the lack of

interaction (Locatelli, Kluwe & Bryant, 2012). This study resulted in significant results for

rumination as the mediator between posting Facebook status posts and subjective well-being of

the user. Social media addiction was found to be a predictor of rumination, and also mediated the

relationship between social media addiction and depression in adolescents (Wang et al., 2018). In

a study that resulted in positive associations between social comparison, rumination, and

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 17

depressive symptoms, participants who ruminated about their inferiority status on Facebook may

be explained by the increase in amount of time spent using their social media site (Feinstein et

al., 2013). Smartphone addiction has also been found to lead to rumination (Liu et al., 2017).

Social media addiction has been found to accompany smartphone addiction (Salehan &

Negahban, 2013; Erçağ, Soykan & Kanbul, 2019), pointing to the conclusion of a positive

relationship between social media addiction and rumination.

Rumination is an important component of this study in explaining the mechanism of

social comparison. Individuals who compare themselves to one another may find themselves in

the process of rumination because they are often stuck in a cycle of comparing their thoughts,

feelings, and decisions to those of others. The idea is if we are ruminating, we are evaluating

ourselves as doing something wrong and without others to compare ourselves to then we would

not know when we are having this problem to be ruminating on. In addition, people can compare

themselves in their own ruminating thoughts such as “why is my life so bad when I see others

have it easy.” This is a form of social comparison during the rumination process to show that it is

important in understanding this concept in relation to one another.

Relationship between Social Media Addiction and Depression

Although social media has been shown to be beneficial for various factors such as

relationship building and communication, there are mixed results for the relationship between

social media use and mental health issues such as depression. According to Lin et al. (2016),

social media use was correlated with increased levels of depression in adults ages 18-32. 70% of

college students reported being online longer than they planned to (Christakis et al., 2011). This

study found a significant link between problematic social media use and moderate to severe

depression. Young people were found to show more addictive behaviors than older people when

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 18

it comes to internet usage (Morrison & Gore, 2010). The group of individuals with internet

addiction used more online chat websites, gaming sites, and websites used for sexual

gratification. Those who display internet addiction behaviors are more likely to use websites as a

replacement for real-life socialization. A meta-analysis showed depression was the most

common mental health issue outcome of social media use (Keles, McCrae, & Grealish, 2020).

Depression symptoms were more likely to occur based on certain social media use behaviors and

attitudes such as social comparison, active or passive use, and the motives for using social media

sites.

The development of depression symptoms has been shown to be correlated with the

amount of time spent using social media sites. Young adults who had the highest number of

social media visits per week were more likely to be diagnosed with depression (Lin et al., 2016).

Although other factors besides frequency of social media use may have more effect on symptoms

of depression, there is some evidence that points a relationship between time using social media

and depression (Keles, McCrae, & Grealish, 2020). One study found the more an individual

checked their social media, the less positive their mood was (Wang et al., 2015). There is

conflicting evidence found that indicates time spent using social media is not related to

depression symptoms (Banjanin et al., 2015). This study found a positive relationship between

internet addiction and depression, however, there was no correlation between the amount of time

using social media sites and depression, assuming this relationship is independent from social

media use. Despite these findings, many other studies have found that when people spend more

time on social media sites, reports of depression are much higher than those who do not spend as

much time on social media sites (Lin et al, 2016; Twenge et al., 2018).

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 19

There is conflicting research on the effects of using social media for social networking.

Many people use social media sites to find social support. According to a study of transitioning

college students, the students' perception of social media increased their beliefs of having a

diverse social support system during their first semester at college (DeAndrea et al., 2012).

Active social media use is perceived as a way to decrease social isolation and users report feeling

less isolated when checking social media daily or interacting with other online users (Shaw &

Gant, 2004; Hajek & König, 2019). However, other studies have found social media use to be

associated with isolation and loneliness (Primack et al., 2017; Whaite et al., 2018). Loneliness is

not only associated with depression, but people with less social support are also more likely to

experience a variety of mental health issues such as depression and anxiety when compared to

people who have more social support (Maulik, Eaton & Bradshaw, 2011). Park et al. found that

perceived social support on Facebook was inversely correlated with depression levels, but

depression and low social support had a relationship when researchers studied the participants

online social interaction and assessed depressive symptoms (2016).

The relationship between social media addiction and depression has been established in

several previous studies. However, there is a gap in existing literature about the reasons for the

link between social media addiction and depression. By doing a mediation study, we want to

look at the explanation for the causal relationship and how the social comparison process affects

this relationship. College students may not directly be susceptible to developing depression,

however, previous studies have shown college students are primary users of social media, and

social media addiction has been linked to depression. With all of these factors in mind,

depressive symptoms shown in college students can be linked due to the popularity of social

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 20

media in this generation. The next step is to explore the possible reasons these variables are

related, which will be considered.

Covid-19 Pandemic and Social Media Use

The Covid-19 pandemic began in March 2020 in the United States and has had many

effects on the lives of individuals, including social media use behaviors. A study done by the

University of Connecticut found that 70% of their participants said their social media use had

increased during the first wave of the pandemic in 2020 and 89% of the participants reported

their social media use increased or stayed the same during the second wave in 2021 (Aldrich,

2022). The amount of time users spent on social media sites increased in the year 2020 to 65

minutes daily compared to 54 - 56 minutes in the previous years (Dixon, 2022). In addition to the

increase in internet usage, problematic social media use behaviors have also increased during the

Covid-19 pandemic as a way of coping with the stress that is caused by the lockdown and stay-

at-home orders (Király et al., 2020; Fernandes et al., 2021). Another study found internet

addictive behaviors where the individual had created a psychological dependence on the internet

had increased during the pandemic (Masaeli & Farhadi, 2021). This study identified this increase

was due to financial hardships, isolation, substance use issues, and mental health issues. Overall,

research has not only shown an increase in use, it has also found an increase in problematic

social media use behaviors since thestart of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Research Question

Hypothesis. Social comparison will mediate the relationship between problematic social

media use and depression symptoms.

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 21

Method

Overview

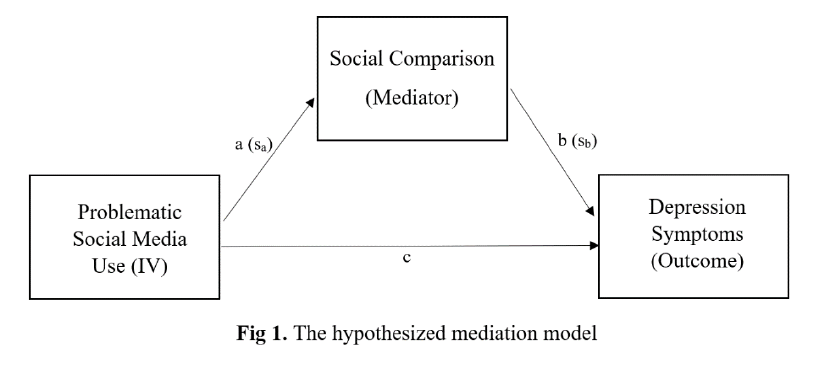

The present study used an online survey of college students recruited from an online

survey website. This study tested the mechanisms that balance the relationship between

problematic social media use and depression symptoms. A mediation model was used to explore

the hypothesis: does social comparison mediate the association between problematic social

media use and depression? Figure 1 presents the conceptual model.

Participants

Data were collected in June 2022. A total of 110 individuals participated and 8 were

removed due to missing data. This study analyzed the data from the remaining 102 participants.

Fifty-five of these participants were male, 45 were female, 1 selected “prefer not to say,” and 1

participant left this item blank. Participants were recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk

(MTurk), an online crowdsourcing system that gives payment to workers to complete tasks,

including surveys. Participants were deemed eligible if they are in the age range of 18 – 25 years

old, are a US high school graduate, and currently live in the United States. The participants

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 22

selected an option to continue the survey that they are a current undergraduate or graduate level

university student.

To conduct a mediation model, the minimum sample size with the preferred power of

80% at an alpha level of .05 is recommended to be 87 participants. An a priori analysis was used

to calculate sample size using a Monte Carlo power analysis simulation on Schoemann’s website

for MC power mediation. This simulation uses bootstrapping, or random resampling, for testing

the indirect effects using Monte Carlo confidence intervals. This method works by drawing

random samples in the population model until the wanted statistical power is met (Schoemann,

Boulton & Short, 2017). The correlations from Wang et al. were entered into the simulation

(2018). Using a 95% confidence interval, the Monte Carlo power analysis simulation calculated

a sample size of 78, which was then multiplied by 10% and added onto the given sample size.

Participants answered demographic questions about their social media usage. Of the 102

participants, 56.9% of them reported they used social media daily when asked how often they

use social media. 42.2% of participants reported using social media for 1-2 hours on the days

they use social media and 30.4% of them reported using social media for 3-4 hours per day.

When asked about social media sites the participants use, 83.3% of the participants reported they

use Instagram, 77.5% use Facebook, 63.7% use YouTube, 58.8% use Twitter and WhatsApp,

and 30.4% of the participants use TikTok.

Procedure

Eligible participants were filtered on MTurk by selecting the following qualifications for

participants that had access to the survey: Ages 18 – 25, US High School Graduate, and current

location is in the United States. Participants then completed the survey through Qualtrics.

Qualtrics is a survey system which gives capabilities to create, administer, and analyze surveys

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 23

online. The participants began the survey by reading the informed consent statement and began

the survey by checking a box confirming they are enrolled at a college or university in the US.

The participants then completed filling out demographic information (age, gender, ethnicity, time

spent on social media use, etc.) Then, the participants completed the measures questionnaires as

discussed below. The participants received a debriefing form once these questionnaires were

completed. Participants were compensated $1.00 for their participation upon entering their

assigned MTurk ID number.

Measures

Problematic Social Media Use

This study used the Facebook Intrusion Questionnaire (FIQ; Elphinston & Noller, 2011)

to measure problematic social media use. This questionnaire consists of 8 items to measure

social media behaviors (e.g. “I often use social media [Facebook] for no particular reason”). All

statements are rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly

agree. A higher score on the FIQ indicates higher levels of problematic social media use. This

study will adapt the FIQ by replacing “Facebook” to “social media sites” in each item to expand

upon different social media site usage. Cronbach’s α for the FIQ is 0.86 in the original validity

study.

The original FIQ items that used the term ‘Facebook’ were replaced by the term ‘social

media.’ The purpose of this was to broaden the lens the participants have of social media sites

they personally use. The reliability of the current study for the FIQ was .70 which is lower than

the original validity study. This could have been influenced by the change in terms, giving the

participants an opportunity to interpret the term ‘social media’ as any platform(s) they consider

to fit in that category.

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 24

Social Comparison

The Iowa Netherlands Comparison Orientation Measure (INCOM; Gibbons & Buunk,

1999) was used to measure social comparison. This questionnaire is made up of 11 items to

measure social comparison tendencies (e.g. “If I want to find out how well I have done

something, I compare what I have done with how others have done.”). The participants respond

by rating themselves on a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). A higher

score on this questionnaire indicates more comparison behaviors. The INCOM has been shown

to have good reliability and validity (Schneider & Schupp, 2014). In the original validity study,

Cronbach’s α for the INCOM is 0.90.

Depressive Symptoms

Depression symptomology was measured using the Epidemiological Studies Depression

Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). This scale contains 20 items that are rated on a 4-point scale (1 =

rarely or none of the time, 4 = most or all of the time). Higher scores on this scale suggest worse

symptoms of depression. In the original validity study, Cronbach’s α for the CES-D is 0.91.

Data analysis

This study was analyzed using a mediation model in SPSS. The mediation model is

composed of three sets of regression. We used SPSS to run an analysis between the variables of

problematic social media use and depression symptoms. We then used SPSS to run the analysis

for problematic social media use and social comparison, then for problematic social media use

and social comparison as predictors of depression symptoms (Baron & Kenny, 1986). To find if

the results are statistically significant, we used the Sobel test method (Preacher & Leonardelli,

2022). In this study, the Sobel test estimates the statistical significance of the indirect effect

using output created by SPSS which includes the standard error between the IV and mediator (a)

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 25

and the mediator and outcome (b) and the raw regression coefficient between the IV and the

mediator (s

a

) and the mediator and the outcome variable (s

b

) (Sobel, 1982). Then this output

created from SPSS was entered into a Sobel test calculator. Then to calculate the unstandardized

coefficient beta, the product of a and b is calculated. When unstandardized coefficient beta

equals zero a full mediation is found. When it does not equal zero, there is a partial mediation.

Results

Means, standard deviations, and correlations are presented in Table 1. The internal

consistencies (Cronbach's α) of each measure were calculated first. The Facebook Intrusion

Questionnaire had an alpha of .696 and the Iowa Netherlands Comparison Scale had an alpha of

.699 which both indicate acceptable internal consistency of these measures. The Epidemiological

Studies Depression Scale had an alpha of .884 showing good internal consistency.

To further examine this sample, we examined suggested cut-off scores for the measures

used in this study. For the Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), Lewinsohn and

colleagues (1977) suggest a cut-off score of 16 or greater using the original scoring of the

assessment to identify individuals who are at risk for clinical depression. Unlike original scoring

methods, which ranges from 0 – 3, this sample used scores from a Likert scale ranging from 1 –

4, so the new converted cut-off score is 36. Using this cut-off score, 96 (94%) participants fall

within the “at risk” category. Therefore, we would predict this sample reports high levels of

depression symptoms.

There are no suggested cut-off scores to determine a potential problematic level of social

comparison. Thus, we have further examined the scores in this sample on the Iowa Netherlands

Comparison Scale. Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree)

to 5 (Strongly agree). When looking at items that compare one’s lifestyle to others, the individual

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 26

item means range from 3.73 (“If I want to find out how well I have done something, I compare

what I have done with how others have done.”) to 3.92 (“I often compare myself with others

with respect to what I have accomplished in life.”). When looking at items that compare one’s

own thoughts and feelings to those of others, the item mean ranges from 3.71 (“I often like to

talk with others about mutual opinions and experiences.”) to 3.87 (“I always like to know what

others in a similar situation would do.”). Therefore, we would presume that the participants in

our sample reported relatively moderate to high levels of social comparison.

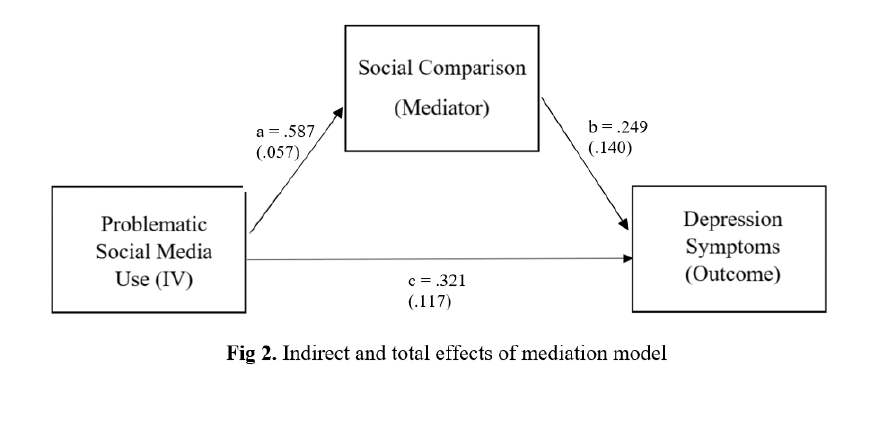

Mediation Analyses

The hypothesis was supported. This study expected social comparison would mediate the

relationship between social media use and depression symptoms in Hypothesis 1 (Table 2). To

determine if there was a predictive utility between problematic social media use and depression

symptoms', and that social comparison mediated this relationship, a Baron and Kenny test for

mediation was performed (Baron and Kenny, 1986).

Step 1 of this model requires a relationship between the causal variable (problematic

social media use) and the outcome variable (depression symptoms). A multiple regression

analysis indicated that social media use was predictive of depression symptoms in this sample, β

= .47, p < .001.

Step 2 of this model requires a relationship between the casual variable (problematic

social media use) and the mediator (social comparison). Results from this multiple regression

indicate that social media use was predictive of social comparison in this sample, β = .59, p <

.001.

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 27

Step 3 examined the effect between the mediator (social comparison) as the casual

variable and problematic social media use as a predictor with the outcome variable (depression

symptoms). Results show that as social comparison increased, depression symptoms also

increased in this sample, β = .25, p = .078. Although the test is not significant, the coefficient is a

nonzero value and steps 1 and 2 were shown to be statistically significant (Kenny, 2021).

Step 4 looked at whether the relationship between the casual variable (problematic social

media use) and the outcome variable (depression symptoms) is completely mediated (β = 0) or

partially mediated (β ≠ 0) by social comparison. In this sample, results indicate the relationship

between social media use and depression symptoms while controlling social comparison was not

zero, β = .32, p = .007. Therefore, social comparison partially mediates the relationship between

social media use and depression symptoms. The amount of mediation was .15. The role of the

Sobel test is to determine if the effect of the mediator (social comparison) is significant when the

effect of the independent variable (problematic social media use) is reduced by including the

mediator. According to Sobel’s test, the partial mediation was statistically significant, Z = 2.08, p

= .037.

Indirect effect: β = .15, p = .037

Direct effect: β = .32, p = .007

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 28

Discussion

This study aimed to examine the underlying mechanisms of depression symptoms in

college students and if problematic social media use and social comparison are related to the

onset of symptoms. With the rise in use of social media sites, especially through the Covid-19

pandemic, the rates of depression are also increasing. Although this is not a new topic of

research, the college student population has less research in this topic, yet they have the fastest

increase of depression rates, which will be discussed in this section and how social comparison

contributes to this relationship.

The hypothesis in this study was predicting the relationship between problematic social

media use and depression students would be mediated by social comparison in college-aged

students. The results found a relationship between problematic social media use and depression

symptoms and that social comparison partially mediated this relationship. This is consistent with

previous research, which includes having tendencies to ruminate on comparing one’s life to

another while also having problematic social media use behaviors (Feinstein et al., 2013; Yang et

al., 2018). This study also found college students are more likely to exhibit social comparison

behaviors, similarly to the results found in this study. This is likely a result of students going

through transition periods which lead to comparing other’s success to their own. This also may

be explained due to the isolation that people have experienced throughout the past two years of

the Covid-19 pandemic. Students have been required to take online classes for multiple

semesters, leading to a decrease in social interactions. The effects of the pandemic may be a

variable to look at in future studies.

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 29

Study Limitations

There are limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results of this study.

The first limitation is that this study is social media use was measured through a self-report

method, which relies on self-perception of one's own social media use. Specifically, participants

may not be able to assess their social media use accurately. In addition, participants may struggle

with reporting honest answers and may exaggerate responses or find it embarrassing to reveal

true facts about themselves.

Another limitation of this study is the use of the data collection source, Amazon

Mechanical Turk (MTurk). Participants who complete these surveys are rewarded with receiving

a determined amount of money and are motivated to complete these surveys in order to receive

their reward. Due to this, participants are likely to complete the study quickly without putting

much time or thought into each item.

In addition, other underlying causal factors that are not measured here are a limitation of

this study. As previous research has shown, there may be other mediating factors that could

influence the correlation between problematic social media use and the onset of depression

symptoms. For example, other factors such as the quality of sleep an individual is getting or the

age the individual began using social media have been shown to be variables involved in this

relationship (Zou et al., 2019; Reihm et al., 2019). This study did not consider other factors such

as these in the surveys and data collection.

Finally, the results could have been affected due to being conducted online during the

Covid-19 global pandemic in Summer 2022. This has resulted in an increase in both social media

use and mental health issues, especially for those who have lost employment and social

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 30

connection due to the pandemic. Individuals have spent more time at home than before the

pandemic due to loss of employment or new work from home orders, which decreases healthy

social functioning. Additionally, many people have sought out social connectivity through social

media platforms, increasing the need and use for social media sites.

Clinical Implications

A rise in rates of depression symptoms and episodes have been occurring in the college

age range population, especially since the Covid-19 pandemic. These symptoms can cause

significant psychological distress in individuals who are experiencing them and their supports.

This study suggests that a focus on decreasing problematic social media use could be beneficial

for symptom management. To replace these habits, individuals can benefit from increasing their

in-person social connectivity as they find it safe. In addition, learning new coping skills for

dealing with the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic could help to decrease the time they spend

online engaging in social comparison behaviors.

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 31

References

Aalbers, G., McNally, R. J., Heeren, A., De Wit, S., & Fried, E. I. (2019). Social media and

depression symptoms: A network perspective. Journal of Experimental Psychology:

General, 148(8), 1454

Ajjan, H., Cao, Y., & Hartshorne, R. (2019). How compulsive social media use influences

college students' performance: a structural equation analysis with gender

comparison. International Journal of Learning Technology, 14(1), 18-41.

Aldrich, Anna Z. (2022, June 24). Finding social support through social media during COVID

lockdowns. UConn Today. https://today.uconn.edu/2022/06/finding-social-support-

through-social-media-during-covid-lockdowns/

Al-Menayes, J. (2014). The relationship between mobile social media use and academic

performance in university students. New Media and Mass Communication, 25, 23-29.

Amin, Z., Mansoor, A., Hussain, S. R., & Hashmat, F. (2016). Impact of social media of

student’s academic performance. International Journal of Business and Management

Invention, 5(4), 22-29.

Auxier, B. & Anderson, M. (2021). Social Media use in 2021. Pew Research Center.

Banjanin, N., Banjanin, N., Dimitrijevic, I., & Pantic, I. (2015). Relationship between internet

use and depression: Focus on physiological mood oscillations, social networking and

online addictive behavior. Computers in Human Behavior, 43, 308-312.

Bányai, F., Zsila, Á., Király, O., Maraz, A., Elekes, Z., Griffiths, M. D., ... & Demetrovics, Z.

(2017). Problematic social media use: Results from a large-scale nationally

representative adolescent sample. PloS one, 12(1), e0169839.

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 32

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social

psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of

personality and social psychology, 51(6), 1173.

Bishop, M. (2019). Healthcare social media for consumer. In Edmunds M, Hass C, Holve E,

eds. Consumer informatics and digital health: solutions for health and health care. Cham,

Switzerland: Springer, pp. 61–86.

Boyle, S. C., LaBrie, J. W., Froidevaux, N. M., & Witkovic, Y. D. (2016). Different digital

paths to the keg? How exposure to peers' alcohol-related social media content influences

drinking among male and female first-year college students. Addictive behaviors, 57, 21-

29.

Brooks, Christopher D, & Pomerantz, Jeffrey. (2017) ECAR Study of Undergraduate Students

and Information Technology, EDUCAUSE Research.

Buunk, B.P., Collins, R.L., Taylor, S.E., Van Yperen, N., & Dakof, G.A. (1990). The affective

consequences of social comparison: Either direction has its ups and downs. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 1238–1249.

Cabral, J. (2008). Is generation Y addicted to social media? Future of Children, 2(1), 5-14.

Chae, J. (2017). Virtual makeover: Selfie-taking and social media use increase selfie-editing

frequency through social comparison. Computers in Human Behavior, 66, 370-376.

Cheng, J., Burke, M., & Davis, E. G. (2019). Understanding perceptions of problematic

Facebook use: When people experience negative life impact and a lack of control.

In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp.

1-13).

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 33

Choi SW, Schalet B, Cook KF, & Cella D. (2014). Establishing a common metric for depressive

symptoms: linking the BDI-II, CES-D, and PHQ-9 to PROMIS depression.

Psychological Assessment.; 26:513–27.

Chou, H.-T. G., & Edge, N. (2012). They are happier and having better lives than i am: The

impact of using facebook on perceptions of others’ lives. Cyberpsychology, Behavior,

and Social Networking, 15(2), 117–121.

Christakis, D. A., Moreno, M. M., Jelenchick, L., Myaing, M. T., & Zhou, C. (2011).

Problematic internet usage in US college students: a pilot study. BMC Medicine, 9(1), 1-

6.

Collins, R.L. (2000). Among the better ones: Upward assimilation in social comparison. In J.

Suls & L. Wheeler (Eds.), Handbook of social comparison (pp. 159–172). New York:

Kluwer Academic/Plenum.

DeAndrea, D. C., Ellison, N. B., LaRose, R., Steinfield, C., & Fiore, A. (2012). Serious social

media: On the use of social media for improving students' adjustment to college. The

Internet and Higher Education, 15(1), 15-23.

Dibb, B., & Foster, M. (2021). Loneliness and Facebook use: the role of social comparison and

rumination. Heliyon, 7(1), e05999.

Dixon, S. (2022, Feb 8). Social media use during Covid-19 worldwide – statistics and facts.

Statistica. https://www.statista.com/topics/7863/social-media-use-during-coronavirus-

covid-19-worldwide/#dossierKeyfigures

Elphinston, R. A., & Noller, P. (2011). Time to face it! Facebook intrusion and the implications

for romantic jealousy and relationship satisfaction. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and

Social Networking, 14(11), 631-635.

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 34

Erçağ, E., Soykan, E., & Kanbul, S. (2019). Determination of the relationship between social

media addictions and smart phone addictions of university students. Religación, 4, 70-

79.

Feinstein, B. A., Hershenberg, R., Bhatia, V., Latack, J. A., Meuwly, N., & Davila, J. (2013).

Negative social comparison on Facebook and depressive symptoms: Rumination as a

mechanism. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 2(3), 161.

Fernandes, Blossom, Bilge Uzun, Caner Aydin, Roseann Tan-Mansukhani, Alma Vallejo,

Ashley Saldaña-Gutierrez, Urmi Nanda Biswas, and Cecilia A. Essau. "Internet use

during COVID-19 lockdown among young people in low-and middle-income countries:

Role of psychological wellbeing." Addictive Behaviors Reports 14 (2021): 100379.

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7(2), 117–140.

Gibbons, F. X., & Buunk, B. P. (1999). Individual differences in social comparison:

Development of a scale of social comparison orientation. Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology, 76(1), 129–142.

Greenwood, S., Perrin, A., & Duggan, M. (2016). Social media update 2016. Pew Research

Center, 11(2), 1-18.

Hajek, A., & König, H. H. (2019). The association between use of online social networks sites

and perceived social isolation among individuals in the second half of life: results based

on a nationally representative sample in Germany. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1-7.

Hankin, B. L., Abramson, L. Y., Moffitt, T. E., Silva, P. A., McGee, R., & Angell, K. E. (1998).

Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: emerging gender

differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 107(1),

128.

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 35

Hawi, N. S., & Samaha, M. (2017). The relations among social media addiction, self-esteem,

and life satisfaction in university students. Social Science Computer Review, 35(5), 576-

586.

Hou, Y., Xiong, D., Jiang, T., Song, L., & Wang, Q. (2019). Social media addiction: Its impact,

mediation, and intervention. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on

Cyberspace, 13(1).

Jiang, S., & Ngien, A. (2020). The Effects of Instagram Use, Social Comparison, and Self-

Esteem on Social Anxiety: A Survey Study in Singapore. Social Media+ Society, 6(2),

2056305120912488.

Just, N., & Alloy, L. B. (1997). The response styles theory of depression: tests and an extension

of the theory. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106(2), 221.

Kim, B., & Kim, Y. (2017). College students’ social media use and communication network

heterogeneity: Implications for social capital and subjective well-being. Computers in

Human Behavior, 73, 620-628.

Kitsantas, T., Chirinos, D. S., Hiller, S. E., & Kitsantas, A. (2016). An examination of Greek

college students’ perceptions of positive and negative effects of social networking use.

In Social Networking and Education (pp. 129-143). Springer, Cham.

Keles, B., McCrae, N., & Grealish, A. (2020). A systematic review: the influence of social

media on depression, anxiety and psychological distress in adolescents. International

Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 25(1), 79-93.

Kenny, David A. (2021, May 4). Mediation. Davidakenny.net.

https://davidakenny.net/cm/mediate.htm

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 36

Király, O., Potenza, M. N., Stein, D. J., King, D. L., Hodgins, D. C., Saunders, J. B., ... &

Demetrovics, Z. (2020). Preventing problematic internet use during the COVID-19

pandemic: Consensus guidance. Comprehensive psychiatry, 100, 152180.

Koval, P., Kuppens, P., Allen, N. B., & Sheeber, L. (2012). Getting stuck in depression: The

roles of rumination and emotional inertia. Cognition & Emotion, 26(8), 1412-1427.

Kross, E., Verduyn, P., Demiralp, E., Park, J., Lee, D. S., Lin, N., et al. (2013). Facebook use

predicts declines in subjective well-being in young adults. PloS One, 8(8), e69841.

Landry, M. (2015). The Effects of Social Media: Is It Hurting College Students?. Perspectives,

7(1), 3.

Lewinsohn, P.M., Seeley, J.R., Roberts, R.E., & Allen, N.B. (1997). Center for Epidemiological

Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) as a screening instrument for depression among

community-residing older adults. Psychology and Aging, 12, 277- 287.

Lin, L. Y., Sidani, J. E., Shensa, A., Radovic, A., Miller, E., Colditz, J. B., ... & Primack, B. A.

(2016). Association between social media use and depression among US young

adults. Depression and Anxiety, 33(4), 323-331.

Liu, D. Y., Gilbert, K. E., & Thompson, R. J. (2019). Emotion differentiation moderates the

effects of rumination on depression: A longitudinal study. Emotion.

Liu, Q. Q., Zhou, Z. K., Yang, X. J., Kong, F. C., Niu, G. F., & Fan, C. Y. (2017). Mobile phone

addiction and sleep quality among Chinese adolescents: A moderated mediation

model. Computers in Human Behavior, 72, 108-114.

Locatelli, S. M., Kluwe, K., & Bryant, F. B. (2012). Facebook use and the tendency to ruminate

among college students: Testing mediational hypotheses. Journal of Educational

Computing Research, 46(4), 377-394.

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 37

Mahmoud, J. S. R., Staten, R. T., Hall, L. A., & Lennie, T. A. (2012). The relationship among

young adult college students’ depression, anxiety, stress, demographics, life satisfaction,

and coping styles. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 33(3),149–156.

Masaeli, N., & Farhadi, H. (2021). Prevalence of Internet-based addictive behaviors during

COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Journal of addictive diseases, 39(4), 468-

488.

Mastrodicasa, J., & Metellus, P. (2013). The impact of social media on college students. Journal

of College and Character, 14(1), 21-30.

Maulik, P., Eaton, W., & Bradshaw, C. (2011). The effect of social networks and social support

on mental health services use, following a life event, among the Baltimore epidemiologic

catchment area cohort. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 38(1),

2950.

McCarthy, P. A., & Morina, N. (2020). Exploring the association of social comparison with

depression and anxiety: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Clinical Psychology &

Psychotherapy, 27(5), 640-671.

Mojtabai, R., Olfson, M., & Han, B. (2016). National trends in the prevalence and treatment of

depression in adolescents and young adults. Pediatrics, 138(6).

Moreno, M. A., Jelenchick, L. A., Koff, R., Eickhoff, J. C., Goniu, N., Davis, A., ... &

Christakis, D. A. (2013). Associations between internet use and fitness among college

students: an experience sampling approach. Journal of Interaction Science, 1(1), 1-8.

Morrison, C. M., & Gore, H. (2010). The relationship between excessive Internet use and

depression: a questionnaire-based study of 1,319 young people and

adults. Psychopathology, 43(2), 121-126.

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 38

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1991). Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of

depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(4), 569–582.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2004). The response styles theory. Depressive rumination, 107.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Morrow, J. (1991). A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic

stress symptoms after a natural disaster: the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 61(1), 115.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Wisco, B. E., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). Rethinking rumination.

Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(5), 400-424.

Okeeffe, G. S., & Clarke-Pearson, K. (2011). The impact of social media on children,

adolescents, and families. Pediatrics, 127(4), 800–804.

Park, J., Lee, D. S., Shablack, H., Verduyn, P., Deldin, P., Ybarra, O., ... & Kross, E. (2016).

When perceptions defy reality: the relationships between depression and actual and

perceived Facebook social support. Journal of Affective Disorders, 200, 37-44.

Perrin, A. (2015). Social media usage: 2005–2015. Retrieved from

http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/10/08 /social-networking-usage-2005-2015/.

Perrin, Andrew & Atske, Sara. (2021). About three-in-ten U.S. adults say they are ‘almost

constantly’ online. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-

tank/2021/03/26/about-three-in-ten-u-s-adults-say-they-are-almost-constantly-online/

Pew Research Center. (2021). Social Media Fact Sheet. Pew Research Center.

https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/social-media/

Preacher, Kristopher J. & Leonardelli, Geoffrey J. (2022) Calculation for the Sobel test: An

interactive calculation tool for mediation tests. Behavior Research Methods.

http://quantpsy.org/sobel/sobel.htm

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 39

Primack, B. A., Shensa, A., Sidani, J. E., Whaite, E. O., yi Lin, L., Rosen, D., ... & Miller, E.

(2017). Social media use and perceived social isolation among young adults in the

US. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 53(1), 1-8.

Qiu, L., Lin, H., Leung, A. K., & Tov, W. (2012). Putting their best foot forward: Emotional

disclosure on Facebook. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 15(10),

569-572.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the

general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385-401.

Riehm, K. E., Feder, K. A., Tormohlen, K. N., Crum, R. M., Young, A. S., Green, K. M., ... &

Mojtabai, R. (2019). Associations between time spent using social media and

internalizing and externalizing problems among US youth. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(12),

1266-1273.

Salehan, M., & Negahban, A. (2013). Social networking on smartphones: When mobile phones

become addictive. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(6), 2632-2639.

Schneider, S. M., & Schupp, J. (2014). Individual differences in social comparison and its

consequences for life satisfaction: introducing a short scale of the Iowa–Netherlands

Comparison Orientation Measure. Social Indicators Research, 115(2), 767-789.

Schoemann, A. M., Boulton, A. J., & Short, S. D. (2017). Determining power and sample size

for simple and complex mediation models. Social Psychological and Personality

Science, 8(4), 379-386.

Shaw, L. H., & Gant, L. M. (2004). In defense of the Internet: The relationship between Internet

communication and depression, loneliness, self-esteem, and perceived social

support. European Journal of Marketing, 54(7).

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 40

Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies:

New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7, 422-445.

Shensa, A., Escobar-Viera, C. G., Sidani, J. E., Bowman, N. D., Marshal, M. P., & Primack, B.

A. (2017). Problematic social media use and depressive symptoms among US young

adults: A nationally-representative study. Social Science & Medicine, 182, 150-157.

Siddiqui, S., & Singh, T. (2016). Social media its impact with positive and negative

aspects. International Journal of Computer Applications Technology and Research, 5(2),

71-75.

Sobel, M. E. (1982). Asymptotic intervals for indirect effects in structural equations models. In

S. Leinhart (Ed.), Sociological methodology 1982 (pp.290-312). San Francisco: Jossey-

Bass.

Starcevic, V. (2013). Is Internet addiction a useful concept?. Australian & New Zealand Journal

of Psychiatry, 47(1), 16-19.

Subrahmanyam, K., Reich, S. M., Waechter, N., & Espinoza, G. (2008). Online and offline

social networks: Use of social networking sites by emerging adults. Journal of Applied

Developmental Psychology, 29(6), 420-433.

Spasojevic, J. E. L. E. N. A., Alloy, L. B., Abramson, L. Y., Maccoon, D., & Robinson, M. S.

(2004). Reactive rumination: Outcomes, mechanisms, and developmental

antecedents. Depressive rumination: Nature, theory and treatment, 43-58.

Talaue, G. M., AlSaad, A., AlRushaidan, N., AlHugail, A., & AlFahhad, S. (2018). The impact

of social media on academic performance of selected college students. International

Journal of Advanced Information Technology, 8(4/5), 27-35.

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 41

Twenge, J. M., Joiner, T. E., Rogers, M. L., & Martin, G. N. (2018). Increases in depressive

symptoms, suicide-related outcomes, and suicide rates among U.S. adolescents after

2010 and links to increased new media screen time. Clinical Psychological Science, 6(1),

3–17.

Vogel, E. A., Rose, J. P., Roberts, L. R., & Eckles, K. (2014). Social comparison, social media,

and self-esteem. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 3(4), 206.

Vogel, E. A., Rose, J. P., Okdie, B. M., Eckles, K., & Franz, B. (2015). Who compares and

despairs? The effect of social comparison orientation on social media use and its

outcomes. Personality and Individual Differences, 86, 249-256.

Wang, Y., Niiya, M., Mark, G., Reich, S. M., & Warschauer, M. (2015). Coming of Age

(Digitally) An Ecological View of Social Media Use among College Students.

In Proceedings of the 18th ACM conference on computer supported cooperative work &

social computing (pp. 571-582).

Wang, R., Wang, W., DaSilva, A., Huckins, J. F., Kelley, W. M., Heatherton, T. F., &

Campbell, A. T. (2018). Tracking depression dynamics in college students using mobile

phone and wearable sensing. Proceedings of the ACM on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable

and Ubiquitous Technologies, 2(1), 1-26.

Wang, P., Wang, X., Wu, Y., Xie, X., Wang, X., Zhao, F., ... & Lei, L. (2018). Social

networking sites addiction and adolescent depression: A moderated mediation model of

rumination and self-esteem. Personality and Individual Differences, 127, 162-167.

Whaite, E. O., Shensa, A., Sidani, J. E., Colditz, J. B., & Primack, B. A. (2018). Social media

use, personality characteristics, and social isolation among young adults in the United

States. Personality and Individual Differences, 124, 45-50.

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 42

Wheeler, L., & Miyake, K. (1992). Social comparisons in everyday life. Journal of Personality

and Social Psychology, 62, 760–773.

Wilkinson, P. O., Croudace, T. J., & Goodyer, I. M. (2013). Rumination, anxiety, depressive

symptoms and subsequent depression in adolescents at risk for psychopathology: a

longitudinal cohort study. BMC Psychiatry, 13(1), 1-9.

Wood, J. V. (1996). What is social comparison and how should we study it?. Personality and

Social Psychology Bulletin, 22(5), 520-537.

Wood, J. V., Giordano-Beech, M., Taylor, K. L., Michela, J. L., & Gaus, V. (1994). Strategies

of social comparison among people with low self-esteem: Self-protection and self-

enhancement. Journal of personality and social psychology, 67(4), 713.

Yang, C. C., Holden, S. M., Carter, M. D., & Webb, J. J. (2018). Social media social

comparison and identity distress at the college transition: A dual-path model. Journal of

Adolescence, 69, 92-102.

Yang, C. C., Carter, M. D., Webb, J. J., & Holden, S. M. (2020). Developmentally salient

psychosocial characteristics, rumination, and compulsive social media use during the

transition to college. Addiction Research & Theory, 28(5), 433-442.

Yoo, W., Yang, J., & Cho, E. (2016). How social media influence college students’ smoking

attitudes and intentions. Computers in Human Behavior, 64, 173-182.

Zou, L., Wu, X., Tao, S., Xu, H., Xie, Y., Yang, Y., & Tao, F. (2019). Mediating effect of sleep

quality on the relationship between problematic mobile phone use and depressive

symptoms in college students. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 822.

Zuschlag, M. K., & Whitbourne, S. K. (1994). Psychosocial development in three generations of

college students. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 23(5), 567-577.

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 43

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics of Study Variables

M

SD

Possible

Range

Observed

Range

α

Problematic Social Media Use

29.25

4.62

8 - 64

16 - 40

.696

Social Comparison

41.94

5.10

5 - 55

26 - 50

.699

Depression Symptoms

53.57

10.23

20 - 80

29 - 73

.884

Note. Problematic Social Media Use = Facebook Intrusion Questionnaire (FIQ); Social Comparison =

Iowa Netherlands Comparison Scale (INCOS); Depression Symptoms = Epidemiological Studies

Depression Scale (CES-D)

Table 2. Mediation Indirect and Total Effects for Hypothesis

Type

Effect

SE

β

p

Indirect

Problematic Social Media Use and Depression

Symptoms

.07

.15

.037

Component

Problematic Social Media Use => Social Comparison

Social Comparison => Depression Symptoms

.06

.14

.59

.25

< .001

.078

Direct

Problematic Social Media Use => Depression

Symptoms

.12

.32

.007

Total

Problematic Social Media Use => Depression

Symptoms

.08

.47

<.001

Table 3. Correlations between variables (N = 102)

Variable

FIQ

INCOS

CES-D

FIQ

--

.72*

.52*

INCOS

--

.48*

CES-D

--

Note. Facebook Intrusion Questionnaire = FIQ, Iowa Netherlands Comparison Scale = INCOS,

Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale = CES-D

* p < .001

PROBLEMATIC SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION 44

Appendix A

Facebook Intrusion Questionnaire (Elphinston & Noller, 2011)

*Answers: 7-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree, 2= disagree, 3= slightly disagree, 4=neutral,

5=slightly agree, 6=agree, 7=strongly agree)

1. I often think about social media [Facebook] when I am not using it.

2. I often use social media [Facebook] for no particular reason.