OBTAINING PARENTAL CONSENT

TO BILL MEDICAID:

An Unnecessary, Time-Consuming and

Emotionally Fraught Process for Districts

and Parents

In December 2022, AASA, The School Superintendents

Association (AASA) along with the National Alliance for

Medicaid in Education (NAME) and the Association of

Educational Service Agencies (AESA) surveyed district

leaders and school-based Medicaid leads at the LEA

and ESA level to better understand the impact of the

U.S. Department of Education’s current parental consent

regulation on the school-based Medicaid program.

AASA, NAME and AESA were interested in

understanding whether there has been increased

difficulty in obtaining signed parental consent forms due

to the pandemic and the increased politicization of

America’s public education system and government. As

the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid finalize the

release of a new administrative claiming guide that will

simplify Medicaid billing for districts and ESAs, now is

the ideal time for the U.S. Department of Education to

also take steps to reduce the confusion and burden of

the parental consent regulation, so districts can adopt a

systematic approach to improving school-based

Medicaid documentation.

This is an analysis of the data collected and issues

identified by the survey, which was completed by 458

respondents in 43 states. Survey respondents had the

opportunity to share their varied experiences with

obtaining parental consent for Medicaid reimbursement

and we have collected and grouped a sample of the

responses to further illustrate the findings.

INTRODUCTION

PAGE | 1

January 2023

SURVEY FINDINGS

PAGE | 2

The first question asked respondents to identify barriers

to obtaining parental consent to billing Medicaid. The

top two barriers identified were 1) overcoming general

concerns by parents about signing any kind of release

form related to Medicaid and the impact it would have

on their child’s insurance and 2) the significant burden

on staff to obtain the signed consent forms.

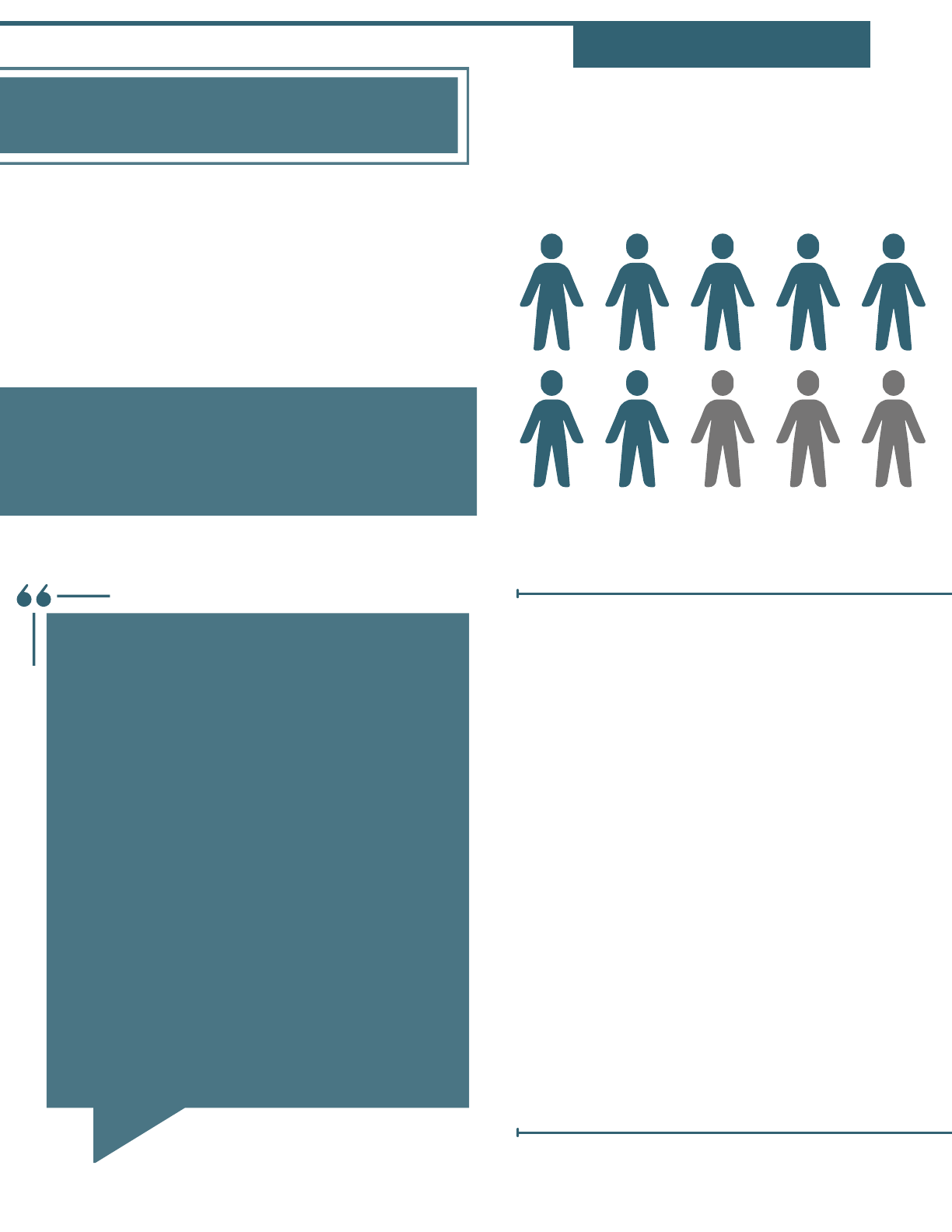

Seventy percent expressed that there is

generalized concern by parents about signing

any kind of consent or release form related to

billing Medicaid.

Since 2005, district personnel have voiced concerns

that presenting a separate signed consent form for

Medicaid reimbursement has been confusing and

problematic for parents. While the U.S. Department of

Education attempted to improve the initial parental

consent regulation in the Individuals with Disabilities

Education Act (IDEA) for Medicaid reimbursement in

2013 for services that are delivered as part of a

student’s individualized education program (IEP),

there is still considerable confusion from parents

about why they should complete the consent form

and why the school needs a separate permission to

bill Medicaid for healthcare services they are

delivering to their child in schools. As districts around

the country begin to bill for non-IEP services the

confusion about signing a consent form has been

amplified. A parent with two children—one with an IEP

and one without—may only be asked to sign a

consent form for the child with the IEP even though

there is a separate requirement under Family

Educational Rights and Privacy Act to receive consent

for accessing Medicaid reimbursement.

“Parents/guardians do not understand what the form is

for, and they are hesitant to sign because of their

financial situation(s) becoming public/known to federal

officials.”

“Some parents just flat out refuse because they believe

there are strings attached; don't fully understand the

process despite trying to educate them.”

“Parents believe the school accessing these funds

reduce the amount of Medicaid funding that is available

over their child’s lifetime.”

“Despite reassurances, parents repeatedly have

expressed fear of how this will impact services outside

of school and they are concerned that the consent may

result in the sharing of information on logs/submissions

that they do not wish to share with ‘the government.’”

“We hear that some families do not wish to give consent

for fear of a stigma associated with Medicaid enrollment

and perceived discrimination.”

FROM THE FIELD

1

PAGE | 3

School-based providers are unique in that they have

roles beyond the healthcare services they deliver to

perform in schools. They are not bound to only

delivering Medicaid services to students with IEPs—

they provide healthcare-related students to 504 plans,

who may or may not be covered under Medicaid, and

who are not Medicaid eligible for other reasons. They

also act in other capacities: they supervise students

in the cafeteria or in homeroom, they may assist with

extracurricular activities, they attend school-wide

events and staff meetings. Moreover, many Medicaid

providers and specialized instructional support

personnel in schools lack the back-office

administrative support of other healthcare settings

where completing Medicaid documentation, IEP

documentation and other billing education and

medical documentation is their responsibility. This

means that chasing down consent forms also falls on

them and takes time away from their other student-

focused responsibilities. Given the national shortage

of these professionals in our schools, it is imperative

that their work being focused on serving the high

caseloads of students they see every week rather

than on obtaining parental consent forms.

“We have to spend a significant amount of time asking

staff to reach out parents to get the consent forms

signed. Staff already have their plates full and feel

overwhelmed with paperwork when working through a

student's IEP. We continually find students that are

receiving services will not have a consent form in place,

however everything else will be correct and they are

eligible for Medicaid billing. It is also very discouraging

to our staff to get all of the other pieces in place, and

then to find out that none of the services we provided

can be reimbursed because an initial consent from the

parent was never obtained.”

“Within a district where over 79 languages are spoken,

the explanation of this consent coupled with language

barriers has a significant impact on our consent

percentages. In addition, we have an extremely high

percentage of students entering the district from

elsewhere and it is typical for the consent to be missing

from the receipt of student records. This results in much

staff time being spent to track the form down or restart

the consent process.”

“Not all districts have the manpower to go after missed

opportunities to obtain consent, as most staff are

wearing many hats. I have even heard of employees

seeking work in districts that do not participate in

Medicaid, so they don't have to do the additional work

that is involved. This ultimately hurts the students.”

“My school district has a low percentage of lower social-

economic students and my staff spends countless

hours trying to obtain parent signatures. I cannot

fathom how much time must be spent by schools with

higher percentages of lower social-economic students.”

“Our Medicaid dollars have dropped significantly due to

our inability to obtain parent consents. Our staff call,

meet, text, message, etc. with parents to explain the

form and what we need, yet we cannot get signed forms

returned.”

FROM THE FIELD

2

Two-thirds of respondents described the burden

on staff to follow-up with parents to complete

forms was significant.

6-10%

51-75%

PAGE | 4

The second question asked survey respondents what

percent of their parental consent forms are not

signed or returned. The answers varied considerably.

“We currently have 37% of Medicaid eligible students

without signed consent. This is a significant amount of

revenue we are not receiving. Contacting parents,

sending and explaining consent forms takes time that

could be spent serving students.”

“Many parents think that by signing the consent it will

affect any outside services they receive. If 20-25% of

parental consents are unattained, then 20-25% of

reimbursement is affected. The need for medical and

mental health in schools has increased dramatically

over last 5 years. Schools cannot keep increasing costs

without reimbursement. This is not sustainable over

long term.”

“Chasing consents is a real problem and takes up many

hours of non-reimbursable time. Having a student or

several students with no parental consent show up in

the annual billing compliance review really hurts our

compliance percentage which in turn drastically reduces

our reimbursement.”

Almost a quarter of respondents said between 1-

10% of their forms are not signed.

Approximately a third said that between 26-50%

of their forms are not completed.

Eighteen percent said their over 50% or more of

their forms are not signed.

The inability to obtain signed consent forms can have

major implications for district finances. A student

with significant healthcare needs that requires a

personal care assistant, multiple services from a

variety of specialized instructional support personnel

and specialized transportation, can easily cost the

district a $100,000 per year to provide. If this student

attends a small or rural school with an operating

budget of $10 million and the parent is scared to sign

the consent form for the district, the district is forced

to spend one percent of their entire budget on

educating this student and are unable to receive any

financial support from Medicaid to cover the cost of

these Medicaid-reimbursable services.

As states look to expand their healthcare services,

particularly their mental health services for students,

Medicaid presents a critical funding stream that

enables districts to provide these additional

healthcare services. While by no means a dollar-to-

dollar match in reimbursement, AASA has found that

most districts utilize Medicaid reimbursement to pay

the salaries for specialized instructional support

personnel. The greater the reimbursement they

receive, the more personnel they can hire to support

students’ healthcare needs. The COVID-19 pandemic

highlighted the importance of the delivery of

healthcare services in schools and how critical the

expansion of these services is to ensuring students

can learn.

Percent of Forms Not Completed

5%

13%

11%

11%

32%

13%

76% or more

0-5%

11-25%

26-50%

FROM THE FIELD

3

PAGE | 5

“Every dollar counts. The inability to successfully

either obtain consent or have the appropriate

processes in place to document that consent has had

a significant impact on the Medicaid reimbursement

received in our county. I believe the reimbursement

received could have been about 50% higher if another

layer of consent was not required.”

“We have many parents in our district who are not

U.S. citizens and they are reluctant to complete any

forms. Even though we continue to provide quality

services, it is at a huge financial impact to our

district.”

“"For every consent form not signed and returned, we

do not receive reimbursement. We have

approximately 30% of our forms not signed or

returned, thereby losing 30% of our reimbursement.”

The third question asked respondents to describe

whether it has become any more difficult to obtain

parental consent now than five years ago.

Fifty-six percent of respondents report that it is

more challenging for districts and ESAs to obtain

parental consent to bill for Medicaid services

than it was in 2017.

Thirty-one percent report that there is no increase or

decrease in the difficulty in obtaining consent forms

while seven percent says it has decreased. The

answers as to why the challenge has increased can

be grouped into three buckets: 1) the increased

politicization of America’s public education system

during the course of the pandemic, 2) changes in

state Medicaid policy that allow districts to bill for

non-IEP services known as “free care” services; 3)

parents intentionally withholding consent as a way to

“punish” districts for what they believe to be

inadequate IDEA services or noncompliance with

IDEA.

FROM THE FIELD

“I’m thrilled our state has decided to expand school-

based Medicaid, but there is no reasonable opportunity

to engage a parent/guardian about the consent form

outside of an IEP meeting. Therefore, the recent

expansion of the program to allow claiming for services

unrelated to IEPs has been meaningless because there

is no realistic way to overcome the parental consent

barrier without an IEP meeting. This is most obviously

true for any unplanned medical and mental health

services and supports. Therefore, no claiming is

occurring for these medically necessary and important

services we are delivering.”

“Our State has now added free-care in our SPA and we

are finding it much more difficult to obtain Medicaid

consent from the general education population.”

“We live in an environment where it is becoming

increasingly difficult for parents to 'trust' signing any

consent form specific to their child, especially anything

involving their child's healthcare or mental health. Our

post-pandemic world has made it even more

challenging. On the heels of locally politically

contentious issues such as masking/not masking,

vaccinations or no vaccinations, parents are less likely

to provide any level of consent to school district officials

related to any access to data or information.”

FROM THE FIELD

PAGE | 6

“Our state is able to claim for ‘Free Care’ services, which

has increased the Medicaid enrolled students we

provide direct health and mental services to that we

could submit claims for. Students with other plans of

care that require parental consent for mental health

services often will not sign the Medicaid consent as it is

confusing to them. The expected reimbursement

increase we thought we would see with ‘Free Care’ is not

apparent at this time."

"We recently had a family revoke consent because they

wanted to file a state complaint related to IEP

implementation. They essentially made the decision out

of anger toward the district."

“Parental consent requirements make it more difficult

for our district to provide resources to support student’s

mental health and emotional needs. Parents refuse to

sign the consent for Medicaid billing, but the district has

the responsibility to provide those supports, which are

expensive. We have a high number of 504 students

receiving services now, but a very difficult time getting

parents to sign the consent form. Anything that could

make it easier for us to receive Medicaid reimbursement

for these services would be appreciated.”

FROM THE FIELD

CONCLUSION

A school’s primary responsibility is to provide

students with a high-quality education. However,

children cannot learn to their fullest potential with

unmet health needs. As districts are faced with more

children with critical health and mental health care

needs and increasing demands for school personnel

to provide those services, the federal government has

a duty to remove any administrative barriers that

stand in the way of districts receiving critical funding

that can support the expansion of these healthcare

services.

AASA, NAME and AESA hope that this new survey

data highlighting the increased challenges in

obtaining parental consent and the impact it has on

the ability of school-based providers to deliver

Medicaid reimbursable services to children, spurs

policy changes at the U.S. Department of Education

that will make it easier for districts to bill Medicaid for

these healthcare services.

PAGE | 7

REFERENCES

1.) The first IDEA regulation (§300.154(d)) requiring

districts to obtain parental consent before accessing

Medicaid reimbursement for school-based services was

issued in 2005 after the reauthorization of the IDEA in 2004.

A revised IDEA Part B regulation (§300.154(d)(2)(iv)) was

issued in 2013, which modified the requirements related to

securing parental consent to access Medicaid

reimbursement. The original regulation required school

personnel to obtain parental consent each time they sought

Medicaid reimbursement. The updated regulations made it

easier for school personnel to access public benefits by

only mandating that parental consent be acquired before

the school system accessed a child’s or parent’s public

benefits or insurance for the first time. It kept the

requirement that the LEA or ESA must send an annual

notice to parents informing them that school district is

billing Medicaid for the school-based services they are

delivering to their child and that the parent can opt-out of

having the school district access Medicaid reimbursement

for those services at any time.

2.) “About The Shortage.” National Coalition on Personnel

Shortages in Special Education and Related Services,

https://specialedshortages.org/about-the-shortage/.

3.) Pudelski, Sasha. "Cutting Medicaid: A Prescription to

Hurt the Neediest Kids." AASA, The School Superintendent's

Association (2017).

The Association of Educational Service Agencies (AESA) is a professional organization serving educational service agencies (ESAs) in 45 states; there

are 553 agencies nationwide. AESA is in the position to reach well over 80% of the public school districts, over 83% of the private schools, over 80%

certified teachers, and more than 80% non-certified school employees, and well over 80% public and private school students. Annual budgets for ESAs

total approximately $15 billion. AESA’s membership is agency wide and includes all ESA employees and board members.

The National Alliance for Medicaid in Education, Inc. (NAME) is a non-profit 501(c) (3) organization comprised of members from the nation's school

districts and state Medicaid and Education agencies who are involved in administration of Medicaid claiming for school-based services. Other

members are those with an interest in the Medicaid-in-education field such as businesses, consulting firms, non-profit organizations and federal

agencies.

AASA, the School Superintendents Association, founded in 1865, is the professional organization for more than 13,000 educational leaders in the

United States and throughout the world. AASA members range from chief executive officers, superintendents and senior level school administrators to

cabinet members, professors and aspiring school system leaders. AASA members are the chief education advocates for children. AASA members

advance the goals of public education and champion children’s causes in their districts and nationwide. As school system leaders, AASA members set

the pace for academic achievement. They help shape policy, oversee its implementation and represent school districts to the public at large.