®

AOTA

THE AMERICAN OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY ASSOCIATION

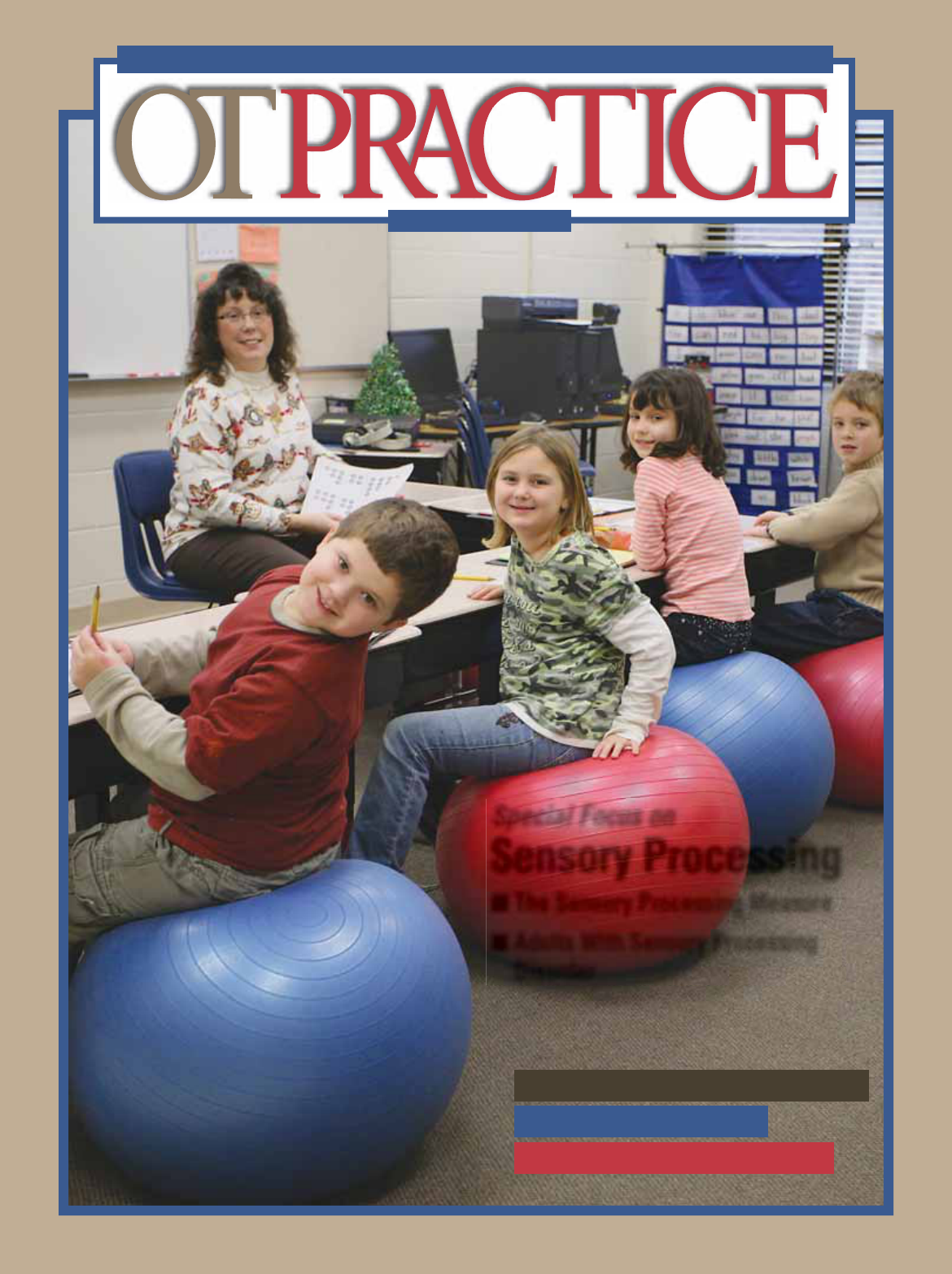

Special Focus on

Sensory Processing

■ The Sensory Processing Measure

■ Adults With Sensory Processing

Disorder

JUNE 15, 2009

PLUS

Proposed Medicare Regulations

Handwriting Training

The Dance of Independence

1

DEPARTMENTS

News 3

Capital Briefi ng 6

Medicare Proposed Regulations

In the Clinic 8

Handwriting Training

for the Nondominant Hand

Continuing Competence 20

Volunteer Service as

Professional Development

Occupation in Action 21

A Strong Foundation

for Independent Living

Calendar 23

Continuing Education Opportunities

Employment Opportunities 27

Living Life To Its Fullest 32

OT Refl ections From the Heart

The Dance of Independence

AOTA • THE AMERICAN OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY ASSOCIATION

VOLUME 14 • ISSUE 10 • JUNE 15, 2009

Discuss OT Practice articles at www.OTConnections.org in the OT Practice Discussions Forum.

Send e-mails regarding editorial content to [email protected].

Visit our Web site at www.aota.org for OT Practice online,

contributor guidelines, and additional news and information.

OT PRACTICE • JUNE 15, 2009

OT Practice serves as a comprehensive source for practical information to help occupational therapists and occupational therapy

assistants to succeed professionally. OT Practice encourages a dialogue among members on professional concerns and views.

The opinions and positions expressed by contributors are their own and not necessarily those of OT Practice’s editors or AOTA.

Advertising is accepted on the basis of conformity with AOTA standards. AOTA is not responsible for statements made by advertisers,

nor does acceptance of advertising imply endorsement, offi cial attitude, or position of OT Practice’s editors, Advisory Board, or

The American Occupational Therapy Association, Inc. For inquiries, contact the advertising department at 800-877-1383, ext. 2715.

Changes of address need to be reported to AOTA at least 6 weeks in advance. Members and subscribers should notify the Membership

department. Copies not delivered because of address changes will not be replaced. Replacements for copies that were damaged in

the mail must be requested within 2 months of the date of issue for domestic subscribers and within 4 months of the date of issue for

foreign subscribers. Send notice of address change to AOTA, PO Box 31220, Bethesda, MD 20824-1220, e-mail to [email protected],

or make the change at our Web site at www.aota.org.

Back issues are available prepaid from AOTA’s Membership department for $16 each for AOTA members and $24.75 each for

nonmembers (U.S. and Canada) while supplies last.

Members who prefer to access this publication electronically may view it as a PDF at www.aota.org. To request each issue in Word

format (without graphics or other design elements), send an e-mail to [email protected].

FEATURES

Using the 9

Sensory Processing

Measure (SPM) in

Multiple Practice Areas

Diana A. Henry, Cheryl E. Ecker, Tara

J. Glennon, & David Herzberg show how

the SPM is used in children’s school and

home environments to help identify the

most appropriate interventions.

Occupational Therapy 15

Intervention for

Adults

With Sensory Processing

Disorder

Teresa A. May-Benson describes a

personalized, intensive protocol

that is tailored to adults and

designed for quick results.

COVER PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY OF DIANA HENRY

Chief Operating Offi cer: Christopher Bluhm

Director of Marketing & Member Communications:

Beth Ledford

Editor: Laura Collins

Senior Editor: Molly Strzelecki

CE Articles Editor: Sarah D. Hertfelder

Art Director: Carol Strauch

Production Manager: Sarah Ely

Director of Sales & Corporate Relations: Jeffrey A. Casper

Account Executive: Tracy Hammond

Advertising Assistant: Clark Collins

Ad inquiries: 800-877-1383, ext. 2715,

or e-mail [email protected]

OT Practice External Advisory Board

Asha Asher, Chairperson, Developmental

Disabilities Special Interest Section

Salvador Bondoc, Chairperson, Physical

Disabilities Special Interest Section

Barbara E. Chandler, Chairperson, Early

Intervention & School Special Interest Section

Sharon J. Elliott, Chairperson, Gerontology

Special Interest Section

Jyothi Gupta, Chairperson, Education Special

Interest Section

Kimberly Hartmann, Chairperson, Technology

Special Interest Section

Christine Kroll, Chairperson, Administration

& Management Special Interest Section

Lisa Mahaffey, Chairperson, Mental Health

Special Interest Section

Kathy Maltchev, Chairperson, Work and

Industry Special Interest Section

Pamela Toto, Chairperson, Special Interest

Sections Council

Karen Vance, Chairperson, Home &

Community Health Special Interest Section

Renee Watling, Chairperson,

Sensory Integration Special Interest Section

AOTA President: Penelope Moyers Cleveland

Executive Director: Frederick P. Somers

Chief Public Affairs Offi cer: Christina Metzler

Chief Financial Offi cer: Chuck Partridge

Chief Professional Affairs Offi cer: Maureen Peterson

© 2009 by The American Occupational Therapy Association, Inc.

OT Practice (ISSN 1084-4902) is published 22 times a year,

semimonthly except only once in January and December by

the American Occupational Therapy Association, Inc., 4720

Montgomery Lane, Bethesda, MD 20814-3425; 301-652-2682.

Periodical postage is paid at Bethesda, MD, and at additional

mailing offi ces.

U.S. Postmaster: Send address changes to OT Practice, AOTA,

PO Box 31220, Bethesda, MD 20824-1220.

Canadian Publications Mail Agreement No. 41071009. Return

Undeliverable Canadian Addresses to PO Box 503, RPO West

Beaver Creek, Richmond Hill ON L4B 4R6.

Mission statement: The American Occupational Therapy Asso-

ciation advances the quality, availability, use, and support of

occupational therapy through standard-setting, advocacy, edu-

cation, and research on behalf of its members and the public.

Annual membership dues are $225 for OTs, $131 for OTAs, and

$75 for Student-Plus members, of which $14 is allocated to the

subscription to this publication. Standard Student membership

dues are $53 and do not include OT Practice. Subscriptions in

the U.S. are $142.50 for individuals and $216.50 for institutions.

Subscriptions in Canada are $205.25 for individuals and $262.50

for institutions. Subscriptions outside the U.S. and Canada

are $310 for individuals and $365 for institutions. Allow 4 to 6

weeks for delivery of the fi rst issue.

Copyright of OT Practice is held by The American Occupational

Therapy Association, Inc. Written permission must be obtained

from AOTA to reproduce or photocopy material appearing in

OT Practice. A fee of $15 per page, or per table or illustration,

including photographs, will be charged and must be paid before

written permission is granted. Direct requests to Permissions,

Publications Department, AOTA, or through the Publications

area of our Web site. Allow 2 weeks for a response.

9

OT PRACTICE • JUNE 15, 2009

PHOTOS COURTESY OF THE AUTHORS

S

ince its publication in

2007, the Sensory Pro-

cessing Measure (SPM)

1

has received positive

reviews for applicabil-

ity in both clinical and

school-based practice, in

part because it can be scored quickly

and easily. This article illustrates

usage through case examples, as well

as discusses important psychometric

properties of the tool.

FOCUS ON COLLABORATION

The SPM is unique in that it was stan-

dardized on the same group of children

in their home and school environ-

ments. Rating forms for both parents

and school staff affords everyone a

chance to document their perspectives

of the child within their respective

environments. As one teacher stated,

“The SPM provides a ‘bird’s eye view’

of the student’s sensory processing

performance in various environments,

including those where I do not see the

student.” This format helps clinicians

realize that the adults in each of the

child’s environments have important

perspectives that must be considered.

In addition to the home and main

classroom, the perspectives of staff

members in that student’s art, music,

and physical education (PE) classes;

during recess; on the bus; and in the

cafeteria can be quickly taken into

consideration via six SPM environment

(reproducible) forms. Each contains

only 15 questions, except the Bus form,

which contains 10. The following case

examples illustrate the importance of

obtaining information from others in

order to gain insight into the student’s

daily sensory processing challenges,

as well as to collaborate for developing

strategies.

SCHOOL-BASED SERVICES

Case Example: Cafeteria Intervention

Before the fi ndings of the SPM had

been implemented, 8-year-old Bob, a

DIANA A. HENRY

CHERYL E. ECKER

TARA J. GLENNON

DAVID HERZBERG

Sensory Processing

Measure

(

SPM

)

The SPM is a quick, easy-to-use, reliable measure of

children’s sensory processing and praxis at home and

in school environments.

Using the

in Multiple

Practice Areas

Figure 2. Chair balls are used for students

with vestibular-seeking behaviors and

postural control issues.

10

JUNE 15, 2009 • WWW.AOTA.ORG

student with attention defi cit hyperac-

tivity disorder, was being reprimanded

daily in the cafeteria, unbeknownst to

other school personnel or his parents.

Bob was self-initiating activities he had

learned in occupational therapy and

speech therapy (e.g., sucking apple-

sauce through a tiny straw), but the

cafeteria worker had not been privy to

Bob’s oral-motor and sensory-seeking

needs. Taking seriously her responsi-

bilities to keep the cafeteria clean and

orderly, she was concerned that Bob’s

oral motor activities often caused a

mess and did not “appear” to be appro-

priate behavior in the cafeteria.

Although the team discussed Bob’s

activities as appropriate sensory seek-

ing/proprioceptive input, the cafete-

ria worker who completed the SPM

Cafeteria form

2

helped the team realize

that Bob was not demonstrating appro-

priate behavior based on what she

expected in the cafeteria. At the same

time, completing the SPM afforded the

worker the opportunity to understand

why Bob was demonstrating what she

considered inappropriate behavior.

She became aware of Bob’s sensory

processing challenges and their impact

on his occupational performance

throughout the school day. This mutual

understanding opened the door for

implementing a successful intervention

plan within all environments, includ-

ing the cafeteria. Progress measured

via the SPM posttest 5 months later

revealed that the strategies, listed

below, were working.

■ Bob learned to appropriately

explain his sensory needs.

■ A sport bottle for sucking was made

available to Bob throughout the day.

■ Bob used an oral motor transition

tool on the way to lunch.

■ Bob drank thick yogurt through

a straw, using a cup with a lid to

obtain oral motor input while keep-

ing the contents from spilling over.

■ Bob took responsibility for cleaning

up after himself.

Case Example:

Response to Intervention (RtI)

Student Study Teams (SST), often com-

posed of classroom and special educa-

tion teachers, a school administrator,

and hopefully an OT, meet to develop

early intervention services when there

is a problem behavior in a classroom.

Under RtI, an SST used the SPM to

identify potential sensory barriers to a

class of children maintaining attention,

resulting in the team suggesting more

movement opportunities throughout

day. In fact, many teachers report

that breaks in general are essential for

alertness and that increased move-

ment experiences positively infl uence

cognition. The staff in this school

implemented movement breaks (e.g.,

shakes and wiggles) (see Figure 1) as a

Tier 1 intervention (general education

strategies for all students) and provided

chair balls for desk work to students

who demonstrated vestibular seeking

behaviors and postural control issues

(a Tier II intervention) (see Figure 2 on

p. 9). This strategy was supported by

research on chair ball use in the class-

room, which reported improved in-seat

behavior and legible word productivity.

3

Case Example: Gym Class

The SPM (including the PE form)

was used for Lucas, a student with

autism, and revealed proprioceptive

concerns, vestibular challenges, poor

bilateral integration, diffi culty with

praxis, and decreased social participa-

tion. Although Lucas was successfully

included in his 4th grade classroom, he

was unable to participate in many PE

activities, including volleyball. He was

unable to maintain focus on the ball, or

to motor plan the timing and sequenc-

ing of his movements to volley back

and forth. Lucas’s school occupational

therapist, PE teacher, and clinic-based

occupational therapist (at his mother’s

suggestion, as Lucas had received

Ayres sensory integration intervention

during the summer) collaborated and

created a plan to have Lucas be a PE

helper as part of his special education

support plan (Tier III intervention).

The ability of the SPM to promote

collaboration between school- and

clinic-based therapists yielded positive

results for Lucas. For example, during

volleyball, he indicated which team

was serving by pushing a milk crate

with weighted materials from one side

of the net to the other (see Figure 3

on p. 11). Several sensory and praxis

goals were addressed in this way, and

his self-esteem increased as he assisted

his teacher in this functional task. This

strategy served as a mechanism for

Lucas to stay engaged in the game,

interact with the other students, and

obtain the sensory input he needed.

CLINIC-BASED SERVICES

Regardless of setting, the SPM can

facilitate a team approach, help guide

discussion, and provide a quantifi able

picture of the child’s sensory process-

ing, with statistical assurance that the

SPM is measuring sensory process-

ing. The SPM has been instrumental

in helping many families and medical

teams to reframe children’s behaviors.

Many parents have described a sense

Figure 1. Students engage in shakes and wiggles as part of a movement break.

11

OT PRACTICE • JUNE 15, 2009

of relief and empowerment when their

descriptions of their children were

quantifi ed to demonstrate sensory pro-

cessing problems. The following section

highlights some of SPM’s clinical uses.

Case Example: Quantifying Dysfunction

for Professionals

Jared, a 6 year old, avoided using any

public bathrooms because of the sound

of the toilet, had bitter fi ghts over teeth

brushing, and had a prolonged morning

routine because of discomfort with his

clothing. His pediatrician responded

to these concerns by prescribing

anti-anxiety medication and providing

instructions to Jared’s parents on set-

ting limits. When Jared’s parents later

found an occupational therapist trained

in sensory integration and completed

the SPM Home form, they fi nally had

quantifi able information that Jared

had “some problems” for hearing and

“defi nite dysfunction” for touch. In

communications with the pediatrician,

the occupational therapist was able to

reframe Jared’s functional problems

by identifying the underlying sensory

processing problems, thus demonstrat-

ing that the behavior issues were not

caused by “poor parenting.” With the

support of the pediatrician Jared began

participating in occupational therapy,

with positive functional outcomes in

the initially identifi ed areas of concern.

Case Example: Reframing Symptoms of

Sensory Processing Disorder

At school, 8-year-old Thomas was

having trouble with social relationships,

following directions, and sitting still.

Because he performed academically at

grade level and his school psychologist

Figure 3. Lucas pushes a milk crate with weighted materials to indicate which team is serving,

which allowed him to participate while addressing his sensory needs.

THE MOST THOROUGH AND PRACTICAL SENSORY INTEGRATION TRAINING IN THE WORLD

USC/WPS Comprehensive Program

in Sensory Integration

This four-course series covers sensory integration theory,

assessment, interpretation, and intervention.

• Learn how sensory systems affect everyday functioning

• Learn how to administer and interpret the

Sensory Integration and Praxis Tests (SIPT)

• Learn how to design and implement effective intervention

• Attain your USC/WPS Certificate in Sensory Integration

For a complete schedule or to register:

Visit wpspublish.com

Call 800-648-8857

Upcoming Courses in:

Cincinnati, OH

Santa Rosa, CA

Miami, FL

Dallas, TX

Western Psychological Services

P-4146

12

JUNE 15, 2009 • WWW.AOTA.ORG

and teacher felt he just had behavior

problems, he did not qualify for occu-

pational therapy services in school. At

the suggestion of a friend, Thomas’s

mother contacted an occupational

therapist in a clinic setting. As part

of the assessment, both the Home

and Main Classroom SPM forms were

completed. The results confi rmed that

Thomas’s challenges at school were

related to sensory processing. When

Thomas’s mother completed the SPM,

she realized that Thomas had extreme

responses to sensory input in his home

and community that she had never

noticed before, because she had been

unknowingly accommodating him. For

example, Thomas was bothered by the

feel of his sheets and clothing; seemed

to not get dizzy; leaned on other peo-

ple; and tended to do everything with

too much force, including petting his

neighbor’s dog and hugging his mother

and sister. The SPM results enabled the

clinic-based therapist to identify goals

that would be medically relevant and

reimbursed by the insurance carrier

(i.e., in 6 months, Thomas will dem-

onstrate increased body awareness

when hugging his mother and sibling

as demonstrated by appropriate force,

lack of injury, and no expression of pain

or discomfort from either recipient,

90% of the time). In addition, the SPM

enabled the clinic-based occupational

therapist to provide suggestions for

sensory-based activities that could be

infused into Thomas’s school day (i.e.,

more movement opportunities between

deskwork activities because his SPM

scores refl ected dysfunction in his

vestibular and proprioception systems.

These suggestions resulted in Thomas

being able to listen more attentively

and sit still more often.

Case Example: Food Sensitivity

Seven-year-old Sera was referred to

occupational therapy because of her

narrow, unhealthy repertoire of foods.

Her scores on the SPM fell in the

typical range, potentially indicating

that there were other reasons for her

disordered eating. However, as the SPM

manual indicates, the therapist should

examine individual items if there is any

reason for concern.

1

A review of the

SPM questions with Sera’s parents, and

clinical observations, indicated sensory

integration problems. For example,

Sera’s parents commented that she

“never” had certain responses to sen-

sory input because she had “overcome”

her sensitivities. When answering

the SPM item, “Does your child show

distress at smells that other children

do not notice?” they reported that she

was not distressed, but she noticed the

slightest fragrances or odors. The SPM

item analysis indicated slight varia-

tions in scores, thus clinical reasoning

yielded additional information, allowing

for a more specifi c intervention plan

and leading Sera to tolerate and accept

a greater range of different nutritious

foods, with less tension during meals.

PSYCHOMETRIC STRENGTH

OF THE SPM

For an assessment tool to be reliable

for clinical practice, it must provide

accurate and consistent information.

This section summarizes evidence dem-

onstrating that the SPM is a valid and

reliable measure of sensory processing,

praxis, and social participation.

The SPM was developed with a

large, demographically representative

normative sample, consisting of 1,051

typically developing children, ranging

in age from 5 to 12 years. The norma-

tive sample was roughly divided among

males and females, ethnically diverse,

and representative of various levels of

socioeconomic status.

A normative sample provides clini-

cians with the expected SPM scores for

typically developing children. There-

fore, when determining whether a child

has a sensory processing disorder, the

clinician simply compares the SPM

scores to the average scores of the

normative sample. This comparison

classifi es the child into one of three

SPM interpretive ranges: (1) typical,

(2) some problems, or (3) defi nite

dysfunction.

Some measurement error is possible

in all tests. When developing the SPM,

a premium was placed on establishing

high reliability, or reducing the amount

of measurement error as much as

possible. One important aspect of reli-

ability is internal consistency, which

expresses how well the items of the

SPM “hang together” to measure clear,

well-defi ned aspects of sensory pro-

cessing. For example, the SPM Hearing

scale is intended to measure problems

with auditory processing. If some of

the items on the Hearing scale had

measured some other construct (e.g.,

attention span, aggressiveness, etc.),

the Hearing scale’s internal consistency

would have been lower. Internal con-

sistency is expressed as a correlation

coeffi cient that ranges in value from

0 to 1, with higher values indicating

greater reliability. In the SPM norma-

tive sample, all of the scales on the

Home and School forms have internal

consistency greater than .70 (and most

are greater than .80), indicating that

they are reliable enough to support

clinical assessment.

Another important aspect of reliabil-

ity is test-retest reliability, or temporal

stability. The SPM and other behavioral

rating scales are presumed to measure

characteristics of children that are

stable over short periods. For example,

one would not expect a child’s level of

dysfunction in auditory processing to

change appreciably over 2 weeks, all

else being equal. The 2-week test-

retest correlations for the SPM scales

are almost all .95 or above, indicating

excellent temporal stability.

The validity of an assessment has

various facets, some theoretical and

some practical. Discriminant validity

refers to the SPM’s ability to differenti-

ate between typically developing chil-

dren and those with sensory processing

dysfunction. As part of the SPM devel-

opment research, a clinical sample was

collected, consisting of 345 children

FOR MORE INFORMATION

AOTA CEonCD™: Response to Intervention:

A Role for Occupational Therapy Practitioners

By G. Frolek Clark, 2008. (Earn .2 AOTA CEUs

[2 NBCOT PDUs/2 contact hours.] $68 for

members, $97 for nonmembers. To order, call

toll free 877-404-AOTA or shop online at http://

store.aota.org. Order #4826-MI.)

FAQ on Response to Intervention

American Occupational Therapy Association,

2008. Bethesda, MD: Author.

http://www.aota.org/Practitioners/PracticeAreas/

Pediatrics/Browse/School/FAQ-Response-to-

Intervention.aspx

Online chat between school and clinic based

therapists hosted on www.otexchange.com

by Deanna Iris Sava and Diana A. Henry.

Go to www.ateachabout.com home page and

click on Discussion chat about the SPM.

Sensory Processing Measure Web site

www.sensoryprocessingmeasure.com

13

OT PRACTICE • JUNE 15, 2009

who were currently receiving occupa-

tional therapy intervention for sensory

and motor problems. These children

had a wide range of conditions, from

sensory processing disorder, to atten-

tion defi cit disorder, to autism.

The SPM scores of the children in the

clinical sample were signifi cantly higher

(worse) on all eight scales than the

scores of typically developing children

from the normative sample. A measure

of effect size was used to determine

whether these SPM score differences

were clinically meaningful, in addition

to being statistically signifi cant. In every

instance, the effect size of these differ-

ences exceeded .8, which is the thresh-

old for a large, clinically signifi cant

effect.

4

These results allow clinicians to

use the SPM with the confi dence that it

identifi es children who need treatment

for sensory processing disorder.

CONCLUSION

The applicability of the SPM in both

school- and clinic-based practice is

clear. In addition to providing fi rst-hand

information from those who are part

of the child’s life and facilitating team

communication, this statistically sound

assessment tool gives therapists the

ability to document the need for occu-

pational therapy services and design

appropriate interventions. (Case

studies under development with the

Sensory Processing Measure—

Preschool [SPM-P, for 2- to 5-year-olds]

are indicating that it too will aid clini-

cians who support children in various

environments.)

■

Acknowledgments

The authors offer grateful thanks to staff, parents,

and students at Horseshoe Trails and Desert Sun

Elementary schools in Arizona; Monroe Road

Elementary in Michigan; and therapists at Rehab

Dynamics in Ohio.

References

1. Parham, L. D., Ecker, C., Miller-Kuhaneck, H.,

Henry, D. A., & Glennon, T. J. (2007). Sensory

Processing Measure (SPM): Manual. Los Ange-

les: Western Psychological Services.

2. Miller-Kuhaneck, H., Henry, D. A., & Glennon, T.

J. (2007). Sensory Processing Measure (SPM)

School Environments Form. Los Angeles: West-

ern Psychological Services.

3. Schilling, O. L., Washington, K., Billingsley, F.

F., & Deitz, J. (2003). Classroom seating for

children with attention defi cit hyperactivity

disorder: Therapy balls versus chairs. American

Journal of Occupational Therapy, 57, 534–541.

4. Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological

Bulletin, 112, 155–159.

Diana A. Henry, MS, OTR/L, FAOTA, president of

Henry Occupational Therapy Services, presents

workshops on the SPM as well as on Sensory Tools

for Tots, Teens, Teachers, and Parents. Traveling

full-time in her RV, she can be reached at www.

ateachabout.com.

Cheryl L. Ecker, MA, OTR/L, BCP, SWC, is the

clinical director at Therapy in Action in Tarzana,

California.

Tara J. Glennon, EdD, OTR/L, FAOTA, is a profes-

sor of Occupational Therapy at Quinnipiac Univer-

sity in Hamden, Connecticut. She is also the owner

of the Center for Pediatric Therapy in Fairfi eld and

Wallingford, Connecticut.

David Herzberg, PhD, is vice president of

Research and Development at Western Psychologi-

cal Services, the publisher of the SPM. He can be

reached at [email protected].

To discuss this article,

go to

www.otconnections.org. Click on

Forums, Public Forums, then

OT Practice Magazine discussion.

Western Psychological Services

wpspublish.com • 800-648-8857

Order your copy of the SPM today!

Easy to Score and Interpret

Other tests make this claim, but the SPM actually lives up

to it. AutoScore™ forms with built-in Profile Sheets give

you rapid scoring and a quick visual summary of results.

Clear Results

SPM scales are described in

simple, nontechnical language:

• Social Participation

• Vision

• Hearing

• Touch

• Body Awareness

• Balance and Motion

• Planning and Ideas

• Total Sensory Systems

Because it’s easy to explain what

you’re measuring, it’s also easy to explain results.

You get a comprehensive, clinically rich picture of

the child that parents intuitively understand.

Direct Comparison of Sensory

Functioning at Home and at School

With Home and School Forms standardized on

the same group of children, the SPM is the only

assessment that allows you to directly compare

the child’s functioning across environments.

Home Form

L. Diane Parham, Ph.D., OTR/L, FAOTA, and Cheryl Ecker, M.A., OTR/L

Main Classroom and School Environments Forms

Heather Miller Kuhaneck, M.S., OTR/L, Diana A. Henry, M.S., OTR/L,

and Tara J. Glennon, Ed.D., OTR/L, FAOTA

The best in every sense

Sensory Processing Measure

KITS

COMPREHENSIVE KIT (W-466) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . $149.00

Includes 25 Home AutoScore™ Forms; 25 Main Classroom AutoScore™ Forms;

School Environments Form CD; Manual

SCHOOL KIT (W-466S) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . $120.00

Includes 25 Main Classroom AutoScore™ Forms; School Environments Form CD; Manual

HOME KIT (W-466H) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . $95.00

Includes 25 Home AutoScore

™

Forms; Manual

At a Glance…

benefit: Provides a complete

picture of children’s sensory processing difficulties

at school, at home, and in the community

ages: 5 to 12 years

administration time: 15 to 20 minutes

format: Parent and/or teacher rating scale; additional

rating sheets completed by other school personnel

norms: Based on a nationally representative sample

of 1,051 children. Additional data were collected on

a clinical sample of 345 children.

P-4147