Clemson University Clemson University

TigerPrints TigerPrints

All Theses Theses

12-2011

An Extension of Social Facilitation Theory to the Decision-Making An Extension of Social Facilitation Theory to the Decision-Making

Domain Domain

Allison Wallace

Clemson University

Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses

Part of the Psychology Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Wallace, Allison, "An Extension of Social Facilitation Theory to the Decision-Making Domain" (2011).

All

Theses

. 1258.

https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1258

This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for

inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact

AN EXTENSION OF SOCIAL FACILITATION THEORY

TO THE DECISION-MAKING DOMAIN

A Thesis

Presented to

the Graduate School of

Clemson University

In Partial Fulfillment

of the Requirements for the Degree

Master of Science

Applied Psychology

by

Allison L. Wallace

November 2011

Accepted by:

Dr. Fred S. Switzer, III, Committee Chair

Dr. Robin Kowalski

Dr. Cynthia Pury

ii

ABSTRACT

Social facilitation has traditionally been defined as the influence of the presence of

others on an individual’s task performance. Social presence has been shown to either

facilitate or impair performance based on various moderating variables, including the

more recent investigation of individual differences, but researchers have yet to extend

social facilitation theory to the domain of decision-making. This study evaluates the

effect of social presence on individual decision-making, using the personality traits of

extraversion, neuroticism, self-esteem, social anxiety, and trait anxiety as potential

moderating variables of this effect. We found that affiliative individuals, marked by high

extraversion and high self-esteem, demonstrated superior decision-making effectiveness

in the social presence condition of a decision-making task. Similarly, avoidant

individuals, marked by high neuroticism, high social anxiety, high trait anxiety, and low

self-esteem, demonstrated superior decision-making effectiveness in the alone condition

of a decision-making task. The influence of these findings on social facilitation theory

and the implications for real-world application are discussed.

Keywords: social facilitation, decision-making, personality

iii

DEDICATION

To my loving husband, Aaron, for his emotional support through all of my

endeavors.

iv

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

TITLE PAGE ....................................................................................................................... i

ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................ii

DEDICATION ................................................................................................................... iii

LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................. vi

LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................................... vii

CHAPTER

I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 1

Early Studies of Social Facilitation.............................................................. 2

Theories of Social Facilitation ..................................................................... 5

A New Direction .......................................................................................... 8

Personality as a Moderator ........................................................................... 9

A Novel Application .................................................................................. 12

II. METHOD ........................................................................................................ 16

Participants ................................................................................................. 16

Measures .................................................................................................... 16

Procedure ................................................................................................... 20

III. RESULTS ........................................................................................................ 22

Observed Distribution of Personality Traits .............................................. 22

Correlation between Personality Traits ...................................................... 23

Decision-Making Outcomes ...................................................................... 24

Comparison of Specific Personality Traits ................................................ 27

Sense of Evaluation.................................................................................... 28

IV. DISCUSSION .................................................................................................. 30

Limitations ....................................................................................................... 32

Future Research ............................................................................................... 32

v

Table of Contents (Continued) Page

V. CONCLUSION ................................................................................................ 35

APPENDICES

A: Personality Assessment Items ......................................................................... 37

B: Decision-Making Task Alternatives ............................................................... 40

REFERENCES .................................................................................................................. 42

vi

LIST OF TABLES

Table Page

3.1 Bivariate Correlation Matrix for Personality Variables ....................................... 23

3.2 Hierarchical Linear Regression for Overall Effectiveness .................................. 24

3.3 Regression for Social Anxiety vs. Trait Anxiety ................................................. 28

vii

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure

3.1 Condition * Propensity to Experience Social Facilitation Interaction ................. 26

1

CHAPTER ONE

INTRODUCTION

Individuals differ greatly in their reaction to the presence of other individuals

while completing a task. While engaged in an activity, an individual’s performance may

be either improved or impaired by the presence of others compared to when completing

the task alone. Recent literature has shown that the influence of social presence on

performance outcomes is dependent on the personality of the individuals involved. Thus,

through an understanding of the personality of individuals, we can determine optimal

settings for task performance. Individuals with personality traits that trigger negative

reactions to social presence will experience the best performance outcomes while

performing tasks alone, whereas individuals with personality traits that trigger positive

reactions to social presence will experience the best performance outcomes while

performing tasks in the presence of others. This theory, referred to as social facilitation

theory, has yet to be applied to the behavioral domain of decision-making. Through an

empirical investigation of the relationships among social presence, personality, and

decision-making, we can take the first, crucial step in understanding how to optimize

decision-making outcomes (e.g., efficiency, productivity, quality) based on the

personality of involved individuals.

Through the course of this paper, we first explain the lengthy evolution of social

facilitation theory, leading up to the recent discovery that personality is the crucial

moderator in the relationship between social presence and performance. Second, we

examine the current literature that assesses various personality traits as moderators,

2

isolating concepts which require further exploration. Third, we demonstrate the

importance of the application of social facilitation theory to the decision-making domain.

Finally, we present the results of a recent study which seeks to apply social facilitation

theory to an individual decision-making task, examining personality moderators of the

relationship between social presence and decision-making outcomes.

Early Studies of Social Facilitation

The concept of social facilitation was first introduced by Norman Triplett in the

late 1890s. Triplett (1898) observed that cyclists completed a race faster when they raced

with other cyclists compared to racing alone. Specifically, cyclists who competed against

each other produced the fastest times, cyclists who raced against a clock and also had the

assistance of a pacesetter produced the next fastest times, and cyclists who raced against

a clock without a pacesetter produced the slowest times. Upon this discovery, Triplett

then decided to test the speed with which children turned a fishing reel while performing

alone as compared to performing side-by-side with another child. Triplett found that

most children reeled the fishing rod faster while in the presence of another child who was

also reeling, as compared to children reeling the fishing rod alone. Triplett offered

several explanations for these findings. He argued that the presence of another reeler,

later termed a coactor, may stimulate a feeling of competitiveness which motivates the

target child to reel faster. Triplett also proposed that the presence of another person

performing the same activity might simply stimulate a thought to move faster. Later

researchers ventured to tease apart social facilitation effects from competition effects;

however, the importance of Triplett’s initial studies cannot be understated. These studies

3

demonstrated that people perform differently in the presence of others, even when they

are not interacting.

Allport (1920) coined the term social facilitation, which he defined as “an

increase in response merely from the sight or sound of others making the same

movement” (1924, p. 262). Allport’s studies were designed to minimize competition

effects, which were a potential confound in Triplett’s earlier studies. Allport’s first

experiments (1920) used two types of mental tasks in which he told participants to avoid

making comparisons with other people, stressing that the tasks were not competitive in

nature. In a word association task, participants were given a word with which they were

asked to free-associate, meaning that they should write down every word that came to

mind. In an argument-generation task, participants wrote down any argument they could

produce from a classic literature selection. For both tasks, participants performed both

alone and in groups. Allport found that people performing in groups made a higher

number of free-associations and generated a higher quantity of arguments from the

passage; however, the quality of the arguments was greater when they were created in the

alone condition.

Allport’s (1920) results were the first to suggest that social presence may have

varying effects depending on the type of task used. Allport also proposed that social

presence facilitates an idea or thought of movement and thus encourages movement.

Allport also noted that rivalry stimulates increased action, suggesting that over-rivalry,

distraction, and emotions could all lead to impaired performance (Aiello & Douthitt,

2001).

4

Triplett (1898) and Allport (1920) conceptualized social facilitation through

coaction, wherein individuals perform the same task in each other’s presence rather than

performing alone. Neither of these early researchers considered the potential effects that

an audience may have on individual performance, later referred to as the passive observer

paradigm (Dashiell, 1930) or audience effects (Zajonc, 1965). Dashiell (1930) proposed

that several forms of social presence exist, including the following: “(a) the mere

presence of observers, (b) the presence of others express attitudes about the individual

(later theories would refer to this as an evaluative audience), (c) the presence of

noncompeting coactors, and (d) the presence of competing cofactors” (Aiello & Douthitt,

p. 165). Dashiell’s studies compared the effects of these four different forms of social

presence and found that, in terms of speed when performing a variety of tasks, the

observed group was typically fastest and the group of competing coactors was typically

second fastest.

These early studies provided insight into the possible explanations for facilitation

and impairment effects resulting from the presence of others. However, these study

results were highly inconsistent, likely due to small sample sizes and poor control over

experimental conditions. Guerin (1993) points out that many of these early experiments

designed to compare performance of individuals influenced by social presence and

performance of individuals working alone often had an experimenter in the room during

the “alone” condition. While valid conclusions cannot be drawn from these early studies

due to these serious confounds, the studies made strong contributions to social facilitation

theory, raising many of the questions that still predominate today’s literature.

5

Theories of Social Facilitation

Numerous theories of social facilitation have been developed over the years. Five

of the main theories are briefly discussed below.

Drive.

Zajonc’s (1965) influential review represented a milestone in the development of

social facilitation theory. Zajonc argued that social presence facilitates performance of

simple, well-learned tasks and inhibits performance of complex, unlearned tasks. Zajonc

acknowledged the inconsistencies in previous studies where some researchers found that

performance is enhanced by the presence of others, whereas others found that

performance is impaired by the presence of others. Based on the Hull-Spence drive

model (Spence, 1956), Zajonc’s theory of social facilitation contended that an

individual’s drive levels automatically increase in the presence of others, and that the

increase in drive or arousal can either enhance performance of simple tasks or impair

performance of complex tasks. Drive theory posits that increased drive enhances the

release of dominant answers and inhibits the release of subordinate answers. On simple

tasks, the dominant response from an individual is usually correct, leading to

performance enhancement; on complex tasks, the dominant response is usually incorrect,

leading to performance impairment. Although other theories of social facilitation have

emerged and challenged Zajonc’s drive theory, Zajonc’s studies were crucial to the

evolution of social facilitation theory in that they introduced task complexity as a

moderator of social facilitation effects on performance, explaining the seemingly

inconsistent results of earlier studies.

6

Evaluation Apprehension.

Shortly after Zajonc’s original drive theory was proposed, Cottrell (1968, 1972)

asserted that the mere presence of others was not enough to increase drive and would not

necessarily lead to social facilitation effects. Cottrell argued that only when individuals

are concerned about how others might evaluate them would drive levels increase and lead

to either social facilitation or impairment effects. Cottrell’s theory of evaluation

apprehension is similar to Zajonc’s drive theory (1965) in that both theories propose

drive as a mediator between social presence and performance. However, Cottrell

proposed that this drive is learned as a result of past experience with social encounters.

In support of Cottrell’s theory, several studies have found that social facilitation only

occurs when observers had an evaluative presence (Cottrell, Wack, Sekerak, & Rittle,

1968; Paulus & Murdoch, 1971). Similarly, Bond (1982) proposed a self-presentational

theory in which social facilitation occurs due to the regulation and maintenance of a

public image of oneself and social impairment occurs due to embarrassment following a

loss of public respect.

Self-Awareness.

Two additional theories of social facilitation argue that social presence causes

individuals to focus their attention inwardly. Duval and Wicklund’s (1972; Wicklund &

Duval, 1971) objective self-awareness theory suggests that people tend to view

themselves from the perspective of their observers. The salience of any difference

between the current observed self and the individual’s ideal self produces an undesirable

state within that individual, motivating their future behavior to reconcile these

7

differences. In a simple task, this additional energy and motivation improves

performance, but in a complex task, the extra effort leads to impaired performance.

Similarly, Carver and Scheier (1981) proposed their control theory in which social

presence stimulates a process of comparing one’s own behavior against a behavioral

standard, stimulating a negative feedback loop in order to reduce any discrepancies with

the standard. In a simple task, outcomes are expected to be high, thus motivating

sustained effort. In a complex task, outcome expectancy decreases so that individuals

withdraw effort, having a negative impact on performance.

Uncertainty.

In a modification of his original drive theory, Zajonc (1980) suggested that social

facilitation effects evolve from the uncertainty that an individual feels in a social

environment. Guerin and Innes (1982; Guerin, 1983, 1993) further developed this idea in

their monitoring theory. Both the modified drive theory and the monitoring theory

propose that social situations pose a variety of threats to individuals, making it necessary

to maintain a high level of awareness in order to react quickly in case of a threat. This

high level of awareness causes an increase in arousal, which then leads to social

facilitation effects. Based on uncertainty theory, one would expect the strongest social

facilitation effects when an individual feels threatened, is unable to monitor the observer,

or is unfamiliar with the observer (Uziel, 2007).

Distraction.

The distraction-conflict theory (Baron, 1986; Baron, Moore, & Sanders, 1978;

Groff, Baron, & Moore, 1983; Sanders, Baron, & Moore, 1978) argues that social

8

presence creates a distraction for the individual, leading to a conflict of attention. Baron

(1986) suggested that this conflict of attention can have social and nonsocial causes, and

is most likely triggered by one of three specific conditions: (a) the distraction is

particularly interesting or difficult to ignore, (b) pressure exists to complete the task

accurately and quickly, and (c) paying attention to the task and the distraction

simultaneously is difficult or even impossible.

A New Direction

Despite the development of social facilitation theory through a large body of

research spanning over 100 years, “no single theory has emerged that can effectively and

parsimoniously account for this phenomenon” (Aiello & Douthitt, 2001, p. 163). Since

the existing theories previously discussed are not mutually exclusive, it is increasingly

likely that two or more theories co-occur as the best explanation for observed social

facilitation effects (Geen, 1989; Guerin, 1993; Uziel, 2007). More recently, social

facilitation research has begun to consider that two orientations toward social presence

exist. A negative orientation, reflected in the uncertainty, evaluation apprehension, and

distraction theories, dominates the social facilitation literature. Other explanations,

though less common, emphasize a positive orientation toward social presence, marked by

high levels of self-assurance and enthusiasm. Previous studies (Cox, 1966, 1968; Geen,

1977; Henchy & Glass, 1968; Seta & Seta, 1995) have attempted to manipulate the

relationships between the target individual and the observers by inducing a sense of

anxiety or self-assurance. Although there is a solid theoretical argument for the

distinction between positive and negative orientations toward social presence, Uziel

9

(2007) points out that experimental manipulations do not necessarily capture it. Uziel

instead proposed the assessment of personality traits, rather than the use of experimental

manipulation, to accurately capture these inherent positive and negative orientations

toward social presence.

Personality as a Moderator

Early researchers (Allport, 1924; Dashiell, 1935; Hollingsworth, 1935; Spence,

1956; Triplett, 1898) acknowledged the existence of individual differences in social

facilitation effects, yet they did not attempt to incorporate individual differences into their

various theories. After Zajonc’s (1965) emphasis on task complexity as the primary

moderator of social presence, later studies virtually ignored the already proven

moderation of individual differences related to social presence effects on performance.

Uziel (2007) notably points out that there is no theoretical basis for task complexity

classification, leading to the use of a vague categorization of simple versus complex

tasks. While the existence of a theoretical basis for task classification can be argued, the

issue is beyond the scope of this study. The crucial idea is that task complexity has more

recently been shown to be a poor moderator of social presence effects.

Bond and Titus (1983) conducted a meta-analysis of 241 social facilitation

studies, finding that social presence accounts for, on average, only a very small amount

of variance (approximately between 0.3 and 3.0%) in simple and complex task

performance. Bond and Titus also noted the rampantly inconsistent and often

contradictory results of studies, pointing to the obvious existence of moderators other

than task complexity. According to Uziel (2007), only 5-7% of social facilitation studies

10

have measured individual differences. These studies have focused on the measurement

of extraversion, trait anxiety, and self-esteem, showing that these three traits are strongly

associated with the positive and negative orientations toward social presence described

above. While extraversion and neuroticism are distinct from one another (Eysenck &

Eysenck, 1985), both are related to self-esteem, such that self-esteem has a moderate

positive correlation with extraversion and a moderate negative correlation with

neuroticism (Robins, Tracy, Trzesniewski, Potter, & Gosling, 2001).

The sociometer theory of self-esteem further demonstrates the relationship

between extraversion, anxiety, and self-esteem (Leary, 1999; Leary & Baumeister, 2000;

Leary & MacDonald, 2003; Leary, Tambor, Terdal, & Downs, 1995). According to

sociometer theory, self-esteem serves as an indication of an individual’s interpersonal

appeal and perceived success. In social settings, extraverts tend to exhibit assertiveness,

optimism, and dominance. These behaviors lead to social approval and a sense of social

acceptance, which in turn is reflected by high levels of self-esteem. On the other hand,

neuroticism tends to lead to anxiety, depression, and shyness in social situations. These

socially undesirable behaviors lead to social rejection and a sense of social exclusion,

reflected by low levels of self-esteem. Therefore, positively oriented individuals (high

extraversion and high self-esteem) demonstrate a tendency toward self-assurance and

enthusiasm in both general and social environments, while negatively oriented

individuals (high neuroticism and low self-esteem) demonstrate a tendency toward

anxiety and apprehension in both general and social environments.

11

In a meta-analysis of 14 studies that measured individual differences, Uziel

(2007) found that social presence is associated with performance improvement in

positively oriented (high extraversion and high self-esteem) individuals and with

performance impairment in negatively oriented (high neuroticism and low self-esteem)

individuals. Most notably, Uziel found that personality is a more substantial moderator

of social presence effects than task complexity. Stein (2009) sought to examine Uziel’s

(2007) assertions regarding individual differences using a true experimental manipulation

rather than a meta-analysis. Stein measured extraversion, anxiety, and self-esteem

together, similar to Uziel’s use of negative and positive orientations, as well as separately

to tease apart the social facilitation effects. Stein argued that anxiety, instead of

neuroticism, was a more appropriate personality indicator to examine social presence

effects. Neuroticism and anxiety, though theoretically very similar, were both measured

in the current study to resolve the argument between Uziel and Stein regarding which is a

more appropriate measure in regard to social presence effects. Stein concluded that

personality traits indeed have an influence on whether individuals are facilitated or

impaired on tasks of varying complexity, but not in the same manner theorized by Uziel.

Stein found that individuals with high extraversion and high self-esteem were facilitated

in the alone condition compared with the social presence condition, and that individuals

high in anxiety did not change in performance between the absence and presence

conditions.

From Uziel (2007) and Stein (2009), it is apparent that individual differences,

specifically extraversion, self-esteem, neuroticism, and anxiety, are important moderators

12

of social presence effects on performance. However, given their conflicting results,

further research is needed to tease apart the true personality effects. It is important to

note that, although the terms positively oriented and negatively oriented accurately

capture these individual differences, these terms have been used as labels for multiple

other concepts in the field of psychology. In order to avoid confusion, we have chosen to

use the terms affiliative (high extraversion and high self-esteem) and avoidant (high

neuroticism, high anxiety, and low self-esteem) to represent these constructs.

Another unique contribution of this study involves clarification of the type of

anxiety that moderates social presence effects on performance. In the previous social

facilitation literature, studies which have analyzed individual differences have solely

employed the construct of trait anxiety. However, sociometer theory, which serves as the

theoretical foundation for explaining why individual differences matter in social

presence, utilizes the construct of social anxiety. Thus, this study attempts to bridge the

disconnect between theoretical basis and experimental investigation by measuring both

social anxiety and trait anxiety. Based on findings from previous studies, we expect to

find that trait anxiety is a moderator of social presence effects on performance, yet we

also expect to find that social anxiety is a stronger moderator of social presence effects on

performance, above and beyond trait anxiety.

A Novel Application

Social facilitation is generally described as “an influence of social presence on

individual performance” (Aiello & Douthitt, 2001, p. 173), an effect most often measured

through speed and accuracy in performance. Aiello and Douthitt noted the importance

13

for future studies to examine the effects of social presence on other qualitative behavioral

variations. However, every study from the lengthy history of social facilitation theory

has focused solely on individual performance on a variety of simple and complex tasks.

No study to date has attempted to extend social facilitation theory to the domain of

decision-making. Social presence may have profound effects on performance in

decision-making tasks, and its effects may differ from those found in the traditionally-

researched individual performance tasks. Understanding how social presence affects

decision-making is crucial to the field of organizational psychology because decision-

making is an integral component in business, often above and beyond individual task

performance. Both individual and group decision-making are critical behavioral domains

for most people; however, we often have little guidance regarding the optimization of

decision-making outcomes. By examining individual decision-making, we can take the

first step in understanding how personality affects decision-making outcomes in the

presence of others. This study therefore seeks to examine the effect of social presence on

individual decision-making.

Building upon the recent studies of individual differences as a moderator of social

presence on performance (Stein, 2009; Uziel, 2007), we expect that certain personality

variables will have a moderating effect on performance in decision-making. Based on

sociometer theory and the existence of affiliative and avoidant orientations toward social

presence, we know that individuals with high extraversion and high self-esteem are

predisposed to having an affiliative orientation toward social presence, and that

individuals with high neuroticism, high anxiety, and low-self esteem are predisposed to

14

having an avoidant orientation toward social presence. An affiliative orientation

indicates a tendency to approach social situations with a positive sense of challenge and

enthusiasm, and the ability to focus on the task at hand. On the other hand, an avoidant

orientation indicates a tendency to approach social situations with a sense of withdrawal,

marked by anxiety, depression, and distraction from the task at hand (Carver, Sutton, &

Scheier, 2000; Fiedler, 2001; Higgins, 1998; Isen, 1987; Mueller, 1992). Given these

tendencies and the type of decision-making task being used, it is expected that affiliative

individuals will experience performance facilitation and avoidant individuals will

experience performance impairment. Specifically, we expect to find that individuals who

are affiliative, measured by high extraversion and high self-esteem, will experience

performance facilitation in the social presence condition of an individual decision-making

task. We also expect to find that individuals who are avoidant, measured by high

neuroticism, high social anxiety, high trait anxiety, and low self-esteem, will experience

performance impairment in the social presence condition of an individual decision-

making task.

H

1

: Affiliative individuals will experience performance facilitation in the social

presence condition as compared to the alone condition, and avoidant individuals

will experience performance impairment in the social presence condition as

compared to the alone condition.

H

1A

: High extraversion is related to performance facilitation.

H

1B

: High self-esteem is related to performance facilitation.

H

1C

: High neuroticism is related to performance impairment.

15

H

1D

: High social anxiety is related to performance impairment.

H

1E

: High trait anxiety is related to performance impairment.

H

1F

: Low self-esteem is related to performance impairment.

Finally, we expect to find that individuals who have high social anxiety will experience

performance impairment, above and beyond the impairment related to high trait anxiety,

in the social presence condition of an individual decision-making task.

H

2

: Participants with high social anxiety will experience performance

impairment, above and beyond the impairment related to high trait anxiety.

16

CHAPTER TWO

METHOD

Participants

Participants for the study were 49 undergraduate students enrolled in introductory

psychology courses at Clemson University. Students received credit toward partial

fulfillment of a research-participation course requirement, as well as the chance to win a

$50 lottery based on performance on the decision-making task. Twenty-four participants

completed an individual decision-making task in a true alone condition with no

experimenter present, and the other twenty-five participants completed the same task in

the presence of an observer. The author served as the observer for all participants to

maintain consistency in the manipulation. Basic demographic information, including

age, gender, race, and educational status, were also collected. Participants were an

average of 19.4 years old, 65.3% female, and 85.7% Caucasian.

Measures

Personality.

Participants completed measures of extraversion, neuroticism, self-esteem, social

anxiety, and trait anxiety. All five scales are rated on a 1-5 Likert scale measuring the

extent to which participants felt that each item accurately described themselves, where

1 = very inaccurate and 5 = very accurate. For negatively scored items, items were

reverse-scored such that 1 = very accurate and 5 = very inaccurate. Scores for each

personality scale were summed to yield total scores for extraversion, neuroticism, self-

esteem, social anxiety, and trait anxiety (see Appendix A for list of items).

17

Extraversion.

Extraversion was assessed with a 20-item scale from the International Personality

Item Pool (IPIP; Goldberg et al., 2006), a highly reliable scale with a Cronbach’s α = .91.

Neuroticism.

Similarly, neuroticism was assessed with a 20-item scale from the International

Personality Item Pool (IPIP; Goldberg et al., 2006), a highly reliable scale with a

Cronbach’s α = .91.

Self-esteem.

Self-esteem was assessed with the 10-item Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (SES;

Rosenberg, 1965). Fleming and Courtney (1984) reported a Cronbach’s α = .88 for the

SES, and demonstrated a correlation of -.64 between the SES and anxiety.

Social anxiety.

Social anxiety was assessed with the 12-item Brief Fear of Negative Evaluation

(BFNE; Leary, 1983) scale, with a Cronbach’s α = .90. The BFNE is a brief version of

the Fear of Negative Evaluation (FNE; Watson & Friend, 1969) scale. Individuals who

score highly on this scale experience greater anxiety when in evaluative settings and

report being more bothered by the possibility of receiving a negative evaluation as

compared to individuals who score low on the scale (Friend & Gilbert, 1973; Goldfried &

Sobocinski, 1975; Leary, Barnes, & Griebel, 1986; Smith & Sarason, 1975).

Trait anxiety.

Trait anxiety was assessed with a 10-item scale from the International Personality

Item Pool (IPIP; Goldberg et al., 2006), with a Cronbach’s α = .83.

18

Decision-Making Task.

The decision-making task was developed by Straus and McGrath (1994). Straus

and McGrath pre-tested the task in a sample comparable to that of the current study to

ensure that the task was considered interesting and was of an appropriate level of

difficulty and length for the given population. The task session is 12 minutes in length.

Participants were asked to decide on appropriate disciplinary actions for a fabricated case

in which a graduate teaching assistant accepted a bribe from a star basketball player to

change the student’s exam grade. The goal of the task is to resolve the following five

issues related to the treatment of both the student-athlete and the teaching assistant: (1)

the student’s exam and course grade, (2) the student’s standing on the basketball team,

(3) the student’s academic standing, (4) the teaching assistant’s work standing as an

instructor, and (5) the teaching assistant’s academic standing.

Participants were instructed to decide upon one choice from a list of alternatives

for each of the five issues (see Appendix B for list of issues and alternatives). For

example, the alternatives for Issue 1 are “give him his original grade on the exam”, “give

him a failing grade on the exam”, and “give him a failing grade in the course” (Straus &

McGrath, 1994, p. 90). Participants were instructed to attempt to reconcile the competing

interests of the athletic department (wanting to maintain the player’s athletic eligibility),

the faculty (wanting to maintain the institution’s academic integrity), and the university

administration (wanting to satisfy both the athletic department and the faculty).

Straus and McGrath’s (1994) scoring system was used to evaluate the responses

to the decision-making task, yielding measures of overall task effectiveness, productivity,

19

and average quality. To obtain an overall measure of effectiveness, the scoring system

consisted of two sets of point values for the issue alternatives. The first point set reflects

the extent to which each alternative supports each faction’s (i.e., the athletic department,

the faculty, and the university administration) interests. For example, the alternative of

failing the student in the course on Issue 1 has a high point value for the faculty because

academic integrity is maintained, but has a low point value for the athletic department

because failing a course makes the student ineligible to play. The second set of point

values corresponds to the importance that each issue has for each faction’s interests. For

example, the issue of the student’s standing on the basketball team is very important to

the athletic department, while the instructor’s status as a student is of little concern. Each

individual was given three scores, one from each of the three factions’ point of views.

Each faction score was composed of the weighted point values for each faction, summed

over all five issues. The overall effectiveness score is thus a product of the three faction

scores. Using a multiplicative procedure ensured that the highest effectiveness scores

were awarded for solutions that involved the highest degree of balance among the three

factions’ interests, and that solutions which were highly favorable for one faction but

unfavorable for the other two factions received a lower overall effectiveness score.

No points were awarded for an unresolved issue so that participants were

rewarded for reaching a decision on all five issues, rather than leaving any issues

unresolved. Productivity was therefore simply measured by the total number of issues

resolved. Average quality was assessed by comparing the effectiveness scores among

20

individuals that resolved all of the issues, and analyzing the distribution of alternatives

chosen among individuals that resolved each specific issue.

Although there is no reliability or validity data available for the decision-making

task, Straus and McGrath’s (1994) article has been widely cited, appearing in 441

scholarly articles. Per the author’s personal correspondence with Dr. Straus, the task and

its scoring system are also frequently requested for use in research experiments.

Procedure

Participants were recruited by signing up for the study using the Human

Participation in Research (HPR) website, an online repository for research experiments

conducted at the university. In the lab, the experimenter conducted the informed consent

process with the participants. Participants first completed a basic demographic

questionnaire. Then participants completed a pre-task 72-item personality assessment,

which included scales for extraversion, neuroticism, self-esteem, social anxiety, and trait

anxiety. The order of the scales in the personality assessment was counterbalanced

across participants. Finally, participants completed the individual decision-making task.

All participants were reminded that the purpose of the task is to create the highest degree

of balance between the interests of the athletic department, the faculty, and the university

administration. In order to achieve this balance, participants were also instructed to

ignore their own preferences in the case. Individuals in the alone condition completed

the decision-making task while completely alone in a room. In the social presence

condition, the experimenter remained seated at a separate desk in the corner of the room

while the participants completed the task. The experimenter informed the participants

21

that “I am just sitting here observing and taking notes about the study process. I am not

evaluating your performance.” Participants answered one post-task question assessing

the extent to which they felt as if they were being evaluated, serving as an assessment of

whether participants’ sense of evaluation differed between the two conditions. Total

participation time was approximately 30 minutes.

22

CHAPTER THREE

RESULTS

Item scores were summed across scales to yield total scale scores for extraversion,

neuroticism, self-esteem, social anxiety, and trait anxiety. Because we hypothesize that

the propensity to experience social facilitation is the sum of multiple factors, we

combined the five scale scores to create an overall “propensity to experience social

facilitation” (PSF) score. Combining the five scale scores into one overall score also

contributes to increased statistical power for analyses. To create an overall measure of

these five personality traits that have an influence on the relationship between social

presence and decision-making, the scale scores for neuroticism, social anxiety, and trait

anxiety were first reverse-scored such that higher scores indicate less presence of the

given trait. The mean and standard deviation for each personality scale was then

calculated and used to standardize the five individual scale scores into z-scores for all

participants. Finally, the five z-scores were averaged to yield the PSF score. Thus, as

PSF increases (i.e., as extraversion and self-esteem increase, and as neuroticism, social

anxiety and trait anxiety decrease), an individual’s propensity for experiencing social

facilitation increases. We first visually inspected the spread of the personality traits to

determine if they were normally distributed.

Observed Distribution of Personality Traits

In order to draw meaningful conclusions, it is important to ensure that the

participant sample demonstrates a wide variety of scores for the five personality traits.

Neuroticism and trait anxiety scores were normally distributed with values observed at

23

both the high and low ends of the scales. Extraversion was also normally distributed,

although extremely low values were unobserved. Social anxiety scores were interestingly

bimodally, normally distributed with values observed at both the high and low ends of the

scale. Self-esteem was the only non-normally distributed personality scale,

demonstrating a significant negative skew. However, this finding is not unexpected

given that many studies (e.g., Blascovich & Tomaka, 1991) have noted that the

distribution of self-esteem scale scores among college students tends to be negatively

skewed (i.e., demonstrating range restriction).

Correlations between Personality Traits

We also calculated bivariate Pearson correlations between the five personality

traits (see Table 3.1). As expected, self-esteem was moderately positively correlated with

extraversion, r(47) = .495, p < .01, and moderately negatively correlated with

neuroticism, r(47) = -.595, p < .01. Neuroticism and trait anxiety were very strongly

positively correlated, r(47) = .918, p < .01, a finding that is later discussed.

Table 3.1. Bivariate Correlation Matrix for Personality Variables

Extraversion Neuroticism Self-Esteem Social Anxiety Trait Anxiety

Trait Anxiety -.369** .918** -.489** .567** 1

Social Anxiety -.437** .563** -.550** 1

Self-Esteem .495** -.595** 1

Neuroticism -.475** 1

Extraversion 1

Note. Correlation is significant at the .01 level (2-tailed).

24

Decision-Making Outcomes

Next, we analyzed the relationship between PSF, experimental condition, and the

interaction between PSF and condition as it relates to the three decision-making

outcomes—overall effectiveness, productivity, and average quality.

Overall Effectiveness.

We conducted a hierarchical linear regression analysis, testing the effect of

experimental condition (alone vs. social presence) and PSF on overall effectiveness in the

first step, and adding the interaction between condition and PSF in the second step (see

Table 3.2). Condition did not significantly predict overall effectiveness, t(45) = .098, p =

.923. PSF also did not significantly predict overall effectiveness, t(45) = -1.197, p =

.238. As hypothesized, the interaction between condition and PSF approached

significance, B = 1913.882, t(45) = 1.962, p = .056. The interaction between condition

and PSF explained an additional 7.7% proportion of the variance, beyond condition and

PSF alone, in overall effectiveness scores, ∆R

2

= .079.

Table 3.2. Hierarchical Linear Regression for Overall Effectiveness

Variables Entered B Std. Error T Cumulative R

2

∆R

2

Step 1

Intercept 6335.114 567.113 — .002 .002

Condition 76.058 794.111 .096

PSF 129.448 502.681 .258

Step 2

Intercept 6356.690 550.441 — .080 .079

Condition 75.330 770.612 .098

PSF -824.482 688.779 -1.197

Condition * PSF 1913.882 975.616 1.962

†

Note.

†

p < .10

25

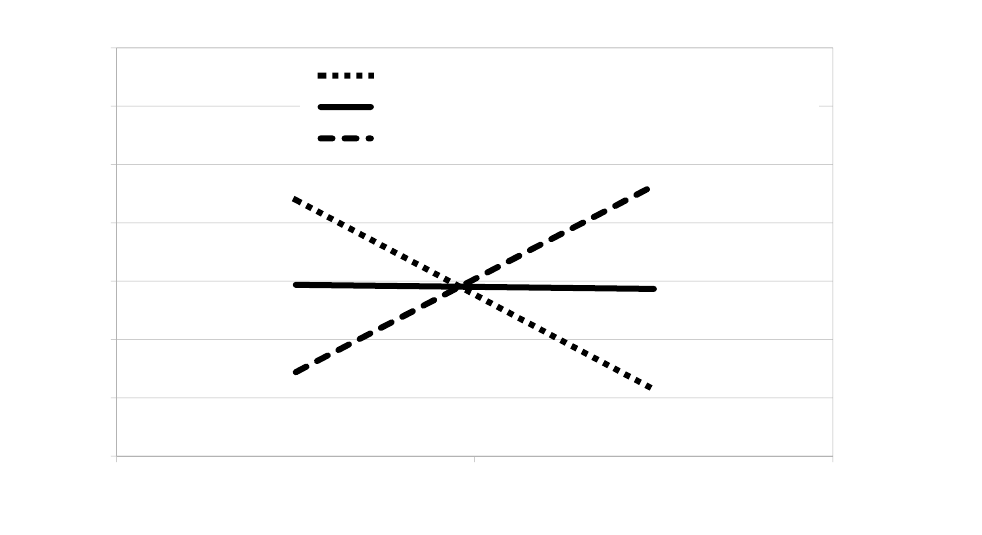

The interaction occurred in the hypothesized direction, illustrated in Figure 3.1.

Individuals with a high propensity to experience social facilitation (M + 1 SD; PSF = .80)

experienced performance facilitation in the social presence condition as compared to the

alone condition, such that overall effectiveness scores were much higher in the social

presence condition (M = 7310) than in the alone condition (M = 5698). Individuals with

a low propensity to experience social facilitation (M – 1 SD; PSF = -.80) experienced

performance impairment in the social presence condition as compared to the alone

condition, such that overall effectiveness scores were much lower in the social presence

condition (M = 5562) than in the alone condition (M = 7014). Individuals with an

average propensity to experience social facilitation (M; PSF = .0) experienced no change

in overall effectiveness scores between the alone and social presence conditions, such

that overall effectiveness scores in the social presence condition (M = 6432) did not

significantly differ from the alone condition (M = 6356). Interestingly, those individuals

with average PSF scores made less effective decisions as compared to both the high PSF

and low PSF individuals in their optimal decision-making contexts (i.e., in the social

presence and the alone condition, respectively).

26

Figure 3.1. Condition * Propensity to Experience Social Facilitation Interaction

Productivity and Average Quality.

Productivity is a simple measure of the number of issues that were resolved by

participants. Only 1 participant out of 49 failed to resolve all five issues; thus, a ceiling

effect eliminated productivity as a meaningful dependent variable.

The average quality of decisions was analyzed in two ways: (1) by comparing

effectiveness scores among only individuals that resolved all of the issues, and (2) by

analyzing the distribution of options chosen for each of the issues among individuals that

resolved that specific issue. Given these analytic methods developed by Straus and

McGrath (1994), an analysis of average quality is effectively rendered useless due to the

ceiling effect. However, we used the first method of analyzing average quality by

removing the one participant who did not resolve all five issues and conducting a simple

5000

5500

6000

6500

7000

7500

8000

8500

Alone Condition Social Presence Condition

Low Propensity to Experience Social Facilitation

Average Propensity to Experience Social Facilitation

High Propensity to Experience Social Facilitation

Overall Effectiveness

27

linear regression analysis testing the effect of experimental condition (alone vs. social

presence), PSF, and the interaction between condition and PSF. We found a slight

improvement in the significance of the interaction between condition and PSF as a

predictor of overall effectiveness, B = 2009.850, t(44) = 2.046, p = .047. The interaction

between condition and PSF explained an additional proportion of variance, beyond

condition and PSF alone, in overall effectiveness scores, ∆R

2

= .087, which is slightly

higher than the model R

2

including all 49 participants.

Comparison of Specific Personality Traits

While our primary research question deals with the overall propensity to

experience social facilitation, we also wanted to conduct preliminary analyses regarding

the effects of certain specific personality factors.

Neuroticism vs. Trait Anxiety.

We previously explained that neuroticism and trait anxiety are theoretically very

similar, but we included both as predictors to resolve the argument between Uziel (2007)

and Stein (2009) regarding which is a more appropriate measure in regard to social

presence effects. Given that the correlation is r(47) = .918, p < .01, we are unable to test

whether neuroticism or trait anxiety is a stronger predictor of social presence effects

given the multi-collinearity between neuroticism and trait anxiety.

Social Anxiety vs. Trait Anxiety.

We ran two simple linear regression analyses to determine if social anxiety or trait

anxiety is a better predictor of overall decision-making effectiveness (see Table 3.3). It is

important to note that neuroticism was not included in either model due to its high

28

correlation with trait anxiety. The first regression analysis included extraversion, self-

esteem, and trait anxiety as predictors of overall effectiveness. Trait anxiety did not

significantly predict overall effectiveness, B = -61.154, t(45) = -.132, p = .895. The

model explained a small proportion of variance in overall effectiveness scores, R

2

= .038.

The second regression analysis included extraversion, self-esteem, and social anxiety as

predictors of overall effectiveness. Social anxiety approached significance as a predictor

of overall effectiveness, B = 831.470, t(45) = 1.755, p = .086. The model also explained

a larger proportion of variance in overall effectiveness scores than the previous model, R

2

= .099. Thus, social anxiety is a stronger predictor of overall effectiveness scores than

trait anxiety.

Table 3.3. Regression for Social Anxiety vs. Trait Anxiety

Variables Entered B Std. Error t ∆R

2

Model 1

Intercept 6373.921 393.924 — .038

Extraversion -573.201 464.636 -1.234

Self-Esteem 447.658 495.144 .904

Trait Anxiety -61.154 462.923 -.132

Model 2

Intercept 6373.920 381.168 — .099

Extraversion -765.052 455.145 -1.681

†

Self-Esteem 55.006 490.273 .112

Social Anxiety 831.470 473.694 1.755

†

Note.

†

p < .10.

Sense of Evaluation

Finally, we conducted a simple comparison of means to determine if participants

in the social presence condition felt a greater sense of evaluation compared to participants

in the alone condition. Sense of evaluation in the social presence condition (M = 3.240,

29

SD = 1.091) did not significantly differ from sense of evaluation in the alone condition

(M = 3.208 SD = 1.250). Rather, participants’ sense of how much they were being

evaluated was related to participants’ social anxiety, r(49) = .277, p = .054. In the alone

condition, participants’ sense of how much they were being evaluated was moderately

correlated with social anxiety, r(24) = .462, p = .023. However, in the social presence

condition, there was no relationship between sense of evaluation and social anxiety, r(25)

= .079, p = .708. Interpretation of the meaningfulness of these split group correlations is

difficult given the low sample size within each group.

30

CHAPTER FOUR

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that personality moderates the relationship between social

presence and decision-making outcomes. Specifically, we established a propensity to

experience social facilitation (PSF) score, which increases as extraversion and self-

esteem increase and as neuroticism, social anxiety, and trait anxiety decrease.

Individuals with higher PSF scores made more effective decisions when making those

decisions in the presence of another person. Individuals with lower PSF scores made

more effective decisions when making those decisions without another person present.

Finally, individuals with average PSF scores (i.e., average scale scores on all of the

personality traits) made equally effective decisions when making those decisions in the

presence of another person or without another person present.

The level of decision-making effectiveness for those individuals with average PSF

scores was notably significantly lower than for both individuals with higher PSF scores in

the social presence condition and individuals with lower PSF scores in the alone

condition. Although individuals with average PSF scores performed equally well

whether in the presence of another person or alone, indicating that they were unaffected

by the experimental manipulation, those with both high PSF scores and low PSF scores

can reach more effective decisions when doing so in their optimal decision-making states

(i.e., in the presence of others for high PSF scores and alone for low PSF scores). This

finding suggests that we can optimize decision-making effectiveness for people who fall

at both the high and low ends of extraversion, neuroticism, self-esteem, social anxiety,

31

and trait anxiety by tailoring the context in which they make decisions; however, people

who are at typical levels in terms of personality cannot increase decision-making

performance by changing the situation in which decisions are made.

Participants demonstrated a very high level of decision-making productivity.

Since the decision-making task was originally structured as a group task by Straus and

McGrath (1994), it makes sense that productivity would vary more when analyzing

groups because of the introduction of multiple individual personalities and the potential

for disagreement. Thus, a measure of productivity proved to not be as meaningful in an

individual task given the absence of these complexities.

We next analyzed several issues regarding the specific personality traits that make

up the PSF score. We could not draw a conclusion regarding whether neuroticism or trait

anxiety is a stronger moderator of social presence effects in decision-making due to the

multi-collinearity between neuroticism and trait anxiety. It is likely that the discrepancies

between our findings and those of Uziel (2007) and Stein (2009) are due to variations in

experimental manipulation. However, from these results, we conclude that neuroticism

and trait anxiety are equally strong predictors of social presence effects. We confirmed

our hypothesis that social anxiety is a much more significant moderator of social

presence effects as compared to trait anxiety. Finally, we contributed to the social

facilitation literature by (1) including social anxiety as a predictor of social presence

effects, and (2) finding that social anxiety is a stronger predictor of social presence

effects than trait anxiety. From this point forward, researchers interested in social

32

facilitation should include social anxiety in their analysis, a decision which is supported

by the sociometer theory literature (rf. Leary et al., 1995) and the findings of this study.

Limitations

There were several limitations to the study which need to be addressed. Although

most of the personality variables comprising the PSF score were normally distributed,

self-esteem was significantly negatively skewed, which is expected in a population of

college students. Using the same manipulation and measurement with another sample

(e.g., employees of a large financial firm), we may find different personality

distributions, leading to results different from the current study. It is also feasible that

college students, given their younger age and lack of experience, may make less effective

decisions than the general population, so another sample may demonstrate a different

pattern of changes in decision-making effectiveness when making decisions either in the

presence of others or alone. However, the topic of the decision-making task was very

relevant to the experiences of college students.

The decision-making task required a considerable amount of social intelligence,

which may have stacked the deck in favor of significant findings related to social anxiety.

Finally, it is important to note that the sample size, especially when making comparisons

between the alone and social presence conditions, is relatively small.

Future Research

Given these limitations, future research should attempt to examine the same

hypothesized relationship in a variety of samples. The hypothesized relationship between

social presence, personality traits, and decision-making outcomes might be opposite of

33

the relationship found in the current study when other types of decision-making tasks are

used. We found that affiliative individuals make better decisions in the presence of

others; however, there are other types of tasks, such as those involving the detection of

danger or a more realistic, rather than optimistic, sense of one’s own abilities for which a

more negative mood may lead to better decision-making. Under certain circumstances, a

sense of optimism may lead to overconfidence or lack of caution, and if the task is such

that overconfidence or lack of caution are heavily penalized, individuals who are more

realistic may perform better on those tasks. Future studies could examine the

relationship between social presence, personality, and decision-making in tasks where

caution is negatively evaluated and where risk is valued. It is also plausible that real-

world tasks, rather than hypothetical tasks such as the one used in this study, may be of

higher complexity and involve higher stakes.

Another direction for future studies is to extend this theory to group decision-

making. The use of groups introduces several other complexities into the decision-

making environment, such as group cohesion, perceived similarity, and the introduction

of multiple, and most likely different, personality types. An interesting direction would

be to examine the same hypotheses in a group decision-making scenario, comparing

groups with homogeneous (i.e., affiliative and avoidant groups) and heterogeneous

personalities. Future research should also examine social presence effects in other types

of group tasks. McGrath (1984) suggested that group tasks can be classified into one of

four categories of basic processes, namely generate, choose, negotiate and execute tasks.

Decision-making tasks such as that used in the current study are a part of the choose

34

category, along with intellectual tasks. The generate category involves generating ideas

and plans through creativity and planning tasks, the execute category involves executing

performance tasks and resolving conflicts of power through competitive and psycho-

motor tasks, and the negotiate category involves resolving conflicts of viewpoint and

conflicts of interest through cognitive conflict and mixed-motive tasks. Future research

should examine social facilitation effects using these other types of group tasks.

35

CHAPTER FIVE

CONCLUSION

Since its introduction in 1898, social facilitation theory has focused solely on the

impact of social presence on performance in individual tasks. Given this study’s findings

of social facilitation effects in decision-making, it is necessary to revise this traditional

definition of social facilitation. Although task performance is an important component of

the everyday duties of employees in the corporate world, decision-making is an even

more crucial and complex component of employee responsibilities. Social presence has a

proven influence on decision-making effectiveness. Using personality as a moderator,

this theory implies that individuals who are affiliative experience benefits from social

presence while engaging in decision-making, while others who are avoidant suffer

detriments from social presence while making decisions. The goal of any business is to

enable employees and managers to make efficient, productive, high-quality decisions.

For those with high extraversion and high self-esteem, they may be optimal decision-

makers while under the supervision or observance of others. For those with high

neuroticism, high anxiety, and low self-esteem, they may be optimal decision-makers

while working alone. An understanding of employees’ personality can provide managers

and supervisors with the ability to tailor decision-making scenarios to obtain the most

effective outcome.

36

APPENDICES

37

Appendix A

Personality Assessment Items

Extraversion (20-item scale; Cronbach’s α = .91)

+ Scored: Feel comfortable around people.

Make friends easily.

Am skilled in handling social situations.

Am the life of the party.

Know how to captivate people.

Start conversations.

Warm up quickly to others.

Talk to a lot of different people at parties.

Don't mind being the center of attention.

Cheer people up.

– Scored: Have little to say.

Keep in the background.

Would describe my experiences as somewhat dull.

Don't like to draw attention to myself.

Don't talk a lot.

Avoid contact with others.

Am hard to get to know.

Retreat from others.

Find it difficult to approach others.

Keep others at a distance.

Neuroticism (20-item scale; Cronbach’s α = .91)

+ Scored: Often feel blue.

Dislike myself.

Am often down in the dumps.

Have frequent mood swings.

Panic easily.

Am filled with doubts about things.

Feel threatened easily.

Get stressed out easily.

Fear for the worst.

Worry about things.

– Scored: Seldom feel blue.

Feel comfortable with myself.

Rarely get irritated.

Am not easily bothered by things.

Am very pleased with myself.

38

Am relaxed most of the time.

Seldom get mad.

Am not easily frustrated.

Remain calm under pressure.

Rarely lose my composure.

Self-Esteem (10-item scale; Cronbach’s α = .88)

+ Scored: I feel that I am a person of worth, at least on an equal basis with others.

I feel that I have a number of good qualities.

I am able to do things as well as most other people.

I take a positive attitude toward myself.

On the whole, I am satisfied with myself.

– Scored: All in all, I am inclined to feel that I am a failure.

I feel I do not have much to be proud of.

I wish I could have more respect for myself.

I certainly feel useless at times.

At times I think I am no good at all.

Social Anxiety (12-item scale; Cronbach’s α = .90)

+ Scored: I am frequently afraid of other people noticing my shortcomings.

I am afraid that others will not approve of me.

I am afraid that people will find fault with me.

When I am talking to someone, I worry about what they may be thinking

about me.

I am usually worried about what kind of impression I make.

Sometimes I think I am too concerned with what other people think of me.

I often worry that I will say or do the wrong things.

I worry about what people will think of me even when I know it doesn’t make

any difference.

– Scored: I rarely worry about what kind of impression I am making on someone.

Other people’s opinions of me do not bother me.

If I know someone is judging me, it has little effect on me.

I am unconcerned even if I know people are forming an unfavorable

impression of me.

Trait Anxiety (10-item scale; Cronbach’s α = .83)

+ Scored:

Worry about things.

Fear for the worst.

Am afraid of many things.

Get stressed out easily.

Get caught up in my problems.

39

–

Scored:

Am not easily bothered by things.

Am relaxed most of the time.

Am not easily disturbed by events.

Don't worry about things that have already happened.

Adapt easily to new situations.

40

Appendix B

Decision-Making Task Alternatives

Issue 1: Jack’s grade in the course

1a. Give Jack his original grade on the exam (a D).

1b. Give Jack a failing grade on the exam.

1c. Give Jack a failing grade in the course.

Issue 2: Jack's status on the basketball team

2a. Make no change in Jack's basketball eligibility.

2b. Suspend Jack from the next basketball game.

2c. Suspend Jack from the basketball team for the rest of the season.

2d. Suspend Jack from the basketball team for an indefinite length of time and

require that he appeal to be reinstated.

2e. Kick Jack off the team.

Issue 3: Jack's status as a college student

3a. Make no change in Jack's college status.

3b. Give Jack a warning, stating that if he is involved in another incident

involving cheating in the future, he will be expelled.

3c. Suspend Jack from college (classes and athletics) for the rest of the semester.

3d. Suspend Jack from the college for an indefinite length of time and require

that he appeal for readmittance.

3e. Expel Jack from the college.

Issue 4: Tom's status as an instructor (Note: If Tom is restricted from teaching, he loses a

source of income that helps pay his way through graduate school.)

4a. Make no change in Tom's teaching status.

4b. Give Tom a reprimand to be placed in his permanent record, which will be

seen by potential employers after he is finished with school.

4c. Suspend Tom from teaching for the rest of the semester.

4d. Suspend Tom from teaching for an indefinite length of time and require that

he appeal to be reinstated.

4e. Do not allow Tom to teach again during his time remaining in graduate

school.

Issue 5: Tom's status as a graduate student

5a. Make no change in Tom's college status.

41

5b. Give Tom a warning, stating that if he is involved in another incident

involving cheating in the future, he will be expelled.

5c. Suspend Tom from the college for the rest of the semester.

5d. Suspend Tom from the college for an indefinite length of time and require

that he appeal for readmittance.

5e. Expel Tom from the college.

42

References

Aiello, J. R., & Douthitt, E. A. (2001). Social facilitation from Triplett to electronic

performance monitoring. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 5(3),

163-180.

Allport, F. H. (1920). The influence of the group upon association and thought. Journal

of Experimental Psychology, 3, 159-182.

Allport, F. H. (1924). Response to social stimulation in the group. In F.H. Allport (Ed.),

Social psychology (pp. 260-291). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Baron, R. S. (1986). Distraction-conflict theory: progress and problems. In L. Berkowitz

(Ed.), Advances in experimental and social psychology, 19, (pp. 1-40).

Baron, R. S., Moore, D., & Sanders, G. S. (1978). Distraction as a source of drive in

social facilitation research. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 36,

816-824.

Blascovich, J., & Tomaka, J. (1991). Measures of self-esteem. In J. R. Robinson, P. R.

Shaver, & L. S. Wrightsman (Eds.), Measures of personality and social

psychological attitudes (pp. 115-160). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Bond, F. C. (1982). Social facilitation: A self-presentational view. Journal of Personality

and Social Psychology, 42, 1042-1050.

Bond, F. C., & Titus, L. J. (1983). Social facilitation: A meta-analysis of 241 studies.

Psychological Bulletin, 94(2), 265-292.

Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (1981). The self-attention induced feedback loop and

social facilitation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 17, 545-568.

Carver, C. S., Sutton, S. K., & Scheier, M. F. (2000). Action, emotion, and personality:

Emerging conceptual integration. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin,

26(6), 741-751.

Cottrell, N. B. (1968). Performance in the presence of other human beings: mere presence

and affiliation effects. In E. C. Simmel, R. A. Hoppe, & G. A. Milton (Eds.),

Social facilitation and imitative behavior (pp. 91-110). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Cottrell, N. B. (1972). Social facilitation. In C. G. McClintock (Ed.), Experimental social

psychology (pp. 185-236). New York: Holt.

43

Cottrell, N. B., Wack, D. L., Sekerak, G. J., & Rittle, R. H. (1968) Social facilitation of

dominant responses by the presence of an audience and the mere presence of

others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9, 245-250.

Cox, F. N. (1966). Some effects of test anxiety and presence or absence of other persons

on boys’ performance on a repetitive motor task. Journal of Experimental Child

Psychology, 3, 100-112.

Cox, F. N. (1968). Some relationship between test anxiety, presence or absence of other

persons and boys’ performance on a repetitive motor task. Journal of

Experimental Child Psychology, 6, 1-12.

Dashiell, J. F. (1930). An experimental analysis of some group effects. Journal of

Abnormal and Social Psychology, 25, 190-199.

Dashiell, J. F. (1935). Experimental studies of the influence of social situations on the

behavior of individual human adults. In C. Murchison (Ed.), A handbook of social

psychology (pp. 1097-1158). Worcester, MA: Clark University Press.

Duval, S., & Wicklund, R. A. (1972). A theory of objective self-awareness. New York:

Academic Press.

Eysenck, H. J., & Eysenck, M. W. (1985). Personality and individual differences. New

York: Plenum Press.

Fiedler, K. (2001). Affective influences on social information processing. In J. P. Forgas

(Ed.), The handbook of affect and social cognition (pp. 163-185). Mahwah, NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum.

Fleming, J. S., & Courtney, B. E. (1984). The dimensionality of self-esteem: Some

results for a college sample. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46,

404-421.

Friend, R., & Gilbert, J. (1973). Threat and fear of negative evaluation as determinants of

locus of social comparison. Journal of Personality, 41, 328–340.

Geen, R. G. (1977). Effects of anticipation of positive and negative outcomes on

audience anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 45(4), 715-716.

Geen, R. G. (1989). Alternative conceptions of social facilitation. In P. B. Paulus (Ed.),

Psychology of group influence (2

nd

ed., pp. 15-51). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

44

Goldberg, L. R., Johnson, J. A., Eber, H. W., Hogan, R., Ashton, M. C., Cloninger, C. R.,

& Gough, H. C. (2006). The international personality item pool and the future of

public-domain personality measures. Journal of Research in Personality, 40, 84-

96.

Goldfried, M., & Sobocinski, D. Effects of irrational beliefs on emotional arousal.

Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 1975, 43, 504-510.

Groff, B. D., Baron, R. S., & Moore, D. L. (1983). Distraction, attentional conflict, and

drivelike behavior. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 19, 359-380.

Guerin, B. (1983). Social facilitation and social monitoring: A test of three models.

British Journal of Social Psychology, 22, 203-214.

Guerin, B. (1993). Social facilitation. Cambridge: University Press.

Guerin, B., & Innes, J. M. (1982). Social facilitation and social monitoring: A new look

at Zajonc’s mere presence hypothesis. British Journal of Social Psychology, 21,

7-18.

Henchy, T., & Glass, D. C. (1968). Evaluation apprehension and the social facilitation of

dominant responses. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 10, 446-454.

Higgins, E. T. (1998). Promotion and prevention: Regulatory focus as a motivational

principle. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol.

30, pp. 1-46). New York: Academic Press.

Hollingsworth, H. L. (1935). The psychology of the audience. New York: American Book

Company.

Irwin, J. R., & McClelland, G. H. (2003). Negative consequences of dichotomizing

continuous predictor variables. Journal of Marketing Research, 40(3), 366-371.

Isen, A. M. (1987). Positive affect, cognitive processes, and social behavior. In L.

Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (pp. 203-251). New

York: Academic Press.

Judge, T. A., Erez, A., Bono, J. E., & Thoresen, C. J. (2002). Are measures of self-

esteem, neuroticism, locus of control, and generalized self-efficacy indicators of a

common core construct? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 693-

710.

Leary, M. R. (1983). A brief version of the fear of negative evaluation scale. Personality

and Social Psychology Bulletin, 9(3), 371-375.

45

Leary, M. R. (1999). Making sense of self-esteem. Current Directions in Psychological

Science, 8, 32-35.

Leary, M. R., Barnes, B. D., & Griebel, C. (1986). Cognitive, affective, and attributional

effects of potential threats to self-esteem. Journal of Social & Clinical

Psychology, 4, 461-474.

Leary, M. R., & Baumeister, R. F. (2000). The nature and function of self-esteem:

sociometer theory. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.). Advances in experimental social

psychology (Vol. 32, pp. 1-62). San Diego: Academic Press.

Leary, M. R., & MacDonald, G. (2003). Individual differences in self-esteem: a review

and theoretical integration. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), Handbook of

self and identity (pp. 401-418). New York: Guilford Press.

Leary, M. R., Tambor, E. S., Terdal, S. K., & Downs, D. L. (1995). Self-esteem as an

interpersonal monitor: The sociometer hypothesis. Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology, 68, 518-530.

McGrath, J. E. (1984). Groups: Interaction and performance. Englewood Cliffs, NJ:

Prentice Hall.

Mueller, J. H. (1992). Anxiety and performance. In A. P. Smith & D. M. Jones (Eds.),

Handbook of human performance (Vol. 3, pp. 127-160). London: Academic

Press.

Paulus, P. B., & Murdoch, P. (1971). Anticipated evaluation and audience presence in the

enhancement of dominant responses. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology,

7, 280-291.

Robins, R. W., Tracy, J. L., Trzesniewski, K., Potter, J., & Gosling, S. (2001).

Personality correlates of self-esteem: Age and sex differences. Journal of

Research in Personality, 35, 463-482.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton

University Press.

Sanders, G. S, Baron, R. S., & Moore, D. L. (1978). Distraction and social comparison as