The Texas Medical Center Library The Texas Medical Center Library

DigitalCommons@TMC DigitalCommons@TMC

Dissertations & Theses (Open Access) School of Public Health

Summer 5-2019

The Relationship Between Social Media Use And Depression In The Relationship Between Social Media Use And Depression In

College Students: A Scoping Review College Students: A Scoping Review

Susan Wu

UTHealth School of Public Health

Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/uthsph_dissertsopen

Part of the Community Psychology Commons, Health Psychology Commons, and the Public Health

Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Wu, Susan, "The Relationship Between Social Media Use And Depression In College Students: A Scoping

Review" (2019).

Dissertations & Theses (Open Access)

. 100.

https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/uthsph_dissertsopen/100

This is brought to you for free and open access by the

School of Public Health at DigitalCommons@TMC. It has

been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations & Theses

(Open Access) by an authorized administrator of

DigitalCommons@TMC. For more information, please

contact digcommons@library.tmc.edu.

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION

IN COLLEGE STUDENTS: A SCOPING REVIEW

by

SUSAN WU, BS

APPROVED:

ACADEMIC ADVISOR AND CULMINATING

EXPERIENCE SUPERVISOR

ADRIANA PEREZ, MS, PhD

CHRISTINE MARKHAM, PhD

Copyright

by

Susan Wu, BS, MPH

2019

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION

IN COLLEGE STUDENTS: A SCOPING REVIEW

by

SUSAN WU

ECOLOGY AND EVOLUTIONARY BIOLOGY BS,

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Cruz, 2012

Presented to the Faculty of The University of Texas

School of Public Health

in Partial Fulfillment

of the Requirements

for the Degree of

MASTER OF PUBLIC HEALTH

THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS

SCHOOL OF PUBLIC HEALTH

Houston, Texas

May, 2019

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SOCIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION

IN COLLEGE STUDENTS: A SCOPING REVIEW

Susan Wu, BS, MPH

The University of Texas

School of Public Health, 2019

Thesis Chair: Adriana Pérez, MS, PhD

Background: In 2017, 17.3 million adults in the U.S. (7.1% of all U.S. adults) have had at least

one major depressive episode, with individuals ages 18-25 having the highest prevalence of

major depression at 13.1%. Studies have looked at the association between social media (SM)

use and depression with mixed findings. The goal of this research is to conduct a scoping review

of existing evidence for the relationship between SM use and depression among college students.

Methods: Searches for articles published in the scientific literature were performed on PubMed,

Embase and Scopus. Articles selected followed an inclusion criteria: studied SM use and

depression in college students over 18 years, were written in English, were published between

October 2013 and October 2018, studied time spent on SM, addiction to SM and/or different SM

behaviors and were cross-sectional, observational, longitudinal or intervention studies. Articles

were screened and imported into citation manager Refworks for duplicate removal. Full-text

articles were found through Pubmed, Embase, Scopus or Google Scholar for eligibility

screening. Articles needing to be purchased were requested through interlibrary loan or

requested from authors.

Results: 14 articles met inclusion criteria; 92.9% were cross-sectional. Half of the articles

measured time spent on SM (including daily hours and frequency), with mixed findings; 42.9%

of articles studied SM addiction, with all studies presenting a significantly positive association

with depression. Over sixty percent (64%) of the articles studied specific SM behaviors, with

mixed findings. Included articles presented a larger correlation between individual

characteristics (e.g. neuroticism, loneliness, suicidal ideation, self-esteem and academic

stressors) and SM addiction and depression than time spent on SM and SM behaviors. The odds

of SM addiction and depression were 40% higher in college students in China than in the U.S

and the risk of SM addiction and depression in college students was found to be 28% higher in

Hong Kong (HK)/Macau and 12% higher in Japan than in the U.S. Only one randomized

controlled trial was identified in this scoping review. After 2 weeks, statistically significant

reductions were observed in both SM addiction and depression through mean rank comparisons

of before and after treatment.

Conclusion: This review reiterated the need for longitudinal studies to access directionality and

the need to standardize measures used to measure social media, depression in college students.

Future studies could continue to focus on the relationship between individual characteristics (i.e.

loneliness, neuroticism and self-esteem), SM addiction, SM comparison and depression and

further study RCTs utilizing treatment periods longer than 2-weeks.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

List of Tables ............................................................................................................................. i

List of Figures ........................................................................................................................... ii

Background ............................................................................................................................... i

Literature Review ................................................................................................................1

Public Health Significance ...................................................................................................4

Hypothesis, Research Question, Specific Aims or Objectives ............................................5

Methods......................................................................................................................................5

Search Strategy ....................................................................................................................5

Eligibility Criteria ................................................................................................................6

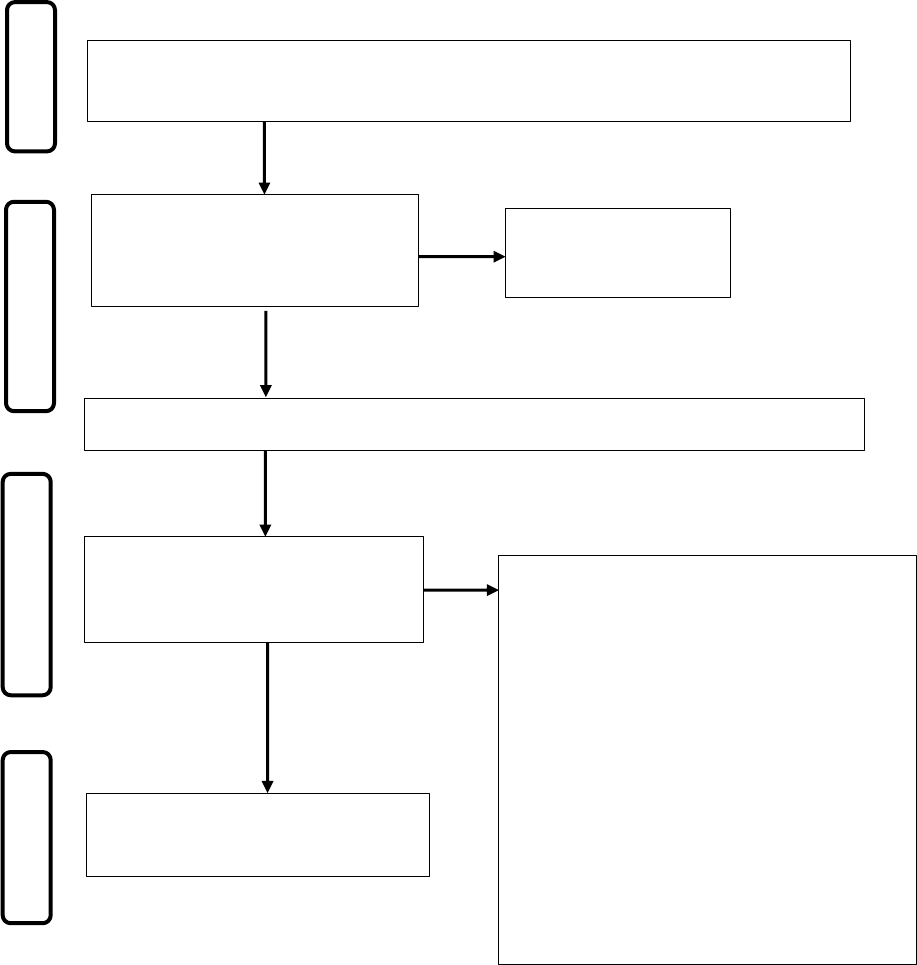

Documentation of Results ....................................................................................................8

Results ........................................................................................................................................9

Discussion ................................................................................................................................16

Conclusion ...............................................................................................................................20

References ................................................................................................................................34

i

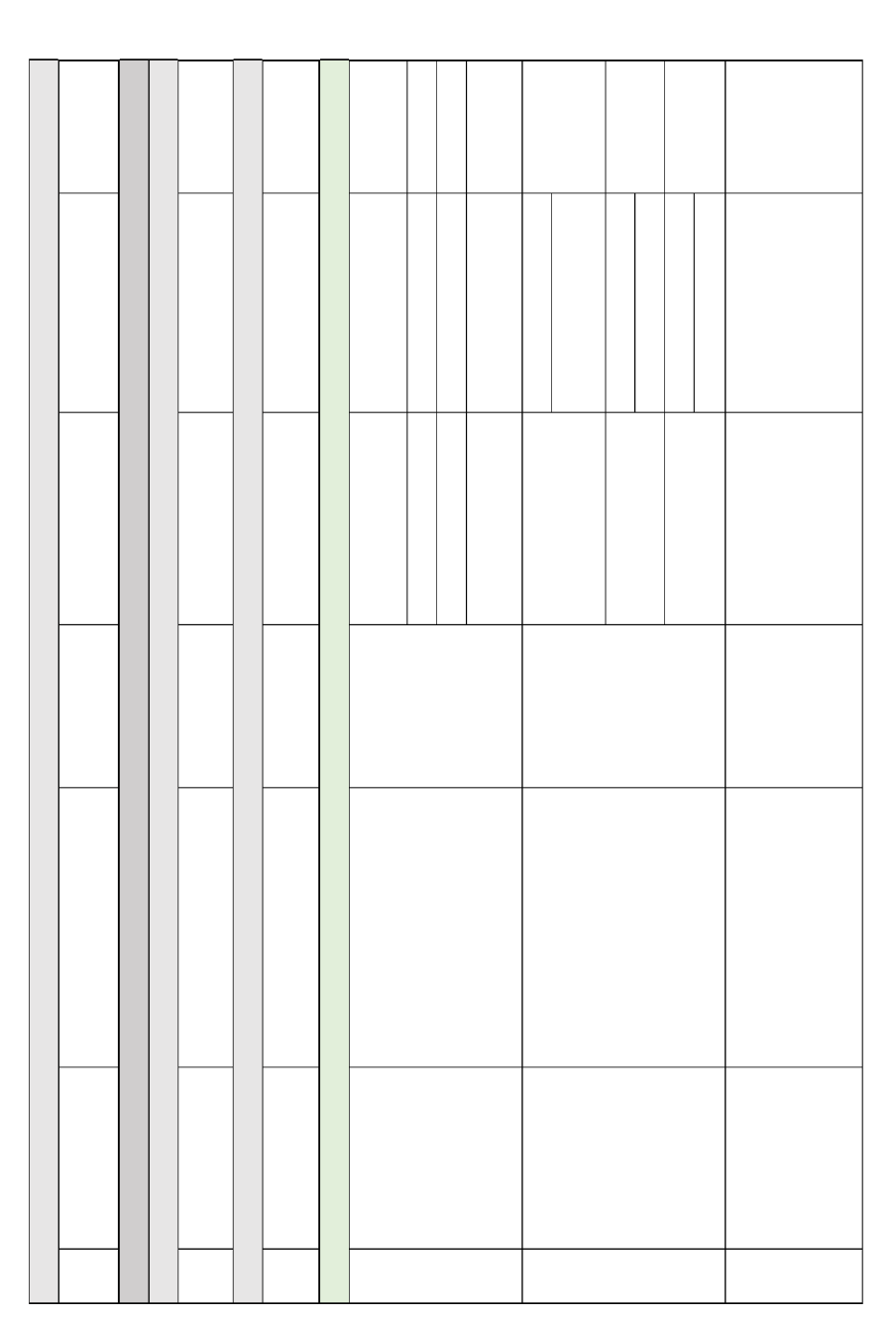

LIST OF TABLES

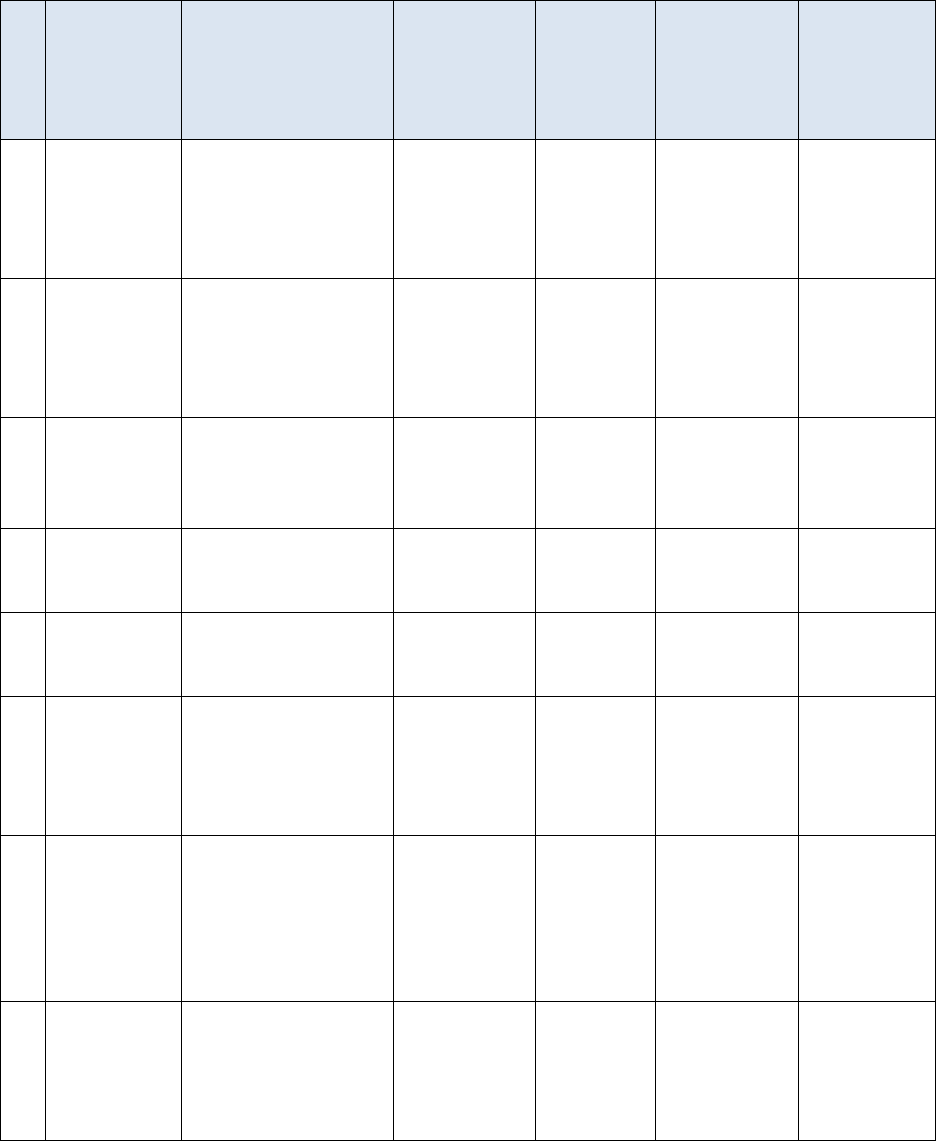

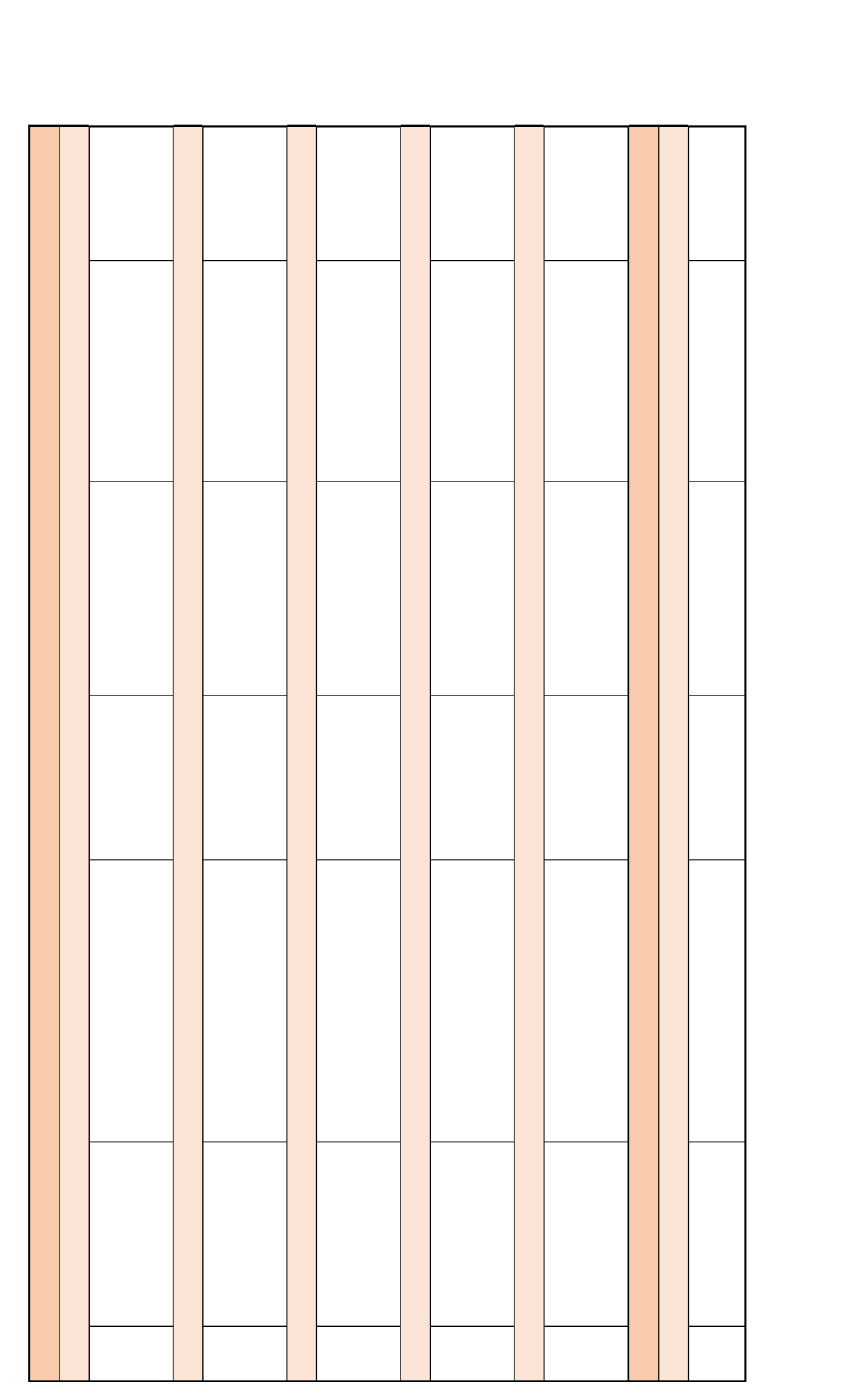

Table 1: Search terms used for the scoping review by main key concepts………………………..6

Table 2: Study inclusion/exclusion criteria of articles for this scoping review on social media and

depression in college students……………………………………………………………………..7

Table 3: Characteristics of Articles Included in this Scoping Review…………………………..23

Table 4: Measurements used in Included Articles to Access Social Media Use and Depression.25

Table 5: Statistics of Social Media Use and Depression/Mental Health/Well-being in College

Students from Scoping Review…………………………………………………………………..27

Table 6: Association between Time on SM, SM Addiction and SM Behaviors and Depression

and Significance………………………………………………………………………………….33

ii

LIST OF FIGURES

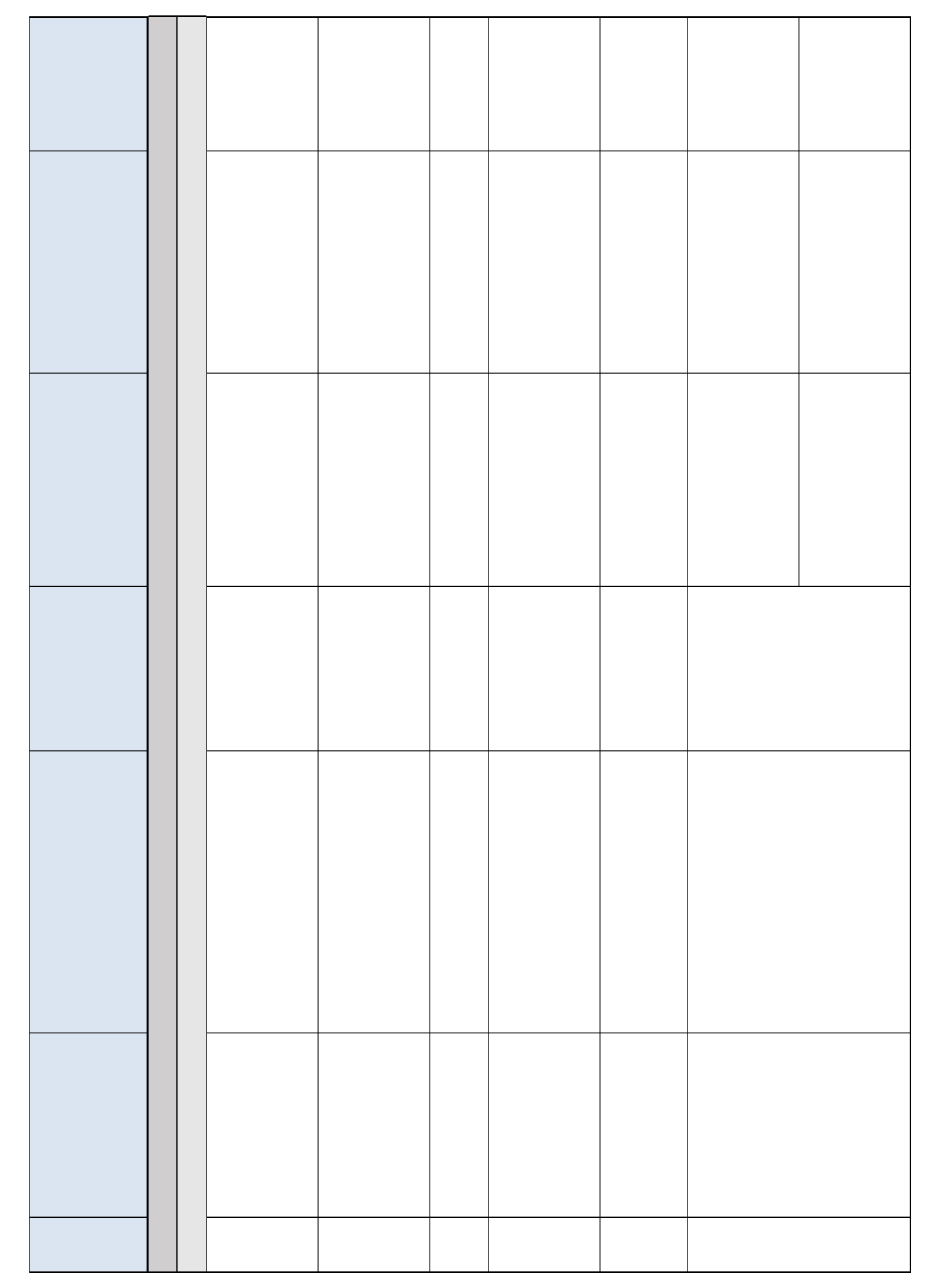

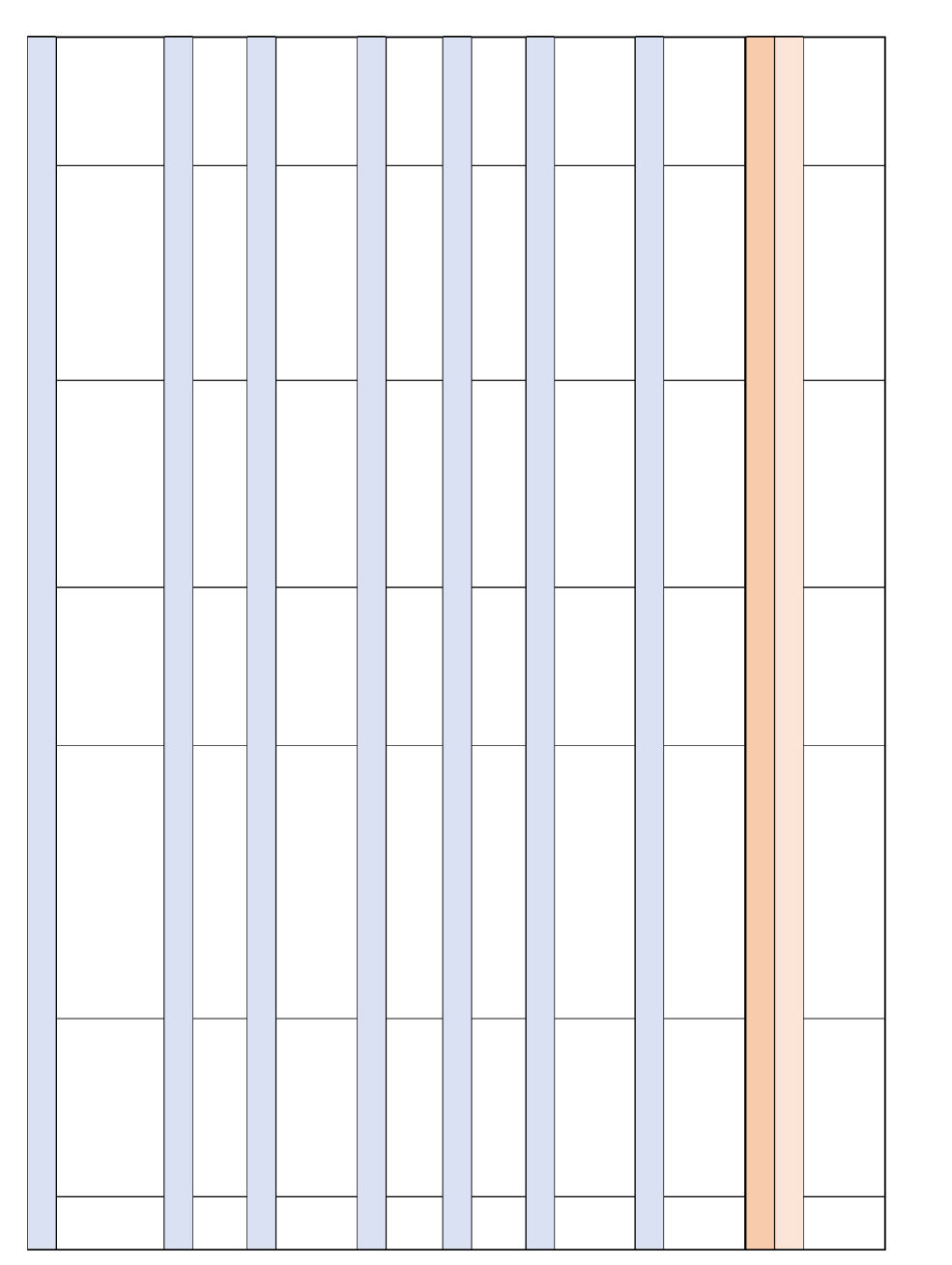

Figure 1: Flowchart of Scoping Review Process of Social Media and Depression in College

Students…………………………………………………………………………………….22

1

BACKGROUND

Literature Review

Depression

In the United States, between 2009 and 2012, 7.6% of people ages 12 and older had self-reported

depression, with depression defined as a serious medical illness with mood, cognitive, and

physical symptoms (Depression in the U.S. Household Population, 2014). According to the

National Institute of Mental Health, major depression is defined as one of the most common

mental disorders in the United States, and for some individuals, can result in severe impairments

that interfere with or limit one’s ability to carry out major life activities (Major Depression, n.d.).

In 2017, 17.3 million adults (7.1% of all U.S. adults) have had at least one major depressive

episode, with individuals ages 18-25 having the highest prevalence of major depression at 13.1%

(Major Depression, n.d.). Depression is the leading cause of disability worldwide, and is a major

contributor to the overall global burden of disease (Depression, 2018

b

). Decreased energy or

fatigue, loss of interest or pleasure in hobbies and activities and difficulty concentrating,

remembering, or making decisions are only some of the signs and symptoms an individual who

is depressed might experience (Depression, 2018

a

). In addition, Health Direct states “Good

mental health is more than just the absence of mental illness. A positive state of wellbeing

includes feeling good and functioning well (Good Mental Health, 2017).” To promote mental

and emotional well-being, the Surgeon General recommends “facilitating social connectedness

and community engagement across the lifespan” and “building strong, positive relationships with

family and friends (Mental and Emotional Well-being, n.d.).”

2

Social Media

Merriam-Webster (2004) defines social media as “forms of electronic communication (such as

websites for social networking and microblogging) through which users create online

communities to share information, ideas, personal messages, and other content (such as videos)

(Social Media, 2004).” With the popularity of social media applications (i.e. Facebook, Twitter,

Instagram, Snapchat and Youtube) (Smith & Anderson, 2018), people are now able to see status

updates of those they follow, which may generate feelings such as “fear of missing out” (FoMO)

or becoming envious (Zimmerman, n.d.). However, because users are also able to modify their

picture by using apps such as photoshop to “beautify” themselves, social media does not always

portray reality (Holland & Tiggemann, 2016). In 2018, about 88% of Americans 18-29 years-

old have indicated that they use a form of social media. Facebook is used by a majority of

Americans; however, Americans ages 18 to 24 are more likely to use Snapchat, Instagram and

Twitter (Smith & Anderson, 2018). Social media has been used for retrieving information

(Tang, Bie, Park & Zie, 2018), for intervention to promote positive behaviors (Hsu, Rouf &

Allman-Farinelli, 2018), and for social support (Klassen, Douglass, Brennan, Truby & Lim,

2018). Social media can also be used for individual entertainment, maintaining relationships or

occupying time, however, it can become an addiction developed from feeling better or more self-

assured when using social media (Guedes et. Al, 2016).

Social Media and Depression

When studying social media’s relationship with mental health outcomes such as depression,

findings suggest mixed results. The relationship is complex and may involve multiple

3

psychological, social, behavioral and individual factors (Baker & Algorta, 2016). Whether social

media is beneficial or harmful to mental health and well-being may partly depend on the quality

of social factors in the social network site’s (SNS) environment (Seabrook, Kern & Rickard,

2016). When studying child and adolescent populations, studies have been consistent in the

relationship between cyberbullying and depression (Hamm et al., 2015). Among the Lesbian,

Gay and Bisexual (LGB) community, social media has been seen to be both a protective (due to

easing geographic isolation and loneliness) and a risk factor (from negative experiences such as

cyberbullying) for depression (Escobar-Viera et. al, 2018). In 18-to-29-year-olds, it has been

found that positive social comparison was significantly negatively associated with depressive

symptoms (Lup, Trub & Rosenthal, 2015). A study has shown an increased odds of depression

in participants spending more time on social media and “Based on uses and gratification theory,

media used in a goal-directed way for individual gratification and satisfaction has similarities

with addiction (Lin, 2016) (Kuss & Griffiths, 2011).” Griffiths defines addictive behavior as

being characterized by six core components of addiction: salience, mood modification, tolerance,

withdrawal symptoms, conflict, and relapse and any behavior that fulfills these six criteria can be

considered as an addiction, including social networking (Guedes et al., 2016). Further research

is needed because of the high prevalence of social media usage (Smith & Anderson, 2018) and

high rates of depression in young adults (Depression, 2018

a

), with depression as the most

common health problem for college students (Depression and College Students, n.d.). A scoping

review can assess the potential size and scope of the available research literature with aims to

identify the nature and extent of current research (Grant & Booth, 2009). A scoping review on

the literature relating social media use and depression in college students in the last 5 years

4

(October 2013 – October 2018) was conducted to describe the association between time, social

media (SM) addiction and/or different behaviors on social media and depression and assist in

determining if a systematic review on this topic might be possible.

Public Health Significance

This scoping summarization of depression and social media usage in college students ages 18-25

has a public health significance with the following aspects: 1) college students between 18 and

25 are a large population; according to the National Center for Education Statistics, was

projected to be 3.2 million in 2018 (Digest of Education Statistics, 2017), 2) in 2018, 18-to-29-

year-olds have the highest percentage using any form of social media (88%) (Smith & Anderson,

2018), 3) in 2016, this age group was listed as having the highest prevalence of depression

(Depression, 2018

a

), 4), while they are more mature than adolescents, their brains are still

developing (Brain Maturity Extends Well Beyond Teen Years, 2011), 5) depression can lead to

difficulties with concentration (Depression, 2018

b

), and 6) students generally need their memory

to study and retain learned material. With young adults ages 18-25 having the highest

prevalence of an episode of major depression in the US in 2016 (Depression, 2018

a

), this study

seeks to describe the association between social media and depression specifically in college

students to provide insight on the focus of future studies to guide intervention and policy

development.

5

Hypothesis, Research Question, Specific Aims or Objectives

The research questions are: 1) What is the relationship between time on social media and

depression in college students? 2) Does social media addiction have a positive correlation with

depression? and 3) What types of social media behaviors are positively correlated with

depression? Studies have determined an association between social media usage and depression.

Different aspects of social media having been studied among young adults (Seabrook, Kern &

Rickard, 2016) such as 1) the association between real-life closeness of social media contacts

(Shensa et al. et al., 2018), 2) actual and perceived support (Park et al. 2016) or 3) negative

Facebook experiences (Rosenthal et al., 2016) and depression. This proposal seeks to perform a

scoping review of literature that explores the relationship between 1) time spent on social media

2) social media addiction and 3) social media behaviors and depression in college students 18-

25.

METHODS

Search Strategy

A modified version of the 14 review steps by the Joanna Briggs Institute was implemented

(Training, 2017). Electronic searches were performed using the following health databases:

PubMed, Embase and Scopus. Searches for articles on the three health databases took place in

January 2019

for articles published within the last five years (October 2013 – October 2018).

The main search terms were based on ‘social media’, ‘depression’ and ‘college’ where social

media was defined according to Merriam-Webster’s definition above and depression was defined

according to the National Institute of Mental Health as a common, but serious mood disorder

6

which can cause severe symptoms that affect feeling, thinking and handling daily activities such

as sleeping, eating or working (Depression, 2018

b

). The terms used in the search are shown in

table 1. Searches were performed for each key concept, with Boolean operator “OR” separating

each term. Key concepts were then all combined using “AND ” Boolean operator.

Table 1 Search terms used for the scoping review by main key concepts

Social Media

Depression

College

Facebook

Depressive disorder

Undergraduate

Instagram

Mental health

University

Reddit

Depression/diagnosis

College

Linkedin

Depression

Students

Twitter

Snapchat

Social media addiction

Social network

Problematic social media

use

Social networking sites

Social comparison

Social media utilization

Social desirability

Social media

Eligibility Criteria

The articles included meet the eligibility criteria presented in table 2. Because studies have

shown consistent findings of cyberbullying and depression, articles that focused on victims of

cyberbullying and depression were excluded from this study (Hamm et al., 2015 & Bottino et al.,

2015). Articles not accessible through open access or interlibrary loan or could not be retrieved

from the author and have not been published within the October 2013 – October 2018 were also

excluded.

7

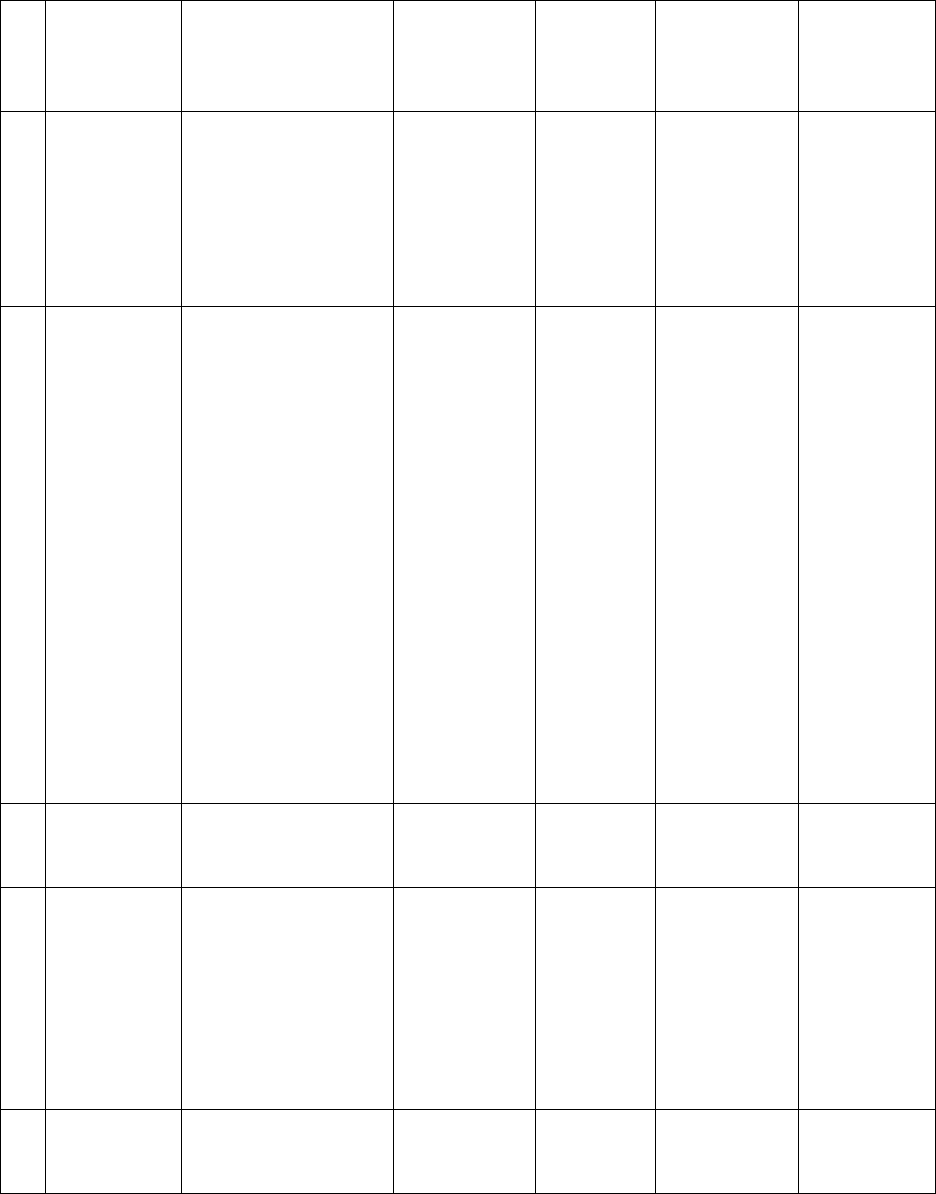

Table 2 Study inclusion/exclusion criteria of articles for this scoping review on social media and

depression in college students

Criteria

Inclusion

Exclusion

Articles

Written in English

Published within the last 5 years

Any geographic location

Not written in English

Study

participants

College students 18 and over

Uses social media platforms such as

Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and

Snapchat

Studies that are broad, not

focusing on social media

platforms (i.e. handheld device or

including searching the web),

depression or college students

Study design

Cross-sectional, observational,

longitudinal and intervention studies

Editorials, commentaries and

systematic reviews

Study

Outcomes

Variables

Depression or the like

Depression symptoms can include

both Physician diagnosed as well as

self-diagnoses

Depression is measured as a scale or

categorized as yes/no

Time on social media

Addiction to social media

Different types of social media

behaviors (posting content, status

updates, aimless scrolling, counting

likes, supporting others and bullying

others)

Articles focused on other mental

health outcomes other than

depression such as suicides or

anxiety, where depression is not

an outcome

Articles focusing on victims of

cyberbullying

Articles that do not include

independent variables associated

with outcome variables

Articles generated from searches were screened through article title and abstract on each health

database. Articles that did not meet inclusion criteria were not selected for full text screening.

Articles that required a full text screening were selected and imported into the citation manager,

RefWorks in folders named according to the heath database in which the article populated (i.e.

Pubmed, Scopus or Embase). Articles that were duplicates were identified through RefWorks

8

once articles were imported and removed prior to in-text screening. The option to view articles,

if accessible was available in Refworks for articles imported from Scopus or Pubmed. Full-text

for articles imported from Embase were searched through Google Scholar or Pubmed. Five

articles were not directly accessible and needed to be paid for. An attempt was made to retrieve

said articles through interlibrary loan; however, no response was received after two weeks. Full

text was requested from the first author of the five articles through e-mail. Four articles were e-

mailed back for full-text screening with one article meeting inclusion criteria. Articles meeting

inclusion criteria after in-text screening were saved as a PDF and remaining articles were deleted

from the RefWorks database. Excluded articles from in-text screening were documented in an

excel spreadsheet. The numbers of articles included and excluded through the in-text screening

process was documented as well as the reasoning for exclusion in a flow diagram according to

PRISMA guidelines (figure 1). This scoping review used published articles and was approved

for exemption by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects (CPHS) of UTHealth

(HSC-SPH-18-1030).

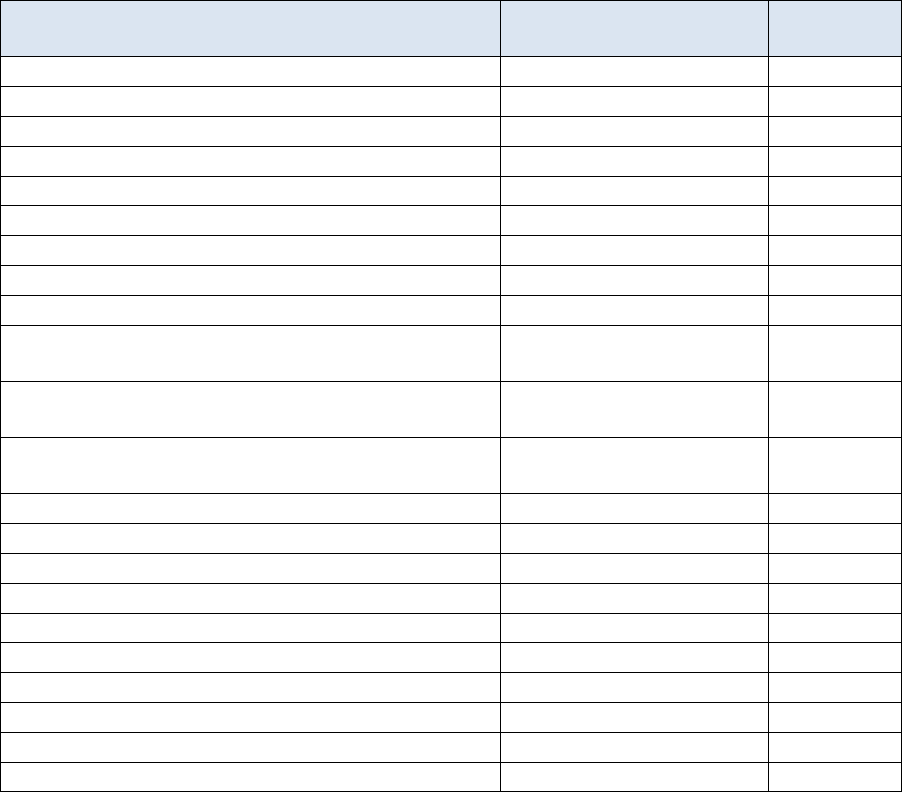

Documentation of Results

Four separate charting forms were developed to record the characteristics of included articles.

The first charting form included the author and published year of the article, the type of social

media used/studied, the population of study (including country), sample size of the study, age

range or mean age of the students included in the study and study design. The second charting

form recorded how measurements were operationalized for social media and how measurements

was operationalized for depression. The third charting form included the author’s last name,

9

publication year, social media measurement, depression measurement, the statistics of

association between the two measurements (i.e. odds ratios, risk ratios, mean rank, regression

coefficients and/or correlation coefficients) and whether the association showed a positive

correlation between social media and depression. Asterisks indicated the significance of the

statistic (one asterisk indicating <0.05 and two asterisks indicating <0.01). Other factors with

moderate correlations were included in this table. The final charting form listed what was

associated with depression, if the association was negative or positive and whether findings were

significant. These charting forms were used to assist in tallying results. Proportions of articles

exploring the associations between social media and depression are reported.

RESULTS

About 43% of the articles included populations in Asia (Singapore, South Korea, China, Hong

Kong, Taiwan, Japan and India) (Jang, Park & Song, 2016, Tang, Koh & Gan, 2017, Tang &

Koh, 2017, Zhang, 2017, Barman, Mukhopadhyay & Bandyopadhyay, 2018 & Tang et al., 2018)

(see table 3). Over a quarter (29%) of articles included other counties (Greece, Iran, Israel and

Mexico) (Kokkinos & Saripanidis, 2017, Rad & Ahmadi, 2018, Jasso-Medrano & Lopez-

Rosales, 2018 & Turel, Poppa & Gil-Or, 2018). Most (93%) of the articles were cross-sectional.

Over a fifth (21%) of articles had participants that were randomly selected (Zhang, 2017,

Barman et al., 2018 & Rad & Ahmadi, 2018). Half (50%) of the articles included participants

whose age in years ranged from 18-25 (Jang et al., 2016, Tang et al., 2017, Tang & Koh, 2017,

Zhang, 2017, Barman et al., 2018, Choukas-Bradley, Nesi, Widman & Higgins, 2018 & Jasso-

Medrano & Lopez-Rosales, 2018), 14% included participants with ages ranging from 18-30 (Rad

10

& Ahmadi, 2018 & Tang et al., 2018), 14% included students over age 30 (Kokkinos &

Saripanidis, 2017 & Kircaburn et al., 2018) and 21% of articles did not mention a maximum age

(Lauckner, Hill & Ingram, 2018, Shensa et al., 2018 & Turel et al., 2018). Half (50%) of the

articles focused on or included Facebook as their type of social media (Jang et al., 2016,

Kokkinos & Saripanidis, 2017, Zhang, 2017, Choukas-Bradley et al., 2018, Jasso-Medrano &

Lopez-Rosales, 2018, Lauckner et al., 2018 & Turel et al., 2018) and half (50%) used social

networking sites in general (Tang et al., 2017, Tang & Koh, 2017, Barman et al., 2018, Rad &

Ahmadi, 2018, Kircaburn et al., 2018, Shensa et al., 2018 & Tang et al., 2018). Instagram and

Twitter were also popular forms of social media and were each included in 21% of selected

articles (Choukas-Bradley et al., 2018, Rad & Ahmadi, 2018 & Lauckner et al., 2018) (see table

3).

Social media measurements

Over a tenth (14%) of articles estimated the amount of time on social media using measurements

(7% used a 6-point frequency response scale (Kokkinos & Saripanidis, 2017) and 7% used free

response, in which participants were asked the average number of hours and minutes spent using

any social media on a typical day (Choukas-Bradley et al., 2018)). To measure social network

addiction, 29% of articles used a modified 6-item Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale (BFAS)

(Tang et al., 2017, Tang & Koh, 2017, Tang et al., 2018 and Turel et al., 2018), 7% used a

different version of an addiction scale (seven-dimension online social networking addiction

scale) (Esmaeili, 2018) and 7% used a social network addiction questionnaire (Jasso-Medrano &

Lopez-Rosales, 2018). Over a tenth (14%) of articles asked questions about Facebook use with

11

answers based on a 5/6-point scale (Jang et al., 2016 & Zhang, 2017) and 14% used a

questionnaire about use of social networking sites (Barman et al., 2018 & Kircaburn et al., 2018).

Less than half (43%) of articles used measurements specific to social media behaviors (i.e. social

comparison on Facebook, impression management, enacted social support, self-disclosure, body

comparison, body survelliance, cyberbullying offending, social network intensity and real-life

closeness of social media contacts) (Jang et al., 2016, Zhang, 2017, Choukas-Bradley et al.,

2018, Kircaburn et al., 2018, Laukner, 2018 & Shensa et al., 2018) (see table 5).

Depression measurements

Most included articles (86%) measured depression; 7% measured mental health (Jang et al.,

2016) and 7% measured well-being (Turel et al., 2018). There were various depression

measurements. The 9-item patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) (21%) (Kokkinos &

Saripanidis, 2017, Zhang, 2017 & Lauckner et al., 2018) and variations of the Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) (21%) (Tang et al., 2017,

Tang & Koh, 2017 &

Tang 2018) were the most popular. The Becks Depression Inventory (BDI) was used in 14% of

articles (Barman et al., 2018 & Rad & Ahmadi, 2018). The Center for Epidemiologic Studies

Depression Scale (CES-D), 4-item patient reported outcomes measurement information system

(PROMIS), short mood and feelings questionnaire and short depression-happiness scale were

each used in 7% of articles (Jasso-Medrano & Lopez-Rosales, 2018, Choukas-Bradley et al.,

2018, Kircaburn et al., 2018 & Shensa et al., 2018).

12

Findings

Time spent on social media

Half (50%) of included articles studied the relationship between time spent on social media and

depression or well-being (Kokkinos & Saripanidis, 2017, Zhang, 2017, Barman et al., 2018,

Choukas-Bradley et al., 2018, Rad & Ahmadi, 2018, Jasso-Medrano & Lopez-Rosales, 2018 &

Turel et al., 2018) with a majority (71% of articles studying time) measured using correlation to

determine a positive or negative correlation with depression (i.e. correlation matrix, Spearman’s

rho, bivariate correlation and zero-order correlation) (Kokkinos & Saripanidis, 2017, Zhang,

2017, Choukas-Bradley et al., 2018, Jasso-Medrano & Lopez-Rosales, 2018 & Turel et al., 2018)

(see table 5); the remaining articles studying time on SM used mean rank comparing less than or

equal to 4 hours or greater than four hours or comparing time and depression before and after

treatment (Barman et al., 2018 & Rad & Ahmadi, 2018). Mean rank scores were correlations

between time spent on social media (including daily hours and daily frequency) and depression

and did not exceed 0.17 (see table 5). These correlations were relatively low compared to other

factors measured and the relationship between time on social media and depression in college

students could not be determined (see table 5).

Social media addiction

About half of included articles (43%) studied social media addiction with definitions including

stated ability to spend a day without SNS or terminology associating addiction with social media

use and all articles showing positive associations (Tang et al., 2017, Tang & Koh, 2017, Barman

et al., 2018, Jasso-Medrano & Lopez-Rosales, 2018, Tang 2018 & Turel et al., 2018). One third

13

of articles studying SM addiction and depression in college students compared US SM addiction

and depression rates in college students with other countries through regression, odds ratios or

relative risk (Tang et al., 2017 & Tang et al., 2018). Articles that reported significantly higher

risks/odds of depression with social media addiction were in China, Hong Kong/Macau and

Japan when compared with the United States. One third (2/6) of articles studying SM addiction

and depression or well-being used a correlation matrix or Spearman’s rho with a moderate

correlation (-0.57) found between SM addiction and well-being (Jasso-Medrano & Lopez-

Rosales, 2018 & Turel et al., 2018). One third of articles studying SM addiction used other

measures (comorbidity and mean rank) (Tang & Koh, 2017 & Barman et al., 2018) and one third

found SM addition and depression in college students more common in females than males

(Tang et al., 2017 & Tang & Koh, 2017). Findings from this scoping review suggest a positive

correlation between social media addiction and depression in college students (see table 5).

Social media behaviors

SM behaviors were studied in 64% of included articles (Jang et al., 2016, Lauckner et al., 2018,

Shensa et al., 2018, Zhang, 2017, Kokkinos & Saripanidis, 2017, Choukas-Bradley et al., 2018,

Kircaburn et al., 2018, Barman et al., 2018 & Turel et al., 2018). Impression management,

Facebook (FB) use, social comparison, enacted social support on FB, indiscreet FB content,

Facebook victimization, self-disclosure, amount/intimacy, honesty, intent, body surveillance,

body comparison, cyberbullying perpetration, problematic social media use, FB network size and

use of FB privacy settings were all measured using variations of correlation measures (i.e. zero-

order, bivariate, Pearson or Spearman’s rho correlations or through a correlation matrix) with

14

depression/mental health/well-being (Jang et al., 2016, Zhang, 2017, Kokkinos & Saripanidis,

2017, Choukas-Bradley et al., 2018, Kircaburn et al., 2018 & Turel et al., 2018). Problematic

SM use, FB victimization, body surveillance, body comparison, cyberbullying perpetration and

comparing oneself on SM were SM behaviors showing the highest correlations with depression,

0.37 being the highest and all showing significantly positive findings (Kircaburn et al., 2018,

Kokkinos & Saripanidis, 2018, Choukas-Bradley et al., 2018 & Jang et al., 2016). Other

measures used to compare social media behaviors include regression, odds ratios and mean rank

and measured excessive social media use, no/distant/close face-to-face (FTF) relationships and

whether social media was used late night/early morning, respectively (Lauckner et al., 2018,

Shensa et al., 2018 & Barman et al., 2018). Having close FTF relationships with social media

contacts had a significantly negative association with depression, while no FTF relationships

with SM contacts and excessive SM use had significantly positive associations with depression

(Shensa et al., 2018). Impression management, disclosure amount, disclosure honesty,

disclosure intent, use of Facebook privacy settings and enacted social support on Facebook did

not have significant evidence of an association with depression (Jang et al., 2016, Zhang, 2017 &

Kokkinos & Saripanidis, 2017) (see table 5).

Other factors measured on social media

Other factors measured and which showed a positive significant association with depression

included: being neurotic, loneliness, having negative social media experiences,

academic/environmental/interpersonal stressors and appearance-related social media

consciousness (Kokkinos & Saripanidis, 2017, Zhang, 2017 & Choukas-Bradley et al., 2018). A

15

majority (64%) of studies also found other factors that had a significant negative association with

depression (i.e. body esteem, life satisfaction, self-esteem, positive suicidal idealization, general

belongingness, age, extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, sex, race and perceived

social support) (Choukas-Bradley et al., 2018, Rad & Ahmadi, 2018, Jang et al., 2016, Jasso-

Medrano & Lopez-Rosales, Kircaburn et al., 2018, Kokkinos & Saripanidis, Shensa et al., 2018,

Tang et al., 2017 and Zhang, 2017). The most common was self-esteem, which was measured in

21% of articles (Jang et al., 2016, Kokkinos & Saripanidis, 2017 & Kircaburn et al., 2018). Self-

esteem was measured with zero-order, bivariate or Pearson’s correlations, 14% correlated self-

esteem with depression with -0.41 being the highest correlation and -0.26 the lowest and 7% of

articles correlated self-esteem with mental health (0.44) (Jang et al., 2016) (see table 5). Other

factors measured using various correlation measures included perceived social support,

neuroticism, loneliness, academic stressors, environmental stressors, interpersonal stressors,

satisfaction with life, extraversion, conscientiousness, agreeableness, Facebook network size,

appearance related social media consciousness, body esteem, suicidal ideation, general

belongingness, sex and age (Jang et al., 2016, Kokkinos & Saripanidis, 2017, Zhang, 2017,

Choukas-Bradley et al., 2018, Jasso-Medrano & Lopez-Rosales, 2018 & Kircaburn et al., 2018).

Neuroticism had the highest correlations. When correlated with depression, neuroticism had a

correlation value of 0.58 and when correlated with well-being had a correlation value of -0.68

(Kokkinos & Saripanidis, 2017 & Turel et al., 2018). Loneliness, suicidal ideation and academic

stressors also had relatively high correlations with depression with correlation values 0.52, 0.48

and 0.42, respectively (Kokkinos & Saripanidis, 2017, Jasso-Medrano & Lopez-Rosales, 2018 &

Zhang, 2017). Other factors studied which showed significantly negative associations with

16

depression included: body esteem, general belongingness, and satisfaction with life (Choukas-

Bradley et al., 2018, Kircaburn et al., 2018 & Zhang, 2017). Indiscrete Facebook content,

knowledge of privacy settings, number of Facebook friends and Facebook network size did not

have significant evidence of an association with depression (Kokkinos & Saripanidis, 2017 &

Zhang, 2017). The number of social network sites used was measured for depression using mean

rank and showed no significance (Barman et al., 2018). The randomized clinical trial included in

this review used an app to control social media use with the intervention group for two weeks.

The study showed the app significantly reduced time spent on social media, anxiety, depression,

sleep quality and life satisfaction in the intervention group (Rad & Ahmadi, 2018).

DISCUSSION

The goal of this scoping review was to study the association between social media use and

depression in college students. This study specifically focused on SM use related to time spent

on social media, social media addiction and social media behaviors; however, individual

characteristics were extracted from final articles as well. There were conflicting findings

regarding time spent on social media and depression and studies showing a significant

relationship between time spent on social media and depression showed a smaller correlation

when comparing depression correlations with other measured factors. According to Choukas-

Bradley et al. (2018), when controlling for time, appearance-related social media consciousness

(ARSM) was significantly associated with depressive symptoms in college women. The

correlation between ARSM was higher than time spent on social media which suggests women’s

SM experience can be more predictive of depression than time spent on social media (Choukas-

17

Bradley et al., 2018). Time spent on social media might also be a result of individual

experiences. According to Kircaburn et al. (2018), students who feel socially isolated may spend

more time on social media to fulfill their need of socializing and feeling connected. The mixed

findings and smaller correlations could mean that time spent on social media is not directly

correlated with depression; however, it is important to note that measurements in studies

measuring time were all different and future studies utilizing a standardized measure could be

useful.

When looking at studies comparing the association between social media addiction and

depression, it was observed that some countries have a higher risk of depression when addicted

to social media. Addiction rates found in Online Social Networking Addiction Among College

Students in Singapore: Comorbidity with Behavioral Addiction and Affective Disorder was

shown to be relatively high (30%), falling in the range of 24-35% of Asian students, found in

previous studies. Chinese students spend more time on social networking sites than US students

(about 10 hours a week vs. 6.4 hours a week) and the long hours can result in getting addicted.

Directionality cannot be assumed due to the cross-sectional nature of the study and being

addicted could lead to more time on social media (Tang et al., 2017). Tang et al. (2017) suggests

SNS addition and depression could be due to FOMO, demands of relationship maintenance,

constant social comparison and frequent violation of privacy. In a three-way model observing

social media addiction, neuroticism and well-being, it was observed that high neuroticism

magnified negative associations between SNS addiction symptoms and well-being in females;

however, addiction symptoms were the same in men, despite levels of neuroticism (Turel et al.,

18

2018). Tang et al. (2017) suggests males tend to be addicted to online games where as females

tend to be addicted to social interaction, which could be due to the male need for power and

control or to explore sexual fantasies and for the female need to share feelings and emotions.

Close relationships with Facebook contacts, social comparison, problematic social media use,

being neurotic, extraversion, agreeableness, cyberbullying perpetration, body surveillance and

excessive social media use were significantly associated with depression. When looking at other

social media behaviors, individual differences appeared to have a higher correlation with

depression. In studies focusing on Facebook, a person having high self-esteem was shown to

have a lower risk of depression. According to Jang et al. (2016), those with low self-esteem

were more likely to compare on Facebook, than those with higher self-esteem, and were more

likely to feel hurt when comparing themselves to others; individuals who managed their

impression on Facebook were also more likely to engage in social comparison (Jang et al., 2016).

Body comparison and surveillance were more common in individuals more conscious of their

appearance on social media (Choukas-Bradley et al., 2018). No face-to-face (FTF) relationships

with social media contacts significantly increased odds of depressive symptoms, while close FTF

relationships with SM contacts significantly decreased odds of depressive symptoms. On social

media, users can present a modified version of themselves and might not provide authentic

relationships; however, using SM to develop online relationships can supplement established

relationships (Shensa et al., 2018). Lack of genuine relationships can lead to loneliness which

was highly correlated with depression (Kokkinos & Saripanidis 2017). Self-disclosure on

Facebook in Hong Kong students could have been due to stressful events and to gain social

19

support; however, posts were modified to maintain their image. Those who practiced self-

disclosure experienced higher life satisfaction, which aligns with findings that talking about your

problems is healthy; however, honest disclosures were associated with lower life satisfaction

(Zhang, 2017). This agrees with findings of posting indiscreet Facebook content being

positively associated with Facebook victimization (Kokkinos & Saripanidis, 2017). Kokkinos &

Saripanidis (2017) suggests posting indiscrete content can make an individual easier to bully and

depression is a predictor of Facebook victimization. Cyberbullying victimization has been found

to be a strong predictor of cyberbullying perpetration via anger and cyberbullying perpetration’s

association with depression has been found to be fully mediated by problematic social media use

(Kircaburan, 2018). Higher problematic social media use was indirectly associated with feeling

less social connectedness, belongingness, and self-esteem via depression (Kircaburan, 2018).

Most of the articles included in this scoping review were cross-sectional and were unable to

determine the directionality the association between the use of social media and depression. It is

possible that depression leads to increased time on social media, social media addiction and

social media behaviors such as problematic social media use; however, longitudinal studies are

needed to provide evidence of causality. According to Lauckner et al. (2018), students with

depressive symptoms could be receptive to technological based interventions. Designed mobile

apps as reality therapy have been shown to reduce social networking addiction and time spent on

social media and depression. The reduced depression rate found in the intervention group

provides possibility that depression related to social media use can be regulated through apps;

however, this RCT was assessed after 2 weeks of use and a longer study is important to confirm

20

findings (Rad & Ahmadi, 2018). Studies used a broad range of measurements to assess SM use

and depression, making comparisons difficult across studies; thus, it would be helpful to be

consistent in social media use and depression measurements to perform systematic reviews/meta-

analyses to determine association. Articles used self-reported measures which could have led to

under-reporting. This could be remedied with diagnostic tools or participation of mental health

professionals (Tang & Koh, 2017). Convenience sampling and lack of diversity could have also

limited generalizability (Lauckner et al., 2018).

Potential Strengths and Limitations

There are currently no scoping or systematic reviews focused on social media usage and

depression in college students and these findings could contribute to ideas for future research on

an issue that currently has a high prevalence. By not restricting to the US population, this

scoping review can observe similarities and differences between nations that have been studied.

A scoping review also reduces potential biases between studies; however, although only one

article was inaccessible, lack of access to articles could have introduced some bias. Limitations

present in this review include: 1) I was the only reviewer and could have missed articles through

the scanning process, 2) this was an exploratory study and including multiple countries may

confuse results and 3) limiting my articles to English-language only articles could eliminate

studies in other languages that would provide additional information.

21

CONCLUSION

This review reiterated the need for longitudinal studies to access directionality and the need to

standardize measures used to measure social media, depression in college students. Articles

consistently showed higher correlations (>.40) between loneliness, neuroticism, self-esteem, SM

addiction, SM comparison and depression in college students, calling for future studies to

continue to focus on the relationship between individual characteristics, SM addiction, SM

comparison and depression. Further studies could also perform RCTs, utilizing treatment

periods longer than 2-weeks.

22

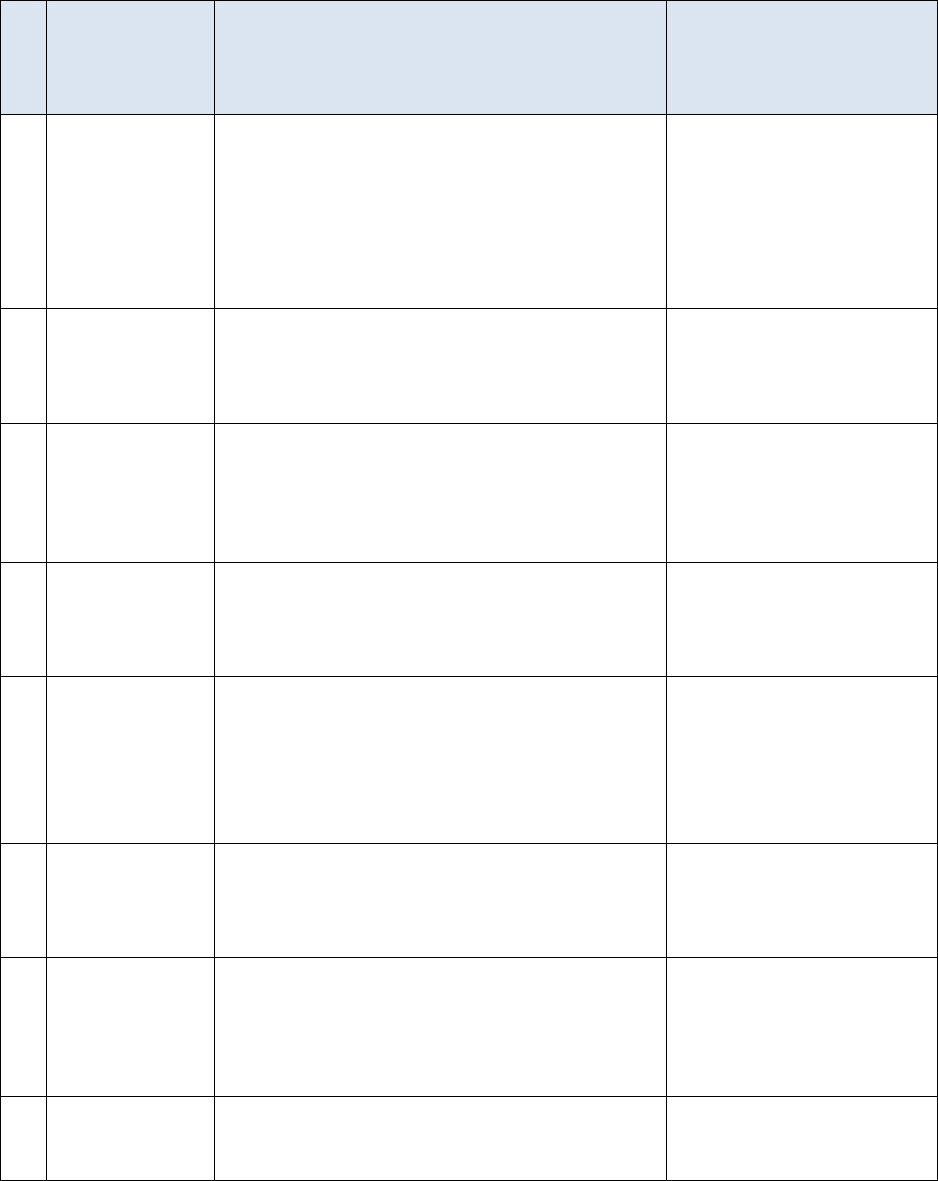

Figure 1: Flowchart of scoping review process of social media and depression in college students

Records identified through database searching

Pubmed (153), Scopus (400), Embase (174)

Records screened in

Phase 1 (title/abstract)

(n=727)

Records excluded

(n = 643)

Records after duplicate removal (n= 63)

Records screened in Phase 2

(full-text)

(n=63)

Full-text articles excluded, with reasons

(n=49)

- Not specific to social media (n=15)

- Did not associate SM time, addiction

or behavior to depression (n=12)

- Not focused on depression (n=8)

- Not focused on college students (n=1)

- Review (n=3)

- Age not 18 or over (n=7)

- Not published in the last 5 years (n=1)

- Depression not an outcome (n=1)

- Interlibrary loan and e-mailed author,

but no response (n=1)

Publications included in

Scoping Review (n=14)

SEARCH

SCREENING

ELIGIBILITY

INCLUDED

23

Table 3 Characteristics of Articles Included in this Scoping Review

Author,

Year

Population of

study

Sample size

and

selection

Age

Study

design

Type of

social

media

included in

study

1

Jang et al.,

2016

Communication

students from a

large private

university in Seoul,

South Korea

313 –

volunteered

Average

age 21.17

years

SD: 1.95

Cross-

sectional

Facebook

2

Kokkinos

&

Saripanidis,

2017

University students

from Greece with a

Facebook account

240 -

availability

and

snowball

sampling

18-51

years

Cross-

sectional

Facebook

3

Tang et al.,

2017

Undergraduate

students from

China, Singapore

and US

3267 –

convenience

sample

18-25

years

Cross-

sectional

Social

Networking

Sites (SNS)

4

Tang &

Koh, 2017

College students

from a University

in Singapore

1110 –

convenience

sample

18-25

years

Cross-

sectional

Social

Networking

Sites (SNS)

5

Zhang,

2017

Students from a

university in Hong

Kong

560 –

random

sampling

18-25

years

Cross-

sectional

Facebook

6

Barman,

2018

Undergraduate

students from a

medical college in

Kolkata, West

Bengal

200 –

random

sampling

21.6 +/-

1.8 years

Cross-

sectional

Social

Networking

Sites (SNS)

7

Choukas-

Bradley,

2018

College women

enrolled in

psychology courses

at a large university

in the southeastern

United States

339 –

enrolled

students

18-19

years

Cross-

sectional

Facebook,

Instagram,

Snapchat,

Twitter,

etc.

8

Jasso-

Medrano &

Lopez-

Rosales,

2018

University students

from Mexico

374 -

recruited

18-24

years

Cross-

sectional

Whats App

and

Facebook

24

9

Kircaburn

et al., 2018

University students

from a state

university in the

US

760 -

volunteer

18-40

years

Cross-

sectional

Social

Networking

Sites (SNS)

10

Lauckner et

al., 2018

University students

at two universities

in Southeastern US

255-

convenience

sample

18 or

older

Cross-

sectional

Facebook,

Snapchat,

Instagram,

Twitter,

Yik Yak

and

Tumbler

11

Rad &

Ahmadi,

2018

Students from the

University of

Technology in

Urmia, Iran

200 –

random

sampling

18-28

years

Randomized

Controlled

Trial where

intervention

group used

mobile app

to control

social

network

addiction,

depression,

anxiety,

sleep

quality,

cognitive

failure and

life

satisfaction

SNS, most

popular

were

Telegram,

Instagram,

and Twitter

12

Shensa et

al., 2018

Students from Mid-

Atlantic US state

university

1124 –

convenience

sample

At least

18 years

old

Cross-

sectional

Social

media

(SM)

13

Tang et al.,

2018

College students

from United States,

Singapore,

HK/Macau, China

(Beijing), South

Korea (Seoul),

Taiwan (Taichung)

and Japan (Kyoto)

8067 –

convenience

sample

18-30

years

Cross-

sectional

Social

Networking

Sites (SNS)

14

Turel et al.,

2018

Israeli college

students who use

Facebook

215 –

convenience

sample

>=18

years

Cross-

sectional

Facebook

25

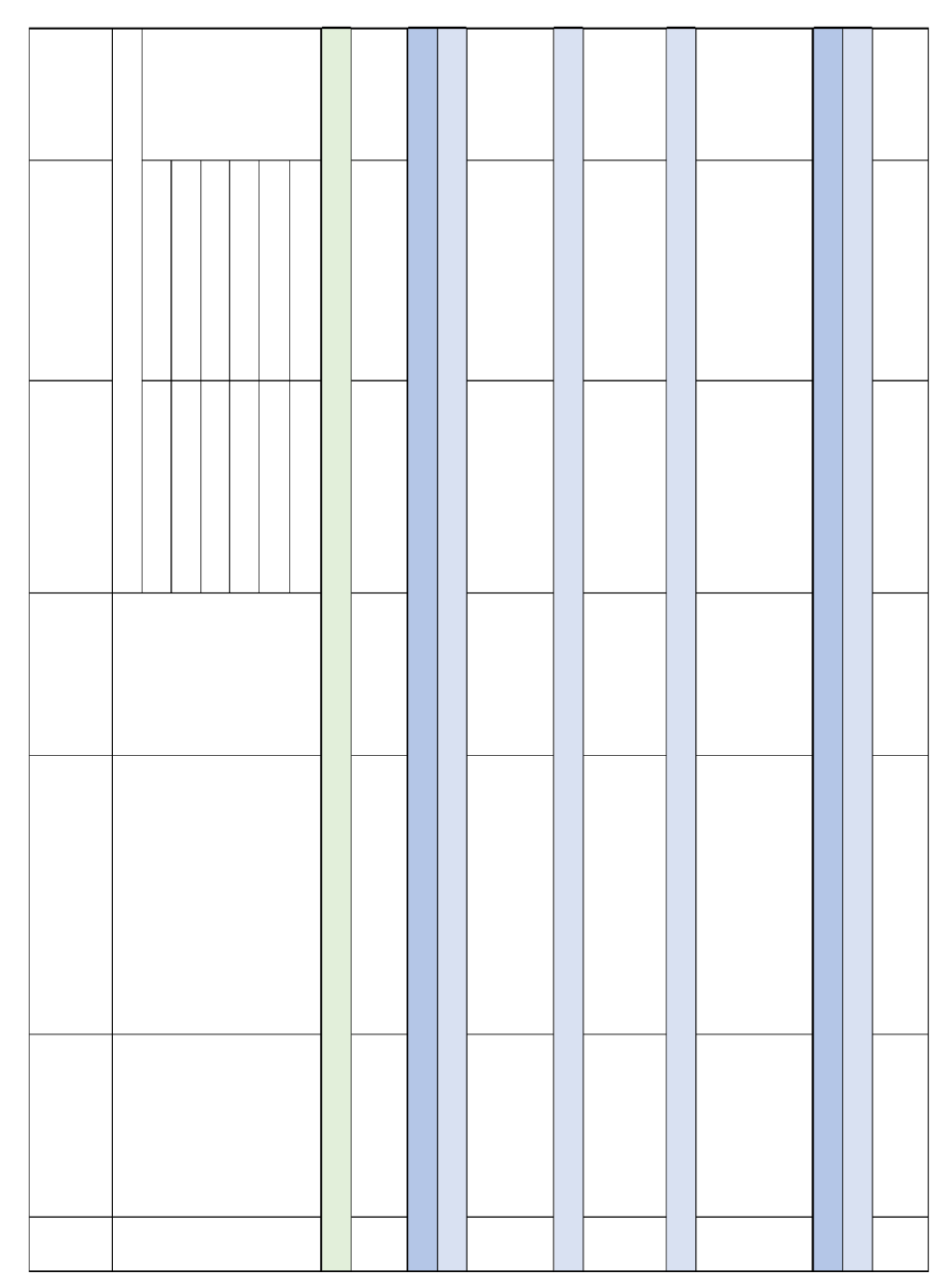

Table 4 Measurements used in Included Articles to Access Social Media Use and Depression

Author, Year

Measurement used to assess social media

use

Measurement used to

assess depression

1

Jang et al.,

2016

Facebook use was measured using 3

questions: 1) how often do you post on

Facebook, 2) how often do you look at other

people’s posts and how often do you use

Facebook. Social comparison on Facebook

and Impression Management were also

measured

Mental health was

measured with 5-item

RAND Mental Health

Inventory

2

Kokkinos &

Saripanidis,

2017

Time spent on social media (how much time

on a 6-point frequency scale) and Facebook

Victimization using a self-report

questionnaire

9-item patient health

questionnaire (PHQ-9)

3

Tang et al.,

2017

Social Network Addiction – Modified 6-

item Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale

(BFAS)

9-item Depression Scale

(adopted from Diagnostic

and Statistical Manual of

Mental Disorders (DSM-

5))

4

Tang & Koh,

2017

Modified 6-item Bergen Facebook

Addiction Scale (BFAS)

Diagnostic and Statistical

Manual of Mental

Disorders (DSM-5)

5

Zhang, 2017

Facebook use: asked if they had a Facebook

profile, how many minutes per day on

average was spent on Facebook in the past

week and how many Facebook friends they

had. Enacted social support and self-

disclosure were also measured

Depression was

measured with the Patient

Health Questionnaire.

(PHQ-9)

6

Barman, 2018

Structured questionnaire for assessment of

the use of SNS

Becks depression

inventory (BDI)

7

Choukas-

Bradley, 2018

Time spent on social media – free response

format of average number of hours and

minutes participants use social media on a

typical day. Body comparison and body

surveillance were also measured

13-item short mood and

feelings questionnaire

8

Jasso-Medrano

& Lopez-

Rosales, 2018

Cuestionario de Addiccion a Redes Sociales

(ARS) (Social Network Addiction

Questionnaire)

Center for Epidemiologic

Studies Depression Scale

(CES-D)

26

9

Kircaburn et

al., 2018

Social Media Use Questionnaire (SMUQ)

and Cyberbullying Offending Scale (CBOS)

Short Depression-

Happiness Scale (SDHS)

10

Lauckner et

al., 2018

Social network intensity

Patient health

questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)

11

Rad &

Ahmadi, 2018

Social media: seven-dimension online social

networking addiction scale

Becks depression

inventory (BDI)

12

Shensa et al.,

2018

Real-life closeness of social media contacts

– 1) no face-to-face (FTF) relationship; 2) a

distant FTF relationship and 3) a close FTF

relationship

4-item patient reported

outcomes measurement

information system

(PROMIS)

13

Tang et al.,

2018

Modified six-item Bergen Facebook

Addiction Scale (BFAS)

9-item depression scale

adopted from DMS-5

14

Turel et al.,

2018

Hebrew translation of the 6-item Bergen

Facebook Addiction Scale

World Health

Organization (WHO) five

item Wellbeing Index

(WHO-5)

27

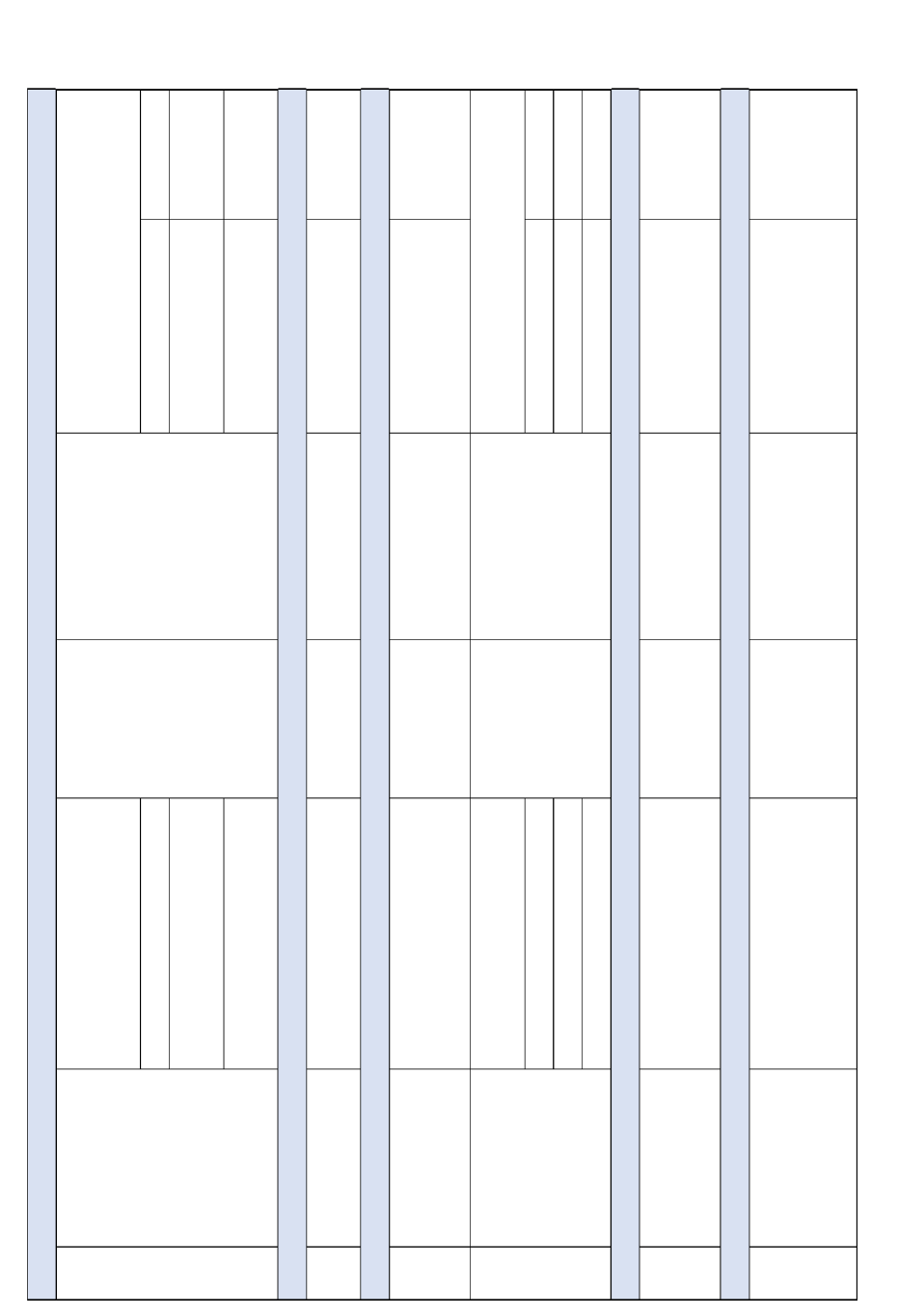

Table

5 Statistics of Social Media Use and Depression/Mental Health/Well

-being in College Students from Scoping Review

Author, Year

Social Media

Measurement

Depression

Measurement

Association

Measurement

Statistic

Positively

associated

with

depression

Association Between Time on Social Media and Depression

Hours spent on SM

1

Kokkinos &

Saripanidis,

2017

6-point scale (

≤10 minutes

(min.), 10

-30 min., 30

-60

min., 1

-2 hours (hrs.), 2

-3

hrs. and

≥ 3 hrs

.)

PHQ

-9

Spearman's Rho

0.15*

Yes

2

Zhang, 2017

6-point scale (

≤ 10 min.,

10-30 min., 31

-60 min., 1

-

2 hrs., 2

-3 hrs. and

≥ 3

hrs.)

PHQ

-9

Zero-order

correlation

0.02

Yes

3

Barman, 2018

Questionnaire

BDI

Mean Rank (<=4 vs

>4 hours)

79.91 vs. 103.85*

Yes

4

Choukas

-

Bradley, 2018

Free response

13-item Short

Mood and

Feelings

Questionnaire

Bivariate

Correlation

0.17**

Yes

5

Jasso

-Medrano

& Lopez

-

Rosales, 2018

Social Network Addiction

Questionnaire

CES-D

Spearman's Rho

-0.07

No

6

Rad & Ahmadi,

2018

Seven

-dimension online

social networking

addiction scale

BDI

Mean

Rank

(intervention

-

before vs. after

treatment)

39.00 vs. 29.00**

(time)

48.10 vs. 50.96**

(depression)

Yes

Mean Rank

(control

- before vs.

after treatment)

37.45 vs. 36.54

(time)

48.10 vs. 50.96

(depression)

No

28

Table 5

Continued

Daily Use Frequency

1

Barman, 2018

Questionnaire

BDI

Mean rank (<4 vs.

>=4 times

77.52 vs. 104.24*

Yes

Association Between Time on Social Media and Wellbeing

Hours spent on SM

1

Turel et al.,

2018

BFAS

WHO

-5

Correlation Matrix

-0.19

Yes

Daily Use Frequency

1

Turel et al.,

2018

BFAS

WHO

-5

Correlation Matrix

-0.07

Yes

Association Between Social Media Addiction and Depression

1

Tang et al., 2017

BFAS

Modified

DSM

-5

Multivariate

Logistic Regression

0.13*

Yes

Odds Ratio

China vs. US

1.398 (1.008

-1.932)

Yes

Singapore vs.

US

1.097 (0.778

-1.547)

Yes

2

Tang & Koh,

2017

BFAS

DSM

-5

Comorbidity

-

Total

SN addition

- 29.5%

Yes

Depression

- 21.0%

Comorbidity

- Male

SN addition

- 22.1%

Yes

Depression

- 13.9%

Comorbidity

-

Female

SN addition

- 33.9%

Yes

Depression

- 25.1%

3

Barman, 2018

Questionnaire

BDI

Mean rank (stated

ability to spend a

day without

accessing SNSs

-yes

vs. no)

92.22 vs. 126.71**

Yes

29

Table 5

Continued

4

Jasso

-Medrano

& Lopez

-

Rosales, 2018

Social Network Addiction

Questionnaire

CES-D

Spearman's Rho

coefficient

0.25**

Yes

5

Tang et al., 2018

BFAS

Modified

DSM

-5

Risk Ratio

Singapore vs. US

1.02 (0.92

- 1.12)

HK/Macau vs. US

1.28 (1.19

-1.39)

China vs. US

1.06 (0.97

- 1.16)

South Korea vs. US

1.02 (0.93

-1.13)

Taiwan vs. US

0.97 (0.89

-1.07)

Japan vs. US

1.12 (1.02-1.22)

Association Between Social Media Addiction and Wellbeing

1

Turel et al.,

2018

BFAS

WHO

-5

Correlation Matrix

-0.57**

Yes

Association Between Social Media Behaviors and Mental Health

Social Comparison

1

Jang et al., 2016

Iowa

-Netherlands

Comparison Orientation

Measure

RAND Mental

Health

Inventory

Zero-order

correlation

-0.15**

Yes

Facebook Use

2

Jang et al., 2016

Free response

RAND Mental

Health

Inventory

Zero-order

correlation

-0.05

Yes

Impression Management

3

Jang et al., 2016

Self-promotion and

ingratiation among the

impression management

scale

RAND Mental

Health

Inventory

Zero-order

correlation

0.01

No

Association Between Social Media Behaviors and Depression

Social Network Intensity

1

Lauckner

et al.,

2018

5-point scale (strongly

disagree to strongly agree)

PHQ

-9

Regression

-0.1

No

30

Table 5

Continued

Face-to-Face Relationship with FB Contacts

2

Shensa et al.,

2018

Proportion of SM

friends

(on platform most used)

with whom they have:

PROMIS

Odds Ratio

-

increased odds of

moderate/severe

depressive

symptoms for every

10% increase in

independent

variable

No FTF Relationship

1.09 (1.05

-1.13)

Yes

Distant FTF

Relationship

1.01 (0.96

-1.05)

Yes

Close FTF

Relationship

0.93 (0.88

-0.97)

No

Enacted Social Support on FB

3

Zhang, 2017

5-item Scale (never to all

the time)

PHQ

-9

Zero-order

correlation

-0.03

No

Self-Disclosure

4

Kokkinos &

Saripanidis,

2017

10-item Self

-Disclosure

Index

PHQ

-9

Pearson correlation

0.14*

Yes

5

Zhang, 2017

General Disclosiveness

Scale

PHQ

-9

Zero-order

correlation

Honesty

-0.07

No

Intent

0.04

Yes

Amount/Intimacy

0.02

Yes

Indiscreet Facebook Content

6

Kokkinos &

Saripanidis,

2017

30-item Questionnaire

PHQ

-9

Pearson correlation

0.16

Yes

Body Surveillance

7

Choukas

-

Bradley, 2018

Objectified Body

Consciousness Scale

13-item Short

Mood and

Feelings

Questionnaire

Bivariate

Correlation

0.25**

Yes

31

Table 5

Continued

Body Comparison

8

Choukas

-

Bradley, 2018

6-item Body Comparison

Orientation Scale

13-item Short

Mood and

Feelings

Questionnaire

Bivariate

Correlation

0.24**

Yes

Problematic Social Media Use

9

Kircaburn et al.,

2018

SMUQ

SDHS

Pearson correlation

0.37**

Yes

Facebook Victimization

10

Kokkinos &

Saripanidis,

2017

Self-report Questionnaire

PHQ

-9

Pearson

correlation

0.29**

Yes

Cyberbullying Perpetration

11

Kircaburn et al.,

2018

Cyberbullying offending

scale

SDHS

Bivariate

Correlation

0.19**

Yes

Used late night/early morning

12

Barman et al.,

2018

Questionnaire

BDI

Mean rank (yes vs.

no)

112.45 vs

85.90**

Yes

Facebook Network Size

13

Zhang, 2017

6-point scale (

≤ 10, 11

-

100, 101

-200, 201

-30,

201-400 and

> than 400)

PHQ

-9

Zero-order

correlation

0

--

Use of FB Privacy Setting

14

Kokkinos &

Saripanidis,

2017

yes/no question

PHQ

-9

Spearman's rho

0.09

Yes

Correlation Between Individual Factors and Mental Health

Self-Esteem

1

Jang et al., 2016

Rosenberg's Self

-Esteem

Scale

RAND Mental

Health

Inventory

Zero-order

correlation

0.44**

Yes

32

Table 5

Continued

Correlation Between Individual Factors and Depression

Self-Esteem

2

Kokkinos &

Saripanidis,

2017

Self-report Questionnaire

PHQ

-9

Pearson correlation

-0.41**

Yes

Neuroticism

3

Kokkinos &

Saripanidis,

2017

Self-report

Questionnaire

PHQ

-9

Pearson correlation

0.58**

Yes

Loneliness

4

Kokkinos &

Saripanidis,

2017

20-item UCLA Loneliness

Scale Version 3

PHQ

-9

Pearson correlation

0.52**

Yes

Academic Stressors

5

Zhang, 2017

5-point scale (did not

occur to occurred and

extremely stressful)

PHQ

-9

Zero-order

correlation

0.42**

Yes

Suicidal Ideation

6

Jasso

-Medrano

& Lopez

-

Rosales, 2018

Positive and Negative

Suicidal Ideation

Inventory

CES-D

Spearman's rho

0.48**

Yes

Correlation Between Individual Factors and

Wellbeing

Neuroticism

1

Turel et al.,

2018

Big five inventory

WHO

-5

Correlation Matrix

-0.68**

Yes

*p<0.05, **p<0.01

33

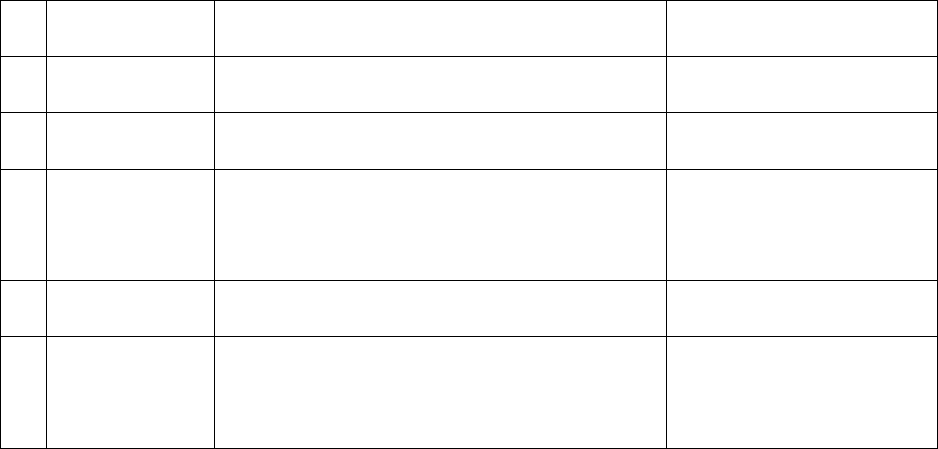

Table 6 Association between Time on SM, SM Addiction and SM Behaviors and Depression

and Significance

Social Media Factors Studied

Association with

depression

Significant

Time on Social Media

Amount in hours

Mixed

Mixed

Daily frequency

Positive

Mixed

Social Media Addiction

Positive

Yes

Social Media Behavior

Social Comparison

Positive

Yes

Facebook Use

Positive

No

Impression Management

Negative

No

Social Network Intensity

Positive

No

Close face-to-face relationship with FB

Contacts

Negative

Yes

Distant face-to-face relationship with FB

Contacts

Positive

No

Negative face-to-face relationship with FB

Contacts

Positive

Yes

Enacted social support on FB

Negative

No

Self-disclosure on FB

Mixed

Mixed

Indiscreet FB content

Positive

No

Body surveillance

Positive

Yes

Body comparison

Positive

Yes

Problematic social media use

Positive

Yes

Facebook Victimization

Positive

Yes

Cyberbullying perpetration

Positive

Yes

Used late-night/early morning

Positive

Yes

Use of privacy settings

Positive

No

34

REFERENCES

Baker, D. A., & Algorta, G. P. (2016). The relationship between online social networking and

depression: A systematic review of quantitative studies. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and

Social Networking, 19(11), 638-648. doi:10.1089/cyber.2016.0206

Barman, L., Mukhopadhyay, D. K., & Bandyopadhyay, G. K. (2018). Use of social networking

site and mental disorders among medical students in kolkata, west bengal. Indian Journal of

Psychiatry, 60(3), 340-345. doi:10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_210_18

Bottino, S. M., Bottino, C. M., Regina, C. G., Correia, A. V., & Ribeiro, W. S. (2015).

Cyberbullying and adolescent mental health: Systematic review. Cadernos De Saúde

Pública, 31(3), 463-475. doi:10.1590/0102-311x00036114

Brain Maturity Extends Well Beyond Teen Years. (2011, October 10). Retrieved March 28,

2019, from https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=141164708

Choukas-Bradley, S., Nesi, J., Widman, L., & Higgins, M. K. (2018). Camera-ready: Young

women’s appearance-related social media consciousness. Psychology of Popular Media

Culture, No Pagination Specified-No Pagination Specified. doi:10.1037/ppm0000196

Depression. (2018

a

, February). Retrieved March 28, 2019, from

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/depression/index.shtml

Depression. (2018

b

, March 22). Retrieved March 28, 2019, from http://www.who.int/en/news-

room/fact-sheets/detail/depression

Depression and College Students. (n.d.). Retrieved from March 28, 2019,

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/depression-and-college-students/index.shtml

35

Depression in the U.S. Household Population, 2009-2012. (2014, December 03). Retrieved

March 28, 2019, from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db172.htm

Digest of Education Statistics, 2017. (n.d.). Retrieved March 28, 2019, from

https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d17/tables/dt17_303.40.asp

Dmytriw, A. A., Sorenson, T. J., Morris, J. M., Nicholson, P. J., Hilditch, C. A., Graffeo, C. S.,

et al. (2018). #Fake news: A systematic review of mechanical thrombectomy results among

neurointerventional stroke surgeons on twitter. Journal of Neurointerventional Surgery,

doi:neurintsurg-2018-014319

Escobar-Viera, C. G., Whitfield, D. L., Wessel, C. B., Shensa et al., A., Sidani, J. E., Brown, A.

L., et al. (2018). For better or for worse? A systematic review of the evidence on social

media use and depression among lesbian, gay, and bisexual minorities. JMIR Mental Health,

5(3), e10496. doi:10.2196/10496

Good mental health. (2017). Retrieved March 28, 2019, from

https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/good-mental-health

Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and

associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91-108.

doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

Guedes, E., Sancassiani, F., Carta, M. G., Campos, C., Machado, S., King, A. L., & Nardi, A. E.

(2016). Internet Addiction and Excessive Social Networks Use: What About Facebook?

Clinical Practice & Epidemiology in Mental Health, 12(1), 43-48.

doi:10.2174/1745017901612010043

36

Hamm, M. P., Newton, A. S., Chisholm, A., Shulhan, J., Milne, A., Sundar, P., et al. (2015).

Prevalence and effect of cyberbullying on children and young people: A scoping review of

social media studies. JAMA Pediatrics, 169(8), 770-777.

doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0944

Holland, G., & Tiggemann, M. (2016). A systematic review of the impact of the use of social

networking sites on body image and disordered eating outcomes. Body Image, 17, 100-110.

doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.02.008

Hsu, M. S. H., Rouf, A., & Allman-Farinelli, M. (2018). Effectiveness and behavioral

mechanisms of social media interventions for positive nutrition behaviors in adolescents: A

systematic review. The Journal of Adolescent Health : Official Publication of the Society for

Adolescent Medicine, doi:S1054-139X(18)30249-0

Jang, K., Park, N., & Song, H. (2016). Social comparison on facebook: Its antecedents and

psychological outcomes doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.082

Jasso-Medrano & Lopez-Rosales, J. L., & López-Rosales, F. (2018). Measuring the relationship

between social media use and addictive behavior and depression and suicide ideation among

university students. Computers in Human Behavior, 87, 183-191.

doi:10.1016/j.chb.2018.05.003

Kircaburn et al., K., Kokkinos & Saripanidis, C. M., Demetrovics, Z., Király, O., Griffiths, M.

D., & Çolak, T. S. (2018). Problematic online behaviors among adolescents and emerging

adults: Associations between cyberbullying perpetration, problematic social media use, and

psychosocial factors. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 1-18.

doi:10.1007/s11469-018-9894-8

37

Klassen, K. M., Douglass, C. H., Brennan, L., Truby, H., & Lim, M. S. C. (2018). Social media

use for nutrition outcomes in young adults: A mixed-methods systematic review. The

International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 15(1), 70.

doi:10.1186/s12966-018-0696-y

Kokkinos & Saripanidis, C. M., & Saripanidis, I. (2017). A lifestyle exposure perspective of

victimization through facebook among university students. do individual differences matter?

Computers in Human Behavior, 74, 235-245. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2017.04.036

Kuss, D. J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2011). Online Social Networking and Addiction—A Review of

the Psychological Literature. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public

Health, 8(9), 3528-3552. doi:10.3390/ijerph8093528

Lauckner, C., Hill, M., & Ingram, L. A. (2018). An exploratory study of the relationship between

social technology use and depression among college students. Journal of College Student

Psychotherapy, doi:10.1080/87568225.2018.1508396

Lin, L. Y. (2016). Association between use of social networking media and depression in

adolescents and young adults. Depress Anxiety, 323-331. doi:10.5353/th_b5805152

Lup, K., Trub, L., & Rosenthal, L. (2015). Instagram #Instasad?: Exploring Associations Among

Instagram Use, Depressive Symptoms, Negative Social Comparison, and Strangers

Followed. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 18(5), 247-252.

doi:10.1089/cyber.2014.0560

Major Depression. (n.d.). Retrieved March 28, 2019, from

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression.shtml

38

Mental and Emotional Well-being. (n.d.). Retrieved April 10, 2019, from

https://www.surgeongeneral.gov/priorities/prevention/strategy/mental-and-emotional-well-

being.html

Park, J., Lee, D. S., Shablack, H., Verduyn, P., Deldin, P., Ybarra, O., . . . Kross, E. (2016).

When perceptions defy reality: The relationships between depression and actual and

perceived Facebook social support. Journal of Affective Disorders, 200, 37-44.

doi:10.1016/j.jad.2016.01.048

Rad, M.E., & Ahmadi, F. (2018). A new method to measure and decrease the online social

networking addiction. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry, 10(4) doi:10.1111/appy.12330

Rosenthal, S. R., Buka, S. L., Marshall, B. D., Carey, K. B., & Clark, M. A. (2016). Negative

Experiences on Facebook and Depressive Symptoms Among Young Adults. Journal of

Adolescent Health, 59(5), 510-516. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.023

Seabrook, E. M., Kern, M. L., & Rickard, N. S. (2016). Social networking sites, depression, and

anxiety: A systematic review. JMIR Mental Health, 3(4), e50. doi:v3i4e50

Shensa et al., A., Sidani, J. E., Escobar-Viera, C. G., Chu, K., Bowman, N. D., Knight, J. M., &

Primack, B. A. (2018). Real-life closeness of social media contacts and depressive

symptoms among university students. Journal of American College Health, 1-8.

doi:10.1080/07448481.2018.1440575

Smith, A., & Anderson, M. (2018, September 19). Social Media Use 2018: Demographics and

Statistics. Retrieved March 28, 2019, from http://www.pewinternet.org/2018/03/01/social-

media-use-in-2018/

39

Social Media. (2004). Retrieved March 28, 2019, from https://www.merriam-

webster.com/dictionary/social media

Tang, C. S., Koh, Y. W., & Gan, Y. (2017). Addiction to internet use, online gaming, and online

social networking among young adults in china, singapore, and the united states. Asia-

Pacific Journal of Public Health, 29(8), 673-682. doi:10.1177/1010539517739558

Tang, C. S. & Koh, Y. Y. W. (2017). Online social networking addiction among college students

in singapore: Comorbidity with behavioral addiction and affective disorder. Asian Journal

of Psychiatry, 25, 175-178. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2016.10.027

Tang, C. S. K., Wu, A. M. S., Yan, E. C. W., Ko, J. H. C., Kwon, J. H., Yogo, M., . . . Koh, Y.

Y. W. (2018). Relative risks of internet-related addictions and mood disturbances among

college students: A 7-country/region comparison. Public Health, 165, 16-25.

doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2018.09.010

Tang, L., Bie, B., Park, S. E., & Zhi, D. (2018). Social media and outbreaks of emerging

infectious diseases: A systematic review of literature. American Journal of Infection

Control, 46(9), 962-972. doi:S0196-6553(18)30105-6

Training, C. (2017, August 31). Doing scoping reviews. Retrieved from March 28, 2019,

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kdsHk84X5g0

Turel, O., Poppa, N. T., & Gil-Or, O. (2018). Neuroticism magnifies the detrimental association

between social media addiction symptoms and wellbeing in women, but not in men: A

three-way moderation model. The Psychiatric Quarterly, 89(3), 605-619.

doi:10.1007/s11126-018-9563-x

40

Zhang, R. (2017). The stress-buffering effect of self-disclosure on facebook: An examination of

stressful life events, social support, and mental health among college students. Computers in

Human Behavior, 75, 527-537. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2017.05.043

Zimmerman, L., PhD. (n.d.). Do you fear missing out? Retrieved March 30, 2019, from

https://www.apa.org/gradpsych/2016/01/missing-out