Supplement / Vol. 69 / No. 1 August 21, 2020

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report

Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance —

United States, 2019

Supplement

The MMWR series of publications is published by the Center for Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC),

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, GA 30329-4027.

Suggested citation: [Author names; first three, then et al., if more than six.] [Title]. MMWR Suppl 2020;69(Suppl-#):[inclusive page numbers].

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Robert R. Redfield, MD, Director

Anne Schuchat, MD, Principal Deputy Director

Chesley L. Richards, MD, MPH, Deputy Director for Public Health Science and Surveillance

Rebecca Bunnell, PhD, MEd, Director, Office of Science

Arlene Greenspan, PhD, Acting Director, Office of Science Quality, Office of Science

Michael F. Iademarco, MD, MPH, Director, Center for Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services

MMWR Editorial and Production Staff (Serials)

Charlotte K. Kent, PhD, MPH, Editor in Chief

Christine G. Casey, MD, Editor

Mary Dott, MD, MPH, Online Editor

Terisa F. Rutledge, Managing Editor

David C. Johnson, Lead Technical Writer-Editor

Catherine B. Lansdowne, MS, Project Editor

Marella Meadows, Project Editor

Guest Editors: Zewditu Demissie, PhD; J. Michael Underwood, PhD

Martha F. Boyd, Lead Visual Information Specialist

Maureen A. Leahy, Julia C. Martinroe,

Stephen R. Spriggs, Tong Yang,

Visual Information Specialists

Quang M. Doan, MBA, Phyllis H. King,

Terraye M. Starr, Moua Yang,

Information Technology Specialists

MMWR Editorial Board

Timothy F. Jones, MD, Chairman

Michelle E. Bonds, MBA

Matthew L. Boulton, MD, MPH

Carolyn Brooks, ScD, MA

Jay C. Butler, MD

Virginia A. Caine, MD

Katherine Lyon Daniel, PhD

Jonathan E. Fielding, MD, MPH, MBA

David W. Fleming, MD

William E. Halperin, MD, DrPH, MPH

Jewel Mullen, MD, MPH, MPA

Jeff Niederdeppe, PhD

Patricia Quinlisk, MD, MPH

Patrick L. Remington, MD, MPH

Carlos Roig, MS, MA

William Schaffner, MD

Morgan Bobb Swanson, BS

CONTENTS

Overview and Methods for the Youth Risk Behavior

Surveillance System — United States, 2019..............................................1

Condom and Contraceptive Use Among Sexually Active High School

Students — Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019

......... 11

Trends in Violence Victimization and Suicide Risk by Sexual Identity

Among High School Students — Youth Risk Behavior Survey,

United States, 2015–2019

............................................................................. 19

Interpersonal Violence Victimization Among High School Students —

Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019

...................................... 28

Prescription Opioid Misuse and Use of Alcohol and Other Substances

Among High School Students — Youth Risk Behavior Survey,

United States, 2019

......................................................................................... 38

Suicidal Ideation and Behaviors Among High School Students —

Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019

................................. 47

Tobacco Product Use Among High School Students — Youth Risk

Behavior Survey, United States, 2019

....................................................... 56

Dietary and Physical Activity Behaviors Among High School

Students — Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019

......... 64

Transportation Risk Behaviors Among High School Students —

Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019

................................. 77

Supplement

MMWR / August 21, 2020 / Vol. 69 / No. 1 1

US Department of Health and Human Services/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Overview and Methods for the Youth Risk Behavior

Surveillance System — United States, 2019

J. Michael Underwood, PhD

1

; Nancy Brener, PhD

1

; Jemekia Thornton, MPA

1

; William A. Harris, MM

1

; Leah N. Bryan, MPH

1

;

Shari L. Shanklin, MPH

1

; Nicholas Deputy, PhD

1,2

; Alice M. Roberts, MS

3

; Barbara Queen, MS

4

, David Chyen, MS

1

; Lisa Whittle, MPH

1

;

Connie Lim, MPA

1

; Yoshimi Yamakawa, MPH

1

; Michelle Leon-Nguyen, MPH

1

; Greta Kilmer, MS

1

; Jennifer Smith-Grant, MSPH

1

;

Zewditu Demissie, PhD

1

; Sherry Everett Jones, PhD, JD

1

; Heather Clayton, PhD

1

; Patricia Dittus, PhD

1

1

Division of Adolescent and School Health, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, CDC;

2

Epidemic Intelligence Service;

3

ICF International, Rockville, Maryland;

4

Westat, Rockville, Maryland

Abstract

Health risk behaviors practiced during adolescence often persist into adulthood and contribute to the leading causes of morbidity

and mortality in the United States. Youth health behavior data at the national, state, territorial, tribal, and local levels help monitor

the effectiveness of public health interventions designed to promote adolescent health. The Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance

System (YRBSS) is the largest public health surveillance system in the United States, monitoring a broad range of health-related

behaviors among high school students. YRBSS includes a nationally representative Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) and separate

state, local school district, territorial, and tribal school–based YRBSs. This overview report describes the surveillance system and

the 2019 survey methodology, including sampling, data collection procedures, response rates, data processing, weighting, and

analyses presented in this MMWR Supplement. A 2019 YRBS participation map, survey response rates, and student demographic

characteristics are included. In 2019, a total of 78 YRBSs were administered to high school student populations across the United

States (national and 44 states, 28 local school districts, three territories, and two tribal governments), the greatest number of

participating sites with representative data since the surveillance system was established in 1991. The nine reports in this MMWR

Supplement are based on national YRBS data collected during August 2018–June 2019. A full description of 2019 YRBS results

and downloadable data are available (https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/index.htm).

Efforts to improve YRBSS and related data are ongoing and include updating reliability testing for the national questionnaire,

transitioning to electronic survey administration (e.g., pilot testing for a tablet platform), and exploring innovative analytic methods

to stratify data by school-level socioeconomic status and geographic location. Stakeholders and public health practitioners can

use YRBS data (comparable across national, state, tribal, territorial, and local jurisdictions) to estimate the prevalence of health-

related behaviors among different student groups, identify student risk behaviors, monitor health behavior trends, guide public

health interventions, and track progress toward national health objectives.

Introduction

Adolescence is typically a healthy period of life, and CDC

reports that youths continue to make better decisions for

their health (1). However, some high school–aged youths

experience disparate health risks that increase the possibility

of acquiring a sexually transmitted disease (STD), including

human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, and increase

opportunities for substance use, mental health problems, and

interpersonal violence or self-harm. Risky health behaviors

practiced during adolescence often persist into adulthood

(2). In 2018, CDC reported that the leading causes of death

Corresponding author: J. Michael Underwood, PhD, Division of

Adolescent and School Health, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral

Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, CDC. Telephone: 404-718-1471;

E-mail: [email protected].

among U.S. adolescents were attributable to motor-vehicle

crashes, followed by suicide and homicide (3). In contrast,

that same year, a separate study reported the leading causes of

death among persons of all ages were heart disease, followed

by cancer and unintentional injuries (e.g., burns, drowning,

falls, poisoning, and motor-vehicle crashes) (4).

The Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS)

monitors health behaviors, conditions, and experiences among

high school students throughout the United States. The system

includes a national Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS),

conducted by CDC, and separate state, local school district,

territorial, and tribal school–based YRBSs, which are referred

to as site-level surveys. YRBSS is designed to monitor priority

health risk behaviors that contribute to the leading causes of

mortality, morbidity, and social problems among youths and

adults. The following categories of behaviors are included

in the system: 1) behaviors that contribute to unintentional

Supplement

2 MMWR / August 21, 2020 / Vol. 69 / No. 1

US Department of Health and Human Services/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

injury and violence; 2) tobacco use; 3) alcohol and other

drug use; 4) sexual behaviors that contribute to unintended

pregnancy and STD/HIV infection; 5) dietary behaviors; and

6) physical inactivity.

This report describes the 2019 YRBS methodology,

including sampling, data collection, processing, weighting,

and analyses. Results include a 2019 YRBS participation

map, survey response rates (1991–2019), and student

demographic characteristics from the national survey.

Furthermore, this overview report is one of nine featured

in this MMWR Supplement. Each report uses YRBS data to

assess a priority public health topic among adolescents. In

addition to this overview report, this supplement includes

national YRBS updates regarding condom and contraceptive

use; violence victimization and suicide ideation by sexual

identity; interpersonal violence victimization; opioid, alcohol,

and other substance use behaviors; suicide ideation and

behaviors; tobacco use, including vaping; dietary behaviors

and physical activity; and transportation risk behaviors. Each

report might not include all national YRBS data related to the

topics that were collected in 2019, and this supplement does

not include any data from site-level surveys; however, all the

data are publicly available. (YRBS data and documentation

are available at https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/

data.htm.) Stakeholders and public health practitioners can

use YRBS data (comparable across national, state, tribal, and

local jurisdictions) to estimate the prevalence of health-related

behaviors among different student groups, identify student

risk behaviors, monitor health behavior trends, guide public

health interventions, and track progress toward national

health objectives.

National YRBS Methodology

Overview

The national YRBS is conducted biennially during the

spring of odd-numbered years and allows CDC to assess how

risk behaviors change temporally among the U.S. high school

population. The national YRBS provides comparable data

across years and allows state and local entities conducting their

own YRBS to demonstrate how the behaviors of their youths

compare with those at the national level. YRBS is conducted

among students in grades 9–12 who attend U.S. public and

private schools. A nationally representative sample of schools

and a random sample of classes within those schools are selected

to participate. The survey is self-administered anonymously by

using a computer-scannable questionnaire booklet and takes

one class period (approximately 45 minutes) to complete.

Questionnaire

In 2019, the YRBS questionnaire consisted of 99 questions.

Eighty-nine of those questions were included in the standard

questionnaire* used by sites. Ten additional questions were

added to the standard questionnaire that reflect areas of interest

for CDC and other stakeholders, forming the 99-question

national YRBS questionnaire. As in all cycles, both the standard

questionnaire and additional national-only questions were

revised to ensure that emerging and prevailing risk behaviors

among high school students were measured. Subject matter

experts from CDC and elsewhere proposed changes, additions,

and deletions to the questionnaire. New and revised questions

were reviewed for format, readability, and clarity and were

subjected to cognitive testing. CDC made further refinements

to the questions on the basis of those testing results.

All questions, except those assessing height, weight, and

race, were multiple choice, with a maximum of eight mutually

exclusive response options and only one possible answer per

question. The survey questions have undergone test-retest

analysis and demonstrated good reliability (5,6). The wording

of each question, including recall periods and response options,

and operational definitions for each variable, are available by

reviewing the 2019 YRBS questionnaire and data user’s guide.

(YRBSS data and documentation are available at https://www.

cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/data.htm.)

Sampling

The 2019 YRBS sampling frame consisted of all regular

public (including charter schools), parochial, and other

nonpublic schools with students in at least one of grades 9–12

in the 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia. Alternative

schools, special education schools, schools operated by the U.S.

Department of Defense, the Bureau of Indian Education, and

vocational schools serving only students who also attended

another school were excluded. Schools with an enrollment

of ≤40 students across grades 9–12 also were excluded. The

sampling frame was based on data sets obtained from Market

Data Retrieval, Inc., and the National Center for Education

Statistics (NCES). NCES data sets were based on the Common

Core of Data (https://nces.ed.gov/ccd) for public schools

and the Private School Universe Survey (https://nces.ed.gov/

surveys/pss) for nonpublic schools.

A three-stage cluster sampling design was used to produce

a nationally representative sample of students in grades 9–12

* The standard YRBSS questionnaire includes 89 questions. YRBS coordinators

(located in CDC-funded states, local school districts, territories, and tribes)

voted for or against each proposed change, addition, and deletion. Final content

of the standard YRBS questionnaire was decided on the basis of the results of

this voting process.

Supplement

MMWR / August 21, 2020 / Vol. 69 / No. 1 3

US Department of Health and Human Services/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

who attend public and private schools. The first-stage sampling

frame comprised 1,257 primary sampling units (PSUs),

consisting of entire counties, groups of smaller adjacent

counties, or parts of larger counties. The 1,257 PSUs were

categorized into 16 strata according to their metropolitan

statistical area status (e.g., urban or rural) and the percentages

of non-Hispanic black (black) and Hispanic students in each

PSU. From the 1,257 PSUs, 54 were sampled with probability

proportional to overall school enrollment size for that PSU. For

the second-stage sampling, secondary sampling units (SSUs)

were defined as a physical school with grades 9–12 or a school

created by combining nearby schools to provide all four grades.

From the 54 PSUs, 162 SSUs were sampled with probability

proportional to school enrollment size. To provide adequate

coverage of students in small schools, an additional 15 small

SSUs were selected from a subsample of 15 PSUs from the 54

PSU sample. These 177 SSUs corresponded to 184 physical

schools. The third stage of sampling comprised random

sampling of one or two classrooms in each of grades 9–12

from either a required subject (e.g., English or social studies)

or a required period (e.g., homeroom or second period).

All students in sampled classes were eligible to participate.

Schools, classes, and students who refused to participate were

not replaced in the sampling design.

Data Collection Procedures

CDC’s Institutional Review Board approved the protocol

for the YRBS. Survey procedures were designed to protect

students’ privacy by allowing for anonymous and voluntary

participation. Before survey administration, local parental

permission procedures were followed. During survey

administration, students completed the self-administered

questionnaire during one class period and recorded their

responses directly on a computer-scannable booklet.

Response Rates and Data Processing

For the 2019 YRBS, 13,872 questionnaires were completed

in 136 schools. The national data set was cleaned and edited

for inconsistencies. Missing data were not statistically imputed.

A questionnaire failed quality control when <20 responses

remained after editing or when it contained the same answer

to ≥15 consecutive questions. Among the 13,872 completed

questionnaires, 195 failed quality control and were excluded

from analysis, resulting in 13,677 usable questionnaires. The

school response rate was 75.1%; the student response rate was

80.3%; and the overall response rate (i.e., [student response

rate] × [school response rate]) was 60.3%.

Race/ethnicity was ascertained from two questions:

1) “Are you Hispanic or Latino?” (with response options of

“yes” or “no”) and 2) “What is your race?” (with response

options of “American Indian or Alaska Native,” “Asian,” “black

or African American,” “Native Hawaiian or other Pacific

Islander,” or “white”). For the second question, students

could select more than one response option. For this report,

students were classified as Hispanic/Latino and are referred

to as Hispanic if they answered “yes” to the first question,

regardless of how they answered the second question. Students

who answered “no” to the first question and selected only black

or African American to the second question were classified as

black or African American and are referred to as black. Students

who answered “no” to the first question and selected only white

to the second question were classified and are referred to as

white. Race/ethnicity was classified as missing for students

who did not answer the first question and for students who

answered “no” to the first question but did not answer the

second question.

To obtain a sufficient sample size for analyses of health-

related behaviors by sexual identity and sex of sexual contacts,

students were divided into groups (Table 1). Students who had

no sexual contact were excluded from analyses related to sexual

behaviors, female students who had sexual contact with only

females were excluded from analyses on condom use and birth

control use, and male students who had sexual contact with

only males were excluded from analyses on birth control use.

Weighting

A weight based on student sex, race/ethnicity, and grade

was applied to each record to adjust for school and student

nonresponse and oversampling of black and Hispanic students.

The overall weights were scaled so that the weighted count

of students equals the total sample size, and the weighted

proportions of students in each grade match the national

population proportions. Therefore, weighted estimates

are nationally representative of all students in grades 9–12

attending U.S. public and private schools.

Analytic Methods

Findings presented in this MMWR Supplement and Youth

Online (https://nccd.cdc.gov/Youthonline/App/Default.aspx),

an interactive data analysis tool that allows access to all YRBSS

data, follow analytic methods similar to what is described in

this overview report. For more information regarding the

analyses presented in this supplement (e.g., variables analyzed,

custom measures, and data years), see the Methods section in

each individual report.

All statistical analyses were conducted on weighted data by

using SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute) and SUDAAN (version

11.0.1; RTI International) software to account for the complex

Supplement

4 MMWR / August 21, 2020 / Vol. 69 / No. 1

US Department of Health and Human Services/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

TABLE 1. Processing of sexual identity and sex of sexual contacts questions — Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019

Question Student response Analytic description

Sexual identity

Which of the following best describes you?

1) Heterosexual (straight), 2) gay or lesbian, 3) bisexual, or

4) not sure

Heterosexual (straight)

Gay or lesbian or bisexual

Not sure

Heterosexual students

Lesbian, gay, or bisexual students

Not-sure students

Sex of sexual contacts

During your life, with whom have you had sexual contact?

1) I have never had sexual contact, 2) females, 3) males, or

4) females and males

What is your sex?

1) Male or 2) female

I have never had sexual contact* Students who had no sexual contact

Contact:

Female

Male

Student:

Male

Female

Students who had sexual contact with only the

opposite sex

Contact:

Male

Females and males

Female

Females and males

Student:

Male

†

Male

Female

†

Female

Students who had sexual contact with only the

same sex or with both sexes

* Excluded from analyses on sexual behaviors.

†

Excluded from analyses on birth control use and condom use.

sampling designs. In all reports, prevalence estimates and

confidence intervals were computed for variables in the YRBS

data set. Pairwise differences between populations (e.g., sex, race/

ethnicity, grade, sexual identity, and sex of sexual contacts) were

determined using t-tests. Prevalence estimates were considered

statistically significant if the t-test p value was <0.05.

In reports that analyzed data related to temporal trends,

prevalence estimates for variables assessed with identically

worded questions were examined. Logistic regression analyses

were used to account for all available estimates; control for

sex, grade, and racial/ethnic changes over time; and assess

long-term linear and quadratic trends. A p value associated

with the regression coefficient that was <0.05 was considered

statistically significant. Linear and quadratic time variables

were treated as continuous and were coded by using orthogonal

coefficients calculated with PROC IML in SAS. A minimum

of 3 survey years was required for calculating linear trends,

and a minimum of 6 survey years was required to calculate

quadratic trends. Separate regression models were used to

assess linear and quadratic trends for every variable. When a

significant quadratic trend was identified, Joinpoint software

was used to automate identification of the year when the

nonlinear (i.e., quadratic) trend changed. Regression models

were used to identify linear trends occurring in each segment.

Cubic and higher-order trends were not assessed. A quadratic

trend indicates a statistically significant but nonlinear trend

in prevalence over time. A long-term temporal change that

includes a significant linear and quadratic trend demonstrates

nonlinear variation (e.g., leveling off or change in direction) in

addition to an overall increase or decrease over time.

In reports that analyzed 2-year changes in health-related

behaviors, prevalence estimates from 2017 and 2019 were

compared by using t-tests for variables assessed with identically

worded questions in both survey years. Prevalence estimates were

considered statistically different if the t-test p value was <0.05.

Data Availability and Dissemination

YRBS data (1991–2019) are available from the YRBSS

data and documentation website (https://www.cdc.gov/

healthyyouth/data/yrbs/data.htm), as are additional resources,

including data documentation and analysis guides. Data are

available in both Access and ASCII formats. SAS and SPSS

programs are provided for converting the ASCII data into

SAS and SPSS data sets. Variables are standardized to facilitate

trend analyses and for combining data. YRBSS data are also

available online by using Youth Online (https://nccd.cdc.gov/

Youthonline/App/Default.aspx), a tool that allows point-and-

click data analysis and creation of customized tables, graphs,

maps, and fact sheets. Youth Online also performs statistical

tests by health topic and filters and sorts data by race/ethnicity,

sex, grade, and sexual orientation (sexual identity and sex of

sexual contacts). Finally, YRBS Explorer is a new application

featuring user-friendly options to view and compare national,

state, and local data via tables and graphs (https://yrbs-explorer.

services.cdc.gov). Data requests and other YRBSS-related

questions can be sent to CDC by using the data request form

(https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/contact.htm).

Supplement

MMWR / August 21, 2020 / Vol. 69 / No. 1 5

US Department of Health and Human Services/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

State, Local School District,

Territorial, and Tribal YRBS

Methodology

Overview

Biennial administration of site-level YRBSs allows state

and local education and health agencies to assess how risk

behaviors change temporally among the high school population

in their respective jurisdiction. Site-level YRBS data provide

comparable data across years and allow comparisons of student

behaviors across jurisdictions (e.g., national or state). Site-

level surveys are conducted among students in grades 9–12

attending public schools by using samples representative of

the state, local, territorial, or tribal jurisdiction where they are

administered. The survey is self-administered anonymously

and takes one class period (approximately 45 minutes) to

complete. State and local institutional review boards approved

the protocol for their respective YRBSs. Survey methodology

for data collection, processing, and analytic methods were the

same as those described for the national YRBS.

Questionnaires

The 2019 YRBS standard questionnaire contained

89 questions and was used as the starting point for site-level

YRBS questionnaires. Sites could add or delete questions but

were required to use at least 60 of the questions on the standard

questionnaire. This flexibility allows YRBS coordinators and

other local stakeholders the opportunity to pursue topics of

interest by customizing their survey.

Sampling

Sites used a two-stage cluster sampling design to produce

a representative sample of students in grades 9–12 in their

jurisdiction. In 41 states, three local school districts, and one

territory, in the first sampling stage, public schools with any

of grades 9–12 were sampled with probability proportional

to school enrollment size. In two states, 25 local school

districts, and two territories, all schools in the jurisdiction

were selected to participate (i.e., a census of schools). In the

second sampling stage, intact classes from either a required

subject (e.g., English or social studies) or a required period

(e.g., homeroom or second period) were sampled randomly.

In three sites (Vermont, the District of Columbia, and Palau),

a census of students was eligible to participate.

Response Rates and Nonresponse

Bias Analyses

Before the 2019 YRBS cycle, CDC required a minimum

60% overall response rate for data from a jurisdiction to be

weighted. As response rates in federal surveys continue to

decline (7), a better understanding of the complex association

between nonresponse and nonresponse bias is needed. In 2019,

CDC chose three YRBS sites with overall response rates of

50%–60% (Nebraska; Texas; and Spartanburg County, South

Carolina) to pilot nonresponse bias analyses to evaluate data

representativeness. Because of data limitations, comparisons

were limited to responding and nonresponding schools by

school size and responding and nonresponding students by

grade. Weighted sample and population percentages by grade,

sex, and race/ethnicity were also compared. Overall, few

statistically significant differences between comparison groups

were found, which suggested that the data were generally

representative of their respective populations. For the 2019

cycle, CDC used nonresponse bias analysis results to help

determine whether data were weighted for sites with overall

response rates <60%.

Weighting

YRBS data were weighted if sites collected data from a

representative sample of students (determined either by an

overall response rate of ≥60% or nonresponse bias analysis

indicating no significant bias). A weight based on student sex,

race/ethnicity, and grade was applied to each record to adjust

for school and student nonresponse in each jurisdiction. The

weighted count of students equals the student population in

each jurisdiction. Data from 44 states and 28 local school

districts were weighted. In 26 states and 13 local school

districts, weighted estimates are representative of all students

in grades 9–12 attending regular public schools, and in

13 states and eight local school districts, weighted estimates are

representative of regular public school students plus students in

grades 9–12 in other types of public schools (e.g., alternative

or vocational schools).

Data Availability and Dissemination

A combined data set including national, state, local school

district, territorial, and tribal YRBS data (1991–2019) is available

from the YRBSS data and documentation website (https://nccd.

cdc.gov/Youthonline/App/Default.aspx). Availability of site

data depends on survey participation, data quality, and data-

sharing policies. Information about YRBSS data is available at

the participation maps and history website (https://www.cdc.

gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/participation.htm). Data requests

Supplement

6 MMWR / August 21, 2020 / Vol. 69 / No. 1

US Department of Health and Human Services/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

and other YRBS-related questions can be sent to CDC by

using the data request form. (The YRBSS question, comment,

and data request form is available at https://www.cdc.gov/

healthyyouth/data/yrbs/contact.htm.) Site-level YRBS data

(from high school and middle school surveys) collected during

1991–2019 are available through Youth Online (https://nccd.

cdc.gov/Youthonline/App/Default.aspx) and YRBS Explorer

(https://yrbs-explorer.services.cdc.gov).

YRBS Response Rates and 2019

Demographic Characteristics

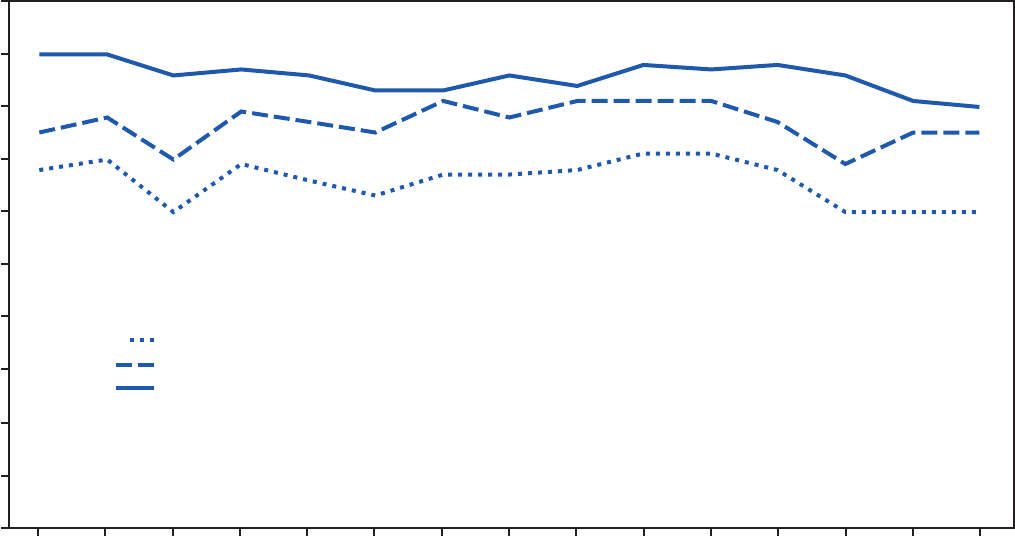

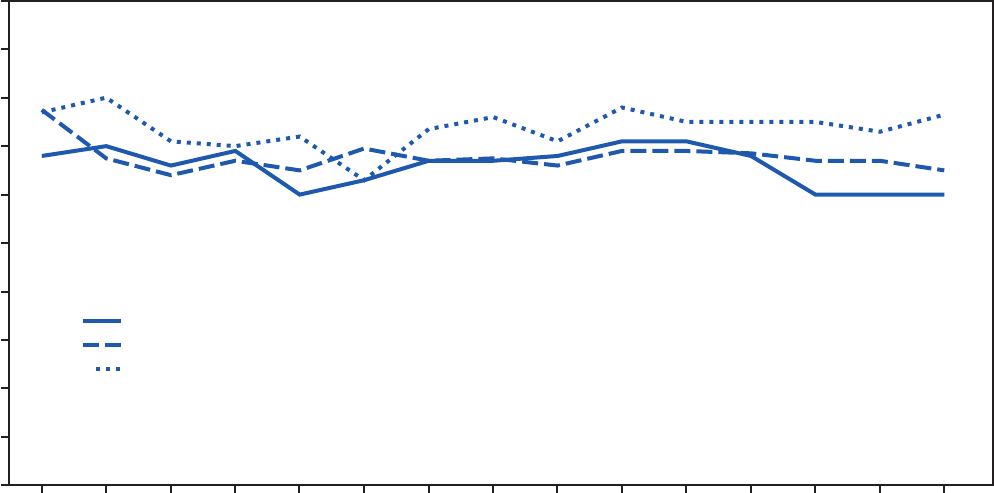

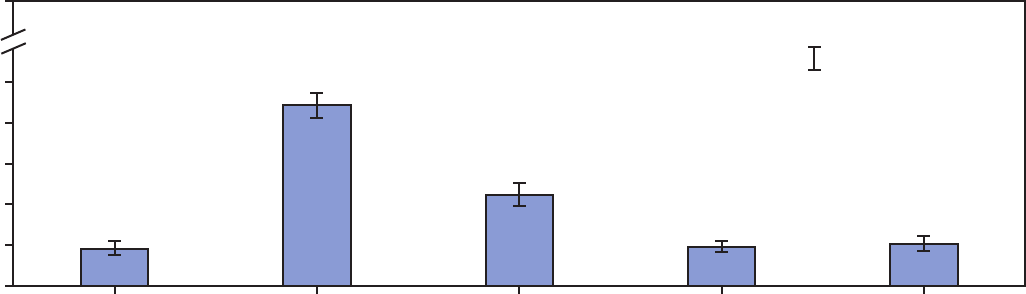

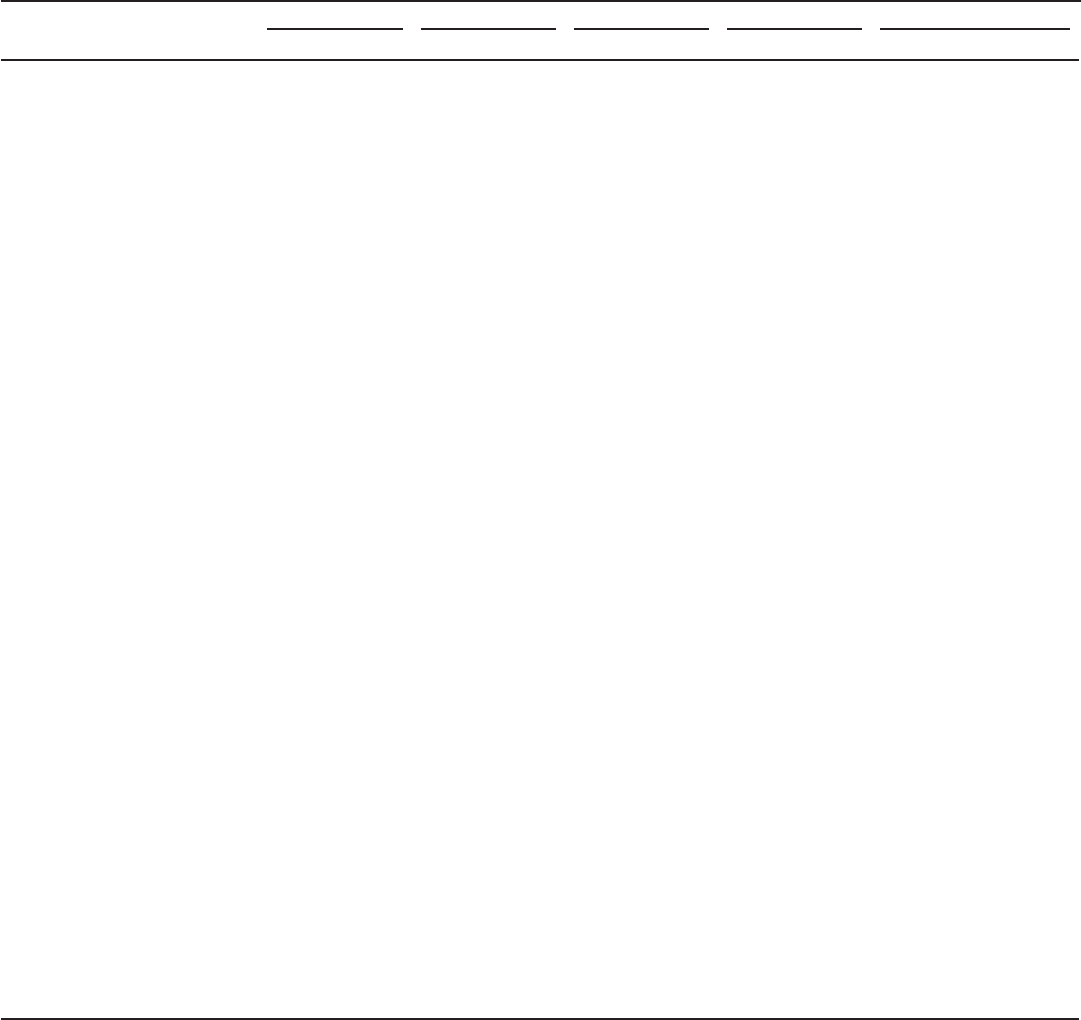

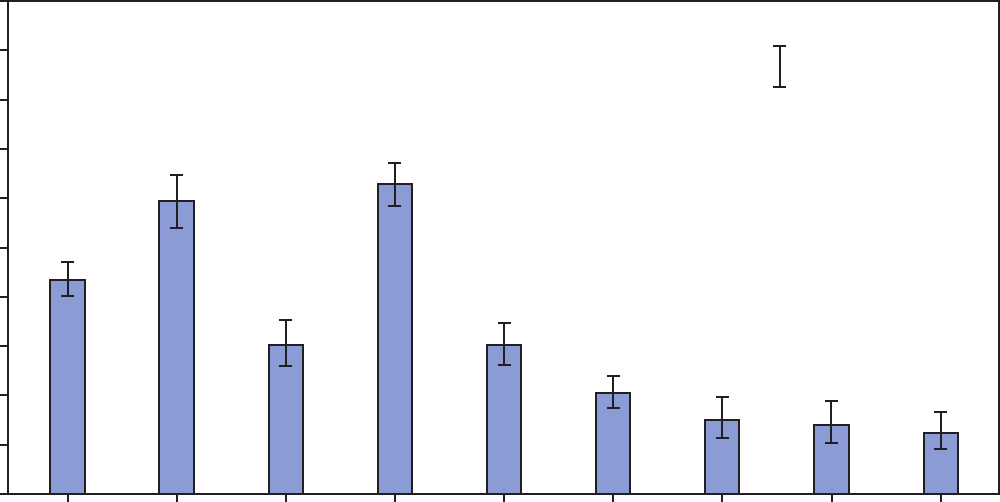

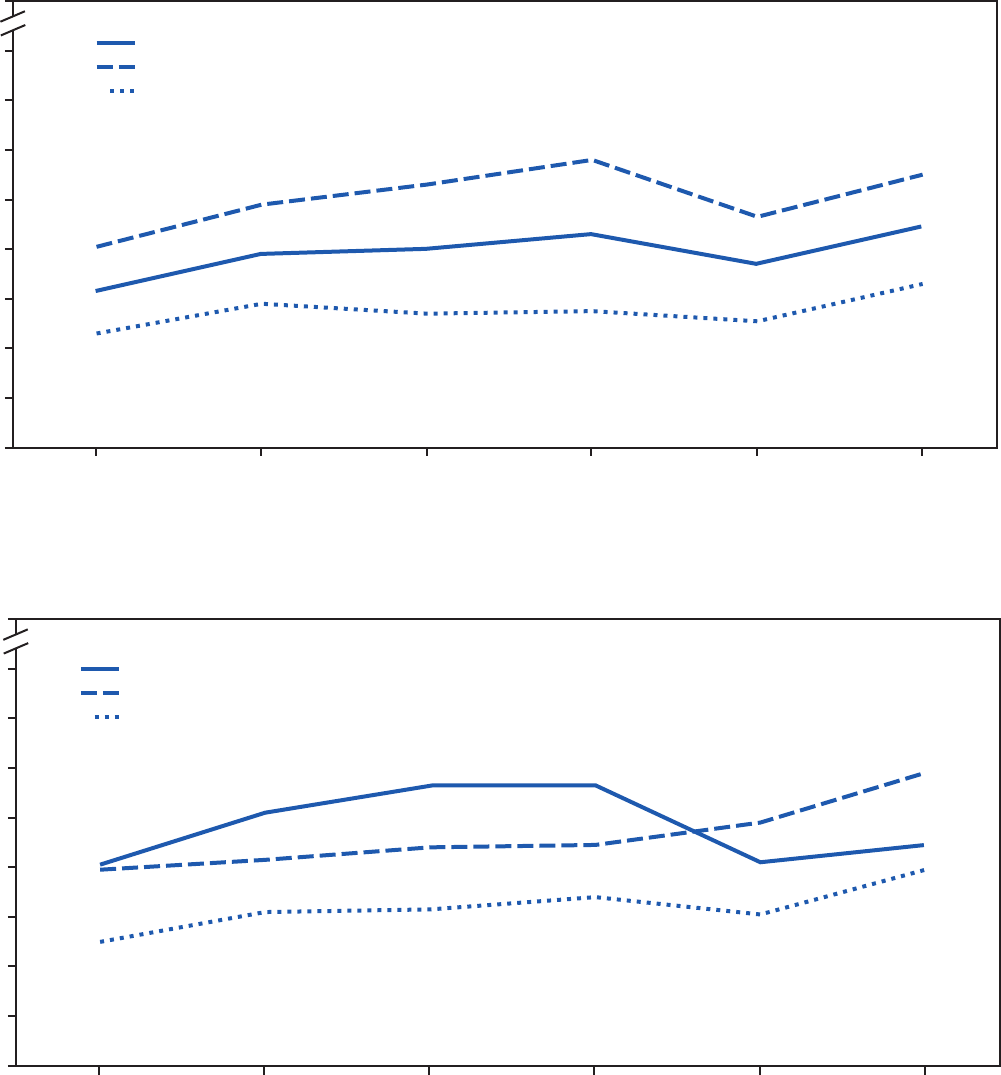

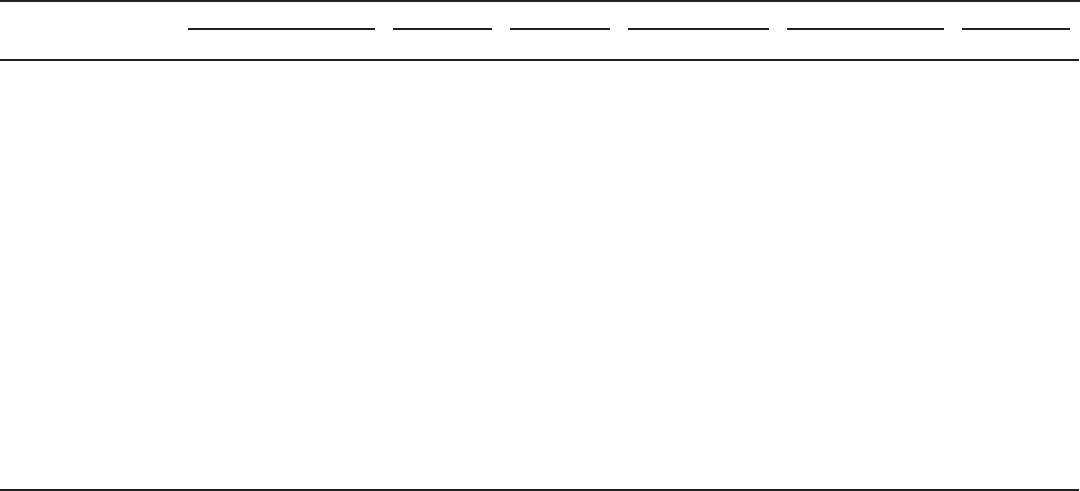

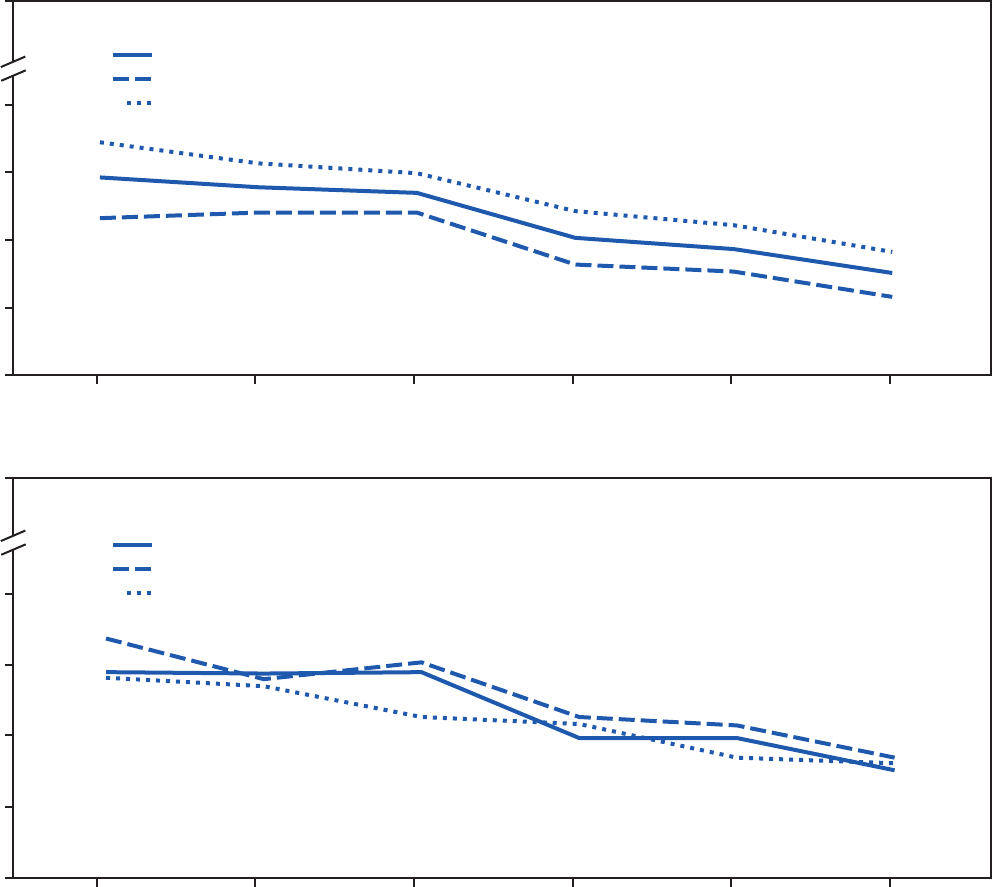

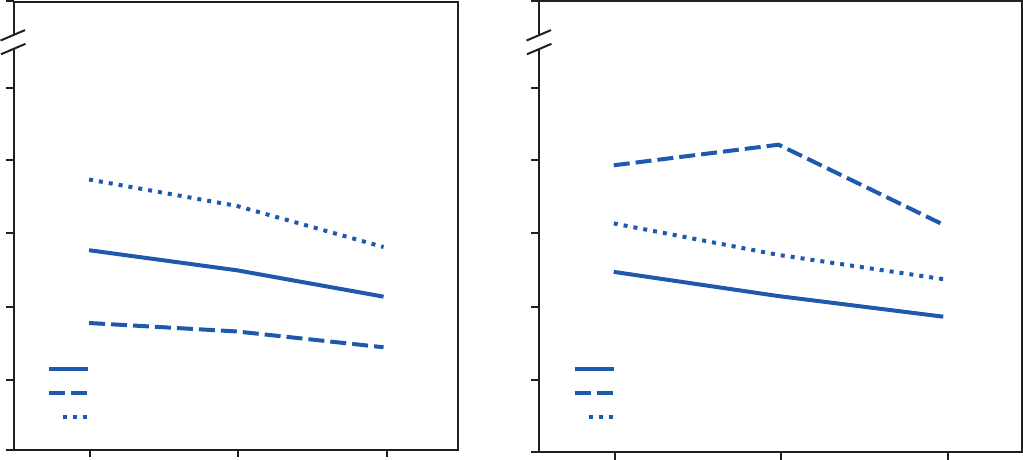

During 1991–2019, national YRBS overall response rates

remained at >60% (Figure 1). They reached a high of 71%

during the 2009 and 2011 YRBS cycles, followed by steady

decreases; response rates have remained in the low 60% range

during the 2015–2019 cycles. Since 1991, school response

rates have varied from 70% to the low 80% range, whereas

student participation rates have been consistent at 80%–90%.

Data were weighted to match national population

proportions. Thus, 50.6% of students were male, and 26.6%

were in 9th grade; 25.5% were in 10th grade; 24.2% were in

11th grade; and 23.5% were in 12th grade (Table 2). In regard

to race/ethnicity, the majority of students were no-Hispanic

FIGURE 1. Overall, school, and student response rates for the national Youth Risk Behavior Surveys — United States, 1991–2019

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019

Percentage

Year

School response rate

Student response rate

Overall response rate

white (white) (51.2%), followed by Hispanic (26.1%), black

(12.2%), and other (10.6%), which is defined as American

Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or other

Pacific Islander, or multiracial but non-Hispanic.

Nationwide, 84.4% of students self-identified as heterosexual,

2.5% as gay or lesbian, and 8.7% as bisexual; 4.5% were not

sure of their sexual identity (Table 3). In 2019, 45.4% of

students had sexual contact with only the opposite sex, 2.2%

with only the same sex, and 4.8% with both sexes; 47.6% had

had no sexual contact.

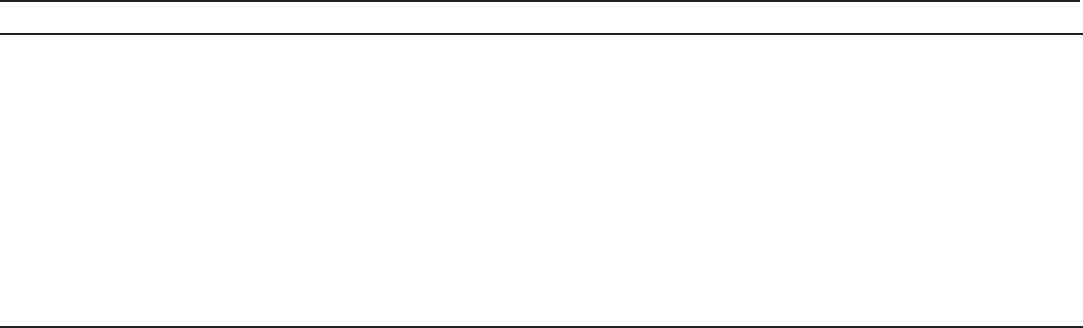

2019 Site-Level YRBS Participation and

Student Response Rates

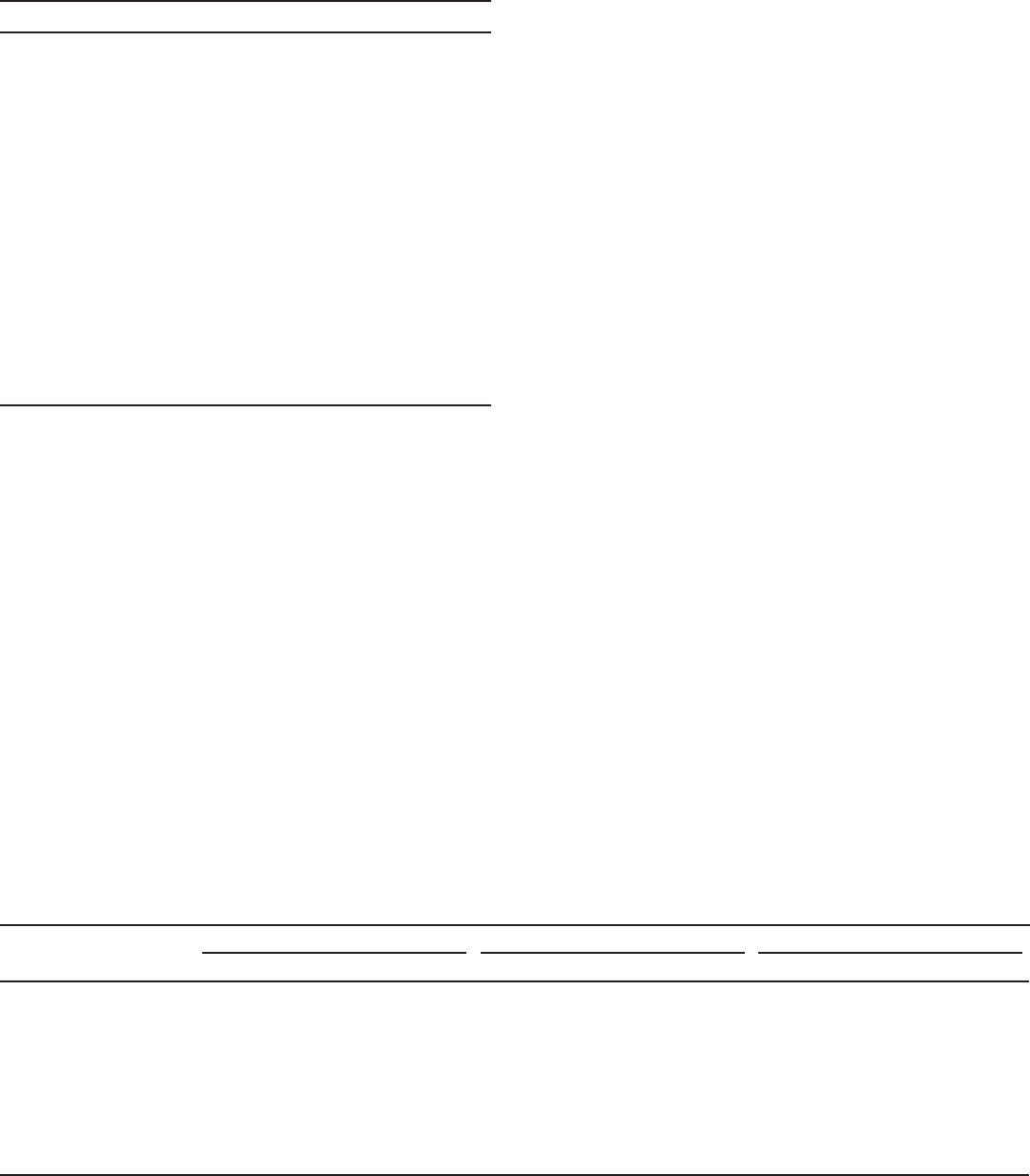

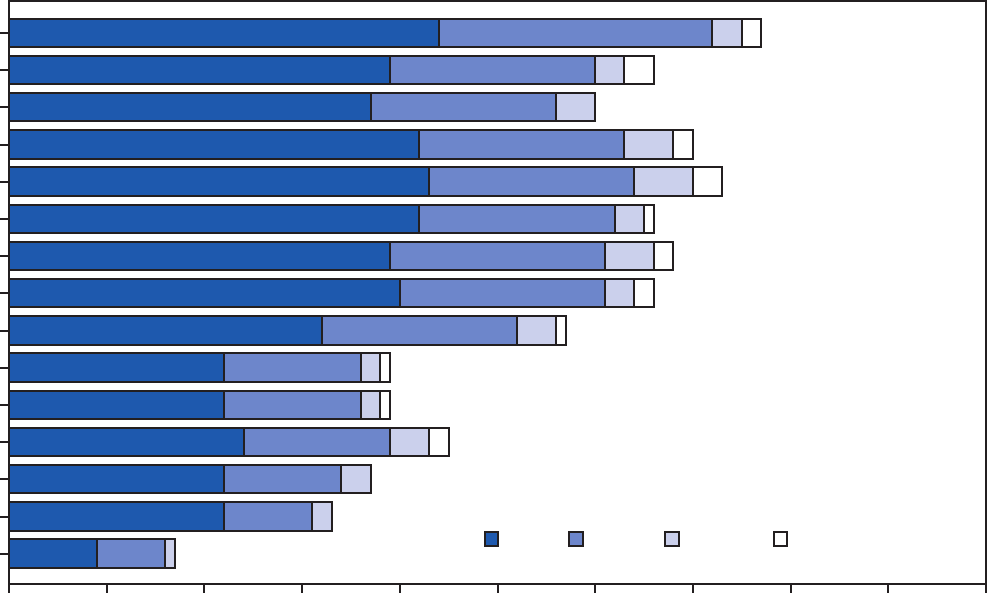

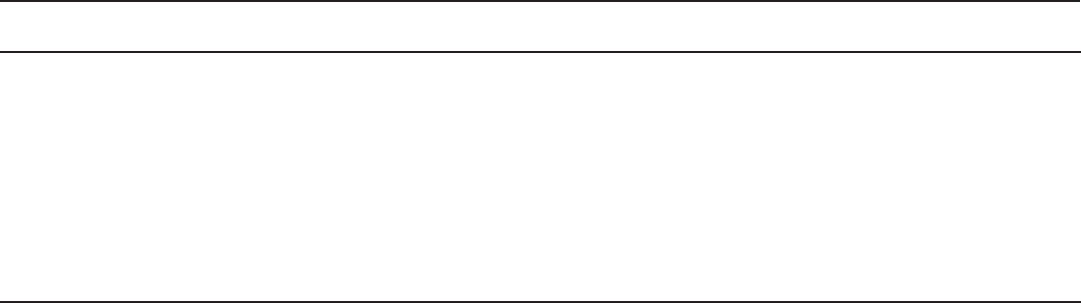

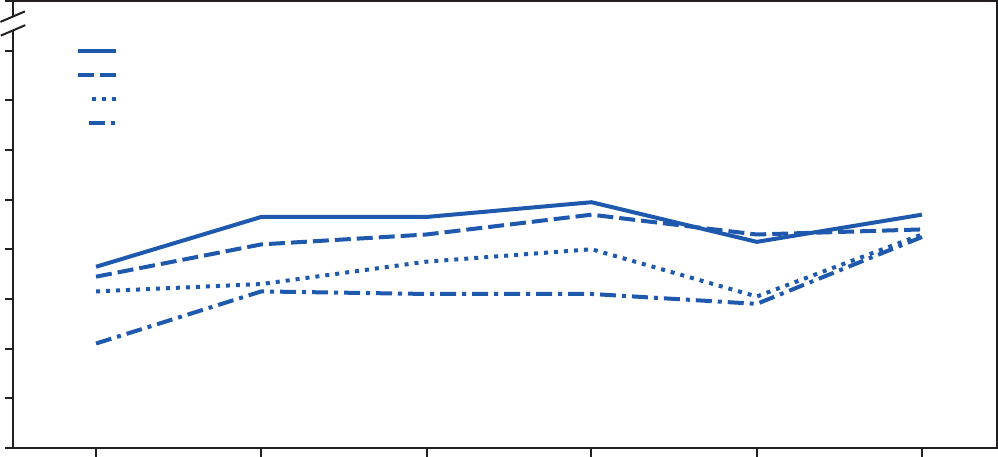

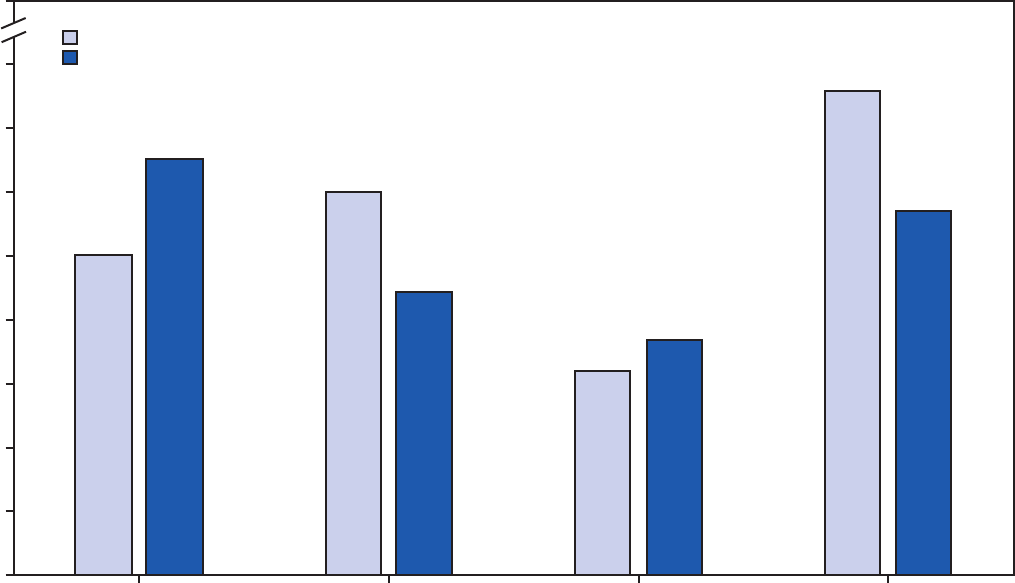

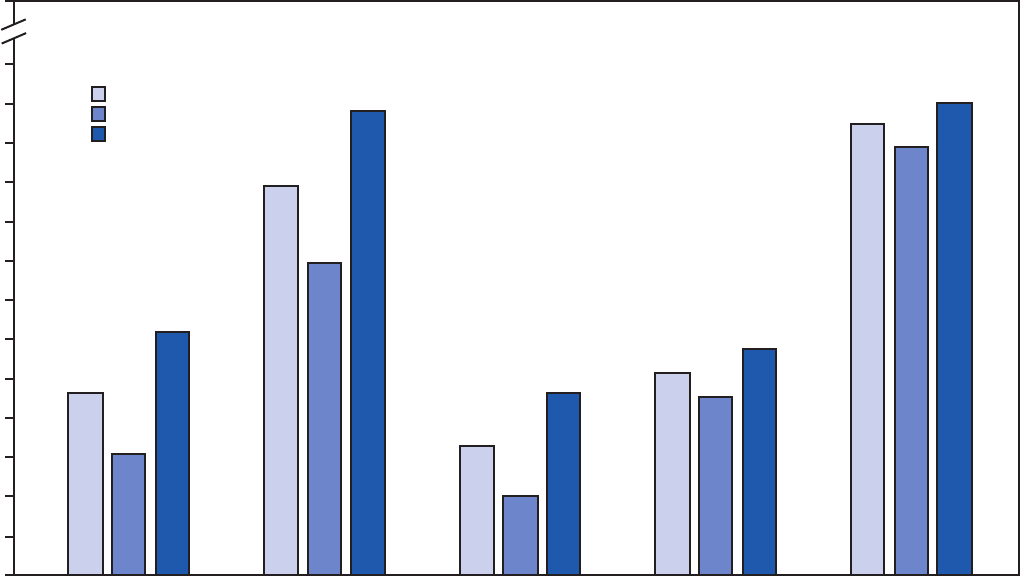

In 2019, a total of 44 states, 28 local school districts, three

territories, and two tribal governments had representative

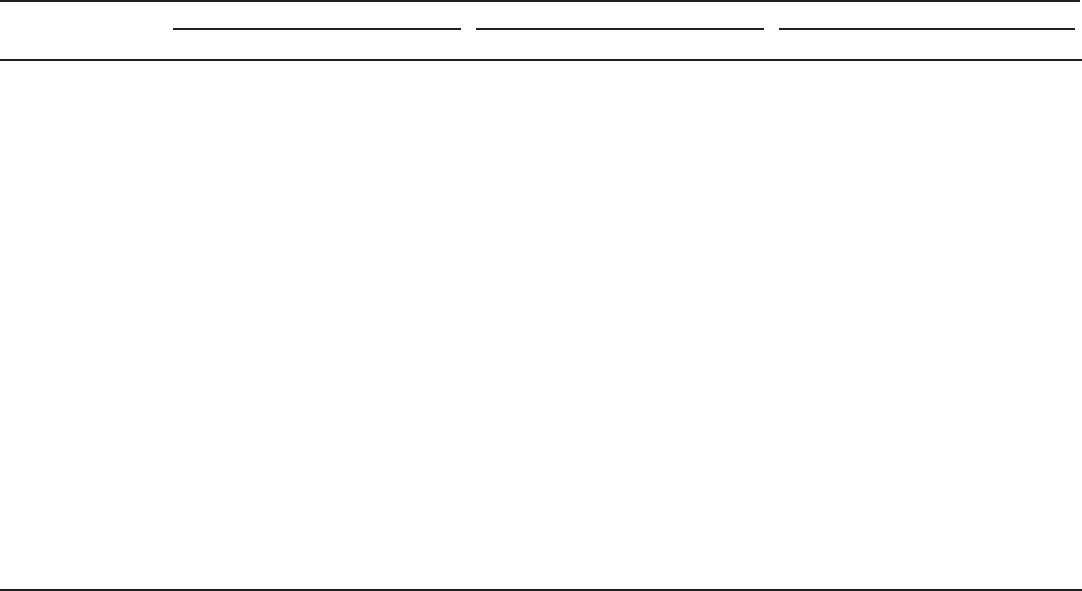

data (Figure 2). In 2019, the median response rate for state

YRBSs with representative data was 65.0% (Figure 3), which

has typically remained at 60%–70% since 1991. The median

response rate for local school district YRBSs with representative

data was 76.5% (Figure 3) and has typically remained at

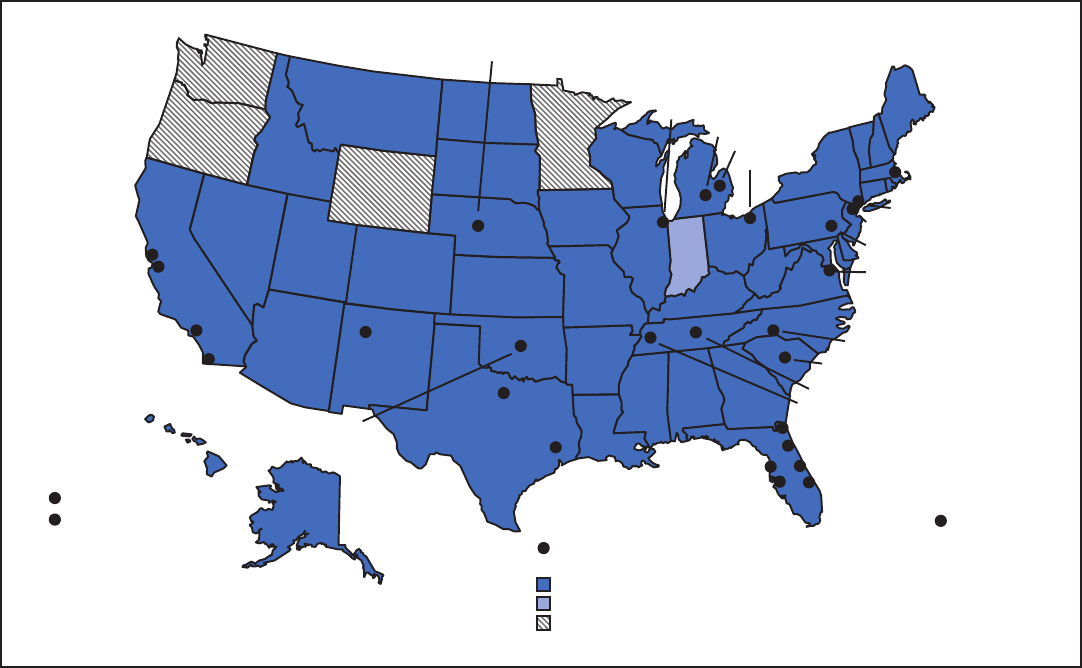

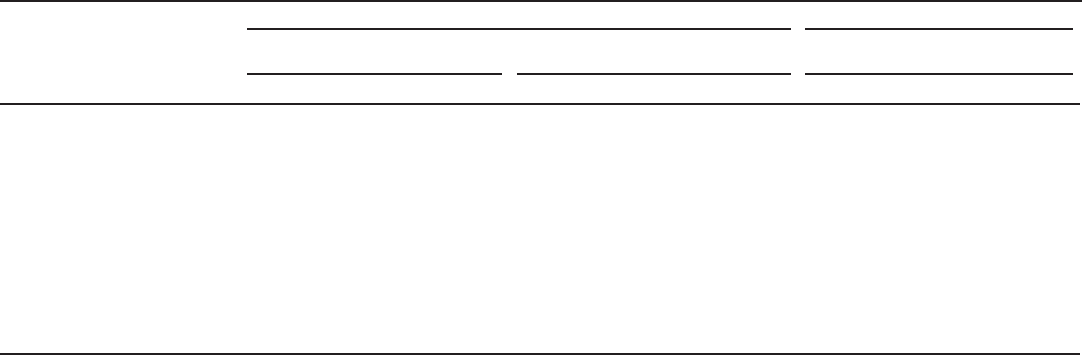

70%–80% since 1991. Since the inception of YRBSS in 1991,

the number of sites with representative data has increased,

reaching a high of 77 in 2019 (Figure 4).

Supplement

MMWR / August 21, 2020 / Vol. 69 / No. 1 7

US Department of Health and Human Services/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

TABLE 2. Youth Risk Behavior Survey student demographic

characteristics — United States, 2019

Characteristic No. (%)

Participating schools 136 (100)

Student sample size 13,677* (100)

Response rates

Schools (75.1)

Students (80.3)

Total (60.3)

Sex

†

Male 6,641 (50.6)

Female 6,885 (49.4)

Race/Ethnicity

†,§

White, non-Hispanic 6,668 (51.2)

Black, non-Hispanic 2,040 (12.2)

Hispanic 3,038 (26.1)

Other 1,493 (10.6)

Grade

†,§

9 3,637 (26.6)

10 3,717 (25.5)

11 3,322 (24.2)

12 2,850 (23.5)

* Among the 13,872 completed questionnaires, 195 failed quality control and

were excluded from analysis, resulting in 13,677 usable questionnaires.

†

Does not included students who responded “ungraded” or “other grade.”

§

Percentages might not total 100% because of rounding.

Discussion

YRBSS is the largest public health surveillance system in the

United States, monitoring multiple health-related behaviors

among high school students. Since 1991, YRBSS has collected

data from approximately 4.9 million high school students in

approximately 2,100 separate surveys. Survey response rates

have remained slightly above 60%, since YRBSS inception.

Consistent and relatively high response rates allow for

long-term trend analyses of student health behaviors and

experiences. During the 2019 cycle, 78 separate jurisdictions

successfully collected YRBS data from a broad diversity of

high school students. Nationally representative data from

adolescents of various demographic profiles (e.g., sex, race

and ethnicity, sexual identity) provide information regarding

TABLE 3. Number and percentage of students, by sexual identity and sex of sexual contacts — Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019

Characteristic

Total Male Female

No. (%) 95% CI No. (%) 95% CI No. (%) 95% CI

Sexual identity

Heterosexual 10,853 (84.4) 83.4–85.3 5,728 (91.2) 90.1–92.3 5,048 (77.6) 75.9–79.3

Gay or lesbian 380 (2.5) 2.1–3.0 157 (2.1) 1.6–2.7 211 (2.9) 2.3–3.6

Bisexual 1,151 (8.7) 8.0–9.4 201 (3.4) 2.8–4.1 929 (13.9) 12.7–15.2

Not sure 591 (4.5) 3.9–5.0 223 (3.2) 2.7–3.9 350 (5.6) 4.7–6.6

Sex of sexual contacts

Opposite sex only 4,856 (45.4) 42.8–48.1 2,642 (49.5) 46.2–52.8 2,214 (41.3) 38.7–44.0

Same sex only 292 (2.2) 1.8–2.7 99 (1.6) 1.2–2.0 193 (2.8) 2.2–3.6

Both sexes 526 (4.8) 4.2–5.5 90 (1.8) 1.4–2.3 436 (7.8) 6.7–9.1

No sexual contact 4,953 (47.6) 44.8–50.4 2,346 (47.1) 43.9–50.4 2,607 (48.0) 45.1–50.9

Abbreviation: CI=confidence interval.

disparities in health-related behaviors and highlight long-term

trends in the prevalence of these behaviors.

In 2019, CDC launched the Public Health Data

Modernization Initiative to enhance the potential of using

data for disease detection and elimination. The initiative

envisions a future in which data drives action efficiently,

flexibly, rapidly, and with impact. CDC leverages technology,

knowledge, leadership, access, and collaboration to harness

the life-saving power of data. YRBSS has both longstanding

and newly implemented features that align with the

modernization initiative. CDC scientists provide technical

support to help state and local education and health agencies

administer their YRBS. Flexibility in the questionnaire

design process allows stakeholders to collect data of interest

across student populations. Detailed YRBS site reports are

rapidly returned to state and local departments of health and

education, often within 16 weeks of survey administration.

In 2019, YRBSS reach (measured by the number of sites with

representative data) has increased to 78 sites including the

national survey, the most in YRBSS history. These data will

help identify student risk behaviors, affect decision-making,

and guide public health interventions.

The public release of YRBS data coincides with the

publication of this nine-part MMWR Supplement and is an

agencywide collaboration. Subject matter experts from selected

CDC programs contributed to this supplement to highlight

public health concerns among U.S. high school students.

YRBS data dissemination is managed through online requests,

Youth Online, and YRBS Explorer. This year, CDC updated

Youth Online to strengthen data presentation, improve user

experience, and ultimately expand reach for YRBS data. These

improvements to data dissemination will improve YRBS access,

expand usage, and maximize impact.

CDC continually works to strengthen YRBSS, and new

developments are under way. In 2019, CDC launched a

project to update reliability testing for the national YRBS

questionnaire. As other school-based surveys move toward

Supplement

8 MMWR / August 21, 2020 / Vol. 69 / No. 1

US Department of Health and Human Services/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

FIGURE 2. State, local school district, territorial, and tribal government Youth Risk Behavior Surveys — selected U.S. sites, 2019

State: representative data

State: no representative data

Local school district, territory,

or tribal government: representative data

Did not participate

New York City

Newark

Philadelphia

District of Columbia

Boston

Cleveland

Genesee

Eaton

Chicago

Duval County

Orange County

Palm Beach County

Broward County

Gaston County

Spartanburg County

Nashville

Shelby County

Northern Mariana Islands

Guam

Puerto Rico

San Francisco

Oakland

San Diego

Los Angeles

Pasco County

Hillsborough County

Houston

Fort Worth

Albuquerque

Cherokee Nation

Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska

electronic platforms (e.g., computer, smart phone, or tablet),

some site-level YRBSs have also transitioned to electronic

survey administration. CDC recently completed pilot

testing for a tablet-based survey administration of the YRBS

questionnaire and is considering using tablets for future

YRBSs. Finally, CDC is exploring innovative analytic methods

to stratify YRBS data by school-level socioeconomic status

and geographic location. A recent study using this approach

reported students attending schools in low socioeconomic

areas were more likely to experience violence, poor emotional

well-being, and suicidality (8).

Limitations

Reports in this supplement include a limitations section

describing the analyses pertaining to that particular report. In

general, YRBSS findings are subject to at least six limitations.

First, these data apply only to youths who attend school and

therefore are not representative of all persons in this age group.

In 2019, approximately 5% of high school–aged youths (ages

14–17 years) were not enrolled in school (9). Those youths

might engage in riskier health behaviors than their peers, and

those behaviors are not captured in the school-administered

YRBS. Second, the extent of underreporting or overreporting

of health-related behaviors cannot be determined, although

the survey questions demonstrate good test–retest reliability

(5,6). Third, not all states and local school districts administer

YRBS, and those that did administer it might not include all

the standard questions on their YRBS questionnaire; therefore,

data for certain variables are not available for some sites. Fourth,

YRBS data analyses are based on cross-sectional surveys and

can only provide an indication of association, not causality.

Moreover, the survey is descriptive and not designed to explain

the reasons behind any observed trends. Fifth, limitations exist

related to assessment of sexual and gender identity. Students

might not be fully aware of their sexual identity at the time of

assessment or might not have understood the sexual identity

question. The category of students who are not sure of their

sexual identity might encompass students who are unsure of

their sexuality, students who were uncomfortable answering

the question, or students who did not understand the question.

In addition, although some sites asked questions about

transgender students, the national YRBS does not include a

question about gender identity; therefore, national prevalence

Supplement

MMWR / August 21, 2020 / Vol. 69 / No. 1 9

US Department of Health and Human Services/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

FIGURE 3. National, state, and local school district Youth Risk Behavior Survey response rates — United States and selected U.S. sites,

1991–2019*

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019

National response rate

State median response rate

Local school district median response rate

Year

Percentage

* Does not include Youth Risk Behavior Survey data from U.S. territories and tribal governments.

estimates for this population of students cannot be assessed.

Finally, a limitation exists regarding the aggregation of race

and ethnicity data. The national YRBS aggregates these data

into broad categories of white, black, and Hispanic. All other

students are classified as “other.” More detailed racial/ethnic

information, as published elsewhere, provides valuable data

regarding health disparities among high school students (10).

Conclusion

YRBSS is the best source for quality data at the national,

state, territorial, tribal, and local school district levels for

monitoring health-related behaviors that contribute to the

leading causes of mortality and morbidity among U.S. high

school students and that can lead to health problems as adults.

A recent report from the National Academies of Sciences,

Engineering, and Medicine used YRBS as its data source

on the basis of the strengths of the system (11). In 2019, in

addition to the national data, 44 states, 28 local school districts,

three territories, and two tribal governments received data

representative of their high school student populations.

This overview report describes YRBSS methods for guiding

the analyses presented in this MMWR Supplement. A full

description of 2019 YRBS results and downloadable data

are available (https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/

index.htm).

Conicts of Interest

All authors have completed and submitted the International

Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of

potential conflicts of interest. No potential conflicts of interest

were disclosed.

References

1. CDC. Youth Risk Behavior Survey: data summary and trends report,

2007–2017. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human

Services, CDC; 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/

trendsreport.pdf

2. Wiium N, Breivik K, Wold B. Growth trajectories of health behaviors

from adolescence through young adulthood. Int J Environ Res Public

Health 2015;12:13711–29. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph121113711

3. Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD, Arias E. Mortality in the United States,

2017. NCHS Data Brief 2018; (328):1–8.

4. Curtin SC, Heron M, Miniño AM, Warner M. Recent increases in injury

mortality among children and adolescents aged 10–19 years in the United

States: 1999–2016. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2018;67:1–16.

5. Brener ND, Kann L, McManus T, Kinchen SA, Sundberg EC, Ross JG.

Reliability of the 1999 youth risk behavior survey questionnaire.

J Adolesc Health 2002;31:336–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/

S1054-139X(02)00339-7

Supplement

10 MMWR / August 21, 2020 / Vol. 69 / No. 1

US Department of Health and Human Services/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

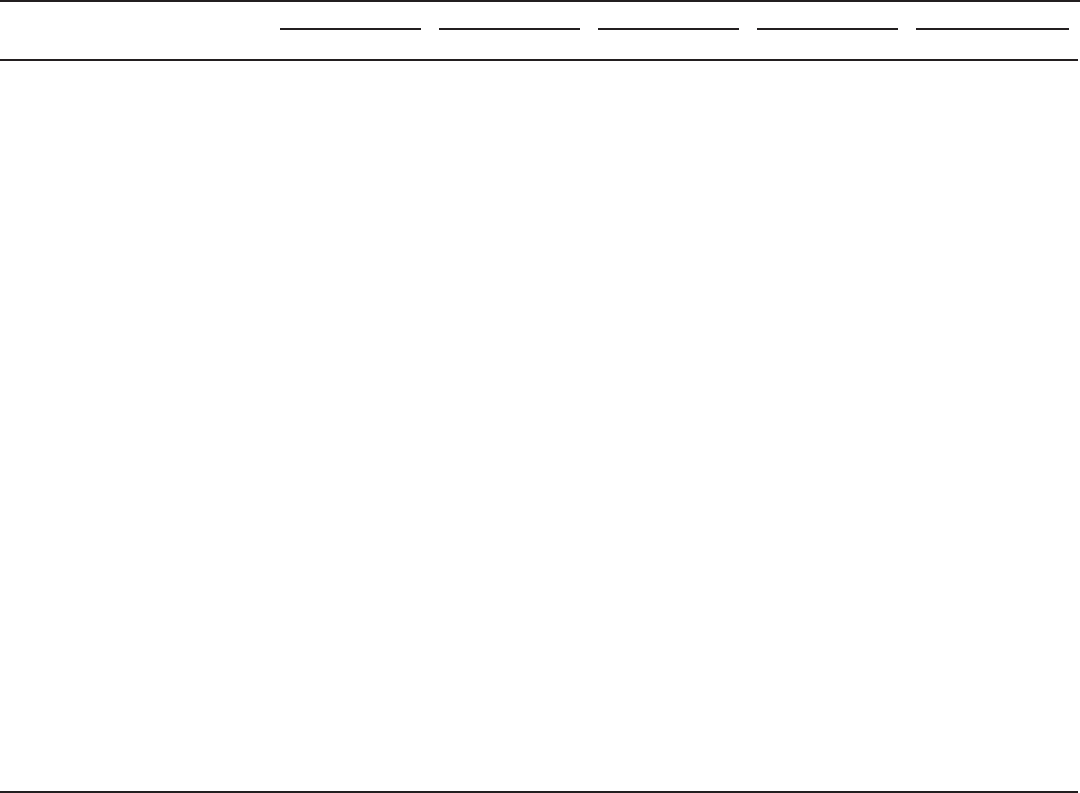

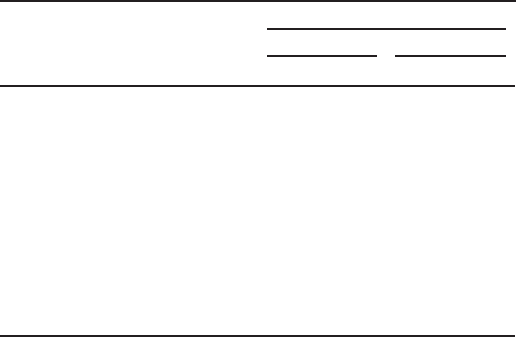

FIGURE 4. Number of states, local school districts, territories, and tribal governments with representative Youth Risk Behavior Survey data, by

year of survey — selected U.S. sites, 1991–2019

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

1991

1993

1995

1997

1999

2001

2003

2005

2007

2009

2011

2013

2015

2017

2019

Number of representative sites

Year

States Districts Territories Tribal governments

6. Brener ND, Mcmanus T, Galuska DA, Lowry R, Wechsler H. Reliability

and validity of self-reported height and weight among high school

students. J Adolesc Health 2003;32:281–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/

S1054-139X(02)00708-5

7. Czajka JL, Beyler A. Declining response rates in federal surveys: trends

and implications. Final report. Vol. I. Washington, DC: Mathematica

Policy Research; 2016. https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/255531/

Decliningresponserates.pdf

8. Everett Jones S, Underwood JM, Pampati S, et al. School-level poverty

and persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness, suicidality, and

experiences with violence victimization among public high school

students. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2020;30 [In press].

9. US Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics.

Fast facts: enrollment trends. Washington, DC: US Department of

Education; 2019. https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=65

10. Lowry R, Eaton DK, Brener ND, Kann L. Prevalence of health-risk

behaviors among Asian American and Pacific Islander high school

students in the U.S., 2001–2007. Public Health Rep 2011;126:39–49.

https://doi.org/10.1177/003335491112600108

11. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Promoting

positive adolescent health behaviors and outcomes: thriving in the 21st

century. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2019. http://

www.nap.edu/catalog/25552/promoting-positive-adolescent-health-

behaviors-and-outcomes-thriving-in-the

Supplement

MMWR / August 21, 2020 / Vol. 69 / No. 1 11

US Department of Health and Human Services/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Condom and Contraceptive Use Among Sexually Active High School

Students — Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019

Leigh E. Szucs, PhD

1

; Richard Lowry, MD

2

; Amy M. Fasula, PhD

3

; Sanjana Pampati, MPH

4

; Casey E. Copen, PhD

5

; Khaleel S. Hussaini, PhD

3

;

Rachel E. Kachur, MPH

5

; Emilia H. Koumans, MD

3

; Riley J. Steiner, PhD

3

1

Division of Adolescent and School Health, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention,

CDC;

2

Office of the Director, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, CDC;

3

Division of Reproductive Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC;

4

Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education;

5

Division of STD Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention CDC

Abstract

Preventing unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

infection, among adolescents is a public health priority. This report presents prevalence estimates for condom and contraceptive

use among sexually active U.S. high school students from the 2019 Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Behaviors examined included

any condom use, primary contraceptive method use, and condom use with a more effective contraceptive method, all reported at

last sexual intercourse. Analyses were limited to sexually active students (i.e., those who had sexual intercourse with one or more

persons during the 3 months before the survey). Except for any condom use, students reporting only same-sex sexual contact were

excluded from analyses. Weighted prevalence estimates were calculated, and bivariate differences in prevalence were examined

by demographic characteristics (sex, race/ethnicity, and grade) and other sexual risk behaviors (age of sexual initiation, previous

3-month and lifetime number of sex partners, and substance use before last sexual intercourse). Nationwide, 27.4% of high school

students reported being sexually active (n = 3,226). Among sexually active students who reported having had sexual contact with

someone of the opposite sex (n = 2,698), most students (89.7%) had used a condom or a primary contraceptive method at last

sexual intercourse. Prevalence of any condom use at last sexual intercourse was 54.3%, and condoms were the most prevalent

primary contraceptive method (43.9% versus 23.3% for birth control pills; 4.8% for intrauterine device [IUD] or implant; and

3.3% for shot, patch, or ring). Approximately 9% had used condoms with an IUD, implant, shot, patch, ring, or birth control pills.

Using no pregnancy prevention method was more common among non-Hispanic black (23.2%) and Hispanic (12.8%) students

compared with non-Hispanic white students (6.8%); compared with Hispanic students, using no pregnancy prevention method

was more common among non-Hispanic black students. Prevalence of condom use was consistently lower among students with

other sexual risk behaviors. Results underscore the need for public health professionals to provide quality sexual and reproductive

health education and clinical services for preventing unintended pregnancy and STDs/HIV and decreasing disparities among

sexually active youths.

Introduction

Preventing unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted

diseases (STDs), including human immunodeficiency virus

(HIV) infection, is a U.S. public health priority, particularly

among adolescents (1). U.S. birth rates among youths aged

15–19 years have decreased to record lows; evidence suggests

that increasing use of a range of contraceptive options,

including intrauterine devices (IUDs) and implants, also

known as long-acting reversible contraception, is a contributing

factor (2). However, U.S. birth rates among adolescents

remain higher than rates in comparable Western industrialized

nations (3). In 2018, U.S. birth rates for persons aged 15–17

Corresponding author: Leigh E. Szucs, PhD, Division of Adolescent

and School Health, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis,

STD, and TB Prevention, CDC. Telephone: 404-718-6785; E-mail:

and 18–19 years were 7.2 and 32.3 births per 1,000 females,

respectively (4). Moreover, racial/ethnic, geographic, and

socioeconomic disparities persist (4). For example, in 2018,

birth rates among non-Hispanic black (black) (26.3) and

Hispanic (26.7) persons aged 15–19 years were almost two

times the rate for non-Hispanic white (white) (12.1) persons (4).

Contraceptive methods vary in effectiveness and highly and

moderately effective methods do not prevent STDs, which

disproportionately affect adolescents (5). Highly effective

reversible contraceptive methods (IUDs and implants) are

associated with a <1% failure rate during the first year of typical

use; moderately effective contraceptive methods (injectables,

patches, rings, and birth control pills) are associated with a

4%–7% failure rate during the first year of typical use; and

less effective methods (condoms, diaphragm, and spermicides)

are associated with a >10% failure rate during the first year

of typical use (6). Condoms, although categorized as a less

Supplement

12 MMWR / August 21, 2020 / Vol. 69 / No. 1

US Department of Health and Human Services/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

effective method of pregnancy prevention (6), remain vital

for STD/HIV prevention and promoting condom use is

particularly important given increasing STD rates in the

United States (5). Professional medical organizations (7,8) and

federal agencies, including CDC, recommend using condoms

for STD/HIV prevention with a more effective method of

contraception for optimal protection against unintended

pregnancy (9). However, recent decreases in condom use

have been documented, and the proportion of adolescents

using condoms with more effective methods of contraception

has been consistently low, with recent national estimates of

approximately 9% of sexually active high school students (10).

Because of these challenges to pregnancy- and STD/HIV-

prevention goals, monitoring condom and contraceptive use

behaviors among sexually active youths is essential. This study

reports prevalence estimates from the 2019 Youth Risk Behavior

Survey (YRBS) for any condom use at last sexual intercourse

among sexually active U.S. high school students. In addition,

prevalence estimates of primary contraceptive method use and

condom use with more effective methods of contraception

at last sexual intercourse among sexually active students who

had sexual contact with the opposite sex during their lifetime

are reported. Variations in these behaviors by demographic

characteristics and sexual risk behaviors were examined to

support public health professionals in implementing quality

sexual and reproductive health education and clinical services

that prevent STDs/HIV and unintended pregnancy.

Methods

Data Source

This report includes data from the 2019 YRBS, a cross-

sectional, school-based survey conducted biennially since

1991. Each survey year, CDC collects data from a nationally

representative sample of public and private school students in

grades 9–12 in the 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia.

Additional information about YRBS sampling, data collection,

response rates, and processing is available in the overview report

of this supplement (11). The prevalence estimates for all sexual

behavior questions for the overall study population and by

sex, race/ethnicity, grade, and sexual orientation are available

at https://nccd.cdc.gov/youthonline/App/Default.aspx. The

full YRBS questionnaire is available at https://www.cdc.gov/

healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/2019/2019_YRBS-National-HS-

Questionnaire.pdf.

Measures

Behaviors analyzed included any condom use, primary

contraceptive method, and condom use with more effective

methods of contraception, all reported at last sexual intercourse.

Any condom use was assessed by the question, “The last time

you had sexual intercourse, did you or your partner use a

condom?” Response options included the following: I have

never had sexual intercourse, yes, or no. Primary contraceptive

method was assessed through a separate question, “The last

time you had sexual intercourse, what one method did you or

your partner use to prevent pregnancy?” Respondents could

select only one response from the following list of options:

I have never had sexual intercourse; no method was used to

prevent pregnancy; birth control pills; condoms; an IUD

(such as Mirena or ParaGard) or implant (such as Implanon

or Nexplanon); a shot (such as Depo-Provera), patch (such

as Ortho Evra), or birth control ring (such as NuvaRing);

withdrawal or some other method; or not sure. Dichotomous

(yes versus no) variables for each response option were created,

except for “not sure”; although participants selecting this

response (n = 93; 3.9%) were included in the analytic sample,

prevalence estimates for this category are not reported.

A dichotomous (yes versus no) variable for any condom

use with an IUD, implant, shot, patch, ring, or birth control

pills was constructed by using the separate items for any

condom use and primary contraceptive method at last sexual

intercourse. These two items were also used to create the

following dichotomous (yes versus no) indicators: condom

use only (yes to any condom use and condoms or no method

for pregnancy prevention); highly or moderately effective

contraceptive use only (no to any condom use and an IUD,

implant, shot, patch, ring, or birth control pills for pregnancy

prevention); withdrawal or some other contraceptive method

use only (no to any condom use and withdrawal or some other

method for pregnancy prevention); and use of no condom and

no primary contraceptive method (no to any condom use and

no method for pregnancy prevention).

Condom and contraceptive use were examined by

demographic characteristics and sexual risk behaviors.

Demographic characteristics included sex (female or male),

race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white [white], non-Hispanic

black [black], or Hispanic; other/multiple responses are not

reported), and grade (9, 10, 11, or 12). Four dichotomous

sexual risk behaviors were created: age of sexual initiation

(<13 years versus ≥13 years); lifetime number of sex partners

(1–3 versus ≥4); number of sex partners during the previous

3 months (1 versus ≥2); and alcohol or drug use before last

sexual intercourse (yes versus no).

Supplement

MMWR / August 21, 2020 / Vol. 69 / No. 1 13

US Department of Health and Human Services/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Analysis

The analytic sample was restricted to sexually active students

(i.e., those who reported having had sexual intercourse with

one or more persons during the 3 months before the survey).

Analyses involving pregnancy prevention methods excluded

students who only had same-sex sexual contacts during their

lifetime, on the basis of an item about respondents’ sex (“What

is your sex?” with response options including female or male)

and another item assessing the sex of sexual contacts (“During

your life, with whom have you had sexual contact?” with

response options including I have never had sexual contact,

females, males, and females and males).

All analyses were conducted using SUDAAN (version 11.0.0;

RTI International) to account for the complex sampling design.

Weighted prevalence estimates and 95% confidence intervals

were calculated for each outcome. Chi-square statistics

were used to examine bivariate differences by demographic

characteristics and sexual risk behaviors. For significant overall

differences by race/ethnicity and grade, t-tests were used to

identify pairwise differences. Differences were considered

significant if p<0.05.

Results

Among the 27.4% of sexually active students (n = 3,226),

approximately half were female (52.2%) and white (52.3%);

approximately one third were in grade 12 (36.9%) (Table 1).

Regarding sexual risk behaviors among those sexually active

students, 7.0% had sexual intercourse for the first time before

age 13 years (3.0% of all YRBS respondents reported having

had sexual intercourse for the first time before age 13 years);

26.9% had sexual intercourse with ≥4 persons during their

lifetime (8.6% of all YRBS respondents reported having had

sexual intercourse with ≥4 persons during their lifetime);

20.5% had sexual intercourse with ≥2 persons during the

previous 3 months; and 21.2% had drunk alcohol or used

drugs before last sexual intercourse.

Among sexually active students, prevalence of any condom

use at last sexual intercourse was 54.3% (Table 2). Among

sexually active students who reported having had sexual

contact with someone of the opposite sex (i.e., excluding

those who reported only same-sex sexual contact) (n = 2,698),

condoms (43.9%) were the most prevalent primary pregnancy

prevention method, based on responses to the distinct item

assessing pregnancy prevention method, followed by birth

control pills (23.3%); withdrawal or other method (10.1%);

IUD or implant (4.8%); and shot, patch, or ring (3.3%). (Of

participants excluded from the analytic sample for primary

method of pregnancy prevention, 95 students reported having

had only same-sex sexual contact and 433 students did not

answer the questions, “What is your sex?” or “During your life,

with whom have you had sexual contact?”) Approximately one

tenth (10.7%) had not used a pregnancy prevention method

at last sexual intercourse; 9.1% had used a condom with an

IUD, implant, shot, patch, ring, or birth control pills at last

sexual intercourse. Prevalence of condom and IUD or implant

use (<1.0%) and condom and shot, patch, or ring use (<1.0%)

was lower than condom and birth control pills use (7.5%).

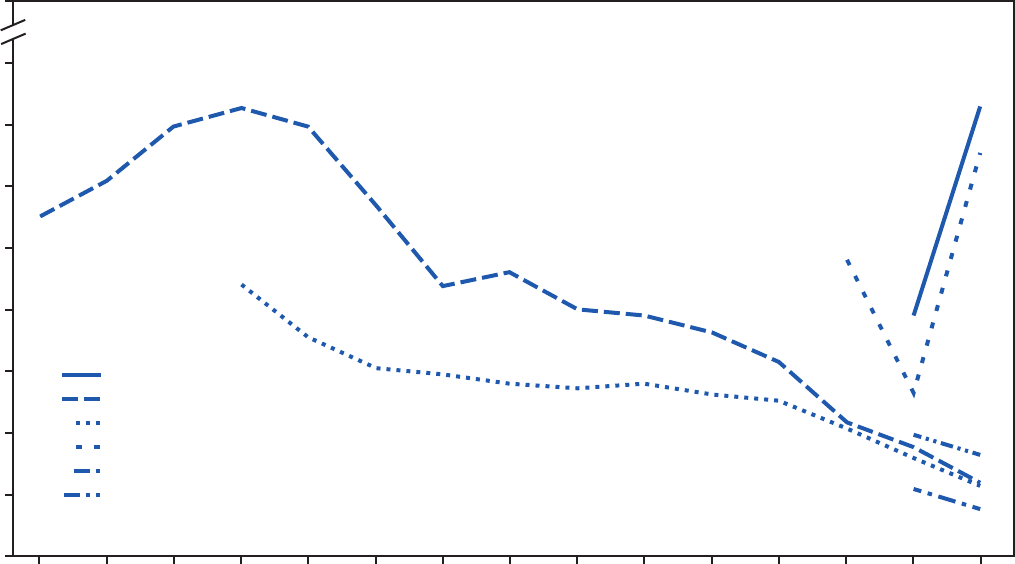

Prevalence estimates for mutually exclusive categories that

reflect both pregnancy and STD/HIV prevention effectiveness

and account for any condom use in addition to a primary

pregnancy prevention method indicate that condom use

only was most common (44.3%), followed by highly or

moderately effective contraceptive method use only (22.2%)

(Figure). Prevalence of condom use with an IUD, implant,

shot, patch, ring, or birth control pills (9.1%) was similar to

prevalence of using withdrawal or other method only (9.5%)

and using no condom and no primary pregnancy prevention

method (10.3%).

Analyses revealed significant differences in any condom

use and primary pregnancy prevention method at last sexual

intercourse by demographic characteristics (Table 2). By

sex, no differences occurred in not using any method of

pregnancy prevention (i.e., no method); however, differences

were identified in type of method used. Compared with male

students’ report of contraceptive use by their female partner,

prevalence as reported by female students was higher for shot,

patch, or ring (4.5% versus 2.1%) and birth control pills

(26.1% versus 20.2%). In contrast, prevalence of condom use

as the primary method for pregnancy prevention reported by

male students (49.4%) was higher than female students’ report

of condom use by their male partner (38.8%), as was any

condom use at last sexual intercourse (60.0% versus 49.6%).

A similar pattern emerged when examining prevalence of

any condom and primary contraceptive method use by grade.

The prevalence of using no method was the same across grades;

however, differences occurred in method type. Any condom

use and condom use as the primary pregnancy prevention

method was more prevalent in lower versus higher grades. In

contrast, use of an IUD or implant; birth control pills; and

condom with an IUD or implant, shot, patch, ring, or birth

control pills was typically more prevalent in higher versus lower

grades. For example, condom use as the primary pregnancy

prevention method was more common among students in

grades 9 (55.3%), 10 (47.7%), and 11 (45.3%) versus students

in grade 12 (37.4%) (and grade 9 versus grade 11), whereas

IUD or implant use was less common among 9th-grade

Supplement

14 MMWR / August 21, 2020 / Vol. 69 / No. 1

US Department of Health and Human Services/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

TABLE 1. Prevalence of demographic characteristics and sexual risk behaviors among sexually active* high school students — Youth Risk

Behavior Survey, United States, 2019

Characteristic No.

†

(%

§

) 95% CI

Sex

Female 1,679 (52.2) 49.4–55.0

Male 1,510 (47.8) 45.0–50.6

Race/Ethnicity

¶

Black, non-Hispanic 474 (11.2) 8.9–14.0

Hispanic 771 (28.4) 22.3–35.5

White, non-Hispanic 1,602 (52.3) 46.4–58.1

Grade

9 389 (11.3) 9.8–13.0

10 741 (21.4) 19.3–23.6

11 967 (30.4) 27.8–33.2

12 1,089 (36.9) 33.4–40.4

Sexual risk behavior

Had sexual intercourse before age 13 years 242 (7.0) 5.7–8.5

Had sexual intercourse with ≥4 persons during their lifetime 854 (26.9) 24.3–29.7

Had sexual intercourse with ≥2 persons during the previous 3 months 658 (20.5) 18.5–22.7

Had drunk alcohol or used drugs before last sexual intercourse 652 (21.2) 18.8–23.9

Abbreviation: CI = confidence interval.

* Defined as having had sexual intercourse with at least one person during the 3 months before the survey (n = 3,226).

†

Unweighted.

§

Weighted estimates.

.

¶

Race/ethnicity values do not total 100% because “other/multiple” responses are not reported (i.e., American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Other

Pacific Islander, and multiple race).

students (<1.0%), compared with students in grades 10 (3.3%),

11 (3.2%), and 12 (8.2%). Prevalence of IUD or implant use

among 10th- and 11th-grade students was also lower than

among 12th-grade students.

In contrast with sex and grade, not using a pregnancy

prevention method differed by race/ethnicity, with higher

prevalence of no method among black (23.2%) and Hispanic

(12.8%) students, compared with white students (6.8%);

compared with Hispanic students, using no pregnancy

prevention method was more common among black students.

Additional racial/ethnic differences in type of method were

identified, with the general pattern that prevalence of using

a more effective method of contraception was lower among

black and Hispanic students compared with white students.

Specifically, prevalence among black and Hispanic students

was lower than among white students for use of an IUD or

implant (2.0% and 1.6% versus 6.7%, respectively); birth

control pills (12.1% and 15.5% versus 29.7%, respectively);

and condom use with an IUD, implant, shot, patch, ring, or

birth control pills (7.5% and 4.8% versus 12.4%, respectively).

In contrast, prevalence of withdrawal or other method use was

higher among black (13.9%) and Hispanic (13.1%) students

than among white students (7.7%). Condom use as the

primary method for pregnancy prevention was higher among

Hispanic students (49.6%), compared with black (37.2%) and

white (42.3%) students, and any condom use at last sexual

intercourse was higher among Hispanic (56.2%) and white

(55.8%) students compared with black students (48.2%).

Differences by sexual risk behaviors in the prevalence of using no

contraceptive method and in the type of method used, including

any condom use, also were observed (Table 3). Comparing

students who had initiated sex before age 13 years with students

who had not, differences in no method use were not significant;

however, prevalence was lower for any condom use at last sexual

intercourse (40.9% versus 55.4%), condom use as the primary

method of pregnancy prevention (30.4% versus 44.8%), and

withdrawal or other method use (5.5% versus 10.4%). Students

who had ≥4 lifetime partners had higher prevalence of no method

use (14.7% versus 9.2%) and lower prevalence of any condom

use (46.6% versus 57.1%); condom use as the primary pregnancy

prevention method (36.2% versus 46.6%); and condom use with

an IUD, implant, shot, patch, ring, or birth control pills (6.5%

versus 10.1%) compared with students who had <4 lifetime sex

partners. A similar pattern was observed for students who reported

having had ≥2 recent partners, although no significant differences

in no method use were observed. Comparing students who had

drunk alcohol or used drugs before last sexual intercourse with

students who had not, use of no method was higher (14.7%

versus 9.6%), whereas any condom use (47.4% versus 56.0%)

and condom use as the primary pregnancy prevention method

(39.3% versus 45.1%) were lower.

Discussion

This report provides the most recent nationally representative

estimates of condom and contraceptive use among sexually

Supplement

MMWR / August 21, 2020 / Vol. 69 / No. 1 15

US Department of Health and Human Services/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

TABLE 2. Prevalence of condom and primary contraceptive use at last sexual intercourse among sexually active* high school students, by

demographic characteristics — Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019

Demographic

characteristic

Any

condom use

†

Primary contraceptive method Condoms and IUD,

implant, shot,

patch, ring, or

birth control pills

IUD or

implant

Shot, patch,

or ring

Birth control

pills

Condom

Withdrawal or

other method

No

method

%

§

(95%

CI)

p

value

¶

%

§

(95%

CI)

p

value

¶

%

§

(95%

CI)

p

value

¶

%

§

(95%

CI)

p

value

¶

%

§

(95%

CI)

p

value

¶

%

§

(95%

CI)

p

value

¶

%

§

(95%

CI)

p

value

¶

%

§

(95%

CI)

p

value

¶

Total 54.3

(52.0–56.6)

NA 4.8

(3.3–7.0)

NA 3.3

(2.3–4.7)

NA 23.3

(19.8–27.2)

NA 43.9

(40.6–47.3)

NA 10.1

(8.5–12.0)

NA 10.7

(8.8–12.8)

NA 9.1

(7.4–11.2)

NA

Sex NA <0.01 NA 0.20 NA <0.05 NA <0.01 NA <0.01 NA 0.34 NA 0.21 NA 0.10

Female 49.6

(45.6–53.6)

NA 5.6

(4.0–7.6)

NA 4.5

(2.9–6.8)

NA 26.1

(22.1–30.5)

NA 38.8

(34.0–44.0)

NA 10.8

(8.9–13.0)

NA 11.9

(9.1–15.3)

NA 10.3

(8.3–12.7)

NA

Male 60.0

(57.0–63.0)

NA 4.0

(2.1–7.4)

NA 2.1

(1.2–3.6)

NA 20.2

(16.4–24.7)

NA 49.4

(45.8–53.1)

NA 9.3

(7.1–12.2)

NA 9.3

(7.1–12.1)

NA 7.9

(5.8–10.7)

NA

Grade NA <0.05 NA <0.01 NA 0.29 NA <0.01 NA <0.01 NA 0.20 NA 0.63 NA <0.01

9 61.3**

(54.6–67.5)

NA 0.1**

,††,§§

(0.0–0.7)

NA 2.4

(0.9–6.2)

NA 10.9**

,††

(6.0–19.1)

NA 55.3**

,††

(47.4–62.9)

NA 10.6

(6.9–15.9)

NA 14.1

(9.1–21.2)

NA 4.7**

(2.7–8.2)

NA

10 55.4

(50.2–60.4)

NA 3.3**

(2.0–5.6)

NA 2.1

(1.0–4.4)

NA 18.2**

,††

(13.4–24.3)

NA 47.7**

(41.2–54.3)

NA 12.5

(9.5–16.4)

NA 10.5

(7.2–15.1)

NA 7.0**

(4.7–10.3)

NA

11 56.3

(51.9–60.6)

NA 3.2

**

(1.8–5.8)

NA 4.2

(2.6–6.7)

NA 25.8

(21.0–31.3)

NA 45.3**

(39.4–51.4)

NA 7.9

(5.9–10.5)

NA 10.1

(7.9–12.8)

NA 8.9

(6.1–12.9)

NA

12 50.3

(46.9–53.8)

NA 8.2

(5.5–12.2)

NA 3.6

(2.0–6.3)

NA 27.7

(23.3–32.5)

NA 37.4

(33.4–41.6)

NA 10.3

(7.9–13.3)

NA 10.2

(6.9–14.9)

NA 11.6

(8.9–15.0)

NA

Race/Ethnicity NA <0.05 NA <0.01 NA 0.07 NA <0.01 NA <0.01 NA <0.01 NA <0.01 NA <0.01

Black, non-Hispanic 48.2

¶¶,

***

(43.2–53.3)

NA 2.0

¶¶

(1.0–4.0)

NA 5.4

(2.9–9.9)

NA 12.1

¶¶

(8.7–16.5)

NA 37.2***

(31.2–43.6)

NA 13.9

¶¶

(8.4–22.2)

NA 23.2

¶¶,

***

(19.2–27.7)

NA 7.5

¶¶

(5.1–10.8)

NA

Hispanic 56.2

(52.0–60.3)

NA 1.6

¶¶

(0.7–3.4)

NA 1.4

(0.6–3.2)

NA 15.5

¶¶

(11.5–20.5)

NA 49.6

¶¶

(44.7–54.4)

NA 13.1

¶¶

(10.0–17.0)

NA 12.8

¶¶

(9.1–17.8)

NA 4.8

¶¶

(3.1–7.4)

NA

White, non-Hispanic 55.8

(52.9–58.6)

NA 6.7

(5.0–9.0)

NA 4.0

(2.5–6.4)

NA 29.7

(25.7–34.0)

NA 42.3

(38.2–46.5)

NA 7.7

(6.1–9.8)

NA 6.8

(5.3–8.6)

NA 12.4

(10.1–15.2)

NA

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; IUD = intrauterine device; NA = not applicable.

* Defined as having had sexual intercourse with at least one person during the 3 months before the survey (n = 3,226). Except for any condom use at last sexual intercourse, students

reporting only same-sex sexual contact use were excluded; therefore, the analytic sample was restricted to sexually active students who reported having had sexual contact with someone

of the opposite sex (n = 2,698). Among sexually active students, excluding those who only had same-sex sexual contact, a total of 93 (3.9%) students answered the pregnancy prevention

question “not sure”; findings are not presented for this group.

†

Any condom use at last sexual intercourse was measured by a separate item from condoms as the primary method used for preventing pregnancy.

§

Weighted estimates.

¶

Significance is defined as p<0.05, by chi-square test.

** Significantly different than grade 12, by linear contrast t-test

††

Significantly different than grade 11, by linear contrast t-test.

§§

Significantly different than grade 10, by linear contrast t-test.

¶¶

Significantly different than white, non-Hispanic race/ethnicity, by linear contrast t-test.

*** Significantly different than Hispanic race/ethnicity, by linear contrast t-test.

active U.S. high school students. In addition, notable differences